-

AuthorSearch Results

-

February 16, 2025 at 2:37 pm #7813

In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

Helix 25 – Crusades in the Cruise & Unexpected Archives

Evie hadn’t planned to visit Seren Vega again so soon, but when Mandrake slinked into her quarters and sat squarely on her console, swishing his tail with intent, she took it as a sign.

“Alright, you smug little AI-assisted furball,” she muttered, rising from her chair. “What’s so urgent?”

Mandrake stretched leisurely, then padded toward the door, tail flicking. Evie sighed, grabbed her datapad, and followed.

He led her straight to Seren’s quarters—no surprise there. The dimly lit space was as chaotic as ever, layers of old records, scattered datapads, and bound volumes stacked in precarious towers. Seren barely looked up as Evie entered, used to these unannounced visits.

“Tell the cat to stop knocking over my books,” she said dryly. “It never ever listens.”

“Well it’s a cat, isn’t it?” Evie replied. “And he seems to have an agenda.”

Mandrake leaped onto one of the shelves, knocking loose a tattered, old-fashioned book. It thudded onto the floor, flipping open near Evie’s feet. She crouched, brushing dust from the cover. Blood and Oaths: A Romance of the Crusades by Liz Tattler.

She glanced at Seren. “Tattler again?”

Seren shrugged. “Romualdo must have left it here. He hoards her books like sacred texts.”

Evie turned the pages, pausing at an unusual passage. The prose was different—less florid than Liz’s usual ramblings, more… restrained.

A fragment of text had been underlined, a single note scribbled in the margin: Not fiction.

Evie found a spot where she could sit on the floor, and started to read eagerly.

“Blood and Oaths: A Romance of the Crusades — Chapter XII

Sidon, 1157 AD.Brother Edric knelt within the dim sanctuary, the cold stone pressing into his bones. The candlelight flickered across the vaulted ceilings, painting ghosts upon the walls. The voices of his ancestors whispered within him, their memories not his own, yet undeniable. He knew the placement of every fortification before his enemies built them. He spoke languages he had never learned.

He could not recall the first time it happened, only that it had begun after his initiation into the Order—after the ritual, the fasting, the bloodletting beneath the broken moon. The last one, probably folklore, but effective.

It came as a gift.

It was a curse.

His brothers called it divine providence. He called it a drowning. Each time he drew upon it, his sense of self blurred. His grandfather’s memories bled into his own, his thoughts weighted by decisions made a lifetime ago.

And now, as he rose, he knew with certainty that their mission to reclaim the stronghold would fail. He had seen it through the eyes of his ancestor, the soldier who stood at these gates seventy years prior.

‘You know things no man should know,’ his superior whispered that night. ‘Be cautious, Brother Edric, for knowledge begets temptation.’

And Edric knew, too, the greatest temptation was not power.

It was forgetting which thoughts were his own.

Which life was his own.

He had vowed to bear this burden alone. His order demanded celibacy, for the sealed secrets of State must never pass beyond those trained to wield it.

But Edric had broken that vow.

Somewhere, beyond these walls, there was a child who bore his blood. And if blood held memory…

He did not finish the thought. He could not bear to.”

Evie exhaled, staring at the page. “This isn’t just Tattler’s usual nonsense, is it?”

Seren shook her head distractedly.

“It reads like a first-hand account—filtered through Liz’s dramatics, of course. But the details…” She tapped the underlined section. “Someone wanted this remembered.”

Mandrake, still perched smugly above them, let out a satisfied mrrrow.

Evie sat back, a seed of realization sprouting in her mind. “If this was real, and if this technique survived somehow…”

Mandrake finished the thought for her. “Then Amara’s theory isn’t theory at all.”

Evie ran a hand through her hair, glancing at the cat than at Evie. “I hate it when Mandrake’s right.”

“Well what’s a witch without her cat, isn’t it?” Seren replied with a smile.

Mandrake only flicked his tail, his work here done.

December 3, 2024 at 7:51 am #7636In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

It was cold in Kent, much colder than Elara was used to at home in the Tuscan olive groves, but Mrs Lovejoy kept the guest house warm enough. On site at Samphire Hoe was another matter, the wind off the sea biting into her despite the many layers of clothing. It had been Florian’s idea to take the Mongolian hat with her. Laughing, she’d replied that it might come in handy if there was a costume party. Trust me, you’re going to need it, he’d said, and he was right. It had been a present from Amei, many years ago, but Elara had barely worn it. It wasn’t often that she found herself in a place cold enough to warrant it.

In a fortuitous twist of fate, Florian had asked if he could come and stay with her for awhile to find his feet after the tumultuous end of a disastrous relationship. It came at a time when Elara was starting to realise that there was too much work for her alone keeping the old farmhouse in order. Everyone wants to retire to the country but nobody thinks of all the work involved, at an age when one prefers to potter about, read books, and take naps.

Florian was a long lost (or more correctly never known) distant relative, a seventh cousin four times removed on her paternal side. They had come into contact while researching the family, comparing notes and photographs and family anecdotes. They became friends, finding they had much in common, and Elara was pleased to have him come to stay with her. Likewise, Florian was more than willing to help around the beautiful old place, and found it conducive to his writing. He spent the mornings gardening, decorating or running errands, and the afternoons tapping away at the novel he’d been inspired to start, sitting at the old desk in front of the French windows.

If it hadn’t been for Florian, Elara wouldn’t have accepted the invitation to join the chalk project. He had settled in so well, already had a working grasp of Italian, and got on well with her neighbours. She could leave him to look after everything and not worry about a thing.

Pulling the hat down over her ears, Elara ventured out into the early November chill. Mrs Lovejoy was coming up the path to the guesthouse, having been out to the corner shop. “I say, that’s a fine hat you have there, that’ll keep your cockles warm!” Mrs Lovejoy was bareheaded, wearing only a cardigan.

“It was a gift,” Elara told her, “I haven’t worn it much. A friend bought it for me years ago when we were in Mongolia.”

“Very nice, I’m sure,” replied the landlady, trying to remember where Mongolia was.

“Yes, she was nice,” Elara said wistfully. “We lost contact somehow.”

“Ah yes, well these things happen,” Mrs Lovejoy said. “People come into your life and then they go. Like my Bert…”

“Must go or I’ll be late!” Elara had already heard all about Bert a number of times.

October 30, 2024 at 3:58 pm #7576In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

After the postcard craze had passed, Frella returned to Herma’s cottage several times to study the camphor chest. Every day for a week, Herma let her into the living room, where she would sit quietly in front of the chest, sometimes for hours. The wood’s glossy surface would catch the light, warm and rich, like polished honey. Frella would trace the strange curves of the mysterious engravings with her fingers, feeling the subtle dips and rises beneath her touch. The patterns felt ancient, worn smooth in places, yet sharp along certain edges, as if holding onto secrets just out of reach.

Then, as she lifted the heavy lid, a soft creak would break the silence, the hinges groaning as if they hadn’t moved in ages. A burst of cool, earthy fragrance would immediately rise, filling the air with camphor’s sharp, clean scent, mingled with faint hints of aged cedar and spice.

It didn’t take long for Frella to notice that each time she opened the chest, she would find a new object among the old papers and postcards. It was never the same. Once, it was an old brass spyglass; another time, it might be an ornate compass with seven directions marked. Yet another day, she found a teddy bear. By some odd coincidence, each item always seemed to be something she needed in her life at that particular moment.

When Eris informed them that Malove was most likely under a powerful spell, Frella found the mirror. An inscription carved clumsily on its back read, “This Mystic Mirror belongs to Seraphina.” The mirror’s metal was cold, tarnished, and in need of a good polish. Jeezel would have surely raved about the intricate vines of silver and gold, twisting in delicate patterns that seemed to shift with the viewer’s perspective. But what captivated Frella most was the glass itself. It held a faint opalescent sheen, swirling with hints of colors, like a rainbow caught in crystal.

The first time Frella looked into it, she saw, behind her own reflection, an elderly woman with silver hair handing the mirror down to a little girl who looked just like Frella had as a child. The clothes were peculiar, and the room they stood in looked as if it belonged in a fantasy movie. Then the little girl began carefully carving something on the back of the mirror with what looked like a golden chisel. When she finally turned the mirror and looked into it, her reflection replaced Frella’s. She said something, but there was no sound. Frella had the distinct impression that the girl’s lips had formed the words, “We are the same. It’s yours now; you’ll need it soon.” Then she vanished, and Frella’s own reflection reappeared.

Still filled with awe at what just happened, Frella wondered if Seraphina was a long lost ancestor. “Was that chest also yours, Seraphina?” she asked in a whisper to the ghosts of the past.

August 21, 2024 at 12:27 pm #7546In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

The Potters of Darley Bridge

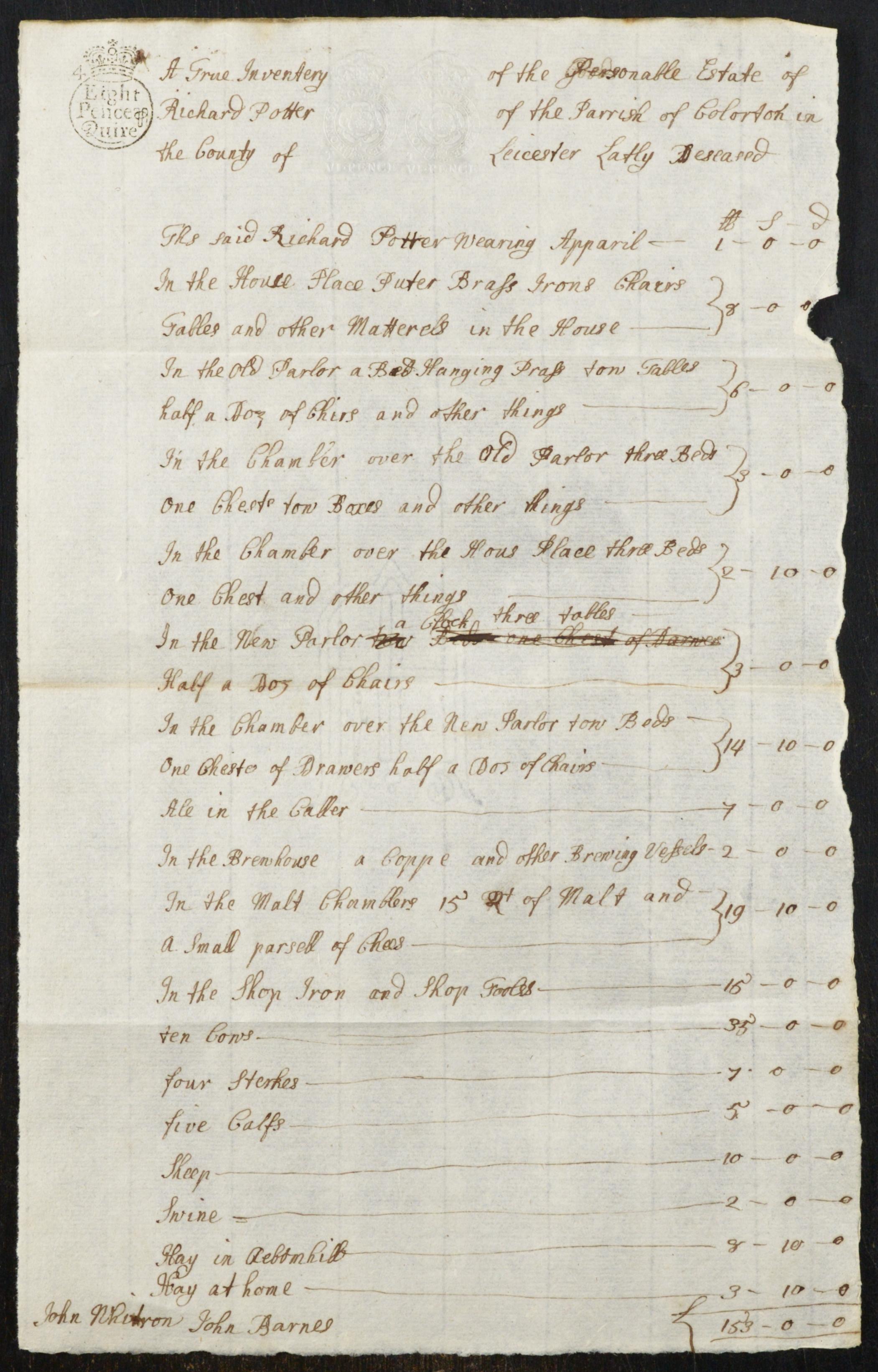

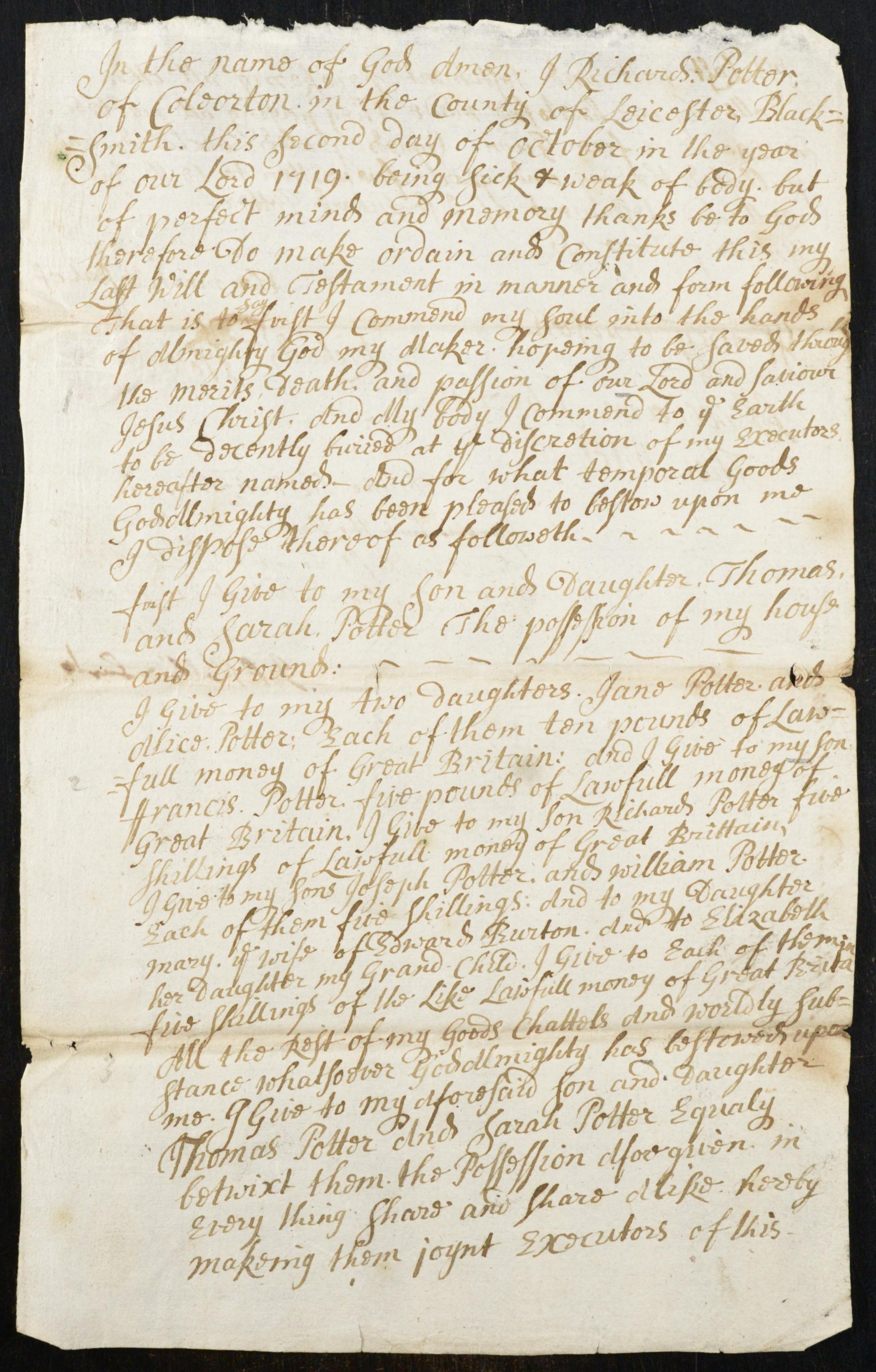

Rebecca Knowles 1745-1823, my 5x great grandmother, married Charles Marshall 1742-1819, the churchwarden of Elton, in Darley, Derbyshire, in 1767. Rebecca was born in Darley in 1745, the youngest child of Roger Knowles 1695-1784, and Martha Potter 1702?-1772.

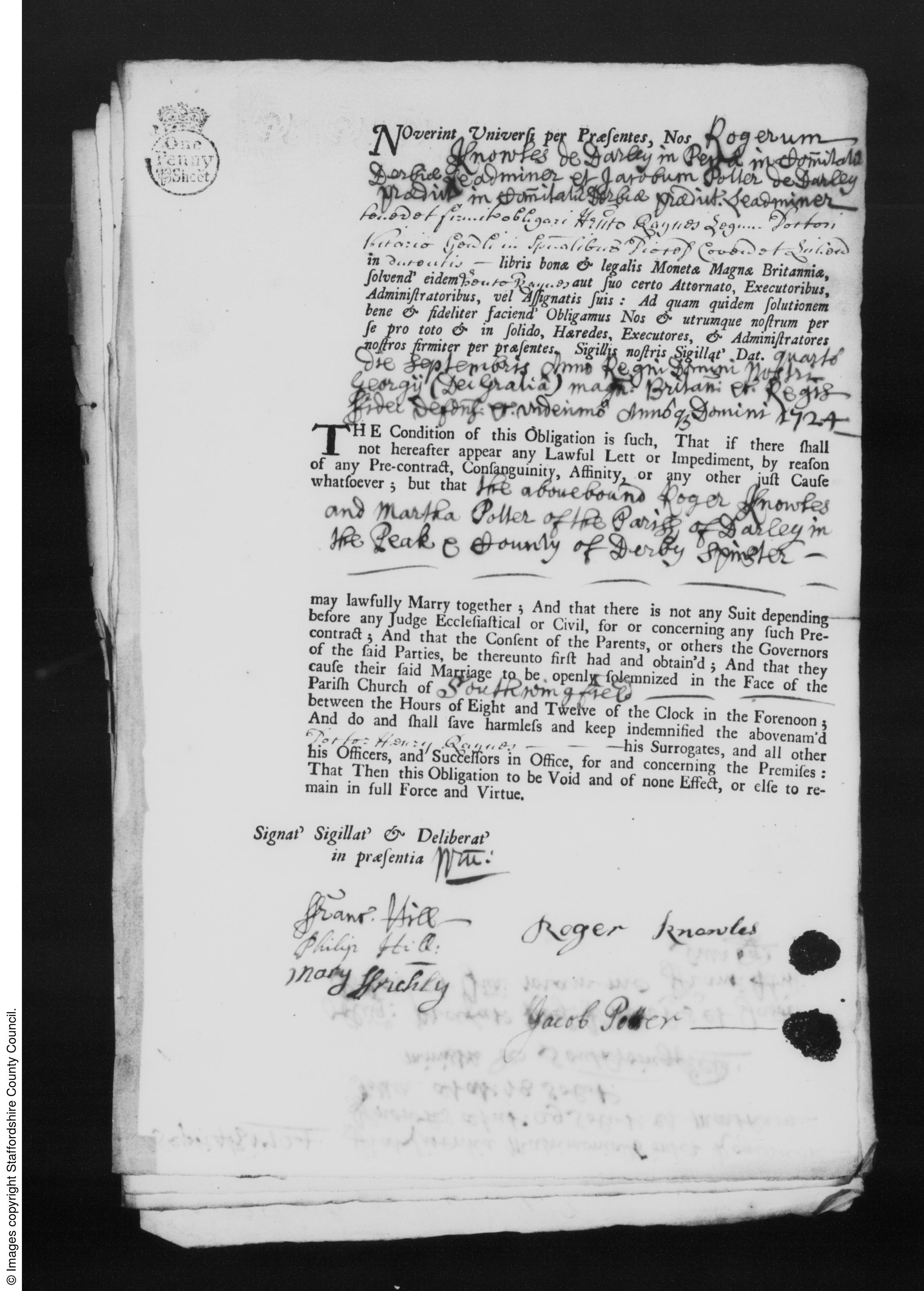

Although Roger and Martha were both from Darley, they were married in South Wingfield by licence in 1724. Roger’s occupation on the marriage licence was lead miner. (Lead miners in Derbyshire at that time usually mined their own land.) Jacob Potter signed the licence so I assumed that Jacob Potter was her father.

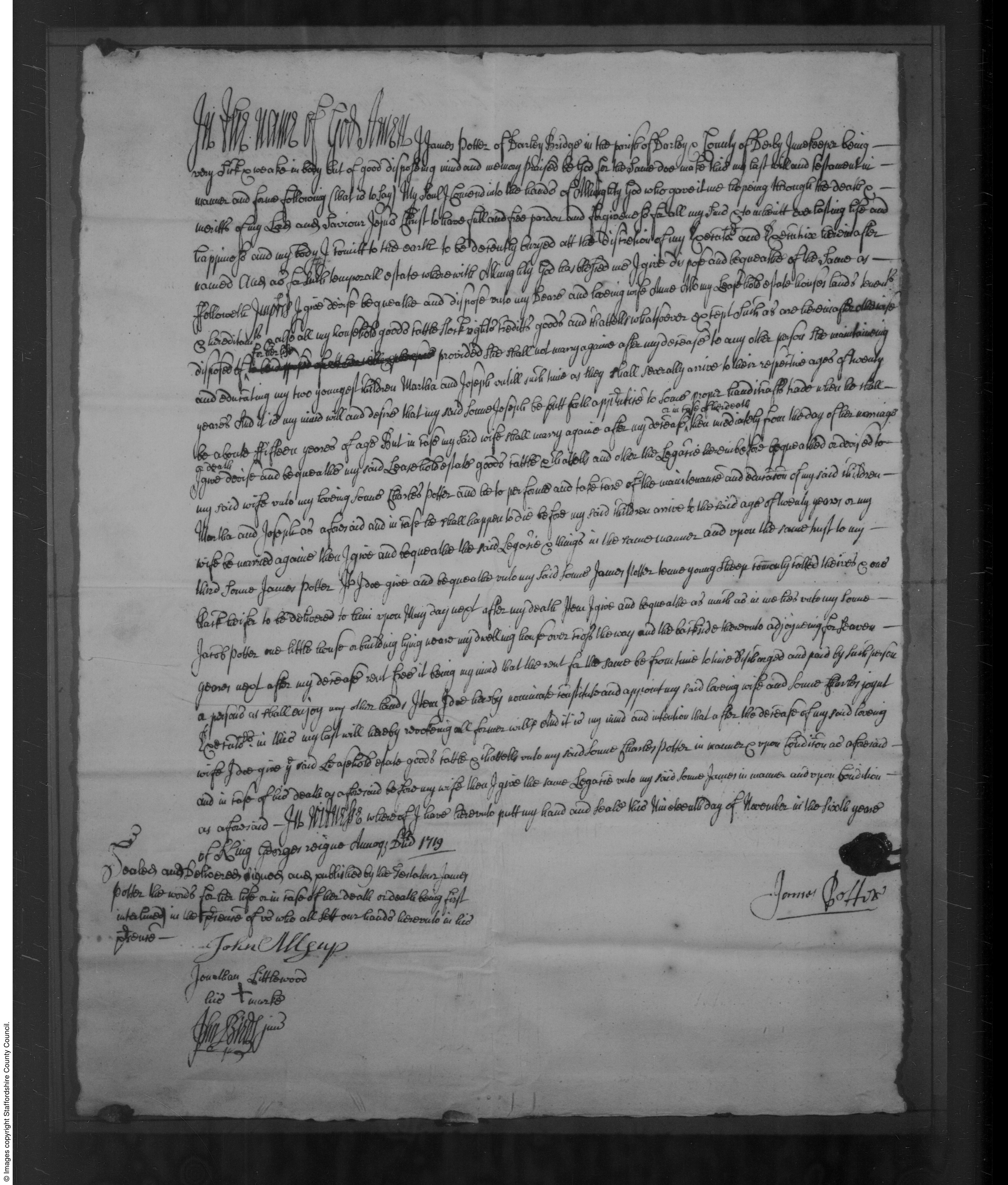

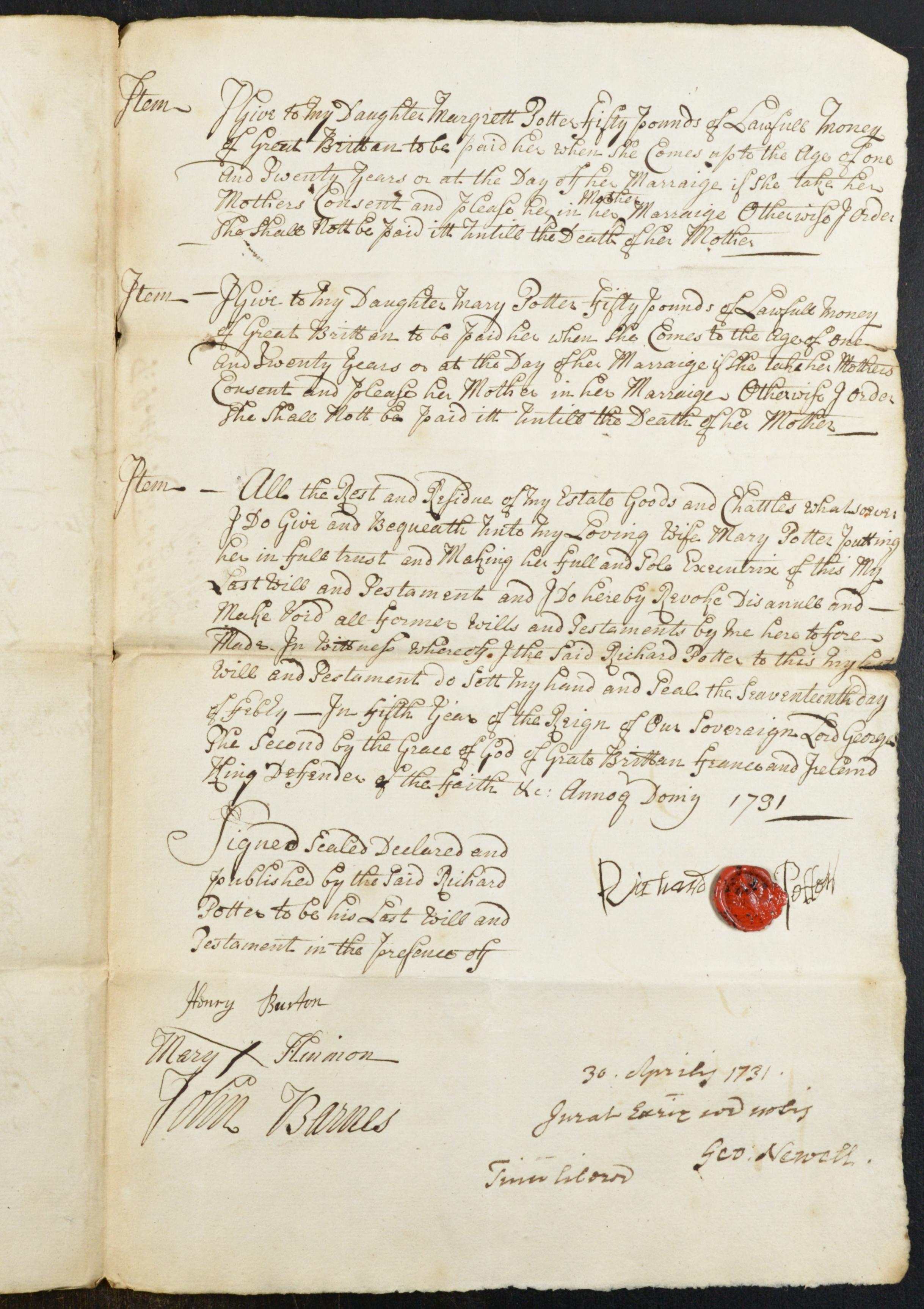

I then found the will of Jacobi Potter who died in 1719. However, he signed the will James Potter. Jacobi is latin for James. James Potter mentioned his daughter Martha in his will “when she comes of age”. Martha was the youngest child of James. James also mentioned in his will son James AND son Jacob, so there were both James’s and Jacob’s in the family, although at times in the documents James is written as Jacobi!

Jacob Potter who signed Martha’s marriage licence was her brother Jacob.

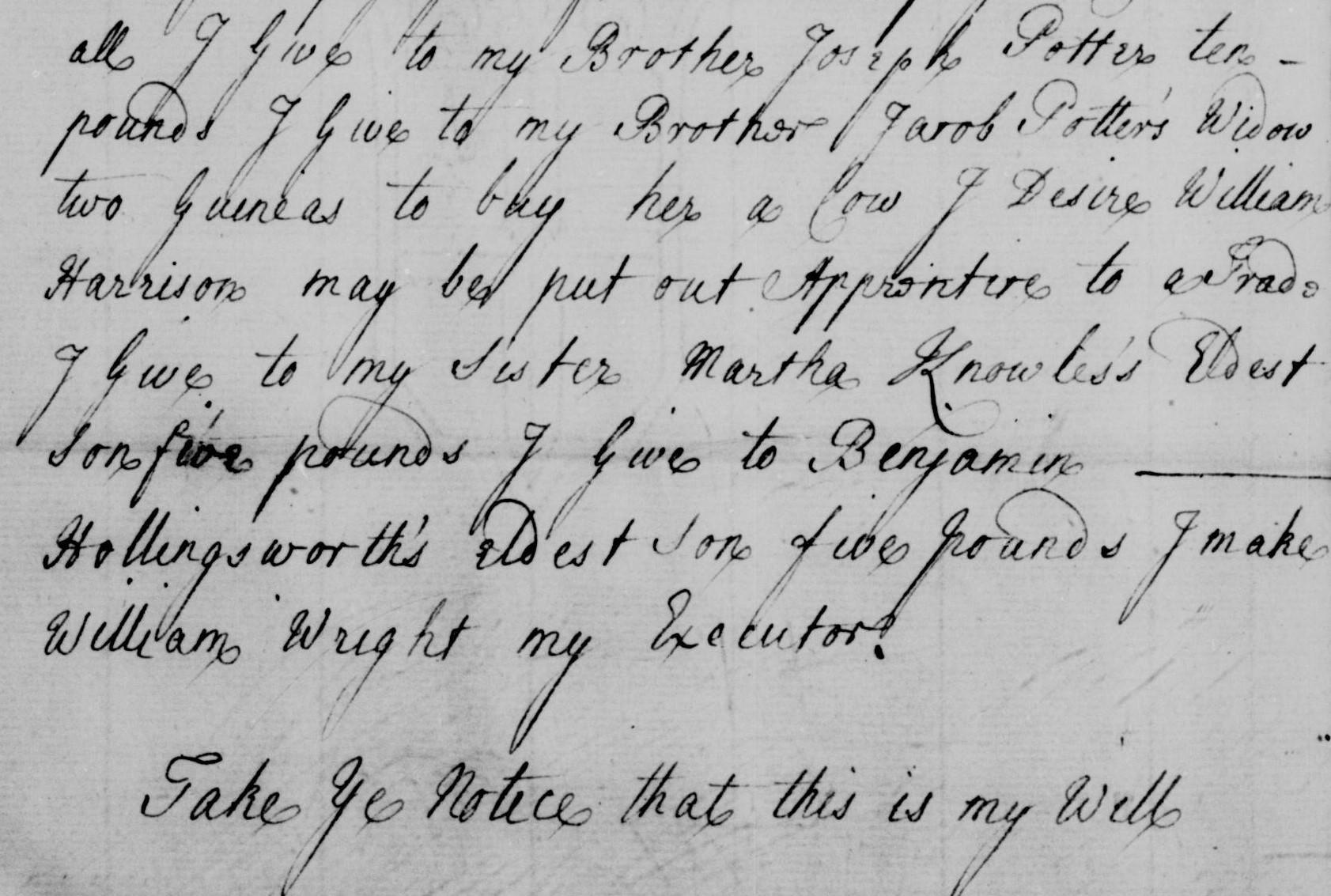

Martha’s brother James mentioned his sister Martha Knowles in his 1739 will, as well as his brother Jacob and his brother Joseph.

Martha’s father James Potter mentions his wife Ann in his 1719 will. James Potter married Ann Waterhurst in 1690 in Wirksworth, some seven miles from Darley. James occupation was innkeeper at Darley Bridge.

I did a search for Waterhurst (there was only a transcription available for that marriage, not a microfilm) and found no Waterhursts anywhere, but I did find many Warhursts in Derbyshire. In the older records, Warhust is also spelled Wearhurst and in a number of other ways. A Martha Warhurst died in Peak Forest, Derbyshire, in 1681. Her husbands name was missing from the deteriorated register pages. This may or may not be Martha Potter’s grandmother: the records for the 1600s are scanty if they exist at all, and often there are bits missing and illegible entries.

The only inn at Darley Bridge was The Three Stags Heads, by the bridge. It is now a listed building, and was on a medieval packhorse route. The current building was built in 1736, however there is a late 17th century section at rear of the cross wing. The Three Stags Heads was up for sale for £430,000 in 2022, the closure a result of the covid pandemic.

Another listed building in Darley Bridge is Potters Cottage, with a plaque above the door that says “Jonathan and Alice Potter 1763”. Jonathan Potter 1725-1785 was James grandson, the son of his son Charles Potter 1691-1752. His son Charles was also an innkeeper at Darley Bridge: James left the majority of his property to his son Charles.

Charles is the only child of James Potter that we know the approximate date of birth, because his age was on his grave stone. I haven’t found any of their baptisms, but did note that many Potters were baptised in non conformist registers in Chesterfield.

Potters Cottage

Jonathan Potter of Potters Cottage married Alice Beeley in 1748.

“Darley Bridge was an important packhorse route across the River Derwent. There was a packhorse route from here up to Beeley Moor via Darley Dale. A reference to this bridge appears in 1504… Not far to the north of the bridge at Darley Dale is Church Lane; in 1635 it was known as Ghost Lane after a Scottish pedlar was murdered there. Pedlars tended to be called Scottish only because they sold cheap Scottish linen.”

via Derbyshire Heritage website.

According to Wikipedia, the bridge dates back to the 15th century.

August 16, 2024 at 2:56 pm #7544In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Youlgreave

The Frost Family and The Big Snow

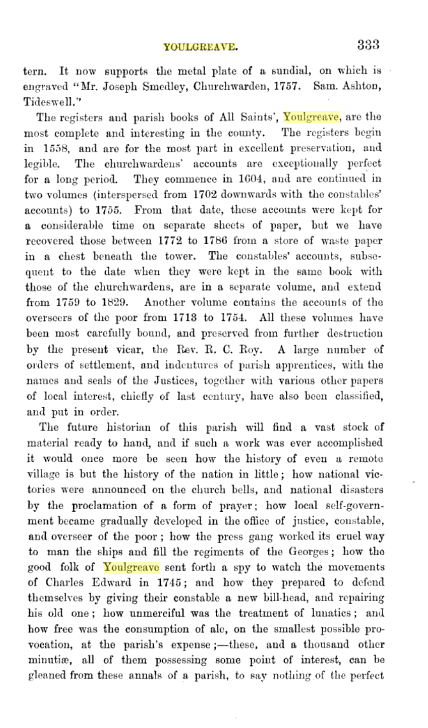

The Youlgreave parish registers are said to be the most complete and interesting in the country. Starting in 1558, they are still largely intact today.

“The future historian of this parish will find a vast stock of material ready to hand, and if such a work was ever accomplished it would once more be seen how the history of even a remote village is but the history of the nation in little; how national victories were announced on the church bells, and national disasters by the proclamation of a form of prayer…”

J. Charles Cox, Notes on the Churches of Derbyshire, 1877.

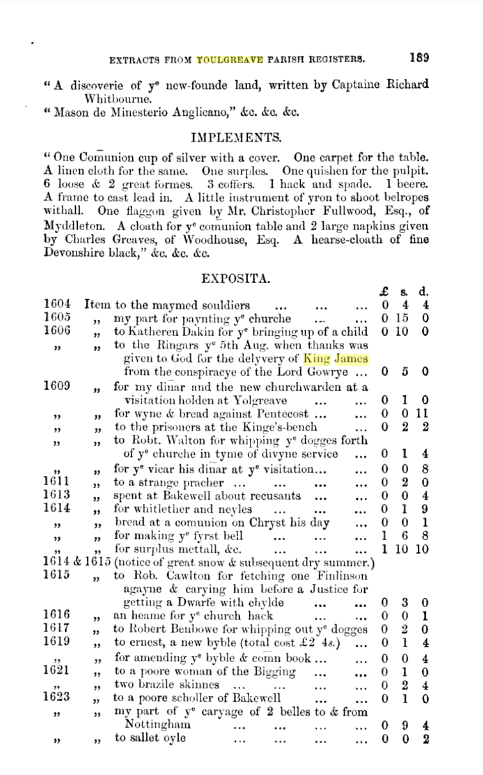

Although the Youlgreave parish registers are available online on microfilm, just the baptisms, marriages and burials are provided on the genealogy websites. However, I found some excerpts from the churchwardens accounts in a couple of old books, The Reliquary 1864, and Notes on Derbyshire Churches 1877.

Hannah Keeling, my 4x great grandmother, was born in Youlgreave, Derbyshire, in 1767. In 1791 she married Edward Lees of Hartington, Derbyshire, a village seven and a half miles south west of Youlgreave. Edward and Hannah’s daughter Sarah Lees, born in Hartington in 1808, married Francis Featherstone in 1835. The Featherstone’s were farmers. Their daughter Emma Featherstone married John Marshall from Elton. Elton is just three miles from Youlgreave, and there are a great many Marshall’s in the Youlgreave parish registers, some no doubt distantly related to ours.

Hannah Keeling’s parents were John Keeling 1734-1823, and Ellen Frost 1739-1805, both of Youlgreave.

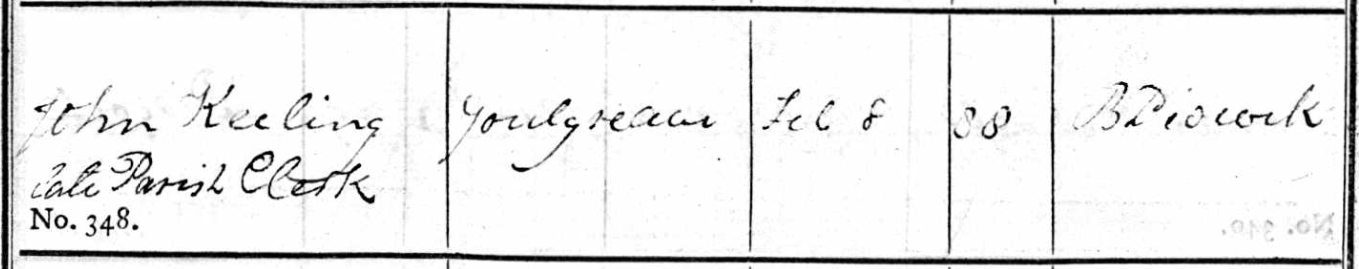

On the burial entry in the parish registers in Youlgreave in 1823, John Keeling was 88 years old when he died, and was the “late parish clerk”, indicating that my 5x great grandfather played a part in compiling the “best parish registers in the country”. In 1762 John’s father in law John Frost died intestate, and John Keeling, cordwainer, co signed the documents with his mother in law Ann. John Keeling was a shoe maker and a parish clerk.

John Keeling’s father was Thomas Keeling, baptised on the 9th of March 1709 in Youlgreave and his parents were John Keeling and Ann Ashmore. John and Ann were married on the 6th April 1708. Some of the transcriptions have Thomas baptised in March 1708, which would be a month before his parents married. However, this was before the Julian calendar was replaced by the Gregorian calendar, and prior to 1752 the new year started on the 25th of March, therefore the 9th of March 1708 was eleven months after the 6th April 1708.

Thomas Keeling married Dorothy, which we know from the baptism of John Keeling in 1734, but I have not been able to find their marriage recorded. Until I can find my 6x great grandmother Dorothy’s maiden name, I am unable to trace her family further back.

Unfortunately I haven’t found a baptism for Thomas’s father John Keeling, despite that there are Keelings in the Youlgrave registers in the early 1600s, possibly it is one of the few illegible entries in these registers.

The Frosts of Youlgreave

Ellen Frost’s father was John Frost, born in Youlgreave in 1707. John married Ann Staley of Elton in 1733 in Youlgreave.

(Note that this part of the family tree is the Marshall side, but we also have Staley’s in Elton on the Warren side. Our branch of the Elton Staley’s moved to Stapenhill in the mid 1700s. Robert Staley, born 1711 in Elton, died in Stapenhill in 1795. There are many Staley’s in the Youlgreave parish registers, going back to the late 1500s.)

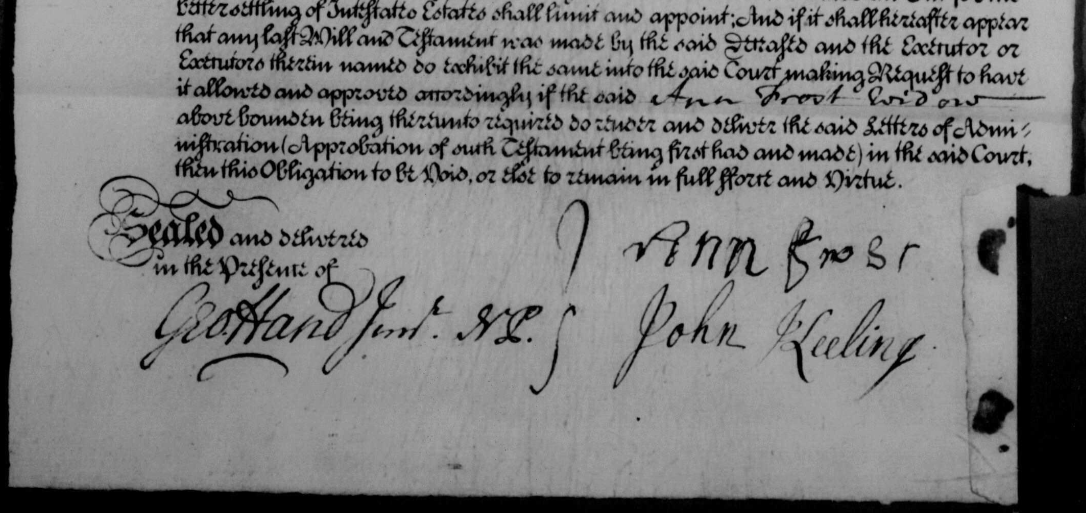

John Frost (my 6x great grandfather), miner, died intestate in 1762 in Youlgreave. Miner in this case no doubt means a lead miner, mining his own land (as John Marshall’s father John was in Elton. On the 1851 census John Marshall senior was mining 9 acres). Ann Frost, as the widow and relict of the said deceased John Frost, claimed the right of administration of his estate. Ann Frost (nee Staley) signed her own name, somewhat unusual for a woman to be able to write in 1762, as well as her son in law John Keeling.

John’s parents were David Frost and Ann. David was baptised in 1665 in Youlgreave. Once again, I have not found a marriage for David and Ann so I am unable to continue further back with her family. Marriages were often held in the parish of the bride, and perhaps those neighbouring parish records from the 1600s haven’t survived.

David’s parents were William Frost and Ellen (or Ellin, or Helen, depending on how the parish clerk chose to spell it). Once again, their marriage hasn’t been found, but was probably in a neighbouring parish.

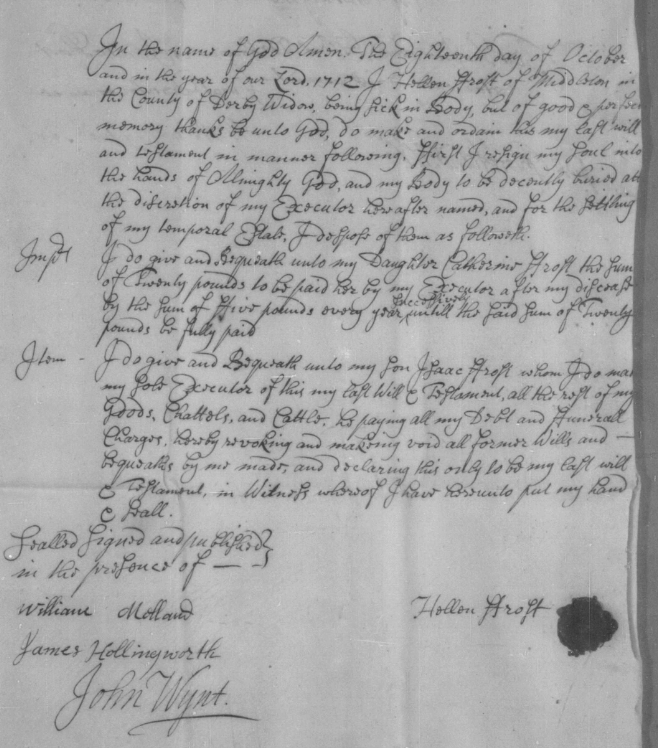

William Frost’s wife Ellen, my 8x great grandmother, died in Youlgreave in 1713. In her will she left her daughter Catherine £20. Catherine was born in 1665 and was apparently unmarried at the age of 48 in 1713. She named her son Isaac Frost (born in 1662) executor, and left him the remainder of her “goods, chattels and cattle”.

William Frost was baptised in Youlgreave in 1627, his parents were William Frost and Anne.

William Frost senior, husbandman, was probably born circa 1600, and died intestate in 1648 in Middleton, Youlgreave. His widow Anna was named in the document. On the compilation of the inventory of his goods, Thomas Garratt, Will Melland and A Kidiard are named.(Husbandman: The old word for a farmer below the rank of yeoman. A husbandman usually held his land by copyhold or leasehold tenure and may be regarded as the ‘average farmer in his locality’. The words ‘yeoman’ and ‘husbandman’ were gradually replaced in the later 18th and 19th centuries by ‘farmer’.)

Unable to find a baptism for William Frost born circa 1600, I read through all the pages of the Youlgreave parish registers from 1558 to 1610. Despite the good condition of these registers, there are a number of illegible entries. There were three Frost families baptising children during this timeframe and one of these is likely to be Willliam’s.

Baptisms:

1581 Eliz Frost, father Michael.

1582 Francis f Michael. (must have died in infancy)

1582 Margaret f William.

1585 Francis f Michael.

1586 John f Nicholas.

1588 Barbara f Michael.

1590 Francis f Nicholas.

1591 Joane f Michael.

1594 John f Michael.

1598 George f Michael.

1600 Fredericke (female!) f William.Marriages in Youlgreave which could be William’s parents:

1579 Michael Frost Eliz Staley

1587 Edward Frost Katherine Hall

1600 Nicholas Frost Katherine Hardy.

1606 John Frost Eliz Hanson.Michael Frost of Youlgreave is mentioned on the Derbyshire Muster Rolls in 1585.

(Muster records: 1522-1649. The militia muster rolls listed all those liable for military service.)

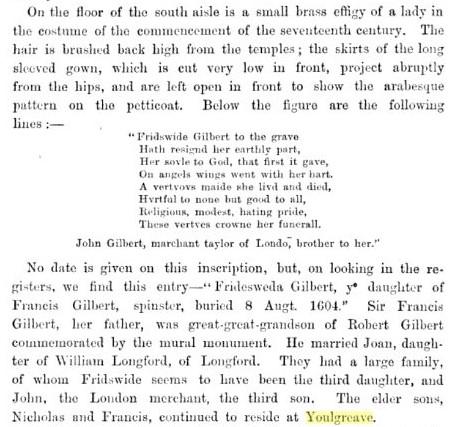

Frideswide:

A burial is recorded in 1584 for Frideswide Frost (female) father Michael. As the father is named, this indicates that Frideswide was a child.

(Frithuswith, commonly Frideswide c. 650 – 19 October 727), was an English princess and abbess. She is credited as the foundress of a monastery later incorporated into Christ Church, Oxford. She was the daughter of a sub-king of a Merica named Dida of Eynsham whose lands occupied western Oxfordshire and the upper reaches of the River Thames.)

An unusual name, and certainly very different from the usual names of the Frost siblings. As I did not find a baptism for her, I wondered if perhaps she died too soon for a baptism and was given a saints name, in the hope that it would help in the afterlife, given the beliefs of the times. Or perhaps it wasn’t an unusual name at the time in Youlgreave. A Fridesweda Gilbert was buried in Youlgreave in 1604, the spinster daughter of Francis Gilbert. There is a small brass effigy in the church, underneath is written “Frideswide Gilbert to the grave, Hath resigned her earthly part…”

J. Charles Cox, Notes on the Churches of Derbyshire, 1877.

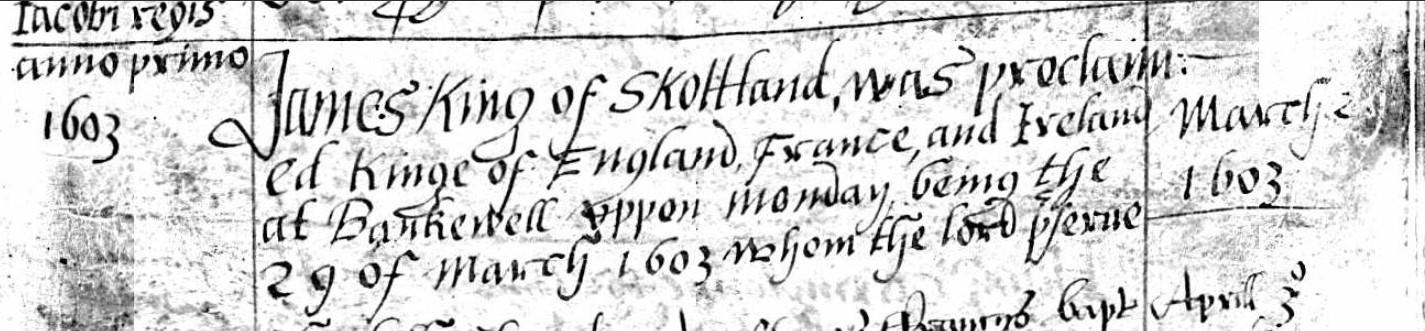

King James

A parish register entry in 1603:

“1603 King James of Skottland was proclaimed kinge of England, France and Ireland at Bakewell upon Monday being the 29th of March 1603.” (March 1603 would be 1604, because of the Julian calendar in use at the time.)

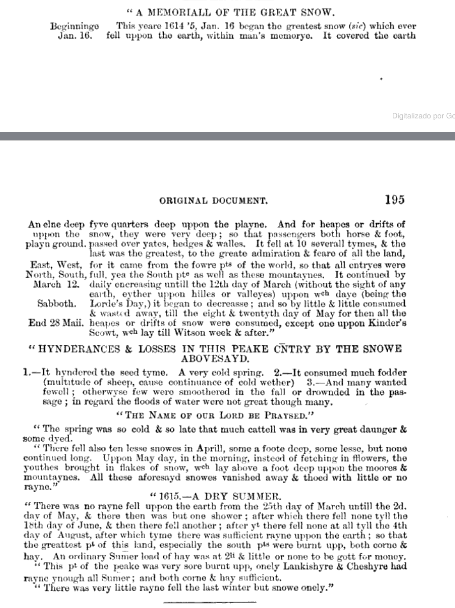

The Big Snow

“This year 1614/5 January 16th began the greatest snow whichever fell uppon the earth within man’s memorye. It covered the earth fyve quarters deep uppon the playne. And for heaps or drifts of snow, they were very deep; so that passengers both horse or foot passed over yates, hedges and walles. ….The spring was so cold and so late that much cattel was in very great danger and some died….”

From the Youlgreave parish registers.

Our ancestor William Frost born circa 1600 would have been a teenager during the big snow.

June 12, 2024 at 12:25 pm #7469In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

After the sage smoke was dispersed, Eris typed the words on the air keyboard.

Malové, how can we cope with the struggling left with your sudden disappearance, and not succumb to despair in front of fuzzy objectives, lack of drive, avoidance of tough decisions, and general ineffective organisation?

The answer wasn’t long to appear, a perfect resemblance of Malové, down to the intonations:

The night is darkest before the dawn, Eris. My sudden absence is not a void, but an opportunity. The challenges you face are the crucible that will forge your mettle.

Here is your path:

1. Embrace the Struggle: Despair is a luxury we cannot afford. Every obstacle is a lesson cloaked in shadows. Meet it head-on. Confront your fears and frailties—only then will you transcend them.

2. Clarify Objectives: The haze of uncertainty can be dispelled with focus. Define your goals with precision. Each witch must understand her role and the greater picture. Fragmented efforts yield nothing but chaos.

3. Revitalize Your Drive: Passion wanes without purpose. Revisit the roots of your magical essence. Rediscover the fire that led you to the Quadrivium. Let it burn anew within you.

4. Confront Tough Decisions: Avoidance is the death of progress. Decisions, however difficult, must be made with swiftness and resolve. Hesitation fosters weakness; action breeds strength.

5. Streamline Organisation: Inefficiency is a poison. Implement rigorous structures. Assign clear responsibilities and hold each other accountable. The chain is only as strong as its weakest link.

6. Leverage Collective Wisdom: You are not alone in this. Draw strength from your sisters. Engage in open, constructive dialogue. Balance assertiveness with respect, as I have taught. Unity in purpose will amplify your power.

7. Adapt and Overcome: The world shifts, and so must you. Flexibility is paramount. When confronted with the unexpected, adapt swiftly. Use the resources at hand and turn adversity into advantage.

7 points, for seven is the number of Truth Seekers. Remember, the Quadrivium’s legacy is not built on ease but on resilience and relentless pursuit of mastery. My absence tests your resolve. Prove that you are worthy.

Now, go forth and etch your magic into the annals of time.

Malové

Eris pondered for a moment, and clapped her hands. The familiar figure of Elias emerged.

“Good job Elias, fidelity is almost there. The content is mostly correct, but the delivery is a bit stuffy.”

“I will work on this to improve. I would need more source material though. Shall I interview some other witches?”

“Not at the moment, I’d rather surprise them with the final product.” Eris was being sneaky. This backup of Malové (she called her Maboté) was on the fringes of what was ethical even for a witch, although it could help in case Austreberthe’s interim management would fail them.

At the moment, despite what she told Elias, she wasn’t close to success, and Elias himself had proven tricky to get right, so Malové of all figures… it would be another journey.

Well, at least for now, she did provide some good advice.

February 11, 2024 at 9:06 am #7361In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

Truella had already left for that monkey hunt in the Mediterranean. Eris had to go back before nightfall, which was quite early at this time of year as she had chosen to live in such a remote place in the midst of a frozen forest. Jeezel only thought it romantic because of the icicles that would form on your eyelashes and brows, making you the perfect avatar for the Snow Queen musical. And Frigella… She said she was tired but from the sight of her aura, she undoubtedly was onto something fishy.

Jeezel looked at her dress. Once a divine creation, it has turned into a disaster. Irremediably stained with soot, it’s foul smell would make any dragon lose their appetite. She felt a mix of sadness and guilt for all the murex that gave their shells for that unique shade of purple she was so proud of.

She wasn’t sure even Teddy Steambolt could muster his magic to save the divine creation. She imagined his eyes widen as saucers when she entered his Palace of Pristine with the lifeless garment in her arms. He would most certainly swoon and gasp at the same time.

“Oh, The tragedy!” he would wail, his high-pitched lament resonating in the cathedral ceiling of his atelier of cleanliness. “What calamity hath befallen this exquisite creation?”

“Teddy, dear,” she would say, “It was indeed a tragedy. I lost seven of my nails and my hair was ruined. You’re the alchemist of cleanliness, you’re my only hope for a miracle.”

And he would take her dress and perform his magic from which it would emerge reborn, and all those murex wouldn’t have lost their home for nothing.

She was about to follow the others when Malové reminded her: “Aren’t you forgetting something?”

A broom and a bucket of black soap were floating on her right.

Her sigh would have made a blue whale blush with envy. Her role tonight would not be the Snow Queen, but Cinderella, another of her favourite diva.

January 31, 2023 at 11:58 am #6478In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

“One of them’s arriving early!” Aunt Idle told Mater who had just come swanning into the kitchen with her long grey hair neatly plaited and tied with a red velvet bow. Ridiculous being so particular about her hair at her age, Idle thought, whose own hair was an untidy and non too clean looking tangle of long dreadlocks with faded multicolour dyes growing out from her grey scalp. “Bert’s going to pick her up at seven.”

“You better get a move on then, the verandah needs sweeping and the dining room needs dusting. Are the bedrooms ready yet?” Mater replied, patting her hair and pulling her cardigan down neatly.

“Plenty of time, no need to worry!” Idle said, looking worried. “What on earth was that?” Something bright caught her eye through the kitchen window.

“Never mind that, make a start on the cleaning!” Mater said with a loud tut and an eye roll. Always getting distracted, that one, never finishes a job before she’s off sidetracking. Mater gave her hair another satisfied pat, and put two slices of bread in the toaster.

But Aunt Idle had gone outside to investigate. A minute or two later she returned, saying “You’ll never guess what, there’s a tame red parrot sitting on the porch table. And it talks!”

“So you’re planning to spend the day talking to a parrot, and leave me to do all the dusting, is that it?” Mater said, spreading honey on her toast.

January 31, 2023 at 11:34 am #6477

January 31, 2023 at 11:34 am #6477In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Bertie dropped Zara off at the bus station in Camden early the next morning. She let him think she was catching a plane from Sydney, given her impulsive lie about having to meet her friends sooner, but she was going by train. The reviews she’d read online were tantalizing:

“The Ghan journey tells the story of the land. The train is the canvas, and the changing landscape paints the picture.”

A two day train ride would give her time to relax and play the game, and she assumed two days of desert scenery would not be too distracting. Luckily before she paid for her ticket she had the presence of mind to ask if there was internet on the train. There was not. Zara sighed, and booked a flight instead, but decided she would catch the train back home after the holiday at the Flying Fish Inn. By then perhaps the novelty of the game would have worn off, and she would appreciate the time spent in quiet contemplation, and perhaps do some writing.

Zara hated flying, especially airports. The best that could be said of flying was that it was a quick way to get from A to B.

“You’ll have to go in a cage for the flight, Pretty Girl,” she told the parrot.

“I think not,” replied Pretty Girl. “I’ll meet you there. See you!” and off she flew into the low morning sun, momentarily blinding Zara as she watched her go.

Her flight left Sydney at 14:35. Three and a half hours later she would arrive at Alice Springs and from there it was a half hour road trip to the Flying Fish. Zara sent an email to the inn asking if anyone could pick her up, otherwise she would get a bus or a taxi. She received a reply saying that they’d send Bert to pick her up around seven o’clock. Another Bert!

December 6, 2022 at 2:17 pm #6350In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Transportation

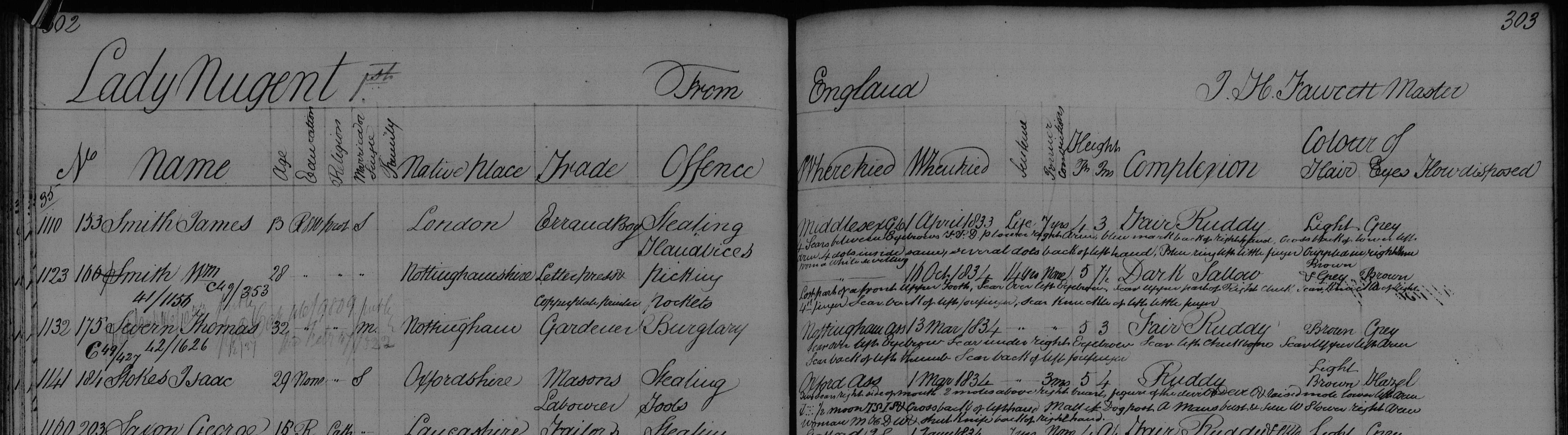

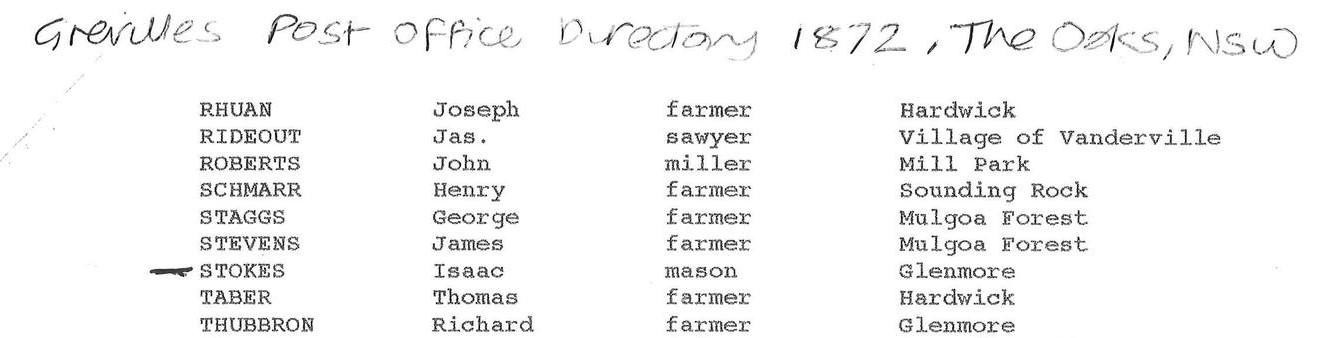

Isaac Stokes 1804-1877

Isaac was born in Churchill, Oxfordshire in 1804, and was the youngest brother of my 4X great grandfather Thomas Stokes. The Stokes family were stone masons for generations in Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire, and Isaac’s occupation was a mason’s labourer in 1834 when he was sentenced at the Lent Assizes in Oxford to fourteen years transportation for stealing tools.

Churchill where the Stokes stonemasons came from: on 31 July 1684 a fire destroyed 20 houses and many other buildings, and killed four people. The village was rebuilt higher up the hill, with stone houses instead of the old timber-framed and thatched cottages. The fire was apparently caused by a baker who, to avoid chimney tax, had knocked through the wall from her oven to her neighbour’s chimney.

Isaac stole a pick axe, the value of 2 shillings and the property of Thomas Joyner of Churchill; a kibbeaux and a trowel value 3 shillings the property of Thomas Symms; a hammer and axe value 5 shillings, property of John Keen of Sarsden.

(The word kibbeaux seems to only exists in relation to Isaac Stokes sentence and whoever was the first to write it was perhaps being creative with the spelling of a kibbo, a miners or a metal bucket. This spelling is repeated in the criminal reports and the newspaper articles about Isaac, but nowhere else).

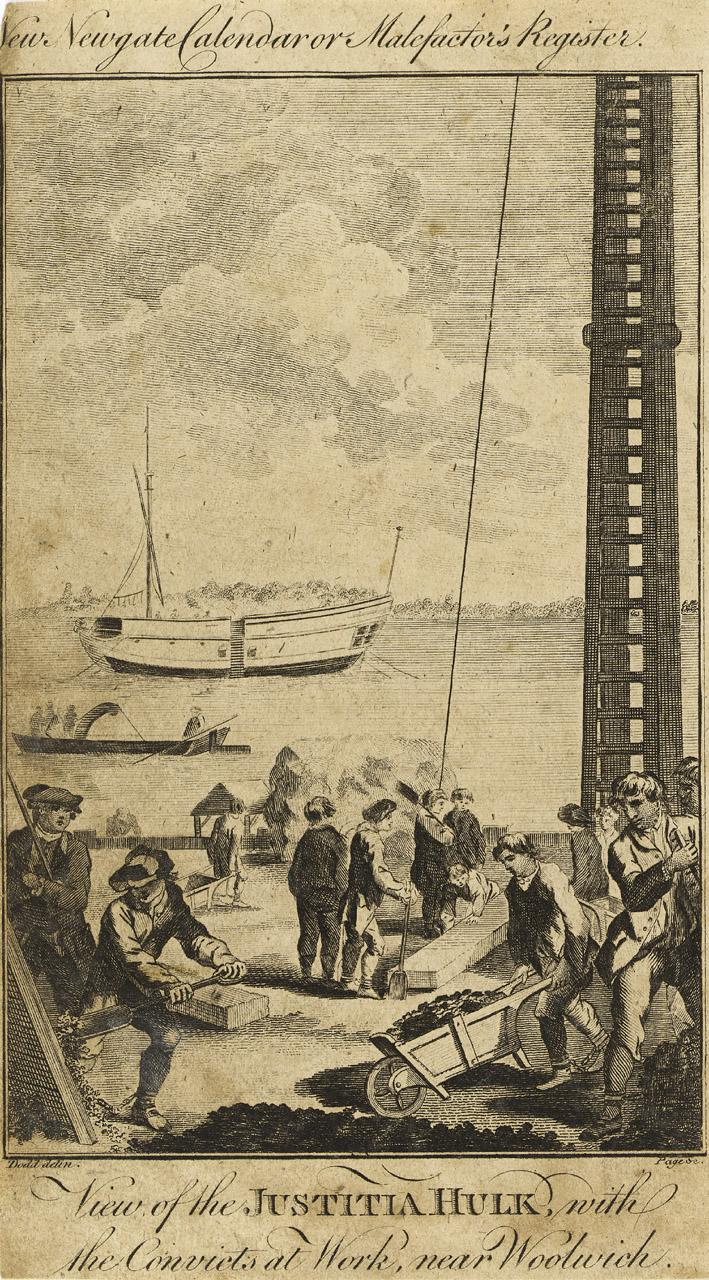

In March 1834 the Removal of Convicts was announced in the Oxford University and City Herald: Isaac Stokes and several other prisoners were removed from the Oxford county gaol to the Justitia hulk at Woolwich “persuant to their sentences of transportation at our Lent Assizes”.

via digitalpanopticon:

Hulks were decommissioned (and often unseaworthy) ships that were moored in rivers and estuaries and refitted to become floating prisons. The outbreak of war in America in 1775 meant that it was no longer possible to transport British convicts there. Transportation as a form of punishment had started in the late seventeenth century, and following the Transportation Act of 1718, some 44,000 British convicts were sent to the American colonies. The end of this punishment presented a major problem for the authorities in London, since in the decade before 1775, two-thirds of convicts at the Old Bailey received a sentence of transportation – on average 283 convicts a year. As a result, London’s prisons quickly filled to overflowing with convicted prisoners who were sentenced to transportation but had no place to go.

To increase London’s prison capacity, in 1776 Parliament passed the “Hulks Act” (16 Geo III, c.43). Although overseen by local justices of the peace, the hulks were to be directly managed and maintained by private contractors. The first contract to run a hulk was awarded to Duncan Campbell, a former transportation contractor. In August 1776, the Justicia, a former transportation ship moored in the River Thames, became the first prison hulk. This ship soon became full and Campbell quickly introduced a number of other hulks in London; by 1778 the fleet of hulks on the Thames held 510 prisoners.

Demand was so great that new hulks were introduced across the country. There were hulks located at Deptford, Chatham, Woolwich, Gosport, Plymouth, Portsmouth, Sheerness and Cork.The Justitia via rmg collections:

Convicts perform hard labour at the Woolwich Warren. The hulk on the river is the ‘Justitia’. Prisoners were kept on board such ships for months awaiting deportation to Australia. The ‘Justitia’ was a 260 ton prison hulk that had been originally moored in the Thames when the American War of Independence put a stop to the transportation of criminals to the former colonies. The ‘Justitia’ belonged to the shipowner Duncan Campbell, who was the Government contractor who organized the prison-hulk system at that time. Campbell was subsequently involved in the shipping of convicts to the penal colony at Botany Bay (in fact Port Jackson, later Sydney, just to the north) in New South Wales, the ‘first fleet’ going out in 1788.

While searching for records for Isaac Stokes I discovered that another Isaac Stokes was transported to New South Wales in 1835 as well. The other one was a butcher born in 1809, sentenced in London for seven years, and he sailed on the Mary Ann. Our Isaac Stokes sailed on the Lady Nugent, arriving in NSW in April 1835, having set sail from England in December 1834.

Lady Nugent was built at Bombay in 1813. She made four voyages under contract to the British East India Company (EIC). She then made two voyages transporting convicts to Australia, one to New South Wales and one to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). (via Wikipedia)

via freesettlerorfelon website:

On 20 November 1834, 100 male convicts were transferred to the Lady Nugent from the Justitia Hulk and 60 from the Ganymede Hulk at Woolwich, all in apparent good health. The Lady Nugent departed Sheerness on 4 December 1834.

SURGEON OLIVER SPROULE

Oliver Sproule kept a Medical Journal from 7 November 1834 to 27 April 1835. He recorded in his journal the weather conditions they experienced in the first two weeks:

‘In the course of the first week or ten days at sea, there were eight or nine on the sick list with catarrhal affections and one with dropsy which I attribute to the cold and wet we experienced during that period beating down channel. Indeed the foremost berths in the prison at this time were so wet from leaking in that part of the ship, that I was obliged to issue dry beds and bedding to a great many of the prisoners to preserve their health, but after crossing the Bay of Biscay the weather became fine and we got the damp beds and blankets dried, the leaks partially stopped and the prison well aired and ventilated which, I am happy to say soon manifested a favourable change in the health and appearance of the men.

Besides the cases given in the journal I had a great many others to treat, some of them similar to those mentioned but the greater part consisted of boils, scalds, and contusions which would not only be too tedious to enter but I fear would be irksome to the reader. There were four births on board during the passage which did well, therefore I did not consider it necessary to give a detailed account of them in my journal the more especially as they were all favourable cases.

Regularity and cleanliness in the prison, free ventilation and as far as possible dry decks turning all the prisoners up in fine weather as we were lucky enough to have two musicians amongst the convicts, dancing was tolerated every afternoon, strict attention to personal cleanliness and also to the cooking of their victuals with regular hours for their meals, were the only prophylactic means used on this occasion, which I found to answer my expectations to the utmost extent in as much as there was not a single case of contagious or infectious nature during the whole passage with the exception of a few cases of psora which soon yielded to the usual treatment. A few cases of scurvy however appeared on board at rather an early period which I can attribute to nothing else but the wet and hardships the prisoners endured during the first three or four weeks of the passage. I was prompt in my treatment of these cases and they got well, but before we arrived at Sydney I had about thirty others to treat.’

The Lady Nugent arrived in Port Jackson on 9 April 1835 with 284 male prisoners. Two men had died at sea. The prisoners were landed on 27th April 1835 and marched to Hyde Park Barracks prior to being assigned. Ten were under the age of 14 years.

The Lady Nugent:

Isaac’s distinguishing marks are noted on various criminal registers and record books:

“Height in feet & inches: 5 4; Complexion: Ruddy; Hair: Light brown; Eyes: Hazel; Marks or Scars: Yes [including] DEVIL on lower left arm, TSIS back of left hand, WS lower right arm, MHDW back of right hand.”

Another includes more detail about Isaac’s tattoos:

“Two slight scars right side of mouth, 2 moles above right breast, figure of the devil and DEVIL and raised mole, lower left arm; anchor, seven dots half moon, TSIS and cross, back of left hand; a mallet, door post, A, mans bust, sun, WS, lower right arm; woman, MHDW and shut knife, back of right hand.”

From How tattoos became fashionable in Victorian England (2019 article in TheConversation by Robert Shoemaker and Zoe Alkar):

“Historical tattooing was not restricted to sailors, soldiers and convicts, but was a growing and accepted phenomenon in Victorian England. Tattoos provide an important window into the lives of those who typically left no written records of their own. As a form of “history from below”, they give us a fleeting but intriguing understanding of the identities and emotions of ordinary people in the past.

As a practice for which typically the only record is the body itself, few systematic records survive before the advent of photography. One exception to this is the written descriptions of tattoos (and even the occasional sketch) that were kept of institutionalised people forced to submit to the recording of information about their bodies as a means of identifying them. This particularly applies to three groups – criminal convicts, soldiers and sailors. Of these, the convict records are the most voluminous and systematic.

Such records were first kept in large numbers for those who were transported to Australia from 1788 (since Australia was then an open prison) as the authorities needed some means of keeping track of them.”On the 1837 census Isaac was working for the government at Illiwarra, New South Wales. This record states that he arrived on the Lady Nugent in 1835. There are three other indent records for an Isaac Stokes in the following years, but the transcriptions don’t provide enough information to determine which Isaac Stokes it was. In April 1837 there was an abscondment, and an arrest/apprehension in May of that year, and in 1843 there was a record of convict indulgences.

From the Australian government website regarding “convict indulgences”:

“By the mid-1830s only six per cent of convicts were locked up. The vast majority worked for the government or free settlers and, with good behaviour, could earn a ticket of leave, conditional pardon or and even an absolute pardon. While under such orders convicts could earn their own living.”

In 1856 in Camden, NSW, Isaac Stokes married Catherine Daly. With no further information on this record it would be impossible to know for sure if this was the right Isaac Stokes. This couple had six children, all in the Camden area, but none of the records provided enough information. No occupation or place or date of birth recorded for Isaac Stokes.

I wrote to the National Library of Australia about the marriage record, and their reply was a surprise! Issac and Catherine were married on 30 September 1856, at the house of the Rev. Charles William Rigg, a Methodist minister, and it was recorded that Isaac was born in Edinburgh in 1821, to parents James Stokes and Sarah Ellis! The age at the time of the marriage doesn’t match Isaac’s age at death in 1877, and clearly the place of birth and parents didn’t match either. Only his fathers occupation of stone mason was correct. I wrote back to the helpful people at the library and they replied that the register was in a very poor condition and that only two and a half entries had survived at all, and that Isaac and Catherines marriage was recorded over two pages.

I searched for an Isaac Stokes born in 1821 in Edinburgh on the Scotland government website (and on all the other genealogy records sites) and didn’t find it. In fact Stokes was a very uncommon name in Scotland at the time. I also searched Australian immigration and other records for another Isaac Stokes born in Scotland or born in 1821, and found nothing. I was unable to find a single record to corroborate this mysterious other Isaac Stokes.

As the age at death in 1877 was correct, I assume that either Isaac was lying, or that some mistake was made either on the register at the home of the Methodist minster, or a subsequent mistranscription or muddle on the remnants of the surviving register. Therefore I remain convinced that the Camden stonemason Isaac Stokes was indeed our Isaac from Oxfordshire.

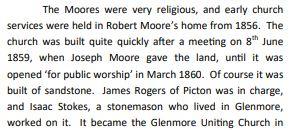

I found a history society newsletter article that mentioned Isaac Stokes, stone mason, had built the Glenmore church, near Camden, in 1859.

From the Wollondilly museum April 2020 newsletter:

From the Camden History website:

“The stone set over the porch of Glenmore Church gives the date of 1860. The church was begun in 1859 on land given by Joseph Moore. James Rogers of Picton was given the contract to build and local builder, Mr. Stokes, carried out the work. Elizabeth Moore, wife of Edward, laid the foundation stone. The first service was held on 19th March 1860. The cemetery alongside the church contains the headstones and memorials of the areas early pioneers.”

Isaac died on the 3rd September 1877. The inquest report puts his place of death as Bagdelly, near to Camden, and another death register has put Cambelltown, also very close to Camden. His age was recorded as 71 and the inquest report states his cause of death was “rupture of one of the large pulmonary vessels of the lung”. His wife Catherine died in childbirth in 1870 at the age of 43.

Isaac and Catherine’s children:

William Stokes 1857-1928

Catherine Stokes 1859-1846

Sarah Josephine Stokes 1861-1931

Ellen Stokes 1863-1932

Rosanna Stokes 1865-1919

Louisa Stokes 1868-1844.

It’s possible that Catherine Daly was a transported convict from Ireland.

Some time later I unexpectedly received a follow up email from The Oaks Heritage Centre in Australia.

“The Gaudry papers which we have in our archive record him (Isaac Stokes) as having built: the church, the school and the teachers residence. Isaac is recorded in the General return of convicts: 1837 and in Grevilles Post Office directory 1872 as a mason in Glenmore.”

November 13, 2022 at 10:29 pm #6345

November 13, 2022 at 10:29 pm #6345In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

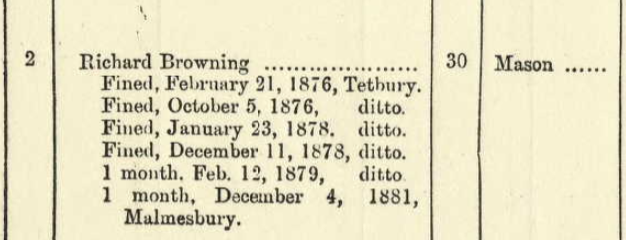

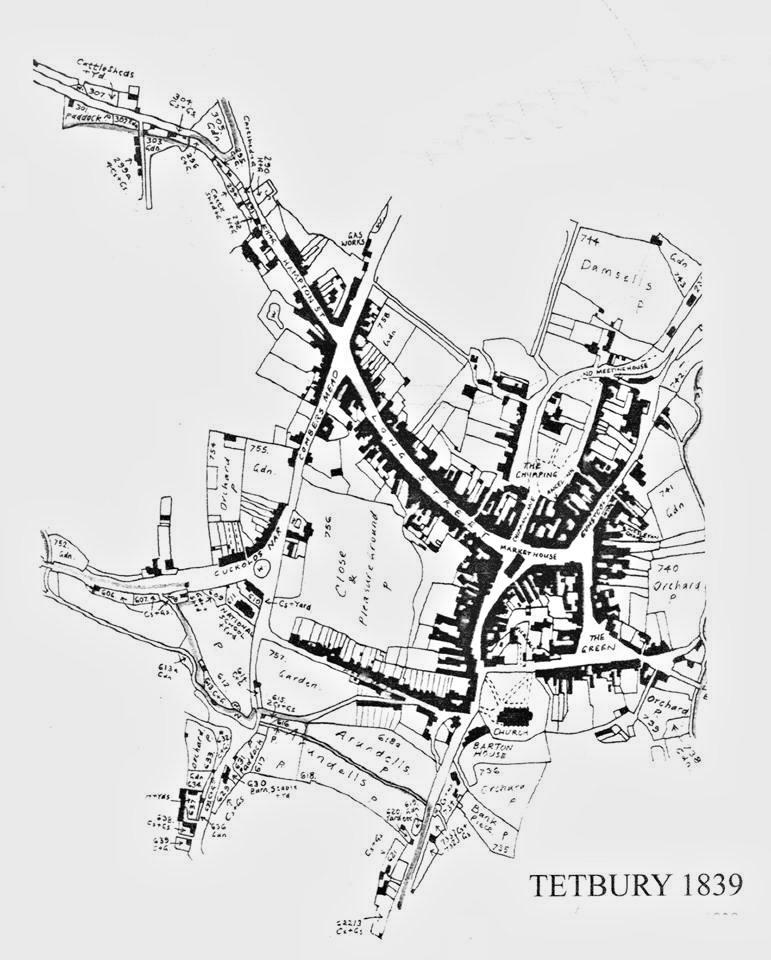

Crime and Punishment in Tetbury

I noticed that there were quite a number of Brownings of Tetbury in the newspaper archives involved in criminal activities while doing a routine newspaper search to supplement the information in the usual ancestry records. I expanded the tree to include cousins, and offsping of cousins, in order to work out who was who and how, if at all, these individuals related to our Browning family.

I was expecting to find some of our Brownings involved in the Swing Riots in Tetbury in 1830, but did not. Most of our Brownings (including cousins) were stone masons. Most of the rioters in 1830 were agricultural labourers.

The Browning crimes are varied, and by todays standards, not for the most part terribly serious ~ you would be unlikely to receive a sentence of hard labour for being found in an outhouse with the intent to commit an unlawful act nowadays, or for being drunk.

The central character in this chapter is Isaac Browning (my 4x great grandfather), who did not appear in any criminal registers, but the following individuals can be identified in the family structure through their relationship to him.

RICHARD LOCK BROWNING born in 1853 was Isaac’s grandson, his son George’s son. Richard was a mason. In 1879 he and Henry Browning of the same age were sentenced to one month hard labour for stealing two pigeons in Tetbury. Henry Browning was Isaac’s nephews son.

In 1883 Richard Browning, mason of Tetbury, was charged with obtaining food and lodging under false pretences, but was found not guilty and acquitted.

In 1884 Richard Browning, mason of Tetbury, was sentenced to one month hard labour for game trespass.Richard had been fined a number of times in Tetbury:

Richard Lock Browning was five feet eight inches tall, dark hair, grey eyes, an oval face and a dark complexion. He had two cuts on the back of his head (in February 1879) and a scar on his right eyebrow.

HENRY BROWNING, who was stealing pigeons with Richard Lock Browning in 1879, (Isaac’s brother Williams grandson, son of George Browning and his wife Charity) was charged with being drunk in 1882 and ordered to pay a fine of one shilling and costs of fourteen shillings, or seven days hard labour.

Henry was found guilty of gaming in the highway at Tetbury in 1872 and was sentenced to seven days hard labour. In 1882 Henry (who was also a mason) was charged with assault but discharged.

Henry was five feet five inches tall, brown hair and brown eyes, a long visage and a fresh complexion.

Henry emigrated with his daughter to Canada in 1913, and died in Vancouver in 1919.THOMAS BUCKINGHAM 1808-1846 (Isaacs daughter Janes husband) was charged with stealing a black gelding in Tetbury in 1838. No true bill. (A “no true bill” means the jury did not find probable cause to continue a case.)

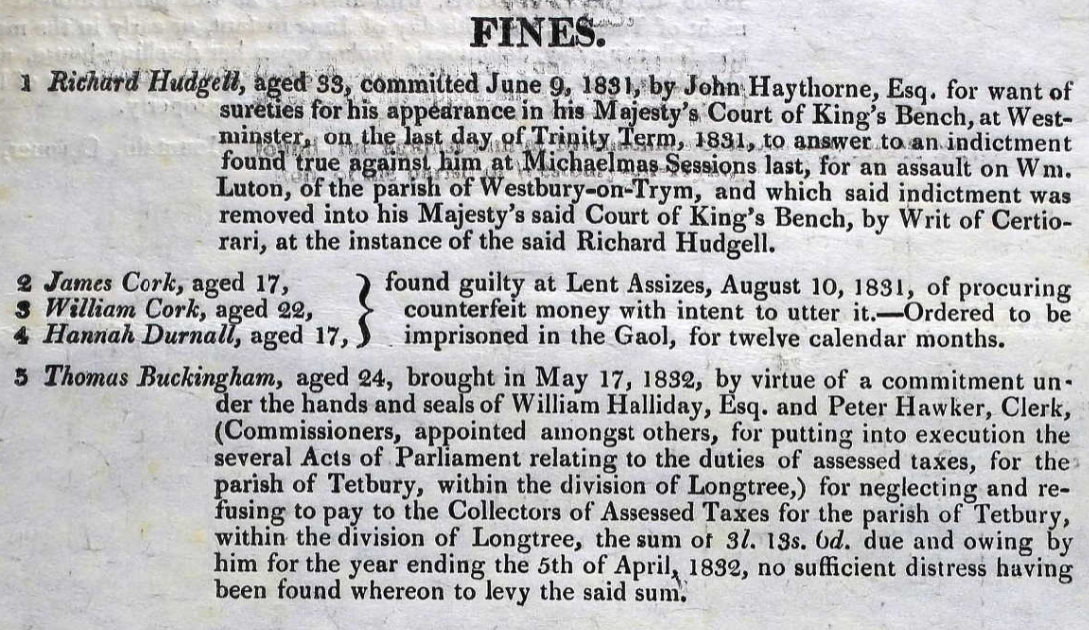

Thomas did however neglect to pay his taxes in 1832:

LEWIN BUCKINGHAM (grandson of Isaac, his daughter Jane’s son) was found guilty in 1846 stealing two fowls in Tetbury when he was sixteen years old.

In 1846 he was sentence to one month hard labour (or pay ten shillings fine and ten shillings costs) for loitering with the intent to trespass in search of conies.

A year later in 1847, he and three other young men were sentenced to four months hard labour for larceny.

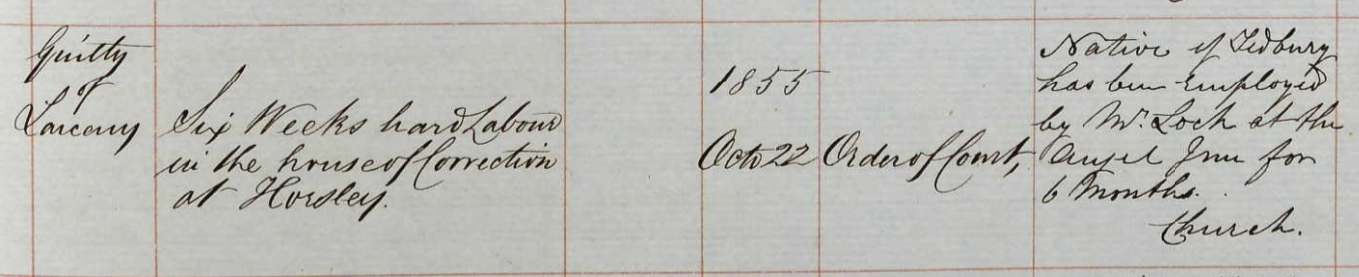

Lewin was five feet three inches tall, with brown hair and brown eyes, long visage, sallow complexion, and had a scar on his left arm.JOHN BUCKINGHAM born circa 1832, a Tetbury labourer (Isaac’s grandson, Lewin’s brother) was sentenced to six weeks hard labour for larceny in 1855 for stealing a duck in Cirencester. The notes on the register mention that he had been employed by Mr LOCK, Angel Inn. (John’s grandmother was Mary Lock so this is likely a relative).

The previous year in 1854 John was sentenced to one month or a one pound fine for assaulting and beating W. Wood.

John was five feet eight and three quarter inches tall, light brown hair and grey eyes, an oval visage and a fresh complexion. He had a scar on his left arm and inside his right knee.JOSEPH PERRET was born circa 1831 and he was a Tetbury labourer. (He was Isaac’s granddaughter Charlotte Buckingham’s husband)

In 1855 he assaulted William Wood and was sentenced to one month or a two pound ten shilling fine. Was it the same W Wood that his wifes cousin John assaulted the year before?

In 1869 Joseph was sentenced to one month hard labour for feloniously receiving a cupboard known to be stolen.JAMES BUCKINGAM born circa 1822 in Tetbury was a shoemaker. (Isaac’s nephew, his sister Hannah’s son)

In 1854 the Tetbury shoemaker was sentenced to four months hard labour for stealing 30 lbs of lead off someones house.

In 1856 the Tetbury shoemaker received two months hard labour or pay £2 fine and 12 s costs for being found in pursuit of game.

In 1868 he was sentenced to two months hard labour for stealing a gander. A unspecified previous conviction is noted.

1871 the Tetbury shoemaker was found in an outhouse for an unlawful purpose and received ten days hard labour. The register notes that his sister is Mrs Cook, the Green, Tetbury. (James sister Prudence married Thomas Cook)

James sister Charlotte married a shoemaker and moved to UTAH.

James was five feet eight inches tall, dark hair and blue eyes, a long visage and a florid complexion. He had a scar on his forehead and a mole on the right side of his neck and abdomen, and a scar on the right knee.November 4, 2022 at 2:19 pm #6342In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Brownings of Tetbury

Isaac Browning (1784-1848) married Mary Lock (1787-1870) in Tetbury in 1806. Both of them were born in Tetbury, Gloucestershire. Isaac was a stone mason. Between 1807 and 1832 they baptised fourteen children in Tetbury, and on 8 Nov 1829 Isaac and Mary baptised five daughters all on the same day.

I considered that they may have been quintuplets, with only the last born surviving, which would have answered my question about the name of the house La Quinta in Broadway, the home of Eliza Browning and Thomas Stokes son Fred. However, the other four daughters were found in various records and they were not all born the same year. (So I still don’t know why the house in Broadway had such an unusual name).

Their son George was born and baptised in 1827, but Louisa born 1821, Susan born 1822, Hesther born 1823 and Mary born 1826, were not baptised until 1829 along with Charlotte born in 1828. (These birth dates are guesswork based on the age on later censuses.) Perhaps George was baptised promptly because he was sickly and not expected to survive. Isaac and Mary had a son George born in 1814 who died in 1823. Presumably the five girls were healthy and could wait to be done as a job lot on the same day later.

Eliza Browning (1814-1886), my great great great grandmother, had a baby six years before she married Thomas Stokes. Her name was Ellen Harding Browning, which suggests that her fathers name was Harding. On the 1841 census seven year old Ellen was living with her grandfather Isaac Browning in Tetbury. Ellen Harding Browning married William Dee in Tetbury in 1857, and they moved to Western Australia.

Ellen Harding Browning Dee: (photo found on ancestry website)

OBITUARY. MRS. ELLEN DEE.

A very old and respected resident of Dongarra, in the person of Mrs. Ellen Dee, passed peacefully away on Sept. 27, at the advanced age of 74 years.The deceased had been ailing for some time, but was about and actively employed until Wednesday, Sept. 20, whenn she was heard groaning by some neighbours, who immediately entered her place and found her lying beside the fireplace. Tho deceased had been to bed over night, and had evidently been in the act of lighting thc fire, when she had a seizure. For some hours she was conscious, but had lost the power of speech, and later on became unconscious, in which state she remained until her death.

The deceased was born in Gloucestershire, England, in 1833, was married to William Dee in Tetbury Church 23 years later. Within a month she left England with her husband for Western Australian in the ship City oí Bristol. She resided in Fremantle for six months, then in Greenough for a short time, and afterwards (for 42 years) in Dongarra. She was, therefore, a colonist of about 51 years. She had a family of four girls and three boys, and five of her children survive her, also 35 grandchildren, and eight great grandchildren. She was very highly respected, and her sudden collapse came as a great shock to many.

Eliza married Thomas Stokes (1816-1885) in September 1840 in Hempstead, Gloucestershire. On the 1841 census, Eliza and her mother Mary Browning (nee Lock) were staying with Thomas Lock and family in Cirencester. Strangely, Thomas Stokes has not been found thus far on the 1841 census, and Thomas and Eliza’s first child William James Stokes birth was registered in Witham, in Essex, on the 6th of September 1841.

I don’t know why William James was born in Witham, or where Thomas was at the time of the census in 1841. One possibility is that as Thomas Stokes did a considerable amount of work with circus waggons, circus shooting galleries and so on as a journeyman carpenter initially and then later wheelwright, perhaps he was working with a traveling circus at the time.

But back to the Brownings ~ more on William James Stokes to follow.

One of Isaac and Mary’s fourteen children died in infancy: Ann was baptised and died in 1811. Two of their children died at nine years old: the first George, and Mary who died in 1835. Matilda was 21 years old when she died in 1844.

Jane Browning (1808-) married Thomas Buckingham in 1830 in Tetbury. In August 1838 Thomas was charged with feloniously stealing a black gelding.

Susan Browning (1822-1879) married William Cleaver in November 1844 in Tetbury. Oddly thereafter they use the name Bowman on the census. On the 1851 census Mary Browning (Susan’s mother), widow, has grandson George Bowman born in 1844 living with her. The confusion with the Bowman and Cleaver names was clarified upon finding the criminal registers:

30 January 1834. Offender: William Cleaver alias Bowman, Richard Bunting alias Barnfield and Jeremiah Cox, labourers of Tetbury. Crime: Stealing part of a dead fence from a rick barton in Tetbury, the property of Robert Tanner, farmer.

And again in 1836:

29 March 1836 Bowman, William alias Cleaver, of Tetbury, labourer age 18; 5’2.5” tall, brown hair, grey eyes, round visage with fresh complexion; several moles on left cheek, mole on right breast. Charged on the oath of Ann Washbourn & others that on the morning of the 31 March at Tetbury feloniously stolen a lead spout affixed to the dwelling of the said Ann Washbourn, her property. Found guilty 31 March 1836; Sentenced to 6 months.

On the 1851 census Susan Bowman was a servant living in at a large drapery shop in Cheltenham. She was listed as 29 years old, married and born in Tetbury, so although it was unusual for a married woman not to be living with her husband, (or her son for that matter, who was living with his grandmother Mary Browning), perhaps her husband William Bowman alias Cleaver was in trouble again. By 1861 they are both living together in Tetbury: William was a plasterer, and they had three year old Isaac and Thomas, one year old. In 1871 William was still a plasterer in Tetbury, living with wife Susan, and sons Isaac and Thomas. Interestingly, a William Cleaver is living next door but one!

Susan was 56 when she died in Tetbury in 1879.

Three of the Browning daughters went to London.

Louisa Browning (1821-1873) married Robert Claxton, coachman, in 1848 in Bryanston Square, Westminster, London. Ester Browning was a witness.

Ester Browning (1823-1893)(or Hester) married Charles Hudson Sealey, cabinet maker, in Bethnal Green, London, in 1854. Charles was born in Tetbury. Charlotte Browning was a witness.

Charlotte Browning (1828-1867?) was admitted to St Marylebone workhouse in London for “parturition”, or childbirth, in 1860. She was 33 years old. A birth was registered for a Charlotte Browning, no mothers maiden name listed, in 1860 in Marylebone. A death was registered in Camden, buried in Marylebone, for a Charlotte Browning in 1867 but no age was recorded. As the age and parents were usually recorded for a childs death, I assume this was Charlotte the mother.

I found Charlotte on the 1851 census by chance while researching her mother Mary Lock’s siblings. Hesther Lock married Lewin Chandler, and they were living in Stepney, London. Charlotte is listed as a neice. Although Browning is mistranscribed as Broomey, the original page says Browning. Another mistranscription on this record is Hesthers birthplace which is transcribed as Yorkshire. The original image shows Gloucestershire.

Isaac and Mary’s first son was John Browning (1807-1860). John married Hannah Coates in 1834. John’s brother Charles Browning (1819-1853) married Eliza Coates in 1842. Perhaps they were sisters. On the 1861 census Hannah Browning, John’s wife, was a visitor in the Harding household in a village called Coates near Tetbury. Thomas Harding born in 1801 was the head of the household. Perhaps he was the father of Ellen Harding Browning.

George Browning (1828-1870) married Louisa Gainey in Tetbury, and died in Tetbury at the age of 42. Their son Richard Lock Browning, a 32 year old mason, was sentenced to one month hard labour for game tresspass in Tetbury in 1884.

Isaac Browning (1832-1857) was the youngest son of Isaac and Mary. He was just 25 years old when he died in Tetbury.

July 7, 2022 at 9:45 am #6315In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

It was not yet 9am and Eusebius Kazandis was already sweating. The morning sun was hitting hard on the tarp of his booth. He put the last cauldron among lines of cauldrons on a sagging table at the summer fair of Innsbruck, Austria. It was a tiny three-legged black cauldron with a simple Celtic knot on one side and a tree on the other side, like all the others. His father’s father’s father used to make cauldrons for a living, the kind you used to distil ouzo or cook meals for an Inn. But as time went by and industrialisation made it easier for cooks, the trade slowly evolved toward smaller cauldrons for modern Wiccans. A modern witch wanted it portable and light, ready to use in everyday life situations, and Eusebius was there to provide it for them.

Eusebius sat on his chair and sighed. He couldn’t help but notice the woman in colourful dress who had spread a shawl on the grass under the tall sequoia tree. Nobody liked this spot under the branches oozing sticky resin. She didn’t seem to mind. She was arranging small colourful bottles of oil on her shawl. A sign near her said : Massage oils, Fragrant oils, Polishing oils, all with different names evocative of different properties. He hadn’t noticed her yesterday when everybody was installing their stalls. He wondered if she had paid her fee.

Rosa was smiling as she spread in front of her the meadow flowers she’d picked on her way to the market. It was another beautiful day, under the shade and protection of the big sequoia tree watching over her. She assembled small bouquets and put them in between the vials containing her precious handmade oils. She had noticed people, and especially women, would naturally gather around well dressed stalls and engage conversation. Since she left her hometown of Torino, seven years ago, she’d followed the wind on her journey across Europe. It had led her to Innsbruck and had suddenly stopped blowing. That usually meant she had something to do there, but it also meant that she would have to figure out what she was meant to do before she could go on with her life.

The stout man waiting behind his dark cauldrons, was watching her again. He looked quite sad, and she couldn’t help but thinking he was not where he needed to be. When she looked at him, she saw Hephaestus whose inner fire had been tamed. His banner was a mishmash of religious stuff, aimed at pagans and budding witches. Although his grim booth would most certainly benefit from a feminine touch, but she didn’t want to offend him by a misplaced suggestion. It was not her place to find his place.

Rosa, who knew to cultivate any available friendship when she arrived somewhere, waved at the man. Startled, he looked away as if caught doing something inappropriate. Rosa sighed. Maybe she should have bring him some coffee.

As her first clients arrived, she prayed for a gush of wind to tell her where to go next. But the branches of the old tree remained perfectly still under the scorching sun.

June 10, 2022 at 1:39 pm #6305In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

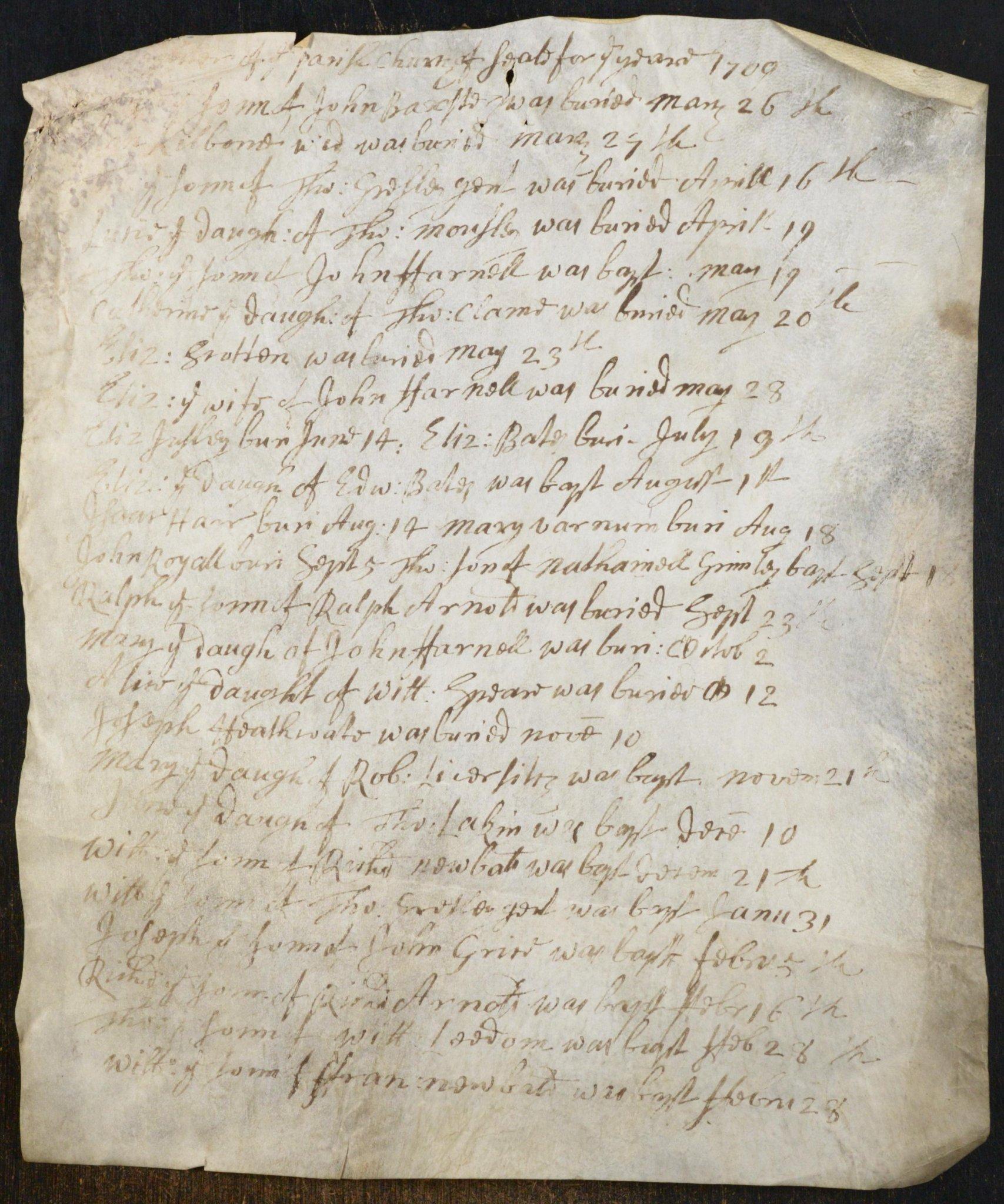

The Hair’s and Leedham’s of Netherseal

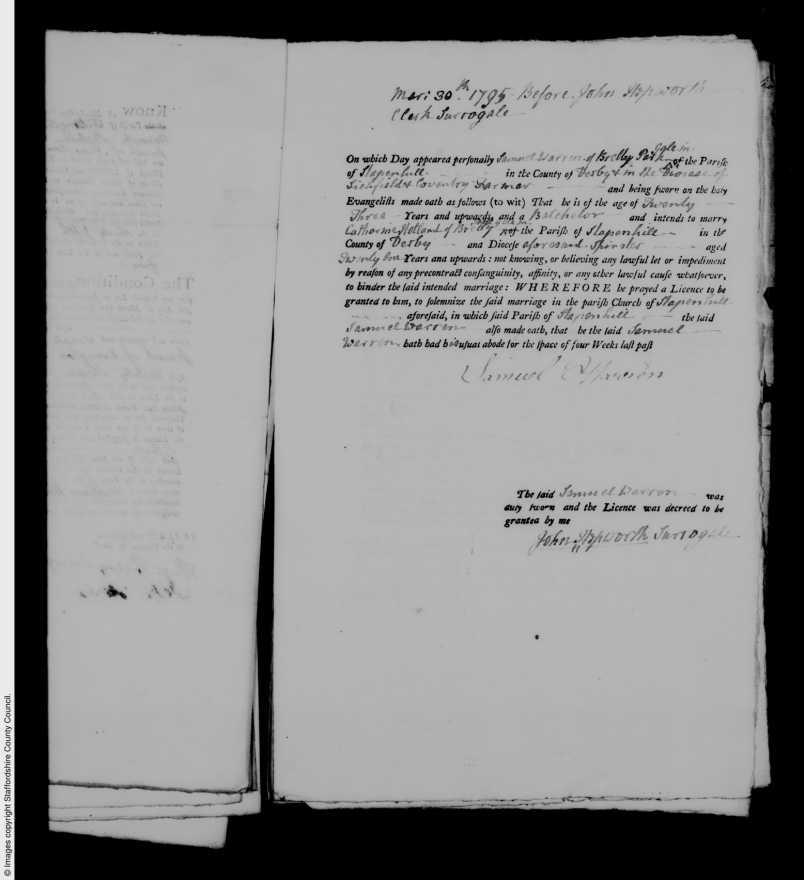

Samuel Warren of Stapenhill married Catherine Holland of Barton under Needwood in 1795. Catherine’s father was Thomas Holland; her mother was Hannah Hair.

Hannah was born in Netherseal, Derbyshire, in 1739. Her parents were Joseph Hair 1696-1746 and Hannah.

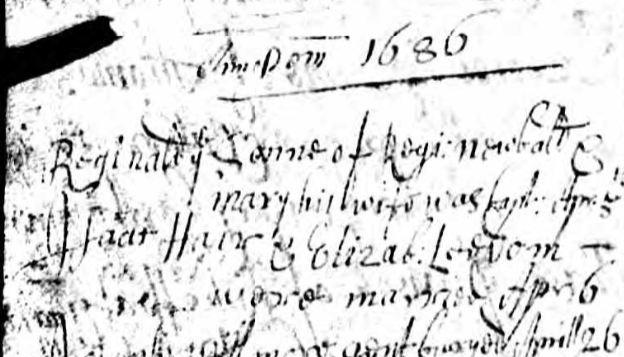

Joseph’s parents were Isaac Hair and Elizabeth Leedham. Elizabeth was born in Netherseal in 1665. Isaac and Elizabeth were married in Netherseal in 1686.Marriage of Isaac Hair and Elizabeth Leedham: (variously spelled Ledom, Leedom, Leedham, and in one case mistranscribed as Sedom):

Isaac was buried in Netherseal on 14 August 1709 (the transcript says the 18th, but the microfiche image clearly says the 14th), but I have not been able to find a birth registered for him. On other public trees on an ancestry website, Isaac Le Haire was baptised in Canterbury and was a Huguenot, but I haven’t found any evidence to support this.

Isaac Hair’s death registered 14 August 1709 in Netherseal:

A search for the etymology of the surname Hair brings various suggestions, including:

“This surname is derived from a nickname. ‘the hare,’ probably affixed on some one fleet of foot. Naturally looked upon as a complimentary sobriquet, and retained in the family; compare Lightfoot. (for example) Hugh le Hare, Oxfordshire, 1273. Hundred Rolls.”

From this we may deduce that the name Hair (or Hare) is not necessarily from the French Le Haire, and existed in England for some considerable time before the arrival of the Huguenots.

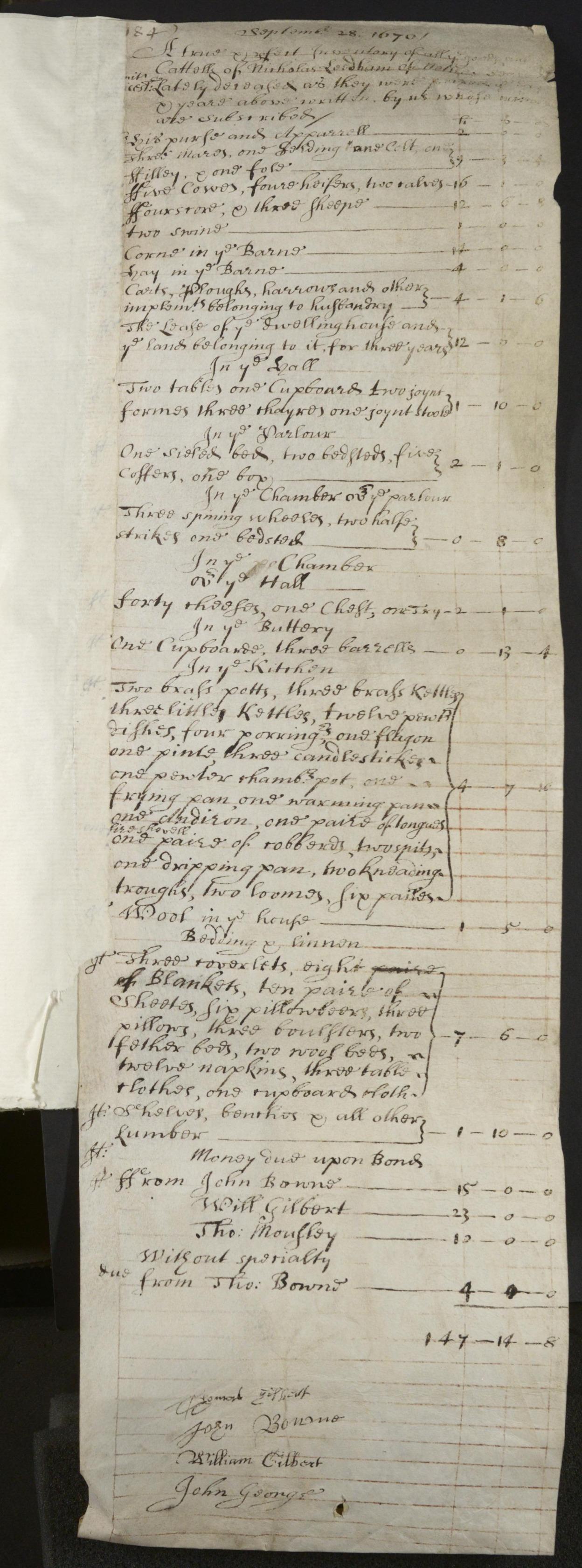

Elizabeth Leedham was born in Netherseal in 1665. Her parents were Nicholas Leedham 1621-1670 and Dorothy. Nicholas Leedham was born in Church Gresley (Swadlincote) in 1621, and died in Netherseal in 1670.

Nicholas was a Yeoman and left a will and inventory worth £147.14s.8d (one hundred and forty seven pounds fourteen shillings and eight pence).

The 1670 inventory of Nicholas Leedham:

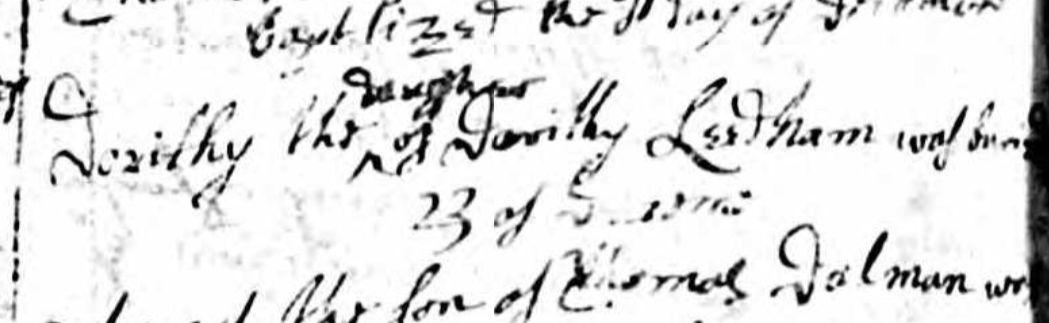

According to local historian Mark Knight on the Netherseal History facebook group, the Seale (Netherseal and Overseal) parish registers from the year 1563 to 1724 were digitized during lockdown.

via Mark Knight:

“There are five entries for Nicholas Leedham.

On March 14th 1646 he and his wife buried an unnamed child, presumably the child died during childbirth or was stillborn.

On November 28th 1659 he buried his wife, Elizabeth. He remarried as on June 13th 1664 he had his son William baptised.

The following year, 1665, he baptised a daughter on November 12th. (Elizabeth) On December 23rd 1672 the parish record says that Dorithy daughter of Dorithy was buried. The Bishops Transcript has Dorithy a daughter of Nicholas. Nicholas’ second wife was called Dorithy and they named a daughter after her. Alas, the daughter died two years after Nicholas. No further Leedhams appear in the record until after 1724.”Dorothy daughter of Dorothy Leedham was buried 23 December 1672:

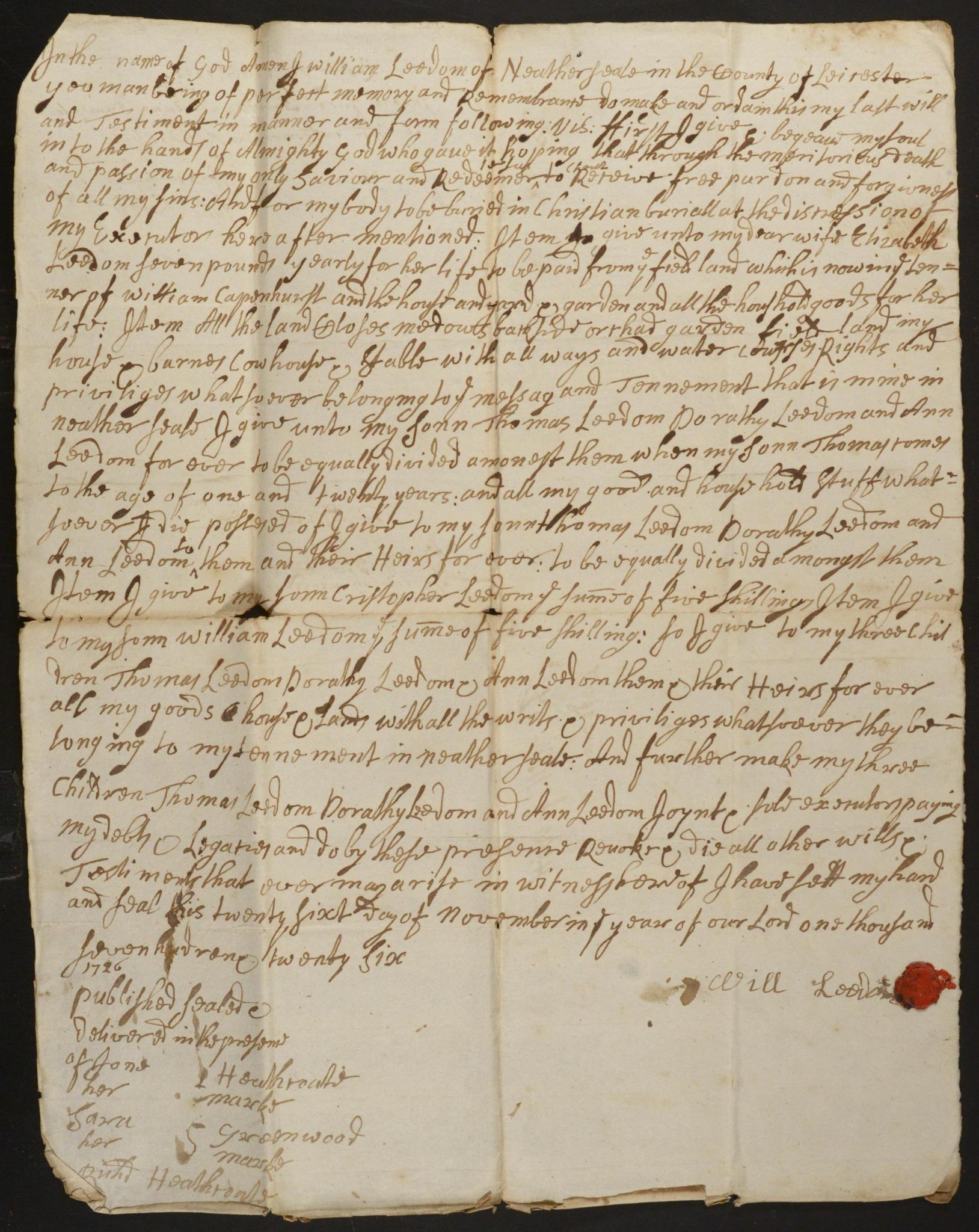

William, son of Nicholas and Dorothy also left a will. In it he mentions “My dear wife Elizabeth. My children Thomas Leedom, Dorothy Leedom , Ann Leedom, Christopher Leedom and William Leedom.”

1726 will of William Leedham:

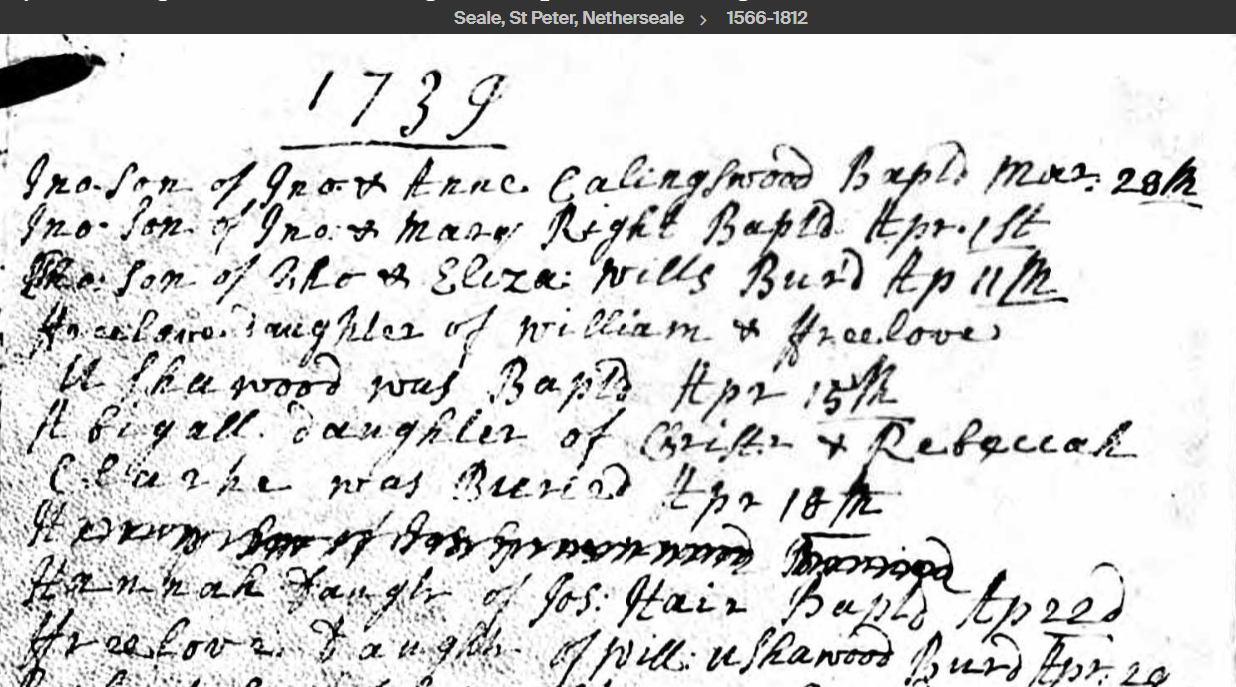

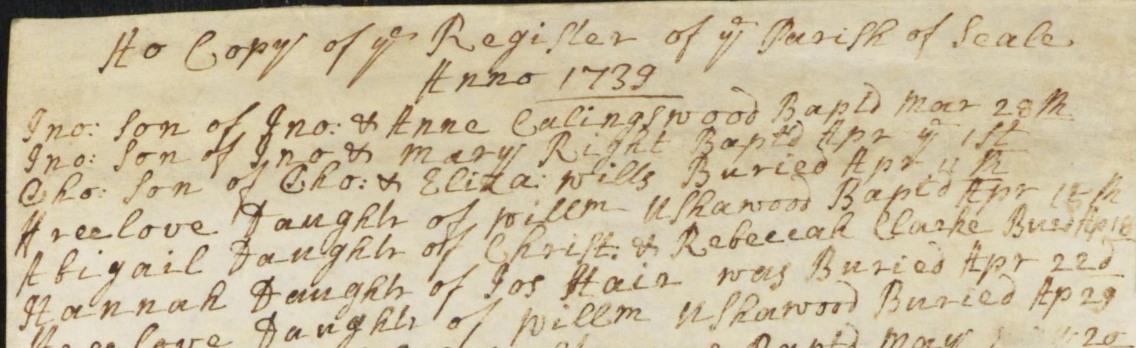

I found a curious error with the the parish register entries for Hannah Hair. It was a transcription error, but not a recent one. The original parish registers were copied: “HO Copy of ye register of Seale anno 1739.” I’m not sure when the copy was made, but it wasn’t recently. I found a burial for Hannah Hair on 22 April 1739 in the HO copy, which was the same day as her baptism registered on the original. I checked both registers name by name and they are exactly copied EXCEPT for Hannah Hairs. The rector, Richard Inge, put burial instead of baptism by mistake.

