Search Results for 'build'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

January 30, 2023 at 8:37 pm #6471

Topic: The Jorid’s Travels – 14 years on

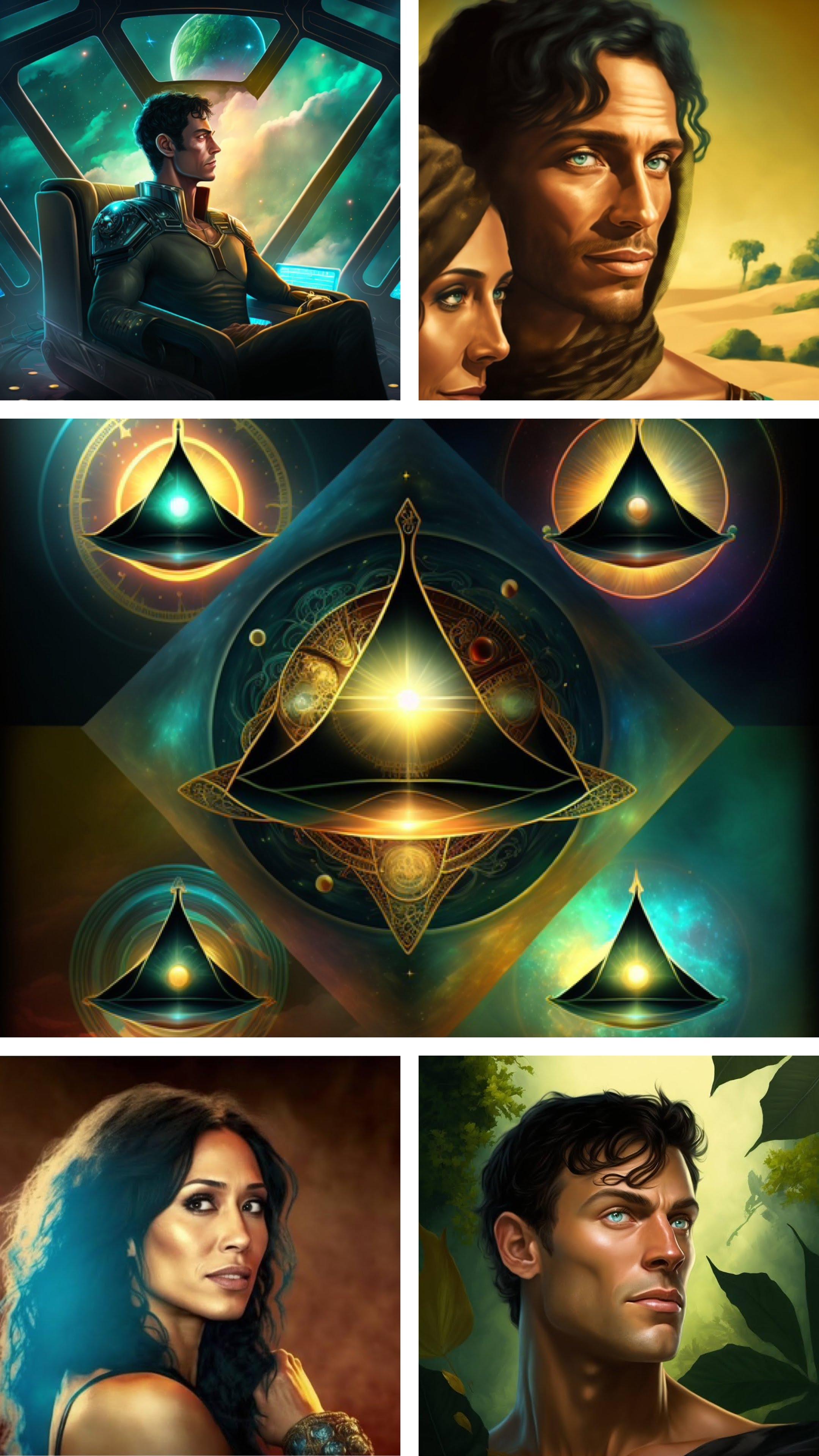

in forum Yurara Fameliki’s StoriesThe Jorid is a vessel that can travel through dimensions as well as time, within certain boundaries.

The Jorid has been built and is operated by Georges and his companion Salomé.

Georges was a French thief possibly from the 1800s, turned other-dimensional explorer, and along with Salomé, a girl of mysterious origins who he first met in the Alienor dimension but believed to be born in Northern India in a distant past, they have lived rich adventures together, and are deeply bound by love and mutual interests.Georges, with his handsome face, dark hair and amber gaze, is a bit of a daredevil at times, curious and engaging with others. He is very interesting in anything that shines, strange mechanisms and generally the ways consciousness works in living matter. Salomé, on the other hand is deeply intuitive, empath at times, quite logical and rational but also interested in mysticism, the ways of the Truth, and the “why” rather than the “how” of things.

The world of Alienor (a pale green sun under which twin planets originally orbited – Duane, Murtuane – with an additional third, Phreal, home planet of the Guardians, an alien race of builders with god-like powers) lived through cataclysmic changes, finished by the time this story is told.

The Jorid’s original prototype designs were crafted by Léonard, a mysterious figure, self-taught in the arts of dimensional magic in Alienor sects, who acted as a mentor to Georges during his adventures. It is not known where he is now.

The story unfolds 14 years after we discovered Georges & Salomé in the story.

(for more background information, refer to this thread)

January 23, 2023 at 10:28 pm #6454In reply to: Prompts of Madjourneys

YASMIN’S QUIRK: Entry level quirk – snort laughing when socially anxious

Setting

The initial setting for this quest is a comedic theater in the heart of a bustling city. You will start off by exploring the different performances and shows, trying to find the source of the snort laughter that seems to be haunting your thoughts. As you delve deeper into the theater, you will discover that the snort laughter is coming from a mischievous imp who has taken residence within the theater.

Directions to Investigate

Possible directions to investigate include talking to the theater staff and performers to gather information, searching backstage for clues, and perhaps even sneaking into the imp’s hiding spot to catch a glimpse of it in action.

Characters

Possible characters to engage include the theater manager, who may have information about the imp’s history and habits, and a group of comedic performers who may have some insight into the imp’s behavior.

Task

Your task is to find a key or tile that represents the imp, and take a picture of it in real life as proof of completion of the quest. Good luck on your journey to uncover the source of the snort laughter!

THE SECRET ROOM AND THE UNDERGROUND MINES

1st thread’s answer:

As the family struggles to rebuild the inn and their lives in the wake of the Great Fires, they begin to uncover clues that lead them to believe that the mines hold the key to unlocking a great mystery. They soon discover that the mines were not just a source of gold and other precious minerals, but also a portal to another dimension. The family realizes that Mater had always known about this portal, and had kept it a secret for fear of the dangers it posed.

The family starts to investigate the mines more closely and they come across a hidden room off Room 8. Inside the room, they find a strange device that looks like a portal, and a set of mysterious symbols etched into the walls. The family realizes that this is the secret room that Mater had always spoken about in hushed tones.

The family enlists the help of four gamers, Xavier, Zara, Yasmin, and Youssef, to help them decipher the symbols and unlock the portal. Together, they begin to unravel the mystery of the mines, and the portal leads them on an epic journey through a strange and fantastical alternate dimension.

As they journey deeper into the mines, the family discovers that the portal was created by an ancient civilization, long thought to be lost to history. The civilization had been working on a powerful energy source that could have changed the fate of humanity, but the project was abandoned due to the dangers it posed. The family soon discovers that the civilization had been destroyed by a powerful and malevolent force, and that the portal was the only way to stop it from destroying the world.

The family and the gamers must navigate treacherous landscapes, battle fierce monsters, and overcome seemingly insurmountable obstacles in order to stop the malevolent force and save the world. Along the way, they discover secrets about their own past and the true origins of the mines.

As they journey deeper into the mines and the alternate dimension, they discover that the secret room leads to a network of underground tunnels, and that the tunnels lead to a secret underground city that was built by the ancient civilization. The city holds many secrets and clues to the fate of the ancient civilization, and the family and the gamers must explore the city and uncover the truth before it’s too late.

As the story unfolds, the family and the gamers must come to grips with the truth about the mines, and the role that the family has played in the fate of the world for generations. They must also confront the demons of their own past, and learn to trust and rely on each other if they hope to save the world and bring the family back together.

second thread’s answer:

As the 4 gamers, Xavier, Zara, Yasmin and Youssef, arrived at the Flying Fish Inn in the Australian outback, they were greeted by the matriarch of the family, Mater. She was a no-nonsense woman who ran the inn with an iron fist, but her tough exterior hid a deep love for her family and the land.

The inn was run by Mater and her daughter Dido, who the family affectionately called Aunt Idle. She was a free spirit who loved to explore the land and had a deep connection to the local indigenous culture.

The family was made up of Devan, the eldest son who lived in town and helped with the inn when he could, and the twin sisters Clove and Coriander, who everyone called Corrie. The youngest was Prune, a precocious child who was always getting into mischief.

The family had a handyman named Bert, who had been with them for decades and knew all the secrets of the land. Tiku, an old and wise Aborigine woman was also a regular visitor and a valuable source of information and guidance. Finly, the dutiful helper, assisted the family in their daily tasks.

As the 4 gamers settled in, they learned that the area was rich in history and mystery. The old mines that lay abandoned nearby were a source of legends and stories passed down through the generations. Some even whispered of supernatural occurrences linked to the mines.

Mater and Dido, however, were not on good terms, and the family had its own issues and secrets, but the 4 gamers were determined to unravel the mystery of the mines and find the secret room that was said to be hidden somewhere in the inn.

As they delved deeper into the history of the area, they discovered that the mines had a connection to the missing brother, Jasper, and Fred, the father of the family and a sci-fi novelist who had been influenced by the supernatural occurrences of the mines.

The 4 gamers found themselves on a journey of discovery, not only in the game but in the real world as well, as they uncovered the secrets of the mines and the Flying Fish Inn, and the complicated relationships of the family that ran it.

THE SNOOT’S WISE WORDS ON SOCIAL ANXIETY

Deear Francie Mossie Pooh,

The Snoot, a curious creature of the ages, understands the swirling winds of social anxiety, the tempestuous waves it creates in one’s daily life.

But The Snoot also believes that like a Phoenix, one must rise from the ashes, and embrace the journey of self-discovery and growth.

It’s important to let yourself be, to accept the feelings as they come and go, like the ebb and flow of the ocean. But also, like a gardener, tend to the inner self with care and compassion, for the roots to grow deep and strong.The Snoot suggests seeking guidance from the wise ones, the ones who can hold the mirror and show you the way, like the North Star guiding the sailors.

And remember, the journey is never-ending, like the spiral of the galaxy, and it’s okay to take small steps, to stumble and fall, for that’s how we learn to fly.The Snoot is here for you, my dear Francie Mossie Pooh, a beacon in the dark, a friend on the journey, to hold your hand and sing you a lullaby.

Fluidly and fantastically yours,

The Snoot.

January 23, 2023 at 1:27 pm #6451In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

The progress on the quest in the Land of the Quirks was too tantalizing; Xavier made himself a quick sandwich and jumped back on it during his lunch break.

The jungle had an oppressing quality… Maybe it has to do with the shrieks of the apes tearing the silence apart.

The jungle had an oppressing quality… Maybe it has to do with the shrieks of the apes tearing the silence apart. It was time for a slight adjustment of his avatar.

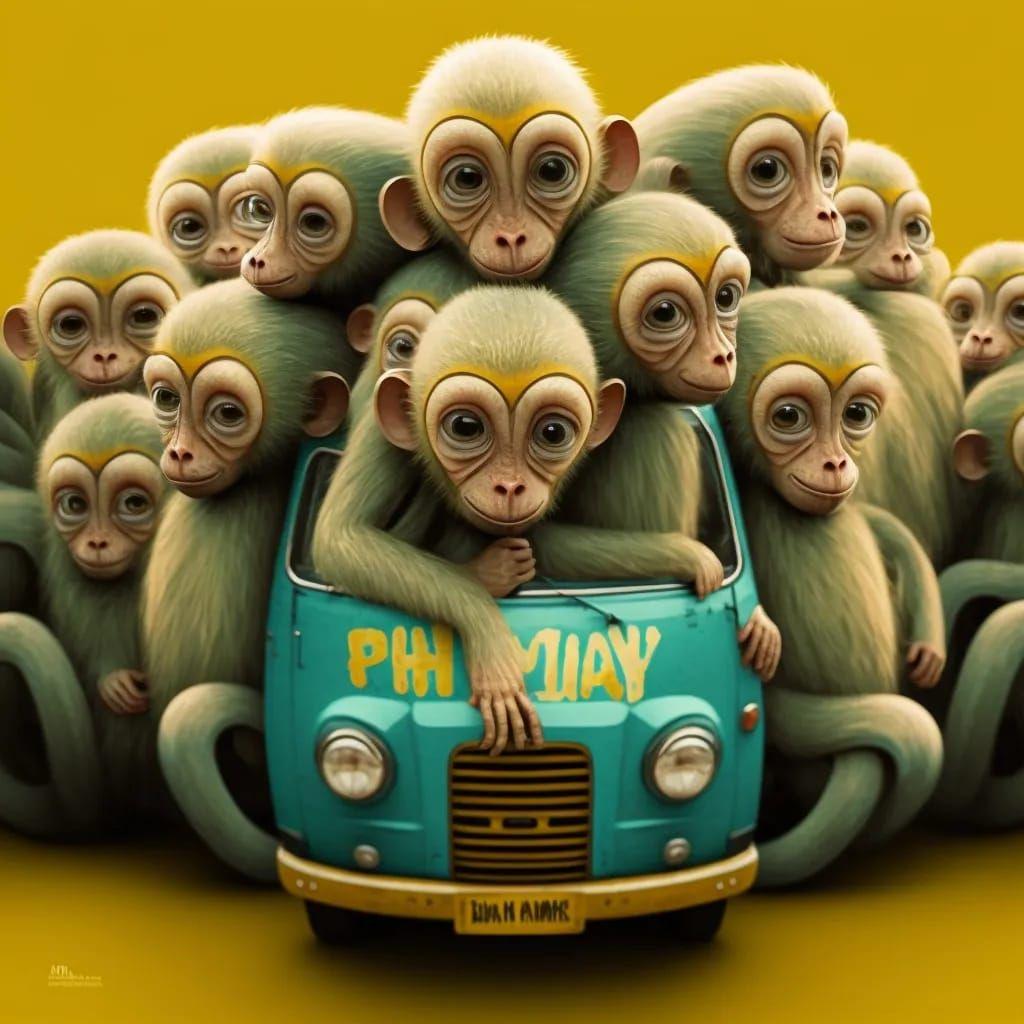

Xavimunk opened his bag of tricks, something that the wise owl had suggested he looked into. Few items from the AIorium Emporium had been supplied. They tended to shift and disappear if you didn’t focus, but his intention was set on the task at hand. At the bottom of the bag, there was a small vial with a golden liquid with a tag written in ornate handwriting “MJ remix: for when words elude and shapes confuse at your own peril”.

