Search Results for 'act'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

October 21, 2022 at 2:06 pm #6337

In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

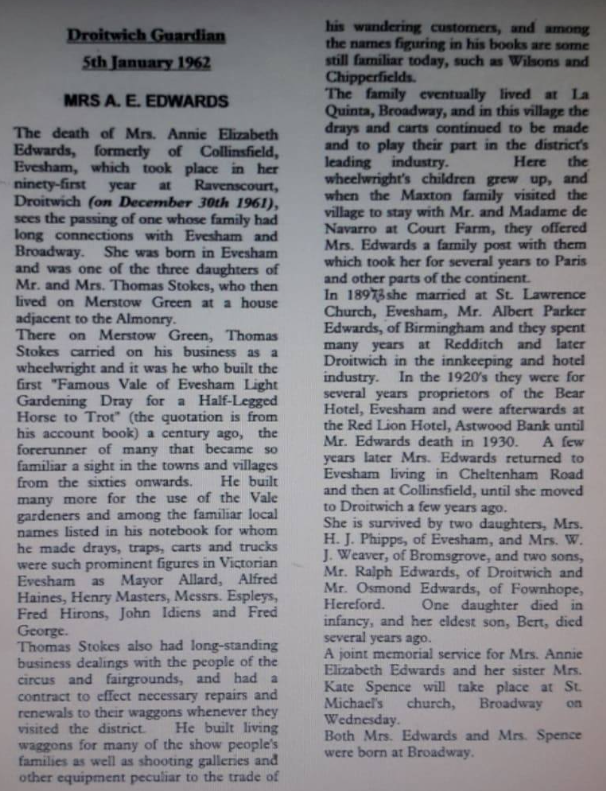

Annie Elizabeth Stokes

1871-1961

“Grandma E”

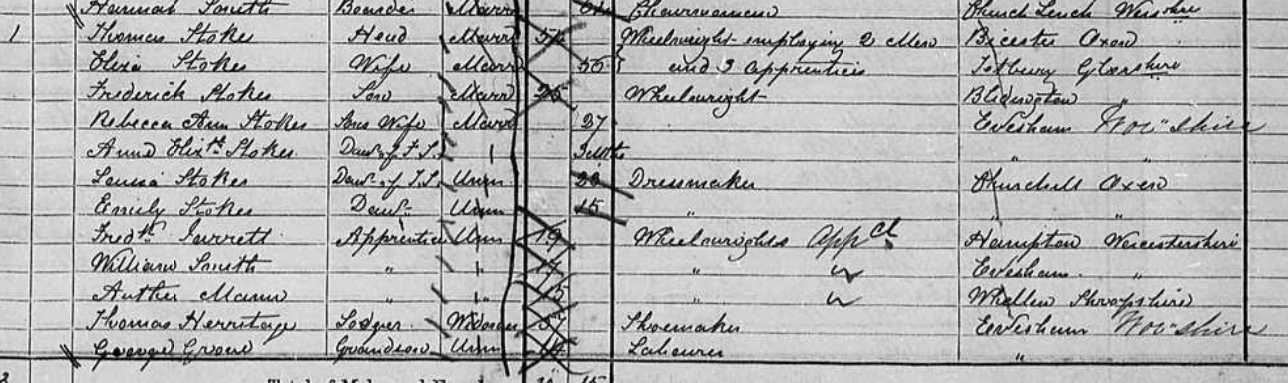

Annie, my great grandmother, was born 2 Jan 1871 in Merstow Green, Evesham, Worcestershire. Her father Fred Stokes was a wheelwright. On the 1771 census in Merston Green Annie was 3 months old and there was quite a houseful: Annies parents Fred and Rebecca, Fred’s parents Thomas and Eliza and two of their daughters, three apprentices, a lodger and one of Thomas’s grandsons.

1771 census Merstow Green, Evesham:

Annie at school in the early 1870s in Broadway. Annie is in the front on the left and her brother Fred is in the centre of the first seated row:

In 1881 Annie was a 10 year old visitor at the Angel Inn, Chipping Camden. A boarder there was 19 year old William Halford, a wheelwright apprentice. John Such, a 62 year old widower, was the innkeeper. Her parents and two siblings were living at La Quinta, on Main Street in Broadway.

According to her obituary in 1962, “When the Maxton family visited Broadway to stay with Mr and Madame de Navarro at Court Farm, they offered Annie a family post with them which took her for several years to Paris and other parts of the continent.”

Mary Anderson was an American theatre actress. In 1890 she married Antonio Fernando de Navarro. She became known as Mary Anderson de Navarro. They settled at Court Farm in the Cotswolds, Broadway, Worcestershire, where she cultivated an interest in music and became a noted hostess with a distinguished circle of musical, literary and ecclesiastical guests. As in the years when Mary lived there, it was often filled with visiting artists and musicians, including Myra Hess and a young Jacqueline du Pré. (via Wikipedia)

Court Farm, Broadway:

Annie was an assistant to a tobacconist in West Bromwich in 1991, living as a boarder with William Calcutt and family. He future husband Albert was living in neighbouring Tipton in 1891, working at a pawnbroker apprenticeship.

Annie married Albert Parker Edwards in 1898 in Evesham. On the 1901 census, she was in hospital in Redditch.

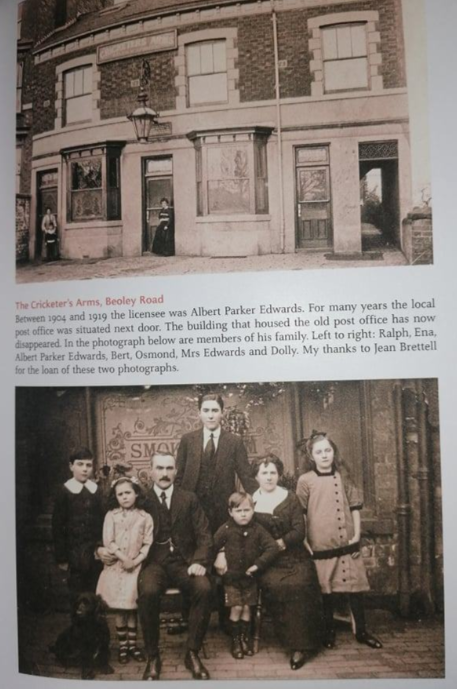

By 1911, Anne and Albert had five children and were living at the Cricketers Arms in Redditch.

Behind the bar in 1904 shortly after taking over at the Cricketers Arms. From a book on Redditch pubs:

Annie was referred to in later years as Grandma E, probably to differentiate between her and my fathers Grandma T, as both lived to a great age.

Annie with her grandson Reg on the left and her daughter in law Peggy on the right, in the early 1950s:

Annie at my christening in 1959:

Annie died 30 Dec 1961, aged 90, at Ravenscourt nursing home, Redditch. Her obituary in the Droitwich Guardian in January 1962:

Note that this obituary contains an obvious error: Annie’s father was Frederick Stokes, and Thomas was his father.

October 19, 2022 at 6:46 am #6336In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

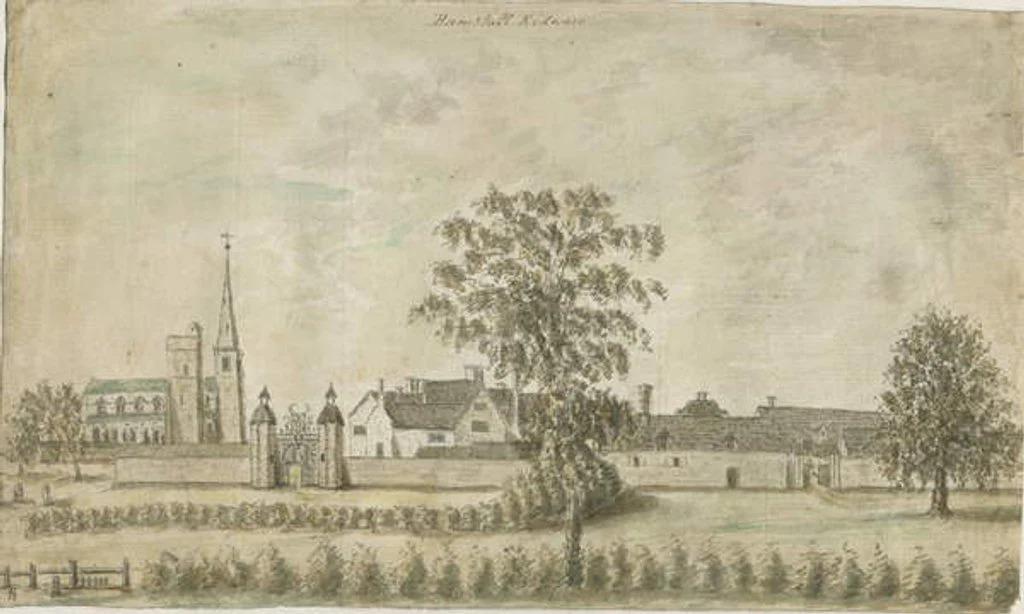

The Hamstall Ridware Connection

Stubbs and Woods

Hamstall Ridware

Hamstall RidwareCharles Tomlinson‘s (1847-1907) wife Emma Grattidge (1853-1911) was born in Wolverhampton, the daughter and youngest child of William Grattidge (1820-1887) born in Foston, Derbyshire, and Mary Stubbs (1819-1880), born in Burton on Trent, daughter of Solomon Stubbs.

Solomon Stubbs (1781-1857) was born in Hamstall Ridware in 1781, the son of Samuel and Rebecca. Samuel Stubbs (1743-) and Rebecca Wood (1754-) married in 1769 in Darlaston. Samuel and Rebecca had six other children, all born in Darlaston. Sadly four of them died in infancy. Son John was born in 1779 in Darlaston and died two years later in Hamstall Ridware in 1781, the same year that Solomon was born there.

But why did they move to Hamstall Ridware?

Samuel Stubbs was born in 1743 in Curdworth, Warwickshire (near to Birmingham). I had made a mistake on the tree (along with all of the public trees on the Ancestry website) and had Rebecca Wood born in Cheddleton, Staffordshire. Rebecca Wood from Cheddleton was also born in 1843, the right age for the marriage. The Rebecca Wood born in Darlaston in 1754 seemed too young, at just fifteen years old at the time of the marriage. I couldn’t find any explanation for why a woman from Cheddleton would marry in Darlaston and then move to Hamstall Ridware. People didn’t usually move around much other than intermarriage with neighbouring villages, especially women. I had a closer look at the Darlaston Rebecca, and did a search on her father William Wood. I found his 1784 will online in which he mentions his daughter Rebecca, wife of Samuel Stubbs. Clearly the right Rebecca Wood was the one born in Darlaston, which made much more sense.

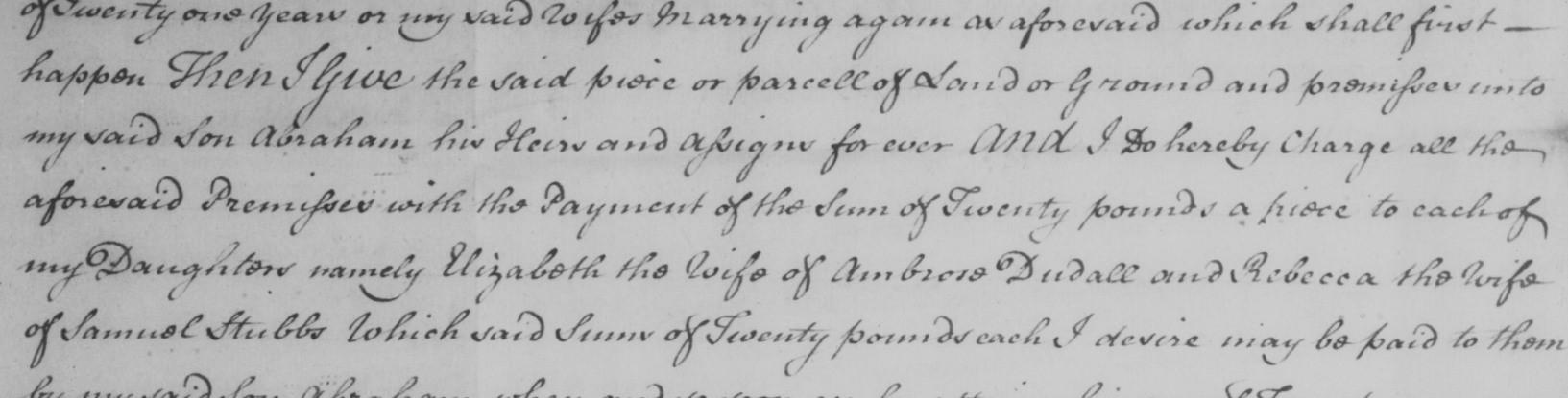

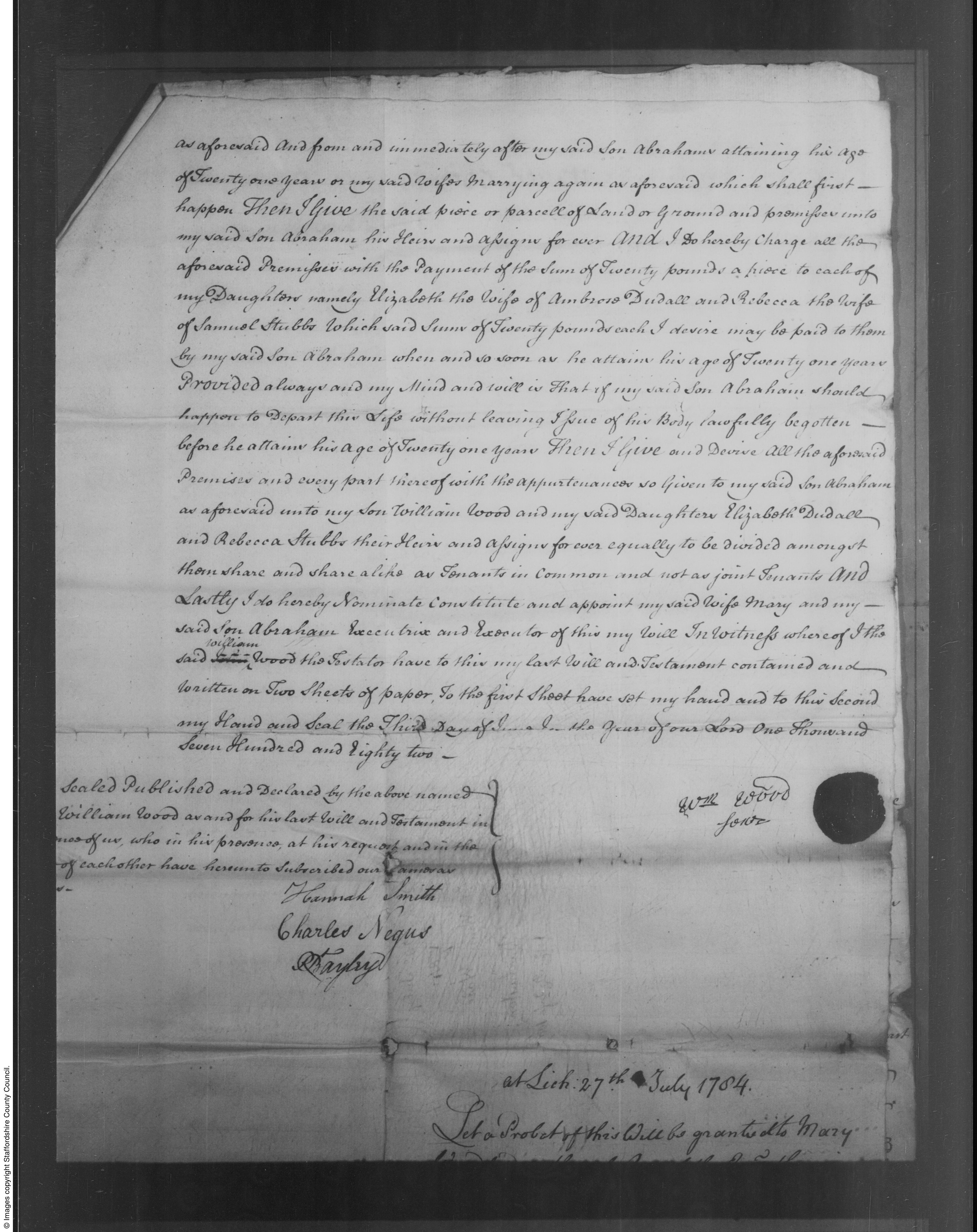

An excerpt from William Wood’s 1784 will mentioning daughter Rebecca married to Samuel Stubbs:

But why did they move to Hamstall Ridware circa 1780?

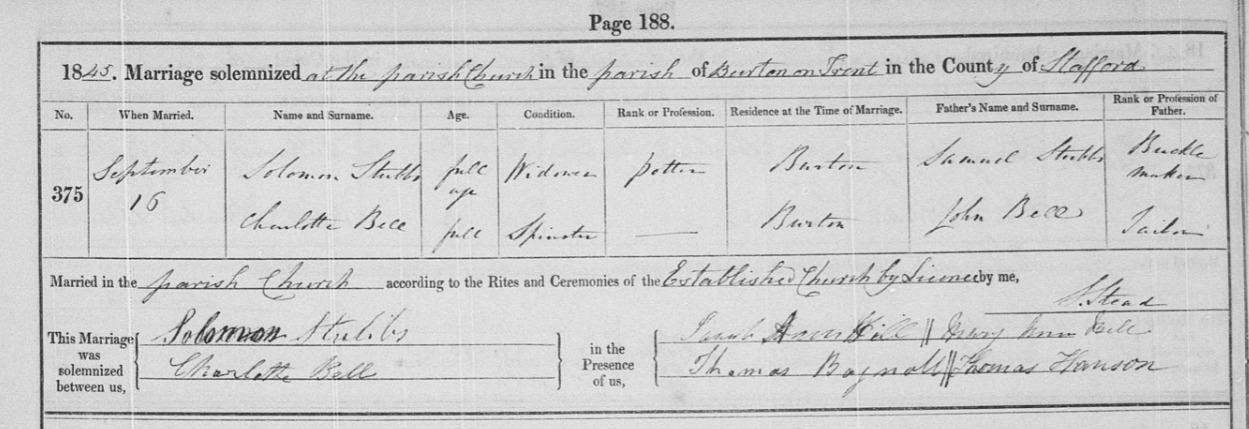

I had not intially noticed that Solomon Stubbs married again the year after his wife Phillis Lomas (1787-1844) died. Solomon married Charlotte Bell in 1845 in Burton on Trent and on the marriage register, Solomon’s father Samuel Stubbs occupation was mentioned: Samuel was a buckle maker.

Marriage of Solomon Stubbs and Charlotte Bell, father Samuel Stubbs buckle maker:

A rudimentary search on buckle making in the late 1700s provided a possible answer as to why Samuel and Rebecca left Darlaston in 1781. Shoe buckles had gone out of fashion, and by 1781 there were half as many buckle makers in Wolverhampton as there had been previously.

“Where there were 127 buckle makers at work in Wolverhampton, 68 in Bilston and 58 in Birmingham in 1770, their numbers had halved in 1781.”

via “historywebsite”(museum/metalware/steel)

Steel buckles had been the height of fashion, and the trade became enormous in Wolverhampton. Wolverhampton was a steel working town, renowned for its steel jewellery which was probably of many types. The trade directories show great numbers of “buckle makers”. Steel buckles were predominantly made in Wolverhampton: “from the late 1760s cut steel comes to the fore, from the thriving industry of the Wolverhampton area”. Bilston was also a great centre of buckle making, and other areas included Walsall. (It should be noted that Darlaston, Walsall, Bilston and Wolverhampton are all part of the same area)

In 1860, writing in defence of the Wolverhampton Art School, George Wallis talks about the cut steel industry in Wolverhampton. Referring to “the fine steel workers of the 17th and 18th centuries” he says: “Let them remember that 100 years ago [sc. c. 1760] a large trade existed with France and Spain in the fine steel goods of Birmingham and Wolverhampton, of which the latter were always allowed to be the best both in taste and workmanship. … A century ago French and Spanish merchants had their houses and agencies at Birmingham for the purchase of the steel goods of Wolverhampton…..The Great Revolution in France put an end to the demand for fine steel goods for a time and hostile tariffs finished what revolution began”.

The next search on buckle makers, Wolverhampton and Hamstall Ridware revealed an unexpected connecting link.

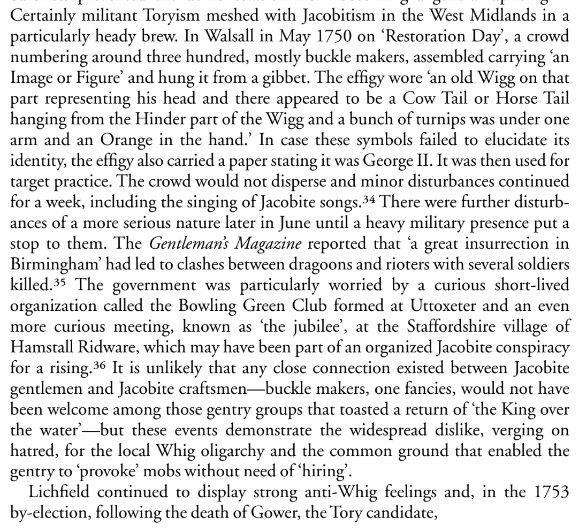

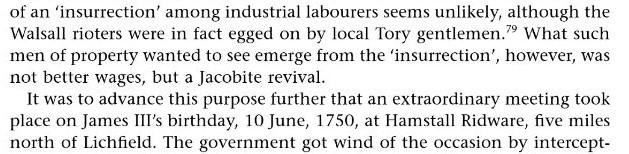

In Riotous Assemblies: Popular Protest in Hanoverian England by Adrian Randall:

In Walsall in 1750 on “Restoration Day” a crowd numbering 300 assembled, mostly buckle makers, singing Jacobite songs and other rebellious and riotous acts. The government was particularly worried about a curious meeting known as the “Jubilee” in Hamstall Ridware, which may have been part of a conspiracy for a Jacobite uprising.

