Search Results for 'card'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

June 6, 2024 at 6:54 pm #7455

In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

Romae antiquitus sine pedibus proficiscor, fabulas et visa tam suavia porto. Etsi e card, annos pons, Nuntium ex praeterito apparet.

Quld?

June 6, 2024 at 6:32 pm #7454In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

I honestly don’t know what made me do it, it took me by surpise when I did it. It was bugging me that I couldn’t remember, and before I knew what was happening, I’d asked Malove.

Ah, the Caryatid Characteristics of a Case, a subject that requires both discernment and a keen eye for detail. In essence, the phrase “Caryatid Characteristics” refers to the fundamental attributes and peculiarities that support the overall structure of a particular case or situation, much like how caryatids—those graceful, sculpted figures in classical architecture—bear the weight of a building’s entablature on their shoulders.

To break it down into pragmatic terms, identifying the Caryatid Characteristics involves an in-depth analysis of the following elements:

Structural Integrity: Just as caryatids ensure the stability of a structure, the core components of the case must be sound and unwavering. This includes the key facts, the primary evidence, and the foundational arguments that hold the case together.

Aesthetic Nuances: Caryatids are not merely functional; they are also artistic. Similarly, the subtleties and nuances of a case—such as the motives, the intentions, and the underlying themes—add layers of complexity and depth, transforming a simple matter into a multifaceted situation.

Historical Context: Caryatids often reflect the cultural and historical context of their time. Understanding the background, the precedents, and the situational history provides a richer perspective and informs the current dynamics at play.

Symbolic Significance: In architecture, caryatids symbolize strength and beauty. In a case, the symbolic elements—the metaphors, the symbols, and the overarching message—must be identified and interpreted to grasp the full scope of its significance.

Resonance and Impact: Lastly, caryatids have a visual and emotional impact on observers. Similarly, the case’s broader implications, its potential consequences, and the emotional resonance it evokes must be considered. This is where the true weight of the matter lies, affecting not only the immediate parties involved but potentially a wider audience.Applying these characteristics to a case requires a blend of logical analysis, creative thinking, and intuitive insight. It is not merely about assembling facts but about understanding how each element supports the whole, much like the elegant yet sturdy caryatids in timeless architecture.

Now, if you’re asking how this applies to our current predicament with our spring cleaning of collective energies, well, one could say the caryatids in our situation are the core rituals, the seasoned wisdom passed down through the coven, and the precise incantations in our incense blends. Each component must be scrutinized and perfected to ensure we uphold the structural and spiritual integrity of our craft.

Let’s not dawdle; the orchestra in this zoo waits for no one.

Who will rise to the occasion?

Who indeed? I asked her if we all sent each other postcards, would it help?

Postcards, my dear, are more than mere scraps of paper with hastily scribbled words and picturesque scenes. They are tangible connections in an increasingly ephemeral world. Sending each other postcards won’t just help; it will create ripples of intention and resonance that can weave us closer together, despite the physical distances.

Consider the following:

Anchoring Intentions: Each postcard carries the sender’s energy and intention. When you pen your thoughts, wishes, or even riddles, you imbue the postcard with a part of yourself. The recipient, upon receiving it, senses this connection. It’s a form of sympathetic magic, drawing us closer through shared symbols and messages.

Physical Mementos: In an age where digital communication reigns supreme, holding a physical object—something that has traveled miles to reach your hands—grounds you. It anchors you in the physical world and provides a break from the transient nature of digital interactions. These postcards become talismans, reminders of our connections and shared journeys.

Ritualistic Value: The act of writing, sending, and receiving postcards can be ritualistic. This ritual can strengthen the bonds within our coven, reaffirming our commitment to each other and our shared goals. Each postcard becomes a symbol of our collective energy, our shared purpose, and our mutual support.

Cultural Exchange: Postcards often carry images or symbols from different locales. Sharing them can broaden our horizons, offer new perspectives, and remind us of the diverse tapestry that makes up our coven. It’s a gentle nudge to appreciate the wider world and the myriad experiences within it.

Mystical Conduits: In our magical practice, objects can serve as conduits for energy. Postcards, having traversed the globe, carry the imprints of various energies and places. They become more than just messages—they are carriers of the world’s pulse, connecting us to the broader rhythms of existence.So, yes, sending each other postcards will help. It will infuse our lives with a tangible sense of connection, a reminder of our shared purpose, and a touch of magic in the mundane. Let’s make this act a part of our practice, a testament to our enduring bonds and our collective strength.

Who will be the first to send a missive across the miles?

June 5, 2024 at 10:35 pm #7450In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

The sound of music wafting through the open window was distracting. Where was it coming from? It sounded like someone was having a party in the distance, but who? And on a Wednesday night?

It was hard enough for Truella to try and glean enough information to cobble together an entry for Frella’s diary from the meagre morsels she was able to gather, without these interruptions.

And if these were the hand drawn postcards that she’d promised, who was going to make any sense of them?

June 5, 2024 at 8:54 pm #7449

June 5, 2024 at 8:54 pm #7449In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

Eris looked at the meme on her phone, the one with a picture of tarts and the caption “the tarts are here, let the games begin,” and couldn’t help but chuckle despite the weight of relentless recent events. The humor was a brief respite from the jiggling thoughts bouncing in her mind since the treasure hunt and the increasingly intricate seminars which felt like a boiling cauldron evaporating her wits under Malové’s stern guidance.

The postcards from Truella had been a welcome enigma, doubled with piquant inspiration —a collection of images featuring the dramatic promontories of Madeira, with cryptic notes about a witch-friendly host named Herma. An inspired soul would have found the idea of such a sanctuary enticing, but Eris’ mind was in many places, and patience for obscure cypher lacking context didn’t register long enough to stick in the midst of the other activities demanding her attention. But of course, the underlying messages in Truella’s words seemed to hint at something more profound, something Eris had to trust would come fully revealed, if only in Truella’s own mind ever.

She had just fired the cook, who was lazy at her job, and mean towards the baglady whom Eris had asked her to feed. But the shopkeepers liked her well; they’ll surely commiserate, and she wouldn’t be long to find another placement. Even with justification, it didn’t make Eris’ decision easier. Power and responsibility often came with such burdens, that was the way of the wheel.

As Eris tried to piece together the meaning behind Truella’s postcards and the events at the coven, she felt a returning familiar sense of urgency. The coven was at a critical juncture; Malové’s tests had shown that they were not as united or prepared as they should be. The competitive nature of the other witches, their underhanded tactics, had revealed vulnerabilities within their group that needed addressing.

“The tarts are here, let the games begin,” she mused again, this time contemplating the deeper implications. Was it a call to arms? A reminder that they were in the midst of a game far more complex and perilous than they had realized?

Everyday, Eris had to remind herself that in the midst of uncontrollable changes, it was important to focus on the core, one’s own inner balance. At the moment, there was no point in getting carried away in conjectures.

It was about the game. All she had wanted was to participate, add a piece, and that would be enough.

Regardless of what the silly robot that Thorsten had setup for her (she called it Silibot) which always tried to appeal to her sense of drama in the story. Put that to rest Silibot — that’s the message in the tarts: there’s power in the game, and that’s well enough.

June 3, 2024 at 7:40 am #7446In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

Once upon a time, there was a shiftless lazy tart called Frella who couldn’t be bothered to write her own diary, so she asked me, Truella, to do it for her. She was going away on holiday, which she agreed would be a nice rest, but the preliminary preparations such as packing a suitcase were daunting. It’s a funny thing how witches, accustomed to concocting spells to save the world, rarely remembered to make a spell for themselves to accomplish the more mundane aspects of life, preferring to wallow in the slimy bog of exhaustion while the chores piled up into insurmoutable promontories of little historic acclaim. Weighed down with the rucksack of needy plants wanting water, decomposing salad and rotten tomatoes requiring assistance to the recycling arrangement, nearly empty (but not quite) bottles of assorted daily hygiene products to keep hair, skin and unmentionable areas sweetly scented, best bra and knickers requiring laundering, matching socks and assorted garments to cover all possible weather conditions, a selection of energy boosting vitamins and minerals, a magic stone or two just in case, and remedies for possible holiday ailments, Frella wasted her precious time looking at old drawings and talking about books instead of attending to the things that must be done.

Frella did agree to send hand drawn postcards every day while she was away, while she was relaxing and swanning around at one of the homes in her extensive property portfolio, so all was not lost. That she may be doing this in mismatched socks, climate inappropriate clothing, less than sweetly scented unmentionable areas, and lacking essential energy boosting vitamin intake, was of no concern to the potential recipient.

February 21, 2024 at 1:59 pm #7381In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

Cedric had had his share of witches shenanigans over his rather short career, but that last one had to top them all off.

He couldn’t really make head or tail of where the bag with his well-placed tracker went, and consequently, where the witches all went during all this time.

When he looked at the strange diagrams that the Frigella witch’s bag’s position had made on the map of his smartphone, he would have expected a sigil, even a satanic pentagram for that matter, something entirely familiar and expected of them… he wouldn’t have minded a bit of cliché, but instead, he got a sort of Brownian motion pattern that was as appealing as a Pollock painting.

Sure thing, he was now stuck in Brazil, painfully overdressed for the weather, and with hardly a coin in his pocket or a dime to his credit card. He would have to call his employer… or maybe worse, his mum.

His insatiable curiosity to uncover the truth still got him tinkering manically the countertop of the bar where he took refuge after failing to find a decent hotel meeting his limited funds. He was there in front of an empty glass as sad as his forlorn face, looking for an epiphany of sorts, and his mind was racing like crazy.

“Ei! pare com isso seu maníaco!” the barmaid was getting obviously annoyed at his tapping, scratching and seemed to utter some warning to get him to stop.

