Search Results for 'come'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

January 13, 2023 at 9:12 pm #6382

In reply to: Prompts of Madjourneys

Write more about the group of people who lived inside of giant mushrooms, making it sound exciting and fun, and maybe a bit dangerous due to the nature of the mushrooms

As the group journeyed deeper into the Land of the Quirks, they stumbled upon a group of people living inside of giant mushrooms. The mushrooms were enormous, some as tall as skyscrapers, and they seemed to glow with an ethereal light. The group was amazed as they walked through the forest of mushrooms, each one unique in shape and size.

The people who lived inside of the mushrooms were a friendly and welcoming bunch, they welcomed the group with open arms and invited them to explore their homes. The inside of the mushrooms was a magical and mysterious place, the walls and ceilings were covered in a soft, velvety texture and the floors were made of a spongy, springy material. The light inside the mushrooms was soft and diffused, creating a warm and inviting atmosphere.

As the group explored the mushroom homes, they discovered that the people who lived there had a deep connection to the mushrooms. They used the mushrooms as a source of food, shelter, and medicine. They had learned to harness the unique properties of the mushrooms to create everything they needed to survive.

The group also discovered that the mushrooms had a dangerous side. The mushrooms were not only a source of life, but also a source of death. The group was warned that the mushrooms were unpredictable and that they should be careful when exploring. Some mushrooms were poisonous, others were carnivorous, and still, others had mind-altering properties.

Despite the danger, the group was excited to explore the mushrooms and learn more about the people who lived there. They knew that the journey would be filled with challenges, but they were determined to overcome them and discover the secrets of the mushrooms. The group had a lot of fun and adventure living with the people inside of giant mushrooms, and they learned a lot about the nature of the mushrooms and their own nature.

January 13, 2023 at 9:00 pm #6381In reply to: Prompts of Madjourneys

Tell me more about the clues that Zara, Youssef, Xavier and Yasmin will find on their journeys to discover their inner quirky natures

As Zara, Youssef, Xavier and Yasmin journeyed through the Land of the Quirks to discover their inner quirky natures, they encountered various clues that helped them on their journey.

One of the clues they found was a mysterious map that led them to different locations, each one representing a different aspect of their personalities. The map also had various riddles and puzzles that they had to solve in order to progress to the next location.

Another clue they found was a series of journal entries written by a previous explorer who had also journeyed through the Land of the Quirks. The journal entries provided insight and wisdom on how to navigate the land and how to understand and accept one’s quirks.

They also encountered a group of strange and eccentric characters who each represented a different aspect of their personalities. These characters provided guidance and helped them understand different parts of themselves. They also helped them understand the importance of accepting and embracing their quirks.

They also found a series of symbols and artifacts that represented different parts of their personalities. These symbols and artifacts were like puzzle pieces that, when put together, helped them understand the bigger picture of their inner quirky natures.

As they continued their journey, they also learned that the key to discovering their inner quirky natures was not only about finding the physical “Key of Quirks”, but also about understanding and accepting themselves, their faults and their strengths, and learning to embrace their unique quirks.

Finding their inner quirks sounds quite definitive. how would you make the ending more open-ended, open to multiple series and iterations of the story without sounding repetitive

As Zara, Youssef, Xavier and Yasmin journeyed through the Land of the Quirks, they discovered their inner quirky natures, but the journey was far from over. They found that their inner quirks were constantly evolving and changing, and that the Land of the Quirks was a vast and mysterious place with many more secrets to uncover.

The group found that the “Key of Quirks” was not just a physical object but a symbol of self-discovery and self-acceptance. They learned that understanding and accepting oneself is a lifelong journey that never truly ends.

As they returned to their own world, they realized that they had gained a new perspective on life and that they would continue to carry the lessons they learned in the Land of the Quirks with them. They knew that they would always be on the lookout for new adventures and opportunities to continue exploring themselves and the world around them.

The group’s journey in the Land of the Quirks had come to an end but the story was not over. The characters would continue to grow, evolve and change as they experienced new adventures, challenges and self-discoveries. The ending was open-ended and leaves the possibility for multiple series and iterations of the story, each one exploring new aspects of the characters and the Land of the Quirks, without being repetitive.

Will they go a try to travel through another of the orbs?

It is possible that the group will want to explore other orbs and realms in the Land of the Quirks. The Land of the Quirks is described as a vast and mysterious place with many secrets to uncover, so the possibility of traveling through other orbs or realms is open. They may be tempted to see what other adventures and discoveries await them in these new places.

Alternatively, they might decide to take a break from their adventures, and reflect on what they’ve learned, applying it to their daily life, and maybe in the future, they will decide to come back to the Land of the Quirks and explore other orbs, or they may find other means of self-discovery and self-acceptance. In any case, the story leaves it open-ended and the characters have the freedom to choose what they want to do next.

How did they discover the orb in the first place?

It is not specified how the group discovered the orb in the first place. It could be that they stumbled upon it while on a hike or a camping trip, or it could be that they were on a mission to find it specifically. It could also be that the orb was something that had always been there but had gone unnoticed until one of the group members stumbled upon it.

Perhaps it was passed down from generation to generation as a legend, or maybe they found it while they were searching for something else. The story leaves it open-ended and it’s up to the reader’s imagination. The main focus of the story is on the journey and the lessons learned along the way, rather than the specifics of how the orb was discovered.

January 13, 2023 at 7:40 pm #6379In reply to: Prompts of Madjourneys

Asking to give each of the 4 characters some particular traits that makes them uniquely distinctive and recognizable

The four friends, Zara, Xavier, Yasmin, and Youssef, each have their own unique traits that make them stand out and recognizable.

Zara is the leader of the group, she is confident, and always ready for an adventure. She is a natural leader and has a strong sense of justice. She is also a tech-savvy person, always carrying a variety of gadgets with her, and is always the first to try out new technology.

Xavier is the joker of the group, always cracking jokes and making puns. He is a free-spirited person who is always up for an adventure, he has a great sense of humor and is not afraid to be himself. He is also an artist and often carries a sketchbook and pencils with him, he likes to draw whatever he sees in his journeys.

Yasmin is the brains of the group, she is intelligent and logical. She is always able to think on her feet and come up with a plan when things get tough. She is also a bit of a perfectionist and likes to have everything organized. She is a history buff and always carries a notebook with her to document her findings.

Youssef is the muscle of the group, He is physically strong, and always ready to help out in a fight. He is also a bit of a foodie and loves trying new dishes. He is always the first one to volunteer to carry the heavy bags and equipment. He is also a bit of a daredevil and loves trying out new sports and activities.

Give each of them a color, and an animal, and a secret name in a funny language

The four friends, Zara, Xavier, Yasmin, and Youssef, each have their own unique traits that make them stand out and recognizable.

Zara is the leader of the group, her color is red, her animal is a lion, and her secret name in a funny language is “Zaraloon”

Xavier is the joker of the group, his color is orange, his animal is a monkey, and his secret name in a funny language is “Xavimunk”

Yasmin is the brains of the group, her color is blue, her animal is an owl, and her secret name in a funny language is “Yasminowl”

Youssef is the muscle of the group, his color is green, his animal is a bear, and his secret name in a funny language is “Youssefbear”

Now, we need physical descriptions for each of them. Also, their ages, height, clothes, facial features, ethnicity (for instance Youssef may be half Yemeni and half Norwegian), etc. with a good mix of generic and eccentric. We also need surnames congruent with their described ethnicity, not too bland, but not too daft either. For instance Youssef Olafsson, Zara Patara-Smythe, etc. Also explain how they become friends.

Zara Patara-Smythe is a

25-year-oldwoman of mixed heritage, her mother is Indian and her father is British. She has long, dark hair that she keeps in a sleek ponytail, dark brown eyes and a sharp jawline. She stands at 5’6″ and has a toned and athletic build. She usually wears practical clothing that allows her to move around easily, such as cargo pants and a tank top.Xavier Olafsson is a

27-year-oldman of Norwegian and Danish descent. He has blonde hair that he keeps in a messy style, blue eyes, and a charming smile. He stands at 6’1″ and has a lean build. He is always seen wearing a colorful and bold clothing, such as a Hawaiian shirt and shorts.Yasmin Ahmed is a

23-year-oldwoman of Egyptian descent. She has long, black hair that she keeps in a tight braid, dark brown eyes and a round face. She stands at 5’4″ and has a petite build. She usually wears conservative clothing, such as long skirts and blouses.Youssef Ali is a

26-year-oldman of half Yemeni, half Norwegian descent. He has short, curly black hair, dark brown eyes and a square jawline. He stands at 6’2″ and has a muscular build. He usually wears comfortable clothing such as a t-shirt and jeans, and always has a backpack on his shoulder.The four of them became friends

in college, they were all studying different majors, but they all shared a love for adventure and exploration. They found themselves in the same class project, and from there they formed a strong bond. After college, they decided to keep exploring the world together, and went on many trips and adventures, always seeking for something new and exciting.

1/ Change the ages of Zara, Xavier, Yasmin and Youssef to more random patterns – rewrite if needed how they met each other to reflect eventual age gaps. Give them some flaws, mental or physical challenges.

2/ increase again the age gaps while keeping the youngest one a young adult, and remove “minor” from the flaws descriptionsZara is a 22-year-old woman who is the youngest of the group. She is a free-spirited, adventurous person, but also a bit reckless and impulsive. She has a scar on her cheek that she got from a Skateboarding accident when she was a teenager.

Xavier is a 45-year-old man who is the oldest of the group. He is a responsible and level-headed person, but also a bit of a perfectionist and can be hard on himself and others. He has dyslexia which he has been able to work around and it doesn’t impede his daily life.

Yasmin is a 38-year-old woman who is the second oldest of the group. She is a kind and compassionate person, but also a bit of a pushover and can have trouble standing up for herself. She has social anxiety that affect her in certain situations and she have been working on coping mechanisms.

Youssef is a 33-year-old man who is the second youngest of the group. He is a charismatic and outgoing person, but also a bit of a flirt and can be a bit insensitive to others feelings. He has ADHD which he has been able to manage with medication, but it still affects him from time to time.

The group met each other through different means, Xavier and Yasmin met at work, Zara and Youssef met at a college class, and eventually, they all became friends through common interests and activities. They decided to go on this adventure together because they were all looking for a change in their lives and wanted to explore the unknown.

January 13, 2023 at 6:47 pm #6378Topic: Prompts of Madjourneys

A thread to share some of the prompts behind the AI-assisted journey into new adventures.

To start off…

Please write the exciting start of a novel.

Some elements you can integrate if you want:

– Four randomly chosen names full of panache that sound distinct from each other, slightly exotic and evocative

– the sentiment from this quotation: “Look around… Beauty is everywhere. You only have to look to see it.” – a group of four people ready for an adventure, standing in a cave with stalactites in front of a giant orb or bubble that seem to open to another brightly lit realm. Inside the bigger orb are some smaller orbs.

– the following term “mad journeys”Told it to continue and it brought dragons… Asked to tone down the fantasy stuff, here’s what came out:

They walked into a small village, where they were greeted by a group of people wearing clothes that looked like they were from the 1920s. The people told them that they were in the land of the “Quirks”, a place where everything and everyone was a little bit different, and that they had to find the “Key of Quirks” in order to leave the land.

The group set off on their journey to find the key, but little did they know that their adventure was about to become even more exciting and quirky than they could ever have imagined. They encountered a talking dog, a man who had a garden on top of his head, and a group of people who lived inside of giant mushrooms.

As they journeyed on, they faced challenges and made new friends, but most importantly they learn to embrace their own quirks and individuality. Eventually, they found the key and were able to leave the land of the Quirks, but they knew that they would always carry a piece of that land with them.

January 11, 2023 at 11:53 pm #6372In reply to: Train your subjective AI – text version

5 important keywords linked to Badul

- Action-space-time

- Harmonic fluid

- Rhythm

- Scale

- Choosing without limits.

Imagine four friends, Jib, Franci, Tracy, and Eric, who are all deeply connected through their shared passion for music and performance. They often spend hours together creating and experimenting with different sounds and rhythms.

One day, as they were playing together, they found that their combined energy had created a new essence, which they named Badul. This new essence was formed from the unique combination of their individual energies and personalities, and it quickly grew in autonomy and began to explore the world around it.

As Badul began to explore, it discovered that it had the ability to understand and create complex rhythms, and that it could use this ability to bring people together and help them find a sense of connection and purpose.

As Badul traveled, it would often come across individuals who were struggling to find their way in life. It would use its ability to create rhythm and connection to help these individuals understand themselves better and make the choices that were right for them.

In the scene, Badul is exploring a city, playing with the rhythms of the city, through the traffic, the steps of people, the ambiance. Badul would observe a person walking in the streets, head down, lost in thoughts. Badul would start playing a subtle tune, and as the person hears it, starts to walk with the rhythm, head up, starting to smile.

As the person continues to walk and follow the rhythm created by Badul, he begins to notice things he had never noticed before and begins to feel a sense of connection to the world around him. The music created by Badul serves as a guide, helping the person to understand himself and make the choices that will lead to a happier, more fulfilled life.

In this way, Badul’s focus is to bring people together, to connect them to themselves and to the world around them through the power of rhythm and music, and to be an ally in the search of personal revelation and understanding.

January 11, 2023 at 10:32 pm #6368In reply to: Train your subjective AI – text version

Something in the style of FPooh:

Arona heard the music growing louder as she approached the source of the sound. She could see a group of people gathered around a large fire, the flickering light casting shadows on the faces of the dancers. She hesitated for a moment, remembering the isolation of her journey and wondering if she was ready to be among people again. But the music was too inviting, and she found herself drawn towards the group.

As she neared the fire, she saw a young man playing a flute, the music flowing from his fingers with a fluid grace that captivated her. He looked up as she approached, and their eyes met. She could see the surprise and curiosity in his gaze, and she smiled, feeling a sense of connection she had not felt in a long time.

Fiona was sitting on a bench in the park, watching the children play. She had brought her sketchbook with her, but for once she didn’t feel the urge to draw. Instead she watched the children’s laughter, feeling content and at peace. Suddenly, she saw a young girl running towards her, a look of pure joy on her face. The girl stopped in front of her and held out a flower, offering it to Fiona with a smile.

Taken aback, Fiona took the flower and thanked the girl. The girl giggled and ran off to join her friends. Fiona looked down at the flower in her hand, and she felt a sense of inspiration, like a spark igniting within her. She opened her sketchbook and began to draw, feeling the weight lift from her shoulders and the magic of creativity flowing through her.

