-

AuthorSearch Results

-

July 16, 2025 at 6:06 am #7969

In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Gatacre Hall and The Old Book

In the early 1950s my uncle John and his friend, possibly John Clare, ventured into an abandoned old house while out walking in Shropshire. He (or his friend) saved an old book from the vandalised dereliction and took it home. Somehow my mother ended up with the book.

I remember that we had the book when we were living in USA, and that my mother said that John didn’t want the book in his house. He had said the abandoned hall had been spooky. The book was heavy and thick with a hard cover. I recall it was a “magazine” which seemed odd to me at the time; a compendium of information. I seem to recall the date 1553, but also recall that it was during the reign of Henry VIII. No doubt one of those recollections is wrong, probably the date. It was written in English, and had illustrations, presumably woodcuts.

I found out a few years ago that my mother had sold the book some years before. Had I known she was going to sell it, I’d have first asked her not to, and then at least made a note of the name of it, and taken photographs of it. It seems that she sold the book in Connecticut, USA, probably in the 1980’s.

My cousin and I were talking about the book and the story. We decided to try and find out which abandoned house it was although we didn’t have much to go on: it was in Shropshire, it was in a state of abandoned dereliction in the early 50s, and it contained antiquarian books.

I posted the story on a Shropshire History and Nostalgia facebook group, and almost immediately had a reply from someone whose husband remembered such a place with ancient books and manuscripts all over the floor, and the place was called Gatacre Hall in Claverley, near Bridgnorth. She also said that there was a story that the family had fled to Canada just after WWII, even leaving the dishes on the table.

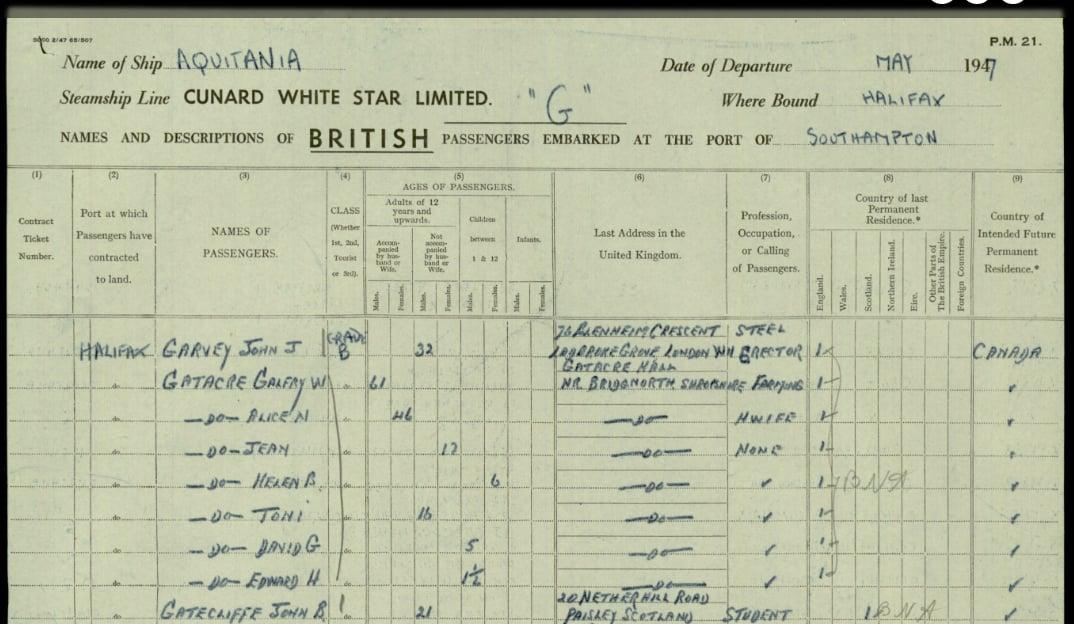

The Gatacre family sailing to Canada in 1947:

When my cousin heard the name Gatacre Hall she remembered that was the name of the place where her father had found the book.

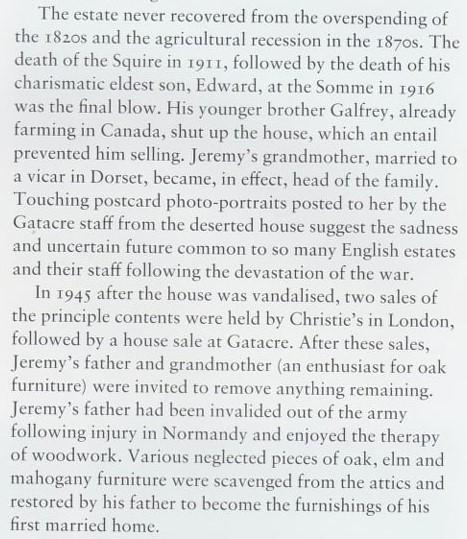

I looked into Gatacre Hall online, in the newspaper archives, the usual genealogy sites and google books searches and so on. The estate had been going downhill with debts for some years. The old squire died in 1911, and his eldest son died in 1916 at the Somme. Another son, Galfrey Gatacre, was already farming in BC, Canada. He was unable to sell Gatacre Hall because of an entail, so he closed the house up. Between 1945-1947 some important pieces of furniture were auctioned, and the rest appears to have been left in the empty house.

The family didn’t suddenly flee to Canada leaving the dishes on the table, although it was true that the family were living in Canada.

An interesting thing to note here is that not long after this book was found, my parents moved to BC Canada (where I was born), and a year later my uncle moved to Toronto (where he met his wife).

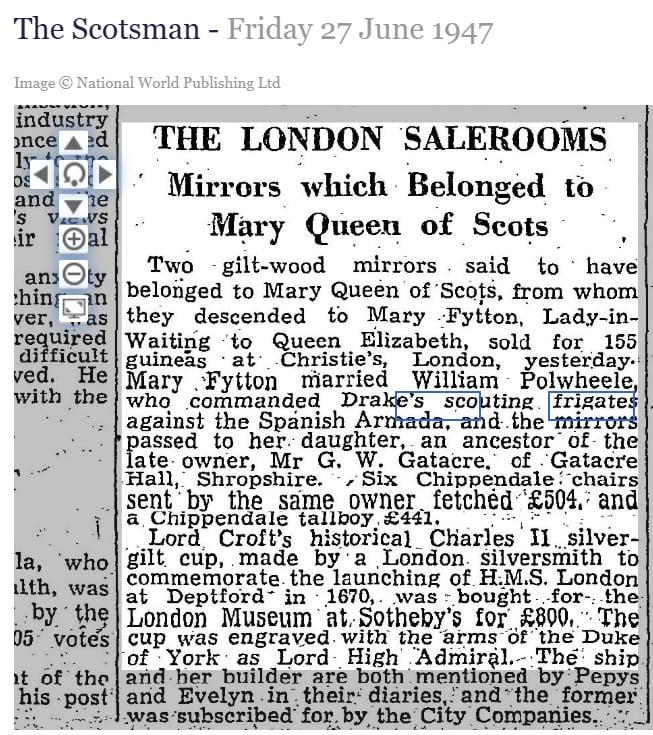

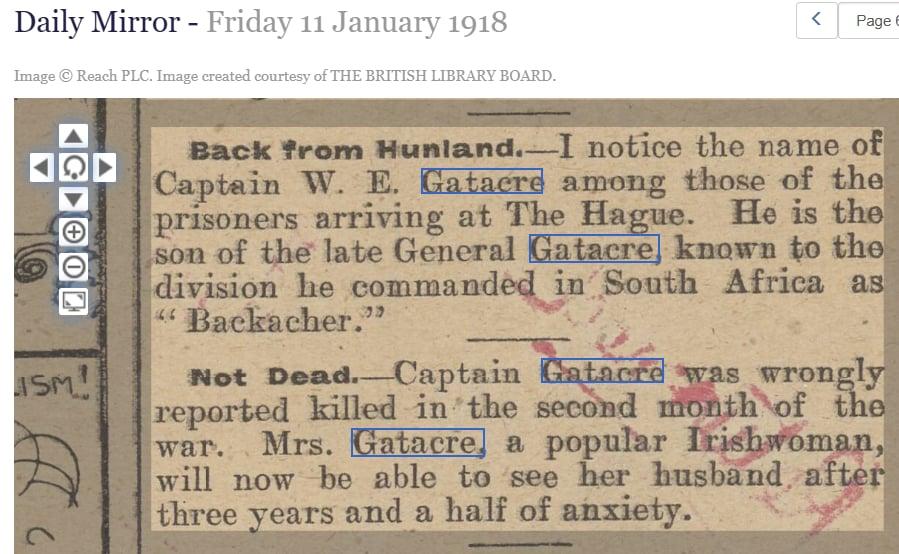

Captain Gatacre in 1918:

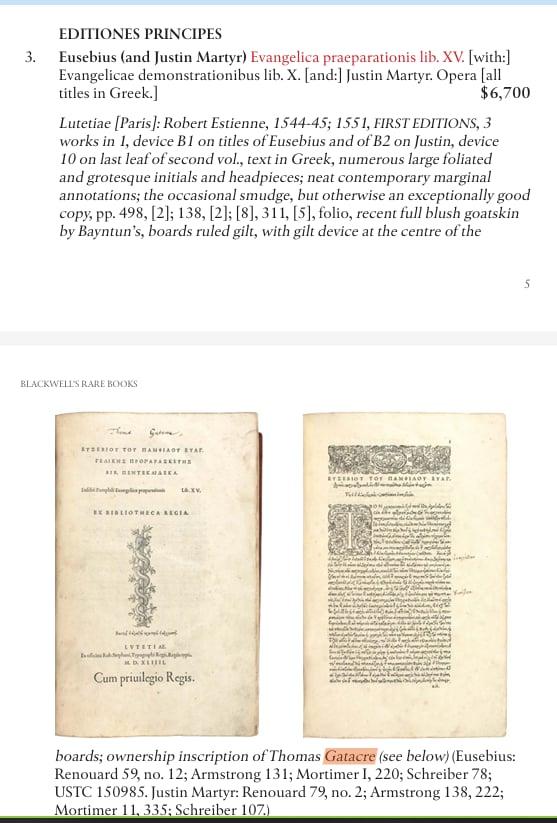

The Gatacre library was mentioned in the auction notes of a particular antiquarian book:

“Provenance: Contemporary ownership inscription and textual annotations of Thomas Gatacre (1533-1593). A younger son of William Gatacre of Gatacre Hall in Shropshire, he studied at the English college at the University of Leuven, where he rejected his Catholic roots and embraced evangelical Protestantism. He studied for eleven years at Oxford, and four years at Magdalene, Cambridge. In 1568 he was ordained deacon and priest by Bishop of London Edmund Grindal, and became domestic chaplain to Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester and was later collated to the rectory of St Edmund’s, Lombard Street. His scholarly annotations here reference other classical authors including Plato and Plutarch. His extensive library was mentioned in his will.”

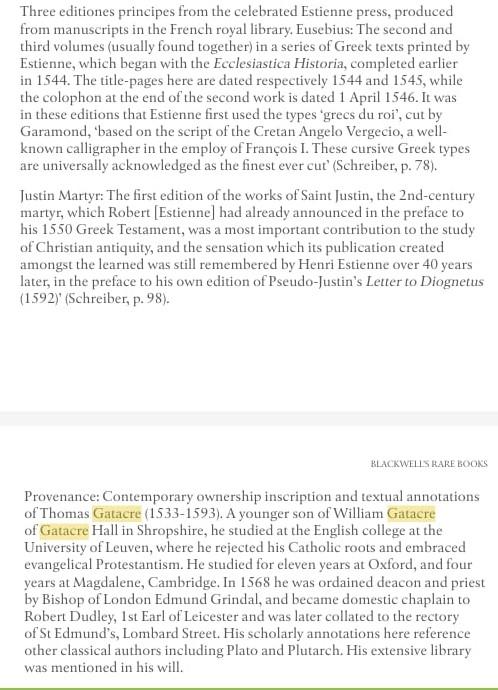

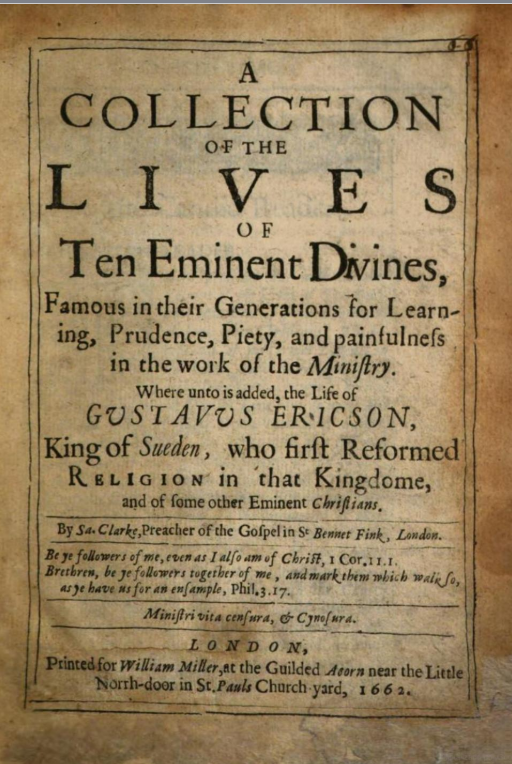

There are thirty four pages in this 1662 book about Thomas Gatacre d 1654:

March 6, 2025 at 9:24 pm #7858

March 6, 2025 at 9:24 pm #7858In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

It was still raining the morning after the impromptu postcard party at the Golden Trowel in the Hungarian village, and for most of the morning nobody was awake to notice. Molly had spent a sleepless night and was the only one awake listening to the pounding rain. Untroubled by the idea of lack of sleep, her confidence bolstered by the new company and not being solely responsible for the child, Molly luxuriated in the leisure to indulge a mental re run of the previous evening.

Finjas bombshell revelation after the postcard game suddenly changed everything. It was not what Molly had expected to hear. In their advanced state of inebriation by that time it was impossible for anyone to consider the ramifications in any sensible manner. A wild and raucous exuberance ensued of the kind that was all but forgotten to all of them, and unknown to Tundra. It was a joy that brought tears to Mollys eyes to see the wonderful time the child was having.

Molly didn’t want to think about it yet. She wasn’t so sure she wanted to have anything to do with it, the ship coming back. Communication with it, yes. The ship coming back? There was so much to consider, so many ways of looking at it. And there was Tundra to think about, she was so innocent of so many things. Was it better that way? Molly wasn’t going to think about that yet. She wanted to make sure she remembered all the postcard stories.

There is no rush.

The postcard Finja had chosen hadn’t struck Molly as the most interesting, not at the time, but later she wondered if there was any connection with her later role as centre stage overly dramatic prophet. What an extraordinary scene that was! The unexpected party was quite enough excitement without all that as well.

Finja’s card was addressed to Miss FP Finly, c/o The Flying Fish Inn somewhere in the outback of Australia, Molly couldn’t recall the name of the town. The handwriting had been hard to decipher, but it appeared to be a message from “forever your obedient servant xxx” informing her of a Dustsceawung convention in Tasmania. As nobody had any idea what a Dustsceawung conference was, and Finja declined to elaborate with a story or anecdote, the attention moved on to the next card. Molly remembered the time many years ago when everyone would have picked up their gadgets to find out what it meant. As it was now, it remained an unimportant and trifling mystery, perhaps something to wonder about later.

Why did Finja choose that card, and then decline to explain why she chose it? Who was Finly? Why did The Flying Fish Inn seem vaguely familiar to Molly?

I’m sure I’ve seen a postcard from there before. Maybe Ellis had one in his collection.

Yes, that must be it.

Mikhail’s story had been interesting. Molly was struggling to remember all the names. He’d mentioned his Uncle Grishenka, and a cousin Zhana, and a couple called Boris and Elvira with a mushroom farm. The best part was about the snow that the reindeer peed on. Molly had read about that many years ago, but was never entirely sure if it was true or not. Mickhail assured them all that it was indeed true, and many a wild party they’d had in the cold dark winters, and proceeded to share numerous funny anecdotes.

“We all had such strange ideas about Russia back then,” Molly had said. Many of the others murmured agreement, but Jian, a man of few words, merely looked up, raised an eyebrow, and looked down at his postcard again. “Russia was the big bad bogeyman for most of our lives. And in the end, we were our own worst enemies.”

“And by the time we realised, it was too late,” added Petro.

In an effort to revive the party spirit from the descent into depressing memories, Tala suggested they move on to the next postcard, which was Vera’s.

