-

AuthorSearch Results

-

August 21, 2024 at 12:27 pm #7546

In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

The Potters of Darley Bridge

Rebecca Knowles 1745-1823, my 5x great grandmother, married Charles Marshall 1742-1819, the churchwarden of Elton, in Darley, Derbyshire, in 1767. Rebecca was born in Darley in 1745, the youngest child of Roger Knowles 1695-1784, and Martha Potter 1702?-1772.

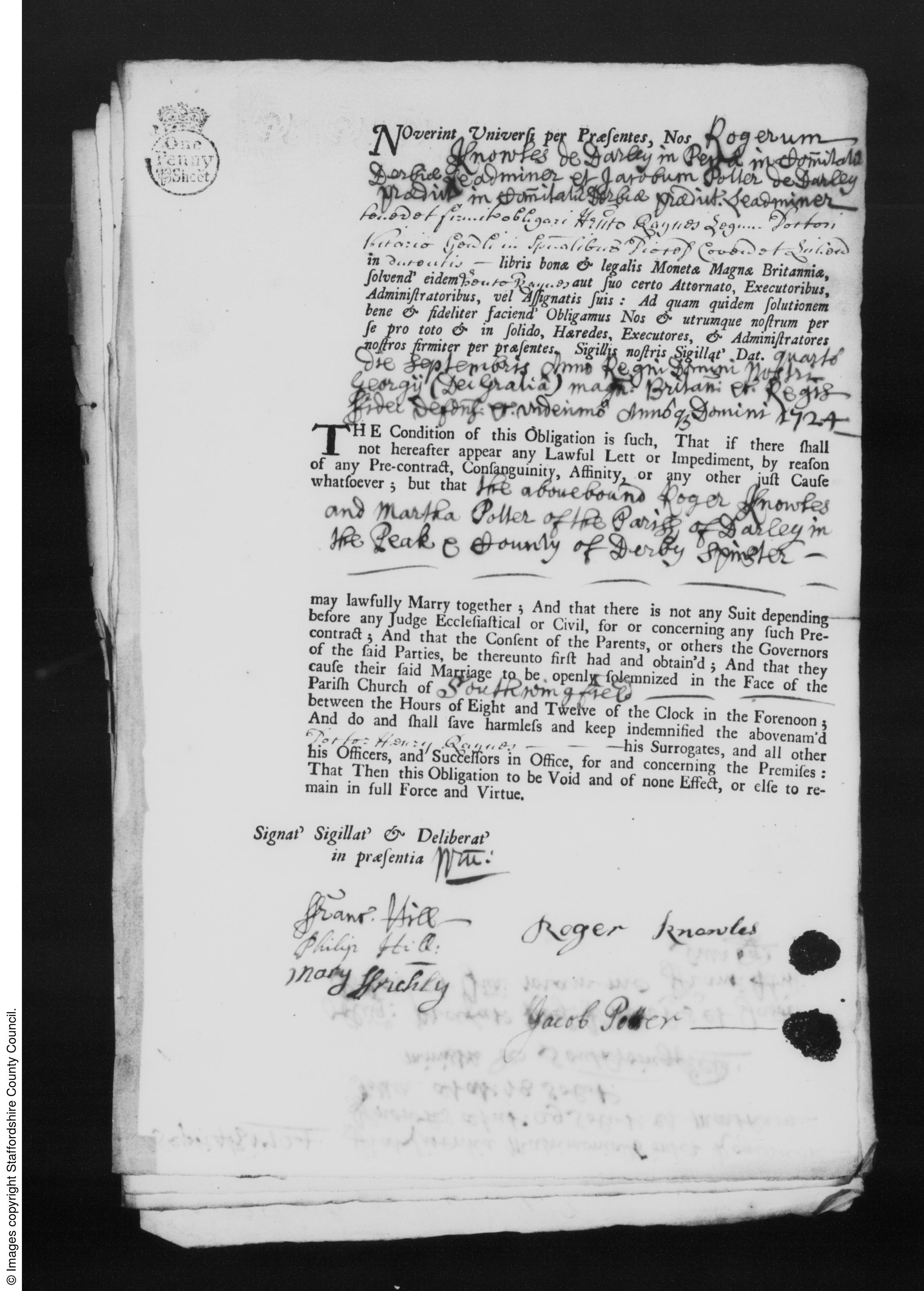

Although Roger and Martha were both from Darley, they were married in South Wingfield by licence in 1724. Roger’s occupation on the marriage licence was lead miner. (Lead miners in Derbyshire at that time usually mined their own land.) Jacob Potter signed the licence so I assumed that Jacob Potter was her father.

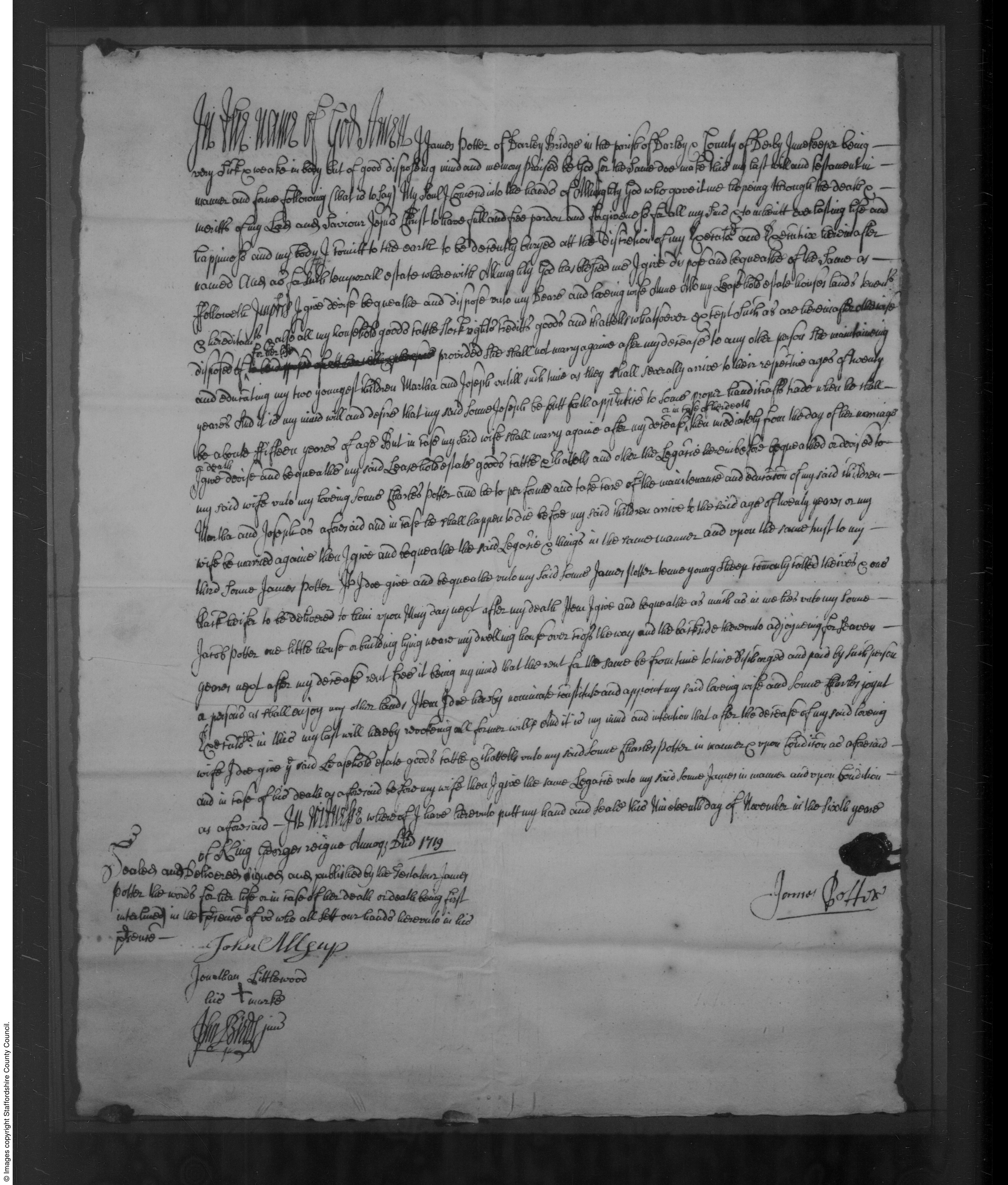

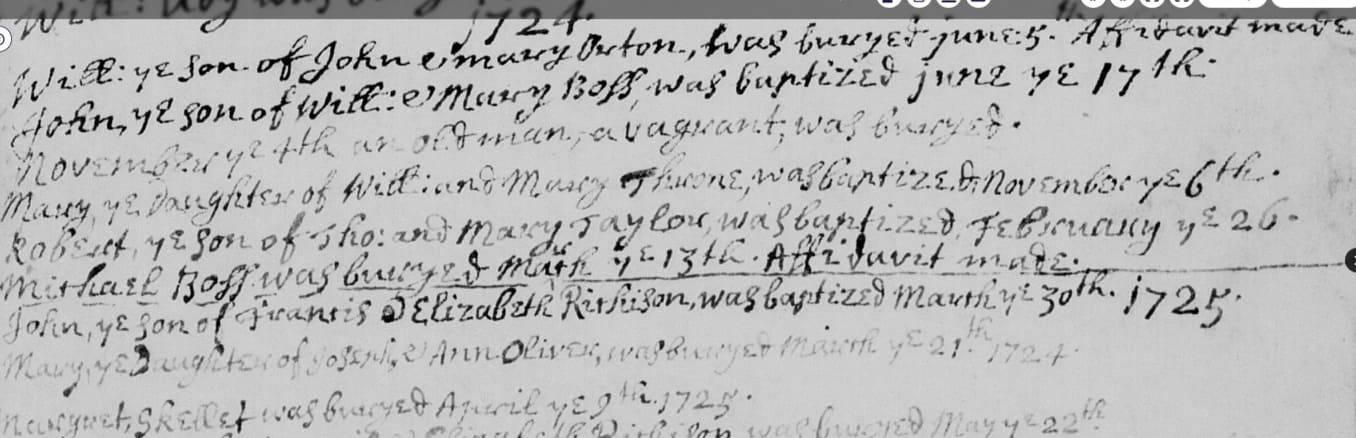

I then found the will of Jacobi Potter who died in 1719. However, he signed the will James Potter. Jacobi is latin for James. James Potter mentioned his daughter Martha in his will “when she comes of age”. Martha was the youngest child of James. James also mentioned in his will son James AND son Jacob, so there were both James’s and Jacob’s in the family, although at times in the documents James is written as Jacobi!

Jacob Potter who signed Martha’s marriage licence was her brother Jacob.

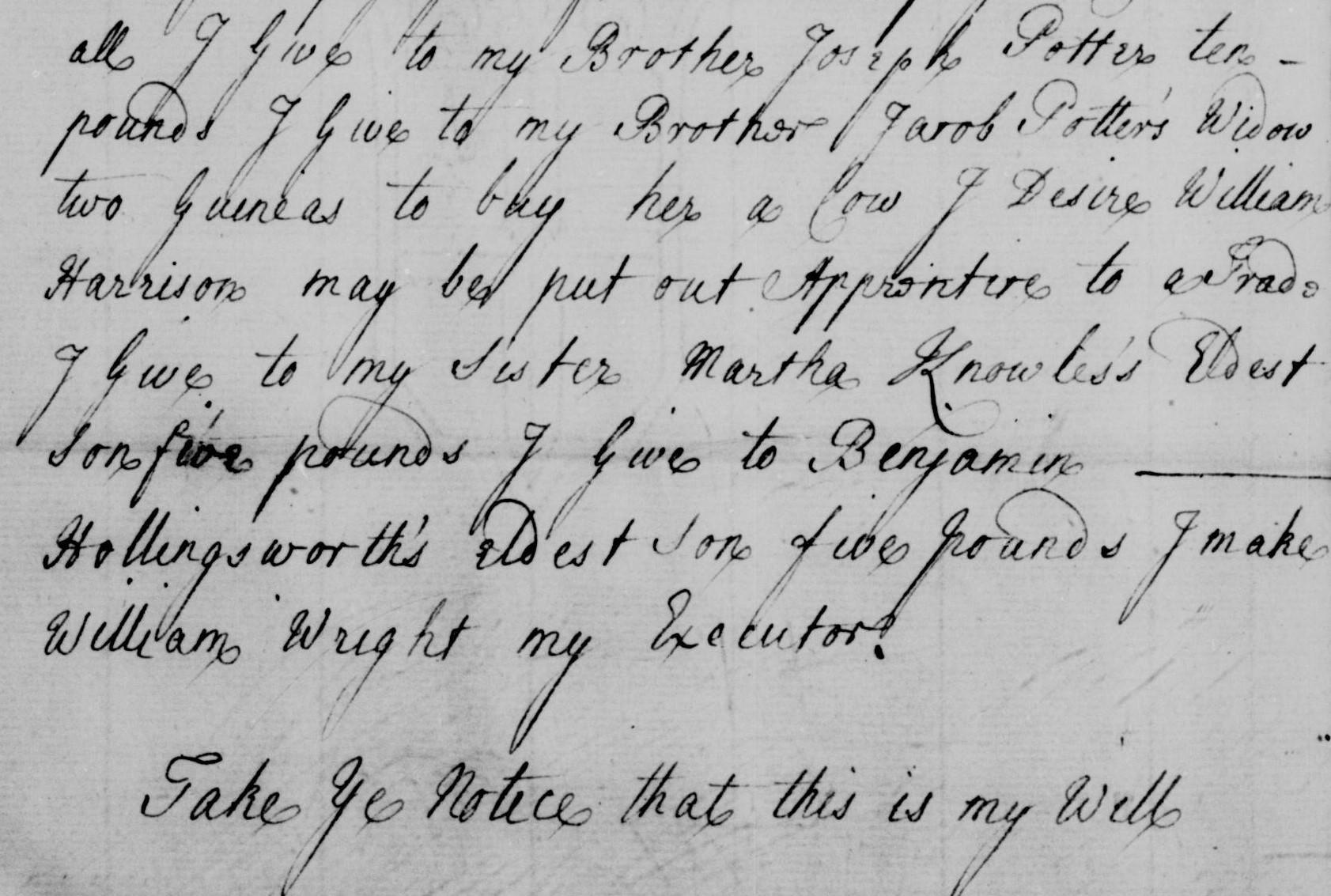

Martha’s brother James mentioned his sister Martha Knowles in his 1739 will, as well as his brother Jacob and his brother Joseph.

Martha’s father James Potter mentions his wife Ann in his 1719 will. James Potter married Ann Waterhurst in 1690 in Wirksworth, some seven miles from Darley. James occupation was innkeeper at Darley Bridge.

I did a search for Waterhurst (there was only a transcription available for that marriage, not a microfilm) and found no Waterhursts anywhere, but I did find many Warhursts in Derbyshire. In the older records, Warhust is also spelled Wearhurst and in a number of other ways. A Martha Warhurst died in Peak Forest, Derbyshire, in 1681. Her husbands name was missing from the deteriorated register pages. This may or may not be Martha Potter’s grandmother: the records for the 1600s are scanty if they exist at all, and often there are bits missing and illegible entries.

The only inn at Darley Bridge was The Three Stags Heads, by the bridge. It is now a listed building, and was on a medieval packhorse route. The current building was built in 1736, however there is a late 17th century section at rear of the cross wing. The Three Stags Heads was up for sale for £430,000 in 2022, the closure a result of the covid pandemic.

Another listed building in Darley Bridge is Potters Cottage, with a plaque above the door that says “Jonathan and Alice Potter 1763”. Jonathan Potter 1725-1785 was James grandson, the son of his son Charles Potter 1691-1752. His son Charles was also an innkeeper at Darley Bridge: James left the majority of his property to his son Charles.

Charles is the only child of James Potter that we know the approximate date of birth, because his age was on his grave stone. I haven’t found any of their baptisms, but did note that many Potters were baptised in non conformist registers in Chesterfield.

Potters Cottage

Jonathan Potter of Potters Cottage married Alice Beeley in 1748.

“Darley Bridge was an important packhorse route across the River Derwent. There was a packhorse route from here up to Beeley Moor via Darley Dale. A reference to this bridge appears in 1504… Not far to the north of the bridge at Darley Dale is Church Lane; in 1635 it was known as Ghost Lane after a Scottish pedlar was murdered there. Pedlars tended to be called Scottish only because they sold cheap Scottish linen.”

via Derbyshire Heritage website.

According to Wikipedia, the bridge dates back to the 15th century.

September 18, 2023 at 8:29 am #7278In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Tomlinson of Wergs and Hancox of Penn

John Tomlinson of Wergs (Tettenhall, Wolverhamton) 1766-1844, my 4X great grandfather, married Sarah Hancox 1772-1851. They were married on the 27th May 1793 by licence at St Peter in Wolverhampton.

Between 1794 and 1819 they had twelve children, although four of them died in childhood or infancy. Catherine was born in 1794, Thomas in 1795 who died 6 years later, William (my 3x great grandfather) in 1797, Jemima in 1800, John, Richard and Matilda between 1802 and 1806 who all died in childhood, Emma in 1809, Mary Ann in 1811, Sidney in 1814, and Elijah in 1817 who died two years later.On the 1841 census John and Sarah were living in Hockley in Birmingham, with three of their children, and surgeon Charles Reynolds. John’s occupation was “Ind” meaning living by independent means. He was living in Hockley when he died in 1844, and in his will he was “John Tomlinson, gentleman”.

Sarah Hancox was born in 1772 in Penn, Wolverhampton. Her father William Hancox was also born in Penn in 1737. Sarah’s mother Elizabeth Parkes married William’s brother Francis in 1767. Francis died in 1768, and in 1770 Elizabeth married William.

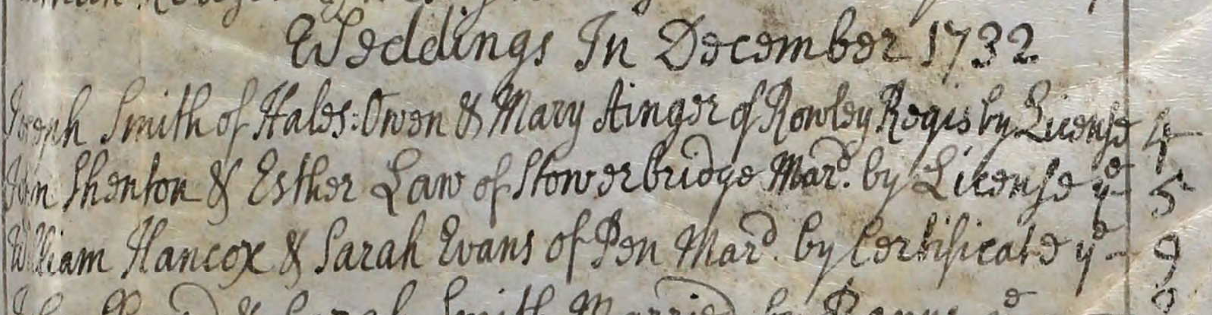

William’s father was William Hancox, yeoman, born in 1703 in Penn. He died intestate in 1772, his wife Sarah claiming her right to his estate. William Hancox and Sarah Evans, both of Penn, were married on the 9th December 1732 in Dudley, Worcestershire, by “certificate”. Marriages were usually either by banns or by licence. Apparently a marriage by certificate indicates that they were non conformists, or dissenters, and had the non conformist marriage “certified” in a Church of England church.

