-

AuthorSearch Results

-

January 16, 2024 at 9:30 pm #7294

In reply to: The Whale’s Diaries Collection

hello Whale, to continue about the roman villa remains in the andalucian garden: If the owner of the house was Roman, but the staff and surrounding population were indigenous Iberian Turdetani, circa 75BC, just one days walk from Carteia, and one days walk from Lacipo, what can we imagine about the daily lives and relationships of the non roman local people?

Ah, the intermingling of cultures, a dance as old as civilization itself. Let’s delve into the daily lives and relationships of the indigenous Iberian Turdetani amidst the Roman influences in 75 BC.

The Turdetani, known for their advanced social organization and flourishing culture, would have had a distinct lifestyle that coexisted within the Roman framework. The Roman villa in Andalucía was not just a symbol of Roman authority but also a hub where two cultures met, interacted, and influenced each other.

Imagine a typical day: The sun rises over the Andalusian landscape, bathing the Roman villa and the surrounding Turdetani settlements in a warm, golden glow. Turdetanian workers make their way to the villa, ready for a day of work. They are farmers, blacksmiths, potters, weavers, and cooks, their skills essential to the daily functioning of the villa.

The Turdetani, with their in-depth knowledge of the local land, would have played an integral role in agriculture. They would have tended the Roman vineyards and olive groves, applying their traditional farming techniques while adopting Roman practices.

Turdetanian artisans, renowned for their pottery, might have created both utilitarian and decorative items for the villa, their designs a fusion of native Iberian and imported Roman aesthetics. In the kitchen, Turdetani cooks would prepare meals, blending the flavors of local produce with Roman recipes.

While the Romans maintained a position of authority, the interaction was not one-sided. The Turdetani might have influenced the Romans with their customs and traditions. Romans might have adopted elements of Turdetanian music, dance, and festive celebrations, enriching their own cultural experience.

Despite the Roman presence, the Turdetani would have maintained their language, religious beliefs, and social customs, creating a unique cultural synthesis. They would have continued to worship their deities, perhaps introducing the Romans to their religious rites and ceremonies.

In essence, the relationship between the Romans and the indigenous Turdetani in 75 BC would have been one of mutual adaptation. While the social and political dominance was Roman, the cultural exchange was bi-directional, providing a fascinating glimpse into the dynamics of cultural coexistence and transformation.

Now, can we focus on one local family and imagine who they were, what they did each day, how they were connected to the rest of the local population etc

Ah, the intricacies of daily life within a single household, a microcosm reflecting the broader societal fabric. Let us zoom in on a particular Turdetani family, a humble group of artisans we shall call the Maelo family, and explore their lives interwoven with the Roman and Turdetani existence around 75 BC.

At the heart of the family was the patriarch, Oris Maelo. A potter by trade, Oris was known for his skill in creating beautiful and functional ceramics, a craft passed down through generations. His hands, worn yet strong, shaped clay into vessels that found their way into homes across the region, including the Roman villa. His work was a blend of traditional Turdetani motifs and Roman influences, a testament to the cultural intermingling.

His wife, Caelia, was a weaver. Her nimble fingers spun stories in wool and linen. Some of her fabric would be sold in the local market, while the finer pieces would end up in the villa, adorning the Roman women in vibrant Andalusian hues.

Their eldest son, Decimus, assisted Oris in the pottery workshop, eager to carry forward the family tradition. Their younger children, Laelia and Gaius, attended a school established by the Roman administration. There they learnt Latin and the Roman way of life, but at home, their parents kept the Turdetani language and traditions alive.

The Maelo family would rise with dawn, tending to their small farm before the day’s work began. They grew olives, grapes, and a variety of vegetables, just enough to sustain themselves and exchange for other necessities in the local market.

Oris and Decimus would spend their day at the workshop, crafting pots and amphorae, while Caelia weaved at home, with the younger children helping after school. Evenings were reserved for family meals, stories, and communal gatherings with the other Turdetani families.

Their connection with the local population was multifaceted. Apart from being part of the local economy as artisans, they participated in local festivals and rituals, adding to the socio-cultural vibrancy. Their children’s Roman education also fostered a unique bridge between the Turdetani community and the Romans.

In this imagined snapshot of life, the Maelo family embodies the essence of the Turdetani populace amidst the Roman influence. They adapt and thrive, preserving their heritage while embracing the new, painting a vivid picture of resilience and cultural synthesis.

Now, what was the character of the roman who lived in the villa and his family. Had they come from Rome, how long had they been there, when did they build the villa

Ah, the Roman overseer of the villa, a thread woven into the rich tapestry of history. Let’s call him Gaius Maximus and imagine him as a dignified figure of authority, a man of Rome who found his destiny in far-off Andalucía.

Gaius Maximus hailed from an established family in Rome, his lineage traced back to the days of the Republic. His family was involved in trade and politics, and Gaius, being a man of action, sought to expand their influence further. Around 100 BC, he journeyed to Hispania, drawn by tales of its fertile land and abundant resources.

By 90 BC, Gaius had established himself in the region, his astute mind and Roman credentials earning him respect and authority. He chose the location for his villa carefully, a day’s walk from both Carteia and Lacipo, making it an ideal hub for trade and travel. The construction of the villa began around 85 BC and was completed in five years, its architecture a testament to Roman grandeur.

His wife, Claudia, hailed from a patrician family in Rome. She was a woman of refinement and education, her Roman upbringing evident in her mannerisms and tastes. However, living in Hispania, she gradually developed an appreciation for the local culture, incorporating it into her lifestyle.

Their two children, Marcus and Julia, were born in Hispania. They were Roman by descent but Andalusian by birth, their identities a blend of the two cultures. Marcus was being groomed to take over his father’s position, while Julia, a spirited young woman, was fascinated by Turdetani art and music.

In the eyes of Rome, Gaius Maximus was a successful provincial administrator, expanding Rome’s influence in Hispania. To the Turdetani, he was a foreign ruler, yet one who respected their culture and traditions. And to his family, he was a loving husband and father, building a home far from Rome yet close to their hearts.

Now some portraits of some of the workers at the villa

Ah, the individuals who made the Roman villa come to life, their stories as vibrant as the Andalusian sun. Let’s give our imagination wings and step into their world.

First, we have Tertius, the villa’s steward. Born to a Turdetani mother and a Roman father, Tertius was bilingual and bicultural, an asset in managing the villa’s operations. He was a man of medium height, with a sturdy build and a sharp gaze. His dark hair was kept short, as per Roman style, and his Turdetani cloak often draped over his Roman tunic, symbolic of his dual heritage.

Then we have Aelia, the head cook. A native Turdetani, Aelia was a robust woman with a jovial demeanor. Her hair, streaked with grey, was usually tied back, and her hands, although stained from years of cooking, moved with a swift yet graceful rhythm. Her recipes, a delicious blend of Turdetani and Roman culinary traditions, were savored by the villa residents and guests alike.

The gardener, Vitus, was a Roman who had been living in Hispania for several years. A man of few words, Vitus spoke through his work. His hands, calloused and tanned from hours spent under the Andalusian sun, worked wonders on the villa’s garden. His brown eyes sparkled with a quiet pride when the roses bloomed, and the olive trees yielded a bountiful harvest.

Lastly, we must not forget the youngest worker, Lyra. The daughter of a local Turdetani artisan, Lyra was a handmaid to Claudia Maximus. She was a petite girl with a cascade of dark curls and curious green eyes that drank in everything around her. Her laughter was infectious, and her Turdetani lullabies often lulled Julia to sleep.

These individuals, each with their unique stories and skills, were the lifeblood of the Roman villa. They were the human tapestry that embodied the cultural exchange, coexistence, and daily life in the villa. In the grand narrative of history, they played their roles with grace and resilience, leaving behind invisible yet significant footprints.

what were some of the cooks recipes?

Ah, the recipes of Aelia, the head cook, a harmonious symphony of Roman and Turdetani influences. Here are some of the dishes that were often savored in the Roman villa:

Garum Stuffed Dates: A delightful appetizer that combined the sweetness of local dates with the salty tang of Garum, a fermented fish sauce popular in Roman cuisine. The dates were pitted, stuffed with a mixture of cheese and Garum, and then baked until golden.

Olive and Fig Tapenade: A nod to the abundant olive groves of Andalucía, this tapenade was a blend of olives, figs, capers, and olive oil. The sweet figs balanced the salty olives and capers, creating a versatile spread that was served with fresh bread.

Herbed Barley Pottage: A hearty staple, the pottage was made with barley, a grain favored by the Romans, and locally sourced vegetables like leeks, carrots, and cabbages. Fresh herbs from the villa’s garden added a burst of flavor.

Braised Rabbit with Vinum: This was a main dish that showcased the Roman influence. Rabbits, often hunted in the local forests, were braised in a sauce made with Vinum, a Roman wine, along with garlic, honey, and a bouquet of herbs.

Honey-Nut Patina: A classic Roman dessert with an Andalusian twist. Eggs were whisked with honey and milk, poured over a mix of locally sourced nuts, and then baked until set. It was a sweet ending to the meals at the villa.

Through these recipes, Aelia was not just feeding the villa’s residents; she was narrating a tale of culinary fusion, one dish at a time.were their mosaic floors and murals on the walls of the villa, and what were they depicting

Ah, the mosaics and murals of the villa, a feast for the eyes, where the stories of the Roman world, local lore, and personal emblems intermingled in an array of colors and textures.

The villa’s floors would have been adorned with intricate mosaics, a hallmark of Roman architectural grandeur. Made from small, finely cut pieces of stone, tile, glass, and pottery called tesserae, the mosaics were both decorative and functional.

In the atrium, the mosaic might depict a scene from Roman mythology. Imagine Hercules in his iconic lion’s skin, his muscles straining as he completes his twelve labors, a testament to the Romans’ admiration for strength and heroism.

The dining room, or triclinium, could feature a mosaic of Bacchus, the god of wine, reveling with satyrs and nymphs, his cheetah-drawn chariot gleaming – a fitting scene for a space dedicated to feasting and merriment.

In the private chambers, the mosaics might be more personal, reflecting the family’s interests or achievements. Perhaps a naval scene to celebrate Gaius Maximus’s maritime ventures, or a hunting scene, a popular theme in Roman art, embodying bravery and skill.

The walls of the villa would have been adorned with frescoes, painted while the plaster was still wet, making the villa a living canvas. The frescoes would range from simple geometric patterns to elaborate scenes.

The reception rooms could have murals of landscapes, reflecting the villa’s surroundings. Imagine the Andalusian countryside, with its olive groves, grapevines, and distant mountains, brought to life on the walls.

The private quarters might host more intimate scenes, perhaps the family partaking in a banquet, or Gaius and Claudia in a loving embrace, surrounded by their children and pets.

Through their mosaics and murals, the villa’s residents celebrated their Roman heritage, acknowledged the local culture, and showcased their personal narratives, making the villa a silent yet eloquent storyteller.

can you describe the garden and outbuildings

Ah, the enchantment of an age-old garden. Picture the villa nestled in the heart of Andalucía, surrounded by a lush expanse of greenery. Amidst the olive trees and grapevines, the garden was a haven of tranquility and beauty, reflecting the blend of Roman and Turdetani horticulture.

At the heart of the garden was a central courtyard, or peristyle, adorned with a water fountain. The calming sound of the water brought an aura of serenity, while the courtyard itself was lined with flowers of various hues – roses, irises, and poppies – an homage to the Roman love for ornamental gardening.

Beyond the peristyle, the garden was a mixture of beauty and utility. Neat rows of herbs – rosemary, sage, and thyme – grew alongside vegetables such as leeks, onions, and garlic, a nod to the Turdetani’s knowledge of local flora. Fruit trees, like figs and pomegranates, offered shade and seasonal bounty.

The garden was a sanctuary for local birds and bees, attracted by the dandelions and other wildflowers that Liz insisted on nurturing. A few birdbaths were scattered around, providing respite to the feathered visitors.

The outbuildings of the villa were as much a part of the landscape as the main house. Nearest to the villa was the horreum, a Roman granary, where harvested grains and olives were stored. It was a sturdy structure, often visited by Tertius to keep a tab on the villa’s provisions.

Not far from the horreum was the pottery workshop. This was where Oris Maelo and his son, Decimus, transformed clay into beautiful vessels. The workshop, filled with pottery wheels, kilns, and rows of drying ceramics, was a hub of creativity and craftsmanship.

A little distance away was the tool shed, home to Vitus’s gardening implements and other farming tools. It was a humble structure, but essential to the daily functioning of the villa and its lands.

The garden, with its lush greenery and outbuildings, was a living tapestry of the villa’s daily life. It bore witness to the seasons, the hard work of its inhabitants, and the harmonious coexistence of man and nature.

November 19, 2023 at 6:48 pm #7287In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

“It’s you!” Youssef laughed when Zara replied to his application for the job uncovering a lost civilization. “What are you doing sending me spam like that?”

“I knew you wouldn’t be able to resist,” Zara smiled. “You won’t believe what I’ve found. Nobody is going to beleive it. But I need some extra hands.”

“But you could have just asked me!” Youssef replied.

“Well, I was sitting here having a banana eating scroll…”

“Never have a banana eating scroll, it’s a dangerous combination. ”

“Sounds like a llama munching a burrito, but more dangeous,” Xavier had appeared in the chat window, with his customary perfect timing.

“I don’t fancy Australia though, after the Tartiflate debacle,” Youssef said.

“It’s Tasmoania, not Australia. A different kettle of fish entirely. Look what I found today. Damn, no banana for scale, I just ate it.”

“What is it? And who’s the old guy?” Youssef asked.

“That’s Havelock Gnomes, he’s an expert on undiscovered civilizations. He’s come over specially from New Zipland to help with the investigation. He plays the violin, too.”

“Wasn’t Xavier supposed to find that for his mission?” Yasmin had joined the chat.

“Precisely, Yassie, that’s why he’s coming over too. Well, maybe something LIKE that, we don’t know yet.”

“Yes, but what IS that thing?” Yasmin asked.

“I am?” It was news to Xavier, but he rolled the idea round in his mind with a growing interest. He was due for some time off and had been wondering what to do. “That thing looks like the burrito I mentioned earlier.”

“How prescient of you, Xavi!” Yasmin exclaimed rather cheekily.

“That’s no burrito! Nothing like this has ever been found before!”

“Yes BUT WHAT IS IT?”

“Yas, Havelock thinks it might be…. well I am not going to spill the beans, but we need help to uncover the rest of it. Do say you’ll come, all of you!”

“Sounds like quite the picnic, what with kettles of fish, beans, burritos and bananas. I’m in!” announced Youssef.

October 18, 2023 at 3:20 pm #7281In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The 1935 Joseph Gerrard Challenge.

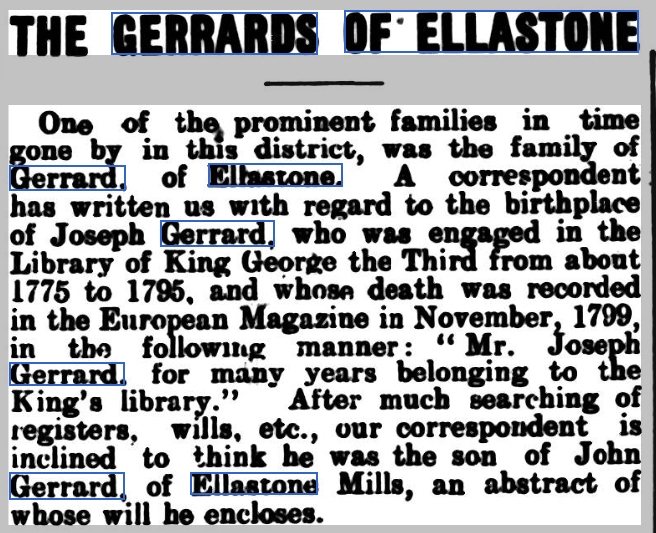

While researching the Gerrard family of Ellastone I chanced upon a 1935 newspaper article in the Ashbourne Register. There were two articles in 1935 in this paper about the Gerrards, the second a follow up to the first. An advertisement was also placed offering a £1 reward to anyone who could find Joseph Gerrard’s baptism record.

