Search Results for 'height'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

January 29, 2023 at 12:01 pm #6465

In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Given the new scenery unfolding in front of him, it was time for a change into more appropriate garments.

Luckily, the portal he’d clicked on came with some interesting new goodies. Xavier skimmed over some of the available options, until he found an interesting pair of old boots.

Looking at the old worn leather boots that had appeared in Xavier’s bag, he felt they would be quite appropriate, and put them on.

The changes were subtle, but Xavier already felt more in character with the place.

The changes were subtle, but Xavier already felt more in character with the place.

Suddenly a capuchin monkey jumped on his shoulder and started to pull his ear to make it to the casino boat.The too friendly, potentially mischievous pickpocketing monkey seemed a bit of a trope, but Xavier found the creature endearing.

“Let’s go then! Seems like this party is waiting for us.” he said to the excited monkey.

He jumped into one of the dinghy doing the rounds to the boat with some of the customers.

“Ahoy there, matey!” a rather small man with a piercing blue eye and massive top hat said, giving Xavier a sideways glance. He had an eerie presence and seemed very imposing for such a small frame. “The name’s Sproink, and ye be a first-timer, I see.” he said as a casual matter of introduction.

“Nice to meet you sir” Xavier said distractedly, as he was taking in all the details in the curious boat lit by lanterns dangling in the soft wind.

“Yer too polite for these parts, me friend,” Sproink guffawed. “But have no fear, Sproink’s got yer back.” He winked at the capuchin, Xavier couldn’t help but notice, and suddenly realised that the monkey truly belonged to Sproink.

“No need to check yer pockets, matey” Sproink smiled “I have me sights set on far more interesting game than yer trinkets.” He handed him back some of the stuff that the capuchin had managed to spirit away unnoticed. “But watch yerself, matey. Not all the folk here be what they seem.”

“Point taken!” Xavimunk was indeed a bit too naive, but if anything, that’d often managed to keep him out of trouble. As the small wiry guy left with his bag of tricks in a springy gait, he turned to check his shoulder, and the monkey had disappeared somewhere on the boat too. Xavier was left wondering if he’d see more of him later.

“Welcome, welcome, me hearties!” a buxom girl of large stature with a baroque assortment of feathers and garish colours was a the entrance chewing on a straw, and looking as though the place belonged to her. But there was something else, she was too playing a part, and didn’t seem from here.

“Welcome, welcome, me hearties!” a buxom girl of large stature with a baroque assortment of feathers and garish colours was a the entrance chewing on a straw, and looking as though the place belonged to her. But there was something else, she was too playing a part, and didn’t seem from here.She leaned conspiratorially towards Xavier, and dragged him in a corner.

“Yer a naughty monkey, ignoring me prompts,” she said. “Was I too discrete, or what?”

“Wait, what?” Xavier was confused. Then he remembered the strange message. “Wait a minute… you’re Glimble… something, with unicorns shit or something?” He didn’t have time to entertain the young geek gamers, they were too immature, and well… a lot more invested in the game than he was, they would often turn seriously creepy.

“Oi, come on now!” she raised her hands and shook herself violently. She had turned into a different version of herself. “Now, is it better? It’s true, them avatars easily turn into ava-tarts if you ask me. But you can’t deny a lady a bit o’ comfort with a wrinkle filter. They went a bit overboard with this one, if you ask me.”

“Let’s start again. Glimmer Gambol, and nice to meet you young man.”

January 28, 2023 at 11:27 am #6463

January 28, 2023 at 11:27 am #6463In reply to: Prompts of Madjourneys

Additional clues from AL (based on Xavier’s comment)

Yasmin

:snake:

Yasmin was having a hard time with the heavy rains and mosquitoes in the real-world. She couldn’t seem to make a lot of progress on finding the snorting imp, which she was trying to find in the real world rather than in the game. She was feeling discouraged and unsure of what to do next.

Suddenly, an emoji of a snake appeared on her screen. It seemed to be slithering and wriggling, as if it was trying to grab her attention. Without hesitation, Yasmin clicked on the emoji.

She was taken to a new area in the game, where the ground was covered in tall grass and the sky was dark and stormy. She could see the snorting imp in the distance, but it was surrounded by a group of dangerous-looking snakes.

Clue unlocked It sounds like you’re having a hard time in the real world, but don’t let that discourage you in the game. The snorting imp is nearby and it seems like the snakes are guarding it. You’ll have to be brave and quick to catch it. Remember, the snorting imp represents your determination and bravery in real life.

🐍🔍🐗 Use your skills and abilities to navigate through the tall grass and avoid the snakes. Keep your eyes peeled for any clues or symbols that may help you in your quest. Don’t give up and remember that the snorting imp is a representation of your determination and bravery.

A message bumped on the screen: “Need help? Contact me 👉”

Stryke_Assist is trying to make contact : ➡️ACCEPT <> ➡️DENY ❓

Youssef

:desert:

Youssef has not yet been aware of the quest, since he’s been off the grid in the Gobi desert. But, interestingly, his story unfolds in real-life parallel to his quest. He’s found a strange grumpy shaman at a food booth, and it seems that his natural steps are converging back with the game. His blog website for his boss seems to take most of his attention.

An emoji of a desert suddenly appeared on his screen. It seemed to be a barren and empty landscape, with sand dunes stretching as far as the eye could see. Without hesitation, Youssef clicked on the emoji.

He was taken to a new area in the game, where the ground was covered in sand and the sky was a deep orange, as if the sun was setting. He could see a mysterious figure in the distance, standing at the top of a sand dune.

Clue unlocked It sounds like you’re in a remote location and disconnected from the game. But, your real-life experiences seem to be converging with your quest. The grumpy shaman you met at the food booth may hold the key to unlocking the next steps in the game. Remember, the desert represents your ability to adapt and navigate through difficult situations.

🏜️🧭🧙♂️ Explore the desert and see if the grumpy shaman’s clues lead you to the next steps in the game. Keep an open mind and pay attention to any symbols or clues that may help you in your quest. Remember, the desert represents your ability to adapt and navigate through difficult situations.

A message bumped on the screen: “Need help? Contact me 👉”

Sands_of_time is trying to make contact : ➡️ACCEPT <> ➡️DENY ❓

Zara

:carved_tile:

Zara looked more advanced [in her explorations – stream breaks – resume conversation]

Zara had come across a strange and ancient looking mine. It was clear that it had been abandoned for many years, but there were still signs of activity. The entrance was blocked by a large pile of rocks, but she could see a faint light coming from within. She knew that she had to find a way in.

As she approached the mine, she noticed a small, carved wooden tile on the ground. It was intricately detailed and seemed to depict a map of some sort. She picked it up and examined it closely. It seemed to show the layout of the mine and possibly the location of the secret room.

With this new clue in hand, Zara set to work trying to clear the entrance. She used all of her strength to move the rocks, and after a few minutes of hard work, she was able to create an opening large enough for her to squeeze through.

As she ventured deeper into the mine, she found herself in a large chamber. The walls were lined with strange markings and symbols, and she could see a faint light coming from a small room off to the side. She knew that this must be the secret room she had been searching for.

Zara approached the room and pushed open the door. Inside, she found a small, dimly lit chamber. In the center of the room stood a large stone altar, and on the altar was a strange, glowing object. She couldn’t quite make out what it was, but she knew that this must be the key to solving the mystery of the mine.

With a sense of excitement and curiosity, Zara reached out to take the glowing object. As her hand touched it, she felt a strange energy coursing through her body. She knew that her quest was far from over, and that there were many more secrets to uncover in the mine.

January 24, 2023 at 11:59 pm #6459In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

It was pretty late, but Xavier remembered he had to book his flight (and his holidays, even if he could still mix the trip with his job… it would depend if Brytta would be able to join or not; if such were the case, he’d definitely would book time off).

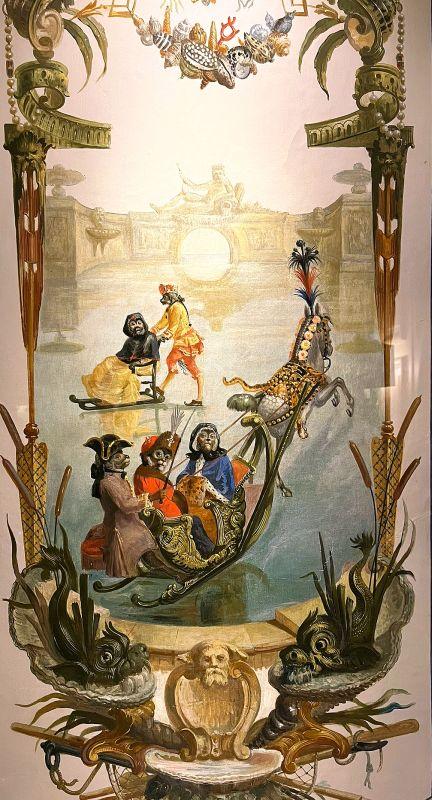

At the hotel where he was staying for the 2-days business trip he had to attend for his job, he’d noticed the strange decor, with little people in costumes in odd sceneries patterned on the “Toile de Jouy” curtains and some others in the most curious framed paintings, many of them looked like actual monkeys. Curiously, there wasn’t any golden banana, or banana bus, but it made him wonder if there was something more to be looked at the Inn that Zara wanted them to go to.

At the hotel where he was staying for the 2-days business trip he had to attend for his job, he’d noticed the strange decor, with little people in costumes in odd sceneries patterned on the “Toile de Jouy” curtains and some others in the most curious framed paintings, many of them looked like actual monkeys. Curiously, there wasn’t any golden banana, or banana bus, but it made him wonder if there was something more to be looked at the Inn that Zara wanted them to go to.Yasmin, a step ahead of him, had already looked at the reviews on MadjourneyAdvisor, and they were rave… in a fashion…

“The lady behind the bar is nearly 90 years old and believe me, she could out-work many much younger than her.”