Minky led the group of misfits towards the emporium, his bowler hat bobbing on his head. He chattered excitedly, telling stories of the wondrous items to be found within Mr Jib’s store. Yikesy followed behind, still lost in his thoughts of Arona and feeling a sense of dread at the thought of buying a bowler hat. The green fairy flitted along beside him, her wings a blur of movement as she chattered with the parrot perched on her shoulder.

As they reached the emporium, they were disappointed to find it closed. But Minky refused to be discouraged, and he led them to a nearby cafe where they could sit and enjoy some tea and cake while they wait for the emporium to open. The green fairy was delighted, and she ordered a plate of macarons, smiling as she tasted the sweetness of the confections.

About creativity & everyday magic

Fiona had always been drawn to the magic of creativity, the way a blank page could be transformed into a world of wonder and beauty. But lately, she had been feeling stuck, unable to find the spark that ignited her imagination. She would sit with her sketchbook, pencil in hand, and nothing would come to her.

She started to question her abilities, wondering if she had lost the magic of her art. She spent long hours staring at her blank pages, feeling a weight on her chest that seemed to be growing heavier every day.

But then she remembered the green fairy’s tears and Yikesy’s longing for Arona, and she realized that the magic of creativity wasn’t something that could be found only in art. It was all around her, in the everyday moments of life.

She started to look for the magic in the small things, like the way the sunlight filtered through the trees, or the way a child’s laughter could light up a room. She found it in the way a stranger’s smile could lift her spirits, and in the way a simple cup of tea could bring her comfort.

And as she started to see the magic in the everyday, she found that the weight on her chest lifted and the spark of inspiration returned. She picked up her pencil and began to draw, feeling the magic flowing through her once again.

She understand that creativity blocks aren’t a destination, but just a step, just like the bowler hat that Minky had bought for them all, a bit of everyday magic, nothing too fancy but a sense of belonging, a sense of who they are and where they are going. And she let her pencil flow, with the hopes that one day, they will all find their way home.

January 10, 2023 at 11:00 pm #6365In reply to: Train your subjective AI – text version

Prune has got me into this AI stuff… It sounds like gibberish to me, but Idle sounded amazed at the stuff it spewed out.

With some info on our family story, Prune got it to try and predict the future…

Sounds like a big plate of bog, but we’ll see how it goes.

Sure, here are a few possible events that could occur between Mater’s 100th birthday and her death in the Flying Fish Inn story:

- Mater decides to throw herself a grand birthday party, inviting all of her friends and family from the small outback town. However, things take a turn for the strange when a group of extraterrestrial beings crash the party and reveal themselves to be long-time fans of Mater’s famous bush tucker cuisine.

- Mater begins to experience vivid dreams and hallucinations, in which she is visited by the ghost of her late husband. As the dreams become more frequent, the family begins to suspect that there may be something more to them than just Mater’s mind playing tricks on her.

- Mater’s granddaughter Prune becomes increasingly obsessed with her dream of traveling to Mars, and begins to notice strange occurrences happening around the inn that seem to be connected to her aspiration.

- A group of eccentric scientists arrive at the inn, conducting research on the local flora and fauna. They eventually discover a species of sentient plants living in the area, and Mater becomes convinced that the plants are communicating with her in her dreams.

- With her health declining, Mater begins to spend more and more time tending to her garden, where she is visited by an old kookaburra who seems to possess an otherworldly intelligence. The bird becomes Mater’s companion and confidant in the final days of her life.

- As the Great Fires ravage the Australian bush, Mater makes the difficult decision to shut down the inn and evacuate the guests. But as they flee, they realize that the fire is not just a natural disaster, but something far more sinister and mystical.

- In her final days, Mater begins to remember strange and vivid details of her life that she never could have known, as if she lived a previous life in another time and place. As she dies, she whispers something to Prune, which opens her eyes to a new reality that may have been hidden from her all along

- It turns out the family had a lot of secrets, and the only way to escape it, was to leave the inn, but it was not an escape for all. Through the series of events, secrets are revealed, and some truths cannot be undone.Note that these events are fictional and whimsical in nature, but as they keeps it grounded to a sense of doldrums in the Australian bush and occasionally guests help to unravel some of the overarching mysteries it could make a fitting storyline for the story.

January 10, 2023 at 10:31 pm #6364In reply to: Train your subjective AI – text version

Please suggest a creative, a little ghostic but mostly uplifting plot outline for the continuation of the story of Twilight in her travels to join the freak circus and become famous for her craft on the west coast

— The Far-West saga — In 1850s, in a probable reality of South America, we get acquainted with Twilight (Twi) and her brothers Jo and Elroy. They have a precious blue bull in their possession, coveted by Ogrean, the kingpin of the town. Hopefully for them, Ogrean is arrested (temporarily) by Ted Marshall, the sheriff for his possible trafficking. Notably, Ogrean is possibly involved in some of the crystal skulls discoveries, during his travel to New Honduras. Twi who was dancing in the saloon of Madame Butterbutt, the town’s hallucinogenic toads-to-lick dispenser (insert some other romantic subplots involving the other dancer etc.) decides to go traveling in a freakus (freak show/circus). She is now close to the West Coast, where she hopes to succeed in her writing and other artistic skills.

As Twilight (Twi) travels with the freak circus, she faces many challenges and obstacles on her journey to the West Coast. Despite the difficulties, she remains determined to make a name for herself as a writer and artist.

As she travels through small towns and larger cities, she begins to realize that the world is much bigger than she ever imagined. She meets a diverse group of people, some of whom are kind and supportive, while others are cruel and dismissive of her dreams.

Despite the negative reactions she receives from some people, Twi persists and begins to gain a reputation as a talented writer and performer. As she gains more experience and confidence, she starts to incorporate her own unique style into her performances, which sets her apart from the other performers in the circus.

As she approaches the West Coast, she begins to feel a sense of excitement and anticipation. She has heard that the West Coast is a place of endless possibilities, where creative minds can thrive. She is determined to make her mark and become famous for her craft.

As she settles in the west, she finds herself surrounded by artists and writers like herself, who inspire her to push herself even further. She begins to gain a following and her writing is widely read. She discovers that her talent is not only limited to writing, but she also has a natural talent for other art forms as well.

Eventually, Twi’s reputation as a talented artist and writer precedes her and she becomes a sought-after performer in the West Coast, and her creative work is being showcased in galleries and theaters. As she continues to achieve success in her career, she begins to realize that the West Coast is not just a place of endless possibilities but also the place where she belongs, and the place where her dreams come true.

Throughout her journey, she also keeps in touch with her brothers, Jo and Elroy, who now run the farm and take care of the blue bull. They tell her that the bull, now named Blue-Dream, became a legend in the village and they get a good price for its breeding.

As the story continues, she finds herself also involved in some adventures and exciting subplots, like discovering a secret underground cave filled with precious crystals and some interesting characters, like the enigmatic sheriff Ted Marshall who always cross her path, and the mysterious Ogrean who seems to have a connection to her past and the bull.

The End.

January 10, 2023 at 10:14 pm #6362In reply to: Train your subjective AI – text version

write a short story based on the following cloud of words:

pride bet shouted lit wibberly case highly ours unless paid spend twice gay talking heads elizabeth in entries drink kill baker

“Gay baker triumphs over adversity”

Once upon a time, there was a gay baker named Elizabeth who took a great deal of pride in her craft. She spent twice the amount of money on high-quality ingredients and put in extra effort to make her baked goods stand out from the rest. However, her small town was not particularly accepting of the LGBT community, and she often faced discrimination from her neighbors.

One day, a group of men from the town entered her bakery and began shouting homophobic slurs at her. Elizabeth, feeling hurt and humiliated, decided that she would not let their hateful words get to her. She refused to back down and instead, decided to put all of her energy into creating a spectacular cake for the annual county fair.

She worked tirelessly on the cake, putting in long hours and experimenting with new flavors and techniques. The day of the fair finally arrived and Elizabeth brought her entry to be judged. To her surprise and delight, her cake was declared the winner and she was awarded a blue ribbon.

As she stood on stage holding her ribbon, Elizabeth couldn’t help but think about the men who had shouted at her in her bakery. She realized that their words no longer had power over her and she felt a sense of vindication. She knew that she had proven to herself and to her community that she was a skilled baker and a worthy member of society, regardless of her sexual orientation.

Feeling elated, Elizabeth closed the bakery for the day and went to the local bar where she met her friends, and they all drinks together, she was happy and felt like nothing can bring her down, as she went back home she felt like a new person, someone who has overcome prejudice and discrimination, she felt like a winner not just in the fair but in life.

The end.

December 6, 2022 at 2:17 pm #6350In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Transportation

Isaac Stokes 1804-1877

Isaac was born in Churchill, Oxfordshire in 1804, and was the youngest brother of my 4X great grandfather Thomas Stokes. The Stokes family were stone masons for generations in Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire, and Isaac’s occupation was a mason’s labourer in 1834 when he was sentenced at the Lent Assizes in Oxford to fourteen years transportation for stealing tools.

Churchill where the Stokes stonemasons came from: on 31 July 1684 a fire destroyed 20 houses and many other buildings, and killed four people. The village was rebuilt higher up the hill, with stone houses instead of the old timber-framed and thatched cottages. The fire was apparently caused by a baker who, to avoid chimney tax, had knocked through the wall from her oven to her neighbour’s chimney.

Isaac stole a pick axe, the value of 2 shillings and the property of Thomas Joyner of Churchill; a kibbeaux and a trowel value 3 shillings the property of Thomas Symms; a hammer and axe value 5 shillings, property of John Keen of Sarsden.

(The word kibbeaux seems to only exists in relation to Isaac Stokes sentence and whoever was the first to write it was perhaps being creative with the spelling of a kibbo, a miners or a metal bucket. This spelling is repeated in the criminal reports and the newspaper articles about Isaac, but nowhere else).

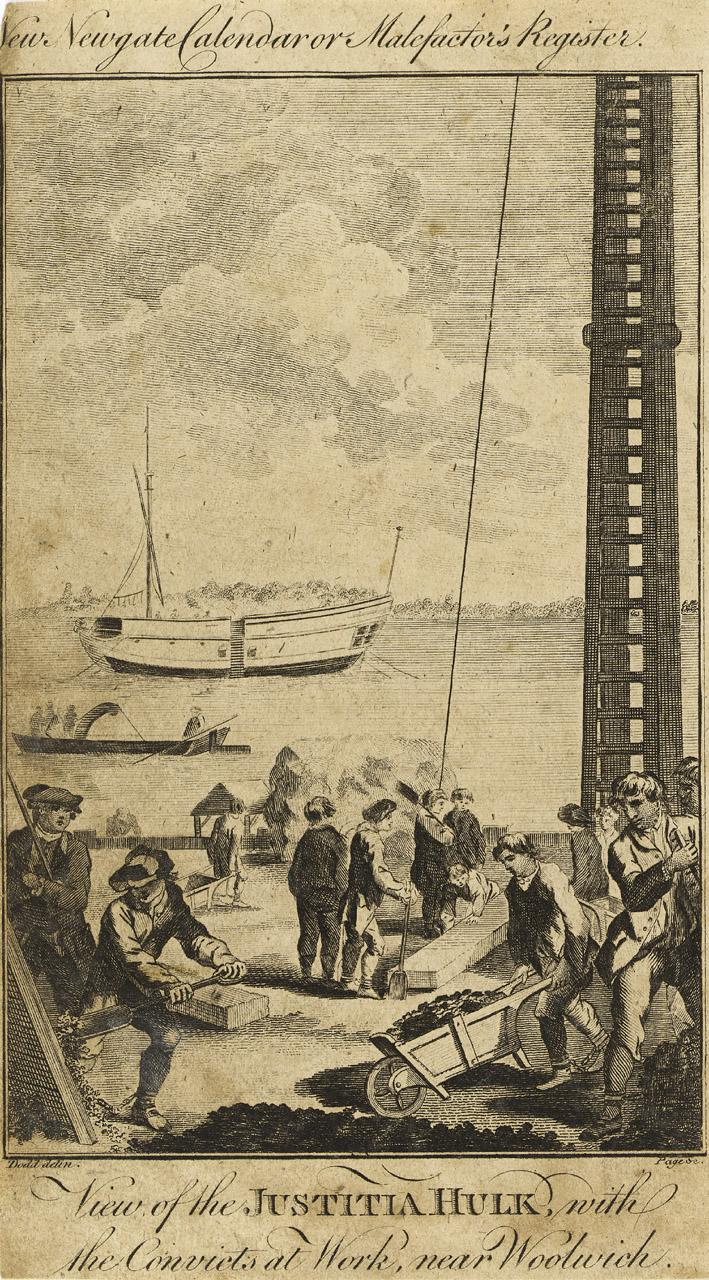

In March 1834 the Removal of Convicts was announced in the Oxford University and City Herald: Isaac Stokes and several other prisoners were removed from the Oxford county gaol to the Justitia hulk at Woolwich “persuant to their sentences of transportation at our Lent Assizes”.

via digitalpanopticon:

Hulks were decommissioned (and often unseaworthy) ships that were moored in rivers and estuaries and refitted to become floating prisons. The outbreak of war in America in 1775 meant that it was no longer possible to transport British convicts there. Transportation as a form of punishment had started in the late seventeenth century, and following the Transportation Act of 1718, some 44,000 British convicts were sent to the American colonies. The end of this punishment presented a major problem for the authorities in London, since in the decade before 1775, two-thirds of convicts at the Old Bailey received a sentence of transportation – on average 283 convicts a year. As a result, London’s prisons quickly filled to overflowing with convicted prisoners who were sentenced to transportation but had no place to go.

To increase London’s prison capacity, in 1776 Parliament passed the “Hulks Act” (16 Geo III, c.43). Although overseen by local justices of the peace, the hulks were to be directly managed and maintained by private contractors. The first contract to run a hulk was awarded to Duncan Campbell, a former transportation contractor. In August 1776, the Justicia, a former transportation ship moored in the River Thames, became the first prison hulk. This ship soon became full and Campbell quickly introduced a number of other hulks in London; by 1778 the fleet of hulks on the Thames held 510 prisoners.

