Search Results for 'days'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

February 2, 2023 at 9:10 pm #6492

In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

With a determined glint in his eye, Xavier set his sights on the slot machines. He scanned the rows of blinking lights and flashing screens until one caught his attention. He approached the machine and inserted a coin, feeling a rush of excitement as he pulled the lever.

With a satisfying whir, the reels began to spin, and before he knew it, the golden banana appeared on the screen, lining up perfectly. The machine erupted in flashing lights and loud noises, and a ticket spilled out onto the floor.

🎰 · 💰

🍌🍌🍌Xavier picked it up, reading aloud the inscriptions on the ticket, “Congratulations on completing your quest. You may enjoy your trip until the next stage of your journey. Look for the cook on the pirate boat, she will give you directions to regroup with your friends. And don’t forget to confirm your bookings.”

Glimmer let out a whoop of trepidation, “Let’s go find that cook, Xav! I can’t wait to see what’s next in store for us!”

But Xavier, feeling a bit worn out, replied with a smile, “Hold on a minute, love. All I need at the moment is just some R&R after all that brouhaha.”

Glimmer nodded in understanding and they both made their way to the deck, taking in the fresh air and the breathtaking scenery as the boat sailed towards its next destination.

As the boat continued its journey, sailing and gliding on the river in the air filled with moist, they could start to see across the mist opening like a heavy curtain a colourful floating market in the distance, and the sounds of haggling and laughter filled the air.

They couldn’t wait to explore and see what treasures and surprises awaited them. The journey was far from over, but for now, they were content to simply enjoy the ride.

Xavier closed his laptop while his friends were still sending messages on the chatroom. He’d had long days of work before leaving to take his flights to Australia, during which he hoped he could rest enough during the flights.

Most of the flights he’d checked had a minimum of 3 layovers, and a unbelievably long durations (not to count the astronomic amount of carbon emissions). Against all common sense, he’d taken one of the longest flight duration. It was 57h, but only 3 layovers. From Berlin, to Stockholm, then Dubai and Sydney. He could probably catch up with Youssef there as apparently he sent a message before boarding. They could go to Alice Spring and the Frying Mush Inn together. He’d try to find the reviews, but they were only listed on boutiquehotelsdownunder.com and didn’t have the rave reviews of the prestigious Kookynie Grand Hotel franchise. God knows what Zara had in mind while booking this place, it’d better be good. Reminded him of the time they all went to that improbably ghastly hotel in Spain (at the time Yasmin was still volunteering in a mission and couldn’t join) for a seminar with other game loonies and cosplayers. Those were the early days of the game, and the technology frankly left a lot to be desired at the time. They’d ended up eating raspberry jam with disposable toothbrushes, and get drunk on laughter.

When Brytta had seen the time it took to go there, she’d reconsidered coming. She couldn’t afford taking that much time off, and spending the equivalent of 4 full days of her hard-won vacation as a nurse into a plane simply for the round-trip —there was simply no way.

Xavier had proposed to shorten his stay, but she’d laughed and said, “you go there, I’ll enjoy some girl time with my friends, and I’ll work on my painting” —it was more convenient when he was gone for business trips, she would be able to put all the materials out, and not care to keep the apartment neat and tidy.The backpack was ready with the essentials; Xavier liked to travel light.

February 2, 2023 at 8:09 am #6489In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

It was a pleasant 25 degrees as Zara stepped off the plane. The flat red land stretched as far as the eye could see, and although she prefered a more undulating terrain there was something awe inspiring about this vast landscape. It was quite a contrast from the past few hours spent inside mine tunnels.

Bert, a weatherbeaten man of indeterminate advanced age, was there to meet her as arranged and led her to the car, a battered old four wheel drive. Although clearly getting on in years, he was tall and spry and dressed in practical working clothes.

“Welcome to Alice,” he said, taking her bag and putting in on the back seat. “I expect you’ll be wanting to know a bit about the place.”

“How long have you lived here?” Zara asked, as Bert settled into the creaky drivers seat and started the car.

Bert gave her a funny look and replied “Longer than a ducks ass.” Zara had never heard that expression before; she assumed it meant a long time but didn’t like to pursue the question.

“All this land belongs to the Arrernte,” he said, pronouncing it Arrunda. “The local aboriginals. 1862 when we got here. Well,” Bert turned to give Zara a lopsided smile, “Not me personally, I aint quite that old.”

Zara chuckled politely as Bert continued, “It got kinda busy around these parts round 1887 with the gold.”

“Oh, are there mines near here?” Zara asked with some excitement.

Bert gave her a sharp look. “Oh there’s mines alright. Abandoned now though, and dangerous. Dangerous places, old mines. You’ll be more interested in the hiking trails than those old mines, some real nice hiking and rock gorges, and it’s a nice temperature this time of year.”

Bert lapsed into silence for a few minutes, frowning.

“If you’da been arriving back then, you’da been on a camel train, that’s how they did it back then. Camel trains. They do camel tours for tourists nowadays.”

“Do you get many tourists?”

“Too dang many tourists if you ask me, Alice is full of them, and Ayers Rock’s crawling with ’em these days. We don’t get many out our way though.” Bert snorted, reminding Zara of Yasmin. “Our visitors like an off the beaten track kind of holiday, know what I mean?” Bert gave Zara another sideways lopsided smile. “I reckon you’ll like it at The Flying Fish Inn. Down to earth, know what I mean? Down to earth and off the wall.” He laughed heartily at that and Zara wasn’t quite sure what to say, so she laughed too.

“Sounds great.”

“Family run, see, makes a difference. No fancy airs and graces, no traffic ~ well, not much of anything really, just beautiful scenery and peace and quiet. Aunt Idle thinks she’s in charge but me and old Mater do most of it, well Finly does most of it to be honest, and you dropped lucky coming now, the twins have just decorated the bedrooms. Real nice they look now, they fancied doing some dreamtime murials on the walls. The twins are Idle’s neices, Clove and Corrie, turned out nice girls, despite everything.”

“Despite ….?”

“What? Oh, living in the outback. Youngsters usually leave and head for the cities. Prune’s the youngest gal, she’s a real imp, that one, a real character. And Devan calls by regular to see Mater, he works at the gas station.”

“Are they all Idle’s neices and nephews? Where are their parents?” Perhaps she shouldn’t have asked, Zara thought when she saw Bert’s face.

“Long gone, mate, long since gone from round here. We’ve taken good care of ’em.” Bert turned off the road onto a dirt road. “Only another five minutes now. We’re outside the town a bit, but there aint much in town anyway. Population 79, our town. About right for a decent sized town if you ask me.”

Bert rounded a bend in a eucalyptus grove and announced, “Here we are, then, the Flying Fish Inn.” He parked the car and retrieved Zara’s bag from the back seat. “Take a seat on the verandah and I’ll find Idle to show you to your room and get you a drink. Oh, and don’t be put off by Idle’s appearance, she’s a sweetheart really.”

Aunt Idle was nowhere to be found though, having decided to go for a walk on impulse, quite forgetting the arrival of the first guest. She saw Bert’s car approaching the hotel from her vantage point on a low hill, which reminded her she should be getting back. It was a lovely evening and she didn’t rush.

Bert found Mater in the dining room gazing out of the window. “Where the bloody hell is Idle? The guest’s outside on the verandah.”

“She’s taken herself off for a walk, can you believe it?” sighed Mater.

“Yep” Bert replied, “I can. Which room’s she in? Can you show her to her room?”

“Yes of course, Bert. Perhaps you’d see to getting a drink for her.”

February 2, 2023 at 12:04 am #6488

February 2, 2023 at 12:04 am #6488In reply to: Prompts of Madjourneys

- Zara completed her tile journey in the tunnels. In RL, she and Pretty Girl the parrot, are headed to Alice Springs in Australia, for a visit at the Flying Fish Inn (FFI). She’ll be the first to arrive.

- Yasmin, still volunteering at an orphanage in Suva in RL, has found a key with the imp, guided by the snake tattoo on a mysterious man named Fred, originating from Australia. She’s booked her flight via Air Fiji, and will be soon arriving to Australia for a few days vacation from her mission.

- Youssef, still in the Gobi desert, has found the grumpy vendor who was the shaman Lama Yoneze and reconnected with his friends in RL. Through the game in the desert, he also connected in VR (virtual reality) and RV (remote viewing) with sands_of_time, and elderly lady playing the game for intel. He still has to confirm his expected arrival to the FFI.

- Xavier has confirmed his flight option as well from Berlin, Germany. He’s planned a few days’ mix of remote working and vacation, but his girlfriend Brytta may still work her 2 shifts, and not necessarily keen to travel in the middle of nowhere in Australia.

They are all enjoying a lot the trail of clues from the game, and expect more adventures to come, with new challenges for each.

As they all make their way to the Flying Fish Inn, they eagerly anticipate what exciting experiences and challenges await them. Zara, Yasmin, Youssef, and Xavier all have unique experiences from their time playing the game and their real-life travels. With their journey to the Flying Fish Inn, they hope to connect with each other and continue the exciting adventures that have already captivated them. They are all looking forward to what is in store for them in the Australian Outback and the Flying Fish Inn.The challenge gets a level up. It requires for each of them to find or procure a unique object, linked to some of their personal quirks and in synch with the real-life experience and the game one. Provide suggestions for each of them of a very specific object or color or shape, that can be remote viewed in the FFI and that they may find in their RL.

- Zara: A golden compass, symbolizing her love for adventure and direction. It can be found in a hidden room in the FFI or as a unique treasure on a nearby beach.

- Yasmine: A silver key, symbolizing her discovery of the key in the game and her love for unlocking secrets. It can be found in a locked box in the FFI’s attic or in a locked drawer in her room.

- Youssef: A red scarf, symbolizing his connection with the shaman in the game and his love for vibrant colors. It can be found in the FFI’s market or in a shop in Alice Springs that sells unique handmade items.

- Xavier: A black notebook, symbolizing his love for organization and his need for clarity. It can be found in the FFI’s library or in a nearby stationary shop in Alice Springs.

January 31, 2023 at 11:34 am #6477In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Bertie dropped Zara off at the bus station in Camden early the next morning. She let him think she was catching a plane from Sydney, given her impulsive lie about having to meet her friends sooner, but she was going by train. The reviews she’d read online were tantalizing:

“The Ghan journey tells the story of the land. The train is the canvas, and the changing landscape paints the picture.”

A two day train ride would give her time to relax and play the game, and she assumed two days of desert scenery would not be too distracting. Luckily before she paid for her ticket she had the presence of mind to ask if there was internet on the train. There was not. Zara sighed, and booked a flight instead, but decided she would catch the train back home after the holiday at the Flying Fish Inn. By then perhaps the novelty of the game would have worn off, and she would appreciate the time spent in quiet contemplation, and perhaps do some writing.

Zara hated flying, especially airports. The best that could be said of flying was that it was a quick way to get from A to B.

“You’ll have to go in a cage for the flight, Pretty Girl,” she told the parrot.

“I think not,” replied Pretty Girl. “I’ll meet you there. See you!” and off she flew into the low morning sun, momentarily blinding Zara as she watched her go.

Her flight left Sydney at 14:35. Three and a half hours later she would arrive at Alice Springs and from there it was a half hour road trip to the Flying Fish. Zara sent an email to the inn asking if anyone could pick her up, otherwise she would get a bus or a taxi. She received a reply saying that they’d send Bert to pick her up around seven o’clock. Another Bert!

January 29, 2023 at 9:30 pm #6470In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Put your thoughts to sleep. Do not let them cast a shadow over the moon of your heart. Let go of thinking.

~ RumiTired from not having any sleep, Zara had found the suburb of Camden unattractive and boring, and her cousin Bertie, although cheerful and kind and eager to show her around, had become increasingly irritating to her. She found herself wishing he’d shut up and take her back to the house so she could play the game again. And then felt even more cranky at how uncomfortable she felt about being so ungrateful. She wondered if she was going to get addicted and spent the rest of her life with her head bent over a gadget and never look up at the real word again, like boring people moaned about on social media.

