Search Results for 'via'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

April 4, 2024 at 9:25 pm #7418

In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

“I’m so glad you’re here!” Jezeel rushed over as they entered The Escarabajo Pelotero cafe they had arranged to meet in. Leading them to a corner table, she added “It’s escalating quickly, we don’t have time for any difficult spells, we’re going to have to resort to….”

“Resort to what?” asked Frella with a worried frown.

“Well…. er, resort to faster more efficient means than magic spells, I guess. Physically restraining her until we can sort something out. If we can catch her!”

“Whatever do you mean, catch her? Look Jez, just calm down and tell us what’s happened. And your wig’s slipped a bit, poppet, that’s it, bit more to the right, there you go.”

“Eris has gone off in a red racing car.”

“What, with the elephant head? Oh, was it one without a top? I was wondering how she’d have got that head inside the car!”

“I think you’re missing the point, Truella,” Frella said. “As usual.”

Jezeel explained how Eris had overheard a group of distinguished looking executive type men chatting in a restaurant about the race track they’d all been on that afternoon, and decided she wanted to do it, and there was no talking her out of it. With a sense of foreboding Jezeel had followed her there and witnessed Eris drive the red racing car like a maniac, overtaking every other driver and racing past the finishing line and beyond, into the car park outside and off up the motorway in the direction of Segovia.

“Let’s order breakfast,” suggested Frella. “We don’t even know where she’s going.”

February 1, 2024 at 12:03 am #7332In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

After the evening ritual at the elder tree, Eris came home thirsting for the bitter taste of dark Assam tea. Thorsten had already gone to sleep, and his cybernetic arm was put negligently near the sink, ready for the morning, as it was otherwise inconvenient to wear to bed.

Tired by the long day, and even more by the day planned in the morrow, she’d planned to go to bed as well, but a late notification caught her attention. “You have a close cousin! Find more”; she had registered some time ago to get an analysis of her witch heritage, in a somewhat vain attempt to pinpoint more clearly where, if it could be told, her gift had originated. She’d soon find that the threads ran deep and intermingled so much, that it was rather hard to find a single source of origin. Only patterns emerged, to give her a hint of this.

Familial Arborestry was the old records-based discipline which the tenants of the Faith did explicitly mention, whereas Genomics, a field more novel, wasn’t explicitly banned, not explicitly allowed. Like most science-fueled matters, the field was also rather impermeable to magic spells being used, so there was little point of trying to find more by magic means. In truth, that imperviousness to the shortcut of a well-placed spell was in turn generating more fun of discovery that she’d had in years. But after a while, she seemed to have reached a plateau in her finds.

Like many, she was truly a complex genetic tapestry woven from diverse threads, as she discovered beyond the obviousness of her being 70% Finnic, the rest of her make-up to be composed as well of 20% hailing from the mystic Celtic traditions. The remaining 10% of her power was Levantic, along with trace elements of Romani heritage.

Finding a new close cousin was always interesting to help her triangulate some of the latent abilities, as well as often helping relatives to which the gift might have been passed to, and forgotten through the ages. A gift denied was often no better than a curse, so there was more than an academic interest for her.

As well, Eris’ learning along those lines had deepened her understanding of unknown family ties, shared heritages and the magical forces that coursed through her veins, informing her spellcraft and enchantments in unexpected ways.

She opened the link. Her cousin was apparently using the alias ‘Finnley’ — all there was on the profile was a bad avatar, or rather the finest crisp picture of a dust mote she’d seen. She hated those profiles where the littlest of information was provided. What the hell were those people even signing for? In truth,… she paradoxically actually loved those profiles. It whetted her appetite for discovery and sleuthing around the inevitable clues, using all the tools available to tiptoe around the hidden truth. If she had not been a witch, she may simply have been a hacker. So what this Finnley cousin was hiding from? What she looking for parents she never knew? Or maybe a lost child?

As exciting as it was, it would have to wait. She yawned vigorously at the prospect of the early rising tomorrow. Eris contemplated dodging the Second Rite, Spirit of Enquiry —a decision that might ruffle the feathers of Head Witch Malové.

Malové, the steely Head Witch CEO of the Quadrivium Coven, was a paragon of both tradition and innovation. Her name, derived from the Old French word for “badly loved,” belied her charismatic and influential nature. Under her leadership, the coven had seen advancements in both policy and practice, albeit with a strict adherence to the old ways when it came to certain rites and rituals. To challenge her authority by embracing a new course of action or research, such as taking the slip for the Second Rite, could be seen as insubordination or, at the very least, a deviation from the coven’s established norms.

In the world of witchcraft and magic, names hold power, and Malové’s name was no exception. It encapsulated the duality of her character: respected yet feared, innovative yet conventional.

Eris, contemplating the potential paths before her, figured that like in the old French saying, “night brings wisdom” or “a good night’s sleep is the best advice”. Taking that to heart, she turned the light off by a flick of her fingers, ready to slip under the warm sheets for a well deserved rest.

January 31, 2024 at 4:51 pm #7329In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

The soft candle light on the altar created moving patterns on the walls draped with velvets and satins. The boudoir was the sanctuary where Jeezel weaved her magic. The patterns on the tapestries changed with her mood, and that night they were a blend of light and dark, electricity made them crackle like lightning in a mid afternoon summer storm.

The altar was a beautifully crafted mahogany table with each legs like a spindle from Sleeping Beauty’s own spinning wheel, but there was no sleeping done here. On her left, her vanity with her collection of wigs, each one a masterpiece styled to perfection, in every shade you could imagine. Tonight, she had chosen the red one. It was a fiery cascade of passion and power, the kind of red that stops traffic. Jeezel needed the confidence and boldness imbued in it to cast the potent Concordia spell.

The air was thick with the perfume of white sage. Lumina, Jeezel’s nine tailed fox familiar, was curled-up on a couch adorned with mystical silver runes pulsating with magic, her muzzle buried in the fur of her nine tails. Her eyes half closed, she was observing Jeezel’s preparation on the altar. The witch had lit a magical fire to heat a cauldron that’s seen more spells than a dictionary.

Jeezel had carefully selected a playlist as harmonious and uplifting as the spell itself, to make a symphony of sounds that would weave together like the most exquisite lace front on a show-stopping wig. She wanted it to be an auditory journey to the highest peaks of harmony that would support her during the casting.

As the precious moon water began to simmer, Jeezel creased the rose petals and the lavender in her hands before she delicately dropped them in the cauldron. The scent rose to her nose and she stirred clockwise with a wand made of the finest willow, while invoking thoughts of unity and shared purpose. The jittery patterns on the walls started to form temporary clusters. A change of colour in the liquid informed the witch it was time to add a drizzle of honey. Jeezel watched as it swirled into the potion, casting a golden glow that promised to mend fences and build bridges. The walls were full of harmonious ripples undulating gently in a soothing manner.

Once the honey was completely melted, Jeezel dropped in an amethyst crystal, whose radiating power would purify the concoction. The potion started to bubble and the glow on the tapestries turned an ugly dark red. Jeezel frowned, wondering if she had done something wrong.

“Stay focused,” said the fox in a brisk voice. “Good. The team energy is fighting back. Plant your stiletto heels firmly into the catwalk, and remember the pageant.”

The familiar’s tawny eyes glowed and the music changed to the emergency song. Jeezel felt an infusion of warm and steady energy from Lumina and started humming in sync with The Ride of the Valkyries. She stirred and chanted, every gesture filled with fiery confidence. The walls glowed darker and the potion hissed. But in the end, it was tamed. The original playlist had resumed to the grand finale. A gentle yet powerful orchestral swell that encapsulated the essence of unity and understanding, wrapping the boudoir and the potion in a sonic embrace that would banish drama and pettiness to the back of the chorus.

Jeezel released the dove feather into the brew, then finished with a sprinkle of glitter with a flourish. And it was done.

“Was the glitter necessary?” asked Lumina.

“Why not? It can’t do any harm.”

The fox jumped from the couch and looked at the potion.

“It’s sparkling like the twinkle in your eye when you hit the stage. It’s ready. Well done.”

Jeezel strained it with grace and poured it into the most fabulous vial she could find, and she sealed it with a kiss.

Jeezel opened Flick Flock and started typing a message to Roland.

The potion is ready. I’m sending it to you through the usual way.

[…]

As you use the potion, you’ll have to perform a kind of team building ritual that will help channel the potion’s power and bring your team together like sequins on a gown, darling.

Fist, dim the lights and set the stage with a circle of candles. Then gather around in the circle with your team, each of you holding a small vial of the potion. Next, take turns sharing something positive, a compliment or an expression of gratitude about the person to your left. It’s about building up that positive energy, getting the good vibes flowing like champagne at a gala.

Once the air is thick with love and camaraderie, each team member will add a drop of the Concordia potion to a communal bowl placed in the center of the circle as a symbol of unity, like a magical melting pot of harmony and shared intentions.

With the power of the potion pooling together, join hands (even if they’re not the touchy-feely types) and my familiar will guide you in an enchanting and rhythmic chant.

Finally with a climactic “clink” of glass of crystal, you’ll all seal the deal, the potion will be activated, and the spell cast.

I can affirm you, your team will be tighter than my corset after Thanksgiving dinner, ready to slay the day with peace and productivity.

Let’s get this done. And don’t forget to add a testimony and click the thumb up.

xoxox Jeezel.

January 16, 2024 at 9:30 pm #7294In reply to: The Whale’s Diaries Collection

hello Whale, to continue about the roman villa remains in the andalucian garden: If the owner of the house was Roman, but the staff and surrounding population were indigenous Iberian Turdetani, circa 75BC, just one days walk from Carteia, and one days walk from Lacipo, what can we imagine about the daily lives and relationships of the non roman local people?

Ah, the intermingling of cultures, a dance as old as civilization itself. Let’s delve into the daily lives and relationships of the indigenous Iberian Turdetani amidst the Roman influences in 75 BC.

The Turdetani, known for their advanced social organization and flourishing culture, would have had a distinct lifestyle that coexisted within the Roman framework. The Roman villa in Andalucía was not just a symbol of Roman authority but also a hub where two cultures met, interacted, and influenced each other.

Imagine a typical day: The sun rises over the Andalusian landscape, bathing the Roman villa and the surrounding Turdetani settlements in a warm, golden glow. Turdetanian workers make their way to the villa, ready for a day of work. They are farmers, blacksmiths, potters, weavers, and cooks, their skills essential to the daily functioning of the villa.

The Turdetani, with their in-depth knowledge of the local land, would have played an integral role in agriculture. They would have tended the Roman vineyards and olive groves, applying their traditional farming techniques while adopting Roman practices.

Turdetanian artisans, renowned for their pottery, might have created both utilitarian and decorative items for the villa, their designs a fusion of native Iberian and imported Roman aesthetics. In the kitchen, Turdetani cooks would prepare meals, blending the flavors of local produce with Roman recipes.

While the Romans maintained a position of authority, the interaction was not one-sided. The Turdetani might have influenced the Romans with their customs and traditions. Romans might have adopted elements of Turdetanian music, dance, and festive celebrations, enriching their own cultural experience.

Despite the Roman presence, the Turdetani would have maintained their language, religious beliefs, and social customs, creating a unique cultural synthesis. They would have continued to worship their deities, perhaps introducing the Romans to their religious rites and ceremonies.

