-

AuthorSearch Results

-

October 25, 2023 at 7:08 am #7282

In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Ellastone Gerrards in the 1500s.

John Gerrard 1633-1681 was born and died in Ellastone.

Other trees on the ancestry website inexplicably have John’s father as Sir John Garrard, baronet of Lamer, who was born in Hertfordshire and died in Buckinghamshire, yet his children were supposedly born in Ellastone.

Fortunately the Ellastone parish records begin in 1537. I found the transcribed register via a googlebooks search, and read all the earliest pages. I had previously contacted the Staffordshire Archives about John’s will, and they informed me that the name Gerrard was Garratt in the earlier records.

I found the baptism of John in the Ellastone parish register on 7th September 1626, father George Garratt. One of John’s brothers was named George, which makes sense as the children were invariably named after parents and siblings. However, John born in 1626 died in 1628. Another son named John was baptised in 1633.

I found the baptisms of ten children with the father George Garratt in the Ellastone register, from 1623 to 1643, and although all the first entries only had the fathers name, the last couple included the mothers name, Judith. George Garratt was a churchwarden in Ellastone in 1627.George Garratt of Ellastone seems to be a much more likely father for John than a baronet from Hertfordshire who mysteriously had a son baptised in Ellastone but does not appear to have ever lived there.

I did not find a marriage of George and Judith in the Ellastone register, however Judith may have come from a neighbouring village and the marriage was usually held in the brides parish. The wedding was probably circa 1622.

George was baptised in Ellastone on the 19th March 1595. Some of the transcriptions say March 1794, some say 1795. The official start of the year on the Julian calendar used to be Lady Day (25th March). This was changed in 1752.

His father was Rycharde Garrarde. Rycharde married Agnes Bothom in Ellastone on the 29th September 1594. George’s parents were married in the September of 1594 and George was born the following March. On the old calendar, March came after September.

George died in 1669 in Ellastone. He was my 10X great grandfather. I have not found a death recorded for his father Rycharde, my 11X great grandfather.

George’s mother Agnes Bothom was baptised in Ellastone on the 9th January 1567. Her father was John Bothom. On the 27th November 1557 John Bothom married Margaret Hurde in Ellastone.

The earliest entry in the Ellastone parish registers is 1537, a bit too late for the baptism of John Bothom, but only by a couple of years. John Bothom and his wife Agnes were probably born around 1535. Obviously the John Bothom baptism in 1550 with father William is too late for a marriage in 1557.

October 18, 2023 at 3:20 pm #7281In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The 1935 Joseph Gerrard Challenge.

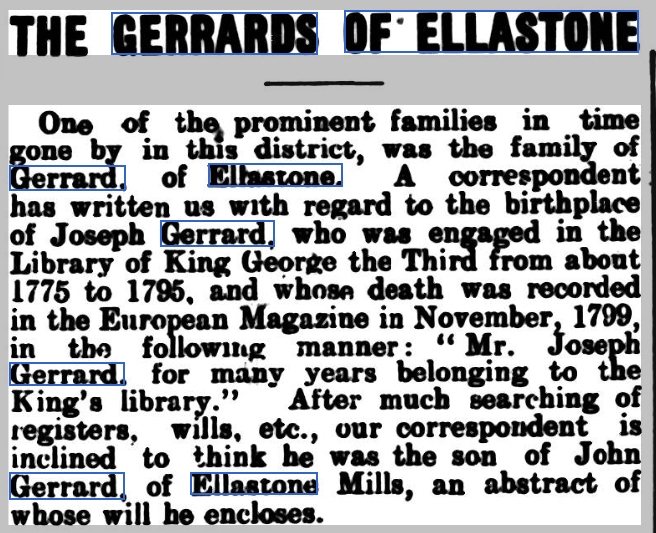

While researching the Gerrard family of Ellastone I chanced upon a 1935 newspaper article in the Ashbourne Register. There were two articles in 1935 in this paper about the Gerrards, the second a follow up to the first. An advertisement was also placed offering a £1 reward to anyone who could find Joseph Gerrard’s baptism record.

