Search Results for 'july'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

October 18, 2023 at 3:20 pm #7281

In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The 1935 Joseph Gerrard Challenge.

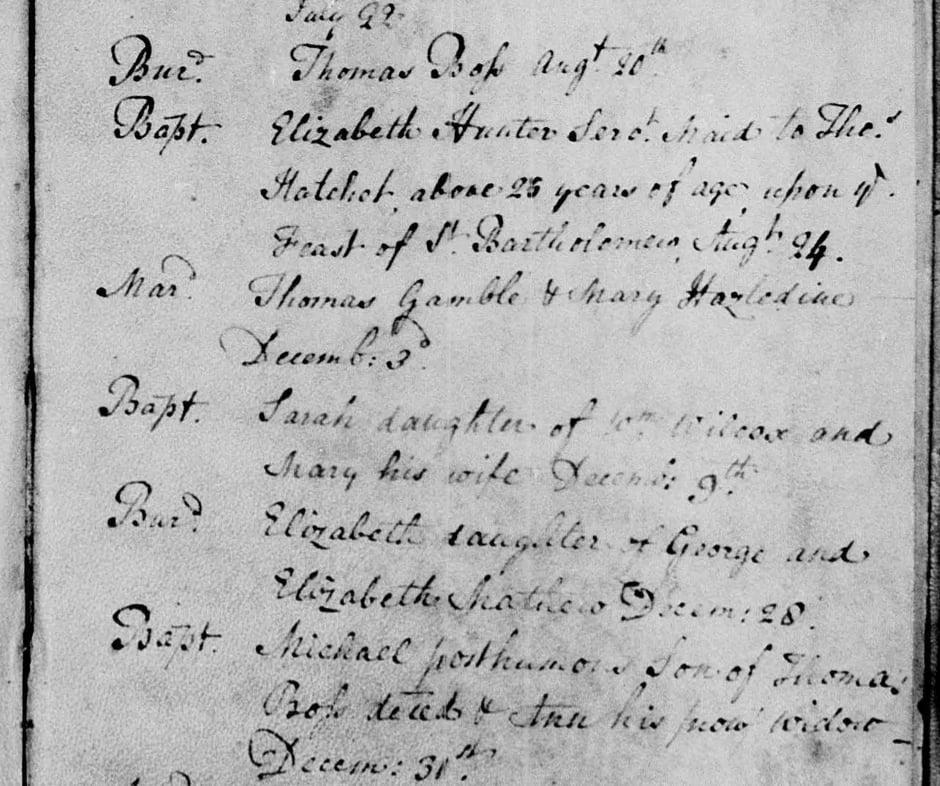

While researching the Gerrard family of Ellastone I chanced upon a 1935 newspaper article in the Ashbourne Register. There were two articles in 1935 in this paper about the Gerrards, the second a follow up to the first. An advertisement was also placed offering a £1 reward to anyone who could find Joseph Gerrard’s baptism record.

Ashbourne Telegraph – Friday 05 April 1935:

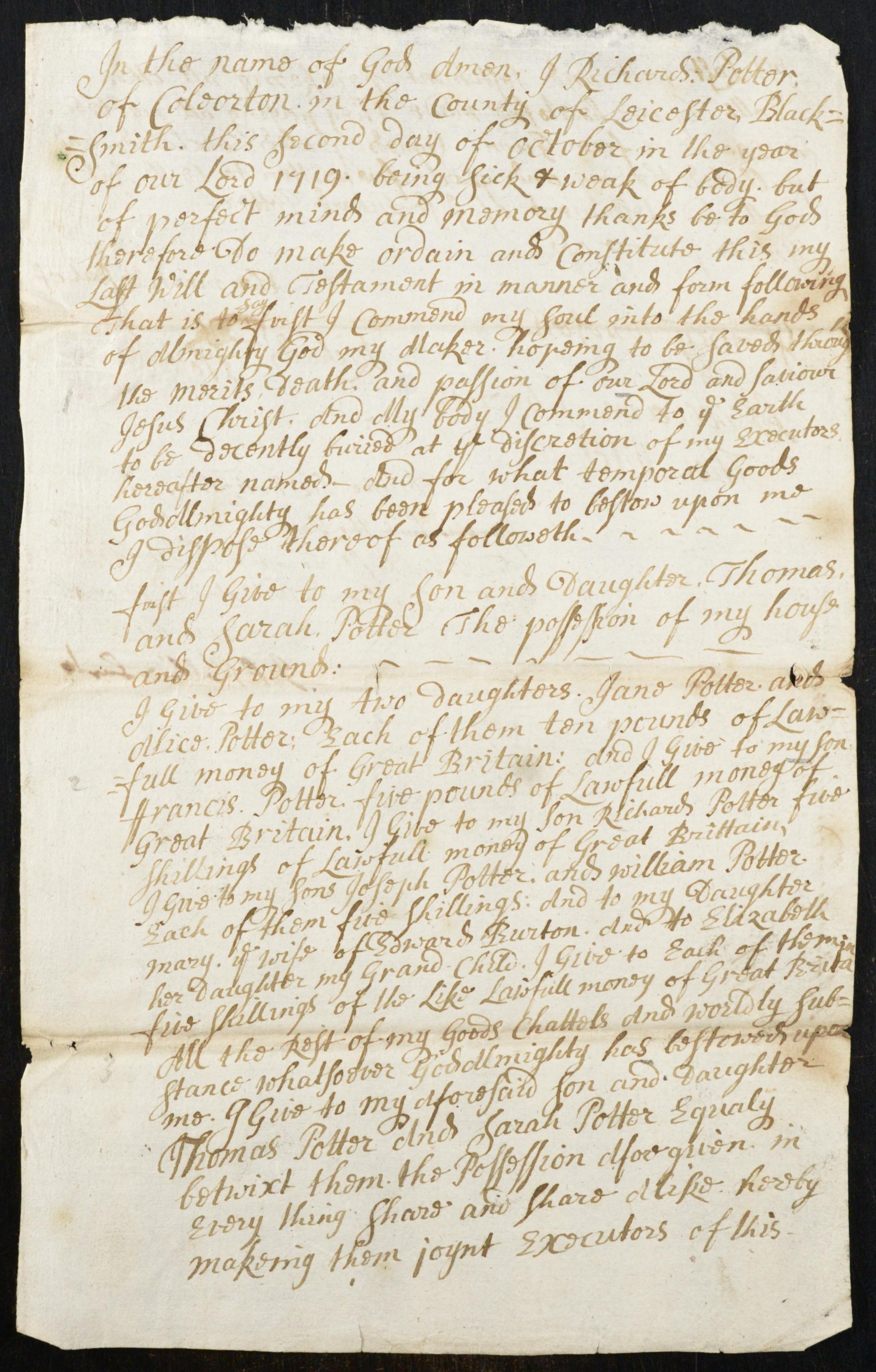

The author wanted to prove that the Joseph Gerrard “who was engaged in the library of King George the third from about 1775 to 1795, and whose death was recorded in the European Magazine in November 1799” was the son of John Gerrard of Ellastone Mills, Staffordshire. Included in the first article was a selected transcription of the 1796 will of John Gerrard. John’s son Joseph is mentioned in this will: John leaves him “£20 to buy a suit of mourning if he thinks proper.”

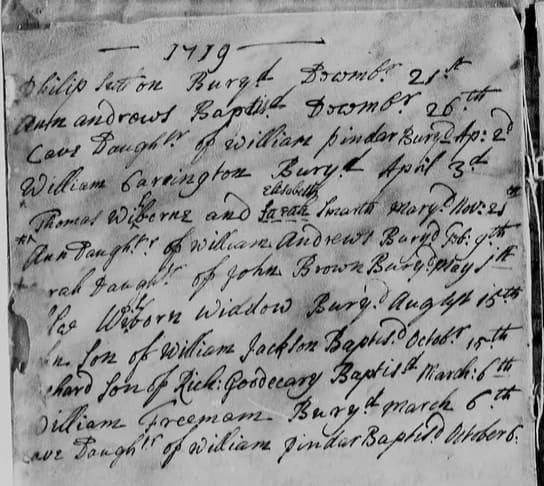

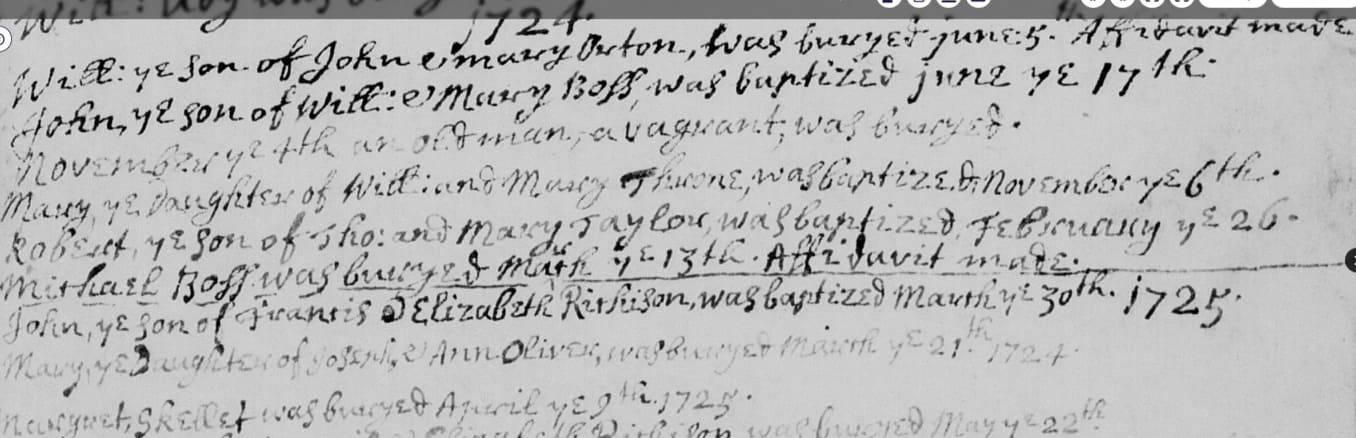

This Joseph Gerrard however, born in 1739, died in 1815 at Brailsford. Joseph’s brother John also died at Brailsford Mill, and both of their ages at death give a birth year of 1739. Maybe they were twins. William Gerrard and Joseph Gerrard of Brailsford Mill are mentioned in a 1811 newspaper article in the Derby Mercury.

I decided that there was nothing susbtantial about this claim, until I read the 1724 will of John Gerrard the elder, the father of John who died in 1796. In his will he leaves £100 to his son Joseph Gerrard, “secretary to the Bishop of Oxford”.

Perhaps there was something to this story after all. Joseph, baptised in 1701 in Ellastone, was the son of John Gerrard the elder.

I found Joseph Gerrard (and his son James Gerrard) mentioned in the Alumni Oxonienses: The Members of the University of Oxford, University of Oxford, Joseph Foster, 1888. “Joseph Gerard son of John of Elleston county Stafford, pleb, Oriel Coll, matric, 30th May 1718, age 18, BA. 9th March 1721-2; of Merton Coll MA 1728.”

In The Works of John Wesley 1735-1738, Joseph Gerrad is mentioned: “Joseph Gerard , matriculated at Oriel College 1718 , aged 18 , ordained 1727 to serve as curate of Cuddesdon , becoming rector of St. Martin’s , Oxford in 1729 , and vicar of Banbury in 1734.”

In The History of Banbury Alfred Beesley 1842 “a visitation of smallpox occured at Banbury (Oxfordshire) in 1731 and continued until 1733.” Joseph Gerrard was the vicar of Banbury in 1734.

According to the The History and Antiquities of the County of Buckingham George Lipscomb · 1847, Joseph Gerrard was made rector of Monks Risborough in 1738 “but he also continued to hold Stewkley until his death”.

The Speculum of Archbishop Thomas Secker by Secker, Thomas, 1693-1768, also mentions Joseph Gerrard under Monks Risborough and adds that he “resides constantly in the Parsonage ho. except when he goes for a few days to Steukley county Bucks (Buckinghamshire) of which he is vicar.” Joseph’s son James Gerrard 1741-1789 is also mentioned as being a rector at Monks Risborough in 1783.

Joseph Gerrard married Elizabeth Reynolds on 23 July 1739 in Monks Risborough, Buckinghamshire. They had five children between 1740 and 1750, including James baptised 1740 and Joseph baptised 1742.

Joseph died in 1785 in Monks Risborough.

So who was Joseph Gerrard of the Kings Library who died in 1799? It wasn’t Joseph’s son Joseph baptised in 1742 in Monks Risborough, because in his father’s 1785 will he mentions “my only son James”, indicating that Joseph died before that date.

September 20, 2023 at 1:48 pm #7279In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

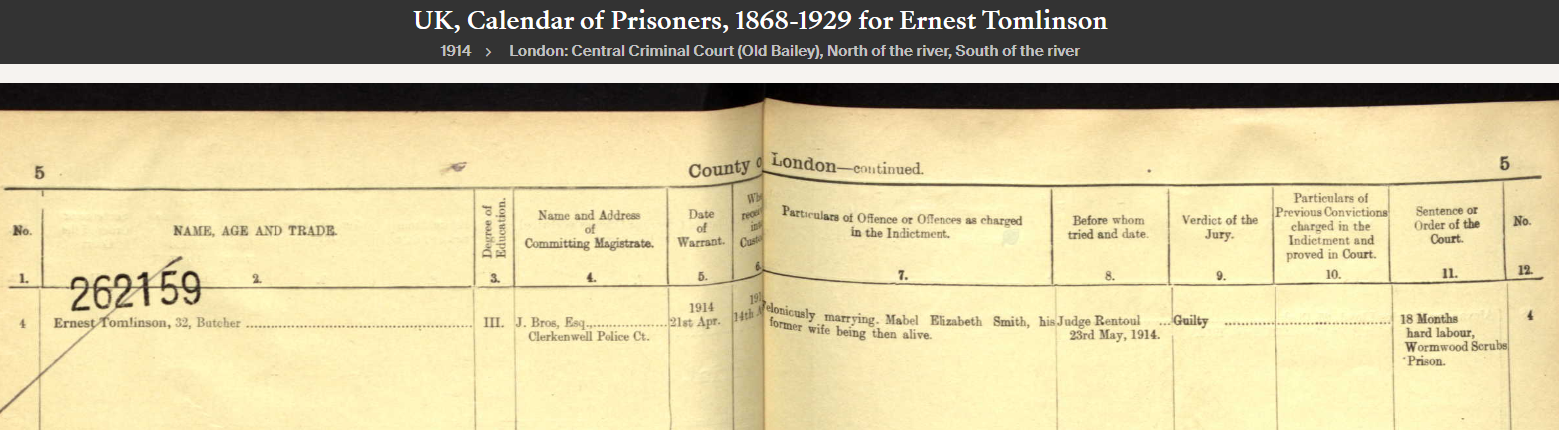

The Bigamist

Ernest Tomlinson 1881-1915

Ernest Tomlinson was my great grandfathers Charles Tomlinson‘s younger brother. Their parents were Charles Tomlinson the elder 1847-1907 and Emma Grattidge 1853-1911.

In 1896, aged 14, Ernest attempted to drown himself in the pond at Penn after his father took his watch off him for arguing with his brothers. Ernest tells the police “It’s all through my brothers putting on me”. The policeman told him he was a very silly and wicked boy and to see the curate at Penn and to try and be a better boy in future. He was discharged.

Bridgnorth Journal and South Shropshire Advertiser. – Saturday 11 July 1896:

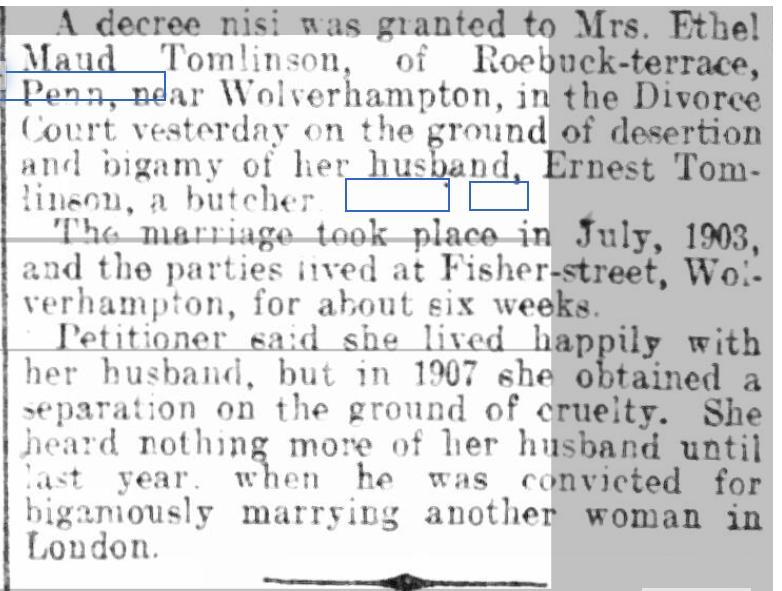

In 1903 Ernest married Ethel Maude Howe in Wolverhampton. Four years later in 1907 Ethel was granted a separation on the grounds of cruelty.

In Islington in London in 1913, Ernest bigamously married Mabel Elizabeth Smith. Mabel left Ernest for treating her very badly. She went to Wolverhampton and found out about his first wife still being alive.

London Evening Standard – Monday 25 May 1914:

In May 1914 Ernest was tried at the Old Bailey and the jury found him guilty of bigamy. In his defense, Ernest said that he had received a letter from his mother saying that she was ill, and a further letter saying that she had died. He said he wrongly assumed that they were referring to his wife, and that he was free to marry. It was his mother who had died. He was sentenced to 18 months hard labour at Wormwood Scrubs prison.

Woolwich Gazette – Tuesday 28 April 1914:

Ethel Maude Tomlinson was granted a decree nisi in 1915.

Birmingham Daily Gazette – Wednesday 02 June 1915:

Ernest died in September 1915 in hospital in Wolverhampton.

September 18, 2023 at 8:29 am #7278In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Tomlinson of Wergs and Hancox of Penn

John Tomlinson of Wergs (Tettenhall, Wolverhamton) 1766-1844, my 4X great grandfather, married Sarah Hancox 1772-1851. They were married on the 27th May 1793 by licence at St Peter in Wolverhampton.

Between 1794 and 1819 they had twelve children, although four of them died in childhood or infancy. Catherine was born in 1794, Thomas in 1795 who died 6 years later, William (my 3x great grandfather) in 1797, Jemima in 1800, John, Richard and Matilda between 1802 and 1806 who all died in childhood, Emma in 1809, Mary Ann in 1811, Sidney in 1814, and Elijah in 1817 who died two years later.On the 1841 census John and Sarah were living in Hockley in Birmingham, with three of their children, and surgeon Charles Reynolds. John’s occupation was “Ind” meaning living by independent means. He was living in Hockley when he died in 1844, and in his will he was “John Tomlinson, gentleman”.

Sarah Hancox was born in 1772 in Penn, Wolverhampton. Her father William Hancox was also born in Penn in 1737. Sarah’s mother Elizabeth Parkes married William’s brother Francis in 1767. Francis died in 1768, and in 1770 Elizabeth married William.

