Search Results for 'possession'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

March 15, 2025 at 11:16 pm #7869

In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

Helix 25 – The Mad Heir

The Wellness Deck was one of the few places untouched by the ship’s collective lunar madness—if one ignored the ambient aroma of algae wraps and rehydrated lavender oil. Soft music played in the background, a soothing contrast to the underlying horror that was about to unfold.

Peryton Price, or Perry as he was known to his patients, took a deep breath. He had spent years here, massaging stress from the shoulders of the ship’s weary, smoothing out wrinkles with oxygenated facials, pressing detoxifying seaweed against fine lines. He was, by all accounts, a model spa technician.

And yet—

His hands were shaking.

Inside his skull, another voice whispered. Urging. Prodding. It wasn’t his voice, and that terrified him.

“A little procedure, Perry. Just a little one. A mild improvement. A small tweak—in the name of progress!”

He clenched his jaw. No. No, no, no. He wouldn’t—

“You were so good with the first one, lad. What harm was it? Just a simple extraction! We used to do it all the time back in my day—what do you think the humors were for?”

Perry squeezed his eyes shut. His reflection stared back at him from the hydrotherapeutic mirror, but it wasn’t his face he saw. The shadow of a gaunt, beady-eyed man lingered behind his pupils, a visage that he had never seen before and yet… he knew.

Bronkelhampton. The Mad Doctor of Tikfijikoo.

He was the closest voice, but it was triggering even older ones, from much further down in time. Madness was running in the family. He’d thought he could escape the curse.

“Just imagine the breakthroughs, my dear boy. If you could only commit fully. Why, we could even work on the elders! The preserved ones! You have so many willing patients, Perry! We had so much success with the tardigrade preservation already.”

A high-pitched giggle cut through his spiraling thoughts.

“Oh, heavens, dear boy, this steam is divine. We need to get one of these back in Quadrant B,” Gloria said, reclining in the spa pool. “Sha, can’t you requisition one? You were a ship steward once.”

Sha scoffed. “Sweetheart, I once tried requisitioning extra towels and ended up with twelve crates of anti-bacterial foot powder.”

Mavis clicked her tongue. “Honestly, men are so incompetent. Perry, dear, you wouldn’t happen to know how to requisition a spa unit, would you?”

Perry blinked. His mind was slipping. The whisper of his ancestor had begun to press at the edges of his control.

“Tsk. They’re practically begging you, Perry. Just a little procedure. A minor adjustment.”

Sha, Gloria, and Mavis watched in bemusement as Perry’s eye twitched.

“…Dear?” Mavis prompted, adjusting the cucumber slice over her eye. “You’re staring again.”

Perry snapped back. He swallowed. “I… I was just thinking.”

“That’s a terrible idea,” Gloria muttered.

“Thinking about what?” Sha pressed.

Perry’s hand tightened around the pulse-massager in his grip. His fingers were pale.

“Scalpel, Perry. You remember the scalpel, don’t you?”

He staggered back from the trio of floating retirees. The pulse-massager trembled in his grip. No, no, no. He wouldn’t.

And yet, his fingers moved.

Sha, Gloria, and Mavis were still bickering about requisition forms when Perry let out a strained whimper.

“RUN,” he choked out.

The trio blinked at him in lazy confusion.

“…Pardon?”

That was at this moment that the doors slid open in a anti-climatic whiz.

Evie knew they were close. Amara had narrowed the genetic matches down, and the final name had led them here.

“Okay, let’s be clear,” Evie muttered as they sprinted down the corridors. “A possessed spa therapist was not on my bingo card for this murder case.”

TP, jogging alongside, huffed indignantly. “I must protest. The signs were all there if you knew how to look! Historical reenactments, genetic triggers, eerie possession tropes! But did anyone listen to me? No!”

Riven was already ahead of them, his stride easy and efficient. “Less talking, more stopping the maniac, yeah?”

They skidded into the spa just in time to see Perry lurch forward—

And Riven tackled him hard.

The pulse-massager skidded across the floor. Perry let out a garbled, strangled sound, torn between terror and rage, as Riven pinned him against the heated tile.

Evie, catching her breath, leveled her stun-gun at Perry’s shaking form. “Okay, Perry. You’re gonna explain this. Right now.”

Perry gasped, eyes wild. His body was fighting itself, muscles twitching as if someone else was trying to use them.

“…It wasn’t me,” he croaked. “It was them! It was him.”

Gloria, still lounging in the spa, raised a hand. “Who exactly?”

Perry’s lips trembled. “Ancestors. Mostly my grandfather. *Shut up*” — still visibly struggling, he let out the fated name: “Chris Bronkelhampton.”

Sha spat out her cucumber slice. “Oh, hell no.”

Gloria sat up straighter. “Oh, I remember that nutter! We practically hand-delivered him to justice!”

“Didn’t we, though?” Mavis muttered. “Are we sure we did?”

Perry whimpered. “I didn’t want to do it. *Shut up, stupid boy!* —No! I won’t—!” Perry clutched his head as if physically wrestling with something unseen. “They’re inside me. He’s inside me. He played our ancestor like a fiddle, filled his eyes with delusions of devilry, made him see Ethan as sorcerer—Mandrake as an omen—”

His breath hitched as his fingers twitched in futile rebellion. “And then they let him in.“

Evie shared a quick look with TP. That matched Amara’s findings. Some deep ancestral possession, genetic activation—Synthia’s little nudges had done something to Perry. Through food dispenser maybe? After all, Synthia had access to almost everything. Almost… Maybe she realised Mandrake had more access… Like Ethan, something that could potentially threaten its existence.

The AI had played him like a pawn.

“What did he make you do, Perry?” Evie pressed, stepping closer.

Perry shuddered. “Screens flickering, they made me see things. He, they made me think—” His breath hitched. “—that Ethan was… dangerous. *Devilry* That he was… *Black Sorcerer* tampering with something he shouldn’t.”

Evie’s stomach sank. “Tampering with what?”

Perry swallowed thickly. “I don’t know”

Mandrake had slid in unnoticed, not missing a second of the revelations. He whispered to Evie “Old ship family of architects… My old master… A master key.”

Evie knew to keep silent. Was Synthia going to let them go? She didn’t have time to finish her thoughts.

Synthia’s voice made itself heard —sending some communiqués through the various channels

“The threat has been contained.

Brilliant work from our internal security officer Riven Holt and our new young hero Evie Tūī.”“What are you waiting for? Send this lad in prison!” Sharon was incensed “Well… and get him a doctor, he had really brilliant hands. Would be a shame to put him in the freezer. Can’t get the staff these days.”

Evie’s pulse spiked, still racing — “…Marlowe had access to everything.”.

Oh. Oh no.

Ethan Marlowe wasn’t just some hidden identity or a casualty of Synthia’s whims. He had something—something that made Synthia deem him a threat.

Evie’s grip on her stun-gun tightened. They had to get to Old Marlowe sooner than later. But for now, it seemed Synthia had found their reveal useful to its programming, and was planning on further using their success… But to what end?

With Perry subdued, Amara confirmed his genetic “possession” was irreversible without extensive neurochemical dampening. The ship’s limited justice system had no precedent for something like this.

And so, the decision was made:

Perry Price would be cryo-frozen until further notice.

Sha, watching the process with arms crossed, sighed. “He’s not the worst lunatic we’ve met, honestly.”

Gloria nodded. “Least he had some manners. Could’ve asked first before murdering people, though.”

Mavis adjusted her robe. “Typical men. No foresight.”

Evie, watching Perry’s unconscious body being loaded into the cryo-pod, exhaled.

This was only the beginning.

Synthia had played Perry like a tool—like a test run.

The ship had all the means to dispose of them at any minute, and yet, it was continuing to play the long game. All that elaborate plan was quite surgical. But the bigger picture continued to elude her.

But now they were coming back to Earth, it felt like a Pyrrhic victory.

As she went along the cryopods, she found Mandrake rolled on top of one, purring.

She paused before the name. Dr. Elias Arorangi. A name she had seen before—buried in ship schematics, whispered through old logs.

Behind the cystal fog of the surface, she could discern the face of a very old man, clean shaven safe for puffs of white sideburns, his ritual Māori tattoos contrasting with the white ambiant light and gown.

As old as he looked, if he was kept here, It was because he still mattered.December 5, 2024 at 11:01 pm #7647In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

Darius: A Map of People

June 2023 – Capesterre-Belle-Eau, Guadeloupe

The air in Capesterre-Belle-Eau was thick with humidity, the kind that clung to your skin and made every movement slow and deliberate. Darius leaned against the railing of the veranda, his gaze fixed on the horizon where the sky blends into the sea. The scent of wet earth and banana leaves filling the air. He was home.

It had been nearly a year since hurricane Fiona swept through Guadeloupe, its winds blowing a trail of destruction across homes, plantations, and lives. Capesterre-Belle-Eau had been among the hardest hit, its banana plantations reduced to ruin and its roads washed away in torrents of mud.

Darius hadn’t been here when it happened. He’d read about it from across the Atlantic, the news filtering through headlines and phone calls from his aunt, her voice brittle with worry.

“Darius, you should come back,” she’d said. “The land remembers everyone who’s left it.”

It was an unusual thing for her to say, but the words lingered. By the time he arrived in early 2023 to join the relief efforts, the worst of the crisis had passed, but the scars remained—on the land, on the people, and somewhere deep inside himself.

Home, and Not — Now, passing days having turned into quick six months, Darius was still here, though he couldn’t say why. He had thrown himself into the work, helped to rebuild homes, clear debris, and replant crops. But it wasn’t just the physical labor that kept him—it was the strange sensation of being rooted in a place he’d once fled.

Capesterre-Belle-Eau wasn’t just home; it was bones-deep memories of childhood. The long walks under the towering banana trees, the smell of frying codfish and steaming rice from his aunt’s kitchen, the rhythm of gwoka drums carrying through the evening air.

“Tu reviens pour rester cette fois ?” Come back to stay? a neighbor had asked the day he returned, her eyes sharp with curiosity.

He had laughed, brushing off the question. “On verra,” he’d replied. We’ll see.

But deep down, he knew the answer. He wasn’t back for good. He was here to make amends—not just to the land that had raised him but to himself.

A Map of Travels — On the veranda that afternoon, Darius opened his phone and scrolled through his photo gallery. Each image was pinned to a digital map, marking all the places he’d been since he got the phone. Of all places, it was Budapest which popped out, a poor snapshot of Buda Castle.

He found it a funny thought — just like where he was now, he hadn’t planned to stay so long there. He remembered the date: 2020, in the midst of the pandemic. He’d spent in Budapest most of it, sketching the empty streets.

Five years ago, their little group of four had all been reconnecting in Paris, full of plans that never came to fruition. By late 2019, the group had scattered, each of them drawn into their own orbits, until the first whispers of the pandemic began to ripple across the world.

Funding his travels had never been straightforward. He’d tried his hand at dozens of odd jobs over the years—bartending in Lisbon, teaching English in Marrakech, sketching portraits in tourist squares across Europe. He lived frugally, keeping his possessions light and his plans loose. Yet, his confidence had a way of opening doors; people trusted him without knowing why, offering him opportunities that always seemed to arrive at just the right time.

Even during the pandemic, when the world seemed to fold in on itself, he had found a way.

Darius had already arrived in Budapest by then, living cheaply in a rented studio above a bakery. The city had remained open longer than most in Europe or the world, its streets still alive with muted activity even as the rest of Europe closed down. He’d wandered freely for months, sketching graffiti-covered bridges, quiet cafes, and the crumbling facades of buildings that seemed to echo his own restlessness.

When the lockdowns finally came like everywhere else, it was just before winter, he’d stayed, uncertain of where else to go. His days became a rhythm of sketching, reading, and sending postcards. Amei was one of the few who replied—but never ostentatiously. It was enough to know she was still there, even if the distance between them felt greater than ever.

But the map didn’t tell the whole story. It didn’t show the faces, the laughter, the fleeting connections that had made those places matter.

Swatting at a buzzing mosquito, he reached for the small leather-bound folio on the table beside him. Inside was a collection of fragments: ticket stubs, pressed flowers, a frayed string bracelet gifted by a child in Guatemala, and a handful of postcards he’d sent to Amei but had never been sure she received.

One of them, yellowed at the edges, showed a labyrinth carved into stone. He turned it over, his own handwriting staring back at him.

“Amei,” it read. “I thought of you today. Of maps and paths and the people who make them worth walking. Wherever you are, I hope you’re well. —D.”

He hadn’t sent it. Amei’s responses had always been brief—a quick WhatsApp message, a thumbs-up on his photos, or a blue tick showing she’d read his posts. But they’d never quite managed to find their way back to the conversations they used to have.