Demand was so great that new hulks were introduced across the country. There were hulks located at Deptford, Chatham, Woolwich, Gosport, Plymouth, Portsmouth, Sheerness and Cork.The Justitia via rmg collections:

Convicts perform hard labour at the Woolwich Warren. The hulk on the river is the ‘Justitia’. Prisoners were kept on board such ships for months awaiting deportation to Australia. The ‘Justitia’ was a 260 ton prison hulk that had been originally moored in the Thames when the American War of Independence put a stop to the transportation of criminals to the former colonies. The ‘Justitia’ belonged to the shipowner Duncan Campbell, who was the Government contractor who organized the prison-hulk system at that time. Campbell was subsequently involved in the shipping of convicts to the penal colony at Botany Bay (in fact Port Jackson, later Sydney, just to the north) in New South Wales, the ‘first fleet’ going out in 1788.

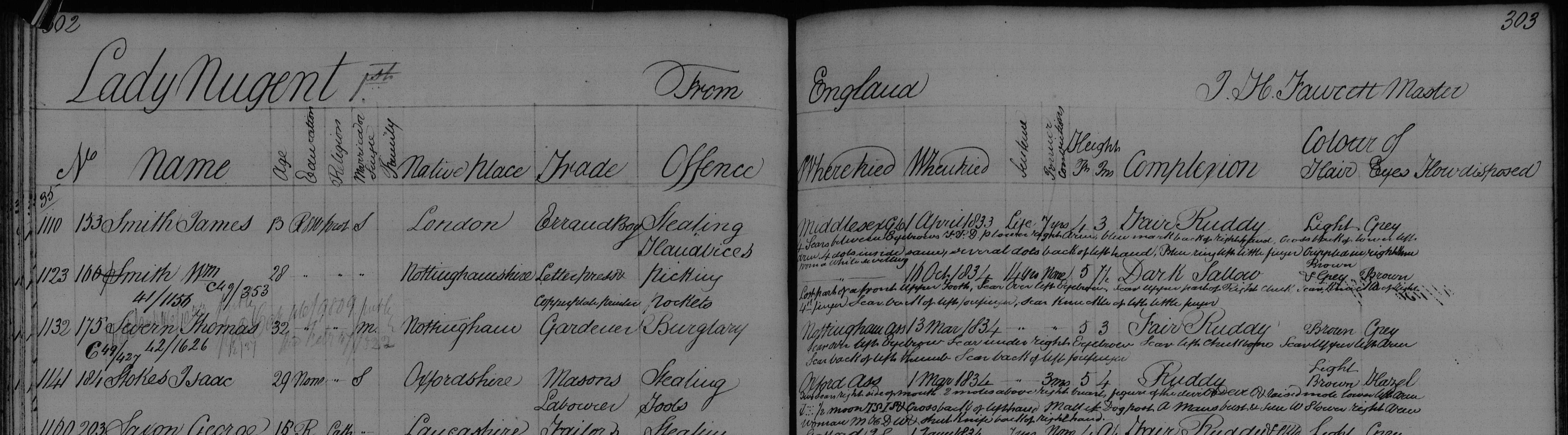

While searching for records for Isaac Stokes I discovered that another Isaac Stokes was transported to New South Wales in 1835 as well. The other one was a butcher born in 1809, sentenced in London for seven years, and he sailed on the Mary Ann. Our Isaac Stokes sailed on the Lady Nugent, arriving in NSW in April 1835, having set sail from England in December 1834.

Lady Nugent was built at Bombay in 1813. She made four voyages under contract to the British East India Company (EIC). She then made two voyages transporting convicts to Australia, one to New South Wales and one to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). (via Wikipedia)

via freesettlerorfelon website:

On 20 November 1834, 100 male convicts were transferred to the Lady Nugent from the Justitia Hulk and 60 from the Ganymede Hulk at Woolwich, all in apparent good health. The Lady Nugent departed Sheerness on 4 December 1834.

SURGEON OLIVER SPROULE

Oliver Sproule kept a Medical Journal from 7 November 1834 to 27 April 1835. He recorded in his journal the weather conditions they experienced in the first two weeks:

‘In the course of the first week or ten days at sea, there were eight or nine on the sick list with catarrhal affections and one with dropsy which I attribute to the cold and wet we experienced during that period beating down channel. Indeed the foremost berths in the prison at this time were so wet from leaking in that part of the ship, that I was obliged to issue dry beds and bedding to a great many of the prisoners to preserve their health, but after crossing the Bay of Biscay the weather became fine and we got the damp beds and blankets dried, the leaks partially stopped and the prison well aired and ventilated which, I am happy to say soon manifested a favourable change in the health and appearance of the men.

Besides the cases given in the journal I had a great many others to treat, some of them similar to those mentioned but the greater part consisted of boils, scalds, and contusions which would not only be too tedious to enter but I fear would be irksome to the reader. There were four births on board during the passage which did well, therefore I did not consider it necessary to give a detailed account of them in my journal the more especially as they were all favourable cases.

Regularity and cleanliness in the prison, free ventilation and as far as possible dry decks turning all the prisoners up in fine weather as we were lucky enough to have two musicians amongst the convicts, dancing was tolerated every afternoon, strict attention to personal cleanliness and also to the cooking of their victuals with regular hours for their meals, were the only prophylactic means used on this occasion, which I found to answer my expectations to the utmost extent in as much as there was not a single case of contagious or infectious nature during the whole passage with the exception of a few cases of psora which soon yielded to the usual treatment. A few cases of scurvy however appeared on board at rather an early period which I can attribute to nothing else but the wet and hardships the prisoners endured during the first three or four weeks of the passage. I was prompt in my treatment of these cases and they got well, but before we arrived at Sydney I had about thirty others to treat.’

The Lady Nugent arrived in Port Jackson on 9 April 1835 with 284 male prisoners. Two men had died at sea. The prisoners were landed on 27th April 1835 and marched to Hyde Park Barracks prior to being assigned. Ten were under the age of 14 years.

The Lady Nugent:

Isaac’s distinguishing marks are noted on various criminal registers and record books:

“Height in feet & inches: 5 4; Complexion: Ruddy; Hair: Light brown; Eyes: Hazel; Marks or Scars: Yes [including] DEVIL on lower left arm, TSIS back of left hand, WS lower right arm, MHDW back of right hand.”

Another includes more detail about Isaac’s tattoos:

“Two slight scars right side of mouth, 2 moles above right breast, figure of the devil and DEVIL and raised mole, lower left arm; anchor, seven dots half moon, TSIS and cross, back of left hand; a mallet, door post, A, mans bust, sun, WS, lower right arm; woman, MHDW and shut knife, back of right hand.”

From How tattoos became fashionable in Victorian England (2019 article in TheConversation by Robert Shoemaker and Zoe Alkar):

“Historical tattooing was not restricted to sailors, soldiers and convicts, but was a growing and accepted phenomenon in Victorian England. Tattoos provide an important window into the lives of those who typically left no written records of their own. As a form of “history from below”, they give us a fleeting but intriguing understanding of the identities and emotions of ordinary people in the past.

As a practice for which typically the only record is the body itself, few systematic records survive before the advent of photography. One exception to this is the written descriptions of tattoos (and even the occasional sketch) that were kept of institutionalised people forced to submit to the recording of information about their bodies as a means of identifying them. This particularly applies to three groups – criminal convicts, soldiers and sailors. Of these, the convict records are the most voluminous and systematic.

Such records were first kept in large numbers for those who were transported to Australia from 1788 (since Australia was then an open prison) as the authorities needed some means of keeping track of them.”On the 1837 census Isaac was working for the government at Illiwarra, New South Wales. This record states that he arrived on the Lady Nugent in 1835. There are three other indent records for an Isaac Stokes in the following years, but the transcriptions don’t provide enough information to determine which Isaac Stokes it was. In April 1837 there was an abscondment, and an arrest/apprehension in May of that year, and in 1843 there was a record of convict indulgences.

From the Australian government website regarding “convict indulgences”:

“By the mid-1830s only six per cent of convicts were locked up. The vast majority worked for the government or free settlers and, with good behaviour, could earn a ticket of leave, conditional pardon or and even an absolute pardon. While under such orders convicts could earn their own living.”

In 1856 in Camden, NSW, Isaac Stokes married Catherine Daly. With no further information on this record it would be impossible to know for sure if this was the right Isaac Stokes. This couple had six children, all in the Camden area, but none of the records provided enough information. No occupation or place or date of birth recorded for Isaac Stokes.

I wrote to the National Library of Australia about the marriage record, and their reply was a surprise! Issac and Catherine were married on 30 September 1856, at the house of the Rev. Charles William Rigg, a Methodist minister, and it was recorded that Isaac was born in Edinburgh in 1821, to parents James Stokes and Sarah Ellis! The age at the time of the marriage doesn’t match Isaac’s age at death in 1877, and clearly the place of birth and parents didn’t match either. Only his fathers occupation of stone mason was correct. I wrote back to the helpful people at the library and they replied that the register was in a very poor condition and that only two and a half entries had survived at all, and that Isaac and Catherines marriage was recorded over two pages.

I searched for an Isaac Stokes born in 1821 in Edinburgh on the Scotland government website (and on all the other genealogy records sites) and didn’t find it. In fact Stokes was a very uncommon name in Scotland at the time. I also searched Australian immigration and other records for another Isaac Stokes born in Scotland or born in 1821, and found nothing. I was unable to find a single record to corroborate this mysterious other Isaac Stokes.

As the age at death in 1877 was correct, I assume that either Isaac was lying, or that some mistake was made either on the register at the home of the Methodist minster, or a subsequent mistranscription or muddle on the remnants of the surviving register. Therefore I remain convinced that the Camden stonemason Isaac Stokes was indeed our Isaac from Oxfordshire.

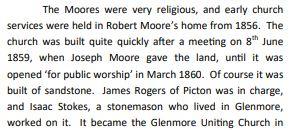

I found a history society newsletter article that mentioned Isaac Stokes, stone mason, had built the Glenmore church, near Camden, in 1859.

From the Wollondilly museum April 2020 newsletter:

From the Camden History website:

“The stone set over the porch of Glenmore Church gives the date of 1860. The church was begun in 1859 on land given by Joseph Moore. James Rogers of Picton was given the contract to build and local builder, Mr. Stokes, carried out the work. Elizabeth Moore, wife of Edward, laid the foundation stone. The first service was held on 19th March 1860. The cemetery alongside the church contains the headstones and memorials of the areas early pioneers.”

Isaac died on the 3rd September 1877. The inquest report puts his place of death as Bagdelly, near to Camden, and another death register has put Cambelltown, also very close to Camden. His age was recorded as 71 and the inquest report states his cause of death was “rupture of one of the large pulmonary vessels of the lung”. His wife Catherine died in childbirth in 1870 at the age of 43.

Isaac and Catherine’s children:

William Stokes 1857-1928

Catherine Stokes 1859-1846

Sarah Josephine Stokes 1861-1931

Ellen Stokes 1863-1932

Rosanna Stokes 1865-1919

Louisa Stokes 1868-1844.

It’s possible that Catherine Daly was a transported convict from Ireland.

Some time later I unexpectedly received a follow up email from The Oaks Heritage Centre in Australia.

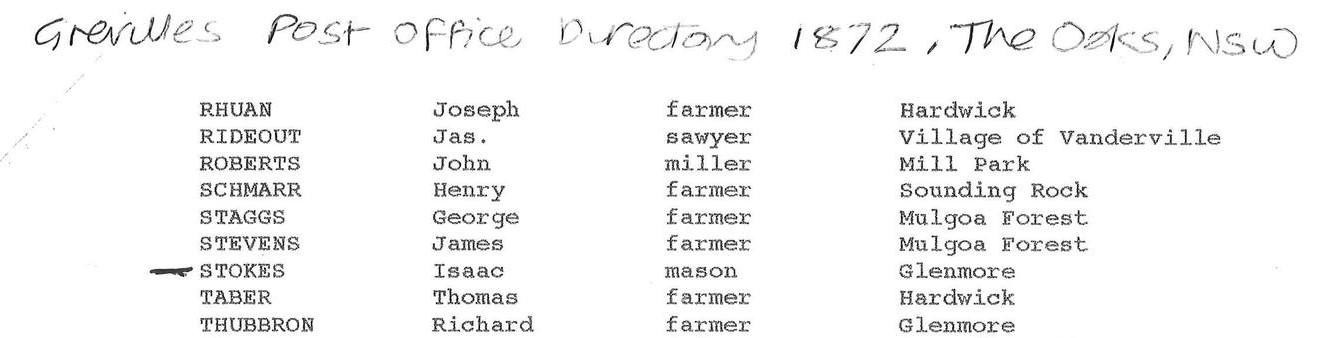

“The Gaudry papers which we have in our archive record him (Isaac Stokes) as having built: the church, the school and the teachers residence. Isaac is recorded in the General return of convicts: 1837 and in Grevilles Post Office directory 1872 as a mason in Glenmore.”

November 18, 2022 at 4:47 pm #6348

November 18, 2022 at 4:47 pm #6348In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Wong Sang

Wong Sang was born in China in 1884. In October 1916 he married Alice Stokes in Oxford.

Alice was the granddaughter of William Stokes of Churchill, Oxfordshire and William was the brother of Thomas Stokes the wheelwright (who was my 3X great grandfather). In other words Alice was my second cousin, three times removed, on my fathers paternal side.

Wong Sang was an interpreter, according to the baptism registers of his children and the Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital admission registers in 1930. The hospital register also notes that he was employed by the Blue Funnel Line, and that his address was 11, Limehouse Causeway, E 14. (London)

“The Blue Funnel Line offered regular First-Class Passenger and Cargo Services From the UK to South Africa, Malaya, China, Japan, Australia, Java, and America. Blue Funnel Line was Owned and Operated by Alfred Holt & Co., Liverpool.

The Blue Funnel Line, so-called because its ships have a blue funnel with a black top, is more appropriately known as the Ocean Steamship Company.”Wong Sang and Alice’s daughter, Frances Eileen Sang, was born on the 14th July, 1916 and baptised in 1920 at St Stephen in Poplar, Tower Hamlets, London. The birth date is noted in the 1920 baptism register and would predate their marriage by a few months, although on the death register in 1921 her age at death is four years old and her year of birth is recorded as 1917.

Charles Ronald Sang was baptised on the same day in May 1920, but his birth is recorded as April of that year. The family were living on Morant Street, Poplar.