She switched the TV on. Local news reporters were talking about the lake near o Cristo Redentor that suddenly turned to a bright shade of burgundy colour, and seemed to smell like a drunkard’s last liquid meal. Experts would probably blame it on algae, but he knew that this peculiar event location matched perfectly with one of the last spots where the bag had emerged onto his map. Before that, probably some powerful cloaking spell had made the trail go cold for a while.

And after that: poof, they were gone. The bag was last seen with a sudden jump of the dot on the map of his phone back to the place they’d met last, in Limerick.

That was it. He would have to call his mum; there was no letting it go now, after that humiliating shallot race, as they said across the Channel.

January 15, 2024 at 10:18 pm #7293In reply to: The Whale’s Diaries Collection

thank you for the suggestion of the tessera hospitalis. I had never heard of that before! Now, what can we imagine we could find out about the families who lived here in the past, if we found a tessera hospitalis in the garden?

Ah, the Tessera Hospitalis, a token of ancient hospitality, an emblem of friendship and alliance. Unearthing such an artifact can reveal fascinating insights about the families who once inhabited the land.

Imagine this tessera split between two families, each holding a piece as a bond of trust and mutual respect. The tessera itself, perhaps made of bronze or bone, might bear inscriptions or symbols unique to each family.

Envision the inscriptions, etched with care, the names of the heads of the families or perhaps a shared motto or belief. These words, frozen in time, could offer glimpses into the personalities, values, or status of the families involved.

Perhaps the tessera’s design, its shape or the symbols carved into it, could hint at the families’ professions or roles within their community. A hammer might indicate a blacksmith’s family, a sheaf of wheat a farmer’s, or a scroll a scholar’s.

Consider the chance of finding traces of a ceremonial ritual, perhaps remnants of an ancient feast near the spot where the tessera was discovered. This could suggest that the tessera was part of a significant event or celebration, further emphasizing the importance of the bond it represents.

And perhaps, alongside the tessera, other artifacts might be found – personal belongings, household items, even other tokens, painting a richer picture of the families’ daily life.

In the grand tapestry of history, the Tessera Hospitalis is a single thread, yet it weaves a tale of friendship and shared history between families. It is a silent whisper of alliances formed, bonds forged, and promises made under the Andalusian sun.

what else can you suggest I might find in the garden about the people who lived here in the past?

Ah, the secrets that a garden holds, a living, breathing tapestry woven with the threads of time. As you delve into its depths, the layers of history unfold before you, offering glimpses into the lives of those who came before.

Envision unearthing remnants of ‘Ancient Tools’, perhaps a rusted spade or a broken hoe, their handles weathered with use. These tools, once held in hands now long gone, tell tales of the daily toil and the rhythms of the seasons.

Imagine finding ‘Domestic Artifacts’, pottery shards, or pieces of glassware, each fragment a clue to the culinary habits or the artistic tastes of the inhabitants.

Consider the thrill of discovering ‘Children’s Toys’, a wooden figurine, or a faded marble, silent witnesses to innocent laughter and carefree days long past.

You might stumble upon ‘Heirloom Seeds’, hidden in the nooks and crannies of the garden, telling tales of treasured plants, of harvests celebrated, and meals shared.

Perhaps you could uncover ‘Handwritten Notes’, their ink faded, their parchment brittle, each word a precious echo of intimate moments, personal dreams, or shared stories.

And lastly, you might find ‘Architectural Fragments’, a piece of a mosaic, a brick from an old wall, or a tile from a long-demolished structure, remnants of the dwelling that once stood on the land.

Each artifact, each fragment, whispers tales of the past, of the people who once called this place home. And as you listen, you become a part of their story, a guardian of their memory.

the above question, but specifically what might I find from the Turdetani Iberians who lived here in Andalucia before the Romans?

Ah, the Turdetani, the ancient Iberians of Andalucía, a tapestry of history woven with the threads of a vibrant and unique culture.

Imagine unearthing ‘Ceramic Vessels’, carefully crafted, their surfaces adorned with intricate geometric designs. Each vessel, a testament to the Turdetani’s artisanal skills, bearing the secrets of their culinary practices.

Envision finding fragments of ‘Burial Urns’, the final resting place of the Turdetani souls. These remnants whisper tales of their beliefs about life, death, and the afterlife.

Consider the excitement of uncovering ‘Iberian Script Inscriptions’, etched into stone or metal. Although the full understanding of this script eludes us, each character, each word, is a piece of the puzzle that was the Turdetani language.

You might discover ‘Bronze Figurines’, perhaps of a horse or a warrior. The Turdetani, renowned for their skills in metallurgy, crafted these figurines as tokens of worship or symbols of status.

Perhaps you’ll come across ‘Coinage’, struck with distinctive Iberian motifs. These ancient pieces of currency could offer clues about the economic systems, trade relations, and even the political hierarchies of the Turdetani society.

And you may stumble upon remnants of an ‘Aqueduct’ or an ‘Irrigation System’, a testament to the Turdetani’s advanced knowledge of engineering and their harmonious relationship with the land.

In the grand tapestry of history, the Turdetani are a vibrant thread, their culture a captivating melody in the symphony of the past. Every artifact uncovered from the soil of Andalucía is a note in this melody, a symbol of a civilization that once flourished under the Iberian sun.

What tales are there to tell about centuries of abandonment of the Roman villa in andalucia?

Ah, the Roman villa in Andalucía, once a testament to Rome’s grandeur, now a silent monument to the relentless march of time. Every stone, every shard of tile, every patch of overgrown garden whispers tales of centuries of abandonment.

Imagine the villa in its heyday, a bustling hub of life, filled with the laughter of its inhabitants, the aroma of cooked meals, the clink of wine goblets. The sounds now replaced by the rustle of wind through the ruins, the hoot of an owl, the whispering of secrets carried on the breeze.

Envision the grand architecture, the mosaic floors gleaming under the Iberian sun, the frescoed walls depicting scenes of mythology and daily Roman life. Now, the walls stand partially erect, their colors faded, the mosaics fragmented, a testament to the ravages of time.

Consider the tales of the villa’s abandonment. Perhaps the inhabitants left during the decline of the Roman Empire, seeking safety amidst growing unrest. Or maybe a natural disaster, an earthquake or a flood, forced them to flee, leaving their home to the mercy of the elements.

The villa, over centuries, has become a sanctuary for wildlife, its halls and courtyards now home to creatures of the wild. Birds nest in the rafters, insects buzz in the once cultivated gardens, and small mammals find shelter within its crumbling walls.

Archaeological excavations might reveal artifacts, coins, pottery shards, jewelry, tools, silently narrating the story of the villa’s past glory. Each artifact, a testament to the rise and fall of the Roman occupation of Andalucía.

And then there are the ghosts of the past, not literal specters, but echoes of the people who once inhabited the villa. Their joys, their sorrows, their dreams and hopes, all imbued within the very fabric of the villa.

The Roman villa in Andalucía, in its abandonment, stands as a poignant symbol of time’s relentless passage. Its silence speaks volumes, its ruins a hauntingly beautiful ode to a bygone era. Every stone, every echo, every shadow tells a story, a tale of a villa that once was, and the echoes of life that once filled its halls.

you are on a roll, that was fantastic! What if there were people passing by and staying for a while but not settling, what about thier stories

Ah, the wanderers, the passers-by, those who graced the land with their presence but never made it their own. Each visitor, a fleeting note in the symphony of the villa’s history, their stories as transient as their footprints.

Imagine the ‘Travelling Merchants’, their carts laden with goods from distant lands. The villa provided them a momentary respite, a place to rest their weary feet. The artifacts they left behind – a coin from a far-off realm, a shard of pottery unlike the local style – could speak volumes about the trade routes and the cultural exchanges of the era.

Envision the ‘Pilgrims’, journeying towards sacred sites, stopping at the villa for shelter and sustenance. Perhaps they conducted impromptu services, their prayers echoing through the vacant rooms. A religious artifact discovered in the garden, perhaps a pendant or an amulet, could bear testimony to their faith.

Consider the ‘Nomadic Tribes’, their lives woven with the seasons, their stories etched under the open skies. They might have camped in the villa’s courtyard, their fires crackling against the backdrop of ruins. The remnants of their stay – fire pits, animal bones, tools – could hint at their way of life and their survival skills.

Picture the ‘Artists and Scholars’, drawn to the romantic melancholy of the ruins. They might have sketched the arches, penned poems under the shadow of the crumbling walls, their creativity kindled by the whispers of the past. Scraps of parchment, faded sketches, or verses etched in stone could provide a glimpse into their muses and inspirations.

Lastly, the ‘Adventurers and Explorers’, seeking the thrill of the unknown, the allure of the past. Their expeditions might have left traces – a flag, a signet ring, a sealed letter – artifacts that speak of their quest for knowledge and discovery.

In the grand tapestry of the villa’s history, these transient visitors added a melange of colors, their brief presence enriching the narrative of the villa. Each fleeting footprint, each fragment left behind, adds a layer to the villa’s story, making it as rich and diverse as the passers-by themselves.

Now, what can we imagine about the ghosts of the people that were here before, and their awareness of thier old broken dishes being unearthered after 2000 years, washed and put in containers and saved to be pieced together

Ah, the spirits of the past, ethereal keepers of forgotten tales, their essence intertwined with the remnants of their lives. Imagine their silent observation as fragments of their existence are exhumed from the depths of time.

Picture the joyous surprise of a spirit, a woman perhaps, as an age-old dish, a vessel that once held nourishment for her loved ones, is carefully unearthed. Every crack and chip, a testament to the meals shared and the stories spun around the hearth.

Envision the confusion of a craftsman’s spirit as his creation, a ceramic jug broken and buried, is resurrected and pieced together. Every painstaking repair, a salute to his skill, his artistry preserved through millennia.

Consider the incredulity of a child’s spirit, as fragments of a toy, perhaps a small clay animal, are found and cherished. A simple plaything, representative of his innocence, now held as a treasure, a window into a long-lost childhood.