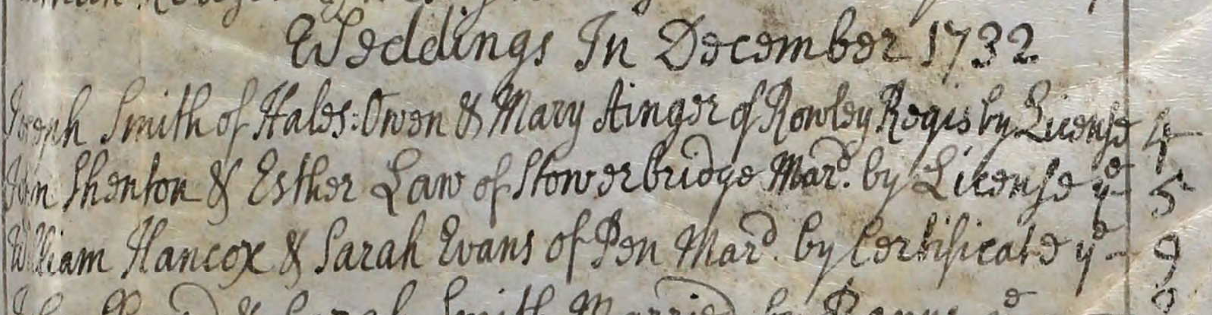

William’s father was William Hancox, yeoman, born in 1703 in Penn. He died intestate in 1772, his wife Sarah claiming her right to his estate. William Hancox and Sarah Evans, both of Penn, were married on the 9th December 1732 in Dudley, Worcestershire, by “certificate”. Marriages were usually either by banns or by licence. Apparently a marriage by certificate indicates that they were non conformists, or dissenters, and had the non conformist marriage “certified” in a Church of England church.

1732 marriage of William Hancox and Sarah Evans:

William and Sarah lost two daughters, Elizabeth, five years old, and Ann, three years old, within eight days of each other in February 1738.

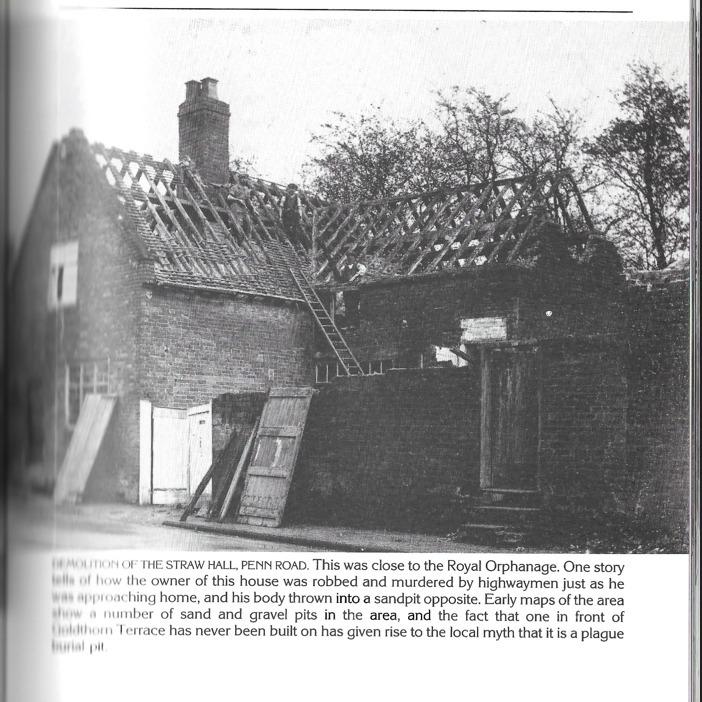

William the elder’s father was John Hancox born in Penn in 1668. He married Elizabeth Wilkes from Sedgley in 1691 at Himley. John Hancox, “of Straw Hall” according to the Wolverhampton burial register, died in 1730. Straw Hall is in Penn. John’s parents were Walter Hancox and Mary Noake. Walter was born in Tettenhall in 1625, his father Richard Hancox. Mary Noake was born in Penn in 1634. Walter died in Penn in 1689.

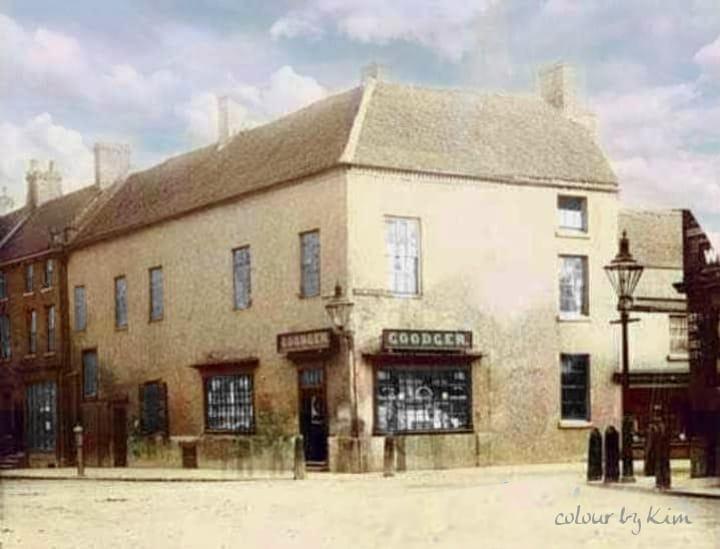

Straw Hall thanks to Bradney Mitchell:

“Here is a picture I have of Straw Hall, Penn Road.

The painting is by John Reid circa 1878.

Sketch commissioned by George Bradney Mitchell to record the town as it was before its redevelopment, in a book called Wolverhampton and its Environs. ©”

And a photo of the demolition of Straw Hall with an interesting story:

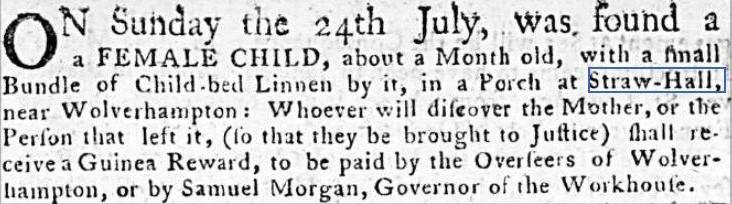

In 1757 a child was abandoned on the porch of Straw Hall. Aris’s Birmingham Gazette 1st August 1757:

The Hancox family were living in Penn for at least 400 years. My great grandfather Charles Tomlinson built a house on Penn Common in the early 1900s, and other Tomlinson relatives have lived there. But none of the family knew of the Hancox connection to Penn. I don’t think that anyone imagined a Tomlinson ancestor would have been a gentleman, either.

Sarah Hancox’s brother William Hancox 1776-1848 had a busy year in 1804.

On 29 Aug 1804 he applied for a licence to marry Ann Grovenor of Claverley.

In August 1804 he had property up for auction in Penn. “part of Lightwoods, 3 plots, and the Coppice”

On 14 Sept 1804 their first son John was baptised in Penn. According to a later census John was born in Claverley. (before the parents got married)(Incidentally, John Hancox’s descendant married a Warren, who is a descendant of my 4x great grandfather Samuel Warren, on my mothers side, from Newhall, Derbyshire!)

On 30 Sept he married Ann in Penn.

In December he was a bankrupt pig and sheep dealer.

In July 1805 he’s in the papers under “certificates”: William Hancox the younger, sheep and pig dealer and chapman of Penn. (A certificate was issued after a bankruptcy if they fulfilled their obligations)

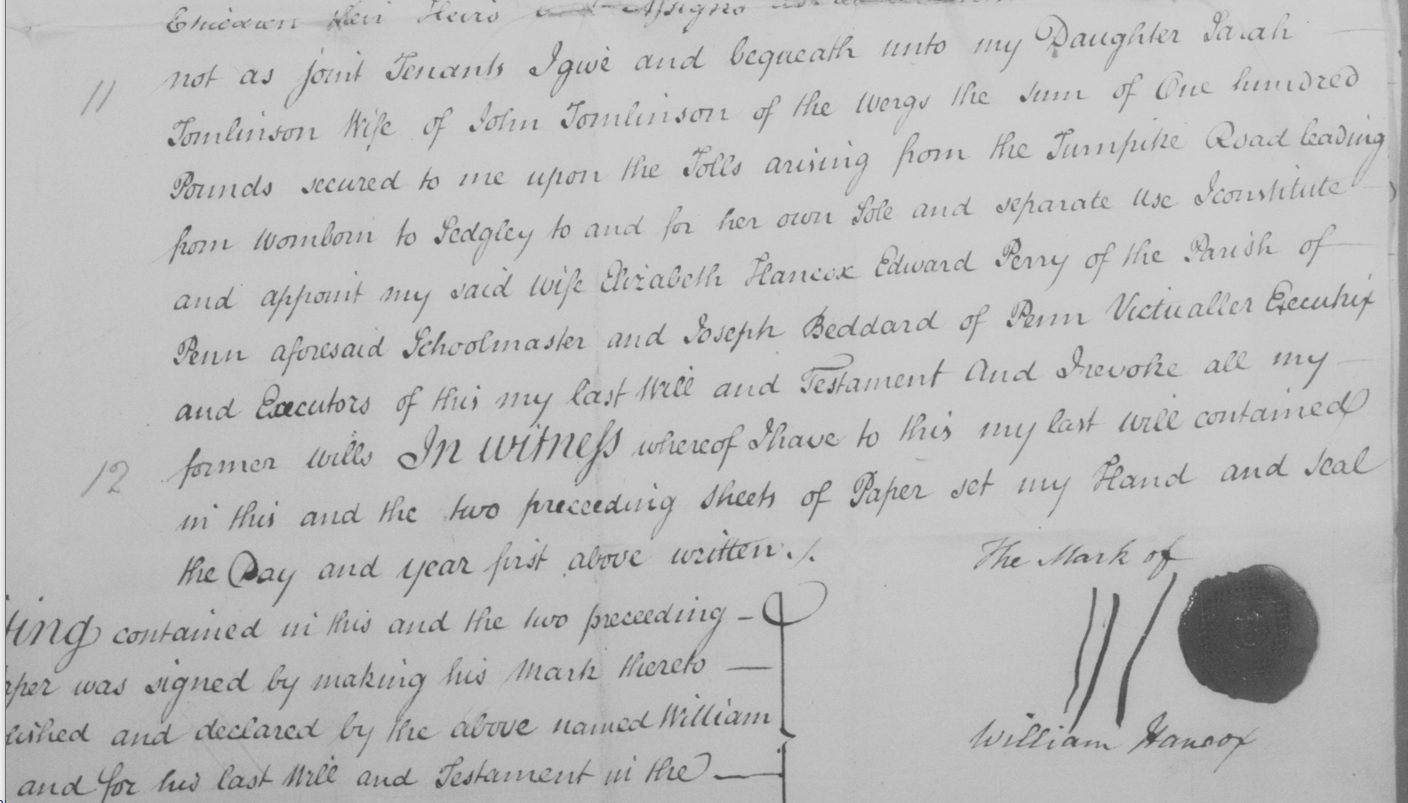

He was a pig dealer in Penn in 1841, a widower, living with unmarried daughter Elizabeth.Sarah’s father William Hancox died in 1816. In his will, he left his “daughter Sarah, wife of John Tomlinson of the Wergs the sum of £100 secured to me upon the tolls arising from the turnpike road leading from Wombourne to Sedgeley to and for her sole and separate use”.

The trustees of toll road would decide not to collect tolls themselves but get someone else to do it by selling the collecting of tolls for a fixed price. This was called “farming the tolls”. The Act of Parliament which set up the trust would authorise the trustees to farm out the tolls. This example is different. The Trustees of turnpikes needed to raise money to carry out work on the highway. The usual way they did this was to mortgage the tolls – they borrowed money from someone and paid the borrower interest; as security they gave the borrower the right, if they were not paid, to take over the collection of tolls and keep the proceeds until they had been paid off. In this case William Hancox has lent £100 to the turnpike and is leaving it (the right to interest and/or have the whole sum repaid) to his daughter Sarah Tomlinson. (this information on tolls from the Wolverhampton family history group.)William Hancox, Penn Wood, maltster, left a considerable amount of property to his children in 1816. All household effects he left to his wife Elizabeth, and after her decease to his son Richard Hancox: four dwelling houses in John St, Wolverhampton, in the occupation of various Pratts, Wright and William Clarke. He left £200 to his daughter Frances Gordon wife of James Gordon, and £100 to his daughter Ann Pratt widow of John Pratt. To his son William Hancox, all his various properties in Penn wood. To Elizabeth Tay wife of Thomas Tay he left £200, and to Richard Hancox various other properties in Penn Wood, and to his daughter Lucy Tay wife of Josiah Tay more property in Lower Penn. All his shops in St John Wolverhamton to his son Edward Hancox, and more properties in Lower Penn to both Francis Hancox and Edward Hancox. To his daughter Ellen York £200, and property in Montgomery and Bilston to his son John Hancox. Sons Francis and Edward were underage at the time of the will. And to his daughter Sarah, his interest in the toll mentioned above.

Sarah Tomlinson, wife of John Tomlinson of the Wergs, in William Hancox will:

July 5, 2023 at 8:21 pm #7263

July 5, 2023 at 8:21 pm #7263In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Solomon Stubbs

1781-1857

Solomon was born in Hamstall Ridware, Staffordshire, parents Samuel Stubbs and Rebecca Wood. (see The Hamstall Ridware Connection chapter)

Solomon married Phillis Lomas at St Modwen’s in Burton on Trent on 30th May 1815. Phillis was the llegitimate daughter of Frances Lomas. No father was named on the baptism on the 17th January 1787 in Sutton on the Hill, Derbyshire, and the entry on the baptism register states that she was illegitimate. Phillis’s mother Frances married Daniel Fox in 1790 in Sutton on the Hill. Unfortunately this means that it’s impossible to find my 5X great grandfather on this side of the family.

Solomon and Phillis had four daughters, the last died in infancy.

Sarah 1816-1867, Mary (my 3X great grandmother) 1819-1880, Phillis 1823-1905, and Maria 1825-1826.Solomon Stubbs of Horninglow St is listed in the 1834 Whites Directory under “China, Glass, Etc Dlrs”. Next to his name is Joanna Warren (earthenware) High St. Joanna Warren is related to me on my maternal side. No doubt Solomon and Joanna knew each other, unaware that several generations later a marriage would take place, not locally but miles away, joining their families.

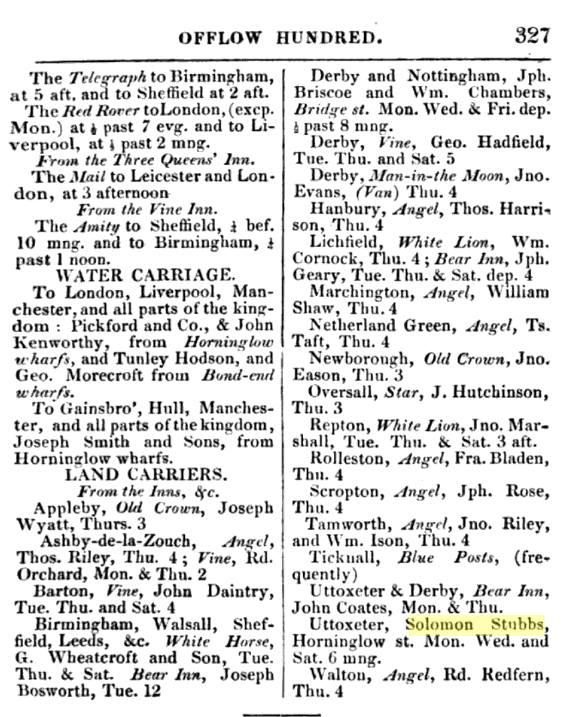

Solomon Stubbs is also listed in Whites Directory in 1831 and 1834 Burton on Trent as a land carrier:

“Land Carriers, from the Inns, Etc: Uttoxeter, Solomon Stubbs, Horninglow St, Mon. Wed. and Sat. 6 mng.”

Solomon is listed in the electoral registers in 1837. The 1837 United Kingdom general election was triggered by the death of King William IV and produced the first Parliament of the reign of his successor, Queen Victoria.

National Archives:

“In 1832, Parliament passed a law that changed the British electoral system. It was known as the Great Reform Act, which basically gave the vote to middle class men, leaving working men disappointed.

The Reform Act became law in response to years of criticism of the electoral system from those outside and inside Parliament. Elections in Britain were neither fair nor representative. In order to vote, a person had to own property or pay certain taxes to qualify, which excluded most working class people.”Via the Burton on Trent History group:

“a very early image of High street and Horninglow street junction, where the original ‘ Bargates’ were in the days of the Abbey. ‘Gate’ is the Saxon meaning Road, ‘Bar’ quite self explanatory, meant ‘to stop entrance’. There was another Bargate across Cat street (Station street), the Abbot had these constructed to regulate the Traders coming into town, in the days when the Abbey ran things. In the photo you can see the Posts on the corner, designed to stop Carts and Carriages mounting the Pavement. Only three Posts remain today and they are Listed.”

On the 1841 census, Solomon’s occupation was Carrier. Daughter Sarah is still living at home, and Sarah Grattidge, 13 years old, lives with them. Solomon’s daughter Mary had married William Grattidge in 1839.

Solomon Stubbs of Horninglow Street, Burton on Trent, is listed as an Earthenware Dealer in the 1842 Pigot’s Directory of Staffordshire.

In May 1844 Solomon’s wife Phillis died. In July 1844 daughter Sarah married Thomas Brandon in Burton on Trent. It was noted in the newspaper announcement that this was the first wedding to take place at the Holy Trinity church.

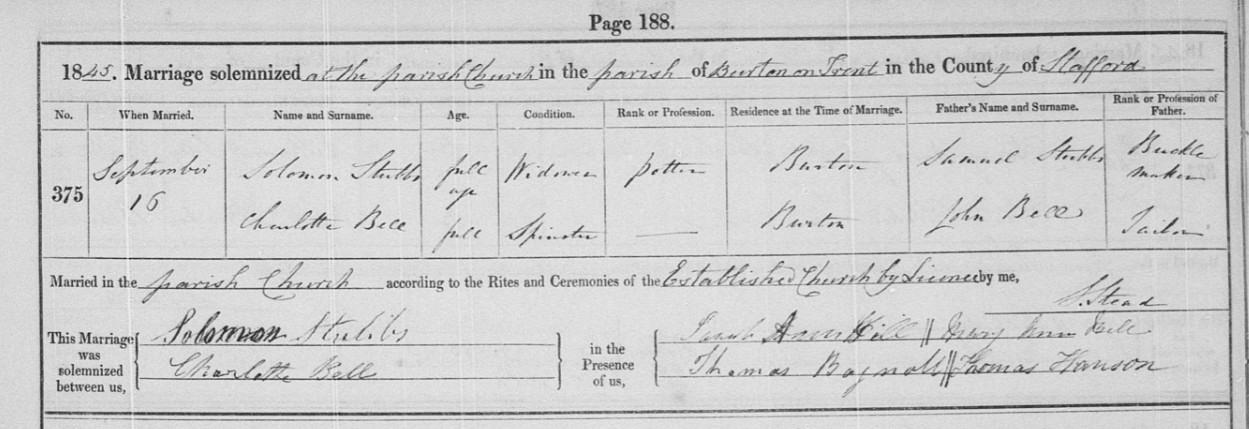

Solomon married Charlotte Bell by licence the following year in 1845. She was considerably younger than him, born in 1824. On the marriage certificate Solomon’s occupation is potter. It seems that he had the earthenware business as well as the land carrier business, in addition to owning a number of properties.

The marriage of Solomon Stubbs and Charlotte Bell:

Also in 1845, Solomon’s daughter Phillis was married in Burton on Trent to John Devitt, son of CD Devitt, Esq, formerly of the General Post Office Dublin.

Solomon Stubbs died in September 1857 in Burton on Trent. In the Staffordshire Advertiser on Saturday 3 October 1857:

“On the 22nd ultimo, suddenly, much respected, Solomon Stubbs, of Guild-street, Burton-on-Trent, aged 74 years.”