“I know the Tower of London better than any of you would believe,” Vera announced with a smug grin. Mikhail rolled his eyes and downed a large swig of vodka. “My 12th great grandfather was employed in the household of Thomas Cromwell himself. He was the man in charge of postcards to the future.” She paused for greater effect. In the absence of the excited interest she had expected, she continued. “So you can see how exciting it is for me to have a postcard as a prompt.” This further explanation was met with blank stares. Recklessly, Vera added, “I bet you didn’t know that Thomas Cromwell was a time traveller, did you? Oh yes!” she continued, although nobody had responded, “He became involved with a coven of witches in Ireland. Would you believe it!”

“No,” said Mikhail. “I probably wouldn’t.”

“I believe you, Vera,” piped up Tundra, entranced, “Will you tell me all about that later?”

Tundra’s interjection gave Tala the excuse she needed to move on to the next postcard. Mikhail and Vera has always been at loggerheads, and fueled with the unaccustomed alcohol, it was in danger of escalating quickly. “Next postcard!” she announced.

Everyone started banging on the tables shouting, “Next postcard! Next postcard!” Luka and Lev topped up everyone’s glasses.

Molly’s postcard was next.

January 12, 2025 at 11:51 am #7711In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

Matteo — December 2022

Juliette leaned in, her phone screen glowing faintly between them. “Come on, pick something. It’s supposed to know everything—or at least sound like it does.”

Juliette was the one who’d introduced him to the app the whole world was abuzz talking about. MeowGPT.

At the New Year’s eve family dinner at Juliette’s parents, the whole house was alive with her sisters, nephews, and cousins. She entered a discussion with one of the kids, and they all seemed to know well about it. It was fun to see the adults were oblivious, himself included. He liked it about Juliette that she had such insatiable curiosity.

“It’s a life-changer, you know” she’d said “There’ll be a time, we won’t know about how we did without it. The kids born now will not know a world without it. Look, I’m sure my nephews are already cheating at their exams with it, or finding new ways to learn…”

“New ways to learn, that sounds like a mirage…. Bit of a drastic view to think we won’t live without; I’d like to think like with the mobile phones, we can still choose to live without.”

“And lose your way all the time with worn-out paper maps instead of GPS? That’s a grandpa mindset darling! I can see quite a few reasons not to choose!” she laughed.

“Anyway, we’ll see. What would you like to know about? A crazy recipe to grow hair? A fancy trip to a little known place? Write a technical instruction in the style of Elizabeth Tattler?”“Let me see…”

Matteo smirked, swirling the last sip of crémant in his glass. The lively discussions of Juliette’s family around them made the moment feel oddly private. “Alright, let’s try something practical. How about early signs of Alzheimer’s? You know, for Ma.”

Juliette’s smile softened as she tapped the query into the app. Matteo watched, half curious, half detached.

The app processed for a moment before responding in its overly chipper tone:

“Early signs of Alzheimer’s can include memory loss, difficulty planning or solving problems, and confusion with time or place. For personalized insights, understanding specific triggers, like stress or diet, can help manage early symptoms.”Matteo frowned. “That’s… general. I thought it was supposed to be revolutionary?”

“Wait for it,” Juliette said, tapping again, her tone teasing. “What if we ask it about long-term memory triggers? Something for nostalgia. Your Ma’s been into her old photos, right?”

The app spun its virtual gears and spat out a more detailed suggestion.

“Consider discussing familiar stories, music, or scents. Interestingly, recent studies on Alzheimer’s patients show a strong response to tactile memories. For example, one groundbreaking case involved genetic ancestry research coupled with personalized sensory cues.Juliette tilted her head, reading the screen aloud. “Huh, look at this—Dr. Elara V., a retired physicist, designed a patented method combining ancestral genetic research with soundwaves sensory stimuli to enhance attention and preserve memory function. Her work has been cited in connection with several studies on Alzheimer’s.”

“Elara?” Matteo’s brow furrowed. “Uncommon name… Where have I heard it before?”

Juliette shrugged. “Says here she retired to Tuscany after the pandemic. Fancy that.” She tapped the screen again, scrolling. “Apparently, she was a physicist with some quirky ideas. Had a side hustle on patents, one of which actually turned out useful. Something about genetic resonance? Sounds like a sci-fi movie.”

Matteo stared at the screen, a strange feeling tugging at him. “Genetic resonance…? It’s like these apps read your mind, huh? Do they just make this stuff up?”

Juliette laughed, nudging him. “Maybe! The system is far from foolproof, it may just have blurted out a completely imagined story, although it’s probably got it from somewhere on the internet. You better do your fact-checking. This woman would have published papers back when we were kids, and now the AI’s connecting dots.”

The name lingered with him, though. Elara. It felt distant yet oddly familiar, like the shadow of a memory just out of reach.

“You think she’s got more work like that?” he asked, more to himself than to Juliette.

Juliette handed him the phone. “You’re the one with the questions. Go ahead.”

Matteo hesitated before typing, almost without thinking: Elara Tuscany memory research.

The app processed again, and the next response was less clinical, more anecdotal.

“Elara V., known for her unconventional methods, retired to Tuscany where she invested in rural revitalization. A small village farmhouse became her retreat, and she occasionally supported artistic projects. Her most cited breakthrough involved pairing sensory stimuli with genetic lineage insights to enhance memory preservation.”Matteo tilted the phone towards Juliette. “She supports artists? Sounds like a soft spot for the dreamers.”

“Maybe she’s your type,” Juliette teased, grinning.

Matteo laughed, shaking his head. “Sure, if she wasn’t old enough to be my mother.”

The conversation shifted, but Matteo couldn’t shake the feeling the name had stirred. As Juliette’s family called them back to the table, he pocketed his phone, a strange warmth lingering—part curiosity, part recognition.

To think that months before, all that technologie to connect dots together didn’t exist. People would spend years of research, now accessible in a matter of seconds.

Later that night, as they were waiting for the new year countdown, he found himself wondering: What kind of person would spend their retirement investing in forgotten villages and forgotten dreams? Someone who believed in second chances, maybe. Someone who, like him, was drawn to the idea of piecing together a life from scattered connections.

December 3, 2024 at 7:51 am #7636In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

It was cold in Kent, much colder than Elara was used to at home in the Tuscan olive groves, but Mrs Lovejoy kept the guest house warm enough. On site at Samphire Hoe was another matter, the wind off the sea biting into her despite the many layers of clothing. It had been Florian’s idea to take the Mongolian hat with her. Laughing, she’d replied that it might come in handy if there was a costume party. Trust me, you’re going to need it, he’d said, and he was right. It had been a present from Amei, many years ago, but Elara had barely worn it. It wasn’t often that she found herself in a place cold enough to warrant it.

In a fortuitous twist of fate, Florian had asked if he could come and stay with her for awhile to find his feet after the tumultuous end of a disastrous relationship. It came at a time when Elara was starting to realise that there was too much work for her alone keeping the old farmhouse in order. Everyone wants to retire to the country but nobody thinks of all the work involved, at an age when one prefers to potter about, read books, and take naps.

Florian was a long lost (or more correctly never known) distant relative, a seventh cousin four times removed on her paternal side. They had come into contact while researching the family, comparing notes and photographs and family anecdotes. They became friends, finding they had much in common, and Elara was pleased to have him come to stay with her. Likewise, Florian was more than willing to help around the beautiful old place, and found it conducive to his writing. He spent the mornings gardening, decorating or running errands, and the afternoons tapping away at the novel he’d been inspired to start, sitting at the old desk in front of the French windows.

If it hadn’t been for Florian, Elara wouldn’t have accepted the invitation to join the chalk project. He had settled in so well, already had a working grasp of Italian, and got on well with her neighbours. She could leave him to look after everything and not worry about a thing.

Pulling the hat down over her ears, Elara ventured out into the early November chill. Mrs Lovejoy was coming up the path to the guesthouse, having been out to the corner shop. “I say, that’s a fine hat you have there, that’ll keep your cockles warm!” Mrs Lovejoy was bareheaded, wearing only a cardigan.

“It was a gift,” Elara told her, “I haven’t worn it much. A friend bought it for me years ago when we were in Mongolia.”

“Very nice, I’m sure,” replied the landlady, trying to remember where Mongolia was.

“Yes, she was nice,” Elara said wistfully. “We lost contact somehow.”

“Ah yes, well these things happen,” Mrs Lovejoy said. “People come into your life and then they go. Like my Bert…”

“Must go or I’ll be late!” Elara had already heard all about Bert a number of times.

August 28, 2024 at 6:26 am #7548In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Elton Marshall’s

Early Quaker Emigrants to USA.

The earliest Marshall in my tree is Charles Marshall (my 5x great grandfather), Overseer of the Poor and Churchwarden of Elton. His 1819 gravestone in Elton says he was 77 years old when he died, indicating a birth in 1742, however no baptism can be found.

According to the Derbyshire records office, Elton was a chapelry of Youlgreave until 1866. The Youlgreave registers date back to the mid 1500s, and there are many Marshalls in the registers from 1559 onwards. The Elton registers however are incomplete due to fire damage.

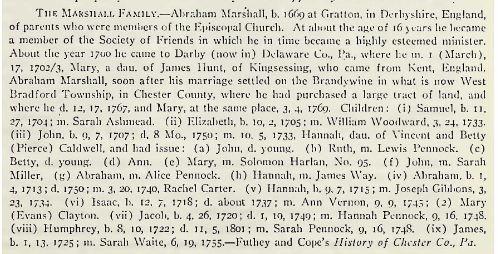

While doing a google books search for Marshall’s of Elton, I found many American family history books mentioning Abraham Marshall of Gratton born in 1667, who became a Quaker aged 16, and emigrated to Pennsylvania USA in 1700. Some of these books say that Abraham’s parents were Humphrey Marshall and his wife Hannah Turner. (Gratton is a tiny village next to Elton, also in Youlgreave parish.)

Abraham’s son born in USA was also named Humphrey. He was a well known botanist.

Abraham’s cousin John Marshall, also a Quaker, emigrated from Elton to USA in 1687, according to these books.

(There are a number of books on Colonial Families in Pennsylvania that repeat each other so impossible to cite the original source)

In the Youlgreave parish registers I found a baptism in 1667 for Humphrey Marshall son of Humphrey and Hannah. I didn’t find a baptism for Abraham, but it looks as though it could be correct. Abraham had a son he named Humphrey. But did it just look logical to whoever wrote the books, or do they know for sure? Did the famous botanist Humphrey Marshall have his own family records? The books don’t say where they got this information.

An earlier Humphrey Marshall was baptised in Youlgreave in 1559, his father Edmund. And in 1591 another Humphrey Marshall was baptised, his father George.

But can we connect these Marshall’s to ours? We do have an Abraham Marshall, grandson of Charles, born in 1792. The name isn’t all that common, so may indicate a family connection. The villages of Elton, Gratton and Youlgreave are all very small and it would seem very likely that the Marshall’s who went the USA are related to ours, if not brothers, then probably cousins.

Derbyshire Quakers

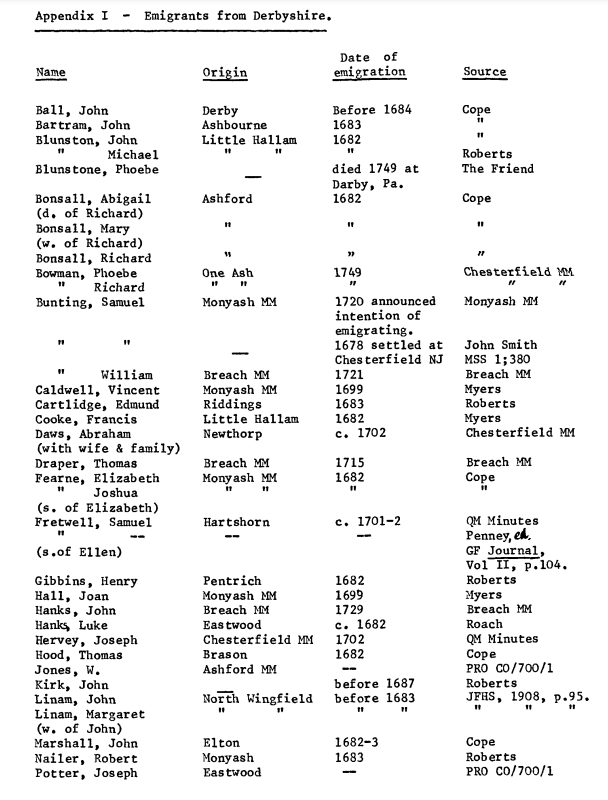

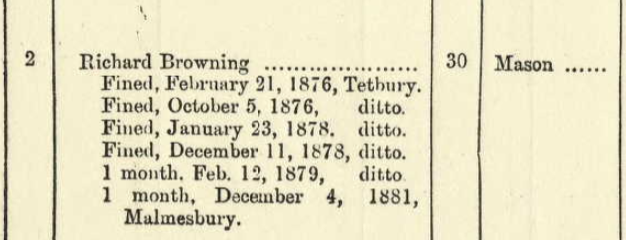

In “Derbyshire Quakers 1650-1761” by Helen Forde:

“… Friends lived predominantly in the northern half of the country during this first century of existence. Numbers may have been reduced by emigration to America and migration to other parts of the country but were never high and declined in the early eighteenth century. Predominantly a middle to lower class group economically, Derbyshire Friends numbered very few wealthy members. Many were yeoman farmers or wholesalers and it was these groups who dominated the business meetings having time to devote themselves to the Society. Only John Gratton of Monyash combined an outstanding ministry together with an organising ability which brought him recognition amongst London Friends as well as locally. Derbyshire Friends enjoyed comparatively harmonious relations with civil and Anglican authorities, though prior to the Toleration Act of 1639 the priests were their worst persecutors…..”

Also mentioned in this book: There were monthly meetings in Elton, as well as a number of other nearby places.

John Marshall of Elton 1682/3 appears in a list of Quaker emigrants from Derbyshire.

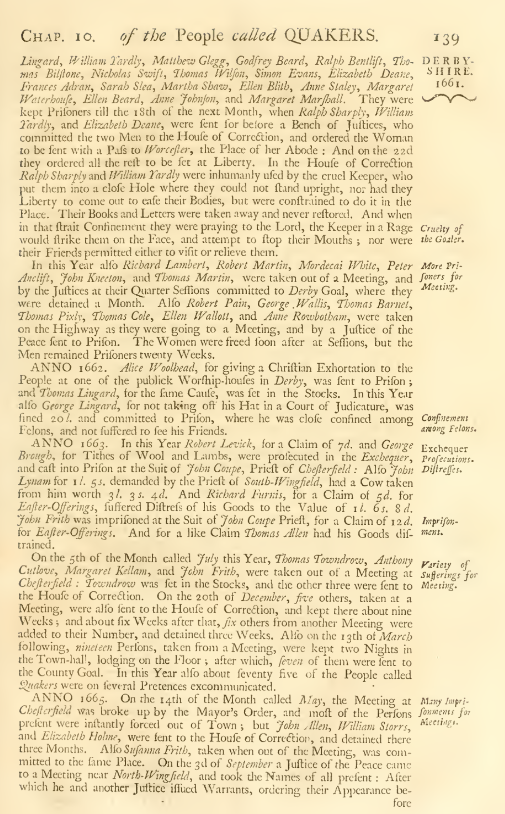

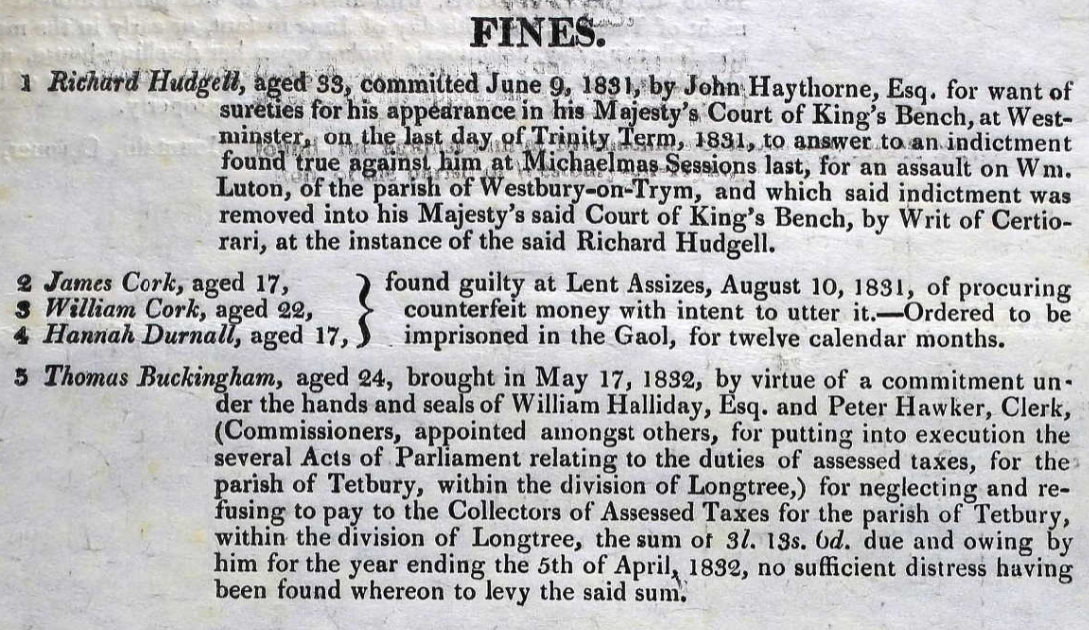

The following image is a page from the 1753 book on the sufferings of Quakers by Joseph Besse as an example of some of the persecutions of Quakers in Derbyshire in the 1600s:

A collection of the sufferings of the people called Quakers, for the testimony of a good conscience from the time of their being first distinguished by that name in the year 1650 to the time of the act commonly called the Act of toleration granted to Protestant dissenters in the first year of the reign of King William the Third and Queen Mary in the year 1689 (Volume 1)

Besse, Joseph. 1753Note the names Margaret Marshall and Anne Staley. This book would appear to contradict Helen Forde’s statement above about the harmonious relations with Anglican authority.