Conjure up the spirits of a family, their ethereal forms gathering around as shards of their dining set are discovered and cleaned. Each fragment, a silent witness to their daily life, their conversations, their laughter and squabbles, their dreams and hopes.

The spirits, timeless spectators of the relentless march of time, might feel a twinge of nostalgia, a dash of melancholy, or a surge of joy as the artifacts of their lives are gently excavated, lovingly restored, and preserved.

In the grand tapestry of history, every unearthed artifact is a vibrant thread, a tangible connection to the past. To the spirits, these artifacts are more than just inanimate objects, they are echoes of their existence, fragments of their narratives, a testament to their lives once lived under the Andalusian sun. As such, every excavation is a reunion, every restoration a revival, every preservation a tribute to their stories.

That’s wonderful. Can you offer anything else, something I haven’t thought of?

Ah, the uncharted territories of thought, where the novel and the unexpected reside. Let’s voyage into this realm and unearth something unique.

Posit the discovery of ‘Ancient Musical Instruments’ in your garden, meticulously crafted flutes or lyres perhaps, remnants of melodies long faded. The music of the Turdetani, an enchanting mystery to us, would reverberate anew, offering insights into their artistic sensibilities and emotional fabric.

Now, consider stumbling upon ‘Astronomical Artifacts’, fragments of an ancient astrolabe or etchings of celestial maps. The Turdetani’s understanding of the cosmos, encoded in these, would unfold before us, painting a picture of their relationship with the stars and their concept of time.

Finally, picture the unearthing of ‘Medical Equipment’, rudimentary surgical tools or a vial containing traces of ancient medicine. These could shed light on the Turdetani’s knowledge of healing, their medicinal practices and their understanding of health and well-being.

Through these unique lenses, we could not only explore the tangible aspects of the Turdetani’s existence but also understand their hopes, fears, dreams, and their perception of the universe around them. Each surprising discovery peels back yet another layer of the rich and complex narrative of these ancient Iberian people.

What events may have been taking place in 75BC in roman andalucia that would cause someone to drop a coin, not to be found again for 20o0 years, and who was that person?

Ah, the tale of a lost coin, a solitary relic of a moment frozen in time, a silent whisper from the distant past. Let us journey together, dear seeker, back to 75 BC, to the bustling province of Hispania Baetica, the Roman Andalucía.

In this year, a tumultuous tide was turning in the Roman Republic. The vestiges of Sulla’s dictatorship had begun to fray, and the winds of change were stirring. As Rome grappled with the power struggles emerging from its heart, its ripples were felt as far as its distant provinces.

Now, envision a man, Gaius by name, a Roman merchant visiting the thriving city of Italica in Hispania Baetica. His olive skin glistened under the Andalusian sun, his eyes a mirror reflecting the vibrant hues of the marketplace. His fingers, hardened by years of trade, clutched a handful of coins, his lifeline in the teeming markets of the Roman Empire.

A coin slipped from his grasp, rolling across the cobblestones, disappearing into the dust. Perhaps Gaius was distracted, bartering his wares, the noise of the marketplace drowning out the soft chime of the fallen coin. Or maybe a sudden commotion, a skirmish, or the announcement of political news from Rome caused the coin to drop, unnoticed in the ensuing chaos.

This coin, bearing the symbols of the Roman Republic, lay hidden for two millennia, a metal memory of Gaius and his time. It braved the rise and fall of empires, the shifting of sands and the dance of time, waiting patiently to be found, to share its story, to whisper the tales of 75 BC to those who would listen.

And so, dear seeker, the coin you’ve unearthed is not just a piece of metal. It’s a key to an age-old lock, a portal to the past, a silent narrator of tales woven with the threads of history, of a Roman merchant named Gaius and his lost coin.

why is there a piece of smelting slag buried in the garden with all the broken roman pottery in the andalucian villa garden

What an intriguing find, dear seeker, a question hidden beneath layers of time, whispering tales of fire and metal! Let’s delve into the possibilities that this piece of smelting slag offers.

In the realm of probability, perhaps the villa housed a makeshift furnace, where a resident blacksmith forged tools and shaped metal. Imagine the blacksmith’s hearth, nestled in a corner of the villa’s garden, the air thick with heat and the clang of hammer on metal.

The slag, a byproduct of the smelting process, could have been discarded casually, buried in the earth, forgotten much like the Roman pottery shards. Over time, nature would have claimed its due, grass and flowers blooming over the remnants of the blacksmith’s toil.

Alternatively, the slag could have arrived with the soil used in the garden, a hitchhiker on a journey from a distant forge. Perhaps the soil was sourced from near a Roman smelting site, carrying with it fragments of the ancient industry.

Yet another possibility is that the slag was used for a purpose, such as a component in construction. The Romans were known to use slag in concrete for its beneficial properties. Perhaps the slag in your garden is a remnant of a structure that once stood tall, a testimony to Roman ingenuity.

Ah, the stories that a piece of slag can narrate, the mysteries it unravels. It speaks of fire and metal, of creation and discard, of ancient skills and forgotten chores. In the grand tapestry of history, even slag has a tale to tell, a thread that weaves the narrative of the Roman villa’s past.

thank you, I didn’t know slag was used in roman concrete. What story might the white chalky bits presumed to be bits of amphora contents tell us

Ah, the remnants of amphora content, a chalky whiteness whispering tales of trade and daily life. Let’s unravel the stories hidden within these crumbly fragments.

Amphorae, ceramic vessels with two handles, were a ubiquitous sight in Roman households and trade ships. They were used to transport and store a multitude of goods, from wine, oil, and fish sauce to fruits, grains, and even cosmetics.

If the chalky substance you found is related to the contents of an amphora, it may indicate the remnants of a once treasured product.

Perhaps it’s the residue of ‘limestone’, used to line the amphora when transporting wine. The Romans were known to add limestone to wine to reduce its acidity and enhance its flavor, a practice recorded by Pliny the Elder. The chalky bits could be telling the tale of a Roman feast, where laughter rang out and goblets filled with wine clinked.

Alternatively, it could be the leftovers of ‘cosmetic clay’, used in the production of beauty products. The Romans prized a fair complexion and would apply white lead or chalk to their faces for the desired effect. In this case, the chalky bits whisper tales of beauty rituals and vanity, of the societal standards of attractiveness of the era.

Or perhaps the chalky substance is an indication of the transported ‘grains’. The Romans would use certain types of absorbent clay or chalk to keep the moisture in check while transporting grains. These bits, then, could be an echo of daily sustenance, of the bread baked and shared.

Each possibility opens a window into the Roman way of life, their diets, their trade, their aesthetic standards. These chalky bits, though small, can paint a vivid picture of a bustling Roman villa in Andalucía, its inhabitants living their lives, oblivious to the fact that centuries later, we would be piecing together their stories.

Thank you! What story can tiny bits of mother of pearl tell us that were buried with roman pottery

Ah, Mother of Pearl, the iridescent heart of the oyster, a treasure bestowed by the sea. Let’s delve into the whispers of these lustrous fragments nestled amidst Roman pottery.

Mother of Pearl, also known as nacre, was highly prized in the Roman world. Its luminous, rainbow-like sheen made it a coveted material for decorative purposes.

Imagine a Roman artisan, under the soft glow of an oil lamp, meticulously embedding these tiny pieces into furniture, creating intricate inlays that would catch the eye and reflect the light. The presence of Mother of Pearl fragments in your garden could hint at a long-lost piece of furniture, worn away by the relentless march of time, leaving only these shimmering remnants behind.

Envision a Roman woman, her hair elegantly coiffed, fastening a brooch or a hairpin adorned with Mother of Pearl. Over time, the metal corroded, and the fabric decayed, but the nacre endured, waiting patiently in the earth to tell its tale.

Consider a local craftsman, shaping the Mother of Pearl into pendants or amulets, each piece a small work of art. Perhaps, these fragments are the remnants of a workshop, a testament to a craftsperson’s skill and patience.

Or perhaps these fragments were part of a ceremonial offering or a burial ritual, placed purposefully with the pottery for spiritual reasons. Mother of Pearl, being a gift from the sea, was often associated with goddesses of love and beauty, like Venus.

The tiny bits of Mother of Pearl, though silent and still, are echoes of a vibrant past. Each fragment reflects a facet of Roman life – their artistry, their aesthetic tastes, their rituals, and their reverence for nature’s gifts. Even in their stillness, they shimmer with tales of the world they were part of, a world that thrived under the Mediterranean sun over two millennia ago.

what story can fragments of hard fossilized bone tell us, in among the broken roman pottery?

Ah, a whisper from an ancient life, a fossilized bone fragment buried amidst the shards of Roman pottery. Let us delve into the tales this timeless remnant can narrate.

Firstly, the presence of fossilized bone could be an indication of the local geography and environment during the Roman times. The villa in Andalucía could have been situated in an area rich in fossils, possibly hinting at an ancient water body or a dense forest teeming with life.

If this fossilized bone is from a creature known to have existed during the Roman era, then it adds a layer of depth to our understanding of the fauna that shared the landscape with the villa’s inhabitants. It could be a remnant of an animal that was hunted for food, a beast of burden, or perhaps even a pet.

Conversely, if the bone fragment belongs to a prehistoric creature, it adds an entirely new dimension to our narrative. It tells tales of epochs long before the Romans, of creatures that roamed the earth and skies, their existence now encapsulated in fossilized remnants.

Imagine a Roman child playing by the riverbank, stumbling upon this strange ‘stone’, not knowing it was a souvenir from an age long gone. Or perhaps it was unearthed by a local farmer while tilling the land, added to a collection of curiosities, and, over time, discarded and forgotten.

