Search Results for 'cart'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

February 7, 2023 at 8:51 pm #6507

In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

To Youssef’s standards, a plane was never big and Flight AL357 was even smaller. When he found his seat, he had to ask a sweaty Chinese man and a snorting woman in a suit with a bowl cut and pink almond shaped glasses to move out so he could squeeze himself in the small space allotted to economy class passengers. On his right, an old lady looked at the size of his arms and almost lost her teeth. She snapped her mouth shut just in time and returned quickly to her magazine. Her hands were trembling and Youssef couldn’t tell if she was annoyed or something else.

The pilote announced they were ready to leave and Youssef sighed with relief. Which was short lived when he got the first bump on the back of his seat. He looked back, apologising to the woman with the bowl cut on his left. Behind him was a kid wearing a false moustache and chewing like a cow. He was swinging his tiny legs, hitting the back of Youssef’s seat with the regularity of a metronome. The kid blew his gum until the bubble exploded. The mother looked ready to open fire if Youssef started to complain. He turned back again and tried to imagine he was getting a massage in one of those Japanese shiatsu chairs you find in some airports.

The woman in front of him had thrown her very blond hair atop her seat and it was all over his screen. The old lady looked at him and offered him a gum. He wondered how she could chew gums with her false teeth, and kindly declined. The woman with the bowl cut and pink glasses started to talk to her sweaty neighbour in Chinese. The man looked at Youssef as if he had been caught by a tiger and was going to get eaten alive. His eyes were begging for help.

As the plane started to move, the old woman started to talk.

« Hi, I’m Gladys. I am afraid of flying, she said. Can I hold your hand during take off ? »

After another bump on his back, Youssef sighed. It was going to be a long flight for everyone.

As soon as they had gained altitude, Youssef let go of the old woman’s hand. She hadn’t stopped talking about her daughter and how she was going to be happy to see her again. The flight attendant passed by with a trolley and offered them a drink and a bag of peanuts. The old woman took a glass of red wine. Youssef was tempted to take a coke and dip the hair of the woman in front of him in it. He had seen a video on LooTube recently with a girl in a similar situation. She had stuck gum and lollypops in the hair of her nemesis, dipped a few strands in her soda and clipped strands randomly with her nail cutter. He could ask the old woman one of her gums, but thought that if a girl could do it, it would certainly not go well for him if he tried.

Instead he asked the flight attendant if there was wifi on board. Sadly there was none. He had hoped at least the could play the game and catch up with his friends during that long flight to Sydney.

When the doors opened, Youssef thought he was free of them all. He was tired, his back hurt, and he couldn’t sleep because the kid behind him kept crying and kicking, the food looked like it had been regurgitated twice by a yak, and the old chatty woman had drained his batteries. She said she wouldn’t sleep on a plane because she had to put her dentures in a glass for hygiene reasons and feared someone would steal them while she had her eyes closed.

He walked with long strides in the corridors up to the custom counters and picked a line, eager to put as much distance between him and the other passengers. Xavier had sent him a message saying he was arriving in Sydney in a few hours. Youssef thought it would be nice to change his flight so that they could go together to Alice Spring. He could do some time with a friend for a change.

His bushy hair stood on end when he heard the voice of the old woman just behind him. He wondered how she had managed to catch up so fast. He saw a small cart driving away.

« I wanted to tell, Gladys said, it was such a nice flight in your company. How long have you before your flight to Alice? We can have a coffee together. »

Youssef mentally said sorry to his friend. He couldn’t wait for the next flight.

February 1, 2023 at 12:12 pm #6486In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

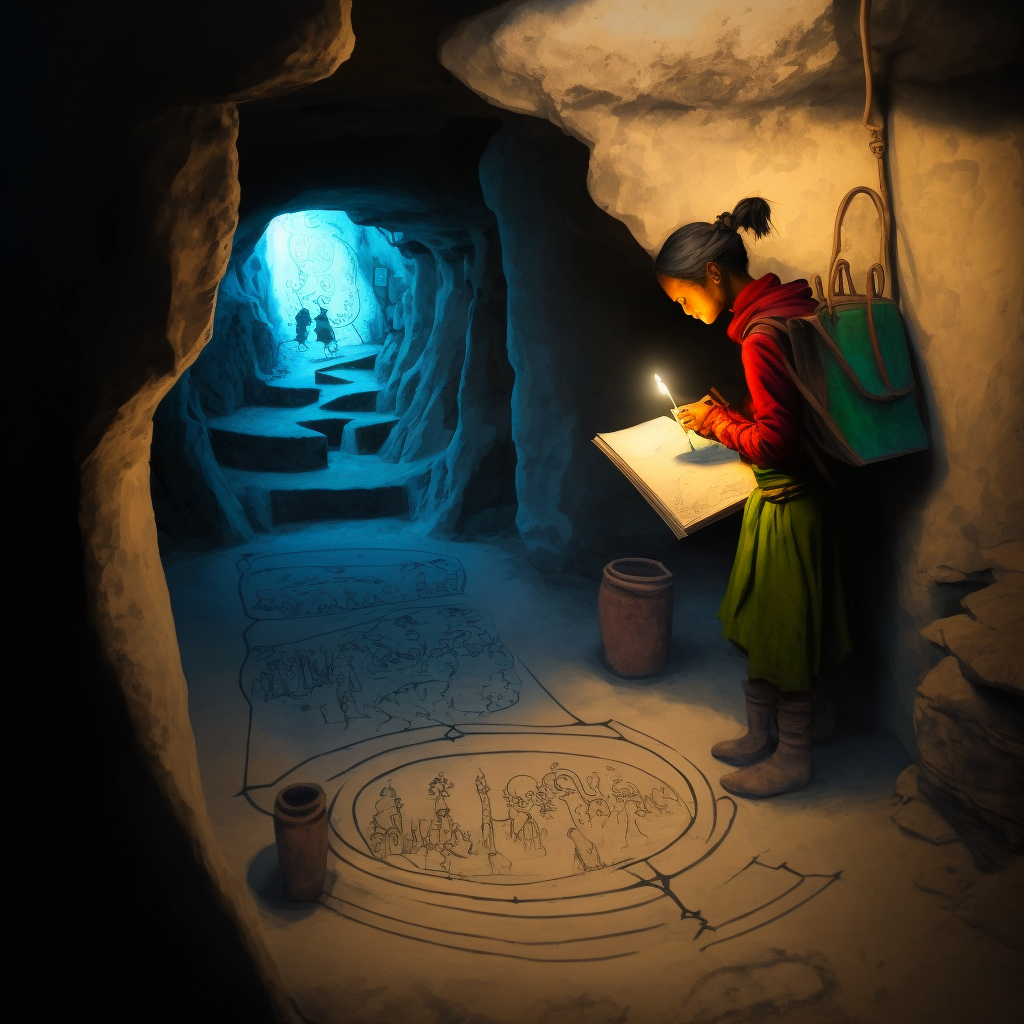

Zara took dozens of screenshots of the many etchings and drawings, as her game character paused to do the same. She had lost sight of the two figures up ahead, and remembered she probably should have been following them.

The tunnel came to a four way junction. There were drawings on the walls and floors of all of them, and a dim light coming from a distance in each. One was more brightly lit than the others, and Zara chose to explore that one first. Presently a side room appeared, with green tiles on the floor similar to the one at the mine entrance. Daylight shone though a small window, and a diagram was drawn onto the wall.

Zara toyed with the idea of simply climbing out through the window while there was still a chance to get out of the mine. She knew she was lost and would not be able to find her way out the way she came. It was tempting, but she just took a screenshot. Maybe when she looked at them later she’d be able to work out how to retrace her steps.

After recording the image of the room of tiles, Zara continued along the tunnel. The light shining from the little window in the tile room faded as she progressed, and she found herself once again in near darkness. She came to a fork. Both ways were equally gloomy, but a faint blue light enticed her to take the right hand tunnel.

So many forks and side tunnels, I am surely completely lost now! And not one of these supposed maps is helping, I can’t decipher any of them. Another etching on the wall caught her eye, and Zara forgot about being lost.

Zara stopped to look at what appeared to be a map on the tunnel wall, but it was unfathomable at this stage. She recorded it for future reference, and then looked around, unsure whether to continue on this path or retrace her stops back to the four way junction. And then she saw him in an alcove.

Osnas! This time Zara did say it out loud, and just as the frog faced stewardess was passing with her cart piled with used cups and cans and empty packets. I swear she just winked at me! Zara did a double take, but the cart and the woman had passed, collecting more rubbish.

With a little smile, Zara noticed that the mask Osnas was wearing was one of those paper pandemic masks. She had expected something a bit more Venice carnival when the prompt mentioned that he always wore a mask, not one of those. She hoped the clue in this case wasn’t the mask, as she had avoided the plague successfully so far and didn’t want to be late to that particular party, but the square green thing on his cart resembled the tile at the mine entrance. What do I do now though? I still don’t know what any of these things mean. Approach him and see if he speaks I suppose.

“Ladies and gentlemen, we are now approaching Alice Springs, please fasten your seatbelts and switch off all your devices ready for landing. We hope you have enjoyed your flight.”

February 1, 2023 at 11:23 am #6485In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

The two figures disappeared from view and Zara continued towards the light. An alcove to her right revealed a grotesque frog like creature with a pile of bones and gruesome looking objects. Zara hurried past.

Bugger, I bet that was Osnas, Zara realized. But she wasn’t going to go back now. It seemed there was only one way to go, towards the light. Although in real life she was sitting on a brightly lit aeroplane with the stewards bustling about with the drinks and snacks cart, she could feel the chill of the tunnels and the uneasy thrill of secrets and danger.

“Tea? Coffee? Soft drink?” smiled the hostess with the blue uniform, leaning over her cart towards Zara.

“Coffee please,” she replied, glancing up with a smile, and then her smile froze as she noticed the frog like features of the woman. “And a packet of secret tiles please,” she added with a giggle.

“Sorry, did you say nuts?”

“Yeah, nuts. Thank you, peanuts will be fine, cheers.”

Sipping coffee in between handfulls of peanuts, Zara returned to the game.

As Zara continued along the tunnels following the light, she noticed the drawings on the floor. She stopped to take a photo, as the two figures continued ahead of her.

I don’t know how I’m supposed to work out what any of this means, though. Just keep going I guess. Zara wished that Pretty Girl was with her. This was the first time she’d played without her.

The walls and floors had many drawings, symbols and diagrams, and Zara stopped to take photos of all of them as she slowly made her way along the tunnel.

Zara meanwhile make screenshots of them all as well. The frisson of fear had given way to curiosity, now that the tunnel was more brightly lit, and there were intriguing things to notice. She was no closer to working out what they meant, but she was enjoying it now and happy to just explore.

But who had etched all these pictures into the rock? You’d expect to see cave paintings in a cave, but in an old mine? How old was the mine? she wondered. The game had been scanty with any kind of factual information about the mine, and it could have been a bronze age mine, a Roman mine, or just a gold rush mine from not so very long ago. She assumed it wasn’t a coal mine, which she deduced from the absence of any coal, and mentally heard her friend Yasmin snort with laughter at her train of thought. She reminded herself that it was just a game and not an archaeology dig, after all, and to just keep exploring. And that Yasmin wasn’t reading her mind and snorting at her thoughts.

February 1, 2023 at 9:52 am #6484In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Will be at Flying Fish this evening, Hope to see you all soon!

Congrats, Xavier!

Congrats, Xavier!

Zara sent a message to Yasmin, Youssef and Xavier just before boarding the plane. Thankfully the plane wasn’t full and the seats next to her were unoccupied. She had a couple of hours to play the game before landing at Alice Springs.

Zara had found the tile in the entry level and had further instructions for the next stage of the game:

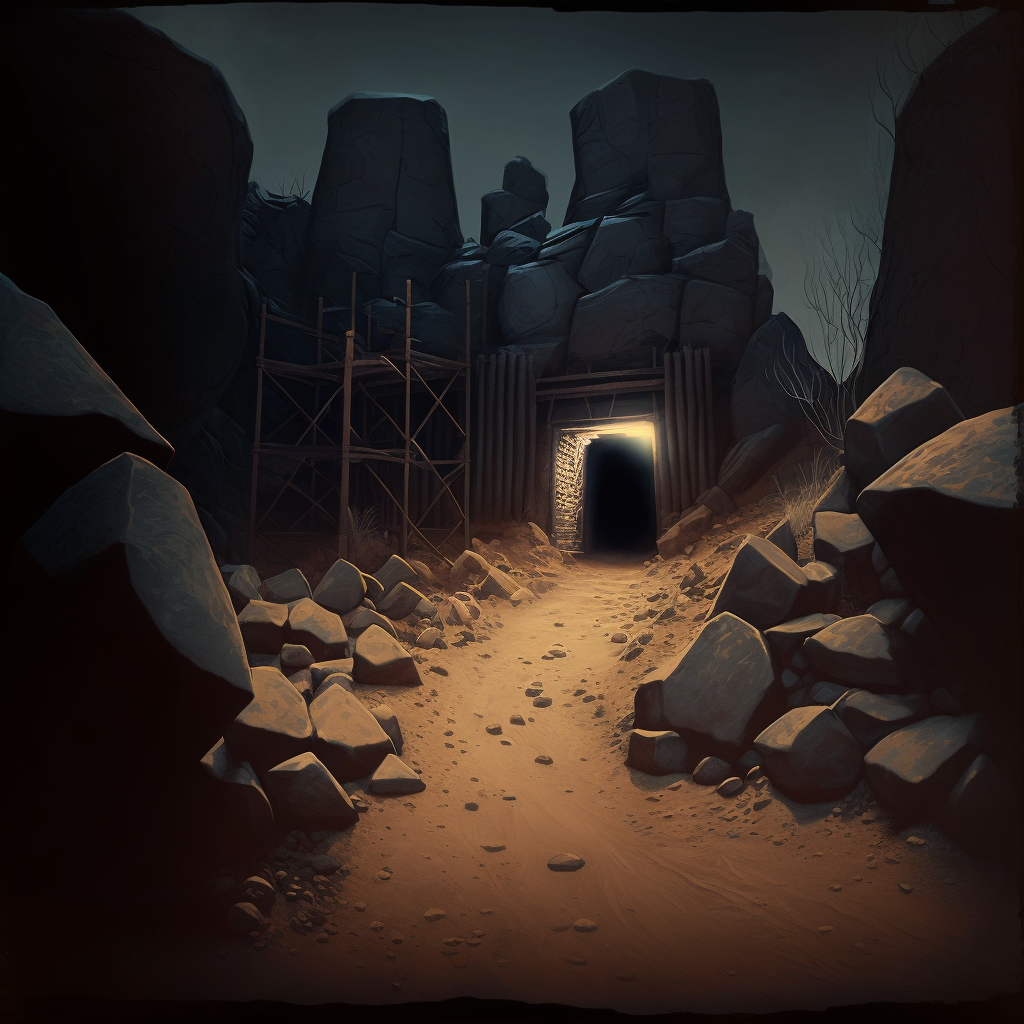

Zara had come across a strange and ancient looking mine. It was clear that it had been abandoned for many years, but there were still signs of activity. The entrance was blocked by a large pile of rocks, but she could see a faint light coming from within. She knew that she had to find a way in.

