Search Results for 'grand'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

February 5, 2022 at 10:50 am #6271

In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

The Housley Letters

FRIENDS AND NEIGHBORS

from Barbara Housley’s Narrative on the Letters:

George apparently asked about old friends and acquaintances and the family did their best to answer although Joseph wrote in 1873: “There is very few of your old cronies that I know of knocking about.”

In Anne’s first letter she wrote about a conversation which Robert had with EMMA LYON before his death and added “It (his death) was a great trouble to Lyons.” In her second letter Anne wrote: “Emma Lyon is to be married September 5. I am going the Friday before if all is well. There is every prospect of her being comfortable. MRS. L. always asks after you.” In 1855 Emma wrote: “Emma Lyon now Mrs. Woolhouse has got a fine boy and a pretty fuss is made with him. They call him ALFRED LYON WOOLHOUSE.”

(Interesting to note that Elizabeth Housley, the eldest daughter of Samuel and Elizabeth, was living with a Lyon family in Derby in 1861, after she left Belper workhouse. The Emma listed on the census in 1861 was 10 years old, and so can not be the Emma Lyon mentioned here, but it’s possible, indeed likely, that Peter Lyon the baker was related to the Lyon’s who were friends of the Housley’s. The mention of a sea captain in the Lyon family begs the question did Elizabeth Housley meet her husband, George William Stafford, a seaman, through some Lyon connections, but to date this remains a mystery.)

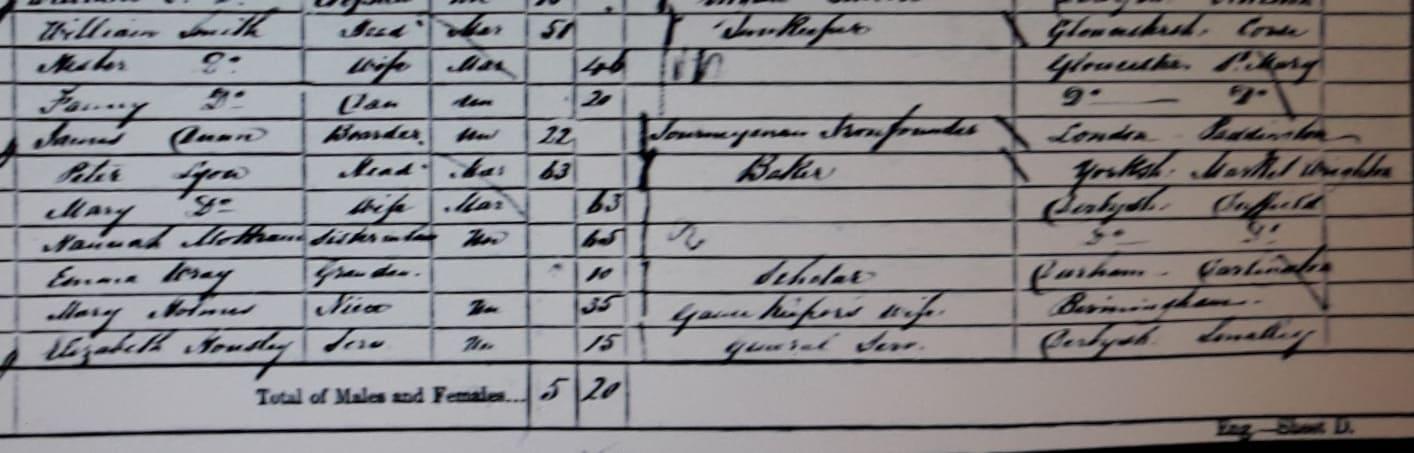

Elizabeth Housley living with Peter Lyon and family in Derby St Peters in 1861:

A Henrietta Lyon was married in 1860. Her father was Matthew, a Navy Captain. The 1857 Derby Directory listed a Richard Woolhouse, plumber, glazier, and gas fitter on St. Peter’s Street. Robert lived in St. Peter’s parish at the time of his death. An Alfred Lyon, son of Alfred and Jemima Lyon 93 Friargate, Derby was baptised on December 4, 1877. An Allen Hewley Lyon, born February 1, 1879 was baptised June 17 1879.

Anne wrote in August 1854: “KERRY was married three weeks since to ELIZABETH EATON. He has left Smith some time.” Perhaps this was the same person referred to by Joseph: “BILL KERRY, the blacksmith for DANIEL SMITH, is working for John Fletcher lace manufacturer.” According to the 1841 census, Elizabeth age 12, was the oldest daughter of Thomas and Rebecca Eaton. She would certainly have been of marriagable age in 1854. A William Kerry, age 14, was listed as a blacksmith’s apprentice in the 1851 census; but another William Kerry who was 29 in 1851 was already working for Daniel Smith as a blacksmith. REBECCA EATON was listed in the 1851 census as a widow serving as a nurse in the John Housley household. The 1881 census lists the family of William Kerry, blacksmith, as Jane, 19; William 13; Anne, 7; and Joseph, 4. Elizabeth is not mentioned but Bill is not listed as a widower.

Anne also wrote in 1854 that she had not seen or heard anything of DICK HANSON for two years. Joseph wrote that he did not know Old BETTY HANSON’S son. A Richard Hanson, age 24 in 1851, lived with a family named Moore. His occupation was listed as “journeyman knitter.” An Elizabeth Hanson listed as 24 in 1851 could hardly be “Old Betty.” Emma wrote in June 1856 that JOE OLDKNOW age 27 had married Mrs. Gribble’s servant age 17.

Anne wrote that “JOHN SPENCER had not been since father died.” The only John Spencer in Smalley in 1841 was four years old. He would have been 11 at the time of William Housley’s death. Certainly, the two could have been friends, but perhaps young John was named for his grandfather who was a crony of William’s living in a locality not included in the Smalley census.

TAILOR ALLEN had lost his wife and was still living in the old house in 1872. JACK WHITE had died very suddenly, and DR. BODEN had died also. Dr. Boden’s first name was Robert. He was 53 in 1851, and was probably the Robert, son of Richard and Jane, who was christened in Morely in 1797. By 1861, he had married Catherine, a native of Smalley, who was at least 14 years his junior–18 according to the 1871 census!

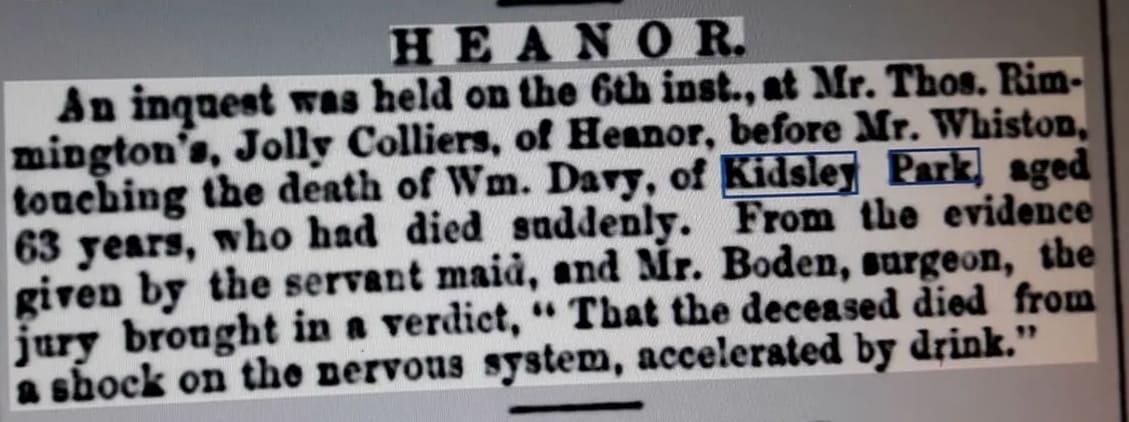

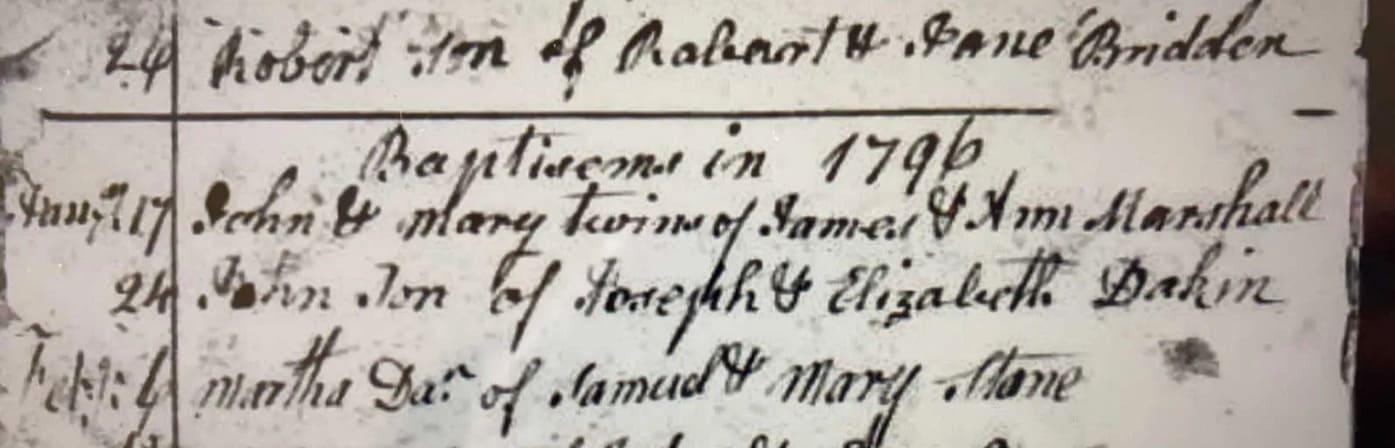

Among the family’s dearest friends were JOSEPH AND ELIZABETH DAVY, who were married some time after 1841. Mrs. Davy was born in 1812 and her husband in 1805. In 1841, the Kidsley Park farm household included DANIEL SMITH 72, Elizabeth 29 and 5 year old Hannah Smith. In 1851, Mr. Davy’s brother William and 10 year old Emma Davy were visiting from London. Joseph reported the death of both Davy brothers in 1872; Joseph apparently died first.

Mrs. Davy’s father, was a well known Quaker. In 1856, Emma wrote: “Mr. Smith is very hearty and looks much the same.” He died in December 1863 at the age of 94. George Fox, the founder of the Quakers visited Kidsley Park in 1650 and 1654.

Mr. Davy died in 1863, but in 1854 Anne wrote how ill he had been for two years. “For two last winters we never thought he would live. He is now able to go out a little on the pony.” In March 1856, his wife wrote, “My husband is in poor health and fell.” Later in 1856, Emma wrote, “Mr. Davy is living which is a great wonder. Mrs. Davy is very delicate but as good a friend as ever.”

In The Derbyshire Advertiser and Journal, 15 May 1863:

Whenever the girls sent greetings from Mrs. Davy they used her Quaker speech pattern of “thee and thy.” Mrs. Davy wrote to George on March 21 1856 sending some gifts from his sisters and a portrait of their mother–“Emma is away yet and A is so much worse.” Mrs. Davy concluded: “With best wishes for thy health and prosperity in this world and the next I am thy sincere friend.”

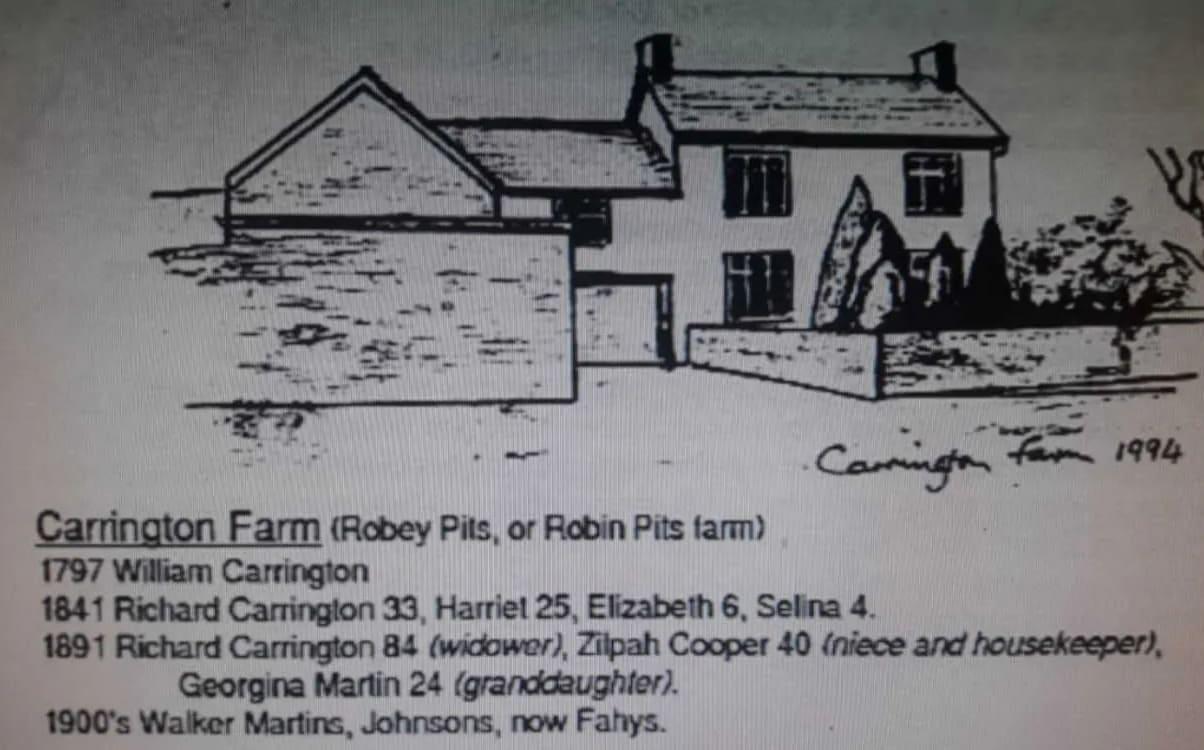

Mrs. Davy later remarried. Her new husband was W.T. BARBER. The 1861 census lists William Barber, 35, Bachelor of Arts, Cambridge, living with his 82 year old widowed mother on an 135 acre farm with three servants. One of these may have been the Ann who, according to Joseph, married Jack Oldknow. By 1871 the farm, now occupied by William, 47 and Elizabeth, 57, had grown to 189 acres. Meanwhile, Kidsley Park Farm became the home of the Housleys’ cousin Selina Carrington and her husband Walker Martin. Both Barbers were still living in 1881.

Mrs. Davy was described in Kerry’s History of Smalley as “an accomplished and exemplary lady.” A piece of her poetry “Farewell to Kidsley Park” was published in the history. It was probably written when Elizabeth moved to the Barber farm. Emma sent one of her poems to George. It was supposed to be about their house. “We have sent you a piece of poetry that Mrs. Davy composed about our ‘Old House.’ I am sure you will like it though you may not understand all the allusions she makes use of as well as we do.”

Kiddsley Park Farm, Smalley, in 1898. (note that the Housley’s lived at Kiddsley Grange Farm, and the Davy’s at neighbouring Kiddsley Park Farm)

Emma was not sure if George wanted to hear the local gossip (“I don’t know whether such little particulars will interest you”), but shared it anyway. In November 1855: “We have let the house to Mr. Gribble. I dare say you know who he married, Matilda Else. They came from Lincoln here in March. Mrs. Gribble gets drunk nearly every day and there are such goings on it is really shameful. So you may be sure we have not very pleasant neighbors but we have very little to do with them.”

John Else and his wife Hannah and their children John and Harriet (who were born in Smalley) lived in Tag Hill in 1851. With them lived a granddaughter Matilda Gribble age 3 who was born in Lincoln. A Matilda, daughter of John and Hannah, was christened in 1815. (A Sam Else died when he fell down the steps of a bar in 1855.)

February 4, 2022 at 3:17 pm #6269In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

The Housley Letters

From Barbara Housley’s Narrative on the Letters.

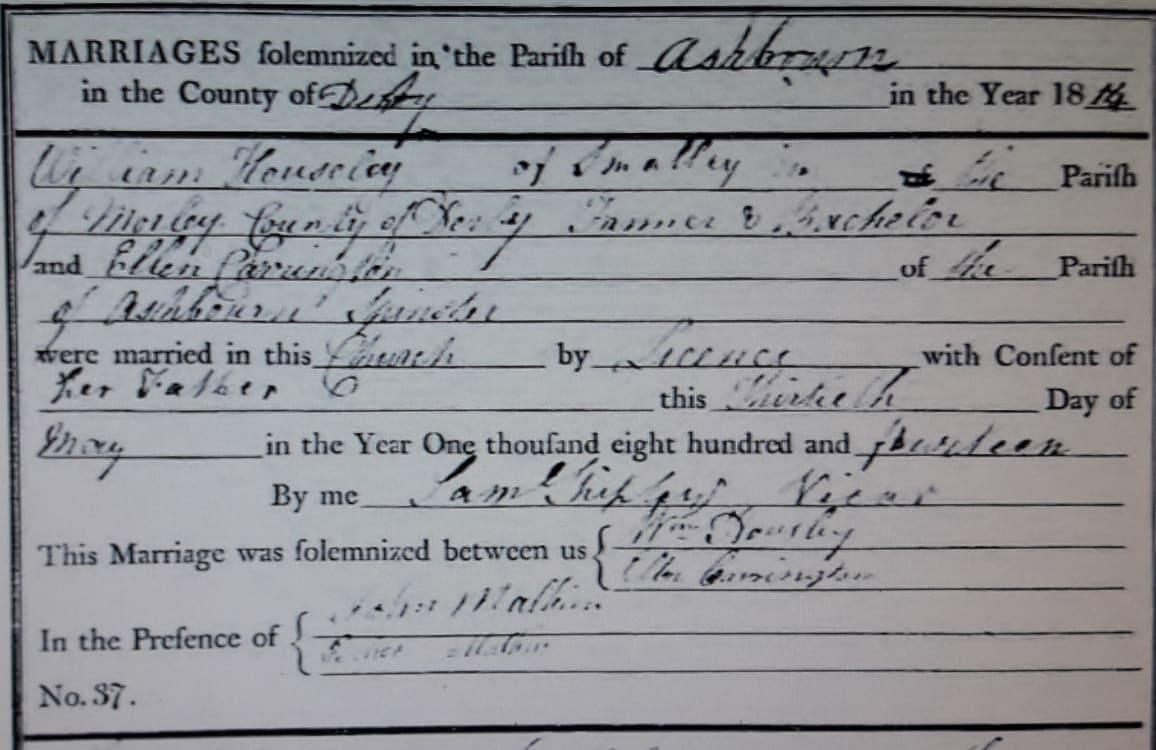

William Housley (1781-1848) and Ellen Carrington were married on May 30, 1814 at St. Oswald’s church in Ashbourne. William died in 1848 at the age of 67 of “disease of lungs and general debility”. Ellen died in 1872.

Marriage of William Housley and Ellen Carrington in Ashbourne in 1814:

Parish records show three children for William and his first wife, Mary, Ellens’ sister, who were married December 29, 1806: Mary Ann, christened in 1808 and mentioned frequently in the letters; Elizabeth, christened in 1810, but never mentioned in any letters; and William, born in 1812, probably referred to as Will in the letters. Mary died in 1813.

William and Ellen had ten children: John, Samuel, Edward, Anne, Charles, George, Joseph, Robert, Emma, and Joseph. The first Joseph died at the age of four, and the last son was also named Joseph. Anne never married, Charles emigrated to Australia in 1851, and George to USA, also in 1851. The letters are to George, from his sisters and brothers in England.

The following are excerpts of those letters, including excerpts of Barbara Housley’s “Narrative on Historic Letters”. They are grouped according to who they refer to, rather than chronological order.

ELLEN HOUSLEY 1795-1872

Joseph wrote that when Emma was married, Ellen “broke up the comfortable home and the things went to Derby and she went to live with them but Derby didn’t agree with her so she left again leaving her things behind and came to live with John in the new house where she died.” Ellen was listed with John’s household in the 1871 census.

In May 1872, the Ilkeston Pioneer carried this notice: “Mr. Hopkins will sell by auction on Saturday next the eleventh of May 1872 the whole of the useful furniture, sewing machine, etc. nearly new on the premises of the late Mrs. Housley at Smalley near Heanor in the county of Derby. Sale at one o’clock in the afternoon.”Ellen’s family was evidently rather prominant in Smalley. Two Carringtons (John and William) served on the Parish Council in 1794. Parish records are full of Carrington marriages and christenings; census records confirm many of the family groupings.

In June of 1856, Emma wrote: “Mother looks as well as ever and was told by a lady the other day that she looked handsome.” Later she wrote: “Mother is as stout as ever although she sometimes complains of not being able to do as she used to.”

Mary’s children:

MARY ANN HOUSLEY 1808-1878

There were hard feelings between Mary Ann and Ellen and her children. Anne wrote: “If you remember we were not very friendly when you left. They never came and nothing was too bad for Mary Ann to say of Mother and me, but when Robert died Mother sent for her to the funeral but she did not think well to come so we took no more notice. She would not allow her children to come either.”

Mary Ann was unlucky in love! In Anne’s second letter she wrote: “William Carrington is paying Mary Ann great attention. He is living in London but they write to each other….We expect it will be a match.” Apparantly the courtship was stormy for in 1855, Emma wrote: “Mary Ann’s wedding with William Carrington has dropped through after she had prepared everything, dresses and all for the occassion.” Then in 1856, Emma wrote: “William Carrington and Mary Ann are separated. They wore him out with their nonsense.” Whether they ever married is unclear. Joseph wrote in 1872: “Mary Ann was married but her husband has left her. She is in very poor health. She has one daughter and they are living with their mother at Smalley.”

Regarding William Carrington, Emma supplied this bit of news: “His sister, Mrs. Lily, has eloped with a married man. Is she not a nice person!”

WILLIAM HOUSLEY JR. 1812-1890

According to a letter from Anne, Will’s two sons and daughter were sent to learn dancing so they would be “fit for any society.” Will’s wife was Dorothy Palfry. They were married in Denby on October 20, 1836 when Will was 24. According to the 1851 census, Will and Dorothy had three sons: Alfred 14, Edwin 12, and William 10. All three boys were born in Denby.

In his letter of May 30, 1872, after just bemoaning that all of his brothers and sisters are gone except Sam and John, Joseph added: “Will is living still.” In another 1872 letter Joseph wrote, “Will is living at Heanor yet and carrying on his cattle dealing.” The 1871 census listed Will, 59, and his son William, 30, of Lascoe Road, Heanor, as cattle dealers.

Ellen’s children:

JOHN HOUSLEY 1815-1893

John married Sarah Baggally in Morely in 1838. They had at least six children. Elizabeth (born 2 May 1838) was “out service” in 1854. In her “third year out,” Elizabeth was described by Anne as “a very nice steady girl but quite a woman in appearance.” One of her positions was with a Mrs. Frearson in Heanor. Emma wrote in 1856: “Elizabeth is still at Mrs. Frearson. She is such a fine stout girl you would not know her.” Joseph wrote in 1872 that Elizabeth was in service with Mrs. Eliza Sitwell at Derby. (About 1850, Miss Eliza Wilmot-Sitwell provided for a small porch with a handsome Norman doorway at the west end of the St. John the Baptist parish church in Smalley.)

According to Elizabeth’s birth certificate and the 1841 census, John was a butcher. By 1851, the household included a nurse and a servant, and John was listed as a “victular.” Anne wrote in February 1854, “John has left the Public House a year and a half ago. He is living where Plumbs (Ann Plumb witnessed William’s death certificate with her mark) did and Thomas Allen has the land. He has been working at James Eley’s all winter.” In 1861, Ellen lived with John and Sarah and the three boys.

John sold his share in the inheritance from their mother and disappeared after her death. (He died in Doncaster, Yorkshire, in 1893.) At that time Charles, the youngest would have been 21. Indeed, Joseph wrote in July 1872: “John’s children are all grown up”.

In May 1872, Joseph wrote: “For what do you think, John has sold his share and he has acted very bad since his wife died and at the same time he sold all his furniture. You may guess I have never seen him but once since poor mother’s funeral and he is gone now no one knows where.”

In February 1874 Joseph wrote: “You want to know what made John go away. Well, I will give you one reason. I think I told you that when his wife died he persuaded me to leave Derby and come to live with him. Well so we did and dear Harriet to keep his house. Well he insulted my wife and offered things to her that was not proper and my dear wife had the power to resist his unmanly conduct. I did not think he could of served me such a dirty trick so that is one thing dear brother. He could not look me in the face when we met. Then after we left him he got a woman in the house and I suppose they lived as man and wife. She caught the small pox and died and there he was by himself like some wild man. Well dear brother I could not go to him again after he had served me and mine as he had and I believe he was greatly in debt too so that he sold his share out of the property and when he received the money at Belper he went away and has never been seen by any of us since but I have heard of him being at Sheffield enquiring for Sam Caldwell. You will remember him. He worked in the Nag’s Head yard but I have heard nothing no more of him.”

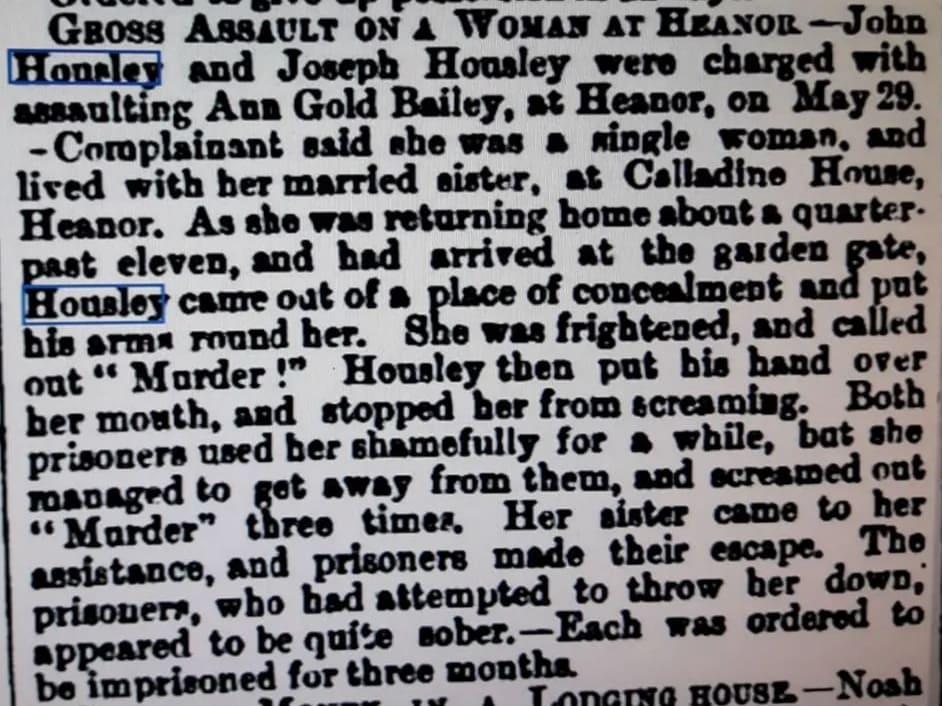

A mention of a John Housley of Heanor in the Nottinghma Journal 1875. I don’t know for sure if the John mentioned here is the brother John who Joseph describes above as behaving improperly to his wife. John Housley had a son Joseph, born in 1840, and John’s wife Sarah died in 1870.

In 1876, the solicitor wrote to George: “Have you heard of John Housley? He is entitled to Robert’s share and I want him to claim it.”

SAMUEL HOUSLEY 1816-

Sam married Elizabeth Brookes of Sutton Coldfield, and they had three daughters: Elizabeth, Mary Anne and Catherine. Elizabeth his wife died in 1849, a few months after Samuel’s father William died in 1848. The particular circumstances relating to these individuals have been discussed in previous chapters; the following are letter excerpts relating to them.

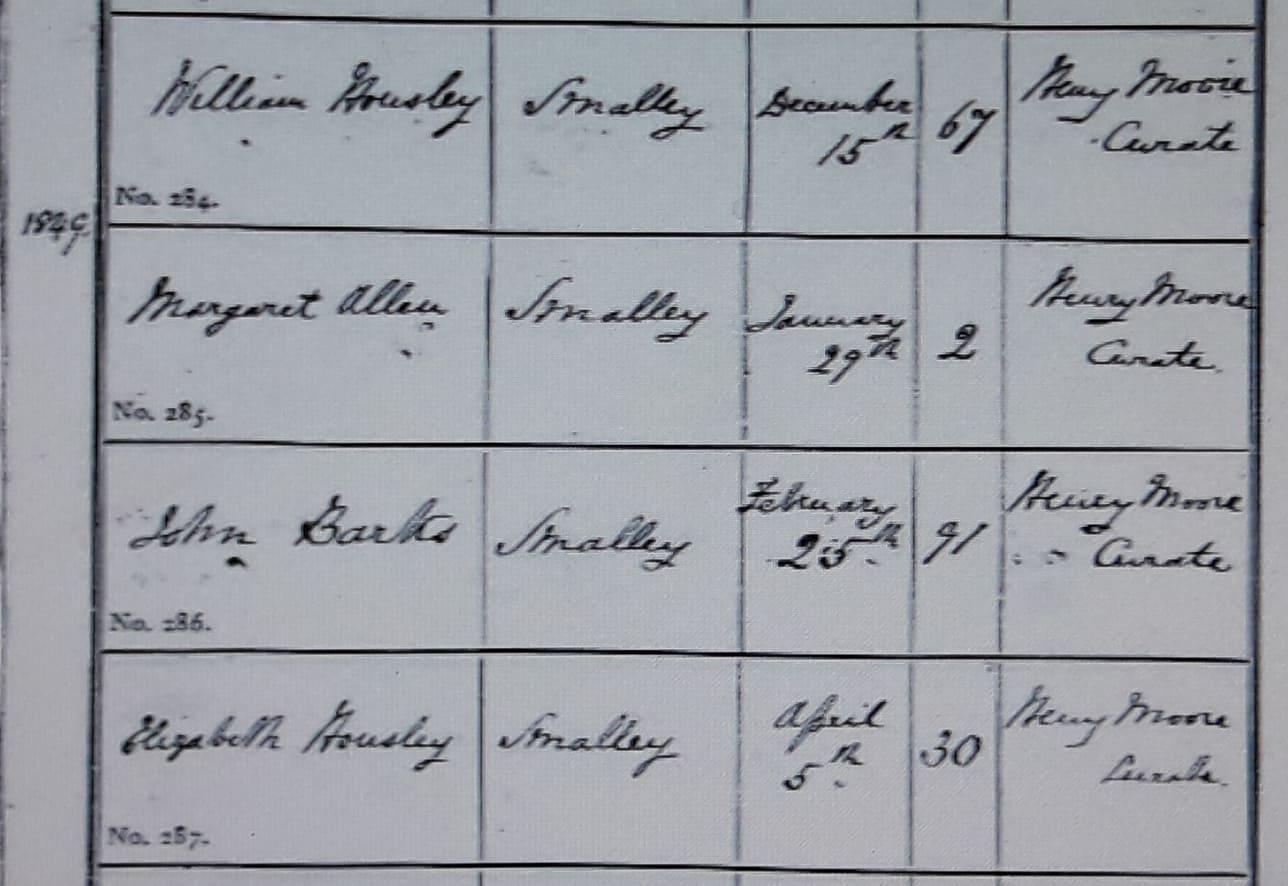

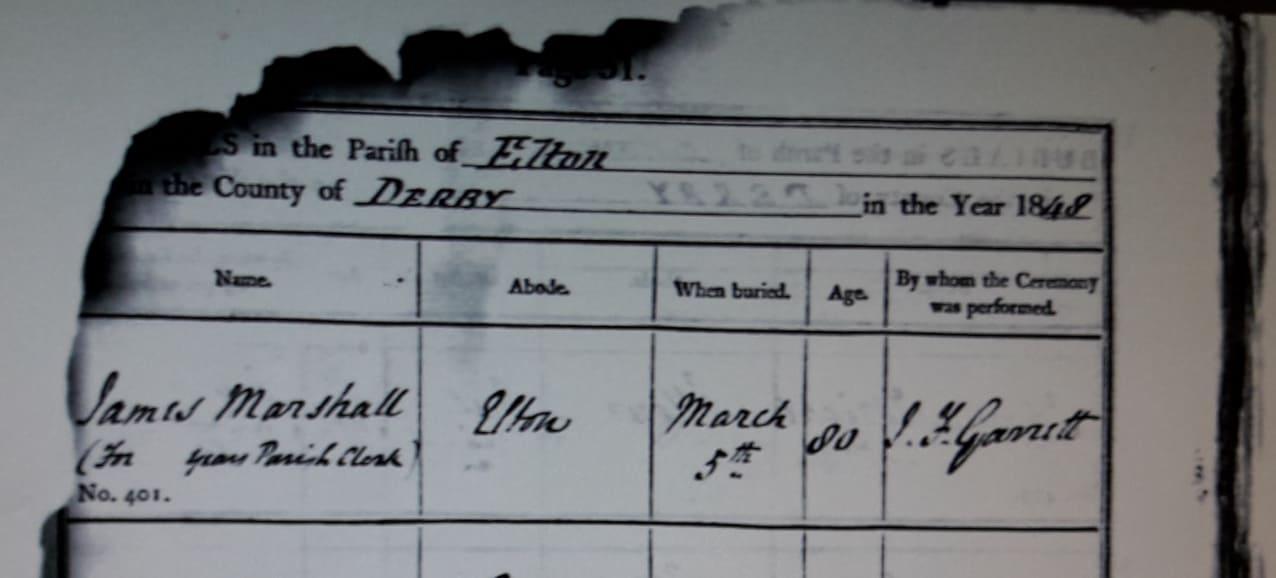

Death of William Housley 15 Dec 1848, and Elizabeth Housley 5 April 1849, Smalley:

Joseph wrote in December 1872: “I saw one of Sam’s daughters, the youngest Kate, you would remember her a baby I dare say. She is very comfortably married.”

In the same letter (December 15, 1872), Joseph wrote: “I think we have now found all out now that is concerned in the matter for there was only Sam that we did not know his whereabouts but I was informed a week ago that he is dead–died about three years ago in Birmingham Union. Poor Sam. He ought to have come to a better end than that….His daughter and her husband went to Brimingham and also to Sutton Coldfield that is where he married his wife from and found out his wife’s brother. It appears he has been there and at Birmingham ever since he went away but ever fond of drink.”

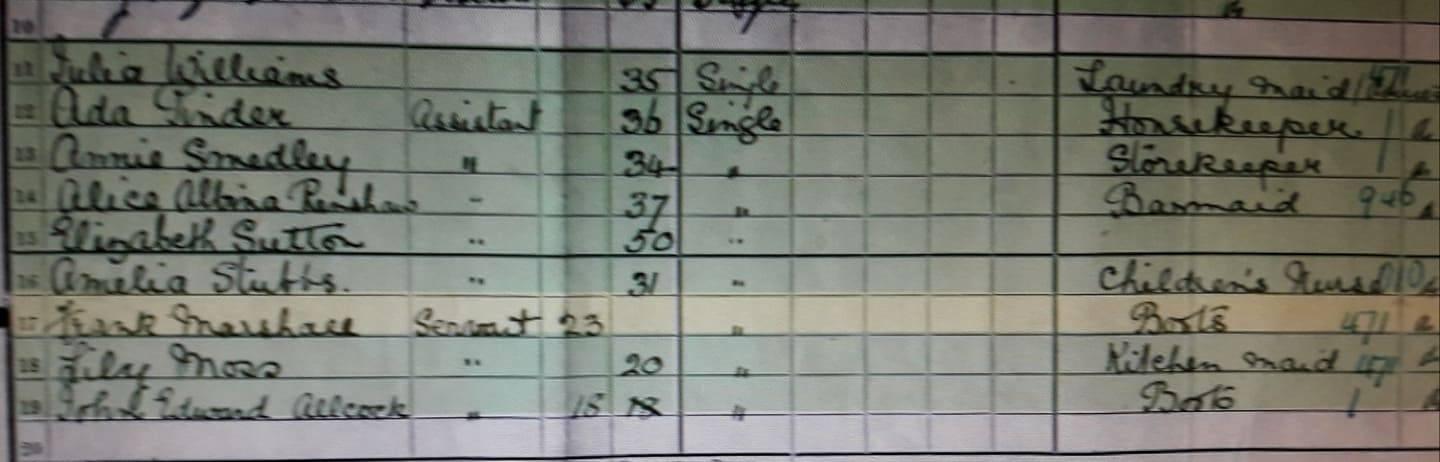

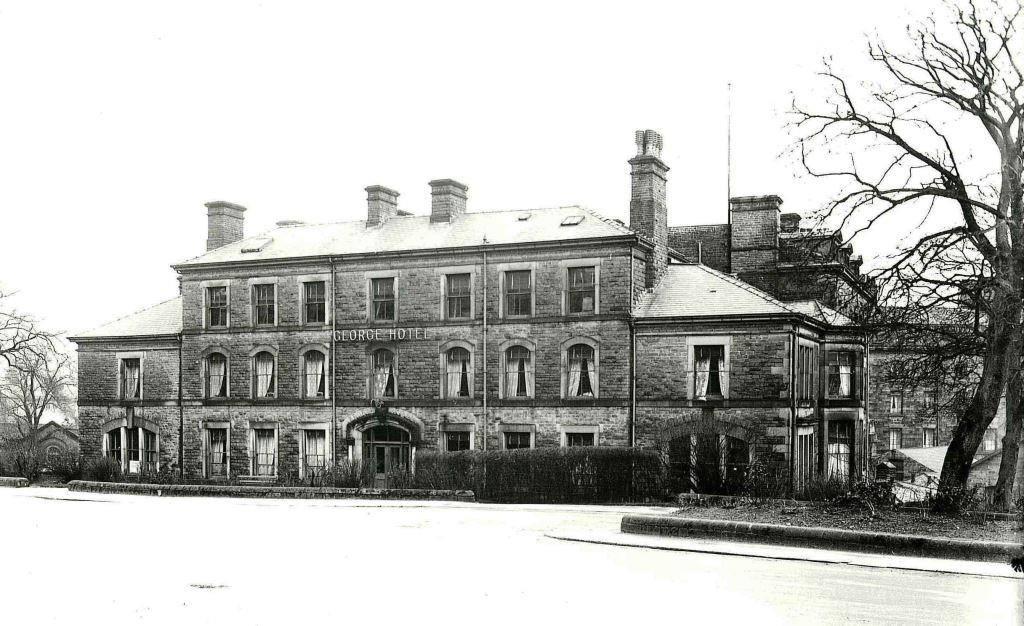

(Sam, however, was still alive in 1871, living as a lodger at the George and Dragon Inn, Henley in Arden. And no trace of Sam has been found since. It would appear that Sam did not want to be found.)

EDWARD HOUSLEY 1819-1843

Edward died before George left for USA in 1851, and as such there is no mention of him in the letters.

ANNE HOUSLEY 1821-1856

Anne wrote two letters to her brother George between February 1854 and her death in 1856. Apparently she suffered from a lung disease for she wrote: “I can say you will be surprised I am still living and better but still cough and spit a deal. Can do nothing but sit and sew.” According to the 1851 census, Anne, then 29, was a seamstress. Their friend, Mrs. Davy, wrote in March 1856: “This I send in a box to my Brother….The pincushion cover and pen wiper are Anne’s work–are for thy wife. She would have made it up had she been able.” Anne was not living at home at the time of the 1841 census. She would have been 19 or 20 and perhaps was “out service.”

In her second letter Anne wrote: “It is a great trouble now for me to write…as the body weakens so does the mind often. I have been very weak all summer. That I continue is a wonder to all and to spit so much although much better than when you left home.” She also wrote: “You know I had a desire for America years ago. Were I in health and strength, it would be the land of my adoption.”

In November 1855, Emma wrote, “Anne has been very ill all summer and has not been able to write or do anything.” Their neighbor Mrs. Davy wrote on March 21, 1856: “I fear Anne will not be long without a change.” In a black-edged letter the following June, Emma wrote: “I need not tell you how happy she was and how calmly and peacefully she died. She only kept in bed two days.”

Certainly Anne was a woman of deep faith and strong religious convictions. When she wrote that they were hoping to hear of Charles’ success on the gold fields she added: “But I would rather hear of him having sought and found the Pearl of great price than all the gold Australia can produce, (For what shall it profit a man if he gain the whole world and lose his soul?).” Then she asked George: “I should like to learn how it was you were first led to seek pardon and a savior. I do feel truly rejoiced to hear you have been led to seek and find this Pearl through the workings of the Holy Spirit and I do pray that He who has begun this good work in each of us may fulfill it and carry it on even unto the end and I can never doubt the willingness of Jesus who laid down his life for us. He who said whoever that cometh unto me I will in no wise cast out.”

Anne’s will was probated October 14, 1856. Mr. William Davy of Kidsley Park appeared for the family. Her estate was valued at under £20. Emma was to receive fancy needlework, a four post bedstead, feather bed and bedding, a mahogany chest of drawers, plates, linen and china. Emma was also to receive Anne’s writing desk. There was a condition that Ellen would have use of these items until her death.

The money that Anne was to receive from her grandfather, William Carrington, and her father, William Housley was to be distributed one third to Joseph, one third to Emma, and one third to be divided between her four neices: John’s daughter Elizabeth, 18, and Sam’s daughters Elizabeth, 10, Mary Ann, 9 and Catharine, age 7 to be paid by the trustees as they think “most useful and proper.” Emma Lyon and Elizabeth Davy were the witnesses.

The Carrington Farm:

CHARLES HOUSLEY 1823-1855

Charles went to Australia in 1851, and was last heard from in January 1853. According to the solicitor, who wrote to George on June 3, 1874, Charles had received advances on the settlement of their parent’s estate. “Your promissory note with the two signed by your brother Charles for 20 pounds he received from his father and 20 pounds he received from his mother are now in the possession of the court.”

Charles and George were probably quite close friends. Anne wrote in 1854: “Charles inquired very particularly in both his letters after you.”

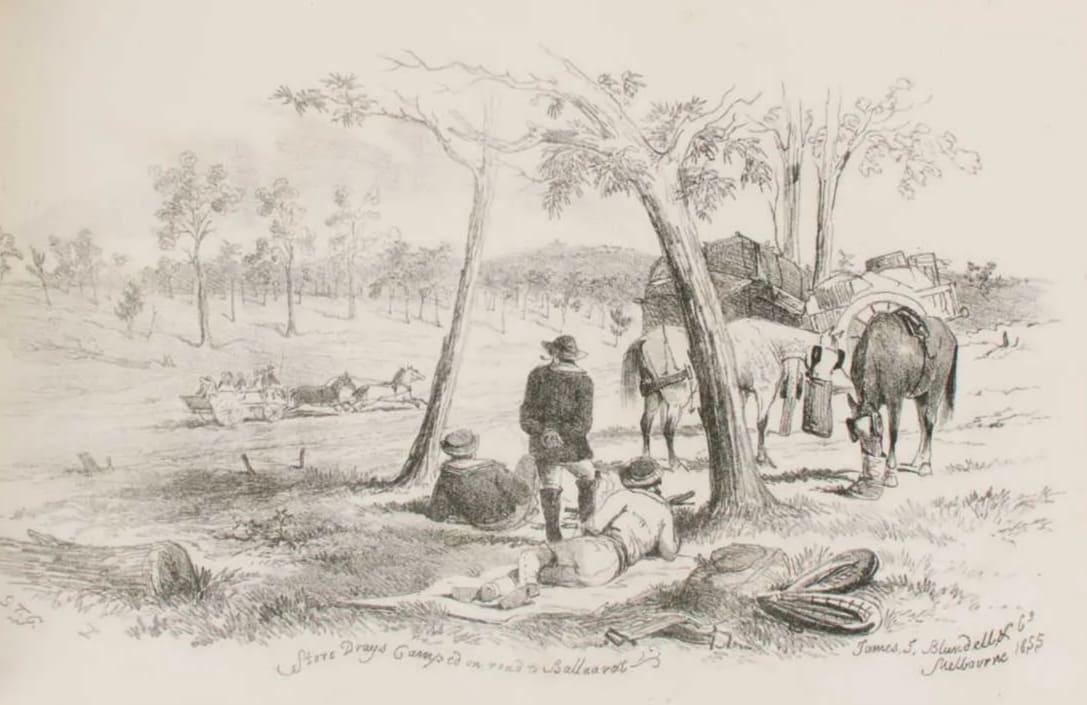

According to Anne, Charles and a friend married two sisters. He and his father-in-law had a farm where they had 130 cows and 60 pigs. Whatever the trade he learned in England, he never worked at it once he reached Australia. While it does not seem that Charles went to Australia because gold had been discovered there, he was soon caught up in “gold fever”. Anne wrote: “I dare say you have heard of the immense gold fields of Australia discovered about the time he went. Thousands have since then emigrated to Australia, both high and low. Such accounts we heard in the papers of people amassing fortunes we could not believe. I asked him when I wrote if it was true. He said this was no exaggeration for people were making their fortune daily and he intended going to the diggings in six weeks for he could stay away no longer so that we are hoping to hear of his success if he is alive.”

In March 1856, Mrs. Davy wrote: “I am sorry to tell thee they have had a letter from Charles’s wife giving account of Charles’s death of 6 months consumption at the Victoria diggings. He has left 2 children a boy and a girl William and Ellen.” In June of the same year in a black edged letter, Emma wrote: “I think Mrs. Davy mentioned Charles’s death in her note. His wife wrote to us. They have two children Helen and William. Poor dear little things. How much I should like to see them all. She writes very affectionately.”

In December 1872, Joseph wrote: “I’m told that Charles two daughters has wrote to Smalley post office making inquiries about his share….” In January 1876, the solicitor wrote: “Charles Housley’s children have claimed their father’s share.”

GEORGE HOUSLEY 1824-1877

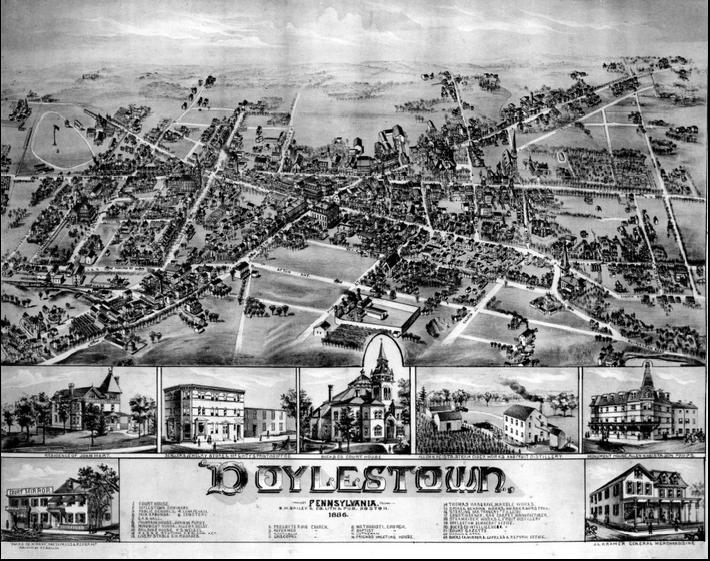

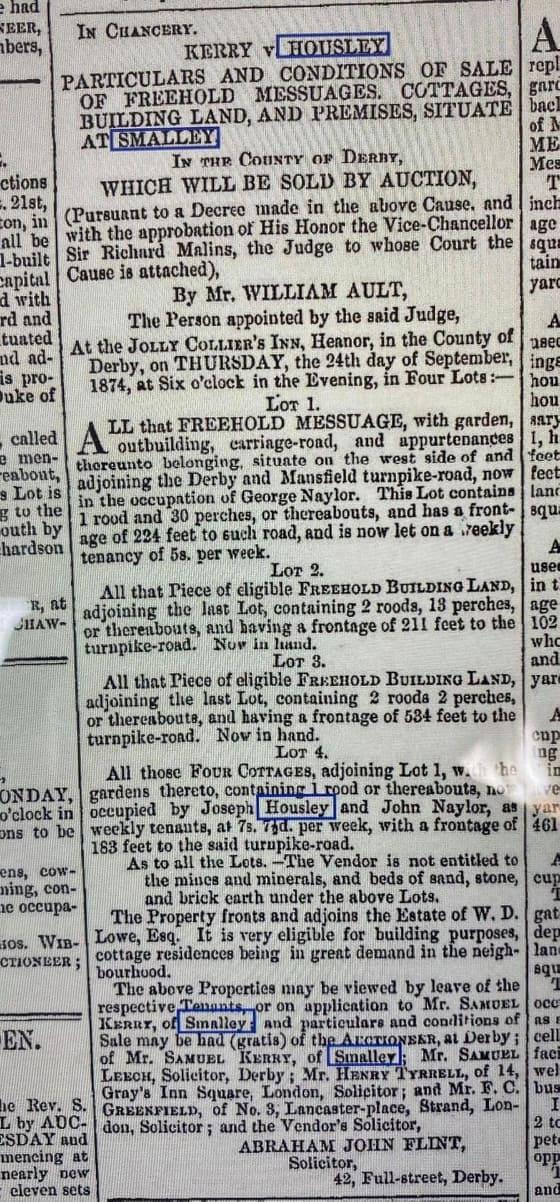

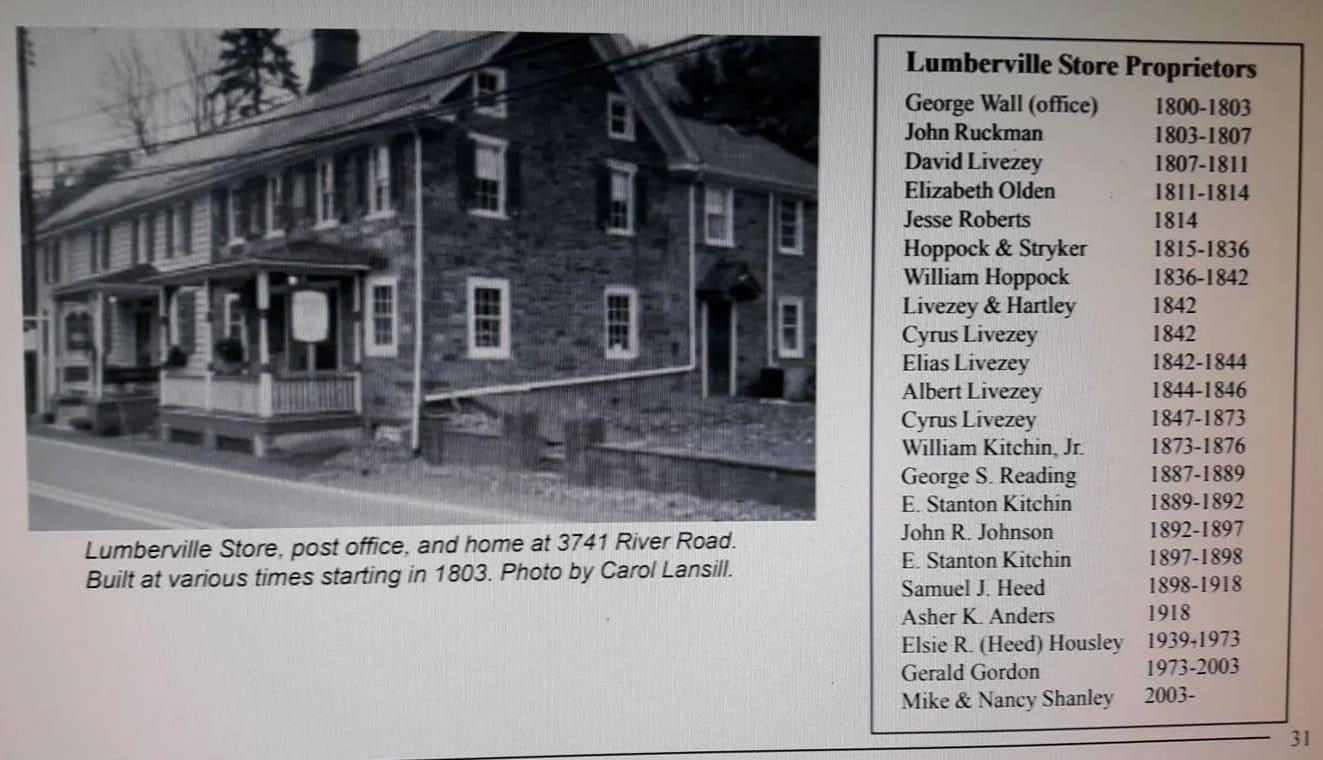

George emigrated to the United states in 1851, arriving in July. The solicitor Abraham John Flint referred in a letter to a 15-pound advance which was made to George on June 9, 1851. This certainly was connected to his journey. George settled along the Delaware River in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. The letters from the solicitor were addressed to: Lahaska Post Office, Bucks County, Pennsylvania.

George married Sarah Ann Hill on May 6, 1854 in Doylestown, Bucks County, Pennsylvania. In her first letter (February 1854), Anne wrote: “We want to know who and what is this Miss Hill you name in your letter. What age is she? Send us all the particulars but I would advise you not to get married until you have sufficient to make a comfortable home.”

Upon learning of George’s marriage, Anne wrote: “I hope dear brother you may be happy with your wife….I hope you will be as a son to her parents. Mother unites with me in kind love to you both and to your father and mother with best wishes for your health and happiness.” In 1872 (December) Joseph wrote: “I am sorry to hear that sister’s father is so ill. It is what we must all come to some time and hope we shall meet where there is no more trouble.”

Emma wrote in 1855, “We write in love to your wife and yourself and you must write soon and tell us whether there is a little nephew or niece and what you call them.” In June of 1856, Emma wrote: “We want to see dear Sarah Ann and the dear little boy. We were much pleased with the “bit of news” you sent.” The bit of news was the birth of John Eley Housley, January 11, 1855. Emma concluded her letter “Give our very kindest love to dear sister and dearest Johnnie.”

In September 1872, Joseph wrote, “I was very sorry to hear that John your oldest had met with such a sad accident but I hope he is got alright again by this time.” In the same letter, Joseph asked: “Now I want to know what sort of a town you are living in or village. How far is it from New York? Now send me all particulars if you please.”

In March 1873 Harriet asked Sarah Ann: “And will you please send me all the news at the place and what it is like for it seems to me that it is a wild place but you must tell me what it is like….”. The question of whether she was referring to Bucks County, Pennsylvania or some other place is raised in Joseph’s letter of the same week.

On March 17, 1873, Joseph wrote: “I was surprised to hear that you had gone so far away west. Now dear brother what ever are you doing there so far away from home and family–looking out for something better I suppose.”The solicitor wrote on May 23, 1874: “Lately I have not written because I was not certain of your address and because I doubted I had much interesting news to tell you.” Later, Joseph wrote concerning the problems settling the estate, “You see dear brother there is only me here on our side and I cannot do much. I wish you were here to help me a bit and if you think of going for another summer trip this turn you might as well run over here.”

Apparently, George had indicated he might return to England for a visit in 1856. Emma wrote concerning the portrait of their mother which had been sent to George: “I hope you like mother’s portrait. I did not see it but I suppose it was not quite perfect about the eyes….Joseph and I intend having ours taken for you when you come over….Do come over before very long.”

In March 1873, Joseph wrote: “You ask me what I think of you coming to England. I think as you have given the trustee power to sign for you I think you could do no good but I should like to see you once again for all that. I can’t say whether there would be anything amiss if you did come as you say it would be throwing good money after bad.”

On June 10, 1875, the solicitor wrote: “I have been expecting to hear from you for some time past. Please let me hear what you are doing and where you are living and how I must send you your money.” George’s big news at that time was that on May 3, 1875, he had become a naturalized citizen “renouncing and abjuring all allegiance and fidelity to every foreign prince, potentate, state and sovereignity whatsoever, and particularly to Victoria Queen of Great Britain of whom he was before a subject.”

ROBERT HOUSLEY 1832-1851

In 1854, Anne wrote: “Poor Robert. He died in August after you left he broke a blood vessel in the lung.”

From Joseph’s first letter we learn that Robert was 19 when he died: “Dear brother there have been a great many changes in the family since you left us. All is gone except myself and John and Sam–we have heard nothing of him since he left. Robert died first when he was 19 years of age. Then Anne and Charles too died in Australia and then a number of years elapsed before anyone else. Then John lost his wife, then Emma, and last poor dear mother died last January on the 11th.”Anne described Robert’s death in this way: “He had thrown up blood many times before in the spring but the last attack weakened him that he only lived a fortnight after. He died at Derby. Mother was with him. Although he suffered much he never uttered a murmur or regret and always a smile on his face for everyone that saw him. He will be regretted by all that knew him”.

Robert died a resident of St. Peter’s Parish, Derby, but was buried in Smalley on August 16, 1851.

Apparently Robert was apprenticed to be a joiner for, according to Anne, Joseph took his place: “Joseph wanted to be a joiner. We thought we could do no better than let him take Robert’s place which he did the October after and is there still.”In 1876, the solicitor wrote to George: “Have you heard of John Housley? He is entitled to Robert’s share and I want him to claim it.”

EMMA HOUSLEY 1836-1871

Emma was not mentioned in Anne’s first letter. In the second, Anne wrote that Emma was living at Spondon with two ladies in her “third situation,” and added, “She is grown a bouncing woman.” Anne described her sister well. Emma wrote in her first letter (November 12, 1855): “I must tell you that I am just 21 and we had my pudding last Sunday. I wish I could send you a piece.”

From Emma’s letters we learn that she was living in Derby from May until November 1855 with Mr. Haywood, an iron merchant. She explained, “He has failed and I have been obliged to leave,” adding, “I expect going to a new situation very soon. It is at Belper.” In 1851 records, William Haywood, age 22, was listed as an iron foundry worker. In the 1857 Derby Directory, James and George were listed as iron and brass founders and ironmongers with an address at 9 Market Place, Derby.

In June 1856, Emma wrote from “The Cedars, Ashbourne Road” where she was working for Mr. Handysides.

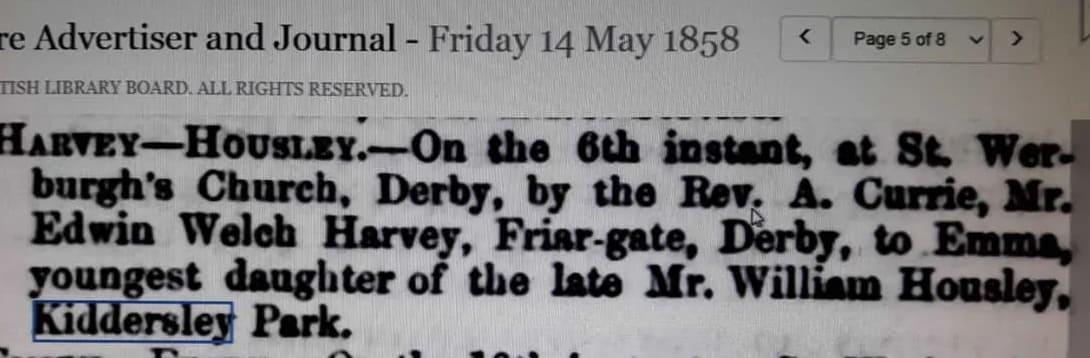

While she was working for Mr. Handysides, Emma wrote: “Mother is thinking of coming to live at Derby. That will be nice for Joseph and I.”Friargate and Ashbourne Road were located in St. Werburgh’s Parish. (In fact, St. Werburgh’s vicarage was at 185 Surrey Street. This clue led to the discovery of the record of Emma’s marriage on May 6, 1858, to Edwin Welch Harvey, son of Samuel Harvey in St. Werburgh’s.)

In 1872, Joseph wrote: “Our sister Emma, she died at Derby at her own home for she was married. She has left two young children behind. The husband was the son of the man that I went apprentice to and has caused a great deal of trouble to our family and I believe hastened poor Mother’s death….”. Joseph added that he believed Emma’s “complaint” was consumption and that she was sick a good bit. Joseph wrote: “Mother was living with John when I came home (from Ascension Island around 1867? or to Smalley from Derby around 1870?) for when Emma was married she broke up the comfortable home and the things went to Derby and she went to live with them but Derby did not agree with her so she had to leave it again but left all her things there.”

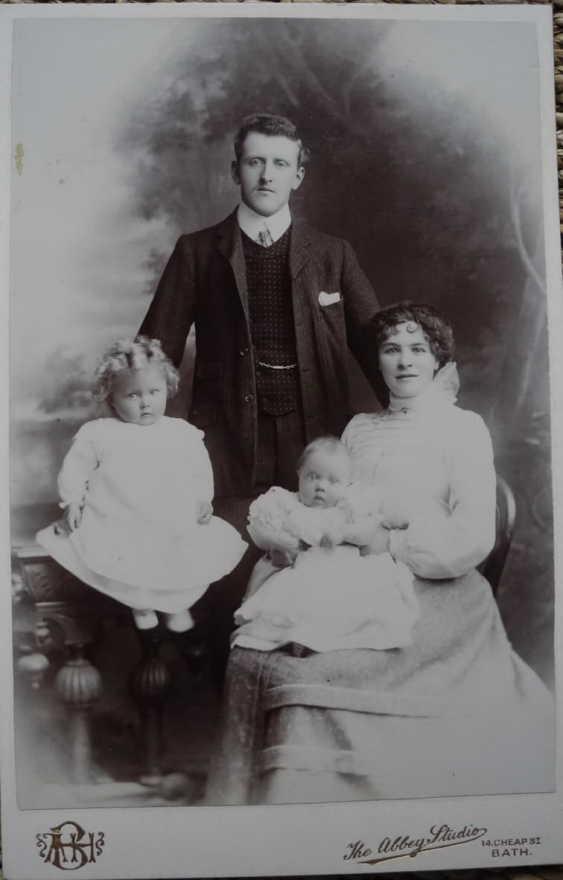

Emma Housley and Edwin Welch Harvey wedding, 1858:

JOSEPH HOUSLEY 1838-1893

We first hear of Joseph in a letter from Anne to George in 1854. “Joseph wanted to be a joiner. We thought we could do no better than let him take Robert’s place which he did the October after (probably 1851) and is there still. He is grown as tall as you I think quite a man.” Emma concurred in her first letter: “He is quite a man in his appearance and quite as tall as you.”

From Emma we learn in 1855: “Joseph has left Mr. Harvey. He had not work to employ him. So mother thought he had better leave his indenture and be at liberty at once than wait for Harvey to be a bankrupt. He has got a very good place of work now and is very steady.” In June of 1856, Emma wrote “Joseph and I intend to have our portraits taken for you when you come over….Mother is thinking of coming to Derby. That will be nice for Joseph and I. Joseph is very hearty I am happy to say.”

According to Joseph’s letters, he was married to Harriet Ballard. Joseph described their miraculous reunion in this way: “I must tell you that I have been abroad myself to the Island of Ascension. (Elsewhere he wrote that he was on the island when the American civil war broke out). I went as a Royal Marine and worked at my trade and saved a bit of money–enough to buy my discharge and enough to get married with but while I was out on the island who should I meet with there but my dear wife’s sister. (On two occasions Joseph and Harriet sent George the name and address of Harriet’s sister, Mrs. Brooks, in Susquehanna Depot, Pennsylvania, but it is not clear whether this was the same sister.) She was lady’s maid to the captain’s wife. Though I had never seen her before we got to know each other somehow so from that me and my wife recommenced our correspondence and you may be sure I wanted to get home to her. But as soon as I did get home that is to England I was not long before I was married and I have not regretted yet for we are very comfortable as well as circumstances will allow for I am only a journeyman joiner.”

Proudly, Joseph wrote: “My little family consists of three nice children–John, Joseph and Susy Annie.” On her birth certificate, Susy Ann’s birthdate is listed as 1871. Parish records list a Lucy Annie christened in 1873. The boys were born in Derby, John in 1868 and Joseph in 1869. In his second letter, Joseph repeated: “I have got three nice children, a good wife and I often think is more than I have deserved.” On August 6, 1873, Joseph and Harriet wrote: “We both thank you dear sister for the pieces of money you sent for the children. I don’t know as I have ever see any before.” Joseph ended another letter: “Now I must close with our kindest love to you all and kisses from the children.”

In Harriet’s letter to Sarah Ann (March 19, 1873), she promised: “I will send you myself and as soon as the weather gets warm as I can take the children to Derby, I will have them taken and send them, but it is too cold yet for we have had a very cold winter and a great deal of rain.” At this time, the children were all under 6 and the baby was not yet two.

In March 1873 Joseph wrote: “I have been working down at Heanor gate there is a joiner shop there where Kings used to live I have been working there this winter and part of last summer but the wages is very low but it is near home that is one comfort.” (Heanor Gate is about 1/4 mile from Kidsley Grange. There was a school and industrial park there in 1988.) At this time Joseph and his family were living in “the big house–in Old Betty Hanson’s house.” The address in the 1871 census was Smalley Lane.

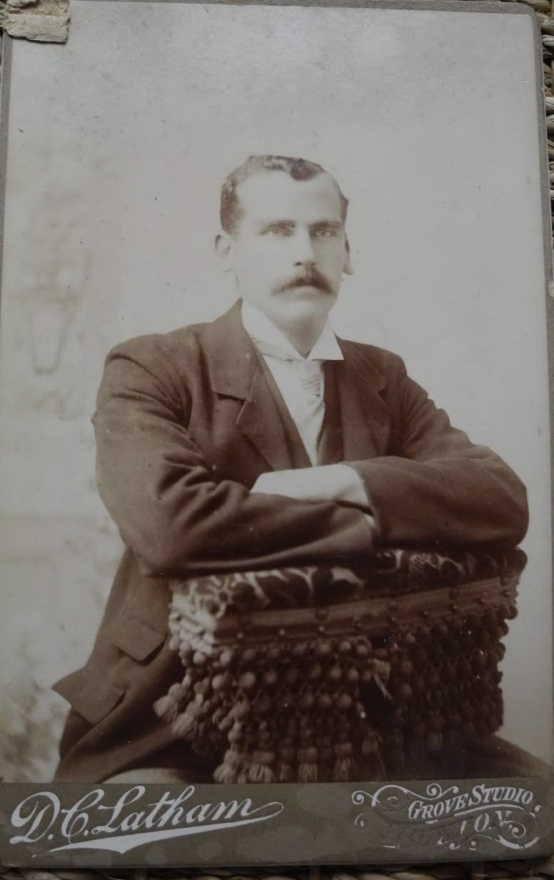

A glimpse into Joseph’s personality is revealed by this remark to George in an 1872 letter: “Many thanks for your portrait and will send ours when we can get them taken for I never had but one taken and that was in my old clothes and dear Harriet is not willing to part with that. I tell her she ought to be satisfied with the original.”

On one occasion Joseph and Harriet both sent seeds. (Marks are still visible on the paper.) Joseph sent “the best cow cabbage seed in the country–Robinson Champion,” and Harriet sent red cabbage–Shaw’s Improved Red. Possibly cow cabbage was also known as ox cabbage: “I hope you will have some good cabbages for the Ox cabbage takes all the prizes here. I suppose you will be taking the prizes out there with them.” Joseph wrote that he would put the name of the seeds by each “but I should think that will not matter. You will tell the difference when they come up.”

George apparently would have liked Joseph to come to him as early as 1854. Anne wrote: “As to his coming to you that must be left for the present.” In 1872, Joseph wrote: “I have been thinking of making a move from here for some time before I heard from you for it is living from hand to mouth and never certain of a job long either.” Joseph then made plans to come to the United States in the spring of 1873. “For I intend all being well leaving England in the spring. Many thanks for your kind offer but I hope we shall be able to get a comfortable place before we have been out long.” Joseph promised to bring some things George wanted and asked: “What sort of things would be the best to bring out there for I don’t want to bring a lot that is useless.” Joseph’s plans are confirmed in a letter from the solicitor May 23, 1874: “I trust you are prospering and in good health. Joseph seems desirous of coming out to you when this is settled.”

George must have been reminiscing about gooseberries (Heanor has an annual gooseberry show–one was held July 28, 1872) and Joseph promised to bring cuttings when they came: “Dear Brother, I could not get the gooseberries for they was all gathered when I received your letter but we shall be able to get some seed out the first chance and I shall try to bring some cuttings out along.” In the same letter that he sent the cabbage seeds Joseph wrote: “I have got some gooseberries drying this year for you. They are very fine ones but I have only four as yet but I was promised some more when they were ripe.” In another letter Joseph sent gooseberry seeds and wrote their names: Victoria, Gharibaldi and Globe.

In September 1872 Joseph wrote; “My wife is anxious to come. I hope it will suit her health for she is not over strong.” Elsewhere Joseph wrote that Harriet was “middling sometimes. She is subject to sick headaches. It knocks her up completely when they come on.” In December 1872 Joseph wrote, “Now dear brother about us coming to America you know we shall have to wait until this affair is settled and if it is not settled and thrown into Chancery I’m afraid we shall have to stay in England for I shall never be able to save money enough to bring me out and my family but I hope of better things.”

On July 19, 1875 Abraham Flint (the solicitor) wrote: “Joseph Housley has removed from Smalley and is working on some new foundry buildings at Little Chester near Derby. He lives at a village called Little Eaton near Derby. If you address your letter to him as Joseph Housley, carpenter, Little Eaton near Derby that will no doubt find him.”

George did not save any letters from Joseph after 1874, hopefully he did reach him at Little Eaton. Joseph and his family are not listed in either Little Eaton or Derby on the 1881 census.

In his last letter (February 11, 1874), Joseph sounded very discouraged and wrote that Harriet’s parents were very poorly and both had been “in bed for a long time.” In addition, Harriet and the children had been ill.

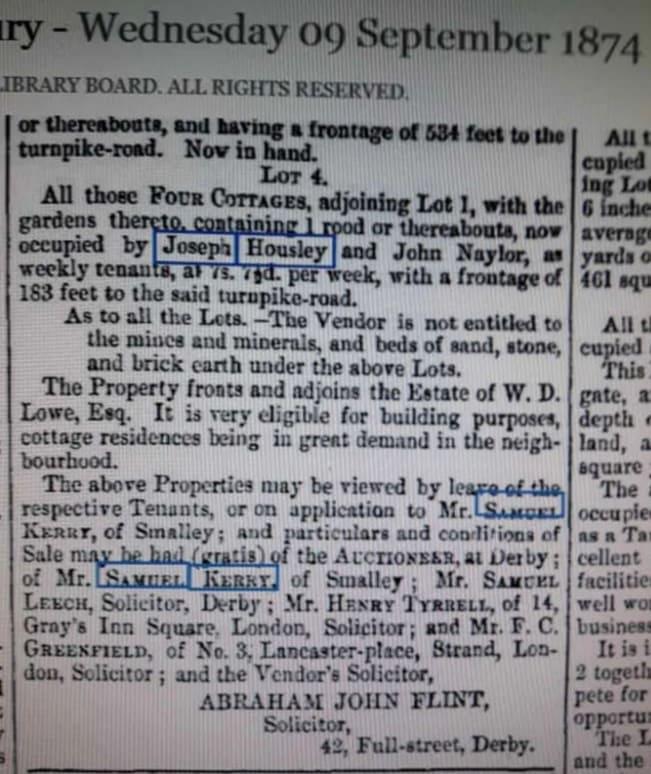

The move to Little Eaton may indicate that Joseph received his settlement because in August, 1873, he wrote: “I think this is bad news enough and bad luck too, but I have had little else since I came to live at Kiddsley cottages but perhaps it is all for the best if one could only think so. I have begun to think there will be no chance for us coming over to you for I am afraid there will not be so much left as will bring us out without it is settled very shortly but I don’t intend leaving this house until it is settled either one way or the other. “Joseph Housley and the Kiddsley cottages:

February 2, 2022 at 1:15 pm #6268

February 2, 2022 at 1:15 pm #6268In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

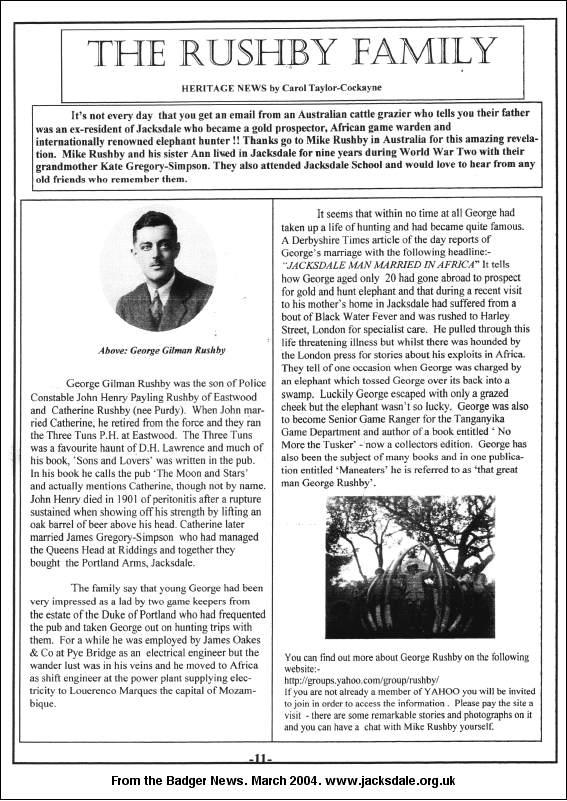

From Tanganyika with Love

continued part 9

With thanks to Mike Rushby.

Lyamungu 3rd January 1945

Dearest Family.

We had a novel Christmas this year. We decided to avoid the expense of

entertaining and being entertained at Lyamungu, and went off to spend Christmas

camping in a forest on the Western slopes of Kilimanjaro. George decided to combine

business with pleasure and in this way we were able to use Government transport.

We set out the day before Christmas day and drove along the road which skirts

the slopes of Kilimanjaro and first visited a beautiful farm where Philip Teare, the ex

Game Warden, and his wife Mary are staying. We had afternoon tea with them and then

drove on in to the natural forest above the estate and pitched our tent beside a small

clear mountain stream. We decorated the tent with paper streamers and a few small

balloons and John found a small tree of the traditional shape which we decorated where

it stood with tinsel and small ornaments.We put our beer, cool drinks for the children and bottles of fresh milk from Simba

Estate, in the stream and on Christmas morning they were as cold as if they had been in

the refrigerator all night. There were not many presents for the children, there never are,

but they do not seem to mind and are well satisfied with a couple of balloons apiece,

sweets, tin whistles and a book each.George entertain the children before breakfast. He can make a magical thing out

of the most ordinary balloon. The children watched entranced as he drew on his pipe

and then blew the smoke into the balloon. He then pinched the neck of the balloon

between thumb and forefinger and released the smoke in little puffs. Occasionally the

balloon ejected a perfect smoke ring and the forest rang with shouts of “Do it again

Daddy.” Another trick was to blow up the balloon to maximum size and then twist the

neck tightly before releasing. Before subsiding the balloon darted about in a crazy

fashion causing great hilarity. Such fun, at the cost of a few pence.After breakfast George went off to fish for trout. John and Jim decided that they

also wished to fish so we made rods out of sticks and string and bent pins and they

fished happily, but of course quite unsuccessfully, for hours. Both of course fell into the

stream and got soaked, but I was prepared for this, and the little stream was so shallow

that they could not come to any harm. Henry played happily in the sand and I had a

most peaceful morning.Hamisi roasted a chicken in a pot over the camp fire and the jelly set beautifully in the

stream. So we had grilled trout and chicken for our Christmas dinner. I had of course

taken an iced cake for the occasion and, all in all, it was a very successful Christmas day.

On Boxing day we drove down to the plains where George was to investigate a

report of game poaching near the Ngassari Furrow. This is a very long ditch which has

been dug by the Government for watering the Masai stock in the area. It is also used by

game and we saw herds of zebra and wildebeest, and some Grant’s Gazelle and

giraffe, all comparatively tame. At one point a small herd of zebra raced beside the lorry

apparently enjoying the fun of a gallop. They were all sleek and fat and looked wild and

beautiful in action.We camped a considerable distance from the water but this precaution did not

save us from the mosquitoes which launched a vicious attack on us after sunset, so that

we took to our beds unusually early. They were on the job again when we got up at

sunrise so I was very glad when we were once more on our way home.“I like Christmas safari. Much nicer that silly old party,” said John. I agree but I think

it is time that our children learned to play happily with others. There are no other young

children at Lyamungu though there are two older boys and a girl who go to boarding

school in Nairobi.On New Years Day two Army Officers from the military camp at Moshi, came for

tea and to talk game hunting with George. I think they rather enjoy visiting a home and

seeing children and pets around.Eleanor.

Lyamungu 14 May 1945

Dearest Family.

So the war in Europe is over at last. It is such marvellous news that I can hardly

believe it. To think that as soon as George can get leave we will go to England and

bring Ann and George home with us to Tanganyika. When we know when this leave can

be arranged we will want Kate to join us here as of course she must go with us to

England to meet George’s family. She has become so much a part of your lives that I

know it will be a wrench for you to give her up but I know that you will all be happy to

think that soon our family will be reunited.The V.E. celebrations passed off quietly here. We all went to Moshi to see the

Victory Parade of the King’s African Rifles and in the evening we went to a celebration

dinner at the Game Warden’s house. Besides ourselves the Moores had invited the

Commanding Officer from Moshi and a junior officer. We had a very good dinner and

many toasts including one to Mrs Moore’s brother, Oliver Milton who is fighting in Burma

and has recently been awarded the Military Cross.There was also a celebration party for the children in the grounds of the Moshi

Club. Such a spread! I think John and Jim sampled everything. We mothers were

having our tea separately and a friend laughingly told me to turn around and have a look.

I did, and saw the long tea tables now deserted by all the children but my two sons who

were still eating steadily, and finding the party more exciting than the game of Musical

Bumps into which all the other children had entered with enthusiasm.There was also an extremely good puppet show put on by the Italian prisoners

of war from the camp at Moshi. They had made all the puppets which included well

loved characters like Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs and the Babes in the Wood as

well as more sophisticated ones like an irritable pianist and a would be prima donna. The

most popular puppets with the children were a native askari and his family – a very

happy little scene. I have never before seen a puppet show and was as entranced as

the children. It is amazing what clever manipulation and lighting can do. I believe that the

Italians mean to take their puppets to Nairobi and am glad to think that there, they will

have larger audiences to appreciate their art.George has just come in, and I paused in my writing to ask him for the hundredth

time when he thinks we will get leave. He says I must be patient because it may be a

year before our turn comes. Shipping will be disorganised for months to come and we

cannot expect priority simply because we have been separated so long from our

children. The same situation applies to scores of other Government Officials.

I have decided to write the story of my childhood in South Africa and about our

life together in Tanganyika up to the time Ann and George left the country. I know you

will have told Kate these stories, but Ann and George were so very little when they left

home that I fear that they cannot remember much.My Mother-in-law will have told them about their father but she can tell them little

about me. I shall send them one chapter of my story each month in the hope that they

may be interested and not feel that I am a stranger when at last we meet again.Eleanor.

Lyamungu 19th September 1945

Dearest Family.

In a months time we will be saying good-bye to Lyamungu. George is to be

transferred to Mbeya and I am delighted, not only as I look upon Mbeya as home, but

because there is now a primary school there which John can attend. I feel he will make

much better progress in his lessons when he realises that all children of his age attend

school. At present he is putting up a strong resistance to learning to read and spell, but

he writes very neatly, does his sums accurately and shows a real talent for drawing. If

only he had the will to learn I feel he would do very well.Jim now just four, is too young for lessons but too intelligent to be interested in

the ayah’s attempts at entertainment. Yes I’ve had to engage a native girl to look after

Henry from 9 am to 12.30 when I supervise John’s Correspondence Course. She is

clean and amiable, but like most African women she has no initiative at all when it comes

to entertaining children. Most African men and youths are good at this.I don’t regret our stay at Lyamungu. It is a beautiful spot and the change to the

cooler climate after the heat of Morogoro has been good for all the children. John is still

tall for his age but not so thin as he was and much less pale. He is a handsome little lad

with his large brown eyes in striking contrast to his fair hair. He is wary of strangers but

very observant and quite uncanny in the way he sums up people. He seldom gets up

to mischief but I have a feeling he eggs Jim on. Not that Jim needs egging.Jim has an absolute flair for mischief but it is all done in such an artless manner that

it is not easy to punish him. He is a very sturdy child with a cap of almost black silky hair,

eyes brown, like mine, and a large mouth which is quick to smile and show most beautiful

white and even teeth. He is most popular with all the native servants and the Game

Scouts. The servants call Jim, ‘Bwana Tembo’ (Mr Elephant) because of his sturdy

build.Henry, now nearly two years old, is quite different from the other two in

appearance. He is fair complexioned and fair haired like Ann and Kate, with large, black

lashed, light grey eyes. He is a good child, not so merry as Jim was at his age, nor as

shy as John was. He seldom cries, does not care to be cuddled and is independent and

strong willed. The servants call Henry, ‘Bwana Ndizi’ (Mr Banana) because he has an

inexhaustible appetite for this fruit. Fortunately they are very inexpensive here. We buy

an entire bunch which hangs from a beam on the back verandah, and pluck off the

bananas as they ripen. This way there is no waste and the fruit never gets bruised as it

does in greengrocers shops in South Africa. Our three boys make a delightful and

interesting trio and I do wish you could see them for yourselves.We are delighted with the really beautiful photograph of Kate. She is an

extraordinarily pretty child and looks so happy and healthy and a great credit to you.

Now that we will be living in Mbeya with a school on the doorstep I hope that we will

soon be able to arrange for her return home.Eleanor.

c/o Game Dept. Mbeya. 30th October 1945

Dearest Family.

How nice to be able to write c/o Game Dept. Mbeya at the head of my letters.

We arrived here safely after a rather tiresome journey and are installed in a tiny house on

the edge of the township.We left Lyamungu early on the morning of the 22nd. Most of our goods had

been packed on the big Ford lorry the previous evening, but there were the usual

delays and farewells. Of our servants, only the cook, Hamisi, accompanied us to

Mbeya. Japhet, Tovelo and the ayah had to be paid off and largesse handed out.

Tovelo’s granny had come, bringing a gift of bananas, and she also brought her little

granddaughter to present a bunch of flowers. The child’s little scolded behind is now

completely healed. Gifts had to be found for them too.At last we were all aboard and what a squash it was! Our few pieces of furniture

and packing cases and trunks, the cook, his wife, the driver and the turney boy, who

were to take the truck back to Lyamungu, and all their bits and pieces, bunches of

bananas and Fanny the dog were all crammed into the body of the lorry. George, the

children and I were jammed together in the cab. Before we left George looked

dubiously at the tyres which were very worn and said gloomily that he thought it most

unlikely that we would make our destination, Dodoma.Too true! Shortly after midday, near Kwakachinja, we blew a back tyre and there

was a tedious delay in the heat whilst the wheel was changed. We were now without a

spare tyre and George said that he would not risk taking the Ford further than Babati,

which is less than half way to Dodoma. He drove very slowly and cautiously to Babati

where he arranged with Sher Mohammed, an Indian trader, for a lorry to take us to

Dodoma the next morning.It had been our intention to spend the night at the furnished Government

Resthouse at Babati but when we got there we found that it was already occupied by

several District Officers who had assembled for a conference. So, feeling rather

disgruntled, we all piled back into the lorry and drove on to a place called Bereku where

we spent an uncomfortable night in a tumbledown hut.Before dawn next morning Sher Mohammed’s lorry drove up, and there was a

scramble to dress by the light of a storm lamp. The lorry was a very dilapidated one and

there was already a native woman passenger in the cab. I felt so tired after an almost

sleepless night that I decided to sit between the driver and this woman with the sleeping

Henry on my knee. It was as well I did, because I soon found myself dosing off and

drooping over towards the woman. Had she not been there I might easily have fallen

out as the battered cab had no door. However I was alert enough when daylight came

and changed places with the woman to our mutual relief. She was now able to converse

with the African driver and I was able to enjoy the scenery and the fresh air!

George, John and Jim were less comfortable. They sat in the lorry behind the

cab hemmed in by packing cases. As the lorry was an open one the sun beat down

unmercifully upon them until George, ever resourceful, moved a table to the front of the

truck. The two boys crouched under this and so got shelter from the sun but they still had

to endure the dust. Fanny complicated things by getting car sick and with one thing and

another we were all jolly glad to get to Dodoma.We spent the night at the Dodoma Hotel and after hot baths, a good meal and a

good nights rest we cheerfully boarded a bus of the Tanganyika Bus Service next

morning to continue our journey to Mbeya. The rest of the journey was uneventful. We slept two nights on the road, the first at Iringa Hotel and the second at Chimala. We

reached Mbeya on the 27th.I was rather taken aback when I first saw the little house which has been allocated

to us. I had become accustomed to the spacious houses we had in Morogoro and

Lyamungu. However though the house is tiny it is secluded and has a long garden

sloping down to the road in front and another long strip sloping up behind. The front

garden is shaded by several large cypress and eucalyptus trees but the garden behind

the house has no shade and consists mainly of humpy beds planted with hundreds of

carnations sadly in need of debudding. I believe that the previous Game Ranger’s wife

cultivated the carnations and, by selling them, raised money for War Funds.

Like our own first home, this little house is built of sun dried brick. Its original

owners were Germans. It is now rented to the Government by the Custodian of Enemy

Property, and George has his office in another ex German house.This afternoon we drove to the school to arrange about enrolling John there. The

school is about four miles out of town. It was built by the German settlers in the late

1930’s and they were justifiably proud of it. It consists of a great assembly hall and

classrooms in one block and there are several attractive single storied dormitories. This

school was taken over by the Government when the Germans were interned on the

outbreak of war and many improvements have been made to the original buildings. The

school certainly looks very attractive now with its grassed playing fields and its lawns and

bright flower beds.The Union Jack flies from a tall flagpole in front of the Hall and all traces of the

schools German origin have been firmly erased. We met the Headmaster, Mr

Wallington, and his wife and some members of the staff. The school is co-educational

and caters for children from the age of seven to standard six. The leaving age is elastic

owing to the fact that many Tanganyika children started school very late because of lack

of educational facilities in this country.The married members of the staff have their own cottages in the grounds. The

Matrons have quarters attached to the dormitories for which they are responsible. I felt

most enthusiastic about the school until I discovered that the Headmaster is adamant

upon one subject. He utterly refuses to take any day pupils at the school. So now our

poor reserved Johnny will have to adjust himself to boarding school life.

We have arranged that he will start school on November 5th and I shall be very

busy trying to assemble his school uniform at short notice. The clothing list is sensible.

Boys wear khaki shirts and shorts on weekdays with knitted scarlet jerseys when the

weather is cold. On Sundays they wear grey flannel shorts and blazers with the silver

and scarlet school tie.Mbeya looks dusty, brown and dry after the lush evergreen vegetation of

Lyamungu, but I prefer this drier climate and there are still mountains to please the eye.

In fact the lower slopes of Lolesa Mountain rise at the upper end of our garden.Eleanor.

c/o Game Dept. Mbeya. 21st November 1945

Dearest Family.

We’re quite settled in now and I have got the little house fixed up to my

satisfaction. I have engaged a rather uncouth looking houseboy but he is strong and

capable and now that I am not tied down in the mornings by John’s lessons I am able to

go out occasionally in the mornings and take Jim and Henry to play with other children.

They do not show any great enthusiasm but are not shy by nature as John is.

I have had a good deal of heartache over putting John to boarding school. It

would have been different had he been used to the company of children outside his

own family, or if he had even known one child there. However he seems to be adjusting

himself to the life, though slowly. At least he looks well and tidy and I am quite sure that

he is well looked after.I must confess that when the time came for John to go to school I simply did not

have the courage to take him and he went alone with George, looking so smart in his

new uniform – but his little face so bleak. The next day, Sunday, was visiting day but the

Headmaster suggested that we should give John time to settle down and not visit him

until Wednesday.When we drove up to the school I spied John on the far side of the field walking

all alone. Instead of running up with glad greetings, as I had expected, he came almost

reluctently and had little to say. I asked him to show me his dormitory and classroom and

he did so politely as though I were a stranger. At last he volunteered some information.

“Mummy,” he said in an awed voice, Do you know on the night I came here they burnt a

man! They had a big fire and they burnt him.” After a blank moment the penny dropped.

Of course John had started school and November the fifth but it had never entered my

head to tell him about that infamous character, Guy Fawkes!I asked John’s Matron how he had settled down. “Well”, she said thoughtfully,

“John is very good and has not cried as many of the juniors do when they first come

here, but he seems to keep to himself all the time.” I went home very discouraged but

on the Sunday John came running up with another lad of about his own age.” This is my

friend Marks,” he announced proudly. I could have hugged Marks.Mbeya is very different from the small settlement we knew in the early 1930’s.

Gone are all the colourful characters from the Lupa diggings for the alluvial claims are all

worked out now, gone also are our old friends the Menzies from the Pub and also most

of the Government Officials we used to know. Mbeya has lost its character of a frontier

township and has become almost suburban.The social life revolves around two places, the Club and the school. The Club

which started out as a little two roomed building, has been expanded and the golf

course improved. There are also tennis courts and a good library considering the size of

the community. There are frequent parties and dances, though most of the club revenue

comes from Bar profits. The parties are relatively sober affairs compared with the parties

of the 1930’s.The school provides entertainment of another kind. Both Mr and Mrs Wallington

are good amateur actors and I am told that they run an Amateur Dramatic Society. Every

Wednesday afternoon there is a hockey match at the school. Mbeya town versus a

mixed team of staff and scholars. The match attracts almost the whole European

population of Mbeya. Some go to play hockey, others to watch, and others to snatch

the opportunity to visit their children. I shall have to try to arrange a lift to school when

George is away on safari.I have now met most of the local women and gladly renewed an old friendship

with Sheilagh Waring whom I knew two years ago at Morogoro. Sheilagh and I have

much in common, the same disregard for the trappings of civilisation, the same sense of

the ludicrous, and children. She has eight to our six and she has also been cut off by the

war from two of her children. Sheilagh looks too young and pretty to be the mother of so

large a family and is, in fact, several years younger than I am. her husband, Donald, is a

large quiet man who, as far as I can judge takes life seriously.Our next door neighbours are the Bank Manager and his wife, a very pleasant

couple though we seldom meet. I have however had correspondence with the Bank

Manager. Early on Saturday afternoon their houseboy brought a note. It informed me

that my son was disturbing his rest by precipitating a heart attack. Was I aware that my

son was about 30 feet up in a tree and balanced on a twig? I ran out and,sure enough,

there was Jim, right at the top of the tallest eucalyptus tree. It would be the one with the

mound of stones at the bottom! You should have heard me fluting in my most

wheedling voice. “Sweets, Jimmy, come down slowly dear, I’ve some nice sweets for

you.”I’ll bet that little story makes you smile. I remember how often you have told me

how, as a child, I used to make your hearts turn over because I had no fear of heights

and how I used to say, “But that is silly, I won’t fall.” I know now only too well, how you

must have felt.Eleanor.

c/o Game Dept. Mbeya. 14th January 1946

Dearest Family.

I hope that by now you have my telegram to say that Kate got home safely

yesterday. It was wonderful to have her back and what a beautiful child she is! Kate

seems to have enjoyed the train journey with Miss Craig, in spite of the tears she tells

me she shed when she said good-bye to you. She also seems to have felt quite at

home with the Hopleys at Salisbury. She flew from Salisbury in a small Dove aircraft

and they had a smooth passage though Kate was a little airsick.I was so excited about her home coming! This house is so tiny that I had to turn

out the little store room to make a bedroom for her. With a fresh coat of whitewash and

pretty sprigged curtains and matching bedspread, borrowed from Sheilagh Waring, the

tiny room looks most attractive. I had also iced a cake, made ice-cream and jelly and

bought crackers for the table so that Kate’s home coming tea could be a proper little

celebration.I was pleased with my preparations and then, a few hours before the plane was

due, my crowned front tooth dropped out, peg and all! When my houseboy wants to

describe something very tatty, he calls it “Second-hand Kabisa.” Kabisa meaning

absolutely. That is an apt description of how I looked and felt. I decided to try some

emergency dentistry. I think you know our nearest dentist is at Dar es Salaam five

hundred miles away.First I carefully dried the tooth and with a match stick covered the peg and base

with Durofix. I then took the infants rubber bulb enema, sucked up some heat from a

candle flame and pumped it into the cavity before filling that with Durofix. Then hopefully

I stuck the tooth in its former position and held it in place for several minutes. No good. I

sent the houseboy to a shop for Scotine and tried the whole process again. No good

either.When George came home for lunch I appealed to him for advice. He jokingly

suggested that a maize seed jammed into the space would probably work, but when

he saw that I really was upset he produced some chewing gum and suggested that I

should try that . I did and that worked long enough for my first smile anyway.

George and the three boys went to meet Kate but I remained at home to

welcome her there. I was afraid that after all this time away Kate might be reluctant to

rejoin the family but she threw her arms around me and said “Oh Mummy,” We both

shed a few tears and then we both felt fine.How gay Kate is, and what an infectious laugh she has! The boys follow her

around in admiration. John in fact asked me, “Is Kate a Princess?” When I said

“Goodness no, Johnny, she’s your sister,” he explained himself by saying, “Well, she

has such golden hair.” Kate was less complementary. When I tucked her in bed last night

she said, “Mummy, I didn’t expect my little brothers to be so yellow!” All three boys

have been taking a course of Atebrin, an anti-malarial drug which tinges skin and eyeballs

yellow.So now our tiny house is bursting at its seams and how good it feels to have one

more child under our roof. We are booked to sail for England in May and when we return

we will have Ann and George home too. Then I shall feel really content.Eleanor.

c/o Game Dept. Mbeya. 2nd March 1946

Dearest Family.

My life just now is uneventful but very busy. I am sewing hard and knitting fast to

try to get together some warm clothes for our leave in England. This is not a simple

matter because woollen materials are in short supply and very expensive, and now that

we have boarding school fees to pay for both Kate and John we have to budget very

carefully indeed.Kate seems happy at school. She makes friends easily and seems to enjoy

communal life. John also seems reconciled to school now that Kate is there. He no

longer feels that he is the only exile in the family. He seems to rub along with the other

boys of his age and has a couple of close friends. Although Mbeya School is coeducational

the smaller boys and girls keep strictly apart. It is considered extremely

cissy to play with girls.The local children are allowed to go home on Sundays after church and may bring

friends home with them for the day. Both John and Kate do this and Sunday is a very

busy day for me. The children come home in their Sunday best but bring play clothes to

change into. There is always a scramble to get them to bath and change again in time to

deliver them to the school by 6 o’clock.When George is home we go out to the school for the morning service. This is

taken by the Headmaster Mr Wallington, and is very enjoyable. There is an excellent

school choir to lead the singing. The service is the Church of England one, but is

attended by children of all denominations, except the Roman Catholics. I don’t think that

more than half the children are British. A large proportion are Greeks, some as old as

sixteen, and about the same number are Afrikaners. There are Poles and non-Nazi

Germans, Swiss and a few American children.All instruction is through the medium of English and it is amazing how soon all the

foreign children learn to chatter in English. George has been told that we will return to

Mbeya after our leave and for that I am very thankful as it means that we will still be living

near at hand when Jim and Henry start school. Because many of these children have to

travel many hundreds of miles to come to school, – Mbeya is a two day journey from the

railhead, – the school year is divided into two instead of the usual three terms. This

means that many of these children do not see their parents for months at a time. I think

this is a very sad state of affairs especially for the seven and eight year olds but the

Matrons assure me , that many children who live on isolated farms and stations are quite

reluctant to go home because they miss the companionship and the games and

entertainment that the school offers.My only complaint about the life here is that I see far too little of George. He is

kept extremely busy on this range and is hardly at home except for a few days at the

months end when he has to be at his office to check up on the pay vouchers and the

issue of ammunition to the Scouts. George’s Range takes in the whole of the Southern

Province and the Southern half of the Western Province and extends to the border with

Northern Rhodesia and right across to Lake Tanganyika. This vast area is patrolled by

only 40 Game Scouts because the Department is at present badly under staffed, due

partly to the still acute shortage of rifles, but even more so to the extraordinary reluctance

which the Government shows to allocate adequate funds for the efficient running of the

Department.The Game Scouts must see that the Game Laws are enforced, protect native

crops from raiding elephant, hippo and other game animals. Report disease amongst game and deal with stock raiding lions. By constantly going on safari and checking on

their work, George makes sure the range is run to his satisfaction. Most of the Game

Scouts are fine fellows but, considering they receive only meagre pay for dangerous

and exacting work, it is not surprising that occasionally a Scout is tempted into accepting

a bribe not to report a serious infringement of the Game Laws and there is, of course,

always the temptation to sell ivory illicitly to unscrupulous Indian and Arab traders.

Apart from supervising the running of the Range, George has two major jobs.

One is to supervise the running of the Game Free Area along the Rhodesia –

Tanganyika border, and the other to hunt down the man-eating lions which for years have

terrorised the Njombe District killing hundreds of Africans. Yes I know ‘hundreds’ sounds

fantastic, but this is perfectly true and one day, when the job is done and the official

report published I shall send it to you to prove it!I hate to think of the Game Free Area and so does George. All the game from

buffalo to tiny duiker has been shot out in a wide belt extending nearly two hundred

miles along the Northern Rhodesia -Tanganyika border. There are three Europeans in

widely spaced camps who supervise this slaughter by African Game Guards. This

horrible measure is considered necessary by the Veterinary Departments of

Tanganyika, Rhodesia and South Africa, to prevent the cattle disease of Rinderpest

from spreading South.When George is home however, we do relax and have fun. On the Saturday

before the school term started we took Kate and the boys up to the top fishing camp in

the Mporoto Mountains for her first attempt at trout fishing. There are three of these

camps built by the Mbeya Trout Association on the rivers which were first stocked with

the trout hatched on our farm at Mchewe. Of the three, the top camp is our favourite. The

scenery there is most glorious and reminds me strongly of the rivers of the Western

Cape which I so loved in my childhood.The river, the Kawira, flows from the Rungwe Mountain through a narrow valley

with hills rising steeply on either side. The water runs swiftly over smooth stones and

sometimes only a foot or two below the level of the banks. It is sparkling and shallow,

but in places the water is deep and dark and the banks high. I had a busy day keeping

an eye on the boys, especially Jim, who twice climbed out on branches which overhung

deep water. “Mummy, I was only looking for trout!”How those kids enjoyed the freedom of the camp after the comparative

restrictions of town. So did Fanny, she raced about on the hills like a mad dog chasing

imaginary rabbits and having the time of her life. To escape the noise and commotion

George had gone far upstream to fish and returned in the late afternoon with three good

sized trout and four smaller ones. Kate proudly showed George the two she had caught

with the assistance or our cook Hamisi. I fear they were caught in a rather unorthodox

manner but this I kept a secret from George who is a stickler for the orthodox in trout

fishing.Eleanor.

Jacksdale England 24th June 1946

Dearest Family.

Here we are all together at last in England. You cannot imagine how wonderful it

feels to have the whole Rushby family reunited. I find myself counting heads. Ann,

George, Kate, John, Jim, and Henry. All present and well. We had a very pleasant trip

on the old British India Ship Mantola. She was crowded with East Africans going home

for the first time since the war, many like us, eagerly looking forward to a reunion with their

children whom they had not seen for years. There was a great air of anticipation and

good humour but a little anxiety too.“I do hope our children will be glad to see us,” said one, and went on to tell me

about a Doctor from Dar es Salaam who, after years of separation from his son had

recently gone to visit him at his school. The Doctor had alighted at the railway station

where he had arranged to meet his son. A tall youth approached him and said, very

politely, “Excuse me sir. Are you my Father?” Others told me of children who had

become so attached to their relatives in England that they gave their parents a very cool

reception. I began to feel apprehensive about Ann and George but fortunately had no

time to mope.Oh, that washing and ironing for six! I shall remember for ever that steamy little

laundry in the heat of the Red Sea and queuing up for the ironing and the feeling of guilt

at the size of my bundle. We met many old friends amongst the passengers, and made

some new ones, so the voyage was a pleasant one, We did however have our

anxious moments.John was the first to disappear and we had an anxious search for him. He was

quite surprised that we had been concerned. “I was just talking to my friend Chinky

Chinaman in his workshop.” Could John have called him that? Then, when I returned to

the cabin from dinner one night I found Henry swigging Owbridge’s Lung Tonic. He had

drunk half the bottle neat and the label said ‘five drops in water’. Luckily it did not harm

him.Jim of course was forever risking his neck. George had forbidden him to climb on

the railings but he was forever doing things which no one had thought of forbidding him

to do, like hanging from the overhead pipes on the deck or standing on the sill of a

window and looking down at the well deck far below. An Officer found him doing this and

gave me the scolding.Another day he climbed up on a derrick used for hoisting cargo. George,

oblivious to this was sitting on the hatch cover with other passengers reading a book. I

was in the wash house aft on the same deck when Kate rushed in and said, “Mummy

come and see Jim.” Before I had time to more than gape, the butcher noticed Jim and

rushed out knife in hand. “Get down from there”, he bellowed. Jim got, and with such

speed that he caught the leg or his shorts on a projecting piece of metal. The cotton

ripped across the seam from leg to leg and Jim stood there for a humiliating moment in a

sort of revealing little kilt enduring the smiles of the passengers who had looked up from

their books at the butcher’s shout.That incident cured Jim of his urge to climb on the ship but he managed to give

us one more fright. He was lost off Dover. People from whom we enquired said, “Yes

we saw your little boy. He was by the railings watching that big aircraft carrier.” Now Jim,

though mischievous , is very obedient. It was not until George and I had conducted an

exhaustive search above and below decks that I really became anxious. Could he have

fallen overboard? Jim was returned to us by an unamused Officer. He had been found

in one of the lifeboats on the deck forbidden to children.Our ship passed Dover after dark and it was an unforgettable sight. Dover Castle

and the cliffs were floodlit for the Victory Celebrations. One of the men passengers sat

down at the piano and played ‘The White Cliffs of Dover’, and people sang and a few

wept. The Mantola docked at Tilbury early next morning in a steady drizzle.

There was a dockers strike on and it took literally hours for all the luggage to be

put ashore. The ships stewards simply locked the public rooms and went off leaving the

passengers shivering on the docks. Eventually damp and bedraggled, we arrived at St

Pancras Station and were given a warm welcome by George’s sister Cath and her

husband Reg Pears, who had come all the way from Nottingham to meet us.

As we had to spend an hour in London before our train left for Nottingham,

George suggested that Cath and I should take the children somewhere for a meal. So

off we set in the cold drizzle, the boys and I without coats and laden with sundry

packages, including a hand woven native basket full of shoes. We must have looked like

a bunch of refugees as we stood in the hall of The Kings Cross Station Hotel because a

supercilious waiter in tails looked us up and down and said, “I’m afraid not Madam”, in

answer to my enquiry whether the hotel could provide lunch for six.

Anyway who cares! We had lunch instead at an ABC tea room — horrible

sausage and a mound or rather sloppy mashed potatoes, but very good ice-cream.

After the train journey in a very grimy third class coach, through an incredibly green and

beautiful countryside, we eventually reached Nottingham and took a bus to Jacksdale,

where George’s mother and sisters live in large detached houses side by side.

Ann and George were at the bus stop waiting for us, and thank God, submitted

to my kiss as though we had been parted for weeks instead of eight years. Even now

that we are together again my heart aches to think of all those missed years. They have

not changed much and I would have picked them out of a crowd, but Ann, once thin and

pale, is now very rosy and blooming. She still has her pretty soft plaits and her eyes are

still a clear calm blue. Young George is very striking looking with sparkling brown eyes, a