Search Results for 'let'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

December 16, 2021 at 1:51 pm #6240

In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Phyllis Ellen Marshall

1909 – 1983

Phyllis, my grandfather George Marshall’s sister, never married. She lived in her parents home in Love Lane, and spent decades of her later life bedridden, living alone and crippled with rheumatoid arthritis. She had her bed in the front downstairs room, and had cords hanging by her bed to open the curtains, turn on the tv and so on, and she had carers and meals on wheels visit her daily. The room was dark and grim, but Phyllis was always smiling and cheerful. Phyllis loved the Degas ballerinas and had a couple of prints on the walls.

I remember visiting her, but it has only recently registered that this was my great grandparents house. When I was a child, we visited her and she indicated a tin on a chest of drawers and said I could take a biscuit. It was a lemon puff, and was the stalest biscuit I’d ever had. To be polite I ate it. Then she offered me another one! I declined, but she thought I was being polite and said “Go on! You can have another!” I ate another one, and have never eaten a lemon puff since that day.

Phyllis’s nephew Bryan Marshall used to visit her regularly. I didn’t realize how close they were until recently, when I resumed contact with Bryan, who emigrated to USA in the 1970s following a successful application for a job selling stained glass windows and church furnishings.

I asked on a Stourbridge facebook group if anyone remembered her.

AF Yes I remember her. My friend and I used to go up from Longlands school every Friday afternoon to do jobs for her. I remember she had a record player and we used to put her 45rpm record on Send in the Clowns for her. Such a lovely lady. She had her bed in the front room.

KW I remember very clearly a lady in a small house in Love Lane with alley at the left hand. I was intrigued by this lady who used to sit with the front door open and she was in a large chair of some sort. I used to see people going in and out and the lady was smiling. I was young then (31) and wondered how she coped but my sense was she had lots of help. I’ve never forgotten that lady in Love Lane sitting in the open door way I suppose when it was warm enough.

LR I used to deliver meals on wheels to her lovely lady.

I sent Bryan the comments from the Stourbridge group and he replied:

Thanks Tracy. I don’t recognize the names here but lovely to see such kind comments.

In the early 70’s neighbors on Corser Street, Mr. & Mrs. Walter Braithwaite would pop around with occasional visits and meals. Walter was my piano teacher for awhile when I was in my early twenties. He was a well known music teacher at Rudolph Steiner School (former Elmfield School) on Love Lane. A very fine school. I seem to recall seeing a good article on Walter recently…perhaps on the Stourbridge News website. He was very well known.

I’m ruminating about life with my Aunt Phyllis. We were very close. Our extra special time was every Saturday at 5pm (I seem to recall) we’d watch Doctor Who. Right from the first episode. We loved it. Likewise I’d do the children’s crossword out of Woman’s Realm magazine…always looking to win a camera but never did ! She opened my mind to the Bible, music and ballet. She once got tickets and had a taxi take us into Birmingham to see the Bolshoi Ballet…at a time when they rarely left their country. It was a very big deal in the early 60’s. ! I’ve many fond memories about her and grandad which I’ll share in due course. I’d change the steel needle on the old record player, following each play of the 78rpm records…oh my…another world.Bryan continues reminiscing about Phyllis in further correspondence:

Yes, I can recall those two Degas prints. I don’t know much of Phyllis’ early history other than she was a hairdresser in Birmingham. I want to say at John Lewis, for some reason (so there must have been a connection and being such a large store I bet they did have a salon?)

You will know that she had severe and debilitating rheumatoid arthritis that eventually gnarled her hands and moved through her body. I remember strapping on her leg/foot braces and hearing her writhe in pain as I did so but she wanted to continue walking standing/ getting up as long as she could. I’d take her out in the wheelchair and I can’t believe I say it along …but down Stanley Road!! (I had subsequent nightmares about what could have happened to her, had I tripped or let go!) She loved Mary Stevens Park, the swans, ducks and of course Canadian geese. Was grateful for everything in creation. As I used to go over Hanbury Hill on my visit to Love Lane, she would always remind me to smell the “sea-air” as I crested the hill.

In the earlier days she smoked cigarettes with one of those long filters…looking like someone from the twenties.I’ll check on “Send in the clowns”. I do recall that music. I remember also she loved to hear Neil Diamond. Her favorites in classical music gave me an appreciation of Elgar and Delius especially. She also loved ballet music such as Swan Lake and Nutcracker. Scheherazade and La Boutique Fantastic also other gems.

When grandad died she and aunt Dorothy shared more about grandma (who died I believe when John and I were nine-months old…therefore early 1951). Grandma (Mary Ann Gilman Purdy) played the piano and loved Strauss and Offenbach. The piano in the picture you sent had a bad (wonky) leg which would fall off and when we had the piano at 4, Mount Road it was rather dangerous. In any event my parents didn’t want me or others “banging on it” for fear of waking the younger brothers so it disappeared at sometime.

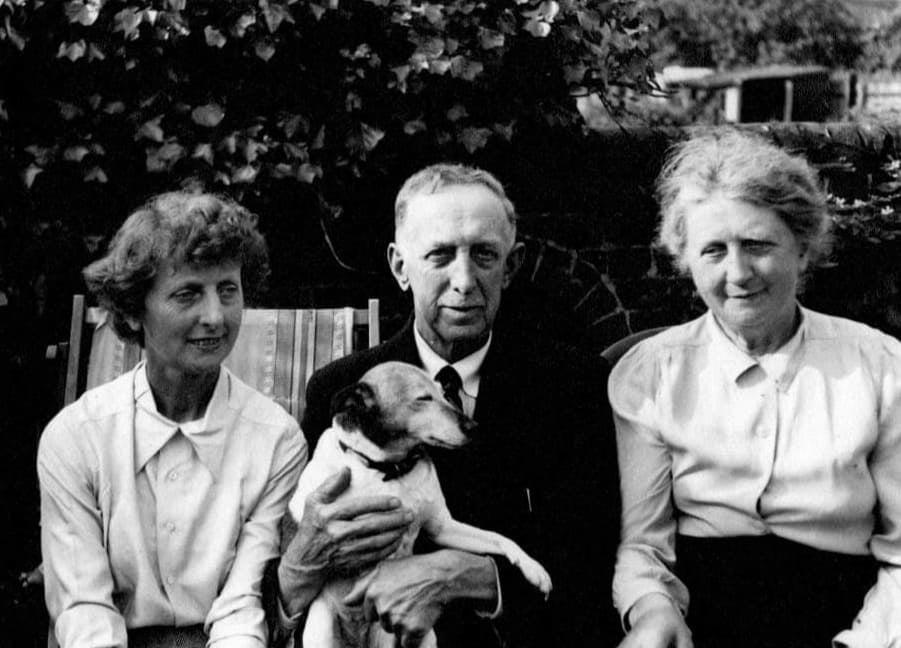

By the way, the dog, Flossy was always so rambunctious (of course, she was a JRT!) she was put on the stairway which fortunately had a door on it. Having said that I’ve always loved dogs so was very excited to see her and disappointed when she was not around.Phyllis with her parents William and Mary Marshall, and Flossie the dog in the garden at Love Lane:

Bryan continues:

I’ll always remember the early days with the outside toilet with the overhead cistern caked in active BIG spider webs. I used to have to light a candle to go outside, shielding the flame until destination. In that space I’d set the candle down and watch the eery shadows move from side to side whilst…well anyway! Then I’d run like hell back into the house. Eventually the kitchen wall was broken through so it became an indoor loo. Phew!

In the early days the house was rented for ten-shillings a week…I know because I used to take over a ten-bob-note to a grumpy lady next door who used to sign the receipt in the rent book. Then, I think she died and it became available for $600.00 yes…the whole house for $600.00 but it wasn’t purchased then. Eventually aunt Phyllis purchased it some years later…perhaps when grandad died.I used to work much in the back garden which was a lovely walled garden with arch-type decorations in the brickwork and semicircular shaped capping bricks. The abundant apple tree. Raspberry and loganberry canes. A gooseberry bush and huge Victoria plum tree on the wall at the bottom of the garden which became a wonderful attraction for wasps! (grandad called the “whasps”). He would stew apples and fruit daily.

Do you remember their black and white cat Twinky? Always sat on the pink-screen TV and when she died they were convinced that “that’s wot got ‘er”. Grandad of course loved all his cats and as he aged, he named them all “Billy”.Have you come across the name “Featherstone” in grandma’s name. I don’t recall any details but Dorothy used to recall this. She did much searching of the family history Such a pity she didn’t hand anything on to anyone. She also said that we had a member of the family who worked with James Watt….but likewise I don’t have details.

Gifts of chocolates to Phyllis were regular and I became the recipient of the overflow!What a pity Dorothy’s family history research has disappeared! I have found the Featherstone’s, and the Purdy who worked with James Watt, but I wonder what else Dorothy knew.

I mentioned DH Lawrence to Bryan, and the connection to Eastwood, where Bryan’s grandma (and Phyllis’s mother) Mary Ann Gilman Purdy was born, and shared with him the story about Francis Purdy, the Primitive Methodist minister, and about Francis’s son William who invented the miners lamp.

He replied:

As a nosy young man I was looking through the family bookcase in Love Lane and came across a brown paper covered book. Intrigued, I found “Sons and Lovers” D.H. Lawrence. I knew it was a taboo book (in those days) as I was growing up but now I see the deeper connection. Of course! I know that Phyllis had I think an earlier boyfriend by the name of Maurice who lived in Perry Barr, Birmingham. I think he later married but was always kind enough to send her a book and fond message each birthday (Feb.12). I guess you know grandad’s birthday – July 28. We’d always celebrate those days. I’d usually be the one to go into Oldswinford and get him a cardigan or pullover and later on, his 2oz tins of St. Bruno tobacco for his pipe (I recall the room filled with smoke as he puffed away).

Dorothy and Phyllis always spoke of their ancestor’s vocation as a Minister. So glad to have this history! Wow, what a story too. The Lord rescued him from mischief indeed. Just goes to show how God can change hearts…one at a time.

So interesting to hear about the Miner’s Lamp. My vicar whilst growing up at St. John’s in Stourbridge was from Durham and each Harvest Festival, there would be a miner’s lamp placed upon the altar as a symbol of the colliery and the bountiful harvest.More recollections from Bryan about the house and garden at Love Lane:

I always recall tea around the three legged oak table bedecked with a colorful seersucker cloth. Battenburg cake. Jam Roll. Rich Tea and Digestive biscuits. Mr. Kipling’s exceedingly good cakes! Home-made jam. Loose tea from the Coronation tin cannister. The ancient mangle outside the back door and the galvanized steel wash tub with hand-operated agitator on the underside of the lid. The hand operated water pump ‘though modernisation allowed for a cold tap only inside, above the single sink and wooden draining board. A small gas stove and very little room for food preparation. Amazing how the Marshalls (×7) managed in this space!

The small window over the sink in the kitchen brought in little light since the neighbor built on a bathroom annex at the back of their house, leaving #47 with limited light, much to to upset of grandad and Phyllis. I do recall it being a gloomy place..i.e.the kitchen and back room.

The garden was lovely. Long and narrow with privet hedge dividing the properties on the right and the lovely wall on the left. Dorothy planted spectacular lilac bushes against the wall. Vivid blues, purples and whites. Double-flora. Amazing…and with stunning fragrance. Grandad loved older victorian type plants such as foxgloves and comfrey. Forget-me-nots and marigolds (calendulas) in abundance. Rhubarb stalks. Always plantings of lettuce and other vegetables. Lots of mint too! A large varigated laurel bush outside the front door!

Such a pleasant walk through the past.

