Search Results for 'april'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

November 6, 2024 at 8:48 pm #7585

In reply to: Two Aunties au Pair and Their Pert Carouses

“Oh sweet revenge…” November was looking gleeful, and truth be told, too smug. With a tinge of orange anticipating a delectable tapestry of chaos.

The results had come as cold as an early winter for a world standing on the precipice of another era under President Lump’s reign.

“The winds of change rustling the curtains of the Beige House once more. And amidst this swirling tempest of political intrigue, our story unfurls with the maids au pair at its heart.”

“Liz, are you sure this is wise to pursue?”

“Oh stop, it Godfrey, the harm is done, November was written already in that story; I knew she would spell trouble from the beginning. And please, don’t interrupt.”

As April and June departed to pursue their ventures—perhaps April embarked on a global crusade for environmental stewardship while June disappeared into the realms of espionage, her whereabouts known only to the shadows—November emerged, a true force of nature. With an iron will and a meticulous attention to detail, she transformed the Beige House into a bastion of order amid political disarray under old Joe Mitten—bless his bumbling heart. Her reign as the clandestine conductor of this domestic symphony was nothing short of legendary.

During those four years, November proved herself indispensable. She orchestrated everything from state dinners to covert intelligence briefings, all while maintaining the perfect façade of domestic tranquility. The press would whisper her name, speculating on her true influence behind the scenes. Little did they know that November had eyes and ears in every corner of the Beige House, including a network of whispering portraits and eavesdropping sconces.

And now, with President Lump’s reelection, November faces her most formidable challenge yet. The political climate is rife with unpredictability—alliances shift like sand, loyalties waver, and secrets simmer beneath the surface. November must navigate this labyrinth with the precision of a masterful chess player, anticipating every move and countermove.

August 16, 2024 at 2:56 pm #7544In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Youlgreave

The Frost Family and The Big Snow

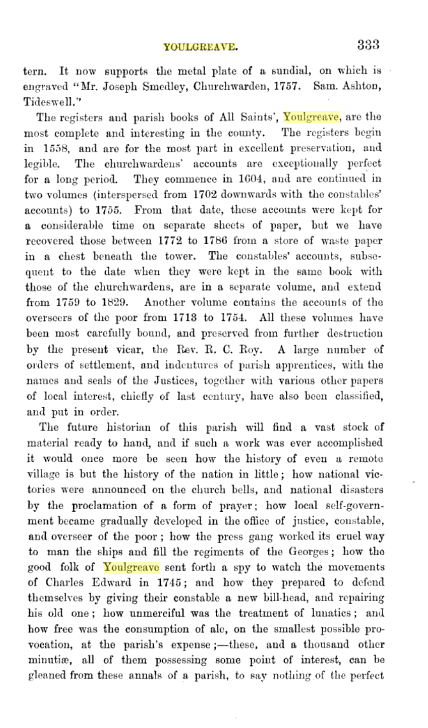

The Youlgreave parish registers are said to be the most complete and interesting in the country. Starting in 1558, they are still largely intact today.

“The future historian of this parish will find a vast stock of material ready to hand, and if such a work was ever accomplished it would once more be seen how the history of even a remote village is but the history of the nation in little; how national victories were announced on the church bells, and national disasters by the proclamation of a form of prayer…”

J. Charles Cox, Notes on the Churches of Derbyshire, 1877.

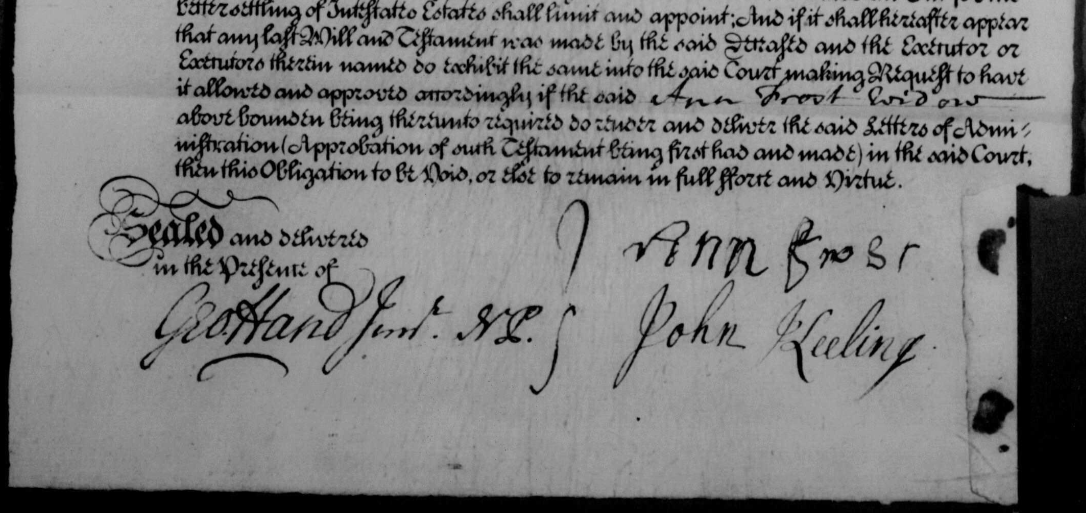

Although the Youlgreave parish registers are available online on microfilm, just the baptisms, marriages and burials are provided on the genealogy websites. However, I found some excerpts from the churchwardens accounts in a couple of old books, The Reliquary 1864, and Notes on Derbyshire Churches 1877.

Hannah Keeling, my 4x great grandmother, was born in Youlgreave, Derbyshire, in 1767. In 1791 she married Edward Lees of Hartington, Derbyshire, a village seven and a half miles south west of Youlgreave. Edward and Hannah’s daughter Sarah Lees, born in Hartington in 1808, married Francis Featherstone in 1835. The Featherstone’s were farmers. Their daughter Emma Featherstone married John Marshall from Elton. Elton is just three miles from Youlgreave, and there are a great many Marshall’s in the Youlgreave parish registers, some no doubt distantly related to ours.

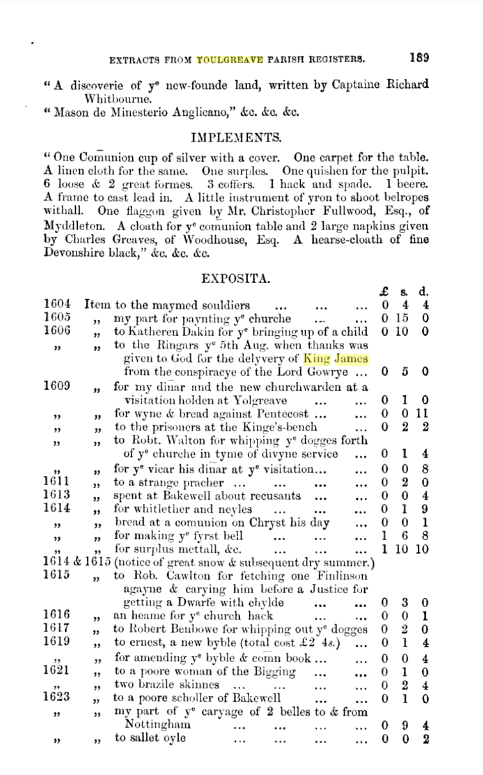

Hannah Keeling’s parents were John Keeling 1734-1823, and Ellen Frost 1739-1805, both of Youlgreave.

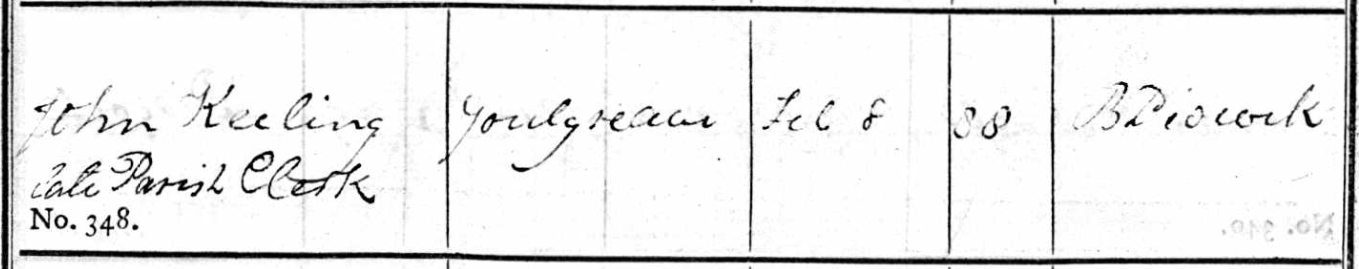

On the burial entry in the parish registers in Youlgreave in 1823, John Keeling was 88 years old when he died, and was the “late parish clerk”, indicating that my 5x great grandfather played a part in compiling the “best parish registers in the country”. In 1762 John’s father in law John Frost died intestate, and John Keeling, cordwainer, co signed the documents with his mother in law Ann. John Keeling was a shoe maker and a parish clerk.

John Keeling’s father was Thomas Keeling, baptised on the 9th of March 1709 in Youlgreave and his parents were John Keeling and Ann Ashmore. John and Ann were married on the 6th April 1708. Some of the transcriptions have Thomas baptised in March 1708, which would be a month before his parents married. However, this was before the Julian calendar was replaced by the Gregorian calendar, and prior to 1752 the new year started on the 25th of March, therefore the 9th of March 1708 was eleven months after the 6th April 1708.

Thomas Keeling married Dorothy, which we know from the baptism of John Keeling in 1734, but I have not been able to find their marriage recorded. Until I can find my 6x great grandmother Dorothy’s maiden name, I am unable to trace her family further back.

Unfortunately I haven’t found a baptism for Thomas’s father John Keeling, despite that there are Keelings in the Youlgrave registers in the early 1600s, possibly it is one of the few illegible entries in these registers.

The Frosts of Youlgreave

Ellen Frost’s father was John Frost, born in Youlgreave in 1707. John married Ann Staley of Elton in 1733 in Youlgreave.

(Note that this part of the family tree is the Marshall side, but we also have Staley’s in Elton on the Warren side. Our branch of the Elton Staley’s moved to Stapenhill in the mid 1700s. Robert Staley, born 1711 in Elton, died in Stapenhill in 1795. There are many Staley’s in the Youlgreave parish registers, going back to the late 1500s.)

John Frost (my 6x great grandfather), miner, died intestate in 1762 in Youlgreave. Miner in this case no doubt means a lead miner, mining his own land (as John Marshall’s father John was in Elton. On the 1851 census John Marshall senior was mining 9 acres). Ann Frost, as the widow and relict of the said deceased John Frost, claimed the right of administration of his estate. Ann Frost (nee Staley) signed her own name, somewhat unusual for a woman to be able to write in 1762, as well as her son in law John Keeling.

John’s parents were David Frost and Ann. David was baptised in 1665 in Youlgreave. Once again, I have not found a marriage for David and Ann so I am unable to continue further back with her family. Marriages were often held in the parish of the bride, and perhaps those neighbouring parish records from the 1600s haven’t survived.

David’s parents were William Frost and Ellen (or Ellin, or Helen, depending on how the parish clerk chose to spell it). Once again, their marriage hasn’t been found, but was probably in a neighbouring parish.

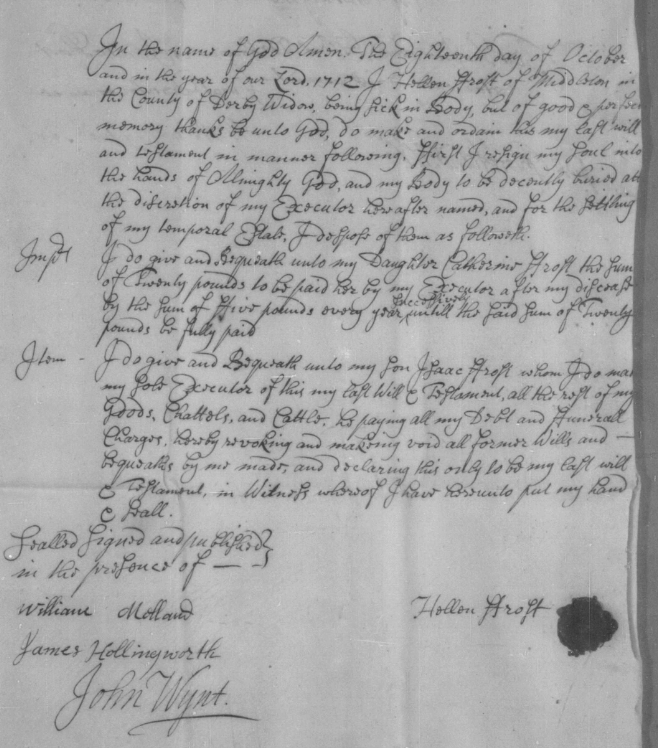

William Frost’s wife Ellen, my 8x great grandmother, died in Youlgreave in 1713. In her will she left her daughter Catherine £20. Catherine was born in 1665 and was apparently unmarried at the age of 48 in 1713. She named her son Isaac Frost (born in 1662) executor, and left him the remainder of her “goods, chattels and cattle”.

William Frost was baptised in Youlgreave in 1627, his parents were William Frost and Anne.

William Frost senior, husbandman, was probably born circa 1600, and died intestate in 1648 in Middleton, Youlgreave. His widow Anna was named in the document. On the compilation of the inventory of his goods, Thomas Garratt, Will Melland and A Kidiard are named.(Husbandman: The old word for a farmer below the rank of yeoman. A husbandman usually held his land by copyhold or leasehold tenure and may be regarded as the ‘average farmer in his locality’. The words ‘yeoman’ and ‘husbandman’ were gradually replaced in the later 18th and 19th centuries by ‘farmer’.)

Unable to find a baptism for William Frost born circa 1600, I read through all the pages of the Youlgreave parish registers from 1558 to 1610. Despite the good condition of these registers, there are a number of illegible entries. There were three Frost families baptising children during this timeframe and one of these is likely to be Willliam’s.

Baptisms:

1581 Eliz Frost, father Michael.

1582 Francis f Michael. (must have died in infancy)

1582 Margaret f William.

1585 Francis f Michael.

1586 John f Nicholas.

1588 Barbara f Michael.

1590 Francis f Nicholas.

1591 Joane f Michael.

1594 John f Michael.

1598 George f Michael.

1600 Fredericke (female!) f William.Marriages in Youlgreave which could be William’s parents:

1579 Michael Frost Eliz Staley

1587 Edward Frost Katherine Hall

1600 Nicholas Frost Katherine Hardy.

1606 John Frost Eliz Hanson.Michael Frost of Youlgreave is mentioned on the Derbyshire Muster Rolls in 1585.

(Muster records: 1522-1649. The militia muster rolls listed all those liable for military service.)

Frideswide:

A burial is recorded in 1584 for Frideswide Frost (female) father Michael. As the father is named, this indicates that Frideswide was a child.

(Frithuswith, commonly Frideswide c. 650 – 19 October 727), was an English princess and abbess. She is credited as the foundress of a monastery later incorporated into Christ Church, Oxford. She was the daughter of a sub-king of a Merica named Dida of Eynsham whose lands occupied western Oxfordshire and the upper reaches of the River Thames.)

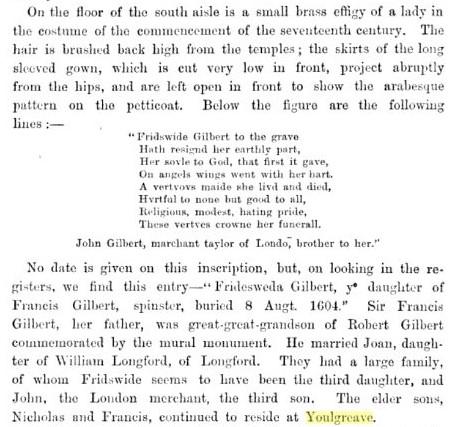

An unusual name, and certainly very different from the usual names of the Frost siblings. As I did not find a baptism for her, I wondered if perhaps she died too soon for a baptism and was given a saints name, in the hope that it would help in the afterlife, given the beliefs of the times. Or perhaps it wasn’t an unusual name at the time in Youlgreave. A Fridesweda Gilbert was buried in Youlgreave in 1604, the spinster daughter of Francis Gilbert. There is a small brass effigy in the church, underneath is written “Frideswide Gilbert to the grave, Hath resigned her earthly part…”

J. Charles Cox, Notes on the Churches of Derbyshire, 1877.

King James

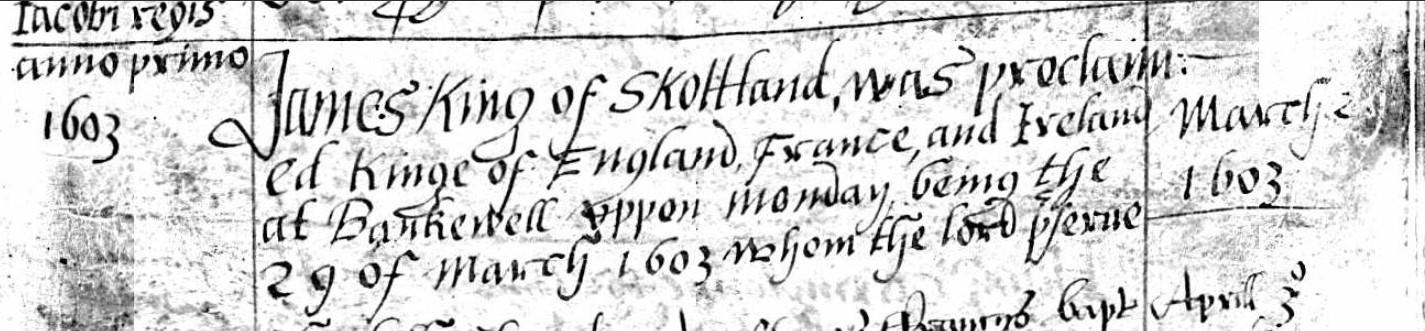

A parish register entry in 1603:

“1603 King James of Skottland was proclaimed kinge of England, France and Ireland at Bakewell upon Monday being the 29th of March 1603.” (March 1603 would be 1604, because of the Julian calendar in use at the time.)

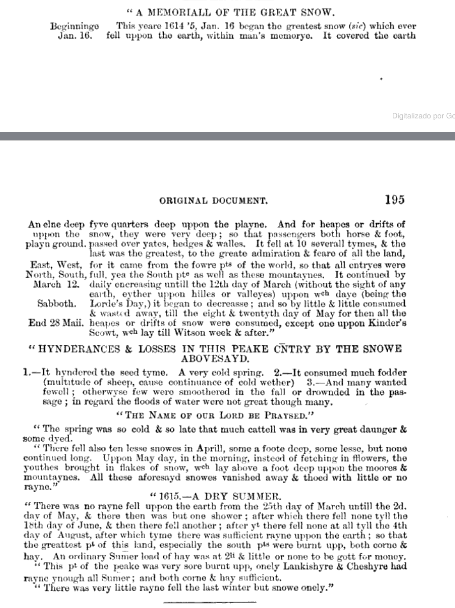

The Big Snow

“This year 1614/5 January 16th began the greatest snow whichever fell uppon the earth within man’s memorye. It covered the earth fyve quarters deep uppon the playne. And for heaps or drifts of snow, they were very deep; so that passengers both horse or foot passed over yates, hedges and walles. ….The spring was so cold and so late that much cattel was in very great danger and some died….”

From the Youlgreave parish registers.

Our ancestor William Frost born circa 1600 would have been a teenager during the big snow.

October 18, 2023 at 3:20 pm #7281In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The 1935 Joseph Gerrard Challenge.

