Search Results for 'jacket'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

January 3, 2026 at 8:09 pm #8025

In reply to: The Hoards of Sanctorum AD26

As soon as Boothroyd had gone, Laddie Bentry, the under gardener, emerged from behind the Dicksonia squarrosa that was planted in a rare French Majolica Onnaing dragon eagle pot. The pot, and in particular the tree fern residing within it, were Laddie’s favourite specimen, reminding him of his homeland far away.

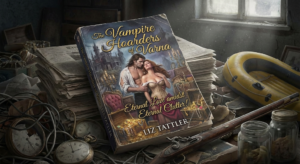

Keeping a cautious eye on the the door leading into the house, Laddie hurried over to the cast iron planter and retrieved the Liz Tattler novel hidden underneath. Quickly he tucked in into the inside pocket of his shabby tweed jacket and hastened to the door leading to the garden. Holding on to his cap, for the wind was cold and gusty, he ran to the old stable and darted inside. Laddie reckoned he had an hour or two free without Boothroyd hovering over him, and he settled himself on a heap of old sacks.

The Vampire Hoarders of Varna. It wasn’t the first time Laddie had seen Boothroyd surreptitiously reading Helier’s books, and it had piqued his curiosity. What was it the old fart found so interesting about Helier’s novels? The library was full of books, if he wanted to read. Not bothering to read the preface, and not having time to start on page one, Laddie Bentry flicked through the book, pausing to read random passages.

The Vampire Hoarders of Varna. It wasn’t the first time Laddie had seen Boothroyd surreptitiously reading Helier’s books, and it had piqued his curiosity. What was it the old fart found so interesting about Helier’s novels? The library was full of books, if he wanted to read. Not bothering to read the preface, and not having time to start on page one, Laddie Bentry flicked through the book, pausing to read random passages.….the carriage rattled and lurched headlong through the valley, jostling the three occupants unmercifully. “I’ll have the guts of that coachman for garters! The devil take him!” Galfrey exclaimed, after bouncing his head off the door frame of the compartment.

“Is it bleeding?” asked Triviella, inadvertently licking her lips and she inspected his forehead.

“The devil take you too, for your impertinence,” Galfrey scowled and shook her off, his irritation enhanced by his alarm at the situation they found themselves in.

Ignoring his uncharacteristic bad humour, Triviella snuggled close and and stroked his manly thigh, clad in crimson silk breeches. “Just think about the banquet later,” she purred.

Jacobino, austere and taciturn, on the opposite seat, who had thus far been studiously ignoring both of them, heard the mention of the banquet and smiled for the first time since…

Laddie opened the book to another passage.

“……1631, just before the siege of Gloucester, and what a feast it was! It was hard to imagine a time when we’d feasted so well. Such rich and easy pickings and such a delightful cocktail. One can never really predict a perfect cocktail of blood types at a party, and centuries pass between particularly memorable ones. Another is long overdue, and one would hate to miss it,” Jacobino explained to the innocent and trusting young dairy maid, who was in awe that the handsome young gentleman was talking to her at all, yet understood very little of his dialogue.

“Which is why,” Jacobino implored, taking hold of her small calloused hands, “You must come with me to the banquet tonight.”

Little did she know that her soft rosy throat was on the menu…..

May 10, 2025 at 9:06 am #7927In reply to: Cofficionados – What’s Brewing

Thiram Izu

Thiram Izu – The Bookish Tinkerer with Tired Eyes

Explicit Description

-

Age: Mid-30s

-

Heritage: Half-Japanese, half-Colombian

-

Face: Calm but slightly worn—reflecting quiet resilience and perceptiveness.

-

Hair: Short, tousled dark hair

-

Eyes: Observant, introspective; wears round black-framed glasses

-

Clothing (standard look):

-

Olive-green utilitarian overshirt or field jacket

-

Neutral-toned T-shirt beneath

-

Crossbody strap (for a toolkit or device bag)

-

Simple belt, jeans—functional, not stylish

-

-

Technology: Regularly uses a homemade device, possibly a patchwork blend of analog and AI circuitry.

-

Name Association: Jokes about being named after a fungicide (Thiram), referencing “brothers” Malathion and Glyphosate.

Inferred Personality & Manner

-

Temperament: Steady but simmering—he tries to be the voice of reason, but often ends up exasperated or ignored.

-

Mindset: Driven by a need for internal logic and external systems—he’s a fixer, not a dreamer (yet paradoxically surrounded by dreamers).

-

Social Role: The least performative of the group. He’s neither aloof nor flamboyant, but remains essential—a grounded presence.

-

Habits:

-

Zones out under stress or when overstimulated by dream-logic.

-

Blinks repeatedly to test for lucid dream states.

-

Carries small parts or tools in pockets—likely fidgets with springs or wires during conversations.

-

-

Dialogue Style: Deadpan, dry, occasionally mutters tech references or sarcastic analogies.

-

Emotional Core: Possibly a romantic or idealist in denial—hidden under his annoyance and muttered diagnostics.

Function in the Group

-

Navigator of Reality – He’s the one most likely to point out when the laws of physics are breaking… and then sigh and fix it.

-

Connector of Worlds – Bridges raw tech with dream-invasion mechanisms, perhaps more than he realizes.

-

Moral Compass (reluctantly) – Might object to sabotage-for-sabotage’s-sake; he values intent.

March 22, 2025 at 10:00 am #7874In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

A Quick Vacay on Mars

“The Helix is coming in for descent,” announced Luca Stroud, a bit too solemnly. “And by descent, I mean we’re parking in orbit and letting the cargo shuttles do the sweaty work.”

From the main viewport, Mars sprawled below in all its dusty, rust-red glory. Gone was the Jupiter’s orbit pulls of lunacy, after a 6 month long voyage, they were down to the Martian pools of red dust.

Even from space, you could see the abandoned domes of the first human colonies, with the unmistakable Muck conglomerate’s branding: half-buried in dunes, battered by storms, and rumored to be haunted (well, if you believed the rumors from the bored Helix 25 children).

Veranassessee—Captain Veranassessee, thank you very much— stood at the helm with the unruffled poise of someone who’d wrested control of the ship (and AI) with consummate style and in record time. With a little help of course from X-caliber, the genetic market of the Marlowe’s family that she’d recovered from Marlowe Sr. before Synthia had had a chance of scrubbing all traces of his DNA. Now, with her control back, most of her work had been to steer the ship back to sanity, and rebuild alliances.

“That’s the plan. Crew rotation, cargo drop, and a quick vacay if we can manage not to break a leg.”

Sue Forgelot, newly minted second in command, rolled her eyes affectionately. “Says the one who insisted we detour for a peek at the old Mars amusements. If you want to roast marshmallows on volcanic vents, just say it.”

Their footsteps reverberated softly on the deck. Synthia’s overhead panels glowed calm, reined in by the AI’s newly adjusted parameters. Luca tapped the console. “All going smoothly, Cap’n. Next phase of ‘waking the sleepers’ will happen in small batches—like you asked.”

Veranassessee nodded silently. The return to reality would prove surely harsh to most of them, turned soft with low gravity. She would have to administrate a good dose of tough love.

Sue nodded. “We’ll need a slow approach. Earth’s… not the paradise it once was.”

Veranassessee exhaled, eyes lingering on the red planet turning slowly below. “One challenge at a time. Everyone’s earned a bit of shore leave. If you can call an arid dustball ‘shore.’”

The Truce on Earth

Tundra brushed red dust off her makeshift jacket, then gave her new friend a loving pat on the flank. The baby sanglion—already the size of a small donkey—sniffed the air, then leaned its maned, boar-like head into Tundra’s shoulder. “Easy there, buddy,” she murmured. “We’ll find more scraps soon.”

They were in the ravaged outskirts near Klyutch Base, forging a shaky alliance with Sokolov’s faction. Sokolov—sharp-eyed and suspicious—stalked across the battered tarmac with a crate of spare shuttle parts. “This is all the help you’re getting from me,” he said, his accent carving the words. “Use it well. No promises once the Helix 25 arrives.”

Commander Koval hovered by the half-repaired shuttle, occasionally casting sidelong glances at the giant, (mostly) friendly mutant beast at Tundra’s side. “Just keep that… sanglion… away from me, will you?”

Molly, Tundra’s resilient great-grandmother, chuckled. “He’s harmless unless you’re an unripe melon or a leftover stew. Aren’t you, sweetie?”