1732 marriage of William Hancox and Sarah Evans:

William and Sarah lost two daughters, Elizabeth, five years old, and Ann, three years old, within eight days of each other in February 1738.

William the elder’s father was John Hancox born in Penn in 1668. He married Elizabeth Wilkes from Sedgley in 1691 at Himley. John Hancox, “of Straw Hall” according to the Wolverhampton burial register, died in 1730. Straw Hall is in Penn. John’s parents were Walter Hancox and Mary Noake. Walter was born in Tettenhall in 1625, his father Richard Hancox. Mary Noake was born in Penn in 1634. Walter died in Penn in 1689.

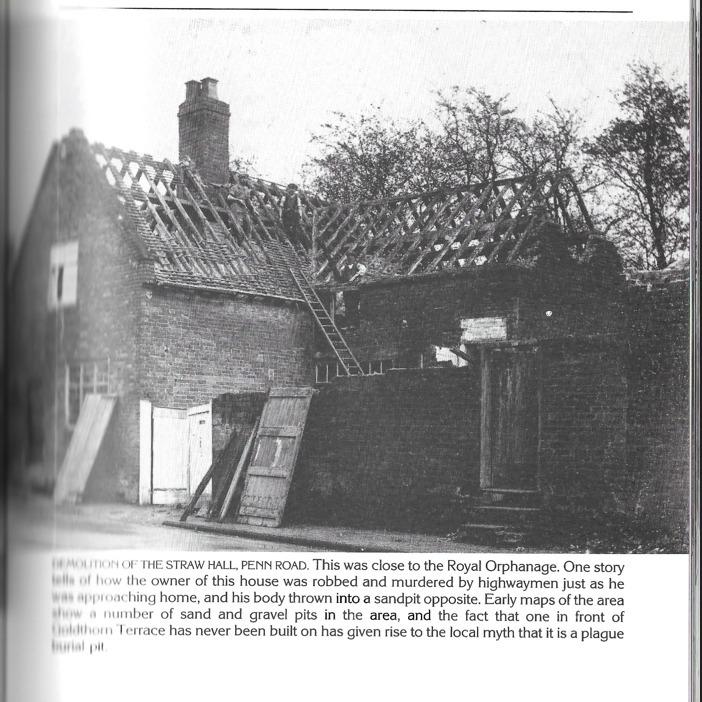

Straw Hall thanks to Bradney Mitchell:

“Here is a picture I have of Straw Hall, Penn Road.

The painting is by John Reid circa 1878.

Sketch commissioned by George Bradney Mitchell to record the town as it was before its redevelopment, in a book called Wolverhampton and its Environs. ©”

And a photo of the demolition of Straw Hall with an interesting story:

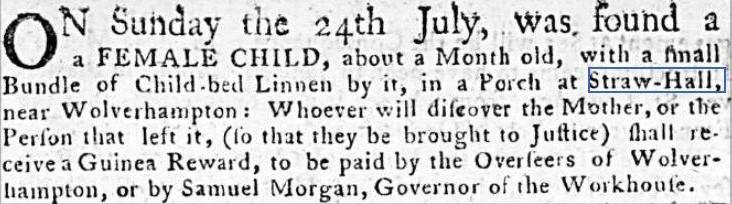

In 1757 a child was abandoned on the porch of Straw Hall. Aris’s Birmingham Gazette 1st August 1757:

The Hancox family were living in Penn for at least 400 years. My great grandfather Charles Tomlinson built a house on Penn Common in the early 1900s, and other Tomlinson relatives have lived there. But none of the family knew of the Hancox connection to Penn. I don’t think that anyone imagined a Tomlinson ancestor would have been a gentleman, either.

Sarah Hancox’s brother William Hancox 1776-1848 had a busy year in 1804.

On 29 Aug 1804 he applied for a licence to marry Ann Grovenor of Claverley.

In August 1804 he had property up for auction in Penn. “part of Lightwoods, 3 plots, and the Coppice”

On 14 Sept 1804 their first son John was baptised in Penn. According to a later census John was born in Claverley. (before the parents got married)(Incidentally, John Hancox’s descendant married a Warren, who is a descendant of my 4x great grandfather Samuel Warren, on my mothers side, from Newhall, Derbyshire!)

On 30 Sept he married Ann in Penn.

In December he was a bankrupt pig and sheep dealer.

In July 1805 he’s in the papers under “certificates”: William Hancox the younger, sheep and pig dealer and chapman of Penn. (A certificate was issued after a bankruptcy if they fulfilled their obligations)

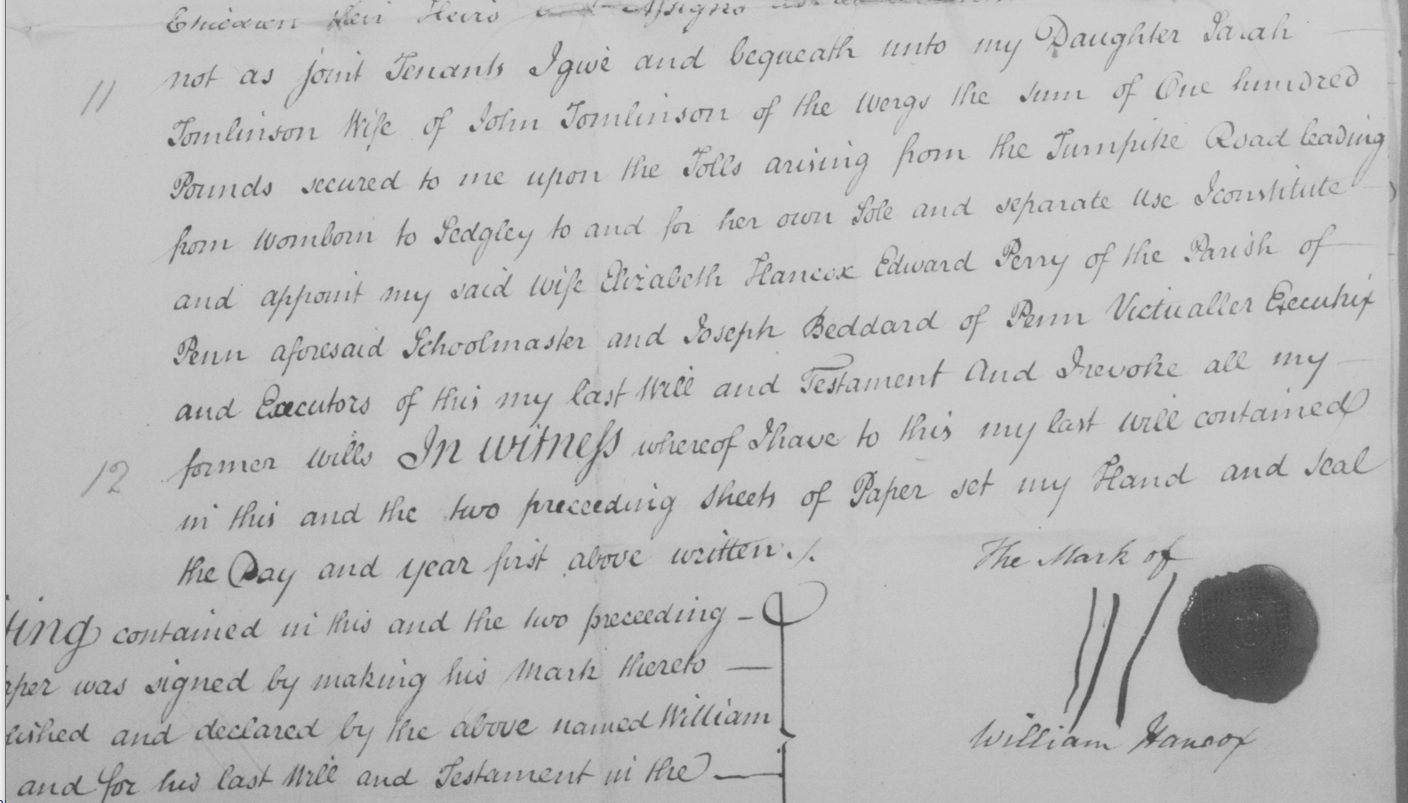

He was a pig dealer in Penn in 1841, a widower, living with unmarried daughter Elizabeth.Sarah’s father William Hancox died in 1816. In his will, he left his “daughter Sarah, wife of John Tomlinson of the Wergs the sum of £100 secured to me upon the tolls arising from the turnpike road leading from Wombourne to Sedgeley to and for her sole and separate use”.

The trustees of toll road would decide not to collect tolls themselves but get someone else to do it by selling the collecting of tolls for a fixed price. This was called “farming the tolls”. The Act of Parliament which set up the trust would authorise the trustees to farm out the tolls. This example is different. The Trustees of turnpikes needed to raise money to carry out work on the highway. The usual way they did this was to mortgage the tolls – they borrowed money from someone and paid the borrower interest; as security they gave the borrower the right, if they were not paid, to take over the collection of tolls and keep the proceeds until they had been paid off. In this case William Hancox has lent £100 to the turnpike and is leaving it (the right to interest and/or have the whole sum repaid) to his daughter Sarah Tomlinson. (this information on tolls from the Wolverhampton family history group.)William Hancox, Penn Wood, maltster, left a considerable amount of property to his children in 1816. All household effects he left to his wife Elizabeth, and after her decease to his son Richard Hancox: four dwelling houses in John St, Wolverhampton, in the occupation of various Pratts, Wright and William Clarke. He left £200 to his daughter Frances Gordon wife of James Gordon, and £100 to his daughter Ann Pratt widow of John Pratt. To his son William Hancox, all his various properties in Penn wood. To Elizabeth Tay wife of Thomas Tay he left £200, and to Richard Hancox various other properties in Penn Wood, and to his daughter Lucy Tay wife of Josiah Tay more property in Lower Penn. All his shops in St John Wolverhamton to his son Edward Hancox, and more properties in Lower Penn to both Francis Hancox and Edward Hancox. To his daughter Ellen York £200, and property in Montgomery and Bilston to his son John Hancox. Sons Francis and Edward were underage at the time of the will. And to his daughter Sarah, his interest in the toll mentioned above.

Sarah Tomlinson, wife of John Tomlinson of the Wergs, in William Hancox will:

August 17, 2023 at 4:32 pm #7268

August 17, 2023 at 4:32 pm #7268In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

William Tomlinson

1797-1867

The Tomlinsons of Wolverhampton were butchers and publicans for several generations. Therefore it was a surprise to find that William’s father was a gentleman of independant means.

William Tomlinson 1797-1867 was born in Wergs, Tettenhall. His birthplace, and that of his first four children, is stated as Wergs on the 1851 census. They were baptised at St Michael and All Angels church in Tettenhall Regis, as were many of the Tomlinson family including William.

Tettenhall, St Michael and All Angels church:

Wergs is a very small area and there was no other William Tomlinson baptised there at the time of William’s birth. It is of course possible that another William Tomlinson was born in Wergs and the record of the baptism hasn’t been found, but there are a number of other documents that prove that John Tomlinson, gentleman of Wergs, was Williams father.

In 1834 on the Shropshire Quarter session rolls there are two documents regarding William. In October 1834 William Tomlinson of Tettenhall, son of John, took an examination. Also in October of 1834 there is a reconizance document for William Tomlinson for “pig dealer”. On the marriage certificate of his son Charles Tomlinson to Emma Grattidge (mistranscribed as Pratadge) in 1872, father William’s occupation is “dealer”.

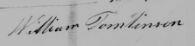

William Tomlinson was a witness at his sister Catherine and Benjamin Smiths wedding in 1822 in Tettenhall. In John Tomlinson’s 1844 will, he mentions his “daughter Catherine Smith, wife of Benjamin Smith”. William’s signature as a witness at Catherine’s marriage matches his signature on the licence for his own marriage to Elizabeth Adams in 1827 in Shareshill, Staffordshire.

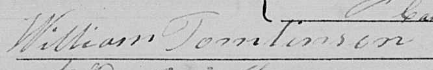

William’s signature on his wedding licence:

Williams signature as a witness to Catherine’s marriage:

William was the eldest surviving son when his father died in 1844, so it is surprising that William only inherited £25. John Tomlinson left his various properties to his daughters, with the exception of Catherine, who also received £25. There was one other surviving son, Sidney, born in 1814. Three of John and Sarah Tomlinson’s sons and one daughter died in infancy. Sidney was still unmarried and living at home when his father died, and in 1851 and 1861 was living with his sister Emma Wilson. He was unmarried when he died in 1867. John left Sidney an income for life in his will, but not property.

In John Tomlinson’s will he also mentions his daughter Jemima, wife of William Smith, farmer, of Great Barr. On the 1841 census William, butcher, is a visitor. His two children Sarah and Thomas are with him. His wife Elizabeth and the rest of the children are at Graisley Street. William is also on the Graisley Street census, occupation castrator. This was no doubt done in error, not realizing that he was also registered on the census where he was visiting at the time.

William’s wife, Elizabeth Adams, was born in Tong, Shropshire in 1807. The Adams in Tong appear to be agricultural labourers, at least on later censuses. Perhaps we can speculate that John didn’t approve of his son marrying an agricutural labourers daughter. Elizabeth would have been twenty years old at the time of the marriage; William thirty.

July 5, 2023 at 8:21 pm #7263In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Solomon Stubbs

1781-1857

Solomon was born in Hamstall Ridware, Staffordshire, parents Samuel Stubbs and Rebecca Wood. (see The Hamstall Ridware Connection chapter)

Solomon married Phillis Lomas at St Modwen’s in Burton on Trent on 30th May 1815. Phillis was the llegitimate daughter of Frances Lomas. No father was named on the baptism on the 17th January 1787 in Sutton on the Hill, Derbyshire, and the entry on the baptism register states that she was illegitimate. Phillis’s mother Frances married Daniel Fox in 1790 in Sutton on the Hill. Unfortunately this means that it’s impossible to find my 5X great grandfather on this side of the family.

Solomon and Phillis had four daughters, the last died in infancy.

Sarah 1816-1867, Mary (my 3X great grandmother) 1819-1880, Phillis 1823-1905, and Maria 1825-1826.Solomon Stubbs of Horninglow St is listed in the 1834 Whites Directory under “China, Glass, Etc Dlrs”. Next to his name is Joanna Warren (earthenware) High St. Joanna Warren is related to me on my maternal side. No doubt Solomon and Joanna knew each other, unaware that several generations later a marriage would take place, not locally but miles away, joining their families.

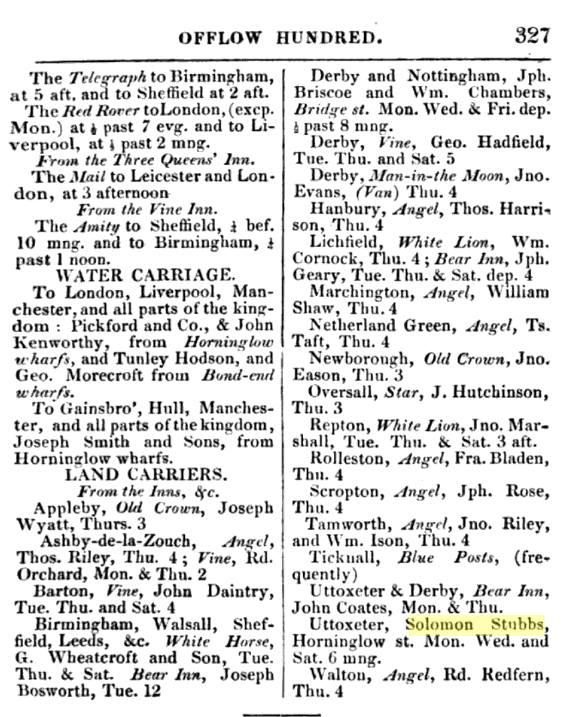

Solomon Stubbs is also listed in Whites Directory in 1831 and 1834 Burton on Trent as a land carrier:

“Land Carriers, from the Inns, Etc: Uttoxeter, Solomon Stubbs, Horninglow St, Mon. Wed. and Sat. 6 mng.”

Solomon is listed in the electoral registers in 1837. The 1837 United Kingdom general election was triggered by the death of King William IV and produced the first Parliament of the reign of his successor, Queen Victoria.

National Archives:

“In 1832, Parliament passed a law that changed the British electoral system. It was known as the Great Reform Act, which basically gave the vote to middle class men, leaving working men disappointed.

The Reform Act became law in response to years of criticism of the electoral system from those outside and inside Parliament. Elections in Britain were neither fair nor representative. In order to vote, a person had to own property or pay certain taxes to qualify, which excluded most working class people.”Via the Burton on Trent History group:

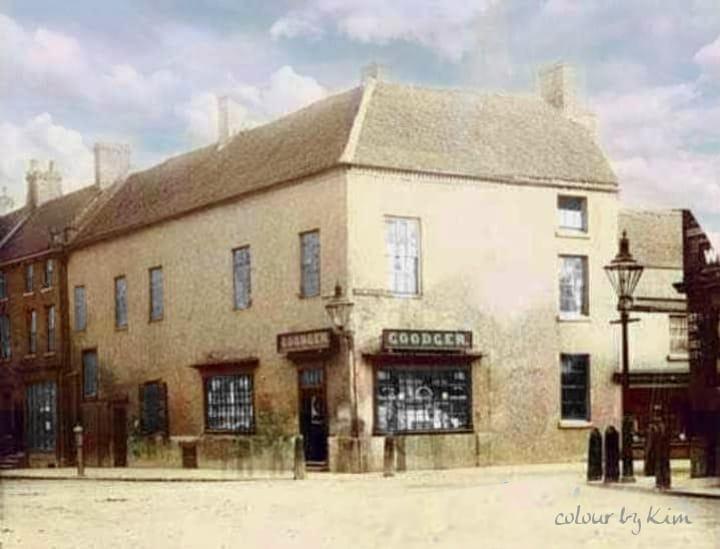

“a very early image of High street and Horninglow street junction, where the original ‘ Bargates’ were in the days of the Abbey. ‘Gate’ is the Saxon meaning Road, ‘Bar’ quite self explanatory, meant ‘to stop entrance’. There was another Bargate across Cat street (Station street), the Abbot had these constructed to regulate the Traders coming into town, in the days when the Abbey ran things. In the photo you can see the Posts on the corner, designed to stop Carts and Carriages mounting the Pavement. Only three Posts remain today and they are Listed.”

