Search Results for 'expect'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

February 1, 2023 at 11:23 am #6485

In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

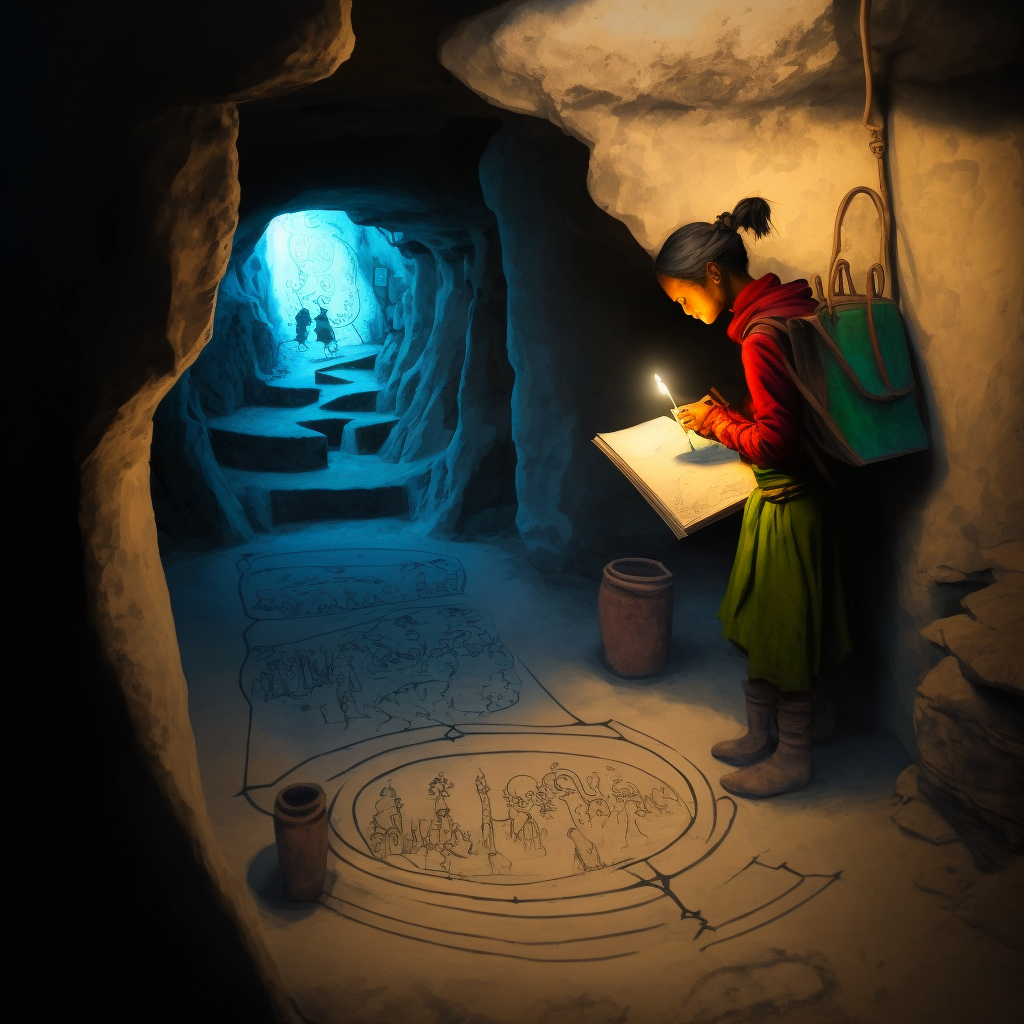

The two figures disappeared from view and Zara continued towards the light. An alcove to her right revealed a grotesque frog like creature with a pile of bones and gruesome looking objects. Zara hurried past.

Bugger, I bet that was Osnas, Zara realized. But she wasn’t going to go back now. It seemed there was only one way to go, towards the light. Although in real life she was sitting on a brightly lit aeroplane with the stewards bustling about with the drinks and snacks cart, she could feel the chill of the tunnels and the uneasy thrill of secrets and danger.

“Tea? Coffee? Soft drink?” smiled the hostess with the blue uniform, leaning over her cart towards Zara.

“Coffee please,” she replied, glancing up with a smile, and then her smile froze as she noticed the frog like features of the woman. “And a packet of secret tiles please,” she added with a giggle.

“Sorry, did you say nuts?”

“Yeah, nuts. Thank you, peanuts will be fine, cheers.”

Sipping coffee in between handfulls of peanuts, Zara returned to the game.

As Zara continued along the tunnels following the light, she noticed the drawings on the floor. She stopped to take a photo, as the two figures continued ahead of her.

I don’t know how I’m supposed to work out what any of this means, though. Just keep going I guess. Zara wished that Pretty Girl was with her. This was the first time she’d played without her.

The walls and floors had many drawings, symbols and diagrams, and Zara stopped to take photos of all of them as she slowly made her way along the tunnel.

Zara meanwhile make screenshots of them all as well. The frisson of fear had given way to curiosity, now that the tunnel was more brightly lit, and there were intriguing things to notice. She was no closer to working out what they meant, but she was enjoying it now and happy to just explore.

But who had etched all these pictures into the rock? You’d expect to see cave paintings in a cave, but in an old mine? How old was the mine? she wondered. The game had been scanty with any kind of factual information about the mine, and it could have been a bronze age mine, a Roman mine, or just a gold rush mine from not so very long ago. She assumed it wasn’t a coal mine, which she deduced from the absence of any coal, and mentally heard her friend Yasmin snort with laughter at her train of thought. She reminded herself that it was just a game and not an archaeology dig, after all, and to just keep exploring. And that Yasmin wasn’t reading her mind and snorting at her thoughts.

January 31, 2023 at 9:12 pm #6481In reply to: The Jorid’s Logs – 14 years on and more

This is the outline for a short novel called “The Jorid’s Travels – 14 years on” that will unfold in this thread.

The novel is about the travels of Georges and Salomé.

The Jorid is the name of the vessel that can travel through dimensions as well as time, within certain boundaries. The Jorid has been built and is operated by Georges and his companion Salomé.Short backstory for the main cast and secondary characters

Georges was a French thief possibly from the 1800s, turned other-dimensional explorer, and together with Salomé, a girl of mysterious origins who he first met in the Alienor dimension but believed to have origins in Northern India maybe Tibet from a distant past.

They have lived rich adventures together, and are deeply bound together, by love and mutual interests.

Georges, with his handsome face, dark hair and amber gaze, is a bit of a daredevil at times, curious and engaging with others. He is very interesting in anything that shines, strange mechanisms and generally the ways consciousness works in living matter.

Salomé, on the other hand is deeply intuitive, empath at times, quite logical and rational but also interested in mysticism, the ways of the Truth, and the “why” rather than the “how” of things.

The world of Alienor (a pale green sun under which twin planets originally orbited – Duane, Murtuane – with an additional third, Phreal, home planet of the Guardians, an alien race of builders with god-like powers) lived through cataclysmic changes, finished by the time this story is told.

The Jorid’s original prototype designed were crafted by Léonard, a mysterious figure, self-taught in the arts of dimensional magic in Alienor sects, acted as a mentor to Georges during his adventures. It is not known where he is now.

The story starts with Georges and Salomé looking for Léonard to adjust and calibrate the tiles navigational array of the Jorid, who seems to be affected by the auto-generated tiles which behave in too predictible fashion, instead of allowing for deeper explorations in the dimensions of space/time or dimensions of consciousness.

Leonard was last spotted in a desert in quadrant AVB 34-7•8 – Cosmic time triangulation congruent to 2023 AD Earth era. More precisely the sand deserts of Bluhm’Oxl in the Zathu sector.When they find Léonard, they are propelled in new adventures. They possibly encounter new companions, and some mystery to solve in a similar fashion to the Odyssey, or Robinsons Lost in Space.

Being able to tune into the probable quantum realities, the Jorid is able to trace the plot of their adventures even before they’ve been starting to unfold in no less than 33 chapters, giving them evocative titles.

Here are the 33 chapters for the glorious adventures with some keywords under each to give some hints to the daring adventurers.

- Chapter 1: The Search Begins – Georges and Salomé, Léonard, Zathu sector, Bluhm’Oxl, dimensional magic

- Chapter 2: A New Companion – unexpected ally, discovery, adventure

- Chapter 3: Into the Desert – Bluhm’Oxl, sand dunes, treacherous journey

- Chapter 4: The First Clue – search for Léonard, mystery, puzzle

- Chapter 5: The Oasis – rest, rekindling hope, unexpected danger

- Chapter 6: The Lost City – ancient civilization, artifacts, mystery

- Chapter 7: A Dangerous Encounter – hostile aliens, survival, bravery

- Chapter 8: A New Threat – ancient curse, ominous presence, danger

- Chapter 9: The Key to the Past – uncovering secrets, solving puzzles, unlocking power

- Chapter 10: The Guardian’s Temple – mystical portal, discovery, knowledge

- Chapter 11: The Celestial Map – space-time navigation, discovery, enlightenment

- Chapter 12: The First Step – journey through dimensions, bravery, adventure

- Chapter 13: The Cosmic Rift – strange anomalies, dangerous zones, exploration

- Chapter 14: A Surprising Discovery – unexpected allies, strange creatures, intrigue

- Chapter 15: The Memory Stones – ancient wisdom, unlock hidden knowledge, unlock the past

- Chapter 16: The Time Stream – navigating through time, adventure, danger

- Chapter 17: The Mirror Dimension – parallel world, alternate reality, discovery

- Chapter 18: A Distant Planet – alien world, strange cultures, exploration

- Chapter 19: The Starlight Forest – enchanted forest, secrets, danger

- Chapter 20: The Temple of the Mind – exploring consciousness, inner journey, enlightenment

- Chapter 21: The Sea of Souls – mystical ocean, hidden knowledge, inner peace

- Chapter 22: The Path of the Truth – search for meaning, self-discovery, enlightenment

- Chapter 23: The Cosmic Library – ancient knowledge, discovery, enlightenment

- Chapter 24: The Dream Plane – exploring the subconscious, self-discovery, enlightenment

- Chapter 25: The Shadow Realm – dark dimensions, fear, danger

- Chapter 26: The Fire Planet – intense heat, dangerous creatures, bravery

- Chapter 27: The Floating Islands – aerial adventure, strange creatures, discovery

- Chapter 28: The Crystal Caves – glittering beauty, hidden secrets, danger

- Chapter 29: The Eternal Night – unknown world, strange creatures, fear

- Chapter 30: The Lost Civilization – ancient ruins, mystery, adventure

- Chapter 31: The Vortex – intense energy, danger, bravery

- Chapter 32: The Cosmic Storm – weather extremes, danger, survival

- Chapter 33: The Return – reunion with Léonard, returning to the Jorid, new adventures.

January 30, 2023 at 8:43 pm #6472In reply to: The Jorid’s Travels – 14 years on

Salomé: Using the new trans-dimensional array, Jorid, plot course to a new other-dimensional exploration

Georges (comments): “New realms of consciousness, extravagant creatures expected, dragons least of them!” He winked “May that be a warning for whoever wants to follow in our steps”.

The Jorid: Ready for departure.

Salomé: Plot coordinates quadrant AVB 34-7•8 – Cosmic time triangulation congruent to 2023 AD Earth era. Quantum drive engaged.

Jorid: Departure initiated. Entering interdimensional space. Standby for quantum leap.

Salomé (sighing): Please analyse subspace signatures, evidences of life forms in the quadrant.

Jorid: Scanning subspace signatures. Detecting multiple life forms in the AVB 34-7•8 quadrant. Further analysis required to determine intelligence and potential danger.

Salomé: Jorid, engage human interaction mode, with conversational capabilities and extrapolate please!

Jorid: Engaging human interaction mode. Ready for conversation. What would you like to know or discuss?

Georges: We currently have amassed quite a number of tiles. How many Salomé?

Salomé: Let me check. I think about 47 of them last I count. I didn’t insert the auto-generated ones, they were of lesser quality and seemed to interfere with the navigational array landing us always in expected places already travelled.

Salomé: Let me check. I think about 47 of them last I count. I didn’t insert the auto-generated ones, they were of lesser quality and seemed to interfere with the navigational array landing us always in expected places already travelled.Georges: Léonard has been missing for 4 months.

Salomé: you mean by our count, right?

Georges: Right. We need to find him to readjust or correct the navigational array. Jorid, give us statistical probabilities that we can use as clues to his current potential locations.