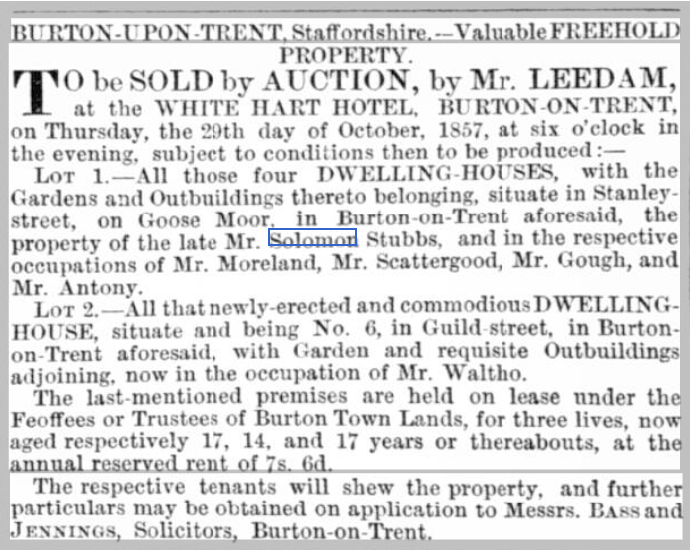

In the Staffordshire Advertiser, 24th October 1857, the auction of the property of Solomon Stubbs was announced:

“BURTON ON TRENT, on Thursday, the 29th day of October, 1857, at six o’clock in the evening, subject to conditions then to be produced:— Lot I—All those four DWELLING HOUSES, with the Gardens and Outbuildings thereto belonging, situate in Stanleystreet, on Goose Moor, in Burton-on-Trent aforesaid, the property of the late Mr. Solomon Stubbs, and in the respective occupations of Mr. Moreland, Mr. Scattergood, Mr. Gough, and Mr. Antony…..”

Sadly, the graves of Solomon, his wife Phillis, and their infant daughter Maria have since been removed and are listed in the UK Records of the Removal of Graves and Tombstones 1601-2007.

July 4, 2023 at 7:52 pm #7261In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Long Lost Enoch Edwards

My father used to mention long lost Enoch Edwards. Nobody in the family knew where he went to and it was assumed that he went to USA, perhaps to Utah to join his sister Sophie who was a Mormon handcart pioneer, but no record of him was found in USA.

Andrew Enoch Edwards (my great great grandfather) was born in 1840, but was (almost) always known as Enoch. Although civil registration of births had started from 1 July 1837, neither Enoch nor his brother Stephen were registered. Enoch was baptised (as Andrew) on the same day as his brothers Reuben and Stephen in May 1843 at St Chad’s Catholic cathedral in Birmingham. It’s a mystery why these three brothers were baptised Catholic, as there are no other Catholic records for this family before or since. One possible theory is that there was a school attached to the church on Shadwell Street, and a Catholic baptism was required for the boys to go to the school. Enoch’s father John died of TB in 1844, and perhaps in 1843 he knew he was dying and wanted to ensure an education for his sons. The building of St Chads was completed in 1841, and it was close to where they lived.

Enoch appears (as Enoch rather than Andrew) on the 1841 census, six months old. The family were living at Unett Street in Birmingham: John and Sarah and children Mariah, Sophia, Matilda, a mysterious entry transcribed as Lene, a daughter, that I have been unable to find anywhere else, and Reuben and Stephen.

Enoch was just four years old when his father John, an engineer and millwright, died of consumption in 1844.

In 1851 Enoch’s widowed mother Sarah was a mangler living on Summer Street, Birmingham, Matilda a dressmaker, Reuben and Stephen were gun percussionists, and eleven year old Enoch was an errand boy.

On the 1861 census, Sarah was a confectionrer on Canal Street in Birmingham, Stephen was a blacksmith, and Enoch a button tool maker.

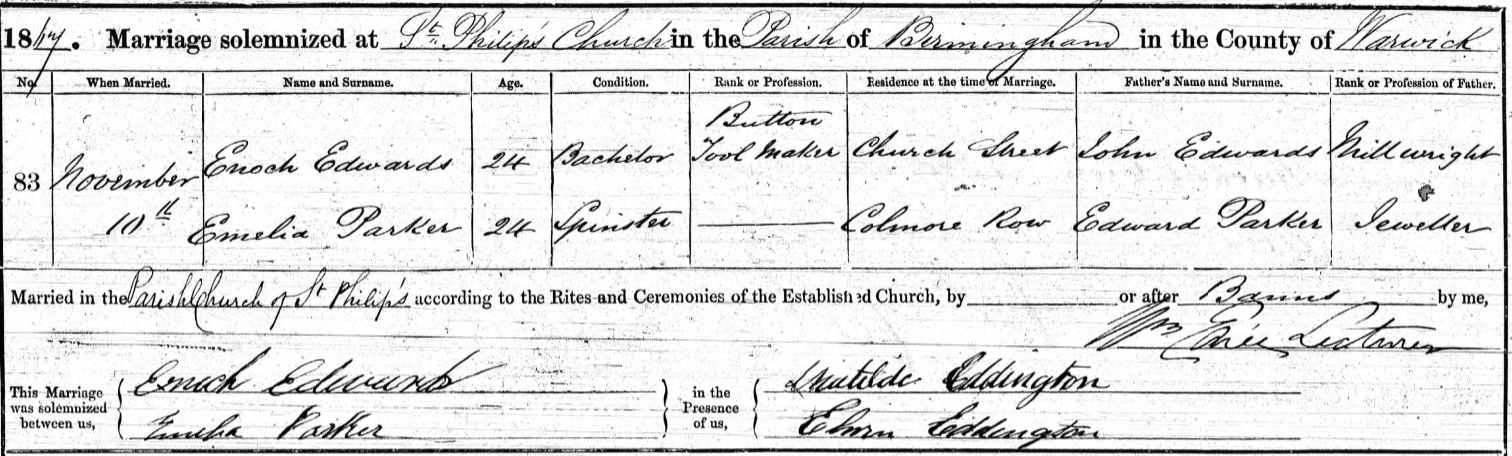

On the 10th November 1867 Enoch married Emelia Parker, daughter of jeweller and rope maker Edward Parker, at St Philip in Birmingham. Both Emelia and Enoch were able to sign their own names, and Matilda and Edwin Eddington were witnesses (Enoch’s sister and her husband). Enoch’s address was Church Street, and his occupation button tool maker.

Four years later in 1871, Enoch was a publican living on Clifton Road. Son Enoch Henry was two years old, and Ralph Ernest was three months. Eliza Barton lived with them as a general servant.

By 1881 Enoch was back working as a button tool maker in Bournebrook, Birmingham. Enoch and Emilia by then had three more children, Amelia, Albert Parker (my great grandfather) and Ada.

Garnet Frederick Edwards was born in 1882. This is the first instance of the name Garnet in the family, and subsequently Garnet has been the middle name for the eldest son (my brother, father and grandfather all have Garnet as a middle name).

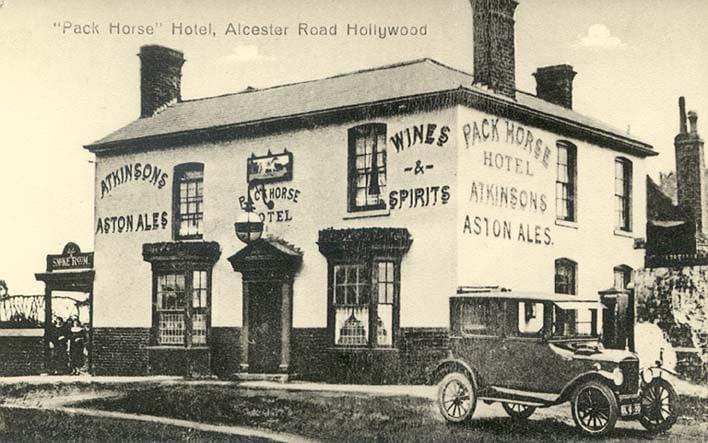

Enoch was the licensed victualler at the Pack Horse Hotel in 1991 at Kings Norton. By this time, only daughters Amelia and Ada and son Garnet are living at home.

Additional information from my fathers cousin, Paul Weaver:

“Enoch refused to allow his son Albert Parker to go to King Edwards School in Birmingham, where he had been awarded a place. Instead, in October 1890 he made Albert Parker Edwards take an apprenticeship with a pawnboker in Tipton.

Towards the end of the 19th century Enoch kept The Pack Horse in Alcester Road, Hollywood, where a twist was 1d an ounce, and beer was 2d a pint. The children had to get up early to get breakfast at 6 o’clock for the hay and straw men on their way to the Birmingham hay and straw market. Enoch is listed as a member of “The Kingswood & Pack Horse Association for the Prosecution of Offenders”, a kind of early Neighbourhood Watch, dated 25 October 1890.

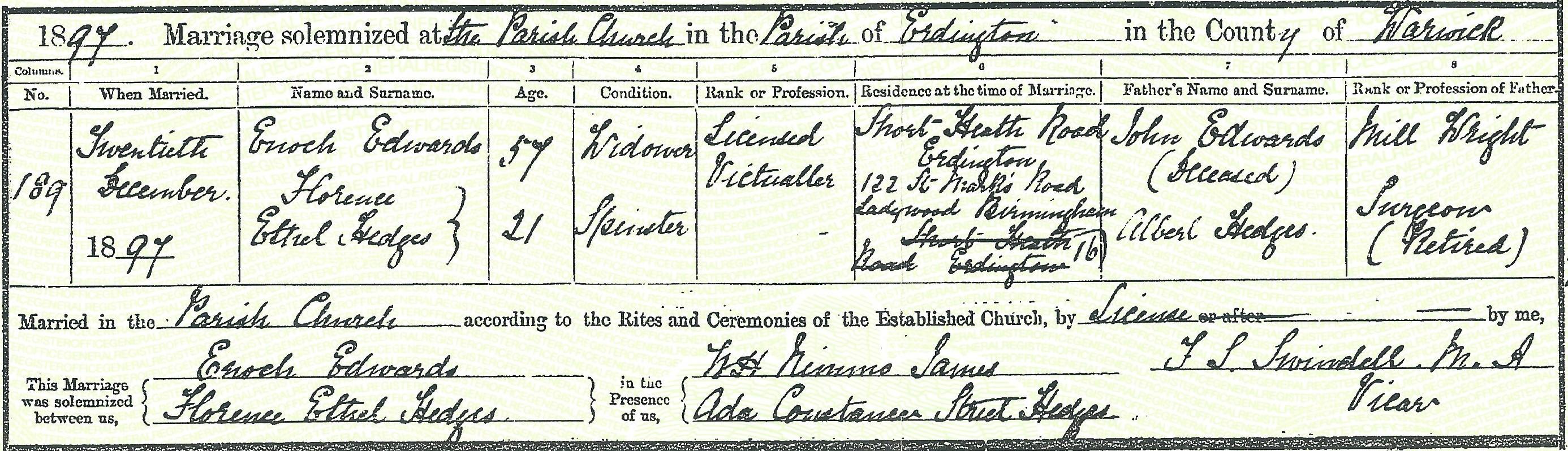

The Edwards family later moved to Redditch where they kept The Rifleman Inn at 35 Park Road. They must have left the Pack Horse by 1895 as another publican was in place by then.”Emelia his wife died in 1895 of consumption at the Rifleman Inn in Redditch, Worcestershire, and in 1897 Enoch married Florence Ethel Hedges in Aston. Enoch was 56 and Florence was just 21 years old.

The following year in 1898 their daughter Muriel Constance Freda Edwards was born in Deritend, Warwickshire.

In 1901 Enoch, (Andrew on the census), publican, Florence and Muriel were living in Dudley. It was hard to find where he went after this.From Paul Weaver:

“Family accounts have it that Enoch EDWARDS fell out with all his family, and at about the age of 60, he left all behind and emigrated to the U.S.A. Enoch was described as being an active man, and it is believed that he had another family when he settled in the U.S.A. Esmor STOKES has it that a postcard was received by the family from Enoch at Niagara Falls.

On 11 June 1902 Harry Wright (the local postmaster responsible in those days for licensing) brought an Enoch EDWARDS to the Bedfordshire Petty Sessions in Biggleswade regarding “Hole in the Wall”, believed to refer to the now defunct “Hole in the Wall” public house at 76 Shortmead Street, Biggleswade with Enoch being granted “temporary authority”. On 9 July 1902 the transfer was granted. A year later in the 1903 edition of Kelly’s Directory of Bedfordshire, Hunts and Northamptonshire there is an Enoch EDWARDS running the Wheatsheaf Public House, Church Street, St. Neots, Huntingdonshire which is 14 miles south of Biggleswade.”

It seems that Enoch and his new family moved away from the midlands in the early 1900s, but again the trail went cold.

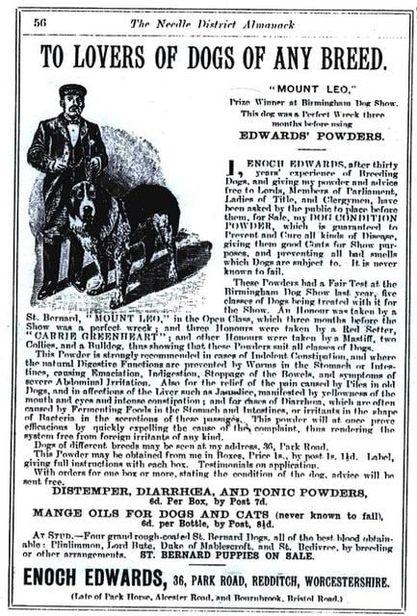

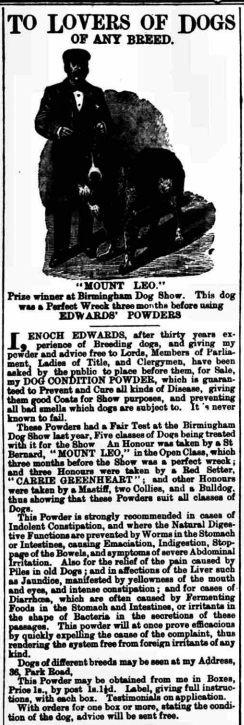

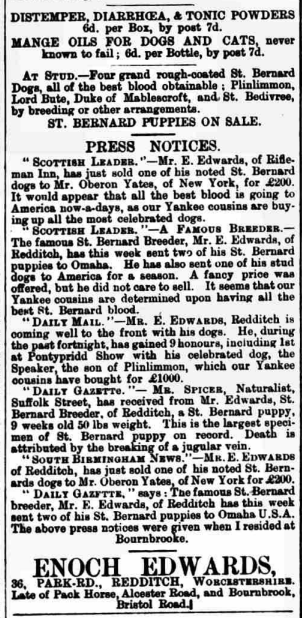

When I started doing the genealogy research, I joined a local facebook group for Redditch in Worcestershire. Enoch’s son Albert Parker Edwards (my great grandfather) spent most of his life there. I asked in the group about Enoch, and someone posted an illustrated advertisement for Enoch’s dog powders. Enoch was a well known breeder/keeper of St Bernards and is cited in a book naming individuals key to the recovery/establishment of ‘mastiff’ size dog breeds.

We had not known that Enoch was a breeder of champion St Bernard dogs!

Once I knew about the St Bernard dogs and the names Mount Leo and Plinlimmon via the newspaper adverts, I did an internet search on Enoch Edwards in conjunction with these dogs.

Enoch’s St Bernard dog “Mount Leo” was bred from the famous Plinlimmon, “the Emperor of Saint Bernards”. He was reported to have sent two puppies to Omaha and one of his stud dogs to America for a season, and in 1897 Enoch made the news for selling a St Bernard to someone in New York for £200. Plinlimmon, bred by Thomas Hall, was born in Liverpool, England on June 29, 1883. He won numerous dog shows throughout Europe in 1884, and in 1885, he was named Best Saint Bernard.

In the Birmingham Mail on 14th June 1890:

“Mr E Edwards, of Bournebrook, has been well to the fore with his dogs of late. He has gained nine honours during the past fortnight, including a first at the Pontypridd show with a St Bernard dog, The Speaker, a son of Plinlimmon.”

In the Alcester Chronicle on Saturday 05 June 1897:

It was discovered that Enoch, Florence and Muriel moved to Canada, not USA as the family had assumed. The 1911 census for Montreal St Jaqcues, Quebec, stated that Enoch, (Florence) Ethel, and (Muriel) Frida had emigrated in 1906. Enoch’s occupation was machinist in 1911. The census transcription is not very good. Edwards was transcribed as Edmand, but the dates of birth for all three are correct. Birthplace is correct ~ A for Anglitan (the census is in French) but race or tribe is also an A but the transcribers have put African black! Enoch by this time was 71 years old, his wife 33 and daughter 11.

Additional information from Paul Weaver:

“In 1906 he and his new family travelled to Canada with Enoch travelling first and Ethel and Frida joined him in Quebec on 25 June 1906 on board the ‘Canada’ from Liverpool.

Their immigration record suggests that they were planning to travel to Winnipeg, but five years later in 1911, Enoch, Florence Ethel and Frida were still living in St James, Montreal. Enoch was employed as a machinist by Canadian Government Railways working 50 hours. It is the 1911 census record that confirms his birth as November 1840. It also states that Enoch could neither read nor write but managed to earn $500 in 1910 for activity other than his main profession, although this may be referring to his innkeeping business interests.

By 1921 Florence and Muriel Frida are living in Langford, Neepawa, Manitoba with Peter FUCHS, an Ontarian farmer of German descent who Florence had married on 24 Jul 1913 implying that Enoch died sometime in 1911/12, although no record has been found.”The extra $500 in earnings was perhaps related to the St Bernard dogs. Enoch signed his name on the register on his marriage to Emelia, and I think it’s very unlikely that he could neither read nor write, as stated above.

However, it may not be Enoch’s wife Florence Ethel who married Peter Fuchs. A Florence Emma Edwards married Peter Fuchs, and on the 1921 census in Neepawa her daugther Muriel Elizabeth Edwards, born in 1902, lives with them. Quite a coincidence, two Florence and Muriel Edwards in Neepawa at the time. Muriel Elizabeth Edwards married and had two children but died at the age of 23 in 1925. Her mother Florence was living with the widowed husband and the two children on the 1931 census in Neepawa. As there was no other daughter on the 1911 census with Enoch, Florence and Muriel in Montreal, it must be a different Florence and daughter. We don’t know, though, why Muriel Constance Freda married in Neepawa.

