Search Results for 'bert'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

November 4, 2022 at 2:19 pm #6342

In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

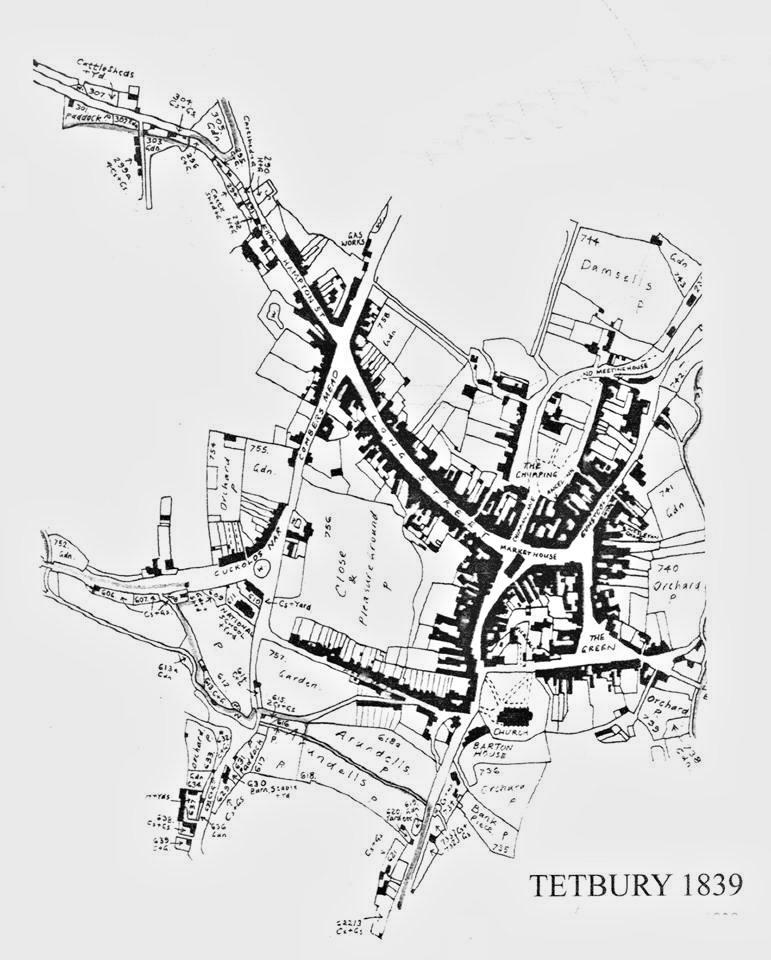

Brownings of Tetbury

Isaac Browning (1784-1848) married Mary Lock (1787-1870) in Tetbury in 1806. Both of them were born in Tetbury, Gloucestershire. Isaac was a stone mason. Between 1807 and 1832 they baptised fourteen children in Tetbury, and on 8 Nov 1829 Isaac and Mary baptised five daughters all on the same day.

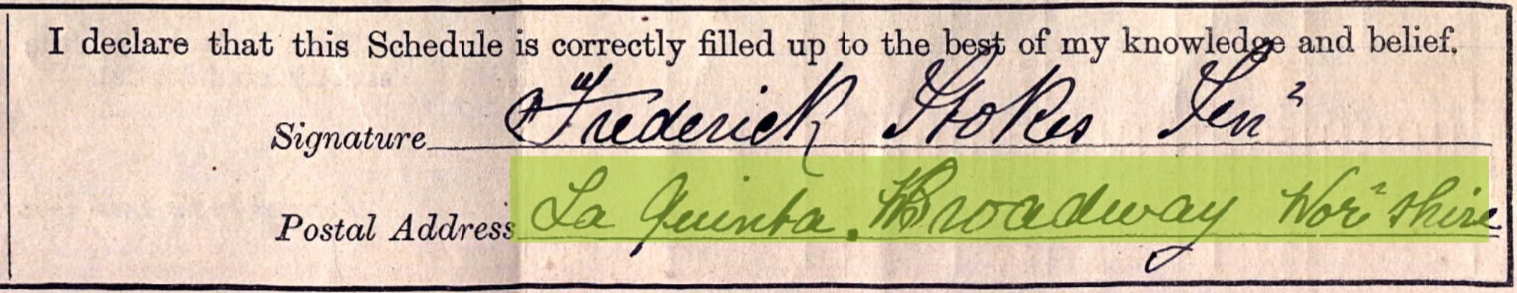

I considered that they may have been quintuplets, with only the last born surviving, which would have answered my question about the name of the house La Quinta in Broadway, the home of Eliza Browning and Thomas Stokes son Fred. However, the other four daughters were found in various records and they were not all born the same year. (So I still don’t know why the house in Broadway had such an unusual name).

Their son George was born and baptised in 1827, but Louisa born 1821, Susan born 1822, Hesther born 1823 and Mary born 1826, were not baptised until 1829 along with Charlotte born in 1828. (These birth dates are guesswork based on the age on later censuses.) Perhaps George was baptised promptly because he was sickly and not expected to survive. Isaac and Mary had a son George born in 1814 who died in 1823. Presumably the five girls were healthy and could wait to be done as a job lot on the same day later.

Eliza Browning (1814-1886), my great great great grandmother, had a baby six years before she married Thomas Stokes. Her name was Ellen Harding Browning, which suggests that her fathers name was Harding. On the 1841 census seven year old Ellen was living with her grandfather Isaac Browning in Tetbury. Ellen Harding Browning married William Dee in Tetbury in 1857, and they moved to Western Australia.

Ellen Harding Browning Dee: (photo found on ancestry website)

OBITUARY. MRS. ELLEN DEE.

A very old and respected resident of Dongarra, in the person of Mrs. Ellen Dee, passed peacefully away on Sept. 27, at the advanced age of 74 years.The deceased had been ailing for some time, but was about and actively employed until Wednesday, Sept. 20, whenn she was heard groaning by some neighbours, who immediately entered her place and found her lying beside the fireplace. Tho deceased had been to bed over night, and had evidently been in the act of lighting thc fire, when she had a seizure. For some hours she was conscious, but had lost the power of speech, and later on became unconscious, in which state she remained until her death.

The deceased was born in Gloucestershire, England, in 1833, was married to William Dee in Tetbury Church 23 years later. Within a month she left England with her husband for Western Australian in the ship City oí Bristol. She resided in Fremantle for six months, then in Greenough for a short time, and afterwards (for 42 years) in Dongarra. She was, therefore, a colonist of about 51 years. She had a family of four girls and three boys, and five of her children survive her, also 35 grandchildren, and eight great grandchildren. She was very highly respected, and her sudden collapse came as a great shock to many.

Eliza married Thomas Stokes (1816-1885) in September 1840 in Hempstead, Gloucestershire. On the 1841 census, Eliza and her mother Mary Browning (nee Lock) were staying with Thomas Lock and family in Cirencester. Strangely, Thomas Stokes has not been found thus far on the 1841 census, and Thomas and Eliza’s first child William James Stokes birth was registered in Witham, in Essex, on the 6th of September 1841.

I don’t know why William James was born in Witham, or where Thomas was at the time of the census in 1841. One possibility is that as Thomas Stokes did a considerable amount of work with circus waggons, circus shooting galleries and so on as a journeyman carpenter initially and then later wheelwright, perhaps he was working with a traveling circus at the time.

But back to the Brownings ~ more on William James Stokes to follow.

One of Isaac and Mary’s fourteen children died in infancy: Ann was baptised and died in 1811. Two of their children died at nine years old: the first George, and Mary who died in 1835. Matilda was 21 years old when she died in 1844.

Jane Browning (1808-) married Thomas Buckingham in 1830 in Tetbury. In August 1838 Thomas was charged with feloniously stealing a black gelding.

Susan Browning (1822-1879) married William Cleaver in November 1844 in Tetbury. Oddly thereafter they use the name Bowman on the census. On the 1851 census Mary Browning (Susan’s mother), widow, has grandson George Bowman born in 1844 living with her. The confusion with the Bowman and Cleaver names was clarified upon finding the criminal registers:

30 January 1834. Offender: William Cleaver alias Bowman, Richard Bunting alias Barnfield and Jeremiah Cox, labourers of Tetbury. Crime: Stealing part of a dead fence from a rick barton in Tetbury, the property of Robert Tanner, farmer.

And again in 1836:

29 March 1836 Bowman, William alias Cleaver, of Tetbury, labourer age 18; 5’2.5” tall, brown hair, grey eyes, round visage with fresh complexion; several moles on left cheek, mole on right breast. Charged on the oath of Ann Washbourn & others that on the morning of the 31 March at Tetbury feloniously stolen a lead spout affixed to the dwelling of the said Ann Washbourn, her property. Found guilty 31 March 1836; Sentenced to 6 months.

On the 1851 census Susan Bowman was a servant living in at a large drapery shop in Cheltenham. She was listed as 29 years old, married and born in Tetbury, so although it was unusual for a married woman not to be living with her husband, (or her son for that matter, who was living with his grandmother Mary Browning), perhaps her husband William Bowman alias Cleaver was in trouble again. By 1861 they are both living together in Tetbury: William was a plasterer, and they had three year old Isaac and Thomas, one year old. In 1871 William was still a plasterer in Tetbury, living with wife Susan, and sons Isaac and Thomas. Interestingly, a William Cleaver is living next door but one!

Susan was 56 when she died in Tetbury in 1879.

Three of the Browning daughters went to London.

Louisa Browning (1821-1873) married Robert Claxton, coachman, in 1848 in Bryanston Square, Westminster, London. Ester Browning was a witness.

Ester Browning (1823-1893)(or Hester) married Charles Hudson Sealey, cabinet maker, in Bethnal Green, London, in 1854. Charles was born in Tetbury. Charlotte Browning was a witness.

Charlotte Browning (1828-1867?) was admitted to St Marylebone workhouse in London for “parturition”, or childbirth, in 1860. She was 33 years old. A birth was registered for a Charlotte Browning, no mothers maiden name listed, in 1860 in Marylebone. A death was registered in Camden, buried in Marylebone, for a Charlotte Browning in 1867 but no age was recorded. As the age and parents were usually recorded for a childs death, I assume this was Charlotte the mother.

I found Charlotte on the 1851 census by chance while researching her mother Mary Lock’s siblings. Hesther Lock married Lewin Chandler, and they were living in Stepney, London. Charlotte is listed as a neice. Although Browning is mistranscribed as Broomey, the original page says Browning. Another mistranscription on this record is Hesthers birthplace which is transcribed as Yorkshire. The original image shows Gloucestershire.

Isaac and Mary’s first son was John Browning (1807-1860). John married Hannah Coates in 1834. John’s brother Charles Browning (1819-1853) married Eliza Coates in 1842. Perhaps they were sisters. On the 1861 census Hannah Browning, John’s wife, was a visitor in the Harding household in a village called Coates near Tetbury. Thomas Harding born in 1801 was the head of the household. Perhaps he was the father of Ellen Harding Browning.

George Browning (1828-1870) married Louisa Gainey in Tetbury, and died in Tetbury at the age of 42. Their son Richard Lock Browning, a 32 year old mason, was sentenced to one month hard labour for game tresspass in Tetbury in 1884.

Isaac Browning (1832-1857) was the youngest son of Isaac and Mary. He was just 25 years old when he died in Tetbury.

October 23, 2022 at 6:57 am #6340In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Wheelwrights of Broadway

Thomas Stokes 1816-1885

Frederick Stokes 1845-1917

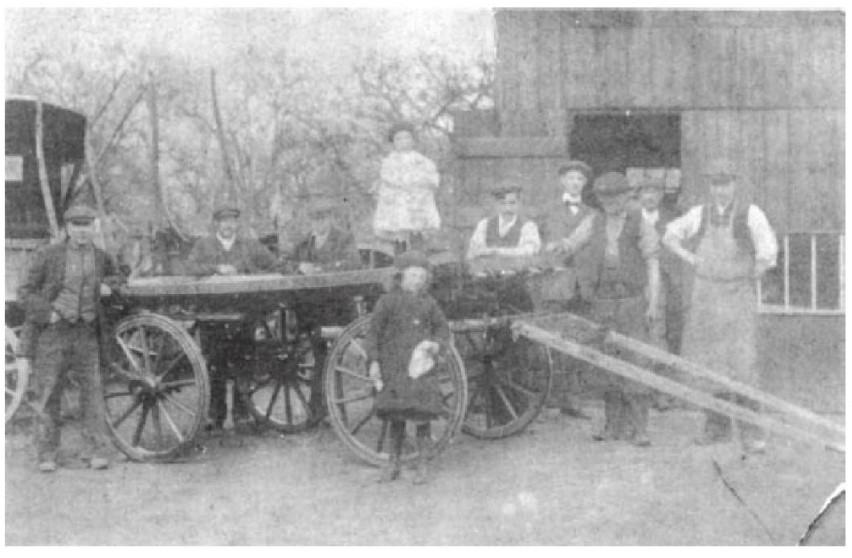

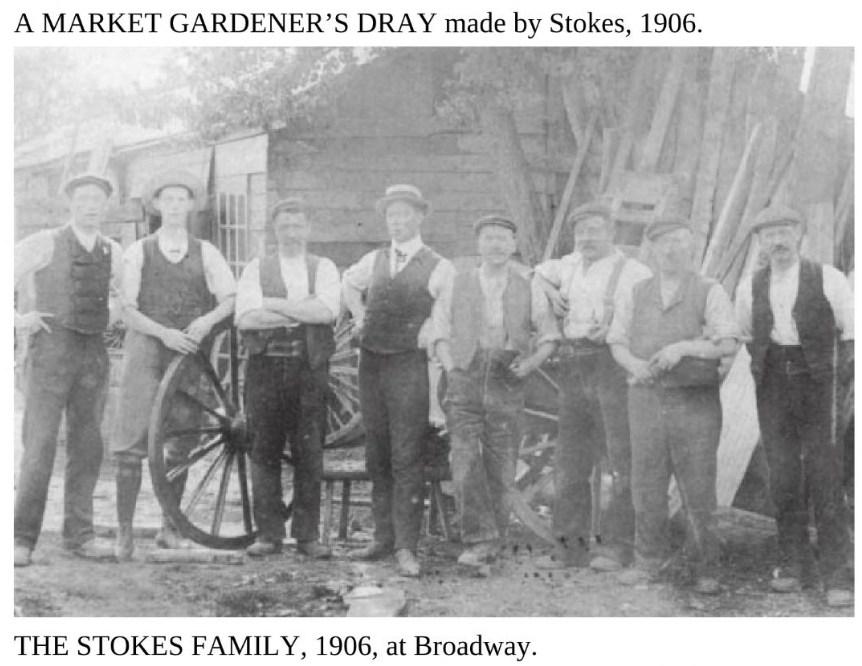

Stokes Wheelwrights. Fred on left of wheel, Thomas his father on right.

Thomas Stokes

Thomas Stokes was born in Bicester, Oxfordshire in 1816. He married Eliza Browning (born in 1814 in Tetbury, Gloucestershire) in Gloucester in 1840 Q3. Their first son William was baptised in Chipping Hill, Witham, Essex, on 3 Oct 1841. This seems a little unusual, and I can’t find Thomas and Eliza on the 1841 census. However both the 1851 and 1861 census state that William was indeed born in Essex.

In 1851 Thomas and Eliza were living in Bledington, Gloucestershire, and Thomas was a journeyman carpenter.

Note that a journeyman does not mean someone who moved around a lot. A journeyman was a tradesman who had served his trade apprenticeship and mastered his craft, not bound to serve a master, but originally hired by the day. The name derives from the French for day – jour.

Also on the 1851 census: their daughter Susan, born in Churchill Oxfordshire in 1844; son Frederick born in Bledington Gloucestershire in 1846; daughter Louisa born in Foxcote Oxfordshire in 1849; and 2 month old daughter Harriet born in Bledington in 1851.

On the 1861 census Thomas and Eliza were living in Evesham, Worcestershire, and daughter Susan was no longer living at home, but William, Fred, Louisa and Harriet were, as well as daughter Emily born in Churchill Oxfordshire in 1856. Thomas was a wheelwright.

On the 1871 census Thomas and Eliza were still living in Evesham, and Thomas was a wheelwright employing three apprentices. Son Fred, also a wheelwright, and his wife Ann Rebecca live with them.