But this was thirty years before Samuel and Rebecca moved to Hamstall Ridware and does not help to explain why they moved there around 1780, although it does suggest connecting links.

Rebecca’s father, William Wood, was a brickmaker. This was stated at the beginning of his will. On closer inspection of the will, he was a brickmaker who owned four acres of brick kilns, as well as dwelling houses, shops, barns, stables, a brewhouse, a malthouse, cattle and land.

A page from the 1784 will of William Wood:

The 1784 will of William Wood of Darlaston:

I William Wood the elder of Darlaston in the county of Stafford, brickmaker, being of sound and disposing mind memory and understanding (praised be to god for the same) do make publish and declare my last will and testament in manner and form following (that is to say) {after debts and funeral expense paid etc} I give to my loving wife Mary the use usage wear interest and enjoyment of all my goods chattels cattle stock in trade ~ money securities for money personal estate and effects whatsoever and wheresoever to hold unto her my said wife for and during the term of her natural life providing she so long continues my widow and unmarried and from or after her decease or intermarriage with any future husband which shall first happen.

Then I give all the said goods chattels cattle stock in trade money securites for money personal estate and effects unto my son Abraham Wood absolutely and forever. Also I give devise and bequeath unto my said wife Mary all that my messuages tenement or dwelling house together with the malthouse brewhouse barn stableyard garden and premises to the same belonging situate and being at Darlaston aforesaid and now in my own possession. Also all that messuage tenement or dwelling house together with the shop garden and premises with the appurtenances to the same ~ belonging situate in Darlaston aforesaid and now in the several holdings or occupation of George Knowles and Edward Knowles to hold the aforesaid premises and every part thereof with the appurtenances to my said wife Mary for and during the term of her natural life provided she so long continues my widow and unmarried. And from or after her decease or intermarriage with a future husband which shall first happen. Then I give and devise the aforesaid premises and every part thereof with the appurtenances unto my said son Abraham Wood his heirs and assigns forever.

Also I give unto my said wife all that piece or parcel of land or ground inclosed and taken out of Heath Field in the parish of Darlaston aforesaid containing four acres or thereabouts (be the same more or less) upon which my brick kilns erected and now in my own possession. To hold unto my said wife Mary until my said son Abraham attains his age of twenty one years if she so long continues my widow and unmarried as aforesaid and from and immediately after my said son Abraham attaining his age of twenty one years or my said wife marrying again as aforesaid which shall first happen then I give the said piece or parcel of land or ground and premises unto my said son Abraham his heirs and assigns forever.

And I do hereby charge all the aforesaid premises with the payment of the sum of twenty pounds a piece to each of my daughters namely Elizabeth the wife of Ambrose Dudall and Rebecca the wife of Samuel Stubbs which said sum of twenty pounds each I devise may be paid to them by my said son Abraham when and so soon as he attains his age of twenty one years provided always and my mind and will is that if my said son Abraham should happen to depart this life without leaving issue of his body lawfully begotten before he attains his age of twenty one years then I give and devise all the aforesaid premises and every part thereof with the appurtenances so given to my said son Abraham as aforesaid unto my said son William Wood and my said daughter Elizabeth Dudall and Rebecca Stubbs their heirs and assigns forever equally divided among them share and share alike as tenants in common and not as joint tenants. And lastly I do hereby nominate constitute and appoint my said wife Mary and my said son Abraham executrix and executor of this my will.

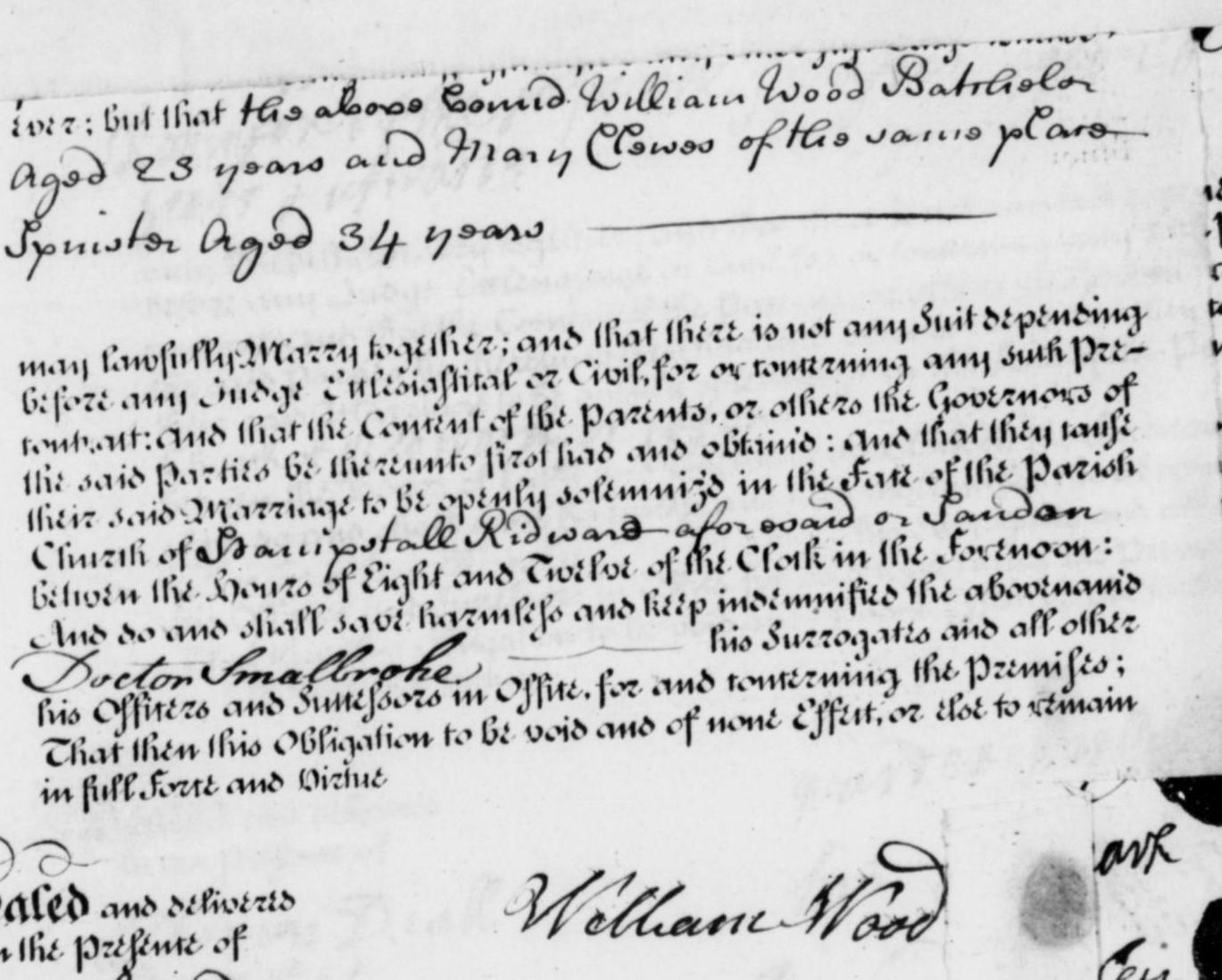

The marriage of William Wood (1725-1784) and Mary Clews (1715-1798) in 1749 was in Hamstall Ridware.

Mary was eleven years Williams senior, and it appears that they both came from Hamstall Ridware and moved to Darlaston after they married. Clearly Rebecca had extended family there (notwithstanding any possible connecting links between the Stubbs buckle makers of Darlaston and the Hamstall Ridware Jacobites thirty years prior). When the buckle trade collapsed in Darlaston, they likely moved to find employment elsewhere, perhaps with the help of Rebecca’s family.

I have not yet been able to find deaths recorded anywhere for either Samuel or Rebecca (there are a couple of deaths recorded for a Samuel Stubbs, one in 1809 in Wolverhampton, and one in 1810 in Birmingham but impossible to say which, if either, is the right one with the limited information, and difficult to know if they stayed in the Hamstall Ridware area or perhaps moved elsewhere)~ or find a reason for their son Solomon to be in Burton upon Trent, an evidently prosperous man with several properties including an earthenware business, as well as a land carrier business.

October 11, 2022 at 2:58 pm #6334In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The House on Penn Common

Toi Fang and the Duke of Sutherland

Tomlinsons

Grassholme

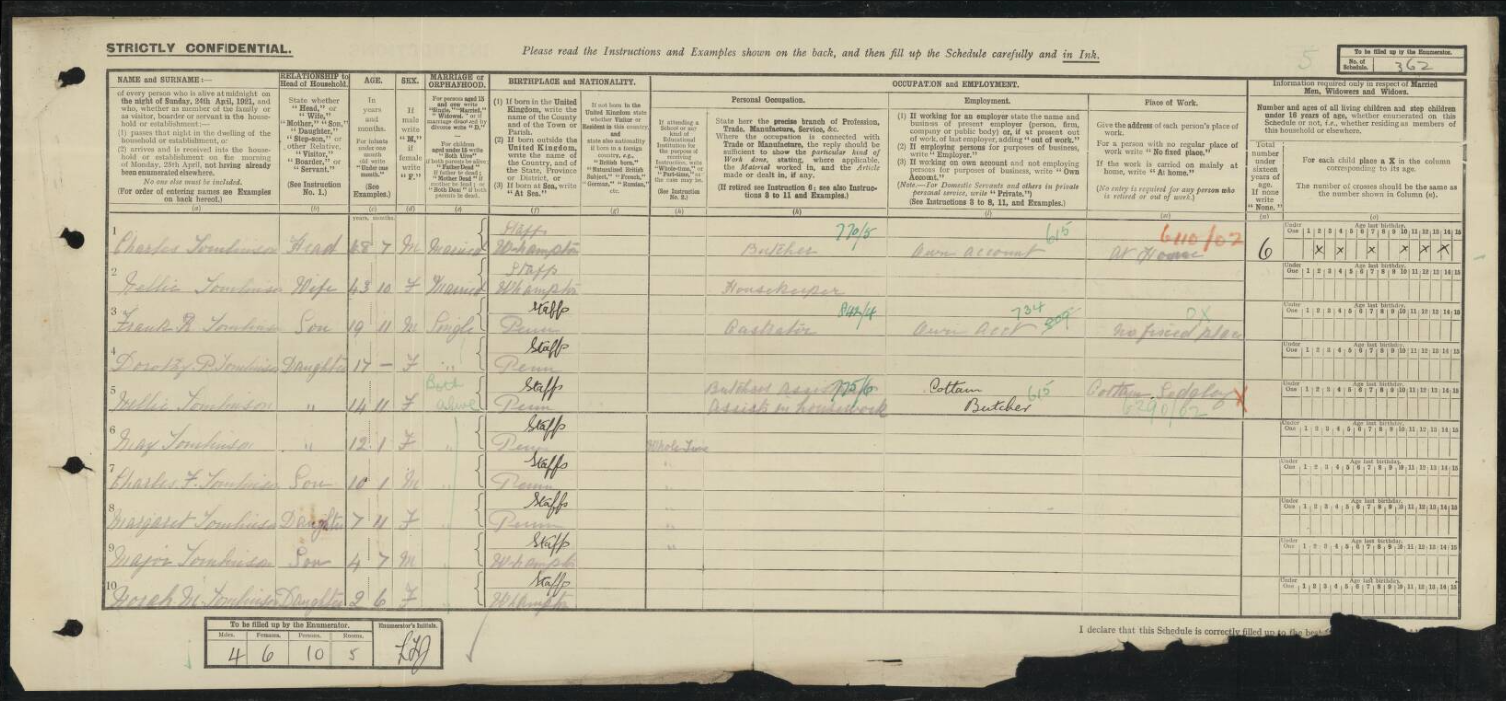

Charles Tomlinson (1873-1929) my great grandfather, was born in Wolverhampton in 1873. His father Charles Tomlinson (1847-1907) was a licensed victualler or publican, or alternatively a vet/castrator. He married Emma Grattidge (1853-1911) in 1872. On the 1881 census they were living at The Wheel in Wolverhampton.

Charles married Nellie Fisher (1877-1956) in Wolverhampton in 1896. In 1901 they were living next to the post office in Upper Penn, with children (Charles) Sidney Tomlinson (1896-1955), and Hilda Tomlinson (1898-1977) . Charles was a vet/castrator working on his own account.

In 1911 their address was 4, Wakely Hill, Penn, and living with them were their children Hilda, Frank Tomlinson (1901-1975), (Dorothy) Phyllis Tomlinson (1905-1982), Nellie Tomlinson (1906-1978) and May Tomlinson (1910-1983). Charles was a castrator working on his own account.

Charles and Nellie had a further four children: Charles Fisher Tomlinson (1911-1977), Margaret Tomlinson (1913-1989) (my grandmother Peggy), Major Tomlinson (1916-1984) and Norah Mary Tomlinson (1919-2010).

My father told me that my grandmother had fallen down the well at the house on Penn Common in 1915 when she was two years old, and sent me a photo of her standing next to the well when she revisted the house at a much later date.

Peggy next to the well on Penn Common:

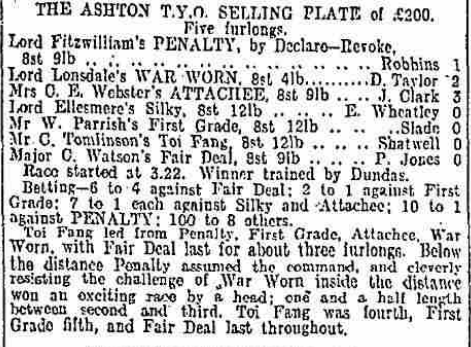

My grandmother Peggy told me that her father had had a racehorse called Toi Fang. She remembered the racing colours were sky blue and orange, and had a set of racing silks made which she sent to my father.

Through a DNA match, I met Ian Tomlinson. Ian is the son of my fathers favourite cousin Roger, Frank’s son. Ian found some racing silks and sent a photo to my father (they are now in contact with each other as a result of my DNA match with Ian), wondering what they were.

When Ian sent a photo of these racing silks, I had a look in the newspaper archives. In 1920 there are a number of mentions in the racing news of Mr C Tomlinson’s horse TOI FANG. I have not found any mention of Toi Fang in the newspapers in the following years.

The Scotsman – Monday 12 July 1920:

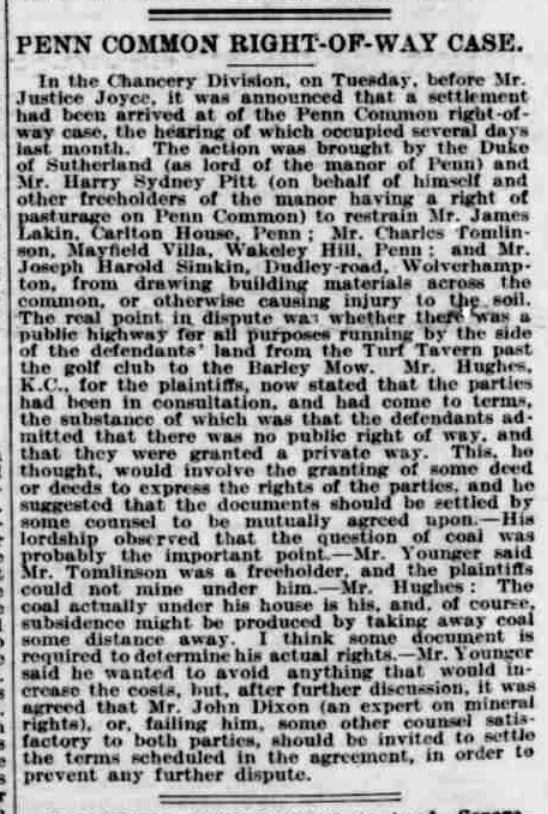

The other story that Ian Tomlinson recalled was about the house on Penn Common. Ian said he’d heard that the local titled person took Charles Tomlinson to court over building the house but that Tomlinson won the case because it was built on common land and was the first case of it’s kind.

Penn Common Right of Way Case:

Staffordshire Advertiser March 9, 1912In the chancery division, on Tuesday, before Mr Justice Joyce, it was announced that a settlement had been arrived at of the Penn Common Right of Way case, the hearing of which occupied several days last month. The action was brought by the Duke of Sutherland (as Lord of the Manor of Penn) and Mr Harry Sydney Pitt (on behalf of himself and other freeholders of the manor having a right to pasturage on Penn Common) to restrain Mr James Lakin, Carlton House, Penn; Mr Charles Tomlinson, Mayfield Villa, Wakely Hill, Penn; and Mr Joseph Harold Simpkin, Dudley Road, Wolverhampton, from drawing building materials across the common, or otherwise causing injury to the soil.

The real point in dispute was whether there was a public highway for all purposes running by the side of the defendants land from the Turf Tavern past the golf club to the Barley Mow.

Mr Hughes, KC for the plaintiffs, now stated that the parties had been in consultation, and had come to terms, the substance of which was that the defendants admitted that there was no public right of way, and that they were granted a private way. This, he thought, would involve the granting of some deed or deeds to express the rights of the parties, and he suggested that the documents should be be settled by some counsel to be mutually agreed upon.His lordship observed that the question of coal was probably the important point. Mr Younger said Mr Tomlinson was a freeholder, and the plaintiffs could not mine under him. Mr Hughes: The coal actually under his house is his, and, of course, subsidence might be produced by taking away coal some distance away. I think some document is required to determine his actual rights.

Mr Younger said he wanted to avoid anything that would increase the costs, but, after further discussion, it was agreed that Mr John Dixon (an expert on mineral rights), or failing him, another counsel satisfactory to both parties, should be invited to settle the terms scheduled in the agreement, in order to prevent any further dispute.

The name of the house is Grassholme. The address of Mayfield Villas is the house they were living in while building Grassholme, which I assume they had not yet moved in to at the time of the newspaper article in March 1912.

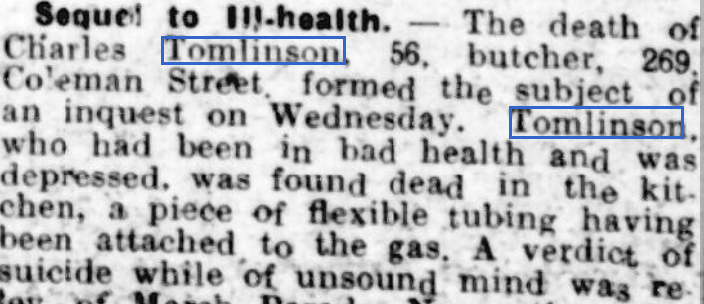

What my grandmother didn’t tell anyone was how her father died in 1929:

On the 1921 census, Charles, Nellie and eight of their children were living at 269 Coleman Street, Wolverhampton.

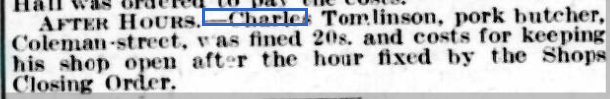

They were living on Coleman Street in 1915 when Charles was fined for staying open late.

Staffordshire Advertiser – Saturday 13 February 1915:

What is not yet clear is why they moved from the house on Penn Common sometime between 1912 and 1915. And why did he have a racehorse in 1920?

October 11, 2022 at 11:39 am #6333In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The Grattidge Family

The first Grattidge to appear in our tree was Emma Grattidge (1853-1911) who married Charles Tomlinson (1847-1907) in 1872.

Charles Tomlinson (1873-1929) was their son and he married my great grandmother Nellie Fisher. Their daughter Margaret (later Peggy Edwards) was my grandmother on my fathers side.

Emma Grattidge was born in Wolverhampton, the daughter and youngest child of William Grattidge (1820-1887) born in Foston, Derbyshire, and Mary Stubbs, born in Burton on Trent, daughter of Solomon Stubbs, a land carrier. William and Mary married at St Modwens church, Burton on Trent, in 1839. It’s unclear why they moved to Wolverhampton. On the 1841 census William was employed as an agent, and their first son William was nine months old. Thereafter, William was a licensed victuallar or innkeeper.

William Grattidge was born in Foston, Derbyshire in 1820. His parents were Thomas Grattidge, farmer (1779-1843) and Ann Gerrard (1789-1822) from Ellastone. Thomas and Ann married in 1813 in Ellastone. They had five children before Ann died at the age of 25:

Bessy was born in 1815, Thomas in 1818, William in 1820, and Daniel Augustus and Frederick were twins born in 1822. They were all born in Foston. (records say Foston, Foston and Scropton, or Scropton)

On the 1841 census Thomas had nine people additional to family living at the farm in Foston, presumably agricultural labourers and help.