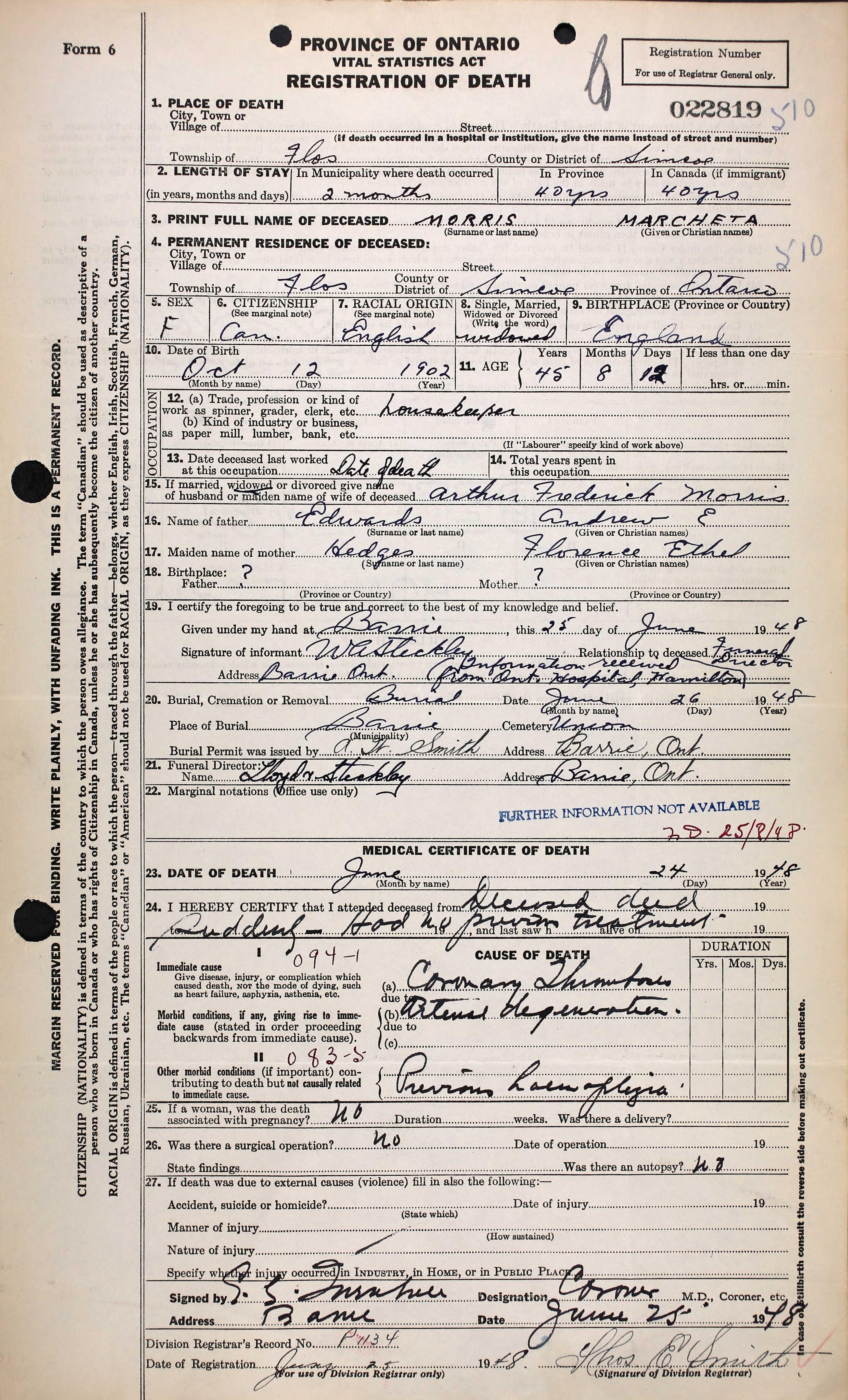

Indeed, Florence was not a widow in 1913. Enoch died in 1924 in Montreal, aged 84. Neither Enoch, Florence or their daughter has been found yet on the 1921 census. The search is not easy, as Enoch sometimes used the name Andrew, Florence used her middle name Ethel, and daughter Muriel used Freda, Valerie (the name she added when she married in Neepawa), and died as Marcheta. The only name she NEVER used was Constance!

A Canadian genealogist living in Montreal phoned the cemetery where Enoch was buried. She said “Enoch Edwards who died on Feb 27 1924 is not buried in the Mount Royal cemetery, he was only cremated there on March 4, 1924. There are no burial records but he died of an abcess and his body was sent to the cemetery for cremation from the Royal Victoria Hospital.”

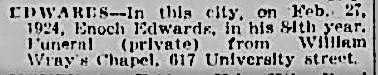

1924 Obituary for Enoch Edwards:

Cimetière Mont-Royal Outremont, Montreal Region, Quebec, Canada

The Montreal Star 29 Feb 1924, Fri · Page 31

Muriel Constance Freda Valerie Edwards married Arthur Frederick Morris on 24 Oct 1925 in Neepawa, Manitoba. (She appears to have added the name Valerie when she married.)

Unexpectedly a death certificate appeared for Muriel via the hints on the ancestry website. Her name was “Marcheta Morris” on this document, however it also states that she was the widow of Arthur Frederick Morris and daughter of Andrew E Edwards and Florence Ethel Hedges. She died suddenly in June 1948 in Flos, Simcoe, Ontario of a coronary thrombosis, where she was living as a housekeeper.

March 19, 2023 at 10:39 pm #7204

March 19, 2023 at 10:39 pm #7204Some handy references for the timelines of the Flying Fish Inn are here…

Year Date Event 1935 March 1, 1935 Birth of Mater 1958 March 13, 1958 Mater marries her childhood sweetheart 1965 August 17, 1965 Birth of Fred 1968 June 8, 1968 Birth of Abcynthia Hogg 1970 July 7, 1970 Birth of Aunt Idle 1978 April 12, 1978 Mater’s husband dies 1987 March 19, 1987 Mines close down – Carts & Lager Festival 1988 December 12, 1988 Idle gives birth to a child in Fiji (Liana) 1989 December 20, 1989 Horace Hogg death – Inn passes down to Abby 1990 May 7, 1990 Fred marries Abcynthia 1998 November 11, 1998 Birth of Devan 2000 November 11, 2000 Birth of Clove and Coriander 2007 March 7, 2007 Hannah Hogg’s death, the Inn passes to Abcynthia 2008 March 10, 2008 Carts and Lager Festival revival 2008 August 20, 2008 Birth of Prune 2009 February 2, 2009 Abcynthia leaves 2009 September 11, 2009 Strange incidents at the mines, Idle sets up the Inn 2010 May 27, 2010 Fred leaves his family, goes into hiding 2014 September 10, 2014 Start of Prune’s journal 2017 March 21, 2017 Visitors from Elsewheres 2020 December 22, 2020 The year of the Great Fires 2021 August 8, 2021 Italian tourists saved the Inn 2023 March 1, 2023 Orbs gamers visitors 2027 September 1, 2027 Prune going to a boarding school 2035 March 21, 2035 Mater 100 and twins on a Waterlark adventure 2049 March 17, 2049 Prune arrives with a commercial flight on Mars, Mater is deceased (would have been 114) December 6, 2022 at 2:17 pm #6350In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Transportation

Isaac Stokes 1804-1877

Isaac was born in Churchill, Oxfordshire in 1804, and was the youngest brother of my 4X great grandfather Thomas Stokes. The Stokes family were stone masons for generations in Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire, and Isaac’s occupation was a mason’s labourer in 1834 when he was sentenced at the Lent Assizes in Oxford to fourteen years transportation for stealing tools.

Churchill where the Stokes stonemasons came from: on 31 July 1684 a fire destroyed 20 houses and many other buildings, and killed four people. The village was rebuilt higher up the hill, with stone houses instead of the old timber-framed and thatched cottages. The fire was apparently caused by a baker who, to avoid chimney tax, had knocked through the wall from her oven to her neighbour’s chimney.

Isaac stole a pick axe, the value of 2 shillings and the property of Thomas Joyner of Churchill; a kibbeaux and a trowel value 3 shillings the property of Thomas Symms; a hammer and axe value 5 shillings, property of John Keen of Sarsden.

(The word kibbeaux seems to only exists in relation to Isaac Stokes sentence and whoever was the first to write it was perhaps being creative with the spelling of a kibbo, a miners or a metal bucket. This spelling is repeated in the criminal reports and the newspaper articles about Isaac, but nowhere else).

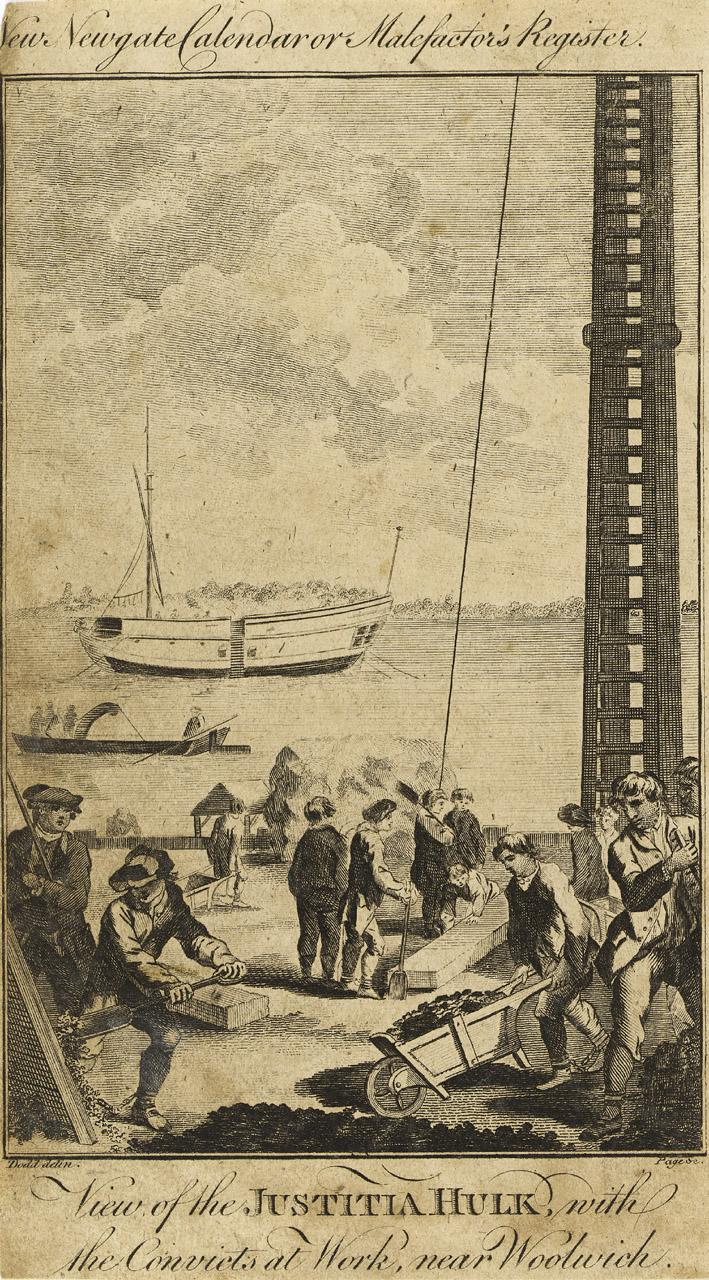

In March 1834 the Removal of Convicts was announced in the Oxford University and City Herald: Isaac Stokes and several other prisoners were removed from the Oxford county gaol to the Justitia hulk at Woolwich “persuant to their sentences of transportation at our Lent Assizes”.

via digitalpanopticon:

Hulks were decommissioned (and often unseaworthy) ships that were moored in rivers and estuaries and refitted to become floating prisons. The outbreak of war in America in 1775 meant that it was no longer possible to transport British convicts there. Transportation as a form of punishment had started in the late seventeenth century, and following the Transportation Act of 1718, some 44,000 British convicts were sent to the American colonies. The end of this punishment presented a major problem for the authorities in London, since in the decade before 1775, two-thirds of convicts at the Old Bailey received a sentence of transportation – on average 283 convicts a year. As a result, London’s prisons quickly filled to overflowing with convicted prisoners who were sentenced to transportation but had no place to go.

To increase London’s prison capacity, in 1776 Parliament passed the “Hulks Act” (16 Geo III, c.43). Although overseen by local justices of the peace, the hulks were to be directly managed and maintained by private contractors. The first contract to run a hulk was awarded to Duncan Campbell, a former transportation contractor. In August 1776, the Justicia, a former transportation ship moored in the River Thames, became the first prison hulk. This ship soon became full and Campbell quickly introduced a number of other hulks in London; by 1778 the fleet of hulks on the Thames held 510 prisoners.

Demand was so great that new hulks were introduced across the country. There were hulks located at Deptford, Chatham, Woolwich, Gosport, Plymouth, Portsmouth, Sheerness and Cork.The Justitia via rmg collections:

Convicts perform hard labour at the Woolwich Warren. The hulk on the river is the ‘Justitia’. Prisoners were kept on board such ships for months awaiting deportation to Australia. The ‘Justitia’ was a 260 ton prison hulk that had been originally moored in the Thames when the American War of Independence put a stop to the transportation of criminals to the former colonies. The ‘Justitia’ belonged to the shipowner Duncan Campbell, who was the Government contractor who organized the prison-hulk system at that time. Campbell was subsequently involved in the shipping of convicts to the penal colony at Botany Bay (in fact Port Jackson, later Sydney, just to the north) in New South Wales, the ‘first fleet’ going out in 1788.

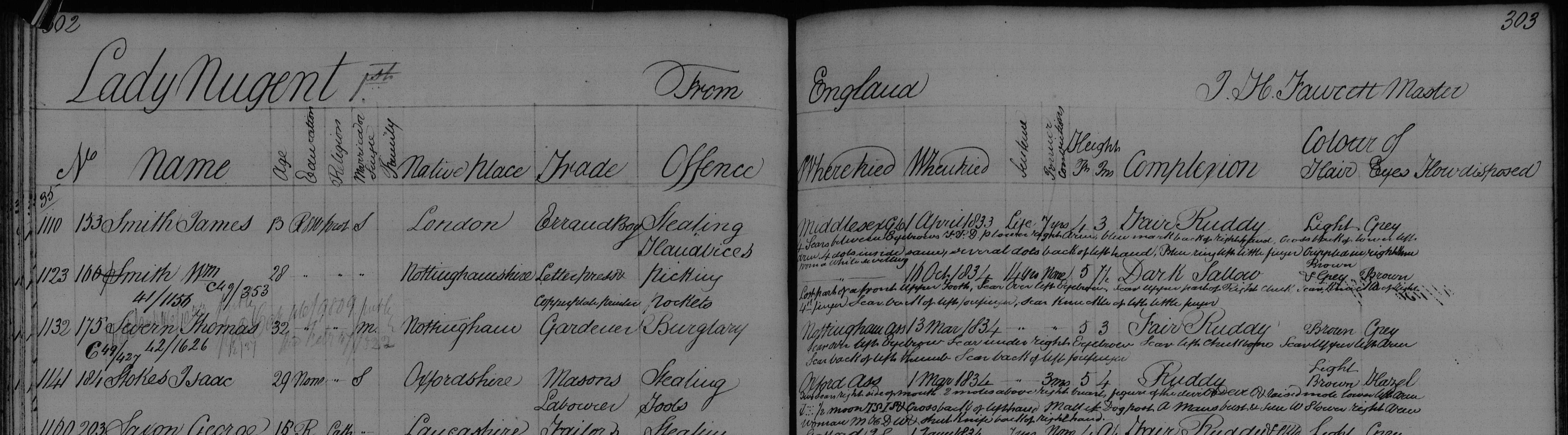

While searching for records for Isaac Stokes I discovered that another Isaac Stokes was transported to New South Wales in 1835 as well. The other one was a butcher born in 1809, sentenced in London for seven years, and he sailed on the Mary Ann. Our Isaac Stokes sailed on the Lady Nugent, arriving in NSW in April 1835, having set sail from England in December 1834.

Lady Nugent was built at Bombay in 1813. She made four voyages under contract to the British East India Company (EIC). She then made two voyages transporting convicts to Australia, one to New South Wales and one to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). (via Wikipedia)

via freesettlerorfelon website:

On 20 November 1834, 100 male convicts were transferred to the Lady Nugent from the Justitia Hulk and 60 from the Ganymede Hulk at Woolwich, all in apparent good health. The Lady Nugent departed Sheerness on 4 December 1834.

SURGEON OLIVER SPROULE

Oliver Sproule kept a Medical Journal from 7 November 1834 to 27 April 1835. He recorded in his journal the weather conditions they experienced in the first two weeks:

‘In the course of the first week or ten days at sea, there were eight or nine on the sick list with catarrhal affections and one with dropsy which I attribute to the cold and wet we experienced during that period beating down channel. Indeed the foremost berths in the prison at this time were so wet from leaking in that part of the ship, that I was obliged to issue dry beds and bedding to a great many of the prisoners to preserve their health, but after crossing the Bay of Biscay the weather became fine and we got the damp beds and blankets dried, the leaks partially stopped and the prison well aired and ventilated which, I am happy to say soon manifested a favourable change in the health and appearance of the men.

Besides the cases given in the journal I had a great many others to treat, some of them similar to those mentioned but the greater part consisted of boils, scalds, and contusions which would not only be too tedious to enter but I fear would be irksome to the reader. There were four births on board during the passage which did well, therefore I did not consider it necessary to give a detailed account of them in my journal the more especially as they were all favourable cases.

Regularity and cleanliness in the prison, free ventilation and as far as possible dry decks turning all the prisoners up in fine weather as we were lucky enough to have two musicians amongst the convicts, dancing was tolerated every afternoon, strict attention to personal cleanliness and also to the cooking of their victuals with regular hours for their meals, were the only prophylactic means used on this occasion, which I found to answer my expectations to the utmost extent in as much as there was not a single case of contagious or infectious nature during the whole passage with the exception of a few cases of psora which soon yielded to the usual treatment. A few cases of scurvy however appeared on board at rather an early period which I can attribute to nothing else but the wet and hardships the prisoners endured during the first three or four weeks of the passage. I was prompt in my treatment of these cases and they got well, but before we arrived at Sydney I had about thirty others to treat.’

The Lady Nugent arrived in Port Jackson on 9 April 1835 with 284 male prisoners. Two men had died at sea. The prisoners were landed on 27th April 1835 and marched to Hyde Park Barracks prior to being assigned. Ten were under the age of 14 years.

The Lady Nugent:

Isaac’s distinguishing marks are noted on various criminal registers and record books:

“Height in feet & inches: 5 4; Complexion: Ruddy; Hair: Light brown; Eyes: Hazel; Marks or Scars: Yes [including] DEVIL on lower left arm, TSIS back of left hand, WS lower right arm, MHDW back of right hand.”

Another includes more detail about Isaac’s tattoos:

“Two slight scars right side of mouth, 2 moles above right breast, figure of the devil and DEVIL and raised mole, lower left arm; anchor, seven dots half moon, TSIS and cross, back of left hand; a mallet, door post, A, mans bust, sun, WS, lower right arm; woman, MHDW and shut knife, back of right hand.”

From How tattoos became fashionable in Victorian England (2019 article in TheConversation by Robert Shoemaker and Zoe Alkar):

“Historical tattooing was not restricted to sailors, soldiers and convicts, but was a growing and accepted phenomenon in Victorian England. Tattoos provide an important window into the lives of those who typically left no written records of their own. As a form of “history from below”, they give us a fleeting but intriguing understanding of the identities and emotions of ordinary people in the past.

As a practice for which typically the only record is the body itself, few systematic records survive before the advent of photography. One exception to this is the written descriptions of tattoos (and even the occasional sketch) that were kept of institutionalised people forced to submit to the recording of information about their bodies as a means of identifying them. This particularly applies to three groups – criminal convicts, soldiers and sailors. Of these, the convict records are the most voluminous and systematic.

Such records were first kept in large numbers for those who were transported to Australia from 1788 (since Australia was then an open prison) as the authorities needed some means of keeping track of them.”On the 1837 census Isaac was working for the government at Illiwarra, New South Wales. This record states that he arrived on the Lady Nugent in 1835. There are three other indent records for an Isaac Stokes in the following years, but the transcriptions don’t provide enough information to determine which Isaac Stokes it was. In April 1837 there was an abscondment, and an arrest/apprehension in May of that year, and in 1843 there was a record of convict indulgences.

From the Australian government website regarding “convict indulgences”:

“By the mid-1830s only six per cent of convicts were locked up. The vast majority worked for the government or free settlers and, with good behaviour, could earn a ticket of leave, conditional pardon or and even an absolute pardon. While under such orders convicts could earn their own living.”

In 1856 in Camden, NSW, Isaac Stokes married Catherine Daly. With no further information on this record it would be impossible to know for sure if this was the right Isaac Stokes. This couple had six children, all in the Camden area, but none of the records provided enough information. No occupation or place or date of birth recorded for Isaac Stokes.

I wrote to the National Library of Australia about the marriage record, and their reply was a surprise! Issac and Catherine were married on 30 September 1856, at the house of the Rev. Charles William Rigg, a Methodist minister, and it was recorded that Isaac was born in Edinburgh in 1821, to parents James Stokes and Sarah Ellis! The age at the time of the marriage doesn’t match Isaac’s age at death in 1877, and clearly the place of birth and parents didn’t match either. Only his fathers occupation of stone mason was correct. I wrote back to the helpful people at the library and they replied that the register was in a very poor condition and that only two and a half entries had survived at all, and that Isaac and Catherines marriage was recorded over two pages.