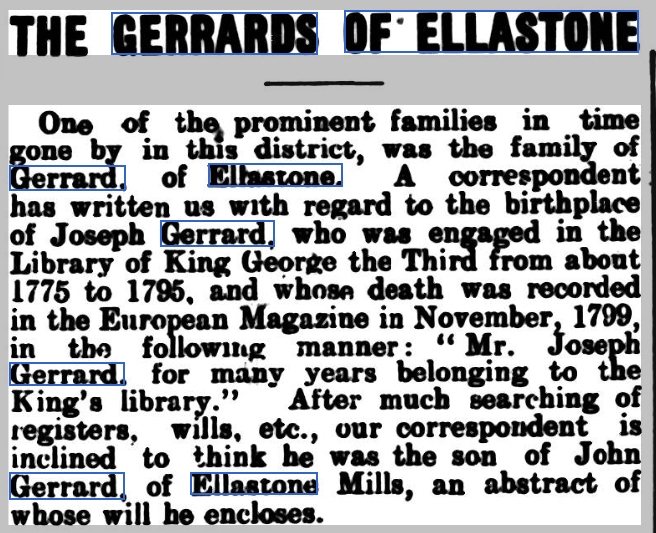

While researching the Gerrard family of Ellastone I chanced upon a 1935 newspaper article in the Ashbourne Register. There were two articles in 1935 in this paper about the Gerrards, the second a follow up to the first. An advertisement was also placed offering a £1 reward to anyone who could find Joseph Gerrard’s baptism record.

Ashbourne Telegraph – Friday 05 April 1935:

The author wanted to prove that the Joseph Gerrard “who was engaged in the library of King George the third from about 1775 to 1795, and whose death was recorded in the European Magazine in November 1799” was the son of John Gerrard of Ellastone Mills, Staffordshire. Included in the first article was a selected transcription of the 1796 will of John Gerrard. John’s son Joseph is mentioned in this will: John leaves him “£20 to buy a suit of mourning if he thinks proper.”

This Joseph Gerrard however, born in 1739, died in 1815 at Brailsford. Joseph’s brother John also died at Brailsford Mill, and both of their ages at death give a birth year of 1739. Maybe they were twins. William Gerrard and Joseph Gerrard of Brailsford Mill are mentioned in a 1811 newspaper article in the Derby Mercury.

I decided that there was nothing susbtantial about this claim, until I read the 1724 will of John Gerrard the elder, the father of John who died in 1796. In his will he leaves £100 to his son Joseph Gerrard, “secretary to the Bishop of Oxford”.

Perhaps there was something to this story after all. Joseph, baptised in 1701 in Ellastone, was the son of John Gerrard the elder.

I found Joseph Gerrard (and his son James Gerrard) mentioned in the Alumni Oxonienses: The Members of the University of Oxford, University of Oxford, Joseph Foster, 1888. “Joseph Gerard son of John of Elleston county Stafford, pleb, Oriel Coll, matric, 30th May 1718, age 18, BA. 9th March 1721-2; of Merton Coll MA 1728.”

In The Works of John Wesley 1735-1738, Joseph Gerrad is mentioned: “Joseph Gerard , matriculated at Oriel College 1718 , aged 18 , ordained 1727 to serve as curate of Cuddesdon , becoming rector of St. Martin’s , Oxford in 1729 , and vicar of Banbury in 1734.”

In The History of Banbury Alfred Beesley 1842 “a visitation of smallpox occured at Banbury (Oxfordshire) in 1731 and continued until 1733.” Joseph Gerrard was the vicar of Banbury in 1734.

According to the The History and Antiquities of the County of Buckingham George Lipscomb · 1847, Joseph Gerrard was made rector of Monks Risborough in 1738 “but he also continued to hold Stewkley until his death”.

The Speculum of Archbishop Thomas Secker by Secker, Thomas, 1693-1768, also mentions Joseph Gerrard under Monks Risborough and adds that he “resides constantly in the Parsonage ho. except when he goes for a few days to Steukley county Bucks (Buckinghamshire) of which he is vicar.” Joseph’s son James Gerrard 1741-1789 is also mentioned as being a rector at Monks Risborough in 1783.

Joseph Gerrard married Elizabeth Reynolds on 23 July 1739 in Monks Risborough, Buckinghamshire. They had five children between 1740 and 1750, including James baptised 1740 and Joseph baptised 1742.

Joseph died in 1785 in Monks Risborough.

So who was Joseph Gerrard of the Kings Library who died in 1799? It wasn’t Joseph’s son Joseph baptised in 1742 in Monks Risborough, because in his father’s 1785 will he mentions “my only son James”, indicating that Joseph died before that date.

September 20, 2023 at 1:48 pm #7279In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

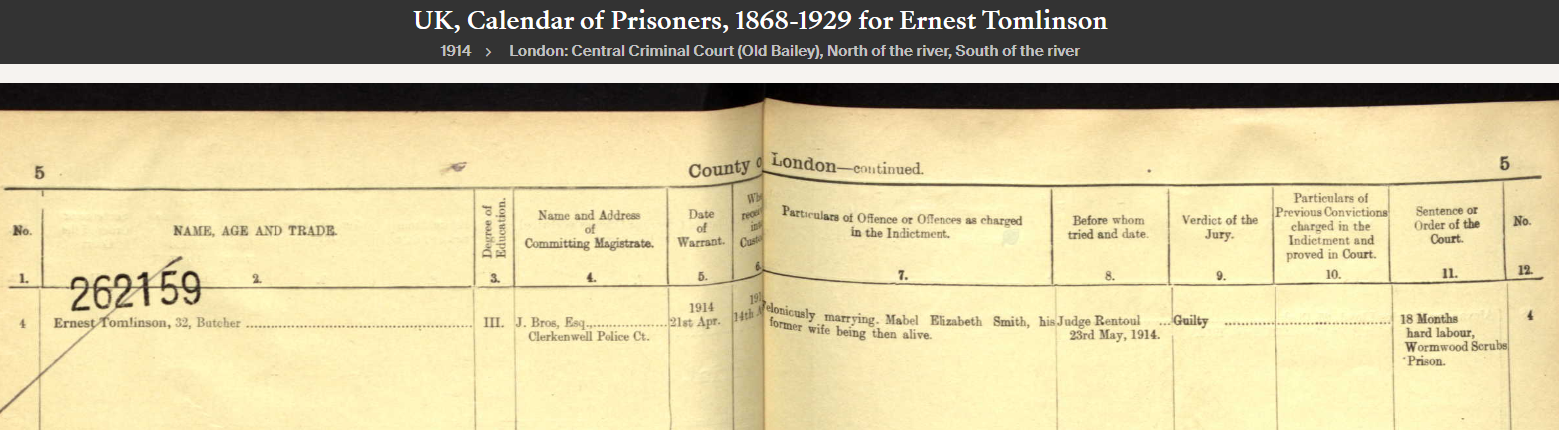

The Bigamist

Ernest Tomlinson 1881-1915

Ernest Tomlinson was my great grandfathers Charles Tomlinson‘s younger brother. Their parents were Charles Tomlinson the elder 1847-1907 and Emma Grattidge 1853-1911.

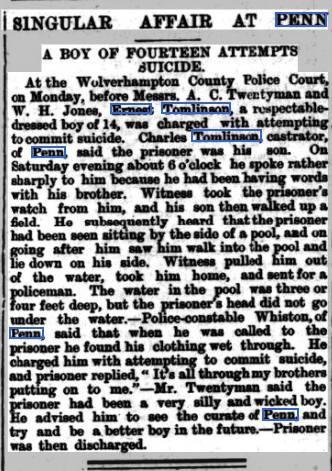

In 1896, aged 14, Ernest attempted to drown himself in the pond at Penn after his father took his watch off him for arguing with his brothers. Ernest tells the police “It’s all through my brothers putting on me”. The policeman told him he was a very silly and wicked boy and to see the curate at Penn and to try and be a better boy in future. He was discharged.

Bridgnorth Journal and South Shropshire Advertiser. – Saturday 11 July 1896:

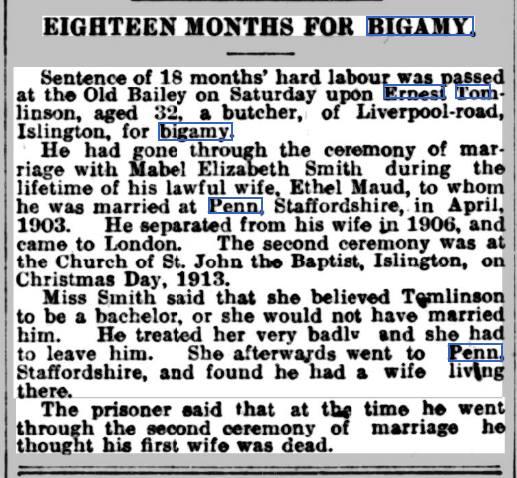

In 1903 Ernest married Ethel Maude Howe in Wolverhampton. Four years later in 1907 Ethel was granted a separation on the grounds of cruelty.

In Islington in London in 1913, Ernest bigamously married Mabel Elizabeth Smith. Mabel left Ernest for treating her very badly. She went to Wolverhampton and found out about his first wife still being alive.

London Evening Standard – Monday 25 May 1914:

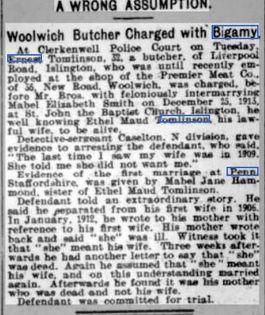

In May 1914 Ernest was tried at the Old Bailey and the jury found him guilty of bigamy. In his defense, Ernest said that he had received a letter from his mother saying that she was ill, and a further letter saying that she had died. He said he wrongly assumed that they were referring to his wife, and that he was free to marry. It was his mother who had died. He was sentenced to 18 months hard labour at Wormwood Scrubs prison.

Woolwich Gazette – Tuesday 28 April 1914:

Ethel Maude Tomlinson was granted a decree nisi in 1915.

Birmingham Daily Gazette – Wednesday 02 June 1915:

Ernest died in September 1915 in hospital in Wolverhampton.

September 5, 2023 at 1:35 pm #7276In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

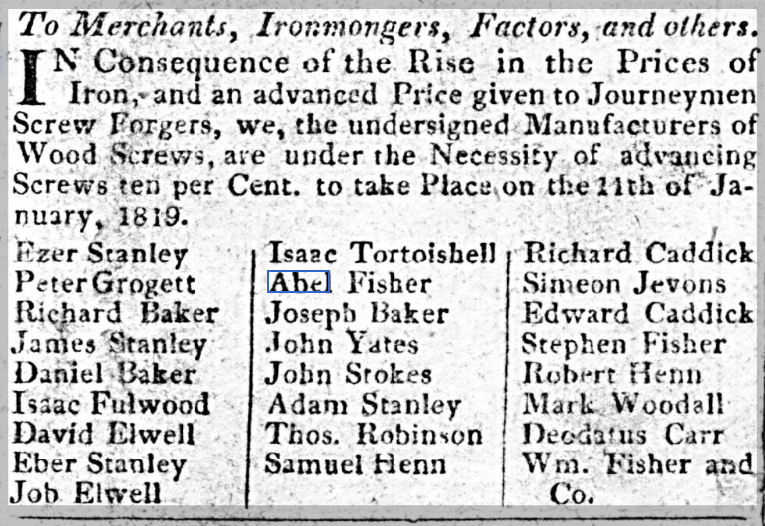

Wood Screw Manufacturers

The Fishers of West Bromwich.

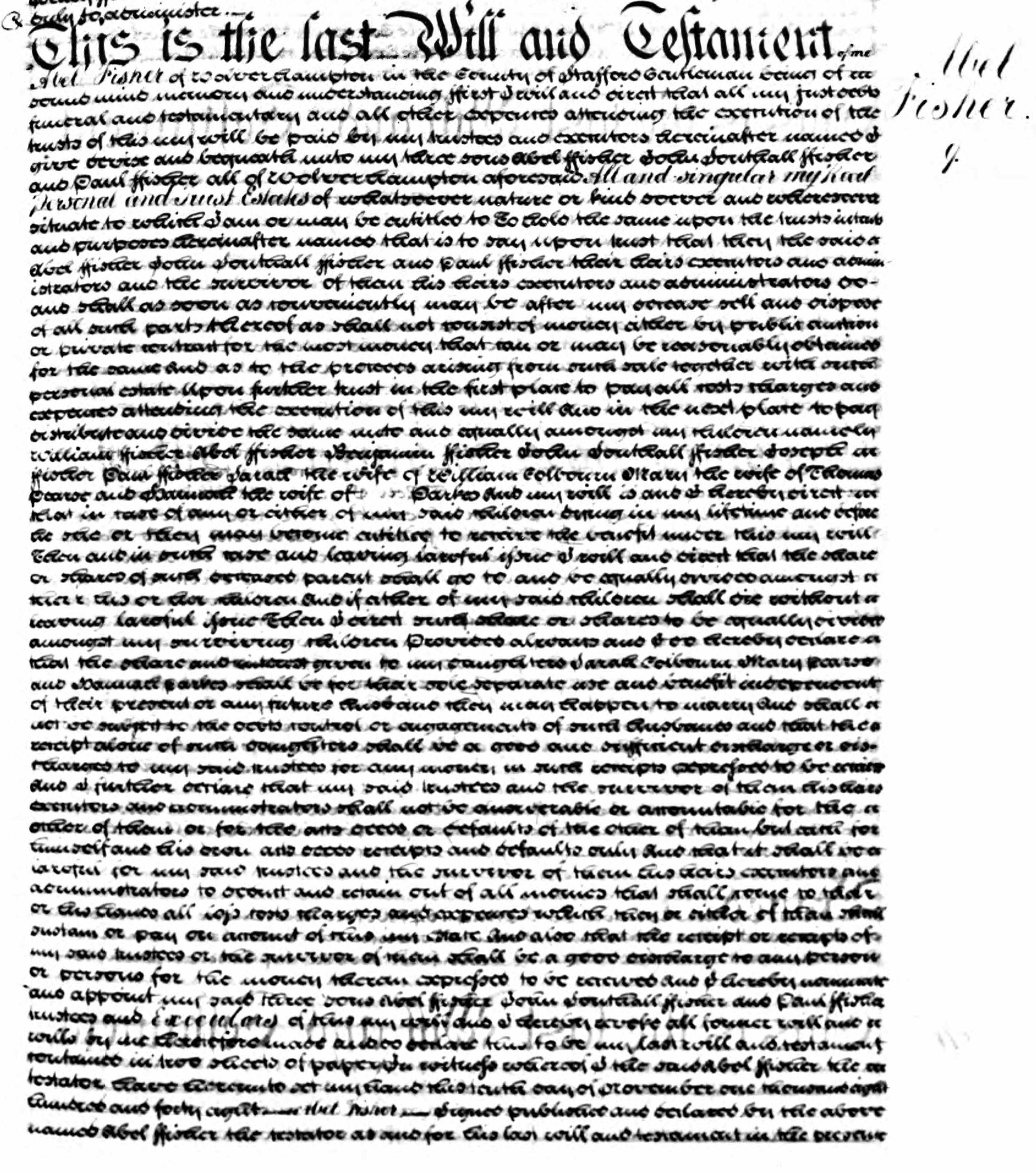

My great grandmother, Nellie Fisher, was born in 1877 in Wolverhampton. Her father William 1834-1916 was a whitesmith, and his father William 1792-1873 was a whitesmith and master screw maker. William’s father was Abel Fisher, wood screw maker, victualler, and according to his 1849 will, a “gentleman”.

Nellie Fisher 1877-1956 :

Abel Fisher was born in 1769 according to his burial document (age 81 in 1849) and on the 1841 census. Abel was a wood screw manufacturer in Wolverhampton.

As no baptism record can be found for Abel Fisher, I read every Fisher will I could find in a 30 year period hoping to find his fathers will. I found three other Fishers who were wood screw manufacurers in neighbouring West Bromwich, which led me to assume that Abel was born in West Bromwich and related to these other Fishers.

The wood screw making industry was a relatively new thing when Abel was born.

“The screw was used in furniture but did not become a common woodworking fastener until efficient machine tools were developed near the end of the 18th century. The earliest record of lathe made wood screws dates to an English patent of 1760. The development of wood screws progressed from a small cottage industry in the late 18th century to a highly mechanized industry by the mid-19th century. This rapid transformation is marked by several technical innovations that help identify the time that a screw was produced. The earliest, handmade wood screws were made from hand-forged blanks. These screws were originally produced in homes and shops in and around the manufacturing centers of 18th century Europe. Individuals, families or small groups participated in the production of screw blanks and the cutting of the threads. These small operations produced screws individually, using a series of files, chisels and cutting tools to form the threads and slot the head. Screws produced by this technique can vary significantly in their shape and the thread pitch. They are most easily identified by the profusion of file marks (in many directions) over the surface. The first record regarding the industrial manufacture of wood screws is an English patent registered to Job and William Wyatt of Staffordshire in 1760.”

Wood Screw Makers of West Bromwich:

Edward Fisher, wood screw maker of West Bromwich, died in 1796. He mentions his wife Pheney and two underage sons in his will. Edward (whose baptism has not been found) married Pheney Mallin on 13 April 1793. Pheney was 17 years old, born in 1776. Her parents were Isaac Mallin and Sarah Firme, who were married in West Bromwich in 1768.

Edward and Pheney’s son Edward was born on 21 October 1793, and their son Isaac in 1795. The executors of Edwards 1796 will are Daniel Fisher the Younger, Isaac Mallin, and Joseph Fisher.There is a marriage allegations and bonds document in 1774 for an Edward Fisher, bachelor and wood screw maker of West Bromwich, aged 25 years and upwards, and Mary Mallin of the same age, father Isaac Mallin. Isaac Mallin and Sarah didn’t marry until 1768 and Mary Mallin would have been born circa 1749. Perhaps Isaac Mallin’s father was the father of Mary Mallin. It’s possible that Edward Fisher was born in 1749 and first married Mary Mallin, and then later Pheney, but it’s also possible that the Edward Fisher who married Mary Mallin in 1774 was Edward Fishers uncle, Daniel’s brother. (I do not know if Daniel had a brother Edward, as I haven’t found a baptism, or marriage, for Daniel Fisher the elder.)

There are two difficulties with finding the records for these West Bromwich families. One is that the West Bromwich registers are not available online in their entirety, and are held by the Sandwell Archives, and even so, they are incomplete. Not only that, the Fishers were non conformist. There is no surviving register prior to 1787. The chapel opened in 1788, and any registers that existed before this date, taken in a meeting houses for example, appear not to have survived.

Daniel Fisher the younger died intestate in 1818. Daniel was a wood screw maker of West Bromwich. He was born in 1751 according to his age stated as 67 on his death in 1818. Daniel’s wife Mary, and his son William Fisher, also a wood screw maker, claimed the estate.

Daniel Fisher the elder was a farmer of West Bromwich, who died in 1806. He was 81 when he died, which makes a birth date of 1725, although no baptism has been found. No marriage has been found either, but he was probably married not earlier than 1746.

Daniel’s sons Daniel and Joseph were the main inheritors, and he also mentions his other children and grandchildren namely William Fisher, Thomas Fisher, Hannah wife of William Hadley, two grandchildren Edward and Isaac Fisher sons of Edward Fisher his son deceased. Daniel the elder presumably refers to the wood screw manufacturing when he says “to my son Daniel Fisher the good will and advantage which may arise from his manufacture or trade now carried on by me.” Daniel does not mention a son called Abel unfortunately, but neither does he mention his other grandchildren. Abel may be Daniel’s son, or he may be a nephew.

The Staffordshire Record Office holds the documents of a Testamentary Case in 1817. The principal people are Isaac Fisher, a legatee; Daniel and Joseph Fisher, executors. Principal place, West Bromwich, and deceased person, Daniel Fisher the elder, farmer.

William and Sarah Fisher baptised six children in the Mares Green Non Conformist registers in West Bromwich between 1786 and 1798. William Fisher and Sarah Birch were married in West Bromwich in 1777. This William was probably born circa 1753 and was probably the son of Daniel Fisher the elder, farmer.

Daniel Fisher the younger and his wife Mary had a son William, as mentioned in the intestacy papers, although I have not found a baptism for William. I did find a baptism for another son, Eutychus Fisher in 1792.

