Search Results for 'hot'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

January 17, 2023 at 8:52 am #6394

In reply to: Scrying the Word Cloud

friday luck bouncer dreams hotel afternoon

janey sold agreed flung fair brown canvas

neither safely useful moment

proper half value paused

January 14, 2023 at 8:13 pm #6387In reply to: Scrying the Word Cloud

Words from the Cloud prompted me to write a story:

song stayed act unexpected recall words spears bus learn king expected followed fright hot wore kianda picture walked playing coast dusty

Once upon a time, in a far-off land, there was a Song that stayed in the hearts of the people. The Song was about an Act of bravery and sacrifice that had taken place many years ago. But one day, an unexpected recall of the Song was issued by the king. He had heard that the Song was not being sung correctly, and he wanted to make sure that the true story was being told. The people were puzzled, as they had learned the Song from their ancestors and had always thought it was accurate. But they followed the king’s orders and set out to learn the correct version of the Song. As they began to recall the words, they realized that there were some discrepancies. They had always sung about the hero wielding a sword, but the true story spoke of him wielding Spears. They were taken aback, but they knew they had to correct the Song. So, they set out on a journey to retrace the hero’s steps.

As they traveled, they encountered unexpected challenges. They faced a bus that broke down, a coastline that was dusty and treacherous, and even a group of bandits. But they pressed on, determined to learn the truth.

As they approached the hero’s final battle, they felt a sense of dread. They had heard that the enemy was fierce, and they were not prepared for what they would find. But they followed the path and soon found themselves at the edge of a hot, barren wasteland.

The heroes wore their Kianda, traditional armor made of woven reeds, and stepped forward, ready for battle. But to their surprise, the enemy was nowhere to be found. Instead, they found a picture etched into the ground, depicting the hero and his enemy locked in a fierce battle.

The people walked around the picture, marveling at the detail and skill of the artist. And as they looked closer, they saw that the hero was holding Spears, not a sword. They realized that they had learned the true story, and they felt a sense of pride and gratitude.

With the Song corrected, they returned home, playing the new version for all to hear. And from that day on, the true story of the hero’s bravery and sacrifice was remembered, and the Song stayed in the hearts of the people forevermore.

January 7, 2023 at 2:19 pm #6357In reply to: Train Your Subjective AI

Drag Queens running away in flying hot air balloon

December 19, 2022 at 9:48 am #6352

December 19, 2022 at 9:48 am #6352In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The Birmingham Bootmaker

Samuel Jones 1816-1875

Samuel Jones the elder was born in Belfast circa 1779. He is one of just two direct ancestors found thus far born in Ireland. Samuel married Jane Elizabeth Brooker (born in St Giles, London) on the 25th January 1807 at St George, Hanover Square in London. Their first child Mary was born in 1808 in London, and then the family moved to Birmingham. Mary was my 3x great grandmother.

But this chapter is about her brother Samuel Jones. I noticed that on a number of other trees on the Ancestry site, Samuel Jones was a convict transported to Australia, but this didn’t tally with the records I’d found for Samuel in Birmingham. In fact another Samuel Jones born at the same time in the same place was transported, but his occupation was a baker. Our Samuel Jones was a bootmaker like his father.

Samuel was born on 28th January 1816 in Birmingham and baptised at St Phillips on the 19th August of that year, the fourth child and first son of Samuel the elder and Jane’s eleven children.

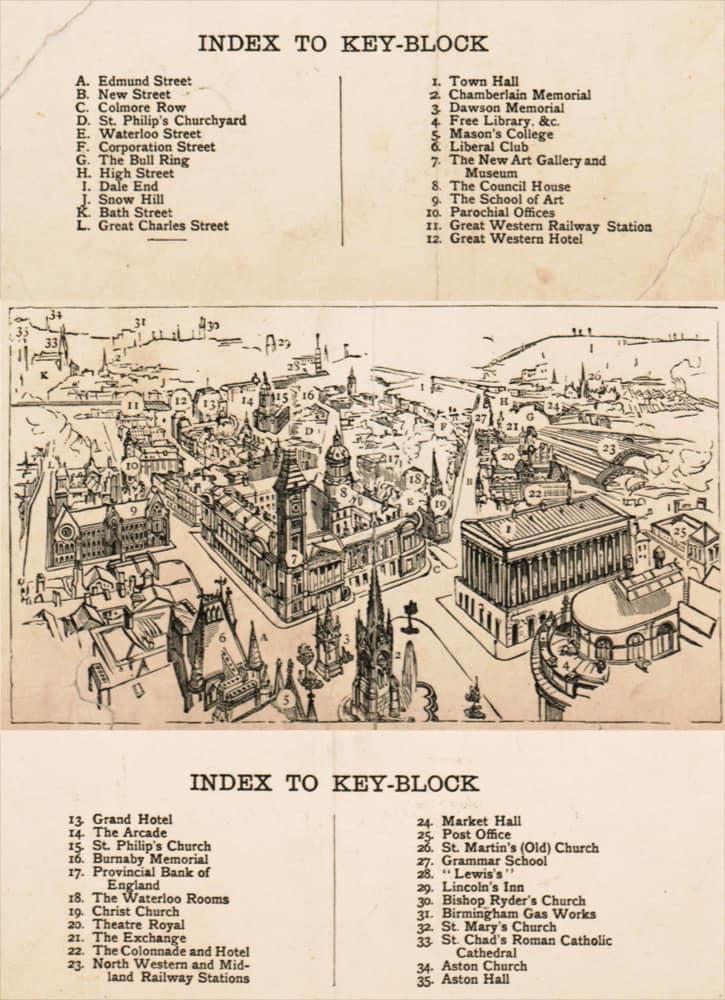

On the 1839 electoral register a Samuel Jones owned a property on Colmore Row, Birmingham.

Samuel Jones, bootmaker of 15, Colmore Row is listed in the 1849 Birmingham post office directory, and in the 1855 White’s Directory.

On the 1851 census, Samuel was an unmarried bootmaker employing sixteen men at 15, Colmore Row. A 9 year old nephew Henry Harris was living with him, and his mother Ruth Harris, as well as a female servant. Samuel’s sister Ruth was born in 1818 and married Henry Harris in 1840. Henry died in 1848.

Samuel was a 45 year old bootmaker at 15 Colmore Row on the 1861 census, living with Maria Walcot, a 26 year old domestic servant.

In October 1863 Samuel married Maria Walcot at St Philips in Birmingham. They don’t appear to have had any children as none appear on the 1871 census, where Samuel and Maria are living at the same address, with another female servant and two male lodgers by the name of Messant from Ipswich.

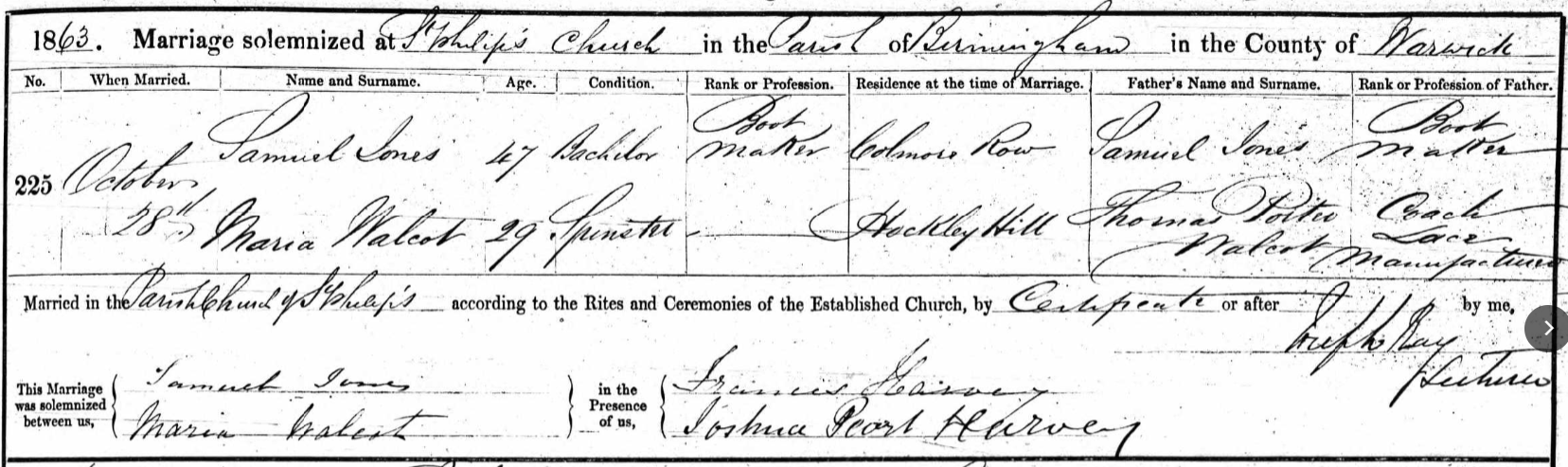

Marriage of Samuel Jones and Maria Walcot:

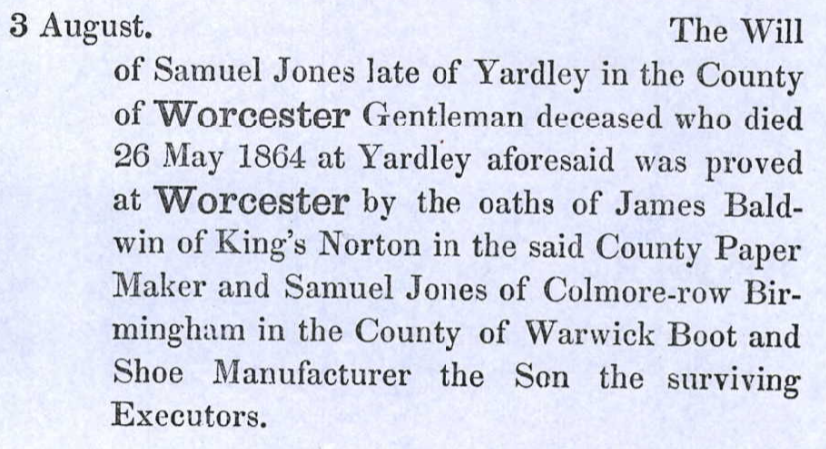

In 1864 Samuel’s father died. Samuel the son is mentioned in the probate records as one of the executors: “Samuel Jones of Colmore Row Birmingham in the county of Warwick boot and shoe manufacturer the son”.

Indeed it could hardly be clearer that this Samuel Jones was not the convict transported to Australia in 1834!

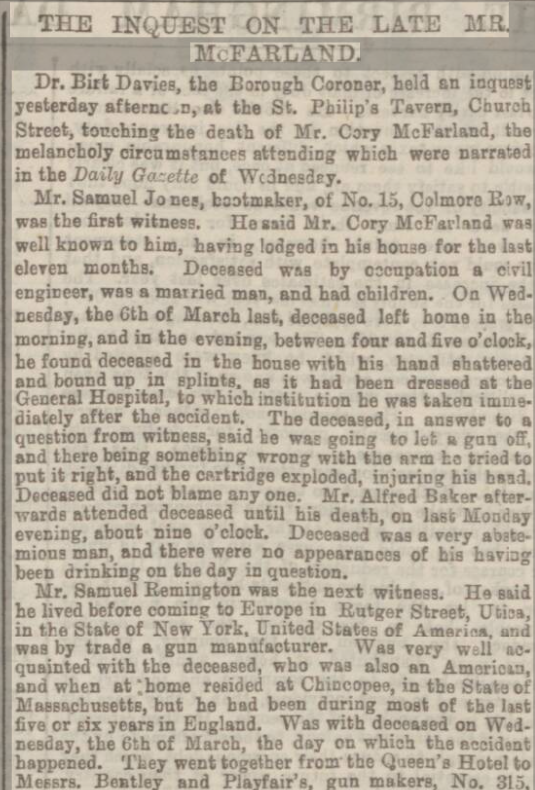

In 1867 Samuel Jones, bootmaker, was mentioned in the Birmingham Daily Gazette with regard to an unfortunate incident involving his American lodger, Cory McFarland. The verdict was accidental death.

Birmingham Daily Gazette – Friday 05 April 1867:

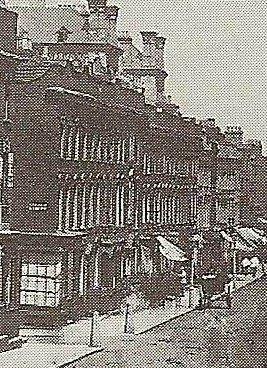

I asked a Birmingham history group for an old photo of Colmore Row. This photo is circa 1870 and number 15 is furthest from the camera. The businesses on the street at the time were as follows:

7 homeopathic chemist George John Morris. 8 surgeon dentist Frederick Sims. 9 Saul & Walter Samuel, Australian merchants. Surgeons occupied 10, pawnbroker John Aaron at 11 & 12. 15 boot & shoemaker. 17 auctioneer…

from Bird’s Eye View of Birmingham, 1886:

December 6, 2022 at 2:17 pm #6350

December 6, 2022 at 2:17 pm #6350In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Transportation

Isaac Stokes 1804-1877

Isaac was born in Churchill, Oxfordshire in 1804, and was the youngest brother of my 4X great grandfather Thomas Stokes. The Stokes family were stone masons for generations in Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire, and Isaac’s occupation was a mason’s labourer in 1834 when he was sentenced at the Lent Assizes in Oxford to fourteen years transportation for stealing tools.

Churchill where the Stokes stonemasons came from: on 31 July 1684 a fire destroyed 20 houses and many other buildings, and killed four people. The village was rebuilt higher up the hill, with stone houses instead of the old timber-framed and thatched cottages. The fire was apparently caused by a baker who, to avoid chimney tax, had knocked through the wall from her oven to her neighbour’s chimney.

Isaac stole a pick axe, the value of 2 shillings and the property of Thomas Joyner of Churchill; a kibbeaux and a trowel value 3 shillings the property of Thomas Symms; a hammer and axe value 5 shillings, property of John Keen of Sarsden.

(The word kibbeaux seems to only exists in relation to Isaac Stokes sentence and whoever was the first to write it was perhaps being creative with the spelling of a kibbo, a miners or a metal bucket. This spelling is repeated in the criminal reports and the newspaper articles about Isaac, but nowhere else).

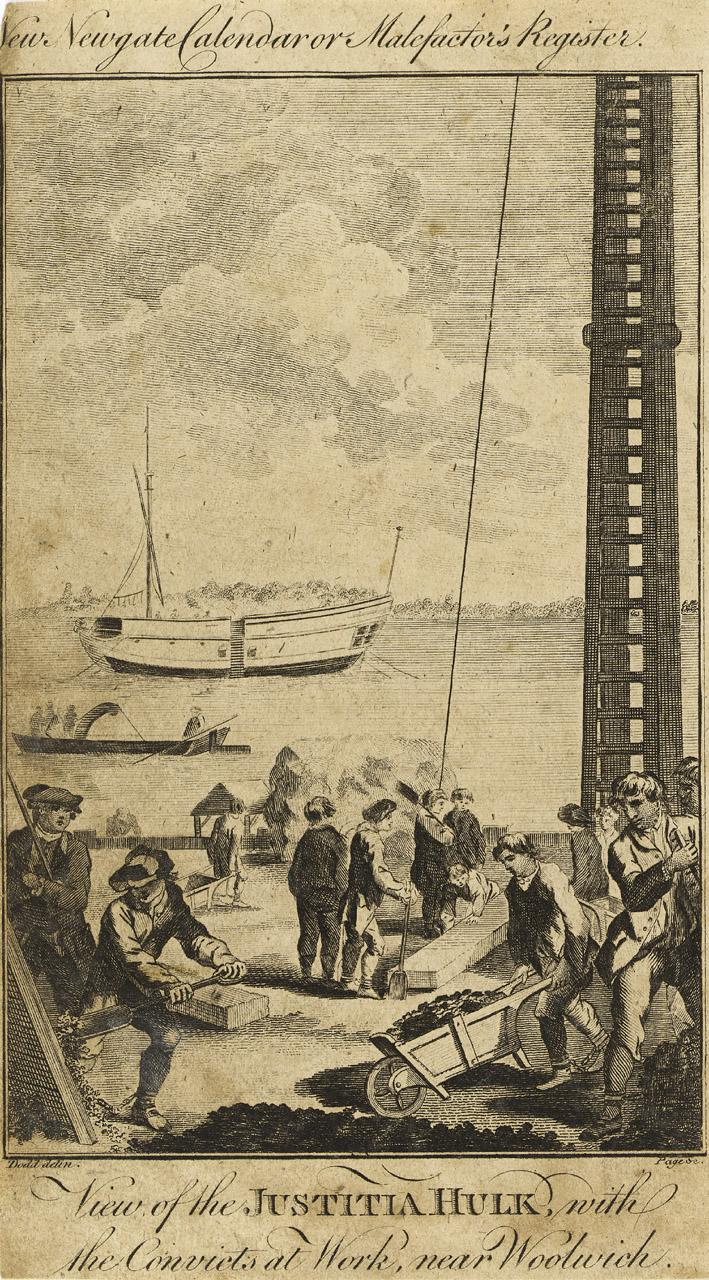

In March 1834 the Removal of Convicts was announced in the Oxford University and City Herald: Isaac Stokes and several other prisoners were removed from the Oxford county gaol to the Justitia hulk at Woolwich “persuant to their sentences of transportation at our Lent Assizes”.

via digitalpanopticon:

Hulks were decommissioned (and often unseaworthy) ships that were moored in rivers and estuaries and refitted to become floating prisons. The outbreak of war in America in 1775 meant that it was no longer possible to transport British convicts there. Transportation as a form of punishment had started in the late seventeenth century, and following the Transportation Act of 1718, some 44,000 British convicts were sent to the American colonies. The end of this punishment presented a major problem for the authorities in London, since in the decade before 1775, two-thirds of convicts at the Old Bailey received a sentence of transportation – on average 283 convicts a year. As a result, London’s prisons quickly filled to overflowing with convicted prisoners who were sentenced to transportation but had no place to go.