“Looks like I have to find another tile with a sort of map on it, Pretty Girl,” Zara spoke out loud, forgetting for a moment that the parrot wasn’t with her. She glanced up, hoping none of the other passengers had heard her. Really she would have to change that birds name!

If you encounter Osnas anywhere in the game, he may have what you seek in his vendors cart, or one of his many masks might be a clue.

A man with a mask and a vendors cart in an old mine, alrighty then, let’s have a look at this mine. Shame we’re not still in that old town. Zara remembered not to say that out loud.

Zara approached the abandoned mine cautiously. There were rocks strewn about the entrance, and a faint light inside.

This looks a bit ominous, thought Zara, and not half as inviting as that old city. She’d had a lifelong curiosity about underground tunnels and caves, and yet felt uneasily claustrophobic inside one. She reminded herself that it was just a game, that she could break the rules, and that she could simply turn it off at any time. She carried on.

Zara stopped to look at the large green tile lying at her feet in the tunnel entrance. It was too big to carry with her so she took a photo of it for future reference. At first glance it looked more like a maze or a labyrinth than a map. The tunnel ahead was dark and she walked slowly, close to the wall.

Oh no don’t walk next to the wall! Zara recalled going down some abandoned mines with a group of friends when she was a teenager. There was water in the middle of the tunnel so she had been walking at the edge to keep her feet dry, as she followed her friend in front who had the torch. Luckily he glanced over his shoulder, and advised her to walk in the middle. “Look” he said after a few more steps, shining his torch to the left. A bottomless dark cavern fell away from the tunnel, which she would surely have fallen into.

Zara moved into the middle of the tunnel and walked steadily into the darkness. Before long a side tunnel appeared with a faintly glowing ghostly light.

It looked eerie, but Zara felt obliged to follow it, as it was pitch black in every other direction. She wasn’t even sure if she could find her way out again, and she’d barely started.

The ghostly light was coming from yet another side tunnel. There were strange markings on the floor that resembled the tile at the mine entrance. Zara saw two figures up ahead, heading towards the light.

January 29, 2023 at 2:30 pm #6467

January 29, 2023 at 2:30 pm #6467In reply to: Newsreel from the Rim of the Realm

“Ricardo, my dear, those new reporters are quite the catch.”

Miss Bossy Pants remarked as she handed him the printed report. “Imagine that, if you can. A preliminary report sent, even before asking, AND with useful details. It’s as though they’re a new generation with improbable traits definitely not inherited from their forebearers…”

Ricardo scanned the document, a look of intrigue on his face. “Indeed, they seem to have a knack for getting things done. I can’t help but notice that our boy Sproink omitted that Sweet Sophie had used her remote viewing skills to point out something was of interest on the Rock of Gibraltar. I wonder how much that influenced his decision to seek out Dr. Patelonus.”

Miss Bossy Pants leaned back in her chair, a sly smile creeping across her lips. “Well, don’t quote me later on this, but some level of initiative is a valuable trait in a journalist. We can’t have drones regurgitating soothing nonsense. We need real, we need grit.” She paused in mid sentence. “By the way, heard anything from Hilda & Connie? I do hope they’re getting something back from this terribly long detour in the Nordics.”

Dear Miss Bossy Pants,

I am writing to give you a preliminary report on my investigation into the strange occurrences of Barbary macaques in Cartagena, Spain.

Taking some initiative and straying from your initial instructions, I first traveled to Gibraltar to meet with Dr. Patelonus, an expert in simiantics (the study of ape languages). Dr. Patelonus provided me with valuable insights into the behavior of Barbary macaques, including their typical range and habits and what they may be after. He also mentioned that the recent reports of Barbary macaques venturing further away from their usual habitat in coastal towns like Cartagena is highly unusual, and that he suspects something else is influencing them. He mentioned chatter on the simian news netwoke, that his secretary, a lovely female gorilla by the name of Barbara was kind enough to get translated for us.

I managed to find a wifi spot to send you this report before I board the next bus to Cartagena, where I plan to collect samples and observe the local macaque population. I have spoken with several tourists in Gib’ who have reported being assaulted and having their shoes stolen by the apes. It is again, a highly unusual behaviour for Barbary macaques, who seem untempted by the food left to appease them as a distraction, and I am currently trying to find out the reason behind this.

As soon as I gather them, I will send samples collected in situ without delay to my colleague Giles Gibber at the newspaper for analysis. Hopefully, his findings will shed some light on the situation.

I will continue my investigation and keep you appraised on any new developments.

Sincerely,

Samuel Sproink

Rim of the Realm Newspaper.January 22, 2023 at 11:35 am #6447In reply to: Newsreel from the Rim of the Realm

Miss Bossy sat at her desk, scanning through the stack of papers on her desk. She was searching for the perfect reporter to send on a mission to investigate a mysterious story that had been brought to her attention. Suddenly, her eyes landed on the name of Samuel Sproink. He was new to the Rim of the Realm Newspaper and had a reputation for being a tenacious and resourceful reporter.

She picked up the phone and dialed his number. “Sproink, I have a job for you,” she said in her gruff voice.

“Yes, Miss Bossy, what can I do for you?” Samuel replied, his voice full of excitement.

“I want you to go down to Cartagena, Spain, in the Golden Banana off the Mediterranean coast. There have been sightings of Barbary macaques happening there and tourists being assaulted and stolen only their shoes, which is odd of course, and also obviously unusual for the apes to be seen so far off the Strait of Gibraltar. I want you to get to the bottom of it. I need you to find out what’s really going on and report back to me with your findings.”

“Consider it done, Miss Bossy,” Samuel said confidently. He had always been interested in wildlife and the idea of investigating a mystery involving monkeys was too good to pass up.

He hang up the phone to go and pack his bags and head to the airport, apparently eager to start his investigation.

“Apes again?” Ricardo who’s been eavesdropping what surprised at the sudden interest. After that whole story about the orangutan man, he thought they’d be done with the menagerie, but apparently, Miss Bossy had something in mind. He would have to quiz Sweet Sophie to remote view on that and anticipate possible links and knots in the plot.

November 18, 2022 at 4:47 pm #6348In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Wong Sang

Wong Sang was born in China in 1884. In October 1916 he married Alice Stokes in Oxford.

Alice was the granddaughter of William Stokes of Churchill, Oxfordshire and William was the brother of Thomas Stokes the wheelwright (who was my 3X great grandfather). In other words Alice was my second cousin, three times removed, on my fathers paternal side.

Wong Sang was an interpreter, according to the baptism registers of his children and the Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital admission registers in 1930. The hospital register also notes that he was employed by the Blue Funnel Line, and that his address was 11, Limehouse Causeway, E 14. (London)

“The Blue Funnel Line offered regular First-Class Passenger and Cargo Services From the UK to South Africa, Malaya, China, Japan, Australia, Java, and America. Blue Funnel Line was Owned and Operated by Alfred Holt & Co., Liverpool.

The Blue Funnel Line, so-called because its ships have a blue funnel with a black top, is more appropriately known as the Ocean Steamship Company.”Wong Sang and Alice’s daughter, Frances Eileen Sang, was born on the 14th July, 1916 and baptised in 1920 at St Stephen in Poplar, Tower Hamlets, London. The birth date is noted in the 1920 baptism register and would predate their marriage by a few months, although on the death register in 1921 her age at death is four years old and her year of birth is recorded as 1917.

Charles Ronald Sang was baptised on the same day in May 1920, but his birth is recorded as April of that year. The family were living on Morant Street, Poplar.

James William Sang’s birth is recorded on the 1939 census and on the death register in 2000 as being the 8th March 1913. This definitely would predate the 1916 marriage in Oxford.

William Norman Sang was born on the 17th October 1922 in Poplar.

Alice and the three sons were living at 11, Limehouse Causeway on the 1939 census, the same address that Wong Sang was living at when he was admitted to Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital on the 15th January 1930. Wong Sang died in the hospital on the 8th March of that year at the age of 46.

Alice married John Patterson in 1933 in Stepney. John was living with Alice and her three sons on Limehouse Causeway on the 1939 census and his occupation was chef.

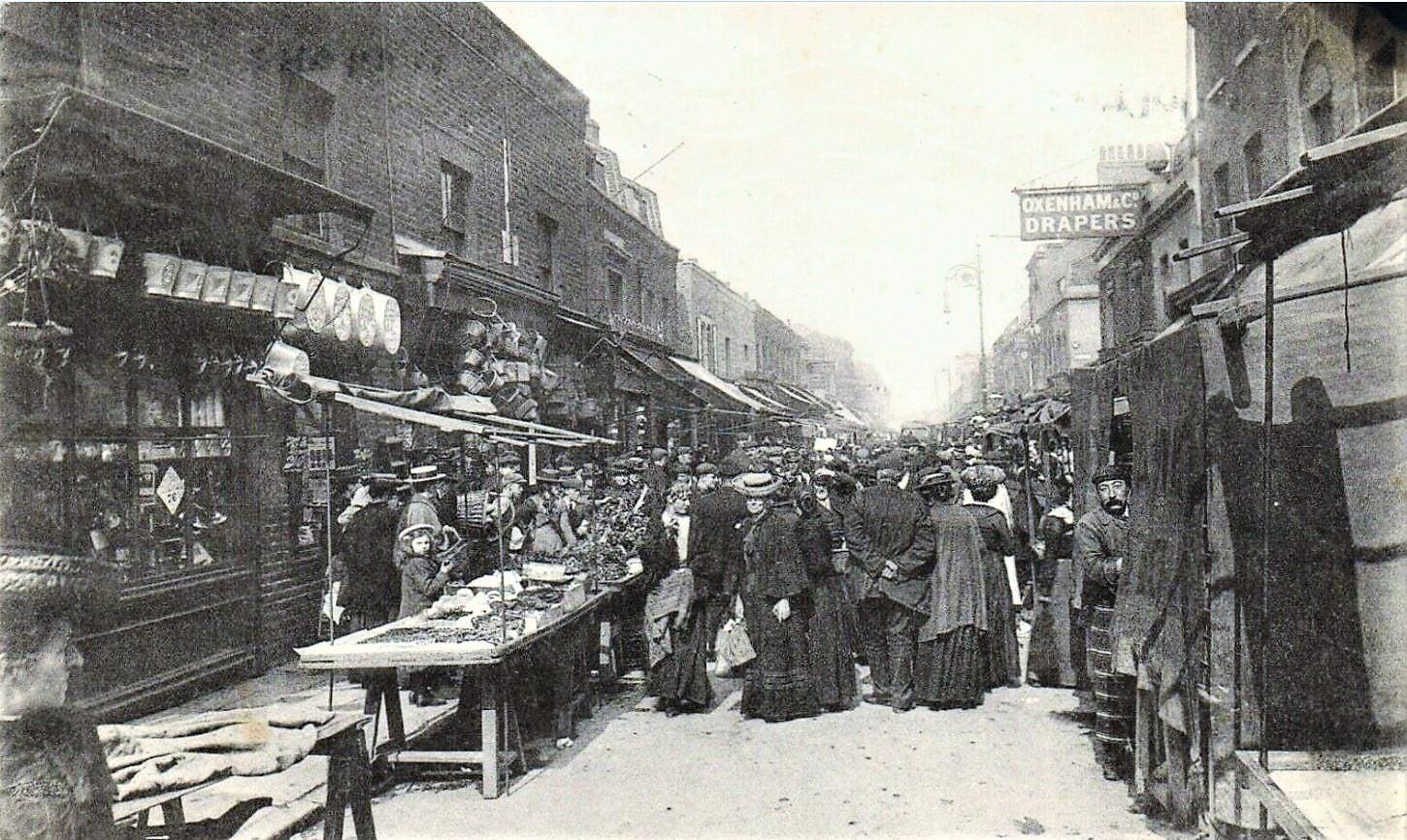

Via Old London Photographs:

“Limehouse Causeway is a street in east London that was the home to the original Chinatown of London. A combination of bomb damage during the Second World War and later redevelopment means that almost nothing is left of the original buildings of the street.”

Limehouse Causeway in 1925:

From The Story of Limehouse’s Lost Chinatown, poplarlondon website:

“Limehouse was London’s first Chinatown, home to a tightly-knit community who were demonised in popular culture and eventually erased from the cityscape.

As recounted in the BBC’s ‘Our Greatest Generation’ series, Connie was born to a Chinese father and an English mother in early 1920s Limehouse, where she used to play in the street with other British and British-Chinese children before running inside for teatime at one of their houses.