James William Sang’s birth is recorded on the 1939 census and on the death register in 2000 as being the 8th March 1913. This definitely would predate the 1916 marriage in Oxford.

William Norman Sang was born on the 17th October 1922 in Poplar.

Alice and the three sons were living at 11, Limehouse Causeway on the 1939 census, the same address that Wong Sang was living at when he was admitted to Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital on the 15th January 1930. Wong Sang died in the hospital on the 8th March of that year at the age of 46.

Alice married John Patterson in 1933 in Stepney. John was living with Alice and her three sons on Limehouse Causeway on the 1939 census and his occupation was chef.

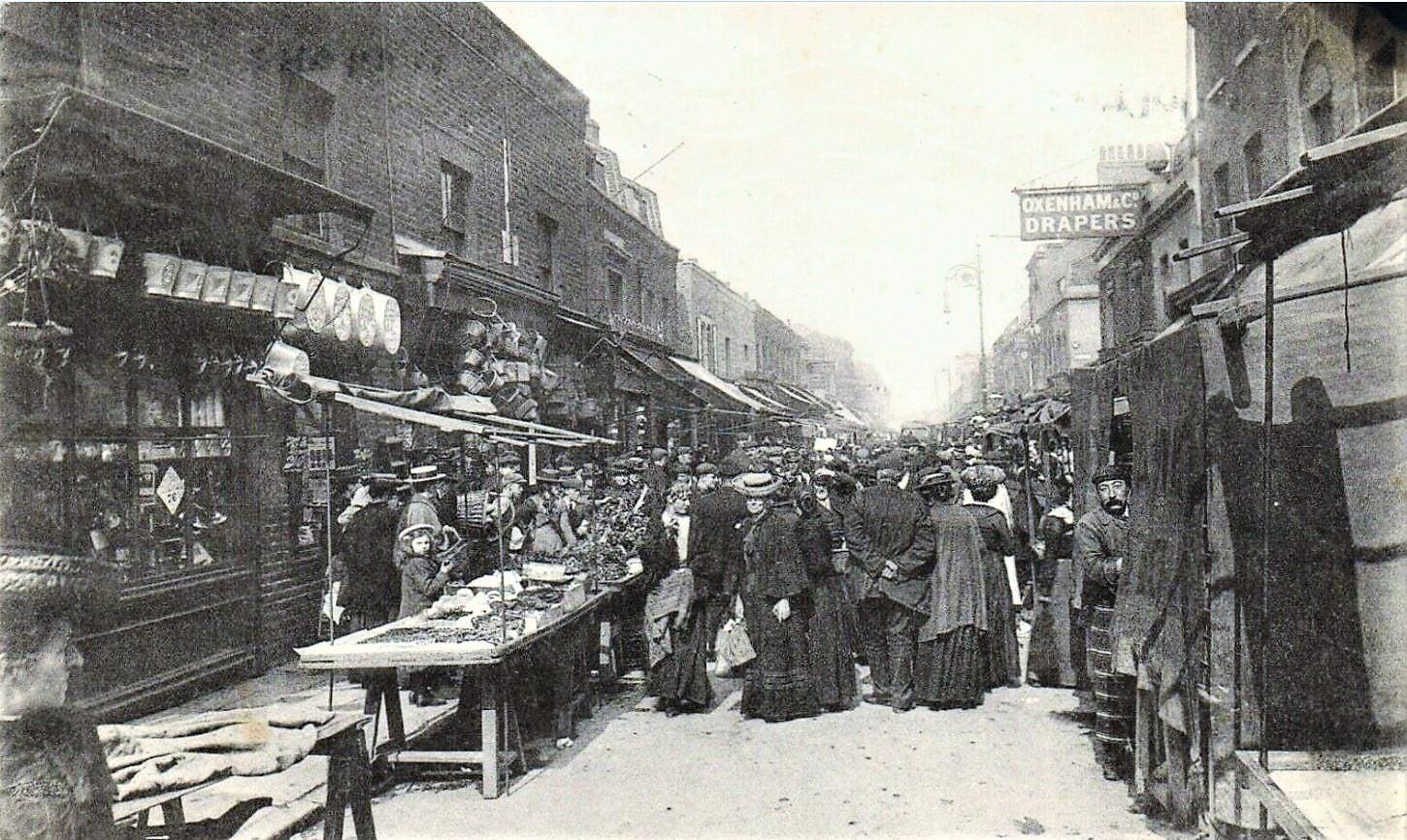

Via Old London Photographs:

“Limehouse Causeway is a street in east London that was the home to the original Chinatown of London. A combination of bomb damage during the Second World War and later redevelopment means that almost nothing is left of the original buildings of the street.”

Limehouse Causeway in 1925:

From The Story of Limehouse’s Lost Chinatown, poplarlondon website:

“Limehouse was London’s first Chinatown, home to a tightly-knit community who were demonised in popular culture and eventually erased from the cityscape.

As recounted in the BBC’s ‘Our Greatest Generation’ series, Connie was born to a Chinese father and an English mother in early 1920s Limehouse, where she used to play in the street with other British and British-Chinese children before running inside for teatime at one of their houses.

Limehouse was London’s first Chinatown between the 1880s and the 1960s, before the current Chinatown off Shaftesbury Avenue was established in the 1970s by an influx of immigrants from Hong Kong.

Connie’s memories of London’s first Chinatown as an “urban village” paint a very different picture to the seedy area portrayed in early twentieth century novels.

The pyramid in St Anne’s church marked the entrance to the opium den of Dr Fu Manchu, a criminal mastermind who threatened Western society by plotting world domination in a series of novels by Sax Rohmer.

Thomas Burke’s Limehouse Nights cemented stereotypes about prostitution, gambling and violence within the Chinese community, and whipped up anxiety about sexual relationships between Chinese men and white women.

Though neither novelist was familiar with the Chinese community, their depictions made Limehouse one of the most notorious areas of London.

Travel agent Thomas Cook even organised tours of the area for daring visitors, despite the rector of Limehouse warning that “those who look for the Limehouse of Mr Thomas Burke simply will not find it.”

All that remains is a handful of Chinese street names, such as Ming Street, Pekin Street, and Canton Street — but what was Limehouse’s chinatown really like, and why did it get swept away?

Chinese migration to Limehouse

Chinese sailors discharged from East India Company ships settled in the docklands from as early as the 1780s.

By the late nineteenth century, men from Shanghai had settled around Pennyfields Lane, while a Cantonese community lived on Limehouse Causeway.

Chinese sailors were often paid less and discriminated against by dock hirers, and so began to diversify their incomes by setting up hand laundry services and restaurants.

Old photographs show shopfronts emblazoned with Chinese characters with horse-drawn carts idling outside or Chinese men in suits and hats standing proudly in the doorways.

In oral histories collected by Yat Ming Loo, Connie’s husband Leslie doesn’t recall seeing any Chinese women as a child, since male Chinese sailors settled in London alone and married working-class English women.

In the 1920s, newspapers fear-mongered about interracial marriages, crime and gambling, and described chinatown as an East End “colony.”

Ironically, Chinese opium-smoking was also demonised in the press, despite Britain waging war against China in the mid-nineteenth century for suppressing the opium trade to alleviate addiction amongst its people.

The number of Chinese people who settled in Limehouse was also greatly exaggerated, and in reality only totalled around 300.

The real Chinatown

Although the press sought to characterise Limehouse as a monolithic Chinese community in the East End, Connie remembers seeing people of all nationalities in the shops and community spaces in Limehouse.

She doesn’t remember feeling discriminated against by other locals, though Connie does recall having her face measured and IQ tested by a member of the British Eugenics Society who was conducting research in the area.

Some of Connie’s happiest childhood memories were from her time at Chung-Hua Club, where she learned about Chinese culture and language.

Why did Chinatown disappear?

The caricature of Limehouse’s Chinatown as a den of vice hastened its erasure.

Police raids and deportations fuelled by the alarmist media coverage threatened the Chinese population of Limehouse, and slum clearance schemes to redevelop low-income areas dispersed Chinese residents in the 1930s.

The Defence of the Realm Act imposed at the beginning of the First World War criminalised opium use, gave the authorities increased powers to deport Chinese people and restricted their ability to work on British ships.

Dwindling maritime trade during World War II further stripped Chinese sailors of opportunities for employment, and any remnants of Chinatown were destroyed during the Blitz or erased by postwar development schemes.”

Wong Sang 1884-1930

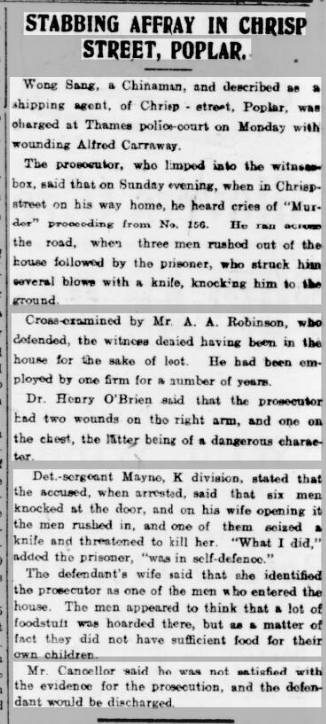

The year 1918 was a troublesome one for Wong Sang, an interpreter and shipping agent for Blue Funnel Line. The Sang family were living at 156, Chrisp Street.

Chrisp Street, Poplar, in 1913 via Old London Photographs:

In February Wong Sang was discharged from a false accusation after defending his home from potential robbers.

East End News and London Shipping Chronicle – Friday 15 February 1918:

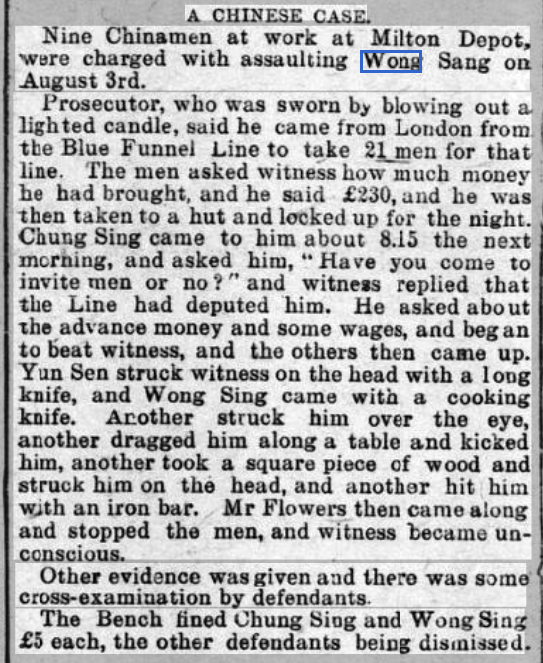

In August of that year he was involved in an incident that left him unconscious.

Faringdon Advertiser and Vale of the White Horse Gazette – Saturday 31 August 1918:

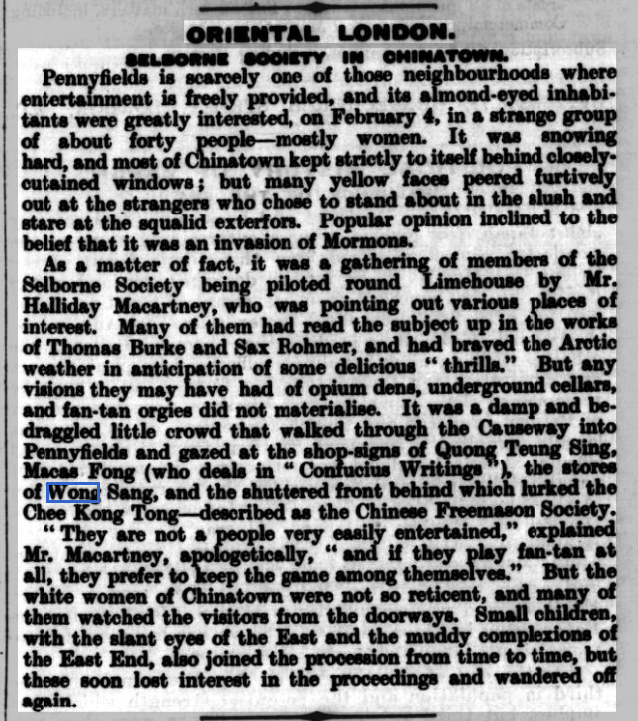

Wong Sang is mentioned in an 1922 article about “Oriental London”.

London and China Express – Thursday 09 February 1922:

A photograph of the Chee Kong Tong Chinese Freemason Society mentioned in the above article, via Old London Photographs:

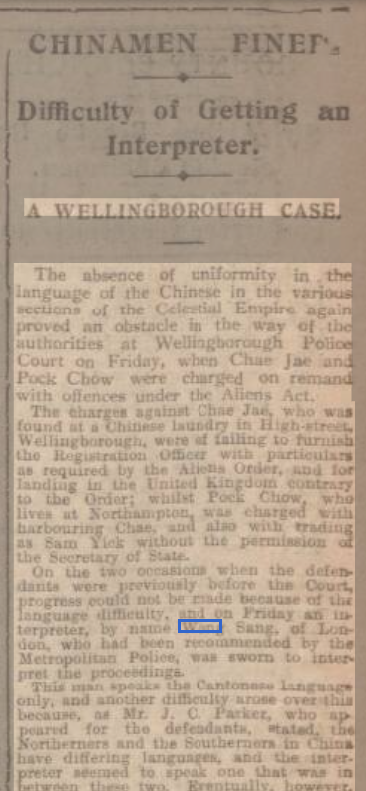

Wong Sang was recommended by the London Metropolitan Police in 1928 to assist in a case in Wellingborough, Northampton.

Difficulty of Getting an Interpreter: Northampton Mercury – Friday 16 March 1928:

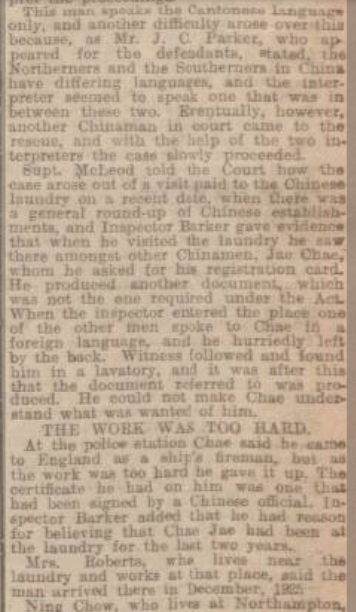

The difficulty was that “this man speaks the Cantonese language only…the Northeners and the Southerners in China have differing languages and the interpreter seemed to speak one that was in between these two.”