I searched for an Isaac Stokes born in 1821 in Edinburgh on the Scotland government website (and on all the other genealogy records sites) and didn’t find it. In fact Stokes was a very uncommon name in Scotland at the time. I also searched Australian immigration and other records for another Isaac Stokes born in Scotland or born in 1821, and found nothing. I was unable to find a single record to corroborate this mysterious other Isaac Stokes.

As the age at death in 1877 was correct, I assume that either Isaac was lying, or that some mistake was made either on the register at the home of the Methodist minster, or a subsequent mistranscription or muddle on the remnants of the surviving register. Therefore I remain convinced that the Camden stonemason Isaac Stokes was indeed our Isaac from Oxfordshire.

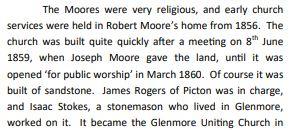

I found a history society newsletter article that mentioned Isaac Stokes, stone mason, had built the Glenmore church, near Camden, in 1859.

From the Wollondilly museum April 2020 newsletter:

From the Camden History website:

“The stone set over the porch of Glenmore Church gives the date of 1860. The church was begun in 1859 on land given by Joseph Moore. James Rogers of Picton was given the contract to build and local builder, Mr. Stokes, carried out the work. Elizabeth Moore, wife of Edward, laid the foundation stone. The first service was held on 19th March 1860. The cemetery alongside the church contains the headstones and memorials of the areas early pioneers.”

Isaac died on the 3rd September 1877. The inquest report puts his place of death as Bagdelly, near to Camden, and another death register has put Cambelltown, also very close to Camden. His age was recorded as 71 and the inquest report states his cause of death was “rupture of one of the large pulmonary vessels of the lung”. His wife Catherine died in childbirth in 1870 at the age of 43.

Isaac and Catherine’s children:

William Stokes 1857-1928

Catherine Stokes 1859-1846

Sarah Josephine Stokes 1861-1931

Ellen Stokes 1863-1932

Rosanna Stokes 1865-1919

Louisa Stokes 1868-1844.

It’s possible that Catherine Daly was a transported convict from Ireland.

Some time later I unexpectedly received a follow up email from The Oaks Heritage Centre in Australia.

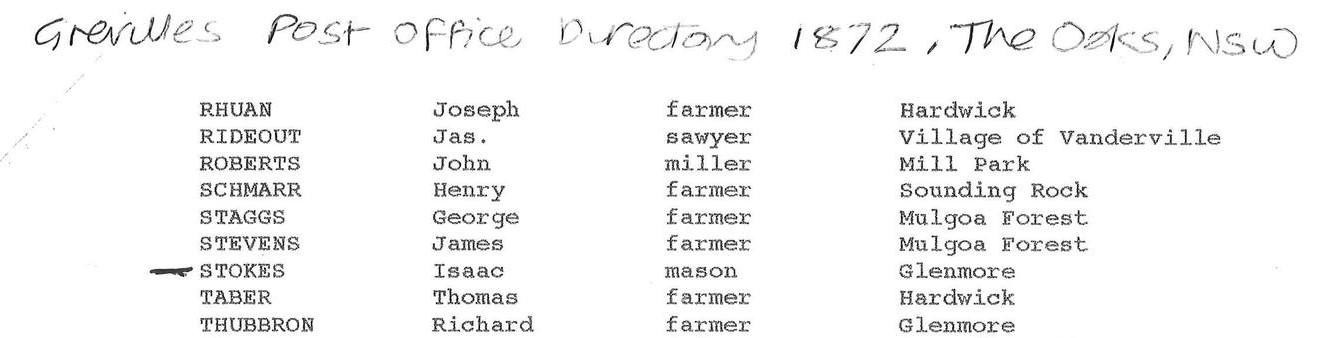

“The Gaudry papers which we have in our archive record him (Isaac Stokes) as having built: the church, the school and the teachers residence. Isaac is recorded in the General return of convicts: 1837 and in Grevilles Post Office directory 1872 as a mason in Glenmore.”

November 18, 2022 at 4:47 pm #6348

November 18, 2022 at 4:47 pm #6348In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Wong Sang

Wong Sang was born in China in 1884. In October 1916 he married Alice Stokes in Oxford.

Alice was the granddaughter of William Stokes of Churchill, Oxfordshire and William was the brother of Thomas Stokes the wheelwright (who was my 3X great grandfather). In other words Alice was my second cousin, three times removed, on my fathers paternal side.

Wong Sang was an interpreter, according to the baptism registers of his children and the Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital admission registers in 1930. The hospital register also notes that he was employed by the Blue Funnel Line, and that his address was 11, Limehouse Causeway, E 14. (London)

“The Blue Funnel Line offered regular First-Class Passenger and Cargo Services From the UK to South Africa, Malaya, China, Japan, Australia, Java, and America. Blue Funnel Line was Owned and Operated by Alfred Holt & Co., Liverpool.

The Blue Funnel Line, so-called because its ships have a blue funnel with a black top, is more appropriately known as the Ocean Steamship Company.”Wong Sang and Alice’s daughter, Frances Eileen Sang, was born on the 14th July, 1916 and baptised in 1920 at St Stephen in Poplar, Tower Hamlets, London. The birth date is noted in the 1920 baptism register and would predate their marriage by a few months, although on the death register in 1921 her age at death is four years old and her year of birth is recorded as 1917.

Charles Ronald Sang was baptised on the same day in May 1920, but his birth is recorded as April of that year. The family were living on Morant Street, Poplar.

James William Sang’s birth is recorded on the 1939 census and on the death register in 2000 as being the 8th March 1913. This definitely would predate the 1916 marriage in Oxford.

William Norman Sang was born on the 17th October 1922 in Poplar.

Alice and the three sons were living at 11, Limehouse Causeway on the 1939 census, the same address that Wong Sang was living at when he was admitted to Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital on the 15th January 1930. Wong Sang died in the hospital on the 8th March of that year at the age of 46.

Alice married John Patterson in 1933 in Stepney. John was living with Alice and her three sons on Limehouse Causeway on the 1939 census and his occupation was chef.

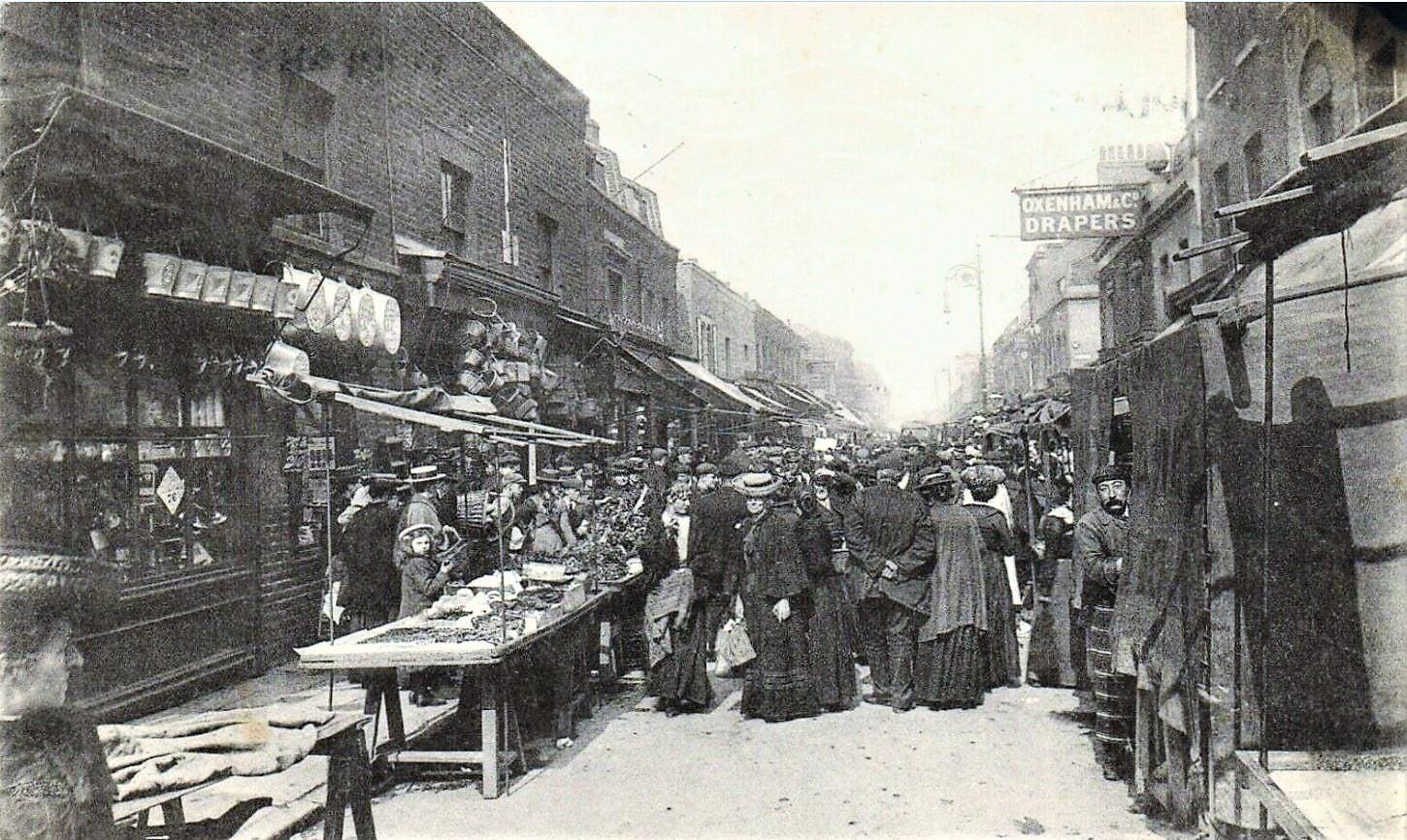

Via Old London Photographs:

“Limehouse Causeway is a street in east London that was the home to the original Chinatown of London. A combination of bomb damage during the Second World War and later redevelopment means that almost nothing is left of the original buildings of the street.”

Limehouse Causeway in 1925:

From The Story of Limehouse’s Lost Chinatown, poplarlondon website:

“Limehouse was London’s first Chinatown, home to a tightly-knit community who were demonised in popular culture and eventually erased from the cityscape.

As recounted in the BBC’s ‘Our Greatest Generation’ series, Connie was born to a Chinese father and an English mother in early 1920s Limehouse, where she used to play in the street with other British and British-Chinese children before running inside for teatime at one of their houses.

Limehouse was London’s first Chinatown between the 1880s and the 1960s, before the current Chinatown off Shaftesbury Avenue was established in the 1970s by an influx of immigrants from Hong Kong.

Connie’s memories of London’s first Chinatown as an “urban village” paint a very different picture to the seedy area portrayed in early twentieth century novels.

The pyramid in St Anne’s church marked the entrance to the opium den of Dr Fu Manchu, a criminal mastermind who threatened Western society by plotting world domination in a series of novels by Sax Rohmer.

Thomas Burke’s Limehouse Nights cemented stereotypes about prostitution, gambling and violence within the Chinese community, and whipped up anxiety about sexual relationships between Chinese men and white women.

Though neither novelist was familiar with the Chinese community, their depictions made Limehouse one of the most notorious areas of London.

Travel agent Thomas Cook even organised tours of the area for daring visitors, despite the rector of Limehouse warning that “those who look for the Limehouse of Mr Thomas Burke simply will not find it.”

All that remains is a handful of Chinese street names, such as Ming Street, Pekin Street, and Canton Street — but what was Limehouse’s chinatown really like, and why did it get swept away?

Chinese migration to Limehouse

Chinese sailors discharged from East India Company ships settled in the docklands from as early as the 1780s.

By the late nineteenth century, men from Shanghai had settled around Pennyfields Lane, while a Cantonese community lived on Limehouse Causeway.

Chinese sailors were often paid less and discriminated against by dock hirers, and so began to diversify their incomes by setting up hand laundry services and restaurants.

Old photographs show shopfronts emblazoned with Chinese characters with horse-drawn carts idling outside or Chinese men in suits and hats standing proudly in the doorways.

In oral histories collected by Yat Ming Loo, Connie’s husband Leslie doesn’t recall seeing any Chinese women as a child, since male Chinese sailors settled in London alone and married working-class English women.

In the 1920s, newspapers fear-mongered about interracial marriages, crime and gambling, and described chinatown as an East End “colony.”

Ironically, Chinese opium-smoking was also demonised in the press, despite Britain waging war against China in the mid-nineteenth century for suppressing the opium trade to alleviate addiction amongst its people.

The number of Chinese people who settled in Limehouse was also greatly exaggerated, and in reality only totalled around 300.

The real Chinatown

Although the press sought to characterise Limehouse as a monolithic Chinese community in the East End, Connie remembers seeing people of all nationalities in the shops and community spaces in Limehouse.

She doesn’t remember feeling discriminated against by other locals, though Connie does recall having her face measured and IQ tested by a member of the British Eugenics Society who was conducting research in the area.

Some of Connie’s happiest childhood memories were from her time at Chung-Hua Club, where she learned about Chinese culture and language.

Why did Chinatown disappear?

The caricature of Limehouse’s Chinatown as a den of vice hastened its erasure.

Police raids and deportations fuelled by the alarmist media coverage threatened the Chinese population of Limehouse, and slum clearance schemes to redevelop low-income areas dispersed Chinese residents in the 1930s.

The Defence of the Realm Act imposed at the beginning of the First World War criminalised opium use, gave the authorities increased powers to deport Chinese people and restricted their ability to work on British ships.

Dwindling maritime trade during World War II further stripped Chinese sailors of opportunities for employment, and any remnants of Chinatown were destroyed during the Blitz or erased by postwar development schemes.”

Wong Sang 1884-1930

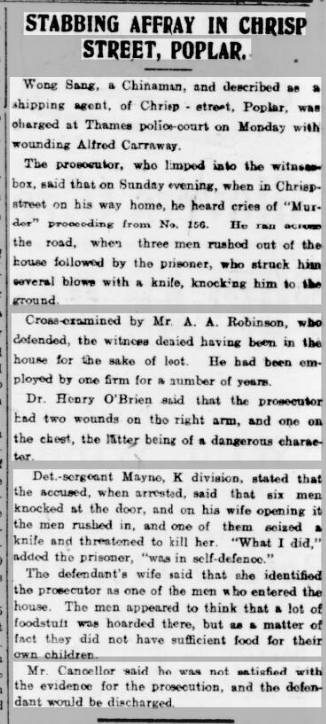

The year 1918 was a troublesome one for Wong Sang, an interpreter and shipping agent for Blue Funnel Line. The Sang family were living at 156, Chrisp Street.

Chrisp Street, Poplar, in 1913 via Old London Photographs:

In February Wong Sang was discharged from a false accusation after defending his home from potential robbers.

East End News and London Shipping Chronicle – Friday 15 February 1918:

In August of that year he was involved in an incident that left him unconscious.

Faringdon Advertiser and Vale of the White Horse Gazette – Saturday 31 August 1918:

Wong Sang is mentioned in an 1922 article about “Oriental London”.

London and China Express – Thursday 09 February 1922:

A photograph of the Chee Kong Tong Chinese Freemason Society mentioned in the above article, via Old London Photographs:

Wong Sang was recommended by the London Metropolitan Police in 1928 to assist in a case in Wellingborough, Northampton.

Difficulty of Getting an Interpreter: Northampton Mercury – Friday 16 March 1928:

The difficulty was that “this man speaks the Cantonese language only…the Northeners and the Southerners in China have differing languages and the interpreter seemed to speak one that was in between these two.”

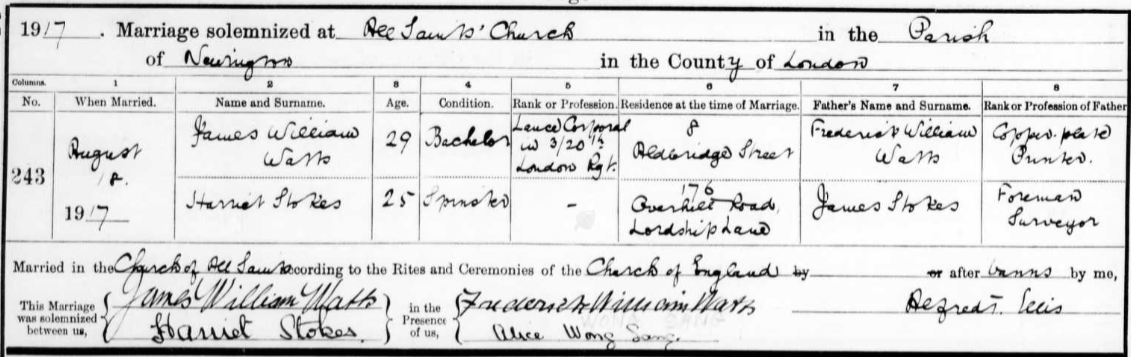

In 1917, Alice Wong Sang was a witness at her sister Harriet Stokes marriage to James William Watts in Southwark, London. Their father James Stokes occupation on the marriage register is foreman surveyor, but on the census he was a council roadman or labourer. (I initially rejected this as the correct marriage for Harriet because of the discrepancy with the occupations. Alice Wong Sang as a witness confirmed that it was indeed the correct one.)

James William Sang 1913-2000 was a clock fitter and watch assembler (on the 1939 census). He married Ivy Laura Fenton in 1963 in Sidcup, Kent. James died in Southwark in 2000.

Charles Ronald Sang 1920-1974 was a draughtsman (1939 census). He married Eileen Burgess in 1947 in Marylebone. Charles and Eileen had two sons: Keith born in 1951 and Roger born in 1952. He died in 1974 in Hertfordshire.

William Norman Sang 1922-2000 was a clerk and telephone operator (1939 census). William enlisted in the Royal Artillery in 1942. He married Lily Mullins in 1949 in Bethnal Green, and they had three daughters: Marion born in 1950, Christine in 1953, and Frances in 1959. He died in Redbridge in 2000.

I then found another two births registered in Poplar by Alice Sang, both daughters. Doris Winifred Sang was born in 1925, and Patricia Margaret Sang was born in 1933 ~ three years after Wong Sang’s death. Neither of the these daughters were on the 1939 census with Alice, John Patterson and the three sons. Margaret had presumably been evacuated because of the war to a family in Taunton, Somerset. Doris would have been fourteen and I have been unable to find her in 1939 (possibly because she died in 2017 and has not had the redaction removed yet on the 1939 census as only deceased people are viewable).

Doris Winifred Sang 1925-2017 was a nursing sister. She didn’t marry, and spent a year in USA between 1954 and 1955. She stayed in London, and died at the age of ninety two in 2017.

Patricia Margaret Sang 1933-1998 was also a nurse. She married Patrick L Nicely in Stepney in 1957. Patricia and Patrick had five children in London: Sharon born 1959, Donald in 1960, Malcolm was born and died in 1966, Alison was born in 1969 and David in 1971.

I was unable to find a birth registered for Alice’s first son, James William Sang (as he appeared on the 1939 census). I found Alice Stokes on the 1911 census as a 17 year old live in servant at a tobacconist on Pekin Street, Limehouse, living with Mr Sui Fong from Hong Kong and his wife Sarah Sui Fong from Berlin. I looked for a birth registered for James William Fong instead of Sang, and found it ~ mothers maiden name Stokes, and his date of birth matched the 1939 census: 8th March, 1913.

On the 1921 census, Wong Sang is not listed as living with them but it is mentioned that Mr Wong Sang was the person returning the census. Also living with Alice and her sons James and Charles in 1921 are two visitors: (Florence) May Stokes, 17 years old, born in Woodstock, and Charles Stokes, aged 14, also born in Woodstock. May and Charles were Alice’s sister and brother.