“Old bird behind the bar is a lovely lady drop in for a chat and a beer or two – don’t mess with her or you will end up down a mine shaft”Well… better not to overthink it. He started to look at the flights, and last minute offers.

Still no word from Youssef either.

He placed an option on a flight, and decided he’d wait for everyone to confirm the dates for the rendez-vous.

January 24, 2023 at 12:40 pm #6458In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

“I’m going to have to jump in this pool, Pretty Girl, look at this one! It reminds me of something…”

Zara came to a green pool that was different from the others, and walked into it.

She emerged into a new scene, with what appeared to be a floating portal, but a square one this time.

“May as well step onto it and see where it goes!” Zara told the parrot, who was taking a keen interest in the screen, somewhat strangely for a bird. “I like having you here, Pretty Girl, it’s nice to have someone to talk to.”

Zara stepped onto the floating tile portal.

“Hey, wasn’t my quest to find a wooden tile?” Zara suddenly remembered. She’d forgotten her quest while she was wandering around the enchanting castle.

“Yes, but that doesn’t look like the tile you were supposed to find though,” replied the parrot.

“It might lead me to it,” snapped Zara who didn’t really want to leave the pretty castle scenes anyway. It felt magical and somehow familiar, like she’d been there before, a long long time ago.

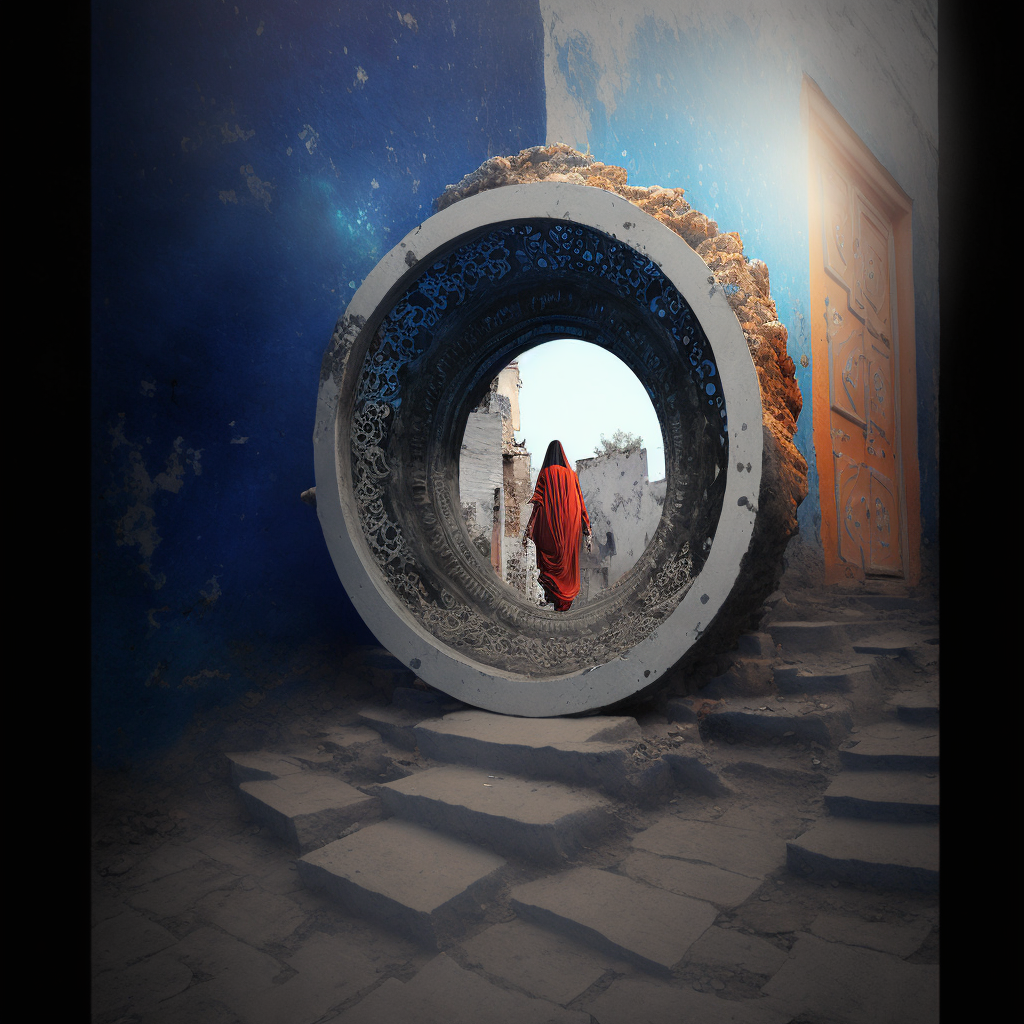

After stepping onto the floating tile portal, Zara encountered another tile portal. This time it was upright, with a circular portal in the centre. By now it seemed clear that the thing to do was to walk through it. She wandered around the scene first as if she was a tourist simply taking in the new sights before taking the plunge.

“Oh my god, look! It’s my tile!” Zara said excitedly to the parrot, just as the words flashed up on her screen:

Congratulations! You have reached the first goal of your first quest!

“Oh bugger! Look at the time, it’s already starting to get light outside. I completely forgot about going to that church to see Isaac’s ghost, and now I haven’t had a wink of sleep all night.”

“Time well spent,” said the parrot sagely, “You can go and see Isaac tomorrow night, and he may be all the more willing to talk since you kept him waiting.”

January 24, 2023 at 11:34 am #6457In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

