Search Results for 'record'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

September 18, 2023 at 8:29 am #7278

In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Tomlinson of Wergs and Hancox of Penn

John Tomlinson of Wergs (Tettenhall, Wolverhamton) 1766-1844, my 4X great grandfather, married Sarah Hancox 1772-1851. They were married on the 27th May 1793 by licence at St Peter in Wolverhampton.

Between 1794 and 1819 they had twelve children, although four of them died in childhood or infancy. Catherine was born in 1794, Thomas in 1795 who died 6 years later, William (my 3x great grandfather) in 1797, Jemima in 1800, John, Richard and Matilda between 1802 and 1806 who all died in childhood, Emma in 1809, Mary Ann in 1811, Sidney in 1814, and Elijah in 1817 who died two years later.On the 1841 census John and Sarah were living in Hockley in Birmingham, with three of their children, and surgeon Charles Reynolds. John’s occupation was “Ind” meaning living by independent means. He was living in Hockley when he died in 1844, and in his will he was “John Tomlinson, gentleman”.

Sarah Hancox was born in 1772 in Penn, Wolverhampton. Her father William Hancox was also born in Penn in 1737. Sarah’s mother Elizabeth Parkes married William’s brother Francis in 1767. Francis died in 1768, and in 1770 Elizabeth married William.

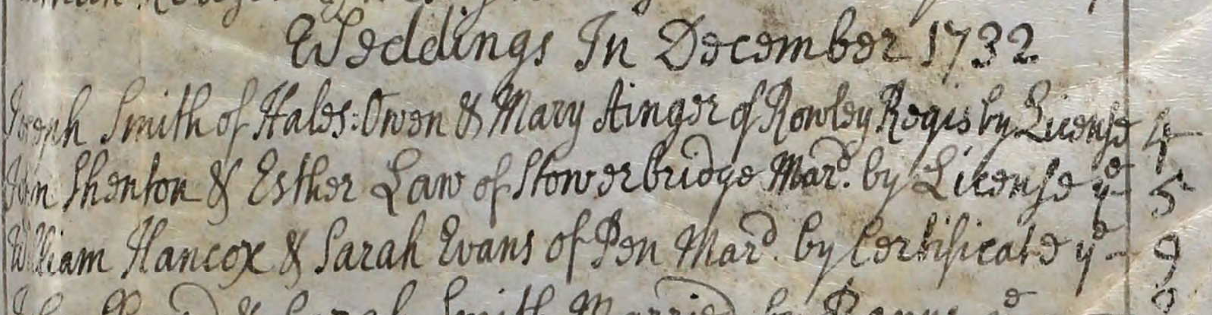

William’s father was William Hancox, yeoman, born in 1703 in Penn. He died intestate in 1772, his wife Sarah claiming her right to his estate. William Hancox and Sarah Evans, both of Penn, were married on the 9th December 1732 in Dudley, Worcestershire, by “certificate”. Marriages were usually either by banns or by licence. Apparently a marriage by certificate indicates that they were non conformists, or dissenters, and had the non conformist marriage “certified” in a Church of England church.

1732 marriage of William Hancox and Sarah Evans:

William and Sarah lost two daughters, Elizabeth, five years old, and Ann, three years old, within eight days of each other in February 1738.

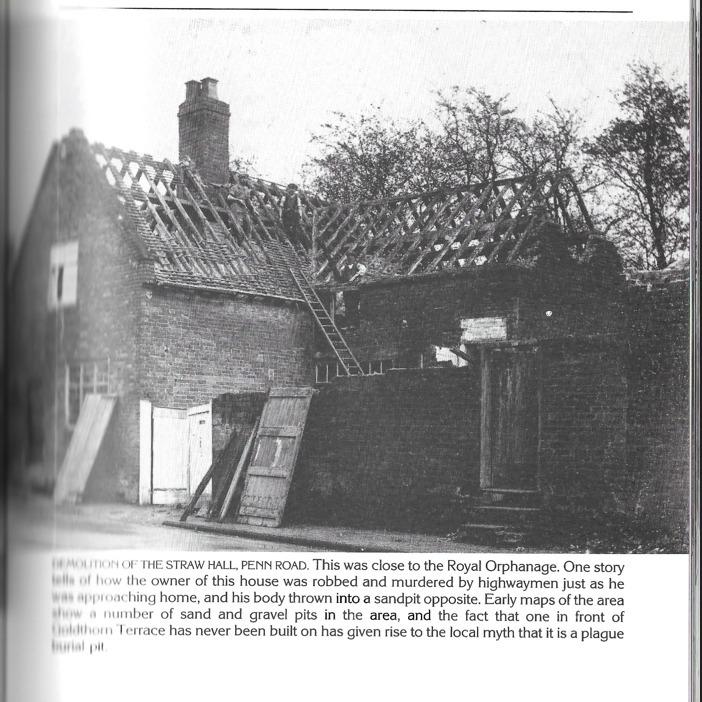

William the elder’s father was John Hancox born in Penn in 1668. He married Elizabeth Wilkes from Sedgley in 1691 at Himley. John Hancox, “of Straw Hall” according to the Wolverhampton burial register, died in 1730. Straw Hall is in Penn. John’s parents were Walter Hancox and Mary Noake. Walter was born in Tettenhall in 1625, his father Richard Hancox. Mary Noake was born in Penn in 1634. Walter died in Penn in 1689.

Straw Hall thanks to Bradney Mitchell:

“Here is a picture I have of Straw Hall, Penn Road.

The painting is by John Reid circa 1878.

Sketch commissioned by George Bradney Mitchell to record the town as it was before its redevelopment, in a book called Wolverhampton and its Environs. ©”

And a photo of the demolition of Straw Hall with an interesting story:

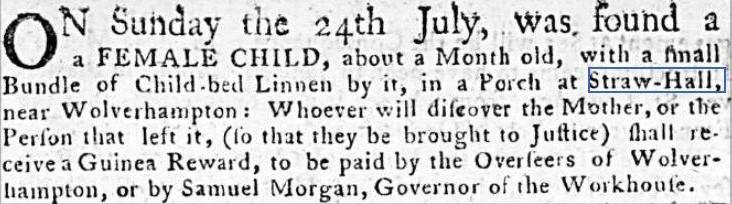

In 1757 a child was abandoned on the porch of Straw Hall. Aris’s Birmingham Gazette 1st August 1757:

The Hancox family were living in Penn for at least 400 years. My great grandfather Charles Tomlinson built a house on Penn Common in the early 1900s, and other Tomlinson relatives have lived there. But none of the family knew of the Hancox connection to Penn. I don’t think that anyone imagined a Tomlinson ancestor would have been a gentleman, either.

Sarah Hancox’s brother William Hancox 1776-1848 had a busy year in 1804.

On 29 Aug 1804 he applied for a licence to marry Ann Grovenor of Claverley.

In August 1804 he had property up for auction in Penn. “part of Lightwoods, 3 plots, and the Coppice”

On 14 Sept 1804 their first son John was baptised in Penn. According to a later census John was born in Claverley. (before the parents got married)(Incidentally, John Hancox’s descendant married a Warren, who is a descendant of my 4x great grandfather Samuel Warren, on my mothers side, from Newhall, Derbyshire!)

On 30 Sept he married Ann in Penn.

In December he was a bankrupt pig and sheep dealer.

In July 1805 he’s in the papers under “certificates”: William Hancox the younger, sheep and pig dealer and chapman of Penn. (A certificate was issued after a bankruptcy if they fulfilled their obligations)

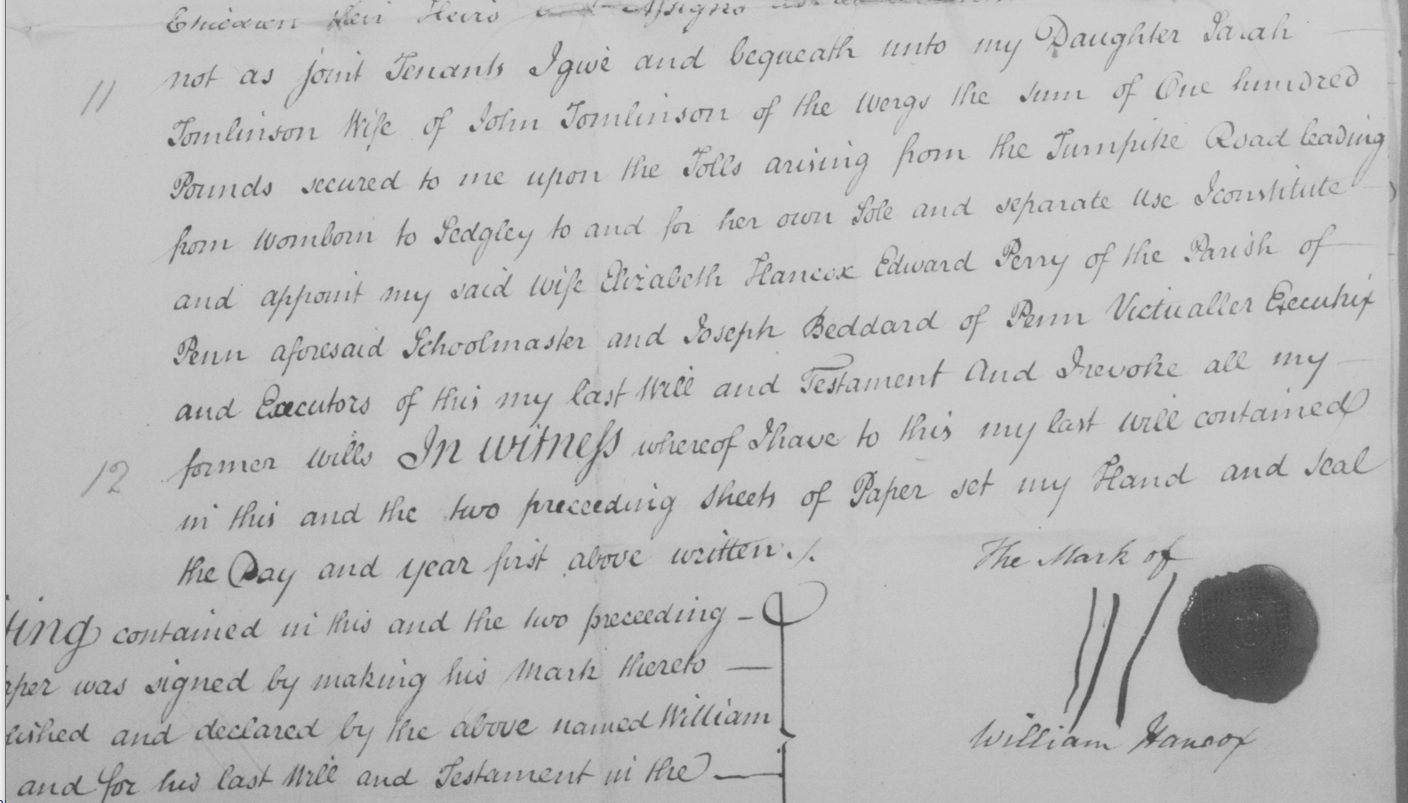

He was a pig dealer in Penn in 1841, a widower, living with unmarried daughter Elizabeth.Sarah’s father William Hancox died in 1816. In his will, he left his “daughter Sarah, wife of John Tomlinson of the Wergs the sum of £100 secured to me upon the tolls arising from the turnpike road leading from Wombourne to Sedgeley to and for her sole and separate use”.

The trustees of toll road would decide not to collect tolls themselves but get someone else to do it by selling the collecting of tolls for a fixed price. This was called “farming the tolls”. The Act of Parliament which set up the trust would authorise the trustees to farm out the tolls. This example is different. The Trustees of turnpikes needed to raise money to carry out work on the highway. The usual way they did this was to mortgage the tolls – they borrowed money from someone and paid the borrower interest; as security they gave the borrower the right, if they were not paid, to take over the collection of tolls and keep the proceeds until they had been paid off. In this case William Hancox has lent £100 to the turnpike and is leaving it (the right to interest and/or have the whole sum repaid) to his daughter Sarah Tomlinson. (this information on tolls from the Wolverhampton family history group.)William Hancox, Penn Wood, maltster, left a considerable amount of property to his children in 1816. All household effects he left to his wife Elizabeth, and after her decease to his son Richard Hancox: four dwelling houses in John St, Wolverhampton, in the occupation of various Pratts, Wright and William Clarke. He left £200 to his daughter Frances Gordon wife of James Gordon, and £100 to his daughter Ann Pratt widow of John Pratt. To his son William Hancox, all his various properties in Penn wood. To Elizabeth Tay wife of Thomas Tay he left £200, and to Richard Hancox various other properties in Penn Wood, and to his daughter Lucy Tay wife of Josiah Tay more property in Lower Penn. All his shops in St John Wolverhamton to his son Edward Hancox, and more properties in Lower Penn to both Francis Hancox and Edward Hancox. To his daughter Ellen York £200, and property in Montgomery and Bilston to his son John Hancox. Sons Francis and Edward were underage at the time of the will. And to his daughter Sarah, his interest in the toll mentioned above.

Sarah Tomlinson, wife of John Tomlinson of the Wergs, in William Hancox will:

September 5, 2023 at 1:35 pm #7276

September 5, 2023 at 1:35 pm #7276In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Wood Screw Manufacturers

The Fishers of West Bromwich.

My great grandmother, Nellie Fisher, was born in 1877 in Wolverhampton. Her father William 1834-1916 was a whitesmith, and his father William 1792-1873 was a whitesmith and master screw maker. William’s father was Abel Fisher, wood screw maker, victualler, and according to his 1849 will, a “gentleman”.

Nellie Fisher 1877-1956 :

Abel Fisher was born in 1769 according to his burial document (age 81 in 1849) and on the 1841 census. Abel was a wood screw manufacturer in Wolverhampton.

As no baptism record can be found for Abel Fisher, I read every Fisher will I could find in a 30 year period hoping to find his fathers will. I found three other Fishers who were wood screw manufacurers in neighbouring West Bromwich, which led me to assume that Abel was born in West Bromwich and related to these other Fishers.

The wood screw making industry was a relatively new thing when Abel was born.

“The screw was used in furniture but did not become a common woodworking fastener until efficient machine tools were developed near the end of the 18th century. The earliest record of lathe made wood screws dates to an English patent of 1760. The development of wood screws progressed from a small cottage industry in the late 18th century to a highly mechanized industry by the mid-19th century. This rapid transformation is marked by several technical innovations that help identify the time that a screw was produced. The earliest, handmade wood screws were made from hand-forged blanks. These screws were originally produced in homes and shops in and around the manufacturing centers of 18th century Europe. Individuals, families or small groups participated in the production of screw blanks and the cutting of the threads. These small operations produced screws individually, using a series of files, chisels and cutting tools to form the threads and slot the head. Screws produced by this technique can vary significantly in their shape and the thread pitch. They are most easily identified by the profusion of file marks (in many directions) over the surface. The first record regarding the industrial manufacture of wood screws is an English patent registered to Job and William Wyatt of Staffordshire in 1760.”

Wood Screw Makers of West Bromwich:

Edward Fisher, wood screw maker of West Bromwich, died in 1796. He mentions his wife Pheney and two underage sons in his will. Edward (whose baptism has not been found) married Pheney Mallin on 13 April 1793. Pheney was 17 years old, born in 1776. Her parents were Isaac Mallin and Sarah Firme, who were married in West Bromwich in 1768.

Edward and Pheney’s son Edward was born on 21 October 1793, and their son Isaac in 1795. The executors of Edwards 1796 will are Daniel Fisher the Younger, Isaac Mallin, and Joseph Fisher.There is a marriage allegations and bonds document in 1774 for an Edward Fisher, bachelor and wood screw maker of West Bromwich, aged 25 years and upwards, and Mary Mallin of the same age, father Isaac Mallin. Isaac Mallin and Sarah didn’t marry until 1768 and Mary Mallin would have been born circa 1749. Perhaps Isaac Mallin’s father was the father of Mary Mallin. It’s possible that Edward Fisher was born in 1749 and first married Mary Mallin, and then later Pheney, but it’s also possible that the Edward Fisher who married Mary Mallin in 1774 was Edward Fishers uncle, Daniel’s brother. (I do not know if Daniel had a brother Edward, as I haven’t found a baptism, or marriage, for Daniel Fisher the elder.)

There are two difficulties with finding the records for these West Bromwich families. One is that the West Bromwich registers are not available online in their entirety, and are held by the Sandwell Archives, and even so, they are incomplete. Not only that, the Fishers were non conformist. There is no surviving register prior to 1787. The chapel opened in 1788, and any registers that existed before this date, taken in a meeting houses for example, appear not to have survived.

Daniel Fisher the younger died intestate in 1818. Daniel was a wood screw maker of West Bromwich. He was born in 1751 according to his age stated as 67 on his death in 1818. Daniel’s wife Mary, and his son William Fisher, also a wood screw maker, claimed the estate.

Daniel Fisher the elder was a farmer of West Bromwich, who died in 1806. He was 81 when he died, which makes a birth date of 1725, although no baptism has been found. No marriage has been found either, but he was probably married not earlier than 1746.

Daniel’s sons Daniel and Joseph were the main inheritors, and he also mentions his other children and grandchildren namely William Fisher, Thomas Fisher, Hannah wife of William Hadley, two grandchildren Edward and Isaac Fisher sons of Edward Fisher his son deceased. Daniel the elder presumably refers to the wood screw manufacturing when he says “to my son Daniel Fisher the good will and advantage which may arise from his manufacture or trade now carried on by me.” Daniel does not mention a son called Abel unfortunately, but neither does he mention his other grandchildren. Abel may be Daniel’s son, or he may be a nephew.