In White’s Directory of Staffordshire in 1834, there are three Fishers who are wood screw makers in Wolverhampton: Eutychus Fisher, Oxford Street; Stephen Fisher, Bloomsbury; and William Fisher, Oxford Street.

Abel’s son William Fisher 1792-1873 was living on Oxford Street on the 1841 census, with his wife Mary and their son William Fisher 1834-1916.

In The European Magazine, and London Review of 1820 (Volume 77 – Page 564) under List of Patents, W Fisher and H Fisher of West Bromwich, wood screw manufacturers, are listed. Also in 1820 in the Birmingham Chronicle, the partnership of William and Hannah Fisher, wood screw manufacturers of West Bromwich, was dissolved.

In the Staffordshire General & Commercial Directory 1818, by W. Parson, three Fisher’s are listed as wood screw makers. Abel Fisher victualler and wood screw maker, Red Lion, Walsal Road; Stephen Fisher wood screw maker, Buggans Lane; and Daniel Fisher wood screw manufacturer, Brickiln Lane.

In Aris’s Birmingham Gazette on 4 January 1819 Abel Fisher is listed with 23 other wood screw manufacturers (Stephen Fisher and William Fisher included) stating that “In consequence of the rise in prices of iron and the advanced price given to journeymen screw forgers, we the undersigned manufacturers of wood screws are under the necessity of advancing screws 10 percent, to take place on the 11th january 1819.”

In Abel Fisher’s 1849 will, he names his three sons Abel Fisher 1796-1869, Paul Fisher 1811-1900 and John Southall Fisher 1801-1871 as the executors. He also mentions his other three sons, William Fisher 1792-1873, Benjamin Fisher 1798-1870, and Joseph Fisher 1803-1876, and daughters Sarah Fisher 1794- wife of William Colbourne, Mary Fisher 1804- wife of Thomas Pearce, and Susannah (Hannah) Fisher 1813- wife of Parkes. His son Silas Fisher 1809-1837 wasn’t mentioned as he died before Abel, nor his sons John Fisher 1799-1800, and Edward Southall Fisher 1806-1843. Abel’s wife Susannah Southall born in 1771 died in 1824. They were married in 1791.

The 1849 will of Abel Fisher:

June 13, 2023 at 10:31 am #7255

June 13, 2023 at 10:31 am #7255In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

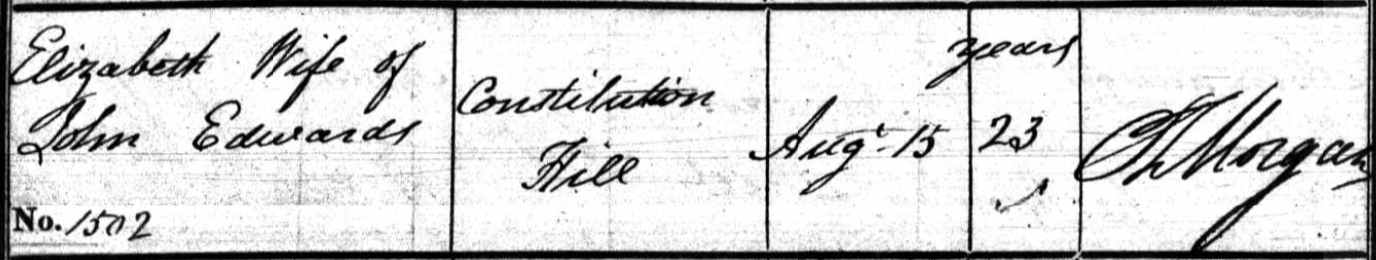

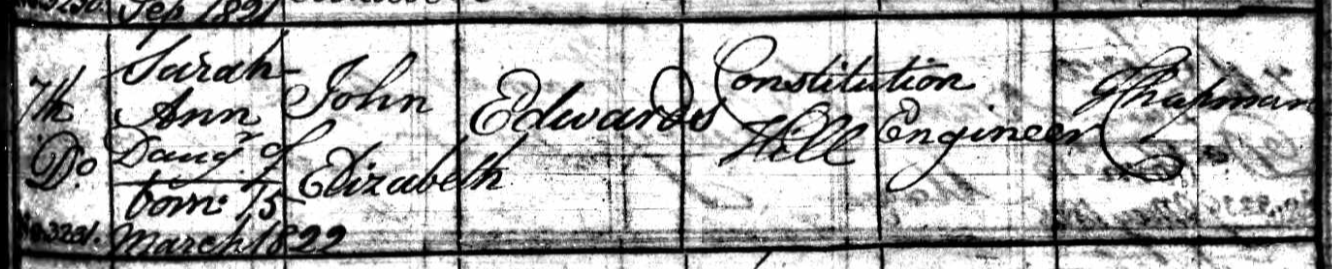

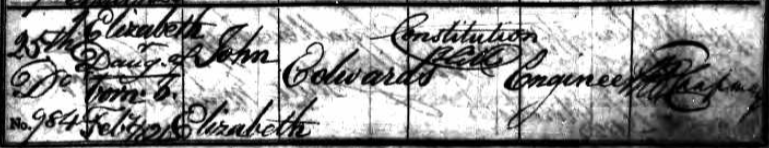

The First Wife of John Edwards

1794-1844

John was a widower when he married Sarah Reynolds from Kinlet. Both my fathers cousin and I had come to a dead end in the Edwards genealogy research as there were a number of possible births of a John Edwards in Birmingham at the time, and a number of possible first wives for a John Edwards at the time.

John Edwards was a millwright on the 1841 census, the only census he appeared on as he died in 1844, and 1841 was the first census. His birth is recorded as 1800, however on the 1841 census the ages were rounded up or down five years. He was an engineer on some of the marriage records of his children with Sarah, and on his death certificate, engineer and millwright, aged 49. The age of 49 at his death from tuberculosis in 1844 is likely to be more accurate than the census (Sarah his wife was present at his death), making a birth date of 1794 or 1795.

John married Sarah Reynolds in January 1827 in Birmingham, and I am descended from this marriage. Any children of John’s first marriage would no doubt have been living with John and Sarah, but had probably left home by the time of the 1841 census.

I found an Elizabeth Edwards, wife of John Edwards of Constitution Hill, died in August 1826 at the age of 23, as stated on the parish death register. It would be logical for a young widower with small children to marry again quickly. If this was John’s first wife, the marriage to Sarah six months later in January 1827 makes sense. Therefore, John’s first wife, I assumed, was Elizabeth, born in 1803.

Death of Elizabeth Edwards, 23 years old. St Mary, Birmingham, 15 Aug 1826:

There were two baptisms recorded for parents John and Elizabeth Edwards, Constitution Hill, and John’s occupation was an engineer on both baptisms.

They were both daughters: Sarah Ann in 1822 and Elizabeth in 1824.Sarah Ann Edwards: St Philip, Birmingham. Born 15 March 1822, baptised 7 September 1822:

Elizabeth Edwards: St Philip, Birmingham. Born 6 February 1824, baptised 25 February 1824:

With John’s occupation as engineer stated, it looked increasingly likely that I’d found John’s first wife and children of that marriage.

Then I found a marriage of Elizabeth Beach to John Edwards in 1819, and subsequently found an Elizabeth Beach baptised in 1803. This appeared to be the right first wife for John, until an Elizabeth Slater turned up, with a marriage to a John Edwards in 1820. An Elizabeth Slater was baptised in 1803. Either Elizabeth Beach or Elizabeth Slater could have been the first wife of John Edwards. As John’s first wife Elizabeth is not related to us, it’s not necessary to go further back, and in a sense, doesn’t really matter which one it was.

But the Slater name caught my eye.

But first, the name Sarah Ann.

Of the possible baptisms for John Edwards, the most likely seemed to be in 1794, parents John and Sarah. John and Sarah had two infant daughters die just prior to John’s birth. The first was Sarah, the second Sarah Ann. Perhaps this was why John named his daughter Sarah Ann? In the absence of any other significant clues, I decided to assume these were the correct parents. I found and read half a dozen wills of any John Edwards I could find within the likely time period of John’s fathers death.

One of them was dated 1803. In this will, John mentions that his children are not yet of age. (John would have been nine years old.)

He leaves his plating business and some properties to his eldest son Thomas Davis Edwards, (just shy of 21 years old at the time of his fathers death in 1803) with the business to be run jointly with his widow, Sarah. He mentions his son John, and leaves several properties to him, when he comes of age. He also leaves various properties to his daughters Elizabeth and Mary, ditto. The baptisms for all of these children, including the infant deaths of Sarah and Sarah Ann have been found. All but Mary’s were in the same parish. (I found one for Mary in Sutton Coldfield, which was apparently correct, as a later census also recorded her birth as Sutton Coldfield. She was living with family on that census, so it would appear to be correct that for whatever reason, their daughter Mary was born in Sutton Coldfield)Mary married John Slater in 1813. The witnesses were Elizabeth Whitehouse and John Edwards, her sister and brother. Elizabeth married William Nicklin Whitehouse in 1805 and one of the witnesses was Mary Edwards.

Mary’s husband John Slater died in 1821. They had no children. Mary never remarried, and lived with her bachelor brother Thomas Davis Edwards in West Bromwich. Thomas never married, and on the census he was either a proprietor of houses, or “sinecura” (earning a living without working).With Mary marrying a Slater, does this indicate that her brother John’s first wife was Elizabeth Slater rather than Elizabeth Beach? It is a compelling possibility, but does not constitute proof.

Not only that, there is no absolute proof that the John Edwards who died in 1803 was our ancestor John Edwards father.

If we can’t be sure which Elizabeth married John Edwards, we can be reasonably sure who their daughters married. On both of the marriage records the father is recorded as John Edwards, engineer.

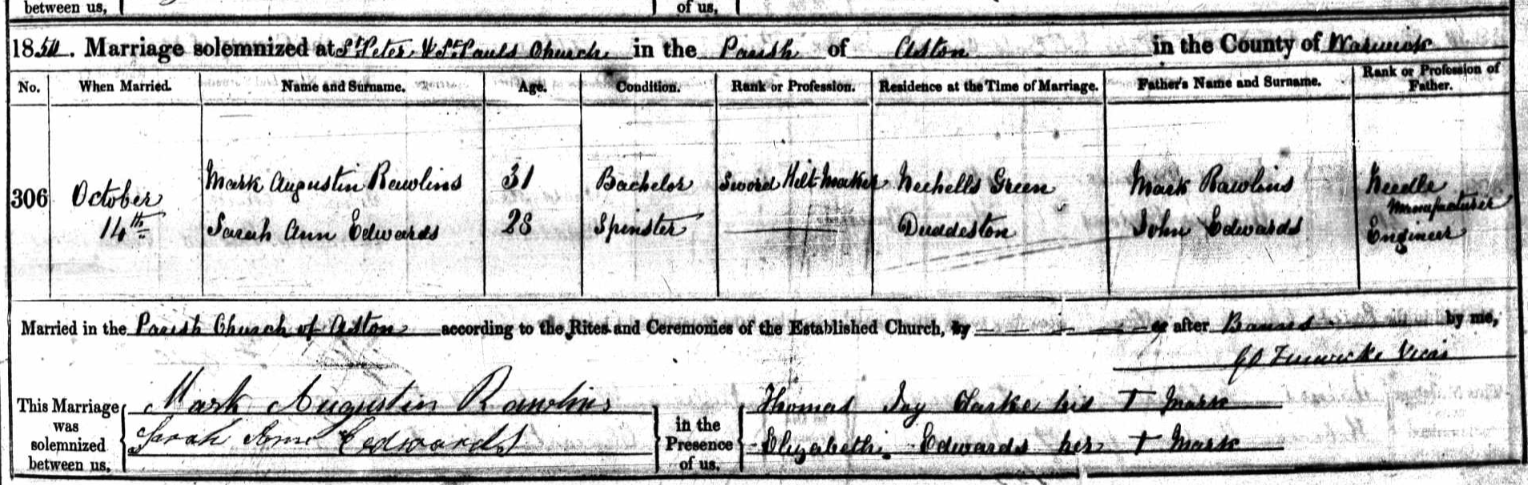

Sarah Ann married Mark Augustin Rawlins in 1850. Mark was a sword hilt maker at the time of the marriage, his father Mark a needle manufacturer. One of the witnesses was Elizabeth Edwards, who signed with her mark. Sarah Ann and Mark however were both able to sign their own names on the register.

Sarah Ann Edwards and Mark Augustin Rawlins marriage 14 October 1850 St Peter and St Paul, Aston, Birmingham:

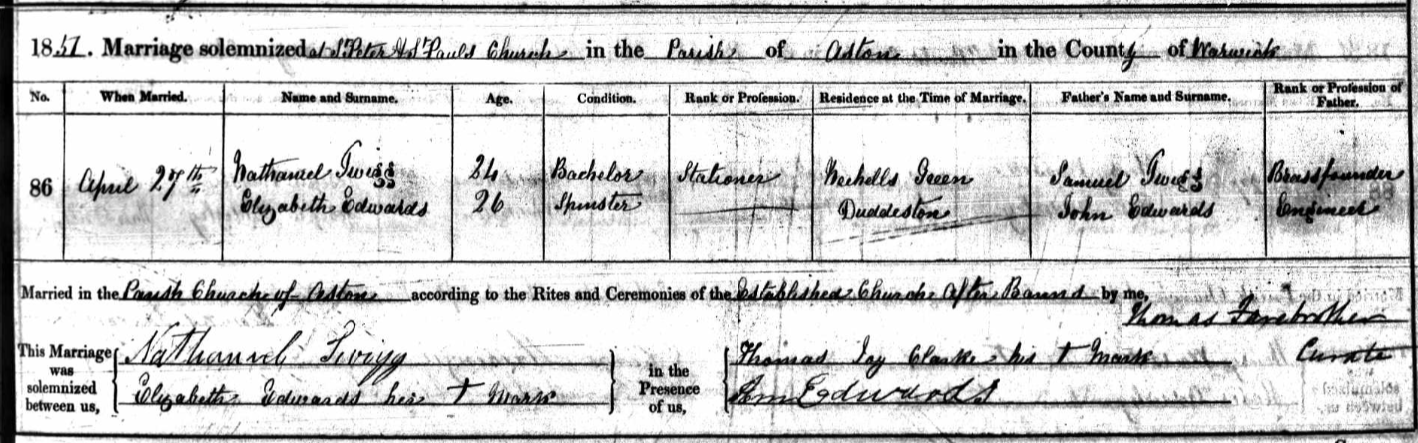

Elizabeth married Nathaniel Twigg in 1851. (She was living with her sister Sarah Ann and Mark Rawlins on the 1851 census, I assume the census was taken before her marriage to Nathaniel on the 27th April 1851.) Nathaniel was a stationer (later on the census a bookseller), his father Samuel a brass founder. Elizabeth signed with her mark, apparently unable to write, and a witness was Ann Edwards. Although Sarah Ann, Elizabeth’s sister, would have been Sarah Ann Rawlins at the time, having married the previous year, she was known as Ann on later censuses. The signature of Ann Edwards looks remarkably similar to Sarah Ann Edwards signature on her own wedding. Perhaps she couldn’t write but had learned how to write her signature for her wedding?

Elizabeth Edwards and Nathaniel Twigg marriage 27 April 1851, St Peter and St Paul, Aston, Birmingham:

Sarah Ann and Mark Rawlins had one daughter and four sons between 1852 and 1859. One of the sons, Edward Rawlins 1857-1931, was a school master and later master of an orphanage.

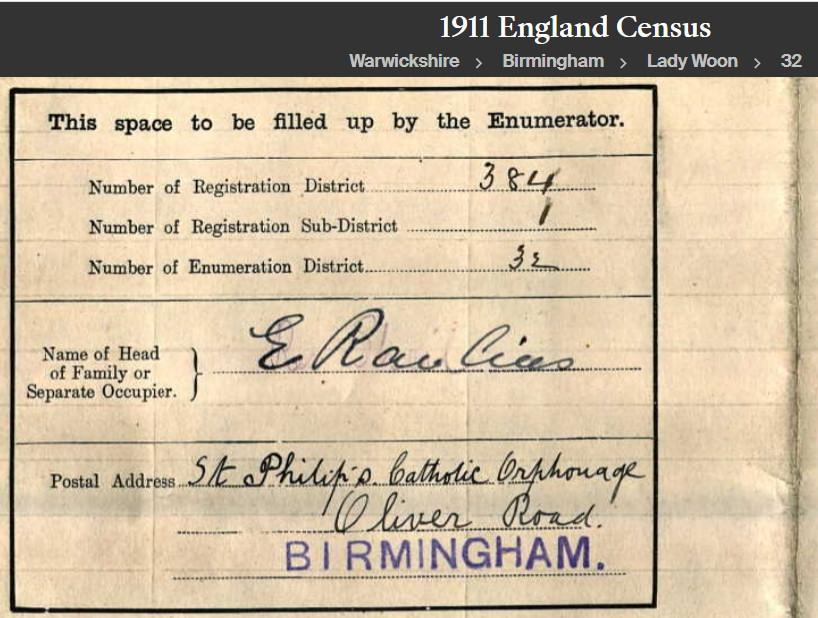

On the 1881 census Edward was a bookseller, in 1891 a stationer, 1901 schoolmaster and his wife Edith was matron, and in 1911 he and Edith were master and matron of St Philip’s Catholic Orphanage on Oliver Road in Birmingham. Edward and Edith did not have any children.

Edward Rawlins, 1911:

Elizabeth and Nathaniel Twigg appear to have had only one son, Arthur Twigg 1862-1943. Arthur was a photographer at 291 Bloomsbury Street, Birmingham. Arthur married Harriet Moseley from Burton on Trent, and they had two daughters, Elizabeth Ann 1897-1954, and Edith 1898-1983. I found a photograph of Edith on her wedding day, with her father Arthur in the picture. Arthur and Harriet also had a son Samuel Arthur, who lived for less than a month, born in 1904. Arthur had mistakenly put this son on the 1911 census stating “less than one month”, but the birth and death of Samuel Arthur Twigg were registered in the same quarter of 1904, and none were found registered for 1911.

Edith Twigg and Leslie A Hancock on their Wedding Day 1925. Arthur Twigg behind the bride. Maybe Elizabeth Ann Twigg seated on the right: (photo found on the ancestry website)

Photographs by Arthur Twigg, 291 Bloomsbury Street, Birmingham:

March 19, 2023 at 10:39 pm #7204

March 19, 2023 at 10:39 pm #7204Some handy references for the timelines of the Flying Fish Inn are here…

Year Date Event 1935 March 1, 1935 Birth of Mater 1958 March 13, 1958 Mater marries her childhood sweetheart 1965 August 17, 1965 Birth of Fred 1968 June 8, 1968 Birth of Abcynthia Hogg 1970 July 7, 1970 Birth of Aunt Idle 1978 April 12, 1978 Mater’s husband dies 1987 March 19, 1987 Mines close down – Carts & Lager Festival 1988 December 12, 1988 Idle gives birth to a child in Fiji (Liana) 1989 December 20, 1989 Horace Hogg death – Inn passes down to Abby 1990 May 7, 1990 Fred marries Abcynthia 1998 November 11, 1998 Birth of Devan 2000 November 11, 2000 Birth of Clove and Coriander 2007 March 7, 2007 Hannah Hogg’s death, the Inn passes to Abcynthia 2008 March 10, 2008 Carts and Lager Festival revival 2008 August 20, 2008 Birth of Prune 2009 February 2, 2009 Abcynthia leaves 2009 September 11, 2009 Strange incidents at the mines, Idle sets up the Inn 2010 May 27, 2010 Fred leaves his family, goes into hiding 2014 September 10, 2014 Start of Prune’s journal 2017 March 21, 2017 Visitors from Elsewheres 2020 December 22, 2020 The year of the Great Fires 2021 August 8, 2021 Italian tourists saved the Inn 2023 March 1, 2023 Orbs gamers visitors 2027 September 1, 2027 Prune going to a boarding school 2035 March 21, 2035 Mater 100 and twins on a Waterlark adventure 2049 March 17, 2049 Prune arrives with a commercial flight on Mars, Mater is deceased (would have been 114) December 19, 2022 at 9:48 am #6352In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The Birmingham Bootmaker

Samuel Jones 1816-1875

Samuel Jones the elder was born in Belfast circa 1779. He is one of just two direct ancestors found thus far born in Ireland. Samuel married Jane Elizabeth Brooker (born in St Giles, London) on the 25th January 1807 at St George, Hanover Square in London. Their first child Mary was born in 1808 in London, and then the family moved to Birmingham. Mary was my 3x great grandmother.