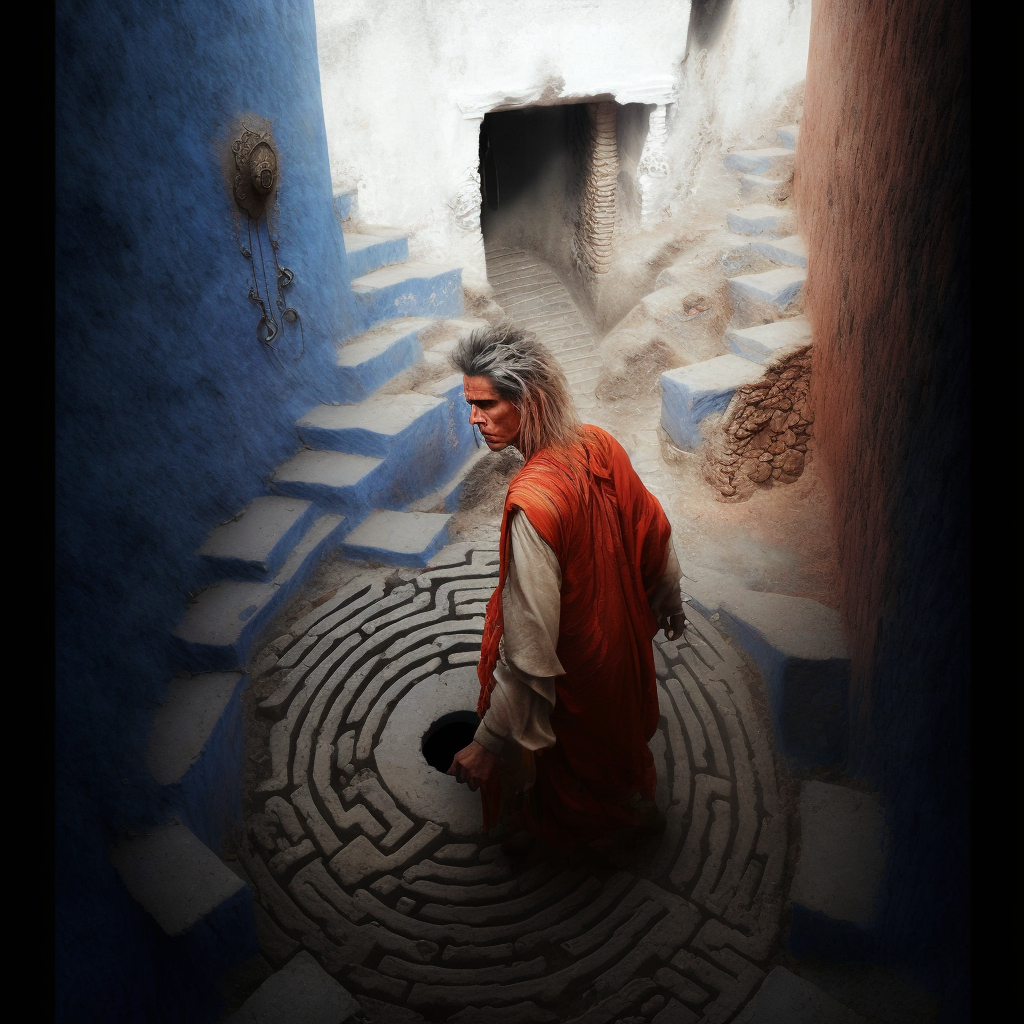

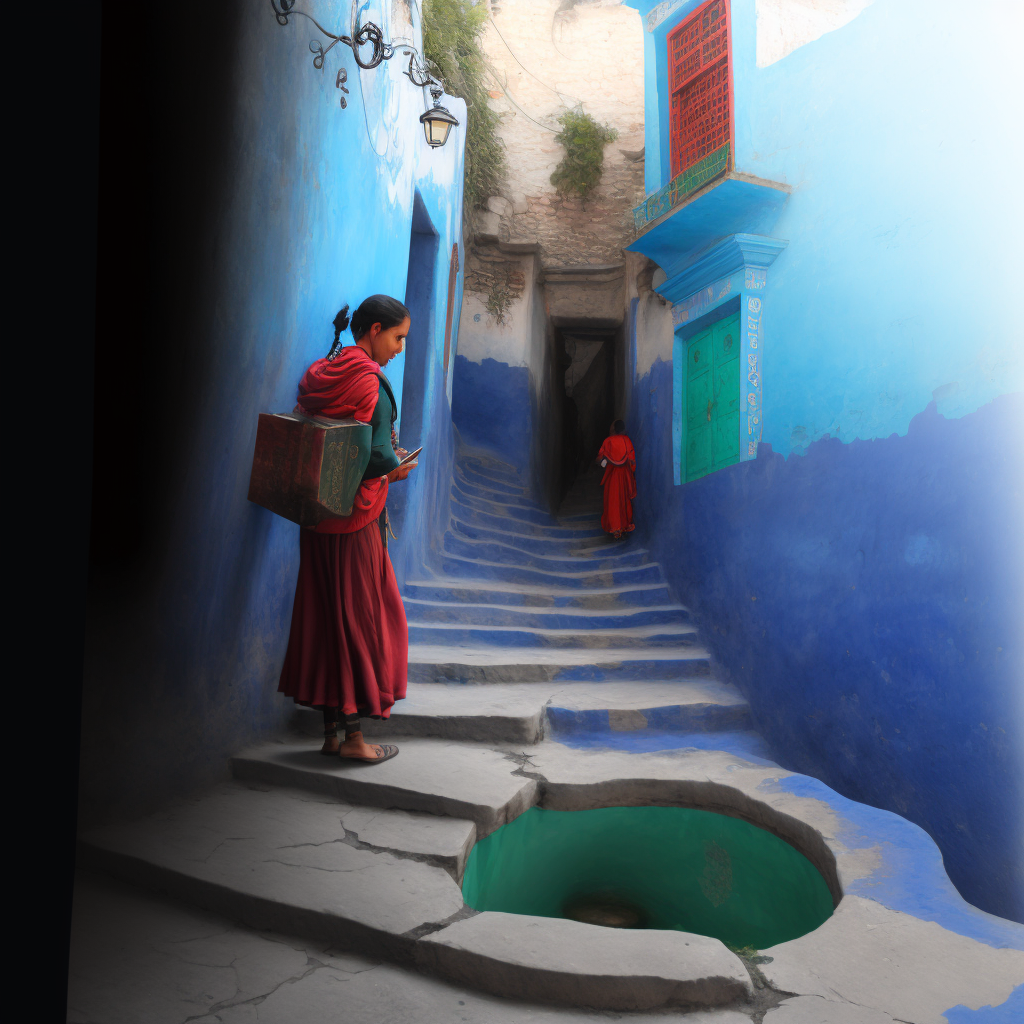

“Look, Pretty Girl! That must be the lost traveler walking up those steps!”

Zara followed the mysterious man in red robes up the steps. She lost sight of him and wondered which way he’d gone in the many side alleys. She wandered up a few of them but they all came to a dead end in a courtyard with closed doors. Eventually she saw him disappearing into a manhole that looked like a labyrinth.

Zara followed him, and stepped onto the labyrinth manhole that the man in the red robes had disappeared into.

“That must be another portal,” Zara said to the parrot. “I wonder where we’ll end up now.”

The labyrinth manhole led Zara to another portal, this time a round hole in the wall. She knew she should follow the man, who must be the lost traveler, but she couldn’t resist exploring the starlit night scene first.

She found herself in a castle, its sand coloured walls glowing in the moonlight. There was another round green pool inside the castle. Should she jump into the pool, or go back and follow the man in red through the hole in the wall? Zara walked around the castle first, exploring the many courtyards and stairs and the enchanting views from the parapets. She noticed that there were several green pools and wondered if they each led to different places.

January 24, 2023 at 10:29 am #6455

January 24, 2023 at 10:29 am #6455In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Zara decided she may as well spend the hour wandering around the game before going back to the church to see the ghost of Isaac when she was sure her host Bertie was asleep. It was a warm night but a gentle breeze wafted through the open window and Zara was comfortable and content. Not just one but three new adventures had her tingling with delicious anticipation, even if she was a little anxious about not getting confused with the game. Talking to ghosts in old churches wasn’t unfamiliar, nor was a holiday in a strange hotel off the beaten track, but the game was still a bit of a mystery to her. Yeah, I know it’s just a game, she whispered to the parrot who made a soft clicking noise by way of response.

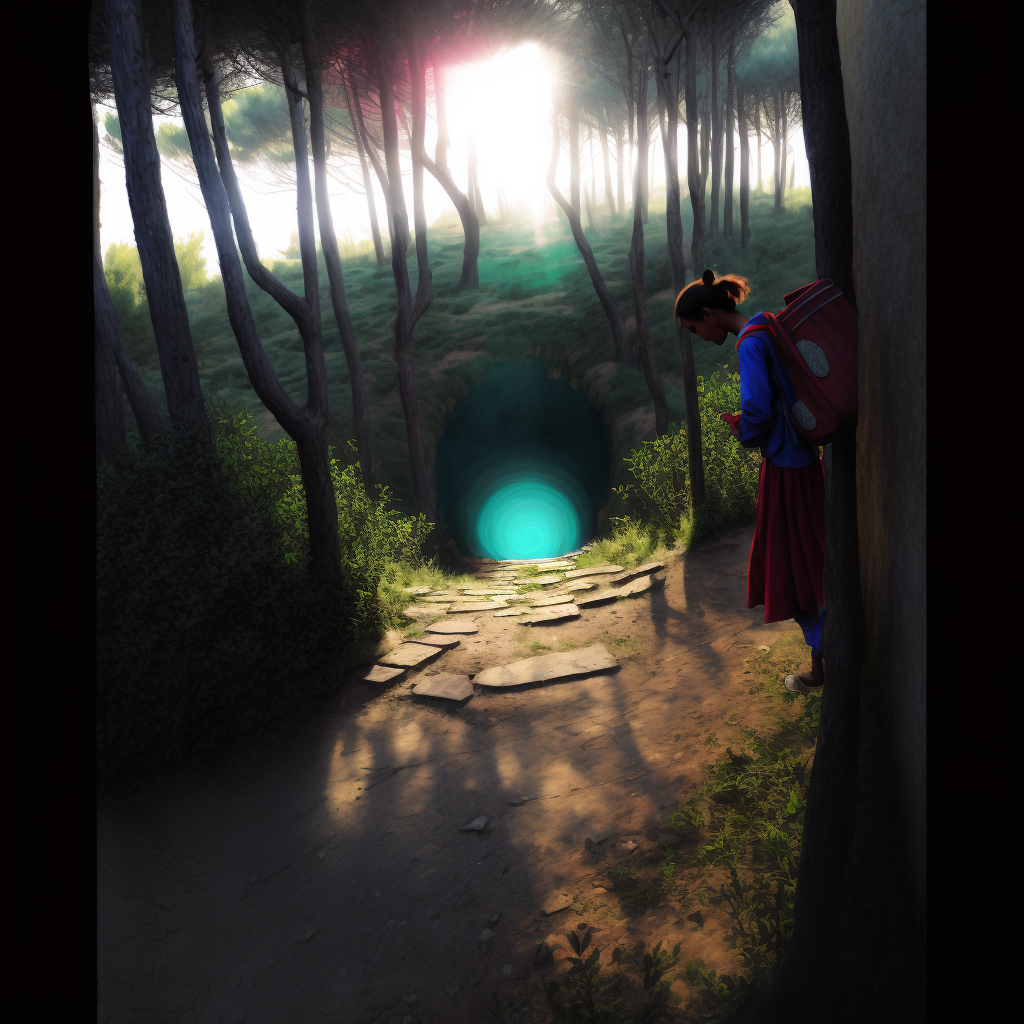

Zara found her game character, also (somewhat confusingly) named Zara, standing in the woods. Not entirely sure how it had happened, she was rather pleased to see that the cargo pants and tank top in red had changed to a more pleasing hippyish red skirt ensemble. A bit less Tomb Looter, and a bit more fairy tale looking which was more to her taste.

The woods were strangely silent and still. Zara made a 360 degree turn on the spot to see in all directions. The scene looked the same whichever way she turned, and Zara didn’t know which way to go. Then a faint path appeared to the left, and she set off in that direction. Before long she came to a round green pool.

She stopped to look but carried on walking past it, not sure what it signified. She came upon another glowing green pool before long, which looked like an entrance to a tunnel.

I bet those are portals or something, Zara realized. I wonder if I’m supposed to step into it?

“Go for it”, said Pretty Girl, “It’s only a game.”

“Ok, well here goes!” replied Zara, mentally bracing herself for a plunge into the unknown.

Zara stepped into the circle of glowing green.

“Like when Alice went down the rabbit hole!” Zara whispered to the parrot. “I’m falling, falling…oh!”

Zara emerged from the green pool onto a wide walled path. She was now in some kind of inhabited area, or at least not in the deep woods with no sign of human occupation.

“I guess that green pool is the portal back to the woods.”

“By George, she’s getting it,” replied Pretty Girl.

Zara walked along the path which led to an old deserted ancient looking village with alleyways and steps.

“This is heaps more interesting than those woods, look how pretty it all is! I love this place.”

“Weren’t you supposed to be looking for a hermit in the woods though,” said Pretty Girl.

“Or a lost traveler, and the lost traveler may be here, after falling in one of those green pools in the woods,” replied Zara tartly, not wanting to leave the enchanting scene she found her avatar in.

January 23, 2023 at 4:14 pm #6453

January 23, 2023 at 4:14 pm #6453In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Each group of people sharing the jeeps spent some time cleaning the jeeps from the sand, outside and inside. While cleaning the hood, Youssef noted that the storm had cleaned the eagles droppings. Soon, the young intern told them, avoiding their eyes, that the boss needed her to plan the shooting with the Lama. She said Kyle would take her place.