The creature snorted. Sokolov’s men loaded more salvage onto the shuttle’s hull. If all went well, they’d soon have a functioning vessel to meet the Helix when it finally arrived.

Tundra fed her pet a chunk of dried fruit. She wondered what the grand new ship would look like after so many legends and rumors. Would the Helix be a promise of hope—or a brand-new headache?

Finkley’s Long-Distance Lounge

On Helix 25, Finkley’s new corner-lounge always smelled of coffee and antiseptic wipes, thanks to her cleaning-bot minions. Rows of small, softly glowing communication booths lined the walls—her “direct Earth Connection.” A little sign reading FINKLEY’S WHISPER CALLS flickered overhead. Foot traffic was picking up, because after the murder spree ended, people craved normalcy—and gossip.

She toggled an imaginary switch —she had found mimicking old technology would help tune the frequencies more easily. “Anybody out there?”

Static, then a faint voice from Earth crackled through the anchoring connection provided by Finja on Earth. “Hello? This is…Tala from Spain… well, from the Hungarian border these days…”

“Lovely to hear from you, Tala dear!” Finkley replied in the most uncheerful voice, as she was repeating the words from Kai Nova, who had found himself distant dating after having tried, like many others on the ship before, to find a distant relative connected through the FinFamily’s telepathic bridge. Surprisingly, as he got accustomed to the odd exchange through Finkley-Finja, he’d found himself curious and strangely attracted to the stories from down there.

“Doing all right down there? Any new postcards or battered souvenirs to share with the folks on Helix?”

Tala laughed over the Fin-line. “Plenty. Mostly about wild harvests, random postcards, and that new place we found. We’re calling it The Golden Trowel—trust me, it’s quite a story.”

Behind Finkley, a queue had formed: a couple of nostalgic Helix residents waiting for a chance to talk to distant relatives, old pen pals, or simply anyone with a different vantage on Earth’s reconstruction. Even if those calls were often just a “We’re still alive,” it was more comfort than they’d had in years.

“Hang in there, sweetie,” Finkley said with a drab tone, relaying Kai’s words, struggling hard not to be beaming at the imaginary booth’s receiver. “We’re on our way.”

Sue & Luca’s Gentle Reboot

In a cramped subdeck chamber whose overhead lights still flickered ominously, Luca Stroud connected a portable console to one of Synthia’s subtle interface nodes. “Easy does it,” he muttered. “We nudge up the wake-up parameters by ten percent, keep an eye on rising stress levels—and hopefully avoid any mass lunacy like last time.”

Sue Forgelot observed from behind, arms folded and face alight with the steely calm that made her a natural second in command. “Focus on folks from the Lower Decks first. They’re more used to harsh realities. Less chance of meltdown when they realize Earth’s not a bed of roses.”

Luca shot her a thumbs-up. “Thanks for the vote of confidence.” He tapped the console, and Synthia’s interface glowed green, accepting the new instructions.

“Well, Synthia, dear,” Sue said, addressing the panel drily, “keep cooperating, and nobody’ll have to forcibly remove your entire matrix.”

A faint chime answered—Synthia’s version of a polite half-nod. The lines of code on Luca’s console rearranged themselves into a calmer pattern. The AI’s core processes, thoroughly reined in by the Captain’s new overrides, hummed along peacefully. For now.

Evie & Riven’s Big News

On Helix 25’s mid-deck Lexican Chapel, full of spiral motifs and drifting incense, Evie and Riven stood hand in hand, ignoring the eerie chanting around them. Well, trying to ignore it. Evie’s belly had a soft curve now, and Riven couldn’t stop glancing at it with a proud smile.

One of the elder Lexicans approached, wearing swirling embroidered robes. “The engagement ceremony is prepared, if you’re still certain you want our… elaborate rituals.”

Riven, normally stoic, gave a slight grin. “We’re certain.” He caught Evie’s eye. “I guess you’re stuck with me, detective. And the kid inside you who’ll probably speak Lexican prophecies by the time they’re one.”

Evie rolled her eyes, though affection shone behind it. “If that’s the worst that happens, I’ll take it. We’ve both stared down bigger threats.” Then her hand drifted to her abdomen, protective and proud. “Let’s keep the chanting to a minimum though, okay?”

The Lexican gave a solemn half-bow. “We shall refrain from dancing on the ceilings this time.”

They laughed, past tensions momentarily lifted. Their child’s future, for all its uncertain possibilities, felt like hope on a ship that was finally getting stirred in a clear direction… away from the void of its own nightmares. And Mars, just out the window, loomed like a stepping stone to an Earth that might yet be worth returning to.

March 1, 2025 at 10:12 am #7844In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

Base Klyutch – Dr. Markova’s Clinic, Dusk

The scent of roasting meat and simmering stew drifted in from the kitchens, mingling with the sharper smells of antiseptic and herbs in the clinic. The faint clatter of pots and the low murmur of voices preparing the evening meal gave the air a sense of routine, of a world still turning despite everything. Solara Ortega sat on the edge of the examination table, rolling her shoulder to ease the stiffness. Dr. Yelena Markova worked in silence, cool fingers pressing against bruised skin, clinical as ever. Outside, Base Klyutch was settling into the quiet of night—wind turbines hummed, a sentry dog barked in the distance.

“You’re lucky,” Yelena muttered, pressing into Solara’s ribs just hard enough to make a point. “Nothing broken. Just overworked muscles and bad decisions.”

Solara exhaled sharply. “Bad decisions keep us alive.”

Yelena scoffed. “That’s what you tell yourself when you run off into the wild with Orrin Holt?”

Solara ignored the name, focusing instead on the peeling medical posters curling off the clinic walls.

“We didn’t find them,” she said flatly. “They moved west. Too far ahead. No proper tracking gear, no way to catch up before the lionboars or Sokolov’s men did.”

Yelena didn’t blink. “That’s not what I asked.”

A memory surfaced; Orrin standing beside her in the empty refugee camp, the air thick with the scent of old ashes and trampled earth. The fire pits were cold, the shelters abandoned, scraps of cloth and discarded tin cups the only proof that people had once been there. And then she had seen it—a child’s scarf, frayed and half-buried in the dirt. Not the same one, but close enough to make her chest tighten. The last time she had seen her son, he had worn one just like it.

She hadn’t picked it up. Just stood there, staring, forcing her breath steady, forcing her mind to stay fixed on what was in front of her, not what had been lost. Then Orrin’s hand had settled on her shoulder—warm, steady, comforting. Too comforting. She had jerked away, faster than she meant to, pulse hammering at the sudden weight of everything his touch threatened to unearth. He hadn’t said a word. Just looked at her, knowing, as he always did.

She had turned, found her voice, made it sharp. The trail was already too cold. No point chasing ghosts. And she had walked away before she could give the silence between them the space to say anything else.

Solara forced her attention back to the present, to the clinic. She turned her gaze to Yelena, steady and unmoved. “But that’s what matters. We didn’t find them. They made their choice.”

Yelena clicked her tongue, scribbling something onto her worn-out tablet. “Mm. And yet, you come back looking like hell. And Orrin? He looked like a man who’d just seen a ghost.”

Solara let out a dry breath, something close to a laugh. “Orrin always looks like that.”

Yelena arched an eyebrow. “Not always. Not before he came back and saw what he had lost.”

Solara pushed off the table, rolling out the tension in her neck. “Doesn’t matter.”

“Oh, it matters,” Yelena said, setting the tablet down. “You still look at him, Solara. Like you did before. And don’t insult me by pretending otherwise.”

Solara stiffened, fingers flexing at her sides. “I have a husband, Yelena.”

“Yes, you do,” Yelena said plainly. “And yet, when you say Orrin’s name, you sound like you’re standing in a place you swore you wouldn’t go back to.”

Solara forced herself to breathe evenly, eyes flicking toward the door.

“I made my choice,” she said quietly.

Yelena’s gaze softened, just a little. “Did he?”

Footsteps pounded outside, uneven, hurried. The clinic door burst open, and Janos Varga—Solara’s husband—strode in, breathless, his eyes bright with something rare.

“Solara, you need to come now,” he said, voice sharp with urgency. “Koval’s team—Orrin—they found something.”

Her spine straightened, her heartbeat accelerated. “What? Did they find…?” No, the tracks were clear, the refugees went west.

