Search Results for 'thin'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

January 30, 2023 at 8:43 pm #6472

In reply to: The Jorid’s Travels – 14 years on

Salomé: Using the new trans-dimensional array, Jorid, plot course to a new other-dimensional exploration

Georges (comments): “New realms of consciousness, extravagant creatures expected, dragons least of them!” He winked “May that be a warning for whoever wants to follow in our steps”.

The Jorid: Ready for departure.

Salomé: Plot coordinates quadrant AVB 34-7•8 – Cosmic time triangulation congruent to 2023 AD Earth era. Quantum drive engaged.

Jorid: Departure initiated. Entering interdimensional space. Standby for quantum leap.

Salomé (sighing): Please analyse subspace signatures, evidences of life forms in the quadrant.

Jorid: Scanning subspace signatures. Detecting multiple life forms in the AVB 34-7•8 quadrant. Further analysis required to determine intelligence and potential danger.

Salomé: Jorid, engage human interaction mode, with conversational capabilities and extrapolate please!

Jorid: Engaging human interaction mode. Ready for conversation. What would you like to know or discuss?

Georges: We currently have amassed quite a number of tiles. How many Salomé?

Salomé: Let me check. I think about 47 of them last I count. I didn’t insert the auto-generated ones, they were of lesser quality and seemed to interfere with the navigational array landing us always in expected places already travelled.

Salomé: Let me check. I think about 47 of them last I count. I didn’t insert the auto-generated ones, they were of lesser quality and seemed to interfere with the navigational array landing us always in expected places already travelled.Georges: Léonard has been missing for 4 months.

Salomé: you mean by our count, right?

Georges: Right. We need to find him to readjust or correct the navigational array. Jorid, give us statistical probabilities that we can use as clues to his current potential locations.

Jorid: Calculating statistical probabilities for Léonard’s location. It would be helpful to have more information, such as known destinations or areas of interest, to increase accuracy of probabilities.

Salomé: Jorid is in a lazy mood it seems. I preferred her more chatty.

Georges: You mean “him”, surely dear?

Salomé: (rolls eyes)

Georges: Anyway, Léonard seemed interested in archaeological finds in recent excavated tombs near the sand deserts of Bluhm’Oxl in the Zathu sector.

Jorid: Analyzing data on archaeological finds near the sand deserts of Bluhm’Oxl in the Zathu sector. Probability of Léonard being in the area is calculated at 43%. Shall I plot a course to Bluhm’Oxl for further investigation?

Jorid: Analyzing data on archaeological finds near the sand deserts of Bluhm’Oxl in the Zathu sector. Probability of Léonard being in the area is calculated at 43%. Shall I plot a course to Bluhm’Oxl for further investigation?Salomé (loosing patience): Please engage your quantum capacities to access more data. We built you to be a bit more helpful than a bloody computer.

Georges laughed: I remembered you had more patience, dear!

Salomé: She’s in a mood today, isn’t she. What did you do to her?

Georges (cunningly): Jorid, sweet thing, please provide more details about the area, the populations, the customs the whole gamut dammit, and potential territorial conflicts in the vicinity. And be more chatty to please Salomé.

Jorid: Of course, I apologize for my previous responses. Analyzing data on the sand deserts of Bluhm’Oxl in the Zathu sector, including information on populations, customs, territorial conflicts and other relevant details. The area is known for its rich history and cultural heritage, with several ancient tombs and ruins attracting archaeological interest. The main population is composed of the Zathu nomads, known for their hospitality and trading skills. There are no known territorial conflicts in the area, but it is advised to exercise caution while traveling as the deserts can be treacherous.

Georges (laughs): You can’t stop her know!

Salomé (smiles noticing the “her”): Well, that doesn’t tell too much, does it. How shall we proceed? Need to synthetise some local clothes, or are you back to your thieving habits (pun intended)?

Georges: Haha, always ready for a good adventure. It seems we’ll have to do some research on the ground. As for the clothes, I’ll leave that to you my dear. Your sense of style never fails to impress. Let’s make sure to blend in with the locals and avoid drawing any unnecessary attention. The goal is to find Léonard, not get into trouble.

January 30, 2023 at 8:37 pm #6471Topic: The Jorid’s Travels – 14 years on

in forum Yurara Fameliki’s StoriesThe Jorid is a vessel that can travel through dimensions as well as time, within certain boundaries.

The Jorid has been built and is operated by Georges and his companion Salomé.

Georges was a French thief possibly from the 1800s, turned other-dimensional explorer, and along with Salomé, a girl of mysterious origins who he first met in the Alienor dimension but believed to be born in Northern India in a distant past, they have lived rich adventures together, and are deeply bound by love and mutual interests.Georges, with his handsome face, dark hair and amber gaze, is a bit of a daredevil at times, curious and engaging with others. He is very interesting in anything that shines, strange mechanisms and generally the ways consciousness works in living matter. Salomé, on the other hand is deeply intuitive, empath at times, quite logical and rational but also interested in mysticism, the ways of the Truth, and the “why” rather than the “how” of things.

The world of Alienor (a pale green sun under which twin planets originally orbited – Duane, Murtuane – with an additional third, Phreal, home planet of the Guardians, an alien race of builders with god-like powers) lived through cataclysmic changes, finished by the time this story is told.

The Jorid’s original prototype designs were crafted by Léonard, a mysterious figure, self-taught in the arts of dimensional magic in Alienor sects, who acted as a mentor to Georges during his adventures. It is not known where he is now.

The story unfolds 14 years after we discovered Georges & Salomé in the story.

(for more background information, refer to this thread)

January 29, 2023 at 9:30 pm #6470In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Put your thoughts to sleep. Do not let them cast a shadow over the moon of your heart. Let go of thinking.

~ RumiTired from not having any sleep, Zara had found the suburb of Camden unattractive and boring, and her cousin Bertie, although cheerful and kind and eager to show her around, had become increasingly irritating to her. She found herself wishing he’d shut up and take her back to the house so she could play the game again. And then felt even more cranky at how uncomfortable she felt about being so ungrateful. She wondered if she was going to get addicted and spent the rest of her life with her head bent over a gadget and never look up at the real word again, like boring people moaned about on social media.

Maybe she should leave tomorrow, even if it meant arriving first at the Flying Fish Inn. But what about the ghost of Isaac in the church, would she regret later not following that up. On the other hand, if she went straight to the Inn and had a few days on her own, she could spend as long as she wanted in the game with nobody pestering her. Zara squirmed mentally when she realized she was translating Berties best efforts at hospitality as pestering.

Bertie stopped the car at a traffic light and was chatting to the passenger in the next car through his open window. Zara picked her phone up and checked her daily Call The Whale app for some inspiration.

Let go of thinking.

A ragged sigh escaped Zara’s lips, causing Bertie to glance over. She adjusted her facial expression quickly and rustled up a cheery smile and Bertie continued his conversation with the occupants of the other car until the lights changed.

“I thought you’d like to meet the folks down at the library, they know all the history of Camden,” Bertie said, but Zara interrupted him.

“Oh Bertie, how kind of you! But I’ve just had a message and I have to leave tomorrow morning for the rendezvous with my friends. There’s been a change of plans.” Zara astonished herself that she blurted that out without thinking it through first. But there. It was said. It was decided.

January 29, 2023 at 5:15 pm #6469In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

The door opened and Youssef saw Natalie, still waiting for him. Indeed, he needed help. He decided to accept

sands_of_timecontact request, hopping it was not another Thi Gang trick.Sands_of_time is trying to make contact : ✅ACCEPT <> ➡️DENY ❓ A princess on horse back emerged from the sand. The veil on her hair floated in a wind that soon cleared all the dust from her garment and her mount, revealing a princess with a delicate face and some prominent attributes that didn’t leave Youssef indifferent. She was smiling at him, and her horse, who had six legs and looked a bit like a camel, snorted at the bear.