But this chapter is about her brother Samuel Jones. I noticed that on a number of other trees on the Ancestry site, Samuel Jones was a convict transported to Australia, but this didn’t tally with the records I’d found for Samuel in Birmingham. In fact another Samuel Jones born at the same time in the same place was transported, but his occupation was a baker. Our Samuel Jones was a bootmaker like his father.

Samuel was born on 28th January 1816 in Birmingham and baptised at St Phillips on the 19th August of that year, the fourth child and first son of Samuel the elder and Jane’s eleven children.

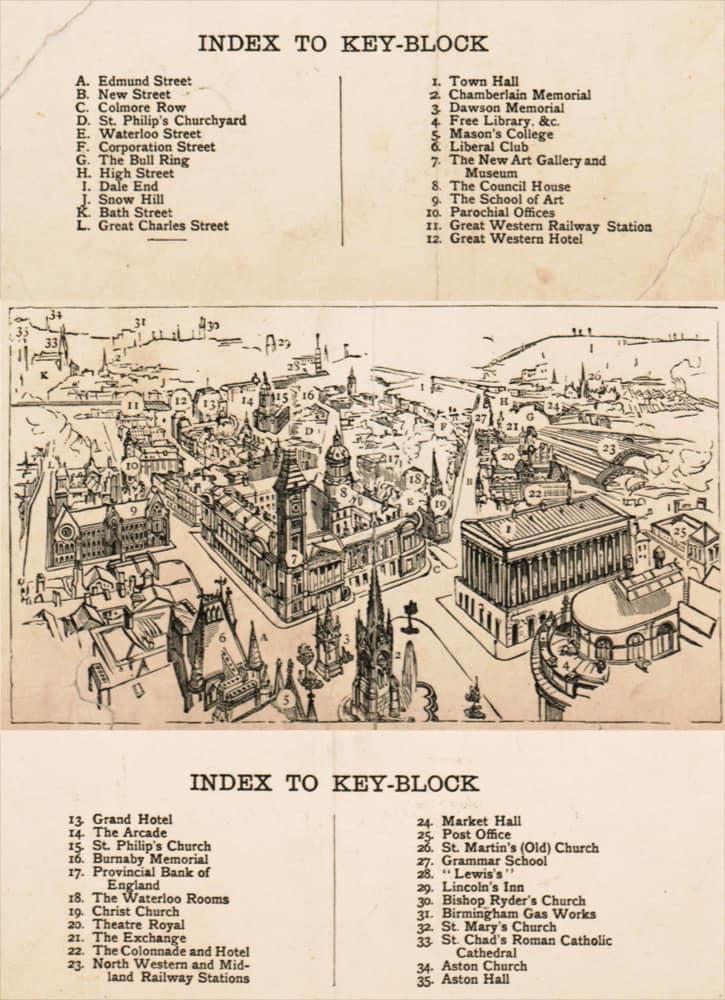

On the 1839 electoral register a Samuel Jones owned a property on Colmore Row, Birmingham.

Samuel Jones, bootmaker of 15, Colmore Row is listed in the 1849 Birmingham post office directory, and in the 1855 White’s Directory.

On the 1851 census, Samuel was an unmarried bootmaker employing sixteen men at 15, Colmore Row. A 9 year old nephew Henry Harris was living with him, and his mother Ruth Harris, as well as a female servant. Samuel’s sister Ruth was born in 1818 and married Henry Harris in 1840. Henry died in 1848.

Samuel was a 45 year old bootmaker at 15 Colmore Row on the 1861 census, living with Maria Walcot, a 26 year old domestic servant.

In October 1863 Samuel married Maria Walcot at St Philips in Birmingham. They don’t appear to have had any children as none appear on the 1871 census, where Samuel and Maria are living at the same address, with another female servant and two male lodgers by the name of Messant from Ipswich.

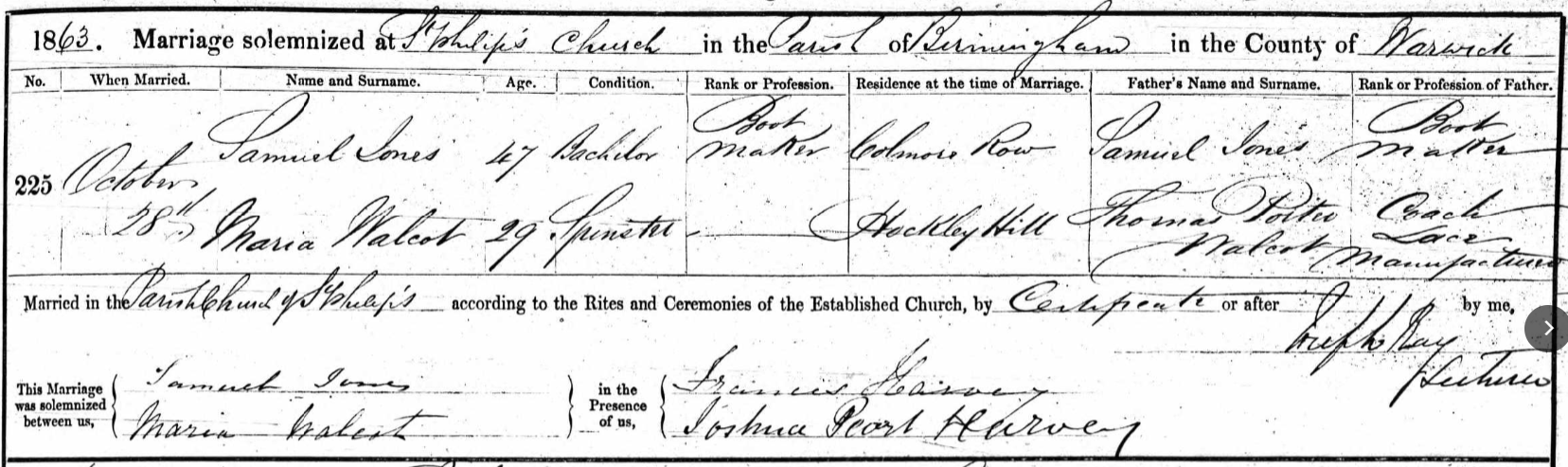

Marriage of Samuel Jones and Maria Walcot:

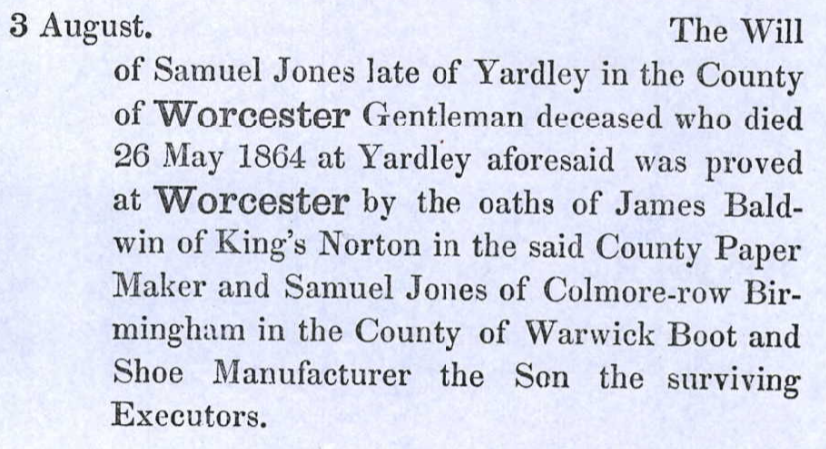

In 1864 Samuel’s father died. Samuel the son is mentioned in the probate records as one of the executors: “Samuel Jones of Colmore Row Birmingham in the county of Warwick boot and shoe manufacturer the son”.

Indeed it could hardly be clearer that this Samuel Jones was not the convict transported to Australia in 1834!

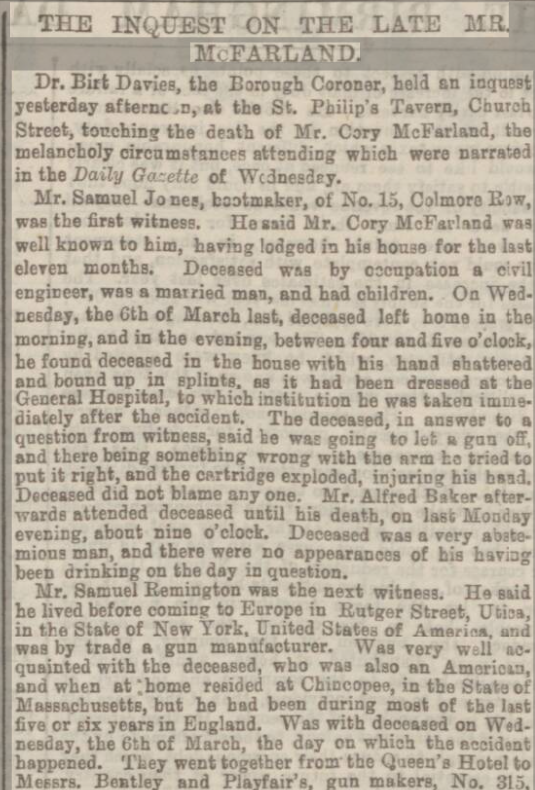

In 1867 Samuel Jones, bootmaker, was mentioned in the Birmingham Daily Gazette with regard to an unfortunate incident involving his American lodger, Cory McFarland. The verdict was accidental death.

Birmingham Daily Gazette – Friday 05 April 1867:

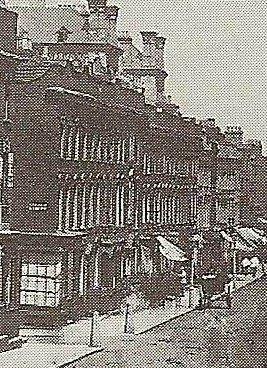

I asked a Birmingham history group for an old photo of Colmore Row. This photo is circa 1870 and number 15 is furthest from the camera. The businesses on the street at the time were as follows:

7 homeopathic chemist George John Morris. 8 surgeon dentist Frederick Sims. 9 Saul & Walter Samuel, Australian merchants. Surgeons occupied 10, pawnbroker John Aaron at 11 & 12. 15 boot & shoemaker. 17 auctioneer…

from Bird’s Eye View of Birmingham, 1886:

December 6, 2022 at 2:17 pm #6350

December 6, 2022 at 2:17 pm #6350In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Transportation

Isaac Stokes 1804-1877

Isaac was born in Churchill, Oxfordshire in 1804, and was the youngest brother of my 4X great grandfather Thomas Stokes. The Stokes family were stone masons for generations in Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire, and Isaac’s occupation was a mason’s labourer in 1834 when he was sentenced at the Lent Assizes in Oxford to fourteen years transportation for stealing tools.

Churchill where the Stokes stonemasons came from: on 31 July 1684 a fire destroyed 20 houses and many other buildings, and killed four people. The village was rebuilt higher up the hill, with stone houses instead of the old timber-framed and thatched cottages. The fire was apparently caused by a baker who, to avoid chimney tax, had knocked through the wall from her oven to her neighbour’s chimney.

Isaac stole a pick axe, the value of 2 shillings and the property of Thomas Joyner of Churchill; a kibbeaux and a trowel value 3 shillings the property of Thomas Symms; a hammer and axe value 5 shillings, property of John Keen of Sarsden.

(The word kibbeaux seems to only exists in relation to Isaac Stokes sentence and whoever was the first to write it was perhaps being creative with the spelling of a kibbo, a miners or a metal bucket. This spelling is repeated in the criminal reports and the newspaper articles about Isaac, but nowhere else).

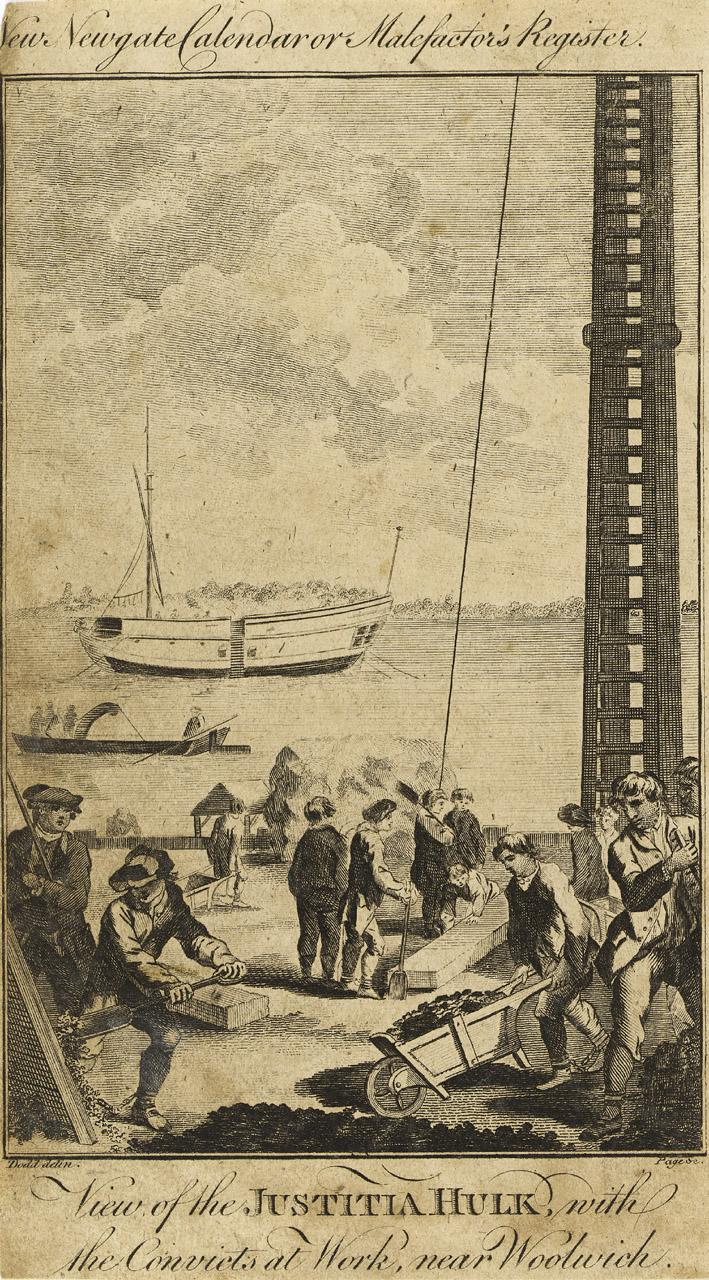

In March 1834 the Removal of Convicts was announced in the Oxford University and City Herald: Isaac Stokes and several other prisoners were removed from the Oxford county gaol to the Justitia hulk at Woolwich “persuant to their sentences of transportation at our Lent Assizes”.

via digitalpanopticon:

Hulks were decommissioned (and often unseaworthy) ships that were moored in rivers and estuaries and refitted to become floating prisons. The outbreak of war in America in 1775 meant that it was no longer possible to transport British convicts there. Transportation as a form of punishment had started in the late seventeenth century, and following the Transportation Act of 1718, some 44,000 British convicts were sent to the American colonies. The end of this punishment presented a major problem for the authorities in London, since in the decade before 1775, two-thirds of convicts at the Old Bailey received a sentence of transportation – on average 283 convicts a year. As a result, London’s prisons quickly filled to overflowing with convicted prisoners who were sentenced to transportation but had no place to go.

To increase London’s prison capacity, in 1776 Parliament passed the “Hulks Act” (16 Geo III, c.43). Although overseen by local justices of the peace, the hulks were to be directly managed and maintained by private contractors. The first contract to run a hulk was awarded to Duncan Campbell, a former transportation contractor. In August 1776, the Justicia, a former transportation ship moored in the River Thames, became the first prison hulk. This ship soon became full and Campbell quickly introduced a number of other hulks in London; by 1778 the fleet of hulks on the Thames held 510 prisoners.

Demand was so great that new hulks were introduced across the country. There were hulks located at Deptford, Chatham, Woolwich, Gosport, Plymouth, Portsmouth, Sheerness and Cork.The Justitia via rmg collections:

Convicts perform hard labour at the Woolwich Warren. The hulk on the river is the ‘Justitia’. Prisoners were kept on board such ships for months awaiting deportation to Australia. The ‘Justitia’ was a 260 ton prison hulk that had been originally moored in the Thames when the American War of Independence put a stop to the transportation of criminals to the former colonies. The ‘Justitia’ belonged to the shipowner Duncan Campbell, who was the Government contractor who organized the prison-hulk system at that time. Campbell was subsequently involved in the shipping of convicts to the penal colony at Botany Bay (in fact Port Jackson, later Sydney, just to the north) in New South Wales, the ‘first fleet’ going out in 1788.

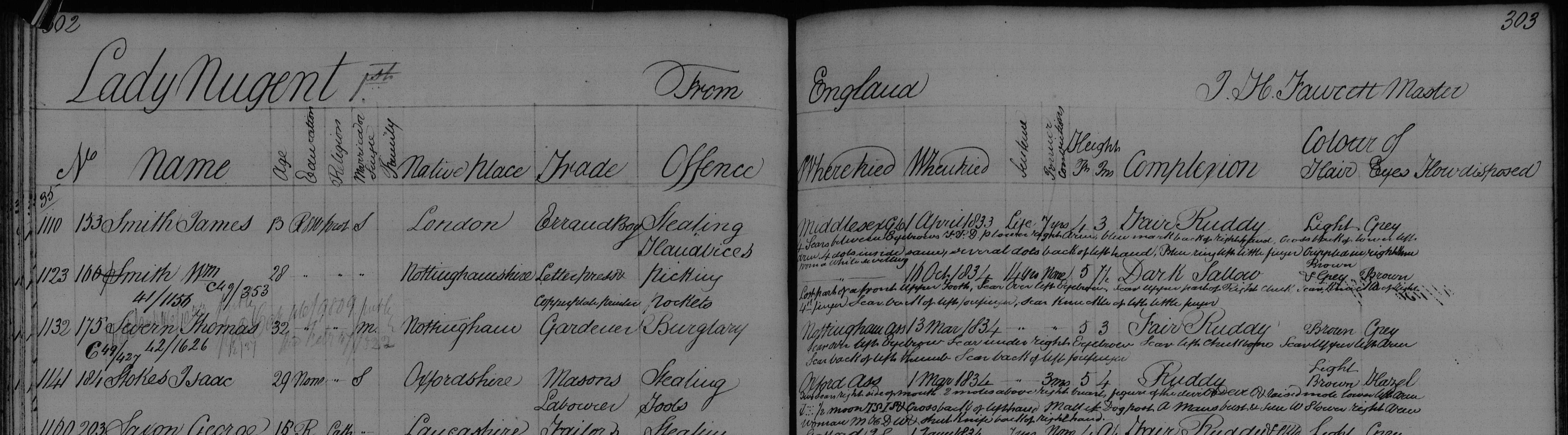

While searching for records for Isaac Stokes I discovered that another Isaac Stokes was transported to New South Wales in 1835 as well. The other one was a butcher born in 1809, sentenced in London for seven years, and he sailed on the Mary Ann. Our Isaac Stokes sailed on the Lady Nugent, arriving in NSW in April 1835, having set sail from England in December 1834.

Lady Nugent was built at Bombay in 1813. She made four voyages under contract to the British East India Company (EIC). She then made two voyages transporting convicts to Australia, one to New South Wales and one to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). (via Wikipedia)

via freesettlerorfelon website:

On 20 November 1834, 100 male convicts were transferred to the Lady Nugent from the Justitia Hulk and 60 from the Ganymede Hulk at Woolwich, all in apparent good health. The Lady Nugent departed Sheerness on 4 December 1834.