Ashbourne Telegraph – Friday 05 April 1935:

The author wanted to prove that the Joseph Gerrard “who was engaged in the library of King George the third from about 1775 to 1795, and whose death was recorded in the European Magazine in November 1799” was the son of John Gerrard of Ellastone Mills, Staffordshire. Included in the first article was a selected transcription of the 1796 will of John Gerrard. John’s son Joseph is mentioned in this will: John leaves him “£20 to buy a suit of mourning if he thinks proper.”

This Joseph Gerrard however, born in 1739, died in 1815 at Brailsford. Joseph’s brother John also died at Brailsford Mill, and both of their ages at death give a birth year of 1739. Maybe they were twins. William Gerrard and Joseph Gerrard of Brailsford Mill are mentioned in a 1811 newspaper article in the Derby Mercury.

I decided that there was nothing susbtantial about this claim, until I read the 1724 will of John Gerrard the elder, the father of John who died in 1796. In his will he leaves £100 to his son Joseph Gerrard, “secretary to the Bishop of Oxford”.

Perhaps there was something to this story after all. Joseph, baptised in 1701 in Ellastone, was the son of John Gerrard the elder.

I found Joseph Gerrard (and his son James Gerrard) mentioned in the Alumni Oxonienses: The Members of the University of Oxford, University of Oxford, Joseph Foster, 1888. “Joseph Gerard son of John of Elleston county Stafford, pleb, Oriel Coll, matric, 30th May 1718, age 18, BA. 9th March 1721-2; of Merton Coll MA 1728.”

In The Works of John Wesley 1735-1738, Joseph Gerrad is mentioned: “Joseph Gerard , matriculated at Oriel College 1718 , aged 18 , ordained 1727 to serve as curate of Cuddesdon , becoming rector of St. Martin’s , Oxford in 1729 , and vicar of Banbury in 1734.”

In The History of Banbury Alfred Beesley 1842 “a visitation of smallpox occured at Banbury (Oxfordshire) in 1731 and continued until 1733.” Joseph Gerrard was the vicar of Banbury in 1734.

According to the The History and Antiquities of the County of Buckingham George Lipscomb · 1847, Joseph Gerrard was made rector of Monks Risborough in 1738 “but he also continued to hold Stewkley until his death”.

The Speculum of Archbishop Thomas Secker by Secker, Thomas, 1693-1768, also mentions Joseph Gerrard under Monks Risborough and adds that he “resides constantly in the Parsonage ho. except when he goes for a few days to Steukley county Bucks (Buckinghamshire) of which he is vicar.” Joseph’s son James Gerrard 1741-1789 is also mentioned as being a rector at Monks Risborough in 1783.

Joseph Gerrard married Elizabeth Reynolds on 23 July 1739 in Monks Risborough, Buckinghamshire. They had five children between 1740 and 1750, including James baptised 1740 and Joseph baptised 1742.

Joseph died in 1785 in Monks Risborough.

So who was Joseph Gerrard of the Kings Library who died in 1799? It wasn’t Joseph’s son Joseph baptised in 1742 in Monks Risborough, because in his father’s 1785 will he mentions “my only son James”, indicating that Joseph died before that date.

September 20, 2023 at 1:48 pm #7279In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

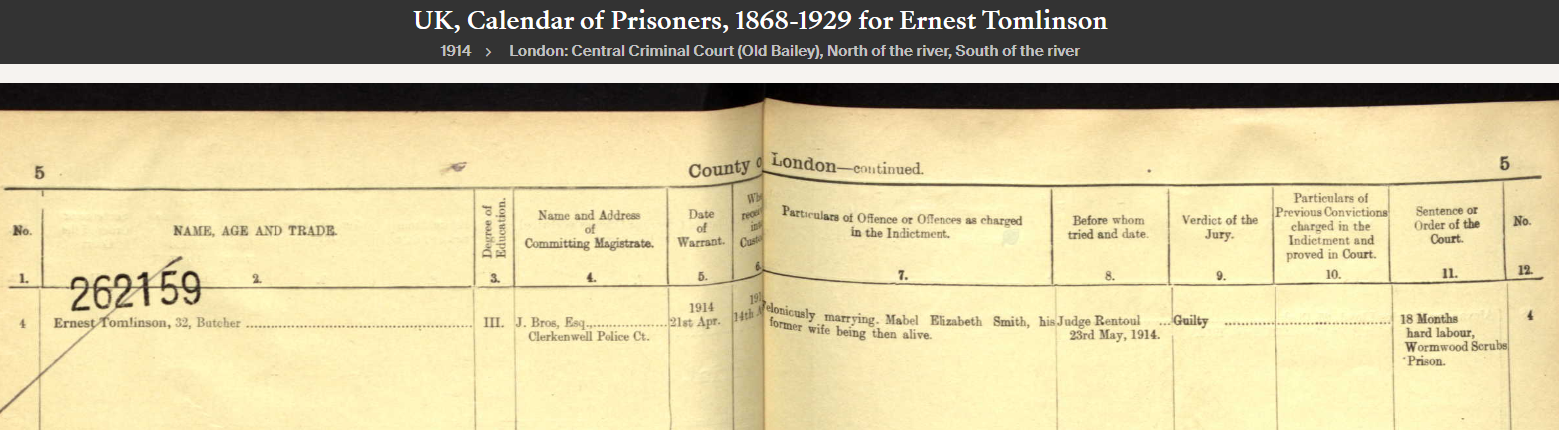

The Bigamist

Ernest Tomlinson 1881-1915

Ernest Tomlinson was my great grandfathers Charles Tomlinson‘s younger brother. Their parents were Charles Tomlinson the elder 1847-1907 and Emma Grattidge 1853-1911.

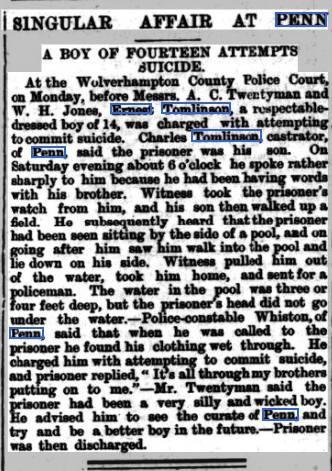

In 1896, aged 14, Ernest attempted to drown himself in the pond at Penn after his father took his watch off him for arguing with his brothers. Ernest tells the police “It’s all through my brothers putting on me”. The policeman told him he was a very silly and wicked boy and to see the curate at Penn and to try and be a better boy in future. He was discharged.

Bridgnorth Journal and South Shropshire Advertiser. – Saturday 11 July 1896:

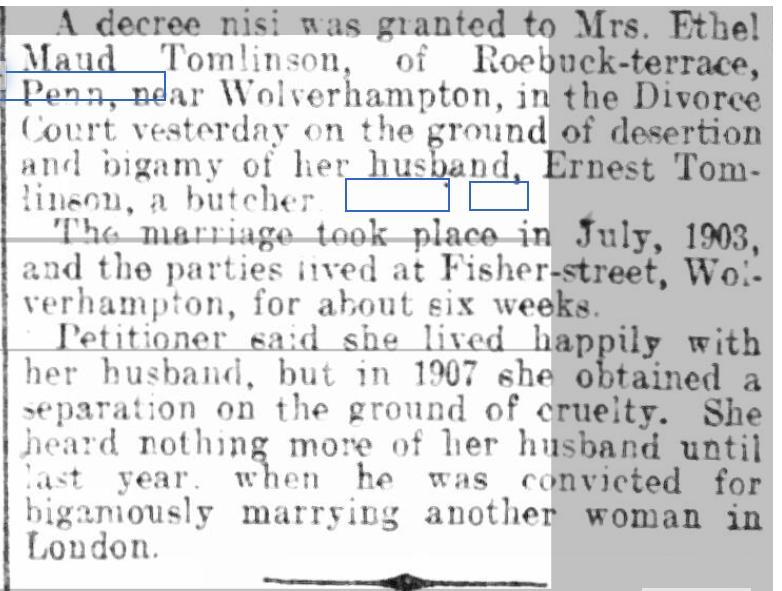

In 1903 Ernest married Ethel Maude Howe in Wolverhampton. Four years later in 1907 Ethel was granted a separation on the grounds of cruelty.

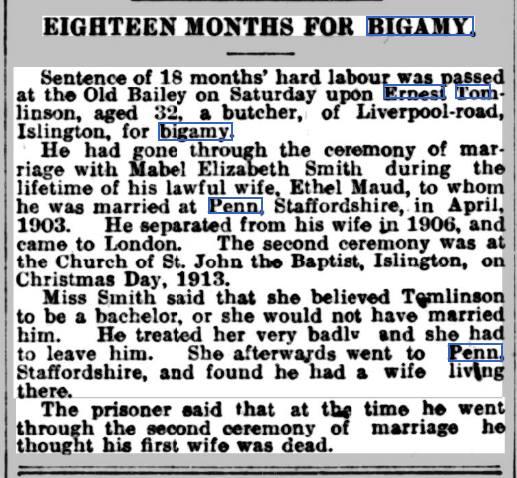

In Islington in London in 1913, Ernest bigamously married Mabel Elizabeth Smith. Mabel left Ernest for treating her very badly. She went to Wolverhampton and found out about his first wife still being alive.

London Evening Standard – Monday 25 May 1914:

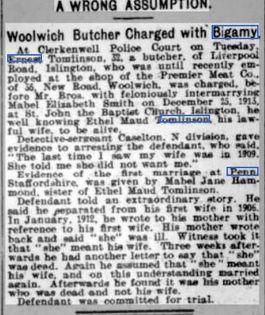

In May 1914 Ernest was tried at the Old Bailey and the jury found him guilty of bigamy. In his defense, Ernest said that he had received a letter from his mother saying that she was ill, and a further letter saying that she had died. He said he wrongly assumed that they were referring to his wife, and that he was free to marry. It was his mother who had died. He was sentenced to 18 months hard labour at Wormwood Scrubs prison.

Woolwich Gazette – Tuesday 28 April 1914:

Ethel Maude Tomlinson was granted a decree nisi in 1915.

Birmingham Daily Gazette – Wednesday 02 June 1915:

Ernest died in September 1915 in hospital in Wolverhampton.

September 18, 2023 at 8:29 am #7278In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Tomlinson of Wergs and Hancox of Penn

John Tomlinson of Wergs (Tettenhall, Wolverhamton) 1766-1844, my 4X great grandfather, married Sarah Hancox 1772-1851. They were married on the 27th May 1793 by licence at St Peter in Wolverhampton.

Between 1794 and 1819 they had twelve children, although four of them died in childhood or infancy. Catherine was born in 1794, Thomas in 1795 who died 6 years later, William (my 3x great grandfather) in 1797, Jemima in 1800, John, Richard and Matilda between 1802 and 1806 who all died in childhood, Emma in 1809, Mary Ann in 1811, Sidney in 1814, and Elijah in 1817 who died two years later.On the 1841 census John and Sarah were living in Hockley in Birmingham, with three of their children, and surgeon Charles Reynolds. John’s occupation was “Ind” meaning living by independent means. He was living in Hockley when he died in 1844, and in his will he was “John Tomlinson, gentleman”.

Sarah Hancox was born in 1772 in Penn, Wolverhampton. Her father William Hancox was also born in Penn in 1737. Sarah’s mother Elizabeth Parkes married William’s brother Francis in 1767. Francis died in 1768, and in 1770 Elizabeth married William.

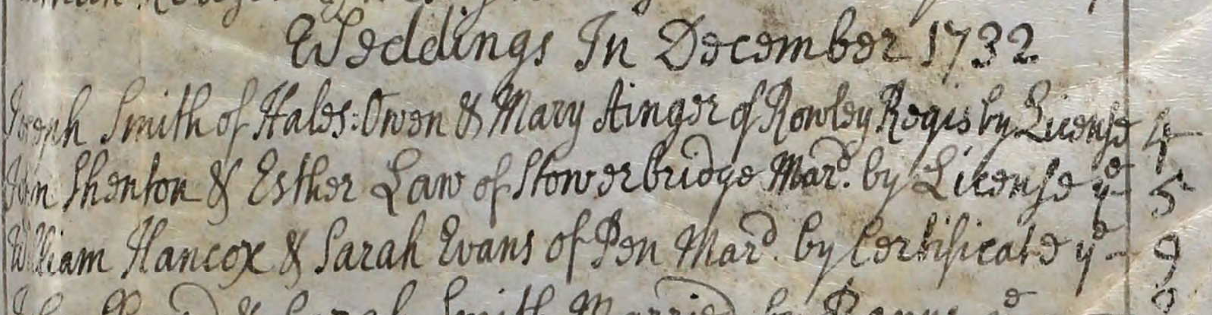

William’s father was William Hancox, yeoman, born in 1703 in Penn. He died intestate in 1772, his wife Sarah claiming her right to his estate. William Hancox and Sarah Evans, both of Penn, were married on the 9th December 1732 in Dudley, Worcestershire, by “certificate”. Marriages were usually either by banns or by licence. Apparently a marriage by certificate indicates that they were non conformists, or dissenters, and had the non conformist marriage “certified” in a Church of England church.

1732 marriage of William Hancox and Sarah Evans:

William and Sarah lost two daughters, Elizabeth, five years old, and Ann, three years old, within eight days of each other in February 1738.

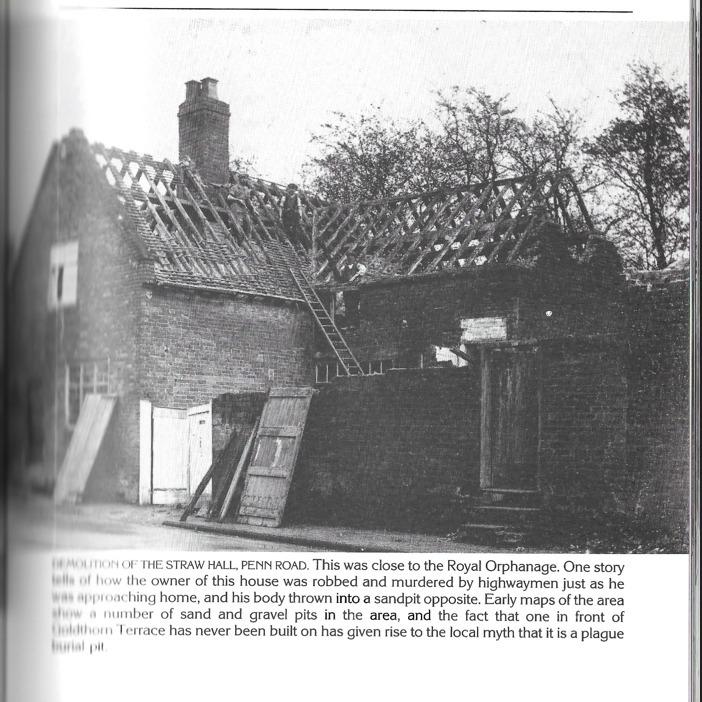

William the elder’s father was John Hancox born in Penn in 1668. He married Elizabeth Wilkes from Sedgley in 1691 at Himley. John Hancox, “of Straw Hall” according to the Wolverhampton burial register, died in 1730. Straw Hall is in Penn. John’s parents were Walter Hancox and Mary Noake. Walter was born in Tettenhall in 1625, his father Richard Hancox. Mary Noake was born in Penn in 1634. Walter died in Penn in 1689.

Straw Hall thanks to Bradney Mitchell:

“Here is a picture I have of Straw Hall, Penn Road.