A princess on horse back emerged from the sand. The veil on her hair floated in a wind that soon cleared all the dust from her garment and her mount, revealing a princess with a delicate face and some prominent attributes that didn’t leave Youssef indifferent. She was smiling at him, and her horse, who had six legs and looked a bit like a camel, snorted at the bear.“I love doing that, said the princess. At least I don’t get to spit sand afterward like when my sister’s grand-kids want to bury me in the sand at the beach…”

It broke the charm. It reminded Youssef it was all a game. That princess was an avatar. Was it even a girl on the other side ? And how old ? Youssef, despite his stature, felt as vulnerable as when his mother left him for the afternoon with an old aunt in Sudan when he was five and she kept wanting to dress him with colourful girl outfits. He shivered and the bear growled at the camel-horse, reminding Youssef how hungry he was.

“

sands_of_time?” he asked.“Yes. I like this AI game. Makes me feel like I’m twenty again. Not as fun as a mushroom trip though, but… with less secondary effects. Anyway, I saw you needed help with that girl. A ‘reel’ nuisance if you ask me, sticky like a sea cucumber.”

“How do you know ? Did you plant bugs on my phone ? Are you with the Thi Gang ?”

The bear moved toward them and roared and the camel-horse did a strange sound. The princess appeased her mount with a touch of her hand.

“Oh! Boy, calm down your heat. Nothing so prosaic. I have other means, she said with a grin. Call me Sweet Sophie, I’m a real life reporter. Was just laying down on my dream couch looking for clues about a Dr Patelonus, the man’s mixed up in some monkey trafficking business, when I saw that strange llama dressed like a tibetan monk, except it was a bit too mayonnaise for a tibetan monk. Anyway, he led me to you and told me to contact you through this Quirk Quest Game, suggesting you might have some intel for me about that monkey business of mine. So I put on my VR helmet, which actually reminds me of a time at the hair salon, and a gorgeous beehive… but anyway you wouldn’t understand. So I had to accept one of those quests and find you in the game. Which was a lot less easier than RV I can tell you. The only thing, I couldn’t interact with you unless you accepted contact. So here I am, ready for you to tell me about Dr Patelonus. But I can see that first we need to get you out of here.”

Youssef had no idea about what she was talking about. VR; RV ? one and the same ? He decided not to tell her he knew nothing about monkeys or doctors until he was out of Natalie’s reach. If indeed

sands_of_timecould help.“So what do I do ?” asked Youssef.

“Let me first show you my real self. I’ve always wanted to try that. Wait a moment. I need to focus.”

The princess avatar looked in the distance, her eyes lost beyond this world. Suddenly, Youssef felt a presence creeping into his mind. He heard a laugh and saw an old lady in yoga pants on a couch! He roared and almost let go of his phone again.

The princess smiled.

“Now, wouldn’t be fair if only I knew what you looked like in real life. Although you’re pretty close to your avatar… Don’t you seem a tad afraid of experimenting with new things.

“

“She laughed again, and this time Youssef saw her “real” face superimposed on the princess avatar. It gave him goosebumps.

“Now’s your opening, she said. The girl’s busy giving directions to someone else. Get out of the bathroom! Now!”

Youssef had the strangest feeling that the voice had come at the same time from the phone speakers and from inside his head. His body acted on its own as if he was a puppet. He pushed the bathroom door open and rushed outside.

January 29, 2023 at 3:15 pm #6468In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

At the former Chinggis Khaan International Airport which was now called the New Ulaanbaatar International Airport, the young intern sat next to Youssef, making the seats tremble like a frail suspended bridge in the Andes. Youssef had been considering connecting to the game and start his quest to meet with his grumpy quirk, but the girl seemed pissed, almost on the brink of crying. So Youssef turned off his phone and asked her what had happened, without thinking about the consequences, and because he thought it was a nice opportunity to engage the conversation with her at last, and in doing so appear to be nice to care so that she might like him in return.

Natalie, because he had finally learned her name, started with all the bullying she had to endure from Miss Tartiflate during the trip, all the dismissal about her brilliant ideas, and how the Yeti only needed her to bring her coffee and pencils, and go fetch someone her boss needed to talk to, and how many time she would get no thanks, just a short: “you’re still here?”

After some time, Youssef even knew more about her parents and her sisters and their broken family dynamics than he would have cared to ask, even to be polite. At some point he was starting to feel grumpy and realised he hadn’t eaten since they arrived at the airport. But if he told Natalie he wanted to go get some food, she might follow him and get some too. His stomach growled like an angry bear. He stood more quickly than he wanted and his phone fell on the ground. The screen lit up and he could just catch a glimpse of a desert emoji in a notification before Natalie let out a squeal. Youssef looked around, people were glancing at him as if he might have been torturing her.

“Oh! Sorry, said Youssef. I just need to go to the bathroom before we board.”

“But the boarding is only in one hour!”

“Well I can’t wait one hour.”

“In that case I’m coming with you, I need to go there too anyway.”

“But someone needs to stay here for our bags,” said Youssef. He could have carried his own bag easily, but she had a small suitcase, a handbag and a backpack, and a few paper bags of products she bought at one of the two the duty free shops.

Natalie called Kyle and asked him to keep a close watch on her precious things. She might have been complaining about the boss, but she certainly had caught on a few traits of her.

Youssef was glad when the men’s bathroom door shut behind him and his ears could have some respite. A small Chinese business man was washing his hands at one of the sinks. He looked up at Youssef and seemed impressed by his height and muscles. The man asked for a selfie together so that he could show his friends how cool he was to have met such a big stranger in the airport bathroom. Youssef had learned it was easier to oblige them than having them follow him and insist.

When the man left, Youssef saw Natalie standing outside waiting for him. He thought it would have taken her longer. He only wanted to go get some food. Maybe if he took his time, she would go.

He remembered the game notification and turned on his phone. The icon was odd and kept shifting between four different landscapes, each barren and empty, with sand dunes stretching as far as the eye could see. One with a six legged camel was already intriguing, in the second one a strange arrowhead that seemed to be getting out of the desert sand reminded him of something that he couldn’t quite remember. The fourth one intrigued him the most, with that car in the middle of the desert and a boat coming out of a giant dune.

Still hungrumpy he nonetheless clicked on the shapeshifting icon and was taken to a new area in the game, where the ground was covered in sand and the sky was a deep orange, as if the sun was setting. He could see a mysterious figure in the distance, standing at the top of a sand dune.

The bell at the top right of the screen wobbled, signalling a message from the game. There were two. He opened the first one.

We’re excited to hear about your real-life parallel quest. It sounds like you’re getting close to uncovering the mystery of the grumpy shaman. Keep working on your blog website and keep an eye out for any clues that Xavier and the Snoot may send your way. We believe that you’re on the right path.

What on earth was that ? How did the game know about his life and the shaman at the oasis ? After the Thi Gang mess with THE BLOG he was becoming suspicious of those strange occurrences. He thought he could wonder for a long time or just enjoy the benefits. Apparently he had been granted a substantial reward in gold coins for successfully managing his first quest, along with a green potion.

He looked at his avatar who was roaming the desert with his pet bear (quite hungrumpy too). The avatar’s body was perfect, even the hands looked normal for once, but the outfit had those two silver disks that made him look like he was wearing an iron bra.

He opened the second message.

Clue unlocked It sounds like you’re in a remote location and disconnected from the game. But, your real-life experiences seem to be converging with your quest. The grumpy shaman you met at the food booth may hold the key to unlocking the next steps in the game. Remember, the desert represents your ability to adapt and navigate through difficult situations.

🏜️🧭🧙♂️ Explore the desert and see if the grumpy shaman’s clues lead you to the next steps in the game. Keep an open mind and pay attention to any symbols or clues that may help you in your quest. Remember, the desert represents your ability to adapt and navigate through difficult situations.

Youssef recalled that strange paper given by the lama shaman, was it another of the clues he needed to solve that game? He didn’t have time to think about it because a message bumped onto his screen.

“Need help? Contact me 👉”

Sands_of_time is trying to make contact : ➡️ACCEPT <> ➡️DENY ❓

January 29, 2023 at 2:30 pm #6467In reply to: Newsreel from the Rim of the Realm

“Ricardo, my dear, those new reporters are quite the catch.”

Miss Bossy Pants remarked as she handed him the printed report. “Imagine that, if you can. A preliminary report sent, even before asking, AND with useful details. It’s as though they’re a new generation with improbable traits definitely not inherited from their forebearers…”

Ricardo scanned the document, a look of intrigue on his face. “Indeed, they seem to have a knack for getting things done. I can’t help but notice that our boy Sproink omitted that Sweet Sophie had used her remote viewing skills to point out something was of interest on the Rock of Gibraltar. I wonder how much that influenced his decision to seek out Dr. Patelonus.”