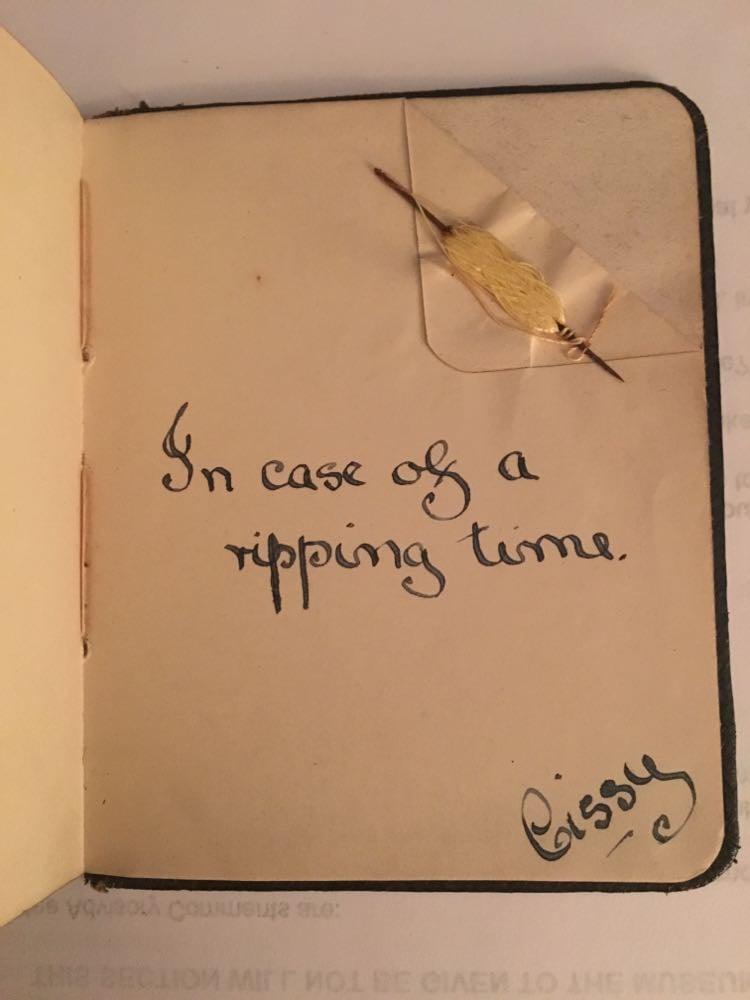

An autograph book belonging to Phyllis from the 1920s has survived in which each friend painted a little picture, drew a cartoon, or wrote a verse. This entry is perhaps my favourite:

December 15, 2021 at 9:34 am #6236

December 15, 2021 at 9:34 am #6236In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

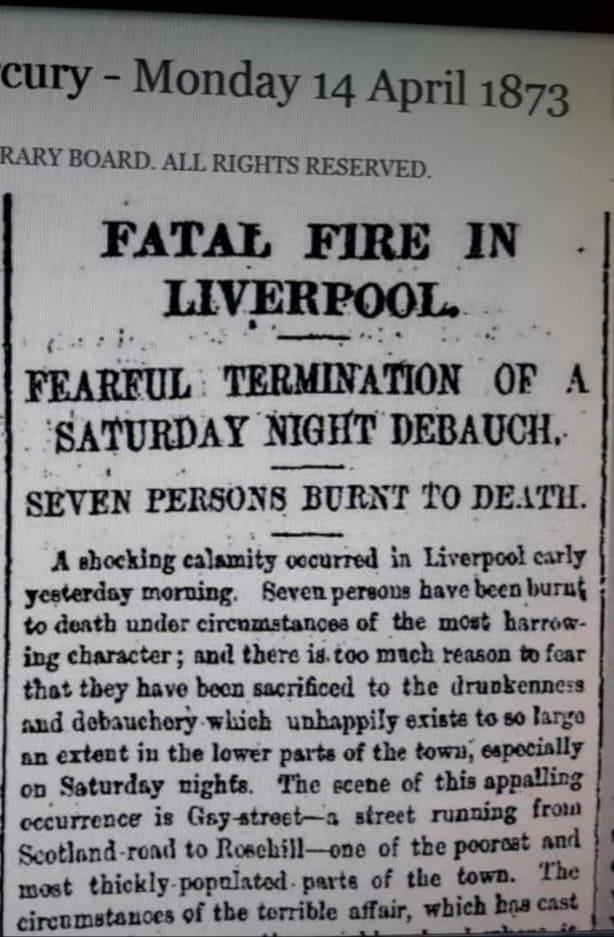

The Liverpool Fires

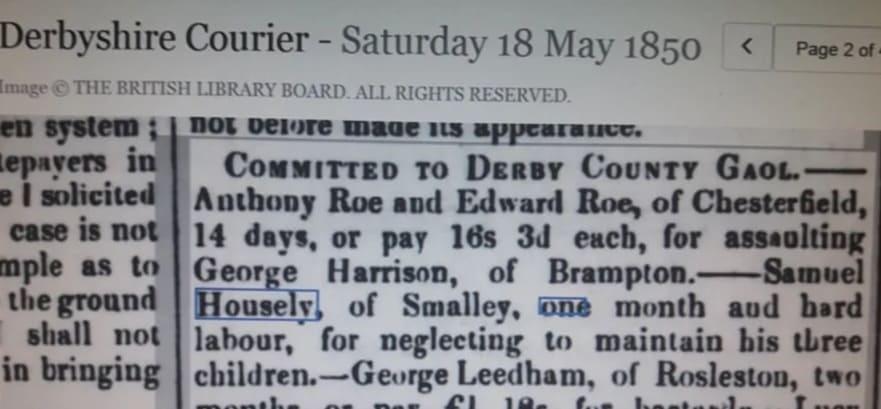

Catherine Housley had two older sisters, Elizabeth 1845-1883 and Mary Anne 1846-1935. Both Elizabeth and Mary Anne grew up in the Belper workhouse after their mother died, and their father was jailed for failing to maintain his three children. Mary Anne married Samuel Gilman and they had a grocers shop in Buxton. Elizabeth married in Liverpool in 1873.

What was she doing in Liverpool? How did she meet William George Stafford?

According to the census, Elizabeth Housley was in Belper workhouse in 1851. In 1861, aged 16, she was a servant in the household of Peter Lyon, a baker in Derby St Peters. We noticed that the Lyon’s were friends of the family and were mentioned in the letters to George in Pennsylvania.

No record of Elizabeth can be found on the 1871 census, but in 1872 the birth and death was registered of Elizabeth and William’s child, Elizabeth Jane Stafford. The parents are registered as William and Elizabeth Stafford, although they were not yet married. William’s occupation is a “refiner”.

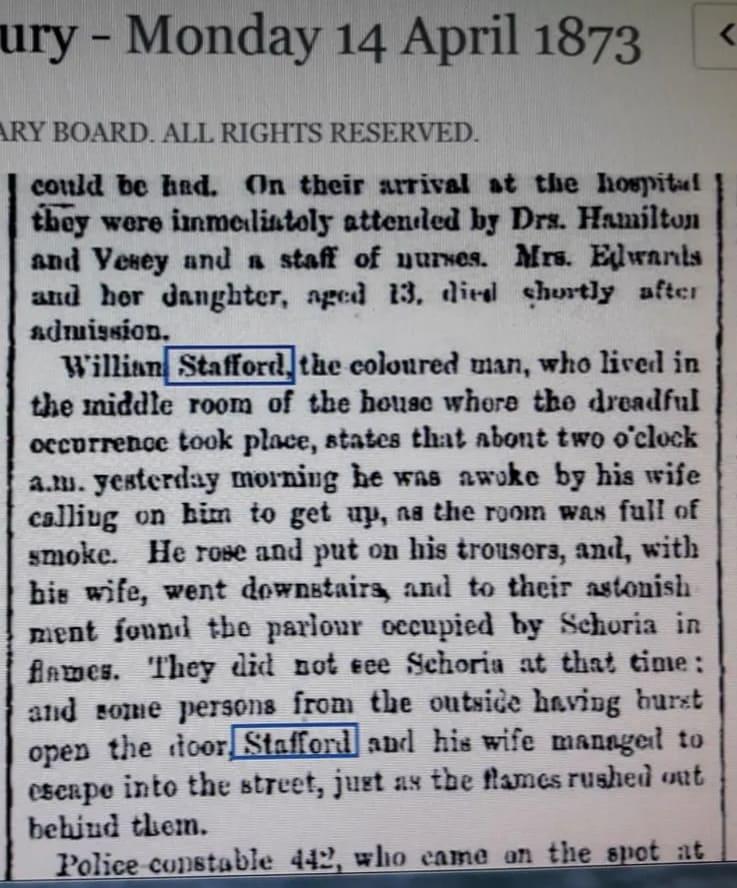

In April, 1873, a Fatal Fire is reported in the Liverpool Mercury. Fearful Termination of a Saturday Night Debauch. Seven Persons Burnt To Death. Interesting to note in the article that “the middle room being let off to a coloured man named William Stafford and his wife”.

We had noted on the census that William Stafford place of birth was “Africa, British subject” but it had not occurred to us that he was “coloured”. A register of birth has not yet been found for William and it is not known where in Africa he was born.

Elizabeth and William survived the fire on Gay Street, and were still living on Gay Street in October 1873 when they got married.

William’s occupation on the marriage register is sugar refiner, and his father is Peter Stafford, farmer. Elizabeth’s father is Samuel Housley, plumber. It does not say Samuel Housley deceased, so perhaps we can assume that Samuel is still alive in 1873.

Eliza Florence Stafford, their second daughter, was born in 1876.

William’s occupation on the 1881 census is “fireman”, in his case, a fire stoker at the sugar refinery, an unpleasant and dangerous job for which they were paid slightly more. William, Elizabeth and Eliza were living in Byrom Terrace.

Byrom Terrace, Liverpool, in 1933

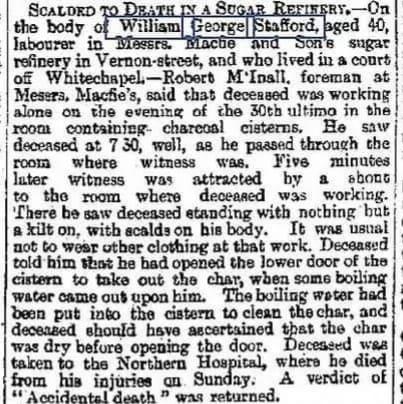

Elizabeth died of heart problems in 1883, when Eliza was six years old, and in 1891 her father died, scalded to death in a tragic accident at the sugar refinery.

Eliza, aged 15, was living as an inmate at the Walton on the Hill Institution in 1891. It’s not clear when she was admitted to the workhouse, perhaps after her mother died in 1883.

In 1901 Eliza Florence Stafford is a 24 year old live in laundrymaid, according to the census, living in West Derby (a part of Liverpool, and not actually in Derby). On the 1911 census there is a Florence Stafford listed as an unnmarried laundress, with a daughter called Florence. In 1901 census she was a laundrymaid in West Derby, Liverpool, and the daughter Florence Stafford was born in 1904 West Derby. It’s likely that this is Eliza Florence, but nothing further has been found so far.

The questions remaining are the location of William’s birth, the name of his mother and his family background, what happened to Eliza and her daughter after 1911, and how did Elizabeth meet William in the first place.

William Stafford was a seaman prior to working in the sugar refinery, and he appears on several ship’s crew lists. Nothing so far has indicated where he might have been born, or where his father came from.

Some months after finding the newspaper article about the fire on Gay Street, I saw an unusual request for information on the Liverpool genealogy group. Someone asked if anyone knew of a fire in Liverpool in the 1870’s. She had watched a programme about children recalling past lives, in this case a memory of a fire. The child recalled pushing her sister into a burning straw mattress by accident, as she attempted to save her from a falling beam. I watched the episode in question hoping for more information to confirm if this was the same fire, but details were scant and it’s impossible to say for sure.