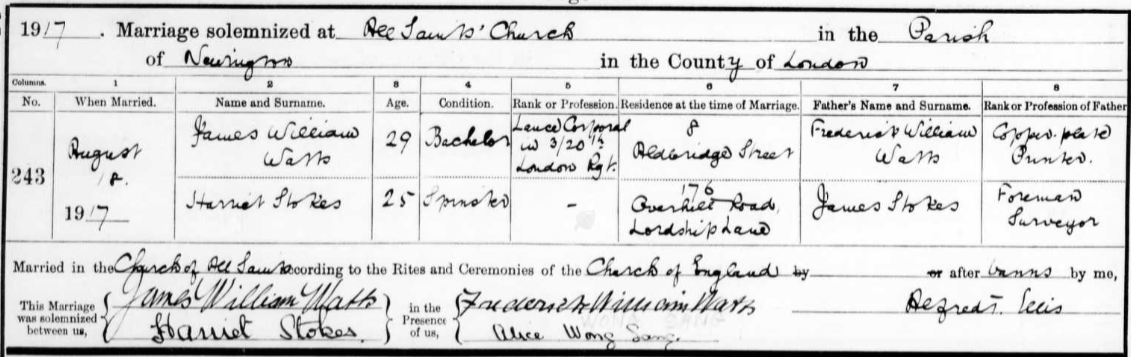

In 1917, Alice Wong Sang was a witness at her sister Harriet Stokes marriage to James William Watts in Southwark, London. Their father James Stokes occupation on the marriage register is foreman surveyor, but on the census he was a council roadman or labourer. (I initially rejected this as the correct marriage for Harriet because of the discrepancy with the occupations. Alice Wong Sang as a witness confirmed that it was indeed the correct one.)

James William Sang 1913-2000 was a clock fitter and watch assembler (on the 1939 census). He married Ivy Laura Fenton in 1963 in Sidcup, Kent. James died in Southwark in 2000.

Charles Ronald Sang 1920-1974 was a draughtsman (1939 census). He married Eileen Burgess in 1947 in Marylebone. Charles and Eileen had two sons: Keith born in 1951 and Roger born in 1952. He died in 1974 in Hertfordshire.

William Norman Sang 1922-2000 was a clerk and telephone operator (1939 census). William enlisted in the Royal Artillery in 1942. He married Lily Mullins in 1949 in Bethnal Green, and they had three daughters: Marion born in 1950, Christine in 1953, and Frances in 1959. He died in Redbridge in 2000.

I then found another two births registered in Poplar by Alice Sang, both daughters. Doris Winifred Sang was born in 1925, and Patricia Margaret Sang was born in 1933 ~ three years after Wong Sang’s death. Neither of the these daughters were on the 1939 census with Alice, John Patterson and the three sons. Margaret had presumably been evacuated because of the war to a family in Taunton, Somerset. Doris would have been fourteen and I have been unable to find her in 1939 (possibly because she died in 2017 and has not had the redaction removed yet on the 1939 census as only deceased people are viewable).

Doris Winifred Sang 1925-2017 was a nursing sister. She didn’t marry, and spent a year in USA between 1954 and 1955. She stayed in London, and died at the age of ninety two in 2017.

Patricia Margaret Sang 1933-1998 was also a nurse. She married Patrick L Nicely in Stepney in 1957. Patricia and Patrick had five children in London: Sharon born 1959, Donald in 1960, Malcolm was born and died in 1966, Alison was born in 1969 and David in 1971.

I was unable to find a birth registered for Alice’s first son, James William Sang (as he appeared on the 1939 census). I found Alice Stokes on the 1911 census as a 17 year old live in servant at a tobacconist on Pekin Street, Limehouse, living with Mr Sui Fong from Hong Kong and his wife Sarah Sui Fong from Berlin. I looked for a birth registered for James William Fong instead of Sang, and found it ~ mothers maiden name Stokes, and his date of birth matched the 1939 census: 8th March, 1913.

On the 1921 census, Wong Sang is not listed as living with them but it is mentioned that Mr Wong Sang was the person returning the census. Also living with Alice and her sons James and Charles in 1921 are two visitors: (Florence) May Stokes, 17 years old, born in Woodstock, and Charles Stokes, aged 14, also born in Woodstock. May and Charles were Alice’s sister and brother.

I found Sharon Nicely on social media and she kindly shared photos of Wong Sang and Alice Stokes:

November 10, 2022 at 10:59 am #6343

November 10, 2022 at 10:59 am #6343In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum

William James Stokes

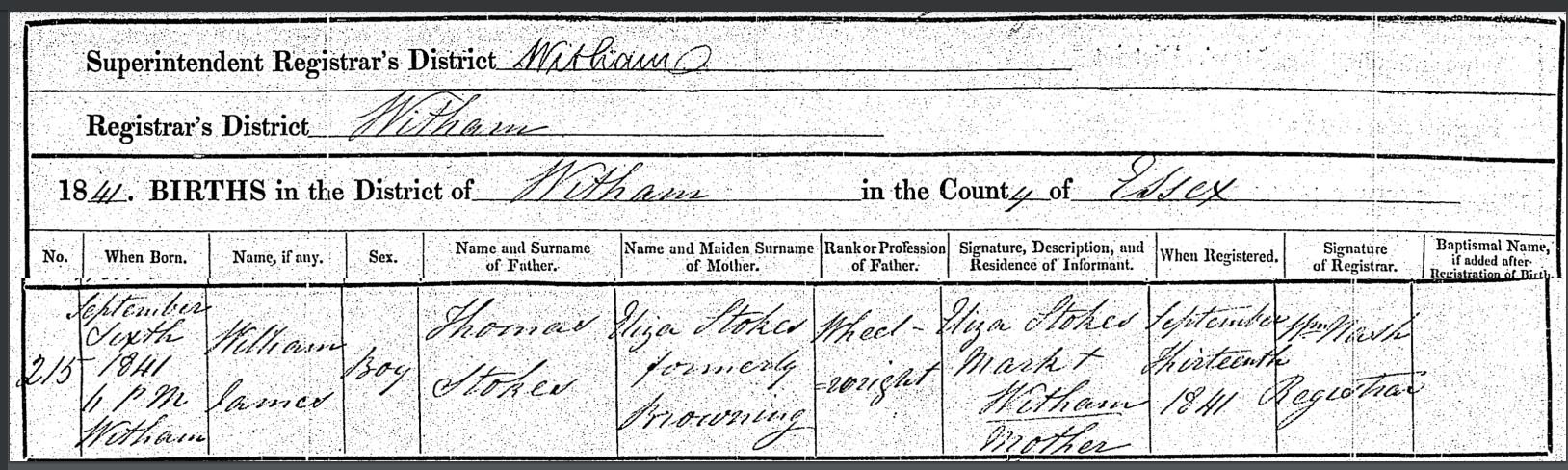

William James Stokes was the first son of Thomas Stokes and Eliza Browning. Oddly, his birth was registered in Witham in Essex, on the 6th September 1841.

Birth certificate of William James Stokes:

His father Thomas Stokes has not yet been found on the 1841 census, and his mother Eliza was staying with her uncle Thomas Lock in Cirencester in 1841. Eliza’s mother Mary Browning (nee Lock) was staying there too. Thomas and Eliza were married in September 1840 in Hempstead in Gloucestershire.

It’s a mystery why William was born in Essex but one possibility is that his father Thomas, who later worked with the Chipperfields making circus wagons, was staying with the Chipperfields who were wheelwrights in Witham in 1841. Or perhaps even away with a traveling circus at the time of the census, learning the circus waggon wheelwright trade. But this is a guess and it’s far from clear why Eliza would make the journey to Witham to have the baby when she was staying in Cirencester a few months prior.

In 1851 Thomas and Eliza, William and four younger siblings were living in Bledington in Oxfordshire.

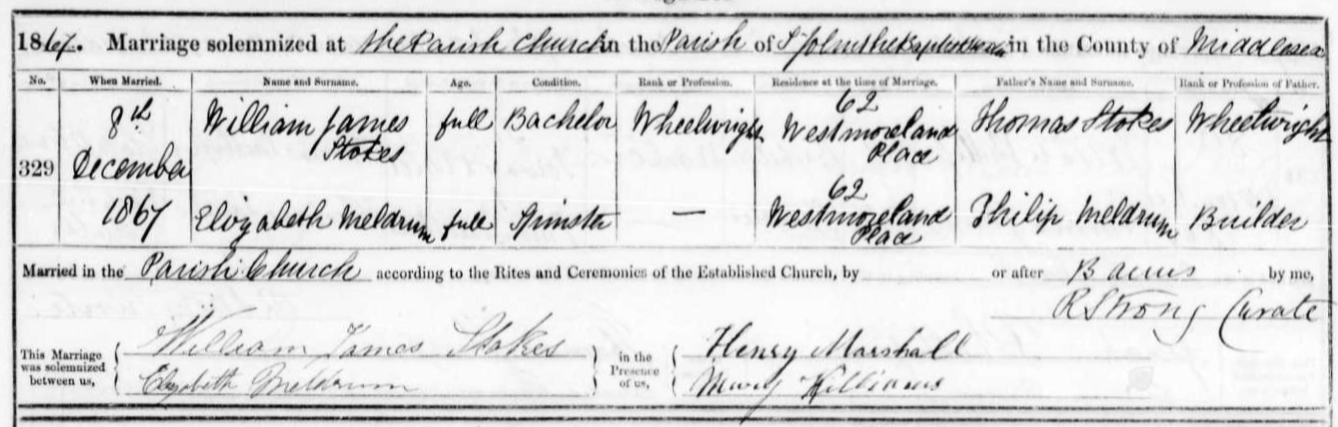

William was a 19 year old wheelwright living with his parents in Evesham in 1861. He married Elizabeth Meldrum in December 1867 in Hackney, London. He and his father are both wheelwrights on the marriage register.

Marriage of William James Stokes and Elizabeth Meldrum in 1867:

William and Elizabeth had a daughter, Elizabeth Emily Stokes, in 1868 in Shoreditch, London.

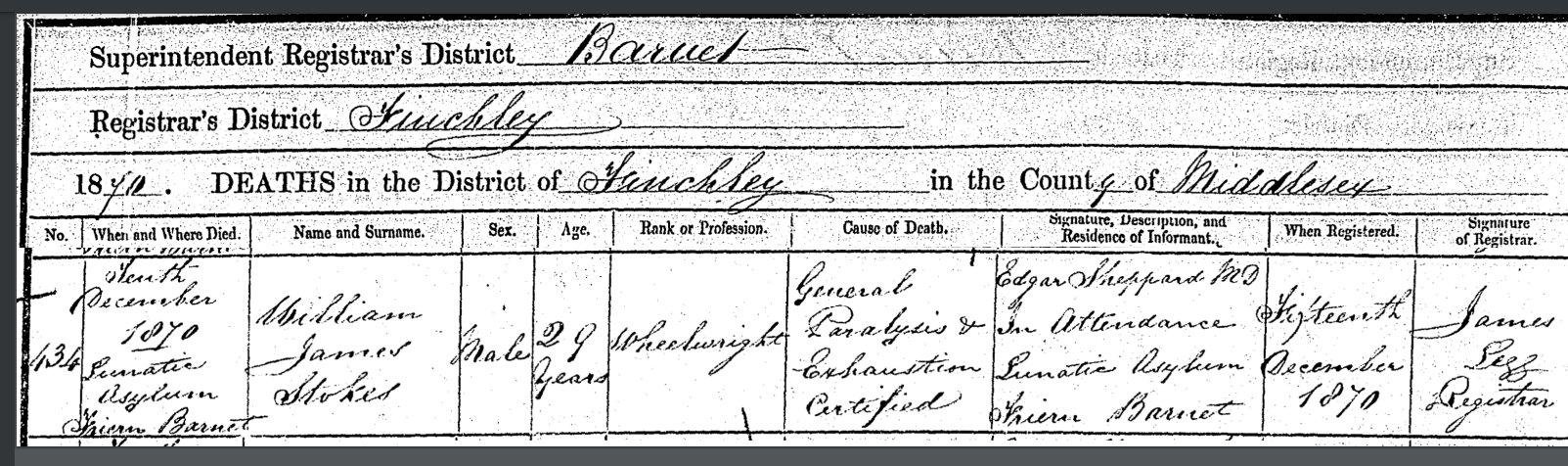

On the 3rd of December 1870, William James Stokes was admitted to Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum. One week later on the 10th of December, he was dead.

On his death certificate the cause of death was “general paralysis and exhaustion, certified. MD Edgar Sheppard in attendance.” William was just 29 years old.

Death certificate William James Stokes:

I asked on a genealogy forum what could possibly have caused this death at such a young age. A retired pathology professor replied that “in medicine the term General Paralysis is only used in one context – that of Tertiary Syphilis.”

“Tertiary syphilis is the third and final stage of syphilis, a sexually transmitted disease that unfolds in stages when the individual affected doesn’t receive appropriate treatment.”From the article “Looking back: This fascinating and fatal disease” by Jennifer Wallis:

“……in asylums across Britain in the late 19th century, with hundreds of people receiving the diagnosis of general paralysis of the insane (GPI). The majority of these were men in their 30s and 40s, all exhibiting one or more of the disease’s telltale signs: grandiose delusions, a staggering gait, disturbed reflexes, asymmetrical pupils, tremulous voice, and muscular weakness. Their prognosis was bleak, most dying within months, weeks, or sometimes days of admission.

The fatal nature of GPI made it of particular concern to asylum superintendents, who became worried that their institutions were full of incurable cases requiring constant care. The social effects of the disease were also significant, attacking men in the prime of life whose admission to the asylum frequently left a wife and children at home. Compounding the problem was the erratic behaviour of the general paralytic, who might get themselves into financial or legal difficulties. Delusions about their vast wealth led some to squander scarce family resources on extravagant purchases – one man’s wife reported he had bought ‘a quantity of hats’ despite their meagre income – and doctors pointed to the frequency of thefts by general paralytics who imagined that everything belonged to them.”

The London Archives hold the records for Colney Hatch, but they informed me that the particular records for the dates that William was admitted and died were in too poor a condition to be accessed without causing further damage.