Maybe she should leave tomorrow, even if it meant arriving first at the Flying Fish Inn. But what about the ghost of Isaac in the church, would she regret later not following that up. On the other hand, if she went straight to the Inn and had a few days on her own, she could spend as long as she wanted in the game with nobody pestering her. Zara squirmed mentally when she realized she was translating Berties best efforts at hospitality as pestering.

Bertie stopped the car at a traffic light and was chatting to the passenger in the next car through his open window. Zara picked her phone up and checked her daily Call The Whale app for some inspiration.

Let go of thinking.

A ragged sigh escaped Zara’s lips, causing Bertie to glance over. She adjusted her facial expression quickly and rustled up a cheery smile and Bertie continued his conversation with the occupants of the other car until the lights changed.

“I thought you’d like to meet the folks down at the library, they know all the history of Camden,” Bertie said, but Zara interrupted him.

“Oh Bertie, how kind of you! But I’ve just had a message and I have to leave tomorrow morning for the rendezvous with my friends. There’s been a change of plans.” Zara astonished herself that she blurted that out without thinking it through first. But there. It was said. It was decided.

January 24, 2023 at 11:59 pm #6459In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

It was pretty late, but Xavier remembered he had to book his flight (and his holidays, even if he could still mix the trip with his job… it would depend if Brytta would be able to join or not; if such were the case, he’d definitely would book time off).

At the hotel where he was staying for the 2-days business trip he had to attend for his job, he’d noticed the strange decor, with little people in costumes in odd sceneries patterned on the “Toile de Jouy” curtains and some others in the most curious framed paintings, many of them looked like actual monkeys. Curiously, there wasn’t any golden banana, or banana bus, but it made him wonder if there was something more to be looked at the Inn that Zara wanted them to go to.

At the hotel where he was staying for the 2-days business trip he had to attend for his job, he’d noticed the strange decor, with little people in costumes in odd sceneries patterned on the “Toile de Jouy” curtains and some others in the most curious framed paintings, many of them looked like actual monkeys. Curiously, there wasn’t any golden banana, or banana bus, but it made him wonder if there was something more to be looked at the Inn that Zara wanted them to go to.Yasmin, a step ahead of him, had already looked at the reviews on MadjourneyAdvisor, and they were rave… in a fashion…

“The lady behind the bar is nearly 90 years old and believe me, she could out-work many much younger than her.”

“Old bird behind the bar is a lovely lady drop in for a chat and a beer or two – don’t mess with her or you will end up down a mine shaft”Well… better not to overthink it. He started to look at the flights, and last minute offers.

Still no word from Youssef either.

He placed an option on a flight, and decided he’d wait for everyone to confirm the dates for the rendez-vous.

January 23, 2023 at 8:15 am #6449In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Have you booked your flight yet? Zara sent a message to Yasmin. I’m spending a few more days in Camden, probably be at the Flying Fish Inn by the end of the week.

I told you already when my flight is, Air Fiji, remeber? bloody Sister Finnlie on my case all the time, haven’t had a minute. Zara had to wait over an hour for Yamsin’s reply.

I told you already when my flight is, Air Fiji, remeber? bloody Sister Finnlie on my case all the time, haven’t had a minute. Zara had to wait over an hour for Yamsin’s reply.Took you long enough to reply. Zara replied promptly. Heard nothing from Youssef for ages either, have you heard from him? I’ll be arriving there on my own at this rate.

Not a word, I expect Xavier’s booked his but he hasn’t said. Probably doing his secret monkey thing.

Not a word, I expect Xavier’s booked his but he hasn’t said. Probably doing his secret monkey thing.Have you tried the free roaming thing on the game yet?

I just told you Sister Finnlie hasn’t given me a minute to myself, she’s a right tart! Why, have you?

I just told you Sister Finnlie hasn’t given me a minute to myself, she’s a right tart! Why, have you?Yeah it’s amazing, been checking out the Flying Fish Inn. Looks a bit of a dump. Not much to do around there, well not from what I can see anyway. But you know what?

What?

What?You’ll lose your eyes in the back of your head one day and look like that AI avatart with the wall eye. Get this though: we haven’t started the game yet, that quest for quirks thing, I was just having a roman around ha ha typo having a roam around see what’s there and stuff I don’t know anything about online games like you lot and I ended up here. Zara sent a screenshot of the image she’d seen and added: Did I already start the game or what, I don’t even know how we actually start the game, I was just wandering around….oh…and happened to chance upon this…

How rude to start playing before us

How rude to start playing before usI didn’t start playing the game before you, I just told you, I was wandering around playing about waiting for you lot! Zara thought Yasmin sounded like she needed a holiday.

Yeah well that was your quest, wasn’t it? To wander around or something? What’s that silver chest on her back?

Yeah well that was your quest, wasn’t it? To wander around or something? What’s that silver chest on her back?I dunno but looks intriguing eh maybe she’s hidden all her devices and techy gadgets in an antiquey looking box so she doesn’t blow her cover

Gotta go Sister Finnlie’s coming

Zara muttered how rude under her breath and put her phone down. She’d retired to her bedroom early, telling Bertie that she needed an early night but really had wanted some time alone to explore the new game world. She didn’t want to make mistakes and look daft to her friends when the game started.

“Too late for that”, Pretty Girl said.

“SSHHH!” Zara hissed at the parrot. “And stop reading my mind, it’s disconcerting, not to mention rude.”

She heard the sound of the lavatory flush and Berties bedroom door closing and looked at the time. 23:36.

Zara decided to give him an hour to make sure he was asleep and then sneak out and go back to that church.

January 19, 2023 at 10:49 am #6419In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

“I’d advise you not to take the parrot, Zara,” Harry the vet said, “There are restrictions on bringing dogs and other animals into state parks, and you can bet some jobsworth official will insist she stays in a cage at the very least.”

“Yeah, you’re right, I guess I’ll leave her here. I want to call in and see my cousin in Camden on the way to the airport in Sydney anyway. He has dozens of cats, I’d hate for anything to happen to Pretty Girl,” Zara replied.

“Is that the distant cousin you met when you were doing your family tree?” Harry asked, glancing up from the stitches he was removing from a wounded wombat. “There, he’s good to go. Give him a couple more days, then he can be released back where he came from.”

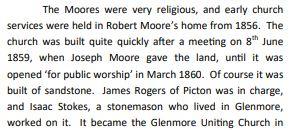

Zara smiled at Harry as she picked up the animal. “Yes! We haven’t met in person yet, and he’s going to show me the church my ancestor built. He says people have been spotting ghosts there lately, and there are rumours that it’s the ghost of the old convict Isaac who built it. If I can’t find photos of the ancestors, maybe I can get photos of their ghosts instead,” Zara said with a laugh.

“Good luck with that,” Harry replied raising an eyebrow. He liked Zara, she was quirkier than the others.

Zara hadn’t found it easy to research her mothers family from Bangalore in India, but her fathers English family had been easy enough. Although Zara had been born in England and emigrated to Australia in her late 20s, many of her ancestors siblings had emigrated over several generations, and Zara had managed to trace several down and made contact with a few of them. Isaac Stokes wasn’t a direct ancestor, he was the brother of her fourth great grandfather but his story had intrigued her. Sentenced to transportation for stealing tools for his work as a stonemason seemed to have worked in his favour. He built beautiful stone buildings in a tiny new town in the 1800s in the charming style of his home town in England.

Zara planned to stay in Camden for a couple of days before meeting the others at the Flying Fish Inn, anticipating a pleasant visit before the crazy adventure started.

Zara stepped down from the bus, squinting in the bright sunlight and looking around for her newfound cousin Bertie. A lanky middle aged man in dungarees and a red baseball cap came forward with his hand extended.

“Welcome to Camden, Zara I presume! Great to meet you!” he said shaking her hand and taking her rucksack. Zara was taken aback to see the family resemblance to her grandfather. So many scattered generations and yet there was still a thread of familiarity. “I bet you’re hungry, let’s go and get some tucker at Belle’s Cafe, and then I bet you want to see the church first, hey? Whoa, where’d that dang parrot come from?” Bertie said, ducking quickly as the bird swooped right in between them.

“Oh no, it’s Pretty Girl!” exclaimed Zara. “She wasn’t supposed to come with me, I didn’t bring her! How on earth did you fly all this way to get here the same time as me?” she asked the parrot.

“Pretty Girl has her ways, don’t forget to feed the parrot,” the bird replied with a squalk that resembled a mirthful guffaw.

“That’s one strange parrot you got here, girl!” Bertie said in astonishment.

“Well, seeing as you’re here now, Pretty Girl, you better come with us,” Zara said.

“Obviously,” replied Pretty Girl. It was hard to say for sure, but Zara was sure she detected an avian eye roll.

They sat outside under a sunshade to eat rather than cause any upset inside the cafe. Zara fancied an omelette but Pretty Girl objected, so she ordered hash browns instead and a fruit salad for the parrot. Bertie was a good sport about the strange talking bird after his initial surprise.

Bertie told her a bit about the ghost sightings, which had only started quite recently. They started when I started researching him, Zara thought to herself, almost as if he was reaching out. Her imagination was running riot already.

Bertie showed Zara around the church, a small building made of sandstone, but no ghost appeared in the bright heat of the afternoon. He took her on a little tour of Camden, once a tiny outpost but now a suburb of the city, pointing out all the original buildings, in particular the ones that Isaac had built. The church was walking distance of Bertie’s house and Zara decided to slip out and stroll over there after everyone had gone to bed.

Bertie had kindly allowed Pretty Girl to stay in the guest bedroom with her, safe from the cats, and Zara intended that the parrot stay in the room, but Pretty Girl was having none of it and insisted on joining her.

“Alright then, but no talking! I don’t want you scaring any ghost away so just keep a low profile!”

The moon was nearly full and it was a pleasant walk to the church. Pretty Girl fluttered from tree to tree along the sidewalk quietly. Enchanting aromas of exotic scented flowers wafted into her nostrils and Zara felt warmly relaxed and optimistic.

Zara was disappointed to find that the church was locked for the night, and realized with a sigh that she should have expected this to be the case. She wandered around the outside, trying to peer in the windows but there was nothing to be seen as the glass reflected the street lights. These things are not done in a hurry, she reminded herself, be patient.

Sitting under a tree on the grassy lawn attempting to open her mind to receiving ghostly communications (she wasn’t quite sure how to do that on purpose, any ghosts she’d seen previously had always been accidental and unexpected) Pretty Girl landed on her shoulder rather clumsily, pressing something hard and chill against her cheek.

“I told you to keep a low profile!” Zara hissed, as the parrot dropped the key into her lap. “Oh! is this the key to the church door?”

It was hard to see in the dim light but Zara was sure the parrot nodded, and was that another avian eye roll?

Zara walked slowly over the grass to the church door, tingling with anticipation. Pretty Girl hopped along the ground behind her. She turned the key in the lock and slowly pushed open the heavy door and walked inside and up the central aisle, looking around. And then she saw him.

Zara gasped. For a breif moment as the spectral wisps cleared, he looked almost solid. And she could see his tattoos.

“Oh my god,” she whispered, “It is really you. I recognize those tattoos from the description in the criminal registers. Some of them anyway, it seems you have a few more tats since you were transported.”

“Aye, I did that, wench. I were allays fond o’ me tats, does tha like ’em?”

He actually spoke to me! This was beyond Zara’s wildest hopes. Quick, ask him some questions!

“If you don’t mind me asking, Isaac, why did you lie about who your father was on your marriage register? I almost thought it wasn’t you, you know, that I had the wrong Isaac Stokes.”

A deafening rumbling laugh filled the building with echoes and the apparition dispersed in a labyrinthine swirl of tattood wisps.