After Ann died, Thomas had three children with Kezia Gibbs (30 years his junior) before marrying her in 1836, then had a further four with her before dying in 1843. Then Kezia married Thomas’s nephew Frederick Augustus Grattidge (born in 1816 in Stafford) in London in 1847 and had two more!

The siblings of William Grattidge (my 3x great grandfather):

Frederick Grattidge (1822-1872) was a schoolmaster and never married. He died at the age of 49 in Tamworth at his twin brother Daniels address.

Daniel Augustus Grattidge (1822-1903) was a grocer at Gungate in Tamworth.

Thomas Grattidge (1818-1871) married in Derby, and then emigrated to Illinois, USA.

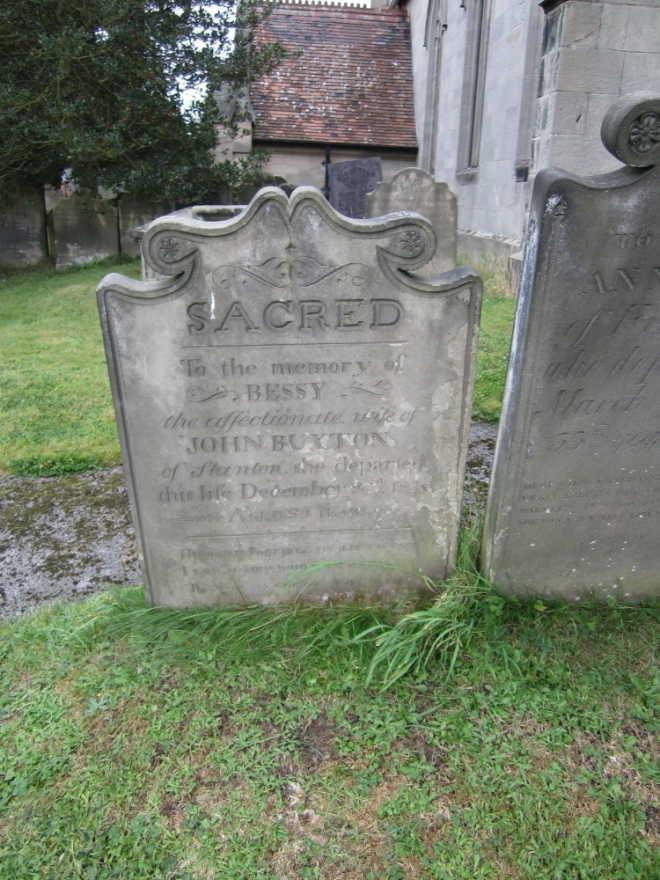

Bessy Grattidge (1815-1840) married John Buxton, farmer, in Ellastone in January 1838. They had three children before Bessy died in December 1840 at the age of 25: Henry in 1838, John in 1839, and Bessy Buxton in 1840. Bessy was baptised in January 1841. Presumably the birth of Bessy caused the death of Bessy the mother.

Bessy Buxton’s gravestone:

“Sacred to the memory of Bessy Buxton, the affectionate wife of John Buxton of Stanton She departed this life December 20th 1840, aged 25 years. “Husband, Farewell my life is Past, I loved you while life did last. Think on my children for my sake, And ever of them with I take.”

20 Dec 1840, Ellastone, Staffordshire

In the 1843 will of Thomas Grattidge, farmer of Foston, he leaves fifth shares of his estate, including freehold real estate at Findern, to his wife Kezia, and sons William, Daniel, Frederick and Thomas. He mentions that the children of his late daughter Bessy, wife of John Buxton, will be taken care of by their father. He leaves the farm to Keziah in confidence that she will maintain, support and educate his children with her.

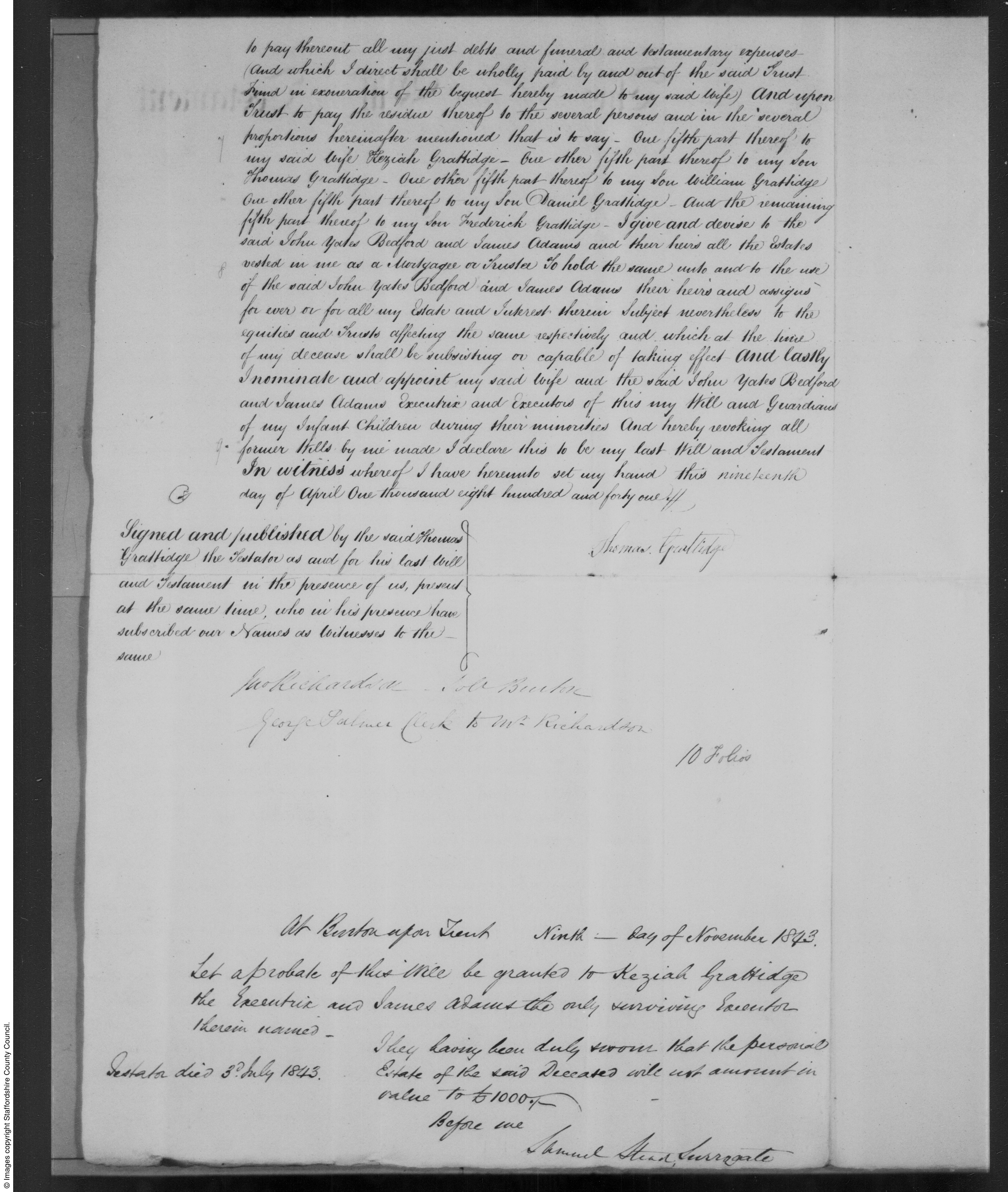

An excerpt from the will:

I give and bequeath unto my dear wife Keziah Grattidge all my household goods and furniture, wearing apparel and plate and plated articles, linen, books, china, glass, and other household effects whatsoever, and also all my implements of husbandry, horses, cattle, hay, corn, crops and live and dead stock whatsoever, and also all the ready money that may be about my person or in my dwelling house at the time of my decease, …I also give my said wife the tenant right and possession of the farm in my occupation….

A page from the 1843 will of Thomas Grattidge:

William Grattidges half siblings (the offspring of Thomas Grattidge and Kezia Gibbs):

Albert Grattidge (1842-1914) was a railway engine driver in Derby. In 1884 he was driving the train when an unfortunate accident occured outside Ambergate. Three children were blackberrying and crossed the rails in front of the train, and one little girl died.

Albert Grattidge:

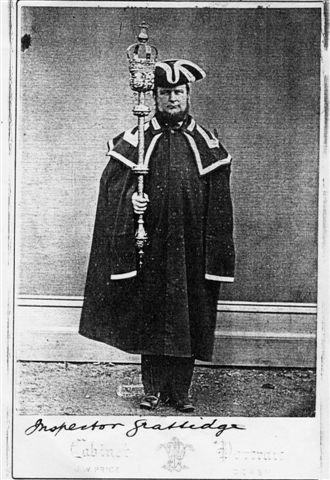

George Grattidge (1826-1876) was baptised Gibbs as this was before Thomas married Kezia. He was a police inspector in Derby.

George Grattidge:

Edwin Grattidge (1837-1852) died at just 15 years old.

Ann Grattidge (1835-) married Charles Fletcher, stone mason, and lived in Derby.

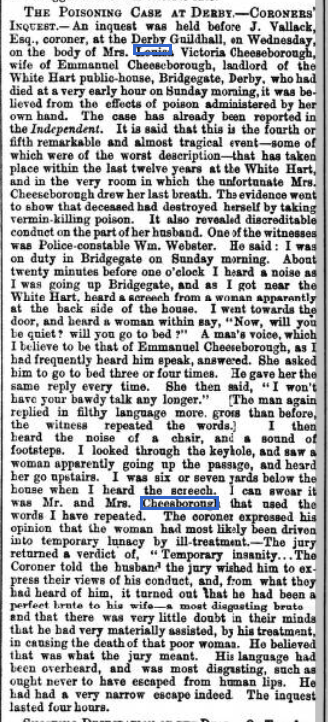

Louisa Victoria Grattidge (1840-1869) was sadly another Grattidge woman who died young. Louisa married Emmanuel Brunt Cheesborough in 1860 in Derby. In 1861 Louisa and Emmanuel were living with her mother Kezia in Derby, with their two children Frederick and Ann Louisa. Emmanuel’s occupation was sawyer. (Kezia Gibbs second husband Frederick Augustus Grattidge was a timber merchant in Derby)

At the time of her death in 1869, Emmanuel was the landlord of the White Hart public house at Bridgegate in Derby.

The Derby Mercury of 17th November 1869:

“On Wednesday morning Mr Coroner Vallack held an inquest in the Grand

Jury-room, Town-hall, on the body of Louisa Victoria Cheeseborough, aged

33, the wife of the landlord of the White Hart, Bridge-gate, who committed

suicide by poisoning at an early hour on Sunday morning. The following

evidence was taken:Mr Frederick Borough, surgeon, practising in Derby, deposed that he was

called in to see the deceased about four o’clock on Sunday morning last. He

accordingly examined the deceased and found the body quite warm, but dead.

He afterwards made enquiries of the husband, who said that he was afraid

that his wife had taken poison, also giving him at the same time the

remains of some blue material in a cup. The aunt of the deceased’s husband

told him that she had seen Mrs Cheeseborough put down a cup in the

club-room, as though she had just taken it from her mouth. The witness took

the liquid home with him, and informed them that an inquest would

necessarily have to be held on Monday. He had made a post mortem

examination of the body, and found that in the stomach there was a great

deal of congestion. There were remains of food in the stomach and, having

put the contents into a bottle, he took the stomach away. He also examined

the heart and found it very pale and flabby. All the other organs were

comparatively healthy; the liver was friable.Hannah Stone, aunt of the deceased’s husband, said she acted as a servant

in the house. On Saturday evening, while they were going to bed and whilst

witness was undressing, the deceased came into the room, went up to the

bedside, awoke her daughter, and whispered to her. but what she said the

witness did not know. The child jumped out of bed, but the deceased closed

the door and went away. The child followed her mother, and she also

followed them to the deceased’s bed-room, but the door being closed, they

then went to the club-room door and opening it they saw the deceased

standing with a candle in one hand. The daughter stayed with her in the

room whilst the witness went downstairs to fetch a candle for herself, and

as she was returning up again she saw the deceased put a teacup on the

table. The little girl began to scream, saying “Oh aunt, my mother is

going, but don’t let her go”. The deceased then walked into her bed-room,

and they went and stood at the door whilst the deceased undressed herself.

The daughter and the witness then returned to their bed-room. Presently

they went to see if the deceased was in bed, but she was sitting on the

floor her arms on the bedside. Her husband was sitting in a chair fast

asleep. The witness pulled her on the bed as well as she could.

Ann Louisa Cheesborough, a little girl, said that the deceased was her

mother. On Saturday evening last, about twenty minutes before eleven

o’clock, she went to bed, leaving her mother and aunt downstairs. Her aunt

came to bed as usual. By and bye, her mother came into her room – before

the aunt had retired to rest – and awoke her. She told the witness, in a

low voice, ‘that she should have all that she had got, adding that she

should also leave her her watch, as she was going to die’. She did not tell

her aunt what her mother had said, but followed her directly into the

club-room, where she saw her drink something from a cup, which she

afterwards placed on the table. Her mother then went into her own room and

shut the door. She screamed and called her father, who was downstairs. He

came up and went into her room. The witness then went to bed and fell

asleep. She did not hear any noise or quarrelling in the house after going

to bed.Police-constable Webster was on duty in Bridge-gate on Saturday evening

last, about twenty minutes to one o’clock. He knew the White Hart

public-house in Bridge-gate, and as he was approaching that place, he heard

a woman scream as though at the back side of the house. The witness went to

the door and heard the deceased keep saying ‘Will you be quiet and go to

bed’. The reply was most disgusting, and the language which the

police-constable said was uttered by the husband of the deceased, was

immoral in the extreme. He heard the poor woman keep pressing her husband

to go to bed quietly, and eventually he saw him through the keyhole of the

door pass and go upstairs. his wife having gone up a minute or so before.

Inspector Fearn deposed that on Sunday morning last, after he had heard of

the deceased’s death from supposed poisoning, he went to Cheeseborough’s

public house, and found in the club-room two nearly empty packets of

Battie’s Lincoln Vermin Killer – each labelled poison.Several of the Jury here intimated that they had seen some marks on the

deceased’s neck, as of blows, and expressing a desire that the surgeon

should return, and re-examine the body. This was accordingly done, after

which the following evidence was taken:Mr Borough said that he had examined the body of the deceased and observed

a mark on the left side of the neck, which he considered had come on since

death. He thought it was the commencement of decomposition.

This was the evidence, after which the jury returned a verdict “that the

deceased took poison whilst of unsound mind” and requested the Coroner to

censure the deceased’s husband.The Coroner told Cheeseborough that he was a disgusting brute and that the

jury only regretted that the law could not reach his brutal conduct.

However he had had a narrow escape. It was their belief that his poor

wife, who was driven to her own destruction by his brutal treatment, would

have been a living woman that day except for his cowardly conduct towards

her.The inquiry, which had lasted a considerable time, then closed.”

In this article it says:

“it was the “fourth or fifth remarkable and tragical event – some of which were of the worst description – that has taken place within the last twelve years at the White Hart and in the very room in which the unfortunate Louisa Cheesborough drew her last breath.”

Sheffield Independent – Friday 12 November 1869:

July 7, 2022 at 5:31 pm #6316

July 7, 2022 at 5:31 pm #6316In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

Myroslava was hungry. She saw ducks flying in the sky and realised she wasn’t too far from the Kal’mius river, south of Dantesk. She took out her sling and hit one with a stone she just picked on the floor. She smiled and said in a low voice : “You see father, I haven’t lost my touch.”

She had traveled several days with a group of reportourists, as she called them. A bunch of war reporters who thought it entertaining to take pictures of bombed areas, going about like peacocks as if they wore a plot armour against Rootian bullets and missiles and discourse at night on the tactics of the different armies. She was glad when she crossed the Rootian lines two days ago. Even if it meant no more dehydrated food and no more plot armour, she was certainly better off without the inane discussions.

She picked the duck and looked for a freshly bombarded place where there was still smoke. She could make some fire without being noticed too much. She didn’t like raw meat that much.

Soon after leaving the group or reportourists, without all the noise they made, she became certain she was being followed. She tried once to surprise them, but they were good at hiding and camouflaging their tracks. She wondered how long it had lasted. She cursed the noisy reporters and cursed her lack of good vodka. Cursing without alcohol was like boxing without fists.

July 7, 2022 at 9:00 am #6314In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

After her visit to the witch of the woods to get some medicine for her Mum who still had bouts of fatigue from her last encounter with the flu, the little Maryechka went back home as instructed.

She found her home empty. Her parents were busy in the fields, as the time of harvest was near, and much remained to be done to prepare, and workers were limited.

She left the pouch of dried herbs in the cabinet, and wondered if she should study. The schools were closed for early holidays, and they didn’t really bother with giving them much homework. She could see the teachers’ minds were worried with other things.

Unlike other children of her age, she wasn’t interested in all the activities online, phone-stuff. The other gen-alpha kids didn’t even bother mocking her “IRL”, glued to their screens while she instead enjoyed looking at the clear blue sky. For all she knew they didn’t even realize they were living in the same world. Now, they were probably over-stressed looking at all the news on replay.

For Maryechka, the war felt far away, even if you could see some of its impacts, with people moving about the nearby town.Looking as it was still early in the day, and she had plenty more time left before having to prepare for dinner, she thought it’d be nice to go and visit her grand-parent and their friends at the old people’s home. They always had nice stale biscuits to share, and they told the strangest stories all the time.

It was just a 15 min walk from the farm, so she’d be there and back in no time.

July 6, 2022 at 11:41 am #6313In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

Egbert Gofindlevsky rapped on the door of room number 22. The letter flapped against his pin striped trouser leg as his hand shook uncontrollably, his habitual tremor exacerbated with the shock. Remembering that Obadiah Sproutwinklov was deaf, he banged loudly on the door with the flat of his hand. Eventually the door creaked open.

Egbert flapped the letter in from of Obadiah’s face. “Have you had one of these?” he asked.

“If you’d stop flapping it about I might be able to see what it is,” Obadiah replied. “Oh that! As a matter of fact I’ve had one just like it. The devils work, I tell you! A practical joke, and in very poor taste!”

Egbert was starting to wish he’d gone to see Olga Herringbonevsky first. “Can I come in?” he hissed, “So we can discuss it in private?”

Reluctantly Obadiah pulled the door open and ushered him inside the room. Egbert looked around for a place to sit, but upon noticing a distinct odour of urine decided to remain standing.

“Ursula is booting us out, where are we to go?”

“Eh?” replied Obadiah, cupping his ear. “Speak up, man!”

Egbert repeated his question.

“No need to shout!”

The two old men endeavoured to conduct a conversation on this unexepected turn of events, the upshot being that Obadiah had no intention of leaving his room at all henceforth, come what may, and would happily starve to death in his room rather than take to the streets.

Egbert considered this form of action unhelpful, as he himself had no wish to starve to death in his room, so he removed himself from room 22 with a disgruntled sigh and made his way to Olga’s room on the third floor.

July 6, 2022 at 11:05 am #6312In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

When she’d heard of the miracle happening at the Flovlinden Tree, Egna initially shrugged it off as another conman’s attempt at fooling the crowds.

“No, it’s real, my Auntie saw it.”

“Stop fretting” she’d told the little girl, as she was carefully removing the lice from her hair. “This is just someone’s idea of a smart joke. Don’t get fooled, you’re smarter than this.”

She sure wasn’t responsible for that one. If that were a true miracle, she would have known. The little calf next week being resuscitated after being dead a few minutes, well, that was her. Shame nobody was even there to notice. Most of the best miracles go about this way anyway.

So, after having lived close to a millennia in relatively rock solid health and with surprisingly unaging looks, Egna had thought she’d seen it all; at least last time the tree started to ooze sacred oil, it didn’t last for too long, people’s greed starting to sell it stopped it right in its tracks.

But maybe there was more to it this time. Egna’d often wondered why God had let her live that long. She was a useful instrument to Her for sure, but living in secrecy, claiming no ownership, most miracles were just facts of life. She somehow failed to see the point, even after 957 years of existence.

The little girl had left to go back to her nearby town. This side of the country was still quite safe from all the craziness. Egna knew well most of the branches of the ancestral trees leading to that particular little leaf. This one had probably no idea she shared a common ancestor with President Voldomeer, but Egna remembered the fellow. He was a clogmaker in the turn of the 18th century, as was his father before. That was until a rather unexpected turn of events precipitated him to a different path as his brother.

She had a book full of these records, as she’d tracked the lives of many, to keep them alive, and maybe remind people they all share so much in common. That is, if people were able to remember more than 2 generations before them.

“Well, that’s set.” she said to herself and to Her as She’s always listening “I’ll go and see for myself.”

her trusty old musty cloak at the door seemed to have been begging for the journey.July 6, 2022 at 11:02 am #6311In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

Most of the pilgims, if one could call them that, flocked to the linden tree in cars, although some came on motorbikes and bicycles. Olek was grateful that they hadn’t started arriving by the bus load, like Italian tourists. But his cousin Ursula was happy with this strange new turn of events.