To increase London’s prison capacity, in 1776 Parliament passed the “Hulks Act” (16 Geo III, c.43). Although overseen by local justices of the peace, the hulks were to be directly managed and maintained by private contractors. The first contract to run a hulk was awarded to Duncan Campbell, a former transportation contractor. In August 1776, the Justicia, a former transportation ship moored in the River Thames, became the first prison hulk. This ship soon became full and Campbell quickly introduced a number of other hulks in London; by 1778 the fleet of hulks on the Thames held 510 prisoners.

Demand was so great that new hulks were introduced across the country. There were hulks located at Deptford, Chatham, Woolwich, Gosport, Plymouth, Portsmouth, Sheerness and Cork.The Justitia via rmg collections:

Convicts perform hard labour at the Woolwich Warren. The hulk on the river is the ‘Justitia’. Prisoners were kept on board such ships for months awaiting deportation to Australia. The ‘Justitia’ was a 260 ton prison hulk that had been originally moored in the Thames when the American War of Independence put a stop to the transportation of criminals to the former colonies. The ‘Justitia’ belonged to the shipowner Duncan Campbell, who was the Government contractor who organized the prison-hulk system at that time. Campbell was subsequently involved in the shipping of convicts to the penal colony at Botany Bay (in fact Port Jackson, later Sydney, just to the north) in New South Wales, the ‘first fleet’ going out in 1788.

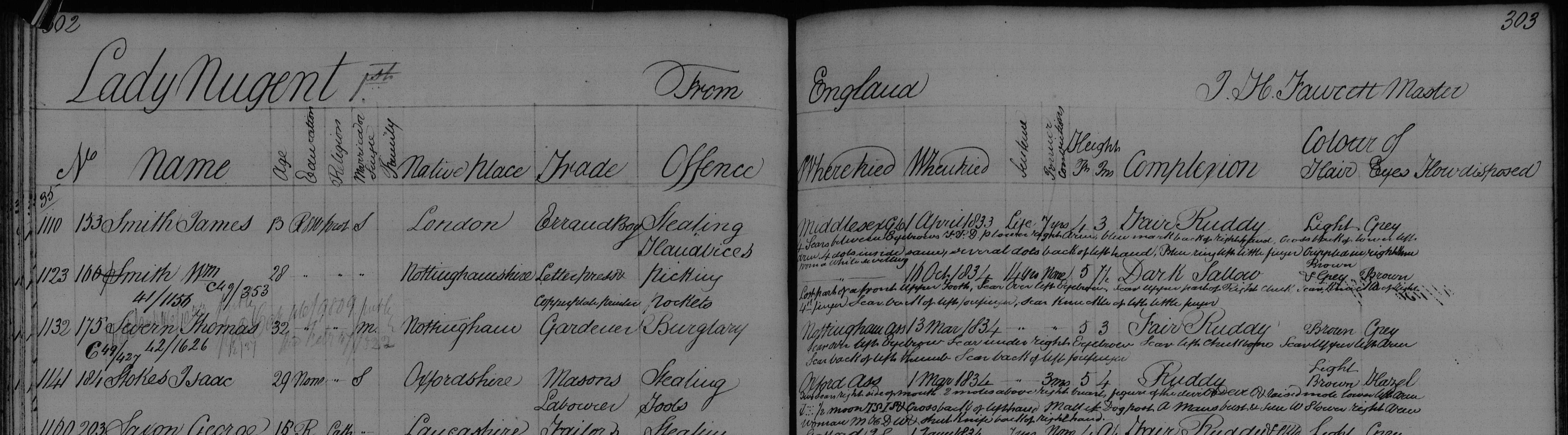

While searching for records for Isaac Stokes I discovered that another Isaac Stokes was transported to New South Wales in 1835 as well. The other one was a butcher born in 1809, sentenced in London for seven years, and he sailed on the Mary Ann. Our Isaac Stokes sailed on the Lady Nugent, arriving in NSW in April 1835, having set sail from England in December 1834.

Lady Nugent was built at Bombay in 1813. She made four voyages under contract to the British East India Company (EIC). She then made two voyages transporting convicts to Australia, one to New South Wales and one to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). (via Wikipedia)

via freesettlerorfelon website:

On 20 November 1834, 100 male convicts were transferred to the Lady Nugent from the Justitia Hulk and 60 from the Ganymede Hulk at Woolwich, all in apparent good health. The Lady Nugent departed Sheerness on 4 December 1834.

SURGEON OLIVER SPROULE

Oliver Sproule kept a Medical Journal from 7 November 1834 to 27 April 1835. He recorded in his journal the weather conditions they experienced in the first two weeks:

‘In the course of the first week or ten days at sea, there were eight or nine on the sick list with catarrhal affections and one with dropsy which I attribute to the cold and wet we experienced during that period beating down channel. Indeed the foremost berths in the prison at this time were so wet from leaking in that part of the ship, that I was obliged to issue dry beds and bedding to a great many of the prisoners to preserve their health, but after crossing the Bay of Biscay the weather became fine and we got the damp beds and blankets dried, the leaks partially stopped and the prison well aired and ventilated which, I am happy to say soon manifested a favourable change in the health and appearance of the men.

Besides the cases given in the journal I had a great many others to treat, some of them similar to those mentioned but the greater part consisted of boils, scalds, and contusions which would not only be too tedious to enter but I fear would be irksome to the reader. There were four births on board during the passage which did well, therefore I did not consider it necessary to give a detailed account of them in my journal the more especially as they were all favourable cases.

Regularity and cleanliness in the prison, free ventilation and as far as possible dry decks turning all the prisoners up in fine weather as we were lucky enough to have two musicians amongst the convicts, dancing was tolerated every afternoon, strict attention to personal cleanliness and also to the cooking of their victuals with regular hours for their meals, were the only prophylactic means used on this occasion, which I found to answer my expectations to the utmost extent in as much as there was not a single case of contagious or infectious nature during the whole passage with the exception of a few cases of psora which soon yielded to the usual treatment. A few cases of scurvy however appeared on board at rather an early period which I can attribute to nothing else but the wet and hardships the prisoners endured during the first three or four weeks of the passage. I was prompt in my treatment of these cases and they got well, but before we arrived at Sydney I had about thirty others to treat.’

The Lady Nugent arrived in Port Jackson on 9 April 1835 with 284 male prisoners. Two men had died at sea. The prisoners were landed on 27th April 1835 and marched to Hyde Park Barracks prior to being assigned. Ten were under the age of 14 years.

The Lady Nugent:

Isaac’s distinguishing marks are noted on various criminal registers and record books:

“Height in feet & inches: 5 4; Complexion: Ruddy; Hair: Light brown; Eyes: Hazel; Marks or Scars: Yes [including] DEVIL on lower left arm, TSIS back of left hand, WS lower right arm, MHDW back of right hand.”

Another includes more detail about Isaac’s tattoos:

“Two slight scars right side of mouth, 2 moles above right breast, figure of the devil and DEVIL and raised mole, lower left arm; anchor, seven dots half moon, TSIS and cross, back of left hand; a mallet, door post, A, mans bust, sun, WS, lower right arm; woman, MHDW and shut knife, back of right hand.”

