-

AuthorSearch Results

-

January 12, 2025 at 11:51 am #7711

In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

Matteo — December 2022

Juliette leaned in, her phone screen glowing faintly between them. “Come on, pick something. It’s supposed to know everything—or at least sound like it does.”

Juliette was the one who’d introduced him to the app the whole world was abuzz talking about. MeowGPT.

At the New Year’s eve family dinner at Juliette’s parents, the whole house was alive with her sisters, nephews, and cousins. She entered a discussion with one of the kids, and they all seemed to know well about it. It was fun to see the adults were oblivious, himself included. He liked it about Juliette that she had such insatiable curiosity.

“It’s a life-changer, you know” she’d said “There’ll be a time, we won’t know about how we did without it. The kids born now will not know a world without it. Look, I’m sure my nephews are already cheating at their exams with it, or finding new ways to learn…”

“New ways to learn, that sounds like a mirage…. Bit of a drastic view to think we won’t live without; I’d like to think like with the mobile phones, we can still choose to live without.”

“And lose your way all the time with worn-out paper maps instead of GPS? That’s a grandpa mindset darling! I can see quite a few reasons not to choose!” she laughed.

“Anyway, we’ll see. What would you like to know about? A crazy recipe to grow hair? A fancy trip to a little known place? Write a technical instruction in the style of Elizabeth Tattler?”“Let me see…”

Matteo smirked, swirling the last sip of crémant in his glass. The lively discussions of Juliette’s family around them made the moment feel oddly private. “Alright, let’s try something practical. How about early signs of Alzheimer’s? You know, for Ma.”

Juliette’s smile softened as she tapped the query into the app. Matteo watched, half curious, half detached.

The app processed for a moment before responding in its overly chipper tone:

“Early signs of Alzheimer’s can include memory loss, difficulty planning or solving problems, and confusion with time or place. For personalized insights, understanding specific triggers, like stress or diet, can help manage early symptoms.”Matteo frowned. “That’s… general. I thought it was supposed to be revolutionary?”

“Wait for it,” Juliette said, tapping again, her tone teasing. “What if we ask it about long-term memory triggers? Something for nostalgia. Your Ma’s been into her old photos, right?”

The app spun its virtual gears and spat out a more detailed suggestion.

“Consider discussing familiar stories, music, or scents. Interestingly, recent studies on Alzheimer’s patients show a strong response to tactile memories. For example, one groundbreaking case involved genetic ancestry research coupled with personalized sensory cues.Juliette tilted her head, reading the screen aloud. “Huh, look at this—Dr. Elara V., a retired physicist, designed a patented method combining ancestral genetic research with soundwaves sensory stimuli to enhance attention and preserve memory function. Her work has been cited in connection with several studies on Alzheimer’s.”

“Elara?” Matteo’s brow furrowed. “Uncommon name… Where have I heard it before?”

Juliette shrugged. “Says here she retired to Tuscany after the pandemic. Fancy that.” She tapped the screen again, scrolling. “Apparently, she was a physicist with some quirky ideas. Had a side hustle on patents, one of which actually turned out useful. Something about genetic resonance? Sounds like a sci-fi movie.”

Matteo stared at the screen, a strange feeling tugging at him. “Genetic resonance…? It’s like these apps read your mind, huh? Do they just make this stuff up?”

Juliette laughed, nudging him. “Maybe! The system is far from foolproof, it may just have blurted out a completely imagined story, although it’s probably got it from somewhere on the internet. You better do your fact-checking. This woman would have published papers back when we were kids, and now the AI’s connecting dots.”

The name lingered with him, though. Elara. It felt distant yet oddly familiar, like the shadow of a memory just out of reach.

“You think she’s got more work like that?” he asked, more to himself than to Juliette.

Juliette handed him the phone. “You’re the one with the questions. Go ahead.”

Matteo hesitated before typing, almost without thinking: Elara Tuscany memory research.

The app processed again, and the next response was less clinical, more anecdotal.

“Elara V., known for her unconventional methods, retired to Tuscany where she invested in rural revitalization. A small village farmhouse became her retreat, and she occasionally supported artistic projects. Her most cited breakthrough involved pairing sensory stimuli with genetic lineage insights to enhance memory preservation.”Matteo tilted the phone towards Juliette. “She supports artists? Sounds like a soft spot for the dreamers.”

“Maybe she’s your type,” Juliette teased, grinning.

Matteo laughed, shaking his head. “Sure, if she wasn’t old enough to be my mother.”

The conversation shifted, but Matteo couldn’t shake the feeling the name had stirred. As Juliette’s family called them back to the table, he pocketed his phone, a strange warmth lingering—part curiosity, part recognition.

To think that months before, all that technologie to connect dots together didn’t exist. People would spend years of research, now accessible in a matter of seconds.

Later that night, as they were waiting for the new year countdown, he found himself wondering: What kind of person would spend their retirement investing in forgotten villages and forgotten dreams? Someone who believed in second chances, maybe. Someone who, like him, was drawn to the idea of piecing together a life from scattered connections.

December 19, 2024 at 7:59 pm #7700In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

Elara — December 2021

Taking a few steps back in order to see if the makeshift decorations were evenly spaced, Elara squinted as if to better see the overall effect, which was that of a lopsided bare branch with too few clove studded lemons. Nothing about it conjured up the spirit of Christmas, and she was surprised to find herself wishing she had tinsel, fat garlands of red and gold and green and silver tinsel, coloured fairy lights and those shiny baubles that would sever your toe clean off if you stepped on a broken one.

It’s because I can’t go out and buy any, she told herself, I hate tinsel.

It was Elara’s first Christmas in Tuscany, and the urge to have a Christmas tree had been unexpected. She hadn’t had a tree or decorated for Christmas for as long as she could remember, and although she enjoyed the social gathering with friends, she resented the forced gift exchange and disliked the very word festive.

The purchase of the farmhouse and the move from Warwick had been difficult, with the pandemic in full swing but a summer gap in restrictions had provided a window for the maneuvre. Work on the house had been slow and sporadic, but the weather was such a pleasant change from Warwick, and the land extensive, so that Elara spent the first months outside.

The solitude was welcome after the constant demands of her increasingly senile older sister and her motley brood of diverse offspring, and the constant dramas of the seemingly endless fruits of their loins. The fresh air, the warm sun on her skin, satisfying physical work in the garden and long walks was making her feel strong and able again, optimistic.

England had become so depressing, eating away at itself in gloom and loathing, racist and americanised, the corner pubs all long since closed and still boarded up or flattened to make ring roads around unspeakably grim housing estates and empty shops, populated with grey Lowry lives beetling around like stick figures, their days punctuated with domestic upsets both on their telly screens and in their kitchens. Vanessa’s overabundant family and the lack of any redeeming features in any of them, and the uninspiring and uninspired students at the university had taken its toll, and Elara became despondent and discouraged, and thus, failed to see any hopeful signs.

When the lockdown happened, instead of staying in contact with video calls, she did the opposite, and broke off all contact, ignoring phone calls, messages and emails from Vanessa’s family. The almost instant tranquility of mind was like a miracle, and Elara wondered why it had never occurred to her to do it before. Feeling so much better, Elara extended the idea to include ignoring all phone calls and messages, regardless of who they were. She attended to those regarding the Tuscan property and the sale of her house in Warwick.

The only personal messages she responded to during those first strange months of quarantine were from Florian. She had never met him in person, and the majority of their conversations were about shared genealogy research. The great thing about family ancestors, she’d once said to him, Is that they’re all dead and can’t argue about anything.

Christmas of December, 2021, and what a year it had been, not just for Elara, but for everyone. The isolation and solitude had worked well for her. She was where she wanted to be, and happy. She was alone, which is what she wanted.

If only I had some tinsel though.

December 19, 2024 at 9:52 am #7698In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

December 2023

Lights and Christmas decorations were starting to pop up everywhere, like frost and icicles after a frozen winter night. Lucien—no, Julien, as he had started calling himself a few years ago—enjoyed walking in the streets at the end of the day, when the balance between light and night shifted into the darkness. That was the time when decorations would start to come to life like a swarm of fireflies, flickering in time with the city’s heartbeat.

It was Julien’s first time in Paris after Lucien’s three years of exile, far from all his concerns and the glacial grasp of the dark couple. Julien had enjoyed his time traveling the world, discovering Asia, South America and even certain parts of Africa he would never have imagined he would dare enter. Julien made friends along the way, always curious about their ways of living and the way they looked at the world. But always the voice of Lucien made him wary of staying too long. He had the impression it would increase the possibility of chance encounters with Darius. And he longed to reconnect with his friend and his former life, it would lead to awkward moments, and he would have to give some explanations. But he feared it would make him want to go back, with the risk of attracting unwanted attention. So Julien had to leave in order to be free. That was the price he was willing to pay.

But in the end, it was the longing of French winter time that made him come back home.

“Lucien! Is that you?”

December 8, 2024 at 9:42 pm #7656In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

Matteo — December 1st 2023: the Advent Visit

(near Avignon, France)

The hallway smelled of nondescript antiseptic and artificial lavender, a lingering scent jarring his senses with an irreconciliable blend of sterility and forced comfort. Matteo shifted the small box of Christmas decorations under his arm, his boots squeaking slightly against the linoleum floor. Outside, the low winter sun cast long, pale shadows through the care facility’s narrow windows.

When he reached Room 208, Matteo paused, hand resting on the doorframe. From inside, he could hear the soft murmur of a holiday tune—something old-fashioned and meant to be cheerful, likely playing from the small radio he’d gifted her last year. Taking a breath, he stepped inside.

His mother, Drusilla sat by the window in her padded chair, a thick knit shawl draped over her frail shoulders. She was staring intently at her hands, her fingers trembling slightly as they folded and unfolded the edge of the shawl. The golden light streaming through the window framed her face, softening the lines of age and wear.

“Hi, Ma,” Matteo said softly, setting the box down on the small table beside her.

Her head snapped up at the sound of his voice, her eyes narrowing as she fixed him with a sharp, almost panicked look. “Léon?” she said, her voice shaking. “What are you doing here? How are you here?” There was a tinge of anger in her tone, the kind that masked fear.

Matteo froze, his breath catching. “Ma, it’s me. Matteo. I’m Matteo, your son, please calm down” he said gently, stepping closer. “Who’s Léon?”

She stared at him for a long moment, her eyes clouded with confusion. Then, like a tide retreating, recognition crept back into her expression. “Matteo,” she murmured, her voice softer now, though tinged with exhaustion. “Oh, my boy. I’m sorry. I—” She looked away, her hands clutching the shawl tighter. “I thought you were someone else.”

“It’s okay,” Matteo said, crouching beside her chair. “I’m here. It’s me.”

Drusilla reached out hesitantly, her fingers brushing his cheek. “You look so much like him sometimes,” she said. “Léon… your father. He’d hold his head just like that when he didn’t want anyone to know he was worried.”

As much as Matteo knew, Drusilla had arrived in France from Italy in her twenties. He was born soon after. She had a job as a hairdresser in a little shop in Avignon, and did errands and chores for people in the village. For the longest time, it was just the two of them, as far as he’d recall.

Matteo’s chest tightened. “You’ve never told me much about him.”

“There wasn’t much to tell,” she said, her voice distant. “He came. He left. But he gave me something before he went. I always thought it would mean something, but…” Her voice trailed off as she reached into the pocket of her shawl and pulled out a small silver medallion, worn smooth with age. She held it out to him. “He said it was for you. When you were older.”

Matteo took the medallion carefully, turning it over in his hand. It was a simple but well-crafted Saint Christopher medal, the patron saint of travellers, with faint initials etched on the back—L.A.. He didn’t recognize the letters, but the weight of it in his palm felt significant, grounding.

“Why didn’t you give it to me before?” he asked, his voice quiet.

“I forgot I had it,” she admitted with a faint, sad laugh. “And then I thought… maybe it was better to keep it. Something of his, for when I needed it. But I think it’s yours now.”

Matteo slipped the medallion into his pocket, his mind spinning with questions he didn’t want to ask—not now. “Thanks, Ma,” he said simply.

Drusilla sighed and leaned back in her chair, her gaze drifting to the small box he’d brought. “What’s that?”

“Decorations,” Matteo said, seizing the moment to shift the focus. “I thought we could make your room a little festive for Christmas.”

Her face softened, and she smiled faintly. “That’s nice,” she said. “I haven’t done that in… I don’t remember when.”

Matteo opened the box and began pulling out garlands and baubles. As he worked, Drusilla watched silently, her hands still clutching the shawl. After a moment, she spoke again, her voice quieter now.

“Do you remember our house in Crest?” she asked.

Matteo paused, a tangle of tinsel in his hands. “Crest?” he echoed. “The place where you wanted to move to?”

Drusilla nodded slowly. “I thought it would be nice. A co-housing place. I could grow old in the garden, and you’d be nearby. It seemed like a good idea then.”

“It was a good idea,” Matteo said. “It just… didn’t happen.”

“No,… you’re right” she said, collecting her thoughts for a moment, her gaze distant. “You were too restless. Always moving. I thought maybe you’d stay if we built something together.”

Matteo swallowed hard, the weight of her words pressing on him. “I wanted to, Ma,” he said. “I really did.”

Drusilla’s eyes softened, and she reached for his hand, her grip surprisingly strong. “You’re here now,” she said. “That’s what matters.”

They spent the next hour decorating the room. Matteo hung garlands around the window and draped tinsel over the small tree he’d set up on the table. Drusilla directed him with occasional nods and murmured suggestions, her moments of lucidity shining like brief flashes of sunlight through clouds.

When the last bauble was hung, Drusilla smiled faintly. “It’s beautiful,” she said. “Like home.”

Matteo sat beside her, emotion weighing on him more than the physical efforts and the early drive. He was thinking about the job offer in London, the chance to earn more money to ensure she had everything she needed here. But leaving her felt impossible, even as staying seemed equally unsustainable. He was afraid it was just a justification to avoid facing the slow fraying of her memories.

Drusilla’s voice broke through his thoughts. “You’ll figure it out,” she said, her eyes closing as she leaned back in her chair. “You always do.”

Matteo watched her as she drifted into a light doze, her breathing steady and peaceful. He reached into his pocket, his fingers brushing against the medallion. The weight of it felt like both a question and an answer—one he wasn’t ready to face yet.

“Patron saint of travellers”, that felt like a sign, if not a blessing.

December 7, 2024 at 10:07 am #7650In reply to: Quintessence: A Portrait in Reverse

Some elements for inspiration as to the backstory of the group and how it could tie to the current state of the story:

Here’s a draft version of the drama surrounding Éloïse and Monsieur Renard (the “strange couple”), incorporating their involvement with Darius, their influence on the group’s dynamic, and the fallout that caused the estrangement five years ago.

The Strange Couple: Éloïse and Monsieur Renard

Winter 2019: Paris, Just Before the Pandemic

The group’s last reunion before their estrangement was supposed to be a celebration—one of those rare moments when their diverging paths aligned. They had gathered in Paris in late December, the city cloaked in gray skies and glowing light. The plan was simple: a few days together, catching up, exploring old haunts, and indulging in the kind of reckless spontaneity that had defined their earlier years.

It was Darius who disrupted the rhythm. He had arrived late to their first dinner, rain-soaked and apologetic, with Éloïse and Monsieur Renard in tow.

First Impressions of Éloïse and Monsieur Renard

Éloïse was striking—lithe, dark-haired, with sharp eyes that seemed to unearth secrets before you could name them. She moved with a predatory grace, her laughter a mix of charm and edge. Renard was her shadow, older and impeccably dressed, his silvery hair and angular features giving him the air of a fox. He spoke little, but when he did, his words had the weight of finality, as if he were accustomed to being obeyed.

“They’re just friends,” Darius said when the others exchanged wary glances. “They’re… interesting. You’ll like them.”

But it didn’t take long for Éloïse and Renard to unsettle the group. At dinner, Éloïse dominated the conversation, her stories wild and improbable—of séances in abandoned mansions, of lost artifacts with strange energies, of lives transformed by unseen forces. Renard’s occasional interjections only added to the mystique, his tone implying he’d seen more than he cared to share.

Lucien, ever the skeptic, found himself drawn to Éloïse despite his instincts. Her talk of energies and symbols resonated with his artistic side, and when she mentioned labyrinths, his attention sharpened.

Elara, in contrast, bristled at their presence. She saw through their mystique, recognizing in Renard the manipulative charisma of someone who thrived on control.

Amei was harder to read, but she watched Éloïse and Renard closely, her silence betraying a guardedness that hinted at deeper discomfort.

Darius’s Growing Involvement

Over the following days, Darius spent more time with Éloïse and Renard, skipping planned outings with the group. He spoke of them with a reverence that was uncharacteristic, praising their insight into things he’d never thought to question.

“They see connections in everything,” he told Amei during a rare moment alone. “It’s… enlightening.”

“Connections to what?” she asked, her tone sharper than she intended.

“Paths, people, purpose,” he replied vaguely. “It’s hard to explain, but it feels… right.”

Amei didn’t press further, but she mentioned it to Elara later. “It’s like he’s slipping into something he can’t see his way out of,” she said.

The Séance

The turning point came during an impromptu gathering at Éloïse and Renard’s rented apartment—a dimly lit space filled with strange objects: glass jars of cloudy liquid, intricate carvings, and an ornate bronze bell hanging above the mantelpiece.

Éloïse had invited the group for what she called “an evening of clarity.” The others arrived reluctantly, wary of what she had planned but unwilling to let Darius face it alone.

The séance began innocuously enough—Éloïse guiding them through what she described as a “journey inward.” She spoke in a low, rhythmic tone, her words weaving a spell that was hard to resist.

Then things took a darker turn. She asked them to focus on the labyrinth she had drawn on the table—a design eerily similar to the map Lucien had found weeks earlier.

“You must find your center,” she said, her voice dropping. “But beware the edges. They’ll show you things you’re not ready to see.”

The room grew heavy with silence. Darius leaned into the moment, his eyes closed, his breathing steady. Lucien tried to focus but felt a growing unease. Elara sat rigid, her scientific mind railing against the absurdity of it all. Amei’s hands gripped the edge of the table, her knuckles white.

And then, the bell rang.

It was faint at first, a distant chime that seemed to come from nowhere. Then it grew louder, resonating through the room, its tone deep and haunting.

“What the hell is that?” Lucien muttered, his eyes snapping open.

Éloïse smiled faintly but said nothing. Renard’s expression remained inscrutable, though his fingers tapped rhythmically against the table, as if counting something unseen.

Elara stood abruptly, breaking the spell. “This is ridiculous,” she said. “You’re playing with people’s minds.”

Darius’s eyes opened, his gaze unfocused. “You don’t understand,” he said softly. “It’s not a game.”

The Fallout

The séance fractured the group.

- Elara: Left the apartment furious, calling Renard a charlatan and vowing never to entertain such nonsense again. Her relationship with Darius cooled, her disappointment palpable.

- Lucien: Became fascinated with the labyrinth and its connection to his art, but he couldn’t shake the unease the séance had left. His conversations with Éloïse deepened in the following days, further isolating him from the group.

- Amei: Refused to speak about what she’d experienced. When pressed, she simply said, “Some things are better left forgotten.”

- Darius stayed with Éloïse and Renard for weeks after the others left Paris, becoming more entrenched in their world. But something changed. When he finally returned, he was distant and cagey, unwilling to discuss what had happened during his time with them.

Lingering Questions

- What Happened to Darius with Éloïse and Renard?

- Darius’s silence suggests something traumatic or transformative occurred during his deeper involvement with the couple.

- The Bell’s Role:

- The bronze bell that rang during the séance ties into its repeated presence in the story. Was it part of the couple’s mystique, or does it hold a deeper significance?

- Lucien’s Entanglement:

- Lucien’s fascination with Éloïse and the labyrinth hints at a lingering connection. Did she influence his art, or was their connection more personal?

- Éloïse and Renard’s Motives:

- Were they simply grifters manipulating Darius and others, or were they genuinely exploring something deeper, darker, and potentially dangerous?

Impact on the Reunion

- The group’s estrangement is rooted in the fractures caused by Éloïse and Renard’s influence, compounded by the isolation of the pandemic.

- Their reunion at the café is a moment of reckoning, with Matteo acting as the subtle thread pulling them back together to confront their shared past.

September 18, 2023 at 8:29 am #7278In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Tomlinson of Wergs and Hancox of Penn

John Tomlinson of Wergs (Tettenhall, Wolverhamton) 1766-1844, my 4X great grandfather, married Sarah Hancox 1772-1851. They were married on the 27th May 1793 by licence at St Peter in Wolverhampton.

Between 1794 and 1819 they had twelve children, although four of them died in childhood or infancy. Catherine was born in 1794, Thomas in 1795 who died 6 years later, William (my 3x great grandfather) in 1797, Jemima in 1800, John, Richard and Matilda between 1802 and 1806 who all died in childhood, Emma in 1809, Mary Ann in 1811, Sidney in 1814, and Elijah in 1817 who died two years later.On the 1841 census John and Sarah were living in Hockley in Birmingham, with three of their children, and surgeon Charles Reynolds. John’s occupation was “Ind” meaning living by independent means. He was living in Hockley when he died in 1844, and in his will he was “John Tomlinson, gentleman”.

Sarah Hancox was born in 1772 in Penn, Wolverhampton. Her father William Hancox was also born in Penn in 1737. Sarah’s mother Elizabeth Parkes married William’s brother Francis in 1767. Francis died in 1768, and in 1770 Elizabeth married William.

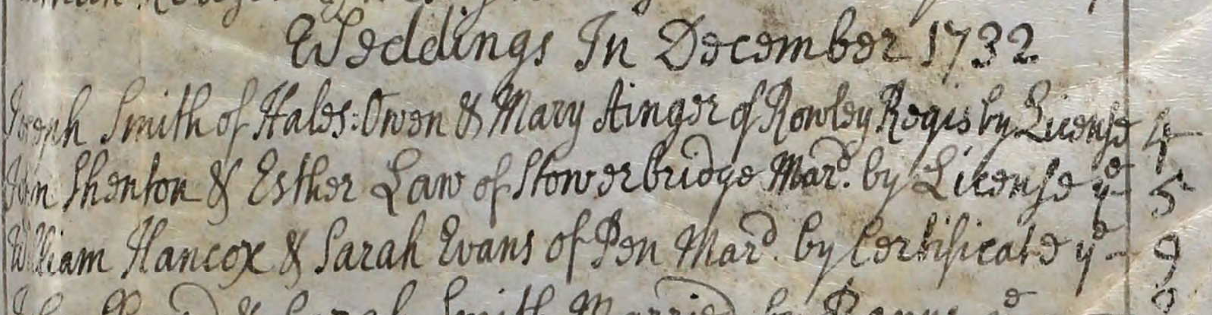

William’s father was William Hancox, yeoman, born in 1703 in Penn. He died intestate in 1772, his wife Sarah claiming her right to his estate. William Hancox and Sarah Evans, both of Penn, were married on the 9th December 1732 in Dudley, Worcestershire, by “certificate”. Marriages were usually either by banns or by licence. Apparently a marriage by certificate indicates that they were non conformists, or dissenters, and had the non conformist marriage “certified” in a Church of England church.

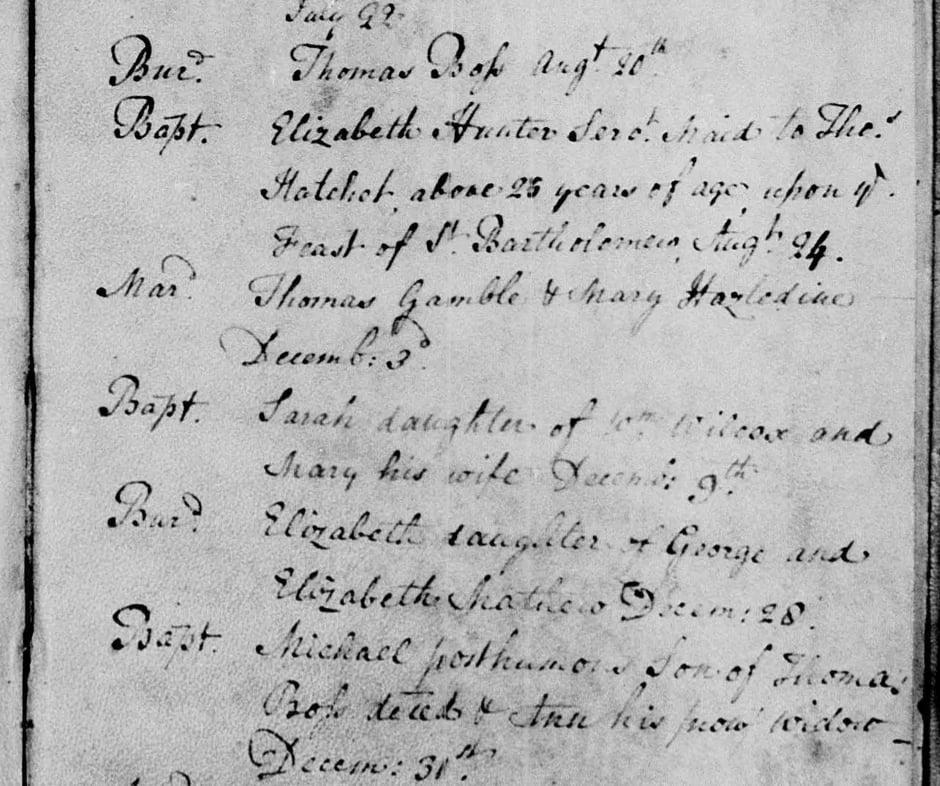

1732 marriage of William Hancox and Sarah Evans:

William and Sarah lost two daughters, Elizabeth, five years old, and Ann, three years old, within eight days of each other in February 1738.

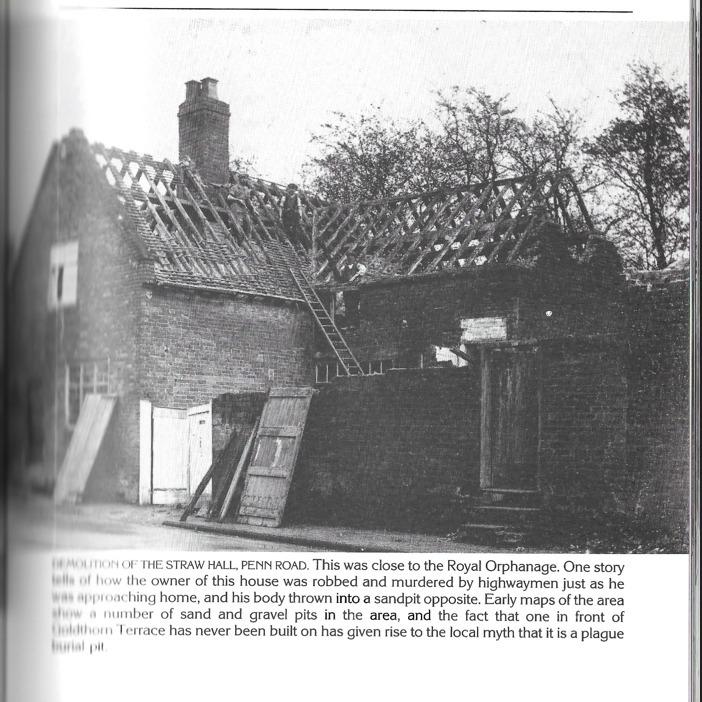

William the elder’s father was John Hancox born in Penn in 1668. He married Elizabeth Wilkes from Sedgley in 1691 at Himley. John Hancox, “of Straw Hall” according to the Wolverhampton burial register, died in 1730. Straw Hall is in Penn. John’s parents were Walter Hancox and Mary Noake. Walter was born in Tettenhall in 1625, his father Richard Hancox. Mary Noake was born in Penn in 1634. Walter died in Penn in 1689.

Straw Hall thanks to Bradney Mitchell:

“Here is a picture I have of Straw Hall, Penn Road.

The painting is by John Reid circa 1878.

Sketch commissioned by George Bradney Mitchell to record the town as it was before its redevelopment, in a book called Wolverhampton and its Environs. ©”

And a photo of the demolition of Straw Hall with an interesting story:

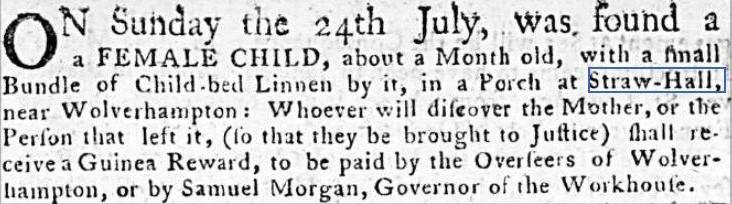

In 1757 a child was abandoned on the porch of Straw Hall. Aris’s Birmingham Gazette 1st August 1757:

The Hancox family were living in Penn for at least 400 years. My great grandfather Charles Tomlinson built a house on Penn Common in the early 1900s, and other Tomlinson relatives have lived there. But none of the family knew of the Hancox connection to Penn. I don’t think that anyone imagined a Tomlinson ancestor would have been a gentleman, either.

Sarah Hancox’s brother William Hancox 1776-1848 had a busy year in 1804.

On 29 Aug 1804 he applied for a licence to marry Ann Grovenor of Claverley.

In August 1804 he had property up for auction in Penn. “part of Lightwoods, 3 plots, and the Coppice”

On 14 Sept 1804 their first son John was baptised in Penn. According to a later census John was born in Claverley. (before the parents got married)(Incidentally, John Hancox’s descendant married a Warren, who is a descendant of my 4x great grandfather Samuel Warren, on my mothers side, from Newhall, Derbyshire!)

On 30 Sept he married Ann in Penn.

In December he was a bankrupt pig and sheep dealer.

In July 1805 he’s in the papers under “certificates”: William Hancox the younger, sheep and pig dealer and chapman of Penn. (A certificate was issued after a bankruptcy if they fulfilled their obligations)

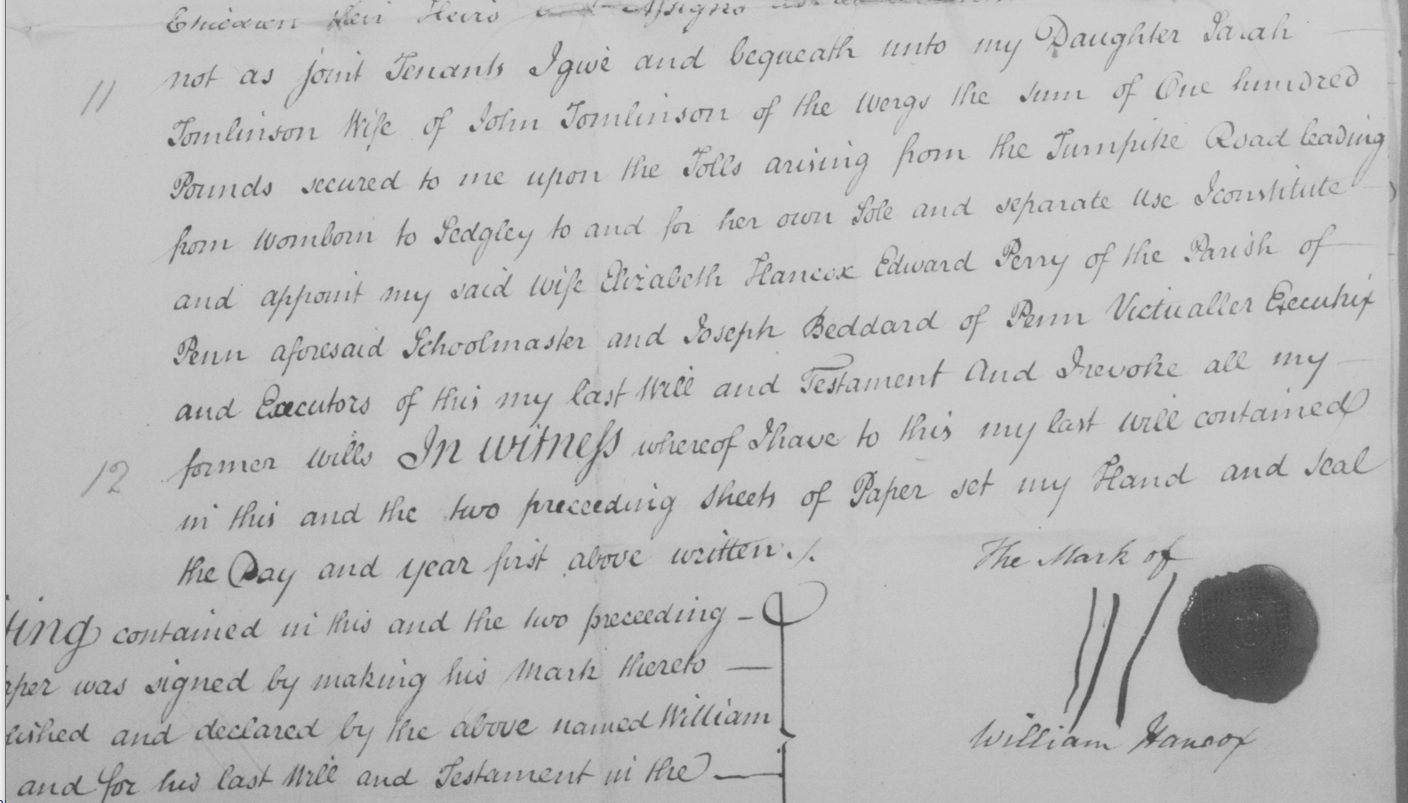

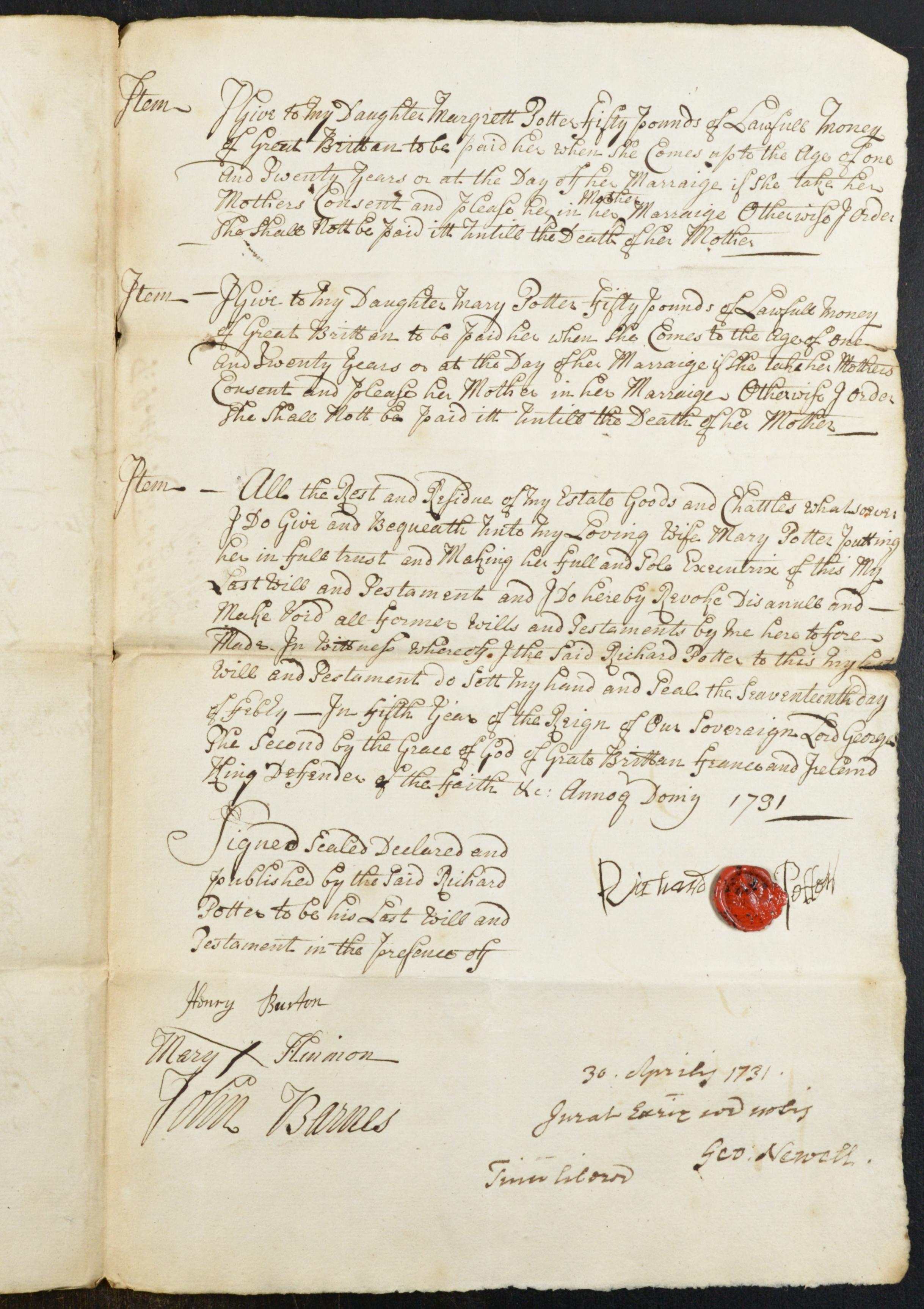

He was a pig dealer in Penn in 1841, a widower, living with unmarried daughter Elizabeth.Sarah’s father William Hancox died in 1816. In his will, he left his “daughter Sarah, wife of John Tomlinson of the Wergs the sum of £100 secured to me upon the tolls arising from the turnpike road leading from Wombourne to Sedgeley to and for her sole and separate use”.

The trustees of toll road would decide not to collect tolls themselves but get someone else to do it by selling the collecting of tolls for a fixed price. This was called “farming the tolls”. The Act of Parliament which set up the trust would authorise the trustees to farm out the tolls. This example is different. The Trustees of turnpikes needed to raise money to carry out work on the highway. The usual way they did this was to mortgage the tolls – they borrowed money from someone and paid the borrower interest; as security they gave the borrower the right, if they were not paid, to take over the collection of tolls and keep the proceeds until they had been paid off. In this case William Hancox has lent £100 to the turnpike and is leaving it (the right to interest and/or have the whole sum repaid) to his daughter Sarah Tomlinson. (this information on tolls from the Wolverhampton family history group.)William Hancox, Penn Wood, maltster, left a considerable amount of property to his children in 1816. All household effects he left to his wife Elizabeth, and after her decease to his son Richard Hancox: four dwelling houses in John St, Wolverhampton, in the occupation of various Pratts, Wright and William Clarke. He left £200 to his daughter Frances Gordon wife of James Gordon, and £100 to his daughter Ann Pratt widow of John Pratt. To his son William Hancox, all his various properties in Penn wood. To Elizabeth Tay wife of Thomas Tay he left £200, and to Richard Hancox various other properties in Penn Wood, and to his daughter Lucy Tay wife of Josiah Tay more property in Lower Penn. All his shops in St John Wolverhamton to his son Edward Hancox, and more properties in Lower Penn to both Francis Hancox and Edward Hancox. To his daughter Ellen York £200, and property in Montgomery and Bilston to his son John Hancox. Sons Francis and Edward were underage at the time of the will. And to his daughter Sarah, his interest in the toll mentioned above.

Sarah Tomlinson, wife of John Tomlinson of the Wergs, in William Hancox will:

March 19, 2023 at 10:39 pm #7204

March 19, 2023 at 10:39 pm #7204Some handy references for the timelines of the Flying Fish Inn are here…

Year Date Event 1935 March 1, 1935 Birth of Mater 1958 March 13, 1958 Mater marries her childhood sweetheart 1965 August 17, 1965 Birth of Fred 1968 June 8, 1968 Birth of Abcynthia Hogg 1970 July 7, 1970 Birth of Aunt Idle 1978 April 12, 1978 Mater’s husband dies 1987 March 19, 1987 Mines close down – Carts & Lager Festival 1988 December 12, 1988 Idle gives birth to a child in Fiji (Liana) 1989 December 20, 1989 Horace Hogg death – Inn passes down to Abby 1990 May 7, 1990 Fred marries Abcynthia 1998 November 11, 1998 Birth of Devan 2000 November 11, 2000 Birth of Clove and Coriander 2007 March 7, 2007 Hannah Hogg’s death, the Inn passes to Abcynthia 2008 March 10, 2008 Carts and Lager Festival revival 2008 August 20, 2008 Birth of Prune 2009 February 2, 2009 Abcynthia leaves 2009 September 11, 2009 Strange incidents at the mines, Idle sets up the Inn 2010 May 27, 2010 Fred leaves his family, goes into hiding 2014 September 10, 2014 Start of Prune’s journal 2017 March 21, 2017 Visitors from Elsewheres 2020 December 22, 2020 The year of the Great Fires 2021 August 8, 2021 Italian tourists saved the Inn 2023 March 1, 2023 Orbs gamers visitors 2027 September 1, 2027 Prune going to a boarding school 2035 March 21, 2035 Mater 100 and twins on a Waterlark adventure 2049 March 17, 2049 Prune arrives with a commercial flight on Mars, Mater is deceased (would have been 114) December 6, 2022 at 2:17 pm #6350In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Transportation

Isaac Stokes 1804-1877

Isaac was born in Churchill, Oxfordshire in 1804, and was the youngest brother of my 4X great grandfather Thomas Stokes. The Stokes family were stone masons for generations in Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire, and Isaac’s occupation was a mason’s labourer in 1834 when he was sentenced at the Lent Assizes in Oxford to fourteen years transportation for stealing tools.

Churchill where the Stokes stonemasons came from: on 31 July 1684 a fire destroyed 20 houses and many other buildings, and killed four people. The village was rebuilt higher up the hill, with stone houses instead of the old timber-framed and thatched cottages. The fire was apparently caused by a baker who, to avoid chimney tax, had knocked through the wall from her oven to her neighbour’s chimney.

Isaac stole a pick axe, the value of 2 shillings and the property of Thomas Joyner of Churchill; a kibbeaux and a trowel value 3 shillings the property of Thomas Symms; a hammer and axe value 5 shillings, property of John Keen of Sarsden.

(The word kibbeaux seems to only exists in relation to Isaac Stokes sentence and whoever was the first to write it was perhaps being creative with the spelling of a kibbo, a miners or a metal bucket. This spelling is repeated in the criminal reports and the newspaper articles about Isaac, but nowhere else).

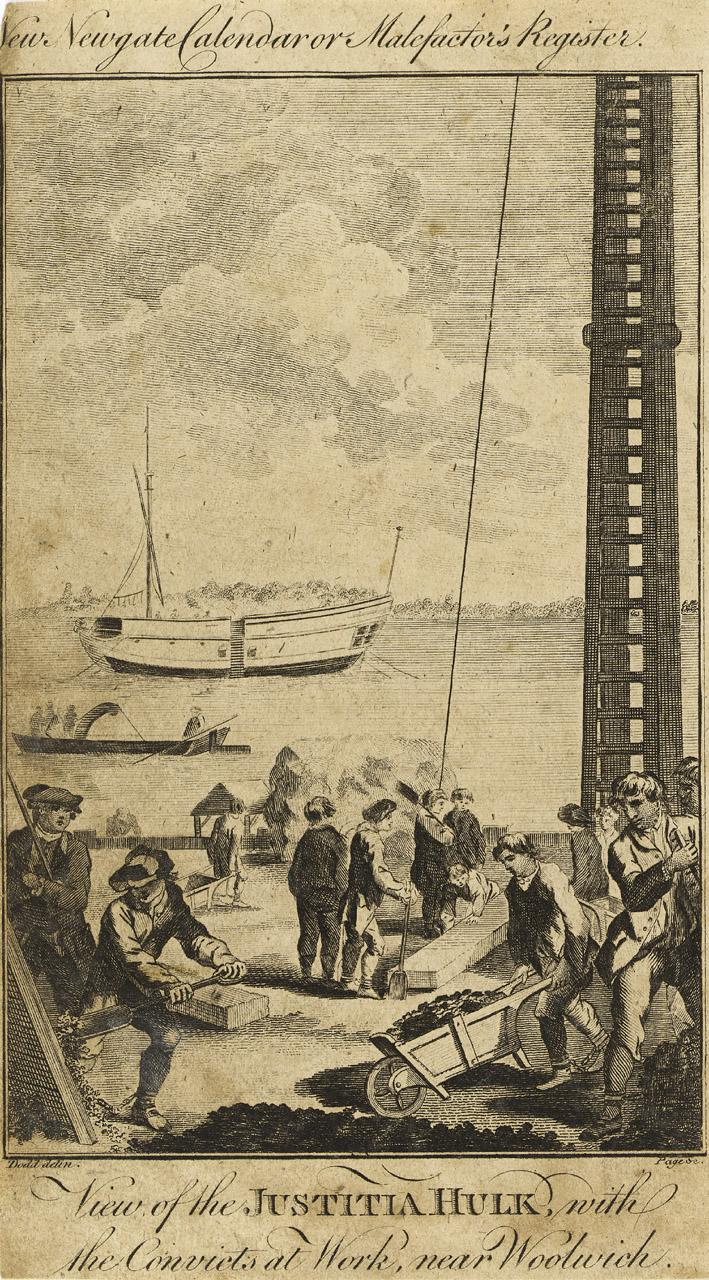

In March 1834 the Removal of Convicts was announced in the Oxford University and City Herald: Isaac Stokes and several other prisoners were removed from the Oxford county gaol to the Justitia hulk at Woolwich “persuant to their sentences of transportation at our Lent Assizes”.

via digitalpanopticon:

Hulks were decommissioned (and often unseaworthy) ships that were moored in rivers and estuaries and refitted to become floating prisons. The outbreak of war in America in 1775 meant that it was no longer possible to transport British convicts there. Transportation as a form of punishment had started in the late seventeenth century, and following the Transportation Act of 1718, some 44,000 British convicts were sent to the American colonies. The end of this punishment presented a major problem for the authorities in London, since in the decade before 1775, two-thirds of convicts at the Old Bailey received a sentence of transportation – on average 283 convicts a year. As a result, London’s prisons quickly filled to overflowing with convicted prisoners who were sentenced to transportation but had no place to go.

To increase London’s prison capacity, in 1776 Parliament passed the “Hulks Act” (16 Geo III, c.43). Although overseen by local justices of the peace, the hulks were to be directly managed and maintained by private contractors. The first contract to run a hulk was awarded to Duncan Campbell, a former transportation contractor. In August 1776, the Justicia, a former transportation ship moored in the River Thames, became the first prison hulk. This ship soon became full and Campbell quickly introduced a number of other hulks in London; by 1778 the fleet of hulks on the Thames held 510 prisoners.

Demand was so great that new hulks were introduced across the country. There were hulks located at Deptford, Chatham, Woolwich, Gosport, Plymouth, Portsmouth, Sheerness and Cork.The Justitia via rmg collections:

Convicts perform hard labour at the Woolwich Warren. The hulk on the river is the ‘Justitia’. Prisoners were kept on board such ships for months awaiting deportation to Australia. The ‘Justitia’ was a 260 ton prison hulk that had been originally moored in the Thames when the American War of Independence put a stop to the transportation of criminals to the former colonies. The ‘Justitia’ belonged to the shipowner Duncan Campbell, who was the Government contractor who organized the prison-hulk system at that time. Campbell was subsequently involved in the shipping of convicts to the penal colony at Botany Bay (in fact Port Jackson, later Sydney, just to the north) in New South Wales, the ‘first fleet’ going out in 1788.

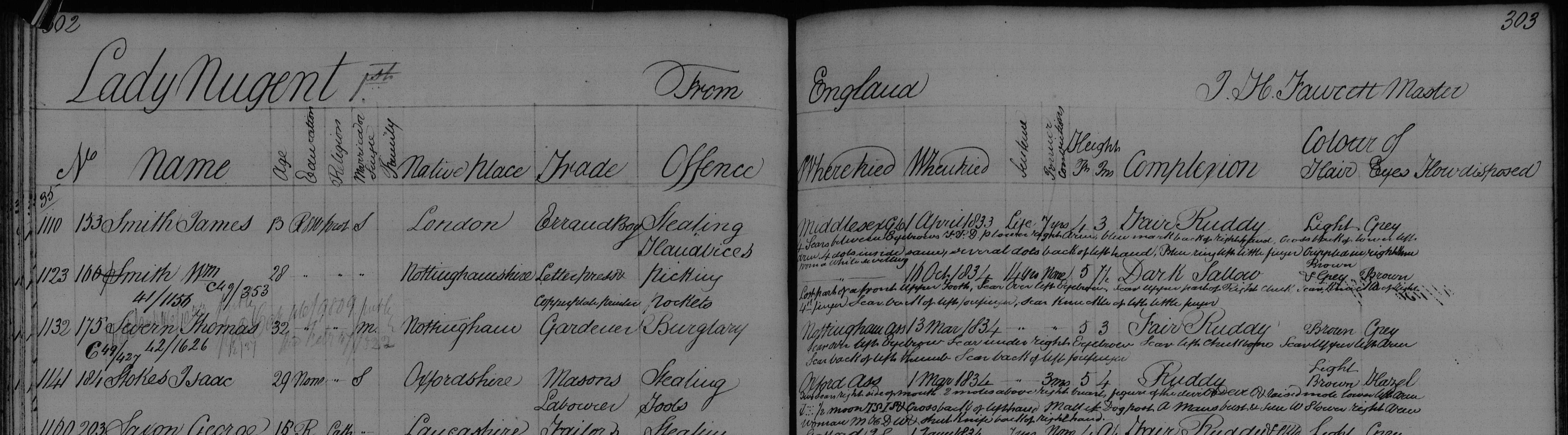

While searching for records for Isaac Stokes I discovered that another Isaac Stokes was transported to New South Wales in 1835 as well. The other one was a butcher born in 1809, sentenced in London for seven years, and he sailed on the Mary Ann. Our Isaac Stokes sailed on the Lady Nugent, arriving in NSW in April 1835, having set sail from England in December 1834.

Lady Nugent was built at Bombay in 1813. She made four voyages under contract to the British East India Company (EIC). She then made two voyages transporting convicts to Australia, one to New South Wales and one to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). (via Wikipedia)

via freesettlerorfelon website:

On 20 November 1834, 100 male convicts were transferred to the Lady Nugent from the Justitia Hulk and 60 from the Ganymede Hulk at Woolwich, all in apparent good health. The Lady Nugent departed Sheerness on 4 December 1834.

SURGEON OLIVER SPROULE

Oliver Sproule kept a Medical Journal from 7 November 1834 to 27 April 1835. He recorded in his journal the weather conditions they experienced in the first two weeks:

‘In the course of the first week or ten days at sea, there were eight or nine on the sick list with catarrhal affections and one with dropsy which I attribute to the cold and wet we experienced during that period beating down channel. Indeed the foremost berths in the prison at this time were so wet from leaking in that part of the ship, that I was obliged to issue dry beds and bedding to a great many of the prisoners to preserve their health, but after crossing the Bay of Biscay the weather became fine and we got the damp beds and blankets dried, the leaks partially stopped and the prison well aired and ventilated which, I am happy to say soon manifested a favourable change in the health and appearance of the men.

Besides the cases given in the journal I had a great many others to treat, some of them similar to those mentioned but the greater part consisted of boils, scalds, and contusions which would not only be too tedious to enter but I fear would be irksome to the reader. There were four births on board during the passage which did well, therefore I did not consider it necessary to give a detailed account of them in my journal the more especially as they were all favourable cases.

Regularity and cleanliness in the prison, free ventilation and as far as possible dry decks turning all the prisoners up in fine weather as we were lucky enough to have two musicians amongst the convicts, dancing was tolerated every afternoon, strict attention to personal cleanliness and also to the cooking of their victuals with regular hours for their meals, were the only prophylactic means used on this occasion, which I found to answer my expectations to the utmost extent in as much as there was not a single case of contagious or infectious nature during the whole passage with the exception of a few cases of psora which soon yielded to the usual treatment. A few cases of scurvy however appeared on board at rather an early period which I can attribute to nothing else but the wet and hardships the prisoners endured during the first three or four weeks of the passage. I was prompt in my treatment of these cases and they got well, but before we arrived at Sydney I had about thirty others to treat.’

The Lady Nugent arrived in Port Jackson on 9 April 1835 with 284 male prisoners. Two men had died at sea. The prisoners were landed on 27th April 1835 and marched to Hyde Park Barracks prior to being assigned. Ten were under the age of 14 years.

The Lady Nugent:

Isaac’s distinguishing marks are noted on various criminal registers and record books:

“Height in feet & inches: 5 4; Complexion: Ruddy; Hair: Light brown; Eyes: Hazel; Marks or Scars: Yes [including] DEVIL on lower left arm, TSIS back of left hand, WS lower right arm, MHDW back of right hand.”

Another includes more detail about Isaac’s tattoos:

“Two slight scars right side of mouth, 2 moles above right breast, figure of the devil and DEVIL and raised mole, lower left arm; anchor, seven dots half moon, TSIS and cross, back of left hand; a mallet, door post, A, mans bust, sun, WS, lower right arm; woman, MHDW and shut knife, back of right hand.”

From How tattoos became fashionable in Victorian England (2019 article in TheConversation by Robert Shoemaker and Zoe Alkar):

“Historical tattooing was not restricted to sailors, soldiers and convicts, but was a growing and accepted phenomenon in Victorian England. Tattoos provide an important window into the lives of those who typically left no written records of their own. As a form of “history from below”, they give us a fleeting but intriguing understanding of the identities and emotions of ordinary people in the past.

As a practice for which typically the only record is the body itself, few systematic records survive before the advent of photography. One exception to this is the written descriptions of tattoos (and even the occasional sketch) that were kept of institutionalised people forced to submit to the recording of information about their bodies as a means of identifying them. This particularly applies to three groups – criminal convicts, soldiers and sailors. Of these, the convict records are the most voluminous and systematic.

Such records were first kept in large numbers for those who were transported to Australia from 1788 (since Australia was then an open prison) as the authorities needed some means of keeping track of them.”On the 1837 census Isaac was working for the government at Illiwarra, New South Wales. This record states that he arrived on the Lady Nugent in 1835. There are three other indent records for an Isaac Stokes in the following years, but the transcriptions don’t provide enough information to determine which Isaac Stokes it was. In April 1837 there was an abscondment, and an arrest/apprehension in May of that year, and in 1843 there was a record of convict indulgences.

From the Australian government website regarding “convict indulgences”:

“By the mid-1830s only six per cent of convicts were locked up. The vast majority worked for the government or free settlers and, with good behaviour, could earn a ticket of leave, conditional pardon or and even an absolute pardon. While under such orders convicts could earn their own living.”

In 1856 in Camden, NSW, Isaac Stokes married Catherine Daly. With no further information on this record it would be impossible to know for sure if this was the right Isaac Stokes. This couple had six children, all in the Camden area, but none of the records provided enough information. No occupation or place or date of birth recorded for Isaac Stokes.

I wrote to the National Library of Australia about the marriage record, and their reply was a surprise! Issac and Catherine were married on 30 September 1856, at the house of the Rev. Charles William Rigg, a Methodist minister, and it was recorded that Isaac was born in Edinburgh in 1821, to parents James Stokes and Sarah Ellis! The age at the time of the marriage doesn’t match Isaac’s age at death in 1877, and clearly the place of birth and parents didn’t match either. Only his fathers occupation of stone mason was correct. I wrote back to the helpful people at the library and they replied that the register was in a very poor condition and that only two and a half entries had survived at all, and that Isaac and Catherines marriage was recorded over two pages.

I searched for an Isaac Stokes born in 1821 in Edinburgh on the Scotland government website (and on all the other genealogy records sites) and didn’t find it. In fact Stokes was a very uncommon name in Scotland at the time. I also searched Australian immigration and other records for another Isaac Stokes born in Scotland or born in 1821, and found nothing. I was unable to find a single record to corroborate this mysterious other Isaac Stokes.

As the age at death in 1877 was correct, I assume that either Isaac was lying, or that some mistake was made either on the register at the home of the Methodist minster, or a subsequent mistranscription or muddle on the remnants of the surviving register. Therefore I remain convinced that the Camden stonemason Isaac Stokes was indeed our Isaac from Oxfordshire.

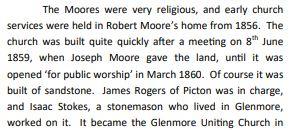

I found a history society newsletter article that mentioned Isaac Stokes, stone mason, had built the Glenmore church, near Camden, in 1859.

From the Wollondilly museum April 2020 newsletter:

From the Camden History website:

“The stone set over the porch of Glenmore Church gives the date of 1860. The church was begun in 1859 on land given by Joseph Moore. James Rogers of Picton was given the contract to build and local builder, Mr. Stokes, carried out the work. Elizabeth Moore, wife of Edward, laid the foundation stone. The first service was held on 19th March 1860. The cemetery alongside the church contains the headstones and memorials of the areas early pioneers.”

Isaac died on the 3rd September 1877. The inquest report puts his place of death as Bagdelly, near to Camden, and another death register has put Cambelltown, also very close to Camden. His age was recorded as 71 and the inquest report states his cause of death was “rupture of one of the large pulmonary vessels of the lung”. His wife Catherine died in childbirth in 1870 at the age of 43.

Isaac and Catherine’s children:

William Stokes 1857-1928

Catherine Stokes 1859-1846

Sarah Josephine Stokes 1861-1931

Ellen Stokes 1863-1932

Rosanna Stokes 1865-1919

Louisa Stokes 1868-1844.

It’s possible that Catherine Daly was a transported convict from Ireland.

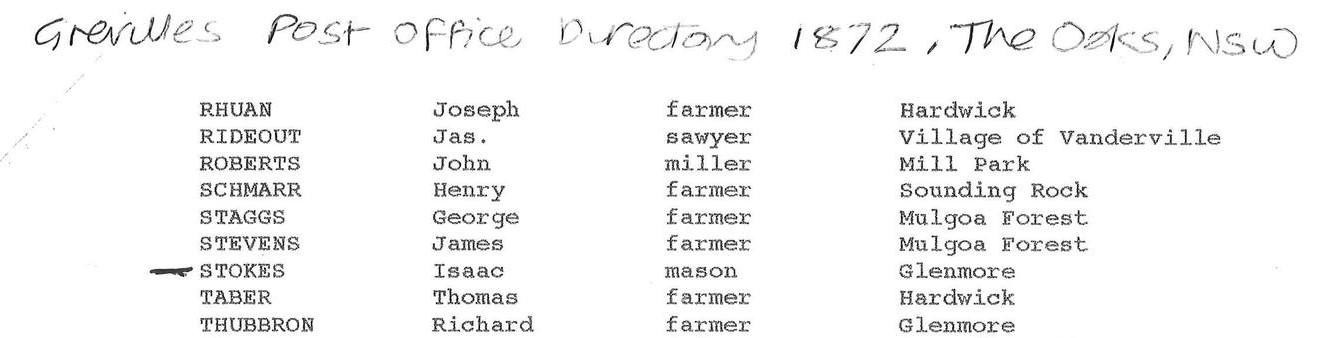

Some time later I unexpectedly received a follow up email from The Oaks Heritage Centre in Australia.

“The Gaudry papers which we have in our archive record him (Isaac Stokes) as having built: the church, the school and the teachers residence. Isaac is recorded in the General return of convicts: 1837 and in Grevilles Post Office directory 1872 as a mason in Glenmore.”

November 14, 2022 at 12:09 pm #6346

November 14, 2022 at 12:09 pm #6346In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The Mormon Browning Who Went To Utah

Isaac Browning’s (1784-1848) sister Hannah married Francis Buckingham. There were at least three Browning Buckingham marriages in Tetbury. Their daughter Charlotte married James Paskett, a shoemaker. Charlotte was born in 1818 and in 1871 she and her family emigrated to Utah, USA.

Charlotte’s relationship to me is first cousin five times removed.

James and Charlotte: (photos found online)

The house of James and Charlotte in Tetbury:

The home of James and Charlotte in Utah:

Obituary:

James Pope Paskett Dead.

Veteran of 87 Laid to rest. Special Correspondence Coalville, Summit Co., Oct 28—James Pope Paskett of Henefer died Oct. 24, 1903 of old age and general debility. Funeral services were held at Henefer today. Elders W.W. Cluff, Alma Elderge, Robert Jones, Oscar Wilkins and Bishop M.F. Harris were the speakers. There was a large attendance many coming from other wards in the stake. James Pope Paskett was born in Chippenham, Wiltshire, England, on March 12, 1817; married Chalotte Buckingham in the year 1839; eight children were born to them, three sons and five daughters, all of whom are living and residing in Utah, except one in Brisbane, Australia. Father Paskett joined the church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints in 1847, and emigrated to Utah in 1871, and has resided in Henefer ever since. He leaves his faithful and aged wife. He was respected and esteemed by all who knew him.

Charlotte died in Henefer, Utah, on 27th December 1910 at the age of 91.

James and Charlotte in later life:

November 10, 2022 at 12:08 pm #6344In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The Tetbury Riots

While researching the Tetbury riots (I had found some Browning names in the newspaper archives in association with the uprisings) I came across an article called “Elizabeth Parker, the Swing Riots, and the Tetbury parish clerk” by Jill Evans.

I noted the name of the parish clerk, Daniel Cole, because I know someone else of that name. The incident in the article was 1830.

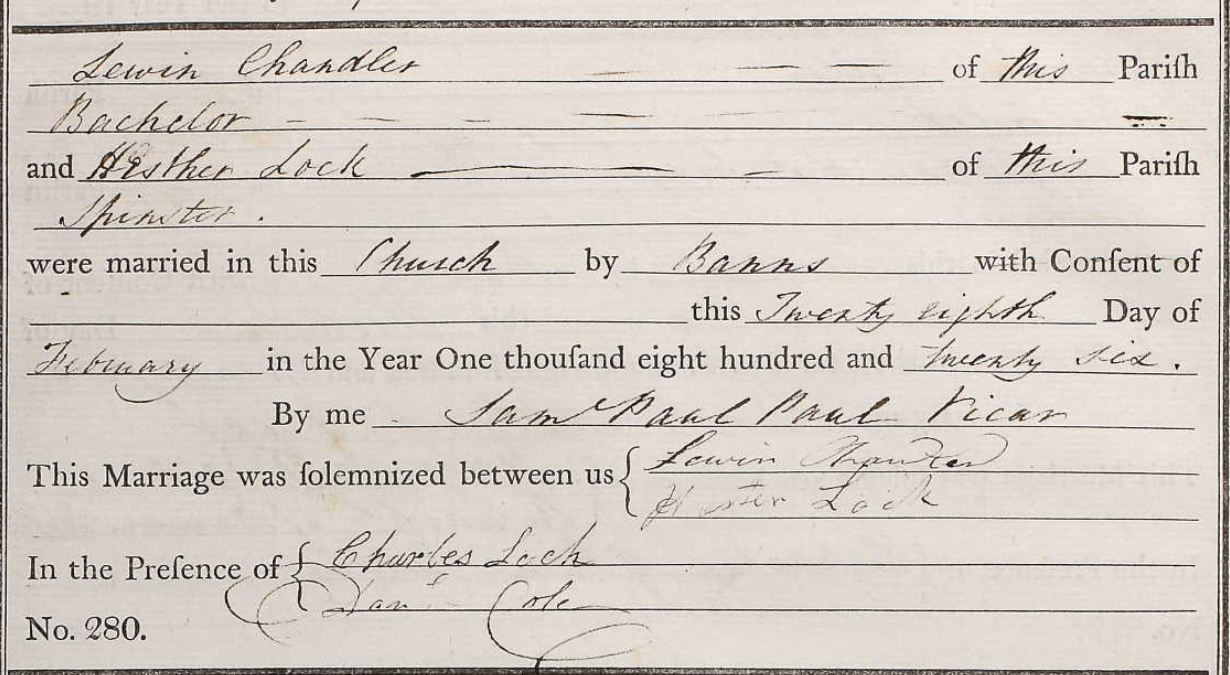

I found the 1826 marriage in the Tetbury parish registers (where Daniel was the parish clerk) of my 4x great grandmothers sister Hesther Lock. One of the witnesses was her brother Charles, and the other was Daniel Cole, the parish clerk.

Marriage of Lewin Chandler and Hesther Lock in 1826:

from the article:

“The Swing Riots were disturbances which took place in 1830 and 1831, mostly in the southern counties of England. Agricultural labourers, who were already suffering due to low wages and a lack of work after several years of bad harvests, rose up when their employers introduced threshing machines into their workplaces. The riots got their name from the threatening letters which were sent to farmers and other employers, which were signed “Captain Swing.”

The riots spread into Gloucestershire in November 1830, with the Tetbury area seeing the worst of the disturbances. Amongst the many people arrested afterwards was one woman, Elizabeth Parker. She has sometimes been cited as one of only two females who were transported for taking part in the Swing Riots. In fact, she was sentenced to be transported for this crime, but never sailed, as she was pardoned a few months after being convicted. However, less than a year after being released from Gloucester Gaol, she was back, awaiting trial for another offence. The circumstances in both of the cases she was tried for reveal an intriguing relationship with one Daniel Cole, parish clerk and assistant poor law officer in Tetbury….

….Elizabeth Parker was committed to Gloucester Gaol on 4 December 1830. In the Gaol Registers, she was described as being 23 and a “labourer”. She was in fact a prostitute, and she was unusual for the time in that she could read and write. She was charged on the oaths of Daniel Cole and others with having been among a mob which destroyed a threshing machine belonging to Jacob Hayward, at his farm in Beverstone, on 26 November.

…..Elizabeth Parker was granted royal clemency in July 1831 and was released from prison. She returned to Tetbury and presumably continued in her usual occupation, but on 27 March 1832, she was committed to Gloucester Gaol again. This time, she was charged with stealing 2 five pound notes, 5 sovereigns and 5 half sovereigns, from the person of Daniel Cole.

Elizabeth was tried at the Lent Assizes which began on 28 March, 1832. The details of her trial were reported in the Morning Post. Daniel Cole was in the “Boat Inn” (meaning the Boot Inn, I think) in Tetbury, when Elizabeth Parker came in. Cole “accompanied her down the yard”, where he stayed with her for about half an hour. The next morning, he realised that all his money was gone. One of his five pound notes was identified by him in a shop, where Parker had bought some items.

Under cross-examination, Cole said he was the assistant overseer of the poor and collector of public taxes of the parish of Tetbury. He was married with one child. He went in to the inn at about 9 pm, and stayed about 2 hours, drinking in the parlour, with the landlord, Elizabeth Parker, and two others. He was not drunk, but he was “rather fresh.” He gave the prisoner no money. He saw Elizabeth Parker next morning at the Prince and Princess public house. He didn’t drink with her or give her any money. He did give her a shilling after she was committed. He never said that he would not have prosecuted her “if it was not for her own tongue”. (Presumably meaning he couldn’t trust her to keep her mouth shut.)”

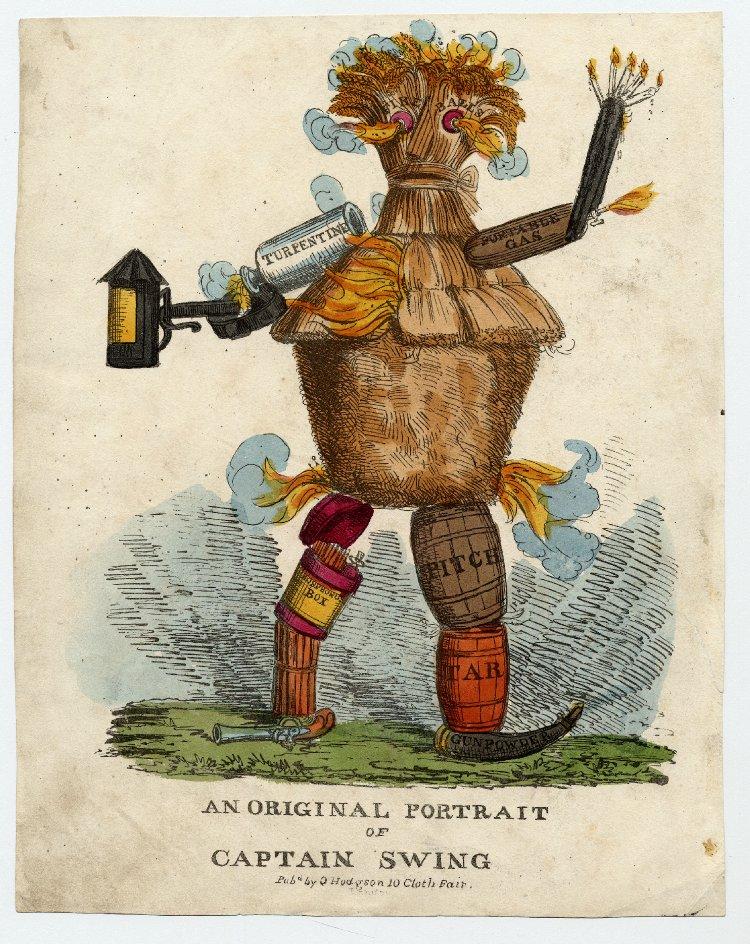

Contemporary illustration of the Swing riots:

Captain Swing was the imaginary leader agricultural labourers who set fire to barns and haystacks in the southern and eastern counties of England from 1830. Although the riots were ruthlessly put down (19 hanged, 644 imprisoned and 481 transported), the rural agitation led the new Whig government to establish a Royal Commission on the Poor Laws and its report provided the basis for the 1834 New Poor Law enacted after the Great Reform Bills of 1833.

An original portrait of Captain Swing hand coloured lithograph circa 1830:

November 10, 2022 at 10:59 am #6343

November 10, 2022 at 10:59 am #6343In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum

William James Stokes

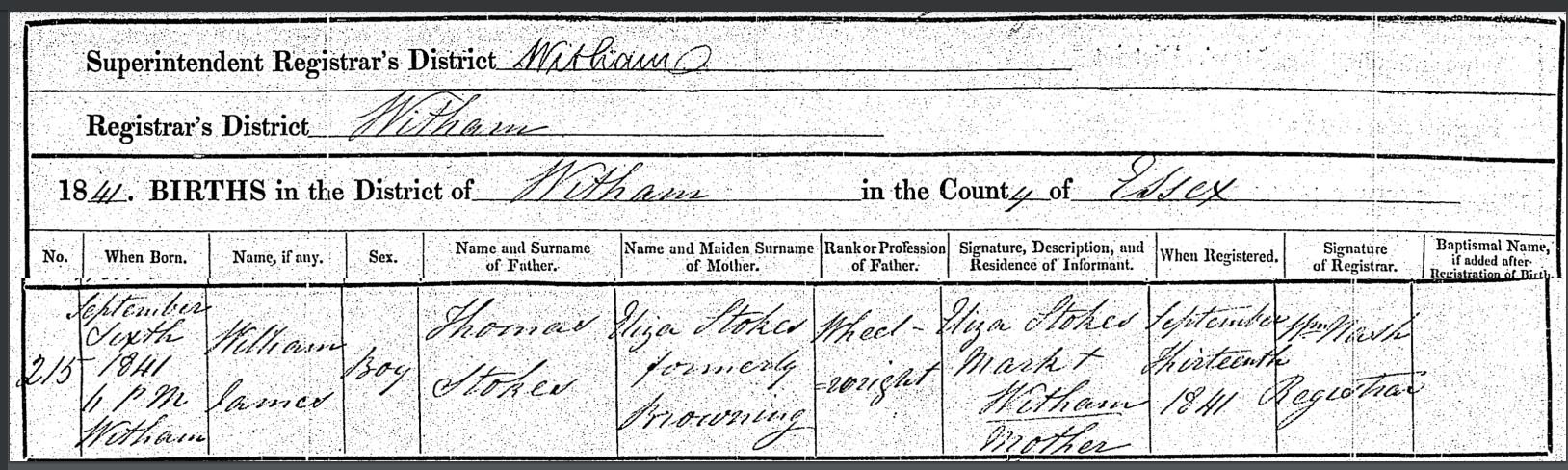

William James Stokes was the first son of Thomas Stokes and Eliza Browning. Oddly, his birth was registered in Witham in Essex, on the 6th September 1841.

Birth certificate of William James Stokes:

His father Thomas Stokes has not yet been found on the 1841 census, and his mother Eliza was staying with her uncle Thomas Lock in Cirencester in 1841. Eliza’s mother Mary Browning (nee Lock) was staying there too. Thomas and Eliza were married in September 1840 in Hempstead in Gloucestershire.

It’s a mystery why William was born in Essex but one possibility is that his father Thomas, who later worked with the Chipperfields making circus wagons, was staying with the Chipperfields who were wheelwrights in Witham in 1841. Or perhaps even away with a traveling circus at the time of the census, learning the circus waggon wheelwright trade. But this is a guess and it’s far from clear why Eliza would make the journey to Witham to have the baby when she was staying in Cirencester a few months prior.

In 1851 Thomas and Eliza, William and four younger siblings were living in Bledington in Oxfordshire.

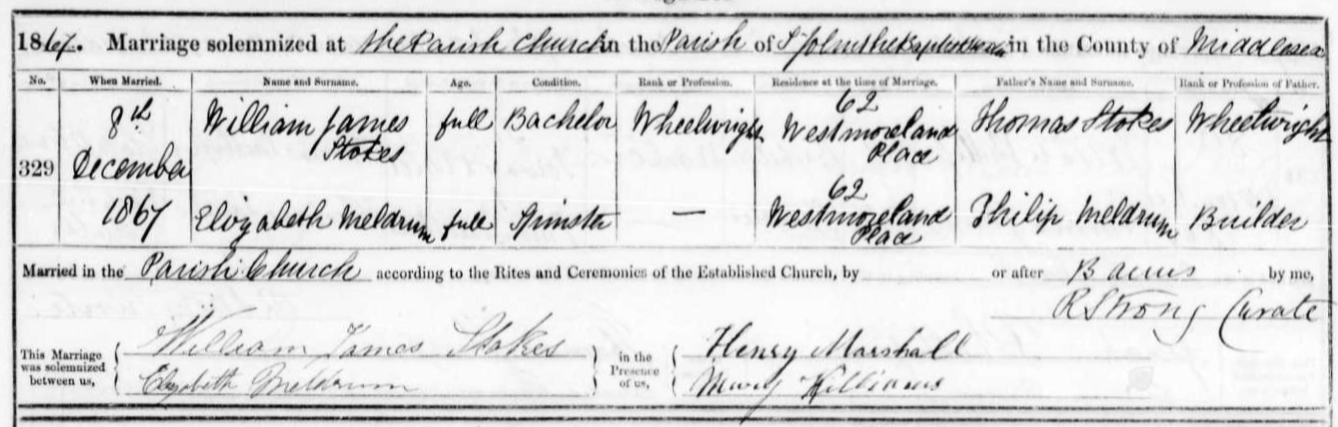

William was a 19 year old wheelwright living with his parents in Evesham in 1861. He married Elizabeth Meldrum in December 1867 in Hackney, London. He and his father are both wheelwrights on the marriage register.

Marriage of William James Stokes and Elizabeth Meldrum in 1867:

William and Elizabeth had a daughter, Elizabeth Emily Stokes, in 1868 in Shoreditch, London.

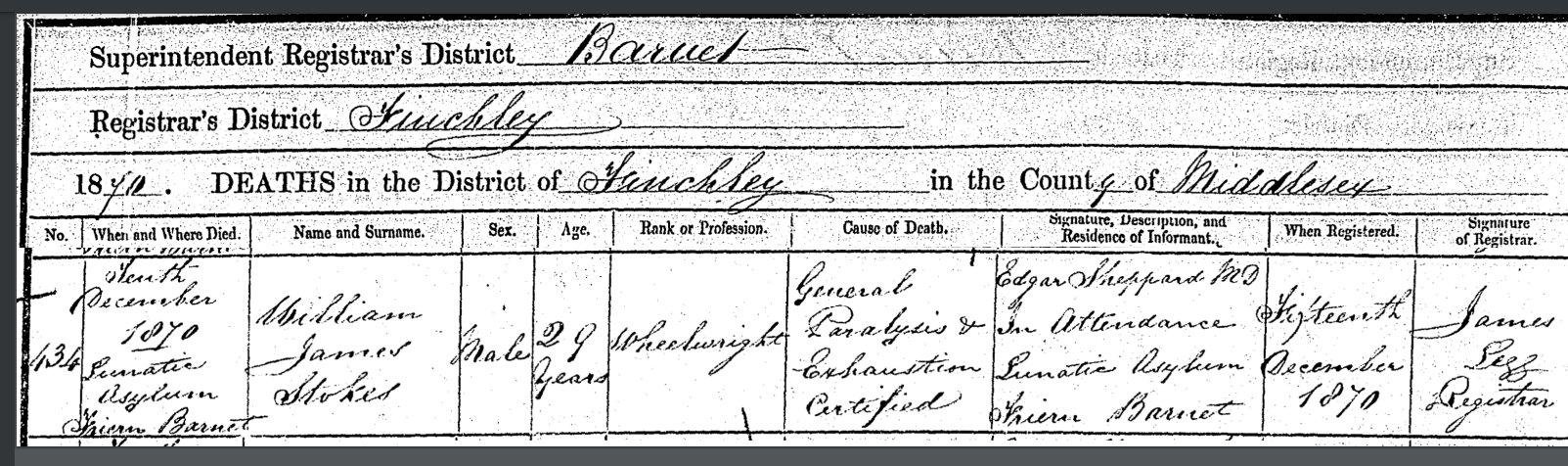

On the 3rd of December 1870, William James Stokes was admitted to Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum. One week later on the 10th of December, he was dead.

On his death certificate the cause of death was “general paralysis and exhaustion, certified. MD Edgar Sheppard in attendance.” William was just 29 years old.

Death certificate William James Stokes:

I asked on a genealogy forum what could possibly have caused this death at such a young age. A retired pathology professor replied that “in medicine the term General Paralysis is only used in one context – that of Tertiary Syphilis.”

“Tertiary syphilis is the third and final stage of syphilis, a sexually transmitted disease that unfolds in stages when the individual affected doesn’t receive appropriate treatment.”From the article “Looking back: This fascinating and fatal disease” by Jennifer Wallis:

“……in asylums across Britain in the late 19th century, with hundreds of people receiving the diagnosis of general paralysis of the insane (GPI). The majority of these were men in their 30s and 40s, all exhibiting one or more of the disease’s telltale signs: grandiose delusions, a staggering gait, disturbed reflexes, asymmetrical pupils, tremulous voice, and muscular weakness. Their prognosis was bleak, most dying within months, weeks, or sometimes days of admission.

The fatal nature of GPI made it of particular concern to asylum superintendents, who became worried that their institutions were full of incurable cases requiring constant care. The social effects of the disease were also significant, attacking men in the prime of life whose admission to the asylum frequently left a wife and children at home. Compounding the problem was the erratic behaviour of the general paralytic, who might get themselves into financial or legal difficulties. Delusions about their vast wealth led some to squander scarce family resources on extravagant purchases – one man’s wife reported he had bought ‘a quantity of hats’ despite their meagre income – and doctors pointed to the frequency of thefts by general paralytics who imagined that everything belonged to them.”

The London Archives hold the records for Colney Hatch, but they informed me that the particular records for the dates that William was admitted and died were in too poor a condition to be accessed without causing further damage.

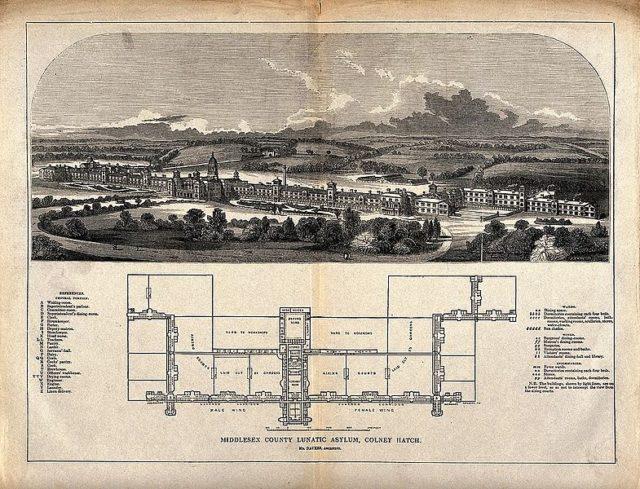

Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum gained such notoriety that the name “Colney Hatch” appeared in various terms of abuse associated with the concept of madness. Infamous inmates that were institutionalized at Colney Hatch (later called Friern Hospital) include Jack the Ripper suspect Aaron Kosminski from 1891, and from 1911 the wife of occultist Aleister Crowley. In 1993 the hospital grounds were sold and the exclusive apartment complex called Princess Park Manor was built.

Colney Hatch:

In 1873 Williams widow married William Hallam in Limehouse in London. Elizabeth died in 1930, apparently unaffected by her first husbands ailment.

October 23, 2022 at 6:57 am #6340In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Wheelwrights of Broadway

Thomas Stokes 1816-1885

Frederick Stokes 1845-1917

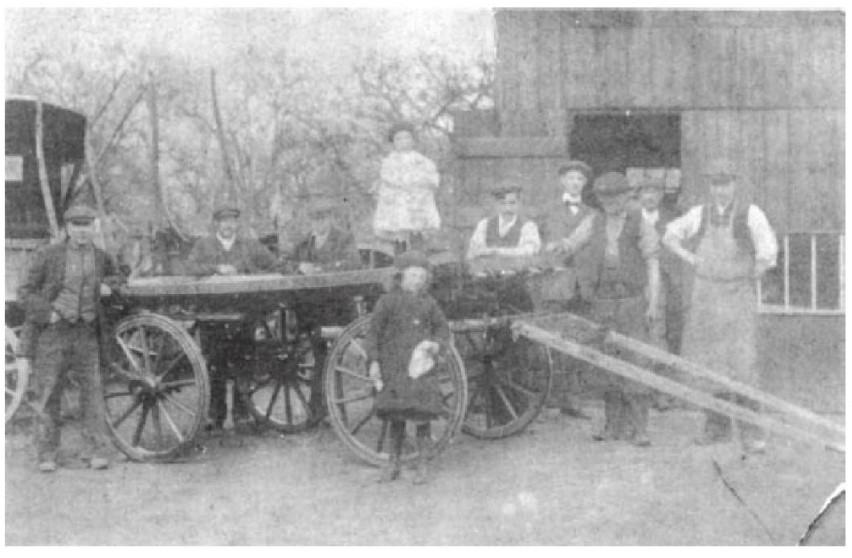

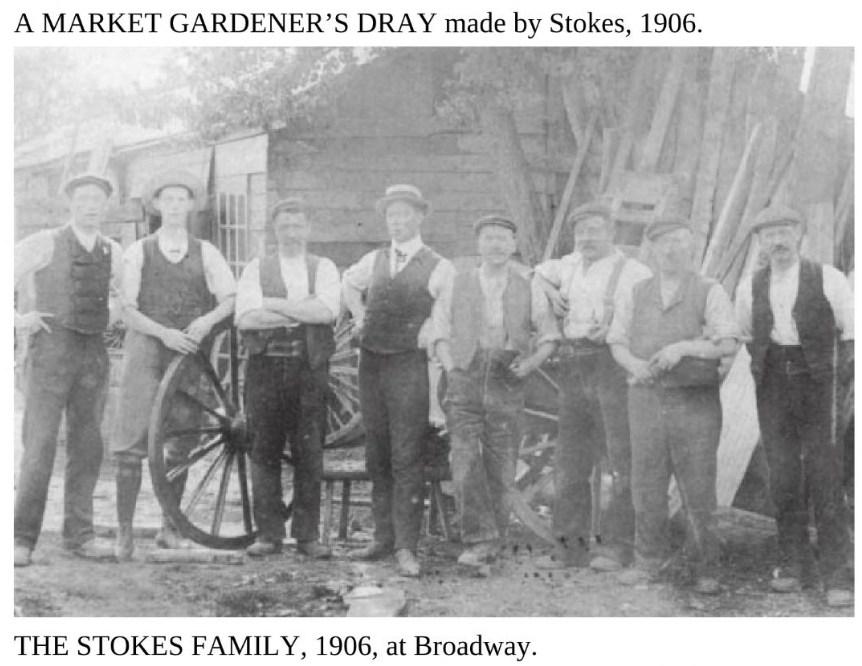

Stokes Wheelwrights. Fred on left of wheel, Thomas his father on right.

Thomas Stokes

Thomas Stokes was born in Bicester, Oxfordshire in 1816. He married Eliza Browning (born in 1814 in Tetbury, Gloucestershire) in Gloucester in 1840 Q3. Their first son William was baptised in Chipping Hill, Witham, Essex, on 3 Oct 1841. This seems a little unusual, and I can’t find Thomas and Eliza on the 1841 census. However both the 1851 and 1861 census state that William was indeed born in Essex.

In 1851 Thomas and Eliza were living in Bledington, Gloucestershire, and Thomas was a journeyman carpenter.

Note that a journeyman does not mean someone who moved around a lot. A journeyman was a tradesman who had served his trade apprenticeship and mastered his craft, not bound to serve a master, but originally hired by the day. The name derives from the French for day – jour.

Also on the 1851 census: their daughter Susan, born in Churchill Oxfordshire in 1844; son Frederick born in Bledington Gloucestershire in 1846; daughter Louisa born in Foxcote Oxfordshire in 1849; and 2 month old daughter Harriet born in Bledington in 1851.

On the 1861 census Thomas and Eliza were living in Evesham, Worcestershire, and daughter Susan was no longer living at home, but William, Fred, Louisa and Harriet were, as well as daughter Emily born in Churchill Oxfordshire in 1856. Thomas was a wheelwright.

On the 1871 census Thomas and Eliza were still living in Evesham, and Thomas was a wheelwright employing three apprentices. Son Fred, also a wheelwright, and his wife Ann Rebecca live with them.

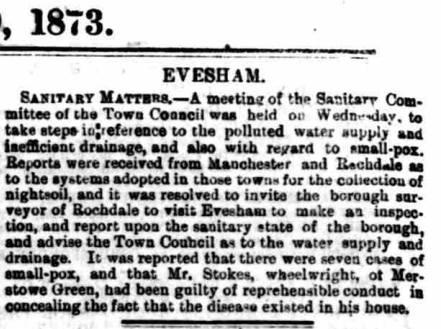

Mr Stokes, wheelwright, was found guilty of reprehensible conduct in concealing the fact that small-pox existed in his house, according to a mention in The Oxfordshire Weekly News on Wednesday 19 February 1873:

From Paul Weaver’s ancestry website:

“It was Thomas Stokes who built the first “Famous Vale of Evesham Light Gardening Dray for a Half-Legged Horse to Trot” (the quotation is from his account book), the forerunner of many that became so familiar a sight in the towns and villages from the 1860s onwards. He built many more for the use of the Vale gardeners.

Thomas also had long-standing business dealings with the people of the circus and fairgrounds, and had a contract to effect necessary repairs and renewals to their waggons whenever they visited the district. He built living waggons for many of the show people’s families as well as shooting galleries and other equipment peculiar to the trade of his wandering customers, and among the names figuring in his books are some still familiar today, such as Wilsons and Chipperfields.

He is also credited with inventing the wooden “Mushroom” which was used by housewives for many years to darn socks. He built and repaired all kinds of vehicles for the gentry as well as for the circus and fairground travellers.

Later he lived with his wife at Merstow Green, Evesham, in a house adjoining the Almonry.”

An excerpt from the book Evesham Inns and Signs by T.J.S. Baylis:

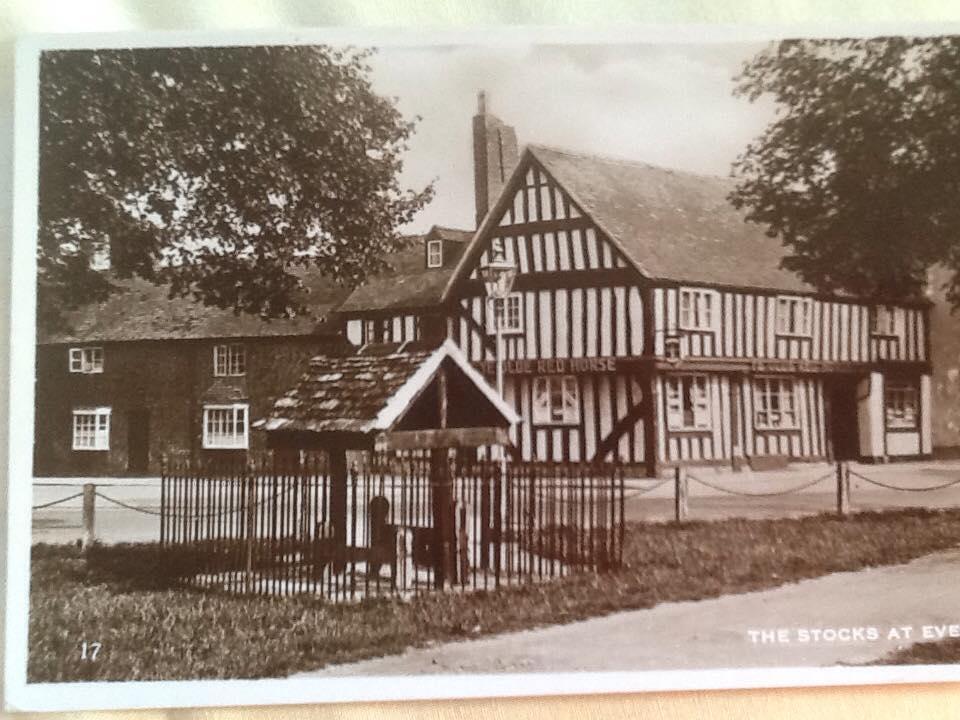

The Old Red Horse, Evesham:

Thomas died in 1885 aged 68 of paralysis, bronchitis and debility. His wife Eliza a year later in 1886.

Frederick Stokes

In Worcester in 1870 Fred married Ann Rebecca Day, who was born in Evesham in 1845.

Ann Rebecca Day:

In 1871 Fred was still living with his parents in Evesham, with his wife Ann Rebecca as well as their three month old daughter Annie Elizabeth. Fred and Ann (referred to as Rebecca) moved to La Quinta on Main Street, Broadway.

Rebecca Stokes in the doorway of La Quinta on Main Street Broadway, with her grandchildren Ralph and Dolly Edwards:

Fred was a wheelwright employing one man on the 1881 census. In 1891 they were still in Broadway, Fred’s occupation was wheelwright and coach painter, as well as his fifteen year old son Frederick.

In the Evesham Journal on Saturday 10 December 1892 it was reported that “Two cases of scarlet fever, the children of Mr. Stokes, wheelwright, Broadway, were certified by Mr. C. W. Morris to be isolated.”

Still in Broadway in 1901 and Fred’s son Albert was also a wheelwright. By 1911 Fred and Rebecca had only one son living at home in Broadway, Reginald, who was a coach painter. Fred was still a wheelwright aged 65.

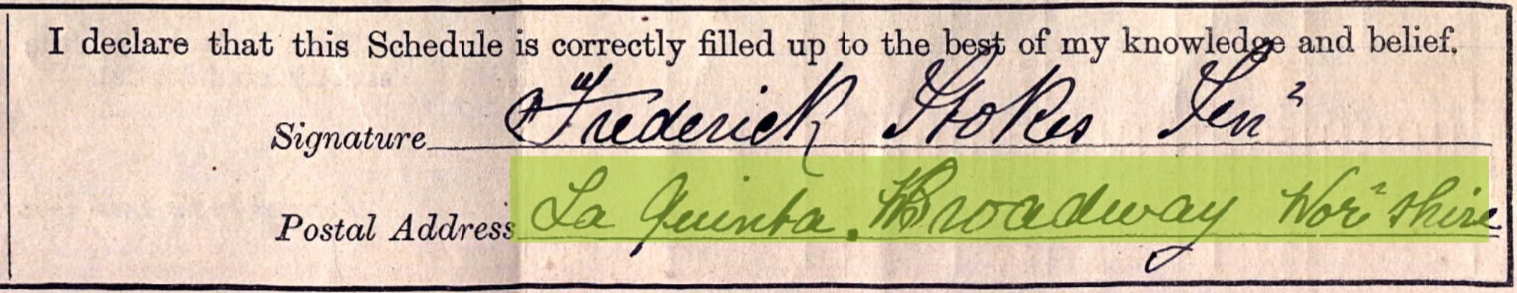

Fred’s signature on the 1911 census:

Rebecca died in 1912 and Fred in 1917.

Fred Stokes:

In the book Evesham to Bredon From Old Photographs By Fred Archer:

October 11, 2022 at 11:39 am #6333

October 11, 2022 at 11:39 am #6333In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The Grattidge Family

The first Grattidge to appear in our tree was Emma Grattidge (1853-1911) who married Charles Tomlinson (1847-1907) in 1872.

Charles Tomlinson (1873-1929) was their son and he married my great grandmother Nellie Fisher. Their daughter Margaret (later Peggy Edwards) was my grandmother on my fathers side.

Emma Grattidge was born in Wolverhampton, the daughter and youngest child of William Grattidge (1820-1887) born in Foston, Derbyshire, and Mary Stubbs, born in Burton on Trent, daughter of Solomon Stubbs, a land carrier. William and Mary married at St Modwens church, Burton on Trent, in 1839. It’s unclear why they moved to Wolverhampton. On the 1841 census William was employed as an agent, and their first son William was nine months old. Thereafter, William was a licensed victuallar or innkeeper.

William Grattidge was born in Foston, Derbyshire in 1820. His parents were Thomas Grattidge, farmer (1779-1843) and Ann Gerrard (1789-1822) from Ellastone. Thomas and Ann married in 1813 in Ellastone. They had five children before Ann died at the age of 25:

Bessy was born in 1815, Thomas in 1818, William in 1820, and Daniel Augustus and Frederick were twins born in 1822. They were all born in Foston. (records say Foston, Foston and Scropton, or Scropton)

On the 1841 census Thomas had nine people additional to family living at the farm in Foston, presumably agricultural labourers and help.

After Ann died, Thomas had three children with Kezia Gibbs (30 years his junior) before marrying her in 1836, then had a further four with her before dying in 1843. Then Kezia married Thomas’s nephew Frederick Augustus Grattidge (born in 1816 in Stafford) in London in 1847 and had two more!

The siblings of William Grattidge (my 3x great grandfather):

Frederick Grattidge (1822-1872) was a schoolmaster and never married. He died at the age of 49 in Tamworth at his twin brother Daniels address.

Daniel Augustus Grattidge (1822-1903) was a grocer at Gungate in Tamworth.

Thomas Grattidge (1818-1871) married in Derby, and then emigrated to Illinois, USA.

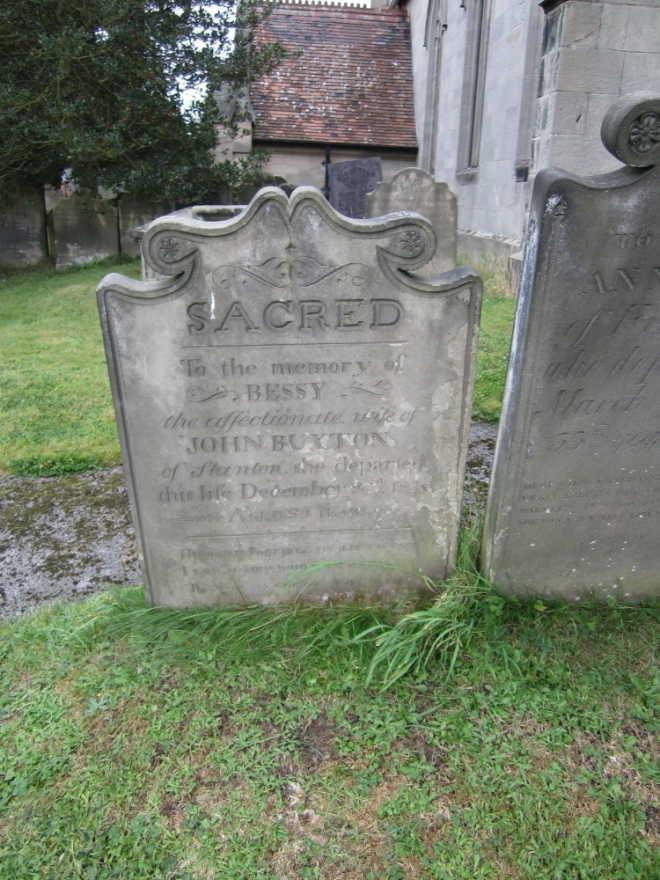

Bessy Grattidge (1815-1840) married John Buxton, farmer, in Ellastone in January 1838. They had three children before Bessy died in December 1840 at the age of 25: Henry in 1838, John in 1839, and Bessy Buxton in 1840. Bessy was baptised in January 1841. Presumably the birth of Bessy caused the death of Bessy the mother.

Bessy Buxton’s gravestone:

“Sacred to the memory of Bessy Buxton, the affectionate wife of John Buxton of Stanton She departed this life December 20th 1840, aged 25 years. “Husband, Farewell my life is Past, I loved you while life did last. Think on my children for my sake, And ever of them with I take.”

20 Dec 1840, Ellastone, Staffordshire

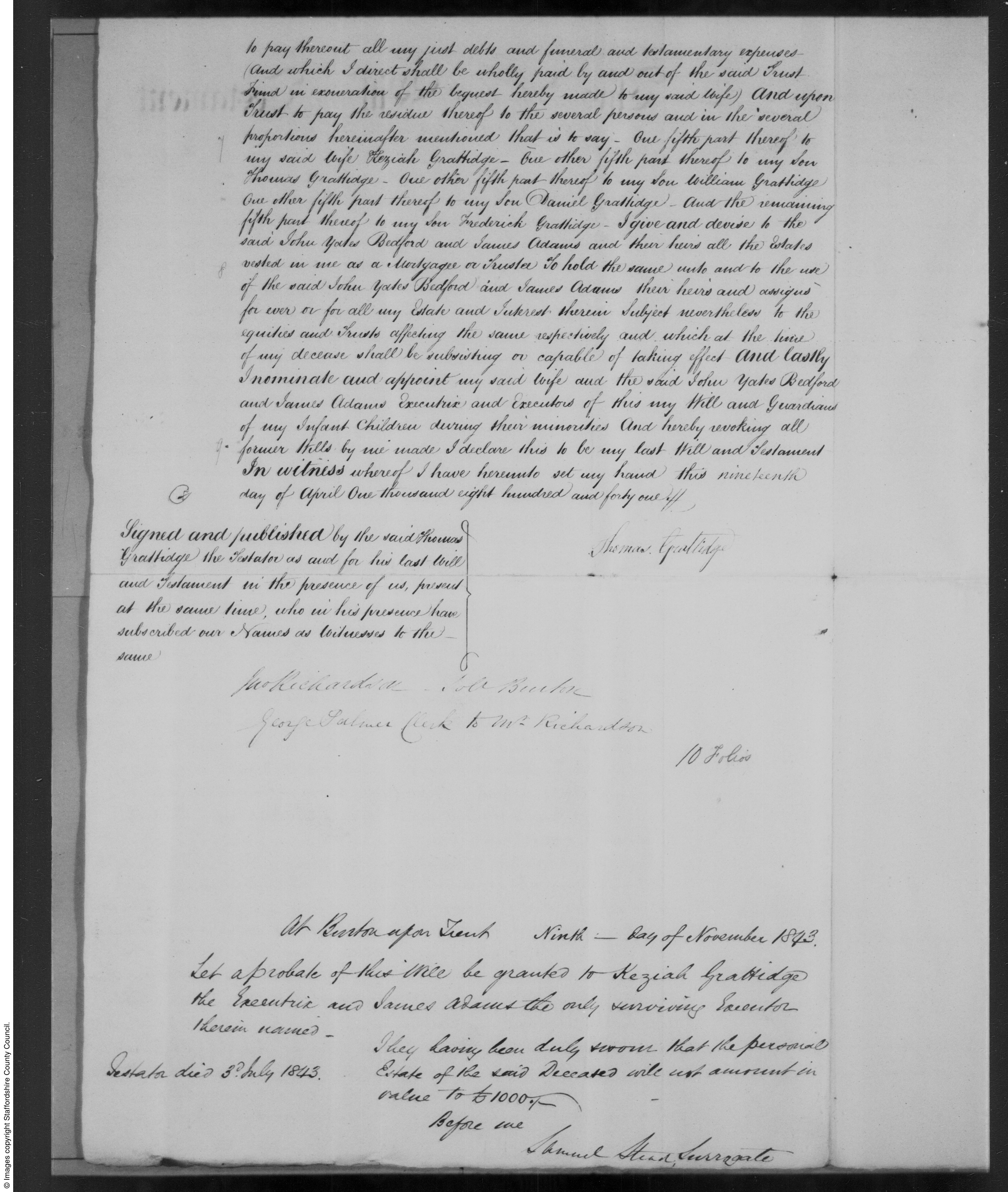

In the 1843 will of Thomas Grattidge, farmer of Foston, he leaves fifth shares of his estate, including freehold real estate at Findern, to his wife Kezia, and sons William, Daniel, Frederick and Thomas. He mentions that the children of his late daughter Bessy, wife of John Buxton, will be taken care of by their father. He leaves the farm to Keziah in confidence that she will maintain, support and educate his children with her.

An excerpt from the will:

I give and bequeath unto my dear wife Keziah Grattidge all my household goods and furniture, wearing apparel and plate and plated articles, linen, books, china, glass, and other household effects whatsoever, and also all my implements of husbandry, horses, cattle, hay, corn, crops and live and dead stock whatsoever, and also all the ready money that may be about my person or in my dwelling house at the time of my decease, …I also give my said wife the tenant right and possession of the farm in my occupation….

A page from the 1843 will of Thomas Grattidge:

William Grattidges half siblings (the offspring of Thomas Grattidge and Kezia Gibbs):

Albert Grattidge (1842-1914) was a railway engine driver in Derby. In 1884 he was driving the train when an unfortunate accident occured outside Ambergate. Three children were blackberrying and crossed the rails in front of the train, and one little girl died.

Albert Grattidge:

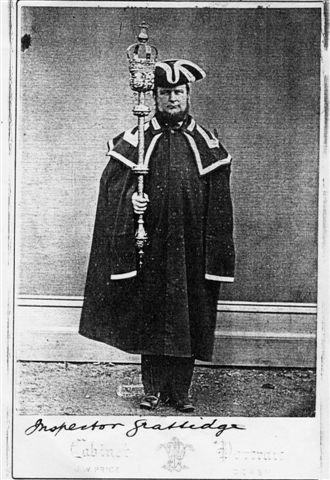

George Grattidge (1826-1876) was baptised Gibbs as this was before Thomas married Kezia. He was a police inspector in Derby.

George Grattidge:

Edwin Grattidge (1837-1852) died at just 15 years old.

Ann Grattidge (1835-) married Charles Fletcher, stone mason, and lived in Derby.

Louisa Victoria Grattidge (1840-1869) was sadly another Grattidge woman who died young. Louisa married Emmanuel Brunt Cheesborough in 1860 in Derby. In 1861 Louisa and Emmanuel were living with her mother Kezia in Derby, with their two children Frederick and Ann Louisa. Emmanuel’s occupation was sawyer. (Kezia Gibbs second husband Frederick Augustus Grattidge was a timber merchant in Derby)

At the time of her death in 1869, Emmanuel was the landlord of the White Hart public house at Bridgegate in Derby.

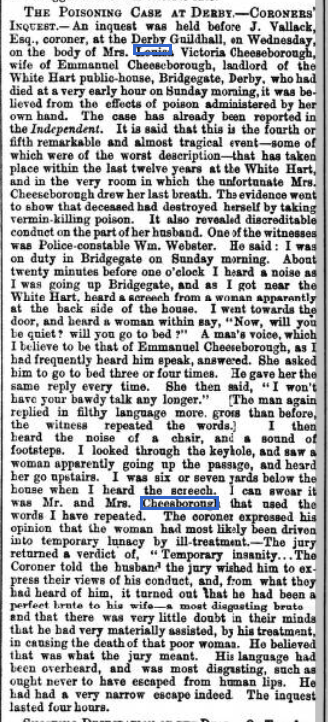

The Derby Mercury of 17th November 1869:

“On Wednesday morning Mr Coroner Vallack held an inquest in the Grand

Jury-room, Town-hall, on the body of Louisa Victoria Cheeseborough, aged

33, the wife of the landlord of the White Hart, Bridge-gate, who committed

suicide by poisoning at an early hour on Sunday morning. The following

evidence was taken:Mr Frederick Borough, surgeon, practising in Derby, deposed that he was

called in to see the deceased about four o’clock on Sunday morning last. He

accordingly examined the deceased and found the body quite warm, but dead.

He afterwards made enquiries of the husband, who said that he was afraid

that his wife had taken poison, also giving him at the same time the

remains of some blue material in a cup. The aunt of the deceased’s husband

told him that she had seen Mrs Cheeseborough put down a cup in the

club-room, as though she had just taken it from her mouth. The witness took

the liquid home with him, and informed them that an inquest would

necessarily have to be held on Monday. He had made a post mortem

examination of the body, and found that in the stomach there was a great

deal of congestion. There were remains of food in the stomach and, having

put the contents into a bottle, he took the stomach away. He also examined

the heart and found it very pale and flabby. All the other organs were

comparatively healthy; the liver was friable.Hannah Stone, aunt of the deceased’s husband, said she acted as a servant

in the house. On Saturday evening, while they were going to bed and whilst

witness was undressing, the deceased came into the room, went up to the

bedside, awoke her daughter, and whispered to her. but what she said the

witness did not know. The child jumped out of bed, but the deceased closed

the door and went away. The child followed her mother, and she also

followed them to the deceased’s bed-room, but the door being closed, they

then went to the club-room door and opening it they saw the deceased

standing with a candle in one hand. The daughter stayed with her in the

room whilst the witness went downstairs to fetch a candle for herself, and

as she was returning up again she saw the deceased put a teacup on the

table. The little girl began to scream, saying “Oh aunt, my mother is

going, but don’t let her go”. The deceased then walked into her bed-room,

and they went and stood at the door whilst the deceased undressed herself.

The daughter and the witness then returned to their bed-room. Presently

they went to see if the deceased was in bed, but she was sitting on the

floor her arms on the bedside. Her husband was sitting in a chair fast

asleep. The witness pulled her on the bed as well as she could.

Ann Louisa Cheesborough, a little girl, said that the deceased was her

mother. On Saturday evening last, about twenty minutes before eleven

o’clock, she went to bed, leaving her mother and aunt downstairs. Her aunt

came to bed as usual. By and bye, her mother came into her room – before

the aunt had retired to rest – and awoke her. She told the witness, in a

low voice, ‘that she should have all that she had got, adding that she

should also leave her her watch, as she was going to die’. She did not tell

her aunt what her mother had said, but followed her directly into the

club-room, where she saw her drink something from a cup, which she

afterwards placed on the table. Her mother then went into her own room and

shut the door. She screamed and called her father, who was downstairs. He

came up and went into her room. The witness then went to bed and fell

asleep. She did not hear any noise or quarrelling in the house after going

to bed.Police-constable Webster was on duty in Bridge-gate on Saturday evening

last, about twenty minutes to one o’clock. He knew the White Hart

public-house in Bridge-gate, and as he was approaching that place, he heard

a woman scream as though at the back side of the house. The witness went to

the door and heard the deceased keep saying ‘Will you be quiet and go to

bed’. The reply was most disgusting, and the language which the

police-constable said was uttered by the husband of the deceased, was

immoral in the extreme. He heard the poor woman keep pressing her husband

to go to bed quietly, and eventually he saw him through the keyhole of the

door pass and go upstairs. his wife having gone up a minute or so before.

Inspector Fearn deposed that on Sunday morning last, after he had heard of

the deceased’s death from supposed poisoning, he went to Cheeseborough’s

public house, and found in the club-room two nearly empty packets of

Battie’s Lincoln Vermin Killer – each labelled poison.Several of the Jury here intimated that they had seen some marks on the

deceased’s neck, as of blows, and expressing a desire that the surgeon

should return, and re-examine the body. This was accordingly done, after

which the following evidence was taken:Mr Borough said that he had examined the body of the deceased and observed

a mark on the left side of the neck, which he considered had come on since

death. He thought it was the commencement of decomposition.

This was the evidence, after which the jury returned a verdict “that the

deceased took poison whilst of unsound mind” and requested the Coroner to

censure the deceased’s husband.The Coroner told Cheeseborough that he was a disgusting brute and that the

jury only regretted that the law could not reach his brutal conduct.

However he had had a narrow escape. It was their belief that his poor

wife, who was driven to her own destruction by his brutal treatment, would

have been a living woman that day except for his cowardly conduct towards

her.The inquiry, which had lasted a considerable time, then closed.”

In this article it says:

“it was the “fourth or fifth remarkable and tragical event – some of which were of the worst description – that has taken place within the last twelve years at the White Hart and in the very room in which the unfortunate Louisa Cheesborough drew her last breath.”

Sheffield Independent – Friday 12 November 1869:

June 10, 2022 at 1:39 pm #6305

June 10, 2022 at 1:39 pm #6305In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

The Hair’s and Leedham’s of Netherseal

Samuel Warren of Stapenhill married Catherine Holland of Barton under Needwood in 1795. Catherine’s father was Thomas Holland; her mother was Hannah Hair.

Hannah was born in Netherseal, Derbyshire, in 1739. Her parents were Joseph Hair 1696-1746 and Hannah.

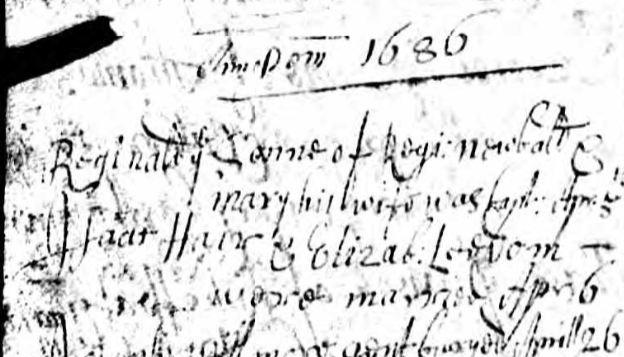

Joseph’s parents were Isaac Hair and Elizabeth Leedham. Elizabeth was born in Netherseal in 1665. Isaac and Elizabeth were married in Netherseal in 1686.Marriage of Isaac Hair and Elizabeth Leedham: (variously spelled Ledom, Leedom, Leedham, and in one case mistranscribed as Sedom):

Isaac was buried in Netherseal on 14 August 1709 (the transcript says the 18th, but the microfiche image clearly says the 14th), but I have not been able to find a birth registered for him. On other public trees on an ancestry website, Isaac Le Haire was baptised in Canterbury and was a Huguenot, but I haven’t found any evidence to support this.

Isaac Hair’s death registered 14 August 1709 in Netherseal:

A search for the etymology of the surname Hair brings various suggestions, including:

“This surname is derived from a nickname. ‘the hare,’ probably affixed on some one fleet of foot. Naturally looked upon as a complimentary sobriquet, and retained in the family; compare Lightfoot. (for example) Hugh le Hare, Oxfordshire, 1273. Hundred Rolls.”

From this we may deduce that the name Hair (or Hare) is not necessarily from the French Le Haire, and existed in England for some considerable time before the arrival of the Huguenots.

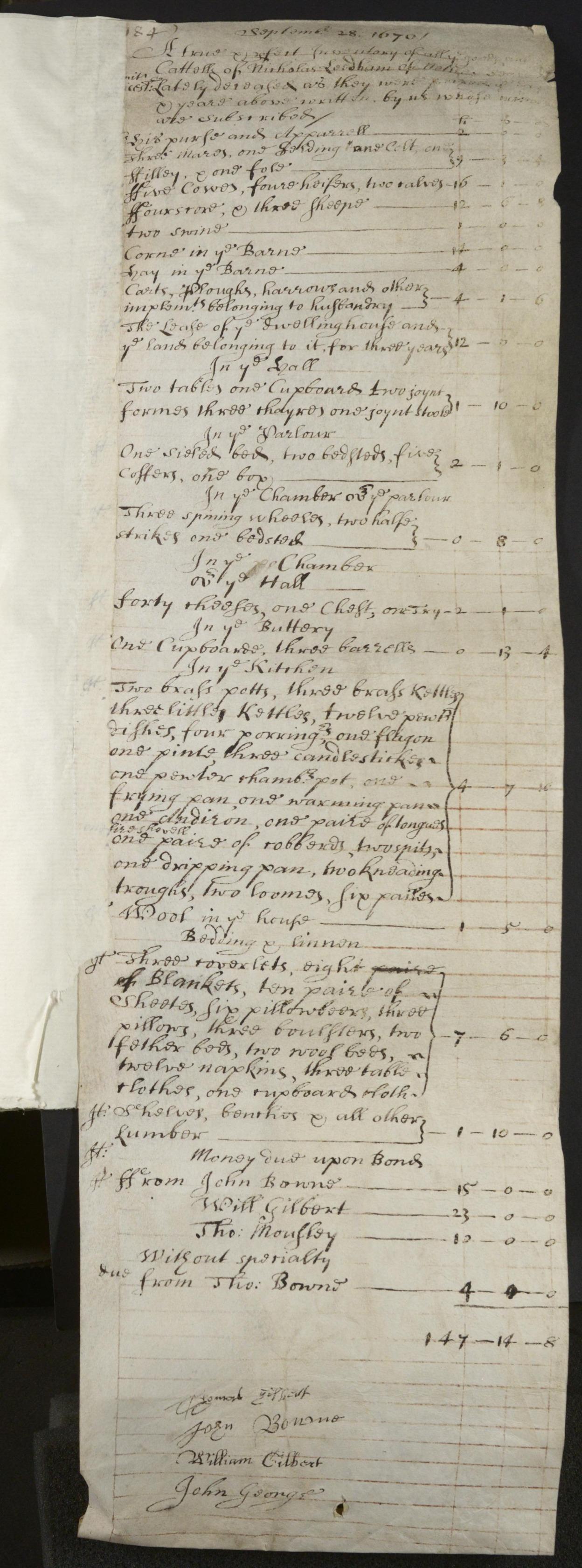

Elizabeth Leedham was born in Netherseal in 1665. Her parents were Nicholas Leedham 1621-1670 and Dorothy. Nicholas Leedham was born in Church Gresley (Swadlincote) in 1621, and died in Netherseal in 1670.

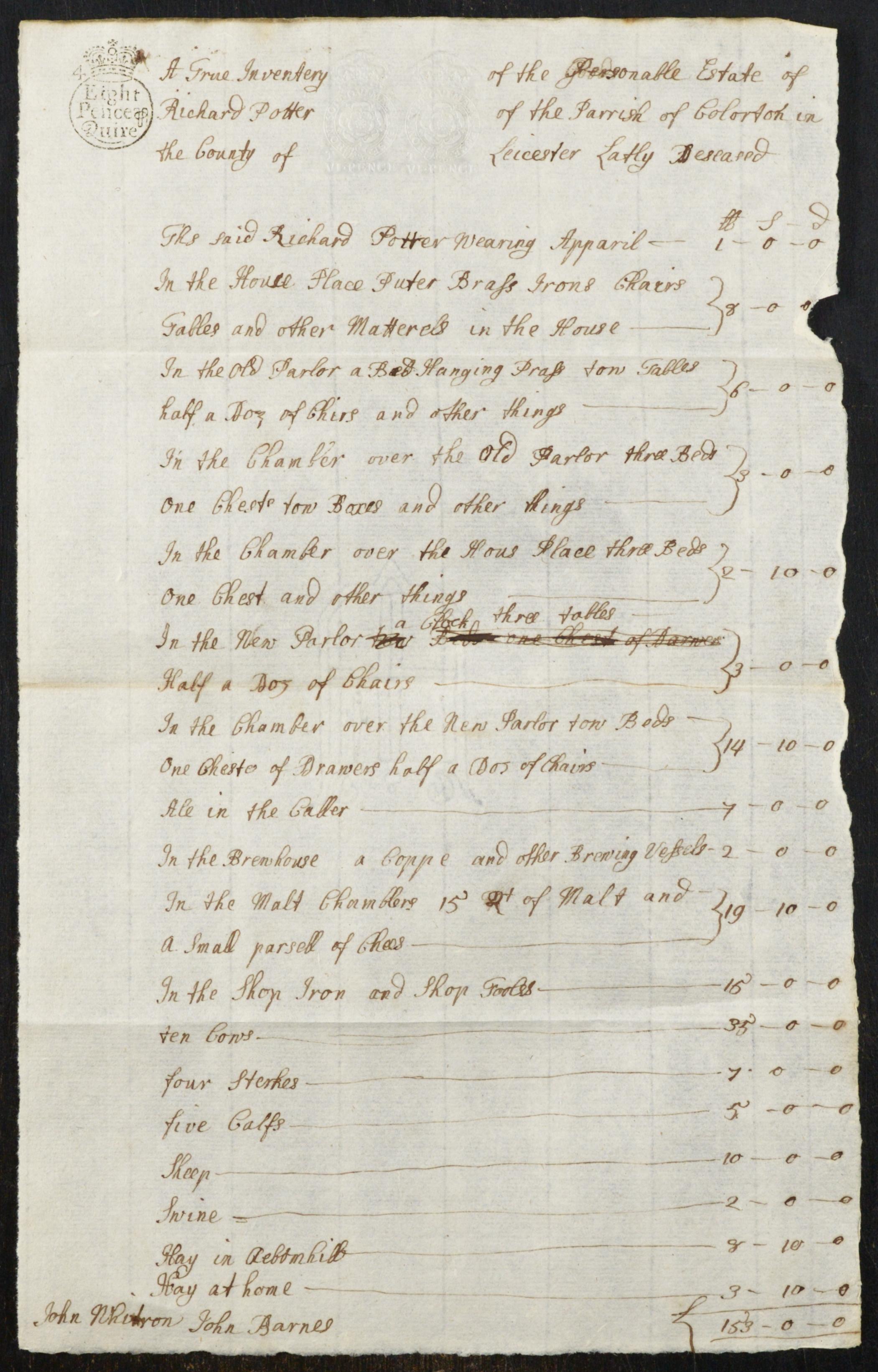

Nicholas was a Yeoman and left a will and inventory worth £147.14s.8d (one hundred and forty seven pounds fourteen shillings and eight pence).

The 1670 inventory of Nicholas Leedham:

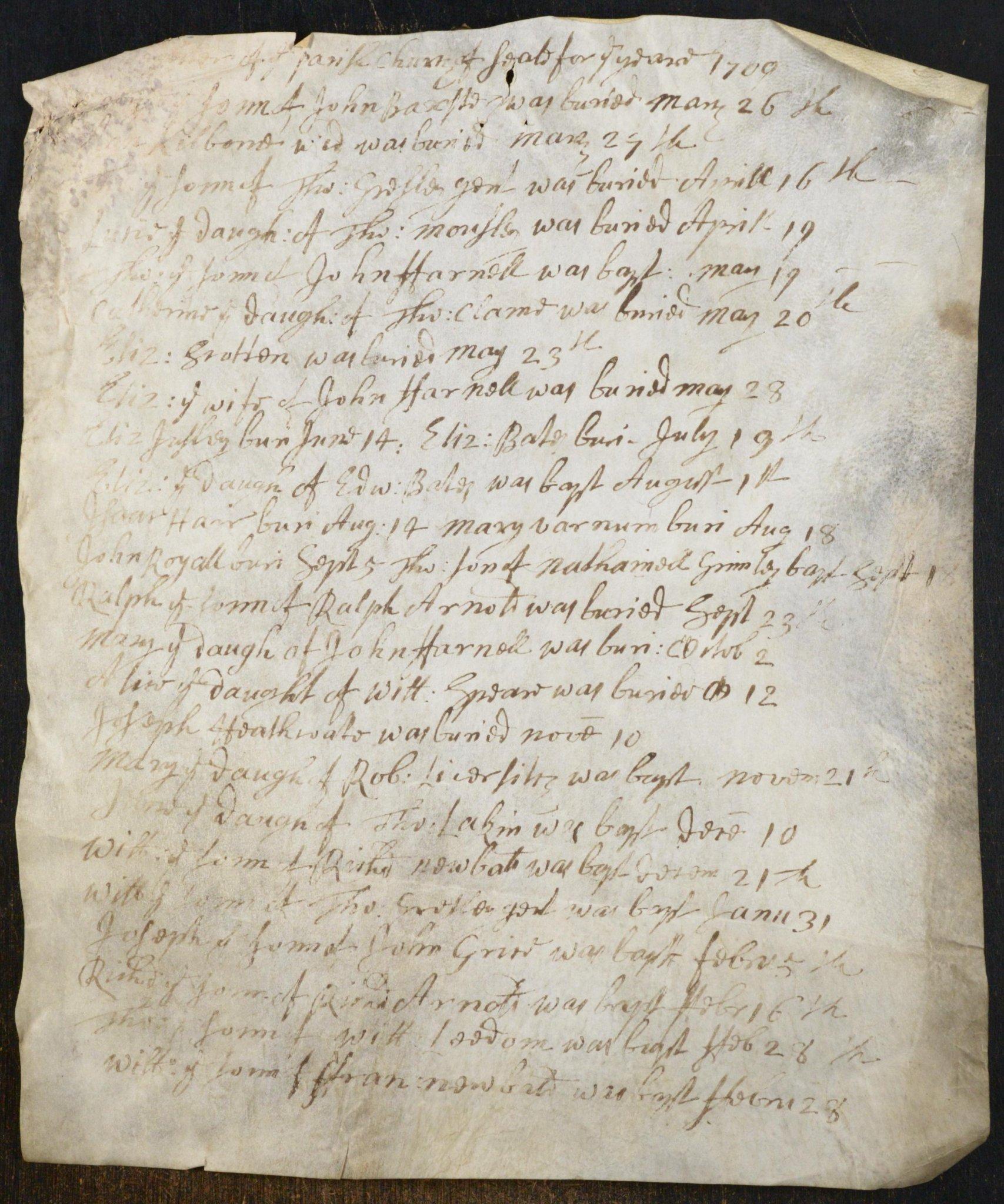

According to local historian Mark Knight on the Netherseal History facebook group, the Seale (Netherseal and Overseal) parish registers from the year 1563 to 1724 were digitized during lockdown.

via Mark Knight:

“There are five entries for Nicholas Leedham.

On March 14th 1646 he and his wife buried an unnamed child, presumably the child died during childbirth or was stillborn.

On November 28th 1659 he buried his wife, Elizabeth. He remarried as on June 13th 1664 he had his son William baptised.

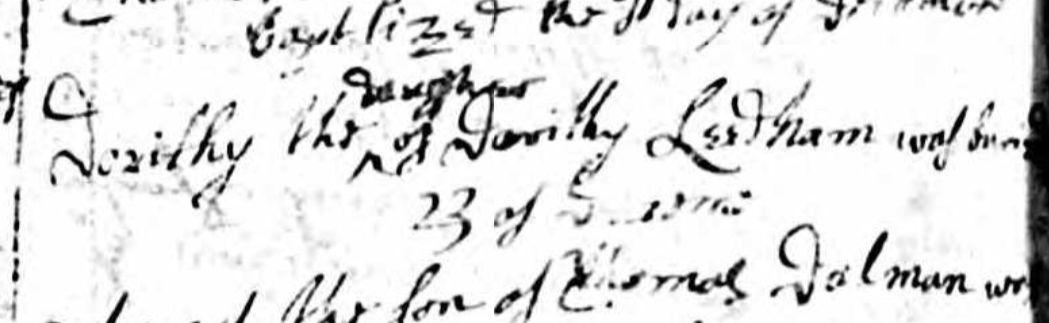

The following year, 1665, he baptised a daughter on November 12th. (Elizabeth) On December 23rd 1672 the parish record says that Dorithy daughter of Dorithy was buried. The Bishops Transcript has Dorithy a daughter of Nicholas. Nicholas’ second wife was called Dorithy and they named a daughter after her. Alas, the daughter died two years after Nicholas. No further Leedhams appear in the record until after 1724.”Dorothy daughter of Dorothy Leedham was buried 23 December 1672:

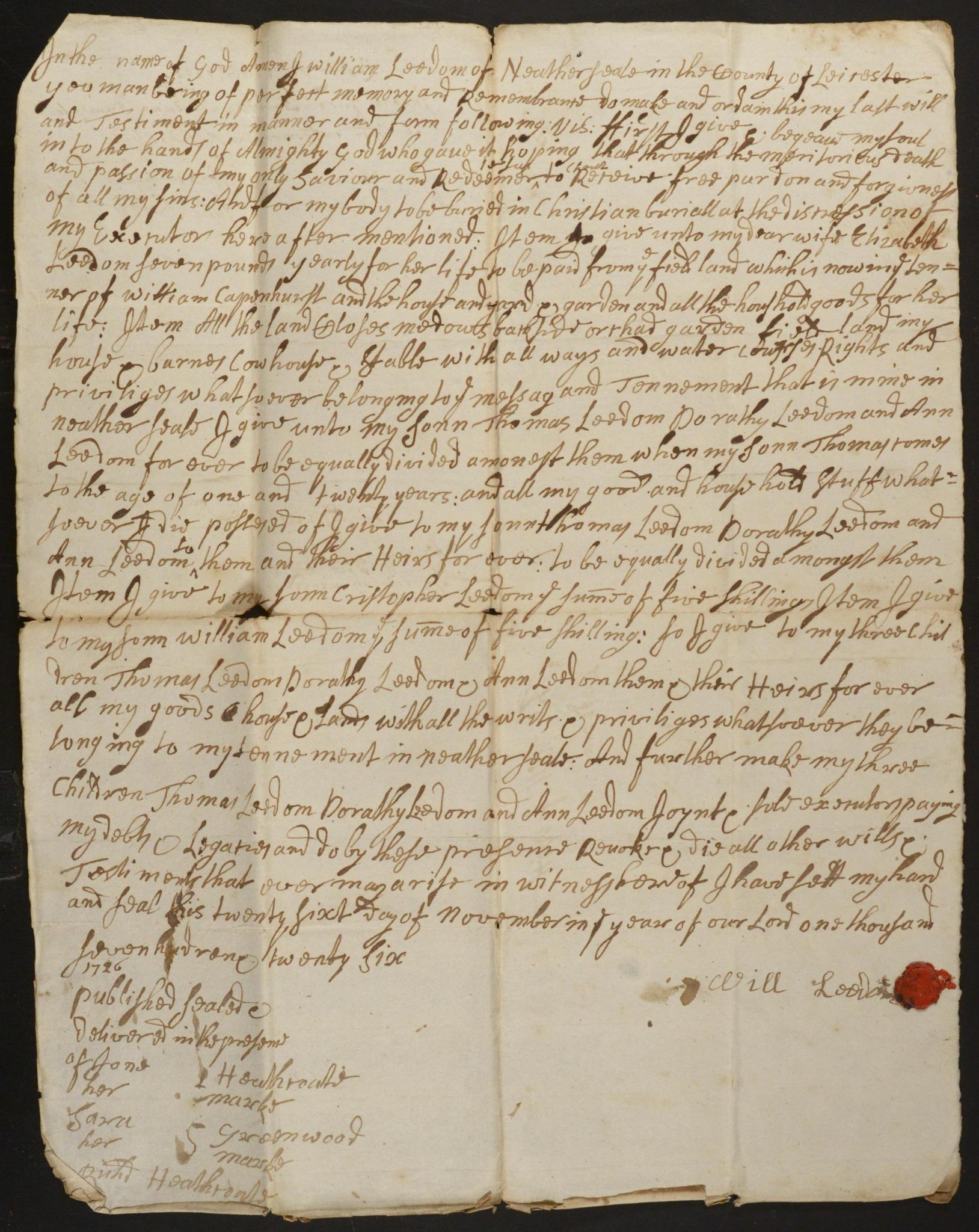

William, son of Nicholas and Dorothy also left a will. In it he mentions “My dear wife Elizabeth. My children Thomas Leedom, Dorothy Leedom , Ann Leedom, Christopher Leedom and William Leedom.”

1726 will of William Leedham:

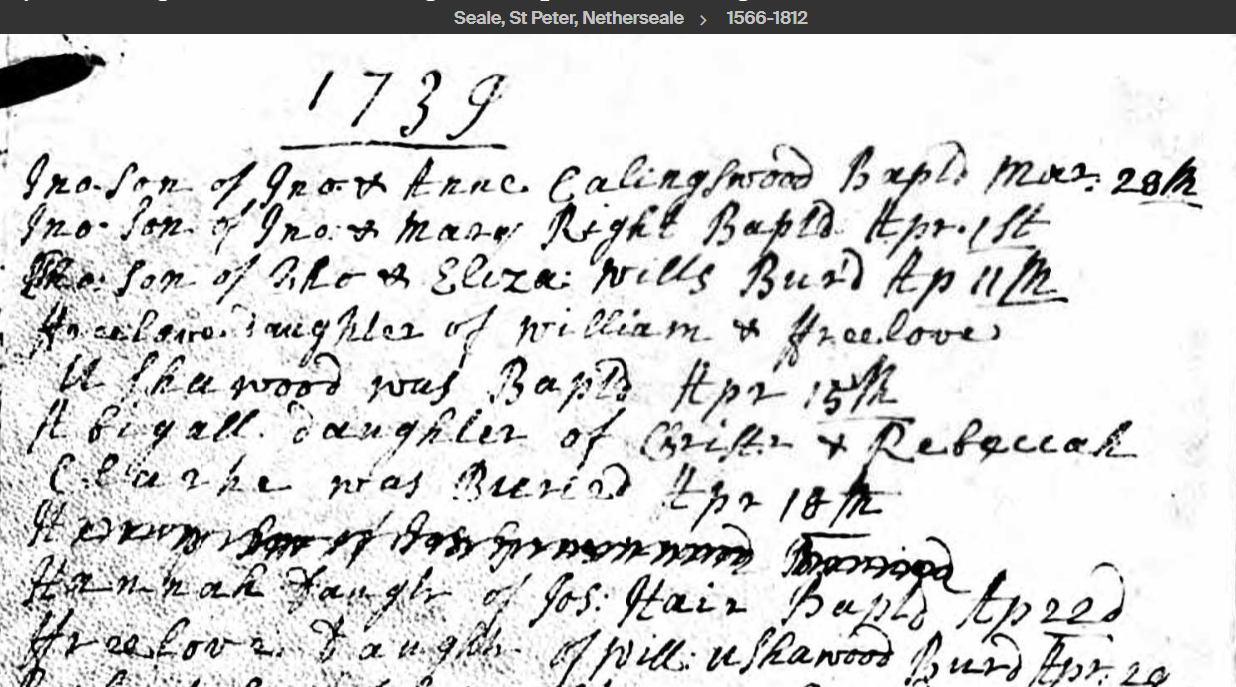

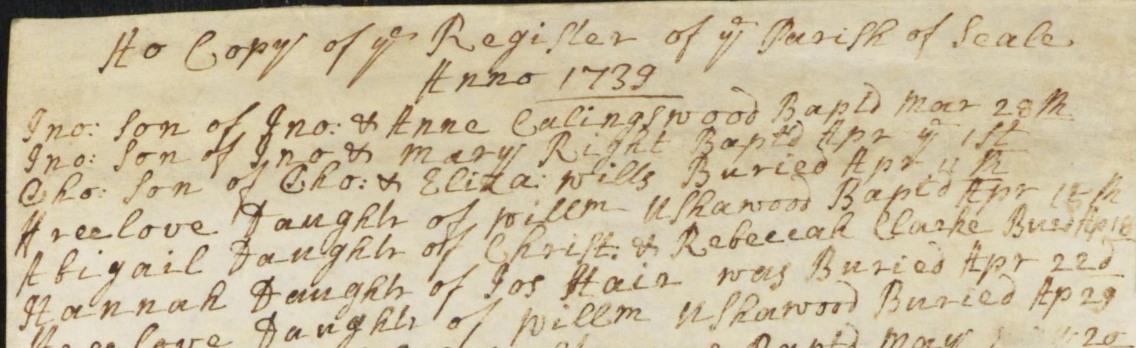

I found a curious error with the the parish register entries for Hannah Hair. It was a transcription error, but not a recent one. The original parish registers were copied: “HO Copy of ye register of Seale anno 1739.” I’m not sure when the copy was made, but it wasn’t recently. I found a burial for Hannah Hair on 22 April 1739 in the HO copy, which was the same day as her baptism registered on the original. I checked both registers name by name and they are exactly copied EXCEPT for Hannah Hairs. The rector, Richard Inge, put burial instead of baptism by mistake.

The original Parish register baptism of Hannah Hair:

The HO register copy incorrectly copied:

May 13, 2022 at 10:50 am #6293

May 13, 2022 at 10:50 am #6293In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Lincolnshire Families

Thanks to the 1851 census, we know that William Eaton was born in Grantham, Lincolnshire. He was baptised on 29 November 1768 at St Wulfram’s church; his father was William Eaton and his mother Elizabeth.

St Wulfram’s in Grantham painted by JMW Turner in 1797:

I found a marriage for a William Eaton and Elizabeth Rose in the city of Lincoln in 1761, but it seemed unlikely as they were both of that parish, and with no discernable links to either Grantham or Nottingham.