On the 1841 census, Solomon’s occupation was Carrier. Daughter Sarah is still living at home, and Sarah Grattidge, 13 years old, lives with them. Solomon’s daughter Mary had married William Grattidge in 1839.

Solomon Stubbs of Horninglow Street, Burton on Trent, is listed as an Earthenware Dealer in the 1842 Pigot’s Directory of Staffordshire.

In May 1844 Solomon’s wife Phillis died. In July 1844 daughter Sarah married Thomas Brandon in Burton on Trent. It was noted in the newspaper announcement that this was the first wedding to take place at the Holy Trinity church.

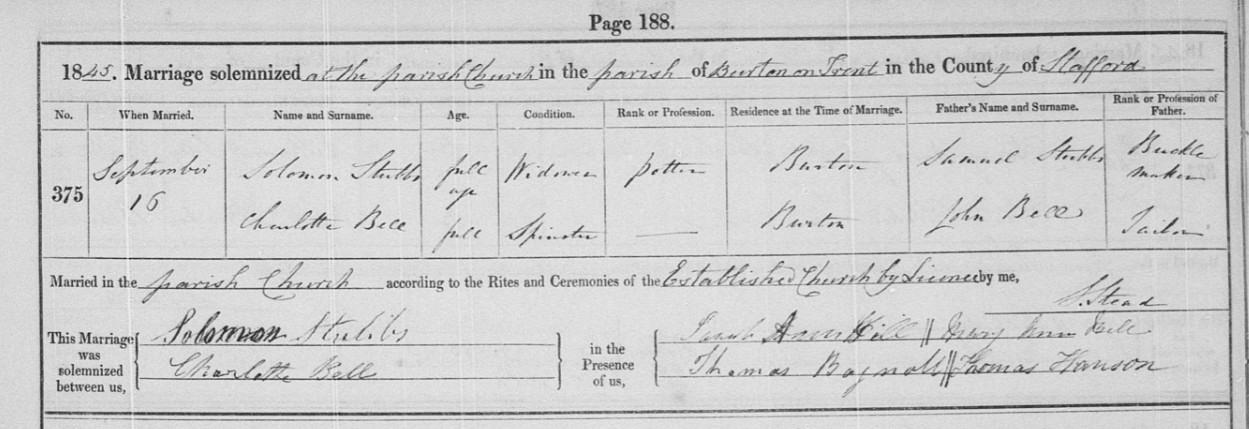

Solomon married Charlotte Bell by licence the following year in 1845. She was considerably younger than him, born in 1824. On the marriage certificate Solomon’s occupation is potter. It seems that he had the earthenware business as well as the land carrier business, in addition to owning a number of properties.

The marriage of Solomon Stubbs and Charlotte Bell:

Also in 1845, Solomon’s daughter Phillis was married in Burton on Trent to John Devitt, son of CD Devitt, Esq, formerly of the General Post Office Dublin.

Solomon Stubbs died in September 1857 in Burton on Trent. In the Staffordshire Advertiser on Saturday 3 October 1857:

“On the 22nd ultimo, suddenly, much respected, Solomon Stubbs, of Guild-street, Burton-on-Trent, aged 74 years.”

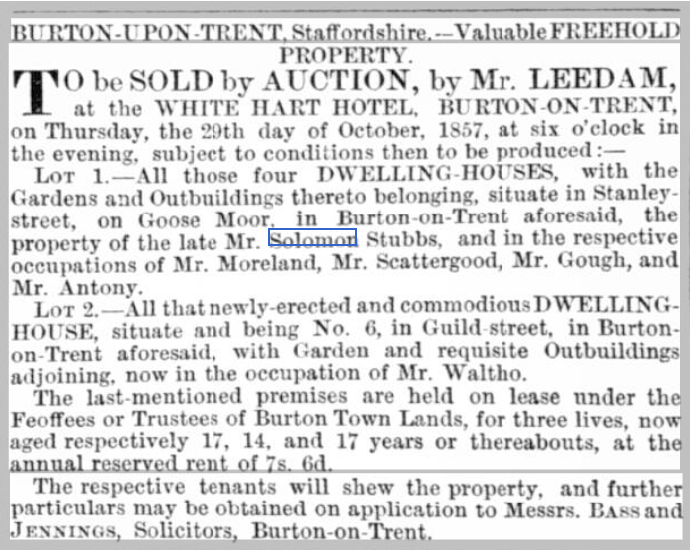

In the Staffordshire Advertiser, 24th October 1857, the auction of the property of Solomon Stubbs was announced:

“BURTON ON TRENT, on Thursday, the 29th day of October, 1857, at six o’clock in the evening, subject to conditions then to be produced:— Lot I—All those four DWELLING HOUSES, with the Gardens and Outbuildings thereto belonging, situate in Stanleystreet, on Goose Moor, in Burton-on-Trent aforesaid, the property of the late Mr. Solomon Stubbs, and in the respective occupations of Mr. Moreland, Mr. Scattergood, Mr. Gough, and Mr. Antony…..”

Sadly, the graves of Solomon, his wife Phillis, and their infant daughter Maria have since been removed and are listed in the UK Records of the Removal of Graves and Tombstones 1601-2007.

July 1, 2022 at 9:51 am #6306In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Looking for Robert Staley

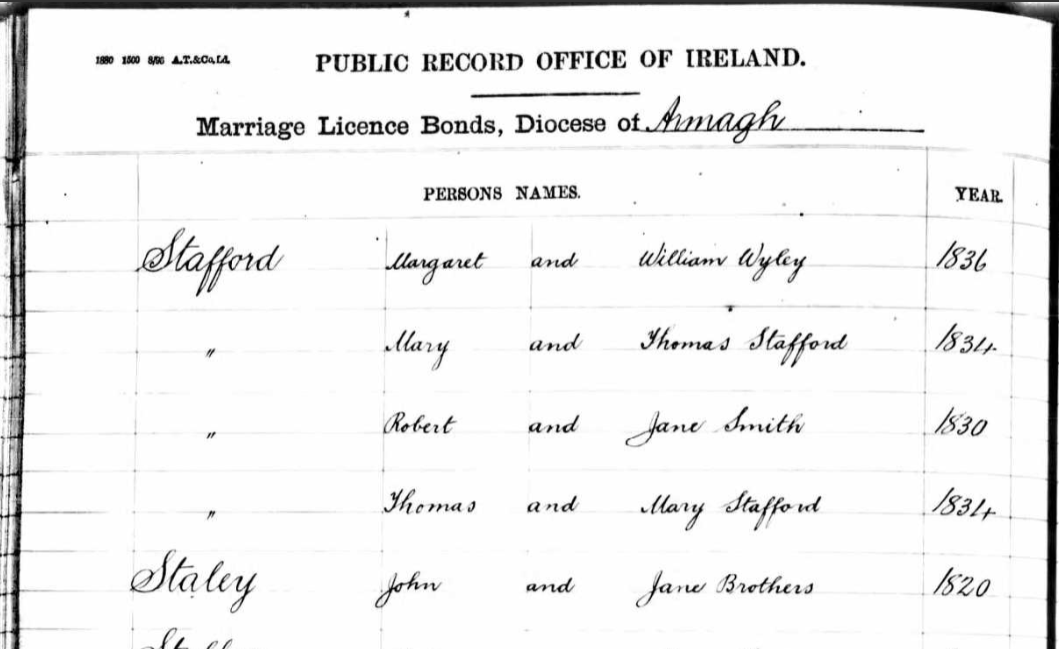

William Warren (1835-1880) of Newhall (Stapenhill) married Elizabeth Staley (1836-1907) in 1858. Elizabeth was born in Newhall, the daughter of John Staley (1795-1876) and Jane Brothers. John was born in Newhall, and Jane was born in Armagh, Ireland, and they were married in Armagh in 1820. Elizabeths older brothers were born in Ireland: William in 1826 and Thomas in Dublin in 1830. Francis was born in Liverpool in 1834, and then Elizabeth in Newhall in 1836; thereafter the children were born in Newhall.

Marriage of John Staley and Jane Brothers in 1820:

My grandmother related a story about an Elizabeth Staley who ran away from boarding school and eloped to Ireland, but later returned. The only Irish connection found so far is Jane Brothers, so perhaps she meant Elizabeth Staley’s mother. A boarding school seems unlikely, and it would seem that it was John Staley who went to Ireland.

The 1841 census states Jane’s age as 33, which would make her just 12 at the time of her marriage. The 1851 census states her age as 44, making her 13 at the time of her 1820 marriage, and the 1861 census estimates her birth year as a more likely 1804. Birth records in Ireland for her have not been found. It’s possible, perhaps, that she was in service in the Newhall area as a teenager (more likely than boarding school), and that John and Jane ran off to get married in Ireland, although I haven’t found any record of a child born to them early in their marriage. John was an agricultural labourer, and later a coal miner.

John Staley was the son of Joseph Staley (1756-1838) and Sarah Dumolo (1764-). Joseph and Sarah were married by licence in Newhall in 1782. Joseph was a carpenter on the marriage licence, but later a collier (although not necessarily a miner).

The Derbyshire Record Office holds records of an “Estimate of Joseph Staley of Newhall for the cost of continuing to work Pisternhill Colliery” dated 1820 and addresssed to Mr Bloud at Calke Abbey (presumably the owner of the mine)

Josephs parents were Robert Staley and Elizabeth. I couldn’t find a baptism or birth record for Robert Staley. Other trees on an ancestry site had his birth in Elton, but with no supporting documents. Robert, as stated in his 1795 will, was a Yeoman.

“Yeoman: A former class of small freeholders who farm their own land; a commoner of good standing.”

“Husbandman: The old word for a farmer below the rank of yeoman. A husbandman usually held his land by copyhold or leasehold tenure and may be regarded as the ‘average farmer in his locality’. The words ‘yeoman’ and ‘husbandman’ were gradually replaced in the later 18th and 19th centuries by ‘farmer’.”He left a number of properties in Newhall and Hartshorne (near Newhall) including dwellings, enclosures, orchards, various yards, barns and acreages. It seemed to me more likely that he had inherited them, rather than moving into the village and buying them.

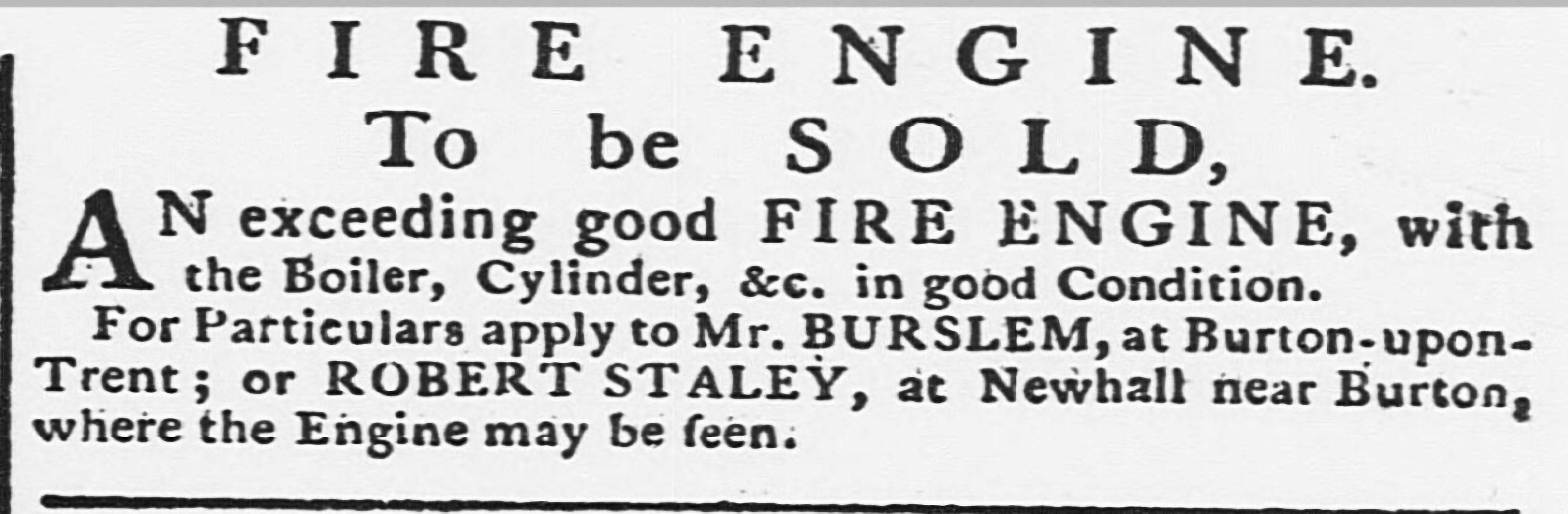

There is a mention of Robert Staley in a 1782 newpaper advertisement.

“Fire Engine To Be Sold. An exceedingly good fire engine, with the boiler, cylinder, etc in good condition. For particulars apply to Mr Burslem at Burton-upon-Trent, or Robert Staley at Newhall near Burton, where the engine may be seen.”

Was the fire engine perhaps connected with a foundry or a coal mine?

I noticed that Robert Staley was the witness at a 1755 marriage in Stapenhill between Barbara Burslem and Richard Daston the younger esquire. The other witness was signed Burslem Jnr.

Looking for Robert Staley

I assumed that once again, in the absence of the correct records, a similarly named and aged persons baptism had been added to the tree regardless of accuracy, so I looked through the Stapenhill/Newhall parish register images page by page. There were no Staleys in Newhall at all in the early 1700s, so it seemed that Robert did come from elsewhere and I expected to find the Staleys in a neighbouring parish. But I still didn’t find any Staleys.

I spoke to a couple of Staley descendants that I’d met during the family research. I met Carole via a DNA match some months previously and contacted her to ask about the Staleys in Elton. She also had Robert Staley born in Elton (indeed, there were many Staleys in Elton) but she didn’t have any documentation for his birth, and we decided to collaborate and try and find out more.

I couldn’t find the earlier Elton parish registers anywhere online, but eventually found the untranscribed microfiche images of the Bishops Transcripts for Elton.

via familysearch:

“In its most basic sense, a bishop’s transcript is a copy of a parish register. As bishop’s transcripts generally contain more or less the same information as parish registers, they are an invaluable resource when a parish register has been damaged, destroyed, or otherwise lost. Bishop’s transcripts are often of value even when parish registers exist, as priests often recorded either additional or different information in their transcripts than they did in the original registers.”Unfortunately there was a gap in the Bishops Transcripts between 1704 and 1711 ~ exactly where I needed to look. I subsequently found out that the Elton registers were incomplete as they had been damaged by fire.

I estimated Robert Staleys date of birth between 1710 and 1715. He died in 1795, and his son Daniel died in 1805: both of these wills were found online. Daniel married Mary Moon in Stapenhill in 1762, making a likely birth date for Daniel around 1740.

The marriage of Robert Staley (assuming this was Robert’s father) and Alice Maceland (or Marsland or Marsden, depending on how the parish clerk chose to spell it presumably) was in the Bishops Transcripts for Elton in 1704. They were married in Elton on 26th February. There followed the missing parish register pages and in all likelihood the records of the baptisms of their first children. No doubt Robert was one of them, probably the first male child.

(Incidentally, my grandfather’s Marshalls also came from Elton, a small Derbyshire village near Matlock. The Staley’s are on my grandmothers Warren side.)

The parish register pages resume in 1711. One of the first entries was the baptism of Robert Staley in 1711, parents Thomas and Ann. This was surely the one we were looking for, and Roberts parents weren’t Robert and Alice.

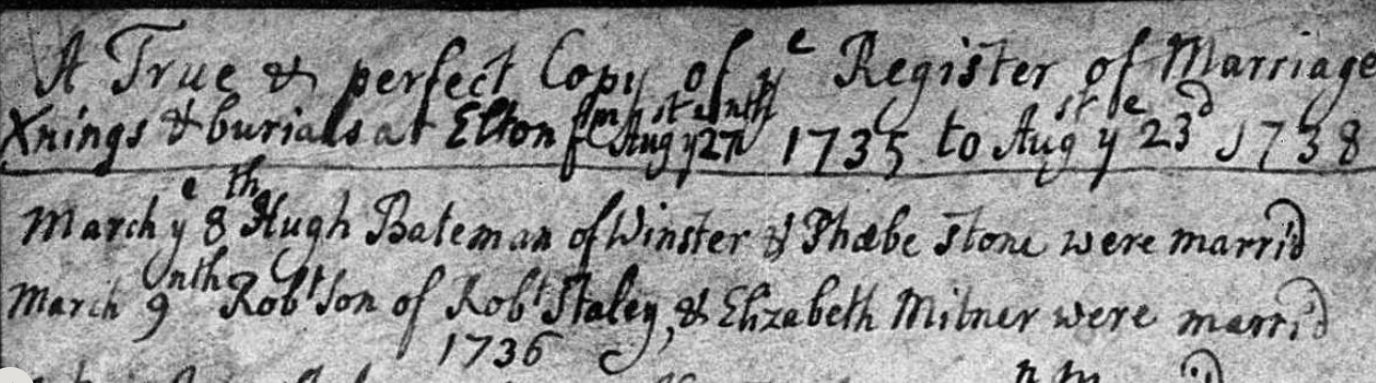

But then in 1735 a marriage was recorded between Robert son of Robert Staley (and this was unusual, the father of the groom isn’t usually recorded on the parish register) and Elizabeth Milner. They were married on the 9th March 1735. We know that the Robert we were looking for married an Elizabeth, as her name was on the Stapenhill baptisms of their later children, including Joseph Staleys. The 1735 marriage also fit with the assumed birth date of Daniel, circa 1740. A baptism was found for a Robert Staley in 1738 in the Elton registers, parents Robert and Elizabeth, as well as the baptism in 1736 for Mary, presumably their first child. Her burial is recorded the following year.

The marriage of Robert Staley and Elizabeth Milner in 1735:

There were several other Staley couples of a similar age in Elton, perhaps brothers and cousins. It seemed that Thomas and Ann’s son Robert was a different Robert, and that the one we were looking for was prior to that and on the missing pages.

Even so, this doesn’t prove that it was Elizabeth Staleys great grandfather who was born in Elton, but no other birth or baptism for Robert Staley has been found. It doesn’t explain why the Staleys moved to Stapenhill either, although the Enclosures Act and the Industrial Revolution could have been factors.

The 18th century saw the rise of the Industrial Revolution and many renowned Derbyshire Industrialists emerged. They created the turning point from what was until then a largely rural economy, to the development of townships based on factory production methods.

The Marsden Connection

There are some possible clues in the records of the Marsden family. Robert Staley married Alice Marsden (or Maceland or Marsland) in Elton in 1704. Robert Staley is mentioned in the 1730 will of John Marsden senior, of Baslow, Innkeeper (Peacock Inne & Whitlands Farm). He mentions his daughter Alice, wife of Robert Staley.

In a 1715 Marsden will there is an intriguing mention of an alias, which might explain the different spellings on various records for the name Marsden: “MARSDEN alias MASLAND, Christopher – of Baslow, husbandman, 28 Dec 1714. son Robert MARSDEN alias MASLAND….” etc.

Some potential reasons for a move from one parish to another are explained in this history of the Marsden family, and indeed this could relate to Robert Staley as he married into the Marsden family and his wife was a beneficiary of a Marsden will. The Chatsworth Estate, at various times, bought a number of farms in order to extend the park.

THE MARSDEN FAMILY

OXCLOSE AND PARKGATE

In the Parishes of

Baslow and Chatsworthby

David Dalrymple-Smith“John Marsden (b1653) another son of Edmund (b1611) faired well. By the time he died in

1730 he was publican of the Peacock, the Inn on Church Lane now called the Cavendish

Hotel, and the farmer at “Whitlands”, almost certainly Bubnell Cliff Farm.”“Coal mining was well known in the Chesterfield area. The coalfield extends as far as the

Gritstone edges, where thin seams outcrop especially in the Baslow area.”“…the occupants were evicted from the farmland below Dobb Edge and

the ground carefully cleared of all traces of occupation and farming. Shelter belts were

planted especially along the Heathy Lea Brook. An imposing new drive was laid to the

Chatsworth House with the Lodges and “The Golden Gates” at its northern end….”Although this particular event was later than any events relating to Robert Staley, it’s an indication of how farms and farmland disappeared, and a reason for families to move to another area:

“The Dukes of Devonshire (of Chatsworth) were major figures in the aristocracy and the government of the

time. Such a position demanded a display of wealth and ostentation. The 6th Duke of

Devonshire, the Bachelor Duke, was not content with the Chatsworth he inherited in 1811,

and immediately started improvements. After major changes around Edensor, he turned his

attention at the north end of the Park. In 1820 plans were made extend the Park up to the

Baslow parish boundary. As this would involve the destruction of most of the Farm at

Oxclose, the farmer at the Higher House Samuel Marsden (b1755) was given the tenancy of

Ewe Close a large farm near Bakewell.

Plans were revised in 1824 when the Dukes of Devonshire and Rutland “Exchanged Lands”,

reputedly during a game of dice. Over 3300 acres were involved in several local parishes, of

which 1000 acres were in Baslow. In the deal Devonshire acquired the southeast corner of

Baslow Parish.

Part of the deal was Gibbet Moor, which was developed for “Sport”. The shelf of land

between Parkgate and Robin Hood and a few extra fields was left untouched. The rest,

between Dobb Edge and Baslow, was agricultural land with farms, fields and houses. It was

this last part that gave the Duke the opportunity to improve the Park beyond his earlier

expectations.”The 1795 will of Robert Staley.

Inriguingly, Robert included the children of his son Daniel Staley in his will, but omitted to leave anything to Daniel. A perusal of Daniels 1808 will sheds some light on this: Daniel left his property to his six reputed children with Elizabeth Moon, and his reputed daughter Mary Brearly. Daniels wife was Mary Moon, Elizabeths husband William Moons daughter.

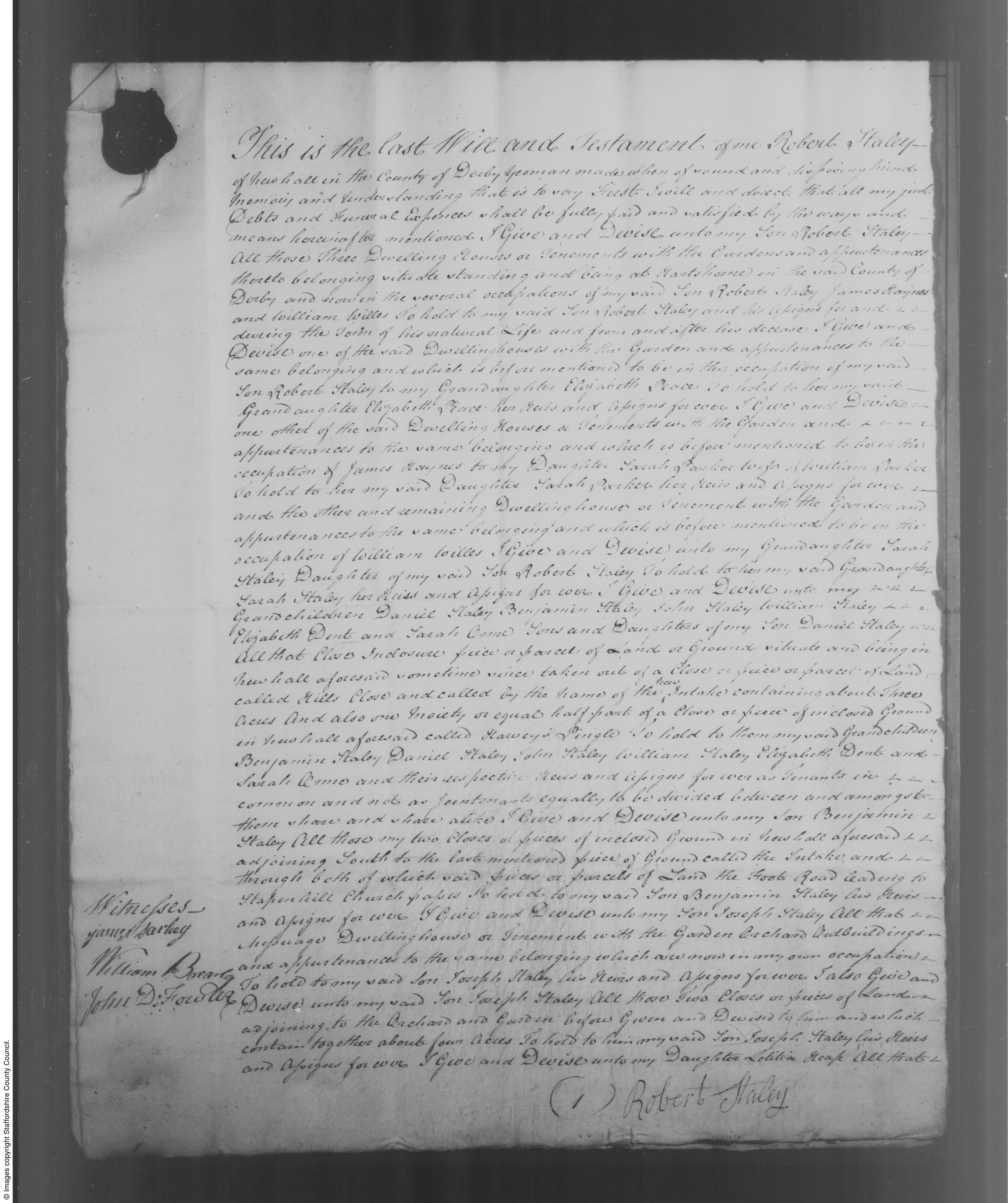

The will of Robert Staley, 1795:

The 1805 will of Daniel Staley, Robert’s son:

This is the last will and testament of me Daniel Staley of the Township of Newhall in the parish of Stapenhill in the County of Derby, Farmer. I will and order all of my just debts, funeral and testamentary expenses to be fully paid and satisfied by my executors hereinafter named by and out of my personal estate as soon as conveniently may be after my decease.

I give, devise and bequeath to Humphrey Trafford Nadin of Church Gresely in the said County of Derby Esquire and John Wilkinson of Newhall aforesaid yeoman all my messuages, lands, tenements, hereditaments and real and personal estates to hold to them, their heirs, executors, administrators and assigns until Richard Moon the youngest of my reputed sons by Elizabeth Moon shall attain his age of twenty one years upon trust that they, my said trustees, (or the survivor of them, his heirs, executors, administrators or assigns), shall and do manage and carry on my farm at Newhall aforesaid and pay and apply the rents, issues and profits of all and every of my said real and personal estates in for and towards the support, maintenance and education of all my reputed children by the said Elizabeth Moon until the said Richard Moon my youngest reputed son shall attain his said age of twenty one years and equally share and share and share alike.

And it is my will and desire that my said trustees or trustee for the time being shall recruit and keep up the stock upon my farm as they in their discretion shall see occasion or think proper and that the same shall not be diminished. And in case any of my said reputed children by the said Elizabeth Moon shall be married before my said reputed youngest son shall attain his age of twenty one years that then it is my will and desire that non of their husbands or wives shall come to my farm or be maintained there or have their abode there. That it is also my will and desire in case my reputed children or any of them shall not be steady to business but instead shall be wild and diminish the stock that then my said trustees or trustee for the time being shall have full power and authority in their discretion to sell and dispose of all or any part of my said personal estate and to put out the money arising from the sale thereof to interest and to pay and apply the interest thereof and also thereunto of the said real estate in for and towards the maintenance, education and support of all my said reputed children by the said

Elizabeth Moon as they my said trustees in their discretion that think proper until the said Richard Moon shall attain his age of twenty one years.Then I give to my grandson Daniel Staley the sum of ten pounds and to each and every of my sons and daughters namely Daniel Staley, Benjamin Staley, John Staley, William Staley, Elizabeth Dent and Sarah Orme and to my niece Ann Brearly the sum of five pounds apiece.

I give to my youngest reputed son Richard Moon one share in the Ashby Canal Navigation and I direct that my said trustees or trustee for the time being shall have full power and authority to pay and apply all or any part of the fortune or legacy hereby intended for my youngest reputed son Richard Moon in placing him out to any trade, business or profession as they in their discretion shall think proper.

And I direct that to my said sons and daughters by my late wife and my said niece shall by wholly paid by my said reputed son Richard Moon out of the fortune herby given him. And it is my will and desire that my said reputed children shall deliver into the hands of my executors all the monies that shall arise from the carrying on of my business that is not wanted to carry on the same unto my acting executor and shall keep a just and true account of all disbursements and receipts of the said business and deliver up the same to my acting executor in order that there may not be any embezzlement or defraud amongst them and from and immediately after my said reputed youngest son Richard Moon shall attain his age of twenty one years then I give, devise and bequeath all my real estate and all the residue and remainder of my personal estate of what nature and kind whatsoever and wheresoever unto and amongst all and every my said reputed sons and daughters namely William Moon, Thomas Moon, Joseph Moon, Richard Moon, Ann Moon, Margaret Moon and to my reputed daughter Mary Brearly to hold to them and their respective heirs, executors, administrator and assigns for ever according to the nature and tenure of the same estates respectively to take the same as tenants in common and not as joint tenants.And lastly I nominate and appoint the said Humphrey Trafford Nadin and John Wilkinson executors of this my last will and testament and guardians of all my reputed children who are under age during their respective minorities hereby revoking all former and other wills by me heretofore made and declaring this only to be my last will.

In witness whereof I the said Daniel Staley the testator have to this my last will and testament set my hand and seal the eleventh day of March in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and five.

June 6, 2022 at 12:58 pm #6303In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

The Hollands of Barton under Needwood

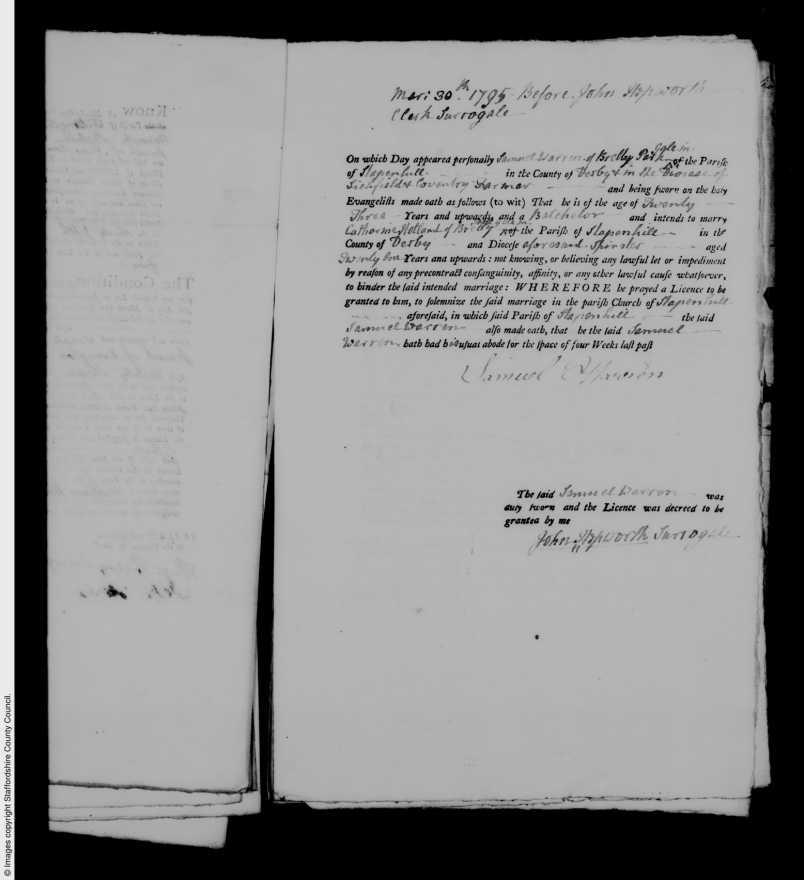

Samuel Warren of Stapenhill married Catherine Holland of Barton under Needwood in 1795.

I joined a Barton under Needwood History group and found an incredible amount of information on the Holland family, but first I wanted to make absolutely sure that our Catherine Holland was one of them as there were also Hollands in Newhall. Not only that, on the marriage licence it says that Catherine Holland was from Bretby Park Gate, Stapenhill.

Then I noticed that one of the witnesses on Samuel’s brother Williams marriage to Ann Holland in 1796 was John Hair. Hannah Hair was the wife of Thomas Holland, and they were the Barton under Needwood parents of Catherine. Catherine was born in 1775, and Ann was born in 1767.

The 1851 census clinched it: Catherine Warren 74 years old, widow and formerly a farmers wife, was living in the household of her son John Warren, and her place of birth is listed as Barton under Needwood. In 1841 Catherine was a 64 year old widow, her husband Samuel having died in 1837, and she was living with her son Samuel, a farmer. The 1841 census did not list place of birth, however. Catherine died on 31 March 1861 and does not appear on the 1861 census.

Once I had established that our Catherine Holland was from Barton under Needwood, I had another look at the information available on the Barton under Needwood History group, compiled by local historian Steve Gardner.

Catherine’s parents were Thomas Holland 1737-1828 and Hannah Hair 1739-1822.

Steve Gardner had posted a long list of the dates, marriages and children of the Holland family. The earliest entries in parish registers were Thomae Holland 1562-1626 and his wife Eunica Edwardes 1565-1632. They married on 10th July 1582. They were born, married and died in Barton under Needwood. They were direct ancestors of Catherine Holland, and as such my direct ancestors too.

The known history of the Holland family in Barton under Needwood goes back to Richard De Holland. (Thanks once again to Steve Gardner of the Barton under Needwood History group for this information.)

“Richard de Holland was the first member of the Holland family to become resident in Barton under Needwood (in about 1312) having been granted lands by the Earl of Lancaster (for whom Richard served as Stud and Stock Keeper of the Peak District) The Holland family stemmed from Upholland in Lancashire and had many family connections working for the Earl of Lancaster, who was one of the biggest Barons in England. Lancaster had his own army and lived at Tutbury Castle, from where he ruled over most of the Midlands area. The Earl of Lancaster was one of the main players in the ‘Barons Rebellion’ and the ensuing Battle of Burton Bridge in 1322. Richard de Holland was very much involved in the proceedings which had so angered Englands King. Holland narrowly escaped with his life, unlike the Earl who was executed.

From the arrival of that first Holland family member, the Hollands were a mainstay family in the community, and were in Barton under Needwood for over 600 years.”Continuing with various items of information regarding the Hollands, thanks to Steve Gardner’s Barton under Needwood history pages:

“PART 6 (Final Part)

Some mentions of The Manor of Barton in the Ancient Staffordshire Rolls:

1330. A Grant was made to Herbert de Ferrars, at le Newland in the Manor of Barton.

1378. The Inquisitio bonorum – Johannis Holand — an interesting Inventory of his goods and their value and his debts.

1380. View of Frankpledge ; the Jury found that Richard Holland was feloniously murdered by his wife Joan and Thomas Graunger, who fled. The goods of the deceased were valued at iiij/. iijj. xid. ; one-third went to the dead man, one-third to his son, one- third to the Lord for the wife’s share. Compare 1 H. V. Indictments. (1413.)

That Thomas Graunger of Barton smyth and Joan the wife of Richard de Holond of Barton on the Feast of St. John the Baptist 10 H. II. (1387) had traitorously killed and murdered at night, at Barton, Richard, the husband of the said Joan. (m. 22.)

The names of various members of the Holland family appear constantly among the listed Jurors on the manorial records printed below : —

1539. Richard Holland and Richard Holland the younger are on the Muster Roll of Barton

1583. Thomas Holland and Unica his wife are living at Barton.

1663-4. Visitations. — Barton under Needword. Disclaimers. William Holland, Senior, William Holland, Junior.

1609. Richard Holland, Clerk and Alice, his wife.

1663-4. Disclaimers at the Visitation. William Holland, Senior, William Holland, Junior.”I was able to find considerably more information on the Hollands in the book “Some Records of the Holland Family (The Hollands of Barton under Needwood, Staffordshire, and the Hollands in History)” by William Richard Holland. Luckily the full text of this book can be found online.

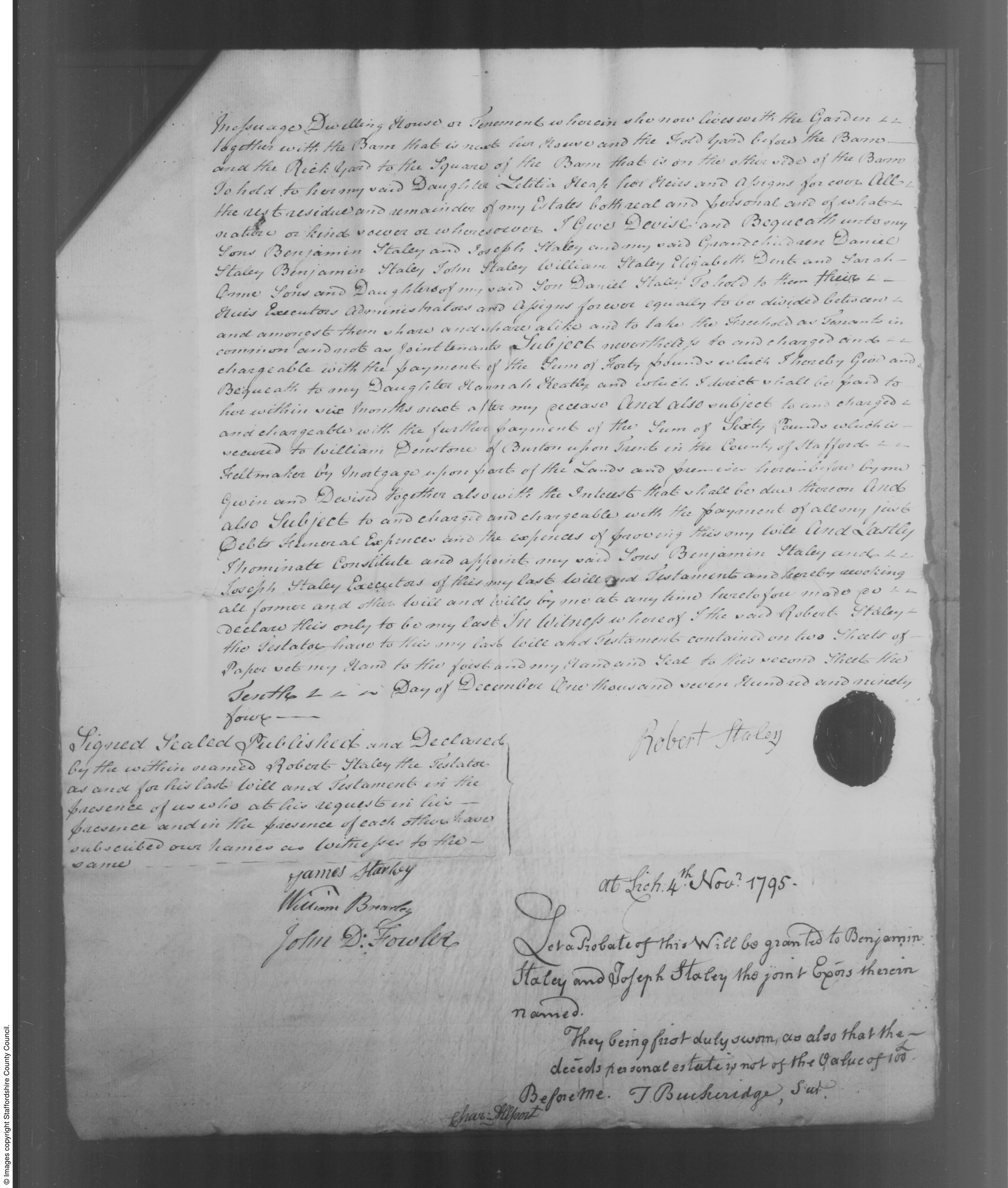

William Richard Holland (Died 1915) An early local Historian and author of the book:

‘Holland House’ taken from the Gardens (sadly demolished in the early 60’s):

Excerpt from the book:

“The charter, dated 1314, granting Richard rights and privileges in Needwood Forest, reads as follows:

“Thomas Earl of Lancaster and Leicester, high-steward of England, to whom all these present shall come, greeting: Know ye, that we have given, &c., to Richard Holland of Barton, and his heirs, housboot, heyboot, and fireboot, and common of pasture, in our forest of Needwood, for all his beasts, as well in places fenced as lying open, with 40 hogs, quit of pawnage in our said forest at all times in the year (except hogs only in fence month). All which premises we will warrant, &c. to the said Richard and his heirs against all people for ever”

“The terms “housboot” “heyboot” and “fireboot” meant that Richard and his heirs were to have the privilege of taking from the Forest, wood needed for house repair and building, hedging material for the repairing of fences, and what was needful for purposes of fuel.”

Further excerpts from the book:

“It may here be mentioned that during the renovation of Barton Church, when the stone pillars were being stripped of the plaster which covered them, “William Holland 1617” was found roughly carved on a pillar near to the belfry gallery, obviously the work of a not too devout member of the family, who, seated in the gallery of that time, occupied himself thus during the service. The inscription can still be seen.”

“The earliest mention of a Holland of Upholland occurs in the reign of John in a Final Concord, made at the Lancashire Assizes, dated November 5th, 1202, in which Uchtred de Chryche, who seems to have had some right in the manor of Upholland, releases his right in fourteen oxgangs* of land to Matthew de Holland, in consideration of the sum of six marks of silver. Thus was planted the Holland Tree, all the early information of which is found in The Victoria County History of Lancaster.

As time went on, the family acquired more land, and with this, increased position. Thus, in the reign of Edward I, a Robert de Holland, son of Thurstan, son of Robert, became possessed of the manor of Orrell adjoining Upholland and of the lordship of Hale in the parish of Childwall, and, through marriage with Elizabeth de Samlesbury (co-heiress of Sir Wm. de Samlesbury of Samlesbury, Hall, near to Preston), of the moiety of that manor….

* An oxgang signified the amount of land that could be ploughed by one ox in one day”

“This Robert de Holland, son of Thurstan, received Knighthood in the reign of Edward I, as did also his brother William, ancestor of that branch of the family which later migrated to Cheshire. Belonging to this branch are such noteworthy personages as Mrs. Gaskell, the talented authoress, her mother being a Holland of this branch, Sir Henry Holland, Physician to Queen Victoria, and his two sons, the first Viscount Knutsford, and Canon Francis Holland ; Sir Henry’s grandson (the present Lord Knutsford), Canon Scott Holland, etc. Captain Frederick Holland, R.N., late of Ashbourne Hall, Derbyshire, may also be mentioned here.*”

Thanks to the Barton under Needwood history group for the following:

WALES END FARM:

In 1509 it was owned and occupied by Mr Johannes Holland De Wallass end who was a well to do Yeoman Farmer (the origin of the areas name – Wales End). Part of the building dates to 1490 making it probably the oldest building still standing in the Village:

I found records for all of the Holland’s listed on the Barton under Needwood History group and added them to my ancestry tree. The earliest will I found was for Eunica Edwardes, then Eunica Holland, who died in 1632.

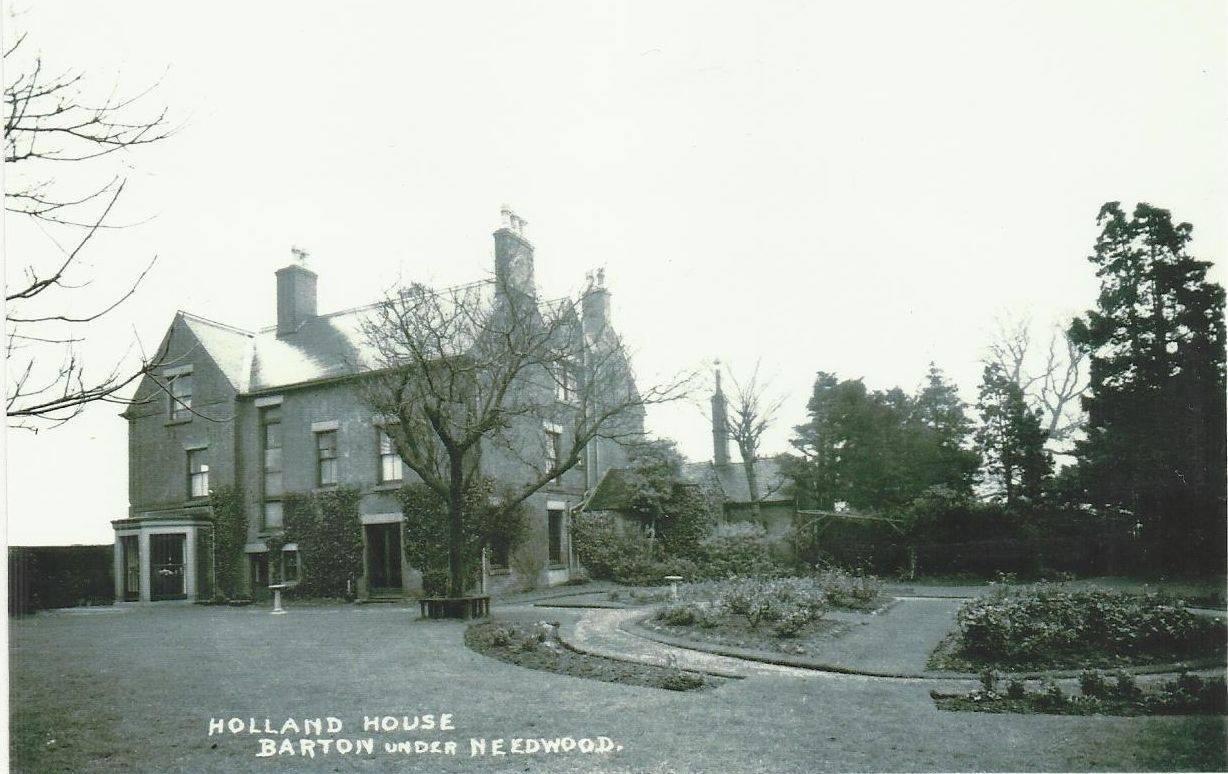

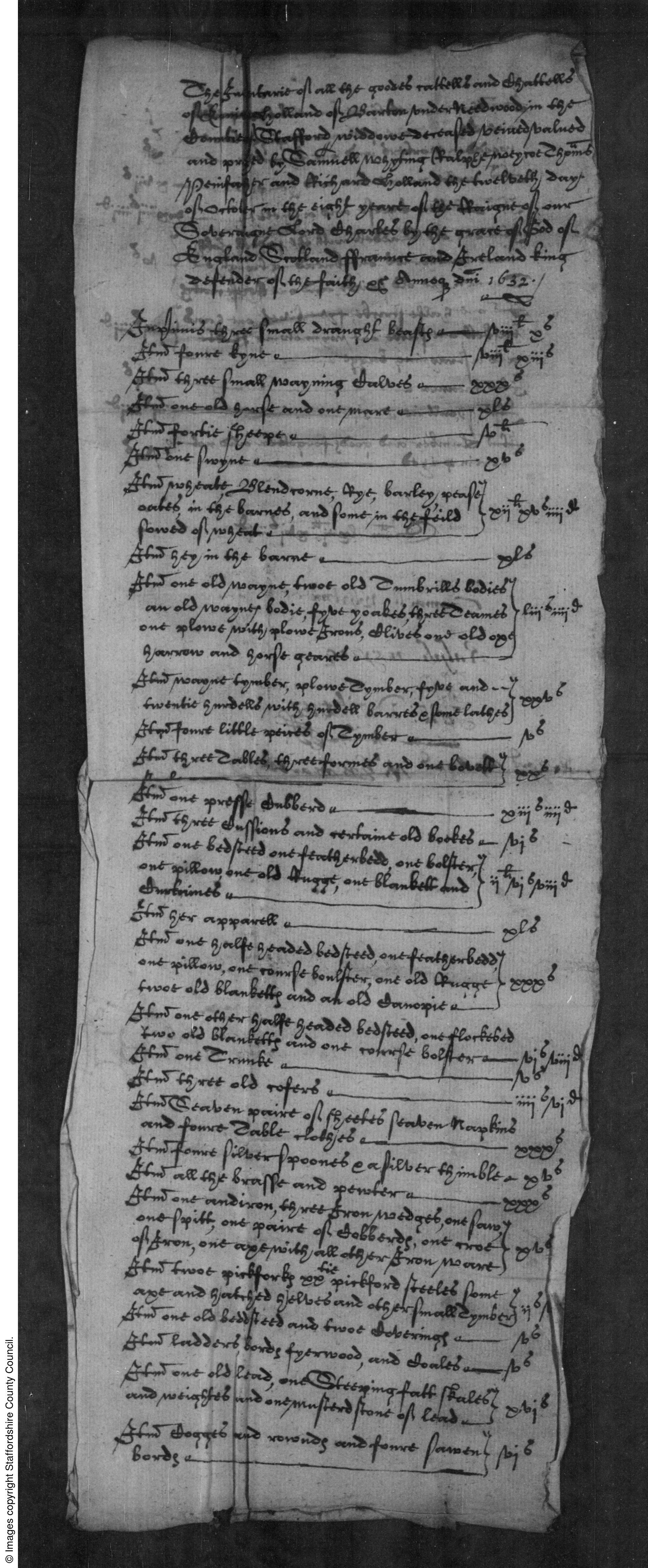

A page from the 1632 will and inventory of Eunica (Unice) Holland:

I’d been reading about “pedigree collapse” just before I found out her maiden name of Edwardes. Edwards is my own maiden name.

“In genealogy, pedigree collapse describes how reproduction between two individuals who knowingly or unknowingly share an ancestor causes the family tree of their offspring to be smaller than it would otherwise be.

Without pedigree collapse, a person’s ancestor tree is a binary tree, formed by the person, the parents, grandparents, and so on. However, the number of individuals in such a tree grows exponentially and will eventually become impossibly high. For example, a single individual alive today would, over 30 generations going back to the High Middle Ages, have roughly a billion ancestors, more than the total world population at the time. This apparent paradox occurs because the individuals in the binary tree are not distinct: instead, a single individual may occupy multiple places in the binary tree. This typically happens when the parents of an ancestor are cousins (sometimes unbeknownst to themselves). For example, the offspring of two first cousins has at most only six great-grandparents instead of the normal eight. This reduction in the number of ancestors is pedigree collapse. It collapses the binary tree into a directed acyclic graph with two different, directed paths starting from the ancestor who in the binary tree would occupy two places.” via wikipediaThere is nothing to suggest, however, that Eunica’s family were related to my fathers family, and the only evidence so far in my tree of pedigree collapse are the marriages of Orgill cousins, where two sets of grandparents are repeated.

A list of Holland ancestors:

Catherine Holland 1775-1861

her parents:

Thomas Holland 1737-1828 Hannah Hair 1739-1832

Thomas’s parents:

William Holland 1696-1756 Susannah Whiteing 1715-1752

William’s parents:

William Holland 1665- Elizabeth Higgs 1675-1720

William’s parents:

Thomas Holland 1634-1681 Katherine Owen 1634-1728

Thomas’s parents:

Thomas Holland 1606-1680 Margaret Belcher 1608-1664

Thomas’s parents:

Thomas Holland 1562-1626 Eunice Edwardes 1565- 1632June 6, 2022 at 9:17 am #6301In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

The Warrens of Stapenhill

There were so many Warren’s in Stapenhill that it was complicated to work out who was who. I had gone back as far as Samuel Warren marrying Catherine Holland, and this was as far back as my cousin Ian Warren had gone in his research some decades ago as well. The Holland family from Barton under Needwood are particularly interesting, and will be a separate chapter.

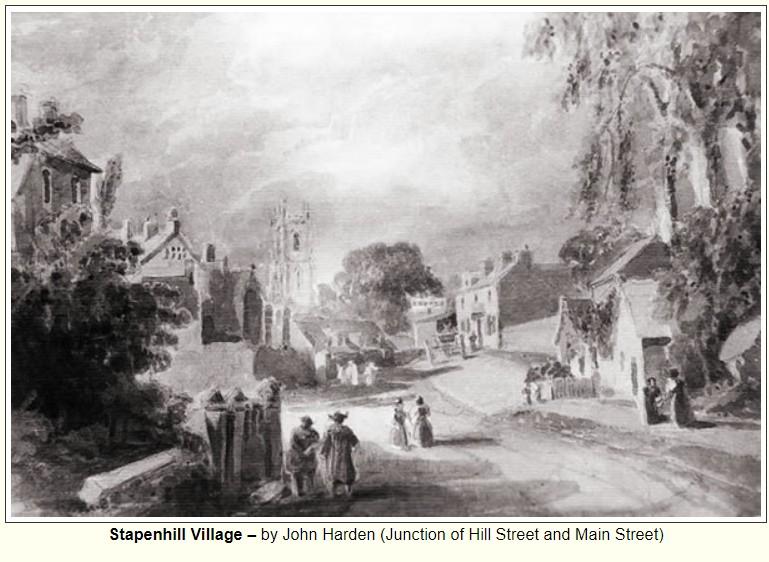

Stapenhill village by John Harden:

Resuming the research on the Warrens, Samuel Warren 1771-1837 married Catherine Holland 1775-1861 in 1795 and their son Samuel Warren 1800-1882 married Elizabeth Bridge, whose childless brother Benjamin Bridge left the Warren Brothers Boiler Works in Newhall to his nephews, the Warren brothers.

Samuel Warren and Catherine Holland marriage licence 1795:

Samuel (born 1771) was baptised at Stapenhill St Peter and his parents were William and Anne Warren. There were at least three William and Ann Warrens in town at the time. One of those William’s was born in 1744, which would seem to be the right age to be Samuel’s father, and one was born in 1710, which seemed a little too old. Another William, Guiliamos Warren (Latin was often used in early parish registers) was baptised in Stapenhill in 1729.

Stapenhill St Peter:

William Warren (born 1744) appeared to have been born several months before his parents wedding. William Warren and Ann Insley married 16 July 1744, but the baptism of William in 1744 was 24 February. This seemed unusual ~ children were often born less than nine months after a wedding, but not usually before the wedding! Then I remembered the change from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar in 1752. Prior to 1752, the first day of the year was Lady Day, March 25th, not January 1st. This meant that the birth in February 1744 was actually after the wedding in July 1744. Now it made sense. The first son was named William, and he was born seven months after the wedding.

William born in 1744 died intestate in 1822, and his wife Ann made a legal claim to his estate. However he didn’t marry Ann Holland (Ann was Catherines Hollands sister, who married Samuel Warren the year before) until 1796, so this William and Ann were not the parents of Samuel.

It seemed likely that William born in 1744 was Samuels brother. William Warren and Ann Insley had at least eight children between 1744 and 1771, and it seems that Samuel was their last child, born when William the elder was 61 and his wife Ann was 47.