Jorid: Calculating statistical probabilities for Léonard’s location. It would be helpful to have more information, such as known destinations or areas of interest, to increase accuracy of probabilities.

Salomé: Jorid is in a lazy mood it seems. I preferred her more chatty.

Georges: You mean “him”, surely dear?

Salomé: (rolls eyes)

Georges: Anyway, Léonard seemed interested in archaeological finds in recent excavated tombs near the sand deserts of Bluhm’Oxl in the Zathu sector.

Jorid: Analyzing data on archaeological finds near the sand deserts of Bluhm’Oxl in the Zathu sector. Probability of Léonard being in the area is calculated at 43%. Shall I plot a course to Bluhm’Oxl for further investigation?

Jorid: Analyzing data on archaeological finds near the sand deserts of Bluhm’Oxl in the Zathu sector. Probability of Léonard being in the area is calculated at 43%. Shall I plot a course to Bluhm’Oxl for further investigation?Salomé (loosing patience): Please engage your quantum capacities to access more data. We built you to be a bit more helpful than a bloody computer.

Georges laughed: I remembered you had more patience, dear!

Salomé: She’s in a mood today, isn’t she. What did you do to her?

Georges (cunningly): Jorid, sweet thing, please provide more details about the area, the populations, the customs the whole gamut dammit, and potential territorial conflicts in the vicinity. And be more chatty to please Salomé.

Jorid: Of course, I apologize for my previous responses. Analyzing data on the sand deserts of Bluhm’Oxl in the Zathu sector, including information on populations, customs, territorial conflicts and other relevant details. The area is known for its rich history and cultural heritage, with several ancient tombs and ruins attracting archaeological interest. The main population is composed of the Zathu nomads, known for their hospitality and trading skills. There are no known territorial conflicts in the area, but it is advised to exercise caution while traveling as the deserts can be treacherous.

Georges (laughs): You can’t stop her know!

Salomé (smiles noticing the “her”): Well, that doesn’t tell too much, does it. How shall we proceed? Need to synthetise some local clothes, or are you back to your thieving habits (pun intended)?

Georges: Haha, always ready for a good adventure. It seems we’ll have to do some research on the ground. As for the clothes, I’ll leave that to you my dear. Your sense of style never fails to impress. Let’s make sure to blend in with the locals and avoid drawing any unnecessary attention. The goal is to find Léonard, not get into trouble.

January 23, 2023 at 8:15 am #6449In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Have you booked your flight yet? Zara sent a message to Yasmin. I’m spending a few more days in Camden, probably be at the Flying Fish Inn by the end of the week.

I told you already when my flight is, Air Fiji, remeber? bloody Sister Finnlie on my case all the time, haven’t had a minute. Zara had to wait over an hour for Yamsin’s reply.

I told you already when my flight is, Air Fiji, remeber? bloody Sister Finnlie on my case all the time, haven’t had a minute. Zara had to wait over an hour for Yamsin’s reply.Took you long enough to reply. Zara replied promptly. Heard nothing from Youssef for ages either, have you heard from him? I’ll be arriving there on my own at this rate.

Not a word, I expect Xavier’s booked his but he hasn’t said. Probably doing his secret monkey thing.

Not a word, I expect Xavier’s booked his but he hasn’t said. Probably doing his secret monkey thing.Have you tried the free roaming thing on the game yet?

I just told you Sister Finnlie hasn’t given me a minute to myself, she’s a right tart! Why, have you?

I just told you Sister Finnlie hasn’t given me a minute to myself, she’s a right tart! Why, have you?Yeah it’s amazing, been checking out the Flying Fish Inn. Looks a bit of a dump. Not much to do around there, well not from what I can see anyway. But you know what?

What?

What?You’ll lose your eyes in the back of your head one day and look like that AI avatart with the wall eye. Get this though: we haven’t started the game yet, that quest for quirks thing, I was just having a roman around ha ha typo having a roam around see what’s there and stuff I don’t know anything about online games like you lot and I ended up here. Zara sent a screenshot of the image she’d seen and added: Did I already start the game or what, I don’t even know how we actually start the game, I was just wandering around….oh…and happened to chance upon this…

How rude to start playing before us

How rude to start playing before usI didn’t start playing the game before you, I just told you, I was wandering around playing about waiting for you lot! Zara thought Yasmin sounded like she needed a holiday.

Yeah well that was your quest, wasn’t it? To wander around or something? What’s that silver chest on her back?

Yeah well that was your quest, wasn’t it? To wander around or something? What’s that silver chest on her back?I dunno but looks intriguing eh maybe she’s hidden all her devices and techy gadgets in an antiquey looking box so she doesn’t blow her cover

Gotta go Sister Finnlie’s coming

Zara muttered how rude under her breath and put her phone down. She’d retired to her bedroom early, telling Bertie that she needed an early night but really had wanted some time alone to explore the new game world. She didn’t want to make mistakes and look daft to her friends when the game started.

“Too late for that”, Pretty Girl said.

“SSHHH!” Zara hissed at the parrot. “And stop reading my mind, it’s disconcerting, not to mention rude.”

She heard the sound of the lavatory flush and Berties bedroom door closing and looked at the time. 23:36.

Zara decided to give him an hour to make sure he was asleep and then sneak out and go back to that church.

January 19, 2023 at 10:49 am #6419In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

“I’d advise you not to take the parrot, Zara,” Harry the vet said, “There are restrictions on bringing dogs and other animals into state parks, and you can bet some jobsworth official will insist she stays in a cage at the very least.”

“Yeah, you’re right, I guess I’ll leave her here. I want to call in and see my cousin in Camden on the way to the airport in Sydney anyway. He has dozens of cats, I’d hate for anything to happen to Pretty Girl,” Zara replied.

“Is that the distant cousin you met when you were doing your family tree?” Harry asked, glancing up from the stitches he was removing from a wounded wombat. “There, he’s good to go. Give him a couple more days, then he can be released back where he came from.”

Zara smiled at Harry as she picked up the animal. “Yes! We haven’t met in person yet, and he’s going to show me the church my ancestor built. He says people have been spotting ghosts there lately, and there are rumours that it’s the ghost of the old convict Isaac who built it. If I can’t find photos of the ancestors, maybe I can get photos of their ghosts instead,” Zara said with a laugh.

“Good luck with that,” Harry replied raising an eyebrow. He liked Zara, she was quirkier than the others.

Zara hadn’t found it easy to research her mothers family from Bangalore in India, but her fathers English family had been easy enough. Although Zara had been born in England and emigrated to Australia in her late 20s, many of her ancestors siblings had emigrated over several generations, and Zara had managed to trace several down and made contact with a few of them. Isaac Stokes wasn’t a direct ancestor, he was the brother of her fourth great grandfather but his story had intrigued her. Sentenced to transportation for stealing tools for his work as a stonemason seemed to have worked in his favour. He built beautiful stone buildings in a tiny new town in the 1800s in the charming style of his home town in England.

Zara planned to stay in Camden for a couple of days before meeting the others at the Flying Fish Inn, anticipating a pleasant visit before the crazy adventure started.

Zara stepped down from the bus, squinting in the bright sunlight and looking around for her newfound cousin Bertie. A lanky middle aged man in dungarees and a red baseball cap came forward with his hand extended.

“Welcome to Camden, Zara I presume! Great to meet you!” he said shaking her hand and taking her rucksack. Zara was taken aback to see the family resemblance to her grandfather. So many scattered generations and yet there was still a thread of familiarity. “I bet you’re hungry, let’s go and get some tucker at Belle’s Cafe, and then I bet you want to see the church first, hey? Whoa, where’d that dang parrot come from?” Bertie said, ducking quickly as the bird swooped right in between them.

“Oh no, it’s Pretty Girl!” exclaimed Zara. “She wasn’t supposed to come with me, I didn’t bring her! How on earth did you fly all this way to get here the same time as me?” she asked the parrot.

“Pretty Girl has her ways, don’t forget to feed the parrot,” the bird replied with a squalk that resembled a mirthful guffaw.

“That’s one strange parrot you got here, girl!” Bertie said in astonishment.

“Well, seeing as you’re here now, Pretty Girl, you better come with us,” Zara said.

“Obviously,” replied Pretty Girl. It was hard to say for sure, but Zara was sure she detected an avian eye roll.

They sat outside under a sunshade to eat rather than cause any upset inside the cafe. Zara fancied an omelette but Pretty Girl objected, so she ordered hash browns instead and a fruit salad for the parrot. Bertie was a good sport about the strange talking bird after his initial surprise.

Bertie told her a bit about the ghost sightings, which had only started quite recently. They started when I started researching him, Zara thought to herself, almost as if he was reaching out. Her imagination was running riot already.

Bertie showed Zara around the church, a small building made of sandstone, but no ghost appeared in the bright heat of the afternoon. He took her on a little tour of Camden, once a tiny outpost but now a suburb of the city, pointing out all the original buildings, in particular the ones that Isaac had built. The church was walking distance of Bertie’s house and Zara decided to slip out and stroll over there after everyone had gone to bed.

Bertie had kindly allowed Pretty Girl to stay in the guest bedroom with her, safe from the cats, and Zara intended that the parrot stay in the room, but Pretty Girl was having none of it and insisted on joining her.

“Alright then, but no talking! I don’t want you scaring any ghost away so just keep a low profile!”

The moon was nearly full and it was a pleasant walk to the church. Pretty Girl fluttered from tree to tree along the sidewalk quietly. Enchanting aromas of exotic scented flowers wafted into her nostrils and Zara felt warmly relaxed and optimistic.

Zara was disappointed to find that the church was locked for the night, and realized with a sigh that she should have expected this to be the case. She wandered around the outside, trying to peer in the windows but there was nothing to be seen as the glass reflected the street lights. These things are not done in a hurry, she reminded herself, be patient.

Sitting under a tree on the grassy lawn attempting to open her mind to receiving ghostly communications (she wasn’t quite sure how to do that on purpose, any ghosts she’d seen previously had always been accidental and unexpected) Pretty Girl landed on her shoulder rather clumsily, pressing something hard and chill against her cheek.

“I told you to keep a low profile!” Zara hissed, as the parrot dropped the key into her lap. “Oh! is this the key to the church door?”

It was hard to see in the dim light but Zara was sure the parrot nodded, and was that another avian eye roll?

Zara walked slowly over the grass to the church door, tingling with anticipation. Pretty Girl hopped along the ground behind her. She turned the key in the lock and slowly pushed open the heavy door and walked inside and up the central aisle, looking around. And then she saw him.

Zara gasped. For a breif moment as the spectral wisps cleared, he looked almost solid. And she could see his tattoos.

“Oh my god,” she whispered, “It is really you. I recognize those tattoos from the description in the criminal registers. Some of them anyway, it seems you have a few more tats since you were transported.”

“Aye, I did that, wench. I were allays fond o’ me tats, does tha like ’em?”

He actually spoke to me! This was beyond Zara’s wildest hopes. Quick, ask him some questions!

“If you don’t mind me asking, Isaac, why did you lie about who your father was on your marriage register? I almost thought it wasn’t you, you know, that I had the wrong Isaac Stokes.”

A deafening rumbling laugh filled the building with echoes and the apparition dispersed in a labyrinthine swirl of tattood wisps.

“A story for another day,” whispered Zara, “Time to go back to Berties. Come on Pretty Girl. And put that key back where you found it.”

January 19, 2023 at 9:38 am #6416

January 19, 2023 at 9:38 am #6416In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

The team had to stop when a sandstorm hit them in the middle of the desert. They only had an hour drive left to reach the oasis where Lama Yoneze had been seen last and Miss Tartiflate insisted, like she always did, against the guides advice that they kept on going. She feared the last shaman would be lost in the storm, maybe croak stuffed with that damn dust. But when they lost the satellite dish and a jeep almost rolled down a sand dune, she finally listened to the guides. They had them park the cars close to each other, then checked the straps and urged everyone to stay in their cars until the storm was over.

Youssef at first thought he was lucky. He managed to get into the same car as Tiff, the young intern he had discussed with the other day. But despite all their precautions, they couldn’t stop the dust to come in. It was everywhere and you had to kept your mouth and eyes shut if you didn’t want to grind your teeth with fine sand. So instead he enjoyed this unexpected respite from his trying to save THE BLOG from the evil Thi Gang, and from Miss Tartiflate’s continuous flow of criticism.