The painting is by John Reid circa 1878.

Sketch commissioned by George Bradney Mitchell to record the town as it was before its redevelopment, in a book called Wolverhampton and its Environs. ©”

And a photo of the demolition of Straw Hall with an interesting story:

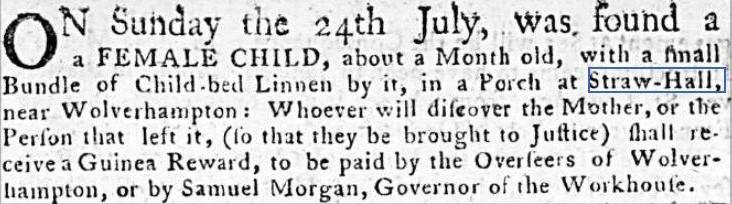

In 1757 a child was abandoned on the porch of Straw Hall. Aris’s Birmingham Gazette 1st August 1757:

The Hancox family were living in Penn for at least 400 years. My great grandfather Charles Tomlinson built a house on Penn Common in the early 1900s, and other Tomlinson relatives have lived there. But none of the family knew of the Hancox connection to Penn. I don’t think that anyone imagined a Tomlinson ancestor would have been a gentleman, either.

Sarah Hancox’s brother William Hancox 1776-1848 had a busy year in 1804.

On 29 Aug 1804 he applied for a licence to marry Ann Grovenor of Claverley.

In August 1804 he had property up for auction in Penn. “part of Lightwoods, 3 plots, and the Coppice”

On 14 Sept 1804 their first son John was baptised in Penn. According to a later census John was born in Claverley. (before the parents got married)(Incidentally, John Hancox’s descendant married a Warren, who is a descendant of my 4x great grandfather Samuel Warren, on my mothers side, from Newhall, Derbyshire!)

On 30 Sept he married Ann in Penn.

In December he was a bankrupt pig and sheep dealer.

In July 1805 he’s in the papers under “certificates”: William Hancox the younger, sheep and pig dealer and chapman of Penn. (A certificate was issued after a bankruptcy if they fulfilled their obligations)

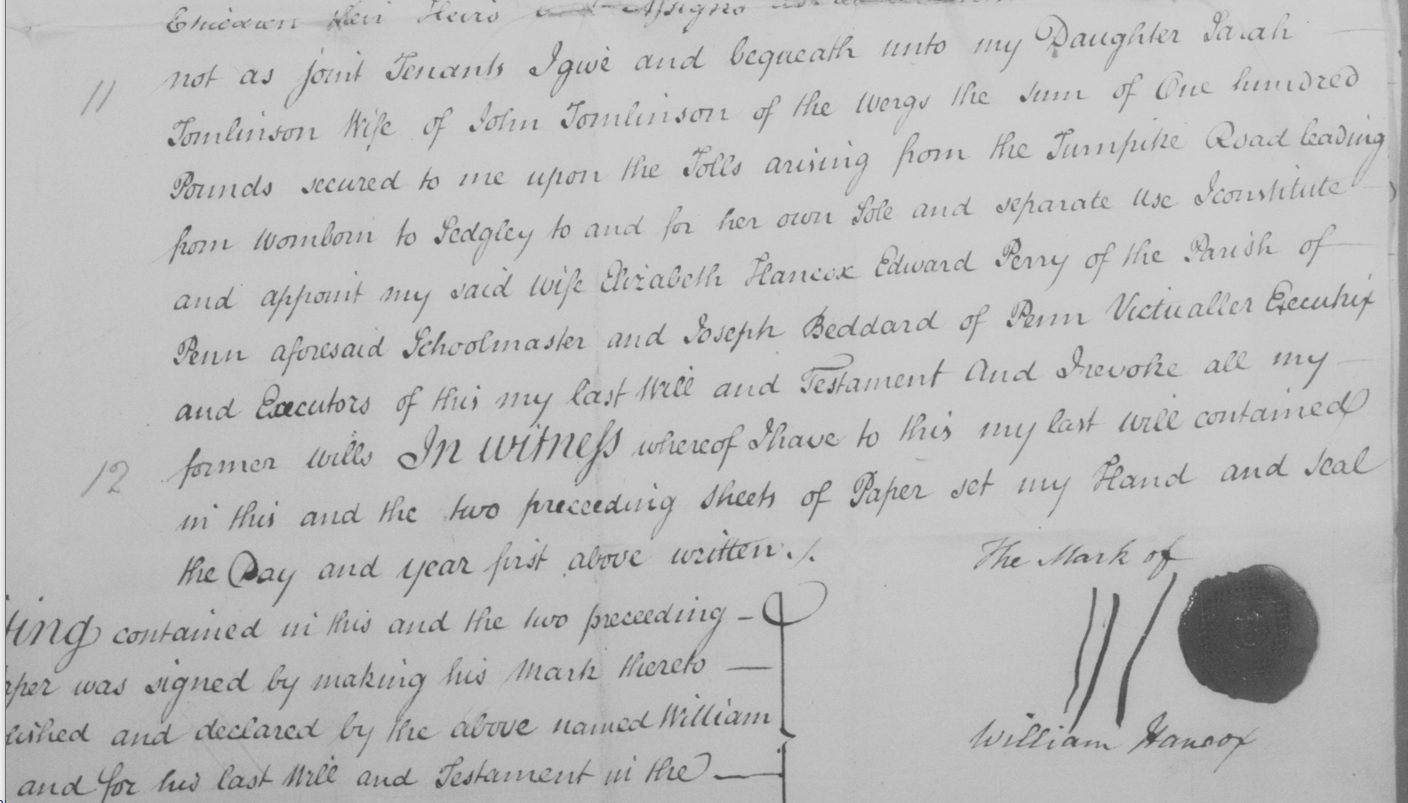

He was a pig dealer in Penn in 1841, a widower, living with unmarried daughter Elizabeth.Sarah’s father William Hancox died in 1816. In his will, he left his “daughter Sarah, wife of John Tomlinson of the Wergs the sum of £100 secured to me upon the tolls arising from the turnpike road leading from Wombourne to Sedgeley to and for her sole and separate use”.

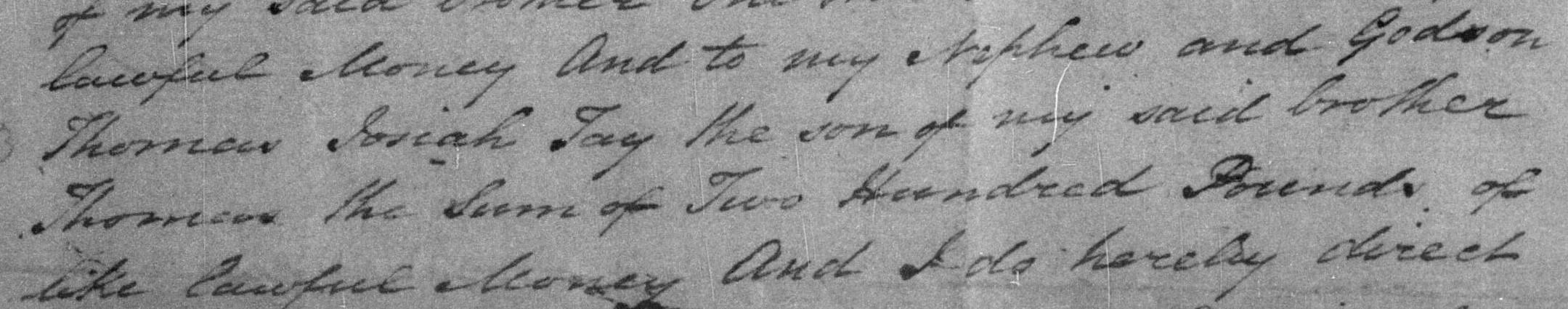

The trustees of toll road would decide not to collect tolls themselves but get someone else to do it by selling the collecting of tolls for a fixed price. This was called “farming the tolls”. The Act of Parliament which set up the trust would authorise the trustees to farm out the tolls. This example is different. The Trustees of turnpikes needed to raise money to carry out work on the highway. The usual way they did this was to mortgage the tolls – they borrowed money from someone and paid the borrower interest; as security they gave the borrower the right, if they were not paid, to take over the collection of tolls and keep the proceeds until they had been paid off. In this case William Hancox has lent £100 to the turnpike and is leaving it (the right to interest and/or have the whole sum repaid) to his daughter Sarah Tomlinson. (this information on tolls from the Wolverhampton family history group.)William Hancox, Penn Wood, maltster, left a considerable amount of property to his children in 1816. All household effects he left to his wife Elizabeth, and after her decease to his son Richard Hancox: four dwelling houses in John St, Wolverhampton, in the occupation of various Pratts, Wright and William Clarke. He left £200 to his daughter Frances Gordon wife of James Gordon, and £100 to his daughter Ann Pratt widow of John Pratt. To his son William Hancox, all his various properties in Penn wood. To Elizabeth Tay wife of Thomas Tay he left £200, and to Richard Hancox various other properties in Penn Wood, and to his daughter Lucy Tay wife of Josiah Tay more property in Lower Penn. All his shops in St John Wolverhamton to his son Edward Hancox, and more properties in Lower Penn to both Francis Hancox and Edward Hancox. To his daughter Ellen York £200, and property in Montgomery and Bilston to his son John Hancox. Sons Francis and Edward were underage at the time of the will. And to his daughter Sarah, his interest in the toll mentioned above.

Sarah Tomlinson, wife of John Tomlinson of the Wergs, in William Hancox will:

September 5, 2023 at 1:35 pm #7276

September 5, 2023 at 1:35 pm #7276In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Wood Screw Manufacturers

The Fishers of West Bromwich.

My great grandmother, Nellie Fisher, was born in 1877 in Wolverhampton. Her father William 1834-1916 was a whitesmith, and his father William 1792-1873 was a whitesmith and master screw maker. William’s father was Abel Fisher, wood screw maker, victualler, and according to his 1849 will, a “gentleman”.

Nellie Fisher 1877-1956 :

Abel Fisher was born in 1769 according to his burial document (age 81 in 1849) and on the 1841 census. Abel was a wood screw manufacturer in Wolverhampton.

As no baptism record can be found for Abel Fisher, I read every Fisher will I could find in a 30 year period hoping to find his fathers will. I found three other Fishers who were wood screw manufacurers in neighbouring West Bromwich, which led me to assume that Abel was born in West Bromwich and related to these other Fishers.

The wood screw making industry was a relatively new thing when Abel was born.

“The screw was used in furniture but did not become a common woodworking fastener until efficient machine tools were developed near the end of the 18th century. The earliest record of lathe made wood screws dates to an English patent of 1760. The development of wood screws progressed from a small cottage industry in the late 18th century to a highly mechanized industry by the mid-19th century. This rapid transformation is marked by several technical innovations that help identify the time that a screw was produced. The earliest, handmade wood screws were made from hand-forged blanks. These screws were originally produced in homes and shops in and around the manufacturing centers of 18th century Europe. Individuals, families or small groups participated in the production of screw blanks and the cutting of the threads. These small operations produced screws individually, using a series of files, chisels and cutting tools to form the threads and slot the head. Screws produced by this technique can vary significantly in their shape and the thread pitch. They are most easily identified by the profusion of file marks (in many directions) over the surface. The first record regarding the industrial manufacture of wood screws is an English patent registered to Job and William Wyatt of Staffordshire in 1760.”

Wood Screw Makers of West Bromwich:

Edward Fisher, wood screw maker of West Bromwich, died in 1796. He mentions his wife Pheney and two underage sons in his will. Edward (whose baptism has not been found) married Pheney Mallin on 13 April 1793. Pheney was 17 years old, born in 1776. Her parents were Isaac Mallin and Sarah Firme, who were married in West Bromwich in 1768.

Edward and Pheney’s son Edward was born on 21 October 1793, and their son Isaac in 1795. The executors of Edwards 1796 will are Daniel Fisher the Younger, Isaac Mallin, and Joseph Fisher.There is a marriage allegations and bonds document in 1774 for an Edward Fisher, bachelor and wood screw maker of West Bromwich, aged 25 years and upwards, and Mary Mallin of the same age, father Isaac Mallin. Isaac Mallin and Sarah didn’t marry until 1768 and Mary Mallin would have been born circa 1749. Perhaps Isaac Mallin’s father was the father of Mary Mallin. It’s possible that Edward Fisher was born in 1749 and first married Mary Mallin, and then later Pheney, but it’s also possible that the Edward Fisher who married Mary Mallin in 1774 was Edward Fishers uncle, Daniel’s brother. (I do not know if Daniel had a brother Edward, as I haven’t found a baptism, or marriage, for Daniel Fisher the elder.)

There are two difficulties with finding the records for these West Bromwich families. One is that the West Bromwich registers are not available online in their entirety, and are held by the Sandwell Archives, and even so, they are incomplete. Not only that, the Fishers were non conformist. There is no surviving register prior to 1787. The chapel opened in 1788, and any registers that existed before this date, taken in a meeting houses for example, appear not to have survived.

Daniel Fisher the younger died intestate in 1818. Daniel was a wood screw maker of West Bromwich. He was born in 1751 according to his age stated as 67 on his death in 1818. Daniel’s wife Mary, and his son William Fisher, also a wood screw maker, claimed the estate.

Daniel Fisher the elder was a farmer of West Bromwich, who died in 1806. He was 81 when he died, which makes a birth date of 1725, although no baptism has been found. No marriage has been found either, but he was probably married not earlier than 1746.

Daniel’s sons Daniel and Joseph were the main inheritors, and he also mentions his other children and grandchildren namely William Fisher, Thomas Fisher, Hannah wife of William Hadley, two grandchildren Edward and Isaac Fisher sons of Edward Fisher his son deceased. Daniel the elder presumably refers to the wood screw manufacturing when he says “to my son Daniel Fisher the good will and advantage which may arise from his manufacture or trade now carried on by me.” Daniel does not mention a son called Abel unfortunately, but neither does he mention his other grandchildren. Abel may be Daniel’s son, or he may be a nephew.

The Staffordshire Record Office holds the documents of a Testamentary Case in 1817. The principal people are Isaac Fisher, a legatee; Daniel and Joseph Fisher, executors. Principal place, West Bromwich, and deceased person, Daniel Fisher the elder, farmer.

William and Sarah Fisher baptised six children in the Mares Green Non Conformist registers in West Bromwich between 1786 and 1798. William Fisher and Sarah Birch were married in West Bromwich in 1777. This William was probably born circa 1753 and was probably the son of Daniel Fisher the elder, farmer.

Daniel Fisher the younger and his wife Mary had a son William, as mentioned in the intestacy papers, although I have not found a baptism for William. I did find a baptism for another son, Eutychus Fisher in 1792.

In White’s Directory of Staffordshire in 1834, there are three Fishers who are wood screw makers in Wolverhampton: Eutychus Fisher, Oxford Street; Stephen Fisher, Bloomsbury; and William Fisher, Oxford Street.

Abel’s son William Fisher 1792-1873 was living on Oxford Street on the 1841 census, with his wife Mary and their son William Fisher 1834-1916.

In The European Magazine, and London Review of 1820 (Volume 77 – Page 564) under List of Patents, W Fisher and H Fisher of West Bromwich, wood screw manufacturers, are listed. Also in 1820 in the Birmingham Chronicle, the partnership of William and Hannah Fisher, wood screw manufacturers of West Bromwich, was dissolved.

In the Staffordshire General & Commercial Directory 1818, by W. Parson, three Fisher’s are listed as wood screw makers. Abel Fisher victualler and wood screw maker, Red Lion, Walsal Road; Stephen Fisher wood screw maker, Buggans Lane; and Daniel Fisher wood screw manufacturer, Brickiln Lane.