“A story for another day,” whispered Zara, “Time to go back to Berties. Come on Pretty Girl. And put that key back where you found it.”

January 17, 2023 at 11:37 am #6407

January 17, 2023 at 11:37 am #6407In reply to: Prompts of Madjourneys

[Following the last comment] Fed the AL this context:

- “A gripshawk is feline-like anthropomorphic creature living in the deserts in a fiction written by Yurara Fameliki. It is the least favorite character to pick by Zara who doesn’t like “fantasy stuff”.

- The “Flying Fish Inn” is a fictional (or maybe real) Inn set in the Australian outback, owned by a family headed by the matriarch Mater and involved in many adventures, sometimes surnatural.

- “AL” is an AI build with Al’s persona (Albert Yokozo being a famous author, possibly a nom de plume of the mysterious Ernrich Lemwon) – it is known as Calli in another story.

Please continue the story unfolding here:

<feeding FP’s comment>“Yeah, I’m not a fan of fantasy stuff either,” Youssef added, agreeing with Zara. “But I’m curious about the Flying Fish Inn and how it relates to the game. Maybe we should check it out and see if there are any clues there.”

“That’s a good idea,” Yasmin said. “I’ve heard the stories about the Inn and the adventures the family has had there. Some of them are quite intriguing, and I wouldn’t be surprised if there was a connection to our game.”

“I’m not sure about the AI,” Xavier said. “It’s still a mystery to me, but I trust AL will guide us in the right direction. I’m curious to see where this all leads.”

“Alright, let’s plan a trip to the Flying Fish Inn,” Zara said, excitedly. “We’ll take a break from the game for a few days, but we’ll come back to it with fresh eyes and new insights. Who knows, maybe we’ll even find some quirky guests along the way.”

As they were discussing their plans, they all felt a sense of excitement and curiosity about what the future holds for them. The game and the world of the Land of the Quirks had captured their imagination and they were eager to see where it would lead them next.

January 17, 2023 at 4:55 am #6392In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

“I can’t play for a few days,” Zara announced firmly. “I’m doing real world stuff at the moment. I saw a cat up a tree that looked computer generated and I’m concerned about my mental health.”

“What only just now worried? Just this minute?” asked Xavier, managing to keep his face serious.

“Quirky Guests,” mused Yasmin.

The others looked at her.

“I didn’t mean to say that out loud,” she laughed putting a hand to her mouth. “It’s nothing really … it’s just that every time I looked at the map I thought it said quirky GUESTS.”

“Guest!” Zara’s face brightened. “Oh! Maybe guest is a clue … maybe it’s a bleed through from the Flying Fish Inn! You know, it wouldn’t surprise me AT ALL if the key was there.”

Xavier screwed up his face.

“What!” snapped Zara. “Go on, spit it out!”

“Well it’s sort of RPG meets Cloud Atlas, isn’t it? But each to their own gripshawk and AL will sort it all out anyway.”

January 10, 2023 at 11:00 pm #6365In reply to: Train your subjective AI – text version

Prune has got me into this AI stuff… It sounds like gibberish to me, but Idle sounded amazed at the stuff it spewed out.

With some info on our family story, Prune got it to try and predict the future…

Sounds like a big plate of bog, but we’ll see how it goes.

Sure, here are a few possible events that could occur between Mater’s 100th birthday and her death in the Flying Fish Inn story:

- Mater decides to throw herself a grand birthday party, inviting all of her friends and family from the small outback town. However, things take a turn for the strange when a group of extraterrestrial beings crash the party and reveal themselves to be long-time fans of Mater’s famous bush tucker cuisine.

- Mater begins to experience vivid dreams and hallucinations, in which she is visited by the ghost of her late husband. As the dreams become more frequent, the family begins to suspect that there may be something more to them than just Mater’s mind playing tricks on her.

- Mater’s granddaughter Prune becomes increasingly obsessed with her dream of traveling to Mars, and begins to notice strange occurrences happening around the inn that seem to be connected to her aspiration.

- A group of eccentric scientists arrive at the inn, conducting research on the local flora and fauna. They eventually discover a species of sentient plants living in the area, and Mater becomes convinced that the plants are communicating with her in her dreams.

- With her health declining, Mater begins to spend more and more time tending to her garden, where she is visited by an old kookaburra who seems to possess an otherworldly intelligence. The bird becomes Mater’s companion and confidant in the final days of her life.

- As the Great Fires ravage the Australian bush, Mater makes the difficult decision to shut down the inn and evacuate the guests. But as they flee, they realize that the fire is not just a natural disaster, but something far more sinister and mystical.

- In her final days, Mater begins to remember strange and vivid details of her life that she never could have known, as if she lived a previous life in another time and place. As she dies, she whispers something to Prune, which opens her eyes to a new reality that may have been hidden from her all along

- It turns out the family had a lot of secrets, and the only way to escape it, was to leave the inn, but it was not an escape for all. Through the series of events, secrets are revealed, and some truths cannot be undone.Note that these events are fictional and whimsical in nature, but as they keeps it grounded to a sense of doldrums in the Australian bush and occasionally guests help to unravel some of the overarching mysteries it could make a fitting storyline for the story.

December 6, 2022 at 2:17 pm #6350In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Transportation

Isaac Stokes 1804-1877

Isaac was born in Churchill, Oxfordshire in 1804, and was the youngest brother of my 4X great grandfather Thomas Stokes. The Stokes family were stone masons for generations in Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire, and Isaac’s occupation was a mason’s labourer in 1834 when he was sentenced at the Lent Assizes in Oxford to fourteen years transportation for stealing tools.

Churchill where the Stokes stonemasons came from: on 31 July 1684 a fire destroyed 20 houses and many other buildings, and killed four people. The village was rebuilt higher up the hill, with stone houses instead of the old timber-framed and thatched cottages. The fire was apparently caused by a baker who, to avoid chimney tax, had knocked through the wall from her oven to her neighbour’s chimney.

Isaac stole a pick axe, the value of 2 shillings and the property of Thomas Joyner of Churchill; a kibbeaux and a trowel value 3 shillings the property of Thomas Symms; a hammer and axe value 5 shillings, property of John Keen of Sarsden.

(The word kibbeaux seems to only exists in relation to Isaac Stokes sentence and whoever was the first to write it was perhaps being creative with the spelling of a kibbo, a miners or a metal bucket. This spelling is repeated in the criminal reports and the newspaper articles about Isaac, but nowhere else).

In March 1834 the Removal of Convicts was announced in the Oxford University and City Herald: Isaac Stokes and several other prisoners were removed from the Oxford county gaol to the Justitia hulk at Woolwich “persuant to their sentences of transportation at our Lent Assizes”.

via digitalpanopticon:

Hulks were decommissioned (and often unseaworthy) ships that were moored in rivers and estuaries and refitted to become floating prisons. The outbreak of war in America in 1775 meant that it was no longer possible to transport British convicts there. Transportation as a form of punishment had started in the late seventeenth century, and following the Transportation Act of 1718, some 44,000 British convicts were sent to the American colonies. The end of this punishment presented a major problem for the authorities in London, since in the decade before 1775, two-thirds of convicts at the Old Bailey received a sentence of transportation – on average 283 convicts a year. As a result, London’s prisons quickly filled to overflowing with convicted prisoners who were sentenced to transportation but had no place to go.

To increase London’s prison capacity, in 1776 Parliament passed the “Hulks Act” (16 Geo III, c.43). Although overseen by local justices of the peace, the hulks were to be directly managed and maintained by private contractors. The first contract to run a hulk was awarded to Duncan Campbell, a former transportation contractor. In August 1776, the Justicia, a former transportation ship moored in the River Thames, became the first prison hulk. This ship soon became full and Campbell quickly introduced a number of other hulks in London; by 1778 the fleet of hulks on the Thames held 510 prisoners.

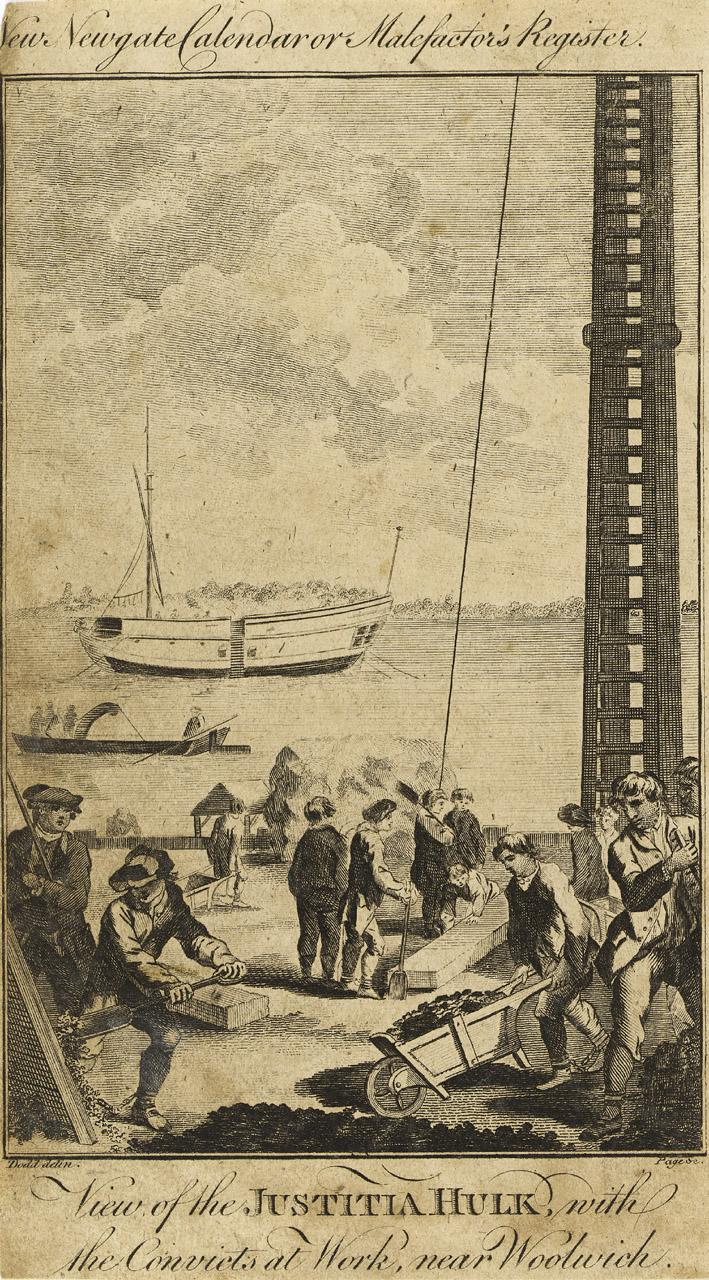

Demand was so great that new hulks were introduced across the country. There were hulks located at Deptford, Chatham, Woolwich, Gosport, Plymouth, Portsmouth, Sheerness and Cork.The Justitia via rmg collections:

Convicts perform hard labour at the Woolwich Warren. The hulk on the river is the ‘Justitia’. Prisoners were kept on board such ships for months awaiting deportation to Australia. The ‘Justitia’ was a 260 ton prison hulk that had been originally moored in the Thames when the American War of Independence put a stop to the transportation of criminals to the former colonies. The ‘Justitia’ belonged to the shipowner Duncan Campbell, who was the Government contractor who organized the prison-hulk system at that time. Campbell was subsequently involved in the shipping of convicts to the penal colony at Botany Bay (in fact Port Jackson, later Sydney, just to the north) in New South Wales, the ‘first fleet’ going out in 1788.