I found Sharon Nicely on social media and she kindly shared photos of Wong Sang and Alice Stokes:

November 10, 2022 at 12:08 pm #6344

November 10, 2022 at 12:08 pm #6344In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The Tetbury Riots

While researching the Tetbury riots (I had found some Browning names in the newspaper archives in association with the uprisings) I came across an article called “Elizabeth Parker, the Swing Riots, and the Tetbury parish clerk” by Jill Evans.

I noted the name of the parish clerk, Daniel Cole, because I know someone else of that name. The incident in the article was 1830.

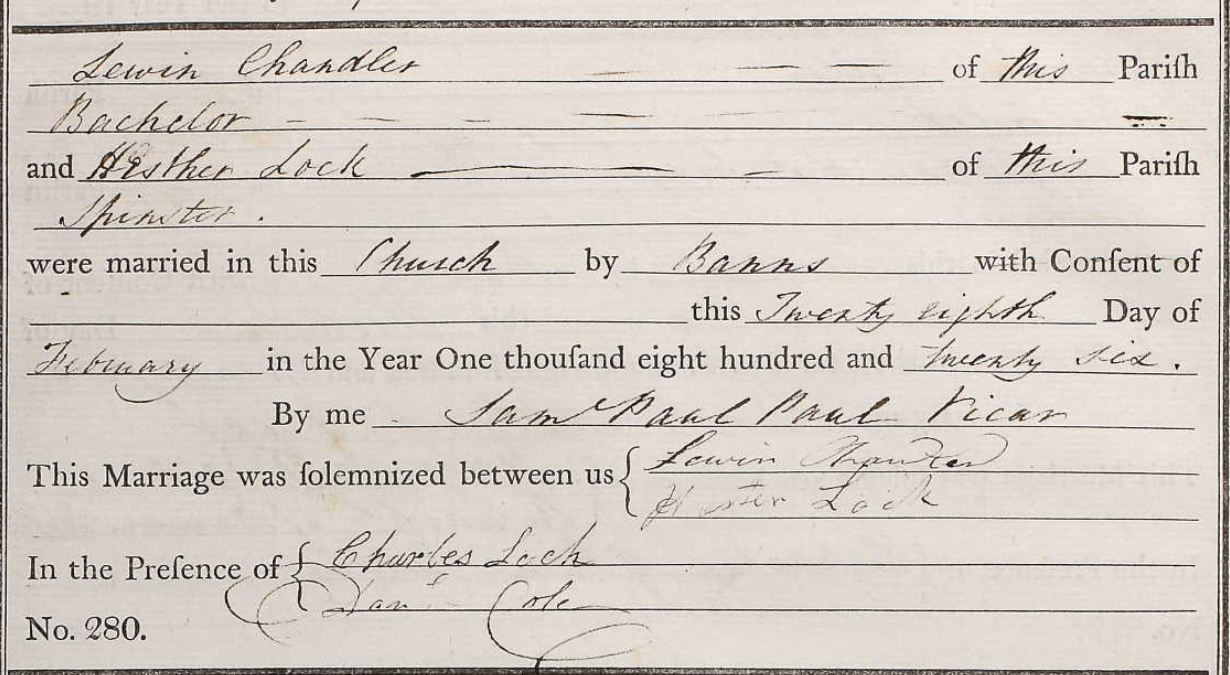

I found the 1826 marriage in the Tetbury parish registers (where Daniel was the parish clerk) of my 4x great grandmothers sister Hesther Lock. One of the witnesses was her brother Charles, and the other was Daniel Cole, the parish clerk.

Marriage of Lewin Chandler and Hesther Lock in 1826:

from the article:

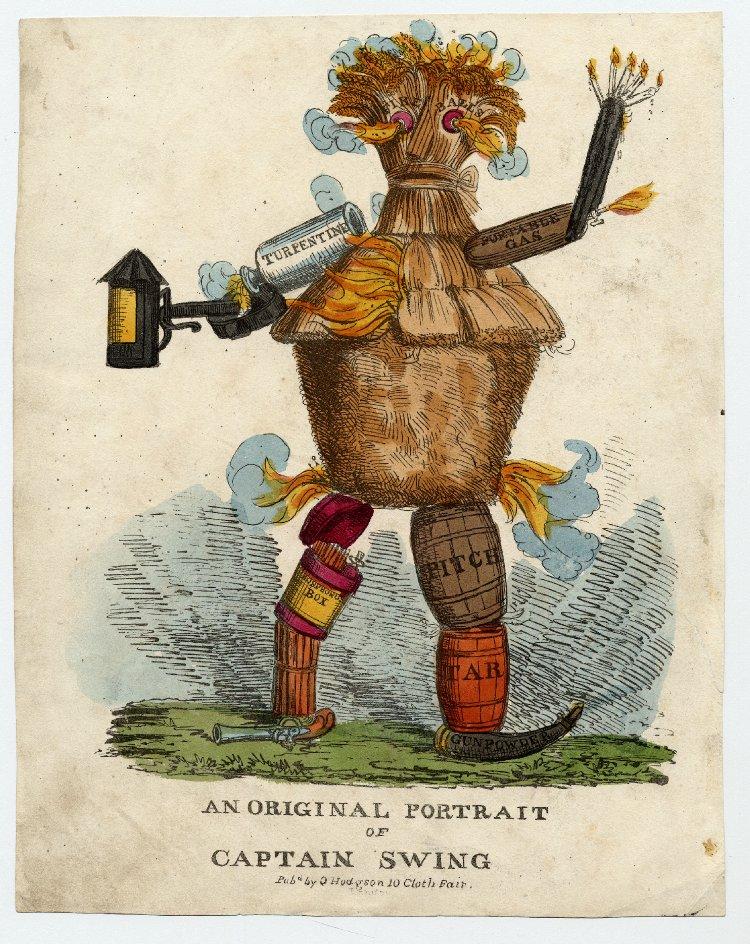

“The Swing Riots were disturbances which took place in 1830 and 1831, mostly in the southern counties of England. Agricultural labourers, who were already suffering due to low wages and a lack of work after several years of bad harvests, rose up when their employers introduced threshing machines into their workplaces. The riots got their name from the threatening letters which were sent to farmers and other employers, which were signed “Captain Swing.”

The riots spread into Gloucestershire in November 1830, with the Tetbury area seeing the worst of the disturbances. Amongst the many people arrested afterwards was one woman, Elizabeth Parker. She has sometimes been cited as one of only two females who were transported for taking part in the Swing Riots. In fact, she was sentenced to be transported for this crime, but never sailed, as she was pardoned a few months after being convicted. However, less than a year after being released from Gloucester Gaol, she was back, awaiting trial for another offence. The circumstances in both of the cases she was tried for reveal an intriguing relationship with one Daniel Cole, parish clerk and assistant poor law officer in Tetbury….

….Elizabeth Parker was committed to Gloucester Gaol on 4 December 1830. In the Gaol Registers, she was described as being 23 and a “labourer”. She was in fact a prostitute, and she was unusual for the time in that she could read and write. She was charged on the oaths of Daniel Cole and others with having been among a mob which destroyed a threshing machine belonging to Jacob Hayward, at his farm in Beverstone, on 26 November.

…..Elizabeth Parker was granted royal clemency in July 1831 and was released from prison. She returned to Tetbury and presumably continued in her usual occupation, but on 27 March 1832, she was committed to Gloucester Gaol again. This time, she was charged with stealing 2 five pound notes, 5 sovereigns and 5 half sovereigns, from the person of Daniel Cole.

Elizabeth was tried at the Lent Assizes which began on 28 March, 1832. The details of her trial were reported in the Morning Post. Daniel Cole was in the “Boat Inn” (meaning the Boot Inn, I think) in Tetbury, when Elizabeth Parker came in. Cole “accompanied her down the yard”, where he stayed with her for about half an hour. The next morning, he realised that all his money was gone. One of his five pound notes was identified by him in a shop, where Parker had bought some items.

Under cross-examination, Cole said he was the assistant overseer of the poor and collector of public taxes of the parish of Tetbury. He was married with one child. He went in to the inn at about 9 pm, and stayed about 2 hours, drinking in the parlour, with the landlord, Elizabeth Parker, and two others. He was not drunk, but he was “rather fresh.” He gave the prisoner no money. He saw Elizabeth Parker next morning at the Prince and Princess public house. He didn’t drink with her or give her any money. He did give her a shilling after she was committed. He never said that he would not have prosecuted her “if it was not for her own tongue”. (Presumably meaning he couldn’t trust her to keep her mouth shut.)”

Contemporary illustration of the Swing riots:

Captain Swing was the imaginary leader agricultural labourers who set fire to barns and haystacks in the southern and eastern counties of England from 1830. Although the riots were ruthlessly put down (19 hanged, 644 imprisoned and 481 transported), the rural agitation led the new Whig government to establish a Royal Commission on the Poor Laws and its report provided the basis for the 1834 New Poor Law enacted after the Great Reform Bills of 1833.

An original portrait of Captain Swing hand coloured lithograph circa 1830:

October 11, 2022 at 2:58 pm #6334

October 11, 2022 at 2:58 pm #6334In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The House on Penn Common

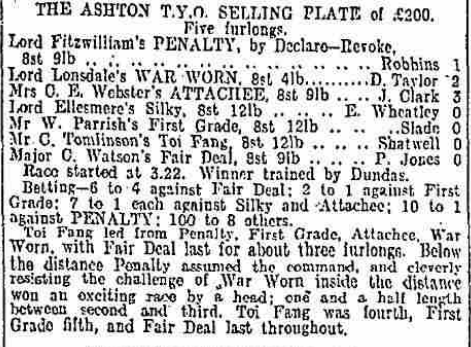

Toi Fang and the Duke of Sutherland

Tomlinsons

Grassholme

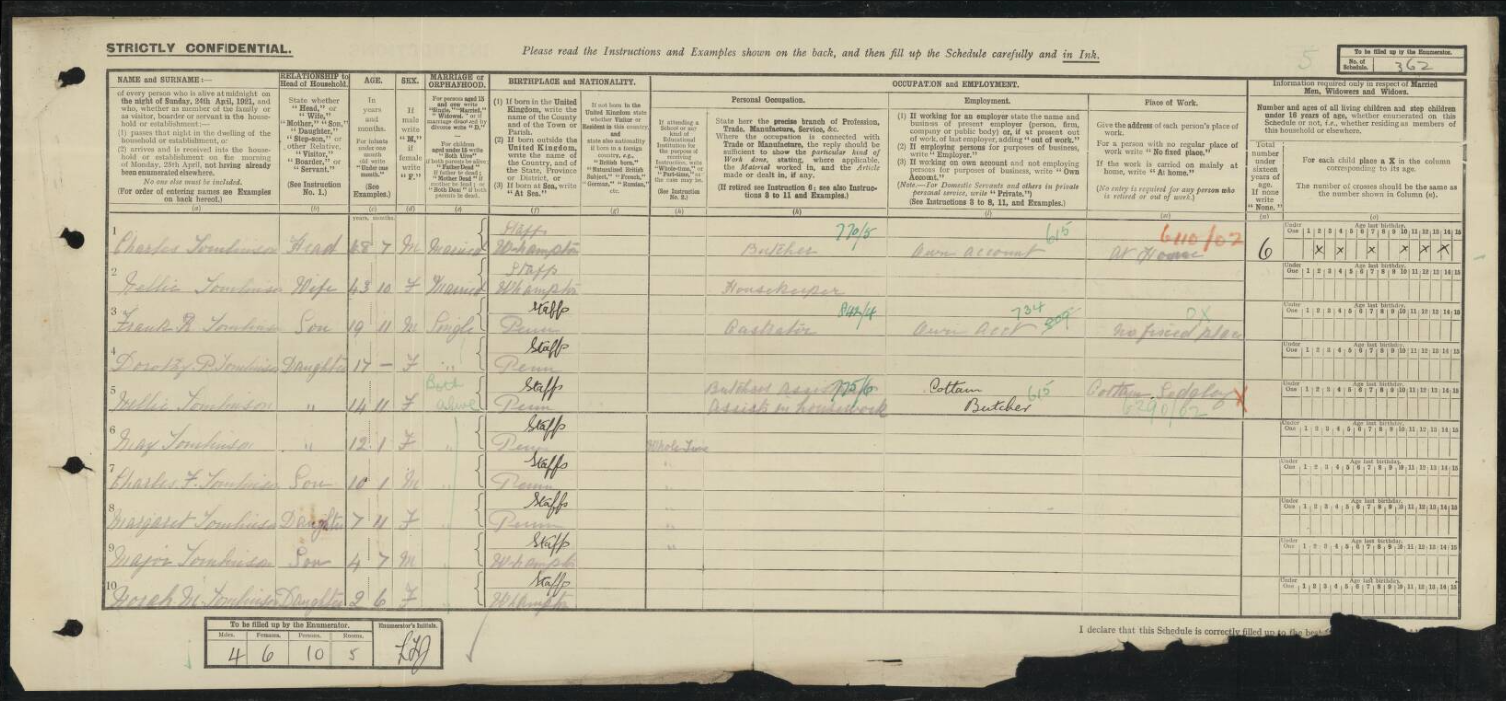

Charles Tomlinson (1873-1929) my great grandfather, was born in Wolverhampton in 1873. His father Charles Tomlinson (1847-1907) was a licensed victualler or publican, or alternatively a vet/castrator. He married Emma Grattidge (1853-1911) in 1872. On the 1881 census they were living at The Wheel in Wolverhampton.

Charles married Nellie Fisher (1877-1956) in Wolverhampton in 1896. In 1901 they were living next to the post office in Upper Penn, with children (Charles) Sidney Tomlinson (1896-1955), and Hilda Tomlinson (1898-1977) . Charles was a vet/castrator working on his own account.

In 1911 their address was 4, Wakely Hill, Penn, and living with them were their children Hilda, Frank Tomlinson (1901-1975), (Dorothy) Phyllis Tomlinson (1905-1982), Nellie Tomlinson (1906-1978) and May Tomlinson (1910-1983). Charles was a castrator working on his own account.

Charles and Nellie had a further four children: Charles Fisher Tomlinson (1911-1977), Margaret Tomlinson (1913-1989) (my grandmother Peggy), Major Tomlinson (1916-1984) and Norah Mary Tomlinson (1919-2010).

My father told me that my grandmother had fallen down the well at the house on Penn Common in 1915 when she was two years old, and sent me a photo of her standing next to the well when she revisted the house at a much later date.

Peggy next to the well on Penn Common:

My grandmother Peggy told me that her father had had a racehorse called Toi Fang. She remembered the racing colours were sky blue and orange, and had a set of racing silks made which she sent to my father.

Through a DNA match, I met Ian Tomlinson. Ian is the son of my fathers favourite cousin Roger, Frank’s son. Ian found some racing silks and sent a photo to my father (they are now in contact with each other as a result of my DNA match with Ian), wondering what they were.

When Ian sent a photo of these racing silks, I had a look in the newspaper archives. In 1920 there are a number of mentions in the racing news of Mr C Tomlinson’s horse TOI FANG. I have not found any mention of Toi Fang in the newspapers in the following years.

The Scotsman – Monday 12 July 1920:

The other story that Ian Tomlinson recalled was about the house on Penn Common. Ian said he’d heard that the local titled person took Charles Tomlinson to court over building the house but that Tomlinson won the case because it was built on common land and was the first case of it’s kind.

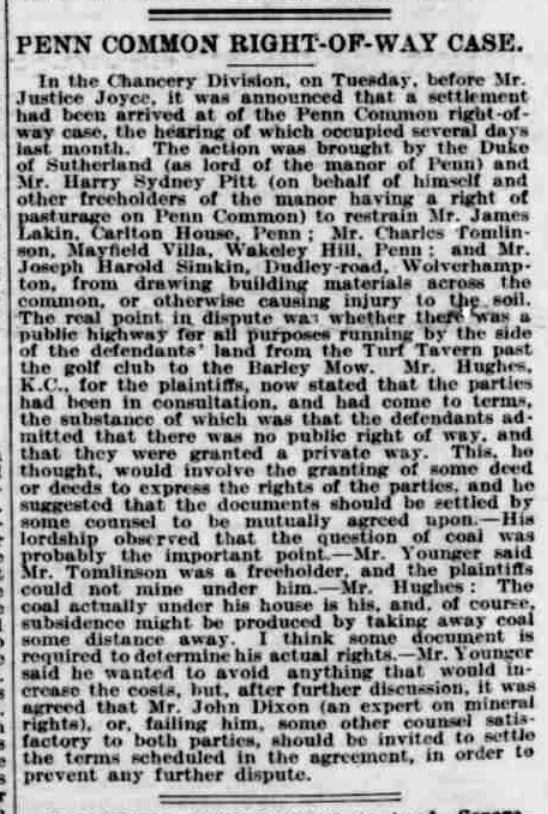

Penn Common Right of Way Case:

Staffordshire Advertiser March 9, 1912In the chancery division, on Tuesday, before Mr Justice Joyce, it was announced that a settlement had been arrived at of the Penn Common Right of Way case, the hearing of which occupied several days last month. The action was brought by the Duke of Sutherland (as Lord of the Manor of Penn) and Mr Harry Sydney Pitt (on behalf of himself and other freeholders of the manor having a right to pasturage on Penn Common) to restrain Mr James Lakin, Carlton House, Penn; Mr Charles Tomlinson, Mayfield Villa, Wakely Hill, Penn; and Mr Joseph Harold Simpkin, Dudley Road, Wolverhampton, from drawing building materials across the common, or otherwise causing injury to the soil.

The real point in dispute was whether there was a public highway for all purposes running by the side of the defendants land from the Turf Tavern past the golf club to the Barley Mow.

Mr Hughes, KC for the plaintiffs, now stated that the parties had been in consultation, and had come to terms, the substance of which was that the defendants admitted that there was no public right of way, and that they were granted a private way. This, he thought, would involve the granting of some deed or deeds to express the rights of the parties, and he suggested that the documents should be be settled by some counsel to be mutually agreed upon.His lordship observed that the question of coal was probably the important point. Mr Younger said Mr Tomlinson was a freeholder, and the plaintiffs could not mine under him. Mr Hughes: The coal actually under his house is his, and, of course, subsidence might be produced by taking away coal some distance away. I think some document is required to determine his actual rights.

Mr Younger said he wanted to avoid anything that would increase the costs, but, after further discussion, it was agreed that Mr John Dixon (an expert on mineral rights), or failing him, another counsel satisfactory to both parties, should be invited to settle the terms scheduled in the agreement, in order to prevent any further dispute.

The name of the house is Grassholme. The address of Mayfield Villas is the house they were living in while building Grassholme, which I assume they had not yet moved in to at the time of the newspaper article in March 1912.

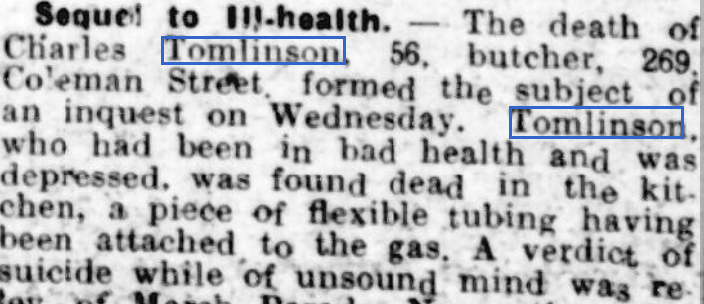

What my grandmother didn’t tell anyone was how her father died in 1929:

On the 1921 census, Charles, Nellie and eight of their children were living at 269 Coleman Street, Wolverhampton.

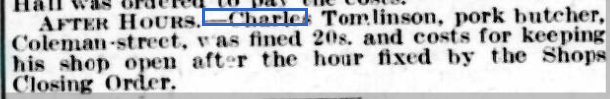

They were living on Coleman Street in 1915 when Charles was fined for staying open late.