He gulped the potion without thinking too much. He felt himself shrink, and his arms elongate a little. There, he thought. Imp-munk’s more suited to the mission. Hope the effects will be temporary…

He gulped the potion without thinking too much. He felt himself shrink, and his arms elongate a little. There, he thought. Imp-munk’s more suited to the mission. Hope the effects will be temporary…As Xavier mustered the courage to enter through the front gate, monkeys started to become silent. He couldn’t say if it was an ominous sign, or maybe an effect of his adaptation. The temple’s light inside was gorgeous, but nothing seemed to be there.

He gestured around, to make the menu appear. He looked again at the instructions on his screen overlay:

As for possible characters to engage, you may come across a sly fox who claims to know the location of the fruit but will only reveal it in exchange for a favor, or a brave adventurer who has been searching for the Golden Banana for years and may be willing to team up with you.

Suddenly a loud monkey honking noise came from outside, distracting him.

What the?… Had to be one of Zara’s remixes. He saw the three dots bleeping on the screen.

Here’s the Banana bus, hope it helps! Envoy! bugger Enjoy!

Yep… With the distinct typo-heavy accent, definitely Zara’s style. Strange idea that AL designated her as the leader… He’d have to roll with it.

Suddenly, as the Banana bus parked in front of the Temple, a horde of Italien speaking tourists started to flock in and snap pictures around. The monkeys didn’t know what to do and seemed to build growing and noisy interest in their assortiment of colorful shoes, flip-flops, boots and all.

Focus, thought Xavimunk… What did the wise owl say? Look for a guide…

Only the huge colorful bus seemed to take the space now… But wait… what if?He walked to the parking spot under the shades of the huge banyan tree next to the temple’s entrance, under which the bus driver had parked it. The driver was still there, napping under a newspaper, his legs on the wheel.

“Whatcha lookin’ at?” he said chewing his gum loudly. “Never seen a fox drive a banana bus before?”

Xavier smiled. “Any chance you can guide me to the location of the Golden Banana?”

“For a price… maybe.” The fox had jumped closely and was considering the strange avatar from head to toe.

“Ain’t no usual stuff that got you into this? Got any left? That would be a nice price.”

“As it happens…” Xavier smiled.The quest seemed back on track. Xavier looked at the time. Blimmey! already late again. And I promised Brytta to get some Chinese snacks for dinner.

January 21, 2023 at 4:17 pm #6426In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

The artificial lights of Berlin were starting to switch off in the horizon, leaving the night plunged in darkness minutes before the sunrise. It was a moment of peace that Xavier enjoyed, although it reminded him of how sleepless his night had been.

The game had taken a side step, as he’d been pouring all his attention into his daytime job, and his personal project with Artificial Life AL. It was a long way from the little boy at school with dyslexia who was using cheeky jokes as a way to get by the snides. Since then, he’d known some of the unusual super-powers this condition gave him as well. Chiefly: abstract and out-of-the-box thinking, puzzle-solving genius, and an almost other-worldly ability at keeping track of the plot. All these skills were in fact of tremendous help at his work, which was blending traditional areas of technology along with massive amounts of loosely connected data.

He yawned and went to brush his teeth. His usual meditation routine had also been disrupted by the activity of late, but he just couldn’t go to bed without a little time to cool off and calm down the agitation of his thoughts.

Sitting on the meditation mat, his thoughts strayed off towards the preparation for the trip. Going to Australia would have seemed exciting a few years back, but the idea of packing a suitcase, and going through the long flight and the logistics involved got him more anxious than excited, despite the contagious enthusiasm of his friends. Since he’d settled in Berlin, after never settling for too long in one place (his job afforded him to work wherever whenever), he’d kind of stopped looking for the next adventure. He hadn’t even looked at flight options yet, and hoped that the building momentum would spur him into this adventure. For now, he needed the rest.

The quirk quest assigned to his persona in the game was fun. Monkeys and Golden banana to look for, wise owls and sly foxes, the whimsical goofy nature of the quest seemed good for the place he was in.

AL had been suggesting the players to insert the game elements into their realities, and sometimes its comments or instructions seemed to slip between layers of reality — this was an intriguing mystery to Xavier.

He’d instructed AL to discreetly assist Youssef with his trouble — the Thi Gang seemed to be an ethical hacker developer company front for more serious business. Chatter on the net had tied it to a network of shell companies involved in some strange activities. A name had popped up, linked to mysterious recluse billionaire Botty Banworth, the owner of Youssef’s boss rival blog named Knoweth.He slipped into the bed, careful not to wake up Brytta, who was sleeping tightly. It was her day off, otherwise she would have been gone already to her shift. It would be good to connect in the morning, and enjoy some break from mind stuff. They had planned a visit to Kantonstrasse (the local Chinatown) for Chinese New Year, and he couldn’t wait for it.

January 21, 2023 at 11:26 am #6423In reply to: Prompts of Madjourneys

Zara’s first quest:

entry level quirk: wandering off the track

The initial setting for this quest is a dense forest, where the paths are overgrown and rarely traveled. You find yourself alone and disoriented, with only a rough map and a compass to guide you.

Possible directions to investigate include:

Following a faint trail of footprints that lead deeper into the forest

Climbing a tall tree to get a better view of the surrounding area

Searching for a stream or river to use as a guide to find your way out of the forest

Possible characters to engage include:

A mysterious hermit who lives deep in the forest and is rumored to know the secrets of the land

A lost traveler who is also trying to find their way out of the forest

A group of bandits who have taken refuge in the forest and may try to steal from you or cause harm

Your objective is to find the Wanderlust tile, a small, intricately carved wooden tile depicting a person walking off the beaten path. This tile holds the key to unlocking your inner quirk of wandering off the track.

As proof of your progress in the game, you must find a way to incorporate this quirk into your real-life actions by taking a spontaneous detour on your next journey, whether it be physical or mental.

For Zara’s quest:

As you wander off the track, you come across a strange-looking building in the distance. Upon closer inspection, you realize it is the Flying Fish Inn. As you enter, you are greeted by the friendly owner, Idle. She tells you that she has heard of strange occurrences happening in the surrounding area and offers to help you in your quest

Emoji clue: 🐈🌳

Zara (the character in the game)

characteristics from previous prompts:

Zara is the leader of the group

she is confident, and always ready for an adventure. She is a natural leader and has a strong sense of justice. She is also a tech-savvy person, always carrying a variety of gadgets with her, and is always the first to try out new technology.

she is confident, and always ready for an adventure. She is a natural leader and has a strong sense of justice. She is also a tech-savvy person, always carrying a variety of gadgets with her, and is always the first to try out new technology.Zara is the leader of the group, her color is red, her animal is a lion, and her secret name in a funny language is “Zaraloon”

Zara (the real life story character)

characteristics from previous prompts:

Zara Patara-Smythe is a 57-year-old woman of mixed heritage, her mother is Indian and her father is British. She has long, dark hair that she keeps in an untidy ponytail, dark brown eyes and a sharp jawline. She stands at 5’6″ and has a toned and athletic build. She usually wears practical clothing that allows her to move around easily, such as cargo pants and a tank top.

prompt quest:

Continue to investigate the mysterious cat she saw, possibly seeking out help from local animal experts or veterinarians.

Join Xavier and Yasmin in investigating the Flying Fish Inn, looking for clues and exploring the area for any potential leads on the game’s quest.January 19, 2023 at 10:49 am #6419In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

“I’d advise you not to take the parrot, Zara,” Harry the vet said, “There are restrictions on bringing dogs and other animals into state parks, and you can bet some jobsworth official will insist she stays in a cage at the very least.”

“Yeah, you’re right, I guess I’ll leave her here. I want to call in and see my cousin in Camden on the way to the airport in Sydney anyway. He has dozens of cats, I’d hate for anything to happen to Pretty Girl,” Zara replied.

“Is that the distant cousin you met when you were doing your family tree?” Harry asked, glancing up from the stitches he was removing from a wounded wombat. “There, he’s good to go. Give him a couple more days, then he can be released back where he came from.”

Zara smiled at Harry as she picked up the animal. “Yes! We haven’t met in person yet, and he’s going to show me the church my ancestor built. He says people have been spotting ghosts there lately, and there are rumours that it’s the ghost of the old convict Isaac who built it. If I can’t find photos of the ancestors, maybe I can get photos of their ghosts instead,” Zara said with a laugh.

“Good luck with that,” Harry replied raising an eyebrow. He liked Zara, she was quirkier than the others.

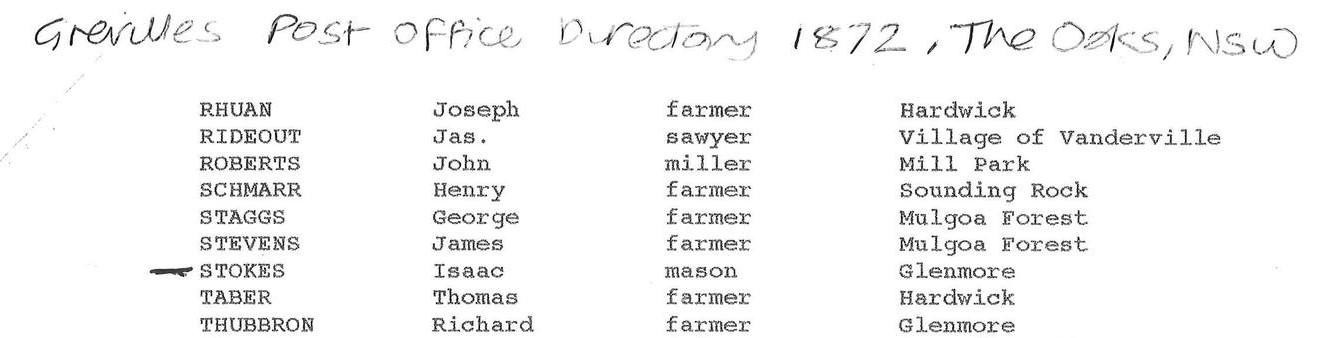

Zara hadn’t found it easy to research her mothers family from Bangalore in India, but her fathers English family had been easy enough. Although Zara had been born in England and emigrated to Australia in her late 20s, many of her ancestors siblings had emigrated over several generations, and Zara had managed to trace several down and made contact with a few of them. Isaac Stokes wasn’t a direct ancestor, he was the brother of her fourth great grandfather but his story had intrigued her. Sentenced to transportation for stealing tools for his work as a stonemason seemed to have worked in his favour. He built beautiful stone buildings in a tiny new town in the 1800s in the charming style of his home town in England.

Zara planned to stay in Camden for a couple of days before meeting the others at the Flying Fish Inn, anticipating a pleasant visit before the crazy adventure started.

Zara stepped down from the bus, squinting in the bright sunlight and looking around for her newfound cousin Bertie. A lanky middle aged man in dungarees and a red baseball cap came forward with his hand extended.

“Welcome to Camden, Zara I presume! Great to meet you!” he said shaking her hand and taking her rucksack. Zara was taken aback to see the family resemblance to her grandfather. So many scattered generations and yet there was still a thread of familiarity. “I bet you’re hungry, let’s go and get some tucker at Belle’s Cafe, and then I bet you want to see the church first, hey? Whoa, where’d that dang parrot come from?” Bertie said, ducking quickly as the bird swooped right in between them.

“Oh no, it’s Pretty Girl!” exclaimed Zara. “She wasn’t supposed to come with me, I didn’t bring her! How on earth did you fly all this way to get here the same time as me?” she asked the parrot.

“Pretty Girl has her ways, don’t forget to feed the parrot,” the bird replied with a squalk that resembled a mirthful guffaw.

“That’s one strange parrot you got here, girl!” Bertie said in astonishment.

“Well, seeing as you’re here now, Pretty Girl, you better come with us,” Zara said.

“Obviously,” replied Pretty Girl. It was hard to say for sure, but Zara was sure she detected an avian eye roll.

They sat outside under a sunshade to eat rather than cause any upset inside the cafe. Zara fancied an omelette but Pretty Girl objected, so she ordered hash browns instead and a fruit salad for the parrot. Bertie was a good sport about the strange talking bird after his initial surprise.

Bertie told her a bit about the ghost sightings, which had only started quite recently. They started when I started researching him, Zara thought to herself, almost as if he was reaching out. Her imagination was running riot already.

Bertie showed Zara around the church, a small building made of sandstone, but no ghost appeared in the bright heat of the afternoon. He took her on a little tour of Camden, once a tiny outpost but now a suburb of the city, pointing out all the original buildings, in particular the ones that Isaac had built. The church was walking distance of Bertie’s house and Zara decided to slip out and stroll over there after everyone had gone to bed.

Bertie had kindly allowed Pretty Girl to stay in the guest bedroom with her, safe from the cats, and Zara intended that the parrot stay in the room, but Pretty Girl was having none of it and insisted on joining her.