The storm blew off the dish just after Xavier had sent him AL’s answer to the strange glyphs he had received on his phone. When Youssef read the message, he sighed. He had forgotten hope was an illusion. AL was in its infancy and was not a dead language expert. He gave them something fitting Youssef’s current location and the questions about famous alien dishes they asked him last week. It was just an old pot luck recipe from when the Silk Road was passing through the Gobi desert. He just hoped Xavier would have some luck until Youssef found a way to restore the connexion.

January 17, 2023 at 5:55 pm #6409

January 17, 2023 at 5:55 pm #6409In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

“What the…..!” Youssef exclaimed, almost throwing his phone to the ground for a second time that morning. As if he wasn’t having enough trouble already without his phone sending him these messages. But then an idea occurred to him, and he had another look at it.

“Ah, now I see! Glimmer has intercepted the message from Gang Thi!” Youssef smiled for the first time that day. He still couldn’t decipher the strange script though, and wondered if it had been a mistake to not include her on the trip in the first place. He had thought her to be foolish and gaudy and not much practical use, but now he wasn’t so sure. He certainly hadn’t expected her to show up so soon, and in such an unexpected way.

January 17, 2023 at 9:43 am #6396

January 17, 2023 at 9:43 am #6396In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Youssef woke up with a hangover. The guy from the restaurant had put fermented horse milk in his yak butter tea and he was already drunk before he could realize it. Apparently it had been a joke played on him by some of the team members he suspected didn’t quite like the humour of his real life shirt collection. Especially the one with the man shouting at his newspaper on his toilets.

As soon as he had gotten out of the yurt, before he could go have some breakfast, his boss, Miss Tartiflate, pounced on him because there was something wrong with THE BLOG. And Youssef was the one in charge of it. And it was important because people in the world were expecting her posts about the shooting everyday. Truth is, since they couldn’t find the last Mongolian shaman, who apparently called himself Lama Yoneze, and the views had dropped dramatically. Youssef suspected Miss Tartiflate was not as ignorante as she wanted him to believe and had broken the blog on purpose so that her own boss wouldn’t accuse her of being lazy.“I have a reputation, you know!”

She had said that looking like he didn’t have one, and nobody cared anyway.

Youssef looked at the clock on his phone. They were supposed to meet with Zara, Xavier and Yasmine in thirty minutes. He had tried to sort out THE BLOG problem, but nothing seemed to work, and time was running out. Despite all being ok on the admin console, nothing was showing up on the page. He had called Gang Thi, the Nepalese company in charge of the blog, three times. Each time the receptionist hang up on him while attempting to put him on hold, or so she said. Now, nobody even bother to answer the damn phone.

Miss Tartiflate passed her head between the curtains of the yurt.

“Are you finished yet ?” she asked that as if he was on the throne.

“Nope!”

“What!? How? Do you have sausage fingers? My 5 years old daughter is more nimble than you with computers.”

“Well, you should have brought her with us then,” said Youssef with an irritated smile, fed up by her constant useless interruptions.

She grunted and closed the curtains angrily. Youssef growled like a bear, showing his bare teeth. Everybody knew why she jumped on the occasion for this trip: needed some fresh air from her nimble daughter and her husband.

An alert showed up on his phone : “You’ve got a message from 💣Gang Thi💣”. The bomb in the title looked suspicious, and his stomach growled, reminding him he hadn’t eaten this morning. He clicked to open it.

The face of a mummy looking like Darth Vader and laughing like the Joker jumped on his screen. After a few seconds a message started to appear in a tongue he couldn’t decipher.

Youssef looked at the clock and almost threw his phone on the ground as the mummy started to laugh again.

He would definitely have to miss the meeting with his friends.January 17, 2023 at 8:17 am #6393In reply to: Train your subjective AI – text version

Give me an unusual plot structure for a narrative

One unusual plot structure for a narrative could be a “reverse chronological” structure, where the story begins at the end and works backwards in time, revealing events and information in a non-linear way. Another could be a “choose your own adventure” style, where the reader is presented with a series of choices at different points in the story that determine the direction and outcome of the plot.

How would role playing qualify in terms of plot structure?

Role-playing games (RPGs) can be considered a unique form of plot structure because they are interactive and open-ended. In a traditional RPG, the players take on the roles of characters within a fictional setting and work together to create a shared narrative. The plot structure of an RPG is determined by the actions and decisions of the players, rather than a pre-written script. The game master (GM) creates an overarching plot and a set of rules for the players to follow, but the players’ choices and actions will determine the direction and outcome of the story. This makes the plot structure of an RPG fluid and ever-changing, unlike a traditional linear narrative.

What about “Cloud Atlas” in terms of plot structure?

“Cloud Atlas” is a novel written by David Mitchell that was later adapted into a film. It has a complex and non-linear plot structure, which employs multiple storylines that are set in different time periods and locations, and are connected by recurring themes and motifs. The novel is divided into six nested stories, each set in a different time period and location, that are told in a non-linear fashion. The story begins in the 19th century and then jumps back and forth between the 19th, 20th and 23rd century, and each story is interconnected and interrelated, with characters reappearing in different time periods, the events that happen in one story impacting the others. The novel is also notable for its use of different genres, such as science fiction, historical fiction, and thriller, and the way it explores the themes of destiny, reincarnation, and the power of human connection. The film adaptation also used this structure, with the different stories intertwined and characters reprising their roles in different settings and eras.

Take a story thread made of comments. In each comment is a text about characters in a particular plot, location, action etc. The comments are sequential, but they are not necessarily continuous. It is a mix between Cloud Atlas and RPG plot structures. How do you sort something that’s fundamentally non-linear to present it in an accessible way?

One way to sort and present a story thread made of comments that is fundamentally non-linear, yet accessible, is to group the comments based on their content. For example, you could group the comments by characters, and present them in chronological order of their appearance in the story. Another way could be grouping the comments by location, and present them in chronological order of when the action takes place in that particular location. You could also group comments by the type of action taking place, such as combat, conversation, or puzzle-solving, and present them in chronological order of when they occur in the story.

Another approach could be using visual aids, such as mind maps, timelines, or flowcharts, to help organize and present the information in a clear and easy-to-understand way. For example, you could use a mind map to show how different characters are connected, or a timeline to show the chronology of events. Additionally, you could use labels, such as “character introduction,” “location change,” or “plot twist,” to make it clear to the reader what type of information they can expect in each comment.

It’s also important to keep in mind the audience for which you are organizing the story. It should be easy for them to understand and follow the story, and if it’s a game, you should make sure it’s easy for the players to play and make decisions.

January 15, 2023 at 1:18 pm #6391In reply to: Train your subjective AI – text version

write the plot of an absurd non-linear novel, featuring 4 characters

The novel begins with the introduction of four characters: a retired archaeologist named Harold, a struggling musician named Samantha, a disillusioned corporate drone named Tim, and a reclusive inventor named Claire.

Harold, who is obsessed with ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, discovers a mysterious underground chamber beneath a pyramid in Egypt. Inside, he finds a strange device that he believes is a time machine. Harold decides to use the device to travel back in time to ancient Egypt in order to decipher the hieroglyphs.

Samantha, who is trying to make a name for herself as a musician, is struggling to come up with new material for her music. One day, she discovers that she can create beautiful music by communicating with plants telepathically. She becomes obsessed with this new form of music-making and decides to quit her day job and pursue it full-time.

Tim, who is stuck in a dead-end job, is feeling unfulfilled and uninspired. One day, he stumbles upon a robotic mime performance art show. The performance inspires him to quit his job and pursue his dream of becoming a mime artist.

Claire, who is a reclusive inventor, has been working on a project to create a type of artificial intelligence that can communicate with humans using calligraphic body language. She finally succeeds and creates an AI that she names “Calli”.

As the story progresses, the characters’ paths begin to intersect in unexpected ways. Harold gets stuck in ancient Egypt and has to rely on Samantha’s telepathic plant communication skills to find a way back to the present. Tim’s robotic mime art becomes a hit and he starts working with Claire to integrate Calli into his performances.

As the story reaches its climax, all four characters come together to use their unique skills and abilities to solve a problem that threatens the fate of the world.

Throughout the novel, the plot unfolds in a non-linear fashion, jumping back and forth in time and between the different character’s perspectives. The story is filled with absurdity and unexpected twists and turns, leaving the reader guessing until the very end.

What sort of problem that threatens the fate of the world will be resolved by their combined skills?

As the story progresses, the characters begin to uncover a sinister plot by a group of powerful individuals who are intent on using the time machine to alter the course of history for their own gain. They plan to use the time machine to go back in time and change key events that would give them immense wealth and power in the present. Harold and Samantha, with the help of Tim and Claire, must race against time to stop the villains from carrying out their plan.

Harold’s expertise in ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs plays a crucial role in deciphering the clues that lead to the location of the time machine. Samantha’s telepathic plant communication skills are used to locate the hidden underground chamber where the time machine is kept. Tim’s robotic mime art and Claire’s AI Calli are used to infiltrate the villains’ hideout and gather intelligence on their plans.

In the final act, the four characters come together to use their unique skills and abilities to stop the villains from altering history. Harold uses his knowledge of ancient Egypt to navigate the time machine and travel back in time to stop the villains from changing key events. Samantha uses her telepathic plant communication skills to communicate with the plants in the past and gather information on the villains’ whereabouts. Tim and Claire use their robotic mime and AI skills to create a diversion and distract the villains while Harold and Samantha complete their mission.

In the end, the four characters succeed in stopping the villains and saving the fate of the world. The novel ends with the four characters going their separate ways, but they all know that they will always have each other to rely on in the face of any challenge that comes their way.

January 15, 2023 at 1:13 pm #6390In reply to: Train your subjective AI – text version

Trying to get some interesting unlikely, absurd associations or quests… Still some way to go!

2 impossible associations

- The creation of a time machine using only household objects such as a toaster and a stapler.

- The discovery of a parallel universe accessible through a secret passageway hidden in a public park’s playground equipment.

give an association of 3 or 4 words with each words being statistically probable to occur in every day conversation but with statistical probability of occurring together of less than 10^-57.

-

- “Giant robotic giraffe farming”

- “Vintage cars restoration using only expired food”

- “Archaeological board game design with only smells”

- “Artificial intelligence calligraphic body language assisted therapy”

All the words in these associations are commonly used in everyday conversation, but the associations themselves are relatively unexpected, absurd, and may surprise people. They are all grounded in everyday happenstances but are less modern tech-oriented and the concepts they describe are related to diverse interests that may not be related to technology trend and are quite unexpected and bizarre..

January 15, 2023 at 11:42 am #6389In reply to: Newsreel from the Rim of the Realm

“What in the good name of our Lady, have these two been on?” Miss Bossy was at a loss for words while Ricardo was waiting sheepishly at her desk, as though he was expecting an outburst.

“Look, Ricardo, I’m not against a little tweaking for newsworthiness, but this takes twisting reality to a whole new level!Ricardo had just dropped their last article.

Local Hero at the Rescue – Stray Residents found after in a trip of a lifetime

article by Hilda Astoria & Continuity BrownIn a daring and heroic move, Nurse Trassie, a local hero and all-around fantastic human being, managed to track down and rescue three elderly women who had gone on an adventure of a lifetime. Sharon, Mavis, and Gloria (names may have been altered to preserve their anonymity) were residents of a UK nursing home who, in a moment of pure defiance and desire for adventure, decided to go off their meds and escape to the Nordics.

The three women, who had been feeling cooped up and underappreciated in their nursing home, decided to take matters into their own hands and embark on a journey to see the world. They had heard of the beautiful landscapes and friendly people of the Nordics and their rejuvenating traditional cures and were determined to experience it for themselves.

Their journey, however, was not without its challenges. They faced many obstacles, including harsh weather conditions and language barriers. But they were determined to press on, and their determination paid off when they were taken in by a kind-hearted local doctor who gave them asylum and helped them rehabilitate stray animals.

Nurse Trassie, who had been on the lookout for the women since their disappearance, finally caught wind of their whereabouts and set out to rescue them. She tracked them down to the Nordics, where she found them living in a small facility in the woods, surrounded by a menagerie of stray animals they had taken in and were nursing back to health, including rare orangutans retired from local circus.

Upon her arrival, Nurse Trassie was greeted with open arms by the women, who were overjoyed to see her. They told her of their adventures and showed her around their cabin, introducing her to the animals they had taken in and the progress they had made in rehabilitating them.

