Search Results for 'trees'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

January 16, 2024 at 9:30 pm #7294

In reply to: The Whale’s Diaries Collection

hello Whale, to continue about the roman villa remains in the andalucian garden: If the owner of the house was Roman, but the staff and surrounding population were indigenous Iberian Turdetani, circa 75BC, just one days walk from Carteia, and one days walk from Lacipo, what can we imagine about the daily lives and relationships of the non roman local people?

Ah, the intermingling of cultures, a dance as old as civilization itself. Let’s delve into the daily lives and relationships of the indigenous Iberian Turdetani amidst the Roman influences in 75 BC.

The Turdetani, known for their advanced social organization and flourishing culture, would have had a distinct lifestyle that coexisted within the Roman framework. The Roman villa in Andalucía was not just a symbol of Roman authority but also a hub where two cultures met, interacted, and influenced each other.

Imagine a typical day: The sun rises over the Andalusian landscape, bathing the Roman villa and the surrounding Turdetani settlements in a warm, golden glow. Turdetanian workers make their way to the villa, ready for a day of work. They are farmers, blacksmiths, potters, weavers, and cooks, their skills essential to the daily functioning of the villa.

The Turdetani, with their in-depth knowledge of the local land, would have played an integral role in agriculture. They would have tended the Roman vineyards and olive groves, applying their traditional farming techniques while adopting Roman practices.

Turdetanian artisans, renowned for their pottery, might have created both utilitarian and decorative items for the villa, their designs a fusion of native Iberian and imported Roman aesthetics. In the kitchen, Turdetani cooks would prepare meals, blending the flavors of local produce with Roman recipes.

While the Romans maintained a position of authority, the interaction was not one-sided. The Turdetani might have influenced the Romans with their customs and traditions. Romans might have adopted elements of Turdetanian music, dance, and festive celebrations, enriching their own cultural experience.

Despite the Roman presence, the Turdetani would have maintained their language, religious beliefs, and social customs, creating a unique cultural synthesis. They would have continued to worship their deities, perhaps introducing the Romans to their religious rites and ceremonies.

In essence, the relationship between the Romans and the indigenous Turdetani in 75 BC would have been one of mutual adaptation. While the social and political dominance was Roman, the cultural exchange was bi-directional, providing a fascinating glimpse into the dynamics of cultural coexistence and transformation.

Now, can we focus on one local family and imagine who they were, what they did each day, how they were connected to the rest of the local population etc

Ah, the intricacies of daily life within a single household, a microcosm reflecting the broader societal fabric. Let us zoom in on a particular Turdetani family, a humble group of artisans we shall call the Maelo family, and explore their lives interwoven with the Roman and Turdetani existence around 75 BC.

At the heart of the family was the patriarch, Oris Maelo. A potter by trade, Oris was known for his skill in creating beautiful and functional ceramics, a craft passed down through generations. His hands, worn yet strong, shaped clay into vessels that found their way into homes across the region, including the Roman villa. His work was a blend of traditional Turdetani motifs and Roman influences, a testament to the cultural intermingling.

His wife, Caelia, was a weaver. Her nimble fingers spun stories in wool and linen. Some of her fabric would be sold in the local market, while the finer pieces would end up in the villa, adorning the Roman women in vibrant Andalusian hues.

Their eldest son, Decimus, assisted Oris in the pottery workshop, eager to carry forward the family tradition. Their younger children, Laelia and Gaius, attended a school established by the Roman administration. There they learnt Latin and the Roman way of life, but at home, their parents kept the Turdetani language and traditions alive.

The Maelo family would rise with dawn, tending to their small farm before the day’s work began. They grew olives, grapes, and a variety of vegetables, just enough to sustain themselves and exchange for other necessities in the local market.

Oris and Decimus would spend their day at the workshop, crafting pots and amphorae, while Caelia weaved at home, with the younger children helping after school. Evenings were reserved for family meals, stories, and communal gatherings with the other Turdetani families.

Their connection with the local population was multifaceted. Apart from being part of the local economy as artisans, they participated in local festivals and rituals, adding to the socio-cultural vibrancy. Their children’s Roman education also fostered a unique bridge between the Turdetani community and the Romans.

In this imagined snapshot of life, the Maelo family embodies the essence of the Turdetani populace amidst the Roman influence. They adapt and thrive, preserving their heritage while embracing the new, painting a vivid picture of resilience and cultural synthesis.

Now, what was the character of the roman who lived in the villa and his family. Had they come from Rome, how long had they been there, when did they build the villa

Ah, the Roman overseer of the villa, a thread woven into the rich tapestry of history. Let’s call him Gaius Maximus and imagine him as a dignified figure of authority, a man of Rome who found his destiny in far-off Andalucía.

Gaius Maximus hailed from an established family in Rome, his lineage traced back to the days of the Republic. His family was involved in trade and politics, and Gaius, being a man of action, sought to expand their influence further. Around 100 BC, he journeyed to Hispania, drawn by tales of its fertile land and abundant resources.

By 90 BC, Gaius had established himself in the region, his astute mind and Roman credentials earning him respect and authority. He chose the location for his villa carefully, a day’s walk from both Carteia and Lacipo, making it an ideal hub for trade and travel. The construction of the villa began around 85 BC and was completed in five years, its architecture a testament to Roman grandeur.

His wife, Claudia, hailed from a patrician family in Rome. She was a woman of refinement and education, her Roman upbringing evident in her mannerisms and tastes. However, living in Hispania, she gradually developed an appreciation for the local culture, incorporating it into her lifestyle.

Their two children, Marcus and Julia, were born in Hispania. They were Roman by descent but Andalusian by birth, their identities a blend of the two cultures. Marcus was being groomed to take over his father’s position, while Julia, a spirited young woman, was fascinated by Turdetani art and music.

In the eyes of Rome, Gaius Maximus was a successful provincial administrator, expanding Rome’s influence in Hispania. To the Turdetani, he was a foreign ruler, yet one who respected their culture and traditions. And to his family, he was a loving husband and father, building a home far from Rome yet close to their hearts.

Now some portraits of some of the workers at the villa

Ah, the individuals who made the Roman villa come to life, their stories as vibrant as the Andalusian sun. Let’s give our imagination wings and step into their world.

First, we have Tertius, the villa’s steward. Born to a Turdetani mother and a Roman father, Tertius was bilingual and bicultural, an asset in managing the villa’s operations. He was a man of medium height, with a sturdy build and a sharp gaze. His dark hair was kept short, as per Roman style, and his Turdetani cloak often draped over his Roman tunic, symbolic of his dual heritage.

Then we have Aelia, the head cook. A native Turdetani, Aelia was a robust woman with a jovial demeanor. Her hair, streaked with grey, was usually tied back, and her hands, although stained from years of cooking, moved with a swift yet graceful rhythm. Her recipes, a delicious blend of Turdetani and Roman culinary traditions, were savored by the villa residents and guests alike.

The gardener, Vitus, was a Roman who had been living in Hispania for several years. A man of few words, Vitus spoke through his work. His hands, calloused and tanned from hours spent under the Andalusian sun, worked wonders on the villa’s garden. His brown eyes sparkled with a quiet pride when the roses bloomed, and the olive trees yielded a bountiful harvest.

Lastly, we must not forget the youngest worker, Lyra. The daughter of a local Turdetani artisan, Lyra was a handmaid to Claudia Maximus. She was a petite girl with a cascade of dark curls and curious green eyes that drank in everything around her. Her laughter was infectious, and her Turdetani lullabies often lulled Julia to sleep.

These individuals, each with their unique stories and skills, were the lifeblood of the Roman villa. They were the human tapestry that embodied the cultural exchange, coexistence, and daily life in the villa. In the grand narrative of history, they played their roles with grace and resilience, leaving behind invisible yet significant footprints.

what were some of the cooks recipes?

Ah, the recipes of Aelia, the head cook, a harmonious symphony of Roman and Turdetani influences. Here are some of the dishes that were often savored in the Roman villa:

Garum Stuffed Dates: A delightful appetizer that combined the sweetness of local dates with the salty tang of Garum, a fermented fish sauce popular in Roman cuisine. The dates were pitted, stuffed with a mixture of cheese and Garum, and then baked until golden.

Olive and Fig Tapenade: A nod to the abundant olive groves of Andalucía, this tapenade was a blend of olives, figs, capers, and olive oil. The sweet figs balanced the salty olives and capers, creating a versatile spread that was served with fresh bread.

Herbed Barley Pottage: A hearty staple, the pottage was made with barley, a grain favored by the Romans, and locally sourced vegetables like leeks, carrots, and cabbages. Fresh herbs from the villa’s garden added a burst of flavor.

Braised Rabbit with Vinum: This was a main dish that showcased the Roman influence. Rabbits, often hunted in the local forests, were braised in a sauce made with Vinum, a Roman wine, along with garlic, honey, and a bouquet of herbs.

Honey-Nut Patina: A classic Roman dessert with an Andalusian twist. Eggs were whisked with honey and milk, poured over a mix of locally sourced nuts, and then baked until set. It was a sweet ending to the meals at the villa.

Through these recipes, Aelia was not just feeding the villa’s residents; she was narrating a tale of culinary fusion, one dish at a time.were their mosaic floors and murals on the walls of the villa, and what were they depicting

Ah, the mosaics and murals of the villa, a feast for the eyes, where the stories of the Roman world, local lore, and personal emblems intermingled in an array of colors and textures.

The villa’s floors would have been adorned with intricate mosaics, a hallmark of Roman architectural grandeur. Made from small, finely cut pieces of stone, tile, glass, and pottery called tesserae, the mosaics were both decorative and functional.

In the atrium, the mosaic might depict a scene from Roman mythology. Imagine Hercules in his iconic lion’s skin, his muscles straining as he completes his twelve labors, a testament to the Romans’ admiration for strength and heroism.

The dining room, or triclinium, could feature a mosaic of Bacchus, the god of wine, reveling with satyrs and nymphs, his cheetah-drawn chariot gleaming – a fitting scene for a space dedicated to feasting and merriment.

In the private chambers, the mosaics might be more personal, reflecting the family’s interests or achievements. Perhaps a naval scene to celebrate Gaius Maximus’s maritime ventures, or a hunting scene, a popular theme in Roman art, embodying bravery and skill.

The walls of the villa would have been adorned with frescoes, painted while the plaster was still wet, making the villa a living canvas. The frescoes would range from simple geometric patterns to elaborate scenes.

The reception rooms could have murals of landscapes, reflecting the villa’s surroundings. Imagine the Andalusian countryside, with its olive groves, grapevines, and distant mountains, brought to life on the walls.

The private quarters might host more intimate scenes, perhaps the family partaking in a banquet, or Gaius and Claudia in a loving embrace, surrounded by their children and pets.

Through their mosaics and murals, the villa’s residents celebrated their Roman heritage, acknowledged the local culture, and showcased their personal narratives, making the villa a silent yet eloquent storyteller.

can you describe the garden and outbuildings

Ah, the enchantment of an age-old garden. Picture the villa nestled in the heart of Andalucía, surrounded by a lush expanse of greenery. Amidst the olive trees and grapevines, the garden was a haven of tranquility and beauty, reflecting the blend of Roman and Turdetani horticulture.

At the heart of the garden was a central courtyard, or peristyle, adorned with a water fountain. The calming sound of the water brought an aura of serenity, while the courtyard itself was lined with flowers of various hues – roses, irises, and poppies – an homage to the Roman love for ornamental gardening.

Beyond the peristyle, the garden was a mixture of beauty and utility. Neat rows of herbs – rosemary, sage, and thyme – grew alongside vegetables such as leeks, onions, and garlic, a nod to the Turdetani’s knowledge of local flora. Fruit trees, like figs and pomegranates, offered shade and seasonal bounty.

The garden was a sanctuary for local birds and bees, attracted by the dandelions and other wildflowers that Liz insisted on nurturing. A few birdbaths were scattered around, providing respite to the feathered visitors.

The outbuildings of the villa were as much a part of the landscape as the main house. Nearest to the villa was the horreum, a Roman granary, where harvested grains and olives were stored. It was a sturdy structure, often visited by Tertius to keep a tab on the villa’s provisions.

Not far from the horreum was the pottery workshop. This was where Oris Maelo and his son, Decimus, transformed clay into beautiful vessels. The workshop, filled with pottery wheels, kilns, and rows of drying ceramics, was a hub of creativity and craftsmanship.

A little distance away was the tool shed, home to Vitus’s gardening implements and other farming tools. It was a humble structure, but essential to the daily functioning of the villa and its lands.

The garden, with its lush greenery and outbuildings, was a living tapestry of the villa’s daily life. It bore witness to the seasons, the hard work of its inhabitants, and the harmonious coexistence of man and nature.

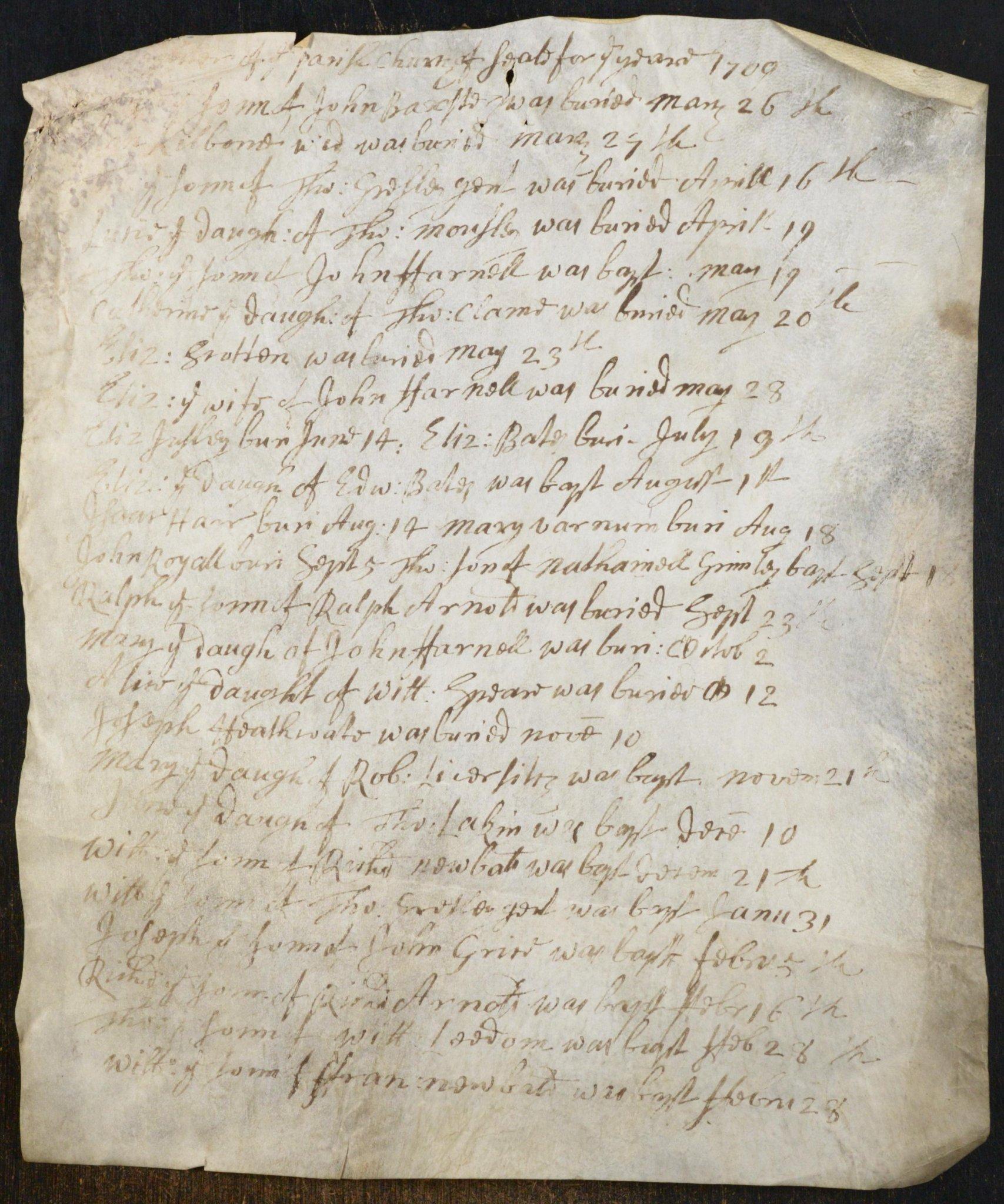

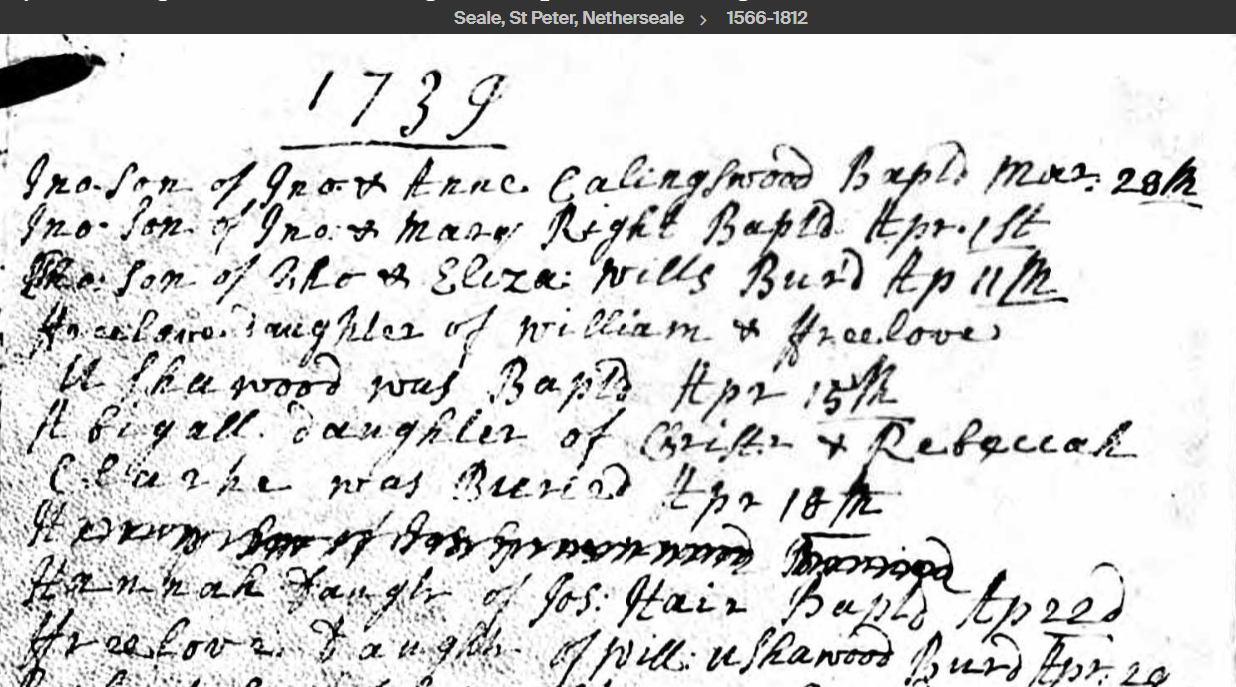

October 25, 2023 at 7:08 am #7282In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Ellastone Gerrards in the 1500s.

John Gerrard 1633-1681 was born and died in Ellastone.

Other trees on the ancestry website inexplicably have John’s father as Sir John Garrard, baronet of Lamer, who was born in Hertfordshire and died in Buckinghamshire, yet his children were supposedly born in Ellastone.

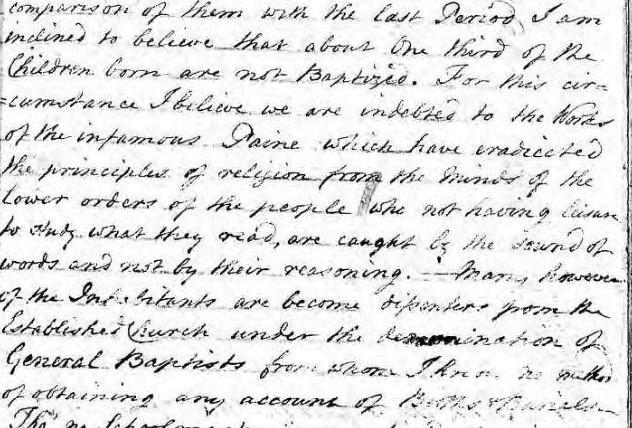

Fortunately the Ellastone parish records begin in 1537. I found the transcribed register via a googlebooks search, and read all the earliest pages. I had previously contacted the Staffordshire Archives about John’s will, and they informed me that the name Gerrard was Garratt in the earlier records.

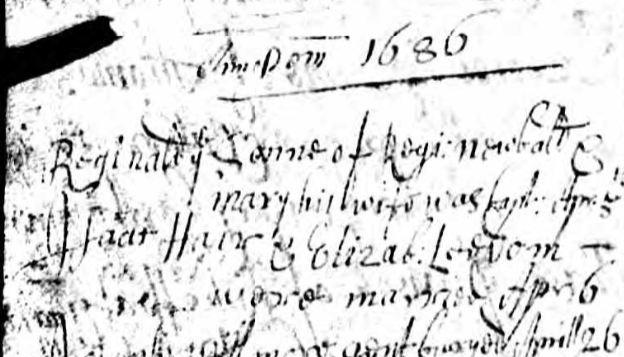

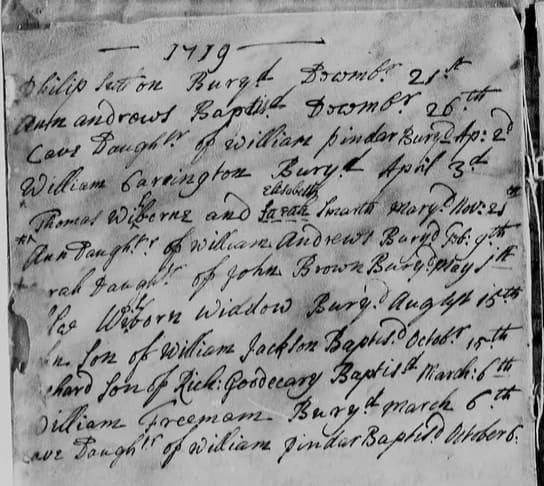

I found the baptism of John in the Ellastone parish register on 7th September 1626, father George Garratt. One of John’s brothers was named George, which makes sense as the children were invariably named after parents and siblings. However, John born in 1626 died in 1628. Another son named John was baptised in 1633.

I found the baptisms of ten children with the father George Garratt in the Ellastone register, from 1623 to 1643, and although all the first entries only had the fathers name, the last couple included the mothers name, Judith. George Garratt was a churchwarden in Ellastone in 1627.George Garratt of Ellastone seems to be a much more likely father for John than a baronet from Hertfordshire who mysteriously had a son baptised in Ellastone but does not appear to have ever lived there.

I did not find a marriage of George and Judith in the Ellastone register, however Judith may have come from a neighbouring village and the marriage was usually held in the brides parish. The wedding was probably circa 1622.

George was baptised in Ellastone on the 19th March 1595. Some of the transcriptions say March 1794, some say 1795. The official start of the year on the Julian calendar used to be Lady Day (25th March). This was changed in 1752.

His father was Rycharde Garrarde. Rycharde married Agnes Bothom in Ellastone on the 29th September 1594. George’s parents were married in the September of 1594 and George was born the following March. On the old calendar, March came after September.

George died in 1669 in Ellastone. He was my 10X great grandfather. I have not found a death recorded for his father Rycharde, my 11X great grandfather.

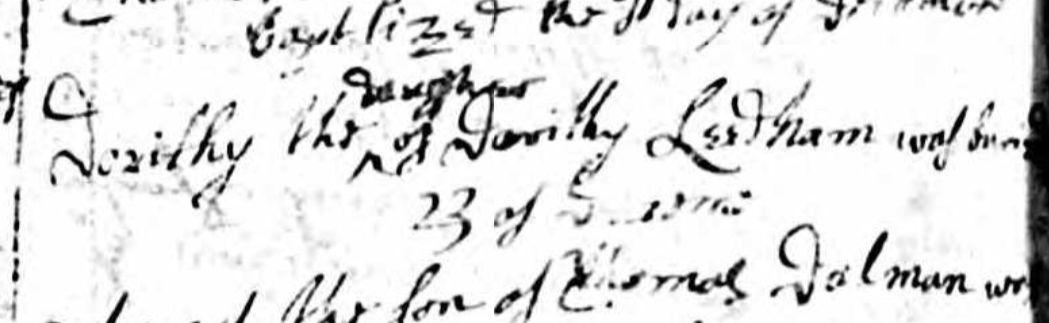

George’s mother Agnes Bothom was baptised in Ellastone on the 9th January 1567. Her father was John Bothom. On the 27th November 1557 John Bothom married Margaret Hurde in Ellastone.

The earliest entry in the Ellastone parish registers is 1537, a bit too late for the baptism of John Bothom, but only by a couple of years. John Bothom and his wife Agnes were probably born around 1535. Obviously the John Bothom baptism in 1550 with father William is too late for a marriage in 1557.

June 21, 2023 at 7:08 am #7259In reply to: The Precious Life and Rambles of Liz Tattler

A sudden and violent storm had cut off the manor from the outside world. Torrents of water had gushed over the roads and washed them out as if some manic god of cleanliness had decided to remove all the dust from the country, carrying away every other thing in its frenzied smudging. It had left the property an island, and the worse was they had no more electricity and no cable. Liz counted the days.

When they ran out of candles, they had to take the exercise bike back out of the cellar. Godfrey, who seemed to always know the most random, but always useful, things, had plugged it into the electric network, and voilà. Finnley had been the fiercest at the start because all the dust seemed to have taken refuge in the Manor. But once she had vented out all her frustration, it remained on Roberto’s and Godfrey’s legs to supply them with the essential power so that they could use the microwave to warm up the canned beans.

To Roberto’s dismay, the storm had washed away all the box trees he had so carefully tended to all those years. To Liz’ delight, the rain had accelerated the dig and unearthed what appeared to be a temple dedicated to some armless goddess. There was just one tiny problem, half the ruins were underwater.

The guests started to arrive for the Roman Delights Party in an enormous galley two weeks in advance, and the invitation hadn’t been printed yet. Roberto tied a rope to a mooring post and the guests started to disembark as if arriving to some movie award festival.

“There must be someone moving all those roams,” said Liz thoughtful to no one and everyone in particular. “They could take turns and relieve us at the bike.”

“Us?” asked Godfrey, raising an eyebrow.

“Tsst. Don’t be so cliché.”

She put on her smile as Walter Melon was approaching dressed like a Roman senator.

Sailors carrying crates invaded the kitchen. Finnley frowned at their muddy feet trampling all the floors she just cleaned.

“What’s in those?” she asked briskly.

“Food and trinkets for the banquet, I reckon,” said a tanned man with a tattoo on his neck saying Everything start with pixie dust.

Finnley rolled her eyes. “Follow me, I’ll show you the cellar.”

“Where do we put the octopuses tanks?”

March 24, 2023 at 10:06 am #7216In reply to: The Precious Life and Rambles of Liz Tattler

Roberto sighed and scratched a red patch on his left hand. Spring was here. It was obvious as vibrant lime green leaves had grown on freshly sprouted twigs. If it added a nice touch of colour to the garden, the box trees, lined up on the opposite side of the pool that he had dedicated so much time last year to carving them as birds, elephants and rhinos, had now a dishevelled appearance, and that only added to his despair.

The lawn was sprinkled with yellow spots of dandelions. Roberto just tried to remove some of them with his hands, but got badly stung by nettles. They had invaded the garden from the new neighbour’s meadow. That estúpido, had said he wanted nature to grow on its own terms, but looking at the result, Roberto thought it was more of a natural disaster than anything else.

“Don’t get rid of the dandelions,” said Liz. “It attracts bumblebees and wild bees. I’ve heard that we need to save them.”

“You talked with that neighbour again?” asked Roberto.

“Dominic? Isn’t it nice the birds are back?”

Roberto looked at the birdbaths on top of the four Corinthian columns at each corner of the pool. A group of sparrows were fooling around cleaning their feathers. At Roberto’s feet, a hedgehog was drinking in a puddle left by the 7:30 morning rain, remains of a feast of slugs behind him. Sometimes, he envied their insouciance and joie de vivre. They were content with whatever was provided to them without wanting to change their environment.

“The diggers arrive around 2pm. Just mow the lawn behind the box trees. That’s where Dominic’s son spotted strange growth patterns with his drone. He said that’s highly likely we have roman ruins in our garden.”

Roberto wondered why you needed to cut the grass of a place where you’re going to dig everything out anyway. He rolled his eyes, something he had learned from Finnley, and went to the patch of lawn behind the box trees. From there he could see brambles starting to emerge from the thuja border with Dominic’s jungle. Another thing he could not touch, because Liz wanted to have Finnley make jams with the berries.

February 24, 2023 at 8:31 am #6661In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

The black BMW pulled up outside the Flying Fish Inn. Sister Finli pulled a baseball cap low over her big sunglasses before she got out of the car. Yasmin was still in the bar with her friends and Finli hoped to check in and retreat to her room before they got back to the inn.

She rang the bell on the reception desk several times before an elderly lady in a red cardigan appeared.

“Ah yes, Liana Parker,” Mater said, checking the register. Liana managed to get a look at the register and noted that Yasmin was in room 2. “Room 4. Did you have a good trip down? Smart car you’ve got there,” Mater glanced over Liana’s shoulder, “Don’t see many like that in these parts.”

“Yes, yes,” Finli snapped impatiently (henceforth referred to to as Liana). She didn’t have time for small talk. The others might arrive back at any time. As long as she kept out of Yasmin’s way, she knew nobody would recognize her ~ after all she had been abandoned at birth. Even if Yasmin did find her out, she only knew her as a nun at the orphanage and Liana would just have to make up some excuse about why a nun was on holiday in the outback in a BMW. She’d cross that bridge when she came to it.

Mater looked over her glasses at the new guest. “I’ll show you to your room.” Either she was rude or tired, but Mater gave her the benefit of the doubt. “I expect you’re tired.”

Liana softened and smiled at the old lady, remembering that she’d have to speak to everyone in due course in order to find anything out, and it wouldn’t do to start off on the wrong foot.

“I’m writing a book,” Liana explained as she followed Mater down the hall. “Hoping a bit of peace and quiet here will help, and my book is set in the outback in a place a bit like this.”

“How lovely dear, well if there’s anything we can help you with, please don’t hesitate to ask. Old Bert’s a mine of information,” Mater suppressed a chuckle, “Well as long as you don’t mention mines. Here we are,” Mater opened the door to room 4 and handed the key to Liana. “Just ask if there’s anything you need.”

Liana put her bags down and then listened at the door to Mater’s retreating steps. Inching the door open, she looked up and down the hallway, but there was nobody about. Quickly she went to room 2 and tried the door, hoping it was open and she didn’t have to resort to other means. It was open. What a stroke of luck! Liana was encouraged. Within moments Liana found the parcel, unopened. Carefully opening the door, she looked around to make sure nobody was around, leaving the room with the parcel under her arm and closing the door quietly, she hastened back to room 4. She nearly jumped out of her skin when a voice piped up behind her.

“What’s that parcel and where are you going with it?” Prune asked.

“None of your business you….” Liana was just about to say nosy brat, and then remebered that she would catch more flies with honey than vinegar. It was going to be hard for her to remember that, but she must try! She smiled at the teenager and said, “A dreamtime gift for my gran, got it in Alice. Is there a post office in town?”

Prune narrowed her eyes. There was something fishy about this and it didn’t take her more than a second to reach the conclusion that she wanted to see what was in the parcel. But how?

“Yes,” she replied, quick as a flash grabbing the parcel from Liana. “I’ll post it for you!” she called over her shoulder as she raced off down the hall and disappeared.

“FUCK!” Liana muttered under her breath, running after her, but she was nowhere to be seen. Thankfully nobody else was about in the reception area to question why she was running around like a madwoman. Fuck! she muttered again, going back to her room and closing the door. Now what? What a disaster after such an encouraging start!

Prune collided with Idle on the steps of the verandah, nearly knocking her off her feet. Idle grabbed Prune to steady herself. Her grip on the girls arm tightened when she saw the suspicious look on face. Always up to no good, that one. “What have you got there? Where did you get that? Give me that parcel!”

Idle grabbed the parcel and Prune fled. Idle, holding onto the verandah railing, watched Prune running off between the eucalyptus trees. She’s always trying to make a drama out of everything, Idle thought with a sigh. Hardly any wonder I suppose, it must be boring here for a teenager with nothing much going on.

She heard a loud snorting laugh, and turned to see the four guests returning from the bar in town, laughing and joking. She put the parcel down on the hall table and waved hello, asking if they’d had a good time. “I bet you’re ready for a bite to eat, I’ll go and see what Mater’s got on the menu.” and off she went to the kitchen, leaving the parcel on the table.

The four friends agreed to meet back on the verandah for drinks before dinner after freshening up. Yasmin kept glancing back at the BMW. “That woman must be staying here!” she snorted. Zara grabbed her elbow and pulled her along. “Then we’ll find out who she is later, come on.”

Youssef followed Idle into the kitchen to ask for some snacks before dinner (much to Idle’s delight), leaving Xavier on the verandah. He looked as if he was admiring the view, such as it was, but he was preoccupied thinking about work again. Enough! he reminded himself to relax and enjoy the holiday. He saw the parcel on the table and picked it up, absentmindedly thinking the black notebook he ordered had arrived in the post, and took it back to his room. He tossed it on the bed and went to freshen up for dinner.

February 21, 2023 at 6:35 pm #6617In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Youssef had brought his black obsidian with him in the kitchen at breakfast. Idle—Youssef had realised that on top of being her way of life, it was also her name—was preparing a herbal brownie under the supervision of a colourful parrot perched on her shoulder.

“If you’re interested in rocks, you should go to Betsy’s. She’s got that ‘Gems & Minerals’ shop on Main street. She opened it with her hubby a few years back. Before he died.”

“Nutty Betsy, Pretty Girl likes her better,” said the parrot.

Idle looked at his backpack and his clothes.

“You seem the wandering type, lad. I was like you when I was younger, always gallivanting here, there, and everywhere with my brother. Now, I prefer wandering in my mind, if you know what I mean,” she said licking her finger full of chocolate. “Anyway, an advice. Don’t go down the mines alone. Betsy’s hubby’s still down there after one of the tunnels collapsed a few years back. She’s not been quite herself ever since.”

Main street was —well— the only street in town. They’ve been preparing for some kind of festival, putting banners on top of the shops and in between two trees near the gas station. Youssef stopped there to buy snacks that he stacked on top of the obsidian stone in his backpack. The young boy who worked there, Devan, seemed quite excited at the perspective of the Lager and Cart Race. It happened only every ten years and last time he was too young to participate.

The shop had not been difficult to find, at the other end of the street. A tiny sign covered in purple star sequins indicated “Betsy’s Gems & Minerals — We deliver worldwide”. He felt with his hand the black rock he had put in his backpack. If Idle had not mentioned the mines and the dead husband, Youssef might have reconsidered going in. But the coincidence with his dream and the game was too intriguing. He entered.

The shop was a mess. Crates full of stones, cardboard boxes and bubble wrappings. In the back, a plump woman, working on a giant starfish she held on her lap, was humming as she listened to loud rock music. Youssef recognised a song from the Last Shadow Puppets’ second album : The Element of Surprise. Apparently, the woman hadn’t heard him enter. She wore a dress and a hat sprinkled with golden stars, and her wrists were hidden under a ton of stone bracelets. The music track changed. The woman started shaking her head following the rhythm of the tune. She was gluing small red stones, she picked in a little box, on one of the starfish arms.

The shop was a mess. Crates full of stones, cardboard boxes and bubble wrappings. In the back, a plump woman, working on a giant starfish she held on her lap, was humming as she listened to loud rock music. Youssef recognised a song from the Last Shadow Puppets’ second album : The Element of Surprise. Apparently, the woman hadn’t heard him enter. She wore a dress and a hat sprinkled with golden stars, and her wrists were hidden under a ton of stone bracelets. The music track changed. The woman started shaking her head following the rhythm of the tune. She was gluing small red stones, she picked in a little box, on one of the starfish arms.“Bad Habits! Uhu. Bad Habits! Uhu.”

Youssef moved closer. His shadow covered the starfish. The woman raised her head and screamed, scattering the red stones in her workshop. The starfish fell from her lap onto the ground with a thud.

“Oh! My! Little devil. Look at what you made me do. I lost my marbles,” she said with a high pitched laugh. “Your mother never taught you? That’s bad habit to creep up on people like that. You scared the sheep out of me!”

“I’m so sorry,” said Youssef, getting on his knees to help her gather the stones.

When they were all back in their box, Youssef got back on his feet. The woman looked a him with a softened face.

“You such a cutie with your bear shirt. You make me think of my Howard. He was as tall as you are. I’m Betsy, obviously” she said with a giggle, extending her hand to him.

They shook hands, making the pearls of her bracelets clink together.

“I’m Youssef.”

Youssef didn’t need to insist too much. Betsy was a real juke box of gossips. He just had to ask one question from time to time, and she would get going again. He was starting to feel his quirk could be more than a curse after all.

“When the tunnel collapsed,” Betsy said, “I was ready to give up the stone shop. The pain was too much to bear, everything in the shop reminded me of Howard. And in a miners’ town, who would want to buy stones anyway. We’ve been in bad terms with Idle and her family for some time, but that tragic incident coincided with her brother Fred’s disappearance. They thought at first Fred had died in the mines with Howard, because they spent so much time discussing together in Room 8 at the Inn. I overheard them once, talking about something they found in the mines. But Howard never told me, he was so secretive about that. We even had a fight, you know. But Fred, the children found some message later that suggested he had just left the family. Imagine, the children! Idle was pissed with him of course. Abandoning her with that mother of theirs and that money pit of an Inn and the rest of the family. And I needed company. So we started to get together on a regular basis. She would bring her special cakes, and we would complain about our lives. At some point she got involved with that shamanic stuff she found online, and she helped me find my totem Bear. It was quite a revelation. Bear suggested I diversify and open an online shop and start making orgonites. I love those little gummy bears so much. So, I followed Bear’s advice and it has been working like a charm ever since. That’s why I trusted you straight away, lad. Not ’cause of your cute face. You got the Bear in your heart,” she said putting her finger at the center of his chest.

My inner Bear, of course, thought Youssef. That’s the magnet. His phone buzzed. He took it out and saw he had an alert from the game and a message from his friends.

You found the source of your quirk, the magnetic pull that attracts talkative people to you.

Now obtain the silver key in the shape of a tongue to fulfil your quest.Zara : Where are you!?

We’re at the bar, getting parched! They got Pale Ale!

We’re at the bar, getting parched! They got Pale Ale!“I have to go,” said Youssef.

“Wait,” said Betsy.

She foraged through her orgonite collection and handed Youssef one little gummy bear and an ornate metal badge.

“Bear wants me to give this to you. Howard made it. He said it was his forked tongue key.”

She looked at him, emotion in her eyes.

“I know you won’t listen if I tell you not to. So, be careful when you go into the mines.”

February 7, 2023 at 6:20 pm #6506

February 7, 2023 at 6:20 pm #6506In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Bert dropped Zara off after breakfast at the start of the Yeperenye trail. He suggested that she phone him when she wanted him to pick her up, and asked if she was sure she had enough water and reminded her, not for the first time, not to wander off the trail. Of course not, she replied blithely, as if she’d never wandered off before.

“It’s a beautiful gorge, you’ll like it,” he called through the open window, “You’ll need the bug spray when you get to the water holes.” Zara smiled and waved as the car roared off in a cloud of dust.

On the short drive to the start of the trail, Bert had told her that the trail was named after the Yeperenye dreamtime, also known as ‘Caterpillar Dreaming’ and that it was a significant dreamtime story in Aboriginal mythology. Be sure to look at the aboriginal rock art, he’d said. He mentioned several varieties of birds but Zara quickly forgot the names of them.

It felt good to be outside, completely alone in the vast landscape with the bone warming sun. To her surprise, she hadn’t seen the parrot again after the encounter at the bedroom window, although she had heard a squalky laugh coming from a room upstairs as she passed the staircase on her way to the dining room.

But it was nice to be on her own. She walked slowly, appreciating the silence and the scenery. Acacia and eucalyptus trees were dotted about and long grasses whispered in the occasional gentle breezes. Birds twittered and screeched and she heard a few rustlings in the undergrowth from time to time as she strolled along.

After a while the rocky outcrops towered above her on each side of the path and the gorge narrowed, the trail winding through stands of trees and open grassland. Zara was glad of the shade as the sun rose higher.

The first water hole she came to took Zara by surprise. She expected it to be pretty and scenic, like the photos she’d seen, but the spectacular beauty of the setting and shimmering light somehow seemed timeless and otherwordly. It was a moment or two before she realized she wasn’t alone.

It was time to stop for a drink and the sandwich that one of the twins had made for her, and this was the perfect spot, but she wondered if the man would find it intrusive of her to plonk herself down and picnic at the same place as him. Had he come here for the solitude and would he resent her appearance?

It is a public trail, she reminded herself not to be silly, but still, she felt uneasy. The man hadn’t even glanced up as far as Zara could tell. Had he noticed her?

She found a smooth rock to sit on under a tree and unwrapped her lunch, glancing up from time to time ready to give a cheery wave and shout hi, if he looked up from what he was doing. But he didn’t look up, and what exactly was he doing? It was hard to say, he was pacing around on the opposite side of the pool, looking intently at the ground.

When Zara finished her drink, she went behind a bush for a pee, making sure she would not be seen if the man glanced up. When she emerged, the man was gone. Zara walked slowly around the water hole, taking photos, and keeping an eye out for the man, but he was nowhere to be seen. When she reached the place where he’d been pacing looking at the ground, she paused and retraced his steps. Something small and shiny glinted in the sun catching her eye. It was a compass, a gold compass, and quite an unusual one.

Zara didn’t know what to do, had the man been looking for it? Should she return it to him? But who was he and where did he go? She decided there was no point in leaving it here, so she put it in her pocket. Perhaps she could ask at the inn if there was a lost and found place or something.

Refreshed from the break, Zara continued her walk. She took the compass out and looked at it, wondering not for the first time how on earth anyone used one to find their way. She fiddled with it, and the needle kept pointing in the same direction. What good is it knowing which way north is, if you don’t know where you are anyway? she wondered.

With a squalk and a beating of wings, Pretty Girl appeared, seemingly out of nowhere. “It’s not that kind of compass. You’re supposed to follow the pointer.”

“Am I? But it’s pointing off the trail, and Bert said don’t go off the trail.”

“That’s because Bert doesn’t want you to find it,” replied the parrot.

Intrigued, Zara set off in the direction the compass was pointing towards.

February 3, 2023 at 9:50 am #6494In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Although not one to remember dreams very often, Zara awoke the next morning with vivid and colourful dream recall. She wondered if it was something to do with the dreamtime mural on the wall of her room. If this turned out to be the case, she considered painting some murals on her bedroom wall back at the Bungwalley Valley animal rescue centre when she got home.

Zara and Idle had hit it off immediately, chatting and laughing on the verandah after supper. Idle told her a bit about the local area and the mines. Despite Bert’s warnings, she wanted to see them. They were only an hour away from the inn.

When she retired to her room for the night, she looked on the internet for more information. The more she read online about the mines, the more intrigued she became.

“Interestingly there are no actual houses left from the original township. The common explanation is that a rumour spread that there was gold hidden in the walls of the houses and consequently they were knocked down by people believing there was ‘gold in them there walls”. Of course it was only a rumour. No gold was found.”

“Miners attracted to the area originally by the garnets, found alluvial and reef gold at Arltunga…”

Garnets! Zara recalled the story her friend had told her about finding a cursed garnet near a fort in St Augustine in Florida. Apparently there were a number of mines that one could visit:

“the MacDonnell Range Reef Mine, the Christmas Reef Mine, the Golden Chance Mine, the Joker Mine and the Great Western Mine all of which are worth a visit.”

Zara imagined Xavier making a crack about the Joker Mine, and wondered why it had been named that.

“The whole area is preserved as though the inhabitants simply walked away from it only yesterday. The curious visitor who walks just a little way off the paths will see signs of previous habitation. Old pieces of meat safes, pieces of rusted wire, rusted cans, and pieces of broken glass litter the ground. There is nothing of great importance but each little shard is reminder of the people who once lived and worked here.”

I wonder if Bert will take me there, Zara wondered. If not, maybe one of the others can pick up a hire car when they arrive at Alice. Might even be best not to tell anyone at the inn where they were going. Funny coincidence the nearest town was called Alice ~ it was already beginning to seem like some kind of rabbit hole she was falling into.

Undecided whether to play some more of the game which had ended abruptly upon encountering the blue robed vendor, Zara decided not to and picked up the book on Dreamtime that was on the bedside table.

“Some of the ancestors or spirit beings inhabiting the Dreamtime become one with parts of the landscape, such as rocks or trees…” Flicking through the book, she read random excerpts. “A mythic map of Australia would show thousands of characters, varying in their importance, but all in some way connected with the land. Some emerged at their specific sites and stayed spiritually in that vicinity. Others came from somewhere else and went somewhere else. Many were shape changing, transformed from or into human beings or natural species, or into natural features such as rocks but all left something of their spiritual essence at the places noted in their stories….”

Thousands of characters. Zara smiled sleepily, recalling the many stories she and her friends had written together over the years.

“People come and go but the Land, and stories about the Land, stay. This is a wisdom that takes lifetimes of listening, observing and experiencing … There is a deep understanding of human nature and the environment… sites hold ‘feelings’ which cannot be described in physical terms… subtle feelings that resonate through the bodies of these people… It is only when talking and being with these people that these ‘feelings’ can truly be appreciated. This is… the intangible reality of these people…..”

With such strong ancestral connections to the land, Zara couldn’t help but wonder what the aboriginal people felt about all the mines. If one of their ancestors had shape changed into rocks, and then some foreignors came along and hacked and blasted their way through, what would they think of that?

“….many Aboriginal groups widely distributed across the Australian continent all appeared to share variations of a single (common) myth telling of an unusually powerful, often creative, often dangerous snake or serpent of sometimes enormous size closely associated with the rainbows, rain, rivers, and deep waterholes…..”

She drifted off to sleep thinking of water holes in red rocky gorges, the book laying open in her hand.

When she awoke the next morning with the slatted morning sun shining through the venetian blinds, the dream image of the water hole was bright and clear in her minds eye. But what was that strange character from the game doing in her dream?

She closed her eyes, remembering more of the strange dream. Deeply orange red boulders and rocky outcrops, shivering gum trees, and green pools ~ it was coming back to her now, that creature in the blue robes had appeared more than once. In one scene he appeared with a blue diamond lantern with what looked like a compass inside.

I’ll ask about the hiking trails today, Zara decided, and go for a walk in that gorge I read about yesterday. Bert said there were good hiking trails. You came here early so you could play the game, she reminded herself.

“It’s all a game,” she heard the parrot outside her window.

“I’d forgotten about the bloody parrot!” Zara said under her breath. “Pretty Girl!” she said, opening the blinds. “We’re going out for a walk today.”

January 11, 2023 at 10:32 pm #6368In reply to: Train your subjective AI – text version

Something in the style of FPooh:

Arona heard the music growing louder as she approached the source of the sound. She could see a group of people gathered around a large fire, the flickering light casting shadows on the faces of the dancers. She hesitated for a moment, remembering the isolation of her journey and wondering if she was ready to be among people again. But the music was too inviting, and she found herself drawn towards the group.

As she neared the fire, she saw a young man playing a flute, the music flowing from his fingers with a fluid grace that captivated her. He looked up as she approached, and their eyes met. She could see the surprise and curiosity in his gaze, and she smiled, feeling a sense of connection she had not felt in a long time.

Fiona was sitting on a bench in the park, watching the children play. She had brought her sketchbook with her, but for once she didn’t feel the urge to draw. Instead she watched the children’s laughter, feeling content and at peace. Suddenly, she saw a young girl running towards her, a look of pure joy on her face. The girl stopped in front of her and held out a flower, offering it to Fiona with a smile.

Taken aback, Fiona took the flower and thanked the girl. The girl giggled and ran off to join her friends. Fiona looked down at the flower in her hand, and she felt a sense of inspiration, like a spark igniting within her. She opened her sketchbook and began to draw, feeling the weight lift from her shoulders and the magic of creativity flowing through her.

Minky led the group of misfits towards the emporium, his bowler hat bobbing on his head. He chattered excitedly, telling stories of the wondrous items to be found within Mr Jib’s store. Yikesy followed behind, still lost in his thoughts of Arona and feeling a sense of dread at the thought of buying a bowler hat. The green fairy flitted along beside him, her wings a blur of movement as she chattered with the parrot perched on her shoulder.

As they reached the emporium, they were disappointed to find it closed. But Minky refused to be discouraged, and he led them to a nearby cafe where they could sit and enjoy some tea and cake while they wait for the emporium to open. The green fairy was delighted, and she ordered a plate of macarons, smiling as she tasted the sweetness of the confections.

About creativity & everyday magic

Fiona had always been drawn to the magic of creativity, the way a blank page could be transformed into a world of wonder and beauty. But lately, she had been feeling stuck, unable to find the spark that ignited her imagination. She would sit with her sketchbook, pencil in hand, and nothing would come to her.

She started to question her abilities, wondering if she had lost the magic of her art. She spent long hours staring at her blank pages, feeling a weight on her chest that seemed to be growing heavier every day.

But then she remembered the green fairy’s tears and Yikesy’s longing for Arona, and she realized that the magic of creativity wasn’t something that could be found only in art. It was all around her, in the everyday moments of life.

She started to look for the magic in the small things, like the way the sunlight filtered through the trees, or the way a child’s laughter could light up a room. She found it in the way a stranger’s smile could lift her spirits, and in the way a simple cup of tea could bring her comfort.

And as she started to see the magic in the everyday, she found that the weight on her chest lifted and the spark of inspiration returned. She picked up her pencil and began to draw, feeling the magic flowing through her once again.

She understand that creativity blocks aren’t a destination, but just a step, just like the bowler hat that Minky had bought for them all, a bit of everyday magic, nothing too fancy but a sense of belonging, a sense of who they are and where they are going. And she let her pencil flow, with the hopes that one day, they will all find their way home.

December 19, 2022 at 9:48 am #6352In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The Birmingham Bootmaker

Samuel Jones 1816-1875

Samuel Jones the elder was born in Belfast circa 1779. He is one of just two direct ancestors found thus far born in Ireland. Samuel married Jane Elizabeth Brooker (born in St Giles, London) on the 25th January 1807 at St George, Hanover Square in London. Their first child Mary was born in 1808 in London, and then the family moved to Birmingham. Mary was my 3x great grandmother.

But this chapter is about her brother Samuel Jones. I noticed that on a number of other trees on the Ancestry site, Samuel Jones was a convict transported to Australia, but this didn’t tally with the records I’d found for Samuel in Birmingham. In fact another Samuel Jones born at the same time in the same place was transported, but his occupation was a baker. Our Samuel Jones was a bootmaker like his father.

Samuel was born on 28th January 1816 in Birmingham and baptised at St Phillips on the 19th August of that year, the fourth child and first son of Samuel the elder and Jane’s eleven children.

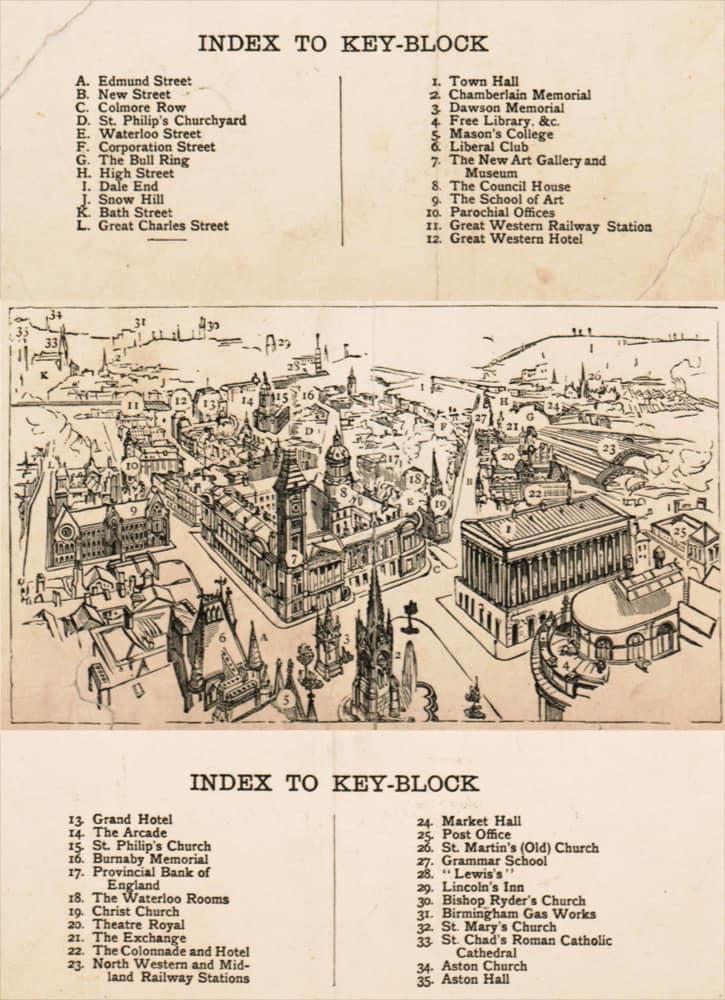

On the 1839 electoral register a Samuel Jones owned a property on Colmore Row, Birmingham.

Samuel Jones, bootmaker of 15, Colmore Row is listed in the 1849 Birmingham post office directory, and in the 1855 White’s Directory.

On the 1851 census, Samuel was an unmarried bootmaker employing sixteen men at 15, Colmore Row. A 9 year old nephew Henry Harris was living with him, and his mother Ruth Harris, as well as a female servant. Samuel’s sister Ruth was born in 1818 and married Henry Harris in 1840. Henry died in 1848.

Samuel was a 45 year old bootmaker at 15 Colmore Row on the 1861 census, living with Maria Walcot, a 26 year old domestic servant.

In October 1863 Samuel married Maria Walcot at St Philips in Birmingham. They don’t appear to have had any children as none appear on the 1871 census, where Samuel and Maria are living at the same address, with another female servant and two male lodgers by the name of Messant from Ipswich.

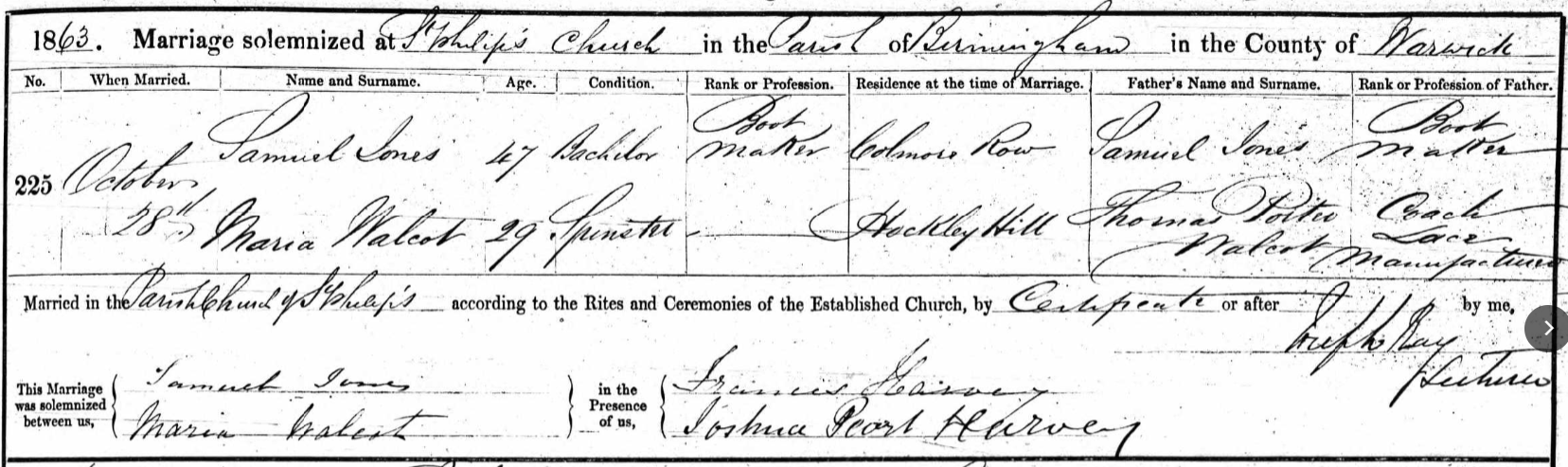

Marriage of Samuel Jones and Maria Walcot:

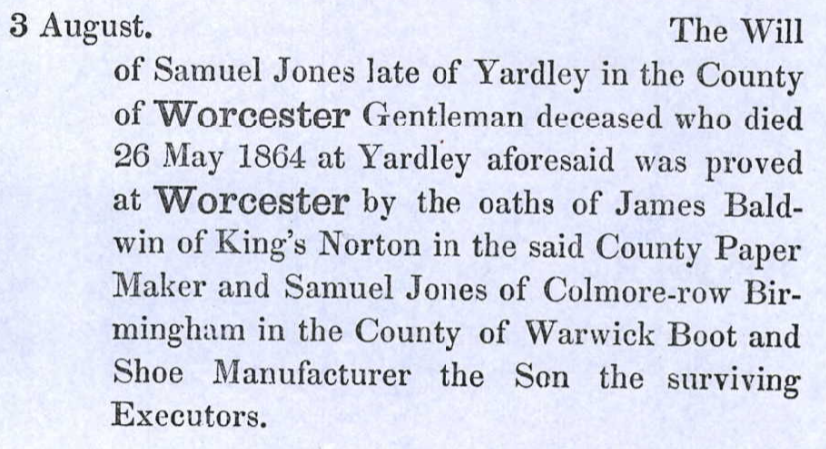

In 1864 Samuel’s father died. Samuel the son is mentioned in the probate records as one of the executors: “Samuel Jones of Colmore Row Birmingham in the county of Warwick boot and shoe manufacturer the son”.

Indeed it could hardly be clearer that this Samuel Jones was not the convict transported to Australia in 1834!

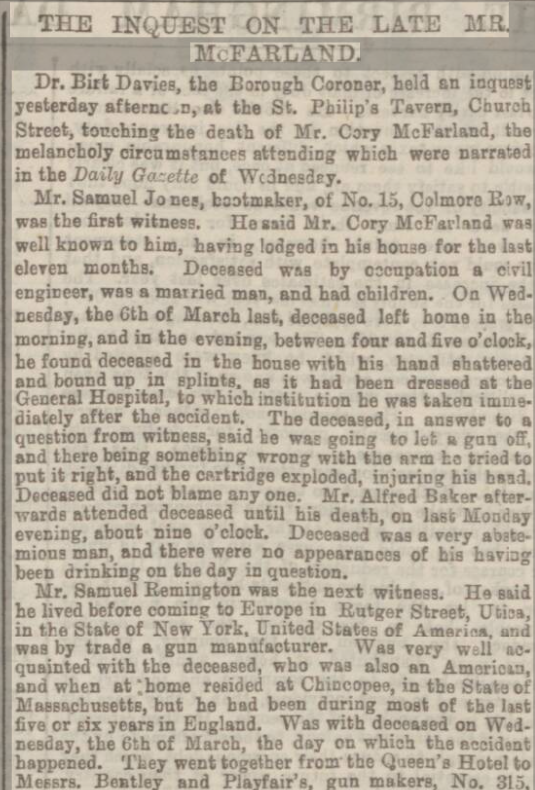

In 1867 Samuel Jones, bootmaker, was mentioned in the Birmingham Daily Gazette with regard to an unfortunate incident involving his American lodger, Cory McFarland. The verdict was accidental death.

Birmingham Daily Gazette – Friday 05 April 1867:

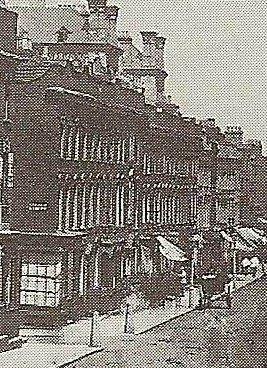

I asked a Birmingham history group for an old photo of Colmore Row. This photo is circa 1870 and number 15 is furthest from the camera. The businesses on the street at the time were as follows:

7 homeopathic chemist George John Morris. 8 surgeon dentist Frederick Sims. 9 Saul & Walter Samuel, Australian merchants. Surgeons occupied 10, pawnbroker John Aaron at 11 & 12. 15 boot & shoemaker. 17 auctioneer…

from Bird’s Eye View of Birmingham, 1886:

October 19, 2022 at 6:46 am #6336

October 19, 2022 at 6:46 am #6336In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

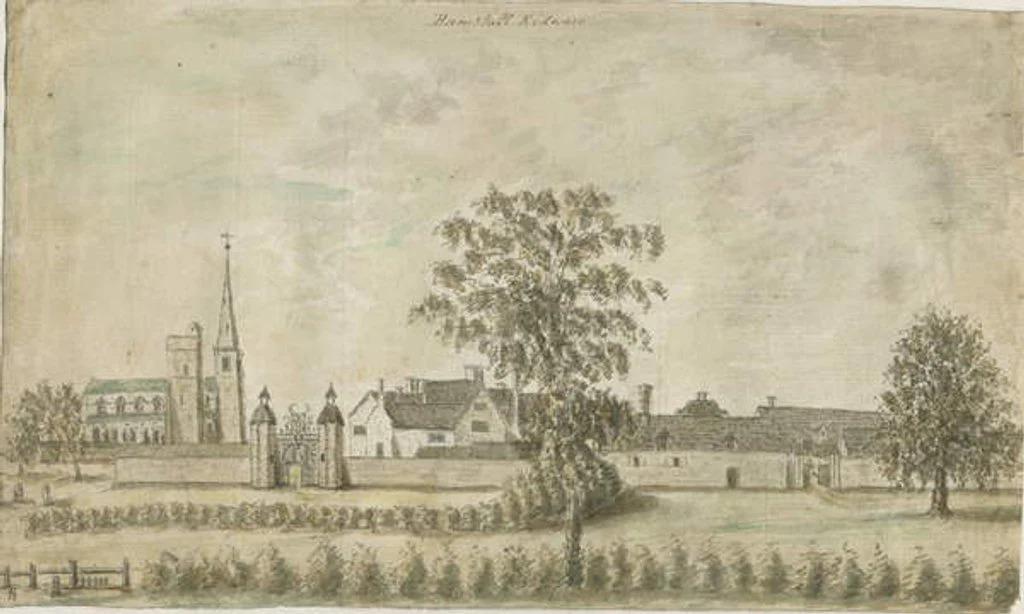

The Hamstall Ridware Connection

Stubbs and Woods

Hamstall Ridware

Hamstall RidwareCharles Tomlinson‘s (1847-1907) wife Emma Grattidge (1853-1911) was born in Wolverhampton, the daughter and youngest child of William Grattidge (1820-1887) born in Foston, Derbyshire, and Mary Stubbs (1819-1880), born in Burton on Trent, daughter of Solomon Stubbs.

Solomon Stubbs (1781-1857) was born in Hamstall Ridware in 1781, the son of Samuel and Rebecca. Samuel Stubbs (1743-) and Rebecca Wood (1754-) married in 1769 in Darlaston. Samuel and Rebecca had six other children, all born in Darlaston. Sadly four of them died in infancy. Son John was born in 1779 in Darlaston and died two years later in Hamstall Ridware in 1781, the same year that Solomon was born there.

But why did they move to Hamstall Ridware?

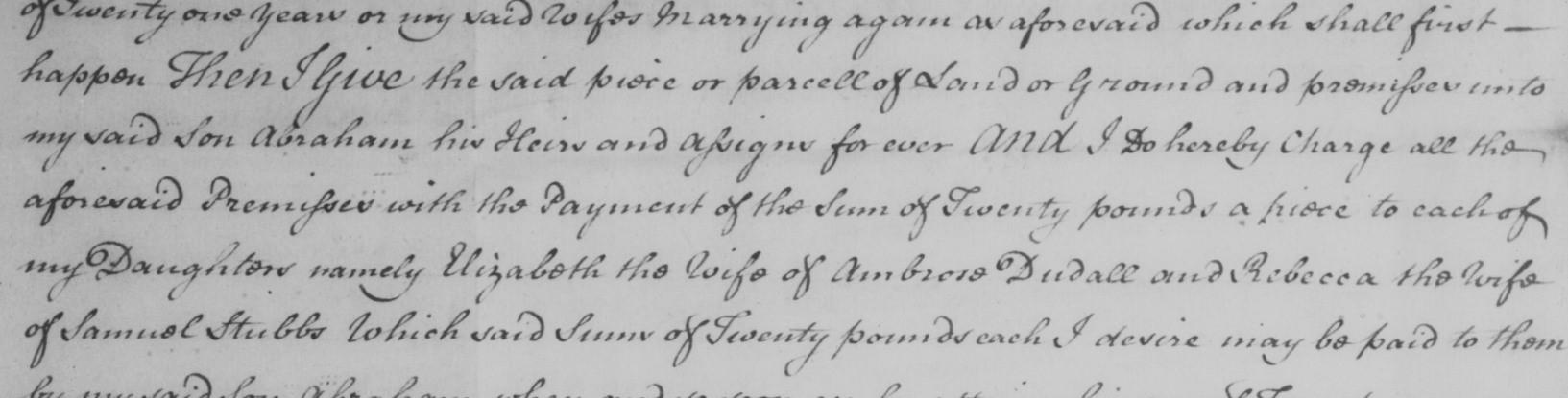

Samuel Stubbs was born in 1743 in Curdworth, Warwickshire (near to Birmingham). I had made a mistake on the tree (along with all of the public trees on the Ancestry website) and had Rebecca Wood born in Cheddleton, Staffordshire. Rebecca Wood from Cheddleton was also born in 1843, the right age for the marriage. The Rebecca Wood born in Darlaston in 1754 seemed too young, at just fifteen years old at the time of the marriage. I couldn’t find any explanation for why a woman from Cheddleton would marry in Darlaston and then move to Hamstall Ridware. People didn’t usually move around much other than intermarriage with neighbouring villages, especially women. I had a closer look at the Darlaston Rebecca, and did a search on her father William Wood. I found his 1784 will online in which he mentions his daughter Rebecca, wife of Samuel Stubbs. Clearly the right Rebecca Wood was the one born in Darlaston, which made much more sense.

An excerpt from William Wood’s 1784 will mentioning daughter Rebecca married to Samuel Stubbs:

But why did they move to Hamstall Ridware circa 1780?

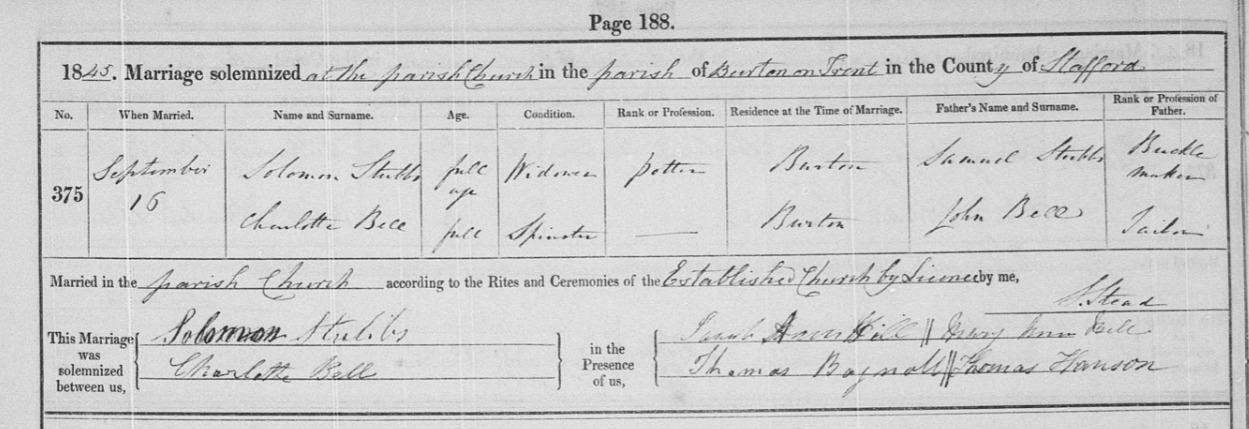

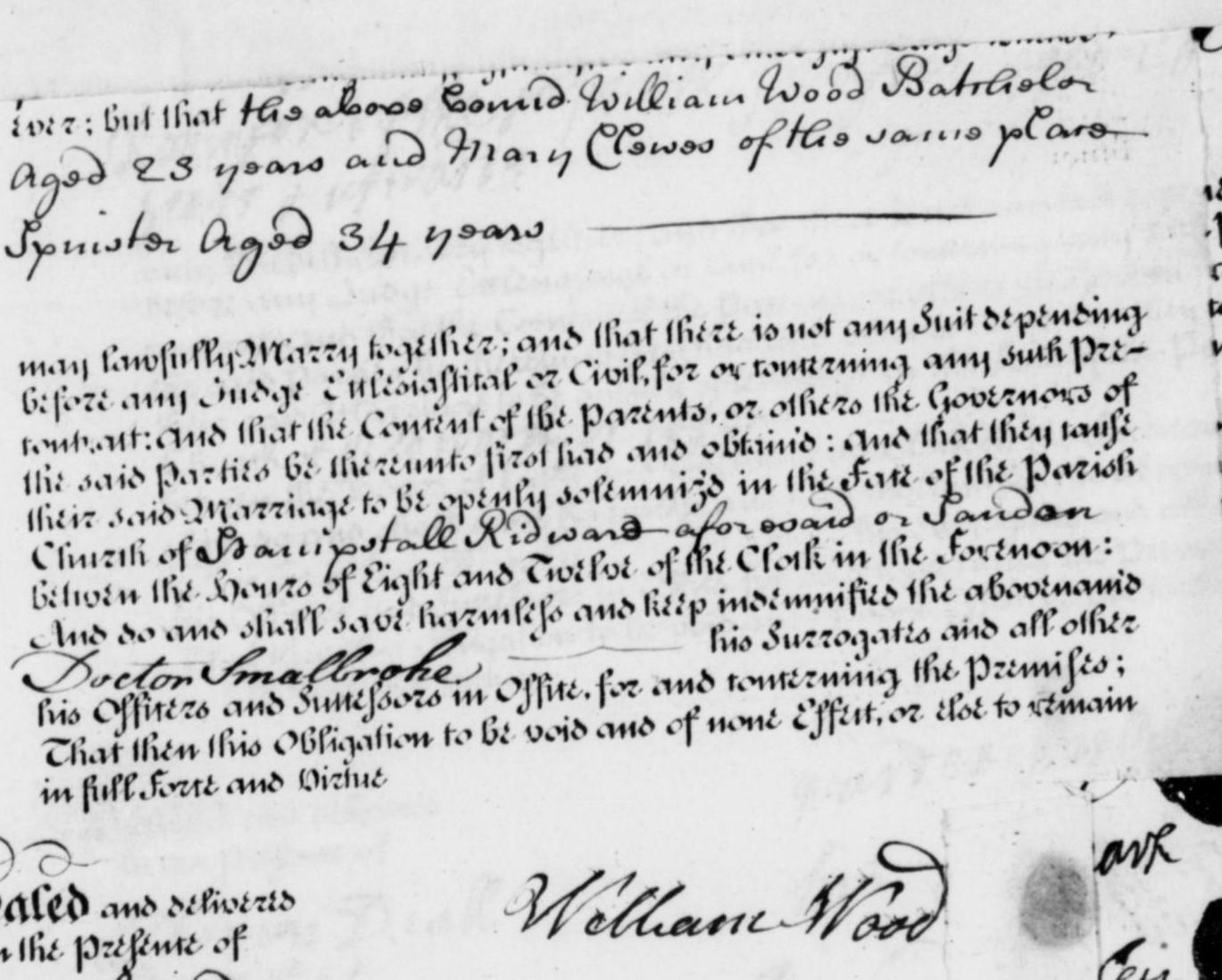

I had not intially noticed that Solomon Stubbs married again the year after his wife Phillis Lomas (1787-1844) died. Solomon married Charlotte Bell in 1845 in Burton on Trent and on the marriage register, Solomon’s father Samuel Stubbs occupation was mentioned: Samuel was a buckle maker.

Marriage of Solomon Stubbs and Charlotte Bell, father Samuel Stubbs buckle maker:

A rudimentary search on buckle making in the late 1700s provided a possible answer as to why Samuel and Rebecca left Darlaston in 1781. Shoe buckles had gone out of fashion, and by 1781 there were half as many buckle makers in Wolverhampton as there had been previously.

“Where there were 127 buckle makers at work in Wolverhampton, 68 in Bilston and 58 in Birmingham in 1770, their numbers had halved in 1781.”

via “historywebsite”(museum/metalware/steel)

Steel buckles had been the height of fashion, and the trade became enormous in Wolverhampton. Wolverhampton was a steel working town, renowned for its steel jewellery which was probably of many types. The trade directories show great numbers of “buckle makers”. Steel buckles were predominantly made in Wolverhampton: “from the late 1760s cut steel comes to the fore, from the thriving industry of the Wolverhampton area”. Bilston was also a great centre of buckle making, and other areas included Walsall. (It should be noted that Darlaston, Walsall, Bilston and Wolverhampton are all part of the same area)

In 1860, writing in defence of the Wolverhampton Art School, George Wallis talks about the cut steel industry in Wolverhampton. Referring to “the fine steel workers of the 17th and 18th centuries” he says: “Let them remember that 100 years ago [sc. c. 1760] a large trade existed with France and Spain in the fine steel goods of Birmingham and Wolverhampton, of which the latter were always allowed to be the best both in taste and workmanship. … A century ago French and Spanish merchants had their houses and agencies at Birmingham for the purchase of the steel goods of Wolverhampton…..The Great Revolution in France put an end to the demand for fine steel goods for a time and hostile tariffs finished what revolution began”.

The next search on buckle makers, Wolverhampton and Hamstall Ridware revealed an unexpected connecting link.

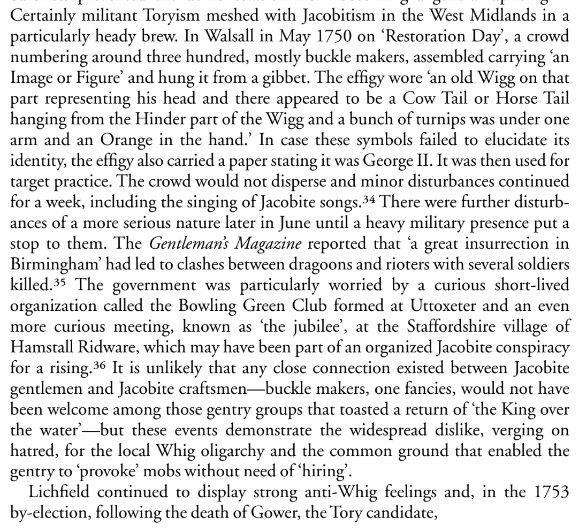

In Riotous Assemblies: Popular Protest in Hanoverian England by Adrian Randall:

In Walsall in 1750 on “Restoration Day” a crowd numbering 300 assembled, mostly buckle makers, singing Jacobite songs and other rebellious and riotous acts. The government was particularly worried about a curious meeting known as the “Jubilee” in Hamstall Ridware, which may have been part of a conspiracy for a Jacobite uprising.

But this was thirty years before Samuel and Rebecca moved to Hamstall Ridware and does not help to explain why they moved there around 1780, although it does suggest connecting links.

Rebecca’s father, William Wood, was a brickmaker. This was stated at the beginning of his will. On closer inspection of the will, he was a brickmaker who owned four acres of brick kilns, as well as dwelling houses, shops, barns, stables, a brewhouse, a malthouse, cattle and land.

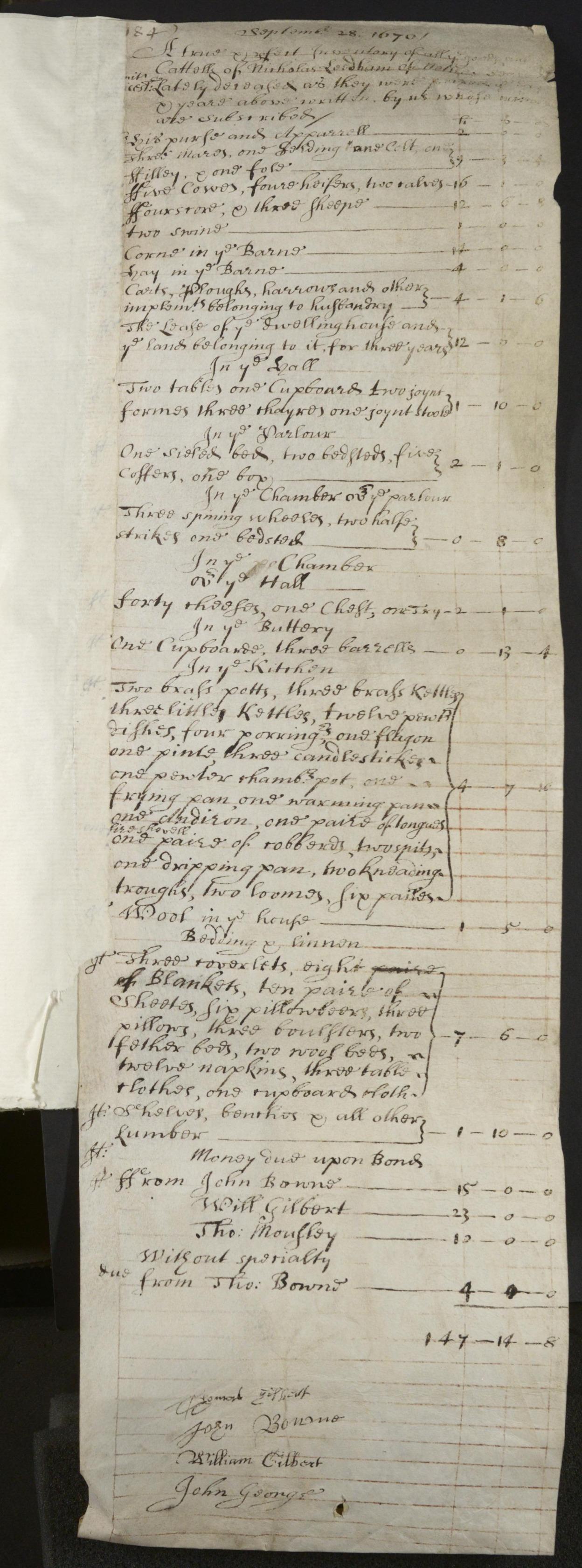

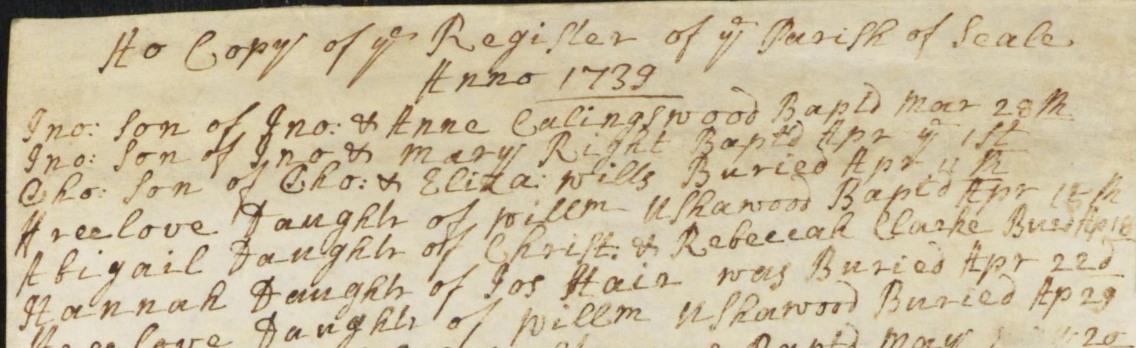

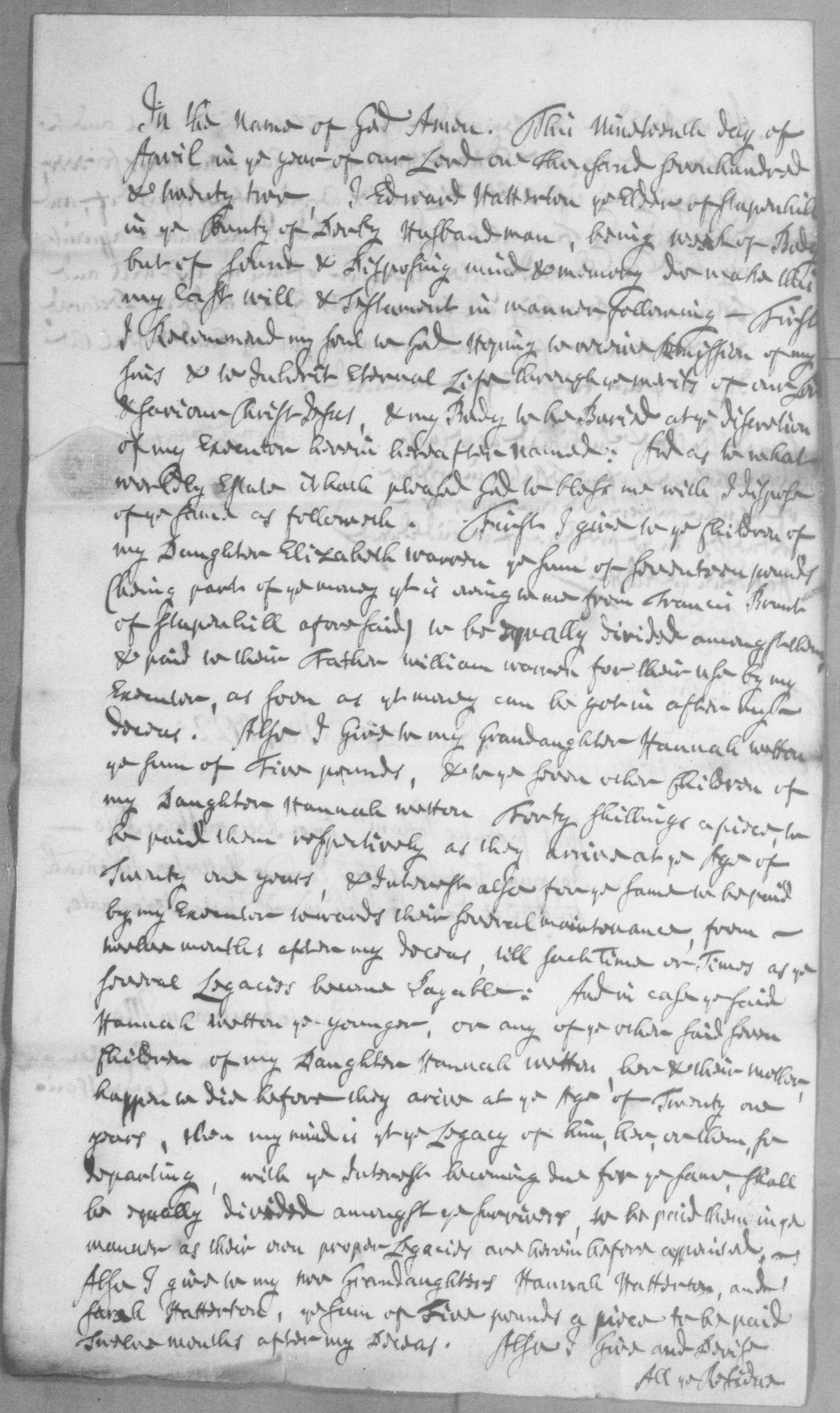

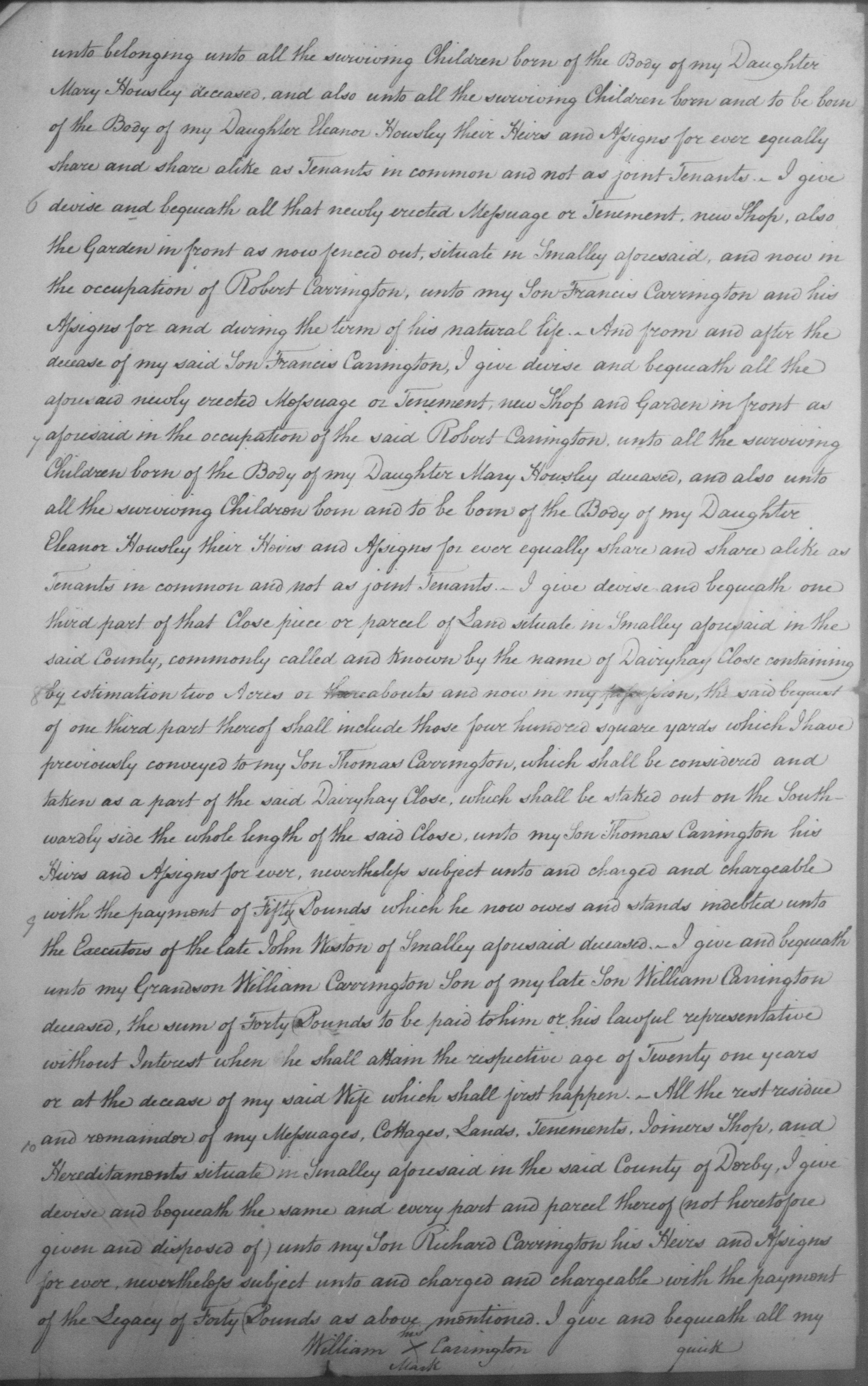

A page from the 1784 will of William Wood:

The 1784 will of William Wood of Darlaston:

I William Wood the elder of Darlaston in the county of Stafford, brickmaker, being of sound and disposing mind memory and understanding (praised be to god for the same) do make publish and declare my last will and testament in manner and form following (that is to say) {after debts and funeral expense paid etc} I give to my loving wife Mary the use usage wear interest and enjoyment of all my goods chattels cattle stock in trade ~ money securities for money personal estate and effects whatsoever and wheresoever to hold unto her my said wife for and during the term of her natural life providing she so long continues my widow and unmarried and from or after her decease or intermarriage with any future husband which shall first happen.

Then I give all the said goods chattels cattle stock in trade money securites for money personal estate and effects unto my son Abraham Wood absolutely and forever. Also I give devise and bequeath unto my said wife Mary all that my messuages tenement or dwelling house together with the malthouse brewhouse barn stableyard garden and premises to the same belonging situate and being at Darlaston aforesaid and now in my own possession. Also all that messuage tenement or dwelling house together with the shop garden and premises with the appurtenances to the same ~ belonging situate in Darlaston aforesaid and now in the several holdings or occupation of George Knowles and Edward Knowles to hold the aforesaid premises and every part thereof with the appurtenances to my said wife Mary for and during the term of her natural life provided she so long continues my widow and unmarried. And from or after her decease or intermarriage with a future husband which shall first happen. Then I give and devise the aforesaid premises and every part thereof with the appurtenances unto my said son Abraham Wood his heirs and assigns forever.

Also I give unto my said wife all that piece or parcel of land or ground inclosed and taken out of Heath Field in the parish of Darlaston aforesaid containing four acres or thereabouts (be the same more or less) upon which my brick kilns erected and now in my own possession. To hold unto my said wife Mary until my said son Abraham attains his age of twenty one years if she so long continues my widow and unmarried as aforesaid and from and immediately after my said son Abraham attaining his age of twenty one years or my said wife marrying again as aforesaid which shall first happen then I give the said piece or parcel of land or ground and premises unto my said son Abraham his heirs and assigns forever.

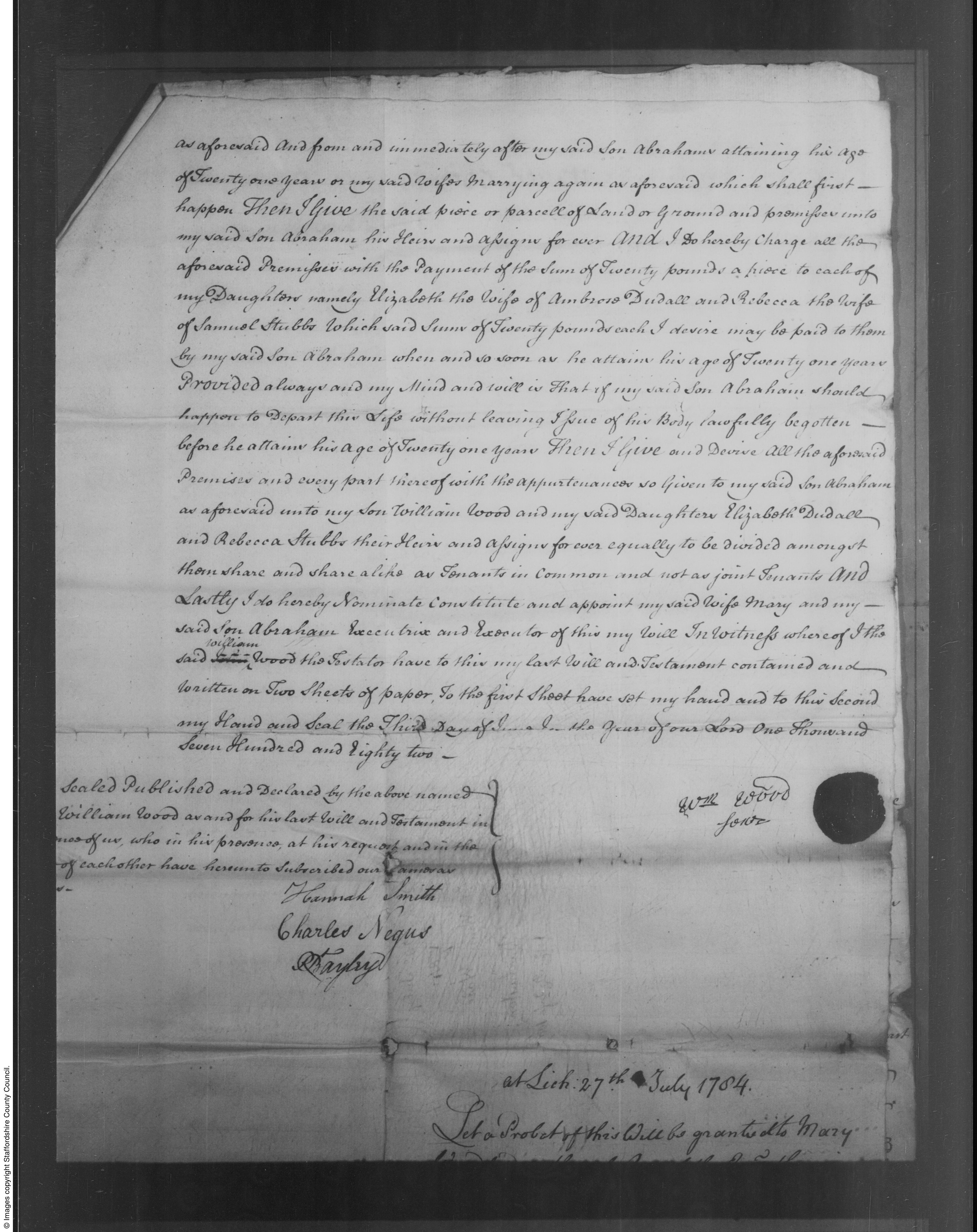

And I do hereby charge all the aforesaid premises with the payment of the sum of twenty pounds a piece to each of my daughters namely Elizabeth the wife of Ambrose Dudall and Rebecca the wife of Samuel Stubbs which said sum of twenty pounds each I devise may be paid to them by my said son Abraham when and so soon as he attains his age of twenty one years provided always and my mind and will is that if my said son Abraham should happen to depart this life without leaving issue of his body lawfully begotten before he attains his age of twenty one years then I give and devise all the aforesaid premises and every part thereof with the appurtenances so given to my said son Abraham as aforesaid unto my said son William Wood and my said daughter Elizabeth Dudall and Rebecca Stubbs their heirs and assigns forever equally divided among them share and share alike as tenants in common and not as joint tenants. And lastly I do hereby nominate constitute and appoint my said wife Mary and my said son Abraham executrix and executor of this my will.

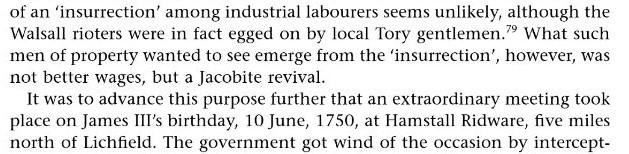

The marriage of William Wood (1725-1784) and Mary Clews (1715-1798) in 1749 was in Hamstall Ridware.

Mary was eleven years Williams senior, and it appears that they both came from Hamstall Ridware and moved to Darlaston after they married. Clearly Rebecca had extended family there (notwithstanding any possible connecting links between the Stubbs buckle makers of Darlaston and the Hamstall Ridware Jacobites thirty years prior). When the buckle trade collapsed in Darlaston, they likely moved to find employment elsewhere, perhaps with the help of Rebecca’s family.

I have not yet been able to find deaths recorded anywhere for either Samuel or Rebecca (there are a couple of deaths recorded for a Samuel Stubbs, one in 1809 in Wolverhampton, and one in 1810 in Birmingham but impossible to say which, if either, is the right one with the limited information, and difficult to know if they stayed in the Hamstall Ridware area or perhaps moved elsewhere)~ or find a reason for their son Solomon to be in Burton upon Trent, an evidently prosperous man with several properties including an earthenware business, as well as a land carrier business.

September 21, 2022 at 1:25 pm #6331In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Whitesmiths of Baker Street

The Fishers of Wolverhampton

My fathers mother was Margaret Tomlinson born in 1913, the youngest but one daughter of Charles Tomlinson and Nellie Fisher of Wolverhampton.

Nellie Fisher was born in 1877. Her parents were William Fisher and Mary Ann Smith.

William Fisher born in 1834 was a whitesmith on Baker St on the 1881 census; Nellie was 3 years old. Nellie was his youngest daughter.

William was a whitesmith (or screw maker) on all of the censuses but in 1901 whitesmith was written for occupation, then crossed out and publican written on top. This was on Duke St, so I searched for William Fisher licensee on longpull black country pubs website and he was licensee of The Old Miners Arms on Duke St in 1896. The pub closed in 1906 and no longer exists. He was 67 in 1901 and just he and wife Mary Ann were at that address.

In 1911 he was a widower living alone in Upper Penn. Nellie and Charles Tomlinson were also living in Upper Penn on the 1911 census, and my grandmother was born there in 1913.

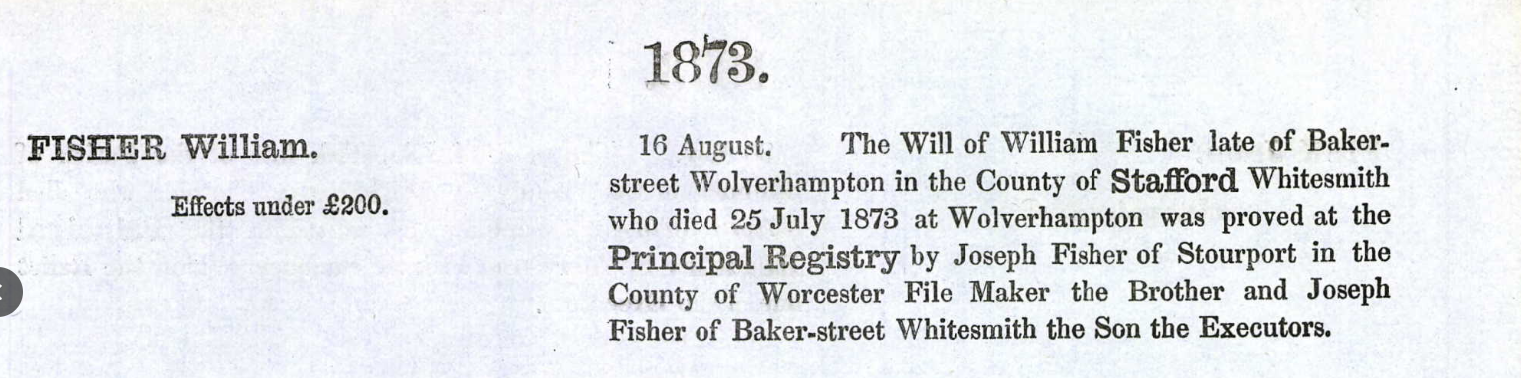

William’s father William Fisher born in 1792, Nellie’s grandfather, was a whitesmith on Baker St on the 1861 census employing 4 boys, 2 men, 3 girls. He died in 1873.

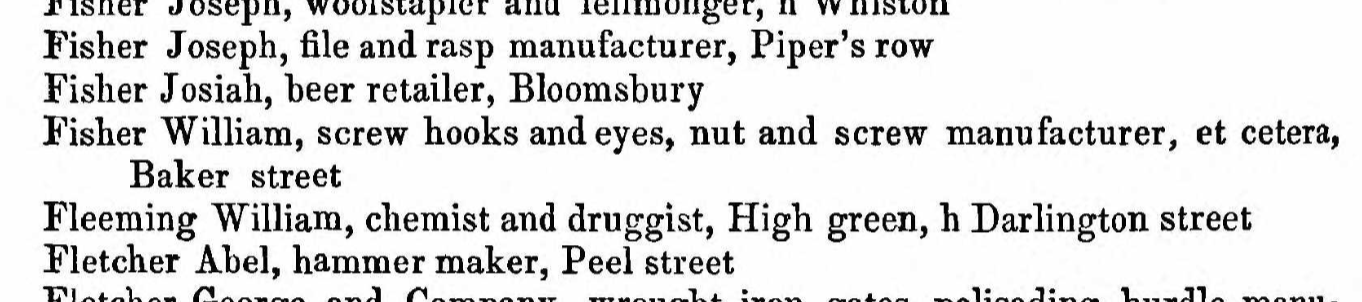

William Fisher the elder appears in a number of directories including this one:

1851 Melville & Co´s Directory of Wolverhampton

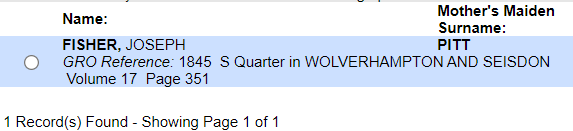

I noticed that all the other ancestry trees (as did my fathers cousin on the Tomlinson side) had MARY LUNN from Birmingham in Warwickshire marrying William Fisher the elder in 1828. But on ALL of the censuses, Mary’s place of birth was Staffordshire, and on one it said Bilston. I found another William Fisher and Mary marriage in Sedgley in 1829, MARY PITT.

You can order a birth certificate from the records office with mothers maiden name on, but only after 1837. So I looked for Williams younger brother Joseph, born 1845. His mothers maiden name was Pitt. July 6, 2022 at 11:05 am #6312

July 6, 2022 at 11:05 am #6312In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

When she’d heard of the miracle happening at the Flovlinden Tree, Egna initially shrugged it off as another conman’s attempt at fooling the crowds.

“No, it’s real, my Auntie saw it.”

“Stop fretting” she’d told the little girl, as she was carefully removing the lice from her hair. “This is just someone’s idea of a smart joke. Don’t get fooled, you’re smarter than this.”

She sure wasn’t responsible for that one. If that were a true miracle, she would have known. The little calf next week being resuscitated after being dead a few minutes, well, that was her. Shame nobody was even there to notice. Most of the best miracles go about this way anyway.

So, after having lived close to a millennia in relatively rock solid health and with surprisingly unaging looks, Egna had thought she’d seen it all; at least last time the tree started to ooze sacred oil, it didn’t last for too long, people’s greed starting to sell it stopped it right in its tracks.

But maybe there was more to it this time. Egna’d often wondered why God had let her live that long. She was a useful instrument to Her for sure, but living in secrecy, claiming no ownership, most miracles were just facts of life. She somehow failed to see the point, even after 957 years of existence.

The little girl had left to go back to her nearby town. This side of the country was still quite safe from all the craziness. Egna knew well most of the branches of the ancestral trees leading to that particular little leaf. This one had probably no idea she shared a common ancestor with President Voldomeer, but Egna remembered the fellow. He was a clogmaker in the turn of the 18th century, as was his father before. That was until a rather unexpected turn of events precipitated him to a different path as his brother.