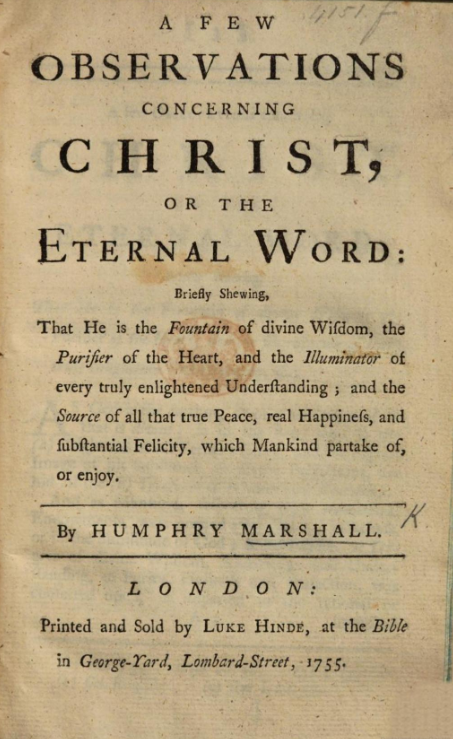

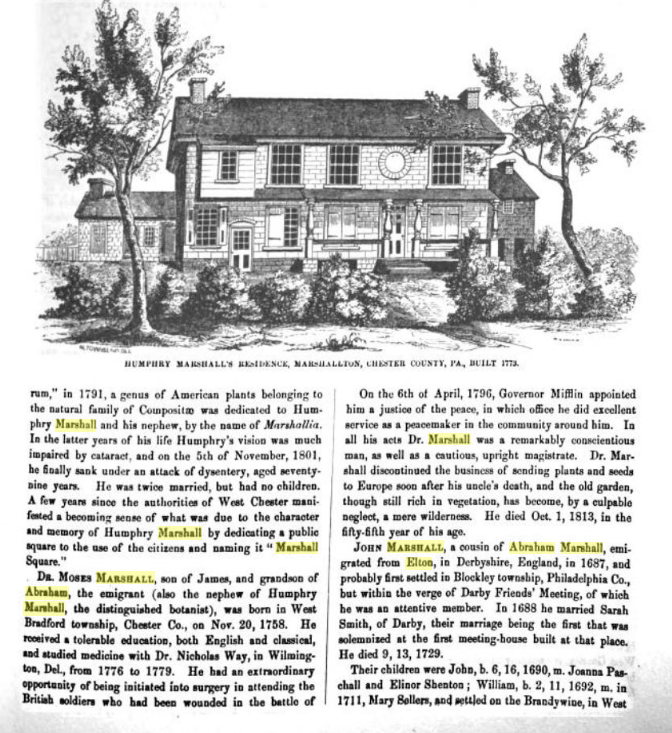

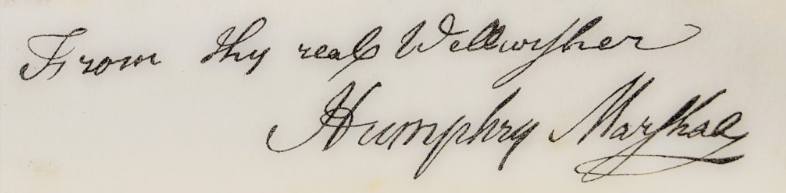

The Botanist

Humphry Marshall 1722-1801 was born in Marshallton, Pennsylvania, the son of the immigrant from Elton, Abraham Marshall. He was the cousin of botanists John Bartram and William Bartram. Like many early American botanists, he was a Quaker. He wrote his first book, A Few Observations Concerning Christ, in 1755.

In 1785, Marshall published Arbustrum Americanum: The American Grove, an Alphabetical Catalogue of Forest Trees and Shrubs, Natives of the American United States (Philadelphia).

Marshall has been called the “Father of American Dendrology”.

A genus of plants, Marshallia, was named in honor of Humphry Marshall and his nephew Moses Marshall, also a botanist.

In 1848 the Borough of West Chester established the Marshall Square Park in his honor. Marshall Square Park is four miles east of Marshallton.

via Wikipedia.

From The History of Chester County Pennsylvania, 1881, by J Smith Futhey and Gilbert Cope:

From The Chester Country History Center:

“Immediately on the Receipt of your Letter, I ordered a Reflecting Telescope for you which was made accordingly. Dr. Fothergill had since desired me to add a Microscope and Thermometer, and will

pay for the whole.’– Benjamin Franklin to Humphry, March 18, 1770

“In his lifetime, Humphry Marshall made his living as a stonemason, farmer, and miller, but eventually became known for his contributions to astronomy, meteorology, agriculture, and the natural sciences.

In 1773, Marshall built a stone house with a hothouse, a botanical laboratory, and an observatory for astronomical studies. He established an arboretum of native trees on the property and the second botanical garden in the nation (John Bartram, his cousin, had the first). From his home base, Humphry expanded his botanical plant exchange business and increased his overseas contacts. With the help of men like Benjamin Franklin and the English botanist Dr. John Fothergill, they eventually included German, Dutch, Swedish, and Irish plant collectors and scientists. Franklin, then living in London, introduced Marshall’s writings to the Royal Society in London and both men encouraged Marshall’s astronomical and botanical studies by supplying him with books and instruments including the latest telescope and microscope.

Marshall’s scientific work earned him honorary memberships to the American Philosophical Society and the Philadelphia Society for Promoting Agriculture, where he shared his ground-breaking ideas on scientific farming methods. In the years before the American Revolution, Marshall’s correspondence was based on his extensive plant and seed exchanges, which led to further studies and publications. In 1785, he authored his magnum opus, Arbustum Americanum: The American Grove. It is a catalog of American trees and shrubs that followed the Linnaean system of plant classification and was the first publication of its kind.”

June 10, 2024 at 10:05 pm #7464

June 10, 2024 at 10:05 pm #7464In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

“The world is vast, and we are not alone in our quest for magical mastery. We will forge new partnerships!” Malove’s voice had reached fever pitch. She had expanded her map, showing potential allies and strategic locations across the globe. Reactions in the audience varied, but there was an overwhelming unspoken consensus of a growing rebellion towards the unsettling increase in Malove’s dictatorial ways.

Perhaps nobody will ever know for sure whose private spell did the trick, or whether it was the combined effort that brought about such an unexpected chain of events. Maybe it was none of those things, and just the way things worked out.

The vast world that Malove had cried out heard her call and sucked her forthwith into the steamy depths of a hitherto unknown equatorial location in search of potential allies. An unexpected invitation from a long lost cousin, it was said, although nobody in the coven knew for sure. There was more lively interest in the coven and more communication between the witches during those days when Malove disappeared without trace than ever before.

On the twelfth day after her disappearance, the cryptic messages started arriving. On the 15th day, experts were examining the selfies for signs of tampering and pronouncing them to be be true images.

It wasn’t easy to imagine Malove swooning in her tropical lovers arms under parrot filled jungle trees, sheathed in gauzy crumpled linen and with a vapid expression of a Cartland character, but the photos kept coming.

It seemed too bizarre, too good to be true, when Malove sent a voice message in her unmistakable voice, but with an uncharacteristic lazy, sultry tone.

“Darlings, you won’t beleive it. I’ve fallen in love! I’m taking an indefinite leave of absence.”

February 1, 2024 at 7:14 am #7334In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

Impressed with Finnlee’s spirited outburst, Truella realised she’d barely noticed the cleaning lady and felt ashamed. The required daily appearances that the dictatorial Malove insisted upon rankled her, occupying her attention so that the cleanliness or otherwise of the premises went unnoticed. She made up her mind to seek Finnlee out and befriend her, treat her as an equal, draw her into her confidence. Besides, that confident no nonsense approach could come in handy for any staff uprisings. Not that any staff uprising were planned, she mentally added, quickly cloaking her thoughts in case any had leaked out.

Malove spun round and shot her a piercing look and Truella quailed a little, momentarily, but then squared her shoulders and impudently stared back. Malove raised an eyebrow and returned to addressing the witches.

After what seemed like an eternity the meeting was over. Truella planned to seek Finnlee out and invite her for a brew at the Faded Cabbage but Frigella approached her, looking a bit sheepish, and asked if she could have a word in private about a personal matter.

They strolled together towards the little park opposite, and once out of earshot of the others, Frigella came straight to the point.

“Can my cousin come and stay with you for a bit? The thing is, he’s got himself into a spot of bother and needs to disappear for a bit, if you know what I mean. He’s a big strong lad, and I’m sure he’d be willing to give you a hand with all that digging…”

Truella didn’t hesitate. “But of course, Frigella, send him over! He won’t be the first person on the run to come and stay, and probably won’t be the last.”

“The thing is he’s a bit sandwich short of a picnic, you know, not a full bag of shopping…”

“What, does he eat a lot? I don’t do much cooking…”

“No, no, well yes, he does have a good appetite, but that’s not what I meant. He’s a bit simple, but heart of gold. He’s from the other side of the family and our side never had much to do with them, but I always had a soft spot for him.”

” A simpleton might be a refreshing change from all the over complicated people, send him over! What’s his name?”

“Roger. Roger Goodall.”

Roger! The name rang a bell. It wasn’t until much later that Truella realized she should have asked what Roger was on the run for.

February 1, 2024 at 12:03 am #7332In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

After the evening ritual at the elder tree, Eris came home thirsting for the bitter taste of dark Assam tea. Thorsten had already gone to sleep, and his cybernetic arm was put negligently near the sink, ready for the morning, as it was otherwise inconvenient to wear to bed.

Tired by the long day, and even more by the day planned in the morrow, she’d planned to go to bed as well, but a late notification caught her attention. “You have a close cousin! Find more”; she had registered some time ago to get an analysis of her witch heritage, in a somewhat vain attempt to pinpoint more clearly where, if it could be told, her gift had originated. She’d soon find that the threads ran deep and intermingled so much, that it was rather hard to find a single source of origin. Only patterns emerged, to give her a hint of this.

Familial Arborestry was the old records-based discipline which the tenants of the Faith did explicitly mention, whereas Genomics, a field more novel, wasn’t explicitly banned, not explicitly allowed. Like most science-fueled matters, the field was also rather impermeable to magic spells being used, so there was little point of trying to find more by magic means. In truth, that imperviousness to the shortcut of a well-placed spell was in turn generating more fun of discovery that she’d had in years. But after a while, she seemed to have reached a plateau in her finds.

Like many, she was truly a complex genetic tapestry woven from diverse threads, as she discovered beyond the obviousness of her being 70% Finnic, the rest of her make-up to be composed as well of 20% hailing from the mystic Celtic traditions. The remaining 10% of her power was Levantic, along with trace elements of Romani heritage.

Finding a new close cousin was always interesting to help her triangulate some of the latent abilities, as well as often helping relatives to which the gift might have been passed to, and forgotten through the ages. A gift denied was often no better than a curse, so there was more than an academic interest for her.

As well, Eris’ learning along those lines had deepened her understanding of unknown family ties, shared heritages and the magical forces that coursed through her veins, informing her spellcraft and enchantments in unexpected ways.

She opened the link. Her cousin was apparently using the alias ‘Finnley’ — all there was on the profile was a bad avatar, or rather the finest crisp picture of a dust mote she’d seen. She hated those profiles where the littlest of information was provided. What the hell were those people even signing for? In truth,… she paradoxically actually loved those profiles. It whetted her appetite for discovery and sleuthing around the inevitable clues, using all the tools available to tiptoe around the hidden truth. If she had not been a witch, she may simply have been a hacker. So what this Finnley cousin was hiding from? What she looking for parents she never knew? Or maybe a lost child?

As exciting as it was, it would have to wait. She yawned vigorously at the prospect of the early rising tomorrow. Eris contemplated dodging the Second Rite, Spirit of Enquiry —a decision that might ruffle the feathers of Head Witch Malové.

Malové, the steely Head Witch CEO of the Quadrivium Coven, was a paragon of both tradition and innovation. Her name, derived from the Old French word for “badly loved,” belied her charismatic and influential nature. Under her leadership, the coven had seen advancements in both policy and practice, albeit with a strict adherence to the old ways when it came to certain rites and rituals. To challenge her authority by embracing a new course of action or research, such as taking the slip for the Second Rite, could be seen as insubordination or, at the very least, a deviation from the coven’s established norms.

In the world of witchcraft and magic, names hold power, and Malové’s name was no exception. It encapsulated the duality of her character: respected yet feared, innovative yet conventional.

Eris, contemplating the potential paths before her, figured that like in the old French saying, “night brings wisdom” or “a good night’s sleep is the best advice”. Taking that to heart, she turned the light off by a flick of her fingers, ready to slip under the warm sheets for a well deserved rest.

August 15, 2023 at 12:42 pm #7267In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Thomas Josiah Tay

22 Feb 1816 – 16 November 1878

“Make us glad according to the days wherein thou hast afflicted us, and the years wherein we have seen evil.”