Ashbourne Telegraph – Friday 05 April 1935:

The author wanted to prove that the Joseph Gerrard “who was engaged in the library of King George the third from about 1775 to 1795, and whose death was recorded in the European Magazine in November 1799” was the son of John Gerrard of Ellastone Mills, Staffordshire. Included in the first article was a selected transcription of the 1796 will of John Gerrard. John’s son Joseph is mentioned in this will: John leaves him “£20 to buy a suit of mourning if he thinks proper.”

This Joseph Gerrard however, born in 1739, died in 1815 at Brailsford. Joseph’s brother John also died at Brailsford Mill, and both of their ages at death give a birth year of 1739. Maybe they were twins. William Gerrard and Joseph Gerrard of Brailsford Mill are mentioned in a 1811 newspaper article in the Derby Mercury.

I decided that there was nothing susbtantial about this claim, until I read the 1724 will of John Gerrard the elder, the father of John who died in 1796. In his will he leaves £100 to his son Joseph Gerrard, “secretary to the Bishop of Oxford”.

Perhaps there was something to this story after all. Joseph, baptised in 1701 in Ellastone, was the son of John Gerrard the elder.

I found Joseph Gerrard (and his son James Gerrard) mentioned in the Alumni Oxonienses: The Members of the University of Oxford, University of Oxford, Joseph Foster, 1888. “Joseph Gerard son of John of Elleston county Stafford, pleb, Oriel Coll, matric, 30th May 1718, age 18, BA. 9th March 1721-2; of Merton Coll MA 1728.”

In The Works of John Wesley 1735-1738, Joseph Gerrad is mentioned: “Joseph Gerard , matriculated at Oriel College 1718 , aged 18 , ordained 1727 to serve as curate of Cuddesdon , becoming rector of St. Martin’s , Oxford in 1729 , and vicar of Banbury in 1734.”

In The History of Banbury Alfred Beesley 1842 “a visitation of smallpox occured at Banbury (Oxfordshire) in 1731 and continued until 1733.” Joseph Gerrard was the vicar of Banbury in 1734.

According to the The History and Antiquities of the County of Buckingham George Lipscomb · 1847, Joseph Gerrard was made rector of Monks Risborough in 1738 “but he also continued to hold Stewkley until his death”.

The Speculum of Archbishop Thomas Secker by Secker, Thomas, 1693-1768, also mentions Joseph Gerrard under Monks Risborough and adds that he “resides constantly in the Parsonage ho. except when he goes for a few days to Steukley county Bucks (Buckinghamshire) of which he is vicar.” Joseph’s son James Gerrard 1741-1789 is also mentioned as being a rector at Monks Risborough in 1783.

Joseph Gerrard married Elizabeth Reynolds on 23 July 1739 in Monks Risborough, Buckinghamshire. They had five children between 1740 and 1750, including James baptised 1740 and Joseph baptised 1742.

Joseph died in 1785 in Monks Risborough.

So who was Joseph Gerrard of the Kings Library who died in 1799? It wasn’t Joseph’s son Joseph baptised in 1742 in Monks Risborough, because in his father’s 1785 will he mentions “my only son James”, indicating that Joseph died before that date.

October 11, 2022 at 11:39 am #6333In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The Grattidge Family

The first Grattidge to appear in our tree was Emma Grattidge (1853-1911) who married Charles Tomlinson (1847-1907) in 1872.

Charles Tomlinson (1873-1929) was their son and he married my great grandmother Nellie Fisher. Their daughter Margaret (later Peggy Edwards) was my grandmother on my fathers side.

Emma Grattidge was born in Wolverhampton, the daughter and youngest child of William Grattidge (1820-1887) born in Foston, Derbyshire, and Mary Stubbs, born in Burton on Trent, daughter of Solomon Stubbs, a land carrier. William and Mary married at St Modwens church, Burton on Trent, in 1839. It’s unclear why they moved to Wolverhampton. On the 1841 census William was employed as an agent, and their first son William was nine months old. Thereafter, William was a licensed victuallar or innkeeper.