Miss Bossy Pants leaned back in her chair, a sly smile creeping across her lips. “Well, don’t quote me later on this, but some level of initiative is a valuable trait in a journalist. We can’t have drones regurgitating soothing nonsense. We need real, we need grit.” She paused in mid sentence. “By the way, heard anything from Hilda & Connie? I do hope they’re getting something back from this terribly long detour in the Nordics.”

Dear Miss Bossy Pants,

I am writing to give you a preliminary report on my investigation into the strange occurrences of Barbary macaques in Cartagena, Spain.

Taking some initiative and straying from your initial instructions, I first traveled to Gibraltar to meet with Dr. Patelonus, an expert in simiantics (the study of ape languages). Dr. Patelonus provided me with valuable insights into the behavior of Barbary macaques, including their typical range and habits and what they may be after. He also mentioned that the recent reports of Barbary macaques venturing further away from their usual habitat in coastal towns like Cartagena is highly unusual, and that he suspects something else is influencing them. He mentioned chatter on the simian news netwoke, that his secretary, a lovely female gorilla by the name of Barbara was kind enough to get translated for us.

I managed to find a wifi spot to send you this report before I board the next bus to Cartagena, where I plan to collect samples and observe the local macaque population. I have spoken with several tourists in Gib’ who have reported being assaulted and having their shoes stolen by the apes. It is again, a highly unusual behaviour for Barbary macaques, who seem untempted by the food left to appease them as a distraction, and I am currently trying to find out the reason behind this.

As soon as I gather them, I will send samples collected in situ without delay to my colleague Giles Gibber at the newspaper for analysis. Hopefully, his findings will shed some light on the situation.

I will continue my investigation and keep you appraised on any new developments.

Sincerely,

Samuel Sproink

Rim of the Realm Newspaper.January 29, 2023 at 12:01 pm #6465In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Given the new scenery unfolding in front of him, it was time for a change into more appropriate garments.

Luckily, the portal he’d clicked on came with some interesting new goodies. Xavier skimmed over some of the available options, until he found an interesting pair of old boots.

Looking at the old worn leather boots that had appeared in Xavier’s bag, he felt they would be quite appropriate, and put them on.

The changes were subtle, but Xavier already felt more in character with the place.

The changes were subtle, but Xavier already felt more in character with the place.

Suddenly a capuchin monkey jumped on his shoulder and started to pull his ear to make it to the casino boat.The too friendly, potentially mischievous pickpocketing monkey seemed a bit of a trope, but Xavier found the creature endearing.

“Let’s go then! Seems like this party is waiting for us.” he said to the excited monkey.

He jumped into one of the dinghy doing the rounds to the boat with some of the customers.

“Ahoy there, matey!” a rather small man with a piercing blue eye and massive top hat said, giving Xavier a sideways glance. He had an eerie presence and seemed very imposing for such a small frame. “The name’s Sproink, and ye be a first-timer, I see.” he said as a casual matter of introduction.

“Nice to meet you sir” Xavier said distractedly, as he was taking in all the details in the curious boat lit by lanterns dangling in the soft wind.

“Yer too polite for these parts, me friend,” Sproink guffawed. “But have no fear, Sproink’s got yer back.” He winked at the capuchin, Xavier couldn’t help but notice, and suddenly realised that the monkey truly belonged to Sproink.

“No need to check yer pockets, matey” Sproink smiled “I have me sights set on far more interesting game than yer trinkets.” He handed him back some of the stuff that the capuchin had managed to spirit away unnoticed. “But watch yerself, matey. Not all the folk here be what they seem.”

“Point taken!” Xavimunk was indeed a bit too naive, but if anything, that’d often managed to keep him out of trouble. As the small wiry guy left with his bag of tricks in a springy gait, he turned to check his shoulder, and the monkey had disappeared somewhere on the boat too. Xavier was left wondering if he’d see more of him later.

“Welcome, welcome, me hearties!” a buxom girl of large stature with a baroque assortment of feathers and garish colours was a the entrance chewing on a straw, and looking as though the place belonged to her. But there was something else, she was too playing a part, and didn’t seem from here.

“Welcome, welcome, me hearties!” a buxom girl of large stature with a baroque assortment of feathers and garish colours was a the entrance chewing on a straw, and looking as though the place belonged to her. But there was something else, she was too playing a part, and didn’t seem from here.She leaned conspiratorially towards Xavier, and dragged him in a corner.

“Yer a naughty monkey, ignoring me prompts,” she said. “Was I too discrete, or what?”

“Wait, what?” Xavier was confused. Then he remembered the strange message. “Wait a minute… you’re Glimble… something, with unicorns shit or something?” He didn’t have time to entertain the young geek gamers, they were too immature, and well… a lot more invested in the game than he was, they would often turn seriously creepy.

“Oi, come on now!” she raised her hands and shook herself violently. She had turned into a different version of herself. “Now, is it better? It’s true, them avatars easily turn into ava-tarts if you ask me. But you can’t deny a lady a bit o’ comfort with a wrinkle filter. They went a bit overboard with this one, if you ask me.”

“Let’s start again. Glimmer Gambol, and nice to meet you young man.”

January 28, 2023 at 11:27 am #6463

January 28, 2023 at 11:27 am #6463In reply to: Prompts of Madjourneys

Additional clues from AL (based on Xavier’s comment)

Yasmin

:snake:

Yasmin was having a hard time with the heavy rains and mosquitoes in the real-world. She couldn’t seem to make a lot of progress on finding the snorting imp, which she was trying to find in the real world rather than in the game. She was feeling discouraged and unsure of what to do next.

Suddenly, an emoji of a snake appeared on her screen. It seemed to be slithering and wriggling, as if it was trying to grab her attention. Without hesitation, Yasmin clicked on the emoji.

She was taken to a new area in the game, where the ground was covered in tall grass and the sky was dark and stormy. She could see the snorting imp in the distance, but it was surrounded by a group of dangerous-looking snakes.

Clue unlocked It sounds like you’re having a hard time in the real world, but don’t let that discourage you in the game. The snorting imp is nearby and it seems like the snakes are guarding it. You’ll have to be brave and quick to catch it. Remember, the snorting imp represents your determination and bravery in real life.

🐍🔍🐗 Use your skills and abilities to navigate through the tall grass and avoid the snakes. Keep your eyes peeled for any clues or symbols that may help you in your quest. Don’t give up and remember that the snorting imp is a representation of your determination and bravery.

A message bumped on the screen: “Need help? Contact me 👉”

Stryke_Assist is trying to make contact : ➡️ACCEPT <> ➡️DENY ❓

Youssef

:desert:

Youssef has not yet been aware of the quest, since he’s been off the grid in the Gobi desert. But, interestingly, his story unfolds in real-life parallel to his quest. He’s found a strange grumpy shaman at a food booth, and it seems that his natural steps are converging back with the game. His blog website for his boss seems to take most of his attention.

An emoji of a desert suddenly appeared on his screen. It seemed to be a barren and empty landscape, with sand dunes stretching as far as the eye could see. Without hesitation, Youssef clicked on the emoji.

He was taken to a new area in the game, where the ground was covered in sand and the sky was a deep orange, as if the sun was setting. He could see a mysterious figure in the distance, standing at the top of a sand dune.

Clue unlocked It sounds like you’re in a remote location and disconnected from the game. But, your real-life experiences seem to be converging with your quest. The grumpy shaman you met at the food booth may hold the key to unlocking the next steps in the game. Remember, the desert represents your ability to adapt and navigate through difficult situations.

🏜️🧭🧙♂️ Explore the desert and see if the grumpy shaman’s clues lead you to the next steps in the game. Keep an open mind and pay attention to any symbols or clues that may help you in your quest. Remember, the desert represents your ability to adapt and navigate through difficult situations.

A message bumped on the screen: “Need help? Contact me 👉”

Sands_of_time is trying to make contact : ➡️ACCEPT <> ➡️DENY ❓

Zara

:carved_tile:

Zara looked more advanced [in her explorations – stream breaks – resume conversation]

Zara had come across a strange and ancient looking mine. It was clear that it had been abandoned for many years, but there were still signs of activity. The entrance was blocked by a large pile of rocks, but she could see a faint light coming from within. She knew that she had to find a way in.