Each group of people sharing the jeeps spent some time cleaning the jeeps from the sand, outside and inside. While cleaning the hood, Youssef noted that the storm had cleaned the eagles droppings. Soon, the young intern told them, avoiding their eyes, that the boss needed her to plan the shooting with the Lama. She said Kyle would take her place.“Phew, the yak I shared the yurt with yesterday smelled better,” he said to the guys when he arrived.

Soon enough, Miss Tartiflate was going from jeep to jeep, her fiery hair half tied in a bun on top of her head, hurrying people to move faster as they needed to catch the shaman before he got away again. She carried her orange backpack at all time, as if she feared someone would steal its content. Rumour had it that it was THE NOTEBOOK where she wrote the blog entries in advance.

“No need to waste more time! We’ll have breakfast at the Oasis!” she shouted as she walked toward Youssef’s jeep. When she spotted him, she left her right index finger as if she just remembered something and turned the other way.

“Dunno what you did to her, but it seems Miss Yeti is avoiding you,” said Kyle with a wry smile.

Youssef grunted. Yeti was the nickname given to Miss Tartiflate by one of her former lover during a trip to Himalaya. First an affectionate nickname based on her first name, Henrietty, it soon started to spread among the production team when the love affair turned sour. It sticked and became widespread in the milieu. Everybody knew, but nobody ever dared say it to her face.

Youssef knew it wouldn’t last. He had heard that there was wifi at the oasis. He took a snack in his own backpack to quiet his stomach.

It took them two hours to arrive as sand dunes had moved on the trail during the storm. Kyle had talked most of the time, boring them to death with detailed accounts of his life back in Boston. He didn’t seem to notice that nobody cared about his love rejection stories or his tips to talk to women.

They parked outside the oasis among buses and vans. Kyle was following Youssef everywhere as if they were friends. Despite his unending flow of words, the guy managed to be funny.

Miss Tartiflate seemed unusually nervous, pulling on a strand of her orange hair and pushing back her glasses up her nose every two minutes. She was bossing everyone around to take the cameras and the lighting gear to the market where the shaman was apparently performing a rain dance. She didn’t want to miss it. When everybody was ready, she came right to Youssef. When she pushed back her glasses on her nose, he noticed her fingers were the colour of her hair. Her mouth was twitching nervously. She told him to find the wifi and restore THE BLOG or he could find another job.

“Phew! said Kyle. I don’t want to be near you when that happens.” He waved and left and joined the rest of the team.

Youssef smiled, happy to be alone at last, he took his backpack containing his laptop and his phone and followed everyone to the market in the luscious oasis.

At the center, near the lake, a crowd of tourists was gathered around a man wearing a colorful attire. Half his teeth and one eye were missing. The one that was left rolled furiously in his socket at the sound of a drum. He danced and jumped around like a monkey, and each of his movements were punctuated by the bells attached to the hem of his costume.

Youssef was glad he was not part of the shooting team, they looked miserable as they assembled the gears under a deluge of orders. As he walked toward the market, the scents of spicy food made his stomach growled. The vendors were looking at the crowd and exchanging comments and laughs. They were certainly waiting for the performance to end and the tourists to flood the place in search of trinkets and spices. Youssef spotted a food stall tucked away on the edge. It seemed too shabby to interest anyone, which was perfect for him.

The taciturn vendor, who looked caucasian, wore a yellow jacket and a bonnet oddly reminiscent of a llama’s scalp and ears. The dish he was preparing made Youssef drool.

“What’s that?” he asked.

“This is Lorgh Drülp

, said the vendor. Ancient recipe from the silk road. Very rare. Very tasty.”

He smiled when Youssef ordered a full plate with a side of tsampa. He told him to sit and wait on a stool beside an old and wobbly table.

January 23, 2023 at 1:27 pm #6451In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

The progress on the quest in the Land of the Quirks was too tantalizing; Xavier made himself a quick sandwich and jumped back on it during his lunch break.

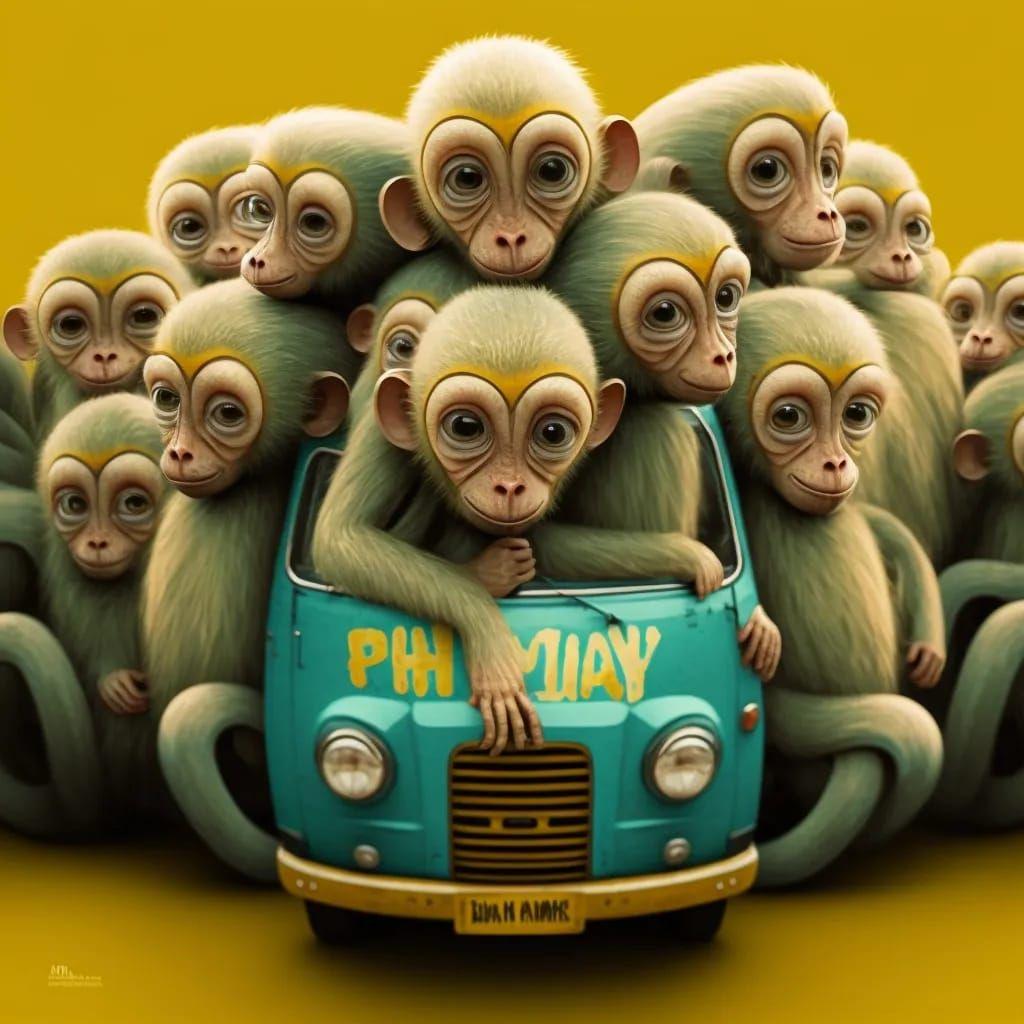

The jungle had an oppressing quality… Maybe it has to do with the shrieks of the apes tearing the silence apart.

The jungle had an oppressing quality… Maybe it has to do with the shrieks of the apes tearing the silence apart. It was time for a slight adjustment of his avatar.

Xavimunk opened his bag of tricks, something that the wise owl had suggested he looked into. Few items from the AIorium Emporium had been supplied. They tended to shift and disappear if you didn’t focus, but his intention was set on the task at hand. At the bottom of the bag, there was a small vial with a golden liquid with a tag written in ornate handwriting “MJ remix: for when words elude and shapes confuse at your own peril”.

He gulped the potion without thinking too much. He felt himself shrink, and his arms elongate a little. There, he thought. Imp-munk’s more suited to the mission. Hope the effects will be temporary…

He gulped the potion without thinking too much. He felt himself shrink, and his arms elongate a little. There, he thought. Imp-munk’s more suited to the mission. Hope the effects will be temporary…As Xavier mustered the courage to enter through the front gate, monkeys started to become silent. He couldn’t say if it was an ominous sign, or maybe an effect of his adaptation. The temple’s light inside was gorgeous, but nothing seemed to be there.

He gestured around, to make the menu appear. He looked again at the instructions on his screen overlay:

As for possible characters to engage, you may come across a sly fox who claims to know the location of the fruit but will only reveal it in exchange for a favor, or a brave adventurer who has been searching for the Golden Banana for years and may be willing to team up with you.

Suddenly a loud monkey honking noise came from outside, distracting him.

What the?… Had to be one of Zara’s remixes. He saw the three dots bleeping on the screen.

Here’s the Banana bus, hope it helps! Envoy! bugger Enjoy!

Yep… With the distinct typo-heavy accent, definitely Zara’s style. Strange idea that AL designated her as the leader… He’d have to roll with it.

Suddenly, as the Banana bus parked in front of the Temple, a horde of Italien speaking tourists started to flock in and snap pictures around. The monkeys didn’t know what to do and seemed to build growing and noisy interest in their assortiment of colorful shoes, flip-flops, boots and all.

Focus, thought Xavimunk… What did the wise owl say? Look for a guide…

Only the huge colorful bus seemed to take the space now… But wait… what if?He walked to the parking spot under the shades of the huge banyan tree next to the temple’s entrance, under which the bus driver had parked it. The driver was still there, napping under a newspaper, his legs on the wheel.