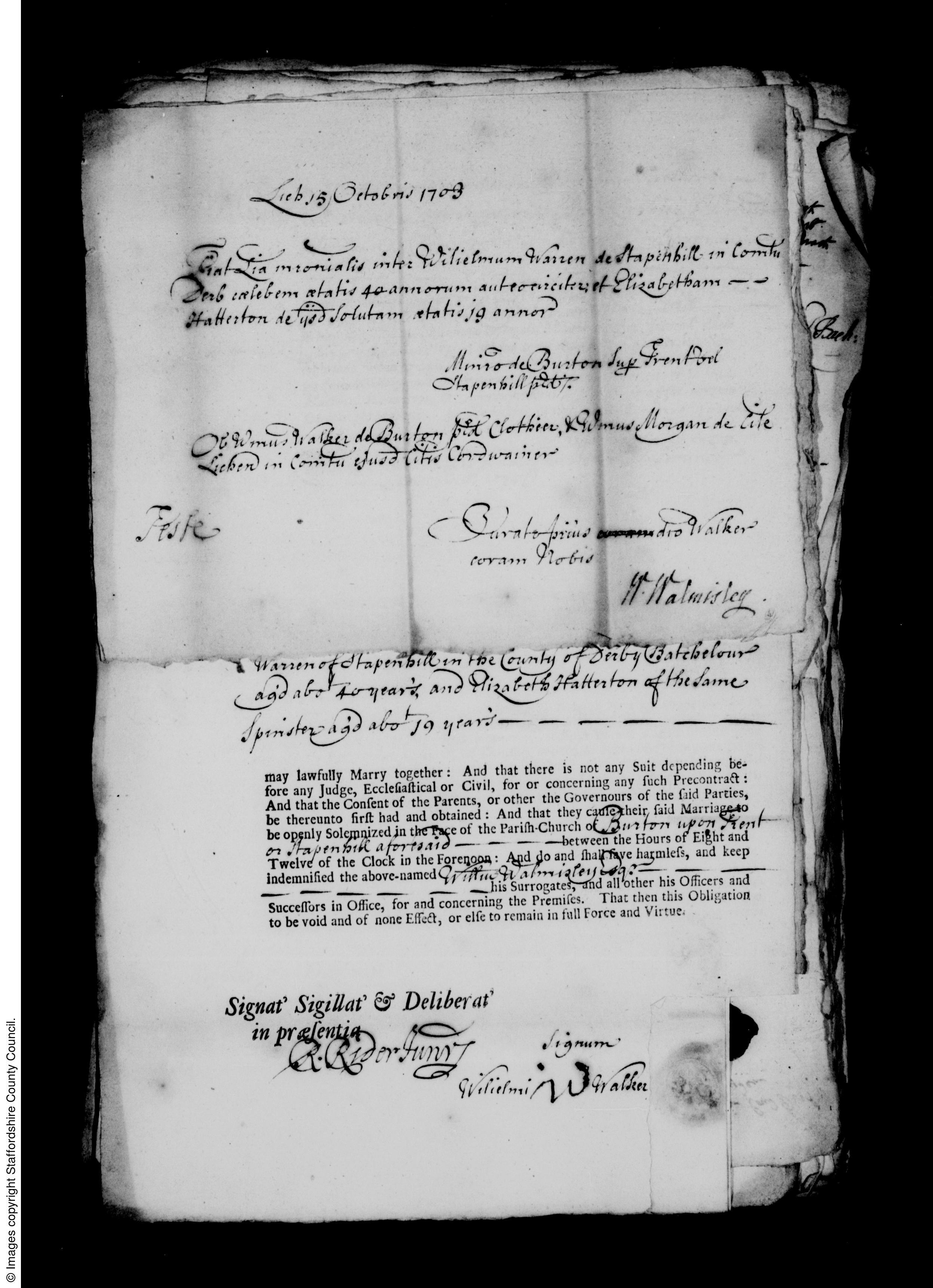

It seems it wasn’t unusual for the Warren men to marry rather late in life. William Warren’s (born 1710) parents were William Warren and Elizabeth Hatterton. On the marriage licence in 1702/1703 (it appears to say 1703 but is transcribed as 1702), William was a 40 year old bachelor from Stapenhill, which puts his date of birth at 1662. Elizabeth was considerably younger, aged 19.

William Warren and Elizabeth Hatterton marriage licence 1703:

These Warren’s were farmers, and they were literate and able to sign their own names on various documents. This is worth noting, as most made the mark of an X.

I found three Warren and Holland marriages. One was Samuel Warren and Catherine Holland in 1795, then William Warren and Ann Holland in 1796. William Warren and Ann Hollands daughter born in 1799 married John Holland in 1824.

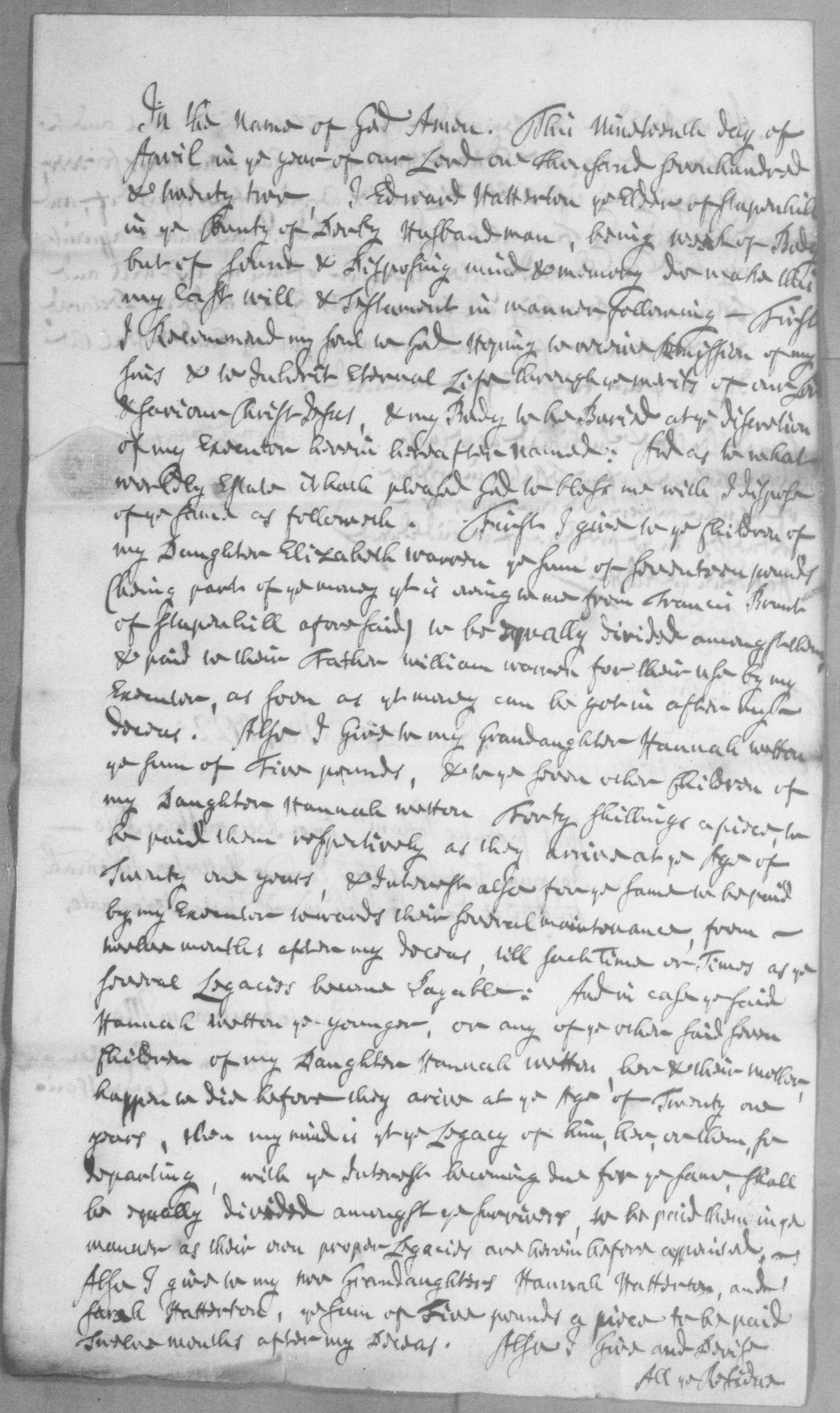

Elizabeth Hatterton (wife of William Warren who was born circa 1662) was born in Burton upon Trent in 1685. Her parents were Edward Hatterton 1655-1722, and Sara.

A page from the 1722 will of Edward Hatterton:

The earliest Warren I found records for was William Warren who married Elizabeth Hatterton in 1703. The marriage licence states his age as 40 and that he was from Stapenhill, but none of the Stapenhill parish records online go back as far as 1662. On other public trees on ancestry websites, a birth record from Suffolk has been chosen, probably because it was the only record to be found online with the right name and date. Once again, I don’t think that is correct, and perhaps one day I’ll find some earlier Stapenhill records to prove that he was born in locally.

Subsequently, I found a list of the 1662 Hearth Tax for Stapenhill. On it were a number of Warrens, three William Warrens including one who was a constable. One of those William Warrens had a son he named William (as they did, hence the number of William Warrens in the tree) the same year as this hearth tax list.

But was it the William Warren with 2 chimneys, the one with one chimney who was too poor to pay it, or the one who was a constable?

from the list:

Will. Warryn 2

Richard Warryn 1

William Warren Constable

These names are not payable by Act:

Will. Warryn 1

Richard Warren John Watson

over seers of the poore and churchwardensThe Hearth Tax:

via wiki:

In England, hearth tax, also known as hearth money, chimney tax, or chimney money, was a tax imposed by Parliament in 1662, to support the Royal Household of King Charles II. Following the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, Parliament calculated that the Royal Household needed an annual income of £1,200,000. The hearth tax was a supplemental tax to make up the shortfall. It was considered easier to establish the number of hearths than the number of heads, hearths forming a more stationary subject for taxation than people. This form of taxation was new to England, but had precedents abroad. It generated considerable debate, but was supported by the economist Sir William Petty, and carried through the Commons by the influential West Country member Sir Courtenay Pole, 2nd Baronet (whose enemies nicknamed him “Sir Chimney Poll” as a result). The bill received Royal Assent on 19 May 1662, with the first payment due on 29 September 1662, Michaelmas.

One shilling was liable to be paid for every firehearth or stove, in all dwellings, houses, edifices or lodgings, and was payable at Michaelmas, 29 September and on Lady Day, 25 March. The tax thus amounted to two shillings per hearth or stove per year. The original bill contained a practical shortcoming in that it did not distinguish between owners and occupiers and was potentially a major burden on the poor as there were no exemptions. The bill was subsequently amended so that the tax was paid by the occupier. Further amendments introduced a range of exemptions that ensured that a substantial proportion of the poorer people did not have to pay the tax.Indeed it seems clear that William Warren the elder came from Stapenhill and not Suffolk, and one of the William Warrens paying hearth tax in 1662 was undoubtedly the father of William Warren who married Elizabeth Hatterton.

April 12, 2022 at 8:13 am #6290In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Leicestershire Blacksmiths

The Orgill’s of Measham led me further into Leicestershire as I traveled back in time.

I also realized I had uncovered a direct line of women and their mothers going back ten generations:

myself, Tracy Edwards 1957-

my mother Gillian Marshall 1933-

my grandmother Florence Warren 1906-1988

her mother and my great grandmother Florence Gretton 1881-1927

her mother Sarah Orgill 1840-1910

her mother Elizabeth Orgill 1803-1876

her mother Sarah Boss 1783-1847

her mother Elizabeth Page 1749-

her mother Mary Potter 1719-1780

and her mother and my 7x great grandmother Mary 1680-You could say it leads us to the very heart of England, as these Leicestershire villages are as far from the coast as it’s possible to be. There are countless other maternal lines to follow, of course, but only one of mothers of mothers, and ours takes us to Leicestershire.

The blacksmiths

Sarah Boss was the daughter of Michael Boss 1755-1807, a blacksmith in Measham, and Elizabeth Page of nearby Hartshorn, just over the county border in Derbyshire.

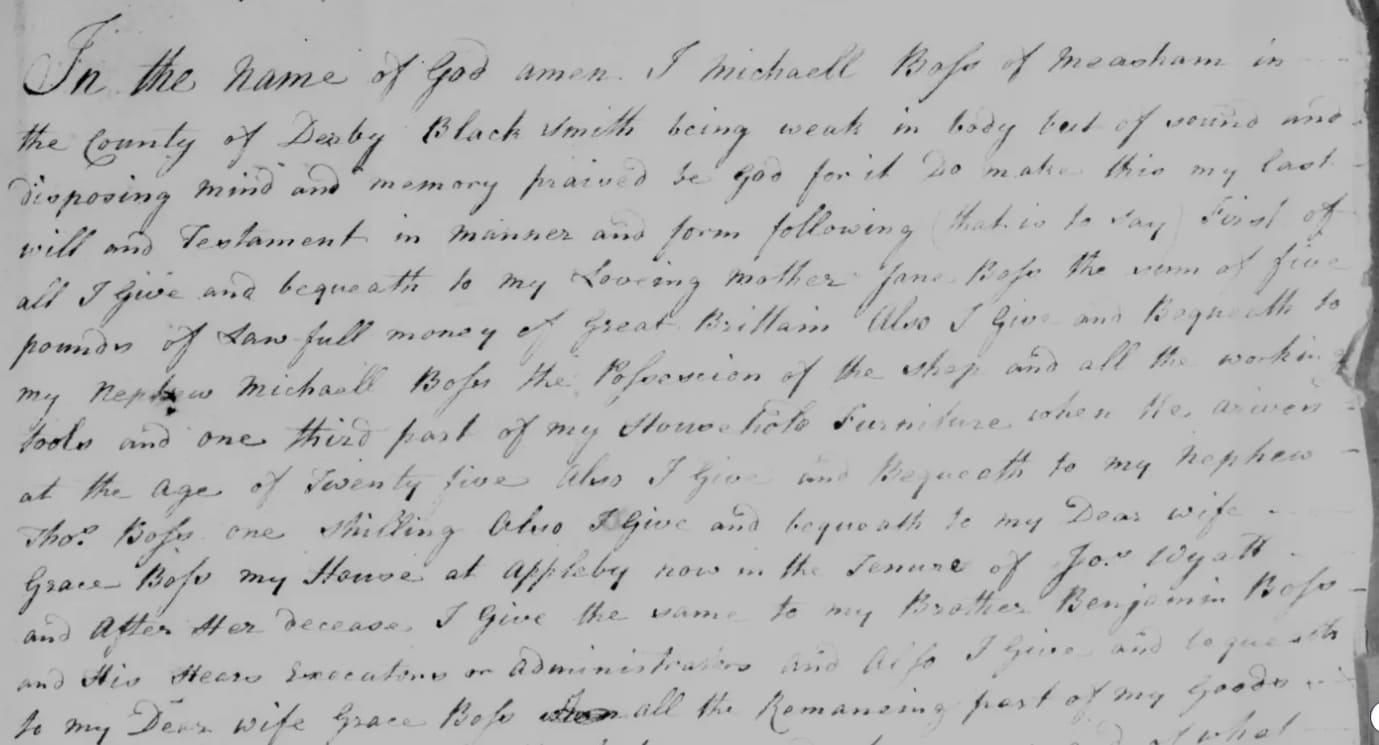

An earlier Michael Boss, a blacksmith of Measham, died in 1772, and in his will he left the possession of the blacksmiths shop and all the working tools and a third of the household furniture to Michael, who he named as his nephew. He left his house in Appleby Magna to his wife Grace, and five pounds to his mother Jane Boss. As none of Michael and Grace’s children are mentioned in the will, perhaps it can be assumed that they were childless.

The will of Michael Boss, 1772, Measham:

Michael Boss the uncle was born in Appleby Magna in 1724. His parents were Michael Boss of Nelson in the Thistles and Jane Peircivall of Appleby Magna, who were married in nearby Mancetter in 1720.

Information worth noting on the Appleby Magna website:

In 1752 the calendar in England was changed from the Julian Calendar to the Gregorian Calendar, as a result 11 days were famously “lost”. But for the recording of Church Registers another very significant change also took place, the start of the year was moved from March 25th to our more familiar January 1st.

Before 1752 the 1st day of each new year was March 25th, Lady Day (a significant date in the Christian calendar). The year number which we all now use for calculating ages didn’t change until March 25th. So, for example, the day after March 24th 1750 was March 25th 1751, and January 1743 followed December 1743.

This March to March recording can be seen very clearly in the Appleby Registers before 1752. Between 1752 and 1768 there appears slightly confused recording, so dates should be carefully checked. After 1768 the recording is more fully by the modern calendar year.Michael Boss the uncle married Grace Cuthbert. I haven’t yet found the birth or parents of Grace, but a blacksmith by the name of Edward Cuthbert is mentioned on an Appleby Magna history website:

An Eighteenth Century Blacksmith’s Shop in Little Appleby

by Alan RobertsCuthberts inventory

The inventory of Edward Cuthbert provides interesting information about the household possessions and living arrangements of an eighteenth century blacksmith. Edward Cuthbert (als. Cutboard) settled in Appleby after the Restoration to join the handful of blacksmiths already established in the parish, including the Wathews who were prominent horse traders. The blacksmiths may have all worked together in the same shop at one time. Edward and his wife Sarah recorded the baptisms of several of their children in the parish register. Somewhat sadly three of the boys named after their father all died either in infancy or as young children. Edward’s inventory which was drawn up in 1732, by which time he was probably a widower and his children had left home, suggests that they once occupied a comfortable two-storey house in Little Appleby with an attached workshop, well equipped with all the tools for repairing farm carts, ploughs and other implements, for shoeing horses and for general ironmongery.

Edward Cuthbert born circa 1660, married Joane Tuvenet in 1684 in Swepston cum Snarestone , and died in Appleby in 1732. Tuvenet is a French name and suggests a Huguenot connection, but this isn’t our family, and indeed this Edward Cuthbert is not likely to be Grace’s father anyway.

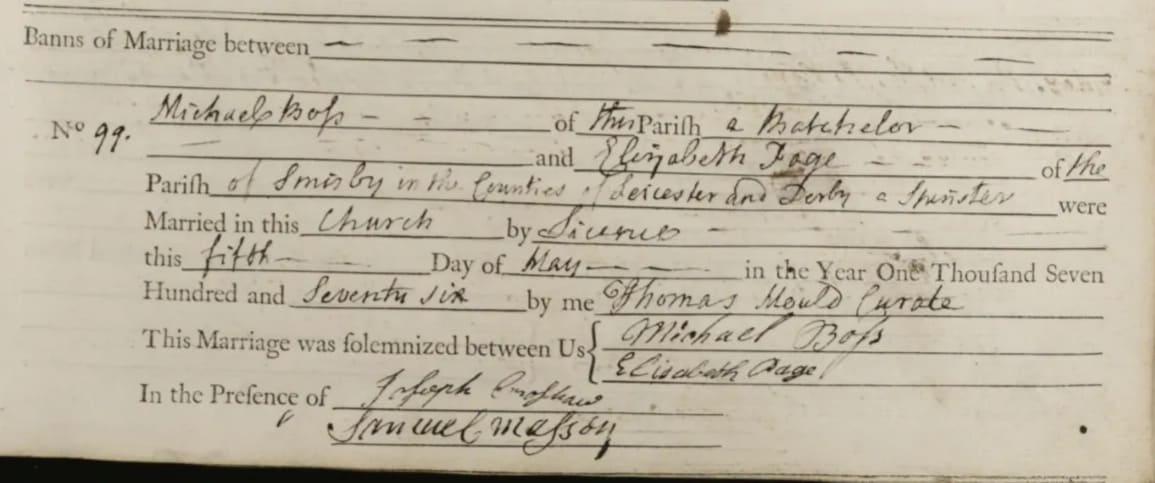

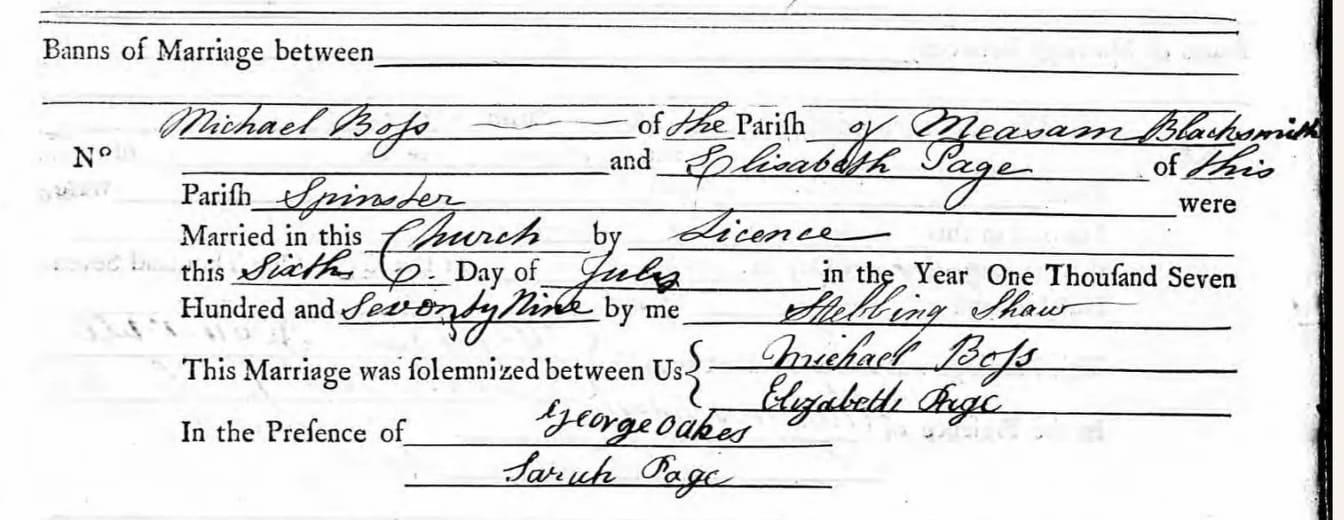

Michael Boss and Elizabeth Page appear to have married twice: once in 1776, and once in 1779. Both of the documents exist and appear correct. Both marriages were by licence. They both mention Michael is a blacksmith.

Their first daughter, Elizabeth, was baptized in February 1777, just nine months after the first wedding. It’s not known when she was born, however, and it’s possible that the marriage was a hasty one. But why marry again three years later?

But Michael Boss and Elizabeth Page did not marry twice.

Elizabeth Page from Smisby was born in 1752 and married Michael Boss on the 5th of May 1776 in Measham. On the marriage licence allegations and bonds, Michael is a bachelor.

Baby Elizabeth was baptised in Measham on the 9th February 1777. Mother Elizabeth died on the 18th February 1777, also in Measham.

In 1779 Michael Boss married another Elizabeth Page! She was born in 1749 in Hartshorn, and Michael is a widower on the marriage licence allegations and bonds.

Hartshorn and Smisby are neighbouring villages, hence the confusion. But a closer look at the documents available revealed the clues. Both Elizabeth Pages were literate, and indeed their signatures on the marriage registers are different:

Marriage of Michael Boss and Elizabeth Page of Smisby in 1776:

Marriage of Michael Boss and Elizabeth Page of Harsthorn in 1779:

Not only did Michael Boss marry two women both called Elizabeth Page but he had an unusual start in life as well. His uncle Michael Boss left him the blacksmith business and a third of his furniture. This was all in the will. But which of Uncle Michaels brothers was nephew Michaels father?

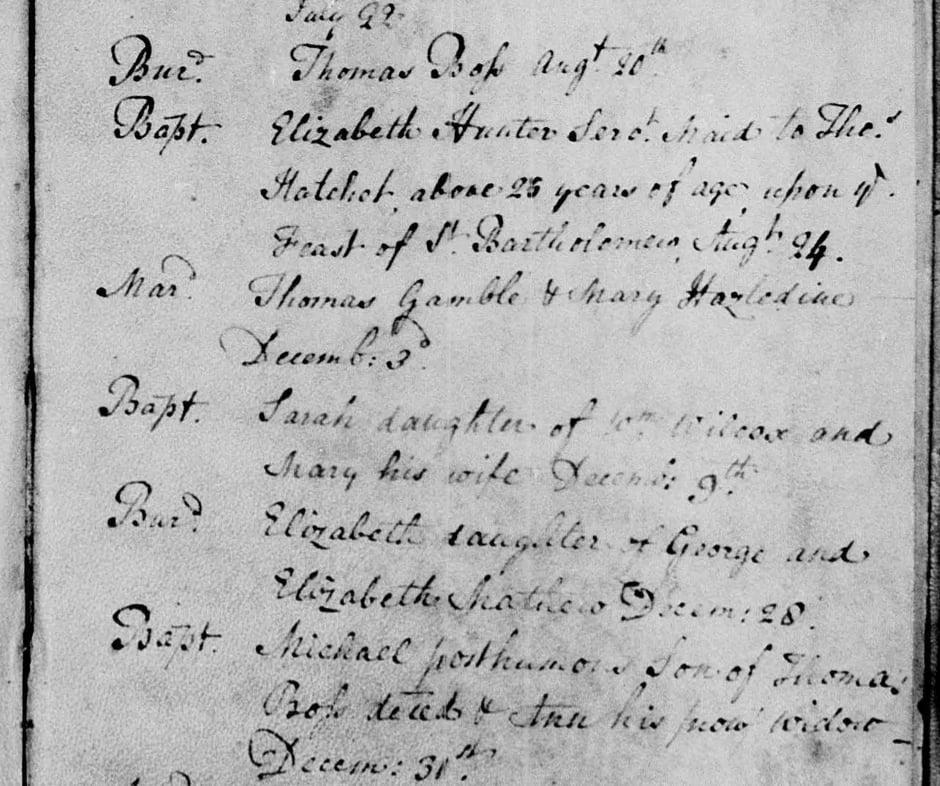

The only Michael Boss born at the right time was in 1750 in Edingale, Staffordshire, about eight miles from Appleby Magna. His parents were Thomas Boss and Ann Parker, married in Edingale in 1747. Thomas died in August 1750, and his son Michael was baptised in the December, posthumus son of Thomas and his widow Ann. Both entries are on the same page of the register.

Ann Boss, the young widow, married again. But perhaps Michael and his brother went to live with their childless uncle and aunt, Michael Boss and Grace Cuthbert.

The great grandfather of Michael Boss (the Measham blacksmith born in 1850) was also Michael Boss, probably born in the 1660s. He died in Newton Regis in Warwickshire in 1724, four years after his son (also Michael Boss born 1693) married Jane Peircivall. The entry on the parish register states that Michael Boss was buried ye 13th Affadavit made.

I had not seen affadavit made on a parish register before, and this relates to the The Burying in Woollen Acts 1666–80. According to Wikipedia:

“Acts of the Parliament of England which required the dead, except plague victims and the destitute, to be buried in pure English woollen shrouds to the exclusion of any foreign textiles. It was a requirement that an affidavit be sworn in front of a Justice of the Peace (usually by a relative of the deceased), confirming burial in wool, with the punishment of a £5 fee for noncompliance. Burial entries in parish registers were marked with the word “affidavit” or its equivalent to confirm that affidavit had been sworn; it would be marked “naked” for those too poor to afford the woollen shroud. The legislation was in force until 1814, but was generally ignored after 1770.”

Michael Boss buried 1724 “Affadavit made”:

Elizabeth Page‘s father was William Page 1717-1783, a wheelwright in Hartshorn. (The father of the first wife Elizabeth was also William Page, but he was a husbandman in Smisby born in 1714. William Page, the father of the second wife, was born in Nailstone, Leicestershire, in 1717. His place of residence on his marriage to Mary Potter was spelled Nelson.)

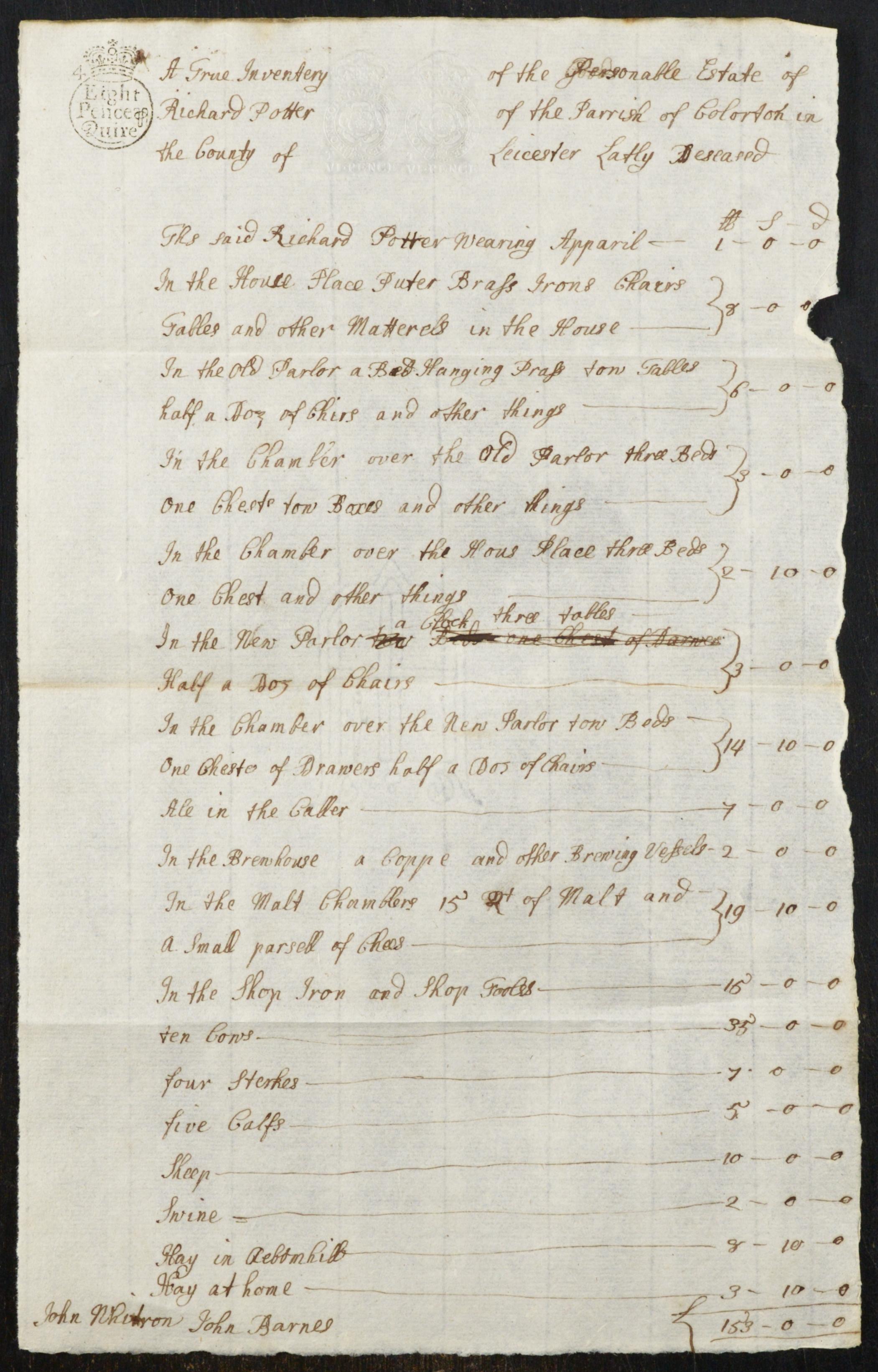

Her mother was Mary Potter 1719- of nearby Coleorton. Mary’s father, Richard Potter 1677-1731, was a blacksmith in Coleorton.

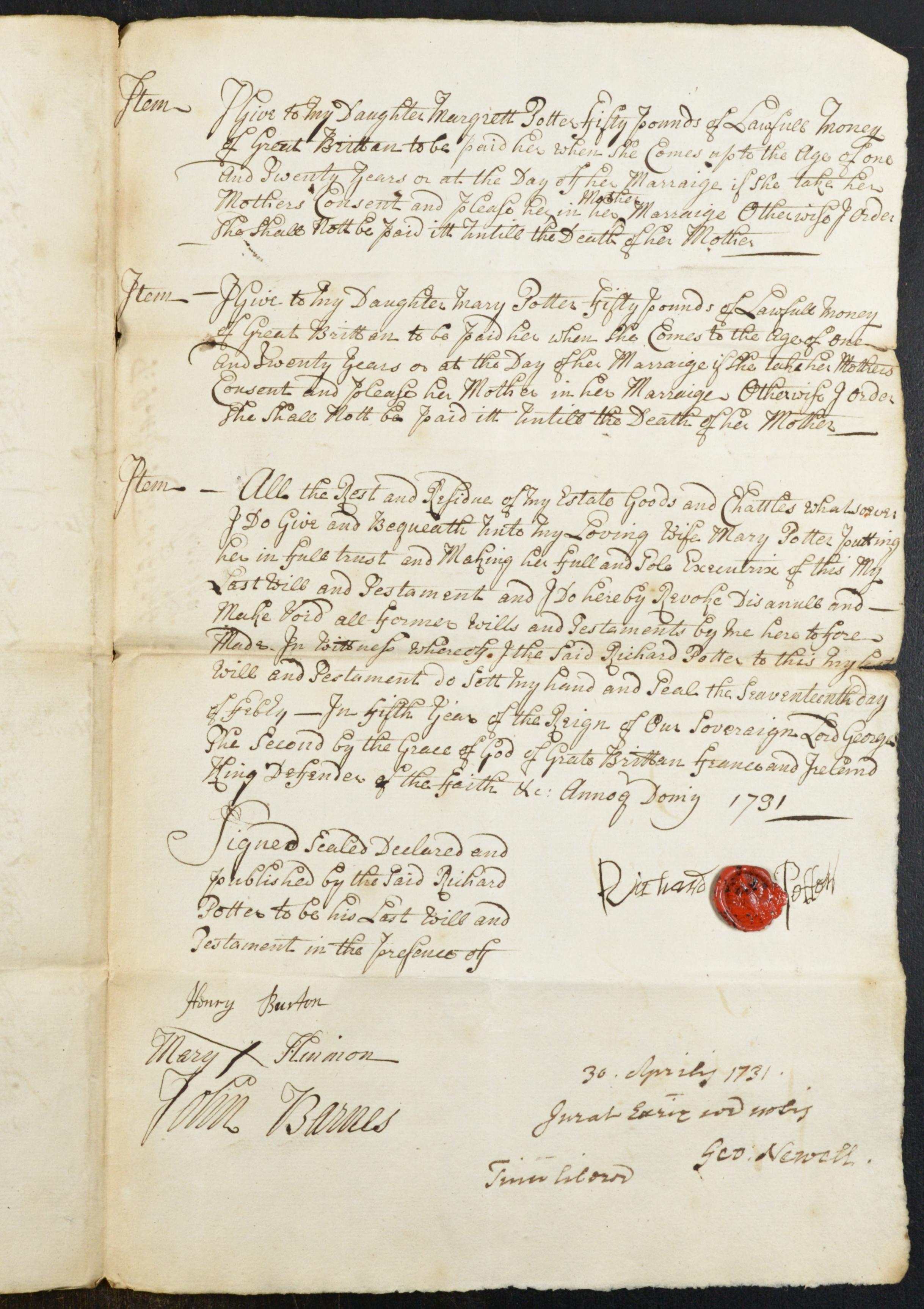

A page of the will of Richard Potter 1731:

Richard Potter states: “I will and order that my son Thomas Potter shall after my decease have one shilling paid to him and no more.” As he left £50 to each of his daughters, one can’t help but wonder what Thomas did to displease his father.

Richard stipulated that his son Thomas should have one shilling paid to him and not more, for several good considerations, and left “the house and ground lying in the parish of Whittwick in a place called the Long Lane to my wife Mary Potter to dispose of as she shall think proper.”

His son Richard inherited the blacksmith business: “I will and order that my son Richard Potter shall live and be with his mother and serve her duly and truly in the business of a blacksmith, and obey and serve her in all lawful commands six years after my decease, and then I give to him and his heirs…. my house and grounds Coulson House in the Liberty of Thringstone”

Richard wanted his son John to be a blacksmith too: “I will and order that my wife bring up my son John Potter at home with her and teach or cause him to be taught the trade of a blacksmith and that he shall serve her duly and truly seven years after my decease after the manner of an apprentice and at the death of his mother I give him that house and shop and building and the ground belonging to it which I now dwell in to him and his heirs forever.”

To his daughters Margrett and Mary Potter, upon their reaching the age of one and twenty, or the day after their marriage, he leaves £50 each. All the rest of his goods are left to his loving wife Mary.

An inventory of the belongings of Richard Potter, 1731:

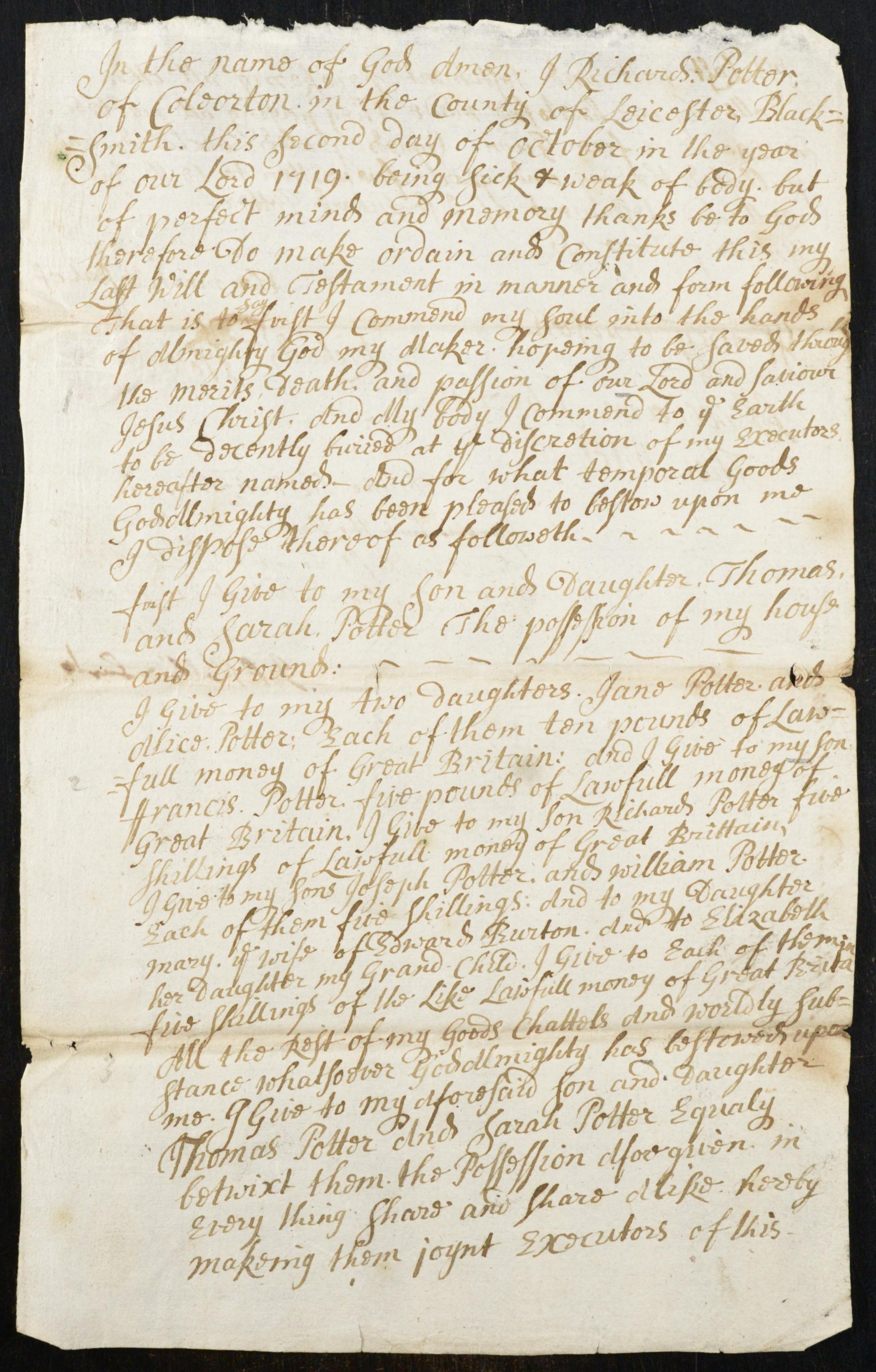

Richard Potters father was also named Richard Potter 1649-1719, and he too was a blacksmith.

Richard Potter of Coleorton in the county of Leicester, blacksmith, stated in his will: “I give to my son and daughter Thomas and Sarah Potter the possession of my house and grounds.”

He leaves ten pounds each to his daughters Jane and Alice, to his son Francis he gives five pounds, and five shillings to his son Richard. Sons Joseph and William also receive five shillings each. To his daughter Mary, wife of Edward Burton, and her daughter Elizabeth, he gives five shillings each. The rest of his good, chattels and wordly substance he leaves equally between his son and daugter Thomas and Sarah. As there is no mention of his wife, it’s assumed that she predeceased him.

The will of Richard Potter, 1719:

Richard Potter’s (1649-1719) parents were William Potter and Alse Huldin, both born in the early 1600s. They were married in 1646 at Breedon on the Hill, Leicestershire. The name Huldin appears to originate in Finland.

William Potter was a blacksmith. In the 1659 parish registers of Breedon on the Hill, William Potter of Breedon blacksmith buryed the 14th July.

December 13, 2021 at 11:29 am #6222In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

George Gilman Rushby: The Cousin Who Went To Africa

The portrait of the woman has “mother of Catherine Housley, Smalley” written on the back, and one of the family photographs has “Francis Purdy” written on the back. My first internet search was “Catherine Housley Smalley Francis Purdy”. Easily found was the family tree of George (Mike) Rushby, on one of the genealogy websites. It seemed that it must be our family, but the African lion hunter seemed unlikely until my mother recalled her father had said that he had a cousin who went to Africa. I also noticed that the lion hunter’s middle name was Gilman ~ the name that Catherine Housley’s daughter ~ my great grandmother, Mary Ann Gilman Purdy ~ adopted, from her aunt and uncle who brought her up.

I tried to contact George (Mike) Rushby via the ancestry website, but got no reply. I searched for his name on Facebook and found a photo of a wildfire in a place called Wardell, in Australia, and he was credited with taking the photograph. A comment on the photo, which was a few years old, got no response, so I found a Wardell Community group on Facebook, and joined it. A very small place, population some 700 or so, and I had an immediate response on the group to my question. They knew Mike, exchanged messages, and we were able to start emailing. I was in the chair at the dentist having an exceptionally long canine root canal at the time that I got the message with his email address, and at that moment the song Down in Africa started playing.

Mike said it was clever of me to track him down which amused me, coming from the son of an elephant and lion hunter. He didn’t know why his father’s middle name was Gilman, and was not aware that Catherine Housley’s sister married a Gilman.

Mike Rushby kindly gave me permission to include his family history research in my book. This is the story of my grandfather George Marshall’s cousin. A detailed account of George Gilman Rushby’s years in Africa can be found in another chapter called From Tanganyika With Love; the letters Eleanor wrote to her family.

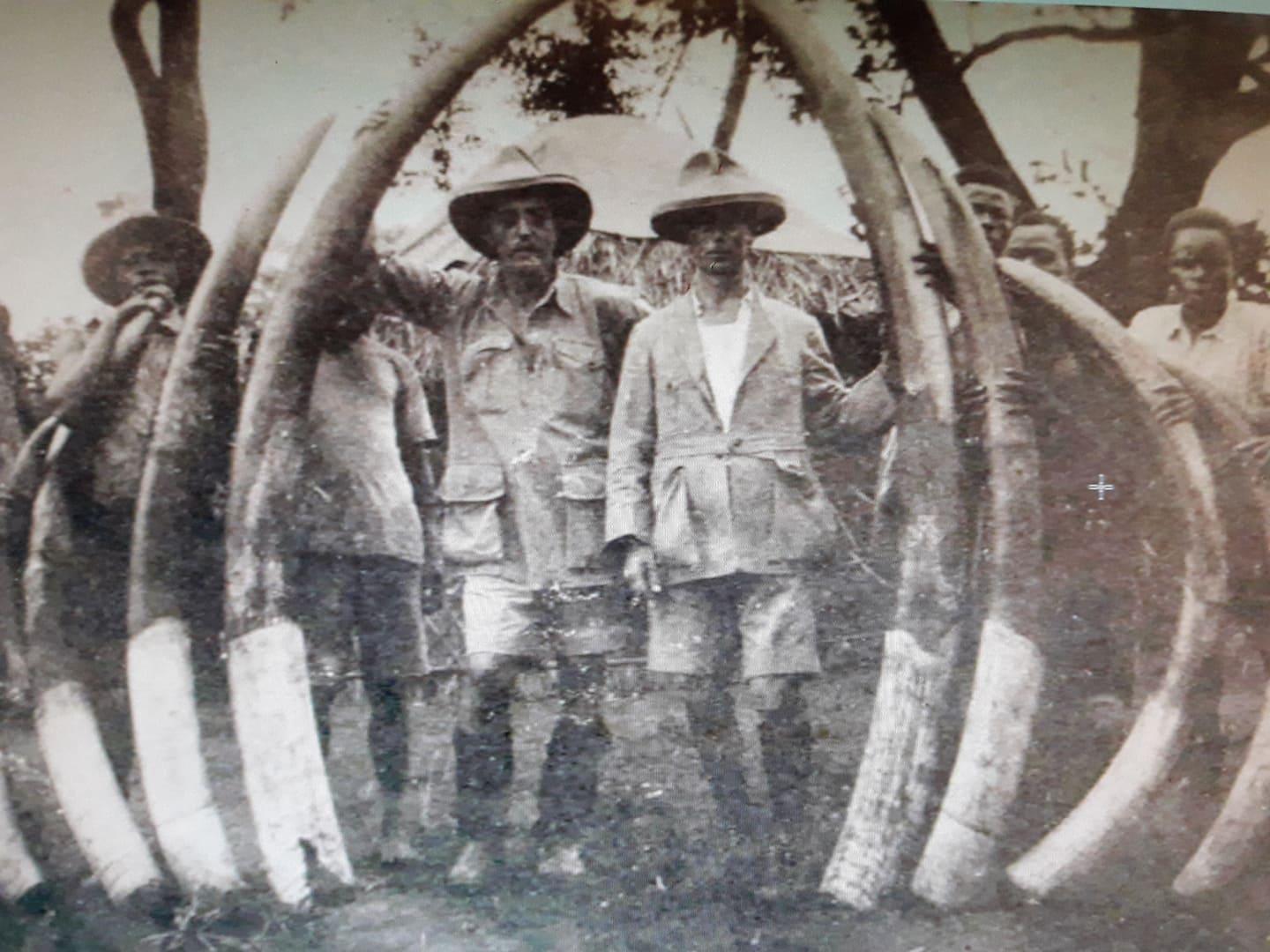

George Gilman Rushby:

The story of George Gilman Rushby 1900-1969, as told by his son Mike:

George Gilman Rushby:

Elephant hunter,poacher, prospector, farmer, forestry officer, game ranger, husband to Eleanor, and father of 6 children who now live around the world.George Gilman Rushby was born in Nottingham on 28 Feb 1900 the son of Catherine Purdy and John Henry Payling Rushby. But John Henry died when his son was only one and a half years old, and George shunned his drunken bullying stepfather Frank Freer and was brought up by Gypsies who taught him how to fight and took him on regular poaching trips. His love of adventure and his ability to hunt were nurtured at an early stage of his life.

The family moved to Eastwood, where his mother Catherine owned and managed The Three Tuns Inn, but when his stepfather died in mysterious circumstances, his mother married a wealthy bookmaker named Gregory Simpson. He could afford to send George to Worksop College and to Rugby School. This was excellent schooling for George, but the boarding school environment, and the lack of a stable home life, contributed to his desire to go out in the world and do his own thing. When he finished school his first job was as a trainee electrician with Oaks & Co at Pye Bridge. He also worked part time as a motor cycle mechanic and as a professional boxer to raise the money for a voyage to South Africa.In May 1920 George arrived in Durban destitute and, like many others, living on the beach and dependant upon the Salvation Army for a daily meal. However he soon got work as an electrical mechanic, and after a couple of months had earned enough money to make the next move North. He went to Lourenco Marques where he was appointed shift engineer for the town’s power station. However he was still restless and left the comfort of Lourenco Marques for Beira in August 1921.

Beira was the start point of the new railway being built from the coast to Nyasaland. George became a professional hunter providing essential meat for the gangs of construction workers building the railway. He was a self employed contractor with his own support crew of African men and began to build up a satisfactory business. However, following an incident where he had to shoot and kill a man who attacked him with a spear in middle of the night whilst he was sleeping, George left the lower Zambezi and took a paddle steamer to Nyasaland (Malawi). On his arrival in Karongo he was encouraged to shoot elephant which had reached plague proportions in the area – wrecking African homes and crops, and threatening the lives of those who opposed them.

His next move was to travel by canoe the five hundred kilometre length of Lake Nyasa to Tanganyika, where he hunted for a while in the Lake Rukwa area, before walking through Northern Rhodesia (Zambia) to the Congo. Hunting his way he overachieved his quota of ivory resulting in his being charged with trespass, the confiscation of his rifles, and a fine of one thousand francs. He hunted his way through the Congo to Leopoldville then on to the Portuguese enclave, near the mouth of the mighty river, where he worked as a barman in a rough and tough bar until he received a message that his old friend Lumb had found gold at Lupa near Chunya. George set sail on the next boat for Antwerp in Belgium, then crossed to England and spent a few weeks with his family in Jacksdale before returning by sea to Dar es Salaam. Arriving at the gold fields he pegged his claim and almost immediately went down with blackwater fever – an illness that used to kill three out of four within a week.

When he recovered from his fever, George exchanged his gold lease for a double barrelled .577 elephant rifle and took out a special elephant control licence with the Tanganyika Government. He then headed for the Congo again and poached elephant in Northern Rhodesia from a base in the Congo. He was known by the Africans as “iNyathi”, or the Buffalo, because he was the most dangerous in the long grass. After a profitable hunting expedition in his favourite hunting ground of the Kilombera River he returned to the Congo via Dar es Salaam and Mombassa. He was after the Kabalo district elephant, but hunting was restricted, so he set up his base in The Central African Republic at a place called Obo on the Congo tributary named the M’bomu River. From there he could make poaching raids into the Congo and the Upper Nile regions of the Sudan. He hunted there for two and a half years. He seldom came across other Europeans; hunters kept their own districts and guarded their own territories. But they respected one another and he made good and lasting friendships with members of that small select band of adventurers.

Leaving for Europe via the Congo, George enjoyed a short holiday in Jacksdale with his mother. On his return trip to East Africa he met his future bride in Cape Town. She was 24 year old Eleanor Dunbar Leslie; a high school teacher and daughter of a magistrate who spent her spare time mountaineering, racing ocean yachts, and riding horses. After a whirlwind romance, they were betrothed within 36 hours.

On 25 July 1930 George landed back in Dar es Salaam. He went directly to the Mbeya district to find a home. For one hundred pounds he purchased the Waizneker’s farm on the banks of the Mntshewe Stream. Eleanor, who had been delayed due to her contract as a teacher, followed in November. Her ship docked in Dar es Salaam on 7 Nov 1930, and they were married that day. At Mchewe Estate, their newly acquired farm, they lived in a tent whilst George with some help built their first home – a lovely mud-brick cottage with a thatched roof. George and Eleanor set about developing a coffee plantation out of a bush block. It was a very happy time for them. There was no electricity, no radio, and no telephone. Newspapers came from London every two months. There were a couple of neighbours within twenty miles, but visitors were seldom seen. The farm was a haven for wild life including snakes, monkeys and leopards. Eleanor had to go South all the way to Capetown for the birth of her first child Ann, but with the onset of civilisation, their first son George was born at a new German Mission hospital that had opened in Mbeya.

Occasionally George had to leave the farm in Eleanor’s care whilst he went off hunting to make his living. Having run the coffee plantation for five years with considerable establishment costs and as yet no return, George reluctantly started taking paying clients on hunting safaris as a “white hunter”. This was an occupation George didn’t enjoy. but it brought him an income in the days when social security didn’t exist. Taking wealthy clients on hunting trips to kill animals for trophies and for pleasure didn’t amuse George who hunted for a business and for a way of life. When one of George’s trackers was killed by a leopard that had been wounded by a careless client, George was particularly upset.

The coffee plantation was approaching the time of its first harvest when it was suddenly attacked by plagues of borer beetles and ring barking snails. At the same time severe hail storms shredded the crop. The pressure of the need for an income forced George back to the Lupa gold fields. He was unlucky in his gold discoveries, but luck came in a different form when he was offered a job with the Forestry Department. The offer had been made in recognition of his initiation and management of Tanganyika’s rainbow trout project. George spent most of his short time with the Forestry Department encouraging the indigenous people to conserve their native forests.In November 1938 he transferred to the Game Department as Ranger for the Eastern Province of Tanganyika, and over several years was based at Nzasa near Dar es Salaam, at the old German town of Morogoro, and at lovely Lyamungu on the slopes of Kilimanjaro. Then the call came for him to be transferred to Mbeya in the Southern Province for there was a serious problem in the Njombe district, and George was selected by the Department as the only man who could possibly fix the problem.

Over a period of several years, people were being attacked and killed by marauding man-eating lions. In the Wagingombe area alone 230 people were listed as having been killed. In the Njombe district, which covered an area about 200 km by 300 km some 1500 people had been killed. Not only was the rural population being decimated, but the morale of the survivors was so low, that many of them believed that the lions were not real. Many thought that evil witch doctors were controlling the lions, or that lion-men were changing form to kill their enemies. Indeed some wichdoctors took advantage of the disarray to settle scores and to kill for reward.

By hunting down and killing the man-eaters, and by showing the flesh and blood to the doubting tribes people, George was able to instil some confidence into the villagers. However the Africans attributed the return of peace and safety, not to the efforts of George Rushby, but to the reinstallation of their deposed chief Matamula Mangera who had previously been stood down for corruption. It was Matamula , in their eyes, who had called off the lions.

Soon after this adventure, George was appointed Deputy Game Warden for Tanganyika, and was based in Arusha. He retired in 1956 to the Njombe district where he developed a coffee plantation, and was one of the first in Tanganyika to plant tea as a major crop. However he sensed a swing in the political fortunes of his beloved Tanganyika, and so sold the plantation and settled in a cottage high on a hill overlooking the Navel Base at Simonstown in the Cape. It was whilst he was there that TV Bulpin wrote his biography “The Hunter is Death” and George wrote his book “No More The Tusker”. He died in the Cape, and his youngest son Henry scattered his ashes at the Southern most tip of Africa where the currents of the Atlantic and Indian Oceans meet .

George Gilman Rushby:

September 25, 2019 at 7:42 am #4830

September 25, 2019 at 7:42 am #4830In reply to: Pop﹡in People Tribulations

“Bloody hell,” said the driver. “Sorry about that. You fellas alright back there?”

“Don’t turn … just keep your eyes on the road … we are fine,” said Maeve. “Are you okay?” she mouthed to Shawn-Paul. He rubbed his temple tentatively and then nodded.

“Yeah, I couldn’t stop,” said the driver. “I’ve only just got my bloody licence back.”

March 31, 2015 at 9:27 am #3733In reply to: Mandala of Ascensions

Geraldine von Truff, also known as Gelly by her friends was sweating profusely and had opened all the windows to get air.

“Fracken hot flashes” she said, taking a wet towel to freshen up. It was barely start of spring, and the temperatures were doing yoyo in the most peculiar fashion.She logged onto Spayce to check if her next client was there. Maybe she’ll put him on audio, because at the rate she was undressing, he would wonder whether he’d signed on the right account. After all, she was a licenced psychoregressor and helped her clients connect to their subconscious in hypnotic trances. This was all very serious.

Actually, to be honest, she was quite baffled by the crock of bollocks the subconscious was telling at times, but hell, it was cathartic for her clients, and their well-being was her utmost priority.

“James? Are you here?”

James was her client from Glasgow, an affable middle-aged man, who seemed to have taken to her robotic German accent and her hypnoregressive sessions.“Yes, Doctor” the sound came in all distorted. “Is it normal I don’t have visual?”

“Ja, alles ist gut my friend, the internet is playing tricks today. Let’s have it just audio, OK?”

“Alright then.”

“I think our session today will be splendid. I already feel all the energies building up.”February 21, 2008 at 3:32 pm #1708In reply to: Synchronicity

Eric gently reminded me (thanks

) that the licence plate of the car was