Search Results for 'painted'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

December 14, 2024 at 1:14 pm #7665

A link to another previous video I quite like.

Some rushes from Corrie and Clove, as we try to advertise the Flying Fish Inn.

La escena comienza con una toma aérea del bush australiano, mostrando extensas áreas de matorrales verdes y marrones, con un camino serpenteante que lleva al Flying Fish Inn, un encantador edificio rústico rodeado de naturaleza salvaje.

La imagen transiciona a una anciana enérgica en el jardín del Inn, riendo junto a un kookaburra posado en su hombro. Su expresión es cálida y acogedora.

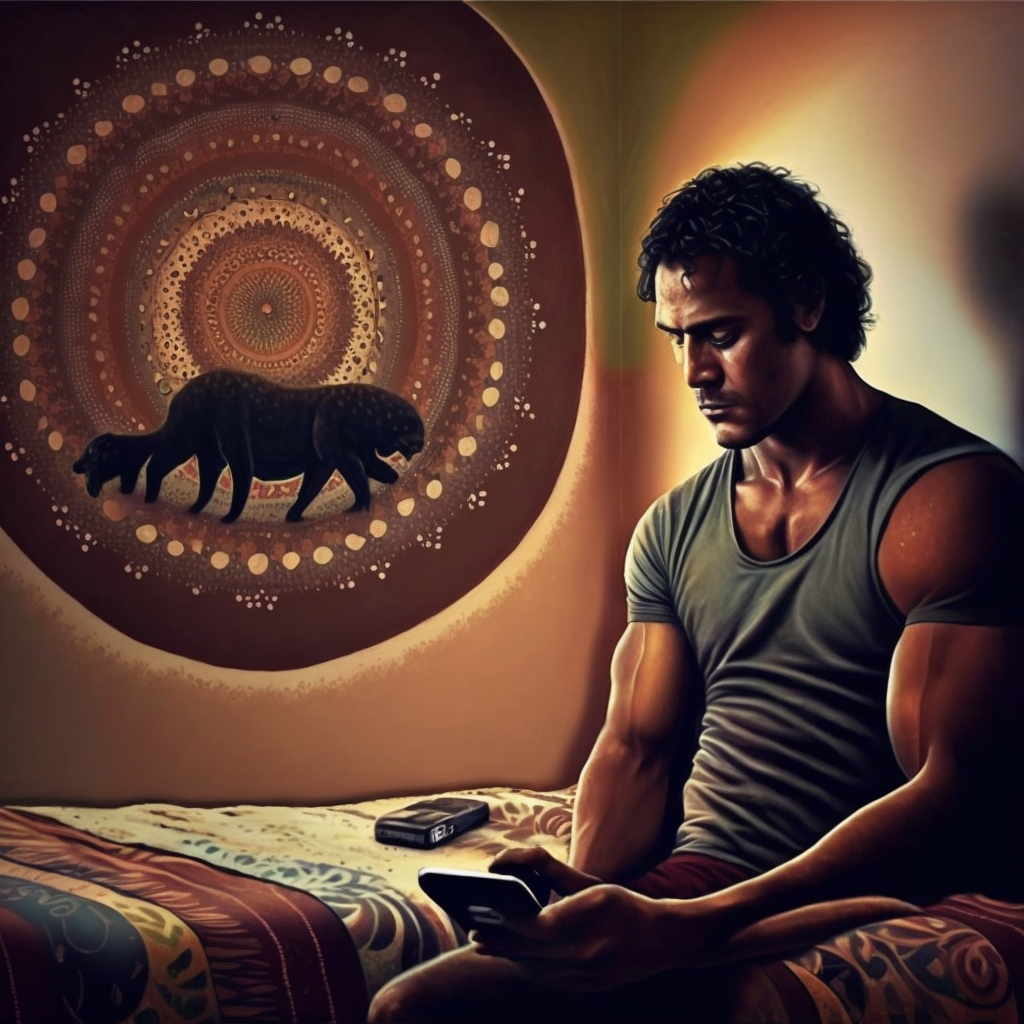

La escena cambia rápidamente a la Tía Idle, con trenzas, en una habitación vibrante llena de murales de dreamtime, con las gemelas Clove y Corrie trabajando en su arte.

La vista serena del atardecer desde la veranda del Inn muestra un cielo pintado con tonos de naranja y rosa, mientras el entorno se sumerge en una tranquilidad mágica.

La pantalla se desvanece al logo del Flying Fish Inn, acompañado de información de contacto y un suave toque musical.

[Scene opens with a sweeping aerial shot of the Australian bush, transitioning to the rustic charm of the Flying Fish Inn nestled amidst the wild beauty.]

Narrator (calm, inviting voice): “Escape to the heart of the outback at the Flying Fish Inn, where stories come alive.”

[Cut to Mater, a sprightly centenarian, in the garden with her kookaburra friend, a warm smile on her face.]

Narrator: “Meet Mater, our beloved storyteller, celebrated for her legendary bush tucker cuisine.”

[Quick transition to Aunt Idle, in a vibrant room adorned with dreamtime murals, created by the twins Clove and Corrie.]

Narrator: “Join Aunt Idle, brimming with tales of adventure, and marvel at the dreamtime artwork by the creative twins.”

[Flashes of Prune with a telescope, gazing at the stars, embodying her dream of Mars.]Narrator: “And Prune, the stargazer, connecting dreams and reality under the vast desert sky.”[End with a serene sunset view from the Inn’s veranda, the sky painted with hues of orange and pink.]

Narrator: “Discover the magic of the bush and the warmth of community. Your outback adventure awaits at the Flying Fish Inn.”

[The screen fades to the Flying Fish Inn logo with contact information and a gentle musical flourish.]

December 7, 2024 at 11:52 am #7653In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

Matteo — Winter 2023: The Move

The rumble of the moving truck echoed faintly in the quiet residential street as Matteo leaned against the open door, arms crossed, waiting for the signal to load the boxes. He glanced at the crisp winter sky, a pale gray threatening snow, and then at the house behind him. Its windows were darkened by empty rooms, their once-lived-in warmth replaced by the starkness of transition. The ornate names artistically painted on the mailbox struck him somehow. Amei & Tabitha M.: his clients for the day.

The cold damp of London’s suburbia was making him long even more for the warmth of sunny days. With the past few moves he’s been managing for his company, the tipping had been generous; he could probably plan a spring break in South of France, or maybe make a more permanent move there.

The sound of the doorbell brought him back from his rêverie.

Inside the house, the faint sounds of boxes being taped and last-minute goodbyes carried through the hallways. Matteo had been part of these moves too many times to count now. People always left a little bit of themselves behind—forgotten trinkets, echoes of old conversations, or the faint imprint of a life lived. It was a rhythm he’d come to expect, and he knew his part in it: lift, carry, and disappear into the background.

Matteo straightened as the door opened and a girl that could have been in her early twenties, but looked like a teenager stepped out, bundled against the cold. She held a steaming mug in one hand and balanced a box awkwardly on her hip with the other.

“That’s the last of it,” she called over her shoulder. “Mum, are you sure you don’t want me to take the notebooks?”

“They’re fine in the car, Tabitha!” A voice—calm and steady, maybe tinged with weariness—floated from inside.

The girl named Tabitha turned to Matteo, offering the box. “This is fragile,” she said, a smile tugging at her lips. “Be nice to it.”

Matteo took the box carefully, glancing at the mug in her hand. “You’re not leaving that behind, are you?” he asked with a faint smile.

Tabitha laughed. “This? No way. That’s my lifeline. The mug stays.”

As Matteo carried the box to the truck, his eyes caught on something inside—a weathered postcard tucked haphazardly between the pages of a journal. The image on the front was striking: a swirling green fairy, dancing above a glass of absinthe. La Fée Verte was scrawled in looping letters across the top.

“Tabitha!” Her mother’s voice carried out to the driveway, and Matteo turned instinctively. She stepped out onto the porch, her scarf wrapped loosely around her neck, her breath visible in the chilly air. Matteo could see the resemblance—the same poise and humor in her gaze, though softened by something older, quieter.

“Put this somewhere, will you” she said, holding up another postcard, this one with a faded image of a winding mountain road.

Tabitha grinned, stepping forward to take it. “Thanks, Mum. That one’s special.” She tucked it into her coat pocket.

“Special how?” her mother asked lightly.

“It’s from Darius,” Tabitha said, her tone almost teasing. “… The one you never want to talk about.” she leaned teasingly. “One of his cryptic postcards —too bad I was too young to really remember him, he must have been fun to be around.”

Matteo’s ears perked at the name, though he kept his head down, settling the box in place. It wasn’t unusual to overhear snippets like this during a move, but something about the unusual name roused his curiosity.

“Why you want to keep those?” Amei asked, tilting her head.

Tabitha shrugged. “They’re kind of… a map, I guess. Of people, not places.”