She had a book full of these records, as she’d tracked the lives of many, to keep them alive, and maybe remind people they all share so much in common. That is, if people were able to remember more than 2 generations before them.

“Well, that’s set.” she said to herself and to Her as She’s always listening “I’ll go and see for myself.”

her trusty old musty cloak at the door seemed to have been begging for the journey.July 1, 2022 at 9:51 am #6306In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Looking for Robert Staley

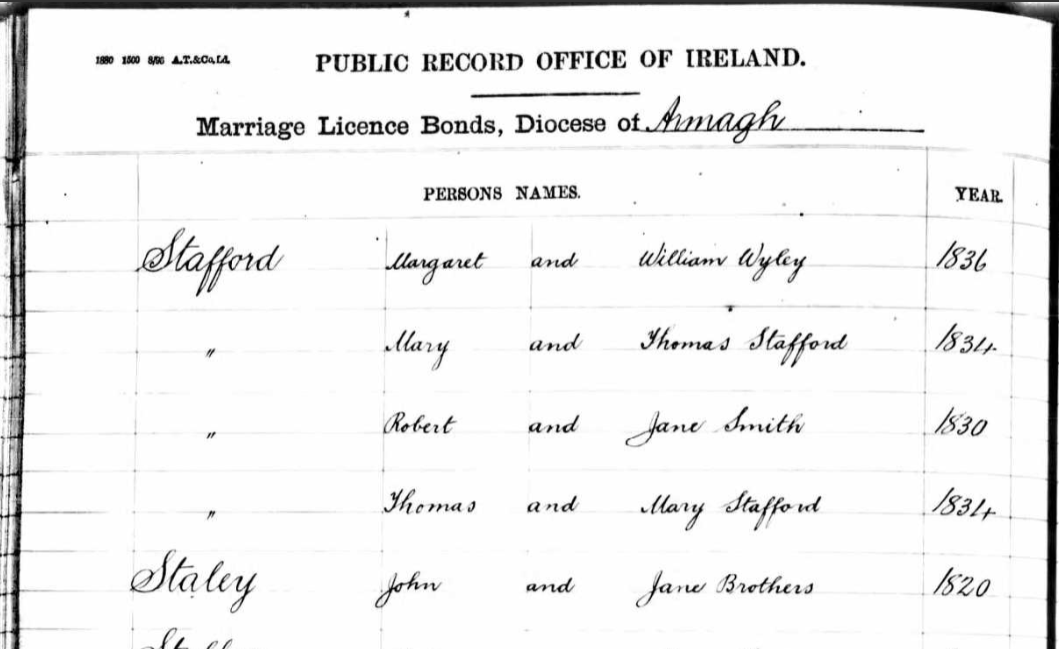

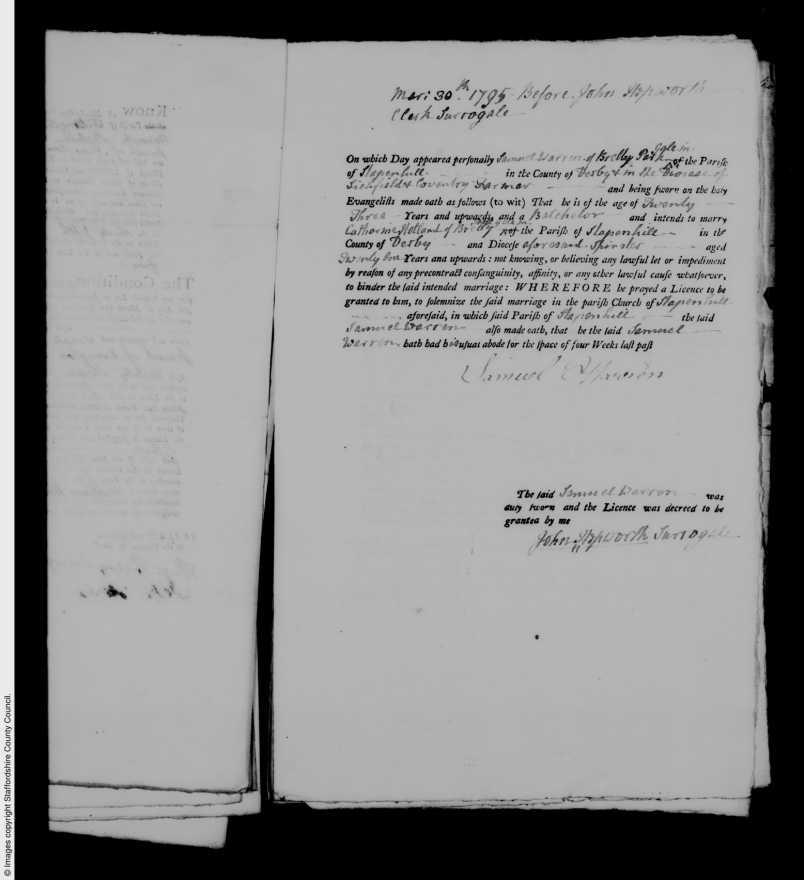

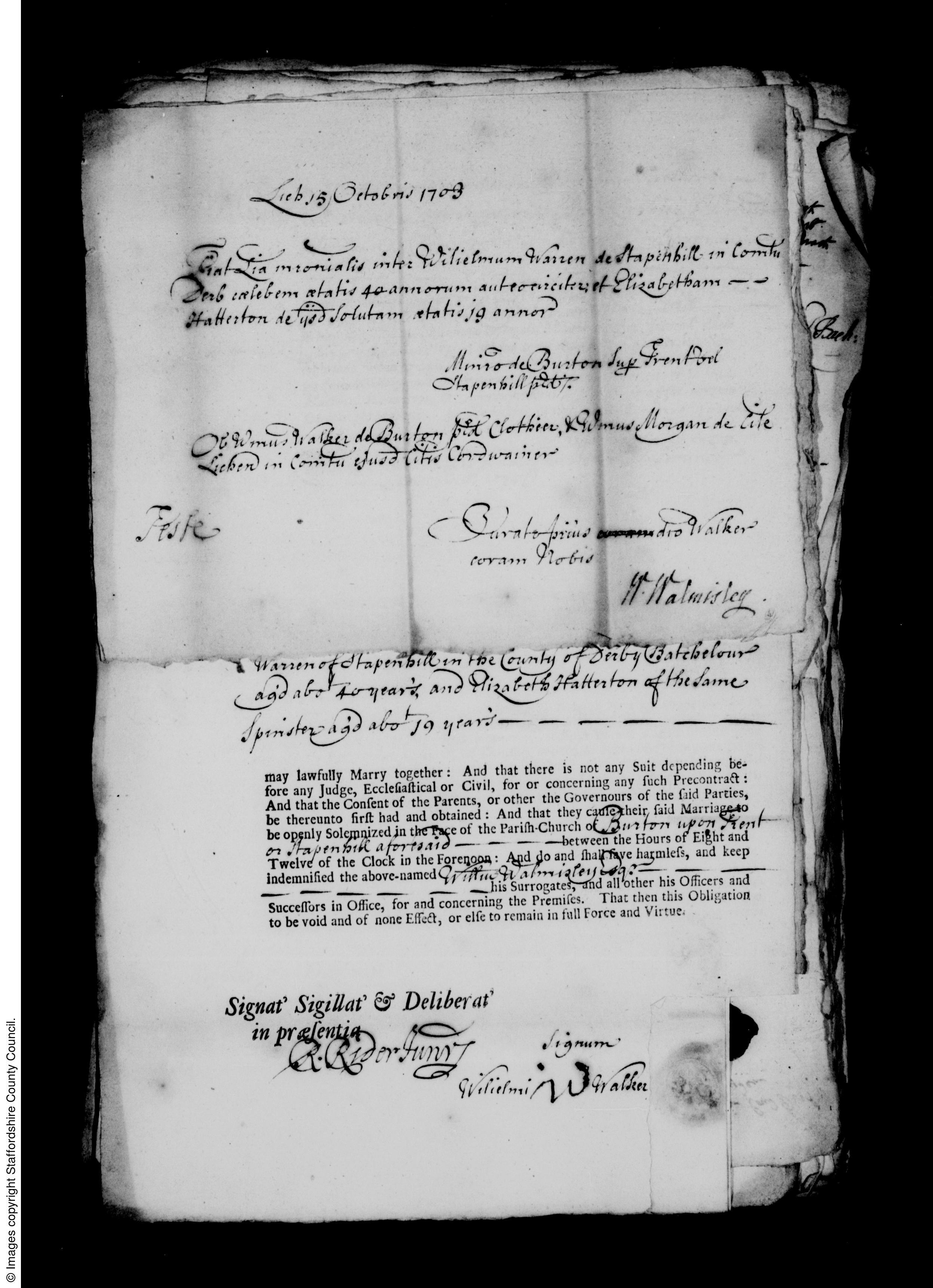

William Warren (1835-1880) of Newhall (Stapenhill) married Elizabeth Staley (1836-1907) in 1858. Elizabeth was born in Newhall, the daughter of John Staley (1795-1876) and Jane Brothers. John was born in Newhall, and Jane was born in Armagh, Ireland, and they were married in Armagh in 1820. Elizabeths older brothers were born in Ireland: William in 1826 and Thomas in Dublin in 1830. Francis was born in Liverpool in 1834, and then Elizabeth in Newhall in 1836; thereafter the children were born in Newhall.

Marriage of John Staley and Jane Brothers in 1820:

My grandmother related a story about an Elizabeth Staley who ran away from boarding school and eloped to Ireland, but later returned. The only Irish connection found so far is Jane Brothers, so perhaps she meant Elizabeth Staley’s mother. A boarding school seems unlikely, and it would seem that it was John Staley who went to Ireland.

The 1841 census states Jane’s age as 33, which would make her just 12 at the time of her marriage. The 1851 census states her age as 44, making her 13 at the time of her 1820 marriage, and the 1861 census estimates her birth year as a more likely 1804. Birth records in Ireland for her have not been found. It’s possible, perhaps, that she was in service in the Newhall area as a teenager (more likely than boarding school), and that John and Jane ran off to get married in Ireland, although I haven’t found any record of a child born to them early in their marriage. John was an agricultural labourer, and later a coal miner.

John Staley was the son of Joseph Staley (1756-1838) and Sarah Dumolo (1764-). Joseph and Sarah were married by licence in Newhall in 1782. Joseph was a carpenter on the marriage licence, but later a collier (although not necessarily a miner).

The Derbyshire Record Office holds records of an “Estimate of Joseph Staley of Newhall for the cost of continuing to work Pisternhill Colliery” dated 1820 and addresssed to Mr Bloud at Calke Abbey (presumably the owner of the mine)

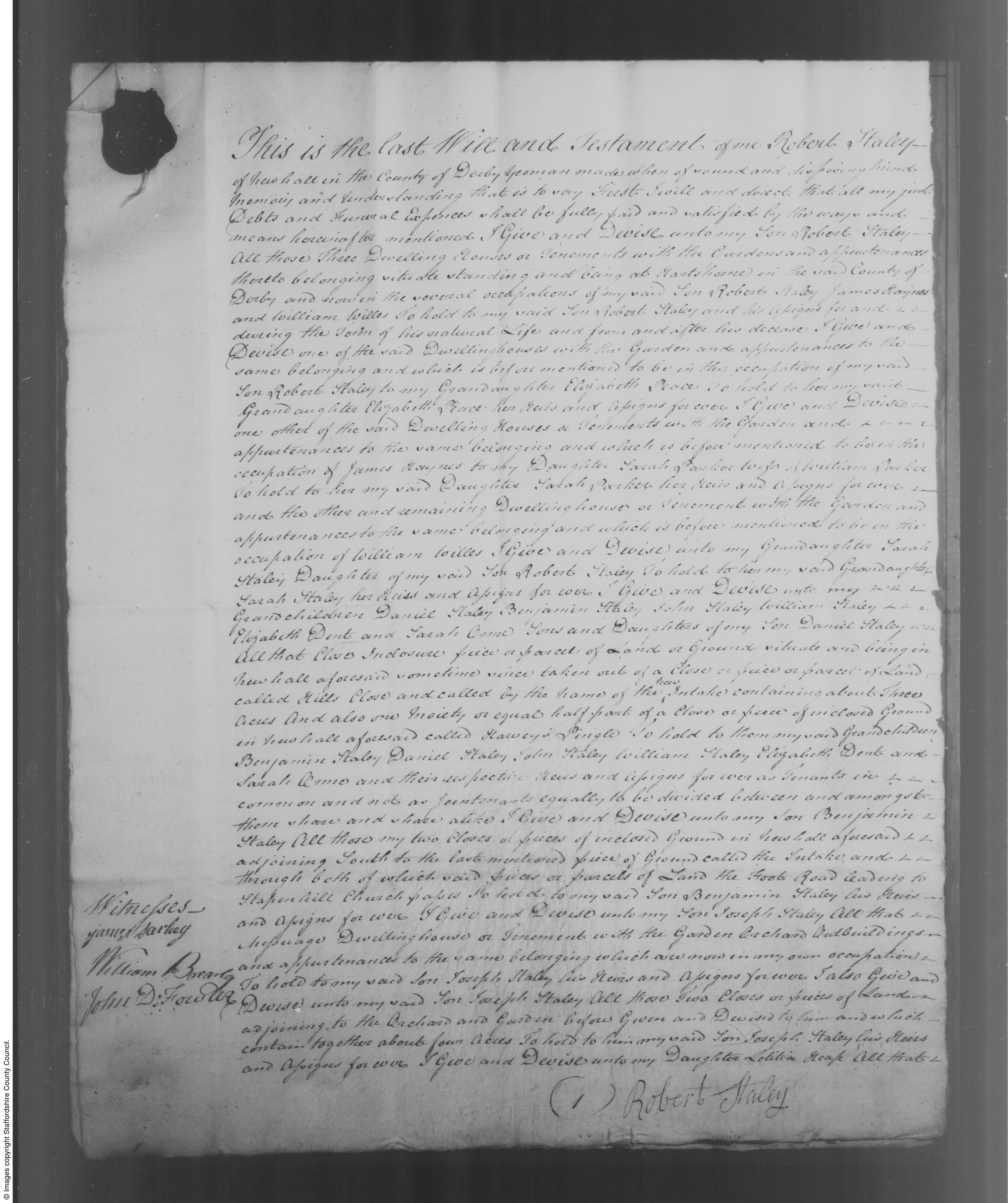

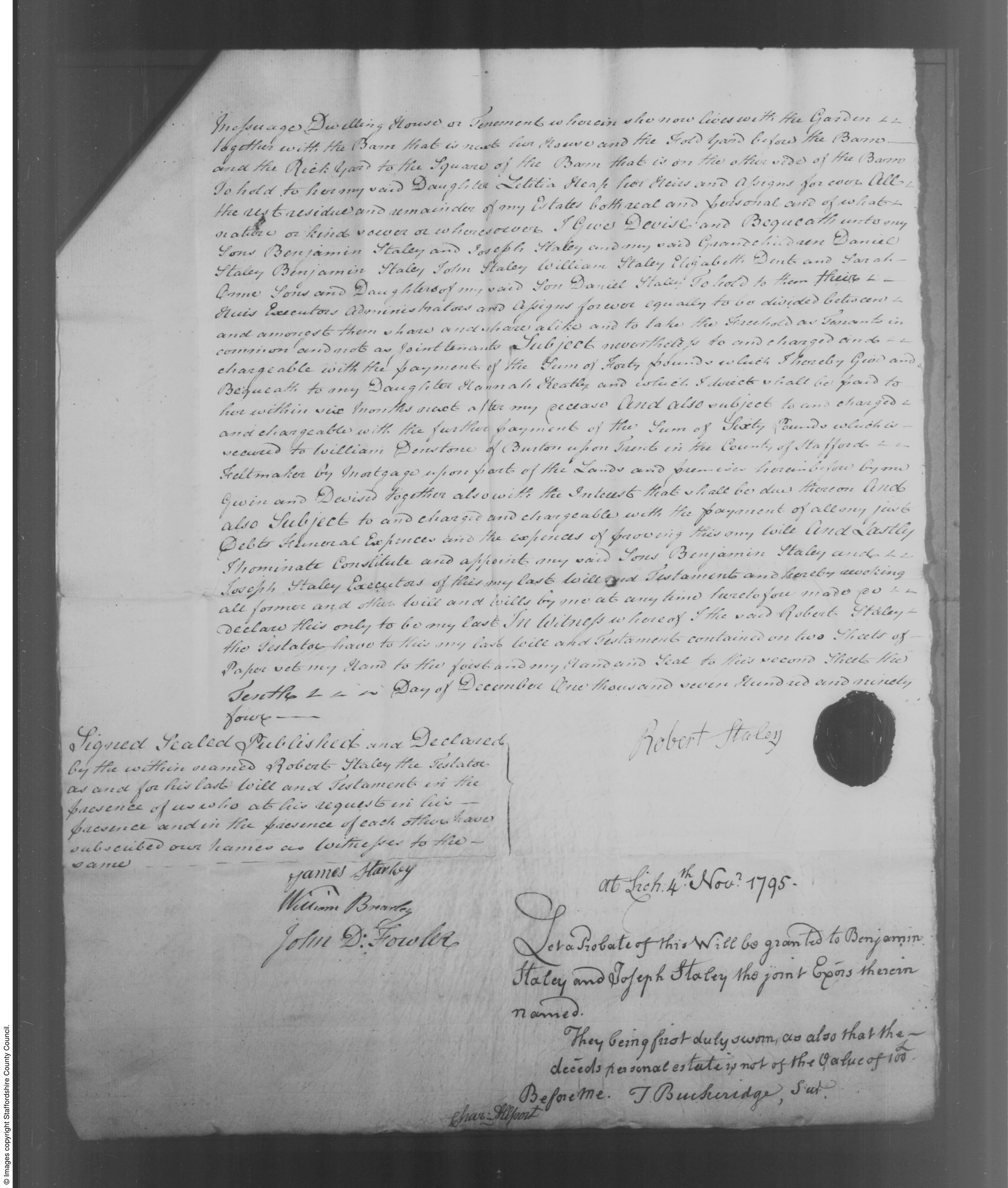

Josephs parents were Robert Staley and Elizabeth. I couldn’t find a baptism or birth record for Robert Staley. Other trees on an ancestry site had his birth in Elton, but with no supporting documents. Robert, as stated in his 1795 will, was a Yeoman.