The original Parish register baptism of Hannah Hair:

The HO register copy incorrectly copied:

June 6, 2022 at 9:17 am #6301

June 6, 2022 at 9:17 am #6301In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

The Warrens of Stapenhill

There were so many Warren’s in Stapenhill that it was complicated to work out who was who. I had gone back as far as Samuel Warren marrying Catherine Holland, and this was as far back as my cousin Ian Warren had gone in his research some decades ago as well. The Holland family from Barton under Needwood are particularly interesting, and will be a separate chapter.

Stapenhill village by John Harden:

Resuming the research on the Warrens, Samuel Warren 1771-1837 married Catherine Holland 1775-1861 in 1795 and their son Samuel Warren 1800-1882 married Elizabeth Bridge, whose childless brother Benjamin Bridge left the Warren Brothers Boiler Works in Newhall to his nephews, the Warren brothers.

Samuel Warren and Catherine Holland marriage licence 1795:

Samuel (born 1771) was baptised at Stapenhill St Peter and his parents were William and Anne Warren. There were at least three William and Ann Warrens in town at the time. One of those William’s was born in 1744, which would seem to be the right age to be Samuel’s father, and one was born in 1710, which seemed a little too old. Another William, Guiliamos Warren (Latin was often used in early parish registers) was baptised in Stapenhill in 1729.

Stapenhill St Peter:

William Warren (born 1744) appeared to have been born several months before his parents wedding. William Warren and Ann Insley married 16 July 1744, but the baptism of William in 1744 was 24 February. This seemed unusual ~ children were often born less than nine months after a wedding, but not usually before the wedding! Then I remembered the change from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar in 1752. Prior to 1752, the first day of the year was Lady Day, March 25th, not January 1st. This meant that the birth in February 1744 was actually after the wedding in July 1744. Now it made sense. The first son was named William, and he was born seven months after the wedding.

William born in 1744 died intestate in 1822, and his wife Ann made a legal claim to his estate. However he didn’t marry Ann Holland (Ann was Catherines Hollands sister, who married Samuel Warren the year before) until 1796, so this William and Ann were not the parents of Samuel.

It seemed likely that William born in 1744 was Samuels brother. William Warren and Ann Insley had at least eight children between 1744 and 1771, and it seems that Samuel was their last child, born when William the elder was 61 and his wife Ann was 47.

It seems it wasn’t unusual for the Warren men to marry rather late in life. William Warren’s (born 1710) parents were William Warren and Elizabeth Hatterton. On the marriage licence in 1702/1703 (it appears to say 1703 but is transcribed as 1702), William was a 40 year old bachelor from Stapenhill, which puts his date of birth at 1662. Elizabeth was considerably younger, aged 19.

William Warren and Elizabeth Hatterton marriage licence 1703:

These Warren’s were farmers, and they were literate and able to sign their own names on various documents. This is worth noting, as most made the mark of an X.

I found three Warren and Holland marriages. One was Samuel Warren and Catherine Holland in 1795, then William Warren and Ann Holland in 1796. William Warren and Ann Hollands daughter born in 1799 married John Holland in 1824.

Elizabeth Hatterton (wife of William Warren who was born circa 1662) was born in Burton upon Trent in 1685. Her parents were Edward Hatterton 1655-1722, and Sara.

A page from the 1722 will of Edward Hatterton:

The earliest Warren I found records for was William Warren who married Elizabeth Hatterton in 1703. The marriage licence states his age as 40 and that he was from Stapenhill, but none of the Stapenhill parish records online go back as far as 1662. On other public trees on ancestry websites, a birth record from Suffolk has been chosen, probably because it was the only record to be found online with the right name and date. Once again, I don’t think that is correct, and perhaps one day I’ll find some earlier Stapenhill records to prove that he was born in locally.

Subsequently, I found a list of the 1662 Hearth Tax for Stapenhill. On it were a number of Warrens, three William Warrens including one who was a constable. One of those William Warrens had a son he named William (as they did, hence the number of William Warrens in the tree) the same year as this hearth tax list.

But was it the William Warren with 2 chimneys, the one with one chimney who was too poor to pay it, or the one who was a constable?

from the list:

Will. Warryn 2

Richard Warryn 1

William Warren Constable

These names are not payable by Act:

Will. Warryn 1

Richard Warren John Watson

over seers of the poore and churchwardensThe Hearth Tax:

via wiki:

In England, hearth tax, also known as hearth money, chimney tax, or chimney money, was a tax imposed by Parliament in 1662, to support the Royal Household of King Charles II. Following the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, Parliament calculated that the Royal Household needed an annual income of £1,200,000. The hearth tax was a supplemental tax to make up the shortfall. It was considered easier to establish the number of hearths than the number of heads, hearths forming a more stationary subject for taxation than people. This form of taxation was new to England, but had precedents abroad. It generated considerable debate, but was supported by the economist Sir William Petty, and carried through the Commons by the influential West Country member Sir Courtenay Pole, 2nd Baronet (whose enemies nicknamed him “Sir Chimney Poll” as a result). The bill received Royal Assent on 19 May 1662, with the first payment due on 29 September 1662, Michaelmas.

One shilling was liable to be paid for every firehearth or stove, in all dwellings, houses, edifices or lodgings, and was payable at Michaelmas, 29 September and on Lady Day, 25 March. The tax thus amounted to two shillings per hearth or stove per year. The original bill contained a practical shortcoming in that it did not distinguish between owners and occupiers and was potentially a major burden on the poor as there were no exemptions. The bill was subsequently amended so that the tax was paid by the occupier. Further amendments introduced a range of exemptions that ensured that a substantial proportion of the poorer people did not have to pay the tax.Indeed it seems clear that William Warren the elder came from Stapenhill and not Suffolk, and one of the William Warrens paying hearth tax in 1662 was undoubtedly the father of William Warren who married Elizabeth Hatterton.

May 3, 2022 at 4:40 pm #6291In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Jane Eaton

The Nottingham Girl

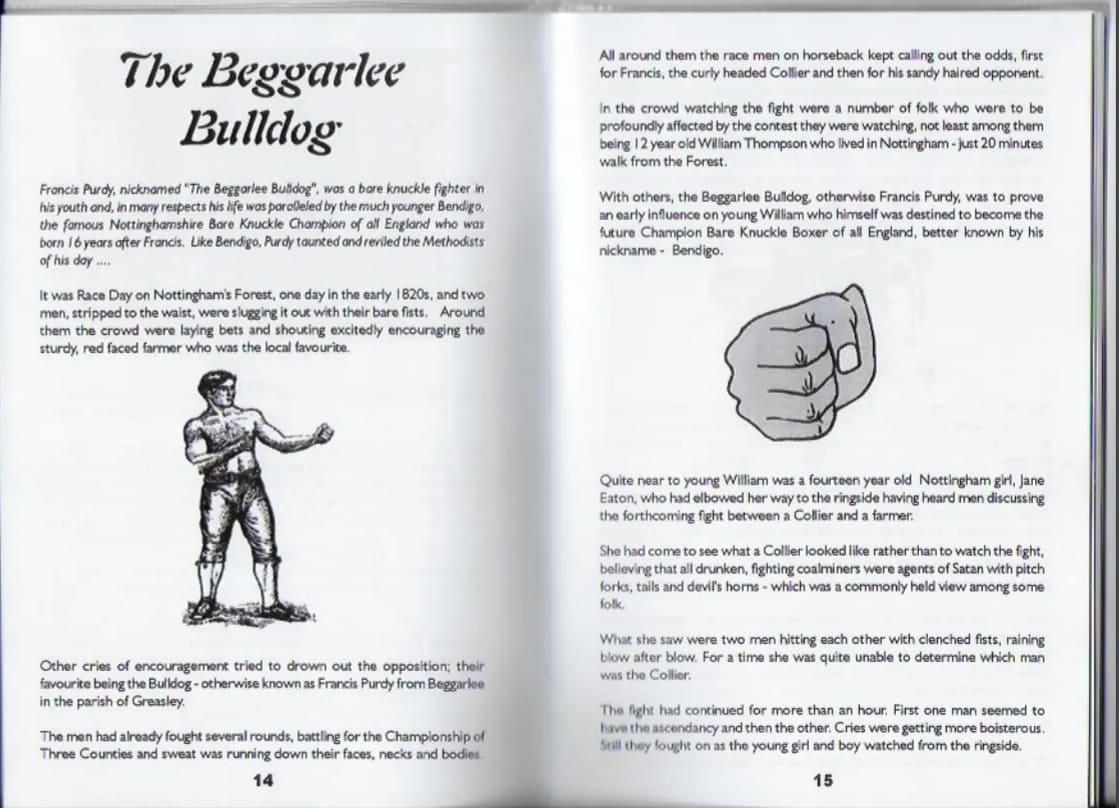

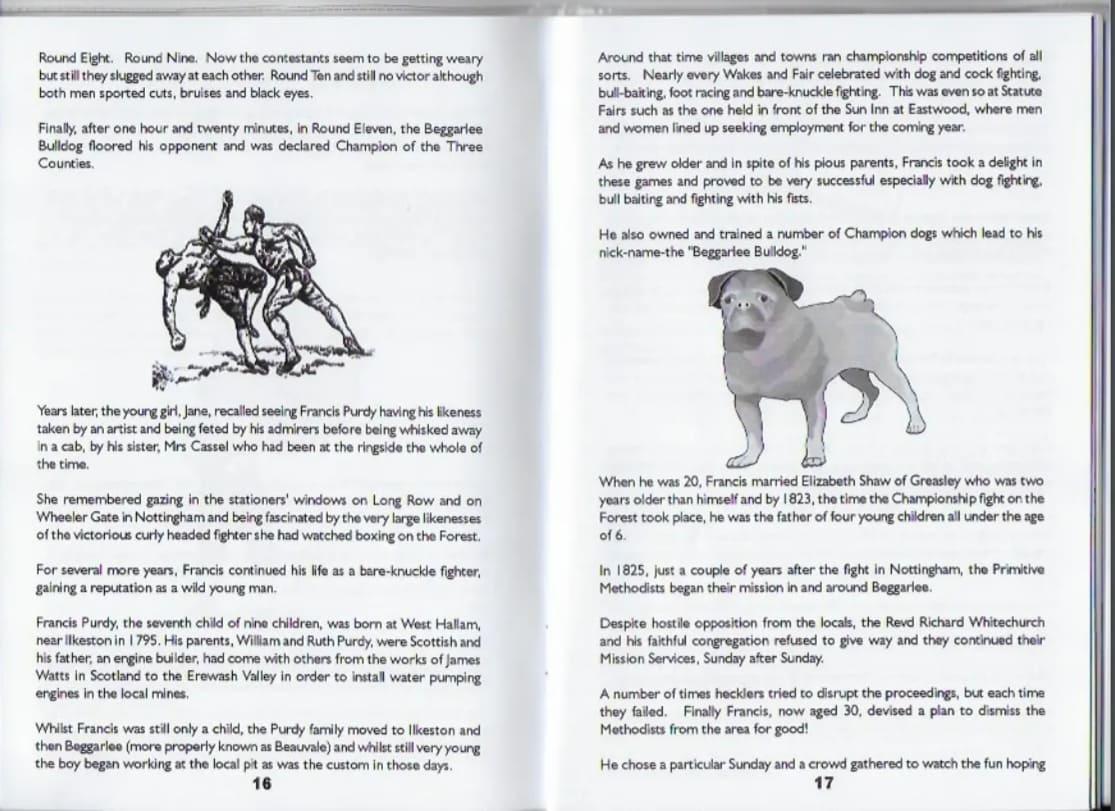

Jane Eaton 1809-1879

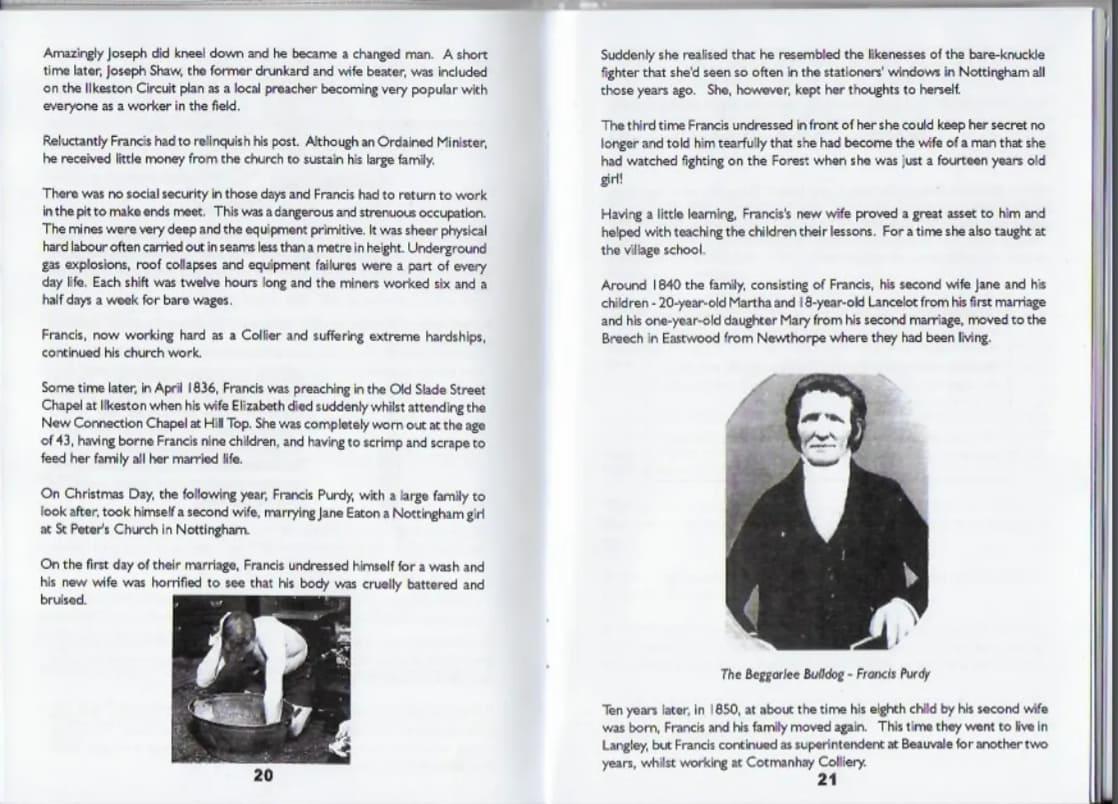

Francis Purdy, the Beggarlea Bulldog and Methodist Minister, married Jane Eaton in 1837 in Nottingham. Jane was his second wife.

Jane Eaton, photo says “Grandma Purdy” on the back:

Jane is described as a “Nottingham girl” in a book excerpt sent to me by Jim Giles, a relation who shares the same 3x great grandparents, Francis and Jane Purdy.

Elizabeth, Francis Purdy’s first wife, died suddenly at chapel in 1836, leaving nine children.

On Christmas day the following year Francis married Jane Eaton at St Peters church in Nottingham. Jane married a Methodist Minister, and didn’t realize she married the bare knuckle fighter she’d seen when she was fourteen until he undressed and she saw his scars.

William Eaton 1767-1851

On the marriage certificate Jane’s father was William Eaton, occupation gardener. Francis’s father was William Purdy, engineer.

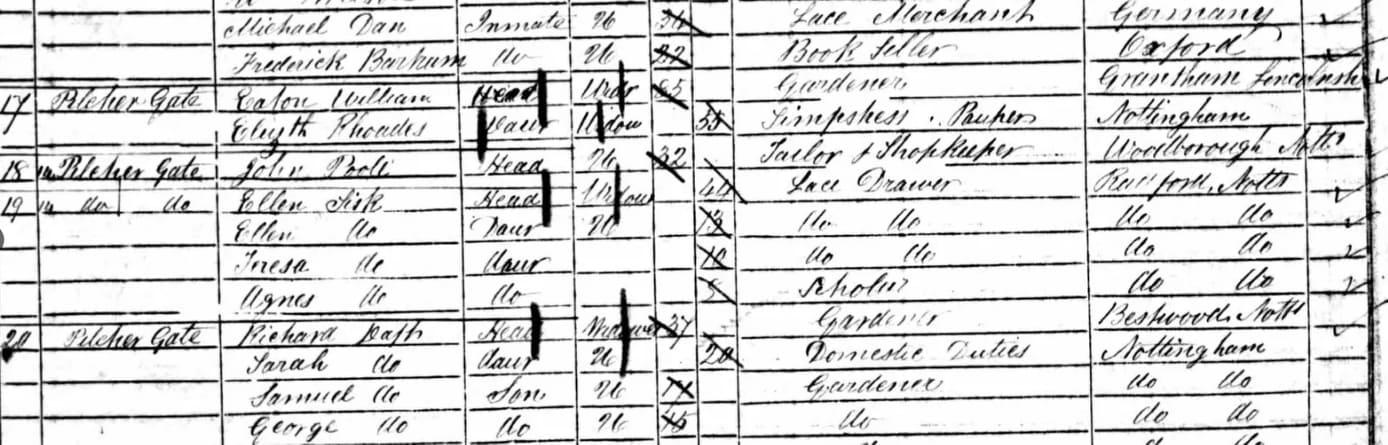

On the 1841 census living in Sollory’s Yard, Nottingham St Mary, William Eaton was a 70 year old gardener. It doesn’t say which county he was born in but indicates that it was not Nottinghamshire. Living with him were Mary Eaton, milliner, age 35, Mary Eaton, milliner, 15, and Elizabeth Rhodes age 35, a sempstress (another word for seamstress). The three women were born in Nottinghamshire.

But who was Elizabeth Rhodes?

Elizabeth Eaton was Jane’s older sister, born in 1797 in Nottingham. She married William Rhodes, a private in the 5th Dragoon Guards, in Leeds in October 1815.

I looked for Elizabeth Rhodes on the 1851 census, which stated that she was a widow. I was also trying to determine which William Eaton death was the right one, and found William Eaton was still living with Elizabeth in 1851 at Pilcher Gate in Nottingham, but his name had been entered backwards: Eaton William. I would not have found him on the 1851 census had I searched for Eaton as a last name.

Pilcher Gate gets its strange name from pilchers or fur dealers and was once a very narrow thoroughfare. At the lower end stood a pub called The Windmill – frequented by the notorious robber and murderer Charlie Peace.

This was a lucky find indeed, because William’s place of birth was listed as Grantham, Lincolnshire. There were a couple of other William Eaton’s born at the same time, both near to Nottingham. It was tricky to work out which was the right one, but as it turned out, neither of them were.

Now we had Nottinghamshire and Lincolnshire border straddlers, so the search moved to the Lincolnshire records.