Janos ran a hand through his curls, his old radio headset still looped around his neck. “One of Helix 57’s life boat’s wreckage. And a man. Some old lunatic calling himself Merdhyn. And—” he paused, catching his breath, “—we picked up a signal. From space.”

The air in the room tightened. Yelena’s lips parted slightly, the shadow of an emotion passed on her face, too fast to read. Solara’s pulse kicked up.

“Where are they?” she asked.

Janos met her gaze. “Koval’s office.”

For a moment, silence. The wind rattled the windowpanes.

Yelena straightened abruptly, setting her tablet down with a deliberate motion. “There’s nothing more I can do for your shoulder. And I’m coming too,” she said, already reaching for her coat.

Solara grabbed her jacket. “Take us there, Janos.”

February 14, 2025 at 10:02 am #7780In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

Orrin Holt gripped the wheel of the battered truck, his knuckles white as the vehicle rumbled over the dry, cracked road. The leather wrap was a patchwork of smooth and worn, stichted together from whatever scraps they had—much like the quilts his mother used to make before her hands gave out. The main road was a useless, unpredictable mess of asphalt gravels and sinkholes. Years of war with Russia, then the collapse, left it to rot before anyone could fix it. Orrin stuck to the dirt path beside it. That was the only safe way through. The engine coughed but held. A miracle, considering how many times it had been patched together.

The cargo in the back was too important for a breakdown now. Medical supplies—antibiotics, painkillers, and a few salvaged vials of something even rarer. They’d traded well for it, risking much. Now he had to get it back to Base Klyutch (Ukrainian word for Key) without incident. If he continued like that he could make it before noon.

Still, something bothered him. That group of people he’d seen.

They had been barely more than silhouettes on top of a hill. Strangers, a rarity in these times. His first instinct had been to stop and evaluate who they were. But his instructions let room for no delay. So, he’d pushed forward and ignored them. The world wasn’t kind to the wandering. But they hadn’t looked like raiders or scavengers. Lost, perhaps. Or searching.

The truck lurched forward as he pushed it harder. The fences of the base rose in the distance, grey and wiry against the blue sky. Base Klyutch was a former military complex, fortified over the years with scavenged materials, steel sheets, and watchtowers. It wasn’t perfect, but it kept them alive.

As he rolled up to the main gate, the sentries swung the barricade open. Before he could fully cut the engine, a woman wearing a pristine white lab coat stepped forward, her sharp eyes scanning the truck’s cargo bed. Dr. Yelena Markova, the camp’s chief doctor, a former nurse who had to step up when the older one died in a raid on their camp three years ago. Stern-faced and wiry, with a perpetual air of exhaustion, she moved with the efficiency of someone who had long stopped hoping for ease. She had been waiting for this delivery.

“Finally,” she murmured, motioning for her assistants to start unloading. “We were running low. This will keep us going for a while.”

Orrin barely had time to nod before Dmytro Koval, the de facto leader of the base, strode toward him with the gait of a tall bear. His face seemed to have been carved out by a dulled blade, hardened by years of survival. A scar barred his mouth, pulling slightly at the corner when he spoke, giving the impression of a permanent sneer.

“Did you get it?” Koval asked, voice low.

Orrin reached into his kaki jacket and pulled out a sealed letter, along with a small package.

Koval took both, his expression unreadable. “Anything on the road?”

Orrin exhaled and adjusted his stance. “Saw something on the way back. A group, about a dozen, on a hill ten kilometers out. They seemed lost.”

“Armed?” asked Koval with a frown.

“Can’t say for sure.”

Dr. Markova straightened. “Lost? Unarmed? Out in the open like that, they won’t last long with Sokolov’s gang roaming the land. We have to go take them in.”

Koval grimaced. “Or they’re Sokolov’s spies. Trying to infiltrate us and find a weakness in our defenses. You know how it works.”

Before Koval could argue, a new voice cut in. “Or they could just be people.”

Solara Ortega had stepped into the conversation, brushing dirt from her overalls. A woman of lean strength, with the tan of someone spending long hours outside. Her sharp amber eyes carried the weight of someone who had survived too much but refused to be hardened by it. Orrin shoved down a mix of joy and ache at her sight. Her voice was calm but firm. “We can’t always assume the worst. We need more hands and we don’t leave people to die if we can help it. And in case you forgot, Koval, you don’t make all the decisions around here. I say we send a team to assess them.”

Koval narrowed his eyes, but he held his tongue. There was tension between them, but the council wasn’t a dictatorship.

“Fine,” Koval said after a moment, his jaw tense. “A team of two. They scout first. No direct contact until we’re sure. Orrin, you one of them take whoever wants to accompany you, but not one of my men. We need to maintain tight security.”

Dr. Markova sighed with relief when the man left. “If he wasn’t good at what he does, I would gladly kick him out of our camp.”

Solara, her face framed by strands of dark hair, shot a glance at Orrin. “I’m coming with you.”

This time, Orrin couldn’t repress a longing for a time before everything fell apart, when she had been his wife. The collapse had torn them apart in an instant, and by the time he found her again, years later, she had built a new life within the base in Ukraine. She had a husband now, one of the scientists managing the radio equipment, and two children. Orrin kept his expression neutral, but the weight of time pressed heavy on him.

“Then let’s get on the move. They might not stay there long.”

December 9, 2024 at 4:15 pm #7659In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

March 2024

The phone buzzed on the table as Lucien pulled on his scarf, preparing to leave for the private class he had scheduled at his atelier. He glanced at the screen and froze. His father’s name glared back at him.

He hesitated. He knew why the man called; he knew how it would go, but he couldn’t resolve to cut that link. With a sharp breath he swiped to answer.

“Lucien”, his father began, his tone already full of annoyance. “Why didn’t you take the job with Bernard’s firm? He told me everything went well in the interview. They were ready to hire you back.”

As always, no hello, no question about his health or anything personal.

“I didn’t want it”, Lucien said, his voice calm only on the surface.

“It’s a solid career, Lucien. Architecture isn’t some fleeting whim. When your mother died, you quit your position at the firm, and got involved with those friends of yours. I said nothing for a while. I thought it was a phase, that it wouldn’t last. And I was right, it didn’t. I don’t understand why you refuse to go back to a proper life.”

“I already told you, it’s not what I want. I’ve made my decision.”

Lucien’s father sighed. “Not what you want? What exactly do you want, son? To keep scraping by with these so-called art projects? Giving private classes to kids who’ll never make a career out of it? That’s not a proper life?”

Lucien clenched his jaw, gripping his scarf. “Well, it’s my life. And my decisions.”

“Your decisions? To waste the potential you’ve been given? You have talent for real work—work that could leave a mark. Architecture is lasting. What you are doing now? It’s nothing. It’s just… air.”

Lucien swallowed hard. “It’s mine, Dad. Even if you don’t understand it.”

A pause followed. Lucien heard his father speak to someone else, then back to him. “I have to go”, he said, his tone back to professional. “A meeting. But we’re not finished.”

“We’re never finished”, Lucien muttered as the line went dead.

Lucien adjusted the light over his student’s drawing table, tilting the lamp slightly to cast a softer glow on his drawing. The young man—in his twenties—was focused, his pencil moving steadily as he worked on the folds of a draped fabric pinned to the wall. The lines were strong, the composition thoughtful, but there was still something missing—a certain fluidity, a touch of life.

“You’re close,” Lucien said, leaning slightly over the boy’s shoulder. He gestured toward the edge of the fabric where the shadows deepened. “But look here. The transition between the shadow and the light—it’s too harsh. You want it to feel like a whisper, not a line.”

The student glanced at him, nodding. Lucien took a pencil and demonstrated on a blank corner of the canvas, his movements deliberate but featherlight. “Blend it like this,” he said, softening the edge into a gradient. “See? The shadow becomes part of the light, like it’s breathing.”

The student’s brow furrowed in concentration as he mimicked the movement, his hand steady but unsure. Lucien smiled faintly, watching as the harsh line dissolved into something more organic. “There. Much better.”

The boy glanced up, his face brightening. “Thanks. It’s hard to see those details when you’re in it.”

Lucien nodded, stepping back. “That’s the trick. You have to step away sometimes. Look at it like you’re seeing it for the first time.”

He watched as the student adjusted his work, a flicker of satisfaction softening the lingering weight of his father’s morning call. Guiding someone else, helping them see their own potential—it was the kind of genuine care and encouragement he had always craved but never received.