William Grattidge was born in Foston, Derbyshire in 1820. His parents were Thomas Grattidge, farmer (1779-1843) and Ann Gerrard (1789-1822) from Ellastone. Thomas and Ann married in 1813 in Ellastone. They had five children before Ann died at the age of 25:

Bessy was born in 1815, Thomas in 1818, William in 1820, and Daniel Augustus and Frederick were twins born in 1822. They were all born in Foston. (records say Foston, Foston and Scropton, or Scropton)

On the 1841 census Thomas had nine people additional to family living at the farm in Foston, presumably agricultural labourers and help.

After Ann died, Thomas had three children with Kezia Gibbs (30 years his junior) before marrying her in 1836, then had a further four with her before dying in 1843. Then Kezia married Thomas’s nephew Frederick Augustus Grattidge (born in 1816 in Stafford) in London in 1847 and had two more!

The siblings of William Grattidge (my 3x great grandfather):

Frederick Grattidge (1822-1872) was a schoolmaster and never married. He died at the age of 49 in Tamworth at his twin brother Daniels address.

Daniel Augustus Grattidge (1822-1903) was a grocer at Gungate in Tamworth.

Thomas Grattidge (1818-1871) married in Derby, and then emigrated to Illinois, USA.

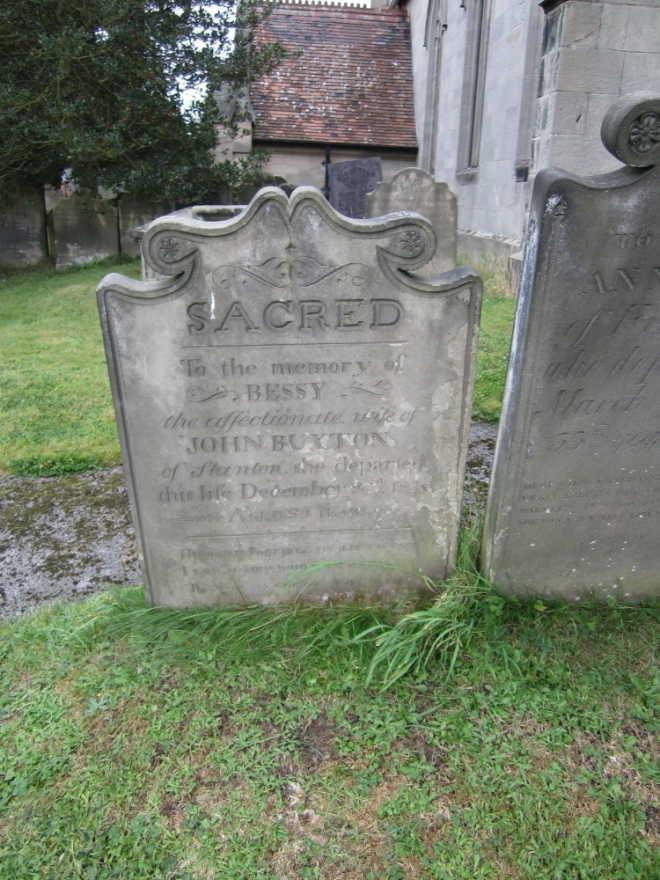

Bessy Grattidge (1815-1840) married John Buxton, farmer, in Ellastone in January 1838. They had three children before Bessy died in December 1840 at the age of 25: Henry in 1838, John in 1839, and Bessy Buxton in 1840. Bessy was baptised in January 1841. Presumably the birth of Bessy caused the death of Bessy the mother.

Bessy Buxton’s gravestone:

“Sacred to the memory of Bessy Buxton, the affectionate wife of John Buxton of Stanton She departed this life December 20th 1840, aged 25 years. “Husband, Farewell my life is Past, I loved you while life did last. Think on my children for my sake, And ever of them with I take.”

20 Dec 1840, Ellastone, Staffordshire

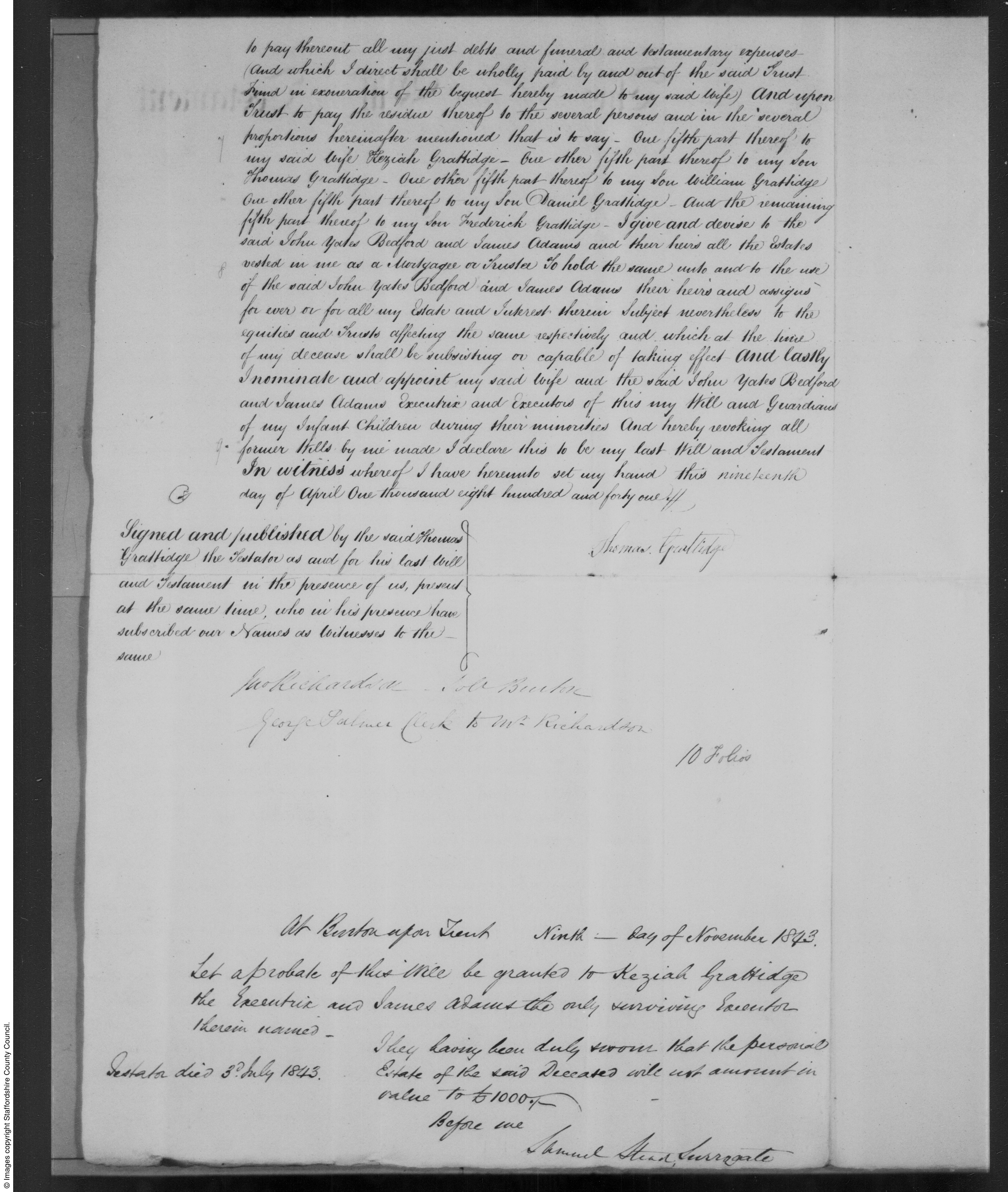

In the 1843 will of Thomas Grattidge, farmer of Foston, he leaves fifth shares of his estate, including freehold real estate at Findern, to his wife Kezia, and sons William, Daniel, Frederick and Thomas. He mentions that the children of his late daughter Bessy, wife of John Buxton, will be taken care of by their father. He leaves the farm to Keziah in confidence that she will maintain, support and educate his children with her.

An excerpt from the will:

I give and bequeath unto my dear wife Keziah Grattidge all my household goods and furniture, wearing apparel and plate and plated articles, linen, books, china, glass, and other household effects whatsoever, and also all my implements of husbandry, horses, cattle, hay, corn, crops and live and dead stock whatsoever, and also all the ready money that may be about my person or in my dwelling house at the time of my decease, …I also give my said wife the tenant right and possession of the farm in my occupation….

A page from the 1843 will of Thomas Grattidge:

William Grattidges half siblings (the offspring of Thomas Grattidge and Kezia Gibbs):

Albert Grattidge (1842-1914) was a railway engine driver in Derby. In 1884 he was driving the train when an unfortunate accident occured outside Ambergate. Three children were blackberrying and crossed the rails in front of the train, and one little girl died.

Albert Grattidge:

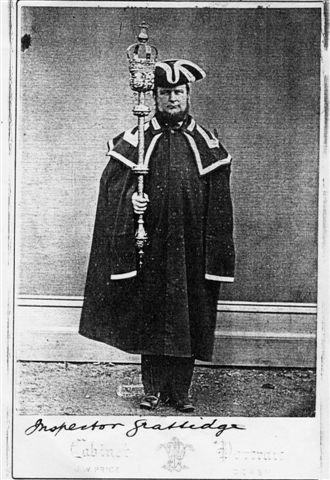

George Grattidge (1826-1876) was baptised Gibbs as this was before Thomas married Kezia. He was a police inspector in Derby.

George Grattidge:

Edwin Grattidge (1837-1852) died at just 15 years old.

Ann Grattidge (1835-) married Charles Fletcher, stone mason, and lived in Derby.

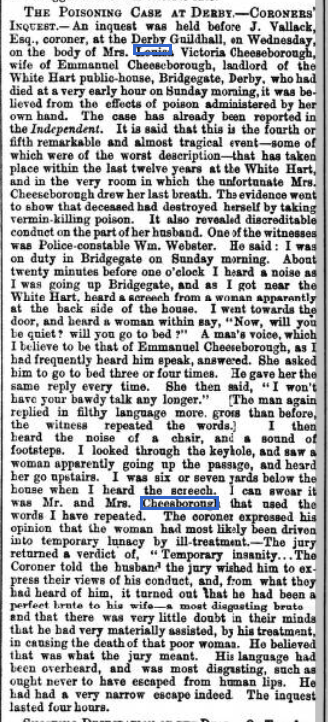

Louisa Victoria Grattidge (1840-1869) was sadly another Grattidge woman who died young. Louisa married Emmanuel Brunt Cheesborough in 1860 in Derby. In 1861 Louisa and Emmanuel were living with her mother Kezia in Derby, with their two children Frederick and Ann Louisa. Emmanuel’s occupation was sawyer. (Kezia Gibbs second husband Frederick Augustus Grattidge was a timber merchant in Derby)

At the time of her death in 1869, Emmanuel was the landlord of the White Hart public house at Bridgegate in Derby.

The Derby Mercury of 17th November 1869:

“On Wednesday morning Mr Coroner Vallack held an inquest in the Grand

Jury-room, Town-hall, on the body of Louisa Victoria Cheeseborough, aged

33, the wife of the landlord of the White Hart, Bridge-gate, who committed

suicide by poisoning at an early hour on Sunday morning. The following

evidence was taken:Mr Frederick Borough, surgeon, practising in Derby, deposed that he was

called in to see the deceased about four o’clock on Sunday morning last. He

accordingly examined the deceased and found the body quite warm, but dead.

He afterwards made enquiries of the husband, who said that he was afraid

that his wife had taken poison, also giving him at the same time the

remains of some blue material in a cup. The aunt of the deceased’s husband

told him that she had seen Mrs Cheeseborough put down a cup in the

club-room, as though she had just taken it from her mouth. The witness took

the liquid home with him, and informed them that an inquest would

necessarily have to be held on Monday. He had made a post mortem

examination of the body, and found that in the stomach there was a great

deal of congestion. There were remains of food in the stomach and, having

put the contents into a bottle, he took the stomach away. He also examined

the heart and found it very pale and flabby. All the other organs were

comparatively healthy; the liver was friable.Hannah Stone, aunt of the deceased’s husband, said she acted as a servant

in the house. On Saturday evening, while they were going to bed and whilst

witness was undressing, the deceased came into the room, went up to the

bedside, awoke her daughter, and whispered to her. but what she said the

witness did not know. The child jumped out of bed, but the deceased closed

the door and went away. The child followed her mother, and she also

followed them to the deceased’s bed-room, but the door being closed, they

then went to the club-room door and opening it they saw the deceased

standing with a candle in one hand. The daughter stayed with her in the

room whilst the witness went downstairs to fetch a candle for herself, and

as she was returning up again she saw the deceased put a teacup on the

table. The little girl began to scream, saying “Oh aunt, my mother is

going, but don’t let her go”. The deceased then walked into her bed-room,

and they went and stood at the door whilst the deceased undressed herself.

The daughter and the witness then returned to their bed-room. Presently

they went to see if the deceased was in bed, but she was sitting on the

floor her arms on the bedside. Her husband was sitting in a chair fast

asleep. The witness pulled her on the bed as well as she could.

Ann Louisa Cheesborough, a little girl, said that the deceased was her

mother. On Saturday evening last, about twenty minutes before eleven

o’clock, she went to bed, leaving her mother and aunt downstairs. Her aunt

came to bed as usual. By and bye, her mother came into her room – before

the aunt had retired to rest – and awoke her. She told the witness, in a

low voice, ‘that she should have all that she had got, adding that she

should also leave her her watch, as she was going to die’. She did not tell

her aunt what her mother had said, but followed her directly into the

club-room, where she saw her drink something from a cup, which she

afterwards placed on the table. Her mother then went into her own room and

shut the door. She screamed and called her father, who was downstairs. He

came up and went into her room. The witness then went to bed and fell

asleep. She did not hear any noise or quarrelling in the house after going

to bed.Police-constable Webster was on duty in Bridge-gate on Saturday evening

last, about twenty minutes to one o’clock. He knew the White Hart

public-house in Bridge-gate, and as he was approaching that place, he heard

a woman scream as though at the back side of the house. The witness went to

the door and heard the deceased keep saying ‘Will you be quiet and go to

bed’. The reply was most disgusting, and the language which the

police-constable said was uttered by the husband of the deceased, was

immoral in the extreme. He heard the poor woman keep pressing her husband

to go to bed quietly, and eventually he saw him through the keyhole of the

door pass and go upstairs. his wife having gone up a minute or so before.

Inspector Fearn deposed that on Sunday morning last, after he had heard of

the deceased’s death from supposed poisoning, he went to Cheeseborough’s

public house, and found in the club-room two nearly empty packets of

Battie’s Lincoln Vermin Killer – each labelled poison.Several of the Jury here intimated that they had seen some marks on the

deceased’s neck, as of blows, and expressing a desire that the surgeon

should return, and re-examine the body. This was accordingly done, after

which the following evidence was taken:Mr Borough said that he had examined the body of the deceased and observed

a mark on the left side of the neck, which he considered had come on since

death. He thought it was the commencement of decomposition.

This was the evidence, after which the jury returned a verdict “that the

deceased took poison whilst of unsound mind” and requested the Coroner to

censure the deceased’s husband.The Coroner told Cheeseborough that he was a disgusting brute and that the

jury only regretted that the law could not reach his brutal conduct.

However he had had a narrow escape. It was their belief that his poor

wife, who was driven to her own destruction by his brutal treatment, would

have been a living woman that day except for his cowardly conduct towards

her.The inquiry, which had lasted a considerable time, then closed.”

In this article it says:

“it was the “fourth or fifth remarkable and tragical event – some of which were of the worst description – that has taken place within the last twelve years at the White Hart and in the very room in which the unfortunate Louisa Cheesborough drew her last breath.”

Sheffield Independent – Friday 12 November 1869:

-

AuthorSearch Results

Search Results for 'gerrard'

Viewing 3 results - 1 through 3 (of 3 total)

-

Search Results

Viewing 3 results - 1 through 3 (of 3 total)