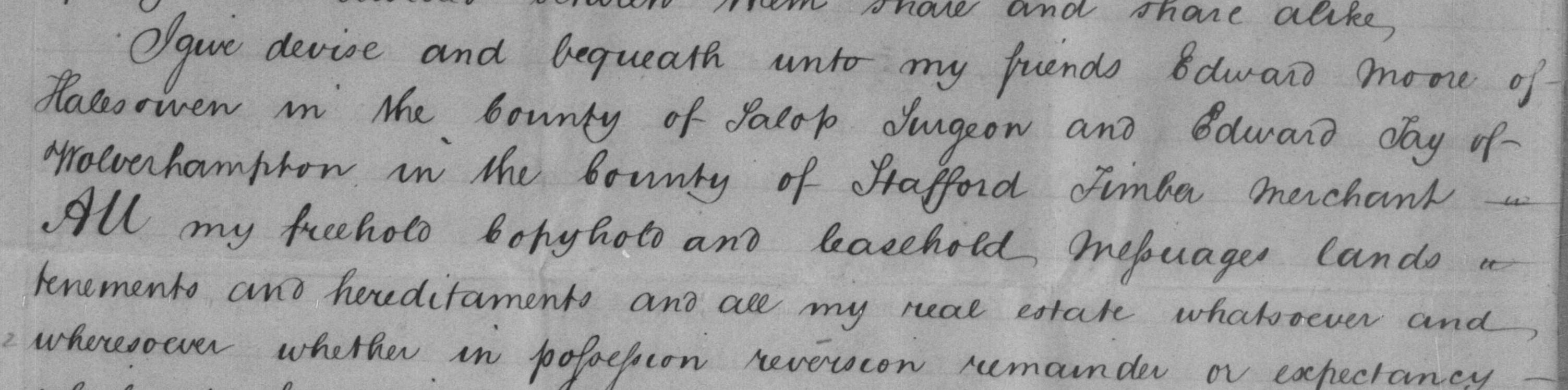

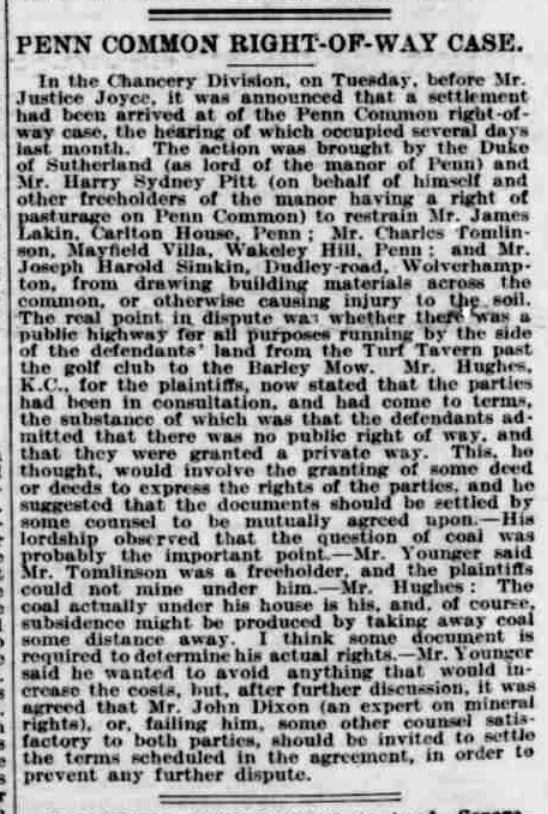

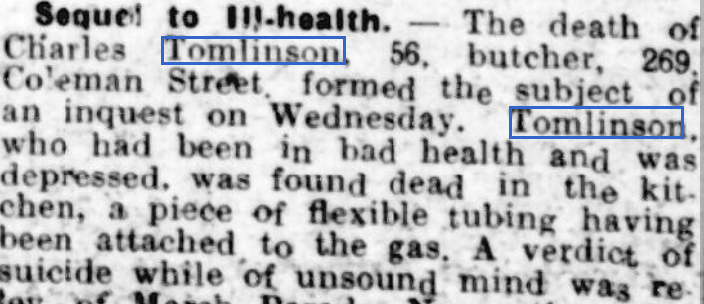

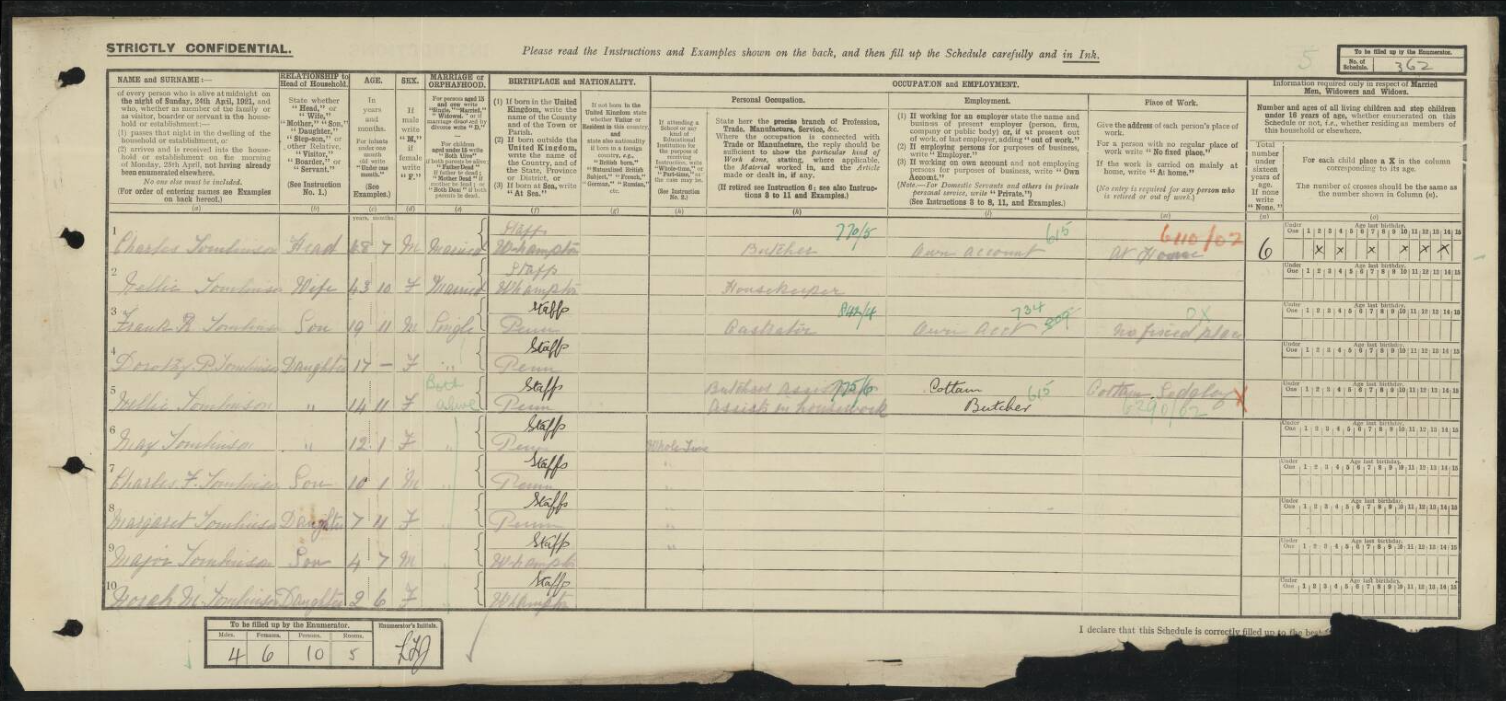

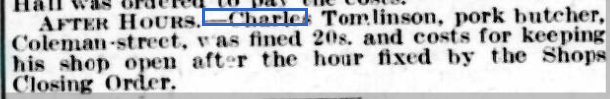

I first came across the name TAY in the 1844 will of John Tomlinson (1766-1844), gentleman of Wergs, Tettenhall. John’s friends, trustees and executors were Edward Moore, surgeon of Halesowen, and Edward Tay, timber merchant of Wolverhampton.

Edward Moore (born in 1805) was the son of John’s wife’s (Sarah Hancox born 1772) sister Lucy Hancox (born 1780) from her first marriage in 1801. In 1810 widowed Lucy married Josiah Tay (1775-1837).

Edward Tay was the son of Sarah Hancox sister Elizabeth (born 1778), who married Thomas Tay in 1800. Thomas Tay (1770-1841) and Josiah Tay were brothers.

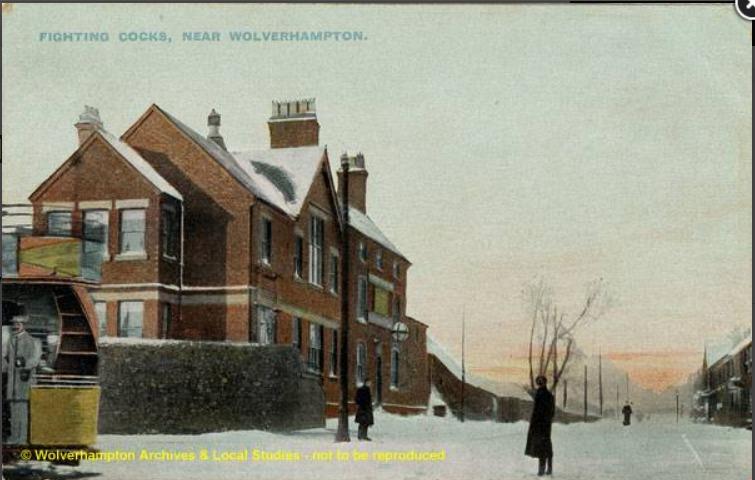

Edward Tay (1803-1862) was born in Sedgley and was buried in Penn. He was innkeeper of The Fighting Cocks, Dudley Road, Wolverhampton, as well as a builder and timber merchant, according to various censuses, trade directories, his marriage registration where his father Thomas Tay is also a timber merchant, as well as being named as a timber merchant in John Tomlinsons will.

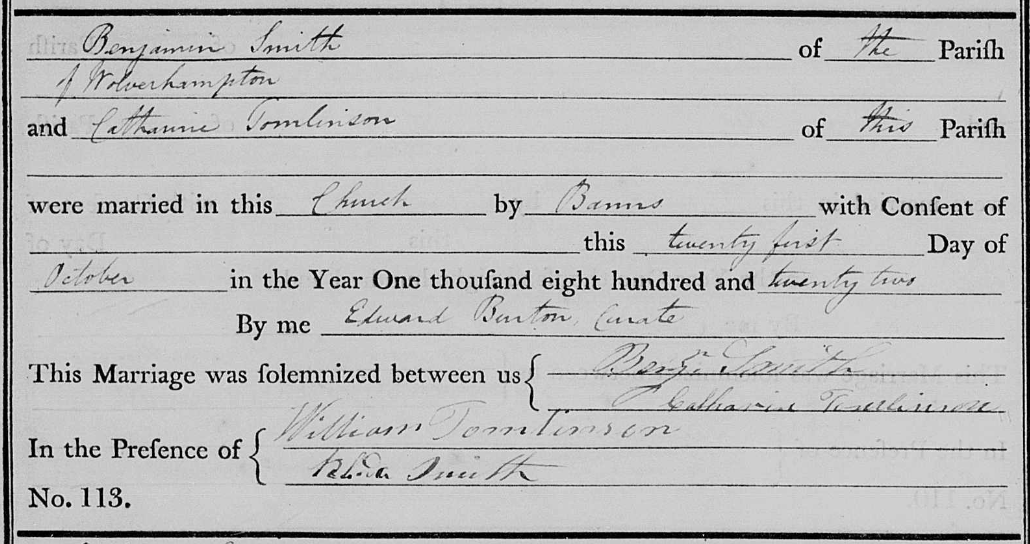

John Tomlinson’s daughter Catherine (born in 1794) married Benjamin Smith in Tettenhall in 1822. William Tomlinson (1797-1867), Catherine’s brother, and my 3x great grandfather, was one of the witnesses.

Their daughter Matilda Sarah Smith (1823-1910) married Thomas Josiah Tay in 1850 in Birmingham. Thomas Josiah Tay (1816-1878) was Edward Tay’s brother, the sons of Elizabeth Hancox and Thomas Tay.

Therefore, William Hancox 1737-1816 (the father of Sarah, Elizabeth and Lucy), was Matilda’s great grandfather and Thomas Josiah Tay’s grandfather.

Thomas Josiah Tay’s relationship to me is the husband of first cousin four times removed, as well as my first cousin, five times removed.

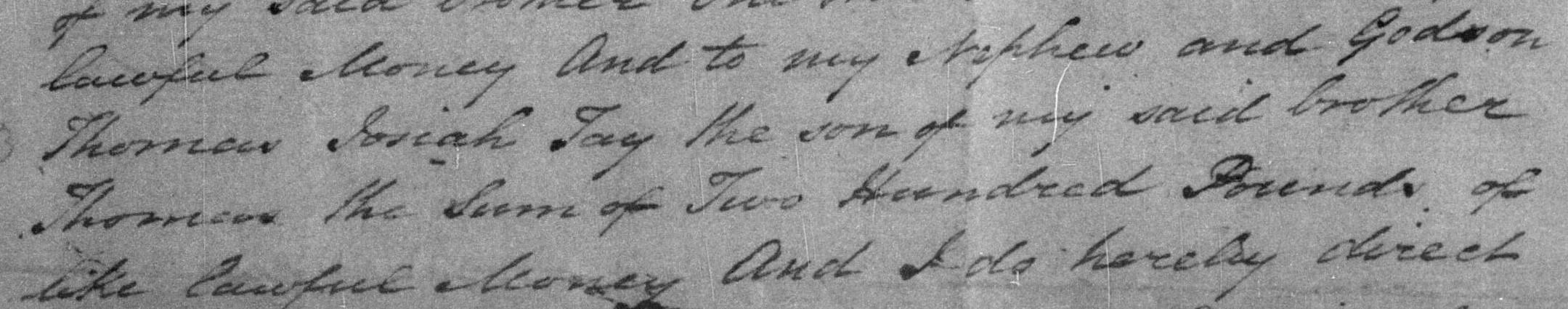

In 1837 Thomas Josiah Tay is mentioned in the will of his uncle Josiah Tay.

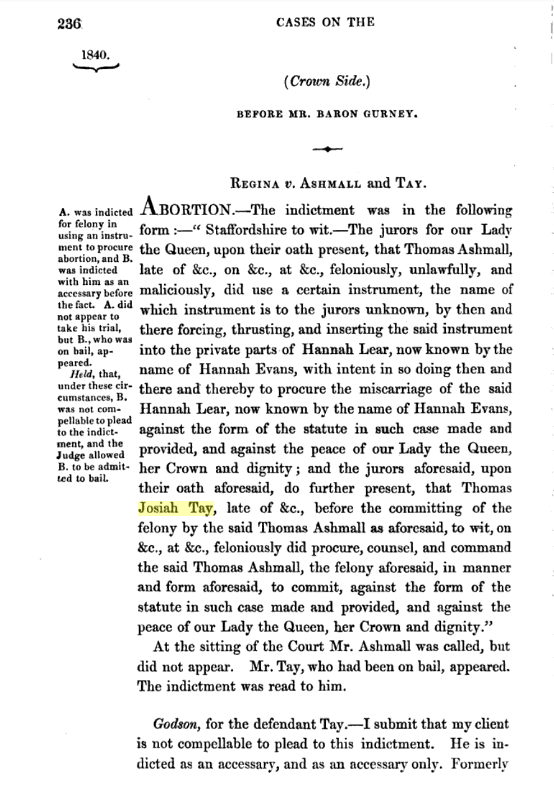

In 1841 Thomas Josiah Tay appears on the Stafford criminal registers for an “attempt to procure miscarriage”. He was found not guilty.

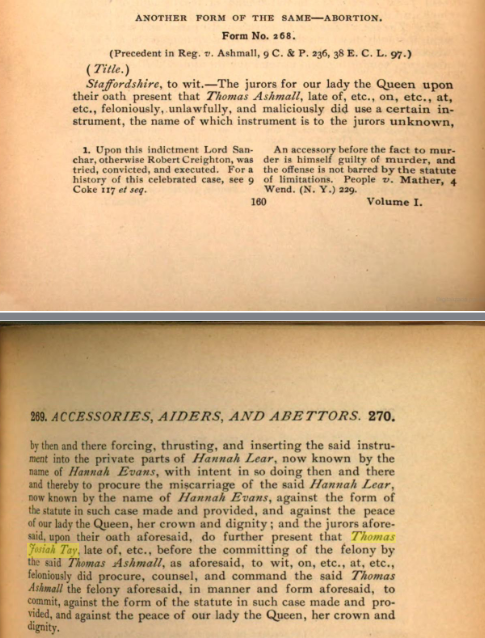

According to the Staffordshire Advertiser on 14th March 1840 the listing for the Assizes included: “Thomas Ashmall and Thomas Josiah Tay, for administering noxious ingredients to Hannah Evans, of Wolverhampton, with intent to procure abortion.”

The London Morning Herald on 19th March 1840 provides further information: “Mr Thomas Josiah Tay, a chemist and druggist, surrendered to take his trial on a charge of having administered drugs to Hannah Lear, now Hannah Evans, with intent to procure abortion.” She entered the service of Tay in 1837 and after four months “an intimacy was formed” and two months later she was “enciente”. Tay advised her to take some pills and a draught which he gave her and she became very ill. The prosecutrix admitted that she had made no mention of this until 1939. Verdict: not guilty.