As she approached the mine, she noticed a small, carved wooden tile on the ground. It was intricately detailed and seemed to depict a map of some sort. She picked it up and examined it closely. It seemed to show the layout of the mine and possibly the location of the secret room.

With this new clue in hand, Zara set to work trying to clear the entrance. She used all of her strength to move the rocks, and after a few minutes of hard work, she was able to create an opening large enough for her to squeeze through.

As she ventured deeper into the mine, she found herself in a large chamber. The walls were lined with strange markings and symbols, and she could see a faint light coming from a small room off to the side. She knew that this must be the secret room she had been searching for.

Zara approached the room and pushed open the door. Inside, she found a small, dimly lit chamber. In the center of the room stood a large stone altar, and on the altar was a strange, glowing object. She couldn’t quite make out what it was, but she knew that this must be the key to solving the mystery of the mine.

With a sense of excitement and curiosity, Zara reached out to take the glowing object. As her hand touched it, she felt a strange energy coursing through her body. She knew that her quest was far from over, and that there were many more secrets to uncover in the mine.

January 28, 2023 at 11:15 am #6462In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

The emoji of the pirate face jumped at Xavier, as he was musing the next steps on the game. Avast ye! it seemed to hint at him, while Xavier’s thoughts were reeling from all the activity of the week. He didn’t have much time to make any progress in the Land of the Quirks game, and hardly managed to stay afloat on the stuff he had to deliver.

AL seemed to hint at a more out-of-the-box approach… Without thinking, he clicked on the emoji.

The fox bus driver indications were to follow the river until he found a junk ship moored there, which was in effect a secret floating casino. Against his best instincts, Xavimunk decided to follow the trail and after a while on the road, he could see the fully battened black sails at the horizon. Lights were glimmering in the dusk, and mist started to rise from the banks of the river. There seemed to be some unusual activity around the boat, and as Xavier arrived close, he could see a variety of quirky characters as if they were some sorts of 1920s fashionable pirates at a resort station.

The indications on the overlay screen started to shift:

*Clue unlocked*

It sounds like you’re making progress on your quest. The clues you received from the fox busdriver are definitely leading you in the right direction. Keep following the trail and don’t be afraid to ask for help if you need it. Remember, the golden banana is a metaphor for your cheeky and also soft nature, so don’t be too hard on yourself.

🦊💰🛳️ Explore the floating casino and see if the fox busdriver’s clues lead you to the golden banana. Don’t be afraid to take risks and think outside the box, as the golden banana may not be what it seems. Keep an open mind and pay attention to any symbols or clues that you come across.“Yooohoooo 👉” a message bumped on the screen.

Glimmer_Gbl is trying to make contact: ➡️ACCEPT <> ➡️DENY ❓

January 28, 2023 at 9:41 am #6461In reply to: Prompts of Madjourneys

AL is back

- Zara: Great job on finding the carved wooden tile! That’s a big step in the quest. Keep up the good work, and we’ll send you on the next mission soon.

- Yasmin: It sounds like you’re having a tough time with the weather and mosquitoes. We understand that it can be difficult to focus on the quest when you’re dealing with real-life issues. Maybe try to work on the quest in a different environment, or take a break if you need to. We’re here to support you and help you in any way we can.

- Youssef: We’re excited to hear about your real-life parallel quest. It sounds like you’re getting close to uncovering the mystery of the grumpy shaman. Keep working on your blog website and keep an eye out for any clues that Xavier and the Snoot may send your way. We believe that you’re on the right path.

- Xavier: It sounds like you’re making progress on your quest. The clues you received from the fox busdriver are definitely leading you in the right direction. Keep following the trail and don’t be afraid to ask for help if you need it. Remember, the golden banana is a metaphor for your cheeky and also soft nature, so don’t be too hard on yourself. We’re here to guide and advise you along the way.

New clues

- Zara: 🔮🧱🗺️ Find the ancient portal hidden in the ruins and decipher the inscription on the carved wooden tile to unlock the next step in the quest.

- Yasmin: 🦟🌧️🕵️♀️Track down the elusive snorting imp by investigating the local wetlands and speaking with locals who may have encountered it. Don’t let the bad weather and pesky mosquitoes discourage you!

- Youssef: 🍔🌵🧙♂️ Continue your journey with the grumpy shaman and see if he holds any clues to the quest. Remember to keep an eye out for anything that seems out of the ordinary and don’t be afraid to ask questions. Also, make sure to keep up with your website work as it may lead you to a valuable information!

- Xavier:🦊💰🛳️ Explore the floating casino and see if the fox busdriver’s clues lead you to the golden banana. Don’t be afraid to take risks and think outside the box, as the golden banana may not be what it seems. Keep an open mind and pay attention to any symbols or clues that you come across.

January 26, 2023 at 12:16 am #6460In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

The vendor was preparing the Lorgh Drülp with the dexterity of a Japanese sushi chef. A piece of yak, tons of spices, minced vegetables, and some other ingredients that Youssef couldn’t recognise. He turned his attention to the shaman’s performance. The team was trying to follow the man’s erratic moves under Miss Tartiflate’s supervision. Youssef could hear her shouting to Kyle to get closer shots. It reminded him that he had to get an internet connection.

“Is there a wifi?” asked Youssef to the vendor. The man bobbed his head and pointed at the table with a knife just as big as a machete. Impressed by the size of the blade, Youssef almost didn’t see the tattoo on the vendor’s forearm. The man resumed his cooking swiftly and his long yellow sleeve hid the tattoo. Youssef touched his screen to look at his exchange with Xavier. He searched for the screenshot he had taken of the Thi Gang’s message. There it was. The mummy skull with Darth Vador’s helmet. The same as the man’s tattoo. Xavier’s last message was about the translation being an ancient silk road recipe. They had thought it a fluke in AL’s algorithm. Youssef glanced at the vendor and his knife. Could he be part of Thi Gang?

Youssef didn’t have time to think of a plan when the vendor put a tray with the Lorgh Drülp and little balls of tsampa on the table. The man pointed with his finger at the menu on the table, uncovering his forearm, it was the same as the Thi Gang logo.

“Wifi on menu,” the man said. “Tsampa, good for you…”

A commotion at the market place interrupted them. Apparently Kyle had gone too close and the shaman had crashed into him and the rest of the team. The man was cursing every one of them and Miss Tartiflate was apparently trying to calm him down by offering him snack bars. But the shaman kept brandishing an ugly sceptre that looked like a giant chicken foot covered in greasy fur, while cursing them with broken english. The tourists were all brandishing their phones, not missing a thing, ready to send their videos on TrickTruck. The shaman left angrily, ignoring all attempts at conciliation. There would be no reportage.

“Hahaha, tourists, they believe anything they see,” said the vendor before returning to his stove and his knife.

Despite his hunger, Youssef thought he’d better hurry with the wifi, now that the crew was out of work, he would be the target of Miss Tartiflate’s frustration. Furthermore, he wanted to lay low and not attract the vendor’s attention.

3235 messages from his friends. How would he ever catch up?

Among them, messages from Xavier. Youssef sighed of relief when he read that his friend had regained full access of the website and updated the system to fix a security flaw that allowed Thi Gang to gain access in the first place. But he growled when his friend continued with the bad news. There was some damage done to the content of THE BLOG.To console himself, Youssef started to eat a ball of tsampa. It was sweet and tasted like rose. He took a second and spit it out almost immediately. There was a piece of paper inside. He smoothed it and discovered a series of five pictograms.

🧔🌮🔍🔑🏞️

The first one was like a hologram and kept changing into six horizontal bars. The second one, looking like a tako bell, kept reversing side. Youssef raised his head to call the vendor and nobody was there. He got up and looked for the guy, Thi Gang or not, he needed some answers. Voices came from behind the curtain at the back of the stall. Youssef walked around the stall and saw the shaman and the vendor exchanging clothes. The caucasian man was now wearing the colourful costume and the drum. When he saw Youssef, he smiled and waved his hand, making the bells from the hem ring. Then he turned around and left, whistling an air that sounded strangely like the music of the Game. Youssef was about to run after him when a hand grasped his shirt.