December 15, 2021 at 7:53 am #6234In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

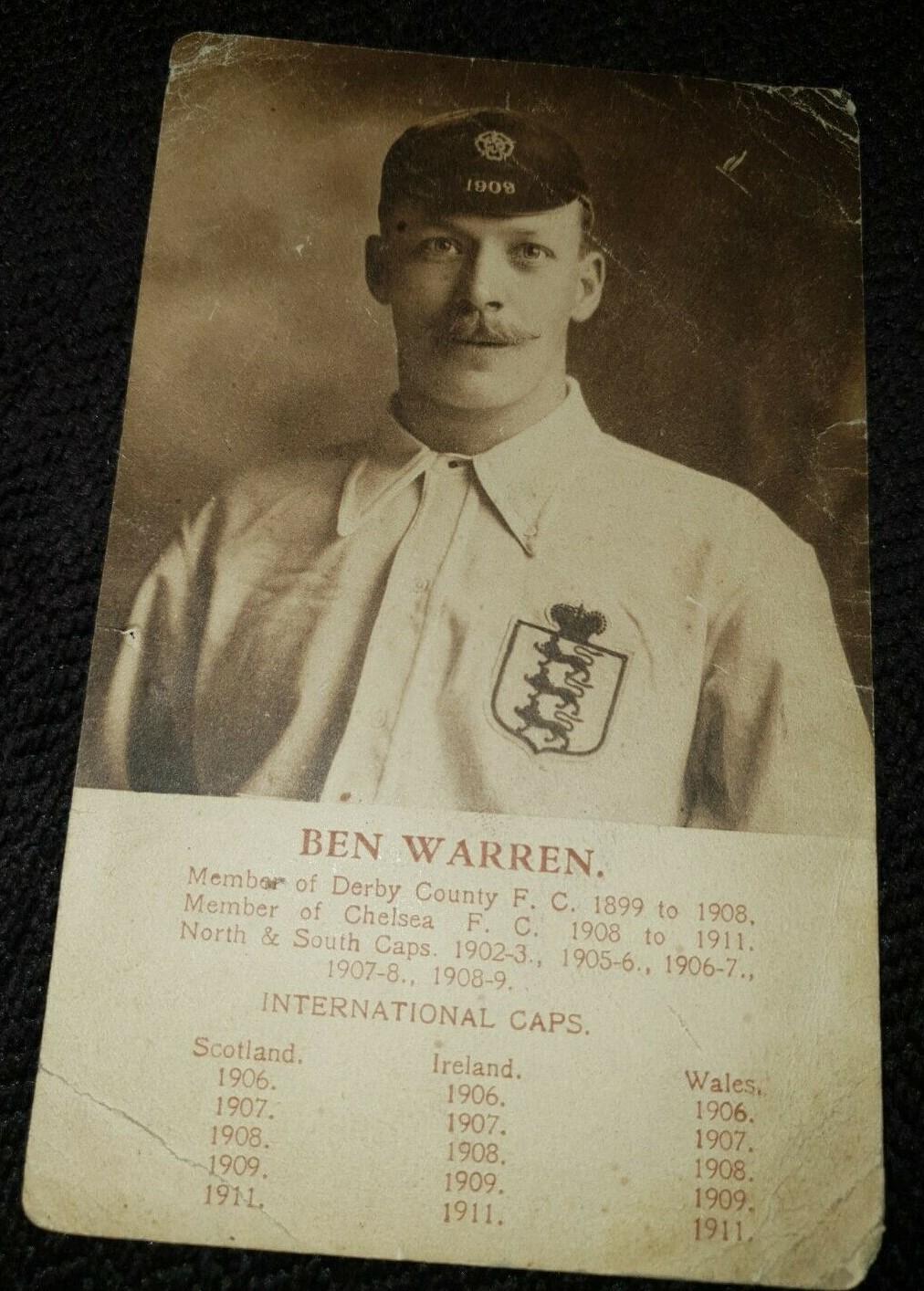

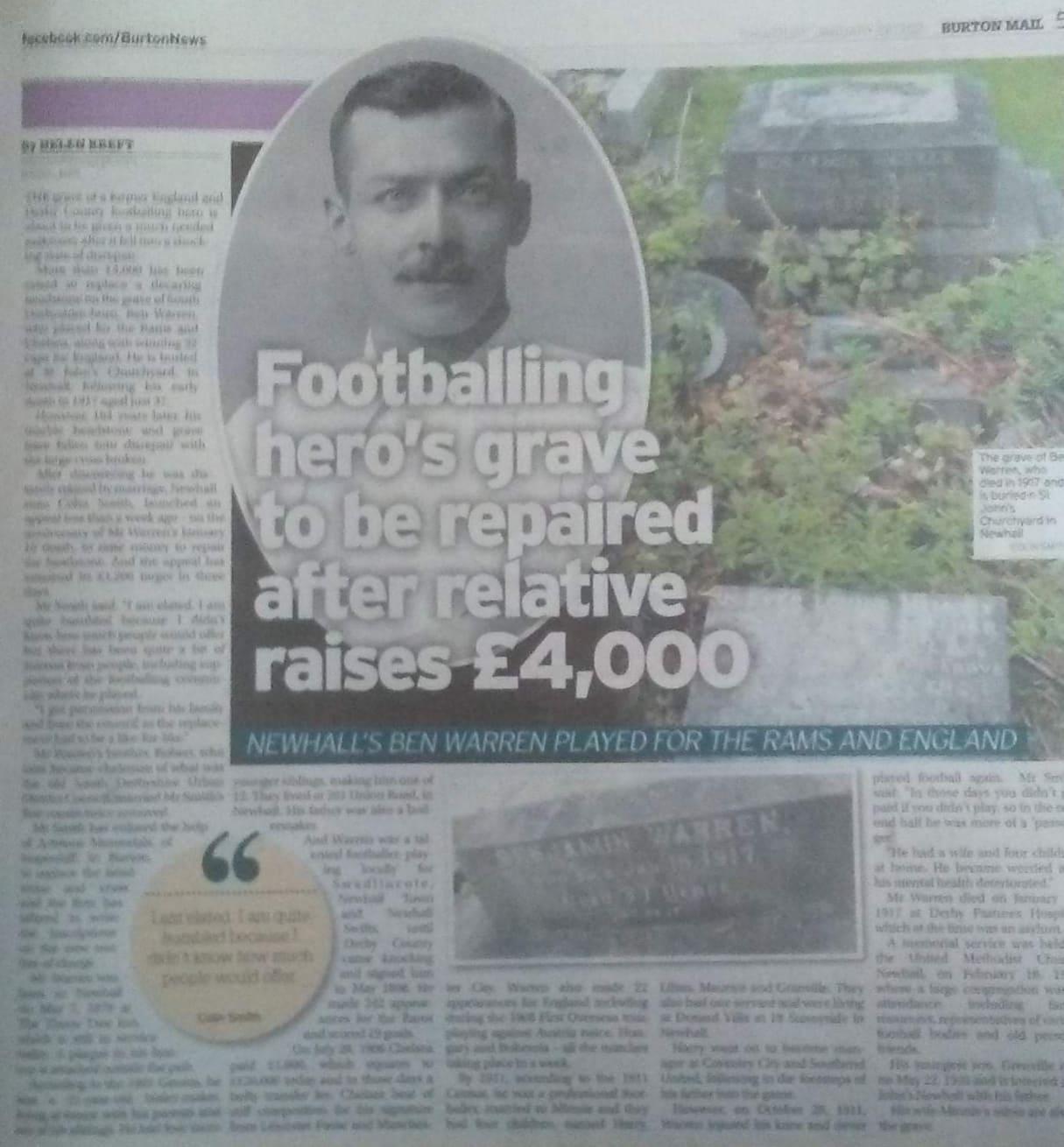

Ben Warren

Derby County and England football legend who died aged 37 penniless and ‘insane’

Ben Warren 1879 – 1917 was Samuel Warren’s (my great grandfather) cousin.

From the Derby Telegraph:

Just 17 months after earning his 22nd England cap, against Scotland at Everton on April 1, 1911, he was certified insane. What triggered his decline was no more than a knock on the knee while playing for Chelsea against Clapton Orient.

The knee would not heal and the longer he was out, the more he fretted about how he’d feed his wife and four children. In those days, if you didn’t play, there was no pay.

…..he had developed “brain fever” and this mild-mannered man had “become very strange and, at times, violent”. The coverage reflected his celebrity status.

On December 15, 1911, as Rick Glanvill records in his Official Biography of Chelsea FC: “He was admitted to a private clinic in Nottingham, suffering from acute mania, delusions that he was being poisoned and hallucinations of hearing and vision.”

He received another blow in February, 1912, when his mother, Emily, died. She had congestion of the lungs and caught influenza, her condition not helped, it was believed, by worrying about Ben.

She had good reason: her famous son would soon be admitted to the unfortunately named Derby County Lunatic Asylum.

As Britain sleepwalked towards the First World War, Ben’s condition deteriorated. Glanvill writes: “His case notes from what would be a five-year stay, catalogue a devastating decline in which he is at various times described as incoherent, restless, destructive, ‘stuporose’ and ‘a danger to himself’.’”

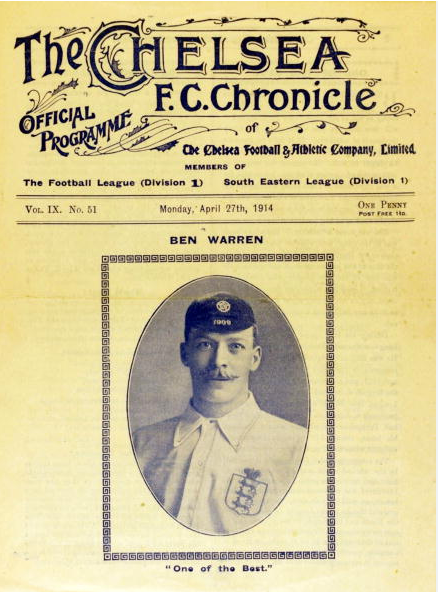

photo: Football 27th April 1914. A souvenir programme for the testimonial game for Chelsea and England’s Ben Warren, (pictured) who had been declared insane and sent to a lunatic asylum. The game was a select XI for the North playing a select XI from The South proceeds going to Warren’s family.

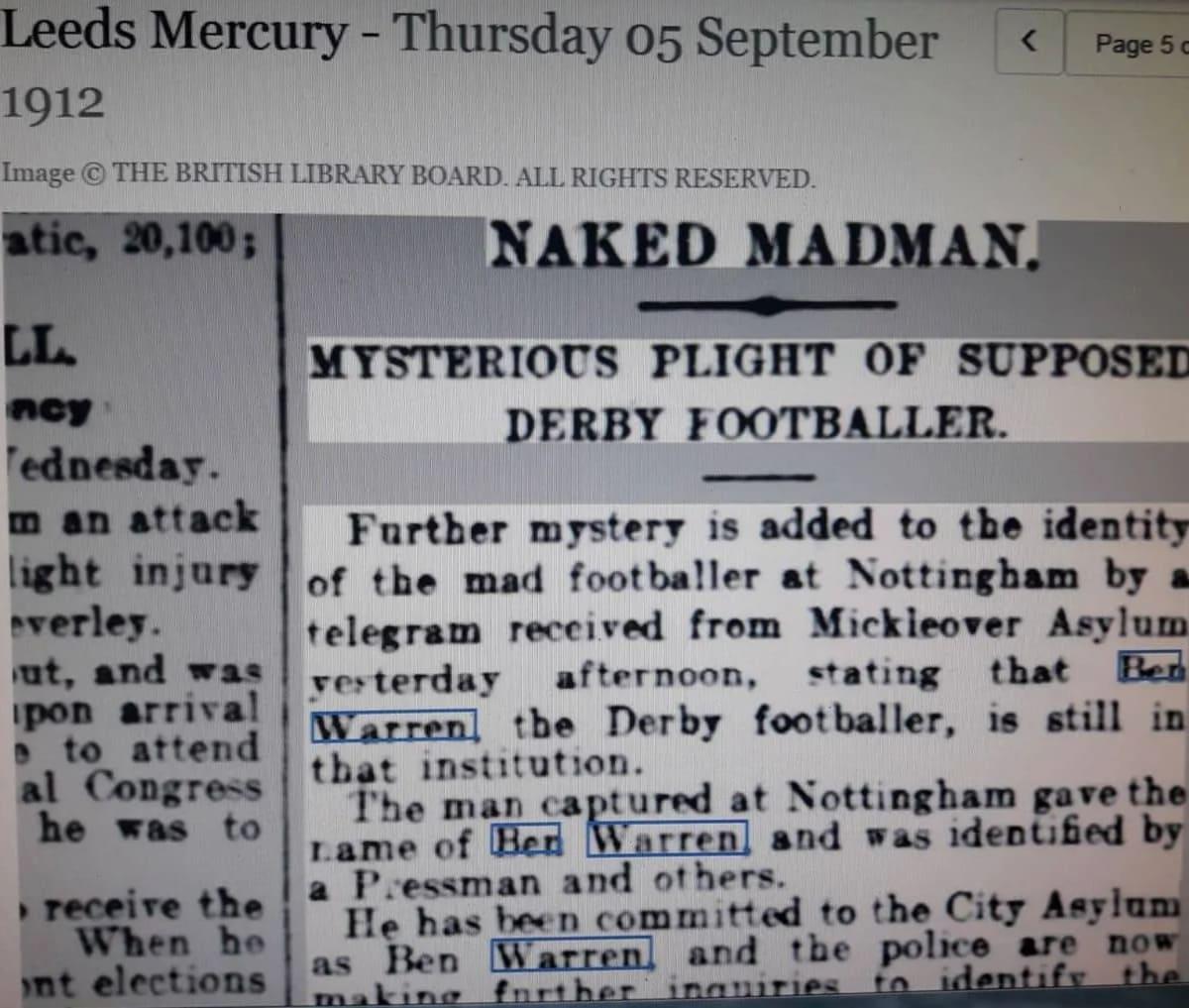

In September, that decline reached a new and pitiable low. The following is an abridged account of what The Courier called “an amazing incident” that took place on September 4.