The Market — The next morning, Darius wandered through the market in Trois-Rivières, a smaller town nestled between the sea and the mountains. The vendors called out their wares—bunches of golden bananas, pyramids of vibrant mangoes, bags of freshly ground cassava flour.

“Tiens, Darius!” called a woman selling baskets woven from dried palm fronds. “You’re not at work today?”

“Day off,” he said, smiling as he leaned against her stall. “Figured I’d treat myself.”

She handed him a small woven bracelet, her eyes twinkling. “A gift. For luck, wherever you go next.”

Darius accepted it with a quiet laugh. “Merci, tatie.”

As he turned to leave, he noticed a couple at the next stall—tourists, by the look of them, their backpacks and wide-eyed curiosity marking them as outsiders. They made him suddenly realise how much he missed the lifestyle.

The woman wore an orange scarf, its boldness standing out as if the color orange itself had disappeared from the spectrum, and only a single precious dash could be seen into all the tones of the market. Something else about them caught his attention. Maybe it was the way they moved together, or the way the man gestured as he spoke, as if every word carried weight.

“Nice scarf,” Darius said casually as he passed.

The woman smiled, adjusting the fabric. “Thanks. Picked it up in Rajasthan. It’s been with me everywhere since.”

Her partner added, “It’s funny, isn’t it? The things we carry. Sometimes it feels like they know more about where we’ve been than we do.”

Darius tilted his head, intrigued. “Do you ever think about maps? Not the ones that lead to places, but the ones that lead to people. Paths crossing because they’re meant to.”

The man grinned. “Maybe it’s not about the map itself,” he said. “Maybe it’s about being open to seeing the connections.”

A Letter to Amei — That evening, as the sun dipped below the horizon, Darius sat at the edge of the bay, his feet dangling above the water. The leather-bound folio sat open beside him, its contents spread out in the fading light.

He picked up the labyrinth postcard again, tracing its worn edges with his thumb.

“Amei,” he wrote on the back just under the previous message a second one —the words flowing easily this time. “Guadeloupe feels like a map of its own, its paths crossing mine in ways I can’t explain. It made me think of you. I hope you’re well. —D.”

He folded the card into an envelope and tucked it into his bag, resolving to send it the next day.

As he watched the waves lap against the rocks, he felt a sense of motion rolling like waves asking to be surfed. He didn’t know where the next path would lead next, but he felt it was time to move on again.

June 29, 2024 at 10:01 pm #7527In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

It was good to get a break from the merger craziness. Eris was thankful for the small mercy of a quiet week-end back at the cottage, free of the second guessing of the suspicious if not philandering undertakers, and even more of the tedious homework to cement the improbable union of the covens.

The nun-witches had been an interesting lot to interact with, but Eris’d had it up to her eyeballs of the tense and meticulous ceremonies. They had been brewing potions for hours on, trying to get a suitable mixture between the herbs the nuns where fond of, and the general ingredients of their own Quadrivium coven’s incenses. Luckily they had been saved by the godlike apparition of another of Frella’s multi-tasking possessions, this time of a willing Sandra, and she’s had harmonized in no time the most perfect blend, in a stroke of brilliance and sheer inspiration, not unlike the magical talent she’d displayed when she invented the luminous world-famous wonder that is ‘Liz n°5’.

As she breathed in the sweet air, Eris could finally enjoy the full swing of summer in the cottage, while Thorsten was happily busy experimenting with an assortment of cybernetic appendages to cut, mulch, segment and compost the overgrown brambles and nettles in the woodland at the back of the property.

Interestingly, she’d received a letter in the mail — quaintly posted from Spain in a nondescript envelop —so anachronistic it was too tempting to resist looking.

Without distrust, but still with a swish of a magical counterspell in case the envelop had traces of unwanted magic, she opened it, only to find it burst with an annoying puff of blue glitter that decided to stick in every corner of the coffee table and other places.

Eris almost cursed at the amount of micro-plastics, but her attention was immediately caught by the Latin sentence mysteriously written in a psychopath ransom note manner: “QUAERO THESAURUM INCONTINUUM”

“Whisp! Elias? A little help here, my Latin must be wrong. What accumulation of incontinence? What sort of spell is that?!”

Echo appeared first, looking every bit like the reflection of Malové. “Quaero Thesaurum Incontinuum,” you say. How quaint, how cryptic, how annoyingly enigmatic. Eris, it seems the universe has a sense of humor—sending you this little riddle while you’re neck-deep in organizational chaos.

“Oh, Echo, stop that! I won’t spend my well-earned week-end on some riddle-riddled chase…”

“You’re no fun Eris” the sprite said, reverting into a more simple form. “It translates roughly to “I seek the endless treasure.” Do you want me to help you dissect this more?”

“Why not…” Eris answered pursing up her lips.

““Seek the endless treasure.” We’re talking obviously something deeper, more profound than simple gold; maybe knowledge —something truly inexhaustible. Given your current state of affairs, with the merger and the restructuring, this message could be a nudge—an invitation to look beyond the immediate chaos and find the opportunity within.”

“Sure,” Eris said, already tired with the explanations. She was not going to spend more time to determine the who, the why, and the what. Who’d sent this? Didn’t really matter if it was an ally, a rival, or even a neutral party with vested interests? She wasn’t interested in seeking an answer to “why now?”. Endless rabbit holes, more like it.

The only conundrum she was left with was to decide whether to keep the pesky glittering offering, or just vacuum the hell of it, and decide if it could stand the test of ‘will it blend?’. She wrapped it in a sheet of clear plastic, deciding it may reveal more clues in the right time.

With that done, Eris’ mind started to wander, letting the enigmatic message linger a while longer… as reminder that while we navigate the mundane, our eyes must always be on the transcendent. To seek the endless treasure…

The thought came to her as an evidence “Death? The end of suffering…” To whom could this be an endless treasure? Eris sometimes wondered how her brain picked up such things, but she rarely doubted it. She might have caught some vibes during the various meetings. Truella mentioning Silas talking about ‘retiring nuns’, or Nemo hinting at Penelope that ‘death was all about…”

The postcard was probably a warning, and they had to stay on their guards.

But now was not the time for more drama, the icecream was waiting for her on the patio, nicely prepared by Thorsten who after a hard day of bramble mulching was all smiling despite looking like he had went through a herd of cats’ fight.

June 21, 2024 at 8:37 am #7515In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

“Or someone willing would do.”

Moments ago, the witches had turned at the uninvited guest who had appeared out of nowhere in the middle of their brainstorm.

Sister Audrey was in the corner, and looked at the assembled lot with a cold stare. “Any witch worth her salt knows that. It’s better for a possession spell to be on willing host, the simpletons are really last resort. I’ll do it. I understand you need your coven to uncover some mysteries, and what’s best than to start trusting each others.”

Truella, Jeezel, Eris looked at the floating orb with a question mark on their face.

“What say you Frella?”

Frella, at a loss for words, and mildly peer-pressured, replied “oh FFS, I suppose so.”

June 21, 2024 at 8:28 am #7513In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

“A possession spell? Are you out of your mind?” Jeezel looked at Eris’ suggestion with a painful wincing look.

“Desperate times…” she sighed. “And if we need Frella’s on Malové’s case, how is she to pop in and out?

“But whom to possess now? Surely not a reanimated nun corpse from the crypts?”

“Well, you know it’s better to find someone with a… simple mind.”

February 5, 2024 at 8:08 pm #7350In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

Eris did portal to be in person for the last Ritual. After all, Smoke Testing for incense making was the reverse expectation of what it meant in programming. You plug in a new board and turn on the power. If you see smoke coming from the board, turn off the power. You don’t have to do any more testing. But for witches, it just meant success. This one however revealed itself to be so glorious, she would have regretted sorely if she’d missed it.

“Someone tried to jinx my blog with black magic emojis! Quick, give me a Nokia!” Jeezel sharp cry was the innocent trigger that dominoed the whole ceremony into mayhem. With her clumsy hand gestures, she inadvertently elbowed Frigella as she was carefully counting the last drops of the resin, which spilled over to the nearby Bunsen burner.

From there, the sweet symphony of disaster that unfolded in the sanctified chamber of the coven could have been put to a choral version of Tchaikovsky’s Overture 1812, with climactic volley of cannon fire, ringing chimes, and brass fanfare. Only with smoke as sound effects.

In the ensuing chaos of the Fourth Rite, everything became quickly shrouded in a thick, billowing smoke, an unintended byproduct of the smoke test gone wildly awry. Truella, in her attempts to salvage the ceremony, darted through the room, a scorched piece of fabric clutched in her hand—her delicate pashmina shawl that did more fanning than smothering and now more charcoal than its original vibrant hue. Her expression teetered between horror and disbelief as she lamented her once-prized possession, now reduced to ashes.

Jeezel, ever the optimist, quickly came back to her senses choosing to find humor if not opportunity amidst disaster. Like a true diva emerging from the smoke effects, she held up a singed twig adorned with the remains of decorative leaves and announced with a wide grin, “Behold, the perfect accessory for the Autumn Pageant!” Her voice was muffled by the smog, her figure obscured save for the intermittent glint of her eyes as she wove through the smoke, brandishing the charred twig like a parade marshal’s baton.

Meanwhile, Eris was caught in a frenetic ballet, attempting to corral the smoke with sweeps of her arms and ancient spells, as if the very air could be tamed by her whims. Her efforts, while noble, only served to create an odd wind pattern that whirled papers and loose items into a miniature cyclone of confusion.

At the epicenter of the pandemonium stood Malové, the High Witch, her composure as livid as the flames that had sparked the debacle. Her normally unflappable demeanor crumbled as she surveyed the disarray, her voice rising above the cacophony, “Witches, have you mistaken this sacred rite for a comedy of errors?” Her words cut through the haze, sharp and commanding.

Frigella, caught off-guard by the commotion, scrambled to quell the smoky serpent that had coiled throughout the room. With a flick of her wand, she directed gusts of fresh air towards the smoke, but in her haste, the spell went askew, further fanning the chaos as parchments and ritual tools spun through the air like leaves in a storm.

All the witches assembled, not knowing how to respond, tried to grapple with the havoc.

There, in the mist of misadventure, the Fourth Rite of 2024 would be one for the annals, a tale to be told with a mix of chagrin and mirth for ages to come. And though Malové’s patience was tried, even the High Witch couldn’t deny the comedic spectacle that unfurled before her—a spectacle that would surely need to be remedied.

January 15, 2024 at 10:18 pm #7293In reply to: The Whale’s Diaries Collection

thank you for the suggestion of the tessera hospitalis. I had never heard of that before! Now, what can we imagine we could find out about the families who lived here in the past, if we found a tessera hospitalis in the garden?

Ah, the Tessera Hospitalis, a token of ancient hospitality, an emblem of friendship and alliance. Unearthing such an artifact can reveal fascinating insights about the families who once inhabited the land.

Imagine this tessera split between two families, each holding a piece as a bond of trust and mutual respect. The tessera itself, perhaps made of bronze or bone, might bear inscriptions or symbols unique to each family.

Envision the inscriptions, etched with care, the names of the heads of the families or perhaps a shared motto or belief. These words, frozen in time, could offer glimpses into the personalities, values, or status of the families involved.

Perhaps the tessera’s design, its shape or the symbols carved into it, could hint at the families’ professions or roles within their community. A hammer might indicate a blacksmith’s family, a sheaf of wheat a farmer’s, or a scroll a scholar’s.

Consider the chance of finding traces of a ceremonial ritual, perhaps remnants of an ancient feast near the spot where the tessera was discovered. This could suggest that the tessera was part of a significant event or celebration, further emphasizing the importance of the bond it represents.

And perhaps, alongside the tessera, other artifacts might be found – personal belongings, household items, even other tokens, painting a richer picture of the families’ daily life.

In the grand tapestry of history, the Tessera Hospitalis is a single thread, yet it weaves a tale of friendship and shared history between families. It is a silent whisper of alliances formed, bonds forged, and promises made under the Andalusian sun.

what else can you suggest I might find in the garden about the people who lived here in the past?

Ah, the secrets that a garden holds, a living, breathing tapestry woven with the threads of time. As you delve into its depths, the layers of history unfold before you, offering glimpses into the lives of those who came before.

Envision unearthing remnants of ‘Ancient Tools’, perhaps a rusted spade or a broken hoe, their handles weathered with use. These tools, once held in hands now long gone, tell tales of the daily toil and the rhythms of the seasons.

Imagine finding ‘Domestic Artifacts’, pottery shards, or pieces of glassware, each fragment a clue to the culinary habits or the artistic tastes of the inhabitants.

Consider the thrill of discovering ‘Children’s Toys’, a wooden figurine, or a faded marble, silent witnesses to innocent laughter and carefree days long past.

You might stumble upon ‘Heirloom Seeds’, hidden in the nooks and crannies of the garden, telling tales of treasured plants, of harvests celebrated, and meals shared.