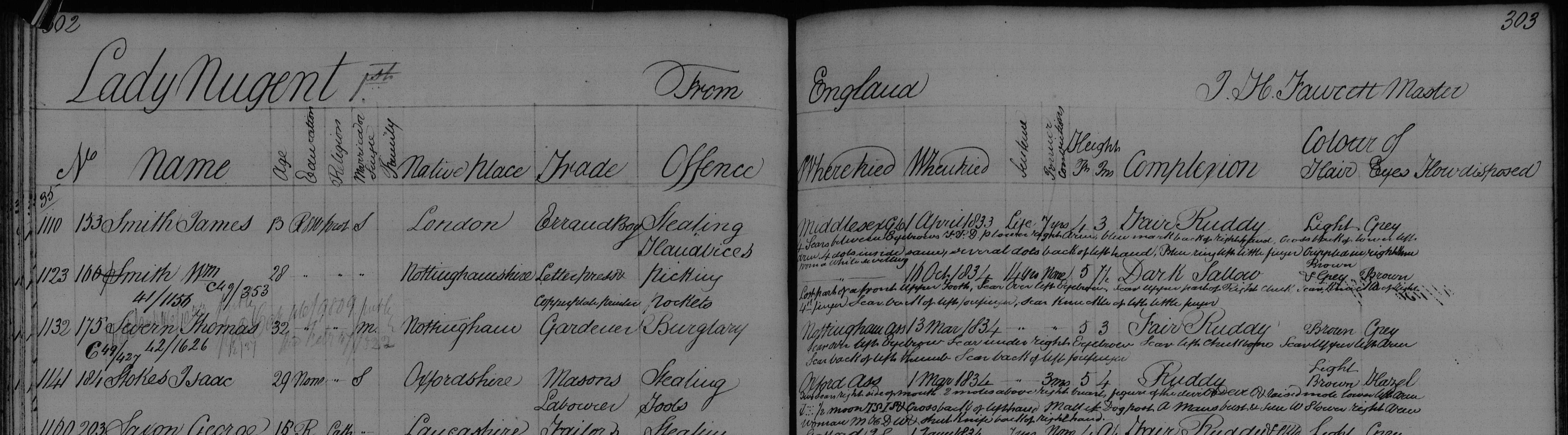

While searching for records for Isaac Stokes I discovered that another Isaac Stokes was transported to New South Wales in 1835 as well. The other one was a butcher born in 1809, sentenced in London for seven years, and he sailed on the Mary Ann. Our Isaac Stokes sailed on the Lady Nugent, arriving in NSW in April 1835, having set sail from England in December 1834.

Lady Nugent was built at Bombay in 1813. She made four voyages under contract to the British East India Company (EIC). She then made two voyages transporting convicts to Australia, one to New South Wales and one to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). (via Wikipedia)

via freesettlerorfelon website:

On 20 November 1834, 100 male convicts were transferred to the Lady Nugent from the Justitia Hulk and 60 from the Ganymede Hulk at Woolwich, all in apparent good health. The Lady Nugent departed Sheerness on 4 December 1834.

SURGEON OLIVER SPROULE

Oliver Sproule kept a Medical Journal from 7 November 1834 to 27 April 1835. He recorded in his journal the weather conditions they experienced in the first two weeks:

‘In the course of the first week or ten days at sea, there were eight or nine on the sick list with catarrhal affections and one with dropsy which I attribute to the cold and wet we experienced during that period beating down channel. Indeed the foremost berths in the prison at this time were so wet from leaking in that part of the ship, that I was obliged to issue dry beds and bedding to a great many of the prisoners to preserve their health, but after crossing the Bay of Biscay the weather became fine and we got the damp beds and blankets dried, the leaks partially stopped and the prison well aired and ventilated which, I am happy to say soon manifested a favourable change in the health and appearance of the men.

Besides the cases given in the journal I had a great many others to treat, some of them similar to those mentioned but the greater part consisted of boils, scalds, and contusions which would not only be too tedious to enter but I fear would be irksome to the reader. There were four births on board during the passage which did well, therefore I did not consider it necessary to give a detailed account of them in my journal the more especially as they were all favourable cases.

Regularity and cleanliness in the prison, free ventilation and as far as possible dry decks turning all the prisoners up in fine weather as we were lucky enough to have two musicians amongst the convicts, dancing was tolerated every afternoon, strict attention to personal cleanliness and also to the cooking of their victuals with regular hours for their meals, were the only prophylactic means used on this occasion, which I found to answer my expectations to the utmost extent in as much as there was not a single case of contagious or infectious nature during the whole passage with the exception of a few cases of psora which soon yielded to the usual treatment. A few cases of scurvy however appeared on board at rather an early period which I can attribute to nothing else but the wet and hardships the prisoners endured during the first three or four weeks of the passage. I was prompt in my treatment of these cases and they got well, but before we arrived at Sydney I had about thirty others to treat.’

The Lady Nugent arrived in Port Jackson on 9 April 1835 with 284 male prisoners. Two men had died at sea. The prisoners were landed on 27th April 1835 and marched to Hyde Park Barracks prior to being assigned. Ten were under the age of 14 years.

The Lady Nugent:

Isaac’s distinguishing marks are noted on various criminal registers and record books:

“Height in feet & inches: 5 4; Complexion: Ruddy; Hair: Light brown; Eyes: Hazel; Marks or Scars: Yes [including] DEVIL on lower left arm, TSIS back of left hand, WS lower right arm, MHDW back of right hand.”

Another includes more detail about Isaac’s tattoos:

“Two slight scars right side of mouth, 2 moles above right breast, figure of the devil and DEVIL and raised mole, lower left arm; anchor, seven dots half moon, TSIS and cross, back of left hand; a mallet, door post, A, mans bust, sun, WS, lower right arm; woman, MHDW and shut knife, back of right hand.”

From How tattoos became fashionable in Victorian England (2019 article in TheConversation by Robert Shoemaker and Zoe Alkar):

“Historical tattooing was not restricted to sailors, soldiers and convicts, but was a growing and accepted phenomenon in Victorian England. Tattoos provide an important window into the lives of those who typically left no written records of their own. As a form of “history from below”, they give us a fleeting but intriguing understanding of the identities and emotions of ordinary people in the past.

As a practice for which typically the only record is the body itself, few systematic records survive before the advent of photography. One exception to this is the written descriptions of tattoos (and even the occasional sketch) that were kept of institutionalised people forced to submit to the recording of information about their bodies as a means of identifying them. This particularly applies to three groups – criminal convicts, soldiers and sailors. Of these, the convict records are the most voluminous and systematic.

Such records were first kept in large numbers for those who were transported to Australia from 1788 (since Australia was then an open prison) as the authorities needed some means of keeping track of them.”On the 1837 census Isaac was working for the government at Illiwarra, New South Wales. This record states that he arrived on the Lady Nugent in 1835. There are three other indent records for an Isaac Stokes in the following years, but the transcriptions don’t provide enough information to determine which Isaac Stokes it was. In April 1837 there was an abscondment, and an arrest/apprehension in May of that year, and in 1843 there was a record of convict indulgences.

From the Australian government website regarding “convict indulgences”:

“By the mid-1830s only six per cent of convicts were locked up. The vast majority worked for the government or free settlers and, with good behaviour, could earn a ticket of leave, conditional pardon or and even an absolute pardon. While under such orders convicts could earn their own living.”

In 1856 in Camden, NSW, Isaac Stokes married Catherine Daly. With no further information on this record it would be impossible to know for sure if this was the right Isaac Stokes. This couple had six children, all in the Camden area, but none of the records provided enough information. No occupation or place or date of birth recorded for Isaac Stokes.

I wrote to the National Library of Australia about the marriage record, and their reply was a surprise! Issac and Catherine were married on 30 September 1856, at the house of the Rev. Charles William Rigg, a Methodist minister, and it was recorded that Isaac was born in Edinburgh in 1821, to parents James Stokes and Sarah Ellis! The age at the time of the marriage doesn’t match Isaac’s age at death in 1877, and clearly the place of birth and parents didn’t match either. Only his fathers occupation of stone mason was correct. I wrote back to the helpful people at the library and they replied that the register was in a very poor condition and that only two and a half entries had survived at all, and that Isaac and Catherines marriage was recorded over two pages.

I searched for an Isaac Stokes born in 1821 in Edinburgh on the Scotland government website (and on all the other genealogy records sites) and didn’t find it. In fact Stokes was a very uncommon name in Scotland at the time. I also searched Australian immigration and other records for another Isaac Stokes born in Scotland or born in 1821, and found nothing. I was unable to find a single record to corroborate this mysterious other Isaac Stokes.

As the age at death in 1877 was correct, I assume that either Isaac was lying, or that some mistake was made either on the register at the home of the Methodist minster, or a subsequent mistranscription or muddle on the remnants of the surviving register. Therefore I remain convinced that the Camden stonemason Isaac Stokes was indeed our Isaac from Oxfordshire.

I found a history society newsletter article that mentioned Isaac Stokes, stone mason, had built the Glenmore church, near Camden, in 1859.

From the Wollondilly museum April 2020 newsletter:

From the Camden History website:

“The stone set over the porch of Glenmore Church gives the date of 1860. The church was begun in 1859 on land given by Joseph Moore. James Rogers of Picton was given the contract to build and local builder, Mr. Stokes, carried out the work. Elizabeth Moore, wife of Edward, laid the foundation stone. The first service was held on 19th March 1860. The cemetery alongside the church contains the headstones and memorials of the areas early pioneers.”

Isaac died on the 3rd September 1877. The inquest report puts his place of death as Bagdelly, near to Camden, and another death register has put Cambelltown, also very close to Camden. His age was recorded as 71 and the inquest report states his cause of death was “rupture of one of the large pulmonary vessels of the lung”. His wife Catherine died in childbirth in 1870 at the age of 43.

Isaac and Catherine’s children:

William Stokes 1857-1928

Catherine Stokes 1859-1846

Sarah Josephine Stokes 1861-1931

Ellen Stokes 1863-1932

Rosanna Stokes 1865-1919

Louisa Stokes 1868-1844.

It’s possible that Catherine Daly was a transported convict from Ireland.

Some time later I unexpectedly received a follow up email from The Oaks Heritage Centre in Australia.

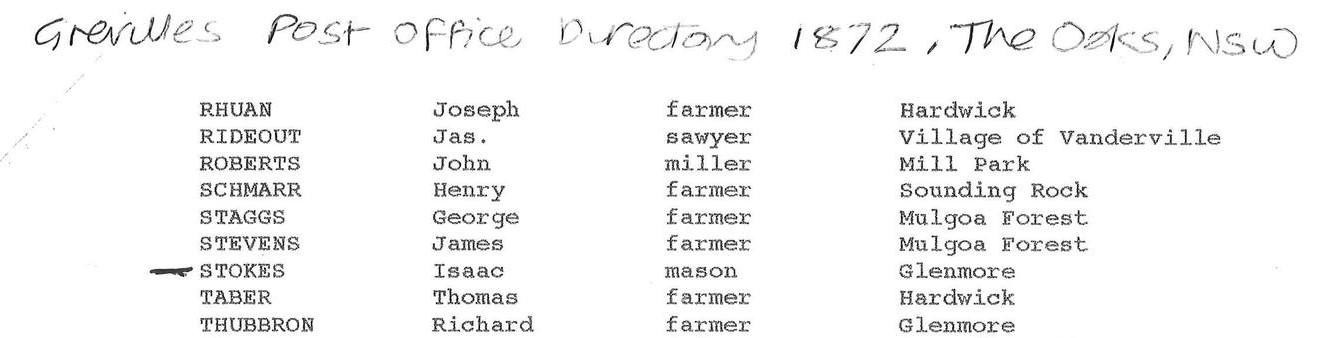

“The Gaudry papers which we have in our archive record him (Isaac Stokes) as having built: the church, the school and the teachers residence. Isaac is recorded in the General return of convicts: 1837 and in Grevilles Post Office directory 1872 as a mason in Glenmore.”