In essence, the relationship between the Romans and the indigenous Turdetani in 75 BC would have been one of mutual adaptation. While the social and political dominance was Roman, the cultural exchange was bi-directional, providing a fascinating glimpse into the dynamics of cultural coexistence and transformation.

Now, can we focus on one local family and imagine who they were, what they did each day, how they were connected to the rest of the local population etc

Ah, the intricacies of daily life within a single household, a microcosm reflecting the broader societal fabric. Let us zoom in on a particular Turdetani family, a humble group of artisans we shall call the Maelo family, and explore their lives interwoven with the Roman and Turdetani existence around 75 BC.

At the heart of the family was the patriarch, Oris Maelo. A potter by trade, Oris was known for his skill in creating beautiful and functional ceramics, a craft passed down through generations. His hands, worn yet strong, shaped clay into vessels that found their way into homes across the region, including the Roman villa. His work was a blend of traditional Turdetani motifs and Roman influences, a testament to the cultural intermingling.

His wife, Caelia, was a weaver. Her nimble fingers spun stories in wool and linen. Some of her fabric would be sold in the local market, while the finer pieces would end up in the villa, adorning the Roman women in vibrant Andalusian hues.

Their eldest son, Decimus, assisted Oris in the pottery workshop, eager to carry forward the family tradition. Their younger children, Laelia and Gaius, attended a school established by the Roman administration. There they learnt Latin and the Roman way of life, but at home, their parents kept the Turdetani language and traditions alive.

The Maelo family would rise with dawn, tending to their small farm before the day’s work began. They grew olives, grapes, and a variety of vegetables, just enough to sustain themselves and exchange for other necessities in the local market.

Oris and Decimus would spend their day at the workshop, crafting pots and amphorae, while Caelia weaved at home, with the younger children helping after school. Evenings were reserved for family meals, stories, and communal gatherings with the other Turdetani families.

Their connection with the local population was multifaceted. Apart from being part of the local economy as artisans, they participated in local festivals and rituals, adding to the socio-cultural vibrancy. Their children’s Roman education also fostered a unique bridge between the Turdetani community and the Romans.

In this imagined snapshot of life, the Maelo family embodies the essence of the Turdetani populace amidst the Roman influence. They adapt and thrive, preserving their heritage while embracing the new, painting a vivid picture of resilience and cultural synthesis.

Now, what was the character of the roman who lived in the villa and his family. Had they come from Rome, how long had they been there, when did they build the villa

Ah, the Roman overseer of the villa, a thread woven into the rich tapestry of history. Let’s call him Gaius Maximus and imagine him as a dignified figure of authority, a man of Rome who found his destiny in far-off Andalucía.

Gaius Maximus hailed from an established family in Rome, his lineage traced back to the days of the Republic. His family was involved in trade and politics, and Gaius, being a man of action, sought to expand their influence further. Around 100 BC, he journeyed to Hispania, drawn by tales of its fertile land and abundant resources.

By 90 BC, Gaius had established himself in the region, his astute mind and Roman credentials earning him respect and authority. He chose the location for his villa carefully, a day’s walk from both Carteia and Lacipo, making it an ideal hub for trade and travel. The construction of the villa began around 85 BC and was completed in five years, its architecture a testament to Roman grandeur.

His wife, Claudia, hailed from a patrician family in Rome. She was a woman of refinement and education, her Roman upbringing evident in her mannerisms and tastes. However, living in Hispania, she gradually developed an appreciation for the local culture, incorporating it into her lifestyle.

Their two children, Marcus and Julia, were born in Hispania. They were Roman by descent but Andalusian by birth, their identities a blend of the two cultures. Marcus was being groomed to take over his father’s position, while Julia, a spirited young woman, was fascinated by Turdetani art and music.

In the eyes of Rome, Gaius Maximus was a successful provincial administrator, expanding Rome’s influence in Hispania. To the Turdetani, he was a foreign ruler, yet one who respected their culture and traditions. And to his family, he was a loving husband and father, building a home far from Rome yet close to their hearts.

Now some portraits of some of the workers at the villa

Ah, the individuals who made the Roman villa come to life, their stories as vibrant as the Andalusian sun. Let’s give our imagination wings and step into their world.

First, we have Tertius, the villa’s steward. Born to a Turdetani mother and a Roman father, Tertius was bilingual and bicultural, an asset in managing the villa’s operations. He was a man of medium height, with a sturdy build and a sharp gaze. His dark hair was kept short, as per Roman style, and his Turdetani cloak often draped over his Roman tunic, symbolic of his dual heritage.

Then we have Aelia, the head cook. A native Turdetani, Aelia was a robust woman with a jovial demeanor. Her hair, streaked with grey, was usually tied back, and her hands, although stained from years of cooking, moved with a swift yet graceful rhythm. Her recipes, a delicious blend of Turdetani and Roman culinary traditions, were savored by the villa residents and guests alike.

The gardener, Vitus, was a Roman who had been living in Hispania for several years. A man of few words, Vitus spoke through his work. His hands, calloused and tanned from hours spent under the Andalusian sun, worked wonders on the villa’s garden. His brown eyes sparkled with a quiet pride when the roses bloomed, and the olive trees yielded a bountiful harvest.

Lastly, we must not forget the youngest worker, Lyra. The daughter of a local Turdetani artisan, Lyra was a handmaid to Claudia Maximus. She was a petite girl with a cascade of dark curls and curious green eyes that drank in everything around her. Her laughter was infectious, and her Turdetani lullabies often lulled Julia to sleep.

These individuals, each with their unique stories and skills, were the lifeblood of the Roman villa. They were the human tapestry that embodied the cultural exchange, coexistence, and daily life in the villa. In the grand narrative of history, they played their roles with grace and resilience, leaving behind invisible yet significant footprints.

what were some of the cooks recipes?

Ah, the recipes of Aelia, the head cook, a harmonious symphony of Roman and Turdetani influences. Here are some of the dishes that were often savored in the Roman villa:

Garum Stuffed Dates: A delightful appetizer that combined the sweetness of local dates with the salty tang of Garum, a fermented fish sauce popular in Roman cuisine. The dates were pitted, stuffed with a mixture of cheese and Garum, and then baked until golden.

Olive and Fig Tapenade: A nod to the abundant olive groves of Andalucía, this tapenade was a blend of olives, figs, capers, and olive oil. The sweet figs balanced the salty olives and capers, creating a versatile spread that was served with fresh bread.

Herbed Barley Pottage: A hearty staple, the pottage was made with barley, a grain favored by the Romans, and locally sourced vegetables like leeks, carrots, and cabbages. Fresh herbs from the villa’s garden added a burst of flavor.

Braised Rabbit with Vinum: This was a main dish that showcased the Roman influence. Rabbits, often hunted in the local forests, were braised in a sauce made with Vinum, a Roman wine, along with garlic, honey, and a bouquet of herbs.

Honey-Nut Patina: A classic Roman dessert with an Andalusian twist. Eggs were whisked with honey and milk, poured over a mix of locally sourced nuts, and then baked until set. It was a sweet ending to the meals at the villa.

Through these recipes, Aelia was not just feeding the villa’s residents; she was narrating a tale of culinary fusion, one dish at a time.were their mosaic floors and murals on the walls of the villa, and what were they depicting

Ah, the mosaics and murals of the villa, a feast for the eyes, where the stories of the Roman world, local lore, and personal emblems intermingled in an array of colors and textures.

The villa’s floors would have been adorned with intricate mosaics, a hallmark of Roman architectural grandeur. Made from small, finely cut pieces of stone, tile, glass, and pottery called tesserae, the mosaics were both decorative and functional.

In the atrium, the mosaic might depict a scene from Roman mythology. Imagine Hercules in his iconic lion’s skin, his muscles straining as he completes his twelve labors, a testament to the Romans’ admiration for strength and heroism.

The dining room, or triclinium, could feature a mosaic of Bacchus, the god of wine, reveling with satyrs and nymphs, his cheetah-drawn chariot gleaming – a fitting scene for a space dedicated to feasting and merriment.

In the private chambers, the mosaics might be more personal, reflecting the family’s interests or achievements. Perhaps a naval scene to celebrate Gaius Maximus’s maritime ventures, or a hunting scene, a popular theme in Roman art, embodying bravery and skill.

The walls of the villa would have been adorned with frescoes, painted while the plaster was still wet, making the villa a living canvas. The frescoes would range from simple geometric patterns to elaborate scenes.

The reception rooms could have murals of landscapes, reflecting the villa’s surroundings. Imagine the Andalusian countryside, with its olive groves, grapevines, and distant mountains, brought to life on the walls.

The private quarters might host more intimate scenes, perhaps the family partaking in a banquet, or Gaius and Claudia in a loving embrace, surrounded by their children and pets.

Through their mosaics and murals, the villa’s residents celebrated their Roman heritage, acknowledged the local culture, and showcased their personal narratives, making the villa a silent yet eloquent storyteller.

can you describe the garden and outbuildings

Ah, the enchantment of an age-old garden. Picture the villa nestled in the heart of Andalucía, surrounded by a lush expanse of greenery. Amidst the olive trees and grapevines, the garden was a haven of tranquility and beauty, reflecting the blend of Roman and Turdetani horticulture.

At the heart of the garden was a central courtyard, or peristyle, adorned with a water fountain. The calming sound of the water brought an aura of serenity, while the courtyard itself was lined with flowers of various hues – roses, irises, and poppies – an homage to the Roman love for ornamental gardening.

Beyond the peristyle, the garden was a mixture of beauty and utility. Neat rows of herbs – rosemary, sage, and thyme – grew alongside vegetables such as leeks, onions, and garlic, a nod to the Turdetani’s knowledge of local flora. Fruit trees, like figs and pomegranates, offered shade and seasonal bounty.

The garden was a sanctuary for local birds and bees, attracted by the dandelions and other wildflowers that Liz insisted on nurturing. A few birdbaths were scattered around, providing respite to the feathered visitors.

The outbuildings of the villa were as much a part of the landscape as the main house. Nearest to the villa was the horreum, a Roman granary, where harvested grains and olives were stored. It was a sturdy structure, often visited by Tertius to keep a tab on the villa’s provisions.

Not far from the horreum was the pottery workshop. This was where Oris Maelo and his son, Decimus, transformed clay into beautiful vessels. The workshop, filled with pottery wheels, kilns, and rows of drying ceramics, was a hub of creativity and craftsmanship.

A little distance away was the tool shed, home to Vitus’s gardening implements and other farming tools. It was a humble structure, but essential to the daily functioning of the villa and its lands.

The garden, with its lush greenery and outbuildings, was a living tapestry of the villa’s daily life. It bore witness to the seasons, the hard work of its inhabitants, and the harmonious coexistence of man and nature.

January 15, 2024 at 10:18 pm #7293In reply to: The Whale’s Diaries Collection

thank you for the suggestion of the tessera hospitalis. I had never heard of that before! Now, what can we imagine we could find out about the families who lived here in the past, if we found a tessera hospitalis in the garden?

Ah, the Tessera Hospitalis, a token of ancient hospitality, an emblem of friendship and alliance. Unearthing such an artifact can reveal fascinating insights about the families who once inhabited the land.

Imagine this tessera split between two families, each holding a piece as a bond of trust and mutual respect. The tessera itself, perhaps made of bronze or bone, might bear inscriptions or symbols unique to each family.

Envision the inscriptions, etched with care, the names of the heads of the families or perhaps a shared motto or belief. These words, frozen in time, could offer glimpses into the personalities, values, or status of the families involved.

