-

AuthorSearch Results

-

March 1, 2025 at 12:41 pm #7847

In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

Helix 25 – The Lexican Quarters – Anuí’s Chambers

Anuí Naskó had been many things in their life—historian, philosopher, linguist, nuisance. But a father? No. No, that was entirely new.

And yet, here they were, rocking a very tiny, very loud creature wrapped in Lexican ceremonial cloth, embroidered with the full unpronounceable name bestowed upon it just moments ago: Hšyra-Mak-Talún i Ešvar—”He Who Cries the Arrival of the Infinite Spiral.”

The baby did, indeed, cry.

“Why do you scream at me?” Anuí muttered, swaying slightly, more in a daze than any real instinct to soothe. “I did not birth you. I did not know you existed until three hours ago. And yet, you are here, squalling, because your other father and your mother have decided to fulfill the Prophecy of the Spiral Throne.”

The Prophecy. The one that spoke of the moment the world would collapse and the Lexicans would ascend. The one nobody took seriously. Until now.

Zoya Kade, sitting across from them, watched with narrowed, calculating eyes. “And what exactly does that entail? This Lexican Dynasty?”

Anuí sighed, looking down at the writhing child who was trying to suck on their sleeves, still stained with the remnants of the protein paste they had spent the better part of the morning brewing. The Atrium’s walls needed to be prepared, after all—Kio’ath could not write the sigils without the proper medium. And as the cycles dictated, the medium must be crafted, fermented, and blessed by the hand of one who walks between identities. It had been a tedious, smelly process, but Anuí had endured worse in the name of preservation.

“Patterns repeat, cycles fold inward.” “Patterns repeat, cycles fold inward. The old texts speak of it, the words carved into the silent bones of forgotten tongues. This, Zoya, is no mere madness. This is the resurgence of what was foretold. A dynasty cannot exist without succession, and history does not move without inheritors. They believe they are ensuring the inevitability of their rise. And they might not be wrong.”

They adjusted their grip on the child, murmuring a phrase in a language so old it barely survived in the archives. “Tz’uran velth ka’an, the root that binds to the branch, the branch that binds to the sky. Our truths do not stand alone.”

The baby flailed, screaming louder. “Yes, yes, you are the heir,” Anuí murmured, bouncing it with more confidence. “Your lineage has been declared, your burden assigned. Accept it and be silent.” “Well, apparently it requires me to be a single parent while they go forth and multiply, securing ‘heirs to the truth.’ A dynasty is no good without an heir and a spare, you see.”

The baby flailed, screaming even louder. “Yes, yes, you are the heir,” Anuí murmured with a hint of irritation, bouncing the baby awkwardly. “You have been declared. Please, cease wailing now.”

Zoya exhaled through her nose, somewhere between disbelief and mild amusement. “And in the middle of all this divine nonsense, the Lexicans have chosen to back me?”

Anuí arched a delicate brow, shifting the baby to one arm with newfound ease. “Of course. The truth-seeker is foretold. The woman who speaks with voices of the past. We have our empire; you are our harbinger.”

Zoya’s lips twitched. “Your empire consists of thirty-eight highly unstable academics and a baby.”

“Thirty-nine. Kio’ath returned from exile yesterday,” Anuí corrected. “They claim the moons have been whispering.”

“Ah. Of course they have.”

Zoya fell silent, fingers tracing the worn etchings of her chair’s armrest. The ship’s hum pressed into her bones, the weight of something stirring in her mind, something old, something waiting.

Anuí’s gaze sharpened, the edges of their thoughts aligning like an ancient lexicon unfurling in front of them. “And now you are hearing it, aren’t you? The echoes of something that was always there. The syllables of the past, reshaped by new tongues, waiting for recognition. The Lexican texts spoke of a fracture in the line, a leader divided, a bridge yet to be found.”

They took a slow breath, fingers tightening over the child’s swaddled form. “The prophecy is not a single moment, Zoya. It is layers upon layers, intersecting at the point where chaos demands order. Where the unseen hand corrects its own forgetting. This is why they back you. Not because you seek the truth, but because you are the conduit through which it must pass.”

Zoya’s breath shallowed. A warmth curled in her chest, not of her own making. Her fingers twitched as if something unseen traced over them, urging her forward. The air around her thickened, charged.

She knew this feeling.

Her head tipped back, and when she spoke, it was not entirely her own voice.

“The past rises in bloodlines and memory,” she intoned, eyes unfocused, gaze burning through Anuí. “The lost sibling walks beneath the ice. The leader sleeps, but he must awaken, for the Spiral Throne cannot stand alone.”

Anuí’s pulse skipped. “Zoya—”

The baby let out a startled hiccup.

But Zoya did not stop.

“The essence calls, older than names, older than the cycle. I am Achaia-Vor, the Echo of Sundered Lineage. The Lost, The Twin, The Nameless Seed. The Spiral cannot turn without its axis. Awaken Victor Holt. He is the lock. You are the key. The path is drawn.

“The cycle bends but does not break. Across the void, the lost ones linger, their voices unheard, their blood unclaimed. The Link must be found. The Speaker walks unknowingly, divided across two worlds. The bridge between past and present, between silence and song. The Marlowe thread is cut, yet the weave remains. To see, you must seek the mirrored souls. To open the path, the twins must speak.”

Achaia-Vor. The name vibrated through the air, curling through the folds of Anuí’s mind like a forgotten melody.

Zoya’s eyes rolled back, body jerking as if caught between two timelines, two truths. She let out a breathless whisper, almost longing.

“Victor, my love. He is waiting for me. I must bring him back.”

Anuí cradled the baby closer, and for the first time, they saw the prophecy not as doctrine but as inevitability. The patterns were aligning—the cut thread of the Marlowes, the mirrored souls, the bridge that must be found.

“It is always the same,” they murmured, almost to themselves. “An axis must be turned, a voice must rise. We have seen this before, written in languages long burned to dust. The same myth, the same cycle, only the names change.”

They met Zoya’s gaze, the air between them thick with the weight of knowing. “And now, we must find the Speaker. Before another voice is silenced.”

“Well,” they muttered, exhaling slowly. “This just got significantly more complicated.”

The baby cooed.

Zoya Kade smiled.

February 16, 2025 at 2:37 pm #7813In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

Helix 25 – Crusades in the Cruise & Unexpected Archives

Evie hadn’t planned to visit Seren Vega again so soon, but when Mandrake slinked into her quarters and sat squarely on her console, swishing his tail with intent, she took it as a sign.

“Alright, you smug little AI-assisted furball,” she muttered, rising from her chair. “What’s so urgent?”

Mandrake stretched leisurely, then padded toward the door, tail flicking. Evie sighed, grabbed her datapad, and followed.

He led her straight to Seren’s quarters—no surprise there. The dimly lit space was as chaotic as ever, layers of old records, scattered datapads, and bound volumes stacked in precarious towers. Seren barely looked up as Evie entered, used to these unannounced visits.

“Tell the cat to stop knocking over my books,” she said dryly. “It never ever listens.”

“Well it’s a cat, isn’t it?” Evie replied. “And he seems to have an agenda.”

Mandrake leaped onto one of the shelves, knocking loose a tattered, old-fashioned book. It thudded onto the floor, flipping open near Evie’s feet. She crouched, brushing dust from the cover. Blood and Oaths: A Romance of the Crusades by Liz Tattler.

She glanced at Seren. “Tattler again?”

Seren shrugged. “Romualdo must have left it here. He hoards her books like sacred texts.”

Evie turned the pages, pausing at an unusual passage. The prose was different—less florid than Liz’s usual ramblings, more… restrained.

A fragment of text had been underlined, a single note scribbled in the margin: Not fiction.

Evie found a spot where she could sit on the floor, and started to read eagerly.

“Blood and Oaths: A Romance of the Crusades — Chapter XII

Sidon, 1157 AD.Brother Edric knelt within the dim sanctuary, the cold stone pressing into his bones. The candlelight flickered across the vaulted ceilings, painting ghosts upon the walls. The voices of his ancestors whispered within him, their memories not his own, yet undeniable. He knew the placement of every fortification before his enemies built them. He spoke languages he had never learned.

He could not recall the first time it happened, only that it had begun after his initiation into the Order—after the ritual, the fasting, the bloodletting beneath the broken moon. The last one, probably folklore, but effective.

It came as a gift.

It was a curse.

His brothers called it divine providence. He called it a drowning. Each time he drew upon it, his sense of self blurred. His grandfather’s memories bled into his own, his thoughts weighted by decisions made a lifetime ago.

And now, as he rose, he knew with certainty that their mission to reclaim the stronghold would fail. He had seen it through the eyes of his ancestor, the soldier who stood at these gates seventy years prior.

‘You know things no man should know,’ his superior whispered that night. ‘Be cautious, Brother Edric, for knowledge begets temptation.’

And Edric knew, too, the greatest temptation was not power.

It was forgetting which thoughts were his own.

Which life was his own.

He had vowed to bear this burden alone. His order demanded celibacy, for the sealed secrets of State must never pass beyond those trained to wield it.

But Edric had broken that vow.

Somewhere, beyond these walls, there was a child who bore his blood. And if blood held memory…

He did not finish the thought. He could not bear to.”

Evie exhaled, staring at the page. “This isn’t just Tattler’s usual nonsense, is it?”

Seren shook her head distractedly.

“It reads like a first-hand account—filtered through Liz’s dramatics, of course. But the details…” She tapped the underlined section. “Someone wanted this remembered.”

Mandrake, still perched smugly above them, let out a satisfied mrrrow.

Evie sat back, a seed of realization sprouting in her mind. “If this was real, and if this technique survived somehow…”

Mandrake finished the thought for her. “Then Amara’s theory isn’t theory at all.”

Evie ran a hand through her hair, glancing at the cat than at Evie. “I hate it when Mandrake’s right.”

“Well what’s a witch without her cat, isn’t it?” Seren replied with a smile.

Mandrake only flicked his tail, his work here done.

February 15, 2025 at 2:26 am #7788In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

At first, no one noticed.

They were still speculating about the truck—where it had come from, where it might be going, whether following it was a brilliant idea or a spectacularly bad one.

And, after all, Finja was always muttering about something. Dust, filth, things not put back where they belonged.

But then her voice rose till she was all but shouting.

“Of course, they’re all savages. I don’t know how I put up with them! Honestly, I AM AT MY WIT’S END!”

“Finja?” Anya called. “Are you okay?”

Finja strode on, intent on her diatribe.

“No, I don’t know where they are going,” she yelled. “If I knew that, I probably wouldn’t be here, would I?”

Tala hurried to catch up and stepped in front of Finja, blocking her path. “Finja, are you okay? Who are you talking to?”

Finja sighed loudly; it was tedious. People were so obsessed with explanations.

“If you must know,” she said, “I am conversing with my Auntie Finnley in Australia.”

“Ooooh!” Vera’s eyes lit up. “ A relative!”

Yulia, walking between Luka and Lev, giggled. She adored the twins and couldn’t decide which one she liked more. They were both so tall and handsome. Others found it hard to tell them apart but she always could. It was rumoured that at birth they had been joined at the hip.

“Finja is totally bonkers,” she declared cheerfully and the twins smiled in unison.

“I will have you know I’m not bonkers.” Finja felt deeply offended and misunderstood. “I have been communicating with Auntie Finnley since childhood. She was highly influential in my formative years.”

“How so?” asked Tala.

“Few people appreciate the importance of hygiene like my Auntie Finnley. She works as a cleaner at the Flying Fish Inn in the Australian Outback. Lovely establishment I gather. But terrible dust.”

Vera nodded sagely. “A sensible place to survive the apocalypse.”

“Exactly.” Finja rewarded her with a tight smile.

Jian raised an eyebrow. “And she’s alive? Your aunt?”

“I don’t converse with ghosts!” Finja waved a hand dismissively. “They all survived there thanks to the bravery of Aunt Finnley. Had to disinfect the whole inn, mind you. Said it was an absolute nightmare.” Finja shuddered at the thought of it.

Gregor snorted. “You’re telling us you have a telepathic connection with your aunt in Australia… and she is also mostly concerned about … hygiene?”

Finja glared at him. “Standards must be maintained,” she admonished. “Even after the end of the world.”

“Do you talk to anyone else?” Tala asked. “Or is it just your aunt?”

Finja regarded Tala through slitted eyes. “I’m also talking to Finkley.”

“Where is this Finkley, dear?” asked Anja gently. “Also at the outback?”

“OMG,” Finja said. “Can you imagine those two together?” She cackled at the thought, then pulled herself together. “No. Finkley is on the Helix 25. Practically runs it by all accounts. But also keeps it spotless, of course.”

“Helix 25? The spaceship?” Mikhail asked, suddenly interested. He exchanged glances with Tala who shrugged helplessly.

Yulia laughed. “She’s definitely mad!”

“So what? Aren’t we all,” said Petro.

Molly, who had been quietly watching with Tundra, finally spoke. “And you say they are both… cleaners?” She wasn’t sure what to make of this group. She wondered if it would be better to continue on alone with Tundra? She didn’t want to put the child in any danger.

“Cleanliness runs in the family,” Finja said. “Now, if you’ll all excuse me, I was mid-conversation.”