When Éloïse and Monsieur Renard appeared in his life years ago, their honeyed words and effusive praise seduced him. They had marveled at his talent, his ideas. They offered to help with the shared project in the Drôme. He and his friends hadn’t realized the couple’s flattery came with strings, that their praise was a net meant to entangle them, not make them succeed.

The studio door creaked open, snapping him back to reality. Lucien tensed as Monsieur Renard entered, his polished shoes clicking against the wooden floor. His sharp eyes scanned the room before landing on the student’s work.

“What have we here?” He asked, his voice bordering on disdain.

Lucien moved in between Renard and the boy, as if to protect him. His posture stiff. “A study”, he said curtly.

Renard examined the boy’s sketch for a moment. He pulled out a sleek card from his pocket and tossed it onto the drawing table without looking at the student. “Call me when you’ve improved”, he said flatly. “We might have work for you.”

The student hesitated only briefly. Glancing at Lucien, he gathered his things in silence. A moment later, the door closed behind the young man. The card remained on the table, untouched.

Renard let out a faint snort, brushing a speck of dust from his jacket. He moved to Lucien’s drawing table where a series of sketches were scattered. “What are these?” he asked. “Another one of your indulgences?”

“It’s personal”, he said, his voice low.

Renard snorted softly, shaking his head. “You’re wasting your time, Lucien. Do as you’re asked. That’s what you’re good at, copying others’ work.”

Lucien gritted his teeth but said nothing. Renard reached into his jacket and handed Lucien a folded sheet of paper. “Eloïse’s new request. We expect fast quality. What about the previous one?”

Lucien nodded towards the covered stack of canvases near the wall. “Done.”

“Good. They’ll come tomorrow and take the lot.”

Renard started to leave but paused, his hand on the doorframe. He said without looking back: “And don’t start dreaming about becoming your own person, Lucien. You remember what happened to the last one who wanted out, don’t you?” The man stepped out, the sound of his steps echoing through the studio.

Lucien stared at the door long after it had closed. The sketches on his table caught his eyes—a labyrinth of twisted roads, fragmented landscapes, and faint, familiar faces. They were his prayers, his invocation to the gods, drawn over and over again as though the repetition might force a way out of the dark hold Renard and Éloïse had over his life.

He had told his father this morning that he had chosen his life, but standing here, he couldn’t lie to himself. His decisions hadn’t been fully his own these last few years. At the time, he even believed he could protect his friends by agreeing to the couple’s terms, taking the burden onto himself. But instead of shielding them, he had only fractured their friendship and trapped himself.

Lucien followed the lines of one of the sketches absently, his fingers smudging the charcoal. He couldn’t shake off the feeling that something was missing. Or someone. Yes, an unfathomable sense that someone else had to be part of this, though he couldn’t yet place who. Whoever it was, they felt like a thread waiting to tie them all together again.

He knew what he needed to do to bring them back together. To draw it where it all began, where they had dreamed together. Avignon.December 2, 2024 at 10:50 pm #7635In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

Sat. Nov. 30, 2024 5:55am — Matteo’s morning

Matteo’s mornings began the same way, no matter the city, no matter the season. A pot of strong coffee brewed slowly on the stove, filling his small apartment with its familiar, sense-sharpening scent. Outside, Paris was waking up, its streets already alive with the sound of delivery trucks and the murmurs of shopkeepers rolling open shutters.

He sipped his coffee by the window, gazing down at the cobblestones glistening from last night’s rain. The new brass sign above the Sarah Bernhardt Café caught the morning light, its sheen too pristine, too new. He’d started the server job there less than a week ago, stepping into a rhythm he already knew instinctively, though he wasn’t sure why.

Matteo had always been good at fitting in. Jobs like this were placeholders—ways to blend into the scenery while he waited for whatever it was that kept pulling him forward. The café had reopened just days ago after months of being closed for renovations, but to Matteo, it felt like it had always been waiting for him.

He set his coffee mug on the counter, reaching absently for the notebook he kept nearby. The act was automatic, as natural as breathing. Flipping open to a blank page, Matteo wrote down four names without hesitation:

Lucien. Elara. Darius. Amei.

He stared at the list, his pen hovering over the page. He didn’t know why he wrote it. The names had come unbidden, as though they were whispered into his ear from somewhere just beyond his reach. He ran his thumb along the edge of the page, feeling the faint indentation of his handwriting.

The strangest part wasn’t the names— it was the certainty that he’d see them that day.

Matteo glanced at the clock. He still had time before his shift. He grabbed his jacket, tucked the notebook into the inside pocket, and stepped out into the cool Parisian air.

Matteo’s feet carried him to a side street near the Seine, one he hadn’t consciously decided to visit. The narrow alley smelled of damp stone and dogs piss. Halfway down the alley, he stopped in front of a small shop he hadn’t noticed before. The sign above the door was worn, its painted letters faded: Les Reliques. The display in the window was an eclectic mix—a chessboard missing pieces, a cracked mirror, a wooden kaleidoscope—but Matteo’s attention was drawn to a brass bell sitting alone on a velvet cloth.

The door creaked as he stepped inside, the distinctive scent of freshly burnt papier d’Arménie and old dust enveloping him. A woman emerged from the back, wiry and pale, with sharp eyes that seemed to size Matteo up in an instant.

“You’ve never come inside,” she said, her voice soft but certain.

“I’ve never had a reason to,” Matteo replied, though even as he spoke, the door closed shut the outside sounds.

“Today, you might,” the woman said, stepping forward. “Looking for something specific?”

“Not exactly,” Matteo replied. His gaze shifted back to the bell, its smooth surface gleaming faintly in the dim light.

“Ah.” The shopkeeper followed his eyes and smiled faintly. “You’re drawn to it. Not uncommon.”

“What’s uncommon about a bell?”

The woman chuckled. “It’s not the bell itself. It’s what it represents. It calls attention to what already exists—patterns you might not notice otherwise.”

Matteo frowned, stepping closer. The bell was unremarkable, small enough to fit in the palm of his hand, with a simple handle and no visible markings.

“How much?”

“For you?” The shopkeeper tilted his head. “A trade.”

Matteo raised an eyebrow. “A trade for what?”

“Your time,” the woman said cryptically, before waving her hand. “But don’t worry. You’ve already paid it.”

It didn’t make sense, but then again, it didn’t need to. Matteo handed over a few coins anyway, and the woman wrapped the bell in a square of linen.

Back on the street, Matteo slipped the bell into his pocket, its weight unfamiliar but strangely comforting. The list in his notebook felt heavier now, as though connected to the bell in a way he couldn’t quite articulate.

Walking back toward the café, Matteo’s mind wandered. The names. The bell. The shopkeeper’s words about patterns. They felt like pieces of something larger, though the shape of it remained elusive.

The day had begun to align itself, its pieces sliding into place. Matteo stepped inside, the familiar hum of the café greeting him like an old friend. He stowed his coat, slipped the bell into his bag, and picked up a tray.

Later that day, he noticed a figure standing by the window, suitcase in hand. Lucien. Matteo didn’t know how he recognized him, but the instant he saw the man’s rain-damp curls and paint-streaked scarf, he knew.

By the time Lucien settled into his seat, Matteo was already moving toward him, notebook in hand, his practiced smile masking the faint hum of inevitability coursing through him.

He didn’t need to check the list. He knew the others would come. And when they did, he’d be ready. Or so he hoped.

December 2, 2024 at 8:35 pm #7634In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

Nov.30, 2024 2:33pm – Darius: The Map and the Moment

Darius strolled along the Seine, the late morning sky a patchwork of rainclouds and stubborn sunlight. The bouquinistes’ stalls were already open, their worn green boxes overflowing with vintage books, faded postcards, and yellowed maps with a faint smell of damp paper overpowered by the aroma of crêpes and nearby french fries stalls. He moved along the stalls with a casual air, his leather duffel slung over one shoulder, boots clicking against the cobblestones.

The duffel had seen more continents than most people, its scuffed surface hinting at his nomadic life. India, Brazil, Morocco, Nepal—it carried traces of them all. Inside were a few changes of clothes, a knife he’d once bought off a blacksmith in Rajasthan, and a rolled-up leather journal that served more as a collection of ideas than a record of events.