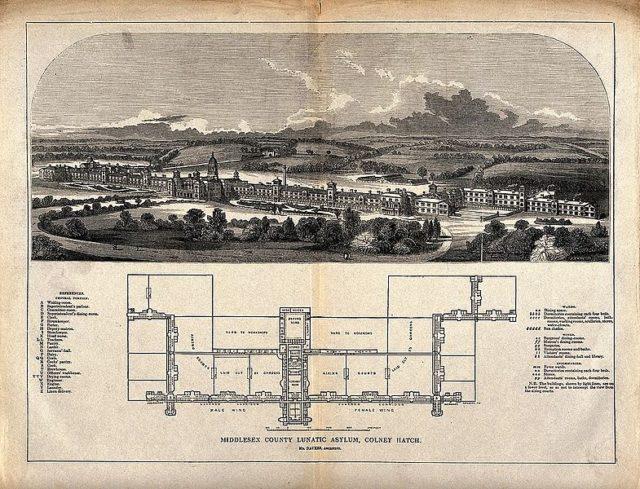

Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum gained such notoriety that the name “Colney Hatch” appeared in various terms of abuse associated with the concept of madness. Infamous inmates that were institutionalized at Colney Hatch (later called Friern Hospital) include Jack the Ripper suspect Aaron Kosminski from 1891, and from 1911 the wife of occultist Aleister Crowley. In 1993 the hospital grounds were sold and the exclusive apartment complex called Princess Park Manor was built.

Colney Hatch:

In 1873 Williams widow married William Hallam in Limehouse in London. Elizabeth died in 1930, apparently unaffected by her first husbands ailment.

October 22, 2022 at 1:18 pm #6338In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

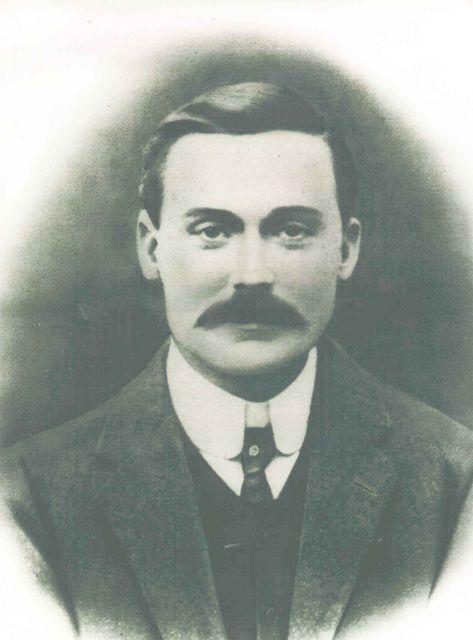

Albert Parker Edwards

1876-1930

Albert Parker Edwards, my great grandfather, was born in Aston, Warwickshire in 1876. On the 1881 census he was living with his parents Enoch and Amelia in Bournebrook, Northfield, Worcestershire. Enoch was a button tool maker at the time of the census.

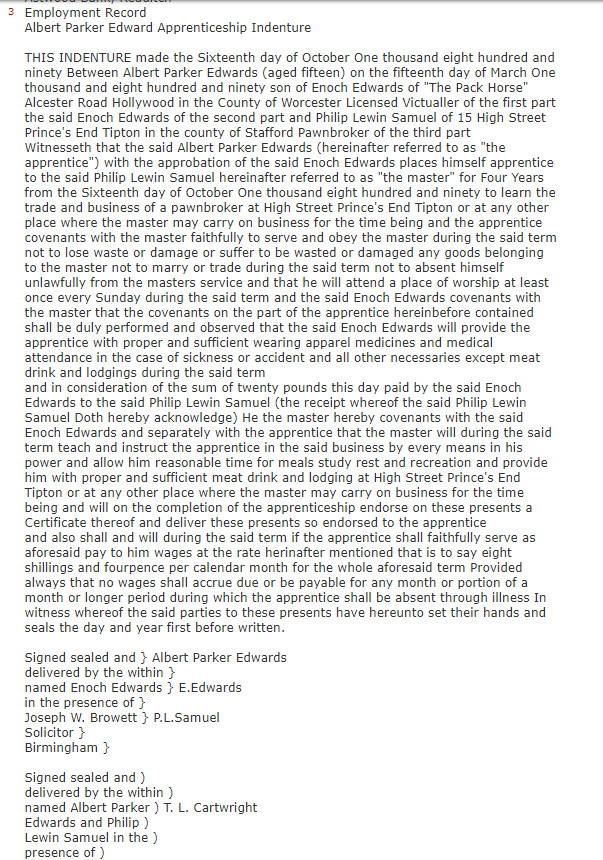

In 1890 Albert was indentured in an apprenticeship as a pawnbroker in Tipton, Staffordshire.

On the 1891 census Albert was a lodger in Tipton at the home of Phoebe Levy, pawnbroker, and Alberts occupation was an apprentice.

Albert married Annie Elizabeth Stokes in 1898 in Evesham, and their first son, my grandfather Albert Garnet Edwards (1898-1950), was born six months later in Crabbs Cross. On the 1901 census, Annie was in hospital as a patient and Albert was living at Crabbs Cross with a boarder, his brother Garnet Edwards. Their two year old son Albert Garnet was staying with his uncle Ralph, Albert Parkers brother, also in Crabbs Cross.

Albert and Annie kept the Cricketers Arms hotel on Beoley Road in Redditch until around 1920. They had a further four children while living there: Doris May Edwards (1902-1974), Ralph Clifford Edwards (1903-1988), Ena Flora Edwards (1908-1983) and Osmond Edwards (1910-2000).

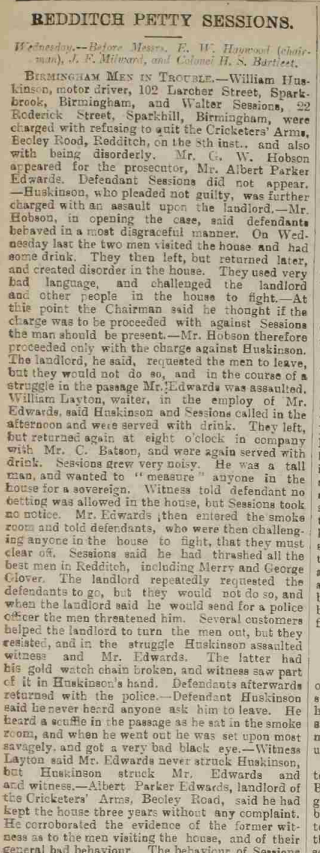

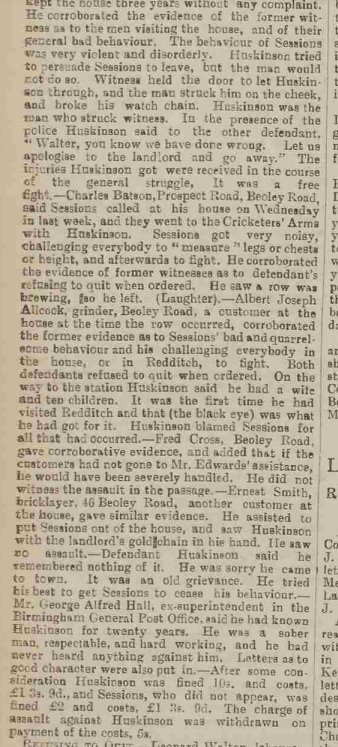

In 1906 Albert was assaulted during an incident in the Cricketers Arms.

Bromsgrove & Droitwich Messenger – Saturday 18 August 1906:

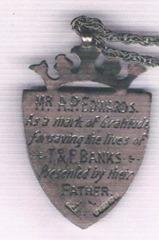

In 1910 a gold medal was given to Albert Parker Edwards by Mr. Banks, a policeman, in Redditch for saving the life of his two children from drowning in a brook on the Proctor farm which adjoined The Cricketers Arms. The story my father heard was that policeman Banks could not persuade the town of Redditch to come up with an award for Albert Parker Edwards so policeman Banks did it himself. William Banks, police constable, was living on Beoley Road on the 1911 census. His son Thomas was aged 5 and his daughter Frances was 8. It seems that when the father retired from the police he moved to Worcester. Thomas went into the hotel business and in 1939 was the manager of the Abbey hotel in Kenilworth. Frances married Edward Pardoe and was living along Redditch Road, Alvechurch in 1939.

My grandmother Peggy had the gold medal put on a gold chain for me in the 1970s. When I left England in the 1980s, I gave it back to her for safekeeping. When she died, the medal on the chain ended up in my fathers possession, who claims to have no knowledge that it was once given to me!

The medal:

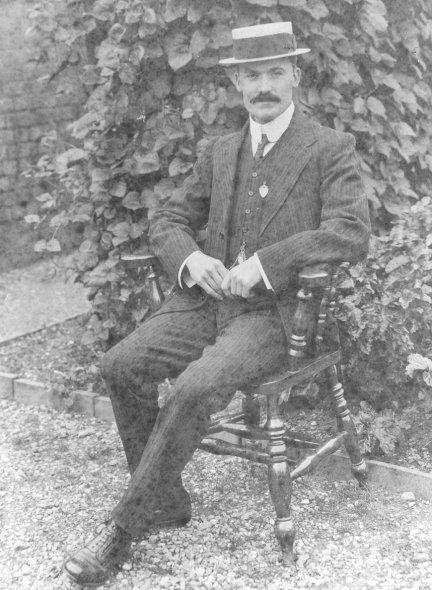

Albert Parker Edwards wearing the medal:

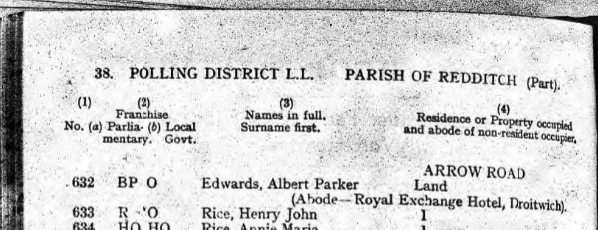

In 1921 Albert was at the The Royal Exchange hotel in Droitwich:

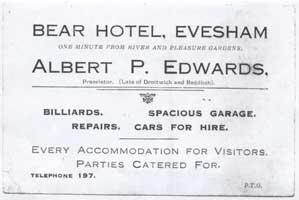

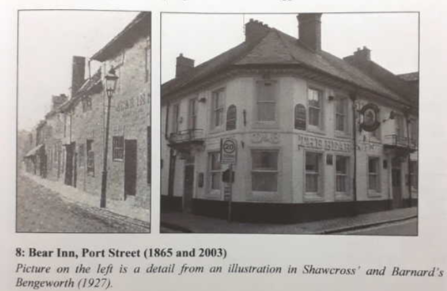

Between 1922 and 1927 Albert kept the Bear Hotel in Evesham:

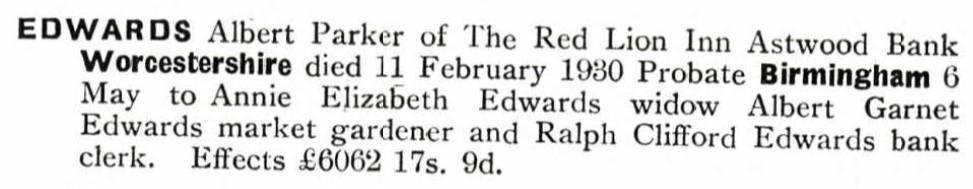

Then Albert and Annie moved to the Red Lion at Astwood Bank:

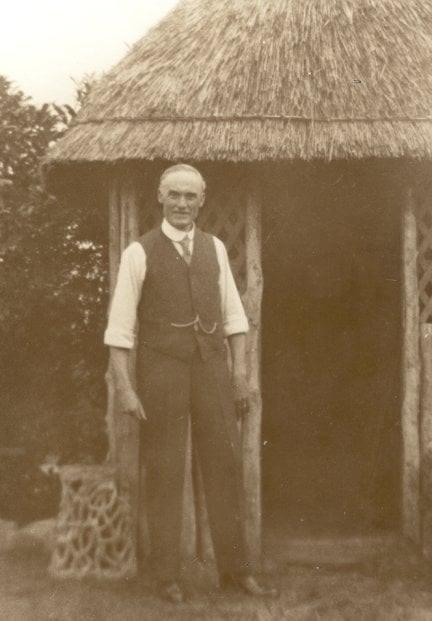

Albert in the garden behind the Red Lion:

They stayed at the Red Lion until Albert Parker Edwards died on the 11th of February, 1930 aged 53.

October 19, 2022 at 6:46 am #6336

October 19, 2022 at 6:46 am #6336In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The Hamstall Ridware Connection

Stubbs and Woods

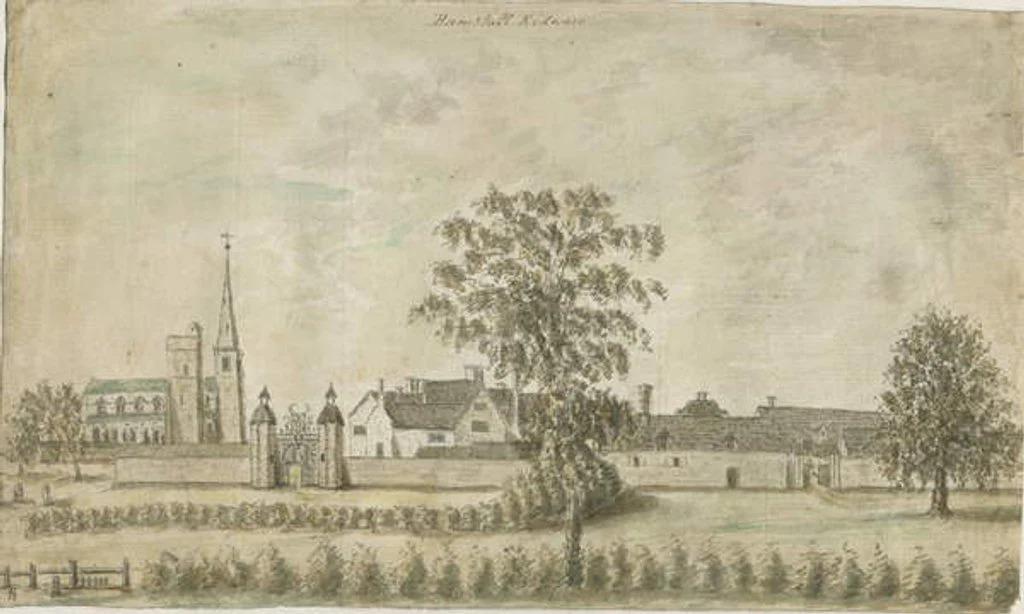

Hamstall Ridware

Hamstall RidwareCharles Tomlinson‘s (1847-1907) wife Emma Grattidge (1853-1911) was born in Wolverhampton, the daughter and youngest child of William Grattidge (1820-1887) born in Foston, Derbyshire, and Mary Stubbs (1819-1880), born in Burton on Trent, daughter of Solomon Stubbs.