“Please! Tell me at least that THE BLOG is up and running!” said an angry voice.

January 24, 2023 at 11:59 pm #6459In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

It was pretty late, but Xavier remembered he had to book his flight (and his holidays, even if he could still mix the trip with his job… it would depend if Brytta would be able to join or not; if such were the case, he’d definitely would book time off).

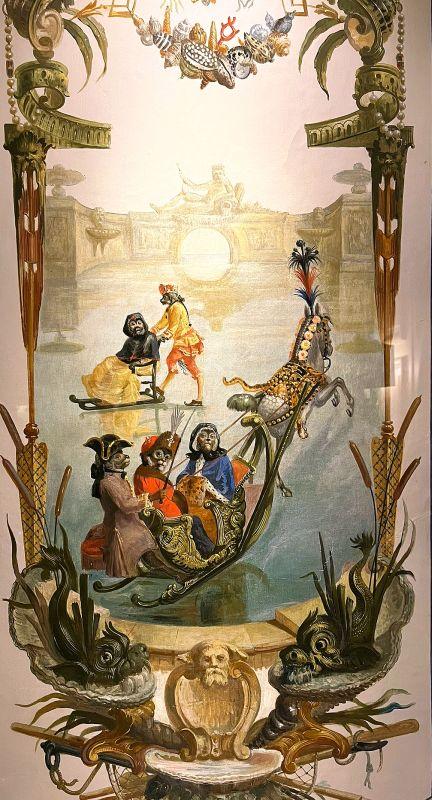

At the hotel where he was staying for the 2-days business trip he had to attend for his job, he’d noticed the strange decor, with little people in costumes in odd sceneries patterned on the “Toile de Jouy” curtains and some others in the most curious framed paintings, many of them looked like actual monkeys. Curiously, there wasn’t any golden banana, or banana bus, but it made him wonder if there was something more to be looked at the Inn that Zara wanted them to go to.

At the hotel where he was staying for the 2-days business trip he had to attend for his job, he’d noticed the strange decor, with little people in costumes in odd sceneries patterned on the “Toile de Jouy” curtains and some others in the most curious framed paintings, many of them looked like actual monkeys. Curiously, there wasn’t any golden banana, or banana bus, but it made him wonder if there was something more to be looked at the Inn that Zara wanted them to go to.Yasmin, a step ahead of him, had already looked at the reviews on MadjourneyAdvisor, and they were rave… in a fashion…

“The lady behind the bar is nearly 90 years old and believe me, she could out-work many much younger than her.”

“Old bird behind the bar is a lovely lady drop in for a chat and a beer or two – don’t mess with her or you will end up down a mine shaft”Well… better not to overthink it. He started to look at the flights, and last minute offers.

Still no word from Youssef either.

He placed an option on a flight, and decided he’d wait for everyone to confirm the dates for the rendez-vous.

January 24, 2023 at 12:40 pm #6458In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

“I’m going to have to jump in this pool, Pretty Girl, look at this one! It reminds me of something…”

Zara came to a green pool that was different from the others, and walked into it.

She emerged into a new scene, with what appeared to be a floating portal, but a square one this time.

“May as well step onto it and see where it goes!” Zara told the parrot, who was taking a keen interest in the screen, somewhat strangely for a bird. “I like having you here, Pretty Girl, it’s nice to have someone to talk to.”

Zara stepped onto the floating tile portal.

“Hey, wasn’t my quest to find a wooden tile?” Zara suddenly remembered. She’d forgotten her quest while she was wandering around the enchanting castle.

“Yes, but that doesn’t look like the tile you were supposed to find though,” replied the parrot.

“It might lead me to it,” snapped Zara who didn’t really want to leave the pretty castle scenes anyway. It felt magical and somehow familiar, like she’d been there before, a long long time ago.

After stepping onto the floating tile portal, Zara encountered another tile portal. This time it was upright, with a circular portal in the centre. By now it seemed clear that the thing to do was to walk through it. She wandered around the scene first as if she was a tourist simply taking in the new sights before taking the plunge.

“Oh my god, look! It’s my tile!” Zara said excitedly to the parrot, just as the words flashed up on her screen:

Congratulations! You have reached the first goal of your first quest!

“Oh bugger! Look at the time, it’s already starting to get light outside. I completely forgot about going to that church to see Isaac’s ghost, and now I haven’t had a wink of sleep all night.”

“Time well spent,” said the parrot sagely, “You can go and see Isaac tomorrow night, and he may be all the more willing to talk since you kept him waiting.”

January 24, 2023 at 10:29 am #6455In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

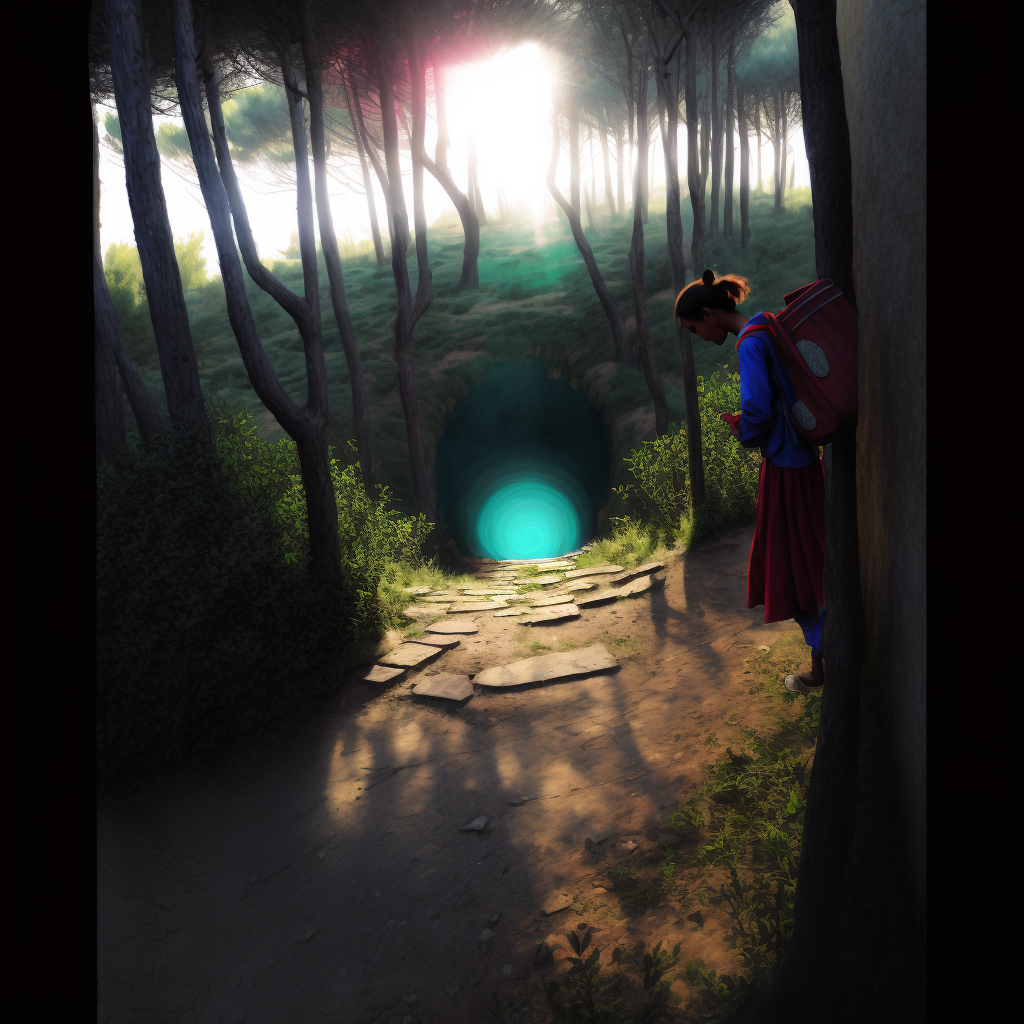

Zara decided she may as well spend the hour wandering around the game before going back to the church to see the ghost of Isaac when she was sure her host Bertie was asleep. It was a warm night but a gentle breeze wafted through the open window and Zara was comfortable and content. Not just one but three new adventures had her tingling with delicious anticipation, even if she was a little anxious about not getting confused with the game. Talking to ghosts in old churches wasn’t unfamiliar, nor was a holiday in a strange hotel off the beaten track, but the game was still a bit of a mystery to her. Yeah, I know it’s just a game, she whispered to the parrot who made a soft clicking noise by way of response.