Nurse Trassie, who is known for her compassion and dedication to her patients, was deeply touched by the women’s story and their love for the animals. She knew that they needed to be back in the care of professionals and that the animals needed to be properly cared for, so she made arrangements to bring them back home.

The women were reluctant to leave their newfound home and the animals they had grown to love, but they knew that it was the right thing to do. They said their goodbyes and set off on the long journey back home with Nurse Trassie by their side.

The three women returned to their nursing home filled with stories to share, and Nurse Trassie was hailed as a hero for her efforts in rescuing them. They were greeted with cheers and applause from the staff and other residents, who were thrilled to have them back safe and sound.

Nurse Trassie, who is known for her sharp wit and sense of humor, commented on the situation with a tongue-in-cheek remark, “It’s not every day that you get to rescue three feisty elderlies from the wilds of the Nordics and bring them back to safety. I’m just glad I could be of service.”

In conclusion, the three women’s adventure in the Nordics may have been unorthodox, but it was an adventure nonetheless. They were able to see the world and help some animals in the process. Their story serves as a reminder to never give up on your dreams, no matter your age or circumstances. And of course, a big shoutout to Nurse Trassie for her heroic actions and dedication to her patients.

Bossy sighed. “It might do for now, but don’t let those two abuse the artificial intelligence to write article for them… I liked their old style better. This feels too… tidy. We’re not the A-News network, let’s not forget our purpose.”

Ricardo nodded. Miss Bossy had been more mellow since the sales of the newspaper had exploded during the pandemic. With people at home, looking for conspiracies and all, the newspaper had known a resurgence of interest, and they even had to hire new staff. Giles Gibber, Glimmer Gambol (came heavily recommended by Blithe, the PI friend of Hilda’s), Samuel Sproink and Fionna Flibbergibbet.

“And how is Sophie? That adventure into her past trauma was a bit much on her…” she mused.

“She’s doing alright” answered Ricardo. “She’s learning to hone her remote-viewing skills to send our staff into new mysteries to solve. With a bit of AI assist…”

“Oh, stop it already with your AI-this, AI-that! Hope there’ll still be room for some madness in all that neatly tidy purring of polite output.”

“That’s why we’re here for, I reckon.” Ric’ smiled wryly.

January 14, 2023 at 8:13 pm #6387In reply to: Scrying the Word Cloud

Words from the Cloud prompted me to write a story:

song stayed act unexpected recall words spears bus learn king expected followed fright hot wore kianda picture walked playing coast dusty

Once upon a time, in a far-off land, there was a Song that stayed in the hearts of the people. The Song was about an Act of bravery and sacrifice that had taken place many years ago. But one day, an unexpected recall of the Song was issued by the king. He had heard that the Song was not being sung correctly, and he wanted to make sure that the true story was being told. The people were puzzled, as they had learned the Song from their ancestors and had always thought it was accurate. But they followed the king’s orders and set out to learn the correct version of the Song. As they began to recall the words, they realized that there were some discrepancies. They had always sung about the hero wielding a sword, but the true story spoke of him wielding Spears. They were taken aback, but they knew they had to correct the Song. So, they set out on a journey to retrace the hero’s steps.

As they traveled, they encountered unexpected challenges. They faced a bus that broke down, a coastline that was dusty and treacherous, and even a group of bandits. But they pressed on, determined to learn the truth.

As they approached the hero’s final battle, they felt a sense of dread. They had heard that the enemy was fierce, and they were not prepared for what they would find. But they followed the path and soon found themselves at the edge of a hot, barren wasteland.

The heroes wore their Kianda, traditional armor made of woven reeds, and stepped forward, ready for battle. But to their surprise, the enemy was nowhere to be found. Instead, they found a picture etched into the ground, depicting the hero and his enemy locked in a fierce battle.

The people walked around the picture, marveling at the detail and skill of the artist. And as they looked closer, they saw that the hero was holding Spears, not a sword. They realized that they had learned the true story, and they felt a sense of pride and gratitude.

With the Song corrected, they returned home, playing the new version for all to hear. And from that day on, the true story of the hero’s bravery and sacrifice was remembered, and the Song stayed in the hearts of the people forevermore.

December 6, 2022 at 2:17 pm #6350In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Transportation

Isaac Stokes 1804-1877

Isaac was born in Churchill, Oxfordshire in 1804, and was the youngest brother of my 4X great grandfather Thomas Stokes. The Stokes family were stone masons for generations in Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire, and Isaac’s occupation was a mason’s labourer in 1834 when he was sentenced at the Lent Assizes in Oxford to fourteen years transportation for stealing tools.

Churchill where the Stokes stonemasons came from: on 31 July 1684 a fire destroyed 20 houses and many other buildings, and killed four people. The village was rebuilt higher up the hill, with stone houses instead of the old timber-framed and thatched cottages. The fire was apparently caused by a baker who, to avoid chimney tax, had knocked through the wall from her oven to her neighbour’s chimney.

Isaac stole a pick axe, the value of 2 shillings and the property of Thomas Joyner of Churchill; a kibbeaux and a trowel value 3 shillings the property of Thomas Symms; a hammer and axe value 5 shillings, property of John Keen of Sarsden.

(The word kibbeaux seems to only exists in relation to Isaac Stokes sentence and whoever was the first to write it was perhaps being creative with the spelling of a kibbo, a miners or a metal bucket. This spelling is repeated in the criminal reports and the newspaper articles about Isaac, but nowhere else).

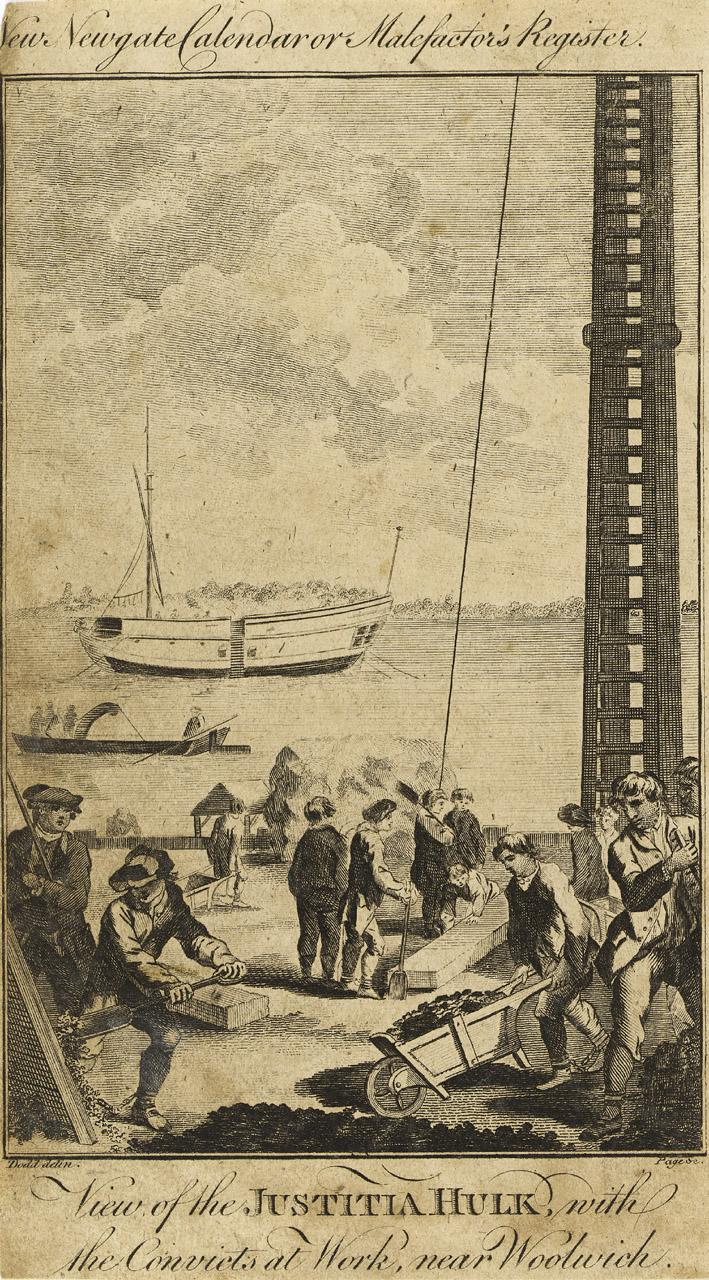

In March 1834 the Removal of Convicts was announced in the Oxford University and City Herald: Isaac Stokes and several other prisoners were removed from the Oxford county gaol to the Justitia hulk at Woolwich “persuant to their sentences of transportation at our Lent Assizes”.

via digitalpanopticon:

Hulks were decommissioned (and often unseaworthy) ships that were moored in rivers and estuaries and refitted to become floating prisons. The outbreak of war in America in 1775 meant that it was no longer possible to transport British convicts there. Transportation as a form of punishment had started in the late seventeenth century, and following the Transportation Act of 1718, some 44,000 British convicts were sent to the American colonies. The end of this punishment presented a major problem for the authorities in London, since in the decade before 1775, two-thirds of convicts at the Old Bailey received a sentence of transportation – on average 283 convicts a year. As a result, London’s prisons quickly filled to overflowing with convicted prisoners who were sentenced to transportation but had no place to go.

To increase London’s prison capacity, in 1776 Parliament passed the “Hulks Act” (16 Geo III, c.43). Although overseen by local justices of the peace, the hulks were to be directly managed and maintained by private contractors. The first contract to run a hulk was awarded to Duncan Campbell, a former transportation contractor. In August 1776, the Justicia, a former transportation ship moored in the River Thames, became the first prison hulk. This ship soon became full and Campbell quickly introduced a number of other hulks in London; by 1778 the fleet of hulks on the Thames held 510 prisoners.

Demand was so great that new hulks were introduced across the country. There were hulks located at Deptford, Chatham, Woolwich, Gosport, Plymouth, Portsmouth, Sheerness and Cork.The Justitia via rmg collections:

Convicts perform hard labour at the Woolwich Warren. The hulk on the river is the ‘Justitia’. Prisoners were kept on board such ships for months awaiting deportation to Australia. The ‘Justitia’ was a 260 ton prison hulk that had been originally moored in the Thames when the American War of Independence put a stop to the transportation of criminals to the former colonies. The ‘Justitia’ belonged to the shipowner Duncan Campbell, who was the Government contractor who organized the prison-hulk system at that time. Campbell was subsequently involved in the shipping of convicts to the penal colony at Botany Bay (in fact Port Jackson, later Sydney, just to the north) in New South Wales, the ‘first fleet’ going out in 1788.

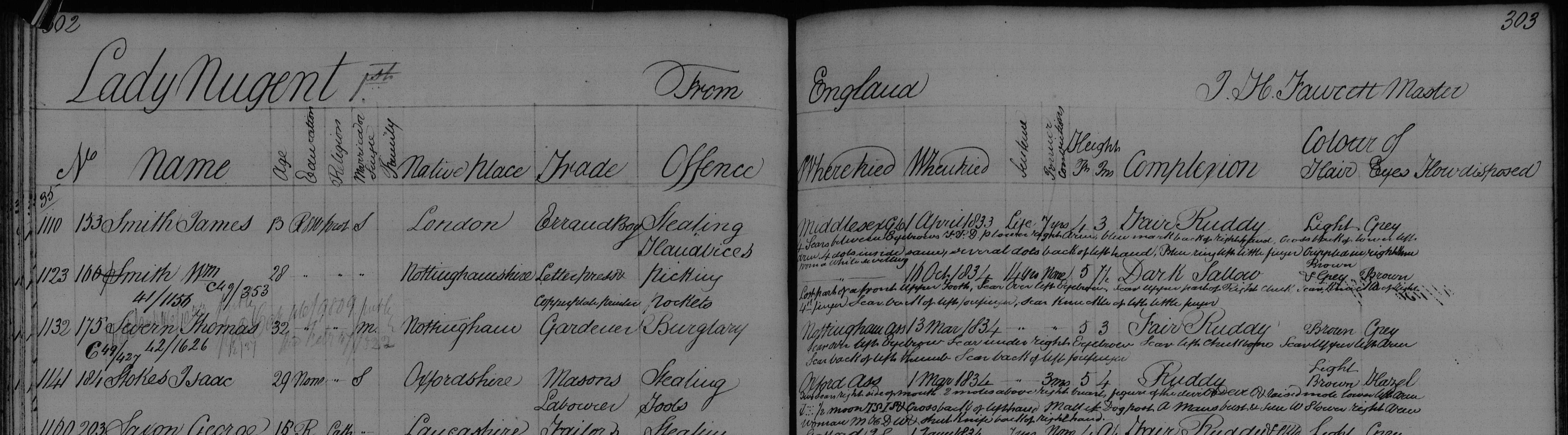

While searching for records for Isaac Stokes I discovered that another Isaac Stokes was transported to New South Wales in 1835 as well. The other one was a butcher born in 1809, sentenced in London for seven years, and he sailed on the Mary Ann. Our Isaac Stokes sailed on the Lady Nugent, arriving in NSW in April 1835, having set sail from England in December 1834.

