Search Results for 'chill'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

January 19, 2023 at 10:49 am #6419

In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

“I’d advise you not to take the parrot, Zara,” Harry the vet said, “There are restrictions on bringing dogs and other animals into state parks, and you can bet some jobsworth official will insist she stays in a cage at the very least.”

“Yeah, you’re right, I guess I’ll leave her here. I want to call in and see my cousin in Camden on the way to the airport in Sydney anyway. He has dozens of cats, I’d hate for anything to happen to Pretty Girl,” Zara replied.

“Is that the distant cousin you met when you were doing your family tree?” Harry asked, glancing up from the stitches he was removing from a wounded wombat. “There, he’s good to go. Give him a couple more days, then he can be released back where he came from.”

Zara smiled at Harry as she picked up the animal. “Yes! We haven’t met in person yet, and he’s going to show me the church my ancestor built. He says people have been spotting ghosts there lately, and there are rumours that it’s the ghost of the old convict Isaac who built it. If I can’t find photos of the ancestors, maybe I can get photos of their ghosts instead,” Zara said with a laugh.

“Good luck with that,” Harry replied raising an eyebrow. He liked Zara, she was quirkier than the others.

Zara hadn’t found it easy to research her mothers family from Bangalore in India, but her fathers English family had been easy enough. Although Zara had been born in England and emigrated to Australia in her late 20s, many of her ancestors siblings had emigrated over several generations, and Zara had managed to trace several down and made contact with a few of them. Isaac Stokes wasn’t a direct ancestor, he was the brother of her fourth great grandfather but his story had intrigued her. Sentenced to transportation for stealing tools for his work as a stonemason seemed to have worked in his favour. He built beautiful stone buildings in a tiny new town in the 1800s in the charming style of his home town in England.

Zara planned to stay in Camden for a couple of days before meeting the others at the Flying Fish Inn, anticipating a pleasant visit before the crazy adventure started.

Zara stepped down from the bus, squinting in the bright sunlight and looking around for her newfound cousin Bertie. A lanky middle aged man in dungarees and a red baseball cap came forward with his hand extended.

“Welcome to Camden, Zara I presume! Great to meet you!” he said shaking her hand and taking her rucksack. Zara was taken aback to see the family resemblance to her grandfather. So many scattered generations and yet there was still a thread of familiarity. “I bet you’re hungry, let’s go and get some tucker at Belle’s Cafe, and then I bet you want to see the church first, hey? Whoa, where’d that dang parrot come from?” Bertie said, ducking quickly as the bird swooped right in between them.

“Oh no, it’s Pretty Girl!” exclaimed Zara. “She wasn’t supposed to come with me, I didn’t bring her! How on earth did you fly all this way to get here the same time as me?” she asked the parrot.

“Pretty Girl has her ways, don’t forget to feed the parrot,” the bird replied with a squalk that resembled a mirthful guffaw.

“That’s one strange parrot you got here, girl!” Bertie said in astonishment.

“Well, seeing as you’re here now, Pretty Girl, you better come with us,” Zara said.

“Obviously,” replied Pretty Girl. It was hard to say for sure, but Zara was sure she detected an avian eye roll.

They sat outside under a sunshade to eat rather than cause any upset inside the cafe. Zara fancied an omelette but Pretty Girl objected, so she ordered hash browns instead and a fruit salad for the parrot. Bertie was a good sport about the strange talking bird after his initial surprise.

Bertie told her a bit about the ghost sightings, which had only started quite recently. They started when I started researching him, Zara thought to herself, almost as if he was reaching out. Her imagination was running riot already.

Bertie showed Zara around the church, a small building made of sandstone, but no ghost appeared in the bright heat of the afternoon. He took her on a little tour of Camden, once a tiny outpost but now a suburb of the city, pointing out all the original buildings, in particular the ones that Isaac had built. The church was walking distance of Bertie’s house and Zara decided to slip out and stroll over there after everyone had gone to bed.

Bertie had kindly allowed Pretty Girl to stay in the guest bedroom with her, safe from the cats, and Zara intended that the parrot stay in the room, but Pretty Girl was having none of it and insisted on joining her.

“Alright then, but no talking! I don’t want you scaring any ghost away so just keep a low profile!”

The moon was nearly full and it was a pleasant walk to the church. Pretty Girl fluttered from tree to tree along the sidewalk quietly. Enchanting aromas of exotic scented flowers wafted into her nostrils and Zara felt warmly relaxed and optimistic.

Zara was disappointed to find that the church was locked for the night, and realized with a sigh that she should have expected this to be the case. She wandered around the outside, trying to peer in the windows but there was nothing to be seen as the glass reflected the street lights. These things are not done in a hurry, she reminded herself, be patient.

Sitting under a tree on the grassy lawn attempting to open her mind to receiving ghostly communications (she wasn’t quite sure how to do that on purpose, any ghosts she’d seen previously had always been accidental and unexpected) Pretty Girl landed on her shoulder rather clumsily, pressing something hard and chill against her cheek.

“I told you to keep a low profile!” Zara hissed, as the parrot dropped the key into her lap. “Oh! is this the key to the church door?”

It was hard to see in the dim light but Zara was sure the parrot nodded, and was that another avian eye roll?

Zara walked slowly over the grass to the church door, tingling with anticipation. Pretty Girl hopped along the ground behind her. She turned the key in the lock and slowly pushed open the heavy door and walked inside and up the central aisle, looking around. And then she saw him.

Zara gasped. For a breif moment as the spectral wisps cleared, he looked almost solid. And she could see his tattoos.

“Oh my god,” she whispered, “It is really you. I recognize those tattoos from the description in the criminal registers. Some of them anyway, it seems you have a few more tats since you were transported.”

“Aye, I did that, wench. I were allays fond o’ me tats, does tha like ’em?”

He actually spoke to me! This was beyond Zara’s wildest hopes. Quick, ask him some questions!

“If you don’t mind me asking, Isaac, why did you lie about who your father was on your marriage register? I almost thought it wasn’t you, you know, that I had the wrong Isaac Stokes.”

A deafening rumbling laugh filled the building with echoes and the apparition dispersed in a labyrinthine swirl of tattood wisps.

“A story for another day,” whispered Zara, “Time to go back to Berties. Come on Pretty Girl. And put that key back where you found it.”

December 6, 2022 at 2:17 pm #6350

December 6, 2022 at 2:17 pm #6350In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Transportation

Isaac Stokes 1804-1877

Isaac was born in Churchill, Oxfordshire in 1804, and was the youngest brother of my 4X great grandfather Thomas Stokes. The Stokes family were stone masons for generations in Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire, and Isaac’s occupation was a mason’s labourer in 1834 when he was sentenced at the Lent Assizes in Oxford to fourteen years transportation for stealing tools.

Churchill where the Stokes stonemasons came from: on 31 July 1684 a fire destroyed 20 houses and many other buildings, and killed four people. The village was rebuilt higher up the hill, with stone houses instead of the old timber-framed and thatched cottages. The fire was apparently caused by a baker who, to avoid chimney tax, had knocked through the wall from her oven to her neighbour’s chimney.

Isaac stole a pick axe, the value of 2 shillings and the property of Thomas Joyner of Churchill; a kibbeaux and a trowel value 3 shillings the property of Thomas Symms; a hammer and axe value 5 shillings, property of John Keen of Sarsden.

(The word kibbeaux seems to only exists in relation to Isaac Stokes sentence and whoever was the first to write it was perhaps being creative with the spelling of a kibbo, a miners or a metal bucket. This spelling is repeated in the criminal reports and the newspaper articles about Isaac, but nowhere else).

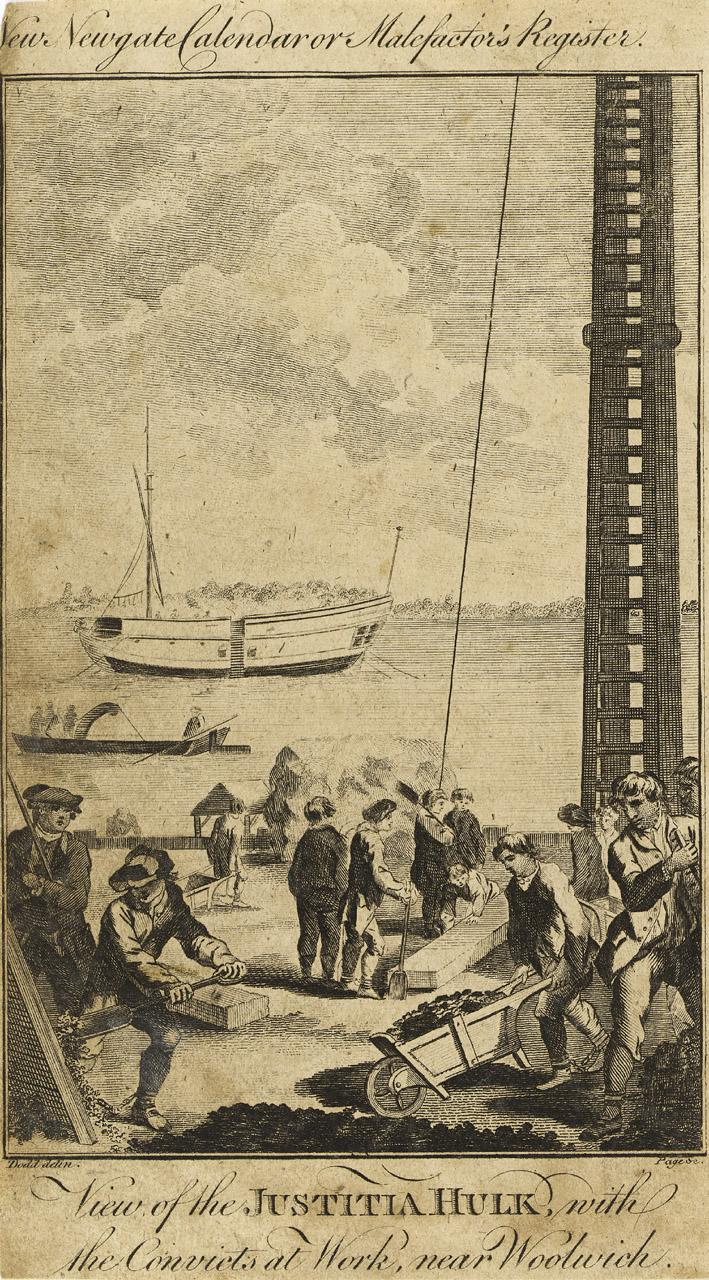

In March 1834 the Removal of Convicts was announced in the Oxford University and City Herald: Isaac Stokes and several other prisoners were removed from the Oxford county gaol to the Justitia hulk at Woolwich “persuant to their sentences of transportation at our Lent Assizes”.

via digitalpanopticon:

Hulks were decommissioned (and often unseaworthy) ships that were moored in rivers and estuaries and refitted to become floating prisons. The outbreak of war in America in 1775 meant that it was no longer possible to transport British convicts there. Transportation as a form of punishment had started in the late seventeenth century, and following the Transportation Act of 1718, some 44,000 British convicts were sent to the American colonies. The end of this punishment presented a major problem for the authorities in London, since in the decade before 1775, two-thirds of convicts at the Old Bailey received a sentence of transportation – on average 283 convicts a year. As a result, London’s prisons quickly filled to overflowing with convicted prisoners who were sentenced to transportation but had no place to go.