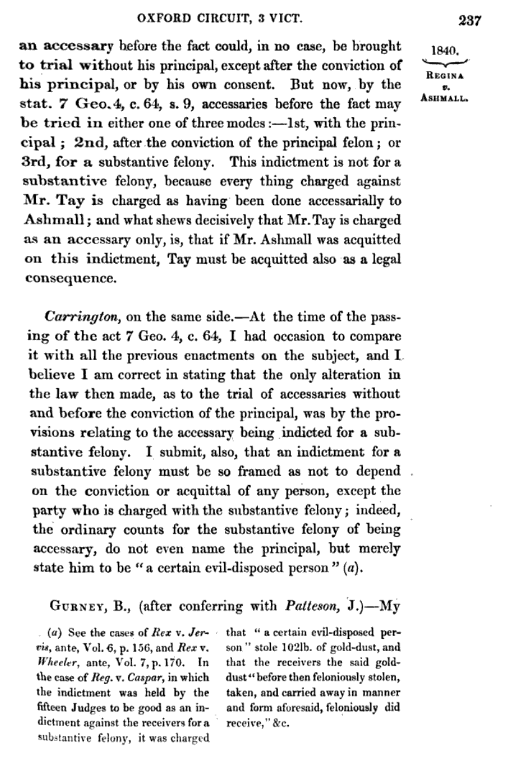

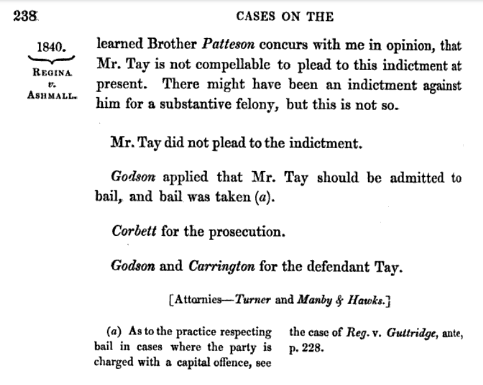

However, the case of Thomas Josiah Tay is also mentioned in a couple of law books, and the story varies slightly. In the 1841 Reports of Cases Argued and Rules at Nisi Prius, the Regina vs Ashmall and Tay case states that Thomas Ashmall feloniously, unlawfully, and maliciously, did use a certain instrument, and that Thomas Josiah Tay did procure the instrument, counsel and command Ashmall in the use of it. It concludes that Tay was not compellable to plead to the indictment, and that he did not.

The Regina vs Ashmall and Tay case is also mentioned in the Encyclopedia of Forms and Precedents, 1896.

In 1845 Thomas Josiah Tay married Isabella Southwick in Tettenhall. Two years later in 1847 Isabella died.

In 1850 Thomas Josiah married Matilda Sarah Smith. (granddaughter of John Tomlinson, as mentioned above)

On the 1851 census Thomas Josiah Tay was a farmer of 100 acres employing two labourers in Shelfield, Walsall, Staffordshire. Thomas Josiah and Matilda Sarah have a daughter Matilda under a year old, and they have a live in house servant.

In 1861 Thomas Josiah Tay, his wife and their four children Ann, James, Josiah and Alice, live in Chelmarsh, Shropshire. He was a farmer of 224 acres. Mercy Smith, Matilda’s sister, lives with them, a 28 year old dairy maid.

In 1863 Thomas Josiah Tay of Hampton Lode (Chelmarsh) Shropshire was bankrupt. Creditors include Frederick Weaver, druggist of Wolverhampton.

In 1869 Thomas Josiah Tay was again bankrupt. He was an innkeeper at The Fighting Cocks on Dudley Road, Wolverhampton, at the time, the same inn as his uncle Edward Tay, aforementioned timber merchant.

In 1871, Thomas Josiah Tay, his wife Matilda, and their three children Alice, Edward and Maryann, were living in Birmingham. Thomas Josiah was a commercial traveller.

He died on the 16th November 1878 at the age of 62 and was buried in Darlaston, Walsall. On his gravestone:

“Make us glad according to the days wherein thou hast afflicted us, and the years wherein we have seen evil.” Psalm XC 15 verse.

Edward Moore, surgeon, was also a MAGISTRATE in later years. On the 1871 census he states his occupation as “magistrate for counties Worcester and Stafford, and deputy lieutenant of Worcester, formerly surgeon”. He lived at Townsend House in Halesowen for many years. His wifes name was PATTERN Lucas. Her mothers name was Pattern Hewlitt from Birmingham, an unusal name that I have not heard before. On the 1871 census, Edward’s son was a 22 year old solicitor.

In 1861 an article appeared in the newspapers about the state of the morality of the women of Dudley. It was claimed that all the local magistrates agreed with the premise of the article, concerning unmarried women and their attitudes towards having illegitimate children. Letters appeared in subsequent newspapers signed by local magistrates, including Edward Moore, strongly disagreeing.

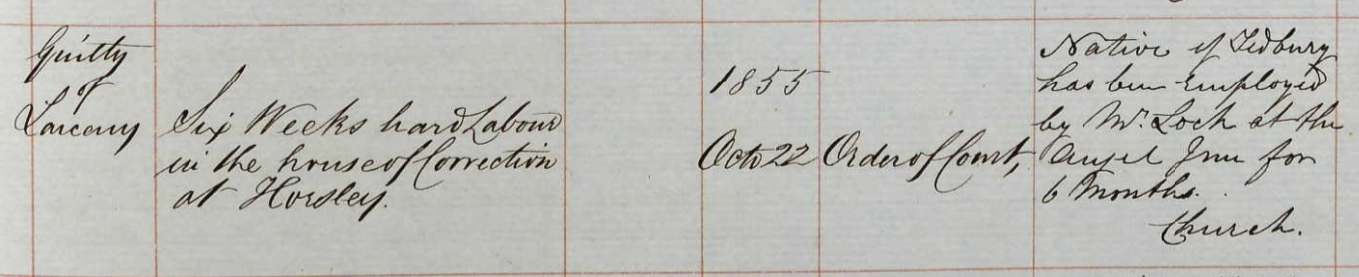

Staffordshire Advertiser 17 August 1861:

July 4, 2023 at 7:52 pm #7261

July 4, 2023 at 7:52 pm #7261In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Long Lost Enoch Edwards

My father used to mention long lost Enoch Edwards. Nobody in the family knew where he went to and it was assumed that he went to USA, perhaps to Utah to join his sister Sophie who was a Mormon handcart pioneer, but no record of him was found in USA.

Andrew Enoch Edwards (my great great grandfather) was born in 1840, but was (almost) always known as Enoch. Although civil registration of births had started from 1 July 1837, neither Enoch nor his brother Stephen were registered. Enoch was baptised (as Andrew) on the same day as his brothers Reuben and Stephen in May 1843 at St Chad’s Catholic cathedral in Birmingham. It’s a mystery why these three brothers were baptised Catholic, as there are no other Catholic records for this family before or since. One possible theory is that there was a school attached to the church on Shadwell Street, and a Catholic baptism was required for the boys to go to the school. Enoch’s father John died of TB in 1844, and perhaps in 1843 he knew he was dying and wanted to ensure an education for his sons. The building of St Chads was completed in 1841, and it was close to where they lived.

Enoch appears (as Enoch rather than Andrew) on the 1841 census, six months old. The family were living at Unett Street in Birmingham: John and Sarah and children Mariah, Sophia, Matilda, a mysterious entry transcribed as Lene, a daughter, that I have been unable to find anywhere else, and Reuben and Stephen.

Enoch was just four years old when his father John, an engineer and millwright, died of consumption in 1844.

In 1851 Enoch’s widowed mother Sarah was a mangler living on Summer Street, Birmingham, Matilda a dressmaker, Reuben and Stephen were gun percussionists, and eleven year old Enoch was an errand boy.

On the 1861 census, Sarah was a confectionrer on Canal Street in Birmingham, Stephen was a blacksmith, and Enoch a button tool maker.

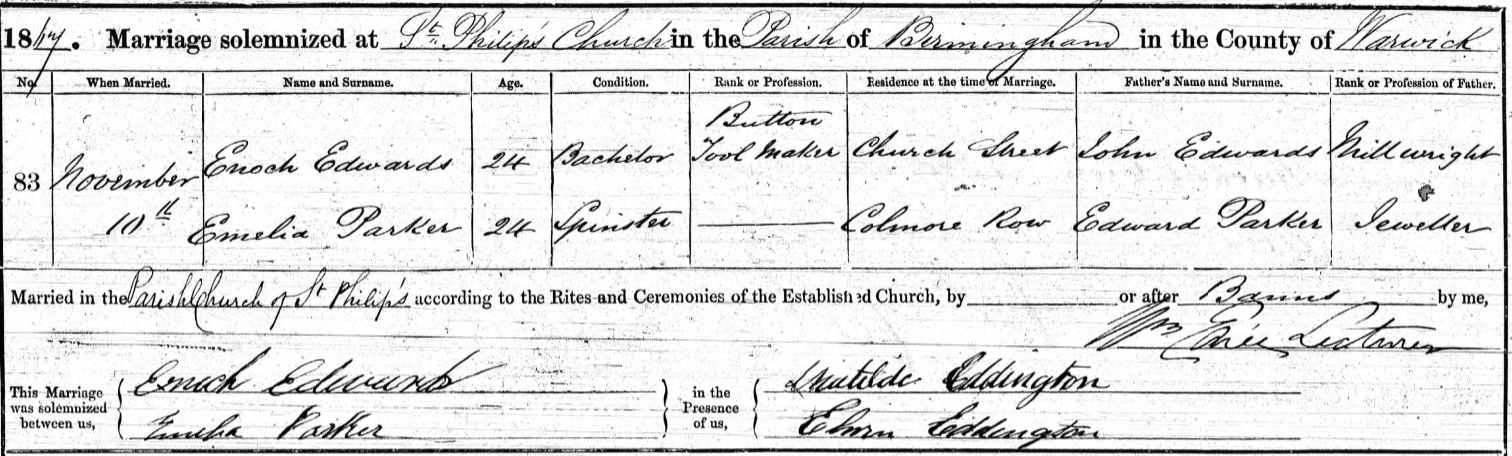

On the 10th November 1867 Enoch married Emelia Parker, daughter of jeweller and rope maker Edward Parker, at St Philip in Birmingham. Both Emelia and Enoch were able to sign their own names, and Matilda and Edwin Eddington were witnesses (Enoch’s sister and her husband). Enoch’s address was Church Street, and his occupation button tool maker.

Four years later in 1871, Enoch was a publican living on Clifton Road. Son Enoch Henry was two years old, and Ralph Ernest was three months. Eliza Barton lived with them as a general servant.

By 1881 Enoch was back working as a button tool maker in Bournebrook, Birmingham. Enoch and Emilia by then had three more children, Amelia, Albert Parker (my great grandfather) and Ada.

Garnet Frederick Edwards was born in 1882. This is the first instance of the name Garnet in the family, and subsequently Garnet has been the middle name for the eldest son (my brother, father and grandfather all have Garnet as a middle name).

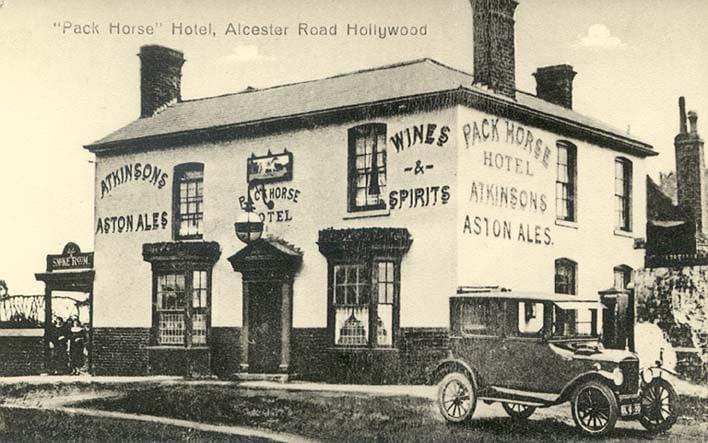

Enoch was the licensed victualler at the Pack Horse Hotel in 1991 at Kings Norton. By this time, only daughters Amelia and Ada and son Garnet are living at home.

Additional information from my fathers cousin, Paul Weaver:

“Enoch refused to allow his son Albert Parker to go to King Edwards School in Birmingham, where he had been awarded a place. Instead, in October 1890 he made Albert Parker Edwards take an apprenticeship with a pawnboker in Tipton.

Towards the end of the 19th century Enoch kept The Pack Horse in Alcester Road, Hollywood, where a twist was 1d an ounce, and beer was 2d a pint. The children had to get up early to get breakfast at 6 o’clock for the hay and straw men on their way to the Birmingham hay and straw market. Enoch is listed as a member of “The Kingswood & Pack Horse Association for the Prosecution of Offenders”, a kind of early Neighbourhood Watch, dated 25 October 1890.

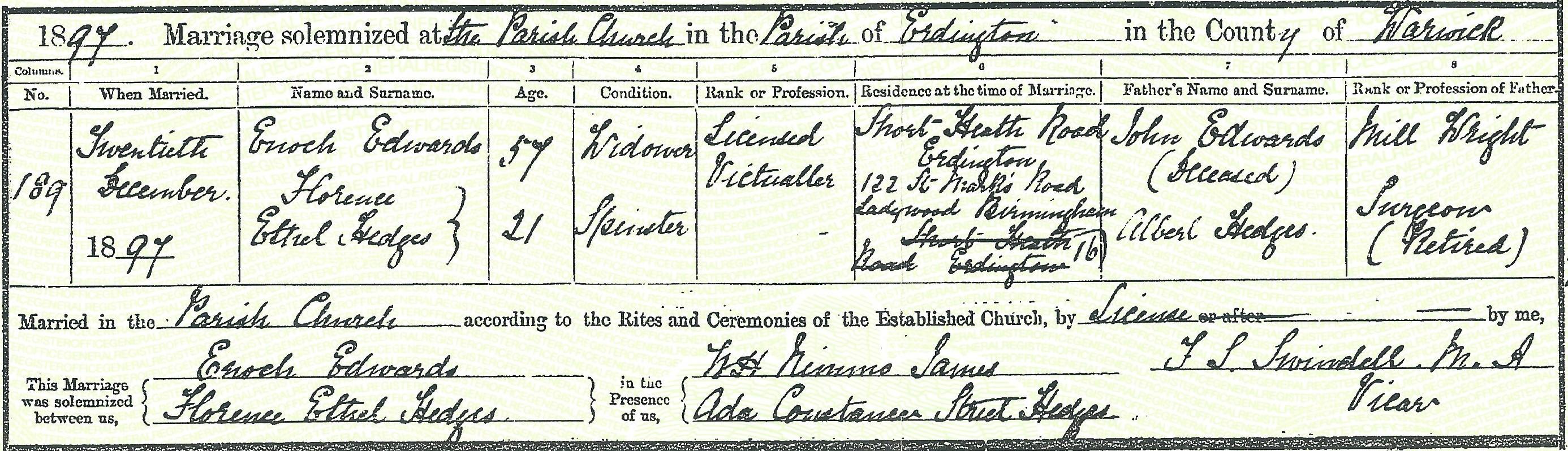

The Edwards family later moved to Redditch where they kept The Rifleman Inn at 35 Park Road. They must have left the Pack Horse by 1895 as another publican was in place by then.”Emelia his wife died in 1895 of consumption at the Rifleman Inn in Redditch, Worcestershire, and in 1897 Enoch married Florence Ethel Hedges in Aston. Enoch was 56 and Florence was just 21 years old.

The following year in 1898 their daughter Muriel Constance Freda Edwards was born in Deritend, Warwickshire.

In 1901 Enoch, (Andrew on the census), publican, Florence and Muriel were living in Dudley. It was hard to find where he went after this.From Paul Weaver:

“Family accounts have it that Enoch EDWARDS fell out with all his family, and at about the age of 60, he left all behind and emigrated to the U.S.A. Enoch was described as being an active man, and it is believed that he had another family when he settled in the U.S.A. Esmor STOKES has it that a postcard was received by the family from Enoch at Niagara Falls.

On 11 June 1902 Harry Wright (the local postmaster responsible in those days for licensing) brought an Enoch EDWARDS to the Bedfordshire Petty Sessions in Biggleswade regarding “Hole in the Wall”, believed to refer to the now defunct “Hole in the Wall” public house at 76 Shortmead Street, Biggleswade with Enoch being granted “temporary authority”. On 9 July 1902 the transfer was granted. A year later in the 1903 edition of Kelly’s Directory of Bedfordshire, Hunts and Northamptonshire there is an Enoch EDWARDS running the Wheatsheaf Public House, Church Street, St. Neots, Huntingdonshire which is 14 miles south of Biggleswade.”

It seems that Enoch and his new family moved away from the midlands in the early 1900s, but again the trail went cold.