Limehouse was London’s first Chinatown between the 1880s and the 1960s, before the current Chinatown off Shaftesbury Avenue was established in the 1970s by an influx of immigrants from Hong Kong.

Connie’s memories of London’s first Chinatown as an “urban village” paint a very different picture to the seedy area portrayed in early twentieth century novels.

The pyramid in St Anne’s church marked the entrance to the opium den of Dr Fu Manchu, a criminal mastermind who threatened Western society by plotting world domination in a series of novels by Sax Rohmer.

Thomas Burke’s Limehouse Nights cemented stereotypes about prostitution, gambling and violence within the Chinese community, and whipped up anxiety about sexual relationships between Chinese men and white women.

Though neither novelist was familiar with the Chinese community, their depictions made Limehouse one of the most notorious areas of London.

Travel agent Thomas Cook even organised tours of the area for daring visitors, despite the rector of Limehouse warning that “those who look for the Limehouse of Mr Thomas Burke simply will not find it.”

All that remains is a handful of Chinese street names, such as Ming Street, Pekin Street, and Canton Street — but what was Limehouse’s chinatown really like, and why did it get swept away?

Chinese migration to Limehouse

Chinese sailors discharged from East India Company ships settled in the docklands from as early as the 1780s.

By the late nineteenth century, men from Shanghai had settled around Pennyfields Lane, while a Cantonese community lived on Limehouse Causeway.

Chinese sailors were often paid less and discriminated against by dock hirers, and so began to diversify their incomes by setting up hand laundry services and restaurants.

Old photographs show shopfronts emblazoned with Chinese characters with horse-drawn carts idling outside or Chinese men in suits and hats standing proudly in the doorways.

In oral histories collected by Yat Ming Loo, Connie’s husband Leslie doesn’t recall seeing any Chinese women as a child, since male Chinese sailors settled in London alone and married working-class English women.

In the 1920s, newspapers fear-mongered about interracial marriages, crime and gambling, and described chinatown as an East End “colony.”

Ironically, Chinese opium-smoking was also demonised in the press, despite Britain waging war against China in the mid-nineteenth century for suppressing the opium trade to alleviate addiction amongst its people.

The number of Chinese people who settled in Limehouse was also greatly exaggerated, and in reality only totalled around 300.

The real Chinatown

Although the press sought to characterise Limehouse as a monolithic Chinese community in the East End, Connie remembers seeing people of all nationalities in the shops and community spaces in Limehouse.

She doesn’t remember feeling discriminated against by other locals, though Connie does recall having her face measured and IQ tested by a member of the British Eugenics Society who was conducting research in the area.

Some of Connie’s happiest childhood memories were from her time at Chung-Hua Club, where she learned about Chinese culture and language.

Why did Chinatown disappear?

The caricature of Limehouse’s Chinatown as a den of vice hastened its erasure.

Police raids and deportations fuelled by the alarmist media coverage threatened the Chinese population of Limehouse, and slum clearance schemes to redevelop low-income areas dispersed Chinese residents in the 1930s.

The Defence of the Realm Act imposed at the beginning of the First World War criminalised opium use, gave the authorities increased powers to deport Chinese people and restricted their ability to work on British ships.

Dwindling maritime trade during World War II further stripped Chinese sailors of opportunities for employment, and any remnants of Chinatown were destroyed during the Blitz or erased by postwar development schemes.”

Wong Sang 1884-1930

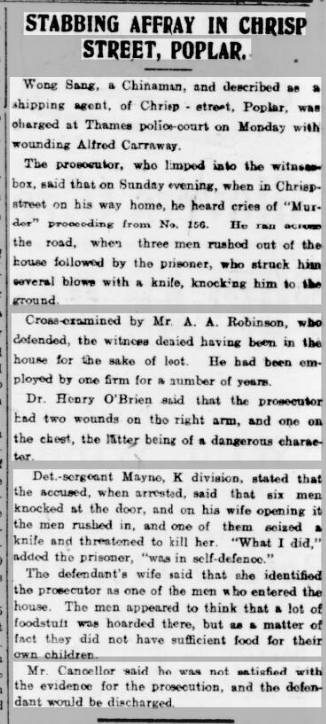

The year 1918 was a troublesome one for Wong Sang, an interpreter and shipping agent for Blue Funnel Line. The Sang family were living at 156, Chrisp Street.

Chrisp Street, Poplar, in 1913 via Old London Photographs:

In February Wong Sang was discharged from a false accusation after defending his home from potential robbers.

East End News and London Shipping Chronicle – Friday 15 February 1918:

In August of that year he was involved in an incident that left him unconscious.

Faringdon Advertiser and Vale of the White Horse Gazette – Saturday 31 August 1918:

Wong Sang is mentioned in an 1922 article about “Oriental London”.

London and China Express – Thursday 09 February 1922:

A photograph of the Chee Kong Tong Chinese Freemason Society mentioned in the above article, via Old London Photographs:

Wong Sang was recommended by the London Metropolitan Police in 1928 to assist in a case in Wellingborough, Northampton.

Difficulty of Getting an Interpreter: Northampton Mercury – Friday 16 March 1928:

The difficulty was that “this man speaks the Cantonese language only…the Northeners and the Southerners in China have differing languages and the interpreter seemed to speak one that was in between these two.”

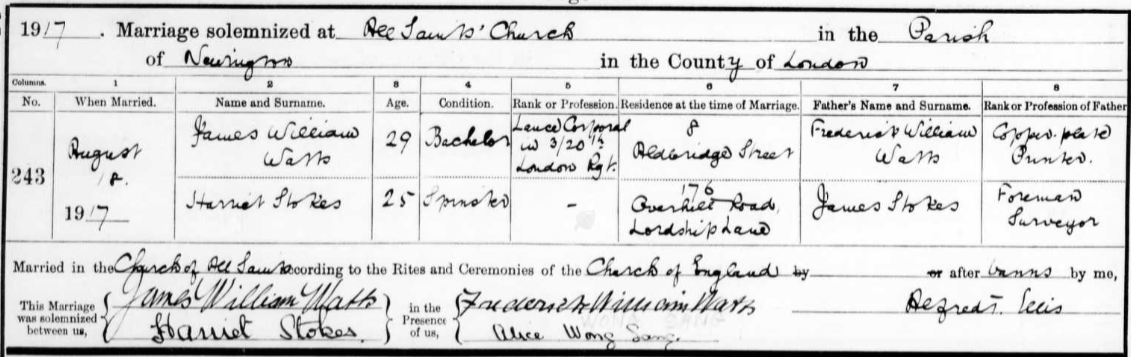

In 1917, Alice Wong Sang was a witness at her sister Harriet Stokes marriage to James William Watts in Southwark, London. Their father James Stokes occupation on the marriage register is foreman surveyor, but on the census he was a council roadman or labourer. (I initially rejected this as the correct marriage for Harriet because of the discrepancy with the occupations. Alice Wong Sang as a witness confirmed that it was indeed the correct one.)

James William Sang 1913-2000 was a clock fitter and watch assembler (on the 1939 census). He married Ivy Laura Fenton in 1963 in Sidcup, Kent. James died in Southwark in 2000.

Charles Ronald Sang 1920-1974 was a draughtsman (1939 census). He married Eileen Burgess in 1947 in Marylebone. Charles and Eileen had two sons: Keith born in 1951 and Roger born in 1952. He died in 1974 in Hertfordshire.

William Norman Sang 1922-2000 was a clerk and telephone operator (1939 census). William enlisted in the Royal Artillery in 1942. He married Lily Mullins in 1949 in Bethnal Green, and they had three daughters: Marion born in 1950, Christine in 1953, and Frances in 1959. He died in Redbridge in 2000.

I then found another two births registered in Poplar by Alice Sang, both daughters. Doris Winifred Sang was born in 1925, and Patricia Margaret Sang was born in 1933 ~ three years after Wong Sang’s death. Neither of the these daughters were on the 1939 census with Alice, John Patterson and the three sons. Margaret had presumably been evacuated because of the war to a family in Taunton, Somerset. Doris would have been fourteen and I have been unable to find her in 1939 (possibly because she died in 2017 and has not had the redaction removed yet on the 1939 census as only deceased people are viewable).

Doris Winifred Sang 1925-2017 was a nursing sister. She didn’t marry, and spent a year in USA between 1954 and 1955. She stayed in London, and died at the age of ninety two in 2017.

Patricia Margaret Sang 1933-1998 was also a nurse. She married Patrick L Nicely in Stepney in 1957. Patricia and Patrick had five children in London: Sharon born 1959, Donald in 1960, Malcolm was born and died in 1966, Alison was born in 1969 and David in 1971.

I was unable to find a birth registered for Alice’s first son, James William Sang (as he appeared on the 1939 census). I found Alice Stokes on the 1911 census as a 17 year old live in servant at a tobacconist on Pekin Street, Limehouse, living with Mr Sui Fong from Hong Kong and his wife Sarah Sui Fong from Berlin. I looked for a birth registered for James William Fong instead of Sang, and found it ~ mothers maiden name Stokes, and his date of birth matched the 1939 census: 8th March, 1913.

On the 1921 census, Wong Sang is not listed as living with them but it is mentioned that Mr Wong Sang was the person returning the census. Also living with Alice and her sons James and Charles in 1921 are two visitors: (Florence) May Stokes, 17 years old, born in Woodstock, and Charles Stokes, aged 14, also born in Woodstock. May and Charles were Alice’s sister and brother.

I found Sharon Nicely on social media and she kindly shared photos of Wong Sang and Alice Stokes:

July 6, 2022 at 9:47 am #6310

July 6, 2022 at 9:47 am #6310In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

Olek wished he wasn’t so easy to find.

The old caretaker of the shrine of Saint Edigna couldn’t have chosen a less conspicuous place to live in this warring time. People were flocking from afar, more and more each day drawn about by the ancient place, and the sacred oil bleeding linden tree which had suddenly and quite miraculously resumed its flow in the midst of the ambiant chaos started by the war.

It wasn’t always like this. A few months ago, the linden tree was just an old linden tree that may or may not have been miraculous, if the old wifes’ tales were to be trusted. Mankind’s memory is a flimsy thing as it occurs, and while for many generations before, speculations had abounded about whether or not the Saint was real, had such or such filiation, et cætera— it now seemed the old tales that were passed down from mother to children had managed to keep alive a knowledge that had but all dried up on old flaky parchments scribbled in pale inks that kept eluding old scholars’ exegesis.

Olek himself wasn’t a learned man. A man of faith, he was a little — more by upbringing than by choice, and by slow attunement to nature it would seem. Over the years, he’d be servicing the country in many ways, and after a rather long carrier started at young age, he had finally managed to retire in this place.

He thought he’d be left alone, to care for a little garden patch, checking in from times to times on the old grumpy neighbours, but alas, the Holy Nation’s destiny still had something in store for him.The latest pilgrim family had brought a message. It was another push to action. “Plan acceleration needs to happen”.

“What clucking plan again?” was his first reaction. Bad temper had a way of flaring right up his vents as in old times. When he’d calmed down, he wondered if he had ever seen a call for slowing down in his life. People were always so busy mindlessly carting around, bumping into the darkness.He smiled thinking of something his old man used to say. He’d never planned for a thing in his life, and was always very carefree it was often scary. His mantra was “People are always getting prepared for the wrong things. They never can prepare for the unexpected, and surely enough, only the unexpected happens.”

That sort of chaos paddling approach to life didn’t seem to bring him any sort of extraordinary success, and while he had the same mixed bag of ups and downs as the rest of his compatriots, just so much less did he suffer for the same result! Olek guessed that was the whole point, even if he really couldn’t accept it until much later in life.Maybe Olek would start playing by his father’s book. Until he could find a way to get lost behind enemy lines.

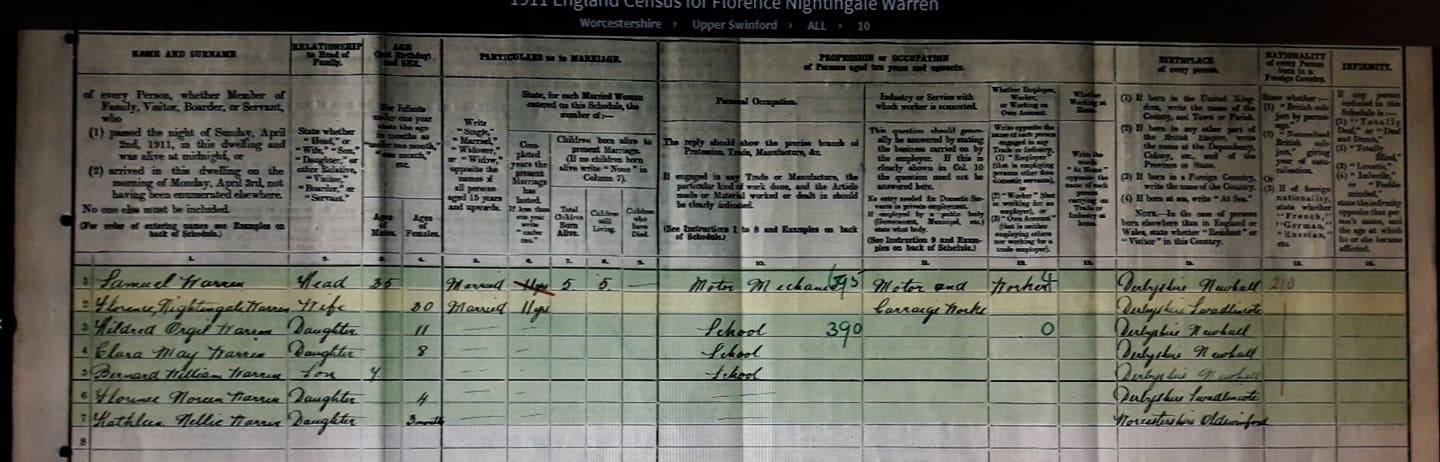

April 12, 2022 at 8:13 am #6290In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Leicestershire Blacksmiths

The Orgill’s of Measham led me further into Leicestershire as I traveled back in time.

