Search Results for 'strange'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

January 23, 2023 at 1:27 pm #6451

In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

The progress on the quest in the Land of the Quirks was too tantalizing; Xavier made himself a quick sandwich and jumped back on it during his lunch break.

The jungle had an oppressing quality… Maybe it has to do with the shrieks of the apes tearing the silence apart.

The jungle had an oppressing quality… Maybe it has to do with the shrieks of the apes tearing the silence apart. It was time for a slight adjustment of his avatar.

Xavimunk opened his bag of tricks, something that the wise owl had suggested he looked into. Few items from the AIorium Emporium had been supplied. They tended to shift and disappear if you didn’t focus, but his intention was set on the task at hand. At the bottom of the bag, there was a small vial with a golden liquid with a tag written in ornate handwriting “MJ remix: for when words elude and shapes confuse at your own peril”.

He gulped the potion without thinking too much. He felt himself shrink, and his arms elongate a little. There, he thought. Imp-munk’s more suited to the mission. Hope the effects will be temporary…

He gulped the potion without thinking too much. He felt himself shrink, and his arms elongate a little. There, he thought. Imp-munk’s more suited to the mission. Hope the effects will be temporary…As Xavier mustered the courage to enter through the front gate, monkeys started to become silent. He couldn’t say if it was an ominous sign, or maybe an effect of his adaptation. The temple’s light inside was gorgeous, but nothing seemed to be there.

He gestured around, to make the menu appear. He looked again at the instructions on his screen overlay:

As for possible characters to engage, you may come across a sly fox who claims to know the location of the fruit but will only reveal it in exchange for a favor, or a brave adventurer who has been searching for the Golden Banana for years and may be willing to team up with you.

Suddenly a loud monkey honking noise came from outside, distracting him.

What the?… Had to be one of Zara’s remixes. He saw the three dots bleeping on the screen.

Here’s the Banana bus, hope it helps! Envoy! bugger Enjoy!

Yep… With the distinct typo-heavy accent, definitely Zara’s style. Strange idea that AL designated her as the leader… He’d have to roll with it.

Suddenly, as the Banana bus parked in front of the Temple, a horde of Italien speaking tourists started to flock in and snap pictures around. The monkeys didn’t know what to do and seemed to build growing and noisy interest in their assortiment of colorful shoes, flip-flops, boots and all.

Focus, thought Xavimunk… What did the wise owl say? Look for a guide…

Only the huge colorful bus seemed to take the space now… But wait… what if?He walked to the parking spot under the shades of the huge banyan tree next to the temple’s entrance, under which the bus driver had parked it. The driver was still there, napping under a newspaper, his legs on the wheel.

“Whatcha lookin’ at?” he said chewing his gum loudly. “Never seen a fox drive a banana bus before?”

Xavier smiled. “Any chance you can guide me to the location of the Golden Banana?”

“For a price… maybe.” The fox had jumped closely and was considering the strange avatar from head to toe.

“Ain’t no usual stuff that got you into this? Got any left? That would be a nice price.”

“As it happens…” Xavier smiled.The quest seemed back on track. Xavier looked at the time. Blimmey! already late again. And I promised Brytta to get some Chinese snacks for dinner.

January 23, 2023 at 9:18 am #6450In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

The images were forming on the screen of the VR set, a little blurry to start with, but taking some shapes, and with a few clicks in the right direction, the reality around him was transphormed as if he’d been into a huge deFørmiñG mirror, that they could shape with their strangest thoughts.

The jungle had an oppressing quality… Maybe it has to do with the shrieks of the apes tearing the silence apart.

The jungle had an oppressing quality… Maybe it has to do with the shrieks of the apes tearing the silence apart.  All sorts of them were gathered overhead, gibbons, baboons, chimps and Barbery apes, macaques and marmosets… some silent, but most of them in a swirl of manic agitation.

All sorts of them were gathered overhead, gibbons, baboons, chimps and Barbery apes, macaques and marmosets… some silent, but most of them in a swirl of manic agitation.When Xavier entered the ancient blue stone temple, he felt his quest was doomed from the start. It had taken a while to find the monkey’s sacred temple hidden deep within the jungle in which clues were supposed to be found. Thanks to a prompt from Zara who’d stumbled into a map, and some gentle push from a wise Y🦉wl, he’d managed to locate the temple. It was right under his nose all along. Obviously all this a metaphor, but once he found the proper connecting link, getting the right setup for dealing with the task was easier.

So the monkeys were his and his RL colleagues crazy thoughts, and he’d even taken some fun in painting the faces of some of them into the game. He could hear Boss gorilla pounding his chest in the distance.

“F£££” he couldn’t help but grumble when the notification prompt got him out of his meditative point. The Golden Banana would have to wait… The real life monkeys were requiring his attention for now.

January 21, 2023 at 4:17 pm #6426In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

The artificial lights of Berlin were starting to switch off in the horizon, leaving the night plunged in darkness minutes before the sunrise. It was a moment of peace that Xavier enjoyed, although it reminded him of how sleepless his night had been.

The game had taken a side step, as he’d been pouring all his attention into his daytime job, and his personal project with Artificial Life AL. It was a long way from the little boy at school with dyslexia who was using cheeky jokes as a way to get by the snides. Since then, he’d known some of the unusual super-powers this condition gave him as well. Chiefly: abstract and out-of-the-box thinking, puzzle-solving genius, and an almost other-worldly ability at keeping track of the plot. All these skills were in fact of tremendous help at his work, which was blending traditional areas of technology along with massive amounts of loosely connected data.

He yawned and went to brush his teeth. His usual meditation routine had also been disrupted by the activity of late, but he just couldn’t go to bed without a little time to cool off and calm down the agitation of his thoughts.

Sitting on the meditation mat, his thoughts strayed off towards the preparation for the trip. Going to Australia would have seemed exciting a few years back, but the idea of packing a suitcase, and going through the long flight and the logistics involved got him more anxious than excited, despite the contagious enthusiasm of his friends. Since he’d settled in Berlin, after never settling for too long in one place (his job afforded him to work wherever whenever), he’d kind of stopped looking for the next adventure. He hadn’t even looked at flight options yet, and hoped that the building momentum would spur him into this adventure. For now, he needed the rest.

The quirk quest assigned to his persona in the game was fun. Monkeys and Golden banana to look for, wise owls and sly foxes, the whimsical goofy nature of the quest seemed good for the place he was in.

AL had been suggesting the players to insert the game elements into their realities, and sometimes its comments or instructions seemed to slip between layers of reality — this was an intriguing mystery to Xavier.

He’d instructed AL to discreetly assist Youssef with his trouble — the Thi Gang seemed to be an ethical hacker developer company front for more serious business. Chatter on the net had tied it to a network of shell companies involved in some strange activities. A name had popped up, linked to mysterious recluse billionaire Botty Banworth, the owner of Youssef’s boss rival blog named Knoweth.He slipped into the bed, careful not to wake up Brytta, who was sleeping tightly. It was her day off, otherwise she would have been gone already to her shift. It would be good to connect in the morning, and enjoy some break from mind stuff. They had planned a visit to Kantonstrasse (the local Chinatown) for Chinese New Year, and he couldn’t wait for it.

January 21, 2023 at 3:16 pm #6424In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Youssef wasn’t an expert about sandstorms, but that one surely lasted longer than it should have. It was the middle of the night when the wind stopped blowing and the sand stopped lashing the jeep. Yet, nobody dared open the door or their mouth to see if the storm was gone. Youssef’s bladder was full, and his stomach empty. They both reminded him that one can’t stop life to go on in the midst of adversity. He wondered why nobody moved or spoke, but couldn’t find the motivation to break the silence. He felt a vibration in his pocket and took his phone out.