She closed her eyes, concentrating. The group watched with interest as her lips moved silently, her brow furrowed in deep thought.

Then, suddenly, she opened her eyes and threw her hands in the air.

“Oh, for goodness’ sake,” she muttered. “Finkley is complaining about dust floating in low gravity. Finnley is complaining about the family not taking their boots off at the door. What a pair of whingers. At least I didn’t inherit THAT.”

She sniffed, adjusted her backpack, and walked on.

The others stood there for a moment, letting it all sink in.

Gregor clapped his hands together. “That was the most wonderfully insane thing I’ve heard since the world ended.”

Mikhail sighed. “So, we are following the direction of the truck?”

Anya nodded. “I’ll keep an eye on Finja. The stress is getting to her, and we have no meds if it escalates.”

February 14, 2025 at 10:02 am #7780In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

Orrin Holt gripped the wheel of the battered truck, his knuckles white as the vehicle rumbled over the dry, cracked road. The leather wrap was a patchwork of smooth and worn, stichted together from whatever scraps they had—much like the quilts his mother used to make before her hands gave out. The main road was a useless, unpredictable mess of asphalt gravels and sinkholes. Years of war with Russia, then the collapse, left it to rot before anyone could fix it. Orrin stuck to the dirt path beside it. That was the only safe way through. The engine coughed but held. A miracle, considering how many times it had been patched together.

The cargo in the back was too important for a breakdown now. Medical supplies—antibiotics, painkillers, and a few salvaged vials of something even rarer. They’d traded well for it, risking much. Now he had to get it back to Base Klyutch (Ukrainian word for Key) without incident. If he continued like that he could make it before noon.

Still, something bothered him. That group of people he’d seen.

They had been barely more than silhouettes on top of a hill. Strangers, a rarity in these times. His first instinct had been to stop and evaluate who they were. But his instructions let room for no delay. So, he’d pushed forward and ignored them. The world wasn’t kind to the wandering. But they hadn’t looked like raiders or scavengers. Lost, perhaps. Or searching.

The truck lurched forward as he pushed it harder. The fences of the base rose in the distance, grey and wiry against the blue sky. Base Klyutch was a former military complex, fortified over the years with scavenged materials, steel sheets, and watchtowers. It wasn’t perfect, but it kept them alive.

As he rolled up to the main gate, the sentries swung the barricade open. Before he could fully cut the engine, a woman wearing a pristine white lab coat stepped forward, her sharp eyes scanning the truck’s cargo bed. Dr. Yelena Markova, the camp’s chief doctor, a former nurse who had to step up when the older one died in a raid on their camp three years ago. Stern-faced and wiry, with a perpetual air of exhaustion, she moved with the efficiency of someone who had long stopped hoping for ease. She had been waiting for this delivery.

“Finally,” she murmured, motioning for her assistants to start unloading. “We were running low. This will keep us going for a while.”

Orrin barely had time to nod before Dmytro Koval, the de facto leader of the base, strode toward him with the gait of a tall bear. His face seemed to have been carved out by a dulled blade, hardened by years of survival. A scar barred his mouth, pulling slightly at the corner when he spoke, giving the impression of a permanent sneer.

“Did you get it?” Koval asked, voice low.

Orrin reached into his kaki jacket and pulled out a sealed letter, along with a small package.

Koval took both, his expression unreadable. “Anything on the road?”

Orrin exhaled and adjusted his stance. “Saw something on the way back. A group, about a dozen, on a hill ten kilometers out. They seemed lost.”

“Armed?” asked Koval with a frown.

“Can’t say for sure.”

Dr. Markova straightened. “Lost? Unarmed? Out in the open like that, they won’t last long with Sokolov’s gang roaming the land. We have to go take them in.”

Koval grimaced. “Or they’re Sokolov’s spies. Trying to infiltrate us and find a weakness in our defenses. You know how it works.”

Before Koval could argue, a new voice cut in. “Or they could just be people.”

Solara Ortega had stepped into the conversation, brushing dirt from her overalls. A woman of lean strength, with the tan of someone spending long hours outside. Her sharp amber eyes carried the weight of someone who had survived too much but refused to be hardened by it. Orrin shoved down a mix of joy and ache at her sight. Her voice was calm but firm. “We can’t always assume the worst. We need more hands and we don’t leave people to die if we can help it. And in case you forgot, Koval, you don’t make all the decisions around here. I say we send a team to assess them.”

Koval narrowed his eyes, but he held his tongue. There was tension between them, but the council wasn’t a dictatorship.

“Fine,” Koval said after a moment, his jaw tense. “A team of two. They scout first. No direct contact until we’re sure. Orrin, you one of them take whoever wants to accompany you, but not one of my men. We need to maintain tight security.”

Dr. Markova sighed with relief when the man left. “If he wasn’t good at what he does, I would gladly kick him out of our camp.”

Solara, her face framed by strands of dark hair, shot a glance at Orrin. “I’m coming with you.”

This time, Orrin couldn’t repress a longing for a time before everything fell apart, when she had been his wife. The collapse had torn them apart in an instant, and by the time he found her again, years later, she had built a new life within the base in Ukraine. She had a husband now, one of the scientists managing the radio equipment, and two children. Orrin kept his expression neutral, but the weight of time pressed heavy on him.

“Then let’s get on the move. They might not stay there long.”

February 8, 2025 at 7:22 pm #7776In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

Epilogue & Prologue

Paris, November 2029 – The Fifth Note Resounds

Tabitha sat by the window at the Sarah Bernhardt Café, letting the murmur of conversations and the occasional purring of the espresso machine settle around her. It was one of the few cafés left in the city where time still moved at a human pace. She stirred her cup absentmindedly. Paris was still Paris, but the world outside had changed in ways her mother’s generation still struggled to grasp.

It wasn’t just the ever-presence of automation and AI making themselves known in subtle ways—screens adjusting to glances, the quiet surveillance woven into everyday life. It wasn’t just the climate shifts, the aircon turned to cold in the midst of November, the summers unpredictable, the air thick with contradictions of progress and collapse of civilization across the Atlantic.

The certainty of impermanence was what defined her generation. BANI world they used to say—Brittle, Anxious, Nonlinear, Incomprehensible. A cold fact: impossible to grasp and impossible to fight. Unlike her mother and her friends, who had spent their lives tethered to a world that no longer existed, she had never known certainty. She was born in the flux.

And yet, this café remained. One of the last to resist full automation, where a human still brought you coffee, where the brass bell above the door still rang, where things still unfolded at a human pace.

The bell above the door rang—the fifth note, as her mother had called it once.

She had never been here before, not in any way that mattered. Yet, she had heard the story. The unlikely reunion five years ago. The night that moved new projects in motion for her mother and her friends.

Tabitha’s fingers traced the worn edges of the notebook in front of her—Lucien’s, then Amei’s, then Darius’s. Pieces of a life written by many hands.

“Some things don’t work the first time. But sometimes, in the ruins of what failed, something else sprouts and takes root.”

And that was what had happened.

The shared housing project they had once dreamed of hadn’t survived—not in its original form. But through their rekindled bond, they had started something else.

True Stories of How It Was.

It had begun as a quiet defiance—a way to preserve real, human stories in an age of synthetic, permanent ephemerality and ephemeral impermanence, constantly changing memory. They were living in a world where AI’s fabricated histories had overwhelmed all the channels of information, where the past was constantly rewritten, altered, repackaged. Authenticity had become a rare currency.

As she graduated in anthropology few years back, she’d wondered about the validity of history —it was, after all, a construct. The same could be said for literature, art, even science. All of them constructs of the human mind, tenuous grasp of the infinite truth, but once, they used to evolve at such a slow pace that they felt solid, reliable. Ultimately their group was not looking for ultimate truth, that would be arrogant and probably ignorant. Authenticity was what they were looking for. And with it, connections, love, genuineness —unquantifiables by means of science and yet, true and precious beyond measure.

Lucien had first suggested it, tracing the idea from his own frustrations—the way art had become a loop of generated iterations, the human touch increasingly erased. He was in a better place since Matteo had helped him settle his score with Renard and, free of influence, he had found confidence in developing of his own art.

Amei —her mother—, had changed in a way Tabitha couldn’t quite define. Her restlessness had quieted, not through settling down but through accepting impermanence as something other than loss. She had started writing again—not as a career, not to publish, but to preserve stories that had no place in a digitized world. Her quiet strength had always been in preserving connections, and she knew they had to move quickly before real history faded beneath layers of fabricated recollections.

Darius, once skeptical, saw its weight—he had spent years avoiding roots, only to realize that stories were the only thing that made places matter. He was somewhere in Morocco now, leading a sustainable design project, bridging cultures rather than simply passing through them.

Elara had left science. Or at least, science as she had known it. The calculations, the certainty, the constraints of academia, with no escape from the automated “enhanced” digital helpers. Her obsession and curiosities had found attract in something more human, more chaotic. She had thrown herself into reviving old knowledge, forgotten architectures, regenerative landscapes.

And Matteo—Matteo had grounded it.

The notebook read: Matteo wasn’t a ghost from our past. He was the missing note, the one we didn’t know we needed. And because of him, we stopped looking backward. We started building something else.

For so long, Matteo had been a ghost of sorts, by his own account, lingering at the edges of their story, the missing note in their unfinished chord. But now, he was fully part of it. His mother had passed, her past history unraveling in ways he had never expected, branching new connections even now. And though he had lost something in that, he had also found something else. Juliette. Or maybe not. The story wasn’t finished.

Tabitha turned the page.

“We were not historians, not preservationists, not even archivists. But we have lived. And as it turned out, that was enough.”

They had begun collecting stories through their networks—not legends, not myths, but true accounts of how it was, from people who still remembered.

A grandfather’s voice recording of a train ride to a city that no longer exists.

Handwritten recipes annotated by generations of hands, each adding something new.

A letter from a protest in 2027, detailing a movement that the history books had since erased.

An old woman’s story of her first love, spoken in a dialect that AI could not translate properly.It had grown in ways they hadn’t expected. People began sending them recordings, letters, transcripts, photos —handwritten scraps of fading ink. Some were anonymous, others carefully curated with full names and details, like makeshift ramparts against the tide of time.

At first, few had noticed. It was never the goal to make it worlwide movement. But little by little, strange things happened, and more began to listen.

There was something undeniably powerful about genuine human memory when it was raw and unfiltered, when it carried unpolished, raw weight of experience, untouched by apologetic watered down adornments and out-of-place generative hallucinations.

Now, there were exhibitions, readings, archives—entire underground movements dedicated to preserving pre-synthetic history. Their project had become something rare, valuable, almost sacred.

And yet, here in the café, none of that felt urgent.

Tabitha looked up as the server approached. Not Matteo, but someone new.

“Another espresso?”

She hesitated, then nodded. “Yes. And a glass of water, please.”

She glanced at the counter, where Matteo was leaning, speaking to someone, laughing. He had changed, too. No longer just an observer, no longer just the quiet figure who knew too much. Now, he belonged here.

A bell rang softly as the door swung open again.

Tabitha smiled to herself. The fifth note always sounded, in the end.

She turned back to the notebook, the city moving around her, the story still unfolding in more directions than one.