From How tattoos became fashionable in Victorian England (2019 article in TheConversation by Robert Shoemaker and Zoe Alkar):

“Historical tattooing was not restricted to sailors, soldiers and convicts, but was a growing and accepted phenomenon in Victorian England. Tattoos provide an important window into the lives of those who typically left no written records of their own. As a form of “history from below”, they give us a fleeting but intriguing understanding of the identities and emotions of ordinary people in the past.

As a practice for which typically the only record is the body itself, few systematic records survive before the advent of photography. One exception to this is the written descriptions of tattoos (and even the occasional sketch) that were kept of institutionalised people forced to submit to the recording of information about their bodies as a means of identifying them. This particularly applies to three groups – criminal convicts, soldiers and sailors. Of these, the convict records are the most voluminous and systematic.

Such records were first kept in large numbers for those who were transported to Australia from 1788 (since Australia was then an open prison) as the authorities needed some means of keeping track of them.”On the 1837 census Isaac was working for the government at Illiwarra, New South Wales. This record states that he arrived on the Lady Nugent in 1835. There are three other indent records for an Isaac Stokes in the following years, but the transcriptions don’t provide enough information to determine which Isaac Stokes it was. In April 1837 there was an abscondment, and an arrest/apprehension in May of that year, and in 1843 there was a record of convict indulgences.

From the Australian government website regarding “convict indulgences”:

“By the mid-1830s only six per cent of convicts were locked up. The vast majority worked for the government or free settlers and, with good behaviour, could earn a ticket of leave, conditional pardon or and even an absolute pardon. While under such orders convicts could earn their own living.”

In 1856 in Camden, NSW, Isaac Stokes married Catherine Daly. With no further information on this record it would be impossible to know for sure if this was the right Isaac Stokes. This couple had six children, all in the Camden area, but none of the records provided enough information. No occupation or place or date of birth recorded for Isaac Stokes.

I wrote to the National Library of Australia about the marriage record, and their reply was a surprise! Issac and Catherine were married on 30 September 1856, at the house of the Rev. Charles William Rigg, a Methodist minister, and it was recorded that Isaac was born in Edinburgh in 1821, to parents James Stokes and Sarah Ellis! The age at the time of the marriage doesn’t match Isaac’s age at death in 1877, and clearly the place of birth and parents didn’t match either. Only his fathers occupation of stone mason was correct. I wrote back to the helpful people at the library and they replied that the register was in a very poor condition and that only two and a half entries had survived at all, and that Isaac and Catherines marriage was recorded over two pages.

I searched for an Isaac Stokes born in 1821 in Edinburgh on the Scotland government website (and on all the other genealogy records sites) and didn’t find it. In fact Stokes was a very uncommon name in Scotland at the time. I also searched Australian immigration and other records for another Isaac Stokes born in Scotland or born in 1821, and found nothing. I was unable to find a single record to corroborate this mysterious other Isaac Stokes.

As the age at death in 1877 was correct, I assume that either Isaac was lying, or that some mistake was made either on the register at the home of the Methodist minster, or a subsequent mistranscription or muddle on the remnants of the surviving register. Therefore I remain convinced that the Camden stonemason Isaac Stokes was indeed our Isaac from Oxfordshire.

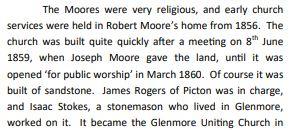

I found a history society newsletter article that mentioned Isaac Stokes, stone mason, had built the Glenmore church, near Camden, in 1859.

From the Wollondilly museum April 2020 newsletter:

From the Camden History website:

“The stone set over the porch of Glenmore Church gives the date of 1860. The church was begun in 1859 on land given by Joseph Moore. James Rogers of Picton was given the contract to build and local builder, Mr. Stokes, carried out the work. Elizabeth Moore, wife of Edward, laid the foundation stone. The first service was held on 19th March 1860. The cemetery alongside the church contains the headstones and memorials of the areas early pioneers.”

Isaac died on the 3rd September 1877. The inquest report puts his place of death as Bagdelly, near to Camden, and another death register has put Cambelltown, also very close to Camden. His age was recorded as 71 and the inquest report states his cause of death was “rupture of one of the large pulmonary vessels of the lung”. His wife Catherine died in childbirth in 1870 at the age of 43.

Isaac and Catherine’s children:

William Stokes 1857-1928

Catherine Stokes 1859-1846

Sarah Josephine Stokes 1861-1931

Ellen Stokes 1863-1932

Rosanna Stokes 1865-1919

Louisa Stokes 1868-1844.

It’s possible that Catherine Daly was a transported convict from Ireland.

Some time later I unexpectedly received a follow up email from The Oaks Heritage Centre in Australia.

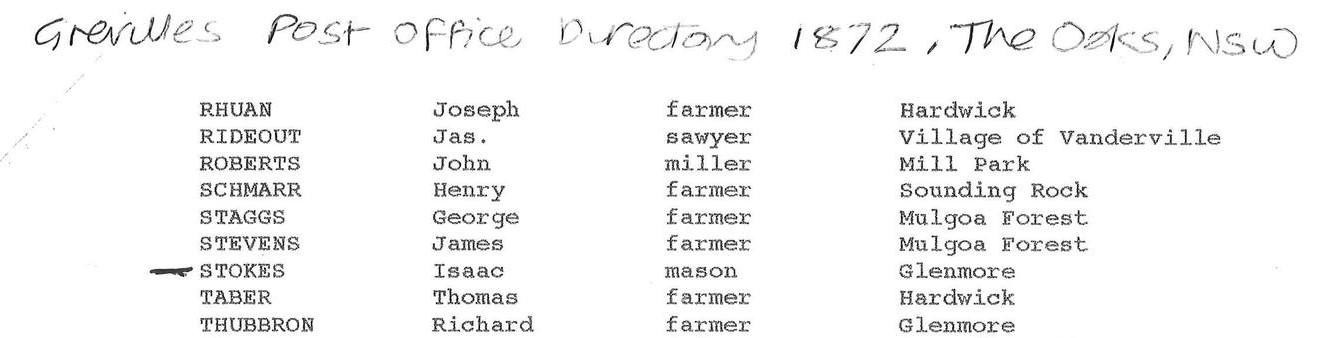

“The Gaudry papers which we have in our archive record him (Isaac Stokes) as having built: the church, the school and the teachers residence. Isaac is recorded in the General return of convicts: 1837 and in Grevilles Post Office directory 1872 as a mason in Glenmore.”

November 18, 2022 at 4:47 pm #6348

November 18, 2022 at 4:47 pm #6348In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Wong Sang

Wong Sang was born in China in 1884. In October 1916 he married Alice Stokes in Oxford.

Alice was the granddaughter of William Stokes of Churchill, Oxfordshire and William was the brother of Thomas Stokes the wheelwright (who was my 3X great grandfather). In other words Alice was my second cousin, three times removed, on my fathers paternal side.

Wong Sang was an interpreter, according to the baptism registers of his children and the Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital admission registers in 1930. The hospital register also notes that he was employed by the Blue Funnel Line, and that his address was 11, Limehouse Causeway, E 14. (London)

“The Blue Funnel Line offered regular First-Class Passenger and Cargo Services From the UK to South Africa, Malaya, China, Japan, Australia, Java, and America. Blue Funnel Line was Owned and Operated by Alfred Holt & Co., Liverpool.

The Blue Funnel Line, so-called because its ships have a blue funnel with a black top, is more appropriately known as the Ocean Steamship Company.”Wong Sang and Alice’s daughter, Frances Eileen Sang, was born on the 14th July, 1916 and baptised in 1920 at St Stephen in Poplar, Tower Hamlets, London. The birth date is noted in the 1920 baptism register and would predate their marriage by a few months, although on the death register in 1921 her age at death is four years old and her year of birth is recorded as 1917.

Charles Ronald Sang was baptised on the same day in May 1920, but his birth is recorded as April of that year. The family were living on Morant Street, Poplar.

James William Sang’s birth is recorded on the 1939 census and on the death register in 2000 as being the 8th March 1913. This definitely would predate the 1916 marriage in Oxford.

William Norman Sang was born on the 17th October 1922 in Poplar.

Alice and the three sons were living at 11, Limehouse Causeway on the 1939 census, the same address that Wong Sang was living at when he was admitted to Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital on the 15th January 1930. Wong Sang died in the hospital on the 8th March of that year at the age of 46.

Alice married John Patterson in 1933 in Stepney. John was living with Alice and her three sons on Limehouse Causeway on the 1939 census and his occupation was chef.