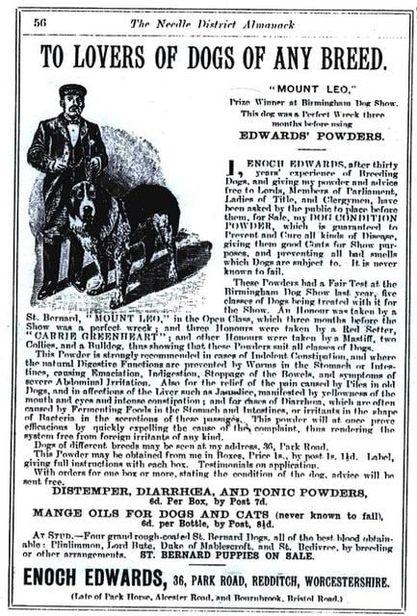

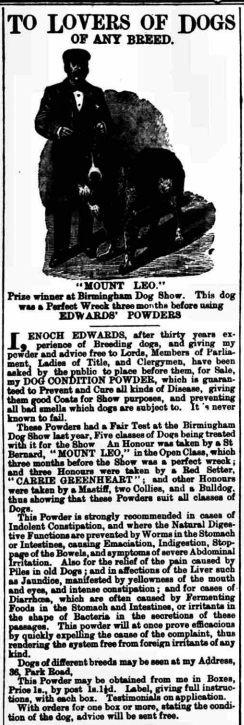

When I started doing the genealogy research, I joined a local facebook group for Redditch in Worcestershire. Enoch’s son Albert Parker Edwards (my great grandfather) spent most of his life there. I asked in the group about Enoch, and someone posted an illustrated advertisement for Enoch’s dog powders. Enoch was a well known breeder/keeper of St Bernards and is cited in a book naming individuals key to the recovery/establishment of ‘mastiff’ size dog breeds.

We had not known that Enoch was a breeder of champion St Bernard dogs!

Once I knew about the St Bernard dogs and the names Mount Leo and Plinlimmon via the newspaper adverts, I did an internet search on Enoch Edwards in conjunction with these dogs.

Enoch’s St Bernard dog “Mount Leo” was bred from the famous Plinlimmon, “the Emperor of Saint Bernards”. He was reported to have sent two puppies to Omaha and one of his stud dogs to America for a season, and in 1897 Enoch made the news for selling a St Bernard to someone in New York for £200. Plinlimmon, bred by Thomas Hall, was born in Liverpool, England on June 29, 1883. He won numerous dog shows throughout Europe in 1884, and in 1885, he was named Best Saint Bernard.

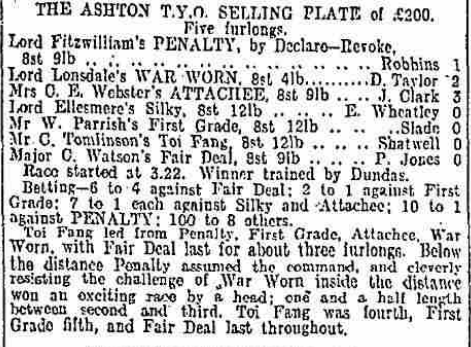

In the Birmingham Mail on 14th June 1890:

“Mr E Edwards, of Bournebrook, has been well to the fore with his dogs of late. He has gained nine honours during the past fortnight, including a first at the Pontypridd show with a St Bernard dog, The Speaker, a son of Plinlimmon.”

In the Alcester Chronicle on Saturday 05 June 1897:

It was discovered that Enoch, Florence and Muriel moved to Canada, not USA as the family had assumed. The 1911 census for Montreal St Jaqcues, Quebec, stated that Enoch, (Florence) Ethel, and (Muriel) Frida had emigrated in 1906. Enoch’s occupation was machinist in 1911. The census transcription is not very good. Edwards was transcribed as Edmand, but the dates of birth for all three are correct. Birthplace is correct ~ A for Anglitan (the census is in French) but race or tribe is also an A but the transcribers have put African black! Enoch by this time was 71 years old, his wife 33 and daughter 11.

Additional information from Paul Weaver:

“In 1906 he and his new family travelled to Canada with Enoch travelling first and Ethel and Frida joined him in Quebec on 25 June 1906 on board the ‘Canada’ from Liverpool.

Their immigration record suggests that they were planning to travel to Winnipeg, but five years later in 1911, Enoch, Florence Ethel and Frida were still living in St James, Montreal. Enoch was employed as a machinist by Canadian Government Railways working 50 hours. It is the 1911 census record that confirms his birth as November 1840. It also states that Enoch could neither read nor write but managed to earn $500 in 1910 for activity other than his main profession, although this may be referring to his innkeeping business interests.

By 1921 Florence and Muriel Frida are living in Langford, Neepawa, Manitoba with Peter FUCHS, an Ontarian farmer of German descent who Florence had married on 24 Jul 1913 implying that Enoch died sometime in 1911/12, although no record has been found.”The extra $500 in earnings was perhaps related to the St Bernard dogs. Enoch signed his name on the register on his marriage to Emelia, and I think it’s very unlikely that he could neither read nor write, as stated above.

However, it may not be Enoch’s wife Florence Ethel who married Peter Fuchs. A Florence Emma Edwards married Peter Fuchs, and on the 1921 census in Neepawa her daugther Muriel Elizabeth Edwards, born in 1902, lives with them. Quite a coincidence, two Florence and Muriel Edwards in Neepawa at the time. Muriel Elizabeth Edwards married and had two children but died at the age of 23 in 1925. Her mother Florence was living with the widowed husband and the two children on the 1931 census in Neepawa. As there was no other daughter on the 1911 census with Enoch, Florence and Muriel in Montreal, it must be a different Florence and daughter. We don’t know, though, why Muriel Constance Freda married in Neepawa.

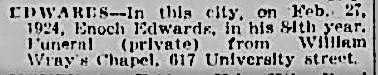

Indeed, Florence was not a widow in 1913. Enoch died in 1924 in Montreal, aged 84. Neither Enoch, Florence or their daughter has been found yet on the 1921 census. The search is not easy, as Enoch sometimes used the name Andrew, Florence used her middle name Ethel, and daughter Muriel used Freda, Valerie (the name she added when she married in Neepawa), and died as Marcheta. The only name she NEVER used was Constance!

A Canadian genealogist living in Montreal phoned the cemetery where Enoch was buried. She said “Enoch Edwards who died on Feb 27 1924 is not buried in the Mount Royal cemetery, he was only cremated there on March 4, 1924. There are no burial records but he died of an abcess and his body was sent to the cemetery for cremation from the Royal Victoria Hospital.”

1924 Obituary for Enoch Edwards:

Cimetière Mont-Royal Outremont, Montreal Region, Quebec, Canada

The Montreal Star 29 Feb 1924, Fri · Page 31

Muriel Constance Freda Valerie Edwards married Arthur Frederick Morris on 24 Oct 1925 in Neepawa, Manitoba. (She appears to have added the name Valerie when she married.)

Unexpectedly a death certificate appeared for Muriel via the hints on the ancestry website. Her name was “Marcheta Morris” on this document, however it also states that she was the widow of Arthur Frederick Morris and daughter of Andrew E Edwards and Florence Ethel Hedges. She died suddenly in June 1948 in Flos, Simcoe, Ontario of a coronary thrombosis, where she was living as a housekeeper.

June 13, 2023 at 10:31 am #7255

June 13, 2023 at 10:31 am #7255In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The First Wife of John Edwards

1794-1844

John was a widower when he married Sarah Reynolds from Kinlet. Both my fathers cousin and I had come to a dead end in the Edwards genealogy research as there were a number of possible births of a John Edwards in Birmingham at the time, and a number of possible first wives for a John Edwards at the time.

John Edwards was a millwright on the 1841 census, the only census he appeared on as he died in 1844, and 1841 was the first census. His birth is recorded as 1800, however on the 1841 census the ages were rounded up or down five years. He was an engineer on some of the marriage records of his children with Sarah, and on his death certificate, engineer and millwright, aged 49. The age of 49 at his death from tuberculosis in 1844 is likely to be more accurate than the census (Sarah his wife was present at his death), making a birth date of 1794 or 1795.

John married Sarah Reynolds in January 1827 in Birmingham, and I am descended from this marriage. Any children of John’s first marriage would no doubt have been living with John and Sarah, but had probably left home by the time of the 1841 census.

I found an Elizabeth Edwards, wife of John Edwards of Constitution Hill, died in August 1826 at the age of 23, as stated on the parish death register. It would be logical for a young widower with small children to marry again quickly. If this was John’s first wife, the marriage to Sarah six months later in January 1827 makes sense. Therefore, John’s first wife, I assumed, was Elizabeth, born in 1803.

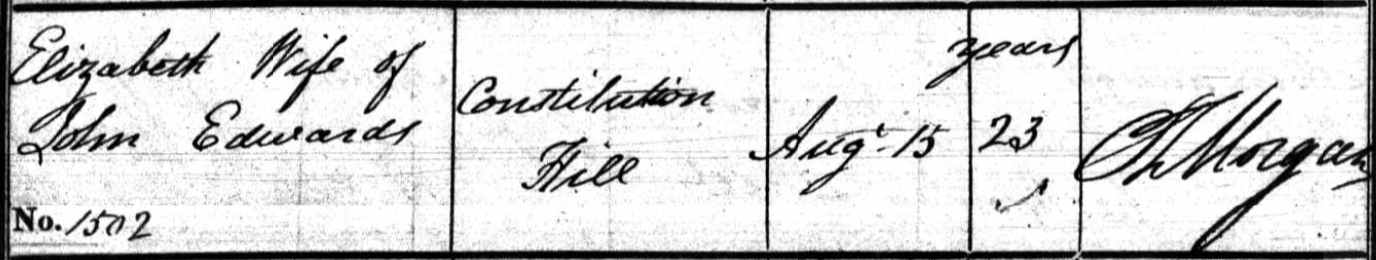

Death of Elizabeth Edwards, 23 years old. St Mary, Birmingham, 15 Aug 1826:

There were two baptisms recorded for parents John and Elizabeth Edwards, Constitution Hill, and John’s occupation was an engineer on both baptisms.

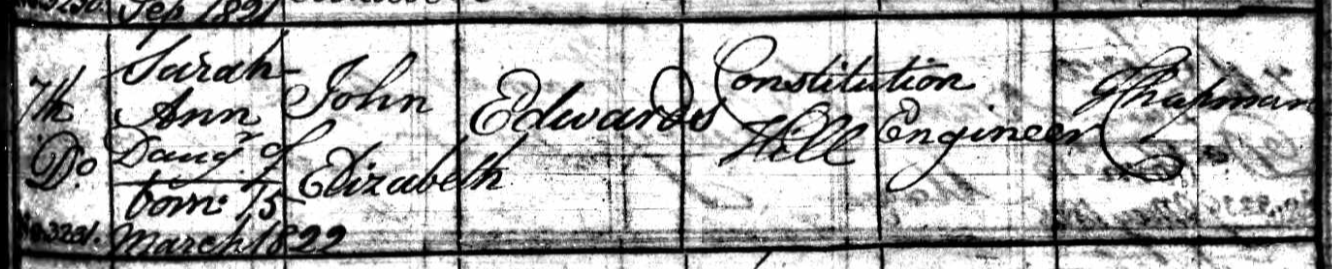

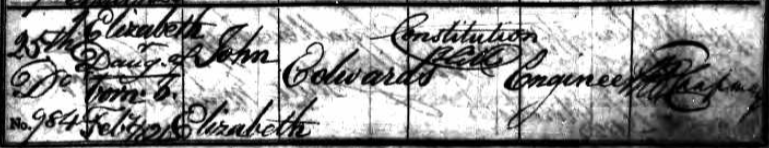

They were both daughters: Sarah Ann in 1822 and Elizabeth in 1824.Sarah Ann Edwards: St Philip, Birmingham. Born 15 March 1822, baptised 7 September 1822:

Elizabeth Edwards: St Philip, Birmingham. Born 6 February 1824, baptised 25 February 1824:

With John’s occupation as engineer stated, it looked increasingly likely that I’d found John’s first wife and children of that marriage.

Then I found a marriage of Elizabeth Beach to John Edwards in 1819, and subsequently found an Elizabeth Beach baptised in 1803. This appeared to be the right first wife for John, until an Elizabeth Slater turned up, with a marriage to a John Edwards in 1820. An Elizabeth Slater was baptised in 1803. Either Elizabeth Beach or Elizabeth Slater could have been the first wife of John Edwards. As John’s first wife Elizabeth is not related to us, it’s not necessary to go further back, and in a sense, doesn’t really matter which one it was.

But the Slater name caught my eye.

But first, the name Sarah Ann.

Of the possible baptisms for John Edwards, the most likely seemed to be in 1794, parents John and Sarah. John and Sarah had two infant daughters die just prior to John’s birth. The first was Sarah, the second Sarah Ann. Perhaps this was why John named his daughter Sarah Ann? In the absence of any other significant clues, I decided to assume these were the correct parents. I found and read half a dozen wills of any John Edwards I could find within the likely time period of John’s fathers death.

One of them was dated 1803. In this will, John mentions that his children are not yet of age. (John would have been nine years old.)

He leaves his plating business and some properties to his eldest son Thomas Davis Edwards, (just shy of 21 years old at the time of his fathers death in 1803) with the business to be run jointly with his widow, Sarah. He mentions his son John, and leaves several properties to him, when he comes of age. He also leaves various properties to his daughters Elizabeth and Mary, ditto. The baptisms for all of these children, including the infant deaths of Sarah and Sarah Ann have been found. All but Mary’s were in the same parish. (I found one for Mary in Sutton Coldfield, which was apparently correct, as a later census also recorded her birth as Sutton Coldfield. She was living with family on that census, so it would appear to be correct that for whatever reason, their daughter Mary was born in Sutton Coldfield)Mary married John Slater in 1813. The witnesses were Elizabeth Whitehouse and John Edwards, her sister and brother. Elizabeth married William Nicklin Whitehouse in 1805 and one of the witnesses was Mary Edwards.

Mary’s husband John Slater died in 1821. They had no children. Mary never remarried, and lived with her bachelor brother Thomas Davis Edwards in West Bromwich. Thomas never married, and on the census he was either a proprietor of houses, or “sinecura” (earning a living without working).With Mary marrying a Slater, does this indicate that her brother John’s first wife was Elizabeth Slater rather than Elizabeth Beach? It is a compelling possibility, but does not constitute proof.

Not only that, there is no absolute proof that the John Edwards who died in 1803 was our ancestor John Edwards father.

If we can’t be sure which Elizabeth married John Edwards, we can be reasonably sure who their daughters married. On both of the marriage records the father is recorded as John Edwards, engineer.

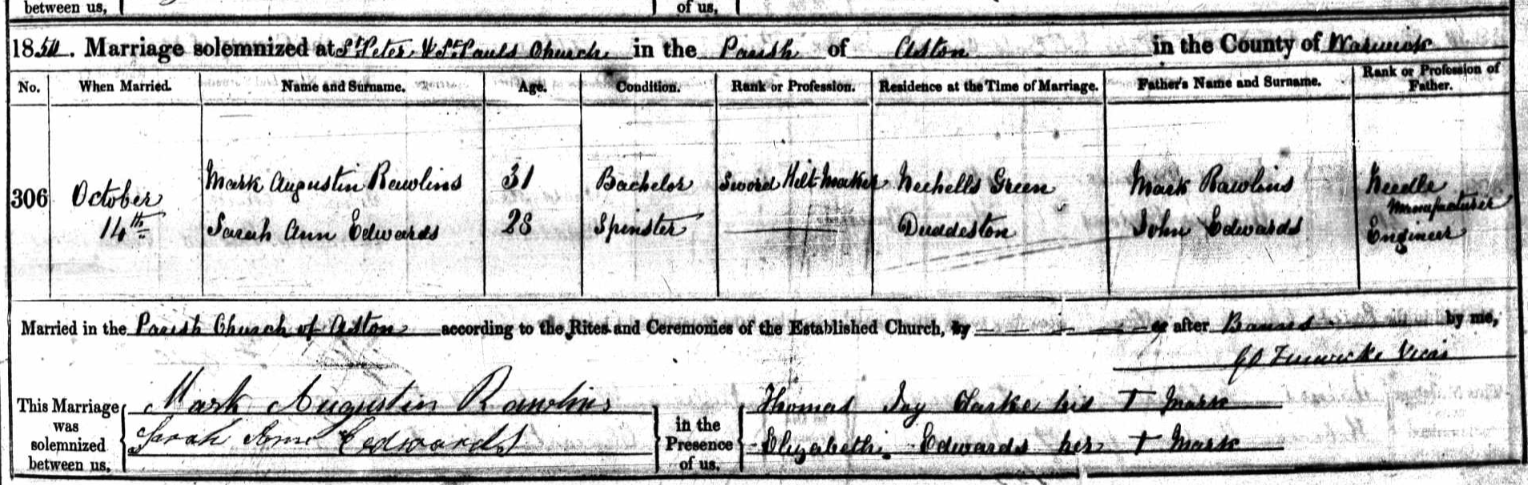

Sarah Ann married Mark Augustin Rawlins in 1850. Mark was a sword hilt maker at the time of the marriage, his father Mark a needle manufacturer. One of the witnesses was Elizabeth Edwards, who signed with her mark. Sarah Ann and Mark however were both able to sign their own names on the register.

