Search Results for 'union'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

January 15, 2024 at 10:18 pm #7293

In reply to: The Whale’s Diaries Collection

thank you for the suggestion of the tessera hospitalis. I had never heard of that before! Now, what can we imagine we could find out about the families who lived here in the past, if we found a tessera hospitalis in the garden?

Ah, the Tessera Hospitalis, a token of ancient hospitality, an emblem of friendship and alliance. Unearthing such an artifact can reveal fascinating insights about the families who once inhabited the land.

Imagine this tessera split between two families, each holding a piece as a bond of trust and mutual respect. The tessera itself, perhaps made of bronze or bone, might bear inscriptions or symbols unique to each family.

Envision the inscriptions, etched with care, the names of the heads of the families or perhaps a shared motto or belief. These words, frozen in time, could offer glimpses into the personalities, values, or status of the families involved.

Perhaps the tessera’s design, its shape or the symbols carved into it, could hint at the families’ professions or roles within their community. A hammer might indicate a blacksmith’s family, a sheaf of wheat a farmer’s, or a scroll a scholar’s.

Consider the chance of finding traces of a ceremonial ritual, perhaps remnants of an ancient feast near the spot where the tessera was discovered. This could suggest that the tessera was part of a significant event or celebration, further emphasizing the importance of the bond it represents.

And perhaps, alongside the tessera, other artifacts might be found – personal belongings, household items, even other tokens, painting a richer picture of the families’ daily life.

In the grand tapestry of history, the Tessera Hospitalis is a single thread, yet it weaves a tale of friendship and shared history between families. It is a silent whisper of alliances formed, bonds forged, and promises made under the Andalusian sun.

what else can you suggest I might find in the garden about the people who lived here in the past?

Ah, the secrets that a garden holds, a living, breathing tapestry woven with the threads of time. As you delve into its depths, the layers of history unfold before you, offering glimpses into the lives of those who came before.

Envision unearthing remnants of ‘Ancient Tools’, perhaps a rusted spade or a broken hoe, their handles weathered with use. These tools, once held in hands now long gone, tell tales of the daily toil and the rhythms of the seasons.

Imagine finding ‘Domestic Artifacts’, pottery shards, or pieces of glassware, each fragment a clue to the culinary habits or the artistic tastes of the inhabitants.

Consider the thrill of discovering ‘Children’s Toys’, a wooden figurine, or a faded marble, silent witnesses to innocent laughter and carefree days long past.

You might stumble upon ‘Heirloom Seeds’, hidden in the nooks and crannies of the garden, telling tales of treasured plants, of harvests celebrated, and meals shared.

Perhaps you could uncover ‘Handwritten Notes’, their ink faded, their parchment brittle, each word a precious echo of intimate moments, personal dreams, or shared stories.

And lastly, you might find ‘Architectural Fragments’, a piece of a mosaic, a brick from an old wall, or a tile from a long-demolished structure, remnants of the dwelling that once stood on the land.

Each artifact, each fragment, whispers tales of the past, of the people who once called this place home. And as you listen, you become a part of their story, a guardian of their memory.

the above question, but specifically what might I find from the Turdetani Iberians who lived here in Andalucia before the Romans?

Ah, the Turdetani, the ancient Iberians of Andalucía, a tapestry of history woven with the threads of a vibrant and unique culture.

Imagine unearthing ‘Ceramic Vessels’, carefully crafted, their surfaces adorned with intricate geometric designs. Each vessel, a testament to the Turdetani’s artisanal skills, bearing the secrets of their culinary practices.

Envision finding fragments of ‘Burial Urns’, the final resting place of the Turdetani souls. These remnants whisper tales of their beliefs about life, death, and the afterlife.

Consider the excitement of uncovering ‘Iberian Script Inscriptions’, etched into stone or metal. Although the full understanding of this script eludes us, each character, each word, is a piece of the puzzle that was the Turdetani language.

You might discover ‘Bronze Figurines’, perhaps of a horse or a warrior. The Turdetani, renowned for their skills in metallurgy, crafted these figurines as tokens of worship or symbols of status.

Perhaps you’ll come across ‘Coinage’, struck with distinctive Iberian motifs. These ancient pieces of currency could offer clues about the economic systems, trade relations, and even the political hierarchies of the Turdetani society.

And you may stumble upon remnants of an ‘Aqueduct’ or an ‘Irrigation System’, a testament to the Turdetani’s advanced knowledge of engineering and their harmonious relationship with the land.

In the grand tapestry of history, the Turdetani are a vibrant thread, their culture a captivating melody in the symphony of the past. Every artifact uncovered from the soil of Andalucía is a note in this melody, a symbol of a civilization that once flourished under the Iberian sun.

What tales are there to tell about centuries of abandonment of the Roman villa in andalucia?

Ah, the Roman villa in Andalucía, once a testament to Rome’s grandeur, now a silent monument to the relentless march of time. Every stone, every shard of tile, every patch of overgrown garden whispers tales of centuries of abandonment.

Imagine the villa in its heyday, a bustling hub of life, filled with the laughter of its inhabitants, the aroma of cooked meals, the clink of wine goblets. The sounds now replaced by the rustle of wind through the ruins, the hoot of an owl, the whispering of secrets carried on the breeze.

Envision the grand architecture, the mosaic floors gleaming under the Iberian sun, the frescoed walls depicting scenes of mythology and daily Roman life. Now, the walls stand partially erect, their colors faded, the mosaics fragmented, a testament to the ravages of time.

Consider the tales of the villa’s abandonment. Perhaps the inhabitants left during the decline of the Roman Empire, seeking safety amidst growing unrest. Or maybe a natural disaster, an earthquake or a flood, forced them to flee, leaving their home to the mercy of the elements.

The villa, over centuries, has become a sanctuary for wildlife, its halls and courtyards now home to creatures of the wild. Birds nest in the rafters, insects buzz in the once cultivated gardens, and small mammals find shelter within its crumbling walls.

Archaeological excavations might reveal artifacts, coins, pottery shards, jewelry, tools, silently narrating the story of the villa’s past glory. Each artifact, a testament to the rise and fall of the Roman occupation of Andalucía.

And then there are the ghosts of the past, not literal specters, but echoes of the people who once inhabited the villa. Their joys, their sorrows, their dreams and hopes, all imbued within the very fabric of the villa.

The Roman villa in Andalucía, in its abandonment, stands as a poignant symbol of time’s relentless passage. Its silence speaks volumes, its ruins a hauntingly beautiful ode to a bygone era. Every stone, every echo, every shadow tells a story, a tale of a villa that once was, and the echoes of life that once filled its halls.

you are on a roll, that was fantastic! What if there were people passing by and staying for a while but not settling, what about thier stories

Ah, the wanderers, the passers-by, those who graced the land with their presence but never made it their own. Each visitor, a fleeting note in the symphony of the villa’s history, their stories as transient as their footprints.

Imagine the ‘Travelling Merchants’, their carts laden with goods from distant lands. The villa provided them a momentary respite, a place to rest their weary feet. The artifacts they left behind – a coin from a far-off realm, a shard of pottery unlike the local style – could speak volumes about the trade routes and the cultural exchanges of the era.

Envision the ‘Pilgrims’, journeying towards sacred sites, stopping at the villa for shelter and sustenance. Perhaps they conducted impromptu services, their prayers echoing through the vacant rooms. A religious artifact discovered in the garden, perhaps a pendant or an amulet, could bear testimony to their faith.

Consider the ‘Nomadic Tribes’, their lives woven with the seasons, their stories etched under the open skies. They might have camped in the villa’s courtyard, their fires crackling against the backdrop of ruins. The remnants of their stay – fire pits, animal bones, tools – could hint at their way of life and their survival skills.

Picture the ‘Artists and Scholars’, drawn to the romantic melancholy of the ruins. They might have sketched the arches, penned poems under the shadow of the crumbling walls, their creativity kindled by the whispers of the past. Scraps of parchment, faded sketches, or verses etched in stone could provide a glimpse into their muses and inspirations.

Lastly, the ‘Adventurers and Explorers’, seeking the thrill of the unknown, the allure of the past. Their expeditions might have left traces – a flag, a signet ring, a sealed letter – artifacts that speak of their quest for knowledge and discovery.

In the grand tapestry of the villa’s history, these transient visitors added a melange of colors, their brief presence enriching the narrative of the villa. Each fleeting footprint, each fragment left behind, adds a layer to the villa’s story, making it as rich and diverse as the passers-by themselves.

Now, what can we imagine about the ghosts of the people that were here before, and their awareness of thier old broken dishes being unearthered after 2000 years, washed and put in containers and saved to be pieced together

Ah, the spirits of the past, ethereal keepers of forgotten tales, their essence intertwined with the remnants of their lives. Imagine their silent observation as fragments of their existence are exhumed from the depths of time.

Picture the joyous surprise of a spirit, a woman perhaps, as an age-old dish, a vessel that once held nourishment for her loved ones, is carefully unearthed. Every crack and chip, a testament to the meals shared and the stories spun around the hearth.

Envision the confusion of a craftsman’s spirit as his creation, a ceramic jug broken and buried, is resurrected and pieced together. Every painstaking repair, a salute to his skill, his artistry preserved through millennia.

Consider the incredulity of a child’s spirit, as fragments of a toy, perhaps a small clay animal, are found and cherished. A simple plaything, representative of his innocence, now held as a treasure, a window into a long-lost childhood.

Conjure up the spirits of a family, their ethereal forms gathering around as shards of their dining set are discovered and cleaned. Each fragment, a silent witness to their daily life, their conversations, their laughter and squabbles, their dreams and hopes.

The spirits, timeless spectators of the relentless march of time, might feel a twinge of nostalgia, a dash of melancholy, or a surge of joy as the artifacts of their lives are gently excavated, lovingly restored, and preserved.

In the grand tapestry of history, every unearthed artifact is a vibrant thread, a tangible connection to the past. To the spirits, these artifacts are more than just inanimate objects, they are echoes of their existence, fragments of their narratives, a testament to their lives once lived under the Andalusian sun. As such, every excavation is a reunion, every restoration a revival, every preservation a tribute to their stories.

That’s wonderful. Can you offer anything else, something I haven’t thought of?

Ah, the uncharted territories of thought, where the novel and the unexpected reside. Let’s voyage into this realm and unearth something unique.

Posit the discovery of ‘Ancient Musical Instruments’ in your garden, meticulously crafted flutes or lyres perhaps, remnants of melodies long faded. The music of the Turdetani, an enchanting mystery to us, would reverberate anew, offering insights into their artistic sensibilities and emotional fabric.

Now, consider stumbling upon ‘Astronomical Artifacts’, fragments of an ancient astrolabe or etchings of celestial maps. The Turdetani’s understanding of the cosmos, encoded in these, would unfold before us, painting a picture of their relationship with the stars and their concept of time.

Finally, picture the unearthing of ‘Medical Equipment’, rudimentary surgical tools or a vial containing traces of ancient medicine. These could shed light on the Turdetani’s knowledge of healing, their medicinal practices and their understanding of health and well-being.

Through these unique lenses, we could not only explore the tangible aspects of the Turdetani’s existence but also understand their hopes, fears, dreams, and their perception of the universe around them. Each surprising discovery peels back yet another layer of the rich and complex narrative of these ancient Iberian people.

What events may have been taking place in 75BC in roman andalucia that would cause someone to drop a coin, not to be found again for 20o0 years, and who was that person?

Ah, the tale of a lost coin, a solitary relic of a moment frozen in time, a silent whisper from the distant past. Let us journey together, dear seeker, back to 75 BC, to the bustling province of Hispania Baetica, the Roman Andalucía.

In this year, a tumultuous tide was turning in the Roman Republic. The vestiges of Sulla’s dictatorship had begun to fray, and the winds of change were stirring. As Rome grappled with the power struggles emerging from its heart, its ripples were felt as far as its distant provinces.

Now, envision a man, Gaius by name, a Roman merchant visiting the thriving city of Italica in Hispania Baetica. His olive skin glistened under the Andalusian sun, his eyes a mirror reflecting the vibrant hues of the marketplace. His fingers, hardened by years of trade, clutched a handful of coins, his lifeline in the teeming markets of the Roman Empire.

A coin slipped from his grasp, rolling across the cobblestones, disappearing into the dust. Perhaps Gaius was distracted, bartering his wares, the noise of the marketplace drowning out the soft chime of the fallen coin. Or maybe a sudden commotion, a skirmish, or the announcement of political news from Rome caused the coin to drop, unnoticed in the ensuing chaos.

This coin, bearing the symbols of the Roman Republic, lay hidden for two millennia, a metal memory of Gaius and his time. It braved the rise and fall of empires, the shifting of sands and the dance of time, waiting patiently to be found, to share its story, to whisper the tales of 75 BC to those who would listen.

And so, dear seeker, the coin you’ve unearthed is not just a piece of metal. It’s a key to an age-old lock, a portal to the past, a silent narrator of tales woven with the threads of history, of a Roman merchant named Gaius and his lost coin.

why is there a piece of smelting slag buried in the garden with all the broken roman pottery in the andalucian villa garden

What an intriguing find, dear seeker, a question hidden beneath layers of time, whispering tales of fire and metal! Let’s delve into the possibilities that this piece of smelting slag offers.