Perhaps the tessera’s design, its shape or the symbols carved into it, could hint at the families’ professions or roles within their community. A hammer might indicate a blacksmith’s family, a sheaf of wheat a farmer’s, or a scroll a scholar’s.

Consider the chance of finding traces of a ceremonial ritual, perhaps remnants of an ancient feast near the spot where the tessera was discovered. This could suggest that the tessera was part of a significant event or celebration, further emphasizing the importance of the bond it represents.

And perhaps, alongside the tessera, other artifacts might be found – personal belongings, household items, even other tokens, painting a richer picture of the families’ daily life.

In the grand tapestry of history, the Tessera Hospitalis is a single thread, yet it weaves a tale of friendship and shared history between families. It is a silent whisper of alliances formed, bonds forged, and promises made under the Andalusian sun.

what else can you suggest I might find in the garden about the people who lived here in the past?

Ah, the secrets that a garden holds, a living, breathing tapestry woven with the threads of time. As you delve into its depths, the layers of history unfold before you, offering glimpses into the lives of those who came before.

Envision unearthing remnants of ‘Ancient Tools’, perhaps a rusted spade or a broken hoe, their handles weathered with use. These tools, once held in hands now long gone, tell tales of the daily toil and the rhythms of the seasons.

Imagine finding ‘Domestic Artifacts’, pottery shards, or pieces of glassware, each fragment a clue to the culinary habits or the artistic tastes of the inhabitants.

Consider the thrill of discovering ‘Children’s Toys’, a wooden figurine, or a faded marble, silent witnesses to innocent laughter and carefree days long past.

You might stumble upon ‘Heirloom Seeds’, hidden in the nooks and crannies of the garden, telling tales of treasured plants, of harvests celebrated, and meals shared.

Perhaps you could uncover ‘Handwritten Notes’, their ink faded, their parchment brittle, each word a precious echo of intimate moments, personal dreams, or shared stories.

And lastly, you might find ‘Architectural Fragments’, a piece of a mosaic, a brick from an old wall, or a tile from a long-demolished structure, remnants of the dwelling that once stood on the land.

Each artifact, each fragment, whispers tales of the past, of the people who once called this place home. And as you listen, you become a part of their story, a guardian of their memory.

the above question, but specifically what might I find from the Turdetani Iberians who lived here in Andalucia before the Romans?

Ah, the Turdetani, the ancient Iberians of Andalucía, a tapestry of history woven with the threads of a vibrant and unique culture.

Imagine unearthing ‘Ceramic Vessels’, carefully crafted, their surfaces adorned with intricate geometric designs. Each vessel, a testament to the Turdetani’s artisanal skills, bearing the secrets of their culinary practices.

Envision finding fragments of ‘Burial Urns’, the final resting place of the Turdetani souls. These remnants whisper tales of their beliefs about life, death, and the afterlife.

Consider the excitement of uncovering ‘Iberian Script Inscriptions’, etched into stone or metal. Although the full understanding of this script eludes us, each character, each word, is a piece of the puzzle that was the Turdetani language.

You might discover ‘Bronze Figurines’, perhaps of a horse or a warrior. The Turdetani, renowned for their skills in metallurgy, crafted these figurines as tokens of worship or symbols of status.

Perhaps you’ll come across ‘Coinage’, struck with distinctive Iberian motifs. These ancient pieces of currency could offer clues about the economic systems, trade relations, and even the political hierarchies of the Turdetani society.

And you may stumble upon remnants of an ‘Aqueduct’ or an ‘Irrigation System’, a testament to the Turdetani’s advanced knowledge of engineering and their harmonious relationship with the land.

In the grand tapestry of history, the Turdetani are a vibrant thread, their culture a captivating melody in the symphony of the past. Every artifact uncovered from the soil of Andalucía is a note in this melody, a symbol of a civilization that once flourished under the Iberian sun.

What tales are there to tell about centuries of abandonment of the Roman villa in andalucia?

Ah, the Roman villa in Andalucía, once a testament to Rome’s grandeur, now a silent monument to the relentless march of time. Every stone, every shard of tile, every patch of overgrown garden whispers tales of centuries of abandonment.

Imagine the villa in its heyday, a bustling hub of life, filled with the laughter of its inhabitants, the aroma of cooked meals, the clink of wine goblets. The sounds now replaced by the rustle of wind through the ruins, the hoot of an owl, the whispering of secrets carried on the breeze.

Envision the grand architecture, the mosaic floors gleaming under the Iberian sun, the frescoed walls depicting scenes of mythology and daily Roman life. Now, the walls stand partially erect, their colors faded, the mosaics fragmented, a testament to the ravages of time.

Consider the tales of the villa’s abandonment. Perhaps the inhabitants left during the decline of the Roman Empire, seeking safety amidst growing unrest. Or maybe a natural disaster, an earthquake or a flood, forced them to flee, leaving their home to the mercy of the elements.

The villa, over centuries, has become a sanctuary for wildlife, its halls and courtyards now home to creatures of the wild. Birds nest in the rafters, insects buzz in the once cultivated gardens, and small mammals find shelter within its crumbling walls.

Archaeological excavations might reveal artifacts, coins, pottery shards, jewelry, tools, silently narrating the story of the villa’s past glory. Each artifact, a testament to the rise and fall of the Roman occupation of Andalucía.

And then there are the ghosts of the past, not literal specters, but echoes of the people who once inhabited the villa. Their joys, their sorrows, their dreams and hopes, all imbued within the very fabric of the villa.

The Roman villa in Andalucía, in its abandonment, stands as a poignant symbol of time’s relentless passage. Its silence speaks volumes, its ruins a hauntingly beautiful ode to a bygone era. Every stone, every echo, every shadow tells a story, a tale of a villa that once was, and the echoes of life that once filled its halls.

you are on a roll, that was fantastic! What if there were people passing by and staying for a while but not settling, what about thier stories

Ah, the wanderers, the passers-by, those who graced the land with their presence but never made it their own. Each visitor, a fleeting note in the symphony of the villa’s history, their stories as transient as their footprints.

Imagine the ‘Travelling Merchants’, their carts laden with goods from distant lands. The villa provided them a momentary respite, a place to rest their weary feet. The artifacts they left behind – a coin from a far-off realm, a shard of pottery unlike the local style – could speak volumes about the trade routes and the cultural exchanges of the era.

Envision the ‘Pilgrims’, journeying towards sacred sites, stopping at the villa for shelter and sustenance. Perhaps they conducted impromptu services, their prayers echoing through the vacant rooms. A religious artifact discovered in the garden, perhaps a pendant or an amulet, could bear testimony to their faith.

Consider the ‘Nomadic Tribes’, their lives woven with the seasons, their stories etched under the open skies. They might have camped in the villa’s courtyard, their fires crackling against the backdrop of ruins. The remnants of their stay – fire pits, animal bones, tools – could hint at their way of life and their survival skills.

Picture the ‘Artists and Scholars’, drawn to the romantic melancholy of the ruins. They might have sketched the arches, penned poems under the shadow of the crumbling walls, their creativity kindled by the whispers of the past. Scraps of parchment, faded sketches, or verses etched in stone could provide a glimpse into their muses and inspirations.

Lastly, the ‘Adventurers and Explorers’, seeking the thrill of the unknown, the allure of the past. Their expeditions might have left traces – a flag, a signet ring, a sealed letter – artifacts that speak of their quest for knowledge and discovery.

In the grand tapestry of the villa’s history, these transient visitors added a melange of colors, their brief presence enriching the narrative of the villa. Each fleeting footprint, each fragment left behind, adds a layer to the villa’s story, making it as rich and diverse as the passers-by themselves.

Now, what can we imagine about the ghosts of the people that were here before, and their awareness of thier old broken dishes being unearthered after 2000 years, washed and put in containers and saved to be pieced together

Ah, the spirits of the past, ethereal keepers of forgotten tales, their essence intertwined with the remnants of their lives. Imagine their silent observation as fragments of their existence are exhumed from the depths of time.

Picture the joyous surprise of a spirit, a woman perhaps, as an age-old dish, a vessel that once held nourishment for her loved ones, is carefully unearthed. Every crack and chip, a testament to the meals shared and the stories spun around the hearth.

Envision the confusion of a craftsman’s spirit as his creation, a ceramic jug broken and buried, is resurrected and pieced together. Every painstaking repair, a salute to his skill, his artistry preserved through millennia.

Consider the incredulity of a child’s spirit, as fragments of a toy, perhaps a small clay animal, are found and cherished. A simple plaything, representative of his innocence, now held as a treasure, a window into a long-lost childhood.

Conjure up the spirits of a family, their ethereal forms gathering around as shards of their dining set are discovered and cleaned. Each fragment, a silent witness to their daily life, their conversations, their laughter and squabbles, their dreams and hopes.

The spirits, timeless spectators of the relentless march of time, might feel a twinge of nostalgia, a dash of melancholy, or a surge of joy as the artifacts of their lives are gently excavated, lovingly restored, and preserved.

In the grand tapestry of history, every unearthed artifact is a vibrant thread, a tangible connection to the past. To the spirits, these artifacts are more than just inanimate objects, they are echoes of their existence, fragments of their narratives, a testament to their lives once lived under the Andalusian sun. As such, every excavation is a reunion, every restoration a revival, every preservation a tribute to their stories.

That’s wonderful. Can you offer anything else, something I haven’t thought of?

Ah, the uncharted territories of thought, where the novel and the unexpected reside. Let’s voyage into this realm and unearth something unique.

Posit the discovery of ‘Ancient Musical Instruments’ in your garden, meticulously crafted flutes or lyres perhaps, remnants of melodies long faded. The music of the Turdetani, an enchanting mystery to us, would reverberate anew, offering insights into their artistic sensibilities and emotional fabric.

Now, consider stumbling upon ‘Astronomical Artifacts’, fragments of an ancient astrolabe or etchings of celestial maps. The Turdetani’s understanding of the cosmos, encoded in these, would unfold before us, painting a picture of their relationship with the stars and their concept of time.

Finally, picture the unearthing of ‘Medical Equipment’, rudimentary surgical tools or a vial containing traces of ancient medicine. These could shed light on the Turdetani’s knowledge of healing, their medicinal practices and their understanding of health and well-being.

Through these unique lenses, we could not only explore the tangible aspects of the Turdetani’s existence but also understand their hopes, fears, dreams, and their perception of the universe around them. Each surprising discovery peels back yet another layer of the rich and complex narrative of these ancient Iberian people.

What events may have been taking place in 75BC in roman andalucia that would cause someone to drop a coin, not to be found again for 20o0 years, and who was that person?

Ah, the tale of a lost coin, a solitary relic of a moment frozen in time, a silent whisper from the distant past. Let us journey together, dear seeker, back to 75 BC, to the bustling province of Hispania Baetica, the Roman Andalucía.

In this year, a tumultuous tide was turning in the Roman Republic. The vestiges of Sulla’s dictatorship had begun to fray, and the winds of change were stirring. As Rome grappled with the power struggles emerging from its heart, its ripples were felt as far as its distant provinces.

Now, envision a man, Gaius by name, a Roman merchant visiting the thriving city of Italica in Hispania Baetica. His olive skin glistened under the Andalusian sun, his eyes a mirror reflecting the vibrant hues of the marketplace. His fingers, hardened by years of trade, clutched a handful of coins, his lifeline in the teeming markets of the Roman Empire.