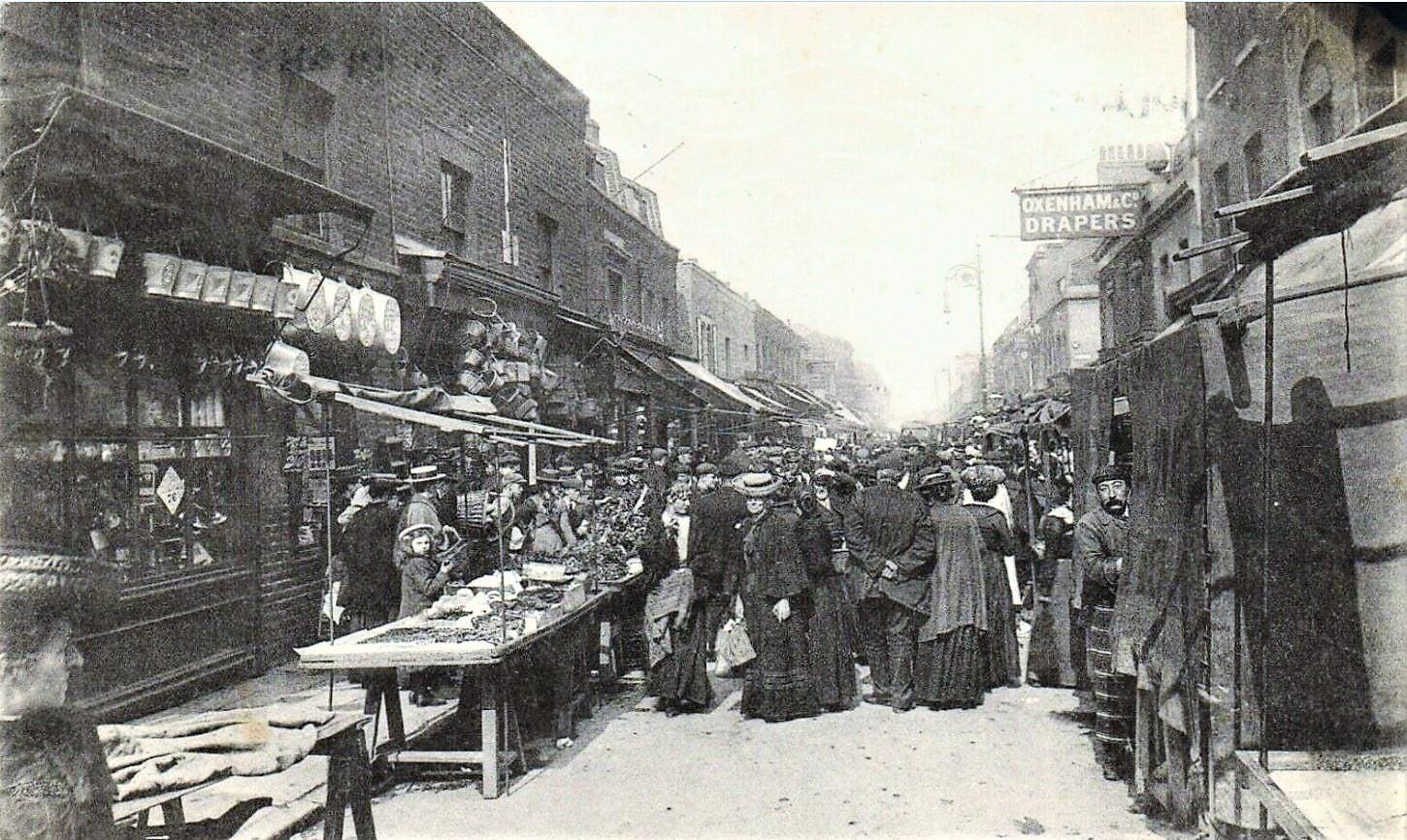

Via Old London Photographs:

“Limehouse Causeway is a street in east London that was the home to the original Chinatown of London. A combination of bomb damage during the Second World War and later redevelopment means that almost nothing is left of the original buildings of the street.”

Limehouse Causeway in 1925:

From The Story of Limehouse’s Lost Chinatown, poplarlondon website:

“Limehouse was London’s first Chinatown, home to a tightly-knit community who were demonised in popular culture and eventually erased from the cityscape.

As recounted in the BBC’s ‘Our Greatest Generation’ series, Connie was born to a Chinese father and an English mother in early 1920s Limehouse, where she used to play in the street with other British and British-Chinese children before running inside for teatime at one of their houses.

Limehouse was London’s first Chinatown between the 1880s and the 1960s, before the current Chinatown off Shaftesbury Avenue was established in the 1970s by an influx of immigrants from Hong Kong.

Connie’s memories of London’s first Chinatown as an “urban village” paint a very different picture to the seedy area portrayed in early twentieth century novels.

The pyramid in St Anne’s church marked the entrance to the opium den of Dr Fu Manchu, a criminal mastermind who threatened Western society by plotting world domination in a series of novels by Sax Rohmer.

Thomas Burke’s Limehouse Nights cemented stereotypes about prostitution, gambling and violence within the Chinese community, and whipped up anxiety about sexual relationships between Chinese men and white women.

Though neither novelist was familiar with the Chinese community, their depictions made Limehouse one of the most notorious areas of London.

Travel agent Thomas Cook even organised tours of the area for daring visitors, despite the rector of Limehouse warning that “those who look for the Limehouse of Mr Thomas Burke simply will not find it.”

All that remains is a handful of Chinese street names, such as Ming Street, Pekin Street, and Canton Street — but what was Limehouse’s chinatown really like, and why did it get swept away?

Chinese migration to Limehouse

Chinese sailors discharged from East India Company ships settled in the docklands from as early as the 1780s.

By the late nineteenth century, men from Shanghai had settled around Pennyfields Lane, while a Cantonese community lived on Limehouse Causeway.

Chinese sailors were often paid less and discriminated against by dock hirers, and so began to diversify their incomes by setting up hand laundry services and restaurants.

Old photographs show shopfronts emblazoned with Chinese characters with horse-drawn carts idling outside or Chinese men in suits and hats standing proudly in the doorways.

In oral histories collected by Yat Ming Loo, Connie’s husband Leslie doesn’t recall seeing any Chinese women as a child, since male Chinese sailors settled in London alone and married working-class English women.

In the 1920s, newspapers fear-mongered about interracial marriages, crime and gambling, and described chinatown as an East End “colony.”

Ironically, Chinese opium-smoking was also demonised in the press, despite Britain waging war against China in the mid-nineteenth century for suppressing the opium trade to alleviate addiction amongst its people.

The number of Chinese people who settled in Limehouse was also greatly exaggerated, and in reality only totalled around 300.

The real Chinatown

Although the press sought to characterise Limehouse as a monolithic Chinese community in the East End, Connie remembers seeing people of all nationalities in the shops and community spaces in Limehouse.

She doesn’t remember feeling discriminated against by other locals, though Connie does recall having her face measured and IQ tested by a member of the British Eugenics Society who was conducting research in the area.

Some of Connie’s happiest childhood memories were from her time at Chung-Hua Club, where she learned about Chinese culture and language.

Why did Chinatown disappear?

The caricature of Limehouse’s Chinatown as a den of vice hastened its erasure.

Police raids and deportations fuelled by the alarmist media coverage threatened the Chinese population of Limehouse, and slum clearance schemes to redevelop low-income areas dispersed Chinese residents in the 1930s.

The Defence of the Realm Act imposed at the beginning of the First World War criminalised opium use, gave the authorities increased powers to deport Chinese people and restricted their ability to work on British ships.

Dwindling maritime trade during World War II further stripped Chinese sailors of opportunities for employment, and any remnants of Chinatown were destroyed during the Blitz or erased by postwar development schemes.”

Wong Sang 1884-1930

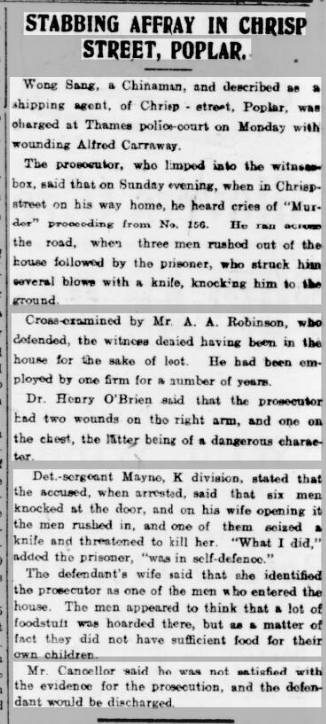

The year 1918 was a troublesome one for Wong Sang, an interpreter and shipping agent for Blue Funnel Line. The Sang family were living at 156, Chrisp Street.