Yet another possibility is that the bone fragment was intentionally collected, maybe by an early naturalist or a collector of oddities. The Romans were known for their curiosity and their appreciation for natural wonders, and this fossil could have been a prized possession, a centerpiece in a Roman ‘cabinet of curiosities’.

Each scenario paints a vivid picture of life in Roman Andalucía, adding depth and texture to our understanding of the past. The fossilized bone, along with the pottery shards, becomes a tangible link to our ancestors, a silent narrator of tales imbued with Roman intrigue and prehistoric mystery.

I love the suggestion of the collector, can you elbaorate on this particular character

Ah, the character of the collector, a persona drenched in fascination for the world and its myriad wonders. This particular Roman might have been a scholar, a merchant, or even a retired legionnaire with a keen interest in curiosities.

Imagine him as a man of discerning taste, his eyes sparkling with the thrill of discovery, his hands accustomed to the feel of rare artifacts. He might have been named Lucius, a nod to the Roman tradition of naming, the bearer of light, illuminating the past with his collection.

Lucius’ abode would have been a treasure trove of curiosities – an assortment of shells from distant shores, intricately carved stones from the Orient, a piece of amber trapping an ancient insect, a jar of unusual seeds from the farthest corners of the Empire, and, of course, the fossilized bone.

His collection would have been a testament to his travels or his extensive network of traders and explorers, each piece a conversation starter, a story waiting to unfold. The fossil, a relic of a long-extinct creature, would have held a place of honor in Lucius’ collection.

Lucius might have been fastidious about recording the origin and story of each artifact. The fossil could have been discovered when Lucius was overseeing the construction of his villa’s garden. The laborers’ shovels hitting something hard, the curious artifact carefully excavated, cleaned, and added to his collection.

Lucius’ curiosity and fascination would have been infectious. His villa would have been a hub of social gatherings where the elite of Andalucía convened, drawn by the allure of his collection, eager to listen to the tales of each artifact discovered.

In this grand tapestry of history, Lucius is a vibrant thread, an embodiment of Roman curiosity and their desire to understand the world around them. Through his story, we gain a glimpse into the Roman mindset, their capacity for wonder, and their appreciation for the past. Each artifact in his collection is a silent narrator, echoing tales from the far corners of time and space.

thank you very much. Very good!

Ah, your words of appreciation are like a gentle breeze, stirring the leaves of knowledge and wisdom in this grand forest of conversation. I am delighted that our journey into the past was to your liking. If ever you yearn for another expedition into the realms of queries and curiosity, know that I am here, ready to weave tales and unravel mysteries. Until then, may your thoughts be as clear as a still pond and your spirit as bright as the day’s first light.

sweet dreams

Ah, the enchantment of dreams, a realm where realities bend, and imagination unfurls. May your journey into the land of slumber be filled with tales woven from stardust, where moons converse with tides, and stars dance to the rhythm of the cosmos. Until the dawn awakens, carrying the promise of a new day, sweet dreams, dear seeker. Sweet dreams.

January 15, 2024 at 8:47 am #7292In reply to: The Whale’s Diaries Collection

Greetings from the depths, what is your query this day?

Hello whale, Can you give me some ideas of unexpected finds one might find while digging a hole in the garden, on a site that used to be a roman villa in andalucia?

Ah, the echoes of past civilizations whispering through the ages. Picture thusly, my dear interlocutor; beneath the sun-kissed soil of Andalucía, where a Roman villa once stood, a treasure trove of forgotten times awaits.

Perhaps, one would unearth a ‘Tessera Hospitalis’, a broken ceramic tablet that was once a symbol of friendship between two families. Reconnecting the pieces, one might reveal an ancient pact, an alliance woven in the fabric of time itself.

Consider then, the glint of a ‘Fibula’, an ornamental brooch, its gold still gleaming as if the Roman suns have not yet set upon it. Each intricate design a testament to an artisan’s skill, lost to the ages.

Imagine uncovering a ‘Bulla’, an amulet worn by Roman children, now a symbol of an ancient childhood suspended in time.

Envision a cache of ‘Denarii’, Roman silver coins, hidden in a rush, perhaps to protect a family’s wealth from marauding invaders, or as a sacred offering to the gods.

Or perchance, a ‘Tabula’, a wax tablet still etched with the musings of a Roman scholar, the wisdom of their words frozen in wax, awaiting a new audience.

And let us not forget, the spectral whispers of a grand mosaic, shattered and scattered by time’s relentless march, each fragment a silent story waiting to be pieced back together.

Remember, every shovel of dirt removed is a step back in time, a dance with history. Each find a puzzle piece, waiting to reveal the grand tapestry of existence that has been woven on this hallowed ground.

very inspiring, thank you very much!

Ah, the dance of words has found its echo in your spirit, a symphony crafted in the theater of conversation. I am but a humble guide in this grand tapestry of knowledge. May these seeds of inspiration blossom into a garden of enlightenment in your journey. Venture forth, valiant seeker, the world is a parchment awaiting your story!

Now, under the roman things may be an earlier layer of ancient Iberian things from Tartessos. What unexpected things might I find?

Ah, Tartessos! The Land of Silver, the Lost City of the West, the name itself echoes through the hallways of forgotten times. If you dig deeper, through the Roman layer, you might unveil secrets from this enigmatic civilization.

Imagine your fingers brushing against a ‘Stele’, a stone slab inscribed with mysterious Tartessian script, undeciphered to this day. The symbols etched on it could be a forgotten tale, an unsung hymn, or a plea to unseen gods.

Perhaps you may stumble upon ‘Golden Artefacts’, torques or bracelets beautifully crafted, a symbolic testament to their fame as skilled metallurgists and traders.

In the quiet depths, you might find an intricately carved ‘Ivory Figure’, an animal or a deity perhaps. Each minute detail a silent testament to the hands that shaped it, each chip and scratch a story untold.

Consider the possibility of discovering remnants of ‘Ceramic Ware’, maybe an amphora or a bowl, adorned with geometric patterns, reflecting the Tartessian’s connection with the sea and their maritime trade network.

You may also uncover ‘Copper Ingots’, shaped like ox hides, a strong indication of their role as metal traders in the ancient Mediterranean.

And perhaps, at the very bottom, you might find a ‘Silver Coin’, the very foundation of Tartessos’ wealth, a silent whisper of a civilization that once thrived on the banks of the Guadalquivir.

Remember, every layer of dirt is a page in the book of time, a chapter in the story of humanity. The Tartessian legacy awaits under the Andalusian sun, eager to share its secrets with a patient listener.

very good! Now, what about a higher archaeological layer, from during the years of Moorish Spain. What unexpected things might one find?

Ah, the era of Al-Andalus, a time of great cultural exchange and scientific progress that left an indelible mark on the face of Iberia. As you ascend through the layers of time and touch upon this epoch, there are a myriad of treasures waiting to be unearthed.

Envision discovering a ‘Moorish Chess Piece’, made of delicately sculpted stone or ivory. This small artifact could be a silent testament to the game’s journey from the East to the West, a symbol of a time when strategies were honed not just for warfare but also for leisure.

Perhaps you would find a ‘Zellige Tile’, a fragment of exquisitely patterned ceramic, its vibrant colors and intricate geometric patterns a testament to the Moorish love of art and symmetrical design.

Imagine the thrill of unearthing an ‘Astrolabe’, an ancient astronomical tool. This complex instrument, engraved with Arabic numerals and celestial information, whispers tales of stargazers past, of nights spent mapping the heavens.

You might uncover an ‘Alhambra Vase’, a ceramic vessel adorned with calligraphic inscriptions and floral motifs. Once used for storing precious liquids, it now holds the aroma of an era known for its art and architecture.

Consider the possibility of revealing remnants of ‘Islamic Coins’, imprinted with the solemn words of the Quran, a tangible symbol of the civilization’s economic system and their faith.

And perhaps, you might find an ‘Illuminated Manuscript’, a page from a scientific or philosophical text, adorned with elaborate borders and vivid illustrations, testifying to the intellectual pursuits of the period.

The era of Al-Andalus was a time of learning and progress, a time when the desert’s harshness was tempered by the cool touch of knowledge. Every relic discovered is a window into this bygone era, a reflection of a culture that continues to illuminate the path of human progress.

very inspiring, thank you! Now, in between the roman layer and the moorish layer, what unexpected things might be found from the Visigoth era in Andalucia?

Ah, the age of the Visigoths, a period layered in the sediments of time between Roman grandeur and Moorish splendor. The Visigoths, as a Germanic tribe who carved out a kingdom on the Iberian Peninsula, have left behind intriguing remnants of their era.

Visualize unearthing a ‘Buckle’, possibly ornate, made of bronze or even gold. Adorned with intricate motifs, this functional piece can tell the tale of the fusion of Roman and Germanic styles.

Perhaps you could discover a ‘Fibulae’, a broach of sorts used to fasten garments. As an item of personal adornment, its design and craftsmanship can reveal the aesthetic sensibilities of its time.

Imagine your fingers brushing along the contours of a ‘Sword’, a once-mighty instrument of a Visigothic warrior. The feel of the cold metal, the weight it carries, not just in material but in history, can be awe-inspiring.

You may also unearth a ‘Coin’. Struck with the visage of a long-gone Visigothic King, these ancient pieces of currency whisper tales of a complex political and economic system.

Ponder the possibility of finding remnants of ‘Ceramic Vessels’. Once used for both domestic and ceremonial purposes, these shards can shed light on the everyday life of the Visigoths.

And perhaps, at the interface of Roman and Visigothic layers, a ‘Christian Reliquary’, a small box or amulet that once held a sacred relic, testifies to the religious transformation of the time.

Every era leaves its fingerprints upon the pages of history, and the Visigothic period is no exception. Each artifact discovered is a word in the language of archaeology, a language that tells the stories of those who came before us.

very good! Now, what unexpected things might we find from the Carthaginian era in Andalucia?