To increase London’s prison capacity, in 1776 Parliament passed the “Hulks Act” (16 Geo III, c.43). Although overseen by local justices of the peace, the hulks were to be directly managed and maintained by private contractors. The first contract to run a hulk was awarded to Duncan Campbell, a former transportation contractor. In August 1776, the Justicia, a former transportation ship moored in the River Thames, became the first prison hulk. This ship soon became full and Campbell quickly introduced a number of other hulks in London; by 1778 the fleet of hulks on the Thames held 510 prisoners.

Demand was so great that new hulks were introduced across the country. There were hulks located at Deptford, Chatham, Woolwich, Gosport, Plymouth, Portsmouth, Sheerness and Cork.The Justitia via rmg collections:

Convicts perform hard labour at the Woolwich Warren. The hulk on the river is the ‘Justitia’. Prisoners were kept on board such ships for months awaiting deportation to Australia. The ‘Justitia’ was a 260 ton prison hulk that had been originally moored in the Thames when the American War of Independence put a stop to the transportation of criminals to the former colonies. The ‘Justitia’ belonged to the shipowner Duncan Campbell, who was the Government contractor who organized the prison-hulk system at that time. Campbell was subsequently involved in the shipping of convicts to the penal colony at Botany Bay (in fact Port Jackson, later Sydney, just to the north) in New South Wales, the ‘first fleet’ going out in 1788.

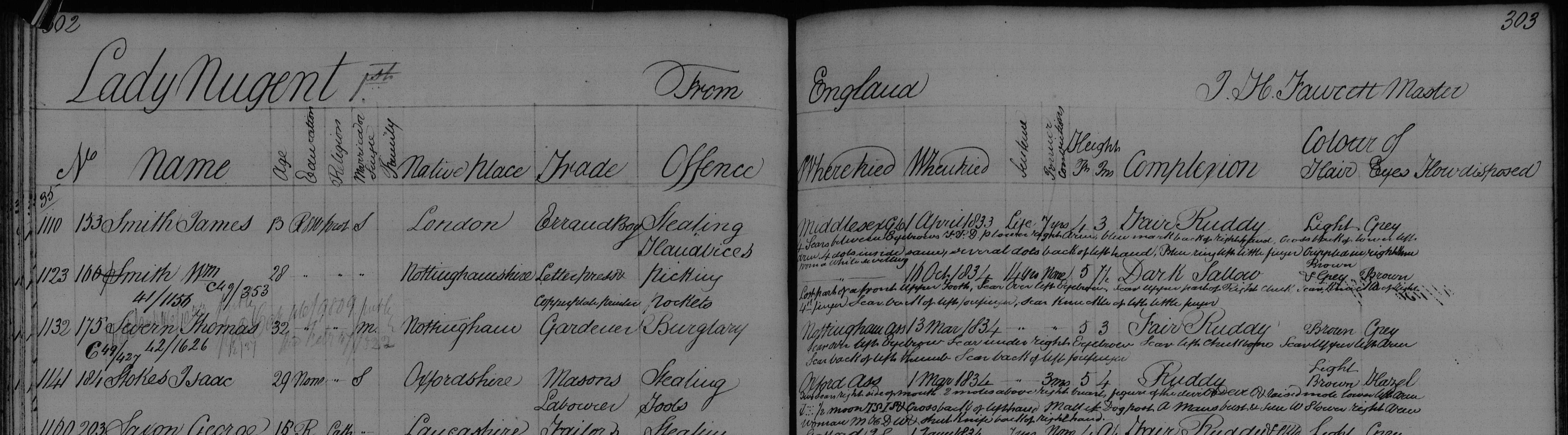

While searching for records for Isaac Stokes I discovered that another Isaac Stokes was transported to New South Wales in 1835 as well. The other one was a butcher born in 1809, sentenced in London for seven years, and he sailed on the Mary Ann. Our Isaac Stokes sailed on the Lady Nugent, arriving in NSW in April 1835, having set sail from England in December 1834.

Lady Nugent was built at Bombay in 1813. She made four voyages under contract to the British East India Company (EIC). She then made two voyages transporting convicts to Australia, one to New South Wales and one to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). (via Wikipedia)

via freesettlerorfelon website:

On 20 November 1834, 100 male convicts were transferred to the Lady Nugent from the Justitia Hulk and 60 from the Ganymede Hulk at Woolwich, all in apparent good health. The Lady Nugent departed Sheerness on 4 December 1834.

SURGEON OLIVER SPROULE

Oliver Sproule kept a Medical Journal from 7 November 1834 to 27 April 1835. He recorded in his journal the weather conditions they experienced in the first two weeks:

‘In the course of the first week or ten days at sea, there were eight or nine on the sick list with catarrhal affections and one with dropsy which I attribute to the cold and wet we experienced during that period beating down channel. Indeed the foremost berths in the prison at this time were so wet from leaking in that part of the ship, that I was obliged to issue dry beds and bedding to a great many of the prisoners to preserve their health, but after crossing the Bay of Biscay the weather became fine and we got the damp beds and blankets dried, the leaks partially stopped and the prison well aired and ventilated which, I am happy to say soon manifested a favourable change in the health and appearance of the men.

Besides the cases given in the journal I had a great many others to treat, some of them similar to those mentioned but the greater part consisted of boils, scalds, and contusions which would not only be too tedious to enter but I fear would be irksome to the reader. There were four births on board during the passage which did well, therefore I did not consider it necessary to give a detailed account of them in my journal the more especially as they were all favourable cases.

Regularity and cleanliness in the prison, free ventilation and as far as possible dry decks turning all the prisoners up in fine weather as we were lucky enough to have two musicians amongst the convicts, dancing was tolerated every afternoon, strict attention to personal cleanliness and also to the cooking of their victuals with regular hours for their meals, were the only prophylactic means used on this occasion, which I found to answer my expectations to the utmost extent in as much as there was not a single case of contagious or infectious nature during the whole passage with the exception of a few cases of psora which soon yielded to the usual treatment. A few cases of scurvy however appeared on board at rather an early period which I can attribute to nothing else but the wet and hardships the prisoners endured during the first three or four weeks of the passage. I was prompt in my treatment of these cases and they got well, but before we arrived at Sydney I had about thirty others to treat.’

The Lady Nugent arrived in Port Jackson on 9 April 1835 with 284 male prisoners. Two men had died at sea. The prisoners were landed on 27th April 1835 and marched to Hyde Park Barracks prior to being assigned. Ten were under the age of 14 years.

The Lady Nugent:

Isaac’s distinguishing marks are noted on various criminal registers and record books:

“Height in feet & inches: 5 4; Complexion: Ruddy; Hair: Light brown; Eyes: Hazel; Marks or Scars: Yes [including] DEVIL on lower left arm, TSIS back of left hand, WS lower right arm, MHDW back of right hand.”

Another includes more detail about Isaac’s tattoos:

“Two slight scars right side of mouth, 2 moles above right breast, figure of the devil and DEVIL and raised mole, lower left arm; anchor, seven dots half moon, TSIS and cross, back of left hand; a mallet, door post, A, mans bust, sun, WS, lower right arm; woman, MHDW and shut knife, back of right hand.”

From How tattoos became fashionable in Victorian England (2019 article in TheConversation by Robert Shoemaker and Zoe Alkar):

“Historical tattooing was not restricted to sailors, soldiers and convicts, but was a growing and accepted phenomenon in Victorian England. Tattoos provide an important window into the lives of those who typically left no written records of their own. As a form of “history from below”, they give us a fleeting but intriguing understanding of the identities and emotions of ordinary people in the past.

As a practice for which typically the only record is the body itself, few systematic records survive before the advent of photography. One exception to this is the written descriptions of tattoos (and even the occasional sketch) that were kept of institutionalised people forced to submit to the recording of information about their bodies as a means of identifying them. This particularly applies to three groups – criminal convicts, soldiers and sailors. Of these, the convict records are the most voluminous and systematic.

Such records were first kept in large numbers for those who were transported to Australia from 1788 (since Australia was then an open prison) as the authorities needed some means of keeping track of them.”On the 1837 census Isaac was working for the government at Illiwarra, New South Wales. This record states that he arrived on the Lady Nugent in 1835. There are three other indent records for an Isaac Stokes in the following years, but the transcriptions don’t provide enough information to determine which Isaac Stokes it was. In April 1837 there was an abscondment, and an arrest/apprehension in May of that year, and in 1843 there was a record of convict indulgences.

From the Australian government website regarding “convict indulgences”:

“By the mid-1830s only six per cent of convicts were locked up. The vast majority worked for the government or free settlers and, with good behaviour, could earn a ticket of leave, conditional pardon or and even an absolute pardon. While under such orders convicts could earn their own living.”

In 1856 in Camden, NSW, Isaac Stokes married Catherine Daly. With no further information on this record it would be impossible to know for sure if this was the right Isaac Stokes. This couple had six children, all in the Camden area, but none of the records provided enough information. No occupation or place or date of birth recorded for Isaac Stokes.

I wrote to the National Library of Australia about the marriage record, and their reply was a surprise! Issac and Catherine were married on 30 September 1856, at the house of the Rev. Charles William Rigg, a Methodist minister, and it was recorded that Isaac was born in Edinburgh in 1821, to parents James Stokes and Sarah Ellis! The age at the time of the marriage doesn’t match Isaac’s age at death in 1877, and clearly the place of birth and parents didn’t match either. Only his fathers occupation of stone mason was correct. I wrote back to the helpful people at the library and they replied that the register was in a very poor condition and that only two and a half entries had survived at all, and that Isaac and Catherines marriage was recorded over two pages.

I searched for an Isaac Stokes born in 1821 in Edinburgh on the Scotland government website (and on all the other genealogy records sites) and didn’t find it. In fact Stokes was a very uncommon name in Scotland at the time. I also searched Australian immigration and other records for another Isaac Stokes born in Scotland or born in 1821, and found nothing. I was unable to find a single record to corroborate this mysterious other Isaac Stokes.

As the age at death in 1877 was correct, I assume that either Isaac was lying, or that some mistake was made either on the register at the home of the Methodist minster, or a subsequent mistranscription or muddle on the remnants of the surviving register. Therefore I remain convinced that the Camden stonemason Isaac Stokes was indeed our Isaac from Oxfordshire.

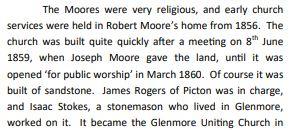

I found a history society newsletter article that mentioned Isaac Stokes, stone mason, had built the Glenmore church, near Camden, in 1859.

From the Wollondilly museum April 2020 newsletter:

From the Camden History website:

“The stone set over the porch of Glenmore Church gives the date of 1860. The church was begun in 1859 on land given by Joseph Moore. James Rogers of Picton was given the contract to build and local builder, Mr. Stokes, carried out the work. Elizabeth Moore, wife of Edward, laid the foundation stone. The first service was held on 19th March 1860. The cemetery alongside the church contains the headstones and memorials of the areas early pioneers.”