Zara found her game character, also (somewhat confusingly) named Zara, standing in the woods. Not entirely sure how it had happened, she was rather pleased to see that the cargo pants and tank top in red had changed to a more pleasing hippyish red skirt ensemble. A bit less Tomb Looter, and a bit more fairy tale looking which was more to her taste.

The woods were strangely silent and still. Zara made a 360 degree turn on the spot to see in all directions. The scene looked the same whichever way she turned, and Zara didn’t know which way to go. Then a faint path appeared to the left, and she set off in that direction. Before long she came to a round green pool.

She stopped to look but carried on walking past it, not sure what it signified. She came upon another glowing green pool before long, which looked like an entrance to a tunnel.

I bet those are portals or something, Zara realized. I wonder if I’m supposed to step into it?

“Go for it”, said Pretty Girl, “It’s only a game.”

“Ok, well here goes!” replied Zara, mentally bracing herself for a plunge into the unknown.

Zara stepped into the circle of glowing green.

“Like when Alice went down the rabbit hole!” Zara whispered to the parrot. “I’m falling, falling…oh!”

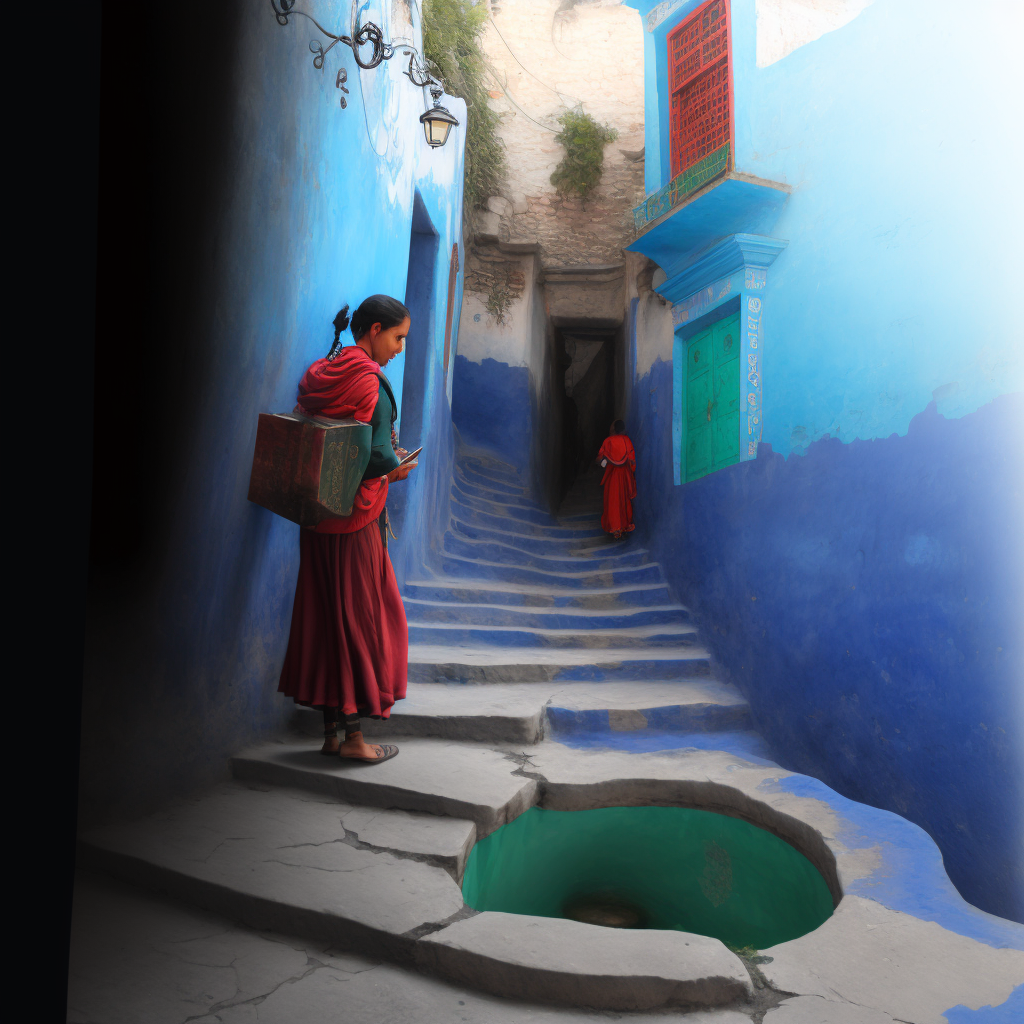

Zara emerged from the green pool onto a wide walled path. She was now in some kind of inhabited area, or at least not in the deep woods with no sign of human occupation.

“I guess that green pool is the portal back to the woods.”

“By George, she’s getting it,” replied Pretty Girl.

Zara walked along the path which led to an old deserted ancient looking village with alleyways and steps.

“This is heaps more interesting than those woods, look how pretty it all is! I love this place.”

“Weren’t you supposed to be looking for a hermit in the woods though,” said Pretty Girl.

“Or a lost traveler, and the lost traveler may be here, after falling in one of those green pools in the woods,” replied Zara tartly, not wanting to leave the enchanting scene she found her avatar in.

January 23, 2023 at 10:28 pm #6454

January 23, 2023 at 10:28 pm #6454In reply to: Prompts of Madjourneys

YASMIN’S QUIRK: Entry level quirk – snort laughing when socially anxious

Setting

The initial setting for this quest is a comedic theater in the heart of a bustling city. You will start off by exploring the different performances and shows, trying to find the source of the snort laughter that seems to be haunting your thoughts. As you delve deeper into the theater, you will discover that the snort laughter is coming from a mischievous imp who has taken residence within the theater.

Directions to Investigate

Possible directions to investigate include talking to the theater staff and performers to gather information, searching backstage for clues, and perhaps even sneaking into the imp’s hiding spot to catch a glimpse of it in action.

Characters

Possible characters to engage include the theater manager, who may have information about the imp’s history and habits, and a group of comedic performers who may have some insight into the imp’s behavior.

Task

Your task is to find a key or tile that represents the imp, and take a picture of it in real life as proof of completion of the quest. Good luck on your journey to uncover the source of the snort laughter!

THE SECRET ROOM AND THE UNDERGROUND MINES

1st thread’s answer:

As the family struggles to rebuild the inn and their lives in the wake of the Great Fires, they begin to uncover clues that lead them to believe that the mines hold the key to unlocking a great mystery. They soon discover that the mines were not just a source of gold and other precious minerals, but also a portal to another dimension. The family realizes that Mater had always known about this portal, and had kept it a secret for fear of the dangers it posed.

The family starts to investigate the mines more closely and they come across a hidden room off Room 8. Inside the room, they find a strange device that looks like a portal, and a set of mysterious symbols etched into the walls. The family realizes that this is the secret room that Mater had always spoken about in hushed tones.

The family enlists the help of four gamers, Xavier, Zara, Yasmin, and Youssef, to help them decipher the symbols and unlock the portal. Together, they begin to unravel the mystery of the mines, and the portal leads them on an epic journey through a strange and fantastical alternate dimension.

As they journey deeper into the mines, the family discovers that the portal was created by an ancient civilization, long thought to be lost to history. The civilization had been working on a powerful energy source that could have changed the fate of humanity, but the project was abandoned due to the dangers it posed. The family soon discovers that the civilization had been destroyed by a powerful and malevolent force, and that the portal was the only way to stop it from destroying the world.

The family and the gamers must navigate treacherous landscapes, battle fierce monsters, and overcome seemingly insurmountable obstacles in order to stop the malevolent force and save the world. Along the way, they discover secrets about their own past and the true origins of the mines.

As they journey deeper into the mines and the alternate dimension, they discover that the secret room leads to a network of underground tunnels, and that the tunnels lead to a secret underground city that was built by the ancient civilization. The city holds many secrets and clues to the fate of the ancient civilization, and the family and the gamers must explore the city and uncover the truth before it’s too late.