The Staffordshire Record Office holds the documents of a Testamentary Case in 1817. The principal people are Isaac Fisher, a legatee; Daniel and Joseph Fisher, executors. Principal place, West Bromwich, and deceased person, Daniel Fisher the elder, farmer.

William and Sarah Fisher baptised six children in the Mares Green Non Conformist registers in West Bromwich between 1786 and 1798. William Fisher and Sarah Birch were married in West Bromwich in 1777. This William was probably born circa 1753 and was probably the son of Daniel Fisher the elder, farmer.

Daniel Fisher the younger and his wife Mary had a son William, as mentioned in the intestacy papers, although I have not found a baptism for William. I did find a baptism for another son, Eutychus Fisher in 1792.

In White’s Directory of Staffordshire in 1834, there are three Fishers who are wood screw makers in Wolverhampton: Eutychus Fisher, Oxford Street; Stephen Fisher, Bloomsbury; and William Fisher, Oxford Street.

Abel’s son William Fisher 1792-1873 was living on Oxford Street on the 1841 census, with his wife Mary and their son William Fisher 1834-1916.

In The European Magazine, and London Review of 1820 (Volume 77 – Page 564) under List of Patents, W Fisher and H Fisher of West Bromwich, wood screw manufacturers, are listed. Also in 1820 in the Birmingham Chronicle, the partnership of William and Hannah Fisher, wood screw manufacturers of West Bromwich, was dissolved.

In the Staffordshire General & Commercial Directory 1818, by W. Parson, three Fisher’s are listed as wood screw makers. Abel Fisher victualler and wood screw maker, Red Lion, Walsal Road; Stephen Fisher wood screw maker, Buggans Lane; and Daniel Fisher wood screw manufacturer, Brickiln Lane.

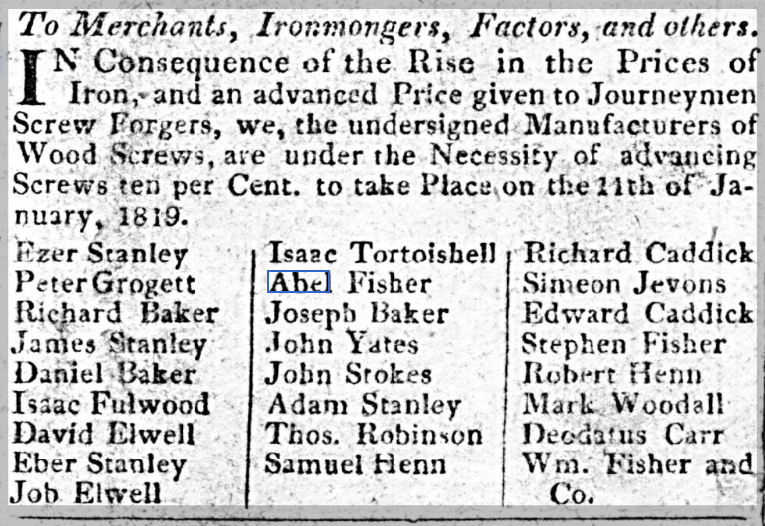

In Aris’s Birmingham Gazette on 4 January 1819 Abel Fisher is listed with 23 other wood screw manufacturers (Stephen Fisher and William Fisher included) stating that “In consequence of the rise in prices of iron and the advanced price given to journeymen screw forgers, we the undersigned manufacturers of wood screws are under the necessity of advancing screws 10 percent, to take place on the 11th january 1819.”

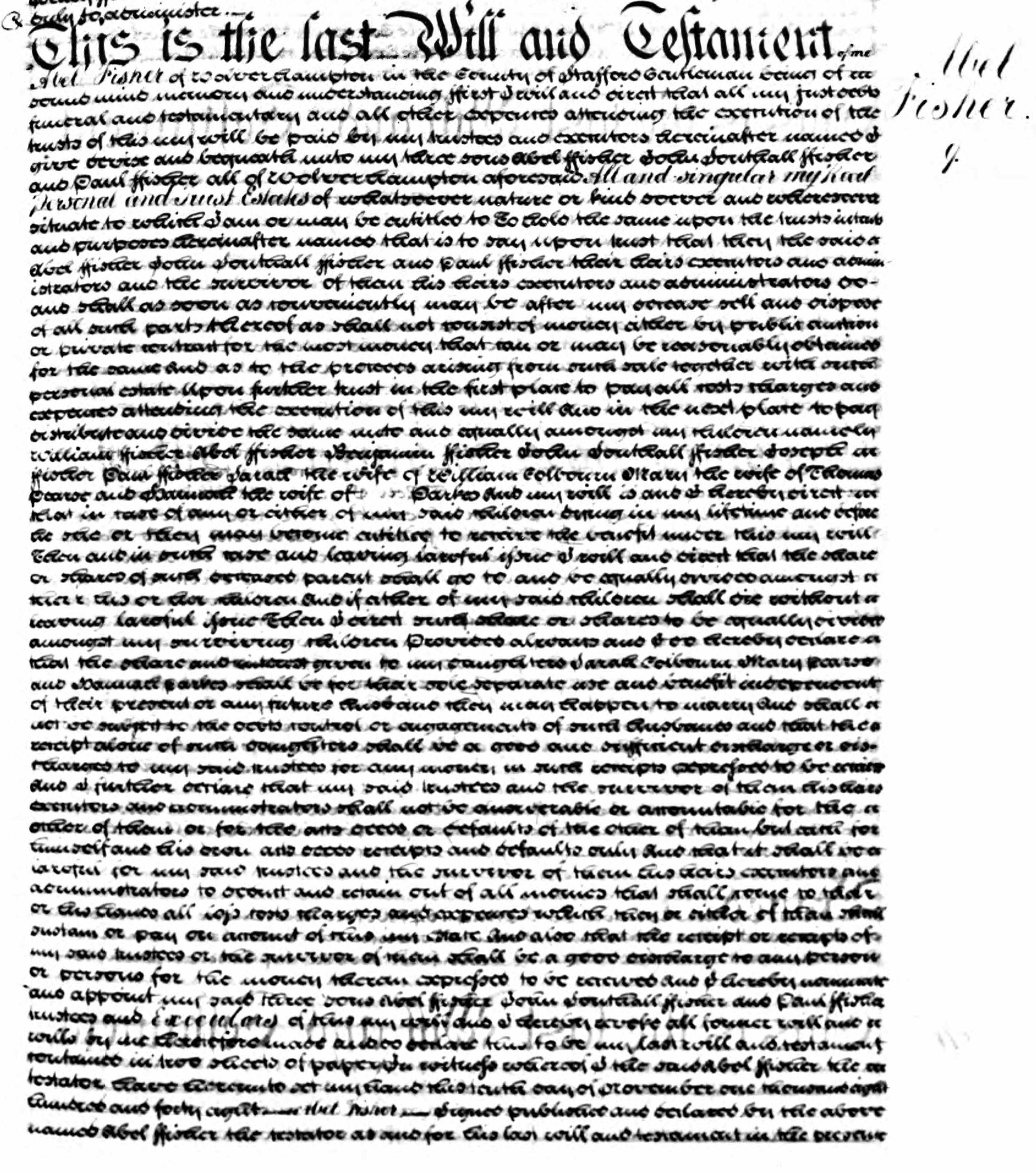

In Abel Fisher’s 1849 will, he names his three sons Abel Fisher 1796-1869, Paul Fisher 1811-1900 and John Southall Fisher 1801-1871 as the executors. He also mentions his other three sons, William Fisher 1792-1873, Benjamin Fisher 1798-1870, and Joseph Fisher 1803-1876, and daughters Sarah Fisher 1794- wife of William Colbourne, Mary Fisher 1804- wife of Thomas Pearce, and Susannah (Hannah) Fisher 1813- wife of Parkes. His son Silas Fisher 1809-1837 wasn’t mentioned as he died before Abel, nor his sons John Fisher 1799-1800, and Edward Southall Fisher 1806-1843. Abel’s wife Susannah Southall born in 1771 died in 1824. They were married in 1791.

The 1849 will of Abel Fisher:

August 17, 2023 at 4:32 pm #7268

August 17, 2023 at 4:32 pm #7268In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

William Tomlinson

1797-1867

The Tomlinsons of Wolverhampton were butchers and publicans for several generations. Therefore it was a surprise to find that William’s father was a gentleman of independant means.

William Tomlinson 1797-1867 was born in Wergs, Tettenhall. His birthplace, and that of his first four children, is stated as Wergs on the 1851 census. They were baptised at St Michael and All Angels church in Tettenhall Regis, as were many of the Tomlinson family including William.

Tettenhall, St Michael and All Angels church:

Wergs is a very small area and there was no other William Tomlinson baptised there at the time of William’s birth. It is of course possible that another William Tomlinson was born in Wergs and the record of the baptism hasn’t been found, but there are a number of other documents that prove that John Tomlinson, gentleman of Wergs, was Williams father.

In 1834 on the Shropshire Quarter session rolls there are two documents regarding William. In October 1834 William Tomlinson of Tettenhall, son of John, took an examination. Also in October of 1834 there is a reconizance document for William Tomlinson for “pig dealer”. On the marriage certificate of his son Charles Tomlinson to Emma Grattidge (mistranscribed as Pratadge) in 1872, father William’s occupation is “dealer”.

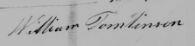

William Tomlinson was a witness at his sister Catherine and Benjamin Smiths wedding in 1822 in Tettenhall. In John Tomlinson’s 1844 will, he mentions his “daughter Catherine Smith, wife of Benjamin Smith”. William’s signature as a witness at Catherine’s marriage matches his signature on the licence for his own marriage to Elizabeth Adams in 1827 in Shareshill, Staffordshire.

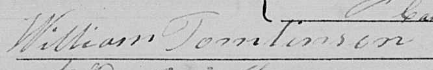

William’s signature on his wedding licence:

Williams signature as a witness to Catherine’s marriage:

William was the eldest surviving son when his father died in 1844, so it is surprising that William only inherited £25. John Tomlinson left his various properties to his daughters, with the exception of Catherine, who also received £25. There was one other surviving son, Sidney, born in 1814. Three of John and Sarah Tomlinson’s sons and one daughter died in infancy. Sidney was still unmarried and living at home when his father died, and in 1851 and 1861 was living with his sister Emma Wilson. He was unmarried when he died in 1867. John left Sidney an income for life in his will, but not property.

In John Tomlinson’s will he also mentions his daughter Jemima, wife of William Smith, farmer, of Great Barr. On the 1841 census William, butcher, is a visitor. His two children Sarah and Thomas are with him. His wife Elizabeth and the rest of the children are at Graisley Street. William is also on the Graisley Street census, occupation castrator. This was no doubt done in error, not realizing that he was also registered on the census where he was visiting at the time.

William’s wife, Elizabeth Adams, was born in Tong, Shropshire in 1807. The Adams in Tong appear to be agricultural labourers, at least on later censuses. Perhaps we can speculate that John didn’t approve of his son marrying an agricutural labourers daughter. Elizabeth would have been twenty years old at the time of the marriage; William thirty.

July 5, 2023 at 8:21 pm #7263In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Solomon Stubbs