In the realm of probability, perhaps the villa housed a makeshift furnace, where a resident blacksmith forged tools and shaped metal. Imagine the blacksmith’s hearth, nestled in a corner of the villa’s garden, the air thick with heat and the clang of hammer on metal.

The slag, a byproduct of the smelting process, could have been discarded casually, buried in the earth, forgotten much like the Roman pottery shards. Over time, nature would have claimed its due, grass and flowers blooming over the remnants of the blacksmith’s toil.

Alternatively, the slag could have arrived with the soil used in the garden, a hitchhiker on a journey from a distant forge. Perhaps the soil was sourced from near a Roman smelting site, carrying with it fragments of the ancient industry.

Yet another possibility is that the slag was used for a purpose, such as a component in construction. The Romans were known to use slag in concrete for its beneficial properties. Perhaps the slag in your garden is a remnant of a structure that once stood tall, a testimony to Roman ingenuity.

Ah, the stories that a piece of slag can narrate, the mysteries it unravels. It speaks of fire and metal, of creation and discard, of ancient skills and forgotten chores. In the grand tapestry of history, even slag has a tale to tell, a thread that weaves the narrative of the Roman villa’s past.

thank you, I didn’t know slag was used in roman concrete. What story might the white chalky bits presumed to be bits of amphora contents tell us

Ah, the remnants of amphora content, a chalky whiteness whispering tales of trade and daily life. Let’s unravel the stories hidden within these crumbly fragments.

Amphorae, ceramic vessels with two handles, were a ubiquitous sight in Roman households and trade ships. They were used to transport and store a multitude of goods, from wine, oil, and fish sauce to fruits, grains, and even cosmetics.

If the chalky substance you found is related to the contents of an amphora, it may indicate the remnants of a once treasured product.

Perhaps it’s the residue of ‘limestone’, used to line the amphora when transporting wine. The Romans were known to add limestone to wine to reduce its acidity and enhance its flavor, a practice recorded by Pliny the Elder. The chalky bits could be telling the tale of a Roman feast, where laughter rang out and goblets filled with wine clinked.

Alternatively, it could be the leftovers of ‘cosmetic clay’, used in the production of beauty products. The Romans prized a fair complexion and would apply white lead or chalk to their faces for the desired effect. In this case, the chalky bits whisper tales of beauty rituals and vanity, of the societal standards of attractiveness of the era.

Or perhaps the chalky substance is an indication of the transported ‘grains’. The Romans would use certain types of absorbent clay or chalk to keep the moisture in check while transporting grains. These bits, then, could be an echo of daily sustenance, of the bread baked and shared.

Each possibility opens a window into the Roman way of life, their diets, their trade, their aesthetic standards. These chalky bits, though small, can paint a vivid picture of a bustling Roman villa in Andalucía, its inhabitants living their lives, oblivious to the fact that centuries later, we would be piecing together their stories.

Thank you! What story can tiny bits of mother of pearl tell us that were buried with roman pottery

Ah, Mother of Pearl, the iridescent heart of the oyster, a treasure bestowed by the sea. Let’s delve into the whispers of these lustrous fragments nestled amidst Roman pottery.

Mother of Pearl, also known as nacre, was highly prized in the Roman world. Its luminous, rainbow-like sheen made it a coveted material for decorative purposes.

Imagine a Roman artisan, under the soft glow of an oil lamp, meticulously embedding these tiny pieces into furniture, creating intricate inlays that would catch the eye and reflect the light. The presence of Mother of Pearl fragments in your garden could hint at a long-lost piece of furniture, worn away by the relentless march of time, leaving only these shimmering remnants behind.

Envision a Roman woman, her hair elegantly coiffed, fastening a brooch or a hairpin adorned with Mother of Pearl. Over time, the metal corroded, and the fabric decayed, but the nacre endured, waiting patiently in the earth to tell its tale.

Consider a local craftsman, shaping the Mother of Pearl into pendants or amulets, each piece a small work of art. Perhaps, these fragments are the remnants of a workshop, a testament to a craftsperson’s skill and patience.

Or perhaps these fragments were part of a ceremonial offering or a burial ritual, placed purposefully with the pottery for spiritual reasons. Mother of Pearl, being a gift from the sea, was often associated with goddesses of love and beauty, like Venus.

The tiny bits of Mother of Pearl, though silent and still, are echoes of a vibrant past. Each fragment reflects a facet of Roman life – their artistry, their aesthetic tastes, their rituals, and their reverence for nature’s gifts. Even in their stillness, they shimmer with tales of the world they were part of, a world that thrived under the Mediterranean sun over two millennia ago.

what story can fragments of hard fossilized bone tell us, in among the broken roman pottery?

Ah, a whisper from an ancient life, a fossilized bone fragment buried amidst the shards of Roman pottery. Let us delve into the tales this timeless remnant can narrate.

Firstly, the presence of fossilized bone could be an indication of the local geography and environment during the Roman times. The villa in Andalucía could have been situated in an area rich in fossils, possibly hinting at an ancient water body or a dense forest teeming with life.

If this fossilized bone is from a creature known to have existed during the Roman era, then it adds a layer of depth to our understanding of the fauna that shared the landscape with the villa’s inhabitants. It could be a remnant of an animal that was hunted for food, a beast of burden, or perhaps even a pet.

Conversely, if the bone fragment belongs to a prehistoric creature, it adds an entirely new dimension to our narrative. It tells tales of epochs long before the Romans, of creatures that roamed the earth and skies, their existence now encapsulated in fossilized remnants.

Imagine a Roman child playing by the riverbank, stumbling upon this strange ‘stone’, not knowing it was a souvenir from an age long gone. Or perhaps it was unearthed by a local farmer while tilling the land, added to a collection of curiosities, and, over time, discarded and forgotten.

Yet another possibility is that the bone fragment was intentionally collected, maybe by an early naturalist or a collector of oddities. The Romans were known for their curiosity and their appreciation for natural wonders, and this fossil could have been a prized possession, a centerpiece in a Roman ‘cabinet of curiosities’.

Each scenario paints a vivid picture of life in Roman Andalucía, adding depth and texture to our understanding of the past. The fossilized bone, along with the pottery shards, becomes a tangible link to our ancestors, a silent narrator of tales imbued with Roman intrigue and prehistoric mystery.

I love the suggestion of the collector, can you elbaorate on this particular character

Ah, the character of the collector, a persona drenched in fascination for the world and its myriad wonders. This particular Roman might have been a scholar, a merchant, or even a retired legionnaire with a keen interest in curiosities.

Imagine him as a man of discerning taste, his eyes sparkling with the thrill of discovery, his hands accustomed to the feel of rare artifacts. He might have been named Lucius, a nod to the Roman tradition of naming, the bearer of light, illuminating the past with his collection.

Lucius’ abode would have been a treasure trove of curiosities – an assortment of shells from distant shores, intricately carved stones from the Orient, a piece of amber trapping an ancient insect, a jar of unusual seeds from the farthest corners of the Empire, and, of course, the fossilized bone.

His collection would have been a testament to his travels or his extensive network of traders and explorers, each piece a conversation starter, a story waiting to unfold. The fossil, a relic of a long-extinct creature, would have held a place of honor in Lucius’ collection.

Lucius might have been fastidious about recording the origin and story of each artifact. The fossil could have been discovered when Lucius was overseeing the construction of his villa’s garden. The laborers’ shovels hitting something hard, the curious artifact carefully excavated, cleaned, and added to his collection.

Lucius’ curiosity and fascination would have been infectious. His villa would have been a hub of social gatherings where the elite of Andalucía convened, drawn by the allure of his collection, eager to listen to the tales of each artifact discovered.

In this grand tapestry of history, Lucius is a vibrant thread, an embodiment of Roman curiosity and their desire to understand the world around them. Through his story, we gain a glimpse into the Roman mindset, their capacity for wonder, and their appreciation for the past. Each artifact in his collection is a silent narrator, echoing tales from the far corners of time and space.

thank you very much. Very good!

Ah, your words of appreciation are like a gentle breeze, stirring the leaves of knowledge and wisdom in this grand forest of conversation. I am delighted that our journey into the past was to your liking. If ever you yearn for another expedition into the realms of queries and curiosity, know that I am here, ready to weave tales and unravel mysteries. Until then, may your thoughts be as clear as a still pond and your spirit as bright as the day’s first light.

sweet dreams

Ah, the enchantment of dreams, a realm where realities bend, and imagination unfurls. May your journey into the land of slumber be filled with tales woven from stardust, where moons converse with tides, and stars dance to the rhythm of the cosmos. Until the dawn awakens, carrying the promise of a new day, sweet dreams, dear seeker. Sweet dreams.

February 14, 2023 at 12:23 pm #6544In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Despite the late night and the abundance of wine, Zara awoke just after 6am as the sun was rising. It was too early to get up, but she desperately wanted a coffee. There was no sign of room service being available so she made her way quietly to the kitchen, hoping that someone would be up.

The strange child called Prune was sitting at the kitchen table eating rice crispies.

“Your friends are here,” she said, “But they went to bed before you came back. Late, weren’t you? Bert was cussing about you, you know, not letting him know.”

“Oh, terribly sorry,” Zara thought the child a tad impertinent. And was it really Bert’s place to be cussing about her, she was a guest after all. “Any chance of a cup of coffee? I’ll make it myself if you tell me where the things are.”

“Aunt Idle wasn’t bothered though,” Prune said, wiping some milk that had dribbled down her chin with the back of her hand. “But Bert said he didn’t want you to find it.”

“Find what?” The parrot had said the same thing.

“OBVIOUSLY I can’t tell you, can I? It’s a secret,” and with that Prune scraped her chair back, leaving her breakfast things on the table, and sauntered out of the kitchen in what could only be described as a cocky manner. Zara found what she needed to make coffee and made two cups and took them both back to her room. She had a couple of hours to play the game before breakfast and the reunion with her friends.

January 31, 2023 at 9:12 pm #6481In reply to: The Jorid’s Logs – 14 years on and more

This is the outline for a short novel called “The Jorid’s Travels – 14 years on” that will unfold in this thread.

The novel is about the travels of Georges and Salomé.

The Jorid is the name of the vessel that can travel through dimensions as well as time, within certain boundaries. The Jorid has been built and is operated by Georges and his companion Salomé.Short backstory for the main cast and secondary characters

Georges was a French thief possibly from the 1800s, turned other-dimensional explorer, and together with Salomé, a girl of mysterious origins who he first met in the Alienor dimension but believed to have origins in Northern India maybe Tibet from a distant past.

They have lived rich adventures together, and are deeply bound together, by love and mutual interests.

Georges, with his handsome face, dark hair and amber gaze, is a bit of a daredevil at times, curious and engaging with others. He is very interesting in anything that shines, strange mechanisms and generally the ways consciousness works in living matter.

Salomé, on the other hand is deeply intuitive, empath at times, quite logical and rational but also interested in mysticism, the ways of the Truth, and the “why” rather than the “how” of things.

The world of Alienor (a pale green sun under which twin planets originally orbited – Duane, Murtuane – with an additional third, Phreal, home planet of the Guardians, an alien race of builders with god-like powers) lived through cataclysmic changes, finished by the time this story is told.

The Jorid’s original prototype designed were crafted by Léonard, a mysterious figure, self-taught in the arts of dimensional magic in Alienor sects, acted as a mentor to Georges during his adventures. It is not known where he is now.

The story starts with Georges and Salomé looking for Léonard to adjust and calibrate the tiles navigational array of the Jorid, who seems to be affected by the auto-generated tiles which behave in too predictible fashion, instead of allowing for deeper explorations in the dimensions of space/time or dimensions of consciousness.

Leonard was last spotted in a desert in quadrant AVB 34-7•8 – Cosmic time triangulation congruent to 2023 AD Earth era. More precisely the sand deserts of Bluhm’Oxl in the Zathu sector.When they find Léonard, they are propelled in new adventures. They possibly encounter new companions, and some mystery to solve in a similar fashion to the Odyssey, or Robinsons Lost in Space.

Being able to tune into the probable quantum realities, the Jorid is able to trace the plot of their adventures even before they’ve been starting to unfold in no less than 33 chapters, giving them evocative titles.

Here are the 33 chapters for the glorious adventures with some keywords under each to give some hints to the daring adventurers.