Her shabby hotel on the outskirts of town had never been so busy and she was already planning to refurbish the premises and evict the decrepit and motley assortment of aged permanent residents who had just about kept her head above water, financially speaking, for the last twenty years. She could charge much more per night to these new tourists, who were smartly dressed and modern and didn’t argue about the price of a room. They did complain about the damp stained wallpaper though and the threadbare bedding. Ursula reckoned she could charge even more for the rooms if she redecorated, and had an idea to approach her nephew Boris the bank manager for a business loan.

But first she had to evict the old timers. It wasn’t her problem, she reminded herself, if they had nowhere else to go. After all, plenty of charitable aid money was flying around these days, they could easily just join up with some fleeing refugees. She’d even sent some of her old dresses to the collection agency. They may have been forty years old and smelled of moth balls, but they were well made and the refugees would surely be grateful.

Ursula wasn’t looking forward to telling them. No, not at all! She rather liked some of them and was dreading their reaction. You are a business woman, Ursula, she told herself, and you have to look after your own interests! But still she quailed at the thought of knocking on their doors, or announcing it in the communal dining room at supper. Then she had an idea. She’d type up some letters instead, and sign them as if they came from her new business manager. When the residents approached her about the letter she would smile sadly and shrug, saying it wasn’t her decision and that she was terribly sorry but her hands were tied.

July 6, 2022 at 9:47 am #6310In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

Olek wished he wasn’t so easy to find.

The old caretaker of the shrine of Saint Edigna couldn’t have chosen a less conspicuous place to live in this warring time. People were flocking from afar, more and more each day drawn about by the ancient place, and the sacred oil bleeding linden tree which had suddenly and quite miraculously resumed its flow in the midst of the ambiant chaos started by the war.

It wasn’t always like this. A few months ago, the linden tree was just an old linden tree that may or may not have been miraculous, if the old wifes’ tales were to be trusted. Mankind’s memory is a flimsy thing as it occurs, and while for many generations before, speculations had abounded about whether or not the Saint was real, had such or such filiation, et cætera— it now seemed the old tales that were passed down from mother to children had managed to keep alive a knowledge that had but all dried up on old flaky parchments scribbled in pale inks that kept eluding old scholars’ exegesis.

Olek himself wasn’t a learned man. A man of faith, he was a little — more by upbringing than by choice, and by slow attunement to nature it would seem. Over the years, he’d be servicing the country in many ways, and after a rather long carrier started at young age, he had finally managed to retire in this place.

He thought he’d be left alone, to care for a little garden patch, checking in from times to times on the old grumpy neighbours, but alas, the Holy Nation’s destiny still had something in store for him.The latest pilgrim family had brought a message. It was another push to action. “Plan acceleration needs to happen”.

“What clucking plan again?” was his first reaction. Bad temper had a way of flaring right up his vents as in old times. When he’d calmed down, he wondered if he had ever seen a call for slowing down in his life. People were always so busy mindlessly carting around, bumping into the darkness.He smiled thinking of something his old man used to say. He’d never planned for a thing in his life, and was always very carefree it was often scary. His mantra was “People are always getting prepared for the wrong things. They never can prepare for the unexpected, and surely enough, only the unexpected happens.”

That sort of chaos paddling approach to life didn’t seem to bring him any sort of extraordinary success, and while he had the same mixed bag of ups and downs as the rest of his compatriots, just so much less did he suffer for the same result! Olek guessed that was the whole point, even if he really couldn’t accept it until much later in life.Maybe Olek would start playing by his father’s book. Until he could find a way to get lost behind enemy lines.

July 1, 2022 at 9:51 am #6306In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

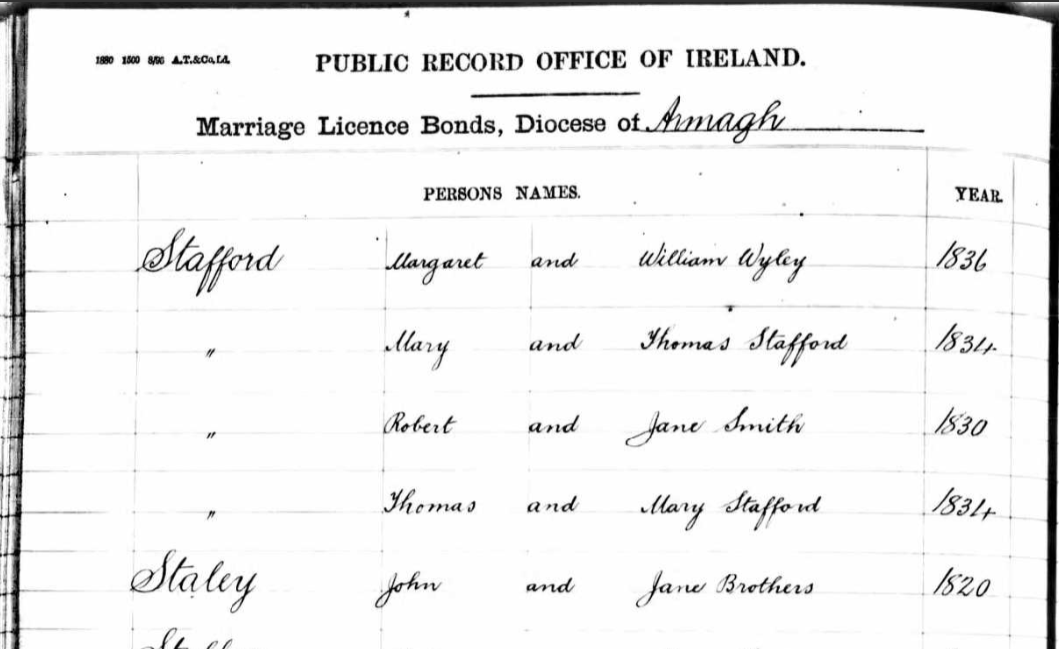

Looking for Robert Staley

William Warren (1835-1880) of Newhall (Stapenhill) married Elizabeth Staley (1836-1907) in 1858. Elizabeth was born in Newhall, the daughter of John Staley (1795-1876) and Jane Brothers. John was born in Newhall, and Jane was born in Armagh, Ireland, and they were married in Armagh in 1820. Elizabeths older brothers were born in Ireland: William in 1826 and Thomas in Dublin in 1830. Francis was born in Liverpool in 1834, and then Elizabeth in Newhall in 1836; thereafter the children were born in Newhall.

Marriage of John Staley and Jane Brothers in 1820:

My grandmother related a story about an Elizabeth Staley who ran away from boarding school and eloped to Ireland, but later returned. The only Irish connection found so far is Jane Brothers, so perhaps she meant Elizabeth Staley’s mother. A boarding school seems unlikely, and it would seem that it was John Staley who went to Ireland.

The 1841 census states Jane’s age as 33, which would make her just 12 at the time of her marriage. The 1851 census states her age as 44, making her 13 at the time of her 1820 marriage, and the 1861 census estimates her birth year as a more likely 1804. Birth records in Ireland for her have not been found. It’s possible, perhaps, that she was in service in the Newhall area as a teenager (more likely than boarding school), and that John and Jane ran off to get married in Ireland, although I haven’t found any record of a child born to them early in their marriage. John was an agricultural labourer, and later a coal miner.

John Staley was the son of Joseph Staley (1756-1838) and Sarah Dumolo (1764-). Joseph and Sarah were married by licence in Newhall in 1782. Joseph was a carpenter on the marriage licence, but later a collier (although not necessarily a miner).

The Derbyshire Record Office holds records of an “Estimate of Joseph Staley of Newhall for the cost of continuing to work Pisternhill Colliery” dated 1820 and addresssed to Mr Bloud at Calke Abbey (presumably the owner of the mine)

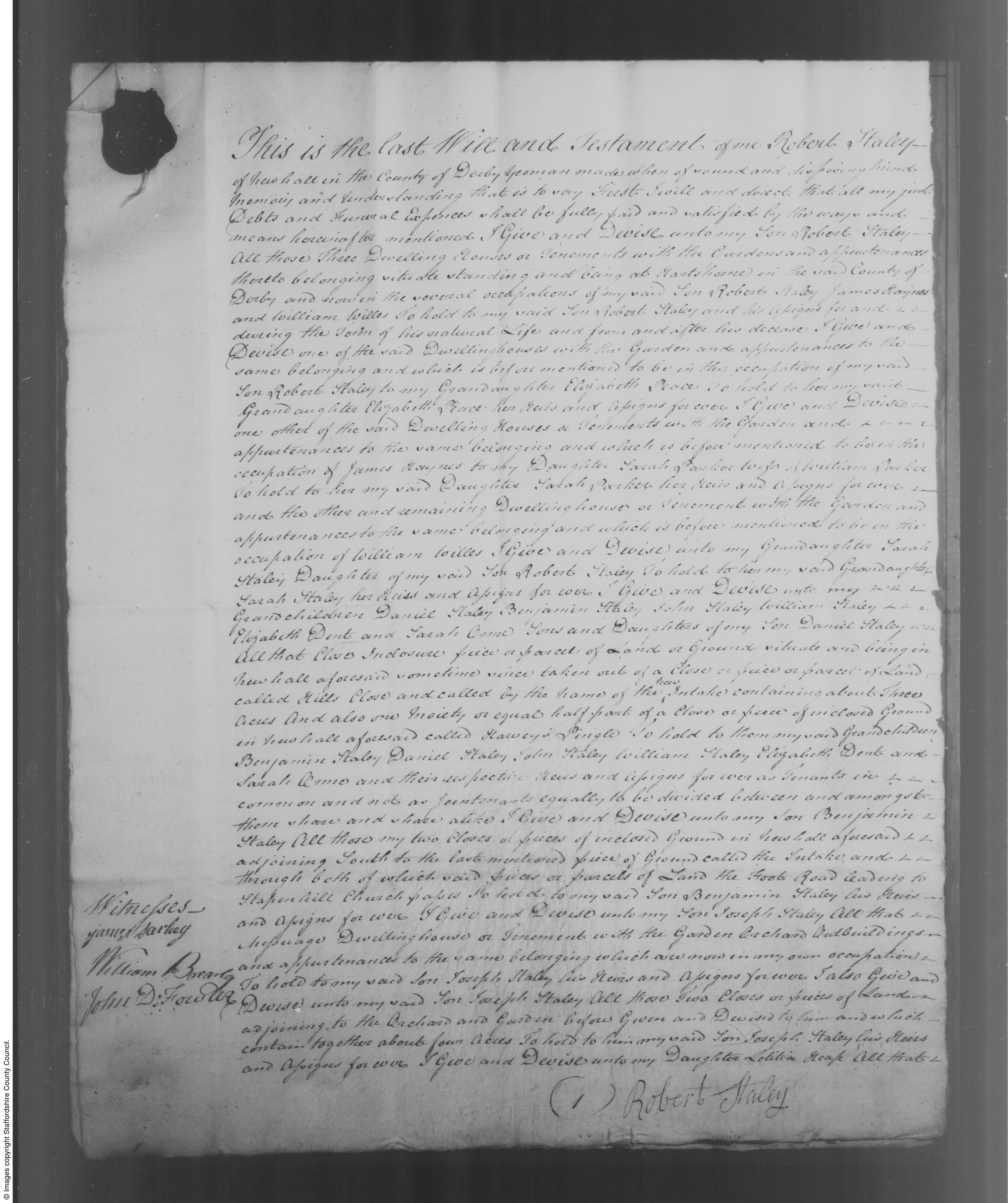

Josephs parents were Robert Staley and Elizabeth. I couldn’t find a baptism or birth record for Robert Staley. Other trees on an ancestry site had his birth in Elton, but with no supporting documents. Robert, as stated in his 1795 will, was a Yeoman.

“Yeoman: A former class of small freeholders who farm their own land; a commoner of good standing.”

“Husbandman: The old word for a farmer below the rank of yeoman. A husbandman usually held his land by copyhold or leasehold tenure and may be regarded as the ‘average farmer in his locality’. The words ‘yeoman’ and ‘husbandman’ were gradually replaced in the later 18th and 19th centuries by ‘farmer’.”He left a number of properties in Newhall and Hartshorne (near Newhall) including dwellings, enclosures, orchards, various yards, barns and acreages. It seemed to me more likely that he had inherited them, rather than moving into the village and buying them.

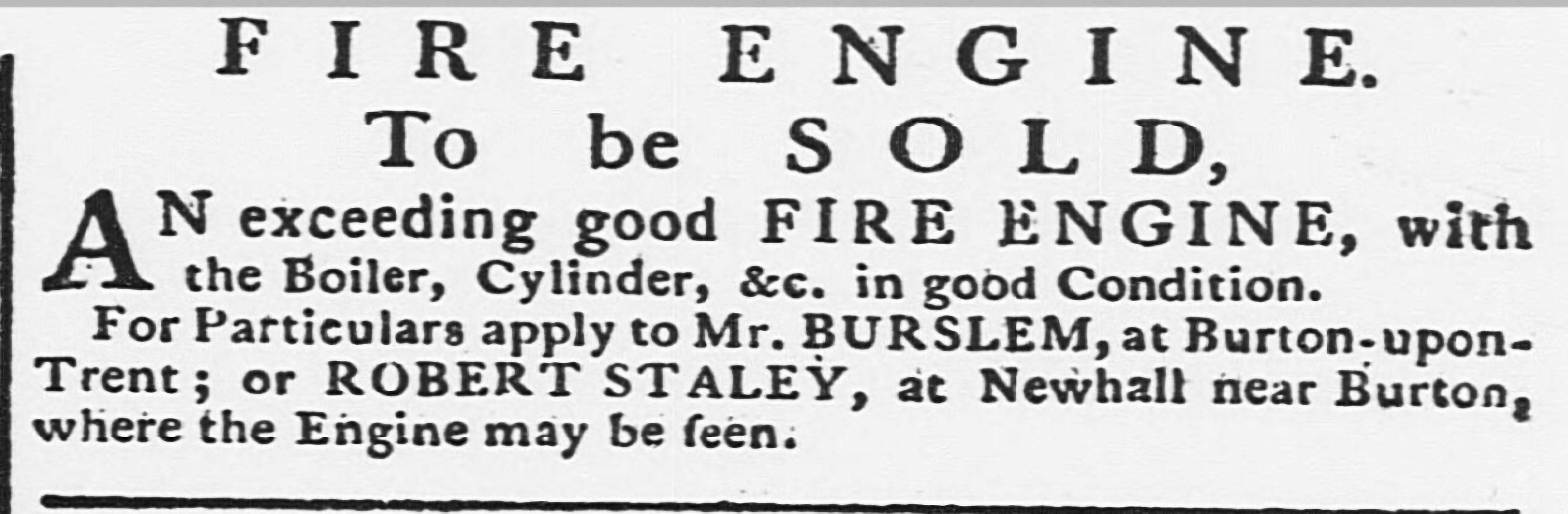

There is a mention of Robert Staley in a 1782 newpaper advertisement.

“Fire Engine To Be Sold. An exceedingly good fire engine, with the boiler, cylinder, etc in good condition. For particulars apply to Mr Burslem at Burton-upon-Trent, or Robert Staley at Newhall near Burton, where the engine may be seen.”

Was the fire engine perhaps connected with a foundry or a coal mine?

I noticed that Robert Staley was the witness at a 1755 marriage in Stapenhill between Barbara Burslem and Richard Daston the younger esquire. The other witness was signed Burslem Jnr.

Looking for Robert Staley

I assumed that once again, in the absence of the correct records, a similarly named and aged persons baptism had been added to the tree regardless of accuracy, so I looked through the Stapenhill/Newhall parish register images page by page. There were no Staleys in Newhall at all in the early 1700s, so it seemed that Robert did come from elsewhere and I expected to find the Staleys in a neighbouring parish. But I still didn’t find any Staleys.

I spoke to a couple of Staley descendants that I’d met during the family research. I met Carole via a DNA match some months previously and contacted her to ask about the Staleys in Elton. She also had Robert Staley born in Elton (indeed, there were many Staleys in Elton) but she didn’t have any documentation for his birth, and we decided to collaborate and try and find out more.

I couldn’t find the earlier Elton parish registers anywhere online, but eventually found the untranscribed microfiche images of the Bishops Transcripts for Elton.

via familysearch:

“In its most basic sense, a bishop’s transcript is a copy of a parish register. As bishop’s transcripts generally contain more or less the same information as parish registers, they are an invaluable resource when a parish register has been damaged, destroyed, or otherwise lost. Bishop’s transcripts are often of value even when parish registers exist, as priests often recorded either additional or different information in their transcripts than they did in the original registers.”Unfortunately there was a gap in the Bishops Transcripts between 1704 and 1711 ~ exactly where I needed to look. I subsequently found out that the Elton registers were incomplete as they had been damaged by fire.

I estimated Robert Staleys date of birth between 1710 and 1715. He died in 1795, and his son Daniel died in 1805: both of these wills were found online. Daniel married Mary Moon in Stapenhill in 1762, making a likely birth date for Daniel around 1740.

The marriage of Robert Staley (assuming this was Robert’s father) and Alice Maceland (or Marsland or Marsden, depending on how the parish clerk chose to spell it presumably) was in the Bishops Transcripts for Elton in 1704. They were married in Elton on 26th February. There followed the missing parish register pages and in all likelihood the records of the baptisms of their first children. No doubt Robert was one of them, probably the first male child.

(Incidentally, my grandfather’s Marshalls also came from Elton, a small Derbyshire village near Matlock. The Staley’s are on my grandmothers Warren side.)

The parish register pages resume in 1711. One of the first entries was the baptism of Robert Staley in 1711, parents Thomas and Ann. This was surely the one we were looking for, and Roberts parents weren’t Robert and Alice.

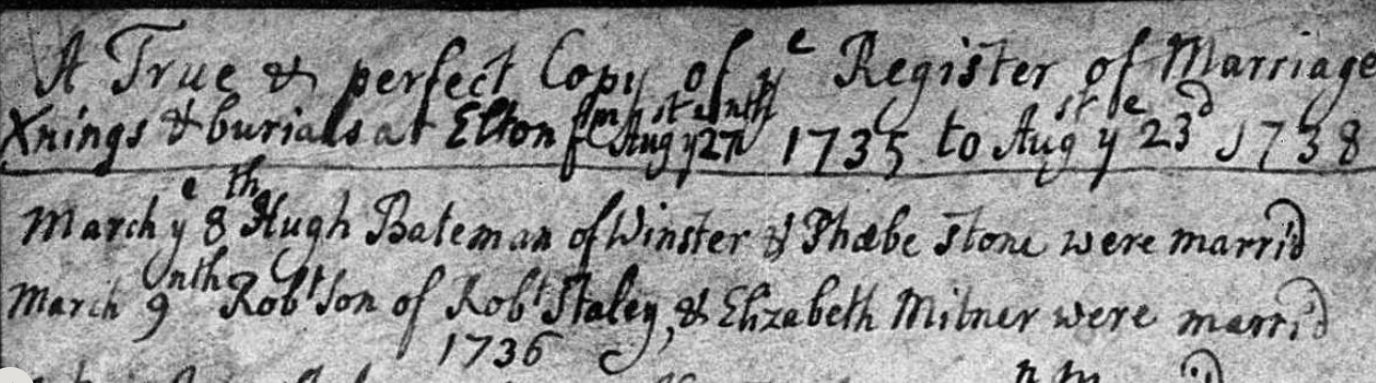

But then in 1735 a marriage was recorded between Robert son of Robert Staley (and this was unusual, the father of the groom isn’t usually recorded on the parish register) and Elizabeth Milner. They were married on the 9th March 1735. We know that the Robert we were looking for married an Elizabeth, as her name was on the Stapenhill baptisms of their later children, including Joseph Staleys. The 1735 marriage also fit with the assumed birth date of Daniel, circa 1740. A baptism was found for a Robert Staley in 1738 in the Elton registers, parents Robert and Elizabeth, as well as the baptism in 1736 for Mary, presumably their first child. Her burial is recorded the following year.

The marriage of Robert Staley and Elizabeth Milner in 1735:

There were several other Staley couples of a similar age in Elton, perhaps brothers and cousins. It seemed that Thomas and Ann’s son Robert was a different Robert, and that the one we were looking for was prior to that and on the missing pages.

Even so, this doesn’t prove that it was Elizabeth Staleys great grandfather who was born in Elton, but no other birth or baptism for Robert Staley has been found. It doesn’t explain why the Staleys moved to Stapenhill either, although the Enclosures Act and the Industrial Revolution could have been factors.

The 18th century saw the rise of the Industrial Revolution and many renowned Derbyshire Industrialists emerged. They created the turning point from what was until then a largely rural economy, to the development of townships based on factory production methods.

The Marsden Connection

There are some possible clues in the records of the Marsden family. Robert Staley married Alice Marsden (or Maceland or Marsland) in Elton in 1704. Robert Staley is mentioned in the 1730 will of John Marsden senior, of Baslow, Innkeeper (Peacock Inne & Whitlands Farm). He mentions his daughter Alice, wife of Robert Staley.

In a 1715 Marsden will there is an intriguing mention of an alias, which might explain the different spellings on various records for the name Marsden: “MARSDEN alias MASLAND, Christopher – of Baslow, husbandman, 28 Dec 1714. son Robert MARSDEN alias MASLAND….” etc.