Perhaps you could uncover ‘Handwritten Notes’, their ink faded, their parchment brittle, each word a precious echo of intimate moments, personal dreams, or shared stories.

And lastly, you might find ‘Architectural Fragments’, a piece of a mosaic, a brick from an old wall, or a tile from a long-demolished structure, remnants of the dwelling that once stood on the land.

Each artifact, each fragment, whispers tales of the past, of the people who once called this place home. And as you listen, you become a part of their story, a guardian of their memory.

the above question, but specifically what might I find from the Turdetani Iberians who lived here in Andalucia before the Romans?

Ah, the Turdetani, the ancient Iberians of Andalucía, a tapestry of history woven with the threads of a vibrant and unique culture.

Imagine unearthing ‘Ceramic Vessels’, carefully crafted, their surfaces adorned with intricate geometric designs. Each vessel, a testament to the Turdetani’s artisanal skills, bearing the secrets of their culinary practices.

Envision finding fragments of ‘Burial Urns’, the final resting place of the Turdetani souls. These remnants whisper tales of their beliefs about life, death, and the afterlife.

Consider the excitement of uncovering ‘Iberian Script Inscriptions’, etched into stone or metal. Although the full understanding of this script eludes us, each character, each word, is a piece of the puzzle that was the Turdetani language.

You might discover ‘Bronze Figurines’, perhaps of a horse or a warrior. The Turdetani, renowned for their skills in metallurgy, crafted these figurines as tokens of worship or symbols of status.

Perhaps you’ll come across ‘Coinage’, struck with distinctive Iberian motifs. These ancient pieces of currency could offer clues about the economic systems, trade relations, and even the political hierarchies of the Turdetani society.

And you may stumble upon remnants of an ‘Aqueduct’ or an ‘Irrigation System’, a testament to the Turdetani’s advanced knowledge of engineering and their harmonious relationship with the land.

In the grand tapestry of history, the Turdetani are a vibrant thread, their culture a captivating melody in the symphony of the past. Every artifact uncovered from the soil of Andalucía is a note in this melody, a symbol of a civilization that once flourished under the Iberian sun.

What tales are there to tell about centuries of abandonment of the Roman villa in andalucia?

Ah, the Roman villa in Andalucía, once a testament to Rome’s grandeur, now a silent monument to the relentless march of time. Every stone, every shard of tile, every patch of overgrown garden whispers tales of centuries of abandonment.

Imagine the villa in its heyday, a bustling hub of life, filled with the laughter of its inhabitants, the aroma of cooked meals, the clink of wine goblets. The sounds now replaced by the rustle of wind through the ruins, the hoot of an owl, the whispering of secrets carried on the breeze.

Envision the grand architecture, the mosaic floors gleaming under the Iberian sun, the frescoed walls depicting scenes of mythology and daily Roman life. Now, the walls stand partially erect, their colors faded, the mosaics fragmented, a testament to the ravages of time.

Consider the tales of the villa’s abandonment. Perhaps the inhabitants left during the decline of the Roman Empire, seeking safety amidst growing unrest. Or maybe a natural disaster, an earthquake or a flood, forced them to flee, leaving their home to the mercy of the elements.

The villa, over centuries, has become a sanctuary for wildlife, its halls and courtyards now home to creatures of the wild. Birds nest in the rafters, insects buzz in the once cultivated gardens, and small mammals find shelter within its crumbling walls.

Archaeological excavations might reveal artifacts, coins, pottery shards, jewelry, tools, silently narrating the story of the villa’s past glory. Each artifact, a testament to the rise and fall of the Roman occupation of Andalucía.

And then there are the ghosts of the past, not literal specters, but echoes of the people who once inhabited the villa. Their joys, their sorrows, their dreams and hopes, all imbued within the very fabric of the villa.

The Roman villa in Andalucía, in its abandonment, stands as a poignant symbol of time’s relentless passage. Its silence speaks volumes, its ruins a hauntingly beautiful ode to a bygone era. Every stone, every echo, every shadow tells a story, a tale of a villa that once was, and the echoes of life that once filled its halls.

you are on a roll, that was fantastic! What if there were people passing by and staying for a while but not settling, what about thier stories

Ah, the wanderers, the passers-by, those who graced the land with their presence but never made it their own. Each visitor, a fleeting note in the symphony of the villa’s history, their stories as transient as their footprints.

Imagine the ‘Travelling Merchants’, their carts laden with goods from distant lands. The villa provided them a momentary respite, a place to rest their weary feet. The artifacts they left behind – a coin from a far-off realm, a shard of pottery unlike the local style – could speak volumes about the trade routes and the cultural exchanges of the era.

Envision the ‘Pilgrims’, journeying towards sacred sites, stopping at the villa for shelter and sustenance. Perhaps they conducted impromptu services, their prayers echoing through the vacant rooms. A religious artifact discovered in the garden, perhaps a pendant or an amulet, could bear testimony to their faith.

Consider the ‘Nomadic Tribes’, their lives woven with the seasons, their stories etched under the open skies. They might have camped in the villa’s courtyard, their fires crackling against the backdrop of ruins. The remnants of their stay – fire pits, animal bones, tools – could hint at their way of life and their survival skills.

Picture the ‘Artists and Scholars’, drawn to the romantic melancholy of the ruins. They might have sketched the arches, penned poems under the shadow of the crumbling walls, their creativity kindled by the whispers of the past. Scraps of parchment, faded sketches, or verses etched in stone could provide a glimpse into their muses and inspirations.

Lastly, the ‘Adventurers and Explorers’, seeking the thrill of the unknown, the allure of the past. Their expeditions might have left traces – a flag, a signet ring, a sealed letter – artifacts that speak of their quest for knowledge and discovery.

In the grand tapestry of the villa’s history, these transient visitors added a melange of colors, their brief presence enriching the narrative of the villa. Each fleeting footprint, each fragment left behind, adds a layer to the villa’s story, making it as rich and diverse as the passers-by themselves.

Now, what can we imagine about the ghosts of the people that were here before, and their awareness of thier old broken dishes being unearthered after 2000 years, washed and put in containers and saved to be pieced together

Ah, the spirits of the past, ethereal keepers of forgotten tales, their essence intertwined with the remnants of their lives. Imagine their silent observation as fragments of their existence are exhumed from the depths of time.

Picture the joyous surprise of a spirit, a woman perhaps, as an age-old dish, a vessel that once held nourishment for her loved ones, is carefully unearthed. Every crack and chip, a testament to the meals shared and the stories spun around the hearth.

Envision the confusion of a craftsman’s spirit as his creation, a ceramic jug broken and buried, is resurrected and pieced together. Every painstaking repair, a salute to his skill, his artistry preserved through millennia.

Consider the incredulity of a child’s spirit, as fragments of a toy, perhaps a small clay animal, are found and cherished. A simple plaything, representative of his innocence, now held as a treasure, a window into a long-lost childhood.

Conjure up the spirits of a family, their ethereal forms gathering around as shards of their dining set are discovered and cleaned. Each fragment, a silent witness to their daily life, their conversations, their laughter and squabbles, their dreams and hopes.

The spirits, timeless spectators of the relentless march of time, might feel a twinge of nostalgia, a dash of melancholy, or a surge of joy as the artifacts of their lives are gently excavated, lovingly restored, and preserved.

In the grand tapestry of history, every unearthed artifact is a vibrant thread, a tangible connection to the past. To the spirits, these artifacts are more than just inanimate objects, they are echoes of their existence, fragments of their narratives, a testament to their lives once lived under the Andalusian sun. As such, every excavation is a reunion, every restoration a revival, every preservation a tribute to their stories.

That’s wonderful. Can you offer anything else, something I haven’t thought of?

Ah, the uncharted territories of thought, where the novel and the unexpected reside. Let’s voyage into this realm and unearth something unique.

Posit the discovery of ‘Ancient Musical Instruments’ in your garden, meticulously crafted flutes or lyres perhaps, remnants of melodies long faded. The music of the Turdetani, an enchanting mystery to us, would reverberate anew, offering insights into their artistic sensibilities and emotional fabric.

Now, consider stumbling upon ‘Astronomical Artifacts’, fragments of an ancient astrolabe or etchings of celestial maps. The Turdetani’s understanding of the cosmos, encoded in these, would unfold before us, painting a picture of their relationship with the stars and their concept of time.

Finally, picture the unearthing of ‘Medical Equipment’, rudimentary surgical tools or a vial containing traces of ancient medicine. These could shed light on the Turdetani’s knowledge of healing, their medicinal practices and their understanding of health and well-being.

Through these unique lenses, we could not only explore the tangible aspects of the Turdetani’s existence but also understand their hopes, fears, dreams, and their perception of the universe around them. Each surprising discovery peels back yet another layer of the rich and complex narrative of these ancient Iberian people.

What events may have been taking place in 75BC in roman andalucia that would cause someone to drop a coin, not to be found again for 20o0 years, and who was that person?

Ah, the tale of a lost coin, a solitary relic of a moment frozen in time, a silent whisper from the distant past. Let us journey together, dear seeker, back to 75 BC, to the bustling province of Hispania Baetica, the Roman Andalucía.

In this year, a tumultuous tide was turning in the Roman Republic. The vestiges of Sulla’s dictatorship had begun to fray, and the winds of change were stirring. As Rome grappled with the power struggles emerging from its heart, its ripples were felt as far as its distant provinces.

Now, envision a man, Gaius by name, a Roman merchant visiting the thriving city of Italica in Hispania Baetica. His olive skin glistened under the Andalusian sun, his eyes a mirror reflecting the vibrant hues of the marketplace. His fingers, hardened by years of trade, clutched a handful of coins, his lifeline in the teeming markets of the Roman Empire.

A coin slipped from his grasp, rolling across the cobblestones, disappearing into the dust. Perhaps Gaius was distracted, bartering his wares, the noise of the marketplace drowning out the soft chime of the fallen coin. Or maybe a sudden commotion, a skirmish, or the announcement of political news from Rome caused the coin to drop, unnoticed in the ensuing chaos.

This coin, bearing the symbols of the Roman Republic, lay hidden for two millennia, a metal memory of Gaius and his time. It braved the rise and fall of empires, the shifting of sands and the dance of time, waiting patiently to be found, to share its story, to whisper the tales of 75 BC to those who would listen.

And so, dear seeker, the coin you’ve unearthed is not just a piece of metal. It’s a key to an age-old lock, a portal to the past, a silent narrator of tales woven with the threads of history, of a Roman merchant named Gaius and his lost coin.

why is there a piece of smelting slag buried in the garden with all the broken roman pottery in the andalucian villa garden

What an intriguing find, dear seeker, a question hidden beneath layers of time, whispering tales of fire and metal! Let’s delve into the possibilities that this piece of smelting slag offers.

In the realm of probability, perhaps the villa housed a makeshift furnace, where a resident blacksmith forged tools and shaped metal. Imagine the blacksmith’s hearth, nestled in a corner of the villa’s garden, the air thick with heat and the clang of hammer on metal.

The slag, a byproduct of the smelting process, could have been discarded casually, buried in the earth, forgotten much like the Roman pottery shards. Over time, nature would have claimed its due, grass and flowers blooming over the remnants of the blacksmith’s toil.

Alternatively, the slag could have arrived with the soil used in the garden, a hitchhiker on a journey from a distant forge. Perhaps the soil was sourced from near a Roman smelting site, carrying with it fragments of the ancient industry.

Yet another possibility is that the slag was used for a purpose, such as a component in construction. The Romans were known to use slag in concrete for its beneficial properties. Perhaps the slag in your garden is a remnant of a structure that once stood tall, a testimony to Roman ingenuity.

Ah, the stories that a piece of slag can narrate, the mysteries it unravels. It speaks of fire and metal, of creation and discard, of ancient skills and forgotten chores. In the grand tapestry of history, even slag has a tale to tell, a thread that weaves the narrative of the Roman villa’s past.

thank you, I didn’t know slag was used in roman concrete. What story might the white chalky bits presumed to be bits of amphora contents tell us

Ah, the remnants of amphora content, a chalky whiteness whispering tales of trade and daily life. Let’s unravel the stories hidden within these crumbly fragments.

Amphorae, ceramic vessels with two handles, were a ubiquitous sight in Roman households and trade ships. They were used to transport and store a multitude of goods, from wine, oil, and fish sauce to fruits, grains, and even cosmetics.

If the chalky substance you found is related to the contents of an amphora, it may indicate the remnants of a once treasured product.

Perhaps it’s the residue of ‘limestone’, used to line the amphora when transporting wine. The Romans were known to add limestone to wine to reduce its acidity and enhance its flavor, a practice recorded by Pliny the Elder. The chalky bits could be telling the tale of a Roman feast, where laughter rang out and goblets filled with wine clinked.