Staffordshire Advertiser – Saturday 13 February 1915:

What is not yet clear is why they moved from the house on Penn Common sometime between 1912 and 1915. And why did he have a racehorse in 1920?

June 6, 2022 at 12:58 pm #6303In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

The Hollands of Barton under Needwood

Samuel Warren of Stapenhill married Catherine Holland of Barton under Needwood in 1795.

I joined a Barton under Needwood History group and found an incredible amount of information on the Holland family, but first I wanted to make absolutely sure that our Catherine Holland was one of them as there were also Hollands in Newhall. Not only that, on the marriage licence it says that Catherine Holland was from Bretby Park Gate, Stapenhill.

Then I noticed that one of the witnesses on Samuel’s brother Williams marriage to Ann Holland in 1796 was John Hair. Hannah Hair was the wife of Thomas Holland, and they were the Barton under Needwood parents of Catherine. Catherine was born in 1775, and Ann was born in 1767.

The 1851 census clinched it: Catherine Warren 74 years old, widow and formerly a farmers wife, was living in the household of her son John Warren, and her place of birth is listed as Barton under Needwood. In 1841 Catherine was a 64 year old widow, her husband Samuel having died in 1837, and she was living with her son Samuel, a farmer. The 1841 census did not list place of birth, however. Catherine died on 31 March 1861 and does not appear on the 1861 census.

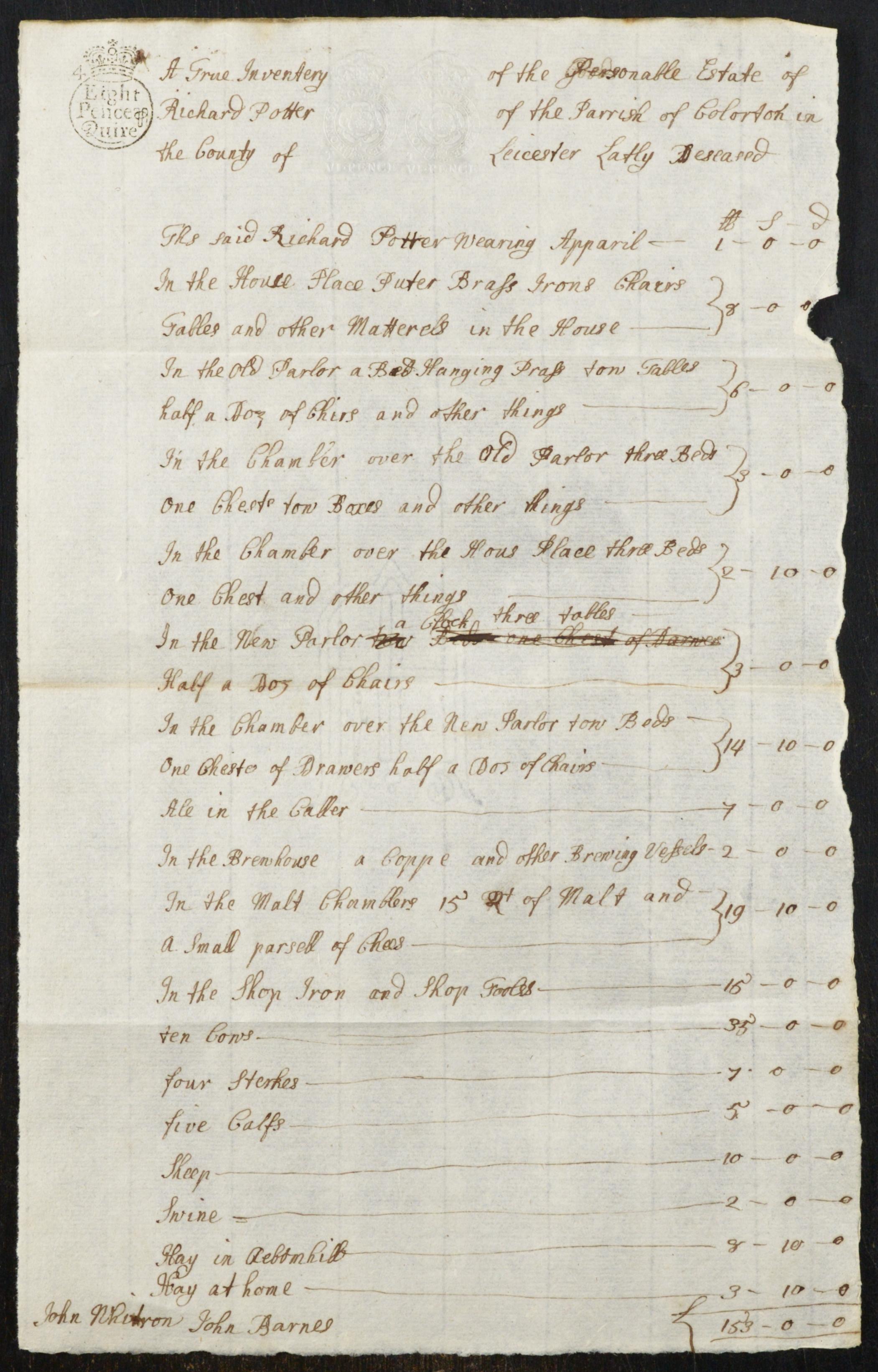

Once I had established that our Catherine Holland was from Barton under Needwood, I had another look at the information available on the Barton under Needwood History group, compiled by local historian Steve Gardner.

Catherine’s parents were Thomas Holland 1737-1828 and Hannah Hair 1739-1822.

Steve Gardner had posted a long list of the dates, marriages and children of the Holland family. The earliest entries in parish registers were Thomae Holland 1562-1626 and his wife Eunica Edwardes 1565-1632. They married on 10th July 1582. They were born, married and died in Barton under Needwood. They were direct ancestors of Catherine Holland, and as such my direct ancestors too.

The known history of the Holland family in Barton under Needwood goes back to Richard De Holland. (Thanks once again to Steve Gardner of the Barton under Needwood History group for this information.)

“Richard de Holland was the first member of the Holland family to become resident in Barton under Needwood (in about 1312) having been granted lands by the Earl of Lancaster (for whom Richard served as Stud and Stock Keeper of the Peak District) The Holland family stemmed from Upholland in Lancashire and had many family connections working for the Earl of Lancaster, who was one of the biggest Barons in England. Lancaster had his own army and lived at Tutbury Castle, from where he ruled over most of the Midlands area. The Earl of Lancaster was one of the main players in the ‘Barons Rebellion’ and the ensuing Battle of Burton Bridge in 1322. Richard de Holland was very much involved in the proceedings which had so angered Englands King. Holland narrowly escaped with his life, unlike the Earl who was executed.

From the arrival of that first Holland family member, the Hollands were a mainstay family in the community, and were in Barton under Needwood for over 600 years.”Continuing with various items of information regarding the Hollands, thanks to Steve Gardner’s Barton under Needwood history pages:

“PART 6 (Final Part)

Some mentions of The Manor of Barton in the Ancient Staffordshire Rolls:

1330. A Grant was made to Herbert de Ferrars, at le Newland in the Manor of Barton.

1378. The Inquisitio bonorum – Johannis Holand — an interesting Inventory of his goods and their value and his debts.

1380. View of Frankpledge ; the Jury found that Richard Holland was feloniously murdered by his wife Joan and Thomas Graunger, who fled. The goods of the deceased were valued at iiij/. iijj. xid. ; one-third went to the dead man, one-third to his son, one- third to the Lord for the wife’s share. Compare 1 H. V. Indictments. (1413.)

That Thomas Graunger of Barton smyth and Joan the wife of Richard de Holond of Barton on the Feast of St. John the Baptist 10 H. II. (1387) had traitorously killed and murdered at night, at Barton, Richard, the husband of the said Joan. (m. 22.)

The names of various members of the Holland family appear constantly among the listed Jurors on the manorial records printed below : —

1539. Richard Holland and Richard Holland the younger are on the Muster Roll of Barton

1583. Thomas Holland and Unica his wife are living at Barton.

1663-4. Visitations. — Barton under Needword. Disclaimers. William Holland, Senior, William Holland, Junior.

1609. Richard Holland, Clerk and Alice, his wife.

1663-4. Disclaimers at the Visitation. William Holland, Senior, William Holland, Junior.”I was able to find considerably more information on the Hollands in the book “Some Records of the Holland Family (The Hollands of Barton under Needwood, Staffordshire, and the Hollands in History)” by William Richard Holland. Luckily the full text of this book can be found online.

William Richard Holland (Died 1915) An early local Historian and author of the book:

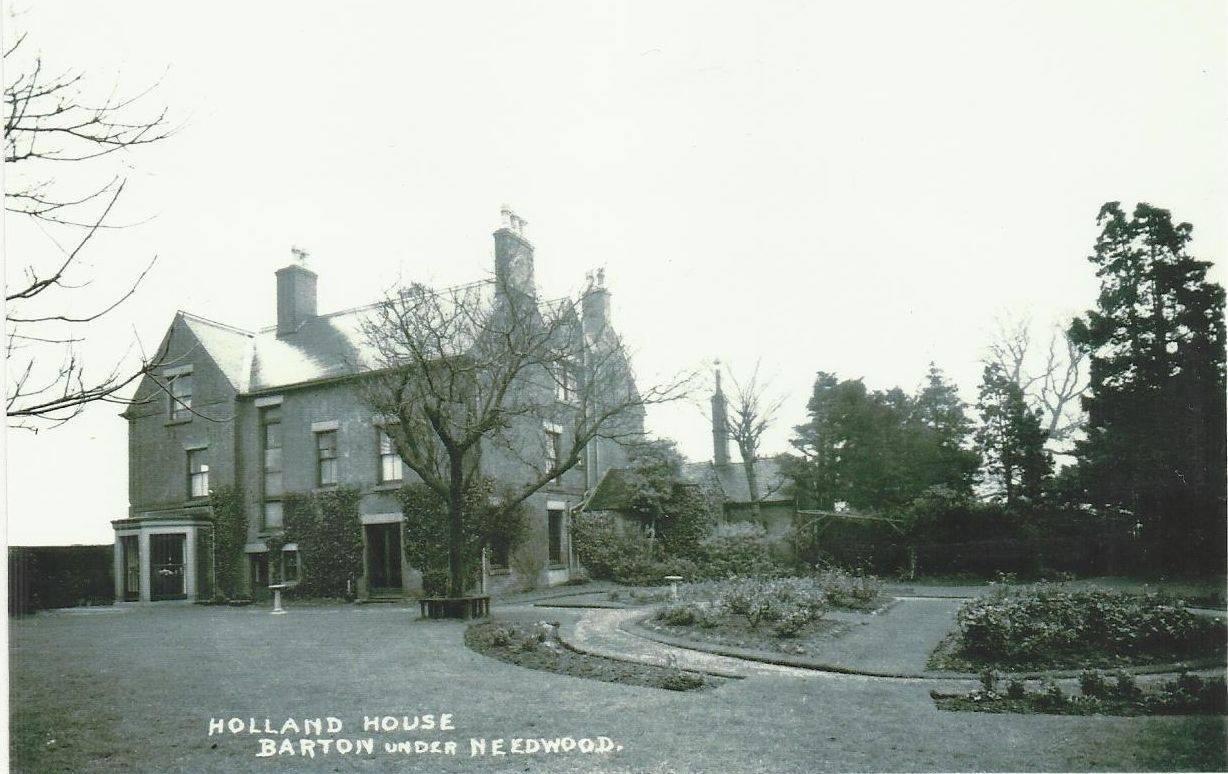

‘Holland House’ taken from the Gardens (sadly demolished in the early 60’s):

Excerpt from the book:

“The charter, dated 1314, granting Richard rights and privileges in Needwood Forest, reads as follows:

“Thomas Earl of Lancaster and Leicester, high-steward of England, to whom all these present shall come, greeting: Know ye, that we have given, &c., to Richard Holland of Barton, and his heirs, housboot, heyboot, and fireboot, and common of pasture, in our forest of Needwood, for all his beasts, as well in places fenced as lying open, with 40 hogs, quit of pawnage in our said forest at all times in the year (except hogs only in fence month). All which premises we will warrant, &c. to the said Richard and his heirs against all people for ever”

“The terms “housboot” “heyboot” and “fireboot” meant that Richard and his heirs were to have the privilege of taking from the Forest, wood needed for house repair and building, hedging material for the repairing of fences, and what was needful for purposes of fuel.”

Further excerpts from the book:

“It may here be mentioned that during the renovation of Barton Church, when the stone pillars were being stripped of the plaster which covered them, “William Holland 1617” was found roughly carved on a pillar near to the belfry gallery, obviously the work of a not too devout member of the family, who, seated in the gallery of that time, occupied himself thus during the service. The inscription can still be seen.”

“The earliest mention of a Holland of Upholland occurs in the reign of John in a Final Concord, made at the Lancashire Assizes, dated November 5th, 1202, in which Uchtred de Chryche, who seems to have had some right in the manor of Upholland, releases his right in fourteen oxgangs* of land to Matthew de Holland, in consideration of the sum of six marks of silver. Thus was planted the Holland Tree, all the early information of which is found in The Victoria County History of Lancaster.

As time went on, the family acquired more land, and with this, increased position. Thus, in the reign of Edward I, a Robert de Holland, son of Thurstan, son of Robert, became possessed of the manor of Orrell adjoining Upholland and of the lordship of Hale in the parish of Childwall, and, through marriage with Elizabeth de Samlesbury (co-heiress of Sir Wm. de Samlesbury of Samlesbury, Hall, near to Preston), of the moiety of that manor….

* An oxgang signified the amount of land that could be ploughed by one ox in one day”

“This Robert de Holland, son of Thurstan, received Knighthood in the reign of Edward I, as did also his brother William, ancestor of that branch of the family which later migrated to Cheshire. Belonging to this branch are such noteworthy personages as Mrs. Gaskell, the talented authoress, her mother being a Holland of this branch, Sir Henry Holland, Physician to Queen Victoria, and his two sons, the first Viscount Knutsford, and Canon Francis Holland ; Sir Henry’s grandson (the present Lord Knutsford), Canon Scott Holland, etc. Captain Frederick Holland, R.N., late of Ashbourne Hall, Derbyshire, may also be mentioned here.*”

Thanks to the Barton under Needwood history group for the following:

WALES END FARM:

In 1509 it was owned and occupied by Mr Johannes Holland De Wallass end who was a well to do Yeoman Farmer (the origin of the areas name – Wales End). Part of the building dates to 1490 making it probably the oldest building still standing in the Village:

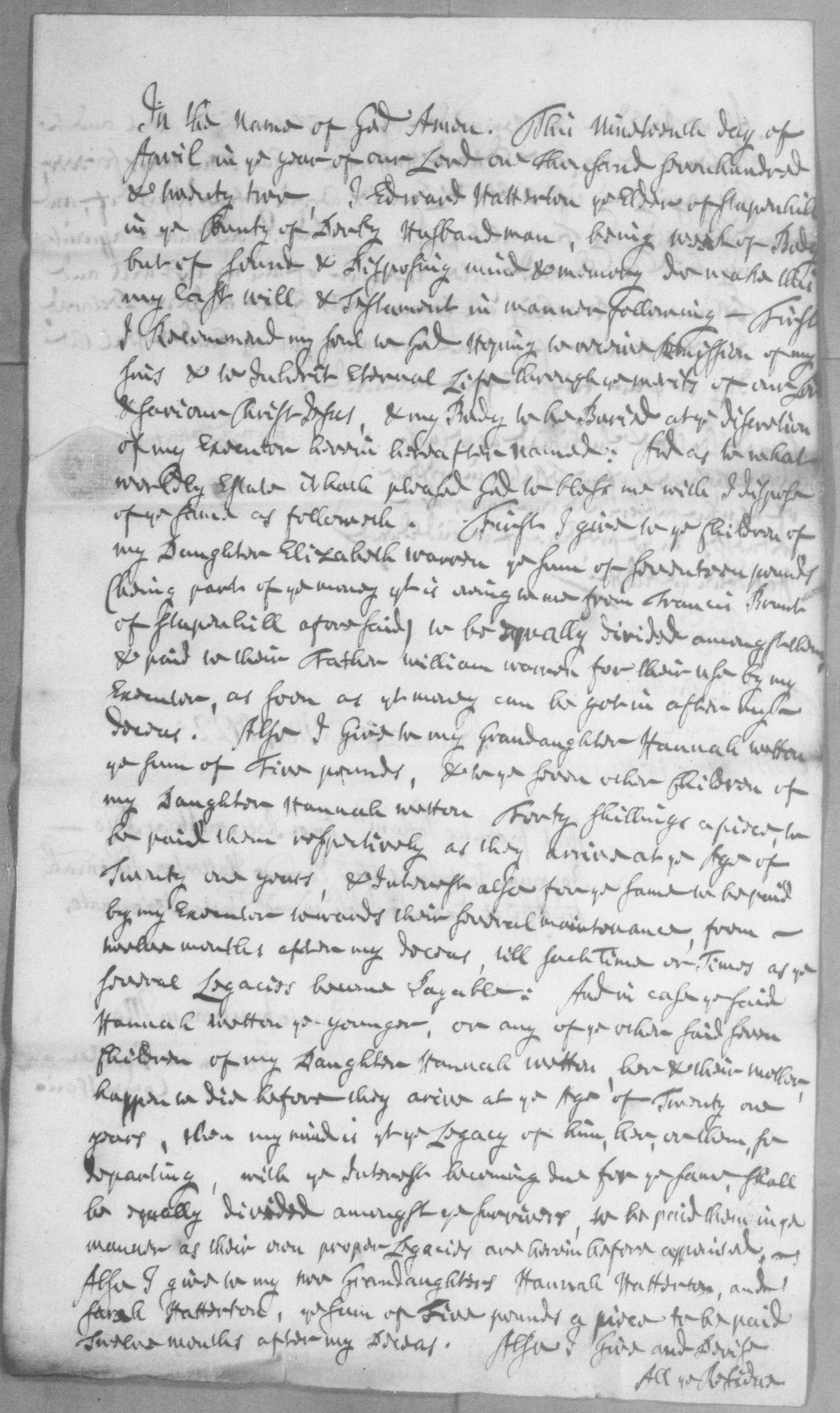

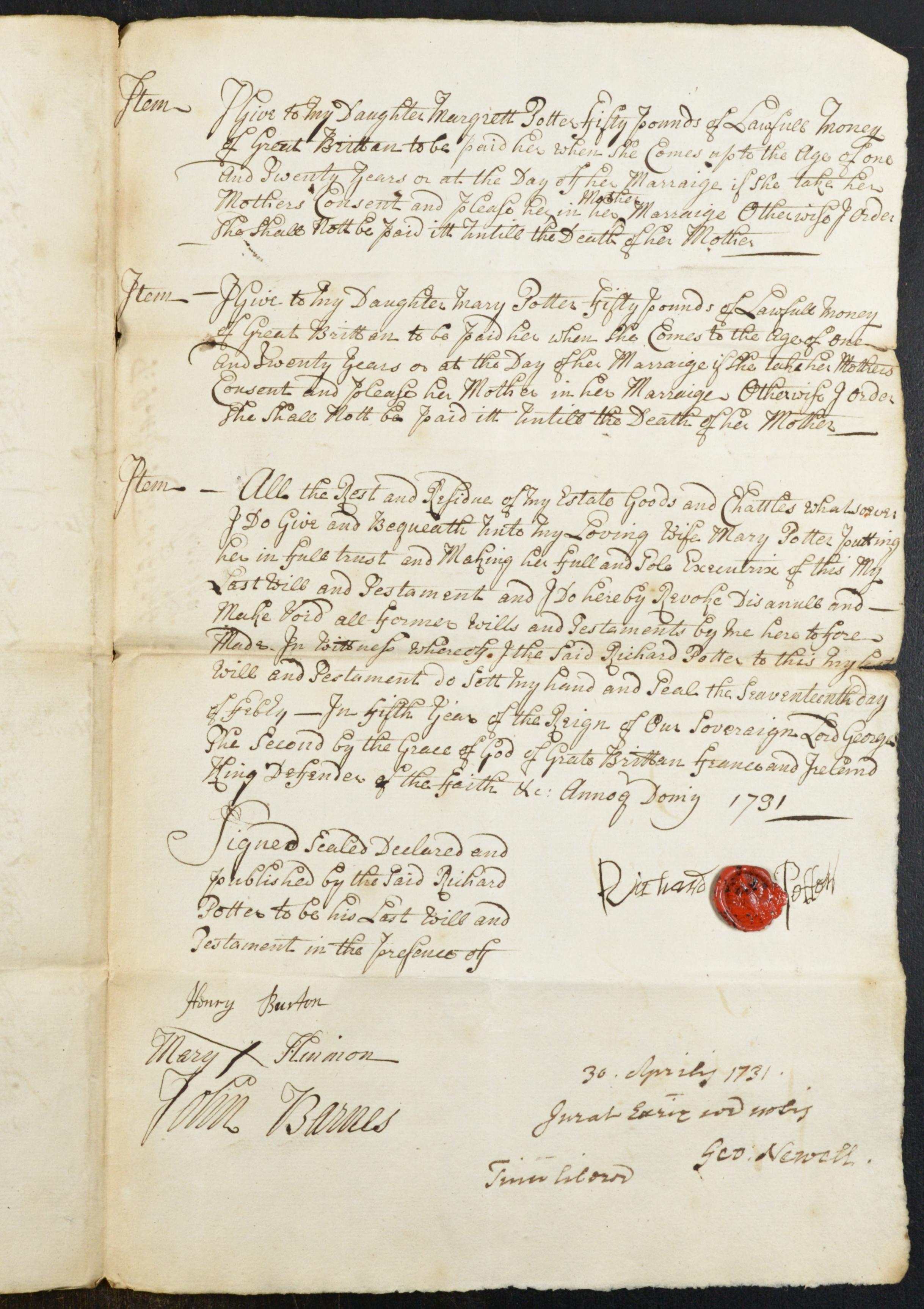

I found records for all of the Holland’s listed on the Barton under Needwood History group and added them to my ancestry tree. The earliest will I found was for Eunica Edwardes, then Eunica Holland, who died in 1632.

