-

AuthorSearch Results

-

May 8, 2025 at 3:01 am #7918

In reply to: Cofficionados Bandits (vs Lucid Dreamers)

Ricardo ducked lower behind the bush and tapped out a message:

spottd lol bush comprmsed abort?

There was a long pause. Then a sharp buzz.

You had ONE job. One. You were meant to observe discreetly. I told you to be “subtle.” Clearly, that was wishful thinking. You are not to ABORT. What part of OBSERVATIONAL STEALTH did you misinterpret? Do I need to define the word STEALTH for you again? Honestly, must I supervise every leaf you crouch behind? You are a trained reporter-slash-agent, not a shrubbery enthusiast. Remain in the bush, maintain surveillance. I can overlook your appalling lack of punctuation and correct spelling but FOR GOODNESS SAKE STOP USING “LOL”.

March 23, 2025 at 10:50 am #7880In reply to: The Precious Life and Rambles of Liz Tattler

“Nice arse,” said Idle non too quietly, admiring Roberto as he stacked firewood beside the hearth. The gardener glanced round and gave her a cheeky wink. He’d noticed her leaning out of an upstairs window watching him weeding the herbacious border.

“Now, now, Idle, no molesting the staff. I’ll write some men into the story for you later,” Liz said, “But first let’s talk about my new book. I’m wondering what to name the six spinsters. Some kind of a theme. Cerise, Fuschia, Scarlett, Coral, Rose and Magenta?”

“What about Cobalt, Lapis, Cerulean, Indigo, Sapphire and Capri?” offered Idle, topping up their wine glasses. “Chartreuse, Emerald, Jade, Fern, Pistachio and Malachite? Marigold, Saffron, Citron, Amber, Maize and Apricot?”

“How about Bratwurst, Chorizo, Salami, Knackwurst, Bologna and Frankfurter?” suggested Godfrey who was still miffed about all the spare parts being disposed of. “Lasagne, Macaroni, Canneloni, Farfali, Linguini and Ravioli?”

Roberto lit the fire and stood up. “I have an idea, you can call them Trowel, Rake, Hoe, Wheelbarrow, Spade and Secateur.”

“Marvelous Roberto, I love it!” gushed Aunt Idle.

“You’re all mad as a box of frogs, madder than Almad,” Finnley said. “How about Duster, Mop, Bleach, Broom, Dustpan and Cloth?”

“I think this incessant rain is driving us all mad,” Liz said, glancing out of the French windows with a sigh.

November 13, 2024 at 8:52 pm #7594In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

“With full pay AND a bonus?” Truella was incredulous. “For all of us?”

“Yes, regardless of past performance,” Frella said pursing her lips.

“Nobody can fault my performances,” Jeezel said with a toss of her magenta feather boa. “Where shall we go, Eris?”

A smile slowly spreading across her face, Eris replied, “We’re on holiday. We don’t have to decide anything yet.”

July 21, 2024 at 11:29 pm #7537In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

“Will you stop flirting with that poor boy, Tru! You can’t help yourself can you?” Frella’s word were softened by the huge smile on her face. “Isn’t this place just grand?”

“Frella! Don’t be sneaking up on a person like that!” Truella gave her friend a hug. “Anyway, you won’t believe it but Malove is going to be here! I mean, talk about unexpected plot twists. And you know she’s not going to be thrilled when she finds out I’ve nabbed her corner pod!” She giggled, albeit a little nervously.

Frella grimaced. “Tru, you’d better be careful. Malove’s not one to take things lightly, especially when it comes to her personal space.”

“Oh don’t worry. It will be fine. Anyway, what about your fancy man? Will he be here doing his important MAMA spy work? I do hope so. Dear Cedric always brings a certain je ne sais quoi to the scene.” Truella rolled her eyes and smirked.

“Oh you mean tart! And he’s NOT my fancy man but yeah, he is going to be here. You should be glad we’ve got someone on the inside. Those MAMA agents can be pesky devils and they’re bound to be sneaking around a gig like this.”

June 17, 2024 at 8:18 pm #7495In reply to: Smoke Signals: Arcanas of the Quadrivium’s incense

Cedric Spellbind:

Cedric Spellbind stood tall, though not imposing, with a wiry frame that belied his years of rigorous witch-hunting. His eyes, a piercing green, darted nervously beneath the brim of his deerstalker hat, giving him the appearance of a man constantly on edge. A seasoned agent of MAMA, he carried an air of determined resolve, despite his recent demotion to desk duty in Limerick.

With a face that seemed perpetually caught between youthful eagerness and a weariness beyond his years, Cedric was a man marked by his contradictions. His dark hair, often disheveled from restless nights, framed a face etched with the lines of a life spent in pursuit of the arcane and the elusive.

Clad in a trench coat that had seen better days, Cedric’s attire was a patchwork of practicality and the remnants of a more distinguished past. Despite his amateurish attempts at stealth and the financial strains of his profession, Cedric’s spirit remained unbroken. He was a man driven by a fascination with the unknown and a cautious curiosity, particularly when it came to the enigmatic Frigella O’Green.

Yet, beneath the veneer of a bumbling spy, there lay a heart of determination and a mind constantly strategizing, always ready to seize the next opportunity to prove his worth in the clandestine world of witch hunting.

February 6, 2024 at 7:27 am #7353In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

Cedric peered through the peephole in his newspaper. He’d have recognised that bogwitch anywhere. Drat that blonde one grabbing her arm, he’d have been able to catch her red handed and arrest her.

Cedric was ambitious. He’d been working for MAMA for thirty years as an agent and wanted a promotion, a nice cushy office job where he could sit in comfort dishing out orders. He’d had enough of traipsing round the countryside and sitting in draughty pubs in the back of beyond and felt it was high time that the Ministry for the Abolition of the Magical Arts recognised his potential as a leader.

Who was that blonde one anyway? Another bogwitch no doubt, covens springing up everywhere these days, defying proper law and order, it was an outrage. She hadn’t seemed too happy to see that old tart Aggie, though. Maybe there was a rift between covens that he could exploit for his own ends. Cedric decided to keep an eye on her, perhaps mislead her into thinking he was on her side. It gave him a frisson of pleasure to think how clever he would look when he made his report.

Frigella her name was, Cedric heard Aggie ask her why she was rushing off.

“Gottta run, I’m babysitting. And just you behave yourself Aggie, I told you, we don’t do things like that around here. It’s witches like you that give us all a bad name.”

Cedric rolled his newspaper up and pulled his deerstalker hat low over his eyes and followed Frigella out onto the street.

February 6, 2023 at 10:46 pm #6501Potential situations and complications:

- While searching for Dumbass Voldomeer, they stumble upon a group of political protesters who are demanding the resignation of the President.

- Dumbass Voldomeer mistakenly takes Maryechka and her friends for secret agents sent to spy on him and tries to escape.

- The group is treated to a unique performance by the local swan-dancing troupe, who are trying to raise awareness about the mysterious swan flu virus.

- Dumbass Voldomeer invites the group to his workshop and shows them his latest creations, including a wooden replica of the Eiffel Tower.

- While looking through the books of families connected to Egna, they find a page with a recipe for a special cocktail that supposedly grants immortality.

- Maryechka and her friends come across a black market for wooden legs, where they meet a man who claims to have the original wooden leg made by Dumbass Voldomeer for the President.

November 18, 2022 at 4:47 pm #6348In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

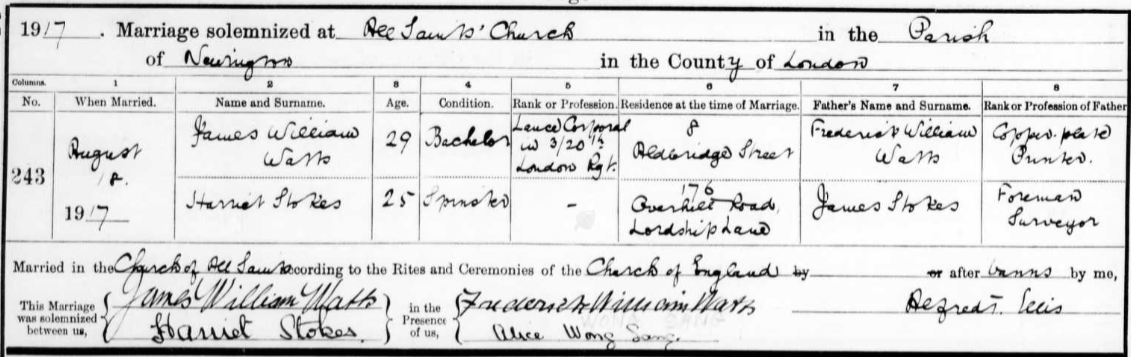

Wong Sang

Wong Sang was born in China in 1884. In October 1916 he married Alice Stokes in Oxford.

Alice was the granddaughter of William Stokes of Churchill, Oxfordshire and William was the brother of Thomas Stokes the wheelwright (who was my 3X great grandfather). In other words Alice was my second cousin, three times removed, on my fathers paternal side.

Wong Sang was an interpreter, according to the baptism registers of his children and the Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital admission registers in 1930. The hospital register also notes that he was employed by the Blue Funnel Line, and that his address was 11, Limehouse Causeway, E 14. (London)

“The Blue Funnel Line offered regular First-Class Passenger and Cargo Services From the UK to South Africa, Malaya, China, Japan, Australia, Java, and America. Blue Funnel Line was Owned and Operated by Alfred Holt & Co., Liverpool.

The Blue Funnel Line, so-called because its ships have a blue funnel with a black top, is more appropriately known as the Ocean Steamship Company.”Wong Sang and Alice’s daughter, Frances Eileen Sang, was born on the 14th July, 1916 and baptised in 1920 at St Stephen in Poplar, Tower Hamlets, London. The birth date is noted in the 1920 baptism register and would predate their marriage by a few months, although on the death register in 1921 her age at death is four years old and her year of birth is recorded as 1917.

Charles Ronald Sang was baptised on the same day in May 1920, but his birth is recorded as April of that year. The family were living on Morant Street, Poplar.

James William Sang’s birth is recorded on the 1939 census and on the death register in 2000 as being the 8th March 1913. This definitely would predate the 1916 marriage in Oxford.

William Norman Sang was born on the 17th October 1922 in Poplar.

Alice and the three sons were living at 11, Limehouse Causeway on the 1939 census, the same address that Wong Sang was living at when he was admitted to Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital on the 15th January 1930. Wong Sang died in the hospital on the 8th March of that year at the age of 46.

Alice married John Patterson in 1933 in Stepney. John was living with Alice and her three sons on Limehouse Causeway on the 1939 census and his occupation was chef.

Via Old London Photographs:

“Limehouse Causeway is a street in east London that was the home to the original Chinatown of London. A combination of bomb damage during the Second World War and later redevelopment means that almost nothing is left of the original buildings of the street.”