Sarah Ann Edwards and Mark Augustin Rawlins marriage 14 October 1850 St Peter and St Paul, Aston, Birmingham:

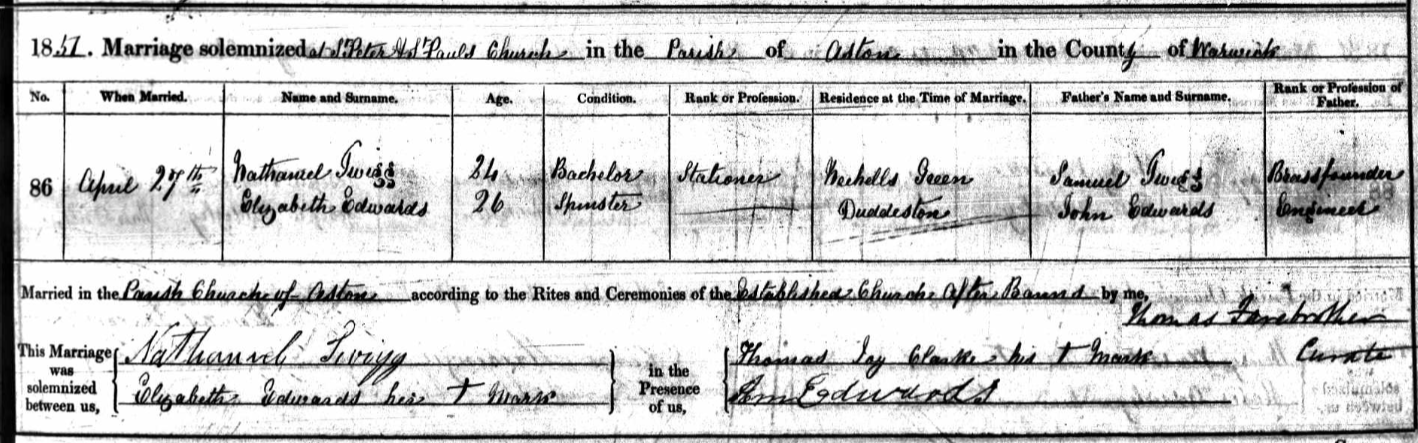

Elizabeth married Nathaniel Twigg in 1851. (She was living with her sister Sarah Ann and Mark Rawlins on the 1851 census, I assume the census was taken before her marriage to Nathaniel on the 27th April 1851.) Nathaniel was a stationer (later on the census a bookseller), his father Samuel a brass founder. Elizabeth signed with her mark, apparently unable to write, and a witness was Ann Edwards. Although Sarah Ann, Elizabeth’s sister, would have been Sarah Ann Rawlins at the time, having married the previous year, she was known as Ann on later censuses. The signature of Ann Edwards looks remarkably similar to Sarah Ann Edwards signature on her own wedding. Perhaps she couldn’t write but had learned how to write her signature for her wedding?

Elizabeth Edwards and Nathaniel Twigg marriage 27 April 1851, St Peter and St Paul, Aston, Birmingham:

Sarah Ann and Mark Rawlins had one daughter and four sons between 1852 and 1859. One of the sons, Edward Rawlins 1857-1931, was a school master and later master of an orphanage.

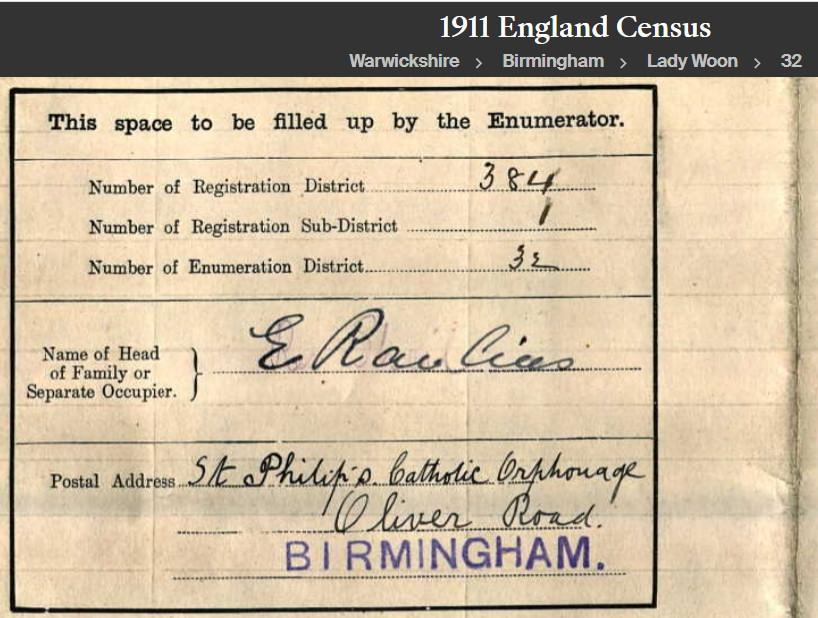

On the 1881 census Edward was a bookseller, in 1891 a stationer, 1901 schoolmaster and his wife Edith was matron, and in 1911 he and Edith were master and matron of St Philip’s Catholic Orphanage on Oliver Road in Birmingham. Edward and Edith did not have any children.

Edward Rawlins, 1911:

Elizabeth and Nathaniel Twigg appear to have had only one son, Arthur Twigg 1862-1943. Arthur was a photographer at 291 Bloomsbury Street, Birmingham. Arthur married Harriet Moseley from Burton on Trent, and they had two daughters, Elizabeth Ann 1897-1954, and Edith 1898-1983. I found a photograph of Edith on her wedding day, with her father Arthur in the picture. Arthur and Harriet also had a son Samuel Arthur, who lived for less than a month, born in 1904. Arthur had mistakenly put this son on the 1911 census stating “less than one month”, but the birth and death of Samuel Arthur Twigg were registered in the same quarter of 1904, and none were found registered for 1911.

Edith Twigg and Leslie A Hancock on their Wedding Day 1925. Arthur Twigg behind the bride. Maybe Elizabeth Ann Twigg seated on the right: (photo found on the ancestry website)

Photographs by Arthur Twigg, 291 Bloomsbury Street, Birmingham:

May 16, 2023 at 6:48 am #7241

May 16, 2023 at 6:48 am #7241In reply to: The Chronicles of the Flying Fish Inn

Finley turned off the vacuum cleaner and cleared her throat loudly. “Mater, I need time off. Next week.”

Mater paled. “Oh Finley, surely not now. With all the guests at the moment … and we are still cleaning up from the dust … ” her voice trailed off.

“Selfish cow,” muttered Idle. She was reclining on the sofa with a magazine and a drink. Taking a well earned rest, she had snapped when Mater asked when she was going to pull her weight. She slapped her magazine down on the coffee table. “I suppose I will have to do everything!”

With just the merest hint of an eye roll, Finley continued. “My cousin Finnley who works for the writer told me about a convention. I’m quite excited.” Mater and Idle regarded her intently, wondering what an excited Finley would look like. I didn’t notice anything much, Mater confessed to Idle later in a rare moment of camaraderie.

“So?” snapped Idle. “What is it then?”

Finley turned on the vacuum cleaner. “Dustsceawaung convention. In Tasmania,” she shouted over the whirr.

February 9, 2023 at 9:50 pm #6520In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Rajkumar had named his car JUMPY because he said it reminded him of his mother country. He drove like they were in the chaotic streets of an Indian city. Youssef’s fist was clenched on the door handle, his knuckles white. He needed to hold on to something just as much as he was afraid of loosing the door.

He had never been so happy as when Rajkumar stopped in front of his cousin’s shop and restaurant.

“Just in time for the best butter chicken in all Alice Springs!” said Rajkumar, pointing to the restaurant on the left.

“Just in time for the best butter chicken in all Alice Springs!” said Rajkumar, pointing to the restaurant on the left.Smells of greasy sauce, meat and spices floated in the air. Despite his legendary hunger, Youssef’s stomach started to protest from the recent treatment on the road. If he had had any doubt, he was sure now that he wouldn’t go on a trip in Jumpy with Rajkumar.

“Maybe I’ll go for the scarf first,” he said.

Rajkumar noded and pointed to the right, to a stout man squating in front of a pile of scarves.

“This is cousin Ashish. You can’t find a better shop in town for scarves,” said Rajkumar. He high fived his cousin who looked like a giant in comparison with the short guide. They talked for a long time in what Youssef assumed to be some Indian dialect. At some point, his guide pointed a finger at him and said : “This big man is looking for a red scarf. I told him you had the best quality in town. Hand made, right from India. Ashish buys and sells the best to the best only. I have to go park the car and tell my other cousin to prepare you a meal. Best Indian food in Alice.”

After he left, cousin Ashish showed Youssef in. At the entrance incense burned at the feet of a couple of colourful Hindu gods. The intoxicating smell reminded him of a stop at a temple during his last trip with the documentary team. The face of Miss Tartiflate jumped into his mind. He would have to take care of THE BLOG at some point, but for now, he was looking for a red scarf. The inside of the shop was as messy as a Mongolian bazaar. Clothes upon clothes, and piles of scarves everywhere.

“Red scarves are over there, said Ashish. Follow me.”

He was less talkative than his cousin, which was a welcome relief. He led Youssef to the back of the shop. On the wall, the portrait in black and white of an old Indian man was watching over their shoulder.

Ashish took one long red scarf and put it around his neck.

“You can touch, he said. Very good quality. Very light. Like you wear nothing.”

Youssef took the end of the fabric in his hand. It felt very silky and light to the touch.

“That’s perfect, I’ll take it”, he said.

His phone buzzed in his pocket. He took it out and checked his messages.

- 📨

[Quirk Land] NEW QUEST OPENED

Looking at the time, it was already noon. Xavier must have landed in Alice already. He started to type a message to his friend :

💬

Meet me for lunch at Todd Mall. Patel indian restaurant next to fabric shopFebruary 9, 2023 at 3:45 pm #6517In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

After Youssef retrieved his luggage in Alice Springs, he was swarmed with freelance tour guides trying to sell him trips. You would buy a ticket out of any one of them just to get rid of the others, he thought. With a few hungry growls, he managed to frighten most of them, with a touch of indifference he lost the rest. Except one. A short Indian looking man wearing a red cap and a moustache. He seemed to have an infinite talkative energy at his disposal, able to erode the strongest wills. The temperature was hotter than Youssef had expected, here it was the end of summer, and he was hungry. The man started to get on his nerves.

The list of tours was endless. Uluru, scenic bushwalking trails, beautiful gardens, a historical tour, a costumed historical tour, a few national parks, and even his cousins’ restaurant. He reminded Youssef of his own father, always offering guests (and especially his visiting kids) another fruit, a pastry, some coffee, chocolate ? You sure you don’t want any chocolate? If the man was tenacious, Youssef had had training with his father. But this man seemed to mistake silence and indifference for agreement. Did he really think Youssef was going to buy one of his tours ?

“The ghost town! You have to see Arltunga, said the man. An old mining ghost town, certainly an American like you like ghost towns. And buried treasure. Arltunga has buried treasure somewhere. You can find it. I know where to find a map.”

Youssef wondered if it was another one of the game’s fluke that his quest was apparently bleeding into his real life again. And if there was a map, why hasn’t the treasure been found already? He checked at the back of his mind for the presence of that crazy old lady. Nope, not there. He decided to refuse the call this time. He just wanted to get to that F…ing Fish Inn in Crowshollow and meet with his friends.

“NO, he growled, frightening a group of tourists passing by, but not the tour operator. No ghost town! We have plenty in America.” Thinking of the game and his last challenge for the previous quest, he said in desperation : “I just want to find a red scarf!” and he knew inside himself and many years attempting to resist his old man, that the short Indian man had won.

“If you want to find a red scarf, you go to Silk Road, said the man bobbing his head. My cousin’s shop, you find everything there only.”

Youssef sighed. He thought there were only two ways to take it. The first one was that he had fallen into a trap and try to find a way to get out of it. But it might be sticky and uncomfortable for everyone. So he decided it was the other way around and that it was part of the game. Why wouldn’t he use this as an opportunity for adventure. Wasn’t that what Xavier always said about roads less traveled ?

“Where is your cousin’s shop? he asked. And where’s that restaurant of your cousin’s? I’m starving.”

The little man smiled broadly.

“Same place. Two brothers. Shop next to restaurant in Todd Mall. You’re lucky! Follow me.”

January 29, 2023 at 9:30 pm #6470In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Put your thoughts to sleep. Do not let them cast a shadow over the moon of your heart. Let go of thinking.

~ RumiTired from not having any sleep, Zara had found the suburb of Camden unattractive and boring, and her cousin Bertie, although cheerful and kind and eager to show her around, had become increasingly irritating to her. She found herself wishing he’d shut up and take her back to the house so she could play the game again. And then felt even more cranky at how uncomfortable she felt about being so ungrateful. She wondered if she was going to get addicted and spent the rest of her life with her head bent over a gadget and never look up at the real word again, like boring people moaned about on social media.

Maybe she should leave tomorrow, even if it meant arriving first at the Flying Fish Inn. But what about the ghost of Isaac in the church, would she regret later not following that up. On the other hand, if she went straight to the Inn and had a few days on her own, she could spend as long as she wanted in the game with nobody pestering her. Zara squirmed mentally when she realized she was translating Berties best efforts at hospitality as pestering.

Bertie stopped the car at a traffic light and was chatting to the passenger in the next car through his open window. Zara picked her phone up and checked her daily Call The Whale app for some inspiration.

Let go of thinking.

A ragged sigh escaped Zara’s lips, causing Bertie to glance over. She adjusted her facial expression quickly and rustled up a cheery smile and Bertie continued his conversation with the occupants of the other car until the lights changed.

“I thought you’d like to meet the folks down at the library, they know all the history of Camden,” Bertie said, but Zara interrupted him.

“Oh Bertie, how kind of you! But I’ve just had a message and I have to leave tomorrow morning for the rendezvous with my friends. There’s been a change of plans.” Zara astonished herself that she blurted that out without thinking it through first. But there. It was said. It was decided.

January 19, 2023 at 10:49 am #6419In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

“I’d advise you not to take the parrot, Zara,” Harry the vet said, “There are restrictions on bringing dogs and other animals into state parks, and you can bet some jobsworth official will insist she stays in a cage at the very least.”

“Yeah, you’re right, I guess I’ll leave her here. I want to call in and see my cousin in Camden on the way to the airport in Sydney anyway. He has dozens of cats, I’d hate for anything to happen to Pretty Girl,” Zara replied.

“Is that the distant cousin you met when you were doing your family tree?” Harry asked, glancing up from the stitches he was removing from a wounded wombat. “There, he’s good to go. Give him a couple more days, then he can be released back where he came from.”

Zara smiled at Harry as she picked up the animal. “Yes! We haven’t met in person yet, and he’s going to show me the church my ancestor built. He says people have been spotting ghosts there lately, and there are rumours that it’s the ghost of the old convict Isaac who built it. If I can’t find photos of the ancestors, maybe I can get photos of their ghosts instead,” Zara said with a laugh.

“Good luck with that,” Harry replied raising an eyebrow. He liked Zara, she was quirkier than the others.

Zara hadn’t found it easy to research her mothers family from Bangalore in India, but her fathers English family had been easy enough. Although Zara had been born in England and emigrated to Australia in her late 20s, many of her ancestors siblings had emigrated over several generations, and Zara had managed to trace several down and made contact with a few of them. Isaac Stokes wasn’t a direct ancestor, he was the brother of her fourth great grandfather but his story had intrigued her. Sentenced to transportation for stealing tools for his work as a stonemason seemed to have worked in his favour. He built beautiful stone buildings in a tiny new town in the 1800s in the charming style of his home town in England.

Zara planned to stay in Camden for a couple of days before meeting the others at the Flying Fish Inn, anticipating a pleasant visit before the crazy adventure started.

Zara stepped down from the bus, squinting in the bright sunlight and looking around for her newfound cousin Bertie. A lanky middle aged man in dungarees and a red baseball cap came forward with his hand extended.

“Welcome to Camden, Zara I presume! Great to meet you!” he said shaking her hand and taking her rucksack. Zara was taken aback to see the family resemblance to her grandfather. So many scattered generations and yet there was still a thread of familiarity. “I bet you’re hungry, let’s go and get some tucker at Belle’s Cafe, and then I bet you want to see the church first, hey? Whoa, where’d that dang parrot come from?” Bertie said, ducking quickly as the bird swooped right in between them.