“Alright then, but no talking! I don’t want you scaring any ghost away so just keep a low profile!”

The moon was nearly full and it was a pleasant walk to the church. Pretty Girl fluttered from tree to tree along the sidewalk quietly. Enchanting aromas of exotic scented flowers wafted into her nostrils and Zara felt warmly relaxed and optimistic.

Zara was disappointed to find that the church was locked for the night, and realized with a sigh that she should have expected this to be the case. She wandered around the outside, trying to peer in the windows but there was nothing to be seen as the glass reflected the street lights. These things are not done in a hurry, she reminded herself, be patient.

Sitting under a tree on the grassy lawn attempting to open her mind to receiving ghostly communications (she wasn’t quite sure how to do that on purpose, any ghosts she’d seen previously had always been accidental and unexpected) Pretty Girl landed on her shoulder rather clumsily, pressing something hard and chill against her cheek.

“I told you to keep a low profile!” Zara hissed, as the parrot dropped the key into her lap. “Oh! is this the key to the church door?”

It was hard to see in the dim light but Zara was sure the parrot nodded, and was that another avian eye roll?

Zara walked slowly over the grass to the church door, tingling with anticipation. Pretty Girl hopped along the ground behind her. She turned the key in the lock and slowly pushed open the heavy door and walked inside and up the central aisle, looking around. And then she saw him.

Zara gasped. For a breif moment as the spectral wisps cleared, he looked almost solid. And she could see his tattoos.

“Oh my god,” she whispered, “It is really you. I recognize those tattoos from the description in the criminal registers. Some of them anyway, it seems you have a few more tats since you were transported.”

“Aye, I did that, wench. I were allays fond o’ me tats, does tha like ’em?”

He actually spoke to me! This was beyond Zara’s wildest hopes. Quick, ask him some questions!

“If you don’t mind me asking, Isaac, why did you lie about who your father was on your marriage register? I almost thought it wasn’t you, you know, that I had the wrong Isaac Stokes.”

A deafening rumbling laugh filled the building with echoes and the apparition dispersed in a labyrinthine swirl of tattood wisps.

“A story for another day,” whispered Zara, “Time to go back to Berties. Come on Pretty Girl. And put that key back where you found it.”

January 17, 2023 at 11:37 am #6407

January 17, 2023 at 11:37 am #6407In reply to: Prompts of Madjourneys

[Following the last comment] Fed the AL this context:

- “A gripshawk is feline-like anthropomorphic creature living in the deserts in a fiction written by Yurara Fameliki. It is the least favorite character to pick by Zara who doesn’t like “fantasy stuff”.

- The “Flying Fish Inn” is a fictional (or maybe real) Inn set in the Australian outback, owned by a family headed by the matriarch Mater and involved in many adventures, sometimes surnatural.

- “AL” is an AI build with Al’s persona (Albert Yokozo being a famous author, possibly a nom de plume of the mysterious Ernrich Lemwon) – it is known as Calli in another story.

Please continue the story unfolding here:

<feeding FP’s comment>“Yeah, I’m not a fan of fantasy stuff either,” Youssef added, agreeing with Zara. “But I’m curious about the Flying Fish Inn and how it relates to the game. Maybe we should check it out and see if there are any clues there.”

“That’s a good idea,” Yasmin said. “I’ve heard the stories about the Inn and the adventures the family has had there. Some of them are quite intriguing, and I wouldn’t be surprised if there was a connection to our game.”

“I’m not sure about the AI,” Xavier said. “It’s still a mystery to me, but I trust AL will guide us in the right direction. I’m curious to see where this all leads.”

“Alright, let’s plan a trip to the Flying Fish Inn,” Zara said, excitedly. “We’ll take a break from the game for a few days, but we’ll come back to it with fresh eyes and new insights. Who knows, maybe we’ll even find some quirky guests along the way.”

As they were discussing their plans, they all felt a sense of excitement and curiosity about what the future holds for them. The game and the world of the Land of the Quirks had captured their imagination and they were eager to see where it would lead them next.

January 13, 2023 at 7:40 pm #6379In reply to: Prompts of Madjourneys

Asking to give each of the 4 characters some particular traits that makes them uniquely distinctive and recognizable

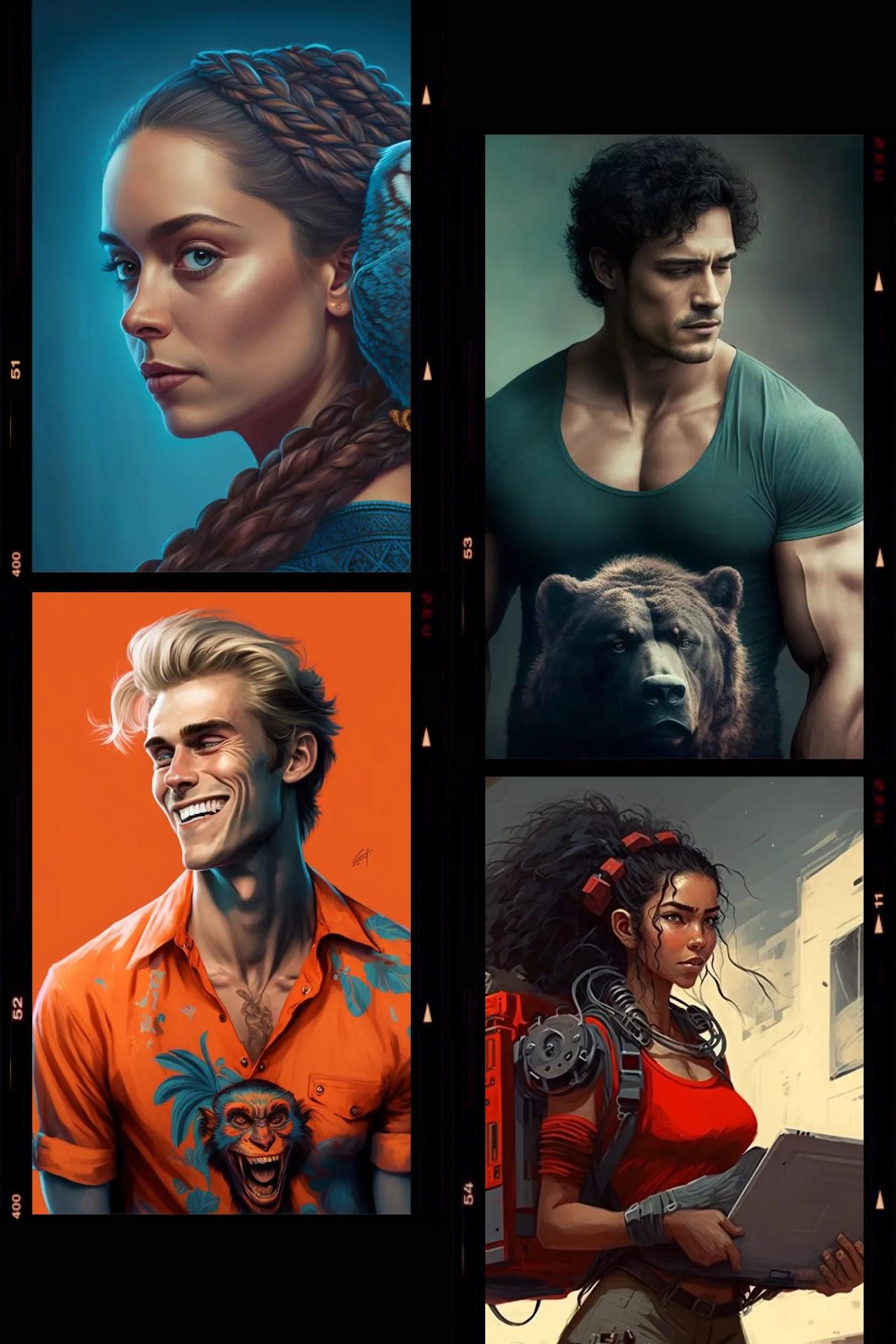

The four friends, Zara, Xavier, Yasmin, and Youssef, each have their own unique traits that make them stand out and recognizable.

Zara is the leader of the group, she is confident, and always ready for an adventure. She is a natural leader and has a strong sense of justice. She is also a tech-savvy person, always carrying a variety of gadgets with her, and is always the first to try out new technology.

Xavier is the joker of the group, always cracking jokes and making puns. He is a free-spirited person who is always up for an adventure, he has a great sense of humor and is not afraid to be himself. He is also an artist and often carries a sketchbook and pencils with him, he likes to draw whatever he sees in his journeys.

Yasmin is the brains of the group, she is intelligent and logical. She is always able to think on her feet and come up with a plan when things get tough. She is also a bit of a perfectionist and likes to have everything organized. She is a history buff and always carries a notebook with her to document her findings.

Youssef is the muscle of the group, He is physically strong, and always ready to help out in a fight. He is also a bit of a foodie and loves trying new dishes. He is always the first one to volunteer to carry the heavy bags and equipment. He is also a bit of a daredevil and loves trying out new sports and activities.

Give each of them a color, and an animal, and a secret name in a funny language

The four friends, Zara, Xavier, Yasmin, and Youssef, each have their own unique traits that make them stand out and recognizable.

Zara is the leader of the group, her color is red, her animal is a lion, and her secret name in a funny language is “Zaraloon”

Xavier is the joker of the group, his color is orange, his animal is a monkey, and his secret name in a funny language is “Xavimunk”

Yasmin is the brains of the group, her color is blue, her animal is an owl, and her secret name in a funny language is “Yasminowl”

Youssef is the muscle of the group, his color is green, his animal is a bear, and his secret name in a funny language is “Youssefbear”

Now, we need physical descriptions for each of them. Also, their ages, height, clothes, facial features, ethnicity (for instance Youssef may be half Yemeni and half Norwegian), etc. with a good mix of generic and eccentric. We also need surnames congruent with their described ethnicity, not too bland, but not too daft either. For instance Youssef Olafsson, Zara Patara-Smythe, etc. Also explain how they become friends.

Zara Patara-Smythe is a

25-year-oldwoman of mixed heritage, her mother is Indian and her father is British. She has long, dark hair that she keeps in a sleek ponytail, dark brown eyes and a sharp jawline. She stands at 5’6″ and has a toned and athletic build. She usually wears practical clothing that allows her to move around easily, such as cargo pants and a tank top.Xavier Olafsson is a

27-year-oldman of Norwegian and Danish descent. He has blonde hair that he keeps in a messy style, blue eyes, and a charming smile. He stands at 6’1″ and has a lean build. He is always seen wearing a colorful and bold clothing, such as a Hawaiian shirt and shorts.Yasmin Ahmed is a

23-year-oldwoman of Egyptian descent. She has long, black hair that she keeps in a tight braid, dark brown eyes and a round face. She stands at 5’4″ and has a petite build. She usually wears conservative clothing, such as long skirts and blouses.Youssef Ali is a

26-year-oldman of half Yemeni, half Norwegian descent. He has short, curly black hair, dark brown eyes and a square jawline. He stands at 6’2″ and has a muscular build. He usually wears comfortable clothing such as a t-shirt and jeans, and always has a backpack on his shoulder.The four of them became friends

in college, they were all studying different majors, but they all shared a love for adventure and exploration. They found themselves in the same class project, and from there they formed a strong bond. After college, they decided to keep exploring the world together, and went on many trips and adventures, always seeking for something new and exciting.

1/ Change the ages of Zara, Xavier, Yasmin and Youssef to more random patterns – rewrite if needed how they met each other to reflect eventual age gaps. Give them some flaws, mental or physical challenges.

2/ increase again the age gaps while keeping the youngest one a young adult, and remove “minor” from the flaws descriptionsZara is a 22-year-old woman who is the youngest of the group. She is a free-spirited, adventurous person, but also a bit reckless and impulsive. She has a scar on her cheek that she got from a Skateboarding accident when she was a teenager.

Xavier is a 45-year-old man who is the oldest of the group. He is a responsible and level-headed person, but also a bit of a perfectionist and can be hard on himself and others. He has dyslexia which he has been able to work around and it doesn’t impede his daily life.

Yasmin is a 38-year-old woman who is the second oldest of the group. She is a kind and compassionate person, but also a bit of a pushover and can have trouble standing up for herself. She has social anxiety that affect her in certain situations and she have been working on coping mechanisms.

Youssef is a 33-year-old man who is the second youngest of the group. He is a charismatic and outgoing person, but also a bit of a flirt and can be a bit insensitive to others feelings. He has ADHD which he has been able to manage with medication, but it still affects him from time to time.

The group met each other through different means, Xavier and Yasmin met at work, Zara and Youssef met at a college class, and eventually, they all became friends through common interests and activities. They decided to go on this adventure together because they were all looking for a change in their lives and wanted to explore the unknown.