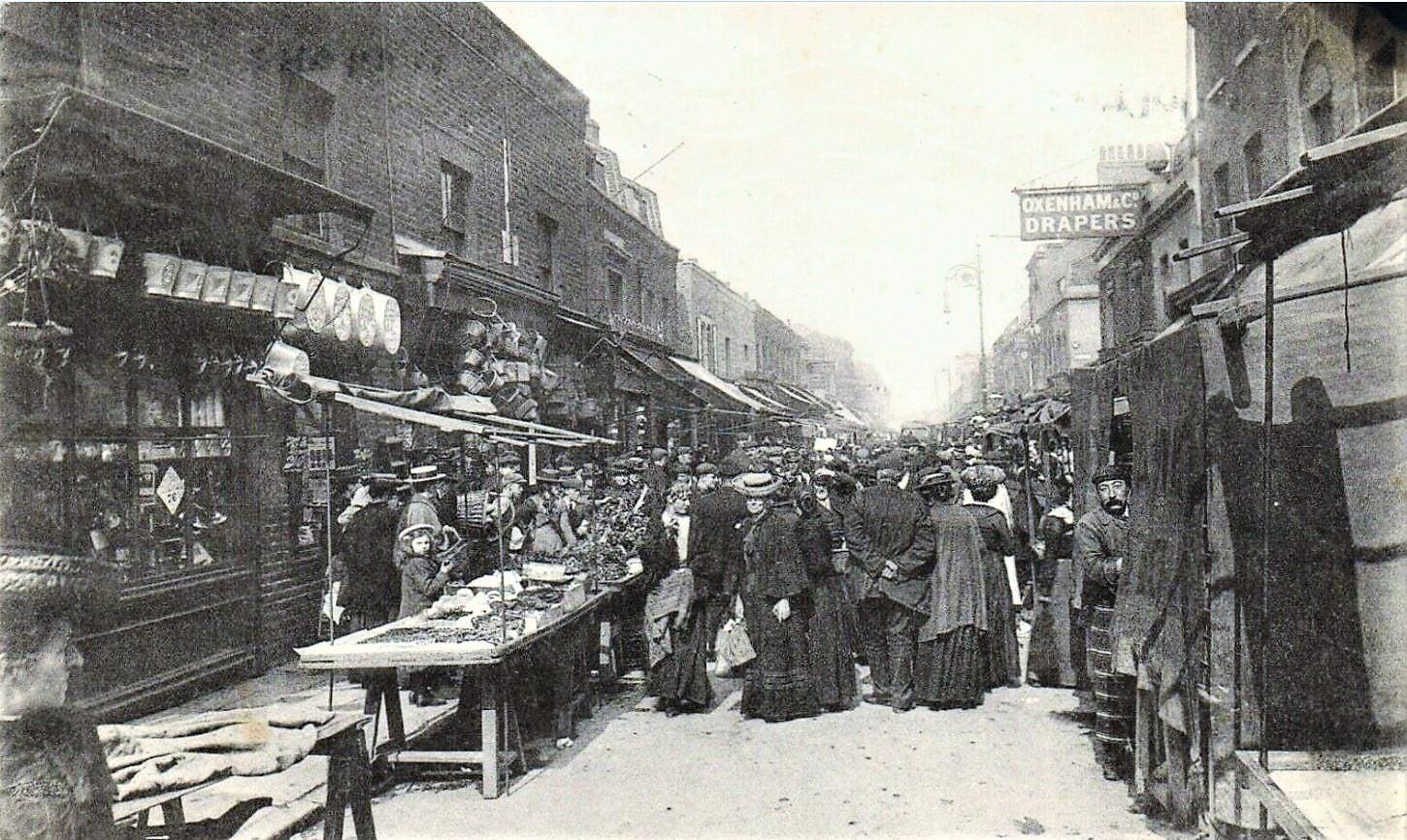

Limehouse Causeway in 1925:

From The Story of Limehouse’s Lost Chinatown, poplarlondon website:

“Limehouse was London’s first Chinatown, home to a tightly-knit community who were demonised in popular culture and eventually erased from the cityscape.

As recounted in the BBC’s ‘Our Greatest Generation’ series, Connie was born to a Chinese father and an English mother in early 1920s Limehouse, where she used to play in the street with other British and British-Chinese children before running inside for teatime at one of their houses.

Limehouse was London’s first Chinatown between the 1880s and the 1960s, before the current Chinatown off Shaftesbury Avenue was established in the 1970s by an influx of immigrants from Hong Kong.

Connie’s memories of London’s first Chinatown as an “urban village” paint a very different picture to the seedy area portrayed in early twentieth century novels.

The pyramid in St Anne’s church marked the entrance to the opium den of Dr Fu Manchu, a criminal mastermind who threatened Western society by plotting world domination in a series of novels by Sax Rohmer.

Thomas Burke’s Limehouse Nights cemented stereotypes about prostitution, gambling and violence within the Chinese community, and whipped up anxiety about sexual relationships between Chinese men and white women.

Though neither novelist was familiar with the Chinese community, their depictions made Limehouse one of the most notorious areas of London.

Travel agent Thomas Cook even organised tours of the area for daring visitors, despite the rector of Limehouse warning that “those who look for the Limehouse of Mr Thomas Burke simply will not find it.”

All that remains is a handful of Chinese street names, such as Ming Street, Pekin Street, and Canton Street — but what was Limehouse’s chinatown really like, and why did it get swept away?

Chinese migration to Limehouse

Chinese sailors discharged from East India Company ships settled in the docklands from as early as the 1780s.

By the late nineteenth century, men from Shanghai had settled around Pennyfields Lane, while a Cantonese community lived on Limehouse Causeway.

Chinese sailors were often paid less and discriminated against by dock hirers, and so began to diversify their incomes by setting up hand laundry services and restaurants.

Old photographs show shopfronts emblazoned with Chinese characters with horse-drawn carts idling outside or Chinese men in suits and hats standing proudly in the doorways.

In oral histories collected by Yat Ming Loo, Connie’s husband Leslie doesn’t recall seeing any Chinese women as a child, since male Chinese sailors settled in London alone and married working-class English women.

In the 1920s, newspapers fear-mongered about interracial marriages, crime and gambling, and described chinatown as an East End “colony.”

Ironically, Chinese opium-smoking was also demonised in the press, despite Britain waging war against China in the mid-nineteenth century for suppressing the opium trade to alleviate addiction amongst its people.

The number of Chinese people who settled in Limehouse was also greatly exaggerated, and in reality only totalled around 300.

The real Chinatown

Although the press sought to characterise Limehouse as a monolithic Chinese community in the East End, Connie remembers seeing people of all nationalities in the shops and community spaces in Limehouse.

She doesn’t remember feeling discriminated against by other locals, though Connie does recall having her face measured and IQ tested by a member of the British Eugenics Society who was conducting research in the area.

Some of Connie’s happiest childhood memories were from her time at Chung-Hua Club, where she learned about Chinese culture and language.

Why did Chinatown disappear?

The caricature of Limehouse’s Chinatown as a den of vice hastened its erasure.

Police raids and deportations fuelled by the alarmist media coverage threatened the Chinese population of Limehouse, and slum clearance schemes to redevelop low-income areas dispersed Chinese residents in the 1930s.

The Defence of the Realm Act imposed at the beginning of the First World War criminalised opium use, gave the authorities increased powers to deport Chinese people and restricted their ability to work on British ships.

Dwindling maritime trade during World War II further stripped Chinese sailors of opportunities for employment, and any remnants of Chinatown were destroyed during the Blitz or erased by postwar development schemes.”

Wong Sang 1884-1930

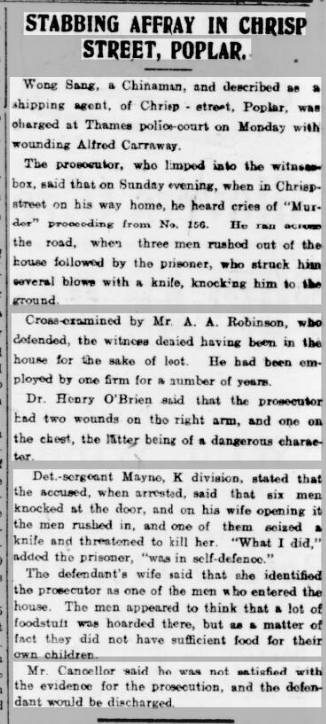

The year 1918 was a troublesome one for Wong Sang, an interpreter and shipping agent for Blue Funnel Line. The Sang family were living at 156, Chrisp Street.

Chrisp Street, Poplar, in 1913 via Old London Photographs:

In February Wong Sang was discharged from a false accusation after defending his home from potential robbers.

East End News and London Shipping Chronicle – Friday 15 February 1918:

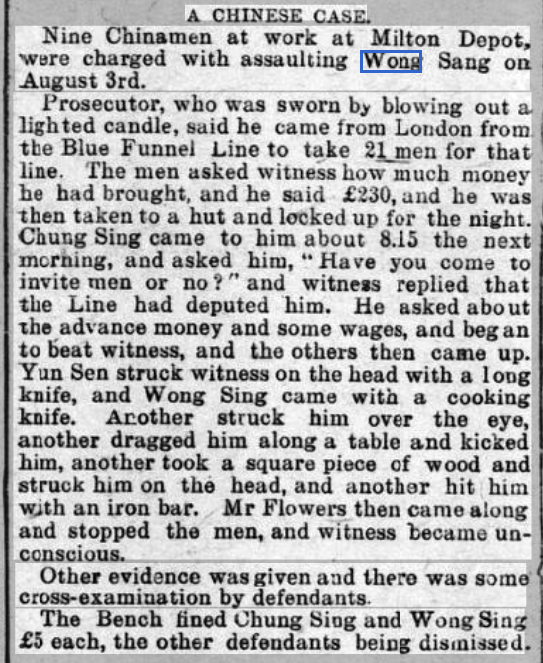

In August of that year he was involved in an incident that left him unconscious.

Faringdon Advertiser and Vale of the White Horse Gazette – Saturday 31 August 1918:

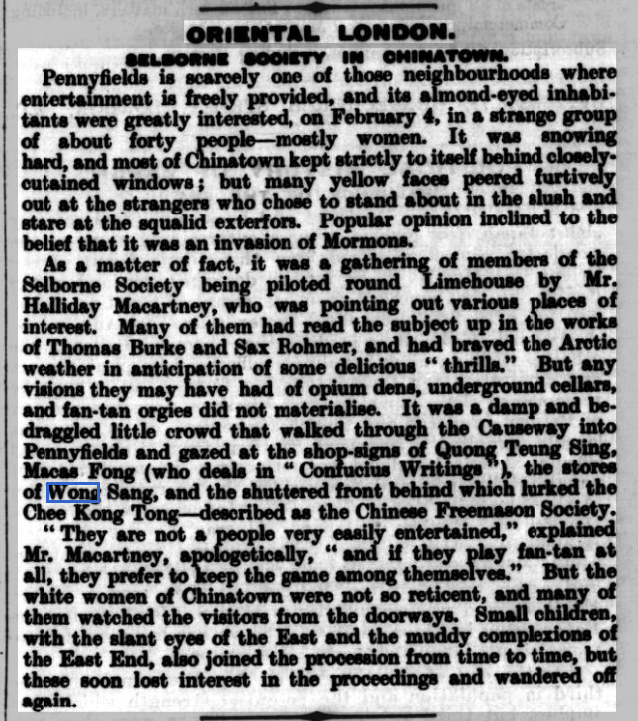

Wong Sang is mentioned in an 1922 article about “Oriental London”.

London and China Express – Thursday 09 February 1922:

A photograph of the Chee Kong Tong Chinese Freemason Society mentioned in the above article, via Old London Photographs:

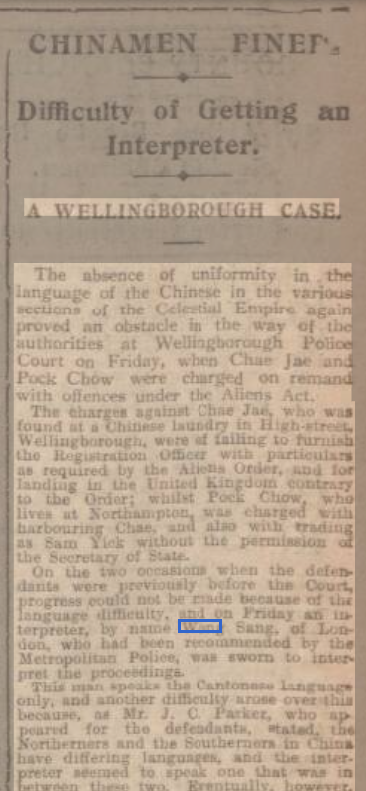

Wong Sang was recommended by the London Metropolitan Police in 1928 to assist in a case in Wellingborough, Northampton.

Difficulty of Getting an Interpreter: Northampton Mercury – Friday 16 March 1928:

The difficulty was that “this man speaks the Cantonese language only…the Northeners and the Southerners in China have differing languages and the interpreter seemed to speak one that was in between these two.”

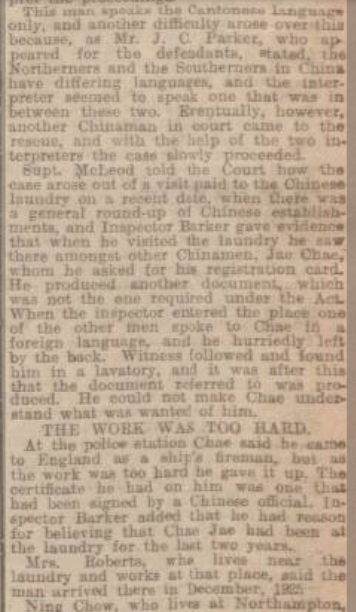

In 1917, Alice Wong Sang was a witness at her sister Harriet Stokes marriage to James William Watts in Southwark, London. Their father James Stokes occupation on the marriage register is foreman surveyor, but on the census he was a council roadman or labourer. (I initially rejected this as the correct marriage for Harriet because of the discrepancy with the occupations. Alice Wong Sang as a witness confirmed that it was indeed the correct one.)

James William Sang 1913-2000 was a clock fitter and watch assembler (on the 1939 census). He married Ivy Laura Fenton in 1963 in Sidcup, Kent. James died in Southwark in 2000.

Charles Ronald Sang 1920-1974 was a draughtsman (1939 census). He married Eileen Burgess in 1947 in Marylebone. Charles and Eileen had two sons: Keith born in 1951 and Roger born in 1952. He died in 1974 in Hertfordshire.

William Norman Sang 1922-2000 was a clerk and telephone operator (1939 census). William enlisted in the Royal Artillery in 1942. He married Lily Mullins in 1949 in Bethnal Green, and they had three daughters: Marion born in 1950, Christine in 1953, and Frances in 1959. He died in Redbridge in 2000.

I then found another two births registered in Poplar by Alice Sang, both daughters. Doris Winifred Sang was born in 1925, and Patricia Margaret Sang was born in 1933 ~ three years after Wong Sang’s death. Neither of the these daughters were on the 1939 census with Alice, John Patterson and the three sons. Margaret had presumably been evacuated because of the war to a family in Taunton, Somerset. Doris would have been fourteen and I have been unable to find her in 1939 (possibly because she died in 2017 and has not had the redaction removed yet on the 1939 census as only deceased people are viewable).

Doris Winifred Sang 1925-2017 was a nursing sister. She didn’t marry, and spent a year in USA between 1954 and 1955. She stayed in London, and died at the age of ninety two in 2017.

Patricia Margaret Sang 1933-1998 was also a nurse. She married Patrick L Nicely in Stepney in 1957. Patricia and Patrick had five children in London: Sharon born 1959, Donald in 1960, Malcolm was born and died in 1966, Alison was born in 1969 and David in 1971.

I was unable to find a birth registered for Alice’s first son, James William Sang (as he appeared on the 1939 census). I found Alice Stokes on the 1911 census as a 17 year old live in servant at a tobacconist on Pekin Street, Limehouse, living with Mr Sui Fong from Hong Kong and his wife Sarah Sui Fong from Berlin. I looked for a birth registered for James William Fong instead of Sang, and found it ~ mothers maiden name Stokes, and his date of birth matched the 1939 census: 8th March, 1913.

On the 1921 census, Wong Sang is not listed as living with them but it is mentioned that Mr Wong Sang was the person returning the census. Also living with Alice and her sons James and Charles in 1921 are two visitors: (Florence) May Stokes, 17 years old, born in Woodstock, and Charles Stokes, aged 14, also born in Woodstock. May and Charles were Alice’s sister and brother.

I found Sharon Nicely on social media and she kindly shared photos of Wong Sang and Alice Stokes:

October 11, 2022 at 11:39 am #6333

October 11, 2022 at 11:39 am #6333In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The Grattidge Family

The first Grattidge to appear in our tree was Emma Grattidge (1853-1911) who married Charles Tomlinson (1847-1907) in 1872.

Charles Tomlinson (1873-1929) was their son and he married my great grandmother Nellie Fisher. Their daughter Margaret (later Peggy Edwards) was my grandmother on my fathers side.

Emma Grattidge was born in Wolverhampton, the daughter and youngest child of William Grattidge (1820-1887) born in Foston, Derbyshire, and Mary Stubbs, born in Burton on Trent, daughter of Solomon Stubbs, a land carrier. William and Mary married at St Modwens church, Burton on Trent, in 1839. It’s unclear why they moved to Wolverhampton. On the 1841 census William was employed as an agent, and their first son William was nine months old. Thereafter, William was a licensed victuallar or innkeeper.

William Grattidge was born in Foston, Derbyshire in 1820. His parents were Thomas Grattidge, farmer (1779-1843) and Ann Gerrard (1789-1822) from Ellastone. Thomas and Ann married in 1813 in Ellastone. They had five children before Ann died at the age of 25:

Bessy was born in 1815, Thomas in 1818, William in 1820, and Daniel Augustus and Frederick were twins born in 1822. They were all born in Foston. (records say Foston, Foston and Scropton, or Scropton)

On the 1841 census Thomas had nine people additional to family living at the farm in Foston, presumably agricultural labourers and help.

After Ann died, Thomas had three children with Kezia Gibbs (30 years his junior) before marrying her in 1836, then had a further four with her before dying in 1843. Then Kezia married Thomas’s nephew Frederick Augustus Grattidge (born in 1816 in Stafford) in London in 1847 and had two more!

The siblings of William Grattidge (my 3x great grandfather):

Frederick Grattidge (1822-1872) was a schoolmaster and never married. He died at the age of 49 in Tamworth at his twin brother Daniels address.

Daniel Augustus Grattidge (1822-1903) was a grocer at Gungate in Tamworth.

Thomas Grattidge (1818-1871) married in Derby, and then emigrated to Illinois, USA.

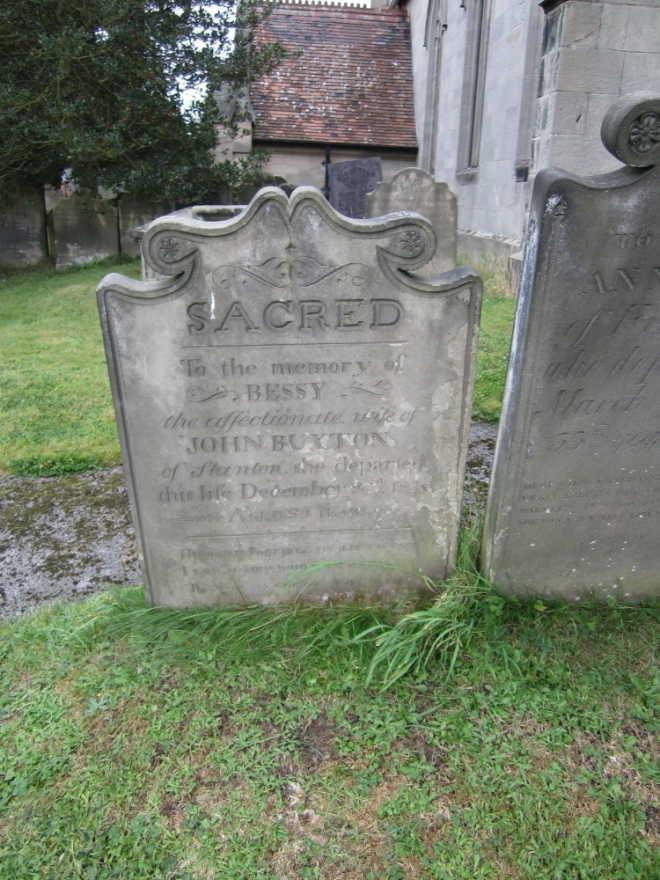

Bessy Grattidge (1815-1840) married John Buxton, farmer, in Ellastone in January 1838. They had three children before Bessy died in December 1840 at the age of 25: Henry in 1838, John in 1839, and Bessy Buxton in 1840. Bessy was baptised in January 1841. Presumably the birth of Bessy caused the death of Bessy the mother.

Bessy Buxton’s gravestone:

“Sacred to the memory of Bessy Buxton, the affectionate wife of John Buxton of Stanton She departed this life December 20th 1840, aged 25 years. “Husband, Farewell my life is Past, I loved you while life did last. Think on my children for my sake, And ever of them with I take.”

20 Dec 1840, Ellastone, Staffordshire

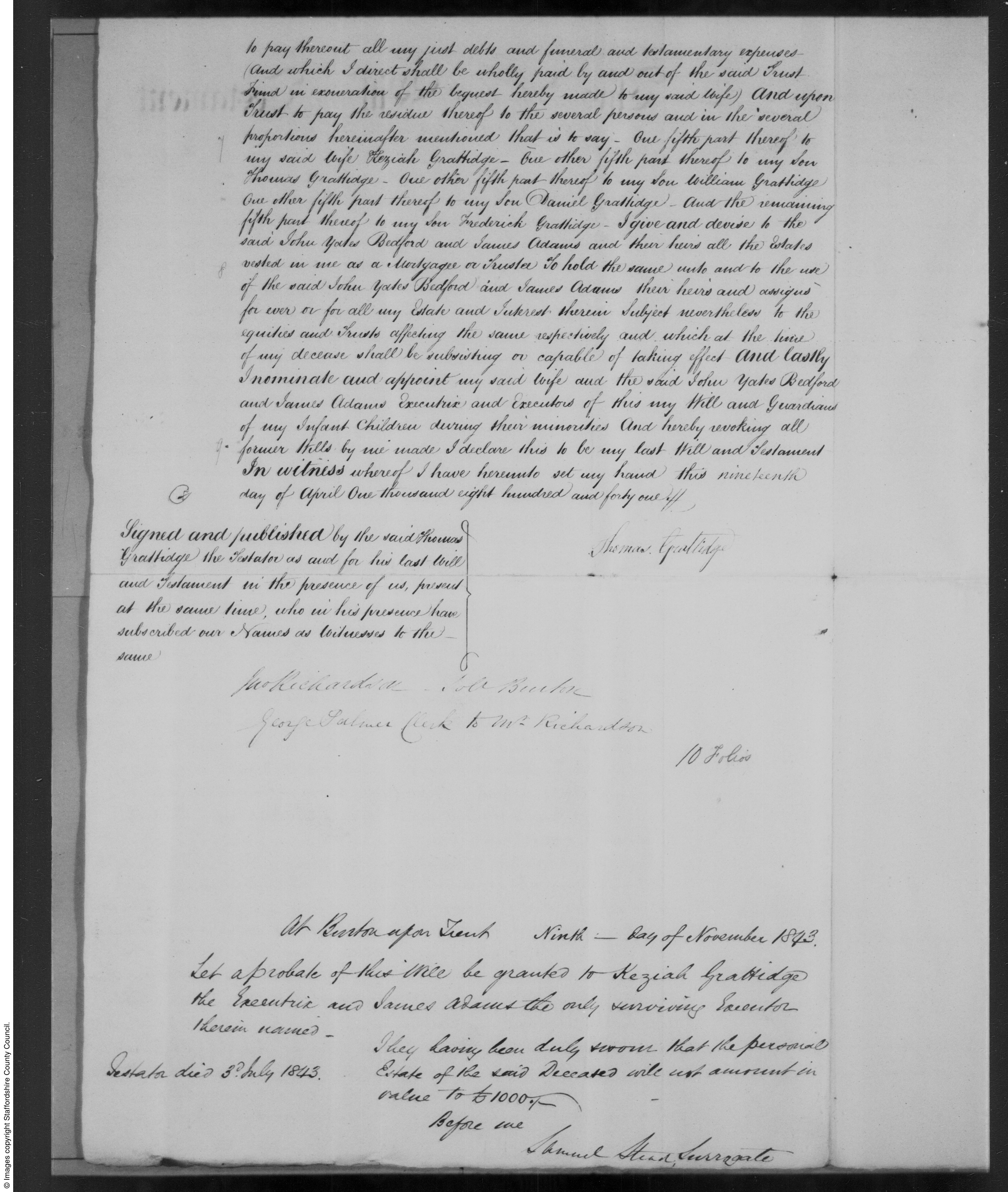

In the 1843 will of Thomas Grattidge, farmer of Foston, he leaves fifth shares of his estate, including freehold real estate at Findern, to his wife Kezia, and sons William, Daniel, Frederick and Thomas. He mentions that the children of his late daughter Bessy, wife of John Buxton, will be taken care of by their father. He leaves the farm to Keziah in confidence that she will maintain, support and educate his children with her.

An excerpt from the will:

I give and bequeath unto my dear wife Keziah Grattidge all my household goods and furniture, wearing apparel and plate and plated articles, linen, books, china, glass, and other household effects whatsoever, and also all my implements of husbandry, horses, cattle, hay, corn, crops and live and dead stock whatsoever, and also all the ready money that may be about my person or in my dwelling house at the time of my decease, …I also give my said wife the tenant right and possession of the farm in my occupation….

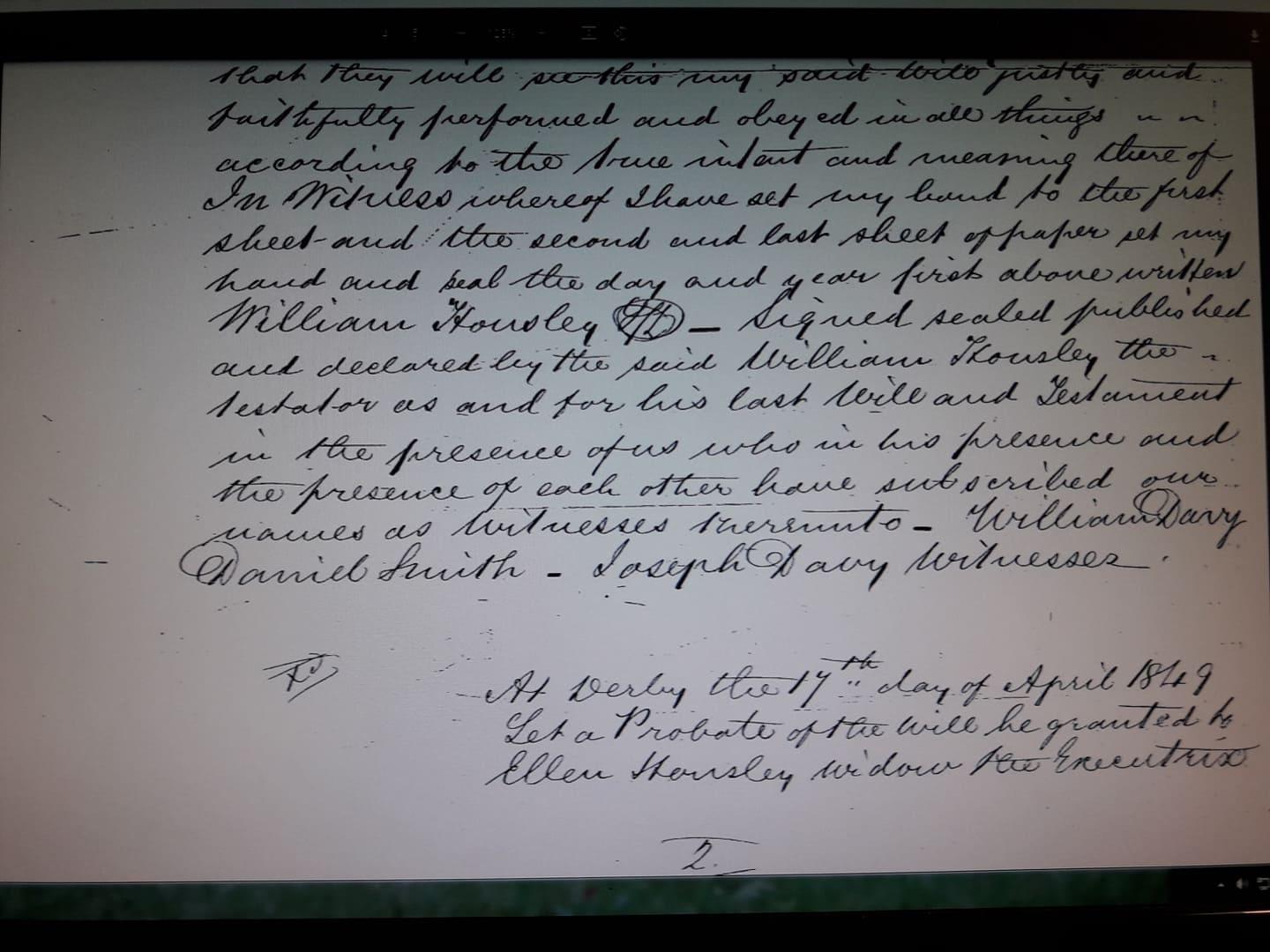

A page from the 1843 will of Thomas Grattidge:

William Grattidges half siblings (the offspring of Thomas Grattidge and Kezia Gibbs):

Albert Grattidge (1842-1914) was a railway engine driver in Derby. In 1884 he was driving the train when an unfortunate accident occured outside Ambergate. Three children were blackberrying and crossed the rails in front of the train, and one little girl died.

Albert Grattidge:

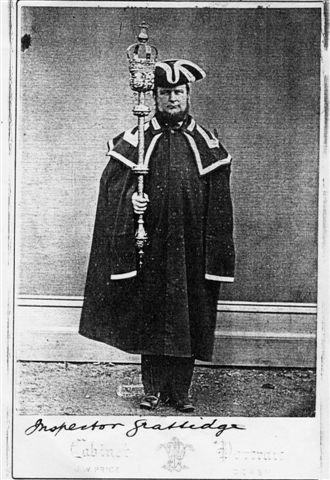

George Grattidge (1826-1876) was baptised Gibbs as this was before Thomas married Kezia. He was a police inspector in Derby.

George Grattidge:

Edwin Grattidge (1837-1852) died at just 15 years old.

Ann Grattidge (1835-) married Charles Fletcher, stone mason, and lived in Derby.

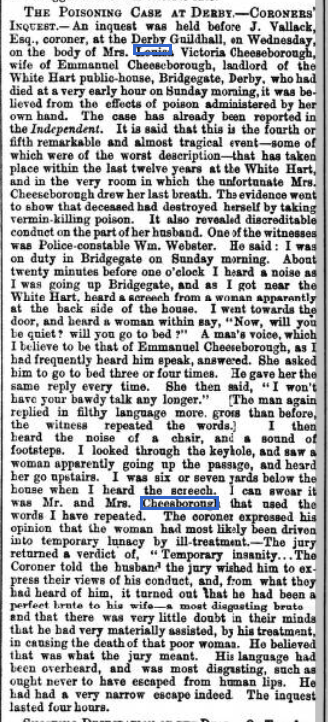

Louisa Victoria Grattidge (1840-1869) was sadly another Grattidge woman who died young. Louisa married Emmanuel Brunt Cheesborough in 1860 in Derby. In 1861 Louisa and Emmanuel were living with her mother Kezia in Derby, with their two children Frederick and Ann Louisa. Emmanuel’s occupation was sawyer. (Kezia Gibbs second husband Frederick Augustus Grattidge was a timber merchant in Derby)

At the time of her death in 1869, Emmanuel was the landlord of the White Hart public house at Bridgegate in Derby.

The Derby Mercury of 17th November 1869:

“On Wednesday morning Mr Coroner Vallack held an inquest in the Grand

Jury-room, Town-hall, on the body of Louisa Victoria Cheeseborough, aged

33, the wife of the landlord of the White Hart, Bridge-gate, who committed

suicide by poisoning at an early hour on Sunday morning. The following

evidence was taken:Mr Frederick Borough, surgeon, practising in Derby, deposed that he was

called in to see the deceased about four o’clock on Sunday morning last. He

accordingly examined the deceased and found the body quite warm, but dead.

He afterwards made enquiries of the husband, who said that he was afraid

that his wife had taken poison, also giving him at the same time the

remains of some blue material in a cup. The aunt of the deceased’s husband

told him that she had seen Mrs Cheeseborough put down a cup in the

club-room, as though she had just taken it from her mouth. The witness took

the liquid home with him, and informed them that an inquest would

necessarily have to be held on Monday. He had made a post mortem

examination of the body, and found that in the stomach there was a great

deal of congestion. There were remains of food in the stomach and, having

put the contents into a bottle, he took the stomach away. He also examined

the heart and found it very pale and flabby. All the other organs were

comparatively healthy; the liver was friable.Hannah Stone, aunt of the deceased’s husband, said she acted as a servant

in the house. On Saturday evening, while they were going to bed and whilst

witness was undressing, the deceased came into the room, went up to the

bedside, awoke her daughter, and whispered to her. but what she said the

witness did not know. The child jumped out of bed, but the deceased closed

the door and went away. The child followed her mother, and she also

followed them to the deceased’s bed-room, but the door being closed, they

then went to the club-room door and opening it they saw the deceased

standing with a candle in one hand. The daughter stayed with her in the

room whilst the witness went downstairs to fetch a candle for herself, and

as she was returning up again she saw the deceased put a teacup on the

table. The little girl began to scream, saying “Oh aunt, my mother is

going, but don’t let her go”. The deceased then walked into her bed-room,

and they went and stood at the door whilst the deceased undressed herself.

The daughter and the witness then returned to their bed-room. Presently

they went to see if the deceased was in bed, but she was sitting on the

floor her arms on the bedside. Her husband was sitting in a chair fast

asleep. The witness pulled her on the bed as well as she could.

Ann Louisa Cheesborough, a little girl, said that the deceased was her

mother. On Saturday evening last, about twenty minutes before eleven

o’clock, she went to bed, leaving her mother and aunt downstairs. Her aunt

came to bed as usual. By and bye, her mother came into her room – before

the aunt had retired to rest – and awoke her. She told the witness, in a

low voice, ‘that she should have all that she had got, adding that she

should also leave her her watch, as she was going to die’. She did not tell

her aunt what her mother had said, but followed her directly into the

club-room, where she saw her drink something from a cup, which she

afterwards placed on the table. Her mother then went into her own room and

shut the door. She screamed and called her father, who was downstairs. He

came up and went into her room. The witness then went to bed and fell

asleep. She did not hear any noise or quarrelling in the house after going

to bed.Police-constable Webster was on duty in Bridge-gate on Saturday evening

last, about twenty minutes to one o’clock. He knew the White Hart

public-house in Bridge-gate, and as he was approaching that place, he heard

a woman scream as though at the back side of the house. The witness went to

the door and heard the deceased keep saying ‘Will you be quiet and go to

bed’. The reply was most disgusting, and the language which the

police-constable said was uttered by the husband of the deceased, was

immoral in the extreme. He heard the poor woman keep pressing her husband

to go to bed quietly, and eventually he saw him through the keyhole of the

door pass and go upstairs. his wife having gone up a minute or so before.

Inspector Fearn deposed that on Sunday morning last, after he had heard of

the deceased’s death from supposed poisoning, he went to Cheeseborough’s

public house, and found in the club-room two nearly empty packets of

Battie’s Lincoln Vermin Killer – each labelled poison.Several of the Jury here intimated that they had seen some marks on the

deceased’s neck, as of blows, and expressing a desire that the surgeon

should return, and re-examine the body. This was accordingly done, after

which the following evidence was taken:Mr Borough said that he had examined the body of the deceased and observed

a mark on the left side of the neck, which he considered had come on since

death. He thought it was the commencement of decomposition.

This was the evidence, after which the jury returned a verdict “that the

deceased took poison whilst of unsound mind” and requested the Coroner to

censure the deceased’s husband.The Coroner told Cheeseborough that he was a disgusting brute and that the

jury only regretted that the law could not reach his brutal conduct.

However he had had a narrow escape. It was their belief that his poor

wife, who was driven to her own destruction by his brutal treatment, would

have been a living woman that day except for his cowardly conduct towards

her.The inquiry, which had lasted a considerable time, then closed.”

In this article it says:

“it was the “fourth or fifth remarkable and tragical event – some of which were of the worst description – that has taken place within the last twelve years at the White Hart and in the very room in which the unfortunate Louisa Cheesborough drew her last breath.”

Sheffield Independent – Friday 12 November 1869:

January 28, 2022 at 2:29 pm #6261

January 28, 2022 at 2:29 pm #6261In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

From Tanganyika with Love

continued

With thanks to Mike Rushby.

Mchewe Estate. 11th July 1931.

Dearest Family,

You say that you would like to know more about our neighbours. Well there is

not much to tell. Kath Wood is very good about coming over to see me. I admire her

very much because she is so capable as well as being attractive. She speaks very

fluent Ki-Swahili and I envy her the way she can carry on a long conversation with the

natives. I am very slow in learning the language possibly because Lamek and the

houseboy both speak basic English.I have very little to do with the Africans apart from the house servants, but I do

run a sort of clinic for the wives and children of our employees. The children suffer chiefly

from sore eyes and worms, and the older ones often have bad ulcers on their legs. All

farmers keep a stock of drugs and bandages.George also does a bit of surgery and last month sewed up the sole of the foot

of a boy who had trodden on the blade of a panga, a sort of sword the Africans use for

hacking down bush. He made an excellent job of it. George tells me that the Africans

have wonderful powers of recuperation. Once in his bachelor days, one of his men was

disembowelled by an elephant. George washed his “guts” in a weak solution of

pot.permang, put them back in the cavity and sewed up the torn flesh and he

recovered.But to get back to the neighbours. We see less of Hicky Wood than of Kath.

Hicky can be charming but is often moody as I believe Irishmen often are.

Major Jones is now at home on his shamba, which he leaves from time to time

for temporary jobs on the district roads. He walks across fairly regularly and we are

always glad to see him for he is a great bearer of news. In this part of Africa there is no

knocking or ringing of doorbells. Front doors are always left open and visitors always

welcome. When a visitor approaches a house he shouts “Hodi”, and the owner of the

house yells “Karibu”, which I believe means “Come near” or approach, and tea is

produced in a matter of minutes no matter what hour of the day it is.

The road that passes all our farms is the only road to the Gold Diggings and

diggers often drop in on the Woods and Major Jones and bring news of the Goldfields.

This news is sometimes about gold but quite often about whose wife is living with

whom. This is a great country for gossip.Major Jones now has his brother Llewyllen living with him. I drove across with

George to be introduced to him. Llewyllen’s health is poor and he looks much older than

his years and very like the portrait of Trader Horn. He has the same emaciated features,

burning eyes and long beard. He is proud of his Welsh tenor voice and often bursts into

song.Both brothers are excellent conversationalists and George enjoys walking over

sometimes on a Sunday for a bit of masculine company. The other day when George

walked across to visit the Joneses, he found both brothers in the shamba and Llew in a

great rage. They had been stooping to inspect a water furrow when Llew backed into a

hornets nest. One furious hornet stung him on the seat and another on the back of his

neck. Llew leapt forward and somehow his false teeth shot out into the furrow and were

carried along by the water. When George arrived Llew had retrieved his teeth but

George swears that, in the commotion, the heavy leather leggings, which Llew always

wears, had swivelled around on his thin legs and were calves to the front.

George has heard that Major Jones is to sell pert of his land to his Swedish brother-in-law, Max Coster, so we will soon have another couple in the neighbourhood.I’ve had a bit of a pantomime here on the farm. On the day we went to Tukuyu,

all our washing was stolen from the clothes line and also our new charcoal iron. George

reported the matter to the police and they sent out a plain clothes policeman. He wears

the long white Arab gown called a Kanzu much in vogue here amongst the African elite

but, alas for secrecy, huge black police boots protrude from beneath the Kanzu and, to

add to this revealing clue, the askari springs to attention and salutes each time I pass by.

Not much hope of finding out the identity of the thief I fear.George’s furrow was entirely successful and we now have water running behind

the kitchen. Our drinking water we get from a lovely little spring on the farm. We boil and

filter it for safety’s sake. I don’t think that is necessary. The furrow water is used for

washing pots and pans and for bath water.Lots of love,

EleanorMchewe Estate. 8th. August 1931

Dearest Family,

I think it is about time I told you that we are going to have a baby. We are both

thrilled about it. I have not seen a Doctor but feel very well and you are not to worry. I

looked it up in my handbook for wives and reckon that the baby is due about February

8th. next year.The announcement came from George, not me! I had been feeling queasy for

days and was waiting for the right moment to tell George. You know. Soft lights and

music etc. However when I was listlessly poking my food around one lunch time

George enquired calmly, “When are you going to tell me about the baby?” Not at all

according to the book! The problem is where to have the baby. February is a very wet

month and the nearest Doctor is over 50 miles away at Tukuyu. I cannot go to stay at

Tukuyu because there is no European accommodation at the hospital, no hotel and no

friend with whom I could stay.George thinks I should go South to you but Capetown is so very far away and I

love my little home here. Also George says he could not come all the way down with

me as he simply must stay here and get the farm on its feet. He would drive me as far

as the railway in Northern Rhodesia. It is a difficult decision to take. Write and tell me what

you think.The days tick by quietly here. The servants are very willing but have to be

supervised and even then a crisis can occur. Last Saturday I was feeling squeamish and

decided not to have lunch. I lay reading on the couch whilst George sat down to a

solitary curry lunch. Suddenly he gave an exclamation and pushed back his chair. I

jumped up to see what was wrong and there, on his plate, gleaming in the curry gravy

were small bits of broken glass. I hurried to the kitchen to confront Lamek with the plate.

He explained that he had dropped the new and expensive bottle of curry powder on

the brick floor of the kitchen. He did not tell me as he thought I would make a “shauri” so

he simply scooped up the curry powder, removed the larger pieces of glass and used

part of the powder for seasoning the lunch.The weather is getting warmer now. It was very cold in June and July and we had

fires in the daytime as well as at night. Now that much of the land has been cleared we

are able to go for pleasant walks in the weekends. My favourite spot is a waterfall on the

Mchewe River just on the boundary of our land. There is a delightful little pool below the

waterfall and one day George intends to stock it with trout.Now that there are more Europeans around to buy meat the natives find it worth

their while to kill an occasional beast. Every now and again a native arrives with a large

bowl of freshly killed beef for sale. One has no way of knowing whether the animal was

healthy and the meat is often still warm and very bloody. I hated handling it at first but am

becoming accustomed to it now and have even started a brine tub. There is no other

way of keeping meat here and it can only be kept in its raw state for a few hours before

going bad. One of the delicacies is the hump which all African cattle have. When corned

it is like the best brisket.See what a housewife I am becoming.

With much love,

Eleanor.Mchewe Estate. Sept.6th. 1931

Dearest Family,

I have grown to love the life here and am sad to think I shall be leaving

Tanganyika soon for several months. Yes I am coming down to have the baby in the

bosom of the family. George thinks it best and so does the doctor. I didn’t mention it

before but I have never recovered fully from the effects of that bad bout of malaria and

so I have been persuaded to leave George and our home and go to the Cape, in the

hope that I shall come back here as fit as when I first arrived in the country plus a really

healthy and bouncing baby. I am torn two ways, I long to see you all – but how I would

love to stay on here.George will drive me down to Northern Rhodesia in early October to catch a

South bound train. I’ll telegraph the date of departure when I know it myself. The road is

very, very bad and the car has been giving a good deal of trouble so, though the baby

is not due until early February, George thinks it best to get the journey over soon as

possible, for the rains break in November and the the roads will then be impassable. It

may take us five or six days to reach Broken Hill as we will take it slowly. I am looking

forward to the drive through new country and to camping out at night.

Our days pass quietly by. George is out on the shamba most of the day. He

goes out before breakfast on weekdays and spends most of the day working with the

men – not only supervising but actually working with his hands and beating the labourers

at their own jobs. He comes to the house for meals and tea breaks. I potter around the

house and garden, sew, mend and read. Lamek continues to be a treasure. he turns out

some surprising dishes. One of his specialities is stuffed chicken. He carefully skins the

chicken removing all bones. He then minces all the chicken meat and adds minced onion

and potatoes. He then stuffs the chicken skin with the minced meat and carefully sews it

together again. The resulting dish is very filling because the boned chicken is twice the

size of a normal one. It lies on its back as round as a football with bloated legs in the air.

Rather repulsive to look at but Lamek is most proud of his accomplishment.

The other day he produced another of his masterpieces – a cooked tortoise. It

was served on a dish covered with parsley and crouched there sans shell but, only too

obviously, a tortoise. I took one look and fled with heaving diaphragm, but George said

it tasted quite good. He tells me that he has had queerer dishes produced by former

cooks. He says that once in his hunting days his cook served up a skinned baby

monkey with its hands folded on its breast. He says it would take a cannibal to eat that

dish.And now for something sad. Poor old Llew died quite suddenly and it was a sad

shock to this tiny community. We went across to the funeral and it was a very simple and

dignified affair. Llew was buried on Joni’s farm in a grave dug by the farm boys. The

body was wrapped in a blanket and bound to some boards and lowered into the

ground. There was no service. The men just said “Good-bye Llew.” and “Sleep well

Llew”, and things like that. Then Joni and his brother-in-law Max, and George shovelled

soil over the body after which the grave was filled in by Joni’s shamba boys. It was a

lovely bright afternoon and I thought how simple and sensible a funeral it was.

I hope you will be glad to have me home. I bet Dad will be holding thumbs that

the baby will be a girl.Very much love,

Eleanor.Note

“There are no letters to my family during the period of Sept. 1931 to June 1932

because during these months I was living with my parents and sister in a suburb of

Cape Town. I had hoped to return to Tanganyika by air with my baby soon after her

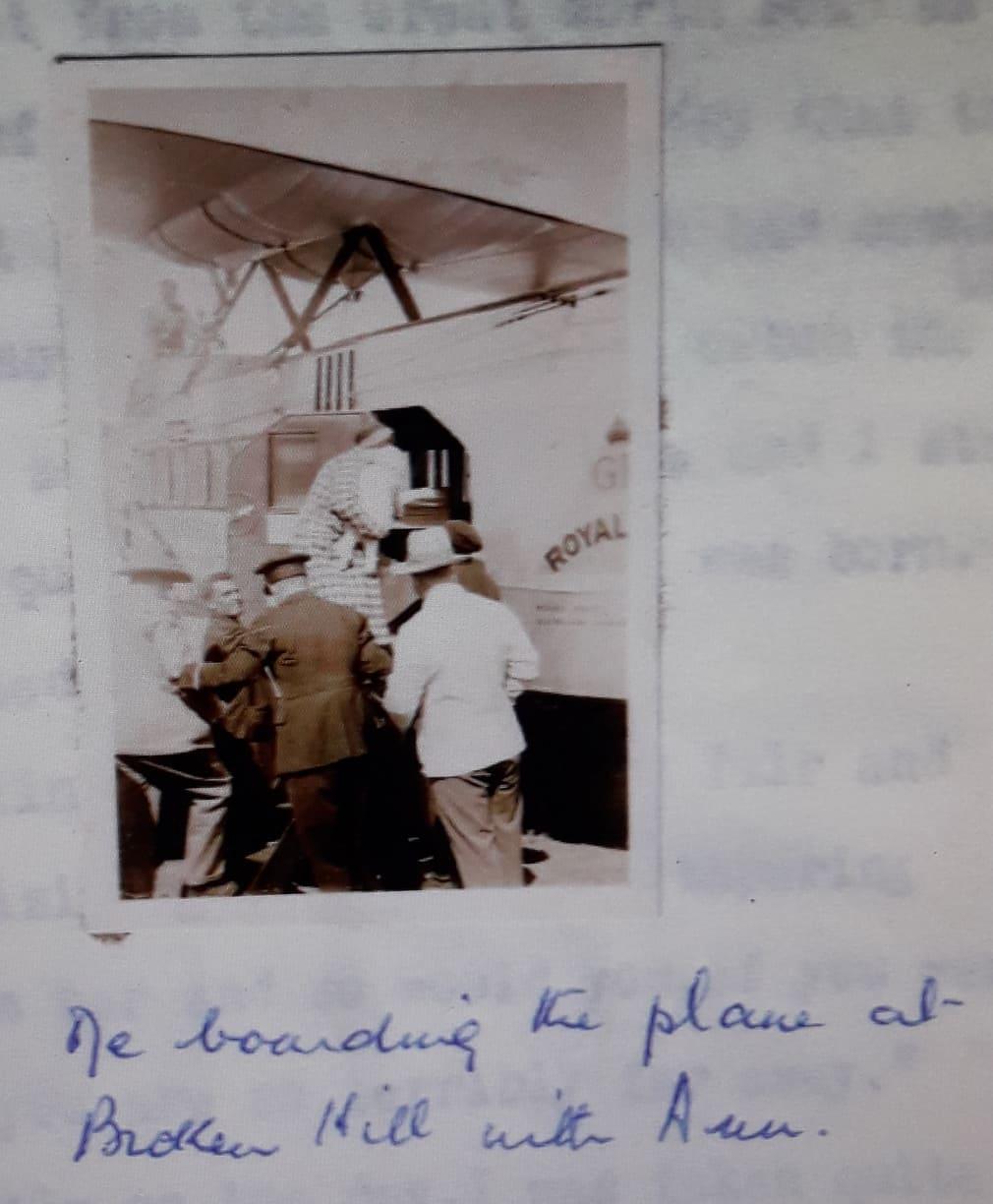

birth in Feb.1932 but the doctor would not permit this.A month before my baby was born, a company called Imperial Airways, had

started the first passenger service between South Africa and England. One of the night

stops was at Mbeya near my husband’s coffee farm, and it was my intention to take the

train to Broken Hill in Northern Rhodesia and to fly from there to Mbeya with my month

old baby. In those days however, commercial flying was still a novelty and the doctor

was not sure that flying at a high altitude might not have an adverse effect upon a young

baby.He strongly advised me to wait until the baby was four months old and I did this

though the long wait was very trying to my husband alone on our farm in Tanganyika,

and to me, cherished though I was in my old home.My story, covering those nine long months is soon told. My husband drove me

down from Mbeya to Broken Hill in NorthernRhodesia. The journey was tedious as the

weather was very hot and dry and the road sandy and rutted, very different from the

Great North road as it is today. The wooden wheel spokes of the car became so dry

that they rattled and George had to bind wet rags around them. We had several

punctures and with one thing and another I was lucky to catch the train.

My parents were at Cape Town station to welcome me and I stayed

comfortably with them, living very quietly, until my baby was born. She arrived exactly

on the appointed day, Feb.8th.I wrote to my husband “Our Charmian Ann is a darling baby. She is very fair and

rather pale and has the most exquisite hands, with long tapering fingers. Daddy

absolutely dotes on her and so would you, if you were here. I can’t bear to think that you

are so terribly far away. Although Ann was born exactly on the day, I was taken quite by

surprise. It was awfully hot on the night before, and before going to bed I had a fancy for

some water melon. The result was that when I woke in the early morning with labour

pains and vomiting I thought it was just an attack of indigestion due to eating too much

melon. The result was that I did not wake Marjorie until the pains were pretty frequent.

She called our next door neighbour who, in his pyjamas, drove me to the nursing home

at breakneck speed. The Matron was very peeved that I had left things so late but all

went well and by nine o’clock, Mother, positively twittering with delight, was allowed to

see me and her first granddaughter . She told me that poor Dad was in such a state of

nerves that he was sick amongst the grapevines. He says that he could not bear to go

through such an anxious time again, — so we will have to have our next eleven in

Tanganyika!”The next four months passed rapidly as my time was taken up by the demands

of my new baby. Dr. Trudy King’s method of rearing babies was then the vogue and I

stuck fanatically to all the rules he laid down, to the intense exasperation of my parents

who longed to cuddle the child.As the time of departure drew near my parents became more and more reluctant

to allow me to face the journey alone with their adored grandchild, so my brother,

Graham, very generously offered to escort us on the train to Broken Hill where he could

put us on the plane for Mbeya.

Mchewe Estate. June 15th 1932

Dearest Family,

You’ll be glad to know that we arrived quite safe and sound and very, very

happy to be home.The train Journey was uneventful. Ann slept nearly all the way.

Graham was very kind and saw to everything. He even sat with the baby whilst I went

to meals in the dining car.We were met at Broken Hill by the Thoms who had arranged accommodation for

us at the hotel for the night. They also drove us to the aerodrome in the morning where

the Airways agent told us that Ann is the first baby to travel by air on this section of the

Cape to England route. The plane trip was very bumpy indeed especially between

Broken Hill and Mpika. Everyone was ill including poor little Ann who sicked up her milk

all over the front of my new coat. I arrived at Mbeya looking a sorry caricature of Radiant

Motherhood. I must have been pale green and the baby was snow white. Under the

circumstances it was a good thing that George did not meet us. We were met instead

by Ken Menzies, the owner of the Mbeya Hotel where we spent the night. Ken was

most fatherly and kind and a good nights rest restored Ann and me to our usual robust

health.Mbeya has greatly changed. The hotel is now finished and can accommodate

fifty guests. It consists of a large main building housing a large bar and dining room and

offices and a number of small cottage bedrooms. It even has electric light. There are

several buildings out at the aerodrome and private houses going up in Mbeya.

After breakfast Ken Menzies drove us out to the farm where we had a warm

welcome from George, who looks well but rather thin. The house was spotless and the

new cook, Abel, had made light scones for tea. George had prepared all sorts of lovely

surprises. There is a new reed ceiling in the living room and a new dresser gay with

willow pattern plates which he had ordered from England. There is also a writing table

and a square table by the door for visitors hats. More personal is a lovely model ship

which George assembled from one of those Hobbie’s kits. It puts the finishing touch to

the rather old world air of our living room.In the bedroom there is a large double bed which George made himself. It has

strips of old car tyres nailed to a frame which makes a fine springy mattress and on top

of this is a thick mattress of kapok.In the kitchen there is a good wood stove which

George salvaged from a Mission dump. It looks a bit battered but works very well. The

new cook is excellent. The only blight is that he will wear rubber soled tennis shoes and

they smell awful. I daren’t hurt his feelings by pointing this out though. Opposite the

kitchen is a new laundry building containing a forty gallon hot water drum and a sink for

washing up. Lovely!George has been working very hard. He now has forty acres of coffee seedlings

planted out and has also found time to plant a rose garden and fruit trees. There are

orange and peach trees, tree tomatoes, paw paws, guavas and berries. He absolutely

adores Ann who has been very good and does not seem at all unsettled by the long

journey.It is absolutely heavenly to be back and I shall be happier than ever now that I

have a baby to play with during the long hours when George is busy on the farm,

Thank you for all your love and care during the many months I was with you. Ann

sends a special bubble for granddad.Your very loving,

Eleanor.Mchewe Estate Mbeya July 18th 1932

Dearest Family,

Ann at five months is enchanting. She is a very good baby, smiles readily and is

gaining weight steadily. She doesn’t sleep much during the day but that does not

matter, because, apart from washing her little things, I have nothing to do but attend to

her. She sleeps very well at night which is a blessing as George has to get up very

early to start work on the shamba and needs a good nights rest.