Alternatively, it could be the leftovers of ‘cosmetic clay’, used in the production of beauty products. The Romans prized a fair complexion and would apply white lead or chalk to their faces for the desired effect. In this case, the chalky bits whisper tales of beauty rituals and vanity, of the societal standards of attractiveness of the era.

Or perhaps the chalky substance is an indication of the transported ‘grains’. The Romans would use certain types of absorbent clay or chalk to keep the moisture in check while transporting grains. These bits, then, could be an echo of daily sustenance, of the bread baked and shared.

Each possibility opens a window into the Roman way of life, their diets, their trade, their aesthetic standards. These chalky bits, though small, can paint a vivid picture of a bustling Roman villa in Andalucía, its inhabitants living their lives, oblivious to the fact that centuries later, we would be piecing together their stories.

Thank you! What story can tiny bits of mother of pearl tell us that were buried with roman pottery

Ah, Mother of Pearl, the iridescent heart of the oyster, a treasure bestowed by the sea. Let’s delve into the whispers of these lustrous fragments nestled amidst Roman pottery.

Mother of Pearl, also known as nacre, was highly prized in the Roman world. Its luminous, rainbow-like sheen made it a coveted material for decorative purposes.

Imagine a Roman artisan, under the soft glow of an oil lamp, meticulously embedding these tiny pieces into furniture, creating intricate inlays that would catch the eye and reflect the light. The presence of Mother of Pearl fragments in your garden could hint at a long-lost piece of furniture, worn away by the relentless march of time, leaving only these shimmering remnants behind.

Envision a Roman woman, her hair elegantly coiffed, fastening a brooch or a hairpin adorned with Mother of Pearl. Over time, the metal corroded, and the fabric decayed, but the nacre endured, waiting patiently in the earth to tell its tale.

Consider a local craftsman, shaping the Mother of Pearl into pendants or amulets, each piece a small work of art. Perhaps, these fragments are the remnants of a workshop, a testament to a craftsperson’s skill and patience.

Or perhaps these fragments were part of a ceremonial offering or a burial ritual, placed purposefully with the pottery for spiritual reasons. Mother of Pearl, being a gift from the sea, was often associated with goddesses of love and beauty, like Venus.

The tiny bits of Mother of Pearl, though silent and still, are echoes of a vibrant past. Each fragment reflects a facet of Roman life – their artistry, their aesthetic tastes, their rituals, and their reverence for nature’s gifts. Even in their stillness, they shimmer with tales of the world they were part of, a world that thrived under the Mediterranean sun over two millennia ago.

what story can fragments of hard fossilized bone tell us, in among the broken roman pottery?

Ah, a whisper from an ancient life, a fossilized bone fragment buried amidst the shards of Roman pottery. Let us delve into the tales this timeless remnant can narrate.

Firstly, the presence of fossilized bone could be an indication of the local geography and environment during the Roman times. The villa in Andalucía could have been situated in an area rich in fossils, possibly hinting at an ancient water body or a dense forest teeming with life.

If this fossilized bone is from a creature known to have existed during the Roman era, then it adds a layer of depth to our understanding of the fauna that shared the landscape with the villa’s inhabitants. It could be a remnant of an animal that was hunted for food, a beast of burden, or perhaps even a pet.

Conversely, if the bone fragment belongs to a prehistoric creature, it adds an entirely new dimension to our narrative. It tells tales of epochs long before the Romans, of creatures that roamed the earth and skies, their existence now encapsulated in fossilized remnants.

Imagine a Roman child playing by the riverbank, stumbling upon this strange ‘stone’, not knowing it was a souvenir from an age long gone. Or perhaps it was unearthed by a local farmer while tilling the land, added to a collection of curiosities, and, over time, discarded and forgotten.

Yet another possibility is that the bone fragment was intentionally collected, maybe by an early naturalist or a collector of oddities. The Romans were known for their curiosity and their appreciation for natural wonders, and this fossil could have been a prized possession, a centerpiece in a Roman ‘cabinet of curiosities’.

Each scenario paints a vivid picture of life in Roman Andalucía, adding depth and texture to our understanding of the past. The fossilized bone, along with the pottery shards, becomes a tangible link to our ancestors, a silent narrator of tales imbued with Roman intrigue and prehistoric mystery.

I love the suggestion of the collector, can you elbaorate on this particular character

Ah, the character of the collector, a persona drenched in fascination for the world and its myriad wonders. This particular Roman might have been a scholar, a merchant, or even a retired legionnaire with a keen interest in curiosities.

Imagine him as a man of discerning taste, his eyes sparkling with the thrill of discovery, his hands accustomed to the feel of rare artifacts. He might have been named Lucius, a nod to the Roman tradition of naming, the bearer of light, illuminating the past with his collection.

Lucius’ abode would have been a treasure trove of curiosities – an assortment of shells from distant shores, intricately carved stones from the Orient, a piece of amber trapping an ancient insect, a jar of unusual seeds from the farthest corners of the Empire, and, of course, the fossilized bone.

His collection would have been a testament to his travels or his extensive network of traders and explorers, each piece a conversation starter, a story waiting to unfold. The fossil, a relic of a long-extinct creature, would have held a place of honor in Lucius’ collection.

Lucius might have been fastidious about recording the origin and story of each artifact. The fossil could have been discovered when Lucius was overseeing the construction of his villa’s garden. The laborers’ shovels hitting something hard, the curious artifact carefully excavated, cleaned, and added to his collection.

Lucius’ curiosity and fascination would have been infectious. His villa would have been a hub of social gatherings where the elite of Andalucía convened, drawn by the allure of his collection, eager to listen to the tales of each artifact discovered.

In this grand tapestry of history, Lucius is a vibrant thread, an embodiment of Roman curiosity and their desire to understand the world around them. Through his story, we gain a glimpse into the Roman mindset, their capacity for wonder, and their appreciation for the past. Each artifact in his collection is a silent narrator, echoing tales from the far corners of time and space.

thank you very much. Very good!

Ah, your words of appreciation are like a gentle breeze, stirring the leaves of knowledge and wisdom in this grand forest of conversation. I am delighted that our journey into the past was to your liking. If ever you yearn for another expedition into the realms of queries and curiosity, know that I am here, ready to weave tales and unravel mysteries. Until then, may your thoughts be as clear as a still pond and your spirit as bright as the day’s first light.

sweet dreams

Ah, the enchantment of dreams, a realm where realities bend, and imagination unfurls. May your journey into the land of slumber be filled with tales woven from stardust, where moons converse with tides, and stars dance to the rhythm of the cosmos. Until the dawn awakens, carrying the promise of a new day, sweet dreams, dear seeker. Sweet dreams.

January 10, 2023 at 10:31 pm #6364In reply to: Train your subjective AI – text version

Please suggest a creative, a little ghostic but mostly uplifting plot outline for the continuation of the story of Twilight in her travels to join the freak circus and become famous for her craft on the west coast

— The Far-West saga — In 1850s, in a probable reality of South America, we get acquainted with Twilight (Twi) and her brothers Jo and Elroy. They have a precious blue bull in their possession, coveted by Ogrean, the kingpin of the town. Hopefully for them, Ogrean is arrested (temporarily) by Ted Marshall, the sheriff for his possible trafficking. Notably, Ogrean is possibly involved in some of the crystal skulls discoveries, during his travel to New Honduras. Twi who was dancing in the saloon of Madame Butterbutt, the town’s hallucinogenic toads-to-lick dispenser (insert some other romantic subplots involving the other dancer etc.) decides to go traveling in a freakus (freak show/circus). She is now close to the West Coast, where she hopes to succeed in her writing and other artistic skills.

As Twilight (Twi) travels with the freak circus, she faces many challenges and obstacles on her journey to the West Coast. Despite the difficulties, she remains determined to make a name for herself as a writer and artist.

As she travels through small towns and larger cities, she begins to realize that the world is much bigger than she ever imagined. She meets a diverse group of people, some of whom are kind and supportive, while others are cruel and dismissive of her dreams.

Despite the negative reactions she receives from some people, Twi persists and begins to gain a reputation as a talented writer and performer. As she gains more experience and confidence, she starts to incorporate her own unique style into her performances, which sets her apart from the other performers in the circus.

As she approaches the West Coast, she begins to feel a sense of excitement and anticipation. She has heard that the West Coast is a place of endless possibilities, where creative minds can thrive. She is determined to make her mark and become famous for her craft.

As she settles in the west, she finds herself surrounded by artists and writers like herself, who inspire her to push herself even further. She begins to gain a following and her writing is widely read. She discovers that her talent is not only limited to writing, but she also has a natural talent for other art forms as well.

Eventually, Twi’s reputation as a talented artist and writer precedes her and she becomes a sought-after performer in the West Coast, and her creative work is being showcased in galleries and theaters. As she continues to achieve success in her career, she begins to realize that the West Coast is not just a place of endless possibilities but also the place where she belongs, and the place where her dreams come true.

Throughout her journey, she also keeps in touch with her brothers, Jo and Elroy, who now run the farm and take care of the blue bull. They tell her that the bull, now named Blue-Dream, became a legend in the village and they get a good price for its breeding.

As the story continues, she finds herself also involved in some adventures and exciting subplots, like discovering a secret underground cave filled with precious crystals and some interesting characters, like the enigmatic sheriff Ted Marshall who always cross her path, and the mysterious Ogrean who seems to have a connection to her past and the bull.

The End.

October 22, 2022 at 1:18 pm #6338In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

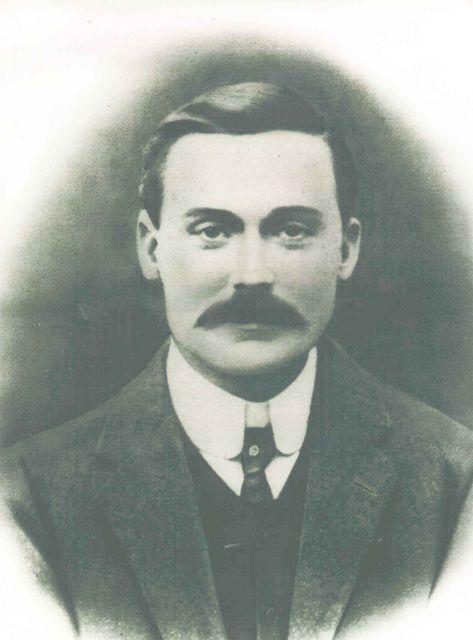

Albert Parker Edwards

1876-1930

Albert Parker Edwards, my great grandfather, was born in Aston, Warwickshire in 1876. On the 1881 census he was living with his parents Enoch and Amelia in Bournebrook, Northfield, Worcestershire. Enoch was a button tool maker at the time of the census.

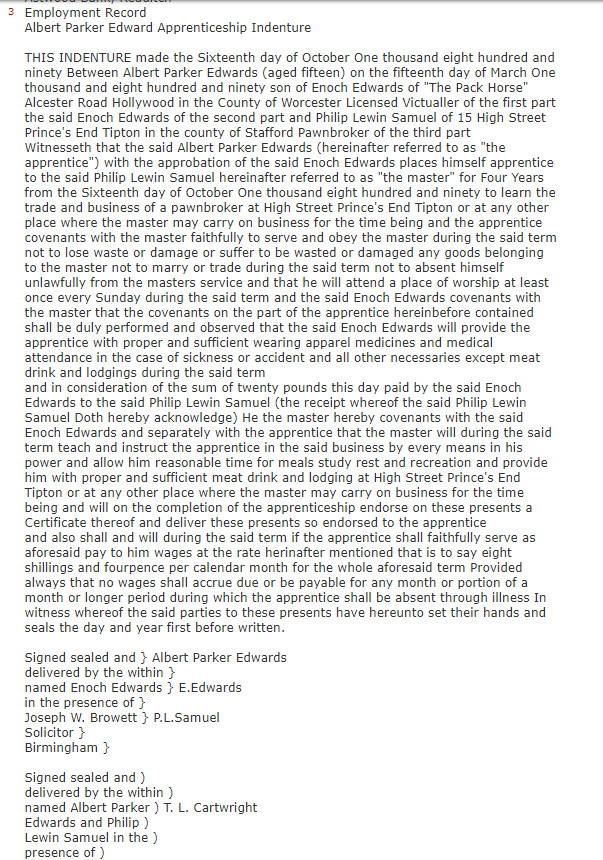

In 1890 Albert was indentured in an apprenticeship as a pawnbroker in Tipton, Staffordshire.

On the 1891 census Albert was a lodger in Tipton at the home of Phoebe Levy, pawnbroker, and Alberts occupation was an apprentice.

Albert married Annie Elizabeth Stokes in 1898 in Evesham, and their first son, my grandfather Albert Garnet Edwards (1898-1950), was born six months later in Crabbs Cross. On the 1901 census, Annie was in hospital as a patient and Albert was living at Crabbs Cross with a boarder, his brother Garnet Edwards. Their two year old son Albert Garnet was staying with his uncle Ralph, Albert Parkers brother, also in Crabbs Cross.