Lady Nugent was built at Bombay in 1813. She made four voyages under contract to the British East India Company (EIC). She then made two voyages transporting convicts to Australia, one to New South Wales and one to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). (via Wikipedia)

via freesettlerorfelon website:

On 20 November 1834, 100 male convicts were transferred to the Lady Nugent from the Justitia Hulk and 60 from the Ganymede Hulk at Woolwich, all in apparent good health. The Lady Nugent departed Sheerness on 4 December 1834.

SURGEON OLIVER SPROULE

Oliver Sproule kept a Medical Journal from 7 November 1834 to 27 April 1835. He recorded in his journal the weather conditions they experienced in the first two weeks:

‘In the course of the first week or ten days at sea, there were eight or nine on the sick list with catarrhal affections and one with dropsy which I attribute to the cold and wet we experienced during that period beating down channel. Indeed the foremost berths in the prison at this time were so wet from leaking in that part of the ship, that I was obliged to issue dry beds and bedding to a great many of the prisoners to preserve their health, but after crossing the Bay of Biscay the weather became fine and we got the damp beds and blankets dried, the leaks partially stopped and the prison well aired and ventilated which, I am happy to say soon manifested a favourable change in the health and appearance of the men.

Besides the cases given in the journal I had a great many others to treat, some of them similar to those mentioned but the greater part consisted of boils, scalds, and contusions which would not only be too tedious to enter but I fear would be irksome to the reader. There were four births on board during the passage which did well, therefore I did not consider it necessary to give a detailed account of them in my journal the more especially as they were all favourable cases.

Regularity and cleanliness in the prison, free ventilation and as far as possible dry decks turning all the prisoners up in fine weather as we were lucky enough to have two musicians amongst the convicts, dancing was tolerated every afternoon, strict attention to personal cleanliness and also to the cooking of their victuals with regular hours for their meals, were the only prophylactic means used on this occasion, which I found to answer my expectations to the utmost extent in as much as there was not a single case of contagious or infectious nature during the whole passage with the exception of a few cases of psora which soon yielded to the usual treatment. A few cases of scurvy however appeared on board at rather an early period which I can attribute to nothing else but the wet and hardships the prisoners endured during the first three or four weeks of the passage. I was prompt in my treatment of these cases and they got well, but before we arrived at Sydney I had about thirty others to treat.’

The Lady Nugent arrived in Port Jackson on 9 April 1835 with 284 male prisoners. Two men had died at sea. The prisoners were landed on 27th April 1835 and marched to Hyde Park Barracks prior to being assigned. Ten were under the age of 14 years.

The Lady Nugent:

Isaac’s distinguishing marks are noted on various criminal registers and record books:

“Height in feet & inches: 5 4; Complexion: Ruddy; Hair: Light brown; Eyes: Hazel; Marks or Scars: Yes [including] DEVIL on lower left arm, TSIS back of left hand, WS lower right arm, MHDW back of right hand.”

Another includes more detail about Isaac’s tattoos:

“Two slight scars right side of mouth, 2 moles above right breast, figure of the devil and DEVIL and raised mole, lower left arm; anchor, seven dots half moon, TSIS and cross, back of left hand; a mallet, door post, A, mans bust, sun, WS, lower right arm; woman, MHDW and shut knife, back of right hand.”

From How tattoos became fashionable in Victorian England (2019 article in TheConversation by Robert Shoemaker and Zoe Alkar):

“Historical tattooing was not restricted to sailors, soldiers and convicts, but was a growing and accepted phenomenon in Victorian England. Tattoos provide an important window into the lives of those who typically left no written records of their own. As a form of “history from below”, they give us a fleeting but intriguing understanding of the identities and emotions of ordinary people in the past.

As a practice for which typically the only record is the body itself, few systematic records survive before the advent of photography. One exception to this is the written descriptions of tattoos (and even the occasional sketch) that were kept of institutionalised people forced to submit to the recording of information about their bodies as a means of identifying them. This particularly applies to three groups – criminal convicts, soldiers and sailors. Of these, the convict records are the most voluminous and systematic.

Such records were first kept in large numbers for those who were transported to Australia from 1788 (since Australia was then an open prison) as the authorities needed some means of keeping track of them.”On the 1837 census Isaac was working for the government at Illiwarra, New South Wales. This record states that he arrived on the Lady Nugent in 1835. There are three other indent records for an Isaac Stokes in the following years, but the transcriptions don’t provide enough information to determine which Isaac Stokes it was. In April 1837 there was an abscondment, and an arrest/apprehension in May of that year, and in 1843 there was a record of convict indulgences.

From the Australian government website regarding “convict indulgences”:

“By the mid-1830s only six per cent of convicts were locked up. The vast majority worked for the government or free settlers and, with good behaviour, could earn a ticket of leave, conditional pardon or and even an absolute pardon. While under such orders convicts could earn their own living.”

In 1856 in Camden, NSW, Isaac Stokes married Catherine Daly. With no further information on this record it would be impossible to know for sure if this was the right Isaac Stokes. This couple had six children, all in the Camden area, but none of the records provided enough information. No occupation or place or date of birth recorded for Isaac Stokes.

I wrote to the National Library of Australia about the marriage record, and their reply was a surprise! Issac and Catherine were married on 30 September 1856, at the house of the Rev. Charles William Rigg, a Methodist minister, and it was recorded that Isaac was born in Edinburgh in 1821, to parents James Stokes and Sarah Ellis! The age at the time of the marriage doesn’t match Isaac’s age at death in 1877, and clearly the place of birth and parents didn’t match either. Only his fathers occupation of stone mason was correct. I wrote back to the helpful people at the library and they replied that the register was in a very poor condition and that only two and a half entries had survived at all, and that Isaac and Catherines marriage was recorded over two pages.

I searched for an Isaac Stokes born in 1821 in Edinburgh on the Scotland government website (and on all the other genealogy records sites) and didn’t find it. In fact Stokes was a very uncommon name in Scotland at the time. I also searched Australian immigration and other records for another Isaac Stokes born in Scotland or born in 1821, and found nothing. I was unable to find a single record to corroborate this mysterious other Isaac Stokes.

As the age at death in 1877 was correct, I assume that either Isaac was lying, or that some mistake was made either on the register at the home of the Methodist minster, or a subsequent mistranscription or muddle on the remnants of the surviving register. Therefore I remain convinced that the Camden stonemason Isaac Stokes was indeed our Isaac from Oxfordshire.

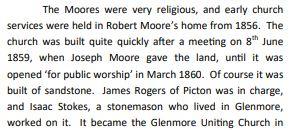

I found a history society newsletter article that mentioned Isaac Stokes, stone mason, had built the Glenmore church, near Camden, in 1859.

From the Wollondilly museum April 2020 newsletter:

From the Camden History website:

“The stone set over the porch of Glenmore Church gives the date of 1860. The church was begun in 1859 on land given by Joseph Moore. James Rogers of Picton was given the contract to build and local builder, Mr. Stokes, carried out the work. Elizabeth Moore, wife of Edward, laid the foundation stone. The first service was held on 19th March 1860. The cemetery alongside the church contains the headstones and memorials of the areas early pioneers.”

Isaac died on the 3rd September 1877. The inquest report puts his place of death as Bagdelly, near to Camden, and another death register has put Cambelltown, also very close to Camden. His age was recorded as 71 and the inquest report states his cause of death was “rupture of one of the large pulmonary vessels of the lung”. His wife Catherine died in childbirth in 1870 at the age of 43.

Isaac and Catherine’s children:

William Stokes 1857-1928

Catherine Stokes 1859-1846

Sarah Josephine Stokes 1861-1931

Ellen Stokes 1863-1932

Rosanna Stokes 1865-1919

Louisa Stokes 1868-1844.

It’s possible that Catherine Daly was a transported convict from Ireland.

Some time later I unexpectedly received a follow up email from The Oaks Heritage Centre in Australia.

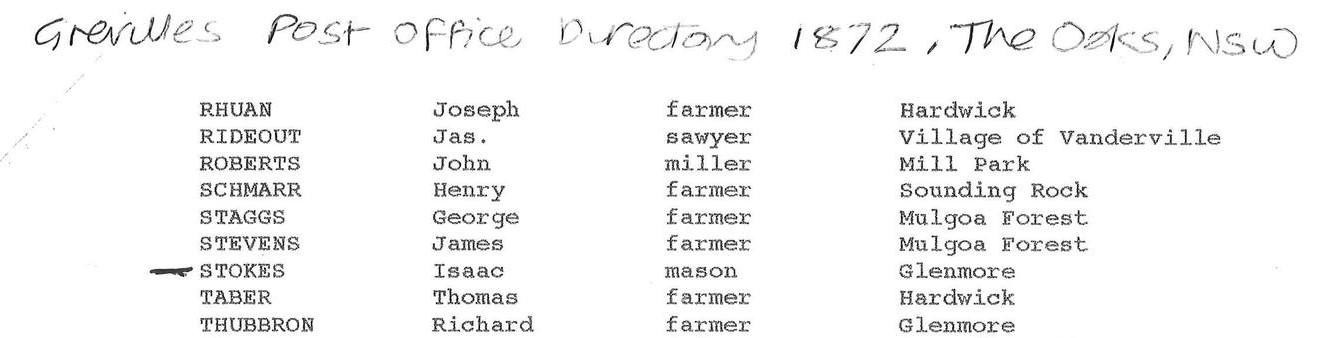

“The Gaudry papers which we have in our archive record him (Isaac Stokes) as having built: the church, the school and the teachers residence. Isaac is recorded in the General return of convicts: 1837 and in Grevilles Post Office directory 1872 as a mason in Glenmore.”

November 13, 2022 at 10:29 pm #6345

November 13, 2022 at 10:29 pm #6345In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

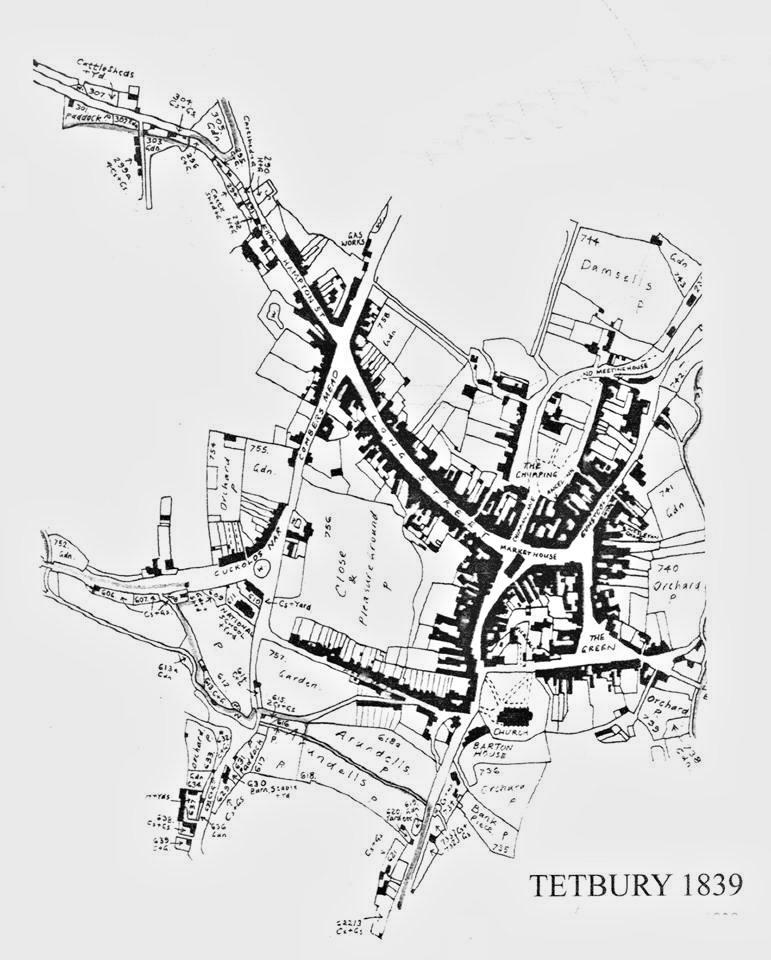

Crime and Punishment in Tetbury

I noticed that there were quite a number of Brownings of Tetbury in the newspaper archives involved in criminal activities while doing a routine newspaper search to supplement the information in the usual ancestry records. I expanded the tree to include cousins, and offsping of cousins, in order to work out who was who and how, if at all, these individuals related to our Browning family.