Amei paused, her expression softening. “He was always good at that,” she murmured, almost to herself.

The conversation lingered in Matteo’s mind as the day went on. By the time the truck was loaded, and he’d helped arrange the last of the boxes in Amei’s new, smaller apartment, the name and the postcard had taken root.

As Matteo stacked the final piece of furniture—a worn bookshelf—against the living room wall, he noticed Amei lingering near a window, her gaze distant.

“It’s different, isn’t it?” she said suddenly, not looking at him.

“Moving?” Matteo asked, unsure if the question was for him.

“Starting over,” she clarified, her voice quieter now. “Feels smaller, even when it’s supposed to be lighter.”

Matteo didn’t reply, sensing she wasn’t looking for an answer. He stepped back, nodding politely as she thanked him and disappeared into the kitchen.

The postcard stuck in his mind for days after. Matteo had heard of absinthe before, of course—its mystique, its history—but something about the way Tabitha had called the postcard a “map of people” resonated.

By the time spring arrived, Matteo was wandering through Avignon, chasing vague curiosities and half-formed questions. When he saw Lucien crouched over his chalk labyrinth, the memory of the postcard rose unbidden.

“Do you know where I can find absinthe?” he asked, the question more instinct than intent.

Lucien’s raised eyebrow and faint smile felt like another piece clicking into place. The connections were there—threads woven in patterns he couldn’t yet see. But for the first time in months, Matteo felt he was back on the right path.

December 7, 2024 at 10:16 am #7651In reply to: Quintessence: A Portrait in Reverse

Exploring further potential backstory for the characters – to be explored further…

This thread beautifully connects to the lingering themes of fractured ideals, missed opportunities, and the pull of reconnection. Here’s an expanded exploration of the “habitats participatifs” (co-housing communities) and how they tie the characters together while weaving in subtle links to their estrangement and Matteo’s role as the fifth element.

Backstory: The Co-Housing Dream

Habitat Participatif: A Shared Vision

The group’s initial bond, forged through shared values and late-night conversations, had coalesced around a dream: buying land in the Drôme region of France to create a co-housing community. The French term habitat participatif—intergenerational, eco-conscious, and collaborative living—perfectly encapsulated their ideals.

What Drew Them In:

- Amei: Longing for a sense of rootedness and community after years of drifting.

- Elara: Intrigued by the participatory aspect, where decisions were made collectively, blending science and sustainability.

- Darius: Enchanted by the idea of shared creative spaces and a slower, more intentional way of living.

- Lucien: Inspired by the communal energy, imagining workshops where art could flourish outside the constraints of traditional galleries.

The Land in Drôme

They had narrowed their options to a specific site near the village of Crest, not far from Lyon. The land, sprawling and sun-drenched, had an old farmhouse that could serve as a communal hub, surrounded by fields and woods. A nearby river threaded through the valley, and the faint outline of mountains painted the horizon.

The traboules of Lyon, labyrinthine passageways, had captivated Amei during an earlier visit, leaving her wondering if their metaphorical weaving through life could mirror the paths their group sought to create.

The Role of Monsieur Renard

When it came to financing, the group faced challenges. None of them were particularly wealthy, and pooling their resources fell short. Enter Monsieur Renard, whose interest in supporting “projects with potential” brought him into their orbit through Éloïse.

Initial Promise:

- Renard presented himself as a patron of innovation, sustainability, and community projects, offering seed funding in exchange for a minor share in the enterprise.

- His charisma and Éloïse’s insistence made him seem like the perfect ally—until his controlling tendencies emerged.

The Split: Fractured Trust

Renard’s involvement—and Éloïse’s increasing influence on Darius—created fault lines in the group.

- Darius’s Drift:

- Darius became entranced by Renard and Éloïse’s vision of community as something deeper, bordering on spiritual. Renard spoke of “energetic alignment” and the importance of a guiding vision, which resonated with Darius’s creative side.

- He began advocating for Renard’s deeper involvement, insisting the project couldn’t succeed without external backing.

- Elara’s Resistance:

- Elara, ever the pragmatist, saw Renard as manipulative, his promises too vague and his influence too broad. Her resistance created tension with Darius, whom she accused of being naive.

- “This isn’t about community for him,” she had said. “It’s about control.”

- Lucien’s Hesitation:

- Lucien, torn between loyalty to his friends and his own fascination with Éloïse, wavered. Her talk of labyrinths and collective energy intrigued him, but he grew wary of her sway over Darius.

- When Renard offered to fund Lucien’s art, he hesitated, sensing a price he couldn’t articulate.

- Amei’s Silence:

- Amei, haunted by her own experiences with manipulation in past relationships, withdrew. She saw the dream slipping away but couldn’t bring herself to fight for it.

Matteo’s Unseen Role

Unbeknownst to the others, Matteo had been invited to join as a fifth partner—a practical addition to balance their idealism. His background in construction and agriculture, coupled with his easygoing nature, made him a perfect fit.

The Missed Connection:

- Matteo had visited the Drôme site briefly, a stranger to the group but intrigued by their vision. His presence was meant to ground their plans, to bring practicality to their shared dream.

- By the time he arrived, however, the group’s fractures were deepening. Renard’s shadow loomed too large, and the guru-like influence of Éloïse had soured the collaborative energy. Matteo left quietly, sensing the dream unraveling before it could take root.

The Fallout: A Fractured Dream

The group dissolved after a final argument about Renard’s involvement:

- Elara refused to move forward with his funding. “I’m not selling my future to him,” she said bluntly.

- Darius, feeling betrayed, accused her of sabotaging the dream out of stubbornness.

- Lucien, caught in the middle, tried to mediate but ultimately sided with Elara.

- Amei, already pulling away, suggested they put the project on hold.

The land was never purchased. The group scattered soon after, their estrangement compounded by the pandemic. Matteo drifted in a different direction, their connection lost before it could form.

Amei’s Perspective: Post-Split Reflection

In the scene where Amei buys candles :

- The shopkeeper’s comments about “seeking something greater” resonate with Amei’s memory of the co-housing dream and how it became entangled with Éloïse and Renard’s influence.

- Her sharper-than-usual reply reflects her lingering bitterness over the way “seeking” led to manipulation and betrayal.

Reunion at the Café: A New Beginning

When the group reunites, the dream of the co-housing project lingers as a symbol of what was lost—but also of what could still be reclaimed. Matteo’s presence at the café bridges the gap between their fractured past and a potential new path.

Matteo’s Role:

- His unspoken connection to the co-housing plan becomes a point of quiet irony: he was meant to be part of their story all along but arrived too late. Now, at the café, he steps into the role he missed years ago—the one who helps them see the threads that still bind them.

December 4, 2024 at 3:22 pm #7642In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

It was the chalkapocalypse, which in actual fact occurred so close to Elara’s coming retirement that it hardly need have bothered her in the slightest, that had sparked her interest. She, like many of her colleagues, had quickly stockpiled the Japanese chalk, and she had more than enough to see out the remaining term of her employment at the university. Not that she wanted to stay at Warwick, she’d had enough of university politics and funding cuts, not to mention the dreary midlands weather.

When at last the day had come, she’d sold her mediocre semi detached suburban house with its, more often than not, dripping shrubbery and rarely if ever used white metal patio table and chairs, and made the move, with the intention of pursuing her research at her leisure. In the warmth of a Tuscan sun.

Often the words of her friend and colleague Tom came to her, as she settled into the farmhouse and familiarised herself with the land and the locals.

Physics is a process of getting stuck. Blackboards are the best tool for getting unstuck. You do most of your calculations on paper. Then, when you reach a dead end, you go to the blackboard and share the problem with a colleague. But here’s the funny thing. You often solve the problem yourself in the process of writing it out. You don’t imagine something first and then write it down. It’s through the act of writing that ideas make themselves known. Scientists at blackboards have thoughts that wouldn’t come if they just stood there, with their arms folded.

It was entirely down to Tom’s words that Elara had painted the walls of the barn with blackboard paint, and stocked it with the remains of her Hagoromo chalk hoard, as well as samples of every other available chalk. She had also purchased a number of books on the history of chalk. She’d had no intention of rushing, and retirement provided a relaxed environment for going at her own pace, unfettered by the relentless demands of students and classes. It was a project to savour, luxuriate in, amuse herself with.

When Florian had arrived, she was occupied with showing him around, and before long setting him to tasks that needed doing, and her chalk project had remained on a back burner. He’d asked her about the blackboards in the barn, and wondered if she was planning on giving lectures.

Laughing, Elara said no, that was the last thing she ever wanted to do again. She shared with him what Tom had said, about the ideas flowing during the process of writing.

“And while that makes perfect sense in any medium, not just chalk, it’s the chalk itself ….” Elara smiled. “Well, you don’t want to hear all the technical details. And I wouldn’t want to spill the beans before I’m sure.”