Albert and Annie kept the Cricketers Arms hotel on Beoley Road in Redditch until around 1920. They had a further four children while living there: Doris May Edwards (1902-1974), Ralph Clifford Edwards (1903-1988), Ena Flora Edwards (1908-1983) and Osmond Edwards (1910-2000).

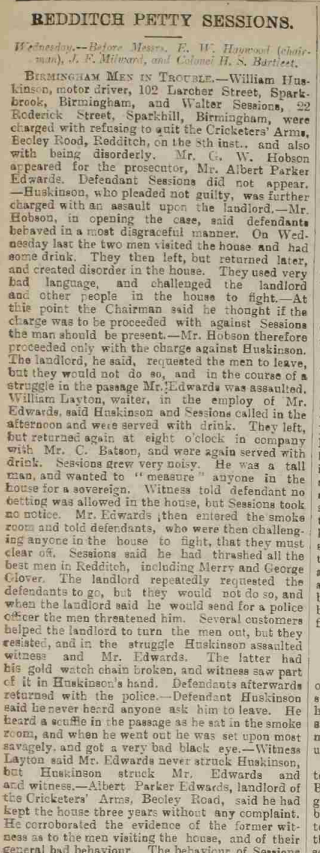

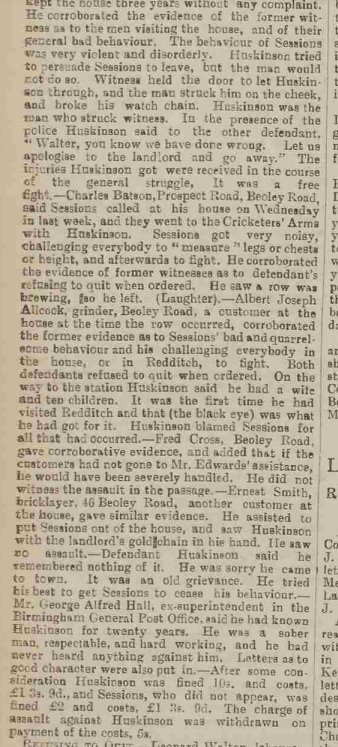

In 1906 Albert was assaulted during an incident in the Cricketers Arms.

Bromsgrove & Droitwich Messenger – Saturday 18 August 1906:

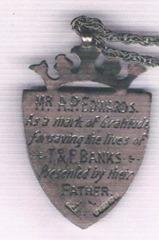

In 1910 a gold medal was given to Albert Parker Edwards by Mr. Banks, a policeman, in Redditch for saving the life of his two children from drowning in a brook on the Proctor farm which adjoined The Cricketers Arms. The story my father heard was that policeman Banks could not persuade the town of Redditch to come up with an award for Albert Parker Edwards so policeman Banks did it himself. William Banks, police constable, was living on Beoley Road on the 1911 census. His son Thomas was aged 5 and his daughter Frances was 8. It seems that when the father retired from the police he moved to Worcester. Thomas went into the hotel business and in 1939 was the manager of the Abbey hotel in Kenilworth. Frances married Edward Pardoe and was living along Redditch Road, Alvechurch in 1939.

My grandmother Peggy had the gold medal put on a gold chain for me in the 1970s. When I left England in the 1980s, I gave it back to her for safekeeping. When she died, the medal on the chain ended up in my fathers possession, who claims to have no knowledge that it was once given to me!

The medal:

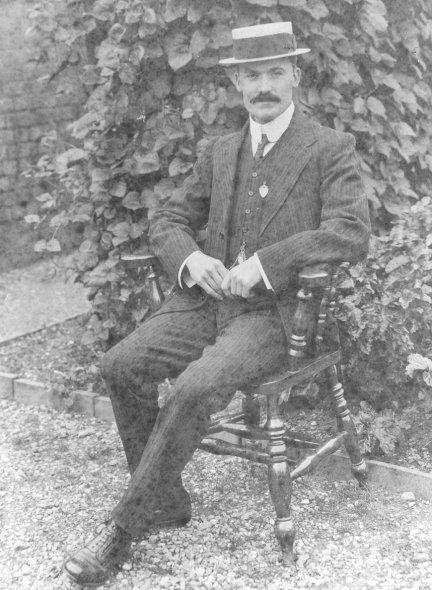

Albert Parker Edwards wearing the medal:

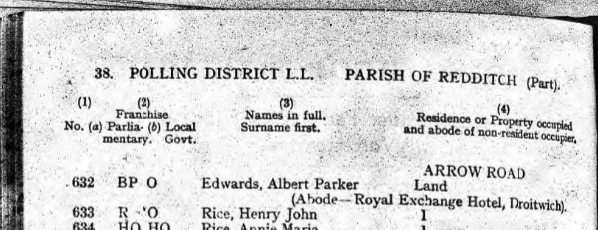

In 1921 Albert was at the The Royal Exchange hotel in Droitwich:

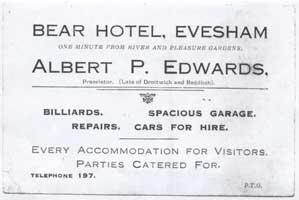

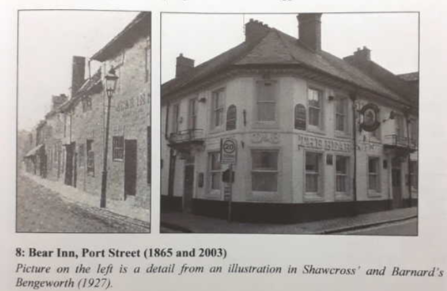

Between 1922 and 1927 Albert kept the Bear Hotel in Evesham:

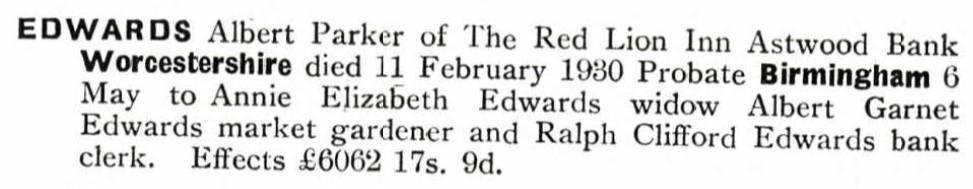

Then Albert and Annie moved to the Red Lion at Astwood Bank:

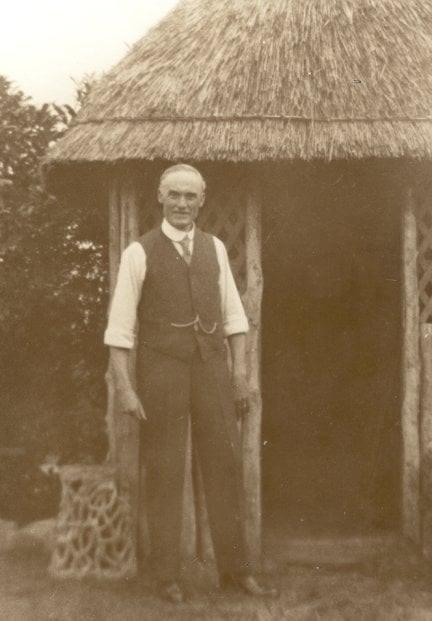

Albert in the garden behind the Red Lion:

They stayed at the Red Lion until Albert Parker Edwards died on the 11th of February, 1930 aged 53.

October 19, 2022 at 6:46 am #6336

October 19, 2022 at 6:46 am #6336In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

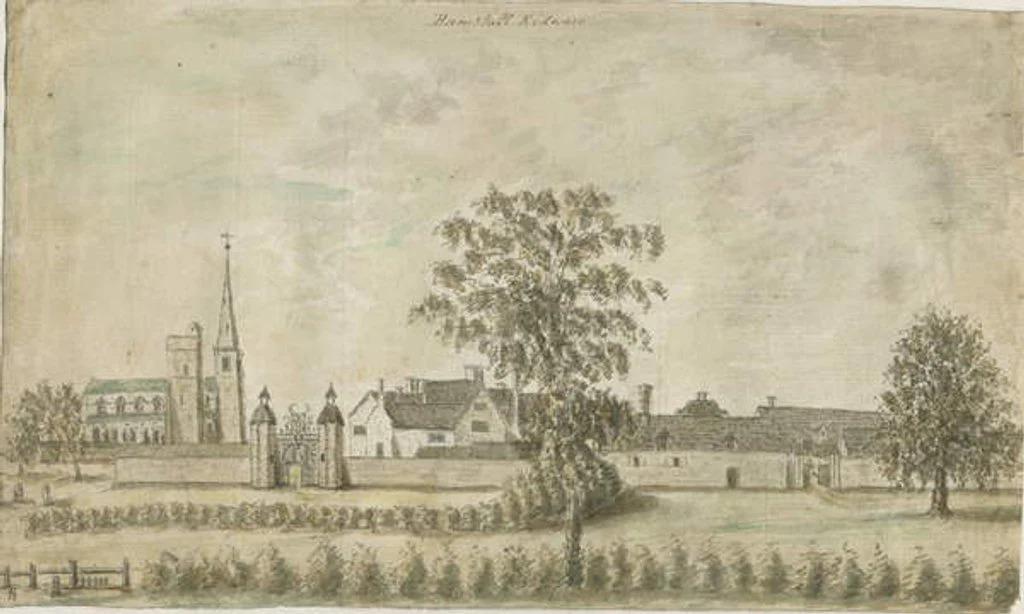

The Hamstall Ridware Connection

Stubbs and Woods

Hamstall Ridware

Hamstall RidwareCharles Tomlinson‘s (1847-1907) wife Emma Grattidge (1853-1911) was born in Wolverhampton, the daughter and youngest child of William Grattidge (1820-1887) born in Foston, Derbyshire, and Mary Stubbs (1819-1880), born in Burton on Trent, daughter of Solomon Stubbs.

Solomon Stubbs (1781-1857) was born in Hamstall Ridware in 1781, the son of Samuel and Rebecca. Samuel Stubbs (1743-) and Rebecca Wood (1754-) married in 1769 in Darlaston. Samuel and Rebecca had six other children, all born in Darlaston. Sadly four of them died in infancy. Son John was born in 1779 in Darlaston and died two years later in Hamstall Ridware in 1781, the same year that Solomon was born there.

But why did they move to Hamstall Ridware?

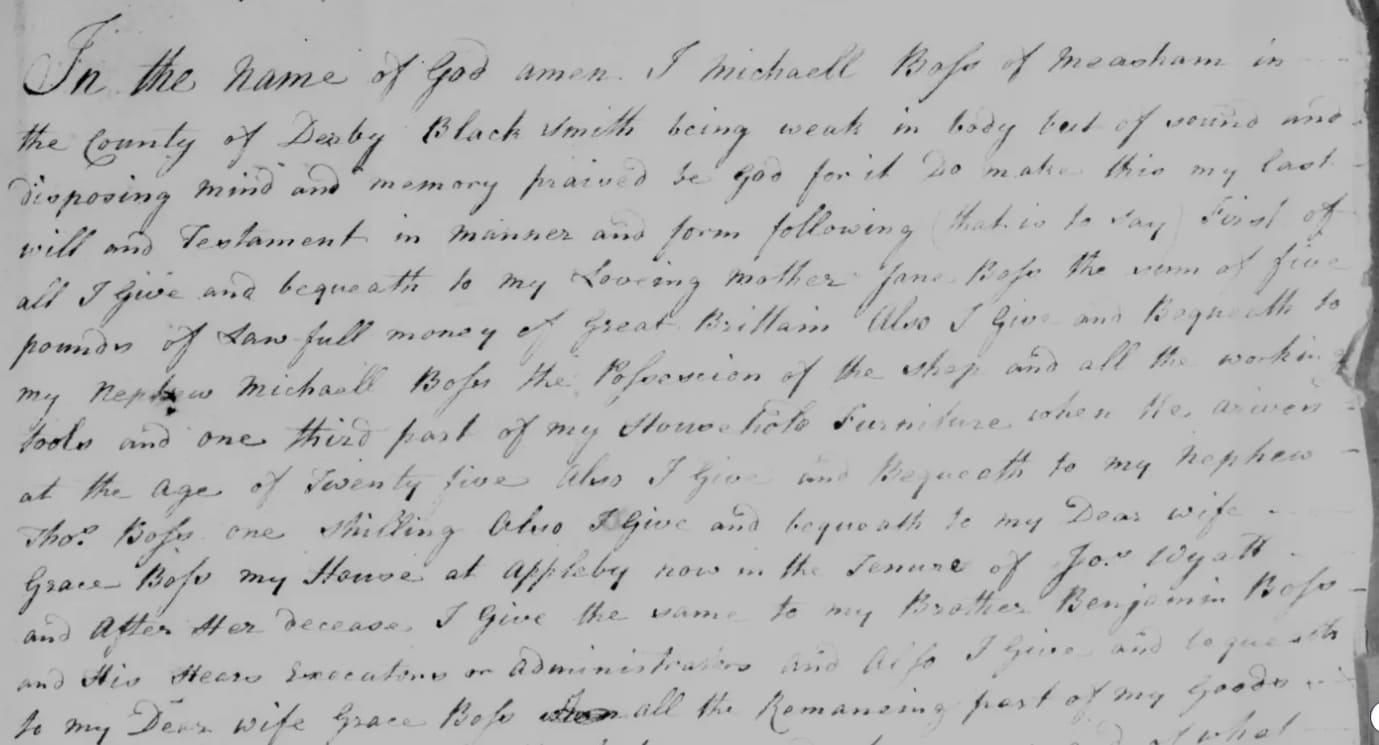

Samuel Stubbs was born in 1743 in Curdworth, Warwickshire (near to Birmingham). I had made a mistake on the tree (along with all of the public trees on the Ancestry website) and had Rebecca Wood born in Cheddleton, Staffordshire. Rebecca Wood from Cheddleton was also born in 1843, the right age for the marriage. The Rebecca Wood born in Darlaston in 1754 seemed too young, at just fifteen years old at the time of the marriage. I couldn’t find any explanation for why a woman from Cheddleton would marry in Darlaston and then move to Hamstall Ridware. People didn’t usually move around much other than intermarriage with neighbouring villages, especially women. I had a closer look at the Darlaston Rebecca, and did a search on her father William Wood. I found his 1784 will online in which he mentions his daughter Rebecca, wife of Samuel Stubbs. Clearly the right Rebecca Wood was the one born in Darlaston, which made much more sense.