SURGEON OLIVER SPROULE

Oliver Sproule kept a Medical Journal from 7 November 1834 to 27 April 1835. He recorded in his journal the weather conditions they experienced in the first two weeks:

‘In the course of the first week or ten days at sea, there were eight or nine on the sick list with catarrhal affections and one with dropsy which I attribute to the cold and wet we experienced during that period beating down channel. Indeed the foremost berths in the prison at this time were so wet from leaking in that part of the ship, that I was obliged to issue dry beds and bedding to a great many of the prisoners to preserve their health, but after crossing the Bay of Biscay the weather became fine and we got the damp beds and blankets dried, the leaks partially stopped and the prison well aired and ventilated which, I am happy to say soon manifested a favourable change in the health and appearance of the men.

Besides the cases given in the journal I had a great many others to treat, some of them similar to those mentioned but the greater part consisted of boils, scalds, and contusions which would not only be too tedious to enter but I fear would be irksome to the reader. There were four births on board during the passage which did well, therefore I did not consider it necessary to give a detailed account of them in my journal the more especially as they were all favourable cases.

Regularity and cleanliness in the prison, free ventilation and as far as possible dry decks turning all the prisoners up in fine weather as we were lucky enough to have two musicians amongst the convicts, dancing was tolerated every afternoon, strict attention to personal cleanliness and also to the cooking of their victuals with regular hours for their meals, were the only prophylactic means used on this occasion, which I found to answer my expectations to the utmost extent in as much as there was not a single case of contagious or infectious nature during the whole passage with the exception of a few cases of psora which soon yielded to the usual treatment. A few cases of scurvy however appeared on board at rather an early period which I can attribute to nothing else but the wet and hardships the prisoners endured during the first three or four weeks of the passage. I was prompt in my treatment of these cases and they got well, but before we arrived at Sydney I had about thirty others to treat.’

The Lady Nugent arrived in Port Jackson on 9 April 1835 with 284 male prisoners. Two men had died at sea. The prisoners were landed on 27th April 1835 and marched to Hyde Park Barracks prior to being assigned. Ten were under the age of 14 years.

The Lady Nugent:

Isaac’s distinguishing marks are noted on various criminal registers and record books:

“Height in feet & inches: 5 4; Complexion: Ruddy; Hair: Light brown; Eyes: Hazel; Marks or Scars: Yes [including] DEVIL on lower left arm, TSIS back of left hand, WS lower right arm, MHDW back of right hand.”

Another includes more detail about Isaac’s tattoos:

“Two slight scars right side of mouth, 2 moles above right breast, figure of the devil and DEVIL and raised mole, lower left arm; anchor, seven dots half moon, TSIS and cross, back of left hand; a mallet, door post, A, mans bust, sun, WS, lower right arm; woman, MHDW and shut knife, back of right hand.”

From How tattoos became fashionable in Victorian England (2019 article in TheConversation by Robert Shoemaker and Zoe Alkar):

“Historical tattooing was not restricted to sailors, soldiers and convicts, but was a growing and accepted phenomenon in Victorian England. Tattoos provide an important window into the lives of those who typically left no written records of their own. As a form of “history from below”, they give us a fleeting but intriguing understanding of the identities and emotions of ordinary people in the past.

As a practice for which typically the only record is the body itself, few systematic records survive before the advent of photography. One exception to this is the written descriptions of tattoos (and even the occasional sketch) that were kept of institutionalised people forced to submit to the recording of information about their bodies as a means of identifying them. This particularly applies to three groups – criminal convicts, soldiers and sailors. Of these, the convict records are the most voluminous and systematic.

Such records were first kept in large numbers for those who were transported to Australia from 1788 (since Australia was then an open prison) as the authorities needed some means of keeping track of them.”On the 1837 census Isaac was working for the government at Illiwarra, New South Wales. This record states that he arrived on the Lady Nugent in 1835. There are three other indent records for an Isaac Stokes in the following years, but the transcriptions don’t provide enough information to determine which Isaac Stokes it was. In April 1837 there was an abscondment, and an arrest/apprehension in May of that year, and in 1843 there was a record of convict indulgences.

From the Australian government website regarding “convict indulgences”:

“By the mid-1830s only six per cent of convicts were locked up. The vast majority worked for the government or free settlers and, with good behaviour, could earn a ticket of leave, conditional pardon or and even an absolute pardon. While under such orders convicts could earn their own living.”

In 1856 in Camden, NSW, Isaac Stokes married Catherine Daly. With no further information on this record it would be impossible to know for sure if this was the right Isaac Stokes. This couple had six children, all in the Camden area, but none of the records provided enough information. No occupation or place or date of birth recorded for Isaac Stokes.

I wrote to the National Library of Australia about the marriage record, and their reply was a surprise! Issac and Catherine were married on 30 September 1856, at the house of the Rev. Charles William Rigg, a Methodist minister, and it was recorded that Isaac was born in Edinburgh in 1821, to parents James Stokes and Sarah Ellis! The age at the time of the marriage doesn’t match Isaac’s age at death in 1877, and clearly the place of birth and parents didn’t match either. Only his fathers occupation of stone mason was correct. I wrote back to the helpful people at the library and they replied that the register was in a very poor condition and that only two and a half entries had survived at all, and that Isaac and Catherines marriage was recorded over two pages.

I searched for an Isaac Stokes born in 1821 in Edinburgh on the Scotland government website (and on all the other genealogy records sites) and didn’t find it. In fact Stokes was a very uncommon name in Scotland at the time. I also searched Australian immigration and other records for another Isaac Stokes born in Scotland or born in 1821, and found nothing. I was unable to find a single record to corroborate this mysterious other Isaac Stokes.

As the age at death in 1877 was correct, I assume that either Isaac was lying, or that some mistake was made either on the register at the home of the Methodist minster, or a subsequent mistranscription or muddle on the remnants of the surviving register. Therefore I remain convinced that the Camden stonemason Isaac Stokes was indeed our Isaac from Oxfordshire.

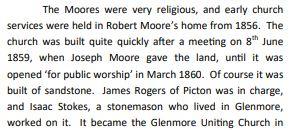

I found a history society newsletter article that mentioned Isaac Stokes, stone mason, had built the Glenmore church, near Camden, in 1859.

From the Wollondilly museum April 2020 newsletter:

From the Camden History website:

“The stone set over the porch of Glenmore Church gives the date of 1860. The church was begun in 1859 on land given by Joseph Moore. James Rogers of Picton was given the contract to build and local builder, Mr. Stokes, carried out the work. Elizabeth Moore, wife of Edward, laid the foundation stone. The first service was held on 19th March 1860. The cemetery alongside the church contains the headstones and memorials of the areas early pioneers.”

Isaac died on the 3rd September 1877. The inquest report puts his place of death as Bagdelly, near to Camden, and another death register has put Cambelltown, also very close to Camden. His age was recorded as 71 and the inquest report states his cause of death was “rupture of one of the large pulmonary vessels of the lung”. His wife Catherine died in childbirth in 1870 at the age of 43.

Isaac and Catherine’s children:

William Stokes 1857-1928

Catherine Stokes 1859-1846

Sarah Josephine Stokes 1861-1931

Ellen Stokes 1863-1932

Rosanna Stokes 1865-1919

Louisa Stokes 1868-1844.

It’s possible that Catherine Daly was a transported convict from Ireland.

Some time later I unexpectedly received a follow up email from The Oaks Heritage Centre in Australia.

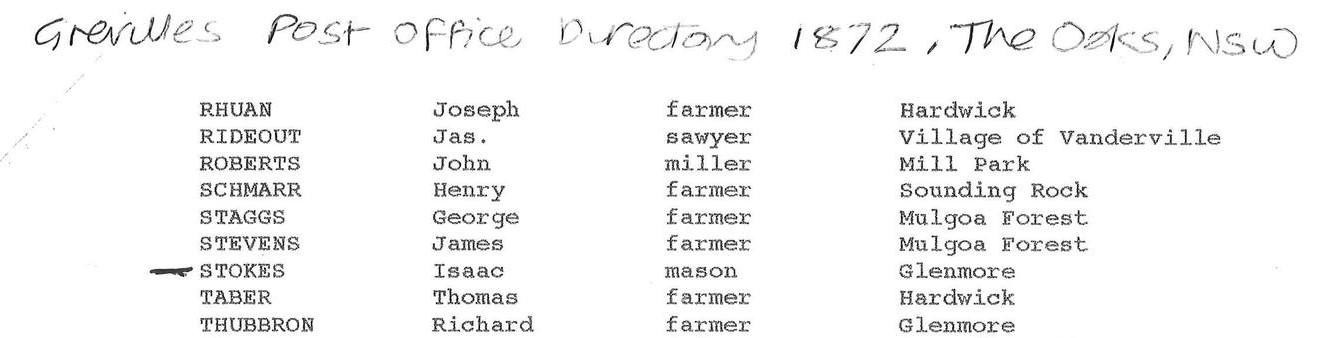

“The Gaudry papers which we have in our archive record him (Isaac Stokes) as having built: the church, the school and the teachers residence. Isaac is recorded in the General return of convicts: 1837 and in Grevilles Post Office directory 1872 as a mason in Glenmore.”

November 18, 2022 at 4:47 pm #6348

November 18, 2022 at 4:47 pm #6348In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Wong Sang

Wong Sang was born in China in 1884. In October 1916 he married Alice Stokes in Oxford.

Alice was the granddaughter of William Stokes of Churchill, Oxfordshire and William was the brother of Thomas Stokes the wheelwright (who was my 3X great grandfather). In other words Alice was my second cousin, three times removed, on my fathers paternal side.

Wong Sang was an interpreter, according to the baptism registers of his children and the Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital admission registers in 1930. The hospital register also notes that he was employed by the Blue Funnel Line, and that his address was 11, Limehouse Causeway, E 14. (London)

“The Blue Funnel Line offered regular First-Class Passenger and Cargo Services From the UK to South Africa, Malaya, China, Japan, Australia, Java, and America. Blue Funnel Line was Owned and Operated by Alfred Holt & Co., Liverpool.

The Blue Funnel Line, so-called because its ships have a blue funnel with a black top, is more appropriately known as the Ocean Steamship Company.”Wong Sang and Alice’s daughter, Frances Eileen Sang, was born on the 14th July, 1916 and baptised in 1920 at St Stephen in Poplar, Tower Hamlets, London. The birth date is noted in the 1920 baptism register and would predate their marriage by a few months, although on the death register in 1921 her age at death is four years old and her year of birth is recorded as 1917.

Charles Ronald Sang was baptised on the same day in May 1920, but his birth is recorded as April of that year. The family were living on Morant Street, Poplar.

James William Sang’s birth is recorded on the 1939 census and on the death register in 2000 as being the 8th March 1913. This definitely would predate the 1916 marriage in Oxford.

William Norman Sang was born on the 17th October 1922 in Poplar.

Alice and the three sons were living at 11, Limehouse Causeway on the 1939 census, the same address that Wong Sang was living at when he was admitted to Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital on the 15th January 1930. Wong Sang died in the hospital on the 8th March of that year at the age of 46.

Alice married John Patterson in 1933 in Stepney. John was living with Alice and her three sons on Limehouse Causeway on the 1939 census and his occupation was chef.

Via Old London Photographs:

“Limehouse Causeway is a street in east London that was the home to the original Chinatown of London. A combination of bomb damage during the Second World War and later redevelopment means that almost nothing is left of the original buildings of the street.”

Limehouse Causeway in 1925:

From The Story of Limehouse’s Lost Chinatown, poplarlondon website:

“Limehouse was London’s first Chinatown, home to a tightly-knit community who were demonised in popular culture and eventually erased from the cityscape.

As recounted in the BBC’s ‘Our Greatest Generation’ series, Connie was born to a Chinese father and an English mother in early 1920s Limehouse, where she used to play in the street with other British and British-Chinese children before running inside for teatime at one of their houses.

Limehouse was London’s first Chinatown between the 1880s and the 1960s, before the current Chinatown off Shaftesbury Avenue was established in the 1970s by an influx of immigrants from Hong Kong.

Connie’s memories of London’s first Chinatown as an “urban village” paint a very different picture to the seedy area portrayed in early twentieth century novels.

The pyramid in St Anne’s church marked the entrance to the opium den of Dr Fu Manchu, a criminal mastermind who threatened Western society by plotting world domination in a series of novels by Sax Rohmer.

Thomas Burke’s Limehouse Nights cemented stereotypes about prostitution, gambling and violence within the Chinese community, and whipped up anxiety about sexual relationships between Chinese men and white women.

Though neither novelist was familiar with the Chinese community, their depictions made Limehouse one of the most notorious areas of London.

Travel agent Thomas Cook even organised tours of the area for daring visitors, despite the rector of Limehouse warning that “those who look for the Limehouse of Mr Thomas Burke simply will not find it.”

All that remains is a handful of Chinese street names, such as Ming Street, Pekin Street, and Canton Street — but what was Limehouse’s chinatown really like, and why did it get swept away?

Chinese migration to Limehouse

Chinese sailors discharged from East India Company ships settled in the docklands from as early as the 1780s.

By the late nineteenth century, men from Shanghai had settled around Pennyfields Lane, while a Cantonese community lived on Limehouse Causeway.

Chinese sailors were often paid less and discriminated against by dock hirers, and so began to diversify their incomes by setting up hand laundry services and restaurants.

Old photographs show shopfronts emblazoned with Chinese characters with horse-drawn carts idling outside or Chinese men in suits and hats standing proudly in the doorways.

In oral histories collected by Yat Ming Loo, Connie’s husband Leslie doesn’t recall seeing any Chinese women as a child, since male Chinese sailors settled in London alone and married working-class English women.

In the 1920s, newspapers fear-mongered about interracial marriages, crime and gambling, and described chinatown as an East End “colony.”

Ironically, Chinese opium-smoking was also demonised in the press, despite Britain waging war against China in the mid-nineteenth century for suppressing the opium trade to alleviate addiction amongst its people.

The number of Chinese people who settled in Limehouse was also greatly exaggerated, and in reality only totalled around 300.

The real Chinatown

Although the press sought to characterise Limehouse as a monolithic Chinese community in the East End, Connie remembers seeing people of all nationalities in the shops and community spaces in Limehouse.

She doesn’t remember feeling discriminated against by other locals, though Connie does recall having her face measured and IQ tested by a member of the British Eugenics Society who was conducting research in the area.

Some of Connie’s happiest childhood memories were from her time at Chung-Hua Club, where she learned about Chinese culture and language.

Why did Chinatown disappear?

The caricature of Limehouse’s Chinatown as a den of vice hastened its erasure.

Police raids and deportations fuelled by the alarmist media coverage threatened the Chinese population of Limehouse, and slum clearance schemes to redevelop low-income areas dispersed Chinese residents in the 1930s.

The Defence of the Realm Act imposed at the beginning of the First World War criminalised opium use, gave the authorities increased powers to deport Chinese people and restricted their ability to work on British ships.

Dwindling maritime trade during World War II further stripped Chinese sailors of opportunities for employment, and any remnants of Chinatown were destroyed during the Blitz or erased by postwar development schemes.”

Wong Sang 1884-1930

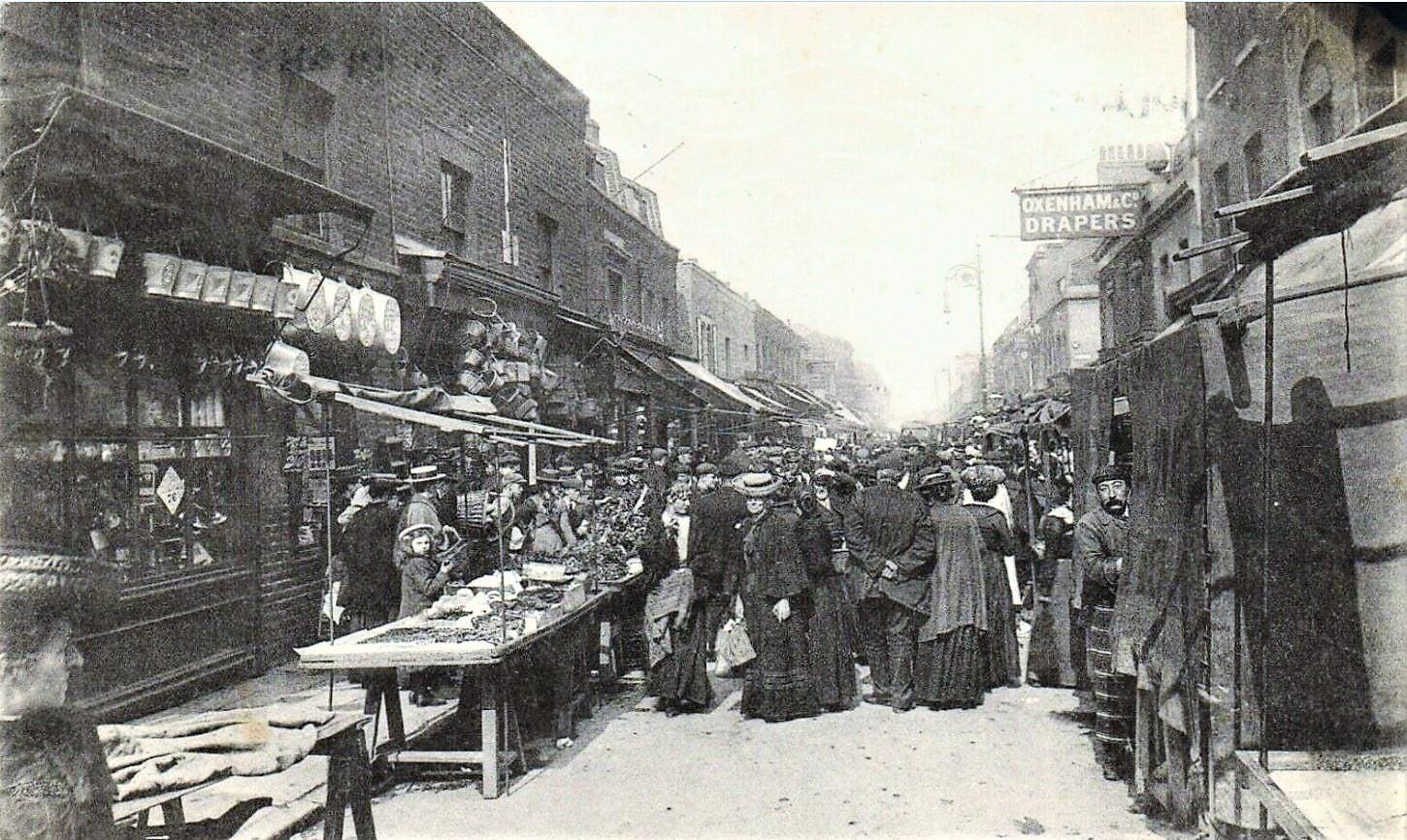

The year 1918 was a troublesome one for Wong Sang, an interpreter and shipping agent for Blue Funnel Line. The Sang family were living at 156, Chrisp Street.

Chrisp Street, Poplar, in 1913 via Old London Photographs:

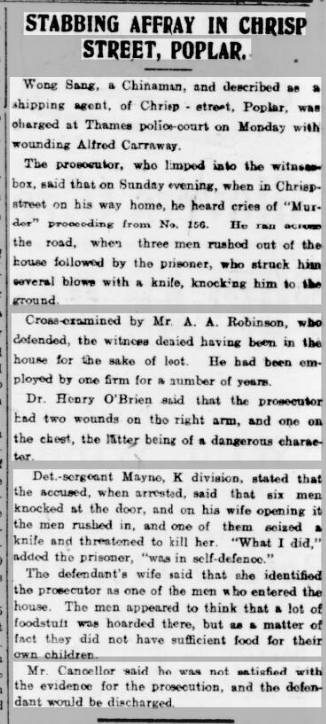

In February Wong Sang was discharged from a false accusation after defending his home from potential robbers.