Solomon Stubbs (1781-1857) was born in Hamstall Ridware in 1781, the son of Samuel and Rebecca. Samuel Stubbs (1743-) and Rebecca Wood (1754-) married in 1769 in Darlaston. Samuel and Rebecca had six other children, all born in Darlaston. Sadly four of them died in infancy. Son John was born in 1779 in Darlaston and died two years later in Hamstall Ridware in 1781, the same year that Solomon was born there.

But why did they move to Hamstall Ridware?

Samuel Stubbs was born in 1743 in Curdworth, Warwickshire (near to Birmingham). I had made a mistake on the tree (along with all of the public trees on the Ancestry website) and had Rebecca Wood born in Cheddleton, Staffordshire. Rebecca Wood from Cheddleton was also born in 1843, the right age for the marriage. The Rebecca Wood born in Darlaston in 1754 seemed too young, at just fifteen years old at the time of the marriage. I couldn’t find any explanation for why a woman from Cheddleton would marry in Darlaston and then move to Hamstall Ridware. People didn’t usually move around much other than intermarriage with neighbouring villages, especially women. I had a closer look at the Darlaston Rebecca, and did a search on her father William Wood. I found his 1784 will online in which he mentions his daughter Rebecca, wife of Samuel Stubbs. Clearly the right Rebecca Wood was the one born in Darlaston, which made much more sense.

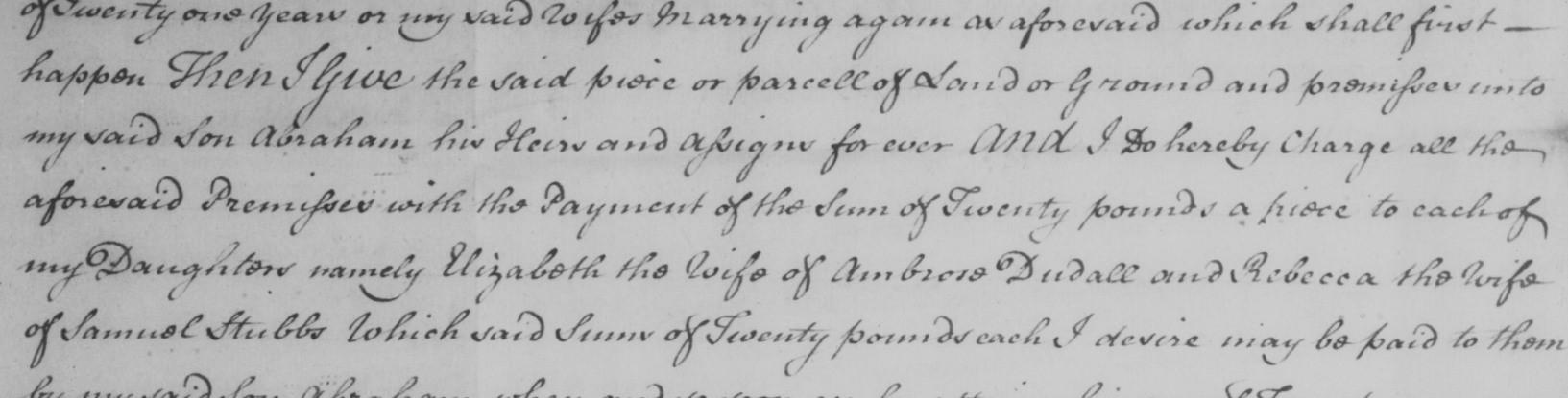

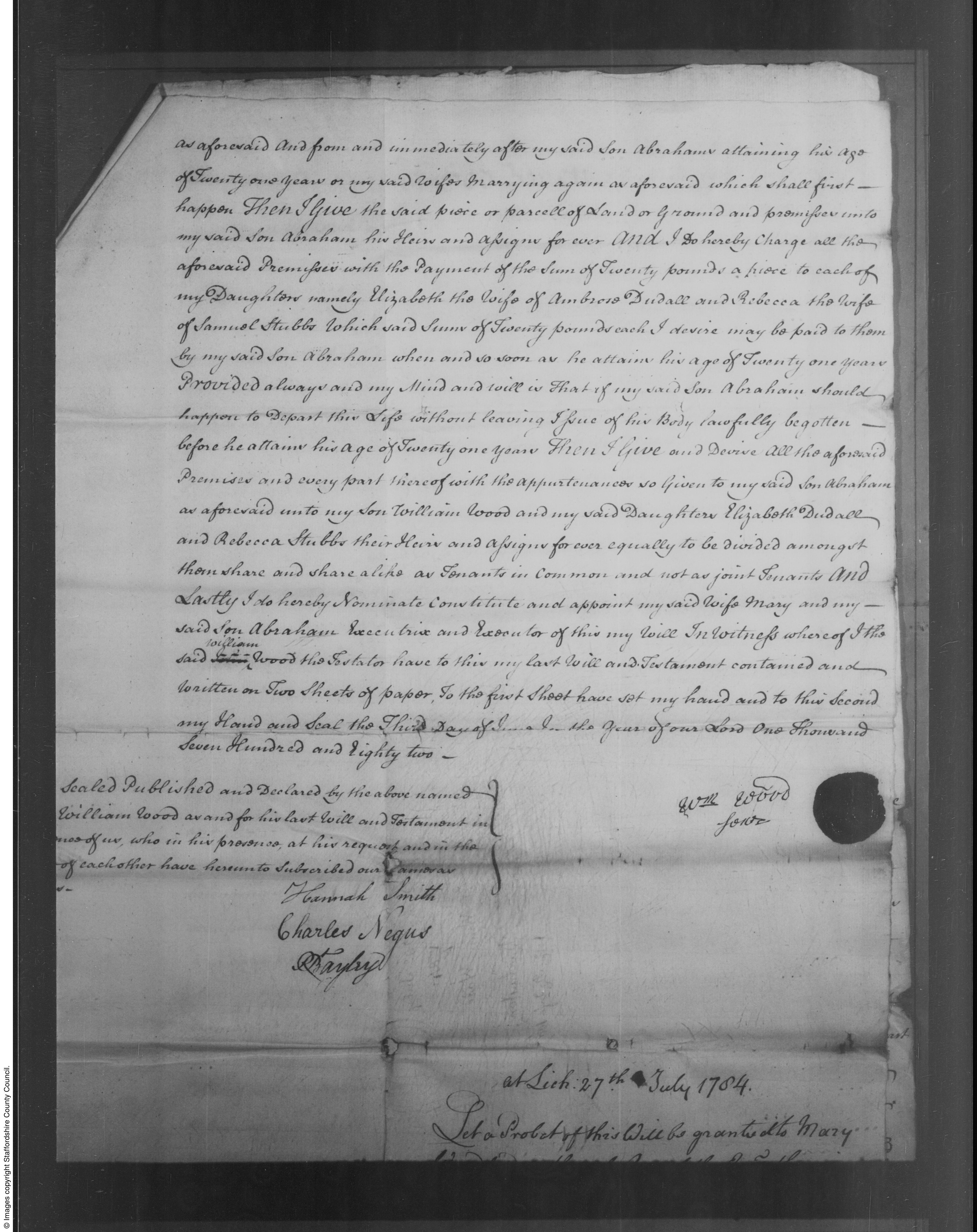

An excerpt from William Wood’s 1784 will mentioning daughter Rebecca married to Samuel Stubbs:

But why did they move to Hamstall Ridware circa 1780?

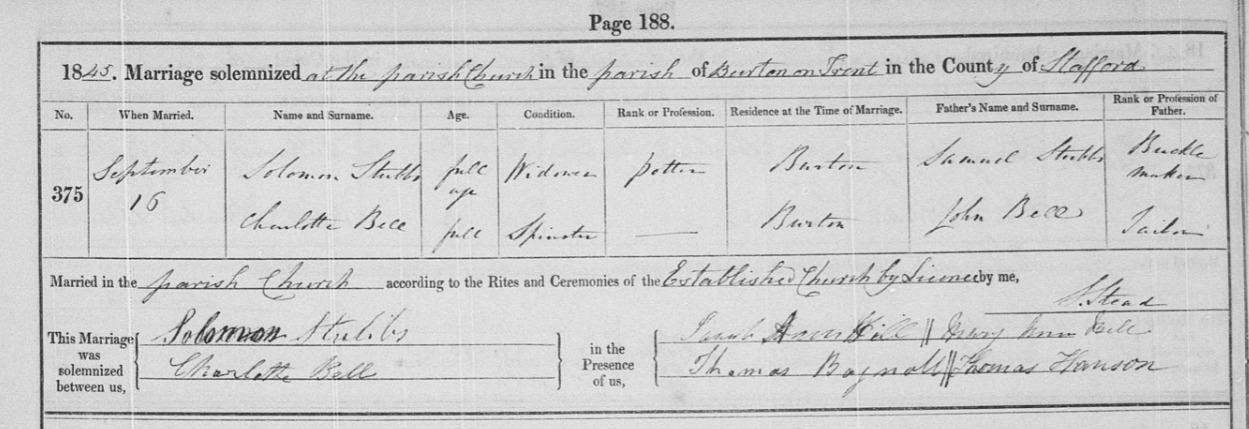

I had not intially noticed that Solomon Stubbs married again the year after his wife Phillis Lomas (1787-1844) died. Solomon married Charlotte Bell in 1845 in Burton on Trent and on the marriage register, Solomon’s father Samuel Stubbs occupation was mentioned: Samuel was a buckle maker.

Marriage of Solomon Stubbs and Charlotte Bell, father Samuel Stubbs buckle maker:

A rudimentary search on buckle making in the late 1700s provided a possible answer as to why Samuel and Rebecca left Darlaston in 1781. Shoe buckles had gone out of fashion, and by 1781 there were half as many buckle makers in Wolverhampton as there had been previously.

“Where there were 127 buckle makers at work in Wolverhampton, 68 in Bilston and 58 in Birmingham in 1770, their numbers had halved in 1781.”

via “historywebsite”(museum/metalware/steel)

Steel buckles had been the height of fashion, and the trade became enormous in Wolverhampton. Wolverhampton was a steel working town, renowned for its steel jewellery which was probably of many types. The trade directories show great numbers of “buckle makers”. Steel buckles were predominantly made in Wolverhampton: “from the late 1760s cut steel comes to the fore, from the thriving industry of the Wolverhampton area”. Bilston was also a great centre of buckle making, and other areas included Walsall. (It should be noted that Darlaston, Walsall, Bilston and Wolverhampton are all part of the same area)

In 1860, writing in defence of the Wolverhampton Art School, George Wallis talks about the cut steel industry in Wolverhampton. Referring to “the fine steel workers of the 17th and 18th centuries” he says: “Let them remember that 100 years ago [sc. c. 1760] a large trade existed with France and Spain in the fine steel goods of Birmingham and Wolverhampton, of which the latter were always allowed to be the best both in taste and workmanship. … A century ago French and Spanish merchants had their houses and agencies at Birmingham for the purchase of the steel goods of Wolverhampton…..The Great Revolution in France put an end to the demand for fine steel goods for a time and hostile tariffs finished what revolution began”.

The next search on buckle makers, Wolverhampton and Hamstall Ridware revealed an unexpected connecting link.

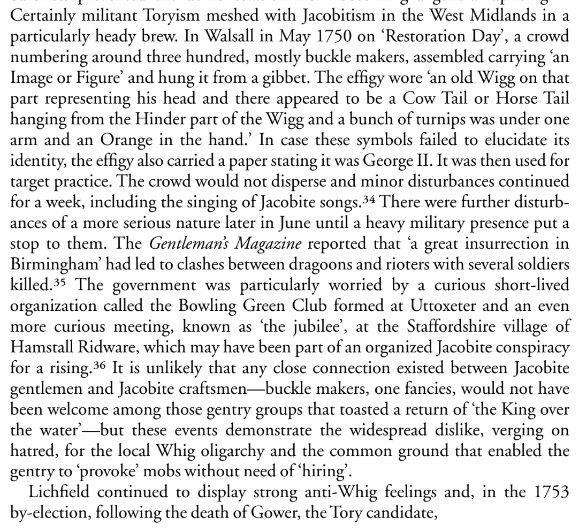

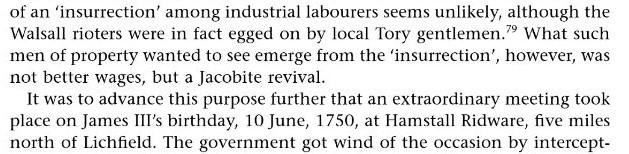

In Riotous Assemblies: Popular Protest in Hanoverian England by Adrian Randall:

In Walsall in 1750 on “Restoration Day” a crowd numbering 300 assembled, mostly buckle makers, singing Jacobite songs and other rebellious and riotous acts. The government was particularly worried about a curious meeting known as the “Jubilee” in Hamstall Ridware, which may have been part of a conspiracy for a Jacobite uprising.

But this was thirty years before Samuel and Rebecca moved to Hamstall Ridware and does not help to explain why they moved there around 1780, although it does suggest connecting links.

Rebecca’s father, William Wood, was a brickmaker. This was stated at the beginning of his will. On closer inspection of the will, he was a brickmaker who owned four acres of brick kilns, as well as dwelling houses, shops, barns, stables, a brewhouse, a malthouse, cattle and land.

A page from the 1784 will of William Wood:

The 1784 will of William Wood of Darlaston:

I William Wood the elder of Darlaston in the county of Stafford, brickmaker, being of sound and disposing mind memory and understanding (praised be to god for the same) do make publish and declare my last will and testament in manner and form following (that is to say) {after debts and funeral expense paid etc} I give to my loving wife Mary the use usage wear interest and enjoyment of all my goods chattels cattle stock in trade ~ money securities for money personal estate and effects whatsoever and wheresoever to hold unto her my said wife for and during the term of her natural life providing she so long continues my widow and unmarried and from or after her decease or intermarriage with any future husband which shall first happen.