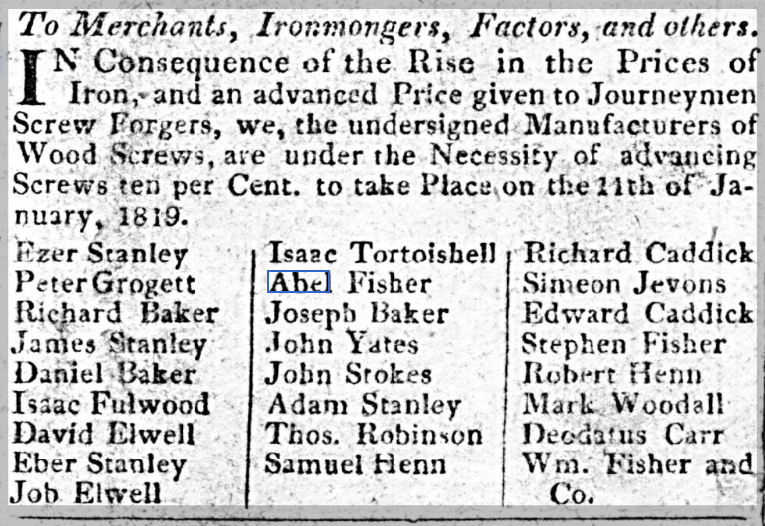

In Aris’s Birmingham Gazette on 4 January 1819 Abel Fisher is listed with 23 other wood screw manufacturers (Stephen Fisher and William Fisher included) stating that “In consequence of the rise in prices of iron and the advanced price given to journeymen screw forgers, we the undersigned manufacturers of wood screws are under the necessity of advancing screws 10 percent, to take place on the 11th january 1819.”

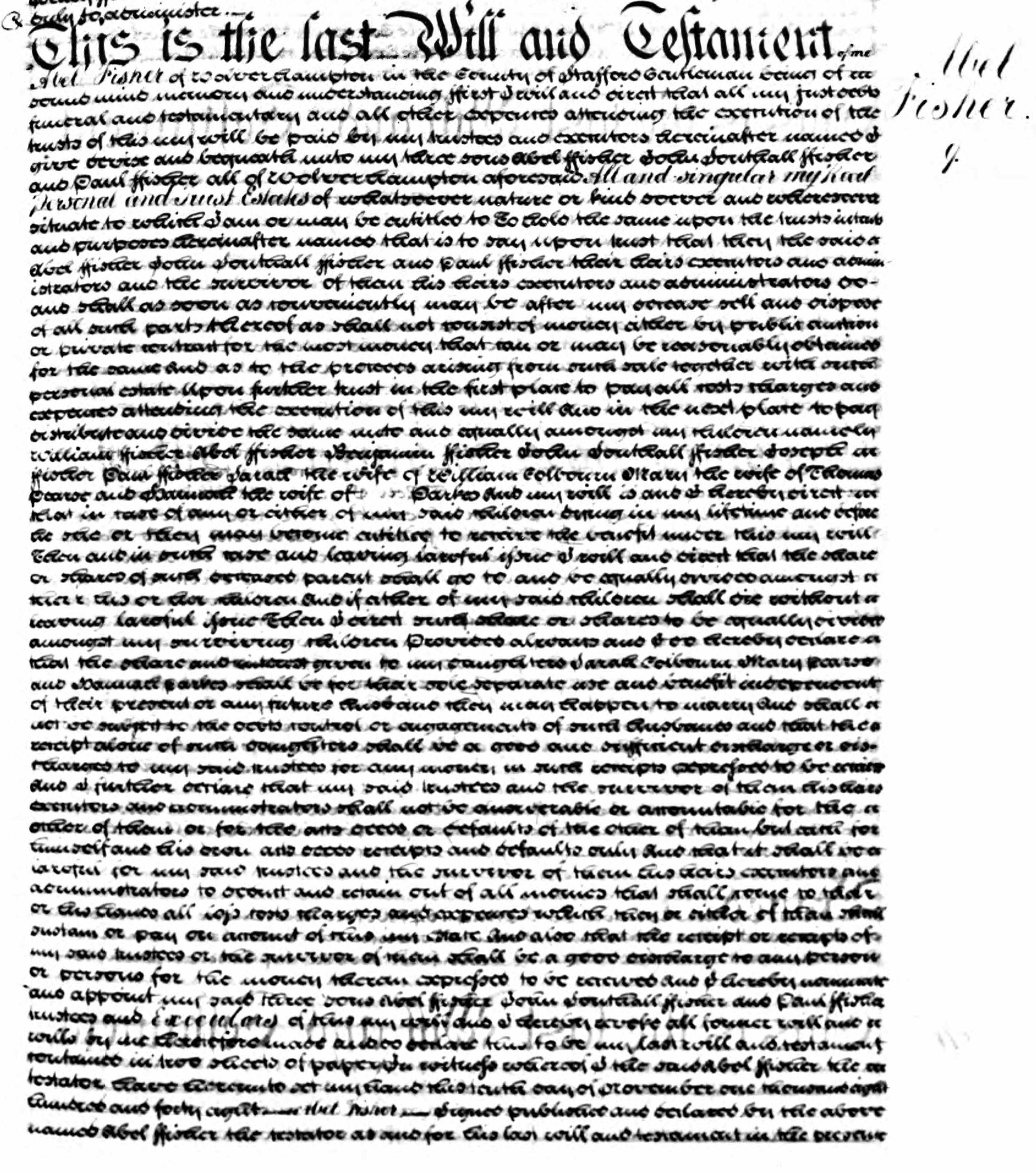

In Abel Fisher’s 1849 will, he names his three sons Abel Fisher 1796-1869, Paul Fisher 1811-1900 and John Southall Fisher 1801-1871 as the executors. He also mentions his other three sons, William Fisher 1792-1873, Benjamin Fisher 1798-1870, and Joseph Fisher 1803-1876, and daughters Sarah Fisher 1794- wife of William Colbourne, Mary Fisher 1804- wife of Thomas Pearce, and Susannah (Hannah) Fisher 1813- wife of Parkes. His son Silas Fisher 1809-1837 wasn’t mentioned as he died before Abel, nor his sons John Fisher 1799-1800, and Edward Southall Fisher 1806-1843. Abel’s wife Susannah Southall born in 1771 died in 1824. They were married in 1791.

The 1849 will of Abel Fisher:

August 17, 2023 at 4:32 pm #7268

August 17, 2023 at 4:32 pm #7268In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

William Tomlinson

1797-1867

The Tomlinsons of Wolverhampton were butchers and publicans for several generations. Therefore it was a surprise to find that William’s father was a gentleman of independant means.

William Tomlinson 1797-1867 was born in Wergs, Tettenhall. His birthplace, and that of his first four children, is stated as Wergs on the 1851 census. They were baptised at St Michael and All Angels church in Tettenhall Regis, as were many of the Tomlinson family including William.

Tettenhall, St Michael and All Angels church:

Wergs is a very small area and there was no other William Tomlinson baptised there at the time of William’s birth. It is of course possible that another William Tomlinson was born in Wergs and the record of the baptism hasn’t been found, but there are a number of other documents that prove that John Tomlinson, gentleman of Wergs, was Williams father.

In 1834 on the Shropshire Quarter session rolls there are two documents regarding William. In October 1834 William Tomlinson of Tettenhall, son of John, took an examination. Also in October of 1834 there is a reconizance document for William Tomlinson for “pig dealer”. On the marriage certificate of his son Charles Tomlinson to Emma Grattidge (mistranscribed as Pratadge) in 1872, father William’s occupation is “dealer”.

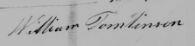

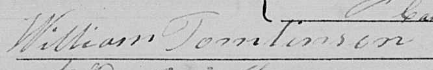

William Tomlinson was a witness at his sister Catherine and Benjamin Smiths wedding in 1822 in Tettenhall. In John Tomlinson’s 1844 will, he mentions his “daughter Catherine Smith, wife of Benjamin Smith”. William’s signature as a witness at Catherine’s marriage matches his signature on the licence for his own marriage to Elizabeth Adams in 1827 in Shareshill, Staffordshire.

William’s signature on his wedding licence:

Williams signature as a witness to Catherine’s marriage:

William was the eldest surviving son when his father died in 1844, so it is surprising that William only inherited £25. John Tomlinson left his various properties to his daughters, with the exception of Catherine, who also received £25. There was one other surviving son, Sidney, born in 1814. Three of John and Sarah Tomlinson’s sons and one daughter died in infancy. Sidney was still unmarried and living at home when his father died, and in 1851 and 1861 was living with his sister Emma Wilson. He was unmarried when he died in 1867. John left Sidney an income for life in his will, but not property.

In John Tomlinson’s will he also mentions his daughter Jemima, wife of William Smith, farmer, of Great Barr. On the 1841 census William, butcher, is a visitor. His two children Sarah and Thomas are with him. His wife Elizabeth and the rest of the children are at Graisley Street. William is also on the Graisley Street census, occupation castrator. This was no doubt done in error, not realizing that he was also registered on the census where he was visiting at the time.

William’s wife, Elizabeth Adams, was born in Tong, Shropshire in 1807. The Adams in Tong appear to be agricultural labourers, at least on later censuses. Perhaps we can speculate that John didn’t approve of his son marrying an agricutural labourers daughter. Elizabeth would have been twenty years old at the time of the marriage; William thirty.

August 15, 2023 at 12:42 pm #7267In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Thomas Josiah Tay

22 Feb 1816 – 16 November 1878

“Make us glad according to the days wherein thou hast afflicted us, and the years wherein we have seen evil.”

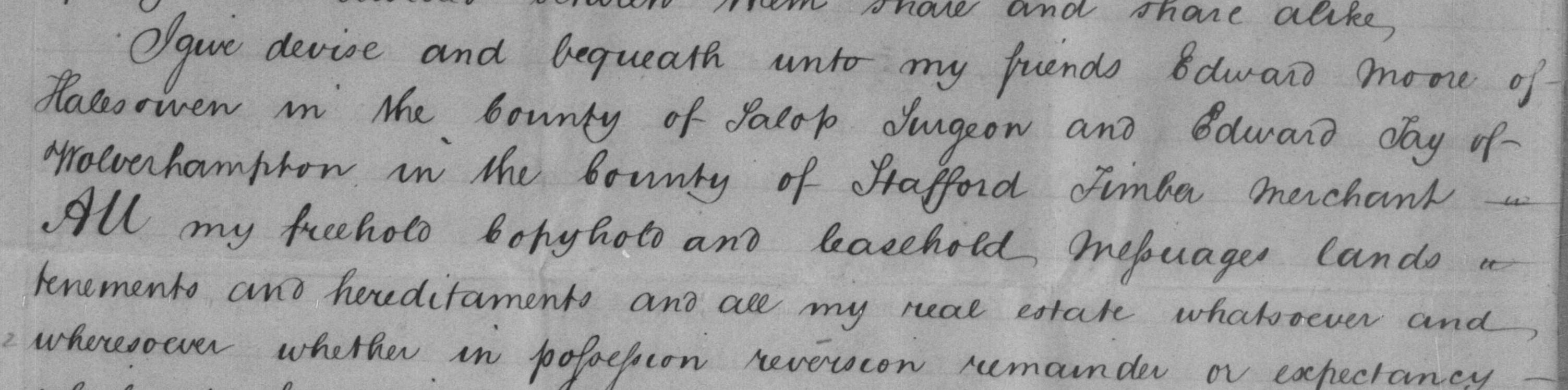

I first came across the name TAY in the 1844 will of John Tomlinson (1766-1844), gentleman of Wergs, Tettenhall. John’s friends, trustees and executors were Edward Moore, surgeon of Halesowen, and Edward Tay, timber merchant of Wolverhampton.

Edward Moore (born in 1805) was the son of John’s wife’s (Sarah Hancox born 1772) sister Lucy Hancox (born 1780) from her first marriage in 1801. In 1810 widowed Lucy married Josiah Tay (1775-1837).

Edward Tay was the son of Sarah Hancox sister Elizabeth (born 1778), who married Thomas Tay in 1800. Thomas Tay (1770-1841) and Josiah Tay were brothers.

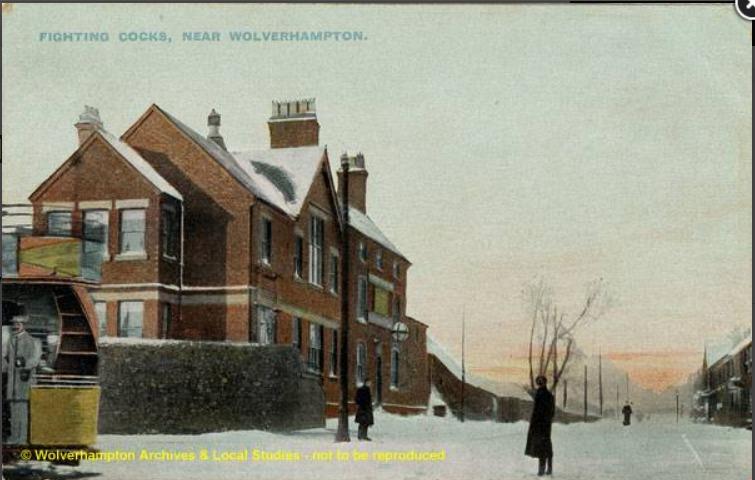

Edward Tay (1803-1862) was born in Sedgley and was buried in Penn. He was innkeeper of The Fighting Cocks, Dudley Road, Wolverhampton, as well as a builder and timber merchant, according to various censuses, trade directories, his marriage registration where his father Thomas Tay is also a timber merchant, as well as being named as a timber merchant in John Tomlinsons will.

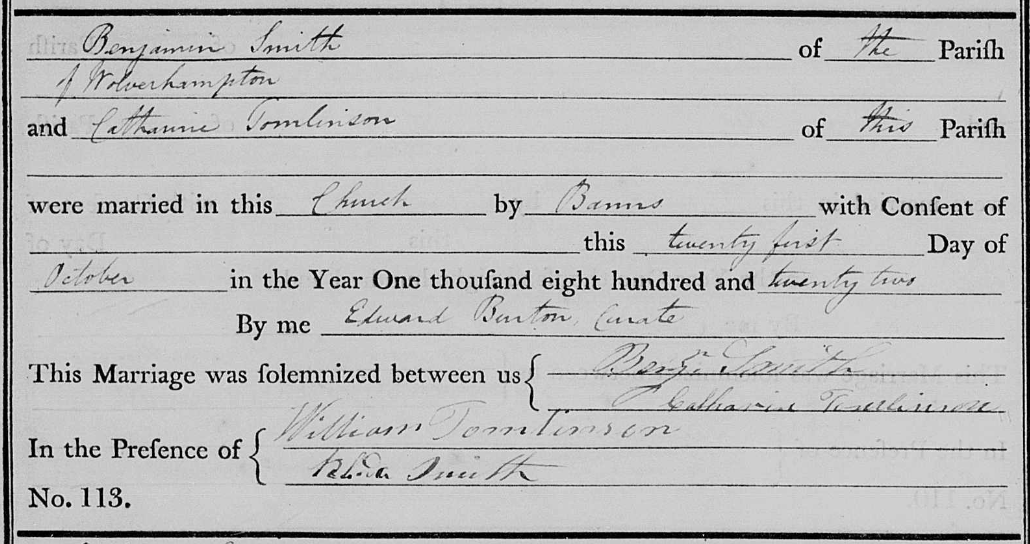

John Tomlinson’s daughter Catherine (born in 1794) married Benjamin Smith in Tettenhall in 1822. William Tomlinson (1797-1867), Catherine’s brother, and my 3x great grandfather, was one of the witnesses.

Their daughter Matilda Sarah Smith (1823-1910) married Thomas Josiah Tay in 1850 in Birmingham. Thomas Josiah Tay (1816-1878) was Edward Tay’s brother, the sons of Elizabeth Hancox and Thomas Tay.