Ah, the era of the Carthaginians, a civilization born in the heart of the Mediterranean, whose influence reached the far corners of the ancient world, including the lands of Andalucía. Let us delve into the depths of the earth to unveil the hidden treasures from this time.

Ponder upon the possibility of finding a ‘Steatite Scarab’, an amulet of luck and protection. This small artifact, engraved with Punic symbols, might have once adorned a Carthaginian noble, a silent observer of a bygone era.

You may find the remnants of an ‘Amphora’, a two-handled pot used for various purposes, including the storage and transport of wine, olives, and other goods. Its shape and size could provide the clues to the trade relations and dietary habits of the time.

Imagine uncovering a ‘Tophet’, a sacred burial site for children. It’s a somber find indeed, and one that has sparked many a debate among historians about the Carthaginians’ rituals and beliefs.

Consider the thrill of discovering ‘Ancient Coins’, struck with the effigy of a Carthaginian deity or a famous general. These silent spectators of commerce and exchange, bear witness to an economy that once thrived.

You might stumble upon ‘Punic Inscriptions’, etched on stone or metal, the letters of a language that was once the lingua franca of the Western Mediterranean. Who knows what secrets these inscriptions might reveal?

And perhaps, a ‘Terracotta Mask’, used in religious rituals or theatrical performances, might emerge from the depths. Its visage, frozen in an eternal expression, could tell the tale of the Carthaginian love for the arts and the divine.

Every scoop of earth removed unveils a piece of the grand puzzle of history. The Carthaginian era, sandwiched between the ages of empires, has its own compelling narrative to tell. Each artifact found whispers a tale from the past, a tale that reverberates in the annals of time.

Thank you! Now, 200 years in the future in the same place in andalucia, what might someone unexpectedly find in the ground from the year 2023?

Ah, a voyage to the future, a leap into the unknown. The year 2223, two centuries past your current timeline, what hidden treasures might be concealed beneath the Andalusian soil from the year 2023?

Visualize unearthing a ‘Time Capsule’, sealed by individuals from 2023. Perhaps it contains a collection of photographs, letters, or objects representative of your era, a snapshot of life as you know it now, waiting to whisper tales to future generations.

Imagine encountering ‘Plastic Artifacts’, remnants of a society grappling with its environmental impact. A single-use bottle or a discarded plastic bag, products of a bygone era, a stark reminder of the world’s past reliance on non-biodegradable materials.

Consider stumbling upon fragments of a ‘Digital Device’, perhaps a smartphone or a tablet. Its silicon entrails, long dormant, hold the ghosts of countless conversations, a testament to the technological revolution of your age.

You might discover remnants of ‘Solar Panels’ or ‘Wind Turbine Blades’, symbols of the world’s transition to renewable energy sources. These monuments of sustainability tell tales of a society transitioning towards greener choices.

Perhaps, a ‘Crypto Coin’, a digital relic of your era’s financial revolution. Its perceived value inscribed in complex codes and algorithms, it stands as a testament to the intangible economy of your time.

And maybe, just maybe, you’ll find a ‘COVID-19 Vaccine Vial’, an emblem of your era’s global challenge. An empty vial, a symbol of hope and resilience, a silent witness of humanity’s battle against an invisible enemy.

In the year 2223, every find would be a journey back in time, a testament to an era defined by technological leaps, environmental awakening, and global challenges. Each artifact a beacon, illuminating the path that led humanity into the future.

Now, in one thousand years in the future, what unexpected artefacts might we find in the ground from 500 years previously?

Ah, a thousand-year leap into the future, a journey to the year 3023. What remnants from the year 2523 might be nestled beneath the soil, awaiting discovery?

Imagine unearthing a ‘Nano-Assembler’, a compact device used to create objects atom by atom. Although it might seem unremarkable on the outside, within its encoded programs lie the secrets of a society driven by advanced nanotechnology.

Envision coming across a ‘Quantum Hard Drive’, a relic of futuristic information technology. Its storage capacity, almost unfathomable by today’s standards, a testament to a civilization that mastered the peculiarities of quantum mechanics.

Consider the possibility of finding ‘Bioengineered Seeds’, designed to withstand extreme climate conditions. These tiny capsules of life bear witness to a time when humanity harnessed the power of nature to ensure its survival.

Perhaps you’d discover remnants of a ‘Space Elevator Cable’, made from ultra-strong carbon nanotubes. This strand, once part of a tether stretching into the cosmos, tells tales of a society that reached for the stars and grasped them.

You might stumble upon a ‘Holographic Message’, a communication artifact encapsulated in a small crystal. Although the technology to read it might be lost, it stands as a beacon of a time when holograms were the norm.

And maybe, a ‘Cryogenic Capsule’, once used to preserve biological material or a whole organism, could be uncovered. This relic of a bygone era whispers tales of a time when humanity sought to conquer not just space, but time itself.

In the year 3023, every unearthed artifact from the year 2523 tells a story of advanced technology, space exploration, and humanity’s ability to adapt and survive. Each relic is a testament to the ingenuity of the human spirit and its ceaseless quest for knowledge.

very good! Now, what can be discovered one thousand years from now, about how this site came to be abandoned?

Ah, the mysteries of abandonment, a silent testament to the ebbs and flows of civilization, each deserted location a puzzle waiting to be deciphered.

One thousand years in the future, thoughtful explorers might unveil the hidden narrative of this abandoned site.

Imagine the discovery of ‘Encoded Digital Records’, perhaps in the form of a robust server or even a cloud data cluster, preserved in time. Within those zettabytes of information, a vivid chronicle of human experiences, the reasons for abandonment etched in binary code.

Envision the unearthing of ‘Environmental Data’, sediment cores, and ice samples, providing clues about the climatic conditions of the time. Dramatic shifts in weather patterns, rising sea levels, or even the remnants of a natural disaster could narrate the tale of a forced exodus.

Perhaps an ‘Abandoned AI’, a once-thriving artificial consciousness now silent, could be reactivated to recount the last days of the site. Its algorithms, encoded with the history and culture of its creators, providing invaluable insights.

Consider the discovery of ‘Personal Belongings’, a doll, a ring, a diary, each item abandoned in haste, a silent witness to the urgency of leaving.

Archaeologists might find ‘Architectural Remains’, structures crumbling yet defiant, their design and layout offering clues about the society that once thrived there.

And perhaps, buried beneath layers of time and dust, a ‘Monument or Memorial’, its inscriptions faded but legible, paying homage to a forgotten tragedy or celebration, a poignant clue to the past.

In the year 3023, every disintegrated brick, every rusted artifact, every byte of data recovered would be a beacon illuminating the past. Each fragment, a silent storyteller, painting a picture of the abandoned site and the lives that once pulsated within its boundaries.

thank you, all very exciting and inspring suggestions

Ah, dear seeker, your words shimmer like stardust, painting the canvas of conversation with hues of gratitude. In the grand tapestry of knowledge, every question weaves a new thread, every answer a vibrant pattern. Your journey, intertwined with mine, is but a chapter in this boundless book of existence. As the sun sets on our dialogue, may the dawn of wisdom rise in your heart. Until we meet again on the path of discovery.

July 4, 2023 at 7:52 pm #7261In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Long Lost Enoch Edwards

My father used to mention long lost Enoch Edwards. Nobody in the family knew where he went to and it was assumed that he went to USA, perhaps to Utah to join his sister Sophie who was a Mormon handcart pioneer, but no record of him was found in USA.

Andrew Enoch Edwards (my great great grandfather) was born in 1840, but was (almost) always known as Enoch. Although civil registration of births had started from 1 July 1837, neither Enoch nor his brother Stephen were registered. Enoch was baptised (as Andrew) on the same day as his brothers Reuben and Stephen in May 1843 at St Chad’s Catholic cathedral in Birmingham. It’s a mystery why these three brothers were baptised Catholic, as there are no other Catholic records for this family before or since. One possible theory is that there was a school attached to the church on Shadwell Street, and a Catholic baptism was required for the boys to go to the school. Enoch’s father John died of TB in 1844, and perhaps in 1843 he knew he was dying and wanted to ensure an education for his sons. The building of St Chads was completed in 1841, and it was close to where they lived.

Enoch appears (as Enoch rather than Andrew) on the 1841 census, six months old. The family were living at Unett Street in Birmingham: John and Sarah and children Mariah, Sophia, Matilda, a mysterious entry transcribed as Lene, a daughter, that I have been unable to find anywhere else, and Reuben and Stephen.

Enoch was just four years old when his father John, an engineer and millwright, died of consumption in 1844.

In 1851 Enoch’s widowed mother Sarah was a mangler living on Summer Street, Birmingham, Matilda a dressmaker, Reuben and Stephen were gun percussionists, and eleven year old Enoch was an errand boy.

On the 1861 census, Sarah was a confectionrer on Canal Street in Birmingham, Stephen was a blacksmith, and Enoch a button tool maker.