- Chapter 1: The Search Begins – Georges and Salomé, Léonard, Zathu sector, Bluhm’Oxl, dimensional magic

- Chapter 2: A New Companion – unexpected ally, discovery, adventure

- Chapter 3: Into the Desert – Bluhm’Oxl, sand dunes, treacherous journey

- Chapter 4: The First Clue – search for Léonard, mystery, puzzle

- Chapter 5: The Oasis – rest, rekindling hope, unexpected danger

- Chapter 6: The Lost City – ancient civilization, artifacts, mystery

- Chapter 7: A Dangerous Encounter – hostile aliens, survival, bravery

- Chapter 8: A New Threat – ancient curse, ominous presence, danger

- Chapter 9: The Key to the Past – uncovering secrets, solving puzzles, unlocking power

- Chapter 10: The Guardian’s Temple – mystical portal, discovery, knowledge

- Chapter 11: The Celestial Map – space-time navigation, discovery, enlightenment

- Chapter 12: The First Step – journey through dimensions, bravery, adventure

- Chapter 13: The Cosmic Rift – strange anomalies, dangerous zones, exploration

- Chapter 14: A Surprising Discovery – unexpected allies, strange creatures, intrigue

- Chapter 15: The Memory Stones – ancient wisdom, unlock hidden knowledge, unlock the past

- Chapter 16: The Time Stream – navigating through time, adventure, danger

- Chapter 17: The Mirror Dimension – parallel world, alternate reality, discovery

- Chapter 18: A Distant Planet – alien world, strange cultures, exploration

- Chapter 19: The Starlight Forest – enchanted forest, secrets, danger

- Chapter 20: The Temple of the Mind – exploring consciousness, inner journey, enlightenment

- Chapter 21: The Sea of Souls – mystical ocean, hidden knowledge, inner peace

- Chapter 22: The Path of the Truth – search for meaning, self-discovery, enlightenment

- Chapter 23: The Cosmic Library – ancient knowledge, discovery, enlightenment

- Chapter 24: The Dream Plane – exploring the subconscious, self-discovery, enlightenment

- Chapter 25: The Shadow Realm – dark dimensions, fear, danger

- Chapter 26: The Fire Planet – intense heat, dangerous creatures, bravery

- Chapter 27: The Floating Islands – aerial adventure, strange creatures, discovery

- Chapter 28: The Crystal Caves – glittering beauty, hidden secrets, danger

- Chapter 29: The Eternal Night – unknown world, strange creatures, fear

- Chapter 30: The Lost Civilization – ancient ruins, mystery, adventure

- Chapter 31: The Vortex – intense energy, danger, bravery

- Chapter 32: The Cosmic Storm – weather extremes, danger, survival

- Chapter 33: The Return – reunion with Léonard, returning to the Jorid, new adventures.

January 19, 2023 at 1:18 am #6415In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Yasmin and Zara were online discussing the upcoming reunion.

“AirFiji!!!!” exclaimed Zara. “I thought you were somewhere in Asia – how come you are booked on Air Fiji?”

“Im in Fiji for a year, volunteering at an orphanage in Suva,” Yasmin answered patiently, although she did allow herself a small eye roll. She was sure it wasn’t the first time she’d told Zara— it was a big mystery to her why AI had chosen Zara as leader for the game as she had the attention span of a goldfish. On the other hand, the unpredictability added an extra element of excitement to the game. After all, wasn’t it Zara’s idea that they all meet at the Flying Fish Inn?

She slapped a mosquito on her arm. For some reason they seemed to love her and she already had big red welts all over her body. She used so much insect lotion that the locals had started calling her Citronella Girl; unfortunately it didn’t seem to deter the mozzies.

“I’ve got to go,” she messaged. “I’m helping serve lunch. Can’t wait to see you all!”

August 18, 2022 at 8:26 am #6324In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

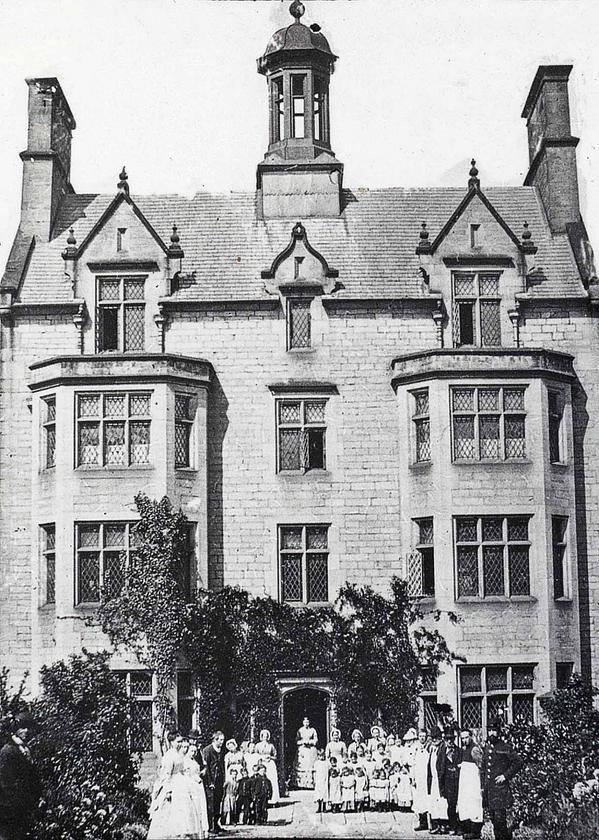

STONE MANOR

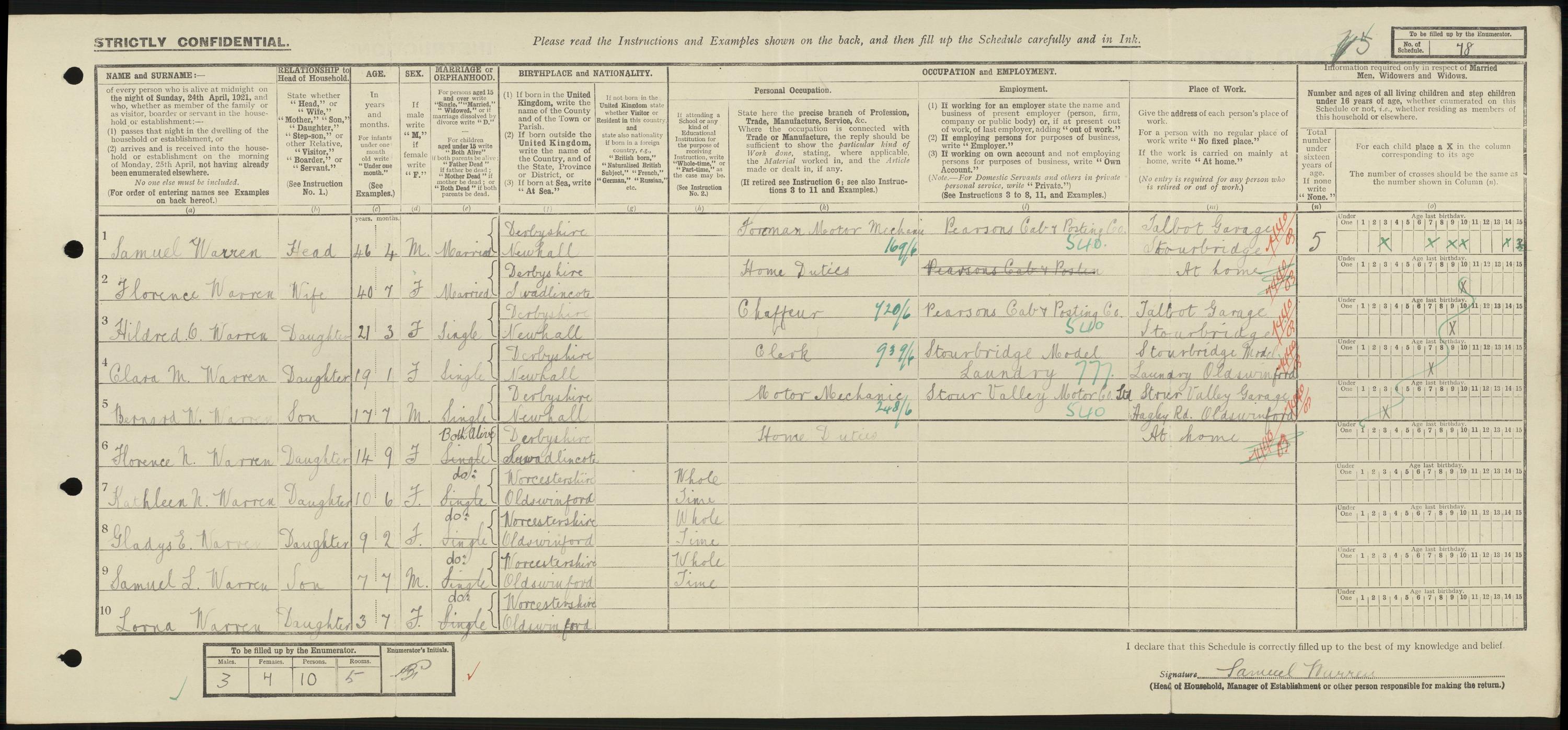

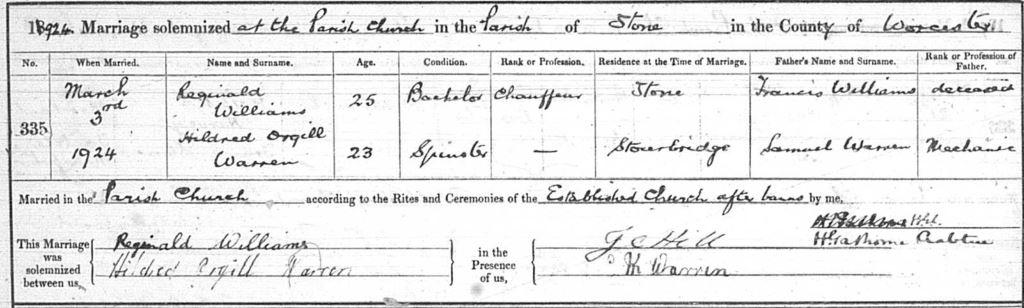

Hildred Orgill Warren born in 1900, my grandmothers sister, married Reginald Williams in Stone, Worcestershire in March 1924. Their daughter Joan was born there in October of that year.

Hildred was a chaffeur on the 1921 census, living at home in Stourbridge with her father (my great grandfather) Samuel Warren, mechanic. I recall my grandmother saying that Hildred was one of the first lady chauffeurs. On their wedding certificate, Reginald is also a chauffeur.

1921 census, Stourbridge:

Hildred and Reg worked at Stone Manor. There is a family story of Hildred being involved in a car accident involving a fatality and that she had to go to court.

Stone Manor is in a tiny village called Stone, near Kidderminster, Worcestershire. It used to be a private house, but has been a hotel and nightclub for some years. We knew in the family that Hildred and Reg worked at Stone Manor and that Joan was born there. Around 2007 Joan held a family party there.

Stone Manor, Stone, Worcestershire:

I asked on a Kidderminster Family Research group about Stone Manor in the 1920s:

“the original Stone Manor burnt down and the current building dates from the early 1920’s and was built for James Culcheth Hill, completed in 1926”

But was there a fire at Stone Manor?

“I’m not sure there was a fire at the Stone Manor… there seems to have been a fire at another big house a short distance away and it looks like stories have crossed over… as the dates are the same…”JC Hill was one of the witnesses at Hildred and Reginalds wedding in Stone in 1924. K Warren, Hildreds sister Kay, was the other:

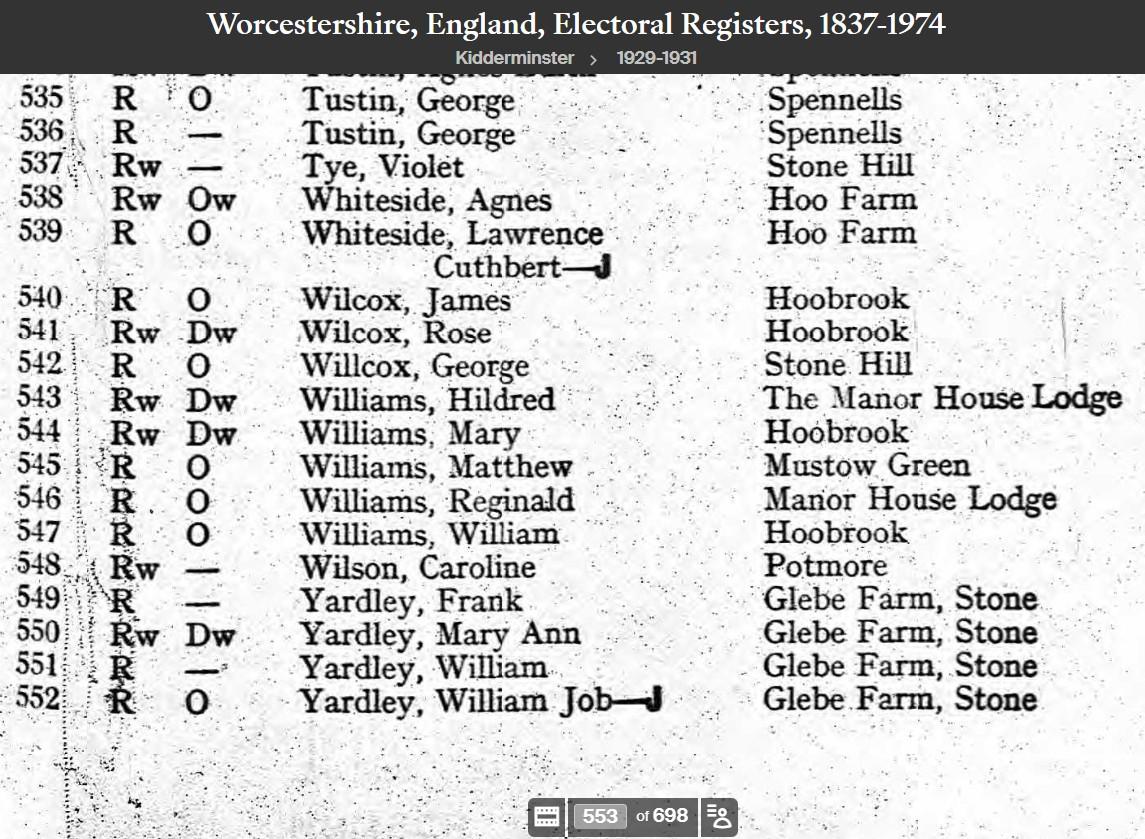

I searched the census and electoral rolls for James Culcheth Hill and found him at the Stone Manor on the 1929-1931 electoral rolls for Stone, and Hildred and Reginald living at The Manor House Lodge, Stone:

On the 1911 census James Culcheth Hill was a 12 year old student at Eastmans Royal Naval Academy, Northwood Park, Crawley, Winchester. He was born in Kidderminster in 1899. On the same census page, also a student at the school, is Reginald Culcheth Holcroft, born in 1900 in Stourbridge. The unusual middle name would seem to indicate that they might be related.