Therefore, William Hancox 1737-1816 (the father of Sarah, Elizabeth and Lucy), was Matilda’s great grandfather and Thomas Josiah Tay’s grandfather.

Thomas Josiah Tay’s relationship to me is the husband of first cousin four times removed, as well as my first cousin, five times removed.

In 1837 Thomas Josiah Tay is mentioned in the will of his uncle Josiah Tay.

In 1841 Thomas Josiah Tay appears on the Stafford criminal registers for an “attempt to procure miscarriage”. He was found not guilty.

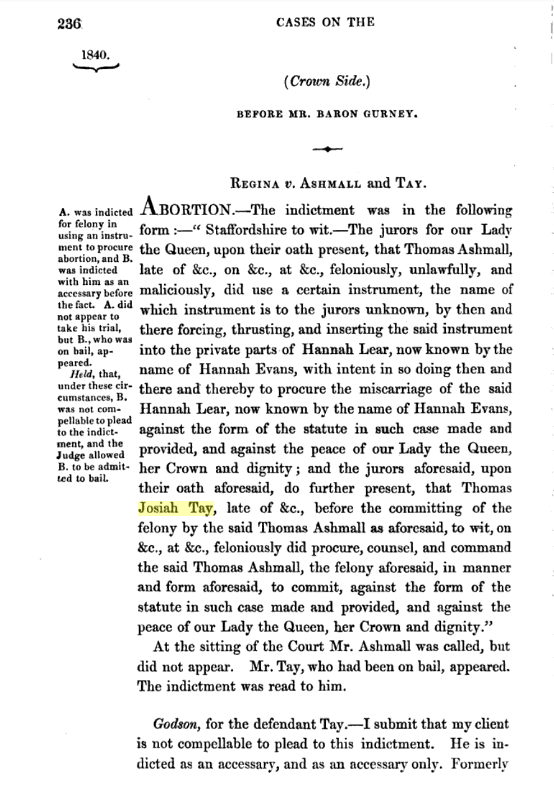

According to the Staffordshire Advertiser on 14th March 1840 the listing for the Assizes included: “Thomas Ashmall and Thomas Josiah Tay, for administering noxious ingredients to Hannah Evans, of Wolverhampton, with intent to procure abortion.”

The London Morning Herald on 19th March 1840 provides further information: “Mr Thomas Josiah Tay, a chemist and druggist, surrendered to take his trial on a charge of having administered drugs to Hannah Lear, now Hannah Evans, with intent to procure abortion.” She entered the service of Tay in 1837 and after four months “an intimacy was formed” and two months later she was “enciente”. Tay advised her to take some pills and a draught which he gave her and she became very ill. The prosecutrix admitted that she had made no mention of this until 1939. Verdict: not guilty.

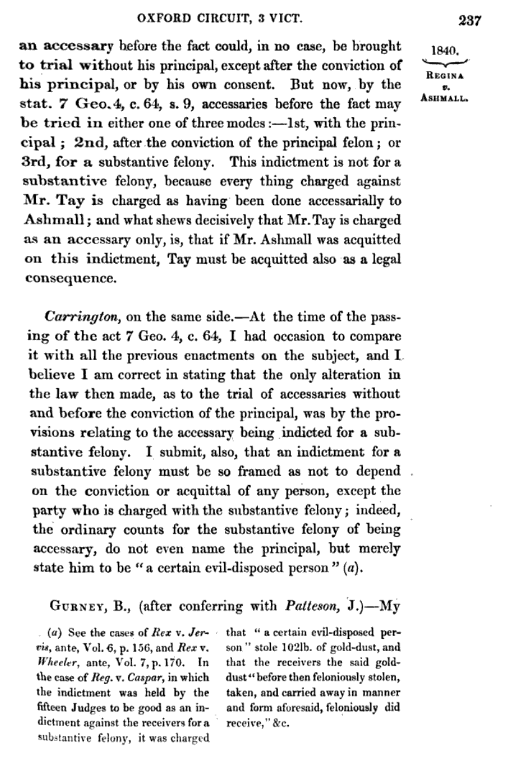

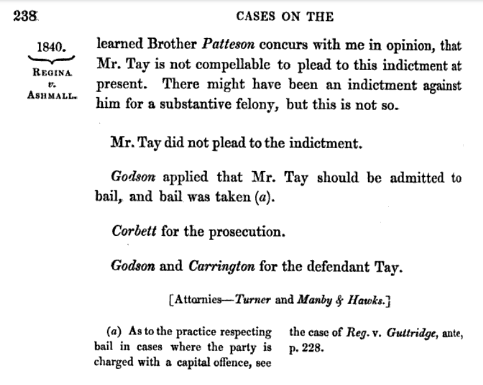

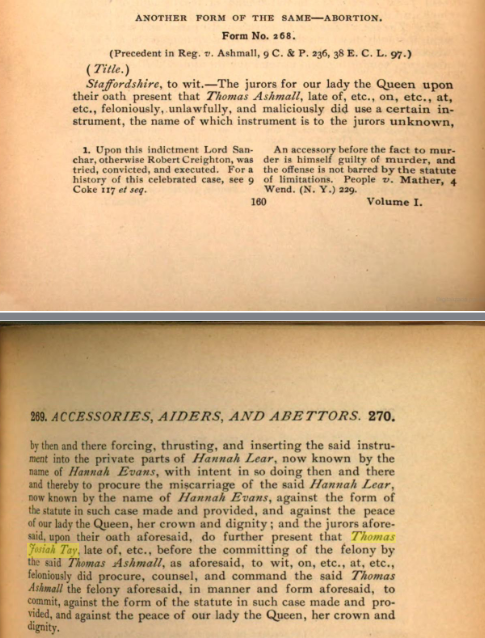

However, the case of Thomas Josiah Tay is also mentioned in a couple of law books, and the story varies slightly. In the 1841 Reports of Cases Argued and Rules at Nisi Prius, the Regina vs Ashmall and Tay case states that Thomas Ashmall feloniously, unlawfully, and maliciously, did use a certain instrument, and that Thomas Josiah Tay did procure the instrument, counsel and command Ashmall in the use of it. It concludes that Tay was not compellable to plead to the indictment, and that he did not.

The Regina vs Ashmall and Tay case is also mentioned in the Encyclopedia of Forms and Precedents, 1896.

In 1845 Thomas Josiah Tay married Isabella Southwick in Tettenhall. Two years later in 1847 Isabella died.

In 1850 Thomas Josiah married Matilda Sarah Smith. (granddaughter of John Tomlinson, as mentioned above)

On the 1851 census Thomas Josiah Tay was a farmer of 100 acres employing two labourers in Shelfield, Walsall, Staffordshire. Thomas Josiah and Matilda Sarah have a daughter Matilda under a year old, and they have a live in house servant.

In 1861 Thomas Josiah Tay, his wife and their four children Ann, James, Josiah and Alice, live in Chelmarsh, Shropshire. He was a farmer of 224 acres. Mercy Smith, Matilda’s sister, lives with them, a 28 year old dairy maid.

In 1863 Thomas Josiah Tay of Hampton Lode (Chelmarsh) Shropshire was bankrupt. Creditors include Frederick Weaver, druggist of Wolverhampton.

In 1869 Thomas Josiah Tay was again bankrupt. He was an innkeeper at The Fighting Cocks on Dudley Road, Wolverhampton, at the time, the same inn as his uncle Edward Tay, aforementioned timber merchant.

In 1871, Thomas Josiah Tay, his wife Matilda, and their three children Alice, Edward and Maryann, were living in Birmingham. Thomas Josiah was a commercial traveller.

He died on the 16th November 1878 at the age of 62 and was buried in Darlaston, Walsall. On his gravestone:

“Make us glad according to the days wherein thou hast afflicted us, and the years wherein we have seen evil.” Psalm XC 15 verse.

Edward Moore, surgeon, was also a MAGISTRATE in later years. On the 1871 census he states his occupation as “magistrate for counties Worcester and Stafford, and deputy lieutenant of Worcester, formerly surgeon”. He lived at Townsend House in Halesowen for many years. His wifes name was PATTERN Lucas. Her mothers name was Pattern Hewlitt from Birmingham, an unusal name that I have not heard before. On the 1871 census, Edward’s son was a 22 year old solicitor.

In 1861 an article appeared in the newspapers about the state of the morality of the women of Dudley. It was claimed that all the local magistrates agreed with the premise of the article, concerning unmarried women and their attitudes towards having illegitimate children. Letters appeared in subsequent newspapers signed by local magistrates, including Edward Moore, strongly disagreeing.

Staffordshire Advertiser 17 August 1861:

July 5, 2023 at 8:21 pm #7263

July 5, 2023 at 8:21 pm #7263In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Solomon Stubbs

1781-1857

Solomon was born in Hamstall Ridware, Staffordshire, parents Samuel Stubbs and Rebecca Wood. (see The Hamstall Ridware Connection chapter)

Solomon married Phillis Lomas at St Modwen’s in Burton on Trent on 30th May 1815. Phillis was the llegitimate daughter of Frances Lomas. No father was named on the baptism on the 17th January 1787 in Sutton on the Hill, Derbyshire, and the entry on the baptism register states that she was illegitimate. Phillis’s mother Frances married Daniel Fox in 1790 in Sutton on the Hill. Unfortunately this means that it’s impossible to find my 5X great grandfather on this side of the family.

Solomon and Phillis had four daughters, the last died in infancy.

Sarah 1816-1867, Mary (my 3X great grandmother) 1819-1880, Phillis 1823-1905, and Maria 1825-1826.Solomon Stubbs of Horninglow St is listed in the 1834 Whites Directory under “China, Glass, Etc Dlrs”. Next to his name is Joanna Warren (earthenware) High St. Joanna Warren is related to me on my maternal side. No doubt Solomon and Joanna knew each other, unaware that several generations later a marriage would take place, not locally but miles away, joining their families.

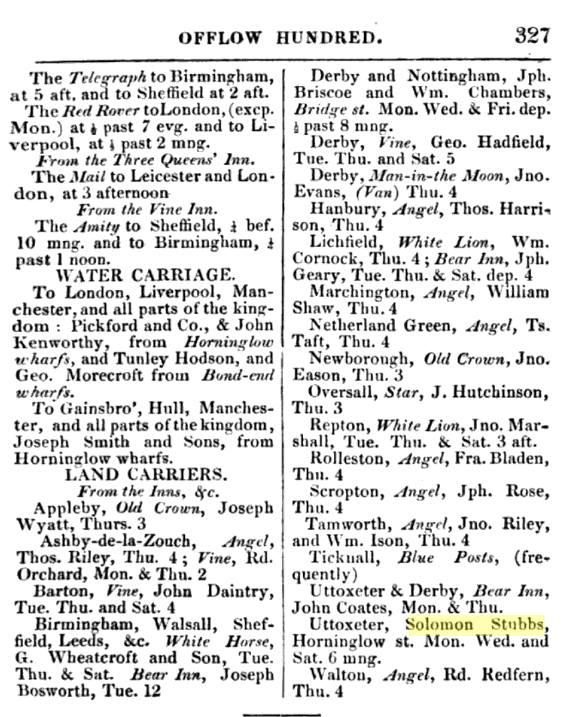

Solomon Stubbs is also listed in Whites Directory in 1831 and 1834 Burton on Trent as a land carrier:

“Land Carriers, from the Inns, Etc: Uttoxeter, Solomon Stubbs, Horninglow St, Mon. Wed. and Sat. 6 mng.”

Solomon is listed in the electoral registers in 1837. The 1837 United Kingdom general election was triggered by the death of King William IV and produced the first Parliament of the reign of his successor, Queen Victoria.

National Archives:

“In 1832, Parliament passed a law that changed the British electoral system. It was known as the Great Reform Act, which basically gave the vote to middle class men, leaving working men disappointed.

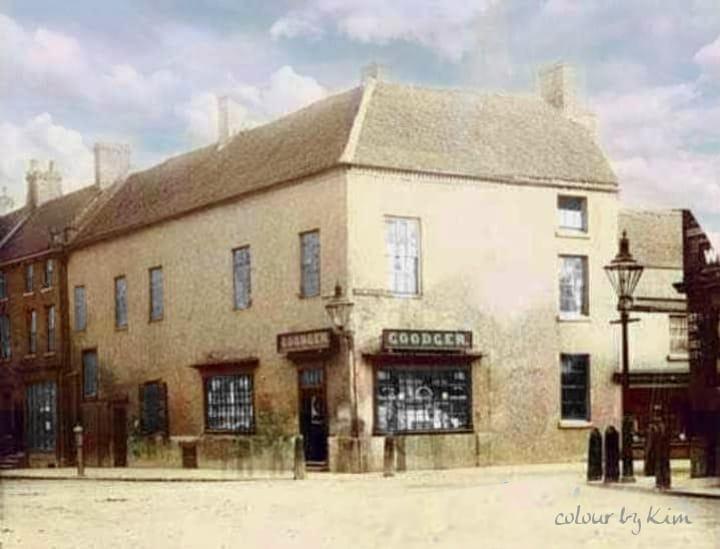

The Reform Act became law in response to years of criticism of the electoral system from those outside and inside Parliament. Elections in Britain were neither fair nor representative. In order to vote, a person had to own property or pay certain taxes to qualify, which excluded most working class people.”Via the Burton on Trent History group:

“a very early image of High street and Horninglow street junction, where the original ‘ Bargates’ were in the days of the Abbey. ‘Gate’ is the Saxon meaning Road, ‘Bar’ quite self explanatory, meant ‘to stop entrance’. There was another Bargate across Cat street (Station street), the Abbot had these constructed to regulate the Traders coming into town, in the days when the Abbey ran things. In the photo you can see the Posts on the corner, designed to stop Carts and Carriages mounting the Pavement. Only three Posts remain today and they are Listed.”

On the 1841 census, Solomon’s occupation was Carrier. Daughter Sarah is still living at home, and Sarah Grattidge, 13 years old, lives with them. Solomon’s daughter Mary had married William Grattidge in 1839.

Solomon Stubbs of Horninglow Street, Burton on Trent, is listed as an Earthenware Dealer in the 1842 Pigot’s Directory of Staffordshire.

In May 1844 Solomon’s wife Phillis died. In July 1844 daughter Sarah married Thomas Brandon in Burton on Trent. It was noted in the newspaper announcement that this was the first wedding to take place at the Holy Trinity church.

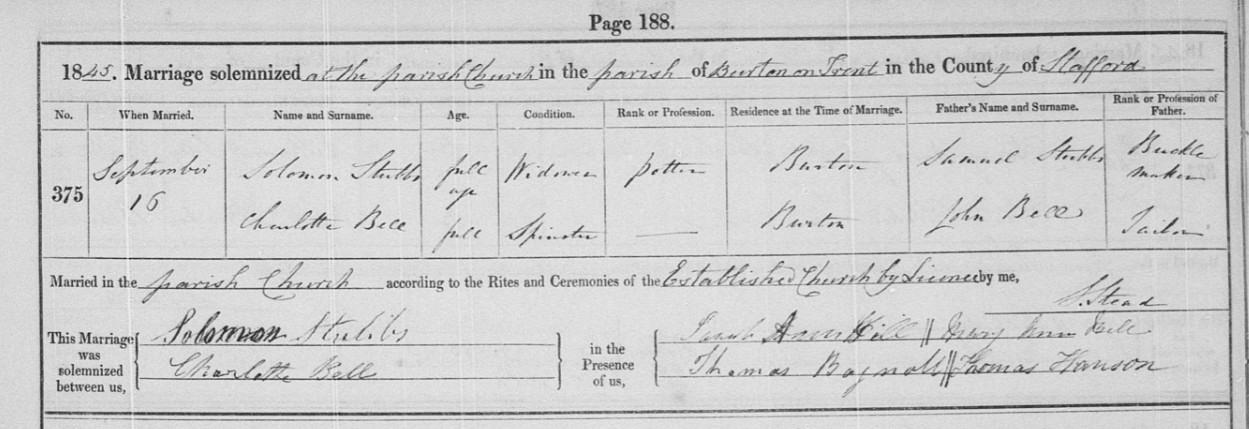

Solomon married Charlotte Bell by licence the following year in 1845. She was considerably younger than him, born in 1824. On the marriage certificate Solomon’s occupation is potter. It seems that he had the earthenware business as well as the land carrier business, in addition to owning a number of properties.