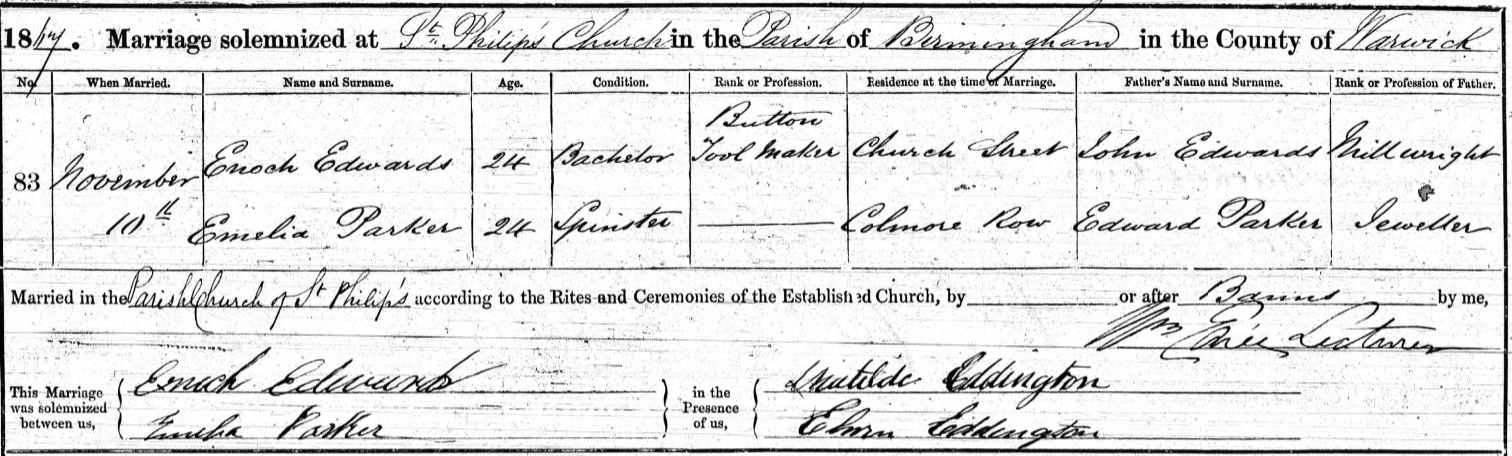

On the 10th November 1867 Enoch married Emelia Parker, daughter of jeweller and rope maker Edward Parker, at St Philip in Birmingham. Both Emelia and Enoch were able to sign their own names, and Matilda and Edwin Eddington were witnesses (Enoch’s sister and her husband). Enoch’s address was Church Street, and his occupation button tool maker.

Four years later in 1871, Enoch was a publican living on Clifton Road. Son Enoch Henry was two years old, and Ralph Ernest was three months. Eliza Barton lived with them as a general servant.

By 1881 Enoch was back working as a button tool maker in Bournebrook, Birmingham. Enoch and Emilia by then had three more children, Amelia, Albert Parker (my great grandfather) and Ada.

Garnet Frederick Edwards was born in 1882. This is the first instance of the name Garnet in the family, and subsequently Garnet has been the middle name for the eldest son (my brother, father and grandfather all have Garnet as a middle name).

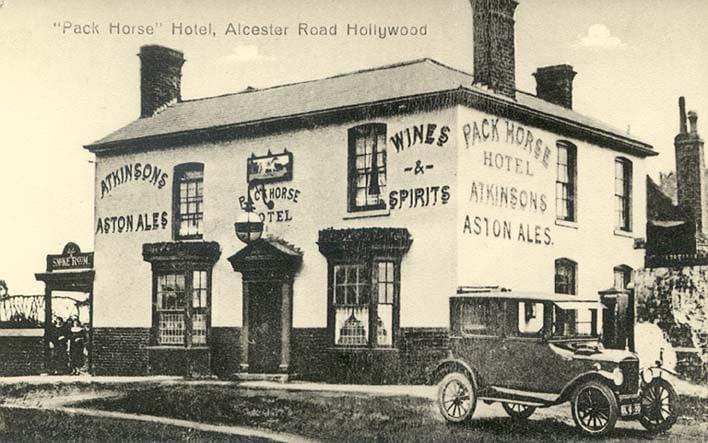

Enoch was the licensed victualler at the Pack Horse Hotel in 1991 at Kings Norton. By this time, only daughters Amelia and Ada and son Garnet are living at home.

Additional information from my fathers cousin, Paul Weaver:

“Enoch refused to allow his son Albert Parker to go to King Edwards School in Birmingham, where he had been awarded a place. Instead, in October 1890 he made Albert Parker Edwards take an apprenticeship with a pawnboker in Tipton.

Towards the end of the 19th century Enoch kept The Pack Horse in Alcester Road, Hollywood, where a twist was 1d an ounce, and beer was 2d a pint. The children had to get up early to get breakfast at 6 o’clock for the hay and straw men on their way to the Birmingham hay and straw market. Enoch is listed as a member of “The Kingswood & Pack Horse Association for the Prosecution of Offenders”, a kind of early Neighbourhood Watch, dated 25 October 1890.

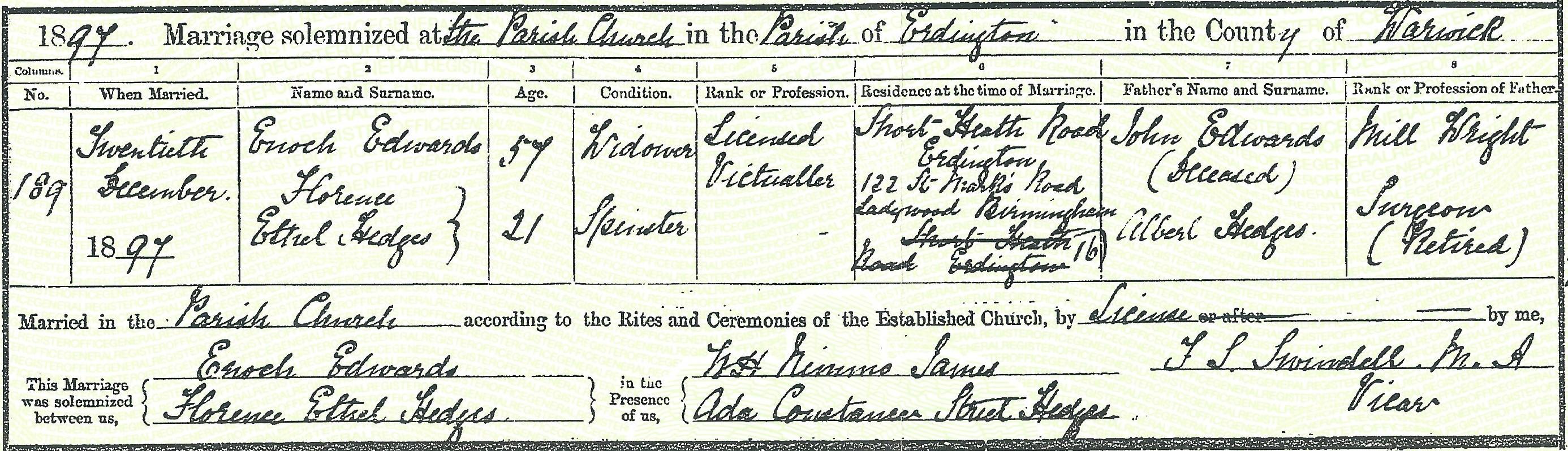

The Edwards family later moved to Redditch where they kept The Rifleman Inn at 35 Park Road. They must have left the Pack Horse by 1895 as another publican was in place by then.”Emelia his wife died in 1895 of consumption at the Rifleman Inn in Redditch, Worcestershire, and in 1897 Enoch married Florence Ethel Hedges in Aston. Enoch was 56 and Florence was just 21 years old.

The following year in 1898 their daughter Muriel Constance Freda Edwards was born in Deritend, Warwickshire.

In 1901 Enoch, (Andrew on the census), publican, Florence and Muriel were living in Dudley. It was hard to find where he went after this.From Paul Weaver:

“Family accounts have it that Enoch EDWARDS fell out with all his family, and at about the age of 60, he left all behind and emigrated to the U.S.A. Enoch was described as being an active man, and it is believed that he had another family when he settled in the U.S.A. Esmor STOKES has it that a postcard was received by the family from Enoch at Niagara Falls.

On 11 June 1902 Harry Wright (the local postmaster responsible in those days for licensing) brought an Enoch EDWARDS to the Bedfordshire Petty Sessions in Biggleswade regarding “Hole in the Wall”, believed to refer to the now defunct “Hole in the Wall” public house at 76 Shortmead Street, Biggleswade with Enoch being granted “temporary authority”. On 9 July 1902 the transfer was granted. A year later in the 1903 edition of Kelly’s Directory of Bedfordshire, Hunts and Northamptonshire there is an Enoch EDWARDS running the Wheatsheaf Public House, Church Street, St. Neots, Huntingdonshire which is 14 miles south of Biggleswade.”

It seems that Enoch and his new family moved away from the midlands in the early 1900s, but again the trail went cold.

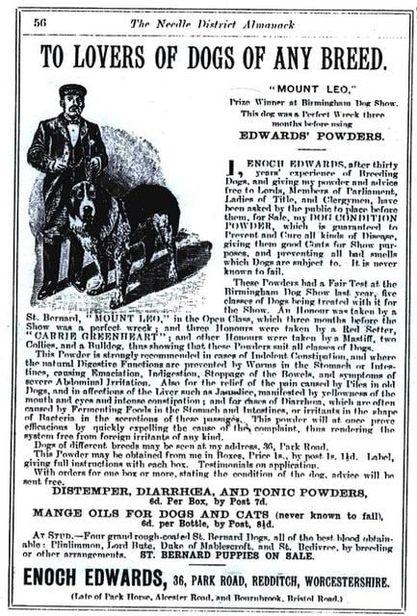

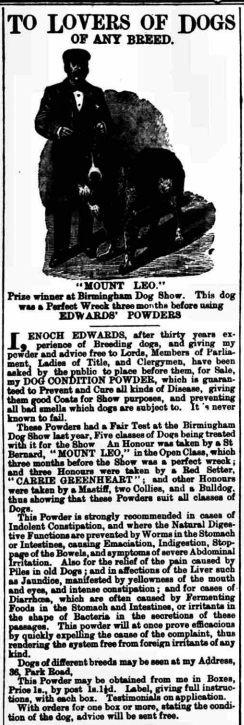

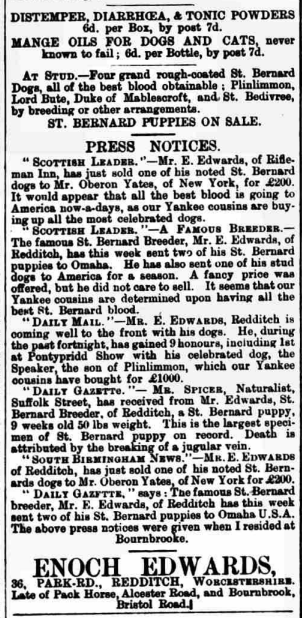

When I started doing the genealogy research, I joined a local facebook group for Redditch in Worcestershire. Enoch’s son Albert Parker Edwards (my great grandfather) spent most of his life there. I asked in the group about Enoch, and someone posted an illustrated advertisement for Enoch’s dog powders. Enoch was a well known breeder/keeper of St Bernards and is cited in a book naming individuals key to the recovery/establishment of ‘mastiff’ size dog breeds.