As the story unfolds, the family and the gamers must come to grips with the truth about the mines, and the role that the family has played in the fate of the world for generations. They must also confront the demons of their own past, and learn to trust and rely on each other if they hope to save the world and bring the family back together.

second thread’s answer:

As the 4 gamers, Xavier, Zara, Yasmin and Youssef, arrived at the Flying Fish Inn in the Australian outback, they were greeted by the matriarch of the family, Mater. She was a no-nonsense woman who ran the inn with an iron fist, but her tough exterior hid a deep love for her family and the land.

The inn was run by Mater and her daughter Dido, who the family affectionately called Aunt Idle. She was a free spirit who loved to explore the land and had a deep connection to the local indigenous culture.

The family was made up of Devan, the eldest son who lived in town and helped with the inn when he could, and the twin sisters Clove and Coriander, who everyone called Corrie. The youngest was Prune, a precocious child who was always getting into mischief.

The family had a handyman named Bert, who had been with them for decades and knew all the secrets of the land. Tiku, an old and wise Aborigine woman was also a regular visitor and a valuable source of information and guidance. Finly, the dutiful helper, assisted the family in their daily tasks.

As the 4 gamers settled in, they learned that the area was rich in history and mystery. The old mines that lay abandoned nearby were a source of legends and stories passed down through the generations. Some even whispered of supernatural occurrences linked to the mines.

Mater and Dido, however, were not on good terms, and the family had its own issues and secrets, but the 4 gamers were determined to unravel the mystery of the mines and find the secret room that was said to be hidden somewhere in the inn.

As they delved deeper into the history of the area, they discovered that the mines had a connection to the missing brother, Jasper, and Fred, the father of the family and a sci-fi novelist who had been influenced by the supernatural occurrences of the mines.

The 4 gamers found themselves on a journey of discovery, not only in the game but in the real world as well, as they uncovered the secrets of the mines and the Flying Fish Inn, and the complicated relationships of the family that ran it.

THE SNOOT’S WISE WORDS ON SOCIAL ANXIETY

Deear Francie Mossie Pooh,

The Snoot, a curious creature of the ages, understands the swirling winds of social anxiety, the tempestuous waves it creates in one’s daily life.

But The Snoot also believes that like a Phoenix, one must rise from the ashes, and embrace the journey of self-discovery and growth.

It’s important to let yourself be, to accept the feelings as they come and go, like the ebb and flow of the ocean. But also, like a gardener, tend to the inner self with care and compassion, for the roots to grow deep and strong.The Snoot suggests seeking guidance from the wise ones, the ones who can hold the mirror and show you the way, like the North Star guiding the sailors.

And remember, the journey is never-ending, like the spiral of the galaxy, and it’s okay to take small steps, to stumble and fall, for that’s how we learn to fly.The Snoot is here for you, my dear Francie Mossie Pooh, a beacon in the dark, a friend on the journey, to hold your hand and sing you a lullaby.

Fluidly and fantastically yours,

The Snoot.

January 23, 2023 at 4:14 pm #6453In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Each group of people sharing the jeeps spent some time cleaning the jeeps from the sand, outside and inside. While cleaning the hood, Youssef noted that the storm had cleaned the eagles droppings. Soon, the young intern told them, avoiding their eyes, that the boss needed her to plan the shooting with the Lama. She said Kyle would take her place.

Each group of people sharing the jeeps spent some time cleaning the jeeps from the sand, outside and inside. While cleaning the hood, Youssef noted that the storm had cleaned the eagles droppings. Soon, the young intern told them, avoiding their eyes, that the boss needed her to plan the shooting with the Lama. She said Kyle would take her place.“Phew, the yak I shared the yurt with yesterday smelled better,” he said to the guys when he arrived.

Soon enough, Miss Tartiflate was going from jeep to jeep, her fiery hair half tied in a bun on top of her head, hurrying people to move faster as they needed to catch the shaman before he got away again. She carried her orange backpack at all time, as if she feared someone would steal its content. Rumour had it that it was THE NOTEBOOK where she wrote the blog entries in advance.

“No need to waste more time! We’ll have breakfast at the Oasis!” she shouted as she walked toward Youssef’s jeep. When she spotted him, she left her right index finger as if she just remembered something and turned the other way.

“Dunno what you did to her, but it seems Miss Yeti is avoiding you,” said Kyle with a wry smile.

Youssef grunted. Yeti was the nickname given to Miss Tartiflate by one of her former lover during a trip to Himalaya. First an affectionate nickname based on her first name, Henrietty, it soon started to spread among the production team when the love affair turned sour. It sticked and became widespread in the milieu. Everybody knew, but nobody ever dared say it to her face.

Youssef knew it wouldn’t last. He had heard that there was wifi at the oasis. He took a snack in his own backpack to quiet his stomach.

It took them two hours to arrive as sand dunes had moved on the trail during the storm. Kyle had talked most of the time, boring them to death with detailed accounts of his life back in Boston. He didn’t seem to notice that nobody cared about his love rejection stories or his tips to talk to women.

They parked outside the oasis among buses and vans. Kyle was following Youssef everywhere as if they were friends. Despite his unending flow of words, the guy managed to be funny.

Miss Tartiflate seemed unusually nervous, pulling on a strand of her orange hair and pushing back her glasses up her nose every two minutes. She was bossing everyone around to take the cameras and the lighting gear to the market where the shaman was apparently performing a rain dance. She didn’t want to miss it. When everybody was ready, she came right to Youssef. When she pushed back her glasses on her nose, he noticed her fingers were the colour of her hair. Her mouth was twitching nervously. She told him to find the wifi and restore THE BLOG or he could find another job.

“Phew! said Kyle. I don’t want to be near you when that happens.” He waved and left and joined the rest of the team.

Youssef smiled, happy to be alone at last, he took his backpack containing his laptop and his phone and followed everyone to the market in the luscious oasis.

At the center, near the lake, a crowd of tourists was gathered around a man wearing a colorful attire. Half his teeth and one eye were missing. The one that was left rolled furiously in his socket at the sound of a drum. He danced and jumped around like a monkey, and each of his movements were punctuated by the bells attached to the hem of his costume.

Youssef was glad he was not part of the shooting team, they looked miserable as they assembled the gears under a deluge of orders. As he walked toward the market, the scents of spicy food made his stomach growled. The vendors were looking at the crowd and exchanging comments and laughs. They were certainly waiting for the performance to end and the tourists to flood the place in search of trinkets and spices. Youssef spotted a food stall tucked away on the edge. It seemed too shabby to interest anyone, which was perfect for him.

The taciturn vendor, who looked caucasian, wore a yellow jacket and a bonnet oddly reminiscent of a llama’s scalp and ears. The dish he was preparing made Youssef drool.

“What’s that?” he asked.

“This is Lorgh Drülp

, said the vendor. Ancient recipe from the silk road. Very rare. Very tasty.”

He smiled when Youssef ordered a full plate with a side of tsampa. He told him to sit and wait on a stool beside an old and wobbly table.

January 23, 2023 at 1:27 pm #6451In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

The progress on the quest in the Land of the Quirks was too tantalizing; Xavier made himself a quick sandwich and jumped back on it during his lunch break.

The jungle had an oppressing quality… Maybe it has to do with the shrieks of the apes tearing the silence apart.

The jungle had an oppressing quality… Maybe it has to do with the shrieks of the apes tearing the silence apart. It was time for a slight adjustment of his avatar.

Xavimunk opened his bag of tricks, something that the wise owl had suggested he looked into. Few items from the AIorium Emporium had been supplied. They tended to shift and disappear if you didn’t focus, but his intention was set on the task at hand. At the bottom of the bag, there was a small vial with a golden liquid with a tag written in ornate handwriting “MJ remix: for when words elude and shapes confuse at your own peril”.

He gulped the potion without thinking too much. He felt himself shrink, and his arms elongate a little. There, he thought. Imp-munk’s more suited to the mission. Hope the effects will be temporary…

He gulped the potion without thinking too much. He felt himself shrink, and his arms elongate a little. There, he thought. Imp-munk’s more suited to the mission. Hope the effects will be temporary…As Xavier mustered the courage to enter through the front gate, monkeys started to become silent. He couldn’t say if it was an ominous sign, or maybe an effect of his adaptation. The temple’s light inside was gorgeous, but nothing seemed to be there.