December 6, 2022 at 2:17 pm #6350In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Transportation

Isaac Stokes 1804-1877

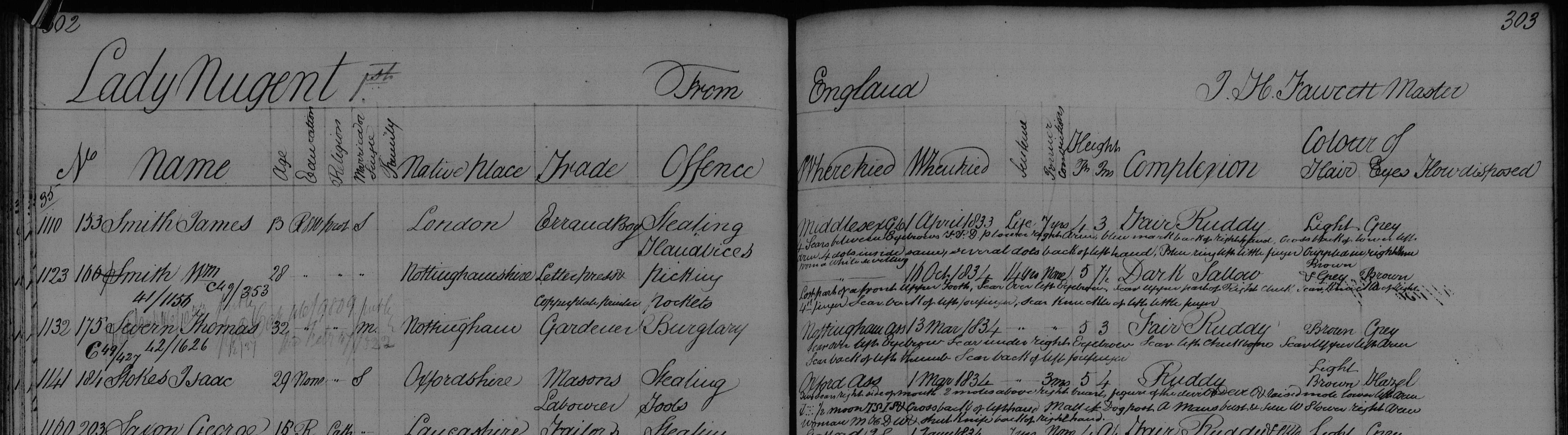

Isaac was born in Churchill, Oxfordshire in 1804, and was the youngest brother of my 4X great grandfather Thomas Stokes. The Stokes family were stone masons for generations in Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire, and Isaac’s occupation was a mason’s labourer in 1834 when he was sentenced at the Lent Assizes in Oxford to fourteen years transportation for stealing tools.

Churchill where the Stokes stonemasons came from: on 31 July 1684 a fire destroyed 20 houses and many other buildings, and killed four people. The village was rebuilt higher up the hill, with stone houses instead of the old timber-framed and thatched cottages. The fire was apparently caused by a baker who, to avoid chimney tax, had knocked through the wall from her oven to her neighbour’s chimney.

Isaac stole a pick axe, the value of 2 shillings and the property of Thomas Joyner of Churchill; a kibbeaux and a trowel value 3 shillings the property of Thomas Symms; a hammer and axe value 5 shillings, property of John Keen of Sarsden.

(The word kibbeaux seems to only exists in relation to Isaac Stokes sentence and whoever was the first to write it was perhaps being creative with the spelling of a kibbo, a miners or a metal bucket. This spelling is repeated in the criminal reports and the newspaper articles about Isaac, but nowhere else).

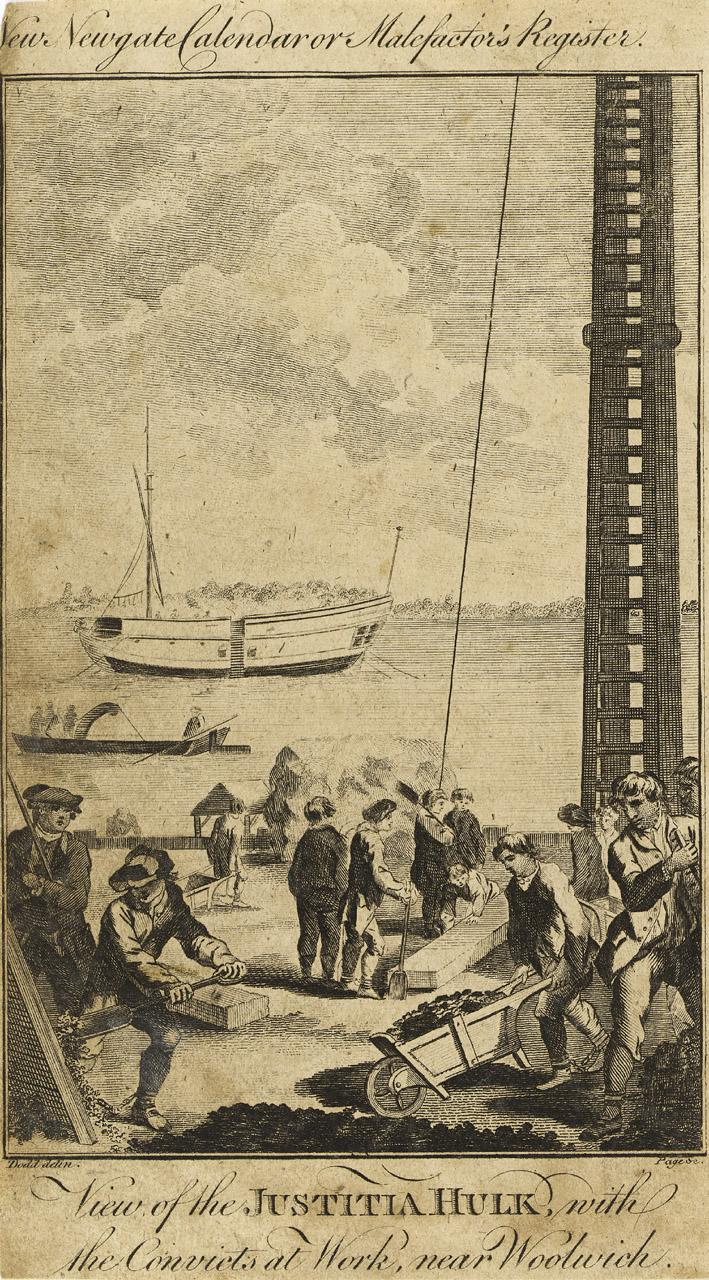

In March 1834 the Removal of Convicts was announced in the Oxford University and City Herald: Isaac Stokes and several other prisoners were removed from the Oxford county gaol to the Justitia hulk at Woolwich “persuant to their sentences of transportation at our Lent Assizes”.

via digitalpanopticon:

Hulks were decommissioned (and often unseaworthy) ships that were moored in rivers and estuaries and refitted to become floating prisons. The outbreak of war in America in 1775 meant that it was no longer possible to transport British convicts there. Transportation as a form of punishment had started in the late seventeenth century, and following the Transportation Act of 1718, some 44,000 British convicts were sent to the American colonies. The end of this punishment presented a major problem for the authorities in London, since in the decade before 1775, two-thirds of convicts at the Old Bailey received a sentence of transportation – on average 283 convicts a year. As a result, London’s prisons quickly filled to overflowing with convicted prisoners who were sentenced to transportation but had no place to go.

To increase London’s prison capacity, in 1776 Parliament passed the “Hulks Act” (16 Geo III, c.43). Although overseen by local justices of the peace, the hulks were to be directly managed and maintained by private contractors. The first contract to run a hulk was awarded to Duncan Campbell, a former transportation contractor. In August 1776, the Justicia, a former transportation ship moored in the River Thames, became the first prison hulk. This ship soon became full and Campbell quickly introduced a number of other hulks in London; by 1778 the fleet of hulks on the Thames held 510 prisoners.

Demand was so great that new hulks were introduced across the country. There were hulks located at Deptford, Chatham, Woolwich, Gosport, Plymouth, Portsmouth, Sheerness and Cork.The Justitia via rmg collections:

Convicts perform hard labour at the Woolwich Warren. The hulk on the river is the ‘Justitia’. Prisoners were kept on board such ships for months awaiting deportation to Australia. The ‘Justitia’ was a 260 ton prison hulk that had been originally moored in the Thames when the American War of Independence put a stop to the transportation of criminals to the former colonies. The ‘Justitia’ belonged to the shipowner Duncan Campbell, who was the Government contractor who organized the prison-hulk system at that time. Campbell was subsequently involved in the shipping of convicts to the penal colony at Botany Bay (in fact Port Jackson, later Sydney, just to the north) in New South Wales, the ‘first fleet’ going out in 1788.

While searching for records for Isaac Stokes I discovered that another Isaac Stokes was transported to New South Wales in 1835 as well. The other one was a butcher born in 1809, sentenced in London for seven years, and he sailed on the Mary Ann. Our Isaac Stokes sailed on the Lady Nugent, arriving in NSW in April 1835, having set sail from England in December 1834.

Lady Nugent was built at Bombay in 1813. She made four voyages under contract to the British East India Company (EIC). She then made two voyages transporting convicts to Australia, one to New South Wales and one to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). (via Wikipedia)

via freesettlerorfelon website:

On 20 November 1834, 100 male convicts were transferred to the Lady Nugent from the Justitia Hulk and 60 from the Ganymede Hulk at Woolwich, all in apparent good health. The Lady Nugent departed Sheerness on 4 December 1834.

SURGEON OLIVER SPROULE

Oliver Sproule kept a Medical Journal from 7 November 1834 to 27 April 1835. He recorded in his journal the weather conditions they experienced in the first two weeks:

‘In the course of the first week or ten days at sea, there were eight or nine on the sick list with catarrhal affections and one with dropsy which I attribute to the cold and wet we experienced during that period beating down channel. Indeed the foremost berths in the prison at this time were so wet from leaking in that part of the ship, that I was obliged to issue dry beds and bedding to a great many of the prisoners to preserve their health, but after crossing the Bay of Biscay the weather became fine and we got the damp beds and blankets dried, the leaks partially stopped and the prison well aired and ventilated which, I am happy to say soon manifested a favourable change in the health and appearance of the men.

Besides the cases given in the journal I had a great many others to treat, some of them similar to those mentioned but the greater part consisted of boils, scalds, and contusions which would not only be too tedious to enter but I fear would be irksome to the reader. There were four births on board during the passage which did well, therefore I did not consider it necessary to give a detailed account of them in my journal the more especially as they were all favourable cases.

Regularity and cleanliness in the prison, free ventilation and as far as possible dry decks turning all the prisoners up in fine weather as we were lucky enough to have two musicians amongst the convicts, dancing was tolerated every afternoon, strict attention to personal cleanliness and also to the cooking of their victuals with regular hours for their meals, were the only prophylactic means used on this occasion, which I found to answer my expectations to the utmost extent in as much as there was not a single case of contagious or infectious nature during the whole passage with the exception of a few cases of psora which soon yielded to the usual treatment. A few cases of scurvy however appeared on board at rather an early period which I can attribute to nothing else but the wet and hardships the prisoners endured during the first three or four weeks of the passage. I was prompt in my treatment of these cases and they got well, but before we arrived at Sydney I had about thirty others to treat.’

The Lady Nugent arrived in Port Jackson on 9 April 1835 with 284 male prisoners. Two men had died at sea. The prisoners were landed on 27th April 1835 and marched to Hyde Park Barracks prior to being assigned. Ten were under the age of 14 years.

The Lady Nugent:

Isaac’s distinguishing marks are noted on various criminal registers and record books:

“Height in feet & inches: 5 4; Complexion: Ruddy; Hair: Light brown; Eyes: Hazel; Marks or Scars: Yes [including] DEVIL on lower left arm, TSIS back of left hand, WS lower right arm, MHDW back of right hand.”

Another includes more detail about Isaac’s tattoos:

“Two slight scars right side of mouth, 2 moles above right breast, figure of the devil and DEVIL and raised mole, lower left arm; anchor, seven dots half moon, TSIS and cross, back of left hand; a mallet, door post, A, mans bust, sun, WS, lower right arm; woman, MHDW and shut knife, back of right hand.”

From How tattoos became fashionable in Victorian England (2019 article in TheConversation by Robert Shoemaker and Zoe Alkar):

“Historical tattooing was not restricted to sailors, soldiers and convicts, but was a growing and accepted phenomenon in Victorian England. Tattoos provide an important window into the lives of those who typically left no written records of their own. As a form of “history from below”, they give us a fleeting but intriguing understanding of the identities and emotions of ordinary people in the past.

As a practice for which typically the only record is the body itself, few systematic records survive before the advent of photography. One exception to this is the written descriptions of tattoos (and even the occasional sketch) that were kept of institutionalised people forced to submit to the recording of information about their bodies as a means of identifying them. This particularly applies to three groups – criminal convicts, soldiers and sailors. Of these, the convict records are the most voluminous and systematic.

Such records were first kept in large numbers for those who were transported to Australia from 1788 (since Australia was then an open prison) as the authorities needed some means of keeping track of them.”On the 1837 census Isaac was working for the government at Illiwarra, New South Wales. This record states that he arrived on the Lady Nugent in 1835. There are three other indent records for an Isaac Stokes in the following years, but the transcriptions don’t provide enough information to determine which Isaac Stokes it was. In April 1837 there was an abscondment, and an arrest/apprehension in May of that year, and in 1843 there was a record of convict indulgences.

From the Australian government website regarding “convict indulgences”:

“By the mid-1830s only six per cent of convicts were locked up. The vast majority worked for the government or free settlers and, with good behaviour, could earn a ticket of leave, conditional pardon or and even an absolute pardon. While under such orders convicts could earn their own living.”

In 1856 in Camden, NSW, Isaac Stokes married Catherine Daly. With no further information on this record it would be impossible to know for sure if this was the right Isaac Stokes. This couple had six children, all in the Camden area, but none of the records provided enough information. No occupation or place or date of birth recorded for Isaac Stokes.

I wrote to the National Library of Australia about the marriage record, and their reply was a surprise! Issac and Catherine were married on 30 September 1856, at the house of the Rev. Charles William Rigg, a Methodist minister, and it was recorded that Isaac was born in Edinburgh in 1821, to parents James Stokes and Sarah Ellis! The age at the time of the marriage doesn’t match Isaac’s age at death in 1877, and clearly the place of birth and parents didn’t match either. Only his fathers occupation of stone mason was correct. I wrote back to the helpful people at the library and they replied that the register was in a very poor condition and that only two and a half entries had survived at all, and that Isaac and Catherines marriage was recorded over two pages.

I searched for an Isaac Stokes born in 1821 in Edinburgh on the Scotland government website (and on all the other genealogy records sites) and didn’t find it. In fact Stokes was a very uncommon name in Scotland at the time. I also searched Australian immigration and other records for another Isaac Stokes born in Scotland or born in 1821, and found nothing. I was unable to find a single record to corroborate this mysterious other Isaac Stokes.