“Whatcha lookin’ at?” he said chewing his gum loudly. “Never seen a fox drive a banana bus before?”

Xavier smiled. “Any chance you can guide me to the location of the Golden Banana?”

“For a price… maybe.” The fox had jumped closely and was considering the strange avatar from head to toe.

“Ain’t no usual stuff that got you into this? Got any left? That would be a nice price.”

“As it happens…” Xavier smiled.The quest seemed back on track. Xavier looked at the time. Blimmey! already late again. And I promised Brytta to get some Chinese snacks for dinner.

January 23, 2023 at 9:18 am #6450In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

The images were forming on the screen of the VR set, a little blurry to start with, but taking some shapes, and with a few clicks in the right direction, the reality around him was transphormed as if he’d been into a huge deFørmiñG mirror, that they could shape with their strangest thoughts.

The jungle had an oppressing quality… Maybe it has to do with the shrieks of the apes tearing the silence apart.

The jungle had an oppressing quality… Maybe it has to do with the shrieks of the apes tearing the silence apart.  All sorts of them were gathered overhead, gibbons, baboons, chimps and Barbery apes, macaques and marmosets… some silent, but most of them in a swirl of manic agitation.

All sorts of them were gathered overhead, gibbons, baboons, chimps and Barbery apes, macaques and marmosets… some silent, but most of them in a swirl of manic agitation.When Xavier entered the ancient blue stone temple, he felt his quest was doomed from the start. It had taken a while to find the monkey’s sacred temple hidden deep within the jungle in which clues were supposed to be found. Thanks to a prompt from Zara who’d stumbled into a map, and some gentle push from a wise Y🦉wl, he’d managed to locate the temple. It was right under his nose all along. Obviously all this a metaphor, but once he found the proper connecting link, getting the right setup for dealing with the task was easier.

So the monkeys were his and his RL colleagues crazy thoughts, and he’d even taken some fun in painting the faces of some of them into the game. He could hear Boss gorilla pounding his chest in the distance.

“F£££” he couldn’t help but grumble when the notification prompt got him out of his meditative point. The Golden Banana would have to wait… The real life monkeys were requiring his attention for now.

January 23, 2023 at 8:15 am #6449In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Have you booked your flight yet? Zara sent a message to Yasmin. I’m spending a few more days in Camden, probably be at the Flying Fish Inn by the end of the week.

I told you already when my flight is, Air Fiji, remeber? bloody Sister Finnlie on my case all the time, haven’t had a minute. Zara had to wait over an hour for Yamsin’s reply.

I told you already when my flight is, Air Fiji, remeber? bloody Sister Finnlie on my case all the time, haven’t had a minute. Zara had to wait over an hour for Yamsin’s reply.Took you long enough to reply. Zara replied promptly. Heard nothing from Youssef for ages either, have you heard from him? I’ll be arriving there on my own at this rate.

Not a word, I expect Xavier’s booked his but he hasn’t said. Probably doing his secret monkey thing.

Not a word, I expect Xavier’s booked his but he hasn’t said. Probably doing his secret monkey thing.Have you tried the free roaming thing on the game yet?

I just told you Sister Finnlie hasn’t given me a minute to myself, she’s a right tart! Why, have you?

I just told you Sister Finnlie hasn’t given me a minute to myself, she’s a right tart! Why, have you?Yeah it’s amazing, been checking out the Flying Fish Inn. Looks a bit of a dump. Not much to do around there, well not from what I can see anyway. But you know what?

What?

What?You’ll lose your eyes in the back of your head one day and look like that AI avatart with the wall eye. Get this though: we haven’t started the game yet, that quest for quirks thing, I was just having a roman around ha ha typo having a roam around see what’s there and stuff I don’t know anything about online games like you lot and I ended up here. Zara sent a screenshot of the image she’d seen and added: Did I already start the game or what, I don’t even know how we actually start the game, I was just wandering around….oh…and happened to chance upon this…

How rude to start playing before us

How rude to start playing before usI didn’t start playing the game before you, I just told you, I was wandering around playing about waiting for you lot! Zara thought Yasmin sounded like she needed a holiday.

Yeah well that was your quest, wasn’t it? To wander around or something? What’s that silver chest on her back?

Yeah well that was your quest, wasn’t it? To wander around or something? What’s that silver chest on her back?I dunno but looks intriguing eh maybe she’s hidden all her devices and techy gadgets in an antiquey looking box so she doesn’t blow her cover

Gotta go Sister Finnlie’s coming

Zara muttered how rude under her breath and put her phone down. She’d retired to her bedroom early, telling Bertie that she needed an early night but really had wanted some time alone to explore the new game world. She didn’t want to make mistakes and look daft to her friends when the game started.

“Too late for that”, Pretty Girl said.

“SSHHH!” Zara hissed at the parrot. “And stop reading my mind, it’s disconcerting, not to mention rude.”

She heard the sound of the lavatory flush and Berties bedroom door closing and looked at the time. 23:36.

Zara decided to give him an hour to make sure he was asleep and then sneak out and go back to that church.

January 21, 2023 at 9:58 pm #6428January 19, 2023 at 10:49 am #6419In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

“I’d advise you not to take the parrot, Zara,” Harry the vet said, “There are restrictions on bringing dogs and other animals into state parks, and you can bet some jobsworth official will insist she stays in a cage at the very least.”

“Yeah, you’re right, I guess I’ll leave her here. I want to call in and see my cousin in Camden on the way to the airport in Sydney anyway. He has dozens of cats, I’d hate for anything to happen to Pretty Girl,” Zara replied.

“Is that the distant cousin you met when you were doing your family tree?” Harry asked, glancing up from the stitches he was removing from a wounded wombat. “There, he’s good to go. Give him a couple more days, then he can be released back where he came from.”

Zara smiled at Harry as she picked up the animal. “Yes! We haven’t met in person yet, and he’s going to show me the church my ancestor built. He says people have been spotting ghosts there lately, and there are rumours that it’s the ghost of the old convict Isaac who built it. If I can’t find photos of the ancestors, maybe I can get photos of their ghosts instead,” Zara said with a laugh.

“Good luck with that,” Harry replied raising an eyebrow. He liked Zara, she was quirkier than the others.

Zara hadn’t found it easy to research her mothers family from Bangalore in India, but her fathers English family had been easy enough. Although Zara had been born in England and emigrated to Australia in her late 20s, many of her ancestors siblings had emigrated over several generations, and Zara had managed to trace several down and made contact with a few of them. Isaac Stokes wasn’t a direct ancestor, he was the brother of her fourth great grandfather but his story had intrigued her. Sentenced to transportation for stealing tools for his work as a stonemason seemed to have worked in his favour. He built beautiful stone buildings in a tiny new town in the 1800s in the charming style of his home town in England.

Zara planned to stay in Camden for a couple of days before meeting the others at the Flying Fish Inn, anticipating a pleasant visit before the crazy adventure started.

Zara stepped down from the bus, squinting in the bright sunlight and looking around for her newfound cousin Bertie. A lanky middle aged man in dungarees and a red baseball cap came forward with his hand extended.

“Welcome to Camden, Zara I presume! Great to meet you!” he said shaking her hand and taking her rucksack. Zara was taken aback to see the family resemblance to her grandfather. So many scattered generations and yet there was still a thread of familiarity. “I bet you’re hungry, let’s go and get some tucker at Belle’s Cafe, and then I bet you want to see the church first, hey? Whoa, where’d that dang parrot come from?” Bertie said, ducking quickly as the bird swooped right in between them.

“Oh no, it’s Pretty Girl!” exclaimed Zara. “She wasn’t supposed to come with me, I didn’t bring her! How on earth did you fly all this way to get here the same time as me?” she asked the parrot.

“Pretty Girl has her ways, don’t forget to feed the parrot,” the bird replied with a squalk that resembled a mirthful guffaw.

“That’s one strange parrot you got here, girl!” Bertie said in astonishment.

“Well, seeing as you’re here now, Pretty Girl, you better come with us,” Zara said.

“Obviously,” replied Pretty Girl. It was hard to say for sure, but Zara was sure she detected an avian eye roll.

They sat outside under a sunshade to eat rather than cause any upset inside the cafe. Zara fancied an omelette but Pretty Girl objected, so she ordered hash browns instead and a fruit salad for the parrot. Bertie was a good sport about the strange talking bird after his initial surprise.

Bertie told her a bit about the ghost sightings, which had only started quite recently. They started when I started researching him, Zara thought to herself, almost as if he was reaching out. Her imagination was running riot already.

Bertie showed Zara around the church, a small building made of sandstone, but no ghost appeared in the bright heat of the afternoon. He took her on a little tour of Camden, once a tiny outpost but now a suburb of the city, pointing out all the original buildings, in particular the ones that Isaac had built. The church was walking distance of Bertie’s house and Zara decided to slip out and stroll over there after everyone had gone to bed.

Bertie had kindly allowed Pretty Girl to stay in the guest bedroom with her, safe from the cats, and Zara intended that the parrot stay in the room, but Pretty Girl was having none of it and insisted on joining her.

“Alright then, but no talking! I don’t want you scaring any ghost away so just keep a low profile!”

The moon was nearly full and it was a pleasant walk to the church. Pretty Girl fluttered from tree to tree along the sidewalk quietly. Enchanting aromas of exotic scented flowers wafted into her nostrils and Zara felt warmly relaxed and optimistic.

Zara was disappointed to find that the church was locked for the night, and realized with a sigh that she should have expected this to be the case. She wandered around the outside, trying to peer in the windows but there was nothing to be seen as the glass reflected the street lights. These things are not done in a hurry, she reminded herself, be patient.