“Yeoman: A former class of small freeholders who farm their own land; a commoner of good standing.”

“Husbandman: The old word for a farmer below the rank of yeoman. A husbandman usually held his land by copyhold or leasehold tenure and may be regarded as the ‘average farmer in his locality’. The words ‘yeoman’ and ‘husbandman’ were gradually replaced in the later 18th and 19th centuries by ‘farmer’.”He left a number of properties in Newhall and Hartshorne (near Newhall) including dwellings, enclosures, orchards, various yards, barns and acreages. It seemed to me more likely that he had inherited them, rather than moving into the village and buying them.

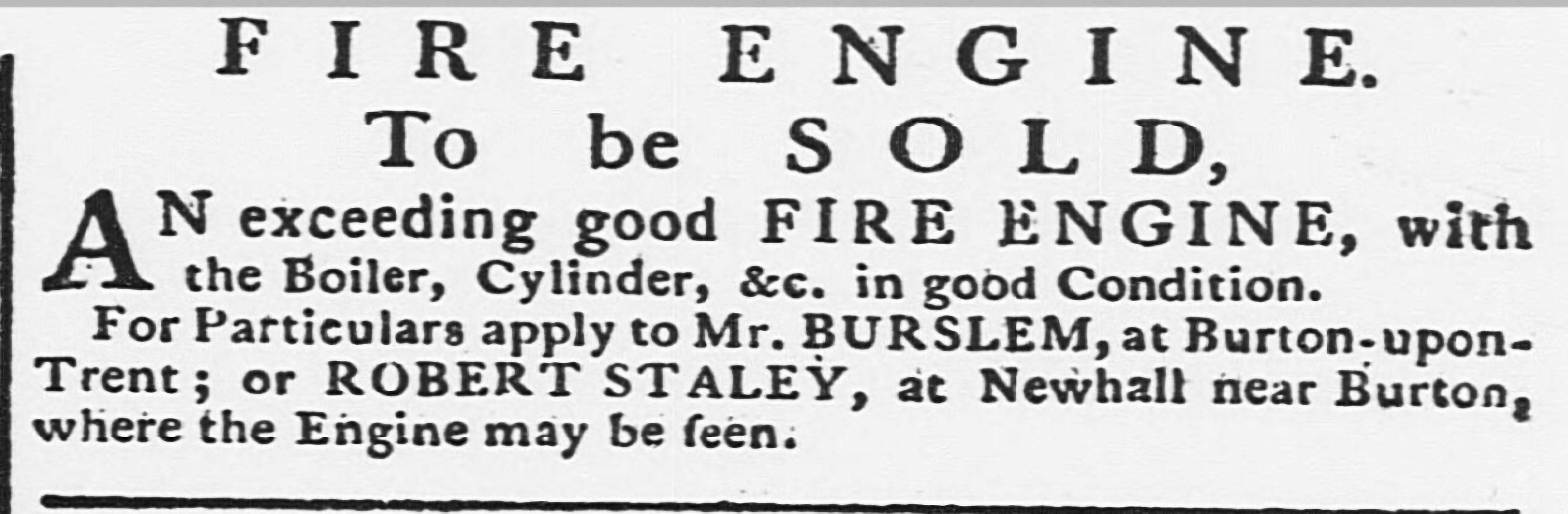

There is a mention of Robert Staley in a 1782 newpaper advertisement.

“Fire Engine To Be Sold. An exceedingly good fire engine, with the boiler, cylinder, etc in good condition. For particulars apply to Mr Burslem at Burton-upon-Trent, or Robert Staley at Newhall near Burton, where the engine may be seen.”

Was the fire engine perhaps connected with a foundry or a coal mine?

I noticed that Robert Staley was the witness at a 1755 marriage in Stapenhill between Barbara Burslem and Richard Daston the younger esquire. The other witness was signed Burslem Jnr.

Looking for Robert Staley

I assumed that once again, in the absence of the correct records, a similarly named and aged persons baptism had been added to the tree regardless of accuracy, so I looked through the Stapenhill/Newhall parish register images page by page. There were no Staleys in Newhall at all in the early 1700s, so it seemed that Robert did come from elsewhere and I expected to find the Staleys in a neighbouring parish. But I still didn’t find any Staleys.

I spoke to a couple of Staley descendants that I’d met during the family research. I met Carole via a DNA match some months previously and contacted her to ask about the Staleys in Elton. She also had Robert Staley born in Elton (indeed, there were many Staleys in Elton) but she didn’t have any documentation for his birth, and we decided to collaborate and try and find out more.

I couldn’t find the earlier Elton parish registers anywhere online, but eventually found the untranscribed microfiche images of the Bishops Transcripts for Elton.

via familysearch:

“In its most basic sense, a bishop’s transcript is a copy of a parish register. As bishop’s transcripts generally contain more or less the same information as parish registers, they are an invaluable resource when a parish register has been damaged, destroyed, or otherwise lost. Bishop’s transcripts are often of value even when parish registers exist, as priests often recorded either additional or different information in their transcripts than they did in the original registers.”Unfortunately there was a gap in the Bishops Transcripts between 1704 and 1711 ~ exactly where I needed to look. I subsequently found out that the Elton registers were incomplete as they had been damaged by fire.

I estimated Robert Staleys date of birth between 1710 and 1715. He died in 1795, and his son Daniel died in 1805: both of these wills were found online. Daniel married Mary Moon in Stapenhill in 1762, making a likely birth date for Daniel around 1740.

The marriage of Robert Staley (assuming this was Robert’s father) and Alice Maceland (or Marsland or Marsden, depending on how the parish clerk chose to spell it presumably) was in the Bishops Transcripts for Elton in 1704. They were married in Elton on 26th February. There followed the missing parish register pages and in all likelihood the records of the baptisms of their first children. No doubt Robert was one of them, probably the first male child.

(Incidentally, my grandfather’s Marshalls also came from Elton, a small Derbyshire village near Matlock. The Staley’s are on my grandmothers Warren side.)

The parish register pages resume in 1711. One of the first entries was the baptism of Robert Staley in 1711, parents Thomas and Ann. This was surely the one we were looking for, and Roberts parents weren’t Robert and Alice.

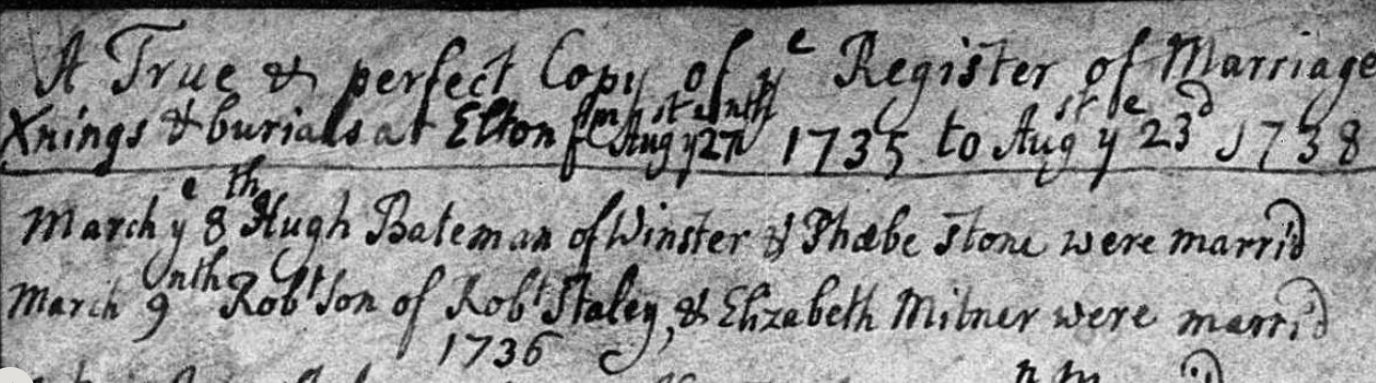

But then in 1735 a marriage was recorded between Robert son of Robert Staley (and this was unusual, the father of the groom isn’t usually recorded on the parish register) and Elizabeth Milner. They were married on the 9th March 1735. We know that the Robert we were looking for married an Elizabeth, as her name was on the Stapenhill baptisms of their later children, including Joseph Staleys. The 1735 marriage also fit with the assumed birth date of Daniel, circa 1740. A baptism was found for a Robert Staley in 1738 in the Elton registers, parents Robert and Elizabeth, as well as the baptism in 1736 for Mary, presumably their first child. Her burial is recorded the following year.

The marriage of Robert Staley and Elizabeth Milner in 1735:

There were several other Staley couples of a similar age in Elton, perhaps brothers and cousins. It seemed that Thomas and Ann’s son Robert was a different Robert, and that the one we were looking for was prior to that and on the missing pages.

Even so, this doesn’t prove that it was Elizabeth Staleys great grandfather who was born in Elton, but no other birth or baptism for Robert Staley has been found. It doesn’t explain why the Staleys moved to Stapenhill either, although the Enclosures Act and the Industrial Revolution could have been factors.

The 18th century saw the rise of the Industrial Revolution and many renowned Derbyshire Industrialists emerged. They created the turning point from what was until then a largely rural economy, to the development of townships based on factory production methods.

The Marsden Connection

There are some possible clues in the records of the Marsden family. Robert Staley married Alice Marsden (or Maceland or Marsland) in Elton in 1704. Robert Staley is mentioned in the 1730 will of John Marsden senior, of Baslow, Innkeeper (Peacock Inne & Whitlands Farm). He mentions his daughter Alice, wife of Robert Staley.

In a 1715 Marsden will there is an intriguing mention of an alias, which might explain the different spellings on various records for the name Marsden: “MARSDEN alias MASLAND, Christopher – of Baslow, husbandman, 28 Dec 1714. son Robert MARSDEN alias MASLAND….” etc.

Some potential reasons for a move from one parish to another are explained in this history of the Marsden family, and indeed this could relate to Robert Staley as he married into the Marsden family and his wife was a beneficiary of a Marsden will. The Chatsworth Estate, at various times, bought a number of farms in order to extend the park.

THE MARSDEN FAMILY

OXCLOSE AND PARKGATE

In the Parishes of

Baslow and Chatsworthby

David Dalrymple-Smith“John Marsden (b1653) another son of Edmund (b1611) faired well. By the time he died in

1730 he was publican of the Peacock, the Inn on Church Lane now called the Cavendish

Hotel, and the farmer at “Whitlands”, almost certainly Bubnell Cliff Farm.”“Coal mining was well known in the Chesterfield area. The coalfield extends as far as the

Gritstone edges, where thin seams outcrop especially in the Baslow area.”“…the occupants were evicted from the farmland below Dobb Edge and

the ground carefully cleared of all traces of occupation and farming. Shelter belts were

planted especially along the Heathy Lea Brook. An imposing new drive was laid to the

Chatsworth House with the Lodges and “The Golden Gates” at its northern end….”Although this particular event was later than any events relating to Robert Staley, it’s an indication of how farms and farmland disappeared, and a reason for families to move to another area:

“The Dukes of Devonshire (of Chatsworth) were major figures in the aristocracy and the government of the

time. Such a position demanded a display of wealth and ostentation. The 6th Duke of

Devonshire, the Bachelor Duke, was not content with the Chatsworth he inherited in 1811,

and immediately started improvements. After major changes around Edensor, he turned his

attention at the north end of the Park. In 1820 plans were made extend the Park up to the

Baslow parish boundary. As this would involve the destruction of most of the Farm at

Oxclose, the farmer at the Higher House Samuel Marsden (b1755) was given the tenancy of

Ewe Close a large farm near Bakewell.

Plans were revised in 1824 when the Dukes of Devonshire and Rutland “Exchanged Lands”,

reputedly during a game of dice. Over 3300 acres were involved in several local parishes, of

which 1000 acres were in Baslow. In the deal Devonshire acquired the southeast corner of

Baslow Parish.

Part of the deal was Gibbet Moor, which was developed for “Sport”. The shelf of land

between Parkgate and Robin Hood and a few extra fields was left untouched. The rest,

between Dobb Edge and Baslow, was agricultural land with farms, fields and houses. It was

this last part that gave the Duke the opportunity to improve the Park beyond his earlier

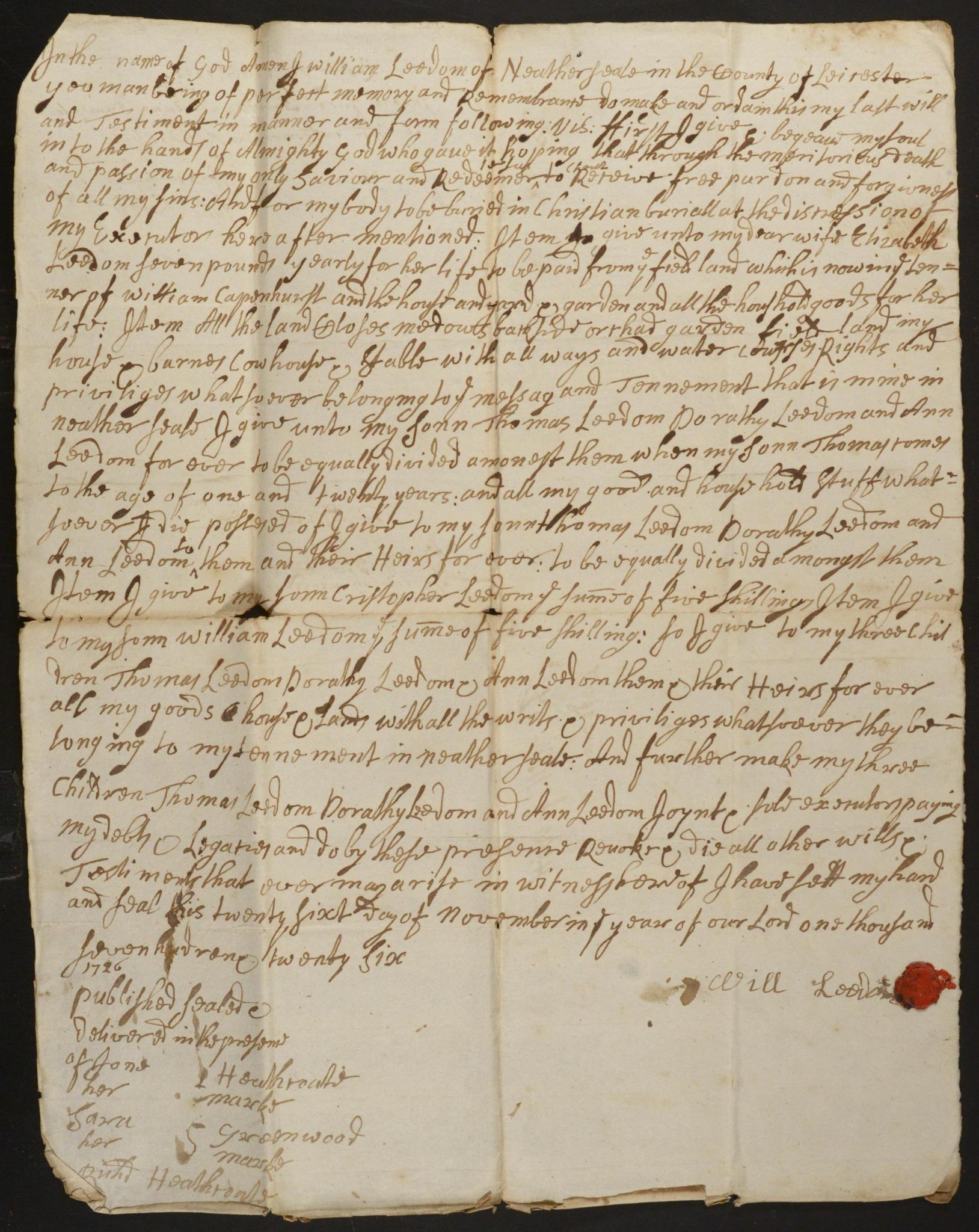

expectations.”The 1795 will of Robert Staley.