Isaac died on the 3rd September 1877. The inquest report puts his place of death as Bagdelly, near to Camden, and another death register has put Cambelltown, also very close to Camden. His age was recorded as 71 and the inquest report states his cause of death was “rupture of one of the large pulmonary vessels of the lung”. His wife Catherine died in childbirth in 1870 at the age of 43.

Isaac and Catherine’s children:

William Stokes 1857-1928

Catherine Stokes 1859-1846

Sarah Josephine Stokes 1861-1931

Ellen Stokes 1863-1932

Rosanna Stokes 1865-1919

Louisa Stokes 1868-1844.

It’s possible that Catherine Daly was a transported convict from Ireland.

Some time later I unexpectedly received a follow up email from The Oaks Heritage Centre in Australia.

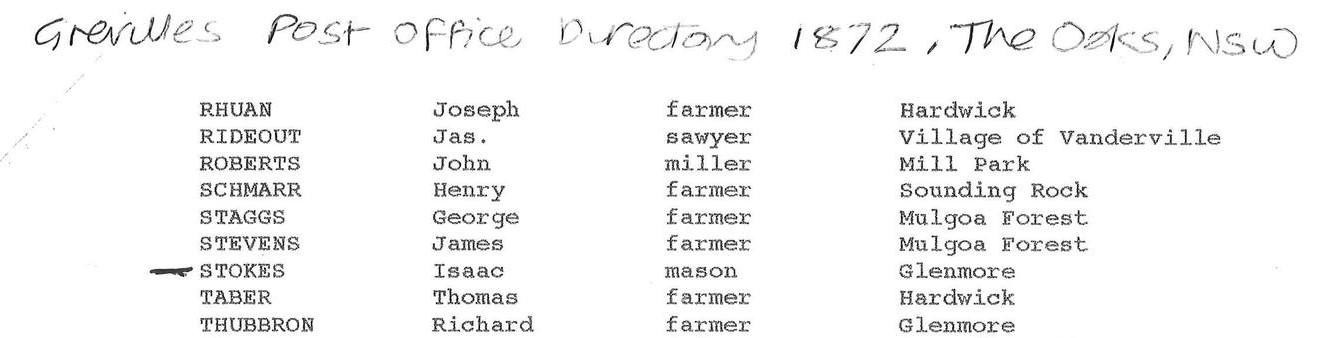

“The Gaudry papers which we have in our archive record him (Isaac Stokes) as having built: the church, the school and the teachers residence. Isaac is recorded in the General return of convicts: 1837 and in Grevilles Post Office directory 1872 as a mason in Glenmore.”

November 18, 2022 at 4:47 pm #6348

November 18, 2022 at 4:47 pm #6348In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Wong Sang

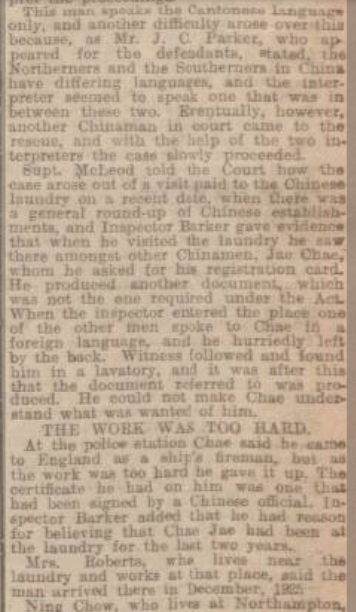

Wong Sang was born in China in 1884. In October 1916 he married Alice Stokes in Oxford.

Alice was the granddaughter of William Stokes of Churchill, Oxfordshire and William was the brother of Thomas Stokes the wheelwright (who was my 3X great grandfather). In other words Alice was my second cousin, three times removed, on my fathers paternal side.

Wong Sang was an interpreter, according to the baptism registers of his children and the Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital admission registers in 1930. The hospital register also notes that he was employed by the Blue Funnel Line, and that his address was 11, Limehouse Causeway, E 14. (London)

“The Blue Funnel Line offered regular First-Class Passenger and Cargo Services From the UK to South Africa, Malaya, China, Japan, Australia, Java, and America. Blue Funnel Line was Owned and Operated by Alfred Holt & Co., Liverpool.

The Blue Funnel Line, so-called because its ships have a blue funnel with a black top, is more appropriately known as the Ocean Steamship Company.”Wong Sang and Alice’s daughter, Frances Eileen Sang, was born on the 14th July, 1916 and baptised in 1920 at St Stephen in Poplar, Tower Hamlets, London. The birth date is noted in the 1920 baptism register and would predate their marriage by a few months, although on the death register in 1921 her age at death is four years old and her year of birth is recorded as 1917.

Charles Ronald Sang was baptised on the same day in May 1920, but his birth is recorded as April of that year. The family were living on Morant Street, Poplar.

James William Sang’s birth is recorded on the 1939 census and on the death register in 2000 as being the 8th March 1913. This definitely would predate the 1916 marriage in Oxford.

William Norman Sang was born on the 17th October 1922 in Poplar.

Alice and the three sons were living at 11, Limehouse Causeway on the 1939 census, the same address that Wong Sang was living at when he was admitted to Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital on the 15th January 1930. Wong Sang died in the hospital on the 8th March of that year at the age of 46.

Alice married John Patterson in 1933 in Stepney. John was living with Alice and her three sons on Limehouse Causeway on the 1939 census and his occupation was chef.

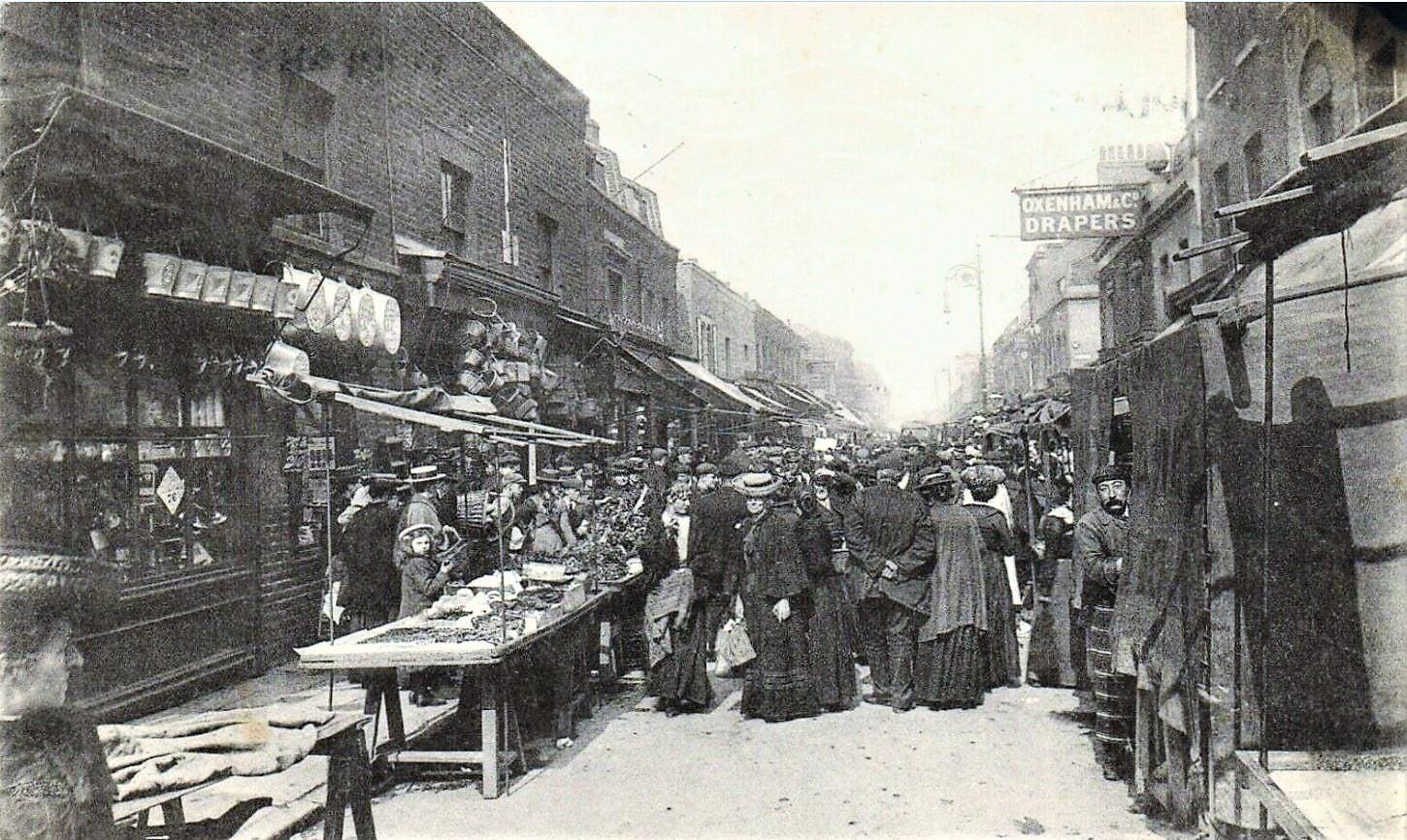

Via Old London Photographs:

“Limehouse Causeway is a street in east London that was the home to the original Chinatown of London. A combination of bomb damage during the Second World War and later redevelopment means that almost nothing is left of the original buildings of the street.”

Limehouse Causeway in 1925:

From The Story of Limehouse’s Lost Chinatown, poplarlondon website:

“Limehouse was London’s first Chinatown, home to a tightly-knit community who were demonised in popular culture and eventually erased from the cityscape.

As recounted in the BBC’s ‘Our Greatest Generation’ series, Connie was born to a Chinese father and an English mother in early 1920s Limehouse, where she used to play in the street with other British and British-Chinese children before running inside for teatime at one of their houses.

Limehouse was London’s first Chinatown between the 1880s and the 1960s, before the current Chinatown off Shaftesbury Avenue was established in the 1970s by an influx of immigrants from Hong Kong.

Connie’s memories of London’s first Chinatown as an “urban village” paint a very different picture to the seedy area portrayed in early twentieth century novels.

The pyramid in St Anne’s church marked the entrance to the opium den of Dr Fu Manchu, a criminal mastermind who threatened Western society by plotting world domination in a series of novels by Sax Rohmer.

Thomas Burke’s Limehouse Nights cemented stereotypes about prostitution, gambling and violence within the Chinese community, and whipped up anxiety about sexual relationships between Chinese men and white women.

Though neither novelist was familiar with the Chinese community, their depictions made Limehouse one of the most notorious areas of London.

Travel agent Thomas Cook even organised tours of the area for daring visitors, despite the rector of Limehouse warning that “those who look for the Limehouse of Mr Thomas Burke simply will not find it.”

All that remains is a handful of Chinese street names, such as Ming Street, Pekin Street, and Canton Street — but what was Limehouse’s chinatown really like, and why did it get swept away?

Chinese migration to Limehouse

Chinese sailors discharged from East India Company ships settled in the docklands from as early as the 1780s.

By the late nineteenth century, men from Shanghai had settled around Pennyfields Lane, while a Cantonese community lived on Limehouse Causeway.

Chinese sailors were often paid less and discriminated against by dock hirers, and so began to diversify their incomes by setting up hand laundry services and restaurants.

Old photographs show shopfronts emblazoned with Chinese characters with horse-drawn carts idling outside or Chinese men in suits and hats standing proudly in the doorways.