I also realized I had uncovered a direct line of women and their mothers going back ten generations:

myself, Tracy Edwards 1957-

my mother Gillian Marshall 1933-

my grandmother Florence Warren 1906-1988

her mother and my great grandmother Florence Gretton 1881-1927

her mother Sarah Orgill 1840-1910

her mother Elizabeth Orgill 1803-1876

her mother Sarah Boss 1783-1847

her mother Elizabeth Page 1749-

her mother Mary Potter 1719-1780

and her mother and my 7x great grandmother Mary 1680-You could say it leads us to the very heart of England, as these Leicestershire villages are as far from the coast as it’s possible to be. There are countless other maternal lines to follow, of course, but only one of mothers of mothers, and ours takes us to Leicestershire.

The blacksmiths

Sarah Boss was the daughter of Michael Boss 1755-1807, a blacksmith in Measham, and Elizabeth Page of nearby Hartshorn, just over the county border in Derbyshire.

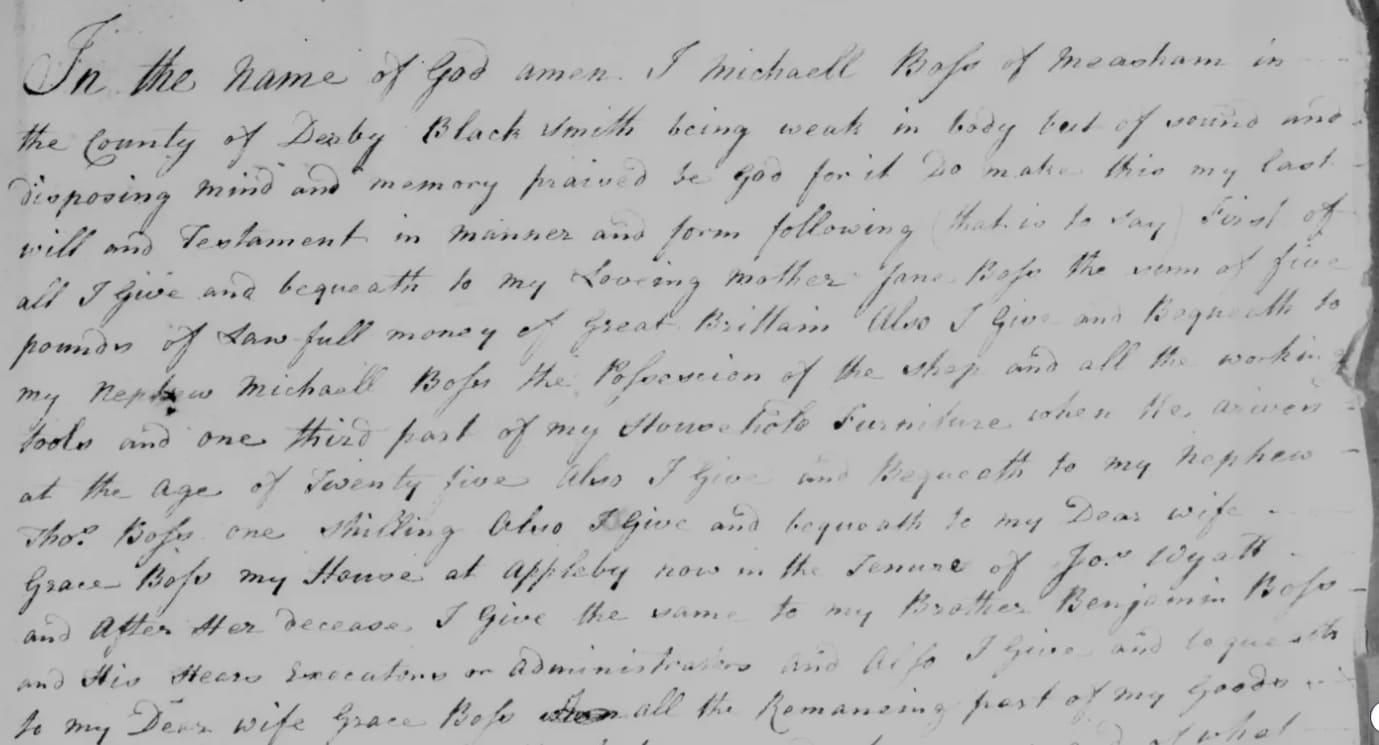

An earlier Michael Boss, a blacksmith of Measham, died in 1772, and in his will he left the possession of the blacksmiths shop and all the working tools and a third of the household furniture to Michael, who he named as his nephew. He left his house in Appleby Magna to his wife Grace, and five pounds to his mother Jane Boss. As none of Michael and Grace’s children are mentioned in the will, perhaps it can be assumed that they were childless.

The will of Michael Boss, 1772, Measham:

Michael Boss the uncle was born in Appleby Magna in 1724. His parents were Michael Boss of Nelson in the Thistles and Jane Peircivall of Appleby Magna, who were married in nearby Mancetter in 1720.

Information worth noting on the Appleby Magna website:

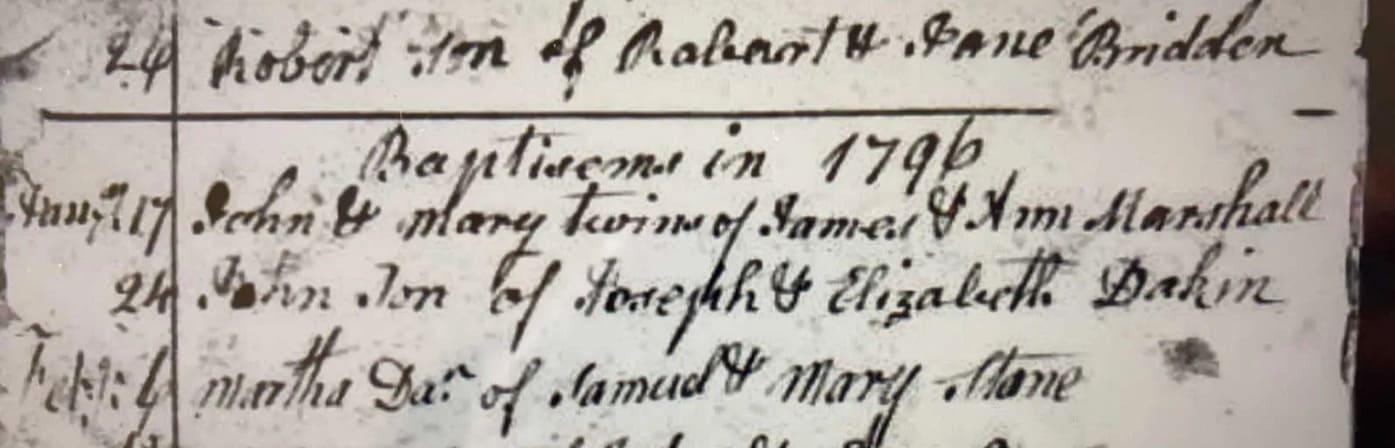

In 1752 the calendar in England was changed from the Julian Calendar to the Gregorian Calendar, as a result 11 days were famously “lost”. But for the recording of Church Registers another very significant change also took place, the start of the year was moved from March 25th to our more familiar January 1st.

Before 1752 the 1st day of each new year was March 25th, Lady Day (a significant date in the Christian calendar). The year number which we all now use for calculating ages didn’t change until March 25th. So, for example, the day after March 24th 1750 was March 25th 1751, and January 1743 followed December 1743.

This March to March recording can be seen very clearly in the Appleby Registers before 1752. Between 1752 and 1768 there appears slightly confused recording, so dates should be carefully checked. After 1768 the recording is more fully by the modern calendar year.Michael Boss the uncle married Grace Cuthbert. I haven’t yet found the birth or parents of Grace, but a blacksmith by the name of Edward Cuthbert is mentioned on an Appleby Magna history website:

An Eighteenth Century Blacksmith’s Shop in Little Appleby

by Alan RobertsCuthberts inventory

The inventory of Edward Cuthbert provides interesting information about the household possessions and living arrangements of an eighteenth century blacksmith. Edward Cuthbert (als. Cutboard) settled in Appleby after the Restoration to join the handful of blacksmiths already established in the parish, including the Wathews who were prominent horse traders. The blacksmiths may have all worked together in the same shop at one time. Edward and his wife Sarah recorded the baptisms of several of their children in the parish register. Somewhat sadly three of the boys named after their father all died either in infancy or as young children. Edward’s inventory which was drawn up in 1732, by which time he was probably a widower and his children had left home, suggests that they once occupied a comfortable two-storey house in Little Appleby with an attached workshop, well equipped with all the tools for repairing farm carts, ploughs and other implements, for shoeing horses and for general ironmongery.

Edward Cuthbert born circa 1660, married Joane Tuvenet in 1684 in Swepston cum Snarestone , and died in Appleby in 1732. Tuvenet is a French name and suggests a Huguenot connection, but this isn’t our family, and indeed this Edward Cuthbert is not likely to be Grace’s father anyway.

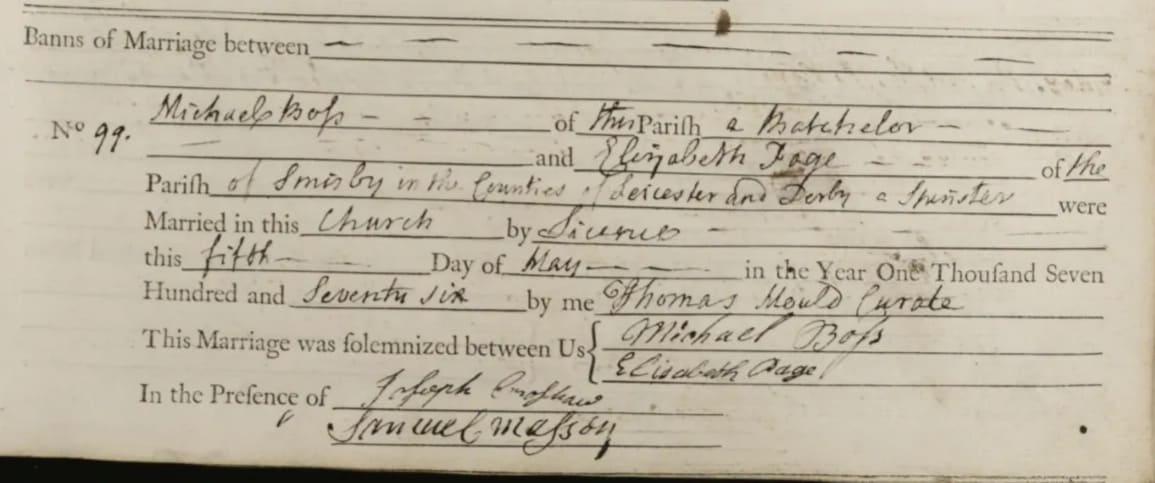

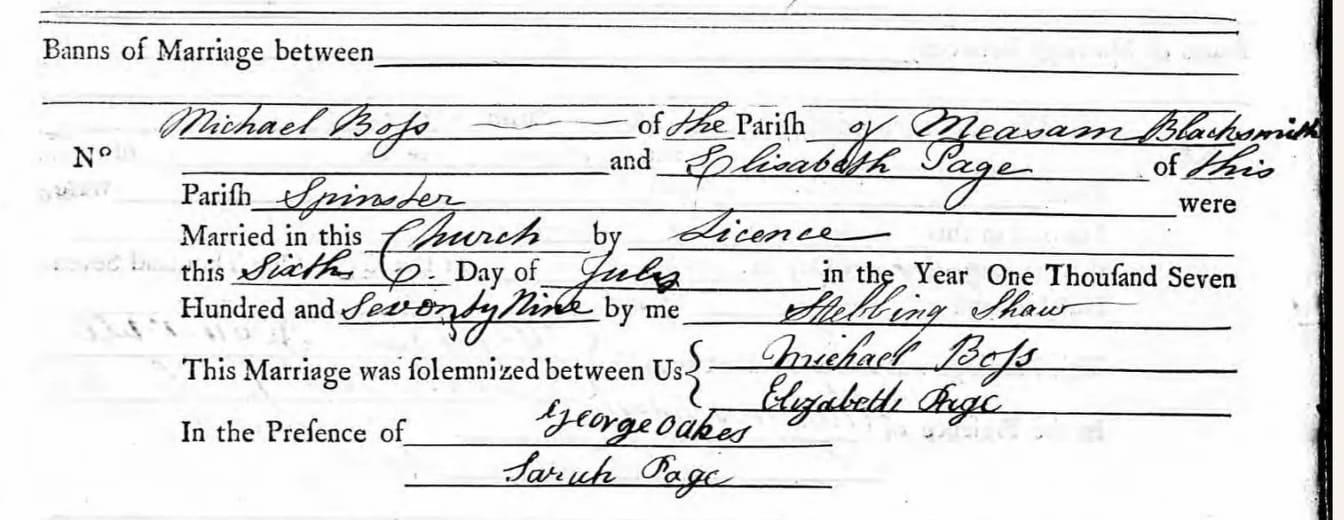

Michael Boss and Elizabeth Page appear to have married twice: once in 1776, and once in 1779. Both of the documents exist and appear correct. Both marriages were by licence. They both mention Michael is a blacksmith.

Their first daughter, Elizabeth, was baptized in February 1777, just nine months after the first wedding. It’s not known when she was born, however, and it’s possible that the marriage was a hasty one. But why marry again three years later?

But Michael Boss and Elizabeth Page did not marry twice.

Elizabeth Page from Smisby was born in 1752 and married Michael Boss on the 5th of May 1776 in Measham. On the marriage licence allegations and bonds, Michael is a bachelor.

Baby Elizabeth was baptised in Measham on the 9th February 1777. Mother Elizabeth died on the 18th February 1777, also in Measham.