As the age at death in 1877 was correct, I assume that either Isaac was lying, or that some mistake was made either on the register at the home of the Methodist minster, or a subsequent mistranscription or muddle on the remnants of the surviving register. Therefore I remain convinced that the Camden stonemason Isaac Stokes was indeed our Isaac from Oxfordshire.

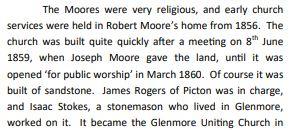

I found a history society newsletter article that mentioned Isaac Stokes, stone mason, had built the Glenmore church, near Camden, in 1859.

From the Wollondilly museum April 2020 newsletter:

From the Camden History website:

“The stone set over the porch of Glenmore Church gives the date of 1860. The church was begun in 1859 on land given by Joseph Moore. James Rogers of Picton was given the contract to build and local builder, Mr. Stokes, carried out the work. Elizabeth Moore, wife of Edward, laid the foundation stone. The first service was held on 19th March 1860. The cemetery alongside the church contains the headstones and memorials of the areas early pioneers.”

Isaac died on the 3rd September 1877. The inquest report puts his place of death as Bagdelly, near to Camden, and another death register has put Cambelltown, also very close to Camden. His age was recorded as 71 and the inquest report states his cause of death was “rupture of one of the large pulmonary vessels of the lung”. His wife Catherine died in childbirth in 1870 at the age of 43.

Isaac and Catherine’s children:

William Stokes 1857-1928

Catherine Stokes 1859-1846

Sarah Josephine Stokes 1861-1931

Ellen Stokes 1863-1932

Rosanna Stokes 1865-1919

Louisa Stokes 1868-1844.

It’s possible that Catherine Daly was a transported convict from Ireland.

Some time later I unexpectedly received a follow up email from The Oaks Heritage Centre in Australia.

“The Gaudry papers which we have in our archive record him (Isaac Stokes) as having built: the church, the school and the teachers residence. Isaac is recorded in the General return of convicts: 1837 and in Grevilles Post Office directory 1872 as a mason in Glenmore.”

November 18, 2022 at 4:47 pm #6348

November 18, 2022 at 4:47 pm #6348In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Wong Sang

Wong Sang was born in China in 1884. In October 1916 he married Alice Stokes in Oxford.

Alice was the granddaughter of William Stokes of Churchill, Oxfordshire and William was the brother of Thomas Stokes the wheelwright (who was my 3X great grandfather). In other words Alice was my second cousin, three times removed, on my fathers paternal side.

Wong Sang was an interpreter, according to the baptism registers of his children and the Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital admission registers in 1930. The hospital register also notes that he was employed by the Blue Funnel Line, and that his address was 11, Limehouse Causeway, E 14. (London)

“The Blue Funnel Line offered regular First-Class Passenger and Cargo Services From the UK to South Africa, Malaya, China, Japan, Australia, Java, and America. Blue Funnel Line was Owned and Operated by Alfred Holt & Co., Liverpool.

The Blue Funnel Line, so-called because its ships have a blue funnel with a black top, is more appropriately known as the Ocean Steamship Company.”Wong Sang and Alice’s daughter, Frances Eileen Sang, was born on the 14th July, 1916 and baptised in 1920 at St Stephen in Poplar, Tower Hamlets, London. The birth date is noted in the 1920 baptism register and would predate their marriage by a few months, although on the death register in 1921 her age at death is four years old and her year of birth is recorded as 1917.

Charles Ronald Sang was baptised on the same day in May 1920, but his birth is recorded as April of that year. The family were living on Morant Street, Poplar.

James William Sang’s birth is recorded on the 1939 census and on the death register in 2000 as being the 8th March 1913. This definitely would predate the 1916 marriage in Oxford.

William Norman Sang was born on the 17th October 1922 in Poplar.

Alice and the three sons were living at 11, Limehouse Causeway on the 1939 census, the same address that Wong Sang was living at when he was admitted to Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital on the 15th January 1930. Wong Sang died in the hospital on the 8th March of that year at the age of 46.

Alice married John Patterson in 1933 in Stepney. John was living with Alice and her three sons on Limehouse Causeway on the 1939 census and his occupation was chef.

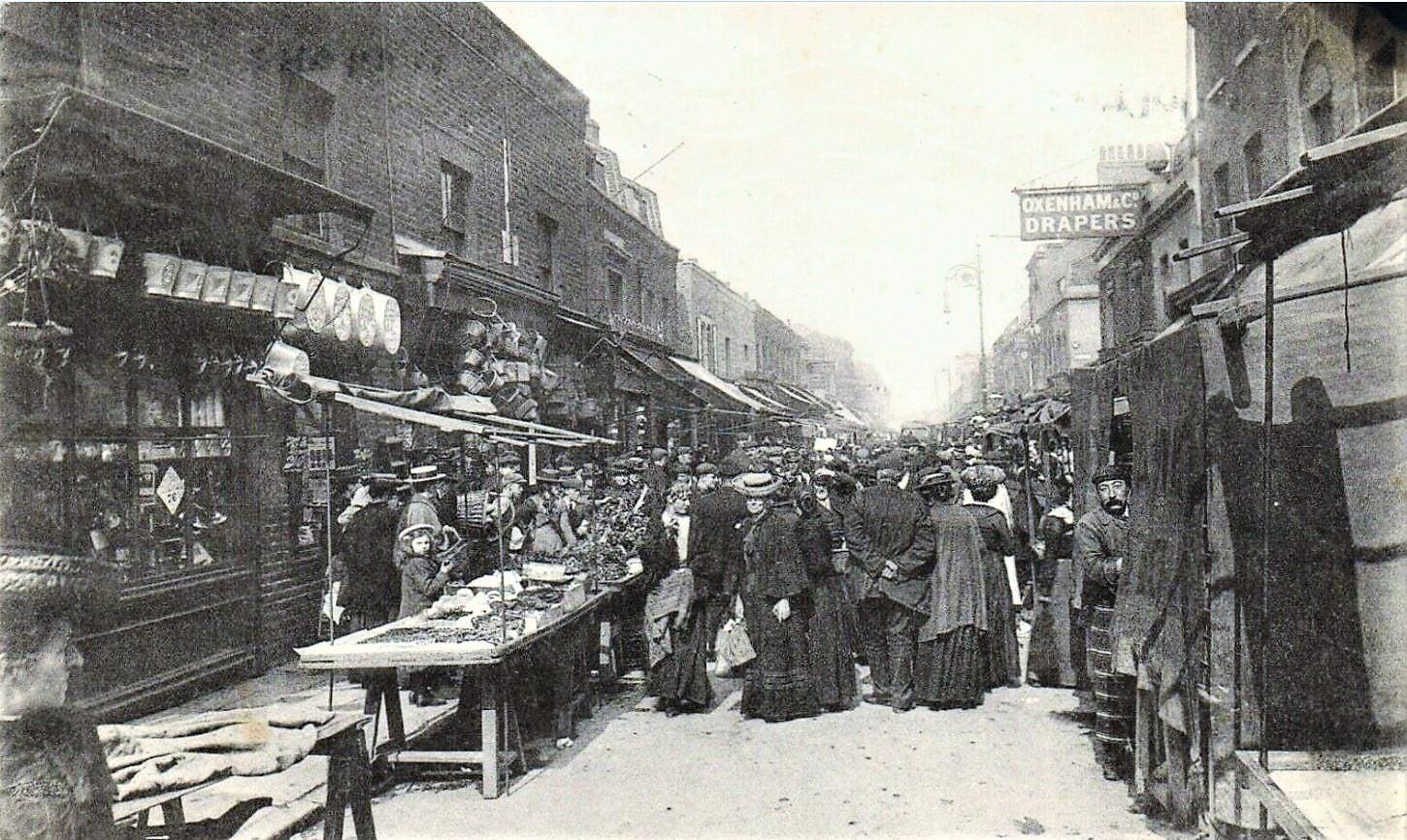

Via Old London Photographs:

“Limehouse Causeway is a street in east London that was the home to the original Chinatown of London. A combination of bomb damage during the Second World War and later redevelopment means that almost nothing is left of the original buildings of the street.”

Limehouse Causeway in 1925:

From The Story of Limehouse’s Lost Chinatown, poplarlondon website:

“Limehouse was London’s first Chinatown, home to a tightly-knit community who were demonised in popular culture and eventually erased from the cityscape.

As recounted in the BBC’s ‘Our Greatest Generation’ series, Connie was born to a Chinese father and an English mother in early 1920s Limehouse, where she used to play in the street with other British and British-Chinese children before running inside for teatime at one of their houses.

Limehouse was London’s first Chinatown between the 1880s and the 1960s, before the current Chinatown off Shaftesbury Avenue was established in the 1970s by an influx of immigrants from Hong Kong.

Connie’s memories of London’s first Chinatown as an “urban village” paint a very different picture to the seedy area portrayed in early twentieth century novels.

The pyramid in St Anne’s church marked the entrance to the opium den of Dr Fu Manchu, a criminal mastermind who threatened Western society by plotting world domination in a series of novels by Sax Rohmer.

Thomas Burke’s Limehouse Nights cemented stereotypes about prostitution, gambling and violence within the Chinese community, and whipped up anxiety about sexual relationships between Chinese men and white women.

Though neither novelist was familiar with the Chinese community, their depictions made Limehouse one of the most notorious areas of London.

Travel agent Thomas Cook even organised tours of the area for daring visitors, despite the rector of Limehouse warning that “those who look for the Limehouse of Mr Thomas Burke simply will not find it.”

All that remains is a handful of Chinese street names, such as Ming Street, Pekin Street, and Canton Street — but what was Limehouse’s chinatown really like, and why did it get swept away?

Chinese migration to Limehouse

Chinese sailors discharged from East India Company ships settled in the docklands from as early as the 1780s.

By the late nineteenth century, men from Shanghai had settled around Pennyfields Lane, while a Cantonese community lived on Limehouse Causeway.

Chinese sailors were often paid less and discriminated against by dock hirers, and so began to diversify their incomes by setting up hand laundry services and restaurants.

Old photographs show shopfronts emblazoned with Chinese characters with horse-drawn carts idling outside or Chinese men in suits and hats standing proudly in the doorways.

In oral histories collected by Yat Ming Loo, Connie’s husband Leslie doesn’t recall seeing any Chinese women as a child, since male Chinese sailors settled in London alone and married working-class English women.

In the 1920s, newspapers fear-mongered about interracial marriages, crime and gambling, and described chinatown as an East End “colony.”

Ironically, Chinese opium-smoking was also demonised in the press, despite Britain waging war against China in the mid-nineteenth century for suppressing the opium trade to alleviate addiction amongst its people.

The number of Chinese people who settled in Limehouse was also greatly exaggerated, and in reality only totalled around 300.

The real Chinatown

Although the press sought to characterise Limehouse as a monolithic Chinese community in the East End, Connie remembers seeing people of all nationalities in the shops and community spaces in Limehouse.

She doesn’t remember feeling discriminated against by other locals, though Connie does recall having her face measured and IQ tested by a member of the British Eugenics Society who was conducting research in the area.

Some of Connie’s happiest childhood memories were from her time at Chung-Hua Club, where she learned about Chinese culture and language.

Why did Chinatown disappear?

The caricature of Limehouse’s Chinatown as a den of vice hastened its erasure.

Police raids and deportations fuelled by the alarmist media coverage threatened the Chinese population of Limehouse, and slum clearance schemes to redevelop low-income areas dispersed Chinese residents in the 1930s.

The Defence of the Realm Act imposed at the beginning of the First World War criminalised opium use, gave the authorities increased powers to deport Chinese people and restricted their ability to work on British ships.

Dwindling maritime trade during World War II further stripped Chinese sailors of opportunities for employment, and any remnants of Chinatown were destroyed during the Blitz or erased by postwar development schemes.”

Wong Sang 1884-1930

The year 1918 was a troublesome one for Wong Sang, an interpreter and shipping agent for Blue Funnel Line. The Sang family were living at 156, Chrisp Street.

Chrisp Street, Poplar, in 1913 via Old London Photographs:

In February Wong Sang was discharged from a false accusation after defending his home from potential robbers.

East End News and London Shipping Chronicle – Friday 15 February 1918:

In August of that year he was involved in an incident that left him unconscious.

Faringdon Advertiser and Vale of the White Horse Gazette – Saturday 31 August 1918:

Wong Sang is mentioned in an 1922 article about “Oriental London”.

London and China Express – Thursday 09 February 1922:

A photograph of the Chee Kong Tong Chinese Freemason Society mentioned in the above article, via Old London Photographs:

Wong Sang was recommended by the London Metropolitan Police in 1928 to assist in a case in Wellingborough, Northampton.

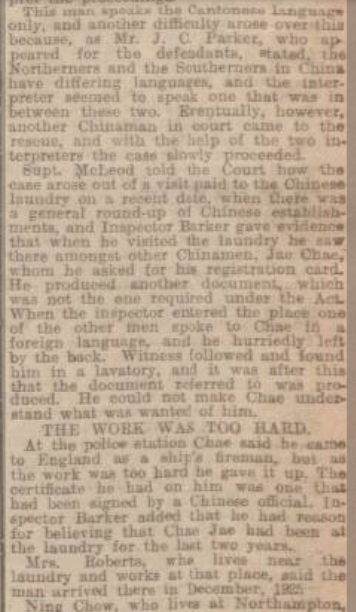

Difficulty of Getting an Interpreter: Northampton Mercury – Friday 16 March 1928:

The difficulty was that “this man speaks the Cantonese language only…the Northeners and the Southerners in China have differing languages and the interpreter seemed to speak one that was in between these two.”