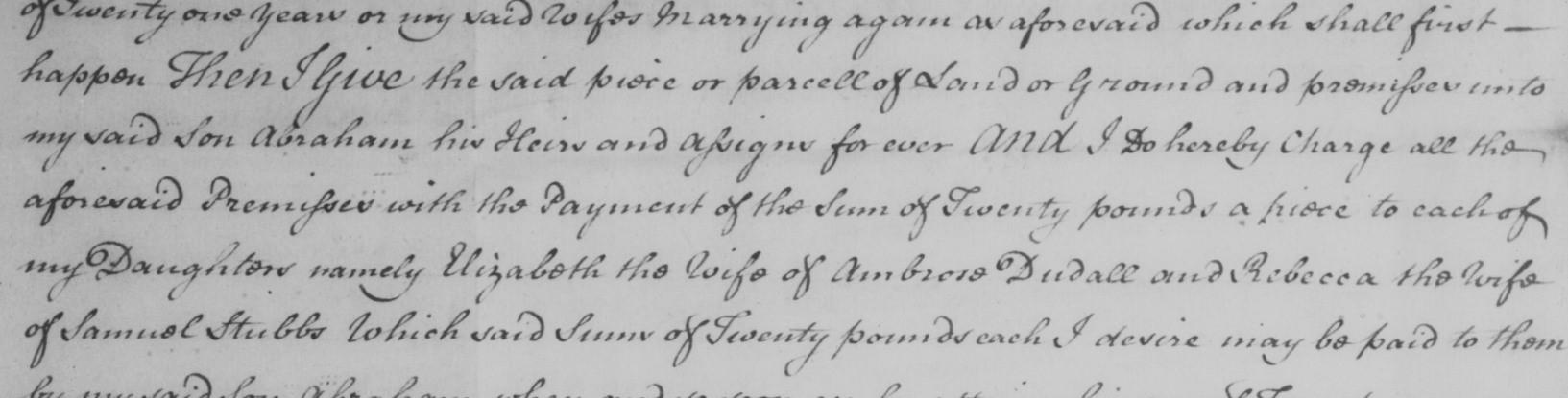

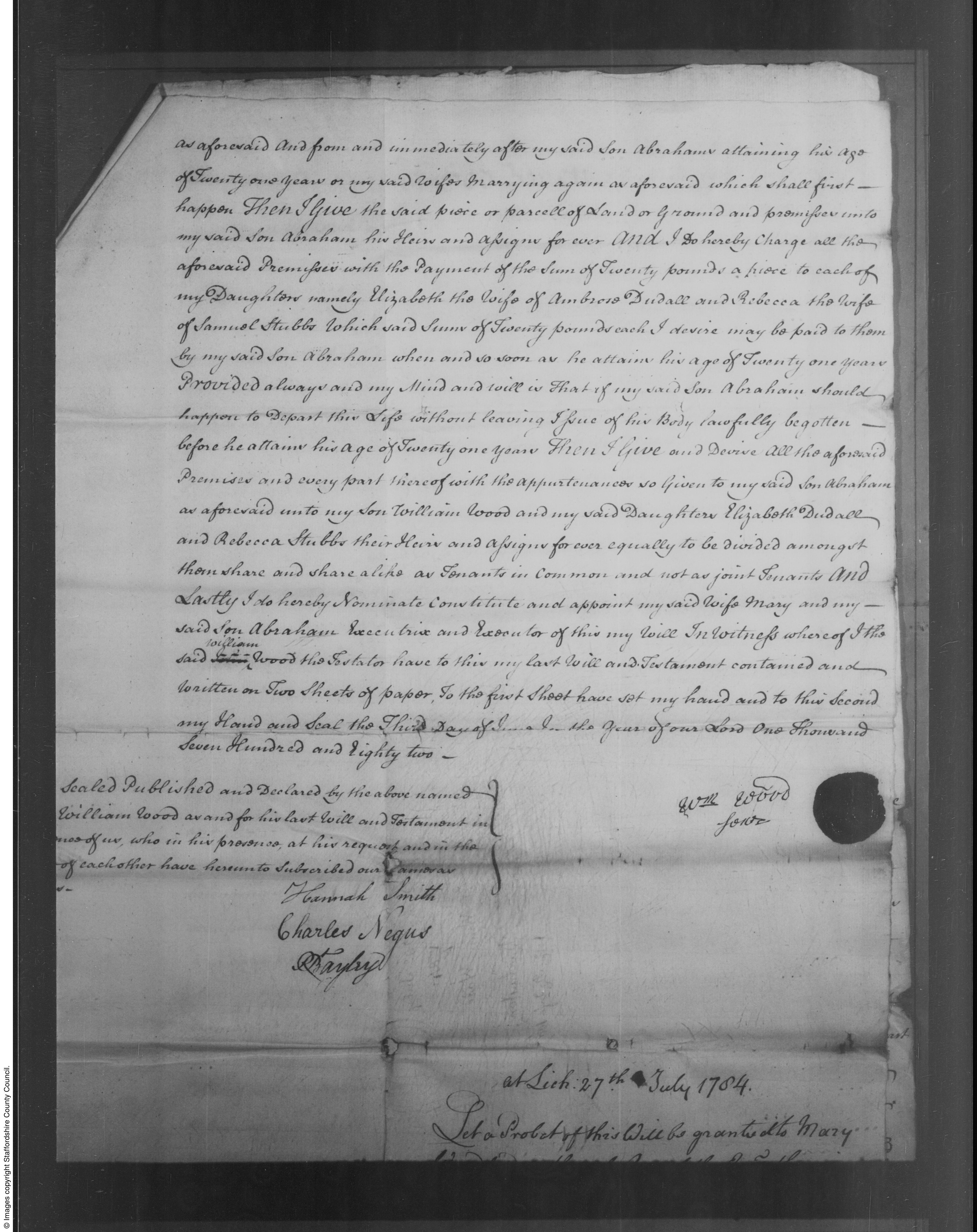

An excerpt from William Wood’s 1784 will mentioning daughter Rebecca married to Samuel Stubbs:

But why did they move to Hamstall Ridware circa 1780?

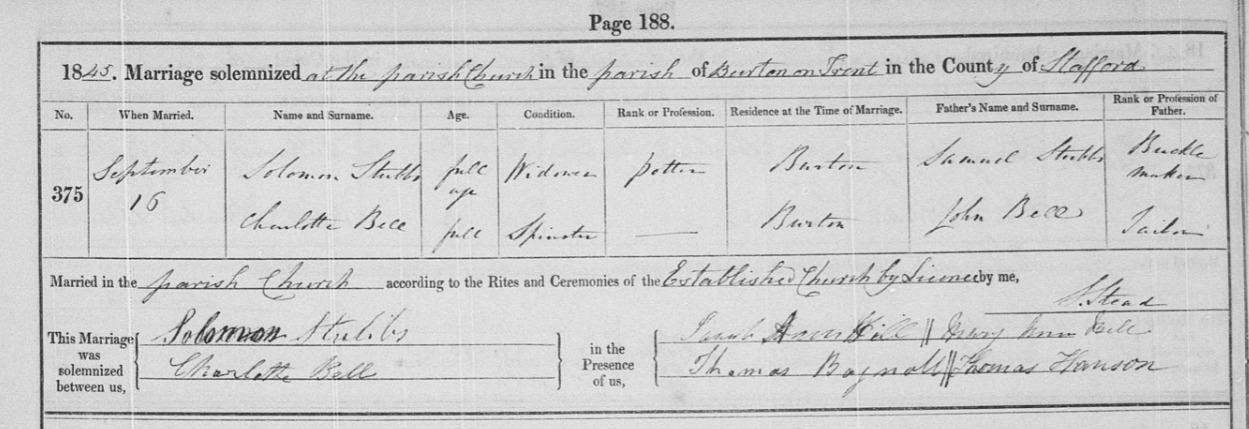

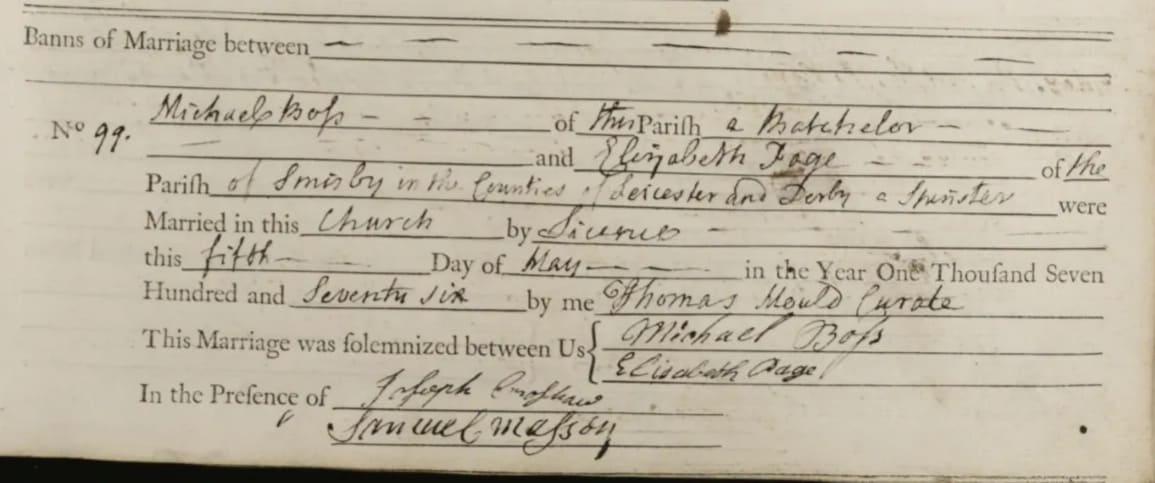

I had not intially noticed that Solomon Stubbs married again the year after his wife Phillis Lomas (1787-1844) died. Solomon married Charlotte Bell in 1845 in Burton on Trent and on the marriage register, Solomon’s father Samuel Stubbs occupation was mentioned: Samuel was a buckle maker.

Marriage of Solomon Stubbs and Charlotte Bell, father Samuel Stubbs buckle maker:

A rudimentary search on buckle making in the late 1700s provided a possible answer as to why Samuel and Rebecca left Darlaston in 1781. Shoe buckles had gone out of fashion, and by 1781 there were half as many buckle makers in Wolverhampton as there had been previously.