1781-1857

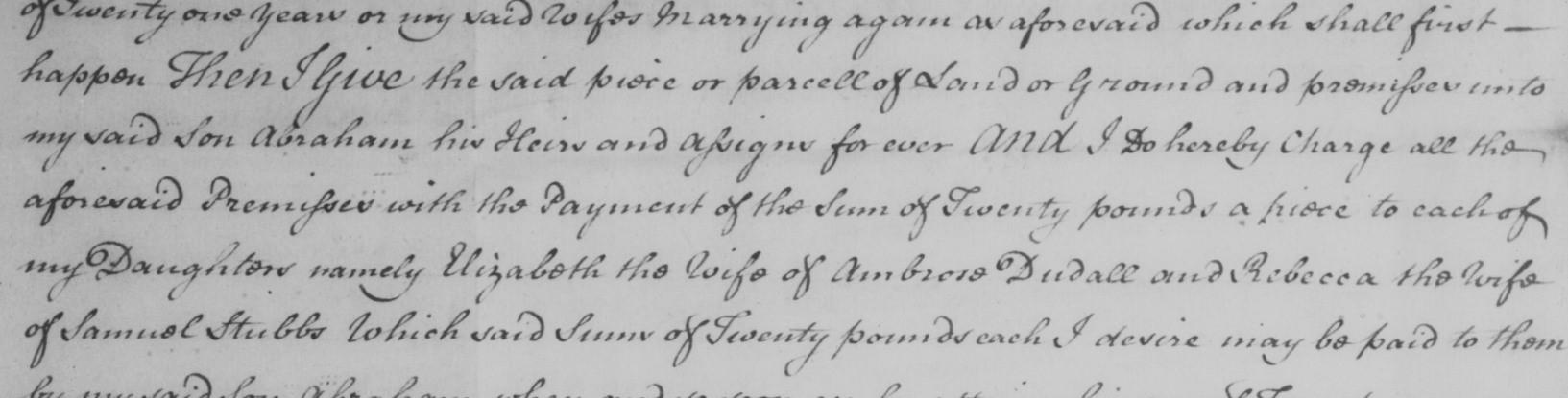

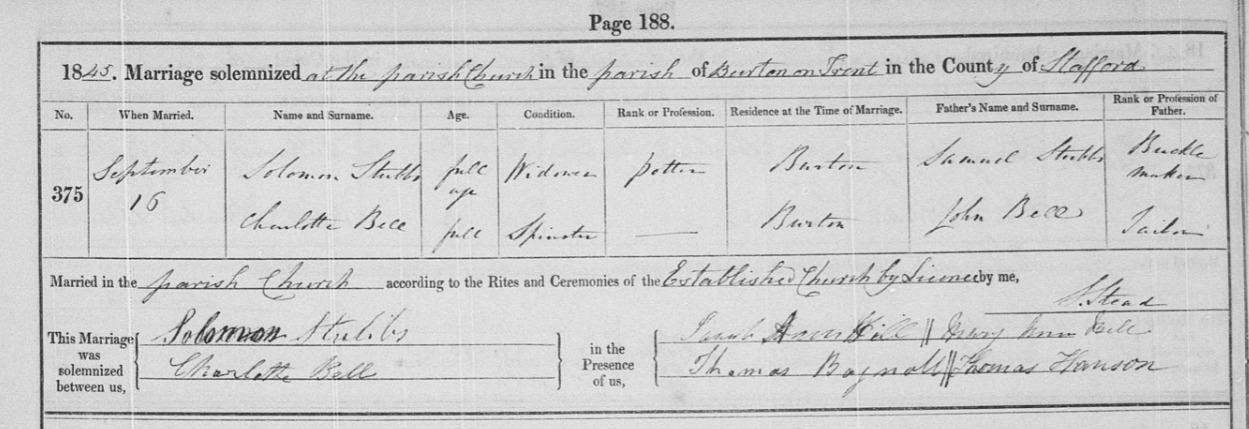

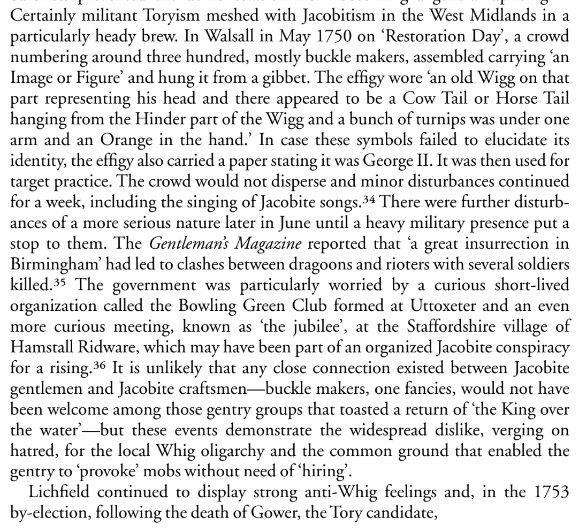

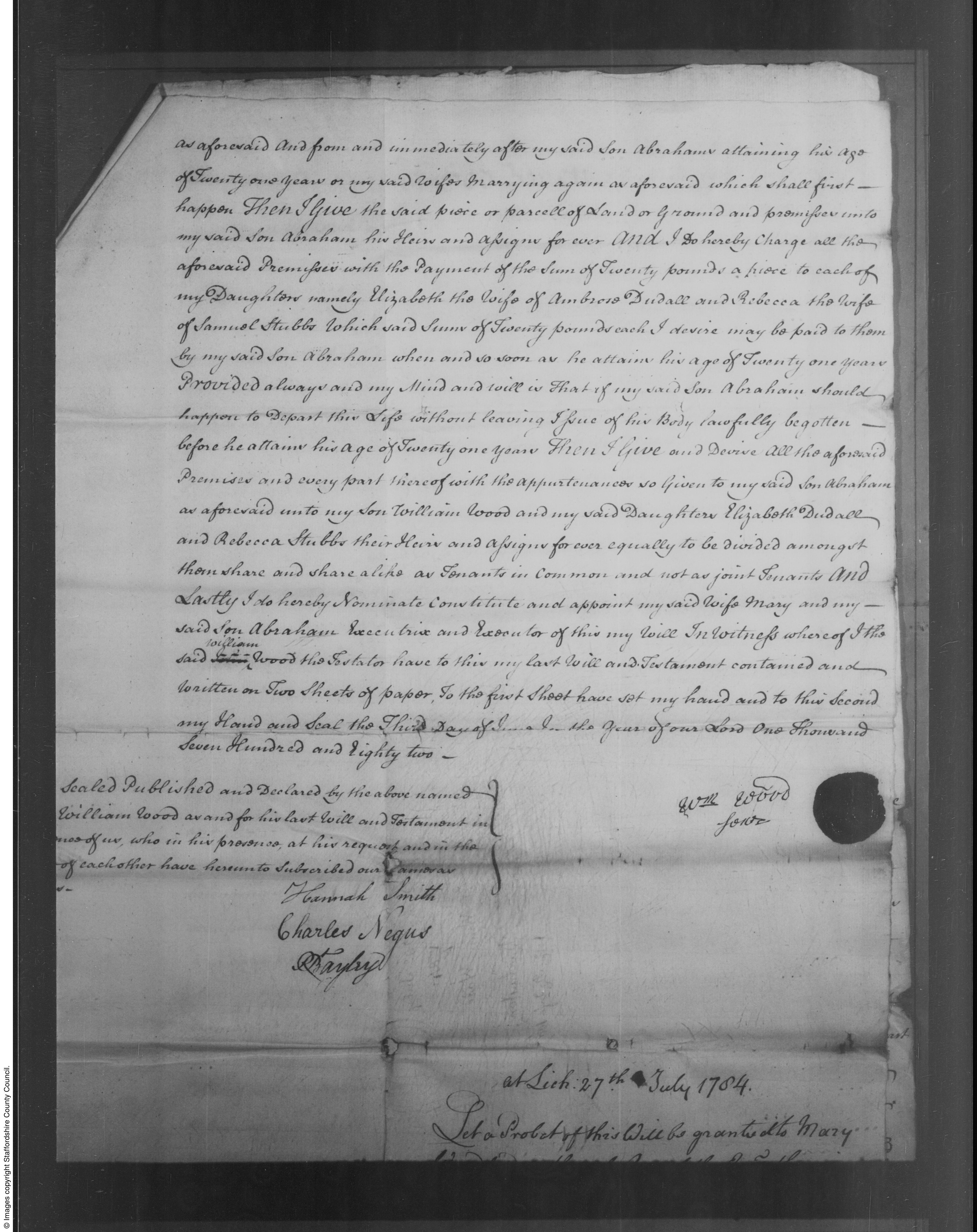

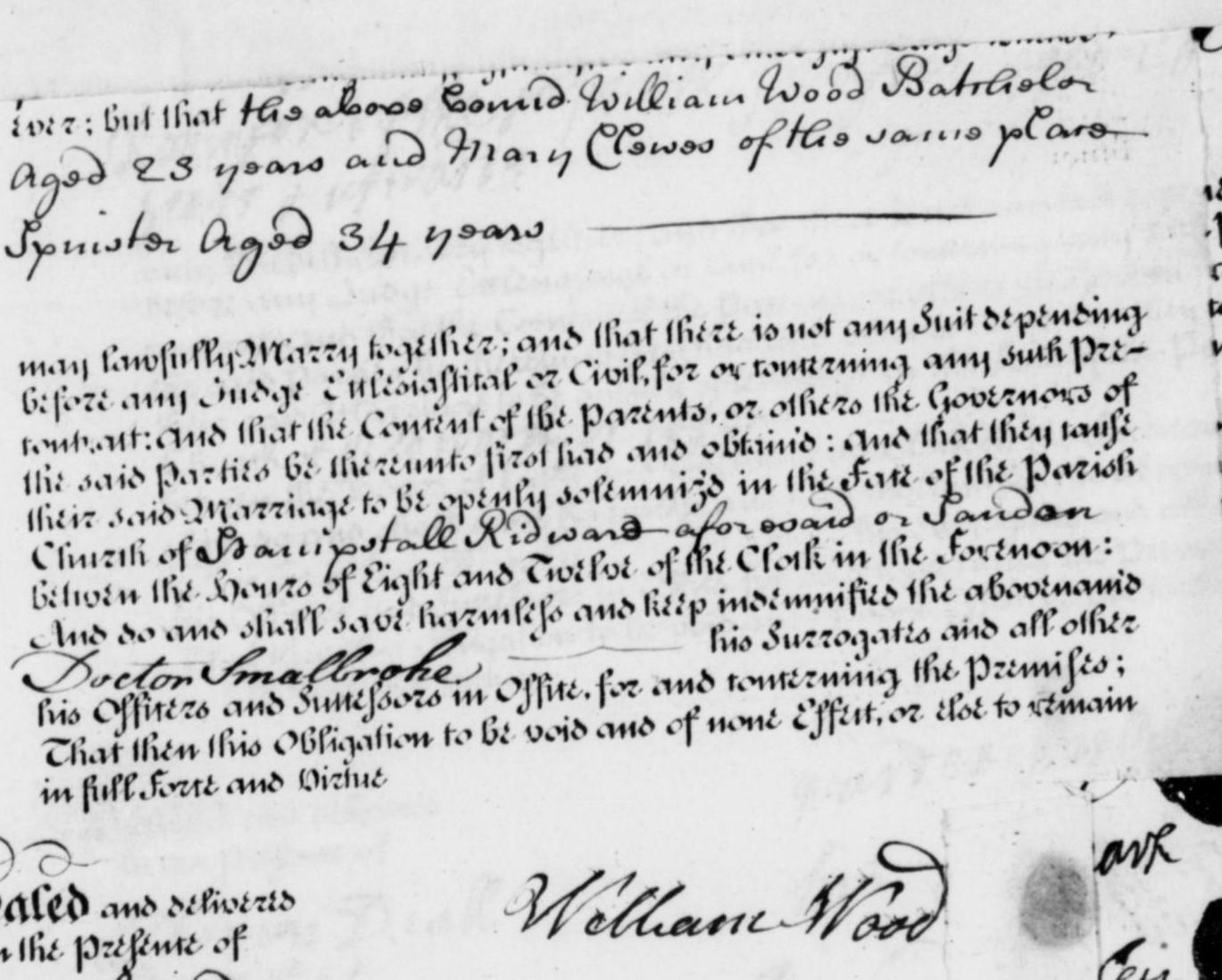

Solomon was born in Hamstall Ridware, Staffordshire, parents Samuel Stubbs and Rebecca Wood. (see The Hamstall Ridware Connection chapter)

Solomon married Phillis Lomas at St Modwen’s in Burton on Trent on 30th May 1815. Phillis was the llegitimate daughter of Frances Lomas. No father was named on the baptism on the 17th January 1787 in Sutton on the Hill, Derbyshire, and the entry on the baptism register states that she was illegitimate. Phillis’s mother Frances married Daniel Fox in 1790 in Sutton on the Hill. Unfortunately this means that it’s impossible to find my 5X great grandfather on this side of the family.

Solomon and Phillis had four daughters, the last died in infancy.

Sarah 1816-1867, Mary (my 3X great grandmother) 1819-1880, Phillis 1823-1905, and Maria 1825-1826.Solomon Stubbs of Horninglow St is listed in the 1834 Whites Directory under “China, Glass, Etc Dlrs”. Next to his name is Joanna Warren (earthenware) High St. Joanna Warren is related to me on my maternal side. No doubt Solomon and Joanna knew each other, unaware that several generations later a marriage would take place, not locally but miles away, joining their families.

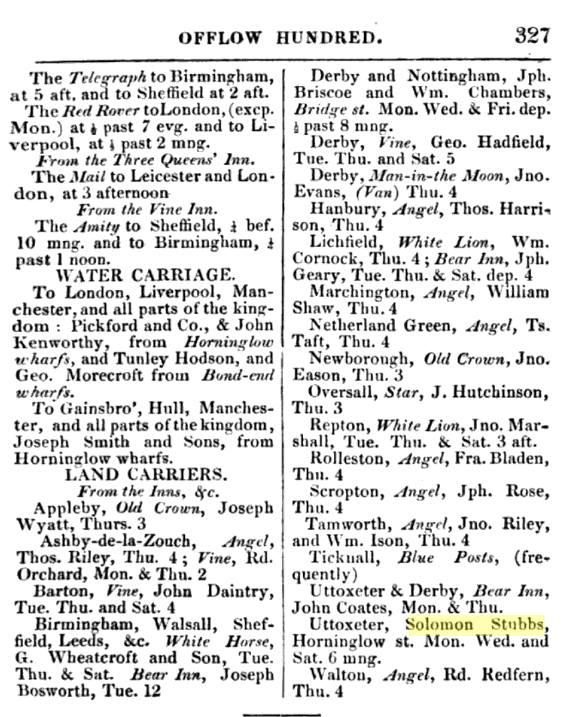

Solomon Stubbs is also listed in Whites Directory in 1831 and 1834 Burton on Trent as a land carrier:

“Land Carriers, from the Inns, Etc: Uttoxeter, Solomon Stubbs, Horninglow St, Mon. Wed. and Sat. 6 mng.”

Solomon is listed in the electoral registers in 1837. The 1837 United Kingdom general election was triggered by the death of King William IV and produced the first Parliament of the reign of his successor, Queen Victoria.

National Archives:

“In 1832, Parliament passed a law that changed the British electoral system. It was known as the Great Reform Act, which basically gave the vote to middle class men, leaving working men disappointed.

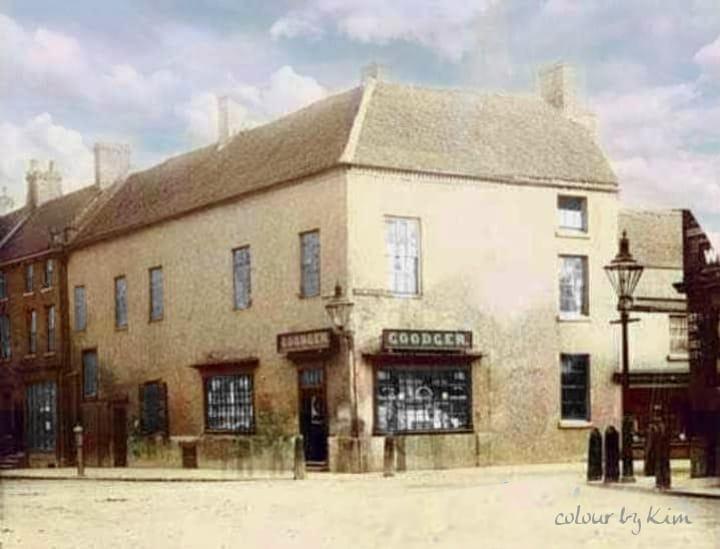

The Reform Act became law in response to years of criticism of the electoral system from those outside and inside Parliament. Elections in Britain were neither fair nor representative. In order to vote, a person had to own property or pay certain taxes to qualify, which excluded most working class people.”Via the Burton on Trent History group:

“a very early image of High street and Horninglow street junction, where the original ‘ Bargates’ were in the days of the Abbey. ‘Gate’ is the Saxon meaning Road, ‘Bar’ quite self explanatory, meant ‘to stop entrance’. There was another Bargate across Cat street (Station street), the Abbot had these constructed to regulate the Traders coming into town, in the days when the Abbey ran things. In the photo you can see the Posts on the corner, designed to stop Carts and Carriages mounting the Pavement. Only three Posts remain today and they are Listed.”

On the 1841 census, Solomon’s occupation was Carrier. Daughter Sarah is still living at home, and Sarah Grattidge, 13 years old, lives with them. Solomon’s daughter Mary had married William Grattidge in 1839.

Solomon Stubbs of Horninglow Street, Burton on Trent, is listed as an Earthenware Dealer in the 1842 Pigot’s Directory of Staffordshire.

In May 1844 Solomon’s wife Phillis died. In July 1844 daughter Sarah married Thomas Brandon in Burton on Trent. It was noted in the newspaper announcement that this was the first wedding to take place at the Holy Trinity church.

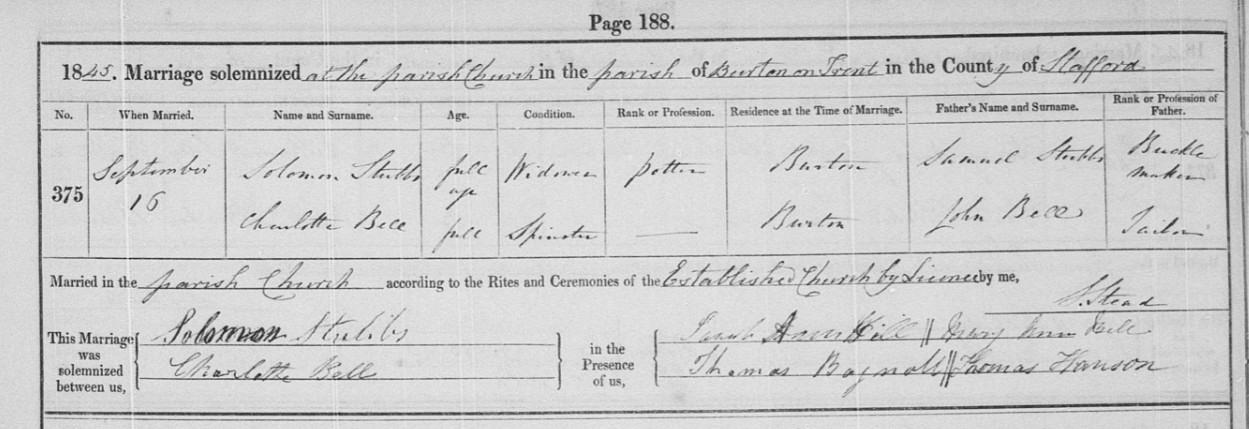

Solomon married Charlotte Bell by licence the following year in 1845. She was considerably younger than him, born in 1824. On the marriage certificate Solomon’s occupation is potter. It seems that he had the earthenware business as well as the land carrier business, in addition to owning a number of properties.

The marriage of Solomon Stubbs and Charlotte Bell:

Also in 1845, Solomon’s daughter Phillis was married in Burton on Trent to John Devitt, son of CD Devitt, Esq, formerly of the General Post Office Dublin.

Solomon Stubbs died in September 1857 in Burton on Trent. In the Staffordshire Advertiser on Saturday 3 October 1857:

“On the 22nd ultimo, suddenly, much respected, Solomon Stubbs, of Guild-street, Burton-on-Trent, aged 74 years.”

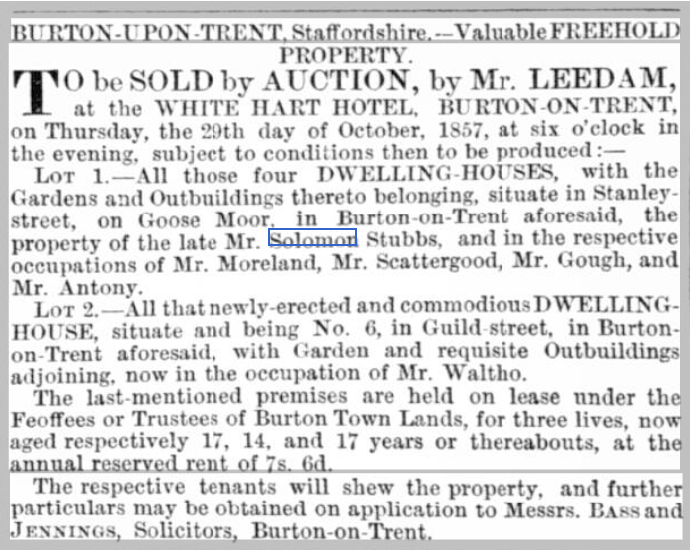

In the Staffordshire Advertiser, 24th October 1857, the auction of the property of Solomon Stubbs was announced:

“BURTON ON TRENT, on Thursday, the 29th day of October, 1857, at six o’clock in the evening, subject to conditions then to be produced:— Lot I—All those four DWELLING HOUSES, with the Gardens and Outbuildings thereto belonging, situate in Stanleystreet, on Goose Moor, in Burton-on-Trent aforesaid, the property of the late Mr. Solomon Stubbs, and in the respective occupations of Mr. Moreland, Mr. Scattergood, Mr. Gough, and Mr. Antony…..”

Sadly, the graves of Solomon, his wife Phillis, and their infant daughter Maria have since been removed and are listed in the UK Records of the Removal of Graves and Tombstones 1601-2007.

July 4, 2023 at 7:52 pm #7261In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Long Lost Enoch Edwards

My father used to mention long lost Enoch Edwards. Nobody in the family knew where he went to and it was assumed that he went to USA, perhaps to Utah to join his sister Sophie who was a Mormon handcart pioneer, but no record of him was found in USA.

Andrew Enoch Edwards (my great great grandfather) was born in 1840, but was (almost) always known as Enoch. Although civil registration of births had started from 1 July 1837, neither Enoch nor his brother Stephen were registered. Enoch was baptised (as Andrew) on the same day as his brothers Reuben and Stephen in May 1843 at St Chad’s Catholic cathedral in Birmingham. It’s a mystery why these three brothers were baptised Catholic, as there are no other Catholic records for this family before or since. One possible theory is that there was a school attached to the church on Shadwell Street, and a Catholic baptism was required for the boys to go to the school. Enoch’s father John died of TB in 1844, and perhaps in 1843 he knew he was dying and wanted to ensure an education for his sons. The building of St Chads was completed in 1841, and it was close to where they lived.

Enoch appears (as Enoch rather than Andrew) on the 1841 census, six months old. The family were living at Unett Street in Birmingham: John and Sarah and children Mariah, Sophia, Matilda, a mysterious entry transcribed as Lene, a daughter, that I have been unable to find anywhere else, and Reuben and Stephen.

Enoch was just four years old when his father John, an engineer and millwright, died of consumption in 1844.

In 1851 Enoch’s widowed mother Sarah was a mangler living on Summer Street, Birmingham, Matilda a dressmaker, Reuben and Stephen were gun percussionists, and eleven year old Enoch was an errand boy.

On the 1861 census, Sarah was a confectionrer on Canal Street in Birmingham, Stephen was a blacksmith, and Enoch a button tool maker.