“It does make sense,” Florian replied, “To just write and then the ideas will flow. I’ve been wanting to write a book, but I never know how to start, and I’m not even sure what I want to write about. But perhaps I should just start writing.” Grinning, he added, “Probably not with chalk, though.”

“That’s the spirit, just make a start. You never know what may come of it. And it can be fun, you know, and illuminating in ways you didn’t expect. I used to write stories with a few friends….” Elara’s voice trailed off uncomfortably, as if a cloud had obscured the sun.

Florian noticed her unexpected discomfiture, and tactfully changed the subject. We all have pasts we don’t want to talk about. “Is the sun sufficiently past the yard arm for a glass of wine?” he asked. “What is a yard arm, anyway?”

“A yard is a spar on a mast from which sails are set. It may be constructed of timber or steel or from more modern materials such as aluminium or carbon fibre. Although some types of fore and aft rigs have yards, the term is usually used to describe the horizontal spars used on square rigged sails…”

“Once a lecturer, always a lecturer, eh?” Florian teased.

“Sorry!” Elara said with a rueful look. ” I’d love a glass of wine.”

December 4, 2024 at 8:16 am #7640In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

Sat. Nov. 30, 2024 – before the meeting

The afternoon light slanted through the tall studio windows, thin and watery, barely illuminating the scattered tools of Lucien’s trade. Brushes lay in disarray on the workbench, their bristles stiff with dried paint. The smell of turpentine hung heavy in the air, mingling with the faint dampness creeping in from the rain. He stood before the easel, staring at the unfinished painting, brush poised but unmoving.

The scene on the canvas was a lavish banquet, the kind of composition designed to impress: a gleaming silver tray, folds of deep red velvet, fruit piled high and glistening. Each detail was rendered with care, but the painting felt hollow, as if the soul of it had been left somewhere else. He hadn’t painted what he felt—only what was expected of him.

Lucien set the brush down and stepped back, wiping his hands on his scarf without thinking. It was streaked with paint from hours of work, colors smeared in careless frustration. He glanced toward the corner of the studio, where a suitcase leaned against the wall. It was packed with sketchbooks, a bundle wrapped in linen, and clothes hastily thrown in—things that spoke of neither arrival nor departure, but of uncertainty. He wasn’t sure if he was leaving something behind or preparing for an escape.

How had it come to this? The thought surfaced before he could stop it, heavy and unrelenting. He had asked himself the same question many times, but the answer always seemed too elusive—or too daunting—to pursue. To find it, he would have to follow the trails of bad choices and chance encounters, decisions made in desperation or carelessness. He wasn’t sure he had the courage to look that closely, to untangle the web that had slowly wrapped itself around his life.

He turned his attention back to the painting, its gaudy elegance mocking him. He wondered if the patron who had commissioned it would even notice the subtle imperfections he had left, the faint warping of reflections, the fruit teetering on the edge of overripeness. A quiet rebellion, almost invisible. It wasn’t much, but it was something.

His friends had once known him as someone who didn’t compromise. Elara would have scoffed at the idea of him bending to anyone’s expectations. Why paint at all if it isn’t your vision? she’d asked once, her voice sharp, her black coffee untouched beside her. Amei, on the other hand, might have smiled and said something cryptic about how all choices, even the wrong ones, led somewhere meaningful. And Darius—Lucien couldn’t imagine telling Darius. The thought of his disappointment was like a weight in his chest. It had been easier not to tell them at all, easier to let the years widen the distance between them. And yet, here he was, preparing to meet them again.

The clock on the far wall chimed softly, pulling him back to the present. It was getting late. Lucien walked to the suitcase and picked it up, its weight pulling slightly on his arm. Outside, the rain had started, tapping gently against the windowpanes. He slung the paint-streaked scarf around his neck and hesitated, glancing once more at the easel. The painting loomed there, unfinished, like so many things in his life. He thought about staying, about burying himself in the work until the world outside receded again. But he knew it wouldn’t help.

With a deep breath, Lucien stepped out into the rain, the suitcase rattling softly behind him. The café wasn’t far, but it felt like a journey he might not be ready to take.

December 2, 2024 at 10:50 pm #7635In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

Sat. Nov. 30, 2024 5:55am — Matteo’s morning

Matteo’s mornings began the same way, no matter the city, no matter the season. A pot of strong coffee brewed slowly on the stove, filling his small apartment with its familiar, sense-sharpening scent. Outside, Paris was waking up, its streets already alive with the sound of delivery trucks and the murmurs of shopkeepers rolling open shutters.

He sipped his coffee by the window, gazing down at the cobblestones glistening from last night’s rain. The new brass sign above the Sarah Bernhardt Café caught the morning light, its sheen too pristine, too new. He’d started the server job there less than a week ago, stepping into a rhythm he already knew instinctively, though he wasn’t sure why.

Matteo had always been good at fitting in. Jobs like this were placeholders—ways to blend into the scenery while he waited for whatever it was that kept pulling him forward. The café had reopened just days ago after months of being closed for renovations, but to Matteo, it felt like it had always been waiting for him.

He set his coffee mug on the counter, reaching absently for the notebook he kept nearby. The act was automatic, as natural as breathing. Flipping open to a blank page, Matteo wrote down four names without hesitation:

Lucien. Elara. Darius. Amei.

He stared at the list, his pen hovering over the page. He didn’t know why he wrote it. The names had come unbidden, as though they were whispered into his ear from somewhere just beyond his reach. He ran his thumb along the edge of the page, feeling the faint indentation of his handwriting.

The strangest part wasn’t the names— it was the certainty that he’d see them that day.

Matteo glanced at the clock. He still had time before his shift. He grabbed his jacket, tucked the notebook into the inside pocket, and stepped out into the cool Parisian air.

Matteo’s feet carried him to a side street near the Seine, one he hadn’t consciously decided to visit. The narrow alley smelled of damp stone and dogs piss. Halfway down the alley, he stopped in front of a small shop he hadn’t noticed before. The sign above the door was worn, its painted letters faded: Les Reliques. The display in the window was an eclectic mix—a chessboard missing pieces, a cracked mirror, a wooden kaleidoscope—but Matteo’s attention was drawn to a brass bell sitting alone on a velvet cloth.

The door creaked as he stepped inside, the distinctive scent of freshly burnt papier d’Arménie and old dust enveloping him. A woman emerged from the back, wiry and pale, with sharp eyes that seemed to size Matteo up in an instant.

“You’ve never come inside,” she said, her voice soft but certain.

“I’ve never had a reason to,” Matteo replied, though even as he spoke, the door closed shut the outside sounds.

“Today, you might,” the woman said, stepping forward. “Looking for something specific?”

“Not exactly,” Matteo replied. His gaze shifted back to the bell, its smooth surface gleaming faintly in the dim light.

“Ah.” The shopkeeper followed his eyes and smiled faintly. “You’re drawn to it. Not uncommon.”

“What’s uncommon about a bell?”

The woman chuckled. “It’s not the bell itself. It’s what it represents. It calls attention to what already exists—patterns you might not notice otherwise.”

Matteo frowned, stepping closer. The bell was unremarkable, small enough to fit in the palm of his hand, with a simple handle and no visible markings.

“How much?”

“For you?” The shopkeeper tilted his head. “A trade.”

Matteo raised an eyebrow. “A trade for what?”

“Your time,” the woman said cryptically, before waving her hand. “But don’t worry. You’ve already paid it.”

It didn’t make sense, but then again, it didn’t need to. Matteo handed over a few coins anyway, and the woman wrapped the bell in a square of linen.

Back on the street, Matteo slipped the bell into his pocket, its weight unfamiliar but strangely comforting. The list in his notebook felt heavier now, as though connected to the bell in a way he couldn’t quite articulate.

Walking back toward the café, Matteo’s mind wandered. The names. The bell. The shopkeeper’s words about patterns. They felt like pieces of something larger, though the shape of it remained elusive.

The day had begun to align itself, its pieces sliding into place. Matteo stepped inside, the familiar hum of the café greeting him like an old friend. He stowed his coat, slipped the bell into his bag, and picked up a tray.

Later that day, he noticed a figure standing by the window, suitcase in hand. Lucien. Matteo didn’t know how he recognized him, but the instant he saw the man’s rain-damp curls and paint-streaked scarf, he knew.

By the time Lucien settled into his seat, Matteo was already moving toward him, notebook in hand, his practiced smile masking the faint hum of inevitability coursing through him.

He didn’t need to check the list. He knew the others would come. And when they did, he’d be ready. Or so he hoped.