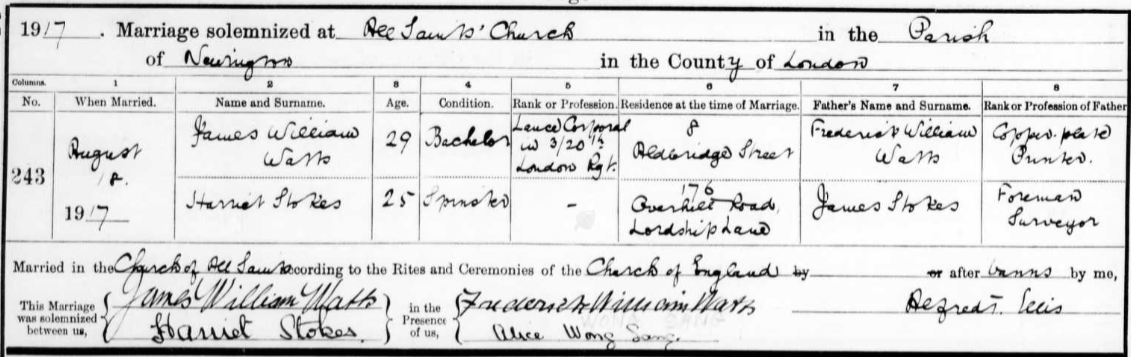

In 1917, Alice Wong Sang was a witness at her sister Harriet Stokes marriage to James William Watts in Southwark, London. Their father James Stokes occupation on the marriage register is foreman surveyor, but on the census he was a council roadman or labourer. (I initially rejected this as the correct marriage for Harriet because of the discrepancy with the occupations. Alice Wong Sang as a witness confirmed that it was indeed the correct one.)

James William Sang 1913-2000 was a clock fitter and watch assembler (on the 1939 census). He married Ivy Laura Fenton in 1963 in Sidcup, Kent. James died in Southwark in 2000.

Charles Ronald Sang 1920-1974 was a draughtsman (1939 census). He married Eileen Burgess in 1947 in Marylebone. Charles and Eileen had two sons: Keith born in 1951 and Roger born in 1952. He died in 1974 in Hertfordshire.

William Norman Sang 1922-2000 was a clerk and telephone operator (1939 census). William enlisted in the Royal Artillery in 1942. He married Lily Mullins in 1949 in Bethnal Green, and they had three daughters: Marion born in 1950, Christine in 1953, and Frances in 1959. He died in Redbridge in 2000.

I then found another two births registered in Poplar by Alice Sang, both daughters. Doris Winifred Sang was born in 1925, and Patricia Margaret Sang was born in 1933 ~ three years after Wong Sang’s death. Neither of the these daughters were on the 1939 census with Alice, John Patterson and the three sons. Margaret had presumably been evacuated because of the war to a family in Taunton, Somerset. Doris would have been fourteen and I have been unable to find her in 1939 (possibly because she died in 2017 and has not had the redaction removed yet on the 1939 census as only deceased people are viewable).

Doris Winifred Sang 1925-2017 was a nursing sister. She didn’t marry, and spent a year in USA between 1954 and 1955. She stayed in London, and died at the age of ninety two in 2017.

Patricia Margaret Sang 1933-1998 was also a nurse. She married Patrick L Nicely in Stepney in 1957. Patricia and Patrick had five children in London: Sharon born 1959, Donald in 1960, Malcolm was born and died in 1966, Alison was born in 1969 and David in 1971.

I was unable to find a birth registered for Alice’s first son, James William Sang (as he appeared on the 1939 census). I found Alice Stokes on the 1911 census as a 17 year old live in servant at a tobacconist on Pekin Street, Limehouse, living with Mr Sui Fong from Hong Kong and his wife Sarah Sui Fong from Berlin. I looked for a birth registered for James William Fong instead of Sang, and found it ~ mothers maiden name Stokes, and his date of birth matched the 1939 census: 8th March, 1913.

On the 1921 census, Wong Sang is not listed as living with them but it is mentioned that Mr Wong Sang was the person returning the census. Also living with Alice and her sons James and Charles in 1921 are two visitors: (Florence) May Stokes, 17 years old, born in Woodstock, and Charles Stokes, aged 14, also born in Woodstock. May and Charles were Alice’s sister and brother.

I found Sharon Nicely on social media and she kindly shared photos of Wong Sang and Alice Stokes:

October 11, 2022 at 2:58 pm #6334

October 11, 2022 at 2:58 pm #6334In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The House on Penn Common

Toi Fang and the Duke of Sutherland

Tomlinsons

Grassholme

Charles Tomlinson (1873-1929) my great grandfather, was born in Wolverhampton in 1873. His father Charles Tomlinson (1847-1907) was a licensed victualler or publican, or alternatively a vet/castrator. He married Emma Grattidge (1853-1911) in 1872. On the 1881 census they were living at The Wheel in Wolverhampton.

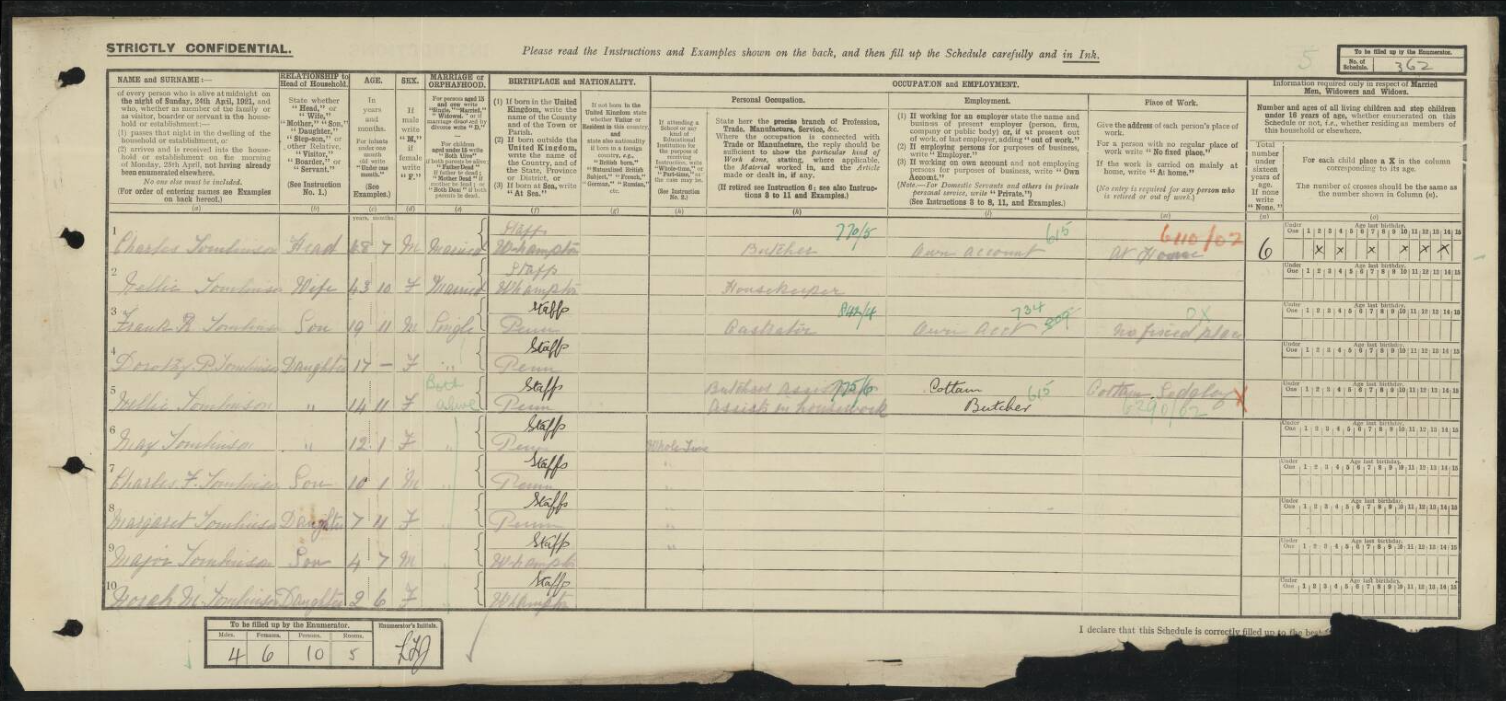

Charles married Nellie Fisher (1877-1956) in Wolverhampton in 1896. In 1901 they were living next to the post office in Upper Penn, with children (Charles) Sidney Tomlinson (1896-1955), and Hilda Tomlinson (1898-1977) . Charles was a vet/castrator working on his own account.

In 1911 their address was 4, Wakely Hill, Penn, and living with them were their children Hilda, Frank Tomlinson (1901-1975), (Dorothy) Phyllis Tomlinson (1905-1982), Nellie Tomlinson (1906-1978) and May Tomlinson (1910-1983). Charles was a castrator working on his own account.

Charles and Nellie had a further four children: Charles Fisher Tomlinson (1911-1977), Margaret Tomlinson (1913-1989) (my grandmother Peggy), Major Tomlinson (1916-1984) and Norah Mary Tomlinson (1919-2010).

My father told me that my grandmother had fallen down the well at the house on Penn Common in 1915 when she was two years old, and sent me a photo of her standing next to the well when she revisted the house at a much later date.

Peggy next to the well on Penn Common:

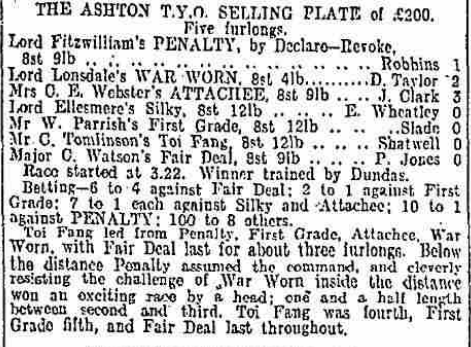

My grandmother Peggy told me that her father had had a racehorse called Toi Fang. She remembered the racing colours were sky blue and orange, and had a set of racing silks made which she sent to my father.

Through a DNA match, I met Ian Tomlinson. Ian is the son of my fathers favourite cousin Roger, Frank’s son. Ian found some racing silks and sent a photo to my father (they are now in contact with each other as a result of my DNA match with Ian), wondering what they were.

When Ian sent a photo of these racing silks, I had a look in the newspaper archives. In 1920 there are a number of mentions in the racing news of Mr C Tomlinson’s horse TOI FANG. I have not found any mention of Toi Fang in the newspapers in the following years.

The Scotsman – Monday 12 July 1920:

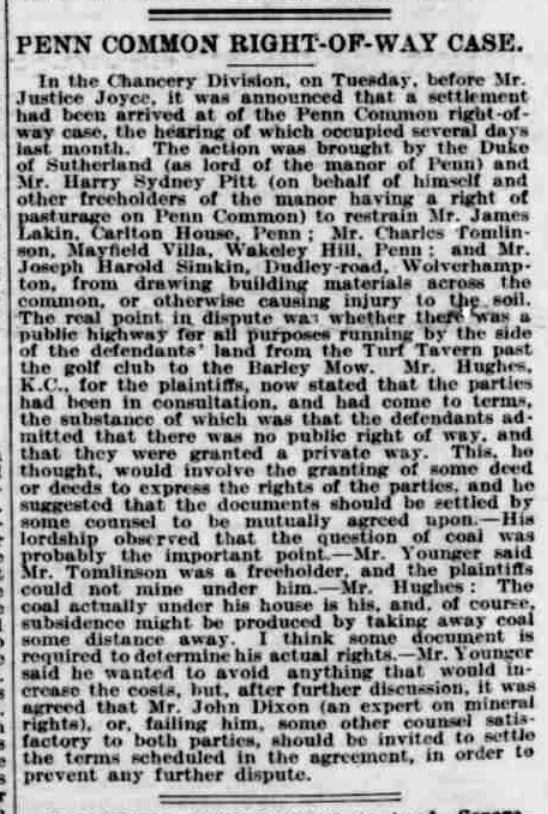

The other story that Ian Tomlinson recalled was about the house on Penn Common. Ian said he’d heard that the local titled person took Charles Tomlinson to court over building the house but that Tomlinson won the case because it was built on common land and was the first case of it’s kind.

Penn Common Right of Way Case:

Staffordshire Advertiser March 9, 1912In the chancery division, on Tuesday, before Mr Justice Joyce, it was announced that a settlement had been arrived at of the Penn Common Right of Way case, the hearing of which occupied several days last month. The action was brought by the Duke of Sutherland (as Lord of the Manor of Penn) and Mr Harry Sydney Pitt (on behalf of himself and other freeholders of the manor having a right to pasturage on Penn Common) to restrain Mr James Lakin, Carlton House, Penn; Mr Charles Tomlinson, Mayfield Villa, Wakely Hill, Penn; and Mr Joseph Harold Simpkin, Dudley Road, Wolverhampton, from drawing building materials across the common, or otherwise causing injury to the soil.

The real point in dispute was whether there was a public highway for all purposes running by the side of the defendants land from the Turf Tavern past the golf club to the Barley Mow.

Mr Hughes, KC for the plaintiffs, now stated that the parties had been in consultation, and had come to terms, the substance of which was that the defendants admitted that there was no public right of way, and that they were granted a private way. This, he thought, would involve the granting of some deed or deeds to express the rights of the parties, and he suggested that the documents should be be settled by some counsel to be mutually agreed upon.His lordship observed that the question of coal was probably the important point. Mr Younger said Mr Tomlinson was a freeholder, and the plaintiffs could not mine under him. Mr Hughes: The coal actually under his house is his, and, of course, subsidence might be produced by taking away coal some distance away. I think some document is required to determine his actual rights.

Mr Younger said he wanted to avoid anything that would increase the costs, but, after further discussion, it was agreed that Mr John Dixon (an expert on mineral rights), or failing him, another counsel satisfactory to both parties, should be invited to settle the terms scheduled in the agreement, in order to prevent any further dispute.

The name of the house is Grassholme. The address of Mayfield Villas is the house they were living in while building Grassholme, which I assume they had not yet moved in to at the time of the newspaper article in March 1912.