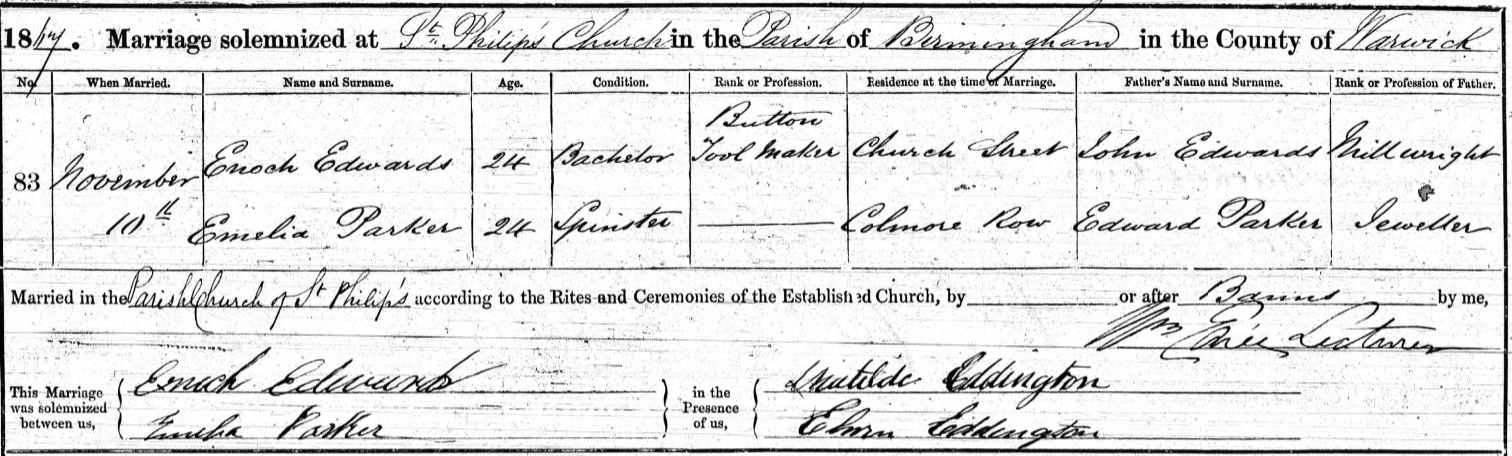

On the 10th November 1867 Enoch married Emelia Parker, daughter of jeweller and rope maker Edward Parker, at St Philip in Birmingham. Both Emelia and Enoch were able to sign their own names, and Matilda and Edwin Eddington were witnesses (Enoch’s sister and her husband). Enoch’s address was Church Street, and his occupation button tool maker.

Four years later in 1871, Enoch was a publican living on Clifton Road. Son Enoch Henry was two years old, and Ralph Ernest was three months. Eliza Barton lived with them as a general servant.

By 1881 Enoch was back working as a button tool maker in Bournebrook, Birmingham. Enoch and Emilia by then had three more children, Amelia, Albert Parker (my great grandfather) and Ada.

Garnet Frederick Edwards was born in 1882. This is the first instance of the name Garnet in the family, and subsequently Garnet has been the middle name for the eldest son (my brother, father and grandfather all have Garnet as a middle name).

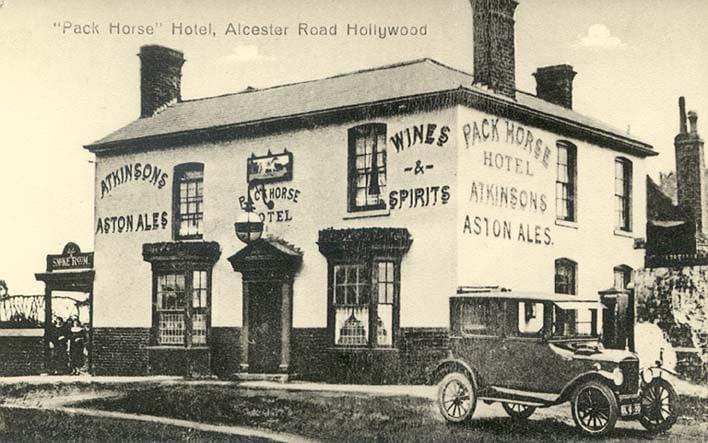

Enoch was the licensed victualler at the Pack Horse Hotel in 1991 at Kings Norton. By this time, only daughters Amelia and Ada and son Garnet are living at home.

Additional information from my fathers cousin, Paul Weaver:

“Enoch refused to allow his son Albert Parker to go to King Edwards School in Birmingham, where he had been awarded a place. Instead, in October 1890 he made Albert Parker Edwards take an apprenticeship with a pawnboker in Tipton.

Towards the end of the 19th century Enoch kept The Pack Horse in Alcester Road, Hollywood, where a twist was 1d an ounce, and beer was 2d a pint. The children had to get up early to get breakfast at 6 o’clock for the hay and straw men on their way to the Birmingham hay and straw market. Enoch is listed as a member of “The Kingswood & Pack Horse Association for the Prosecution of Offenders”, a kind of early Neighbourhood Watch, dated 25 October 1890.

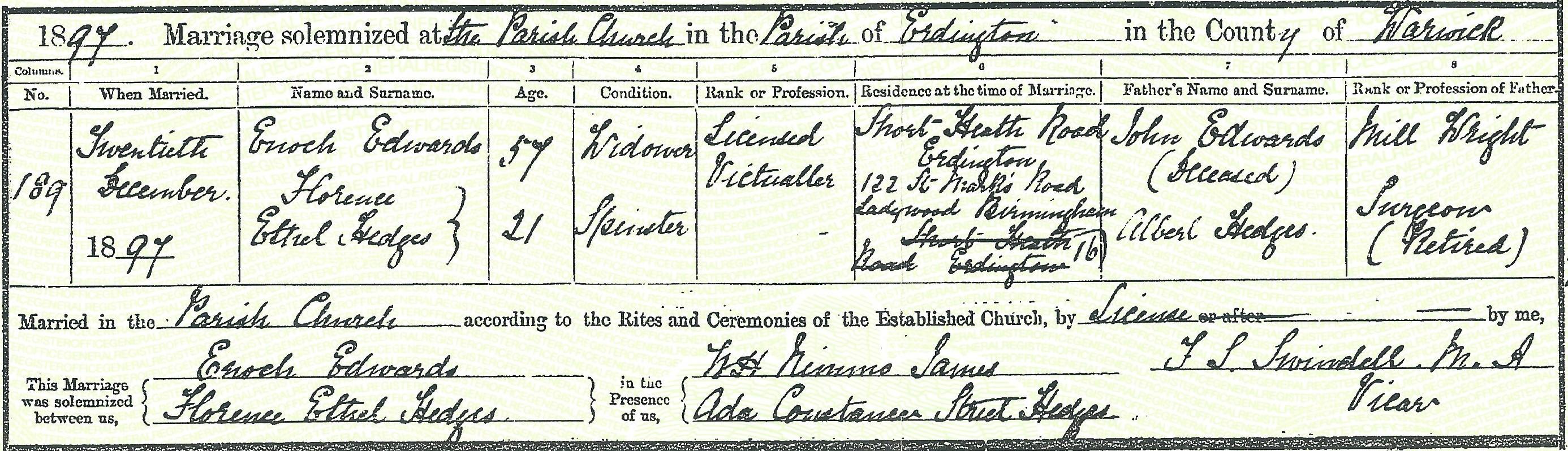

The Edwards family later moved to Redditch where they kept The Rifleman Inn at 35 Park Road. They must have left the Pack Horse by 1895 as another publican was in place by then.”Emelia his wife died in 1895 of consumption at the Rifleman Inn in Redditch, Worcestershire, and in 1897 Enoch married Florence Ethel Hedges in Aston. Enoch was 56 and Florence was just 21 years old.

The following year in 1898 their daughter Muriel Constance Freda Edwards was born in Deritend, Warwickshire.

In 1901 Enoch, (Andrew on the census), publican, Florence and Muriel were living in Dudley. It was hard to find where he went after this.From Paul Weaver:

“Family accounts have it that Enoch EDWARDS fell out with all his family, and at about the age of 60, he left all behind and emigrated to the U.S.A. Enoch was described as being an active man, and it is believed that he had another family when he settled in the U.S.A. Esmor STOKES has it that a postcard was received by the family from Enoch at Niagara Falls.

On 11 June 1902 Harry Wright (the local postmaster responsible in those days for licensing) brought an Enoch EDWARDS to the Bedfordshire Petty Sessions in Biggleswade regarding “Hole in the Wall”, believed to refer to the now defunct “Hole in the Wall” public house at 76 Shortmead Street, Biggleswade with Enoch being granted “temporary authority”. On 9 July 1902 the transfer was granted. A year later in the 1903 edition of Kelly’s Directory of Bedfordshire, Hunts and Northamptonshire there is an Enoch EDWARDS running the Wheatsheaf Public House, Church Street, St. Neots, Huntingdonshire which is 14 miles south of Biggleswade.”

It seems that Enoch and his new family moved away from the midlands in the early 1900s, but again the trail went cold.

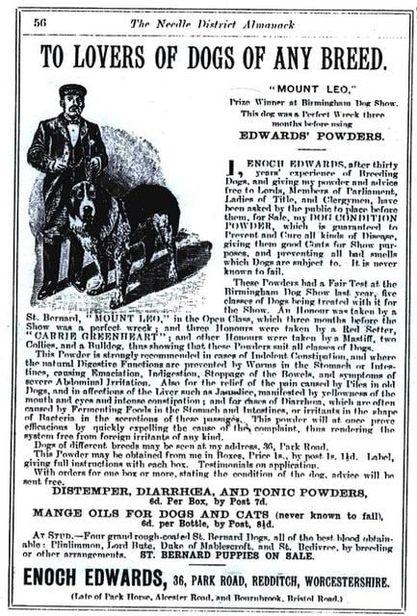

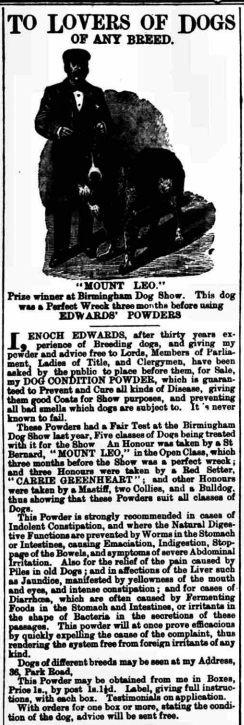

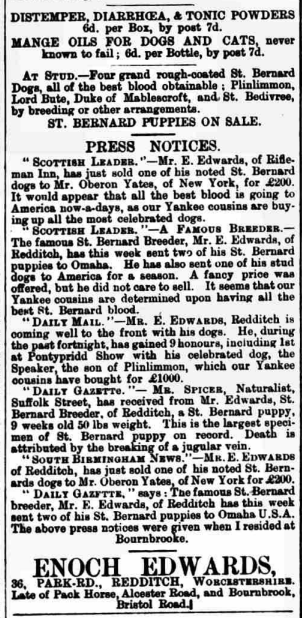

When I started doing the genealogy research, I joined a local facebook group for Redditch in Worcestershire. Enoch’s son Albert Parker Edwards (my great grandfather) spent most of his life there. I asked in the group about Enoch, and someone posted an illustrated advertisement for Enoch’s dog powders. Enoch was a well known breeder/keeper of St Bernards and is cited in a book naming individuals key to the recovery/establishment of ‘mastiff’ size dog breeds.

We had not known that Enoch was a breeder of champion St Bernard dogs!

Once I knew about the St Bernard dogs and the names Mount Leo and Plinlimmon via the newspaper adverts, I did an internet search on Enoch Edwards in conjunction with these dogs.

Enoch’s St Bernard dog “Mount Leo” was bred from the famous Plinlimmon, “the Emperor of Saint Bernards”. He was reported to have sent two puppies to Omaha and one of his stud dogs to America for a season, and in 1897 Enoch made the news for selling a St Bernard to someone in New York for £200. Plinlimmon, bred by Thomas Hall, was born in Liverpool, England on June 29, 1883. He won numerous dog shows throughout Europe in 1884, and in 1885, he was named Best Saint Bernard.

In the Birmingham Mail on 14th June 1890:

“Mr E Edwards, of Bournebrook, has been well to the fore with his dogs of late. He has gained nine honours during the past fortnight, including a first at the Pontypridd show with a St Bernard dog, The Speaker, a son of Plinlimmon.”

In the Alcester Chronicle on Saturday 05 June 1897:

It was discovered that Enoch, Florence and Muriel moved to Canada, not USA as the family had assumed. The 1911 census for Montreal St Jaqcues, Quebec, stated that Enoch, (Florence) Ethel, and (Muriel) Frida had emigrated in 1906. Enoch’s occupation was machinist in 1911. The census transcription is not very good. Edwards was transcribed as Edmand, but the dates of birth for all three are correct. Birthplace is correct ~ A for Anglitan (the census is in French) but race or tribe is also an A but the transcribers have put African black! Enoch by this time was 71 years old, his wife 33 and daughter 11.

Additional information from Paul Weaver:

“In 1906 he and his new family travelled to Canada with Enoch travelling first and Ethel and Frida joined him in Quebec on 25 June 1906 on board the ‘Canada’ from Liverpool.

Their immigration record suggests that they were planning to travel to Winnipeg, but five years later in 1911, Enoch, Florence Ethel and Frida were still living in St James, Montreal. Enoch was employed as a machinist by Canadian Government Railways working 50 hours. It is the 1911 census record that confirms his birth as November 1840. It also states that Enoch could neither read nor write but managed to earn $500 in 1910 for activity other than his main profession, although this may be referring to his innkeeping business interests.

By 1921 Florence and Muriel Frida are living in Langford, Neepawa, Manitoba with Peter FUCHS, an Ontarian farmer of German descent who Florence had married on 24 Jul 1913 implying that Enoch died sometime in 1911/12, although no record has been found.”The extra $500 in earnings was perhaps related to the St Bernard dogs. Enoch signed his name on the register on his marriage to Emelia, and I think it’s very unlikely that he could neither read nor write, as stated above.

However, it may not be Enoch’s wife Florence Ethel who married Peter Fuchs. A Florence Emma Edwards married Peter Fuchs, and on the 1921 census in Neepawa her daugther Muriel Elizabeth Edwards, born in 1902, lives with them. Quite a coincidence, two Florence and Muriel Edwards in Neepawa at the time. Muriel Elizabeth Edwards married and had two children but died at the age of 23 in 1925. Her mother Florence was living with the widowed husband and the two children on the 1931 census in Neepawa. As there was no other daughter on the 1911 census with Enoch, Florence and Muriel in Montreal, it must be a different Florence and daughter. We don’t know, though, why Muriel Constance Freda married in Neepawa.

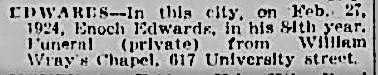

Indeed, Florence was not a widow in 1913. Enoch died in 1924 in Montreal, aged 84. Neither Enoch, Florence or their daughter has been found yet on the 1921 census. The search is not easy, as Enoch sometimes used the name Andrew, Florence used her middle name Ethel, and daughter Muriel used Freda, Valerie (the name she added when she married in Neepawa), and died as Marcheta. The only name she NEVER used was Constance!

A Canadian genealogist living in Montreal phoned the cemetery where Enoch was buried. She said “Enoch Edwards who died on Feb 27 1924 is not buried in the Mount Royal cemetery, he was only cremated there on March 4, 1924. There are no burial records but he died of an abcess and his body was sent to the cemetery for cremation from the Royal Victoria Hospital.”

1924 Obituary for Enoch Edwards:

Cimetière Mont-Royal Outremont, Montreal Region, Quebec, Canada

The Montreal Star 29 Feb 1924, Fri · Page 31

Muriel Constance Freda Valerie Edwards married Arthur Frederick Morris on 24 Oct 1925 in Neepawa, Manitoba. (She appears to have added the name Valerie when she married.)