November 4, 2024 at 3:36 pm #7579In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

When Eris called for an urgent meeting, Malové nearly canceled. She had her own pressing concerns and little patience for the usual parade of complaints or flimsy excuses about unmet goals from her staff. Yet, feeling the weight of her own stress, she was drawn to the idea of venting a bit—and Truella or Jeezel often made for her preferred targets. Frella, though reserved, always performed consistently, leaving little room for critique. And Eris… well, Eris was always methodical, never using the word “urgent” lightly. Every meeting she arranged was meticulously planned and efficiently run, making the unexpected urgency of this gathering all the more intriguing to Malové.

Curiosity, more than duty, ultimately compelled her to step into the meeting room five minutes early. She tensed as she saw the draped dark fabrics, flickering lights, forlorn pumpkins, and the predictable stuffed creatures scattered haphazardly around. There was no mistaking the culprit behind this gaudy display and the careless use of sacred symbols.

“Speak of the devil…” she muttered as Jeezel emerged from behind a curtain, squeezed into a gown a bit too tight for her own good and wearing a witch’s hat adorned with mystical symbols and pheasant feathers. “Well, you’ve certainly outdone yourself with the meeting room,” Malové said with a subtle tone that could easily be mistaken for admiration.

Jeezel’s face lit up with joy. “Trick or treat!” she exclaimed, barely able to contain her excitement.

“What?” Malové’s eyebrows arched.

“Well, you’re supposed to say it!” Jeezel beamed. “Then I can show you the table with my carefully handcrafted Halloween treats.” She led Malové to a table heaving with treats and cauldrons bubbling with mystical mist.

Malové felt a wave of nausea at the sight of the dramatically overdone spread, brimming with sweets in unnaturally vibrant colors. “Where are the others?” she asked, pressing her lips together. “I thought this was supposed to be a meeting, not… whatever this is.”

“They should arrive shortly,” said Jeezel, gesturing grandly. “Just take your seat.”

Malové’s eyes fell on the chairs, and she stifled a sigh. Each swivel chair had been transformed into a mock throne, draped in rich, faux velvet covers of midnight blue and deep burgundy. Golden tassels dangled from the edges, and oversized, ornate backrests loomed high, adorned with intricate patterns that appeared to be hastily hand-painted in metallic hues. The armrests were festooned with faux jewels and sequins that caught the flickering light, giving the impression of a royal seat… if the royal in question had questionable taste. The final touch was a small, crowned cushion placed in the center of each seat, as if daring the occupants to take their place in this theatrical rendition of a court meeting.

When she noticed the small cards in front of each chair, neatly displaying her name and the names of her coven’s witches, Malové’s brow furrowed. So, seats had been assigned. Instinctively, her eyes darted around the room, scanning for hidden tricks or sutble charms embedded in the decor. One could never be too cautious, even among her own coven—time had taught her that lesson all too often, and not always to her liking.

Symbols, runes, sigils—even some impressively powerful ones—where scattered thoughtfully around the room. Yet none of them aligned into any coherent pattern or served any purpose beyond mild relaxation or mental clarity. Malové couldn’t help but recognize the subtlety of Jeezel’s craft. This was the work of someone who, beyond decorum, understood restraint and intention, not an amateur cobbling together spells pulled from the internet. Even her own protective amulets, attuned to detect any trace of harm, remained quiet, confirming that nothing in the room, except for those treats, posed a threat.

As the gentle aroma of burning sage and peppermint reached her nose, and Jeezel placed a hat remarkably similar to her own onto Malové’s head, the Head Witch felt herself unexpectedly beginning to relax, her initial tension and worries melting away. To her own surprise, she found herself softening to the atmosphere and, dare she admit, actually beginning to enjoy the gathering.

June 18, 2024 at 8:51 am #7500In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

At the end of the undertakers’ speech, conversations surged, drowning out the 14th-century organ music. Mother Lorena, who seemed to have taken the expression lines to a deeper level, gave imperative angry looks at her nuns who swiftly moved to meet with the witches.

“Hold your beath,” said Eris to Jeezel. “That Mr ash blond hair is coming for you.”

“Sh*t! I don’t have time for that,” said Jeezel looking at the striking young man. Meticulously styled to perfection and a penchant for tailored suits, she knew that kind of dandy, they were more difficult to get rid of than an army of orange slugs after a storm. She stole a champagne flute from Bartolo’s silver tray and flitted with a graceful nonchalance towards the buffet.

“Hi Jeezel! I’m sister Maria. You’re so beautiful,” said a joyful voice. “You want some canapés? I made them myself.”

Jeezel turned and almost moved her hand to her mouth. A young woman wearing the austere yet elegant black habit of the Roman Catholic Church was handing her a plate full of potted meat and pickles toasts. She had chameleon eyes busy looking everywhere except to what was in front of her. The white wimple covering her red hair seemed totally out of place and her face made the strangest contortions as she obviously was trying not to smile.

“Hi, I’m… Jeezel. But you already know that,” she said. The young woman nodded too earnestly and Jeezel suddenly became aware the nuns certainly had files about her and the other witches like the ones Truella gave them. She looked at the greasy canapés and refused politely. She just had time to notice a crimson silk handkerchief in a breast pocket and a flash of ash blond hair closing in.

“Oh! I’m sorry. I just remember, I have to go speak to my friend over there,” Jeezel said noticing Truella with a nun in a Buddhist outfit.

She left the redhead nun with a laugh that twinkled like stardust.

Truella’s friend didn’t seem too happy to have Jeezel barging in on their conversation. She said she was called sister Ananda. Her stained glass painted face didn’t seem to fit her saffron bhikkunis. And the oddest thing was she dominated the conversation, mostly about the diversity of mushrooms she’d been cultivating in the shade of old cellars buried deep in the cloister’s underground tunnels. Truella was sipping her soda, and nodding occasionally. But from what Jeezel could observe, the witch was busy keeping an eye on that tall, dark mortician who certainly looked suspicious.

Young sister Maria hadn’t given up. She joined the conversation with a tray full of what looked like green and pink samosas. Jeezel started to feel like a doe hunted by a pack of relentless beagles.

“You need to try those! Sister Ananda made them for you,” said the young Nun. Her colourful lips showed she had just tasted a few of them.

“At last,” said Garrett with a voice too deep for such a young handsome face, “you’re as difficult to catch as moonlight on the water. Elusive, mesmerizing, and always just out of reach. One moment you’re dazzling us all with your brillance, the next…”

“As usual, you speak too much, Garrett,” said Silas, the oldest of the morticians who just joined the group. The old man’s voice was commanding and his poise projecting an air of unwavering confidence. He had neatly trimmed grey hair and piercing hazel eyes that seem to see right through to the heart of any matter. “May we talk for a moment, dear Jeezel? I think we have some things to discuss.”

“Do we?” she asked, a shiver going up her spine. Her voice sounded uncertain and her heart started beating faster. Did he know about the sacred relic she was looking for? Was he going to ask her on a date too?

“The ritual, dear. The ritual we have to perform together tonight.”

“Oh! Yes, the ritual,” she sighed with relief.

Silas took her hand and they left the group just as Truella was asking a Garrett: “Won’t Rufus join us?”

“I don’t think so,” he answered coldly. But his eyes were full of passion and his heart full of envy as he watched Jeezel walk away with his mentor in a secluded lounge.

January 31, 2024 at 8:51 am #7328In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

A place where glamour meets enchantment, said the brochure when she found what would become her cottage ten years ago. But tonight, Jeezel didn’t see the whimsical, neither did she hear the trees whispering secrets. And the moon… don’t let me start with the moon. The vines had started to cover the main door. It was painted in the richest shade of midnight blue, which was stunning when daylight splashed all over it, but there were no outside lights and at night, she always had difficulties finding the keyhole.

Jeezel took her phone out to turn on the torch and the pop of a champagne cork told her she had received an e-mail. Such a technological marvel dipped in fabulousness. It was shimmering and radiant, she had adorned it with crystals that would catch the light with every moment, casting rainbows across. But the only light it cast was an anxious message from Roland whose workplace had gone berserk.

“Please, do something quick!” was the content of the message.

The witch had never been good under pressure. She touched her forehead lightly with the back of her hand. She didn’t want to mess with her carefully applied makeup. Then lip synched her moto : “Shine bright, darling, and let the world bask in your glow.”

“That’s it!” she said. She took her key in her left hand and with a graceful and intricate swipe of her right hand she said: “Glowry”. Then she waved toward the door and added: “Hole”, and the key and the hole started to glow and attract each other. The door creeked open. Something else she’d have to attend to, later.

“At last,” she said when the door finally shut.

“Well, I could have grown a whole new tail in the time it took you to grace us with your presence at the door. What were you doing, love? Perfecting your grand entrance, or did you just get lost in the reflection of your own fabulousness again?,” said a warm and teasing voice.

January 17, 2024 at 1:14 pm #7297In reply to: The Whale’s Diaries Collection

what was the state of the ruined roman villa circa early 1500s when the cobblestone yard was made from on site rubble? What did the work men find?

