Search Results for 'peter'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

January 4, 2026 at 6:59 pm #8029

In reply to: The Hoards of Sanctorum AD26

“While you’re off to another wild dragon chase, I’m calling the plumber,” Yvoise announced. She’d found one who accepted payment in Roman denarii. She began tapping furiously on her smartphone to recover the phone number, incensed at having been blocked again from Faceterest for sharing potentially unchecked facts (ignorants! she wanted to shout at the screen).

After a bit of struggle, the appointment was set. She adjusted her blazer; she had a ‘Health and Safety in the Workplace’ seminar to lead at Sanctus Training in twenty minutes, and she couldn’t smell like wet dog.

After a bit of struggle, the appointment was set. She adjusted her blazer; she had a ‘Health and Safety in the Workplace’ seminar to lead at Sanctus Training in twenty minutes, and she couldn’t smell like wet dog.“Make sure you bill it to the company account…!” Helier shouted over the noise Spirius was making huffing and struggling to load the antique musket.

“…under ‘Facility Maintenance’!”

“Obviously,” Yvoise scoffed. “We are a legitimate enterprise. Sanctus House has a reputation to uphold. Even if the landlord at Olympus Park keeps asking why our water consumption rivals a small water park.”

Spirius shuddered at the name. “Olympus Park. Pagan nonsense. I told you we should have bought the unit in St. Peter’s Industrial Estate.”

“The zoning laws were restrictive, Spirius,” Yvoise sighed. “Besides, ‘Sanctus Training Ltd’ looks excellent on a letterhead. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I have six junior executives coming in for a workshop on ‘Conflict Resolution.’ I plan to read them the entirety of the Treaty of Arras until they submit.”

“And dear old Boothroyd and I have a sewer dragon to exterminate in the name of all that’s Holy. Care to join, Helier?”

“Not really, had my share of those back in the day. I’ll help Yvoise with the plumbing. That’s more pressing. And might I remind you the dragon messing with the plumbing is only the first of the three tasks that Austreberthe placed in her will to be accomplished in the month following her demise…”

“Not now, Helier, I really need to get going!” Yvoise was feeling overwhelmed. “And where’s Cerenise? She could help with the second task. Finding the living descendants of the last named Austreberthe, was it? It’s all behind-desk type of stuff and doesn’t require her to get rid of anything…” she knew well Cerenise and her buttons.

“Yet.” Helier cut. “The third task may well be the toughest.”

“Don’t say it!” They all recoiled in horror.

“The No-ve-na of Cleans-ing” he said in a lugubrious voice.

“Damn it, Helier. You’re such a mood killer. Maybe better to look for a loophole for that one. We can’t just throw stuff away to make place for hers, as nice her tastes for floor tiling were.” Yvoise was in a rush to get to her appointment and couldn’t be bothered to enter a debate. She rushed to the front door.

“See you later… Helier-gator” snickered Laddie under her breath, as she was pretending to clean the unkempt cupboards.

September 18, 2023 at 8:29 am #7278In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Tomlinson of Wergs and Hancox of Penn

John Tomlinson of Wergs (Tettenhall, Wolverhamton) 1766-1844, my 4X great grandfather, married Sarah Hancox 1772-1851. They were married on the 27th May 1793 by licence at St Peter in Wolverhampton.

Between 1794 and 1819 they had twelve children, although four of them died in childhood or infancy. Catherine was born in 1794, Thomas in 1795 who died 6 years later, William (my 3x great grandfather) in 1797, Jemima in 1800, John, Richard and Matilda between 1802 and 1806 who all died in childhood, Emma in 1809, Mary Ann in 1811, Sidney in 1814, and Elijah in 1817 who died two years later.On the 1841 census John and Sarah were living in Hockley in Birmingham, with three of their children, and surgeon Charles Reynolds. John’s occupation was “Ind” meaning living by independent means. He was living in Hockley when he died in 1844, and in his will he was “John Tomlinson, gentleman”.

Sarah Hancox was born in 1772 in Penn, Wolverhampton. Her father William Hancox was also born in Penn in 1737. Sarah’s mother Elizabeth Parkes married William’s brother Francis in 1767. Francis died in 1768, and in 1770 Elizabeth married William.

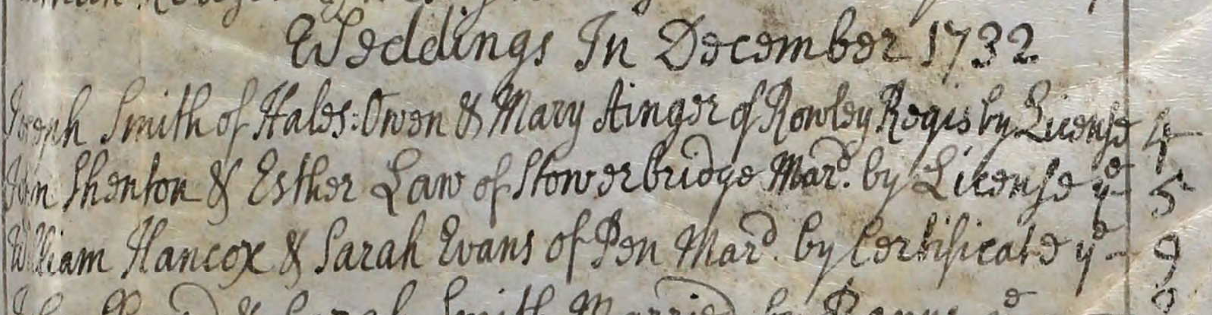

William’s father was William Hancox, yeoman, born in 1703 in Penn. He died intestate in 1772, his wife Sarah claiming her right to his estate. William Hancox and Sarah Evans, both of Penn, were married on the 9th December 1732 in Dudley, Worcestershire, by “certificate”. Marriages were usually either by banns or by licence. Apparently a marriage by certificate indicates that they were non conformists, or dissenters, and had the non conformist marriage “certified” in a Church of England church.

1732 marriage of William Hancox and Sarah Evans:

William and Sarah lost two daughters, Elizabeth, five years old, and Ann, three years old, within eight days of each other in February 1738.

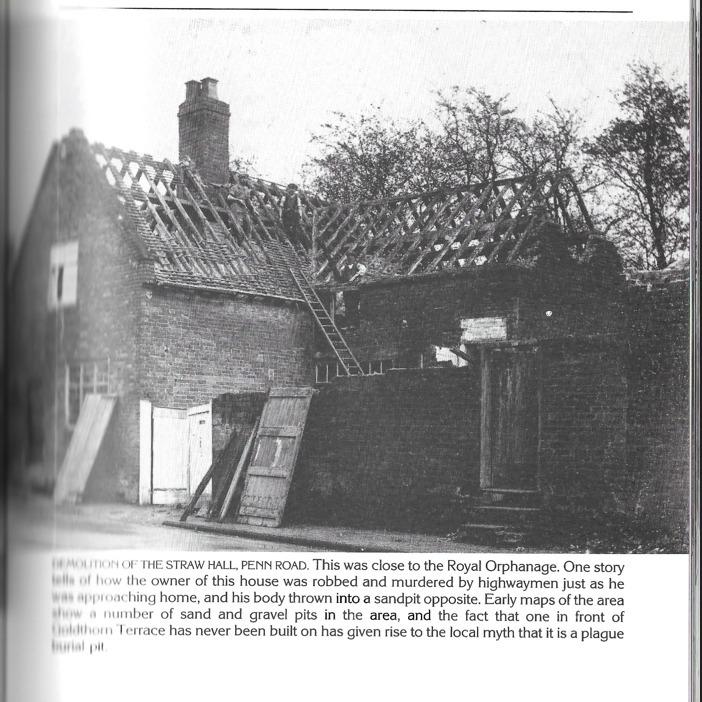

William the elder’s father was John Hancox born in Penn in 1668. He married Elizabeth Wilkes from Sedgley in 1691 at Himley. John Hancox, “of Straw Hall” according to the Wolverhampton burial register, died in 1730. Straw Hall is in Penn. John’s parents were Walter Hancox and Mary Noake. Walter was born in Tettenhall in 1625, his father Richard Hancox. Mary Noake was born in Penn in 1634. Walter died in Penn in 1689.

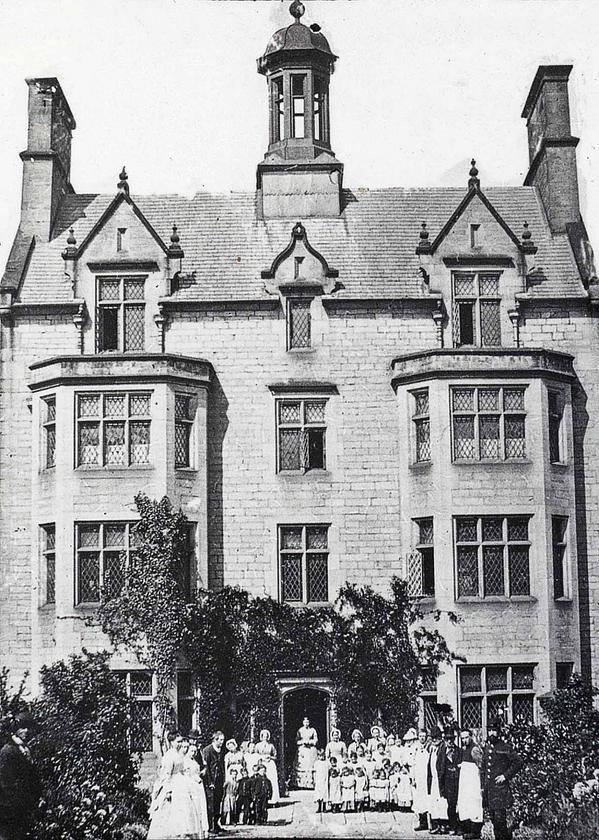

Straw Hall thanks to Bradney Mitchell:

“Here is a picture I have of Straw Hall, Penn Road.

The painting is by John Reid circa 1878.

Sketch commissioned by George Bradney Mitchell to record the town as it was before its redevelopment, in a book called Wolverhampton and its Environs. ©”

And a photo of the demolition of Straw Hall with an interesting story:

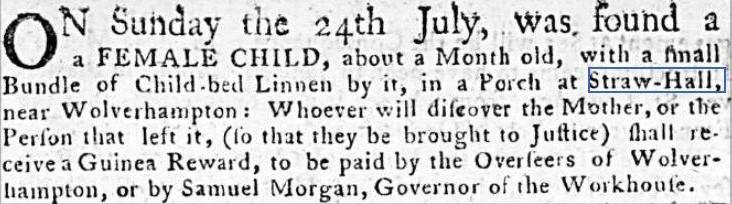

In 1757 a child was abandoned on the porch of Straw Hall. Aris’s Birmingham Gazette 1st August 1757:

The Hancox family were living in Penn for at least 400 years. My great grandfather Charles Tomlinson built a house on Penn Common in the early 1900s, and other Tomlinson relatives have lived there. But none of the family knew of the Hancox connection to Penn. I don’t think that anyone imagined a Tomlinson ancestor would have been a gentleman, either.

Sarah Hancox’s brother William Hancox 1776-1848 had a busy year in 1804.

On 29 Aug 1804 he applied for a licence to marry Ann Grovenor of Claverley.

In August 1804 he had property up for auction in Penn. “part of Lightwoods, 3 plots, and the Coppice”

On 14 Sept 1804 their first son John was baptised in Penn. According to a later census John was born in Claverley. (before the parents got married)(Incidentally, John Hancox’s descendant married a Warren, who is a descendant of my 4x great grandfather Samuel Warren, on my mothers side, from Newhall, Derbyshire!)

On 30 Sept he married Ann in Penn.

In December he was a bankrupt pig and sheep dealer.

In July 1805 he’s in the papers under “certificates”: William Hancox the younger, sheep and pig dealer and chapman of Penn. (A certificate was issued after a bankruptcy if they fulfilled their obligations)

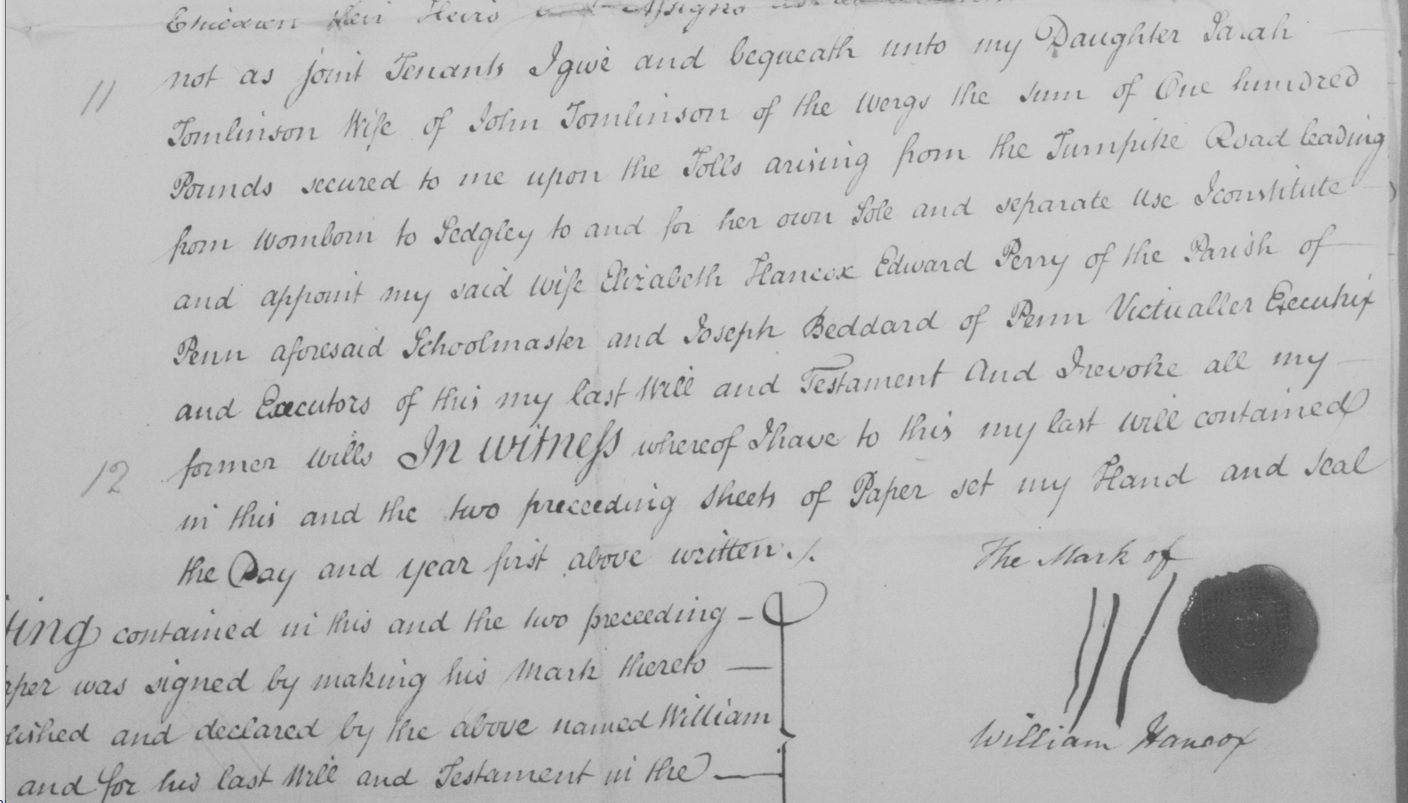

He was a pig dealer in Penn in 1841, a widower, living with unmarried daughter Elizabeth.Sarah’s father William Hancox died in 1816. In his will, he left his “daughter Sarah, wife of John Tomlinson of the Wergs the sum of £100 secured to me upon the tolls arising from the turnpike road leading from Wombourne to Sedgeley to and for her sole and separate use”.

The trustees of toll road would decide not to collect tolls themselves but get someone else to do it by selling the collecting of tolls for a fixed price. This was called “farming the tolls”. The Act of Parliament which set up the trust would authorise the trustees to farm out the tolls. This example is different. The Trustees of turnpikes needed to raise money to carry out work on the highway. The usual way they did this was to mortgage the tolls – they borrowed money from someone and paid the borrower interest; as security they gave the borrower the right, if they were not paid, to take over the collection of tolls and keep the proceeds until they had been paid off. In this case William Hancox has lent £100 to the turnpike and is leaving it (the right to interest and/or have the whole sum repaid) to his daughter Sarah Tomlinson. (this information on tolls from the Wolverhampton family history group.)William Hancox, Penn Wood, maltster, left a considerable amount of property to his children in 1816. All household effects he left to his wife Elizabeth, and after her decease to his son Richard Hancox: four dwelling houses in John St, Wolverhampton, in the occupation of various Pratts, Wright and William Clarke. He left £200 to his daughter Frances Gordon wife of James Gordon, and £100 to his daughter Ann Pratt widow of John Pratt. To his son William Hancox, all his various properties in Penn wood. To Elizabeth Tay wife of Thomas Tay he left £200, and to Richard Hancox various other properties in Penn Wood, and to his daughter Lucy Tay wife of Josiah Tay more property in Lower Penn. All his shops in St John Wolverhamton to his son Edward Hancox, and more properties in Lower Penn to both Francis Hancox and Edward Hancox. To his daughter Ellen York £200, and property in Montgomery and Bilston to his son John Hancox. Sons Francis and Edward were underage at the time of the will. And to his daughter Sarah, his interest in the toll mentioned above.

Sarah Tomlinson, wife of John Tomlinson of the Wergs, in William Hancox will:

July 4, 2023 at 7:52 pm #7261

July 4, 2023 at 7:52 pm #7261In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Long Lost Enoch Edwards

My father used to mention long lost Enoch Edwards. Nobody in the family knew where he went to and it was assumed that he went to USA, perhaps to Utah to join his sister Sophie who was a Mormon handcart pioneer, but no record of him was found in USA.