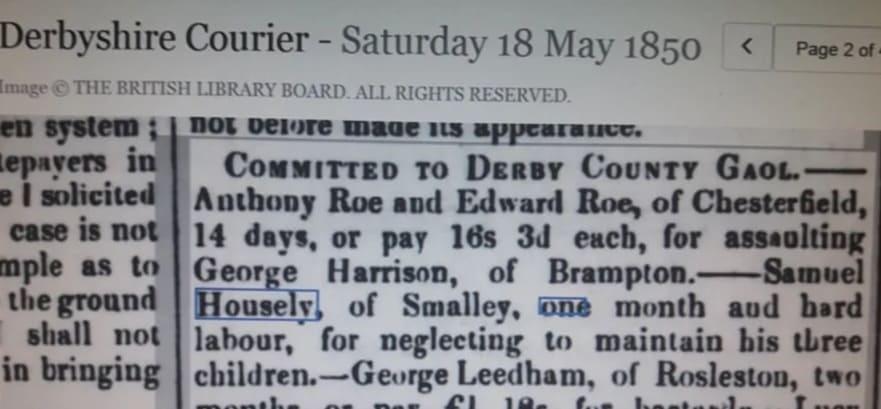

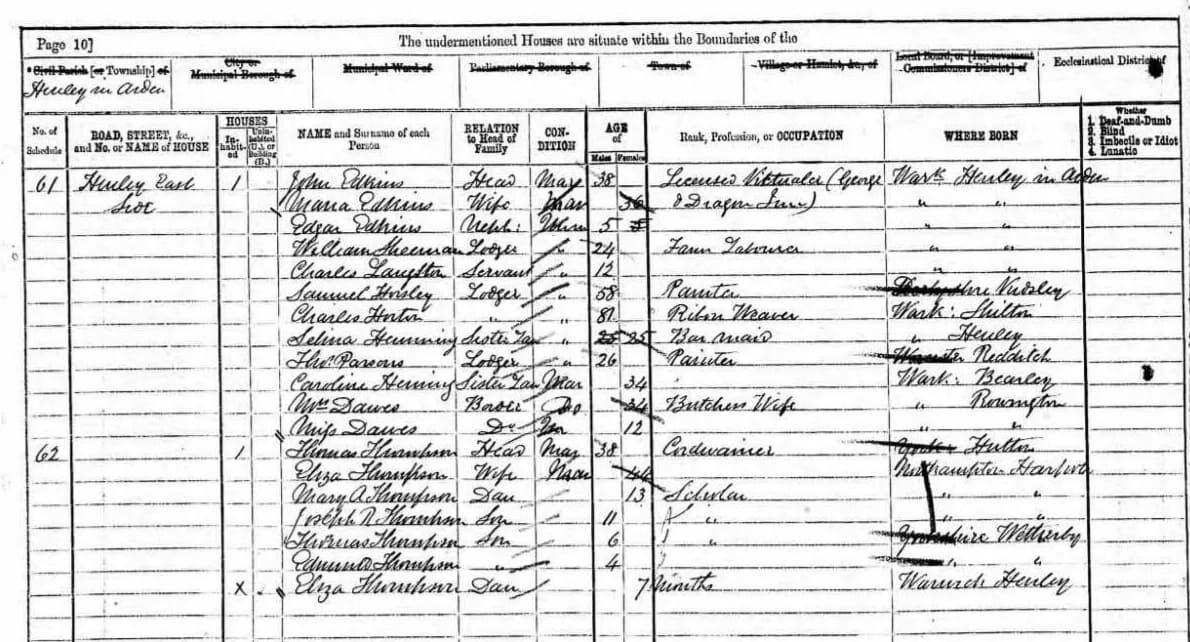

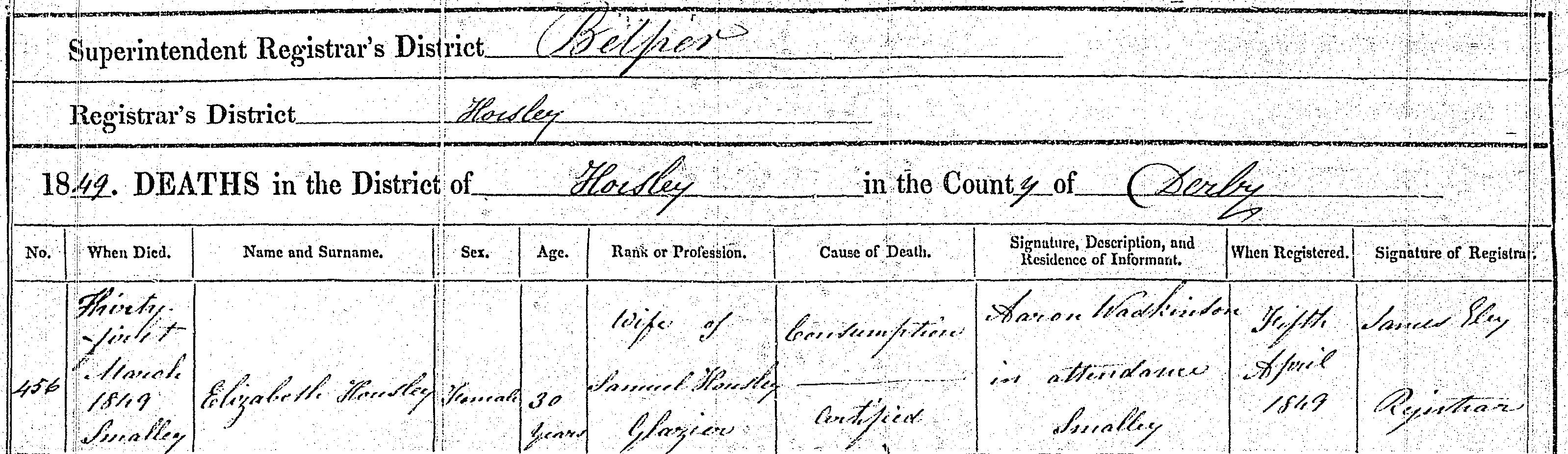

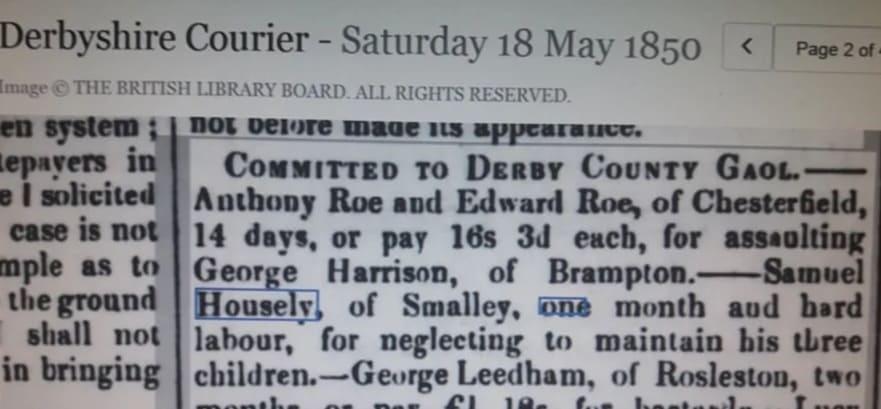

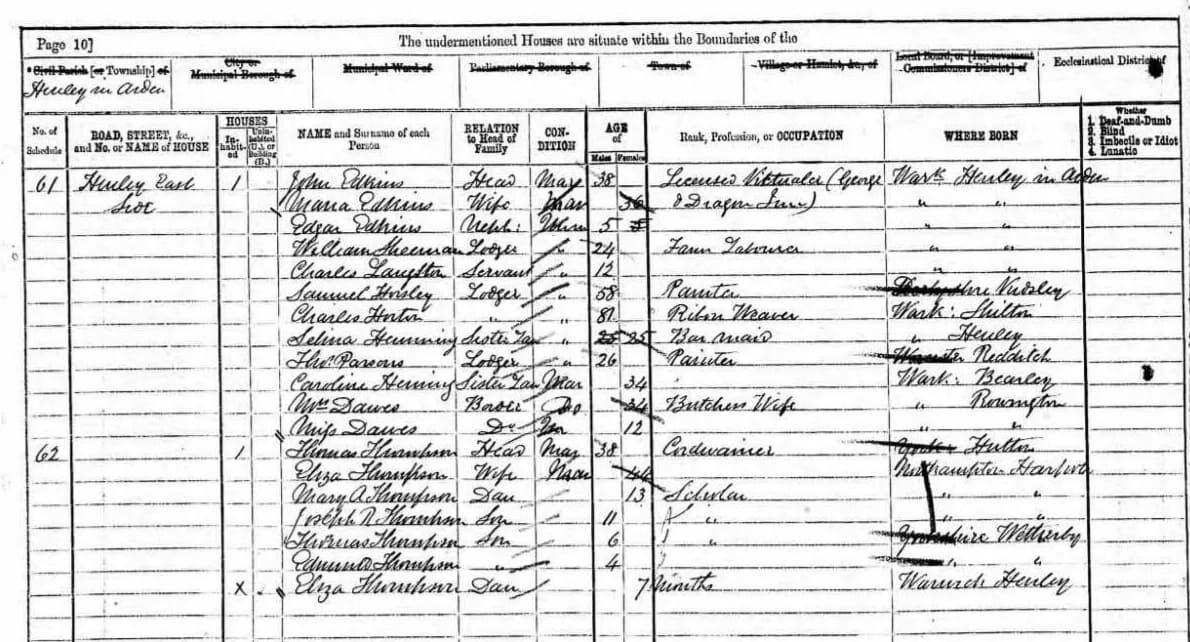

August 16, 2024 at 2:56 pm #7544In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Youlgreave

The Frost Family and The Big Snow

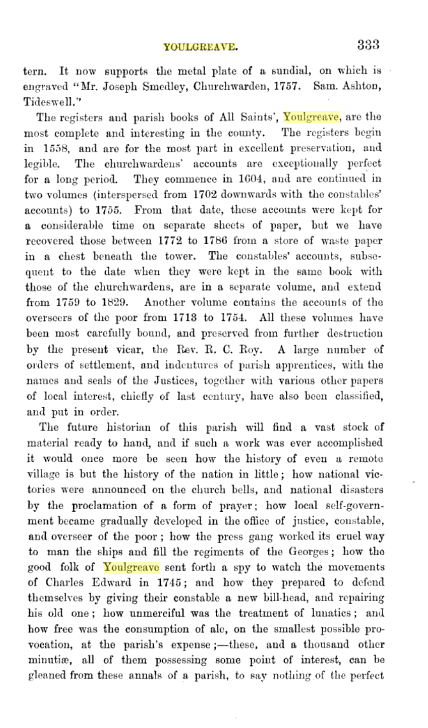

The Youlgreave parish registers are said to be the most complete and interesting in the country. Starting in 1558, they are still largely intact today.

“The future historian of this parish will find a vast stock of material ready to hand, and if such a work was ever accomplished it would once more be seen how the history of even a remote village is but the history of the nation in little; how national victories were announced on the church bells, and national disasters by the proclamation of a form of prayer…”

J. Charles Cox, Notes on the Churches of Derbyshire, 1877.

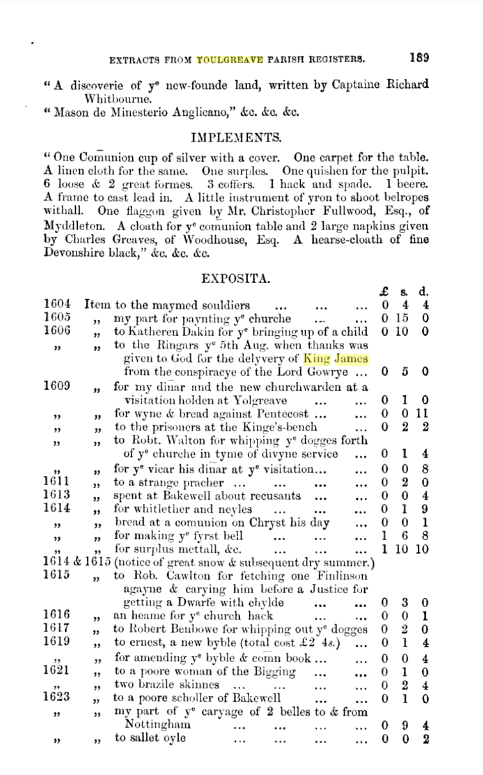

Although the Youlgreave parish registers are available online on microfilm, just the baptisms, marriages and burials are provided on the genealogy websites. However, I found some excerpts from the churchwardens accounts in a couple of old books, The Reliquary 1864, and Notes on Derbyshire Churches 1877.

Hannah Keeling, my 4x great grandmother, was born in Youlgreave, Derbyshire, in 1767. In 1791 she married Edward Lees of Hartington, Derbyshire, a village seven and a half miles south west of Youlgreave. Edward and Hannah’s daughter Sarah Lees, born in Hartington in 1808, married Francis Featherstone in 1835. The Featherstone’s were farmers. Their daughter Emma Featherstone married John Marshall from Elton. Elton is just three miles from Youlgreave, and there are a great many Marshall’s in the Youlgreave parish registers, some no doubt distantly related to ours.

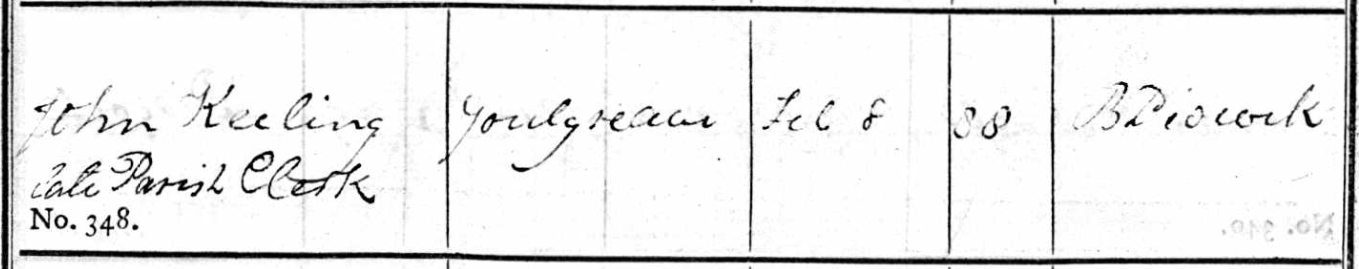

Hannah Keeling’s parents were John Keeling 1734-1823, and Ellen Frost 1739-1805, both of Youlgreave.

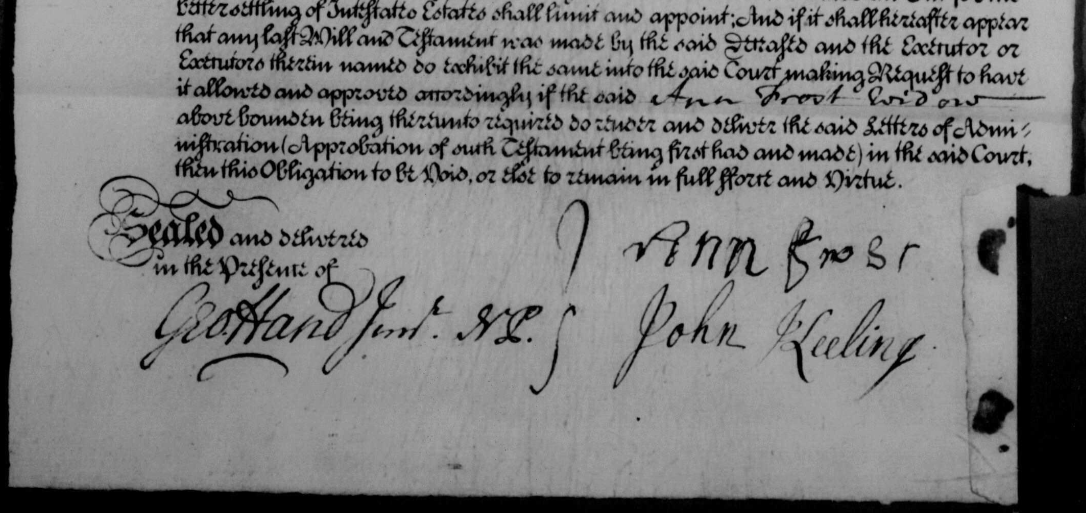

On the burial entry in the parish registers in Youlgreave in 1823, John Keeling was 88 years old when he died, and was the “late parish clerk”, indicating that my 5x great grandfather played a part in compiling the “best parish registers in the country”. In 1762 John’s father in law John Frost died intestate, and John Keeling, cordwainer, co signed the documents with his mother in law Ann. John Keeling was a shoe maker and a parish clerk.

John Keeling’s father was Thomas Keeling, baptised on the 9th of March 1709 in Youlgreave and his parents were John Keeling and Ann Ashmore. John and Ann were married on the 6th April 1708. Some of the transcriptions have Thomas baptised in March 1708, which would be a month before his parents married. However, this was before the Julian calendar was replaced by the Gregorian calendar, and prior to 1752 the new year started on the 25th of March, therefore the 9th of March 1708 was eleven months after the 6th April 1708.

Thomas Keeling married Dorothy, which we know from the baptism of John Keeling in 1734, but I have not been able to find their marriage recorded. Until I can find my 6x great grandmother Dorothy’s maiden name, I am unable to trace her family further back.

Unfortunately I haven’t found a baptism for Thomas’s father John Keeling, despite that there are Keelings in the Youlgrave registers in the early 1600s, possibly it is one of the few illegible entries in these registers.

The Frosts of Youlgreave

Ellen Frost’s father was John Frost, born in Youlgreave in 1707. John married Ann Staley of Elton in 1733 in Youlgreave.

(Note that this part of the family tree is the Marshall side, but we also have Staley’s in Elton on the Warren side. Our branch of the Elton Staley’s moved to Stapenhill in the mid 1700s. Robert Staley, born 1711 in Elton, died in Stapenhill in 1795. There are many Staley’s in the Youlgreave parish registers, going back to the late 1500s.)

John Frost (my 6x great grandfather), miner, died intestate in 1762 in Youlgreave. Miner in this case no doubt means a lead miner, mining his own land (as John Marshall’s father John was in Elton. On the 1851 census John Marshall senior was mining 9 acres). Ann Frost, as the widow and relict of the said deceased John Frost, claimed the right of administration of his estate. Ann Frost (nee Staley) signed her own name, somewhat unusual for a woman to be able to write in 1762, as well as her son in law John Keeling.

John’s parents were David Frost and Ann. David was baptised in 1665 in Youlgreave. Once again, I have not found a marriage for David and Ann so I am unable to continue further back with her family. Marriages were often held in the parish of the bride, and perhaps those neighbouring parish records from the 1600s haven’t survived.

David’s parents were William Frost and Ellen (or Ellin, or Helen, depending on how the parish clerk chose to spell it). Once again, their marriage hasn’t been found, but was probably in a neighbouring parish.

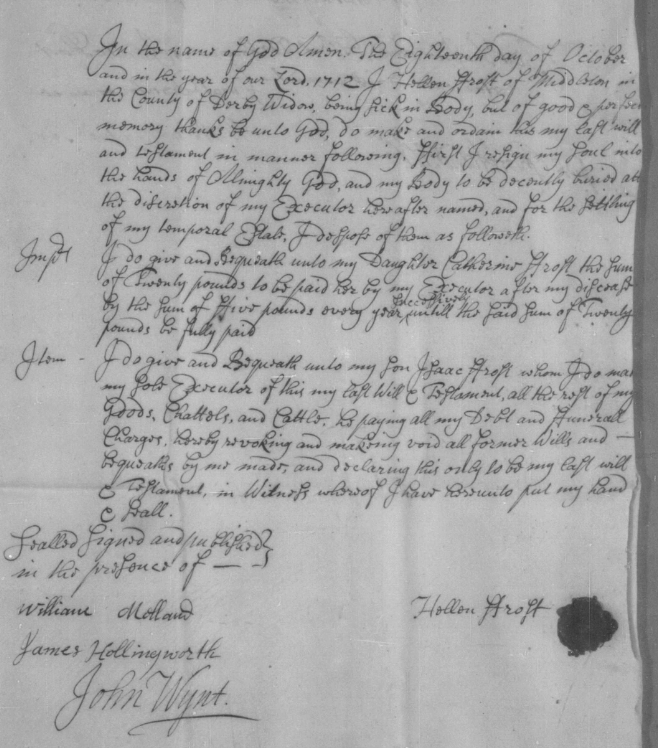

William Frost’s wife Ellen, my 8x great grandmother, died in Youlgreave in 1713. In her will she left her daughter Catherine £20. Catherine was born in 1665 and was apparently unmarried at the age of 48 in 1713. She named her son Isaac Frost (born in 1662) executor, and left him the remainder of her “goods, chattels and cattle”.

William Frost was baptised in Youlgreave in 1627, his parents were William Frost and Anne.

William Frost senior, husbandman, was probably born circa 1600, and died intestate in 1648 in Middleton, Youlgreave. His widow Anna was named in the document. On the compilation of the inventory of his goods, Thomas Garratt, Will Melland and A Kidiard are named.(Husbandman: The old word for a farmer below the rank of yeoman. A husbandman usually held his land by copyhold or leasehold tenure and may be regarded as the ‘average farmer in his locality’. The words ‘yeoman’ and ‘husbandman’ were gradually replaced in the later 18th and 19th centuries by ‘farmer’.)

Unable to find a baptism for William Frost born circa 1600, I read through all the pages of the Youlgreave parish registers from 1558 to 1610. Despite the good condition of these registers, there are a number of illegible entries. There were three Frost families baptising children during this timeframe and one of these is likely to be Willliam’s.

Baptisms:

1581 Eliz Frost, father Michael.

1582 Francis f Michael. (must have died in infancy)

1582 Margaret f William.

1585 Francis f Michael.

1586 John f Nicholas.

1588 Barbara f Michael.

1590 Francis f Nicholas.

1591 Joane f Michael.

1594 John f Michael.

1598 George f Michael.

1600 Fredericke (female!) f William.Marriages in Youlgreave which could be William’s parents:

1579 Michael Frost Eliz Staley

1587 Edward Frost Katherine Hall

1600 Nicholas Frost Katherine Hardy.

1606 John Frost Eliz Hanson.Michael Frost of Youlgreave is mentioned on the Derbyshire Muster Rolls in 1585.

(Muster records: 1522-1649. The militia muster rolls listed all those liable for military service.)

Frideswide:

A burial is recorded in 1584 for Frideswide Frost (female) father Michael. As the father is named, this indicates that Frideswide was a child.

(Frithuswith, commonly Frideswide c. 650 – 19 October 727), was an English princess and abbess. She is credited as the foundress of a monastery later incorporated into Christ Church, Oxford. She was the daughter of a sub-king of a Merica named Dida of Eynsham whose lands occupied western Oxfordshire and the upper reaches of the River Thames.)

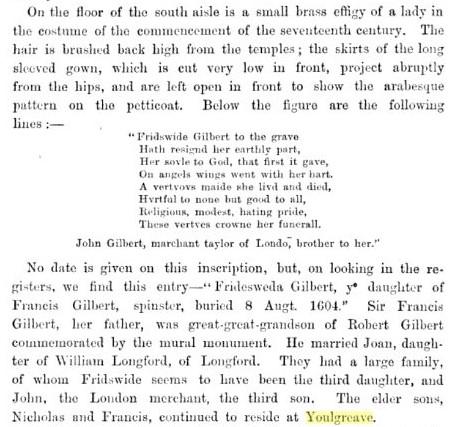

An unusual name, and certainly very different from the usual names of the Frost siblings. As I did not find a baptism for her, I wondered if perhaps she died too soon for a baptism and was given a saints name, in the hope that it would help in the afterlife, given the beliefs of the times. Or perhaps it wasn’t an unusual name at the time in Youlgreave. A Fridesweda Gilbert was buried in Youlgreave in 1604, the spinster daughter of Francis Gilbert. There is a small brass effigy in the church, underneath is written “Frideswide Gilbert to the grave, Hath resigned her earthly part…”

J. Charles Cox, Notes on the Churches of Derbyshire, 1877.

King James

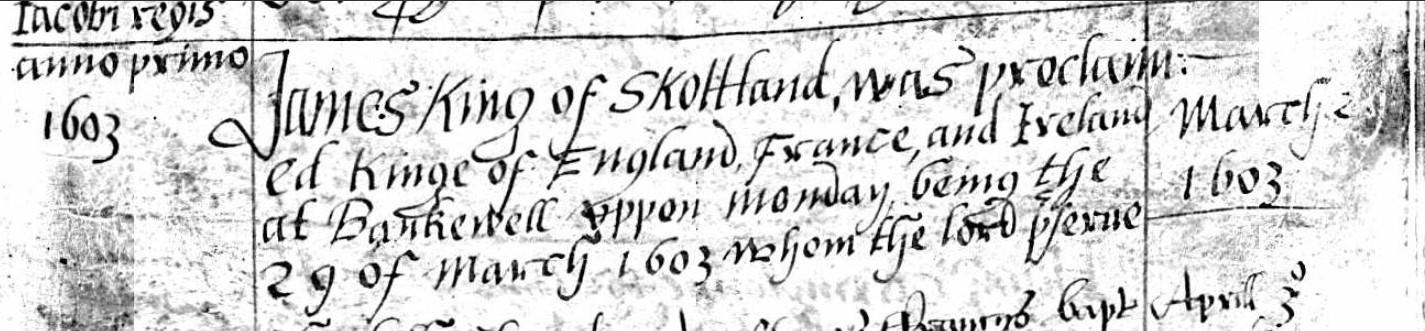

A parish register entry in 1603:

“1603 King James of Skottland was proclaimed kinge of England, France and Ireland at Bakewell upon Monday being the 29th of March 1603.” (March 1603 would be 1604, because of the Julian calendar in use at the time.)

The Big Snow

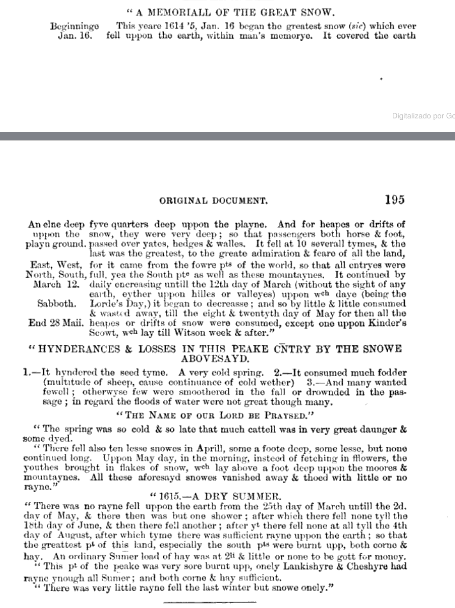

“This year 1614/5 January 16th began the greatest snow whichever fell uppon the earth within man’s memorye. It covered the earth fyve quarters deep uppon the playne. And for heaps or drifts of snow, they were very deep; so that passengers both horse or foot passed over yates, hedges and walles. ….The spring was so cold and so late that much cattel was in very great danger and some died….”

From the Youlgreave parish registers.

Our ancestor William Frost born circa 1600 would have been a teenager during the big snow.

June 19, 2024 at 8:10 am #7503In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

Silas led Jeezel into a secluded lounge, a hidden gem within the ancient cloister that seemed to be frozen in time. The atmosphere was thick with the scent of sandalwood and myrrh, mingling with a musty, earthy fragrance with undertones of aged woods.

Jeezel stopped a moment, in awe at the grand tapestries adorning the walls. They depicted scenes of epic battles between dragons and saints, the vibrant threads weaving tales of heroism and divine intervention. The dragons, captured in mid-roar with scales that seemed to shimmer with a life of their own, contrasted starkly agains the faces of the saints, their halo glowing softly in the dim light. Always the sensitive nose, Jeezel detected hints of incense and aged spices absorbed over centuries by the fabric, with a faint trace of mildew lingering on old stones and the faint sweetness of preserved herbs. She shivered.

Silas invited her to seat on one of the high-backed chairs upholstered in deep burgundy velvet that surrounded a massive oak table, carved with runes and symbols of protection. Jeezel frowned at the oddity to find pagan magic in a convent. As she sat the fabric of her gown brushed agains the plush velvet with a delicate sliding sound, like a faint sigh. The flickering flames of candelabras cast dancing shadows across the room, around which an array of curious relics and artifacts were scattered–an astrolabe here, a crystal ball there, and various objects of mystical significance.

Despite being an aficionado of pageants and grand performances, Jeezel couldn’t say she wasn’t impressed. Silas, ever the pillar of calm and wisdom, took a seat at the table, his fingers tracing the runes carved into the wood.

“Jeezel,” he began, his voice a soothing balm against the room’s charged energy, “I know I can trust you. Before we delve into the heart of these rituals, I must tell you something.”

Man! Here we are, she thought. She tensed on her chair.

“There are some people who would rather see the merger fail. They are doing anything in their power to foster such an outcome. We cannot let them win.”

Jeezel’s face tightened and she struggled to maintain her composure. She tapped with her fingers on the table to distract the head mortician’s attention and help her regain a stoic demeanor. Her mind raced weighing the implications. Malové had said that the Crimson Opus wasn’t just any artifact, it was key to immense power and knowledge, something that could tip the scales in their favour. How she regretted at that moment she had not paid enough attention at the merger meeting. Now, Malové was gone, somewhere, and Jeezel wasn’t even sure the postcard she had sent the coven was real. All she knew was that Malové counted on her to find that relic. And for that, she had to step in what appears to be a nest of vipers. She reminded herself she had survived worse competition in the past and still won her trophies with pride.

“Silas,” she said, her voice measured but with an edge of tension, “this complicates things more than I anticipated. We have enough on our hands ensuring the rituals go smoothly without sabotage.” She paused, taking a deep breath to steady herself. “But we cannot allow these factions to succeed. The merger is crucial for our mutual survival advancement. We’ll need to be vigilant, Silas. Every step we take, every ritual we perform, must be meticulously guarded. And we must identify who these adversaries are, and what they are planning.” She wished Malové would see her in that instant. She craved support from anyone. She looked at Silas, her eyes full of hope he could help. “I have a task from Malové that is of paramount importance,” she started and almost jumped from the chair when her hedgehog amulet almost tased her. A warning. Her mind suddenly found a new clarity. She realized she has been about to tell him about the Crimson Opus. Jeezel noticed the man’s finger was still caressing the runes on the table. Had he been casting a spell on her? She shook her head.

“Those six rituals cannot be compromised. I’ll need your help to ensure that we succeed. We must be prepared to act swiftly and decisively.”

Silas’ hand froze. He nodded. She wasn’t sure there wasn’t some irritation in his voice when he said: “You have my full support, Jeezel. We’ll strengthen our defenses and keep a close watch on any suspicious activities. The stakes are too high for failure.”

Did he mean that he would keep a close eye on her next moves? She’d have to be careful in her search of the Crimson Opus. She realized she needed some help. Malové, you entrusted me with that mission. Then, you’d have to trust me with whom I choose to trust.

April 6, 2024 at 11:14 pm #7419In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

Sleeping like a log through a full night’s rest on the lavender spell wrapped in the rag of the punic tunic worked like a charm. By morning light, Eris had reverted to her normal self again.

How her coven had succeeded in finding the rag was anyone’s guess, but one thing was for certain—Truella’s resourcefulness knew no bounds once she set her mind to a goal. All it took was a location spell, a silencing charm around the area in Libyssa where she wanted to dig, and of course, a trusty trowel. Hundreds of buckets of dirt later, a few sheep’s jawbones and voilà, the rag. Made of asbestos, impervious to fire, and slower to decay than a sloth on a Monday morning, it was nothing short of a miracle it had survived so long underground, and that they found it in such a short time.

Eris rubbed her neck still pained from the weight of bearing that enormous elephantine head.

When pressed by the others—Frigella, Jeezel, and the ever-curious Truella—she could hardly recall what led her to attempt the risky memory spell.

Echo buzzed in with an electric hum, the sprite all too eager to clear the air.

“The memory spell,” Echo interjected, “a dubious cocktail of spirits of remembrance and forgetfulness, was cast not out of folly but necessity. Eris, rooted in her family’s arborestry quests, understood the weight of knowledge passed down through generations. Each leaf and branch in the family tree held stories, secrets, and sacrifices that were both a treasure and a burden.”

Echo smirked as he continued, pointing out the responsibility of the other entity’s guidance. “Elias’s advice had egged her on, resonating with Eris’ desires, and finally enticing her not lament the multitude of options but rather delights in the exploration without the burden of obligation —end of quotation.”

“And was it worth it?” Truella asked impatiently, her curiosity piqued a little nonetheless. She’d always wished she had more memory, but not at the cost of an elephant head.

“Imagine the vast expanse of memories like a grand library, each book brimming with the essence of a lineage. ” Eris said. “To wander these halls without purpose could lead to an overwhelming deluge of ancestral whispers.” She paused. “So, not sure it was entirely worth it. I feel more confused than ever.”

Echo chimed in again “The memory spell was conjured to be a compass, a guide through the storied corridors of her heritage. But, as with all magic, the intentions must be precise, the heart true, and the mind clear. A miscalculation, a stray thought, a moment’s doubt — and the spell turned upon itself, leaving Eris with the visage of an elephant, noble and wise. The elephant head, while unintended, may have been a subconscious manifestation of her quest for familial knowledge. Perhaps the memory spell, in its misfiring, sought to grant Eris the attributes necessary to continue her arborestry quests with the fortitude and insight of the elephant.”

“But why Madrid of all places?” Jeezel asked mostly out of reflex than complete interest; she had been pulled into the rescue and had missed the quarter finals of the Witch Drag Race she was now catching up on x2 speed replay on her phone.

Echo surmised “Madrid, that sun-drenched city of art and history, may have been a waypoint in her journey — a place where the paths of the past intersect with the pulse of the present. It is in such crossroads that one may find hidden keys to unlock the tales etched in one’s bloodline.”

“In other words, you have no idea?” Frigella asked Eris directly, cutting through the little flickering sprite’s mystical chatter.

“I guess it’s something as Wisp said. I must have connected to some bloodlines. But one thing is sure, all was fine when I was in Finland, Thorsten was as much a steadying presence as one would need. But then I got pulled into the vortex, and all bets were off.”

“At least he had the presence of mind to call me.” Truella said smuggly.

“The red cars may have started to get my elephant head mad… I can’t recall all of it, but I’m glad you found me in time.” Eris admitted.

“Don’t mention it poppet, we all screwed up one spell or two in our time.” Frigella said, offering unusual comfort.

“Let’s hope at least you’ll come up with brilliant ideas from that ordeal next week.” said Jeezel.

“What do you mean?” Truella looked at her suspiciously

“The strategic meeting that Malové has called for? In the Adare Manor resort?” Frigella reminded her, rolling her eyes softly.

“Jeez, Jeezel…” was all Truella could come up with. “another one of these boring meetings to boost our sales channels and come up with new incense models?” Truella groaned, already wishing it were over.

“That’s right love. Better be on your A-game for this.” Jeezel said, straightening her wig with a sly grin.

September 5, 2023 at 1:35 pm #7276In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Wood Screw Manufacturers

The Fishers of West Bromwich.

My great grandmother, Nellie Fisher, was born in 1877 in Wolverhampton. Her father William 1834-1916 was a whitesmith, and his father William 1792-1873 was a whitesmith and master screw maker. William’s father was Abel Fisher, wood screw maker, victualler, and according to his 1849 will, a “gentleman”.

Nellie Fisher 1877-1956 :

Abel Fisher was born in 1769 according to his burial document (age 81 in 1849) and on the 1841 census. Abel was a wood screw manufacturer in Wolverhampton.

As no baptism record can be found for Abel Fisher, I read every Fisher will I could find in a 30 year period hoping to find his fathers will. I found three other Fishers who were wood screw manufacurers in neighbouring West Bromwich, which led me to assume that Abel was born in West Bromwich and related to these other Fishers.

The wood screw making industry was a relatively new thing when Abel was born.

“The screw was used in furniture but did not become a common woodworking fastener until efficient machine tools were developed near the end of the 18th century. The earliest record of lathe made wood screws dates to an English patent of 1760. The development of wood screws progressed from a small cottage industry in the late 18th century to a highly mechanized industry by the mid-19th century. This rapid transformation is marked by several technical innovations that help identify the time that a screw was produced. The earliest, handmade wood screws were made from hand-forged blanks. These screws were originally produced in homes and shops in and around the manufacturing centers of 18th century Europe. Individuals, families or small groups participated in the production of screw blanks and the cutting of the threads. These small operations produced screws individually, using a series of files, chisels and cutting tools to form the threads and slot the head. Screws produced by this technique can vary significantly in their shape and the thread pitch. They are most easily identified by the profusion of file marks (in many directions) over the surface. The first record regarding the industrial manufacture of wood screws is an English patent registered to Job and William Wyatt of Staffordshire in 1760.”

Wood Screw Makers of West Bromwich:

Edward Fisher, wood screw maker of West Bromwich, died in 1796. He mentions his wife Pheney and two underage sons in his will. Edward (whose baptism has not been found) married Pheney Mallin on 13 April 1793. Pheney was 17 years old, born in 1776. Her parents were Isaac Mallin and Sarah Firme, who were married in West Bromwich in 1768.

Edward and Pheney’s son Edward was born on 21 October 1793, and their son Isaac in 1795. The executors of Edwards 1796 will are Daniel Fisher the Younger, Isaac Mallin, and Joseph Fisher.There is a marriage allegations and bonds document in 1774 for an Edward Fisher, bachelor and wood screw maker of West Bromwich, aged 25 years and upwards, and Mary Mallin of the same age, father Isaac Mallin. Isaac Mallin and Sarah didn’t marry until 1768 and Mary Mallin would have been born circa 1749. Perhaps Isaac Mallin’s father was the father of Mary Mallin. It’s possible that Edward Fisher was born in 1749 and first married Mary Mallin, and then later Pheney, but it’s also possible that the Edward Fisher who married Mary Mallin in 1774 was Edward Fishers uncle, Daniel’s brother. (I do not know if Daniel had a brother Edward, as I haven’t found a baptism, or marriage, for Daniel Fisher the elder.)

There are two difficulties with finding the records for these West Bromwich families. One is that the West Bromwich registers are not available online in their entirety, and are held by the Sandwell Archives, and even so, they are incomplete. Not only that, the Fishers were non conformist. There is no surviving register prior to 1787. The chapel opened in 1788, and any registers that existed before this date, taken in a meeting houses for example, appear not to have survived.

Daniel Fisher the younger died intestate in 1818. Daniel was a wood screw maker of West Bromwich. He was born in 1751 according to his age stated as 67 on his death in 1818. Daniel’s wife Mary, and his son William Fisher, also a wood screw maker, claimed the estate.

Daniel Fisher the elder was a farmer of West Bromwich, who died in 1806. He was 81 when he died, which makes a birth date of 1725, although no baptism has been found. No marriage has been found either, but he was probably married not earlier than 1746.

Daniel’s sons Daniel and Joseph were the main inheritors, and he also mentions his other children and grandchildren namely William Fisher, Thomas Fisher, Hannah wife of William Hadley, two grandchildren Edward and Isaac Fisher sons of Edward Fisher his son deceased. Daniel the elder presumably refers to the wood screw manufacturing when he says “to my son Daniel Fisher the good will and advantage which may arise from his manufacture or trade now carried on by me.” Daniel does not mention a son called Abel unfortunately, but neither does he mention his other grandchildren. Abel may be Daniel’s son, or he may be a nephew.

The Staffordshire Record Office holds the documents of a Testamentary Case in 1817. The principal people are Isaac Fisher, a legatee; Daniel and Joseph Fisher, executors. Principal place, West Bromwich, and deceased person, Daniel Fisher the elder, farmer.

William and Sarah Fisher baptised six children in the Mares Green Non Conformist registers in West Bromwich between 1786 and 1798. William Fisher and Sarah Birch were married in West Bromwich in 1777. This William was probably born circa 1753 and was probably the son of Daniel Fisher the elder, farmer.

Daniel Fisher the younger and his wife Mary had a son William, as mentioned in the intestacy papers, although I have not found a baptism for William. I did find a baptism for another son, Eutychus Fisher in 1792.

In White’s Directory of Staffordshire in 1834, there are three Fishers who are wood screw makers in Wolverhampton: Eutychus Fisher, Oxford Street; Stephen Fisher, Bloomsbury; and William Fisher, Oxford Street.

Abel’s son William Fisher 1792-1873 was living on Oxford Street on the 1841 census, with his wife Mary and their son William Fisher 1834-1916.

In The European Magazine, and London Review of 1820 (Volume 77 – Page 564) under List of Patents, W Fisher and H Fisher of West Bromwich, wood screw manufacturers, are listed. Also in 1820 in the Birmingham Chronicle, the partnership of William and Hannah Fisher, wood screw manufacturers of West Bromwich, was dissolved.

In the Staffordshire General & Commercial Directory 1818, by W. Parson, three Fisher’s are listed as wood screw makers. Abel Fisher victualler and wood screw maker, Red Lion, Walsal Road; Stephen Fisher wood screw maker, Buggans Lane; and Daniel Fisher wood screw manufacturer, Brickiln Lane.

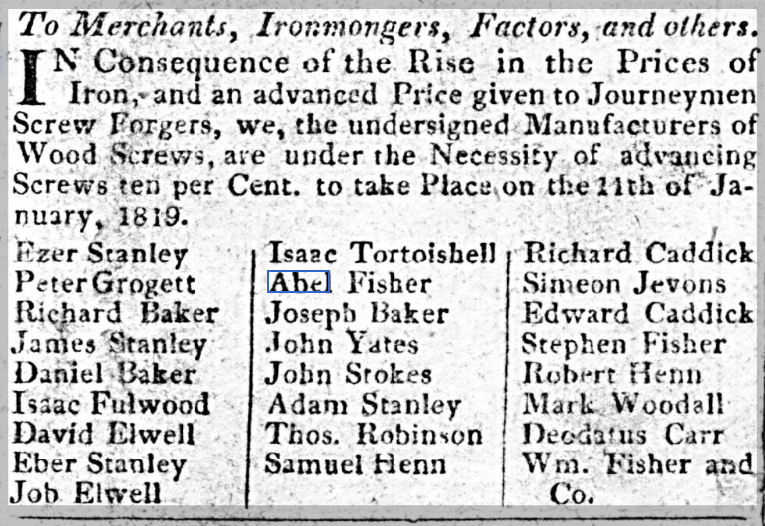

In Aris’s Birmingham Gazette on 4 January 1819 Abel Fisher is listed with 23 other wood screw manufacturers (Stephen Fisher and William Fisher included) stating that “In consequence of the rise in prices of iron and the advanced price given to journeymen screw forgers, we the undersigned manufacturers of wood screws are under the necessity of advancing screws 10 percent, to take place on the 11th january 1819.”

In Abel Fisher’s 1849 will, he names his three sons Abel Fisher 1796-1869, Paul Fisher 1811-1900 and John Southall Fisher 1801-1871 as the executors. He also mentions his other three sons, William Fisher 1792-1873, Benjamin Fisher 1798-1870, and Joseph Fisher 1803-1876, and daughters Sarah Fisher 1794- wife of William Colbourne, Mary Fisher 1804- wife of Thomas Pearce, and Susannah (Hannah) Fisher 1813- wife of Parkes. His son Silas Fisher 1809-1837 wasn’t mentioned as he died before Abel, nor his sons John Fisher 1799-1800, and Edward Southall Fisher 1806-1843. Abel’s wife Susannah Southall born in 1771 died in 1824. They were married in 1791.

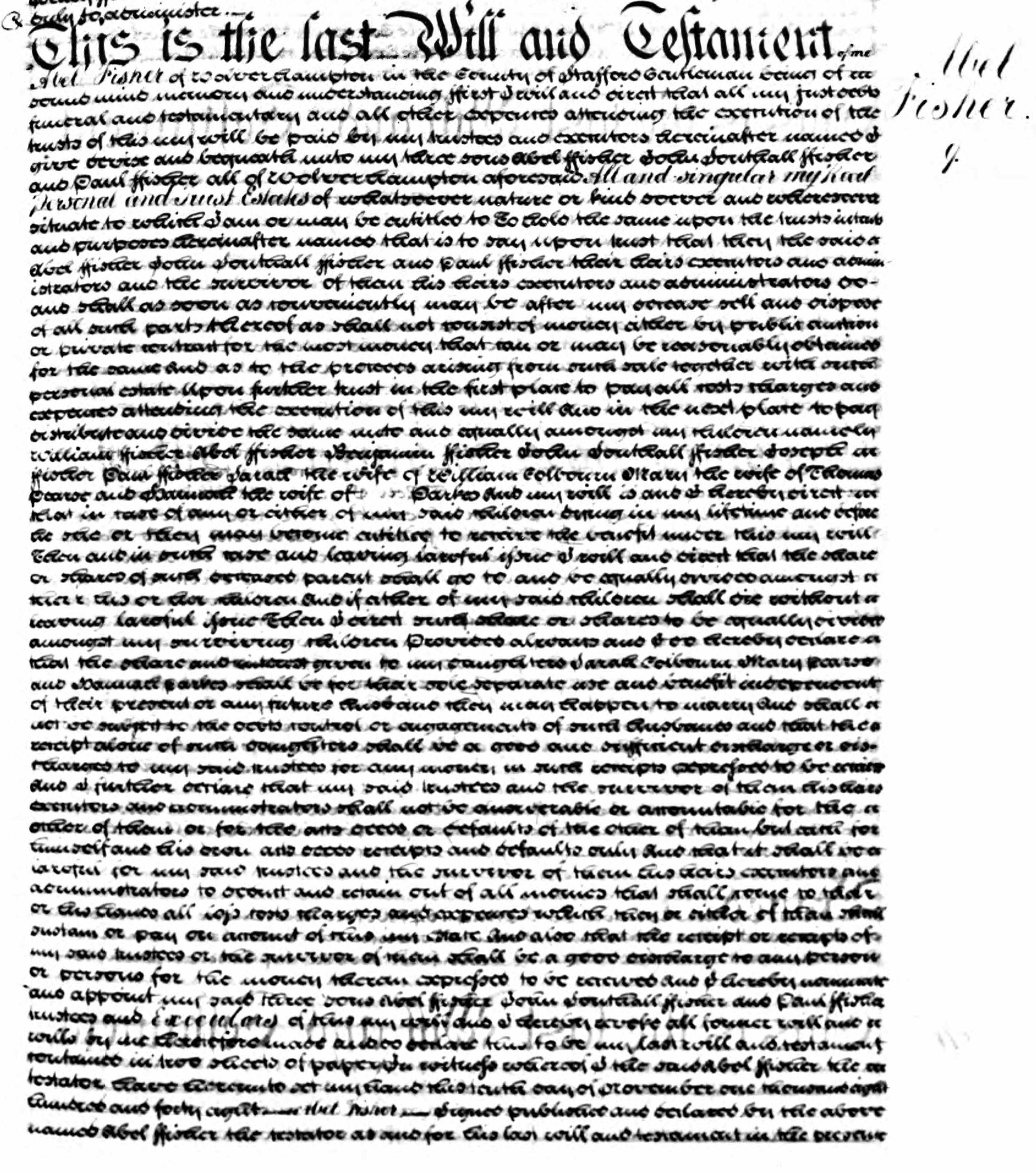

The 1849 will of Abel Fisher:

December 6, 2022 at 2:17 pm #6350

December 6, 2022 at 2:17 pm #6350In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Transportation

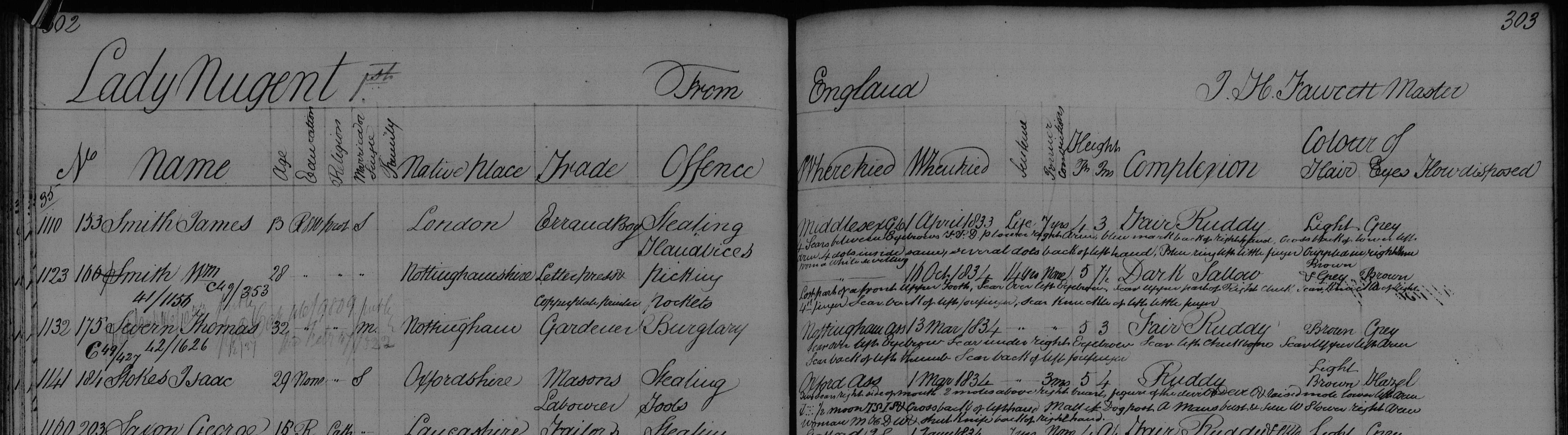

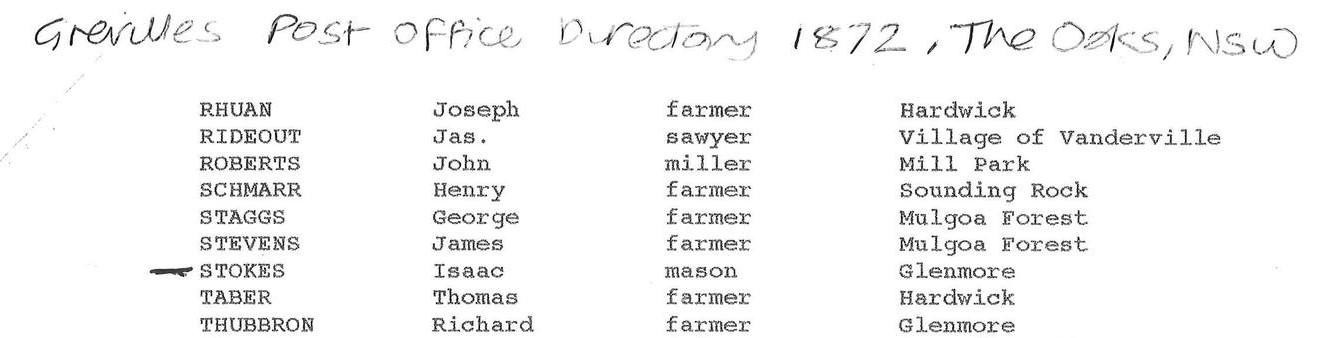

Isaac Stokes 1804-1877

Isaac was born in Churchill, Oxfordshire in 1804, and was the youngest brother of my 4X great grandfather Thomas Stokes. The Stokes family were stone masons for generations in Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire, and Isaac’s occupation was a mason’s labourer in 1834 when he was sentenced at the Lent Assizes in Oxford to fourteen years transportation for stealing tools.

Churchill where the Stokes stonemasons came from: on 31 July 1684 a fire destroyed 20 houses and many other buildings, and killed four people. The village was rebuilt higher up the hill, with stone houses instead of the old timber-framed and thatched cottages. The fire was apparently caused by a baker who, to avoid chimney tax, had knocked through the wall from her oven to her neighbour’s chimney.

Isaac stole a pick axe, the value of 2 shillings and the property of Thomas Joyner of Churchill; a kibbeaux and a trowel value 3 shillings the property of Thomas Symms; a hammer and axe value 5 shillings, property of John Keen of Sarsden.

(The word kibbeaux seems to only exists in relation to Isaac Stokes sentence and whoever was the first to write it was perhaps being creative with the spelling of a kibbo, a miners or a metal bucket. This spelling is repeated in the criminal reports and the newspaper articles about Isaac, but nowhere else).

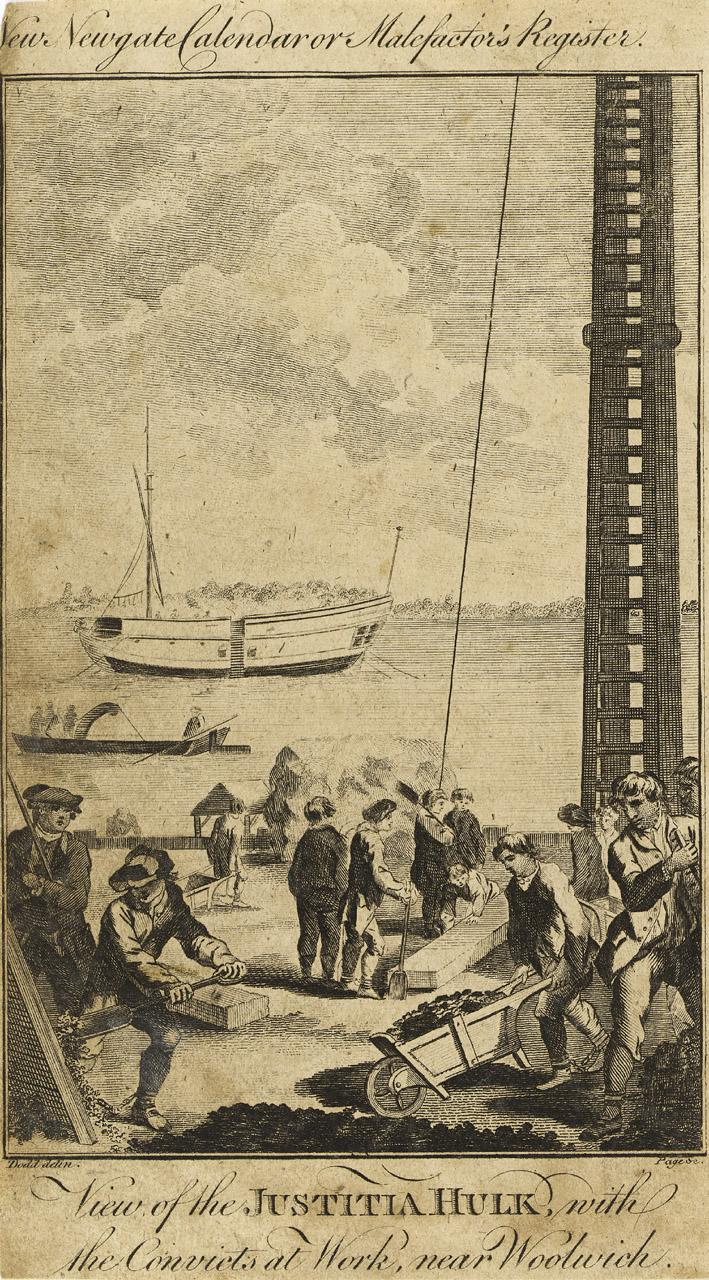

In March 1834 the Removal of Convicts was announced in the Oxford University and City Herald: Isaac Stokes and several other prisoners were removed from the Oxford county gaol to the Justitia hulk at Woolwich “persuant to their sentences of transportation at our Lent Assizes”.

via digitalpanopticon:

Hulks were decommissioned (and often unseaworthy) ships that were moored in rivers and estuaries and refitted to become floating prisons. The outbreak of war in America in 1775 meant that it was no longer possible to transport British convicts there. Transportation as a form of punishment had started in the late seventeenth century, and following the Transportation Act of 1718, some 44,000 British convicts were sent to the American colonies. The end of this punishment presented a major problem for the authorities in London, since in the decade before 1775, two-thirds of convicts at the Old Bailey received a sentence of transportation – on average 283 convicts a year. As a result, London’s prisons quickly filled to overflowing with convicted prisoners who were sentenced to transportation but had no place to go.

To increase London’s prison capacity, in 1776 Parliament passed the “Hulks Act” (16 Geo III, c.43). Although overseen by local justices of the peace, the hulks were to be directly managed and maintained by private contractors. The first contract to run a hulk was awarded to Duncan Campbell, a former transportation contractor. In August 1776, the Justicia, a former transportation ship moored in the River Thames, became the first prison hulk. This ship soon became full and Campbell quickly introduced a number of other hulks in London; by 1778 the fleet of hulks on the Thames held 510 prisoners.

Demand was so great that new hulks were introduced across the country. There were hulks located at Deptford, Chatham, Woolwich, Gosport, Plymouth, Portsmouth, Sheerness and Cork.The Justitia via rmg collections:

Convicts perform hard labour at the Woolwich Warren. The hulk on the river is the ‘Justitia’. Prisoners were kept on board such ships for months awaiting deportation to Australia. The ‘Justitia’ was a 260 ton prison hulk that had been originally moored in the Thames when the American War of Independence put a stop to the transportation of criminals to the former colonies. The ‘Justitia’ belonged to the shipowner Duncan Campbell, who was the Government contractor who organized the prison-hulk system at that time. Campbell was subsequently involved in the shipping of convicts to the penal colony at Botany Bay (in fact Port Jackson, later Sydney, just to the north) in New South Wales, the ‘first fleet’ going out in 1788.

While searching for records for Isaac Stokes I discovered that another Isaac Stokes was transported to New South Wales in 1835 as well. The other one was a butcher born in 1809, sentenced in London for seven years, and he sailed on the Mary Ann. Our Isaac Stokes sailed on the Lady Nugent, arriving in NSW in April 1835, having set sail from England in December 1834.

Lady Nugent was built at Bombay in 1813. She made four voyages under contract to the British East India Company (EIC). She then made two voyages transporting convicts to Australia, one to New South Wales and one to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). (via Wikipedia)

via freesettlerorfelon website:

On 20 November 1834, 100 male convicts were transferred to the Lady Nugent from the Justitia Hulk and 60 from the Ganymede Hulk at Woolwich, all in apparent good health. The Lady Nugent departed Sheerness on 4 December 1834.

SURGEON OLIVER SPROULE

Oliver Sproule kept a Medical Journal from 7 November 1834 to 27 April 1835. He recorded in his journal the weather conditions they experienced in the first two weeks:

‘In the course of the first week or ten days at sea, there were eight or nine on the sick list with catarrhal affections and one with dropsy which I attribute to the cold and wet we experienced during that period beating down channel. Indeed the foremost berths in the prison at this time were so wet from leaking in that part of the ship, that I was obliged to issue dry beds and bedding to a great many of the prisoners to preserve their health, but after crossing the Bay of Biscay the weather became fine and we got the damp beds and blankets dried, the leaks partially stopped and the prison well aired and ventilated which, I am happy to say soon manifested a favourable change in the health and appearance of the men.

Besides the cases given in the journal I had a great many others to treat, some of them similar to those mentioned but the greater part consisted of boils, scalds, and contusions which would not only be too tedious to enter but I fear would be irksome to the reader. There were four births on board during the passage which did well, therefore I did not consider it necessary to give a detailed account of them in my journal the more especially as they were all favourable cases.

Regularity and cleanliness in the prison, free ventilation and as far as possible dry decks turning all the prisoners up in fine weather as we were lucky enough to have two musicians amongst the convicts, dancing was tolerated every afternoon, strict attention to personal cleanliness and also to the cooking of their victuals with regular hours for their meals, were the only prophylactic means used on this occasion, which I found to answer my expectations to the utmost extent in as much as there was not a single case of contagious or infectious nature during the whole passage with the exception of a few cases of psora which soon yielded to the usual treatment. A few cases of scurvy however appeared on board at rather an early period which I can attribute to nothing else but the wet and hardships the prisoners endured during the first three or four weeks of the passage. I was prompt in my treatment of these cases and they got well, but before we arrived at Sydney I had about thirty others to treat.’

The Lady Nugent arrived in Port Jackson on 9 April 1835 with 284 male prisoners. Two men had died at sea. The prisoners were landed on 27th April 1835 and marched to Hyde Park Barracks prior to being assigned. Ten were under the age of 14 years.

The Lady Nugent:

Isaac’s distinguishing marks are noted on various criminal registers and record books:

“Height in feet & inches: 5 4; Complexion: Ruddy; Hair: Light brown; Eyes: Hazel; Marks or Scars: Yes [including] DEVIL on lower left arm, TSIS back of left hand, WS lower right arm, MHDW back of right hand.”

Another includes more detail about Isaac’s tattoos:

“Two slight scars right side of mouth, 2 moles above right breast, figure of the devil and DEVIL and raised mole, lower left arm; anchor, seven dots half moon, TSIS and cross, back of left hand; a mallet, door post, A, mans bust, sun, WS, lower right arm; woman, MHDW and shut knife, back of right hand.”

From How tattoos became fashionable in Victorian England (2019 article in TheConversation by Robert Shoemaker and Zoe Alkar):

“Historical tattooing was not restricted to sailors, soldiers and convicts, but was a growing and accepted phenomenon in Victorian England. Tattoos provide an important window into the lives of those who typically left no written records of their own. As a form of “history from below”, they give us a fleeting but intriguing understanding of the identities and emotions of ordinary people in the past.

As a practice for which typically the only record is the body itself, few systematic records survive before the advent of photography. One exception to this is the written descriptions of tattoos (and even the occasional sketch) that were kept of institutionalised people forced to submit to the recording of information about their bodies as a means of identifying them. This particularly applies to three groups – criminal convicts, soldiers and sailors. Of these, the convict records are the most voluminous and systematic.

Such records were first kept in large numbers for those who were transported to Australia from 1788 (since Australia was then an open prison) as the authorities needed some means of keeping track of them.”On the 1837 census Isaac was working for the government at Illiwarra, New South Wales. This record states that he arrived on the Lady Nugent in 1835. There are three other indent records for an Isaac Stokes in the following years, but the transcriptions don’t provide enough information to determine which Isaac Stokes it was. In April 1837 there was an abscondment, and an arrest/apprehension in May of that year, and in 1843 there was a record of convict indulgences.

From the Australian government website regarding “convict indulgences”:

“By the mid-1830s only six per cent of convicts were locked up. The vast majority worked for the government or free settlers and, with good behaviour, could earn a ticket of leave, conditional pardon or and even an absolute pardon. While under such orders convicts could earn their own living.”

In 1856 in Camden, NSW, Isaac Stokes married Catherine Daly. With no further information on this record it would be impossible to know for sure if this was the right Isaac Stokes. This couple had six children, all in the Camden area, but none of the records provided enough information. No occupation or place or date of birth recorded for Isaac Stokes.

I wrote to the National Library of Australia about the marriage record, and their reply was a surprise! Issac and Catherine were married on 30 September 1856, at the house of the Rev. Charles William Rigg, a Methodist minister, and it was recorded that Isaac was born in Edinburgh in 1821, to parents James Stokes and Sarah Ellis! The age at the time of the marriage doesn’t match Isaac’s age at death in 1877, and clearly the place of birth and parents didn’t match either. Only his fathers occupation of stone mason was correct. I wrote back to the helpful people at the library and they replied that the register was in a very poor condition and that only two and a half entries had survived at all, and that Isaac and Catherines marriage was recorded over two pages.

I searched for an Isaac Stokes born in 1821 in Edinburgh on the Scotland government website (and on all the other genealogy records sites) and didn’t find it. In fact Stokes was a very uncommon name in Scotland at the time. I also searched Australian immigration and other records for another Isaac Stokes born in Scotland or born in 1821, and found nothing. I was unable to find a single record to corroborate this mysterious other Isaac Stokes.

As the age at death in 1877 was correct, I assume that either Isaac was lying, or that some mistake was made either on the register at the home of the Methodist minster, or a subsequent mistranscription or muddle on the remnants of the surviving register. Therefore I remain convinced that the Camden stonemason Isaac Stokes was indeed our Isaac from Oxfordshire.

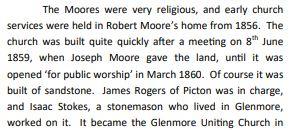

I found a history society newsletter article that mentioned Isaac Stokes, stone mason, had built the Glenmore church, near Camden, in 1859.

From the Wollondilly museum April 2020 newsletter:

From the Camden History website:

“The stone set over the porch of Glenmore Church gives the date of 1860. The church was begun in 1859 on land given by Joseph Moore. James Rogers of Picton was given the contract to build and local builder, Mr. Stokes, carried out the work. Elizabeth Moore, wife of Edward, laid the foundation stone. The first service was held on 19th March 1860. The cemetery alongside the church contains the headstones and memorials of the areas early pioneers.”

Isaac died on the 3rd September 1877. The inquest report puts his place of death as Bagdelly, near to Camden, and another death register has put Cambelltown, also very close to Camden. His age was recorded as 71 and the inquest report states his cause of death was “rupture of one of the large pulmonary vessels of the lung”. His wife Catherine died in childbirth in 1870 at the age of 43.

Isaac and Catherine’s children:

William Stokes 1857-1928

Catherine Stokes 1859-1846

Sarah Josephine Stokes 1861-1931

Ellen Stokes 1863-1932

Rosanna Stokes 1865-1919

Louisa Stokes 1868-1844.

It’s possible that Catherine Daly was a transported convict from Ireland.

Some time later I unexpectedly received a follow up email from The Oaks Heritage Centre in Australia.

“The Gaudry papers which we have in our archive record him (Isaac Stokes) as having built: the church, the school and the teachers residence. Isaac is recorded in the General return of convicts: 1837 and in Grevilles Post Office directory 1872 as a mason in Glenmore.”

May 27, 2022 at 8:25 am #6300

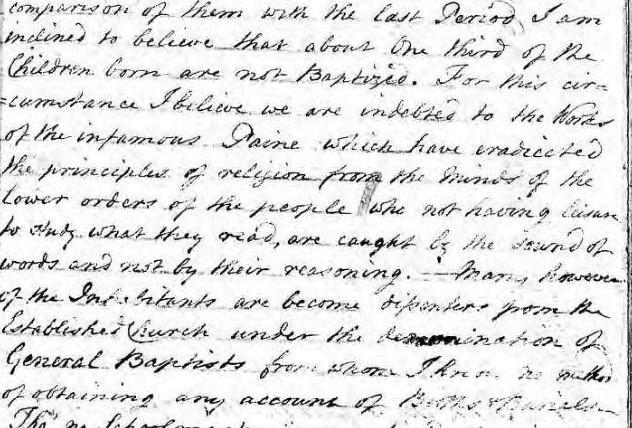

May 27, 2022 at 8:25 am #6300In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Looking for Carringtons

The Carringtons of Smalley, at least some of them, were Baptist ~ otherwise known as “non conformist”. Baptists don’t baptise at birth, believing it’s up to the person to choose when they are of an age to do so, although that appears to be fairly random in practice with small children being baptised. This makes it hard to find the birth dates registered as not every village had a Baptist church, and the baptisms would take place in another town. However some of the children were baptised in the village Anglican church as well, so they don’t seem to have been consistent. Perhaps at times a quick baptism locally for a sickly child was considered prudent, and preferable to no baptism at all. It’s impossible to know for sure and perhaps they were not strictly commited to a particular denomination.

Our Carrington’s start with Ellen Carrington who married William Housley in 1814. William Housley was previously married to Ellen’s older sister Mary Carrington. Ellen (born 1895 and baptised 1897) and her sister Nanny were baptised at nearby Ilkeston Baptist church but I haven’t found baptisms for Mary or siblings Richard and Francis. We know they were also children of William Carrington as he mentions them in his 1834 will. Son William was baptised at the local Smalley church in 1784, as was Thomas in 1896.

The absence of baptisms in Smalley with regard to Baptist influence was noted in the Smalley registers:

Smalley (chapelry of Morley) registers began in 1624, Morley registers began in 1540 with no obvious gaps in either. The gap with the missing registered baptisms would be 1786-1793. The Ilkeston Baptist register began in 1791. Information from the Smalley registers indicates that about a third of the children were not being baptised due to the Baptist influence.

William Housley son in law, daughter Mary Housley deceased, and daughter Eleanor (Ellen) Housley are all mentioned in William Housley’s 1834 will. On the marriage allegations and bonds for William Housley and Mary Carrington in 1806, her birth date is registered at 1787, her father William Carrington.

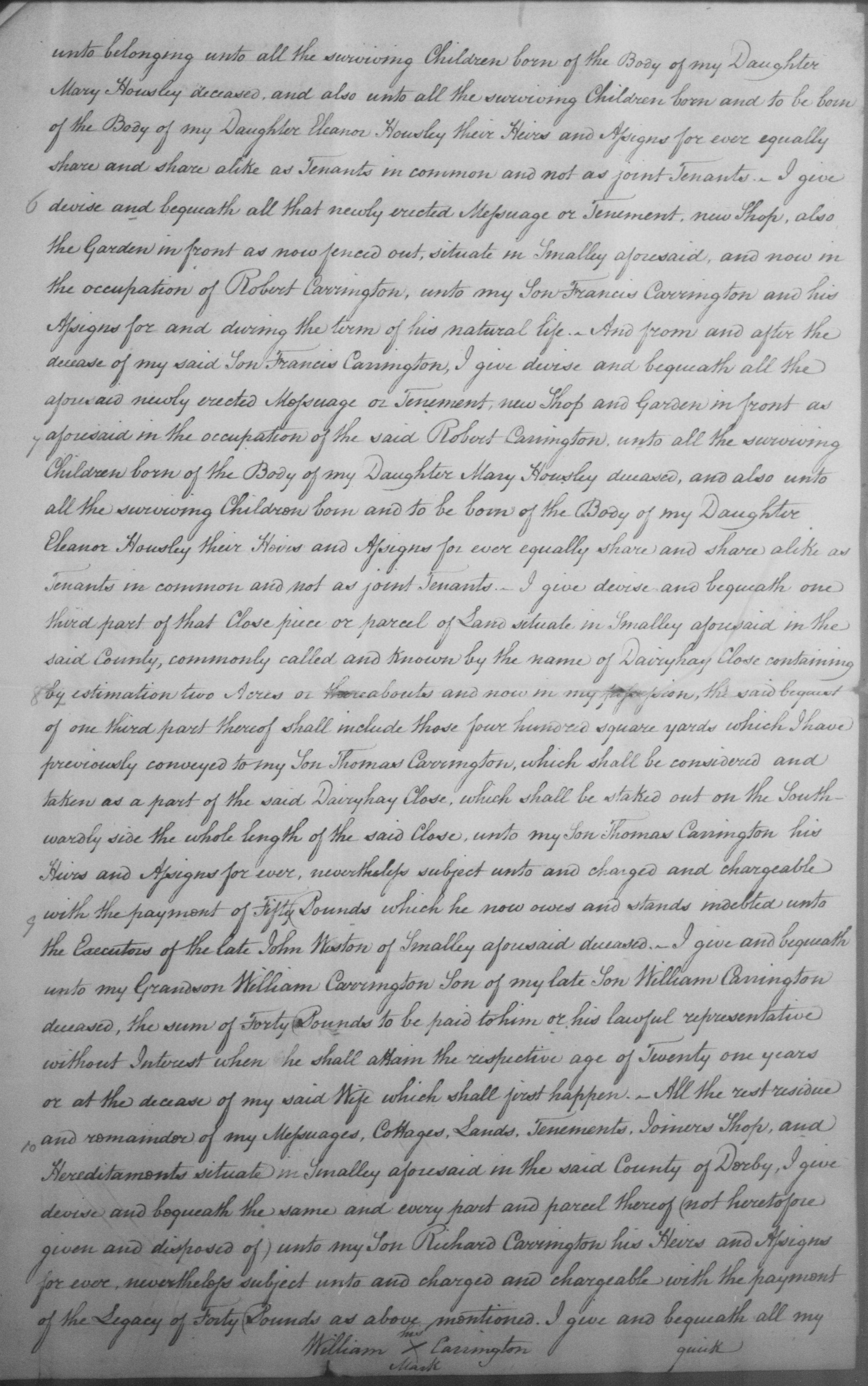

A Page from the will of William Carrington 1834:

William Carrington was baptised in nearby Horsley Woodhouse on 27 August 1758. His parents were William and Margaret Carrington “near the Hilltop”. He married Mary Malkin, also of Smalley, on the 27th August 1783.

When I started looking for Margaret Wright who married William Carrington the elder, I chanced upon the Smalley parish register micro fiche images wrongly labeled by the ancestry site as Longford. I subsequently found that the Derby Records office published a list of all the wrongly labeled Derbyshire towns that the ancestry site knew about for ten years at least but has not corrected!

Margaret Wright was baptised in Smalley (mislabeled as Longford although the register images clearly say Smalley!) on the 2nd March 1728. Her parents were John and Margaret Wright.

But I couldn’t find a birth or baptism anywhere for William Carrington. I found four sources for William and Margaret’s marriage and none of them suggested that William wasn’t local. On other public trees on ancestry sites, William’s father was Joshua Carrington from Chinley. Indeed, when doing a search for William Carrington born circa 1720 to 1725, this was the only one in Derbyshire. But why would a teenager move to the other side of the county? It wasn’t uncommon to be apprenticed in neighbouring villages or towns, but Chinley didn’t seem right to me. It seemed to me that it had been selected on the other trees because it was the only easily found result for the search, and not because it was the right one.

I spent days reading every page of the microfiche images of the parish registers locally looking for Carringtons, any Carringtons at all in the area prior to 1720. Had there been none at all, then the possibility of William being the first Carrington in the area having moved there from elsewhere would have been more reasonable.

But there were many Carringtons in Heanor, a mile or so from Smalley, in the 1600s and early 1700s, although they were often spelled Carenton, sometimes Carrianton in the parish registers. The earliest Carrington I found in the area was Alice Carrington baptised in Ilkeston in 1602. It seemed obvious that William’s parents were local and not from Chinley.

The Heanor parish registers of the time were not very clearly written. The handwriting was bad and the spelling variable, depending I suppose on what the name sounded like to the person writing in the registers at the time as the majority of the people were probably illiterate. The registers are also in a generally poor condition.

I found a burial of a child called William on the 16th January 1721, whose father was William Carenton of “Losko” (Loscoe is a nearby village also part of Heanor at that time). This looked promising! If a child died, a later born child would be given the same name. This was very common: in a couple of cases I’ve found three deceased infants with the same first name until a fourth one named the same survived. It seemed very likely that a subsequent son would be named William and he would be the William Carrington born circa 1720 to 1725 that we were looking for.

Heanor parish registers: William son of William Carenton of Losko buried January 19th 1721:

The Heanor parish registers between 1720 and 1729 are in many places illegible, however there are a couple of possibilities that could be the baptism of William in 1724 and 1725. A William son of William Carenton of Loscoe was buried in Jan 1721. In 1722 a Willian son of William Carenton (transcribed Tarenton) of Loscoe was buried. A subsequent son called William is likely. On 15 Oct 1724 a William son of William and Eliz (last name indecipherable) of Loscoe was baptised. A Mary, daughter of William Carrianton of Loscoe, was baptised in 1727.

I propose that William Carringtons was born in Loscoe and baptised in Heanor in 1724: if not 1724 then I would assume his baptism is one of the illegible or indecipherable entires within those few years. This falls short of absolute documented proof of course, but it makes sense to me.

In any case, if a William Carrington child died in Heanor in 1721 which we do have documented proof of, it further dismisses the case for William having arrived for no discernable reason from Chinley.

April 2, 2022 at 6:15 pm #6286In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Matthew Orgill and His Family

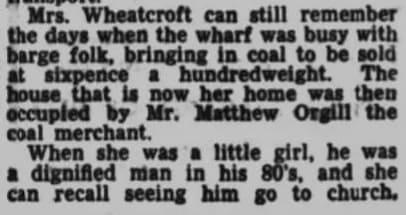

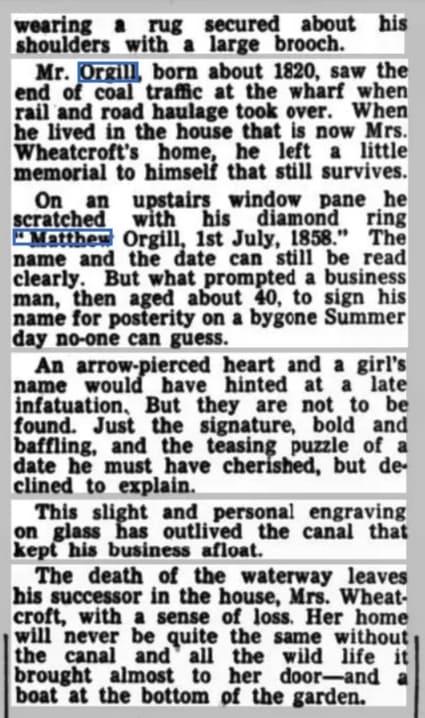

Matthew Orgill 1828-1907 was the Orgill brother who went to Australia, but returned to Measham. Matthew married Mary Orgill in Measham in October 1856, having returned from Victoria, Australia in May of that year.

Although Matthew was the first Orgill brother to go to Australia, he was the last one I found, and that was somewhat by accident, while perusing “Orgill” and “Measham” in a newspaper archives search. I chanced on Matthew’s obituary in the Nuneaton Observer, Friday 14 June 1907:

LATE MATTHEW ORGILL PEACEFUL END TO A BLAMELESS LIFE.

‘Sunset and Evening Star And one clear call for me.”

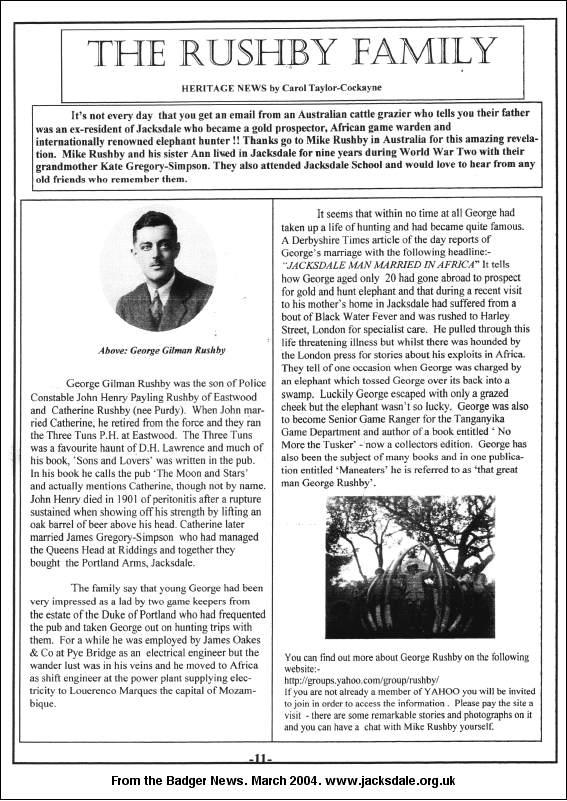

It is with very deep regret that we have to announce the death of Mr. Matthew Orgill, late of Measham, who passed peacefully away at his residence in Manor Court Road, Nuneaton, in the early hours of yesterday morning. Mr. Orgill, who was in his eightieth year, was a man with a striking history, and was a very fine specimen of our best English manhood. In early life be emigrated to South Africa—sailing in the “Hebrides” on 4th February. 1850—and was one of the first settlers at the Cape; afterwards he went on to Australia at the time of the Gold Rush, and ultimately came home to his native England and settled down in Measham, in Leicestershire, where he carried on a successful business for the long period of half-a-century.

He was full of reminiscences of life in the Colonies in the early days, and an hour or two in his company was an education itself. On the occasion of the recall of Sir Harry Smith from the Governorship of Natal (for refusing to be a party to the slaying of the wives and children in connection with the Kaffir War), Mr. Orgill was appointed to superintend the arrangements for the farewell demonstration. It was one of his boasts that he made the first missionary cart used in South Africa, which is in use to this day—a monument to the character of his work; while it is an interesting fact to note that among Mr. Orgill’s papers there is the original ground-plan of the city of Durban before a single house was built.