In 1779 Michael Boss married another Elizabeth Page! She was born in 1749 in Hartshorn, and Michael is a widower on the marriage licence allegations and bonds.

Hartshorn and Smisby are neighbouring villages, hence the confusion. But a closer look at the documents available revealed the clues. Both Elizabeth Pages were literate, and indeed their signatures on the marriage registers are different:

Marriage of Michael Boss and Elizabeth Page of Smisby in 1776:

Marriage of Michael Boss and Elizabeth Page of Harsthorn in 1779:

Not only did Michael Boss marry two women both called Elizabeth Page but he had an unusual start in life as well. His uncle Michael Boss left him the blacksmith business and a third of his furniture. This was all in the will. But which of Uncle Michaels brothers was nephew Michaels father?

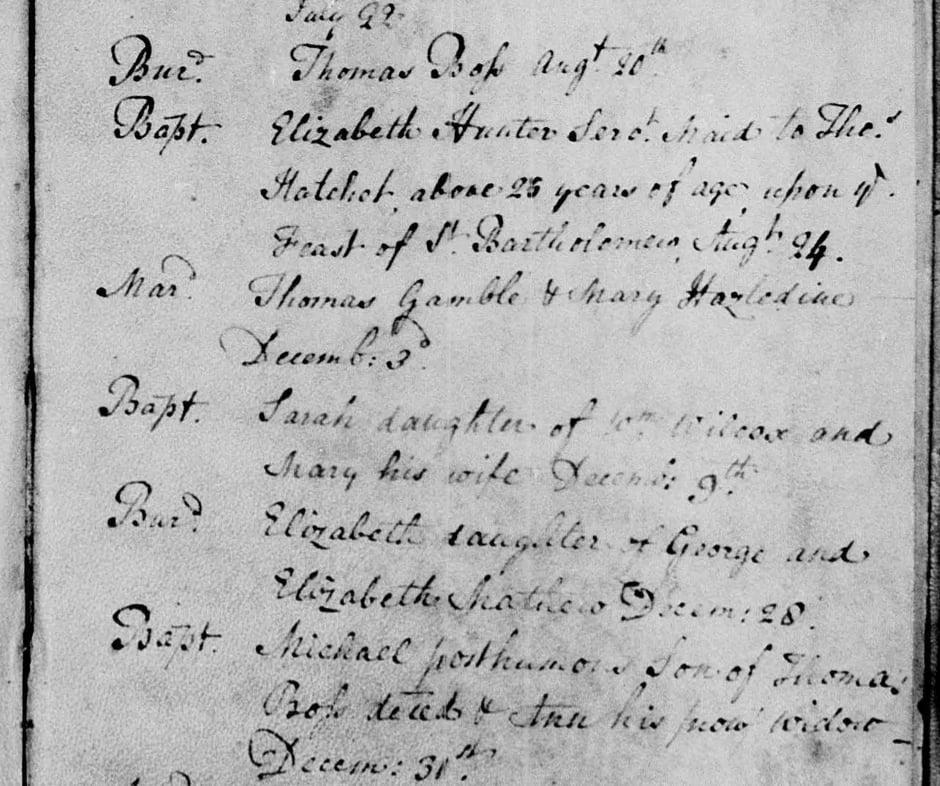

The only Michael Boss born at the right time was in 1750 in Edingale, Staffordshire, about eight miles from Appleby Magna. His parents were Thomas Boss and Ann Parker, married in Edingale in 1747. Thomas died in August 1750, and his son Michael was baptised in the December, posthumus son of Thomas and his widow Ann. Both entries are on the same page of the register.

Ann Boss, the young widow, married again. But perhaps Michael and his brother went to live with their childless uncle and aunt, Michael Boss and Grace Cuthbert.

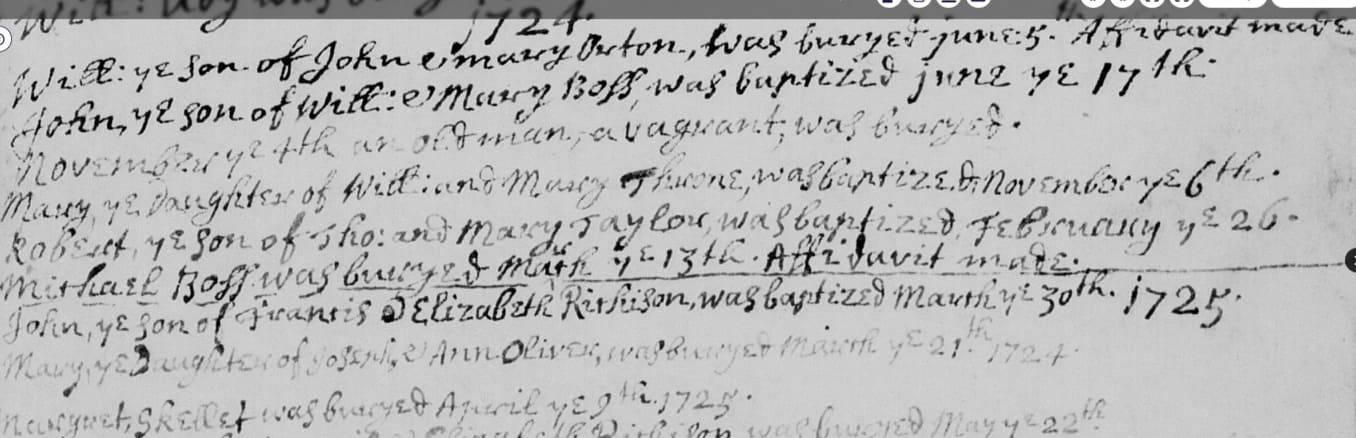

The great grandfather of Michael Boss (the Measham blacksmith born in 1850) was also Michael Boss, probably born in the 1660s. He died in Newton Regis in Warwickshire in 1724, four years after his son (also Michael Boss born 1693) married Jane Peircivall. The entry on the parish register states that Michael Boss was buried ye 13th Affadavit made.

I had not seen affadavit made on a parish register before, and this relates to the The Burying in Woollen Acts 1666–80. According to Wikipedia:

“Acts of the Parliament of England which required the dead, except plague victims and the destitute, to be buried in pure English woollen shrouds to the exclusion of any foreign textiles. It was a requirement that an affidavit be sworn in front of a Justice of the Peace (usually by a relative of the deceased), confirming burial in wool, with the punishment of a £5 fee for noncompliance. Burial entries in parish registers were marked with the word “affidavit” or its equivalent to confirm that affidavit had been sworn; it would be marked “naked” for those too poor to afford the woollen shroud. The legislation was in force until 1814, but was generally ignored after 1770.”

Michael Boss buried 1724 “Affadavit made”:

Elizabeth Page‘s father was William Page 1717-1783, a wheelwright in Hartshorn. (The father of the first wife Elizabeth was also William Page, but he was a husbandman in Smisby born in 1714. William Page, the father of the second wife, was born in Nailstone, Leicestershire, in 1717. His place of residence on his marriage to Mary Potter was spelled Nelson.)

Her mother was Mary Potter 1719- of nearby Coleorton. Mary’s father, Richard Potter 1677-1731, was a blacksmith in Coleorton.

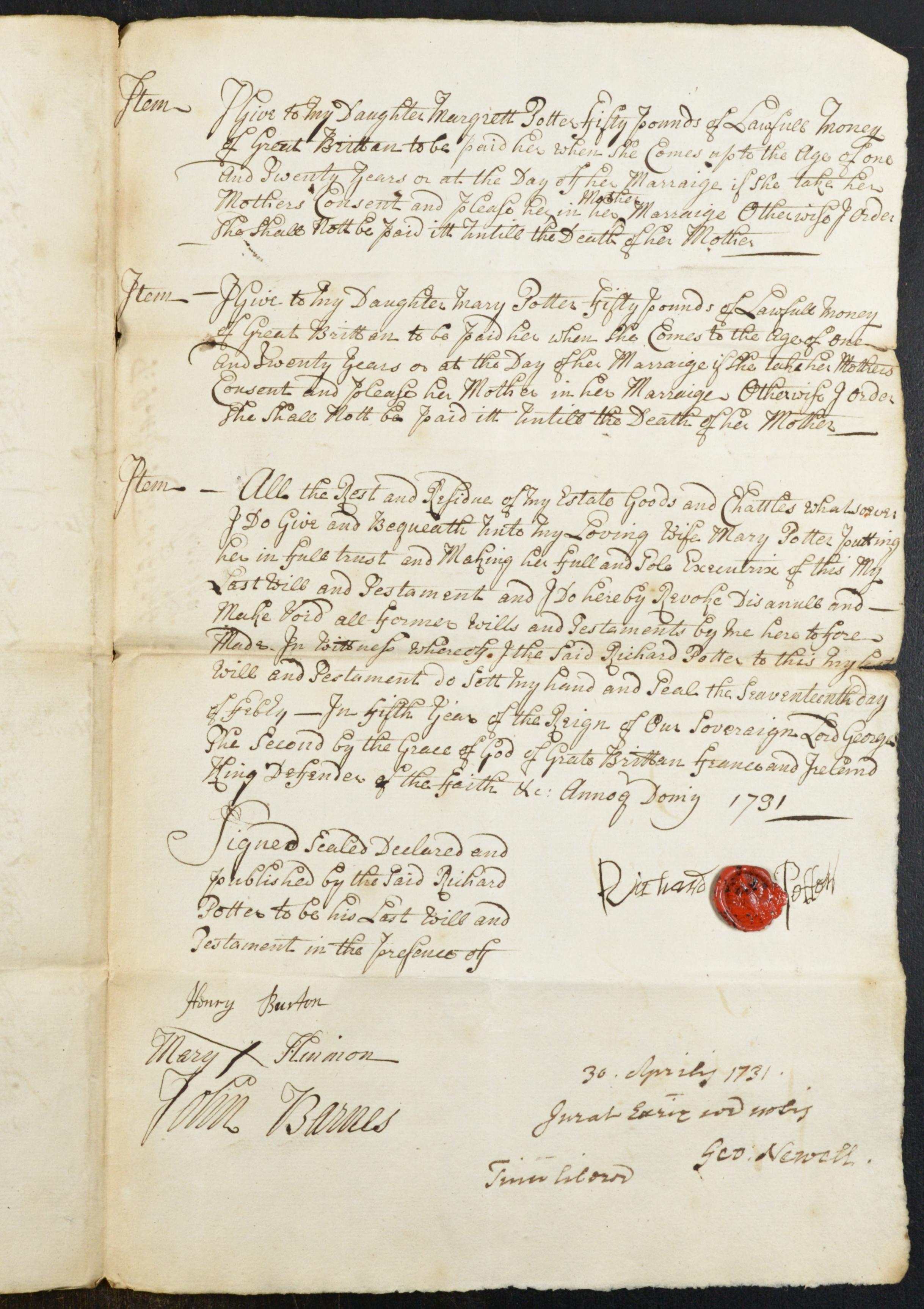

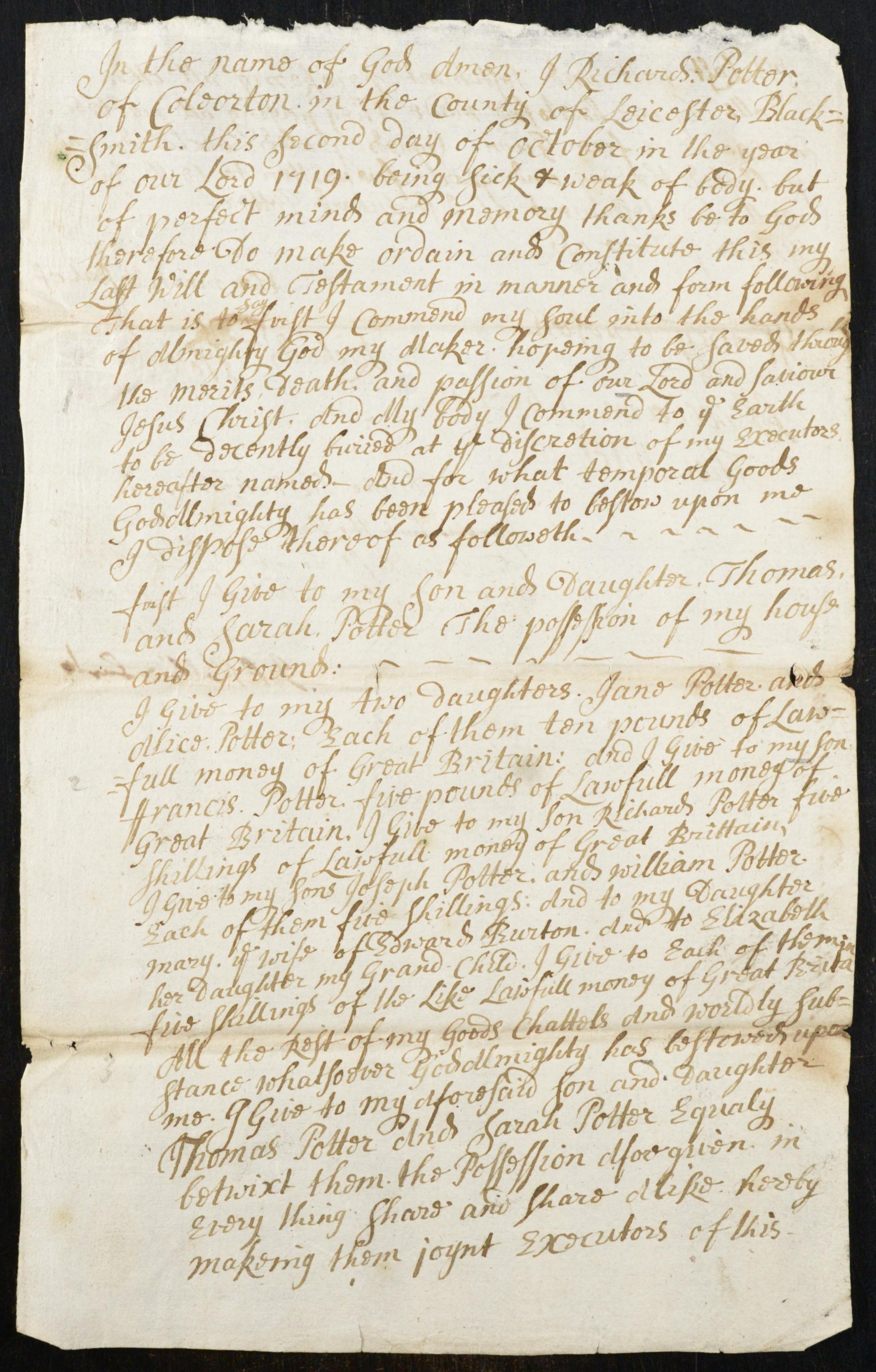

A page of the will of Richard Potter 1731:

Richard Potter states: “I will and order that my son Thomas Potter shall after my decease have one shilling paid to him and no more.” As he left £50 to each of his daughters, one can’t help but wonder what Thomas did to displease his father.