The marriage of Solomon Stubbs and Charlotte Bell:

Also in 1845, Solomon’s daughter Phillis was married in Burton on Trent to John Devitt, son of CD Devitt, Esq, formerly of the General Post Office Dublin.

Solomon Stubbs died in September 1857 in Burton on Trent. In the Staffordshire Advertiser on Saturday 3 October 1857:

“On the 22nd ultimo, suddenly, much respected, Solomon Stubbs, of Guild-street, Burton-on-Trent, aged 74 years.”

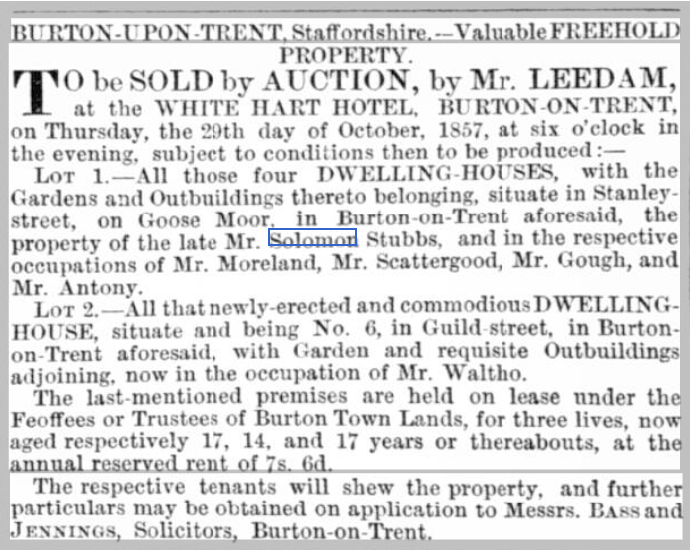

In the Staffordshire Advertiser, 24th October 1857, the auction of the property of Solomon Stubbs was announced:

“BURTON ON TRENT, on Thursday, the 29th day of October, 1857, at six o’clock in the evening, subject to conditions then to be produced:— Lot I—All those four DWELLING HOUSES, with the Gardens and Outbuildings thereto belonging, situate in Stanleystreet, on Goose Moor, in Burton-on-Trent aforesaid, the property of the late Mr. Solomon Stubbs, and in the respective occupations of Mr. Moreland, Mr. Scattergood, Mr. Gough, and Mr. Antony…..”

Sadly, the graves of Solomon, his wife Phillis, and their infant daughter Maria have since been removed and are listed in the UK Records of the Removal of Graves and Tombstones 1601-2007.

July 4, 2023 at 7:52 pm #7261In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Long Lost Enoch Edwards

My father used to mention long lost Enoch Edwards. Nobody in the family knew where he went to and it was assumed that he went to USA, perhaps to Utah to join his sister Sophie who was a Mormon handcart pioneer, but no record of him was found in USA.

Andrew Enoch Edwards (my great great grandfather) was born in 1840, but was (almost) always known as Enoch. Although civil registration of births had started from 1 July 1837, neither Enoch nor his brother Stephen were registered. Enoch was baptised (as Andrew) on the same day as his brothers Reuben and Stephen in May 1843 at St Chad’s Catholic cathedral in Birmingham. It’s a mystery why these three brothers were baptised Catholic, as there are no other Catholic records for this family before or since. One possible theory is that there was a school attached to the church on Shadwell Street, and a Catholic baptism was required for the boys to go to the school. Enoch’s father John died of TB in 1844, and perhaps in 1843 he knew he was dying and wanted to ensure an education for his sons. The building of St Chads was completed in 1841, and it was close to where they lived.

Enoch appears (as Enoch rather than Andrew) on the 1841 census, six months old. The family were living at Unett Street in Birmingham: John and Sarah and children Mariah, Sophia, Matilda, a mysterious entry transcribed as Lene, a daughter, that I have been unable to find anywhere else, and Reuben and Stephen.

Enoch was just four years old when his father John, an engineer and millwright, died of consumption in 1844.

In 1851 Enoch’s widowed mother Sarah was a mangler living on Summer Street, Birmingham, Matilda a dressmaker, Reuben and Stephen were gun percussionists, and eleven year old Enoch was an errand boy.

On the 1861 census, Sarah was a confectionrer on Canal Street in Birmingham, Stephen was a blacksmith, and Enoch a button tool maker.

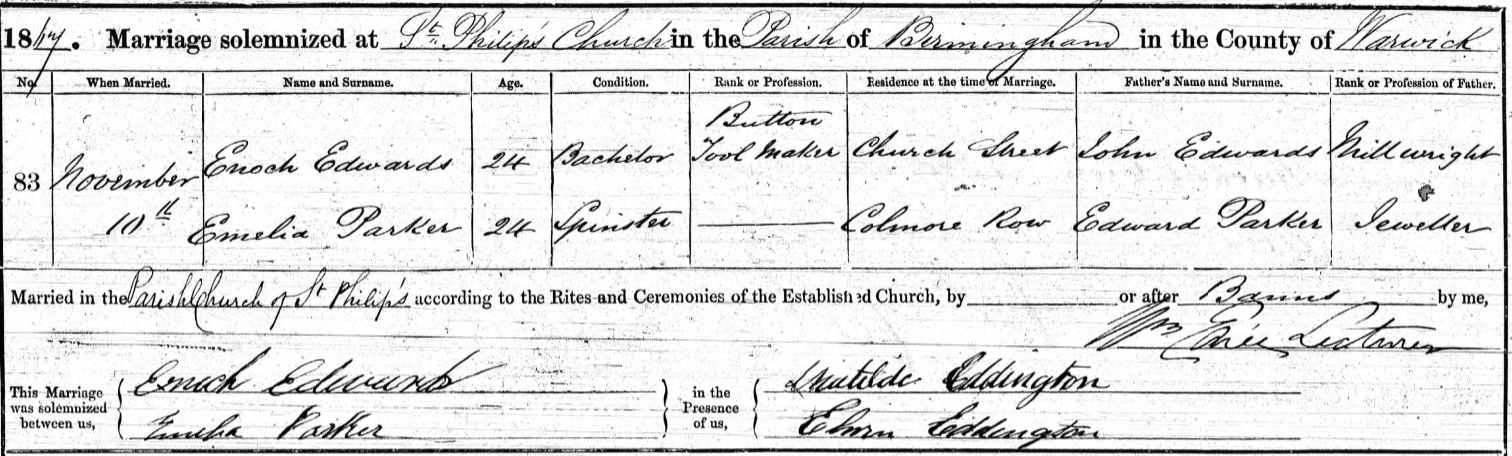

On the 10th November 1867 Enoch married Emelia Parker, daughter of jeweller and rope maker Edward Parker, at St Philip in Birmingham. Both Emelia and Enoch were able to sign their own names, and Matilda and Edwin Eddington were witnesses (Enoch’s sister and her husband). Enoch’s address was Church Street, and his occupation button tool maker.

Four years later in 1871, Enoch was a publican living on Clifton Road. Son Enoch Henry was two years old, and Ralph Ernest was three months. Eliza Barton lived with them as a general servant.

By 1881 Enoch was back working as a button tool maker in Bournebrook, Birmingham. Enoch and Emilia by then had three more children, Amelia, Albert Parker (my great grandfather) and Ada.

Garnet Frederick Edwards was born in 1882. This is the first instance of the name Garnet in the family, and subsequently Garnet has been the middle name for the eldest son (my brother, father and grandfather all have Garnet as a middle name).

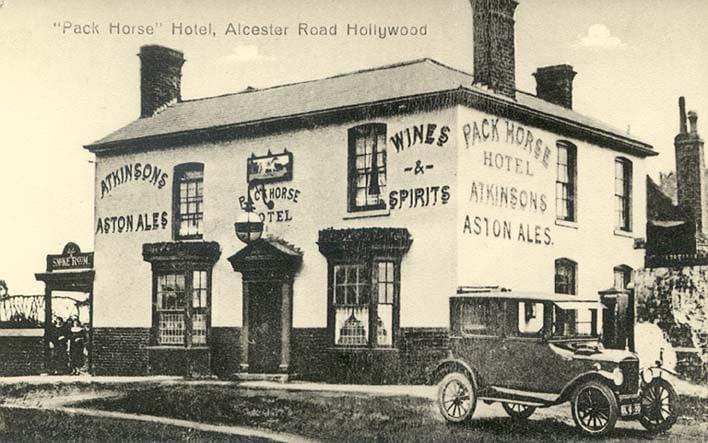

Enoch was the licensed victualler at the Pack Horse Hotel in 1991 at Kings Norton. By this time, only daughters Amelia and Ada and son Garnet are living at home.

Additional information from my fathers cousin, Paul Weaver:

“Enoch refused to allow his son Albert Parker to go to King Edwards School in Birmingham, where he had been awarded a place. Instead, in October 1890 he made Albert Parker Edwards take an apprenticeship with a pawnboker in Tipton.

Towards the end of the 19th century Enoch kept The Pack Horse in Alcester Road, Hollywood, where a twist was 1d an ounce, and beer was 2d a pint. The children had to get up early to get breakfast at 6 o’clock for the hay and straw men on their way to the Birmingham hay and straw market. Enoch is listed as a member of “The Kingswood & Pack Horse Association for the Prosecution of Offenders”, a kind of early Neighbourhood Watch, dated 25 October 1890.

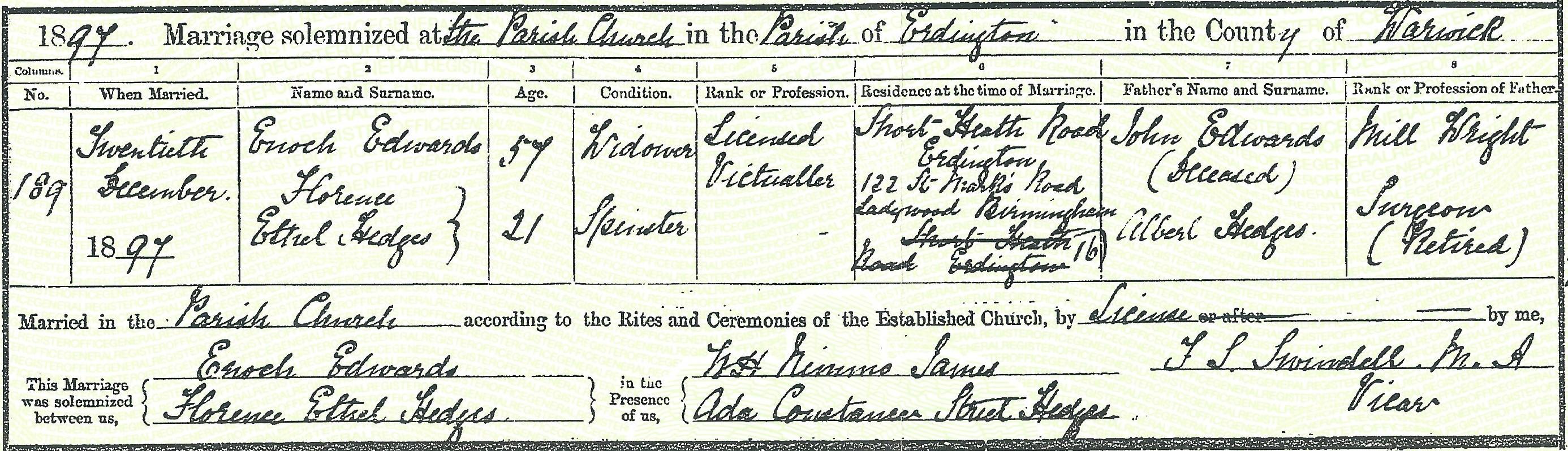

The Edwards family later moved to Redditch where they kept The Rifleman Inn at 35 Park Road. They must have left the Pack Horse by 1895 as another publican was in place by then.”Emelia his wife died in 1895 of consumption at the Rifleman Inn in Redditch, Worcestershire, and in 1897 Enoch married Florence Ethel Hedges in Aston. Enoch was 56 and Florence was just 21 years old.

The following year in 1898 their daughter Muriel Constance Freda Edwards was born in Deritend, Warwickshire.

In 1901 Enoch, (Andrew on the census), publican, Florence and Muriel were living in Dudley. It was hard to find where he went after this.From Paul Weaver:

“Family accounts have it that Enoch EDWARDS fell out with all his family, and at about the age of 60, he left all behind and emigrated to the U.S.A. Enoch was described as being an active man, and it is believed that he had another family when he settled in the U.S.A. Esmor STOKES has it that a postcard was received by the family from Enoch at Niagara Falls.

On 11 June 1902 Harry Wright (the local postmaster responsible in those days for licensing) brought an Enoch EDWARDS to the Bedfordshire Petty Sessions in Biggleswade regarding “Hole in the Wall”, believed to refer to the now defunct “Hole in the Wall” public house at 76 Shortmead Street, Biggleswade with Enoch being granted “temporary authority”. On 9 July 1902 the transfer was granted. A year later in the 1903 edition of Kelly’s Directory of Bedfordshire, Hunts and Northamptonshire there is an Enoch EDWARDS running the Wheatsheaf Public House, Church Street, St. Neots, Huntingdonshire which is 14 miles south of Biggleswade.”

It seems that Enoch and his new family moved away from the midlands in the early 1900s, but again the trail went cold.

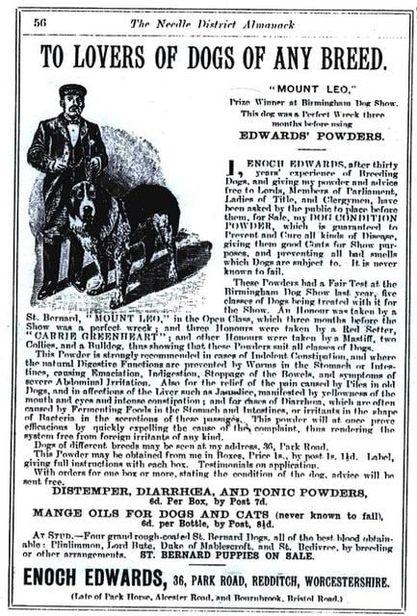

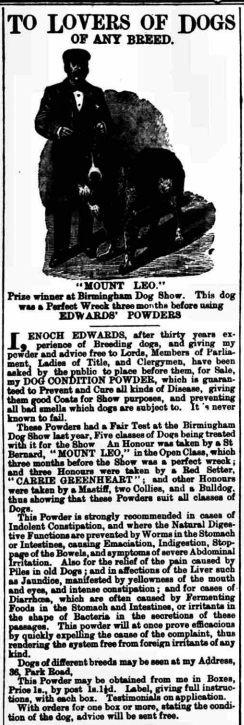

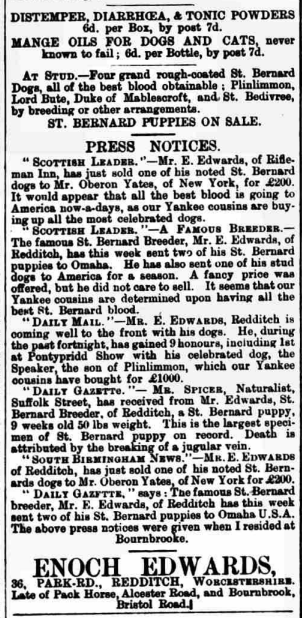

When I started doing the genealogy research, I joined a local facebook group for Redditch in Worcestershire. Enoch’s son Albert Parker Edwards (my great grandfather) spent most of his life there. I asked in the group about Enoch, and someone posted an illustrated advertisement for Enoch’s dog powders. Enoch was a well known breeder/keeper of St Bernards and is cited in a book naming individuals key to the recovery/establishment of ‘mastiff’ size dog breeds.