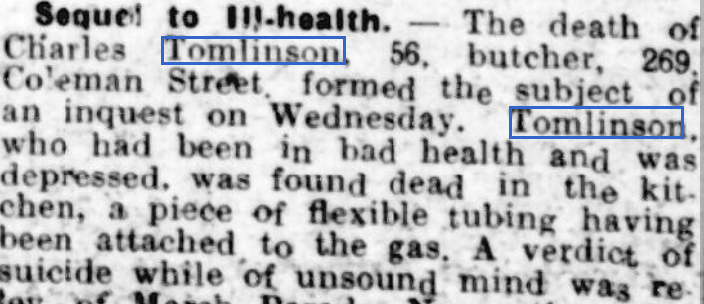

What my grandmother didn’t tell anyone was how her father died in 1929:

On the 1921 census, Charles, Nellie and eight of their children were living at 269 Coleman Street, Wolverhampton.

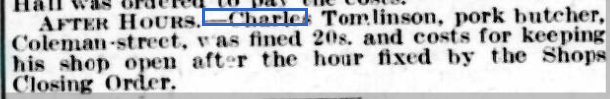

They were living on Coleman Street in 1915 when Charles was fined for staying open late.

Staffordshire Advertiser – Saturday 13 February 1915:

What is not yet clear is why they moved from the house on Penn Common sometime between 1912 and 1915. And why did he have a racehorse in 1920?

August 18, 2022 at 8:26 am #6324In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

STONE MANOR

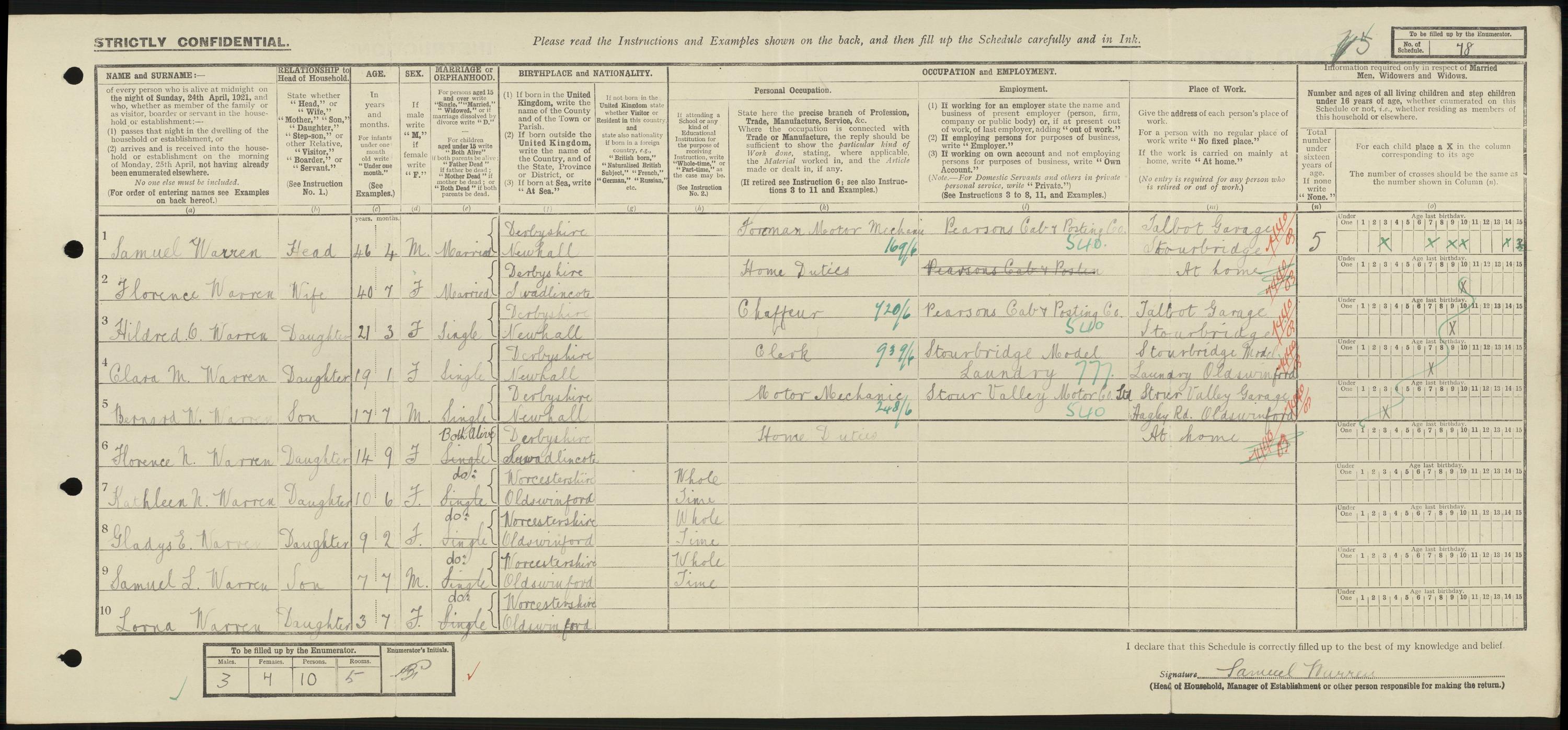

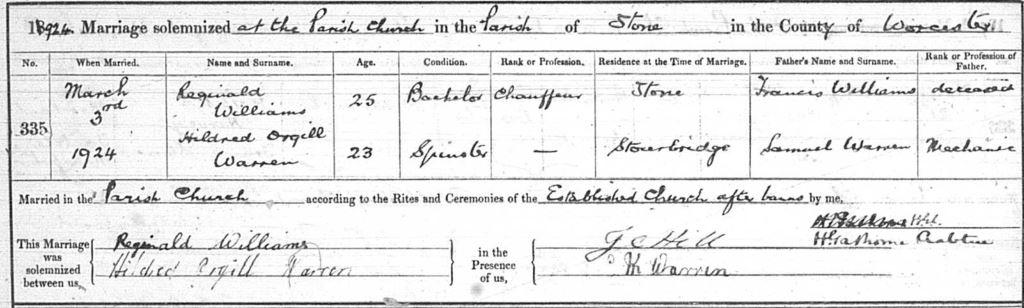

Hildred Orgill Warren born in 1900, my grandmothers sister, married Reginald Williams in Stone, Worcestershire in March 1924. Their daughter Joan was born there in October of that year.

Hildred was a chaffeur on the 1921 census, living at home in Stourbridge with her father (my great grandfather) Samuel Warren, mechanic. I recall my grandmother saying that Hildred was one of the first lady chauffeurs. On their wedding certificate, Reginald is also a chauffeur.

1921 census, Stourbridge:

Hildred and Reg worked at Stone Manor. There is a family story of Hildred being involved in a car accident involving a fatality and that she had to go to court.

Stone Manor is in a tiny village called Stone, near Kidderminster, Worcestershire. It used to be a private house, but has been a hotel and nightclub for some years. We knew in the family that Hildred and Reg worked at Stone Manor and that Joan was born there. Around 2007 Joan held a family party there.

Stone Manor, Stone, Worcestershire:

I asked on a Kidderminster Family Research group about Stone Manor in the 1920s:

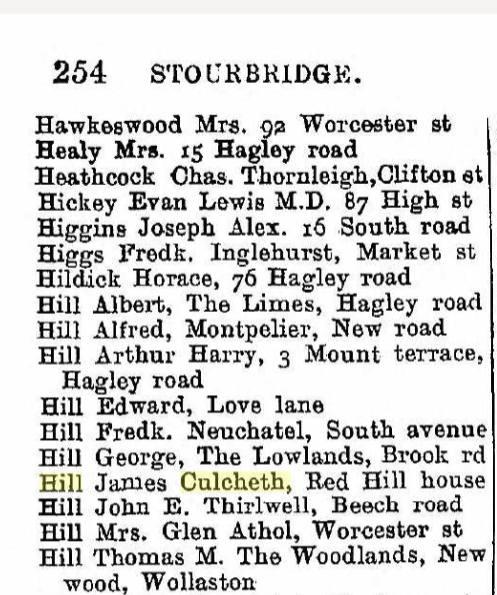

“the original Stone Manor burnt down and the current building dates from the early 1920’s and was built for James Culcheth Hill, completed in 1926”

But was there a fire at Stone Manor?

“I’m not sure there was a fire at the Stone Manor… there seems to have been a fire at another big house a short distance away and it looks like stories have crossed over… as the dates are the same…”JC Hill was one of the witnesses at Hildred and Reginalds wedding in Stone in 1924. K Warren, Hildreds sister Kay, was the other:

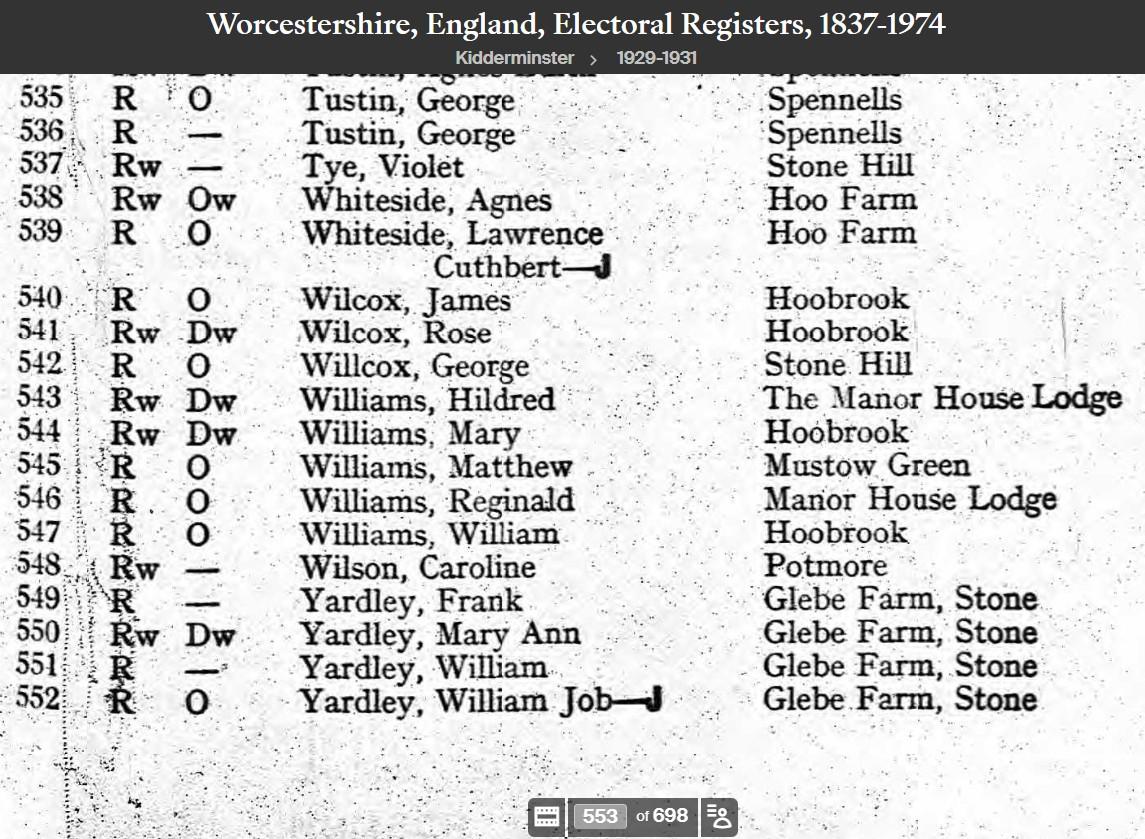

I searched the census and electoral rolls for James Culcheth Hill and found him at the Stone Manor on the 1929-1931 electoral rolls for Stone, and Hildred and Reginald living at The Manor House Lodge, Stone:

On the 1911 census James Culcheth Hill was a 12 year old student at Eastmans Royal Naval Academy, Northwood Park, Crawley, Winchester. He was born in Kidderminster in 1899. On the same census page, also a student at the school, is Reginald Culcheth Holcroft, born in 1900 in Stourbridge. The unusual middle name would seem to indicate that they might be related.

A member of the Kidderminster Family Research group kindly provided this article:

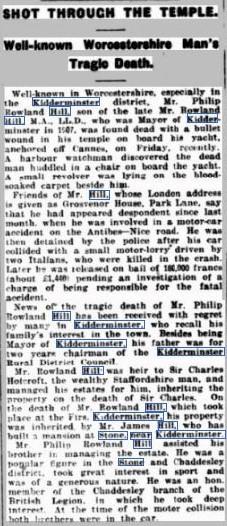

SHOT THROUGH THE TEMPLE

Well known Worcestershire man’s tragic death.

Dudley Chronicle 27 March 1930.

Well known in Worcestershire, especially the Kidderminster district, Mr Philip Rowland Hill MA LLD who was mayor of Kidderminster in 1907 was found dead with a bullet wound through his temple on board his yacht, anchored off Cannes, on Friday, recently. A harbour watchman discovered the dead man huddled in a chair on board the yacht. A small revolver was lying on the blood soaked carpet beside him.

Friends of Mr Hill, whose London address is given as Grosvenor House, Park Lane, say that he appeared despondent since last month when he was involved in a motor car accident on the Antibes ~ Nice road. He was then detained by the police after his car collided with a small motor lorry driven by two Italians, who were killed in the crash. Later he was released on bail of 180,000 francs (£1440) pending an investigation of a charge of being responsible for the fatal accident. …….

Mr Rowland Hill (Philips father) was heir to Sir Charles Holcroft, the wealthy Staffordshire man, and managed his estates for him, inheriting the property on the death of Sir Charles. On the death of Mr Rowland HIll, which took place at the Firs, Kidderminster, his property was inherited by Mr James (Culcheth) Hill who had built a mansion at Stone, near Kidderminster. Mr Philip Rowland Hill assisted his brother in managing the estate. …….

At the time of the collison both brothers were in the car.