East End News and London Shipping Chronicle – Friday 15 February 1918:

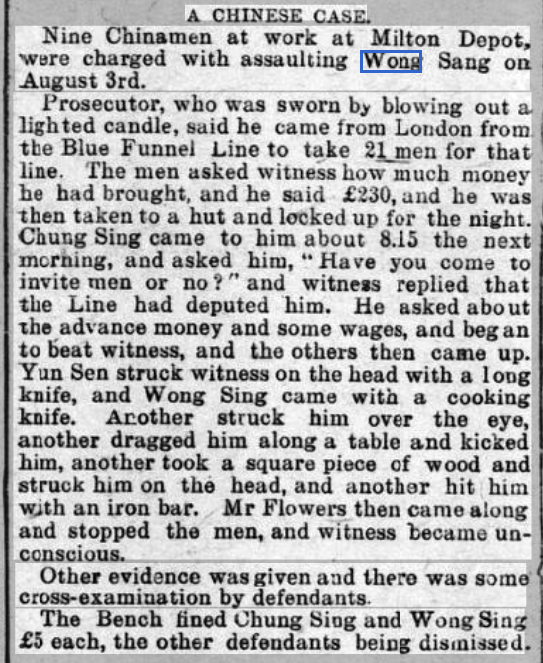

In August of that year he was involved in an incident that left him unconscious.

Faringdon Advertiser and Vale of the White Horse Gazette – Saturday 31 August 1918:

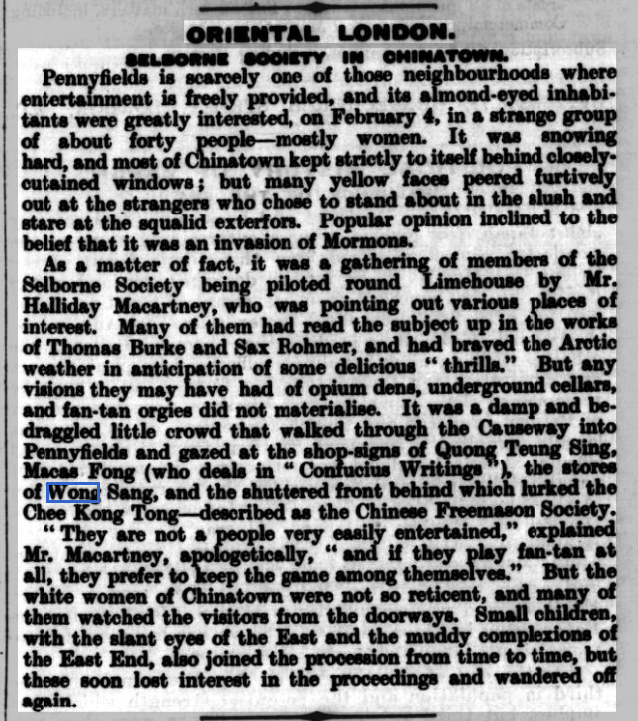

Wong Sang is mentioned in an 1922 article about “Oriental London”.

London and China Express – Thursday 09 February 1922:

A photograph of the Chee Kong Tong Chinese Freemason Society mentioned in the above article, via Old London Photographs:

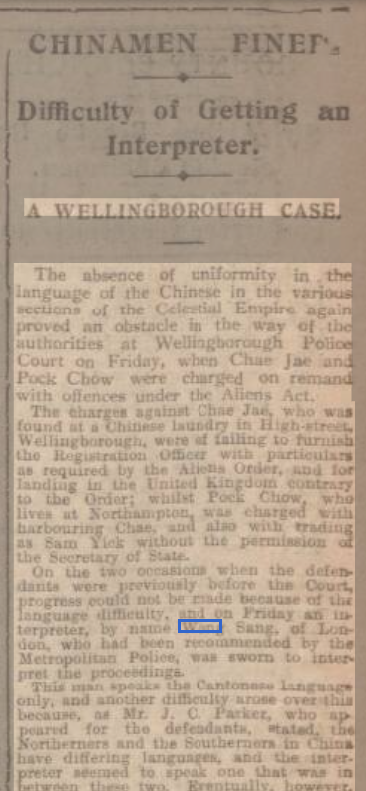

Wong Sang was recommended by the London Metropolitan Police in 1928 to assist in a case in Wellingborough, Northampton.

Difficulty of Getting an Interpreter: Northampton Mercury – Friday 16 March 1928:

The difficulty was that “this man speaks the Cantonese language only…the Northeners and the Southerners in China have differing languages and the interpreter seemed to speak one that was in between these two.”

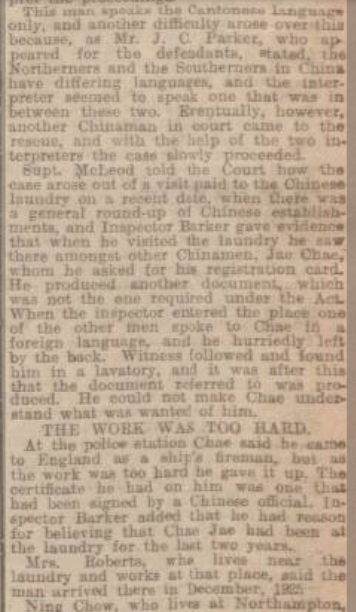

In 1917, Alice Wong Sang was a witness at her sister Harriet Stokes marriage to James William Watts in Southwark, London. Their father James Stokes occupation on the marriage register is foreman surveyor, but on the census he was a council roadman or labourer. (I initially rejected this as the correct marriage for Harriet because of the discrepancy with the occupations. Alice Wong Sang as a witness confirmed that it was indeed the correct one.)

James William Sang 1913-2000 was a clock fitter and watch assembler (on the 1939 census). He married Ivy Laura Fenton in 1963 in Sidcup, Kent. James died in Southwark in 2000.

Charles Ronald Sang 1920-1974 was a draughtsman (1939 census). He married Eileen Burgess in 1947 in Marylebone. Charles and Eileen had two sons: Keith born in 1951 and Roger born in 1952. He died in 1974 in Hertfordshire.

William Norman Sang 1922-2000 was a clerk and telephone operator (1939 census). William enlisted in the Royal Artillery in 1942. He married Lily Mullins in 1949 in Bethnal Green, and they had three daughters: Marion born in 1950, Christine in 1953, and Frances in 1959. He died in Redbridge in 2000.

I then found another two births registered in Poplar by Alice Sang, both daughters. Doris Winifred Sang was born in 1925, and Patricia Margaret Sang was born in 1933 ~ three years after Wong Sang’s death. Neither of the these daughters were on the 1939 census with Alice, John Patterson and the three sons. Margaret had presumably been evacuated because of the war to a family in Taunton, Somerset. Doris would have been fourteen and I have been unable to find her in 1939 (possibly because she died in 2017 and has not had the redaction removed yet on the 1939 census as only deceased people are viewable).

Doris Winifred Sang 1925-2017 was a nursing sister. She didn’t marry, and spent a year in USA between 1954 and 1955. She stayed in London, and died at the age of ninety two in 2017.

Patricia Margaret Sang 1933-1998 was also a nurse. She married Patrick L Nicely in Stepney in 1957. Patricia and Patrick had five children in London: Sharon born 1959, Donald in 1960, Malcolm was born and died in 1966, Alison was born in 1969 and David in 1971.

I was unable to find a birth registered for Alice’s first son, James William Sang (as he appeared on the 1939 census). I found Alice Stokes on the 1911 census as a 17 year old live in servant at a tobacconist on Pekin Street, Limehouse, living with Mr Sui Fong from Hong Kong and his wife Sarah Sui Fong from Berlin. I looked for a birth registered for James William Fong instead of Sang, and found it ~ mothers maiden name Stokes, and his date of birth matched the 1939 census: 8th March, 1913.

On the 1921 census, Wong Sang is not listed as living with them but it is mentioned that Mr Wong Sang was the person returning the census. Also living with Alice and her sons James and Charles in 1921 are two visitors: (Florence) May Stokes, 17 years old, born in Woodstock, and Charles Stokes, aged 14, also born in Woodstock. May and Charles were Alice’s sister and brother.

I found Sharon Nicely on social media and she kindly shared photos of Wong Sang and Alice Stokes:

September 21, 2022 at 1:16 pm #6330

September 21, 2022 at 1:16 pm #6330Topic: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

in forum TP’s Family BooksMy Fathers Family

Edwards ~ Tomlinson ~ Stokes ~ Fisher

Reginald Garnet Edwards was born on 2 April 1934 at the Worcester Cross pub in Kidderminster.

The X on right is the room he was born in:

I hadn’t done much research on the Edwards family because my fathers cousin, Paul Weaver, had already done it and had an excellent website online. I decided to start from scratch and do it all myself because it’s so much more interesting to do the research myself than look at lists of names and dates that don’t really mean anything. Immediately after I decided to do this, I found that Paul’s family tree website was no longer online to refer to anyway!

I started with the Edwards family in Birmingham and immediately had a problem: there were far too many John Edwards in Birmingham at the time. I’ll return to the Edwards in a later chapter, and start with my fathers mothers mothers family, the Fishers.

June 10, 2022 at 1:39 pm #6305In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

The Hair’s and Leedham’s of Netherseal

Samuel Warren of Stapenhill married Catherine Holland of Barton under Needwood in 1795. Catherine’s father was Thomas Holland; her mother was Hannah Hair.

Hannah was born in Netherseal, Derbyshire, in 1739. Her parents were Joseph Hair 1696-1746 and Hannah.

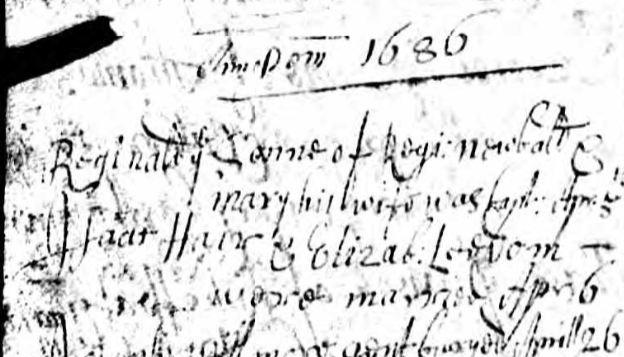

Joseph’s parents were Isaac Hair and Elizabeth Leedham. Elizabeth was born in Netherseal in 1665. Isaac and Elizabeth were married in Netherseal in 1686.Marriage of Isaac Hair and Elizabeth Leedham: (variously spelled Ledom, Leedom, Leedham, and in one case mistranscribed as Sedom):

Isaac was buried in Netherseal on 14 August 1709 (the transcript says the 18th, but the microfiche image clearly says the 14th), but I have not been able to find a birth registered for him. On other public trees on an ancestry website, Isaac Le Haire was baptised in Canterbury and was a Huguenot, but I haven’t found any evidence to support this.

Isaac Hair’s death registered 14 August 1709 in Netherseal:

A search for the etymology of the surname Hair brings various suggestions, including:

“This surname is derived from a nickname. ‘the hare,’ probably affixed on some one fleet of foot. Naturally looked upon as a complimentary sobriquet, and retained in the family; compare Lightfoot. (for example) Hugh le Hare, Oxfordshire, 1273. Hundred Rolls.”

From this we may deduce that the name Hair (or Hare) is not necessarily from the French Le Haire, and existed in England for some considerable time before the arrival of the Huguenots.

Elizabeth Leedham was born in Netherseal in 1665. Her parents were Nicholas Leedham 1621-1670 and Dorothy. Nicholas Leedham was born in Church Gresley (Swadlincote) in 1621, and died in Netherseal in 1670.

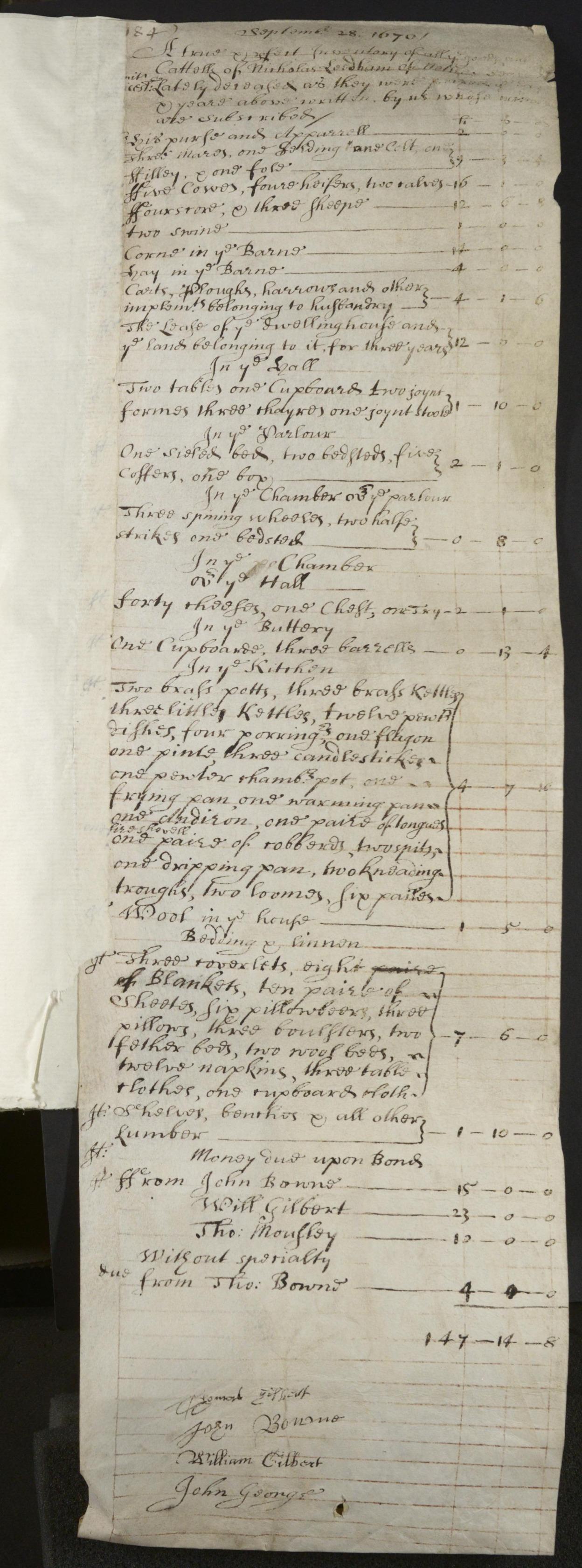

Nicholas was a Yeoman and left a will and inventory worth £147.14s.8d (one hundred and forty seven pounds fourteen shillings and eight pence).

The 1670 inventory of Nicholas Leedham:

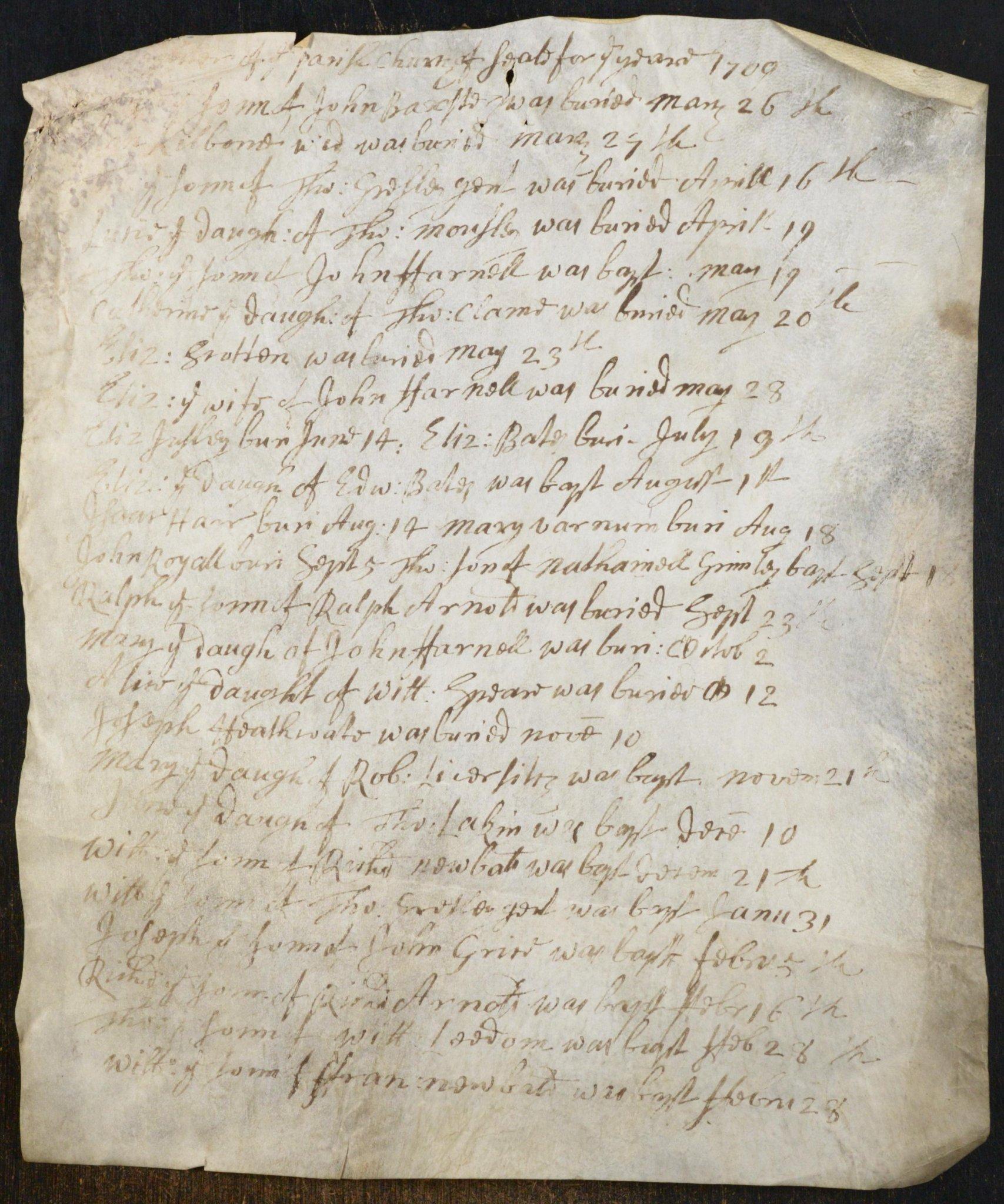

According to local historian Mark Knight on the Netherseal History facebook group, the Seale (Netherseal and Overseal) parish registers from the year 1563 to 1724 were digitized during lockdown.

via Mark Knight:

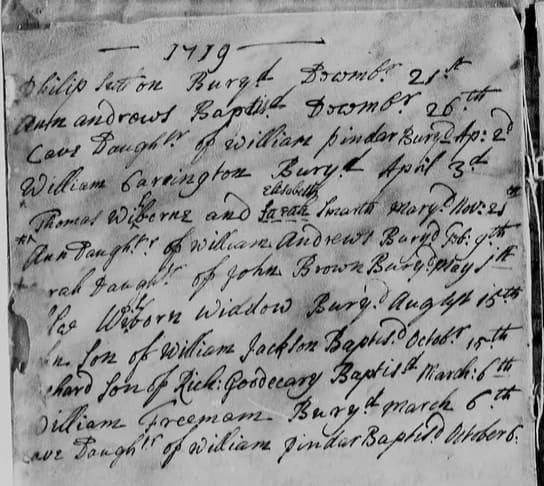

“There are five entries for Nicholas Leedham.

On March 14th 1646 he and his wife buried an unnamed child, presumably the child died during childbirth or was stillborn.

On November 28th 1659 he buried his wife, Elizabeth. He remarried as on June 13th 1664 he had his son William baptised.