My nights are not so good, because we are having a plague of rats which frisk

around in the bedroom at night. Great big ones that come up out of the long grass in the

gorge beside the house and make cosy homes on our reed ceiling and in the thatch of

the roof.We always have a night light burning so that, if necessary, I can attend to Ann

with a minimum of fuss, and the things I see in that dim light! There are gaps between

the reeds and one night I heard, plop! and there, before my horrified gaze, lay a newly

born hairless baby rat on the floor by the bed, plop, plop! and there lay two more.

Quite dead, poor things – but what a careless mother.I have also seen rats scampering around on the tops of the mosquito nets and

sometimes we have them on our bed. They have a lovely game. They swarm down

the cord from which the mosquito net is suspended, leap onto the bed and onto the

floor. We do not have our net down now the cold season is here and there are few

mosquitoes.Last week a rat crept under Ann’s net which hung to the floor and bit her little

finger, so now I tuck the net in under the mattress though it makes it difficult for me to

attend to her at night. We shall have to get a cat somewhere. Ann’s pram has not yet

arrived so George carries her when we go walking – to her great content.

The native women around here are most interested in Ann. They come to see

her, bearing small gifts, and usually bring a child or two with them. They admire my child

and I admire theirs and there is an exchange of gifts. They produce a couple of eggs or

a few bananas or perhaps a skinny fowl and I hand over sugar, salt or soap as they

value these commodities. The most lavish gift went to the wife of Thomas our headman,

who produced twin daughters in the same week as I had Ann.Our neighbours have all been across to welcome me back and to admire the

baby. These include Marion Coster who came out to join her husband whilst I was in

South Africa. The two Hickson-Wood children came over on a fat old white donkey.

They made a pretty picture sitting astride, one behind the other – Maureen with her arms

around small Michael’s waist. A native toto led the donkey and the children’ s ayah

walked beside it.It is quite cold here now but the sun is bright and the air dry. The whole

countryside is beautifully green and we are a very happy little family.Lots and lots of love,

Eleanor.Mchewe Estate August 11th 1932

Dearest Family,

George has been very unwell for the past week. He had a nasty gash on his

knee which went septic. He had a swelling in the groin and a high temperature and could

not sleep at night for the pain in his leg. Ann was very wakeful too during the same

period, I think she is teething. I luckily have kept fit though rather harassed. Yesterday the

leg looked so inflamed that George decided to open up the wound himself. he made

quite a big cut in exactly the right place. You should have seen the blackish puss

pouring out.After he had thoroughly cleaned the wound George sewed it up himself. he has

the proper surgical needles and gut. He held the cut together with his left hand and

pushed the needle through the flesh with his right. I pulled the needle out and passed it

to George for the next stitch. I doubt whether a surgeon could have made a neater job

of it. He is still confined to the couch but today his temperature is normal. Some

husband!The previous week was hectic in another way. We had a visit from lions! George

and I were having supper about 8.30 on Tuesday night when the back verandah was

suddenly invaded by women and children from the servants quarters behind the kitchen.

They were all yelling “Simba, Simba.” – simba means lions. The door opened suddenly

and the houseboy rushed in to say that there were lions at the huts. George got up

swiftly, fetched gun and ammunition from the bedroom and with the houseboy carrying

the lamp, went off to investigate. I remained at the table, carrying on with my supper as I

felt a pioneer’s wife should! Suddenly something big leapt through the open window

behind me. You can imagine what I thought! I know now that it is quite true to say one’s

hair rises when one is scared. However it was only Kelly, our huge Irish wolfhound,

taking cover.George returned quite soon to say that apparently the commotion made by the

women and children had frightened the lions off. He found their tracks in the soft earth

round the huts and a bag of maize that had been playfully torn open but the lions had

moved on.Next day we heard that they had moved to Hickson-Wood’s shamba. Hicky

came across to say that the lions had jumped over the wall of his cattle boma and killed

both his white Muskat riding donkeys.

He and a friend sat up all next night over the remains but the lions did not return to

the kill.Apart from the little set back last week, Ann is blooming. She has a cap of very

fine fair hair and clear blue eyes under straight brow. She also has lovely dimples in both

cheeks. We are very proud of her.Our neighbours are picking coffee but the crops are small and the price is low. I

am amazed that they are so optimistic about the future. No one in these parts ever

seems to grouse though all are living on capital. They all say “Well if the worst happens

we can always go up to the Lupa Diggings.”Don’t worry about us, we have enough to tide us over for some time yet.

Much love to all,

Eleanor.Mchewe Estate. 28th Sept. 1932

Dearest Family,

News! News! I’m going to have another baby. George and I are delighted and I

hope it will be a boy this time. I shall be able to have him at Mbeya because things are

rapidly changing here. Several German families have moved to Mbeya including a

German doctor who means to build a hospital there. I expect he will make a very good

living because there must now be some hundreds of Europeans within a hundred miles

radius of Mbeya. The Europeans are mostly British or German but there are also

Greeks and, I believe, several other nationalities are represented on the Lupa Diggings.

Ann is blooming and developing according to the Book except that she has no

teeth yet! Kath Hickson-Wood has given her a very nice high chair and now she has

breakfast and lunch at the table with us. Everything within reach goes on the floor to her

amusement and my exasperation!You ask whether we have any Church of England missionaries in our part. No we

haven’t though there are Lutheran and Roman Catholic Missions. I have never even

heard of a visiting Church of England Clergyman to these parts though there are babies

in plenty who have not been baptised. Jolly good thing I had Ann Christened down

there.The R.C. priests in this area are called White Fathers. They all have beards and

wear white cassocks and sun helmets. One, called Father Keiling, calls around frequently.

Though none of us in this area is Catholic we take it in turn to put him up for the night. The

Catholic Fathers in their turn are most hospitable to travellers regardless of their beliefs.

Rather a sad thing has happened. Lucas our old chicken-boy is dead. I shall miss

his toothy smile. George went to the funeral and fired two farewell shots from his rifle

over the grave – a gesture much appreciated by the locals. Lucas in his day was a good

hunter.Several of the locals own muzzle loading guns but the majority hunt with dogs

and spears. The dogs wear bells which make an attractive jingle but I cannot bear the

idea of small antelope being run down until they are exhausted before being clubbed of

stabbed to death. We seldom eat venison as George does not care to shoot buck.

Recently though, he shot an eland and Abel rendered down the fat which is excellent for

cooking and very like beef fat.Much love to all,

Eleanor.Mchewe Estate. P.O.Mbeya 21st November 1932

Dearest Family,

George has gone off to the Lupa for a week with John Molteno. John came up

here with the idea of buying a coffee farm but he has changed his mind and now thinks of

staking some claims on the diggings and also setting up as a gold buyer.Did I tell you about his arrival here? John and George did some elephant hunting

together in French Equatorial Africa and when John heard that George had married and

settled in Tanganyika, he also decided to come up here. He drove up from Cape Town

in a Baby Austin and arrived just as our labourers were going home for the day. The little

car stopped half way up our hill and John got out to investigate. You should have heard

the astonished exclamations when John got out – all 6 ft 5 ins. of him! He towered over

the little car and even to me it seemed impossible for him to have made the long

journey in so tiny a car.Kath Wood has been over several times lately. She is slim and looks so right in

the shirt and corduroy slacks she almost always wears. She was here yesterday when

the shamba boy, digging in the front garden, unearthed a large earthenware cooking pot,

sealed at the top. I was greatly excited and had an instant mental image of fabulous

wealth. We made the boy bring the pot carefully on to the verandah and opened it in

happy anticipation. What do you think was inside? Nothing but a grinning skull! Such a

treat for a pregnant female.We have a tree growing here that had lovely straight branches covered by a

smooth bark. I got the garden boy to cut several of these branches of a uniform size,

peeled off the bark and have made Ann a playpen with the poles which are much like

broom sticks. Now I can leave her unattended when I do my chores. The other morning

after breakfast I put Ann in her playpen on the verandah and gave her a piece of toast

and honey to keep her quiet whilst I laundered a few of her things. When I looked out a

little later I was horrified to see a number of bees buzzing around her head whilst she

placidly concentrated on her toast. I made a rapid foray and rescued her but I still don’t

know whether that was the thing to do.We all send our love,

Eleanor.Mbeya Hospital. April 25th. 1933

Dearest Family,

Here I am, installed at the very new hospital, built by Dr Eckhardt, awaiting the

arrival of the new baby. George has gone back to the farm on foot but will walk in again

to spend the weekend with us. Ann is with me and enjoys the novelty of playing with

other children. The Eckhardts have two, a pretty little girl of two and a half and a very fair

roly poly boy of Ann’s age. Ann at fourteen months is very active. She is quite a little girl

now with lovely dimples. She walks well but is backward in teething.George, Ann and I had a couple of days together at the hotel before I moved in

here and several of the local women visited me and have promised to visit me in

hospital. The trip from farm to town was very entertaining if not very comfortable. There

is ten miles of very rough road between our farm and Utengule Mission and beyond the

Mission there is a fair thirteen or fourteen mile road to Mbeya.As we have no car now the doctor’s wife offered to drive us from the Mission to

Mbeya but she would not risk her car on the road between the Mission and our farm.

The upshot was that I rode in the Hickson-Woods machila for that ten mile stretch. The

machila is a canopied hammock, slung from a bamboo pole, in which I reclined, not too

comfortably in my unwieldy state, with Ann beside me or sometime straddling me. Four

of our farm boys carried the machila on their shoulders, two fore and two aft. The relief

bearers walked on either side. There must have been a dozen in all and they sang a sort

of sea shanty song as they walked. One man would sing a verse and the others took up

the chorus. They often improvise as they go. They moaned about my weight (at least

George said so! I don’t follow Ki-Swahili well yet) and expressed the hope that I would

have a son and that George would reward them handsomely.George and Kelly, the dog, followed close behind the machila and behind

George came Abel our cook and his wife and small daughter Annalie, all in their best

attire. The cook wore a palm beach suit, large Terai hat and sunglasses and two colour

shoes and quite lent a tone to the proceedings! Right at the back came the rag tag and

bobtail who joined the procession just for fun.Mrs Eckhardt was already awaiting us at the Mission when we arrived and we had

an uneventful trip to the Mbeya Hotel.During my last week at the farm I felt very tired and engaged the cook’s small

daughter, Annalie, to amuse Ann for an hour after lunch so that I could have a rest. They

played in the small verandah room which adjoins our bedroom and where I keep all my

sewing materials. One afternoon I was startled by a scream from Ann. I rushed to the

room and found Ann with blood steaming from her cheek. Annalie knelt beside her,

looking startled and frightened, with my embroidery scissors in her hand. She had cut off

half of the long curling golden lashes on one of Ann’s eyelids and, in trying to finish the

job, had cut off a triangular flap of skin off Ann’s cheek bone.I called Abel, the cook, and demanded that he should chastise his daughter there and

then and I soon heard loud shrieks from behind the kitchen. He spanked her with a

bamboo switch but I am sure not as well as she deserved. Africans are very tolerant

towards their children though I have seen husbands and wives fighting furiously.

I feel very well but long to have the confinement over.Very much love,

Eleanor.Mbeya Hospital. 2nd May 1933.

Dearest Family,

Little George arrived at 7.30 pm on Saturday evening 29 th. April. George was

with me at the time as he had walked in from the farm for news, and what a wonderful bit

of luck that was. The doctor was away on a case on the Diggings and I was bathing Ann

with George looking on, when the pains started. George dried Ann and gave her

supper and put her to bed. Afterwards he sat on the steps outside my room and a

great comfort it was to know that he was there.The confinement was short but pretty hectic. The Doctor returned to the Hospital

just in time to deliver the baby. He is a grand little boy, beautifully proportioned. The

doctor says he has never seen a better formed baby. He is however rather funny

looking just now as his head is, very temporarily, egg shaped. He has a shock of black

silky hair like a gollywog and believe it or not, he has a slight black moustache.

George came in, looked at the baby, looked at me, and we both burst out

laughing. The doctor was shocked and said so. He has no sense of humour and couldn’t

understand that we, though bursting with pride in our son, could never the less laugh at

him.Friends in Mbeya have sent me the most gorgeous flowers and my room is

transformed with delphiniums, roses and carnations. The room would be very austere

without the flowers. Curtains, bedspread and enamelware, walls and ceiling are all

snowy white.George hired a car and took Ann home next day. I have little George for

company during the day but he is removed at night. I am longing to get him home and

away from the German nurse who feeds him on black tea when he cries. She insists that

tea is a medicine and good for him.Much love from a proud mother of two.

Eleanor.Mchewe Estate 12May 1933

Dearest Family,

We are all together at home again and how lovely it feels. Even the house

servants seem pleased. The boy had decorated the lounge with sprays of

bougainvillaea and Abel had backed one of his good sponge cakes.Ann looked fat and rosy but at first was only moderately interested in me and the

new baby but she soon thawed. George is good with her and will continue to dress Ann

in the mornings and put her to bed until I am satisfied with Georgie.He, poor mite, has a nasty rash on face and neck. I am sure it is just due to that

tea the nurse used to give him at night. He has lost his moustache and is fast loosing his

wild black hair and emerging as quite a handsome babe. He is a very masculine looking

infant with much more strongly marked eyebrows and a larger nose that Ann had. He is

very good and lies quietly in his basket even when awake.George has been making a hatching box for brown trout ova and has set it up in

a small clear stream fed by a spring in readiness for the ova which is expected from

South Africa by next weeks plane. Some keen fishermen from Mbeya and the District

have clubbed together to buy the ova. The fingerlings are later to be transferred to

streams in Mbeya and Tukuyu Districts.I shall now have my hands full with the two babies and will not have much time for the

garden, or I fear, for writing very long letters. Remember though, that no matter how

large my family becomes, I shall always love you as much as ever.Your affectionate,

Eleanor.Mchewe Estate. 14th June 1933

Dearest Family,

The four of us are all well but alas we have lost our dear Kelly. He was rather a

silly dog really, although he grew so big he retained all his puppy ways but we were all

very fond of him, especially George because Kelly attached himself to George whilst I

was away having Ann and from that time on he was George’s shadow. I think he had

some form of biliary fever. He died stretched out on the living room couch late last night,

with George sitting beside him so that he would not feel alone.The children are growing fast. Georgie is a darling. He now has a fluff of pale

brown hair and his eyes are large and dark brown. Ann is very plump and fair.

We have had several visitors lately. Apart from neighbours, a car load of diggers

arrived one night and John Molteno and his bride were here. She is a very attractive girl

but, I should say, more suited to life in civilisation than in this back of beyond. She has

gone out to the diggings with her husband and will have to walk a good stretch of the fifty

or so miles.The diggers had to sleep in the living room on the couch and on hastily erected

camp beds. They arrived late at night and left after breakfast next day. One had half a

beard, the other side of his face had been forcibly shaved in the bar the night before.your affectionate,

EleanorMchewe Estate. August 10 th. 1933

Dearest Family,

George is away on safari with two Indian Army officers. The money he will get for

his services will be very welcome because this coffee growing is a slow business, and

our capitol is rapidly melting away. The job of acting as White Hunter was unexpected

or George would not have taken on the job of hatching the ova which duly arrived from

South Africa.George and the District Commissioner, David Pollock, went to meet the plane

by which the ova had been consigned but the pilot knew nothing about the package. It

came to light in the mail bag with the parcels! However the ova came to no harm. David

Pollock and George brought the parcel to the farm and carefully transferred the ova to

the hatching box. It was interesting to watch the tiny fry hatch out – a process which took

several days. Many died in the process and George removed the dead by sucking

them up in a glass tube.When hatched, the tiny fry were fed on ant eggs collected by the boys. I had to

take over the job of feeding and removing the dead when George left on safari. The fry

have to be fed every four hours, like the baby, so each time I have fed Georgie. I hurry

down to feed the trout.The children are very good but keep me busy. Ann can now say several words

and understands more. She adores Georgie. I long to show them off to you.Very much love

Eleanor.Mchewe Estate. October 27th 1933

Dear Family,

All just over flu. George and Ann were very poorly. I did not fare so badly and

Georgie came off best. He is on a bottle now.There was some excitement here last Wednesday morning. At 6.30 am. I called

for boiling water to make Georgie’s food. No water arrived but muffled shouting and the

sound of blows came from the kitchen. I went to investigate and found a fierce fight in

progress between the house boy and the kitchen boy. In my efforts to make them stop

fighting I went too close and got a sharp bang on the mouth with the edge of an

enamelled plate the kitchen boy was using as a weapon. My teeth cut my lip inside and

the plate cut it outside and blood flowed from mouth to chin. The boys were petrified.

By the time I had fed Georgie the lip was stiff and swollen. George went in wrath

to the kitchen and by breakfast time both house boy and kitchen boy had swollen faces

too. Since then I have a kettle of boiling water to hand almost before the words are out

of my mouth. I must say that the fight was because the house boy had clouted the

kitchen boy for keeping me waiting! In this land of piece work it is the job of the kitchen

boy to light the fire and boil the kettle but the houseboy’s job to carry the kettle to me.

I have seen little of Kath Wood or Marion Coster for the past two months. Major

Jones is the neighbour who calls most regularly. He has a wireless set and calls on all of

us to keep us up to date with world as well as local news. He often brings oranges for

Ann who adores him. He is a very nice person but no oil painting and makes no effort to

entertain Ann but she thinks he is fine. Perhaps his monocle appeals to her.George has bought a six foot long galvanised bath which is a great improvement

on the smaller oval one we have used until now. The smaller one had grown battered

from much use and leaks like a sieve. Fortunately our bathroom has a cement floor,

because one had to fill the bath to the brim and then bath extremely quickly to avoid

being left high and dry.Lots and lots of love,

Eleanor.Mchewe Estate. P.O. Mbeya 1st December 1933

Dearest Family,

Ann has not been well. We think she has had malaria. She has grown a good

deal lately and looks much thinner and rather pale. Georgie is thriving and has such

sparkling brown eyes and a ready smile. He and Ann make a charming pair, one so fair

and the other dark.The Moltenos’ spent a few days here and took Georgie and me to Mbeya so

that Georgie could be vaccinated. However it was an unsatisfactory trip because the

doctor had no vaccine.George went to the Lupa with the Moltenos and returned to the farm in their Baby

Austin which they have lent to us for a week. This was to enable me to go to Mbeya to

have a couple of teeth filled by a visiting dentist.We went to Mbeya in the car on Saturday. It was quite a squash with the four of

us on the front seat of the tiny car. Once George grabbed the babies foot instead of the

gear knob! We had Georgie vaccinated at the hospital and then went to the hotel where

the dentist was installed. Mr Dare, the dentist, had few instruments and they were very

tarnished. I sat uncomfortably on a kitchen chair whilst he tinkered with my teeth. He filled

three but two of the fillings came out that night. This meant another trip to Mbeya in the

Baby Austin but this time they seem all right.The weather is very hot and dry and the garden a mess. We are having trouble

with the young coffee trees too. Cut worms are killing off seedlings in the nursery and

there is a borer beetle in the planted out coffee.George bought a large grey donkey from some wandering Masai and we hope

the children will enjoy riding it later on.Very much love,

Eleanor.Mchewe Estate. 14th February 1934.

Dearest Family,

You will be sorry to hear that little Ann has been very ill, indeed we were terribly

afraid that we were going to lose her. She enjoyed her birthday on the 8th. All the toys

you, and her English granny, sent were unwrapped with such delight. However next

day she seemed listless and a bit feverish so I tucked her up in bed after lunch. I dosed

her with quinine and aspirin and she slept fitfully. At about eleven o’clock I was

awakened by a strange little cry. I turned up the night light and was horrified to see that

Ann was in a convulsion. I awakened George who, as always in an emergency, was

perfectly calm and practical. He filled the small bath with very warm water and emersed

Ann in it, placing a cold wet cloth on her head. We then wrapped her in blankets and

gave her an enema and she settled down to sleep. A few hours later we had the same

thing over again.At first light we sent a runner to Mbeya to fetch the doctor but waited all day in

vain and in the evening the runner returned to say that the doctor had gone to a case on

the diggings. Ann had been feverish all day with two or three convulsions. Neither

George or I wished to leave the bedroom, but there was Georgie to consider, and in

the afternoon I took him out in the garden for a while whilst George sat with Ann.

That night we both sat up all night and again Ann had those wretched attacks of

convulsions. George and I were worn out with anxiety by the time the doctor arrived the

next afternoon. Ann had not been able to keep down any quinine and had had only

small sips of water since the onset of the attack.The doctor at once diagnosed the trouble as malaria aggravated by teething.

George held Ann whilst the Doctor gave her an injection. At the first attempt the needle

bent into a bow, George was furious! The second attempt worked and after a few hours

Ann’s temperature dropped and though she was ill for two days afterwards she is now

up and about. She has also cut the last of her baby teeth, thank God. She looks thin and

white, but should soon pick up. It has all been a great strain to both of us. Georgie

behaved like an angel throughout. He played happily in his cot and did not seem to

sense any tension as people say, babies do. Our baby was cheerful and not at all

subdued.This is the rainy season and it is a good thing that some work has been done on

our road or the doctor might not have got through.Much love to all,

Eleanor.Mchewe Estate. 1st October 1934

Dearest Family,

We are all well now, thank goodness, but last week Georgie gave us such a

fright. I was sitting on the verandah, busy with some sewing and not watching Ann and

Georgie, who were trying to reach a bunch of bananas which hung on a rope from a

beam of the verandah. Suddenly I heard a crash, Georgie had fallen backward over the

edge of the verandah and hit the back of his head on the edge of the brick furrow which

carries away the rainwater. He lay flat on his back with his arms spread out and did not

move or cry. When I picked him up he gave a little whimper, I carried him to his cot and

bathed his face and soon he began sitting up and appeared quite normal. The trouble

began after he had vomited up his lunch. He began to whimper and bang his head