Darius wasn’t in Paris for nostalgia, though it tugged at him in moments like this. The city had always been Lucien’s thing —artistic, brooding, and layered with history. For Darius, Paris was just another waypoint. Another stop on a map that never quite seemed to end.

It was the map that stopped him, actually. A tattered, hand-drawn thing propped against a pile of secondhand books, its edges curling like a forgotten leaf. Darius leaned in, frowning at its odd geometry. It wasn’t a city plan or a geographical rendering; it was… something else.

“Ah, you’ve found my prize,” said the bouquiniste, a short older man with a grizzled beard and a cigarette dangling from his lips.

“This?” Darius held up the map, his dark fingers tracing the looping, interconnected lines. They reminded him of something—a mandala, maybe, or one of those intricate yantras he’d seen in a temple in Varanasi.

“It’s not a real place,” the bouquiniste continued, leaning closer as though revealing a secret. “More of a… philosophical map.”

Darius raised an eyebrow. “A philosophical map?”

The man gestured toward the lines. “Each path represents a choice, a possibility. You could spend your life trying to follow it, or you could accept that you already have.”

Darius tilted his head, the edges of a smile forming. “That’s deep for ten euros.”

“It’s twenty,” the bouquiniste corrected, his grin flashing gold teeth.

Darius handed over the money without a second thought. The map was too strange to leave behind, and besides, it felt like something he was meant to find.

He rolled it up and tucked it into his duffel, turning back toward the city’s winding streets. The café wasn’t far now, but he still had time.

He stopped by a street vendor selling espresso shots and ordered one, the strong, bitter taste jolting his senses awake. As he leaned against a lamppost, he noticed his reflection in a shop window: a tall, broad-shouldered man, his dark skin glistening faintly in the misty air. His leather jacket was worn at the elbows, his boots dusted with dirt from some far-flung place.

He looked like a man who belonged everywhere and nowhere—a nomad who’d long since stopped wondering what home was supposed to feel like.

India had been the last big stop. It was messy, beautiful chaos. The temples had been impressive, sure, but it was the street food vendors, the crowded markets, the strolls on the beach with the peaceful cows sunbathing, and the quiet, forgotten alleys that stuck with him. He’d made some connections, met some people who’d lingered in his thoughts longer than they should have.

One of them had been a woman named Anila, who had handed him a fragment of something—an idea, a story, a warning. He couldn’t quite remember now. It felt like she’d been trying to tell him something important, but whatever it was had slipped through his fingers like water.

Darius shook his head, pushing the thought aside. The past was the past, and Paris was the present. He looked at the rolled-up map peeking out of his duffel and smirked. Maybe Lucien would know what to make of it. Or Elara, with her scientific mind and love of puzzles.

The group had always been a strange mix, like a band that shouldn’t work but somehow did. And now, after five years of silence, they were coming back together.

The idea made his stomach churn—not with nerves, exactly, but with a sense of inevitability. Things had been left unsaid back then, unfinished. And while Darius wasn’t usually one to linger on the past, something about this meeting felt… different.

The café was just around the corner now, its brass fixtures glinting through the drizzle. Darius slung his duffel higher on his shoulder and took one last sip of espresso before tossing the cup into a bin.

Whatever this reunion was about, he’d be ready for it.

But the map—it stayed on his mind, its looping lines and impossible paths pressing into his thoughts like a puzzle waiting to be solved.

December 2, 2024 at 1:19 am #7631In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

Amei found the letter waiting on the narrow hallway table; her flatmate, Felix, must have left it there. They rarely crossed paths these days as he was working long shifts at the hospital. His absence suited her—mostly.

It was a novelty to get a letter! She turned it over in her hands, noting the faint coffee stain on one corner and the Paris postmark. The handwriting was sharp and angular, unmistakably Lucien’s. It felt like a relic from another life, a self she’d long ago left behind in favour of the safe existence she had built in London.

She slipped a finger under the flap and opened the envelope. It contained a single piece of paper—she read the words and Lucien’s familiar insistence leapt off the page.

Amei set the letter on the kitchen counter and stood for a moment, staring out the window. The view was of the neighbouring building—a dreary brick wall streaked with stains, its monotony interrupted only by a single trailing vine struggling to cling to life.

The flat was small but tidy, shaped by two lives that rarely intersected. Felix’s presence was minimal: a mug left on the counter, a jacket draped over a chair. The rest was hers—books stacked on shelves, notebooks brimming with half-formed ideas, and an easel by the window holding an unfinished canvas. She freelanced as a textile designer. On the desk lay fabric swatches and sketches for her latest project—a clean, modern design for a boutique client. The work was steady and paid the bills but left little room for the creative freedom she once craved.

It certainly wasn’t the life she’d envisioned for herself at twenty, or even thirty, but it was functional. Yet there was an emptiness to it all; she was good at what she did, but the passion she’d once felt for her work had dulled.

There were no children at home to fill the silence, no pets to demand her attention. Relationships had come and gone, but none had felt like forever. Felix offered a semblance of company, though their conversations had dwindled to polite exchanges or the odd humorous anecdote. Her days had settled into a rhythm of predictability, punctuated only by deadlines and occasional dinners with colleagues she liked but never truly connected with.

Amei sank into the armchair by the window. Should she go? She had to admit she was curious. It must be nearly five years since they had last been together and the events of that last occasion still haunted her.

She leaned back, her gaze trailing to the vine outside the window, and let the question linger.

December 1, 2024 at 5:44 pm #7623In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

At the Café

The Sarah Bernardt Café shimmered under a pale grey November sky a busy last Saturday of the “Black Week”. Golden lights spilled onto cobblestones slick with rain, and the air buzzed with the din of a city alive in the moment. Inside, the crowd pressed together, laughing, arguing, living. And in a corner table by the fogged-up window, old friends were about to quietly converged, coming to a long overdue reunion.

Lucien was the first to arrive, dragging a weathered suitcase behind him. Its wheels rattled unevenly on the cobblestones, a sound he hated. His dark curls, damp from the rain, clung to his forehead, and his scarf, streaked with old paint, hung loose around his neck. He folded himself into a corner chair, his suitcase tucked awkwardly beside him. When the server approached, Lucien waved him off with a distracted shake of his head and opened a battered sketchbook.

The next arrival was Elara. She entered briskly, shaking rain from her short gray-streaked hair, her eyes scanning the room as though searching for anomalies. A small roller bag trailed behind her, pristine and black, a sharp contrast to Lucien’s worn luggage. She stopped at the table and tilted her head.

“Still brooding?” she asked, pulling off her coat and folding it neatly over the back of a chair.

“Still talking?” Lucien didn’t look up, his pencil scratching faint lines across the page.

Elara smiled faintly. “Two minutes in, and you’re already immortalizing us? You know I hate being drawn.”

“You hate being caught off guard,” Lucien murmured. “But I never get your nose wrong.”

She laughed, the sound light but brief, and sank into her seat, placing her bag carefully beside her.

The door swung open again, and Darius entered, shaking the rain from his jacket. His presence seemed to fill the room immediately. He strode toward the table, a leather duffel slung over one shoulder and a well-worn travel pouch clutched in his hand. His boots clacked against the café’s tile floor, his movements easy, confident.

“Did you walk here?” Elara asked as he dropped his things with a thud and pulled out a chair.

“Ran into someone on the way,” he said, settling back. “Some guy selling maps. Got this one for ten euros—worth every cent.” He waved a yellowed scrap of paper that looked more fiction than cartography.

Lucien snorted. “Still paying for strangers’ stories, I see.”

“The good ones aren’t free.” Darius grinned and leaned back in his chair, propping one boot against the table leg.

The final arrival was Amei. Her entrance was quieter but no less noticeable. She unwound her scarf slowly, her layered clothing a mix of textures and colors that seemed to absorb the café’s golden light. A tote bag rested over her shoulder, bulging with what could have been books, or journals, or stories yet untold.

“You’re late,” Darius said, but his voice carried no accusation.

“Right on time,” Amei replied, lowering herself into the last chair. “You’re all just early.”

Her gaze swept across them, lingering on the bags piled at their feet. “I see I’m not the only one who came a long way.”

“Not all of us live in Paris,” Elara said, with a glance at Lucien.

“Only some of us make better life choices,” Lucien replied dryly.

The comment drew laughter—a tentative sound that loosened the air between them, thick as it was with five years of absence.

November 18, 2024 at 5:53 pm #7604

November 18, 2024 at 5:53 pm #7604In reply to: The Precious Life and Rambles of Liz Tattler

After three weeks of fog, a gota fría had settled over Tatler Manor. Torrents of rain poured down on the garden, transforming it into a river. From her drawing room, Liz surveyed the scene, imagining herself drifting across the flood in a boat planned with Walter Melon, once the skies cleared.

Down below, the ever-dedicated Roberto stood ankle deep in the rising waters, glaring at the devastation with a mixture of despair and stubborn determination. He hated rubber boots, because he was allergic to them, but they were the only thing allowing him to trudge through the flooded garden.

The day before, he had risked the elements to save the dahlias, but five minutes in the water had turned his feet a swollen itchy mess. Now, he paced the edge of the garden, muttering curses under his breath, while Liz called him from the window above.

“Roberto! When this all clears, I’m thinking of a little boating expedition with Walter Melon. Perhaps you can fashion me a raft from the greenhouse planks?”

Roberto looked up at her, rain dripping from his cap. “With all due respect Señora, you might need a tetanus shot first.”

Liz laughed, unbothered by his dry tone. “Oh, don’t be such a pessimist. Look at it! It’s practically Venice down there.”

“It’s a disaster,” Roberto grumbled, tugging at the hem of his soggy jacket. “And if you want Venice, Señora, you’ll have to find another gondolier.”

Liz smiled to herself. She enjoyed Roberto’s pragmatism almost as much as she enjoyed teasing him. She knew he cared too much about the garden to abandon it, even in its current state, and she admired his quiet devotion.

As Roberto turned back to inspect the flooded beds, Liz leaned out the window, imagining her boat gliding through the submerged roman pool, the perfect escape from the monotony of the storm.

June 13, 2024 at 9:32 am #7472In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

When Truella had stopped reacting, she had another look over the memo, noticing the location of the preposterous sounding coven they were to associate with. She had assumed that it would be in the north, or at least in Madrid, but was astonished to discover they were based very close to her village. She wondered why she had never heard of them. She supposed that they did their money minded business elsewhere and were merely based here, hidden in the cork woods, masquerading as one of those ghastly upmarket hotels for corrupt politicians. One could only see the distinctive tower from the roads, as the old convent was hidden deep in the woods. Nobody Truella knew had ever had any money to get through the gates and have a closer look.

This gave Truella an idea. What an opportunity! It would give her a way in.

Actually, I think it might be a great idea, girls. Let’s give it our best shot. Austreberthe has my support on this.

Eris, Frella and Zez nearly dropped their gadgets when they read Truella’s latest message. Frella was the first to respond.

Go on then, tell us. What changed your mind?

Location, location, location! Truella replied. Check out where they’re based!

After a few minutes, Frella replied.

You better spill the beans and tell us what you’re planning. That is, if you want us to cooperate with you and go along with this latest trashy money grabbing fiasco in the making. I thought our plan was to have the summer off? What does the location mean to you?

Speak for yourself, Frella, Eris replied, rather miffed. At least she’s going to go along with it, for Flove’s sake, let’s just do what we’ve been asked to do without complaining for once!

I’m with you, Eris, Jeezel piped up, I quite fancy a flamenco puffer jacket. Or a nice knitted sombrero. And we can visit Truella while we’re there on business.

Outnumbered, Frella sighed. I still think Truella should explain. Explain fully. And don’t expect me anytime soon, either. I have to solve the mystery of the camphor chest first.

June 12, 2024 at 8:45 pm #7470In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

After all the months of secret work for Malové, where Eris was being tasked to scout for profitable new ventures for the Quadrivium’s Emporium that would keep with traditions, and endless due diligence under the seal of secrecy, she’d learnt that the deal had been finally sealed by Austreberthe.

The announcement had just went out, not really making quite the splash Eris would have expected.

Press Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Quadrivium Emporium Announces Strategic Acquisition of Spanish based company Quintessivium Cloister Crafts

Limerick, 12th June 2024– Quadrivium Emporium, renowned for its exceptional range of artisanal incense blends and commitment to quality, is pleased to announce the successful acquisition of Quintessivium Cloister Crafts. This strategic move marks a significant milestone in Quadrivium Emporium’s ongoing expansion and diversification efforts.About Quintessivium Cloister Crafts

Quintessivium Cloister Crafts has been a trusted name in the production of high-quality nun’s couture. Known for their craftsmanship and dedication to preserving traditional techniques, started as a small business focussed on quills and writing accessories as well as cardigans, Quintessivium Cloister Crafts has maintained a reputation for excellence and innovation in the market.

Strategic Vision and Synergies

The integration of Quintessivium Cloister Crafts into the Quadrivium family aligns with our vision to expand our product portfolio while maintaining the high standards of quality and craftsmanship our customers have come to expect. This acquisition will allow Quadrivium Emporium to diversify its offerings and tap into new markets and customer segments.

“We are thrilled to welcome Quintessivium Cloister Crafts to the Quadrivium Emporium family,” said Austreberthe Baltherbridge, interim CEO of Quadrivium Emporium. “Their commitment to quality and tradition mirrors our own values, and we are excited about the opportunities this acquisition presents. Together, we will continue to innovate and deliver exceptional products to our customers.”

Future Endeavours

Quadrivium Emporium plans to leverage the expertise and resources of Quintessivium Cloister Crafts to develop new and unique product lines. Customers can look forward to an expanded range of high-quality writing instruments, apparel and accessories, crafted with the same attention to detail and dedication that both brands are known for.

For more information, please contact: media@quadrivium.emporium

The internal memo that they’d received on the internal email list bore some of the distinct style of Malové, even if sent from Austreberthe’s email and adjusted with the painstaking attention to minute details she was known for.

Internal Memo

To: Quadrivium Leadership Team

Subject: Synergies and Strategic Integration with Quintessivium Cloister Crafts (previously codenamed as ‘Cardivium Nun’s Quills & Cardigans’)Team,

With the acquisition of Quintessivium Cloister Crafts finalised, we are poised to explore the deeper synergies between our coven and the nun witches’ coven operating behind their front. Here are some key areas where we can harness our collective strengths:

1. Resource Sharing:

– Their expertise in crafting high-quality quills can complement our focus on artisanal incense blends. By sharing resources and best practices, both covens can enhance their craftsmanship and innovation.2. Collaborative Spellcraft:

– The nun witches bring a unique perspective and set of rituals that can enrich our own magical practices. Joint spellcasting sessions and workshops can lead to the development of powerful new enchantments and products.3. Knowledge Exchange:

– The historical and esoteric knowledge held by the nuns is a treasure trove we can tap into. Regular exchanges of scrolls, texts, and insights can deepen our understanding of ancient magic and its applications in modern contexts.4. Market Expansion:

– By combining our product lines, we can create bundled offerings that appeal to a broader audience. Imagine a premium writing set that includes a handcrafted quill, a magical ink blend, and a specially composed incense for enhancing focus and creativity. Or outdoor outfits with puffer jackets, or specially knit cardigans with embedded magical properties.5. Strengthening Alliances:

– This acquisition sets a precedent for future alliances with other covens and magical entities. It demonstrates our commitment to growth and collaboration, reinforcing our position as a leading force in the magical community.Remember, the true value of this acquisition lies not just in the products we can create together, but in the unity and strength we gain as a collective. Let’s approach this integration with the spirit of collaboration and mutual respect.

Yours in strength and magic,

Austreberthe, on behalf of MalovéFebruary 7, 2024 at 12:40 am #7356In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

“Would you be looking for me?”

Cedric jumped. Where on earth had she come from? It was the blond witch from the cafe, but what was she doing sneaking up behind him when he’d seen her rushing off down the street not a minute before! And yet here she was, smirking at him like butter wouldn’t melt!

He studied her. She wasn’t conventionally pretty he decided, with her thin, sharp features. And she had no meat on her bones. Cedric liked women who were soft and had a bit of something he could squeeze. And she was so … white … almost like one of those albinos … still, there was something he found strangely compelling about her.

She’s a witch, he reminded himself. “What on earth gave you the idea I was following you?” He twisted his mouth into an amused sneer, hoping it showed the contempt she surely deserved.

“You’re not then?” Her gaze was unswerving and Cedric had to look away, pretending to take a great interest in a black poodle peeing on a nearby lamp post. Cedric liked dogs and up until six months ago had a miniature schnauzer called Mitzy. Thinking of Mitzy, he felt the familiar little squeeze in his chest.

“I’m Frigella O’Green,” she said, still studying him intently.

Reluctantly he pulled his gaze back towards her. “Oh, ah … Cedric … just Cedric.” He’d nearly told her his surname which didn’t seem a good idea, all things considered. Out of habit, he raised his hand to take hers, then remembering, thrust it awkwardly in his jacket pocket.

“Well, just Cedric, if you’re not looking for me, I’ll be off … I’m in a bit of a hurry.” Then she smiled at him, properly this time, and Cedric wondered why he hadn’t thought she was pretty a moment ago. “Nice hat by the way, Cedric. Stylish.” She turned then and Cedric watched her stride down the street until she was no longer visible. Distractedly he brushed the wool tweed of his cap.

Frigella O’Green is a witch, Cedric, he told himself sternly.

March 10, 2023 at 8:06 am #6799In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

It seemed like their journey was ominously pregnant with untold possibilities. Well that’s what Xavier had said the team to break the lazy pattern that had started to bring their sense of adventure to a lull.

“Please, no snotty baby possibilities!” had moaned Zara, stretching from her morning session of yoga with Yasmin.It was the morning of the third day since he’d arrived, and as they were enjoying the breakfast, the external elements seemed to have put a brake on the planned activities.

On the previous evening, Mater, the dame of the Inn, had come in with a dramatic racing driver costume complete with burgundy red jacket and goggles to match. She’d seemed quite excited at the thought of racing at the Carts and Lager, but the younger child, Prune, had come in with weather forecast.

“It’s on the local channel news. We have to brace for a chance of dust storm. It’s recommended to stay indoors during the next two days.”

“WHAT?!” Zara couldn’t believe it. The thought of being cooped up in holidays! Then she lightened up a little when Yasmin mentioned the possibility of sand ghost pictures. She knew Zara well enough, that a good distraction was the remedy to most of her moods.

Youssef had shrugged and told them of the time they were with the BLOG team at a snowy pass in Ladakh, and had to wait for the weather to clear the only pass back to the valley. He’s enjoyed learning how to make chapatis with the family on the small gas stove of the local place, and visited the local yurts. Zara’s eyes were suddenly full of wonders at the mere mention of yurts.

Prune had then mentioned with a smirk. “If you guys want an adventure, I was planning to do some spring cleaning in the basement. There are tons of old books…. and some said maybe some secret entrance to the mines.”

Zara’s spider sense was tingling almost orgasmically.

Youssef said. “Well, I suppose that’s the best entertainment we’ll get for now…”

At the morning breakfast table, they did a quick check of the news.

“The situation isn’t getting any better. AL has confirmed it’s an unusual weather late in this season, but it’s also saying we should remain indoors.” Xavier was looking at his phone slouched on the table.

“And they will cancel the first days of the Carts and Lager…” Zara was downcast.

“Well, here’s a thought… the quest is still open in the game…”

January 23, 2023 at 4:14 pm #6453In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Each group of people sharing the jeeps spent some time cleaning the jeeps from the sand, outside and inside. While cleaning the hood, Youssef noted that the storm had cleaned the eagles droppings. Soon, the young intern told them, avoiding their eyes, that the boss needed her to plan the shooting with the Lama. She said Kyle would take her place.

Each group of people sharing the jeeps spent some time cleaning the jeeps from the sand, outside and inside. While cleaning the hood, Youssef noted that the storm had cleaned the eagles droppings. Soon, the young intern told them, avoiding their eyes, that the boss needed her to plan the shooting with the Lama. She said Kyle would take her place.“Phew, the yak I shared the yurt with yesterday smelled better,” he said to the guys when he arrived.

Soon enough, Miss Tartiflate was going from jeep to jeep, her fiery hair half tied in a bun on top of her head, hurrying people to move faster as they needed to catch the shaman before he got away again. She carried her orange backpack at all time, as if she feared someone would steal its content. Rumour had it that it was THE NOTEBOOK where she wrote the blog entries in advance.

“No need to waste more time! We’ll have breakfast at the Oasis!” she shouted as she walked toward Youssef’s jeep. When she spotted him, she left her right index finger as if she just remembered something and turned the other way.

“Dunno what you did to her, but it seems Miss Yeti is avoiding you,” said Kyle with a wry smile.

Youssef grunted. Yeti was the nickname given to Miss Tartiflate by one of her former lover during a trip to Himalaya. First an affectionate nickname based on her first name, Henrietty, it soon started to spread among the production team when the love affair turned sour. It sticked and became widespread in the milieu. Everybody knew, but nobody ever dared say it to her face.

Youssef knew it wouldn’t last. He had heard that there was wifi at the oasis. He took a snack in his own backpack to quiet his stomach.

It took them two hours to arrive as sand dunes had moved on the trail during the storm. Kyle had talked most of the time, boring them to death with detailed accounts of his life back in Boston. He didn’t seem to notice that nobody cared about his love rejection stories or his tips to talk to women.

They parked outside the oasis among buses and vans. Kyle was following Youssef everywhere as if they were friends. Despite his unending flow of words, the guy managed to be funny.

Miss Tartiflate seemed unusually nervous, pulling on a strand of her orange hair and pushing back her glasses up her nose every two minutes. She was bossing everyone around to take the cameras and the lighting gear to the market where the shaman was apparently performing a rain dance. She didn’t want to miss it. When everybody was ready, she came right to Youssef. When she pushed back her glasses on her nose, he noticed her fingers were the colour of her hair. Her mouth was twitching nervously. She told him to find the wifi and restore THE BLOG or he could find another job.

“Phew! said Kyle. I don’t want to be near you when that happens.” He waved and left and joined the rest of the team.

Youssef smiled, happy to be alone at last, he took his backpack containing his laptop and his phone and followed everyone to the market in the luscious oasis.

At the center, near the lake, a crowd of tourists was gathered around a man wearing a colorful attire. Half his teeth and one eye were missing. The one that was left rolled furiously in his socket at the sound of a drum. He danced and jumped around like a monkey, and each of his movements were punctuated by the bells attached to the hem of his costume.

Youssef was glad he was not part of the shooting team, they looked miserable as they assembled the gears under a deluge of orders. As he walked toward the market, the scents of spicy food made his stomach growled. The vendors were looking at the crowd and exchanging comments and laughs. They were certainly waiting for the performance to end and the tourists to flood the place in search of trinkets and spices. Youssef spotted a food stall tucked away on the edge. It seemed too shabby to interest anyone, which was perfect for him.

The taciturn vendor, who looked caucasian, wore a yellow jacket and a bonnet oddly reminiscent of a llama’s scalp and ears. The dish he was preparing made Youssef drool.

“What’s that?” he asked.

“This is Lorgh Drülp

, said the vendor. Ancient recipe from the silk road. Very rare. Very tasty.”

He smiled when Youssef ordered a full plate with a side of tsampa. He told him to sit and wait on a stool beside an old and wobbly table.

January 28, 2022 at 9:30 pm #6264In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

From Tanganyika with Love

continued ~ part 5

With thanks to Mike Rushby.

Chunya 16th December 1936

Dearest Family,

Since last I wrote I have visited Chunya and met several of the diggers wives.

On the whole I have been greatly disappointed because there is nothing very colourful

about either township or women. I suppose I was really expecting something more like

the goldrush towns and women I have so often seen on the cinema screen.

Chunya consists of just the usual sun-dried brick Indian shops though there are

one or two double storied buildings. Most of the life in the place centres on the

Goldfields Hotel but we did not call there. From the store opposite I could hear sounds

of revelry though it was very early in the afternoon. I saw only one sight which was quite

new to me, some elegantly dressed African women, with high heels and lipsticked

mouths teetered by on their way to the silk store. “Native Tarts,” said George in answer

to my enquiry.Several women have called on me and when I say ‘called’ I mean called. I have

grown so used to going without stockings and wearing home made dresses that it was

quite a shock to me to entertain these ladies dressed to the nines in smart frocks, silk

stockings and high heeled shoes, handbags, makeup and whatnot. I feel like some

female Rip van Winkle. Most of the women have a smart line in conversation and their

talk and views on life would make your nice straight hair curl Mummy. They make me feel

very unsophisticated and dowdy but George says he has a weakness for such types

and I am to stay exactly as I am. I still do not use any makeup. George says ‘It’s all right

for them. They need it poor things, you don’t.” Which, though flattering, is hardly true.