This article doesn’t mention who was driving the car ~ could the family story of a car accident be this one? Hildred and Reg were working at Stone Manor, both were (or at least previously had been) chauffeurs, and Philip Hill was helping James Culcheth Hill manage the Stone Manor estate at the time.

This photograph was taken circa 1931 in Llanaeron, Wales. Hildred is in the middle on the back row:

Sally Gray sent the photo with this message:

“Joan gave me a short note: Photo was taken when they lived in Wales, at Llanaeron, before Janet was born, & Aunty Lorna (my mother) lived with them, to take Joan to school in Aberaeron, as they only spoke Welsh at the local school.”

Hildred and Reginalds daughter Janet was born in 1932 in Stratford. It would appear that Hildred and Reg moved to Wales just after the car accident, and shortly afterwards moved to Stratford.

In 1921 James Culcheth Hill was living at Red Hill House in Stourbridge. Although I have not been able to trace Reginald Williams yet, perhaps this Stourbridge connection with his employer explains how Hildred met Reginald.

Sir Reginald Culcheth Holcroft, the other pupil at the school in Winchester with James Culcheth Hill, was indeed related, as Sir Holcroft left his estate to James Culcheth Hill’s father. Sir Reginald was born in 1899 in Upper Swinford, Stourbridge. Hildred also lived in that part of Stourbridge in the early 1900s.

1921 Red Hill House:

The 2007 family reunion organized by Joan Williams at Stone Manor: Joan in black and white at the front.

Unrelated to the Warrens, my fathers friends (and customers at The Fox when my grandmother Peggy Edwards owned it) Geoff and Beryl Lamb later bought Stone Manor.

June 6, 2022 at 12:58 pm #6303In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

The Hollands of Barton under Needwood

Samuel Warren of Stapenhill married Catherine Holland of Barton under Needwood in 1795.

I joined a Barton under Needwood History group and found an incredible amount of information on the Holland family, but first I wanted to make absolutely sure that our Catherine Holland was one of them as there were also Hollands in Newhall. Not only that, on the marriage licence it says that Catherine Holland was from Bretby Park Gate, Stapenhill.

Then I noticed that one of the witnesses on Samuel’s brother Williams marriage to Ann Holland in 1796 was John Hair. Hannah Hair was the wife of Thomas Holland, and they were the Barton under Needwood parents of Catherine. Catherine was born in 1775, and Ann was born in 1767.

The 1851 census clinched it: Catherine Warren 74 years old, widow and formerly a farmers wife, was living in the household of her son John Warren, and her place of birth is listed as Barton under Needwood. In 1841 Catherine was a 64 year old widow, her husband Samuel having died in 1837, and she was living with her son Samuel, a farmer. The 1841 census did not list place of birth, however. Catherine died on 31 March 1861 and does not appear on the 1861 census.

Once I had established that our Catherine Holland was from Barton under Needwood, I had another look at the information available on the Barton under Needwood History group, compiled by local historian Steve Gardner.

Catherine’s parents were Thomas Holland 1737-1828 and Hannah Hair 1739-1822.

Steve Gardner had posted a long list of the dates, marriages and children of the Holland family. The earliest entries in parish registers were Thomae Holland 1562-1626 and his wife Eunica Edwardes 1565-1632. They married on 10th July 1582. They were born, married and died in Barton under Needwood. They were direct ancestors of Catherine Holland, and as such my direct ancestors too.

The known history of the Holland family in Barton under Needwood goes back to Richard De Holland. (Thanks once again to Steve Gardner of the Barton under Needwood History group for this information.)

“Richard de Holland was the first member of the Holland family to become resident in Barton under Needwood (in about 1312) having been granted lands by the Earl of Lancaster (for whom Richard served as Stud and Stock Keeper of the Peak District) The Holland family stemmed from Upholland in Lancashire and had many family connections working for the Earl of Lancaster, who was one of the biggest Barons in England. Lancaster had his own army and lived at Tutbury Castle, from where he ruled over most of the Midlands area. The Earl of Lancaster was one of the main players in the ‘Barons Rebellion’ and the ensuing Battle of Burton Bridge in 1322. Richard de Holland was very much involved in the proceedings which had so angered Englands King. Holland narrowly escaped with his life, unlike the Earl who was executed.

From the arrival of that first Holland family member, the Hollands were a mainstay family in the community, and were in Barton under Needwood for over 600 years.”Continuing with various items of information regarding the Hollands, thanks to Steve Gardner’s Barton under Needwood history pages:

“PART 6 (Final Part)

Some mentions of The Manor of Barton in the Ancient Staffordshire Rolls:

1330. A Grant was made to Herbert de Ferrars, at le Newland in the Manor of Barton.

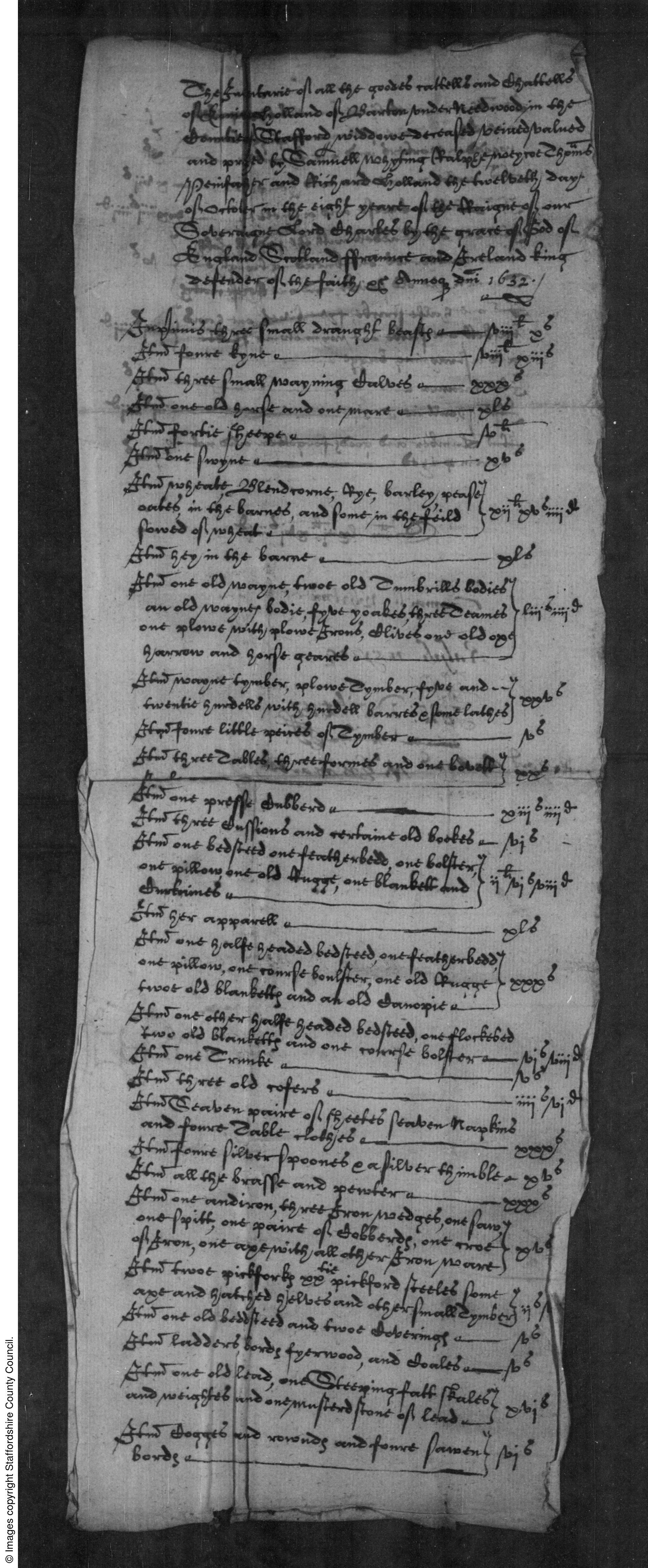

1378. The Inquisitio bonorum – Johannis Holand — an interesting Inventory of his goods and their value and his debts.

1380. View of Frankpledge ; the Jury found that Richard Holland was feloniously murdered by his wife Joan and Thomas Graunger, who fled. The goods of the deceased were valued at iiij/. iijj. xid. ; one-third went to the dead man, one-third to his son, one- third to the Lord for the wife’s share. Compare 1 H. V. Indictments. (1413.)

That Thomas Graunger of Barton smyth and Joan the wife of Richard de Holond of Barton on the Feast of St. John the Baptist 10 H. II. (1387) had traitorously killed and murdered at night, at Barton, Richard, the husband of the said Joan. (m. 22.)

The names of various members of the Holland family appear constantly among the listed Jurors on the manorial records printed below : —

1539. Richard Holland and Richard Holland the younger are on the Muster Roll of Barton

1583. Thomas Holland and Unica his wife are living at Barton.

1663-4. Visitations. — Barton under Needword. Disclaimers. William Holland, Senior, William Holland, Junior.

1609. Richard Holland, Clerk and Alice, his wife.

1663-4. Disclaimers at the Visitation. William Holland, Senior, William Holland, Junior.”I was able to find considerably more information on the Hollands in the book “Some Records of the Holland Family (The Hollands of Barton under Needwood, Staffordshire, and the Hollands in History)” by William Richard Holland. Luckily the full text of this book can be found online.

William Richard Holland (Died 1915) An early local Historian and author of the book:

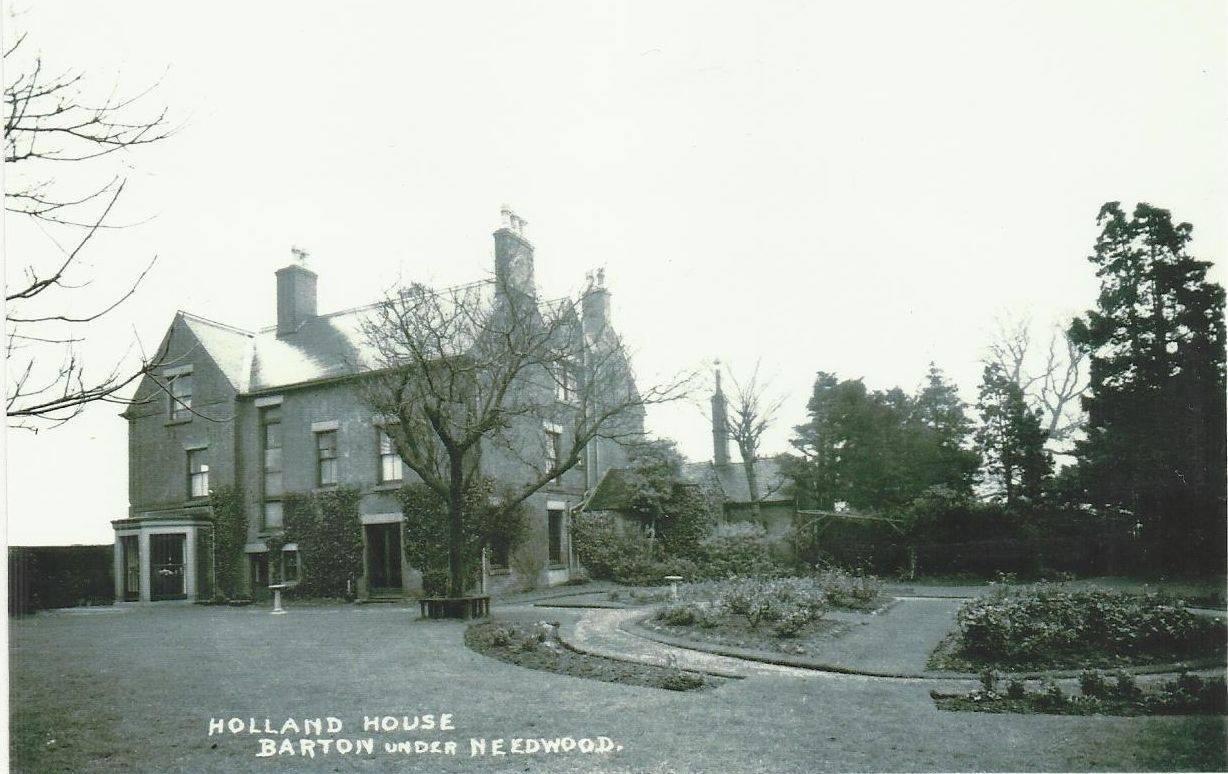

‘Holland House’ taken from the Gardens (sadly demolished in the early 60’s):

Excerpt from the book:

“The charter, dated 1314, granting Richard rights and privileges in Needwood Forest, reads as follows:

“Thomas Earl of Lancaster and Leicester, high-steward of England, to whom all these present shall come, greeting: Know ye, that we have given, &c., to Richard Holland of Barton, and his heirs, housboot, heyboot, and fireboot, and common of pasture, in our forest of Needwood, for all his beasts, as well in places fenced as lying open, with 40 hogs, quit of pawnage in our said forest at all times in the year (except hogs only in fence month). All which premises we will warrant, &c. to the said Richard and his heirs against all people for ever”

“The terms “housboot” “heyboot” and “fireboot” meant that Richard and his heirs were to have the privilege of taking from the Forest, wood needed for house repair and building, hedging material for the repairing of fences, and what was needful for purposes of fuel.”

Further excerpts from the book:

“It may here be mentioned that during the renovation of Barton Church, when the stone pillars were being stripped of the plaster which covered them, “William Holland 1617” was found roughly carved on a pillar near to the belfry gallery, obviously the work of a not too devout member of the family, who, seated in the gallery of that time, occupied himself thus during the service. The inscription can still be seen.”

“The earliest mention of a Holland of Upholland occurs in the reign of John in a Final Concord, made at the Lancashire Assizes, dated November 5th, 1202, in which Uchtred de Chryche, who seems to have had some right in the manor of Upholland, releases his right in fourteen oxgangs* of land to Matthew de Holland, in consideration of the sum of six marks of silver. Thus was planted the Holland Tree, all the early information of which is found in The Victoria County History of Lancaster.