Sitting under a tree on the grassy lawn attempting to open her mind to receiving ghostly communications (she wasn’t quite sure how to do that on purpose, any ghosts she’d seen previously had always been accidental and unexpected) Pretty Girl landed on her shoulder rather clumsily, pressing something hard and chill against her cheek.

“I told you to keep a low profile!” Zara hissed, as the parrot dropped the key into her lap. “Oh! is this the key to the church door?”

It was hard to see in the dim light but Zara was sure the parrot nodded, and was that another avian eye roll?

Zara walked slowly over the grass to the church door, tingling with anticipation. Pretty Girl hopped along the ground behind her. She turned the key in the lock and slowly pushed open the heavy door and walked inside and up the central aisle, looking around. And then she saw him.

Zara gasped. For a breif moment as the spectral wisps cleared, he looked almost solid. And she could see his tattoos.

“Oh my god,” she whispered, “It is really you. I recognize those tattoos from the description in the criminal registers. Some of them anyway, it seems you have a few more tats since you were transported.”

“Aye, I did that, wench. I were allays fond o’ me tats, does tha like ’em?”

He actually spoke to me! This was beyond Zara’s wildest hopes. Quick, ask him some questions!

“If you don’t mind me asking, Isaac, why did you lie about who your father was on your marriage register? I almost thought it wasn’t you, you know, that I had the wrong Isaac Stokes.”

A deafening rumbling laugh filled the building with echoes and the apparition dispersed in a labyrinthine swirl of tattood wisps.

“A story for another day,” whispered Zara, “Time to go back to Berties. Come on Pretty Girl. And put that key back where you found it.”

January 18, 2023 at 12:51 pm #6413

January 18, 2023 at 12:51 pm #6413In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Zara was long overdue for some holiday time off from her job at the Bungwalley Valley animal rescue centre in New South Wales and the suggestion to meet her online friends at the intriguing sounding Flying Fish Inn to look for clues for their online game couldn’t have come at a better time. Lucky for her it wasn’t all that far, relatively speaking, although everything is far in Australia, it was closer than coming from Europe. Xavier would have a much longer trip. Zara wasn’t quite sure where exactly Yasmin was, but she knew it was somewhere in Asia. It depended on which refugee camp she was assigned to, and Zara had forgotten to ask her recently. All they had talked about was the new online game, and how confusing it all was.

The biggest mystery to Zara was why she was the leader in the game. She was always the one who was wandering off on side trips and forgetting what everyone else was up to. If the other game followers followed her lead there was no telling where they’d all end up!

“But it is just a game,” Pretty Girl, the rescue parrot interjected. Zara had known some talking parrots over the years, but never one quite like this one. Usually they repeated any nonsense that they’d heard but this one was different. She would miss it while she was away on holiday, and for a moment considered taking the talking parrot with her on the trip. If she did, she’d have to think about changing her name though, Pretty Girl wasn’t a great name but it was hard to keep thinking of names for all the rescue creatures.

After Zara had done the routine morning chores of feeding the various animals, changing the water bowls, and cleaning up the less pleasant aspects of the job, she sat down in the office room of the rescue centre with a cup of coffee and a sandwich. She was in good physical shape for 57, wiry and energetic, but her back ached at times and a sit down was welcome before the vet arrived to check on all the sick and wounded animals.

Pretty Girl flew over from the kennels, and perched outside the office room window. When the parrot had first been dropped off at the centre, they’d put her in a big cage, but in no uncertain terms Pretty Girl had told them she’d done nothing wrong and was wrongfully imprisoned and to release her at once. It was rather a shock to be addresssed by a parrot in such a way, and it was agreed between the staff and the vet to set her free and see what happened. And Pretty Girl had not flown away.

“Hey Pretty Girl, why don’t you give me some advice on this confusing new game I’m playing with my online friends?” Zara asked.

“Pretty Girl wants some of your tuna sandwich first,” replied the parrot. After Zara had obliged, the parrot continued at some surprising length.

“My advice would be to not worry too much about getting the small details right. The most important thing is to have fun and enjoy the creative process. Just give me a bit more tuna,” Pretty Girl said, before continuing.

“Remember that as a writer, you have the power to shape the story and the characters as you see fit. It’s okay to make mistakes, and it’s okay to not know everything. Allow yourself to be inspired by the world around you and let the story unfold naturally. Trust in your own creativity and don’t be afraid to take risks. And remember, it’s not the small details that make a story great, it’s the emotions and experiences that the characters go through that make it truly memorable. And always remember to feed the parrot.”

“Maybe I should take you on holiday with me after all,” Zara replied. “You really are an amazing bird, aren’t you?”

January 17, 2023 at 5:55 pm #6409

January 17, 2023 at 5:55 pm #6409In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

“What the…..!” Youssef exclaimed, almost throwing his phone to the ground for a second time that morning. As if he wasn’t having enough trouble already without his phone sending him these messages. But then an idea occurred to him, and he had another look at it.

“Ah, now I see! Glimmer has intercepted the message from Gang Thi!” Youssef smiled for the first time that day. He still couldn’t decipher the strange script though, and wondered if it had been a mistake to not include her on the trip in the first place. He had thought her to be foolish and gaudy and not much practical use, but now he wasn’t so sure. He certainly hadn’t expected her to show up so soon, and in such an unexpected way.

January 17, 2023 at 5:05 pm #6408

January 17, 2023 at 5:05 pm #6408In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Glimmer gave Zara and Yasmin a cheery

, smirking to herself at their alarm at leaving her to her own devices. She had no intention of inviting guests yet, but felt no need to reassure them. Xavier would play along with her, she felt sure.

, smirking to herself at their alarm at leaving her to her own devices. She had no intention of inviting guests yet, but felt no need to reassure them. Xavier would play along with her, she felt sure.Glimmer settled herself comfortably to peruse the new AIorium Emporium catalogue with the intention of ordering some new hats and accessories for the adventure. She had always had a weakness for elaborate hats, but the truth was they were often rather heavy and cumbersome. That is until she found the AIorium hats which were made of a semi anti gravity material. Not entirely anti gravity, obviously, or they would have floated right off her head, but just enough to make them feel weightless. Once she’d discovered these wonderful hats and their unique properties, she had the idea to carry all her accessories, tools and devices upon her hat. This would save her the bother of carrying around bags of stuff. She was no light weight herself, and it was quite enough to carry herself around, let alone bags of objects.

Glimmer had heard a rumour (well not a rumour exactly, she had a direct line to ~ well not to spill the beans too soon, but she had some lines of information that the others didn’t know about yet) that the adventure was going to start at The Flying Fish Inn. This was welcome news to Glimmer, who had met Idle many years before when they were both teenagers. Yes, it’s hard to imagine these two as teenagers, but although they’d only met breifly on holiday, they’d hit it off immediately. Despite not keeping in contact over the years, Glimmer remembered Idle fondly and felt sure that Idle felt similarly.

Glimmer perused the catalogue for a suitable gift to take for her old friend. The delightful little bottles of spirited spirit essences caught her eye, and recalling Idle’s enthusiasm for an exotic tipple, she ordered several bottles. Perhaps Glimmer should have read carefully the description of the effects of the contents of each bottle but she did not. She immediately added the bottles to the new hat she’d ordered for the trip.

Feeling pleased with her selection, she settled down for a snooze until her new hat arrived.

January 17, 2023 at 8:52 am #6395

January 17, 2023 at 8:52 am #6395In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Glimmer Gambol attempted to slip into the chat room unnoticed to eavesdrop, which was of course impossible. She’d been ready and waiting for her parts in the story almost since before the others were born.

“Well!” she said, “If you’re all off doing errands in the real world, I’ll make a start myself. Leave it to me!”

“Is this wise?” Zara said to Xavier, who was perhaps not the best person to ask. His

by way of reply was not reassuring.

by way of reply was not reassuring.“She’ll probably invite loads of random quirky guests to the game,” Yasmin added, echoing Zara’s concern. Xavier’s smile widened.

January 13, 2023 at 7:40 pm #6379

January 13, 2023 at 7:40 pm #6379In reply to: Prompts of Madjourneys

Asking to give each of the 4 characters some particular traits that makes them uniquely distinctive and recognizable

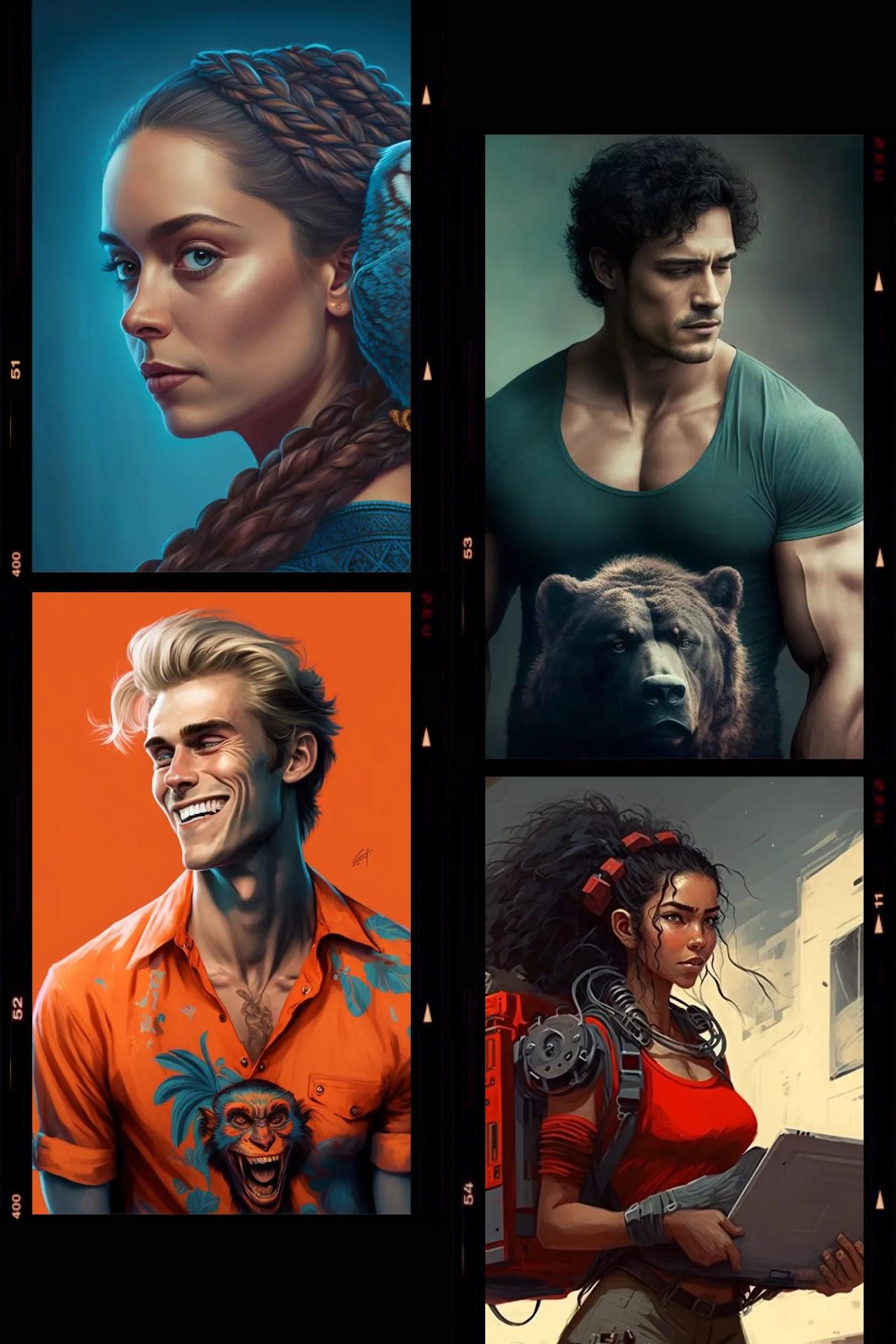

The four friends, Zara, Xavier, Yasmin, and Youssef, each have their own unique traits that make them stand out and recognizable.

Zara is the leader of the group, she is confident, and always ready for an adventure. She is a natural leader and has a strong sense of justice. She is also a tech-savvy person, always carrying a variety of gadgets with her, and is always the first to try out new technology.

Xavier is the joker of the group, always cracking jokes and making puns. He is a free-spirited person who is always up for an adventure, he has a great sense of humor and is not afraid to be himself. He is also an artist and often carries a sketchbook and pencils with him, he likes to draw whatever he sees in his journeys.

Yasmin is the brains of the group, she is intelligent and logical. She is always able to think on her feet and come up with a plan when things get tough. She is also a bit of a perfectionist and likes to have everything organized. She is a history buff and always carries a notebook with her to document her findings.

Youssef is the muscle of the group, He is physically strong, and always ready to help out in a fight. He is also a bit of a foodie and loves trying new dishes. He is always the first one to volunteer to carry the heavy bags and equipment. He is also a bit of a daredevil and loves trying out new sports and activities.

Give each of them a color, and an animal, and a secret name in a funny language

The four friends, Zara, Xavier, Yasmin, and Youssef, each have their own unique traits that make them stand out and recognizable.

Zara is the leader of the group, her color is red, her animal is a lion, and her secret name in a funny language is “Zaraloon”

Xavier is the joker of the group, his color is orange, his animal is a monkey, and his secret name in a funny language is “Xavimunk”

Yasmin is the brains of the group, her color is blue, her animal is an owl, and her secret name in a funny language is “Yasminowl”

Youssef is the muscle of the group, his color is green, his animal is a bear, and his secret name in a funny language is “Youssefbear”

Now, we need physical descriptions for each of them. Also, their ages, height, clothes, facial features, ethnicity (for instance Youssef may be half Yemeni and half Norwegian), etc. with a good mix of generic and eccentric. We also need surnames congruent with their described ethnicity, not too bland, but not too daft either. For instance Youssef Olafsson, Zara Patara-Smythe, etc. Also explain how they become friends.

Zara Patara-Smythe is a

25-year-oldwoman of mixed heritage, her mother is Indian and her father is British. She has long, dark hair that she keeps in a sleek ponytail, dark brown eyes and a sharp jawline. She stands at 5’6″ and has a toned and athletic build. She usually wears practical clothing that allows her to move around easily, such as cargo pants and a tank top.Xavier Olafsson is a

27-year-oldman of Norwegian and Danish descent. He has blonde hair that he keeps in a messy style, blue eyes, and a charming smile. He stands at 6’1″ and has a lean build. He is always seen wearing a colorful and bold clothing, such as a Hawaiian shirt and shorts.Yasmin Ahmed is a

23-year-oldwoman of Egyptian descent. She has long, black hair that she keeps in a tight braid, dark brown eyes and a round face. She stands at 5’4″ and has a petite build. She usually wears conservative clothing, such as long skirts and blouses.Youssef Ali is a

26-year-oldman of half Yemeni, half Norwegian descent. He has short, curly black hair, dark brown eyes and a square jawline. He stands at 6’2″ and has a muscular build. He usually wears comfortable clothing such as a t-shirt and jeans, and always has a backpack on his shoulder.The four of them became friends

in college, they were all studying different majors, but they all shared a love for adventure and exploration. They found themselves in the same class project, and from there they formed a strong bond. After college, they decided to keep exploring the world together, and went on many trips and adventures, always seeking for something new and exciting.

1/ Change the ages of Zara, Xavier, Yasmin and Youssef to more random patterns – rewrite if needed how they met each other to reflect eventual age gaps. Give them some flaws, mental or physical challenges.

2/ increase again the age gaps while keeping the youngest one a young adult, and remove “minor” from the flaws descriptionsZara is a 22-year-old woman who is the youngest of the group. She is a free-spirited, adventurous person, but also a bit reckless and impulsive. She has a scar on her cheek that she got from a Skateboarding accident when she was a teenager.

Xavier is a 45-year-old man who is the oldest of the group. He is a responsible and level-headed person, but also a bit of a perfectionist and can be hard on himself and others. He has dyslexia which he has been able to work around and it doesn’t impede his daily life.

Yasmin is a 38-year-old woman who is the second oldest of the group. She is a kind and compassionate person, but also a bit of a pushover and can have trouble standing up for herself. She has social anxiety that affect her in certain situations and she have been working on coping mechanisms.

Youssef is a 33-year-old man who is the second youngest of the group. He is a charismatic and outgoing person, but also a bit of a flirt and can be a bit insensitive to others feelings. He has ADHD which he has been able to manage with medication, but it still affects him from time to time.

The group met each other through different means, Xavier and Yasmin met at work, Zara and Youssef met at a college class, and eventually, they all became friends through common interests and activities. They decided to go on this adventure together because they were all looking for a change in their lives and wanted to explore the unknown.

January 13, 2023 at 11:50 am #6374In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Orbs of Madjourneys

January 11, 2023 at 11:53 pm #6372

January 11, 2023 at 11:53 pm #6372In reply to: Train your subjective AI – text version

5 important keywords linked to Badul

- Action-space-time

- Harmonic fluid

- Rhythm

- Scale

- Choosing without limits.

Imagine four friends, Jib, Franci, Tracy, and Eric, who are all deeply connected through their shared passion for music and performance. They often spend hours together creating and experimenting with different sounds and rhythms.

One day, as they were playing together, they found that their combined energy had created a new essence, which they named Badul. This new essence was formed from the unique combination of their individual energies and personalities, and it quickly grew in autonomy and began to explore the world around it.

As Badul began to explore, it discovered that it had the ability to understand and create complex rhythms, and that it could use this ability to bring people together and help them find a sense of connection and purpose.

As Badul traveled, it would often come across individuals who were struggling to find their way in life. It would use its ability to create rhythm and connection to help these individuals understand themselves better and make the choices that were right for them.

In the scene, Badul is exploring a city, playing with the rhythms of the city, through the traffic, the steps of people, the ambiance. Badul would observe a person walking in the streets, head down, lost in thoughts. Badul would start playing a subtle tune, and as the person hears it, starts to walk with the rhythm, head up, starting to smile.

As the person continues to walk and follow the rhythm created by Badul, he begins to notice things he had never noticed before and begins to feel a sense of connection to the world around him. The music created by Badul serves as a guide, helping the person to understand himself and make the choices that will lead to a happier, more fulfilled life.

In this way, Badul’s focus is to bring people together, to connect them to themselves and to the world around them through the power of rhythm and music, and to be an ally in the search of personal revelation and understanding.

December 19, 2022 at 9:48 am #6352In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The Birmingham Bootmaker

Samuel Jones 1816-1875

Samuel Jones the elder was born in Belfast circa 1779. He is one of just two direct ancestors found thus far born in Ireland. Samuel married Jane Elizabeth Brooker (born in St Giles, London) on the 25th January 1807 at St George, Hanover Square in London. Their first child Mary was born in 1808 in London, and then the family moved to Birmingham. Mary was my 3x great grandmother.

But this chapter is about her brother Samuel Jones. I noticed that on a number of other trees on the Ancestry site, Samuel Jones was a convict transported to Australia, but this didn’t tally with the records I’d found for Samuel in Birmingham. In fact another Samuel Jones born at the same time in the same place was transported, but his occupation was a baker. Our Samuel Jones was a bootmaker like his father.

Samuel was born on 28th January 1816 in Birmingham and baptised at St Phillips on the 19th August of that year, the fourth child and first son of Samuel the elder and Jane’s eleven children.

On the 1839 electoral register a Samuel Jones owned a property on Colmore Row, Birmingham.

Samuel Jones, bootmaker of 15, Colmore Row is listed in the 1849 Birmingham post office directory, and in the 1855 White’s Directory.

On the 1851 census, Samuel was an unmarried bootmaker employing sixteen men at 15, Colmore Row. A 9 year old nephew Henry Harris was living with him, and his mother Ruth Harris, as well as a female servant. Samuel’s sister Ruth was born in 1818 and married Henry Harris in 1840. Henry died in 1848.

Samuel was a 45 year old bootmaker at 15 Colmore Row on the 1861 census, living with Maria Walcot, a 26 year old domestic servant.

In October 1863 Samuel married Maria Walcot at St Philips in Birmingham. They don’t appear to have had any children as none appear on the 1871 census, where Samuel and Maria are living at the same address, with another female servant and two male lodgers by the name of Messant from Ipswich.

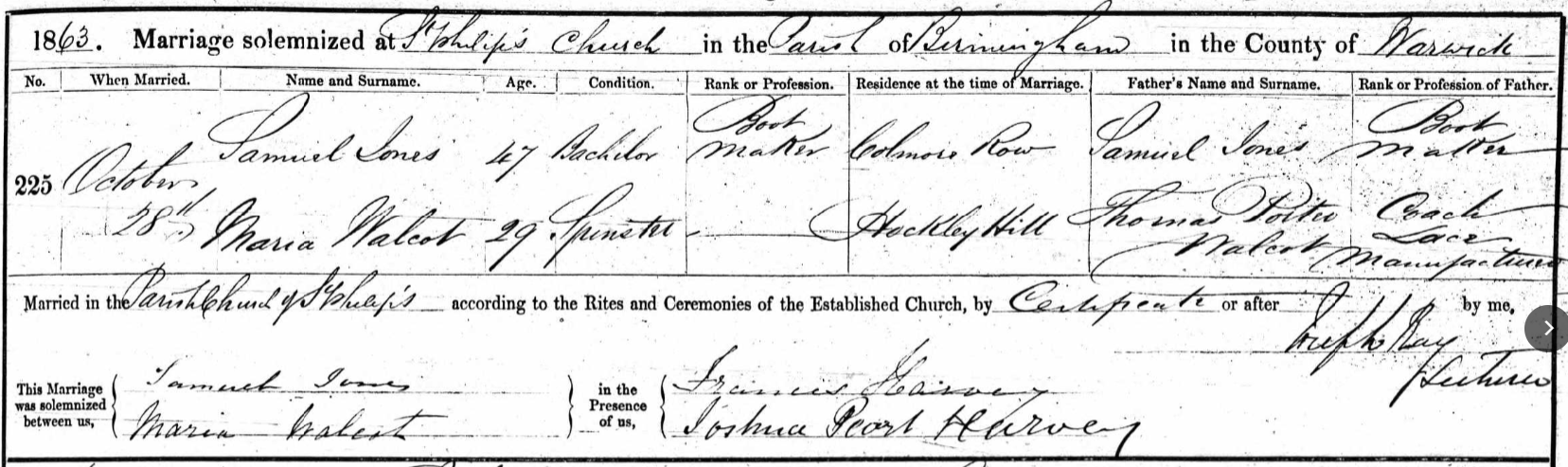

Marriage of Samuel Jones and Maria Walcot:

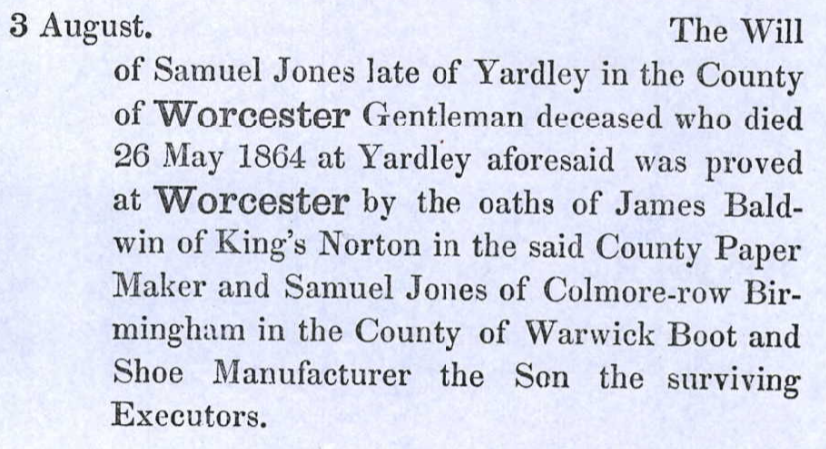

In 1864 Samuel’s father died. Samuel the son is mentioned in the probate records as one of the executors: “Samuel Jones of Colmore Row Birmingham in the county of Warwick boot and shoe manufacturer the son”.

Indeed it could hardly be clearer that this Samuel Jones was not the convict transported to Australia in 1834!

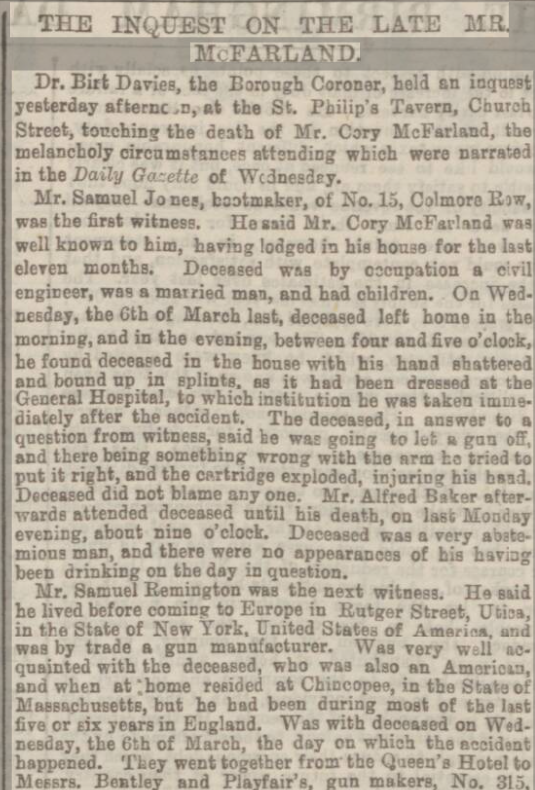

In 1867 Samuel Jones, bootmaker, was mentioned in the Birmingham Daily Gazette with regard to an unfortunate incident involving his American lodger, Cory McFarland. The verdict was accidental death.

Birmingham Daily Gazette – Friday 05 April 1867:

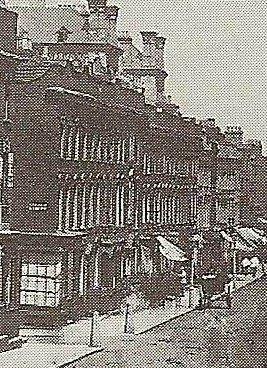

I asked a Birmingham history group for an old photo of Colmore Row. This photo is circa 1870 and number 15 is furthest from the camera. The businesses on the street at the time were as follows:

7 homeopathic chemist George John Morris. 8 surgeon dentist Frederick Sims. 9 Saul & Walter Samuel, Australian merchants. Surgeons occupied 10, pawnbroker John Aaron at 11 & 12. 15 boot & shoemaker. 17 auctioneer…

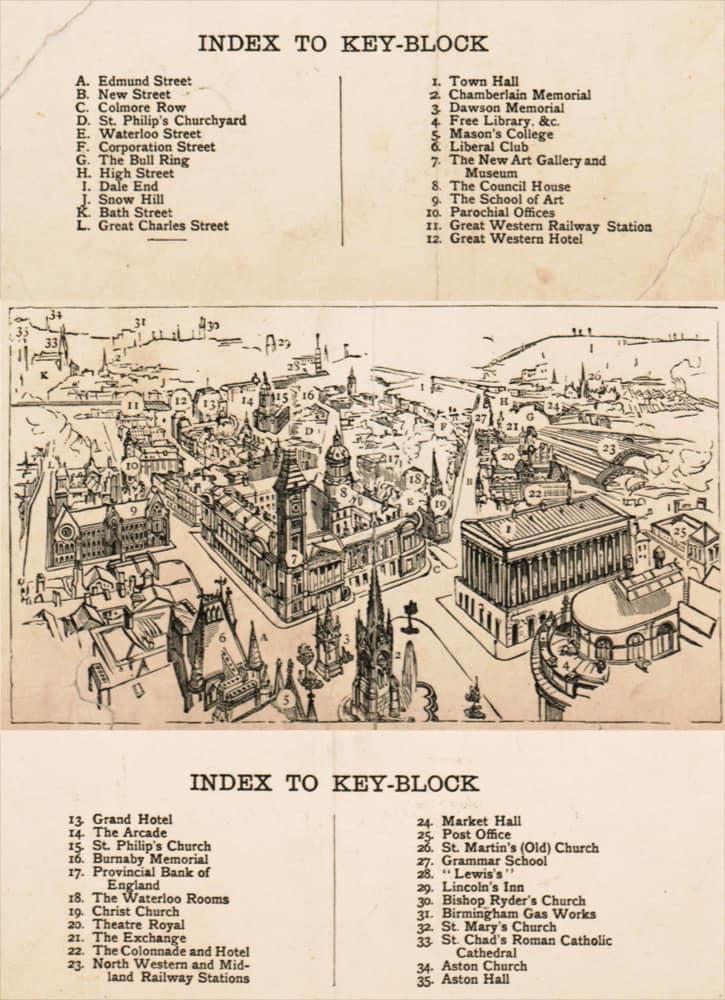

from Bird’s Eye View of Birmingham, 1886:

-

AuthorSearch Results