November 13, 2022 at 10:29 pm #6345

November 13, 2022 at 10:29 pm #6345In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Crime and Punishment in Tetbury

I noticed that there were quite a number of Brownings of Tetbury in the newspaper archives involved in criminal activities while doing a routine newspaper search to supplement the information in the usual ancestry records. I expanded the tree to include cousins, and offsping of cousins, in order to work out who was who and how, if at all, these individuals related to our Browning family.

I was expecting to find some of our Brownings involved in the Swing Riots in Tetbury in 1830, but did not. Most of our Brownings (including cousins) were stone masons. Most of the rioters in 1830 were agricultural labourers.

The Browning crimes are varied, and by todays standards, not for the most part terribly serious ~ you would be unlikely to receive a sentence of hard labour for being found in an outhouse with the intent to commit an unlawful act nowadays, or for being drunk.

The central character in this chapter is Isaac Browning (my 4x great grandfather), who did not appear in any criminal registers, but the following individuals can be identified in the family structure through their relationship to him.

RICHARD LOCK BROWNING born in 1853 was Isaac’s grandson, his son George’s son. Richard was a mason. In 1879 he and Henry Browning of the same age were sentenced to one month hard labour for stealing two pigeons in Tetbury. Henry Browning was Isaac’s nephews son.

In 1883 Richard Browning, mason of Tetbury, was charged with obtaining food and lodging under false pretences, but was found not guilty and acquitted.

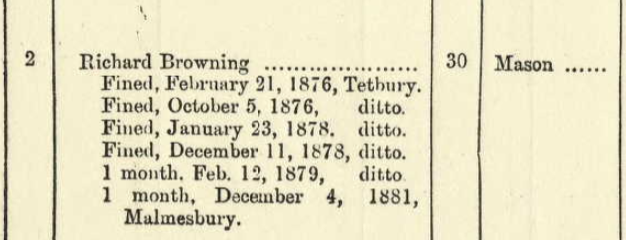

In 1884 Richard Browning, mason of Tetbury, was sentenced to one month hard labour for game trespass.Richard had been fined a number of times in Tetbury:

Richard Lock Browning was five feet eight inches tall, dark hair, grey eyes, an oval face and a dark complexion. He had two cuts on the back of his head (in February 1879) and a scar on his right eyebrow.

HENRY BROWNING, who was stealing pigeons with Richard Lock Browning in 1879, (Isaac’s brother Williams grandson, son of George Browning and his wife Charity) was charged with being drunk in 1882 and ordered to pay a fine of one shilling and costs of fourteen shillings, or seven days hard labour.

Henry was found guilty of gaming in the highway at Tetbury in 1872 and was sentenced to seven days hard labour. In 1882 Henry (who was also a mason) was charged with assault but discharged.

Henry was five feet five inches tall, brown hair and brown eyes, a long visage and a fresh complexion.

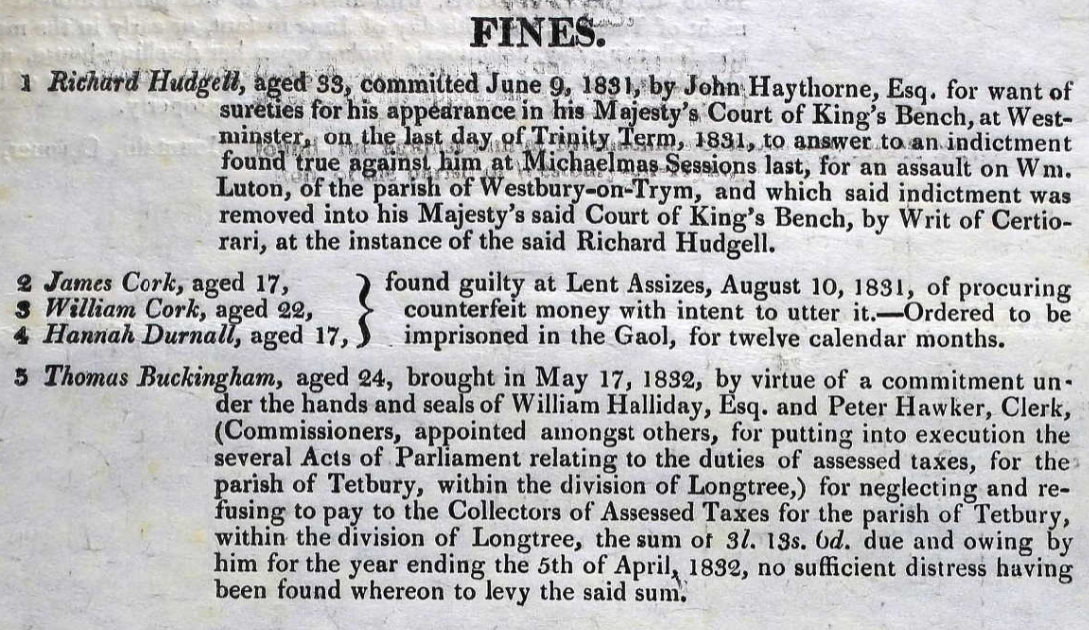

Henry emigrated with his daughter to Canada in 1913, and died in Vancouver in 1919.THOMAS BUCKINGHAM 1808-1846 (Isaacs daughter Janes husband) was charged with stealing a black gelding in Tetbury in 1838. No true bill. (A “no true bill” means the jury did not find probable cause to continue a case.)

Thomas did however neglect to pay his taxes in 1832:

LEWIN BUCKINGHAM (grandson of Isaac, his daughter Jane’s son) was found guilty in 1846 stealing two fowls in Tetbury when he was sixteen years old.

In 1846 he was sentence to one month hard labour (or pay ten shillings fine and ten shillings costs) for loitering with the intent to trespass in search of conies.

A year later in 1847, he and three other young men were sentenced to four months hard labour for larceny.

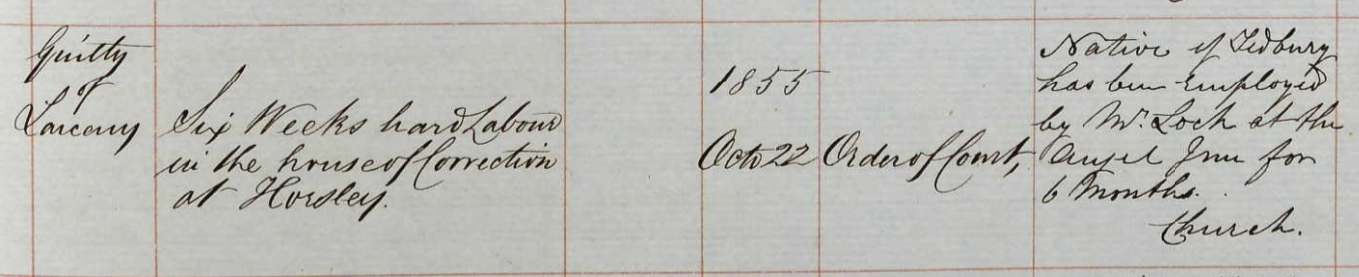

Lewin was five feet three inches tall, with brown hair and brown eyes, long visage, sallow complexion, and had a scar on his left arm.JOHN BUCKINGHAM born circa 1832, a Tetbury labourer (Isaac’s grandson, Lewin’s brother) was sentenced to six weeks hard labour for larceny in 1855 for stealing a duck in Cirencester. The notes on the register mention that he had been employed by Mr LOCK, Angel Inn. (John’s grandmother was Mary Lock so this is likely a relative).

The previous year in 1854 John was sentenced to one month or a one pound fine for assaulting and beating W. Wood.

John was five feet eight and three quarter inches tall, light brown hair and grey eyes, an oval visage and a fresh complexion. He had a scar on his left arm and inside his right knee.JOSEPH PERRET was born circa 1831 and he was a Tetbury labourer. (He was Isaac’s granddaughter Charlotte Buckingham’s husband)

In 1855 he assaulted William Wood and was sentenced to one month or a two pound ten shilling fine. Was it the same W Wood that his wifes cousin John assaulted the year before?

In 1869 Joseph was sentenced to one month hard labour for feloniously receiving a cupboard known to be stolen.JAMES BUCKINGAM born circa 1822 in Tetbury was a shoemaker. (Isaac’s nephew, his sister Hannah’s son)

In 1854 the Tetbury shoemaker was sentenced to four months hard labour for stealing 30 lbs of lead off someones house.

In 1856 the Tetbury shoemaker received two months hard labour or pay £2 fine and 12 s costs for being found in pursuit of game.

In 1868 he was sentenced to two months hard labour for stealing a gander. A unspecified previous conviction is noted.

1871 the Tetbury shoemaker was found in an outhouse for an unlawful purpose and received ten days hard labour. The register notes that his sister is Mrs Cook, the Green, Tetbury. (James sister Prudence married Thomas Cook)

James sister Charlotte married a shoemaker and moved to UTAH.

James was five feet eight inches tall, dark hair and blue eyes, a long visage and a florid complexion. He had a scar on his forehead and a mole on the right side of his neck and abdomen, and a scar on the right knee.November 10, 2022 at 10:59 am #6343In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum

William James Stokes

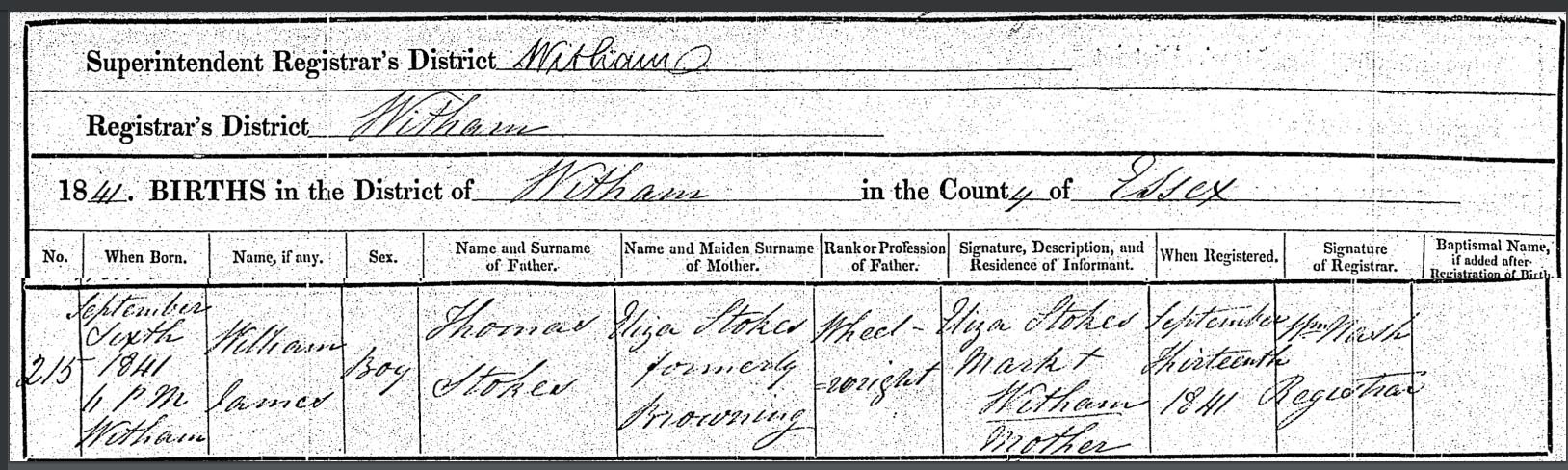

William James Stokes was the first son of Thomas Stokes and Eliza Browning. Oddly, his birth was registered in Witham in Essex, on the 6th September 1841.

Birth certificate of William James Stokes:

His father Thomas Stokes has not yet been found on the 1841 census, and his mother Eliza was staying with her uncle Thomas Lock in Cirencester in 1841. Eliza’s mother Mary Browning (nee Lock) was staying there too. Thomas and Eliza were married in September 1840 in Hempstead in Gloucestershire.