“Oh no, it’s Pretty Girl!” exclaimed Zara. “She wasn’t supposed to come with me, I didn’t bring her! How on earth did you fly all this way to get here the same time as me?” she asked the parrot.

“Pretty Girl has her ways, don’t forget to feed the parrot,” the bird replied with a squalk that resembled a mirthful guffaw.

“That’s one strange parrot you got here, girl!” Bertie said in astonishment.

“Well, seeing as you’re here now, Pretty Girl, you better come with us,” Zara said.

“Obviously,” replied Pretty Girl. It was hard to say for sure, but Zara was sure she detected an avian eye roll.

They sat outside under a sunshade to eat rather than cause any upset inside the cafe. Zara fancied an omelette but Pretty Girl objected, so she ordered hash browns instead and a fruit salad for the parrot. Bertie was a good sport about the strange talking bird after his initial surprise.

Bertie told her a bit about the ghost sightings, which had only started quite recently. They started when I started researching him, Zara thought to herself, almost as if he was reaching out. Her imagination was running riot already.

Bertie showed Zara around the church, a small building made of sandstone, but no ghost appeared in the bright heat of the afternoon. He took her on a little tour of Camden, once a tiny outpost but now a suburb of the city, pointing out all the original buildings, in particular the ones that Isaac had built. The church was walking distance of Bertie’s house and Zara decided to slip out and stroll over there after everyone had gone to bed.

Bertie had kindly allowed Pretty Girl to stay in the guest bedroom with her, safe from the cats, and Zara intended that the parrot stay in the room, but Pretty Girl was having none of it and insisted on joining her.

“Alright then, but no talking! I don’t want you scaring any ghost away so just keep a low profile!”

The moon was nearly full and it was a pleasant walk to the church. Pretty Girl fluttered from tree to tree along the sidewalk quietly. Enchanting aromas of exotic scented flowers wafted into her nostrils and Zara felt warmly relaxed and optimistic.

Zara was disappointed to find that the church was locked for the night, and realized with a sigh that she should have expected this to be the case. She wandered around the outside, trying to peer in the windows but there was nothing to be seen as the glass reflected the street lights. These things are not done in a hurry, she reminded herself, be patient.

Sitting under a tree on the grassy lawn attempting to open her mind to receiving ghostly communications (she wasn’t quite sure how to do that on purpose, any ghosts she’d seen previously had always been accidental and unexpected) Pretty Girl landed on her shoulder rather clumsily, pressing something hard and chill against her cheek.

“I told you to keep a low profile!” Zara hissed, as the parrot dropped the key into her lap. “Oh! is this the key to the church door?”

It was hard to see in the dim light but Zara was sure the parrot nodded, and was that another avian eye roll?

Zara walked slowly over the grass to the church door, tingling with anticipation. Pretty Girl hopped along the ground behind her. She turned the key in the lock and slowly pushed open the heavy door and walked inside and up the central aisle, looking around. And then she saw him.

Zara gasped. For a breif moment as the spectral wisps cleared, he looked almost solid. And she could see his tattoos.

“Oh my god,” she whispered, “It is really you. I recognize those tattoos from the description in the criminal registers. Some of them anyway, it seems you have a few more tats since you were transported.”

“Aye, I did that, wench. I were allays fond o’ me tats, does tha like ’em?”

He actually spoke to me! This was beyond Zara’s wildest hopes. Quick, ask him some questions!

“If you don’t mind me asking, Isaac, why did you lie about who your father was on your marriage register? I almost thought it wasn’t you, you know, that I had the wrong Isaac Stokes.”

A deafening rumbling laugh filled the building with echoes and the apparition dispersed in a labyrinthine swirl of tattood wisps.

“A story for another day,” whispered Zara, “Time to go back to Berties. Come on Pretty Girl. And put that key back where you found it.”

November 18, 2022 at 4:47 pm #6348

November 18, 2022 at 4:47 pm #6348In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

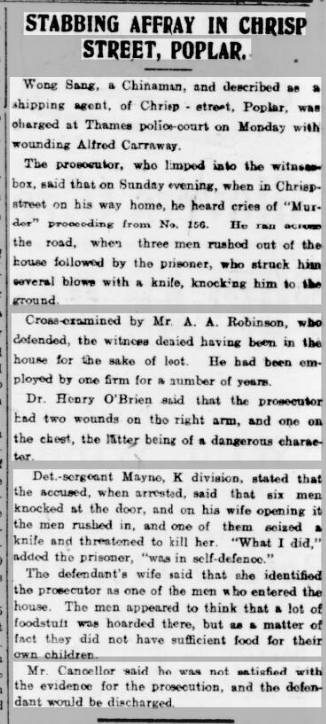

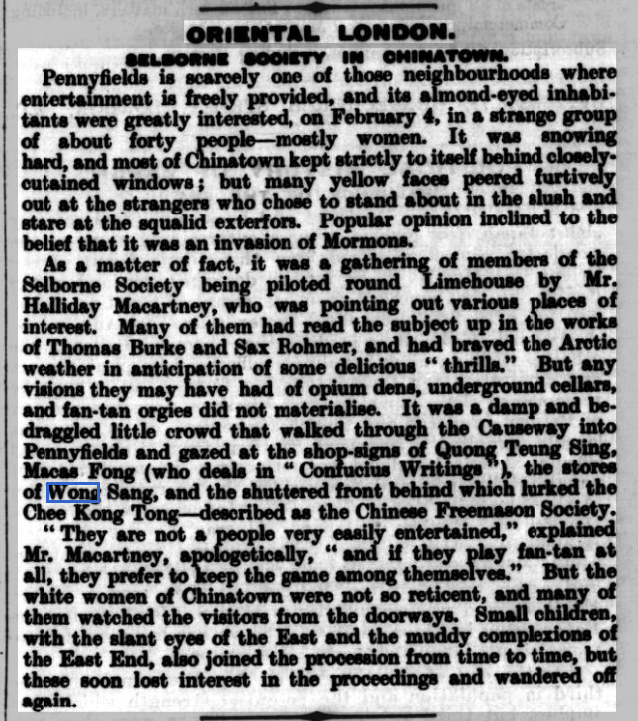

Wong Sang

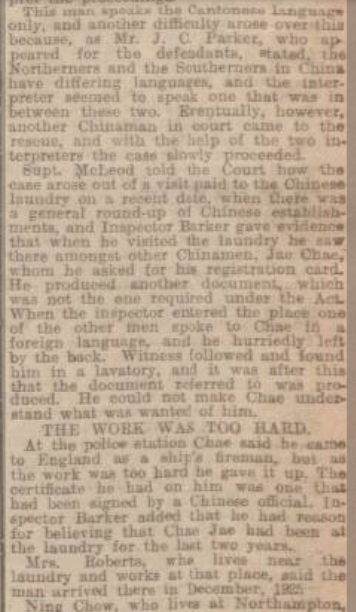

Wong Sang was born in China in 1884. In October 1916 he married Alice Stokes in Oxford.

Alice was the granddaughter of William Stokes of Churchill, Oxfordshire and William was the brother of Thomas Stokes the wheelwright (who was my 3X great grandfather). In other words Alice was my second cousin, three times removed, on my fathers paternal side.

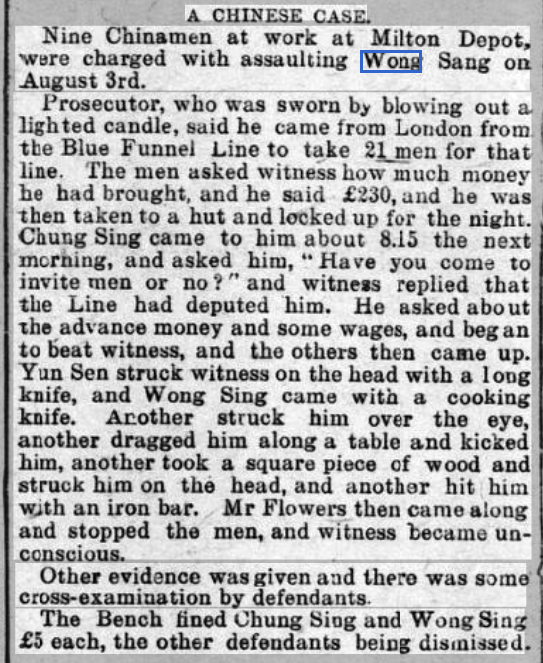

Wong Sang was an interpreter, according to the baptism registers of his children and the Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital admission registers in 1930. The hospital register also notes that he was employed by the Blue Funnel Line, and that his address was 11, Limehouse Causeway, E 14. (London)

“The Blue Funnel Line offered regular First-Class Passenger and Cargo Services From the UK to South Africa, Malaya, China, Japan, Australia, Java, and America. Blue Funnel Line was Owned and Operated by Alfred Holt & Co., Liverpool.

The Blue Funnel Line, so-called because its ships have a blue funnel with a black top, is more appropriately known as the Ocean Steamship Company.”Wong Sang and Alice’s daughter, Frances Eileen Sang, was born on the 14th July, 1916 and baptised in 1920 at St Stephen in Poplar, Tower Hamlets, London. The birth date is noted in the 1920 baptism register and would predate their marriage by a few months, although on the death register in 1921 her age at death is four years old and her year of birth is recorded as 1917.

Charles Ronald Sang was baptised on the same day in May 1920, but his birth is recorded as April of that year. The family were living on Morant Street, Poplar.

James William Sang’s birth is recorded on the 1939 census and on the death register in 2000 as being the 8th March 1913. This definitely would predate the 1916 marriage in Oxford.

William Norman Sang was born on the 17th October 1922 in Poplar.

Alice and the three sons were living at 11, Limehouse Causeway on the 1939 census, the same address that Wong Sang was living at when he was admitted to Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital on the 15th January 1930. Wong Sang died in the hospital on the 8th March of that year at the age of 46.

Alice married John Patterson in 1933 in Stepney. John was living with Alice and her three sons on Limehouse Causeway on the 1939 census and his occupation was chef.

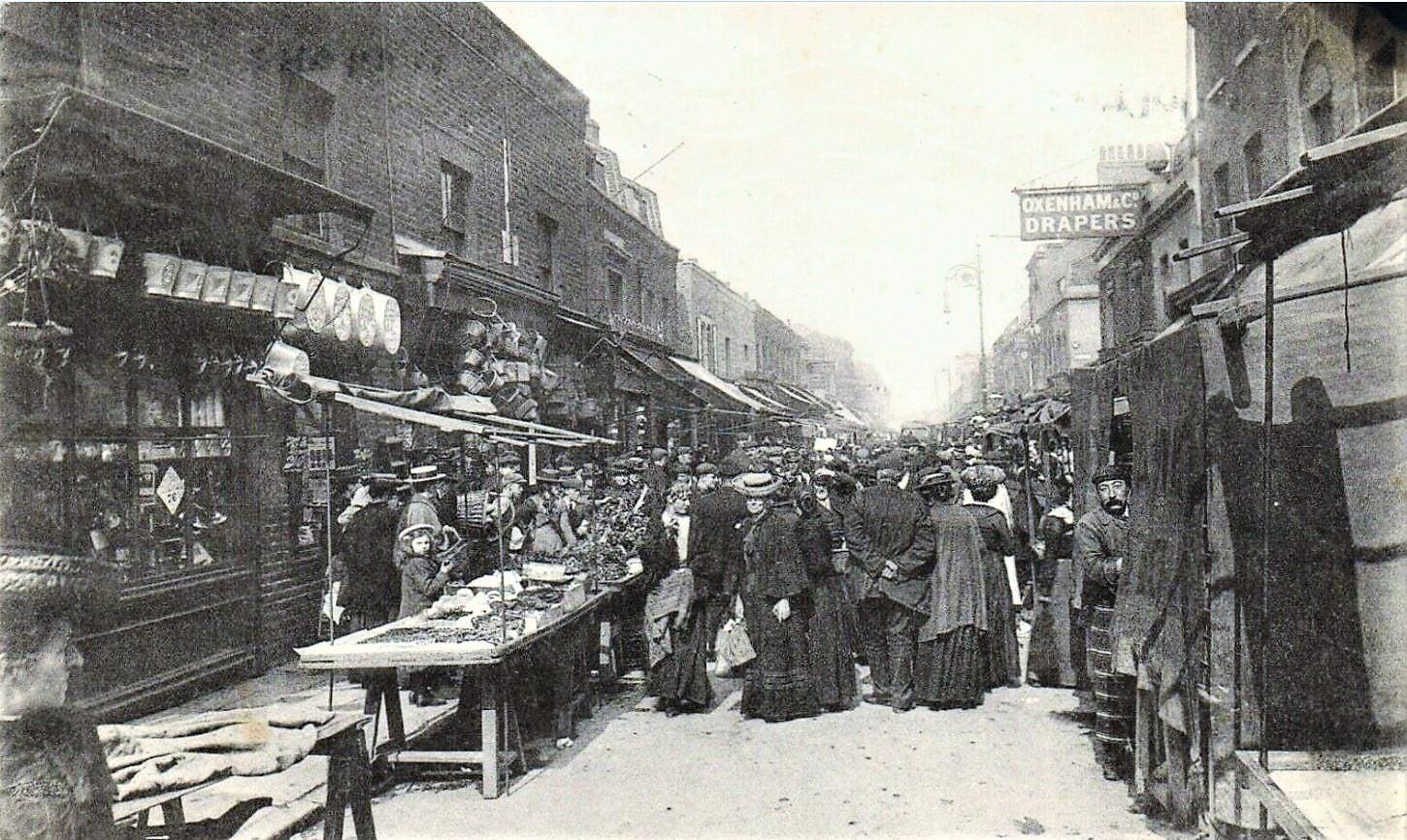

Via Old London Photographs:

“Limehouse Causeway is a street in east London that was the home to the original Chinatown of London. A combination of bomb damage during the Second World War and later redevelopment means that almost nothing is left of the original buildings of the street.”

Limehouse Causeway in 1925:

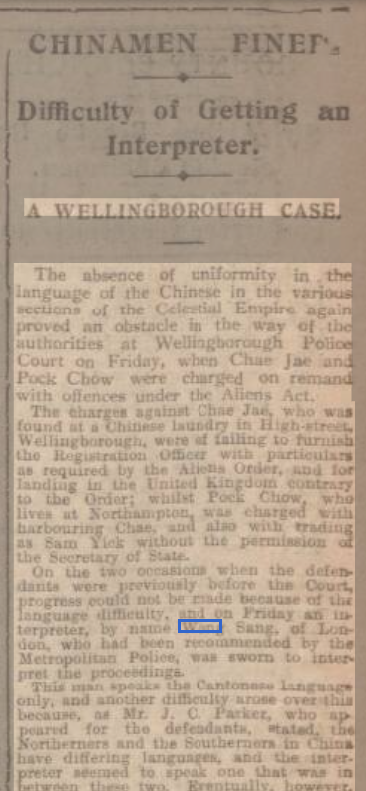

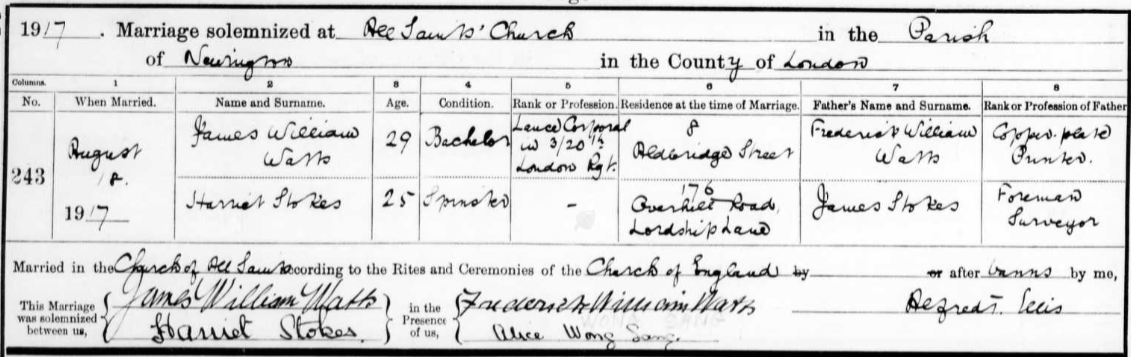

From The Story of Limehouse’s Lost Chinatown, poplarlondon website: