Search Results for 'nature'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

December 6, 2022 at 2:17 pm #6350

In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Transportation

Isaac Stokes 1804-1877

Isaac was born in Churchill, Oxfordshire in 1804, and was the youngest brother of my 4X great grandfather Thomas Stokes. The Stokes family were stone masons for generations in Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire, and Isaac’s occupation was a mason’s labourer in 1834 when he was sentenced at the Lent Assizes in Oxford to fourteen years transportation for stealing tools.

Churchill where the Stokes stonemasons came from: on 31 July 1684 a fire destroyed 20 houses and many other buildings, and killed four people. The village was rebuilt higher up the hill, with stone houses instead of the old timber-framed and thatched cottages. The fire was apparently caused by a baker who, to avoid chimney tax, had knocked through the wall from her oven to her neighbour’s chimney.

Isaac stole a pick axe, the value of 2 shillings and the property of Thomas Joyner of Churchill; a kibbeaux and a trowel value 3 shillings the property of Thomas Symms; a hammer and axe value 5 shillings, property of John Keen of Sarsden.

(The word kibbeaux seems to only exists in relation to Isaac Stokes sentence and whoever was the first to write it was perhaps being creative with the spelling of a kibbo, a miners or a metal bucket. This spelling is repeated in the criminal reports and the newspaper articles about Isaac, but nowhere else).

In March 1834 the Removal of Convicts was announced in the Oxford University and City Herald: Isaac Stokes and several other prisoners were removed from the Oxford county gaol to the Justitia hulk at Woolwich “persuant to their sentences of transportation at our Lent Assizes”.

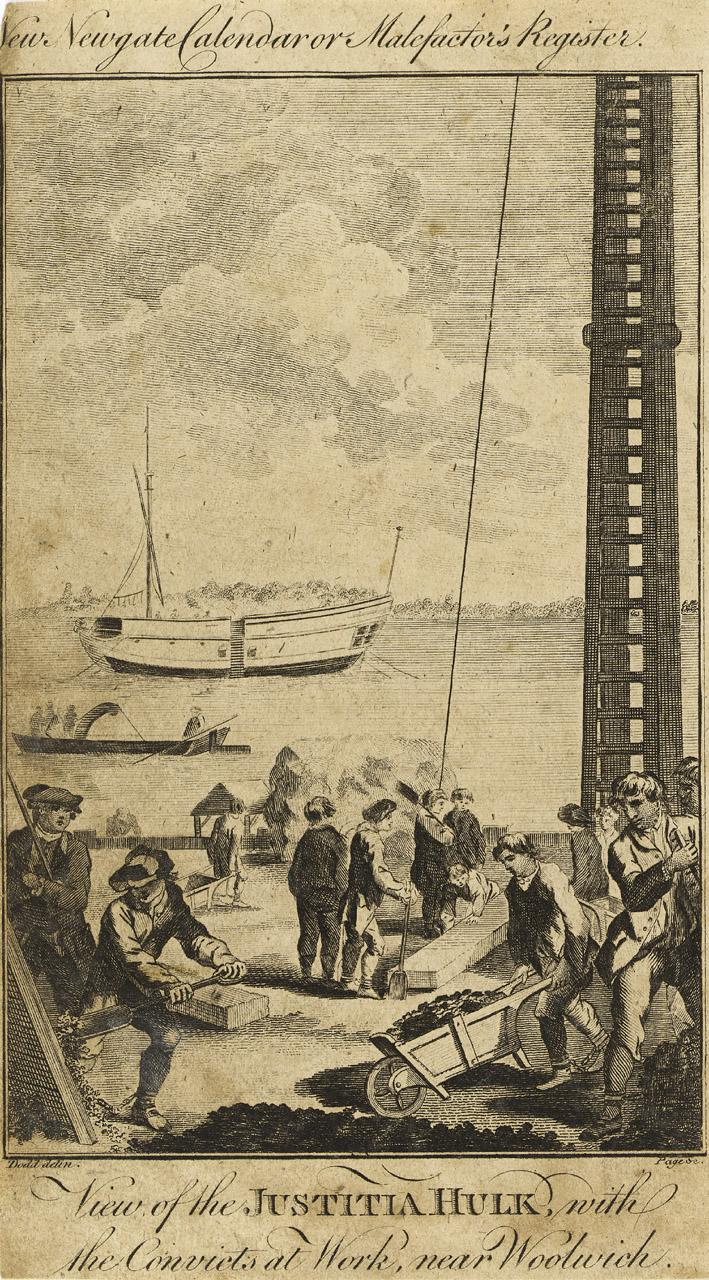

via digitalpanopticon:

Hulks were decommissioned (and often unseaworthy) ships that were moored in rivers and estuaries and refitted to become floating prisons. The outbreak of war in America in 1775 meant that it was no longer possible to transport British convicts there. Transportation as a form of punishment had started in the late seventeenth century, and following the Transportation Act of 1718, some 44,000 British convicts were sent to the American colonies. The end of this punishment presented a major problem for the authorities in London, since in the decade before 1775, two-thirds of convicts at the Old Bailey received a sentence of transportation – on average 283 convicts a year. As a result, London’s prisons quickly filled to overflowing with convicted prisoners who were sentenced to transportation but had no place to go.

To increase London’s prison capacity, in 1776 Parliament passed the “Hulks Act” (16 Geo III, c.43). Although overseen by local justices of the peace, the hulks were to be directly managed and maintained by private contractors. The first contract to run a hulk was awarded to Duncan Campbell, a former transportation contractor. In August 1776, the Justicia, a former transportation ship moored in the River Thames, became the first prison hulk. This ship soon became full and Campbell quickly introduced a number of other hulks in London; by 1778 the fleet of hulks on the Thames held 510 prisoners.

Demand was so great that new hulks were introduced across the country. There were hulks located at Deptford, Chatham, Woolwich, Gosport, Plymouth, Portsmouth, Sheerness and Cork.The Justitia via rmg collections:

Convicts perform hard labour at the Woolwich Warren. The hulk on the river is the ‘Justitia’. Prisoners were kept on board such ships for months awaiting deportation to Australia. The ‘Justitia’ was a 260 ton prison hulk that had been originally moored in the Thames when the American War of Independence put a stop to the transportation of criminals to the former colonies. The ‘Justitia’ belonged to the shipowner Duncan Campbell, who was the Government contractor who organized the prison-hulk system at that time. Campbell was subsequently involved in the shipping of convicts to the penal colony at Botany Bay (in fact Port Jackson, later Sydney, just to the north) in New South Wales, the ‘first fleet’ going out in 1788.

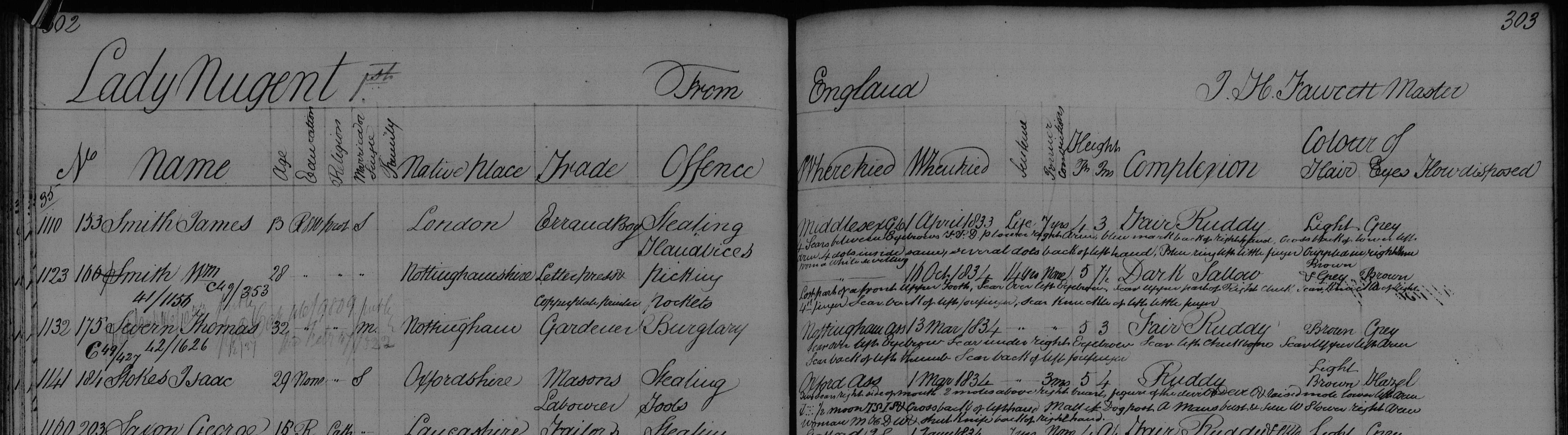

While searching for records for Isaac Stokes I discovered that another Isaac Stokes was transported to New South Wales in 1835 as well. The other one was a butcher born in 1809, sentenced in London for seven years, and he sailed on the Mary Ann. Our Isaac Stokes sailed on the Lady Nugent, arriving in NSW in April 1835, having set sail from England in December 1834.

Lady Nugent was built at Bombay in 1813. She made four voyages under contract to the British East India Company (EIC). She then made two voyages transporting convicts to Australia, one to New South Wales and one to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). (via Wikipedia)

via freesettlerorfelon website:

On 20 November 1834, 100 male convicts were transferred to the Lady Nugent from the Justitia Hulk and 60 from the Ganymede Hulk at Woolwich, all in apparent good health. The Lady Nugent departed Sheerness on 4 December 1834.

SURGEON OLIVER SPROULE

Oliver Sproule kept a Medical Journal from 7 November 1834 to 27 April 1835. He recorded in his journal the weather conditions they experienced in the first two weeks:

‘In the course of the first week or ten days at sea, there were eight or nine on the sick list with catarrhal affections and one with dropsy which I attribute to the cold and wet we experienced during that period beating down channel. Indeed the foremost berths in the prison at this time were so wet from leaking in that part of the ship, that I was obliged to issue dry beds and bedding to a great many of the prisoners to preserve their health, but after crossing the Bay of Biscay the weather became fine and we got the damp beds and blankets dried, the leaks partially stopped and the prison well aired and ventilated which, I am happy to say soon manifested a favourable change in the health and appearance of the men.

Besides the cases given in the journal I had a great many others to treat, some of them similar to those mentioned but the greater part consisted of boils, scalds, and contusions which would not only be too tedious to enter but I fear would be irksome to the reader. There were four births on board during the passage which did well, therefore I did not consider it necessary to give a detailed account of them in my journal the more especially as they were all favourable cases.

Regularity and cleanliness in the prison, free ventilation and as far as possible dry decks turning all the prisoners up in fine weather as we were lucky enough to have two musicians amongst the convicts, dancing was tolerated every afternoon, strict attention to personal cleanliness and also to the cooking of their victuals with regular hours for their meals, were the only prophylactic means used on this occasion, which I found to answer my expectations to the utmost extent in as much as there was not a single case of contagious or infectious nature during the whole passage with the exception of a few cases of psora which soon yielded to the usual treatment. A few cases of scurvy however appeared on board at rather an early period which I can attribute to nothing else but the wet and hardships the prisoners endured during the first three or four weeks of the passage. I was prompt in my treatment of these cases and they got well, but before we arrived at Sydney I had about thirty others to treat.’

The Lady Nugent arrived in Port Jackson on 9 April 1835 with 284 male prisoners. Two men had died at sea. The prisoners were landed on 27th April 1835 and marched to Hyde Park Barracks prior to being assigned. Ten were under the age of 14 years.

The Lady Nugent:

Isaac’s distinguishing marks are noted on various criminal registers and record books:

“Height in feet & inches: 5 4; Complexion: Ruddy; Hair: Light brown; Eyes: Hazel; Marks or Scars: Yes [including] DEVIL on lower left arm, TSIS back of left hand, WS lower right arm, MHDW back of right hand.”

Another includes more detail about Isaac’s tattoos:

“Two slight scars right side of mouth, 2 moles above right breast, figure of the devil and DEVIL and raised mole, lower left arm; anchor, seven dots half moon, TSIS and cross, back of left hand; a mallet, door post, A, mans bust, sun, WS, lower right arm; woman, MHDW and shut knife, back of right hand.”

From How tattoos became fashionable in Victorian England (2019 article in TheConversation by Robert Shoemaker and Zoe Alkar):

“Historical tattooing was not restricted to sailors, soldiers and convicts, but was a growing and accepted phenomenon in Victorian England. Tattoos provide an important window into the lives of those who typically left no written records of their own. As a form of “history from below”, they give us a fleeting but intriguing understanding of the identities and emotions of ordinary people in the past.

As a practice for which typically the only record is the body itself, few systematic records survive before the advent of photography. One exception to this is the written descriptions of tattoos (and even the occasional sketch) that were kept of institutionalised people forced to submit to the recording of information about their bodies as a means of identifying them. This particularly applies to three groups – criminal convicts, soldiers and sailors. Of these, the convict records are the most voluminous and systematic.

Such records were first kept in large numbers for those who were transported to Australia from 1788 (since Australia was then an open prison) as the authorities needed some means of keeping track of them.”On the 1837 census Isaac was working for the government at Illiwarra, New South Wales. This record states that he arrived on the Lady Nugent in 1835. There are three other indent records for an Isaac Stokes in the following years, but the transcriptions don’t provide enough information to determine which Isaac Stokes it was. In April 1837 there was an abscondment, and an arrest/apprehension in May of that year, and in 1843 there was a record of convict indulgences.

From the Australian government website regarding “convict indulgences”:

“By the mid-1830s only six per cent of convicts were locked up. The vast majority worked for the government or free settlers and, with good behaviour, could earn a ticket of leave, conditional pardon or and even an absolute pardon. While under such orders convicts could earn their own living.”

In 1856 in Camden, NSW, Isaac Stokes married Catherine Daly. With no further information on this record it would be impossible to know for sure if this was the right Isaac Stokes. This couple had six children, all in the Camden area, but none of the records provided enough information. No occupation or place or date of birth recorded for Isaac Stokes.

I wrote to the National Library of Australia about the marriage record, and their reply was a surprise! Issac and Catherine were married on 30 September 1856, at the house of the Rev. Charles William Rigg, a Methodist minister, and it was recorded that Isaac was born in Edinburgh in 1821, to parents James Stokes and Sarah Ellis! The age at the time of the marriage doesn’t match Isaac’s age at death in 1877, and clearly the place of birth and parents didn’t match either. Only his fathers occupation of stone mason was correct. I wrote back to the helpful people at the library and they replied that the register was in a very poor condition and that only two and a half entries had survived at all, and that Isaac and Catherines marriage was recorded over two pages.

I searched for an Isaac Stokes born in 1821 in Edinburgh on the Scotland government website (and on all the other genealogy records sites) and didn’t find it. In fact Stokes was a very uncommon name in Scotland at the time. I also searched Australian immigration and other records for another Isaac Stokes born in Scotland or born in 1821, and found nothing. I was unable to find a single record to corroborate this mysterious other Isaac Stokes.

As the age at death in 1877 was correct, I assume that either Isaac was lying, or that some mistake was made either on the register at the home of the Methodist minster, or a subsequent mistranscription or muddle on the remnants of the surviving register. Therefore I remain convinced that the Camden stonemason Isaac Stokes was indeed our Isaac from Oxfordshire.

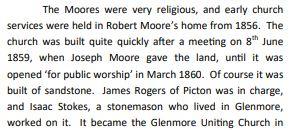

I found a history society newsletter article that mentioned Isaac Stokes, stone mason, had built the Glenmore church, near Camden, in 1859.

From the Wollondilly museum April 2020 newsletter:

From the Camden History website:

“The stone set over the porch of Glenmore Church gives the date of 1860. The church was begun in 1859 on land given by Joseph Moore. James Rogers of Picton was given the contract to build and local builder, Mr. Stokes, carried out the work. Elizabeth Moore, wife of Edward, laid the foundation stone. The first service was held on 19th March 1860. The cemetery alongside the church contains the headstones and memorials of the areas early pioneers.”

Isaac died on the 3rd September 1877. The inquest report puts his place of death as Bagdelly, near to Camden, and another death register has put Cambelltown, also very close to Camden. His age was recorded as 71 and the inquest report states his cause of death was “rupture of one of the large pulmonary vessels of the lung”. His wife Catherine died in childbirth in 1870 at the age of 43.

Isaac and Catherine’s children:

William Stokes 1857-1928

Catherine Stokes 1859-1846

Sarah Josephine Stokes 1861-1931

Ellen Stokes 1863-1932

Rosanna Stokes 1865-1919

Louisa Stokes 1868-1844.

It’s possible that Catherine Daly was a transported convict from Ireland.

Some time later I unexpectedly received a follow up email from The Oaks Heritage Centre in Australia.

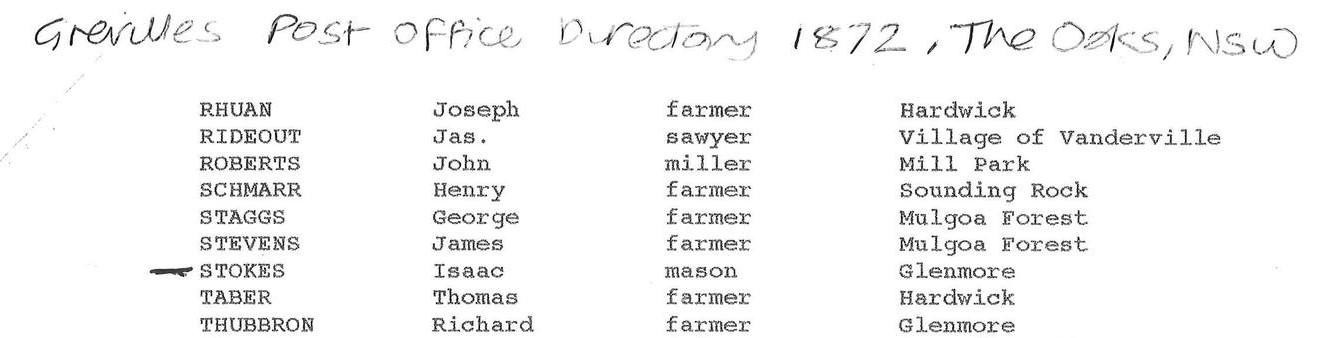

“The Gaudry papers which we have in our archive record him (Isaac Stokes) as having built: the church, the school and the teachers residence. Isaac is recorded in the General return of convicts: 1837 and in Grevilles Post Office directory 1872 as a mason in Glenmore.”

November 10, 2022 at 10:59 am #6343

November 10, 2022 at 10:59 am #6343In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum

William James Stokes

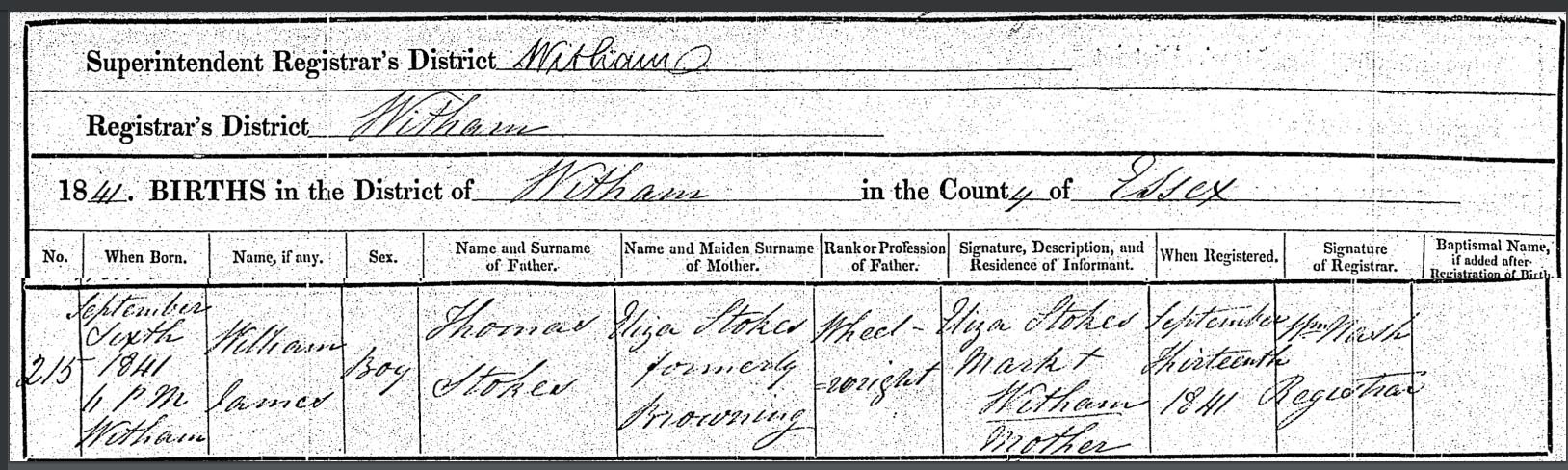

William James Stokes was the first son of Thomas Stokes and Eliza Browning. Oddly, his birth was registered in Witham in Essex, on the 6th September 1841.

Birth certificate of William James Stokes:

His father Thomas Stokes has not yet been found on the 1841 census, and his mother Eliza was staying with her uncle Thomas Lock in Cirencester in 1841. Eliza’s mother Mary Browning (nee Lock) was staying there too. Thomas and Eliza were married in September 1840 in Hempstead in Gloucestershire.

It’s a mystery why William was born in Essex but one possibility is that his father Thomas, who later worked with the Chipperfields making circus wagons, was staying with the Chipperfields who were wheelwrights in Witham in 1841. Or perhaps even away with a traveling circus at the time of the census, learning the circus waggon wheelwright trade. But this is a guess and it’s far from clear why Eliza would make the journey to Witham to have the baby when she was staying in Cirencester a few months prior.

In 1851 Thomas and Eliza, William and four younger siblings were living in Bledington in Oxfordshire.

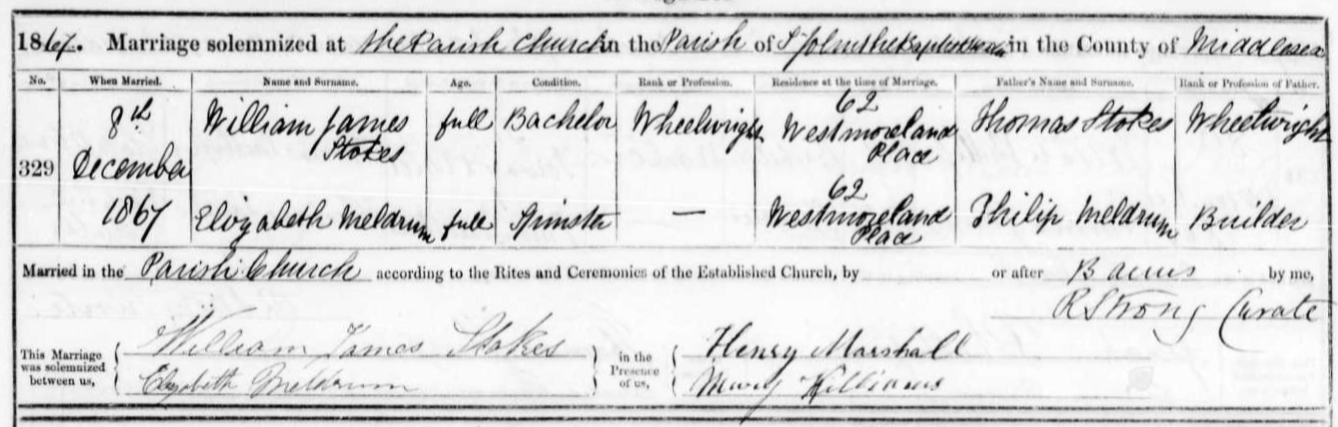

William was a 19 year old wheelwright living with his parents in Evesham in 1861. He married Elizabeth Meldrum in December 1867 in Hackney, London. He and his father are both wheelwrights on the marriage register.

Marriage of William James Stokes and Elizabeth Meldrum in 1867:

William and Elizabeth had a daughter, Elizabeth Emily Stokes, in 1868 in Shoreditch, London.

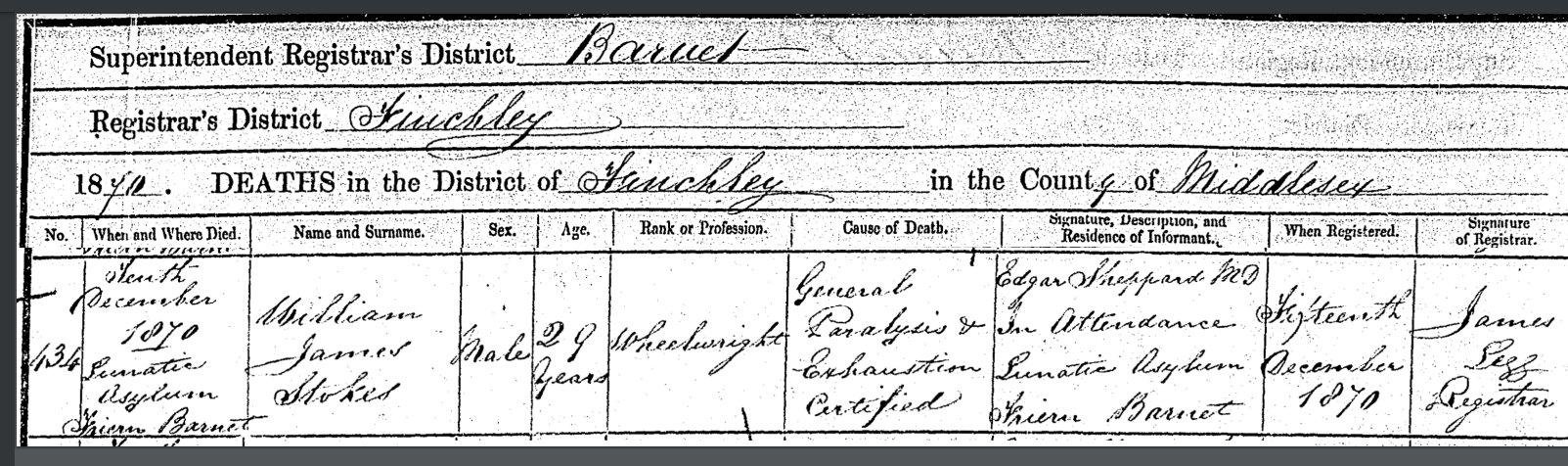

On the 3rd of December 1870, William James Stokes was admitted to Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum. One week later on the 10th of December, he was dead.

On his death certificate the cause of death was “general paralysis and exhaustion, certified. MD Edgar Sheppard in attendance.” William was just 29 years old.

Death certificate William James Stokes:

I asked on a genealogy forum what could possibly have caused this death at such a young age. A retired pathology professor replied that “in medicine the term General Paralysis is only used in one context – that of Tertiary Syphilis.”

“Tertiary syphilis is the third and final stage of syphilis, a sexually transmitted disease that unfolds in stages when the individual affected doesn’t receive appropriate treatment.”From the article “Looking back: This fascinating and fatal disease” by Jennifer Wallis:

“……in asylums across Britain in the late 19th century, with hundreds of people receiving the diagnosis of general paralysis of the insane (GPI). The majority of these were men in their 30s and 40s, all exhibiting one or more of the disease’s telltale signs: grandiose delusions, a staggering gait, disturbed reflexes, asymmetrical pupils, tremulous voice, and muscular weakness. Their prognosis was bleak, most dying within months, weeks, or sometimes days of admission.

The fatal nature of GPI made it of particular concern to asylum superintendents, who became worried that their institutions were full of incurable cases requiring constant care. The social effects of the disease were also significant, attacking men in the prime of life whose admission to the asylum frequently left a wife and children at home. Compounding the problem was the erratic behaviour of the general paralytic, who might get themselves into financial or legal difficulties. Delusions about their vast wealth led some to squander scarce family resources on extravagant purchases – one man’s wife reported he had bought ‘a quantity of hats’ despite their meagre income – and doctors pointed to the frequency of thefts by general paralytics who imagined that everything belonged to them.”

The London Archives hold the records for Colney Hatch, but they informed me that the particular records for the dates that William was admitted and died were in too poor a condition to be accessed without causing further damage.

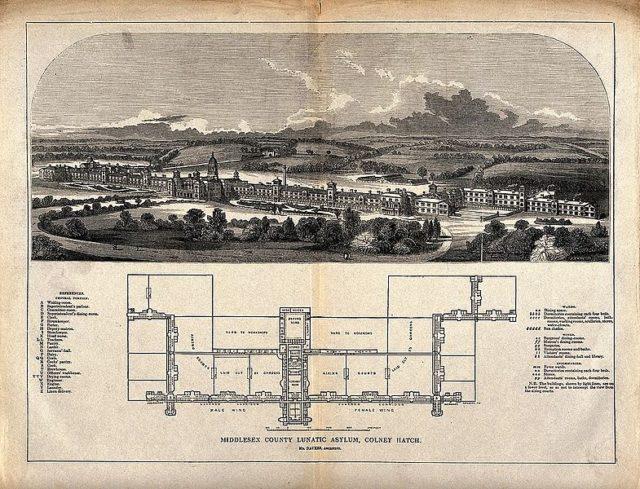

Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum gained such notoriety that the name “Colney Hatch” appeared in various terms of abuse associated with the concept of madness. Infamous inmates that were institutionalized at Colney Hatch (later called Friern Hospital) include Jack the Ripper suspect Aaron Kosminski from 1891, and from 1911 the wife of occultist Aleister Crowley. In 1993 the hospital grounds were sold and the exclusive apartment complex called Princess Park Manor was built.

Colney Hatch:

In 1873 Williams widow married William Hallam in Limehouse in London. Elizabeth died in 1930, apparently unaffected by her first husbands ailment.

October 23, 2022 at 6:57 am #6340In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Wheelwrights of Broadway

Thomas Stokes 1816-1885

Frederick Stokes 1845-1917

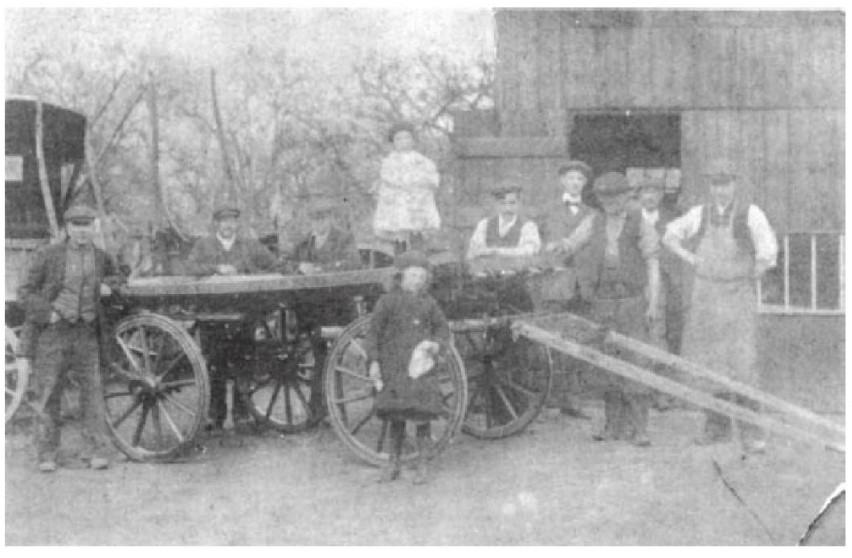

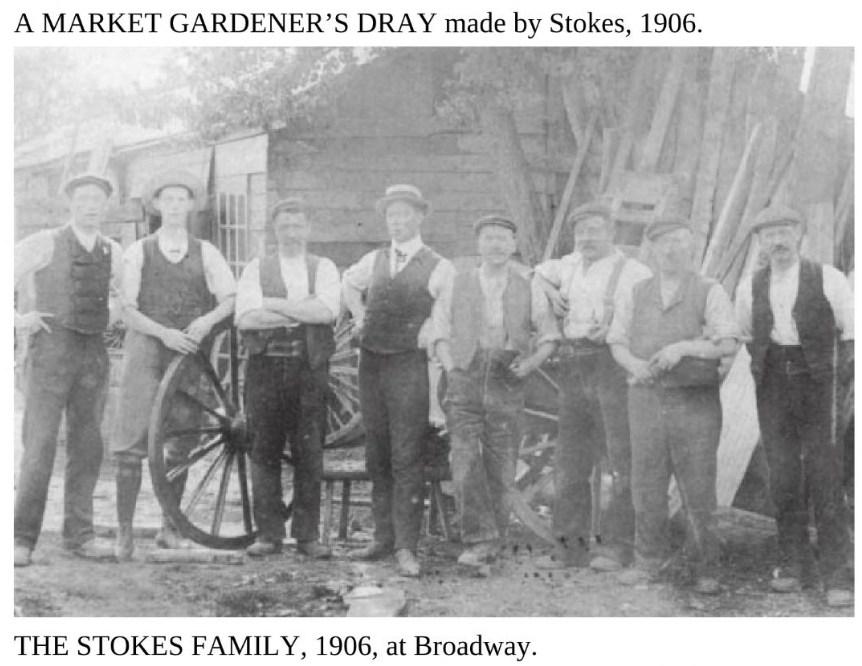

Stokes Wheelwrights. Fred on left of wheel, Thomas his father on right.

Thomas Stokes

Thomas Stokes was born in Bicester, Oxfordshire in 1816. He married Eliza Browning (born in 1814 in Tetbury, Gloucestershire) in Gloucester in 1840 Q3. Their first son William was baptised in Chipping Hill, Witham, Essex, on 3 Oct 1841. This seems a little unusual, and I can’t find Thomas and Eliza on the 1841 census. However both the 1851 and 1861 census state that William was indeed born in Essex.

In 1851 Thomas and Eliza were living in Bledington, Gloucestershire, and Thomas was a journeyman carpenter.

Note that a journeyman does not mean someone who moved around a lot. A journeyman was a tradesman who had served his trade apprenticeship and mastered his craft, not bound to serve a master, but originally hired by the day. The name derives from the French for day – jour.

Also on the 1851 census: their daughter Susan, born in Churchill Oxfordshire in 1844; son Frederick born in Bledington Gloucestershire in 1846; daughter Louisa born in Foxcote Oxfordshire in 1849; and 2 month old daughter Harriet born in Bledington in 1851.

On the 1861 census Thomas and Eliza were living in Evesham, Worcestershire, and daughter Susan was no longer living at home, but William, Fred, Louisa and Harriet were, as well as daughter Emily born in Churchill Oxfordshire in 1856. Thomas was a wheelwright.

On the 1871 census Thomas and Eliza were still living in Evesham, and Thomas was a wheelwright employing three apprentices. Son Fred, also a wheelwright, and his wife Ann Rebecca live with them.

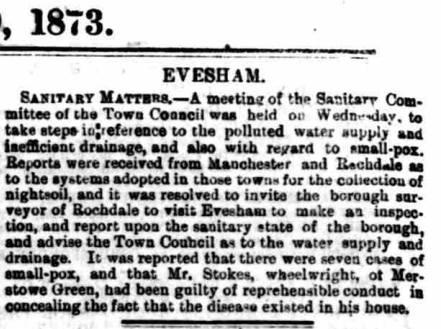

Mr Stokes, wheelwright, was found guilty of reprehensible conduct in concealing the fact that small-pox existed in his house, according to a mention in The Oxfordshire Weekly News on Wednesday 19 February 1873:

From Paul Weaver’s ancestry website:

“It was Thomas Stokes who built the first “Famous Vale of Evesham Light Gardening Dray for a Half-Legged Horse to Trot” (the quotation is from his account book), the forerunner of many that became so familiar a sight in the towns and villages from the 1860s onwards. He built many more for the use of the Vale gardeners.

Thomas also had long-standing business dealings with the people of the circus and fairgrounds, and had a contract to effect necessary repairs and renewals to their waggons whenever they visited the district. He built living waggons for many of the show people’s families as well as shooting galleries and other equipment peculiar to the trade of his wandering customers, and among the names figuring in his books are some still familiar today, such as Wilsons and Chipperfields.

He is also credited with inventing the wooden “Mushroom” which was used by housewives for many years to darn socks. He built and repaired all kinds of vehicles for the gentry as well as for the circus and fairground travellers.

Later he lived with his wife at Merstow Green, Evesham, in a house adjoining the Almonry.”

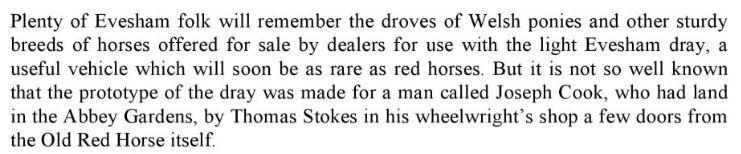

An excerpt from the book Evesham Inns and Signs by T.J.S. Baylis:

The Old Red Horse, Evesham:

Thomas died in 1885 aged 68 of paralysis, bronchitis and debility. His wife Eliza a year later in 1886.

Frederick Stokes

In Worcester in 1870 Fred married Ann Rebecca Day, who was born in Evesham in 1845.

Ann Rebecca Day:

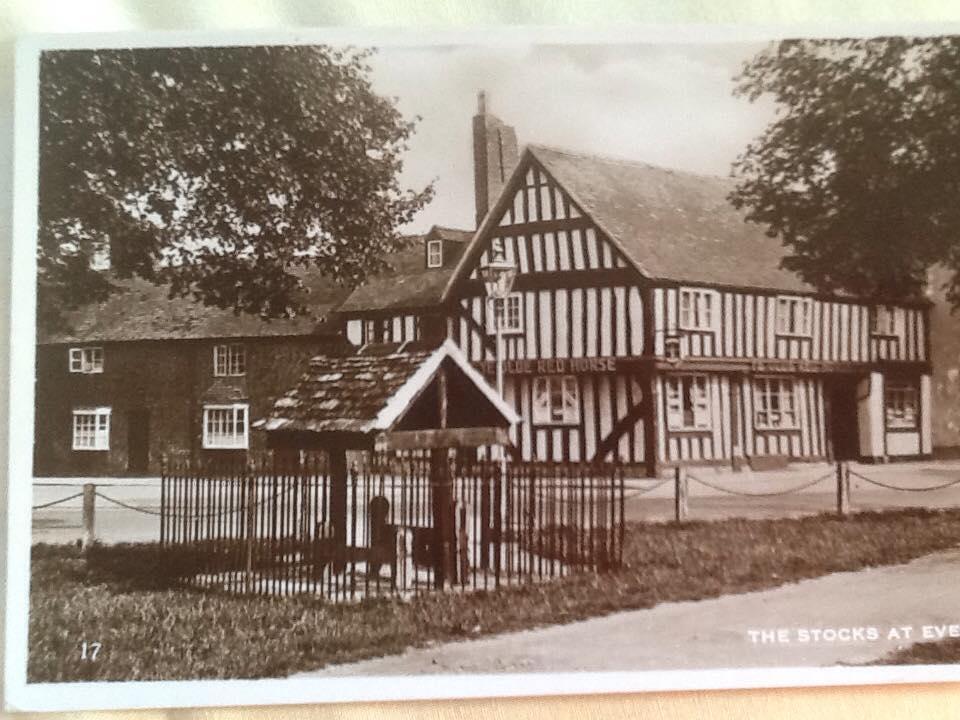

In 1871 Fred was still living with his parents in Evesham, with his wife Ann Rebecca as well as their three month old daughter Annie Elizabeth. Fred and Ann (referred to as Rebecca) moved to La Quinta on Main Street, Broadway.

Rebecca Stokes in the doorway of La Quinta on Main Street Broadway, with her grandchildren Ralph and Dolly Edwards:

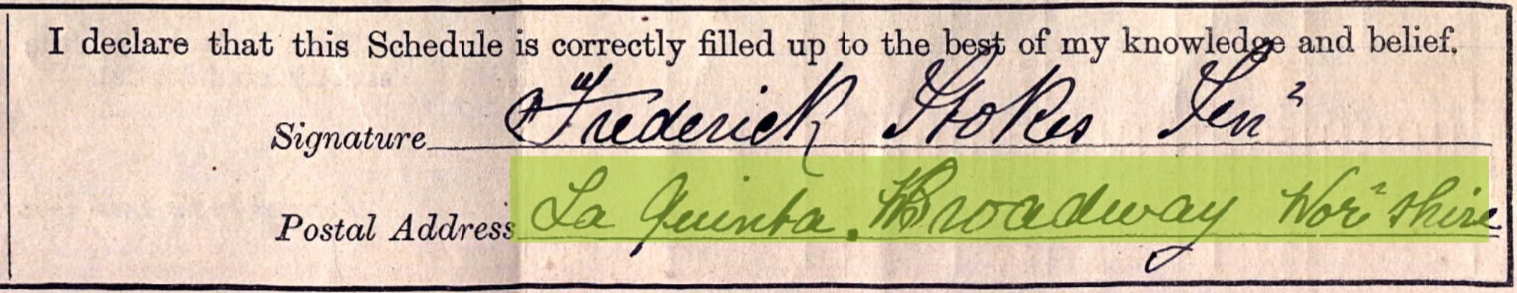

Fred was a wheelwright employing one man on the 1881 census. In 1891 they were still in Broadway, Fred’s occupation was wheelwright and coach painter, as well as his fifteen year old son Frederick.

In the Evesham Journal on Saturday 10 December 1892 it was reported that “Two cases of scarlet fever, the children of Mr. Stokes, wheelwright, Broadway, were certified by Mr. C. W. Morris to be isolated.”

Still in Broadway in 1901 and Fred’s son Albert was also a wheelwright. By 1911 Fred and Rebecca had only one son living at home in Broadway, Reginald, who was a coach painter. Fred was still a wheelwright aged 65.

Fred’s signature on the 1911 census:

Rebecca died in 1912 and Fred in 1917.

Fred Stokes:

In the book Evesham to Bredon From Old Photographs By Fred Archer:

July 6, 2022 at 9:47 am #6310

July 6, 2022 at 9:47 am #6310In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

Olek wished he wasn’t so easy to find.

The old caretaker of the shrine of Saint Edigna couldn’t have chosen a less conspicuous place to live in this warring time. People were flocking from afar, more and more each day drawn about by the ancient place, and the sacred oil bleeding linden tree which had suddenly and quite miraculously resumed its flow in the midst of the ambiant chaos started by the war.

It wasn’t always like this. A few months ago, the linden tree was just an old linden tree that may or may not have been miraculous, if the old wifes’ tales were to be trusted. Mankind’s memory is a flimsy thing as it occurs, and while for many generations before, speculations had abounded about whether or not the Saint was real, had such or such filiation, et cætera— it now seemed the old tales that were passed down from mother to children had managed to keep alive a knowledge that had but all dried up on old flaky parchments scribbled in pale inks that kept eluding old scholars’ exegesis.

Olek himself wasn’t a learned man. A man of faith, he was a little — more by upbringing than by choice, and by slow attunement to nature it would seem. Over the years, he’d be servicing the country in many ways, and after a rather long carrier started at young age, he had finally managed to retire in this place.

He thought he’d be left alone, to care for a little garden patch, checking in from times to times on the old grumpy neighbours, but alas, the Holy Nation’s destiny still had something in store for him.The latest pilgrim family had brought a message. It was another push to action. “Plan acceleration needs to happen”.

“What clucking plan again?” was his first reaction. Bad temper had a way of flaring right up his vents as in old times. When he’d calmed down, he wondered if he had ever seen a call for slowing down in his life. People were always so busy mindlessly carting around, bumping into the darkness.He smiled thinking of something his old man used to say. He’d never planned for a thing in his life, and was always very carefree it was often scary. His mantra was “People are always getting prepared for the wrong things. They never can prepare for the unexpected, and surely enough, only the unexpected happens.”

That sort of chaos paddling approach to life didn’t seem to bring him any sort of extraordinary success, and while he had the same mixed bag of ups and downs as the rest of his compatriots, just so much less did he suffer for the same result! Olek guessed that was the whole point, even if he really couldn’t accept it until much later in life.Maybe Olek would start playing by his father’s book. Until he could find a way to get lost behind enemy lines.

July 1, 2022 at 9:51 am #6306In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Looking for Robert Staley

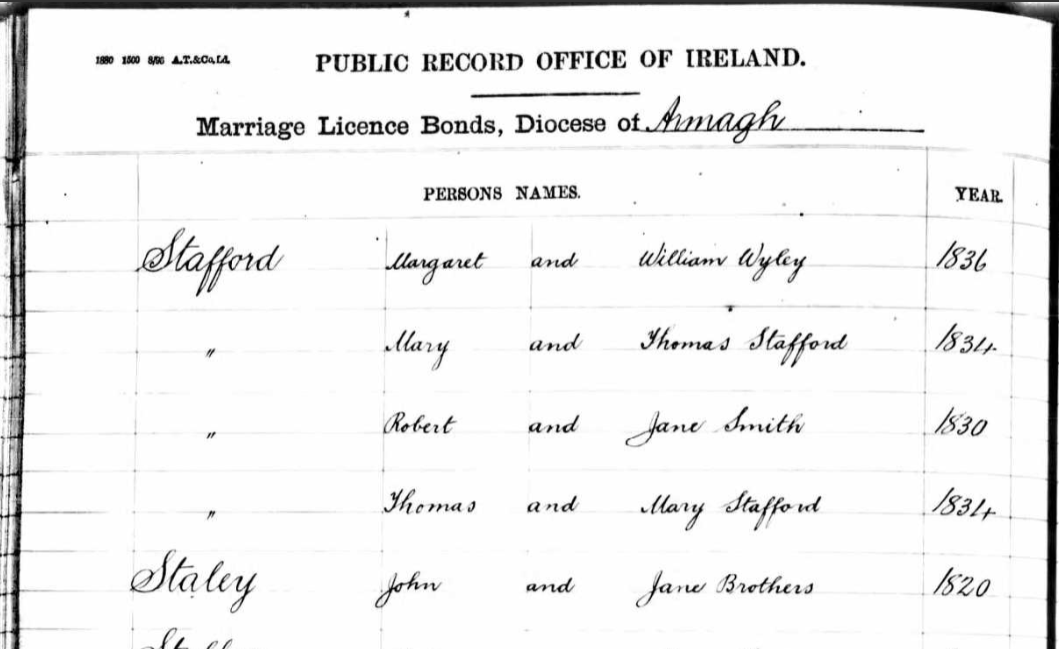

William Warren (1835-1880) of Newhall (Stapenhill) married Elizabeth Staley (1836-1907) in 1858. Elizabeth was born in Newhall, the daughter of John Staley (1795-1876) and Jane Brothers. John was born in Newhall, and Jane was born in Armagh, Ireland, and they were married in Armagh in 1820. Elizabeths older brothers were born in Ireland: William in 1826 and Thomas in Dublin in 1830. Francis was born in Liverpool in 1834, and then Elizabeth in Newhall in 1836; thereafter the children were born in Newhall.

Marriage of John Staley and Jane Brothers in 1820:

My grandmother related a story about an Elizabeth Staley who ran away from boarding school and eloped to Ireland, but later returned. The only Irish connection found so far is Jane Brothers, so perhaps she meant Elizabeth Staley’s mother. A boarding school seems unlikely, and it would seem that it was John Staley who went to Ireland.

The 1841 census states Jane’s age as 33, which would make her just 12 at the time of her marriage. The 1851 census states her age as 44, making her 13 at the time of her 1820 marriage, and the 1861 census estimates her birth year as a more likely 1804. Birth records in Ireland for her have not been found. It’s possible, perhaps, that she was in service in the Newhall area as a teenager (more likely than boarding school), and that John and Jane ran off to get married in Ireland, although I haven’t found any record of a child born to them early in their marriage. John was an agricultural labourer, and later a coal miner.

John Staley was the son of Joseph Staley (1756-1838) and Sarah Dumolo (1764-). Joseph and Sarah were married by licence in Newhall in 1782. Joseph was a carpenter on the marriage licence, but later a collier (although not necessarily a miner).

The Derbyshire Record Office holds records of an “Estimate of Joseph Staley of Newhall for the cost of continuing to work Pisternhill Colliery” dated 1820 and addresssed to Mr Bloud at Calke Abbey (presumably the owner of the mine)

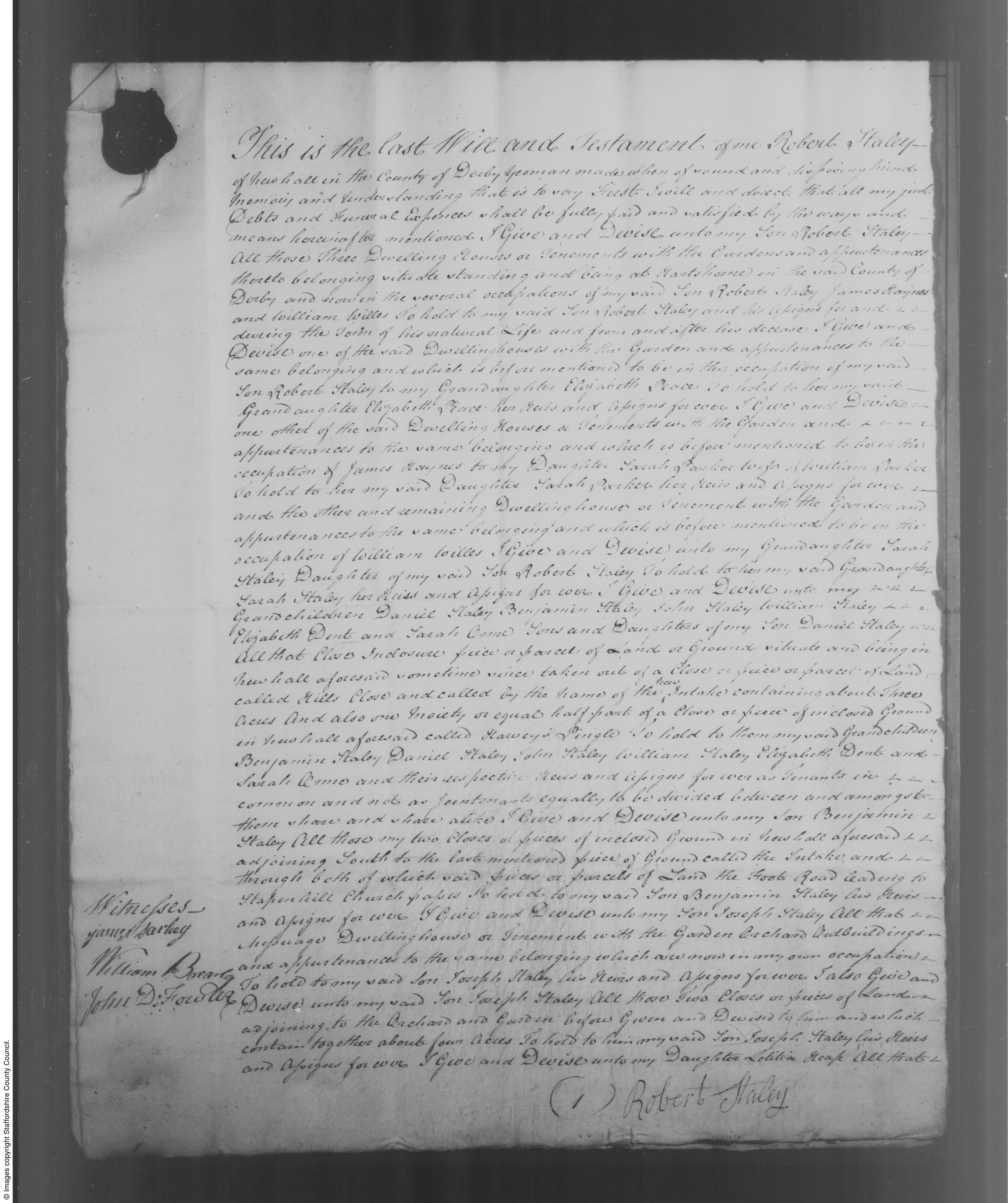

Josephs parents were Robert Staley and Elizabeth. I couldn’t find a baptism or birth record for Robert Staley. Other trees on an ancestry site had his birth in Elton, but with no supporting documents. Robert, as stated in his 1795 will, was a Yeoman.

“Yeoman: A former class of small freeholders who farm their own land; a commoner of good standing.”

“Husbandman: The old word for a farmer below the rank of yeoman. A husbandman usually held his land by copyhold or leasehold tenure and may be regarded as the ‘average farmer in his locality’. The words ‘yeoman’ and ‘husbandman’ were gradually replaced in the later 18th and 19th centuries by ‘farmer’.”He left a number of properties in Newhall and Hartshorne (near Newhall) including dwellings, enclosures, orchards, various yards, barns and acreages. It seemed to me more likely that he had inherited them, rather than moving into the village and buying them.

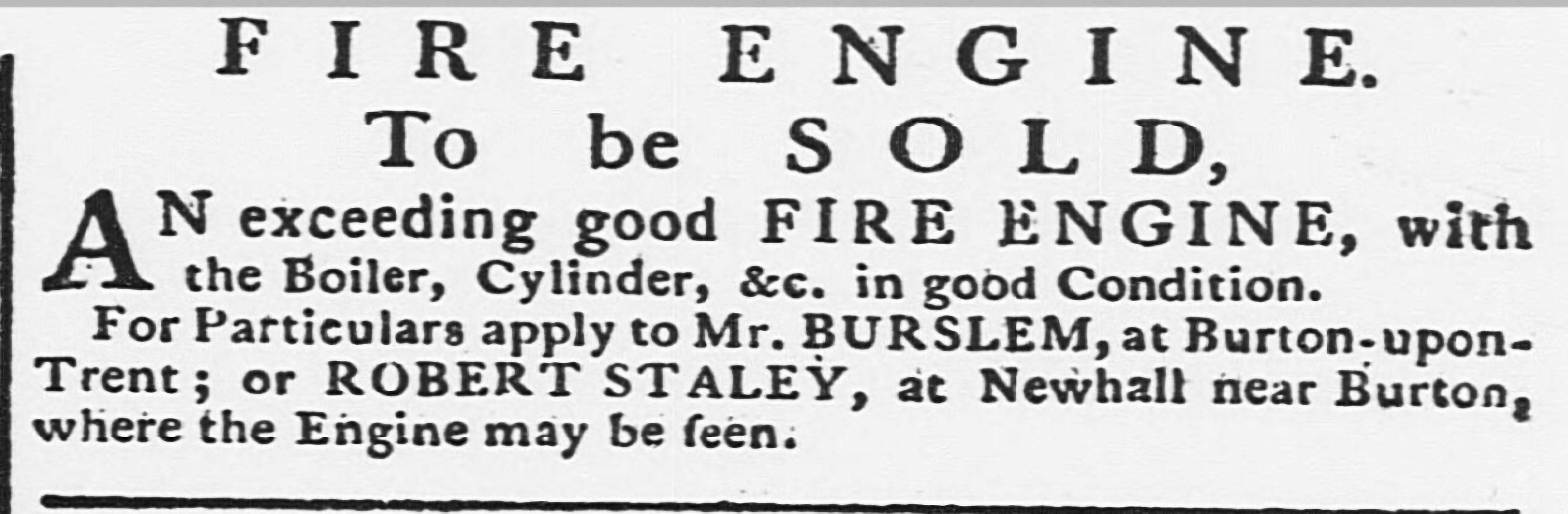

There is a mention of Robert Staley in a 1782 newpaper advertisement.

“Fire Engine To Be Sold. An exceedingly good fire engine, with the boiler, cylinder, etc in good condition. For particulars apply to Mr Burslem at Burton-upon-Trent, or Robert Staley at Newhall near Burton, where the engine may be seen.”

Was the fire engine perhaps connected with a foundry or a coal mine?

I noticed that Robert Staley was the witness at a 1755 marriage in Stapenhill between Barbara Burslem and Richard Daston the younger esquire. The other witness was signed Burslem Jnr.

Looking for Robert Staley

I assumed that once again, in the absence of the correct records, a similarly named and aged persons baptism had been added to the tree regardless of accuracy, so I looked through the Stapenhill/Newhall parish register images page by page. There were no Staleys in Newhall at all in the early 1700s, so it seemed that Robert did come from elsewhere and I expected to find the Staleys in a neighbouring parish. But I still didn’t find any Staleys.

I spoke to a couple of Staley descendants that I’d met during the family research. I met Carole via a DNA match some months previously and contacted her to ask about the Staleys in Elton. She also had Robert Staley born in Elton (indeed, there were many Staleys in Elton) but she didn’t have any documentation for his birth, and we decided to collaborate and try and find out more.

I couldn’t find the earlier Elton parish registers anywhere online, but eventually found the untranscribed microfiche images of the Bishops Transcripts for Elton.

via familysearch:

“In its most basic sense, a bishop’s transcript is a copy of a parish register. As bishop’s transcripts generally contain more or less the same information as parish registers, they are an invaluable resource when a parish register has been damaged, destroyed, or otherwise lost. Bishop’s transcripts are often of value even when parish registers exist, as priests often recorded either additional or different information in their transcripts than they did in the original registers.”Unfortunately there was a gap in the Bishops Transcripts between 1704 and 1711 ~ exactly where I needed to look. I subsequently found out that the Elton registers were incomplete as they had been damaged by fire.

I estimated Robert Staleys date of birth between 1710 and 1715. He died in 1795, and his son Daniel died in 1805: both of these wills were found online. Daniel married Mary Moon in Stapenhill in 1762, making a likely birth date for Daniel around 1740.

The marriage of Robert Staley (assuming this was Robert’s father) and Alice Maceland (or Marsland or Marsden, depending on how the parish clerk chose to spell it presumably) was in the Bishops Transcripts for Elton in 1704. They were married in Elton on 26th February. There followed the missing parish register pages and in all likelihood the records of the baptisms of their first children. No doubt Robert was one of them, probably the first male child.

(Incidentally, my grandfather’s Marshalls also came from Elton, a small Derbyshire village near Matlock. The Staley’s are on my grandmothers Warren side.)

The parish register pages resume in 1711. One of the first entries was the baptism of Robert Staley in 1711, parents Thomas and Ann. This was surely the one we were looking for, and Roberts parents weren’t Robert and Alice.

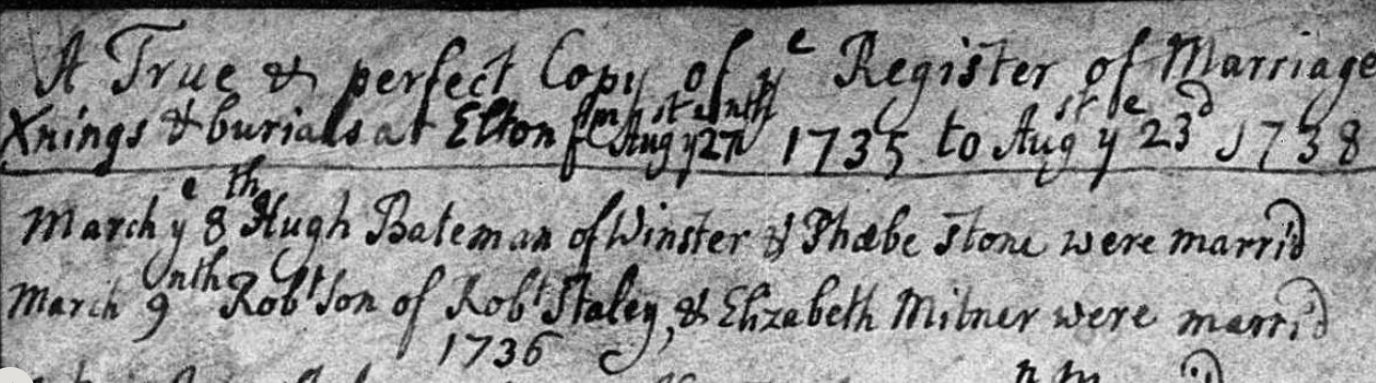

But then in 1735 a marriage was recorded between Robert son of Robert Staley (and this was unusual, the father of the groom isn’t usually recorded on the parish register) and Elizabeth Milner. They were married on the 9th March 1735. We know that the Robert we were looking for married an Elizabeth, as her name was on the Stapenhill baptisms of their later children, including Joseph Staleys. The 1735 marriage also fit with the assumed birth date of Daniel, circa 1740. A baptism was found for a Robert Staley in 1738 in the Elton registers, parents Robert and Elizabeth, as well as the baptism in 1736 for Mary, presumably their first child. Her burial is recorded the following year.

The marriage of Robert Staley and Elizabeth Milner in 1735:

There were several other Staley couples of a similar age in Elton, perhaps brothers and cousins. It seemed that Thomas and Ann’s son Robert was a different Robert, and that the one we were looking for was prior to that and on the missing pages.

Even so, this doesn’t prove that it was Elizabeth Staleys great grandfather who was born in Elton, but no other birth or baptism for Robert Staley has been found. It doesn’t explain why the Staleys moved to Stapenhill either, although the Enclosures Act and the Industrial Revolution could have been factors.

The 18th century saw the rise of the Industrial Revolution and many renowned Derbyshire Industrialists emerged. They created the turning point from what was until then a largely rural economy, to the development of townships based on factory production methods.

The Marsden Connection

There are some possible clues in the records of the Marsden family. Robert Staley married Alice Marsden (or Maceland or Marsland) in Elton in 1704. Robert Staley is mentioned in the 1730 will of John Marsden senior, of Baslow, Innkeeper (Peacock Inne & Whitlands Farm). He mentions his daughter Alice, wife of Robert Staley.

In a 1715 Marsden will there is an intriguing mention of an alias, which might explain the different spellings on various records for the name Marsden: “MARSDEN alias MASLAND, Christopher – of Baslow, husbandman, 28 Dec 1714. son Robert MARSDEN alias MASLAND….” etc.

Some potential reasons for a move from one parish to another are explained in this history of the Marsden family, and indeed this could relate to Robert Staley as he married into the Marsden family and his wife was a beneficiary of a Marsden will. The Chatsworth Estate, at various times, bought a number of farms in order to extend the park.

THE MARSDEN FAMILY

OXCLOSE AND PARKGATE

In the Parishes of

Baslow and Chatsworthby

David Dalrymple-Smith“John Marsden (b1653) another son of Edmund (b1611) faired well. By the time he died in

1730 he was publican of the Peacock, the Inn on Church Lane now called the Cavendish

Hotel, and the farmer at “Whitlands”, almost certainly Bubnell Cliff Farm.”“Coal mining was well known in the Chesterfield area. The coalfield extends as far as the

Gritstone edges, where thin seams outcrop especially in the Baslow area.”“…the occupants were evicted from the farmland below Dobb Edge and

the ground carefully cleared of all traces of occupation and farming. Shelter belts were

planted especially along the Heathy Lea Brook. An imposing new drive was laid to the

Chatsworth House with the Lodges and “The Golden Gates” at its northern end….”Although this particular event was later than any events relating to Robert Staley, it’s an indication of how farms and farmland disappeared, and a reason for families to move to another area:

“The Dukes of Devonshire (of Chatsworth) were major figures in the aristocracy and the government of the

time. Such a position demanded a display of wealth and ostentation. The 6th Duke of

Devonshire, the Bachelor Duke, was not content with the Chatsworth he inherited in 1811,

and immediately started improvements. After major changes around Edensor, he turned his

attention at the north end of the Park. In 1820 plans were made extend the Park up to the

Baslow parish boundary. As this would involve the destruction of most of the Farm at

Oxclose, the farmer at the Higher House Samuel Marsden (b1755) was given the tenancy of

Ewe Close a large farm near Bakewell.