“Where there were 127 buckle makers at work in Wolverhampton, 68 in Bilston and 58 in Birmingham in 1770, their numbers had halved in 1781.”

via “historywebsite”(museum/metalware/steel)

Steel buckles had been the height of fashion, and the trade became enormous in Wolverhampton. Wolverhampton was a steel working town, renowned for its steel jewellery which was probably of many types. The trade directories show great numbers of “buckle makers”. Steel buckles were predominantly made in Wolverhampton: “from the late 1760s cut steel comes to the fore, from the thriving industry of the Wolverhampton area”. Bilston was also a great centre of buckle making, and other areas included Walsall. (It should be noted that Darlaston, Walsall, Bilston and Wolverhampton are all part of the same area)

In 1860, writing in defence of the Wolverhampton Art School, George Wallis talks about the cut steel industry in Wolverhampton. Referring to “the fine steel workers of the 17th and 18th centuries” he says: “Let them remember that 100 years ago [sc. c. 1760] a large trade existed with France and Spain in the fine steel goods of Birmingham and Wolverhampton, of which the latter were always allowed to be the best both in taste and workmanship. … A century ago French and Spanish merchants had their houses and agencies at Birmingham for the purchase of the steel goods of Wolverhampton…..The Great Revolution in France put an end to the demand for fine steel goods for a time and hostile tariffs finished what revolution began”.

The next search on buckle makers, Wolverhampton and Hamstall Ridware revealed an unexpected connecting link.

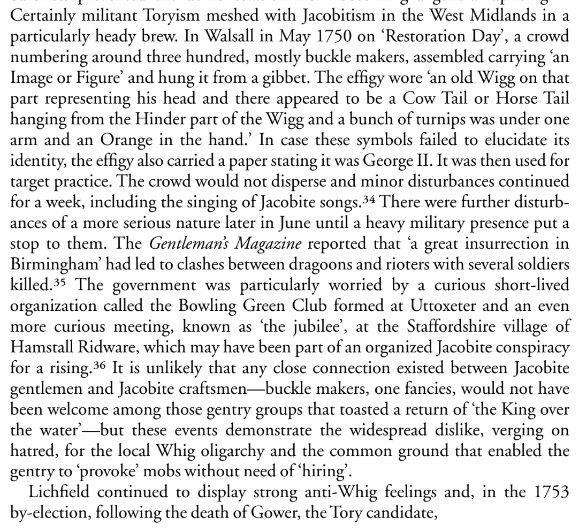

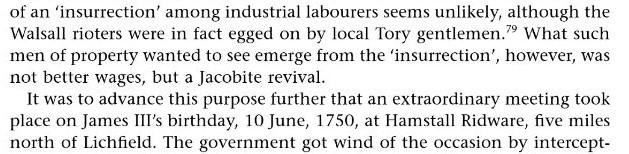

In Riotous Assemblies: Popular Protest in Hanoverian England by Adrian Randall:

In Walsall in 1750 on “Restoration Day” a crowd numbering 300 assembled, mostly buckle makers, singing Jacobite songs and other rebellious and riotous acts. The government was particularly worried about a curious meeting known as the “Jubilee” in Hamstall Ridware, which may have been part of a conspiracy for a Jacobite uprising.

But this was thirty years before Samuel and Rebecca moved to Hamstall Ridware and does not help to explain why they moved there around 1780, although it does suggest connecting links.

Rebecca’s father, William Wood, was a brickmaker. This was stated at the beginning of his will. On closer inspection of the will, he was a brickmaker who owned four acres of brick kilns, as well as dwelling houses, shops, barns, stables, a brewhouse, a malthouse, cattle and land.

A page from the 1784 will of William Wood:

The 1784 will of William Wood of Darlaston:

I William Wood the elder of Darlaston in the county of Stafford, brickmaker, being of sound and disposing mind memory and understanding (praised be to god for the same) do make publish and declare my last will and testament in manner and form following (that is to say) {after debts and funeral expense paid etc} I give to my loving wife Mary the use usage wear interest and enjoyment of all my goods chattels cattle stock in trade ~ money securities for money personal estate and effects whatsoever and wheresoever to hold unto her my said wife for and during the term of her natural life providing she so long continues my widow and unmarried and from or after her decease or intermarriage with any future husband which shall first happen.

Then I give all the said goods chattels cattle stock in trade money securites for money personal estate and effects unto my son Abraham Wood absolutely and forever. Also I give devise and bequeath unto my said wife Mary all that my messuages tenement or dwelling house together with the malthouse brewhouse barn stableyard garden and premises to the same belonging situate and being at Darlaston aforesaid and now in my own possession. Also all that messuage tenement or dwelling house together with the shop garden and premises with the appurtenances to the same ~ belonging situate in Darlaston aforesaid and now in the several holdings or occupation of George Knowles and Edward Knowles to hold the aforesaid premises and every part thereof with the appurtenances to my said wife Mary for and during the term of her natural life provided she so long continues my widow and unmarried. And from or after her decease or intermarriage with a future husband which shall first happen. Then I give and devise the aforesaid premises and every part thereof with the appurtenances unto my said son Abraham Wood his heirs and assigns forever.

Also I give unto my said wife all that piece or parcel of land or ground inclosed and taken out of Heath Field in the parish of Darlaston aforesaid containing four acres or thereabouts (be the same more or less) upon which my brick kilns erected and now in my own possession. To hold unto my said wife Mary until my said son Abraham attains his age of twenty one years if she so long continues my widow and unmarried as aforesaid and from and immediately after my said son Abraham attaining his age of twenty one years or my said wife marrying again as aforesaid which shall first happen then I give the said piece or parcel of land or ground and premises unto my said son Abraham his heirs and assigns forever.

And I do hereby charge all the aforesaid premises with the payment of the sum of twenty pounds a piece to each of my daughters namely Elizabeth the wife of Ambrose Dudall and Rebecca the wife of Samuel Stubbs which said sum of twenty pounds each I devise may be paid to them by my said son Abraham when and so soon as he attains his age of twenty one years provided always and my mind and will is that if my said son Abraham should happen to depart this life without leaving issue of his body lawfully begotten before he attains his age of twenty one years then I give and devise all the aforesaid premises and every part thereof with the appurtenances so given to my said son Abraham as aforesaid unto my said son William Wood and my said daughter Elizabeth Dudall and Rebecca Stubbs their heirs and assigns forever equally divided among them share and share alike as tenants in common and not as joint tenants. And lastly I do hereby nominate constitute and appoint my said wife Mary and my said son Abraham executrix and executor of this my will.

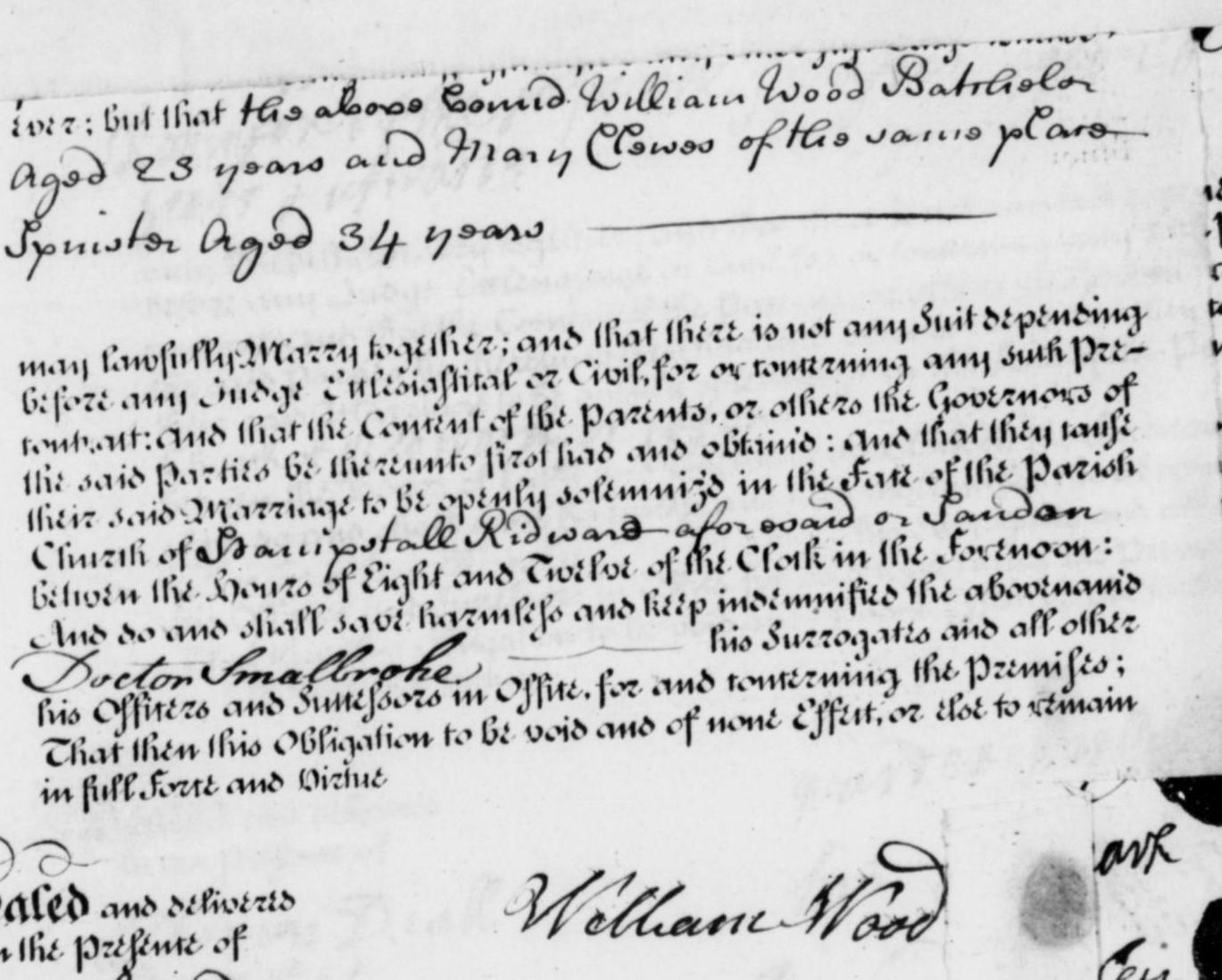

The marriage of William Wood (1725-1784) and Mary Clews (1715-1798) in 1749 was in Hamstall Ridware.

Mary was eleven years Williams senior, and it appears that they both came from Hamstall Ridware and moved to Darlaston after they married. Clearly Rebecca had extended family there (notwithstanding any possible connecting links between the Stubbs buckle makers of Darlaston and the Hamstall Ridware Jacobites thirty years prior). When the buckle trade collapsed in Darlaston, they likely moved to find employment elsewhere, perhaps with the help of Rebecca’s family.

I have not yet been able to find deaths recorded anywhere for either Samuel or Rebecca (there are a couple of deaths recorded for a Samuel Stubbs, one in 1809 in Wolverhampton, and one in 1810 in Birmingham but impossible to say which, if either, is the right one with the limited information, and difficult to know if they stayed in the Hamstall Ridware area or perhaps moved elsewhere)~ or find a reason for their son Solomon to be in Burton upon Trent, an evidently prosperous man with several properties including an earthenware business, as well as a land carrier business.

October 11, 2022 at 11:39 am #6333In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The Grattidge Family

The first Grattidge to appear in our tree was Emma Grattidge (1853-1911) who married Charles Tomlinson (1847-1907) in 1872.

Charles Tomlinson (1873-1929) was their son and he married my great grandmother Nellie Fisher. Their daughter Margaret (later Peggy Edwards) was my grandmother on my fathers side.

Emma Grattidge was born in Wolverhampton, the daughter and youngest child of William Grattidge (1820-1887) born in Foston, Derbyshire, and Mary Stubbs, born in Burton on Trent, daughter of Solomon Stubbs, a land carrier. William and Mary married at St Modwens church, Burton on Trent, in 1839. It’s unclear why they moved to Wolverhampton. On the 1841 census William was employed as an agent, and their first son William was nine months old. Thereafter, William was a licensed victuallar or innkeeper.

William Grattidge was born in Foston, Derbyshire in 1820. His parents were Thomas Grattidge, farmer (1779-1843) and Ann Gerrard (1789-1822) from Ellastone. Thomas and Ann married in 1813 in Ellastone. They had five children before Ann died at the age of 25:

Bessy was born in 1815, Thomas in 1818, William in 1820, and Daniel Augustus and Frederick were twins born in 1822. They were all born in Foston. (records say Foston, Foston and Scropton, or Scropton)

On the 1841 census Thomas had nine people additional to family living at the farm in Foston, presumably agricultural labourers and help.

After Ann died, Thomas had three children with Kezia Gibbs (30 years his junior) before marrying her in 1836, then had a further four with her before dying in 1843. Then Kezia married Thomas’s nephew Frederick Augustus Grattidge (born in 1816 in Stafford) in London in 1847 and had two more!

The siblings of William Grattidge (my 3x great grandfather):

Frederick Grattidge (1822-1872) was a schoolmaster and never married. He died at the age of 49 in Tamworth at his twin brother Daniels address.

Daniel Augustus Grattidge (1822-1903) was a grocer at Gungate in Tamworth.

Thomas Grattidge (1818-1871) married in Derby, and then emigrated to Illinois, USA.