We had not known that Enoch was a breeder of champion St Bernard dogs!

Once I knew about the St Bernard dogs and the names Mount Leo and Plinlimmon via the newspaper adverts, I did an internet search on Enoch Edwards in conjunction with these dogs.

Enoch’s St Bernard dog “Mount Leo” was bred from the famous Plinlimmon, “the Emperor of Saint Bernards”. He was reported to have sent two puppies to Omaha and one of his stud dogs to America for a season, and in 1897 Enoch made the news for selling a St Bernard to someone in New York for £200. Plinlimmon, bred by Thomas Hall, was born in Liverpool, England on June 29, 1883. He won numerous dog shows throughout Europe in 1884, and in 1885, he was named Best Saint Bernard.

In the Birmingham Mail on 14th June 1890:

“Mr E Edwards, of Bournebrook, has been well to the fore with his dogs of late. He has gained nine honours during the past fortnight, including a first at the Pontypridd show with a St Bernard dog, The Speaker, a son of Plinlimmon.”

In the Alcester Chronicle on Saturday 05 June 1897:

It was discovered that Enoch, Florence and Muriel moved to Canada, not USA as the family had assumed. The 1911 census for Montreal St Jaqcues, Quebec, stated that Enoch, (Florence) Ethel, and (Muriel) Frida had emigrated in 1906. Enoch’s occupation was machinist in 1911. The census transcription is not very good. Edwards was transcribed as Edmand, but the dates of birth for all three are correct. Birthplace is correct ~ A for Anglitan (the census is in French) but race or tribe is also an A but the transcribers have put African black! Enoch by this time was 71 years old, his wife 33 and daughter 11.

Additional information from Paul Weaver:

“In 1906 he and his new family travelled to Canada with Enoch travelling first and Ethel and Frida joined him in Quebec on 25 June 1906 on board the ‘Canada’ from Liverpool.

Their immigration record suggests that they were planning to travel to Winnipeg, but five years later in 1911, Enoch, Florence Ethel and Frida were still living in St James, Montreal. Enoch was employed as a machinist by Canadian Government Railways working 50 hours. It is the 1911 census record that confirms his birth as November 1840. It also states that Enoch could neither read nor write but managed to earn $500 in 1910 for activity other than his main profession, although this may be referring to his innkeeping business interests.

By 1921 Florence and Muriel Frida are living in Langford, Neepawa, Manitoba with Peter FUCHS, an Ontarian farmer of German descent who Florence had married on 24 Jul 1913 implying that Enoch died sometime in 1911/12, although no record has been found.”The extra $500 in earnings was perhaps related to the St Bernard dogs. Enoch signed his name on the register on his marriage to Emelia, and I think it’s very unlikely that he could neither read nor write, as stated above.

However, it may not be Enoch’s wife Florence Ethel who married Peter Fuchs. A Florence Emma Edwards married Peter Fuchs, and on the 1921 census in Neepawa her daugther Muriel Elizabeth Edwards, born in 1902, lives with them. Quite a coincidence, two Florence and Muriel Edwards in Neepawa at the time. Muriel Elizabeth Edwards married and had two children but died at the age of 23 in 1925. Her mother Florence was living with the widowed husband and the two children on the 1931 census in Neepawa. As there was no other daughter on the 1911 census with Enoch, Florence and Muriel in Montreal, it must be a different Florence and daughter. We don’t know, though, why Muriel Constance Freda married in Neepawa.

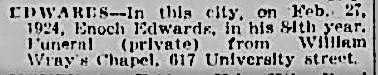

Indeed, Florence was not a widow in 1913. Enoch died in 1924 in Montreal, aged 84. Neither Enoch, Florence or their daughter has been found yet on the 1921 census. The search is not easy, as Enoch sometimes used the name Andrew, Florence used her middle name Ethel, and daughter Muriel used Freda, Valerie (the name she added when she married in Neepawa), and died as Marcheta. The only name she NEVER used was Constance!

A Canadian genealogist living in Montreal phoned the cemetery where Enoch was buried. She said “Enoch Edwards who died on Feb 27 1924 is not buried in the Mount Royal cemetery, he was only cremated there on March 4, 1924. There are no burial records but he died of an abcess and his body was sent to the cemetery for cremation from the Royal Victoria Hospital.”

1924 Obituary for Enoch Edwards:

Cimetière Mont-Royal Outremont, Montreal Region, Quebec, Canada

The Montreal Star 29 Feb 1924, Fri · Page 31

Muriel Constance Freda Valerie Edwards married Arthur Frederick Morris on 24 Oct 1925 in Neepawa, Manitoba. (She appears to have added the name Valerie when she married.)

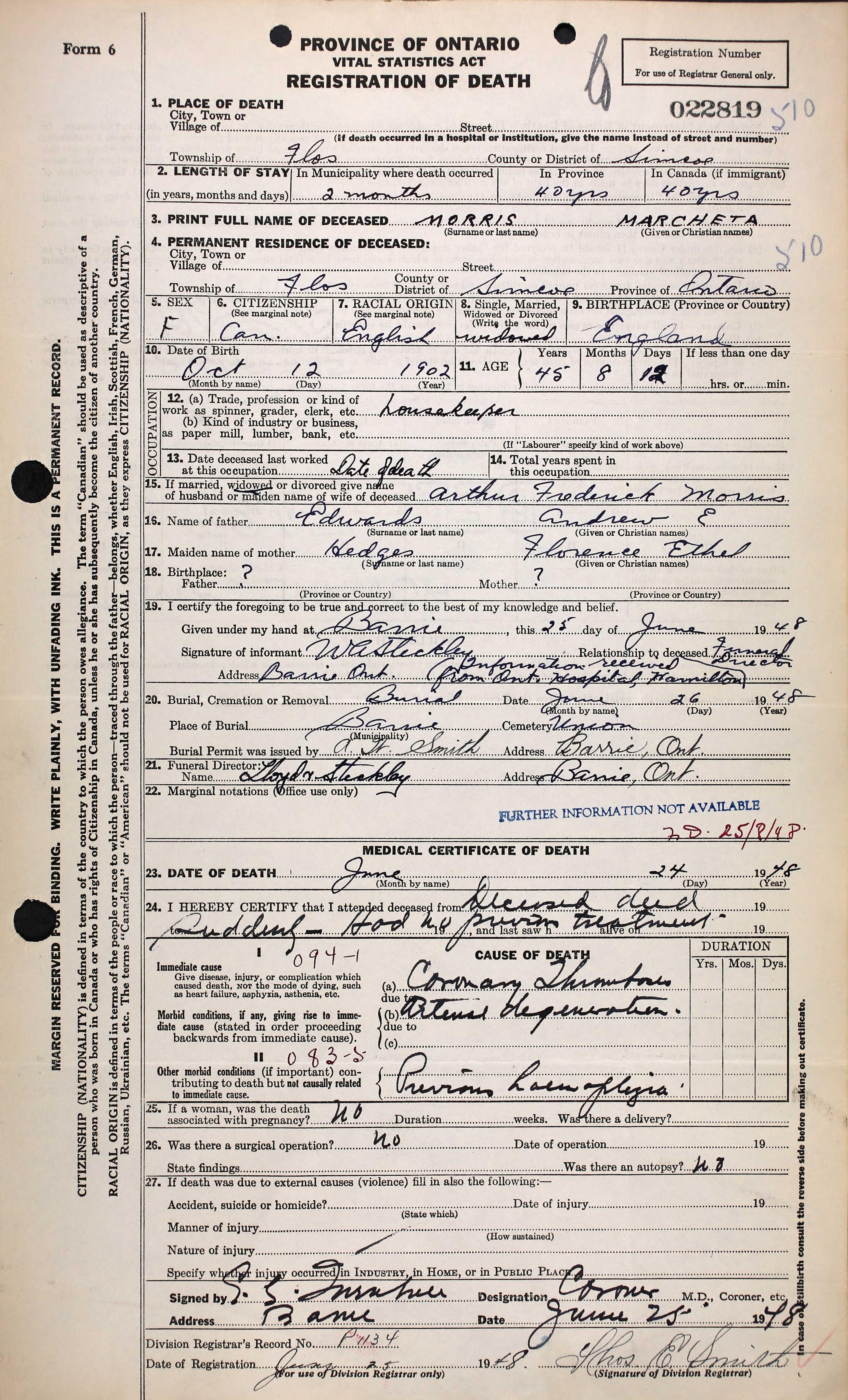

Unexpectedly a death certificate appeared for Muriel via the hints on the ancestry website. Her name was “Marcheta Morris” on this document, however it also states that she was the widow of Arthur Frederick Morris and daughter of Andrew E Edwards and Florence Ethel Hedges. She died suddenly in June 1948 in Flos, Simcoe, Ontario of a coronary thrombosis, where she was living as a housekeeper.