We had not known that Enoch was a breeder of champion St Bernard dogs!

Once I knew about the St Bernard dogs and the names Mount Leo and Plinlimmon via the newspaper adverts, I did an internet search on Enoch Edwards in conjunction with these dogs.

Enoch’s St Bernard dog “Mount Leo” was bred from the famous Plinlimmon, “the Emperor of Saint Bernards”. He was reported to have sent two puppies to Omaha and one of his stud dogs to America for a season, and in 1897 Enoch made the news for selling a St Bernard to someone in New York for £200. Plinlimmon, bred by Thomas Hall, was born in Liverpool, England on June 29, 1883. He won numerous dog shows throughout Europe in 1884, and in 1885, he was named Best Saint Bernard.

In the Birmingham Mail on 14th June 1890:

“Mr E Edwards, of Bournebrook, has been well to the fore with his dogs of late. He has gained nine honours during the past fortnight, including a first at the Pontypridd show with a St Bernard dog, The Speaker, a son of Plinlimmon.”

In the Alcester Chronicle on Saturday 05 June 1897:

It was discovered that Enoch, Florence and Muriel moved to Canada, not USA as the family had assumed. The 1911 census for Montreal St Jaqcues, Quebec, stated that Enoch, (Florence) Ethel, and (Muriel) Frida had emigrated in 1906. Enoch’s occupation was machinist in 1911. The census transcription is not very good. Edwards was transcribed as Edmand, but the dates of birth for all three are correct. Birthplace is correct ~ A for Anglitan (the census is in French) but race or tribe is also an A but the transcribers have put African black! Enoch by this time was 71 years old, his wife 33 and daughter 11.

Additional information from Paul Weaver:

“In 1906 he and his new family travelled to Canada with Enoch travelling first and Ethel and Frida joined him in Quebec on 25 June 1906 on board the ‘Canada’ from Liverpool.

Their immigration record suggests that they were planning to travel to Winnipeg, but five years later in 1911, Enoch, Florence Ethel and Frida were still living in St James, Montreal. Enoch was employed as a machinist by Canadian Government Railways working 50 hours. It is the 1911 census record that confirms his birth as November 1840. It also states that Enoch could neither read nor write but managed to earn $500 in 1910 for activity other than his main profession, although this may be referring to his innkeeping business interests.

By 1921 Florence and Muriel Frida are living in Langford, Neepawa, Manitoba with Peter FUCHS, an Ontarian farmer of German descent who Florence had married on 24 Jul 1913 implying that Enoch died sometime in 1911/12, although no record has been found.”The extra $500 in earnings was perhaps related to the St Bernard dogs. Enoch signed his name on the register on his marriage to Emelia, and I think it’s very unlikely that he could neither read nor write, as stated above.

However, it may not be Enoch’s wife Florence Ethel who married Peter Fuchs. A Florence Emma Edwards married Peter Fuchs, and on the 1921 census in Neepawa her daugther Muriel Elizabeth Edwards, born in 1902, lives with them. Quite a coincidence, two Florence and Muriel Edwards in Neepawa at the time. Muriel Elizabeth Edwards married and had two children but died at the age of 23 in 1925. Her mother Florence was living with the widowed husband and the two children on the 1931 census in Neepawa. As there was no other daughter on the 1911 census with Enoch, Florence and Muriel in Montreal, it must be a different Florence and daughter. We don’t know, though, why Muriel Constance Freda married in Neepawa.

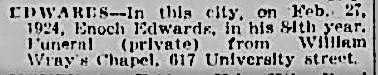

Indeed, Florence was not a widow in 1913. Enoch died in 1924 in Montreal, aged 84. Neither Enoch, Florence or their daughter has been found yet on the 1921 census. The search is not easy, as Enoch sometimes used the name Andrew, Florence used her middle name Ethel, and daughter Muriel used Freda, Valerie (the name she added when she married in Neepawa), and died as Marcheta. The only name she NEVER used was Constance!

A Canadian genealogist living in Montreal phoned the cemetery where Enoch was buried. She said “Enoch Edwards who died on Feb 27 1924 is not buried in the Mount Royal cemetery, he was only cremated there on March 4, 1924. There are no burial records but he died of an abcess and his body was sent to the cemetery for cremation from the Royal Victoria Hospital.”

1924 Obituary for Enoch Edwards:

Cimetière Mont-Royal Outremont, Montreal Region, Quebec, Canada

The Montreal Star 29 Feb 1924, Fri · Page 31

Muriel Constance Freda Valerie Edwards married Arthur Frederick Morris on 24 Oct 1925 in Neepawa, Manitoba. (She appears to have added the name Valerie when she married.)

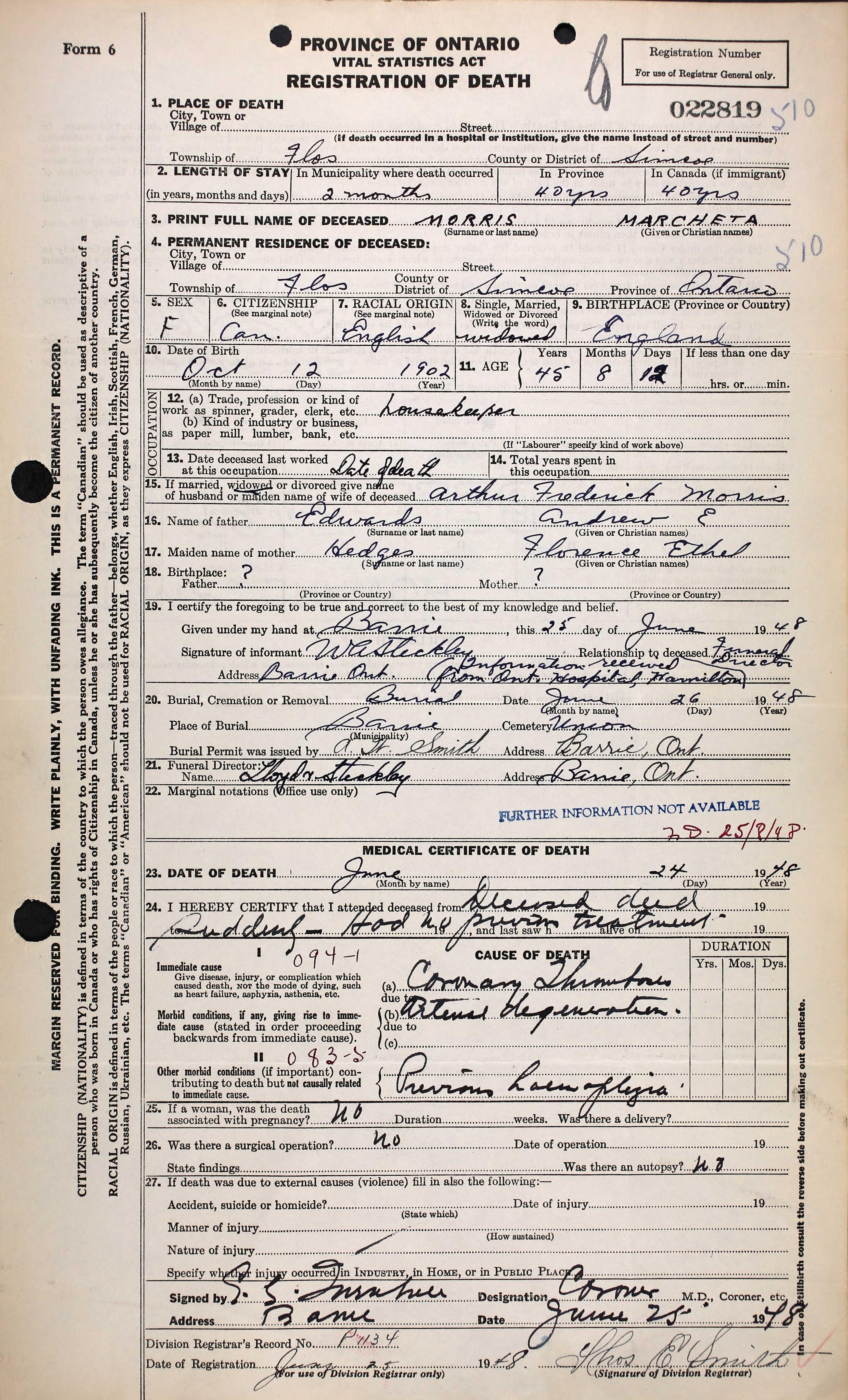

Unexpectedly a death certificate appeared for Muriel via the hints on the ancestry website. Her name was “Marcheta Morris” on this document, however it also states that she was the widow of Arthur Frederick Morris and daughter of Andrew E Edwards and Florence Ethel Hedges. She died suddenly in June 1948 in Flos, Simcoe, Ontario of a coronary thrombosis, where she was living as a housekeeper.

June 13, 2023 at 10:31 am #7255

June 13, 2023 at 10:31 am #7255In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The First Wife of John Edwards

1794-1844

John was a widower when he married Sarah Reynolds from Kinlet. Both my fathers cousin and I had come to a dead end in the Edwards genealogy research as there were a number of possible births of a John Edwards in Birmingham at the time, and a number of possible first wives for a John Edwards at the time.

John Edwards was a millwright on the 1841 census, the only census he appeared on as he died in 1844, and 1841 was the first census. His birth is recorded as 1800, however on the 1841 census the ages were rounded up or down five years. He was an engineer on some of the marriage records of his children with Sarah, and on his death certificate, engineer and millwright, aged 49. The age of 49 at his death from tuberculosis in 1844 is likely to be more accurate than the census (Sarah his wife was present at his death), making a birth date of 1794 or 1795.

John married Sarah Reynolds in January 1827 in Birmingham, and I am descended from this marriage. Any children of John’s first marriage would no doubt have been living with John and Sarah, but had probably left home by the time of the 1841 census.

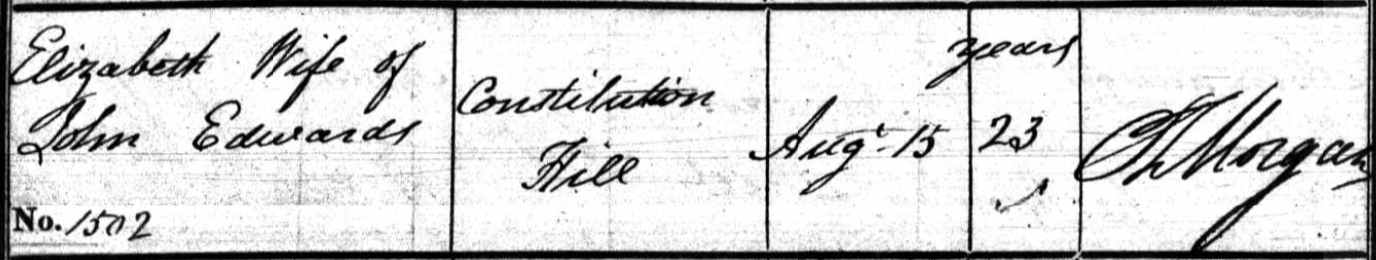

I found an Elizabeth Edwards, wife of John Edwards of Constitution Hill, died in August 1826 at the age of 23, as stated on the parish death register. It would be logical for a young widower with small children to marry again quickly. If this was John’s first wife, the marriage to Sarah six months later in January 1827 makes sense. Therefore, John’s first wife, I assumed, was Elizabeth, born in 1803.

Death of Elizabeth Edwards, 23 years old. St Mary, Birmingham, 15 Aug 1826:

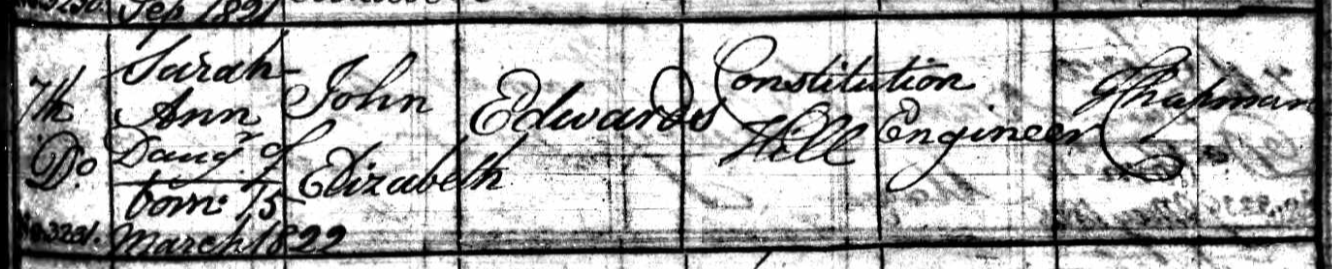

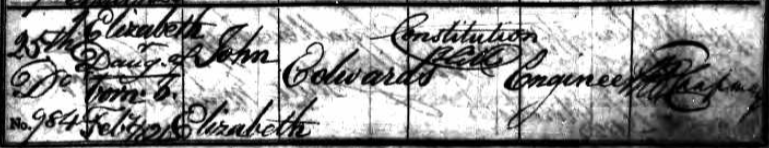

There were two baptisms recorded for parents John and Elizabeth Edwards, Constitution Hill, and John’s occupation was an engineer on both baptisms.

They were both daughters: Sarah Ann in 1822 and Elizabeth in 1824.Sarah Ann Edwards: St Philip, Birmingham. Born 15 March 1822, baptised 7 September 1822:

Elizabeth Edwards: St Philip, Birmingham. Born 6 February 1824, baptised 25 February 1824:

With John’s occupation as engineer stated, it looked increasingly likely that I’d found John’s first wife and children of that marriage.

Then I found a marriage of Elizabeth Beach to John Edwards in 1819, and subsequently found an Elizabeth Beach baptised in 1803. This appeared to be the right first wife for John, until an Elizabeth Slater turned up, with a marriage to a John Edwards in 1820. An Elizabeth Slater was baptised in 1803. Either Elizabeth Beach or Elizabeth Slater could have been the first wife of John Edwards. As John’s first wife Elizabeth is not related to us, it’s not necessary to go further back, and in a sense, doesn’t really matter which one it was.

But the Slater name caught my eye.

But first, the name Sarah Ann.

Of the possible baptisms for John Edwards, the most likely seemed to be in 1794, parents John and Sarah. John and Sarah had two infant daughters die just prior to John’s birth. The first was Sarah, the second Sarah Ann. Perhaps this was why John named his daughter Sarah Ann? In the absence of any other significant clues, I decided to assume these were the correct parents. I found and read half a dozen wills of any John Edwards I could find within the likely time period of John’s fathers death.

One of them was dated 1803. In this will, John mentions that his children are not yet of age. (John would have been nine years old.)

He leaves his plating business and some properties to his eldest son Thomas Davis Edwards, (just shy of 21 years old at the time of his fathers death in 1803) with the business to be run jointly with his widow, Sarah. He mentions his son John, and leaves several properties to him, when he comes of age. He also leaves various properties to his daughters Elizabeth and Mary, ditto. The baptisms for all of these children, including the infant deaths of Sarah and Sarah Ann have been found. All but Mary’s were in the same parish. (I found one for Mary in Sutton Coldfield, which was apparently correct, as a later census also recorded her birth as Sutton Coldfield. She was living with family on that census, so it would appear to be correct that for whatever reason, their daughter Mary was born in Sutton Coldfield)Mary married John Slater in 1813. The witnesses were Elizabeth Whitehouse and John Edwards, her sister and brother. Elizabeth married William Nicklin Whitehouse in 1805 and one of the witnesses was Mary Edwards.

Mary’s husband John Slater died in 1821. They had no children. Mary never remarried, and lived with her bachelor brother Thomas Davis Edwards in West Bromwich. Thomas never married, and on the census he was either a proprietor of houses, or “sinecura” (earning a living without working).With Mary marrying a Slater, does this indicate that her brother John’s first wife was Elizabeth Slater rather than Elizabeth Beach? It is a compelling possibility, but does not constitute proof.

Not only that, there is no absolute proof that the John Edwards who died in 1803 was our ancestor John Edwards father.

If we can’t be sure which Elizabeth married John Edwards, we can be reasonably sure who their daughters married. On both of the marriage records the father is recorded as John Edwards, engineer.

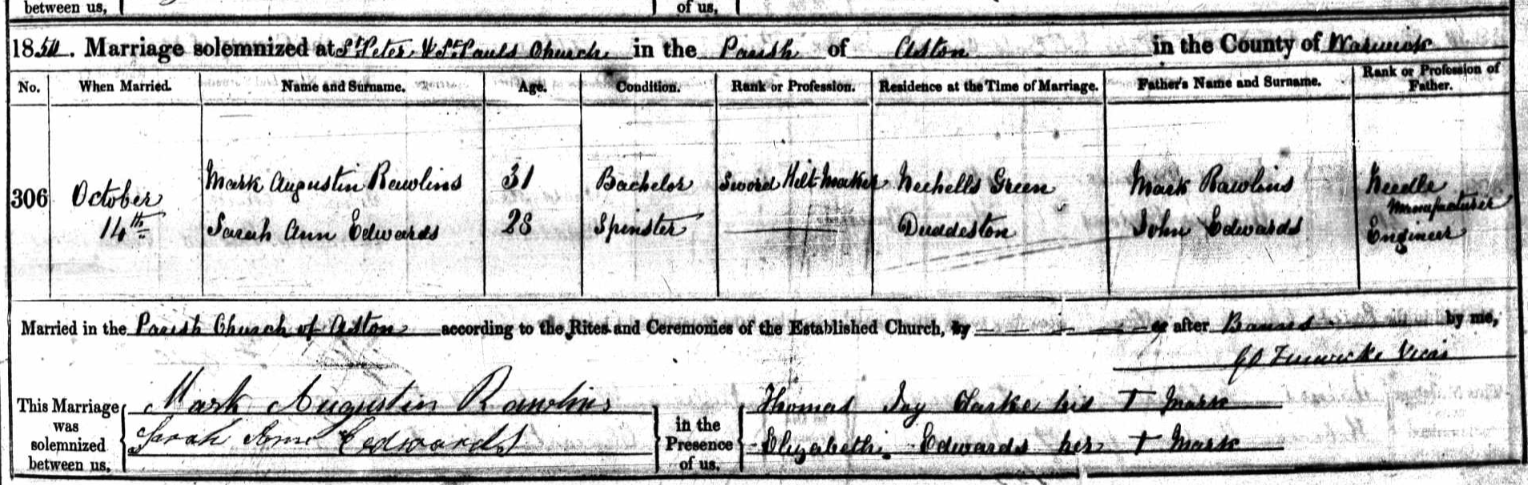

Sarah Ann married Mark Augustin Rawlins in 1850. Mark was a sword hilt maker at the time of the marriage, his father Mark a needle manufacturer. One of the witnesses was Elizabeth Edwards, who signed with her mark. Sarah Ann and Mark however were both able to sign their own names on the register.

Sarah Ann Edwards and Mark Augustin Rawlins marriage 14 October 1850 St Peter and St Paul, Aston, Birmingham:

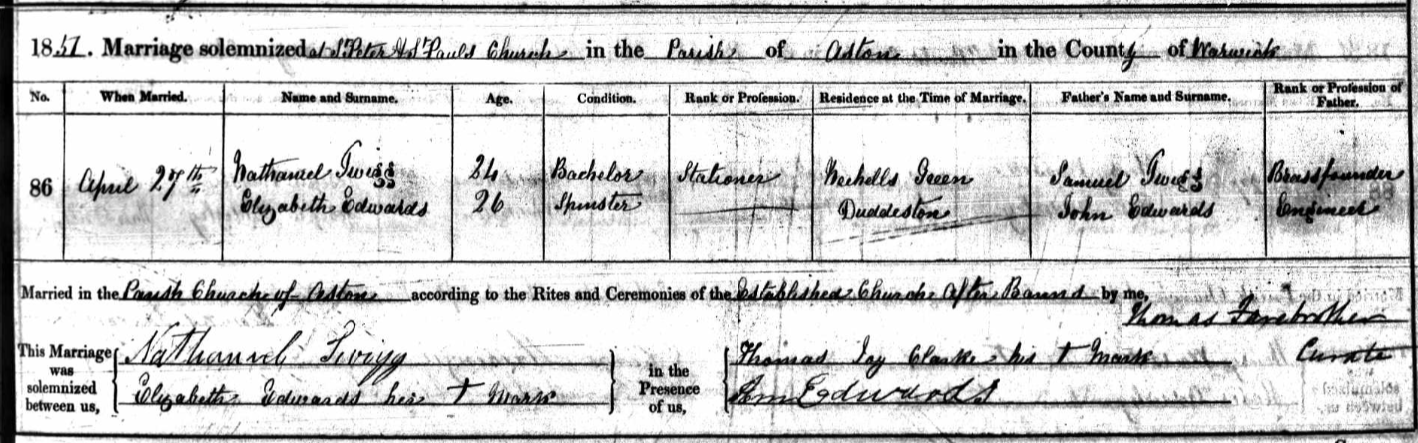

Elizabeth married Nathaniel Twigg in 1851. (She was living with her sister Sarah Ann and Mark Rawlins on the 1851 census, I assume the census was taken before her marriage to Nathaniel on the 27th April 1851.) Nathaniel was a stationer (later on the census a bookseller), his father Samuel a brass founder. Elizabeth signed with her mark, apparently unable to write, and a witness was Ann Edwards. Although Sarah Ann, Elizabeth’s sister, would have been Sarah Ann Rawlins at the time, having married the previous year, she was known as Ann on later censuses. The signature of Ann Edwards looks remarkably similar to Sarah Ann Edwards signature on her own wedding. Perhaps she couldn’t write but had learned how to write her signature for her wedding?

Elizabeth Edwards and Nathaniel Twigg marriage 27 April 1851, St Peter and St Paul, Aston, Birmingham:

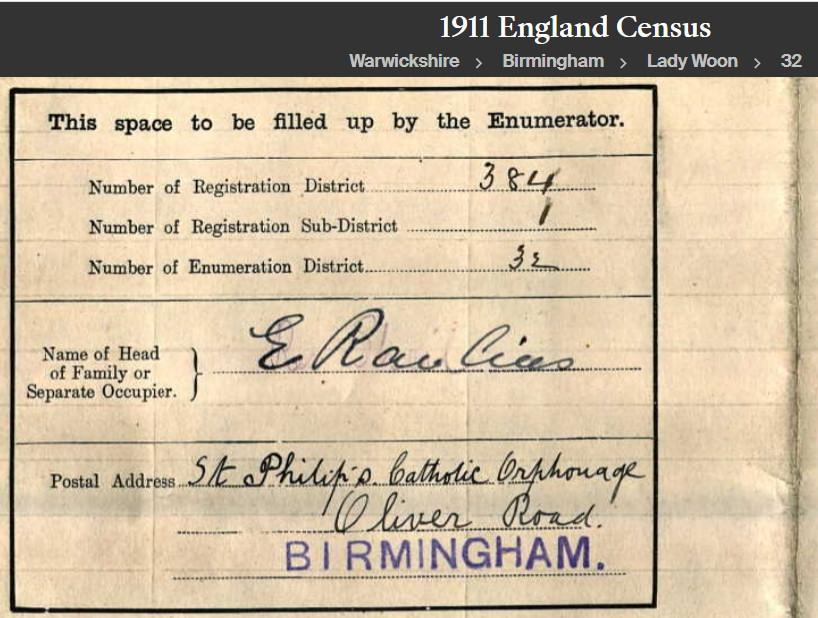

Sarah Ann and Mark Rawlins had one daughter and four sons between 1852 and 1859. One of the sons, Edward Rawlins 1857-1931, was a school master and later master of an orphanage.

On the 1881 census Edward was a bookseller, in 1891 a stationer, 1901 schoolmaster and his wife Edith was matron, and in 1911 he and Edith were master and matron of St Philip’s Catholic Orphanage on Oliver Road in Birmingham. Edward and Edith did not have any children.

Edward Rawlins, 1911:

Elizabeth and Nathaniel Twigg appear to have had only one son, Arthur Twigg 1862-1943. Arthur was a photographer at 291 Bloomsbury Street, Birmingham. Arthur married Harriet Moseley from Burton on Trent, and they had two daughters, Elizabeth Ann 1897-1954, and Edith 1898-1983. I found a photograph of Edith on her wedding day, with her father Arthur in the picture. Arthur and Harriet also had a son Samuel Arthur, who lived for less than a month, born in 1904. Arthur had mistakenly put this son on the 1911 census stating “less than one month”, but the birth and death of Samuel Arthur Twigg were registered in the same quarter of 1904, and none were found registered for 1911.

Edith Twigg and Leslie A Hancock on their Wedding Day 1925. Arthur Twigg behind the bride. Maybe Elizabeth Ann Twigg seated on the right: (photo found on the ancestry website)

Photographs by Arthur Twigg, 291 Bloomsbury Street, Birmingham:

May 16, 2023 at 10:52 am #7242

May 16, 2023 at 10:52 am #7242In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Any news on Yasmin? Xavier sent a message to Zara. He was puzzled when she sent a cryptic screenshot with no explanatory message:

Xavier forwarded the message to Youssef and then his phone rang. It was an important call that went on at some length and he forgot to add that Zara had sent it to him with no explanation. Youssef frowned, and forwarded the screenshot to Zara. In a strange but by no means uncommon coincidence, Youssef was also called away before he had time to add a message of his own.

When Zara received the message from Youssef, her first thought was that somehow Youssef was involved with Yasmin’s disappearance, but what were they both doing at a dust convention? But she was having a busy day at the wombat rescue centre, and didn’t have time for this new puzzling development until the evening.

Zara had started the new job a week before, and had not been expecting it to be so busy. It was for this reason that it took her several days to realize that Yasmin hadn’t replied to any of her brief daily messages. When she tried phoning, the automated message informed her that the phone was switched off or outside of network, so Zara phoned the meditation centre where Yasmin was still staying when Zara left to start her new job. They said she had left a few days ago, and nobody knew where she was going to. They added that it was not their business to know such things, and that they were only interested in silence and contemplation. Zara sighed, and wished she wasn’t too busy to get a bus over to the retreat and ask around but it was a two hour journey and it would have to wait until her next day off.

Going back over the most recent messages from Yasmin, Zara realized that the very last communication was the odd message about dust. It hadn’t seemed particularly strange the other day, after all, there were so many odd people at meditation retreats and they all had strange quirks and wacky ideas, but then she’d seen a flyer pinned to the cork board at the wombat rescue centre about a Dustsceawung Convention. Had Yasmin gone to that?

The more that Zara thought about it, the more likely it seemed. While Zara herself hadn’t been very serious about the meditation regime at the retreat and had mostly snoozed during the sessions, Yasmin had been smitten and was in danger, to Zara’s way of thinking, of going over the top on the woo stuff. Kept going on about being enlightened and so on. But she’d also taken to sniffing everything, and not just flowers. Zara had seen her sniffing deeply with a rapturous expression on several occasions ~ once she even saw her on her knees sniffing the carpet.

When Zara asked her about it, a glazed look came over Yasmin’s face and she garbled something about it being the highest level of enlightenment, the scent was stronger and more precise than the word, and all the answers were in the scents and that we’d all been misled into thinking words were the key to the truth, when really it was our nose that was the key.

Zara had noticed that Yasmin wasn’t snorting as much, and decided to say no more on the topic. If it was doing Yasmin good and curing the snorting, then all well and good. But it was that saintly expression on her face that was worrying, and Zara hoped she’d snap out of it in due course.

I had better explain all this to Xavier and Youssef, Zara decided, and then see if I can find out more about the dust convention. Maybe we can use the game quest to help. Not that I have any time for game playing with all these wombats though!

May 12, 2023 at 12:19 pm #7231In reply to: Washed off the sea ~ Creative larks

photo: Lara Maiklen, London mudlark.

“a tiny window into the 18th century: a cast-off shoe, a lost halfpenny, broken pipes and smashed plates and tea bowls….”

The Whale:

As the muddy banks of the Thames river receded, a treasure trove of small, lost items were revealed. Among them, a cast-off shoe, a lost halfpenny, broken pipes, and smashed plates and tea bowls. It was as if a tiny window into the 18th century had been opened, offering a glimpse into the lives of those long gone. As archaeologists carefully examined each item, they pieced together a story of a bustling riverfront community, where goods were transported and traded, and daily life was filled with both hardships and small joys. The lost halfpenny spoke of a hard day’s work, the broken pipes of moments of relaxation, and the smashed plates and tea bowls of hurried meals and perhaps even some arguments. Although these items may have been considered insignificant in their time, they now offer a precious insight into a bygone era, reminding us of the rich history that lies just beneath the muddy surface of the Thames river.March 31, 2023 at 8:00 pm #7221In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Zara took the notebook to the door of the hut where there was more light. The notebook fell open in the middle. A poem was written:

In the dry and dusty Outback land,

Where once gold was king and gold was grand,

Now a new treasure has taken hold,

A precious resource worth more than gold.

It flows beneath the sun-baked ground,

And in its depths, a fortune’s found,

For golfers come from far and wide,

To play on greens that should have died.

The mines that once lay abandoned and still,

Now hold the key to this water’s thrill,

For deep within their shadowed halls,

The liquid flows and never stalls.

But this is no natural spring,

The water here is a stolen thing,

Drilled and pumped with greedy hands,

To feed the golf course’s demands.

And so the land is left to bake,

While the greens stay lush and never break,

A crime against the thirsty earth,

A selfish act of financial worth.

For water is the lifeblood of this place,

A scarce resource that they should embrace,

Instead, they steal and hoard and sell,

A priceless gem, a living well.

So let us remember,

as we play and roam,

That water is not a thing to own,

But a gift from nature, pure and true,

That we must cherish and protect anew.

Golf! Zara wasn’t expecting that! As she closed the notebook she noticed a green pool had appeared just outside the hut, which had not been there before she found the poem. Pool! Water! Those green pools of water!

Zara almost dived headlong into the pool, and then remembered this was a group exercise and that she really ought to find out where the others were and share her finds with them.

February 22, 2023 at 8:54 am #6621In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

As the four of them walked into the tavern, having walked the mile or so from the Flying Fish Inn to the main street of the tiny town, Zara noticed the black BMW that she and Yasmin had seen parked outside the Piggly supermarket on the way back from the airport in Alice. She elbowed Yasmin in the ribs to point it out, but there was no need as Yasmin was already snorting nervously at the sight of it.

Sister Finli caught sight of them as she was just about to leave Betsy’s gem shop and paused until they’d disappeared into the bar before leaving the shop. It was the first time that Finli had seen Betsy in the flesh, and what a lot of flesh there was to see. Finli was horrifed, comparing her own elegant thin fingers with the fat sausage like digits of Betsy. She would never have expected Betsy to look this way. Still, it had thrown her, and she lost her usual efficient composure and quickly purchased a pink speckled gummy bear necklace. Annoyingly, this transaction reminded her that she seemed to have lost her crucifix.