Some potential reasons for a move from one parish to another are explained in this history of the Marsden family, and indeed this could relate to Robert Staley as he married into the Marsden family and his wife was a beneficiary of a Marsden will. The Chatsworth Estate, at various times, bought a number of farms in order to extend the park.

THE MARSDEN FAMILY

OXCLOSE AND PARKGATE

In the Parishes of

Baslow and Chatsworthby

David Dalrymple-Smith“John Marsden (b1653) another son of Edmund (b1611) faired well. By the time he died in

1730 he was publican of the Peacock, the Inn on Church Lane now called the Cavendish

Hotel, and the farmer at “Whitlands”, almost certainly Bubnell Cliff Farm.”“Coal mining was well known in the Chesterfield area. The coalfield extends as far as the

Gritstone edges, where thin seams outcrop especially in the Baslow area.”“…the occupants were evicted from the farmland below Dobb Edge and

the ground carefully cleared of all traces of occupation and farming. Shelter belts were

planted especially along the Heathy Lea Brook. An imposing new drive was laid to the

Chatsworth House with the Lodges and “The Golden Gates” at its northern end….”Although this particular event was later than any events relating to Robert Staley, it’s an indication of how farms and farmland disappeared, and a reason for families to move to another area:

“The Dukes of Devonshire (of Chatsworth) were major figures in the aristocracy and the government of the

time. Such a position demanded a display of wealth and ostentation. The 6th Duke of

Devonshire, the Bachelor Duke, was not content with the Chatsworth he inherited in 1811,

and immediately started improvements. After major changes around Edensor, he turned his

attention at the north end of the Park. In 1820 plans were made extend the Park up to the

Baslow parish boundary. As this would involve the destruction of most of the Farm at

Oxclose, the farmer at the Higher House Samuel Marsden (b1755) was given the tenancy of

Ewe Close a large farm near Bakewell.

Plans were revised in 1824 when the Dukes of Devonshire and Rutland “Exchanged Lands”,

reputedly during a game of dice. Over 3300 acres were involved in several local parishes, of

which 1000 acres were in Baslow. In the deal Devonshire acquired the southeast corner of

Baslow Parish.

Part of the deal was Gibbet Moor, which was developed for “Sport”. The shelf of land

between Parkgate and Robin Hood and a few extra fields was left untouched. The rest,

between Dobb Edge and Baslow, was agricultural land with farms, fields and houses. It was

this last part that gave the Duke the opportunity to improve the Park beyond his earlier

expectations.”The 1795 will of Robert Staley.

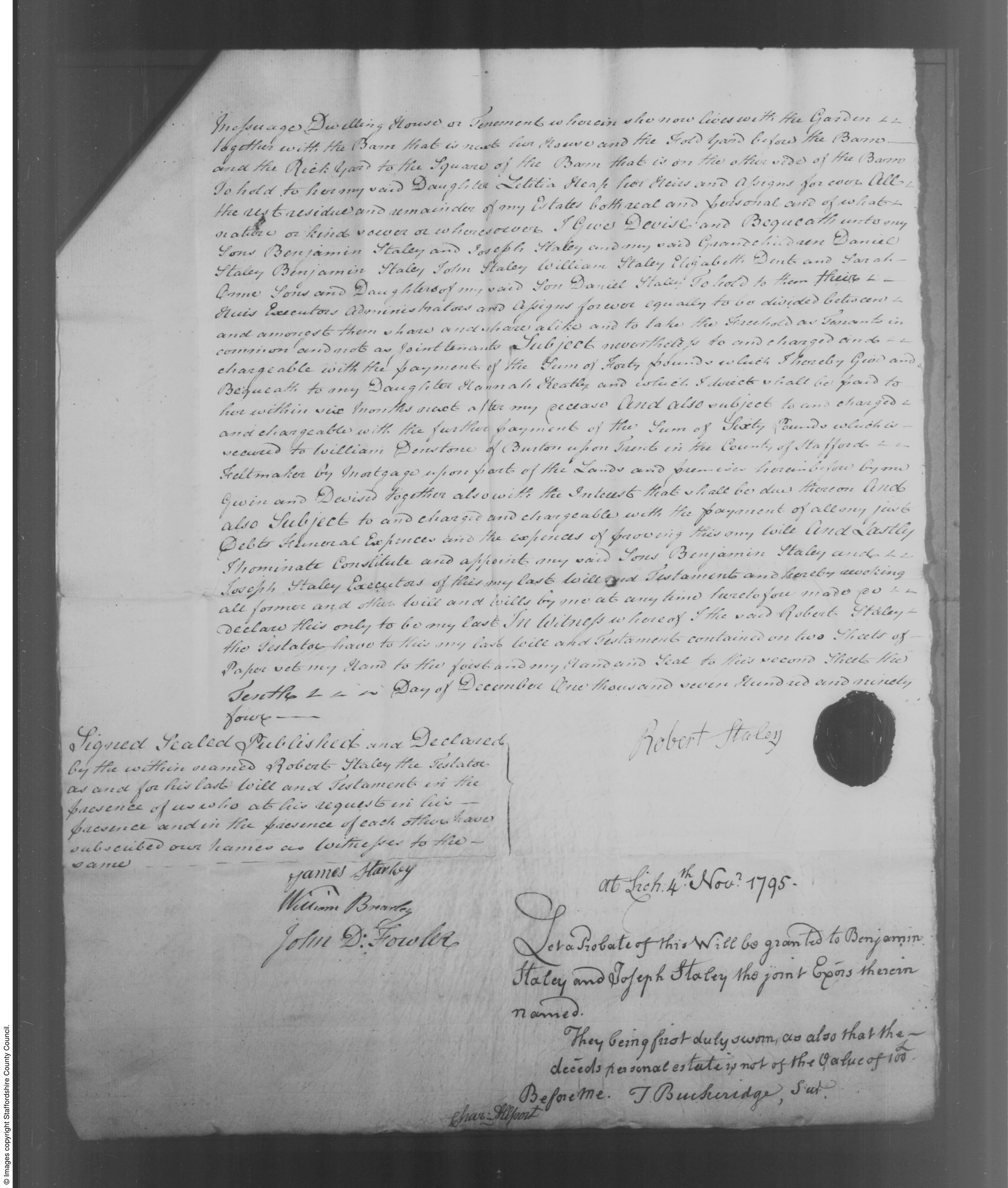

Inriguingly, Robert included the children of his son Daniel Staley in his will, but omitted to leave anything to Daniel. A perusal of Daniels 1808 will sheds some light on this: Daniel left his property to his six reputed children with Elizabeth Moon, and his reputed daughter Mary Brearly. Daniels wife was Mary Moon, Elizabeths husband William Moons daughter.

The will of Robert Staley, 1795:

The 1805 will of Daniel Staley, Robert’s son:

This is the last will and testament of me Daniel Staley of the Township of Newhall in the parish of Stapenhill in the County of Derby, Farmer. I will and order all of my just debts, funeral and testamentary expenses to be fully paid and satisfied by my executors hereinafter named by and out of my personal estate as soon as conveniently may be after my decease.

I give, devise and bequeath to Humphrey Trafford Nadin of Church Gresely in the said County of Derby Esquire and John Wilkinson of Newhall aforesaid yeoman all my messuages, lands, tenements, hereditaments and real and personal estates to hold to them, their heirs, executors, administrators and assigns until Richard Moon the youngest of my reputed sons by Elizabeth Moon shall attain his age of twenty one years upon trust that they, my said trustees, (or the survivor of them, his heirs, executors, administrators or assigns), shall and do manage and carry on my farm at Newhall aforesaid and pay and apply the rents, issues and profits of all and every of my said real and personal estates in for and towards the support, maintenance and education of all my reputed children by the said Elizabeth Moon until the said Richard Moon my youngest reputed son shall attain his said age of twenty one years and equally share and share and share alike.

And it is my will and desire that my said trustees or trustee for the time being shall recruit and keep up the stock upon my farm as they in their discretion shall see occasion or think proper and that the same shall not be diminished. And in case any of my said reputed children by the said Elizabeth Moon shall be married before my said reputed youngest son shall attain his age of twenty one years that then it is my will and desire that non of their husbands or wives shall come to my farm or be maintained there or have their abode there. That it is also my will and desire in case my reputed children or any of them shall not be steady to business but instead shall be wild and diminish the stock that then my said trustees or trustee for the time being shall have full power and authority in their discretion to sell and dispose of all or any part of my said personal estate and to put out the money arising from the sale thereof to interest and to pay and apply the interest thereof and also thereunto of the said real estate in for and towards the maintenance, education and support of all my said reputed children by the said

Elizabeth Moon as they my said trustees in their discretion that think proper until the said Richard Moon shall attain his age of twenty one years.Then I give to my grandson Daniel Staley the sum of ten pounds and to each and every of my sons and daughters namely Daniel Staley, Benjamin Staley, John Staley, William Staley, Elizabeth Dent and Sarah Orme and to my niece Ann Brearly the sum of five pounds apiece.

I give to my youngest reputed son Richard Moon one share in the Ashby Canal Navigation and I direct that my said trustees or trustee for the time being shall have full power and authority to pay and apply all or any part of the fortune or legacy hereby intended for my youngest reputed son Richard Moon in placing him out to any trade, business or profession as they in their discretion shall think proper.

And I direct that to my said sons and daughters by my late wife and my said niece shall by wholly paid by my said reputed son Richard Moon out of the fortune herby given him. And it is my will and desire that my said reputed children shall deliver into the hands of my executors all the monies that shall arise from the carrying on of my business that is not wanted to carry on the same unto my acting executor and shall keep a just and true account of all disbursements and receipts of the said business and deliver up the same to my acting executor in order that there may not be any embezzlement or defraud amongst them and from and immediately after my said reputed youngest son Richard Moon shall attain his age of twenty one years then I give, devise and bequeath all my real estate and all the residue and remainder of my personal estate of what nature and kind whatsoever and wheresoever unto and amongst all and every my said reputed sons and daughters namely William Moon, Thomas Moon, Joseph Moon, Richard Moon, Ann Moon, Margaret Moon and to my reputed daughter Mary Brearly to hold to them and their respective heirs, executors, administrator and assigns for ever according to the nature and tenure of the same estates respectively to take the same as tenants in common and not as joint tenants.And lastly I nominate and appoint the said Humphrey Trafford Nadin and John Wilkinson executors of this my last will and testament and guardians of all my reputed children who are under age during their respective minorities hereby revoking all former and other wills by me heretofore made and declaring this only to be my last will.

In witness whereof I the said Daniel Staley the testator have to this my last will and testament set my hand and seal the eleventh day of March in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and five.

June 10, 2022 at 1:39 pm #6305In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

The Hair’s and Leedham’s of Netherseal

Samuel Warren of Stapenhill married Catherine Holland of Barton under Needwood in 1795. Catherine’s father was Thomas Holland; her mother was Hannah Hair.

Hannah was born in Netherseal, Derbyshire, in 1739. Her parents were Joseph Hair 1696-1746 and Hannah.

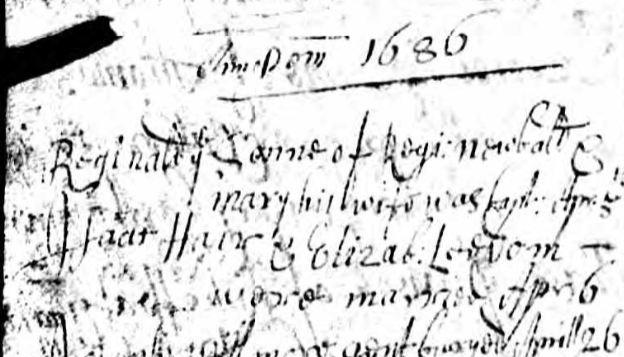

Joseph’s parents were Isaac Hair and Elizabeth Leedham. Elizabeth was born in Netherseal in 1665. Isaac and Elizabeth were married in Netherseal in 1686.Marriage of Isaac Hair and Elizabeth Leedham: (variously spelled Ledom, Leedom, Leedham, and in one case mistranscribed as Sedom):

Isaac was buried in Netherseal on 14 August 1709 (the transcript says the 18th, but the microfiche image clearly says the 14th), but I have not been able to find a birth registered for him. On other public trees on an ancestry website, Isaac Le Haire was baptised in Canterbury and was a Huguenot, but I haven’t found any evidence to support this.

Isaac Hair’s death registered 14 August 1709 in Netherseal:

A search for the etymology of the surname Hair brings various suggestions, including:

“This surname is derived from a nickname. ‘the hare,’ probably affixed on some one fleet of foot. Naturally looked upon as a complimentary sobriquet, and retained in the family; compare Lightfoot. (for example) Hugh le Hare, Oxfordshire, 1273. Hundred Rolls.”

From this we may deduce that the name Hair (or Hare) is not necessarily from the French Le Haire, and existed in England for some considerable time before the arrival of the Huguenots.

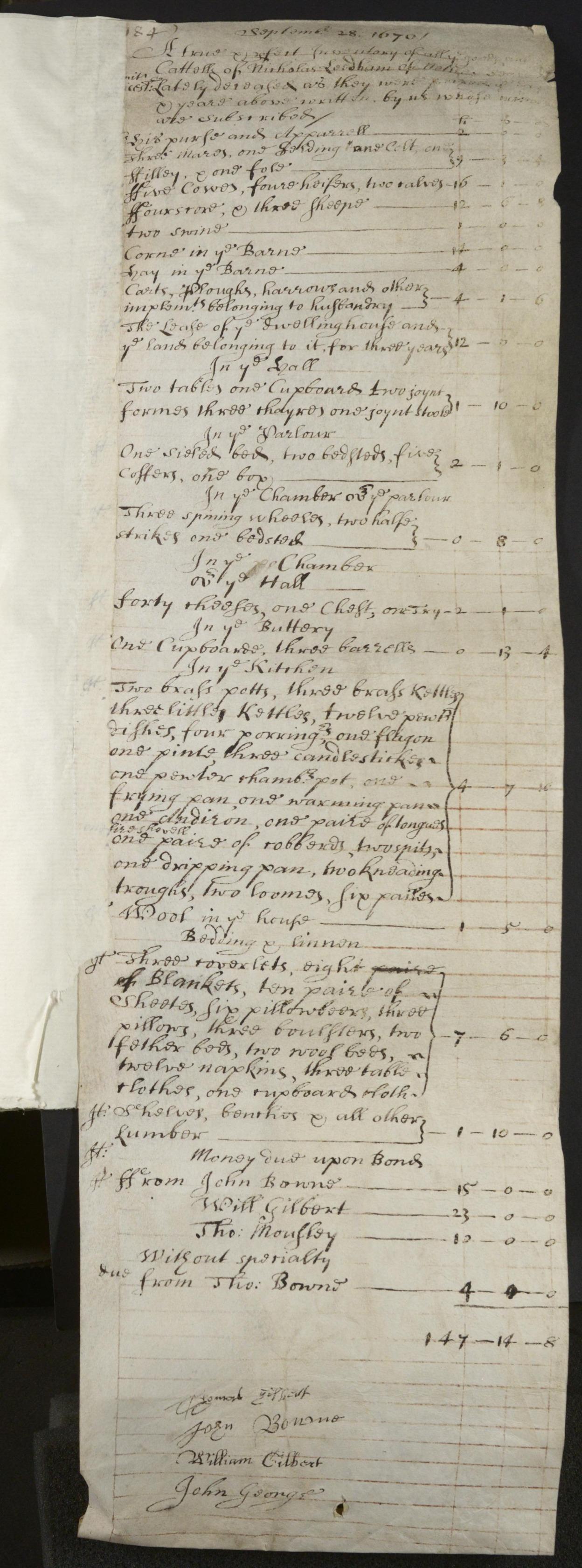

Elizabeth Leedham was born in Netherseal in 1665. Her parents were Nicholas Leedham 1621-1670 and Dorothy. Nicholas Leedham was born in Church Gresley (Swadlincote) in 1621, and died in Netherseal in 1670.

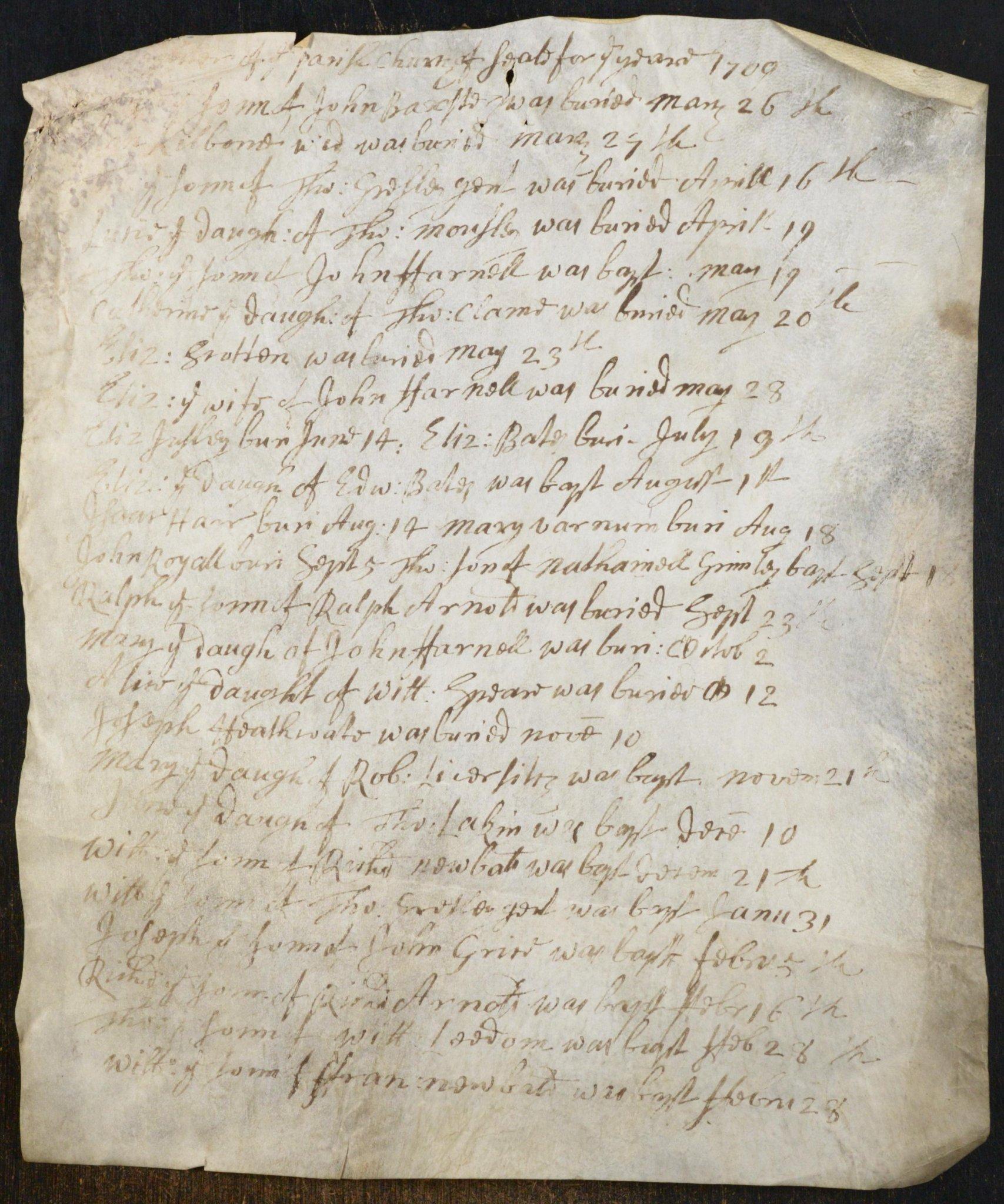

Nicholas was a Yeoman and left a will and inventory worth £147.14s.8d (one hundred and forty seven pounds fourteen shillings and eight pence).

The 1670 inventory of Nicholas Leedham:

According to local historian Mark Knight on the Netherseal History facebook group, the Seale (Netherseal and Overseal) parish registers from the year 1563 to 1724 were digitized during lockdown.

via Mark Knight:

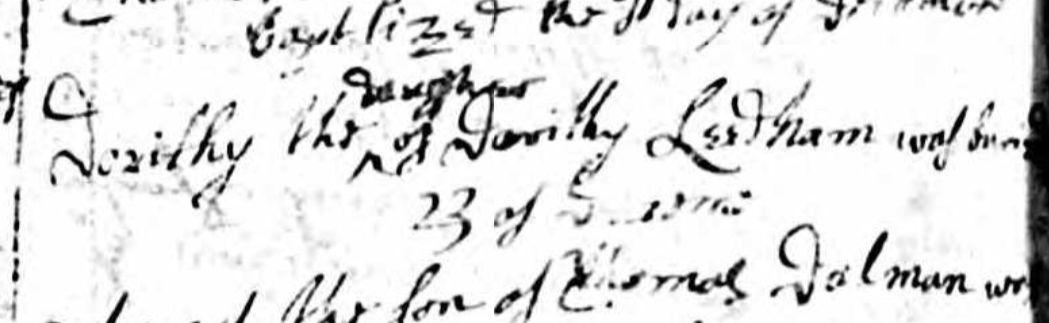

“There are five entries for Nicholas Leedham.