It’s a mystery why William was born in Essex but one possibility is that his father Thomas, who later worked with the Chipperfields making circus wagons, was staying with the Chipperfields who were wheelwrights in Witham in 1841. Or perhaps even away with a traveling circus at the time of the census, learning the circus waggon wheelwright trade. But this is a guess and it’s far from clear why Eliza would make the journey to Witham to have the baby when she was staying in Cirencester a few months prior.

In 1851 Thomas and Eliza, William and four younger siblings were living in Bledington in Oxfordshire.

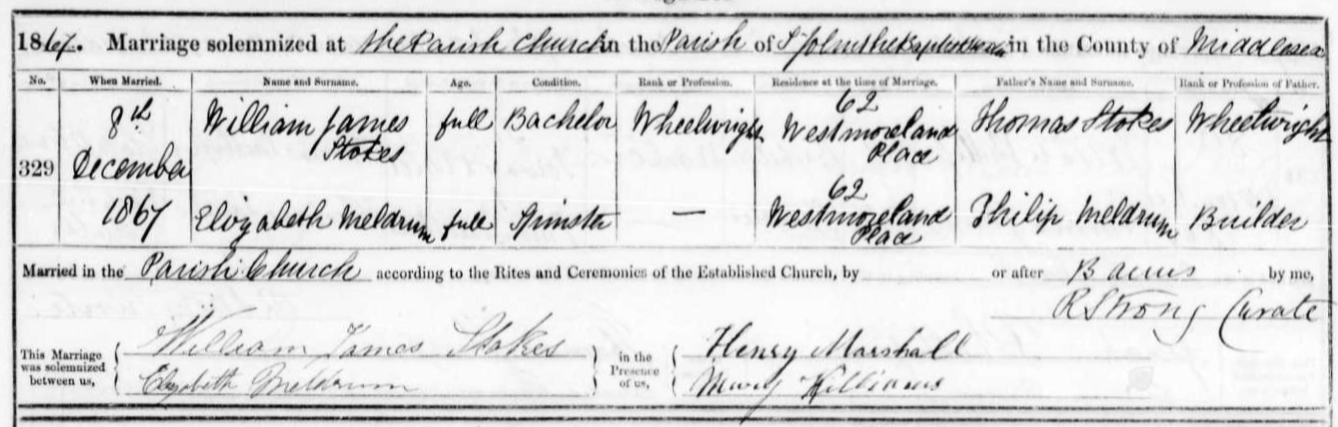

William was a 19 year old wheelwright living with his parents in Evesham in 1861. He married Elizabeth Meldrum in December 1867 in Hackney, London. He and his father are both wheelwrights on the marriage register.

Marriage of William James Stokes and Elizabeth Meldrum in 1867:

William and Elizabeth had a daughter, Elizabeth Emily Stokes, in 1868 in Shoreditch, London.

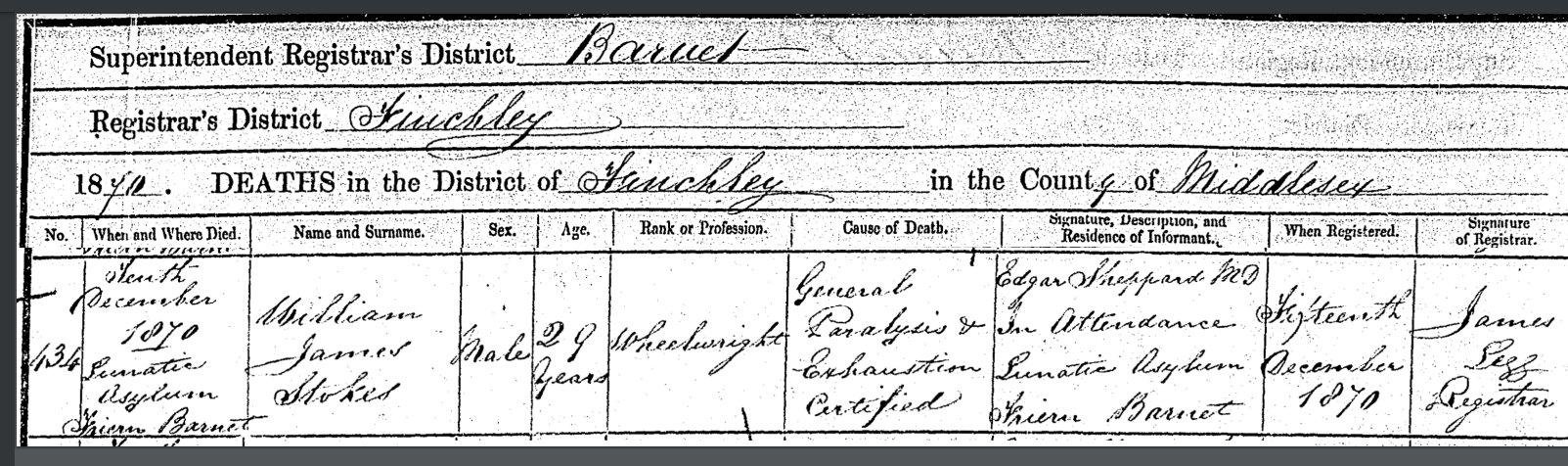

On the 3rd of December 1870, William James Stokes was admitted to Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum. One week later on the 10th of December, he was dead.

On his death certificate the cause of death was “general paralysis and exhaustion, certified. MD Edgar Sheppard in attendance.” William was just 29 years old.

Death certificate William James Stokes:

I asked on a genealogy forum what could possibly have caused this death at such a young age. A retired pathology professor replied that “in medicine the term General Paralysis is only used in one context – that of Tertiary Syphilis.”

“Tertiary syphilis is the third and final stage of syphilis, a sexually transmitted disease that unfolds in stages when the individual affected doesn’t receive appropriate treatment.”From the article “Looking back: This fascinating and fatal disease” by Jennifer Wallis:

“……in asylums across Britain in the late 19th century, with hundreds of people receiving the diagnosis of general paralysis of the insane (GPI). The majority of these were men in their 30s and 40s, all exhibiting one or more of the disease’s telltale signs: grandiose delusions, a staggering gait, disturbed reflexes, asymmetrical pupils, tremulous voice, and muscular weakness. Their prognosis was bleak, most dying within months, weeks, or sometimes days of admission.

The fatal nature of GPI made it of particular concern to asylum superintendents, who became worried that their institutions were full of incurable cases requiring constant care. The social effects of the disease were also significant, attacking men in the prime of life whose admission to the asylum frequently left a wife and children at home. Compounding the problem was the erratic behaviour of the general paralytic, who might get themselves into financial or legal difficulties. Delusions about their vast wealth led some to squander scarce family resources on extravagant purchases – one man’s wife reported he had bought ‘a quantity of hats’ despite their meagre income – and doctors pointed to the frequency of thefts by general paralytics who imagined that everything belonged to them.”

The London Archives hold the records for Colney Hatch, but they informed me that the particular records for the dates that William was admitted and died were in too poor a condition to be accessed without causing further damage.

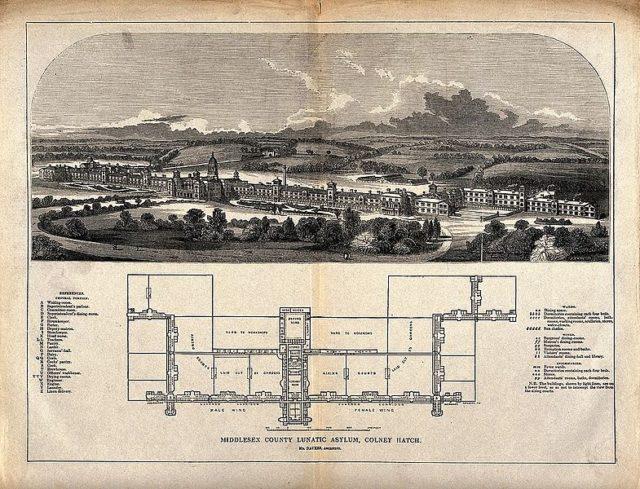

Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum gained such notoriety that the name “Colney Hatch” appeared in various terms of abuse associated with the concept of madness. Infamous inmates that were institutionalized at Colney Hatch (later called Friern Hospital) include Jack the Ripper suspect Aaron Kosminski from 1891, and from 1911 the wife of occultist Aleister Crowley. In 1993 the hospital grounds were sold and the exclusive apartment complex called Princess Park Manor was built.

Colney Hatch:

In 1873 Williams widow married William Hallam in Limehouse in London. Elizabeth died in 1930, apparently unaffected by her first husbands ailment.

October 11, 2022 at 2:58 pm #6334In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The House on Penn Common

Toi Fang and the Duke of Sutherland

Tomlinsons

Grassholme

Charles Tomlinson (1873-1929) my great grandfather, was born in Wolverhampton in 1873. His father Charles Tomlinson (1847-1907) was a licensed victualler or publican, or alternatively a vet/castrator. He married Emma Grattidge (1853-1911) in 1872. On the 1881 census they were living at The Wheel in Wolverhampton.

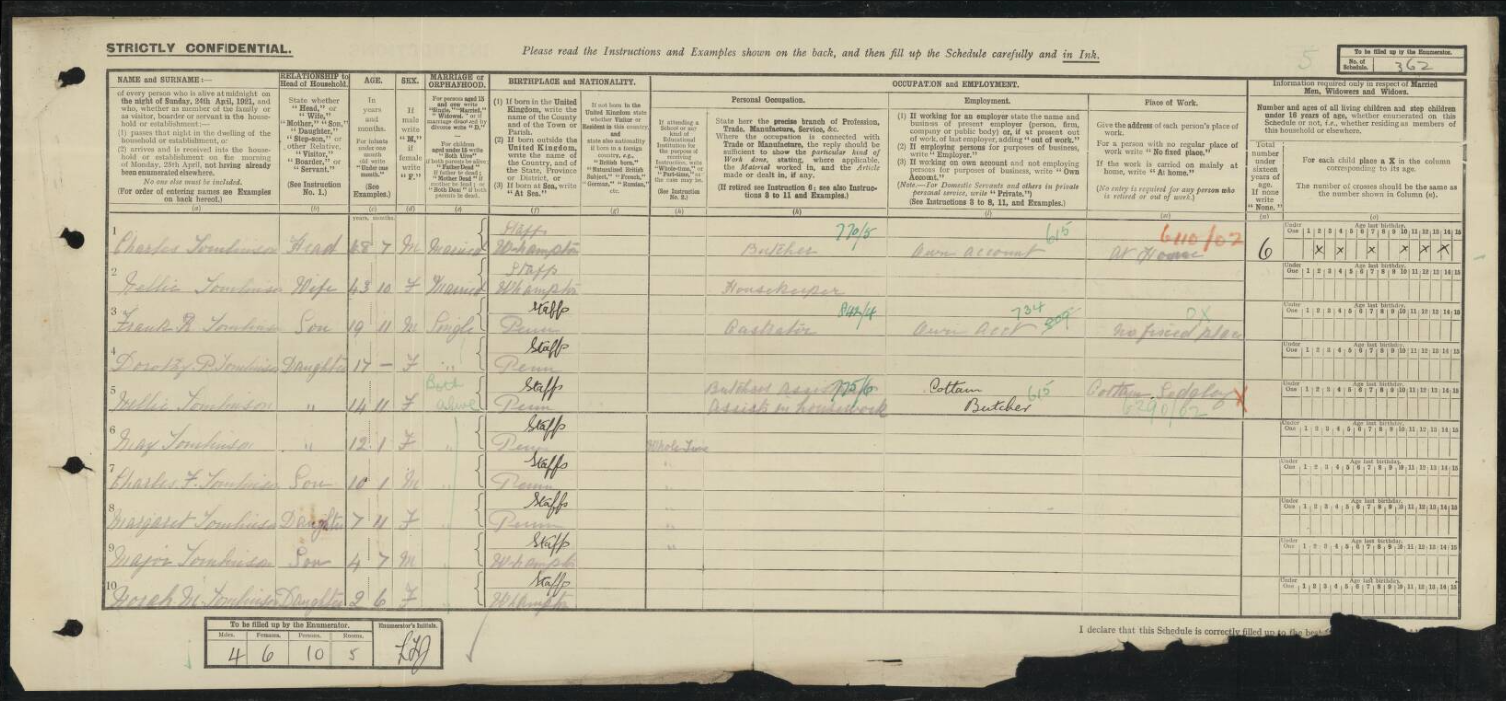

Charles married Nellie Fisher (1877-1956) in Wolverhampton in 1896. In 1901 they were living next to the post office in Upper Penn, with children (Charles) Sidney Tomlinson (1896-1955), and Hilda Tomlinson (1898-1977) . Charles was a vet/castrator working on his own account.