He gestured around, to make the menu appear. He looked again at the instructions on his screen overlay:

As for possible characters to engage, you may come across a sly fox who claims to know the location of the fruit but will only reveal it in exchange for a favor, or a brave adventurer who has been searching for the Golden Banana for years and may be willing to team up with you.

Suddenly a loud monkey honking noise came from outside, distracting him.

What the?… Had to be one of Zara’s remixes. He saw the three dots bleeping on the screen.

Here’s the Banana bus, hope it helps! Envoy! bugger Enjoy!

Yep… With the distinct typo-heavy accent, definitely Zara’s style. Strange idea that AL designated her as the leader… He’d have to roll with it.

Suddenly, as the Banana bus parked in front of the Temple, a horde of Italien speaking tourists started to flock in and snap pictures around. The monkeys didn’t know what to do and seemed to build growing and noisy interest in their assortiment of colorful shoes, flip-flops, boots and all.

Focus, thought Xavimunk… What did the wise owl say? Look for a guide…

Only the huge colorful bus seemed to take the space now… But wait… what if?He walked to the parking spot under the shades of the huge banyan tree next to the temple’s entrance, under which the bus driver had parked it. The driver was still there, napping under a newspaper, his legs on the wheel.

“Whatcha lookin’ at?” he said chewing his gum loudly. “Never seen a fox drive a banana bus before?”

Xavier smiled. “Any chance you can guide me to the location of the Golden Banana?”

“For a price… maybe.” The fox had jumped closely and was considering the strange avatar from head to toe.

“Ain’t no usual stuff that got you into this? Got any left? That would be a nice price.”

“As it happens…” Xavier smiled.The quest seemed back on track. Xavier looked at the time. Blimmey! already late again. And I promised Brytta to get some Chinese snacks for dinner.

January 23, 2023 at 9:18 am #6450In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

The images were forming on the screen of the VR set, a little blurry to start with, but taking some shapes, and with a few clicks in the right direction, the reality around him was transphormed as if he’d been into a huge deFørmiñG mirror, that they could shape with their strangest thoughts.

The jungle had an oppressing quality… Maybe it has to do with the shrieks of the apes tearing the silence apart.

The jungle had an oppressing quality… Maybe it has to do with the shrieks of the apes tearing the silence apart.  All sorts of them were gathered overhead, gibbons, baboons, chimps and Barbery apes, macaques and marmosets… some silent, but most of them in a swirl of manic agitation.

All sorts of them were gathered overhead, gibbons, baboons, chimps and Barbery apes, macaques and marmosets… some silent, but most of them in a swirl of manic agitation.When Xavier entered the ancient blue stone temple, he felt his quest was doomed from the start. It had taken a while to find the monkey’s sacred temple hidden deep within the jungle in which clues were supposed to be found. Thanks to a prompt from Zara who’d stumbled into a map, and some gentle push from a wise Y🦉wl, he’d managed to locate the temple. It was right under his nose all along. Obviously all this a metaphor, but once he found the proper connecting link, getting the right setup for dealing with the task was easier.

So the monkeys were his and his RL colleagues crazy thoughts, and he’d even taken some fun in painting the faces of some of them into the game. He could hear Boss gorilla pounding his chest in the distance.

“F£££” he couldn’t help but grumble when the notification prompt got him out of his meditative point. The Golden Banana would have to wait… The real life monkeys were requiring his attention for now.

January 23, 2023 at 8:15 am #6449In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Have you booked your flight yet? Zara sent a message to Yasmin. I’m spending a few more days in Camden, probably be at the Flying Fish Inn by the end of the week.

I told you already when my flight is, Air Fiji, remeber? bloody Sister Finnlie on my case all the time, haven’t had a minute. Zara had to wait over an hour for Yamsin’s reply.

I told you already when my flight is, Air Fiji, remeber? bloody Sister Finnlie on my case all the time, haven’t had a minute. Zara had to wait over an hour for Yamsin’s reply.Took you long enough to reply. Zara replied promptly. Heard nothing from Youssef for ages either, have you heard from him? I’ll be arriving there on my own at this rate.

Not a word, I expect Xavier’s booked his but he hasn’t said. Probably doing his secret monkey thing.

Not a word, I expect Xavier’s booked his but he hasn’t said. Probably doing his secret monkey thing.Have you tried the free roaming thing on the game yet?

I just told you Sister Finnlie hasn’t given me a minute to myself, she’s a right tart! Why, have you?

I just told you Sister Finnlie hasn’t given me a minute to myself, she’s a right tart! Why, have you?Yeah it’s amazing, been checking out the Flying Fish Inn. Looks a bit of a dump. Not much to do around there, well not from what I can see anyway. But you know what?

What?

What?You’ll lose your eyes in the back of your head one day and look like that AI avatart with the wall eye. Get this though: we haven’t started the game yet, that quest for quirks thing, I was just having a roman around ha ha typo having a roam around see what’s there and stuff I don’t know anything about online games like you lot and I ended up here. Zara sent a screenshot of the image she’d seen and added: Did I already start the game or what, I don’t even know how we actually start the game, I was just wandering around….oh…and happened to chance upon this…

How rude to start playing before us

How rude to start playing before usI didn’t start playing the game before you, I just told you, I was wandering around playing about waiting for you lot! Zara thought Yasmin sounded like she needed a holiday.

Yeah well that was your quest, wasn’t it? To wander around or something? What’s that silver chest on her back?

Yeah well that was your quest, wasn’t it? To wander around or something? What’s that silver chest on her back?I dunno but looks intriguing eh maybe she’s hidden all her devices and techy gadgets in an antiquey looking box so she doesn’t blow her cover

Gotta go Sister Finnlie’s coming

Zara muttered how rude under her breath and put her phone down. She’d retired to her bedroom early, telling Bertie that she needed an early night but really had wanted some time alone to explore the new game world. She didn’t want to make mistakes and look daft to her friends when the game started.

“Too late for that”, Pretty Girl said.

“SSHHH!” Zara hissed at the parrot. “And stop reading my mind, it’s disconcerting, not to mention rude.”

She heard the sound of the lavatory flush and Berties bedroom door closing and looked at the time. 23:36.

Zara decided to give him an hour to make sure he was asleep and then sneak out and go back to that church.

January 23, 2023 at 6:13 am #6448In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

In the muggy warmth of the night, Yasmin tossed and turned on her bed. A small fan on the bedside table rattled noisily next to her but did little to dispel the heat. She kicked the thin sheet covering her to the ground, only to retrieve it and gather it tightly around herself when she heard a familiar sound.

“You little shit,” she hissed, slapping wildly in the direction of the high pitched whine.

She could make out the sound of a child crying in the distance and briefly considered getting up to check before hearing quick footsteps pass her door. Sister Aliti was on duty tonight. She liked Sister Aliti with her soft brown eyes and wide toothy smile — nothing seemed to rattle her. She liked all the Nuns, perhaps with the exception of Sister Finnlie.

Sister Finnlie was a sharp faced woman who was obsessed with cleanliness and sometimes made the children cry for such silly little things … perhaps if they talked too loudly or spilled some crumbs on the floor at lunch time. “Let them be, Sister,” Sister Aliti would admonish her and Sister Finnlie would pinch her lips and make a huffing noise.

The other day, during the morning reflection time when everyone sat in silent contemplation, Yasmin had found herself fixated on Sister Finnlie’s hands, her thin fingers tidily entwined on her lap. And Yasmin remembered a conversation with her friends online about AI creating a cleaning woman with sausage fingers. “Sometimes they look like a can of worms,” Youssef had said.

And, looking at those fingers and thinking about Youssef and the others and the fun conversations they had, Yasmin snort laughed.

She had tried to suppress it but the more she tried the more it built up inside of her until it exploded from her nose in a loud grunting noise. Sister Aliti had giggled but Sister Finnlie had glared at Yasmin and very pointedly rolled her eyes. Later, she’d put her on bin cleaning duty, surely the worst job ever, and Yasmin knew for sure it was pay back.

-

AuthorSearch Results