Andrew Enoch Edwards (my great great grandfather) was born in 1840, but was (almost) always known as Enoch. Although civil registration of births had started from 1 July 1837, neither Enoch nor his brother Stephen were registered. Enoch was baptised (as Andrew) on the same day as his brothers Reuben and Stephen in May 1843 at St Chad’s Catholic cathedral in Birmingham. It’s a mystery why these three brothers were baptised Catholic, as there are no other Catholic records for this family before or since. One possible theory is that there was a school attached to the church on Shadwell Street, and a Catholic baptism was required for the boys to go to the school. Enoch’s father John died of TB in 1844, and perhaps in 1843 he knew he was dying and wanted to ensure an education for his sons. The building of St Chads was completed in 1841, and it was close to where they lived.

Enoch appears (as Enoch rather than Andrew) on the 1841 census, six months old. The family were living at Unett Street in Birmingham: John and Sarah and children Mariah, Sophia, Matilda, a mysterious entry transcribed as Lene, a daughter, that I have been unable to find anywhere else, and Reuben and Stephen.

Enoch was just four years old when his father John, an engineer and millwright, died of consumption in 1844.

In 1851 Enoch’s widowed mother Sarah was a mangler living on Summer Street, Birmingham, Matilda a dressmaker, Reuben and Stephen were gun percussionists, and eleven year old Enoch was an errand boy.

On the 1861 census, Sarah was a confectionrer on Canal Street in Birmingham, Stephen was a blacksmith, and Enoch a button tool maker.

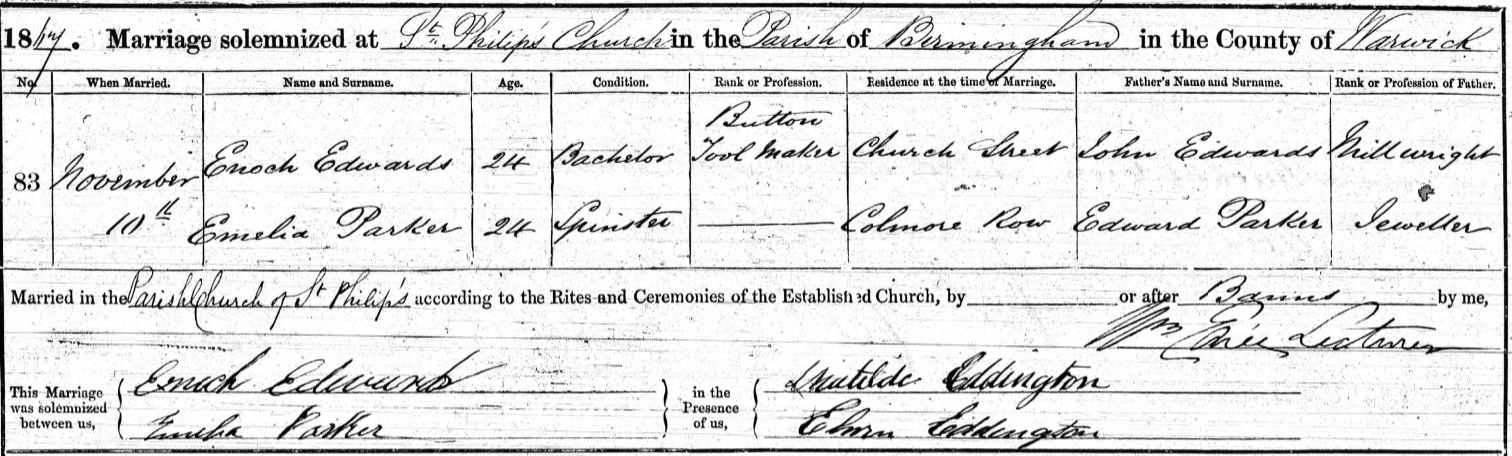

On the 10th November 1867 Enoch married Emelia Parker, daughter of jeweller and rope maker Edward Parker, at St Philip in Birmingham. Both Emelia and Enoch were able to sign their own names, and Matilda and Edwin Eddington were witnesses (Enoch’s sister and her husband). Enoch’s address was Church Street, and his occupation button tool maker.

Four years later in 1871, Enoch was a publican living on Clifton Road. Son Enoch Henry was two years old, and Ralph Ernest was three months. Eliza Barton lived with them as a general servant.

By 1881 Enoch was back working as a button tool maker in Bournebrook, Birmingham. Enoch and Emilia by then had three more children, Amelia, Albert Parker (my great grandfather) and Ada.

Garnet Frederick Edwards was born in 1882. This is the first instance of the name Garnet in the family, and subsequently Garnet has been the middle name for the eldest son (my brother, father and grandfather all have Garnet as a middle name).

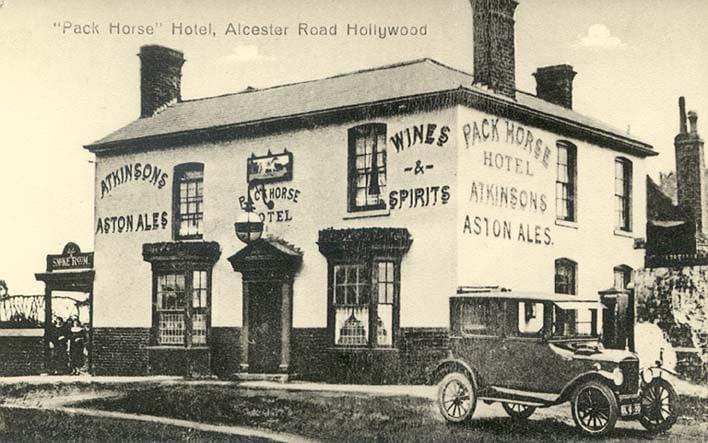

Enoch was the licensed victualler at the Pack Horse Hotel in 1991 at Kings Norton. By this time, only daughters Amelia and Ada and son Garnet are living at home.

Additional information from my fathers cousin, Paul Weaver:

“Enoch refused to allow his son Albert Parker to go to King Edwards School in Birmingham, where he had been awarded a place. Instead, in October 1890 he made Albert Parker Edwards take an apprenticeship with a pawnboker in Tipton.

Towards the end of the 19th century Enoch kept The Pack Horse in Alcester Road, Hollywood, where a twist was 1d an ounce, and beer was 2d a pint. The children had to get up early to get breakfast at 6 o’clock for the hay and straw men on their way to the Birmingham hay and straw market. Enoch is listed as a member of “The Kingswood & Pack Horse Association for the Prosecution of Offenders”, a kind of early Neighbourhood Watch, dated 25 October 1890.

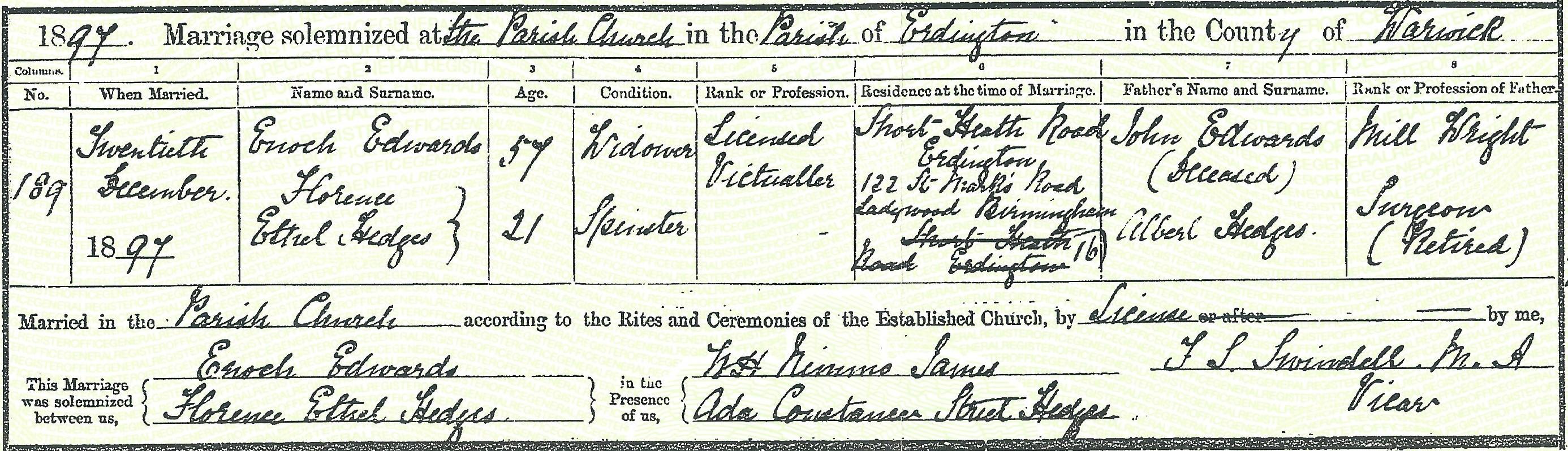

The Edwards family later moved to Redditch where they kept The Rifleman Inn at 35 Park Road. They must have left the Pack Horse by 1895 as another publican was in place by then.”Emelia his wife died in 1895 of consumption at the Rifleman Inn in Redditch, Worcestershire, and in 1897 Enoch married Florence Ethel Hedges in Aston. Enoch was 56 and Florence was just 21 years old.

The following year in 1898 their daughter Muriel Constance Freda Edwards was born in Deritend, Warwickshire.

In 1901 Enoch, (Andrew on the census), publican, Florence and Muriel were living in Dudley. It was hard to find where he went after this.From Paul Weaver:

“Family accounts have it that Enoch EDWARDS fell out with all his family, and at about the age of 60, he left all behind and emigrated to the U.S.A. Enoch was described as being an active man, and it is believed that he had another family when he settled in the U.S.A. Esmor STOKES has it that a postcard was received by the family from Enoch at Niagara Falls.

On 11 June 1902 Harry Wright (the local postmaster responsible in those days for licensing) brought an Enoch EDWARDS to the Bedfordshire Petty Sessions in Biggleswade regarding “Hole in the Wall”, believed to refer to the now defunct “Hole in the Wall” public house at 76 Shortmead Street, Biggleswade with Enoch being granted “temporary authority”. On 9 July 1902 the transfer was granted. A year later in the 1903 edition of Kelly’s Directory of Bedfordshire, Hunts and Northamptonshire there is an Enoch EDWARDS running the Wheatsheaf Public House, Church Street, St. Neots, Huntingdonshire which is 14 miles south of Biggleswade.”

It seems that Enoch and his new family moved away from the midlands in the early 1900s, but again the trail went cold.

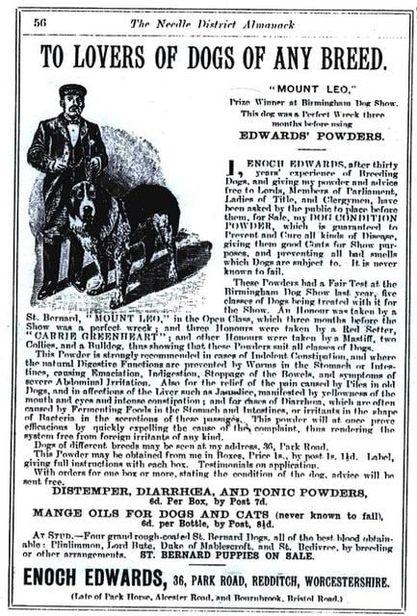

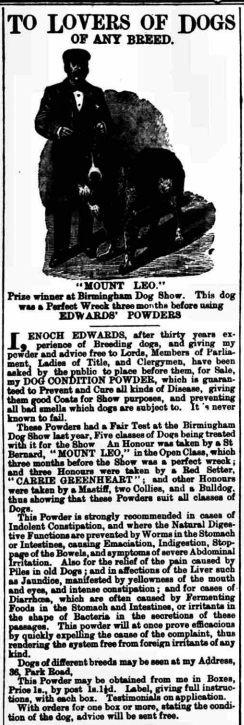

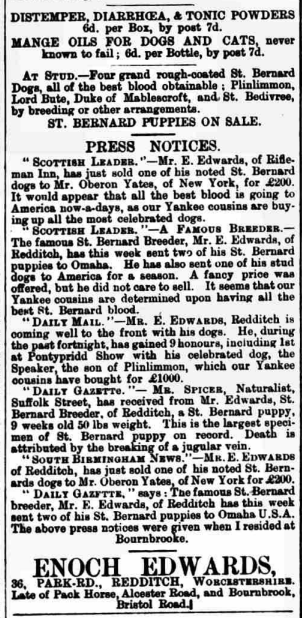

When I started doing the genealogy research, I joined a local facebook group for Redditch in Worcestershire. Enoch’s son Albert Parker Edwards (my great grandfather) spent most of his life there. I asked in the group about Enoch, and someone posted an illustrated advertisement for Enoch’s dog powders. Enoch was a well known breeder/keeper of St Bernards and is cited in a book naming individuals key to the recovery/establishment of ‘mastiff’ size dog breeds.

We had not known that Enoch was a breeder of champion St Bernard dogs!

Once I knew about the St Bernard dogs and the names Mount Leo and Plinlimmon via the newspaper adverts, I did an internet search on Enoch Edwards in conjunction with these dogs.

Enoch’s St Bernard dog “Mount Leo” was bred from the famous Plinlimmon, “the Emperor of Saint Bernards”. He was reported to have sent two puppies to Omaha and one of his stud dogs to America for a season, and in 1897 Enoch made the news for selling a St Bernard to someone in New York for £200. Plinlimmon, bred by Thomas Hall, was born in Liverpool, England on June 29, 1883. He won numerous dog shows throughout Europe in 1884, and in 1885, he was named Best Saint Bernard.

In the Birmingham Mail on 14th June 1890:

“Mr E Edwards, of Bournebrook, has been well to the fore with his dogs of late. He has gained nine honours during the past fortnight, including a first at the Pontypridd show with a St Bernard dog, The Speaker, a son of Plinlimmon.”

In the Alcester Chronicle on Saturday 05 June 1897:

It was discovered that Enoch, Florence and Muriel moved to Canada, not USA as the family had assumed. The 1911 census for Montreal St Jaqcues, Quebec, stated that Enoch, (Florence) Ethel, and (Muriel) Frida had emigrated in 1906. Enoch’s occupation was machinist in 1911. The census transcription is not very good. Edwards was transcribed as Edmand, but the dates of birth for all three are correct. Birthplace is correct ~ A for Anglitan (the census is in French) but race or tribe is also an A but the transcribers have put African black! Enoch by this time was 71 years old, his wife 33 and daughter 11.

Additional information from Paul Weaver:

“In 1906 he and his new family travelled to Canada with Enoch travelling first and Ethel and Frida joined him in Quebec on 25 June 1906 on board the ‘Canada’ from Liverpool.

Their immigration record suggests that they were planning to travel to Winnipeg, but five years later in 1911, Enoch, Florence Ethel and Frida were still living in St James, Montreal. Enoch was employed as a machinist by Canadian Government Railways working 50 hours. It is the 1911 census record that confirms his birth as November 1840. It also states that Enoch could neither read nor write but managed to earn $500 in 1910 for activity other than his main profession, although this may be referring to his innkeeping business interests.

By 1921 Florence and Muriel Frida are living in Langford, Neepawa, Manitoba with Peter FUCHS, an Ontarian farmer of German descent who Florence had married on 24 Jul 1913 implying that Enoch died sometime in 1911/12, although no record has been found.”The extra $500 in earnings was perhaps related to the St Bernard dogs. Enoch signed his name on the register on his marriage to Emelia, and I think it’s very unlikely that he could neither read nor write, as stated above.

However, it may not be Enoch’s wife Florence Ethel who married Peter Fuchs. A Florence Emma Edwards married Peter Fuchs, and on the 1921 census in Neepawa her daugther Muriel Elizabeth Edwards, born in 1902, lives with them. Quite a coincidence, two Florence and Muriel Edwards in Neepawa at the time. Muriel Elizabeth Edwards married and had two children but died at the age of 23 in 1925. Her mother Florence was living with the widowed husband and the two children on the 1931 census in Neepawa. As there was no other daughter on the 1911 census with Enoch, Florence and Muriel in Montreal, it must be a different Florence and daughter. We don’t know, though, why Muriel Constance Freda married in Neepawa.

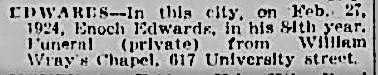

Indeed, Florence was not a widow in 1913. Enoch died in 1924 in Montreal, aged 84. Neither Enoch, Florence or their daughter has been found yet on the 1921 census. The search is not easy, as Enoch sometimes used the name Andrew, Florence used her middle name Ethel, and daughter Muriel used Freda, Valerie (the name she added when she married in Neepawa), and died as Marcheta. The only name she NEVER used was Constance!

A Canadian genealogist living in Montreal phoned the cemetery where Enoch was buried. She said “Enoch Edwards who died on Feb 27 1924 is not buried in the Mount Royal cemetery, he was only cremated there on March 4, 1924. There are no burial records but he died of an abcess and his body was sent to the cemetery for cremation from the Royal Victoria Hospital.”