“Spotted by a group of men while walking down Derby Road in Nottingham, a man was acting strangely, smoking a cigarette and had nothing on but a collar and tie.

“He jumped about the pavement and roadway, as though playing an imaginary game of football. When approached, he told them he was going to Trent Bridge to play in a match and had to be there by 3.30.”

Eventually he was taken to a police station and recognised by a reporter as England’s erstwhile right-half. What made the story even harder to digest was that Ben had escaped from the asylum and walked the 20 miles to Nottingham apparently unnoticed.

He had played at “Trent Bridge” many times – at least on Nottingham Forest’s adjacent City Ground.

As a shocked nation came to terms with the desperate plight of one of its finest footballers, some papers suggested his career was not yet over. And his relatives claimed that he had been suffering from nothing more than a severe nervous breakdown.

He would never be the same again – as a player or a man. He wasn’t even a shadow of the weird “footballer” who had walked 20 miles to Nottingham.

Then, he had nothing on, now he just had nothing – least of all self-respect. He ripped sheets into shreds and attempted suicide, saying: “I’m no use to anyone – and ought to be out of the way.”

“A year before his suicide attempt in 1916 the ominous symptom of ‘dry cough’ had been noted. Two months after it, in October 1916, the unmistakable signs of tuberculosis were noted and his enfeebled body rapidly succumbed.

At 11.30pm on 15 January 1917, international footballer Ben Warren was found dead by a night attendant.

He was 37 and when they buried him the records described him as a “pauper’.”

However you look at it, it is the salutary tale of a footballer worrying about money. And it began with a knock on the knee.

On 14th November 2021, Gill Castle posted on the Newhall and Swadlincote group:

I would like to thank Colin Smith and everyone who supported him in getting my great grandfather’s grave restored (Ben Warren who played for Derby, Chelsea and England)

The month before, Colin Smith posted:

My Ben Warren Journey is nearly complete.

It started two years ago when I was sent a family wedding photograph asking if I recognised anyone. My Great Great Grandmother was on there. But soon found out it was the wedding of Ben’s brother Robert to my 1st cousin twice removed, Eveline in 1910.

I researched Ben and his football career and found his resting place in St Johns Newhall, all overgrown and in a poor state with the large cross all broken off. I stood there and decided he needed to new memorial & headstone. He was our local hero, playing Internationally for England 22 times. He needs to be remembered.

After seeking family permission and Council approval, I had a quote from Art Stone Memorials, Burton on Trent to undertake the work. Fundraising then started and the memorial ordered.

Covid came along and slowed the process of getting materials etc. But we have eventually reached the final installation today.

I am deeply humbled for everyone who donated in January this year to support me and finally a massive thank you to everyone, local people, football supporters of Newhall, Derby County & Chelsea and football clubs for their donations.

Ben will now be remembered more easily when anyone walks through St Johns and see this beautiful memorial just off the pathway.

Finally a huge thank you for Art Stone Memorials Team in everything they have done from the first day I approached them. The team have worked endlessly on this project to provide this for Ben and his family as a lasting memorial. Thank you again Alex, Pat, Matt & Owen for everything. Means a lot to me.

The final chapter is when we have a dedication service at the grave side in a few weeks time,

Ben was born in The Thorntree Inn Newhall South Derbyshire and lived locally all his life.

He played local football for Swadlincote, Newhall Town and Newhall Swifts until Derby County signed Ben in May 1898. He made 242 appearances and scored 19 goals at Derby County.

28th July 1908 Chelsea won the bidding beating Leicester Fosse & Manchester City bids.

Ben also made 22 appearance’s for England including the 1908 First Overseas tour playing Austria twice, Hungary and Bohemia all in a week.

28 October 1911 Ben Injured his knee and never played football again

Ben is often compared with Steven Gerard for his style of play and team ethic in the modern era.

Herbert Chapman ( Player & Manager ) comments “ Warren was a human steam engine who played through 90 minutes with intimidating strength and speed”.

Charles Buchan comments “I am certain that a better half back could not be found, Part of the Best England X1 of all time”

Chelsea allowed Ben to live in Sunnyside Newhall, he used to run 5 miles every day round Bretby Park and had his own gym at home. He was compared to the likes of a Homing Pigeon, as he always came back to Newhall after his football matches.

Ben married Minnie Staley 21st October 1902 at Emmanuel Church Swadlincote and had four children, Harry, Lillian, Maurice & Grenville. Harry went on to be Manager at Coventry & Southend following his father in his own career as football Manager.

After Ben’s football career ended in 1911 his health deteriorated until his passing at Derby Pastures Hospital aged 37yrs

Ben’s youngest son, Grenville passed away 22nd May 1929 and is interred together in St John’s Newhall with his Father

His wife, Minnie’s ashes are also with Ben & Grenville.

Thank you again everyone.

RIP Ben Warren, our local Newhall Hero. You are remembered.

December 14, 2021 at 9:28 pm #6231

December 14, 2021 at 9:28 pm #6231In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Gladstone Road

My mother remembers her grandfather Samuel Warren’s house at 3 Gladstone Road, Stourbridge. She was born in 1933, so this would be late 1930s early 1940s.

“Opening a big wooden gate in a high brick wall off the sidewalk I went down a passage with a very high hedge to the main house which was entered on this side through a sort of glassed-in lean-to then into the dark and damp scullery and then into a large room with a fireplace which was dining room and living room for most of the time. The house was Georgian and had wooden interior shutters at the windows. My Grandad sat by the fire probably most of the day. The fireplace may have had an oven built over or to the side of the fire which was common in those days and was used for cooking.

That room led into a hall going three ways and the main front door was here. One hall went to the pantry which had stone slabs for keeping food cool, such a long way from the kitchen! Opposite the pantry was the door to the cellar. One hall led to two large rooms with big windows overlooking the garden. There was also a door at the end of this hallway which opened into the garden. The stairs went up opposite the front door with a box room at the top then along a landing to another hall going right and left with two bedrooms down each hall.

The toilet got to from the scullery and lean-to was outside down another passage all overgrown near the pigsty. No outside lights!

On Christmas day the families would all have the day here. I think the menfolk went over to the pub {Gate Hangs Well?} for a drink while the women cooked dinner. Chris would take all the children down the dark, damp cellar steps and tell us ghost stories scaring us all. A fire would be lit in one of the big main rooms {probably only used once a year} and we’d sit in there and dinner was served in the other big main room. When the house was originally built the servants would have used the other room and scullery.

I have a recollection of going upstairs and into a bedroom off the right hand hall and someone was in bed, I thought an old lady but I was uncomfortable in there and never went in again. Seemed that person was there a long time. I did go upstairs with Betty to her room which was the opposite way down the hall and loved it. She was dating lots of soldiers during the war years. One in particular I remember was an American Army Officer that she was fond of but he was killed when he left England to fight in Germany.

I wonder if the person in bed that nobody spoke about was an old housekeeper?

My mother used to say there was a white lady who floated around in the garden. I think Kay died at Gladstone Road!”Samuel Warren, born in 1874 in Newhall, Derbyshire, was my grandmothers father. This is the only photograph we’ve seen of him (seated on right with cap). Kay, who died of TB in 1938, is holding the teddy bear. Samuel died in 1950, in Stourbridge, at the age of 76.

Left to right: back row: Leslie Warren. Hildred Williams / Griffiths (Nee Warren). Billy Warren. 2nd row: Gladys (Gary) Warren. Kay Warren (holding teddy bear). Samuel Warren (father). Hildred’s son Chris Williams (on knee). Lorna Warren. Joan Williams. Peggy Williams (Hildreds daughters). Jack Warren. Betty Warren.

December 13, 2021 at 2:34 pm #6227In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

The Scottish Connection

My grandfather always used to say we had some Scottish blood because his “mother was a Purdy”, and that they were from the low counties of Scotland near to the English border.

My mother had a Scottish hat in among the boxes of souvenirs and old photographs. In one of her recent house moves, she finally threw it away, not knowing why we had it or where it came from, and of course has since regretted it! It probably came from one of her aunts, either Phyllis or Dorothy. Neither of them had children, and they both died in 1983. My grandfather was executor of the estate in both cases, and it’s assumed that the portraits, the many photographs, the booklet on Primitive Methodists, and the Scottish hat, all relating to his mother’s side of the family, came into his possession then. His sister Phyllis never married and was living in her parents home until she died, and is the likeliest candidate for the keeper of the family souvenirs.

Catherine Housley married George Purdy, and his father was Francis Purdy, the Primitive Methodist preacher. William Purdy was the father of Francis.

Record searches find William Purdy was born on 16 July 1767 in Carluke, Lanarkshire, near Glasgow in Scotland. He worked for James Watt, the inventor of the steam engine, and moved to Derbyshire for the purpose of installing steam driven pumps to remove the water from the collieries in the area.

Another descendant of Francis Purdy found the following in a book in a library in Eastwood:

William married a local girl, Ruth Clarke, in Duffield in Derbyshire in 1786. William and Ruth had nine children, and the seventh was Francis who was born at West Hallam in 1795.

Perhaps the Scottish hat came from William Purdy, but there is another story of Scottish connections in Smalley: Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobite Rebellion of 1745. Although the Purdy’s were not from Smalley, Catherine Housley was.

From an article on the Heanor and District Local History Society website:

The Jacobites in Smalley

Few people would readily associate the village of Smalley, situated about two miles west of Heanor, with Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobite Rebellion of 1745 – but there is a clear link.

During the winter of 1745, Charles Edward Stuart, the “Bonnie Prince” or “The Young Pretender”, marched south from Scotland. His troops reached Derby on 4 December, and looted the town, staying for two days before they commenced a fateful retreat as the Duke of Cumberland’s army approached.

While staying in Derby, or during the retreat, some of the Jacobites are said to have visited some of the nearby villages, including Smalley.

A history of the local aspects of this escapade was written in 1933 by L. Eardley-Simpson, entitled “Derby and the ‘45,” from which the following is an extract:

“The presence of a party at Smalley is attested by several local traditions and relics. Not long ago there were people living who remember to have seen at least a dozen old pikes in a room adjoining the stables at Smalley Hall, and these were stated to have been left by a party of Highlanders who came to exchange their ponies for horses belonging to the then owner, Mrs Richardson; in 1907, one of these pikes still remained. Another resident of Smalley had a claymore which was alleged to have been found on Drumhill, Breadsall Moor, while the writer of the History of Smalley himself (Reverend C. Kerry) had a magnificent Andrew Ferrara, with a guard of finely wrought iron, engraved with two heads in Tudor helmets, of the same style, he states, as the one left at Wingfield Manor, though why the outlying bands of Army should have gone so far afield, he omits to mention. Smalley is also mentioned in another strange story as to the origin of the family of Woolley of Collingham who attained more wealth and a better position in the world than some of their relatives. The story is to the effect that when the Scots who had visited Mrs Richardson’s stables were returning to Derby, they fell in with one Woolley of Smalley, a coal carrier, and impressed him with horse and cart for the conveyance of certain heavy baggage. On the retreat, the party with Woolley was surprised by some of the Elector’s troopers (the Royal army) who pursued the Scots, leaving Woolley to shift for himself. This he did, and, his suspicion that the baggage he was carrying was part of the Prince’s treasure turning out to be correct, he retired to Collingham, and spent the rest of his life there in the enjoyment of his luckily acquired gains. Another story of a similar sort was designed to explain the rise of the well-known Derbyshire family of Cox of Brailsford, but the dates by no means agree with the family pedigree, and in any event the suggestion – for it is little more – is entirely at variance with the views as to the rights of the Royal House of Stuart which were expressed by certain members of the Cox family who were alive not many years ago.”