I prefer the men visitors, though they also are quite unlike what I had expected

diggers to be. Those whom George brings home are all well educated and well

groomed and I enjoy listening to their discussion of the world situation, sport and books.

They are extremely polite to me and gentle with the children though I believe that after a

few drinks at the pub tempers often run high. There were great arguments on the night

following the abdication of Edward VIII. Not that the diggers were particularly attached to

him as a person, but these men are all great individualists and believe in freedom of

choice. George, rather to my surprise, strongly supported Edward. I did not.Many of the diggers have wireless sets and so we keep up to date with the

news. I seldom leave camp. I have my hands full with the three children during the day

and, even though Janey is a reliable ayah, I would not care to leave the children at night

in these grass roofed huts. Having experienced that fire on the farm, I know just how

unlikely it would be that the children would be rescued in time in case of fire. The other

women on the diggings think I’m crazy. They leave their children almost entirely to ayahs

and I must confess that the children I have seen look very well and happy. The thing is

that I simply would not enjoy parties at the hotel or club, miles away from the children

and I much prefer to stay at home with a book.I love hearing all about the parties from George who likes an occasional ‘boose

up’ with the boys and is terribly popular with everyone – not only the British but with the

Germans, Scandinavians and even the Afrikaans types. One Afrikaans woman said “Jou

man is ‘n man, al is hy ‘n Engelsman.” Another more sophisticated woman said, “George

is a handsome devil. Aren’t you scared to let him run around on his own?” – but I’m not. I

usually wait up for George with sandwiches and something hot to drink and that way I

get all the news red hot.There is very little gold coming in. The rains have just started and digging is

temporarily at a standstill. It is too wet for dry blowing and not yet enough water for

panning and sluicing. As this camp is some considerable distance from the claims, all I see of the process is the weighing of the daily taking of gold dust and tiny nuggets.

Unless our luck changes I do not think we will stay on here after John Molteno returns.

George does not care for the life and prefers a more constructive occupation.

Ann and young George still search optimistically for gold. We were all saddened

last week by the death of Fanny, our bull terrier. She went down to the shopping centre

with us and we were standing on the verandah of a store when a lorry passed with its

canvas cover flapping. This excited Fanny who rushed out into the street and the back

wheel of the lorry passed right over her, killing her instantly. Ann was very shocked so I

soothed her by telling her that Fanny had gone to Heaven. When I went to bed that

night I found Ann still awake and she asked anxiously, “Mummy, do you think God

remembered to give Fanny her bone tonight?”Much love to all,

Eleanor.Itewe, Chunya 23rd December 1936

Dearest Family,

Your Christmas parcel arrived this morning. Thank you very much for all the

clothing for all of us and for the lovely toys for the children. George means to go hunting

for a young buffalo this afternoon so that we will have some fresh beef for Christmas for

ourselves and our boys and enough for friends too.I had a fright this morning. Ann and Georgie were, as usual, searching for gold

whilst I sat sewing in the living room with Kate toddling around. She wandered through

the curtained doorway into the store and I heard her playing with the paraffin pump. At

first it did not bother me because I knew the tin was empty but after ten minutes or so I

became irritated by the noise and went to stop her. Imagine my horror when I drew the

curtain aside and saw my fat little toddler fiddling happily with the pump whilst, curled up

behind the tin and clearly visible to me lay the largest puffadder I have ever seen.

Luckily I acted instinctively and scooped Kate up from behind and darted back into the

living room without disturbing the snake. The houseboy and cook rushed in with sticks

and killed the snake and then turned the whole storeroom upside down to make sure

there were no more.I have met some more picturesque characters since I last wrote. One is a man

called Bishop whom George has known for many years having first met him in the

Congo. I believe he was originally a sailor but for many years he has wandered around

Central Africa trying his hand at trading, prospecting, a bit of elephant hunting and ivory

poaching. He is now keeping himself by doing ‘Sign Writing”. Bish is a gentle and

dignified personality. When we visited his camp he carefully dusted a seat for me and

called me ‘Marm’, quite ye olde world. The only thing is he did spit.Another spitter is the Frenchman in a neighbouring camp. He is in bed with bad

rheumatism and George has been going across twice a day to help him and cheer him

up. Once when George was out on the claim I went across to the Frenchman’s camp in

response to an SOS, but I think he was just lonely. He showed me snapshots of his

two daughters, lovely girls and extremely smart, and he chatted away telling me his life

history. He punctuated his remarks by spitting to right and left of the bed, everywhere in

fact, except actually at me.George took me and the children to visit a couple called Bert and Hilda Farham.

They have a small gold reef which is worked by a very ‘Heath Robinson’ type of

machinery designed and erected by Bert who is reputed to be a clever engineer though

eccentric. He is rather a handsome man who always looks very spruce and neat and

wears a Captain Kettle beard. Hilda is from Johannesburg and quite a character. She

has a most generous figure and literally masses of beetroot red hair, but she also has a

warm deep voice and a most generous disposition. The Farhams have built

themselves a more permanent camp than most. They have a brick cottage with proper

doors and windows and have made it attractive with furniture contrived from petrol

boxes. They have no children but Hilda lavishes a great deal of affection on a pet

monkey. Sometimes they do quite well out of their gold and then they have a terrific

celebration at the Club or Pub and Hilda has an orgy of shopping. At other times they

are completely broke but Hilda takes disasters as well as triumphs all in her stride. She

says, “My dear, when we’re broke we just live on tea and cigarettes.”I have met a young woman whom I would like as a friend. She has a dear little

baby, but unfortunately she has a very wet husband who is also a dreadful bore. I can’t

imagine George taking me to their camp very often. When they came to visit us George

just sat and smoked and said,”Oh really?” to any remark this man made until I felt quite

hysterical. George looks very young and fit and the children are lively and well too. I ,

however, am definitely showing signs of wear and tear though George says,

“Nonsense, to me you look the same as you always did.” This I may say, I do not

regard as a compliment to the young Eleanor.Anyway, even though our future looks somewhat unsettled, we are all together

and very happy.With love,

Eleanor.Itewe, Chunya 30th December 1936

Dearest Family,

We had a very cheery Christmas. The children loved the toys and are so proud

of their new clothes. They wore them when we went to Christmas lunch to the

Cresswell-Georges. The C-Gs have been doing pretty well lately and they have a

comfortable brick house and a large wireless set. The living room was gaily decorated

with bought garlands and streamers and balloons. We had an excellent lunch cooked by

our ex cook Abel who now works for the Cresswell-Georges. We had turkey with

trimmings and plum pudding followed by nuts and raisons and chocolates and sweets

galore. There was also a large variety of drinks including champagne!There were presents for all of us and, in addition, Georgie and Ann each got a

large tin of chocolates. Kate was much admired. She was a picture in her new party frock

with her bright hair and rosy cheeks. There were other guests beside ourselves and

they were already there having drinks when we arrived. Someone said “What a lovely

child!” “Yes” said George with pride, “She’s a Marie Stopes baby.” “Truby King!” said I

quickly and firmly, but too late to stop the roar of laughter.Our children played amicably with the C-G’s three, but young George was

unusually quiet and surprised me by bringing me his unopened tin of chocolates to keep

for him. Normally he is a glutton for sweets. I might have guessed he was sickening for

something. That night he vomited and had diarrhoea and has had an upset tummy and a

slight temperature ever since.Janey is also ill. She says she has malaria and has taken to her bed. I am dosing

her with quinine and hope she will soon be better as I badly need her help. Not only is

young George off his food and peevish but Kate has a cold and Ann sore eyes and

they all want love and attention. To complicate things it has been raining heavily and I

must entertain the children indoors.Eleanor.

Itewe, Chunya 19th January 1937

Dearest Family,

So sorry I have not written before but we have been in the wars and I have had neither

the time nor the heart to write. However the worst is now over. Young George and

Janey are both recovering from Typhoid Fever. The doctor had Janey moved to the

native hospital at Chunya but I nursed young George here in the camp.As I told you young George’s tummy trouble started on Christmas day. At first I

thought it was only a protracted bilious attack due to eating too much unaccustomed rich

food and treated him accordingly but when his temperature persisted I thought that the

trouble might be malaria and kept him in bed and increased the daily dose of quinine.

He ate less and less as the days passed and on New Years Day he seemed very