On March 14th 1646 he and his wife buried an unnamed child, presumably the child died during childbirth or was stillborn.

On November 28th 1659 he buried his wife, Elizabeth. He remarried as on June 13th 1664 he had his son William baptised.

The following year, 1665, he baptised a daughter on November 12th. (Elizabeth) On December 23rd 1672 the parish record says that Dorithy daughter of Dorithy was buried. The Bishops Transcript has Dorithy a daughter of Nicholas. Nicholas’ second wife was called Dorithy and they named a daughter after her. Alas, the daughter died two years after Nicholas. No further Leedhams appear in the record until after 1724.”Dorothy daughter of Dorothy Leedham was buried 23 December 1672:

William, son of Nicholas and Dorothy also left a will. In it he mentions “My dear wife Elizabeth. My children Thomas Leedom, Dorothy Leedom , Ann Leedom, Christopher Leedom and William Leedom.”

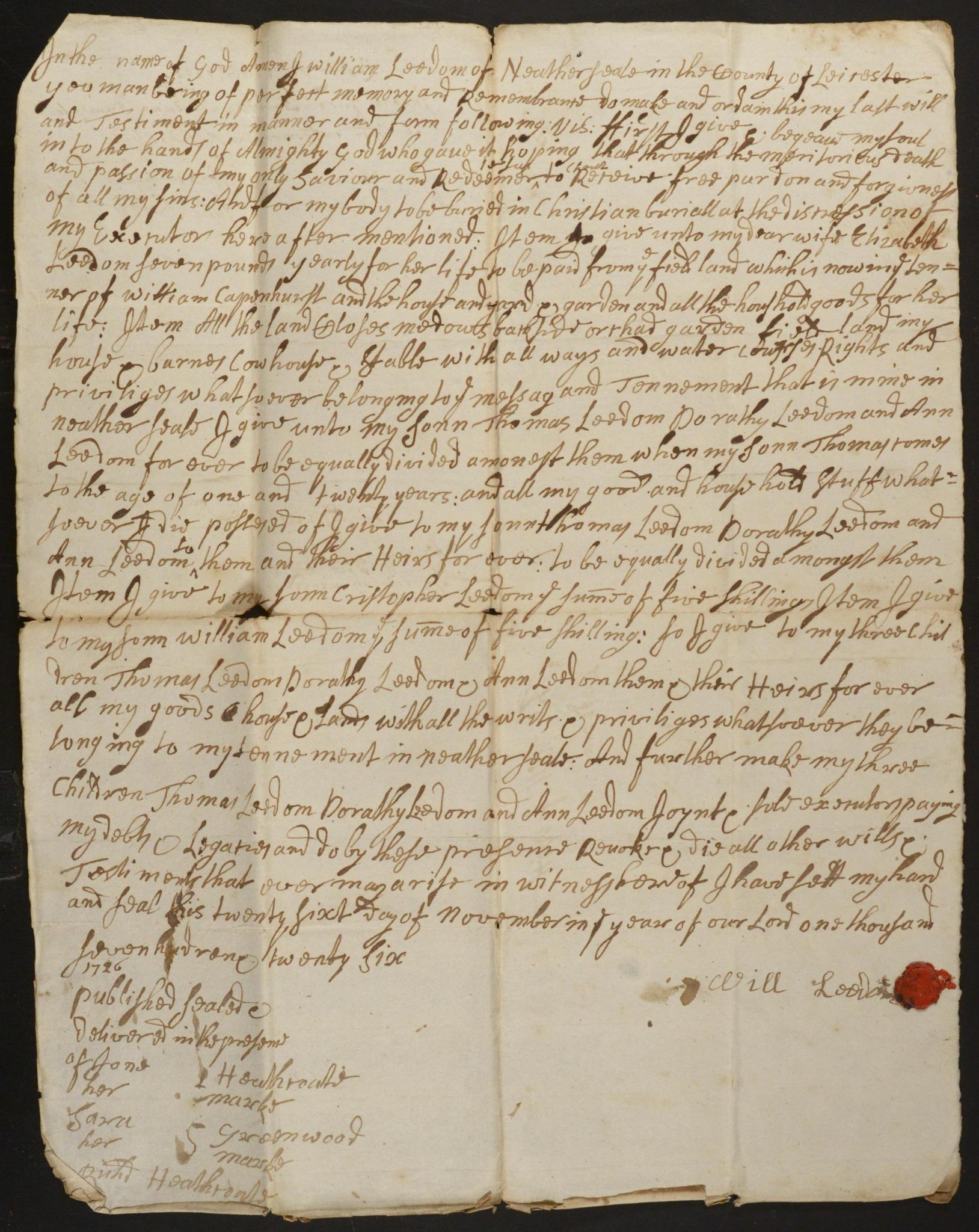

1726 will of William Leedham:

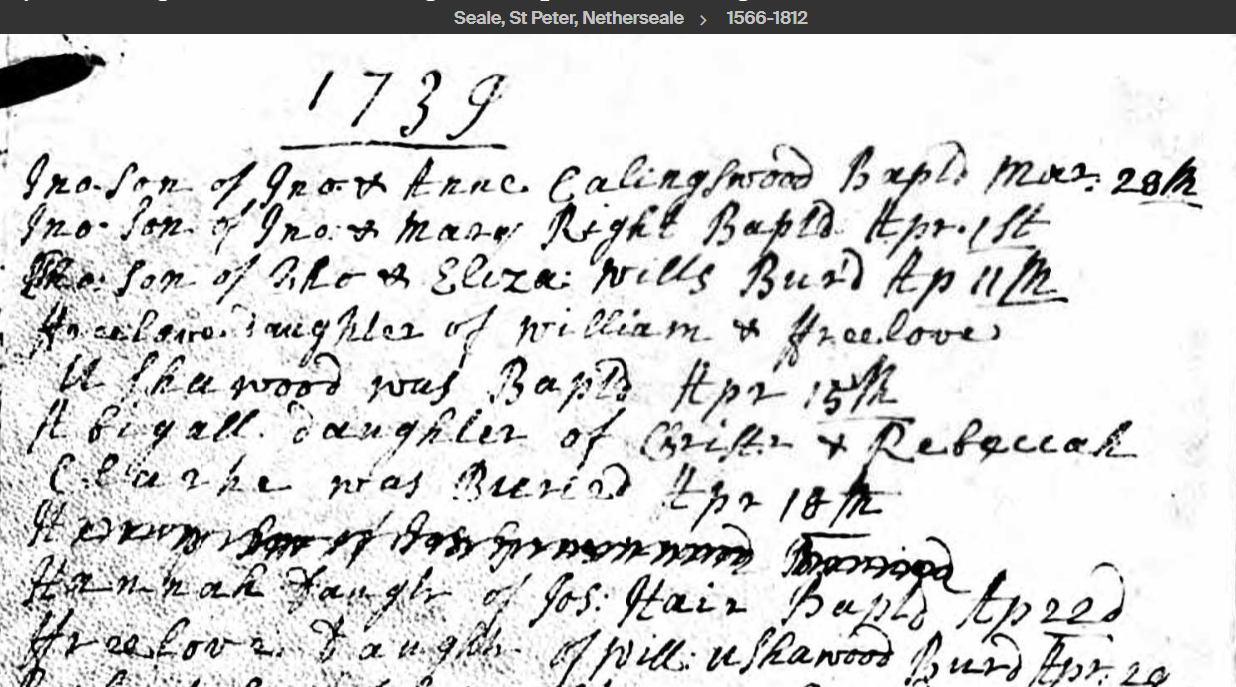

I found a curious error with the the parish register entries for Hannah Hair. It was a transcription error, but not a recent one. The original parish registers were copied: “HO Copy of ye register of Seale anno 1739.” I’m not sure when the copy was made, but it wasn’t recently. I found a burial for Hannah Hair on 22 April 1739 in the HO copy, which was the same day as her baptism registered on the original. I checked both registers name by name and they are exactly copied EXCEPT for Hannah Hairs. The rector, Richard Inge, put burial instead of baptism by mistake.

The original Parish register baptism of Hannah Hair:

The HO register copy incorrectly copied:

June 6, 2022 at 9:17 am #6301

June 6, 2022 at 9:17 am #6301In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

The Warrens of Stapenhill

There were so many Warren’s in Stapenhill that it was complicated to work out who was who. I had gone back as far as Samuel Warren marrying Catherine Holland, and this was as far back as my cousin Ian Warren had gone in his research some decades ago as well. The Holland family from Barton under Needwood are particularly interesting, and will be a separate chapter.

Stapenhill village by John Harden:

Resuming the research on the Warrens, Samuel Warren 1771-1837 married Catherine Holland 1775-1861 in 1795 and their son Samuel Warren 1800-1882 married Elizabeth Bridge, whose childless brother Benjamin Bridge left the Warren Brothers Boiler Works in Newhall to his nephews, the Warren brothers.

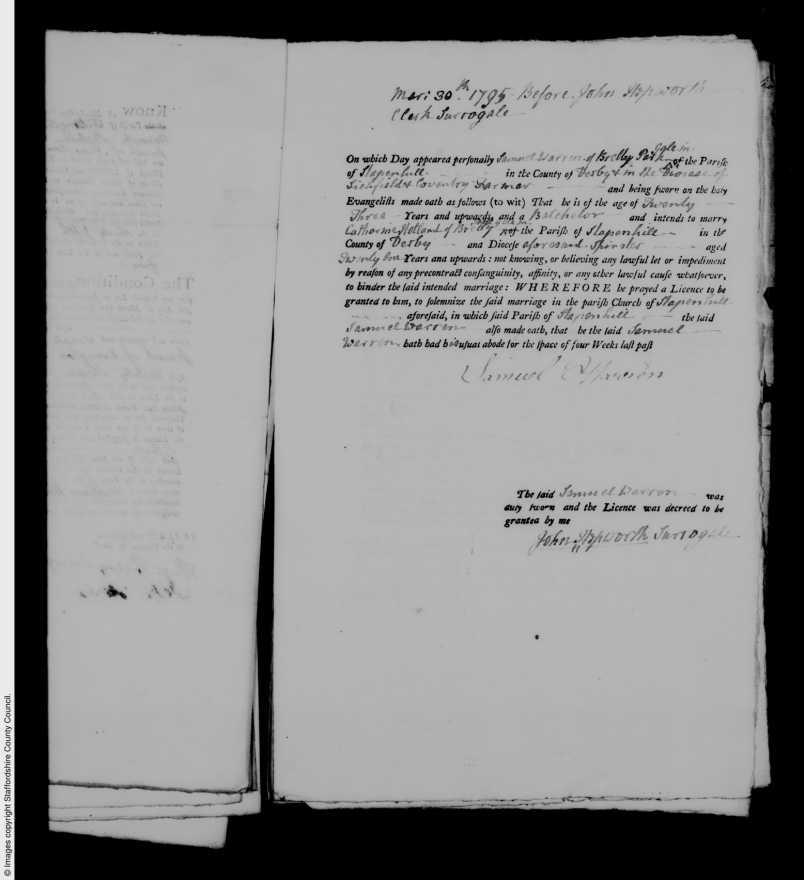

Samuel Warren and Catherine Holland marriage licence 1795:

Samuel (born 1771) was baptised at Stapenhill St Peter and his parents were William and Anne Warren. There were at least three William and Ann Warrens in town at the time. One of those William’s was born in 1744, which would seem to be the right age to be Samuel’s father, and one was born in 1710, which seemed a little too old. Another William, Guiliamos Warren (Latin was often used in early parish registers) was baptised in Stapenhill in 1729.

Stapenhill St Peter:

William Warren (born 1744) appeared to have been born several months before his parents wedding. William Warren and Ann Insley married 16 July 1744, but the baptism of William in 1744 was 24 February. This seemed unusual ~ children were often born less than nine months after a wedding, but not usually before the wedding! Then I remembered the change from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar in 1752. Prior to 1752, the first day of the year was Lady Day, March 25th, not January 1st. This meant that the birth in February 1744 was actually after the wedding in July 1744. Now it made sense. The first son was named William, and he was born seven months after the wedding.

William born in 1744 died intestate in 1822, and his wife Ann made a legal claim to his estate. However he didn’t marry Ann Holland (Ann was Catherines Hollands sister, who married Samuel Warren the year before) until 1796, so this William and Ann were not the parents of Samuel.

It seemed likely that William born in 1744 was Samuels brother. William Warren and Ann Insley had at least eight children between 1744 and 1771, and it seems that Samuel was their last child, born when William the elder was 61 and his wife Ann was 47.

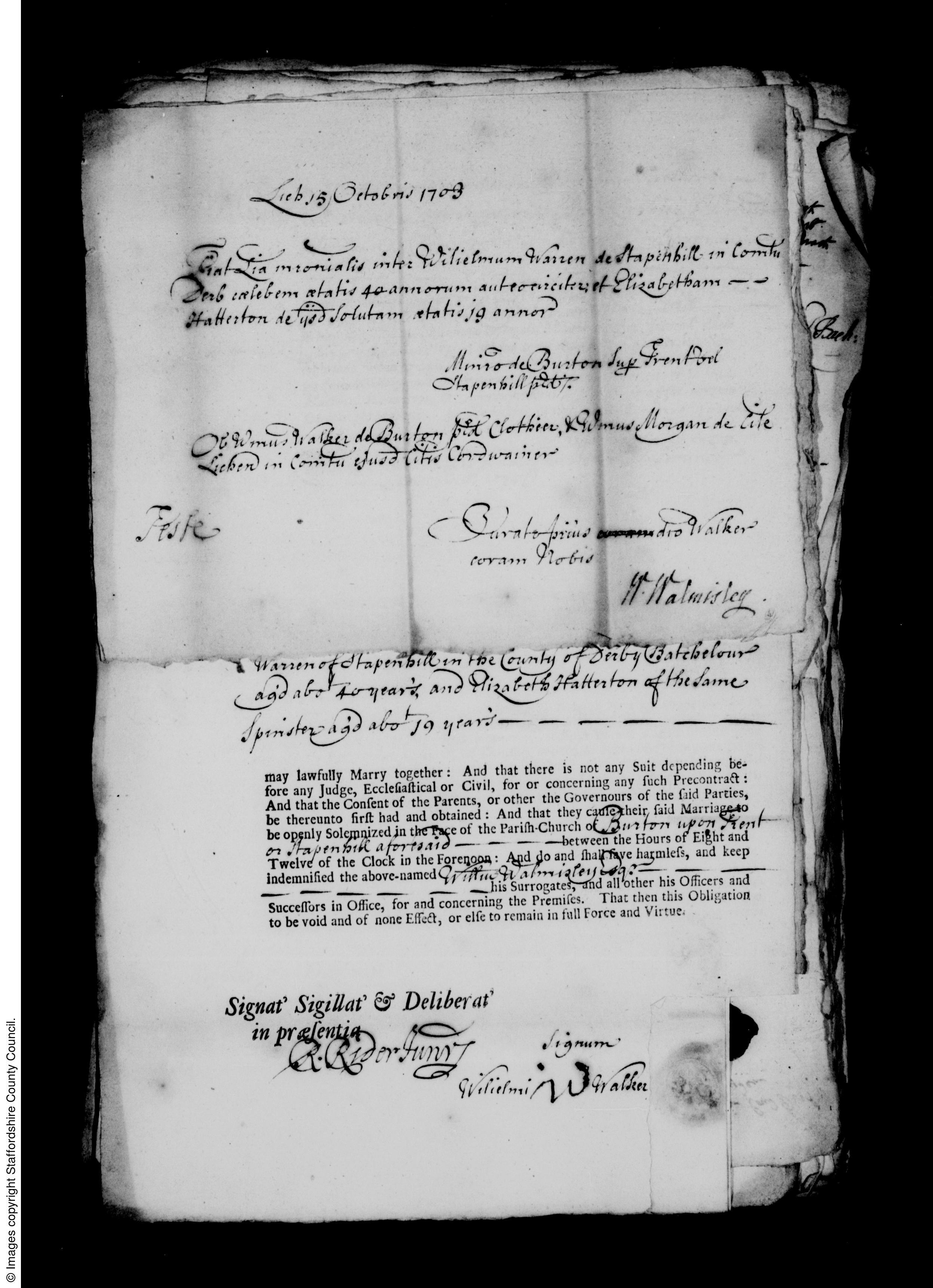

It seems it wasn’t unusual for the Warren men to marry rather late in life. William Warren’s (born 1710) parents were William Warren and Elizabeth Hatterton. On the marriage licence in 1702/1703 (it appears to say 1703 but is transcribed as 1702), William was a 40 year old bachelor from Stapenhill, which puts his date of birth at 1662. Elizabeth was considerably younger, aged 19.

William Warren and Elizabeth Hatterton marriage licence 1703:

These Warren’s were farmers, and they were literate and able to sign their own names on various documents. This is worth noting, as most made the mark of an X.

I found three Warren and Holland marriages. One was Samuel Warren and Catherine Holland in 1795, then William Warren and Ann Holland in 1796. William Warren and Ann Hollands daughter born in 1799 married John Holland in 1824.

Elizabeth Hatterton (wife of William Warren who was born circa 1662) was born in Burton upon Trent in 1685. Her parents were Edward Hatterton 1655-1722, and Sara.

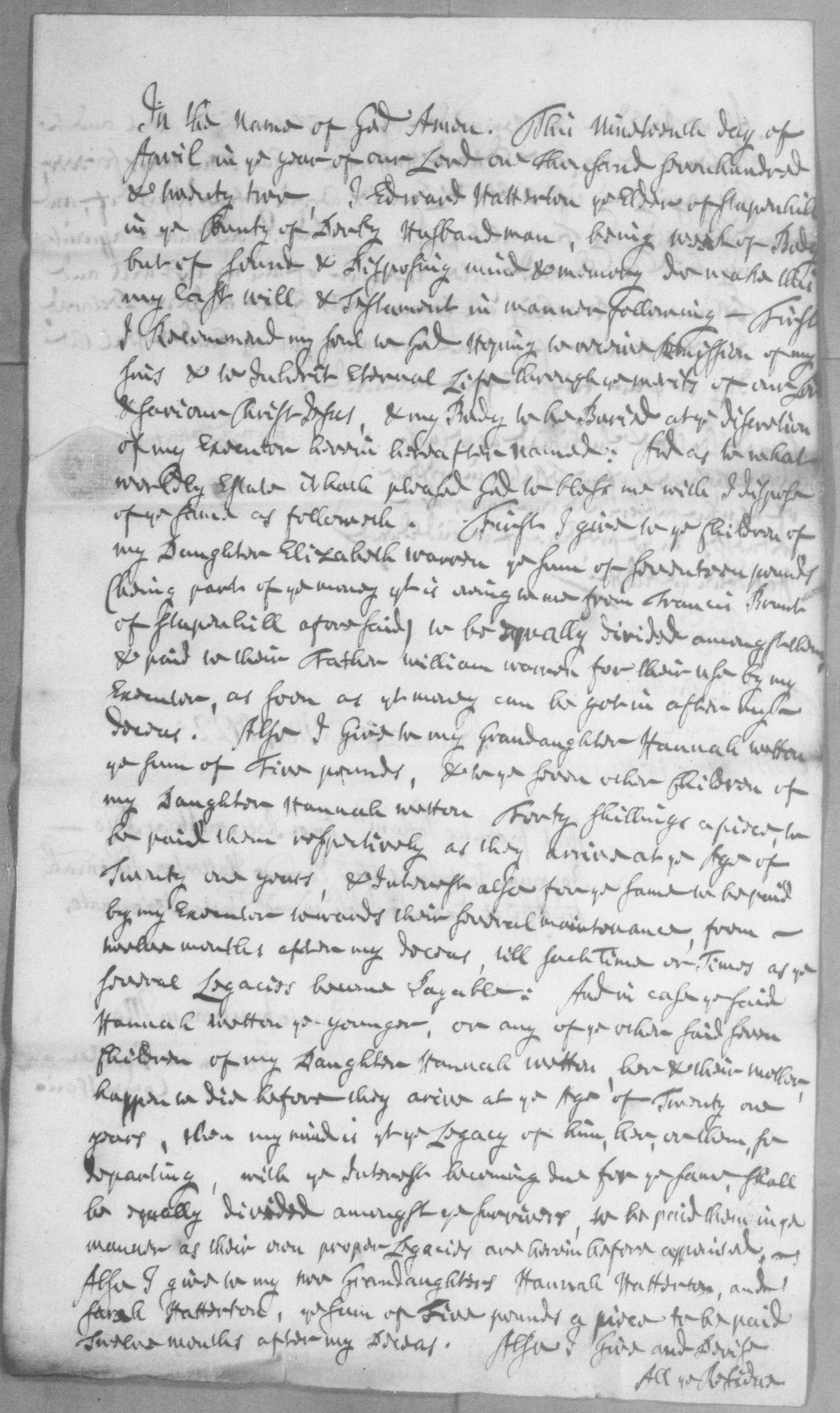

A page from the 1722 will of Edward Hatterton:

The earliest Warren I found records for was William Warren who married Elizabeth Hatterton in 1703. The marriage licence states his age as 40 and that he was from Stapenhill, but none of the Stapenhill parish records online go back as far as 1662. On other public trees on ancestry websites, a birth record from Suffolk has been chosen, probably because it was the only record to be found online with the right name and date. Once again, I don’t think that is correct, and perhaps one day I’ll find some earlier Stapenhill records to prove that he was born in locally.