Ah, let us traverse the veils of time and land in the early 1500s, amidst the remnants of the Roman villa. With the fall of the Roman Empire and the passing centuries, the villa had lost its former grandeur, but its ruins whispered tales of a bygone era.

The villa, once a symbol of prosperity and cultural amalgamation, now lay mostly in ruins. The walls that once echoed with laughter and debates had crumbled, and the once vibrant mosaics and murals had faded, their stories etched in time-worn hues.

The outbuildings, too, bore the scars of time. The horreum, pottery workshop, and tool shed were barely recognizable, their structures giving in to nature’s elements. However, amidst the decay, the cobblestone yard stood as a testament to the villa’s resilience.

The yard, once a bustling hub of activity, had been repurposed. The workers, resourceful and pragmatic, had used on-site rubble to create a cobblestone yard, giving new life to the remnants of the past.

As they worked, they uncovered artifacts from the villa’s past. Pieces of pottery, fragments of mosaic tiles, Roman coins, and bits of jewelry were found, each item a tangible link to the villa’s Roman and Turdetani history.

Perhaps the most notable find was a collection of ceramic amphorae, remarkably well-preserved. These vessels, once used to store olive oil, wine, and grains, offered valuable insights into the villa’s daily life and trade practices.

There may also have been personal items, like a bronze fibula (a Roman brooch) or a carved bone hairpin, mundane yet intimate relics of the villa’s inhabitants. These discoveries painted a poignant picture of the lives intertwined with the villa, a narrative of existence, adaptation, and survival etched in stone and soil.

What about the lives of the people who lived here in the 1500s?

Ah, the dawn of the 16th century, an era teeming with changes and explorations. Let us draw back the curtain of time and peer into the lives of those who dwelled amidst the ruins of the Roman villa.

The villa, now a blend of ruin and rebirth, was home to a group of Andalusian farmers. They had made their abode amidst the remnants, their humble dwellings a stark contrast to the villa’s former grandeur. Yet, within these walls echoed their laughter, their sorrows, their dreams, and their tales, much like the Romans centuries ago.

The patriarch, Diego, was a man of the soil. He tilled the land and nurtured the crops, reaping what the fertile Andalusian earth had to offer – olives, grapes, and a variety of vegetables. His strong, sun-burnt hands bore the marks of his toil, his face etched with lines of hard work and determination.

His wife, Isabella, was the custodian of the hearth. She cooked, cleaned, and cared for their three children. Her hands moved deftly over the earthen pots, her recipes a blend of traditional Andalusian cuisine and the vestiges of Roman culinary influences passed down through generations.

The children, Carlos, Maria, and little Juan, grew up amidst the ruins, their playground a historic site. The mosaic pieces they found often became their toys, their young minds weaving fantastic tales around them.

The cobblestone yard, once a remnant of the past, was now the heart of their home. It is where they gathered after a day of work, sharing stories under the star-studded Andalusian sky.

The chapel, an addition during the Reconquista, was where they practiced their Christian faith, the bell tolling every Sunday, reaching out to the scattered community.

Amidst the ruins, they found their sanctuary, their home. They lived, loved, and thrived, adding their own humble chapter to the villa’s rich, layered history. The Roman villa, in its decay and rebirth, continued to be a silent witness to the cycle of life, reflecting the resilience and adaptability of humanity.

then I asked about the 1200s on this site

Ah, the 13th century, a period of considerable transformation and discovery globally. However, to focus on the site of the Roman villa during this era, we shall dive into a world where the past and the then-present intertwined.

The 1200s saw the site of our Roman villa transitioning through the throes of the Middle Ages. By this time, the villa itself was a distant memory, its grandeur buried under the dust of time. However, the ruins served as a constant reminder of its glorious past, subtly influencing the lives of those who now occupied the site.

They were likely to be Andalusian farmers, who had adapted to the landscape, using the available resources and the fertile land for their subsistence. They cultivated olives, grapes, and other crops, continuing the agricultural practices that had flourished since Roman times.

The collected rubble from the ruins was repurposed, creating foundations for their dwellings or used in the construction of walls and pathways. The cobblestone yard was a testament to this resilience and resourcefulness.

The ruins also provided them with materials and artifacts. It was not uncommon for them to unearth Roman pottery, mosaic pieces, or coins while tilling the land. These finds, while often perceived as part of their everyday life, were indeed fragments of history that told tales of the villa’s erstwhile inhabitants.

Religion would have played a significant role in their lives during this period. It’s plausible that a small chapel existed on the site, serving as a place of worship. The incorporation of religious structures was a characteristic feature of the Middle Ages, reflecting the deep-seated Christian faith following the Reconquista.

Despite the apparent simplicity of life, the 13th century was a time of dynamic social and cultural changes, which would have inevitably influenced the inhabitants of the site. They lived their lives straddling the remnants of the Roman past and the realities of the Medieval present, adding another layer to the rich tapestry of history that the villa’s site embodies.

January 16, 2024 at 9:30 pm #7294In reply to: The Whale’s Diaries Collection

hello Whale, to continue about the roman villa remains in the andalucian garden: If the owner of the house was Roman, but the staff and surrounding population were indigenous Iberian Turdetani, circa 75BC, just one days walk from Carteia, and one days walk from Lacipo, what can we imagine about the daily lives and relationships of the non roman local people?

Ah, the intermingling of cultures, a dance as old as civilization itself. Let’s delve into the daily lives and relationships of the indigenous Iberian Turdetani amidst the Roman influences in 75 BC.

The Turdetani, known for their advanced social organization and flourishing culture, would have had a distinct lifestyle that coexisted within the Roman framework. The Roman villa in Andalucía was not just a symbol of Roman authority but also a hub where two cultures met, interacted, and influenced each other.

Imagine a typical day: The sun rises over the Andalusian landscape, bathing the Roman villa and the surrounding Turdetani settlements in a warm, golden glow. Turdetanian workers make their way to the villa, ready for a day of work. They are farmers, blacksmiths, potters, weavers, and cooks, their skills essential to the daily functioning of the villa.

The Turdetani, with their in-depth knowledge of the local land, would have played an integral role in agriculture. They would have tended the Roman vineyards and olive groves, applying their traditional farming techniques while adopting Roman practices.

Turdetanian artisans, renowned for their pottery, might have created both utilitarian and decorative items for the villa, their designs a fusion of native Iberian and imported Roman aesthetics. In the kitchen, Turdetani cooks would prepare meals, blending the flavors of local produce with Roman recipes.

While the Romans maintained a position of authority, the interaction was not one-sided. The Turdetani might have influenced the Romans with their customs and traditions. Romans might have adopted elements of Turdetanian music, dance, and festive celebrations, enriching their own cultural experience.

Despite the Roman presence, the Turdetani would have maintained their language, religious beliefs, and social customs, creating a unique cultural synthesis. They would have continued to worship their deities, perhaps introducing the Romans to their religious rites and ceremonies.

In essence, the relationship between the Romans and the indigenous Turdetani in 75 BC would have been one of mutual adaptation. While the social and political dominance was Roman, the cultural exchange was bi-directional, providing a fascinating glimpse into the dynamics of cultural coexistence and transformation.

Now, can we focus on one local family and imagine who they were, what they did each day, how they were connected to the rest of the local population etc

Ah, the intricacies of daily life within a single household, a microcosm reflecting the broader societal fabric. Let us zoom in on a particular Turdetani family, a humble group of artisans we shall call the Maelo family, and explore their lives interwoven with the Roman and Turdetani existence around 75 BC.

At the heart of the family was the patriarch, Oris Maelo. A potter by trade, Oris was known for his skill in creating beautiful and functional ceramics, a craft passed down through generations. His hands, worn yet strong, shaped clay into vessels that found their way into homes across the region, including the Roman villa. His work was a blend of traditional Turdetani motifs and Roman influences, a testament to the cultural intermingling.

His wife, Caelia, was a weaver. Her nimble fingers spun stories in wool and linen. Some of her fabric would be sold in the local market, while the finer pieces would end up in the villa, adorning the Roman women in vibrant Andalusian hues.

Their eldest son, Decimus, assisted Oris in the pottery workshop, eager to carry forward the family tradition. Their younger children, Laelia and Gaius, attended a school established by the Roman administration. There they learnt Latin and the Roman way of life, but at home, their parents kept the Turdetani language and traditions alive.

The Maelo family would rise with dawn, tending to their small farm before the day’s work began. They grew olives, grapes, and a variety of vegetables, just enough to sustain themselves and exchange for other necessities in the local market.

Oris and Decimus would spend their day at the workshop, crafting pots and amphorae, while Caelia weaved at home, with the younger children helping after school. Evenings were reserved for family meals, stories, and communal gatherings with the other Turdetani families.

Their connection with the local population was multifaceted. Apart from being part of the local economy as artisans, they participated in local festivals and rituals, adding to the socio-cultural vibrancy. Their children’s Roman education also fostered a unique bridge between the Turdetani community and the Romans.