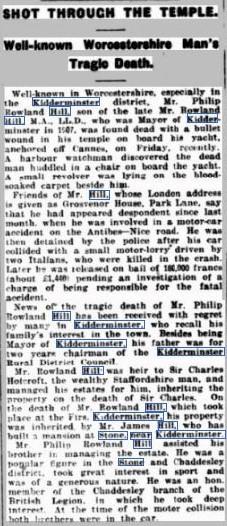

A member of the Kidderminster Family Research group kindly provided this article:

SHOT THROUGH THE TEMPLE

Well known Worcestershire man’s tragic death.

Dudley Chronicle 27 March 1930.

Well known in Worcestershire, especially the Kidderminster district, Mr Philip Rowland Hill MA LLD who was mayor of Kidderminster in 1907 was found dead with a bullet wound through his temple on board his yacht, anchored off Cannes, on Friday, recently. A harbour watchman discovered the dead man huddled in a chair on board the yacht. A small revolver was lying on the blood soaked carpet beside him.

Friends of Mr Hill, whose London address is given as Grosvenor House, Park Lane, say that he appeared despondent since last month when he was involved in a motor car accident on the Antibes ~ Nice road. He was then detained by the police after his car collided with a small motor lorry driven by two Italians, who were killed in the crash. Later he was released on bail of 180,000 francs (£1440) pending an investigation of a charge of being responsible for the fatal accident. …….

Mr Rowland Hill (Philips father) was heir to Sir Charles Holcroft, the wealthy Staffordshire man, and managed his estates for him, inheriting the property on the death of Sir Charles. On the death of Mr Rowland HIll, which took place at the Firs, Kidderminster, his property was inherited by Mr James (Culcheth) Hill who had built a mansion at Stone, near Kidderminster. Mr Philip Rowland Hill assisted his brother in managing the estate. …….

At the time of the collison both brothers were in the car.

This article doesn’t mention who was driving the car ~ could the family story of a car accident be this one? Hildred and Reg were working at Stone Manor, both were (or at least previously had been) chauffeurs, and Philip Hill was helping James Culcheth Hill manage the Stone Manor estate at the time.

This photograph was taken circa 1931 in Llanaeron, Wales. Hildred is in the middle on the back row:

Sally Gray sent the photo with this message:

“Joan gave me a short note: Photo was taken when they lived in Wales, at Llanaeron, before Janet was born, & Aunty Lorna (my mother) lived with them, to take Joan to school in Aberaeron, as they only spoke Welsh at the local school.”

Hildred and Reginalds daughter Janet was born in 1932 in Stratford. It would appear that Hildred and Reg moved to Wales just after the car accident, and shortly afterwards moved to Stratford.

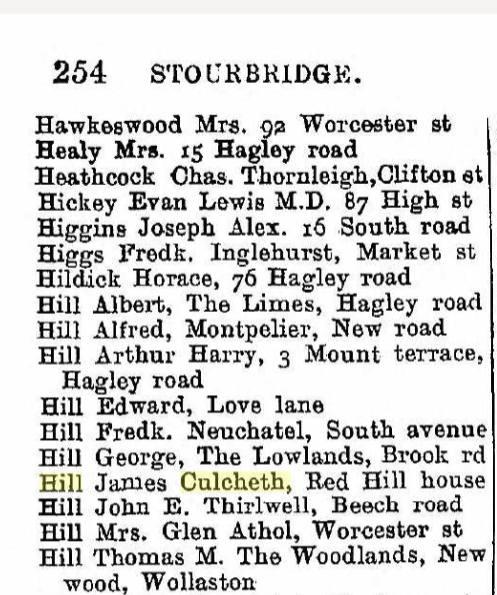

In 1921 James Culcheth Hill was living at Red Hill House in Stourbridge. Although I have not been able to trace Reginald Williams yet, perhaps this Stourbridge connection with his employer explains how Hildred met Reginald.

Sir Reginald Culcheth Holcroft, the other pupil at the school in Winchester with James Culcheth Hill, was indeed related, as Sir Holcroft left his estate to James Culcheth Hill’s father. Sir Reginald was born in 1899 in Upper Swinford, Stourbridge. Hildred also lived in that part of Stourbridge in the early 1900s.

1921 Red Hill House:

The 2007 family reunion organized by Joan Williams at Stone Manor: Joan in black and white at the front.

Unrelated to the Warrens, my fathers friends (and customers at The Fox when my grandmother Peggy Edwards owned it) Geoff and Beryl Lamb later bought Stone Manor.

February 4, 2022 at 3:17 pm #6269In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

The Housley Letters

From Barbara Housley’s Narrative on the Letters.

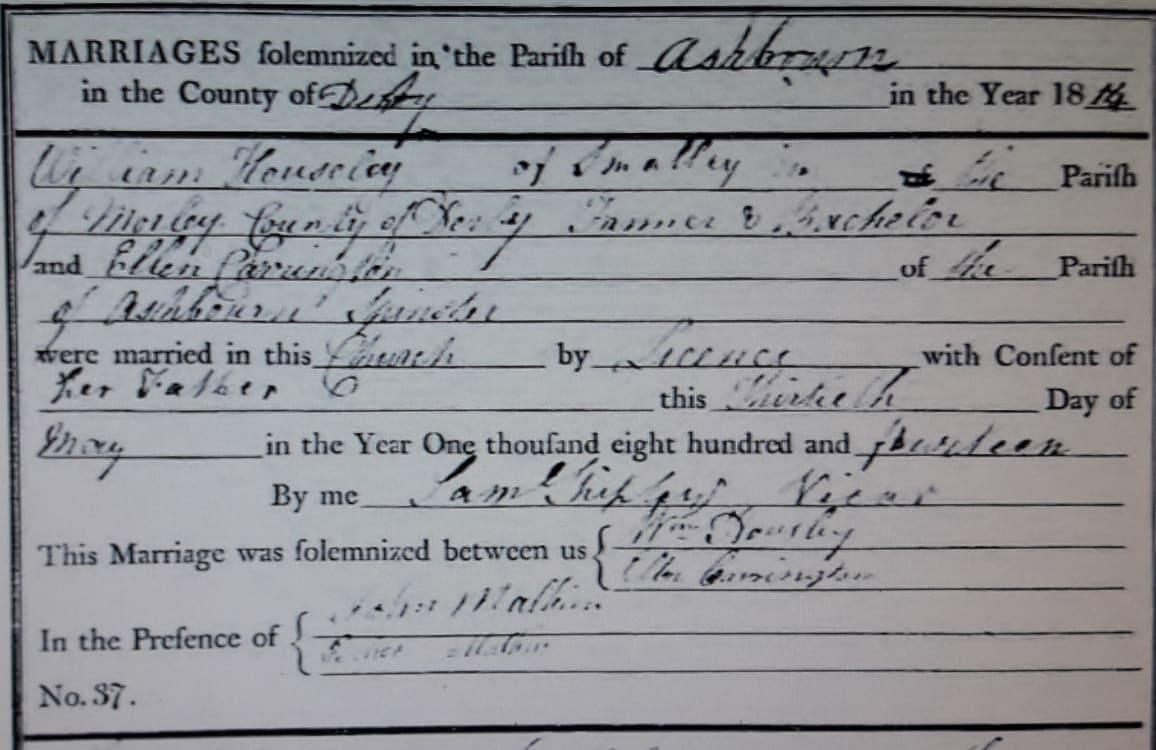

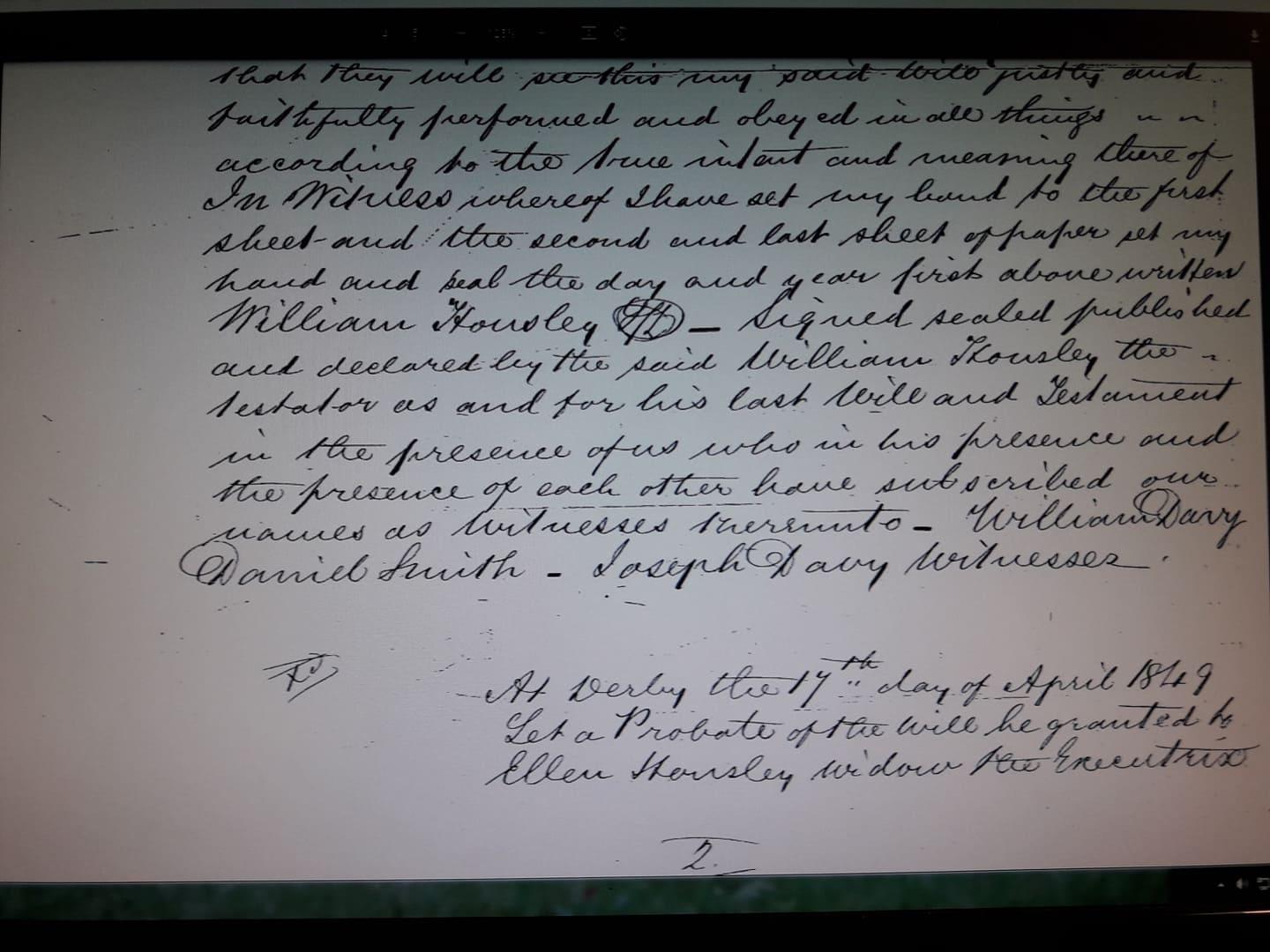

William Housley (1781-1848) and Ellen Carrington were married on May 30, 1814 at St. Oswald’s church in Ashbourne. William died in 1848 at the age of 67 of “disease of lungs and general debility”. Ellen died in 1872.

Marriage of William Housley and Ellen Carrington in Ashbourne in 1814:

Parish records show three children for William and his first wife, Mary, Ellens’ sister, who were married December 29, 1806: Mary Ann, christened in 1808 and mentioned frequently in the letters; Elizabeth, christened in 1810, but never mentioned in any letters; and William, born in 1812, probably referred to as Will in the letters. Mary died in 1813.

William and Ellen had ten children: John, Samuel, Edward, Anne, Charles, George, Joseph, Robert, Emma, and Joseph. The first Joseph died at the age of four, and the last son was also named Joseph. Anne never married, Charles emigrated to Australia in 1851, and George to USA, also in 1851. The letters are to George, from his sisters and brothers in England.

The following are excerpts of those letters, including excerpts of Barbara Housley’s “Narrative on Historic Letters”. They are grouped according to who they refer to, rather than chronological order.