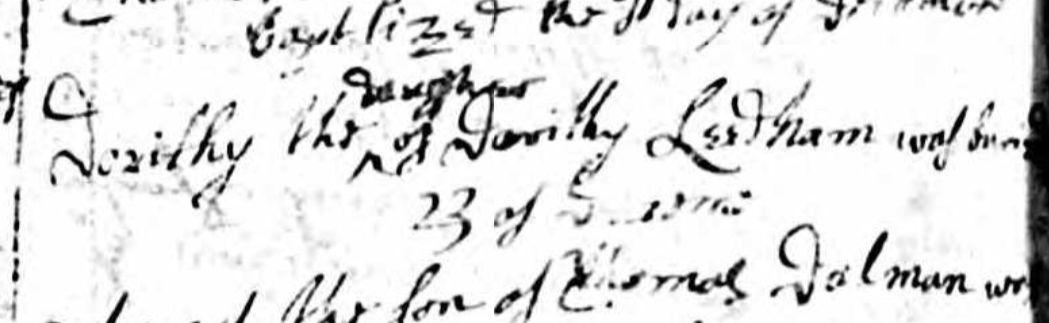

The following year, 1665, he baptised a daughter on November 12th. (Elizabeth) On December 23rd 1672 the parish record says that Dorithy daughter of Dorithy was buried. The Bishops Transcript has Dorithy a daughter of Nicholas. Nicholas’ second wife was called Dorithy and they named a daughter after her. Alas, the daughter died two years after Nicholas. No further Leedhams appear in the record until after 1724.”Dorothy daughter of Dorothy Leedham was buried 23 December 1672:

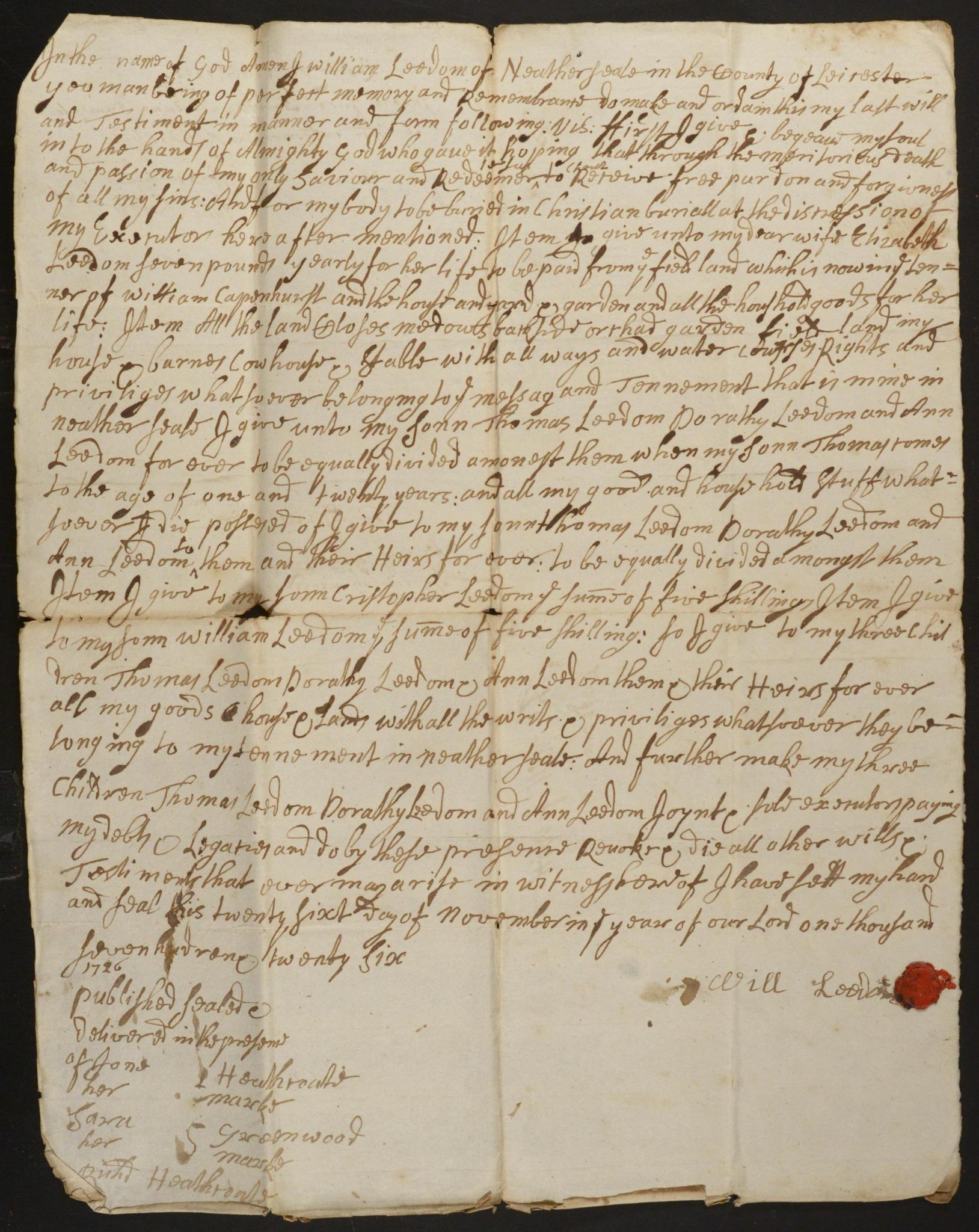

William, son of Nicholas and Dorothy also left a will. In it he mentions “My dear wife Elizabeth. My children Thomas Leedom, Dorothy Leedom , Ann Leedom, Christopher Leedom and William Leedom.”

1726 will of William Leedham:

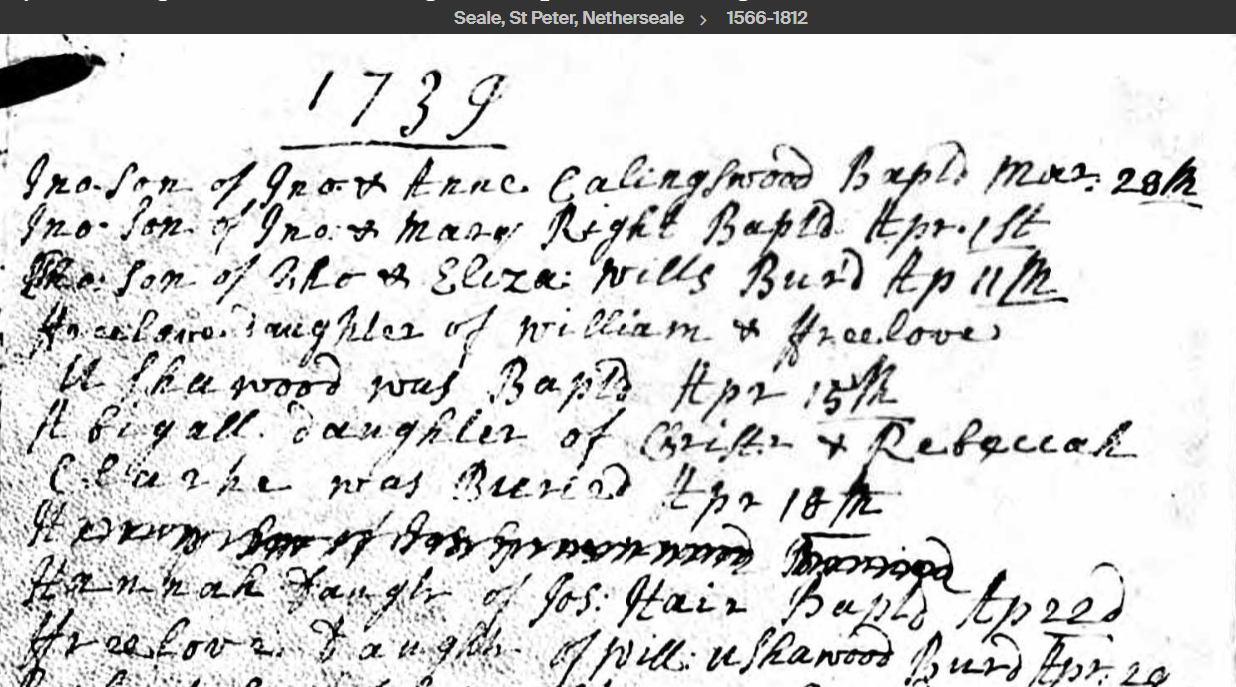

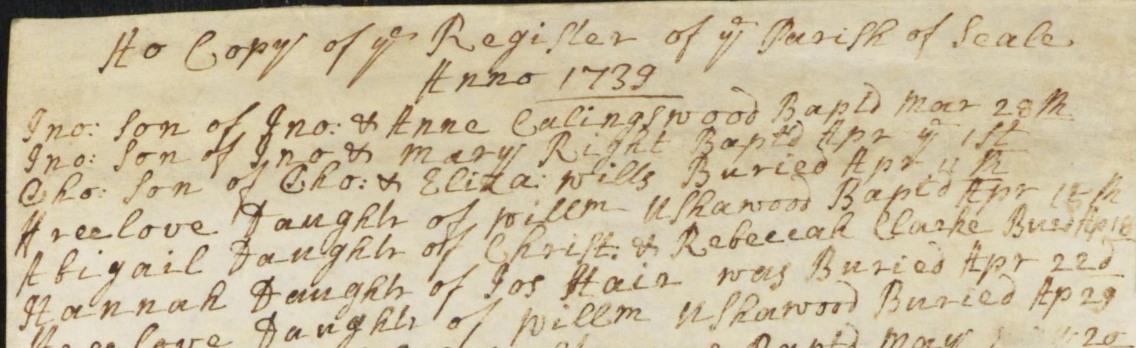

I found a curious error with the the parish register entries for Hannah Hair. It was a transcription error, but not a recent one. The original parish registers were copied: “HO Copy of ye register of Seale anno 1739.” I’m not sure when the copy was made, but it wasn’t recently. I found a burial for Hannah Hair on 22 April 1739 in the HO copy, which was the same day as her baptism registered on the original. I checked both registers name by name and they are exactly copied EXCEPT for Hannah Hairs. The rector, Richard Inge, put burial instead of baptism by mistake.

The original Parish register baptism of Hannah Hair:

The HO register copy incorrectly copied:

May 13, 2022 at 10:50 am #6293

May 13, 2022 at 10:50 am #6293In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Lincolnshire Families

Thanks to the 1851 census, we know that William Eaton was born in Grantham, Lincolnshire. He was baptised on 29 November 1768 at St Wulfram’s church; his father was William Eaton and his mother Elizabeth.

St Wulfram’s in Grantham painted by JMW Turner in 1797:

I found a marriage for a William Eaton and Elizabeth Rose in the city of Lincoln in 1761, but it seemed unlikely as they were both of that parish, and with no discernable links to either Grantham or Nottingham.

But there were two marriages registered for William Eaton and Elizabeth Rose: one in Lincoln in 1761 and one in Hawkesworth Nottinghamshire in 1767, the year before William junior was baptised in Grantham. Hawkesworth is between Grantham and Nottingham, and this seemed much more likely.

Elizabeth’s name is spelled Rose on her marriage records, but spelled Rouse on her baptism. It’s not unusual for spelling variations to occur, as the majority of people were illiterate and whoever was recording the event wrote what it sounded like.

Elizabeth Rouse was baptised on 26th December 1746 in Gunby St Nicholas (there is another Gunby in Lincolnshire), a short distance from Grantham. Her father was Richard Rouse; her mother Cave Pindar. Cave is a curious name and I wondered if it had been mistranscribed, but it appears to be correct and clearly says Cave on several records.

Richard Rouse married Cave Pindar 21 July 1744 in South Witham, not far from Grantham.

Richard was born in 1716 in North Witham. His father was William Rouse; his mothers name was Jane.

Cave Pindar was born in 1719 in Gunby St Nicholas, near Grantham. Her father was William Pindar, but sadly her mothers name is not recorded in the parish baptism register. However a marriage was registered between William Pindar and Elizabeth Holmes in Gunby St Nicholas in October 1712.

William Pindar buried a daughter Cave on 2 April 1719 and baptised a daughter Cave on 6 Oct 1719:

Elizabeth Holmes was baptised in Gunby St Nicholas on 6th December 1691. Her father was John Holmes; her mother Margaret Hod.

Margaret Hod would have been born circa 1650 to 1670 and I haven’t yet found a baptism record for her. According to several other public trees on an ancestry website, she was born in 1654 in Essenheim, Germany. This was surprising! According to these trees, her father was Johannes Hod (Blodt|Hoth) (1609–1677) and her mother was Maria Appolonia Witters (1620–1656).

I did not think it very likely that a young woman born in Germany would appear in Gunby St Nicholas in the late 1600’s, and did a search for Hod’s in and around Grantham. Indeed there were Hod’s living in the area as far back as the 1500’s, (a Robert Hod was baptised in Grantham in 1552), and no doubt before, but the parish records only go so far back. I think it’s much more likely that her parents were local, and that the page with her baptism recorded on the registers is missing.

Of the many reasons why parish registers or some of the pages would be destroyed or lost, this is another possibility. Lincolnshire is on the east coast of England:

“All of England suffered from a “monster” storm in November of 1703 that killed a reported 8,000 people. Seaside villages suffered greatly and their church and civil records may have been lost.”

A Margeret Hod, widow, died in Gunby St Nicholas in 1691, the same year that Elizabeth Holmes was born. Elizabeth’s mother was Margaret Hod. Perhaps the widow who died was Margaret Hod’s mother? I did wonder if Margaret Hod had died shortly after her daughter’s birth, and that her husband had died sometime between the conception and birth of his child. The Black Death or Plague swept through Lincolnshire in 1680 through 1690; such an eventually would be possible. But Margaret’s name would have been registered as Holmes, not Hod.

Cave Pindar’s father William was born in Swinstead, Lincolnshire, also near to Grantham, on the 28th December, 1690, and he died in Gunby St Nicholas in 1756. William’s father is recorded as Thomas Pinder; his mother Elizabeth.

GUNBY: The village name derives from a “farmstead or village of a man called Gunni”, from the Old Scandinavian person name, and ‘by’, a farmstead, village or settlement.

Gunby Grade II listed Anglican church is dedicated to St Nicholas. Of 15th-century origin, it was rebuilt by Richard Coad in 1869, although the Perpendicular tower remained. March 17, 2022 at 10:37 am #6283

March 17, 2022 at 10:37 am #6283In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Purdy Cousins

My great grandmother Mary Ann Gilman Purdy was one of five children. Her sister Ellen Purdy was a well traveled nurse, and her sister Kate Rushby was a publican whose son who went to Africa. But what of her eldest sister Elizabeth and her brother Richard?

Elizabeth Purdy 1869-1905 married Benjamin George Little in 1892 in Basford, Nottinghamshire. Their first child, Frieda Olive Little, was born in Eastwood in December 1896, and their second daughter Catherine Jane Little was born in Warrington, Cheshire, in 1898. A third daughter, Edna Francis Little was born in 1900, but died three months later.

When I noticed that this unidentified photograph in our family collection was taken by a photographer in Warrington, and as no other family has been found in Warrington, I concluded that these two little girls are Frieda and Catherine:

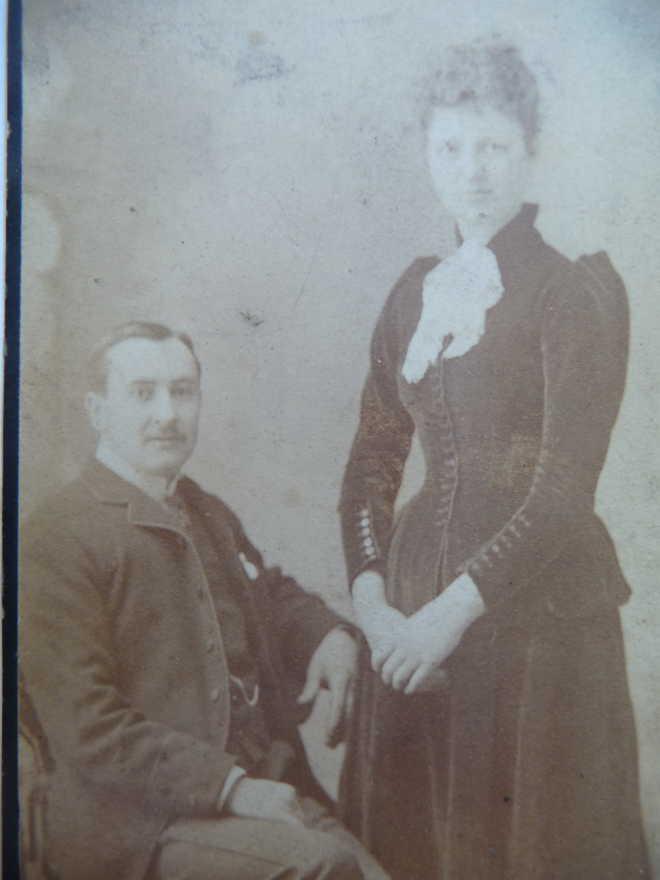

Benjamin Little, born in 1869, was the manager of a boot shop, according to the 1901 census, and a boot maker on the 1911 census. I found a photograph of Benjamin and Elizabeth Little on an ancestry website:

Frieda Olive Little 1896-1977 married Robert Warburton in 1924.

Frieda and Robert had two sons and a daughter, although one son died in infancy. They lived in Leominster, in Herefordshire, but Frieda died in 1977 at Enfield Farm in Warrington, four years after the death of her husband Robert.

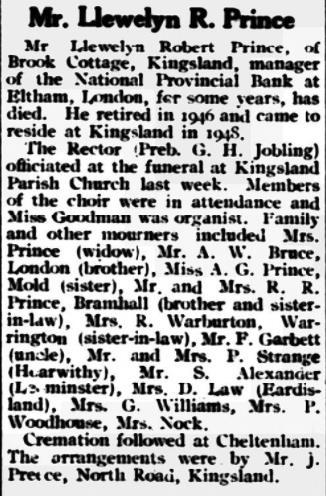

Catherine Jane Little 1899-1975 married Llewelyn Robert Prince 1884-1950. They do not appear to have had any children. Llewelyn was manager of the National Provinical Bank at Eltham in London, but died at Brook Cottage in Kingsland, Herefordshire. His wifes aunt Ellen Purdy the nurse had also lived at Brook Cottage. Ellen died in 1947, but her husband Frank Garbett was at the funeral:

Richard Purdy 1877-1940

Richard was born in Eastwood, Nottinghamshire. When his mother Catherine died in 1884 Richard was six years old. My great grandmother Mary Ann and her sister Ellen went to live with the Gilman’s in Buxton, but Richard and the two older sisters, Elizabeth and Kate, stayed with their father George Purdy, who remarried soon afterwards.

Richard married Ada Elizabeth Clarke in 1899. In 1901 Richard was an earthenware packer at a pottery, and on the 1939 census he was a colliery dataller. A dataller was a day wage man, paid on a daily basis for work done as required.

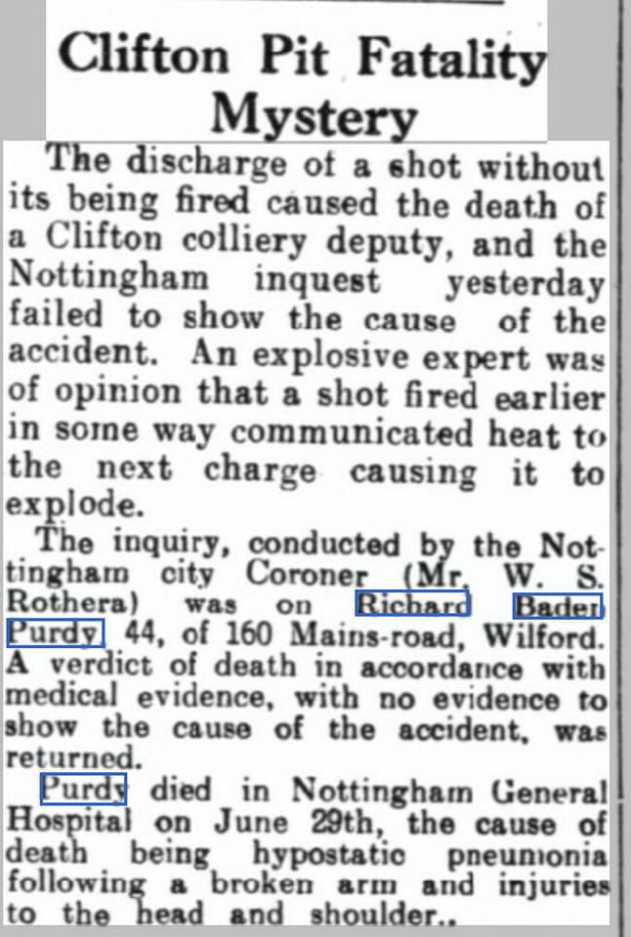

Richard and Ada had four children: Richard Baden Purdy 1900-1945, Winifred Maude 1903-1974, John Frederick 1907-1945, and Violet Gertrude 1910-1974.