Chrisp Street, Poplar, in 1913 via Old London Photographs:

In February Wong Sang was discharged from a false accusation after defending his home from potential robbers.

East End News and London Shipping Chronicle – Friday 15 February 1918:

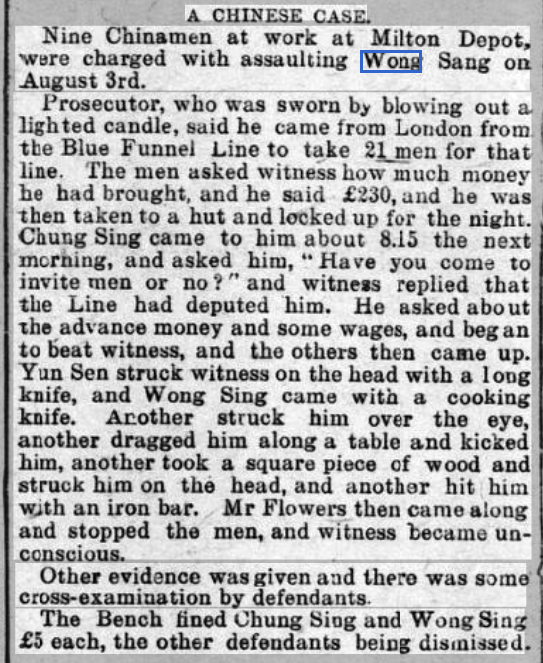

In August of that year he was involved in an incident that left him unconscious.

Faringdon Advertiser and Vale of the White Horse Gazette – Saturday 31 August 1918:

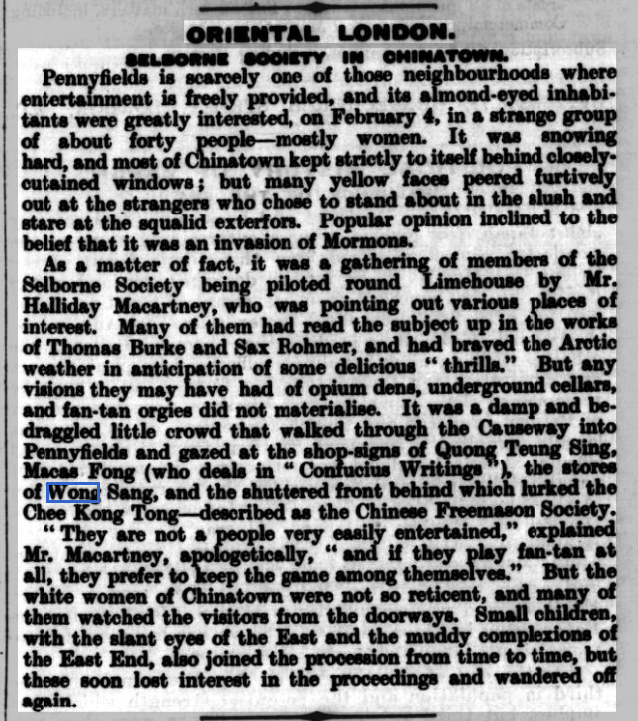

Wong Sang is mentioned in an 1922 article about “Oriental London”.

London and China Express – Thursday 09 February 1922:

A photograph of the Chee Kong Tong Chinese Freemason Society mentioned in the above article, via Old London Photographs:

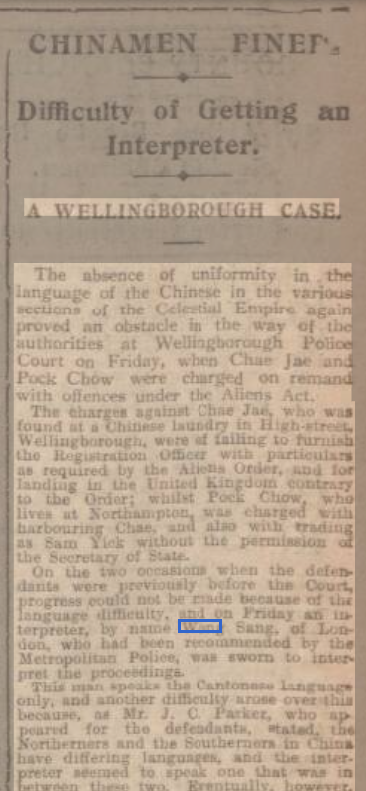

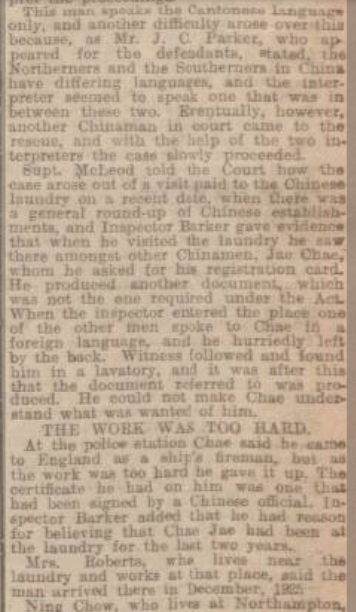

Wong Sang was recommended by the London Metropolitan Police in 1928 to assist in a case in Wellingborough, Northampton.

Difficulty of Getting an Interpreter: Northampton Mercury – Friday 16 March 1928:

The difficulty was that “this man speaks the Cantonese language only…the Northeners and the Southerners in China have differing languages and the interpreter seemed to speak one that was in between these two.”

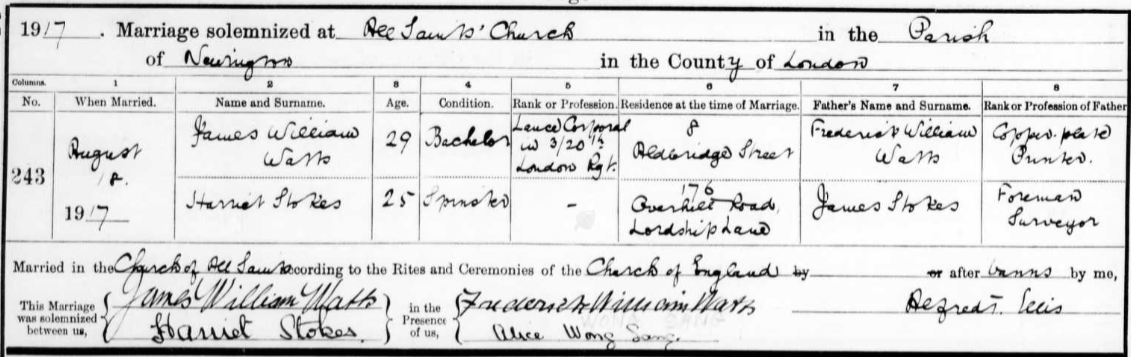

In 1917, Alice Wong Sang was a witness at her sister Harriet Stokes marriage to James William Watts in Southwark, London. Their father James Stokes occupation on the marriage register is foreman surveyor, but on the census he was a council roadman or labourer. (I initially rejected this as the correct marriage for Harriet because of the discrepancy with the occupations. Alice Wong Sang as a witness confirmed that it was indeed the correct one.)

James William Sang 1913-2000 was a clock fitter and watch assembler (on the 1939 census). He married Ivy Laura Fenton in 1963 in Sidcup, Kent. James died in Southwark in 2000.

Charles Ronald Sang 1920-1974 was a draughtsman (1939 census). He married Eileen Burgess in 1947 in Marylebone. Charles and Eileen had two sons: Keith born in 1951 and Roger born in 1952. He died in 1974 in Hertfordshire.

William Norman Sang 1922-2000 was a clerk and telephone operator (1939 census). William enlisted in the Royal Artillery in 1942. He married Lily Mullins in 1949 in Bethnal Green, and they had three daughters: Marion born in 1950, Christine in 1953, and Frances in 1959. He died in Redbridge in 2000.

I then found another two births registered in Poplar by Alice Sang, both daughters. Doris Winifred Sang was born in 1925, and Patricia Margaret Sang was born in 1933 ~ three years after Wong Sang’s death. Neither of the these daughters were on the 1939 census with Alice, John Patterson and the three sons. Margaret had presumably been evacuated because of the war to a family in Taunton, Somerset. Doris would have been fourteen and I have been unable to find her in 1939 (possibly because she died in 2017 and has not had the redaction removed yet on the 1939 census as only deceased people are viewable).