1924 Obituary for Enoch Edwards:

Cimetière Mont-Royal Outremont, Montreal Region, Quebec, Canada

The Montreal Star 29 Feb 1924, Fri · Page 31

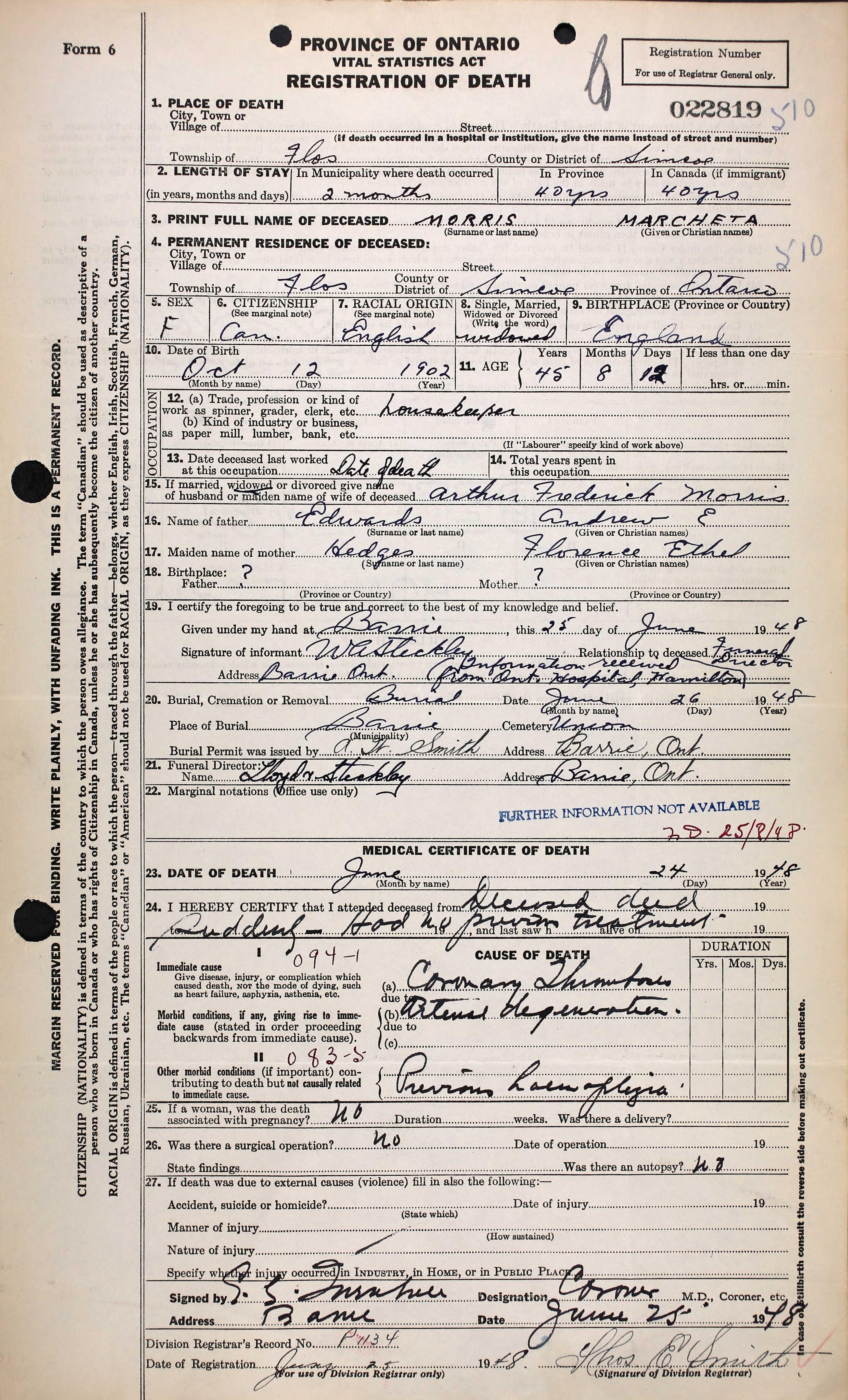

Muriel Constance Freda Valerie Edwards married Arthur Frederick Morris on 24 Oct 1925 in Neepawa, Manitoba. (She appears to have added the name Valerie when she married.)

Unexpectedly a death certificate appeared for Muriel via the hints on the ancestry website. Her name was “Marcheta Morris” on this document, however it also states that she was the widow of Arthur Frederick Morris and daughter of Andrew E Edwards and Florence Ethel Hedges. She died suddenly in June 1948 in Flos, Simcoe, Ontario of a coronary thrombosis, where she was living as a housekeeper.

June 13, 2023 at 10:31 am #7255

June 13, 2023 at 10:31 am #7255In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The First Wife of John Edwards

1794-1844

John was a widower when he married Sarah Reynolds from Kinlet. Both my fathers cousin and I had come to a dead end in the Edwards genealogy research as there were a number of possible births of a John Edwards in Birmingham at the time, and a number of possible first wives for a John Edwards at the time.

John Edwards was a millwright on the 1841 census, the only census he appeared on as he died in 1844, and 1841 was the first census. His birth is recorded as 1800, however on the 1841 census the ages were rounded up or down five years. He was an engineer on some of the marriage records of his children with Sarah, and on his death certificate, engineer and millwright, aged 49. The age of 49 at his death from tuberculosis in 1844 is likely to be more accurate than the census (Sarah his wife was present at his death), making a birth date of 1794 or 1795.

John married Sarah Reynolds in January 1827 in Birmingham, and I am descended from this marriage. Any children of John’s first marriage would no doubt have been living with John and Sarah, but had probably left home by the time of the 1841 census.

I found an Elizabeth Edwards, wife of John Edwards of Constitution Hill, died in August 1826 at the age of 23, as stated on the parish death register. It would be logical for a young widower with small children to marry again quickly. If this was John’s first wife, the marriage to Sarah six months later in January 1827 makes sense. Therefore, John’s first wife, I assumed, was Elizabeth, born in 1803.

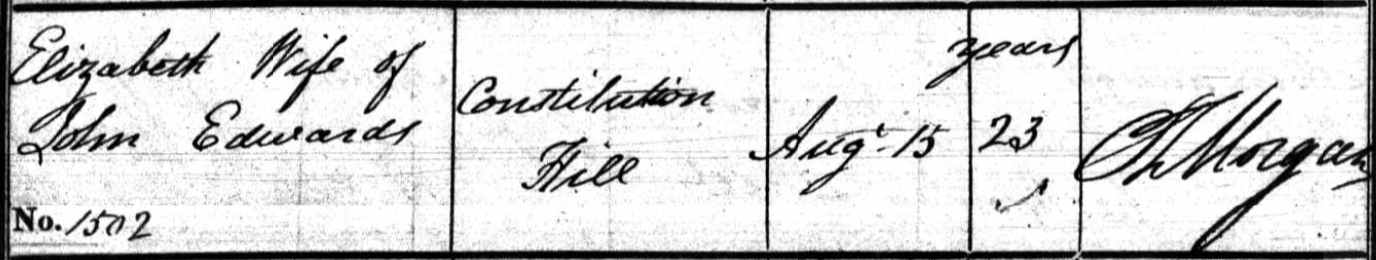

Death of Elizabeth Edwards, 23 years old. St Mary, Birmingham, 15 Aug 1826:

There were two baptisms recorded for parents John and Elizabeth Edwards, Constitution Hill, and John’s occupation was an engineer on both baptisms.

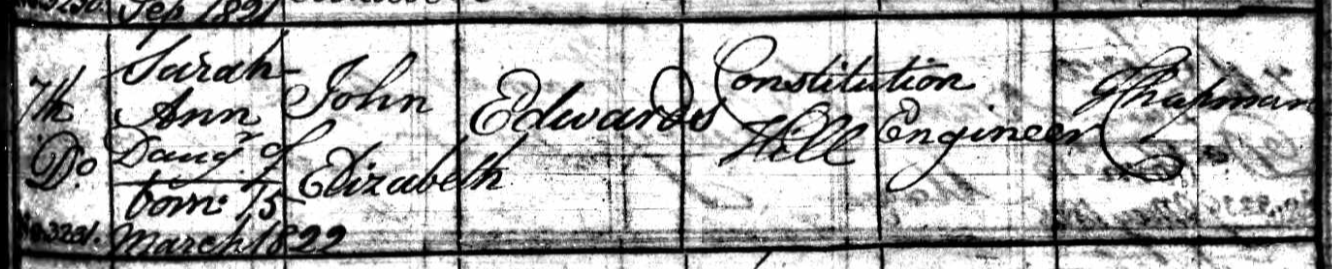

They were both daughters: Sarah Ann in 1822 and Elizabeth in 1824.Sarah Ann Edwards: St Philip, Birmingham. Born 15 March 1822, baptised 7 September 1822:

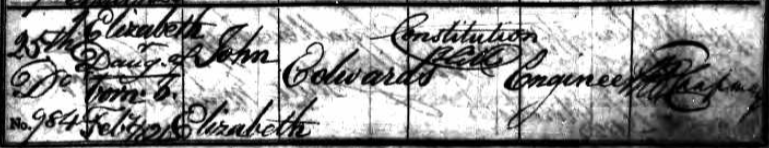

Elizabeth Edwards: St Philip, Birmingham. Born 6 February 1824, baptised 25 February 1824:

With John’s occupation as engineer stated, it looked increasingly likely that I’d found John’s first wife and children of that marriage.

Then I found a marriage of Elizabeth Beach to John Edwards in 1819, and subsequently found an Elizabeth Beach baptised in 1803. This appeared to be the right first wife for John, until an Elizabeth Slater turned up, with a marriage to a John Edwards in 1820. An Elizabeth Slater was baptised in 1803. Either Elizabeth Beach or Elizabeth Slater could have been the first wife of John Edwards. As John’s first wife Elizabeth is not related to us, it’s not necessary to go further back, and in a sense, doesn’t really matter which one it was.

But the Slater name caught my eye.

But first, the name Sarah Ann.

Of the possible baptisms for John Edwards, the most likely seemed to be in 1794, parents John and Sarah. John and Sarah had two infant daughters die just prior to John’s birth. The first was Sarah, the second Sarah Ann. Perhaps this was why John named his daughter Sarah Ann? In the absence of any other significant clues, I decided to assume these were the correct parents. I found and read half a dozen wills of any John Edwards I could find within the likely time period of John’s fathers death.

One of them was dated 1803. In this will, John mentions that his children are not yet of age. (John would have been nine years old.)

He leaves his plating business and some properties to his eldest son Thomas Davis Edwards, (just shy of 21 years old at the time of his fathers death in 1803) with the business to be run jointly with his widow, Sarah. He mentions his son John, and leaves several properties to him, when he comes of age. He also leaves various properties to his daughters Elizabeth and Mary, ditto. The baptisms for all of these children, including the infant deaths of Sarah and Sarah Ann have been found. All but Mary’s were in the same parish. (I found one for Mary in Sutton Coldfield, which was apparently correct, as a later census also recorded her birth as Sutton Coldfield. She was living with family on that census, so it would appear to be correct that for whatever reason, their daughter Mary was born in Sutton Coldfield)Mary married John Slater in 1813. The witnesses were Elizabeth Whitehouse and John Edwards, her sister and brother. Elizabeth married William Nicklin Whitehouse in 1805 and one of the witnesses was Mary Edwards.

Mary’s husband John Slater died in 1821. They had no children. Mary never remarried, and lived with her bachelor brother Thomas Davis Edwards in West Bromwich. Thomas never married, and on the census he was either a proprietor of houses, or “sinecura” (earning a living without working).With Mary marrying a Slater, does this indicate that her brother John’s first wife was Elizabeth Slater rather than Elizabeth Beach? It is a compelling possibility, but does not constitute proof.

Not only that, there is no absolute proof that the John Edwards who died in 1803 was our ancestor John Edwards father.

If we can’t be sure which Elizabeth married John Edwards, we can be reasonably sure who their daughters married. On both of the marriage records the father is recorded as John Edwards, engineer.

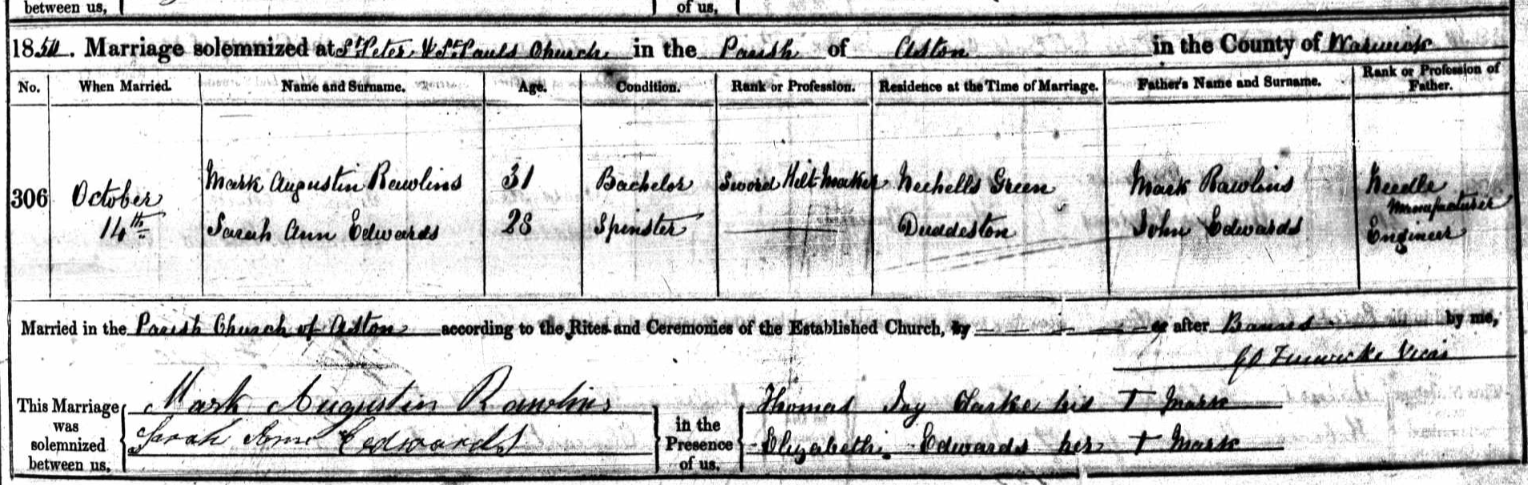

Sarah Ann married Mark Augustin Rawlins in 1850. Mark was a sword hilt maker at the time of the marriage, his father Mark a needle manufacturer. One of the witnesses was Elizabeth Edwards, who signed with her mark. Sarah Ann and Mark however were both able to sign their own names on the register.

Sarah Ann Edwards and Mark Augustin Rawlins marriage 14 October 1850 St Peter and St Paul, Aston, Birmingham:

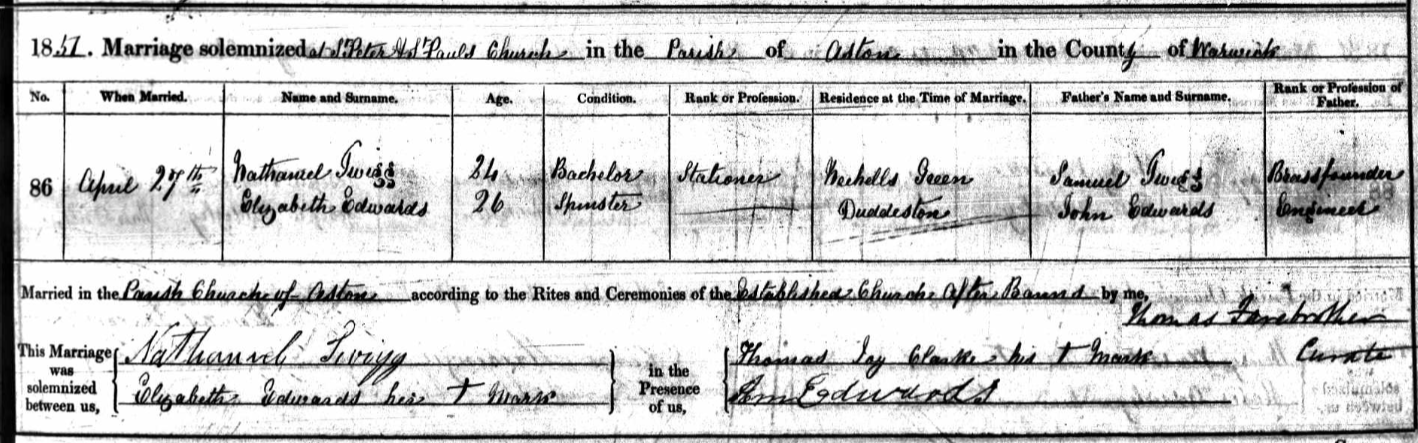

Elizabeth married Nathaniel Twigg in 1851. (She was living with her sister Sarah Ann and Mark Rawlins on the 1851 census, I assume the census was taken before her marriage to Nathaniel on the 27th April 1851.) Nathaniel was a stationer (later on the census a bookseller), his father Samuel a brass founder. Elizabeth signed with her mark, apparently unable to write, and a witness was Ann Edwards. Although Sarah Ann, Elizabeth’s sister, would have been Sarah Ann Rawlins at the time, having married the previous year, she was known as Ann on later censuses. The signature of Ann Edwards looks remarkably similar to Sarah Ann Edwards signature on her own wedding. Perhaps she couldn’t write but had learned how to write her signature for her wedding?

Elizabeth Edwards and Nathaniel Twigg marriage 27 April 1851, St Peter and St Paul, Aston, Birmingham:

Sarah Ann and Mark Rawlins had one daughter and four sons between 1852 and 1859. One of the sons, Edward Rawlins 1857-1931, was a school master and later master of an orphanage.

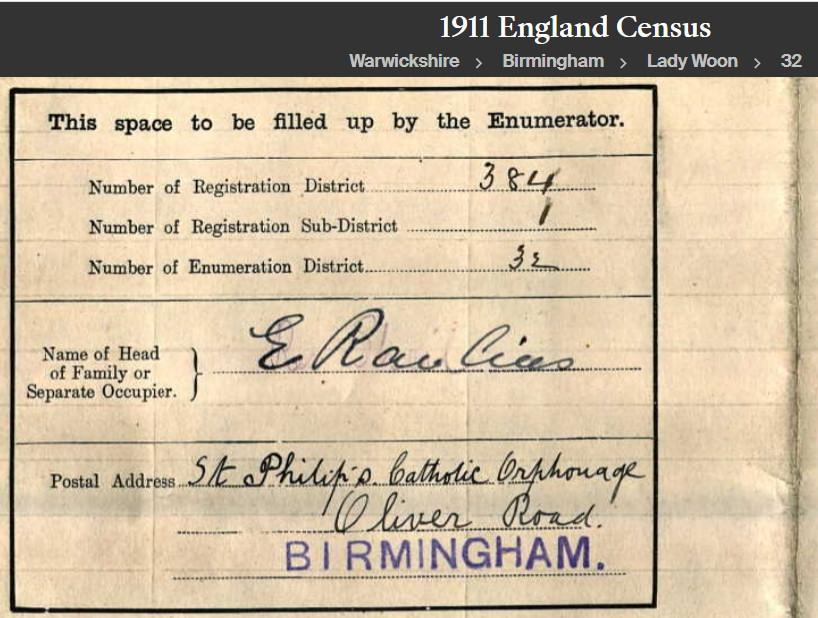

On the 1881 census Edward was a bookseller, in 1891 a stationer, 1901 schoolmaster and his wife Edith was matron, and in 1911 he and Edith were master and matron of St Philip’s Catholic Orphanage on Oliver Road in Birmingham. Edward and Edith did not have any children.