Richard stipulated that his son Thomas should have one shilling paid to him and not more, for several good considerations, and left “the house and ground lying in the parish of Whittwick in a place called the Long Lane to my wife Mary Potter to dispose of as she shall think proper.”

His son Richard inherited the blacksmith business: “I will and order that my son Richard Potter shall live and be with his mother and serve her duly and truly in the business of a blacksmith, and obey and serve her in all lawful commands six years after my decease, and then I give to him and his heirs…. my house and grounds Coulson House in the Liberty of Thringstone”

Richard wanted his son John to be a blacksmith too: “I will and order that my wife bring up my son John Potter at home with her and teach or cause him to be taught the trade of a blacksmith and that he shall serve her duly and truly seven years after my decease after the manner of an apprentice and at the death of his mother I give him that house and shop and building and the ground belonging to it which I now dwell in to him and his heirs forever.”

To his daughters Margrett and Mary Potter, upon their reaching the age of one and twenty, or the day after their marriage, he leaves £50 each. All the rest of his goods are left to his loving wife Mary.

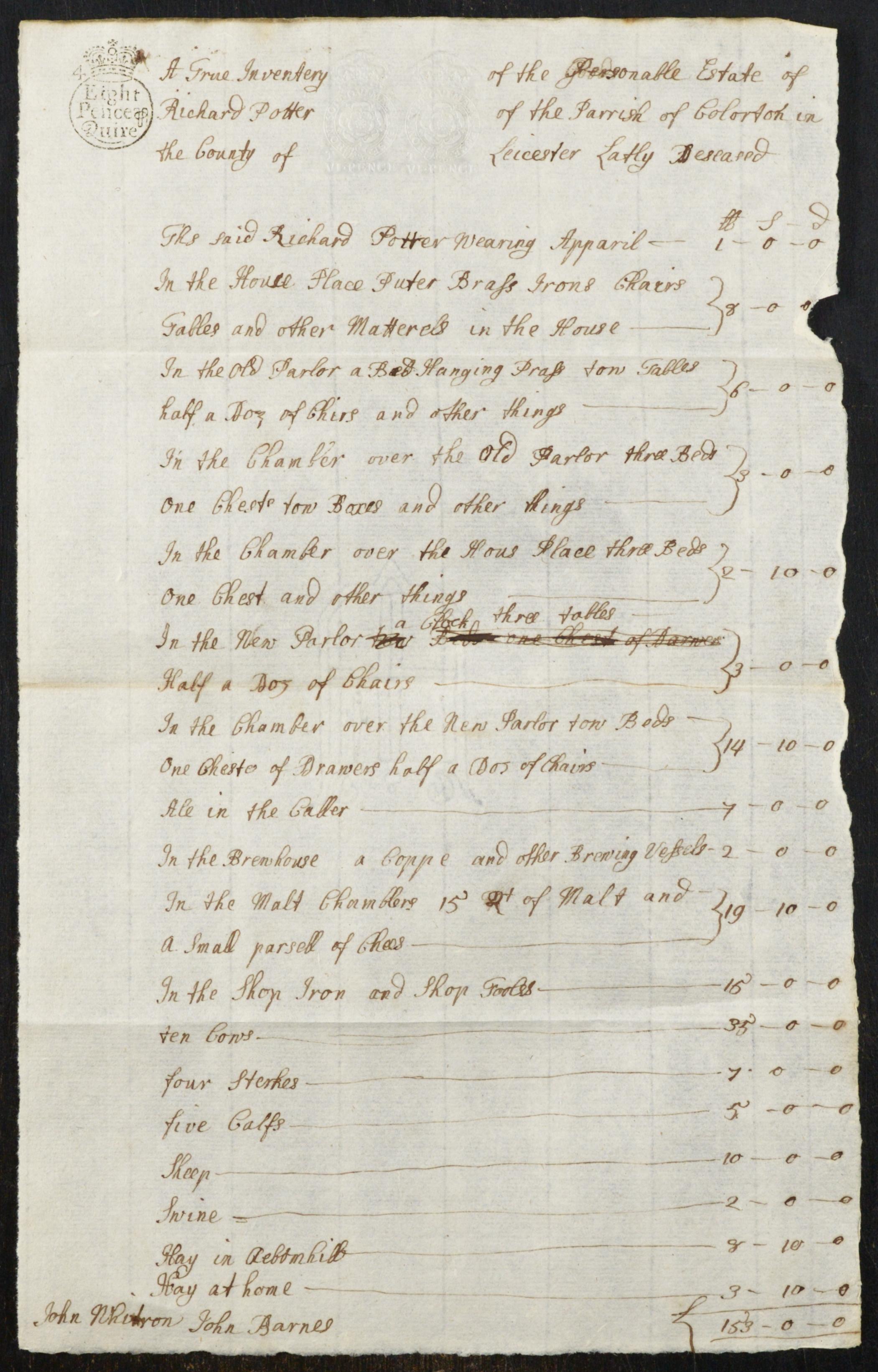

An inventory of the belongings of Richard Potter, 1731:

Richard Potters father was also named Richard Potter 1649-1719, and he too was a blacksmith.

Richard Potter of Coleorton in the county of Leicester, blacksmith, stated in his will: “I give to my son and daughter Thomas and Sarah Potter the possession of my house and grounds.”

He leaves ten pounds each to his daughters Jane and Alice, to his son Francis he gives five pounds, and five shillings to his son Richard. Sons Joseph and William also receive five shillings each. To his daughter Mary, wife of Edward Burton, and her daughter Elizabeth, he gives five shillings each. The rest of his good, chattels and wordly substance he leaves equally between his son and daugter Thomas and Sarah. As there is no mention of his wife, it’s assumed that she predeceased him.

The will of Richard Potter, 1719:

Richard Potter’s (1649-1719) parents were William Potter and Alse Huldin, both born in the early 1600s. They were married in 1646 at Breedon on the Hill, Leicestershire. The name Huldin appears to originate in Finland.

William Potter was a blacksmith. In the 1659 parish registers of Breedon on the Hill, William Potter of Breedon blacksmith buryed the 14th July.

April 2, 2022 at 6:15 pm #6286In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Matthew Orgill and His Family

Matthew Orgill 1828-1907 was the Orgill brother who went to Australia, but returned to Measham. Matthew married Mary Orgill in Measham in October 1856, having returned from Victoria, Australia in May of that year.

Although Matthew was the first Orgill brother to go to Australia, he was the last one I found, and that was somewhat by accident, while perusing “Orgill” and “Measham” in a newspaper archives search. I chanced on Matthew’s obituary in the Nuneaton Observer, Friday 14 June 1907:

LATE MATTHEW ORGILL PEACEFUL END TO A BLAMELESS LIFE.

‘Sunset and Evening Star And one clear call for me.”

It is with very deep regret that we have to announce the death of Mr. Matthew Orgill, late of Measham, who passed peacefully away at his residence in Manor Court Road, Nuneaton, in the early hours of yesterday morning. Mr. Orgill, who was in his eightieth year, was a man with a striking history, and was a very fine specimen of our best English manhood. In early life be emigrated to South Africa—sailing in the “Hebrides” on 4th February. 1850—and was one of the first settlers at the Cape; afterwards he went on to Australia at the time of the Gold Rush, and ultimately came home to his native England and settled down in Measham, in Leicestershire, where he carried on a successful business for the long period of half-a-century.

He was full of reminiscences of life in the Colonies in the early days, and an hour or two in his company was an education itself. On the occasion of the recall of Sir Harry Smith from the Governorship of Natal (for refusing to be a party to the slaying of the wives and children in connection with the Kaffir War), Mr. Orgill was appointed to superintend the arrangements for the farewell demonstration. It was one of his boasts that he made the first missionary cart used in South Africa, which is in use to this day—a monument to the character of his work; while it is an interesting fact to note that among Mr. Orgill’s papers there is the original ground-plan of the city of Durban before a single house was built.

In Africa Mr. Orgill came in contact with the great missionary, David Livingstone, and between the two men there was a striking resemblance in character and a deep and lasting friendship. Mr. Orgill could give a most graphic description of the wreck of the “Birkenhead,” having been in the vicinity at the time when the ill-fated vessel went down. He played a most prominent part on the occasion of the famous wreck of the emigrant ship, “Minerva.” when, in conjunction with some half-a-dozen others, and at the eminent risk of their own lives, they rescued more than 100 of the unfortunate passengers. He was afterwards presented with an interesting relic as a memento of that thrilling experience, being a copper bolt from the vessel on which was inscribed the following words: “Relic of the ship Minerva, wrecked off Bluff Point, Port Natal. 8.A.. about 2 a.m.. Friday, July 5, 1850.”

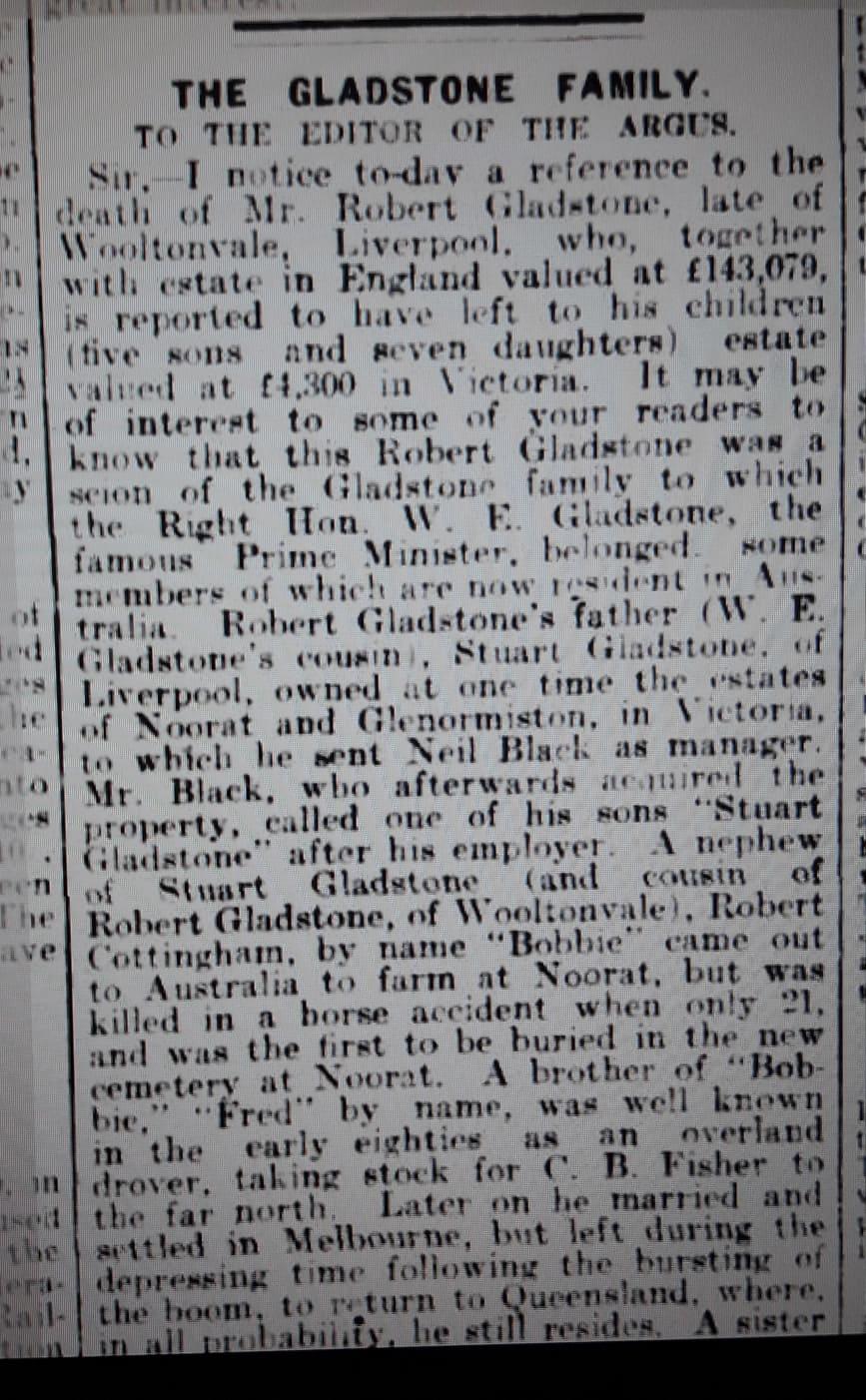

Mr. Orgill was followed to the Colonies by no fewer than six of his brothers, all of whom did well, and one of whom married a niece (brother’s daughter) of the late Mr. William Ewart Gladstone.

On settling down in Measham his kindly and considerate disposition soon won for him a unique place in the hearts of all the people, by whom he was greatly beloved. He was a man of sterling worth and integrity. Upright and honourable in all his dealings, he led a Christian life that was a pattern to all with whom he came in contact, and of him it could truly he said that he wore the white flower of a blameless life.