In 1911 their address was 4, Wakely Hill, Penn, and living with them were their children Hilda, Frank Tomlinson (1901-1975), (Dorothy) Phyllis Tomlinson (1905-1982), Nellie Tomlinson (1906-1978) and May Tomlinson (1910-1983). Charles was a castrator working on his own account.

Charles and Nellie had a further four children: Charles Fisher Tomlinson (1911-1977), Margaret Tomlinson (1913-1989) (my grandmother Peggy), Major Tomlinson (1916-1984) and Norah Mary Tomlinson (1919-2010).

My father told me that my grandmother had fallen down the well at the house on Penn Common in 1915 when she was two years old, and sent me a photo of her standing next to the well when she revisted the house at a much later date.

Peggy next to the well on Penn Common:

My grandmother Peggy told me that her father had had a racehorse called Toi Fang. She remembered the racing colours were sky blue and orange, and had a set of racing silks made which she sent to my father.

Through a DNA match, I met Ian Tomlinson. Ian is the son of my fathers favourite cousin Roger, Frank’s son. Ian found some racing silks and sent a photo to my father (they are now in contact with each other as a result of my DNA match with Ian), wondering what they were.

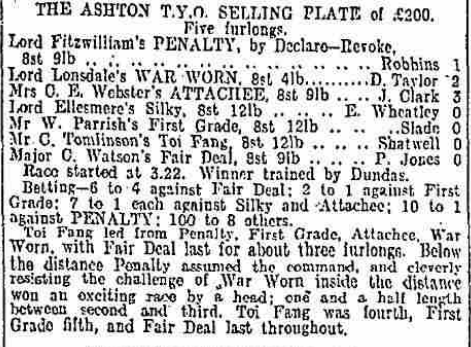

When Ian sent a photo of these racing silks, I had a look in the newspaper archives. In 1920 there are a number of mentions in the racing news of Mr C Tomlinson’s horse TOI FANG. I have not found any mention of Toi Fang in the newspapers in the following years.

The Scotsman – Monday 12 July 1920:

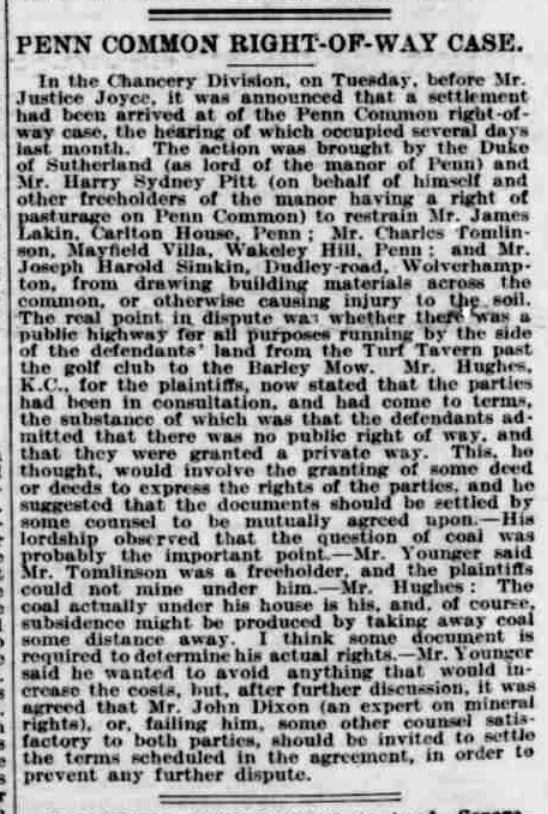

The other story that Ian Tomlinson recalled was about the house on Penn Common. Ian said he’d heard that the local titled person took Charles Tomlinson to court over building the house but that Tomlinson won the case because it was built on common land and was the first case of it’s kind.

Penn Common Right of Way Case:

Staffordshire Advertiser March 9, 1912In the chancery division, on Tuesday, before Mr Justice Joyce, it was announced that a settlement had been arrived at of the Penn Common Right of Way case, the hearing of which occupied several days last month. The action was brought by the Duke of Sutherland (as Lord of the Manor of Penn) and Mr Harry Sydney Pitt (on behalf of himself and other freeholders of the manor having a right to pasturage on Penn Common) to restrain Mr James Lakin, Carlton House, Penn; Mr Charles Tomlinson, Mayfield Villa, Wakely Hill, Penn; and Mr Joseph Harold Simpkin, Dudley Road, Wolverhampton, from drawing building materials across the common, or otherwise causing injury to the soil.

The real point in dispute was whether there was a public highway for all purposes running by the side of the defendants land from the Turf Tavern past the golf club to the Barley Mow.

Mr Hughes, KC for the plaintiffs, now stated that the parties had been in consultation, and had come to terms, the substance of which was that the defendants admitted that there was no public right of way, and that they were granted a private way. This, he thought, would involve the granting of some deed or deeds to express the rights of the parties, and he suggested that the documents should be be settled by some counsel to be mutually agreed upon.His lordship observed that the question of coal was probably the important point. Mr Younger said Mr Tomlinson was a freeholder, and the plaintiffs could not mine under him. Mr Hughes: The coal actually under his house is his, and, of course, subsidence might be produced by taking away coal some distance away. I think some document is required to determine his actual rights.

Mr Younger said he wanted to avoid anything that would increase the costs, but, after further discussion, it was agreed that Mr John Dixon (an expert on mineral rights), or failing him, another counsel satisfactory to both parties, should be invited to settle the terms scheduled in the agreement, in order to prevent any further dispute.

The name of the house is Grassholme. The address of Mayfield Villas is the house they were living in while building Grassholme, which I assume they had not yet moved in to at the time of the newspaper article in March 1912.

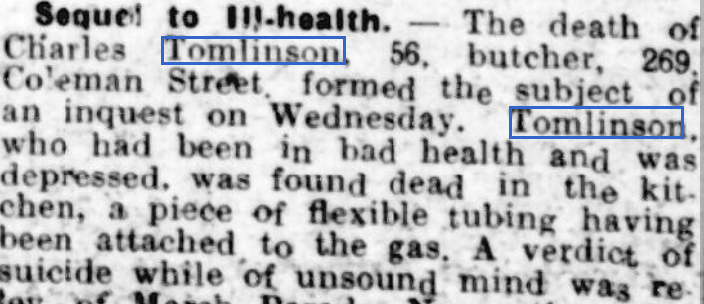

What my grandmother didn’t tell anyone was how her father died in 1929:

On the 1921 census, Charles, Nellie and eight of their children were living at 269 Coleman Street, Wolverhampton.

They were living on Coleman Street in 1915 when Charles was fined for staying open late.

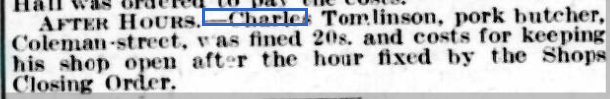

Staffordshire Advertiser – Saturday 13 February 1915:

What is not yet clear is why they moved from the house on Penn Common sometime between 1912 and 1915. And why did he have a racehorse in 1920?

July 12, 2022 at 8:30 am #6319In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

“Calm yourself, Egbert, and sit down. And be quiet! I can barely hear myself think with your frantic gibbering and flailing around,” Olga said, closing her eyes. “I need to think.”

Egbert clutched the eiderdown on either side of his bony trembling knees and clamped his remaining teeth together, drawing ragged whistling breaths in an attempt to calm himself. Olga was right, he needed to calm down. Besides the unfortunate effects of the letter on his habitual tremor, he felt sure his blood pressure had risen alarmingly. He dared not become so ill that he needed medical assistance, not with the state of the hospitals these days. He’d be lucky to survive the plague ridden wards.

What had become of him! He imagined his younger self looking on with horror, appalled at his feeble body and shattered mind. Imagine becoming so desperate that he wanted to fight to stay in this godforsaken dump, what had become of him! If only he knew of somewhere else to go, somewhere safe and pleasant, somewhere that smelled sweetly of meadows and honesuckle and freshly baked cherry pies, with the snorting of pigs in the yard…

But wait, that was Olga snoring. Useless old bag had fallen asleep! For the first time since Viktor had died he felt close to tears. What a sad sorry pathetic old man he’d become, desperately counting on a old woman to save him.

“Stop sniveling, Egbert, and go and pack a bag.” Olga had woken up from her momentary but illuminating lapse. “Don’t bring too much, we may have much walking to do. I hear the buses and trains are in a shambles and full of refugees. We don’t want to get herded up with them.”

Astonished, Egbert asked where they were going.

“To see Rosa. My cousins father in laws neice. Don’t look at me like that, immediate family are seldom the ones who help. The distant ones are another matter. And be honest Egbert,” Olga said with a piercing look, “Do we really want to stay here? You may think you do, but it’s the fear of change, that’s all. Change feels like too much bother, doesn’t it?”

Egbert nodded sadly, his eyes fixed on the stain on the grey carpet.

Olga leaned forward and took his hand gently. “Egbert, look at me.” He raised his head and looked into her eyes. He’d never seen a sparkle in her faded blue eyes before. “I still have another adventure in me. How about you?”

July 7, 2022 at 5:31 pm #6316In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

Myroslava was hungry. She saw ducks flying in the sky and realised she wasn’t too far from the Kal’mius river, south of Dantesk. She took out her sling and hit one with a stone she just picked on the floor. She smiled and said in a low voice : “You see father, I haven’t lost my touch.”

She had traveled several days with a group of reportourists, as she called them. A bunch of war reporters who thought it entertaining to take pictures of bombed areas, going about like peacocks as if they wore a plot armour against Rootian bullets and missiles and discourse at night on the tactics of the different armies. She was glad when she crossed the Rootian lines two days ago. Even if it meant no more dehydrated food and no more plot armour, she was certainly better off without the inane discussions.

She picked the duck and looked for a freshly bombarded place where there was still smoke. She could make some fire without being noticed too much. She didn’t like raw meat that much.

Soon after leaving the group or reportourists, without all the noise they made, she became certain she was being followed. She tried once to surprise them, but they were good at hiding and camouflaging their tracks. She wondered how long it had lasted. She cursed the noisy reporters and cursed her lack of good vodka. Cursing without alcohol was like boxing without fists.

July 7, 2022 at 9:00 am #6314In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

After her visit to the witch of the woods to get some medicine for her Mum who still had bouts of fatigue from her last encounter with the flu, the little Maryechka went back home as instructed.

She found her home empty. Her parents were busy in the fields, as the time of harvest was near, and much remained to be done to prepare, and workers were limited.

She left the pouch of dried herbs in the cabinet, and wondered if she should study. The schools were closed for early holidays, and they didn’t really bother with giving them much homework. She could see the teachers’ minds were worried with other things.

Unlike other children of her age, she wasn’t interested in all the activities online, phone-stuff. The other gen-alpha kids didn’t even bother mocking her “IRL”, glued to their screens while she instead enjoyed looking at the clear blue sky. For all she knew they didn’t even realize they were living in the same world. Now, they were probably over-stressed looking at all the news on replay.