Doris Winifred Sang 1925-2017 was a nursing sister. She didn’t marry, and spent a year in USA between 1954 and 1955. She stayed in London, and died at the age of ninety two in 2017.

Patricia Margaret Sang 1933-1998 was also a nurse. She married Patrick L Nicely in Stepney in 1957. Patricia and Patrick had five children in London: Sharon born 1959, Donald in 1960, Malcolm was born and died in 1966, Alison was born in 1969 and David in 1971.

I was unable to find a birth registered for Alice’s first son, James William Sang (as he appeared on the 1939 census). I found Alice Stokes on the 1911 census as a 17 year old live in servant at a tobacconist on Pekin Street, Limehouse, living with Mr Sui Fong from Hong Kong and his wife Sarah Sui Fong from Berlin. I looked for a birth registered for James William Fong instead of Sang, and found it ~ mothers maiden name Stokes, and his date of birth matched the 1939 census: 8th March, 1913.

On the 1921 census, Wong Sang is not listed as living with them but it is mentioned that Mr Wong Sang was the person returning the census. Also living with Alice and her sons James and Charles in 1921 are two visitors: (Florence) May Stokes, 17 years old, born in Woodstock, and Charles Stokes, aged 14, also born in Woodstock. May and Charles were Alice’s sister and brother.

I found Sharon Nicely on social media and she kindly shared photos of Wong Sang and Alice Stokes:

November 14, 2022 at 12:09 pm #6346

November 14, 2022 at 12:09 pm #6346In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The Mormon Browning Who Went To Utah

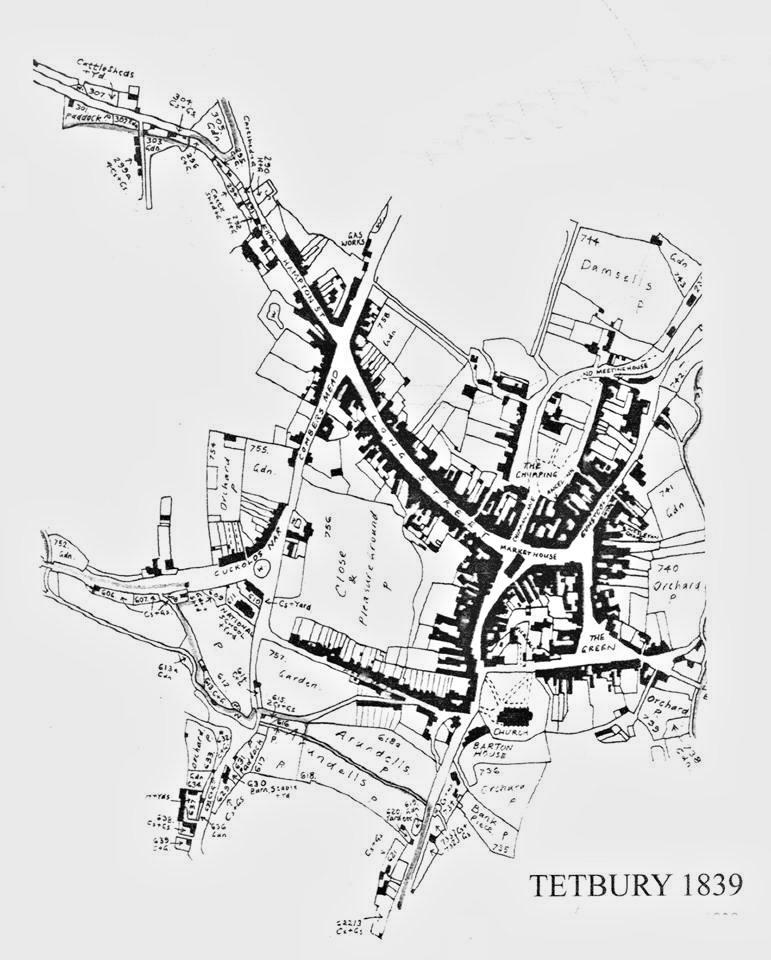

Isaac Browning’s (1784-1848) sister Hannah married Francis Buckingham. There were at least three Browning Buckingham marriages in Tetbury. Their daughter Charlotte married James Paskett, a shoemaker. Charlotte was born in 1818 and in 1871 she and her family emigrated to Utah, USA.

Charlotte’s relationship to me is first cousin five times removed.

James and Charlotte: (photos found online)

The house of James and Charlotte in Tetbury:

The home of James and Charlotte in Utah:

Obituary:

James Pope Paskett Dead.

Veteran of 87 Laid to rest. Special Correspondence Coalville, Summit Co., Oct 28—James Pope Paskett of Henefer died Oct. 24, 1903 of old age and general debility. Funeral services were held at Henefer today. Elders W.W. Cluff, Alma Elderge, Robert Jones, Oscar Wilkins and Bishop M.F. Harris were the speakers. There was a large attendance many coming from other wards in the stake. James Pope Paskett was born in Chippenham, Wiltshire, England, on March 12, 1817; married Chalotte Buckingham in the year 1839; eight children were born to them, three sons and five daughters, all of whom are living and residing in Utah, except one in Brisbane, Australia. Father Paskett joined the church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints in 1847, and emigrated to Utah in 1871, and has resided in Henefer ever since. He leaves his faithful and aged wife. He was respected and esteemed by all who knew him.

Charlotte died in Henefer, Utah, on 27th December 1910 at the age of 91.

James and Charlotte in later life:

November 4, 2022 at 2:19 pm #6342In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Brownings of Tetbury

Isaac Browning (1784-1848) married Mary Lock (1787-1870) in Tetbury in 1806. Both of them were born in Tetbury, Gloucestershire. Isaac was a stone mason. Between 1807 and 1832 they baptised fourteen children in Tetbury, and on 8 Nov 1829 Isaac and Mary baptised five daughters all on the same day.

I considered that they may have been quintuplets, with only the last born surviving, which would have answered my question about the name of the house La Quinta in Broadway, the home of Eliza Browning and Thomas Stokes son Fred. However, the other four daughters were found in various records and they were not all born the same year. (So I still don’t know why the house in Broadway had such an unusual name).

Their son George was born and baptised in 1827, but Louisa born 1821, Susan born 1822, Hesther born 1823 and Mary born 1826, were not baptised until 1829 along with Charlotte born in 1828. (These birth dates are guesswork based on the age on later censuses.) Perhaps George was baptised promptly because he was sickly and not expected to survive. Isaac and Mary had a son George born in 1814 who died in 1823. Presumably the five girls were healthy and could wait to be done as a job lot on the same day later.

Eliza Browning (1814-1886), my great great great grandmother, had a baby six years before she married Thomas Stokes. Her name was Ellen Harding Browning, which suggests that her fathers name was Harding. On the 1841 census seven year old Ellen was living with her grandfather Isaac Browning in Tetbury. Ellen Harding Browning married William Dee in Tetbury in 1857, and they moved to Western Australia.

Ellen Harding Browning Dee: (photo found on ancestry website)

OBITUARY. MRS. ELLEN DEE.

A very old and respected resident of Dongarra, in the person of Mrs. Ellen Dee, passed peacefully away on Sept. 27, at the advanced age of 74 years.The deceased had been ailing for some time, but was about and actively employed until Wednesday, Sept. 20, whenn she was heard groaning by some neighbours, who immediately entered her place and found her lying beside the fireplace. Tho deceased had been to bed over night, and had evidently been in the act of lighting thc fire, when she had a seizure. For some hours she was conscious, but had lost the power of speech, and later on became unconscious, in which state she remained until her death.

The deceased was born in Gloucestershire, England, in 1833, was married to William Dee in Tetbury Church 23 years later. Within a month she left England with her husband for Western Australian in the ship City oí Bristol. She resided in Fremantle for six months, then in Greenough for a short time, and afterwards (for 42 years) in Dongarra. She was, therefore, a colonist of about 51 years. She had a family of four girls and three boys, and five of her children survive her, also 35 grandchildren, and eight great grandchildren. She was very highly respected, and her sudden collapse came as a great shock to many.

Eliza married Thomas Stokes (1816-1885) in September 1840 in Hempstead, Gloucestershire. On the 1841 census, Eliza and her mother Mary Browning (nee Lock) were staying with Thomas Lock and family in Cirencester. Strangely, Thomas Stokes has not been found thus far on the 1841 census, and Thomas and Eliza’s first child William James Stokes birth was registered in Witham, in Essex, on the 6th of September 1841.