In oral histories collected by Yat Ming Loo, Connie’s husband Leslie doesn’t recall seeing any Chinese women as a child, since male Chinese sailors settled in London alone and married working-class English women.

In the 1920s, newspapers fear-mongered about interracial marriages, crime and gambling, and described chinatown as an East End “colony.”

Ironically, Chinese opium-smoking was also demonised in the press, despite Britain waging war against China in the mid-nineteenth century for suppressing the opium trade to alleviate addiction amongst its people.

The number of Chinese people who settled in Limehouse was also greatly exaggerated, and in reality only totalled around 300.

The real Chinatown

Although the press sought to characterise Limehouse as a monolithic Chinese community in the East End, Connie remembers seeing people of all nationalities in the shops and community spaces in Limehouse.

She doesn’t remember feeling discriminated against by other locals, though Connie does recall having her face measured and IQ tested by a member of the British Eugenics Society who was conducting research in the area.

Some of Connie’s happiest childhood memories were from her time at Chung-Hua Club, where she learned about Chinese culture and language.

Why did Chinatown disappear?

The caricature of Limehouse’s Chinatown as a den of vice hastened its erasure.

Police raids and deportations fuelled by the alarmist media coverage threatened the Chinese population of Limehouse, and slum clearance schemes to redevelop low-income areas dispersed Chinese residents in the 1930s.

The Defence of the Realm Act imposed at the beginning of the First World War criminalised opium use, gave the authorities increased powers to deport Chinese people and restricted their ability to work on British ships.

Dwindling maritime trade during World War II further stripped Chinese sailors of opportunities for employment, and any remnants of Chinatown were destroyed during the Blitz or erased by postwar development schemes.”

Wong Sang 1884-1930

The year 1918 was a troublesome one for Wong Sang, an interpreter and shipping agent for Blue Funnel Line. The Sang family were living at 156, Chrisp Street.

Chrisp Street, Poplar, in 1913 via Old London Photographs:

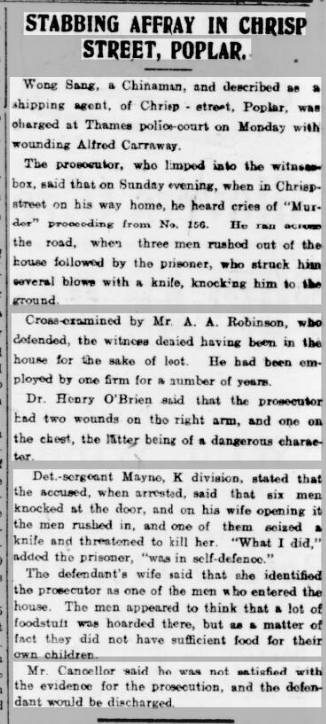

In February Wong Sang was discharged from a false accusation after defending his home from potential robbers.

East End News and London Shipping Chronicle – Friday 15 February 1918:

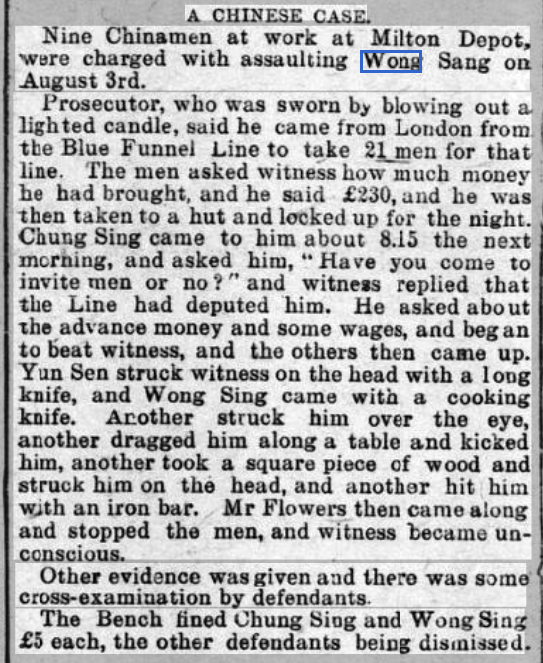

In August of that year he was involved in an incident that left him unconscious.

Faringdon Advertiser and Vale of the White Horse Gazette – Saturday 31 August 1918:

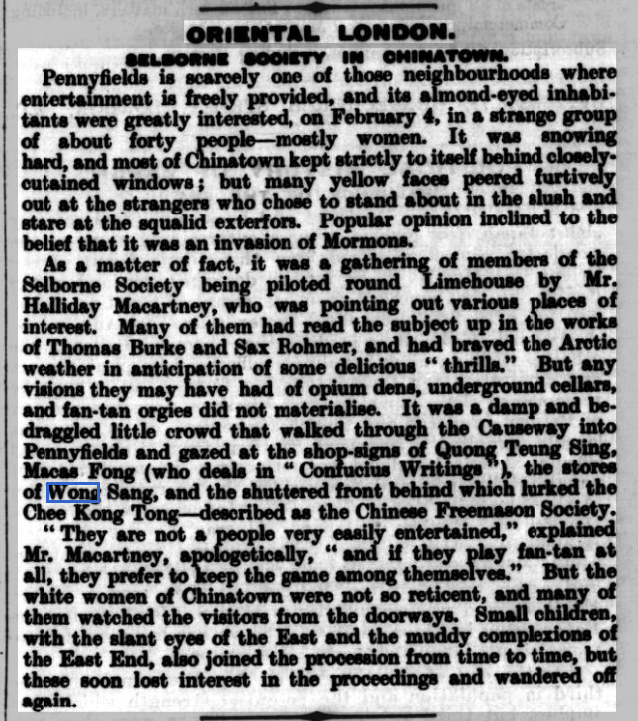

Wong Sang is mentioned in an 1922 article about “Oriental London”.

London and China Express – Thursday 09 February 1922:

A photograph of the Chee Kong Tong Chinese Freemason Society mentioned in the above article, via Old London Photographs:

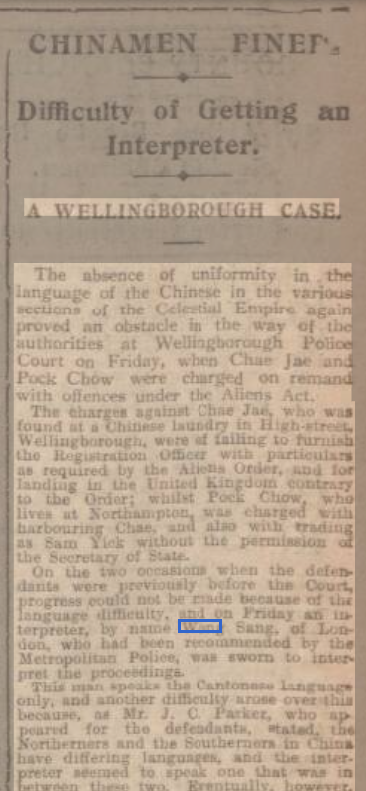

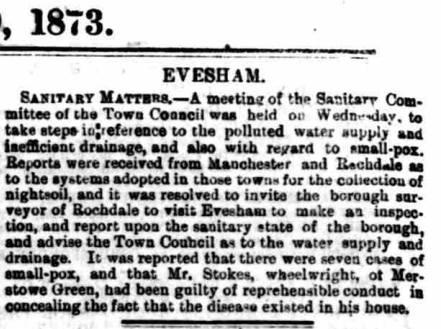

Wong Sang was recommended by the London Metropolitan Police in 1928 to assist in a case in Wellingborough, Northampton.

Difficulty of Getting an Interpreter: Northampton Mercury – Friday 16 March 1928:

The difficulty was that “this man speaks the Cantonese language only…the Northeners and the Southerners in China have differing languages and the interpreter seemed to speak one that was in between these two.”

In 1917, Alice Wong Sang was a witness at her sister Harriet Stokes marriage to James William Watts in Southwark, London. Their father James Stokes occupation on the marriage register is foreman surveyor, but on the census he was a council roadman or labourer. (I initially rejected this as the correct marriage for Harriet because of the discrepancy with the occupations. Alice Wong Sang as a witness confirmed that it was indeed the correct one.)

James William Sang 1913-2000 was a clock fitter and watch assembler (on the 1939 census). He married Ivy Laura Fenton in 1963 in Sidcup, Kent. James died in Southwark in 2000.

Charles Ronald Sang 1920-1974 was a draughtsman (1939 census). He married Eileen Burgess in 1947 in Marylebone. Charles and Eileen had two sons: Keith born in 1951 and Roger born in 1952. He died in 1974 in Hertfordshire.

William Norman Sang 1922-2000 was a clerk and telephone operator (1939 census). William enlisted in the Royal Artillery in 1942. He married Lily Mullins in 1949 in Bethnal Green, and they had three daughters: Marion born in 1950, Christine in 1953, and Frances in 1959. He died in Redbridge in 2000.

I then found another two births registered in Poplar by Alice Sang, both daughters. Doris Winifred Sang was born in 1925, and Patricia Margaret Sang was born in 1933 ~ three years after Wong Sang’s death. Neither of the these daughters were on the 1939 census with Alice, John Patterson and the three sons. Margaret had presumably been evacuated because of the war to a family in Taunton, Somerset. Doris would have been fourteen and I have been unable to find her in 1939 (possibly because she died in 2017 and has not had the redaction removed yet on the 1939 census as only deceased people are viewable).

Doris Winifred Sang 1925-2017 was a nursing sister. She didn’t marry, and spent a year in USA between 1954 and 1955. She stayed in London, and died at the age of ninety two in 2017.

Patricia Margaret Sang 1933-1998 was also a nurse. She married Patrick L Nicely in Stepney in 1957. Patricia and Patrick had five children in London: Sharon born 1959, Donald in 1960, Malcolm was born and died in 1966, Alison was born in 1969 and David in 1971.

I was unable to find a birth registered for Alice’s first son, James William Sang (as he appeared on the 1939 census). I found Alice Stokes on the 1911 census as a 17 year old live in servant at a tobacconist on Pekin Street, Limehouse, living with Mr Sui Fong from Hong Kong and his wife Sarah Sui Fong from Berlin. I looked for a birth registered for James William Fong instead of Sang, and found it ~ mothers maiden name Stokes, and his date of birth matched the 1939 census: 8th March, 1913.

On the 1921 census, Wong Sang is not listed as living with them but it is mentioned that Mr Wong Sang was the person returning the census. Also living with Alice and her sons James and Charles in 1921 are two visitors: (Florence) May Stokes, 17 years old, born in Woodstock, and Charles Stokes, aged 14, also born in Woodstock. May and Charles were Alice’s sister and brother.

I found Sharon Nicely on social media and she kindly shared photos of Wong Sang and Alice Stokes:

October 23, 2022 at 6:57 am #6340

October 23, 2022 at 6:57 am #6340In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Wheelwrights of Broadway

Thomas Stokes 1816-1885

Frederick Stokes 1845-1917

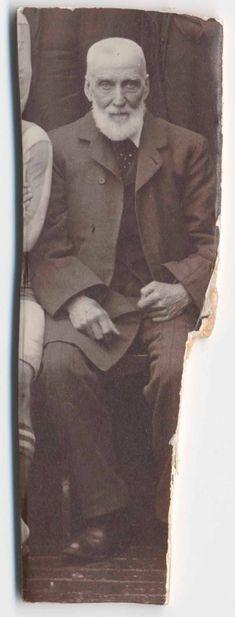

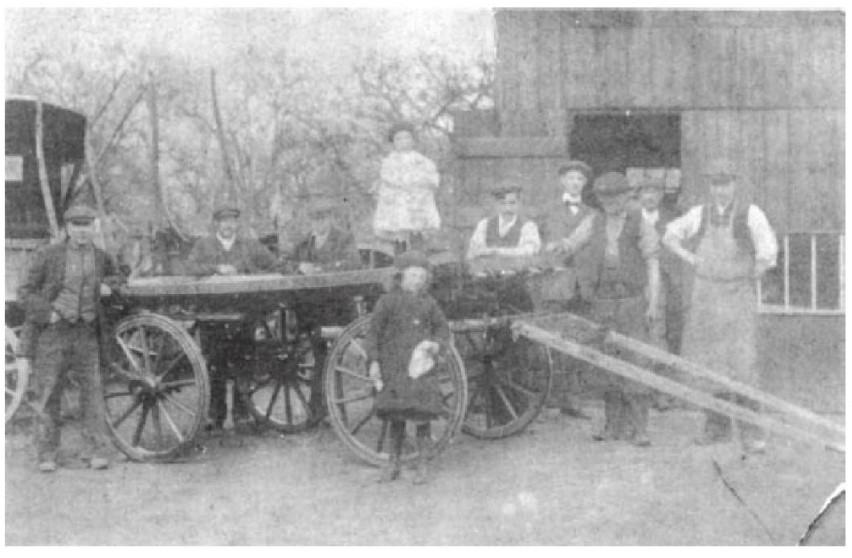

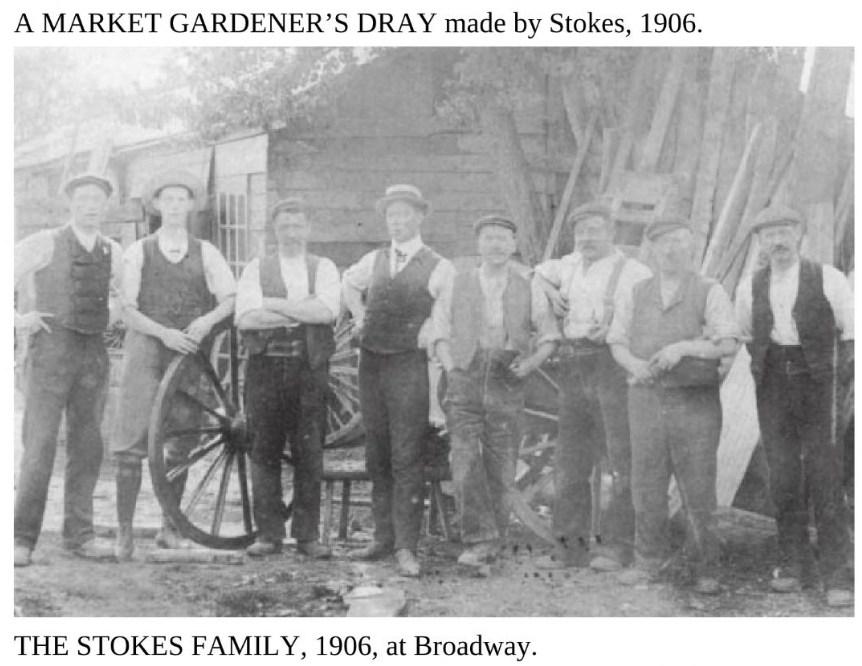

Stokes Wheelwrights. Fred on left of wheel, Thomas his father on right.

Thomas Stokes

Thomas Stokes was born in Bicester, Oxfordshire in 1816. He married Eliza Browning (born in 1814 in Tetbury, Gloucestershire) in Gloucester in 1840 Q3. Their first son William was baptised in Chipping Hill, Witham, Essex, on 3 Oct 1841. This seems a little unusual, and I can’t find Thomas and Eliza on the 1841 census. However both the 1851 and 1861 census state that William was indeed born in Essex.

In 1851 Thomas and Eliza were living in Bledington, Gloucestershire, and Thomas was a journeyman carpenter.

Note that a journeyman does not mean someone who moved around a lot. A journeyman was a tradesman who had served his trade apprenticeship and mastered his craft, not bound to serve a master, but originally hired by the day. The name derives from the French for day – jour.

Also on the 1851 census: their daughter Susan, born in Churchill Oxfordshire in 1844; son Frederick born in Bledington Gloucestershire in 1846; daughter Louisa born in Foxcote Oxfordshire in 1849; and 2 month old daughter Harriet born in Bledington in 1851.

On the 1861 census Thomas and Eliza were living in Evesham, Worcestershire, and daughter Susan was no longer living at home, but William, Fred, Louisa and Harriet were, as well as daughter Emily born in Churchill Oxfordshire in 1856. Thomas was a wheelwright.

On the 1871 census Thomas and Eliza were still living in Evesham, and Thomas was a wheelwright employing three apprentices. Son Fred, also a wheelwright, and his wife Ann Rebecca live with them.

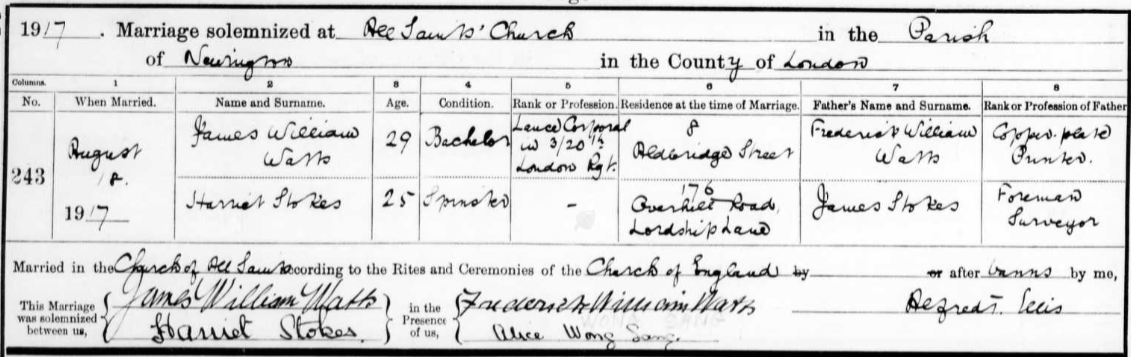

Mr Stokes, wheelwright, was found guilty of reprehensible conduct in concealing the fact that small-pox existed in his house, according to a mention in The Oxfordshire Weekly News on Wednesday 19 February 1873:

From Paul Weaver’s ancestry website:

“It was Thomas Stokes who built the first “Famous Vale of Evesham Light Gardening Dray for a Half-Legged Horse to Trot” (the quotation is from his account book), the forerunner of many that became so familiar a sight in the towns and villages from the 1860s onwards. He built many more for the use of the Vale gardeners.

Thomas also had long-standing business dealings with the people of the circus and fairgrounds, and had a contract to effect necessary repairs and renewals to their waggons whenever they visited the district. He built living waggons for many of the show people’s families as well as shooting galleries and other equipment peculiar to the trade of his wandering customers, and among the names figuring in his books are some still familiar today, such as Wilsons and Chipperfields.

He is also credited with inventing the wooden “Mushroom” which was used by housewives for many years to darn socks. He built and repaired all kinds of vehicles for the gentry as well as for the circus and fairground travellers.

Later he lived with his wife at Merstow Green, Evesham, in a house adjoining the Almonry.”

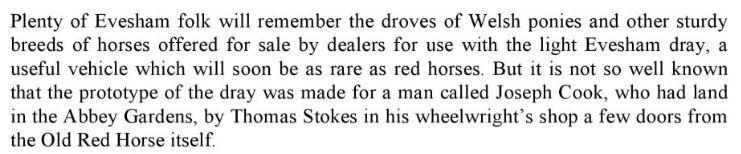

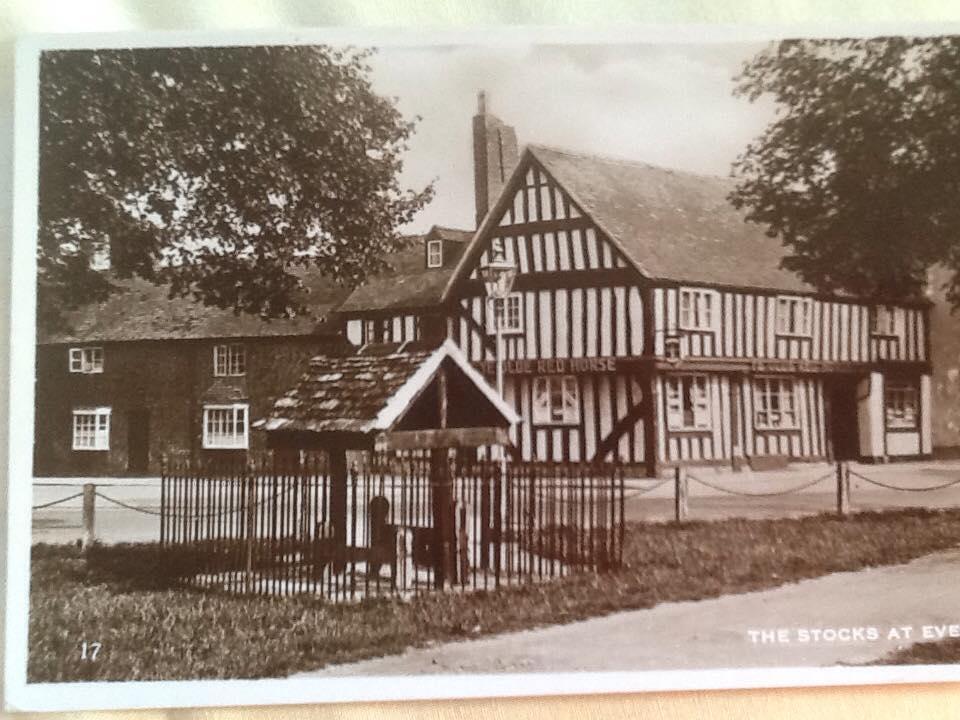

An excerpt from the book Evesham Inns and Signs by T.J.S. Baylis:

The Old Red Horse, Evesham:

Thomas died in 1885 aged 68 of paralysis, bronchitis and debility. His wife Eliza a year later in 1886.

Frederick Stokes

In Worcester in 1870 Fred married Ann Rebecca Day, who was born in Evesham in 1845.

Ann Rebecca Day:

In 1871 Fred was still living with his parents in Evesham, with his wife Ann Rebecca as well as their three month old daughter Annie Elizabeth. Fred and Ann (referred to as Rebecca) moved to La Quinta on Main Street, Broadway.

Rebecca Stokes in the doorway of La Quinta on Main Street Broadway, with her grandchildren Ralph and Dolly Edwards:

Fred was a wheelwright employing one man on the 1881 census. In 1891 they were still in Broadway, Fred’s occupation was wheelwright and coach painter, as well as his fifteen year old son Frederick.

In the Evesham Journal on Saturday 10 December 1892 it was reported that “Two cases of scarlet fever, the children of Mr. Stokes, wheelwright, Broadway, were certified by Mr. C. W. Morris to be isolated.”

Still in Broadway in 1901 and Fred’s son Albert was also a wheelwright. By 1911 Fred and Rebecca had only one son living at home in Broadway, Reginald, who was a coach painter. Fred was still a wheelwright aged 65.

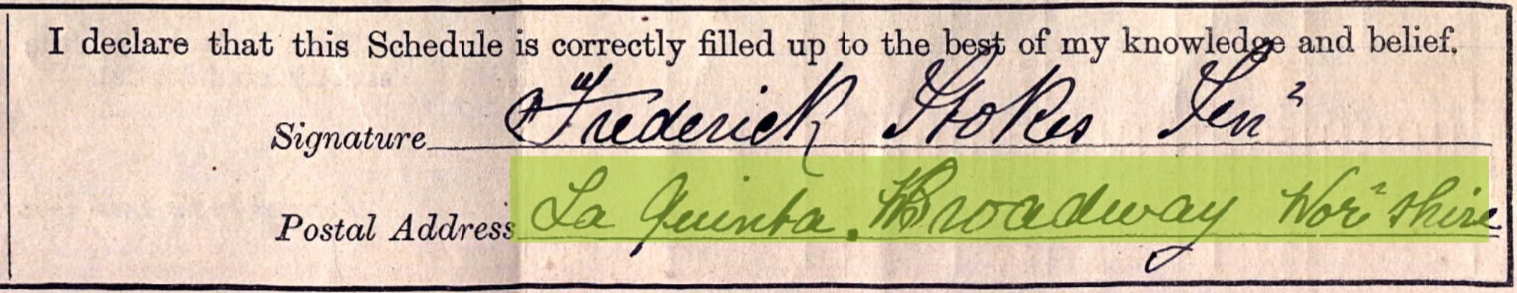

Fred’s signature on the 1911 census:

Rebecca died in 1912 and Fred in 1917.

Fred Stokes:

In the book Evesham to Bredon From Old Photographs By Fred Archer:

February 2, 2022 at 12:33 pm #6266

February 2, 2022 at 12:33 pm #6266In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

From Tanganyika with Love

continued part 7

With thanks to Mike Rushby.

Oldeani Hospital. 19th September 1938

Dearest Family,

George arrived today to take us home to Mbulu but Sister Marianne will not allow

me to travel for another week as I had a bit of a set back after baby’s birth. At first I was

very fit and on the third day Sister stripped the bed and, dictionary in hand, started me

off on ante natal exercises. “Now make a bridge Mrs Rushby. So. Up down, up down,’

whilst I obediently hoisted myself aloft on heels and head. By the sixth day she

considered it was time for me to be up and about but alas, I soon had to return to bed

with a temperature and a haemorrhage. I got up and walked outside for the first time this

morning.I have had lots of visitors because the local German settlers seem keen to see

the first British baby born in the hospital. They have been most kind, sending flowers

and little German cards of congratulations festooned with cherubs and rather sweet. Most

of the women, besides being pleasant, are very smart indeed, shattering my illusion that

German matrons are invariably fat and dowdy. They are all much concerned about the

Czecko-Slovakian situation, especially Sister Marianne whose home is right on the

border and has several relations who are Sudentan Germans. She is ant-Nazi and

keeps on asking me whether I think England will declare war if Hitler invades Czecko-

Slovakia, as though I had inside information.George tells me that he has had a grass ‘banda’ put up for us at Mbulu as we are

both determined not to return to those prison-like quarters in the Fort. Sister Marianne is

horrified at the idea of taking a new baby to live in a grass hut. She told George,

“No,No,Mr Rushby. I find that is not to be allowed!” She is an excellent Sister but rather

prim and George enjoys teasing her. This morning he asked with mock seriousness,

“Sister, why has my wife not received her medal?” Sister fluttered her dictionary before

asking. “What medal Mr Rushby”. “Why,” said George, “The medal that Hitler gives to

women who have borne four children.” Sister started a long and involved explanation

about the medal being only for German mothers whilst George looked at me and

grinned.Later. Great Jubilation here. By the noise in Sister Marianne’s sitting room last night it

sounded as though the whole German population had gathered to listen to the wireless

news. I heard loud exclamations of joy and then my bedroom door burst open and

several women rushed in. “Thank God “, they cried, “for Neville Chamberlain. Now there

will be no war.” They pumped me by the hand as though I were personally responsible

for the whole thing.George on the other hand is disgusted by Chamberlain’s lack of guts. Doesn’t

know what England is coming to these days. I feel too content to concern myself with

world affairs. I have a fine husband and four wonderful children and am happy, happy,

happy.Eleanor.

Mbulu. 30th September 1938

Dearest Family,

Here we are, comfortably installed in our little green house made of poles and

rushes from a nearby swamp. The house has of course, no doors or windows, but

there are rush blinds which roll up in the day time. There are two rooms and a little porch

and out at the back there is a small grass kitchen.Here we have the privacy which we prize so highly as we are screened on one

side by a Forest Department plantation and on the other three sides there is nothing but

the rolling countryside cropped bare by the far too large herds of cattle and goats of the

Wambulu. I have a lovely lazy time. I still have Kesho-Kutwa and the cook we brought

with us from the farm. They are both faithful and willing souls though not very good at

their respective jobs. As one of these Mbeya boys goes on safari with George whose

job takes him from home for three weeks out of four, I have taken on a local boy to cut

firewood and heat my bath water and generally make himself useful. His name is Saa,

which means ‘Clock’We had an uneventful but very dusty trip from Oldeani. Johnny Jo travelled in his

pram in the back of the boxbody and got covered in dust but seems none the worst for

it. As the baby now takes up much of my time and Kate was showing signs of

boredom, I have engaged a little African girl to come and play with Kate every morning.

She is the daughter of the head police Askari and a very attractive and dignified little

person she is. Her name is Kajyah. She is scrupulously clean, as all Mohammedan

Africans seem to be. Alas, Kajyah, though beautiful, is a bore. She simply does not

know how to play, so they just wander around hand in hand.There are only two drawbacks to this little house. Mbulu is a very windy spot so

our little reed house is very draughty. I have made a little tent of sheets in one corner of

the ‘bedroom’ into which I can retire with Johnny when I wish to bathe or sponge him.

The other drawback is that many insects are attracted at night by the lamp and make it

almost impossible to read or sew and they have a revolting habit of falling into the soup.

There are no dangerous wild animals in this area so I am not at all nervous in this

flimsy little house when George is on safari. Most nights hyaenas come around looking

for scraps but our dogs, Fanny and Paddy, soon see them off.Eleanor.

Mbulu. 25th October 1938

Dearest Family,

Great news! a vacancy has occurred in the Game Department. George is to

transfer to it next month. There will be an increase in salary and a brighter prospect for

the future. It will mean a change of scene and I shall be glad of that. We like Mbulu and

the people here but the rains have started and our little reed hut is anything but water

tight.Before the rain came we had very unpleasant dust storms. I think I told you that

this is a treeless area and the grass which normally covers the veldt has been cropped

to the roots by the hungry native cattle and goats. When the wind blows the dust

collects in tall black columns which sweep across the country in a most spectacular

fashion. One such dust devil struck our hut one day whilst we were at lunch. George

swept Kate up in a second and held her face against his chest whilst I rushed to Johnny

Jo who was asleep in his pram, and stooped over the pram to protect him. The hut

groaned and creaked and clouds of dust blew in through the windows and walls covering

our persons, food, and belongings in a black pall. The dogs food bowls and an empty

petrol tin outside the hut were whirled up and away. It was all over in a moment but you

should have seen what a family of sweeps we looked. George looked at our blackened

Johnny and mimicked in Sister Marianne’s primmest tones, “I find that this is not to be

allowed.”The first rain storm caught me unprepared when George was away on safari. It

was a terrific thunderstorm. The quite violent thunder and lightening were followed by a

real tropical downpour. As the hut is on a slight slope, the storm water poured through

the hut like a river, covering the entire floor, and the roof leaked like a lawn sprinkler.

Johnny Jo was snug enough in the pram with the hood raised, but Kate and I had a

damp miserable night. Next morning I had deep drains dug around the hut and when

George returned from safari he managed to borrow an enormous tarpaulin which is now

lashed down over the roof.It did not rain during the next few days George was home but the very next night

we were in trouble again. I was awakened by screams from Kate and hurriedly turned up

the lamp to see that we were in the midst of an invasion of siafu ants. Kate’s bed was

covered in them. Others appeared to be raining down from the thatch. I quickly stripped

Kate and carried her across to my bed, whilst I rushed to the pram to see whether

Johnny Jo was all right. He was fast asleep, bless him, and slept on through all the

commotion, whilst I struggled to pick all the ants out of Kate’s hair, stopping now and

again to attend to my own discomfort. These ants have a painful bite and seem to

choose all the most tender spots. Kate fell asleep eventually but I sat up for the rest of

the night to make sure that the siafu kept clear of the children. Next morning the servants

dispersed them by laying hot ash.In spite of the dampness of the hut both children are blooming. Kate has rosy

cheeks and Johnny Jo now has a fuzz of fair hair and has lost his ‘old man’ look. He

reminds me of Ann at his age.Eleanor.

Iringa. 30th November 1938

Dearest Family,

Here we are back in the Southern Highlands and installed on the second floor of

another German Fort. This one has been modernised however and though not so

romantic as the Mbulu Fort from the outside, it is much more comfortable.We are all well

and I am really proud of our two safari babies who stood up splendidly to a most trying

journey North from Mbulu to Arusha and then South down the Great North Road to

Iringa where we expect to stay for a month.At Arusha George reported to the headquarters of the Game Department and

was instructed to come on down here on Rinderpest Control. There is a great flap on in

case the rinderpest spread to Northern Rhodesia and possibly onwards to Southern

Rhodesia and South Africa. Extra veterinary officers have been sent to this area to

inoculate all the cattle against the disease whilst George and his African game Scouts will

comb the bush looking for and destroying diseased game. If the rinderpest spreads,

George says it may be necessary to shoot out all the game in a wide belt along the

border between the Southern Highlands of Tanganyika and Northern Rhodesia, to

prevent the disease spreading South. The very idea of all this destruction sickens us

both.George left on a foot safari the day after our arrival and I expect I shall be lucky if I

see him occasionally at weekends until this job is over. When rinderpest is under control

George is to be stationed at a place called Nzassa in the Eastern Province about 18

miles from Dar es Salaam. George’s orderly, who is a tall, cheerful Game Scout called

Juma, tells me that he has been stationed at Nzassa and it is a frightful place! However I

refuse to be depressed. I now have the cheering prospect of leave to England in thirty

months time when we will be able to fetch Ann and George and be a proper family

again. Both Ann and George look happy in the snapshots which mother-in-law sends

frequently. Ann is doing very well at school and loves it.To get back to our journey from Mbulu. It really was quite an experience. It

poured with rain most of the way and the road was very slippery and treacherous the

120 miles between Mbulu and Arusha. This is a little used earth road and the drains are

so blocked with silt as to be practically non existent. As usual we started our move with

the V8 loaded to capacity. I held Johnny on my knee and Kate squeezed in between

George and me. All our goods and chattels were in wooden boxes stowed in the back

and the two houseboys and the two dogs had to adjust themselves to the space that

remained. We soon ran into trouble and it took us all day to travel 47 miles. We stuck

several times in deep mud and had some most nasty skids. I simply clutched Kate in

one hand and Johnny Jo in the other and put my trust in George who never, under any

circumstances, loses his head. Poor Johnny only got his meals when circumstances

permitted. Unfortunately I had put him on a bottle only a few days before we left Mbulu

and, as I was unable to buy either a primus stove or Thermos flask there we had to

make a fire and boil water for each meal. Twice George sat out in the drizzle with a rain

coat rapped over his head to protect a miserable little fire of wet sticks drenched with

paraffin. Whilst we waited for the water to boil I pacified John by letting him suck a cube

of Tate and Lyles sugar held between my rather grubby fingers. Not at all according to

the book.That night George, the children and I slept in the car having dumped our boxes

and the two servants in a deserted native hut. The rain poured down relentlessly all night

and by morning the road was more of a morass than ever. We swerved and skidded

alarmingly till eventually one of the wheel chains broke and had to be tied together with

string which constantly needed replacing. George was so patient though he was wet

and muddy and tired and both children were very good. Shortly before reaching the Great North Road we came upon Jack Gowan, the Stock Inspector from Mbulu. His car

was bogged down to its axles in black mud. He refused George’s offer of help saying

that he had sent his messenger to a nearby village for help.I hoped that conditions would be better on the Great North Road but how over

optimistic I was. For miles the road runs through a belt of ‘black cotton soil’. which was

churned up into the consistency of chocolate blancmange by the heavy lorry traffic which

runs between Dodoma and Arusha. Soon the car was skidding more fantastically than

ever. Once it skidded around in a complete semi circle so George decided that it would

be safer for us all to walk whilst he negotiated the very bad patches. You should have

seen me plodding along in the mud and drizzle with the baby in one arm and Kate

clinging to the other. I was terrified of slipping with Johnny. Each time George reached

firm ground he would return on foot to carry Kate and in this way we covered many bad

patches.We were more fortunate than many other travellers. We passed several lorries

ditched on the side of the road and one car load of German men, all elegantly dressed in

lounge suits. One was busy with his camera so will have a record of their plight to laugh

over in the years to come. We spent another night camping on the road and next day

set out on the last lap of the journey. That also was tiresome but much better than the

previous day and we made the haven of the Arusha Hotel before dark. What a picture

we made as we walked through the hall in our mud splattered clothes! Even Johnny was

well splashed with mud but no harm was done and both he and Kate are blooming.

We rested for two days at Arusha and then came South to Iringa. Luckily the sun

came out and though for the first day the road was muddy it was no longer so slippery

and the second day found us driving through parched country and along badly

corrugated roads. The further South we came, the warmer the sun which at times blazed

through the windscreen and made us all uncomfortably hot. I have described the country

between Arusha and Dodoma before so I shan’t do it again. We reached Iringa without

mishap and after a good nights rest all felt full of beans.Eleanor.

Mchewe Estate, Mbeya. 7th January 1939.

Dearest Family,

You will be surprised to note that we are back on the farm! At least the children

and I are here. George is away near the Rhodesian border somewhere, still on

Rinderpest control.I had a pleasant time at Iringa, lots of invitations to morning tea and Kate had a

wonderful time enjoying the novelty of playing with children of her own age. She is not

shy but nevertheless likes me to be within call if not within sight. It was all very suburban

but pleasant enough. A few days before Christmas George turned up at Iringa and

suggested that, as he would be working in the Mbeya area, it might be a good idea for

the children and me to move to the farm. I agreed enthusiastically, completely forgetting

that after my previous trouble with the leopard I had vowed to myself that I would never

again live alone on the farm.Alas no sooner had we arrived when Thomas, our farm headman, brought the

news that there were now two leopards terrorising the neighbourhood, and taking dogs,

goats and sheep and chickens. Traps and poisoned bait had been tried in vain and he

was sure that the female was the same leopard which had besieged our home before.

Other leopards said Thomas, came by stealth but this one advertised her whereabouts

in the most brazen manner.George stayed with us on the farm over Christmas and all was quiet at night so I

cheered up and took the children for walks along the overgrown farm paths. However on

New Years Eve that darned leopard advertised her presence again with the most blood

chilling grunts and snarls. Horrible! Fanny and Paddy barked and growled and woke up

both children. Kate wept and kept saying, “Send it away mummy. I don’t like it.” Johnny

Jo howled in sympathy. What a picnic. So now the whole performance of bodyguards

has started again and ‘till George returns we confine our exercise to the garden.

Our little house is still cosy and sweet but the coffee plantation looks very

neglected. I wish to goodness we could sell it.Eleanor.

Nzassa 14th February 1939.

Dearest Family,

After three months of moving around with two small children it is heavenly to be

settled in our own home, even though Nzassa is an isolated spot and has the reputation

of being unhealthy.We travelled by car from Mbeya to Dodoma by now a very familiar stretch of

country, but from Dodoma to Dar es Salaam by train which made a nice change. We

spent two nights and a day in the Splendid Hotel in Dar es Salaam, George had some

official visits to make and I did some shopping and we took the children to the beach.

The bay is so sheltered that the sea is as calm as a pond and the water warm. It is

wonderful to see the sea once more and to hear tugs hooting and to watch the Arab

dhows putting out to sea with their oddly shaped sails billowing. I do love the bush, but

I love the sea best of all, as you know.We made an early start for Nzassa on the 3rd. For about four miles we bowled

along a good road. This brought us to a place called Temeke where George called on

the District Officer. His house appears to be the only European type house there. The

road between Temeke and the turn off to Nzassa is quite good, but the six mile stretch

from the turn off to Nzassa is a very neglected bush road. There is nothing to be seen

but the impenetrable bush on both sides with here and there a patch of swampy

ground where rice is planted in the wet season.After about six miles of bumpy road we reached Nzassa which is nothing more

than a sandy clearing in the bush. Our house however is a fine one. It was originally built

for the District Officer and there is a small court house which is now George’s office. The

District Officer died of blackwater fever so Nzassa was abandoned as an administrative

station being considered too unhealthy for Administrative Officers but suitable as

Headquarters for a Game Ranger. Later a bachelor Game Ranger was stationed here

but his health also broke down and he has been invalided to England. So now the

healthy Rushbys are here and we don’t mean to let the place get us down. So don’t

worry.The house consists of three very large and airy rooms with their doors opening

on to a wide front verandah which we shall use as a living room. There is also a wide

back verandah with a store room at one end and a bathroom at the other. Both

verandahs and the end windows of the house are screened my mosquito gauze wire

and further protected by a trellis work of heavy expanded metal. Hasmani, the Game

Scout, who has been acting as caretaker, tells me that the expanded metal is very

necessary because lions often come out of the bush at night and roam around the

house. Such a comforting thought!On our very first evening we discovered how necessary the mosquito gauze is.

After sunset the air outside is thick with mosquitos from the swamps. About an acre of

land has been cleared around the house. This is a sandy waste because there is no

water laid on here and absolutely nothing grows here except a rather revolting milky

desert bush called ‘Manyara’, and a few acacia trees. A little way from the house there is

a patch of citrus trees, grape fruit, I think, but whether they ever bear fruit I don’t know.

The clearing is bordered on three sides by dense dusty thorn bush which is

‘lousy with buffalo’ according to George. The open side is the road which leads down to

George’s office and the huts for the Game Scouts. Only Hasmani and George’s orderly

Juma and their wives and families live there, and the other huts provide shelter for the

Game Scouts from the bush who come to Nzassa to collect their pay and for a short

rest. I can see that my daily walk will always be the same, down the road to the huts and

back! However I don’t mind because it is far too hot to take much exercise.The climate here is really tropical and worse than on the coast because the thick

bush cuts us off from any sea breeze. George says it will be cooler when the rains start

but just now we literally drip all day. Kate wears nothing but a cotton sun suit, and Johnny

a napkin only, but still their little bodies are always moist. I have shorn off all Kate’s lovely

shoulder length curls and got George to cut my hair very short too.We simply must buy a refrigerator. The butter, and even the cheese we bought

in Dar. simply melted into pools of oil overnight, and all our meat went bad, so we are

living out of tins. However once we get organised I shall be quite happy here. I like this

spacious house and I have good servants. The cook, Hamisi Issa, is a Swahili from Lindi

whom we engaged in Dar es Salaam. He is a very dignified person, and like most

devout Mohammedan Cooks, keeps both his person and the kitchen spotless. I

engaged the house boy here. He is rather a timid little body but is very willing and quite

capable. He has an excessively plain but cheerful wife whom I have taken on as ayah. I

do not really need help with the children but feel I must have a woman around just in

case I go down with malaria when George is away on safari.Eleanor.

Nzassa 28th February 1939.

Dearest Family,

George’s birthday and we had a special tea party this afternoon which the

children much enjoyed. We have our frig now so I am able to make jellies and provide

them with really cool drinks.Our very first visitor left this morning after spending only one night here. He is Mr

Ionides, the Game Ranger from the Southern Province. He acted as stand in here for a

short while after George’s predecessor left for England on sick leave, and where he has

since died. Mr Ionides returned here to hand over the range and office formally to

George. He seems a strange man and is from all accounts a bit of a hermit. He was at

one time an Officer in the Regular Army but does not look like a soldier, he wears the

most extraordinary clothes but nevertheless contrives to look top-drawer. He was

educated at Rugby and Sandhurst and is, I should say, well read. Ionides told us that he

hated Nzassa, particularly the house which he thinks sinister and says he always slept

down in the office.The house, or at least one bedroom, seems to have the same effect on Kate.

She has been very nervous at night ever since we arrived. At first the children occupied

the bedroom which is now George’s. One night, soon after our arrival, Kate woke up

screaming to say that ‘something’ had looked at her through the mosquito net. She was

in such a hysterical state that inspite of the heat and discomfort I was obliged to crawl into

her little bed with her and remained there for the rest of the night.Next night I left a night lamp burning but even so I had to sit by her bed until she

dropped off to sleep. Again I was awakened by ear-splitting screams and this time

found Kate standing rigid on her bed. I lifted her out and carried her to a chair meaning to

comfort her but she screeched louder than ever, “Look Mummy it’s under the bed. It’s

looking at us.” In vain I pointed out that there was nothing at all there. By this time

George had joined us and he carried Kate off to his bed in the other room whilst I got into

Kate’s bed thinking she might have been frightened by a rat which might also disturb

Johnny.Next morning our houseboy remarked that he had heard Kate screaming in the

night from his room behind the kitchen. I explained what had happened and he must

have told the old Scout Hasmani who waylaid me that afternoon and informed me quite

seriously that that particular room was haunted by a ‘sheitani’ (devil) who hates children.

He told me that whilst he was acting as caretaker before our arrival he one night had his

wife and small daughter in the room to keep him company. He said that his small

daughter woke up and screamed exactly as Kate had done! Silly coincidence I

suppose, but such strange things happen in Africa that I decided to move the children

into our room and George sleeps in solitary state in the haunted room! Kate now sleeps

peacefully once she goes to sleep but I have to stay with her until she does.I like this house and it does not seem at all sinister to me. As I mentioned before,

the rooms are high ceilinged and airy, and have cool cement floors. We have made one

end of the enclosed verandah into the living room and the other end is the playroom for

the children. The space in between is a sort of no-mans land taken over by the dogs as

their special territory.Eleanor.

Nzassa 25th March 1939.

Dearest Family,

George is on safari down in the Rufigi River area. He is away for about three

weeks in the month on this job. I do hate to see him go and just manage to tick over until

he comes back. But what fun and excitement when he does come home.

Usually he returns after dark by which time the children are in bed and I have

settled down on the verandah with a book. The first warning is usually given by the

dogs, Fanny and her son Paddy. They stir, sit up, look at each other and then go and sit

side by side by the door with their noses practically pressed to the mosquito gauze and

ears pricked. Soon I can hear the hum of the car, and so can Hasmani, the old Game

Scout who sleeps on the back verandah with rifle and ammunition by his side when

George is away. When he hears the car he turns up his lamp and hurries out to rouse

Juma, the houseboy. Juma pokes up the fire and prepares tea which George always

drinks whist a hot meal is being prepared. In the meantime I hurriedly comb my hair and

powder my nose so that when the car stops I am ready to rush out and welcome

George home. The boy and Hasmani and the garden boy appear to help with the

luggage and to greet George and the cook, who always accompanies George on

Safari. The home coming is always a lively time with much shouting of greetings.

‘Jambo’, and ‘Habari ya safari’, whilst the dogs, beside themselves with excitement,

rush around like lunatics.As though his return were not happiness enough, George usually collects the

mail on his way home so there is news of Ann and young George and letters from you

and bundles of newspapers and magazines. On the day following his return home,

George has to deal with official mail in the office but if the following day is a weekday we

all, the house servants as well as ourselves, pile into the boxbody and go to Dar es

Salaam. To us this means a mornings shopping followed by an afternoon on the beach.

It is a bit cooler now that the rains are on but still very humid. Kate keeps chubby

and rosy in spite of the climate but Johnny is too pale though sturdy enough. He is such

a good baby which is just as well because Kate is a very demanding little girl though

sunny tempered and sweet. I appreciate her company very much when George is

away because we are so far off the beaten track that no one ever calls.Eleanor.

Nzassa 28th April 1939.

Dearest Family,

You all seem to wonder how I can stand the loneliness and monotony of living at

Nzassa when George is on safari, but really and truly I do not mind. Hamisi the cook

always goes on safari with George and then the houseboy Juma takes over the cooking

and I do the lighter housework. the children are great company during the day, and when

they are settled for the night I sit on the verandah and read or write letters or I just dream.

The verandah is entirely enclosed with both wire mosquito gauze and a trellis

work of heavy expanded metal, so I am safe from all intruders be they human, animal, or

insect. Outside the air is alive with mosquitos and the cicadas keep up their monotonous

singing all night long. My only companions on the verandah are the pale ghecco lizards

on the wall and the two dogs. Fanny the white bull terrier, lies always near my feet

dozing happily, but her son Paddy, who is half Airedale has a less phlegmatic

disposition. He sits alert and on guard by the metal trellis work door. Often a lion grunts

from the surrounding bush and then his hackles rise and he stands up stiffly with his nose

pressed to the door. Old Hasmani from his bedroll on the back verandah, gives a little

cough just to show he is awake. Sometimes the lions are very close and then I hear the

click of a rifle bolt as Hasmani loads his rifle – but this is usually much later at night when

the lights are out. One morning I saw large pug marks between the wall of my bedroom

and the garage but I do not fear lions like I did that beastly leopard on the farm.

A great deal of witchcraft is still practiced in the bush villages in the

neighbourhood. I must tell you about old Hasmani’s baby in connection with this. Last

week Hasmani came to me in great distress to say that his baby was ‘Ngongwa sana ‘

(very ill) and he thought it would die. I hurried down to the Game Scouts quarters to see

whether I could do anything for the child and found the mother squatting in the sun

outside her hut with the baby on her lap. The mother was a young woman but not an

attractive one. She appeared sullen and indifferent compared with old Hasmani who

was very distressed. The child was very feverish and breathing with difficulty and

seemed to me to be suffering from bronchitis if not pneumonia. I rubbed his back and

chest with camphorated oil and dosed him with aspirin and liquid quinine. I repeated the

treatment every four hours, but next day there was no apparent improvement.

In the afternoon Hasmani begged me to give him that night off duty and asked for

a loan of ten shillings. He explained to me that it seemed to him that the white man’s

medicine had failed to cure his child and now he wished to take the child to the local witch

doctor. “For ten shillings” said Hasmani, “the Maganga will drive the devil out of my

child.” “How?” asked I. “With drums”, said Hasmani confidently. I did not know what to

do. I thought the child was too ill to be exposed to the night air, yet I knew that if I

refused his request and the child were to die, Hasmani and all the other locals would hold

me responsible. I very reluctantly granted his request. I was so troubled by the matter

that I sent for George’s office clerk. Daniel, and asked him to accompany Hasmani to the

ceremony and to report to me the next morning. It started to rain after dark and all night

long I lay awake in bed listening to the drums and the light rain. Next morning when I

went out to the kitchen to order breakfast I found a beaming Hasmani awaiting me.

“Memsahib”, he said. “My child is well, the fever is now quite gone, the Maganga drove

out the devil just as I told you.” Believe it or not, when I hurried to his quarters after

breakfast I found the mother suckling a perfectly healthy child! It may be my imagination

but I thought the mother looked pretty smug.The clerk Daniel told me that after Hasmani

had presented gifts of money and food to the ‘Maganga’, the naked baby was placed

on a goat skin near the drums. Most of the time he just lay there but sometimes the witch

doctor picked him up and danced with the child in his arms. Daniel seemed reluctant to

talk about it. Whatever mumbo jumbo was used all this happened a week ago and the

baby has never looked back.Eleanor.

Nzassa 3rd July 1939.

Dearest Family,

Did I tell you that one of George’s Game Scouts was murdered last month in the

Maneromango area towards the Rufigi border. He was on routine patrol, with a porter

carrying his bedding and food, when they suddenly came across a group of African

hunters who were busy cutting up a giraffe which they had just killed. These hunters were

all armed with muzzle loaders, spears and pangas, but as it is illegal to kill giraffe without

a permit, the Scout went up to the group to take their names. Some argument ensued

and the Scout was stabbed.The District Officer went to the area to investigate and decided to call in the Police

from Dar es Salaam. A party of police went out to search for the murderers but after

some days returned without making any arrests. George was on an elephant control

safari in the Bagamoyo District and on his return through Dar es Salaam he heard of the

murder. George was furious and distressed to hear the news and called in here for an

hour on his way to Maneromango to search for the murderers himself.After a great deal of strenuous investigation he arrested three poachers, put them

in jail for the night at Maneromango and then brought them to Dar es Salaam where they

are all now behind bars. George will now have to prosecute in the Magistrate’s Court

and try and ‘make a case’ so that the prisoners may be committed to the High Court to

be tried for murder. George is convinced of their guilt and justifiably proud to have

succeeded where the police failed.George had to borrow handcuffs for the prisoners from the Chief at

Maneromango and these he brought back to Nzassa after delivering the prisoners to

Dar es Salaam so that he may return them to the Chief when he revisits the area next

week.I had not seen handcuffs before and picked up a pair to examine them. I said to

George, engrossed in ‘The Times’, “I bet if you were arrested they’d never get

handcuffs on your wrist. Not these anyway, they look too small.” “Standard pattern,”

said George still concentrating on the newspaper, but extending an enormous relaxed

left wrist. So, my dears, I put a bracelet round his wrist and as there was a wide gap I

gave a hard squeeze with both hands. There was a sharp click as the handcuff engaged

in the first notch. George dropped the paper and said, “Now you’ve done it, my love,

one set of keys are in the Dar es Salaam Police Station, and the others with the Chief at

Maneromango.” You can imagine how utterly silly I felt but George was an angel about it

and said as he would have to go to Dar es Salaam we might as well all go.So we all piled into the car, George, the children and I in the front, and the cook

and houseboy, immaculate in snowy khanzus and embroidered white caps, a Game

Scout and the ayah in the back. George never once complain of the discomfort of the

handcuff but I was uncomfortably aware that it was much too tight because his arm

above the cuff looked red and swollen and the hand unnaturally pale. As the road is so

bad George had to use both hands on the wheel and all the time the dangling handcuff

clanked against the dashboard in an accusing way.We drove straight to the Police Station and I could hear the roars of laughter as

George explained his predicament. Later I had to put up with a good deal of chaffing

and congratulations upon putting the handcuffs on George.Eleanor.

Nzassa 5th August 1939

Dearest Family,

George made a point of being here for Kate’s fourth birthday last week. Just

because our children have no playmates George and I always do all we can to make

birthdays very special occasions. We went to Dar es Salaam the day before the

birthday and bought Kate a very sturdy tricycle with which she is absolutely delighted.

You will be glad to know that your parcels arrived just in time and Kate loved all your

gifts especially the little shop from Dad with all the miniature tins and packets of

groceries. The tea set was also a great success and is much in use.We had a lively party which ended with George and me singing ‘Happy

Birthday to you’, and ended with a wild game with balloons. Kate wore her frilly white net

party frock and looked so pretty that it seemed a shame that there was no one but us to

see her. Anyway it was a good party. I wish so much that you could see the children.

Kate keeps rosy and has not yet had malaria. Johnny Jo is sturdy but pale. He

runs a temperature now and again but I am not sure whether this is due to teething or

malaria. Both children of course take quinine every day as George and I do. George

quite frequently has malaria in spite of prophylactic quinine but this is not surprising as he

got the germ thoroughly established in his system in his early elephant hunting days. I

get it too occasionally but have not been really ill since that first time a month after my

arrival in the country.Johnny is such a good baby. His chief claim to beauty is his head of soft golden

curls but these are due to come off on his first birthday as George considers them too

girlish. George left on safari the day after the party and the very next morning our wood

boy had a most unfortunate accident. He was chopping a rather tough log when a chip

flew up and split his upper lip clean through from mouth to nostril exposing teeth and

gums. A truly horrible sight and very bloody. I cleaned up the wound as best I could

and sent him off to the hospital at Dar es Salaam on the office bicycle. He wobbled

away wretchedly down the road with a white cloth tied over his mouth to keep off the

dust. He returned next day with his lip stitched and very swollen and bearing a

resemblance to my lip that time I used the hair remover.Eleanor.

Splendid Hotel. Dar es Salaam 7th September 1939

Dearest Family,

So now another war has started and it has disrupted even our lives. We have left

Nzassa for good. George is now a Lieutenant in the King’s African Rifles and the children

and I are to go to a place called Morogoro to await further developments.

I was glad to read in today’s paper that South Africa has declared war on

Germany. I would have felt pretty small otherwise in this hotel which is crammed full of

men who have been called up for service in the Army. George seems exhilarated by

the prospect of active service. He is bursting out of his uniform ( at the shoulders only!)

and all too ready for the fray.The war came as a complete surprise to me stuck out in the bush as I was without

wireless or mail. George had been away for a fortnight so you can imagine how

surprised I was when a messenger arrived on a bicycle with a note from George. The

note informed me that war had been declared and that George, as a Reserve Officer in

the KAR had been called up. I was to start packing immediately and be ready by noon