Subsequently, I found a list of the 1662 Hearth Tax for Stapenhill. On it were a number of Warrens, three William Warrens including one who was a constable. One of those William Warrens had a son he named William (as they did, hence the number of William Warrens in the tree) the same year as this hearth tax list.

But was it the William Warren with 2 chimneys, the one with one chimney who was too poor to pay it, or the one who was a constable?

from the list:

Will. Warryn 2

Richard Warryn 1

William Warren Constable

These names are not payable by Act:

Will. Warryn 1

Richard Warren John Watson

over seers of the poore and churchwardensThe Hearth Tax:

via wiki:

In England, hearth tax, also known as hearth money, chimney tax, or chimney money, was a tax imposed by Parliament in 1662, to support the Royal Household of King Charles II. Following the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, Parliament calculated that the Royal Household needed an annual income of £1,200,000. The hearth tax was a supplemental tax to make up the shortfall. It was considered easier to establish the number of hearths than the number of heads, hearths forming a more stationary subject for taxation than people. This form of taxation was new to England, but had precedents abroad. It generated considerable debate, but was supported by the economist Sir William Petty, and carried through the Commons by the influential West Country member Sir Courtenay Pole, 2nd Baronet (whose enemies nicknamed him “Sir Chimney Poll” as a result). The bill received Royal Assent on 19 May 1662, with the first payment due on 29 September 1662, Michaelmas.

One shilling was liable to be paid for every firehearth or stove, in all dwellings, houses, edifices or lodgings, and was payable at Michaelmas, 29 September and on Lady Day, 25 March. The tax thus amounted to two shillings per hearth or stove per year. The original bill contained a practical shortcoming in that it did not distinguish between owners and occupiers and was potentially a major burden on the poor as there were no exemptions. The bill was subsequently amended so that the tax was paid by the occupier. Further amendments introduced a range of exemptions that ensured that a substantial proportion of the poorer people did not have to pay the tax.Indeed it seems clear that William Warren the elder came from Stapenhill and not Suffolk, and one of the William Warrens paying hearth tax in 1662 was undoubtedly the father of William Warren who married Elizabeth Hatterton.

May 27, 2022 at 8:25 am #6300In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Looking for Carringtons

The Carringtons of Smalley, at least some of them, were Baptist ~ otherwise known as “non conformist”. Baptists don’t baptise at birth, believing it’s up to the person to choose when they are of an age to do so, although that appears to be fairly random in practice with small children being baptised. This makes it hard to find the birth dates registered as not every village had a Baptist church, and the baptisms would take place in another town. However some of the children were baptised in the village Anglican church as well, so they don’t seem to have been consistent. Perhaps at times a quick baptism locally for a sickly child was considered prudent, and preferable to no baptism at all. It’s impossible to know for sure and perhaps they were not strictly commited to a particular denomination.

Our Carrington’s start with Ellen Carrington who married William Housley in 1814. William Housley was previously married to Ellen’s older sister Mary Carrington. Ellen (born 1895 and baptised 1897) and her sister Nanny were baptised at nearby Ilkeston Baptist church but I haven’t found baptisms for Mary or siblings Richard and Francis. We know they were also children of William Carrington as he mentions them in his 1834 will. Son William was baptised at the local Smalley church in 1784, as was Thomas in 1896.

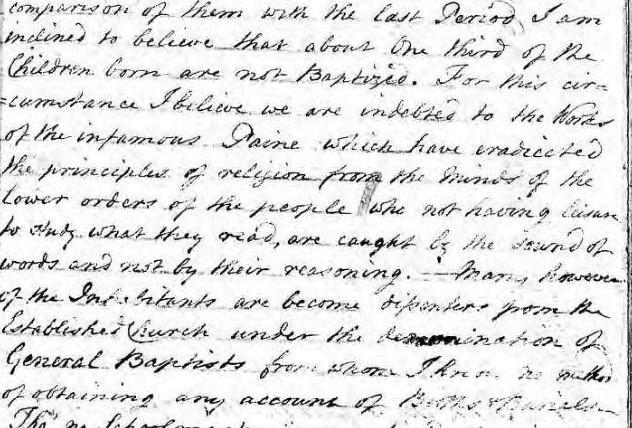

The absence of baptisms in Smalley with regard to Baptist influence was noted in the Smalley registers:

Smalley (chapelry of Morley) registers began in 1624, Morley registers began in 1540 with no obvious gaps in either. The gap with the missing registered baptisms would be 1786-1793. The Ilkeston Baptist register began in 1791. Information from the Smalley registers indicates that about a third of the children were not being baptised due to the Baptist influence.

William Housley son in law, daughter Mary Housley deceased, and daughter Eleanor (Ellen) Housley are all mentioned in William Housley’s 1834 will. On the marriage allegations and bonds for William Housley and Mary Carrington in 1806, her birth date is registered at 1787, her father William Carrington.

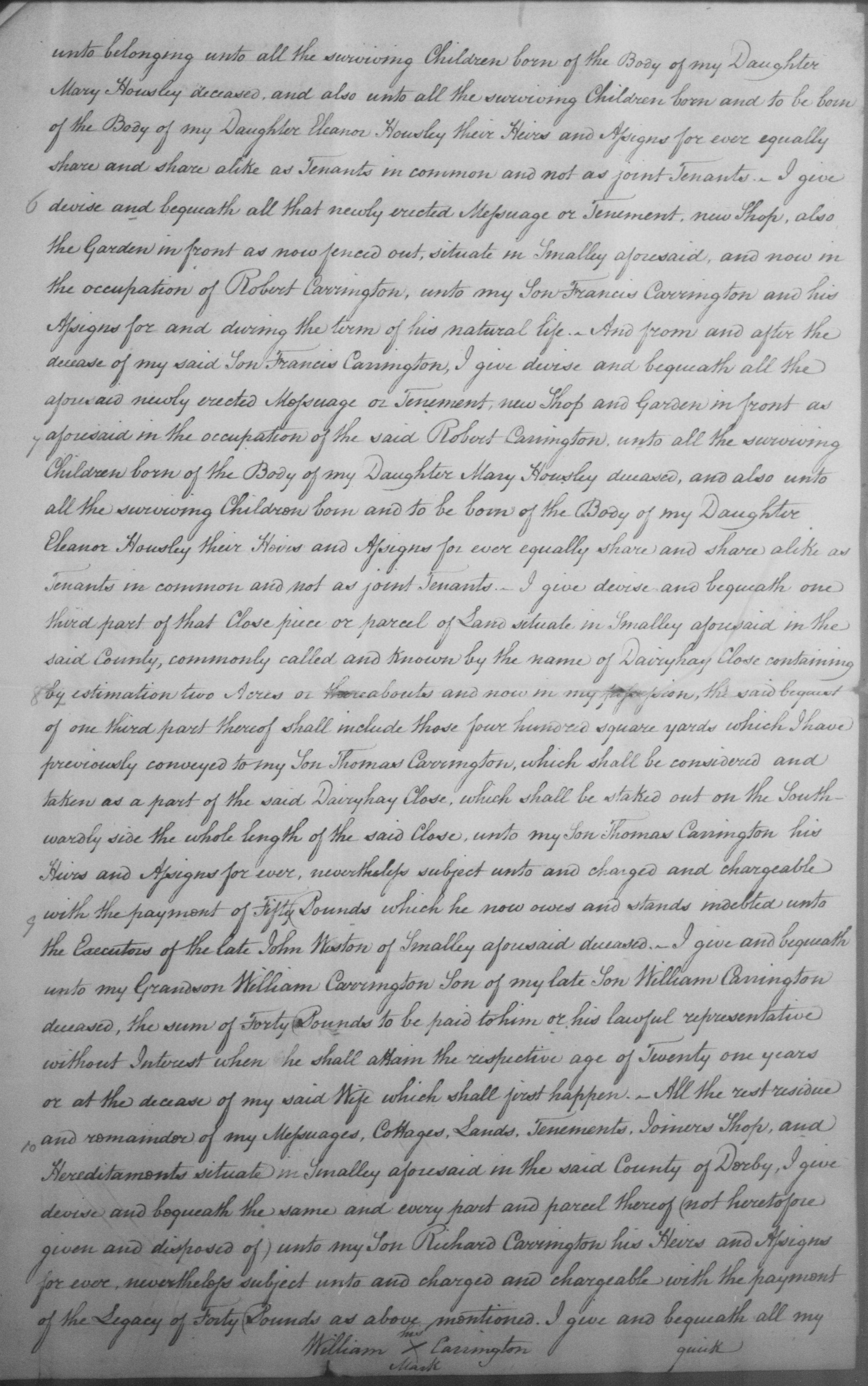

A Page from the will of William Carrington 1834:

William Carrington was baptised in nearby Horsley Woodhouse on 27 August 1758. His parents were William and Margaret Carrington “near the Hilltop”. He married Mary Malkin, also of Smalley, on the 27th August 1783.

When I started looking for Margaret Wright who married William Carrington the elder, I chanced upon the Smalley parish register micro fiche images wrongly labeled by the ancestry site as Longford. I subsequently found that the Derby Records office published a list of all the wrongly labeled Derbyshire towns that the ancestry site knew about for ten years at least but has not corrected!

Margaret Wright was baptised in Smalley (mislabeled as Longford although the register images clearly say Smalley!) on the 2nd March 1728. Her parents were John and Margaret Wright.

But I couldn’t find a birth or baptism anywhere for William Carrington. I found four sources for William and Margaret’s marriage and none of them suggested that William wasn’t local. On other public trees on ancestry sites, William’s father was Joshua Carrington from Chinley. Indeed, when doing a search for William Carrington born circa 1720 to 1725, this was the only one in Derbyshire. But why would a teenager move to the other side of the county? It wasn’t uncommon to be apprenticed in neighbouring villages or towns, but Chinley didn’t seem right to me. It seemed to me that it had been selected on the other trees because it was the only easily found result for the search, and not because it was the right one.

I spent days reading every page of the microfiche images of the parish registers locally looking for Carringtons, any Carringtons at all in the area prior to 1720. Had there been none at all, then the possibility of William being the first Carrington in the area having moved there from elsewhere would have been more reasonable.

But there were many Carringtons in Heanor, a mile or so from Smalley, in the 1600s and early 1700s, although they were often spelled Carenton, sometimes Carrianton in the parish registers. The earliest Carrington I found in the area was Alice Carrington baptised in Ilkeston in 1602. It seemed obvious that William’s parents were local and not from Chinley.

The Heanor parish registers of the time were not very clearly written. The handwriting was bad and the spelling variable, depending I suppose on what the name sounded like to the person writing in the registers at the time as the majority of the people were probably illiterate. The registers are also in a generally poor condition.

I found a burial of a child called William on the 16th January 1721, whose father was William Carenton of “Losko” (Loscoe is a nearby village also part of Heanor at that time). This looked promising! If a child died, a later born child would be given the same name. This was very common: in a couple of cases I’ve found three deceased infants with the same first name until a fourth one named the same survived. It seemed very likely that a subsequent son would be named William and he would be the William Carrington born circa 1720 to 1725 that we were looking for.

Heanor parish registers: William son of William Carenton of Losko buried January 19th 1721:

The Heanor parish registers between 1720 and 1729 are in many places illegible, however there are a couple of possibilities that could be the baptism of William in 1724 and 1725. A William son of William Carenton of Loscoe was buried in Jan 1721. In 1722 a Willian son of William Carenton (transcribed Tarenton) of Loscoe was buried. A subsequent son called William is likely. On 15 Oct 1724 a William son of William and Eliz (last name indecipherable) of Loscoe was baptised. A Mary, daughter of William Carrianton of Loscoe, was baptised in 1727.

I propose that William Carringtons was born in Loscoe and baptised in Heanor in 1724: if not 1724 then I would assume his baptism is one of the illegible or indecipherable entires within those few years. This falls short of absolute documented proof of course, but it makes sense to me.

In any case, if a William Carrington child died in Heanor in 1721 which we do have documented proof of, it further dismisses the case for William having arrived for no discernable reason from Chinley.

May 21, 2022 at 9:34 am #6299In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

Looking at the blemish feverish man on the camp bed, General Lyaksandro Rudechenko clenched his fists. The wooden leg, that had been the symbol of the Oocranian Resistance for the last year was now lying on the floor. President Voldomeer had contracted a virus that confounded their best doctors and the remaining chiefs of the Oocranian Resistance feared he would soon join the men fallen for their country.

— Nobody must know that the sexiest man of Oocrane is incapacitated. We need a replacement, said the General.

— President Voldomeer told me of a man, the very man who made that wooden leg, said Major Myroslava Kovalev, the candle light reflecting in her glass eye. He lives in the Dumbass region. He’s a secret twin or something, President Voldomeer was not so clear about that part, but at least they look alike. To make it more real, we can have his leg removed, she added pointing at the wooden leg.

She was proud of being one of the only women ranking that high in the military. His fellow people might not be Lazies, but they had some old idea about women, that were not the best choice for fighting. Myroslava had always wanted to prove them wrong, and this conflict had been her chance to rise almost to the top. She looked at the dying man who was once her ladder. He had been sexy, and certainly could do many things with his wooden leg. Now he was but the shadow of a man, pale and blurry as cataract. If she had loved him, she might have shed a tear.

Myroslava looked at General Rudechenko’s pockmarked face and shivered. She wouldn’t even share a cab with him. But he was the next in command, and before Voldomeer fell ill, she was on her way to take his place, even closer to the top.

— Let me bring him to you, she added.

— That’s a suicide mission, said the general. Permission granted.

— Thank you General ! said Myroslava doing the military salute before leaving the tent.

Despite his being from Dumbass and having made some mistakes in his life, Lyaksandro was not stupid. He knew quite well what that woman wanted. He called, Glib, his aide-de-camp.

— Make sure she gets lost behind the enemy lines.

April 12, 2022 at 8:13 am #6290In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