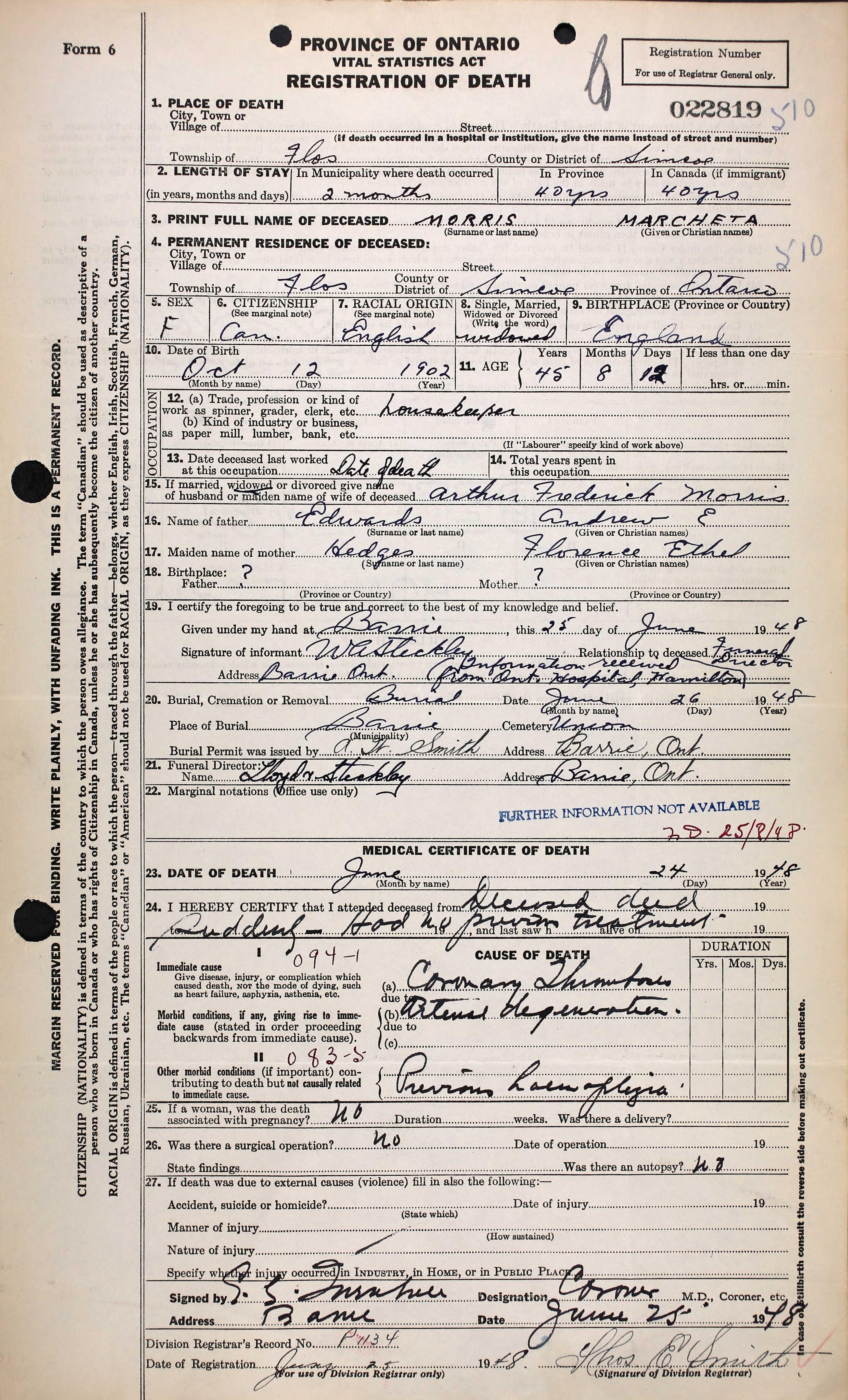

Unexpectedly a death certificate appeared for Muriel via the hints on the ancestry website. Her name was “Marcheta Morris” on this document, however it also states that she was the widow of Arthur Frederick Morris and daughter of Andrew E Edwards and Florence Ethel Hedges. She died suddenly in June 1948 in Flos, Simcoe, Ontario of a coronary thrombosis, where she was living as a housekeeper.

June 13, 2023 at 10:31 am #7255

June 13, 2023 at 10:31 am #7255In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The First Wife of John Edwards

1794-1844

John was a widower when he married Sarah Reynolds from Kinlet. Both my fathers cousin and I had come to a dead end in the Edwards genealogy research as there were a number of possible births of a John Edwards in Birmingham at the time, and a number of possible first wives for a John Edwards at the time.

John Edwards was a millwright on the 1841 census, the only census he appeared on as he died in 1844, and 1841 was the first census. His birth is recorded as 1800, however on the 1841 census the ages were rounded up or down five years. He was an engineer on some of the marriage records of his children with Sarah, and on his death certificate, engineer and millwright, aged 49. The age of 49 at his death from tuberculosis in 1844 is likely to be more accurate than the census (Sarah his wife was present at his death), making a birth date of 1794 or 1795.

John married Sarah Reynolds in January 1827 in Birmingham, and I am descended from this marriage. Any children of John’s first marriage would no doubt have been living with John and Sarah, but had probably left home by the time of the 1841 census.

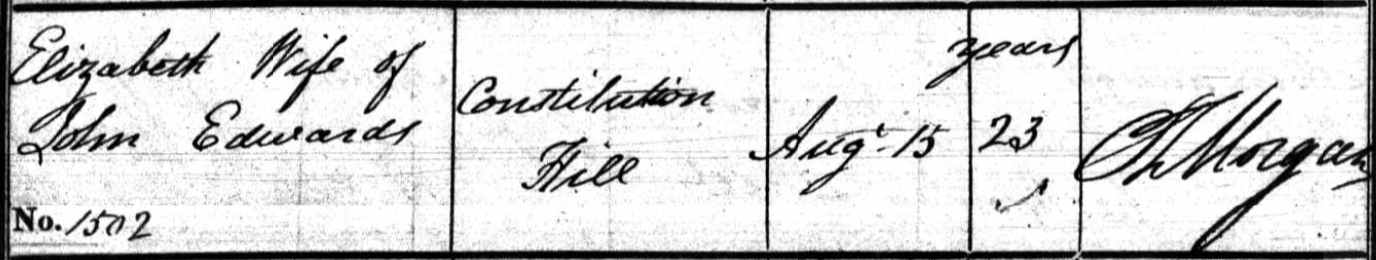

I found an Elizabeth Edwards, wife of John Edwards of Constitution Hill, died in August 1826 at the age of 23, as stated on the parish death register. It would be logical for a young widower with small children to marry again quickly. If this was John’s first wife, the marriage to Sarah six months later in January 1827 makes sense. Therefore, John’s first wife, I assumed, was Elizabeth, born in 1803.

Death of Elizabeth Edwards, 23 years old. St Mary, Birmingham, 15 Aug 1826:

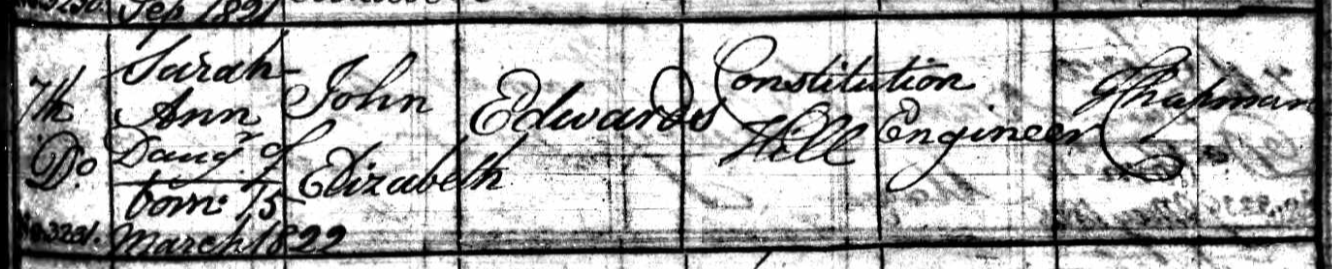

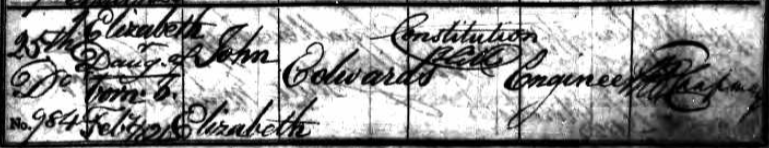

There were two baptisms recorded for parents John and Elizabeth Edwards, Constitution Hill, and John’s occupation was an engineer on both baptisms.

They were both daughters: Sarah Ann in 1822 and Elizabeth in 1824.Sarah Ann Edwards: St Philip, Birmingham. Born 15 March 1822, baptised 7 September 1822:

Elizabeth Edwards: St Philip, Birmingham. Born 6 February 1824, baptised 25 February 1824:

With John’s occupation as engineer stated, it looked increasingly likely that I’d found John’s first wife and children of that marriage.

Then I found a marriage of Elizabeth Beach to John Edwards in 1819, and subsequently found an Elizabeth Beach baptised in 1803. This appeared to be the right first wife for John, until an Elizabeth Slater turned up, with a marriage to a John Edwards in 1820. An Elizabeth Slater was baptised in 1803. Either Elizabeth Beach or Elizabeth Slater could have been the first wife of John Edwards. As John’s first wife Elizabeth is not related to us, it’s not necessary to go further back, and in a sense, doesn’t really matter which one it was.

But the Slater name caught my eye.

But first, the name Sarah Ann.

Of the possible baptisms for John Edwards, the most likely seemed to be in 1794, parents John and Sarah. John and Sarah had two infant daughters die just prior to John’s birth. The first was Sarah, the second Sarah Ann. Perhaps this was why John named his daughter Sarah Ann? In the absence of any other significant clues, I decided to assume these were the correct parents. I found and read half a dozen wills of any John Edwards I could find within the likely time period of John’s fathers death.

One of them was dated 1803. In this will, John mentions that his children are not yet of age. (John would have been nine years old.)

He leaves his plating business and some properties to his eldest son Thomas Davis Edwards, (just shy of 21 years old at the time of his fathers death in 1803) with the business to be run jointly with his widow, Sarah. He mentions his son John, and leaves several properties to him, when he comes of age. He also leaves various properties to his daughters Elizabeth and Mary, ditto. The baptisms for all of these children, including the infant deaths of Sarah and Sarah Ann have been found. All but Mary’s were in the same parish. (I found one for Mary in Sutton Coldfield, which was apparently correct, as a later census also recorded her birth as Sutton Coldfield. She was living with family on that census, so it would appear to be correct that for whatever reason, their daughter Mary was born in Sutton Coldfield)Mary married John Slater in 1813. The witnesses were Elizabeth Whitehouse and John Edwards, her sister and brother. Elizabeth married William Nicklin Whitehouse in 1805 and one of the witnesses was Mary Edwards.

Mary’s husband John Slater died in 1821. They had no children. Mary never remarried, and lived with her bachelor brother Thomas Davis Edwards in West Bromwich. Thomas never married, and on the census he was either a proprietor of houses, or “sinecura” (earning a living without working).With Mary marrying a Slater, does this indicate that her brother John’s first wife was Elizabeth Slater rather than Elizabeth Beach? It is a compelling possibility, but does not constitute proof.

Not only that, there is no absolute proof that the John Edwards who died in 1803 was our ancestor John Edwards father.

If we can’t be sure which Elizabeth married John Edwards, we can be reasonably sure who their daughters married. On both of the marriage records the father is recorded as John Edwards, engineer.

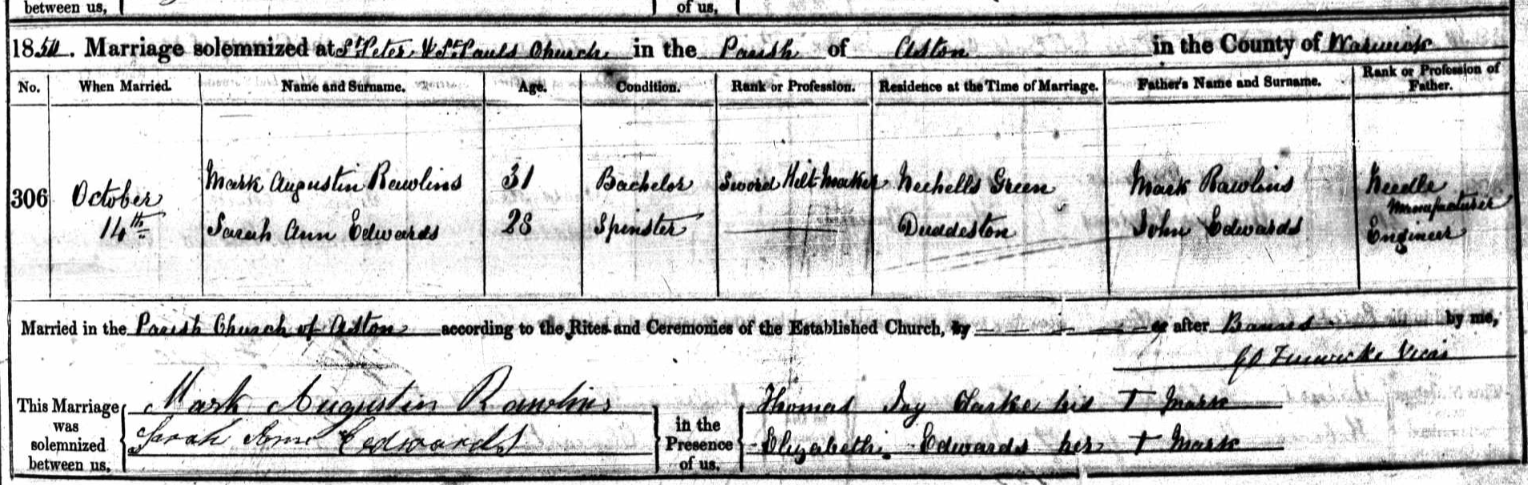

Sarah Ann married Mark Augustin Rawlins in 1850. Mark was a sword hilt maker at the time of the marriage, his father Mark a needle manufacturer. One of the witnesses was Elizabeth Edwards, who signed with her mark. Sarah Ann and Mark however were both able to sign their own names on the register.

Sarah Ann Edwards and Mark Augustin Rawlins marriage 14 October 1850 St Peter and St Paul, Aston, Birmingham:

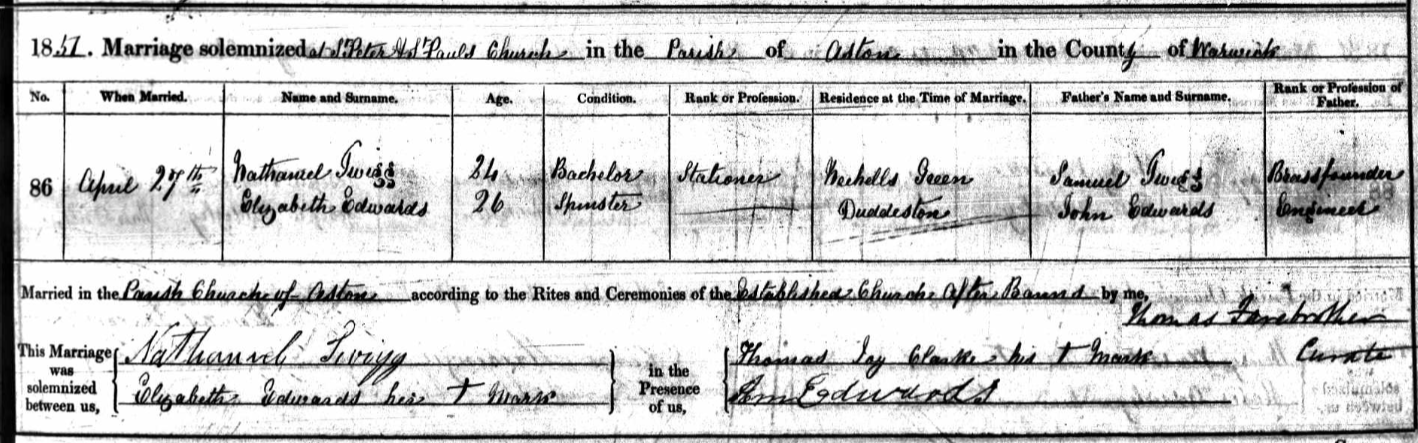

Elizabeth married Nathaniel Twigg in 1851. (She was living with her sister Sarah Ann and Mark Rawlins on the 1851 census, I assume the census was taken before her marriage to Nathaniel on the 27th April 1851.) Nathaniel was a stationer (later on the census a bookseller), his father Samuel a brass founder. Elizabeth signed with her mark, apparently unable to write, and a witness was Ann Edwards. Although Sarah Ann, Elizabeth’s sister, would have been Sarah Ann Rawlins at the time, having married the previous year, she was known as Ann on later censuses. The signature of Ann Edwards looks remarkably similar to Sarah Ann Edwards signature on her own wedding. Perhaps she couldn’t write but had learned how to write her signature for her wedding?

Elizabeth Edwards and Nathaniel Twigg marriage 27 April 1851, St Peter and St Paul, Aston, Birmingham:

Sarah Ann and Mark Rawlins had one daughter and four sons between 1852 and 1859. One of the sons, Edward Rawlins 1857-1931, was a school master and later master of an orphanage.

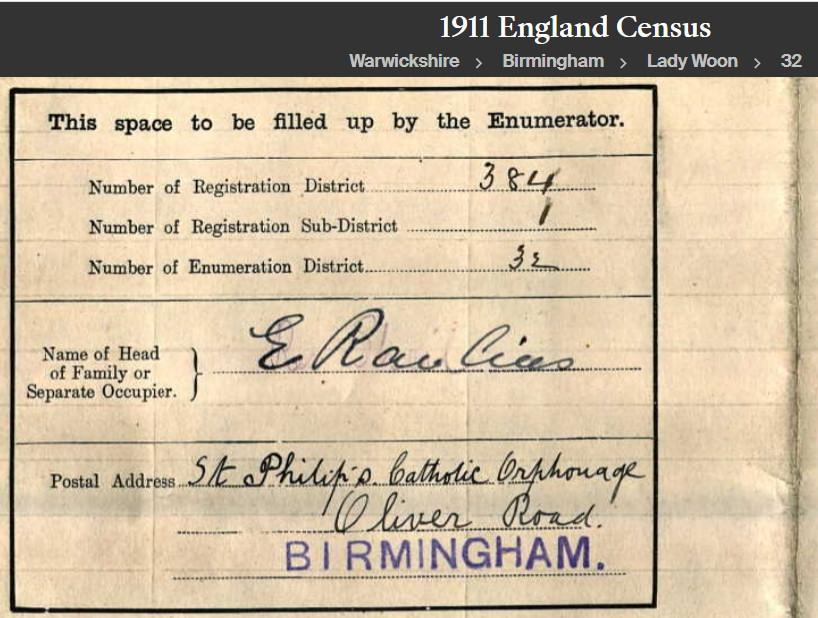

On the 1881 census Edward was a bookseller, in 1891 a stationer, 1901 schoolmaster and his wife Edith was matron, and in 1911 he and Edith were master and matron of St Philip’s Catholic Orphanage on Oliver Road in Birmingham. Edward and Edith did not have any children.