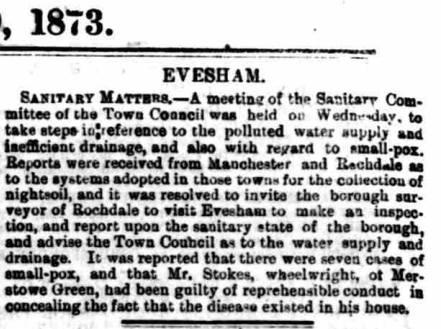

Mr Stokes, wheelwright, was found guilty of reprehensible conduct in concealing the fact that small-pox existed in his house, according to a mention in The Oxfordshire Weekly News on Wednesday 19 February 1873:

From Paul Weaver’s ancestry website:

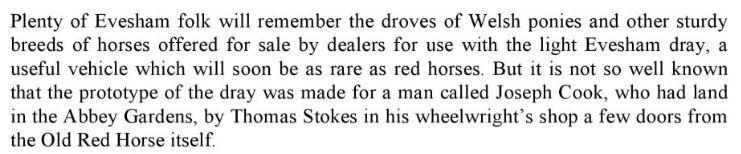

“It was Thomas Stokes who built the first “Famous Vale of Evesham Light Gardening Dray for a Half-Legged Horse to Trot” (the quotation is from his account book), the forerunner of many that became so familiar a sight in the towns and villages from the 1860s onwards. He built many more for the use of the Vale gardeners.

Thomas also had long-standing business dealings with the people of the circus and fairgrounds, and had a contract to effect necessary repairs and renewals to their waggons whenever they visited the district. He built living waggons for many of the show people’s families as well as shooting galleries and other equipment peculiar to the trade of his wandering customers, and among the names figuring in his books are some still familiar today, such as Wilsons and Chipperfields.

He is also credited with inventing the wooden “Mushroom” which was used by housewives for many years to darn socks. He built and repaired all kinds of vehicles for the gentry as well as for the circus and fairground travellers.

Later he lived with his wife at Merstow Green, Evesham, in a house adjoining the Almonry.”

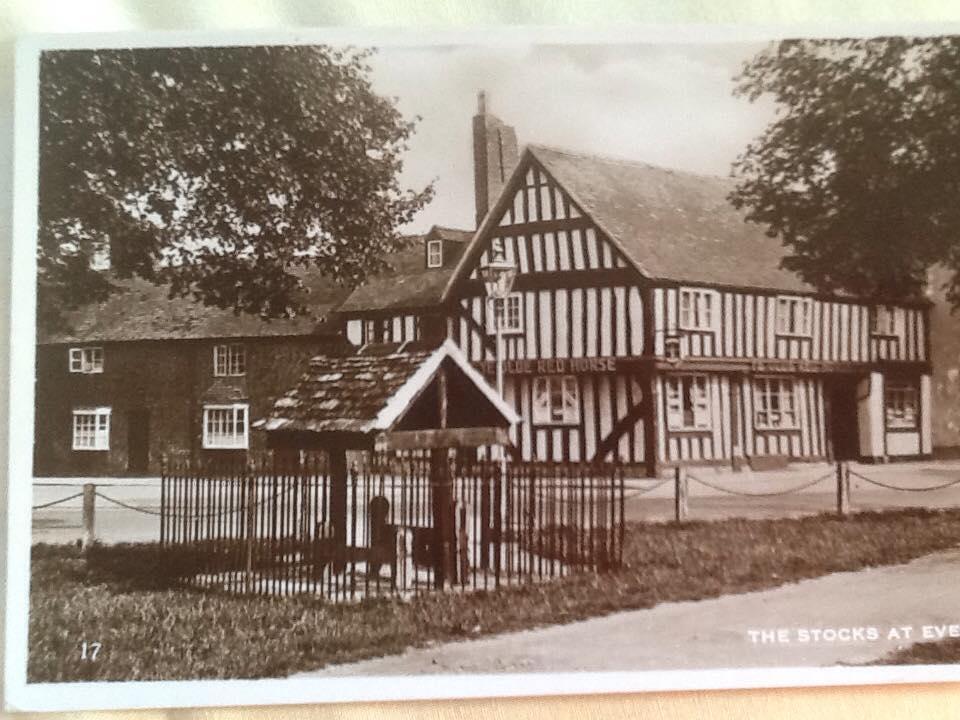

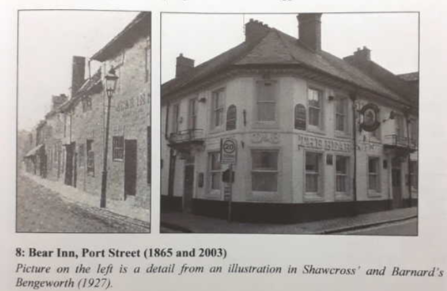

An excerpt from the book Evesham Inns and Signs by T.J.S. Baylis:

The Old Red Horse, Evesham:

Thomas died in 1885 aged 68 of paralysis, bronchitis and debility. His wife Eliza a year later in 1886.

Frederick Stokes

In Worcester in 1870 Fred married Ann Rebecca Day, who was born in Evesham in 1845.

Ann Rebecca Day:

In 1871 Fred was still living with his parents in Evesham, with his wife Ann Rebecca as well as their three month old daughter Annie Elizabeth. Fred and Ann (referred to as Rebecca) moved to La Quinta on Main Street, Broadway.

Rebecca Stokes in the doorway of La Quinta on Main Street Broadway, with her grandchildren Ralph and Dolly Edwards:

Fred was a wheelwright employing one man on the 1881 census. In 1891 they were still in Broadway, Fred’s occupation was wheelwright and coach painter, as well as his fifteen year old son Frederick.

In the Evesham Journal on Saturday 10 December 1892 it was reported that “Two cases of scarlet fever, the children of Mr. Stokes, wheelwright, Broadway, were certified by Mr. C. W. Morris to be isolated.”

Still in Broadway in 1901 and Fred’s son Albert was also a wheelwright. By 1911 Fred and Rebecca had only one son living at home in Broadway, Reginald, who was a coach painter. Fred was still a wheelwright aged 65.

Fred’s signature on the 1911 census:

Rebecca died in 1912 and Fred in 1917.

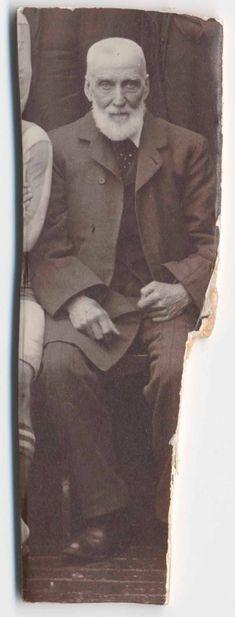

Fred Stokes:

In the book Evesham to Bredon From Old Photographs By Fred Archer:

October 22, 2022 at 1:18 pm #6338

October 22, 2022 at 1:18 pm #6338In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

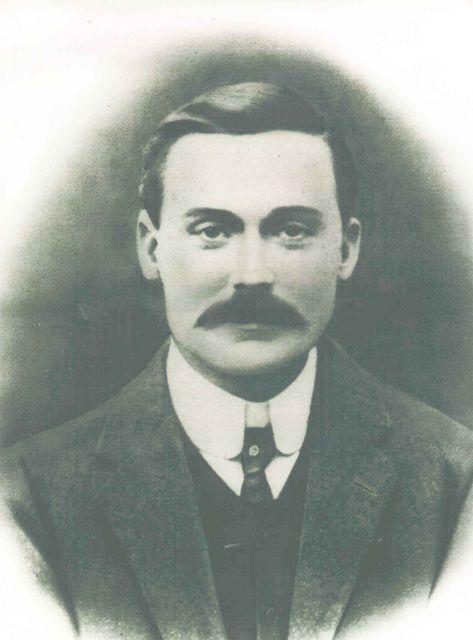

Albert Parker Edwards

1876-1930

Albert Parker Edwards, my great grandfather, was born in Aston, Warwickshire in 1876. On the 1881 census he was living with his parents Enoch and Amelia in Bournebrook, Northfield, Worcestershire. Enoch was a button tool maker at the time of the census.

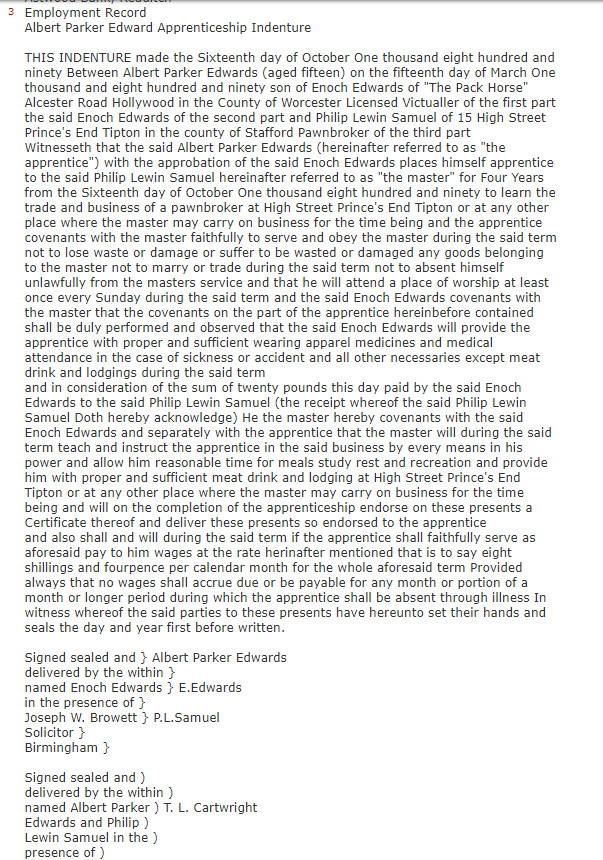

In 1890 Albert was indentured in an apprenticeship as a pawnbroker in Tipton, Staffordshire.

On the 1891 census Albert was a lodger in Tipton at the home of Phoebe Levy, pawnbroker, and Alberts occupation was an apprentice.

Albert married Annie Elizabeth Stokes in 1898 in Evesham, and their first son, my grandfather Albert Garnet Edwards (1898-1950), was born six months later in Crabbs Cross. On the 1901 census, Annie was in hospital as a patient and Albert was living at Crabbs Cross with a boarder, his brother Garnet Edwards. Their two year old son Albert Garnet was staying with his uncle Ralph, Albert Parkers brother, also in Crabbs Cross.

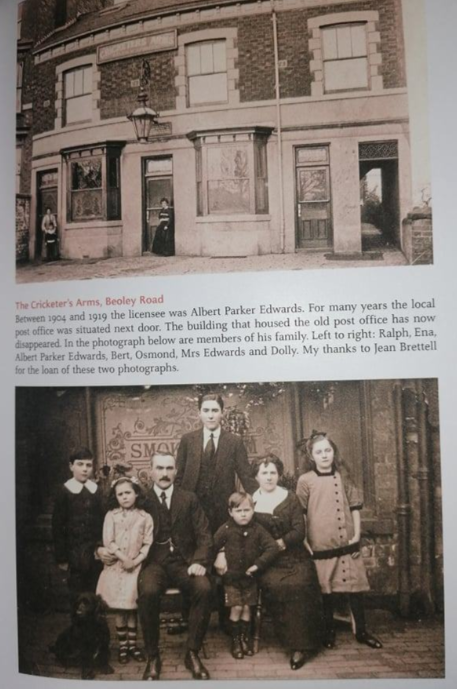

Albert and Annie kept the Cricketers Arms hotel on Beoley Road in Redditch until around 1920. They had a further four children while living there: Doris May Edwards (1902-1974), Ralph Clifford Edwards (1903-1988), Ena Flora Edwards (1908-1983) and Osmond Edwards (1910-2000).

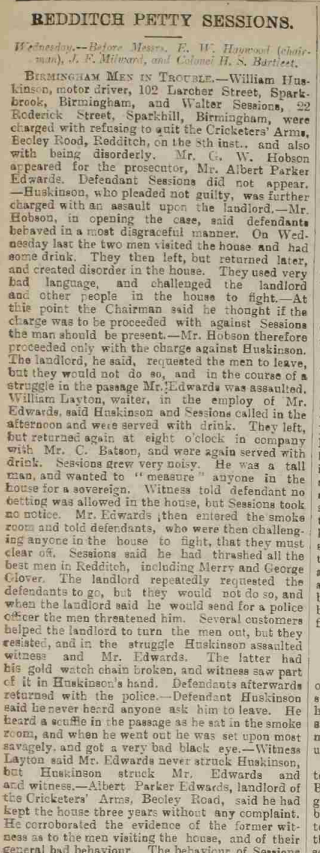

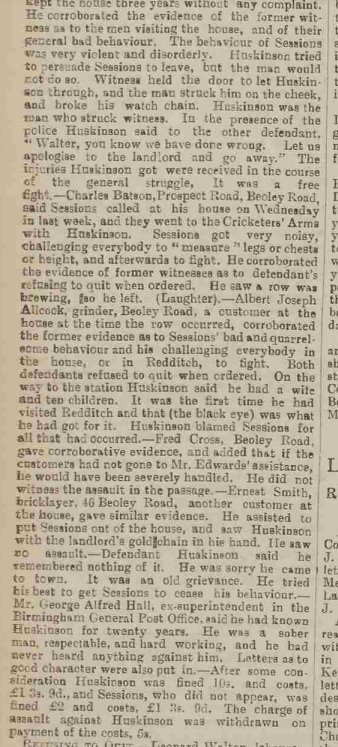

In 1906 Albert was assaulted during an incident in the Cricketers Arms.

Bromsgrove & Droitwich Messenger – Saturday 18 August 1906:

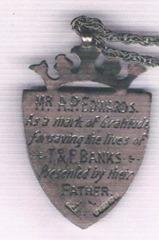

In 1910 a gold medal was given to Albert Parker Edwards by Mr. Banks, a policeman, in Redditch for saving the life of his two children from drowning in a brook on the Proctor farm which adjoined The Cricketers Arms. The story my father heard was that policeman Banks could not persuade the town of Redditch to come up with an award for Albert Parker Edwards so policeman Banks did it himself. William Banks, police constable, was living on Beoley Road on the 1911 census. His son Thomas was aged 5 and his daughter Frances was 8. It seems that when the father retired from the police he moved to Worcester. Thomas went into the hotel business and in 1939 was the manager of the Abbey hotel in Kenilworth. Frances married Edward Pardoe and was living along Redditch Road, Alvechurch in 1939.

My grandmother Peggy had the gold medal put on a gold chain for me in the 1970s. When I left England in the 1980s, I gave it back to her for safekeeping. When she died, the medal on the chain ended up in my fathers possession, who claims to have no knowledge that it was once given to me!

The medal:

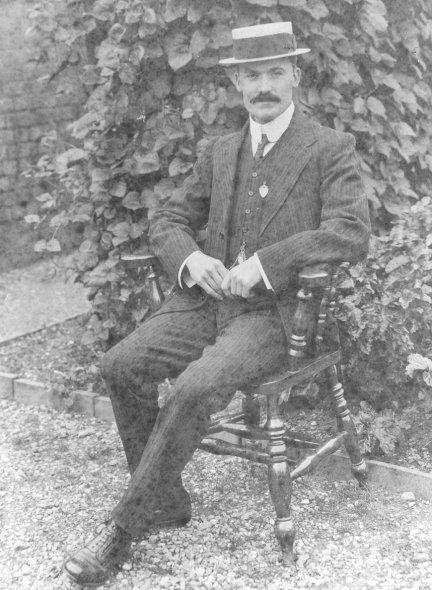

Albert Parker Edwards wearing the medal:

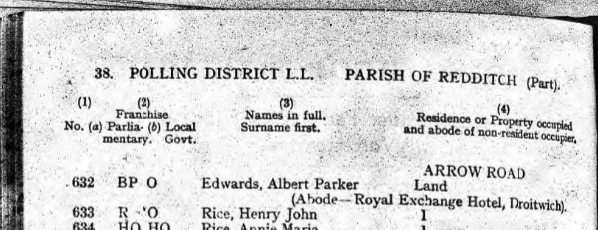

In 1921 Albert was at the The Royal Exchange hotel in Droitwich:

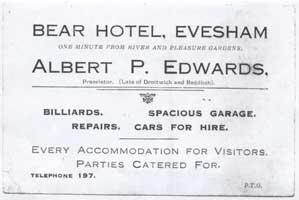

Between 1922 and 1927 Albert kept the Bear Hotel in Evesham:

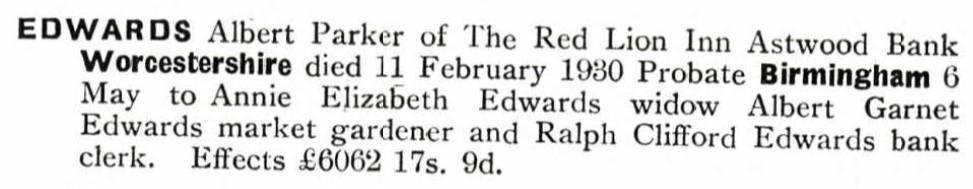

Then Albert and Annie moved to the Red Lion at Astwood Bank:

Albert in the garden behind the Red Lion:

They stayed at the Red Lion until Albert Parker Edwards died on the 11th of February, 1930 aged 53.

October 21, 2022 at 2:06 pm #6337

October 21, 2022 at 2:06 pm #6337In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Annie Elizabeth Stokes

1871-1961

“Grandma E”

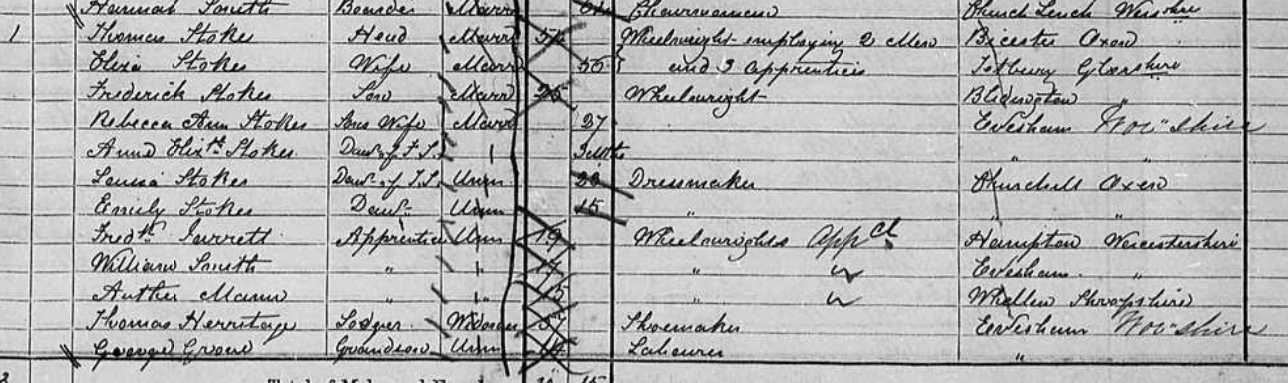

Annie, my great grandmother, was born 2 Jan 1871 in Merstow Green, Evesham, Worcestershire. Her father Fred Stokes was a wheelwright. On the 1771 census in Merston Green Annie was 3 months old and there was quite a houseful: Annies parents Fred and Rebecca, Fred’s parents Thomas and Eliza and two of their daughters, three apprentices, a lodger and one of Thomas’s grandsons.

1771 census Merstow Green, Evesham:

Annie at school in the early 1870s in Broadway. Annie is in the front on the left and her brother Fred is in the centre of the first seated row:

In 1881 Annie was a 10 year old visitor at the Angel Inn, Chipping Camden. A boarder there was 19 year old William Halford, a wheelwright apprentice. John Such, a 62 year old widower, was the innkeeper. Her parents and two siblings were living at La Quinta, on Main Street in Broadway.

According to her obituary in 1962, “When the Maxton family visited Broadway to stay with Mr and Madame de Navarro at Court Farm, they offered Annie a family post with them which took her for several years to Paris and other parts of the continent.”

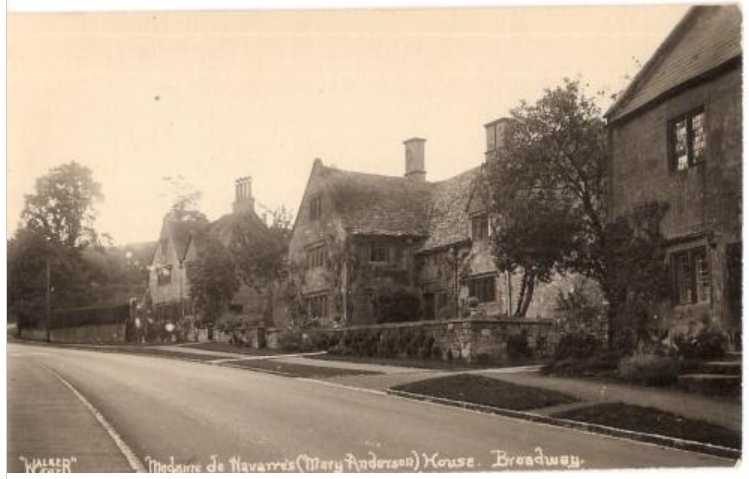

Mary Anderson was an American theatre actress. In 1890 she married Antonio Fernando de Navarro. She became known as Mary Anderson de Navarro. They settled at Court Farm in the Cotswolds, Broadway, Worcestershire, where she cultivated an interest in music and became a noted hostess with a distinguished circle of musical, literary and ecclesiastical guests. As in the years when Mary lived there, it was often filled with visiting artists and musicians, including Myra Hess and a young Jacqueline du Pré. (via Wikipedia)

Court Farm, Broadway:

Annie was an assistant to a tobacconist in West Bromwich in 1991, living as a boarder with William Calcutt and family. He future husband Albert was living in neighbouring Tipton in 1891, working at a pawnbroker apprenticeship.

Annie married Albert Parker Edwards in 1898 in Evesham. On the 1901 census, she was in hospital in Redditch.

By 1911, Anne and Albert had five children and were living at the Cricketers Arms in Redditch.

Behind the bar in 1904 shortly after taking over at the Cricketers Arms. From a book on Redditch pubs:

Annie was referred to in later years as Grandma E, probably to differentiate between her and my fathers Grandma T, as both lived to a great age.

Annie with her grandson Reg on the left and her daughter in law Peggy on the right, in the early 1950s:

Annie at my christening in 1959:

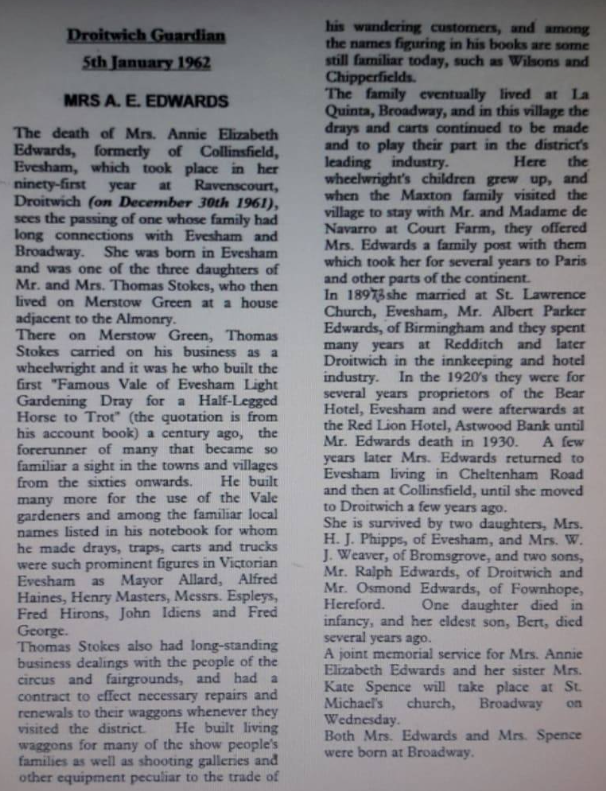

Annie died 30 Dec 1961, aged 90, at Ravenscourt nursing home, Redditch. Her obituary in the Droitwich Guardian in January 1962:

Note that this obituary contains an obvious error: Annie’s father was Frederick Stokes, and Thomas was his father.

October 12, 2022 at 12:16 pm #6335In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

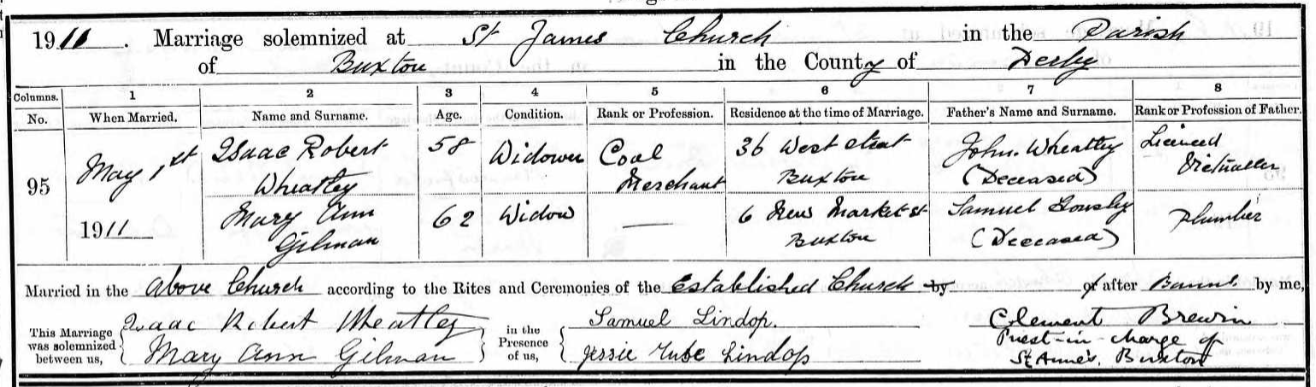

I looked for a death for Mary Anne Gilman nee Housley after the death of her husband Samuel Gilman, grocer in Buxton, in 1909, and couldn’t find one. I was not expecting to find that she remarried!

In 1911 in Buxton Mary Anne married Isaac Robert Wheatley, a widowed coal merchant.

Mary Anne Wheatley was buried in the same grave as her first husband Samuel Gilman. She died in Buxton in 1932 at the age of 82.

October 11, 2022 at 11:39 am #6333

October 11, 2022 at 11:39 am #6333In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The Grattidge Family

The first Grattidge to appear in our tree was Emma Grattidge (1853-1911) who married Charles Tomlinson (1847-1907) in 1872.

Charles Tomlinson (1873-1929) was their son and he married my great grandmother Nellie Fisher. Their daughter Margaret (later Peggy Edwards) was my grandmother on my fathers side.

Emma Grattidge was born in Wolverhampton, the daughter and youngest child of William Grattidge (1820-1887) born in Foston, Derbyshire, and Mary Stubbs, born in Burton on Trent, daughter of Solomon Stubbs, a land carrier. William and Mary married at St Modwens church, Burton on Trent, in 1839. It’s unclear why they moved to Wolverhampton. On the 1841 census William was employed as an agent, and their first son William was nine months old. Thereafter, William was a licensed victuallar or innkeeper.

William Grattidge was born in Foston, Derbyshire in 1820. His parents were Thomas Grattidge, farmer (1779-1843) and Ann Gerrard (1789-1822) from Ellastone. Thomas and Ann married in 1813 in Ellastone. They had five children before Ann died at the age of 25:

Bessy was born in 1815, Thomas in 1818, William in 1820, and Daniel Augustus and Frederick were twins born in 1822. They were all born in Foston. (records say Foston, Foston and Scropton, or Scropton)

On the 1841 census Thomas had nine people additional to family living at the farm in Foston, presumably agricultural labourers and help.

After Ann died, Thomas had three children with Kezia Gibbs (30 years his junior) before marrying her in 1836, then had a further four with her before dying in 1843. Then Kezia married Thomas’s nephew Frederick Augustus Grattidge (born in 1816 in Stafford) in London in 1847 and had two more!

The siblings of William Grattidge (my 3x great grandfather):

Frederick Grattidge (1822-1872) was a schoolmaster and never married. He died at the age of 49 in Tamworth at his twin brother Daniels address.

Daniel Augustus Grattidge (1822-1903) was a grocer at Gungate in Tamworth.

Thomas Grattidge (1818-1871) married in Derby, and then emigrated to Illinois, USA.

Bessy Grattidge (1815-1840) married John Buxton, farmer, in Ellastone in January 1838. They had three children before Bessy died in December 1840 at the age of 25: Henry in 1838, John in 1839, and Bessy Buxton in 1840. Bessy was baptised in January 1841. Presumably the birth of Bessy caused the death of Bessy the mother.

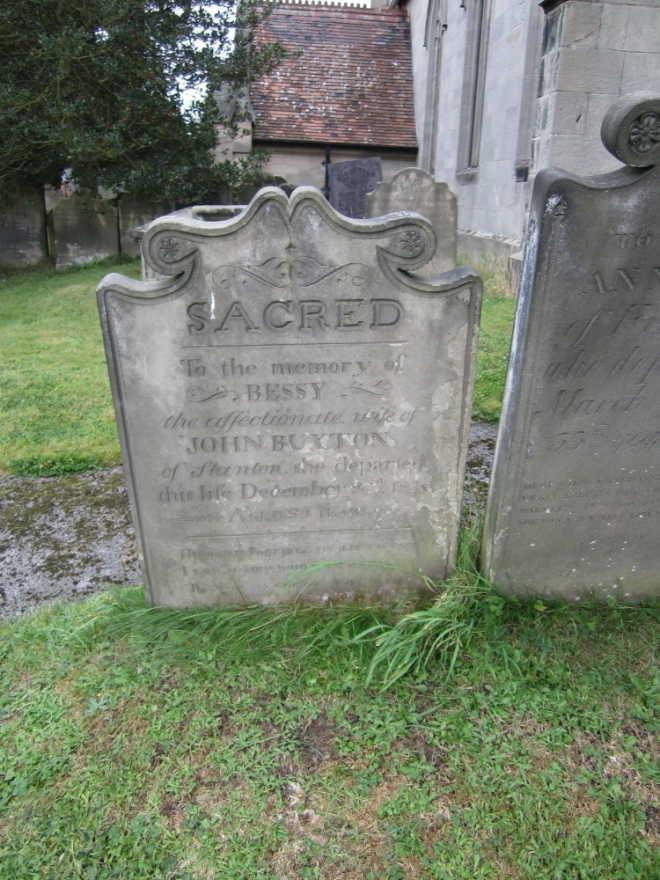

Bessy Buxton’s gravestone:

“Sacred to the memory of Bessy Buxton, the affectionate wife of John Buxton of Stanton She departed this life December 20th 1840, aged 25 years. “Husband, Farewell my life is Past, I loved you while life did last. Think on my children for my sake, And ever of them with I take.”

20 Dec 1840, Ellastone, Staffordshire

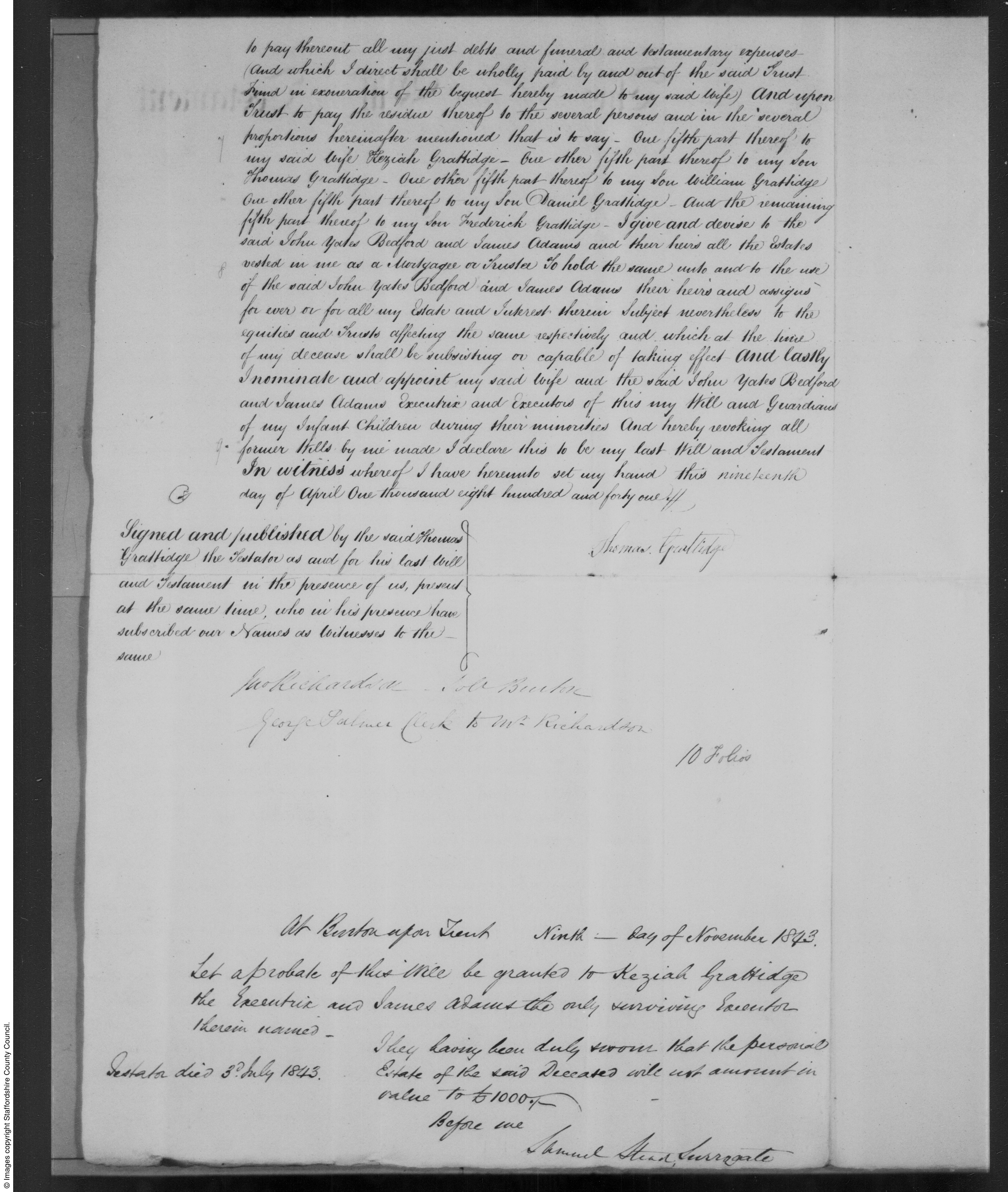

In the 1843 will of Thomas Grattidge, farmer of Foston, he leaves fifth shares of his estate, including freehold real estate at Findern, to his wife Kezia, and sons William, Daniel, Frederick and Thomas. He mentions that the children of his late daughter Bessy, wife of John Buxton, will be taken care of by their father. He leaves the farm to Keziah in confidence that she will maintain, support and educate his children with her.

An excerpt from the will:

I give and bequeath unto my dear wife Keziah Grattidge all my household goods and furniture, wearing apparel and plate and plated articles, linen, books, china, glass, and other household effects whatsoever, and also all my implements of husbandry, horses, cattle, hay, corn, crops and live and dead stock whatsoever, and also all the ready money that may be about my person or in my dwelling house at the time of my decease, …I also give my said wife the tenant right and possession of the farm in my occupation….

A page from the 1843 will of Thomas Grattidge:

William Grattidges half siblings (the offspring of Thomas Grattidge and Kezia Gibbs):

Albert Grattidge (1842-1914) was a railway engine driver in Derby. In 1884 he was driving the train when an unfortunate accident occured outside Ambergate. Three children were blackberrying and crossed the rails in front of the train, and one little girl died.

Albert Grattidge:

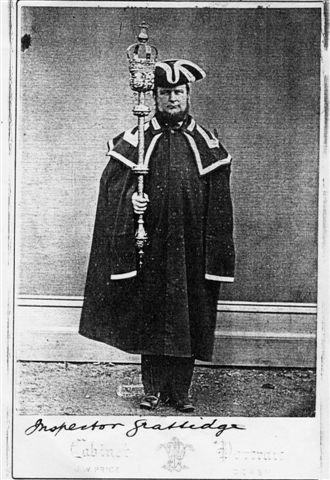

George Grattidge (1826-1876) was baptised Gibbs as this was before Thomas married Kezia. He was a police inspector in Derby.

George Grattidge:

Edwin Grattidge (1837-1852) died at just 15 years old.

Ann Grattidge (1835-) married Charles Fletcher, stone mason, and lived in Derby.

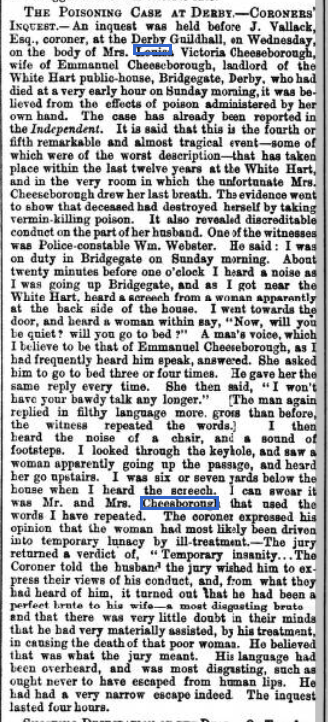

Louisa Victoria Grattidge (1840-1869) was sadly another Grattidge woman who died young. Louisa married Emmanuel Brunt Cheesborough in 1860 in Derby. In 1861 Louisa and Emmanuel were living with her mother Kezia in Derby, with their two children Frederick and Ann Louisa. Emmanuel’s occupation was sawyer. (Kezia Gibbs second husband Frederick Augustus Grattidge was a timber merchant in Derby)

At the time of her death in 1869, Emmanuel was the landlord of the White Hart public house at Bridgegate in Derby.

The Derby Mercury of 17th November 1869:

“On Wednesday morning Mr Coroner Vallack held an inquest in the Grand

Jury-room, Town-hall, on the body of Louisa Victoria Cheeseborough, aged

33, the wife of the landlord of the White Hart, Bridge-gate, who committed

suicide by poisoning at an early hour on Sunday morning. The following

evidence was taken:Mr Frederick Borough, surgeon, practising in Derby, deposed that he was

called in to see the deceased about four o’clock on Sunday morning last. He

accordingly examined the deceased and found the body quite warm, but dead.

He afterwards made enquiries of the husband, who said that he was afraid

that his wife had taken poison, also giving him at the same time the

remains of some blue material in a cup. The aunt of the deceased’s husband

told him that she had seen Mrs Cheeseborough put down a cup in the

club-room, as though she had just taken it from her mouth. The witness took

the liquid home with him, and informed them that an inquest would

necessarily have to be held on Monday. He had made a post mortem

examination of the body, and found that in the stomach there was a great

deal of congestion. There were remains of food in the stomach and, having

put the contents into a bottle, he took the stomach away. He also examined

the heart and found it very pale and flabby. All the other organs were

comparatively healthy; the liver was friable.Hannah Stone, aunt of the deceased’s husband, said she acted as a servant

in the house. On Saturday evening, while they were going to bed and whilst

witness was undressing, the deceased came into the room, went up to the

bedside, awoke her daughter, and whispered to her. but what she said the

witness did not know. The child jumped out of bed, but the deceased closed

the door and went away. The child followed her mother, and she also

followed them to the deceased’s bed-room, but the door being closed, they

then went to the club-room door and opening it they saw the deceased

standing with a candle in one hand. The daughter stayed with her in the

room whilst the witness went downstairs to fetch a candle for herself, and

as she was returning up again she saw the deceased put a teacup on the

table. The little girl began to scream, saying “Oh aunt, my mother is

going, but don’t let her go”. The deceased then walked into her bed-room,

and they went and stood at the door whilst the deceased undressed herself.

The daughter and the witness then returned to their bed-room. Presently

they went to see if the deceased was in bed, but she was sitting on the

floor her arms on the bedside. Her husband was sitting in a chair fast

asleep. The witness pulled her on the bed as well as she could.

Ann Louisa Cheesborough, a little girl, said that the deceased was her

mother. On Saturday evening last, about twenty minutes before eleven

o’clock, she went to bed, leaving her mother and aunt downstairs. Her aunt

came to bed as usual. By and bye, her mother came into her room – before

the aunt had retired to rest – and awoke her. She told the witness, in a

low voice, ‘that she should have all that she had got, adding that she

should also leave her her watch, as she was going to die’. She did not tell

her aunt what her mother had said, but followed her directly into the

club-room, where she saw her drink something from a cup, which she

afterwards placed on the table. Her mother then went into her own room and

shut the door. She screamed and called her father, who was downstairs. He

came up and went into her room. The witness then went to bed and fell

asleep. She did not hear any noise or quarrelling in the house after going

to bed.Police-constable Webster was on duty in Bridge-gate on Saturday evening

last, about twenty minutes to one o’clock. He knew the White Hart

public-house in Bridge-gate, and as he was approaching that place, he heard

a woman scream as though at the back side of the house. The witness went to

the door and heard the deceased keep saying ‘Will you be quiet and go to

bed’. The reply was most disgusting, and the language which the

police-constable said was uttered by the husband of the deceased, was

immoral in the extreme. He heard the poor woman keep pressing her husband

to go to bed quietly, and eventually he saw him through the keyhole of the

door pass and go upstairs. his wife having gone up a minute or so before.

Inspector Fearn deposed that on Sunday morning last, after he had heard of

the deceased’s death from supposed poisoning, he went to Cheeseborough’s

public house, and found in the club-room two nearly empty packets of

Battie’s Lincoln Vermin Killer – each labelled poison.Several of the Jury here intimated that they had seen some marks on the

deceased’s neck, as of blows, and expressing a desire that the surgeon

should return, and re-examine the body. This was accordingly done, after

which the following evidence was taken:Mr Borough said that he had examined the body of the deceased and observed

a mark on the left side of the neck, which he considered had come on since

death. He thought it was the commencement of decomposition.

This was the evidence, after which the jury returned a verdict “that the

deceased took poison whilst of unsound mind” and requested the Coroner to

censure the deceased’s husband.The Coroner told Cheeseborough that he was a disgusting brute and that the

jury only regretted that the law could not reach his brutal conduct.

However he had had a narrow escape. It was their belief that his poor

wife, who was driven to her own destruction by his brutal treatment, would

have been a living woman that day except for his cowardly conduct towards

her.The inquiry, which had lasted a considerable time, then closed.”

In this article it says:

“it was the “fourth or fifth remarkable and tragical event – some of which were of the worst description – that has taken place within the last twelve years at the White Hart and in the very room in which the unfortunate Louisa Cheesborough drew her last breath.”

Sheffield Independent – Friday 12 November 1869:

September 4, 2022 at 6:00 pm #6326

September 4, 2022 at 6:00 pm #6326In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

Stung by Egberts question, Olga reeled and almost lost her footing on the stairs. What had happened to her? That damned selfish individualism that was running rampant must have seeped into her room through the gaps in the windows or under the door. “No!” she shouted, her voice cracking.

“Say it isn’t true, Olga,” Egbert said, his voice breaking. “Not you as well.”

It took Olga a minute or two to still her racing heart. The near fall down the stairs had shaken her but with trembling hands she levered herself round to sit beside Egbert on the step.

Gripping his bony knee with her knobbly arthritic fingers, she took a deep breath.

“You are right to have said that, Egbert. If there is one thing we must hold onto, it’s our hearts. Nothing else matters, or at least nothing else matters as much as that. We are old and tired and we don’t like change. But if we escalate the importance of this frankly dreary and depressing home to the point where we lose our hearts…” she faltered and continued. “We will be homeless soon, very soon, and we know not what will happen to us. We must trust in the kindness of strangers, we must hope they have a heart.”

Egbert winced as Olga squeezed his knee. “And that is why”, Olga continued, slapping Egberts thigh with gusto, “We must have a heart…”

“If you’d just stop squeezing and hitting me, Olga…”

Olga loosened her grip on the old mans thigh bone and peered into his eyes. Quietly she thanked him. “You’ve cleared my mind and given me something to live for, and I thank you for that. But you do need to launder your clothes more often,” she added, pulling a face. She didn’t want the old coot to start blubbing, and he looked alarmingly close to tears.

“Come on, let’s go and see Obadiah. We’re all in this together. Homelessness and adventure can wait until tomorrow.” Olga heaved herself upright with a surprising burst of vitality. Noticing a weak smile trembling on Egberts lips, she said “That’s the spirit!”

July 13, 2022 at 3:09 am #6323In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

“Watch where you are going, Child!” Egbert’s tone was sharp.

“Excuse me,” said Maryechka, hunching her shoulders and making herself small as a mouse so she could squeeze past Egbert’s oversized suitcase.

“To be fair, Old Man,” said Olga, glad of the excuse to pause, “you are taking up all the available space on the stairs with those bags.” She peered at Maryechka. “You are Obadiah’s girl aren’t you?”

Maryechka nodded shyly. “He’s my grandpa.” She frowned at the suitcases. “Are you going on holiday?”

“Never you mind that,” said Egbert. “You run along and see your Grandpa.”

Maryechka ducked past the bag and ran up the steps.

“Oy,” said Olga. “What I wouldn’t give for the agility of youth again.” Gripping the wooden hand rail, she stretched out her ankle and grimaced.

“Obadiah is stubborn as a mule,” said Egbert. “I tried warning him! He said he’d die in his room if it came to it.”

“Pfft,” said Olga. “That one will land on his big stinking feet. And he can hear better than he lets on. Is it him spreading the tales about me?”

Egbert dropped his bags and sat heavily on the step. He put his head in his hands and groaned. “Is it right though, Olga? Is it right that we leave our friends to their fate?”

It occurred to Olga that Egbert may be hiding his head so as not to answer her question. However, realising his mental state was fragile, she thought it prudent to keep to the matter at hand. It will keep, she thought.

“Obadiah and myself, we grew up together,” continued Egbert with what sounded like a sob. “We worked together on the farm as young men.” He raised his head and glared at Olga. “How can you expect me to leave him without a word of farewell? Have you no heart?”

July 12, 2022 at 8:30 am #6319In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

“Calm yourself, Egbert, and sit down. And be quiet! I can barely hear myself think with your frantic gibbering and flailing around,” Olga said, closing her eyes. “I need to think.”

Egbert clutched the eiderdown on either side of his bony trembling knees and clamped his remaining teeth together, drawing ragged whistling breaths in an attempt to calm himself. Olga was right, he needed to calm down. Besides the unfortunate effects of the letter on his habitual tremor, he felt sure his blood pressure had risen alarmingly. He dared not become so ill that he needed medical assistance, not with the state of the hospitals these days. He’d be lucky to survive the plague ridden wards.

What had become of him! He imagined his younger self looking on with horror, appalled at his feeble body and shattered mind. Imagine becoming so desperate that he wanted to fight to stay in this godforsaken dump, what had become of him! If only he knew of somewhere else to go, somewhere safe and pleasant, somewhere that smelled sweetly of meadows and honesuckle and freshly baked cherry pies, with the snorting of pigs in the yard…

But wait, that was Olga snoring. Useless old bag had fallen asleep! For the first time since Viktor had died he felt close to tears. What a sad sorry pathetic old man he’d become, desperately counting on a old woman to save him.

“Stop sniveling, Egbert, and go and pack a bag.” Olga had woken up from her momentary but illuminating lapse. “Don’t bring too much, we may have much walking to do. I hear the buses and trains are in a shambles and full of refugees. We don’t want to get herded up with them.”

Astonished, Egbert asked where they were going.

“To see Rosa. My cousins father in laws neice. Don’t look at me like that, immediate family are seldom the ones who help. The distant ones are another matter. And be honest Egbert,” Olga said with a piercing look, “Do we really want to stay here? You may think you do, but it’s the fear of change, that’s all. Change feels like too much bother, doesn’t it?”

Egbert nodded sadly, his eyes fixed on the stain on the grey carpet.

Olga leaned forward and took his hand gently. “Egbert, look at me.” He raised his head and looked into her eyes. He’d never seen a sparkle in her faded blue eyes before. “I still have another adventure in me. How about you?”

July 12, 2022 at 2:00 am #6318In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

“You’d better sit down,” said Olga gesturing to the end of her bed. As a rule, she did not have visitors so she saw no need to clutter up the available space in her tiny room with an extra chair. A large proportion of her life was spent in her armchair and she was content that way. While Egbert perched on the end of the bed, she lowered herself into the soft and familiar confines of her armchair and felt instantly soothed. It was true, sometimes she felt a tinge of regret when she considered how disappointed her younger self would be to see her now. But she hadn’t lived through what I’ve lived through so she can mind her own damn business,” she thought.

“It is just a story, twisted in the telling I expect.” Olga knew her voice held no conviction.

Egbert opened his mouth as though to speak. Closed it again.

“You look like a fish,” said Olga folding her arms.

“They say you and the Mayor go back a long way. Are you telling me that is not true?

“And what if we do?”

“You know he is Ursula’s uncle and a very powerful man. They say even the great president Voldomeer Zumbaskee holds him in great regard. They say …”

“Pfft! They say!” snapped Olga. “Who are these chattering fools you listen to, Egbert Gofindlevsky? I’d rather end up on the streets than ask a favour from that mountebank.”

Egbert jumped up from the bed and shook a fist at her. “And end up on the streets you will, Olga Herringbonevsky, along with the rest of us. You really want that on your conscience?”

July 10, 2022 at 2:36 am #6317In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

The sharp rat-a-tat on the door startled Olga Herringbonevsky. The initial surprise quickly turned to annoyance. It was 11am and she wasn’t expecting a knock on the door at 11am. At 10am she expected a knock. It would be Larysa with the lukewarm cup of tea and a stale biscuit. Sometimes Olga complained about it and Larysa would say, Well you’re on the third floor so what do you expect? And she’d look cross and pour the tea so some of it slopped into the saucer. So the biscuits go stale on the way up do they? Olga would mutter. At 10:30am Larysa would return to collect the cup and saucer. I can’t do this much longer, she’d say. I’m not young any more and all these damn stairs. She’d been saying that for as long as Olga could remember.

For a moment, Olga contemplated ignoring the intrusion but the knocking started up again, this time accompanied by someone shouting her name.

With a very loud sigh, she put her book on the side table, face down so she would not lose her place for it was a most enjoyable whodunit, and hauled herself up from the chair. Her ankle was not good since she’d gone over on it the other day and Olga was in a very poor mood by the time she reached the door.

“Yes?” She glowered at Egbert.

“Have you seen this?” Egbert was waving a piece of paper at her.

“No,” Olga started to close the door.

“Olga stop!” Egbert’s face had reddened and Olga wondered if he might cry. Again, he waved the piece of paper in her face and then let his hand fall defeated to his side. “Olga, it’s bad news. You should have got a letter .”

Olga glanced at the pile of unopened letters on her dresser. It was never good news. She couldn’t be bothered with letters any more.

“Well, Egbert, I suppose you’d better come in”.

“That Ursula has a heart of steel,” said Olga when she’d heard the news.

“Pfft,” said Egbert. “She has no heart. This place has always been about money for her.”

“It’s bad times, Egbert. Bad times.”

Egbert nodded. “It is, Olga. But there must be something we can do.” He pursed his lips and Olga noticed that he would not meet her eyes.

“What? Spit it out, Old Man.”

He looked at her briefly before his eyes slid back to the dirty grey carpet. “I have heard stories, Olga. That you are … well connected. That you know people.”

Olga noticed that it had become difficult to breathe. Seeing Egbert looking at her with concern, she made an effort to steady herself. She took an extra big gasp of air and pointed to the book face-down on the side table. “That is a very good book I am reading. You may borrow it when I have finished.”

Egbert nodded. “Thank you.” he said and they both stared at the book.

“It was a long time ago, Egbert. And no business of anyone else.” Olga knew her voice was sharp but not sharp enough it seemed as Egbert was not done yet with all his prying words.

“Olga, you said it yourself. These are bad times. And desperate measures are needed or we will all perish.” Now he looked her in the eyes. “Old woman, swallow your pride. You must save yourself and all of us here.”

July 6, 2022 at 11:41 am #6313In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

Egbert Gofindlevsky rapped on the door of room number 22. The letter flapped against his pin striped trouser leg as his hand shook uncontrollably, his habitual tremor exacerbated with the shock. Remembering that Obadiah Sproutwinklov was deaf, he banged loudly on the door with the flat of his hand. Eventually the door creaked open.

Egbert flapped the letter in from of Obadiah’s face. “Have you had one of these?” he asked.

“If you’d stop flapping it about I might be able to see what it is,” Obadiah replied. “Oh that! As a matter of fact I’ve had one just like it. The devils work, I tell you! A practical joke, and in very poor taste!”

Egbert was starting to wish he’d gone to see Olga Herringbonevsky first. “Can I come in?” he hissed, “So we can discuss it in private?”

Reluctantly Obadiah pulled the door open and ushered him inside the room. Egbert looked around for a place to sit, but upon noticing a distinct odour of urine decided to remain standing.

“Ursula is booting us out, where are we to go?”

“Eh?” replied Obadiah, cupping his ear. “Speak up, man!”

Egbert repeated his question.

“No need to shout!”

The two old men endeavoured to conduct a conversation on this unexepected turn of events, the upshot being that Obadiah had no intention of leaving his room at all henceforth, come what may, and would happily starve to death in his room rather than take to the streets.

Egbert considered this form of action unhelpful, as he himself had no wish to starve to death in his room, so he removed himself from room 22 with a disgruntled sigh and made his way to Olga’s room on the third floor.

July 1, 2022 at 9:51 am #6306In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Looking for Robert Staley

William Warren (1835-1880) of Newhall (Stapenhill) married Elizabeth Staley (1836-1907) in 1858. Elizabeth was born in Newhall, the daughter of John Staley (1795-1876) and Jane Brothers. John was born in Newhall, and Jane was born in Armagh, Ireland, and they were married in Armagh in 1820. Elizabeths older brothers were born in Ireland: William in 1826 and Thomas in Dublin in 1830. Francis was born in Liverpool in 1834, and then Elizabeth in Newhall in 1836; thereafter the children were born in Newhall.

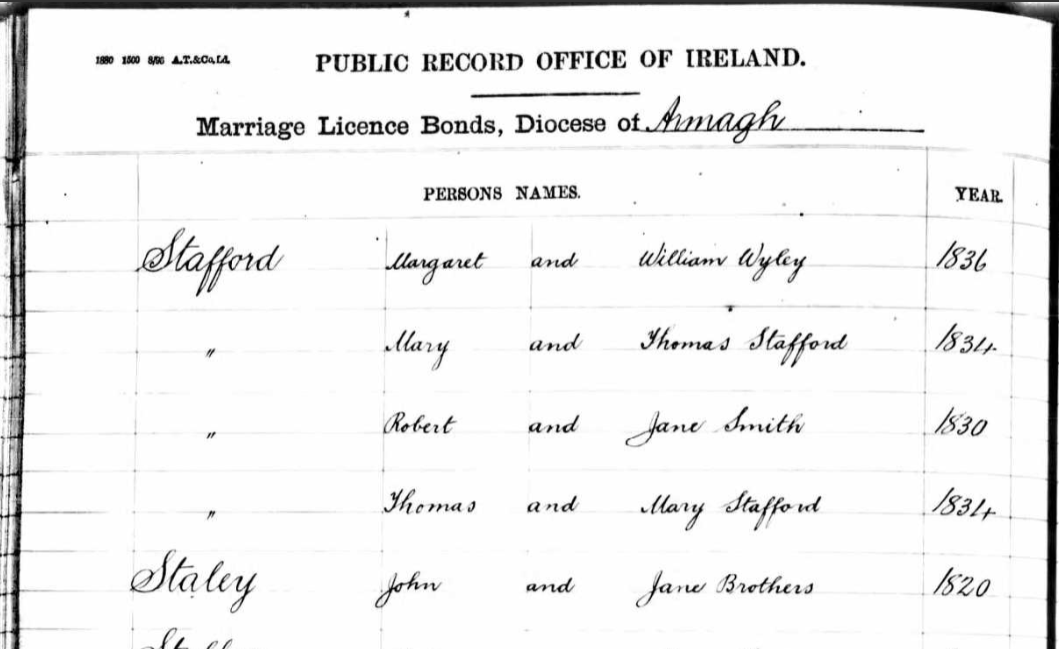

Marriage of John Staley and Jane Brothers in 1820:

My grandmother related a story about an Elizabeth Staley who ran away from boarding school and eloped to Ireland, but later returned. The only Irish connection found so far is Jane Brothers, so perhaps she meant Elizabeth Staley’s mother. A boarding school seems unlikely, and it would seem that it was John Staley who went to Ireland.

The 1841 census states Jane’s age as 33, which would make her just 12 at the time of her marriage. The 1851 census states her age as 44, making her 13 at the time of her 1820 marriage, and the 1861 census estimates her birth year as a more likely 1804. Birth records in Ireland for her have not been found. It’s possible, perhaps, that she was in service in the Newhall area as a teenager (more likely than boarding school), and that John and Jane ran off to get married in Ireland, although I haven’t found any record of a child born to them early in their marriage. John was an agricultural labourer, and later a coal miner.

John Staley was the son of Joseph Staley (1756-1838) and Sarah Dumolo (1764-). Joseph and Sarah were married by licence in Newhall in 1782. Joseph was a carpenter on the marriage licence, but later a collier (although not necessarily a miner).

The Derbyshire Record Office holds records of an “Estimate of Joseph Staley of Newhall for the cost of continuing to work Pisternhill Colliery” dated 1820 and addresssed to Mr Bloud at Calke Abbey (presumably the owner of the mine)

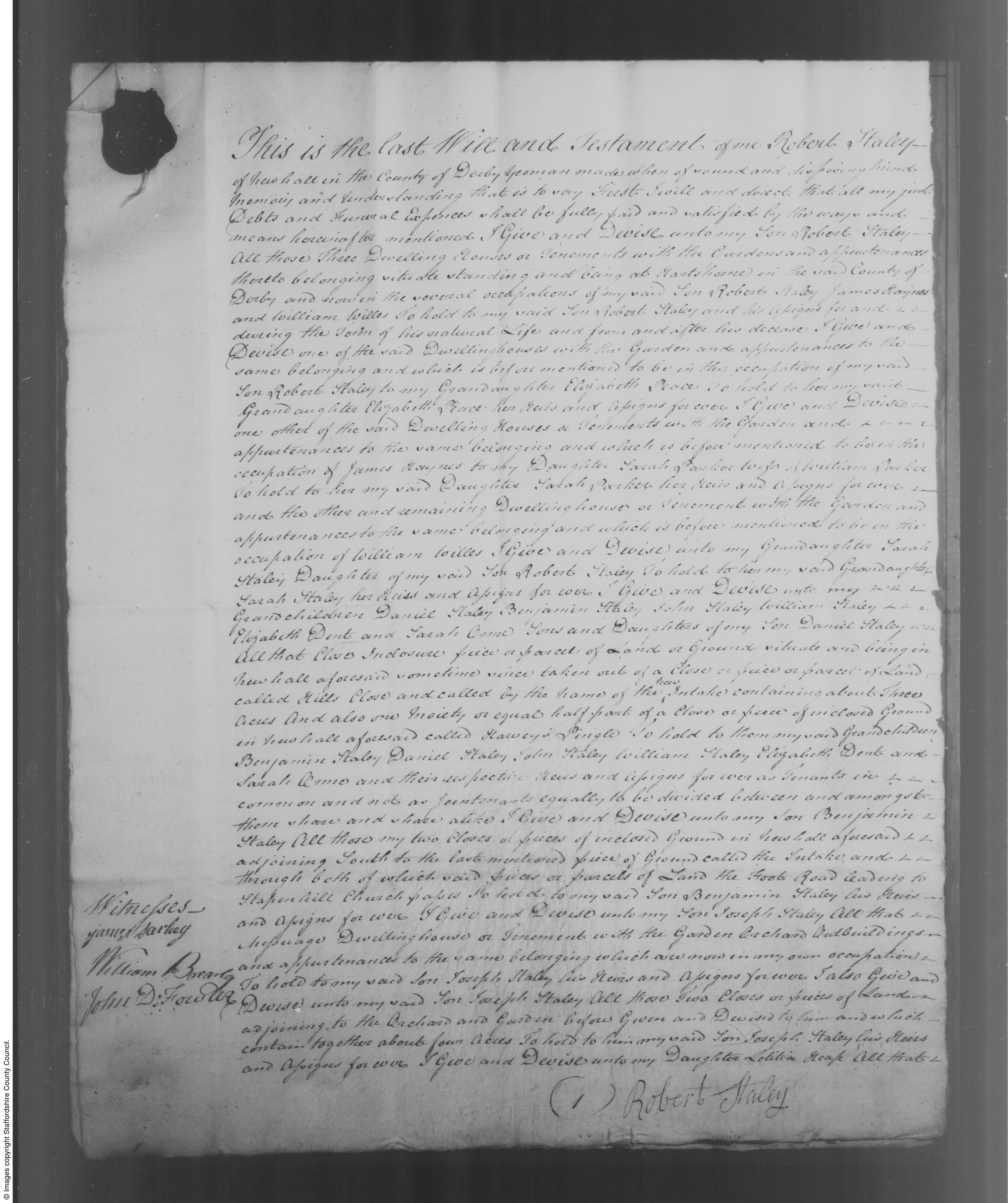

Josephs parents were Robert Staley and Elizabeth. I couldn’t find a baptism or birth record for Robert Staley. Other trees on an ancestry site had his birth in Elton, but with no supporting documents. Robert, as stated in his 1795 will, was a Yeoman.

“Yeoman: A former class of small freeholders who farm their own land; a commoner of good standing.”

“Husbandman: The old word for a farmer below the rank of yeoman. A husbandman usually held his land by copyhold or leasehold tenure and may be regarded as the ‘average farmer in his locality’. The words ‘yeoman’ and ‘husbandman’ were gradually replaced in the later 18th and 19th centuries by ‘farmer’.”He left a number of properties in Newhall and Hartshorne (near Newhall) including dwellings, enclosures, orchards, various yards, barns and acreages. It seemed to me more likely that he had inherited them, rather than moving into the village and buying them.

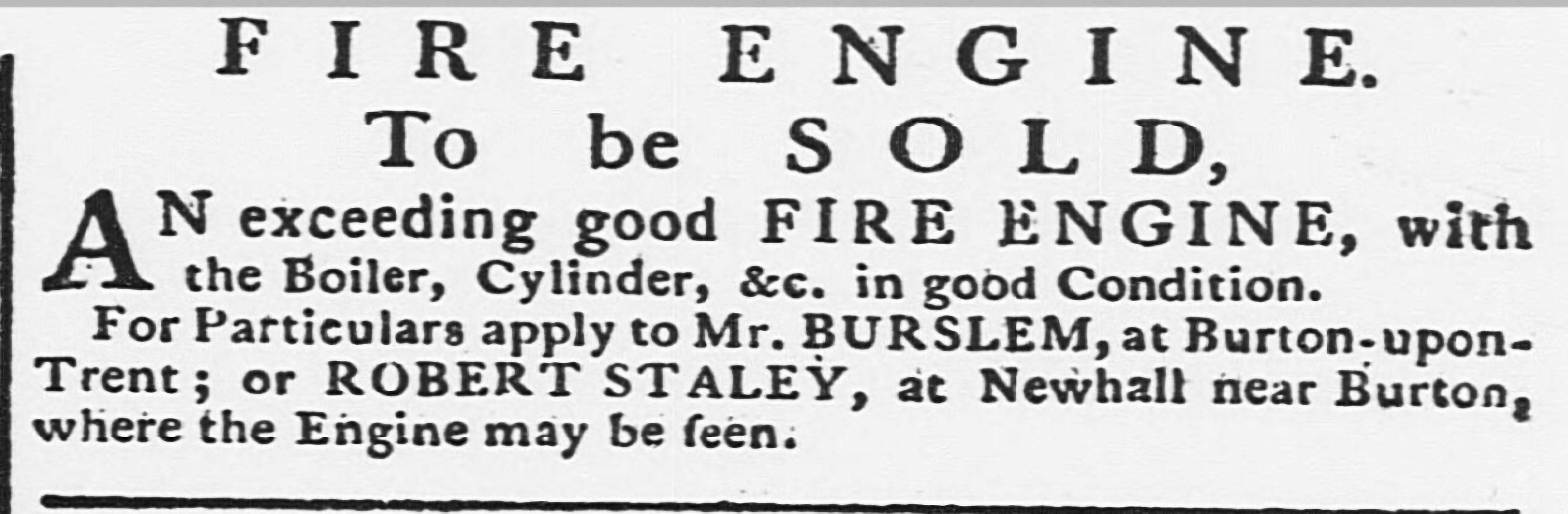

There is a mention of Robert Staley in a 1782 newpaper advertisement.

“Fire Engine To Be Sold. An exceedingly good fire engine, with the boiler, cylinder, etc in good condition. For particulars apply to Mr Burslem at Burton-upon-Trent, or Robert Staley at Newhall near Burton, where the engine may be seen.”

Was the fire engine perhaps connected with a foundry or a coal mine?

I noticed that Robert Staley was the witness at a 1755 marriage in Stapenhill between Barbara Burslem and Richard Daston the younger esquire. The other witness was signed Burslem Jnr.

Looking for Robert Staley

I assumed that once again, in the absence of the correct records, a similarly named and aged persons baptism had been added to the tree regardless of accuracy, so I looked through the Stapenhill/Newhall parish register images page by page. There were no Staleys in Newhall at all in the early 1700s, so it seemed that Robert did come from elsewhere and I expected to find the Staleys in a neighbouring parish. But I still didn’t find any Staleys.

I spoke to a couple of Staley descendants that I’d met during the family research. I met Carole via a DNA match some months previously and contacted her to ask about the Staleys in Elton. She also had Robert Staley born in Elton (indeed, there were many Staleys in Elton) but she didn’t have any documentation for his birth, and we decided to collaborate and try and find out more.

I couldn’t find the earlier Elton parish registers anywhere online, but eventually found the untranscribed microfiche images of the Bishops Transcripts for Elton.

via familysearch:

“In its most basic sense, a bishop’s transcript is a copy of a parish register. As bishop’s transcripts generally contain more or less the same information as parish registers, they are an invaluable resource when a parish register has been damaged, destroyed, or otherwise lost. Bishop’s transcripts are often of value even when parish registers exist, as priests often recorded either additional or different information in their transcripts than they did in the original registers.”Unfortunately there was a gap in the Bishops Transcripts between 1704 and 1711 ~ exactly where I needed to look. I subsequently found out that the Elton registers were incomplete as they had been damaged by fire.

I estimated Robert Staleys date of birth between 1710 and 1715. He died in 1795, and his son Daniel died in 1805: both of these wills were found online. Daniel married Mary Moon in Stapenhill in 1762, making a likely birth date for Daniel around 1740.

The marriage of Robert Staley (assuming this was Robert’s father) and Alice Maceland (or Marsland or Marsden, depending on how the parish clerk chose to spell it presumably) was in the Bishops Transcripts for Elton in 1704. They were married in Elton on 26th February. There followed the missing parish register pages and in all likelihood the records of the baptisms of their first children. No doubt Robert was one of them, probably the first male child.

(Incidentally, my grandfather’s Marshalls also came from Elton, a small Derbyshire village near Matlock. The Staley’s are on my grandmothers Warren side.)

The parish register pages resume in 1711. One of the first entries was the baptism of Robert Staley in 1711, parents Thomas and Ann. This was surely the one we were looking for, and Roberts parents weren’t Robert and Alice.

But then in 1735 a marriage was recorded between Robert son of Robert Staley (and this was unusual, the father of the groom isn’t usually recorded on the parish register) and Elizabeth Milner. They were married on the 9th March 1735. We know that the Robert we were looking for married an Elizabeth, as her name was on the Stapenhill baptisms of their later children, including Joseph Staleys. The 1735 marriage also fit with the assumed birth date of Daniel, circa 1740. A baptism was found for a Robert Staley in 1738 in the Elton registers, parents Robert and Elizabeth, as well as the baptism in 1736 for Mary, presumably their first child. Her burial is recorded the following year.

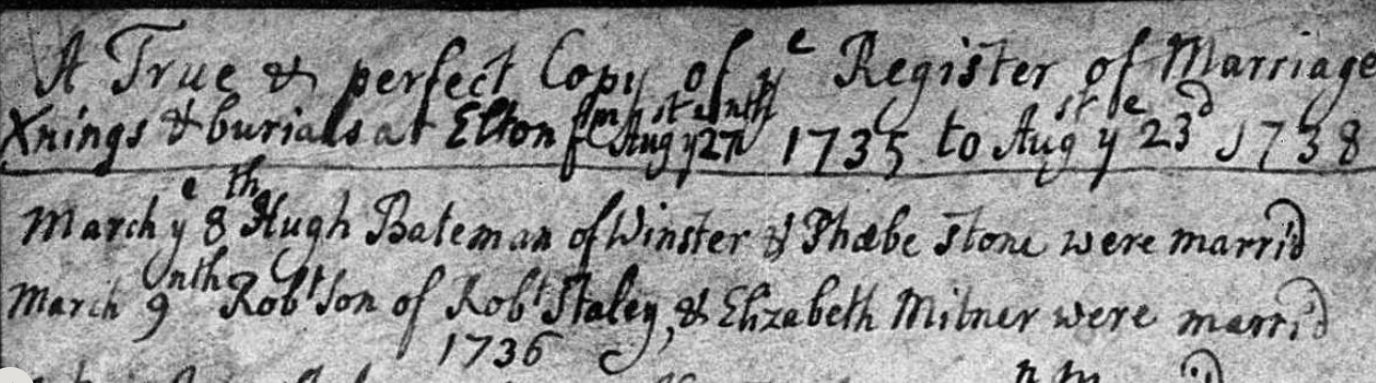

The marriage of Robert Staley and Elizabeth Milner in 1735:

There were several other Staley couples of a similar age in Elton, perhaps brothers and cousins. It seemed that Thomas and Ann’s son Robert was a different Robert, and that the one we were looking for was prior to that and on the missing pages.

Even so, this doesn’t prove that it was Elizabeth Staleys great grandfather who was born in Elton, but no other birth or baptism for Robert Staley has been found. It doesn’t explain why the Staleys moved to Stapenhill either, although the Enclosures Act and the Industrial Revolution could have been factors.

The 18th century saw the rise of the Industrial Revolution and many renowned Derbyshire Industrialists emerged. They created the turning point from what was until then a largely rural economy, to the development of townships based on factory production methods.

The Marsden Connection

There are some possible clues in the records of the Marsden family. Robert Staley married Alice Marsden (or Maceland or Marsland) in Elton in 1704. Robert Staley is mentioned in the 1730 will of John Marsden senior, of Baslow, Innkeeper (Peacock Inne & Whitlands Farm). He mentions his daughter Alice, wife of Robert Staley.

In a 1715 Marsden will there is an intriguing mention of an alias, which might explain the different spellings on various records for the name Marsden: “MARSDEN alias MASLAND, Christopher – of Baslow, husbandman, 28 Dec 1714. son Robert MARSDEN alias MASLAND….” etc.

Some potential reasons for a move from one parish to another are explained in this history of the Marsden family, and indeed this could relate to Robert Staley as he married into the Marsden family and his wife was a beneficiary of a Marsden will. The Chatsworth Estate, at various times, bought a number of farms in order to extend the park.

THE MARSDEN FAMILY

OXCLOSE AND PARKGATE

In the Parishes of

Baslow and Chatsworthby

David Dalrymple-Smith“John Marsden (b1653) another son of Edmund (b1611) faired well. By the time he died in

1730 he was publican of the Peacock, the Inn on Church Lane now called the Cavendish

Hotel, and the farmer at “Whitlands”, almost certainly Bubnell Cliff Farm.”“Coal mining was well known in the Chesterfield area. The coalfield extends as far as the

Gritstone edges, where thin seams outcrop especially in the Baslow area.”“…the occupants were evicted from the farmland below Dobb Edge and

the ground carefully cleared of all traces of occupation and farming. Shelter belts were

planted especially along the Heathy Lea Brook. An imposing new drive was laid to the

Chatsworth House with the Lodges and “The Golden Gates” at its northern end….”Although this particular event was later than any events relating to Robert Staley, it’s an indication of how farms and farmland disappeared, and a reason for families to move to another area:

“The Dukes of Devonshire (of Chatsworth) were major figures in the aristocracy and the government of the

time. Such a position demanded a display of wealth and ostentation. The 6th Duke of

Devonshire, the Bachelor Duke, was not content with the Chatsworth he inherited in 1811,

and immediately started improvements. After major changes around Edensor, he turned his

attention at the north end of the Park. In 1820 plans were made extend the Park up to the

Baslow parish boundary. As this would involve the destruction of most of the Farm at

Oxclose, the farmer at the Higher House Samuel Marsden (b1755) was given the tenancy of

Ewe Close a large farm near Bakewell.

Plans were revised in 1824 when the Dukes of Devonshire and Rutland “Exchanged Lands”,

reputedly during a game of dice. Over 3300 acres were involved in several local parishes, of

which 1000 acres were in Baslow. In the deal Devonshire acquired the southeast corner of

Baslow Parish.

Part of the deal was Gibbet Moor, which was developed for “Sport”. The shelf of land

between Parkgate and Robin Hood and a few extra fields was left untouched. The rest,

between Dobb Edge and Baslow, was agricultural land with farms, fields and houses. It was

this last part that gave the Duke the opportunity to improve the Park beyond his earlier

expectations.”The 1795 will of Robert Staley.

Inriguingly, Robert included the children of his son Daniel Staley in his will, but omitted to leave anything to Daniel. A perusal of Daniels 1808 will sheds some light on this: Daniel left his property to his six reputed children with Elizabeth Moon, and his reputed daughter Mary Brearly. Daniels wife was Mary Moon, Elizabeths husband William Moons daughter.

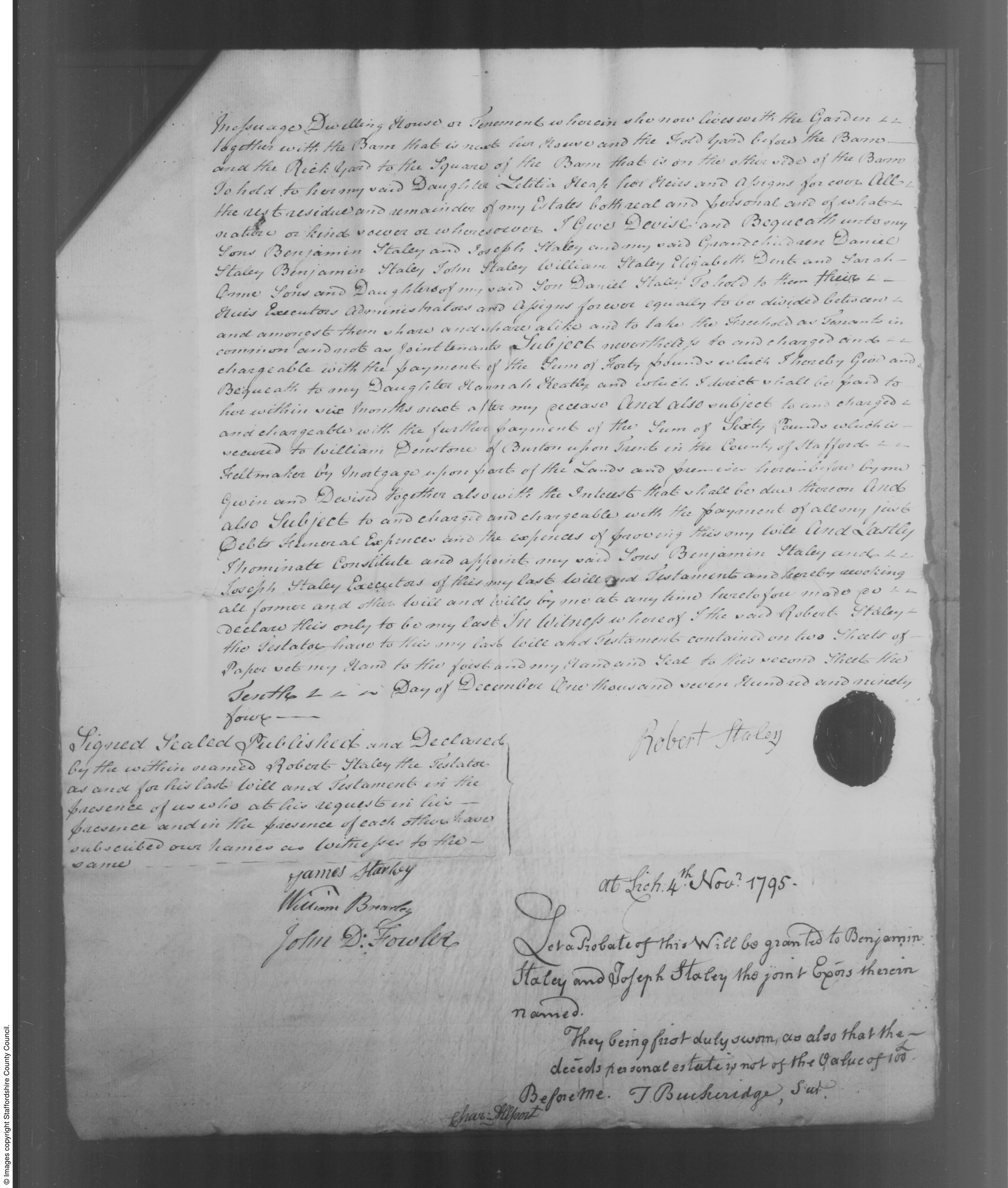

The will of Robert Staley, 1795:

The 1805 will of Daniel Staley, Robert’s son:

This is the last will and testament of me Daniel Staley of the Township of Newhall in the parish of Stapenhill in the County of Derby, Farmer. I will and order all of my just debts, funeral and testamentary expenses to be fully paid and satisfied by my executors hereinafter named by and out of my personal estate as soon as conveniently may be after my decease.

I give, devise and bequeath to Humphrey Trafford Nadin of Church Gresely in the said County of Derby Esquire and John Wilkinson of Newhall aforesaid yeoman all my messuages, lands, tenements, hereditaments and real and personal estates to hold to them, their heirs, executors, administrators and assigns until Richard Moon the youngest of my reputed sons by Elizabeth Moon shall attain his age of twenty one years upon trust that they, my said trustees, (or the survivor of them, his heirs, executors, administrators or assigns), shall and do manage and carry on my farm at Newhall aforesaid and pay and apply the rents, issues and profits of all and every of my said real and personal estates in for and towards the support, maintenance and education of all my reputed children by the said Elizabeth Moon until the said Richard Moon my youngest reputed son shall attain his said age of twenty one years and equally share and share and share alike.

And it is my will and desire that my said trustees or trustee for the time being shall recruit and keep up the stock upon my farm as they in their discretion shall see occasion or think proper and that the same shall not be diminished. And in case any of my said reputed children by the said Elizabeth Moon shall be married before my said reputed youngest son shall attain his age of twenty one years that then it is my will and desire that non of their husbands or wives shall come to my farm or be maintained there or have their abode there. That it is also my will and desire in case my reputed children or any of them shall not be steady to business but instead shall be wild and diminish the stock that then my said trustees or trustee for the time being shall have full power and authority in their discretion to sell and dispose of all or any part of my said personal estate and to put out the money arising from the sale thereof to interest and to pay and apply the interest thereof and also thereunto of the said real estate in for and towards the maintenance, education and support of all my said reputed children by the said

Elizabeth Moon as they my said trustees in their discretion that think proper until the said Richard Moon shall attain his age of twenty one years.Then I give to my grandson Daniel Staley the sum of ten pounds and to each and every of my sons and daughters namely Daniel Staley, Benjamin Staley, John Staley, William Staley, Elizabeth Dent and Sarah Orme and to my niece Ann Brearly the sum of five pounds apiece.

I give to my youngest reputed son Richard Moon one share in the Ashby Canal Navigation and I direct that my said trustees or trustee for the time being shall have full power and authority to pay and apply all or any part of the fortune or legacy hereby intended for my youngest reputed son Richard Moon in placing him out to any trade, business or profession as they in their discretion shall think proper.

And I direct that to my said sons and daughters by my late wife and my said niece shall by wholly paid by my said reputed son Richard Moon out of the fortune herby given him. And it is my will and desire that my said reputed children shall deliver into the hands of my executors all the monies that shall arise from the carrying on of my business that is not wanted to carry on the same unto my acting executor and shall keep a just and true account of all disbursements and receipts of the said business and deliver up the same to my acting executor in order that there may not be any embezzlement or defraud amongst them and from and immediately after my said reputed youngest son Richard Moon shall attain his age of twenty one years then I give, devise and bequeath all my real estate and all the residue and remainder of my personal estate of what nature and kind whatsoever and wheresoever unto and amongst all and every my said reputed sons and daughters namely William Moon, Thomas Moon, Joseph Moon, Richard Moon, Ann Moon, Margaret Moon and to my reputed daughter Mary Brearly to hold to them and their respective heirs, executors, administrator and assigns for ever according to the nature and tenure of the same estates respectively to take the same as tenants in common and not as joint tenants.And lastly I nominate and appoint the said Humphrey Trafford Nadin and John Wilkinson executors of this my last will and testament and guardians of all my reputed children who are under age during their respective minorities hereby revoking all former and other wills by me heretofore made and declaring this only to be my last will.

In witness whereof I the said Daniel Staley the testator have to this my last will and testament set my hand and seal the eleventh day of March in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and five.

June 6, 2022 at 12:58 pm #6303In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

The Hollands of Barton under Needwood

Samuel Warren of Stapenhill married Catherine Holland of Barton under Needwood in 1795.

I joined a Barton under Needwood History group and found an incredible amount of information on the Holland family, but first I wanted to make absolutely sure that our Catherine Holland was one of them as there were also Hollands in Newhall. Not only that, on the marriage licence it says that Catherine Holland was from Bretby Park Gate, Stapenhill.

Then I noticed that one of the witnesses on Samuel’s brother Williams marriage to Ann Holland in 1796 was John Hair. Hannah Hair was the wife of Thomas Holland, and they were the Barton under Needwood parents of Catherine. Catherine was born in 1775, and Ann was born in 1767.

The 1851 census clinched it: Catherine Warren 74 years old, widow and formerly a farmers wife, was living in the household of her son John Warren, and her place of birth is listed as Barton under Needwood. In 1841 Catherine was a 64 year old widow, her husband Samuel having died in 1837, and she was living with her son Samuel, a farmer. The 1841 census did not list place of birth, however. Catherine died on 31 March 1861 and does not appear on the 1861 census.

Once I had established that our Catherine Holland was from Barton under Needwood, I had another look at the information available on the Barton under Needwood History group, compiled by local historian Steve Gardner.

Catherine’s parents were Thomas Holland 1737-1828 and Hannah Hair 1739-1822.

Steve Gardner had posted a long list of the dates, marriages and children of the Holland family. The earliest entries in parish registers were Thomae Holland 1562-1626 and his wife Eunica Edwardes 1565-1632. They married on 10th July 1582. They were born, married and died in Barton under Needwood. They were direct ancestors of Catherine Holland, and as such my direct ancestors too.

The known history of the Holland family in Barton under Needwood goes back to Richard De Holland. (Thanks once again to Steve Gardner of the Barton under Needwood History group for this information.)

“Richard de Holland was the first member of the Holland family to become resident in Barton under Needwood (in about 1312) having been granted lands by the Earl of Lancaster (for whom Richard served as Stud and Stock Keeper of the Peak District) The Holland family stemmed from Upholland in Lancashire and had many family connections working for the Earl of Lancaster, who was one of the biggest Barons in England. Lancaster had his own army and lived at Tutbury Castle, from where he ruled over most of the Midlands area. The Earl of Lancaster was one of the main players in the ‘Barons Rebellion’ and the ensuing Battle of Burton Bridge in 1322. Richard de Holland was very much involved in the proceedings which had so angered Englands King. Holland narrowly escaped with his life, unlike the Earl who was executed.

From the arrival of that first Holland family member, the Hollands were a mainstay family in the community, and were in Barton under Needwood for over 600 years.”Continuing with various items of information regarding the Hollands, thanks to Steve Gardner’s Barton under Needwood history pages:

“PART 6 (Final Part)

Some mentions of The Manor of Barton in the Ancient Staffordshire Rolls:

1330. A Grant was made to Herbert de Ferrars, at le Newland in the Manor of Barton.

1378. The Inquisitio bonorum – Johannis Holand — an interesting Inventory of his goods and their value and his debts.

1380. View of Frankpledge ; the Jury found that Richard Holland was feloniously murdered by his wife Joan and Thomas Graunger, who fled. The goods of the deceased were valued at iiij/. iijj. xid. ; one-third went to the dead man, one-third to his son, one- third to the Lord for the wife’s share. Compare 1 H. V. Indictments. (1413.)

That Thomas Graunger of Barton smyth and Joan the wife of Richard de Holond of Barton on the Feast of St. John the Baptist 10 H. II. (1387) had traitorously killed and murdered at night, at Barton, Richard, the husband of the said Joan. (m. 22.)

The names of various members of the Holland family appear constantly among the listed Jurors on the manorial records printed below : —

1539. Richard Holland and Richard Holland the younger are on the Muster Roll of Barton

1583. Thomas Holland and Unica his wife are living at Barton.

1663-4. Visitations. — Barton under Needword. Disclaimers. William Holland, Senior, William Holland, Junior.

1609. Richard Holland, Clerk and Alice, his wife.

1663-4. Disclaimers at the Visitation. William Holland, Senior, William Holland, Junior.”I was able to find considerably more information on the Hollands in the book “Some Records of the Holland Family (The Hollands of Barton under Needwood, Staffordshire, and the Hollands in History)” by William Richard Holland. Luckily the full text of this book can be found online.

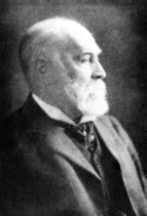

William Richard Holland (Died 1915) An early local Historian and author of the book:

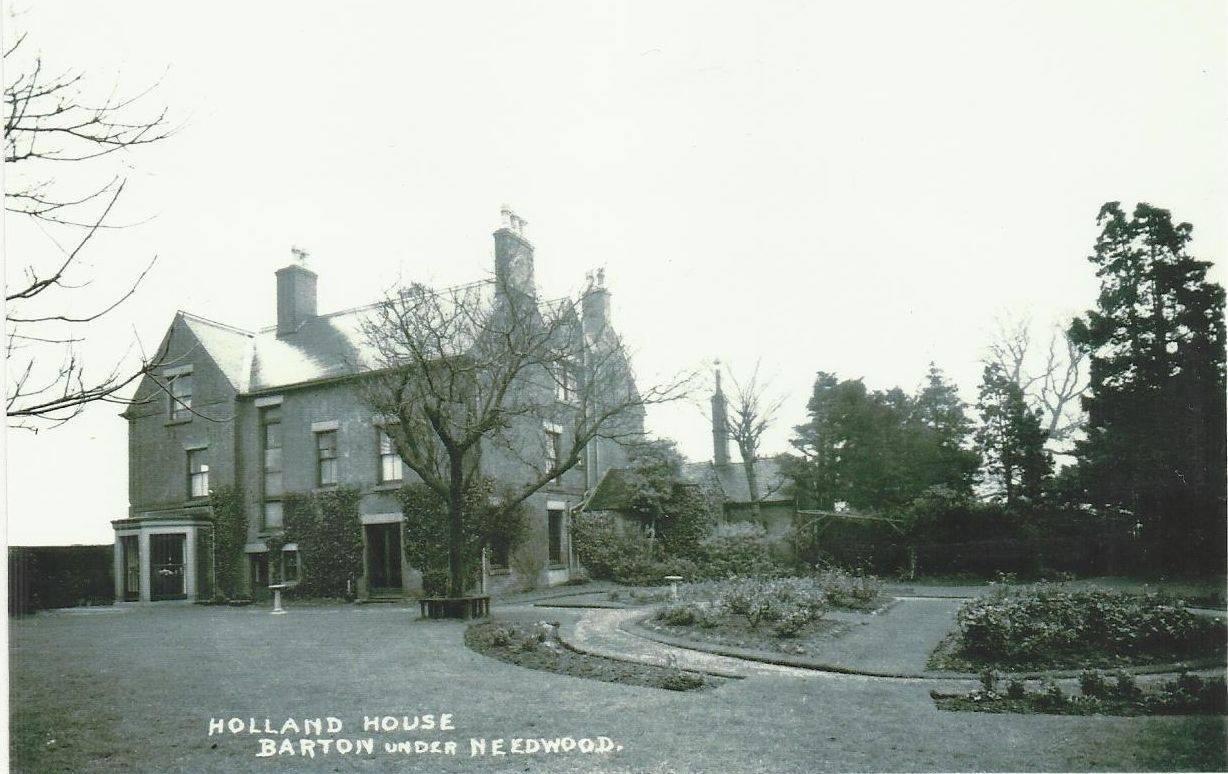

‘Holland House’ taken from the Gardens (sadly demolished in the early 60’s):

Excerpt from the book:

“The charter, dated 1314, granting Richard rights and privileges in Needwood Forest, reads as follows:

“Thomas Earl of Lancaster and Leicester, high-steward of England, to whom all these present shall come, greeting: Know ye, that we have given, &c., to Richard Holland of Barton, and his heirs, housboot, heyboot, and fireboot, and common of pasture, in our forest of Needwood, for all his beasts, as well in places fenced as lying open, with 40 hogs, quit of pawnage in our said forest at all times in the year (except hogs only in fence month). All which premises we will warrant, &c. to the said Richard and his heirs against all people for ever”

“The terms “housboot” “heyboot” and “fireboot” meant that Richard and his heirs were to have the privilege of taking from the Forest, wood needed for house repair and building, hedging material for the repairing of fences, and what was needful for purposes of fuel.”

Further excerpts from the book:

“It may here be mentioned that during the renovation of Barton Church, when the stone pillars were being stripped of the plaster which covered them, “William Holland 1617” was found roughly carved on a pillar near to the belfry gallery, obviously the work of a not too devout member of the family, who, seated in the gallery of that time, occupied himself thus during the service. The inscription can still be seen.”

“The earliest mention of a Holland of Upholland occurs in the reign of John in a Final Concord, made at the Lancashire Assizes, dated November 5th, 1202, in which Uchtred de Chryche, who seems to have had some right in the manor of Upholland, releases his right in fourteen oxgangs* of land to Matthew de Holland, in consideration of the sum of six marks of silver. Thus was planted the Holland Tree, all the early information of which is found in The Victoria County History of Lancaster.

As time went on, the family acquired more land, and with this, increased position. Thus, in the reign of Edward I, a Robert de Holland, son of Thurstan, son of Robert, became possessed of the manor of Orrell adjoining Upholland and of the lordship of Hale in the parish of Childwall, and, through marriage with Elizabeth de Samlesbury (co-heiress of Sir Wm. de Samlesbury of Samlesbury, Hall, near to Preston), of the moiety of that manor….

* An oxgang signified the amount of land that could be ploughed by one ox in one day”

“This Robert de Holland, son of Thurstan, received Knighthood in the reign of Edward I, as did also his brother William, ancestor of that branch of the family which later migrated to Cheshire. Belonging to this branch are such noteworthy personages as Mrs. Gaskell, the talented authoress, her mother being a Holland of this branch, Sir Henry Holland, Physician to Queen Victoria, and his two sons, the first Viscount Knutsford, and Canon Francis Holland ; Sir Henry’s grandson (the present Lord Knutsford), Canon Scott Holland, etc. Captain Frederick Holland, R.N., late of Ashbourne Hall, Derbyshire, may also be mentioned here.*”

Thanks to the Barton under Needwood history group for the following:

WALES END FARM:

In 1509 it was owned and occupied by Mr Johannes Holland De Wallass end who was a well to do Yeoman Farmer (the origin of the areas name – Wales End). Part of the building dates to 1490 making it probably the oldest building still standing in the Village:

I found records for all of the Holland’s listed on the Barton under Needwood History group and added them to my ancestry tree. The earliest will I found was for Eunica Edwardes, then Eunica Holland, who died in 1632.

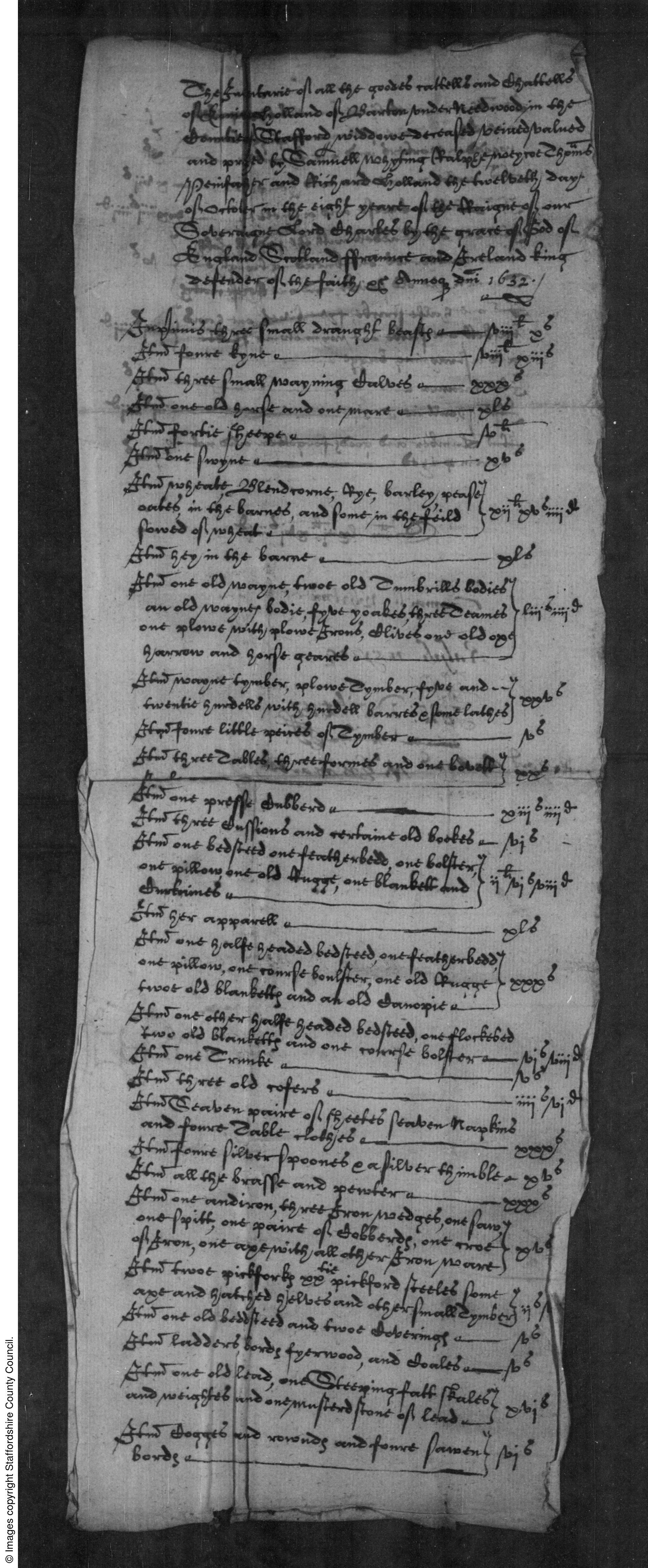

A page from the 1632 will and inventory of Eunica (Unice) Holland:

I’d been reading about “pedigree collapse” just before I found out her maiden name of Edwardes. Edwards is my own maiden name.

“In genealogy, pedigree collapse describes how reproduction between two individuals who knowingly or unknowingly share an ancestor causes the family tree of their offspring to be smaller than it would otherwise be.

Without pedigree collapse, a person’s ancestor tree is a binary tree, formed by the person, the parents, grandparents, and so on. However, the number of individuals in such a tree grows exponentially and will eventually become impossibly high. For example, a single individual alive today would, over 30 generations going back to the High Middle Ages, have roughly a billion ancestors, more than the total world population at the time. This apparent paradox occurs because the individuals in the binary tree are not distinct: instead, a single individual may occupy multiple places in the binary tree. This typically happens when the parents of an ancestor are cousins (sometimes unbeknownst to themselves). For example, the offspring of two first cousins has at most only six great-grandparents instead of the normal eight. This reduction in the number of ancestors is pedigree collapse. It collapses the binary tree into a directed acyclic graph with two different, directed paths starting from the ancestor who in the binary tree would occupy two places.” via wikipediaThere is nothing to suggest, however, that Eunica’s family were related to my fathers family, and the only evidence so far in my tree of pedigree collapse are the marriages of Orgill cousins, where two sets of grandparents are repeated.

A list of Holland ancestors:

Catherine Holland 1775-1861

her parents:

Thomas Holland 1737-1828 Hannah Hair 1739-1832

Thomas’s parents:

William Holland 1696-1756 Susannah Whiteing 1715-1752

William’s parents:

William Holland 1665- Elizabeth Higgs 1675-1720

William’s parents:

Thomas Holland 1634-1681 Katherine Owen 1634-1728

Thomas’s parents:

Thomas Holland 1606-1680 Margaret Belcher 1608-1664

Thomas’s parents:

Thomas Holland 1562-1626 Eunice Edwardes 1565- 1632May 13, 2022 at 10:50 am #6293In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Lincolnshire Families

Thanks to the 1851 census, we know that William Eaton was born in Grantham, Lincolnshire. He was baptised on 29 November 1768 at St Wulfram’s church; his father was William Eaton and his mother Elizabeth.

St Wulfram’s in Grantham painted by JMW Turner in 1797:

I found a marriage for a William Eaton and Elizabeth Rose in the city of Lincoln in 1761, but it seemed unlikely as they were both of that parish, and with no discernable links to either Grantham or Nottingham.

But there were two marriages registered for William Eaton and Elizabeth Rose: one in Lincoln in 1761 and one in Hawkesworth Nottinghamshire in 1767, the year before William junior was baptised in Grantham. Hawkesworth is between Grantham and Nottingham, and this seemed much more likely.

Elizabeth’s name is spelled Rose on her marriage records, but spelled Rouse on her baptism. It’s not unusual for spelling variations to occur, as the majority of people were illiterate and whoever was recording the event wrote what it sounded like.

Elizabeth Rouse was baptised on 26th December 1746 in Gunby St Nicholas (there is another Gunby in Lincolnshire), a short distance from Grantham. Her father was Richard Rouse; her mother Cave Pindar. Cave is a curious name and I wondered if it had been mistranscribed, but it appears to be correct and clearly says Cave on several records.

Richard Rouse married Cave Pindar 21 July 1744 in South Witham, not far from Grantham.

Richard was born in 1716 in North Witham. His father was William Rouse; his mothers name was Jane.

Cave Pindar was born in 1719 in Gunby St Nicholas, near Grantham. Her father was William Pindar, but sadly her mothers name is not recorded in the parish baptism register. However a marriage was registered between William Pindar and Elizabeth Holmes in Gunby St Nicholas in October 1712.

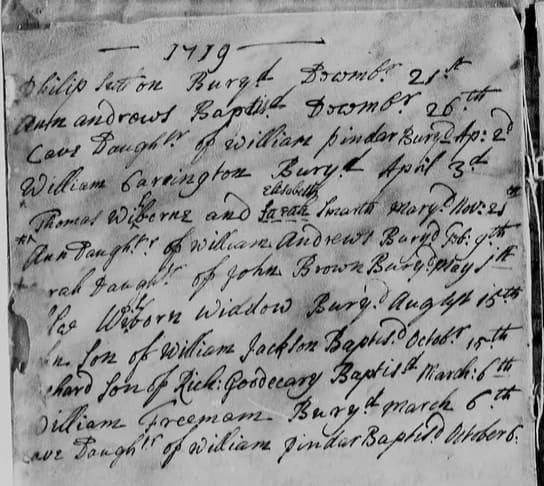

William Pindar buried a daughter Cave on 2 April 1719 and baptised a daughter Cave on 6 Oct 1719:

Elizabeth Holmes was baptised in Gunby St Nicholas on 6th December 1691. Her father was John Holmes; her mother Margaret Hod.

Margaret Hod would have been born circa 1650 to 1670 and I haven’t yet found a baptism record for her. According to several other public trees on an ancestry website, she was born in 1654 in Essenheim, Germany. This was surprising! According to these trees, her father was Johannes Hod (Blodt|Hoth) (1609–1677) and her mother was Maria Appolonia Witters (1620–1656).

I did not think it very likely that a young woman born in Germany would appear in Gunby St Nicholas in the late 1600’s, and did a search for Hod’s in and around Grantham. Indeed there were Hod’s living in the area as far back as the 1500’s, (a Robert Hod was baptised in Grantham in 1552), and no doubt before, but the parish records only go so far back. I think it’s much more likely that her parents were local, and that the page with her baptism recorded on the registers is missing.

Of the many reasons why parish registers or some of the pages would be destroyed or lost, this is another possibility. Lincolnshire is on the east coast of England:

“All of England suffered from a “monster” storm in November of 1703 that killed a reported 8,000 people. Seaside villages suffered greatly and their church and civil records may have been lost.”

A Margeret Hod, widow, died in Gunby St Nicholas in 1691, the same year that Elizabeth Holmes was born. Elizabeth’s mother was Margaret Hod. Perhaps the widow who died was Margaret Hod’s mother? I did wonder if Margaret Hod had died shortly after her daughter’s birth, and that her husband had died sometime between the conception and birth of his child. The Black Death or Plague swept through Lincolnshire in 1680 through 1690; such an eventually would be possible. But Margaret’s name would have been registered as Holmes, not Hod.

Cave Pindar’s father William was born in Swinstead, Lincolnshire, also near to Grantham, on the 28th December, 1690, and he died in Gunby St Nicholas in 1756. William’s father is recorded as Thomas Pinder; his mother Elizabeth.

GUNBY: The village name derives from a “farmstead or village of a man called Gunni”, from the Old Scandinavian person name, and ‘by’, a farmstead, village or settlement.

Gunby Grade II listed Anglican church is dedicated to St Nicholas. Of 15th-century origin, it was rebuilt by Richard Coad in 1869, although the Perpendicular tower remained. April 12, 2022 at 8:13 am #6290

April 12, 2022 at 8:13 am #6290In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

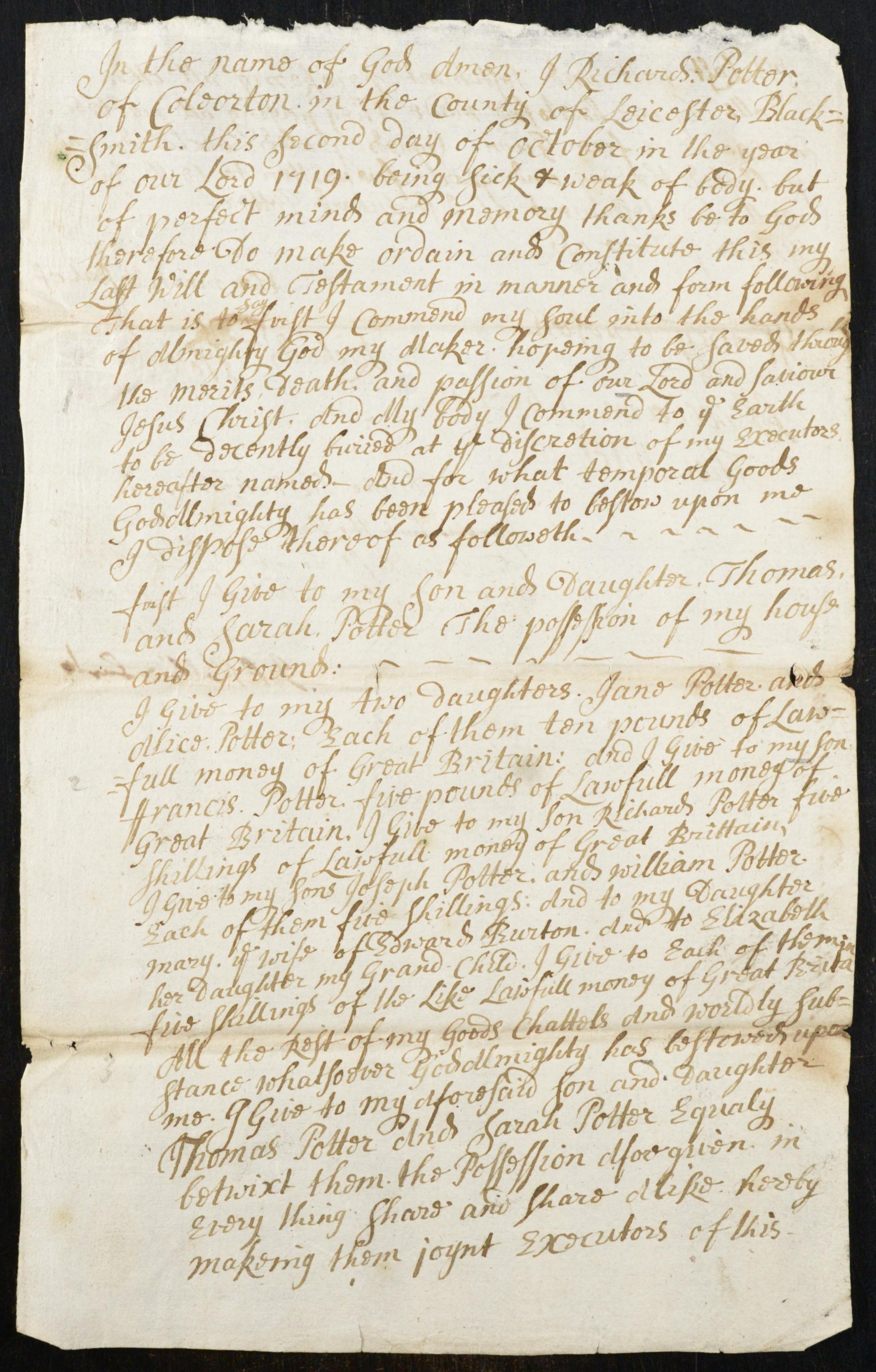

Leicestershire Blacksmiths

The Orgill’s of Measham led me further into Leicestershire as I traveled back in time.

I also realized I had uncovered a direct line of women and their mothers going back ten generations:

myself, Tracy Edwards 1957-

my mother Gillian Marshall 1933-

my grandmother Florence Warren 1906-1988

her mother and my great grandmother Florence Gretton 1881-1927

her mother Sarah Orgill 1840-1910

her mother Elizabeth Orgill 1803-1876

her mother Sarah Boss 1783-1847

her mother Elizabeth Page 1749-

her mother Mary Potter 1719-1780

and her mother and my 7x great grandmother Mary 1680-You could say it leads us to the very heart of England, as these Leicestershire villages are as far from the coast as it’s possible to be. There are countless other maternal lines to follow, of course, but only one of mothers of mothers, and ours takes us to Leicestershire.

The blacksmiths

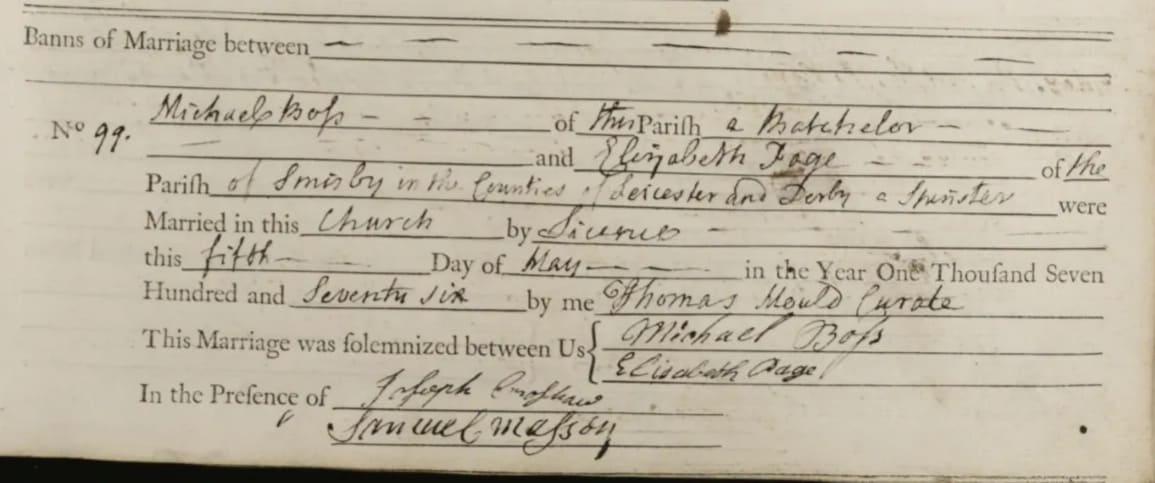

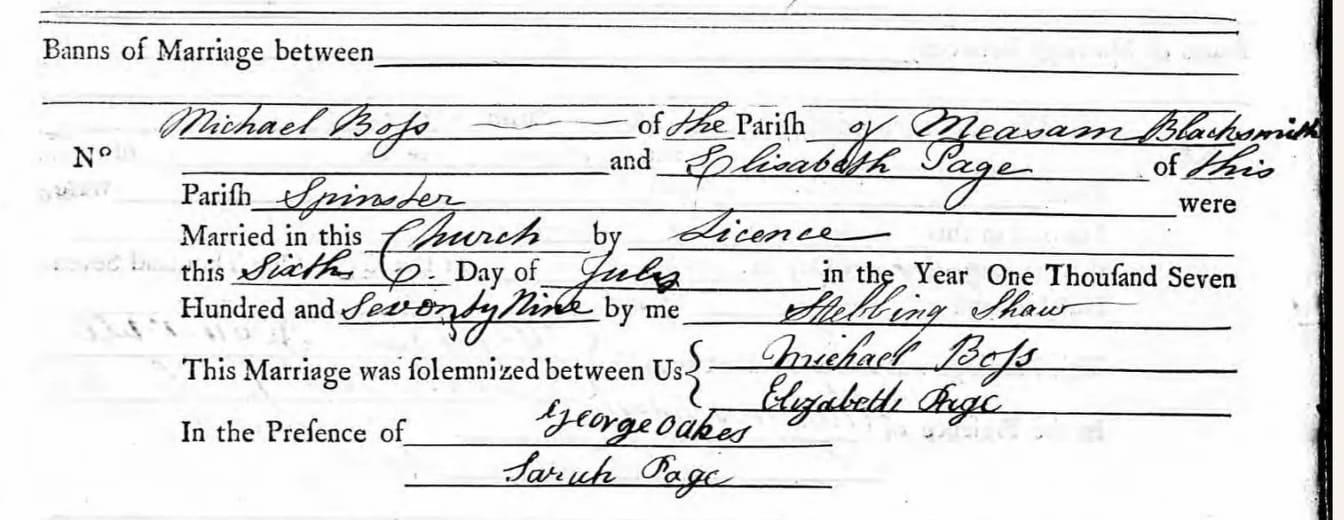

Sarah Boss was the daughter of Michael Boss 1755-1807, a blacksmith in Measham, and Elizabeth Page of nearby Hartshorn, just over the county border in Derbyshire.

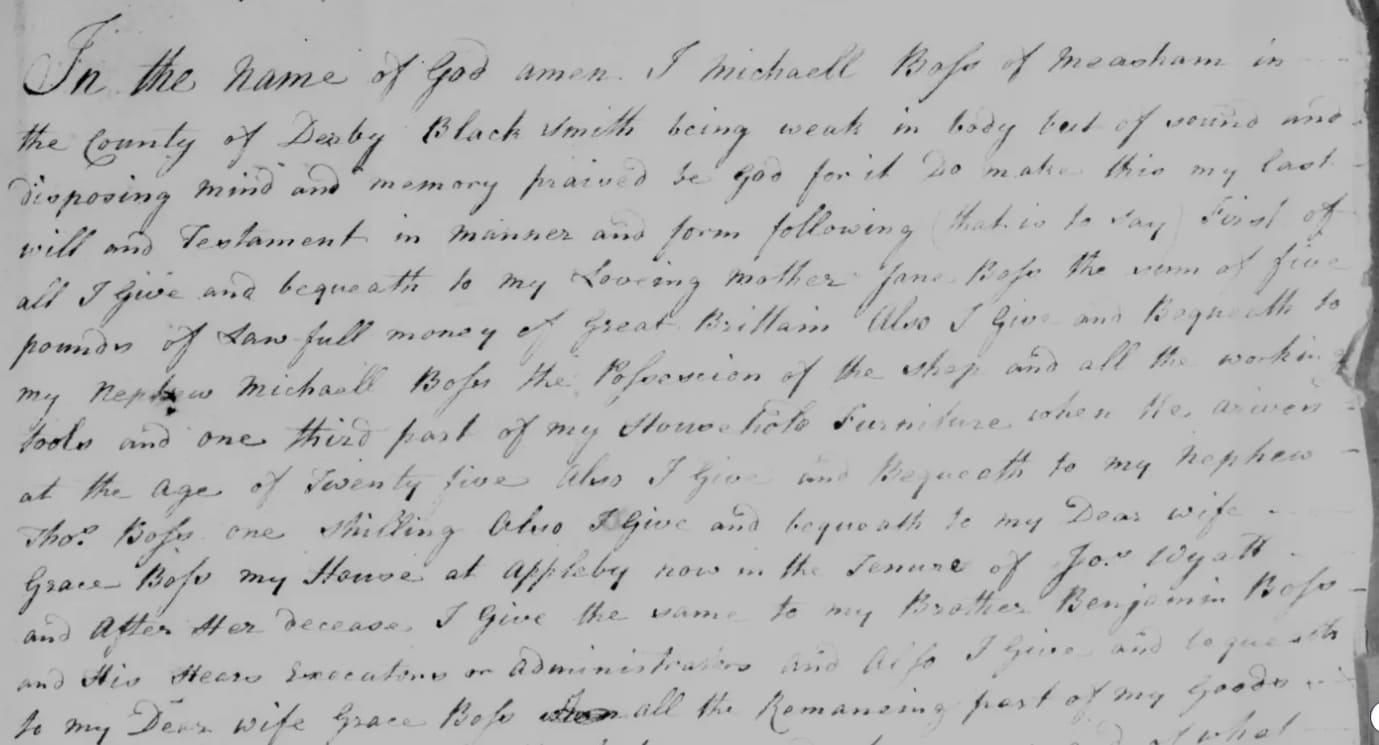

An earlier Michael Boss, a blacksmith of Measham, died in 1772, and in his will he left the possession of the blacksmiths shop and all the working tools and a third of the household furniture to Michael, who he named as his nephew. He left his house in Appleby Magna to his wife Grace, and five pounds to his mother Jane Boss. As none of Michael and Grace’s children are mentioned in the will, perhaps it can be assumed that they were childless.

The will of Michael Boss, 1772, Measham:

Michael Boss the uncle was born in Appleby Magna in 1724. His parents were Michael Boss of Nelson in the Thistles and Jane Peircivall of Appleby Magna, who were married in nearby Mancetter in 1720.

Information worth noting on the Appleby Magna website:

In 1752 the calendar in England was changed from the Julian Calendar to the Gregorian Calendar, as a result 11 days were famously “lost”. But for the recording of Church Registers another very significant change also took place, the start of the year was moved from March 25th to our more familiar January 1st.