Richard Baden Purdy married Ethel May Potter in Mansfield, Nottinghamshire, in 1926. He was listed on the 1939 census as a colliery deputy. In 1945 Richard Baden Purdy died as a result of injuries in a mine explosion.

John Frederick Purdy married Iris Merryweather in 1938. On the 1939 census John and Iris live in Arnold, Nottinghamshire, and John’s occupation is a colliery hewer. Their daughter Barbara Elizabeth was born later that year. John died in 1945, the same year as his brother Richard Baden Purdy. It is not known without purchasing the death certificate what the cause of death was.

A memorial was posted in the Nottingham Evening Post on 29 June 1948:

PURDY, loving memories, Richard Baden, accidentally killed June 29th 1945; John Frederick, died 1 April 1945; Richard Purdy, father, died December 1940. Too dearly loved to be forgotten. Mother, families.

Violet Gertrude Purdy married Sidney Garland in 1932 in Southwell, Nottinghamshire. She died in Edwinstowe, Nottinghamshire, in 1974.

Winifred Maude Purdy married Bernard Fowler in Southwell in 1928. She also died in 1974, in Mansfield.

The two brothers died the same year, in 1945, and the two sisters died the same year, in 1974.

February 25, 2022 at 8:21 am #6277In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

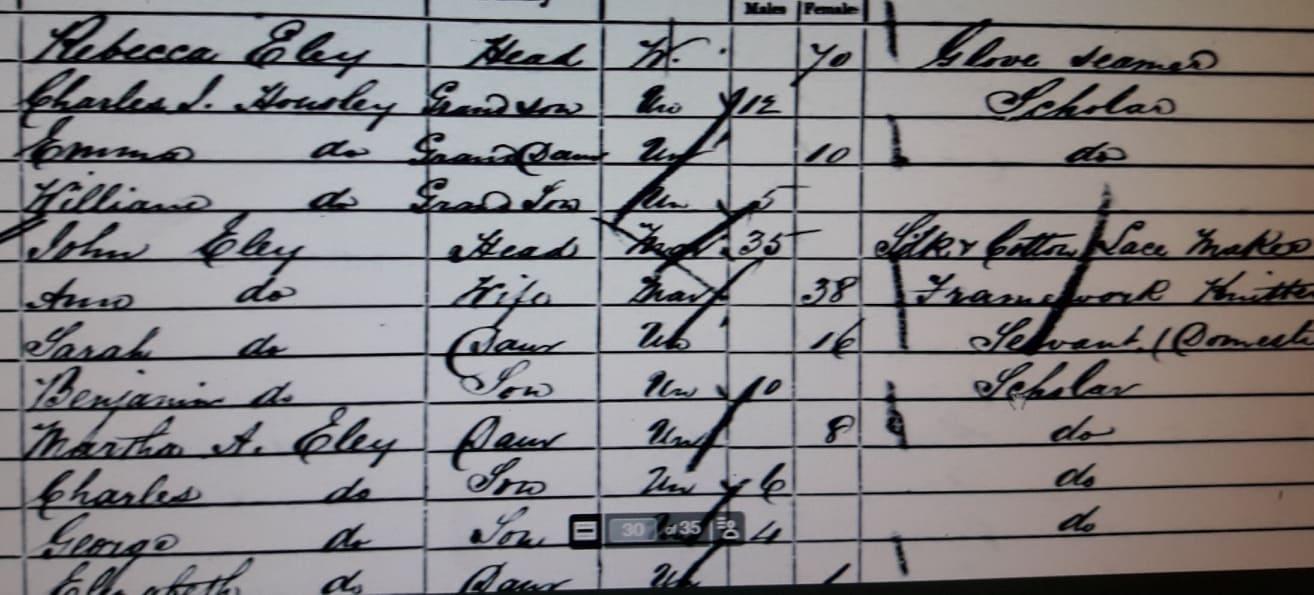

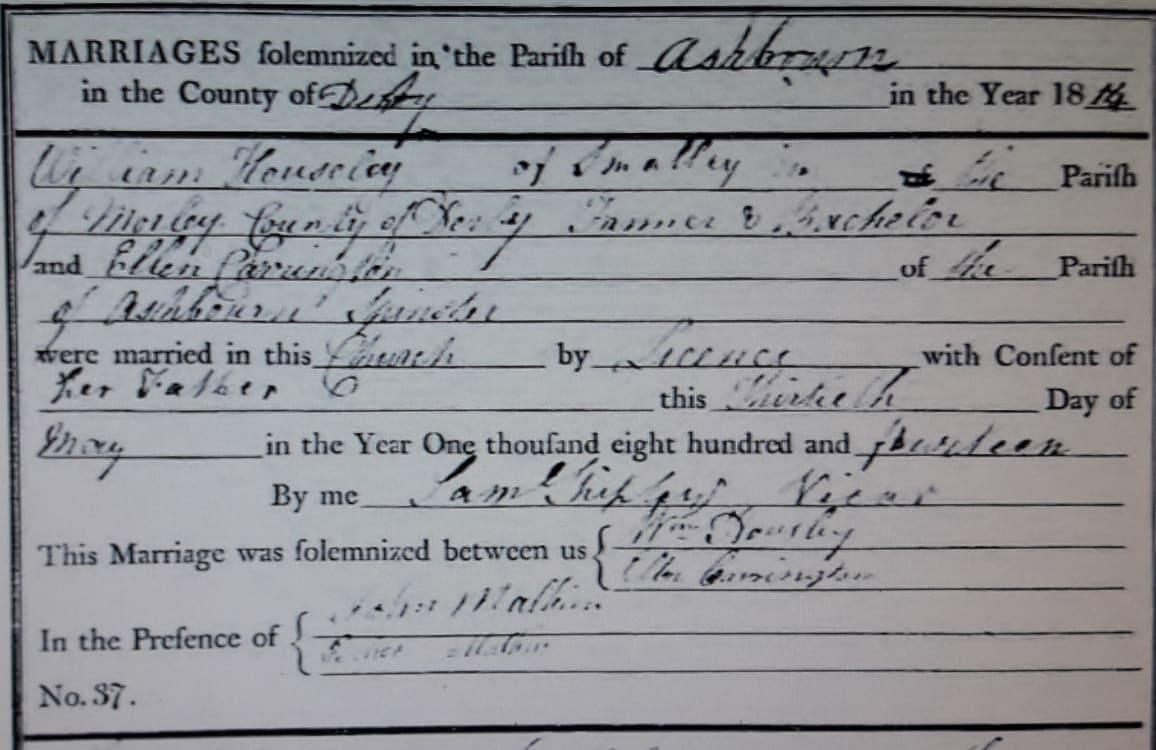

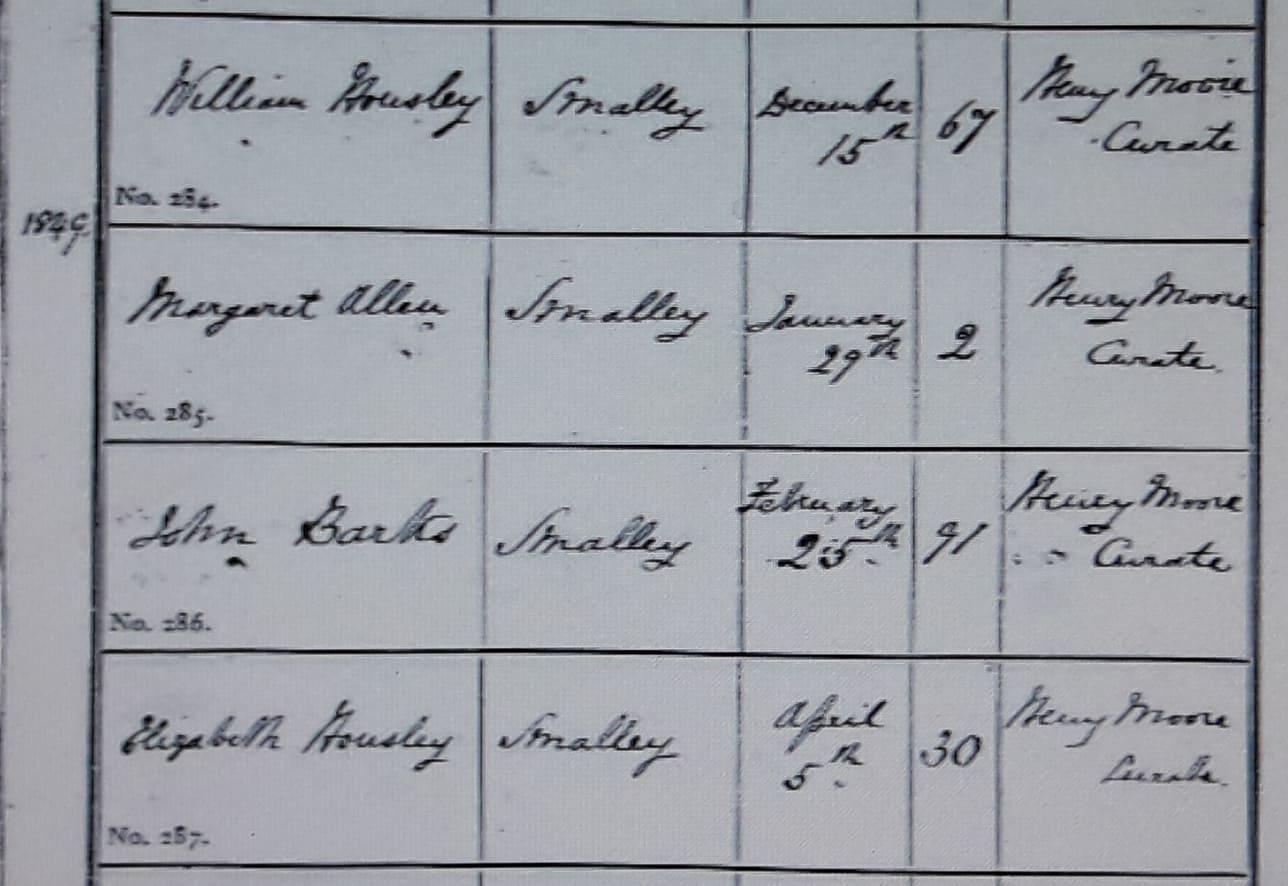

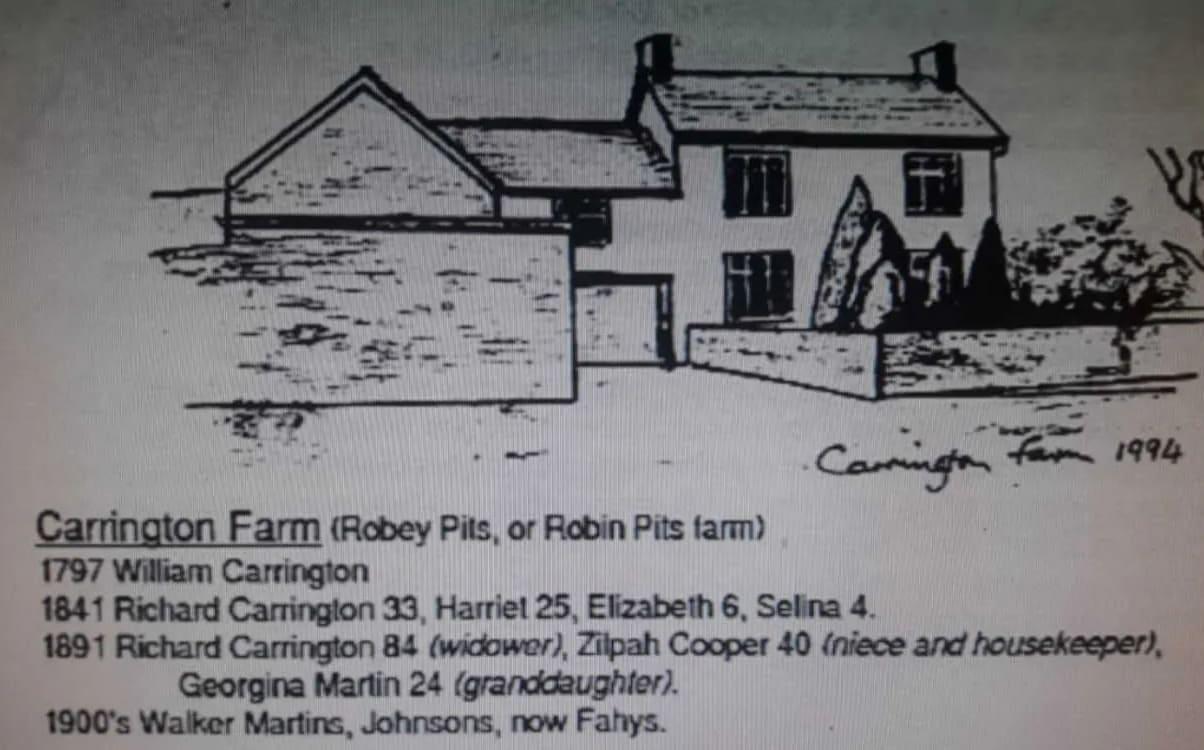

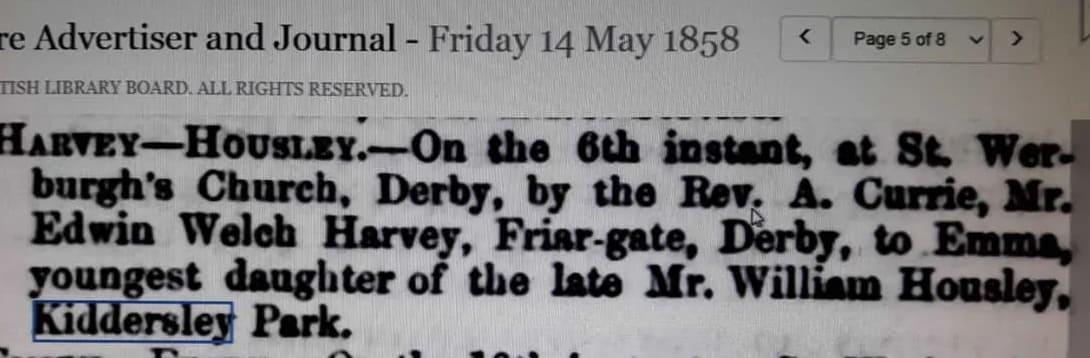

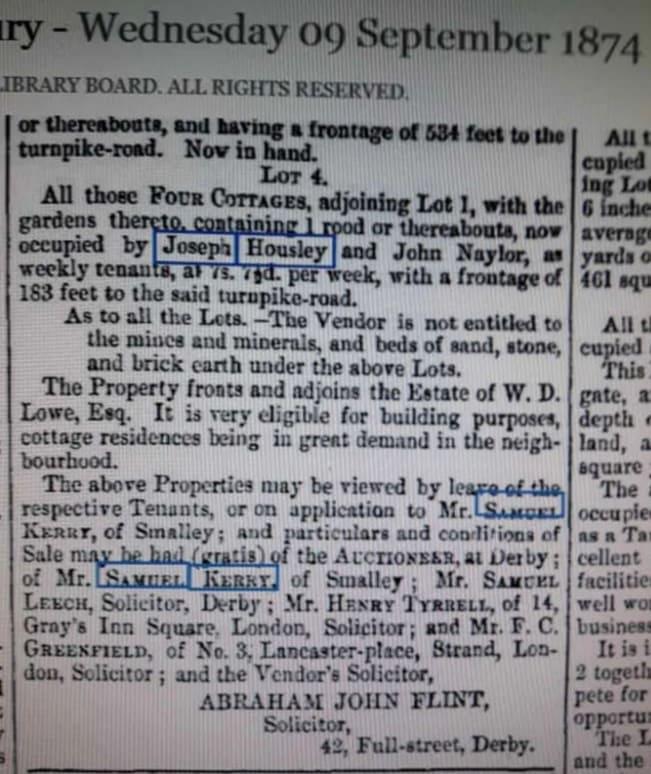

William Housley the Elder

Intestate

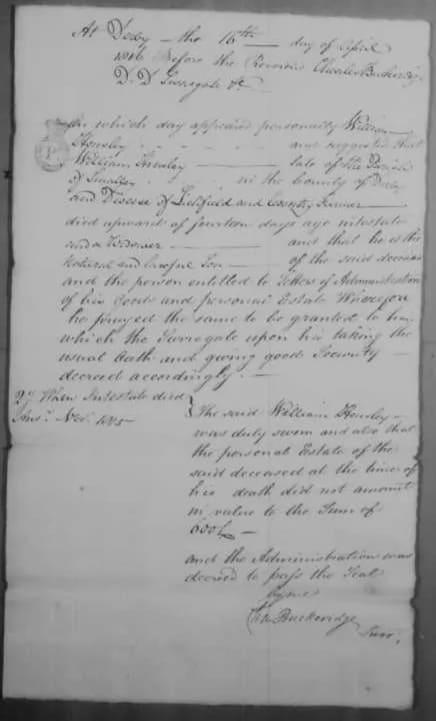

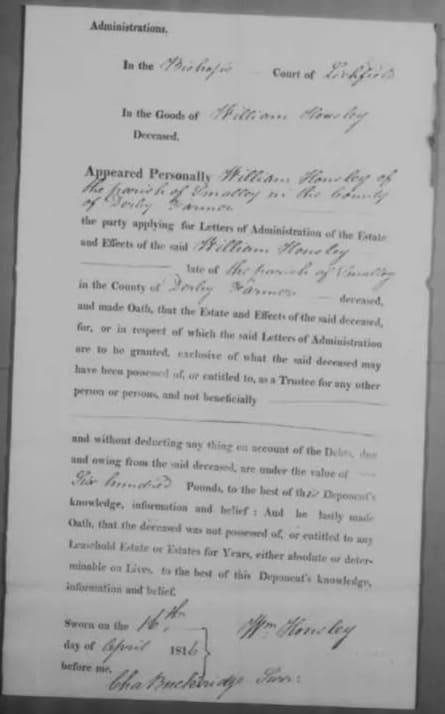

William Housley of Kidsley Grange Farm in Smalley, Derbyshire, was born in 1781 in Selston, just over the county border in Nottinghamshire. His father was also called William Housley, and he was born in Selston in 1735. It would appear from the records that William the father married late in life and only had one son (unless of course other records are missing or have not yet been found). Never the less, William Housley of Kidsley was the eldest son, or eldest surviving son, evident from the legal document written in 1816 regarding William the fathers’ estate.

William Housley died in Smalley in 1815, intestate. William the son claims that “he is the natural and lawful son of the said deceased and the person entitled to letters of administration of his goods and personal estate”.

Derby the 16th day of April 1816:

I transcribed three pages of this document, which was mostly repeated legal jargon. It appears that William Housley the elder died intestate, but that William the younger claimed that he was the sole heir. £1200 is mentioned to be held until the following year until such time that there is certainty than no will was found and so on. On the last page “no more than £600” is mentioned and I can’t quite make out why both figures are mentioned! However, either would have been a considerable sum in 1816.

I also found a land tax register in William Housley’s the elders name in Smalley (as William the son would have been too young at the time, in 1798). William the elder was an occupant of one of his properties, and paid tax on two others, with other occupants named, so presumably he owned three properties in Smalley.