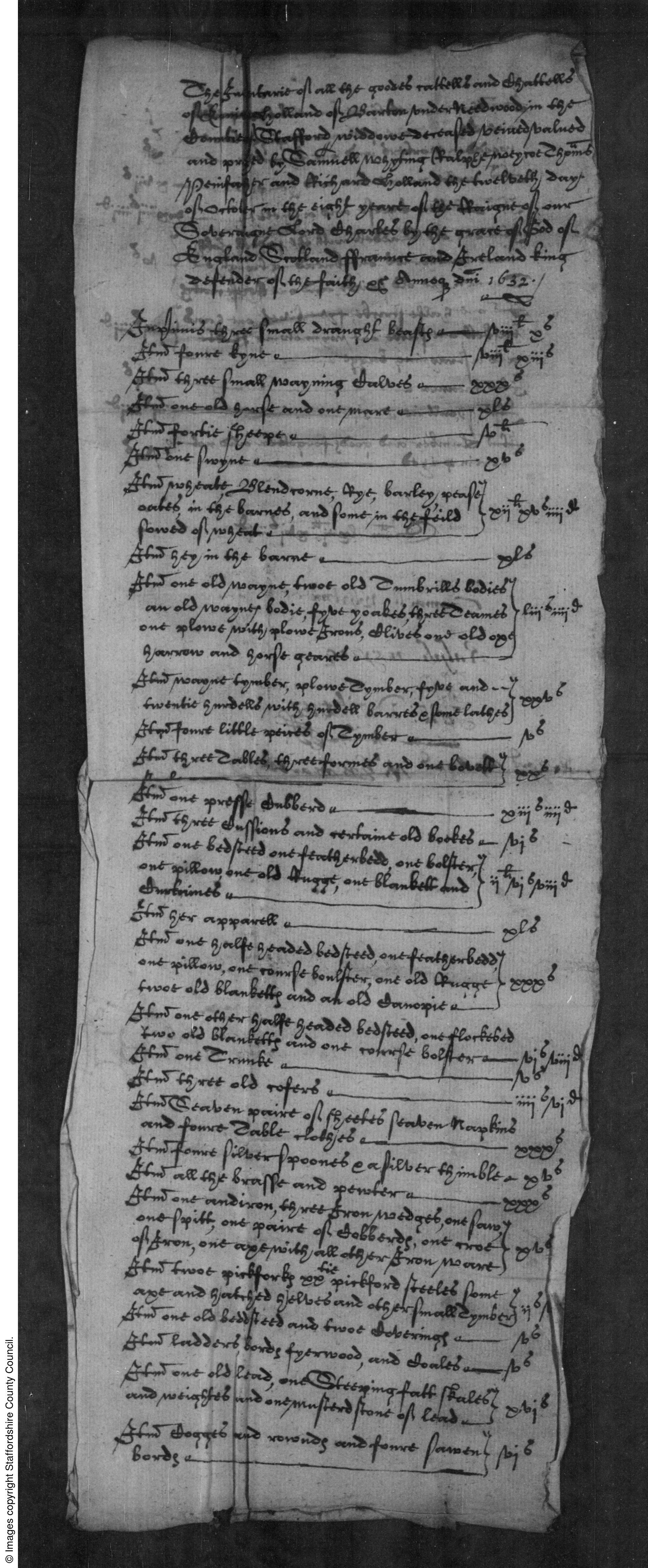

A page from the 1632 will and inventory of Eunica (Unice) Holland:

I’d been reading about “pedigree collapse” just before I found out her maiden name of Edwardes. Edwards is my own maiden name.

“In genealogy, pedigree collapse describes how reproduction between two individuals who knowingly or unknowingly share an ancestor causes the family tree of their offspring to be smaller than it would otherwise be.

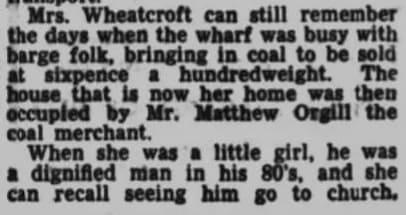

Without pedigree collapse, a person’s ancestor tree is a binary tree, formed by the person, the parents, grandparents, and so on. However, the number of individuals in such a tree grows exponentially and will eventually become impossibly high. For example, a single individual alive today would, over 30 generations going back to the High Middle Ages, have roughly a billion ancestors, more than the total world population at the time. This apparent paradox occurs because the individuals in the binary tree are not distinct: instead, a single individual may occupy multiple places in the binary tree. This typically happens when the parents of an ancestor are cousins (sometimes unbeknownst to themselves). For example, the offspring of two first cousins has at most only six great-grandparents instead of the normal eight. This reduction in the number of ancestors is pedigree collapse. It collapses the binary tree into a directed acyclic graph with two different, directed paths starting from the ancestor who in the binary tree would occupy two places.” via wikipediaThere is nothing to suggest, however, that Eunica’s family were related to my fathers family, and the only evidence so far in my tree of pedigree collapse are the marriages of Orgill cousins, where two sets of grandparents are repeated.

A list of Holland ancestors:

Catherine Holland 1775-1861

her parents:

Thomas Holland 1737-1828 Hannah Hair 1739-1832

Thomas’s parents:

William Holland 1696-1756 Susannah Whiteing 1715-1752

William’s parents:

William Holland 1665- Elizabeth Higgs 1675-1720

William’s parents:

Thomas Holland 1634-1681 Katherine Owen 1634-1728

Thomas’s parents:

Thomas Holland 1606-1680 Margaret Belcher 1608-1664

Thomas’s parents:

Thomas Holland 1562-1626 Eunice Edwardes 1565- 1632June 6, 2022 at 9:17 am #6301In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

The Warrens of Stapenhill

There were so many Warren’s in Stapenhill that it was complicated to work out who was who. I had gone back as far as Samuel Warren marrying Catherine Holland, and this was as far back as my cousin Ian Warren had gone in his research some decades ago as well. The Holland family from Barton under Needwood are particularly interesting, and will be a separate chapter.

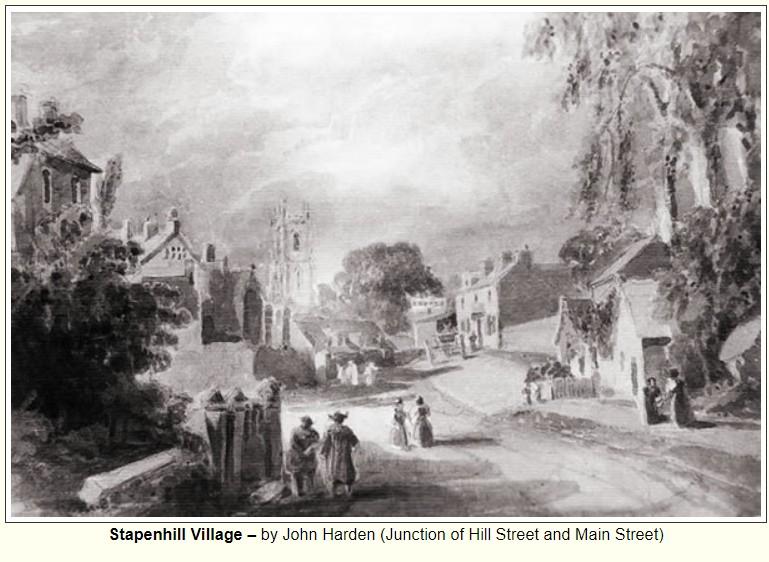

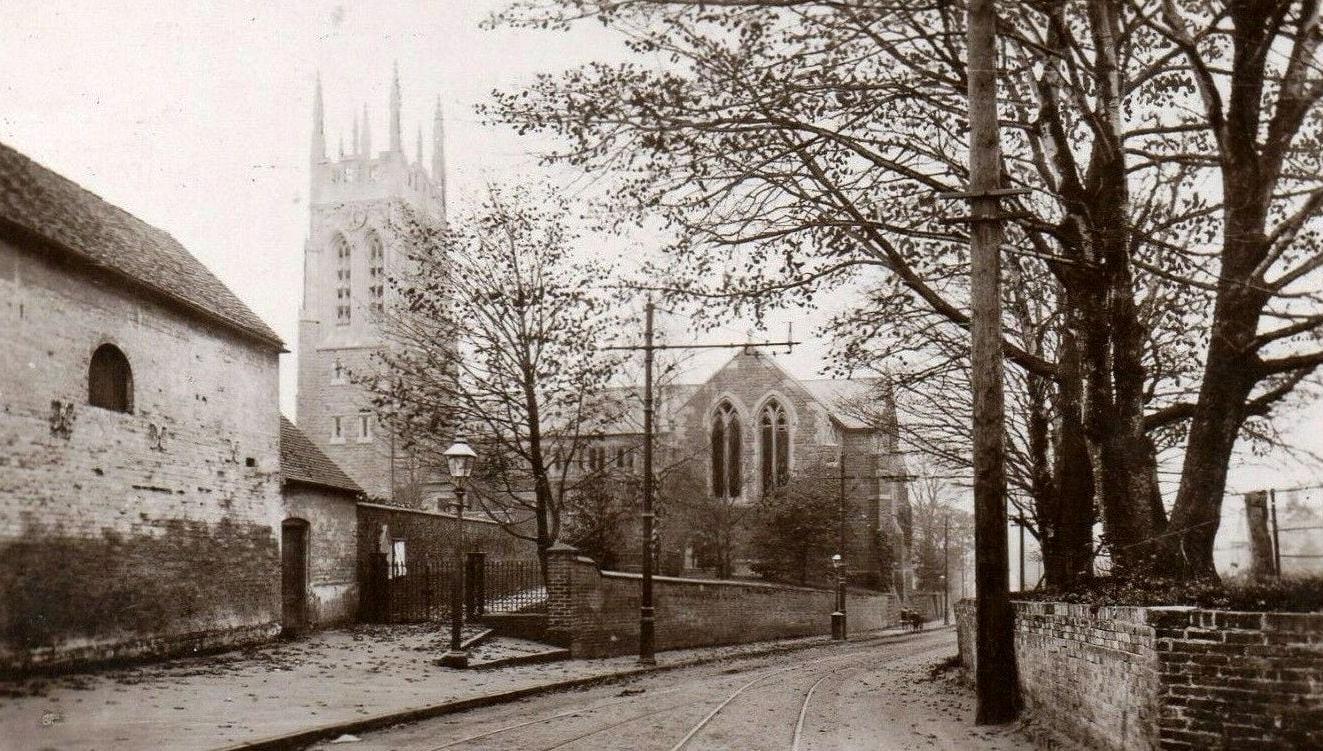

Stapenhill village by John Harden:

Resuming the research on the Warrens, Samuel Warren 1771-1837 married Catherine Holland 1775-1861 in 1795 and their son Samuel Warren 1800-1882 married Elizabeth Bridge, whose childless brother Benjamin Bridge left the Warren Brothers Boiler Works in Newhall to his nephews, the Warren brothers.

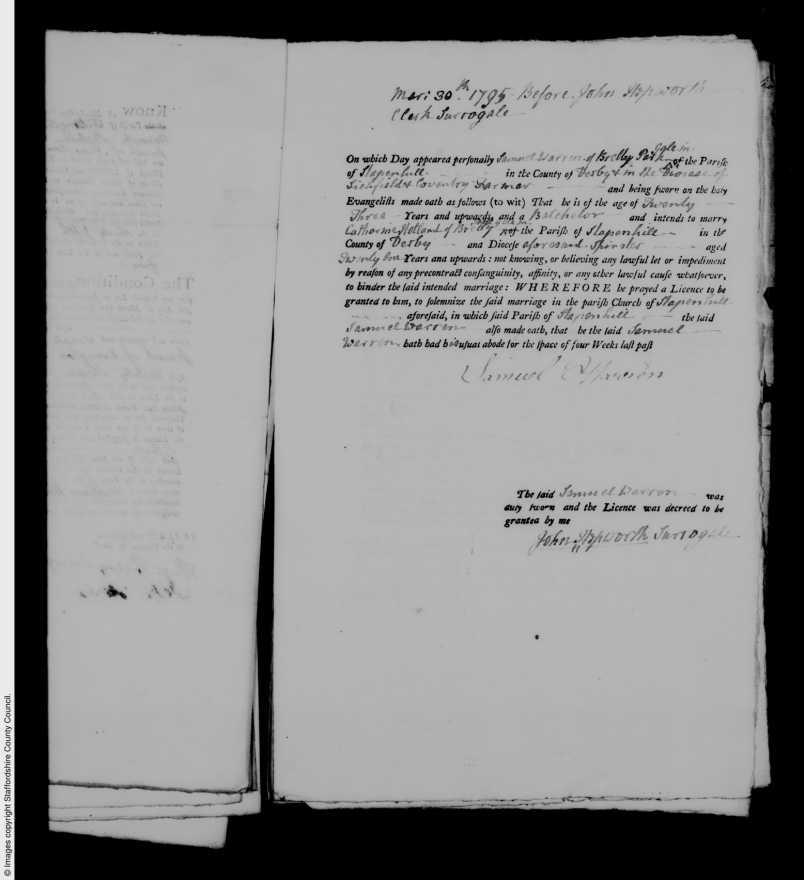

Samuel Warren and Catherine Holland marriage licence 1795:

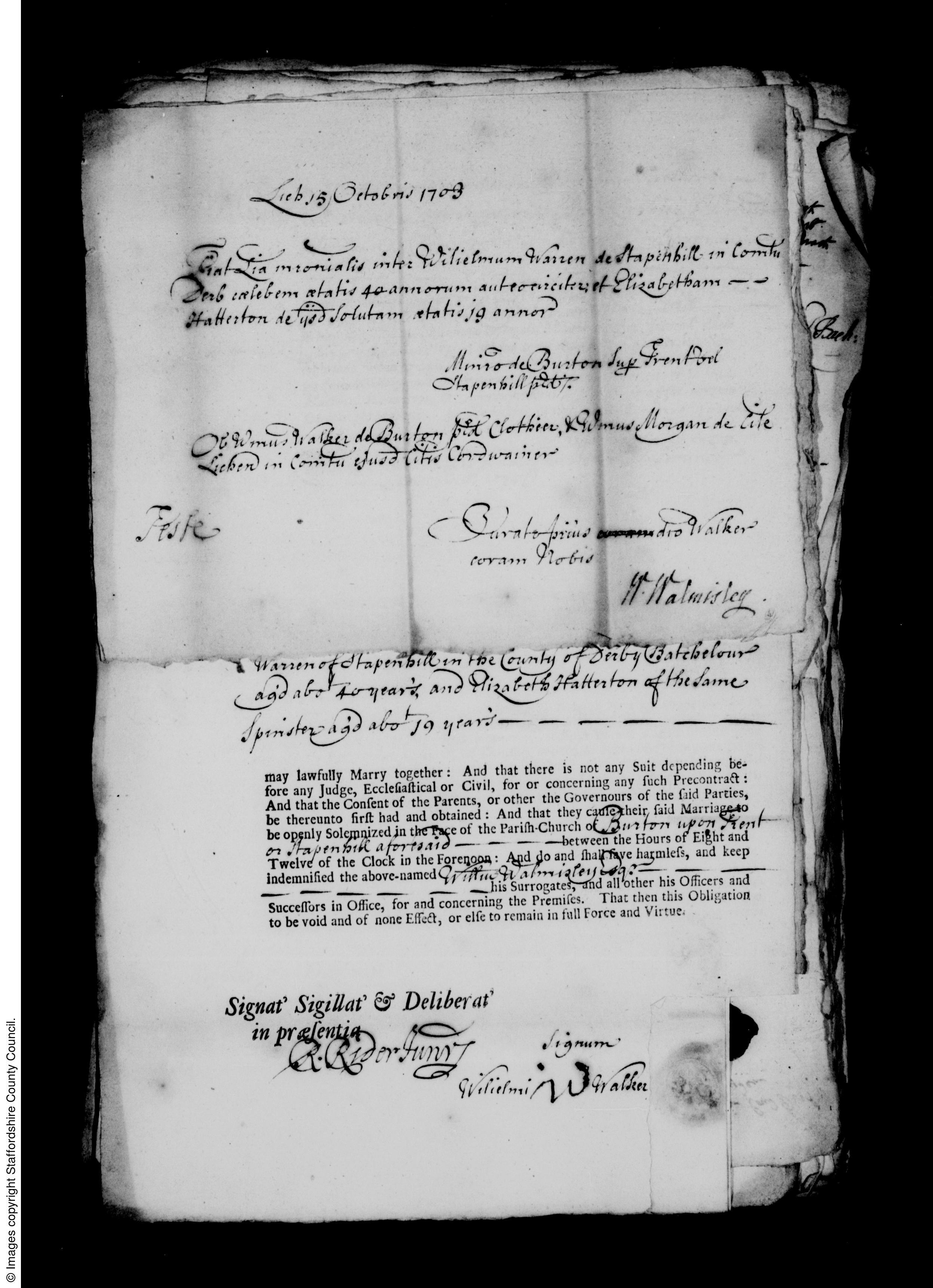

Samuel (born 1771) was baptised at Stapenhill St Peter and his parents were William and Anne Warren. There were at least three William and Ann Warrens in town at the time. One of those William’s was born in 1744, which would seem to be the right age to be Samuel’s father, and one was born in 1710, which seemed a little too old. Another William, Guiliamos Warren (Latin was often used in early parish registers) was baptised in Stapenhill in 1729.

Stapenhill St Peter: