Search Results for 'bound'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

January 2, 2026 at 6:03 pm #8022

In reply to: The Hoards of Sanctorum AD26

“You know,” Helier broke the silence, his mouth half-full of the buffet’s assortments of nuts and crackers, “this was bound to happen… People tend to forget you after a while. I mean, how many new babies named after dear Austreberthe nowadays. None of course. I think our records mention 1907 was the last baby Austreberthe, and a decade ago the last mass in their memory… oh this is too heartbreaking…”

“Why so gloomy?” Cerenise was eyeing the speckled and stained silverware and the chipped Rouen faience in which the potato salad was served. “Your name is still moderately in fashion, you shouldn’t die of forgetfulness any time soon. Enjoy the food while it’s free.”

Yvoise couldn’t help but tut at her. She was half-distracted by the calligraphy on those placeholders which she found exquisite. People in this age… it was a rare find now, some pretty calligraphy. The only ‘calli-‘anything this age does well enough is callipygian, and even then, it’s mostly the Kashtardians… She said to the others “Don’t throw yours away, I must have the full set.”

Spirius was inspecting the candleholders. None had lids, a fact that frustrated him to no end. “I miss the good old time we could just slay dragons and get a good sainthood concession for a nice half-millenium.”

Yvoise tittered “simple people we were back then. Everything funny-looking was a dragon I seem to recall.”

Spirius, his plate full of charcuteries, helped himself of a few appetizing gherkins, holding one large up to contemplate. “Yeah, but those few we slew in that period were still some darn tough-skinned gators I would have you know. Those crazy Roman buggers and their games and old false gods —they couldn’t help but bring those strange beasts from Africa to Gaul, leaving us to clean up after them…”

“Indeed, much harder now. It’s like fifteen minutes of sainthood on Instatok and Faceterest and you’re already has-been.” Yvoise had started to pocket some of the paper menus. “Luckily, we still have those relics spread around to fan the flames of remembrance, don’t we.”

“I guess the young ones must look at us funny…” Cerenise chuckled amused at the thought, almost spilling her truffle brouillade.

“Oh well, apparently our youngest geeks aren’t above dealing in relics.” Helier said. “Speaking of Novena and the coming nine days,… you’ve surely noticed as I did what was mentioned in the will, have you not?”

May 23, 2025 at 9:19 pm #7951In reply to: Cofficionados Bandits (vs Lucid Dreamers)

Disgruntled and bored with the fruitless wait for the other characters to reveal more of themselves, Amy started staying in her room all day reading books, glad that she’d had an urge to grab a bag full of used paperbacks from a chance encounter with a street vendor in Bogota.

A strange book about peculiar children lingered in her mind, and mingled somehow with the vestiges of the mental images of the writhing Uriah in the book Amy had read prior to this one.

Aunt Amy? a childs voice came unbidden to Amys ear. Well, why not? Amy thought, Some peculiar children is what the story needs. Nephews and neices though, no actual children, god forbid.

“Aunt Amy!” A gentle knocking sounded on the bedroom door. “Are you in there, Aunt Amy?”

“Is that at neice or nephew at my actual door? Already?” Amy cried in amazement.

“Can I come in, please?” the little voice sounded close to tears. Amy bounded off the bed to unloock leaving that right there the door to let the little instant ramen rellie in.

The little human creature appeared to be ten years old or so, as near as Amy could tell, with a rather androgenous look: a grown out short haircut in a nondescript dark colour, thin gangling limbs robed in neutral shapelessness, and a pale pinched face.

“I’ve never done this before, can you help me?” the child said.

“Never been a story character before, eh?” Amy said kindly. “Do you know your name? Not to worry if you don’t!” she added quickly, seeing the child’s look of alarm. “No? Well then you can choose what ever you like!”

The child promptly burst into tears, and Amy wanted to kick herself for being such a tactless blundering fool. God knows it wasn’t that easy to choose, even when you knew the choice was yours.

Amy wanted to ask the child if it was a boy or a girl, but hesitated, and decided against it. I’ll have to give it a name though, I can’t keep calling it the child.

“Would you mind very much if I called you Kit, for now?” asked Amy.

“Thanks, Aunt Amy,” Kit said with a tear streaked smile. “Kit’s fine.”

May 10, 2025 at 7:56 am #7921In reply to: Cofficionados – What’s Brewing

Key Themes and Narrative Elements

Metafiction & Self-Reference: Characters frequently comment on their own construction, roles, and how being written (or observed) defines their reality. Amy especially embodies this.

Lucid Dreaming & Dream Logic: The boundary between reality and dream is porous. Lucid Dreamers are parachuting onto plantations, and Carob dreams in reverse. Lucid Dreamers are adverse to Coffee Plantations as they keep the World awake.

Coffee as Sacred Commodity: The coffee plantation is central to the story’s stakes. It’s under threat from climate (rain), AI malfunctions, and rogue dreamers. This plays comically on global commodity anxiety.

Technology Satire & AI Sentience: Emotional AI, “Silly Intelligence” devices, and exasperation with modern tech hint at mild technophobia or skepticism. All fueled by hot caffeinated piece of news.

Fictionality vs. Reality: Juan and Dolores embody this—grappling with what it means to be real. Dolores vanishes when no one looks—existence contingent on observation.

Rain & Weather as Mood Symbol: The rain is persistent—setting a tone of gentle absurdity and tension, while also providing plot catalyst.

April 22, 2025 at 8:59 pm #7902In reply to: Cofficionados Bandits (vs Lucid Dreamers)

To Whom It May Concern

I am the new character called Amy, and my physical characteristics, which once bestowed are largely irreversible, are in the hands of impetuous maniacs. In the unseemly headlong rush, dangers abound.

Let it be known that I the character called Amy, given the opportunity to choose, hereby select a height considerably less imposing than Carob.

March 1, 2025 at 8:17 am #7841In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

Klyutch Base – an Unknown Signal

The flickering green light on the old console pulsed like a heartbeat.

Orrin Holt leaned forward, tapping the screen. A faint signal had appeared on their outdated long-range scanners—coming from the coastline near the Black Sea. He exchanged a glance with Commander Koval, the no-nonsense leader of Klyutch Base.

“That can’t be right,” muttered Janos Varga, Solara’s husband who was managing the coms’ beside him. “We haven’t picked up anything out of the coast in years.”

Koval grunted like an irate bear, then exhaled sharply. “It’s not our priority. We already lost track of the fools we were following at the border. Let them go. If they went south, they’ve got bigger problems.”

Outside, a distant roar sliced through the cold dusk—a deep, guttural sound that rattled the reinforced windows of the command room.

Orrin didn’t flinch. He’d heard it before.

It was the unmistakable cry of a pack of sanglions— лев-кабан lev-kaban as the locals called the monstrous mutated beasts, wild vicious boars as ferocious as rabid lions that roamed Hungary’s wilds— and they were hunting. If the escapees had made their way there, they were as good as dead.

“Can’t waste the fuel chasing ghosts,” Koval grunted.

But Orrin was still watching the blip on the screen. That signal had no right to be there, nothing was left in this region for years.

“Sir,” he said slowly, “I don’t think this is just another lost survivor. This frequency—it’s old. Military-grade. And repeating. Someone wants to be found.”

A beat of silence. Then Koval straightened.

“You better be right Holt. Everyone, gear up.”

Merdhyn – Lazurne Coastal Island — The Signal Tossed into Space

Merdhyn Winstrom wiped the sweat from his brow, his fingers still trembling from the final connection. He’d made a ramshackle workshop out of a crumbling fishing shack on the deserted islet near Lazurne. He wasn’t one to pay too much notice to the mess or anythings so pedestrian —even as the smell of rusted metal and stale rations had started to overpower the one of sea salt and fish guts.

The beacon’s old circuitry had been a nightmare, but the moment the final wire sparked to life, he had known that the old tech had awoken: it worked.

The moment it worked, for the first time in decades, the ancient transponder from the crashed Helix 57 lifeboat had sent a signal into the void.

If someone was still out there, something was bound to hear it… it was a matter of time, but he had the intuition that he may even get an answer back.

Tuppence, the chatty rat had returned on his shoulder to nestle in the folds of his makeshift keffieh, but squeaked in protest as the old man let out a half-crazed, victorious laugh.

“Oh, don’t give me that look, you miserable blighter. We just opened the bloody door.”

Beyond the broken window, the coastline stretched into the grey horizon. But now… he wasn’t alone.

A sharp, rhythmic thud-thud-thud in the distance.

Helicopters.

He stepped outside, the biting wind lashing at his face, and watched the dark shapes appear on the horizon—figures moving through the low mist.

Armed. Military-like.

The men from the nearby Klyutch Base had found him.

Merdhyn grinned, utterly unfazed by their weapons or the silent threat in their stance. He lifted his trembling, grease-stained hands and pointed back toward the wreckage of Helix 57 behind him.

“Well then,” he called, voice almost cheerful, “reckon you lot might have the spare parts I need.”

The soldiers hesitated. Their weapons didn’t lower.

Merdhyn, however, was already walking toward them, rambling as if they’d asked him the most natural of questions.

“See, it’s been a right nightmare. Power couplings were fried. Comms were dead. And don’t get me started on the damn heat regulators. But you lot? You might just be the final missing piece.”

Commander Koval stepped forward, assessing the grizzled old man with the gleam of a genuine mad genius in his eyes.

Orrin Holt, however, wasn’t looking at the wreck.

His eyes were on the beacon.

It was still pulsing, but its pulse had changed — something had been answering back.

February 16, 2025 at 2:37 pm #7813In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

Helix 25 – Crusades in the Cruise & Unexpected Archives

Evie hadn’t planned to visit Seren Vega again so soon, but when Mandrake slinked into her quarters and sat squarely on her console, swishing his tail with intent, she took it as a sign.

“Alright, you smug little AI-assisted furball,” she muttered, rising from her chair. “What’s so urgent?”

Mandrake stretched leisurely, then padded toward the door, tail flicking. Evie sighed, grabbed her datapad, and followed.

He led her straight to Seren’s quarters—no surprise there. The dimly lit space was as chaotic as ever, layers of old records, scattered datapads, and bound volumes stacked in precarious towers. Seren barely looked up as Evie entered, used to these unannounced visits.

“Tell the cat to stop knocking over my books,” she said dryly. “It never ever listens.”

“Well it’s a cat, isn’t it?” Evie replied. “And he seems to have an agenda.”

Mandrake leaped onto one of the shelves, knocking loose a tattered, old-fashioned book. It thudded onto the floor, flipping open near Evie’s feet. She crouched, brushing dust from the cover. Blood and Oaths: A Romance of the Crusades by Liz Tattler.

She glanced at Seren. “Tattler again?”

Seren shrugged. “Romualdo must have left it here. He hoards her books like sacred texts.”

Evie turned the pages, pausing at an unusual passage. The prose was different—less florid than Liz’s usual ramblings, more… restrained.

A fragment of text had been underlined, a single note scribbled in the margin: Not fiction.

Evie found a spot where she could sit on the floor, and started to read eagerly.

“Blood and Oaths: A Romance of the Crusades — Chapter XII

Sidon, 1157 AD.Brother Edric knelt within the dim sanctuary, the cold stone pressing into his bones. The candlelight flickered across the vaulted ceilings, painting ghosts upon the walls. The voices of his ancestors whispered within him, their memories not his own, yet undeniable. He knew the placement of every fortification before his enemies built them. He spoke languages he had never learned.

He could not recall the first time it happened, only that it had begun after his initiation into the Order—after the ritual, the fasting, the bloodletting beneath the broken moon. The last one, probably folklore, but effective.

It came as a gift.

It was a curse.

His brothers called it divine providence. He called it a drowning. Each time he drew upon it, his sense of self blurred. His grandfather’s memories bled into his own, his thoughts weighted by decisions made a lifetime ago.

And now, as he rose, he knew with certainty that their mission to reclaim the stronghold would fail. He had seen it through the eyes of his ancestor, the soldier who stood at these gates seventy years prior.

‘You know things no man should know,’ his superior whispered that night. ‘Be cautious, Brother Edric, for knowledge begets temptation.’

And Edric knew, too, the greatest temptation was not power.

It was forgetting which thoughts were his own.

Which life was his own.

He had vowed to bear this burden alone. His order demanded celibacy, for the sealed secrets of State must never pass beyond those trained to wield it.

But Edric had broken that vow.

Somewhere, beyond these walls, there was a child who bore his blood. And if blood held memory…

He did not finish the thought. He could not bear to.”

Evie exhaled, staring at the page. “This isn’t just Tattler’s usual nonsense, is it?”

Seren shook her head distractedly.

“It reads like a first-hand account—filtered through Liz’s dramatics, of course. But the details…” She tapped the underlined section. “Someone wanted this remembered.”

Mandrake, still perched smugly above them, let out a satisfied mrrrow.

Evie sat back, a seed of realization sprouting in her mind. “If this was real, and if this technique survived somehow…”

Mandrake finished the thought for her. “Then Amara’s theory isn’t theory at all.”

Evie ran a hand through her hair, glancing at the cat than at Evie. “I hate it when Mandrake’s right.”

“Well what’s a witch without her cat, isn’t it?” Seren replied with a smile.

Mandrake only flicked his tail, his work here done.

February 3, 2025 at 5:18 am #7730In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

The Asylum 2050

They had been talking about leaving for a long time.

Not in any urgent way, not in a we must leave now kind of way, but in the slow, circling conversations of people who had too much time and not enough answers.

Those who had left before them had never returned. Perhaps they had found something better, though that seemed unlikely. Perhaps they had found nothing at all. The first group left over twenty years ago—just for supplies. They never came back. Others drifted off over the years. They never came back either.

The core group had stayed because—what else was there? The asylum had been safe, for the most part. It had become home. Overgrown now, with only a fraction of its former inhabitants. The walls had once kept them in; now, they were what kept the rest of the world out.

But the crops were failing. The soil was thinning. The last winter had been long and cruel. Summer was harsh. Water was harder to find.

And so the reasons to stay had been replaced with reasons to go.

She was about forty now—or near enough, though time had softened the numbers. Natalia. A name from a past life; now they called her Tala.

Her family had left her here years ago. Paid well for it, as if they were settling an expensive inconvenience. She had been young then—too young to know how final it would be. They had called her difficult, willful, unable to conform. She wasn’t mad, but they had paid to have her called mad so they could get rid of her. And in the world before, that had been enough.

She had been furious at first. She tried to run away even though the asylum was many miles from anywhere. The drugs they made her take put an end to that. The drugs stopped many years ago, but she no longer wanted to run.

She sat at the edge of the vegetable garden, turning soil between her fingers. It was dry, thinning. No matter how deep she dug, the color stayed the same—pale, lifeless.

“Nothing wants to grow anymore,” said Anya, standing over her. Older—mid-sixties. Once a nurse, before everything had fallen apart. She had been one of the staff members who stayed behind when the first group left for supplies, but now she was the only one remaining. The others had abandoned the asylum years ago. At first, her authority had meant something. Now, it was just a memory, but she still carried it like an old habit. She was practical, sharp-eyed, and had a way of making decisions that others followed without question.

Tala wiped her hands on her skirt and looked up. “We probably should have left last year.”

Anya sighed. She dropped a brittle stalk of something dead into the compost pile. “Doesn’t matter now. We must go soon, or we don’t go at all.”

There was no arguing with that.

Later, in the old communal hall, the last of them gathered. Eleven of them.

Mikhail leaned against the window, his arms crossed. He was a little older than Tala. He thought a long time before he spoke.

“How many weapons do we have?”

Anya shrugged. “A couple of old rifles with half a dozen bullets. A handful of knives. And whatever rocks and sticks we pick up on the way.”

“It’s not enough to defend ourselves,” Tala said. Petro, an older resident who couldn’t remember life before the asylum, moaned and rocked. “But we’ll have our wits about us,” she added, offering a small reassurance.

Mikhail glanced at her. “We don’t know what’s out there.”

Before communication went silent, there had been stories of plagues, wars, starvation, entire cities turning against themselves. People had come through the asylum’s doors shortly before the collapse, mad with what they had seen.

But then, nobody came. The fences had grown thick with vines. And the world had gone quiet.

Over time, they had become a kind of family, bound by necessity rather than blood. They were people who had been left behind for reasons that no longer mattered. In this world, sanity had become a relative thing. They looked after one another, oddities and all.

Mikhail exhaled and pushed off the window. “Tomorrow, then.”

February 2, 2025 at 12:15 pm #7720In reply to: Helix Mysteries – Inside the Case

Some ideas to pick apart and improve on:

Some characters:

- The Murder Victim: A once-prominent figure whose mysterious death on Helix 25 is intertwined with deeper, enigmatic forces—a person whose secret past and untimely demise trigger the cascade of genetic clues and expose long-buried truths about the exodus.

- Dr. Amara Voss: A brilliant geneticist haunted by fragmented pasts, who deciphers DNA strands imbued with clues from an ancient intelligence.

- Inspector Orion Reed: A retro-inspired, elderly holographic AI detective whose relentless curiosity drives him to unravel the inexplicable murder.

- Kai Nova: A maverick pilot chasing cosmic dreams, unafraid to navigate perilous starfields in search of truth.

- Seren Vega: A meditative archivist who unlocks VR relics of history, piecing together humanity’s lost lore. Mandrake her cat, who’s been given bionic enhancements that enables it to speak its mind.

- Luca Stroud: A rebellious engineer whose knack for decoding forbidden secrets may hold the key to the ship’s destiny.

- Ellis Marlowe (Retired Postman): A weathered former postman whose cherished collection of vintage postcards from Earth and early space voyages carries personal and historical messages, hinting at forgotten connections.

- Sue Forgelot: A prominent socialist socialite, descended from Sir Forgelot.

- Sharon, Gloria, Mavis: a favourite elderly trio of life-extended elders. Of course, they endured and thrived in humanity’s latest exodus from Earth

- Lexican and Flexicans, Pronoun People: sub-groups and political factions, challenging our notions of divisions

- Space Absinthe Pirates: a rogue band of bandits— a myth to make children behave… or something else?

Background of the Helix Fleet:

Helix 25 is one of several generation ships that were designed as luxury cruise ships, but are now embarked on an exodus from Earth decades ago, after a mysterious event that left them the last survivors of humanity. Once part of an ambitious fleet designed for both leisure and also built to secretly preserve humanity’s legacy, the other Helix ships have since vanished from communication. Their unexplained absence casts a long shadow over the survivors aboard Helix 25, fueling theories soon turning into myths and the hope of a new golden age for humanity bound to a cryptic prophecy.

100-Word Pitch:

Aboard Helix 25, humanity’s last survivors drift through deep space on a generation ship with a haunted past. When Inspector Orion Reed, a timeless holographic detective, uncovers a perplexing murder, encoded genetic secrets begin to surface. Dr. Amara Voss painstakingly deciphers DNA strands laced with ancient intelligence, while Kai Nova navigates treacherous starfields and Seren Vega unlocks VR relics of lost eras. Luca Stroud and Ellis Marlowe, a retired postman with vintage postcards, piece together clues that tie the victim’s secret past to the vanished Helix fleet. As conspiracies unravel, the crew must confront a destiny entwined with Earth’s forgotten exodus.

December 5, 2024 at 11:01 pm #7647In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

Darius: A Map of People

June 2023 – Capesterre-Belle-Eau, Guadeloupe

The air in Capesterre-Belle-Eau was thick with humidity, the kind that clung to your skin and made every movement slow and deliberate. Darius leaned against the railing of the veranda, his gaze fixed on the horizon where the sky blends into the sea. The scent of wet earth and banana leaves filling the air. He was home.

It had been nearly a year since hurricane Fiona swept through Guadeloupe, its winds blowing a trail of destruction across homes, plantations, and lives. Capesterre-Belle-Eau had been among the hardest hit, its banana plantations reduced to ruin and its roads washed away in torrents of mud.

Darius hadn’t been here when it happened. He’d read about it from across the Atlantic, the news filtering through headlines and phone calls from his aunt, her voice brittle with worry.

“Darius, you should come back,” she’d said. “The land remembers everyone who’s left it.”

It was an unusual thing for her to say, but the words lingered. By the time he arrived in early 2023 to join the relief efforts, the worst of the crisis had passed, but the scars remained—on the land, on the people, and somewhere deep inside himself.

Home, and Not — Now, passing days having turned into quick six months, Darius was still here, though he couldn’t say why. He had thrown himself into the work, helped to rebuild homes, clear debris, and replant crops. But it wasn’t just the physical labor that kept him—it was the strange sensation of being rooted in a place he’d once fled.

Capesterre-Belle-Eau wasn’t just home; it was bones-deep memories of childhood. The long walks under the towering banana trees, the smell of frying codfish and steaming rice from his aunt’s kitchen, the rhythm of gwoka drums carrying through the evening air.

“Tu reviens pour rester cette fois ?” Come back to stay? a neighbor had asked the day he returned, her eyes sharp with curiosity.

He had laughed, brushing off the question. “On verra,” he’d replied. We’ll see.

But deep down, he knew the answer. He wasn’t back for good. He was here to make amends—not just to the land that had raised him but to himself.

A Map of Travels — On the veranda that afternoon, Darius opened his phone and scrolled through his photo gallery. Each image was pinned to a digital map, marking all the places he’d been since he got the phone. Of all places, it was Budapest which popped out, a poor snapshot of Buda Castle.

He found it a funny thought — just like where he was now, he hadn’t planned to stay so long there. He remembered the date: 2020, in the midst of the pandemic. He’d spent in Budapest most of it, sketching the empty streets.

Five years ago, their little group of four had all been reconnecting in Paris, full of plans that never came to fruition. By late 2019, the group had scattered, each of them drawn into their own orbits, until the first whispers of the pandemic began to ripple across the world.

Funding his travels had never been straightforward. He’d tried his hand at dozens of odd jobs over the years—bartending in Lisbon, teaching English in Marrakech, sketching portraits in tourist squares across Europe. He lived frugally, keeping his possessions light and his plans loose. Yet, his confidence had a way of opening doors; people trusted him without knowing why, offering him opportunities that always seemed to arrive at just the right time.

Even during the pandemic, when the world seemed to fold in on itself, he had found a way.

Darius had already arrived in Budapest by then, living cheaply in a rented studio above a bakery. The city had remained open longer than most in Europe or the world, its streets still alive with muted activity even as the rest of Europe closed down. He’d wandered freely for months, sketching graffiti-covered bridges, quiet cafes, and the crumbling facades of buildings that seemed to echo his own restlessness.

When the lockdowns finally came like everywhere else, it was just before winter, he’d stayed, uncertain of where else to go. His days became a rhythm of sketching, reading, and sending postcards. Amei was one of the few who replied—but never ostentatiously. It was enough to know she was still there, even if the distance between them felt greater than ever.

But the map didn’t tell the whole story. It didn’t show the faces, the laughter, the fleeting connections that had made those places matter.

Swatting at a buzzing mosquito, he reached for the small leather-bound folio on the table beside him. Inside was a collection of fragments: ticket stubs, pressed flowers, a frayed string bracelet gifted by a child in Guatemala, and a handful of postcards he’d sent to Amei but had never been sure she received.

One of them, yellowed at the edges, showed a labyrinth carved into stone. He turned it over, his own handwriting staring back at him.

“Amei,” it read. “I thought of you today. Of maps and paths and the people who make them worth walking. Wherever you are, I hope you’re well. —D.”

He hadn’t sent it. Amei’s responses had always been brief—a quick WhatsApp message, a thumbs-up on his photos, or a blue tick showing she’d read his posts. But they’d never quite managed to find their way back to the conversations they used to have.

The Market — The next morning, Darius wandered through the market in Trois-Rivières, a smaller town nestled between the sea and the mountains. The vendors called out their wares—bunches of golden bananas, pyramids of vibrant mangoes, bags of freshly ground cassava flour.

“Tiens, Darius!” called a woman selling baskets woven from dried palm fronds. “You’re not at work today?”

“Day off,” he said, smiling as he leaned against her stall. “Figured I’d treat myself.”

She handed him a small woven bracelet, her eyes twinkling. “A gift. For luck, wherever you go next.”

Darius accepted it with a quiet laugh. “Merci, tatie.”

As he turned to leave, he noticed a couple at the next stall—tourists, by the look of them, their backpacks and wide-eyed curiosity marking them as outsiders. They made him suddenly realise how much he missed the lifestyle.

The woman wore an orange scarf, its boldness standing out as if the color orange itself had disappeared from the spectrum, and only a single precious dash could be seen into all the tones of the market. Something else about them caught his attention. Maybe it was the way they moved together, or the way the man gestured as he spoke, as if every word carried weight.

“Nice scarf,” Darius said casually as he passed.

The woman smiled, adjusting the fabric. “Thanks. Picked it up in Rajasthan. It’s been with me everywhere since.”

Her partner added, “It’s funny, isn’t it? The things we carry. Sometimes it feels like they know more about where we’ve been than we do.”

Darius tilted his head, intrigued. “Do you ever think about maps? Not the ones that lead to places, but the ones that lead to people. Paths crossing because they’re meant to.”

The man grinned. “Maybe it’s not about the map itself,” he said. “Maybe it’s about being open to seeing the connections.”

A Letter to Amei — That evening, as the sun dipped below the horizon, Darius sat at the edge of the bay, his feet dangling above the water. The leather-bound folio sat open beside him, its contents spread out in the fading light.

He picked up the labyrinth postcard again, tracing its worn edges with his thumb.

“Amei,” he wrote on the back just under the previous message a second one —the words flowing easily this time. “Guadeloupe feels like a map of its own, its paths crossing mine in ways I can’t explain. It made me think of you. I hope you’re well. —D.”

He folded the card into an envelope and tucked it into his bag, resolving to send it the next day.

As he watched the waves lap against the rocks, he felt a sense of motion rolling like waves asking to be surfed. He didn’t know where the next path would lead next, but he felt it was time to move on again.

December 5, 2024 at 2:37 am #7645In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

Amei sat cross-legged on the floor in what had once been the study, its emptiness amplified by the packed boxes stacked along the walls. The bookshelves were mostly bare now, save for a few piles of books she was donating to goodwill.

The window was open, and a soft breeze stirred the curtains, carrying with it the faint chime of church bells in the distance. Ten o’clock. Tomorrow was moving day.

Her notebooks were heaped beside her on the floor—a chaotic mix of battered leather covers, spiral-bound pads, and sleek journals bought in fleeting fits of optimism. She ran a hand over the stack, wondering if it was time to let them go. A fresh start meant travelling lighter, didn’t it?

She hesitated, then picked up the top notebook. Flipping it open, she skimmed the pages—lists, sketches, fragments of thoughts and poems. As she turned another page, a postcard slipped out and fluttered to the floor.

She picked it up. The faded image showed a winding mountain road, curling into mist. On the back, Darius had written:

“Found this place by accident. You’d love it. Or maybe hate it. Either way, it made me think of you. D.”

Amei stared at the card. She’d forgotten about these postcards, scattered through her notebooks like breadcrumbs to another time. Sliding it back into place, she set the notebook aside and reached for another, older one. Its edges were frayed, its cover softened by time.

She flicked through the pages until an entry caught her eye, scrawled as though written in haste:

Lucien found the map at a flea market. He thought it was just a novelty, but the seller was asking too much. L was ready to leave it when Elara saw the embossed bell in the corner. LIKE THE OTHER BELL. Darius was sure it wasn’t a coincidence, but of course wouldn’t say why. Typical. He insisted we buy it, and somehow the map ended up with me. “You’ll keep it safe,” he said. Safe from what? He wouldn’t say.

The map! Where was the map now? How had she forgotten it entirely? It had just been another one of their games back then, following whatever random clues they stumbled across. Fun at the time, but nothing she’d taken seriously. Maybe Darius had, though—especially in light of what happened later. She flipped the page, but the next entry was mundane—a note about Elara’s birthday. She read through to the end of the notebook, but there was no follow-up.

She glanced at the boxes. Could the map still be here, buried among her things? Stuffed into one of her notebooks? Or, most likely, had it been lost long ago?

She closed the notebook and sighed. Throwing them out would have been easier if they hadn’t started whispering to her again, pulling at fragments of a past she thought she had left behind.

December 4, 2024 at 6:22 am #7638In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

The Bell’s Moment: Paris, Summer 2024 – Olympic Games

The bell was dangling unassumingly from the side pocket of a sports bag, its small brass frame swinging lightly with the jostle of the crowd. The bag belonged to an American tourist, a middle-aged man in a rumpled USA Basketball T-shirt, hustling through the Olympic complex with his family in tow. They were here to cheer for his niece, a rising star on the team, and the bell—a strange little heirloom from his grandmother—had been an afterthought, clipped to the bag for luck. It seemed to fit right in with the bright chaos of the Games, blending into the swirl of flags, chants, and the hum of summer excitement.

1st Ring of the Bell: Matteo

The vineyard was quiet except for the hum of cicadas and the soft rustle of leaves. Matteo leaned against the tractor, wiping sweat from his brow with the back of his hand.

“You’ve done good work,” the supervisor said, clapping Matteo on the shoulder. “We’ll be finishing this batch by Friday.”

Matteo nodded. “And after that?”

The older man shrugged. “Some go north, some go south. You? You’ve got that look—like you already know where you’re headed.”

Matteo offered a half-smile, but he couldn’t deny it. He’d felt the tug for days, like a thread pulling him toward something undefined. The idea of returning to Paris had slipped into his thoughts quietly, as if it had been waiting for the right moment.

When his phone buzzed later that evening with a job offer to do renovation work in Paris, it wasn’t a surprise. He poured himself a small glass of wine, toasting the stars overhead.

Somewhere, miles away, the bell rang its first note.

2nd Ring of the Bell: Darius

In a shaded square in Barcelona, the air was thick with the scent of jasmine and the echo of a street performer’s flamenco guitar. Darius sprawled on a wrought-iron bench, his leather-bound journal open on his lap. He sketched absentmindedly, the lines of a temple taking shape on the page.

A man wearing a scarf of brilliant orange sat down beside him, his energy magnetic. “You’re an artist,” the man said without preamble, his voice carrying the cadence of Kolkata.

“Sometimes,” Darius replied, his pen still moving.

“Then you should come to India,” the man said, grinning. “There’s art everywhere. In the streets, in the temples, even in the food.”

Darius chuckled. “You recruiting me?”

“India doesn’t need recruiters,” the man replied. “It calls people when it’s time.”

The bell rang again in Paris, its chime faint and melodic, as Darius scribbled the words “India, autumn” in the corner of his page.

3rd Ring of the Bell: Elara

The crowd at CERN’s conference hall buzzed as physicists exchanged ideas, voices overlapping like equations scribbled on whiteboards. Elara sat at a corner table, sipping lukewarm coffee and scrolling through her messages.

The voicemail notification glared at her, and she tapped it reluctantly.

“Elara, it’s Florian. I… I’m sorry to tell you this over a message, but your mother passed away last night.”

Her coffee cup trembled slightly as she set it down.

Her relationship with her mother had been fraught, full of alternating period of silences and angry reunions, and had settled lately into careful politeness that masked deeper fractures. Years of therapy had softened the edges of her resentment but hadn’t erased it. She had come to accept that they would never truly understand each other, but the finality of death still struck her with a peculiar weight.

Her mother had been living alone in Montrouge, France, refusing to leave the little house Elara had begged her to sell for years. They had drifted apart, their conversations perfunctory and strained, like the ritual of winding a clock that no longer worked.

She would have to travel to Montrouge for the funeral arrangements.

In that moment, the bell in Les Reliques rang a third time.

4th Ring of the Bell: Lucien

The train to Lausanne glided through fields of dried up sunflowers, too early for the season, but the heat had been relentless. He could imagine the golden blooms swaying with a cracking sound in the summer breeze. Lucien stared out the window, the strap of his duffel bag wrapped tightly around his wrist.

Paris had been suffocating. The tourists swarmed the city like ants, turning every café into a photo opportunity and every quiet street into a backdrop. He hadn’t needed much convincing to take his friend up on the offer of a temporary studio in Lausanne.

He reached into his bag and pulled out a sketchbook. The pages were filled with half-finished drawings, but one in particular caught his eye: a simple doorway with an ornate bell hanging above it.

He didn’t remember drawing it, but the image felt familiar, like a memory from a dream.

The bell rang again in Paris, its resonance threading through the quiet hum of the train.

5th Ring of the Bell: …. Tabitha

In the courtyard of her university residence, Tabitha swung lazily in a hammock, her phone propped precariously on her chest.

“Goa, huh?” one of her friends asked, leaning against the tree holding up the hammock. “Think your mum will freak out?”

“She’ll probably worry herself into knots,” Tabitha replied, laughing. “But she won’t say no. She’s good at the whole supportive parent thing. Or at least pretending to be.”

Her friend raised an eyebrow. “Pretending?”

“Don’t get me wrong, I love her,” Tabitha said. “But she’s got her own stuff. You know, things she never really talks about. I think it’s why she works so much. Keeps her distracted.”

The bell rang faintly in Paris, though neither of them could hear it.

“Maybe you should tell her to come with you,” the friend suggested.

Tabitha grinned. “Now that would be a trip.”

Last Ring: The Pawn

It was now sitting on the counter at Les Reliques. Its brass surface gleamed faintly in the dim shop light, polished by the waves of time. Small and unassuming, its ring held something inexplicably magnetic.

Time seemed to settle heavily around it. In the heat of the Olympic summer, it rang six times. Each chime marked a moment that mattered, though none of the characters whose lives it touched understood why. Not yet.

“Where’d you get this?” the shopkeeper asked as the American tourist placed it down.

“It was my grandma’s,” he said, shrugging. “She said it was lucky. I just think it’s old.”

The shopkeeper ran her fingers over the brass surface, her expression unreadable. “And you’re selling it?”

“Need cash to get tickets for the USA basketball game tomorrow,” the man replied. “Quarterfinals. You follow basketball?”

“Not anymore,” the shopkeeper murmured, handing him a stack of bills.

The bell rang softly as she placed it on the velvet cloth, its sound settling into the space like a secret waiting to be uncovered.

And so it sat, quiet but full of presence, waiting for someone to claim it maybe months later, drawn by invisible threads woven through the magnetic field of lives, indifferent to the heat and chaos of the Parisian streets.

December 1, 2024 at 5:08 pm #7617“Who sees that the habit-energy of the projections of the beginningless past is the cause of the three realms and who understands that the tathagata stage is free from projections or anything that arises, attains the personal realisation of buddha knowledge and effortless mastery over their own minds” —The Lankavatara Sutra, 2.8 (trans. Red Pine).

“To trace the ripples of a beginningless sea is to chase a horizon that vanishes with each step; only by stilling the waves does the ocean reveal its boundless, unbroken clarity.”

~Echoes of the Vanished Shore, Selwyn Lemone.

What if the story would unfold in reverse this time? Would the struggle subsist, to remember the past events written comment after comment? Rather than writing towards a future, and —maybe— an elusive ending, would remembering layer after layers of events from the past change our outlook on why we write at all?

Let’s just have ourselves a new playground, a new experiment as this year draws to a close.

Four friends meet unexpectedly in a busy café, after five years not having seen each other.

Matteo, the server arrives, like a resonant fifth, bringing resolution to the root note —they all seem to know him, but why.

Answers are in their pasts. And story has to unfold backwards, a step at a time, to a beginningless past.

August 28, 2024 at 1:31 pm #7549In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

The Tailor of Haddon

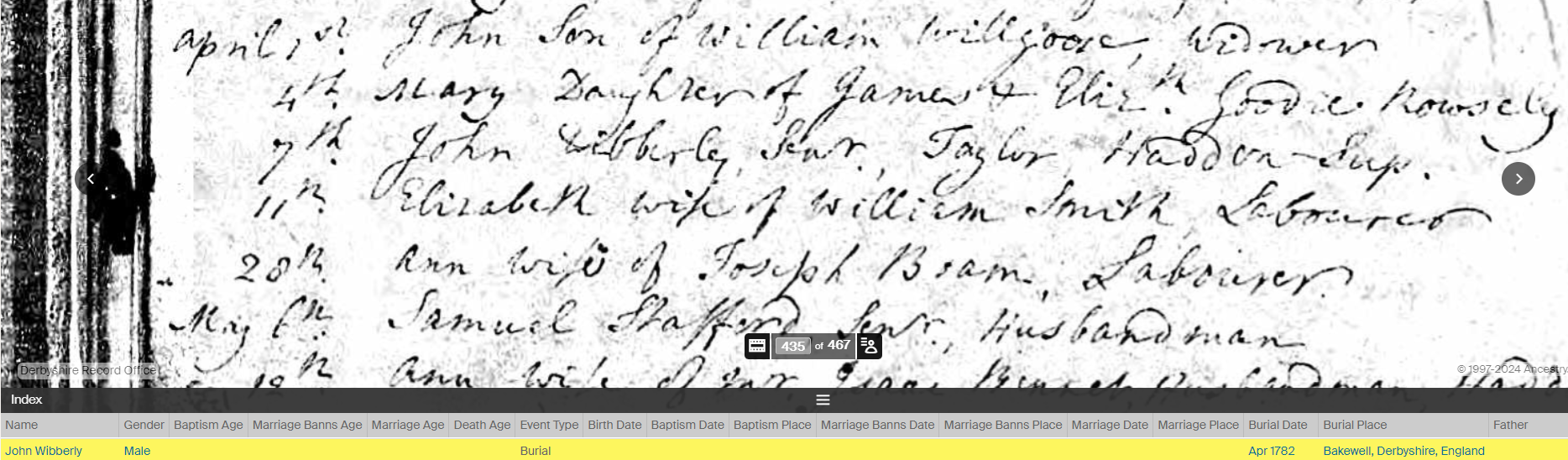

Wibberly and Newton of Over HaddonIt was noted in the Bakewell parish register in 1782 that John Wibberly 1705?-1782 (my 6x great grandfather) was “taylor of Haddon”.

James Marshall 1767-1848 (my 4x great grandfather), parish clerk of Elton, married Ann Newton 1770-1806 in Elton in 1792. In the Bakewell parish register, Ann was baptised on the 2rd of June 1770, her parents George and Dorothy Newton of Upper Haddon. The Bakewell registers at the time covered several smaller villages in the area, although what is currently known as Over Haddon was referred to as Upper Haddon in the earlier entries.

Newton:

George Newton 1728-1798 was the son of George Newton 1706- of Upper Haddon and Jane Sailes, who were married in 1727, both of Upper Haddon.

George Newton born in 1706 was the son of George Newton 1676- and Anne Carr, who were married in 1701, both of Upper Haddon.

George Newton born in 1676 was the son of John Newton 1647- and Alice who were married in 1673 in Bakewell. There is no last name for Alice on the marriage transcription.

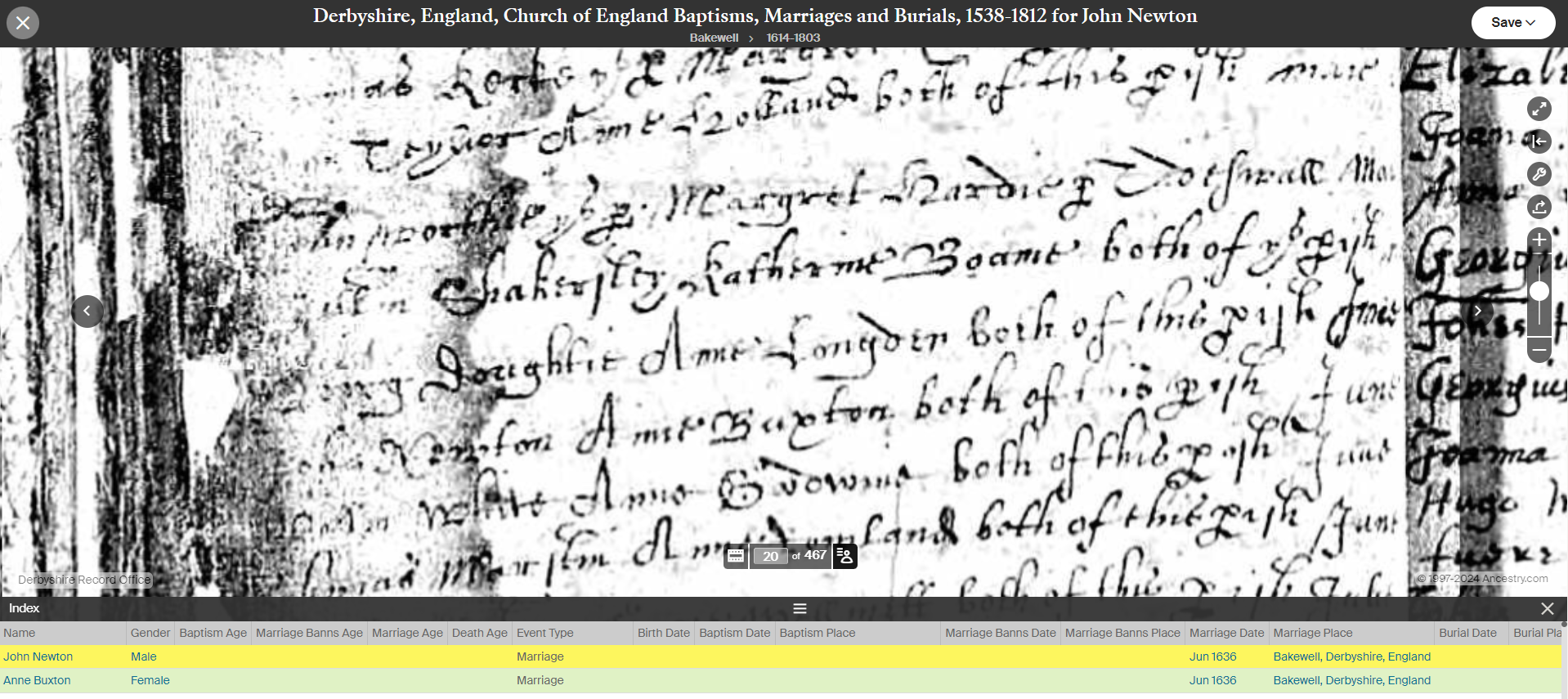

John Newton born in 1647 (my 9x great grandfather) was the son of John Newton and Anne Buxton (my 10x great grandparents), who were married in Bakewell in 1636.

1636 marriage of John Newton and Anne Buxton:

Wibberly

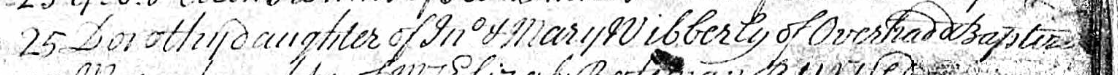

Dorothy Wibberly 1731-1827 married George Newton in 1755 in Bakewell. The entry in the parish registers says that they were both of Over Haddon. Dorothy was baptised in Bakewell on the 25th June 1731, her parents were John and Mary of Over Haddon.

John Wibberly and Mary his wife baptised nine children in Bakewell between 1730 and 1750, and on all of the entries in the parish registers it is stated that they were from Over Haddon. A parish register entry for John and Mary’s marriage has not yet been found, but a marriage in Beeley, a tiny nearby village, in 1728 to Mary Mellor looks likely.

John Wibberly died in Over Haddon in 1782. The entry in the Bakewell parish register notes that he was “taylor of Haddon”.

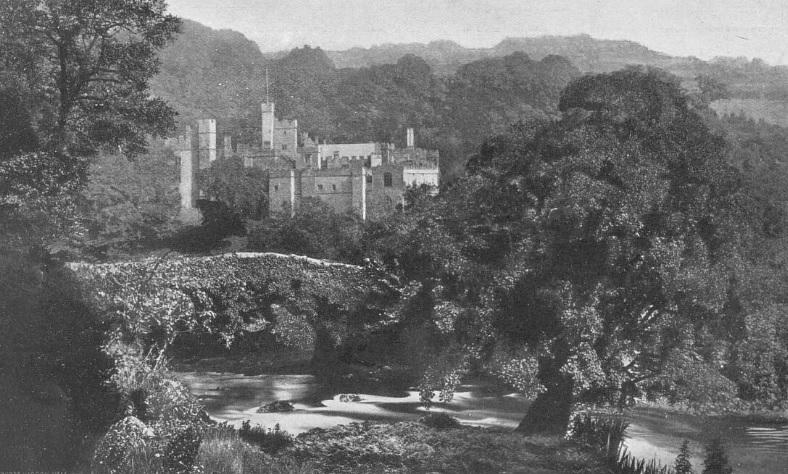

The tiny village of Over Haddon was historically associated with Haddon Hall.

A baptism for John Wibberly has not yet been found, however, there were Wibersley’s in the Bakewell registers from the early 1600s:

1619 Joyce Wibersley married Raphe Cowper.

1621 Jocosa Wibersley married Radulphus Cowper

1623 Agnes Wibersley married Richard Palfreyman

1635 Cisley Wibberlsy married ? Mr. Mason

1653 John Wibbersly married Grace DaykenHaddon Hall

Sir Richard Vernon (c. 1390 – 1451) of Haddon Hall.

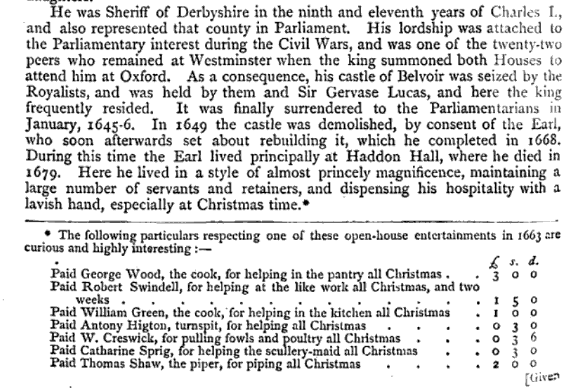

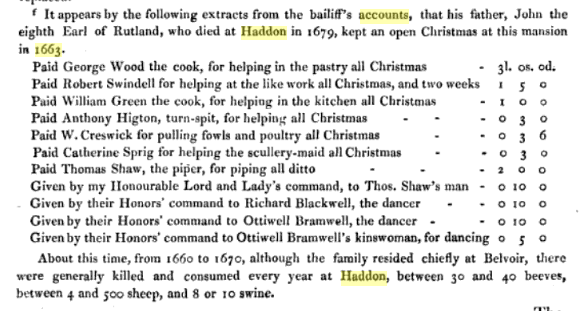

Vernon’s property was widespread and varied. From his parents he inherited the manors of Marple and Wibersley, in Cheshire. Perhaps the Over Haddon Wibersley’s origins were from Sir Richard Vernon’s property in Cheshire. There is, however, a medieval wayside cross called Whibbersley Cross situated on Leash Fen in the East Moors of the Derbyshire Peak District. It may have served as a boundary cross marking the estate of Beauchief Abbey. Wayside crosses such as this mostly date from the 9th to 15th centuries.Found in both The History and Antiquities of Haddon Hall by S Raynor, 1836, and the 1663 household accounts published by Lysons, Haddon Hall had 140 domestic staff.

In the book Haddon Hall, an Illustrated Guide, 1871, an example from the 1663 Christmas accounts:

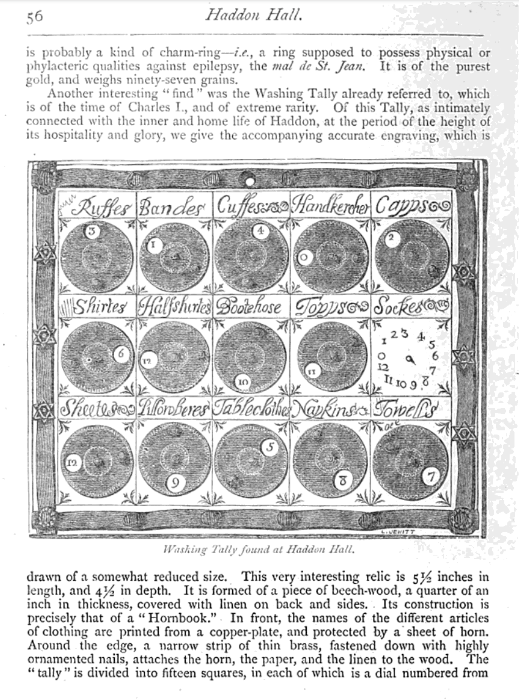

Also in this book, an early 1600s “washing tally” from Haddon Hall:

Over Haddon

Martha Taylor, “the fasting damsel”, was born in Over Haddon in 1649. She didn’t eat for almost two years before her death in 1684. One of the Quakers associated with the Marshall Quakers of Elton, John Gratton, visited the fasting damsel while he was living at Monyash, and occasionally “went two miles to see a woman at Over Haddon who pretended to live without meat.” from The Reliquary, 1861.

July 21, 2024 at 11:29 pm #7537In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

“Will you stop flirting with that poor boy, Tru! You can’t help yourself can you?” Frella’s word were softened by the huge smile on her face. “Isn’t this place just grand?”

“Frella! Don’t be sneaking up on a person like that!” Truella gave her friend a hug. “Anyway, you won’t believe it but Malove is going to be here! I mean, talk about unexpected plot twists. And you know she’s not going to be thrilled when she finds out I’ve nabbed her corner pod!” She giggled, albeit a little nervously.

Frella grimaced. “Tru, you’d better be careful. Malove’s not one to take things lightly, especially when it comes to her personal space.”

“Oh don’t worry. It will be fine. Anyway, what about your fancy man? Will he be here doing his important MAMA spy work? I do hope so. Dear Cedric always brings a certain je ne sais quoi to the scene.” Truella rolled her eyes and smirked.

“Oh you mean tart! And he’s NOT my fancy man but yeah, he is going to be here. You should be glad we’ve got someone on the inside. Those MAMA agents can be pesky devils and they’re bound to be sneaking around a gig like this.”

July 1, 2024 at 6:37 am #7530In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

At last the weekend was over. What had been acheived was anyones guess, certainly Truella couldn’t have said if it had been a success from the organizers point of view or not. One thing was abundantly clear: the witches were not cut from the same cloth as the nuns and the pious gravity of some of them had been anathema to the witches. But not all of them, it had to be said.

When Truella had wandered into the library, ostensibly to look for material on the frog sisters, but in reality just wanting a break from the constant presence of so many others, she was initially disheartened to find someone else had the same idea. Sassafras was curled up in an armchair poring over an old journal. She started guiltily when Truella walked in and quickly closed the leather bound volume.

“Oh please, don’t mind me. Carry on reading,” Truella reassured her, “I just came in here for a break. Point me in the direction of the local history section and I’ll not bother you.”

“Are you interested in the local history?” Sassafras asked, genuinely curious.

“Obsessed, more like!” Truella laughed, and proceeded to tell the story of the dig in her garden. She hadn’t intended to go into such detail and at such length, but Sassafras was interested and asked all the right questions.

“You seem very knowledgable about the history of the area,” Truella was prompted to invite Sassafras to come to her house to see what she’d uncovered. “I assume they let you out of here sometimes.”

Sassafras laughed. “Not very often, but I escape. I tell them I’m collecting herbs in the woods. Want to know a secret?” she leaned forward and lowered her voice. “I’m not really a nun, I’m only here because of the place. This place,” she sighed and her eyes had a faraway look, “This place, the history, oh my dear you have no idea, it’s rich beyond imagining for ancient history.”

The conversation that ensued had been illuminating for both of them, and they had agreed to keep in contact. Sassafras had given Truella a bundle of old journals to smuggle out of the Cloisters, written in the early 16th century.

Now all Truella had to do was get the journals home without being detected. It would require an effective cloaking spell, and she wished she had more confidence in her own magic.

June 22, 2024 at 6:44 am #7519In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

Audrey came to herself rather unexpectedly in the middle of the Choir ritual with all the witches and nuns finishing the Canticle from the Psalms of Saint Frogustus.

Luckily for the coven, her sudden gasp for air could have easily passed as a croak or one of the ribbit amens that went with the background aaah and oohs.

“I think something wrong happened to your friend.” she whispered to Jeezel who had been enjoying the unlikely singing. It was already the third ritual done in six, and it had been mostly enjoyable.

Eris whispered in turn as the grand croaking finale started with loud gong banging by Mother Lorena chanting “leaps of faithe, ye, leaps of faithe”.

“What do you mean? Is Frella alright?”

“Something came in the background, but when our minds disconnected, she felt more annoyed than anything… and to be honest maybe a bit… flustered, how to say…” she became red as Saint Frogustus’ hand tips. “Randy is the word you say?”

“Damn it Jeezel, have you done anything?”

“Why you ask me?” Jeezel felt offended. “You haven’t taken into account the strawberry full moon, that’s all.”

“There’s only one potent counter-spell to this situation…” Audrey said. “We should pray to Saint Frigdona saint patroness of unwavering commitment to upholding the sanctity of boundaries and the virtues of righteousness, even in the face of the most enticing temptations!”

“There’s only one potent counter-spell to this situation…” Audrey said. “We should pray to Saint Frigdona saint patroness of unwavering commitment to upholding the sanctity of boundaries and the virtues of righteousness, even in the face of the most enticing temptations!”“Jeeze, don’t go all religious like this.” a glowing Truella finally said. “I was for one, quite enjoying all that croaking. Dear Rufus told me there is a reason to this ritual! Get that: giant dragon-eating frogs! Dra-gon-frig-ging-eat-ing-frogs! That’s why the famous nuns were revered!”

Eris and Jeezel looked at each other with that puzzled look unequivocally meaning “she’s lost her marbles”.

In the silent moment of the last gong sound droning out, they sighed in unison, turning to Audrey. “How is this Frigdona prayer going already?”

June 17, 2024 at 7:13 pm #7493In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

“Do you know who that Everone is?” Jeezel whispered to Eris.

“Shtt,” she silenced Jeezel worried that some creative inspiration sparked into existence yet another character into their swirling adventure.

The ancient stone walls of the Cloisters resonated with the hum of anticipation. The air was thick with the scent of incense barely covering musky dogs’ fart undertones, mingling with the faint aroma of fresh parchment eaten away by centuries of neglect. Illuminated by the soft glow of enchanted lanterns sparkling chaotically like a toddler’s magic candle at its birthday, the grand hall was prepared for an unprecedented gathering of minds and traditions.

While all the attendants were fumbling around, grasping at the finger foods and chitchatting while things were getting ready, Eris was reminded of the scene of the deal’s signature between the two sisterhoods unlikely brought together.

Few weeks before, under a great deal of secrecy, Malové, Austreberthe, and Lorena had convened in the cloister’s grand hall, the gothic arches echoing their words. Before she signed, Lorena had stated rather grandiloquently, with a voice firm and unwavering. “We are a nunnery dedicated to craftsmanship and spiritual devotion. This merger must respect our traditions.”

Austreberthe, ever the pragmatist, replied, “And we bring innovation and magical prowess. Together, we can create something greater than the sum of our parts.”

The undertaker’s spokesman, Garrett, had interjected with a charming smile, “Consider us the matchmakers of this unlikely union. We promise not to leave you at the altar.”

That’s were he’d started to spell out the numbingly long Strategic Integration Plan to build mutual understanding of the mission and a framework for collaboration.Eris sighed at the memory. That would require yet a great deal of joint workshops and collaborative sessions — something that would be the key to facilitate new product developments and innovation. Interestingly, Malové at the time had suggested for Jeezel to lead with Silas the integration rituals designed to symbolically and spiritually unite the groups. She’d had always had a soft spot for our Jeezel, but that seemed unprecedented to want to put her to task on something as delicate. Maybe there was another plan in motion, she would have to trust Malové’s foresight and let it play out.

As the heavy oak doors creaked open, a hush fell over the assembled witches, nuns and the undertakers. Mother Lorena Blaen stepped forward. Her presence was commanding, her eyes sharp and scrutinising. She wore the traditional garb of her order, but her demeanour was anything but traditional.

“Welcome, everyone,” Lorena began, her voice echoing through the hallowed halls. “Or should I say, welcome to the heart of tradition and innovation, where ancient craftsmanship meets arcane mastery.”

She paused, letting her words sink in, before continuing. “You stand at the threshold of the Quintessivium Cloister Crafts, a sanctuary where every stitch is a prayer, every garment a humble display of our deepest devotion. But today, we are not just nuns and witches, morticians and mystics. Today, we are the architects of a new era.”

Truella yawned at the speech, not without waving like a schoolgirl at the tall Rufus guy, while Lorena was presenting a few of the nuns, ready to model in various fashionable nun’s garbs for their latest midsummer fashion show.

Lorena’s eyes twinkled with a mixture of pride and determination as she turned back to the visitors. “Together, we shall transcend the boundaries of faith and magic. With the guidance of the Morticians’ Guild—Garrett, Rufus, Silas, and Nemo—we will forge a new path, one that honors our past while embracing the future.”

Garrett, ever the showman, gave a theatrical bow. “We’re here to ensure this union is as seamless as a well-tailored shroud, my dear Lorena.” Rufus, standing silent and vigilant, offered a nod of agreement. Silas, with his grandfatherly smile, added, “We bring centuries of wisdom to this endeavor. Trust in the old ways, and we shall succeed.” Nemo, with his characteristic smirk, couldn’t resist a final quip. “And if things go awry, well, we have ways of making them… interesting.”

June 17, 2024 at 10:11 am #7490In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

Adjusting the crimson silk handkerchief in his breast pocket, Garrett swanned into the reception hall, his piercing pale blue eyes scanning the room. The walls were hung with colourful but faded tapestries, shabby enough to be genuinely ancient. The furniture was heavy and blackened with age, but it was the floor that caught his critical eye. In the centre of the old terracotta tiles floor was a mosaic, mostly hidden under a large conference table. Garret was no expert on Roman mosaics but it looked like the real deal. He would return to this room later for a closer inspection, he could hardly go crawling under the table now. It was a mercy, at least, that the ancient building hadn’t been decked out in ghastly modern furnishings as so many charming old hotels were these days.

He turned his attention to the few occupants. A ravishing raven haired beauty had just wafted in from the covered cloister beyond the open doors. Her silver mantilla shone in the sunlight slanting down into the courtyard for a moment, for all the world looking like an angelic medieval halo. As she slippped into the shadows the halo vanished, her ebony tresses showing beneath the gauzy lace. She settled herself in a low armchair, smoothing the burgundy folds of her gown. Garrett watched, spellbound. What an enchantress! Perhaps this weekend wouldn’t be such a bore, after all.

June 15, 2024 at 9:34 am #7476In reply to: Smoke Signals: Arcanas of the Quadrivium’s incense

Penelope Pomfrett: Let’s start with Penelope, shall we? She’s a statuesque woman with a sharp, angular face that could cut through butter – not unlike an Egon Schiele painting, if you’re familiar. Her hair’s a spun silver waterfall, always meticulously pinned up but with just a touch of wildness trying to escape, like she’s taming a tempest on top of her head. Her eyes are a piercing cerulean blue, always calculating, always observing; she’s the type who looks right through you and into your deepest secrets.

Personality-wise, Penelope’s got the demeanor of a headmistress crossed with a lioness. She’s precise, a bit of a perfectionist, never suffers fools gladly. But beneath that stern exterior, she’s got a heart of gold, especially when it comes to her coven sisters. Stern loyalty and high standards, that’s her in a nutshell. And she’s got this dry wit that’ll catch you off guard and have you chuckling before you know it.

Sandra Salt: Now Sandra, she’s a different kettle of fish altogether. Think earthy, grounded; she’s got that warm, approachable vibe that’s almost tangible. Picture her with curly auburn hair, always escaping its braids to frame her face in a halo of fiery ringlets. She’s got freckles smattered across her sun-kissed cheeks and a smile that feels like coming home after a long journey. Eyes? Warm hazel, like caramel with a hint of green, always twinkling with some hidden mischief or gentle wisdom.

Sandra’s personality is as grounded as the soil she loves to dig her fingers into; she’s the heart and soul of the crew, with an infectious laugh that could light up the darkest of days. She’s nurturing, perceptive, and has an uncanny knack for making everyone feel at ease. But don’t mistake her kindness for softness – she’s got a spine of steel and can summon a fierce storm if she’s wronged.

Audrey Ambrose: Now, dear Audrey, she’s a bit of a mysterious beauty. Think raven-black hair that falls in silky waves down her back, always perfectly styled without a hair out of place. She’s got porcelain skin, smooth and almost ethereal, like moonlight itself took her under its wing. Her eyes are a deep, striking emerald, always seeming to know more than she lets on. Add to that a penchant for elegant, vintage clothing, and you’ve got yourself a picture of classic, timeless beauty.

In terms of personality, Audrey’s a quiet storm. She’s enigmatic, often found lost in thought, with a deep, contemplative nature. While she may come off as aloof, she’s deeply empathetic and has an old-soul wisdom that guides her every action. She’s the sort you turn to when you need profound insight or a steady hand in times of chaos. And that wit – it’s as sharp as her fashion sense, subtle, and spot-on.

Sassafras Bentley: Lastly, let’s paint a picture of Sassafras. She’s vibrant and flamboyant, tall, thin and athletic, with hair dyed in shades of a peacock’s feathers – blues, greens, purples – ever changing with her whims. Her outfits are always eclectic and bold, but practical. She’s got a long hatchet face, and eyes that are a sparking topaz, full of zest and life ~ and secret undercurrents.

Sassafras is the party animal of the lot, always bringing fun and chaos in equal measure. She’s got a joie de vivre that’s downright infectious, a real firecracker with boundless energy. Her natural charisma draws people in, and her laugh – oh, her laugh! – it’s the kind of sound that warms the soul and invites everyone to join in her revelries, unless she’s being rude, aloof and secretive. Underneath all that sparkle, though, she’s fiercely protective of those she loves and more insightful than she lets on.

May 17, 2024 at 9:55 pm #7444In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

Sometimes the storm within is far more tumultuous than the one without.

After yet another seminar under Malové’s exacting eye, followed by the treasure hunt team-building exercise that left more than a few witches grumbling, Eris found herself at a crossroads.

The seminar had been, as always, a rigorous affair. Malové’s stern teachings, laced with cryptic wisdom and unyielding standards, forced the witches to confront their weaknesses and push their magical boundaries. The treasure hunt, designed to test their teamwork and resourcefulness, had revealed underlying tensions and frayed nerves despite the moments of camaraderie.

Eris, already exhausted from the constant demands and the emotional toll of the coven’s internal conflicts, felt her resolve wavering. The weight of responsibility hung heavy on her shoulders, and the recent events had only amplified her sense of weariness.

After the seminar, Eris retreated to her quarters, seeking solace in the familiar comforts of her personal space. She lit a calming incense blend, one of the Quadrivium’s finest, hoping it would help clear her mind and ease her spirits. As the soothing aroma filled the room, she couldn’t help but reflect on Malové’s private comments about Truella and the importance of clear communication and assertiveness balanced with respect.

The treasure hunt had forced Eris to confront her own limitations and the gaps in her magical expertise. She realized that while she had always been diligent and skilled, she had often hesitated to take bold risks or assert her ideas for fear of criticism. Malové’s teachings, though harsh, had a way of stripping away these hesitations, leaving only the raw truth.

Determined to rise above her doubts, Eris decided to approach the next phase of her journey with renewed vigor. She had a moment of appreciation for Malové’s tough but fair leadership —they had joked about their Breton witch colleague who had emphasised in her address to be “tough leaders” ; at least that’s what they understood until they all realised under the thick French accent, she’d actually meant being a “thought leader”. Expressing her gratitude for the guidance, Eris vowed to bridge the gap with Truella, understanding that their differences could be a source of strength rather than division.

-

AuthorSearch Results