For Maryechka, the war felt far away, even if you could see some of its impacts, with people moving about the nearby town.Looking as it was still early in the day, and she had plenty more time left before having to prepare for dinner, she thought it’d be nice to go and visit her grand-parent and their friends at the old people’s home. They always had nice stale biscuits to share, and they told the strangest stories all the time.

It was just a 15 min walk from the farm, so she’d be there and back in no time.

July 6, 2022 at 11:02 am #6311In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

Most of the pilgims, if one could call them that, flocked to the linden tree in cars, although some came on motorbikes and bicycles. Olek was grateful that they hadn’t started arriving by the bus load, like Italian tourists. But his cousin Ursula was happy with this strange new turn of events.

Her shabby hotel on the outskirts of town had never been so busy and she was already planning to refurbish the premises and evict the decrepit and motley assortment of aged permanent residents who had just about kept her head above water, financially speaking, for the last twenty years. She could charge much more per night to these new tourists, who were smartly dressed and modern and didn’t argue about the price of a room. They did complain about the damp stained wallpaper though and the threadbare bedding. Ursula reckoned she could charge even more for the rooms if she redecorated, and had an idea to approach her nephew Boris the bank manager for a business loan.

But first she had to evict the old timers. It wasn’t her problem, she reminded herself, if they had nowhere else to go. After all, plenty of charitable aid money was flying around these days, they could easily just join up with some fleeing refugees. She’d even sent some of her old dresses to the collection agency. They may have been forty years old and smelled of moth balls, but they were well made and the refugees would surely be grateful.

Ursula wasn’t looking forward to telling them. No, not at all! She rather liked some of them and was dreading their reaction. You are a business woman, Ursula, she told herself, and you have to look after your own interests! But still she quailed at the thought of knocking on their doors, or announcing it in the communal dining room at supper. Then she had an idea. She’d type up some letters instead, and sign them as if they came from her new business manager. When the residents approached her about the letter she would smile sadly and shrug, saying it wasn’t her decision and that she was terribly sorry but her hands were tied.

May 27, 2022 at 8:25 am #6300In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Looking for Carringtons

The Carringtons of Smalley, at least some of them, were Baptist ~ otherwise known as “non conformist”. Baptists don’t baptise at birth, believing it’s up to the person to choose when they are of an age to do so, although that appears to be fairly random in practice with small children being baptised. This makes it hard to find the birth dates registered as not every village had a Baptist church, and the baptisms would take place in another town. However some of the children were baptised in the village Anglican church as well, so they don’t seem to have been consistent. Perhaps at times a quick baptism locally for a sickly child was considered prudent, and preferable to no baptism at all. It’s impossible to know for sure and perhaps they were not strictly commited to a particular denomination.

Our Carrington’s start with Ellen Carrington who married William Housley in 1814. William Housley was previously married to Ellen’s older sister Mary Carrington. Ellen (born 1895 and baptised 1897) and her sister Nanny were baptised at nearby Ilkeston Baptist church but I haven’t found baptisms for Mary or siblings Richard and Francis. We know they were also children of William Carrington as he mentions them in his 1834 will. Son William was baptised at the local Smalley church in 1784, as was Thomas in 1896.

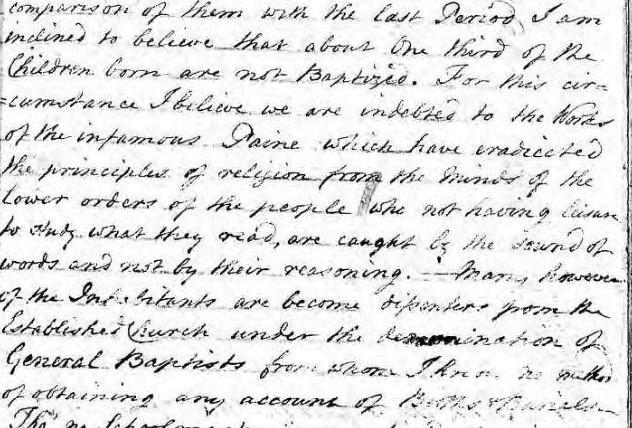

The absence of baptisms in Smalley with regard to Baptist influence was noted in the Smalley registers:

Smalley (chapelry of Morley) registers began in 1624, Morley registers began in 1540 with no obvious gaps in either. The gap with the missing registered baptisms would be 1786-1793. The Ilkeston Baptist register began in 1791. Information from the Smalley registers indicates that about a third of the children were not being baptised due to the Baptist influence.

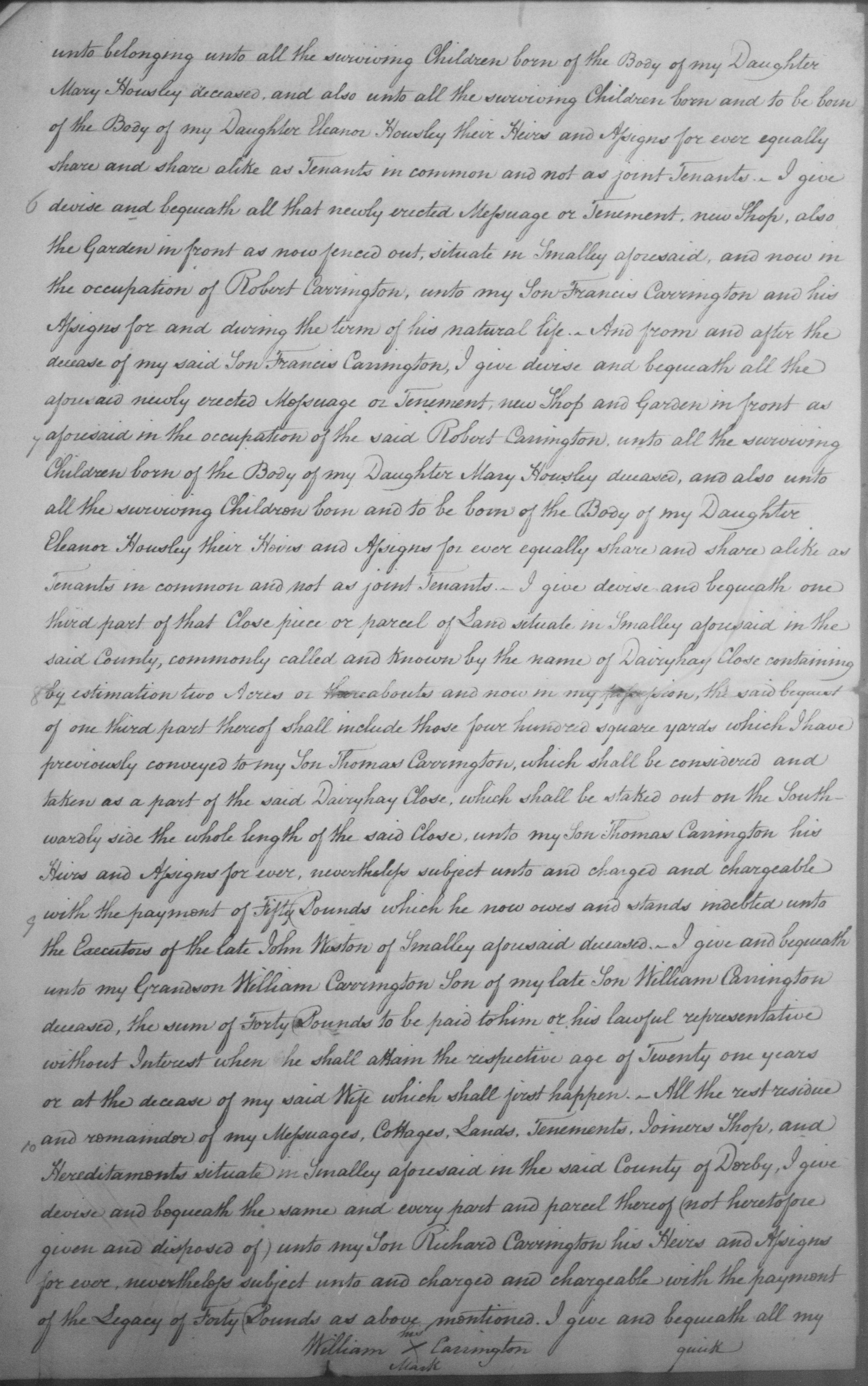

William Housley son in law, daughter Mary Housley deceased, and daughter Eleanor (Ellen) Housley are all mentioned in William Housley’s 1834 will. On the marriage allegations and bonds for William Housley and Mary Carrington in 1806, her birth date is registered at 1787, her father William Carrington.

A Page from the will of William Carrington 1834:

William Carrington was baptised in nearby Horsley Woodhouse on 27 August 1758. His parents were William and Margaret Carrington “near the Hilltop”. He married Mary Malkin, also of Smalley, on the 27th August 1783.

When I started looking for Margaret Wright who married William Carrington the elder, I chanced upon the Smalley parish register micro fiche images wrongly labeled by the ancestry site as Longford. I subsequently found that the Derby Records office published a list of all the wrongly labeled Derbyshire towns that the ancestry site knew about for ten years at least but has not corrected!

Margaret Wright was baptised in Smalley (mislabeled as Longford although the register images clearly say Smalley!) on the 2nd March 1728. Her parents were John and Margaret Wright.

But I couldn’t find a birth or baptism anywhere for William Carrington. I found four sources for William and Margaret’s marriage and none of them suggested that William wasn’t local. On other public trees on ancestry sites, William’s father was Joshua Carrington from Chinley. Indeed, when doing a search for William Carrington born circa 1720 to 1725, this was the only one in Derbyshire. But why would a teenager move to the other side of the county? It wasn’t uncommon to be apprenticed in neighbouring villages or towns, but Chinley didn’t seem right to me. It seemed to me that it had been selected on the other trees because it was the only easily found result for the search, and not because it was the right one.

I spent days reading every page of the microfiche images of the parish registers locally looking for Carringtons, any Carringtons at all in the area prior to 1720. Had there been none at all, then the possibility of William being the first Carrington in the area having moved there from elsewhere would have been more reasonable.

But there were many Carringtons in Heanor, a mile or so from Smalley, in the 1600s and early 1700s, although they were often spelled Carenton, sometimes Carrianton in the parish registers. The earliest Carrington I found in the area was Alice Carrington baptised in Ilkeston in 1602. It seemed obvious that William’s parents were local and not from Chinley.

The Heanor parish registers of the time were not very clearly written. The handwriting was bad and the spelling variable, depending I suppose on what the name sounded like to the person writing in the registers at the time as the majority of the people were probably illiterate. The registers are also in a generally poor condition.

I found a burial of a child called William on the 16th January 1721, whose father was William Carenton of “Losko” (Loscoe is a nearby village also part of Heanor at that time). This looked promising! If a child died, a later born child would be given the same name. This was very common: in a couple of cases I’ve found three deceased infants with the same first name until a fourth one named the same survived. It seemed very likely that a subsequent son would be named William and he would be the William Carrington born circa 1720 to 1725 that we were looking for.

Heanor parish registers: William son of William Carenton of Losko buried January 19th 1721:

The Heanor parish registers between 1720 and 1729 are in many places illegible, however there are a couple of possibilities that could be the baptism of William in 1724 and 1725. A William son of William Carenton of Loscoe was buried in Jan 1721. In 1722 a Willian son of William Carenton (transcribed Tarenton) of Loscoe was buried. A subsequent son called William is likely. On 15 Oct 1724 a William son of William and Eliz (last name indecipherable) of Loscoe was baptised. A Mary, daughter of William Carrianton of Loscoe, was baptised in 1727.

I propose that William Carringtons was born in Loscoe and baptised in Heanor in 1724: if not 1724 then I would assume his baptism is one of the illegible or indecipherable entires within those few years. This falls short of absolute documented proof of course, but it makes sense to me.

In any case, if a William Carrington child died in Heanor in 1721 which we do have documented proof of, it further dismisses the case for William having arrived for no discernable reason from Chinley.

-

AuthorSearch Results