Edward Rawlins, 1911:

Elizabeth and Nathaniel Twigg appear to have had only one son, Arthur Twigg 1862-1943. Arthur was a photographer at 291 Bloomsbury Street, Birmingham. Arthur married Harriet Moseley from Burton on Trent, and they had two daughters, Elizabeth Ann 1897-1954, and Edith 1898-1983. I found a photograph of Edith on her wedding day, with her father Arthur in the picture. Arthur and Harriet also had a son Samuel Arthur, who lived for less than a month, born in 1904. Arthur had mistakenly put this son on the 1911 census stating “less than one month”, but the birth and death of Samuel Arthur Twigg were registered in the same quarter of 1904, and none were found registered for 1911.

Edith Twigg and Leslie A Hancock on their Wedding Day 1925. Arthur Twigg behind the bride. Maybe Elizabeth Ann Twigg seated on the right: (photo found on the ancestry website)

Photographs by Arthur Twigg, 291 Bloomsbury Street, Birmingham:

March 24, 2023 at 7:49 am #7214

March 24, 2023 at 7:49 am #7214In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

“Bossy, isn’t she?” muttered Yasmin, not quite out of earshot of Finly. “I haven’t even had a shower yet,” she added, picking up her phone and sandals.

Yasmin, Youssef and Zara left the maid to her cleaning and walked down towards Xaviers room. “I’d go and get coffee from the kitchen, but…” Youssef said, turning pleading eyes towards Zara, “Idle might be in there.”

Smiling, Zara told him not to risk it, she would go.

“Come in,” Xavier called when Yasmin knocked on the door. “God, what a dream,” he said when they piled in to his room. “It was awful. I was dreaming that Idle was threading an enormous long needle with baler twine saying she was going to sew us all together in a tailored story cut in a cloth of continuity.” He rubbed his eyes and then shook his head, trying to erase the image in his mind. “What are you two up so early for?”

“Zara’s gone to get the coffee,” Youssef told him, likewise trying to shake off the image of Idle that Xavier had conjured up. “We’re going to have a couple of hours on the game before the cart race ~ or the dust storm, whichever happens first I guess. There are some wierd looking vans and campers and oddballs milling around outside already.”

Zara pushed the door open with her shoulder, four mugs in her hands. “You should see the wierdos outside, going to be a great photo opportunity out there later.”

“Come on then,” said Xavier, “The game will get that awful dream out of my head. Let’s go!”

“You’re supposed to be the leader, you start the game,” Yasmin said to Zara. Zara rolled her eyes good naturedly and opened the game. “Let’s ask for some clues first then. I still don’t know why I’m the so called leader when you,” she looked pointedly as Xavier and Youssef, “Know much more about games than I do. Ok here goes:”

“The riddle “In the quietest place, the loudest secrets are kept” is a clue to help the group find the first missing page of the book “The Lost Pages of Creativity,” which is an integral part of the group quest. The riddle suggests that the missing page is hidden in a quiet place where secrets are kept, meaning that it’s likely to be somewhere in the hidden library underground the Flying Fish Inn where the group is currently situated.”

“Is there a cellar here do you think?” Zara mused. “Imagine finding a real underground library!” The idea of a grand all encompassing library had first been suggested to Zara many years ago in a series of old books by a channeler, and many a time she had imagined visiting it. The idea of leaving paper records and books for future generations had always appealed to her. She often thought of the old sepia portrait photographs of her ancestors, still intact after a hundred years ~ and yet her own photos taken ten years ago had been lost in a computer hard drive incident. What would the current generation leave for future anthropologists? Piles of plastic unreadable gadgets, she suspected.

“Youssef can ask Idle later,” Xavier said with a cheeky grin. “Maybe she’ll take him down there.” Youssef snorted, and Yasmin said “Hey! Don’t you start snorting too! Right then, Zara, so we find the cellar in the game then and go down and find the library? Then what?”

“The phrase “quietest place” can refer to a secluded spot or a place with minimal noise, which could be a hint at a specific location within the library. The phrase “loudest secrets” implies that there is something important to be discovered, but it’s hidden in plain sight.”

Hidden in plain sight reminded Yasmin of the parcel under her mattress, but she thrust it from her mind and focused on the game. She made up her mind to discuss it with everyone later, including the whacky suppositions that Zara had come up with. They couldn’t possibly confront Idle with it, they had absolutely no proof. I mean, you can’t go round saying to people, hey, that’s your abandoned child over there maybe. But they could include Xavier and Youssef in the mystery.

“The riddle is relevant to the game of quirks because it challenges the group to think creatively and work together to solve the puzzle. This requires them to communicate effectively and use their problem-solving skills to interpret the clues and find the missing page. It’s an opportunity to demonstrate their individual strengths and also learn from each other in the process.”

“Work together, communicate effectively” Yasmin repeated, as if to underline her resolution to discuss the parcel and Sister Finli a.k.a. Liana with the boys and Zara later. “A problem shared is a problem hopelessly convoluted, probably.”

The others looked up and said “What?” in unison, and Yasmin snorted nervously and said “Never mind, tell you later.”

February 22, 2023 at 8:54 am #6621In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

As the four of them walked into the tavern, having walked the mile or so from the Flying Fish Inn to the main street of the tiny town, Zara noticed the black BMW that she and Yasmin had seen parked outside the Piggly supermarket on the way back from the airport in Alice. She elbowed Yasmin in the ribs to point it out, but there was no need as Yasmin was already snorting nervously at the sight of it.

Sister Finli caught sight of them as she was just about to leave Betsy’s gem shop and paused until they’d disappeared into the bar before leaving the shop. It was the first time that Finli had seen Betsy in the flesh, and what a lot of flesh there was to see. Finli was horrifed, comparing her own elegant thin fingers with the fat sausage like digits of Betsy. She would never have expected Betsy to look this way. Still, it had thrown her, and she lost her usual efficient composure and quickly purchased a pink speckled gummy bear necklace. Annoyingly, this transaction reminded her that she seemed to have lost her crucifix.

Finli was an orphan. The nuns had named her Finean Lisa. Finean meant beautiful daughter, and Lisa meant devoted to god. Later they shortened it to Finli. She’d spent all her life at the orphanage in Suva, having been deposited there at birth, and although she had no particular calling to be a nun, she had not known what else to do with her life. It was the only family she’d ever known, and so she stayed on. It was only in the past year or two that she’d had any curiosity about who her real parents were, when she read about DNA tests and ancestry research. She’d been told in the past that no records existed as she had been found on the doorstep of the orphanage one morning 43 years ago. The knowledge had filled her with comtempt for her parents, whoever they were, and for the most part she pushed them from her mind, not caring to know. But when she read about all the successes of adopted people finding their real parents, she was consumed with curiosity. At first she just wanted to know who they were. But once she had found their names, she wanted to know more. She wanted to know why. One thing led to another.

Her real father had disappeared, lost down some mines although the story there was far from clear. Indeed, that particular story was a darn sight more than unclear, it was downright fishy. Her real mother was was alive and kicking, and living near to the mines where Howard had disappeared. Finli deduced that she must have been born, or at least conceived, in this godforsaken place in the outback. What an ignominous start to her uneventful life.

She knew that Fred was her uncle, but she had not told him she knew that. Did Fred know who she was? He’d always been kind to her, but then, he was affable to everyone. When it came to her knowledge that Fred had given that tiresome snorting volunteer girl a parcel to take with her, to, of all places! that very town in the outback, Finli simply had to know what was in it. But she didn’t want to spill the beans too soon, in case it hindered her attempts to find the truth about Howard, her father. She decided to travel to the town incognito. But how was she going to find the money for it? Well, she knew she was burning her bridges, but she had to do it. She stole the golden chalice from the church and sold it on Ubay. She was suprised at how much money it fetched. Not only could she afford the trip, she could do it in style.

It was an exciting adventure, but Finli was not accustomed to travel and adventure. In fact, she was dreading meeting her mother. At times she wished she’d just stayed at the orphanage. But it was too late now. She was here.

February 18, 2023 at 11:28 am #6551

February 18, 2023 at 11:28 am #6551In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Xavier had woken up in the middle of the night that felt surprisingly alive bursting with a quiet symphony of sounds from nocturnal creatures and nearby nature, painted on a canvas of eerie spacious silence.

It often took him a while to get accustomed to any new place, and it was not uncommon for him to have his mind racing in the middle of the night. Generally Brytta had a soothing presence and that often managed to nudge him back to sleep, otherwise, he would simply wake up until the train of thoughts had left the station.

It was beginning of the afternoon in Berlin; Brytta would be in a middle of a shift, so he recorded a little message for her to find when she would get back to her phone. It was funny to think they’d met thanks to Yasmin and Zara, at the time the three girls were members of the same photography club, which was called ‘Focusgroupfocus’ or something similar…

With that done, he’d turned around for something to do but there wasn’t much in the room to explore or to distract him sufficiently. Not even a book in the nightstand drawer. The decoration itself had a mesmerising nature, but after a while it didn’t help with the racing thoughts.He was tempted to check in the game — there was something satisfactory in finishing a quest that left his monkey brain satiated for a while, so he gave in and logged back in.

Completing the quest didn’t take him too long this time. The main difficulty initially was to find the portal from where his avatar had landed. It was a strange carousel of blue storks that span into different dimensions one could open with the proper incantation.

As usual, stating the quirk was the key to the location, and the carousel portal propelled him right away to Midnight town, which was clearly a ghost town in more ways than one. Interestingly, he was chatting on the side with Glimmer, who’d run into new adventures of her own while continuing to ask him what was up, and as soon as he’d reached Midnight town, all communication channels suddenly went dark. He’d laughed to himself thinking how frustrated Glimmer would have been about that. But maybe the game took care of sending her AI-generated messages simulating his presence. Despite the disturbing thought of having an AI generated clone of himself, he almost hoped for it (he’d probably signed the consent for this without realising), so that he wouldn’t have to do a tedious recap about all what she’d missed.

Once he arrived in the town, the adventure followed a predictable pattern. The clues were also rather simple to follow.

The townspeople are all frozen in time, stuck in their daily routines and unable to move on. Your mission is to find the missing piece of continuity, a small hourglass that will set time back in motion and allow the townspeople to move forward.

The clue to finding the hourglass lies within a discarded pocket watch that can be found in the mayor’s office. You must unscrew the back and retrieve a hidden key. The key will unlock a secret compartment in the town clock tower, where the hourglass is kept.

Be careful as you search for the hourglass, as the town is not as abandoned as it seems. Spectral figures roam the streets, and strange whispers can be heard in the wind. You may also encounter a mysterious old man who seems to know more about the town’s secrets than he lets on.

Evading the ghosts and spectres wasn’t too difficult once you got the hang of it. The old man however had been quite an elusive figure to find, but he was clearly the highlight of the whole adventure; he had been hiding in plain sight since the beginning of the adventure. One of the blue storks in the town that he’d thought had come with him through the portal was in actuality not a bird at all.

While he was focused on finishing the quest, the interaction with the hermit didn’t seem very helpful. Was he really from the game construct? When it was time to complete the quest and turn the hourglass to set the town back in motion, and resume continuity, some of his words came back to Xavier.

“The town isn’t what it seems. Recognise this precious moment where everything is still and you can realise it for the illusion that it is, a projection of your busy mind. When motion resumes, you will need to keep your mind quiet. The prize in the quest is not the completion of it, but the realisation you can stop the agitation at any moment, and return to what truly matters.”

The hermit had turned to him with clear dark eyes and asked “do you know what you are seeking in these adventures? do you know what truly matters to you?”

When he came out of the game, his quest completed, Xavier felt the words resonate ominously.

A buzz of the phone snapped him out of it.

It was a message from Zara. Apparently she’d found her way back to modernity.

[4:57] “Going to pick up Yasmin at the airport. You better sleep away the jetlag you lazy slugs, we have poultry damn plenty planned ahead – cackling bugger cooking lessons not looking forward to, but can be fun. Talk to you later. Z”

He had the impulse to go with her, but the lack of sleep was hitting back at him now, and he thought he’d better catch some so he could manage to realign with the timezone.

“The old man was right… that sounds like a lot of agitation coming our way…”

February 6, 2023 at 10:15 pm #6498Some background information on The Sexy Wooden Leg and potential plot developments.

Setting

(nearby Duckailingtown in Dumbass, Oocrane)

The Rootians (a fictitious nationality) invaded Oocrane (a fictitious country) under the guise of freeing the Dumbass region from Lazies. They burned crops and buildings, including the home of a man named Dumbass Voldomeer who was known for his wooden leg and carpenter skills. After the war, Voldomeer was hungry and saw a nest of swan eggs. He went back to his home, carved nine wooden eggs, and replaced the real eggs with the wooden ones so he could eat the eggs for food. The swans still appeared to be brooding on their eggs by the end of summer.Note: There seem to be a bird thematic at play.

The swans’ eggs introduce the plot. The mysterious virus is likely a swan flu. Town in Oocrane often have reminiscing tones of birds’ species.

Bird To(w)nes: (Oocrane/crane, Keav/kea, Spovlar/shoveler, Dilove/dove…)

Also the town’s nursing home/hotel’s name is Vyriy from a mythical place in Slavic mythology (also Iriy, Vyrai, or Irij) where “birds fly for winter and souls go after death” which is sometimes identified with paradise. It is believed that spring has come to Earth from Vyrai.At the Keav Headquarters

(🗺️ Capital of Oocrane)

General Rudechenko and Major Myroslava Kovalev are discussing the incapacitation of President Voldomeer who is suffering from a mysterious virus. The President had told Major Kovalev about a man in the Dumbass region who looked similar to him and could be used as a replacement. The Major volunteers to bring the man to the General, but the General fears it is a suicide mission. He grants her permission but orders his aide to ensure she gets lost behind enemy lines.

Myroslava, the ambitious Major goes undercover as a former war reporter, is now traveling on her own after leaving a group of journalists. She is being followed but tries to lose her pursuers by hunting and making fire in bombed areas. She is frustrated and curses her lack of alcohol.

The Shrine of the Flovlinden Tree

(🗺️ Shpovlar, geographical center of Oocrane)

Olek is the caretaker of the shrine of Saint Edigna and lives near the sacred linden tree. People have been flocking to the shrine due to the miraculous flow of oil from the tree. Olek had retired to this place after a long career, but now a pilgrim family has brought a message of a plan acceleration, which upsets Olek. He reflects on his life and the chaos of people always rushing around and preparing for the wrong things. He thinks about his father’s approach to life, which was carefree and resulted in the same ups and downs as others, but with less suffering. Olek may consider adopting this approach until he can find a way to hide from the enemy.

Rosa and the Cauldron Maker

(young Oocranian wiccan travelling to Innsbruck, Austria)

Eusebius Kazandis is selling black cauldrons at the summer fair of Innsbruck, Austria. He is watching Rosa, a woman selling massage oils, fragrant oils, and polishing oils. Rosa notices Eusebius is sad and thinks he is not where he needs to be. She waves at him, but he looks away as if caught doing something wrong. Rosa is on a journey across Europe, following the wind, and is hoping for a gust to tell her where to go next. However, the branches of the tree she is under remain still.

The Nursing Home

(Nearby the town of Dilove, Oocrane, on Roomhen border somewhere in Transcarpetya)

Egna, who has lived for almost a millennium, initially thinks the recent miracle at the Flovlinden Tree is just another con. She has performed many miracles in her life, but mostly goes unnoticed. She has a book full of records of the lives of many people she has tracked, and reminisces that she has a connection to the President Voldomeer. She decides to go and see the Flovlinden Tree for herself.

🗺️ (the Vyriy hotel at Dilove, Oocrane, on Roomhen border)

Ursula, the owner of a hotel on the outskirts of town, is experiencing a surge in business from the increased number of pilgrims visiting the linden tree. She plans to refurbish the hotel to charge more per night and plans to get a business loan from her nephew Boris, the bank manager. However, she must first evict the old residents of the hotel, which she is dreading. To avoid confrontation, she decides to send letters signed by a fake business manager.

Egbert Gofindlevsky, Olga Herringbonevsky and Obadiah Sproutwinklov are elderly residents of an old hotel turned nursing home who receive a letter informing them that they must leave. Egbert goes to see Obadiah about the letter, but finds a bad odor in his room and decides to see Olga instead.

Maryechka, Obadiah’s granddaughter, goes back home after getting medicine for her sick mother and finds her home empty. She decides to visit her grandfather and his friends at the old people’s home, since the schools are closed and she’s not interested in online activities.

Olga and Egbert have a conversation about their current situation and decide to leave the nursing home and visit Rosa, Olga’s distant relative. Maryechka encounters Egbert and Olga on the stairs and overhears them talking about leaving their friends behind. Olga realizes that it is important to hold onto their hearts and have faith in the kindness of strangers. They then go to see Obadiah, with Olga showing a burst of energy and Egbert with a weak smile.Thus starts their escape and unfolding adventure on the roads of war-torn Oocrane.

Character Keyword Characteristics Sentiment Egbert old man, sharp tone sad, fragile Maryechka Obadiah’s granddaughter, shy innocent Olga old woman, knobbly fingers conflicted, determined Obadiah stubborn as a mule, old friend of Egbert unyielding, possibly deaf February 2, 2023 at 2:47 pm #6491In reply to: Newsreel from the Rim of the Realm

Sophie was glad she could help that young guy Youssef get out of this mess with that false ingenue. She was clearly not for him, he needed someone more mature who would know how to handle his big body. She looked at Miss Bossy Pants’ office. Ricardo was there again and they seem to be in another of their grand discussions. When Miss Bossy saw Sophie watching, she moved to the big window and shut the venetian blind. What were they all about, always plotting things in the back of their journalists. If Sophie didn’t have an ounce of ethic, she would have RVed them long ago, but she made a point to only use her abilities for good, and at times good gossip with friends.

She went out to the elevator and called it. While she waited, she started writing a message : “The boy is on his way. I did like you asked. Now book me a place to that Akashic Record training as promised.”