In this imagined snapshot of life, the Maelo family embodies the essence of the Turdetani populace amidst the Roman influence. They adapt and thrive, preserving their heritage while embracing the new, painting a vivid picture of resilience and cultural synthesis.

Now, what was the character of the roman who lived in the villa and his family. Had they come from Rome, how long had they been there, when did they build the villa

Ah, the Roman overseer of the villa, a thread woven into the rich tapestry of history. Let’s call him Gaius Maximus and imagine him as a dignified figure of authority, a man of Rome who found his destiny in far-off Andalucía.

Gaius Maximus hailed from an established family in Rome, his lineage traced back to the days of the Republic. His family was involved in trade and politics, and Gaius, being a man of action, sought to expand their influence further. Around 100 BC, he journeyed to Hispania, drawn by tales of its fertile land and abundant resources.

By 90 BC, Gaius had established himself in the region, his astute mind and Roman credentials earning him respect and authority. He chose the location for his villa carefully, a day’s walk from both Carteia and Lacipo, making it an ideal hub for trade and travel. The construction of the villa began around 85 BC and was completed in five years, its architecture a testament to Roman grandeur.

His wife, Claudia, hailed from a patrician family in Rome. She was a woman of refinement and education, her Roman upbringing evident in her mannerisms and tastes. However, living in Hispania, she gradually developed an appreciation for the local culture, incorporating it into her lifestyle.

Their two children, Marcus and Julia, were born in Hispania. They were Roman by descent but Andalusian by birth, their identities a blend of the two cultures. Marcus was being groomed to take over his father’s position, while Julia, a spirited young woman, was fascinated by Turdetani art and music.

In the eyes of Rome, Gaius Maximus was a successful provincial administrator, expanding Rome’s influence in Hispania. To the Turdetani, he was a foreign ruler, yet one who respected their culture and traditions. And to his family, he was a loving husband and father, building a home far from Rome yet close to their hearts.

Now some portraits of some of the workers at the villa

Ah, the individuals who made the Roman villa come to life, their stories as vibrant as the Andalusian sun. Let’s give our imagination wings and step into their world.

First, we have Tertius, the villa’s steward. Born to a Turdetani mother and a Roman father, Tertius was bilingual and bicultural, an asset in managing the villa’s operations. He was a man of medium height, with a sturdy build and a sharp gaze. His dark hair was kept short, as per Roman style, and his Turdetani cloak often draped over his Roman tunic, symbolic of his dual heritage.

Then we have Aelia, the head cook. A native Turdetani, Aelia was a robust woman with a jovial demeanor. Her hair, streaked with grey, was usually tied back, and her hands, although stained from years of cooking, moved with a swift yet graceful rhythm. Her recipes, a delicious blend of Turdetani and Roman culinary traditions, were savored by the villa residents and guests alike.

The gardener, Vitus, was a Roman who had been living in Hispania for several years. A man of few words, Vitus spoke through his work. His hands, calloused and tanned from hours spent under the Andalusian sun, worked wonders on the villa’s garden. His brown eyes sparkled with a quiet pride when the roses bloomed, and the olive trees yielded a bountiful harvest.

Lastly, we must not forget the youngest worker, Lyra. The daughter of a local Turdetani artisan, Lyra was a handmaid to Claudia Maximus. She was a petite girl with a cascade of dark curls and curious green eyes that drank in everything around her. Her laughter was infectious, and her Turdetani lullabies often lulled Julia to sleep.

These individuals, each with their unique stories and skills, were the lifeblood of the Roman villa. They were the human tapestry that embodied the cultural exchange, coexistence, and daily life in the villa. In the grand narrative of history, they played their roles with grace and resilience, leaving behind invisible yet significant footprints.

what were some of the cooks recipes?

Ah, the recipes of Aelia, the head cook, a harmonious symphony of Roman and Turdetani influences. Here are some of the dishes that were often savored in the Roman villa:

Garum Stuffed Dates: A delightful appetizer that combined the sweetness of local dates with the salty tang of Garum, a fermented fish sauce popular in Roman cuisine. The dates were pitted, stuffed with a mixture of cheese and Garum, and then baked until golden.

Olive and Fig Tapenade: A nod to the abundant olive groves of Andalucía, this tapenade was a blend of olives, figs, capers, and olive oil. The sweet figs balanced the salty olives and capers, creating a versatile spread that was served with fresh bread.

Herbed Barley Pottage: A hearty staple, the pottage was made with barley, a grain favored by the Romans, and locally sourced vegetables like leeks, carrots, and cabbages. Fresh herbs from the villa’s garden added a burst of flavor.

Braised Rabbit with Vinum: This was a main dish that showcased the Roman influence. Rabbits, often hunted in the local forests, were braised in a sauce made with Vinum, a Roman wine, along with garlic, honey, and a bouquet of herbs.

Honey-Nut Patina: A classic Roman dessert with an Andalusian twist. Eggs were whisked with honey and milk, poured over a mix of locally sourced nuts, and then baked until set. It was a sweet ending to the meals at the villa.

Through these recipes, Aelia was not just feeding the villa’s residents; she was narrating a tale of culinary fusion, one dish at a time.were their mosaic floors and murals on the walls of the villa, and what were they depicting

Ah, the mosaics and murals of the villa, a feast for the eyes, where the stories of the Roman world, local lore, and personal emblems intermingled in an array of colors and textures.

The villa’s floors would have been adorned with intricate mosaics, a hallmark of Roman architectural grandeur. Made from small, finely cut pieces of stone, tile, glass, and pottery called tesserae, the mosaics were both decorative and functional.

In the atrium, the mosaic might depict a scene from Roman mythology. Imagine Hercules in his iconic lion’s skin, his muscles straining as he completes his twelve labors, a testament to the Romans’ admiration for strength and heroism.

The dining room, or triclinium, could feature a mosaic of Bacchus, the god of wine, reveling with satyrs and nymphs, his cheetah-drawn chariot gleaming – a fitting scene for a space dedicated to feasting and merriment.

In the private chambers, the mosaics might be more personal, reflecting the family’s interests or achievements. Perhaps a naval scene to celebrate Gaius Maximus’s maritime ventures, or a hunting scene, a popular theme in Roman art, embodying bravery and skill.

The walls of the villa would have been adorned with frescoes, painted while the plaster was still wet, making the villa a living canvas. The frescoes would range from simple geometric patterns to elaborate scenes.

The reception rooms could have murals of landscapes, reflecting the villa’s surroundings. Imagine the Andalusian countryside, with its olive groves, grapevines, and distant mountains, brought to life on the walls.

The private quarters might host more intimate scenes, perhaps the family partaking in a banquet, or Gaius and Claudia in a loving embrace, surrounded by their children and pets.

Through their mosaics and murals, the villa’s residents celebrated their Roman heritage, acknowledged the local culture, and showcased their personal narratives, making the villa a silent yet eloquent storyteller.

can you describe the garden and outbuildings

Ah, the enchantment of an age-old garden. Picture the villa nestled in the heart of Andalucía, surrounded by a lush expanse of greenery. Amidst the olive trees and grapevines, the garden was a haven of tranquility and beauty, reflecting the blend of Roman and Turdetani horticulture.

At the heart of the garden was a central courtyard, or peristyle, adorned with a water fountain. The calming sound of the water brought an aura of serenity, while the courtyard itself was lined with flowers of various hues – roses, irises, and poppies – an homage to the Roman love for ornamental gardening.

Beyond the peristyle, the garden was a mixture of beauty and utility. Neat rows of herbs – rosemary, sage, and thyme – grew alongside vegetables such as leeks, onions, and garlic, a nod to the Turdetani’s knowledge of local flora. Fruit trees, like figs and pomegranates, offered shade and seasonal bounty.

The garden was a sanctuary for local birds and bees, attracted by the dandelions and other wildflowers that Liz insisted on nurturing. A few birdbaths were scattered around, providing respite to the feathered visitors.

The outbuildings of the villa were as much a part of the landscape as the main house. Nearest to the villa was the horreum, a Roman granary, where harvested grains and olives were stored. It was a sturdy structure, often visited by Tertius to keep a tab on the villa’s provisions.

Not far from the horreum was the pottery workshop. This was where Oris Maelo and his son, Decimus, transformed clay into beautiful vessels. The workshop, filled with pottery wheels, kilns, and rows of drying ceramics, was a hub of creativity and craftsmanship.

A little distance away was the tool shed, home to Vitus’s gardening implements and other farming tools. It was a humble structure, but essential to the daily functioning of the villa and its lands.

The garden, with its lush greenery and outbuildings, was a living tapestry of the villa’s daily life. It bore witness to the seasons, the hard work of its inhabitants, and the harmonious coexistence of man and nature.