A letter from Charles Kerry, dated 30 July 1903, narrates another strange twist to the tale. When the Highlanders turned up in Smalley, a large crowd, mainly women, gathered. “On a command in Gaelic, the regiment stooped, and throwing their kilts over their backs revealed to the astonished ladies and all what modesty is careful to conceal. Father, who told me, said they were not any more troubled with crowds of women.”

Folklore or fact? We are unlikely to know, but the Scottish artefacts in the Smalley area certainly suggest that some of the story is based on fact.

We are unlikely to know where that Scottish hat came from, but we did find the Scottish connection. William Purdy’s mother was Grizel Gibson, and her mother was Grizel Murray, both of Lanarkshire in Scotland. The name Grizel is a Scottish form of the name Griselda, and means “grey battle maiden”. But with the exception of the name Murray, The Purdy and Gibson names are not traditionally Scottish, so there is not much of a Scottish connection after all. But the mystery of the Scottish hat remains unsolved.

December 13, 2021 at 11:29 am #6222In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

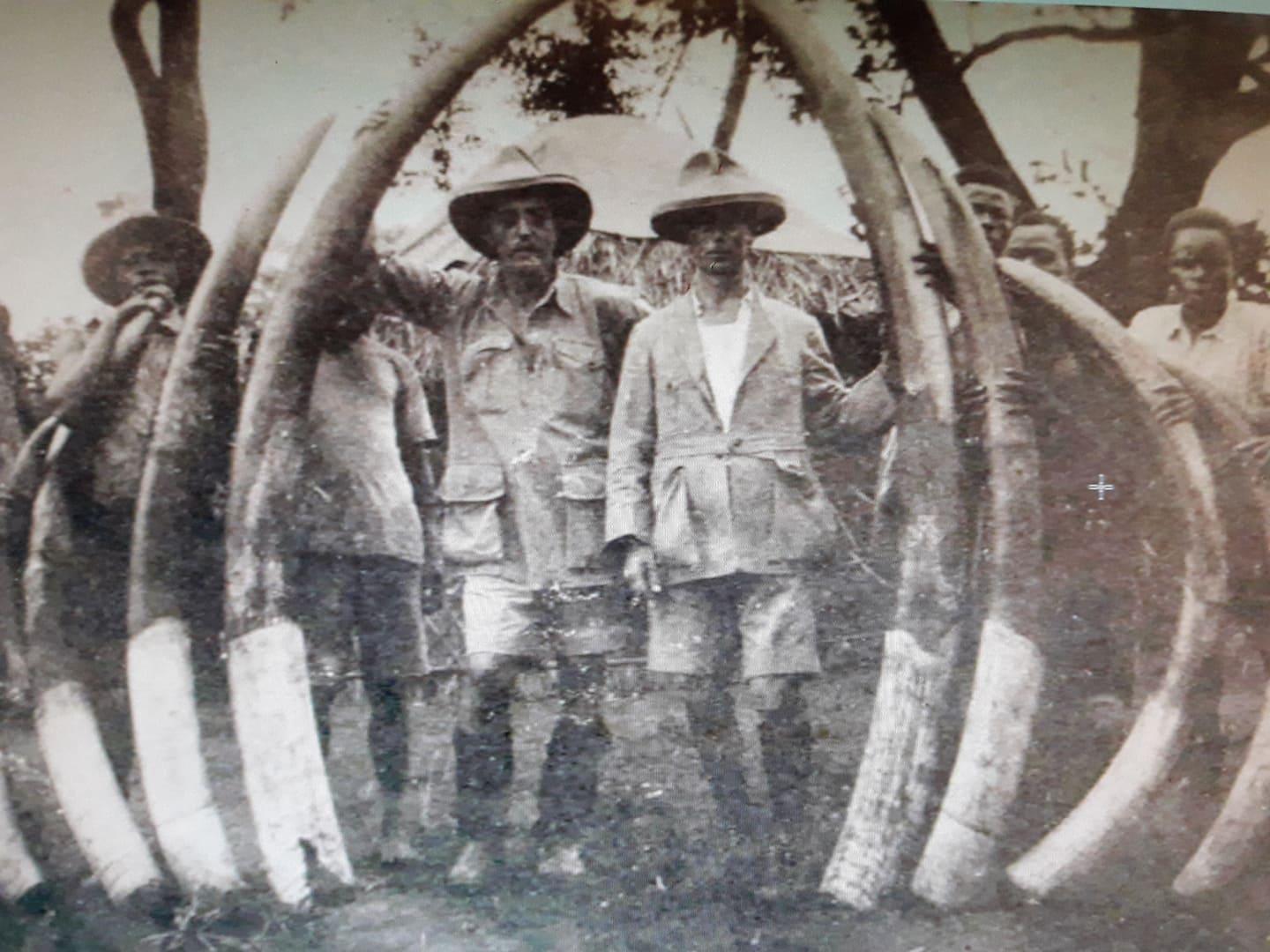

George Gilman Rushby: The Cousin Who Went To Africa

The portrait of the woman has “mother of Catherine Housley, Smalley” written on the back, and one of the family photographs has “Francis Purdy” written on the back. My first internet search was “Catherine Housley Smalley Francis Purdy”. Easily found was the family tree of George (Mike) Rushby, on one of the genealogy websites. It seemed that it must be our family, but the African lion hunter seemed unlikely until my mother recalled her father had said that he had a cousin who went to Africa. I also noticed that the lion hunter’s middle name was Gilman ~ the name that Catherine Housley’s daughter ~ my great grandmother, Mary Ann Gilman Purdy ~ adopted, from her aunt and uncle who brought her up.

I tried to contact George (Mike) Rushby via the ancestry website, but got no reply. I searched for his name on Facebook and found a photo of a wildfire in a place called Wardell, in Australia, and he was credited with taking the photograph. A comment on the photo, which was a few years old, got no response, so I found a Wardell Community group on Facebook, and joined it. A very small place, population some 700 or so, and I had an immediate response on the group to my question. They knew Mike, exchanged messages, and we were able to start emailing. I was in the chair at the dentist having an exceptionally long canine root canal at the time that I got the message with his email address, and at that moment the song Down in Africa started playing.

Mike said it was clever of me to track him down which amused me, coming from the son of an elephant and lion hunter. He didn’t know why his father’s middle name was Gilman, and was not aware that Catherine Housley’s sister married a Gilman.

Mike Rushby kindly gave me permission to include his family history research in my book. This is the story of my grandfather George Marshall’s cousin. A detailed account of George Gilman Rushby’s years in Africa can be found in another chapter called From Tanganyika With Love; the letters Eleanor wrote to her family.

George Gilman Rushby:

The story of George Gilman Rushby 1900-1969, as told by his son Mike:

George Gilman Rushby:

Elephant hunter,poacher, prospector, farmer, forestry officer, game ranger, husband to Eleanor, and father of 6 children who now live around the world.George Gilman Rushby was born in Nottingham on 28 Feb 1900 the son of Catherine Purdy and John Henry Payling Rushby. But John Henry died when his son was only one and a half years old, and George shunned his drunken bullying stepfather Frank Freer and was brought up by Gypsies who taught him how to fight and took him on regular poaching trips. His love of adventure and his ability to hunt were nurtured at an early stage of his life.

The family moved to Eastwood, where his mother Catherine owned and managed The Three Tuns Inn, but when his stepfather died in mysterious circumstances, his mother married a wealthy bookmaker named Gregory Simpson. He could afford to send George to Worksop College and to Rugby School. This was excellent schooling for George, but the boarding school environment, and the lack of a stable home life, contributed to his desire to go out in the world and do his own thing. When he finished school his first job was as a trainee electrician with Oaks & Co at Pye Bridge. He also worked part time as a motor cycle mechanic and as a professional boxer to raise the money for a voyage to South Africa.In May 1920 George arrived in Durban destitute and, like many others, living on the beach and dependant upon the Salvation Army for a daily meal. However he soon got work as an electrical mechanic, and after a couple of months had earned enough money to make the next move North. He went to Lourenco Marques where he was appointed shift engineer for the town’s power station. However he was still restless and left the comfort of Lourenco Marques for Beira in August 1921.

Beira was the start point of the new railway being built from the coast to Nyasaland. George became a professional hunter providing essential meat for the gangs of construction workers building the railway. He was a self employed contractor with his own support crew of African men and began to build up a satisfactory business. However, following an incident where he had to shoot and kill a man who attacked him with a spear in middle of the night whilst he was sleeping, George left the lower Zambezi and took a paddle steamer to Nyasaland (Malawi). On his arrival in Karongo he was encouraged to shoot elephant which had reached plague proportions in the area – wrecking African homes and crops, and threatening the lives of those who opposed them.

His next move was to travel by canoe the five hundred kilometre length of Lake Nyasa to Tanganyika, where he hunted for a while in the Lake Rukwa area, before walking through Northern Rhodesia (Zambia) to the Congo. Hunting his way he overachieved his quota of ivory resulting in his being charged with trespass, the confiscation of his rifles, and a fine of one thousand francs. He hunted his way through the Congo to Leopoldville then on to the Portuguese enclave, near the mouth of the mighty river, where he worked as a barman in a rough and tough bar until he received a message that his old friend Lumb had found gold at Lupa near Chunya. George set sail on the next boat for Antwerp in Belgium, then crossed to England and spent a few weeks with his family in Jacksdale before returning by sea to Dar es Salaam. Arriving at the gold fields he pegged his claim and almost immediately went down with blackwater fever – an illness that used to kill three out of four within a week.

When he recovered from his fever, George exchanged his gold lease for a double barrelled .577 elephant rifle and took out a special elephant control licence with the Tanganyika Government. He then headed for the Congo again and poached elephant in Northern Rhodesia from a base in the Congo. He was known by the Africans as “iNyathi”, or the Buffalo, because he was the most dangerous in the long grass. After a profitable hunting expedition in his favourite hunting ground of the Kilombera River he returned to the Congo via Dar es Salaam and Mombassa. He was after the Kabalo district elephant, but hunting was restricted, so he set up his base in The Central African Republic at a place called Obo on the Congo tributary named the M’bomu River. From there he could make poaching raids into the Congo and the Upper Nile regions of the Sudan. He hunted there for two and a half years. He seldom came across other Europeans; hunters kept their own districts and guarded their own territories. But they respected one another and he made good and lasting friendships with members of that small select band of adventurers.

Leaving for Europe via the Congo, George enjoyed a short holiday in Jacksdale with his mother. On his return trip to East Africa he met his future bride in Cape Town. She was 24 year old Eleanor Dunbar Leslie; a high school teacher and daughter of a magistrate who spent her spare time mountaineering, racing ocean yachts, and riding horses. After a whirlwind romance, they were betrothed within 36 hours.

On 25 July 1930 George landed back in Dar es Salaam. He went directly to the Mbeya district to find a home. For one hundred pounds he purchased the Waizneker’s farm on the banks of the Mntshewe Stream. Eleanor, who had been delayed due to her contract as a teacher, followed in November. Her ship docked in Dar es Salaam on 7 Nov 1930, and they were married that day. At Mchewe Estate, their newly acquired farm, they lived in a tent whilst George with some help built their first home – a lovely mud-brick cottage with a thatched roof. George and Eleanor set about developing a coffee plantation out of a bush block. It was a very happy time for them. There was no electricity, no radio, and no telephone. Newspapers came from London every two months. There were a couple of neighbours within twenty miles, but visitors were seldom seen. The farm was a haven for wild life including snakes, monkeys and leopards. Eleanor had to go South all the way to Capetown for the birth of her first child Ann, but with the onset of civilisation, their first son George was born at a new German Mission hospital that had opened in Mbeya.

Occasionally George had to leave the farm in Eleanor’s care whilst he went off hunting to make his living. Having run the coffee plantation for five years with considerable establishment costs and as yet no return, George reluctantly started taking paying clients on hunting safaris as a “white hunter”. This was an occupation George didn’t enjoy. but it brought him an income in the days when social security didn’t exist. Taking wealthy clients on hunting trips to kill animals for trophies and for pleasure didn’t amuse George who hunted for a business and for a way of life. When one of George’s trackers was killed by a leopard that had been wounded by a careless client, George was particularly upset.

The coffee plantation was approaching the time of its first harvest when it was suddenly attacked by plagues of borer beetles and ring barking snails. At the same time severe hail storms shredded the crop. The pressure of the need for an income forced George back to the Lupa gold fields. He was unlucky in his gold discoveries, but luck came in a different form when he was offered a job with the Forestry Department. The offer had been made in recognition of his initiation and management of Tanganyika’s rainbow trout project. George spent most of his short time with the Forestry Department encouraging the indigenous people to conserve their native forests.In November 1938 he transferred to the Game Department as Ranger for the Eastern Province of Tanganyika, and over several years was based at Nzasa near Dar es Salaam, at the old German town of Morogoro, and at lovely Lyamungu on the slopes of Kilimanjaro. Then the call came for him to be transferred to Mbeya in the Southern Province for there was a serious problem in the Njombe district, and George was selected by the Department as the only man who could possibly fix the problem.

Over a period of several years, people were being attacked and killed by marauding man-eating lions. In the Wagingombe area alone 230 people were listed as having been killed. In the Njombe district, which covered an area about 200 km by 300 km some 1500 people had been killed. Not only was the rural population being decimated, but the morale of the survivors was so low, that many of them believed that the lions were not real. Many thought that evil witch doctors were controlling the lions, or that lion-men were changing form to kill their enemies. Indeed some wichdoctors took advantage of the disarray to settle scores and to kill for reward.

By hunting down and killing the man-eaters, and by showing the flesh and blood to the doubting tribes people, George was able to instil some confidence into the villagers. However the Africans attributed the return of peace and safety, not to the efforts of George Rushby, but to the reinstallation of their deposed chief Matamula Mangera who had previously been stood down for corruption. It was Matamula , in their eyes, who had called off the lions.

Soon after this adventure, George was appointed Deputy Game Warden for Tanganyika, and was based in Arusha. He retired in 1956 to the Njombe district where he developed a coffee plantation, and was one of the first in Tanganyika to plant tea as a major crop. However he sensed a swing in the political fortunes of his beloved Tanganyika, and so sold the plantation and settled in a cottage high on a hill overlooking the Navel Base at Simonstown in the Cape. It was whilst he was there that TV Bulpin wrote his biography “The Hunter is Death” and George wrote his book “No More The Tusker”. He died in the Cape, and his youngest son Henry scattered his ashes at the Southern most tip of Africa where the currents of the Atlantic and Indian Oceans meet .

George Gilman Rushby:

December 13, 2021 at 10:39 am #6220

December 13, 2021 at 10:39 am #6220In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Helper Belper: “Let’s start at the beginning.”

When I found a huge free genealogy tree website with lots of our family already on it, I couldn’t believe my luck. Quite soon after a perusal, I found I had a number of questions. Was it really possible that our Warren family tree had been traced back to 500AD? I asked on a genealogy forum: only if you can latch onto an aristocratic line somewhere, in which case that lineage will be already documented, as normally parish records only go back to the 1600s, if you are lucky. It is very hard to prove and the validity of it met with some not inconsiderable skepticism among the long term hard core genealogists. This is not to say that it isn’t possible, but is more likely a response to the obvious desire of many to be able to trace their lineage back to some kind of royalty, regardless of the documentation and proof.

Another question I had on this particular website was about the entries attached to Catherine Housley that made no sense. The immense public family tree there that anyone can add to had Catherine Housley’s mother as Catherine Marriot. But Catherine Marriot had another daughter called Catherine, two years before our Catherine was born, who didn’t die beforehand. It wasn’t unusual to name another child the same name if an earlier one had died in infancy, but this wasn’t the case.

I asked this question on a British Genealogy forum, and learned that other people’s family trees are never to be trusted. One should always start with oneself, and trace back with documentation every step of the way. Fortified with all kinds of helpful information, I still couldn’t find out who Catherine Housley’s mother was, so I posted her portrait on the forum and asked for help to find her. Among the many helpful replies, one of the members asked if she could send me a private message. She had never had the urge to help someone find a person before, but felt a compulsion to find Catherine Housley’s mother. Eight months later and counting at time of writing, and she is still my most amazing Helper. The first thing she said in the message was “Right. Let’s start at the beginning. What do you know for sure.” I said Mary Ann Gilman Purdy, my great grandmother, and we started from there.

Fran found all the documentation and proof, a perfect and necessary compliment to my own haphazard meanderings. She taught me how to find the proof, how to spot inconsistencies, and what to look for and where. I still continue my own haphazard wanderings as well, which also bear fruit.

It was decided to order the birth certificate, a paper copy that could be stuck onto the back of the portrait, so my mother in Wales ordered it as she has the portrait. When it arrived, she read the names of Catherine’s parents to me over the phone. We were expecting it to be John Housley and Sarah Baggaley. But it wasn’t! It was his brother Samuel Housley and Elizabeth Brookes! I had been looking at the photograph of the portrait thinking it was Catherine Marriot, then looking at it thinking her name was Sarah Baggaley, and now the woman in the portrait was Elizabeth Brookes. And she was from Wolverhampton. My helper, unknown to me, had ordered a digital copy, which arrived the same day.

Months later, Fran, visiting friends in Derby, made a special trip to Smalley, a tiny village not far from Derby, to look for Housley gravestones in the two churchyards. There are numerous Housley burials registered in the Smalley parish records, but she could only find one Housley grave, that of Sarah Baggaley. Unfortunately the documentation had already proved that Sarah was not the woman in the portrait, Catherine Housley’s mother, but Catherine’s aunt.

Sarah Housley nee Baggaley’s grave stone in Smalley:

December 13, 2021 at 10:09 am #6219

December 13, 2021 at 10:09 am #6219Topic: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

in forum TP’s Family BooksThe following stories started with a single question.

Who was Catherine Housley’s mother?

But one question leads to another, and another, and so this book will never be finished. This is the first in a collection of stories of a family history research project, not a complete family history. There will always be more questions and more searches, and each new find presents more questions.

A list of names and dates is only moderately interesting, and doesn’t mean much unless you get to know the characters along the way. For example, a cousin on my fathers side has already done a great deal of thorough and accurate family research. I copied one branch of the family onto my tree, going back to the 1500’s, but lost interest in it after about an hour or so, because I didn’t feel I knew any of the individuals.

Parish registers, the census every ten years, birth, death and marriage certificates can tell you so much, but they can’t tell you why. They don’t tell you why parents chose the names they did for their children, or why they moved, or why they married in another town. They don’t tell you why a person lived in another household, or for how long. The census every ten years doesn’t tell you what people were doing in the intervening years, and in the case of the UK and the hundred year privacy rule, we can’t even use those for the past century. The first census was in 1831 in England, prior to that all we have are parish registers. An astonishing amount of them have survived and have been transcribed and are one way or another available to see, both transcriptions and microfiche images. Not all of them survived, however. Sometimes the writing has faded to white, sometimes pages are missing, and in some case the entire register is lost or damaged.

Sometimes if you are lucky, you may find mention of an ancestor in an obscure little local history book or a journal or diary. Wills, court cases, and newspaper archives often provide interesting information. Town memories and history groups on social media are another excellent source of information, from old photographs of the area, old maps, local history, and of course, distantly related relatives still living in the area. Local history societies can be useful, and some if not all are very helpful.

If you’re very lucky indeed, you might find a distant relative in another country whose grandparents saved and transcribed bundles of old letters found in the attic, from the family in England to the brother who emigrated, written in the 1800s. More on this later, as it merits its own chapter as the most exciting find so far.

The social history of the time and place is important and provides many clues as to why people moved and why the family professions and occupations changed over generations. The Enclosures Act and the Industrial Revolution in England created difficulties for rural farmers, factories replaced cottage industries, and the sons of land owning farmers became shop keepers and miners in the local towns. For the most part (at least in my own research) people didn’t move around much unless there was a reason. There are no reasons mentioned in the various registers, records and documents, but with a little reading of social history you can sometimes make a good guess. Samuel Housley, for example, a plumber, probably moved from rural Derbyshire to urban Wolverhampton, when there was a big project to install indoor plumbing to areas of the city in the early 1800s. Derbyshire nailmakers were offered a job and a house if they moved to Wolverhampton a generation earlier.

Occasionally a couple would marry in another parish, although usually they married in their own. Again, there was often a reason. William Housley and Ellen Carrington married in Ashbourne, not in Smalley. In this case, William’s first wife was Mary Carrington, Ellen’s sister. It was not uncommon for a man to marry a deceased wife’s sister, but it wasn’t strictly speaking legal. This caused some problems later when William died, as the children of the first wife contested the will, on the grounds of the second marriage being illegal.

Needless to say, there are always questions remaining, and often a fresh pair of eyes can help find a vital piece of information that has escaped you. In one case, I’d been looking for the death of a widow, Mary Anne Gilman, and had failed to notice that she remarried at a late age. Her death was easy to find, once I searched for it with her second husbands name.

This brings me to the topic of maternal family lines. One tends to think of their lineage with the focus on paternal surnames, but very quickly the number of surnames increases, and all of the maternal lines are directly related as much as the paternal name. This is of course obvious, if you start from the beginning with yourself and work back. In other words, there is not much point in simply looking for your fathers name hundreds of years ago because there are hundreds of other names that are equally your own family ancestors. And in my case, although not intentionally, I’ve investigated far more maternal lines than paternal.

This book, which I hope will be the first of several, will concentrate on my mothers family: The story so far that started with the portrait of Catherine Housley’s mother.

This painting, now in my mothers house, used to hang over the piano in the home of her grandparents. It says on the back “Catherine Housley’s mother, Smalley”.

The portrait of Catherine Housley’s mother can be seen above the piano. Back row Ronald Marshall, my grandfathers brother, William Marshall, my great grandfather, Mary Ann Gilman Purdy Marshall in the middle, my great grandmother, with her daughters Dorothy on the left and Phyllis on the right, at the Marshall’s house on Love Lane in Stourbridge.

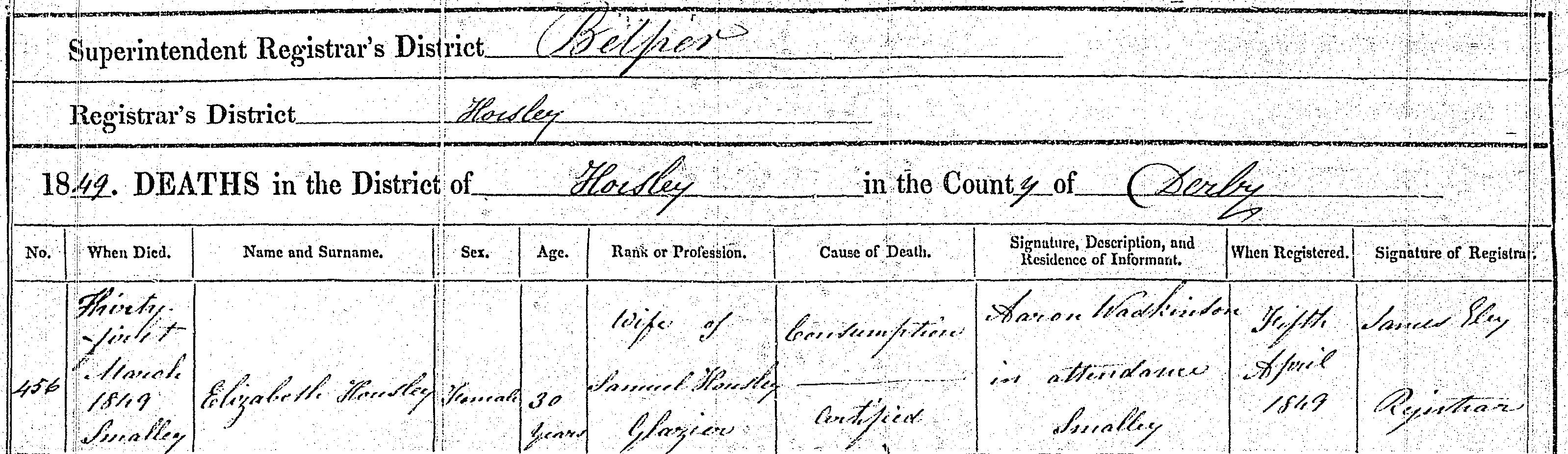

The Search for Samuel Housley

As soon as the search for Catherine Housley’s mother was resolved, achieved by ordering a paper copy of her birth certificate, the search for Catherine Housley’s father commenced. We know he was born in Smalley in 1816, son of William Housley and Ellen Carrington, and that he married Elizabeth Brookes in Wolverhampton in 1844. He was a plumber and glazier. His three daughters born between 1845 and 1849 were born in Smalley. Elizabeth died in 1849 of consumption, but Samuel didn’t register her death. A 20 year old neighbour called Aaron Wadkinson did.

Where was Samuel?

On the 1851 census, two of Samuel’s daughters were listed as inmates in the Belper Workhouse, and the third, 2 year old Catherine, was listed as living with John Benniston and his family in nearby Heanor. Benniston was a framework knitter.

Where was Samuel?

A long search through the microfiche workhouse registers provided an answer. The reason for Elizabeth and Mary Anne’s admission in June 1850 was given as “father in prison”. In May 1850, Samuel Housley was sentenced to one month hard labour at Derby Gaol for failing to maintain his three children. What happened to those little girls in the year after their mothers death, before their father was sentenced, and they entered the workhouse? Where did Catherine go, a six week old baby? We have yet to find out.

And where was Samuel Housley in 1851? He hasn’t appeared on any census.

According to the Belper workhouse registers, Mary Anne was discharged on trial as a servant February 1860. She was readmitted a month later in March 1860, the reason given: unwell.

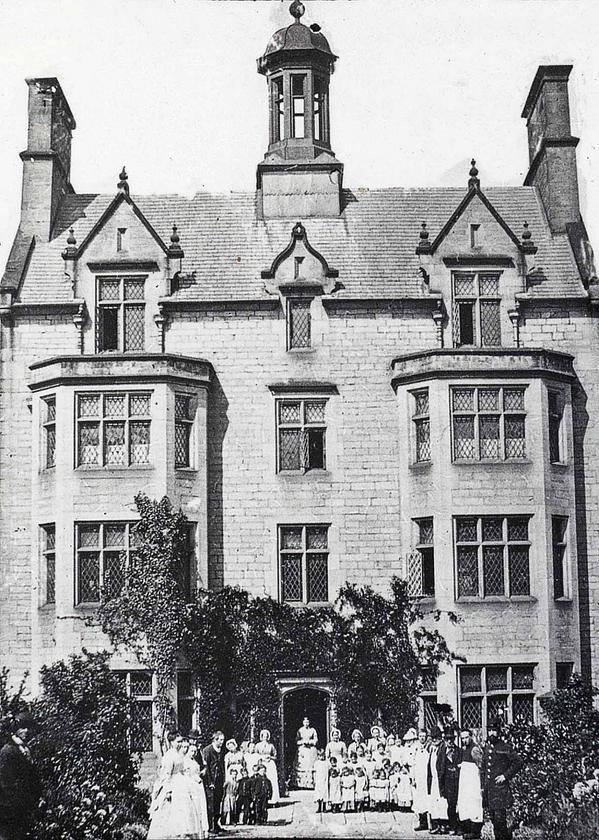

Belper Workhouse:

Eventually, Mary Anne and Elizabeth were discharged, in April 1860, with an aunt and uncle. The workhouse register doesn’t name the aunt and uncle. One can only wonder why it took them so long.

On the 1861 census, Elizabeth, 16 years old, is a servant in St Peters, Derby, and Mary Anne, 15 years old, is a servant in St Werburghs, Derby.But where was Samuel?

After some considerable searching, we found him, despite a mistranscription of his name, on the 1861 census, living as a lodger and plumber in Darlaston, Walsall.

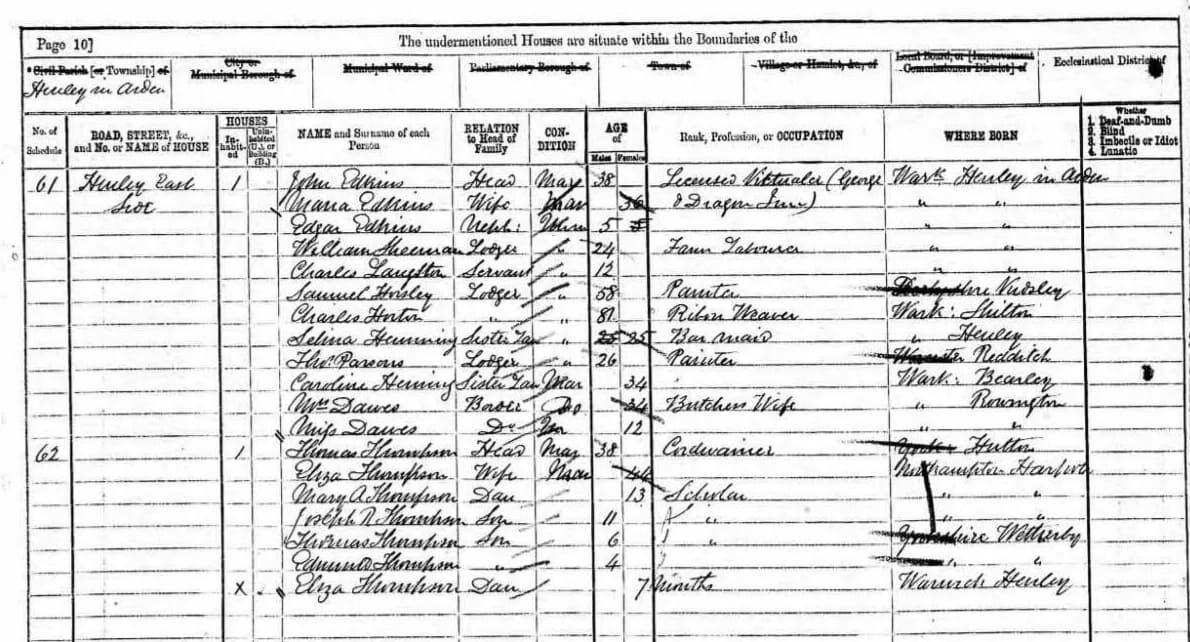

Eventually we found him on a 1871 census living as a lodger at the George and Dragon in Henley in Arden. The age is not exactly right, but close enough, he is listed as an unmarried painter, also close enough, and his birth is listed as Kidsley, Derbyshire. He was born at Kidsley Grange Farm. We can assume that he was probably alive in 1872, the year his mother died, and the following year, 1873, during the Kerry vs Housley court case.

I found some living Housley descendants in USA. Samuel Housley’s brother George emigrated there in 1851. The Housley’s in USA found letters in the attic, from the family in Smalley ~ written between 1851 and 1870s. They sent me a “Narrative on the Letters” with many letter excerpts.

The Housley family were embroiled in a complicated will and court case in the early 1870s. In December 15, 1872, Joseph (Samuel’s brother) wrote to George:

“I think we have now found all out now that is concerned in the matter for there was only Sam that we did not know his whereabouts but I was informed a week ago that he is dead–died about three years ago in Birmingham Union. Poor Sam. He ought to have come to a better end than that….His daughter and her husband went to Birmingham and also to Sutton Coldfield that is where he married his wife from and found out his wife’s brother. It appears he has been there and at Birmingham ever since he went away but ever fond of drink.”

No record of Samuel Housley’s death can be found for the Birmingham Union in 1869 or thereabouts.

But if he was alive in 1871 in Henley In Arden…..

Did Samuel tell his wife’s brother to tell them he was dead? Or did the brothers say he was dead so they could have his share?We still haven’t found a death for Samuel Housley.

June 12, 2021 at 9:37 pm #6208In reply to: Newsreel from the Rim of the Realm

“Not so fast!” Glor muttered grimly, grabbing a flapping retreating arm of each of her friends, and yanking them to her sides. “Now’s our chance. It’s a trap, dontcha see? They got the wind up, and they’re gonna round us all up, it don’t bear thinking about what they’ll do next!”

With her free hand Mavis felt Gloria’s forehead, her palm slipping unpleasantly over the feverish salty slick. “Her’s deplirious, Sha, not right in the ‘ead, the ‘eat’s got to her. Solar over dose or whatever they call it nowadays.”

“My life depends on going to the bloody assembly hall, Glor, let go of my arm before I give yer a Glasgow kiss,” Sharon hissed, ignoring Mavis.

“I’m trying to save you!” screeched Gloria, her head exploding in exasperation. She took a deep breath. Told herself to stop screeching like that, wasn’t helping her cause. Should she just let go of Sharon’s arm?

Mavis started trying to take the pulse on Glor’s restraining wrists, provoking Gloria beyond endurance, and she lashed out and slapped Mavis’s free hand away, unintentionally freeing Sharon from her grasp. This further upset the balance and Gloria tumbled into Mavis at the moment of slapping her hand, causing a considerably more forceful manoeuvre than was intended.

Sharon didn’t hesitate to defend Mavis from the apparently deranged attack, and dived on to Gloria, pinning her arms behind her back.

Mavis scrambled to her feet and backed away slowly, nursing her hand, wide eyed and slack jawed in astonishment.

Where was this going?

February 21, 2021 at 8:09 pm #6188In reply to: Twists and One Return From the Time Capsule

Reddening, Bob stammered, “Yeah, yes, uh, yeah. Um…”

Clara squeezed her grandfathers arm reassuringly. “We’re looking for my friend Nora.” she interrupted, to give him time to compose himself. Poor dear was easily flustered these days. Turning to Will, “She was hiking over to visit us and should have arrived yesterday and she’d have passed right by here, but her phone seems to be dead.”

Will had to think quickly. If he could keep them both here with Nora long enough to get the box ~ or better yet, replace the contents with something else. Yes, that was it! He could take a sack of random stuff to put in the box, and they’d never suspect a thing. He was going to hide the contents in a statue anyway, so he didn’t even need the box.

Spreading his arms wide in welcome and smiling broadly, he said “This is your lucky day! Come inside and I’ll put the kettle on, Nora’s gone up to take some photos of the old ruin, she’ll be back soon.”

Bob and Clara relaxed and returned the smile and allowed themselves to be ushered into the kitchen and seated at the table.

Will lit the gas flame under the soup before filling the kettle with water. They’d be too polite to refuse, if he put a bowl in front of them, and if they didn’t drink it, well then he’d have to resort to plan B. He put a little pinch of powder from a tiny jar into each cup of tea; it wouldn’t hurt and would likely make them more biddable. Then the soup would do the trick.

Will steered the conversation to pleasant banter about the wildflowers on the way up to the ruins that he’d said Nora was visiting, and the birds that were migrating at this time of year, keeping the topics off anything potentially agitating. The tea was starting to take effect and Clara and Bob relaxed and enjoyed the conversation. They sipped the soup without protest, although Bob did grimace a bit at the thought of eating on an agitated stomach. He’d have indigestion for days, but didn’t want to be rude and refuse. He was enjoying the respite from all the vexation, though, and was quite happy for the moment just to let the man prattle on while he ate the damn soup.

“Oh, I think Nora must be back! I just heard her voice!” exclaimed Clara.

Will had heard it too, but he said, “That wasn’t Nora, that was the parrot! It’s a fast leaner, and Nora’s been training it to say things….I tell you what, you stay here and finish your soup, and I’ll go and fetch the parrot.”

“Parrot? What parrot?” Clara and Bob said in unison. They both found it inordinately funny and by the time Will had exited the kitchen, locking the door from the outside, they were hooting and wiping the tears of laughter from their cheeks.

“What the hell was in that tea!” Clara joked, finishing her soup.

What was Nora doing awake already? Will didn’t have to keep her quiet for long, but he needed to keep her quiet now, just until the soup took effect on the others.

Either that or find a parrot.

January 29, 2021 at 10:03 am #6178In reply to: Twists and One Return From the Time Capsule

Nora woke to the sun streaming in the little dormer window in the attic bedroom. She stretched under the feather quilt and her feet encountered the cool air, an intoxicating contrast to the snug warmth of the bed. She couldn’t remember the last time she’d slept so well and was reluctant to awaken fully and confront the day. She felt peaceful and rested, and oddly, at home.

Unfortunately that thought roused her to sit and frown, and look around the room. The dust was dancing in the sunbeams and rivulets of condensation trickled down the window panes. A small statue of an owl was silhouetted on the sill, and a pitcher of dried herbs or flowers, strands of spider webs sparkled like silver thread between the desiccated buds.

An old whicker chair in the corner was piled with folded blankets and bed linens, and the bookshelf behind it ~ Nora threw back the covers and padded over to the books. Why were they all facing the wall? The spines were at the back, with just the pages showing. Intrigued, Nora extracted a book to see what it was, just as a gentle knock sounded on the door.

Yes? she said, turning, placing the book on top of the pile of bedclothes on the chair, her thoughts now on the events of the previous night.

“I expect you’re ready for some coffee!” Will called brightly. Nora opened the door, smiling. What a nice man he was, making her so welcome, and such a pleasant evening they’d spent, drinking sweet home made wine and sharing stories. It had been late, very late, when he’d shown her to her room. Nora has been tempted to invite him in with her (very tempted if the truth be known) and wasn’t quite sure why she hadn’t.

“I slept so well!” she said, thanking him as he handed her the mug. “It looks like a lovely day today,” she added brightly, and then frowned a little. She didn’t really want to leave. She was supposed to continue her journey, of course she knew that. But she really wanted to stay a little bit longer.

“I’ve got a surprise planned for lunch,” he said, “and something I’d like to show you this morning. No rush!” he added with a twinkly smile.

Nora beamed at him and promptly ditched any thoughts of continuing her trip today.

“No rush” she repeated softly.

January 18, 2021 at 10:36 am #6176In reply to: The Precious Life and Rambles of Liz Tattler

Godfrey was getting itchy. The hazmat suit with built-in peanut dispenser was getting stickier by the minute, but he needed it to stay in the room, and provide the moral support Liz’ needed during her bout of glowid.

She’d caught a mean streak, some said a Tartessian variant, which like all version caused the subject to gradually lose sense of inhibition (which in the case of Liz’ made the changes in her normal behaviour so subtle, it could have explain why it wasn’t detected until much later). After that, the usual symptoms of glowing started to display themselves. At first, Liz’ had dismissed them as hot flashes, but when she started to faintly glow in the dark, there was no longer room for hesitation. She had to be put in solitary confinement and monitored to keep her from sparkling, which was the severe form of the malady.

“Bronkel has called” Godfrey said in between mouthfuls. “Actually his secretary did. He sent a list of words to inspire you back into writing.”

“Trend surfing keywords now?” Liz’ was inflamed and started to blink like a police siren. “I AM setting the future trends, so he’d rather let me do my job, or I’ll publish elsewhere.”

“And…” Godfrey ventured softly “… care to share what new trends you’ve been blazing lately?”

Finnley chuckled at the inappropriate choice of words.

January 5, 2021 at 9:03 pm #6175In reply to: Twists and One Return From the Time Capsule

“”Sorry, I’m only just telling you this about the note now, lovie. Your Grandma’s been on at me to tell you. Just in my thoughts I mean!” he added quickly.

Jane smirked and tapped her forehead. “Careful, Old Man. She’ll think you’ve completely lost it!”

Clara stared at him, a small frown creasing her brow. “So, the note said you were to call him?”

Bob nodded uneasily. Clara had that look on her face. The one that means she aren’t happy with the way things are proceeding.

“And then what?” asked Clara slowly.

“I dunno.” Bob shrugged. “Guess they’d bury it again? They was pretty clear they didn’t want it found. Now, how about I put the kettle on?” Bob stood quickly and began to busy himself filling the jug with water from the tap.

Clara shook her head firmly. “No.”

“No to a cup of tea?”

“No we can’t call this man.”

“I don’t know Clara. It’s getting odd it is. Strangers leaving maps in collars and whatnot. It’s not right.”

“Well, I agree it needs further investigation. But we can’t call him … not without knowing why and what’s in it.” She tapped her fingers on the table. “I’ll try and get hold of Nora again.”

January 4, 2021 at 4:53 am #6174In reply to: Twists and One Return From the Time Capsule

Clara breathed a sigh of relief when she saw VanGogh running towards her; in the moonlight he looked like a pale ghost.

“Where’ve you been eh?” she asked as he nuzzled her excitedly. She crouched down to pat him. “And what’s this?” A piece of paper folded into quarters had been tucked into VanGogh’s collar. Clara stood upright and looked uneasily around the garden; a small wind made the leaves rustle and the deep shadows stirred. Clara shivered.

“Clara?” called Bob from the door.

“It’s okay Grandpa, I found him. We’re coming in now.”

In the warm light of the kitchen, Clara showed Bob the piece of paper. “It’s a map, but I don’t know those place names.”

“And it was stuffed into his collar you say?” Bob frowned. “That’s very strange indeed. Who’d of done that?”

Clara shook her head. “It wasn’t Mr Willets because I saw him drive off. But why didn’t VanGogh bark? He always barks when someone comes on the property.”

“You really should tell her about the note,” said Jane. She was perched on the kitchen bench. VanGogh pricked his ears up and wagged his tail as he looked towards her. Bob couldn’t figure out if the dog could see Jane or just somehow sensed her there. He nodded.

“What?” asked Clara.

“There’s something I should tell you, Clara. It’s about that box you found.”

December 23, 2020 at 8:48 pm #6171In reply to: Twists and One Return From the Time Capsule

Nora was relieved when the man with the donkey knew her name and was expecting her. She assumed that Clara had made contact with him, but when she mentioned her friend, he shook his head with a puzzled frown. I don’t know anyone called Clara, he said. Here, get yourself up on Manolete, it’ll be easier if you ride. We’ll be home in half an hour.

The gentle rhythmic rocking astride the donkey soothed her as she relaxed and observed her surroundings. The woods had opened out into a wide path beside an orchard. Nora felt the innocuous hospitability of the orchard in comparison to the unpredictability of the woods, although she felt that idea would require further consideration at a later date. One never knew how much influence films and stories and the like had on one’s ideas, likely substantial, Nora thought ~ another consideration not lost on Nora was the feeling of safety she had now that she wasn’t alone, and that she was with someone who clearly knew where he was going.

Notwithstanding simultaneous time, Nora wondered which came first ~ the orchard, the man with the donkey, or the feeling of safety and hospitability itself?

It was me, said the man leading the donkey, turning round with a smile. I came first. Remember?

December 22, 2020 at 1:47 am #6168In reply to: Tart Wreck Repackage

The wardrobe was sitting solidly in the middle of the office, exactly where they had left it.

Or was it?

“I was expecting a room full of middle-aged ladies,” said Star, her voice troubled. She frowned at the wardrobe. “Has it moved a little do you think? I’m sure it was closer to the window before. Or was it smaller. There’s something different about it …”

“Maybe they are inside,” whispered Tara.

“What! All of them?” Star sniggered nervously.

“We should check.” But Tara didn’t move— she felt an odd reluctance to approach the wardrobe. “You check, Star.”

Star shook her head. “Where’s Rosamund? Checking wardrobes for middle-aged drug mules is the sort of job she should be doing.”

“Are you looking for me?” asked a soft voice from the doorway. Tara and Star spun round.

“Good grief!” exclaimed Tara. “Rosamund! What are you wearing?”

Rosamund was dressed in a silky yellow thing that floated to her ankles. Her feet were bare and her long hair, usually worn loose, was now neatly plaited. Encircling the top of her head was a daisy chain. She smiled gently at Star and Tara. “Peace, my friends.” Dozens of gold bracelets jangled as she extended her hands to them. “Come, my dear friends, let us partake of carrot juice together.”

December 19, 2020 at 2:04 am #6167In reply to: Twists and One Return From the Time Capsule

“Box?” said Bob placing a hand on his chest. “Not the … ”

“Not box, Grandpa. Crops.” Clara spoke loudly. Poor old Grandpa must be going a bit deaf as well—he’d gone downhill since Grandma died. “His dogs got into your garden and dug up the crops. He says he’ll come by in the morning and fix up the damage. ”

“No, need to shout, Clara. I swear you said box. I thought you meant the box in the garage.”

“Oh, no that would be awful!” Clara shuddered at the thought of anything happening to her precious treasure. “Maybe we should bring the box inside, Grandpa? Make sure it’s safe.”

Bob sighed. Last thing he wanted was the damn box inside the house. But Clara had that look on her face, the one that means she’s made up her mind. He glanced around, wondering where they could put it so it was out of the way.

“Hey!” exclaimed Clara. “Where’s VanGogh gone? Did he sneak outside when Mr Willets came.” She went to the door and peered out into the darkness. “VanGogh! Here, Boy!” she shouted. “VanGogh!”

December 18, 2020 at 9:23 pm #6166In reply to: Twists and One Return From the Time Capsule

“Grandpa,” Clara said, partly to distract him ~ poor dear was looking a little anxious ~ and partly because she was starting to get twangs of gilt about Nora, “Grandpa, do you remember that guy who used to make sculptures? I can’t recall his name and need his phone number. Do you remember, used to see him driving around with gargoyles in the back of his truck. You look awfully pale, are you alright?”

“No idea,” Bob replied weakly.

Tell her! said Jane.

“No!” Bob exclaimed, feeling vexed. He wasn’t sure why, but he didn’t want to rush into anything. Why was Clara asking about the man whose phone number was on the note? What did she know about all this? What did he, Bob, know for that matter!

“I only asked!” replied Clara, then seeing his face, patted his arm gently and said “It’s ok, Grandpa.”

For the love of god will you just tell her!

“Tell who what?” asked Clara.

“What! What did you say?” Bob wondered where this was going and if it would ever end. It began to feel surreal.

They were both relieved when the door bell rang, shattering the unaccustomed tension between them.

“Who can that be?” they asked in unison, as Clara rose from the table.

Bob waited expectantly, pushing his plate away. It would take days to settle his digestive system down after all this upset at a meal time.

“You look like you’ve just seen a ghost, Clara! Who was it?” Bob said as Clara returned from the front door. “Not the water board again to cut us off I hope!”

“It’s the neighbour, Mr Willets, he says he’s ever so sorry but his dogs, they got loose and got into some kind of a box on your property. He said…”

December 14, 2020 at 9:10 pm #6161In reply to: Twists and One Return From the Time Capsule

Dispersee sat on a fallen tree trunk, lost in thought. A long walk in the woods had seemed just the ticket……

Nora wasn’t surprised to encounter a fallen tree trunk no more than 22 seconds after the random thought wafted through her mind ~ if thought was was the word for it ~ about Dispersee sitting on a fallen tree trunk. Nora sat on the tree trunk ~ of course she had to sit on it; how could she not ~ simultaneously stretching her aching back and wondering who Dispersee might be. Was it a Roman name? Something to do with the garum on the shopping receipt?

Nora knew she wasn’t going to get to the little village before night fall. Her attempts to consult the map failed. It was like a black hole. No signal, no connection, just a blank screen. She looked up at the sky. The lowering dark clouds were turning orange and red as the sun went down behind the mountains, etching the tree skeletons in charcoal black in the middle distance.

In a sudden flash of wordless alarm, Nora realized she was going to be out alone in the woods at night and wild boars are nocturnal and a long challenging walk in broad daylight was one thing but alone at night in the woods with the wild boars was quite another, and in a very short time indeed had worked herself up into a state approaching panic, and then had another flash of alarm when she realized she felt she would swoon in any moment and fall off the fallen trunk. The pounding of her, by then racing, heartbeats was yet further cause for alarm, and as is often the case, the combination of factors was sufficiently noteworthy to initiate a thankfully innate ability to re establish a calm lucidity, and pragmatic attention to soothe the beating physical heart as a matter of priority.

It was at the blessed moment of restored equilibrium and curiosity (and the dissipation of the alarm and associated malfunctions) that the man appeared with the white donkey.

December 13, 2020 at 8:14 am #6159In reply to: Twists and One Return From the Time Capsule

Nora moves silently along the path, placing her feet with care. It is more overgrown in the wood than she remembers, but then it is such a long time since she came this way. She can see in the distance something small and pale. A gentle gust of wind and It seems to stir, as if shivering, as if caught.

Nora feels strange, there is a strong sense of deja vu now that she has entered the forest.