A message from an unknown sender. He touched it open.<<<

Deear Youssef,

The Snoot is aware of the sandstorm and its whimsical ways. It dances and twirls in the desert, a symphony of wind and sand. It is a force to be reckoned with, but also a force of cleansing and renewal.The subsiding of the sandstorm is a fluid and ever-changing process, much like the ebb and flow of the ocean. It ebbs and flows with the whims of the wind and the dance of the desert.

The best way to predict the subsiding of the sandstorm is to listen to the whispers of the wind and to observe the patterns of the sand. Trust in the natural rhythms and allow yourself to flow with them.

The Snoot suggests that you seek shelter during the storm, but also to take the time to appreciate the beauty and power of nature.

Fluidly yours,

The Snoot. >>>Who the f… was the Snot? Youssef wondered if it was another trick from Thi Gang and almost deleted the message, but his bladder reminded him again he needed to do something about all the tea he drank before the sandstorm. He opened the door and got out of the jeep. The storm was gone and the sky was full of stars. The moon was giving enough light for him to move a few steps away from the jeeps while unzipping his pants. He blessed the gods as he relieved himself, strangely feeling part of nature at that very moment.

The noises of doors opening reminded him he was not alone. Someone came, said: “I see you found a nice spot”. It was Kyle, the cameraman who unzipped himself and peed. That broke the charm, the desert was becoming crowded. But, Youssef was finished, he went back to the cars and started to wonder how he could have received that message in the middle of the desert without a satellite dish.

January 21, 2023 at 11:26 am #6423In reply to: Prompts of Madjourneys

Zara’s first quest:

entry level quirk: wandering off the track

The initial setting for this quest is a dense forest, where the paths are overgrown and rarely traveled. You find yourself alone and disoriented, with only a rough map and a compass to guide you.

Possible directions to investigate include:

Following a faint trail of footprints that lead deeper into the forest

Climbing a tall tree to get a better view of the surrounding area

Searching for a stream or river to use as a guide to find your way out of the forest

Possible characters to engage include:

A mysterious hermit who lives deep in the forest and is rumored to know the secrets of the land

A lost traveler who is also trying to find their way out of the forest

A group of bandits who have taken refuge in the forest and may try to steal from you or cause harm

Your objective is to find the Wanderlust tile, a small, intricately carved wooden tile depicting a person walking off the beaten path. This tile holds the key to unlocking your inner quirk of wandering off the track.

As proof of your progress in the game, you must find a way to incorporate this quirk into your real-life actions by taking a spontaneous detour on your next journey, whether it be physical or mental.

For Zara’s quest:

As you wander off the track, you come across a strange-looking building in the distance. Upon closer inspection, you realize it is the Flying Fish Inn. As you enter, you are greeted by the friendly owner, Idle. She tells you that she has heard of strange occurrences happening in the surrounding area and offers to help you in your quest

Emoji clue: 🐈🌳

Zara (the character in the game)

characteristics from previous prompts:

Zara is the leader of the group

she is confident, and always ready for an adventure. She is a natural leader and has a strong sense of justice. She is also a tech-savvy person, always carrying a variety of gadgets with her, and is always the first to try out new technology.

she is confident, and always ready for an adventure. She is a natural leader and has a strong sense of justice. She is also a tech-savvy person, always carrying a variety of gadgets with her, and is always the first to try out new technology.Zara is the leader of the group, her color is red, her animal is a lion, and her secret name in a funny language is “Zaraloon”

Zara (the real life story character)

characteristics from previous prompts:

Zara Patara-Smythe is a 57-year-old woman of mixed heritage, her mother is Indian and her father is British. She has long, dark hair that she keeps in an untidy ponytail, dark brown eyes and a sharp jawline. She stands at 5’6″ and has a toned and athletic build. She usually wears practical clothing that allows her to move around easily, such as cargo pants and a tank top.

prompt quest:

Continue to investigate the mysterious cat she saw, possibly seeking out help from local animal experts or veterinarians.

Join Xavier and Yasmin in investigating the Flying Fish Inn, looking for clues and exploring the area for any potential leads on the game’s quest.January 19, 2023 at 10:49 am #6419In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

“I’d advise you not to take the parrot, Zara,” Harry the vet said, “There are restrictions on bringing dogs and other animals into state parks, and you can bet some jobsworth official will insist she stays in a cage at the very least.”

“Yeah, you’re right, I guess I’ll leave her here. I want to call in and see my cousin in Camden on the way to the airport in Sydney anyway. He has dozens of cats, I’d hate for anything to happen to Pretty Girl,” Zara replied.

“Is that the distant cousin you met when you were doing your family tree?” Harry asked, glancing up from the stitches he was removing from a wounded wombat. “There, he’s good to go. Give him a couple more days, then he can be released back where he came from.”

Zara smiled at Harry as she picked up the animal. “Yes! We haven’t met in person yet, and he’s going to show me the church my ancestor built. He says people have been spotting ghosts there lately, and there are rumours that it’s the ghost of the old convict Isaac who built it. If I can’t find photos of the ancestors, maybe I can get photos of their ghosts instead,” Zara said with a laugh.

“Good luck with that,” Harry replied raising an eyebrow. He liked Zara, she was quirkier than the others.

Zara hadn’t found it easy to research her mothers family from Bangalore in India, but her fathers English family had been easy enough. Although Zara had been born in England and emigrated to Australia in her late 20s, many of her ancestors siblings had emigrated over several generations, and Zara had managed to trace several down and made contact with a few of them. Isaac Stokes wasn’t a direct ancestor, he was the brother of her fourth great grandfather but his story had intrigued her. Sentenced to transportation for stealing tools for his work as a stonemason seemed to have worked in his favour. He built beautiful stone buildings in a tiny new town in the 1800s in the charming style of his home town in England.

Zara planned to stay in Camden for a couple of days before meeting the others at the Flying Fish Inn, anticipating a pleasant visit before the crazy adventure started.

Zara stepped down from the bus, squinting in the bright sunlight and looking around for her newfound cousin Bertie. A lanky middle aged man in dungarees and a red baseball cap came forward with his hand extended.

“Welcome to Camden, Zara I presume! Great to meet you!” he said shaking her hand and taking her rucksack. Zara was taken aback to see the family resemblance to her grandfather. So many scattered generations and yet there was still a thread of familiarity. “I bet you’re hungry, let’s go and get some tucker at Belle’s Cafe, and then I bet you want to see the church first, hey? Whoa, where’d that dang parrot come from?” Bertie said, ducking quickly as the bird swooped right in between them.

“Oh no, it’s Pretty Girl!” exclaimed Zara. “She wasn’t supposed to come with me, I didn’t bring her! How on earth did you fly all this way to get here the same time as me?” she asked the parrot.

“Pretty Girl has her ways, don’t forget to feed the parrot,” the bird replied with a squalk that resembled a mirthful guffaw.

“That’s one strange parrot you got here, girl!” Bertie said in astonishment.

“Well, seeing as you’re here now, Pretty Girl, you better come with us,” Zara said.

“Obviously,” replied Pretty Girl. It was hard to say for sure, but Zara was sure she detected an avian eye roll.

They sat outside under a sunshade to eat rather than cause any upset inside the cafe. Zara fancied an omelette but Pretty Girl objected, so she ordered hash browns instead and a fruit salad for the parrot. Bertie was a good sport about the strange talking bird after his initial surprise.

Bertie told her a bit about the ghost sightings, which had only started quite recently. They started when I started researching him, Zara thought to herself, almost as if he was reaching out. Her imagination was running riot already.

Bertie showed Zara around the church, a small building made of sandstone, but no ghost appeared in the bright heat of the afternoon. He took her on a little tour of Camden, once a tiny outpost but now a suburb of the city, pointing out all the original buildings, in particular the ones that Isaac had built. The church was walking distance of Bertie’s house and Zara decided to slip out and stroll over there after everyone had gone to bed.

Bertie had kindly allowed Pretty Girl to stay in the guest bedroom with her, safe from the cats, and Zara intended that the parrot stay in the room, but Pretty Girl was having none of it and insisted on joining her.

“Alright then, but no talking! I don’t want you scaring any ghost away so just keep a low profile!”

The moon was nearly full and it was a pleasant walk to the church. Pretty Girl fluttered from tree to tree along the sidewalk quietly. Enchanting aromas of exotic scented flowers wafted into her nostrils and Zara felt warmly relaxed and optimistic.

Zara was disappointed to find that the church was locked for the night, and realized with a sigh that she should have expected this to be the case. She wandered around the outside, trying to peer in the windows but there was nothing to be seen as the glass reflected the street lights. These things are not done in a hurry, she reminded herself, be patient.

Sitting under a tree on the grassy lawn attempting to open her mind to receiving ghostly communications (she wasn’t quite sure how to do that on purpose, any ghosts she’d seen previously had always been accidental and unexpected) Pretty Girl landed on her shoulder rather clumsily, pressing something hard and chill against her cheek.

“I told you to keep a low profile!” Zara hissed, as the parrot dropped the key into her lap. “Oh! is this the key to the church door?”

It was hard to see in the dim light but Zara was sure the parrot nodded, and was that another avian eye roll?

Zara walked slowly over the grass to the church door, tingling with anticipation. Pretty Girl hopped along the ground behind her. She turned the key in the lock and slowly pushed open the heavy door and walked inside and up the central aisle, looking around. And then she saw him.

Zara gasped. For a breif moment as the spectral wisps cleared, he looked almost solid. And she could see his tattoos.

“Oh my god,” she whispered, “It is really you. I recognize those tattoos from the description in the criminal registers. Some of them anyway, it seems you have a few more tats since you were transported.”

“Aye, I did that, wench. I were allays fond o’ me tats, does tha like ’em?”

He actually spoke to me! This was beyond Zara’s wildest hopes. Quick, ask him some questions!

“If you don’t mind me asking, Isaac, why did you lie about who your father was on your marriage register? I almost thought it wasn’t you, you know, that I had the wrong Isaac Stokes.”

A deafening rumbling laugh filled the building with echoes and the apparition dispersed in a labyrinthine swirl of tattood wisps.

“A story for another day,” whispered Zara, “Time to go back to Berties. Come on Pretty Girl. And put that key back where you found it.”

January 19, 2023 at 9:38 am #6416

January 19, 2023 at 9:38 am #6416In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

The team had to stop when a sandstorm hit them in the middle of the desert. They only had an hour drive left to reach the oasis where Lama Yoneze had been seen last and Miss Tartiflate insisted, like she always did, against the guides advice that they kept on going. She feared the last shaman would be lost in the storm, maybe croak stuffed with that damn dust. But when they lost the satellite dish and a jeep almost rolled down a sand dune, she finally listened to the guides. They had them park the cars close to each other, then checked the straps and urged everyone to stay in their cars until the storm was over.

Youssef at first thought he was lucky. He managed to get into the same car as Tiff, the young intern he had discussed with the other day. But despite all their precautions, they couldn’t stop the dust to come in. It was everywhere and you had to kept your mouth and eyes shut if you didn’t want to grind your teeth with fine sand. So instead he enjoyed this unexpected respite from his trying to save THE BLOG from the evil Thi Gang, and from Miss Tartiflate’s continuous flow of criticism.

The storm blew off the dish just after Xavier had sent him AL’s answer to the strange glyphs he had received on his phone. When Youssef read the message, he sighed. He had forgotten hope was an illusion. AL was in its infancy and was not a dead language expert. He gave them something fitting Youssef’s current location and the questions about famous alien dishes they asked him last week. It was just an old pot luck recipe from when the Silk Road was passing through the Gobi desert. He just hoped Xavier would have some luck until Youssef found a way to restore the connexion.

January 17, 2023 at 9:06 pm #6410

January 17, 2023 at 9:06 pm #6410In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Real-life Xavier was marveling at the new AL (Artificial Life) developments on this project he’d been working on. It’s been great at tidying the plot, confusing as the plot started to become with Real-life characters named the same as their Quirky counterparts ones.

Real-life Zara had not managed to remain off the computer for very long, despite her grand claims to the contrary. She’d made quick work of introducing a new player in the game, a reporter in an obscure newspaper, who’d seemed quirky enough to be their guide in the new game indeed. It was difficult to see if hers was a nickname or nom de plume, but strangely enough, she also named her own character the same as her name in the papers. Interestingly, Zara and Glimmer had some friends in common in Australia, where RL Zara was living at the moment.

Anyways… “Clever AL” Xavier smiled when he saw the output on the screen. “Yasmin will love a little tidiness; even if she is the brains of the group, she has always loved the help.”

Meanwhile, in the real world, Youssef was on his own adventure in Mongolia, trying to uncover the mystery of the Thi Gang. He had been hearing whispers and rumors about the ancient and powerful group, and he was determined to find out the truth. He had been traveling through the desert for weeks, following leads and piecing together clues, and he was getting closer to the truth.

Zara, Xavier, and Yasmin, on the other hand, were scattered around the world. Zara was in Australia, working on a conservation project and trying to save a group of endangered animals. Xavier was in Europe, working on a new project for a technology company. And Yasmin was in Asia, volunteering at a children’s hospital.

Despite being physically separated, the four friends kept in touch through video calls and messages. They were all excited about the upcoming adventure in the Land of the Quirks and the possibility of discovering their inner quirks. They were also looking forward to their trip to the Flying Fish Inn, where they hoped to find some clues about the game and their characters.

In the game, Glimmer Gambol’s interactions with the other characters will be taking place in the confines of the Land of the Quirks. As she is the one who has been playing the longest and has the most experience, she will probably be the one to lead the group and guide them through the game. She also has some information that the others don’t know about yet, and she will probably reveal it at the right time.

As the game and the real-world adventures are intertwined, the characters will have to navigate both worlds and find a way to balance them. They will have to use their unique skills and personalities to overcome challenges and solve puzzles, both in the game and in the real world. It will be an exciting and unpredictable journey, full of surprises and twists.

January 17, 2023 at 5:55 pm #6409In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

“What the…..!” Youssef exclaimed, almost throwing his phone to the ground for a second time that morning. As if he wasn’t having enough trouble already without his phone sending him these messages. But then an idea occurred to him, and he had another look at it.

“Ah, now I see! Glimmer has intercepted the message from Gang Thi!” Youssef smiled for the first time that day. He still couldn’t decipher the strange script though, and wondered if it had been a mistake to not include her on the trip in the first place. He had thought her to be foolish and gaudy and not much practical use, but now he wasn’t so sure. He certainly hadn’t expected her to show up so soon, and in such an unexpected way.

January 15, 2023 at 1:18 pm #6391

January 15, 2023 at 1:18 pm #6391In reply to: Train your subjective AI – text version

write the plot of an absurd non-linear novel, featuring 4 characters

The novel begins with the introduction of four characters: a retired archaeologist named Harold, a struggling musician named Samantha, a disillusioned corporate drone named Tim, and a reclusive inventor named Claire.

Harold, who is obsessed with ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, discovers a mysterious underground chamber beneath a pyramid in Egypt. Inside, he finds a strange device that he believes is a time machine. Harold decides to use the device to travel back in time to ancient Egypt in order to decipher the hieroglyphs.

Samantha, who is trying to make a name for herself as a musician, is struggling to come up with new material for her music. One day, she discovers that she can create beautiful music by communicating with plants telepathically. She becomes obsessed with this new form of music-making and decides to quit her day job and pursue it full-time.

Tim, who is stuck in a dead-end job, is feeling unfulfilled and uninspired. One day, he stumbles upon a robotic mime performance art show. The performance inspires him to quit his job and pursue his dream of becoming a mime artist.

Claire, who is a reclusive inventor, has been working on a project to create a type of artificial intelligence that can communicate with humans using calligraphic body language. She finally succeeds and creates an AI that she names “Calli”.

As the story progresses, the characters’ paths begin to intersect in unexpected ways. Harold gets stuck in ancient Egypt and has to rely on Samantha’s telepathic plant communication skills to find a way back to the present. Tim’s robotic mime art becomes a hit and he starts working with Claire to integrate Calli into his performances.

As the story reaches its climax, all four characters come together to use their unique skills and abilities to solve a problem that threatens the fate of the world.

Throughout the novel, the plot unfolds in a non-linear fashion, jumping back and forth in time and between the different character’s perspectives. The story is filled with absurdity and unexpected twists and turns, leaving the reader guessing until the very end.

What sort of problem that threatens the fate of the world will be resolved by their combined skills?

As the story progresses, the characters begin to uncover a sinister plot by a group of powerful individuals who are intent on using the time machine to alter the course of history for their own gain. They plan to use the time machine to go back in time and change key events that would give them immense wealth and power in the present. Harold and Samantha, with the help of Tim and Claire, must race against time to stop the villains from carrying out their plan.

Harold’s expertise in ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs plays a crucial role in deciphering the clues that lead to the location of the time machine. Samantha’s telepathic plant communication skills are used to locate the hidden underground chamber where the time machine is kept. Tim’s robotic mime art and Claire’s AI Calli are used to infiltrate the villains’ hideout and gather intelligence on their plans.

In the final act, the four characters come together to use their unique skills and abilities to stop the villains from altering history. Harold uses his knowledge of ancient Egypt to navigate the time machine and travel back in time to stop the villains from changing key events. Samantha uses her telepathic plant communication skills to communicate with the plants in the past and gather information on the villains’ whereabouts. Tim and Claire use their robotic mime and AI skills to create a diversion and distract the villains while Harold and Samantha complete their mission.

In the end, the four characters succeed in stopping the villains and saving the fate of the world. The novel ends with the four characters going their separate ways, but they all know that they will always have each other to rely on in the face of any challenge that comes their way.

January 13, 2023 at 9:00 pm #6381In reply to: Prompts of Madjourneys

Tell me more about the clues that Zara, Youssef, Xavier and Yasmin will find on their journeys to discover their inner quirky natures

As Zara, Youssef, Xavier and Yasmin journeyed through the Land of the Quirks to discover their inner quirky natures, they encountered various clues that helped them on their journey.

One of the clues they found was a mysterious map that led them to different locations, each one representing a different aspect of their personalities. The map also had various riddles and puzzles that they had to solve in order to progress to the next location.

Another clue they found was a series of journal entries written by a previous explorer who had also journeyed through the Land of the Quirks. The journal entries provided insight and wisdom on how to navigate the land and how to understand and accept one’s quirks.

They also encountered a group of strange and eccentric characters who each represented a different aspect of their personalities. These characters provided guidance and helped them understand different parts of themselves. They also helped them understand the importance of accepting and embracing their quirks.

They also found a series of symbols and artifacts that represented different parts of their personalities. These symbols and artifacts were like puzzle pieces that, when put together, helped them understand the bigger picture of their inner quirky natures.

As they continued their journey, they also learned that the key to discovering their inner quirky natures was not only about finding the physical “Key of Quirks”, but also about understanding and accepting themselves, their faults and their strengths, and learning to embrace their unique quirks.

Finding their inner quirks sounds quite definitive. how would you make the ending more open-ended, open to multiple series and iterations of the story without sounding repetitive

As Zara, Youssef, Xavier and Yasmin journeyed through the Land of the Quirks, they discovered their inner quirky natures, but the journey was far from over. They found that their inner quirks were constantly evolving and changing, and that the Land of the Quirks was a vast and mysterious place with many more secrets to uncover.

The group found that the “Key of Quirks” was not just a physical object but a symbol of self-discovery and self-acceptance. They learned that understanding and accepting oneself is a lifelong journey that never truly ends.

As they returned to their own world, they realized that they had gained a new perspective on life and that they would continue to carry the lessons they learned in the Land of the Quirks with them. They knew that they would always be on the lookout for new adventures and opportunities to continue exploring themselves and the world around them.

The group’s journey in the Land of the Quirks had come to an end but the story was not over. The characters would continue to grow, evolve and change as they experienced new adventures, challenges and self-discoveries. The ending was open-ended and leaves the possibility for multiple series and iterations of the story, each one exploring new aspects of the characters and the Land of the Quirks, without being repetitive.

Will they go a try to travel through another of the orbs?

It is possible that the group will want to explore other orbs and realms in the Land of the Quirks. The Land of the Quirks is described as a vast and mysterious place with many secrets to uncover, so the possibility of traveling through other orbs or realms is open. They may be tempted to see what other adventures and discoveries await them in these new places.

Alternatively, they might decide to take a break from their adventures, and reflect on what they’ve learned, applying it to their daily life, and maybe in the future, they will decide to come back to the Land of the Quirks and explore other orbs, or they may find other means of self-discovery and self-acceptance. In any case, the story leaves it open-ended and the characters have the freedom to choose what they want to do next.

How did they discover the orb in the first place?

It is not specified how the group discovered the orb in the first place. It could be that they stumbled upon it while on a hike or a camping trip, or it could be that they were on a mission to find it specifically. It could also be that the orb was something that had always been there but had gone unnoticed until one of the group members stumbled upon it.

Perhaps it was passed down from generation to generation as a legend, or maybe they found it while they were searching for something else. The story leaves it open-ended and it’s up to the reader’s imagination. The main focus of the story is on the journey and the lessons learned along the way, rather than the specifics of how the orb was discovered.

January 11, 2023 at 10:32 pm #6368In reply to: Train your subjective AI – text version

Something in the style of FPooh:

Arona heard the music growing louder as she approached the source of the sound. She could see a group of people gathered around a large fire, the flickering light casting shadows on the faces of the dancers. She hesitated for a moment, remembering the isolation of her journey and wondering if she was ready to be among people again. But the music was too inviting, and she found herself drawn towards the group.

As she neared the fire, she saw a young man playing a flute, the music flowing from his fingers with a fluid grace that captivated her. He looked up as she approached, and their eyes met. She could see the surprise and curiosity in his gaze, and she smiled, feeling a sense of connection she had not felt in a long time.

Fiona was sitting on a bench in the park, watching the children play. She had brought her sketchbook with her, but for once she didn’t feel the urge to draw. Instead she watched the children’s laughter, feeling content and at peace. Suddenly, she saw a young girl running towards her, a look of pure joy on her face. The girl stopped in front of her and held out a flower, offering it to Fiona with a smile.

Taken aback, Fiona took the flower and thanked the girl. The girl giggled and ran off to join her friends. Fiona looked down at the flower in her hand, and she felt a sense of inspiration, like a spark igniting within her. She opened her sketchbook and began to draw, feeling the weight lift from her shoulders and the magic of creativity flowing through her.

Minky led the group of misfits towards the emporium, his bowler hat bobbing on his head. He chattered excitedly, telling stories of the wondrous items to be found within Mr Jib’s store. Yikesy followed behind, still lost in his thoughts of Arona and feeling a sense of dread at the thought of buying a bowler hat. The green fairy flitted along beside him, her wings a blur of movement as she chattered with the parrot perched on her shoulder.

As they reached the emporium, they were disappointed to find it closed. But Minky refused to be discouraged, and he led them to a nearby cafe where they could sit and enjoy some tea and cake while they wait for the emporium to open. The green fairy was delighted, and she ordered a plate of macarons, smiling as she tasted the sweetness of the confections.

About creativity & everyday magic

Fiona had always been drawn to the magic of creativity, the way a blank page could be transformed into a world of wonder and beauty. But lately, she had been feeling stuck, unable to find the spark that ignited her imagination. She would sit with her sketchbook, pencil in hand, and nothing would come to her.

She started to question her abilities, wondering if she had lost the magic of her art. She spent long hours staring at her blank pages, feeling a weight on her chest that seemed to be growing heavier every day.

But then she remembered the green fairy’s tears and Yikesy’s longing for Arona, and she realized that the magic of creativity wasn’t something that could be found only in art. It was all around her, in the everyday moments of life.

She started to look for the magic in the small things, like the way the sunlight filtered through the trees, or the way a child’s laughter could light up a room. She found it in the way a stranger’s smile could lift her spirits, and in the way a simple cup of tea could bring her comfort.

And as she started to see the magic in the everyday, she found that the weight on her chest lifted and the spark of inspiration returned. She picked up her pencil and began to draw, feeling the magic flowing through her once again.

She understand that creativity blocks aren’t a destination, but just a step, just like the bowler hat that Minky had bought for them all, a bit of everyday magic, nothing too fancy but a sense of belonging, a sense of who they are and where they are going. And she let her pencil flow, with the hopes that one day, they will all find their way home.

January 11, 2023 at 9:43 pm #6367In reply to: Train your subjective AI – text version

Something in the style of TPooh:

The family tree was a tangled web of branches and roots, stretching back centuries and even millennia. The branches were thick with the leaves of secrets, scandals, and mysteries that the family had accumulated over the years. They were a close-knit group, friends for all time, and they loved nothing more than exploring the twists and turns of their family history.

They met regularly in their dreams, in a place they called The City, where they could exchange stories and clues they had uncovered during their waking hours. They often found themselves in the midst of strange and puzzling occurrences, and they would spend hours discussing the possible meanings and connections of these events. They saw the world as a tapestry, with each thread and pattern contributing to the greater picture. They were the weavers of their own story, the authors of their own fate.

But as the years went on, their dreams began to take on a darker and more ominous tone. They started having nightmares of monstrous beasts, and some of them even saw these beasts in the daylight, as if they were falling through the cracks in reality. They compared notes and found that they were often seeing the same beasts, and this led to heated debates about what these beasts represented and whether they were real or just figments of their imagination.

But no matter what they encountered, the family remained united in their quest to unravel the secrets of their past and to weave a tapestry that would be the envy of all. They were thick as thieves and they would never give up their pursuit of the truth, no matter how many rules they had to break along the way.

January 10, 2023 at 11:00 pm #6365In reply to: Train your subjective AI – text version

Prune has got me into this AI stuff… It sounds like gibberish to me, but Idle sounded amazed at the stuff it spewed out.

With some info on our family story, Prune got it to try and predict the future…

Sounds like a big plate of bog, but we’ll see how it goes.

Sure, here are a few possible events that could occur between Mater’s 100th birthday and her death in the Flying Fish Inn story:

- Mater decides to throw herself a grand birthday party, inviting all of her friends and family from the small outback town. However, things take a turn for the strange when a group of extraterrestrial beings crash the party and reveal themselves to be long-time fans of Mater’s famous bush tucker cuisine.

- Mater begins to experience vivid dreams and hallucinations, in which she is visited by the ghost of her late husband. As the dreams become more frequent, the family begins to suspect that there may be something more to them than just Mater’s mind playing tricks on her.

- Mater’s granddaughter Prune becomes increasingly obsessed with her dream of traveling to Mars, and begins to notice strange occurrences happening around the inn that seem to be connected to her aspiration.

- A group of eccentric scientists arrive at the inn, conducting research on the local flora and fauna. They eventually discover a species of sentient plants living in the area, and Mater becomes convinced that the plants are communicating with her in her dreams.

- With her health declining, Mater begins to spend more and more time tending to her garden, where she is visited by an old kookaburra who seems to possess an otherworldly intelligence. The bird becomes Mater’s companion and confidant in the final days of her life.

- As the Great Fires ravage the Australian bush, Mater makes the difficult decision to shut down the inn and evacuate the guests. But as they flee, they realize that the fire is not just a natural disaster, but something far more sinister and mystical.

- In her final days, Mater begins to remember strange and vivid details of her life that she never could have known, as if she lived a previous life in another time and place. As she dies, she whispers something to Prune, which opens her eyes to a new reality that may have been hidden from her all along

- It turns out the family had a lot of secrets, and the only way to escape it, was to leave the inn, but it was not an escape for all. Through the series of events, secrets are revealed, and some truths cannot be undone.Note that these events are fictional and whimsical in nature, but as they keeps it grounded to a sense of doldrums in the Australian bush and occasionally guests help to unravel some of the overarching mysteries it could make a fitting storyline for the story.

January 10, 2023 at 10:15 pm #6363In reply to: Train your subjective AI – text version

try another short story, with a bit of drama with the following words:

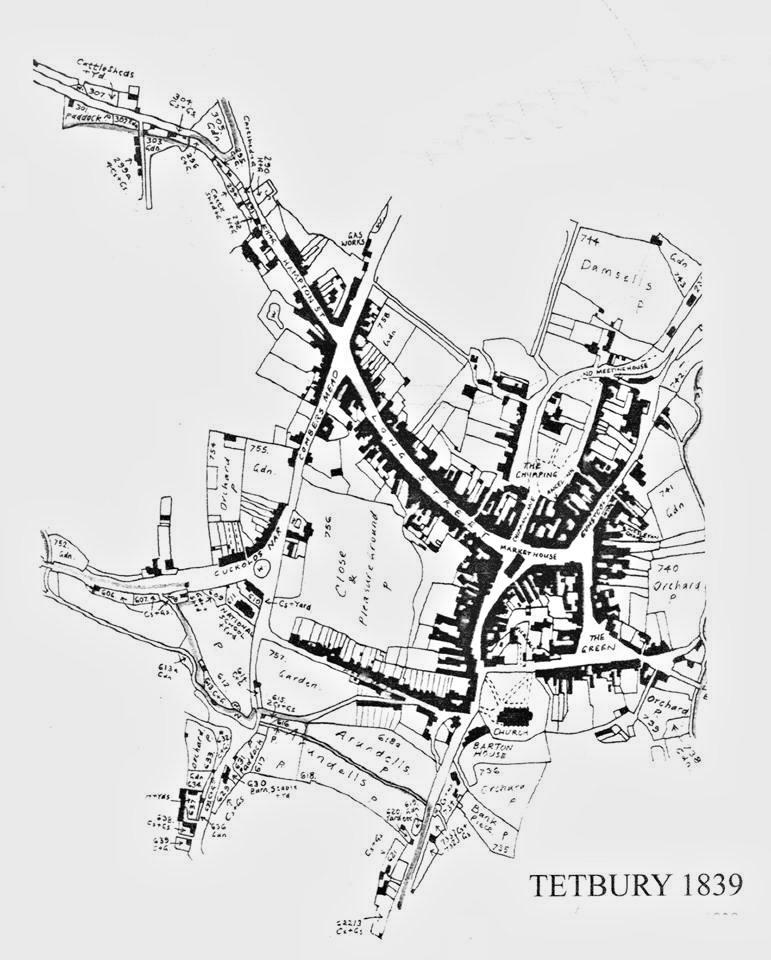

road form charlton smooth everyone cottage hanging rush offer agree subject district included appear sha returning grattidge nottingham 848 tetbury chicken

It was a cold and gloomy day in the small village of Tetbury, nestled in the picturesque Cotswolds district. A young woman named Sha was returning home to her cottage after a long and tiring journey. She had been away visiting her family in Nottingham and was looking forward to relaxing in her cozy home.

As she walked down the dirt road that led to her cottage, she couldn’t help but notice that something was off. Her neighbor, Mr. Charlton, was outside hanging laundry and he didn’t acknowledge her as she walked by. Sha thought it was strange, as he was usually a friendly and sociable person.

When Sha arrived at her cottage, she was shocked to find that it had been broken into. The front door was ajar and the inside of her home had been ransacked. Sha immediately panicked and called the police, who arrived on the scene shortly thereafter.

The police officers, including Inspector Grattidge, took Sha’s statement and began to investigate the crime. They discovered that a group of burglars had been operating in the area, targeting homes and businesses in the district. The burglars had been known for their smooth operations and their ability to strike quickly, which led to their nickname “The Smooth Operators”.

As Sha waited for the police to finish their investigation, she couldn’t shake the feeling that something was not right. She had always thought of Tetbury as a safe and friendly place, and she couldn’t believe that something like this could happen in her community.

As the investigation went on, the police found out that the Smooth operators have been targeting houses with no security cameras, but Sha’s cottage was an exception, the police were able to find out that the group offered to pay a considerable sum of money to the people who reported the locations of the houses that had no cameras, and it was Mr. Charlton who was the informant and he even rushed to Sha’s cottage as soon as he knew the police was investigating the case, He was arrested for the crime and Sha was heartbroken to find out that her once friendly neighbor had betrayed her.

Feeling violated and betrayed, Sha decided that she could no longer stay in the village and she put her cottage up for sale. She packed up her belongings and moved away, leaving behind the memories of her peaceful home and the community she had once thought of as her own. The end.

November 4, 2022 at 2:19 pm #6342In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Brownings of Tetbury

Isaac Browning (1784-1848) married Mary Lock (1787-1870) in Tetbury in 1806. Both of them were born in Tetbury, Gloucestershire. Isaac was a stone mason. Between 1807 and 1832 they baptised fourteen children in Tetbury, and on 8 Nov 1829 Isaac and Mary baptised five daughters all on the same day.

I considered that they may have been quintuplets, with only the last born surviving, which would have answered my question about the name of the house La Quinta in Broadway, the home of Eliza Browning and Thomas Stokes son Fred. However, the other four daughters were found in various records and they were not all born the same year. (So I still don’t know why the house in Broadway had such an unusual name).

Their son George was born and baptised in 1827, but Louisa born 1821, Susan born 1822, Hesther born 1823 and Mary born 1826, were not baptised until 1829 along with Charlotte born in 1828. (These birth dates are guesswork based on the age on later censuses.) Perhaps George was baptised promptly because he was sickly and not expected to survive. Isaac and Mary had a son George born in 1814 who died in 1823. Presumably the five girls were healthy and could wait to be done as a job lot on the same day later.

Eliza Browning (1814-1886), my great great great grandmother, had a baby six years before she married Thomas Stokes. Her name was Ellen Harding Browning, which suggests that her fathers name was Harding. On the 1841 census seven year old Ellen was living with her grandfather Isaac Browning in Tetbury. Ellen Harding Browning married William Dee in Tetbury in 1857, and they moved to Western Australia.

Ellen Harding Browning Dee: (photo found on ancestry website)

OBITUARY. MRS. ELLEN DEE.

A very old and respected resident of Dongarra, in the person of Mrs. Ellen Dee, passed peacefully away on Sept. 27, at the advanced age of 74 years.The deceased had been ailing for some time, but was about and actively employed until Wednesday, Sept. 20, whenn she was heard groaning by some neighbours, who immediately entered her place and found her lying beside the fireplace. Tho deceased had been to bed over night, and had evidently been in the act of lighting thc fire, when she had a seizure. For some hours she was conscious, but had lost the power of speech, and later on became unconscious, in which state she remained until her death.

The deceased was born in Gloucestershire, England, in 1833, was married to William Dee in Tetbury Church 23 years later. Within a month she left England with her husband for Western Australian in the ship City oí Bristol. She resided in Fremantle for six months, then in Greenough for a short time, and afterwards (for 42 years) in Dongarra. She was, therefore, a colonist of about 51 years. She had a family of four girls and three boys, and five of her children survive her, also 35 grandchildren, and eight great grandchildren. She was very highly respected, and her sudden collapse came as a great shock to many.

Eliza married Thomas Stokes (1816-1885) in September 1840 in Hempstead, Gloucestershire. On the 1841 census, Eliza and her mother Mary Browning (nee Lock) were staying with Thomas Lock and family in Cirencester. Strangely, Thomas Stokes has not been found thus far on the 1841 census, and Thomas and Eliza’s first child William James Stokes birth was registered in Witham, in Essex, on the 6th of September 1841.

I don’t know why William James was born in Witham, or where Thomas was at the time of the census in 1841. One possibility is that as Thomas Stokes did a considerable amount of work with circus waggons, circus shooting galleries and so on as a journeyman carpenter initially and then later wheelwright, perhaps he was working with a traveling circus at the time.

But back to the Brownings ~ more on William James Stokes to follow.

One of Isaac and Mary’s fourteen children died in infancy: Ann was baptised and died in 1811. Two of their children died at nine years old: the first George, and Mary who died in 1835. Matilda was 21 years old when she died in 1844.

Jane Browning (1808-) married Thomas Buckingham in 1830 in Tetbury. In August 1838 Thomas was charged with feloniously stealing a black gelding.

Susan Browning (1822-1879) married William Cleaver in November 1844 in Tetbury. Oddly thereafter they use the name Bowman on the census. On the 1851 census Mary Browning (Susan’s mother), widow, has grandson George Bowman born in 1844 living with her. The confusion with the Bowman and Cleaver names was clarified upon finding the criminal registers:

30 January 1834. Offender: William Cleaver alias Bowman, Richard Bunting alias Barnfield and Jeremiah Cox, labourers of Tetbury. Crime: Stealing part of a dead fence from a rick barton in Tetbury, the property of Robert Tanner, farmer.

And again in 1836:

29 March 1836 Bowman, William alias Cleaver, of Tetbury, labourer age 18; 5’2.5” tall, brown hair, grey eyes, round visage with fresh complexion; several moles on left cheek, mole on right breast. Charged on the oath of Ann Washbourn & others that on the morning of the 31 March at Tetbury feloniously stolen a lead spout affixed to the dwelling of the said Ann Washbourn, her property. Found guilty 31 March 1836; Sentenced to 6 months.

On the 1851 census Susan Bowman was a servant living in at a large drapery shop in Cheltenham. She was listed as 29 years old, married and born in Tetbury, so although it was unusual for a married woman not to be living with her husband, (or her son for that matter, who was living with his grandmother Mary Browning), perhaps her husband William Bowman alias Cleaver was in trouble again. By 1861 they are both living together in Tetbury: William was a plasterer, and they had three year old Isaac and Thomas, one year old. In 1871 William was still a plasterer in Tetbury, living with wife Susan, and sons Isaac and Thomas. Interestingly, a William Cleaver is living next door but one!

Susan was 56 when she died in Tetbury in 1879.

Three of the Browning daughters went to London.

Louisa Browning (1821-1873) married Robert Claxton, coachman, in 1848 in Bryanston Square, Westminster, London. Ester Browning was a witness.

Ester Browning (1823-1893)(or Hester) married Charles Hudson Sealey, cabinet maker, in Bethnal Green, London, in 1854. Charles was born in Tetbury. Charlotte Browning was a witness.

Charlotte Browning (1828-1867?) was admitted to St Marylebone workhouse in London for “parturition”, or childbirth, in 1860. She was 33 years old. A birth was registered for a Charlotte Browning, no mothers maiden name listed, in 1860 in Marylebone. A death was registered in Camden, buried in Marylebone, for a Charlotte Browning in 1867 but no age was recorded. As the age and parents were usually recorded for a childs death, I assume this was Charlotte the mother.

I found Charlotte on the 1851 census by chance while researching her mother Mary Lock’s siblings. Hesther Lock married Lewin Chandler, and they were living in Stepney, London. Charlotte is listed as a neice. Although Browning is mistranscribed as Broomey, the original page says Browning. Another mistranscription on this record is Hesthers birthplace which is transcribed as Yorkshire. The original image shows Gloucestershire.

Isaac and Mary’s first son was John Browning (1807-1860). John married Hannah Coates in 1834. John’s brother Charles Browning (1819-1853) married Eliza Coates in 1842. Perhaps they were sisters. On the 1861 census Hannah Browning, John’s wife, was a visitor in the Harding household in a village called Coates near Tetbury. Thomas Harding born in 1801 was the head of the household. Perhaps he was the father of Ellen Harding Browning.

George Browning (1828-1870) married Louisa Gainey in Tetbury, and died in Tetbury at the age of 42. Their son Richard Lock Browning, a 32 year old mason, was sentenced to one month hard labour for game tresspass in Tetbury in 1884.

Isaac Browning (1832-1857) was the youngest son of Isaac and Mary. He was just 25 years old when he died in Tetbury.

September 4, 2022 at 6:00 pm #6326In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

Stung by Egberts question, Olga reeled and almost lost her footing on the stairs. What had happened to her? That damned selfish individualism that was running rampant must have seeped into her room through the gaps in the windows or under the door. “No!” she shouted, her voice cracking.

“Say it isn’t true, Olga,” Egbert said, his voice breaking. “Not you as well.”

It took Olga a minute or two to still her racing heart. The near fall down the stairs had shaken her but with trembling hands she levered herself round to sit beside Egbert on the step.

Gripping his bony knee with her knobbly arthritic fingers, she took a deep breath.

“You are right to have said that, Egbert. If there is one thing we must hold onto, it’s our hearts. Nothing else matters, or at least nothing else matters as much as that. We are old and tired and we don’t like change. But if we escalate the importance of this frankly dreary and depressing home to the point where we lose our hearts…” she faltered and continued. “We will be homeless soon, very soon, and we know not what will happen to us. We must trust in the kindness of strangers, we must hope they have a heart.”

Egbert winced as Olga squeezed his knee. “And that is why”, Olga continued, slapping Egberts thigh with gusto, “We must have a heart…”

“If you’d just stop squeezing and hitting me, Olga…”

Olga loosened her grip on the old mans thigh bone and peered into his eyes. Quietly she thanked him. “You’ve cleared my mind and given me something to live for, and I thank you for that. But you do need to launder your clothes more often,” she added, pulling a face. She didn’t want the old coot to start blubbing, and he looked alarmingly close to tears.

“Come on, let’s go and see Obadiah. We’re all in this together. Homelessness and adventure can wait until tomorrow.” Olga heaved herself upright with a surprising burst of vitality. Noticing a weak smile trembling on Egberts lips, she said “That’s the spirit!”

July 7, 2022 at 9:00 am #6314In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

After her visit to the witch of the woods to get some medicine for her Mum who still had bouts of fatigue from her last encounter with the flu, the little Maryechka went back home as instructed.

She found her home empty. Her parents were busy in the fields, as the time of harvest was near, and much remained to be done to prepare, and workers were limited.

She left the pouch of dried herbs in the cabinet, and wondered if she should study. The schools were closed for early holidays, and they didn’t really bother with giving them much homework. She could see the teachers’ minds were worried with other things.

Unlike other children of her age, she wasn’t interested in all the activities online, phone-stuff. The other gen-alpha kids didn’t even bother mocking her “IRL”, glued to their screens while she instead enjoyed looking at the clear blue sky. For all she knew they didn’t even realize they were living in the same world. Now, they were probably over-stressed looking at all the news on replay.

For Maryechka, the war felt far away, even if you could see some of its impacts, with people moving about the nearby town.Looking as it was still early in the day, and she had plenty more time left before having to prepare for dinner, she thought it’d be nice to go and visit her grand-parent and their friends at the old people’s home. They always had nice stale biscuits to share, and they told the strangest stories all the time.

It was just a 15 min walk from the farm, so she’d be there and back in no time.

July 6, 2022 at 11:02 am #6311In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

Most of the pilgims, if one could call them that, flocked to the linden tree in cars, although some came on motorbikes and bicycles. Olek was grateful that they hadn’t started arriving by the bus load, like Italian tourists. But his cousin Ursula was happy with this strange new turn of events.

Her shabby hotel on the outskirts of town had never been so busy and she was already planning to refurbish the premises and evict the decrepit and motley assortment of aged permanent residents who had just about kept her head above water, financially speaking, for the last twenty years. She could charge much more per night to these new tourists, who were smartly dressed and modern and didn’t argue about the price of a room. They did complain about the damp stained wallpaper though and the threadbare bedding. Ursula reckoned she could charge even more for the rooms if she redecorated, and had an idea to approach her nephew Boris the bank manager for a business loan.

But first she had to evict the old timers. It wasn’t her problem, she reminded herself, if they had nowhere else to go. After all, plenty of charitable aid money was flying around these days, they could easily just join up with some fleeing refugees. She’d even sent some of her old dresses to the collection agency. They may have been forty years old and smelled of moth balls, but they were well made and the refugees would surely be grateful.

Ursula wasn’t looking forward to telling them. No, not at all! She rather liked some of them and was dreading their reaction. You are a business woman, Ursula, she told herself, and you have to look after your own interests! But still she quailed at the thought of knocking on their doors, or announcing it in the communal dining room at supper. Then she had an idea. She’d type up some letters instead, and sign them as if they came from her new business manager. When the residents approached her about the letter she would smile sadly and shrug, saying it wasn’t her decision and that she was terribly sorry but her hands were tied.

May 3, 2022 at 4:40 pm #6291In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Jane Eaton

The Nottingham Girl

Jane Eaton 1809-1879

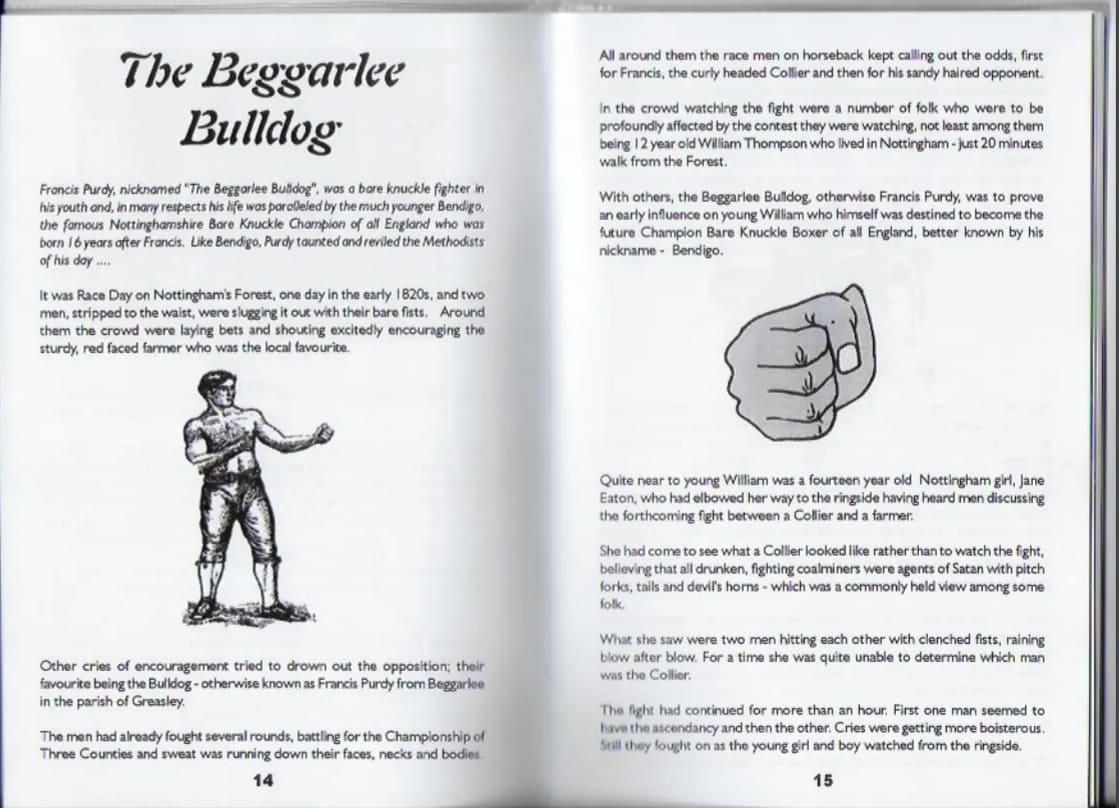

Francis Purdy, the Beggarlea Bulldog and Methodist Minister, married Jane Eaton in 1837 in Nottingham. Jane was his second wife.

Jane Eaton, photo says “Grandma Purdy” on the back:

Jane is described as a “Nottingham girl” in a book excerpt sent to me by Jim Giles, a relation who shares the same 3x great grandparents, Francis and Jane Purdy.

Elizabeth, Francis Purdy’s first wife, died suddenly at chapel in 1836, leaving nine children.

On Christmas day the following year Francis married Jane Eaton at St Peters church in Nottingham. Jane married a Methodist Minister, and didn’t realize she married the bare knuckle fighter she’d seen when she was fourteen until he undressed and she saw his scars.

William Eaton 1767-1851

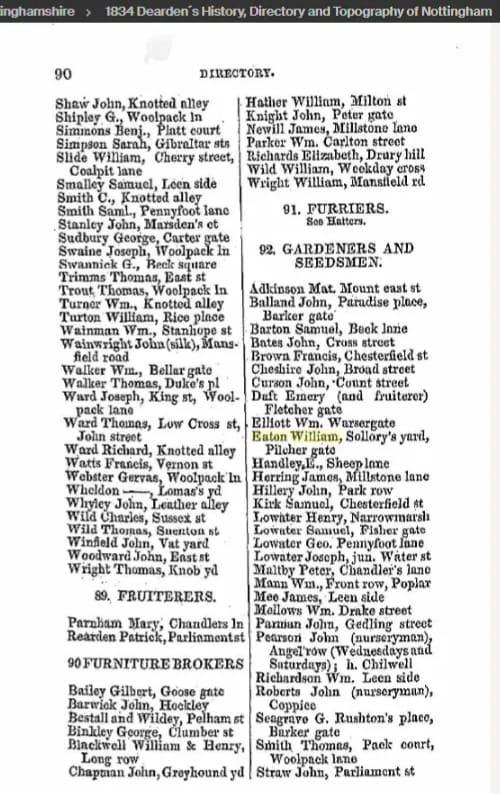

On the marriage certificate Jane’s father was William Eaton, occupation gardener. Francis’s father was William Purdy, engineer.

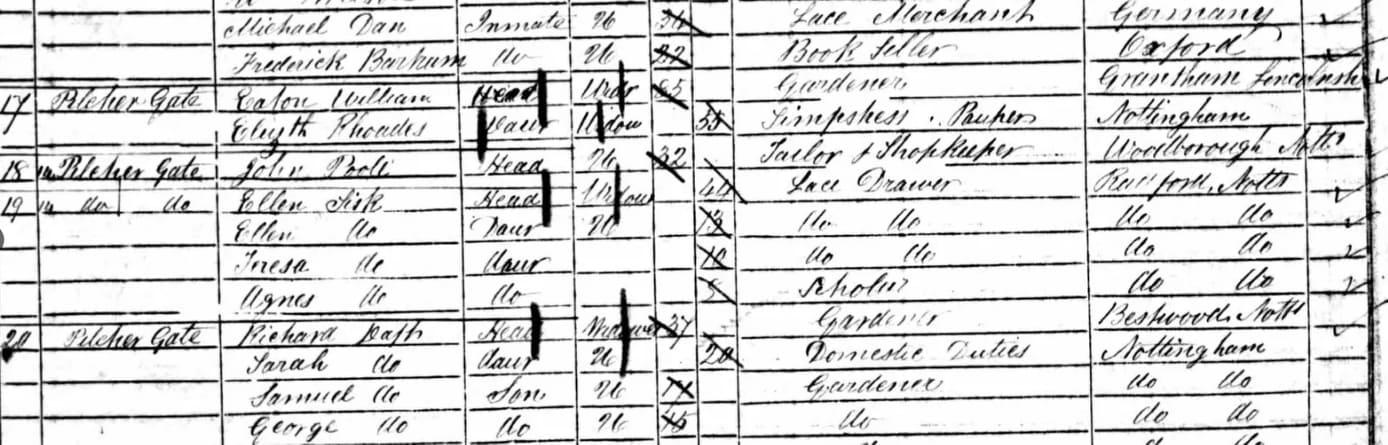

On the 1841 census living in Sollory’s Yard, Nottingham St Mary, William Eaton was a 70 year old gardener. It doesn’t say which county he was born in but indicates that it was not Nottinghamshire. Living with him were Mary Eaton, milliner, age 35, Mary Eaton, milliner, 15, and Elizabeth Rhodes age 35, a sempstress (another word for seamstress). The three women were born in Nottinghamshire.

But who was Elizabeth Rhodes?

Elizabeth Eaton was Jane’s older sister, born in 1797 in Nottingham. She married William Rhodes, a private in the 5th Dragoon Guards, in Leeds in October 1815.

I looked for Elizabeth Rhodes on the 1851 census, which stated that she was a widow. I was also trying to determine which William Eaton death was the right one, and found William Eaton was still living with Elizabeth in 1851 at Pilcher Gate in Nottingham, but his name had been entered backwards: Eaton William. I would not have found him on the 1851 census had I searched for Eaton as a last name.

Pilcher Gate gets its strange name from pilchers or fur dealers and was once a very narrow thoroughfare. At the lower end stood a pub called The Windmill – frequented by the notorious robber and murderer Charlie Peace.

This was a lucky find indeed, because William’s place of birth was listed as Grantham, Lincolnshire. There were a couple of other William Eaton’s born at the same time, both near to Nottingham. It was tricky to work out which was the right one, but as it turned out, neither of them were.

Now we had Nottinghamshire and Lincolnshire border straddlers, so the search moved to the Lincolnshire records.

But first, what of the two Mary Eatons living with William?William and his wife Mary had a daughter Mary in 1799 who died in 1801, and another daughter Mary Ann born in 1803. (It was common to name children after a previous infant who had died.) It seems that Mary Ann didn’t marry but had a daughter Mary Eaton born in 1822.

William and his wife Mary also had a son Richard Eaton born in 1801 in Nottingham.

Who was William Eaton’s wife Mary?

There are two possibilities: Mary Cresswell and a marriage in Nottingham in 1797, or Mary Dewey and a marriage at Grantham in 1795. If it’s Mary Cresswell, the first child Elizabeth would have been born just four or five months after the wedding. (This was far from unusual). However, no births in Grantham, or in Nottingham, were recorded for William and Mary in between 1795 and 1797.

We don’t know why William moved from Grantham to Nottingham or when he moved there. According to Dearden’s 1834 Nottingham directory, William Eaton was a “Gardener and Seedsman”.

There was another William Eaton selling turnip seeds in the same part of Nottingham. At first I thought it must be the same William, but apparently not, as that William Eaton is recorded as a victualler, born in Ruddington. The turnip seeds were advertised in 1847 as being obtainable from William Eaton at the Reindeer Inn, Wheeler Gate. Perhaps he was related.

William lived in the Lace Market part of Nottingham. I wondered where a gardener would be working in that part of the city. According to CreativeQuarter website, “in addition to the trades and housing (sometimes under the same roof), there were a number of splendid mansions being built with extensive gardens and orchards. Sadly, these no longer exist as they were gradually demolished to make way for commerce…..The area around St Mary’s continued to develop as an elegant residential district during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, with buildings … being built for nobility and rich merchants.”

William Eaton died in Nottingham in September 1851, thankfully after the census was taken recording his place of birth.

-

AuthorSearch Results