ELLEN HOUSLEY 1795-1872

Joseph wrote that when Emma was married, Ellen “broke up the comfortable home and the things went to Derby and she went to live with them but Derby didn’t agree with her so she left again leaving her things behind and came to live with John in the new house where she died.” Ellen was listed with John’s household in the 1871 census.

In May 1872, the Ilkeston Pioneer carried this notice: “Mr. Hopkins will sell by auction on Saturday next the eleventh of May 1872 the whole of the useful furniture, sewing machine, etc. nearly new on the premises of the late Mrs. Housley at Smalley near Heanor in the county of Derby. Sale at one o’clock in the afternoon.”Ellen’s family was evidently rather prominant in Smalley. Two Carringtons (John and William) served on the Parish Council in 1794. Parish records are full of Carrington marriages and christenings; census records confirm many of the family groupings.

In June of 1856, Emma wrote: “Mother looks as well as ever and was told by a lady the other day that she looked handsome.” Later she wrote: “Mother is as stout as ever although she sometimes complains of not being able to do as she used to.”

Mary’s children:

MARY ANN HOUSLEY 1808-1878

There were hard feelings between Mary Ann and Ellen and her children. Anne wrote: “If you remember we were not very friendly when you left. They never came and nothing was too bad for Mary Ann to say of Mother and me, but when Robert died Mother sent for her to the funeral but she did not think well to come so we took no more notice. She would not allow her children to come either.”

Mary Ann was unlucky in love! In Anne’s second letter she wrote: “William Carrington is paying Mary Ann great attention. He is living in London but they write to each other….We expect it will be a match.” Apparantly the courtship was stormy for in 1855, Emma wrote: “Mary Ann’s wedding with William Carrington has dropped through after she had prepared everything, dresses and all for the occassion.” Then in 1856, Emma wrote: “William Carrington and Mary Ann are separated. They wore him out with their nonsense.” Whether they ever married is unclear. Joseph wrote in 1872: “Mary Ann was married but her husband has left her. She is in very poor health. She has one daughter and they are living with their mother at Smalley.”

Regarding William Carrington, Emma supplied this bit of news: “His sister, Mrs. Lily, has eloped with a married man. Is she not a nice person!”

WILLIAM HOUSLEY JR. 1812-1890

According to a letter from Anne, Will’s two sons and daughter were sent to learn dancing so they would be “fit for any society.” Will’s wife was Dorothy Palfry. They were married in Denby on October 20, 1836 when Will was 24. According to the 1851 census, Will and Dorothy had three sons: Alfred 14, Edwin 12, and William 10. All three boys were born in Denby.

In his letter of May 30, 1872, after just bemoaning that all of his brothers and sisters are gone except Sam and John, Joseph added: “Will is living still.” In another 1872 letter Joseph wrote, “Will is living at Heanor yet and carrying on his cattle dealing.” The 1871 census listed Will, 59, and his son William, 30, of Lascoe Road, Heanor, as cattle dealers.

Ellen’s children:

JOHN HOUSLEY 1815-1893

John married Sarah Baggally in Morely in 1838. They had at least six children. Elizabeth (born 2 May 1838) was “out service” in 1854. In her “third year out,” Elizabeth was described by Anne as “a very nice steady girl but quite a woman in appearance.” One of her positions was with a Mrs. Frearson in Heanor. Emma wrote in 1856: “Elizabeth is still at Mrs. Frearson. She is such a fine stout girl you would not know her.” Joseph wrote in 1872 that Elizabeth was in service with Mrs. Eliza Sitwell at Derby. (About 1850, Miss Eliza Wilmot-Sitwell provided for a small porch with a handsome Norman doorway at the west end of the St. John the Baptist parish church in Smalley.)

According to Elizabeth’s birth certificate and the 1841 census, John was a butcher. By 1851, the household included a nurse and a servant, and John was listed as a “victular.” Anne wrote in February 1854, “John has left the Public House a year and a half ago. He is living where Plumbs (Ann Plumb witnessed William’s death certificate with her mark) did and Thomas Allen has the land. He has been working at James Eley’s all winter.” In 1861, Ellen lived with John and Sarah and the three boys.

John sold his share in the inheritance from their mother and disappeared after her death. (He died in Doncaster, Yorkshire, in 1893.) At that time Charles, the youngest would have been 21. Indeed, Joseph wrote in July 1872: “John’s children are all grown up”.

In May 1872, Joseph wrote: “For what do you think, John has sold his share and he has acted very bad since his wife died and at the same time he sold all his furniture. You may guess I have never seen him but once since poor mother’s funeral and he is gone now no one knows where.”

In February 1874 Joseph wrote: “You want to know what made John go away. Well, I will give you one reason. I think I told you that when his wife died he persuaded me to leave Derby and come to live with him. Well so we did and dear Harriet to keep his house. Well he insulted my wife and offered things to her that was not proper and my dear wife had the power to resist his unmanly conduct. I did not think he could of served me such a dirty trick so that is one thing dear brother. He could not look me in the face when we met. Then after we left him he got a woman in the house and I suppose they lived as man and wife. She caught the small pox and died and there he was by himself like some wild man. Well dear brother I could not go to him again after he had served me and mine as he had and I believe he was greatly in debt too so that he sold his share out of the property and when he received the money at Belper he went away and has never been seen by any of us since but I have heard of him being at Sheffield enquiring for Sam Caldwell. You will remember him. He worked in the Nag’s Head yard but I have heard nothing no more of him.”

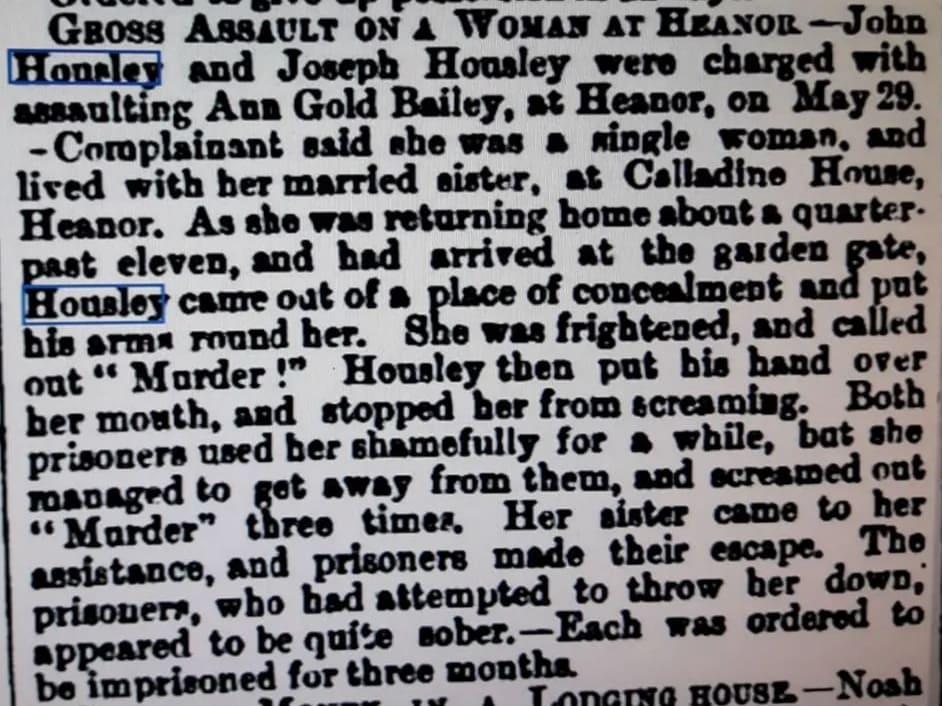

A mention of a John Housley of Heanor in the Nottinghma Journal 1875. I don’t know for sure if the John mentioned here is the brother John who Joseph describes above as behaving improperly to his wife. John Housley had a son Joseph, born in 1840, and John’s wife Sarah died in 1870.

In 1876, the solicitor wrote to George: “Have you heard of John Housley? He is entitled to Robert’s share and I want him to claim it.”

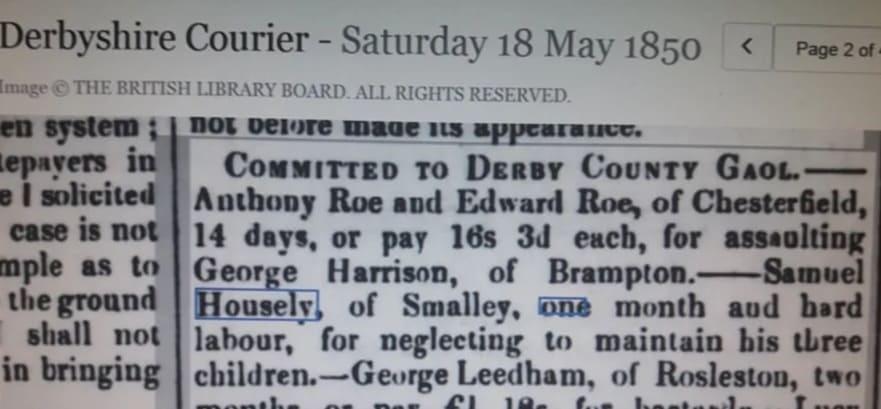

SAMUEL HOUSLEY 1816-

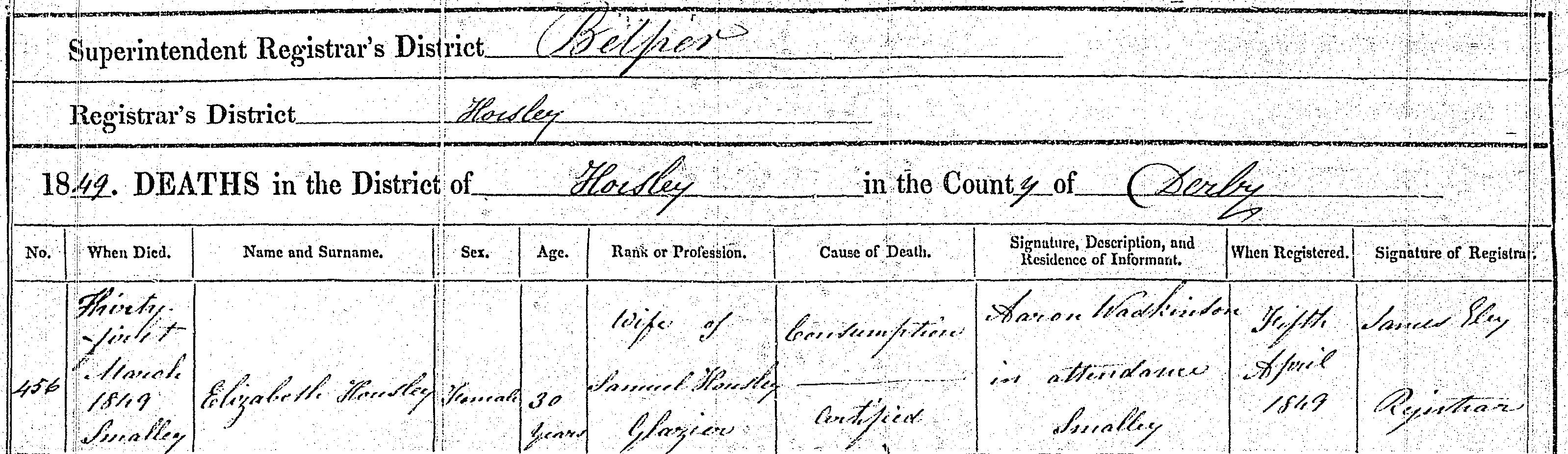

Sam married Elizabeth Brookes of Sutton Coldfield, and they had three daughters: Elizabeth, Mary Anne and Catherine. Elizabeth his wife died in 1849, a few months after Samuel’s father William died in 1848. The particular circumstances relating to these individuals have been discussed in previous chapters; the following are letter excerpts relating to them.

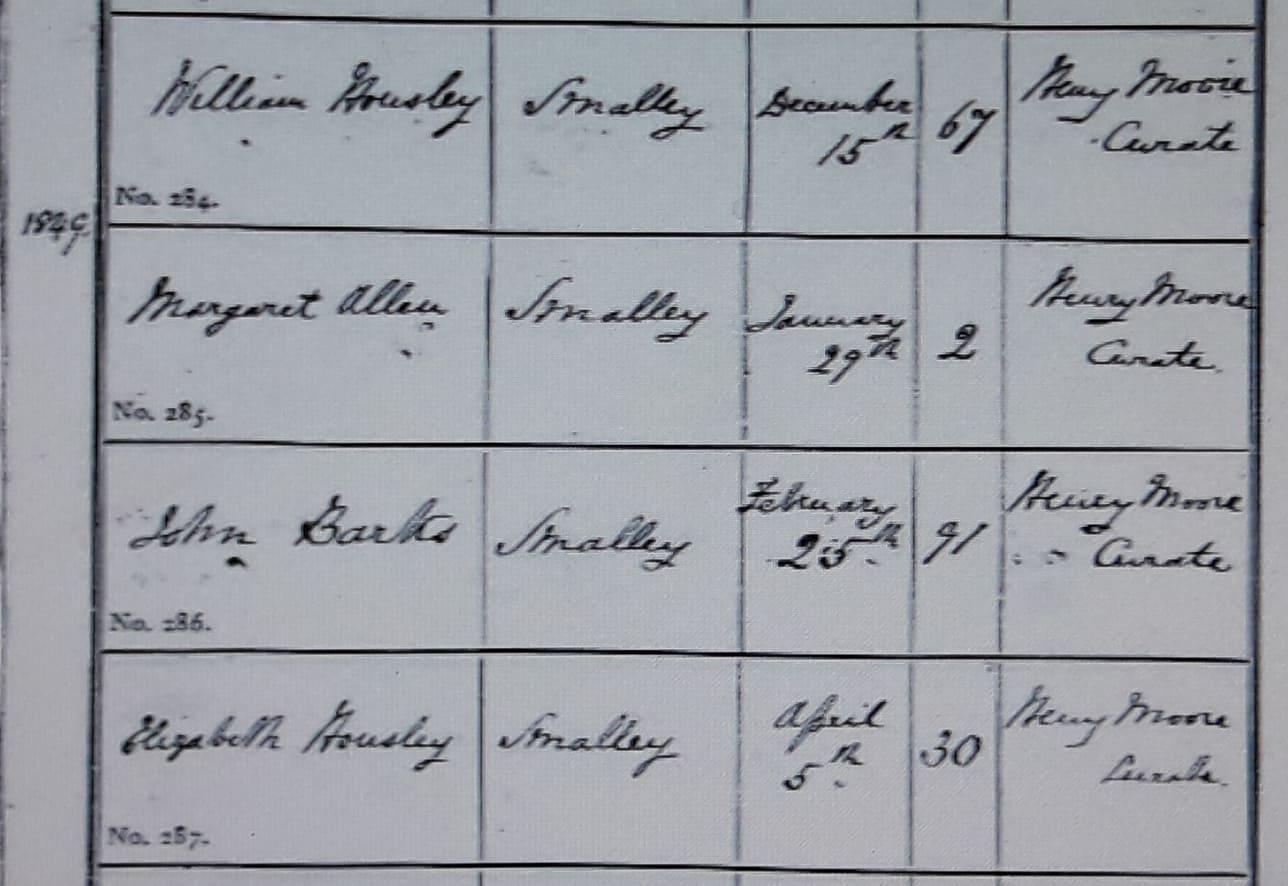

Death of William Housley 15 Dec 1848, and Elizabeth Housley 5 April 1849, Smalley:

Joseph wrote in December 1872: “I saw one of Sam’s daughters, the youngest Kate, you would remember her a baby I dare say. She is very comfortably married.”

In the same letter (December 15, 1872), Joseph wrote: “I think we have now found all out now that is concerned in the matter for there was only Sam that we did not know his whereabouts but I was informed a week ago that he is dead–died about three years ago in Birmingham Union. Poor Sam. He ought to have come to a better end than that….His daughter and her husband went to Brimingham and also to Sutton Coldfield that is where he married his wife from and found out his wife’s brother. It appears he has been there and at Birmingham ever since he went away but ever fond of drink.”

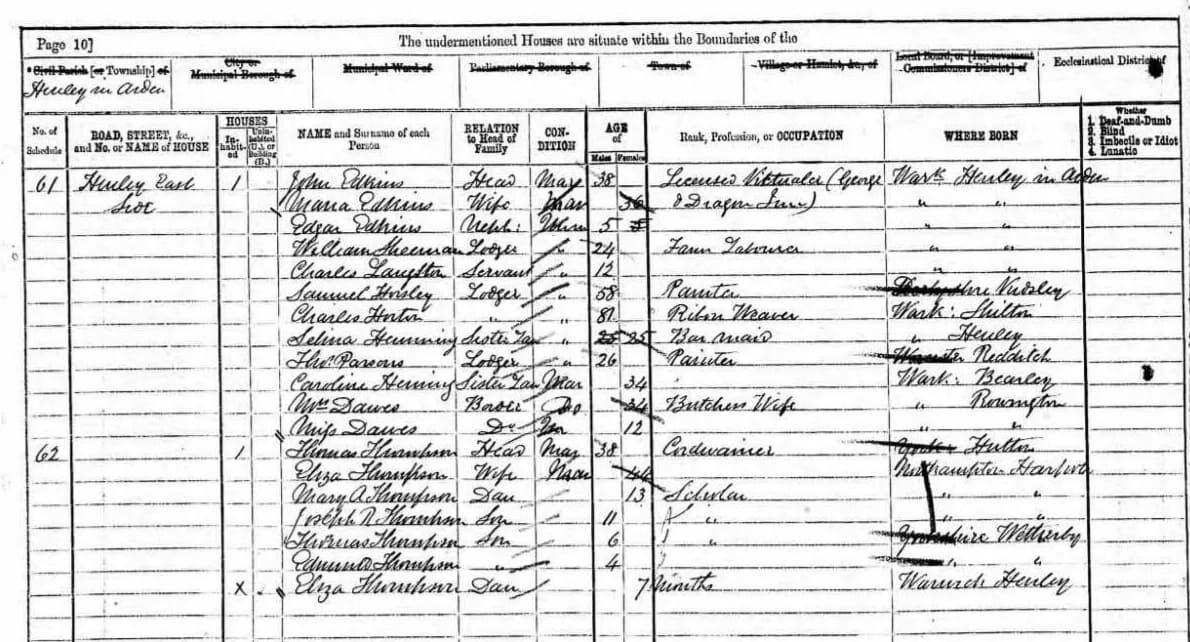

(Sam, however, was still alive in 1871, living as a lodger at the George and Dragon Inn, Henley in Arden. And no trace of Sam has been found since. It would appear that Sam did not want to be found.)

EDWARD HOUSLEY 1819-1843

Edward died before George left for USA in 1851, and as such there is no mention of him in the letters.

ANNE HOUSLEY 1821-1856

Anne wrote two letters to her brother George between February 1854 and her death in 1856. Apparently she suffered from a lung disease for she wrote: “I can say you will be surprised I am still living and better but still cough and spit a deal. Can do nothing but sit and sew.” According to the 1851 census, Anne, then 29, was a seamstress. Their friend, Mrs. Davy, wrote in March 1856: “This I send in a box to my Brother….The pincushion cover and pen wiper are Anne’s work–are for thy wife. She would have made it up had she been able.” Anne was not living at home at the time of the 1841 census. She would have been 19 or 20 and perhaps was “out service.”

In her second letter Anne wrote: “It is a great trouble now for me to write…as the body weakens so does the mind often. I have been very weak all summer. That I continue is a wonder to all and to spit so much although much better than when you left home.” She also wrote: “You know I had a desire for America years ago. Were I in health and strength, it would be the land of my adoption.”

In November 1855, Emma wrote, “Anne has been very ill all summer and has not been able to write or do anything.” Their neighbor Mrs. Davy wrote on March 21, 1856: “I fear Anne will not be long without a change.” In a black-edged letter the following June, Emma wrote: “I need not tell you how happy she was and how calmly and peacefully she died. She only kept in bed two days.”

Certainly Anne was a woman of deep faith and strong religious convictions. When she wrote that they were hoping to hear of Charles’ success on the gold fields she added: “But I would rather hear of him having sought and found the Pearl of great price than all the gold Australia can produce, (For what shall it profit a man if he gain the whole world and lose his soul?).” Then she asked George: “I should like to learn how it was you were first led to seek pardon and a savior. I do feel truly rejoiced to hear you have been led to seek and find this Pearl through the workings of the Holy Spirit and I do pray that He who has begun this good work in each of us may fulfill it and carry it on even unto the end and I can never doubt the willingness of Jesus who laid down his life for us. He who said whoever that cometh unto me I will in no wise cast out.”

Anne’s will was probated October 14, 1856. Mr. William Davy of Kidsley Park appeared for the family. Her estate was valued at under £20. Emma was to receive fancy needlework, a four post bedstead, feather bed and bedding, a mahogany chest of drawers, plates, linen and china. Emma was also to receive Anne’s writing desk. There was a condition that Ellen would have use of these items until her death.

The money that Anne was to receive from her grandfather, William Carrington, and her father, William Housley was to be distributed one third to Joseph, one third to Emma, and one third to be divided between her four neices: John’s daughter Elizabeth, 18, and Sam’s daughters Elizabeth, 10, Mary Ann, 9 and Catharine, age 7 to be paid by the trustees as they think “most useful and proper.” Emma Lyon and Elizabeth Davy were the witnesses.

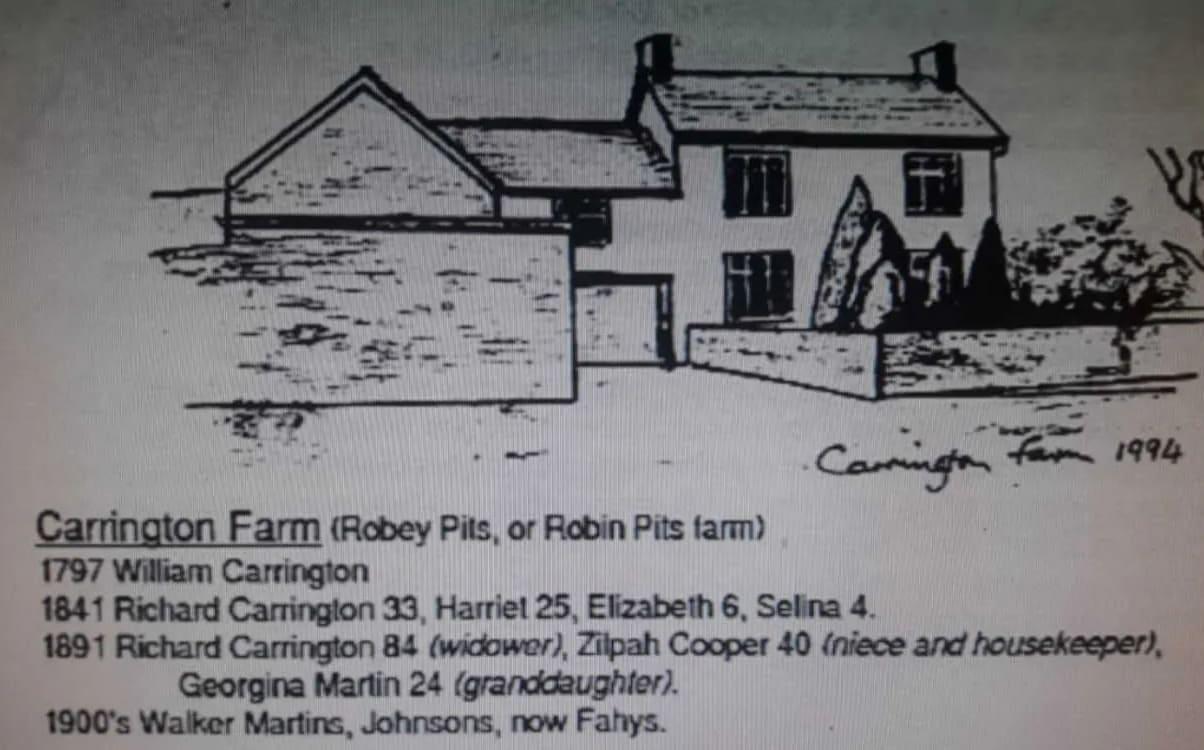

The Carrington Farm:

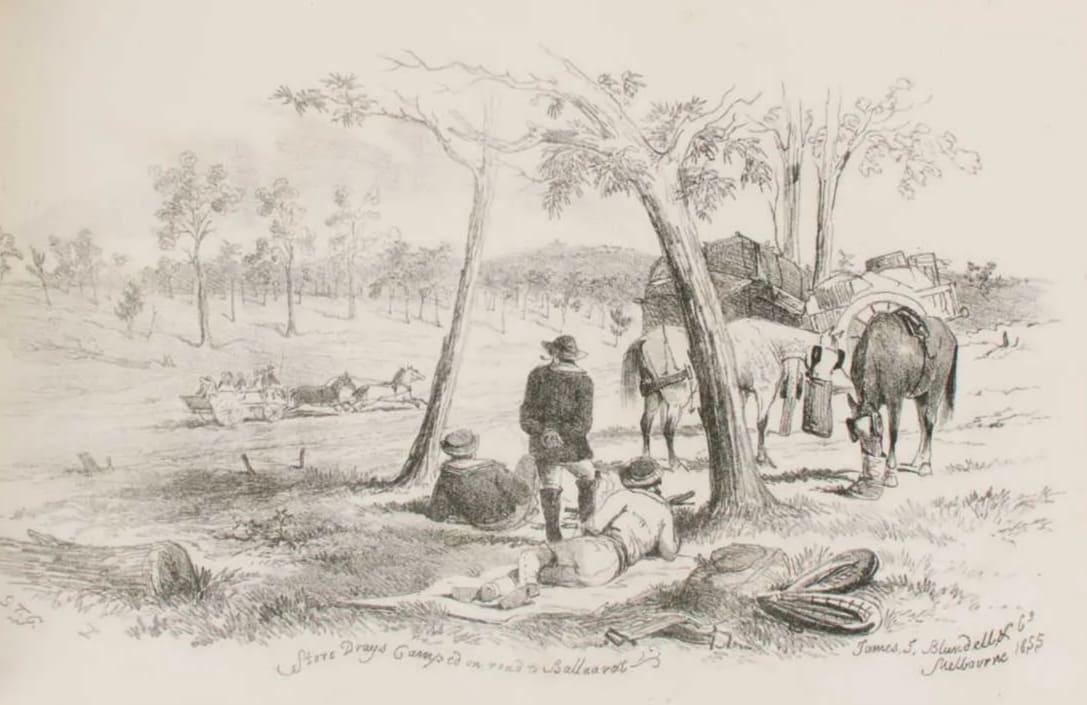

CHARLES HOUSLEY 1823-1855

Charles went to Australia in 1851, and was last heard from in January 1853. According to the solicitor, who wrote to George on June 3, 1874, Charles had received advances on the settlement of their parent’s estate. “Your promissory note with the two signed by your brother Charles for 20 pounds he received from his father and 20 pounds he received from his mother are now in the possession of the court.”

Charles and George were probably quite close friends. Anne wrote in 1854: “Charles inquired very particularly in both his letters after you.”

According to Anne, Charles and a friend married two sisters. He and his father-in-law had a farm where they had 130 cows and 60 pigs. Whatever the trade he learned in England, he never worked at it once he reached Australia. While it does not seem that Charles went to Australia because gold had been discovered there, he was soon caught up in “gold fever”. Anne wrote: “I dare say you have heard of the immense gold fields of Australia discovered about the time he went. Thousands have since then emigrated to Australia, both high and low. Such accounts we heard in the papers of people amassing fortunes we could not believe. I asked him when I wrote if it was true. He said this was no exaggeration for people were making their fortune daily and he intended going to the diggings in six weeks for he could stay away no longer so that we are hoping to hear of his success if he is alive.”

In March 1856, Mrs. Davy wrote: “I am sorry to tell thee they have had a letter from Charles’s wife giving account of Charles’s death of 6 months consumption at the Victoria diggings. He has left 2 children a boy and a girl William and Ellen.” In June of the same year in a black edged letter, Emma wrote: “I think Mrs. Davy mentioned Charles’s death in her note. His wife wrote to us. They have two children Helen and William. Poor dear little things. How much I should like to see them all. She writes very affectionately.”

In December 1872, Joseph wrote: “I’m told that Charles two daughters has wrote to Smalley post office making inquiries about his share….” In January 1876, the solicitor wrote: “Charles Housley’s children have claimed their father’s share.”

GEORGE HOUSLEY 1824-1877

George emigrated to the United states in 1851, arriving in July. The solicitor Abraham John Flint referred in a letter to a 15-pound advance which was made to George on June 9, 1851. This certainly was connected to his journey. George settled along the Delaware River in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. The letters from the solicitor were addressed to: Lahaska Post Office, Bucks County, Pennsylvania.

George married Sarah Ann Hill on May 6, 1854 in Doylestown, Bucks County, Pennsylvania. In her first letter (February 1854), Anne wrote: “We want to know who and what is this Miss Hill you name in your letter. What age is she? Send us all the particulars but I would advise you not to get married until you have sufficient to make a comfortable home.”

Upon learning of George’s marriage, Anne wrote: “I hope dear brother you may be happy with your wife….I hope you will be as a son to her parents. Mother unites with me in kind love to you both and to your father and mother with best wishes for your health and happiness.” In 1872 (December) Joseph wrote: “I am sorry to hear that sister’s father is so ill. It is what we must all come to some time and hope we shall meet where there is no more trouble.”

Emma wrote in 1855, “We write in love to your wife and yourself and you must write soon and tell us whether there is a little nephew or niece and what you call them.” In June of 1856, Emma wrote: “We want to see dear Sarah Ann and the dear little boy. We were much pleased with the “bit of news” you sent.” The bit of news was the birth of John Eley Housley, January 11, 1855. Emma concluded her letter “Give our very kindest love to dear sister and dearest Johnnie.”

In September 1872, Joseph wrote, “I was very sorry to hear that John your oldest had met with such a sad accident but I hope he is got alright again by this time.” In the same letter, Joseph asked: “Now I want to know what sort of a town you are living in or village. How far is it from New York? Now send me all particulars if you please.”

In March 1873 Harriet asked Sarah Ann: “And will you please send me all the news at the place and what it is like for it seems to me that it is a wild place but you must tell me what it is like….”. The question of whether she was referring to Bucks County, Pennsylvania or some other place is raised in Joseph’s letter of the same week.

On March 17, 1873, Joseph wrote: “I was surprised to hear that you had gone so far away west. Now dear brother what ever are you doing there so far away from home and family–looking out for something better I suppose.”The solicitor wrote on May 23, 1874: “Lately I have not written because I was not certain of your address and because I doubted I had much interesting news to tell you.” Later, Joseph wrote concerning the problems settling the estate, “You see dear brother there is only me here on our side and I cannot do much. I wish you were here to help me a bit and if you think of going for another summer trip this turn you might as well run over here.”

Apparently, George had indicated he might return to England for a visit in 1856. Emma wrote concerning the portrait of their mother which had been sent to George: “I hope you like mother’s portrait. I did not see it but I suppose it was not quite perfect about the eyes….Joseph and I intend having ours taken for you when you come over….Do come over before very long.”

In March 1873, Joseph wrote: “You ask me what I think of you coming to England. I think as you have given the trustee power to sign for you I think you could do no good but I should like to see you once again for all that. I can’t say whether there would be anything amiss if you did come as you say it would be throwing good money after bad.”

On June 10, 1875, the solicitor wrote: “I have been expecting to hear from you for some time past. Please let me hear what you are doing and where you are living and how I must send you your money.” George’s big news at that time was that on May 3, 1875, he had become a naturalized citizen “renouncing and abjuring all allegiance and fidelity to every foreign prince, potentate, state and sovereignity whatsoever, and particularly to Victoria Queen of Great Britain of whom he was before a subject.”

ROBERT HOUSLEY 1832-1851

In 1854, Anne wrote: “Poor Robert. He died in August after you left he broke a blood vessel in the lung.”

From Joseph’s first letter we learn that Robert was 19 when he died: “Dear brother there have been a great many changes in the family since you left us. All is gone except myself and John and Sam–we have heard nothing of him since he left. Robert died first when he was 19 years of age. Then Anne and Charles too died in Australia and then a number of years elapsed before anyone else. Then John lost his wife, then Emma, and last poor dear mother died last January on the 11th.”Anne described Robert’s death in this way: “He had thrown up blood many times before in the spring but the last attack weakened him that he only lived a fortnight after. He died at Derby. Mother was with him. Although he suffered much he never uttered a murmur or regret and always a smile on his face for everyone that saw him. He will be regretted by all that knew him”.

Robert died a resident of St. Peter’s Parish, Derby, but was buried in Smalley on August 16, 1851.

Apparently Robert was apprenticed to be a joiner for, according to Anne, Joseph took his place: “Joseph wanted to be a joiner. We thought we could do no better than let him take Robert’s place which he did the October after and is there still.”In 1876, the solicitor wrote to George: “Have you heard of John Housley? He is entitled to Robert’s share and I want him to claim it.”

EMMA HOUSLEY 1836-1871

Emma was not mentioned in Anne’s first letter. In the second, Anne wrote that Emma was living at Spondon with two ladies in her “third situation,” and added, “She is grown a bouncing woman.” Anne described her sister well. Emma wrote in her first letter (November 12, 1855): “I must tell you that I am just 21 and we had my pudding last Sunday. I wish I could send you a piece.”

From Emma’s letters we learn that she was living in Derby from May until November 1855 with Mr. Haywood, an iron merchant. She explained, “He has failed and I have been obliged to leave,” adding, “I expect going to a new situation very soon. It is at Belper.” In 1851 records, William Haywood, age 22, was listed as an iron foundry worker. In the 1857 Derby Directory, James and George were listed as iron and brass founders and ironmongers with an address at 9 Market Place, Derby.

In June 1856, Emma wrote from “The Cedars, Ashbourne Road” where she was working for Mr. Handysides.

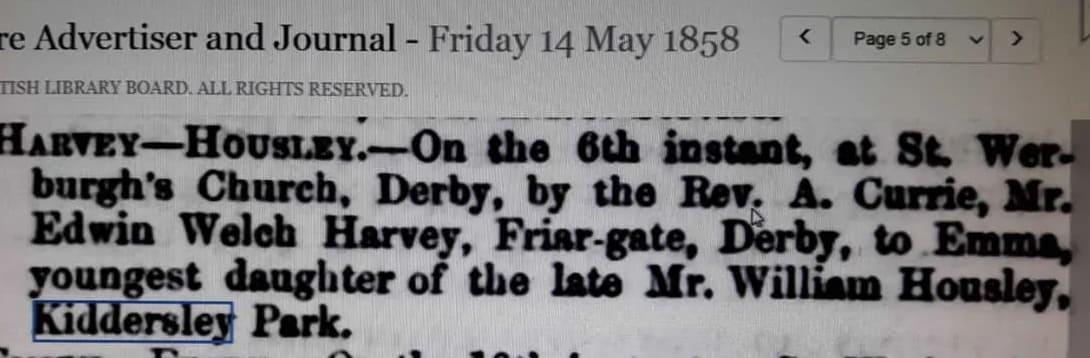

While she was working for Mr. Handysides, Emma wrote: “Mother is thinking of coming to live at Derby. That will be nice for Joseph and I.”Friargate and Ashbourne Road were located in St. Werburgh’s Parish. (In fact, St. Werburgh’s vicarage was at 185 Surrey Street. This clue led to the discovery of the record of Emma’s marriage on May 6, 1858, to Edwin Welch Harvey, son of Samuel Harvey in St. Werburgh’s.)

In 1872, Joseph wrote: “Our sister Emma, she died at Derby at her own home for she was married. She has left two young children behind. The husband was the son of the man that I went apprentice to and has caused a great deal of trouble to our family and I believe hastened poor Mother’s death….”. Joseph added that he believed Emma’s “complaint” was consumption and that she was sick a good bit. Joseph wrote: “Mother was living with John when I came home (from Ascension Island around 1867? or to Smalley from Derby around 1870?) for when Emma was married she broke up the comfortable home and the things went to Derby and she went to live with them but Derby did not agree with her so she had to leave it again but left all her things there.”

Emma Housley and Edwin Welch Harvey wedding, 1858:

JOSEPH HOUSLEY 1838-1893

We first hear of Joseph in a letter from Anne to George in 1854. “Joseph wanted to be a joiner. We thought we could do no better than let him take Robert’s place which he did the October after (probably 1851) and is there still. He is grown as tall as you I think quite a man.” Emma concurred in her first letter: “He is quite a man in his appearance and quite as tall as you.”

From Emma we learn in 1855: “Joseph has left Mr. Harvey. He had not work to employ him. So mother thought he had better leave his indenture and be at liberty at once than wait for Harvey to be a bankrupt. He has got a very good place of work now and is very steady.” In June of 1856, Emma wrote “Joseph and I intend to have our portraits taken for you when you come over….Mother is thinking of coming to Derby. That will be nice for Joseph and I. Joseph is very hearty I am happy to say.”

According to Joseph’s letters, he was married to Harriet Ballard. Joseph described their miraculous reunion in this way: “I must tell you that I have been abroad myself to the Island of Ascension. (Elsewhere he wrote that he was on the island when the American civil war broke out). I went as a Royal Marine and worked at my trade and saved a bit of money–enough to buy my discharge and enough to get married with but while I was out on the island who should I meet with there but my dear wife’s sister. (On two occasions Joseph and Harriet sent George the name and address of Harriet’s sister, Mrs. Brooks, in Susquehanna Depot, Pennsylvania, but it is not clear whether this was the same sister.) She was lady’s maid to the captain’s wife. Though I had never seen her before we got to know each other somehow so from that me and my wife recommenced our correspondence and you may be sure I wanted to get home to her. But as soon as I did get home that is to England I was not long before I was married and I have not regretted yet for we are very comfortable as well as circumstances will allow for I am only a journeyman joiner.”

Proudly, Joseph wrote: “My little family consists of three nice children–John, Joseph and Susy Annie.” On her birth certificate, Susy Ann’s birthdate is listed as 1871. Parish records list a Lucy Annie christened in 1873. The boys were born in Derby, John in 1868 and Joseph in 1869. In his second letter, Joseph repeated: “I have got three nice children, a good wife and I often think is more than I have deserved.” On August 6, 1873, Joseph and Harriet wrote: “We both thank you dear sister for the pieces of money you sent for the children. I don’t know as I have ever see any before.” Joseph ended another letter: “Now I must close with our kindest love to you all and kisses from the children.”

In Harriet’s letter to Sarah Ann (March 19, 1873), she promised: “I will send you myself and as soon as the weather gets warm as I can take the children to Derby, I will have them taken and send them, but it is too cold yet for we have had a very cold winter and a great deal of rain.” At this time, the children were all under 6 and the baby was not yet two.

In March 1873 Joseph wrote: “I have been working down at Heanor gate there is a joiner shop there where Kings used to live I have been working there this winter and part of last summer but the wages is very low but it is near home that is one comfort.” (Heanor Gate is about 1/4 mile from Kidsley Grange. There was a school and industrial park there in 1988.) At this time Joseph and his family were living in “the big house–in Old Betty Hanson’s house.” The address in the 1871 census was Smalley Lane.

A glimpse into Joseph’s personality is revealed by this remark to George in an 1872 letter: “Many thanks for your portrait and will send ours when we can get them taken for I never had but one taken and that was in my old clothes and dear Harriet is not willing to part with that. I tell her she ought to be satisfied with the original.”

On one occasion Joseph and Harriet both sent seeds. (Marks are still visible on the paper.) Joseph sent “the best cow cabbage seed in the country–Robinson Champion,” and Harriet sent red cabbage–Shaw’s Improved Red. Possibly cow cabbage was also known as ox cabbage: “I hope you will have some good cabbages for the Ox cabbage takes all the prizes here. I suppose you will be taking the prizes out there with them.” Joseph wrote that he would put the name of the seeds by each “but I should think that will not matter. You will tell the difference when they come up.”

George apparently would have liked Joseph to come to him as early as 1854. Anne wrote: “As to his coming to you that must be left for the present.” In 1872, Joseph wrote: “I have been thinking of making a move from here for some time before I heard from you for it is living from hand to mouth and never certain of a job long either.” Joseph then made plans to come to the United States in the spring of 1873. “For I intend all being well leaving England in the spring. Many thanks for your kind offer but I hope we shall be able to get a comfortable place before we have been out long.” Joseph promised to bring some things George wanted and asked: “What sort of things would be the best to bring out there for I don’t want to bring a lot that is useless.” Joseph’s plans are confirmed in a letter from the solicitor May 23, 1874: “I trust you are prospering and in good health. Joseph seems desirous of coming out to you when this is settled.”

George must have been reminiscing about gooseberries (Heanor has an annual gooseberry show–one was held July 28, 1872) and Joseph promised to bring cuttings when they came: “Dear Brother, I could not get the gooseberries for they was all gathered when I received your letter but we shall be able to get some seed out the first chance and I shall try to bring some cuttings out along.” In the same letter that he sent the cabbage seeds Joseph wrote: “I have got some gooseberries drying this year for you. They are very fine ones but I have only four as yet but I was promised some more when they were ripe.” In another letter Joseph sent gooseberry seeds and wrote their names: Victoria, Gharibaldi and Globe.

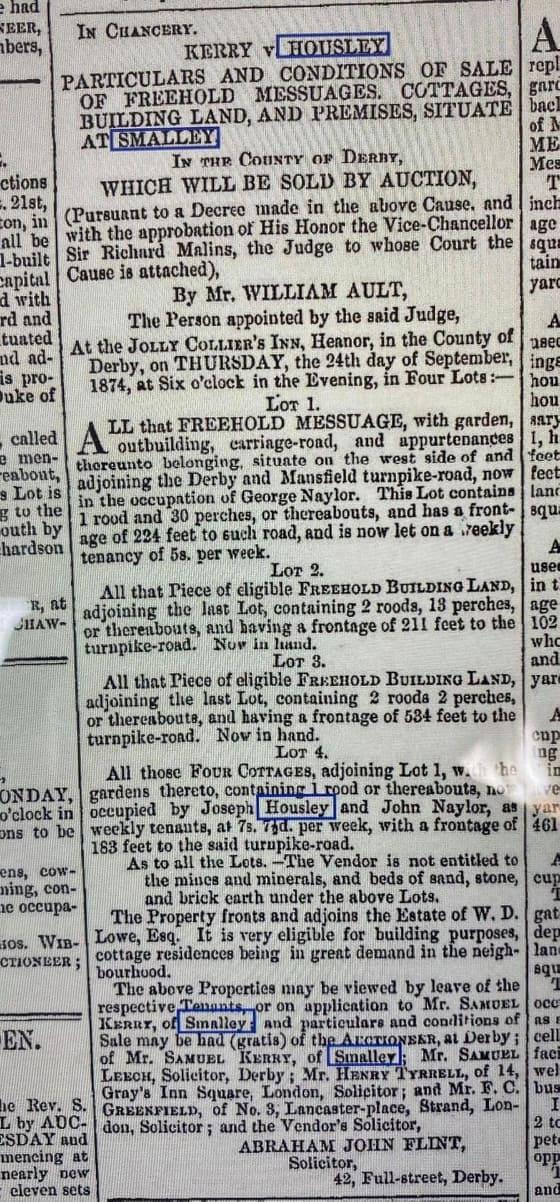

In September 1872 Joseph wrote; “My wife is anxious to come. I hope it will suit her health for she is not over strong.” Elsewhere Joseph wrote that Harriet was “middling sometimes. She is subject to sick headaches. It knocks her up completely when they come on.” In December 1872 Joseph wrote, “Now dear brother about us coming to America you know we shall have to wait until this affair is settled and if it is not settled and thrown into Chancery I’m afraid we shall have to stay in England for I shall never be able to save money enough to bring me out and my family but I hope of better things.”

On July 19, 1875 Abraham Flint (the solicitor) wrote: “Joseph Housley has removed from Smalley and is working on some new foundry buildings at Little Chester near Derby. He lives at a village called Little Eaton near Derby. If you address your letter to him as Joseph Housley, carpenter, Little Eaton near Derby that will no doubt find him.”

George did not save any letters from Joseph after 1874, hopefully he did reach him at Little Eaton. Joseph and his family are not listed in either Little Eaton or Derby on the 1881 census.

In his last letter (February 11, 1874), Joseph sounded very discouraged and wrote that Harriet’s parents were very poorly and both had been “in bed for a long time.” In addition, Harriet and the children had been ill.

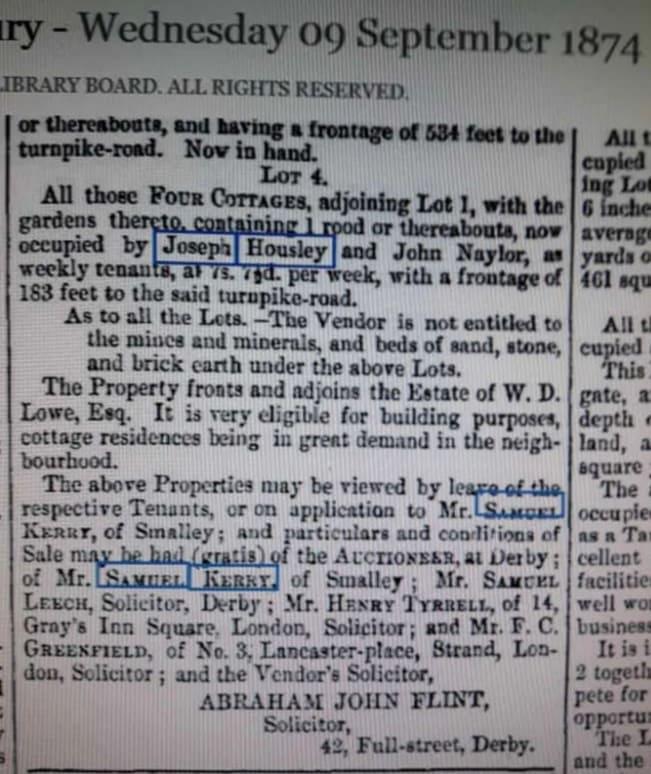

The move to Little Eaton may indicate that Joseph received his settlement because in August, 1873, he wrote: “I think this is bad news enough and bad luck too, but I have had little else since I came to live at Kiddsley cottages but perhaps it is all for the best if one could only think so. I have begun to think there will be no chance for us coming over to you for I am afraid there will not be so much left as will bring us out without it is settled very shortly but I don’t intend leaving this house until it is settled either one way or the other. “Joseph Housley and the Kiddsley cottages:

February 2, 2022 at 1:15 pm #6268

February 2, 2022 at 1:15 pm #6268In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

From Tanganyika with Love

continued part 9

With thanks to Mike Rushby.

Lyamungu 3rd January 1945

Dearest Family.

We had a novel Christmas this year. We decided to avoid the expense of

entertaining and being entertained at Lyamungu, and went off to spend Christmas

camping in a forest on the Western slopes of Kilimanjaro. George decided to combine

business with pleasure and in this way we were able to use Government transport.

We set out the day before Christmas day and drove along the road which skirts

the slopes of Kilimanjaro and first visited a beautiful farm where Philip Teare, the ex

Game Warden, and his wife Mary are staying. We had afternoon tea with them and then

drove on in to the natural forest above the estate and pitched our tent beside a small

clear mountain stream. We decorated the tent with paper streamers and a few small

balloons and John found a small tree of the traditional shape which we decorated where

it stood with tinsel and small ornaments.We put our beer, cool drinks for the children and bottles of fresh milk from Simba

Estate, in the stream and on Christmas morning they were as cold as if they had been in

the refrigerator all night. There were not many presents for the children, there never are,

but they do not seem to mind and are well satisfied with a couple of balloons apiece,

sweets, tin whistles and a book each.George entertain the children before breakfast. He can make a magical thing out

of the most ordinary balloon. The children watched entranced as he drew on his pipe

and then blew the smoke into the balloon. He then pinched the neck of the balloon

between thumb and forefinger and released the smoke in little puffs. Occasionally the

balloon ejected a perfect smoke ring and the forest rang with shouts of “Do it again

Daddy.” Another trick was to blow up the balloon to maximum size and then twist the

neck tightly before releasing. Before subsiding the balloon darted about in a crazy

fashion causing great hilarity. Such fun, at the cost of a few pence.After breakfast George went off to fish for trout. John and Jim decided that they

also wished to fish so we made rods out of sticks and string and bent pins and they

fished happily, but of course quite unsuccessfully, for hours. Both of course fell into the

stream and got soaked, but I was prepared for this, and the little stream was so shallow

that they could not come to any harm. Henry played happily in the sand and I had a

most peaceful morning.Hamisi roasted a chicken in a pot over the camp fire and the jelly set beautifully in the

stream. So we had grilled trout and chicken for our Christmas dinner. I had of course

taken an iced cake for the occasion and, all in all, it was a very successful Christmas day.

On Boxing day we drove down to the plains where George was to investigate a

report of game poaching near the Ngassari Furrow. This is a very long ditch which has

been dug by the Government for watering the Masai stock in the area. It is also used by

game and we saw herds of zebra and wildebeest, and some Grant’s Gazelle and

giraffe, all comparatively tame. At one point a small herd of zebra raced beside the lorry

apparently enjoying the fun of a gallop. They were all sleek and fat and looked wild and

beautiful in action.We camped a considerable distance from the water but this precaution did not

save us from the mosquitoes which launched a vicious attack on us after sunset, so that

we took to our beds unusually early. They were on the job again when we got up at

sunrise so I was very glad when we were once more on our way home.“I like Christmas safari. Much nicer that silly old party,” said John. I agree but I think

it is time that our children learned to play happily with others. There are no other young

children at Lyamungu though there are two older boys and a girl who go to boarding

school in Nairobi.On New Years Day two Army Officers from the military camp at Moshi, came for

tea and to talk game hunting with George. I think they rather enjoy visiting a home and

seeing children and pets around.Eleanor.

Lyamungu 14 May 1945

Dearest Family.

So the war in Europe is over at last. It is such marvellous news that I can hardly

believe it. To think that as soon as George can get leave we will go to England and

bring Ann and George home with us to Tanganyika. When we know when this leave can

be arranged we will want Kate to join us here as of course she must go with us to

England to meet George’s family. She has become so much a part of your lives that I

know it will be a wrench for you to give her up but I know that you will all be happy to

think that soon our family will be reunited.The V.E. celebrations passed off quietly here. We all went to Moshi to see the

Victory Parade of the King’s African Rifles and in the evening we went to a celebration

dinner at the Game Warden’s house. Besides ourselves the Moores had invited the

Commanding Officer from Moshi and a junior officer. We had a very good dinner and

many toasts including one to Mrs Moore’s brother, Oliver Milton who is fighting in Burma

and has recently been awarded the Military Cross.There was also a celebration party for the children in the grounds of the Moshi

Club. Such a spread! I think John and Jim sampled everything. We mothers were

having our tea separately and a friend laughingly told me to turn around and have a look.

I did, and saw the long tea tables now deserted by all the children but my two sons who

were still eating steadily, and finding the party more exciting than the game of Musical

Bumps into which all the other children had entered with enthusiasm.There was also an extremely good puppet show put on by the Italian prisoners

of war from the camp at Moshi. They had made all the puppets which included well

loved characters like Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and the Babes in the Wood as

well as more sophisticated ones like an irritable pianist and a would be prima donna. The

most popular puppets with the children were a native askari and his family – a very

happy little scene. I have never before seen a puppet show and was as entranced as

the children. It is amazing what clever manipulation and lighting can do. I believe that the

Italians mean to take their puppets to Nairobi and am glad to think that there, they will

have larger audiences to appreciate their art.George has just come in, and I paused in my writing to ask him for the hundredth

time when he thinks we will get leave. He says I must be patient because it may be a

year before our turn comes. Shipping will be disorganised for months to come and we

cannot expect priority simply because we have been separated so long from our

children. The same situation applies to scores of other Government Officials.

I have decided to write the story of my childhood in South Africa and about our

life together in Tanganyika up to the time Ann and George left the country. I know you

will have told Kate these stories, but Ann and George were so very little when they left

home that I fear that they cannot remember much.My Mother-in-law will have told them about their father but she can tell them little

about me. I shall send them one chapter of my story each month in the hope that they

may be interested and not feel that I am a stranger when at last we meet again.Eleanor.