But first, what of the two Mary Eatons living with William?William and his wife Mary had a daughter Mary in 1799 who died in 1801, and another daughter Mary Ann born in 1803. (It was common to name children after a previous infant who had died.) It seems that Mary Ann didn’t marry but had a daughter Mary Eaton born in 1822.

William and his wife Mary also had a son Richard Eaton born in 1801 in Nottingham.

Who was William Eaton’s wife Mary?

There are two possibilities: Mary Cresswell and a marriage in Nottingham in 1797, or Mary Dewey and a marriage at Grantham in 1795. If it’s Mary Cresswell, the first child Elizabeth would have been born just four or five months after the wedding. (This was far from unusual). However, no births in Grantham, or in Nottingham, were recorded for William and Mary in between 1795 and 1797.

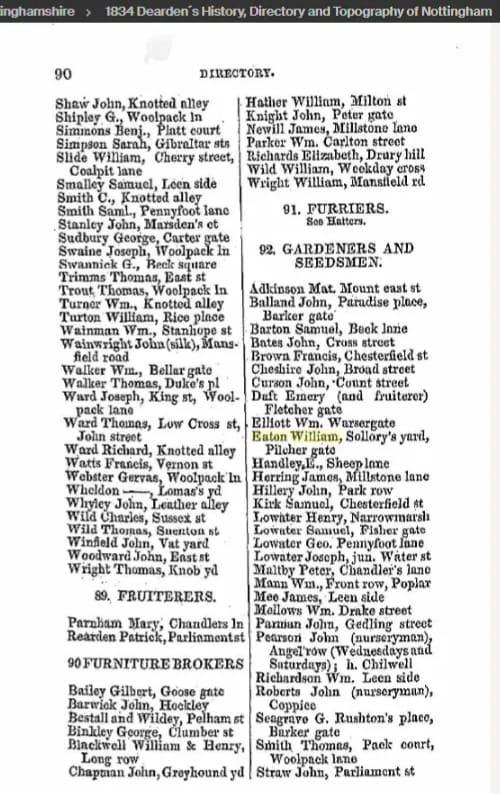

We don’t know why William moved from Grantham to Nottingham or when he moved there. According to Dearden’s 1834 Nottingham directory, William Eaton was a “Gardener and Seedsman”.

There was another William Eaton selling turnip seeds in the same part of Nottingham. At first I thought it must be the same William, but apparently not, as that William Eaton is recorded as a victualler, born in Ruddington. The turnip seeds were advertised in 1847 as being obtainable from William Eaton at the Reindeer Inn, Wheeler Gate. Perhaps he was related.

William lived in the Lace Market part of Nottingham. I wondered where a gardener would be working in that part of the city. According to CreativeQuarter website, “in addition to the trades and housing (sometimes under the same roof), there were a number of splendid mansions being built with extensive gardens and orchards. Sadly, these no longer exist as they were gradually demolished to make way for commerce…..The area around St Mary’s continued to develop as an elegant residential district during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, with buildings … being built for nobility and rich merchants.”

William Eaton died in Nottingham in September 1851, thankfully after the census was taken recording his place of birth.

April 12, 2022 at 8:13 am #6290In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Leicestershire Blacksmiths

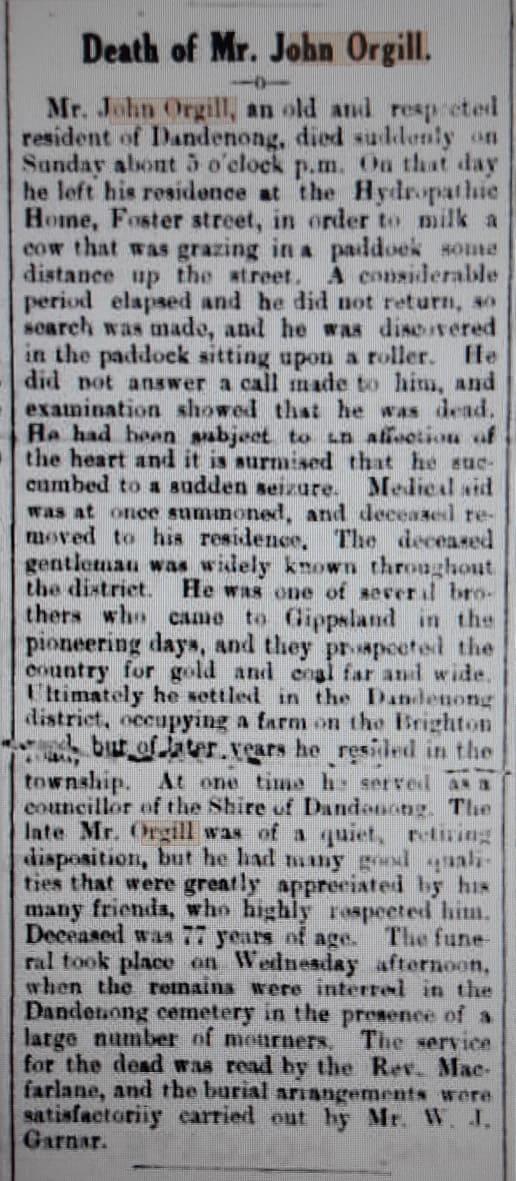

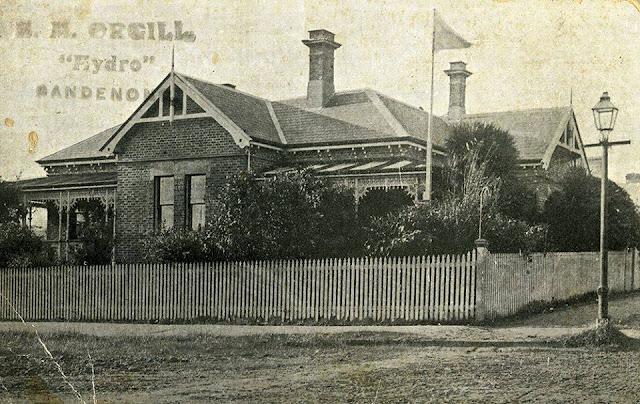

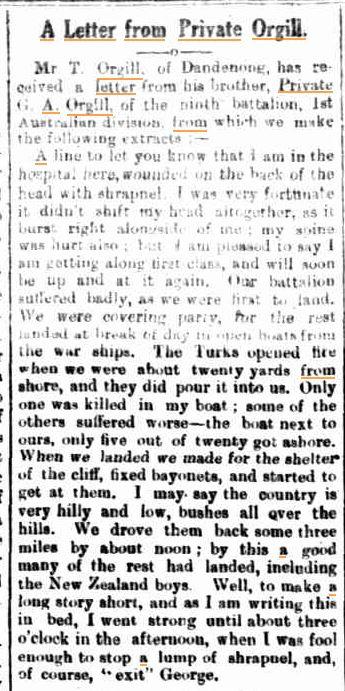

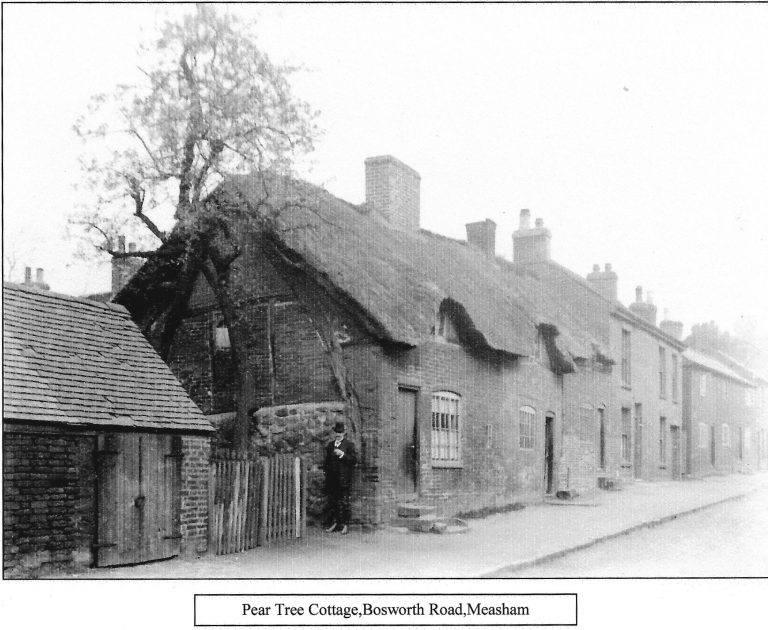

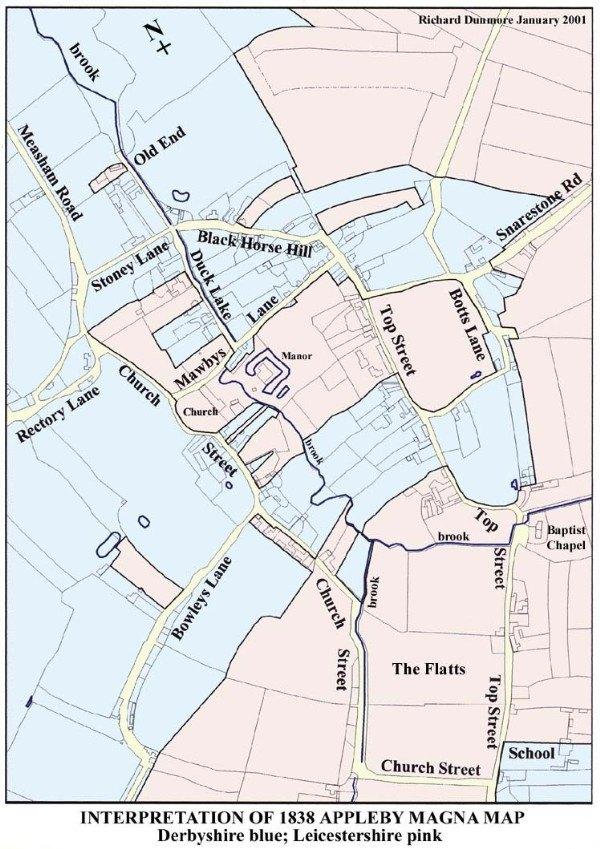

The Orgill’s of Measham led me further into Leicestershire as I traveled back in time.

I also realized I had uncovered a direct line of women and their mothers going back ten generations:

myself, Tracy Edwards 1957-

my mother Gillian Marshall 1933-

my grandmother Florence Warren 1906-1988

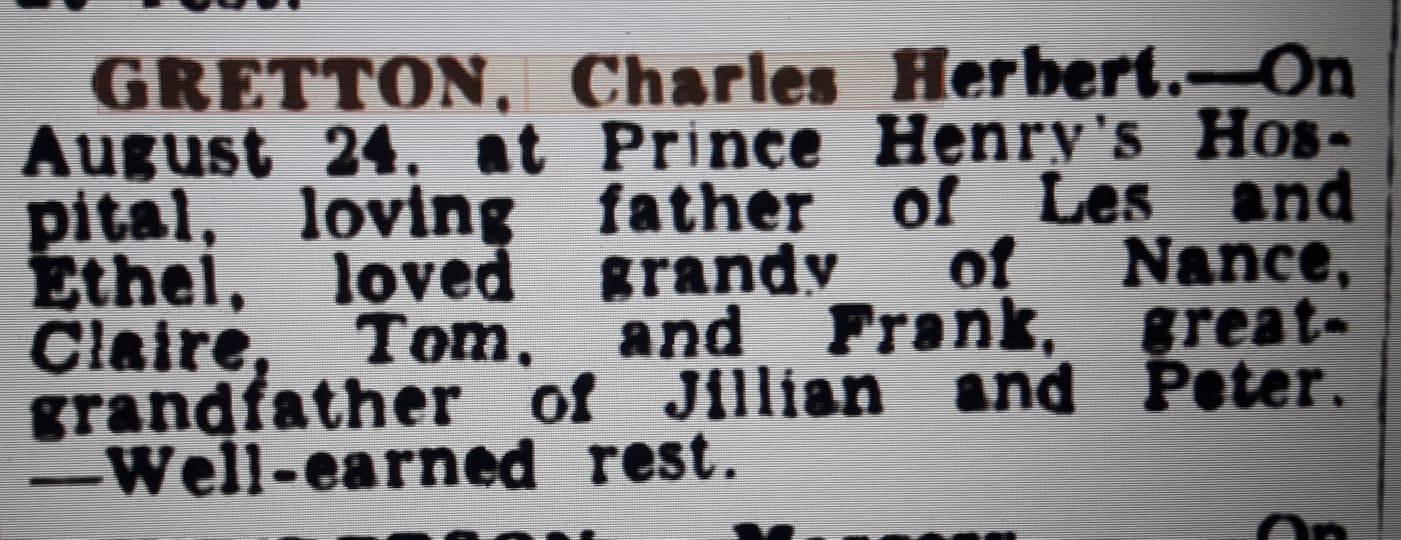

her mother and my great grandmother Florence Gretton 1881-1927

her mother Sarah Orgill 1840-1910

her mother Elizabeth Orgill 1803-1876

her mother Sarah Boss 1783-1847

her mother Elizabeth Page 1749-

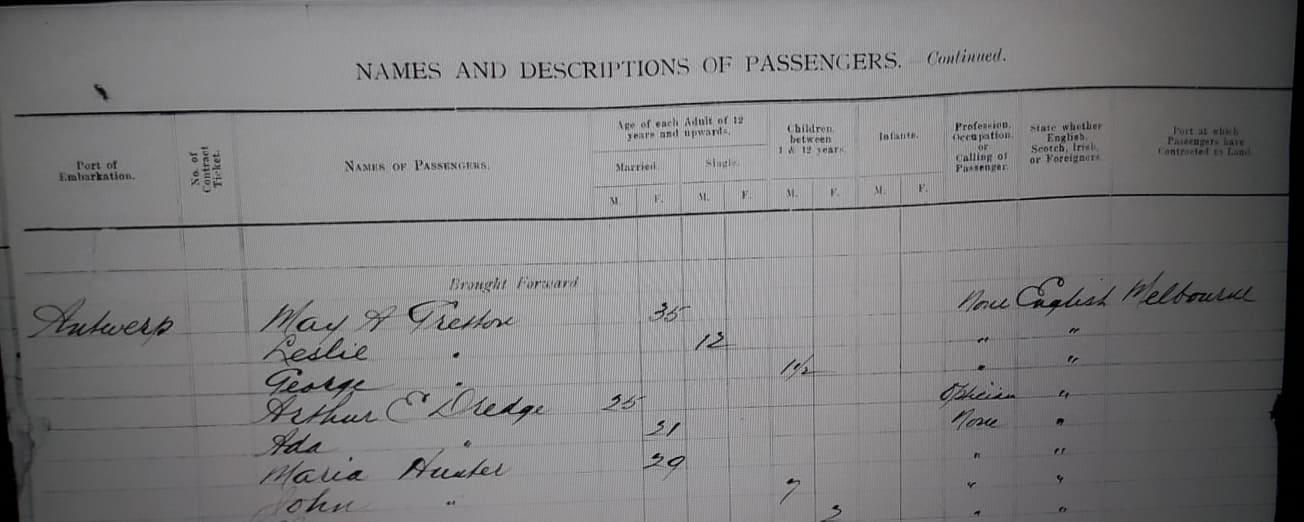

her mother Mary Potter 1719-1780

and her mother and my 7x great grandmother Mary 1680-You could say it leads us to the very heart of England, as these Leicestershire villages are as far from the coast as it’s possible to be. There are countless other maternal lines to follow, of course, but only one of mothers of mothers, and ours takes us to Leicestershire.

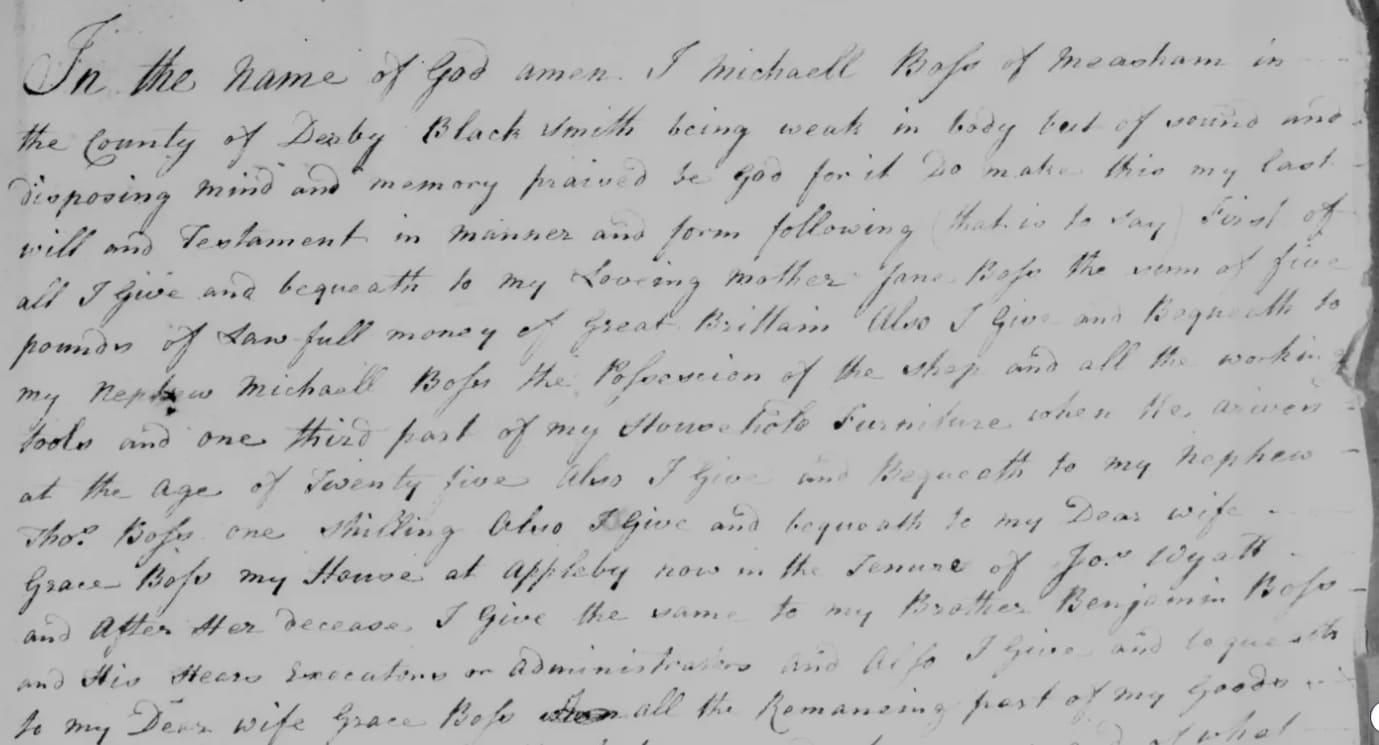

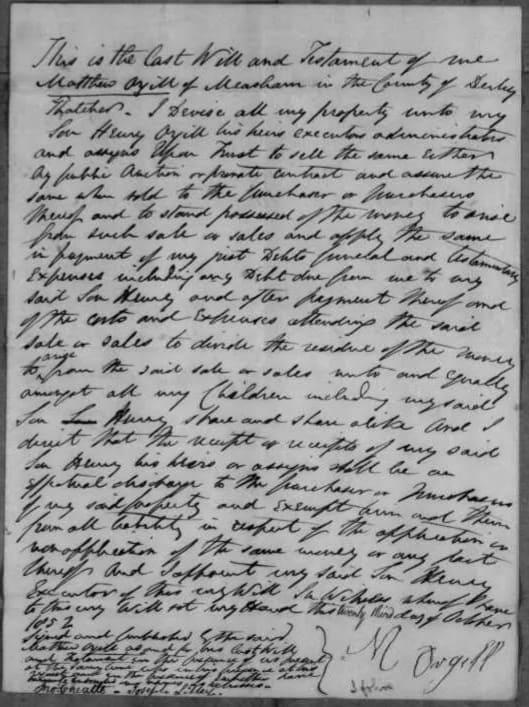

The blacksmiths