Plans were revised in 1824 when the Dukes of Devonshire and Rutland “Exchanged Lands”,

reputedly during a game of dice. Over 3300 acres were involved in several local parishes, of

which 1000 acres were in Baslow. In the deal Devonshire acquired the southeast corner of

Baslow Parish.

Part of the deal was Gibbet Moor, which was developed for “Sport”. The shelf of land

between Parkgate and Robin Hood and a few extra fields was left untouched. The rest,

between Dobb Edge and Baslow, was agricultural land with farms, fields and houses. It was

this last part that gave the Duke the opportunity to improve the Park beyond his earlier

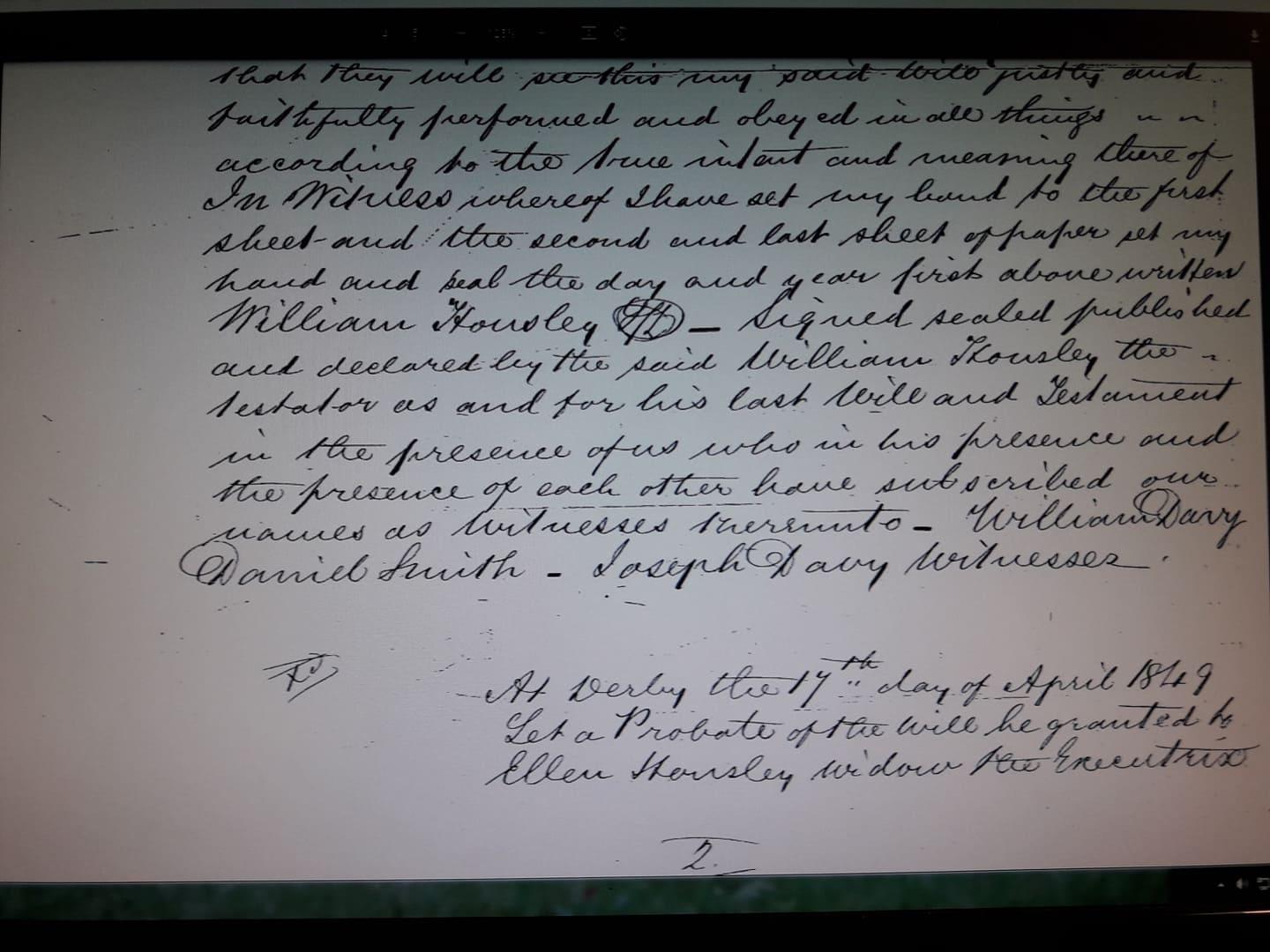

expectations.”The 1795 will of Robert Staley.

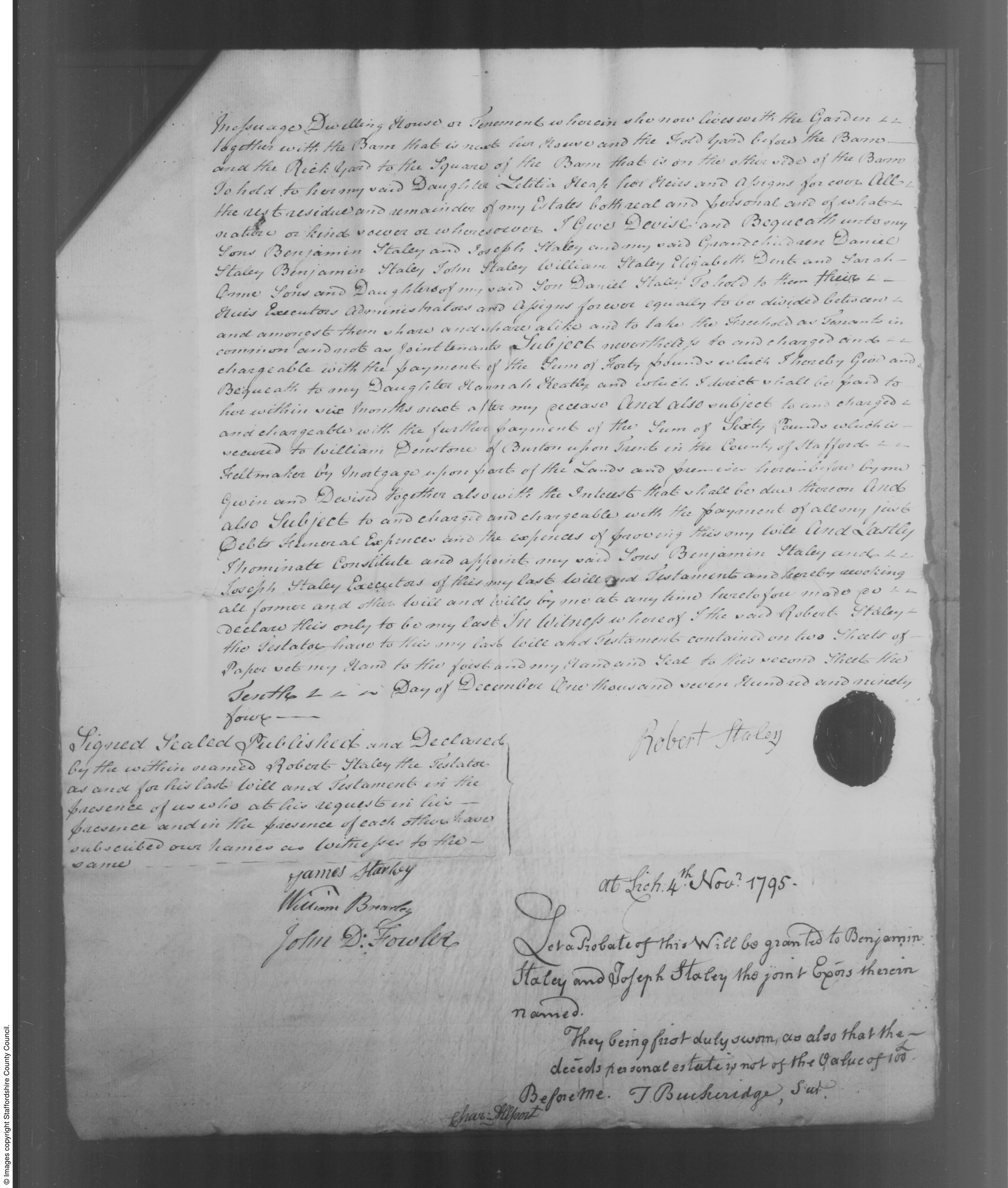

Inriguingly, Robert included the children of his son Daniel Staley in his will, but omitted to leave anything to Daniel. A perusal of Daniels 1808 will sheds some light on this: Daniel left his property to his six reputed children with Elizabeth Moon, and his reputed daughter Mary Brearly. Daniels wife was Mary Moon, Elizabeths husband William Moons daughter.

The will of Robert Staley, 1795:

The 1805 will of Daniel Staley, Robert’s son:

This is the last will and testament of me Daniel Staley of the Township of Newhall in the parish of Stapenhill in the County of Derby, Farmer. I will and order all of my just debts, funeral and testamentary expenses to be fully paid and satisfied by my executors hereinafter named by and out of my personal estate as soon as conveniently may be after my decease.

I give, devise and bequeath to Humphrey Trafford Nadin of Church Gresely in the said County of Derby Esquire and John Wilkinson of Newhall aforesaid yeoman all my messuages, lands, tenements, hereditaments and real and personal estates to hold to them, their heirs, executors, administrators and assigns until Richard Moon the youngest of my reputed sons by Elizabeth Moon shall attain his age of twenty one years upon trust that they, my said trustees, (or the survivor of them, his heirs, executors, administrators or assigns), shall and do manage and carry on my farm at Newhall aforesaid and pay and apply the rents, issues and profits of all and every of my said real and personal estates in for and towards the support, maintenance and education of all my reputed children by the said Elizabeth Moon until the said Richard Moon my youngest reputed son shall attain his said age of twenty one years and equally share and share and share alike.

And it is my will and desire that my said trustees or trustee for the time being shall recruit and keep up the stock upon my farm as they in their discretion shall see occasion or think proper and that the same shall not be diminished. And in case any of my said reputed children by the said Elizabeth Moon shall be married before my said reputed youngest son shall attain his age of twenty one years that then it is my will and desire that non of their husbands or wives shall come to my farm or be maintained there or have their abode there. That it is also my will and desire in case my reputed children or any of them shall not be steady to business but instead shall be wild and diminish the stock that then my said trustees or trustee for the time being shall have full power and authority in their discretion to sell and dispose of all or any part of my said personal estate and to put out the money arising from the sale thereof to interest and to pay and apply the interest thereof and also thereunto of the said real estate in for and towards the maintenance, education and support of all my said reputed children by the said

Elizabeth Moon as they my said trustees in their discretion that think proper until the said Richard Moon shall attain his age of twenty one years.Then I give to my grandson Daniel Staley the sum of ten pounds and to each and every of my sons and daughters namely Daniel Staley, Benjamin Staley, John Staley, William Staley, Elizabeth Dent and Sarah Orme and to my niece Ann Brearly the sum of five pounds apiece.

I give to my youngest reputed son Richard Moon one share in the Ashby Canal Navigation and I direct that my said trustees or trustee for the time being shall have full power and authority to pay and apply all or any part of the fortune or legacy hereby intended for my youngest reputed son Richard Moon in placing him out to any trade, business or profession as they in their discretion shall think proper.

And I direct that to my said sons and daughters by my late wife and my said niece shall by wholly paid by my said reputed son Richard Moon out of the fortune herby given him. And it is my will and desire that my said reputed children shall deliver into the hands of my executors all the monies that shall arise from the carrying on of my business that is not wanted to carry on the same unto my acting executor and shall keep a just and true account of all disbursements and receipts of the said business and deliver up the same to my acting executor in order that there may not be any embezzlement or defraud amongst them and from and immediately after my said reputed youngest son Richard Moon shall attain his age of twenty one years then I give, devise and bequeath all my real estate and all the residue and remainder of my personal estate of what nature and kind whatsoever and wheresoever unto and amongst all and every my said reputed sons and daughters namely William Moon, Thomas Moon, Joseph Moon, Richard Moon, Ann Moon, Margaret Moon and to my reputed daughter Mary Brearly to hold to them and their respective heirs, executors, administrator and assigns for ever according to the nature and tenure of the same estates respectively to take the same as tenants in common and not as joint tenants.And lastly I nominate and appoint the said Humphrey Trafford Nadin and John Wilkinson executors of this my last will and testament and guardians of all my reputed children who are under age during their respective minorities hereby revoking all former and other wills by me heretofore made and declaring this only to be my last will.

In witness whereof I the said Daniel Staley the testator have to this my last will and testament set my hand and seal the eleventh day of March in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and five.

April 12, 2022 at 8:13 am #6290In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Leicestershire Blacksmiths

The Orgill’s of Measham led me further into Leicestershire as I traveled back in time.

I also realized I had uncovered a direct line of women and their mothers going back ten generations:

myself, Tracy Edwards 1957-

my mother Gillian Marshall 1933-

my grandmother Florence Warren 1906-1988

her mother and my great grandmother Florence Gretton 1881-1927

her mother Sarah Orgill 1840-1910

her mother Elizabeth Orgill 1803-1876

her mother Sarah Boss 1783-1847

her mother Elizabeth Page 1749-

her mother Mary Potter 1719-1780

and her mother and my 7x great grandmother Mary 1680-You could say it leads us to the very heart of England, as these Leicestershire villages are as far from the coast as it’s possible to be. There are countless other maternal lines to follow, of course, but only one of mothers of mothers, and ours takes us to Leicestershire.

The blacksmiths

Sarah Boss was the daughter of Michael Boss 1755-1807, a blacksmith in Measham, and Elizabeth Page of nearby Hartshorn, just over the county border in Derbyshire.

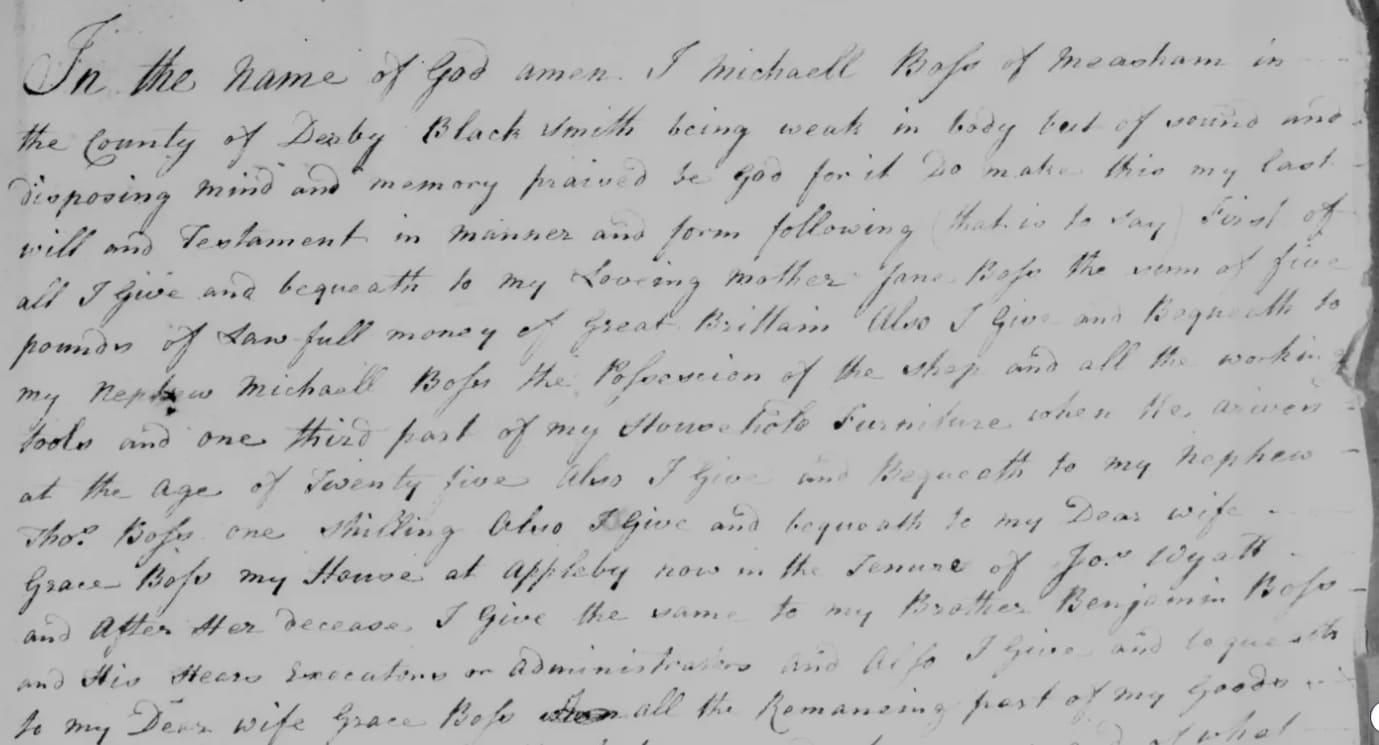

An earlier Michael Boss, a blacksmith of Measham, died in 1772, and in his will he left the possession of the blacksmiths shop and all the working tools and a third of the household furniture to Michael, who he named as his nephew. He left his house in Appleby Magna to his wife Grace, and five pounds to his mother Jane Boss. As none of Michael and Grace’s children are mentioned in the will, perhaps it can be assumed that they were childless.

The will of Michael Boss, 1772, Measham:

Michael Boss the uncle was born in Appleby Magna in 1724. His parents were Michael Boss of Nelson in the Thistles and Jane Peircivall of Appleby Magna, who were married in nearby Mancetter in 1720.

Information worth noting on the Appleby Magna website:

In 1752 the calendar in England was changed from the Julian Calendar to the Gregorian Calendar, as a result 11 days were famously “lost”. But for the recording of Church Registers another very significant change also took place, the start of the year was moved from March 25th to our more familiar January 1st.

Before 1752 the 1st day of each new year was March 25th, Lady Day (a significant date in the Christian calendar). The year number which we all now use for calculating ages didn’t change until March 25th. So, for example, the day after March 24th 1750 was March 25th 1751, and January 1743 followed December 1743.

This March to March recording can be seen very clearly in the Appleby Registers before 1752. Between 1752 and 1768 there appears slightly confused recording, so dates should be carefully checked. After 1768 the recording is more fully by the modern calendar year.Michael Boss the uncle married Grace Cuthbert. I haven’t yet found the birth or parents of Grace, but a blacksmith by the name of Edward Cuthbert is mentioned on an Appleby Magna history website:

An Eighteenth Century Blacksmith’s Shop in Little Appleby

by Alan RobertsCuthberts inventory

The inventory of Edward Cuthbert provides interesting information about the household possessions and living arrangements of an eighteenth century blacksmith. Edward Cuthbert (als. Cutboard) settled in Appleby after the Restoration to join the handful of blacksmiths already established in the parish, including the Wathews who were prominent horse traders. The blacksmiths may have all worked together in the same shop at one time. Edward and his wife Sarah recorded the baptisms of several of their children in the parish register. Somewhat sadly three of the boys named after their father all died either in infancy or as young children. Edward’s inventory which was drawn up in 1732, by which time he was probably a widower and his children had left home, suggests that they once occupied a comfortable two-storey house in Little Appleby with an attached workshop, well equipped with all the tools for repairing farm carts, ploughs and other implements, for shoeing horses and for general ironmongery.

Edward Cuthbert born circa 1660, married Joane Tuvenet in 1684 in Swepston cum Snarestone , and died in Appleby in 1732. Tuvenet is a French name and suggests a Huguenot connection, but this isn’t our family, and indeed this Edward Cuthbert is not likely to be Grace’s father anyway.

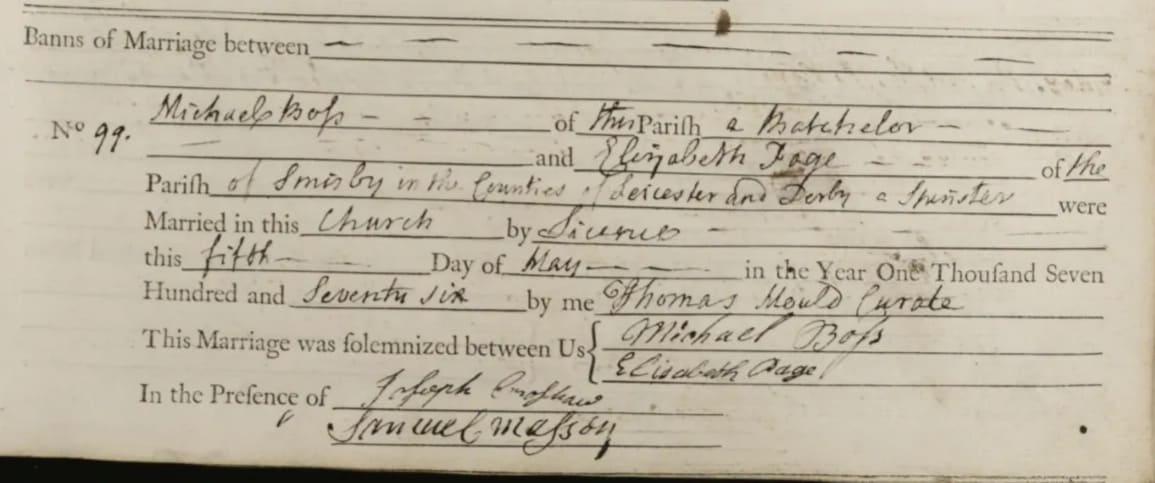

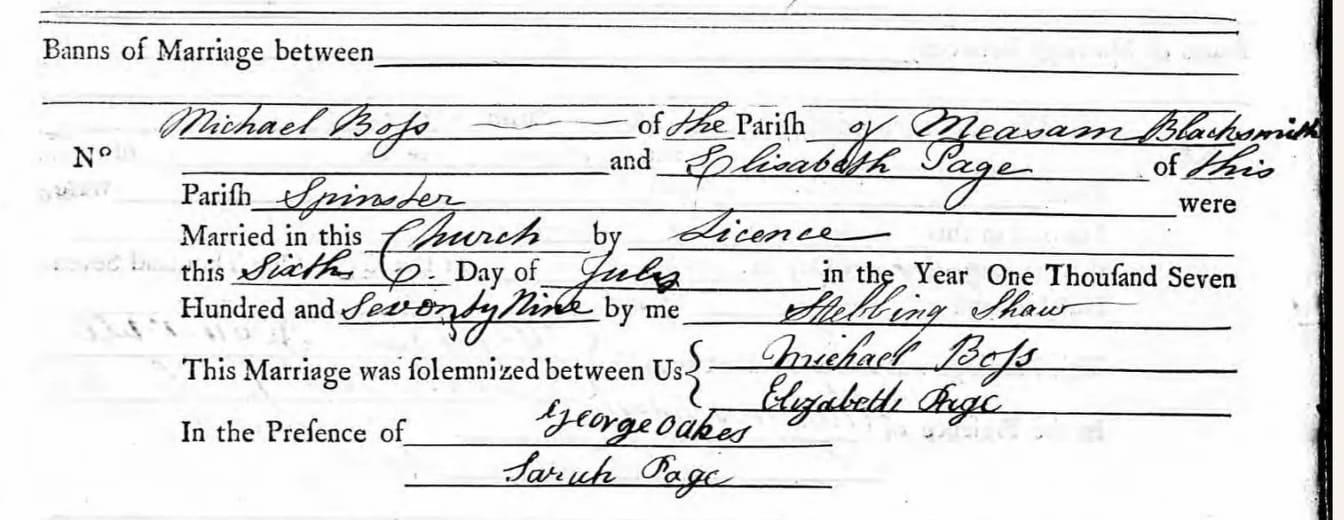

Michael Boss and Elizabeth Page appear to have married twice: once in 1776, and once in 1779. Both of the documents exist and appear correct. Both marriages were by licence. They both mention Michael is a blacksmith.

Their first daughter, Elizabeth, was baptized in February 1777, just nine months after the first wedding. It’s not known when she was born, however, and it’s possible that the marriage was a hasty one. But why marry again three years later?

But Michael Boss and Elizabeth Page did not marry twice.

Elizabeth Page from Smisby was born in 1752 and married Michael Boss on the 5th of May 1776 in Measham. On the marriage licence allegations and bonds, Michael is a bachelor.

Baby Elizabeth was baptised in Measham on the 9th February 1777. Mother Elizabeth died on the 18th February 1777, also in Measham.

In 1779 Michael Boss married another Elizabeth Page! She was born in 1749 in Hartshorn, and Michael is a widower on the marriage licence allegations and bonds.

Hartshorn and Smisby are neighbouring villages, hence the confusion. But a closer look at the documents available revealed the clues. Both Elizabeth Pages were literate, and indeed their signatures on the marriage registers are different:

Marriage of Michael Boss and Elizabeth Page of Smisby in 1776:

Marriage of Michael Boss and Elizabeth Page of Harsthorn in 1779:

Not only did Michael Boss marry two women both called Elizabeth Page but he had an unusual start in life as well. His uncle Michael Boss left him the blacksmith business and a third of his furniture. This was all in the will. But which of Uncle Michaels brothers was nephew Michaels father?

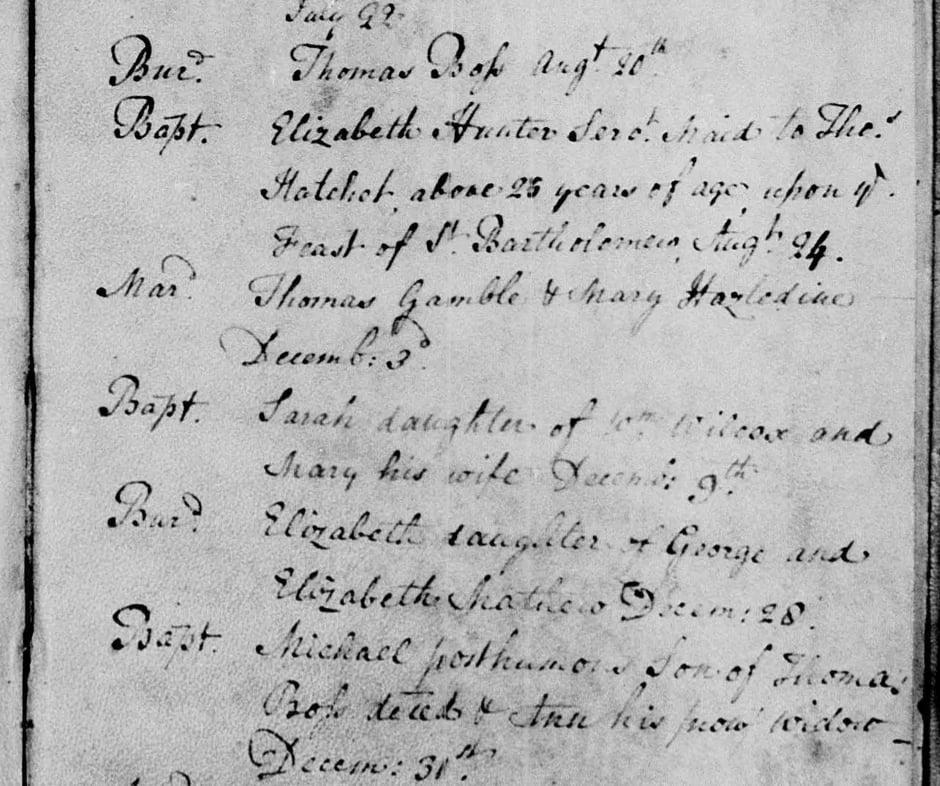

The only Michael Boss born at the right time was in 1750 in Edingale, Staffordshire, about eight miles from Appleby Magna. His parents were Thomas Boss and Ann Parker, married in Edingale in 1747. Thomas died in August 1750, and his son Michael was baptised in the December, posthumus son of Thomas and his widow Ann. Both entries are on the same page of the register.

Ann Boss, the young widow, married again. But perhaps Michael and his brother went to live with their childless uncle and aunt, Michael Boss and Grace Cuthbert.

The great grandfather of Michael Boss (the Measham blacksmith born in 1850) was also Michael Boss, probably born in the 1660s. He died in Newton Regis in Warwickshire in 1724, four years after his son (also Michael Boss born 1693) married Jane Peircivall. The entry on the parish register states that Michael Boss was buried ye 13th Affadavit made.

I had not seen affadavit made on a parish register before, and this relates to the The Burying in Woollen Acts 1666–80. According to Wikipedia:

“Acts of the Parliament of England which required the dead, except plague victims and the destitute, to be buried in pure English woollen shrouds to the exclusion of any foreign textiles. It was a requirement that an affidavit be sworn in front of a Justice of the Peace (usually by a relative of the deceased), confirming burial in wool, with the punishment of a £5 fee for noncompliance. Burial entries in parish registers were marked with the word “affidavit” or its equivalent to confirm that affidavit had been sworn; it would be marked “naked” for those too poor to afford the woollen shroud. The legislation was in force until 1814, but was generally ignored after 1770.”

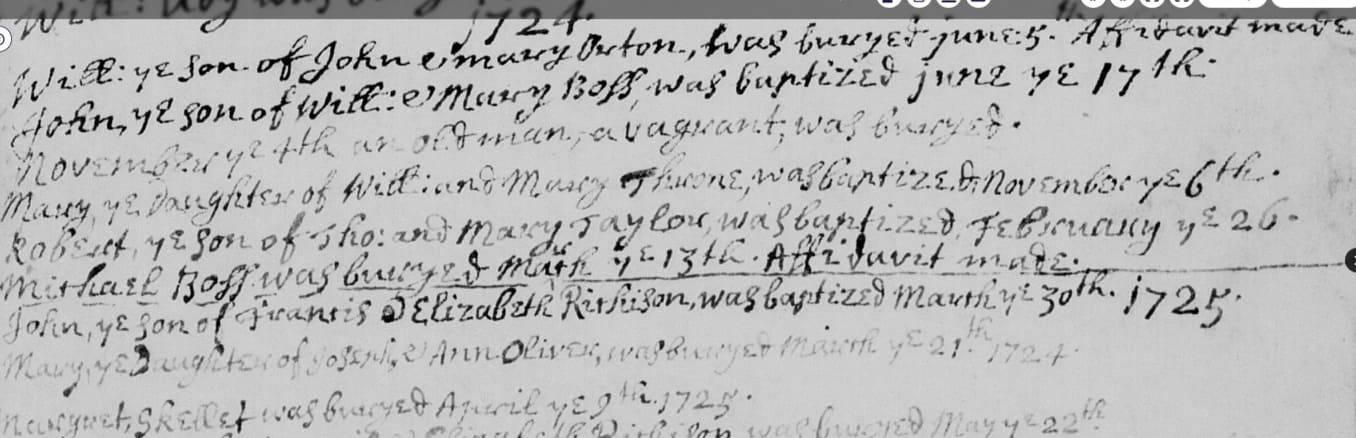

Michael Boss buried 1724 “Affadavit made”:

Elizabeth Page‘s father was William Page 1717-1783, a wheelwright in Hartshorn. (The father of the first wife Elizabeth was also William Page, but he was a husbandman in Smisby born in 1714. William Page, the father of the second wife, was born in Nailstone, Leicestershire, in 1717. His place of residence on his marriage to Mary Potter was spelled Nelson.)

Her mother was Mary Potter 1719- of nearby Coleorton. Mary’s father, Richard Potter 1677-1731, was a blacksmith in Coleorton.

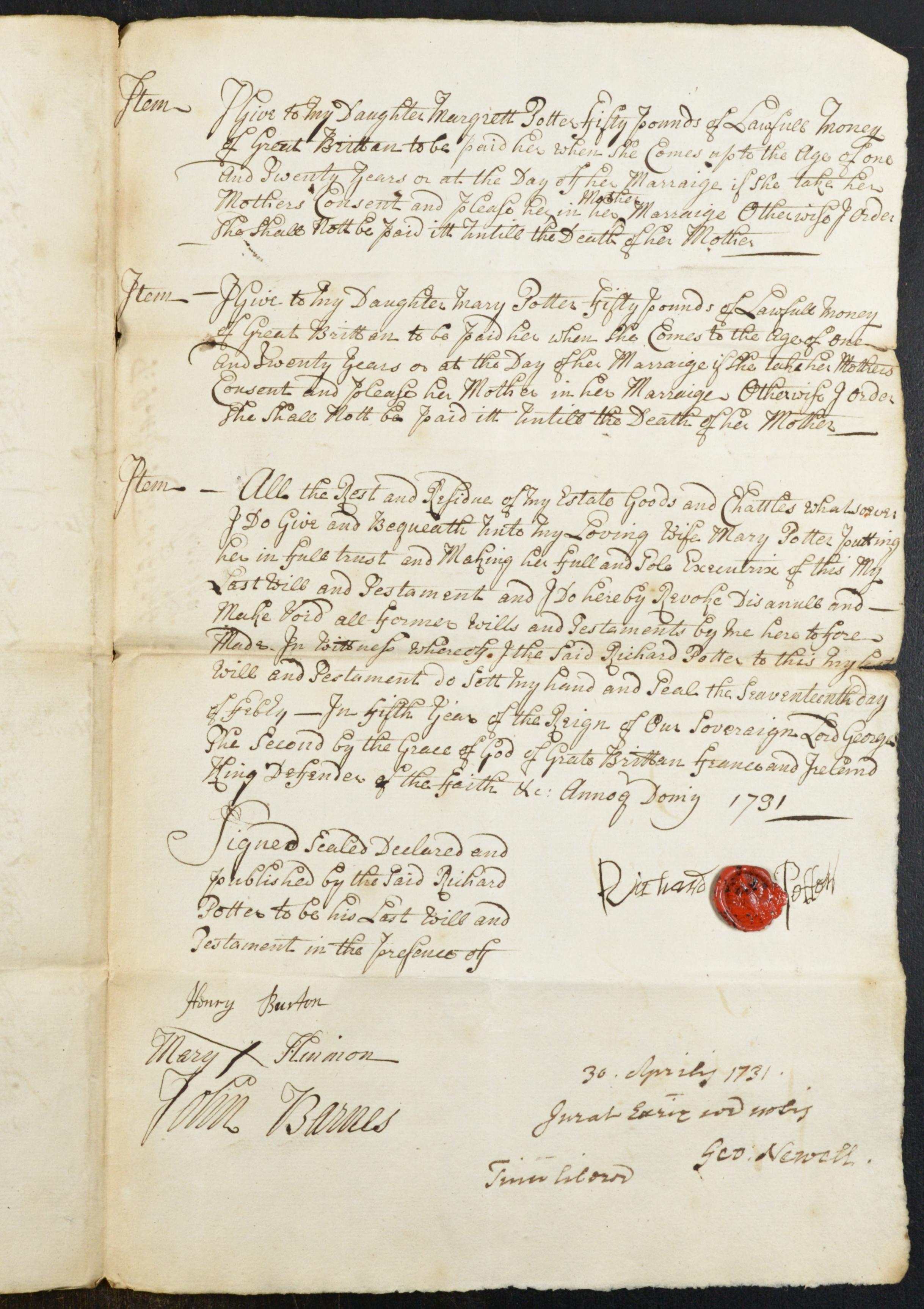

A page of the will of Richard Potter 1731:

Richard Potter states: “I will and order that my son Thomas Potter shall after my decease have one shilling paid to him and no more.” As he left £50 to each of his daughters, one can’t help but wonder what Thomas did to displease his father.

Richard stipulated that his son Thomas should have one shilling paid to him and not more, for several good considerations, and left “the house and ground lying in the parish of Whittwick in a place called the Long Lane to my wife Mary Potter to dispose of as she shall think proper.”

His son Richard inherited the blacksmith business: “I will and order that my son Richard Potter shall live and be with his mother and serve her duly and truly in the business of a blacksmith, and obey and serve her in all lawful commands six years after my decease, and then I give to him and his heirs…. my house and grounds Coulson House in the Liberty of Thringstone”

Richard wanted his son John to be a blacksmith too: “I will and order that my wife bring up my son John Potter at home with her and teach or cause him to be taught the trade of a blacksmith and that he shall serve her duly and truly seven years after my decease after the manner of an apprentice and at the death of his mother I give him that house and shop and building and the ground belonging to it which I now dwell in to him and his heirs forever.”

To his daughters Margrett and Mary Potter, upon their reaching the age of one and twenty, or the day after their marriage, he leaves £50 each. All the rest of his goods are left to his loving wife Mary.

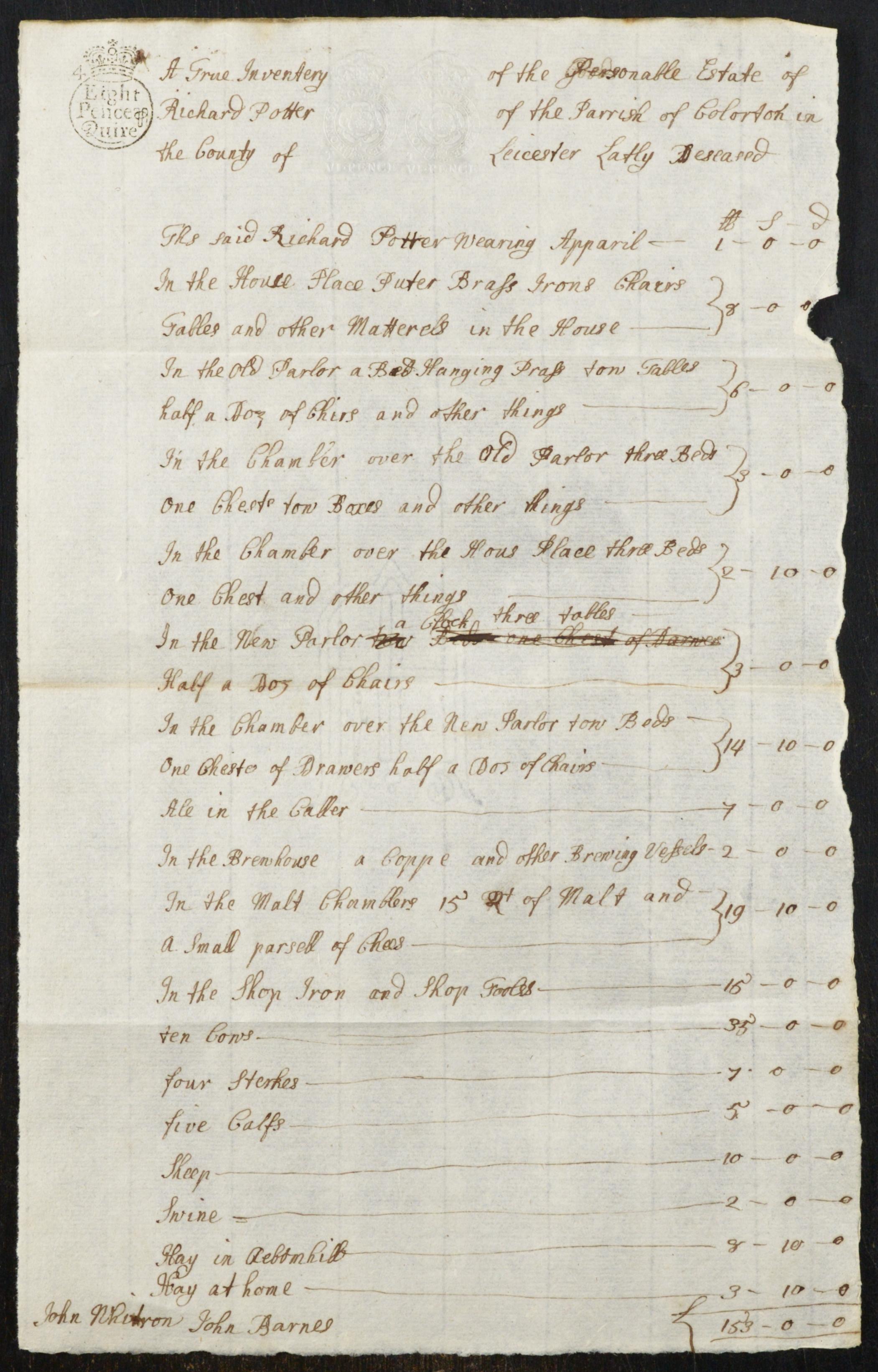

An inventory of the belongings of Richard Potter, 1731:

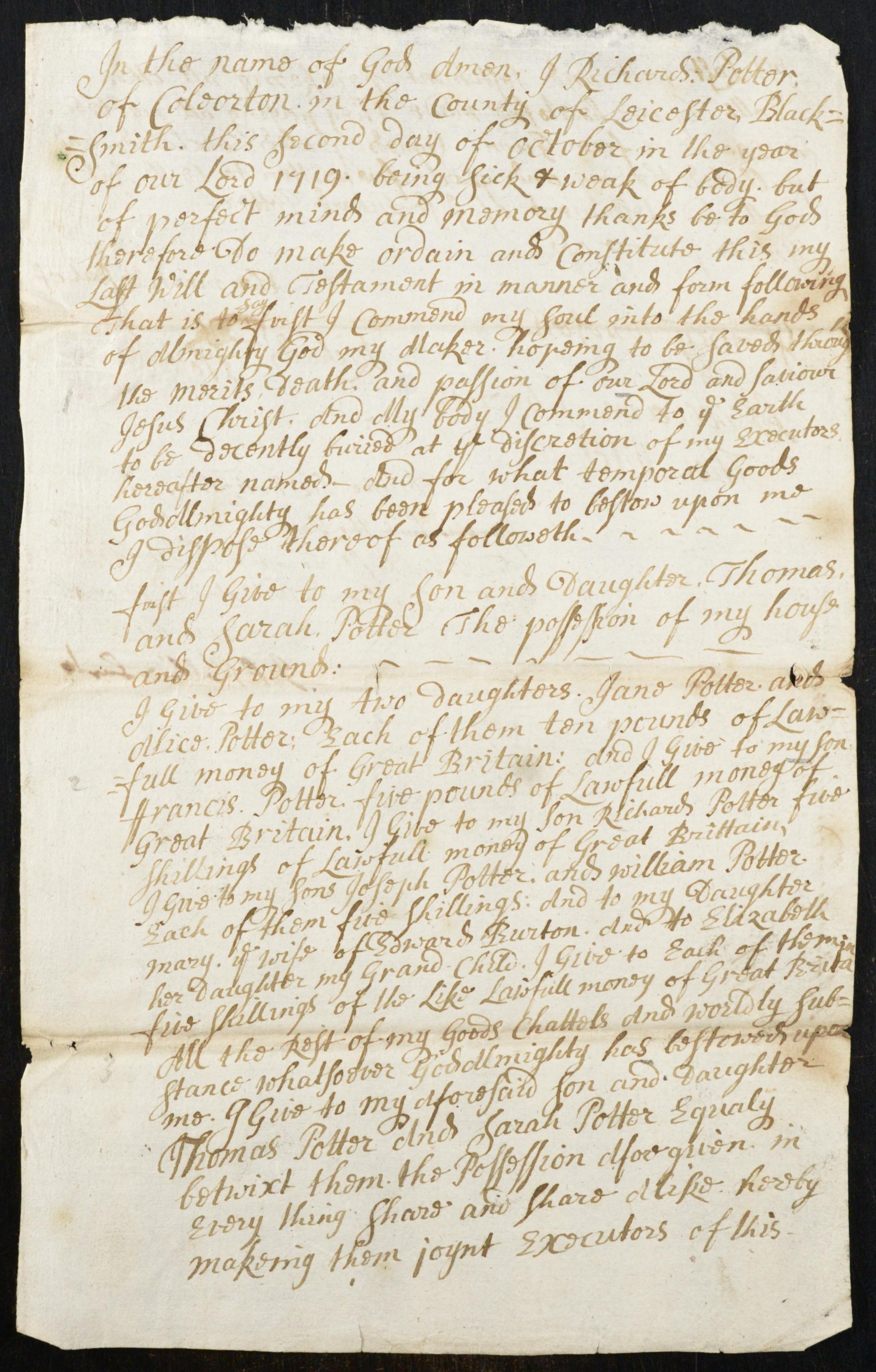

Richard Potters father was also named Richard Potter 1649-1719, and he too was a blacksmith.

Richard Potter of Coleorton in the county of Leicester, blacksmith, stated in his will: “I give to my son and daughter Thomas and Sarah Potter the possession of my house and grounds.”

He leaves ten pounds each to his daughters Jane and Alice, to his son Francis he gives five pounds, and five shillings to his son Richard. Sons Joseph and William also receive five shillings each. To his daughter Mary, wife of Edward Burton, and her daughter Elizabeth, he gives five shillings each. The rest of his good, chattels and wordly substance he leaves equally between his son and daugter Thomas and Sarah. As there is no mention of his wife, it’s assumed that she predeceased him.

The will of Richard Potter, 1719:

Richard Potter’s (1649-1719) parents were William Potter and Alse Huldin, both born in the early 1600s. They were married in 1646 at Breedon on the Hill, Leicestershire. The name Huldin appears to originate in Finland.

William Potter was a blacksmith. In the 1659 parish registers of Breedon on the Hill, William Potter of Breedon blacksmith buryed the 14th July.

February 2, 2022 at 1:15 pm #6268In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

From Tanganyika with Love

continued part 9

With thanks to Mike Rushby.

Lyamungu 3rd January 1945

Dearest Family.

We had a novel Christmas this year. We decided to avoid the expense of

entertaining and being entertained at Lyamungu, and went off to spend Christmas

camping in a forest on the Western slopes of Kilimanjaro. George decided to combine

business with pleasure and in this way we were able to use Government transport.

We set out the day before Christmas day and drove along the road which skirts

the slopes of Kilimanjaro and first visited a beautiful farm where Philip Teare, the ex

Game Warden, and his wife Mary are staying. We had afternoon tea with them and then

drove on in to the natural forest above the estate and pitched our tent beside a small

clear mountain stream. We decorated the tent with paper streamers and a few small

balloons and John found a small tree of the traditional shape which we decorated where

it stood with tinsel and small ornaments.We put our beer, cool drinks for the children and bottles of fresh milk from Simba

Estate, in the stream and on Christmas morning they were as cold as if they had been in

the refrigerator all night. There were not many presents for the children, there never are,

but they do not seem to mind and are well satisfied with a couple of balloons apiece,

sweets, tin whistles and a book each.George entertain the children before breakfast. He can make a magical thing out

of the most ordinary balloon. The children watched entranced as he drew on his pipe

and then blew the smoke into the balloon. He then pinched the neck of the balloon

between thumb and forefinger and released the smoke in little puffs. Occasionally the

balloon ejected a perfect smoke ring and the forest rang with shouts of “Do it again

Daddy.” Another trick was to blow up the balloon to maximum size and then twist the

neck tightly before releasing. Before subsiding the balloon darted about in a crazy

fashion causing great hilarity. Such fun, at the cost of a few pence.After breakfast George went off to fish for trout. John and Jim decided that they

also wished to fish so we made rods out of sticks and string and bent pins and they

fished happily, but of course quite unsuccessfully, for hours. Both of course fell into the

stream and got soaked, but I was prepared for this, and the little stream was so shallow

that they could not come to any harm. Henry played happily in the sand and I had a

most peaceful morning.Hamisi roasted a chicken in a pot over the camp fire and the jelly set beautifully in the

stream. So we had grilled trout and chicken for our Christmas dinner. I had of course

taken an iced cake for the occasion and, all in all, it was a very successful Christmas day.

On Boxing day we drove down to the plains where George was to investigate a

report of game poaching near the Ngassari Furrow. This is a very long ditch which has

been dug by the Government for watering the Masai stock in the area. It is also used by

game and we saw herds of zebra and wildebeest, and some Grant’s Gazelle and

giraffe, all comparatively tame. At one point a small herd of zebra raced beside the lorry

apparently enjoying the fun of a gallop. They were all sleek and fat and looked wild and

beautiful in action.We camped a considerable distance from the water but this precaution did not

save us from the mosquitoes which launched a vicious attack on us after sunset, so that

we took to our beds unusually early. They were on the job again when we got up at

sunrise so I was very glad when we were once more on our way home.“I like Christmas safari. Much nicer that silly old party,” said John. I agree but I think

it is time that our children learned to play happily with others. There are no other young

children at Lyamungu though there are two older boys and a girl who go to boarding

school in Nairobi.On New Years Day two Army Officers from the military camp at Moshi, came for

tea and to talk game hunting with George. I think they rather enjoy visiting a home and

seeing children and pets around.Eleanor.

Lyamungu 14 May 1945

Dearest Family.

So the war in Europe is over at last. It is such marvellous news that I can hardly

believe it. To think that as soon as George can get leave we will go to England and

bring Ann and George home with us to Tanganyika. When we know when this leave can

be arranged we will want Kate to join us here as of course she must go with us to

England to meet George’s family. She has become so much a part of your lives that I

know it will be a wrench for you to give her up but I know that you will all be happy to

think that soon our family will be reunited.The V.E. celebrations passed off quietly here. We all went to Moshi to see the

Victory Parade of the King’s African Rifles and in the evening we went to a celebration

dinner at the Game Warden’s house. Besides ourselves the Moores had invited the

Commanding Officer from Moshi and a junior officer. We had a very good dinner and

many toasts including one to Mrs Moore’s brother, Oliver Milton who is fighting in Burma

and has recently been awarded the Military Cross.There was also a celebration party for the children in the grounds of the Moshi

Club. Such a spread! I think John and Jim sampled everything. We mothers were

having our tea separately and a friend laughingly told me to turn around and have a look.

I did, and saw the long tea tables now deserted by all the children but my two sons who

were still eating steadily, and finding the party more exciting than the game of Musical

Bumps into which all the other children had entered with enthusiasm.There was also an extremely good puppet show put on by the Italian prisoners

of war from the camp at Moshi. They had made all the puppets which included well

loved characters like Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and the Babes in the Wood as

well as more sophisticated ones like an irritable pianist and a would be prima donna. The

most popular puppets with the children were a native askari and his family – a very

happy little scene. I have never before seen a puppet show and was as entranced as

the children. It is amazing what clever manipulation and lighting can do. I believe that the

Italians mean to take their puppets to Nairobi and am glad to think that there, they will

have larger audiences to appreciate their art.George has just come in, and I paused in my writing to ask him for the hundredth

time when he thinks we will get leave. He says I must be patient because it may be a

year before our turn comes. Shipping will be disorganised for months to come and we

cannot expect priority simply because we have been separated so long from our

children. The same situation applies to scores of other Government Officials.

I have decided to write the story of my childhood in South Africa and about our

life together in Tanganyika up to the time Ann and George left the country. I know you

will have told Kate these stories, but Ann and George were so very little when they left

home that I fear that they cannot remember much.My Mother-in-law will have told them about their father but she can tell them little

about me. I shall send them one chapter of my story each month in the hope that they

may be interested and not feel that I am a stranger when at last we meet again.Eleanor.

Lyamungu 19th September 1945

Dearest Family.

In a months time we will be saying good-bye to Lyamungu. George is to be

transferred to Mbeya and I am delighted, not only as I look upon Mbeya as home, but

because there is now a primary school there which John can attend. I feel he will make

much better progress in his lessons when he realises that all children of his age attend

school. At present he is putting up a strong resistance to learning to read and spell, but

he writes very neatly, does his sums accurately and shows a real talent for drawing. If

only he had the will to learn I feel he would do very well.Jim now just four, is too young for lessons but too intelligent to be interested in

the ayah’s attempts at entertainment. Yes I’ve had to engage a native girl to look after

Henry from 9 am to 12.30 when I supervise John’s Correspondence Course. She is

clean and amiable, but like most African women she has no initiative at all when it comes

to entertaining children. Most African men and youths are good at this.I don’t regret our stay at Lyamungu. It is a beautiful spot and the change to the

cooler climate after the heat of Morogoro has been good for all the children. John is still

tall for his age but not so thin as he was and much less pale. He is a handsome little lad

with his large brown eyes in striking contrast to his fair hair. He is wary of strangers but

very observant and quite uncanny in the way he sums up people. He seldom gets up

to mischief but I have a feeling he eggs Jim on. Not that Jim needs egging.Jim has an absolute flair for mischief but it is all done in such an artless manner that

it is not easy to punish him. He is a very sturdy child with a cap of almost black silky hair,

eyes brown, like mine, and a large mouth which is quick to smile and show most beautiful

white and even teeth. He is most popular with all the native servants and the Game

Scouts. The servants call Jim, ‘Bwana Tembo’ (Mr Elephant) because of his sturdy

build.Henry, now nearly two years old, is quite different from the other two in

appearance. He is fair complexioned and fair haired like Ann and Kate, with large, black

lashed, light grey eyes. He is a good child, not so merry as Jim was at his age, nor as

shy as John was. He seldom cries, does not care to be cuddled and is independent and

strong willed. The servants call Henry, ‘Bwana Ndizi’ (Mr Banana) because he has an

inexhaustible appetite for this fruit. Fortunately they are very inexpensive here. We buy

an entire bunch which hangs from a beam on the back verandah, and pluck off the

bananas as they ripen. This way there is no waste and the fruit never gets bruised as it

does in greengrocers shops in South Africa. Our three boys make a delightful and

interesting trio and I do wish you could see them for yourselves.We are delighted with the really beautiful photograph of Kate. She is an

extraordinarily pretty child and looks so happy and healthy and a great credit to you.

Now that we will be living in Mbeya with a school on the doorstep I hope that we will

soon be able to arrange for her return home.Eleanor.

c/o Game Dept. Mbeya. 30th October 1945

Dearest Family.

How nice to be able to write c/o Game Dept. Mbeya at the head of my letters.

We arrived here safely after a rather tiresome journey and are installed in a tiny house on

the edge of the township.We left Lyamungu early on the morning of the 22nd. Most of our goods had

been packed on the big Ford lorry the previous evening, but there were the usual

delays and farewells. Of our servants, only the cook, Hamisi, accompanied us to

Mbeya. Japhet, Tovelo and the ayah had to be paid off and largesse handed out.

Tovelo’s granny had come, bringing a gift of bananas, and she also brought her little

granddaughter to present a bunch of flowers. The child’s little scolded behind is now

completely healed. Gifts had to be found for them too.At last we were all aboard and what a squash it was! Our few pieces of furniture

and packing cases and trunks, the cook, his wife, the driver and the turney boy, who

were to take the truck back to Lyamungu, and all their bits and pieces, bunches of

bananas and Fanny the dog were all crammed into the body of the lorry. George, the

children and I were jammed together in the cab. Before we left George looked

dubiously at the tyres which were very worn and said gloomily that he thought it most

unlikely that we would make our destination, Dodoma.Too true! Shortly after midday, near Kwakachinja, we blew a back tyre and there

was a tedious delay in the heat whilst the wheel was changed. We were now without a

spare tyre and George said that he would not risk taking the Ford further than Babati,

which is less than half way to Dodoma. He drove very slowly and cautiously to Babati

where he arranged with Sher Mohammed, an Indian trader, for a lorry to take us to

Dodoma the next morning.It had been our intention to spend the night at the furnished Government

Resthouse at Babati but when we got there we found that it was already occupied by

several District Officers who had assembled for a conference. So, feeling rather

disgruntled, we all piled back into the lorry and drove on to a place called Bereku where

we spent an uncomfortable night in a tumbledown hut.Before dawn next morning Sher Mohammed’s lorry drove up, and there was a

scramble to dress by the light of a storm lamp. The lorry was a very dilapidated one and

there was already a native woman passenger in the cab. I felt so tired after an almost

sleepless night that I decided to sit between the driver and this woman with the sleeping

Henry on my knee. It was as well I did, because I soon found myself dosing off and

drooping over towards the woman. Had she not been there I might easily have fallen

out as the battered cab had no door. However I was alert enough when daylight came

and changed places with the woman to our mutual relief. She was now able to converse

with the African driver and I was able to enjoy the scenery and the fresh air!

George, John and Jim were less comfortable. They sat in the lorry behind the

cab hemmed in by packing cases. As the lorry was an open one the sun beat down

unmercifully upon them until George, ever resourceful, moved a table to the front of the

truck. The two boys crouched under this and so got shelter from the sun but they still had

to endure the dust. Fanny complicated things by getting car sick and with one thing and

another we were all jolly glad to get to Dodoma.We spent the night at the Dodoma Hotel and after hot baths, a good meal and a

good nights rest we cheerfully boarded a bus of the Tanganyika Bus Service next

morning to continue our journey to Mbeya. The rest of the journey was uneventful. We slept two nights on the road, the first at Iringa Hotel and the second at Chimala. We

reached Mbeya on the 27th.I was rather taken aback when I first saw the little house which has been allocated

to us. I had become accustomed to the spacious houses we had in Morogoro and

Lyamungu. However though the house is tiny it is secluded and has a long garden

sloping down to the road in front and another long strip sloping up behind. The front

garden is shaded by several large cypress and eucalyptus trees but the garden behind

the house has no shade and consists mainly of humpy beds planted with hundreds of

carnations sadly in need of debudding. I believe that the previous Game Ranger’s wife

cultivated the carnations and, by selling them, raised money for War Funds.

Like our own first home, this little house is built of sun dried brick. Its original

owners were Germans. It is now rented to the Government by the Custodian of Enemy

Property, and George has his office in another ex German house.This afternoon we drove to the school to arrange about enrolling John there. The

school is about four miles out of town. It was built by the German settlers in the late

1930’s and they were justifiably proud of it. It consists of a great assembly hall and

classrooms in one block and there are several attractive single storied dormitories. This

school was taken over by the Government when the Germans were interned on the

outbreak of war and many improvements have been made to the original buildings. The

school certainly looks very attractive now with its grassed playing fields and its lawns and

bright flower beds.The Union Jack flies from a tall flagpole in front of the Hall and all traces of the

schools German origin have been firmly erased. We met the Headmaster, Mr

Wallington, and his wife and some members of the staff. The school is co-educational

and caters for children from the age of seven to standard six. The leaving age is elastic

owing to the fact that many Tanganyika children started school very late because of lack

of educational facilities in this country.The married members of the staff have their own cottages in the grounds. The

Matrons have quarters attached to the dormitories for which they are responsible. I felt

most enthusiastic about the school until I discovered that the Headmaster is adamant

upon one subject. He utterly refuses to take any day pupils at the school. So now our

poor reserved Johnny will have to adjust himself to boarding school life.

We have arranged that he will start school on November 5th and I shall be very

busy trying to assemble his school uniform at short notice. The clothing list is sensible.

Boys wear khaki shirts and shorts on weekdays with knitted scarlet jerseys when the

weather is cold. On Sundays they wear grey flannel shorts and blazers with the silver

and scarlet school tie.Mbeya looks dusty, brown and dry after the lush evergreen vegetation of

Lyamungu, but I prefer this drier climate and there are still mountains to please the eye.

In fact the lower slopes of Lolesa Mountain rise at the upper end of our garden.Eleanor.

c/o Game Dept. Mbeya. 21st November 1945

Dearest Family.

We’re quite settled in now and I have got the little house fixed up to my

satisfaction. I have engaged a rather uncouth looking houseboy but he is strong and

capable and now that I am not tied down in the mornings by John’s lessons I am able to

go out occasionally in the mornings and take Jim and Henry to play with other children.

They do not show any great enthusiasm but are not shy by nature as John is.

I have had a good deal of heartache over putting John to boarding school. It

would have been different had he been used to the company of children outside his

own family, or if he had even known one child there. However he seems to be adjusting

himself to the life, though slowly. At least he looks well and tidy and I am quite sure that

he is well looked after.I must confess that when the time came for John to go to school I simply did not

have the courage to take him and he went alone with George, looking so smart in his

new uniform – but his little face so bleak. The next day, Sunday, was visiting day but the

Headmaster suggested that we should give John time to settle down and not visit him

until Wednesday.When we drove up to the school I spied John on the far side of the field walking

all alone. Instead of running up with glad greetings, as I had expected, he came almost

reluctently and had little to say. I asked him to show me his dormitory and classroom and

he did so politely as though I were a stranger. At last he volunteered some information.

“Mummy,” he said in an awed voice, Do you know on the night I came here they burnt a

man! They had a big fire and they burnt him.” After a blank moment the penny dropped.

Of course John had started school and November the fifth but it had never entered my

head to tell him about that infamous character, Guy Fawkes!I asked John’s Matron how he had settled down. “Well”, she said thoughtfully,

“John is very good and has not cried as many of the juniors do when they first come

here, but he seems to keep to himself all the time.” I went home very discouraged but

on the Sunday John came running up with another lad of about his own age.” This is my

friend Marks,” he announced proudly. I could have hugged Marks.Mbeya is very different from the small settlement we knew in the early 1930’s.

Gone are all the colourful characters from the Lupa diggings for the alluvial claims are all

worked out now, gone also are our old friends the Menzies from the Pub and also most

of the Government Officials we used to know. Mbeya has lost its character of a frontier

township and has become almost suburban.The social life revolves around two places, the Club and the school. The Club

which started out as a little two roomed building, has been expanded and the golf

course improved. There are also tennis courts and a good library considering the size of

the community. There are frequent parties and dances, though most of the club revenue

comes from Bar profits. The parties are relatively sober affairs compared with the parties

of the 1930’s.The school provides entertainment of another kind. Both Mr and Mrs Wallington

are good amateur actors and I am told that they run an Amateur Dramatic Society. Every

Wednesday afternoon there is a hockey match at the school. Mbeya town versus a

mixed team of staff and scholars. The match attracts almost the whole European

population of Mbeya. Some go to play hockey, others to watch, and others to snatch

the opportunity to visit their children. I shall have to try to arrange a lift to school when

George is away on safari.I have now met most of the local women and gladly renewed an old friendship

with Sheilagh Waring whom I knew two years ago at Morogoro. Sheilagh and I have

much in common, the same disregard for the trappings of civilisation, the same sense of

the ludicrous, and children. She has eight to our six and she has also been cut off by the

war from two of her children. Sheilagh looks too young and pretty to be the mother of so

large a family and is, in fact, several years younger than I am. her husband, Donald, is a

large quiet man who, as far as I can judge takes life seriously.Our next door neighbours are the Bank Manager and his wife, a very pleasant

couple though we seldom meet. I have however had correspondence with the Bank

Manager. Early on Saturday afternoon their houseboy brought a note. It informed me

that my son was disturbing his rest by precipitating a heart attack. Was I aware that my

son was about 30 feet up in a tree and balanced on a twig? I ran out and,sure enough,

there was Jim, right at the top of the tallest eucalyptus tree. It would be the one with the

mound of stones at the bottom! You should have heard me fluting in my most

wheedling voice. “Sweets, Jimmy, come down slowly dear, I’ve some nice sweets for

you.”I’ll bet that little story makes you smile. I remember how often you have told me

how, as a child, I used to make your hearts turn over because I had no fear of heights

and how I used to say, “But that is silly, I won’t fall.” I know now only too well, how you

must have felt.Eleanor.

c/o Game Dept. Mbeya. 14th January 1946

Dearest Family.

I hope that by now you have my telegram to say that Kate got home safely

yesterday. It was wonderful to have her back and what a beautiful child she is! Kate

seems to have enjoyed the train journey with Miss Craig, in spite of the tears she tells

me she shed when she said good-bye to you. She also seems to have felt quite at

home with the Hopleys at Salisbury. She flew from Salisbury in a small Dove aircraft

and they had a smooth passage though Kate was a little airsick.I was so excited about her home coming! This house is so tiny that I had to turn