I was expecting to find some of our Brownings involved in the Swing Riots in Tetbury in 1830, but did not. Most of our Brownings (including cousins) were stone masons. Most of the rioters in 1830 were agricultural labourers.

The Browning crimes are varied, and by todays standards, not for the most part terribly serious ~ you would be unlikely to receive a sentence of hard labour for being found in an outhouse with the intent to commit an unlawful act nowadays, or for being drunk.

The central character in this chapter is Isaac Browning (my 4x great grandfather), who did not appear in any criminal registers, but the following individuals can be identified in the family structure through their relationship to him.

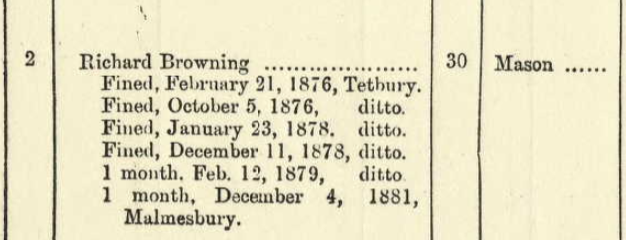

RICHARD LOCK BROWNING born in 1853 was Isaac’s grandson, his son George’s son. Richard was a mason. In 1879 he and Henry Browning of the same age were sentenced to one month hard labour for stealing two pigeons in Tetbury. Henry Browning was Isaac’s nephews son.

In 1883 Richard Browning, mason of Tetbury, was charged with obtaining food and lodging under false pretences, but was found not guilty and acquitted.

In 1884 Richard Browning, mason of Tetbury, was sentenced to one month hard labour for game trespass.Richard had been fined a number of times in Tetbury:

Richard Lock Browning was five feet eight inches tall, dark hair, grey eyes, an oval face and a dark complexion. He had two cuts on the back of his head (in February 1879) and a scar on his right eyebrow.

HENRY BROWNING, who was stealing pigeons with Richard Lock Browning in 1879, (Isaac’s brother Williams grandson, son of George Browning and his wife Charity) was charged with being drunk in 1882 and ordered to pay a fine of one shilling and costs of fourteen shillings, or seven days hard labour.

Henry was found guilty of gaming in the highway at Tetbury in 1872 and was sentenced to seven days hard labour. In 1882 Henry (who was also a mason) was charged with assault but discharged.

Henry was five feet five inches tall, brown hair and brown eyes, a long visage and a fresh complexion.

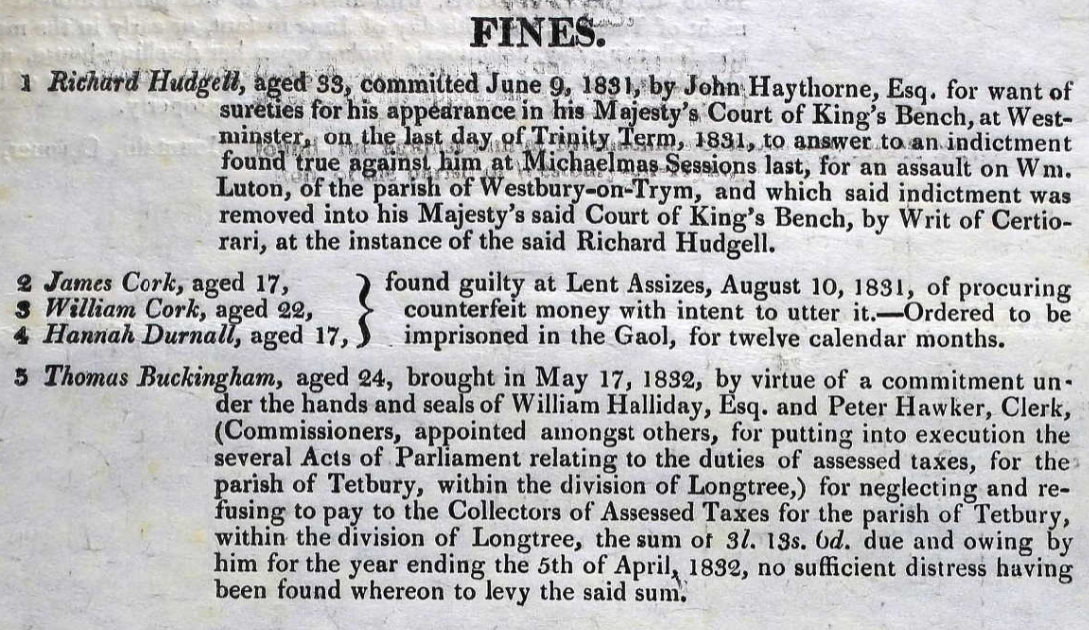

Henry emigrated with his daughter to Canada in 1913, and died in Vancouver in 1919.THOMAS BUCKINGHAM 1808-1846 (Isaacs daughter Janes husband) was charged with stealing a black gelding in Tetbury in 1838. No true bill. (A “no true bill” means the jury did not find probable cause to continue a case.)

Thomas did however neglect to pay his taxes in 1832:

LEWIN BUCKINGHAM (grandson of Isaac, his daughter Jane’s son) was found guilty in 1846 stealing two fowls in Tetbury when he was sixteen years old.

In 1846 he was sentence to one month hard labour (or pay ten shillings fine and ten shillings costs) for loitering with the intent to trespass in search of conies.

A year later in 1847, he and three other young men were sentenced to four months hard labour for larceny.

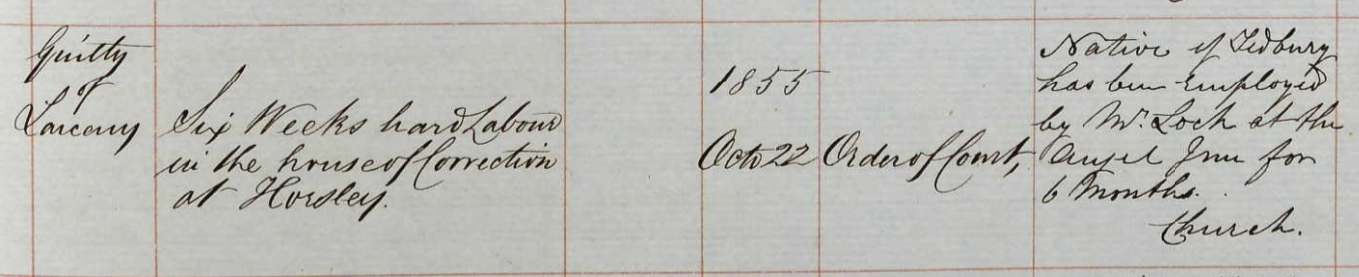

Lewin was five feet three inches tall, with brown hair and brown eyes, long visage, sallow complexion, and had a scar on his left arm.JOHN BUCKINGHAM born circa 1832, a Tetbury labourer (Isaac’s grandson, Lewin’s brother) was sentenced to six weeks hard labour for larceny in 1855 for stealing a duck in Cirencester. The notes on the register mention that he had been employed by Mr LOCK, Angel Inn. (John’s grandmother was Mary Lock so this is likely a relative).

The previous year in 1854 John was sentenced to one month or a one pound fine for assaulting and beating W. Wood.

John was five feet eight and three quarter inches tall, light brown hair and grey eyes, an oval visage and a fresh complexion. He had a scar on his left arm and inside his right knee.JOSEPH PERRET was born circa 1831 and he was a Tetbury labourer. (He was Isaac’s granddaughter Charlotte Buckingham’s husband)

In 1855 he assaulted William Wood and was sentenced to one month or a two pound ten shilling fine. Was it the same W Wood that his wifes cousin John assaulted the year before?

In 1869 Joseph was sentenced to one month hard labour for feloniously receiving a cupboard known to be stolen.JAMES BUCKINGAM born circa 1822 in Tetbury was a shoemaker. (Isaac’s nephew, his sister Hannah’s son)

In 1854 the Tetbury shoemaker was sentenced to four months hard labour for stealing 30 lbs of lead off someones house.

In 1856 the Tetbury shoemaker received two months hard labour or pay £2 fine and 12 s costs for being found in pursuit of game.

In 1868 he was sentenced to two months hard labour for stealing a gander. A unspecified previous conviction is noted.

1871 the Tetbury shoemaker was found in an outhouse for an unlawful purpose and received ten days hard labour. The register notes that his sister is Mrs Cook, the Green, Tetbury. (James sister Prudence married Thomas Cook)

James sister Charlotte married a shoemaker and moved to UTAH.

James was five feet eight inches tall, dark hair and blue eyes, a long visage and a florid complexion. He had a scar on his forehead and a mole on the right side of his neck and abdomen, and a scar on the right knee.November 4, 2022 at 2:19 pm #6342In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Brownings of Tetbury

Isaac Browning (1784-1848) married Mary Lock (1787-1870) in Tetbury in 1806. Both of them were born in Tetbury, Gloucestershire. Isaac was a stone mason. Between 1807 and 1832 they baptised fourteen children in Tetbury, and on 8 Nov 1829 Isaac and Mary baptised five daughters all on the same day.

I considered that they may have been quintuplets, with only the last born surviving, which would have answered my question about the name of the house La Quinta in Broadway, the home of Eliza Browning and Thomas Stokes son Fred. However, the other four daughters were found in various records and they were not all born the same year. (So I still don’t know why the house in Broadway had such an unusual name).

Their son George was born and baptised in 1827, but Louisa born 1821, Susan born 1822, Hesther born 1823 and Mary born 1826, were not baptised until 1829 along with Charlotte born in 1828. (These birth dates are guesswork based on the age on later censuses.) Perhaps George was baptised promptly because he was sickly and not expected to survive. Isaac and Mary had a son George born in 1814 who died in 1823. Presumably the five girls were healthy and could wait to be done as a job lot on the same day later.

Eliza Browning (1814-1886), my great great great grandmother, had a baby six years before she married Thomas Stokes. Her name was Ellen Harding Browning, which suggests that her fathers name was Harding. On the 1841 census seven year old Ellen was living with her grandfather Isaac Browning in Tetbury. Ellen Harding Browning married William Dee in Tetbury in 1857, and they moved to Western Australia.

Ellen Harding Browning Dee: (photo found on ancestry website)

OBITUARY. MRS. ELLEN DEE.

A very old and respected resident of Dongarra, in the person of Mrs. Ellen Dee, passed peacefully away on Sept. 27, at the advanced age of 74 years.The deceased had been ailing for some time, but was about and actively employed until Wednesday, Sept. 20, whenn she was heard groaning by some neighbours, who immediately entered her place and found her lying beside the fireplace. Tho deceased had been to bed over night, and had evidently been in the act of lighting thc fire, when she had a seizure. For some hours she was conscious, but had lost the power of speech, and later on became unconscious, in which state she remained until her death.

The deceased was born in Gloucestershire, England, in 1833, was married to William Dee in Tetbury Church 23 years later. Within a month she left England with her husband for Western Australian in the ship City oí Bristol. She resided in Fremantle for six months, then in Greenough for a short time, and afterwards (for 42 years) in Dongarra. She was, therefore, a colonist of about 51 years. She had a family of four girls and three boys, and five of her children survive her, also 35 grandchildren, and eight great grandchildren. She was very highly respected, and her sudden collapse came as a great shock to many.

Eliza married Thomas Stokes (1816-1885) in September 1840 in Hempstead, Gloucestershire. On the 1841 census, Eliza and her mother Mary Browning (nee Lock) were staying with Thomas Lock and family in Cirencester. Strangely, Thomas Stokes has not been found thus far on the 1841 census, and Thomas and Eliza’s first child William James Stokes birth was registered in Witham, in Essex, on the 6th of September 1841.

I don’t know why William James was born in Witham, or where Thomas was at the time of the census in 1841. One possibility is that as Thomas Stokes did a considerable amount of work with circus waggons, circus shooting galleries and so on as a journeyman carpenter initially and then later wheelwright, perhaps he was working with a traveling circus at the time.