March 14, 2023 at 8:37 pm #7166In reply to: The Precious Life and Rambles of Liz Tattler

Godfrey had been in a mood. Which one, it was hard to tell; he was switching from overwhelmed, grumpy and snappy, to surprised and inspired in a flicker of a second.

Maybe it had to do with the quantity of material he’d been reviewing. Maybe there were secret codes in it, or it was simply the sleep deprivation.

Inspired by Elizabeth active play with her digital assistant —which she called humorously Whinley, he’d tried various experiments with her series of written, half-written, second-hand, discarded, published and unpublished, drivel-labeled manuscripts he could put his hand on to try to see if something —anything— would come out of it.

After all, Liz’ generous prose had always to be severely edited to meet the editorial standards, and as she’d failed to produce new best-sellers since the pandemic had hit, he’d had to resort to exploring old material to meet the shareholders expectations.

He had to be careful, since some were so tartied up, that at times the botty Whinley would deem them banworthy. “Botty Banworth” was Liz’ character name for this special alternate prudish identity of her assistant. She’d run after that to write about it. After all, “you simply can’t ignore a story character when they pop in, that would be rude” was her motto.

So Godfrey in turn took to enlist Whinley to see what could be made of the raw material and he’d been both terribly disappointed and at the same time completely awestruck by the results. Terribly disappointed of course, as Whinley repeatedly failed to grasp most of the subtleties, or any of the contextual finely layered structures. While it was good at outlining, summarising, extracting some characters, or content, it couldn’t imagine, excite, or transcend the content it was fed with.

Which had come as the awestruck surprise for Godfrey. No matter how raw, unpolished, completely off-the-charts rank with madness or replete with seeming randomness the content was, there was always something that could be inferred from it. Even more, there was no end to what could be seen into it. It was like life itself. Or looking at a shining gem or kaleidoscope, it would take endless configurations and had almost infinite potential.

It was rather incredible and revisited his opinion of what being a writer meant. It was not simply aligning words. There was some magic at play there to infuse them, to dance with intentions, and interpret the subtle undercurrents of the imagination. In a sense, the words were dead, but the meaning behind them was still alive somehow, captured in the amber of the composition, as a fount of potentials.

What crafting or editing of the story meant for him, was that he had to help the writer reconnect with this intent and cast her spell of words to surf on the waves of potential towards an uncharted destination. But the map of stories he was thinking about was not the territory. Each story could be revisited in endless variations and remain fresh. There was a difference between being a map maker, and being a tour-operator or guide.

He could glimpse Liz’ intention had never been to be either of these roles. She was only the happy bumbling explorer on the unchartered territories of her fertile mind, enlisting her readers for the journey. Like a Columbus of stories, she’d sell a dream trusting she would somehow make it safely to new lands and even bigger explorations.

Just as Godfrey was lost in abyss of perplexity, the door to his office burst open. Liz, Finnley, and Roberto stood in the doorway, all dressed in costumes made of odds and ends.

“You are late for the fancy dress rehearsal!” Liz shouted, in her a pirate captain outfit, her painted eye patch showing her eye with an old stitched red plush thing that looked like a rat perched on her shoulder supposed to look like a mock parrot.

“What was the occasion again?”

“I may have found a new husband.” she said blushing like a young damsel.

Finnley, in her mummy costume made with TP rolls, well… did her thing she does with her eyes.

February 21, 2023 at 1:54 pm #6616In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

“Imagine that! a Big Banana…”

After a brisk walk trying to catch up with his winged psittacine friend, Xavier had stumbled on a large concrete sculpture painted bright yellow in the middle of a field.

He’s read somewhere Australia was known for its fondness of “big things”, but he didn’t expect one here – it was quite fun.“I think you just made my day Pretty Girl” he said to the bird. “Not that I don’t like to venture more, but I get the feeling I have to come back.” He checked his phone, there were a few messages, including one from Youssef who’d found some surprisingly interesting stuff during his shopping visit.

“We wouldn’t want to be caught off-guard by a bunyip, you know…” he said more to himself than to anyone in particular.

“Suuuit yourself.” said the bright red parrot, “No need to fear bunyip. Just don’t follow Min min lights. And stay away from mines.” and it flew away in a different direction.

February 18, 2023 at 11:28 am #6551In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Xavier had woken up in the middle of the night that felt surprisingly alive bursting with a quiet symphony of sounds from nocturnal creatures and nearby nature, painted on a canvas of eerie spacious silence.

It often took him a while to get accustomed to any new place, and it was not uncommon for him to have his mind racing in the middle of the night. Generally Brytta had a soothing presence and that often managed to nudge him back to sleep, otherwise, he would simply wake up until the train of thoughts had left the station.

It was beginning of the afternoon in Berlin; Brytta would be in a middle of a shift, so he recorded a little message for her to find when she would get back to her phone. It was funny to think they’d met thanks to Yasmin and Zara, at the time the three girls were members of the same photography club, which was called ‘Focusgroupfocus’ or something similar…

With that done, he’d turned around for something to do but there wasn’t much in the room to explore or to distract him sufficiently. Not even a book in the nightstand drawer. The decoration itself had a mesmerising nature, but after a while it didn’t help with the racing thoughts.He was tempted to check in the game — there was something satisfactory in finishing a quest that left his monkey brain satiated for a while, so he gave in and logged back in.

Completing the quest didn’t take him too long this time. The main difficulty initially was to find the portal from where his avatar had landed. It was a strange carousel of blue storks that span into different dimensions one could open with the proper incantation.

As usual, stating the quirk was the key to the location, and the carousel portal propelled him right away to Midnight town, which was clearly a ghost town in more ways than one. Interestingly, he was chatting on the side with Glimmer, who’d run into new adventures of her own while continuing to ask him what was up, and as soon as he’d reached Midnight town, all communication channels suddenly went dark. He’d laughed to himself thinking how frustrated Glimmer would have been about that. But maybe the game took care of sending her AI-generated messages simulating his presence. Despite the disturbing thought of having an AI generated clone of himself, he almost hoped for it (he’d probably signed the consent for this without realising), so that he wouldn’t have to do a tedious recap about all what she’d missed.

Once he arrived in the town, the adventure followed a predictable pattern. The clues were also rather simple to follow.

The townspeople are all frozen in time, stuck in their daily routines and unable to move on. Your mission is to find the missing piece of continuity, a small hourglass that will set time back in motion and allow the townspeople to move forward.

The clue to finding the hourglass lies within a discarded pocket watch that can be found in the mayor’s office. You must unscrew the back and retrieve a hidden key. The key will unlock a secret compartment in the town clock tower, where the hourglass is kept.

Be careful as you search for the hourglass, as the town is not as abandoned as it seems. Spectral figures roam the streets, and strange whispers can be heard in the wind. You may also encounter a mysterious old man who seems to know more about the town’s secrets than he lets on.

Evading the ghosts and spectres wasn’t too difficult once you got the hang of it. The old man however had been quite an elusive figure to find, but he was clearly the highlight of the whole adventure; he had been hiding in plain sight since the beginning of the adventure. One of the blue storks in the town that he’d thought had come with him through the portal was in actuality not a bird at all.

While he was focused on finishing the quest, the interaction with the hermit didn’t seem very helpful. Was he really from the game construct? When it was time to complete the quest and turn the hourglass to set the town back in motion, and resume continuity, some of his words came back to Xavier.

“The town isn’t what it seems. Recognise this precious moment where everything is still and you can realise it for the illusion that it is, a projection of your busy mind. When motion resumes, you will need to keep your mind quiet. The prize in the quest is not the completion of it, but the realisation you can stop the agitation at any moment, and return to what truly matters.”

The hermit had turned to him with clear dark eyes and asked “do you know what you are seeking in these adventures? do you know what truly matters to you?”

When he came out of the game, his quest completed, Xavier felt the words resonate ominously.

A buzz of the phone snapped him out of it.

It was a message from Zara. Apparently she’d found her way back to modernity.

[4:57] “Going to pick up Yasmin at the airport. You better sleep away the jetlag you lazy slugs, we have poultry damn plenty planned ahead – cackling bugger cooking lessons not looking forward to, but can be fun. Talk to you later. Z”

He had the impulse to go with her, but the lack of sleep was hitting back at him now, and he thought he’d better catch some so he could manage to realign with the timezone.

“The old man was right… that sounds like a lot of agitation coming our way…”

February 14, 2023 at 8:48 pm #6545In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

The road was stretching endlessly and monotonously, a straight line disappearing into a nothingness of dry landscapes that reminded Youssef of the Gobi desert where he had been driving not too long ago. At regular speed, the car barely seemed to progress.

> O Time suspend thy flight!