The answer came only a few seconds later : “consider it done”

The elevator bell rang and the door opened. Sophie got in with a big satisfied smile on her face.”

February 1, 2023 at 12:12 pm #6486In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Zara took dozens of screenshots of the many etchings and drawings, as her game character paused to do the same. She had lost sight of the two figures up ahead, and remembered she probably should have been following them.

The tunnel came to a four way junction. There were drawings on the walls and floors of all of them, and a dim light coming from a distance in each. One was more brightly lit than the others, and Zara chose to explore that one first. Presently a side room appeared, with green tiles on the floor similar to the one at the mine entrance. Daylight shone though a small window, and a diagram was drawn onto the wall.

Zara toyed with the idea of simply climbing out through the window while there was still a chance to get out of the mine. She knew she was lost and would not be able to find her way out the way she came. It was tempting, but she just took a screenshot. Maybe when she looked at them later she’d be able to work out how to retrace her steps.

After recording the image of the room of tiles, Zara continued along the tunnel. The light shining from the little window in the tile room faded as she progressed, and she found herself once again in near darkness. She came to a fork. Both ways were equally gloomy, but a faint blue light enticed her to take the right hand tunnel.

So many forks and side tunnels, I am surely completely lost now! And not one of these supposed maps is helping, I can’t decipher any of them. Another etching on the wall caught her eye, and Zara forgot about being lost.

Zara stopped to look at what appeared to be a map on the tunnel wall, but it was unfathomable at this stage. She recorded it for future reference, and then looked around, unsure whether to continue on this path or retrace her stops back to the four way junction. And then she saw him in an alcove.

Osnas! This time Zara did say it out loud, and just as the frog faced stewardess was passing with her cart piled with used cups and cans and empty packets. I swear she just winked at me! Zara did a double take, but the cart and the woman had passed, collecting more rubbish.

With a little smile, Zara noticed that the mask Osnas was wearing was one of those paper pandemic masks. She had expected something a bit more Venice carnival when the prompt mentioned that he always wore a mask, not one of those. She hoped the clue in this case wasn’t the mask, as she had avoided the plague successfully so far and didn’t want to be late to that particular party, but the square green thing on his cart resembled the tile at the mine entrance. What do I do now though? I still don’t know what any of these things mean. Approach him and see if he speaks I suppose.

“Ladies and gentlemen, we are now approaching Alice Springs, please fasten your seatbelts and switch off all your devices ready for landing. We hope you have enjoyed your flight.”

January 31, 2023 at 8:33 pm #6480For temporal logs and quantum flux in probabilities recordings.

Background elements provided as narrative may arise.

Consistency possibly sketchy, time and space continuum span of epic proportions, with minute attention to insignificant details.

Factuality in progress…

December 19, 2022 at 9:48 am #6352In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The Birmingham Bootmaker

Samuel Jones 1816-1875

Samuel Jones the elder was born in Belfast circa 1779. He is one of just two direct ancestors found thus far born in Ireland. Samuel married Jane Elizabeth Brooker (born in St Giles, London) on the 25th January 1807 at St George, Hanover Square in London. Their first child Mary was born in 1808 in London, and then the family moved to Birmingham. Mary was my 3x great grandmother.

But this chapter is about her brother Samuel Jones. I noticed that on a number of other trees on the Ancestry site, Samuel Jones was a convict transported to Australia, but this didn’t tally with the records I’d found for Samuel in Birmingham. In fact another Samuel Jones born at the same time in the same place was transported, but his occupation was a baker. Our Samuel Jones was a bootmaker like his father.

Samuel was born on 28th January 1816 in Birmingham and baptised at St Phillips on the 19th August of that year, the fourth child and first son of Samuel the elder and Jane’s eleven children.

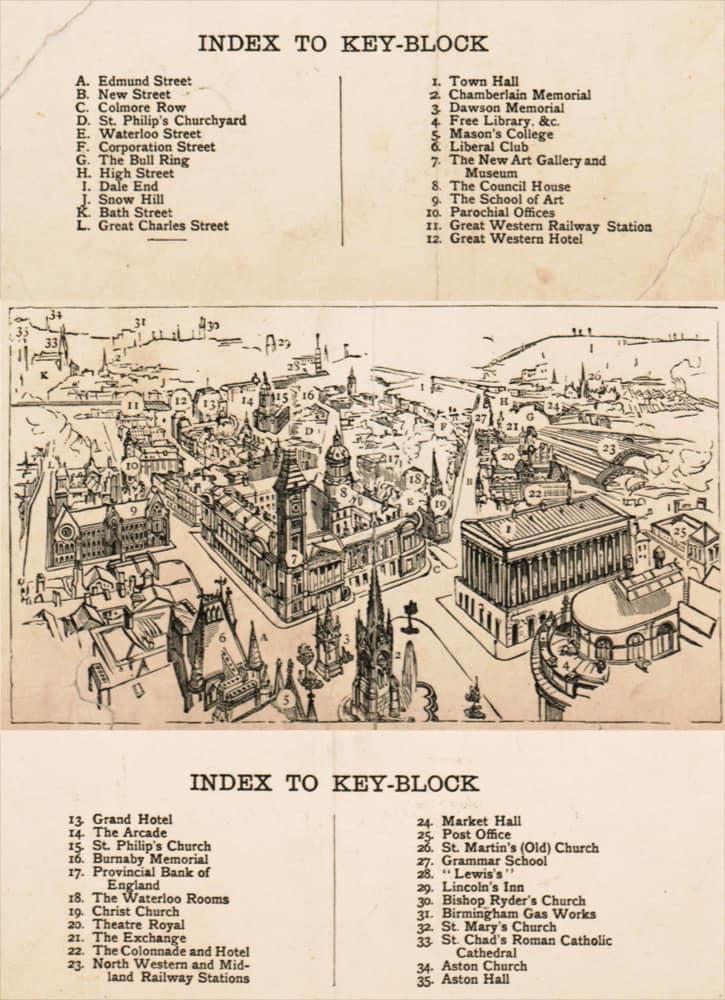

On the 1839 electoral register a Samuel Jones owned a property on Colmore Row, Birmingham.

Samuel Jones, bootmaker of 15, Colmore Row is listed in the 1849 Birmingham post office directory, and in the 1855 White’s Directory.

On the 1851 census, Samuel was an unmarried bootmaker employing sixteen men at 15, Colmore Row. A 9 year old nephew Henry Harris was living with him, and his mother Ruth Harris, as well as a female servant. Samuel’s sister Ruth was born in 1818 and married Henry Harris in 1840. Henry died in 1848.

Samuel was a 45 year old bootmaker at 15 Colmore Row on the 1861 census, living with Maria Walcot, a 26 year old domestic servant.

In October 1863 Samuel married Maria Walcot at St Philips in Birmingham. They don’t appear to have had any children as none appear on the 1871 census, where Samuel and Maria are living at the same address, with another female servant and two male lodgers by the name of Messant from Ipswich.

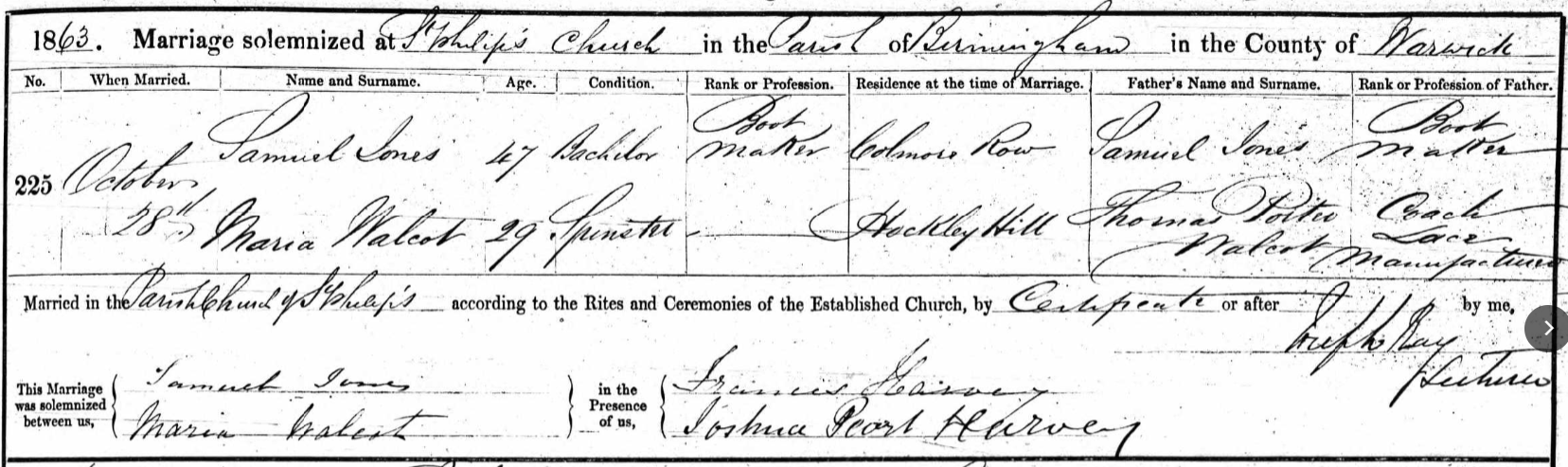

Marriage of Samuel Jones and Maria Walcot:

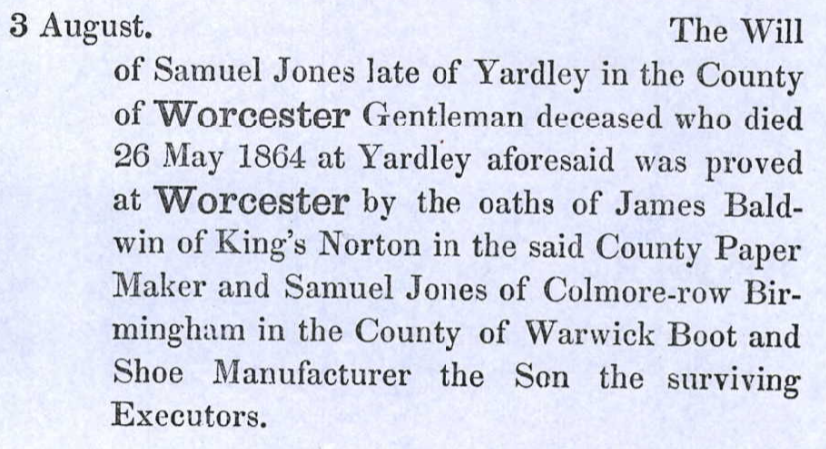

In 1864 Samuel’s father died. Samuel the son is mentioned in the probate records as one of the executors: “Samuel Jones of Colmore Row Birmingham in the county of Warwick boot and shoe manufacturer the son”.

Indeed it could hardly be clearer that this Samuel Jones was not the convict transported to Australia in 1834!

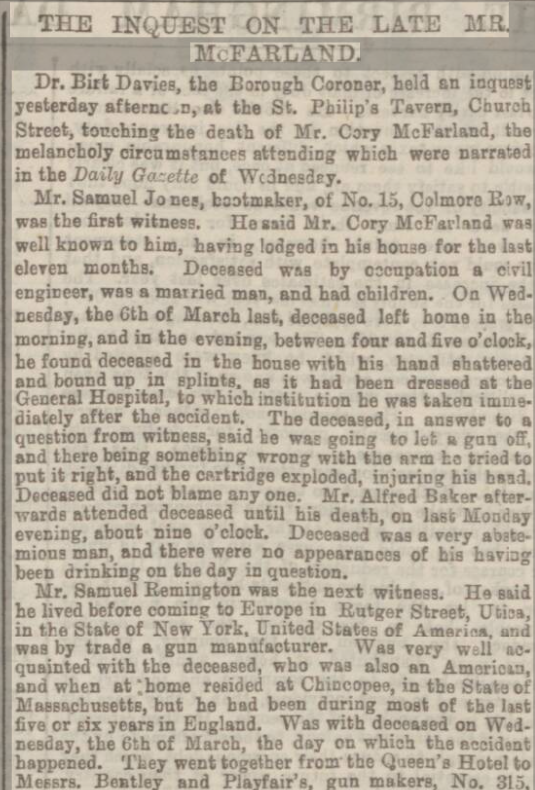

In 1867 Samuel Jones, bootmaker, was mentioned in the Birmingham Daily Gazette with regard to an unfortunate incident involving his American lodger, Cory McFarland. The verdict was accidental death.

Birmingham Daily Gazette – Friday 05 April 1867:

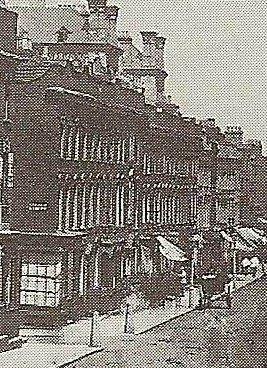

I asked a Birmingham history group for an old photo of Colmore Row. This photo is circa 1870 and number 15 is furthest from the camera. The businesses on the street at the time were as follows:

7 homeopathic chemist George John Morris. 8 surgeon dentist Frederick Sims. 9 Saul & Walter Samuel, Australian merchants. Surgeons occupied 10, pawnbroker John Aaron at 11 & 12. 15 boot & shoemaker. 17 auctioneer…

from Bird’s Eye View of Birmingham, 1886:

December 6, 2022 at 2:17 pm #6350

December 6, 2022 at 2:17 pm #6350In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Transportation