But back to the Brownings ~ more on William James Stokes to follow.

One of Isaac and Mary’s fourteen children died in infancy: Ann was baptised and died in 1811. Two of their children died at nine years old: the first George, and Mary who died in 1835. Matilda was 21 years old when she died in 1844.

Jane Browning (1808-) married Thomas Buckingham in 1830 in Tetbury. In August 1838 Thomas was charged with feloniously stealing a black gelding.

Susan Browning (1822-1879) married William Cleaver in November 1844 in Tetbury. Oddly thereafter they use the name Bowman on the census. On the 1851 census Mary Browning (Susan’s mother), widow, has grandson George Bowman born in 1844 living with her. The confusion with the Bowman and Cleaver names was clarified upon finding the criminal registers:

30 January 1834. Offender: William Cleaver alias Bowman, Richard Bunting alias Barnfield and Jeremiah Cox, labourers of Tetbury. Crime: Stealing part of a dead fence from a rick barton in Tetbury, the property of Robert Tanner, farmer.

And again in 1836:

29 March 1836 Bowman, William alias Cleaver, of Tetbury, labourer age 18; 5’2.5” tall, brown hair, grey eyes, round visage with fresh complexion; several moles on left cheek, mole on right breast. Charged on the oath of Ann Washbourn & others that on the morning of the 31 March at Tetbury feloniously stolen a lead spout affixed to the dwelling of the said Ann Washbourn, her property. Found guilty 31 March 1836; Sentenced to 6 months.

On the 1851 census Susan Bowman was a servant living in at a large drapery shop in Cheltenham. She was listed as 29 years old, married and born in Tetbury, so although it was unusual for a married woman not to be living with her husband, (or her son for that matter, who was living with his grandmother Mary Browning), perhaps her husband William Bowman alias Cleaver was in trouble again. By 1861 they are both living together in Tetbury: William was a plasterer, and they had three year old Isaac and Thomas, one year old. In 1871 William was still a plasterer in Tetbury, living with wife Susan, and sons Isaac and Thomas. Interestingly, a William Cleaver is living next door but one!

Susan was 56 when she died in Tetbury in 1879.

Three of the Browning daughters went to London.

Louisa Browning (1821-1873) married Robert Claxton, coachman, in 1848 in Bryanston Square, Westminster, London. Ester Browning was a witness.

Ester Browning (1823-1893)(or Hester) married Charles Hudson Sealey, cabinet maker, in Bethnal Green, London, in 1854. Charles was born in Tetbury. Charlotte Browning was a witness.

Charlotte Browning (1828-1867?) was admitted to St Marylebone workhouse in London for “parturition”, or childbirth, in 1860. She was 33 years old. A birth was registered for a Charlotte Browning, no mothers maiden name listed, in 1860 in Marylebone. A death was registered in Camden, buried in Marylebone, for a Charlotte Browning in 1867 but no age was recorded. As the age and parents were usually recorded for a childs death, I assume this was Charlotte the mother.

I found Charlotte on the 1851 census by chance while researching her mother Mary Lock’s siblings. Hesther Lock married Lewin Chandler, and they were living in Stepney, London. Charlotte is listed as a neice. Although Browning is mistranscribed as Broomey, the original page says Browning. Another mistranscription on this record is Hesthers birthplace which is transcribed as Yorkshire. The original image shows Gloucestershire.

Isaac and Mary’s first son was John Browning (1807-1860). John married Hannah Coates in 1834. John’s brother Charles Browning (1819-1853) married Eliza Coates in 1842. Perhaps they were sisters. On the 1861 census Hannah Browning, John’s wife, was a visitor in the Harding household in a village called Coates near Tetbury. Thomas Harding born in 1801 was the head of the household. Perhaps he was the father of Ellen Harding Browning.

George Browning (1828-1870) married Louisa Gainey in Tetbury, and died in Tetbury at the age of 42. Their son Richard Lock Browning, a 32 year old mason, was sentenced to one month hard labour for game tresspass in Tetbury in 1884.

Isaac Browning (1832-1857) was the youngest son of Isaac and Mary. He was just 25 years old when he died in Tetbury.

October 19, 2022 at 6:46 am #6336In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

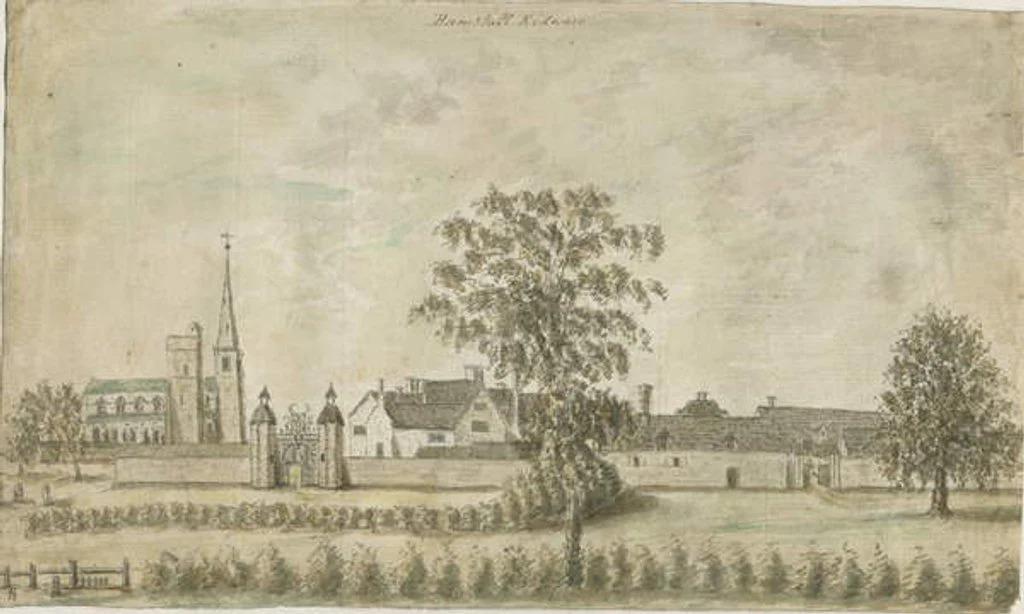

The Hamstall Ridware Connection

Stubbs and Woods

Hamstall Ridware

Hamstall RidwareCharles Tomlinson‘s (1847-1907) wife Emma Grattidge (1853-1911) was born in Wolverhampton, the daughter and youngest child of William Grattidge (1820-1887) born in Foston, Derbyshire, and Mary Stubbs (1819-1880), born in Burton on Trent, daughter of Solomon Stubbs.

Solomon Stubbs (1781-1857) was born in Hamstall Ridware in 1781, the son of Samuel and Rebecca. Samuel Stubbs (1743-) and Rebecca Wood (1754-) married in 1769 in Darlaston. Samuel and Rebecca had six other children, all born in Darlaston. Sadly four of them died in infancy. Son John was born in 1779 in Darlaston and died two years later in Hamstall Ridware in 1781, the same year that Solomon was born there.

But why did they move to Hamstall Ridware?

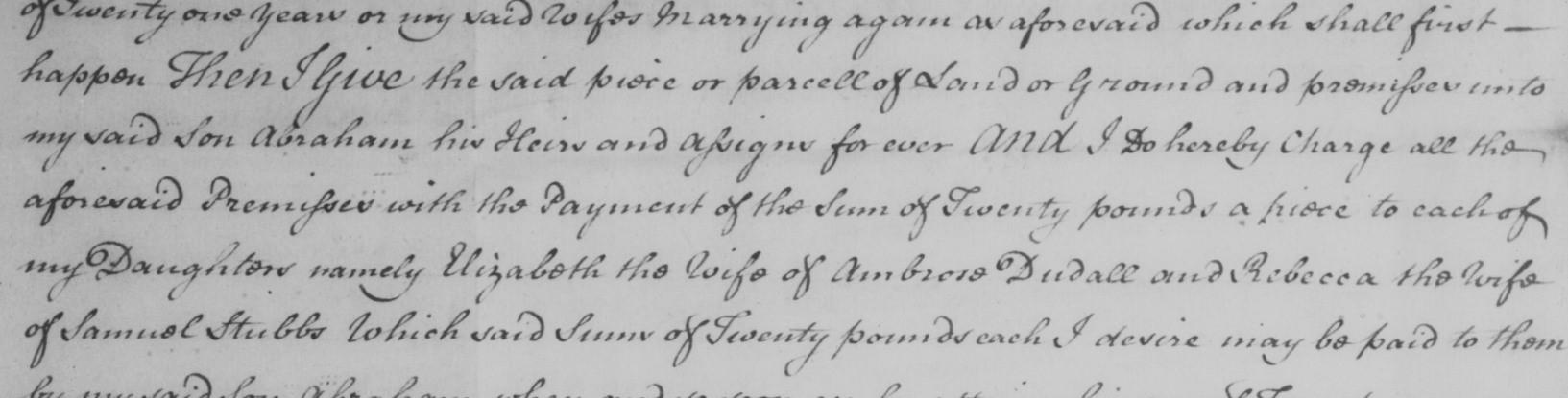

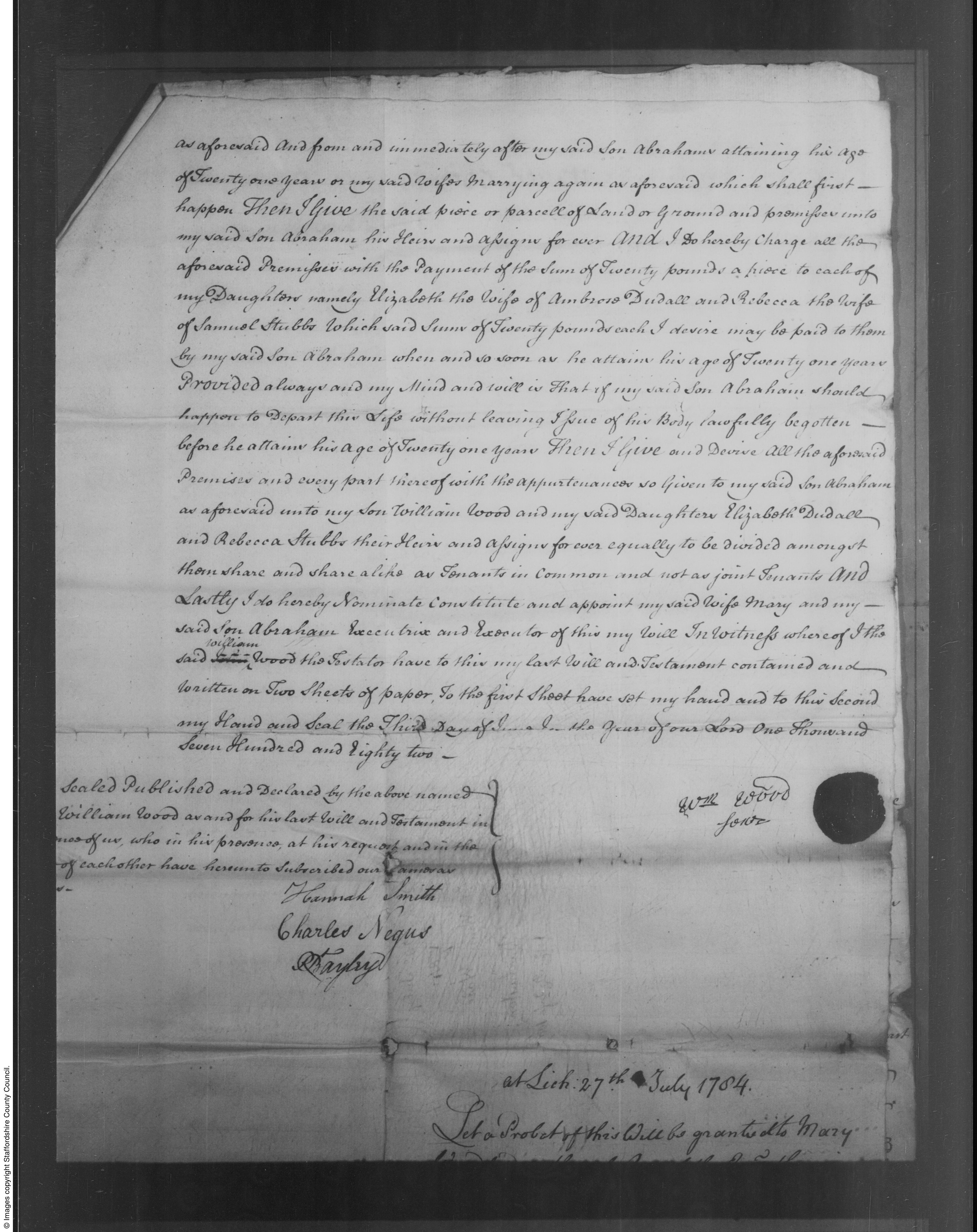

Samuel Stubbs was born in 1743 in Curdworth, Warwickshire (near to Birmingham). I had made a mistake on the tree (along with all of the public trees on the Ancestry website) and had Rebecca Wood born in Cheddleton, Staffordshire. Rebecca Wood from Cheddleton was also born in 1843, the right age for the marriage. The Rebecca Wood born in Darlaston in 1754 seemed too young, at just fifteen years old at the time of the marriage. I couldn’t find any explanation for why a woman from Cheddleton would marry in Darlaston and then move to Hamstall Ridware. People didn’t usually move around much other than intermarriage with neighbouring villages, especially women. I had a closer look at the Darlaston Rebecca, and did a search on her father William Wood. I found his 1784 will online in which he mentions his daughter Rebecca, wife of Samuel Stubbs. Clearly the right Rebecca Wood was the one born in Darlaston, which made much more sense.