Edward Rawlins, 1911:

Elizabeth and Nathaniel Twigg appear to have had only one son, Arthur Twigg 1862-1943. Arthur was a photographer at 291 Bloomsbury Street, Birmingham. Arthur married Harriet Moseley from Burton on Trent, and they had two daughters, Elizabeth Ann 1897-1954, and Edith 1898-1983. I found a photograph of Edith on her wedding day, with her father Arthur in the picture. Arthur and Harriet also had a son Samuel Arthur, who lived for less than a month, born in 1904. Arthur had mistakenly put this son on the 1911 census stating “less than one month”, but the birth and death of Samuel Arthur Twigg were registered in the same quarter of 1904, and none were found registered for 1911.

Edith Twigg and Leslie A Hancock on their Wedding Day 1925. Arthur Twigg behind the bride. Maybe Elizabeth Ann Twigg seated on the right: (photo found on the ancestry website)

Photographs by Arthur Twigg, 291 Bloomsbury Street, Birmingham:

June 6, 2022 at 9:17 am #6301

June 6, 2022 at 9:17 am #6301In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

The Warrens of Stapenhill

There were so many Warren’s in Stapenhill that it was complicated to work out who was who. I had gone back as far as Samuel Warren marrying Catherine Holland, and this was as far back as my cousin Ian Warren had gone in his research some decades ago as well. The Holland family from Barton under Needwood are particularly interesting, and will be a separate chapter.

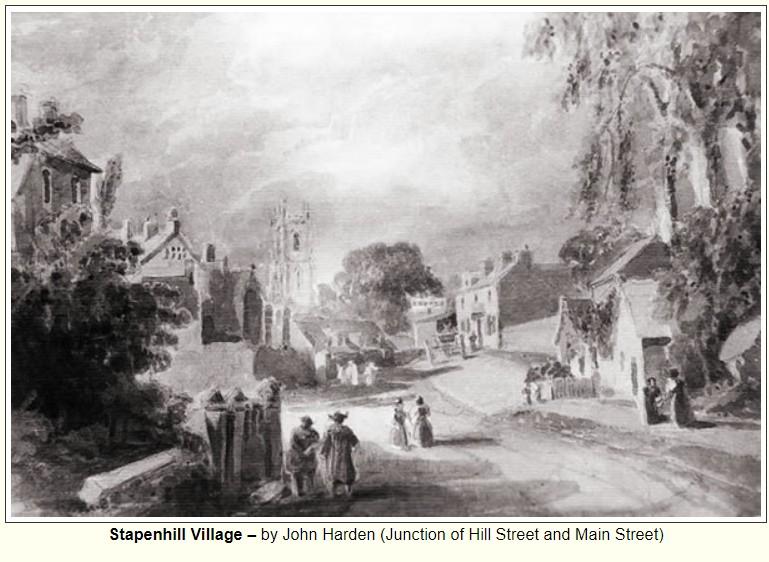

Stapenhill village by John Harden:

Resuming the research on the Warrens, Samuel Warren 1771-1837 married Catherine Holland 1775-1861 in 1795 and their son Samuel Warren 1800-1882 married Elizabeth Bridge, whose childless brother Benjamin Bridge left the Warren Brothers Boiler Works in Newhall to his nephews, the Warren brothers.

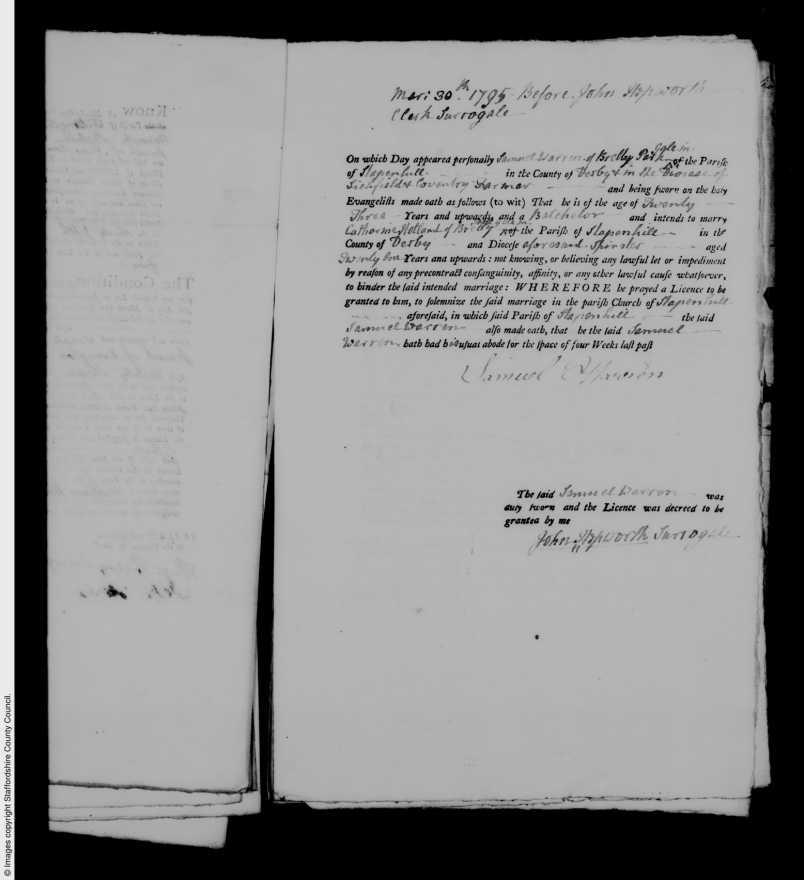

Samuel Warren and Catherine Holland marriage licence 1795:

Samuel (born 1771) was baptised at Stapenhill St Peter and his parents were William and Anne Warren. There were at least three William and Ann Warrens in town at the time. One of those William’s was born in 1744, which would seem to be the right age to be Samuel’s father, and one was born in 1710, which seemed a little too old. Another William, Guiliamos Warren (Latin was often used in early parish registers) was baptised in Stapenhill in 1729.

Stapenhill St Peter:

William Warren (born 1744) appeared to have been born several months before his parents wedding. William Warren and Ann Insley married 16 July 1744, but the baptism of William in 1744 was 24 February. This seemed unusual ~ children were often born less than nine months after a wedding, but not usually before the wedding! Then I remembered the change from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar in 1752. Prior to 1752, the first day of the year was Lady Day, March 25th, not January 1st. This meant that the birth in February 1744 was actually after the wedding in July 1744. Now it made sense. The first son was named William, and he was born seven months after the wedding.

William born in 1744 died intestate in 1822, and his wife Ann made a legal claim to his estate. However he didn’t marry Ann Holland (Ann was Catherines Hollands sister, who married Samuel Warren the year before) until 1796, so this William and Ann were not the parents of Samuel.

It seemed likely that William born in 1744 was Samuels brother. William Warren and Ann Insley had at least eight children between 1744 and 1771, and it seems that Samuel was their last child, born when William the elder was 61 and his wife Ann was 47.

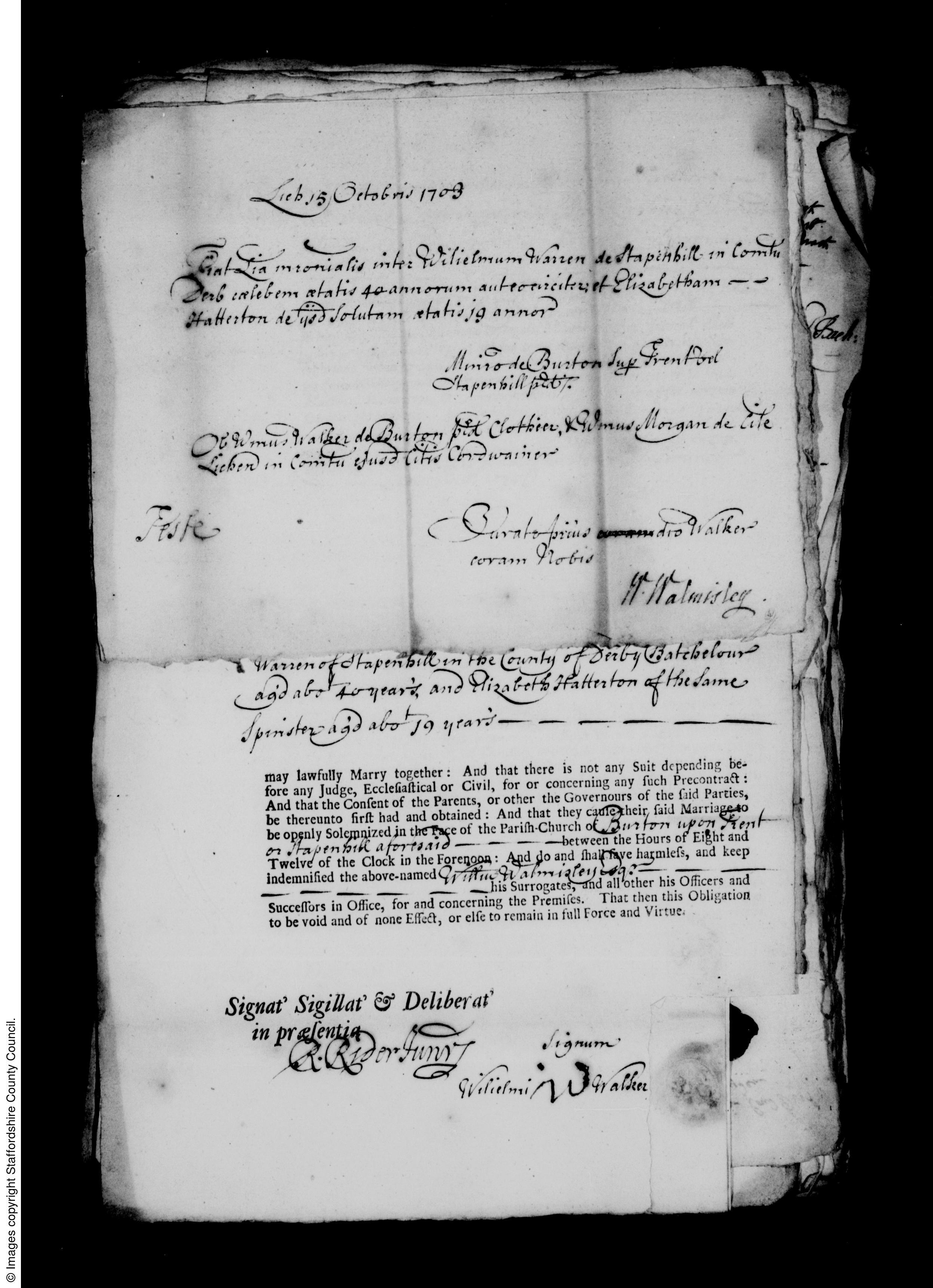

It seems it wasn’t unusual for the Warren men to marry rather late in life. William Warren’s (born 1710) parents were William Warren and Elizabeth Hatterton. On the marriage licence in 1702/1703 (it appears to say 1703 but is transcribed as 1702), William was a 40 year old bachelor from Stapenhill, which puts his date of birth at 1662. Elizabeth was considerably younger, aged 19.

William Warren and Elizabeth Hatterton marriage licence 1703:

These Warren’s were farmers, and they were literate and able to sign their own names on various documents. This is worth noting, as most made the mark of an X.

I found three Warren and Holland marriages. One was Samuel Warren and Catherine Holland in 1795, then William Warren and Ann Holland in 1796. William Warren and Ann Hollands daughter born in 1799 married John Holland in 1824.

Elizabeth Hatterton (wife of William Warren who was born circa 1662) was born in Burton upon Trent in 1685. Her parents were Edward Hatterton 1655-1722, and Sara.

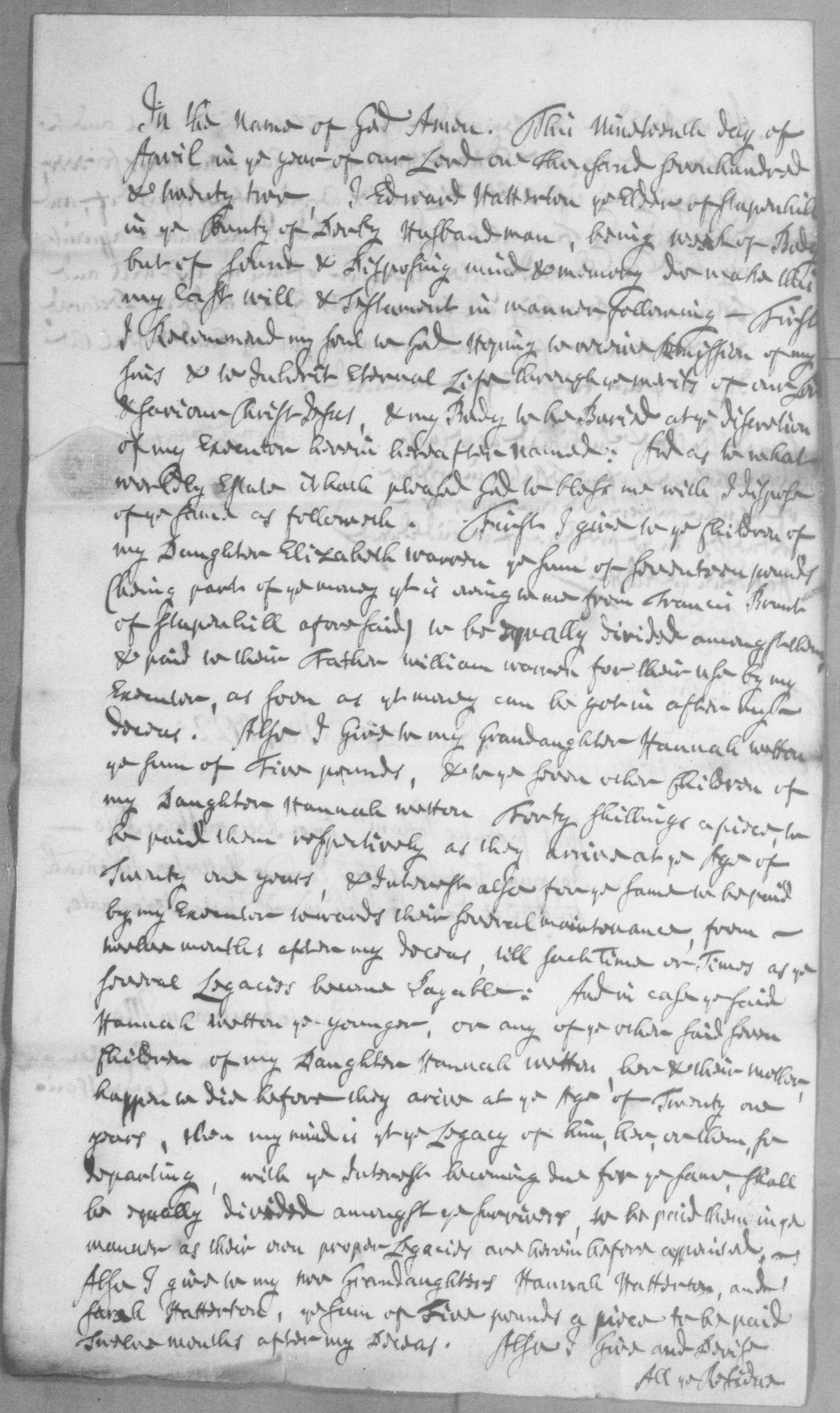

A page from the 1722 will of Edward Hatterton:

The earliest Warren I found records for was William Warren who married Elizabeth Hatterton in 1703. The marriage licence states his age as 40 and that he was from Stapenhill, but none of the Stapenhill parish records online go back as far as 1662. On other public trees on ancestry websites, a birth record from Suffolk has been chosen, probably because it was the only record to be found online with the right name and date. Once again, I don’t think that is correct, and perhaps one day I’ll find some earlier Stapenhill records to prove that he was born in locally.

Subsequently, I found a list of the 1662 Hearth Tax for Stapenhill. On it were a number of Warrens, three William Warrens including one who was a constable. One of those William Warrens had a son he named William (as they did, hence the number of William Warrens in the tree) the same year as this hearth tax list.

But was it the William Warren with 2 chimneys, the one with one chimney who was too poor to pay it, or the one who was a constable?

from the list:

Will. Warryn 2

Richard Warryn 1

William Warren Constable

These names are not payable by Act:

Will. Warryn 1

Richard Warren John Watson

over seers of the poore and churchwardensThe Hearth Tax:

via wiki:

In England, hearth tax, also known as hearth money, chimney tax, or chimney money, was a tax imposed by Parliament in 1662, to support the Royal Household of King Charles II. Following the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, Parliament calculated that the Royal Household needed an annual income of £1,200,000. The hearth tax was a supplemental tax to make up the shortfall. It was considered easier to establish the number of hearths than the number of heads, hearths forming a more stationary subject for taxation than people. This form of taxation was new to England, but had precedents abroad. It generated considerable debate, but was supported by the economist Sir William Petty, and carried through the Commons by the influential West Country member Sir Courtenay Pole, 2nd Baronet (whose enemies nicknamed him “Sir Chimney Poll” as a result). The bill received Royal Assent on 19 May 1662, with the first payment due on 29 September 1662, Michaelmas.

One shilling was liable to be paid for every firehearth or stove, in all dwellings, houses, edifices or lodgings, and was payable at Michaelmas, 29 September and on Lady Day, 25 March. The tax thus amounted to two shillings per hearth or stove per year. The original bill contained a practical shortcoming in that it did not distinguish between owners and occupiers and was potentially a major burden on the poor as there were no exemptions. The bill was subsequently amended so that the tax was paid by the occupier. Further amendments introduced a range of exemptions that ensured that a substantial proportion of the poorer people did not have to pay the tax.Indeed it seems clear that William Warren the elder came from Stapenhill and not Suffolk, and one of the William Warrens paying hearth tax in 1662 was undoubtedly the father of William Warren who married Elizabeth Hatterton.

May 3, 2022 at 4:40 pm #6291In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Jane Eaton

The Nottingham Girl

Jane Eaton 1809-1879

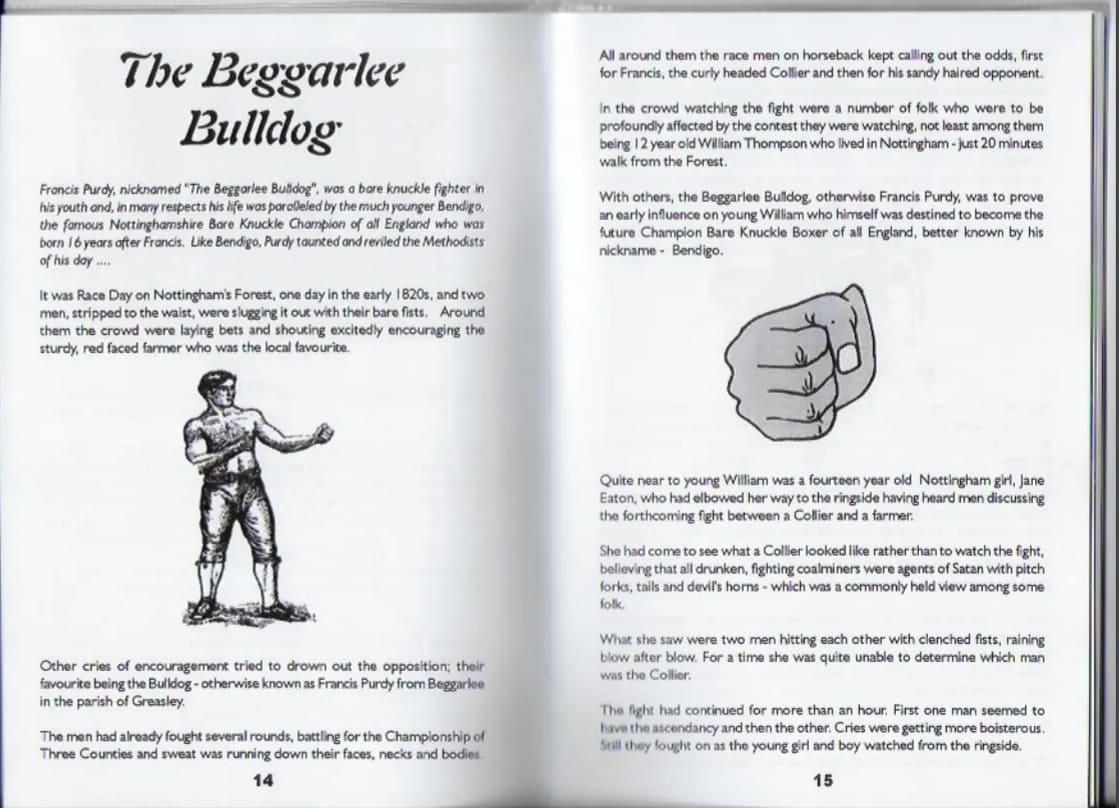

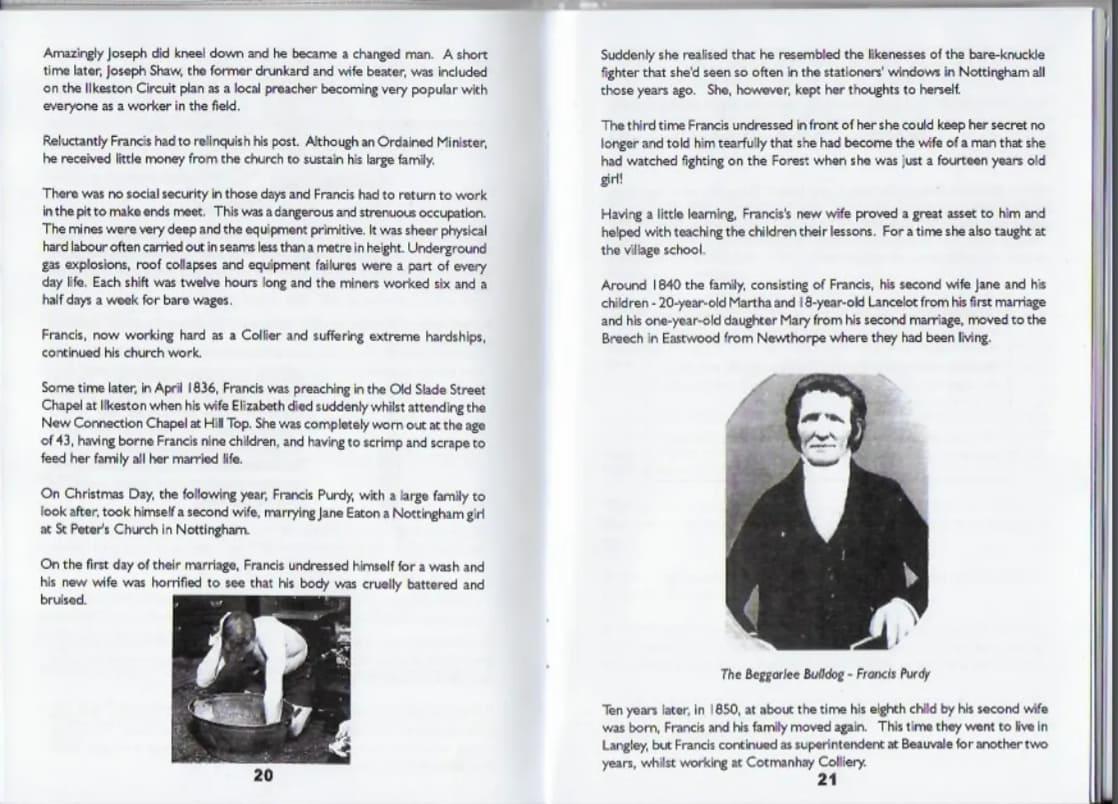

Francis Purdy, the Beggarlea Bulldog and Methodist Minister, married Jane Eaton in 1837 in Nottingham. Jane was his second wife.

Jane Eaton, photo says “Grandma Purdy” on the back:

Jane is described as a “Nottingham girl” in a book excerpt sent to me by Jim Giles, a relation who shares the same 3x great grandparents, Francis and Jane Purdy.

Elizabeth, Francis Purdy’s first wife, died suddenly at chapel in 1836, leaving nine children.

On Christmas day the following year Francis married Jane Eaton at St Peters church in Nottingham. Jane married a Methodist Minister, and didn’t realize she married the bare knuckle fighter she’d seen when she was fourteen until he undressed and she saw his scars.

William Eaton 1767-1851

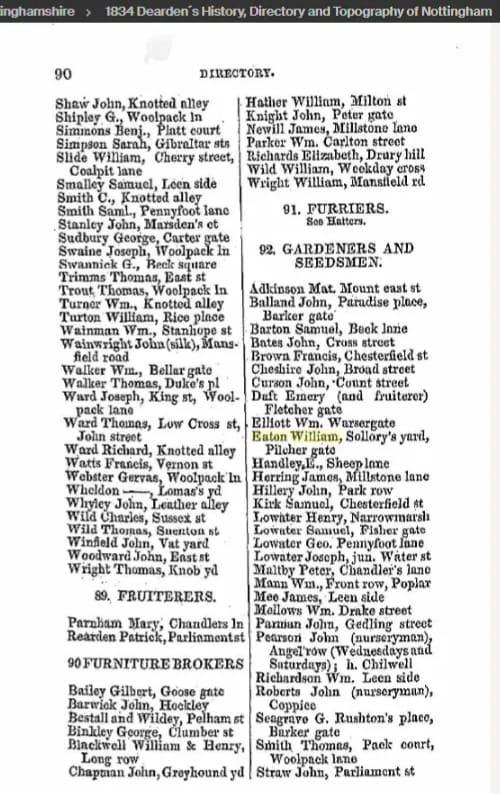

On the marriage certificate Jane’s father was William Eaton, occupation gardener. Francis’s father was William Purdy, engineer.

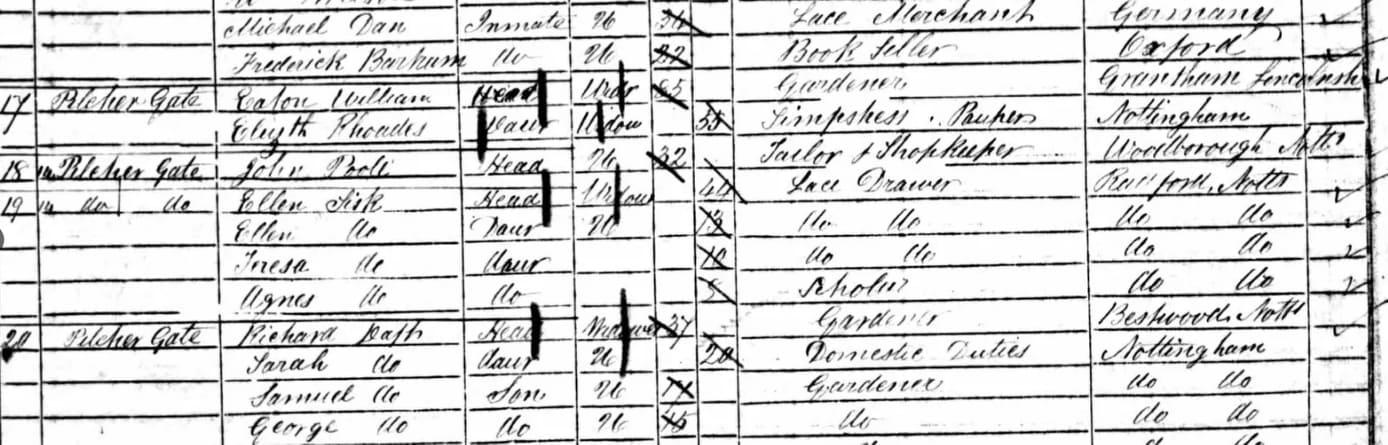

On the 1841 census living in Sollory’s Yard, Nottingham St Mary, William Eaton was a 70 year old gardener. It doesn’t say which county he was born in but indicates that it was not Nottinghamshire. Living with him were Mary Eaton, milliner, age 35, Mary Eaton, milliner, 15, and Elizabeth Rhodes age 35, a sempstress (another word for seamstress). The three women were born in Nottinghamshire.

But who was Elizabeth Rhodes?

Elizabeth Eaton was Jane’s older sister, born in 1797 in Nottingham. She married William Rhodes, a private in the 5th Dragoon Guards, in Leeds in October 1815.

I looked for Elizabeth Rhodes on the 1851 census, which stated that she was a widow. I was also trying to determine which William Eaton death was the right one, and found William Eaton was still living with Elizabeth in 1851 at Pilcher Gate in Nottingham, but his name had been entered backwards: Eaton William. I would not have found him on the 1851 census had I searched for Eaton as a last name.

Pilcher Gate gets its strange name from pilchers or fur dealers and was once a very narrow thoroughfare. At the lower end stood a pub called The Windmill – frequented by the notorious robber and murderer Charlie Peace.

This was a lucky find indeed, because William’s place of birth was listed as Grantham, Lincolnshire. There were a couple of other William Eaton’s born at the same time, both near to Nottingham. It was tricky to work out which was the right one, but as it turned out, neither of them were.

Now we had Nottinghamshire and Lincolnshire border straddlers, so the search moved to the Lincolnshire records.

But first, what of the two Mary Eatons living with William?William and his wife Mary had a daughter Mary in 1799 who died in 1801, and another daughter Mary Ann born in 1803. (It was common to name children after a previous infant who had died.) It seems that Mary Ann didn’t marry but had a daughter Mary Eaton born in 1822.

William and his wife Mary also had a son Richard Eaton born in 1801 in Nottingham.

Who was William Eaton’s wife Mary?

There are two possibilities: Mary Cresswell and a marriage in Nottingham in 1797, or Mary Dewey and a marriage at Grantham in 1795. If it’s Mary Cresswell, the first child Elizabeth would have been born just four or five months after the wedding. (This was far from unusual). However, no births in Grantham, or in Nottingham, were recorded for William and Mary in between 1795 and 1797.

We don’t know why William moved from Grantham to Nottingham or when he moved there. According to Dearden’s 1834 Nottingham directory, William Eaton was a “Gardener and Seedsman”.

There was another William Eaton selling turnip seeds in the same part of Nottingham. At first I thought it must be the same William, but apparently not, as that William Eaton is recorded as a victualler, born in Ruddington. The turnip seeds were advertised in 1847 as being obtainable from William Eaton at the Reindeer Inn, Wheeler Gate. Perhaps he was related.

William lived in the Lace Market part of Nottingham. I wondered where a gardener would be working in that part of the city. According to CreativeQuarter website, “in addition to the trades and housing (sometimes under the same roof), there were a number of splendid mansions being built with extensive gardens and orchards. Sadly, these no longer exist as they were gradually demolished to make way for commerce…..The area around St Mary’s continued to develop as an elegant residential district during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, with buildings … being built for nobility and rich merchants.”

William Eaton died in Nottingham in September 1851, thankfully after the census was taken recording his place of birth.

March 10, 2022 at 7:40 am #6281In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

The Measham Thatchers

Orgills, Finches and Wards

Measham is a large village in north west Leicestershire, England, near the Derbyshire, Staffordshire and Warwickshire boundaries. Our family has a penchant for border straddling, and the Orgill’s of Measham take this a step further living on the boundaries of four counties. Historically it was in an exclave of Derbyshire absorbed into Leicestershire in 1897, so once again we have two sets of county records to search.

ORGILL

Richard Gretton, the baker of Swadlincote and my great grandmother Florence Nightingale Grettons’ father, married Sarah Orgill (1840-1910) in 1861.

(Incidentally, Florence Nightingale Warren nee Gretton’s first child Hildred born in 1900 had the middle name Orgill. Florence’s brother John Orgill Gretton emigrated to USA.)

When they first married, they lived with Sarah’s widowed mother Elizabeth in Measham. Elizabeth Orgill is listed on the 1861 census as a farmer of two acres.

Sarah Orgill’s father Matthew Orgill (1798-1859) was a thatcher, as was his father Matthew Orgill (1771-1852).

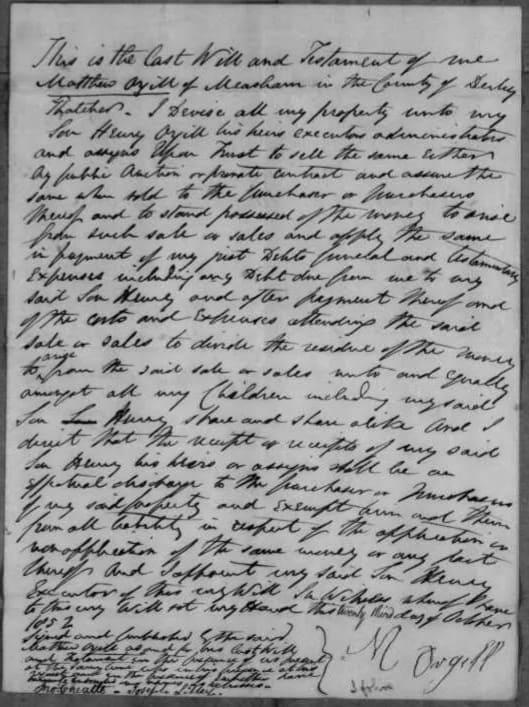

Matthew Orgill the elder left his property to his son Henry:

Sarah’s mother Elizabeth (1803-1876) was also an Orgill before her marriage to Matthew.

According to Pigot & Co’s Commercial Directory for Derbyshire, in Measham in 1835 Elizabeth Orgill was a straw bonnet maker, an ideal occupation for a thatchers wife.

Matthew Orgill, thatcher, is listed in White’s directory in 1857, and other Orgill’s are mentioned in Measham:

Mary Orgill, straw hat maker; Henry Orgill, grocer; Daniel Orgill, painter; another Matthew Orgill is a coal merchant and wheelwright. Likewise a number of Orgill’s are listed in the directories for Measham in the subsequent years, as farmers, plumbers, painters, grocers, thatchers, wheelwrights, coal merchants and straw bonnet makers.

Matthew and Elizabeth Orgill, Measham Baptist church:

According to a history of thatching, for every six or seven thatchers appearing in the 1851 census there are now less than one. Another interesting fact in the history of thatched roofs (via thatchinginfo dot com):

The Watling Street Divide…

The biggest dividing line of all, that between the angular thatching of the Northern and Eastern traditions and the rounded Southern style, still roughly follows a very ancient line; the northern section of the old Roman road of Watling Street, the modern A5. Seemingly of little significance today; this was once the border between two peoples. Agreed in the peace treaty, between the Saxon King Alfred and Guthrum, the Danish Viking leader; over eleven centuries ago.

After making their peace, various Viking armies settled down, to the north and east of the old road; firstly, in what was known as The Danelaw and later in Norse kingdoms, based in York. They quickly formed a class of farmers and peasants. Although the Saxon kings soon regained this area; these people stayed put. Their influence is still seen, for example, in the widespread use of boarded gable ends, so common in Danish thatching.

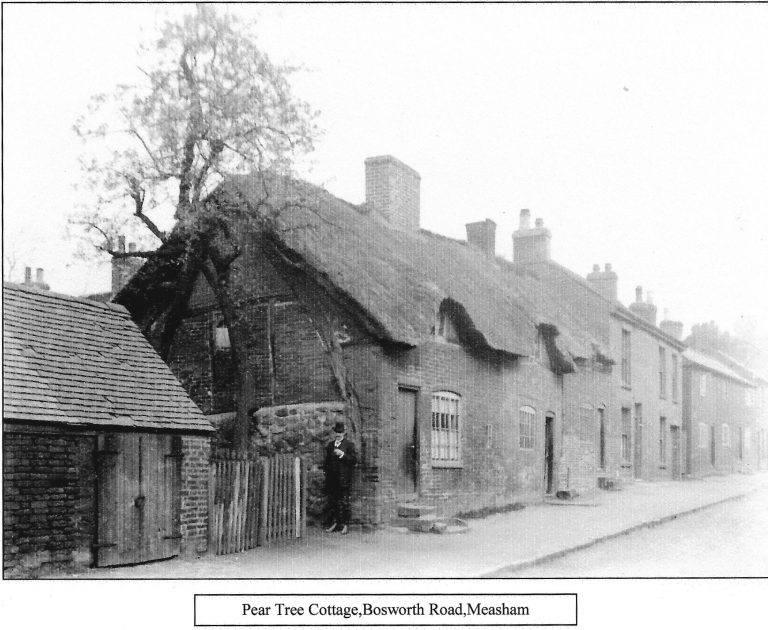

Over time, the Southern and Northern traditions have slipped across the old road, by a few miles either way. But even today, travelling across the old highway will often bring the differing thatching traditions quickly into view.Pear Tree Cottage, Bosworth Road, Measham. 1900. Matthew Orgill was a thatcher living on Bosworth road.

FINCH

Matthew the elder married Frances Finch 1771-1848, also of Measham. On the 1851 census Matthew is an 80 year old thatcher living with his daughter Mary and her husband Samuel Piner, a coal miner.

Henry Finch 1743- and Mary Dennis 1749- , both of Measham, were Frances parents. Henry’s father was also Henry Finch, born in 1707 in Measham, and he married Frances Ward, also born in 1707, and also from Measham.

WARD

The ancient boundary between the kingdom of Mercia and the Danelaw

I didn’t find much information on the history of Measham, but I did find a great deal of ancient history on the nearby village of Appleby Magna, two miles away. The parish records indicate that the Ward and Finch branches of our family date back to the 1500’s in the village, and we can assume that the ancient history of the neighbouring village would be relevant to our history.

There is evidence of human settlement in Appleby from the early Neolithic period, 6,000 years ago, and there are also Iron Age and Bronze Age sites in the vicinity. There is evidence of further activity within the village during the Roman period, including evidence of a villa or farm and a temple. Appleby is near three known Roman roads: Watling Street, 10 miles south of the village; Bath Lane, 5 miles north of the village; and Salt Street, which forms the parish’s south boundary.

But it is the Scandinavian invasions that are particularly intriguing, with regard to my 58% Scandinavian DNA (and virtually 100% Midlands England ancestry). Repton is 13 miles from Measham. In the early 10th century Chilcote, Measham and Willesley were part of the royal Derbyshire estate of Repton.

The arrival of Scandinavian invaders in the second half of the ninth century caused widespread havoc throughout northern England. By the AD 870s the Danish army was occupying Mercia and it spent the winter of 873-74 at Repton, the headquarters of the Mercian kings. The events are recorded in detail in the Peterborough manuscript of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles…

Although the Danes held power for only 40 years, a strong, even subversive, Danish element remained in the population for many years to come.

A Scandinavian influence may also be detected among the field names of the parish. Although many fields have relatively modern names, some clearly have elements which reach back to the time of Danish incursion and control.

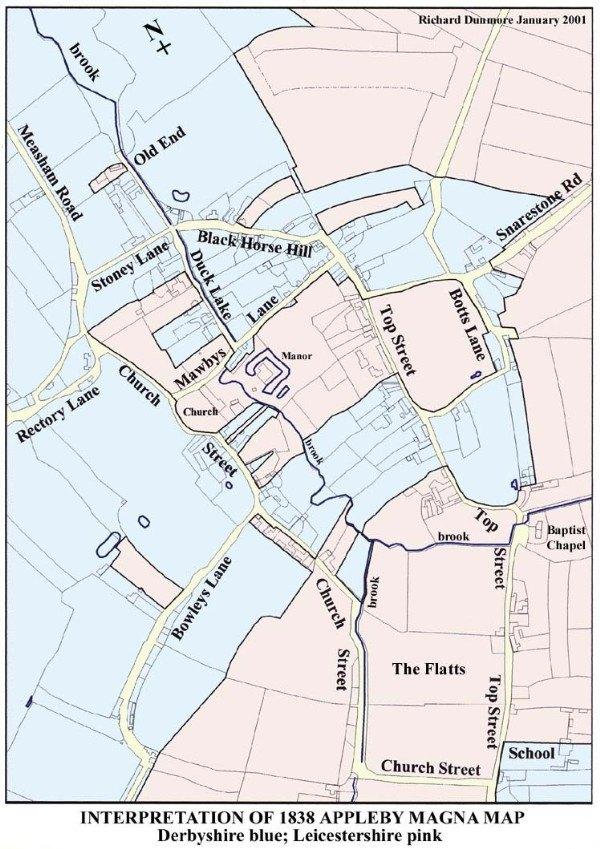

The Borders:

The name ‘aeppel byg’ is given in the will of Wulfic Spot of AD 1004……………..The decision at Domesday to include this land in Derbyshire, as one of Burton Abbey’s Derbyshire manors, resulted in the division of the village of Appleby Magna between the counties of Leicester and Derby for the next 800 years

Richard Dunmore’s Appleby Magma website.

This division of Appleby between Leicestershire and Derbyshire persisted from Domesday until 1897, when the recently created county councils (1889) simplified the administration of many villages in this area by a radical realignment of the boundary:

I would appear that our family not only straddle county borders, but straddle ancient kingdom borders as well. This particular branch of the family (we assume, given the absence of written records that far back) were living on the edge of the Danelaw and a strong element of the Danes survives to this day in my DNA.

February 5, 2022 at 10:50 am #6271In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

The Housley Letters

FRIENDS AND NEIGHBORS

from Barbara Housley’s Narrative on the Letters:

George apparently asked about old friends and acquaintances and the family did their best to answer although Joseph wrote in 1873: “There is very few of your old cronies that I know of knocking about.”

In Anne’s first letter she wrote about a conversation which Robert had with EMMA LYON before his death and added “It (his death) was a great trouble to Lyons.” In her second letter Anne wrote: “Emma Lyon is to be married September 5. I am going the Friday before if all is well. There is every prospect of her being comfortable. MRS. L. always asks after you.” In 1855 Emma wrote: “Emma Lyon now Mrs. Woolhouse has got a fine boy and a pretty fuss is made with him. They call him ALFRED LYON WOOLHOUSE.”

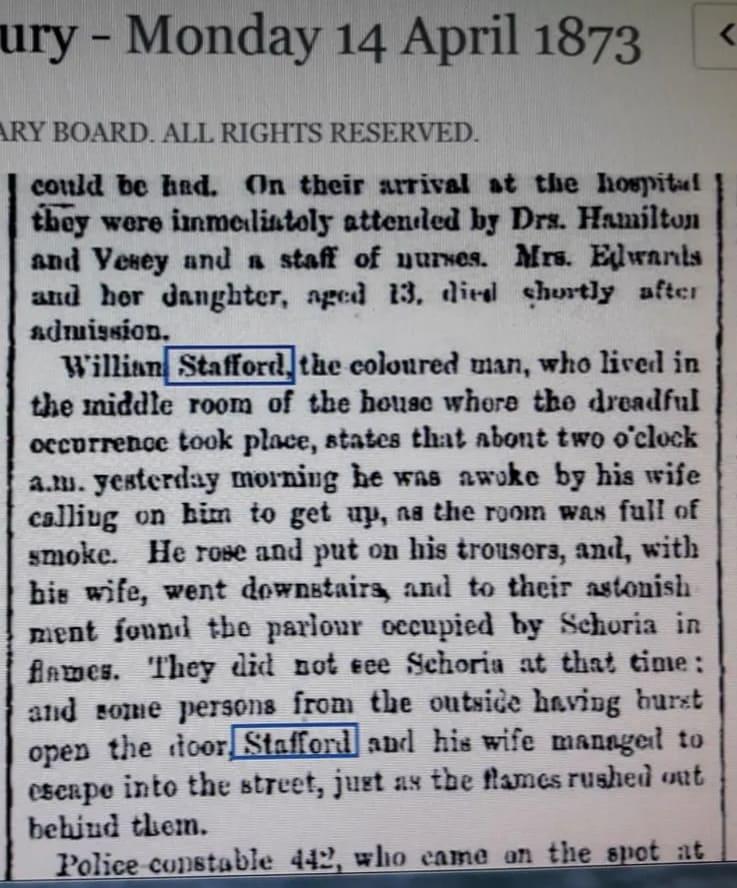

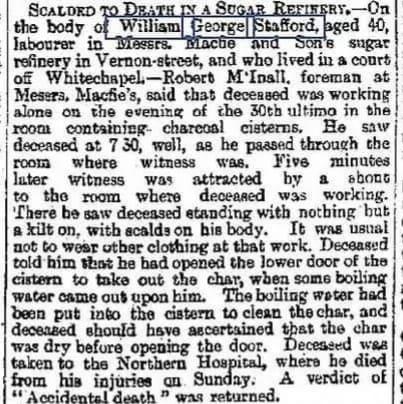

(Interesting to note that Elizabeth Housley, the eldest daughter of Samuel and Elizabeth, was living with a Lyon family in Derby in 1861, after she left Belper workhouse. The Emma listed on the census in 1861 was 10 years old, and so can not be the Emma Lyon mentioned here, but it’s possible, indeed likely, that Peter Lyon the baker was related to the Lyon’s who were friends of the Housley’s. The mention of a sea captain in the Lyon family begs the question did Elizabeth Housley meet her husband, George William Stafford, a seaman, through some Lyon connections, but to date this remains a mystery.)

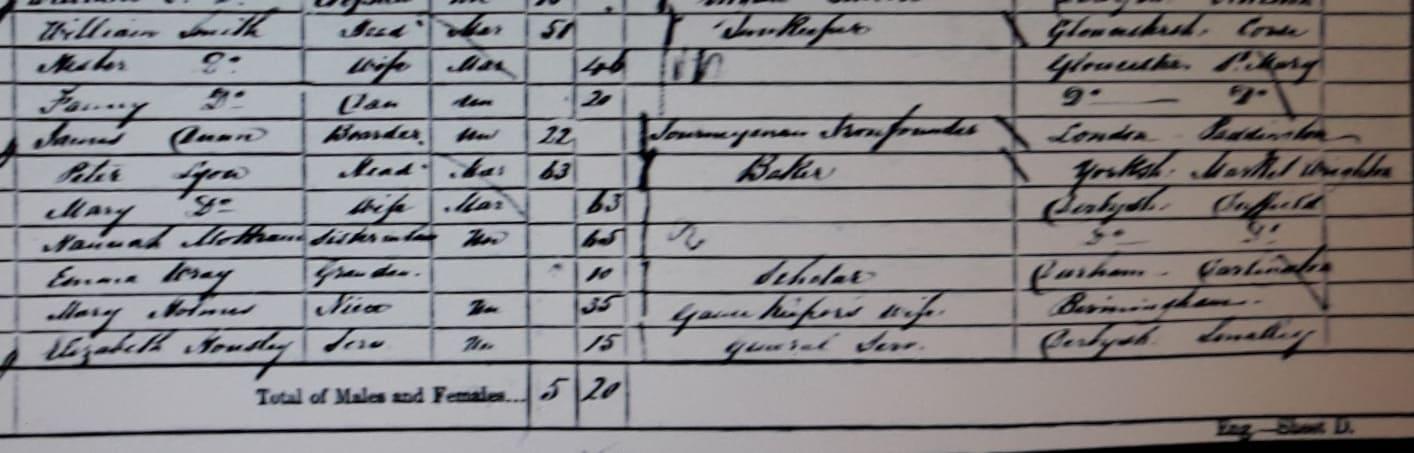

Elizabeth Housley living with Peter Lyon and family in Derby St Peters in 1861:

A Henrietta Lyon was married in 1860. Her father was Matthew, a Navy Captain. The 1857 Derby Directory listed a Richard Woolhouse, plumber, glazier, and gas fitter on St. Peter’s Street. Robert lived in St. Peter’s parish at the time of his death. An Alfred Lyon, son of Alfred and Jemima Lyon 93 Friargate, Derby was baptised on December 4, 1877. An Allen Hewley Lyon, born February 1, 1879 was baptised June 17 1879.

Anne wrote in August 1854: “KERRY was married three weeks since to ELIZABETH EATON. He has left Smith some time.” Perhaps this was the same person referred to by Joseph: “BILL KERRY, the blacksmith for DANIEL SMITH, is working for John Fletcher lace manufacturer.” According to the 1841 census, Elizabeth age 12, was the oldest daughter of Thomas and Rebecca Eaton. She would certainly have been of marriagable age in 1854. A William Kerry, age 14, was listed as a blacksmith’s apprentice in the 1851 census; but another William Kerry who was 29 in 1851 was already working for Daniel Smith as a blacksmith. REBECCA EATON was listed in the 1851 census as a widow serving as a nurse in the John Housley household. The 1881 census lists the family of William Kerry, blacksmith, as Jane, 19; William 13; Anne, 7; and Joseph, 4. Elizabeth is not mentioned but Bill is not listed as a widower.

Anne also wrote in 1854 that she had not seen or heard anything of DICK HANSON for two years. Joseph wrote that he did not know Old BETTY HANSON’S son. A Richard Hanson, age 24 in 1851, lived with a family named Moore. His occupation was listed as “journeyman knitter.” An Elizabeth Hanson listed as 24 in 1851 could hardly be “Old Betty.” Emma wrote in June 1856 that JOE OLDKNOW age 27 had married Mrs. Gribble’s servant age 17.

Anne wrote that “JOHN SPENCER had not been since father died.” The only John Spencer in Smalley in 1841 was four years old. He would have been 11 at the time of William Housley’s death. Certainly, the two could have been friends, but perhaps young John was named for his grandfather who was a crony of William’s living in a locality not included in the Smalley census.

TAILOR ALLEN had lost his wife and was still living in the old house in 1872. JACK WHITE had died very suddenly, and DR. BODEN had died also. Dr. Boden’s first name was Robert. He was 53 in 1851, and was probably the Robert, son of Richard and Jane, who was christened in Morely in 1797. By 1861, he had married Catherine, a native of Smalley, who was at least 14 years his junior–18 according to the 1871 census!

Among the family’s dearest friends were JOSEPH AND ELIZABETH DAVY, who were married some time after 1841. Mrs. Davy was born in 1812 and her husband in 1805. In 1841, the Kidsley Park farm household included DANIEL SMITH 72, Elizabeth 29 and 5 year old Hannah Smith. In 1851, Mr. Davy’s brother William and 10 year old Emma Davy were visiting from London. Joseph reported the death of both Davy brothers in 1872; Joseph apparently died first.

Mrs. Davy’s father, was a well known Quaker. In 1856, Emma wrote: “Mr. Smith is very hearty and looks much the same.” He died in December 1863 at the age of 94. George Fox, the founder of the Quakers visited Kidsley Park in 1650 and 1654.

Mr. Davy died in 1863, but in 1854 Anne wrote how ill he had been for two years. “For two last winters we never thought he would live. He is now able to go out a little on the pony.” In March 1856, his wife wrote, “My husband is in poor health and fell.” Later in 1856, Emma wrote, “Mr. Davy is living which is a great wonder. Mrs. Davy is very delicate but as good a friend as ever.”

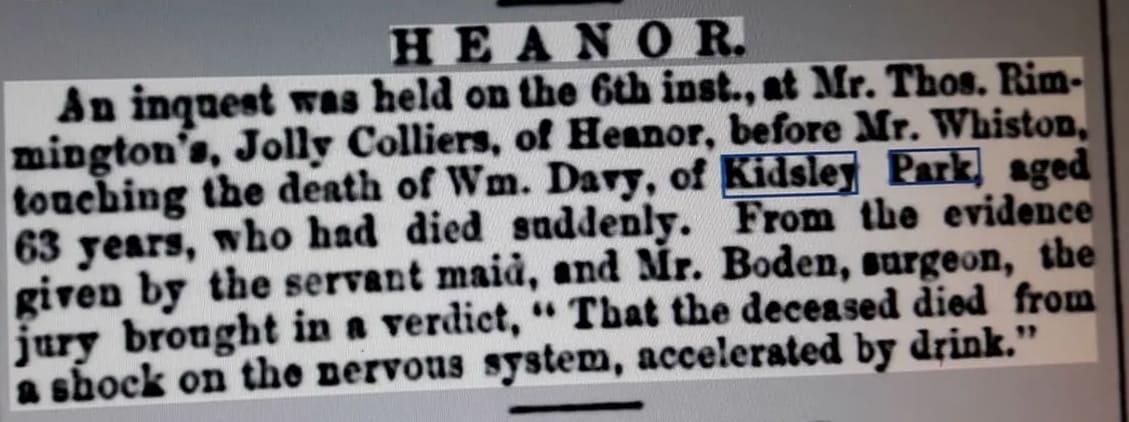

In The Derbyshire Advertiser and Journal, 15 May 1863:

Whenever the girls sent greetings from Mrs. Davy they used her Quaker speech pattern of “thee and thy.” Mrs. Davy wrote to George on March 21 1856 sending some gifts from his sisters and a portrait of their mother–“Emma is away yet and A is so much worse.” Mrs. Davy concluded: “With best wishes for thy health and prosperity in this world and the next I am thy sincere friend.”

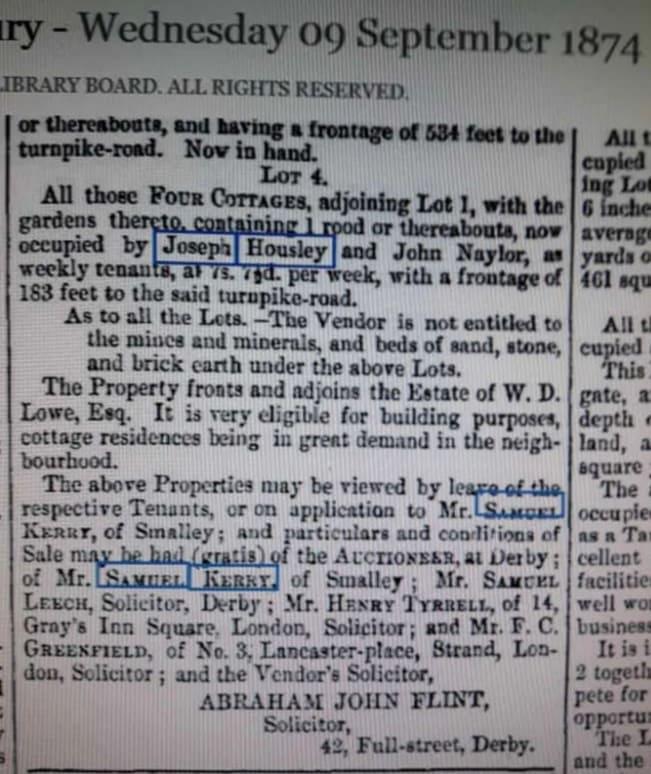

Mrs. Davy later remarried. Her new husband was W.T. BARBER. The 1861 census lists William Barber, 35, Bachelor of Arts, Cambridge, living with his 82 year old widowed mother on an 135 acre farm with three servants. One of these may have been the Ann who, according to Joseph, married Jack Oldknow. By 1871 the farm, now occupied by William, 47 and Elizabeth, 57, had grown to 189 acres. Meanwhile, Kidsley Park Farm became the home of the Housleys’ cousin Selina Carrington and her husband Walker Martin. Both Barbers were still living in 1881.

Mrs. Davy was described in Kerry’s History of Smalley as “an accomplished and exemplary lady.” A piece of her poetry “Farewell to Kidsley Park” was published in the history. It was probably written when Elizabeth moved to the Barber farm. Emma sent one of her poems to George. It was supposed to be about their house. “We have sent you a piece of poetry that Mrs. Davy composed about our ‘Old House.’ I am sure you will like it though you may not understand all the allusions she makes use of as well as we do.”

Kiddsley Park Farm, Smalley, in 1898. (note that the Housley’s lived at Kiddsley Grange Farm, and the Davy’s at neighbouring Kiddsley Park Farm)

Emma was not sure if George wanted to hear the local gossip (“I don’t know whether such little particulars will interest you”), but shared it anyway. In November 1855: “We have let the house to Mr. Gribble. I dare say you know who he married, Matilda Else. They came from Lincoln here in March. Mrs. Gribble gets drunk nearly every day and there are such goings on it is really shameful. So you may be sure we have not very pleasant neighbors but we have very little to do with them.”

John Else and his wife Hannah and their children John and Harriet (who were born in Smalley) lived in Tag Hill in 1851. With them lived a granddaughter Matilda Gribble age 3 who was born in Lincoln. A Matilda, daughter of John and Hannah, was christened in 1815. (A Sam Else died when he fell down the steps of a bar in 1855.)

February 4, 2022 at 3:17 pm #6269In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

The Housley Letters

From Barbara Housley’s Narrative on the Letters.

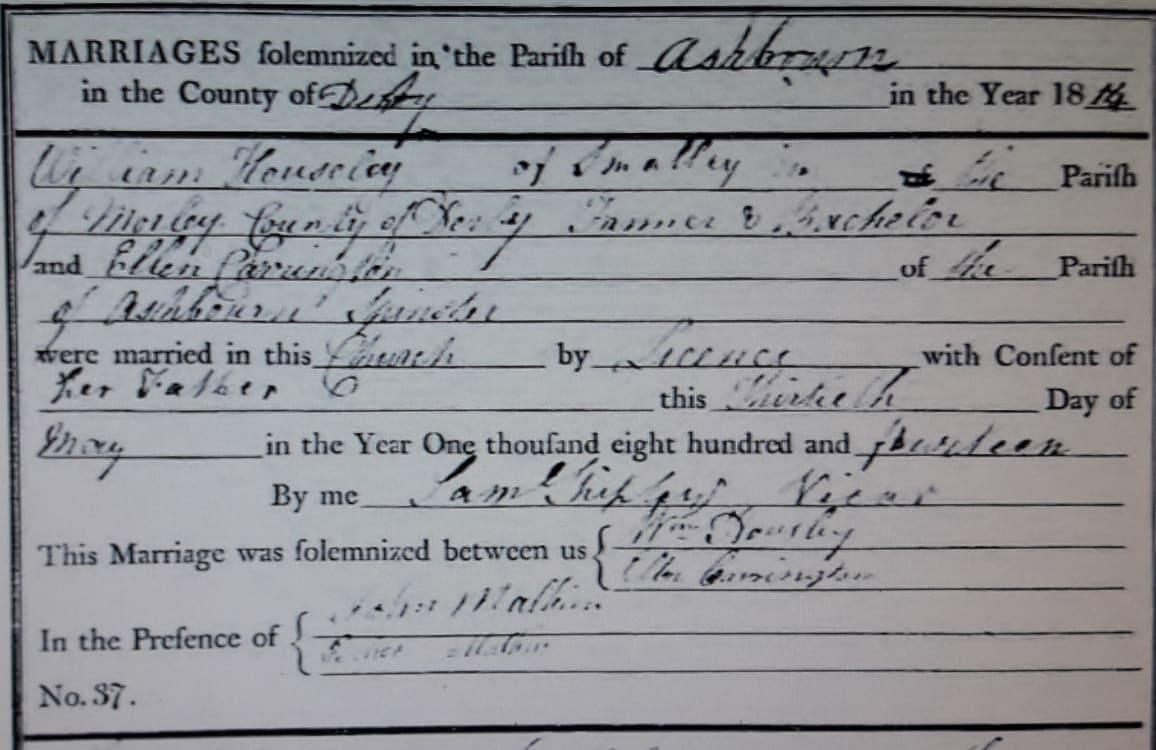

William Housley (1781-1848) and Ellen Carrington were married on May 30, 1814 at St. Oswald’s church in Ashbourne. William died in 1848 at the age of 67 of “disease of lungs and general debility”. Ellen died in 1872.

Marriage of William Housley and Ellen Carrington in Ashbourne in 1814:

Parish records show three children for William and his first wife, Mary, Ellens’ sister, who were married December 29, 1806: Mary Ann, christened in 1808 and mentioned frequently in the letters; Elizabeth, christened in 1810, but never mentioned in any letters; and William, born in 1812, probably referred to as Will in the letters. Mary died in 1813.

William and Ellen had ten children: John, Samuel, Edward, Anne, Charles, George, Joseph, Robert, Emma, and Joseph. The first Joseph died at the age of four, and the last son was also named Joseph. Anne never married, Charles emigrated to Australia in 1851, and George to USA, also in 1851. The letters are to George, from his sisters and brothers in England.

The following are excerpts of those letters, including excerpts of Barbara Housley’s “Narrative on Historic Letters”. They are grouped according to who they refer to, rather than chronological order.

ELLEN HOUSLEY 1795-1872

Joseph wrote that when Emma was married, Ellen “broke up the comfortable home and the things went to Derby and she went to live with them but Derby didn’t agree with her so she left again leaving her things behind and came to live with John in the new house where she died.” Ellen was listed with John’s household in the 1871 census.

In May 1872, the Ilkeston Pioneer carried this notice: “Mr. Hopkins will sell by auction on Saturday next the eleventh of May 1872 the whole of the useful furniture, sewing machine, etc. nearly new on the premises of the late Mrs. Housley at Smalley near Heanor in the county of Derby. Sale at one o’clock in the afternoon.”Ellen’s family was evidently rather prominant in Smalley. Two Carringtons (John and William) served on the Parish Council in 1794. Parish records are full of Carrington marriages and christenings; census records confirm many of the family groupings.

In June of 1856, Emma wrote: “Mother looks as well as ever and was told by a lady the other day that she looked handsome.” Later she wrote: “Mother is as stout as ever although she sometimes complains of not being able to do as she used to.”

Mary’s children:

MARY ANN HOUSLEY 1808-1878

There were hard feelings between Mary Ann and Ellen and her children. Anne wrote: “If you remember we were not very friendly when you left. They never came and nothing was too bad for Mary Ann to say of Mother and me, but when Robert died Mother sent for her to the funeral but she did not think well to come so we took no more notice. She would not allow her children to come either.”

Mary Ann was unlucky in love! In Anne’s second letter she wrote: “William Carrington is paying Mary Ann great attention. He is living in London but they write to each other….We expect it will be a match.” Apparantly the courtship was stormy for in 1855, Emma wrote: “Mary Ann’s wedding with William Carrington has dropped through after she had prepared everything, dresses and all for the occassion.” Then in 1856, Emma wrote: “William Carrington and Mary Ann are separated. They wore him out with their nonsense.” Whether they ever married is unclear. Joseph wrote in 1872: “Mary Ann was married but her husband has left her. She is in very poor health. She has one daughter and they are living with their mother at Smalley.”

Regarding William Carrington, Emma supplied this bit of news: “His sister, Mrs. Lily, has eloped with a married man. Is she not a nice person!”

WILLIAM HOUSLEY JR. 1812-1890

According to a letter from Anne, Will’s two sons and daughter were sent to learn dancing so they would be “fit for any society.” Will’s wife was Dorothy Palfry. They were married in Denby on October 20, 1836 when Will was 24. According to the 1851 census, Will and Dorothy had three sons: Alfred 14, Edwin 12, and William 10. All three boys were born in Denby.

In his letter of May 30, 1872, after just bemoaning that all of his brothers and sisters are gone except Sam and John, Joseph added: “Will is living still.” In another 1872 letter Joseph wrote, “Will is living at Heanor yet and carrying on his cattle dealing.” The 1871 census listed Will, 59, and his son William, 30, of Lascoe Road, Heanor, as cattle dealers.

Ellen’s children:

JOHN HOUSLEY 1815-1893

John married Sarah Baggally in Morely in 1838. They had at least six children. Elizabeth (born 2 May 1838) was “out service” in 1854. In her “third year out,” Elizabeth was described by Anne as “a very nice steady girl but quite a woman in appearance.” One of her positions was with a Mrs. Frearson in Heanor. Emma wrote in 1856: “Elizabeth is still at Mrs. Frearson. She is such a fine stout girl you would not know her.” Joseph wrote in 1872 that Elizabeth was in service with Mrs. Eliza Sitwell at Derby. (About 1850, Miss Eliza Wilmot-Sitwell provided for a small porch with a handsome Norman doorway at the west end of the St. John the Baptist parish church in Smalley.)

According to Elizabeth’s birth certificate and the 1841 census, John was a butcher. By 1851, the household included a nurse and a servant, and John was listed as a “victular.” Anne wrote in February 1854, “John has left the Public House a year and a half ago. He is living where Plumbs (Ann Plumb witnessed William’s death certificate with her mark) did and Thomas Allen has the land. He has been working at James Eley’s all winter.” In 1861, Ellen lived with John and Sarah and the three boys.

John sold his share in the inheritance from their mother and disappeared after her death. (He died in Doncaster, Yorkshire, in 1893.) At that time Charles, the youngest would have been 21. Indeed, Joseph wrote in July 1872: “John’s children are all grown up”.

In May 1872, Joseph wrote: “For what do you think, John has sold his share and he has acted very bad since his wife died and at the same time he sold all his furniture. You may guess I have never seen him but once since poor mother’s funeral and he is gone now no one knows where.”

In February 1874 Joseph wrote: “You want to know what made John go away. Well, I will give you one reason. I think I told you that when his wife died he persuaded me to leave Derby and come to live with him. Well so we did and dear Harriet to keep his house. Well he insulted my wife and offered things to her that was not proper and my dear wife had the power to resist his unmanly conduct. I did not think he could of served me such a dirty trick so that is one thing dear brother. He could not look me in the face when we met. Then after we left him he got a woman in the house and I suppose they lived as man and wife. She caught the small pox and died and there he was by himself like some wild man. Well dear brother I could not go to him again after he had served me and mine as he had and I believe he was greatly in debt too so that he sold his share out of the property and when he received the money at Belper he went away and has never been seen by any of us since but I have heard of him being at Sheffield enquiring for Sam Caldwell. You will remember him. He worked in the Nag’s Head yard but I have heard nothing no more of him.”

A mention of a John Housley of Heanor in the Nottinghma Journal 1875. I don’t know for sure if the John mentioned here is the brother John who Joseph describes above as behaving improperly to his wife. John Housley had a son Joseph, born in 1840, and John’s wife Sarah died in 1870.

In 1876, the solicitor wrote to George: “Have you heard of John Housley? He is entitled to Robert’s share and I want him to claim it.”

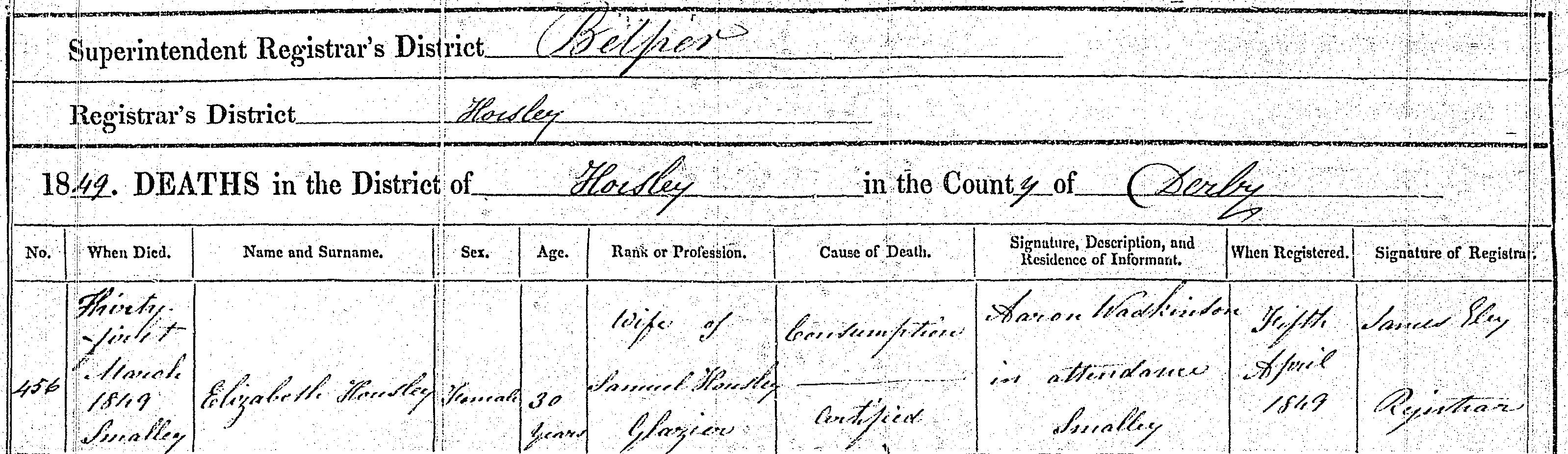

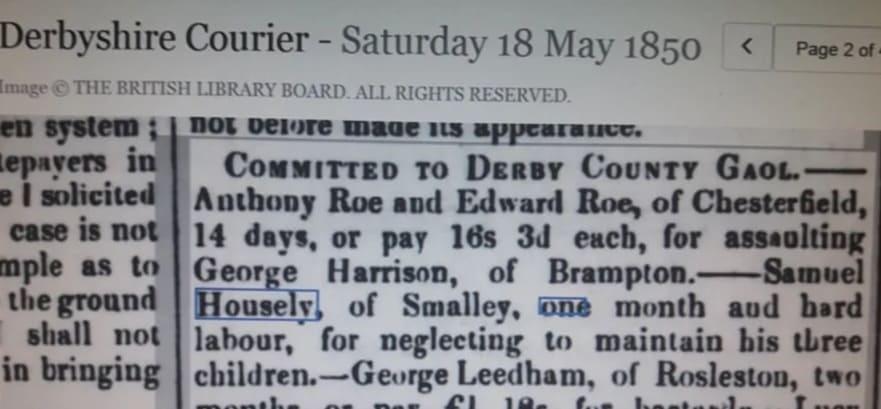

SAMUEL HOUSLEY 1816-

Sam married Elizabeth Brookes of Sutton Coldfield, and they had three daughters: Elizabeth, Mary Anne and Catherine. Elizabeth his wife died in 1849, a few months after Samuel’s father William died in 1848. The particular circumstances relating to these individuals have been discussed in previous chapters; the following are letter excerpts relating to them.

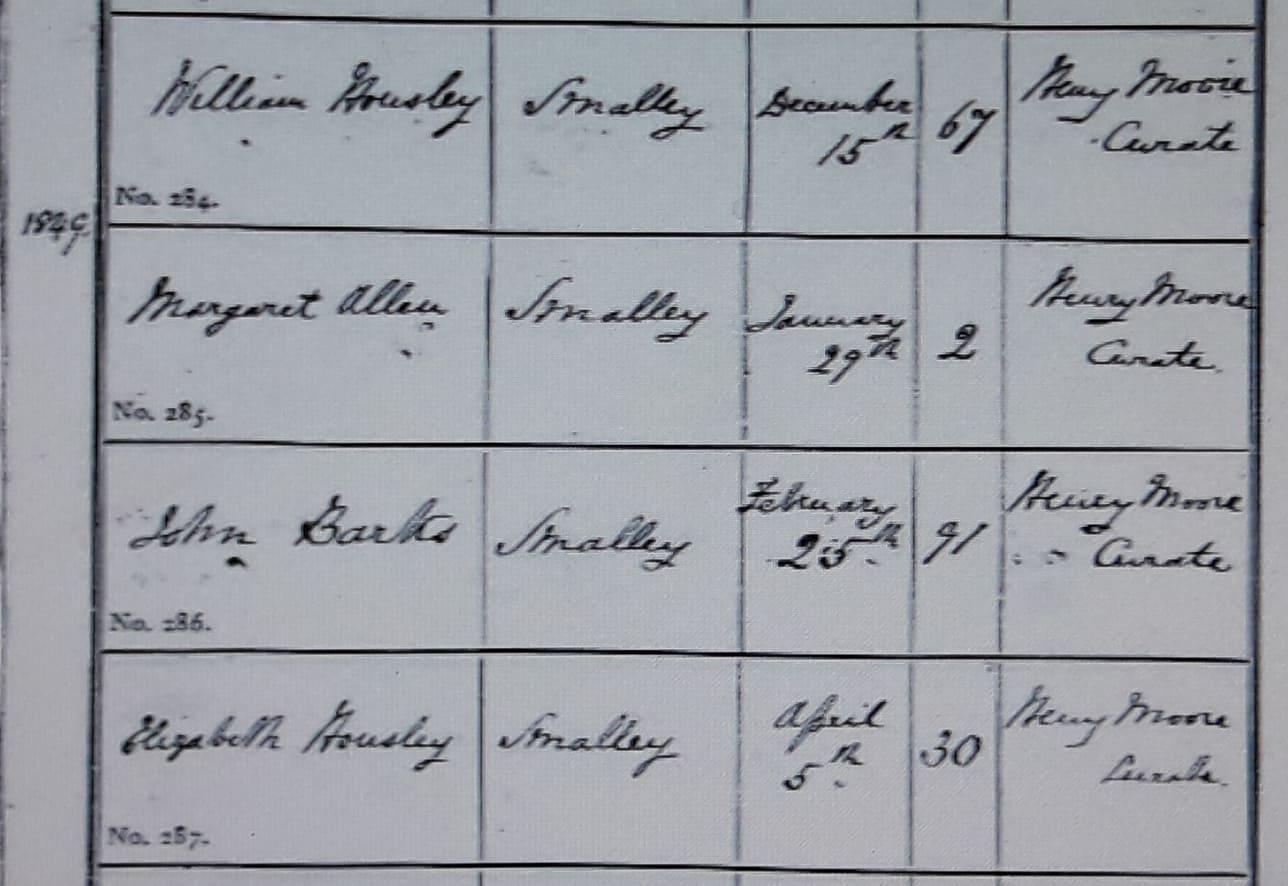

Death of William Housley 15 Dec 1848, and Elizabeth Housley 5 April 1849, Smalley:

Joseph wrote in December 1872: “I saw one of Sam’s daughters, the youngest Kate, you would remember her a baby I dare say. She is very comfortably married.”

In the same letter (December 15, 1872), Joseph wrote: “I think we have now found all out now that is concerned in the matter for there was only Sam that we did not know his whereabouts but I was informed a week ago that he is dead–died about three years ago in Birmingham Union. Poor Sam. He ought to have come to a better end than that….His daughter and her husband went to Brimingham and also to Sutton Coldfield that is where he married his wife from and found out his wife’s brother. It appears he has been there and at Birmingham ever since he went away but ever fond of drink.”

(Sam, however, was still alive in 1871, living as a lodger at the George and Dragon Inn, Henley in Arden. And no trace of Sam has been found since. It would appear that Sam did not want to be found.)

EDWARD HOUSLEY 1819-1843

Edward died before George left for USA in 1851, and as such there is no mention of him in the letters.

ANNE HOUSLEY 1821-1856

Anne wrote two letters to her brother George between February 1854 and her death in 1856. Apparently she suffered from a lung disease for she wrote: “I can say you will be surprised I am still living and better but still cough and spit a deal. Can do nothing but sit and sew.” According to the 1851 census, Anne, then 29, was a seamstress. Their friend, Mrs. Davy, wrote in March 1856: “This I send in a box to my Brother….The pincushion cover and pen wiper are Anne’s work–are for thy wife. She would have made it up had she been able.” Anne was not living at home at the time of the 1841 census. She would have been 19 or 20 and perhaps was “out service.”

In her second letter Anne wrote: “It is a great trouble now for me to write…as the body weakens so does the mind often. I have been very weak all summer. That I continue is a wonder to all and to spit so much although much better than when you left home.” She also wrote: “You know I had a desire for America years ago. Were I in health and strength, it would be the land of my adoption.”

In November 1855, Emma wrote, “Anne has been very ill all summer and has not been able to write or do anything.” Their neighbor Mrs. Davy wrote on March 21, 1856: “I fear Anne will not be long without a change.” In a black-edged letter the following June, Emma wrote: “I need not tell you how happy she was and how calmly and peacefully she died. She only kept in bed two days.”

Certainly Anne was a woman of deep faith and strong religious convictions. When she wrote that they were hoping to hear of Charles’ success on the gold fields she added: “But I would rather hear of him having sought and found the Pearl of great price than all the gold Australia can produce, (For what shall it profit a man if he gain the whole world and lose his soul?).” Then she asked George: “I should like to learn how it was you were first led to seek pardon and a savior. I do feel truly rejoiced to hear you have been led to seek and find this Pearl through the workings of the Holy Spirit and I do pray that He who has begun this good work in each of us may fulfill it and carry it on even unto the end and I can never doubt the willingness of Jesus who laid down his life for us. He who said whoever that cometh unto me I will in no wise cast out.”

Anne’s will was probated October 14, 1856. Mr. William Davy of Kidsley Park appeared for the family. Her estate was valued at under £20. Emma was to receive fancy needlework, a four post bedstead, feather bed and bedding, a mahogany chest of drawers, plates, linen and china. Emma was also to receive Anne’s writing desk. There was a condition that Ellen would have use of these items until her death.

The money that Anne was to receive from her grandfather, William Carrington, and her father, William Housley was to be distributed one third to Joseph, one third to Emma, and one third to be divided between her four neices: John’s daughter Elizabeth, 18, and Sam’s daughters Elizabeth, 10, Mary Ann, 9 and Catharine, age 7 to be paid by the trustees as they think “most useful and proper.” Emma Lyon and Elizabeth Davy were the witnesses.

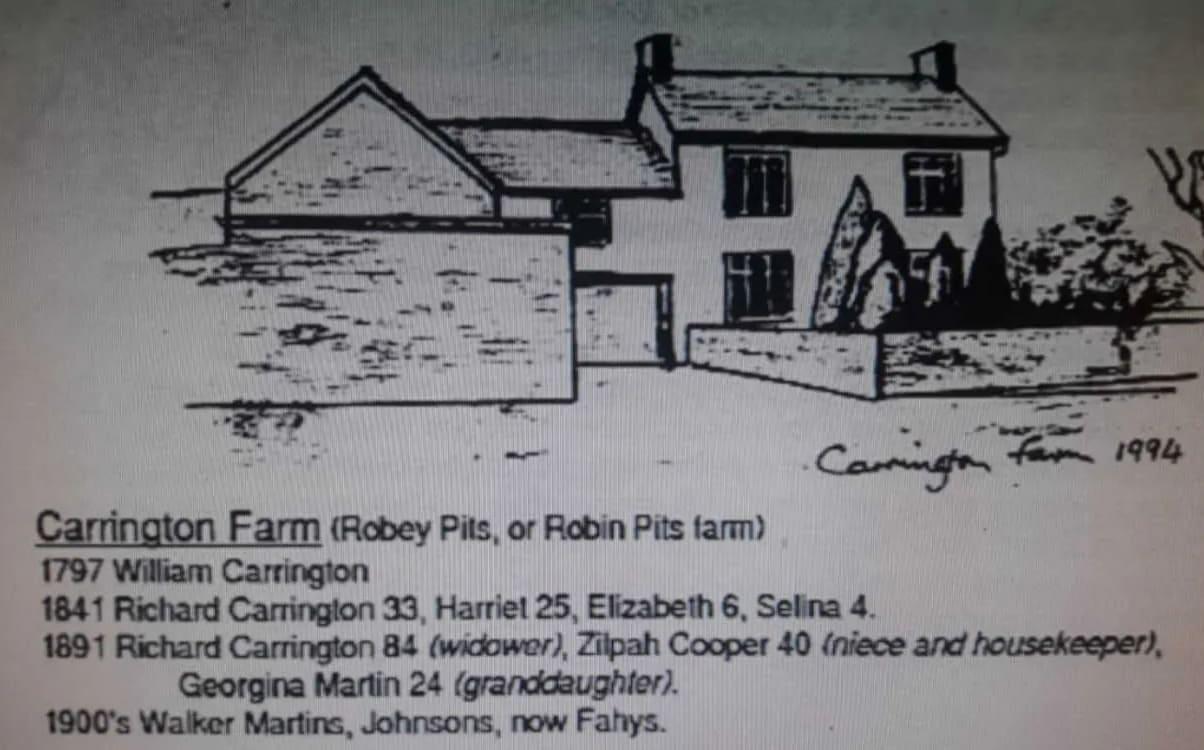

The Carrington Farm:

CHARLES HOUSLEY 1823-1855

Charles went to Australia in 1851, and was last heard from in January 1853. According to the solicitor, who wrote to George on June 3, 1874, Charles had received advances on the settlement of their parent’s estate. “Your promissory note with the two signed by your brother Charles for 20 pounds he received from his father and 20 pounds he received from his mother are now in the possession of the court.”

Charles and George were probably quite close friends. Anne wrote in 1854: “Charles inquired very particularly in both his letters after you.”

According to Anne, Charles and a friend married two sisters. He and his father-in-law had a farm where they had 130 cows and 60 pigs. Whatever the trade he learned in England, he never worked at it once he reached Australia. While it does not seem that Charles went to Australia because gold had been discovered there, he was soon caught up in “gold fever”. Anne wrote: “I dare say you have heard of the immense gold fields of Australia discovered about the time he went. Thousands have since then emigrated to Australia, both high and low. Such accounts we heard in the papers of people amassing fortunes we could not believe. I asked him when I wrote if it was true. He said this was no exaggeration for people were making their fortune daily and he intended going to the diggings in six weeks for he could stay away no longer so that we are hoping to hear of his success if he is alive.”

In March 1856, Mrs. Davy wrote: “I am sorry to tell thee they have had a letter from Charles’s wife giving account of Charles’s death of 6 months consumption at the Victoria diggings. He has left 2 children a boy and a girl William and Ellen.” In June of the same year in a black edged letter, Emma wrote: “I think Mrs. Davy mentioned Charles’s death in her note. His wife wrote to us. They have two children Helen and William. Poor dear little things. How much I should like to see them all. She writes very affectionately.”

In December 1872, Joseph wrote: “I’m told that Charles two daughters has wrote to Smalley post office making inquiries about his share….” In January 1876, the solicitor wrote: “Charles Housley’s children have claimed their father’s share.”

GEORGE HOUSLEY 1824-1877

George emigrated to the United states in 1851, arriving in July. The solicitor Abraham John Flint referred in a letter to a 15-pound advance which was made to George on June 9, 1851. This certainly was connected to his journey. George settled along the Delaware River in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. The letters from the solicitor were addressed to: Lahaska Post Office, Bucks County, Pennsylvania.

George married Sarah Ann Hill on May 6, 1854 in Doylestown, Bucks County, Pennsylvania. In her first letter (February 1854), Anne wrote: “We want to know who and what is this Miss Hill you name in your letter. What age is she? Send us all the particulars but I would advise you not to get married until you have sufficient to make a comfortable home.”

Upon learning of George’s marriage, Anne wrote: “I hope dear brother you may be happy with your wife….I hope you will be as a son to her parents. Mother unites with me in kind love to you both and to your father and mother with best wishes for your health and happiness.” In 1872 (December) Joseph wrote: “I am sorry to hear that sister’s father is so ill. It is what we must all come to some time and hope we shall meet where there is no more trouble.”

Emma wrote in 1855, “We write in love to your wife and yourself and you must write soon and tell us whether there is a little nephew or niece and what you call them.” In June of 1856, Emma wrote: “We want to see dear Sarah Ann and the dear little boy. We were much pleased with the “bit of news” you sent.” The bit of news was the birth of John Eley Housley, January 11, 1855. Emma concluded her letter “Give our very kindest love to dear sister and dearest Johnnie.”

In September 1872, Joseph wrote, “I was very sorry to hear that John your oldest had met with such a sad accident but I hope he is got alright again by this time.” In the same letter, Joseph asked: “Now I want to know what sort of a town you are living in or village. How far is it from New York? Now send me all particulars if you please.”

In March 1873 Harriet asked Sarah Ann: “And will you please send me all the news at the place and what it is like for it seems to me that it is a wild place but you must tell me what it is like….”. The question of whether she was referring to Bucks County, Pennsylvania or some other place is raised in Joseph’s letter of the same week.

On March 17, 1873, Joseph wrote: “I was surprised to hear that you had gone so far away west. Now dear brother what ever are you doing there so far away from home and family–looking out for something better I suppose.”The solicitor wrote on May 23, 1874: “Lately I have not written because I was not certain of your address and because I doubted I had much interesting news to tell you.” Later, Joseph wrote concerning the problems settling the estate, “You see dear brother there is only me here on our side and I cannot do much. I wish you were here to help me a bit and if you think of going for another summer trip this turn you might as well run over here.”

Apparently, George had indicated he might return to England for a visit in 1856. Emma wrote concerning the portrait of their mother which had been sent to George: “I hope you like mother’s portrait. I did not see it but I suppose it was not quite perfect about the eyes….Joseph and I intend having ours taken for you when you come over….Do come over before very long.”

In March 1873, Joseph wrote: “You ask me what I think of you coming to England. I think as you have given the trustee power to sign for you I think you could do no good but I should like to see you once again for all that. I can’t say whether there would be anything amiss if you did come as you say it would be throwing good money after bad.”

On June 10, 1875, the solicitor wrote: “I have been expecting to hear from you for some time past. Please let me hear what you are doing and where you are living and how I must send you your money.” George’s big news at that time was that on May 3, 1875, he had become a naturalized citizen “renouncing and abjuring all allegiance and fidelity to every foreign prince, potentate, state and sovereignity whatsoever, and particularly to Victoria Queen of Great Britain of whom he was before a subject.”

ROBERT HOUSLEY 1832-1851

In 1854, Anne wrote: “Poor Robert. He died in August after you left he broke a blood vessel in the lung.”

From Joseph’s first letter we learn that Robert was 19 when he died: “Dear brother there have been a great many changes in the family since you left us. All is gone except myself and John and Sam–we have heard nothing of him since he left. Robert died first when he was 19 years of age. Then Anne and Charles too died in Australia and then a number of years elapsed before anyone else. Then John lost his wife, then Emma, and last poor dear mother died last January on the 11th.”Anne described Robert’s death in this way: “He had thrown up blood many times before in the spring but the last attack weakened him that he only lived a fortnight after. He died at Derby. Mother was with him. Although he suffered much he never uttered a murmur or regret and always a smile on his face for everyone that saw him. He will be regretted by all that knew him”.

Robert died a resident of St. Peter’s Parish, Derby, but was buried in Smalley on August 16, 1851.

Apparently Robert was apprenticed to be a joiner for, according to Anne, Joseph took his place: “Joseph wanted to be a joiner. We thought we could do no better than let him take Robert’s place which he did the October after and is there still.”In 1876, the solicitor wrote to George: “Have you heard of John Housley? He is entitled to Robert’s share and I want him to claim it.”

EMMA HOUSLEY 1836-1871

Emma was not mentioned in Anne’s first letter. In the second, Anne wrote that Emma was living at Spondon with two ladies in her “third situation,” and added, “She is grown a bouncing woman.” Anne described her sister well. Emma wrote in her first letter (November 12, 1855): “I must tell you that I am just 21 and we had my pudding last Sunday. I wish I could send you a piece.”

From Emma’s letters we learn that she was living in Derby from May until November 1855 with Mr. Haywood, an iron merchant. She explained, “He has failed and I have been obliged to leave,” adding, “I expect going to a new situation very soon. It is at Belper.” In 1851 records, William Haywood, age 22, was listed as an iron foundry worker. In the 1857 Derby Directory, James and George were listed as iron and brass founders and ironmongers with an address at 9 Market Place, Derby.

In June 1856, Emma wrote from “The Cedars, Ashbourne Road” where she was working for Mr. Handysides.

While she was working for Mr. Handysides, Emma wrote: “Mother is thinking of coming to live at Derby. That will be nice for Joseph and I.”Friargate and Ashbourne Road were located in St. Werburgh’s Parish. (In fact, St. Werburgh’s vicarage was at 185 Surrey Street. This clue led to the discovery of the record of Emma’s marriage on May 6, 1858, to Edwin Welch Harvey, son of Samuel Harvey in St. Werburgh’s.)

In 1872, Joseph wrote: “Our sister Emma, she died at Derby at her own home for she was married. She has left two young children behind. The husband was the son of the man that I went apprentice to and has caused a great deal of trouble to our family and I believe hastened poor Mother’s death….”. Joseph added that he believed Emma’s “complaint” was consumption and that she was sick a good bit. Joseph wrote: “Mother was living with John when I came home (from Ascension Island around 1867? or to Smalley from Derby around 1870?) for when Emma was married she broke up the comfortable home and the things went to Derby and she went to live with them but Derby did not agree with her so she had to leave it again but left all her things there.”

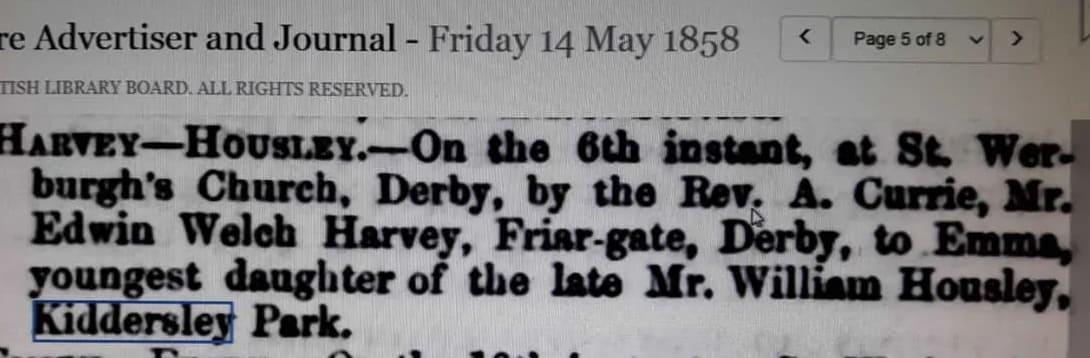

Emma Housley and Edwin Welch Harvey wedding, 1858:

JOSEPH HOUSLEY 1838-1893

We first hear of Joseph in a letter from Anne to George in 1854. “Joseph wanted to be a joiner. We thought we could do no better than let him take Robert’s place which he did the October after (probably 1851) and is there still. He is grown as tall as you I think quite a man.” Emma concurred in her first letter: “He is quite a man in his appearance and quite as tall as you.”