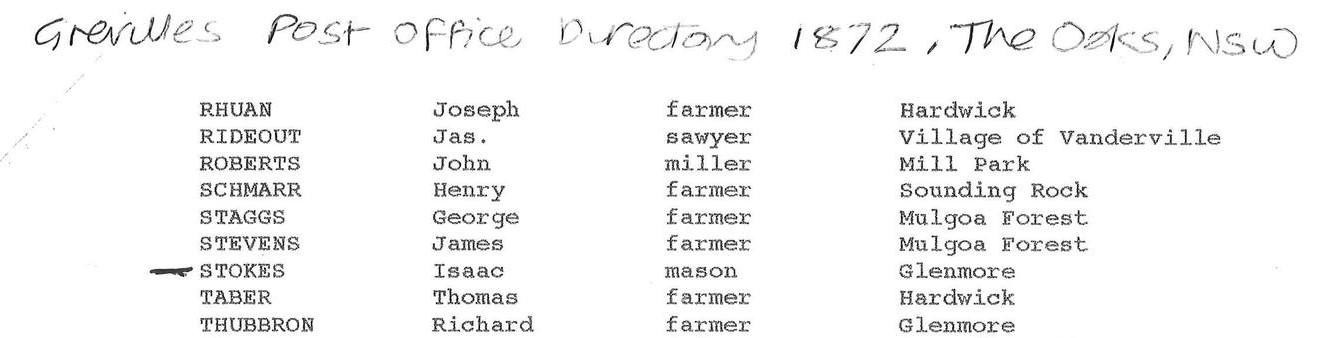

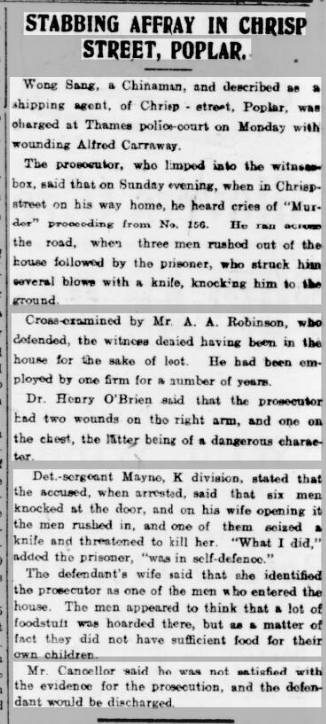

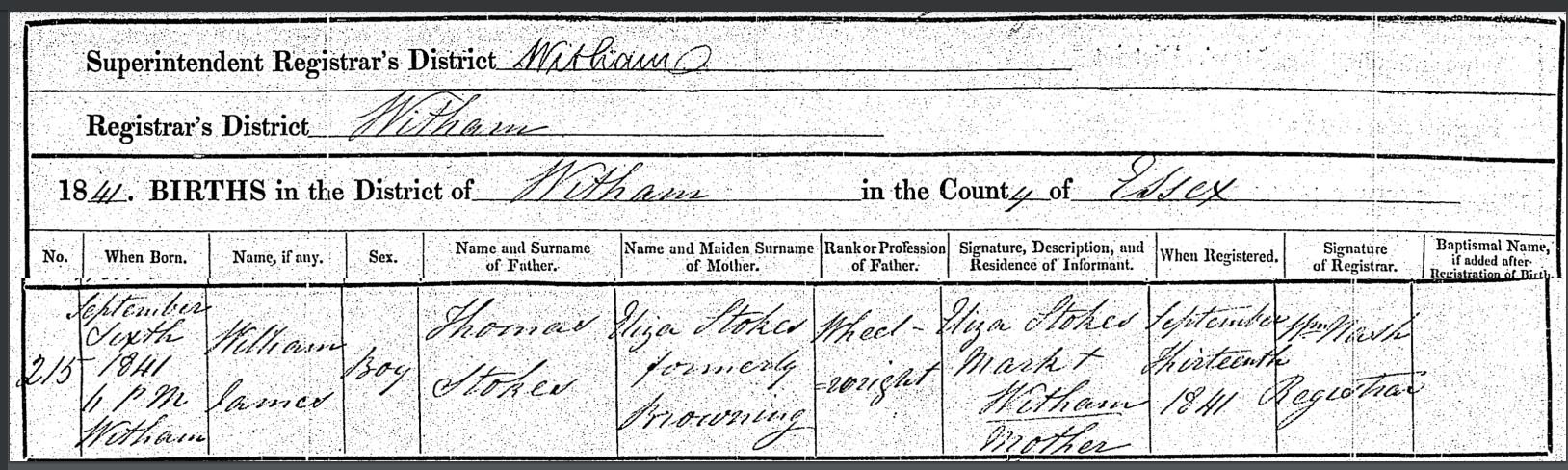

Isaac Stokes 1804-1877

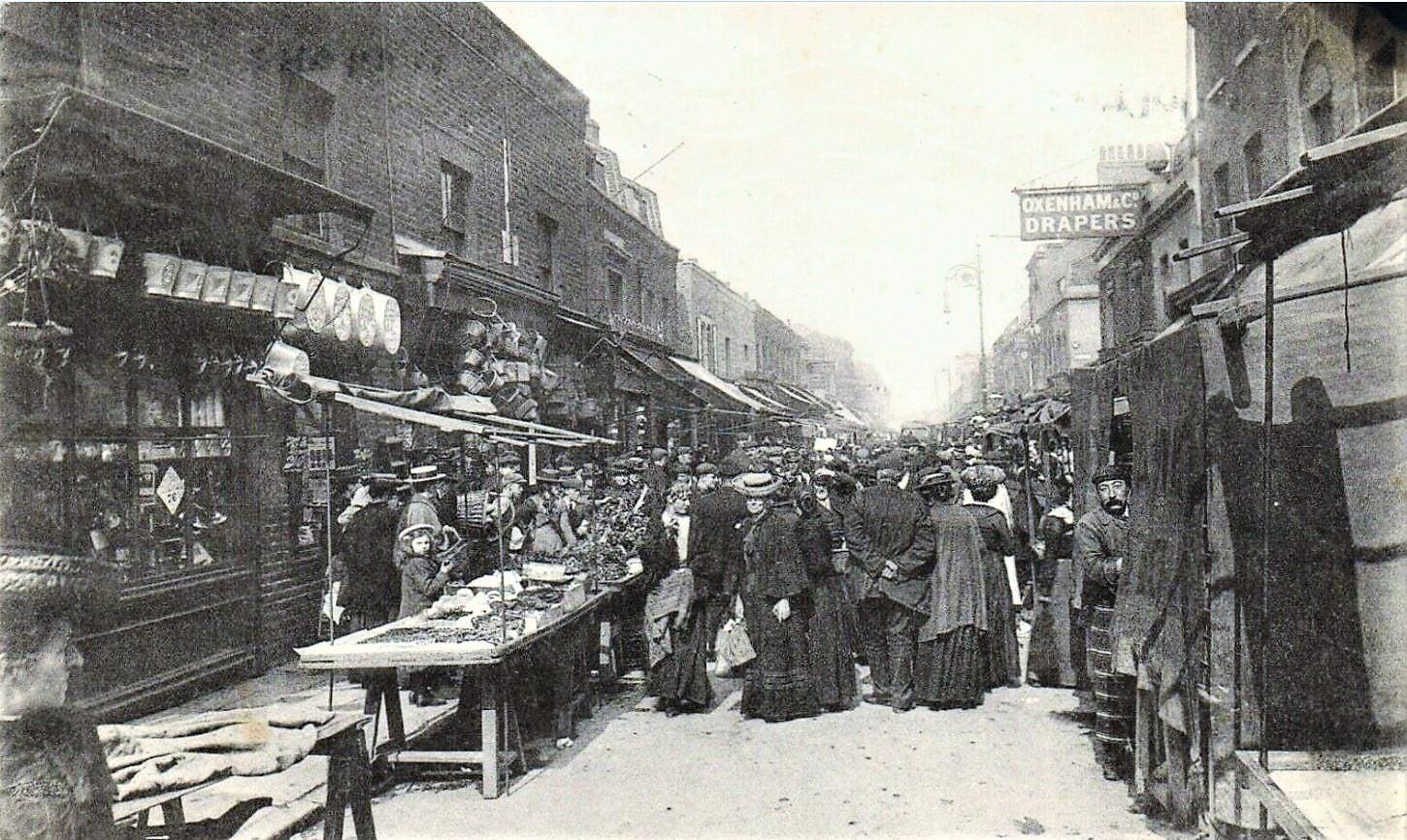

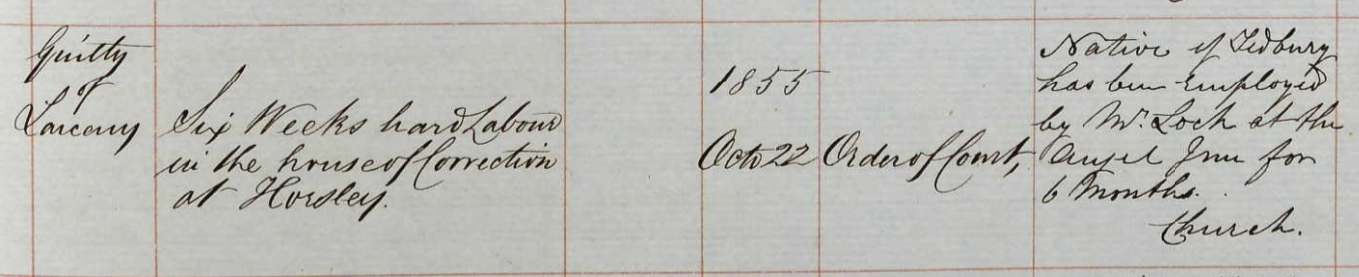

Isaac was born in Churchill, Oxfordshire in 1804, and was the youngest brother of my 4X great grandfather Thomas Stokes. The Stokes family were stone masons for generations in Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire, and Isaac’s occupation was a mason’s labourer in 1834 when he was sentenced at the Lent Assizes in Oxford to fourteen years transportation for stealing tools.

Churchill where the Stokes stonemasons came from: on 31 July 1684 a fire destroyed 20 houses and many other buildings, and killed four people. The village was rebuilt higher up the hill, with stone houses instead of the old timber-framed and thatched cottages. The fire was apparently caused by a baker who, to avoid chimney tax, had knocked through the wall from her oven to her neighbour’s chimney.

Isaac stole a pick axe, the value of 2 shillings and the property of Thomas Joyner of Churchill; a kibbeaux and a trowel value 3 shillings the property of Thomas Symms; a hammer and axe value 5 shillings, property of John Keen of Sarsden.

(The word kibbeaux seems to only exists in relation to Isaac Stokes sentence and whoever was the first to write it was perhaps being creative with the spelling of a kibbo, a miners or a metal bucket. This spelling is repeated in the criminal reports and the newspaper articles about Isaac, but nowhere else).

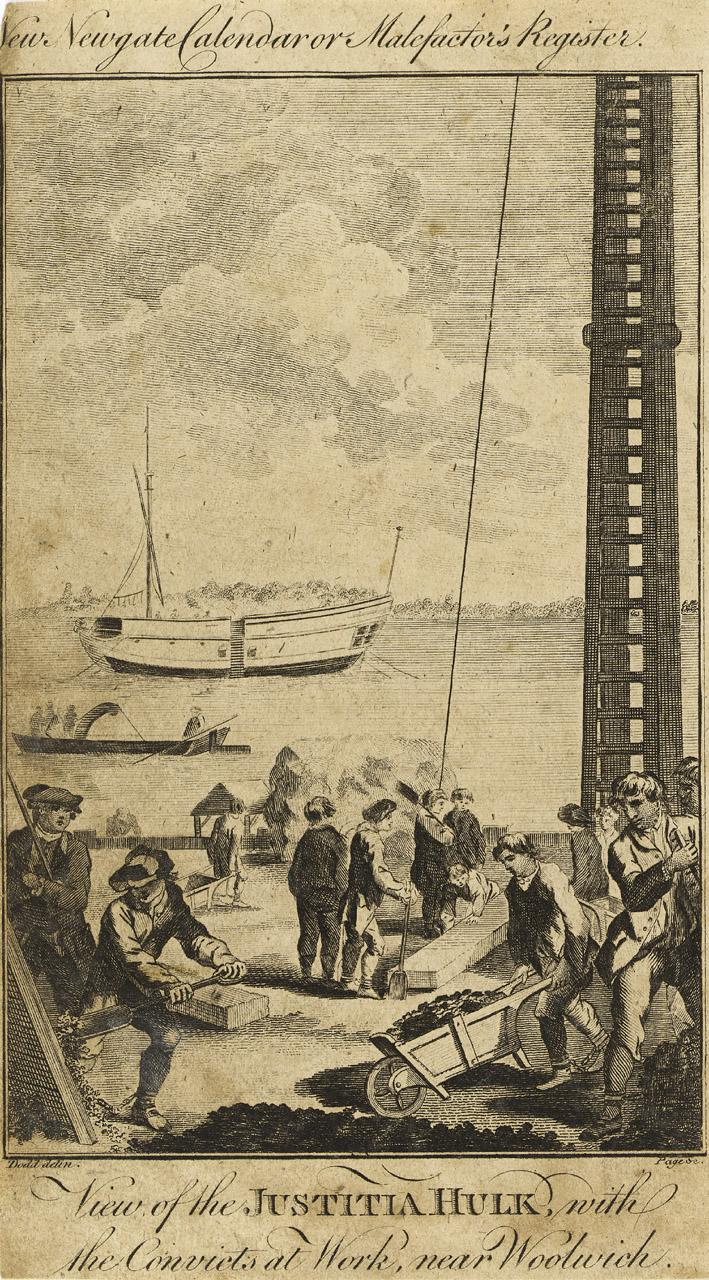

In March 1834 the Removal of Convicts was announced in the Oxford University and City Herald: Isaac Stokes and several other prisoners were removed from the Oxford county gaol to the Justitia hulk at Woolwich “persuant to their sentences of transportation at our Lent Assizes”.

via digitalpanopticon:

Hulks were decommissioned (and often unseaworthy) ships that were moored in rivers and estuaries and refitted to become floating prisons. The outbreak of war in America in 1775 meant that it was no longer possible to transport British convicts there. Transportation as a form of punishment had started in the late seventeenth century, and following the Transportation Act of 1718, some 44,000 British convicts were sent to the American colonies. The end of this punishment presented a major problem for the authorities in London, since in the decade before 1775, two-thirds of convicts at the Old Bailey received a sentence of transportation – on average 283 convicts a year. As a result, London’s prisons quickly filled to overflowing with convicted prisoners who were sentenced to transportation but had no place to go.

To increase London’s prison capacity, in 1776 Parliament passed the “Hulks Act” (16 Geo III, c.43). Although overseen by local justices of the peace, the hulks were to be directly managed and maintained by private contractors. The first contract to run a hulk was awarded to Duncan Campbell, a former transportation contractor. In August 1776, the Justicia, a former transportation ship moored in the River Thames, became the first prison hulk. This ship soon became full and Campbell quickly introduced a number of other hulks in London; by 1778 the fleet of hulks on the Thames held 510 prisoners.

Demand was so great that new hulks were introduced across the country. There were hulks located at Deptford, Chatham, Woolwich, Gosport, Plymouth, Portsmouth, Sheerness and Cork.The Justitia via rmg collections:

Convicts perform hard labour at the Woolwich Warren. The hulk on the river is the ‘Justitia’. Prisoners were kept on board such ships for months awaiting deportation to Australia. The ‘Justitia’ was a 260 ton prison hulk that had been originally moored in the Thames when the American War of Independence put a stop to the transportation of criminals to the former colonies. The ‘Justitia’ belonged to the shipowner Duncan Campbell, who was the Government contractor who organized the prison-hulk system at that time. Campbell was subsequently involved in the shipping of convicts to the penal colony at Botany Bay (in fact Port Jackson, later Sydney, just to the north) in New South Wales, the ‘first fleet’ going out in 1788.

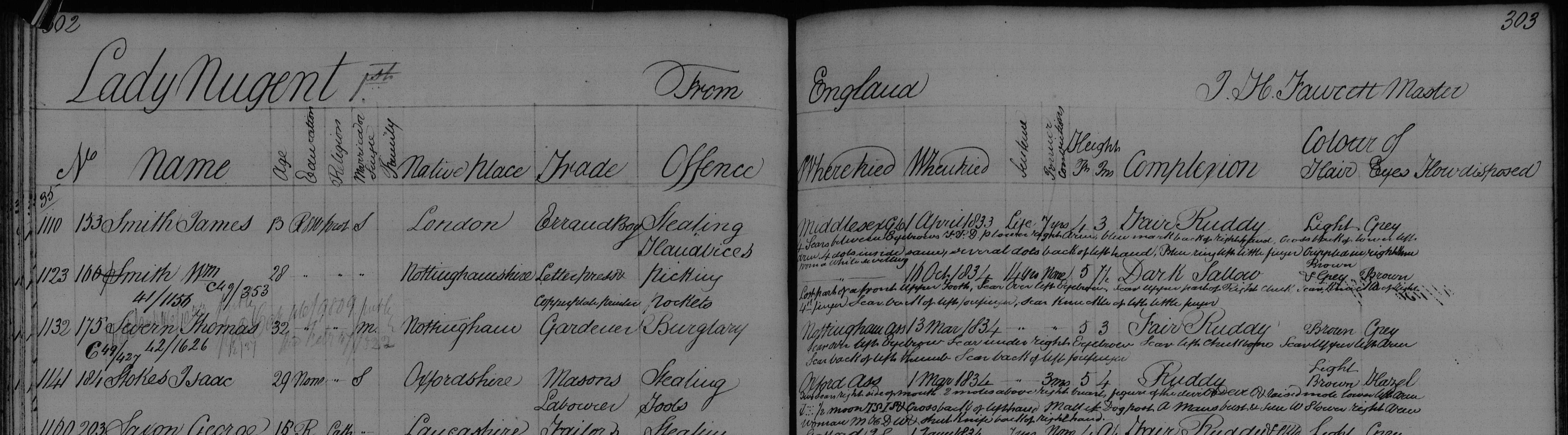

While searching for records for Isaac Stokes I discovered that another Isaac Stokes was transported to New South Wales in 1835 as well. The other one was a butcher born in 1809, sentenced in London for seven years, and he sailed on the Mary Ann. Our Isaac Stokes sailed on the Lady Nugent, arriving in NSW in April 1835, having set sail from England in December 1834.

Lady Nugent was built at Bombay in 1813. She made four voyages under contract to the British East India Company (EIC). She then made two voyages transporting convicts to Australia, one to New South Wales and one to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). (via Wikipedia)

via freesettlerorfelon website:

On 20 November 1834, 100 male convicts were transferred to the Lady Nugent from the Justitia Hulk and 60 from the Ganymede Hulk at Woolwich, all in apparent good health. The Lady Nugent departed Sheerness on 4 December 1834.

SURGEON OLIVER SPROULE

Oliver Sproule kept a Medical Journal from 7 November 1834 to 27 April 1835. He recorded in his journal the weather conditions they experienced in the first two weeks:

‘In the course of the first week or ten days at sea, there were eight or nine on the sick list with catarrhal affections and one with dropsy which I attribute to the cold and wet we experienced during that period beating down channel. Indeed the foremost berths in the prison at this time were so wet from leaking in that part of the ship, that I was obliged to issue dry beds and bedding to a great many of the prisoners to preserve their health, but after crossing the Bay of Biscay the weather became fine and we got the damp beds and blankets dried, the leaks partially stopped and the prison well aired and ventilated which, I am happy to say soon manifested a favourable change in the health and appearance of the men.

Besides the cases given in the journal I had a great many others to treat, some of them similar to those mentioned but the greater part consisted of boils, scalds, and contusions which would not only be too tedious to enter but I fear would be irksome to the reader. There were four births on board during the passage which did well, therefore I did not consider it necessary to give a detailed account of them in my journal the more especially as they were all favourable cases.

Regularity and cleanliness in the prison, free ventilation and as far as possible dry decks turning all the prisoners up in fine weather as we were lucky enough to have two musicians amongst the convicts, dancing was tolerated every afternoon, strict attention to personal cleanliness and also to the cooking of their victuals with regular hours for their meals, were the only prophylactic means used on this occasion, which I found to answer my expectations to the utmost extent in as much as there was not a single case of contagious or infectious nature during the whole passage with the exception of a few cases of psora which soon yielded to the usual treatment. A few cases of scurvy however appeared on board at rather an early period which I can attribute to nothing else but the wet and hardships the prisoners endured during the first three or four weeks of the passage. I was prompt in my treatment of these cases and they got well, but before we arrived at Sydney I had about thirty others to treat.’

The Lady Nugent arrived in Port Jackson on 9 April 1835 with 284 male prisoners. Two men had died at sea. The prisoners were landed on 27th April 1835 and marched to Hyde Park Barracks prior to being assigned. Ten were under the age of 14 years.

The Lady Nugent:

Isaac’s distinguishing marks are noted on various criminal registers and record books:

“Height in feet & inches: 5 4; Complexion: Ruddy; Hair: Light brown; Eyes: Hazel; Marks or Scars: Yes [including] DEVIL on lower left arm, TSIS back of left hand, WS lower right arm, MHDW back of right hand.”

Another includes more detail about Isaac’s tattoos:

“Two slight scars right side of mouth, 2 moles above right breast, figure of the devil and DEVIL and raised mole, lower left arm; anchor, seven dots half moon, TSIS and cross, back of left hand; a mallet, door post, A, mans bust, sun, WS, lower right arm; woman, MHDW and shut knife, back of right hand.”

From How tattoos became fashionable in Victorian England (2019 article in TheConversation by Robert Shoemaker and Zoe Alkar):

“Historical tattooing was not restricted to sailors, soldiers and convicts, but was a growing and accepted phenomenon in Victorian England. Tattoos provide an important window into the lives of those who typically left no written records of their own. As a form of “history from below”, they give us a fleeting but intriguing understanding of the identities and emotions of ordinary people in the past.