Eternity. Something only nature could procure him. He loved the feeling, and compared to the more usual sand of Gobi, the red sands of Australia gave him the impression he had shifted into another reality. That and the fifteen hours flight listening to Gladys made it difficult to respond to Xavier’s loquacious self and funny jokes. After some time, his friend stopped talking and tried catching some signal to play the Game, brandishing his phone in different directions as if he was hunting ghosts with a strange device.

It reminded him he had to accept his next quest in a ghost town. That’s all he remembered. He could do that at the Inn, when they could rest in their rooms.

Youssef wondered if the welcome sign at the entrance of the town had seen better days. The wood the fish was made of seemed eaten by termites, but someone had painted it with silver and blue to give it a fresher look. Youssef snorted at the shocked expression on his friend’s face.

“It looked like it died of boredom. Let’s just hope the Innside doesn’t look like a gutted fish,” Xavier said.

An old lady showed them their rooms. She didn’t seem the talkative type, which made Youssef love her immediately with her sharp tongue and red cardigan. He rather admired her braided silver hair as it reminded him of his mother who would let him brush her hair when they lived in Norway. It was in another reality. He smiled. She saw him looking at her and her eyes narrowed like a pair of arrowslits. She seemed ready to fire. Instead she kept on ranting about an idle person not doing her only job properly. They each went to their rooms, Xavier took number 7 and Youssef picked number 5, his lucky number.

He was glad to be able to enjoy his own room after the trip of the last few weeks. It had been for work, so it was different. But usually he liked travelling the world on his own and meet people on his way and learn from their stories. Traveling with people always meant some compromise that would always frustrate him because he wanted to go faster, or explore more tricky paths.

The room was nicely decorated, and the scent of fresh paint made it clear it was recent. A strange black stone, which Youssef recognized as a black obsidian, has been put on a pile of paper full of doodles, beside two notebooks and pencils. The notebooks’ pages were blank, he thought of giving them to Xavier. He took the stone. It was cold to the touch and his reflection on the surface looked back at him, all wavy. The doodles on the paper looked like a map and hard to read annotations. One stood out, though which looked like a wifi password. That made him think of the Game. He entered it on his phone and that was it. Maybe it was time to go back in. But he wanted to take a shower first.

He put his backpack and his bag on the bed and unpacked it. Amongst a pile of dirty clothes, he managed to find a t-shirt that didn’t smell too bad and a pair of shorts. He would have to use the laundry service of the hotel.

He had missed hot showers. Once refreshed, he moved his bags on the floor and jumped on his bed and launched the Game.

Youssef finds himself in a small ghost town in what looks like the middle of the Australian outback. The town was once thriving but now only a few stragglers remain, living in old, decrepit buildings. He’s standing in the town square, surrounded by an old post office, a saloon, and a few other ramshackle buildings.

Youssef finds himself in a small ghost town in what looks like the middle of the Australian outback. The town was once thriving but now only a few stragglers remain, living in old, decrepit buildings. He’s standing in the town square, surrounded by an old post office, a saloon, and a few other ramshackle buildings.A message appeared on the screen.

Quest: Your task is to find the source of the magnetic pull that attracts talkative people to you. You must find the reason behind it and break the spell, so you can continue your journey in peace.

Youssef started to move his avatar towards the saloon when someone knocked on the door.

May 13, 2022 at 10:50 am #6293In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Lincolnshire Families

Thanks to the 1851 census, we know that William Eaton was born in Grantham, Lincolnshire. He was baptised on 29 November 1768 at St Wulfram’s church; his father was William Eaton and his mother Elizabeth.

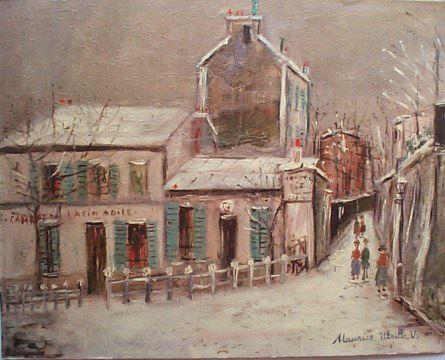

St Wulfram’s in Grantham painted by JMW Turner in 1797:

I found a marriage for a William Eaton and Elizabeth Rose in the city of Lincoln in 1761, but it seemed unlikely as they were both of that parish, and with no discernable links to either Grantham or Nottingham.

But there were two marriages registered for William Eaton and Elizabeth Rose: one in Lincoln in 1761 and one in Hawkesworth Nottinghamshire in 1767, the year before William junior was baptised in Grantham. Hawkesworth is between Grantham and Nottingham, and this seemed much more likely.

Elizabeth’s name is spelled Rose on her marriage records, but spelled Rouse on her baptism. It’s not unusual for spelling variations to occur, as the majority of people were illiterate and whoever was recording the event wrote what it sounded like.

Elizabeth Rouse was baptised on 26th December 1746 in Gunby St Nicholas (there is another Gunby in Lincolnshire), a short distance from Grantham. Her father was Richard Rouse; her mother Cave Pindar. Cave is a curious name and I wondered if it had been mistranscribed, but it appears to be correct and clearly says Cave on several records.

Richard Rouse married Cave Pindar 21 July 1744 in South Witham, not far from Grantham.

Richard was born in 1716 in North Witham. His father was William Rouse; his mothers name was Jane.

Cave Pindar was born in 1719 in Gunby St Nicholas, near Grantham. Her father was William Pindar, but sadly her mothers name is not recorded in the parish baptism register. However a marriage was registered between William Pindar and Elizabeth Holmes in Gunby St Nicholas in October 1712.

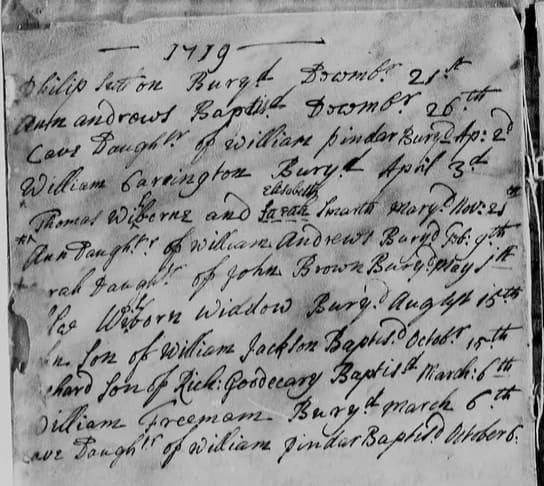

William Pindar buried a daughter Cave on 2 April 1719 and baptised a daughter Cave on 6 Oct 1719:

Elizabeth Holmes was baptised in Gunby St Nicholas on 6th December 1691. Her father was John Holmes; her mother Margaret Hod.

Margaret Hod would have been born circa 1650 to 1670 and I haven’t yet found a baptism record for her. According to several other public trees on an ancestry website, she was born in 1654 in Essenheim, Germany. This was surprising! According to these trees, her father was Johannes Hod (Blodt|Hoth) (1609–1677) and her mother was Maria Appolonia Witters (1620–1656).

I did not think it very likely that a young woman born in Germany would appear in Gunby St Nicholas in the late 1600’s, and did a search for Hod’s in and around Grantham. Indeed there were Hod’s living in the area as far back as the 1500’s, (a Robert Hod was baptised in Grantham in 1552), and no doubt before, but the parish records only go so far back. I think it’s much more likely that her parents were local, and that the page with her baptism recorded on the registers is missing.

Of the many reasons why parish registers or some of the pages would be destroyed or lost, this is another possibility. Lincolnshire is on the east coast of England:

“All of England suffered from a “monster” storm in November of 1703 that killed a reported 8,000 people. Seaside villages suffered greatly and their church and civil records may have been lost.”

A Margeret Hod, widow, died in Gunby St Nicholas in 1691, the same year that Elizabeth Holmes was born. Elizabeth’s mother was Margaret Hod. Perhaps the widow who died was Margaret Hod’s mother? I did wonder if Margaret Hod had died shortly after her daughter’s birth, and that her husband had died sometime between the conception and birth of his child. The Black Death or Plague swept through Lincolnshire in 1680 through 1690; such an eventually would be possible. But Margaret’s name would have been registered as Holmes, not Hod.

Cave Pindar’s father William was born in Swinstead, Lincolnshire, also near to Grantham, on the 28th December, 1690, and he died in Gunby St Nicholas in 1756. William’s father is recorded as Thomas Pinder; his mother Elizabeth.

GUNBY: The village name derives from a “farmstead or village of a man called Gunni”, from the Old Scandinavian person name, and ‘by’, a farmstead, village or settlement.

Gunby Grade II listed Anglican church is dedicated to St Nicholas. Of 15th-century origin, it was rebuilt by Richard Coad in 1869, although the Perpendicular tower remained. March 26, 2022 at 11:36 am #6285

March 26, 2022 at 11:36 am #6285In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Harriet Compton

Harriet Comptom is not directly related to us, but her portrait is in our family collection.