He was a member of the Baptist Church, and although beyond much active service since settling down in Nuneaton less than two years ago he leaves behind him a record in Christian service attained by few. In politics he was a Radical of the old school. A great reader, he studied all the questions of the day, and could back up every belief he held by sound and fearless argument. The South African – war was a great grief to him. He knew the Boers from personal experience, and although he suffered at the time of the war for his outspoken condemnation, he had the satisfaction of living to see the people of England fully recognising their awful blunder. To give anything like an adequate idea of Mr. Orgill’s history would take up a great amount of space, and besides much of it has been written and commented on before; suffice it to say that it was strenuous, interesting, and eventful, and yet all through his hands remained unspotted and his heart was pure.

He is survived by three daughters, and was father-in-law to Mr. J. S. Massey. St Kilda. Manor Court Road, to whom deep and loving sympathy is extended in their sore bereavement by a wide circle of friends. The funeral is arranged to leave for Measham on Monday at twelve noon.

“To give anything like an adequate idea of Mr. Orgill’s history would take up a great amount of space, and besides much of it has been written and commented on before…”

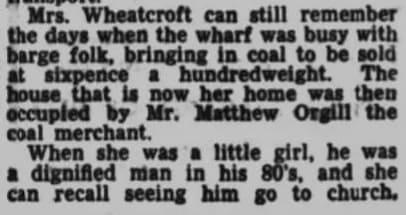

I had another look in the newspaper archives and found a number of articles mentioning him, including an intriguing excerpt in an article about local history published in the Burton Observer and Chronicle 8 August 1963:

on an upstairs window pane he scratched with his diamond ring “Matthew Orgill, 1st July, 1858”

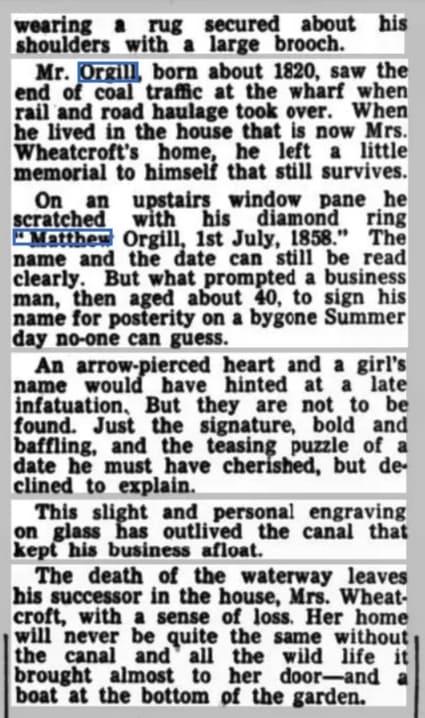

I asked on a Measham facebook group if anyone knew the location of the house mentioned in the article and someone kindly responded. This is the same building, seen from either side:

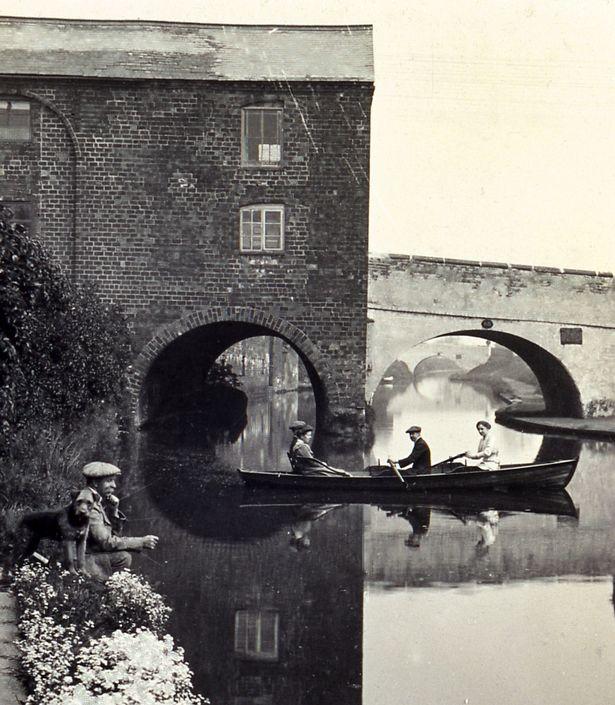

Coincidentally, I had already found this wonderful photograph of the same building, taken in 1910 ~ three years after Matthew’s death.

But what to make of the inscription in the window?

Matthew and Mary married in October 1856, and their first child (according to the records I’d found thus far) was a daughter Mary born in 1860. I had a look for a Matthew Orgill birth registered in 1858, the date Matthew had etched on the window, and found a death for a Matthew Orgill in 1859. Assuming I would find the birth of Matthew Orgill registered on the first of July 1958, to match the etching in the window, the corresponding birth was in July 1857!

Matthew and Mary had four children. Matthew, Mary, Clara and Hannah. Hannah Proudman Orgill married Joseph Stanton Massey. The Orgill name continues with their son Stanley Orgill Massey 1900-1979, who was a doctor and surgeon. Two of Stanley’s four sons were doctors, Paul Mackintosh Orgill Massey 1929-2009, and Michael Joseph Orgill Massey 1932-1989.

Mary Orgill 1827-1894, Matthews wife, was an Orgill too.

And this is where the Orgill branch of the tree gets complicated.

Mary’s father was Henry Orgill born in 1805 and her mother was Hannah Proudman born in 1805.

Henry Orgill’s father was Matthew Orgill born in 1769 and his mother was Frances Finch born in 1771.Mary’s husband Matthews parents are Matthew Orgill born in 1798 and Elizabeth Orgill born in 1803.

Another Orgill Orgill marriage!

Matthews parents, Matthew and Elizabeth, have the same grandparents as each other, Matthew Orgill born in 1736 and Ann Proudman born in 1735.

But Matthews grandparents are none other than Matthew Orgill born in 1769 and Frances Finch born in 1771 ~ the same grandparents as his wife Mary!

February 2, 2022 at 11:53 am #6265In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

From Tanganyika with Love

continued ~ part 6

With thanks to Mike Rushby.

Mchewe 6th June 1937

Dearest Family,

Home again! We had an uneventful journey. Kate was as good as gold all the

way. We stopped for an hour at Bulawayo where we had to change trains but

everything was simplified for me by a very pleasant man whose wife shared my

compartment. Not only did he see me through customs but he installed us in our new

train and his wife turned up to see us off with magazines for me and fruit and sweets for

Kate. Very, very kind, don’t you think?Kate and I shared the compartment with a very pretty and gentle girl called

Clarice Simpson. She was very worried and upset because she was going home to

Broken Hill in response to a telegram informing her that her young husband was

dangerously ill from Blackwater Fever. She was very helpful with Kate whose

cheerfulness helped Clarice, I think, though I, quite unintentionally was the biggest help

at the end of our journey. Remember the partial dentures I had had made just before

leaving Cape Town? I know I shall never get used to the ghastly things, I’ve had them

two weeks now and they still wobble. Well this day I took them out and wrapped them

in a handkerchief, but when we were packing up to leave the train I could find the

handkerchief but no teeth! We searched high and low until the train had slowed down to

enter Broken Hill station. Then Clarice, lying flat on the floor, spied the teeth in the dark

corner under the bottom bunk. With much stretching she managed to retrieve the

dentures covered in grime and fluff. My look of horror, when I saw them, made young

Clarice laugh. She was met at the station by a very grave elderly couple. I do wonder

how things turned out for her.I stayed overnight with Kate at the Great Northern Hotel, and we set off for

Mbeya by plane early in the morning. One of our fellow passengers was a young

mother with a three week old baby. How ideas have changed since Ann was born. This

time we had a smooth passage and I was the only passenger to get airsick. Although

there were other women passengers it was a man once again, who came up and

offered to help. Kate went off with him amiably and he entertained her until we touched

down at Mbeya.George was there to meet us with a wonderful surprise, a little red two seater

Ford car. She is a bit battered and looks a bit odd because the boot has been

converted into a large wooden box for carrying raw salt, but she goes like the wind.

Where did George raise the cash to buy a car? Whilst we were away he found a small

cave full of bat guano near a large cave which is worked by a man called Bob Sargent.

As Sargent did not want any competition he bought the contents of the cave from

George giving him the small car as part payment.It was lovely to return to our little home and find everything fresh and tidy and the

garden full of colour. But it was heartbreaking to go into the bedroom and see George’s

precious forgotten boots still standing by his empty bed.With much love,

Eleanor.Mchewe 25th June 1937

Dearest Family,

Last Friday George took Kate and me in the little red Ford to visit Mr Sargent’s

camp on the Songwe River which cuts the Mbeya-Mbosi road. Mr Sargent bought

Hicky-Wood’s guano deposit and also our small cave and is making a good living out of

selling the bat guano to the coffee farmers in this province. George went to try to interest

him in a guano deposit near Kilwa in the Southern Province. Mr Sargent agreed to pay

25 pounds to cover the cost of the car trip and pegging costs. George will make the trip

to peg the claim and take samples for analysis. If the quality is sufficiently high, George

and Mr Sargent will go into partnership. George will work the claim and ship out the

guano from Kilwa which is on the coast of the Southern Province of Tanganyika. So now

we are busy building castles in the air once more.On Saturday we went to Mbeya where George had to attend a meeting of the

Trout Association. In the afternoon he played in a cricket match so Kate and I spent the

whole day with the wife of the new Superintendent of Police. They have a very nice

new house with lawns and a sunken rose garden. Kate had a lovely romp with Kit, her

three year old son.Mrs Wolten also has two daughters by a previous marriage. The elder girl said to

me, “Oh Mrs Rushby your husband is exactly like the strong silent type of man I

expected to see in Africa but he is the only one I have seen. I think he looks exactly like

those men in the ‘Barney’s Tobacco’ advertisements.”I went home with a huge pile of magazines to keep me entertained whilst

George is away on the Kilwa trip.Lots of love,

Eleanor.Mchewe 9th July 1937

Dearest Family,

George returned on Monday from his Kilwa safari. He had an entertaining

tale to tell.Before he approached Mr Sargent about going shares in the Kilwa guano

deposit he first approached a man on the Lupa who had done very well out of a small

gold reef. This man, however said he was not interested so you can imagine how

indignant George was when he started on his long trip, to find himself being trailed by

this very man and a co-driver in a powerful Ford V8 truck. George stopped his car and

had some heated things to say – awful threats I imagine as to what would happen to

anyone who staked his claim. Then he climbed back into our ancient little two seater and

went off like a bullet driving all day and most of the night. As the others took turns in

driving you can imagine what a feat it was for George to arrive in Kilwa ahead of them.

When they drove into Kilwa he met them with a bright smile and a bit of bluff –

quite justifiable under the circumstances I think. He said, you chaps can have a rest now,

you’re too late.” He then whipped off and pegged the claim. he brought some samples

of guano back but until it has been analysed he will not know whether the guano will be

an economic proposition or not. George is not very hopeful. He says there is a good

deal of sand mixed with the guano and that much of it was damp.The trip was pretty eventful for Kianda, our houseboy. The little two seater car

had been used by its previous owner for carting bags of course salt from his salt pans.

For this purpose the dicky seat behind the cab had been removed, and a kind of box

built into the boot of the car. George’s camp kit and provisions were packed into this

open box and Kianda perched on top to keep an eye on the belongings. George

travelled so fast on the rough road that at some point during the night Kianda was

bumped off in the middle of the Game Reserve. George did not notice that he was

missing until the next morning. He concluded, quite rightly as it happened, that Kianda

would be picked up by the rival truck so he continued his journey and Kianda rejoined

him at Kilwa.Believe it or not, the same thing happened on the way back but fortunately this

time George noticed his absence. He stopped the car and had just started back on his

tracks when Kianda came running down the road still clutching the unlighted storm lamp

which he was holding in his hand when he fell. The glass was not even cracked.

We are finding it difficult just now to buy native chickens and eggs. There has

been an epidemic amongst the poultry and one hesitates to eat the survivors. I have a

brine tub in which I preserve our surplus meat but I need the chickens for soup.

I hope George will be home for some months. He has arranged to take a Mr

Blackburn, a wealthy fruit farmer from Elgin, Cape, on a hunting safari during September

and October and that should bring in some much needed cash. Lillian Eustace has

invited Kate and me to spend the whole of October with her in Tukuyu.

I am so glad that you so much enjoy having Ann and George with you. We miss

them dreadfully. Kate is a pretty little girl and such a little madam. You should hear the

imperious way in which she calls the kitchenboy for her meals. “Boy Brekkis, Boy Lunch,

and Boy Eggy!” are her three calls for the day. She knows no Ki-Swahili.Eleanor

Mchewe 8th October 1937

Dearest Family,

I am rapidly becoming as superstitious as our African boys. They say the wild

animals always know when George is away from home and come down to have their

revenge on me because he has killed so many.I am being besieged at night by a most beastly leopard with a half grown cub. I

have grown used to hearing leopards grunt as they hunt in the hills at night but never

before have I had one roaming around literally under the windows. It has been so hot at

night lately that I have been sleeping with my bedroom door open onto the verandah. I

felt quite safe because the natives hereabouts are law-abiding and in any case I always

have a boy armed with a club sleeping in the kitchen just ten yards away. As an added

precaution I also have a loaded .45 calibre revolver on my bedside table, and Fanny

our bullterrier, sleeps on the mat by my bed. I am also looking after Barney, a fine

Airedale dog belonging to the Costers. He slept on a mat by the open bedroom door

near a dimly burning storm lamp.As usual I went to sleep with an easy mind on Monday night, but was awakened

in the early hours of Tuesday by the sound of a scuffle on the front verandah. The noise

was followed by a scream of pain from Barney. I jumped out of bed and, grabbing the

lamp with my left hand and the revolver in my right, I rushed outside just in time to see

two animal figures roll over the edge of the verandah into the garden below. There they

engaged in a terrific tug of war. Fortunately I was too concerned for Barney to be

nervous. I quickly fired two shots from the revolver, which incidentally makes a noise like

a cannon, and I must have startled the leopard for both animals, still locked together,

disappeared over the edge of the terrace. I fired two more shots and in a few moments

heard the leopard making a hurried exit through the dry leaves which lie thick under the

wild fig tree just beyond the terrace. A few seconds later Barney appeared on the low

terrace wall. I called his name but he made no move to come but stood with hanging

head. In desperation I rushed out, felt blood on my hands when I touched him, so I

picked him up bodily and carried him into the house. As I regained the verandah the boy

appeared, club in hand, having been roused by the shots. He quickly grasped what had

happened when he saw my blood saturated nightie. He fetched a bowl of water and a

clean towel whilst I examined Barney’s wounds. These were severe, the worst being a

gaping wound in his throat. I washed the gashes with a strong solution of pot permang

and I am glad to say they are healing remarkably well though they are bound to leave

scars. Fanny, very prudently, had taken no part in the fighting except for frenzied barking

which she kept up all night. The shots had of course wakened Kate but she seemed

more interested than alarmed and kept saying “Fanny bark bark, Mummy bang bang.

Poor Barney lots of blood.”In the morning we inspected the tracks in the garden. There was a shallow furrow

on the terrace where Barney and the leopard had dragged each other to and fro and

claw marks on the trunk of the wild fig tree into which the leopard climbed after I fired the

shots. The affair was of course a drama after the Africans’ hearts and several of our

shamba boys called to see me next day to make sympathetic noises and discuss the

affair.I went to bed early that night hoping that the leopard had been scared off for

good but I must confess I shut all windows and doors. Alas for my hopes of a restful

night. I had hardly turned down the lamp when the leopard started its terrifying grunting

just under the bedroom windows. If only she would sniff around quietly I should not

mind, but the noise is ghastly, something like the first sickening notes of a braying

donkey, amplified here by the hills and the gorge which is only a stones throw from the

bedroom. Barney was too sick to bark but Fanny barked loud enough for two and the more

frantic she became the hungrier the leopard sounded. Kate of course woke up and this

time she was frightened though I assured her that the noise was just a donkey having

fun. Neither of us slept until dawn when the leopard returned to the hills. When we

examined the tracks next morning we found that the leopard had been accompanied by

a fair sized cub and that together they had prowled around the house, kitchen, and out

houses, visiting especially the places to which the dogs had been during the day.

As I feel I cannot bear many more of these nights, I am sending a note to the

District Commissioner, Mbeya by the messenger who takes this letter to the post,

asking him to send a game scout or an armed policeman to deal with the leopard.

So don’t worry, for by the time this reaches you I feel sure this particular trouble

will be over.Eleanor.

Mchewe 17th October 1937

Dearest Family,

More about the leopard I fear! My messenger returned from Mbeya to say that

the District Officer was on safari so he had given the message to the Assistant District

Officer who also apparently left on safari later without bothering to reply to my note, so

there was nothing for me to do but to send for the village Nimrod and his muzzle loader

and offer him a reward if he could frighten away or kill the leopard.The hunter, Laza, suggested that he should sleep at the house so I went to bed

early leaving Laza and his two pals to make themselves comfortable on the living room

floor by the fire. Laza was armed with a formidable looking muzzle loader, crammed I

imagine with nuts and bolts and old rusty nails. One of his pals had a spear and the other

a panga. This fellow was also in charge of the Petromax pressure lamp whose light was

hidden under a packing case. I left the campaign entirely to Laza’s direction.

As usual the leopard came at midnight stealing down from the direction of the

kitchen and announcing its presence and position with its usual ghastly grunts. Suddenly

pandemonium broke loose on the back verandah. I heard the roar of the muzzle loader

followed by a vigourous tattoo beaten on an empty paraffin tin and I rushed out hoping

to find the dead leopard. however nothing of the kind had happened except that the

noise must have scared the beast because she did not return again that night. Next

morning Laza solemnly informed me that, though he had shot many leopards in his day,

this was no ordinary leopard but a “sheitani” (devil) and that as his gun was no good

against witchcraft he thought he might as well retire from the hunt. Scared I bet, and I

don’t blame him either.You can imagine my relief when a car rolled up that afternoon bringing Messers

Stewart and Griffiths, two farmers who live about 15 miles away, between here and

Mbeya. They had a note from the Assistant District Officer asking them to help me and

they had come to set up a trap gun in the garden. That night the leopard sniffed all

around the gun and I had the added strain of waiting for the bang and wondering what I

should do if the beast were only wounded. I conjured up horrible visions of the two little

totos trotting up the garden path with the early morning milk and being horribly mauled,

but I needn’t have worried because the leopard was far too wily to be caught that way.

Two more ghastly nights passed and then I had another visitor, a Dr Jackson of

the Tsetse Department on safari in the District. He listened sympathetically to my story

and left his shotgun and some SSG cartridges with me and instructed me to wait until the

leopard was pretty close and blow its b—– head off. It was good of him to leave his

gun. George always says there are three things a man should never lend, ‘His wife, his

gun and his dog.’ (I think in that order!)I felt quite cheered by Dr Jackson’s visit and sent

once again for Laza last night and arranged a real show down. In the afternoon I draped

heavy blankets over the living room windows to shut out the light of the pressure lamp

and the four of us, Laza and his two stooges and I waited up for the leopard. When we

guessed by her grunts that she was somewhere between the kitchen and the back door

we all rushed out, first the boy with the panga and the lamp, next Laza with his muzzle

loader, then me with the shotgun followed closely by the boy with the spear. What a

farce! The lamp was our undoing. We were blinded by the light and did not even

glimpse the leopard which made off with a derisive grunt. Laza said smugly that he knew

it was hopeless to try and now I feel tired and discouraged too.This morning I sent a runner to Mbeya to order the hotel taxi for tomorrow and I

shall go to friends in Mbeya for a day or two and then on to Tukuyu where I shall stay

with the Eustaces until George returns from Safari.Eleanor.

Mchewe 18th November 1937

My darling Ann,

Here we are back in our own home and how lovely it is to have Daddy back from

safari. Thank you very much for your letter. I hope by now you have got mine telling you

how very much I liked the beautiful tray cloth you made for my birthday. I bet there are

not many little girls of five who can embroider as well as you do, darling. The boy,

Matafari, washes and irons it so carefully and it looks lovely on the tea tray.Daddy and I had some fun last night. I was in bed and Daddy was undressing

when we heard a funny scratching noise on the roof. I thought it was the leopard. Daddy

quickly loaded his shotgun and ran outside. He had only his shirt on and he looked so

funny. I grabbed the loaded revolver from the cupboard and ran after Dad in my nightie

but after all the rush it was only your cat, Winnie, though I don’t know how she managed

to make such a noise. We felt so silly, we laughed and laughed.Kate talks a lot now but in such a funny way you would laugh to her her. She

hears the houseboys call me Memsahib so sometimes instead of calling me Mummy

she calls me “Oompaab”. She calls the bedroom a ‘bippon’ and her little behind she

calls her ‘sittendump’. She loves to watch Mandawi’s cattle go home along the path

behind the kitchen. Joseph your donkey, always leads the cows. He has a lazy life now.

I am glad you had such fun on Guy Fawkes Day. You will be sad to leave

Plumstead but I am sure you will like going to England on the big ship with granny Kate.

I expect you will start school when you get to England and I am sure you will find that

fun.God bless my dear little girl. Lots of love from Daddy and Kate,

and MummyMchewe 18th November 1937

Hello George Darling,

Thank you for your lovely drawing of Daddy shooting an elephant. Daddy says

that the only thing is that you have drawn him a bit too handsome.I went onto the verandah a few minutes ago to pick a banana for Kate from the

bunch hanging there and a big hornet flew out and stung my elbow! There are lots of

them around now and those stinging flies too. Kate wears thick corduroy dungarees so

that she will not get her fat little legs bitten. She is two years old now and is a real little

pickle. She loves running out in the rain so I have ordered a pair of red Wellingtons and a

tiny umbrella from a Nairobi shop for her Christmas present.Fanny’s puppies have their eyes open now and have very sharp little teeth.

They love to nip each other. We are keeping the fiercest little one whom we call Paddy

but are giving the others to friends. The coffee bushes are full of lovely white flowers

and the bees and ants are very busy stealing their honey.Yesterday a troop of baboons came down the hill and Dad shot a big one to

scare the others off. They are a nuisance because they steal the maize and potatoes

from the native shambas and then there is not enough food for the totos.

Dad and I are very proud of you for not making a fuss when you went to the

dentist to have that tooth out.Bye bye, my fine little son.

Three bags full of love from Kate, Dad and Mummy.Mchewe 12th February, 1938

Dearest Family,

here is some news that will please you. George has been offered and has

accepted a job as Forester at Mbulu in the Northern Province of Tanganyika. George

would have preferred a job as Game Ranger, but though the Game Warden, Philip

Teare, is most anxious to have him in the Game Department, there is no vacancy at

present. Anyway if one crops up later, George can always transfer from one

Government Department to another. Poor George, he hates the idea of taking a job. He

says that hitherto he has always been his own master and he detests the thought of

being pushed around by anyone.Now however he has no choice. Our capitol is almost exhausted and the coffee

market shows no signs of improving. With three children and another on the way, he

feels he simply must have a fixed income. I shall be sad to leave this little farm. I love

our little home and we have been so very happy here, but my heart rejoices at the

thought of overseas leave every thirty months. Now we shall be able to fetch Ann and

George from England and in three years time we will all be together in Tanganyika once

more.There is no sale for farms so we will just shut the house and keep on a very small

labour force just to keep the farm from going derelict. We are eating our hens but will

take our two dogs, Fanny and Paddy with us.One thing I shall be glad to leave is that leopard. She still comes grunting around

at night but not as badly as she did before. I do not mind at all when George is here but

until George was accepted for this forestry job I was afraid he might go back to the

Diggings and I should once more be left alone to be cursed by the leopard’s attentions.

Knowing how much I dreaded this George was most anxious to shoot the leopard and

for weeks he kept his shotgun and a powerful torch handy at night.One night last week we woke to hear it grunting near the kitchen. We got up very

quietly and whilst George loaded the shotgun with SSG, I took the torch and got the

heavy revolver from the cupboard. We crept out onto the dark verandah where George

whispered to me to not switch on the torch until he had located the leopard. It was pitch

black outside so all he could do was listen intently. And then of course I spoilt all his

plans. I trod on the dog’s tin bowl and made a terrific clatter! George ordered me to

switch on the light but it was too late and the leopard vanished into the long grass of the

Kalonga, grunting derisively, or so it sounded.She never comes into the clearing now but grunts from the hillside just above it.

Eleanor.

Mbulu 18th March, 1938

Dearest Family,

Journeys end at last. here we are at Mbulu, installed in our new quarters which are

as different as they possibly could be from our own cosy little home at Mchewe. We

live now, my dears, in one wing of a sort of ‘Beau Geste’ fort but I’ll tell you more about

it in my next letter. We only arrived yesterday and have not had time to look around.

This letter will tell you just about our trip from Mbeya.We left the farm in our little red Ford two seater with all our portable goods and

chattels plus two native servants and the two dogs. Before driving off, George took one

look at the flattened springs and declared that he would be surprised if we reached

Mbeya without a breakdown and that we would never make Mbulu with the car so

overloaded.However luck was with us. We reached Mbeya without mishap and at one of the

local garages saw a sturdy used Ford V8 boxbody car for sale. The garage agreed to

take our small car as part payment and George drew on our little remaining capitol for the

rest. We spent that night in the house of the Forest Officer and next morning set out in

comfort for the Northern Province of Tanganyika.I had done the journey from Dodoma to Mbeya seven years before so was

familiar with the scenery but the road was much improved and the old pole bridges had

been replaced by modern steel ones. Kate was as good as gold all the way. We

avoided hotels and camped by the road and she found this great fun.

The road beyond Dodoma was new to me and very interesting country, flat and

dry and dusty, as little rain falls there. The trees are mostly thorn trees but here and there

one sees a giant baobab, weird trees with fantastically thick trunks and fat squat branches

with meagre foliage. The inhabitants of this area I found interesting though. They are

called Wagogo and are a primitive people who ape the Masai in dress and customs

though they are much inferior to the Masai in physique. They are also great herders of

cattle which, rather surprisingly, appear to thrive in that dry area.The scenery alters greatly as one nears Babati, which one approaches by a high

escarpment from which one has a wonderful view of the Rift Valley. Babati township

appears to be just a small group of Indian shops and shabby native houses, but I

believe there are some good farms in the area. Though the little township is squalid,

there is a beautiful lake and grand mountains to please the eye. We stopped only long

enough to fill up with petrol and buy some foodstuffs. Beyond Babati there is a tsetse

fly belt and George warned our two native servants to see that no tsetse flies settled on

the dogs.We stopped for the night in a little rest house on the road about 80 miles from

Arusha where we were to spend a few days with the Forest Officer before going on to

Mbulu. I enjoyed this section of the road very much because it runs across wide plains

which are bounded on the West by the blue mountains of the Rift Valley wall. Here for

the first time I saw the Masai on their home ground guarding their vast herds of cattle. I

also saw their strange primitive hovels called Manyattas, with their thorn walled cattle

bomas and lots of plains game – giraffe, wildebeest, ostriches and antelope. Kate was

wildly excited and entranced with the game especially the giraffe which stood gazing

curiously and unafraid of us, often within a few yards of the road.Finally we came across the greatest thrill of all, my first view of Mt Meru the extinct

volcano about 16,000 feet high which towers over Arusha township. The approach to

Arusha is through flourishing coffee plantations very different alas from our farm at Mchewe. George says that at Arusha coffee growing is still a paying proposition