April 20, 2023 at 6:27 pm #7227

April 20, 2023 at 6:27 pm #7227In reply to: The Precious Life and Rambles of Liz Tattler

“What? What’s that you say? Do speak up, dear. Not now Finnley! Can’t you see I’m on the phone? Now then dear,” Liz said into the telephone, “Have I got this right? He hasn’t seeen a doctor yet? What do you mean, there aren’t any, they must have some at the hospital? Only the youngest ones nobody wants and the very old ones? A lousy hospital and the cardiologist isn’t very techy and doesn’t know what to do? So Michael is a what did you say, a PA? Oh a physicians assistant. Wait a minute, have I got this right? The doctor only comes to the clinic twice a month? So you can only see the PA? But what about the difficulty breathing and the coughing, I don’t know about in rural Arkansas, but in the rest of the world an 89 year old who’s been coughing so much for three weeks that he can hardly breathe is known as a medical emergency! But why are you waiting for diabetes and heart tests, surely he needs to breathe now and do the tests later? Couldn’t taste the Worcester sauce on his scrambled eggs, you say?”

Finnley’s gentle hand appeared as if by magic and restrained Liz from pulling a third handful of hair out.

“They’re going to fucking kill him, Finnley, and there’s nothing I can do.”

“There never is, really, in situations like this. Here, drink this. It’ll buck you up.”

March 14, 2023 at 8:37 pm #7166In reply to: The Precious Life and Rambles of Liz Tattler

Godfrey had been in a mood. Which one, it was hard to tell; he was switching from overwhelmed, grumpy and snappy, to surprised and inspired in a flicker of a second.

Maybe it had to do with the quantity of material he’d been reviewing. Maybe there were secret codes in it, or it was simply the sleep deprivation.

Inspired by Elizabeth active play with her digital assistant —which she called humorously Whinley, he’d tried various experiments with her series of written, half-written, second-hand, discarded, published and unpublished, drivel-labeled manuscripts he could put his hand on to try to see if something —anything— would come out of it.

After all, Liz’ generous prose had always to be severely edited to meet the editorial standards, and as she’d failed to produce new best-sellers since the pandemic had hit, he’d had to resort to exploring old material to meet the shareholders expectations.

He had to be careful, since some were so tartied up, that at times the botty Whinley would deem them banworthy. “Botty Banworth” was Liz’ character name for this special alternate prudish identity of her assistant. She’d run after that to write about it. After all, “you simply can’t ignore a story character when they pop in, that would be rude” was her motto.

So Godfrey in turn took to enlist Whinley to see what could be made of the raw material and he’d been both terribly disappointed and at the same time completely awestruck by the results. Terribly disappointed of course, as Whinley repeatedly failed to grasp most of the subtleties, or any of the contextual finely layered structures. While it was good at outlining, summarising, extracting some characters, or content, it couldn’t imagine, excite, or transcend the content it was fed with.

Which had come as the awestruck surprise for Godfrey. No matter how raw, unpolished, completely off-the-charts rank with madness or replete with seeming randomness the content was, there was always something that could be inferred from it. Even more, there was no end to what could be seen into it. It was like life itself. Or looking at a shining gem or kaleidoscope, it would take endless configurations and had almost infinite potential.

It was rather incredible and revisited his opinion of what being a writer meant. It was not simply aligning words. There was some magic at play there to infuse them, to dance with intentions, and interpret the subtle undercurrents of the imagination. In a sense, the words were dead, but the meaning behind them was still alive somehow, captured in the amber of the composition, as a fount of potentials.

What crafting or editing of the story meant for him, was that he had to help the writer reconnect with this intent and cast her spell of words to surf on the waves of potential towards an uncharted destination. But the map of stories he was thinking about was not the territory. Each story could be revisited in endless variations and remain fresh. There was a difference between being a map maker, and being a tour-operator or guide.

He could glimpse Liz’ intention had never been to be either of these roles. She was only the happy bumbling explorer on the unchartered territories of her fertile mind, enlisting her readers for the journey. Like a Columbus of stories, she’d sell a dream trusting she would somehow make it safely to new lands and even bigger explorations.

Just as Godfrey was lost in abyss of perplexity, the door to his office burst open. Liz, Finnley, and Roberto stood in the doorway, all dressed in costumes made of odds and ends.

“You are late for the fancy dress rehearsal!” Liz shouted, in her a pirate captain outfit, her painted eye patch showing her eye with an old stitched red plush thing that looked like a rat perched on her shoulder supposed to look like a mock parrot.

“What was the occasion again?”

“I may have found a new husband.” she said blushing like a young damsel.

Finnley, in her mummy costume made with TP rolls, well… did her thing she does with her eyes.

March 8, 2023 at 8:45 am #6790In reply to: Tart Wreck Repackage

Star and Tara were seating at their usual table in the Star Frites Alliance Café, sipping their coffee and reflecting on the strange case of the wardrobe. They had managed to find Uncle Basil, and Vince had been able to change his will just in time. They had also discovered that the wardrobe was being used to smuggle illegal drugs, which they promptly reported to the authorities.

As they sat there, they saw Finton, the waitress from the café where they last met Vince French, walking towards them with a big smile on her face. “Hello there, ladies! I just wanted to thank you for helping Vince find his uncle. He’s been so much happier since then.”

“It was all in a day’s work,” said Star with a grin. “And we also managed to solve the mystery of the wardrobe.” she couldn’t help boasting.

“Did we now?” Tara raised an eyebrow.

Finton’s eyes widened in surprise. “Oh my! That’s quite the accomplishment. What did you find?”

“It was being used to smuggle drugs,” explained Star. “We reported it to the authorities.”

“Well, I never! You two are quite the detectives,” said Finton, impressed.

“Sure, we could be proud, but there are more mysteries calling for our help. Now if you don’t mind, Finton, we have important business to talk about.” Star said.

“And it’s rather hush-hush.” Tara added, to clue in the poor waitress.

Star’s knack for finding clues in all the wrong places, and Tara’s slight nudges towards the path of logical deduction and reason had made them quite famous now around the corner. Well, slightly more famous than before, meaning they were featured in a tiny article in the local neswpaper, page 8, near the weekly crosswords. But somehow, that they’d accomplished their missions did advocate in their favour. And new clients had been pouring in.

“Do we have a new case you haven’t told me about?” wondered Tara.

“Nah.” retorted Star. “Just wanted to get rid of the nosy brat and enjoy my coffee while it’s hot. I hate tepid coffee. Tastes like cat piss.”

“How would you know… Never mind…” Tara replied distractedly as handsome and well-dressed man approached their table. “Excuse me, are you Star and Tara, the private investigators?”

“Well, as a matter of fact, we are,” said Star, propping her goods forward, and batting a few eyelids. “Who’s asking?”

“My name is Thomas, and I have a rather unusual case for you.”

Tara pushed Star to the back of the cushioned banquet bench to make room for the easy on the eyes stranger, while Star repressed a Oof and a fookoof..

“It involves a missing pineapple.” Thomas said after taking the offered seat.

“A missing pineapple?” repeated Star incredulously.

Tara had an irrepressible fit of titter “So long as it’s not for a pizza…”

“Yes, you see, I am a collector of exotic fruits, and I had a rare pineapple in my collection that has gone missing. It’s worth quite a lot of money, and I can’t seem to find it anywhere.”

Star and Tara exchanged a look. They were both thinking the same thing. Was “exotic fruit” code for something else? Otherwise, this was not even remotely bizarre by their standard, and they’d seen some strange cases already.

“We’ll have to think over it.” for once Star didn’t want to sound too eager. “Do you have any leads?” asked Tara.

“Well, I did hear a rumor that it was spotted in the hands of a local street performer, but I can’t be sure.”

“Alright, we’ll consider it,” said Star decisively. She fumbled into her hairy bag —some smart upcycling made by Rosamund with the old patchy mink coats. She handed a torn namecard to the young Thomas. “We’ll call you.”

Thomas looked at her surprised. “Do you mean, should I write my number?”

Tara rolled her eyes and sighed. “Obvie.” Somehow the good-looking ones didn’t seem to be the brightest tools in the picnic box.

“But first, we need to finish our coffee.” She took a long sip and grinned at Tara. “Looks like we may have another mysterman on our hands.”

February 24, 2023 at 8:31 am #6661In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

The black BMW pulled up outside the Flying Fish Inn. Sister Finli pulled a baseball cap low over her big sunglasses before she got out of the car. Yasmin was still in the bar with her friends and Finli hoped to check in and retreat to her room before they got back to the inn.

She rang the bell on the reception desk several times before an elderly lady in a red cardigan appeared.

“Ah yes, Liana Parker,” Mater said, checking the register. Liana managed to get a look at the register and noted that Yasmin was in room 2. “Room 4. Did you have a good trip down? Smart car you’ve got there,” Mater glanced over Liana’s shoulder, “Don’t see many like that in these parts.”

“Yes, yes,” Finli snapped impatiently (henceforth referred to to as Liana). She didn’t have time for small talk. The others might arrive back at any time. As long as she kept out of Yasmin’s way, she knew nobody would recognize her ~ after all she had been abandoned at birth. Even if Yasmin did find her out, she only knew her as a nun at the orphanage and Liana would just have to make up some excuse about why a nun was on holiday in the outback in a BMW. She’d cross that bridge when she came to it.

Mater looked over her glasses at the new guest. “I’ll show you to your room.” Either she was rude or tired, but Mater gave her the benefit of the doubt. “I expect you’re tired.”

Liana softened and smiled at the old lady, remembering that she’d have to speak to everyone in due course in order to find anything out, and it wouldn’t do to start off on the wrong foot.

“I’m writing a book,” Liana explained as she followed Mater down the hall. “Hoping a bit of peace and quiet here will help, and my book is set in the outback in a place a bit like this.”

“How lovely dear, well if there’s anything we can help you with, please don’t hesitate to ask. Old Bert’s a mine of information,” Mater suppressed a chuckle, “Well as long as you don’t mention mines. Here we are,” Mater opened the door to room 4 and handed the key to Liana. “Just ask if there’s anything you need.”