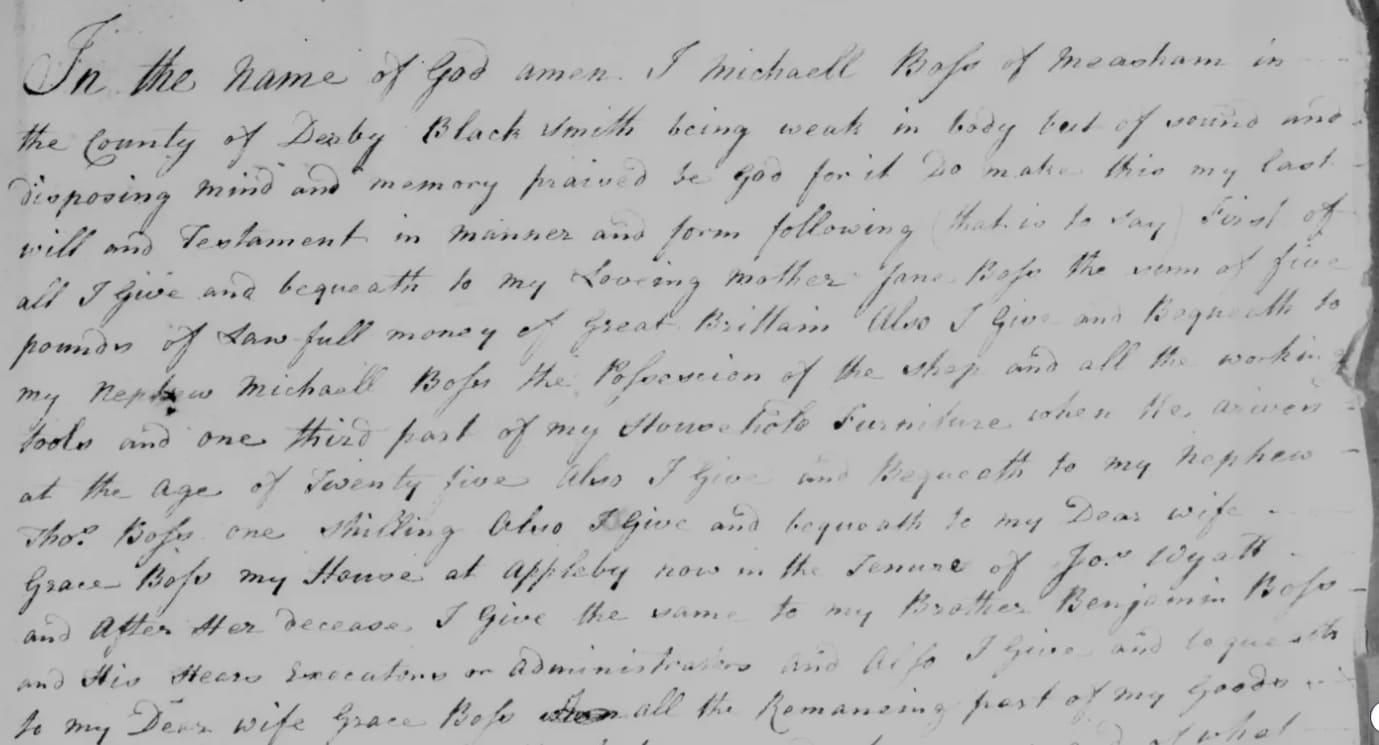

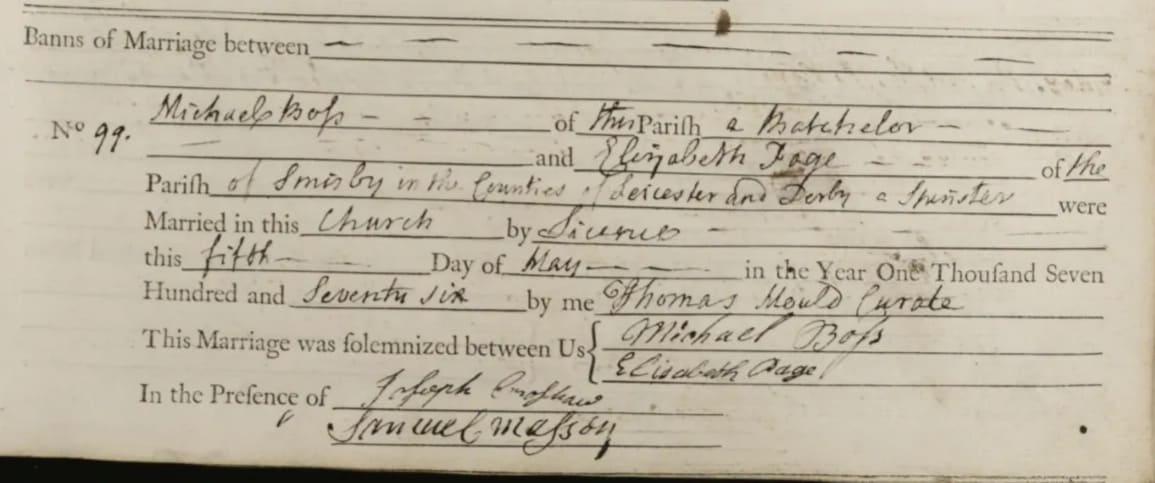

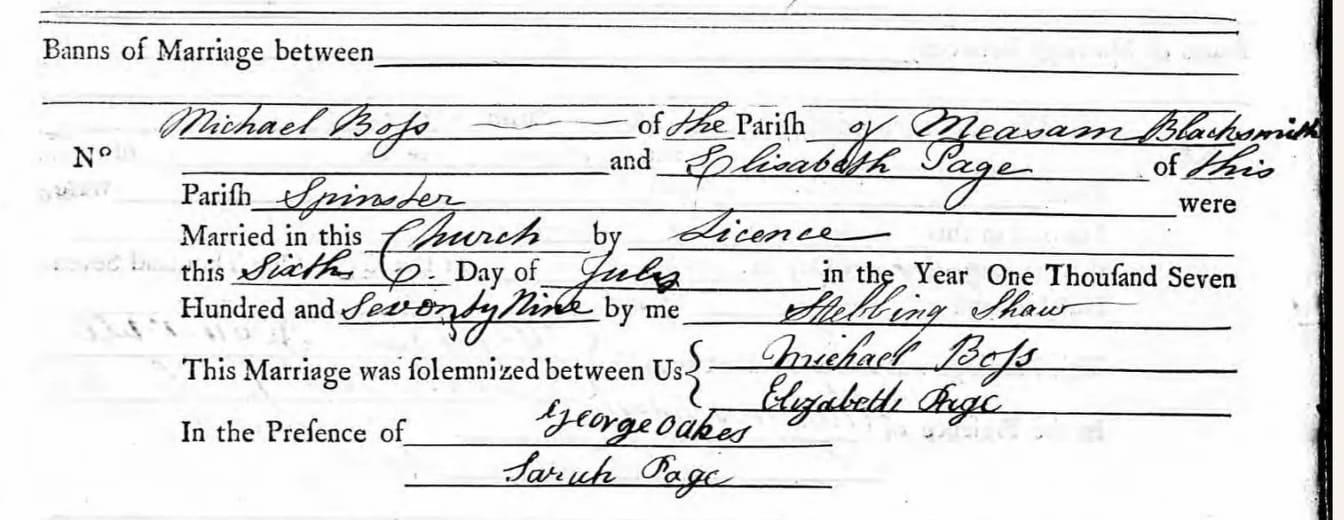

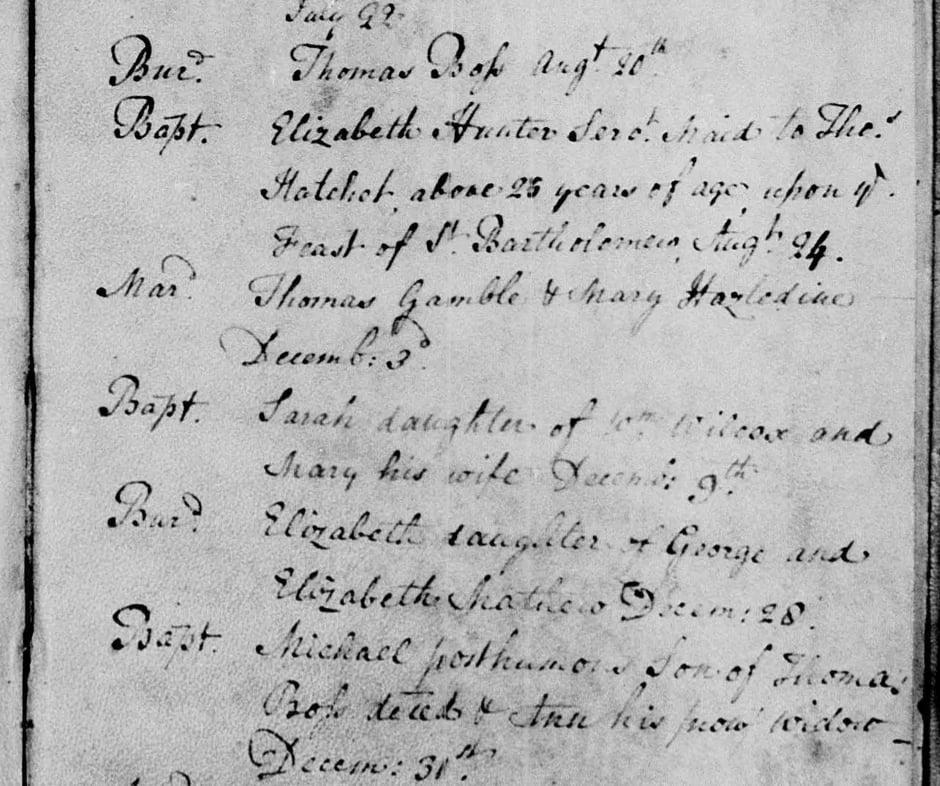

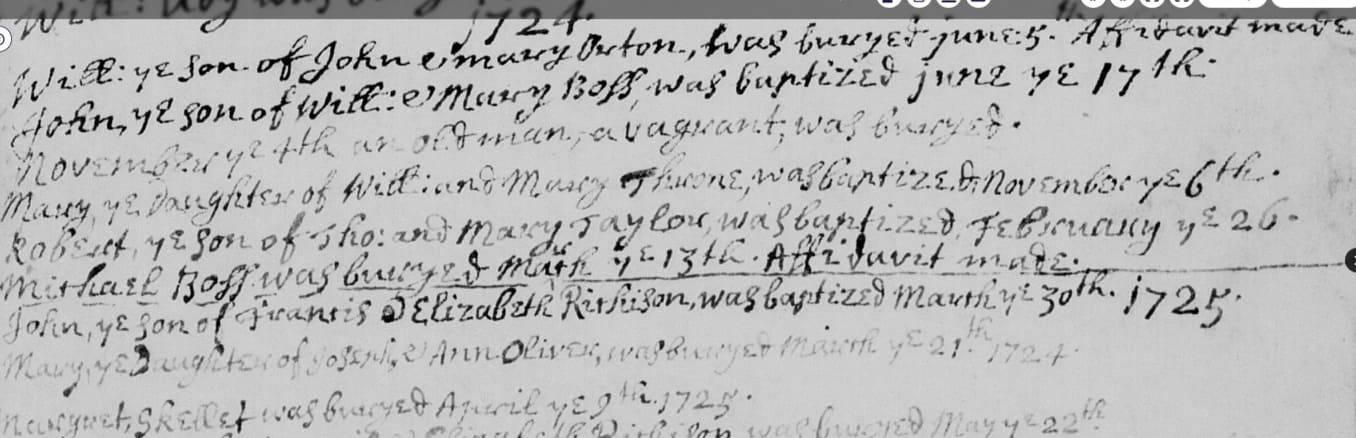

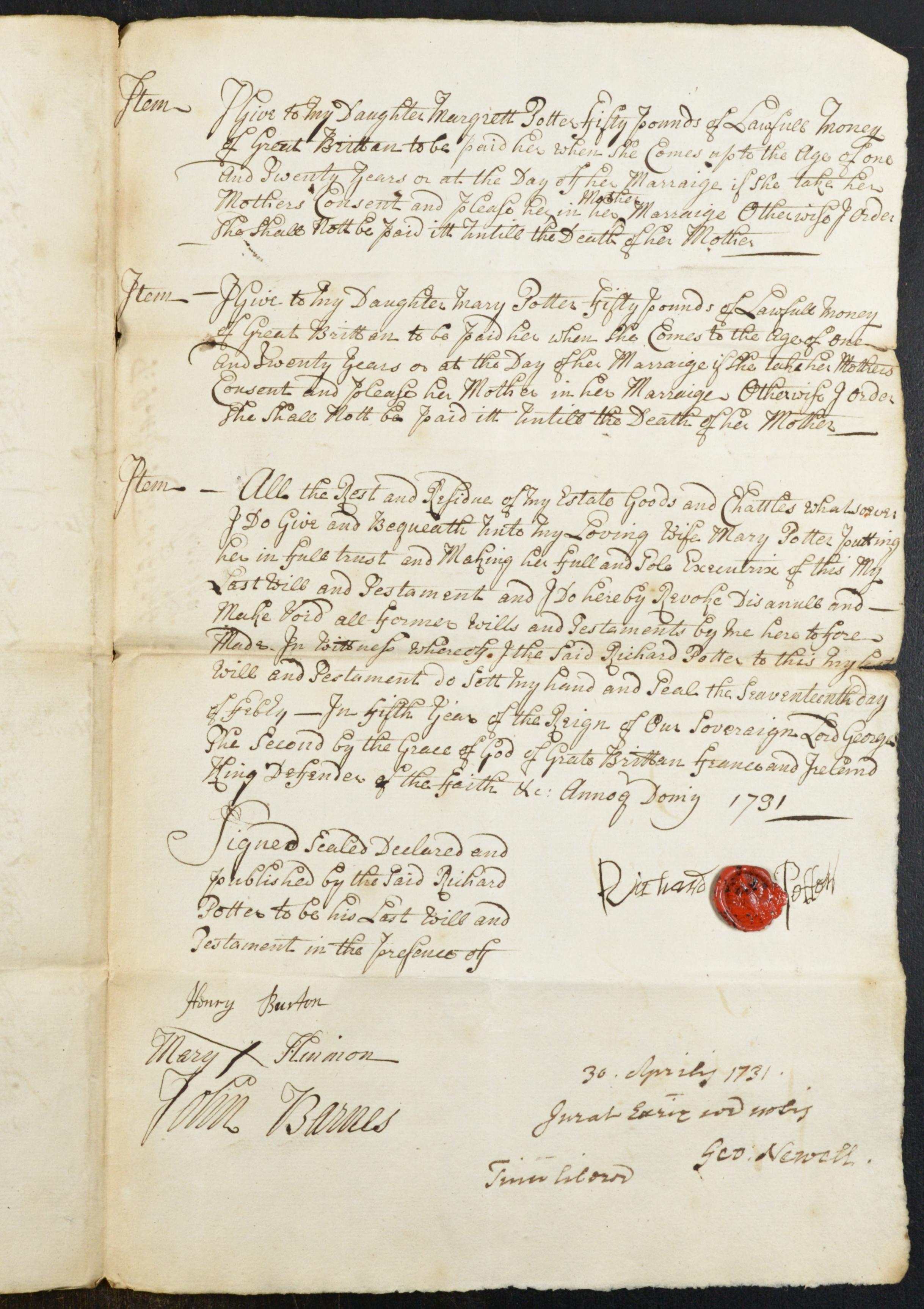

Leicestershire Blacksmiths

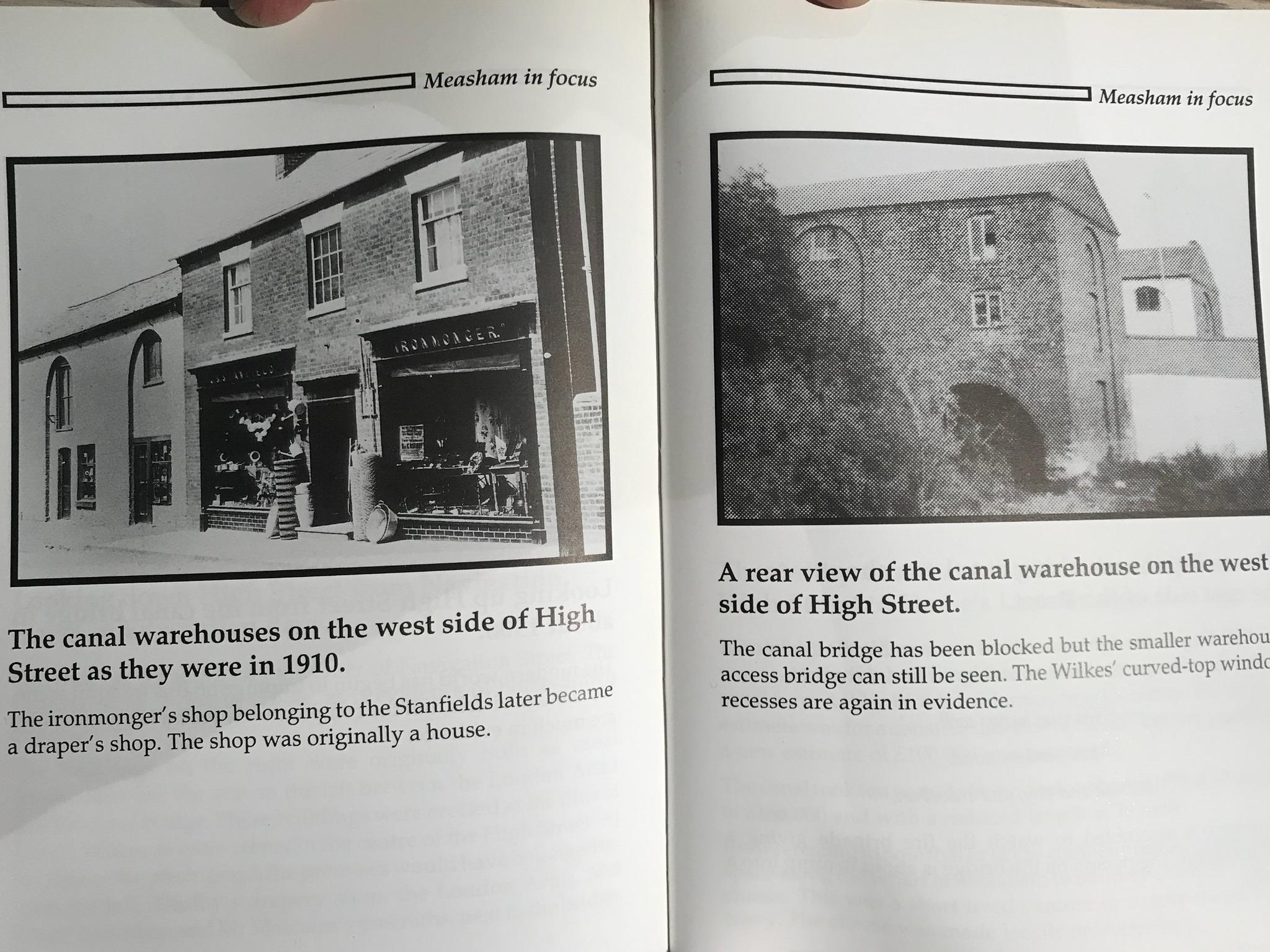

The Orgill’s of Measham led me further into Leicestershire as I traveled back in time.

I also realized I had uncovered a direct line of women and their mothers going back ten generations:

myself, Tracy Edwards 1957-

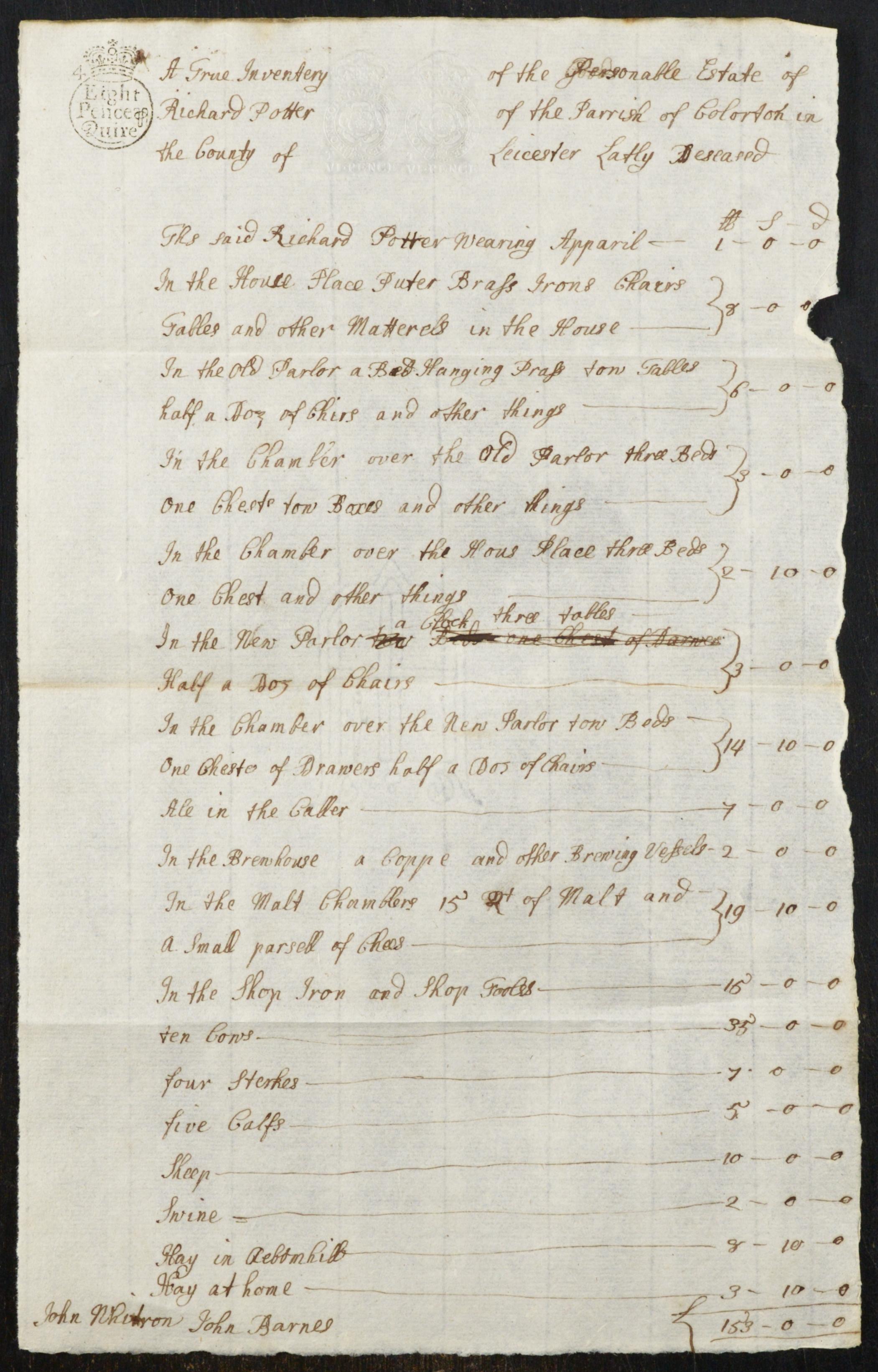

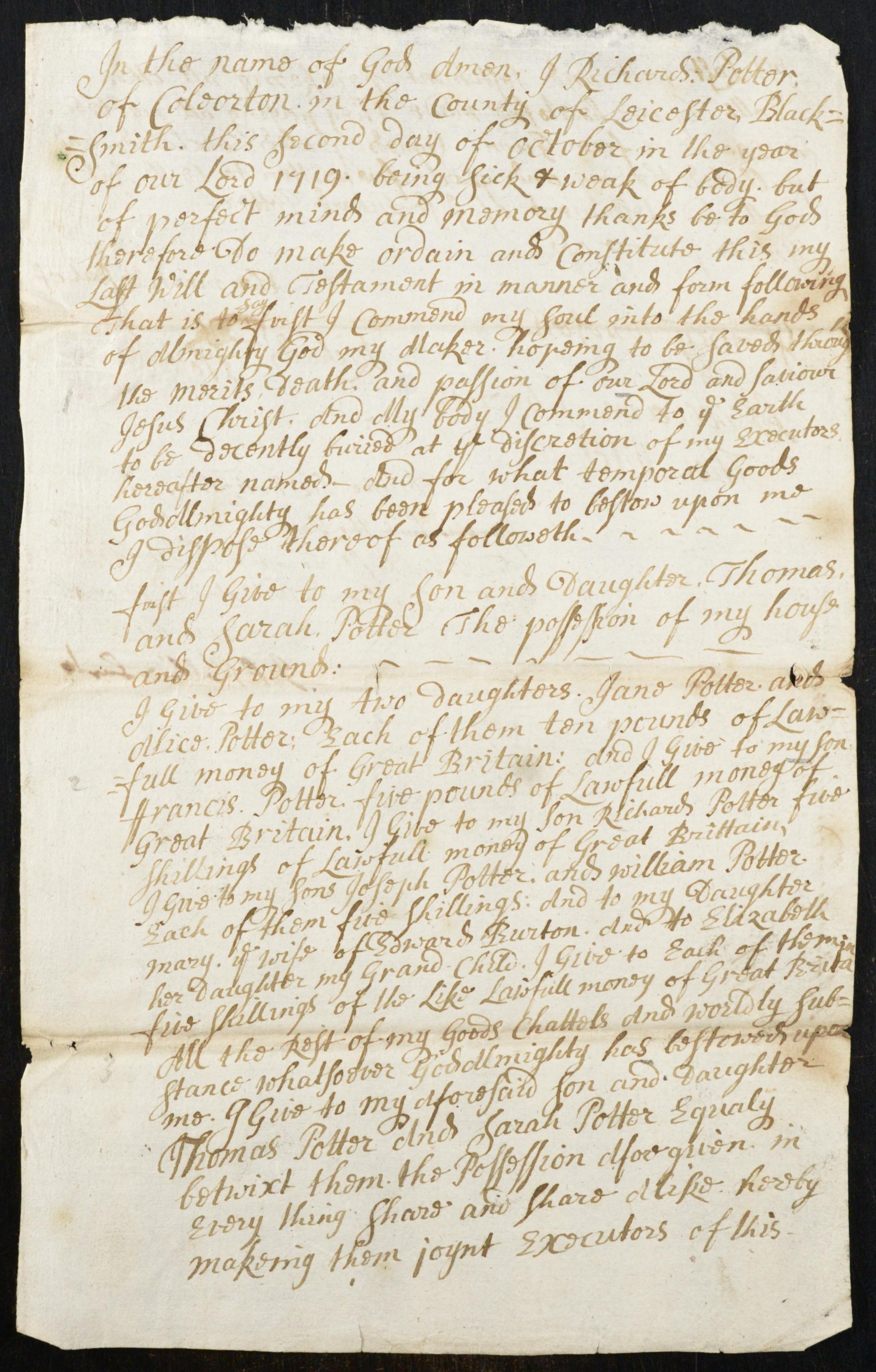

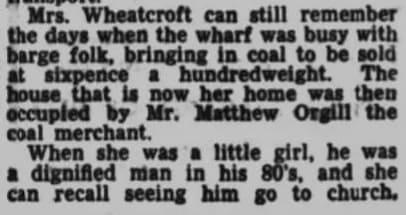

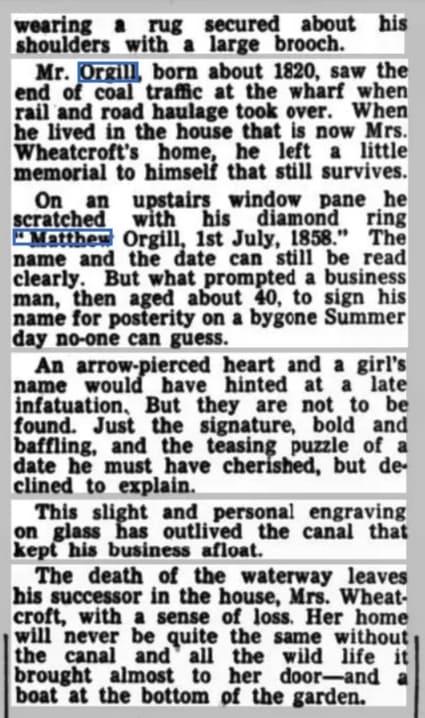

my mother Gillian Marshall 1933-