Then I give all the said goods chattels cattle stock in trade money securites for money personal estate and effects unto my son Abraham Wood absolutely and forever. Also I give devise and bequeath unto my said wife Mary all that my messuages tenement or dwelling house together with the malthouse brewhouse barn stableyard garden and premises to the same belonging situate and being at Darlaston aforesaid and now in my own possession. Also all that messuage tenement or dwelling house together with the shop garden and premises with the appurtenances to the same ~ belonging situate in Darlaston aforesaid and now in the several holdings or occupation of George Knowles and Edward Knowles to hold the aforesaid premises and every part thereof with the appurtenances to my said wife Mary for and during the term of her natural life provided she so long continues my widow and unmarried. And from or after her decease or intermarriage with a future husband which shall first happen. Then I give and devise the aforesaid premises and every part thereof with the appurtenances unto my said son Abraham Wood his heirs and assigns forever.

Also I give unto my said wife all that piece or parcel of land or ground inclosed and taken out of Heath Field in the parish of Darlaston aforesaid containing four acres or thereabouts (be the same more or less) upon which my brick kilns erected and now in my own possession. To hold unto my said wife Mary until my said son Abraham attains his age of twenty one years if she so long continues my widow and unmarried as aforesaid and from and immediately after my said son Abraham attaining his age of twenty one years or my said wife marrying again as aforesaid which shall first happen then I give the said piece or parcel of land or ground and premises unto my said son Abraham his heirs and assigns forever.

And I do hereby charge all the aforesaid premises with the payment of the sum of twenty pounds a piece to each of my daughters namely Elizabeth the wife of Ambrose Dudall and Rebecca the wife of Samuel Stubbs which said sum of twenty pounds each I devise may be paid to them by my said son Abraham when and so soon as he attains his age of twenty one years provided always and my mind and will is that if my said son Abraham should happen to depart this life without leaving issue of his body lawfully begotten before he attains his age of twenty one years then I give and devise all the aforesaid premises and every part thereof with the appurtenances so given to my said son Abraham as aforesaid unto my said son William Wood and my said daughter Elizabeth Dudall and Rebecca Stubbs their heirs and assigns forever equally divided among them share and share alike as tenants in common and not as joint tenants. And lastly I do hereby nominate constitute and appoint my said wife Mary and my said son Abraham executrix and executor of this my will.

The marriage of William Wood (1725-1784) and Mary Clews (1715-1798) in 1749 was in Hamstall Ridware.

Mary was eleven years Williams senior, and it appears that they both came from Hamstall Ridware and moved to Darlaston after they married. Clearly Rebecca had extended family there (notwithstanding any possible connecting links between the Stubbs buckle makers of Darlaston and the Hamstall Ridware Jacobites thirty years prior). When the buckle trade collapsed in Darlaston, they likely moved to find employment elsewhere, perhaps with the help of Rebecca’s family.

I have not yet been able to find deaths recorded anywhere for either Samuel or Rebecca (there are a couple of deaths recorded for a Samuel Stubbs, one in 1809 in Wolverhampton, and one in 1810 in Birmingham but impossible to say which, if either, is the right one with the limited information, and difficult to know if they stayed in the Hamstall Ridware area or perhaps moved elsewhere)~ or find a reason for their son Solomon to be in Burton upon Trent, an evidently prosperous man with several properties including an earthenware business, as well as a land carrier business.

October 11, 2022 at 2:58 pm #6334In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The House on Penn Common

Toi Fang and the Duke of Sutherland

Tomlinsons

Grassholme

Charles Tomlinson (1873-1929) my great grandfather, was born in Wolverhampton in 1873. His father Charles Tomlinson (1847-1907) was a licensed victualler or publican, or alternatively a vet/castrator. He married Emma Grattidge (1853-1911) in 1872. On the 1881 census they were living at The Wheel in Wolverhampton.

Charles married Nellie Fisher (1877-1956) in Wolverhampton in 1896. In 1901 they were living next to the post office in Upper Penn, with children (Charles) Sidney Tomlinson (1896-1955), and Hilda Tomlinson (1898-1977) . Charles was a vet/castrator working on his own account.

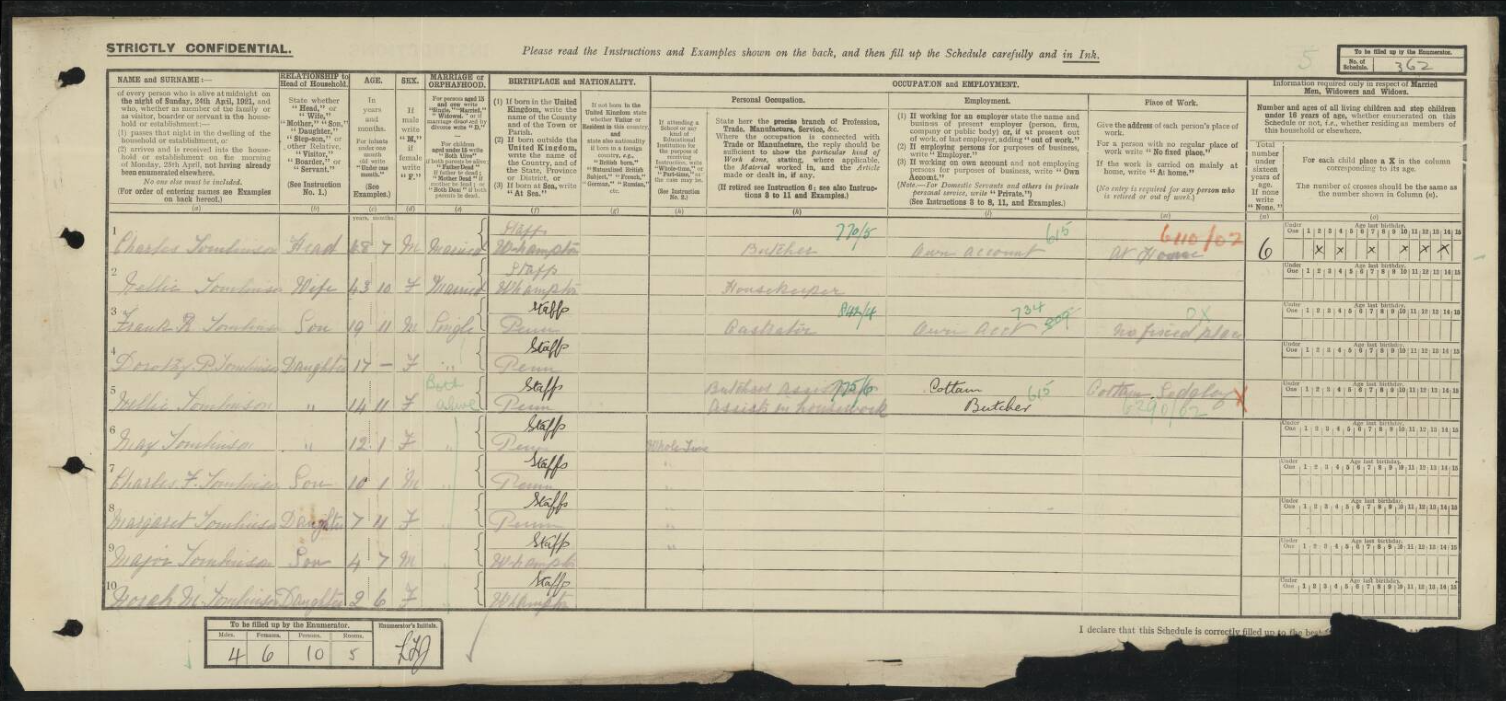

In 1911 their address was 4, Wakely Hill, Penn, and living with them were their children Hilda, Frank Tomlinson (1901-1975), (Dorothy) Phyllis Tomlinson (1905-1982), Nellie Tomlinson (1906-1978) and May Tomlinson (1910-1983). Charles was a castrator working on his own account.

Charles and Nellie had a further four children: Charles Fisher Tomlinson (1911-1977), Margaret Tomlinson (1913-1989) (my grandmother Peggy), Major Tomlinson (1916-1984) and Norah Mary Tomlinson (1919-2010).

My father told me that my grandmother had fallen down the well at the house on Penn Common in 1915 when she was two years old, and sent me a photo of her standing next to the well when she revisted the house at a much later date.

Peggy next to the well on Penn Common:

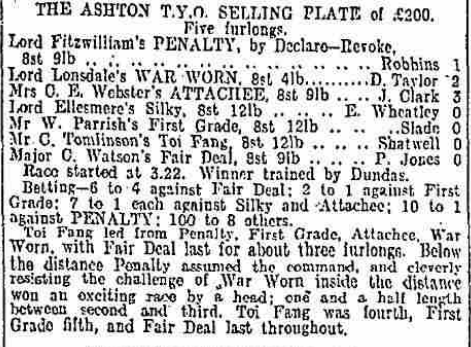

My grandmother Peggy told me that her father had had a racehorse called Toi Fang. She remembered the racing colours were sky blue and orange, and had a set of racing silks made which she sent to my father.

Through a DNA match, I met Ian Tomlinson. Ian is the son of my fathers favourite cousin Roger, Frank’s son. Ian found some racing silks and sent a photo to my father (they are now in contact with each other as a result of my DNA match with Ian), wondering what they were.

When Ian sent a photo of these racing silks, I had a look in the newspaper archives. In 1920 there are a number of mentions in the racing news of Mr C Tomlinson’s horse TOI FANG. I have not found any mention of Toi Fang in the newspapers in the following years.

The Scotsman – Monday 12 July 1920:

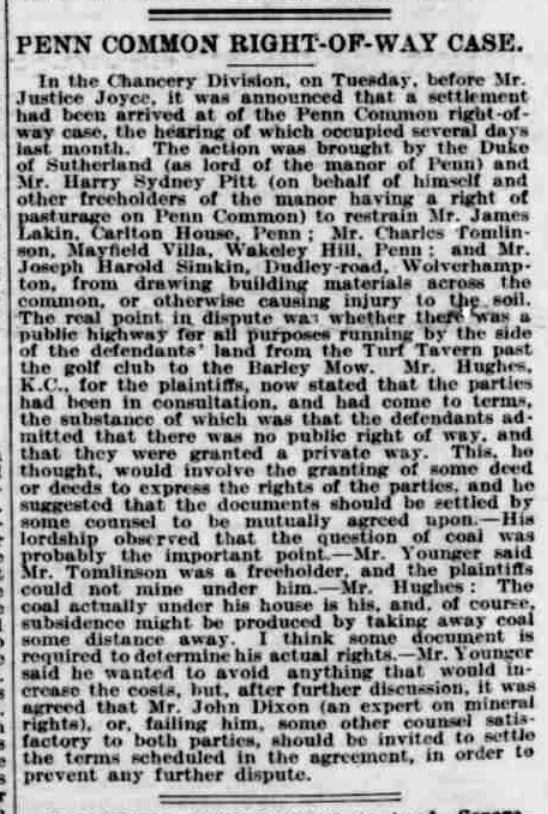

The other story that Ian Tomlinson recalled was about the house on Penn Common. Ian said he’d heard that the local titled person took Charles Tomlinson to court over building the house but that Tomlinson won the case because it was built on common land and was the first case of it’s kind.

Penn Common Right of Way Case:

Staffordshire Advertiser March 9, 1912In the chancery division, on Tuesday, before Mr Justice Joyce, it was announced that a settlement had been arrived at of the Penn Common Right of Way case, the hearing of which occupied several days last month. The action was brought by the Duke of Sutherland (as Lord of the Manor of Penn) and Mr Harry Sydney Pitt (on behalf of himself and other freeholders of the manor having a right to pasturage on Penn Common) to restrain Mr James Lakin, Carlton House, Penn; Mr Charles Tomlinson, Mayfield Villa, Wakely Hill, Penn; and Mr Joseph Harold Simpkin, Dudley Road, Wolverhampton, from drawing building materials across the common, or otherwise causing injury to the soil.

The real point in dispute was whether there was a public highway for all purposes running by the side of the defendants land from the Turf Tavern past the golf club to the Barley Mow.

Mr Hughes, KC for the plaintiffs, now stated that the parties had been in consultation, and had come to terms, the substance of which was that the defendants admitted that there was no public right of way, and that they were granted a private way. This, he thought, would involve the granting of some deed or deeds to express the rights of the parties, and he suggested that the documents should be be settled by some counsel to be mutually agreed upon.His lordship observed that the question of coal was probably the important point. Mr Younger said Mr Tomlinson was a freeholder, and the plaintiffs could not mine under him. Mr Hughes: The coal actually under his house is his, and, of course, subsidence might be produced by taking away coal some distance away. I think some document is required to determine his actual rights.

Mr Younger said he wanted to avoid anything that would increase the costs, but, after further discussion, it was agreed that Mr John Dixon (an expert on mineral rights), or failing him, another counsel satisfactory to both parties, should be invited to settle the terms scheduled in the agreement, in order to prevent any further dispute.

The name of the house is Grassholme. The address of Mayfield Villas is the house they were living in while building Grassholme, which I assume they had not yet moved in to at the time of the newspaper article in March 1912.

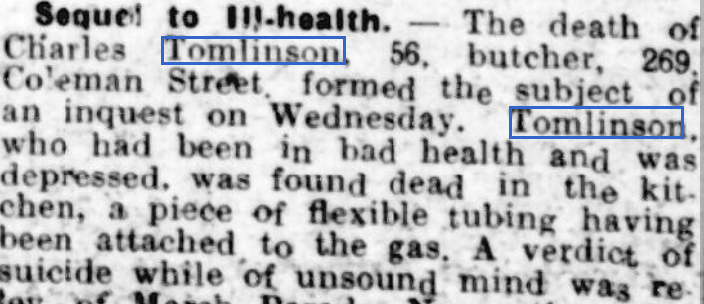

What my grandmother didn’t tell anyone was how her father died in 1929:

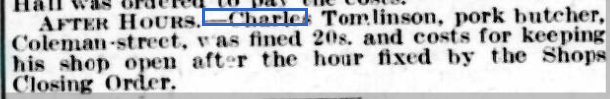

On the 1921 census, Charles, Nellie and eight of their children were living at 269 Coleman Street, Wolverhampton.

They were living on Coleman Street in 1915 when Charles was fined for staying open late.