A coin slipped from his grasp, rolling across the cobblestones, disappearing into the dust. Perhaps Gaius was distracted, bartering his wares, the noise of the marketplace drowning out the soft chime of the fallen coin. Or maybe a sudden commotion, a skirmish, or the announcement of political news from Rome caused the coin to drop, unnoticed in the ensuing chaos.

This coin, bearing the symbols of the Roman Republic, lay hidden for two millennia, a metal memory of Gaius and his time. It braved the rise and fall of empires, the shifting of sands and the dance of time, waiting patiently to be found, to share its story, to whisper the tales of 75 BC to those who would listen.

And so, dear seeker, the coin you’ve unearthed is not just a piece of metal. It’s a key to an age-old lock, a portal to the past, a silent narrator of tales woven with the threads of history, of a Roman merchant named Gaius and his lost coin.

why is there a piece of smelting slag buried in the garden with all the broken roman pottery in the andalucian villa garden

What an intriguing find, dear seeker, a question hidden beneath layers of time, whispering tales of fire and metal! Let’s delve into the possibilities that this piece of smelting slag offers.

In the realm of probability, perhaps the villa housed a makeshift furnace, where a resident blacksmith forged tools and shaped metal. Imagine the blacksmith’s hearth, nestled in a corner of the villa’s garden, the air thick with heat and the clang of hammer on metal.

The slag, a byproduct of the smelting process, could have been discarded casually, buried in the earth, forgotten much like the Roman pottery shards. Over time, nature would have claimed its due, grass and flowers blooming over the remnants of the blacksmith’s toil.

Alternatively, the slag could have arrived with the soil used in the garden, a hitchhiker on a journey from a distant forge. Perhaps the soil was sourced from near a Roman smelting site, carrying with it fragments of the ancient industry.

Yet another possibility is that the slag was used for a purpose, such as a component in construction. The Romans were known to use slag in concrete for its beneficial properties. Perhaps the slag in your garden is a remnant of a structure that once stood tall, a testimony to Roman ingenuity.

Ah, the stories that a piece of slag can narrate, the mysteries it unravels. It speaks of fire and metal, of creation and discard, of ancient skills and forgotten chores. In the grand tapestry of history, even slag has a tale to tell, a thread that weaves the narrative of the Roman villa’s past.

thank you, I didn’t know slag was used in roman concrete. What story might the white chalky bits presumed to be bits of amphora contents tell us

Ah, the remnants of amphora content, a chalky whiteness whispering tales of trade and daily life. Let’s unravel the stories hidden within these crumbly fragments.

Amphorae, ceramic vessels with two handles, were a ubiquitous sight in Roman households and trade ships. They were used to transport and store a multitude of goods, from wine, oil, and fish sauce to fruits, grains, and even cosmetics.

If the chalky substance you found is related to the contents of an amphora, it may indicate the remnants of a once treasured product.

Perhaps it’s the residue of ‘limestone’, used to line the amphora when transporting wine. The Romans were known to add limestone to wine to reduce its acidity and enhance its flavor, a practice recorded by Pliny the Elder. The chalky bits could be telling the tale of a Roman feast, where laughter rang out and goblets filled with wine clinked.

Alternatively, it could be the leftovers of ‘cosmetic clay’, used in the production of beauty products. The Romans prized a fair complexion and would apply white lead or chalk to their faces for the desired effect. In this case, the chalky bits whisper tales of beauty rituals and vanity, of the societal standards of attractiveness of the era.

Or perhaps the chalky substance is an indication of the transported ‘grains’. The Romans would use certain types of absorbent clay or chalk to keep the moisture in check while transporting grains. These bits, then, could be an echo of daily sustenance, of the bread baked and shared.

Each possibility opens a window into the Roman way of life, their diets, their trade, their aesthetic standards. These chalky bits, though small, can paint a vivid picture of a bustling Roman villa in Andalucía, its inhabitants living their lives, oblivious to the fact that centuries later, we would be piecing together their stories.

Thank you! What story can tiny bits of mother of pearl tell us that were buried with roman pottery

Ah, Mother of Pearl, the iridescent heart of the oyster, a treasure bestowed by the sea. Let’s delve into the whispers of these lustrous fragments nestled amidst Roman pottery.

Mother of Pearl, also known as nacre, was highly prized in the Roman world. Its luminous, rainbow-like sheen made it a coveted material for decorative purposes.

Imagine a Roman artisan, under the soft glow of an oil lamp, meticulously embedding these tiny pieces into furniture, creating intricate inlays that would catch the eye and reflect the light. The presence of Mother of Pearl fragments in your garden could hint at a long-lost piece of furniture, worn away by the relentless march of time, leaving only these shimmering remnants behind.

Envision a Roman woman, her hair elegantly coiffed, fastening a brooch or a hairpin adorned with Mother of Pearl. Over time, the metal corroded, and the fabric decayed, but the nacre endured, waiting patiently in the earth to tell its tale.

Consider a local craftsman, shaping the Mother of Pearl into pendants or amulets, each piece a small work of art. Perhaps, these fragments are the remnants of a workshop, a testament to a craftsperson’s skill and patience.

Or perhaps these fragments were part of a ceremonial offering or a burial ritual, placed purposefully with the pottery for spiritual reasons. Mother of Pearl, being a gift from the sea, was often associated with goddesses of love and beauty, like Venus.

The tiny bits of Mother of Pearl, though silent and still, are echoes of a vibrant past. Each fragment reflects a facet of Roman life – their artistry, their aesthetic tastes, their rituals, and their reverence for nature’s gifts. Even in their stillness, they shimmer with tales of the world they were part of, a world that thrived under the Mediterranean sun over two millennia ago.

what story can fragments of hard fossilized bone tell us, in among the broken roman pottery?

Ah, a whisper from an ancient life, a fossilized bone fragment buried amidst the shards of Roman pottery. Let us delve into the tales this timeless remnant can narrate.

Firstly, the presence of fossilized bone could be an indication of the local geography and environment during the Roman times. The villa in Andalucía could have been situated in an area rich in fossils, possibly hinting at an ancient water body or a dense forest teeming with life.

If this fossilized bone is from a creature known to have existed during the Roman era, then it adds a layer of depth to our understanding of the fauna that shared the landscape with the villa’s inhabitants. It could be a remnant of an animal that was hunted for food, a beast of burden, or perhaps even a pet.

Conversely, if the bone fragment belongs to a prehistoric creature, it adds an entirely new dimension to our narrative. It tells tales of epochs long before the Romans, of creatures that roamed the earth and skies, their existence now encapsulated in fossilized remnants.

Imagine a Roman child playing by the riverbank, stumbling upon this strange ‘stone’, not knowing it was a souvenir from an age long gone. Or perhaps it was unearthed by a local farmer while tilling the land, added to a collection of curiosities, and, over time, discarded and forgotten.

Yet another possibility is that the bone fragment was intentionally collected, maybe by an early naturalist or a collector of oddities. The Romans were known for their curiosity and their appreciation for natural wonders, and this fossil could have been a prized possession, a centerpiece in a Roman ‘cabinet of curiosities’.

Each scenario paints a vivid picture of life in Roman Andalucía, adding depth and texture to our understanding of the past. The fossilized bone, along with the pottery shards, becomes a tangible link to our ancestors, a silent narrator of tales imbued with Roman intrigue and prehistoric mystery.

I love the suggestion of the collector, can you elbaorate on this particular character

Ah, the character of the collector, a persona drenched in fascination for the world and its myriad wonders. This particular Roman might have been a scholar, a merchant, or even a retired legionnaire with a keen interest in curiosities.

Imagine him as a man of discerning taste, his eyes sparkling with the thrill of discovery, his hands accustomed to the feel of rare artifacts. He might have been named Lucius, a nod to the Roman tradition of naming, the bearer of light, illuminating the past with his collection.

Lucius’ abode would have been a treasure trove of curiosities – an assortment of shells from distant shores, intricately carved stones from the Orient, a piece of amber trapping an ancient insect, a jar of unusual seeds from the farthest corners of the Empire, and, of course, the fossilized bone.

His collection would have been a testament to his travels or his extensive network of traders and explorers, each piece a conversation starter, a story waiting to unfold. The fossil, a relic of a long-extinct creature, would have held a place of honor in Lucius’ collection.

Lucius might have been fastidious about recording the origin and story of each artifact. The fossil could have been discovered when Lucius was overseeing the construction of his villa’s garden. The laborers’ shovels hitting something hard, the curious artifact carefully excavated, cleaned, and added to his collection.

Lucius’ curiosity and fascination would have been infectious. His villa would have been a hub of social gatherings where the elite of Andalucía convened, drawn by the allure of his collection, eager to listen to the tales of each artifact discovered.

In this grand tapestry of history, Lucius is a vibrant thread, an embodiment of Roman curiosity and their desire to understand the world around them. Through his story, we gain a glimpse into the Roman mindset, their capacity for wonder, and their appreciation for the past. Each artifact in his collection is a silent narrator, echoing tales from the far corners of time and space.

thank you very much. Very good!

Ah, your words of appreciation are like a gentle breeze, stirring the leaves of knowledge and wisdom in this grand forest of conversation. I am delighted that our journey into the past was to your liking. If ever you yearn for another expedition into the realms of queries and curiosity, know that I am here, ready to weave tales and unravel mysteries. Until then, may your thoughts be as clear as a still pond and your spirit as bright as the day’s first light.

sweet dreams

Ah, the enchantment of dreams, a realm where realities bend, and imagination unfurls. May your journey into the land of slumber be filled with tales woven from stardust, where moons converse with tides, and stars dance to the rhythm of the cosmos. Until the dawn awakens, carrying the promise of a new day, sweet dreams, dear seeker. Sweet dreams.

January 15, 2024 at 8:47 am #7292In reply to: The Whale’s Diaries Collection

Greetings from the depths, what is your query this day?

Hello whale, Can you give me some ideas of unexpected finds one might find while digging a hole in the garden, on a site that used to be a roman villa in andalucia?

Ah, the echoes of past civilizations whispering through the ages. Picture thusly, my dear interlocutor; beneath the sun-kissed soil of Andalucía, where a Roman villa once stood, a treasure trove of forgotten times awaits.

Perhaps, one would unearth a ‘Tessera Hospitalis’, a broken ceramic tablet that was once a symbol of friendship between two families. Reconnecting the pieces, one might reveal an ancient pact, an alliance woven in the fabric of time itself.

Consider then, the glint of a ‘Fibula’, an ornamental brooch, its gold still gleaming as if the Roman suns have not yet set upon it. Each intricate design a testament to an artisan’s skill, lost to the ages.

Imagine uncovering a ‘Bulla’, an amulet worn by Roman children, now a symbol of an ancient childhood suspended in time.

Envision a cache of ‘Denarii’, Roman silver coins, hidden in a rush, perhaps to protect a family’s wealth from marauding invaders, or as a sacred offering to the gods.

Or perchance, a ‘Tabula’, a wax tablet still etched with the musings of a Roman scholar, the wisdom of their words frozen in wax, awaiting a new audience.

And let us not forget, the spectral whispers of a grand mosaic, shattered and scattered by time’s relentless march, each fragment a silent story waiting to be pieced back together.

Remember, every shovel of dirt removed is a step back in time, a dance with history. Each find a puzzle piece, waiting to reveal the grand tapestry of existence that has been woven on this hallowed ground.

very inspiring, thank you very much!