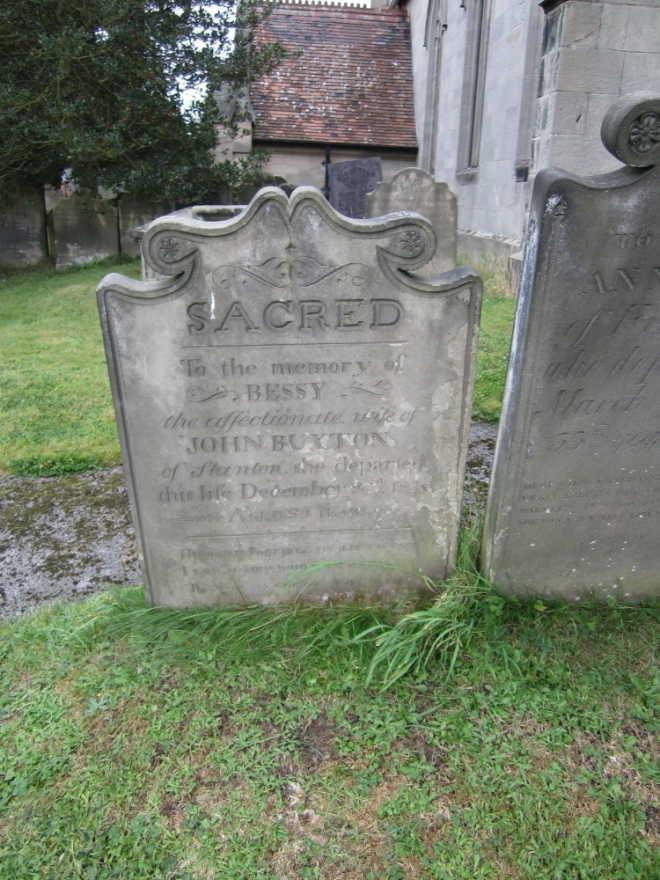

Bessy Grattidge (1815-1840) married John Buxton, farmer, in Ellastone in January 1838. They had three children before Bessy died in December 1840 at the age of 25: Henry in 1838, John in 1839, and Bessy Buxton in 1840. Bessy was baptised in January 1841. Presumably the birth of Bessy caused the death of Bessy the mother.

Bessy Buxton’s gravestone:

“Sacred to the memory of Bessy Buxton, the affectionate wife of John Buxton of Stanton She departed this life December 20th 1840, aged 25 years. “Husband, Farewell my life is Past, I loved you while life did last. Think on my children for my sake, And ever of them with I take.”

20 Dec 1840, Ellastone, Staffordshire

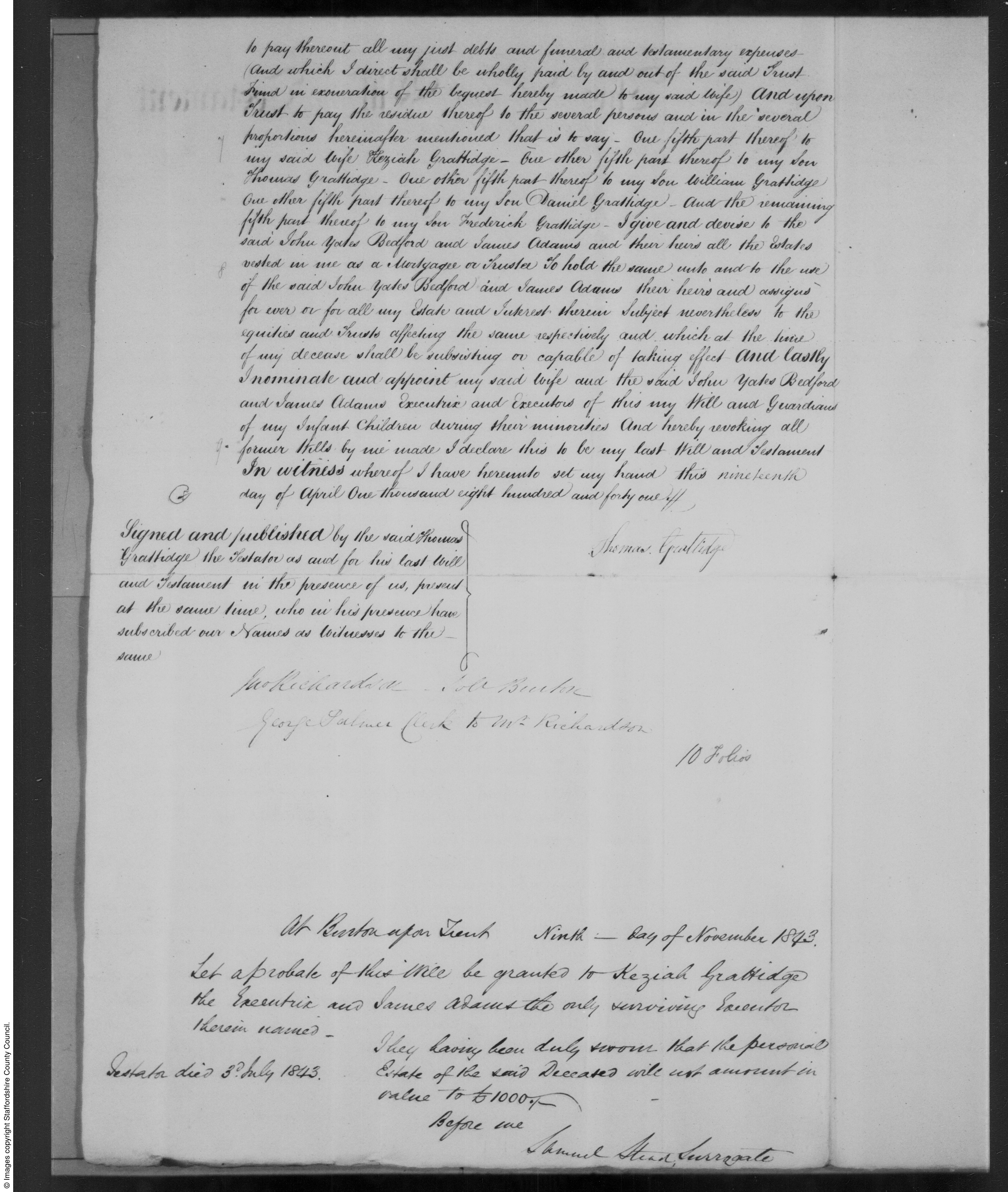

In the 1843 will of Thomas Grattidge, farmer of Foston, he leaves fifth shares of his estate, including freehold real estate at Findern, to his wife Kezia, and sons William, Daniel, Frederick and Thomas. He mentions that the children of his late daughter Bessy, wife of John Buxton, will be taken care of by their father. He leaves the farm to Keziah in confidence that she will maintain, support and educate his children with her.

An excerpt from the will:

I give and bequeath unto my dear wife Keziah Grattidge all my household goods and furniture, wearing apparel and plate and plated articles, linen, books, china, glass, and other household effects whatsoever, and also all my implements of husbandry, horses, cattle, hay, corn, crops and live and dead stock whatsoever, and also all the ready money that may be about my person or in my dwelling house at the time of my decease, …I also give my said wife the tenant right and possession of the farm in my occupation….

A page from the 1843 will of Thomas Grattidge:

William Grattidges half siblings (the offspring of Thomas Grattidge and Kezia Gibbs):

Albert Grattidge (1842-1914) was a railway engine driver in Derby. In 1884 he was driving the train when an unfortunate accident occured outside Ambergate. Three children were blackberrying and crossed the rails in front of the train, and one little girl died.

Albert Grattidge:

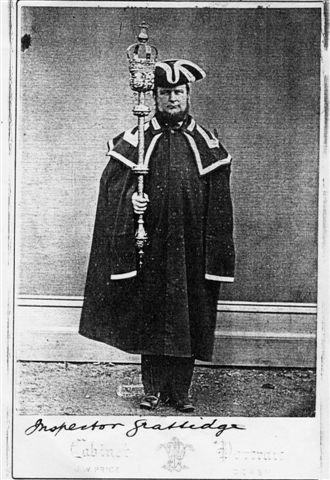

George Grattidge (1826-1876) was baptised Gibbs as this was before Thomas married Kezia. He was a police inspector in Derby.

George Grattidge:

Edwin Grattidge (1837-1852) died at just 15 years old.

Ann Grattidge (1835-) married Charles Fletcher, stone mason, and lived in Derby.

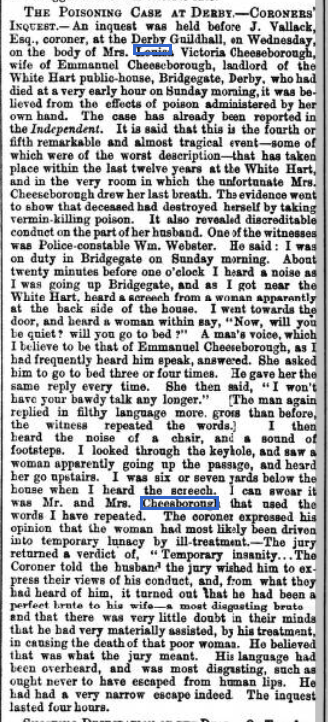

Louisa Victoria Grattidge (1840-1869) was sadly another Grattidge woman who died young. Louisa married Emmanuel Brunt Cheesborough in 1860 in Derby. In 1861 Louisa and Emmanuel were living with her mother Kezia in Derby, with their two children Frederick and Ann Louisa. Emmanuel’s occupation was sawyer. (Kezia Gibbs second husband Frederick Augustus Grattidge was a timber merchant in Derby)

At the time of her death in 1869, Emmanuel was the landlord of the White Hart public house at Bridgegate in Derby.

The Derby Mercury of 17th November 1869:

“On Wednesday morning Mr Coroner Vallack held an inquest in the Grand

Jury-room, Town-hall, on the body of Louisa Victoria Cheeseborough, aged

33, the wife of the landlord of the White Hart, Bridge-gate, who committed

suicide by poisoning at an early hour on Sunday morning. The following

evidence was taken:Mr Frederick Borough, surgeon, practising in Derby, deposed that he was

called in to see the deceased about four o’clock on Sunday morning last. He

accordingly examined the deceased and found the body quite warm, but dead.

He afterwards made enquiries of the husband, who said that he was afraid

that his wife had taken poison, also giving him at the same time the

remains of some blue material in a cup. The aunt of the deceased’s husband

told him that she had seen Mrs Cheeseborough put down a cup in the

club-room, as though she had just taken it from her mouth. The witness took

the liquid home with him, and informed them that an inquest would

necessarily have to be held on Monday. He had made a post mortem

examination of the body, and found that in the stomach there was a great

deal of congestion. There were remains of food in the stomach and, having

put the contents into a bottle, he took the stomach away. He also examined

the heart and found it very pale and flabby. All the other organs were

comparatively healthy; the liver was friable.Hannah Stone, aunt of the deceased’s husband, said she acted as a servant

in the house. On Saturday evening, while they were going to bed and whilst

witness was undressing, the deceased came into the room, went up to the

bedside, awoke her daughter, and whispered to her. but what she said the

witness did not know. The child jumped out of bed, but the deceased closed

the door and went away. The child followed her mother, and she also

followed them to the deceased’s bed-room, but the door being closed, they

then went to the club-room door and opening it they saw the deceased

standing with a candle in one hand. The daughter stayed with her in the

room whilst the witness went downstairs to fetch a candle for herself, and

as she was returning up again she saw the deceased put a teacup on the

table. The little girl began to scream, saying “Oh aunt, my mother is

going, but don’t let her go”. The deceased then walked into her bed-room,

and they went and stood at the door whilst the deceased undressed herself.

The daughter and the witness then returned to their bed-room. Presently

they went to see if the deceased was in bed, but she was sitting on the

floor her arms on the bedside. Her husband was sitting in a chair fast

asleep. The witness pulled her on the bed as well as she could.

Ann Louisa Cheesborough, a little girl, said that the deceased was her

mother. On Saturday evening last, about twenty minutes before eleven

o’clock, she went to bed, leaving her mother and aunt downstairs. Her aunt

came to bed as usual. By and bye, her mother came into her room – before

the aunt had retired to rest – and awoke her. She told the witness, in a

low voice, ‘that she should have all that she had got, adding that she

should also leave her her watch, as she was going to die’. She did not tell

her aunt what her mother had said, but followed her directly into the

club-room, where she saw her drink something from a cup, which she

afterwards placed on the table. Her mother then went into her own room and

shut the door. She screamed and called her father, who was downstairs. He

came up and went into her room. The witness then went to bed and fell

asleep. She did not hear any noise or quarrelling in the house after going

to bed.Police-constable Webster was on duty in Bridge-gate on Saturday evening

last, about twenty minutes to one o’clock. He knew the White Hart