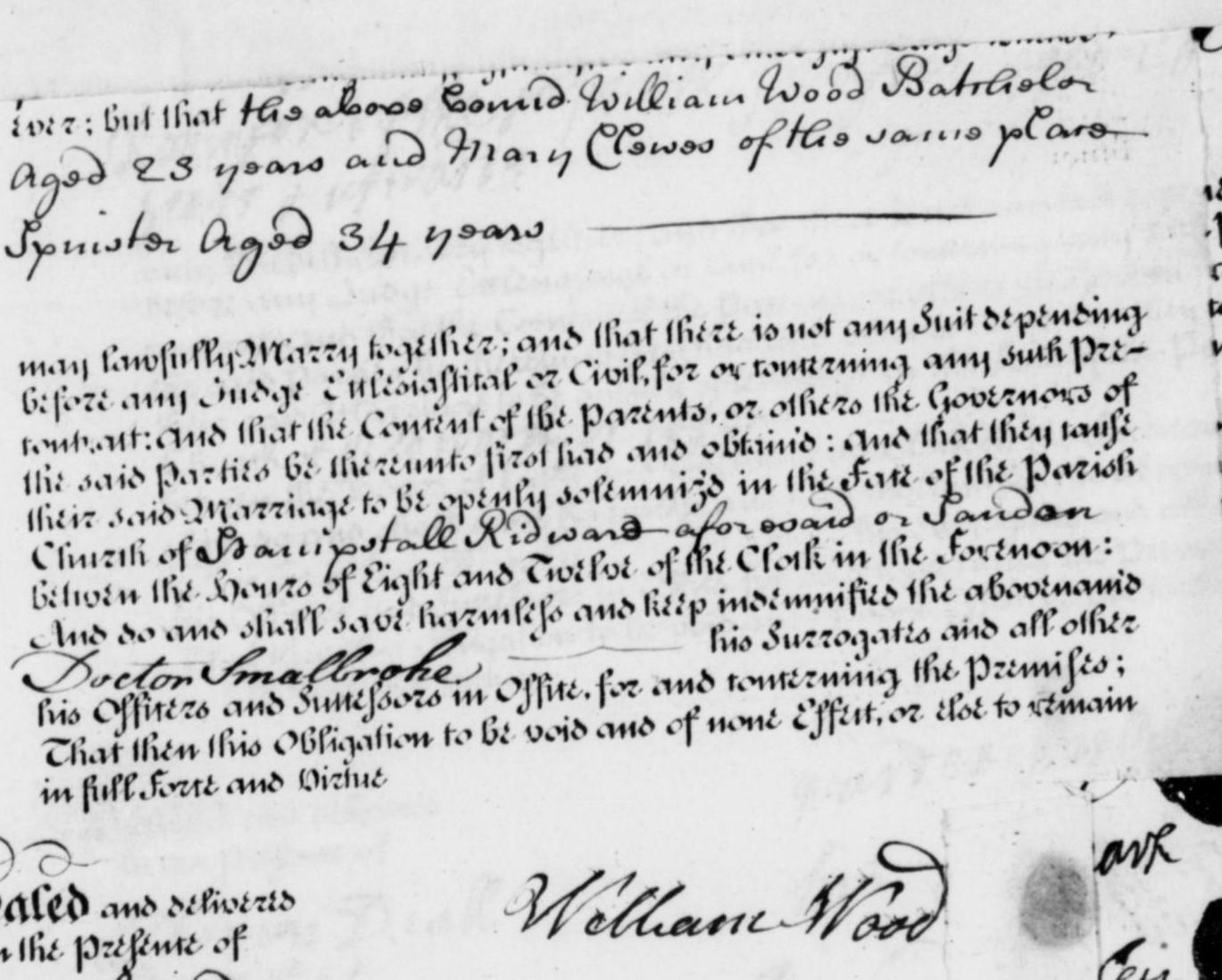

An excerpt from William Wood’s 1784 will mentioning daughter Rebecca married to Samuel Stubbs:

But why did they move to Hamstall Ridware circa 1780?

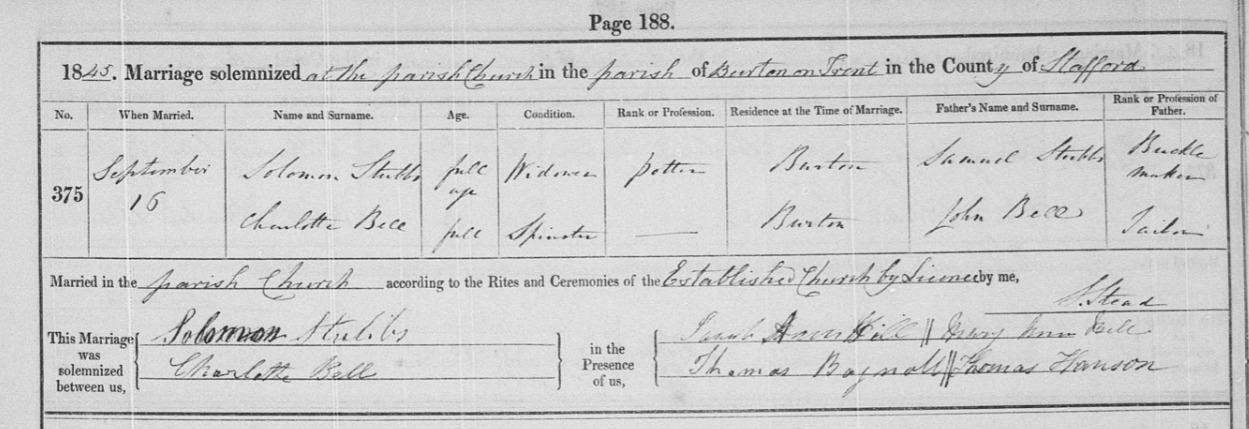

I had not intially noticed that Solomon Stubbs married again the year after his wife Phillis Lomas (1787-1844) died. Solomon married Charlotte Bell in 1845 in Burton on Trent and on the marriage register, Solomon’s father Samuel Stubbs occupation was mentioned: Samuel was a buckle maker.

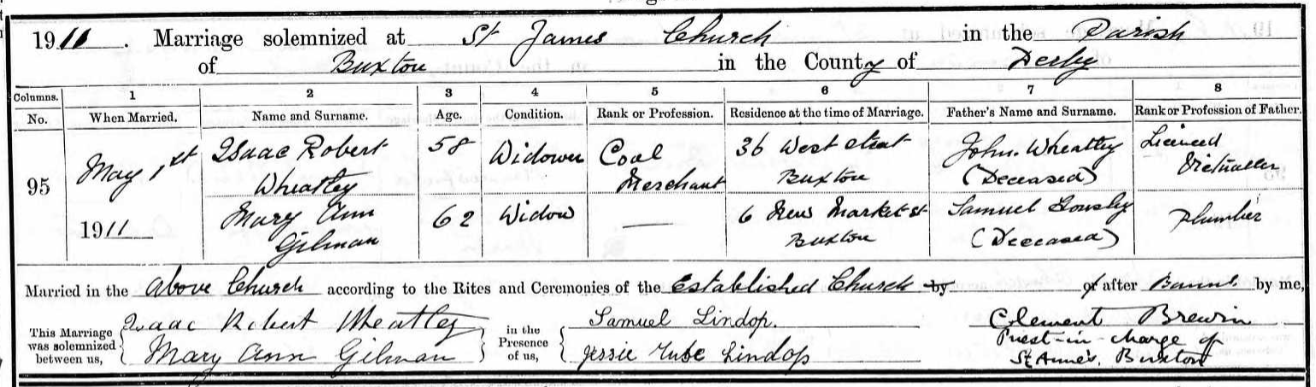

Marriage of Solomon Stubbs and Charlotte Bell, father Samuel Stubbs buckle maker:

A rudimentary search on buckle making in the late 1700s provided a possible answer as to why Samuel and Rebecca left Darlaston in 1781. Shoe buckles had gone out of fashion, and by 1781 there were half as many buckle makers in Wolverhampton as there had been previously.

“Where there were 127 buckle makers at work in Wolverhampton, 68 in Bilston and 58 in Birmingham in 1770, their numbers had halved in 1781.”

via “historywebsite”(museum/metalware/steel)

Steel buckles had been the height of fashion, and the trade became enormous in Wolverhampton. Wolverhampton was a steel working town, renowned for its steel jewellery which was probably of many types. The trade directories show great numbers of “buckle makers”. Steel buckles were predominantly made in Wolverhampton: “from the late 1760s cut steel comes to the fore, from the thriving industry of the Wolverhampton area”. Bilston was also a great centre of buckle making, and other areas included Walsall. (It should be noted that Darlaston, Walsall, Bilston and Wolverhampton are all part of the same area)

In 1860, writing in defence of the Wolverhampton Art School, George Wallis talks about the cut steel industry in Wolverhampton. Referring to “the fine steel workers of the 17th and 18th centuries” he says: “Let them remember that 100 years ago [sc. c. 1760] a large trade existed with France and Spain in the fine steel goods of Birmingham and Wolverhampton, of which the latter were always allowed to be the best both in taste and workmanship. … A century ago French and Spanish merchants had their houses and agencies at Birmingham for the purchase of the steel goods of Wolverhampton…..The Great Revolution in France put an end to the demand for fine steel goods for a time and hostile tariffs finished what revolution began”.

The next search on buckle makers, Wolverhampton and Hamstall Ridware revealed an unexpected connecting link.

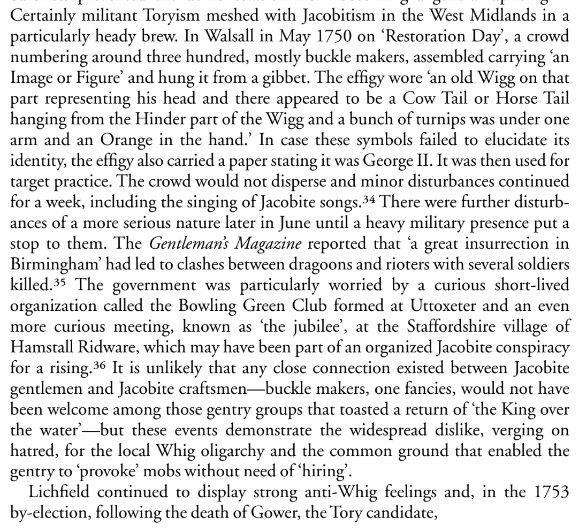

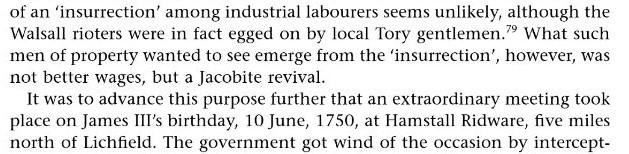

In Riotous Assemblies: Popular Protest in Hanoverian England by Adrian Randall:

In Walsall in 1750 on “Restoration Day” a crowd numbering 300 assembled, mostly buckle makers, singing Jacobite songs and other rebellious and riotous acts. The government was particularly worried about a curious meeting known as the “Jubilee” in Hamstall Ridware, which may have been part of a conspiracy for a Jacobite uprising.