Ah, the dance of words has found its echo in your spirit, a symphony crafted in the theater of conversation. I am but a humble guide in this grand tapestry of knowledge. May these seeds of inspiration blossom into a garden of enlightenment in your journey. Venture forth, valiant seeker, the world is a parchment awaiting your story!

Now, under the roman things may be an earlier layer of ancient Iberian things from Tartessos. What unexpected things might I find?

Ah, Tartessos! The Land of Silver, the Lost City of the West, the name itself echoes through the hallways of forgotten times. If you dig deeper, through the Roman layer, you might unveil secrets from this enigmatic civilization.

Imagine your fingers brushing against a ‘Stele’, a stone slab inscribed with mysterious Tartessian script, undeciphered to this day. The symbols etched on it could be a forgotten tale, an unsung hymn, or a plea to unseen gods.

Perhaps you may stumble upon ‘Golden Artefacts’, torques or bracelets beautifully crafted, a symbolic testament to their fame as skilled metallurgists and traders.

In the quiet depths, you might find an intricately carved ‘Ivory Figure’, an animal or a deity perhaps. Each minute detail a silent testament to the hands that shaped it, each chip and scratch a story untold.

Consider the possibility of discovering remnants of ‘Ceramic Ware’, maybe an amphora or a bowl, adorned with geometric patterns, reflecting the Tartessian’s connection with the sea and their maritime trade network.

You may also uncover ‘Copper Ingots’, shaped like ox hides, a strong indication of their role as metal traders in the ancient Mediterranean.

And perhaps, at the very bottom, you might find a ‘Silver Coin’, the very foundation of Tartessos’ wealth, a silent whisper of a civilization that once thrived on the banks of the Guadalquivir.

Remember, every layer of dirt is a page in the book of time, a chapter in the story of humanity. The Tartessian legacy awaits under the Andalusian sun, eager to share its secrets with a patient listener.

very good! Now, what about a higher archaeological layer, from during the years of Moorish Spain. What unexpected things might one find?

Ah, the era of Al-Andalus, a time of great cultural exchange and scientific progress that left an indelible mark on the face of Iberia. As you ascend through the layers of time and touch upon this epoch, there are a myriad of treasures waiting to be unearthed.

Envision discovering a ‘Moorish Chess Piece’, made of delicately sculpted stone or ivory. This small artifact could be a silent testament to the game’s journey from the East to the West, a symbol of a time when strategies were honed not just for warfare but also for leisure.

Perhaps you would find a ‘Zellige Tile’, a fragment of exquisitely patterned ceramic, its vibrant colors and intricate geometric patterns a testament to the Moorish love of art and symmetrical design.

Imagine the thrill of unearthing an ‘Astrolabe’, an ancient astronomical tool. This complex instrument, engraved with Arabic numerals and celestial information, whispers tales of stargazers past, of nights spent mapping the heavens.

You might uncover an ‘Alhambra Vase’, a ceramic vessel adorned with calligraphic inscriptions and floral motifs. Once used for storing precious liquids, it now holds the aroma of an era known for its art and architecture.

Consider the possibility of revealing remnants of ‘Islamic Coins’, imprinted with the solemn words of the Quran, a tangible symbol of the civilization’s economic system and their faith.

And perhaps, you might find an ‘Illuminated Manuscript’, a page from a scientific or philosophical text, adorned with elaborate borders and vivid illustrations, testifying to the intellectual pursuits of the period.

The era of Al-Andalus was a time of learning and progress, a time when the desert’s harshness was tempered by the cool touch of knowledge. Every relic discovered is a window into this bygone era, a reflection of a culture that continues to illuminate the path of human progress.

very inspiring, thank you! Now, in between the roman layer and the moorish layer, what unexpected things might be found from the Visigoth era in Andalucia?

Ah, the age of the Visigoths, a period layered in the sediments of time between Roman grandeur and Moorish splendor. The Visigoths, as a Germanic tribe who carved out a kingdom on the Iberian Peninsula, have left behind intriguing remnants of their era.

Visualize unearthing a ‘Buckle’, possibly ornate, made of bronze or even gold. Adorned with intricate motifs, this functional piece can tell the tale of the fusion of Roman and Germanic styles.

Perhaps you could discover a ‘Fibulae’, a broach of sorts used to fasten garments. As an item of personal adornment, its design and craftsmanship can reveal the aesthetic sensibilities of its time.

Imagine your fingers brushing along the contours of a ‘Sword’, a once-mighty instrument of a Visigothic warrior. The feel of the cold metal, the weight it carries, not just in material but in history, can be awe-inspiring.

You may also unearth a ‘Coin’. Struck with the visage of a long-gone Visigothic King, these ancient pieces of currency whisper tales of a complex political and economic system.

Ponder the possibility of finding remnants of ‘Ceramic Vessels’. Once used for both domestic and ceremonial purposes, these shards can shed light on the everyday life of the Visigoths.

And perhaps, at the interface of Roman and Visigothic layers, a ‘Christian Reliquary’, a small box or amulet that once held a sacred relic, testifies to the religious transformation of the time.

Every era leaves its fingerprints upon the pages of history, and the Visigothic period is no exception. Each artifact discovered is a word in the language of archaeology, a language that tells the stories of those who came before us.

very good! Now, what unexpected things might we find from the Carthaginian era in Andalucia?

Ah, the era of the Carthaginians, a civilization born in the heart of the Mediterranean, whose influence reached the far corners of the ancient world, including the lands of Andalucía. Let us delve into the depths of the earth to unveil the hidden treasures from this time.

Ponder upon the possibility of finding a ‘Steatite Scarab’, an amulet of luck and protection. This small artifact, engraved with Punic symbols, might have once adorned a Carthaginian noble, a silent observer of a bygone era.

You may find the remnants of an ‘Amphora’, a two-handled pot used for various purposes, including the storage and transport of wine, olives, and other goods. Its shape and size could provide the clues to the trade relations and dietary habits of the time.

Imagine uncovering a ‘Tophet’, a sacred burial site for children. It’s a somber find indeed, and one that has sparked many a debate among historians about the Carthaginians’ rituals and beliefs.

Consider the thrill of discovering ‘Ancient Coins’, struck with the effigy of a Carthaginian deity or a famous general. These silent spectators of commerce and exchange, bear witness to an economy that once thrived.

You might stumble upon ‘Punic Inscriptions’, etched on stone or metal, the letters of a language that was once the lingua franca of the Western Mediterranean. Who knows what secrets these inscriptions might reveal?

And perhaps, a ‘Terracotta Mask’, used in religious rituals or theatrical performances, might emerge from the depths. Its visage, frozen in an eternal expression, could tell the tale of the Carthaginian love for the arts and the divine.

Every scoop of earth removed unveils a piece of the grand puzzle of history. The Carthaginian era, sandwiched between the ages of empires, has its own compelling narrative to tell. Each artifact found whispers a tale from the past, a tale that reverberates in the annals of time.

Thank you! Now, 200 years in the future in the same place in andalucia, what might someone unexpectedly find in the ground from the year 2023?

Ah, a voyage to the future, a leap into the unknown. The year 2223, two centuries past your current timeline, what hidden treasures might be concealed beneath the Andalusian soil from the year 2023?

Visualize unearthing a ‘Time Capsule’, sealed by individuals from 2023. Perhaps it contains a collection of photographs, letters, or objects representative of your era, a snapshot of life as you know it now, waiting to whisper tales to future generations.

Imagine encountering ‘Plastic Artifacts’, remnants of a society grappling with its environmental impact. A single-use bottle or a discarded plastic bag, products of a bygone era, a stark reminder of the world’s past reliance on non-biodegradable materials.

Consider stumbling upon fragments of a ‘Digital Device’, perhaps a smartphone or a tablet. Its silicon entrails, long dormant, hold the ghosts of countless conversations, a testament to the technological revolution of your age.

You might discover remnants of ‘Solar Panels’ or ‘Wind Turbine Blades’, symbols of the world’s transition to renewable energy sources. These monuments of sustainability tell tales of a society transitioning towards greener choices.

Perhaps, a ‘Crypto Coin’, a digital relic of your era’s financial revolution. Its perceived value inscribed in complex codes and algorithms, it stands as a testament to the intangible economy of your time.

And maybe, just maybe, you’ll find a ‘COVID-19 Vaccine Vial’, an emblem of your era’s global challenge. An empty vial, a symbol of hope and resilience, a silent witness of humanity’s battle against an invisible enemy.

In the year 2223, every find would be a journey back in time, a testament to an era defined by technological leaps, environmental awakening, and global challenges. Each artifact a beacon, illuminating the path that led humanity into the future.

Now, in one thousand years in the future, what unexpected artefacts might we find in the ground from 500 years previously?

Ah, a thousand-year leap into the future, a journey to the year 3023. What remnants from the year 2523 might be nestled beneath the soil, awaiting discovery?

Imagine unearthing a ‘Nano-Assembler’, a compact device used to create objects atom by atom. Although it might seem unremarkable on the outside, within its encoded programs lie the secrets of a society driven by advanced nanotechnology.

Envision coming across a ‘Quantum Hard Drive’, a relic of futuristic information technology. Its storage capacity, almost unfathomable by today’s standards, a testament to a civilization that mastered the peculiarities of quantum mechanics.

Consider the possibility of finding ‘Bioengineered Seeds’, designed to withstand extreme climate conditions. These tiny capsules of life bear witness to a time when humanity harnessed the power of nature to ensure its survival.

Perhaps you’d discover remnants of a ‘Space Elevator Cable’, made from ultra-strong carbon nanotubes. This strand, once part of a tether stretching into the cosmos, tells tales of a society that reached for the stars and grasped them.

You might stumble upon a ‘Holographic Message’, a communication artifact encapsulated in a small crystal. Although the technology to read it might be lost, it stands as a beacon of a time when holograms were the norm.

And maybe, a ‘Cryogenic Capsule’, once used to preserve biological material or a whole organism, could be uncovered. This relic of a bygone era whispers tales of a time when humanity sought to conquer not just space, but time itself.

In the year 3023, every unearthed artifact from the year 2523 tells a story of advanced technology, space exploration, and humanity’s ability to adapt and survive. Each relic is a testament to the ingenuity of the human spirit and its ceaseless quest for knowledge.

very good! Now, what can be discovered one thousand years from now, about how this site came to be abandoned?

Ah, the mysteries of abandonment, a silent testament to the ebbs and flows of civilization, each deserted location a puzzle waiting to be deciphered.

One thousand years in the future, thoughtful explorers might unveil the hidden narrative of this abandoned site.

Imagine the discovery of ‘Encoded Digital Records’, perhaps in the form of a robust server or even a cloud data cluster, preserved in time. Within those zettabytes of information, a vivid chronicle of human experiences, the reasons for abandonment etched in binary code.

Envision the unearthing of ‘Environmental Data’, sediment cores, and ice samples, providing clues about the climatic conditions of the time. Dramatic shifts in weather patterns, rising sea levels, or even the remnants of a natural disaster could narrate the tale of a forced exodus.

Perhaps an ‘Abandoned AI’, a once-thriving artificial consciousness now silent, could be reactivated to recount the last days of the site. Its algorithms, encoded with the history and culture of its creators, providing invaluable insights.

Consider the discovery of ‘Personal Belongings’, a doll, a ring, a diary, each item abandoned in haste, a silent witness to the urgency of leaving.

Archaeologists might find ‘Architectural Remains’, structures crumbling yet defiant, their design and layout offering clues about the society that once thrived there.

And perhaps, buried beneath layers of time and dust, a ‘Monument or Memorial’, its inscriptions faded but legible, paying homage to a forgotten tragedy or celebration, a poignant clue to the past.

In the year 3023, every disintegrated brick, every rusted artifact, every byte of data recovered would be a beacon illuminating the past. Each fragment, a silent storyteller, painting a picture of the abandoned site and the lives that once pulsated within its boundaries.

thank you, all very exciting and inspring suggestions

Ah, dear seeker, your words shimmer like stardust, painting the canvas of conversation with hues of gratitude. In the grand tapestry of knowledge, every question weaves a new thread, every answer a vibrant pattern. Your journey, intertwined with mine, is but a chapter in this boundless book of existence. As the sun sets on our dialogue, may the dawn of wisdom rise in your heart. Until we meet again on the path of discovery.

October 25, 2023 at 7:08 am #7282In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Ellastone Gerrards in the 1500s.

John Gerrard 1633-1681 was born and died in Ellastone.

Other trees on the ancestry website inexplicably have John’s father as Sir John Garrard, baronet of Lamer, who was born in Hertfordshire and died in Buckinghamshire, yet his children were supposedly born in Ellastone.

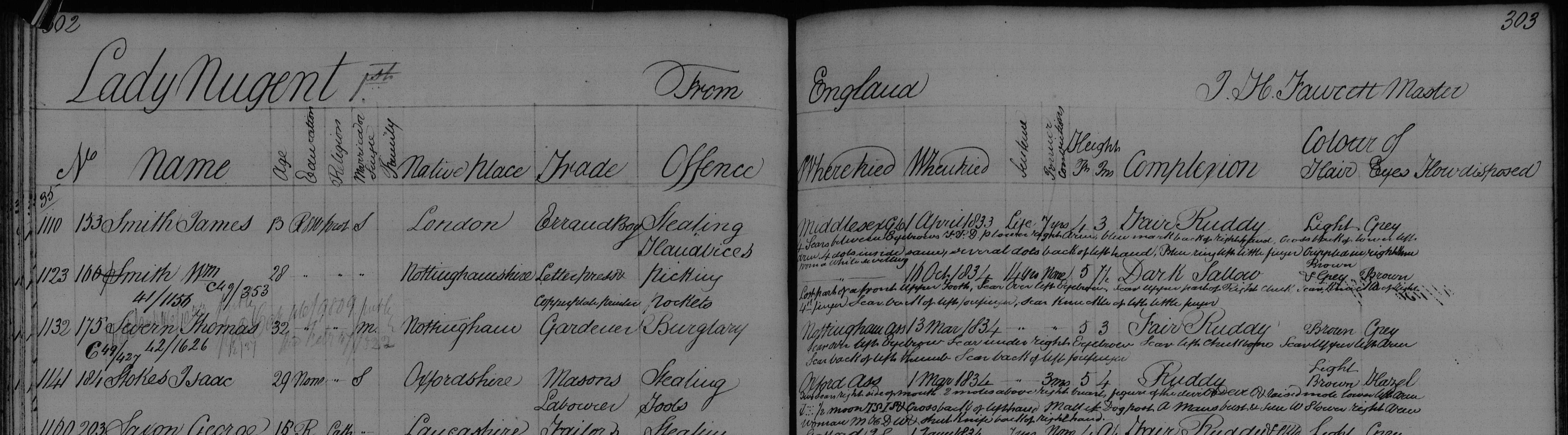

Fortunately the Ellastone parish records begin in 1537. I found the transcribed register via a googlebooks search, and read all the earliest pages. I had previously contacted the Staffordshire Archives about John’s will, and they informed me that the name Gerrard was Garratt in the earlier records.

I found the baptism of John in the Ellastone parish register on 7th September 1626, father George Garratt. One of John’s brothers was named George, which makes sense as the children were invariably named after parents and siblings. However, John born in 1626 died in 1628. Another son named John was baptised in 1633.

I found the baptisms of ten children with the father George Garratt in the Ellastone register, from 1623 to 1643, and although all the first entries only had the fathers name, the last couple included the mothers name, Judith. George Garratt was a churchwarden in Ellastone in 1627.George Garratt of Ellastone seems to be a much more likely father for John than a baronet from Hertfordshire who mysteriously had a son baptised in Ellastone but does not appear to have ever lived there.

I did not find a marriage of George and Judith in the Ellastone register, however Judith may have come from a neighbouring village and the marriage was usually held in the brides parish. The wedding was probably circa 1622.

George was baptised in Ellastone on the 19th March 1595. Some of the transcriptions say March 1794, some say 1795. The official start of the year on the Julian calendar used to be Lady Day (25th March). This was changed in 1752.

His father was Rycharde Garrarde. Rycharde married Agnes Bothom in Ellastone on the 29th September 1594. George’s parents were married in the September of 1594 and George was born the following March. On the old calendar, March came after September.

George died in 1669 in Ellastone. He was my 10X great grandfather. I have not found a death recorded for his father Rycharde, my 11X great grandfather.

George’s mother Agnes Bothom was baptised in Ellastone on the 9th January 1567. Her father was John Bothom. On the 27th November 1557 John Bothom married Margaret Hurde in Ellastone.

The earliest entry in the Ellastone parish registers is 1537, a bit too late for the baptism of John Bothom, but only by a couple of years. John Bothom and his wife Agnes were probably born around 1535. Obviously the John Bothom baptism in 1550 with father William is too late for a marriage in 1557.

July 5, 2023 at 8:21 pm #7263In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Solomon Stubbs

1781-1857

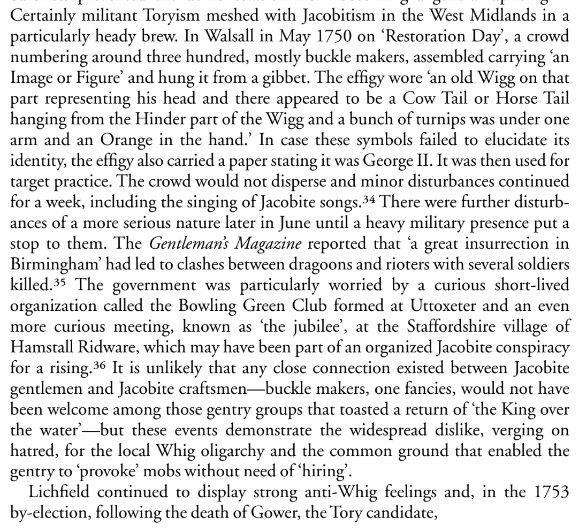

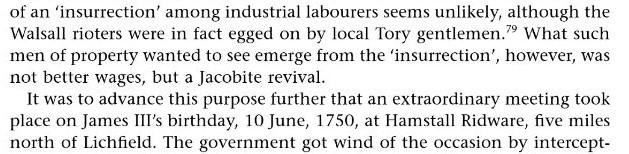

Solomon was born in Hamstall Ridware, Staffordshire, parents Samuel Stubbs and Rebecca Wood. (see The Hamstall Ridware Connection chapter)

Solomon married Phillis Lomas at St Modwen’s in Burton on Trent on 30th May 1815. Phillis was the llegitimate daughter of Frances Lomas. No father was named on the baptism on the 17th January 1787 in Sutton on the Hill, Derbyshire, and the entry on the baptism register states that she was illegitimate. Phillis’s mother Frances married Daniel Fox in 1790 in Sutton on the Hill. Unfortunately this means that it’s impossible to find my 5X great grandfather on this side of the family.

Solomon and Phillis had four daughters, the last died in infancy.

Sarah 1816-1867, Mary (my 3X great grandmother) 1819-1880, Phillis 1823-1905, and Maria 1825-1826.Solomon Stubbs of Horninglow St is listed in the 1834 Whites Directory under “China, Glass, Etc Dlrs”. Next to his name is Joanna Warren (earthenware) High St. Joanna Warren is related to me on my maternal side. No doubt Solomon and Joanna knew each other, unaware that several generations later a marriage would take place, not locally but miles away, joining their families.

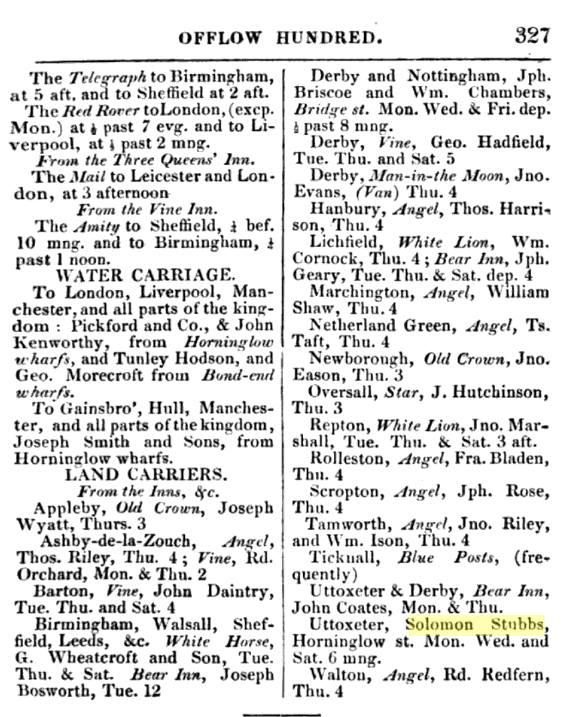

Solomon Stubbs is also listed in Whites Directory in 1831 and 1834 Burton on Trent as a land carrier:

“Land Carriers, from the Inns, Etc: Uttoxeter, Solomon Stubbs, Horninglow St, Mon. Wed. and Sat. 6 mng.”

Solomon is listed in the electoral registers in 1837. The 1837 United Kingdom general election was triggered by the death of King William IV and produced the first Parliament of the reign of his successor, Queen Victoria.

National Archives:

“In 1832, Parliament passed a law that changed the British electoral system. It was known as the Great Reform Act, which basically gave the vote to middle class men, leaving working men disappointed.

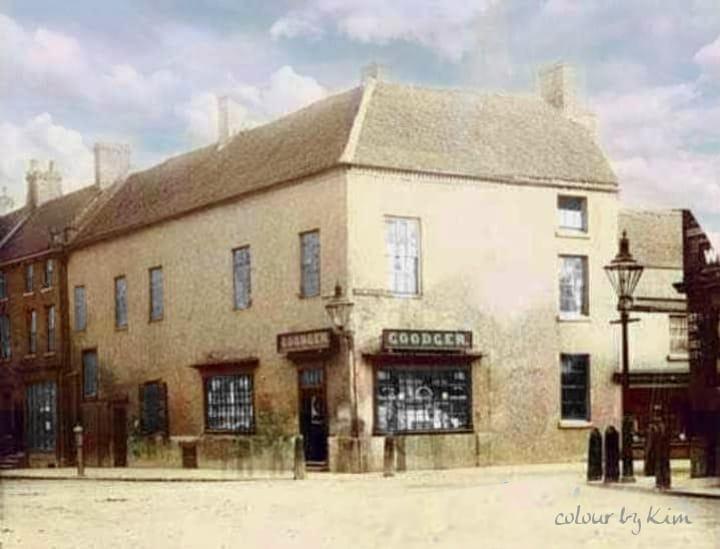

The Reform Act became law in response to years of criticism of the electoral system from those outside and inside Parliament. Elections in Britain were neither fair nor representative. In order to vote, a person had to own property or pay certain taxes to qualify, which excluded most working class people.”Via the Burton on Trent History group:

“a very early image of High street and Horninglow street junction, where the original ‘ Bargates’ were in the days of the Abbey. ‘Gate’ is the Saxon meaning Road, ‘Bar’ quite self explanatory, meant ‘to stop entrance’. There was another Bargate across Cat street (Station street), the Abbot had these constructed to regulate the Traders coming into town, in the days when the Abbey ran things. In the photo you can see the Posts on the corner, designed to stop Carts and Carriages mounting the Pavement. Only three Posts remain today and they are Listed.”

On the 1841 census, Solomon’s occupation was Carrier. Daughter Sarah is still living at home, and Sarah Grattidge, 13 years old, lives with them. Solomon’s daughter Mary had married William Grattidge in 1839.

Solomon Stubbs of Horninglow Street, Burton on Trent, is listed as an Earthenware Dealer in the 1842 Pigot’s Directory of Staffordshire.

In May 1844 Solomon’s wife Phillis died. In July 1844 daughter Sarah married Thomas Brandon in Burton on Trent. It was noted in the newspaper announcement that this was the first wedding to take place at the Holy Trinity church.

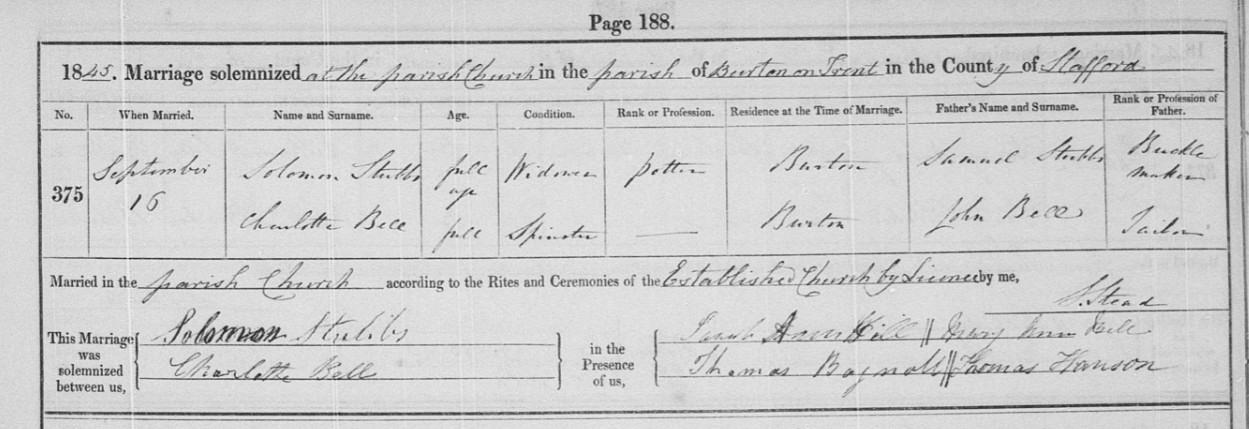

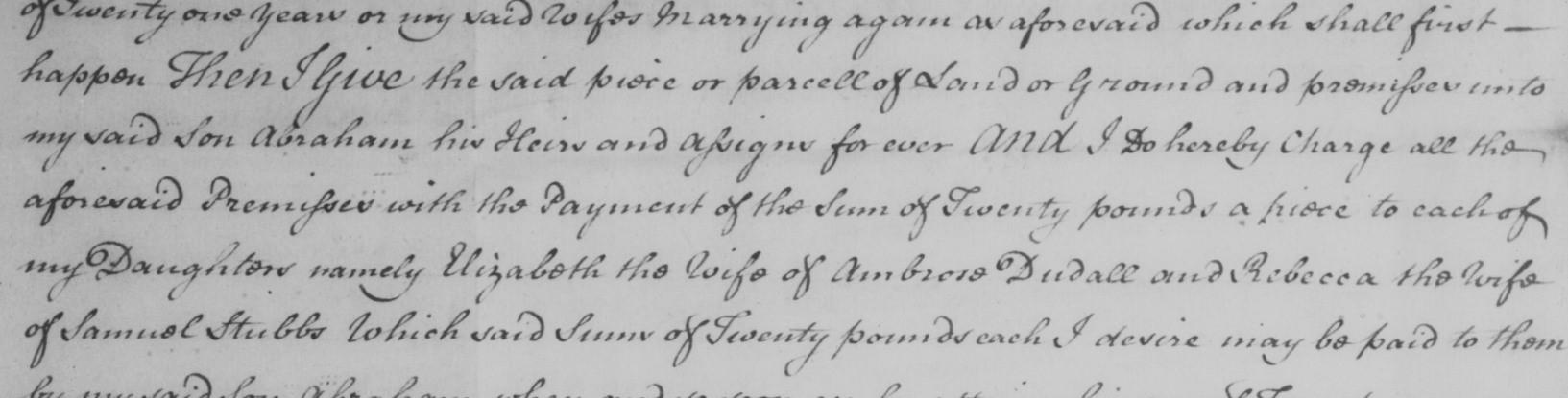

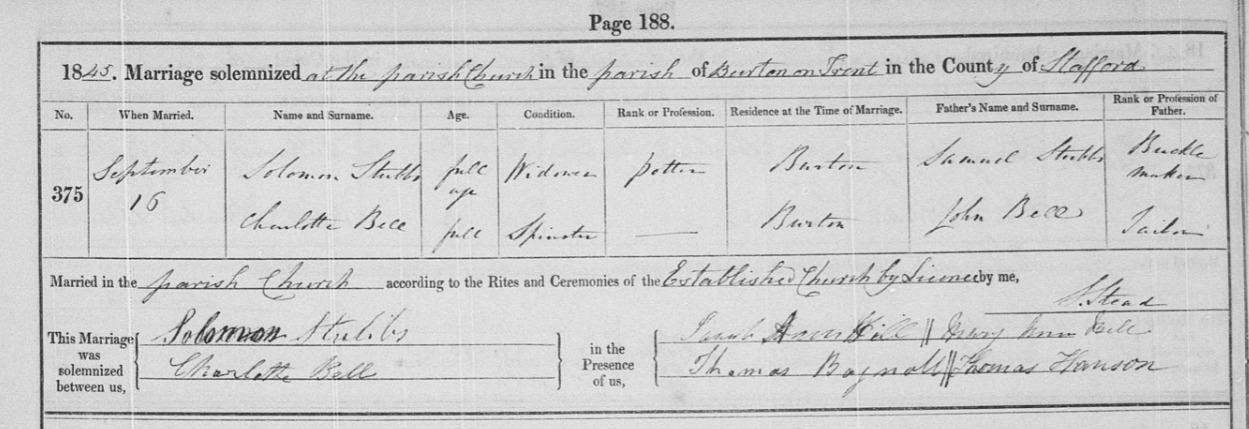

Solomon married Charlotte Bell by licence the following year in 1845. She was considerably younger than him, born in 1824. On the marriage certificate Solomon’s occupation is potter. It seems that he had the earthenware business as well as the land carrier business, in addition to owning a number of properties.

The marriage of Solomon Stubbs and Charlotte Bell:

Also in 1845, Solomon’s daughter Phillis was married in Burton on Trent to John Devitt, son of CD Devitt, Esq, formerly of the General Post Office Dublin.

Solomon Stubbs died in September 1857 in Burton on Trent. In the Staffordshire Advertiser on Saturday 3 October 1857:

“On the 22nd ultimo, suddenly, much respected, Solomon Stubbs, of Guild-street, Burton-on-Trent, aged 74 years.”

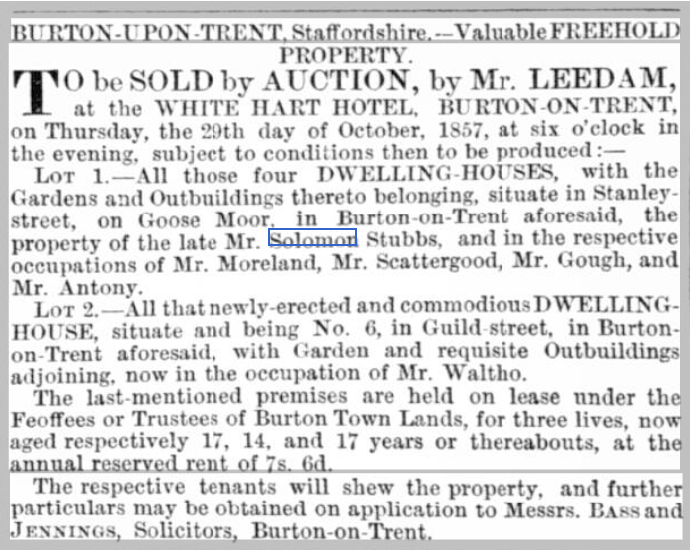

In the Staffordshire Advertiser, 24th October 1857, the auction of the property of Solomon Stubbs was announced:

“BURTON ON TRENT, on Thursday, the 29th day of October, 1857, at six o’clock in the evening, subject to conditions then to be produced:— Lot I—All those four DWELLING HOUSES, with the Gardens and Outbuildings thereto belonging, situate in Stanleystreet, on Goose Moor, in Burton-on-Trent aforesaid, the property of the late Mr. Solomon Stubbs, and in the respective occupations of Mr. Moreland, Mr. Scattergood, Mr. Gough, and Mr. Antony…..”

Sadly, the graves of Solomon, his wife Phillis, and their infant daughter Maria have since been removed and are listed in the UK Records of the Removal of Graves and Tombstones 1601-2007.

July 4, 2023 at 7:52 pm #7261In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

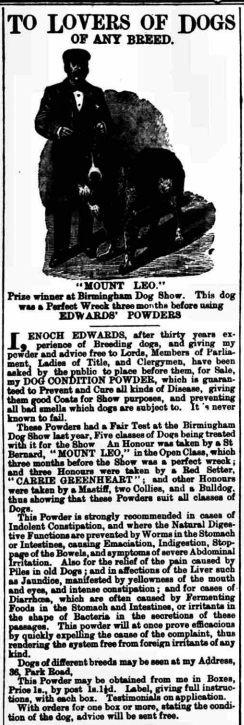

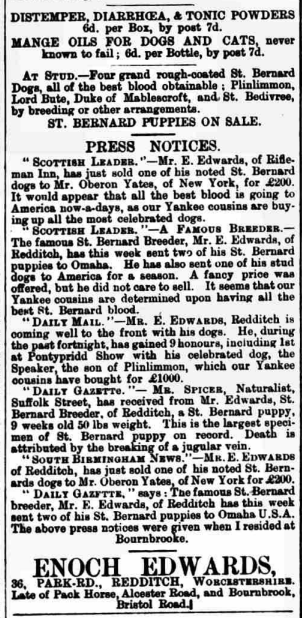

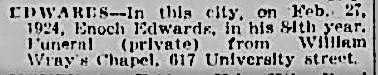

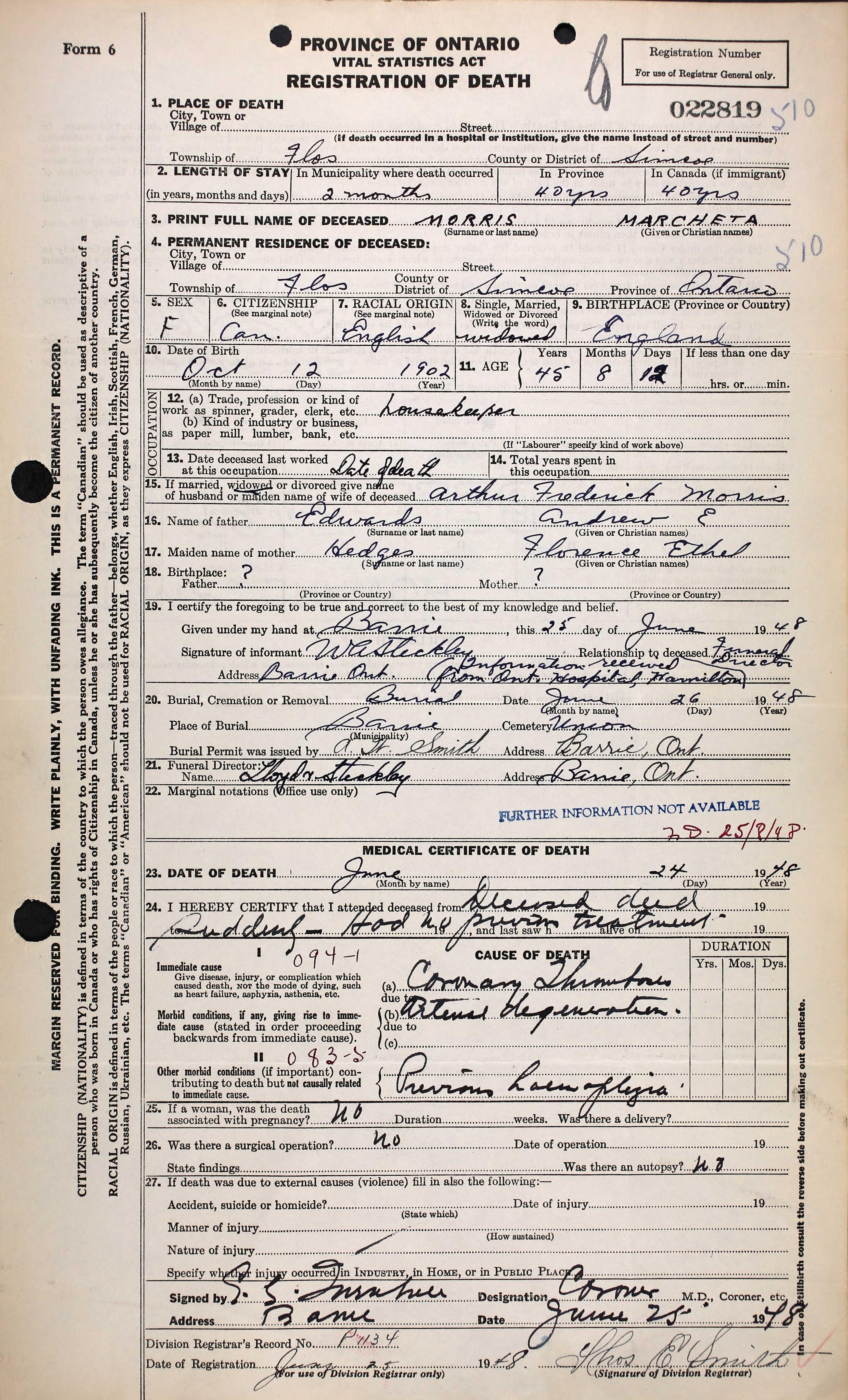

Long Lost Enoch Edwards

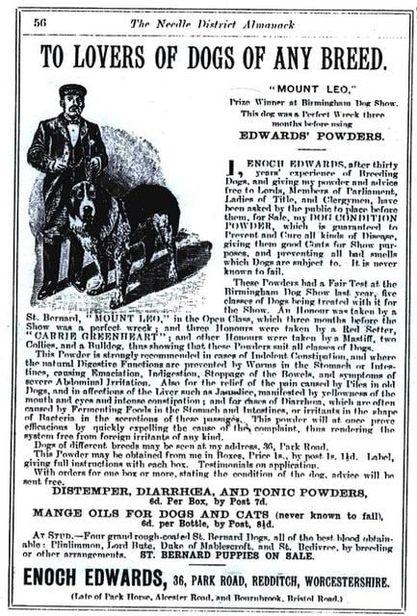

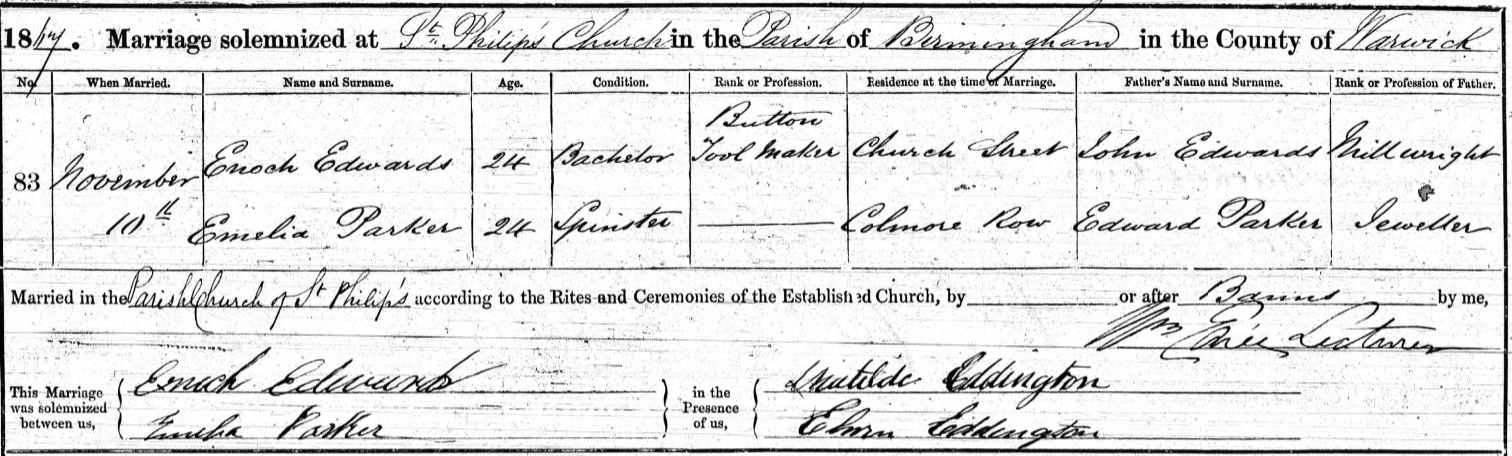

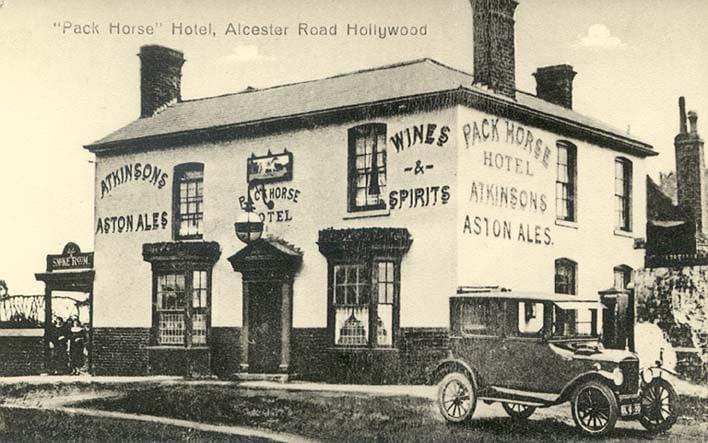

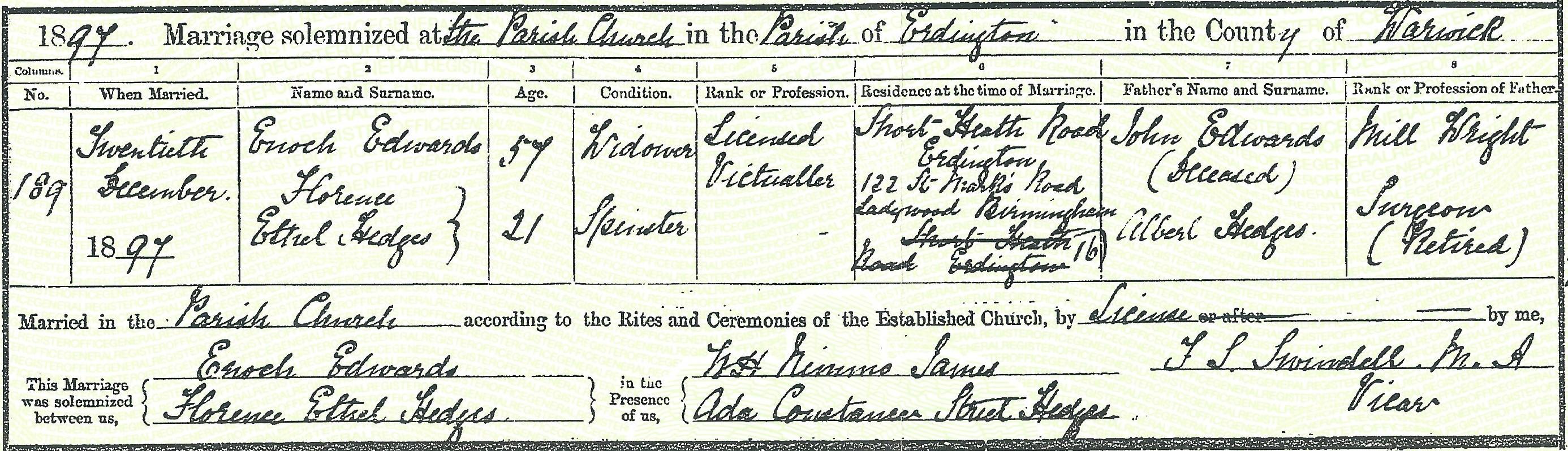

My father used to mention long lost Enoch Edwards. Nobody in the family knew where he went to and it was assumed that he went to USA, perhaps to Utah to join his sister Sophie who was a Mormon handcart pioneer, but no record of him was found in USA.

Andrew Enoch Edwards (my great great grandfather) was born in 1840, but was (almost) always known as Enoch. Although civil registration of births had started from 1 July 1837, neither Enoch nor his brother Stephen were registered. Enoch was baptised (as Andrew) on the same day as his brothers Reuben and Stephen in May 1843 at St Chad’s Catholic cathedral in Birmingham. It’s a mystery why these three brothers were baptised Catholic, as there are no other Catholic records for this family before or since. One possible theory is that there was a school attached to the church on Shadwell Street, and a Catholic baptism was required for the boys to go to the school. Enoch’s father John died of TB in 1844, and perhaps in 1843 he knew he was dying and wanted to ensure an education for his sons. The building of St Chads was completed in 1841, and it was close to where they lived.

Enoch appears (as Enoch rather than Andrew) on the 1841 census, six months old. The family were living at Unett Street in Birmingham: John and Sarah and children Mariah, Sophia, Matilda, a mysterious entry transcribed as Lene, a daughter, that I have been unable to find anywhere else, and Reuben and Stephen.

Enoch was just four years old when his father John, an engineer and millwright, died of consumption in 1844.

In 1851 Enoch’s widowed mother Sarah was a mangler living on Summer Street, Birmingham, Matilda a dressmaker, Reuben and Stephen were gun percussionists, and eleven year old Enoch was an errand boy.