I don’t know why William James was born in Witham, or where Thomas was at the time of the census in 1841. One possibility is that as Thomas Stokes did a considerable amount of work with circus waggons, circus shooting galleries and so on as a journeyman carpenter initially and then later wheelwright, perhaps he was working with a traveling circus at the time.

But back to the Brownings ~ more on William James Stokes to follow.

One of Isaac and Mary’s fourteen children died in infancy: Ann was baptised and died in 1811. Two of their children died at nine years old: the first George, and Mary who died in 1835. Matilda was 21 years old when she died in 1844.

Jane Browning (1808-) married Thomas Buckingham in 1830 in Tetbury. In August 1838 Thomas was charged with feloniously stealing a black gelding.

Susan Browning (1822-1879) married William Cleaver in November 1844 in Tetbury. Oddly thereafter they use the name Bowman on the census. On the 1851 census Mary Browning (Susan’s mother), widow, has grandson George Bowman born in 1844 living with her. The confusion with the Bowman and Cleaver names was clarified upon finding the criminal registers:

30 January 1834. Offender: William Cleaver alias Bowman, Richard Bunting alias Barnfield and Jeremiah Cox, labourers of Tetbury. Crime: Stealing part of a dead fence from a rick barton in Tetbury, the property of Robert Tanner, farmer.

And again in 1836:

29 March 1836 Bowman, William alias Cleaver, of Tetbury, labourer age 18; 5’2.5” tall, brown hair, grey eyes, round visage with fresh complexion; several moles on left cheek, mole on right breast. Charged on the oath of Ann Washbourn & others that on the morning of the 31 March at Tetbury feloniously stolen a lead spout affixed to the dwelling of the said Ann Washbourn, her property. Found guilty 31 March 1836; Sentenced to 6 months.

On the 1851 census Susan Bowman was a servant living in at a large drapery shop in Cheltenham. She was listed as 29 years old, married and born in Tetbury, so although it was unusual for a married woman not to be living with her husband, (or her son for that matter, who was living with his grandmother Mary Browning), perhaps her husband William Bowman alias Cleaver was in trouble again. By 1861 they are both living together in Tetbury: William was a plasterer, and they had three year old Isaac and Thomas, one year old. In 1871 William was still a plasterer in Tetbury, living with wife Susan, and sons Isaac and Thomas. Interestingly, a William Cleaver is living next door but one!

Susan was 56 when she died in Tetbury in 1879.

Three of the Browning daughters went to London.

Louisa Browning (1821-1873) married Robert Claxton, coachman, in 1848 in Bryanston Square, Westminster, London. Ester Browning was a witness.

Ester Browning (1823-1893)(or Hester) married Charles Hudson Sealey, cabinet maker, in Bethnal Green, London, in 1854. Charles was born in Tetbury. Charlotte Browning was a witness.

Charlotte Browning (1828-1867?) was admitted to St Marylebone workhouse in London for “parturition”, or childbirth, in 1860. She was 33 years old. A birth was registered for a Charlotte Browning, no mothers maiden name listed, in 1860 in Marylebone. A death was registered in Camden, buried in Marylebone, for a Charlotte Browning in 1867 but no age was recorded. As the age and parents were usually recorded for a childs death, I assume this was Charlotte the mother.

I found Charlotte on the 1851 census by chance while researching her mother Mary Lock’s siblings. Hesther Lock married Lewin Chandler, and they were living in Stepney, London. Charlotte is listed as a neice. Although Browning is mistranscribed as Broomey, the original page says Browning. Another mistranscription on this record is Hesthers birthplace which is transcribed as Yorkshire. The original image shows Gloucestershire.

Isaac and Mary’s first son was John Browning (1807-1860). John married Hannah Coates in 1834. John’s brother Charles Browning (1819-1853) married Eliza Coates in 1842. Perhaps they were sisters. On the 1861 census Hannah Browning, John’s wife, was a visitor in the Harding household in a village called Coates near Tetbury. Thomas Harding born in 1801 was the head of the household. Perhaps he was the father of Ellen Harding Browning.

George Browning (1828-1870) married Louisa Gainey in Tetbury, and died in Tetbury at the age of 42. Their son Richard Lock Browning, a 32 year old mason, was sentenced to one month hard labour for game tresspass in Tetbury in 1884.

Isaac Browning (1832-1857) was the youngest son of Isaac and Mary. He was just 25 years old when he died in Tetbury.

October 23, 2022 at 6:57 am #6340In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Wheelwrights of Broadway

Thomas Stokes 1816-1885

Frederick Stokes 1845-1917

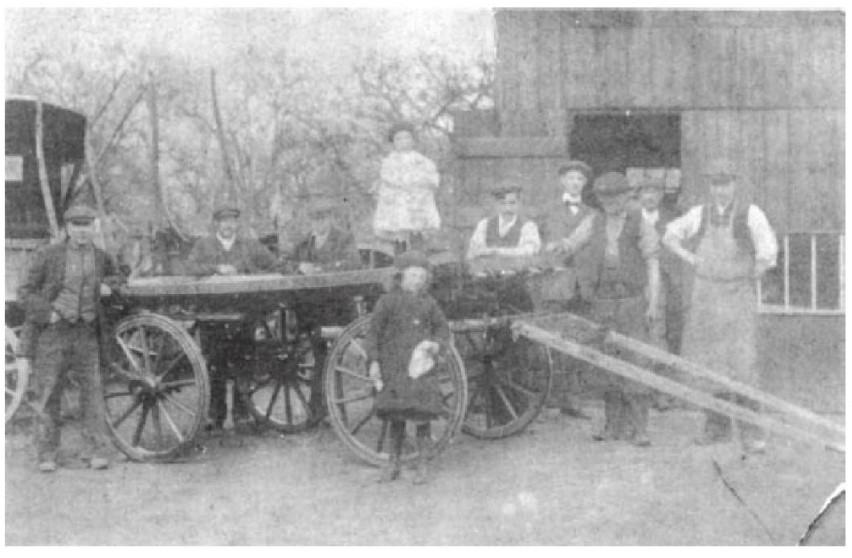

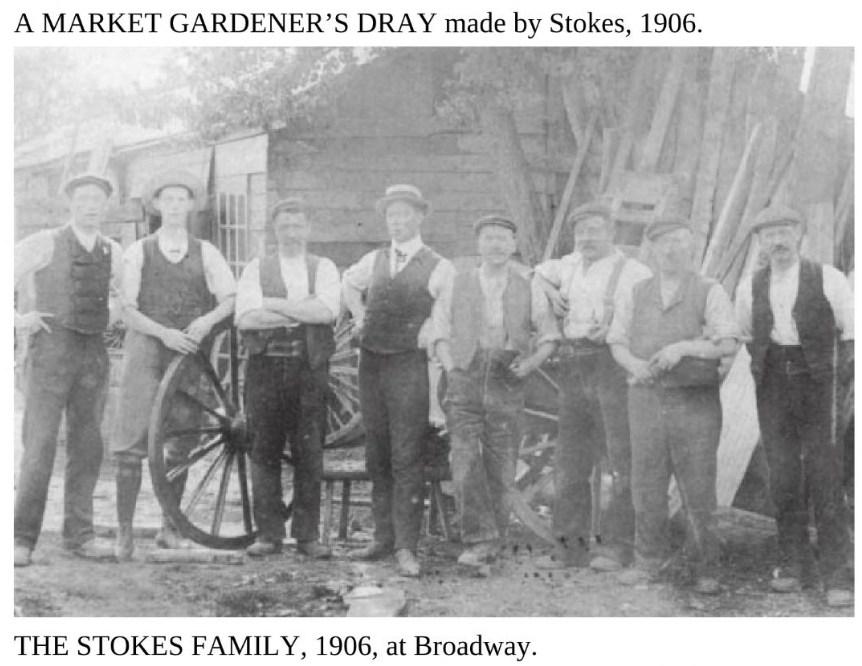

Stokes Wheelwrights. Fred on left of wheel, Thomas his father on right.

Thomas Stokes

Thomas Stokes was born in Bicester, Oxfordshire in 1816. He married Eliza Browning (born in 1814 in Tetbury, Gloucestershire) in Gloucester in 1840 Q3. Their first son William was baptised in Chipping Hill, Witham, Essex, on 3 Oct 1841. This seems a little unusual, and I can’t find Thomas and Eliza on the 1841 census. However both the 1851 and 1861 census state that William was indeed born in Essex.

In 1851 Thomas and Eliza were living in Bledington, Gloucestershire, and Thomas was a journeyman carpenter.

Note that a journeyman does not mean someone who moved around a lot. A journeyman was a tradesman who had served his trade apprenticeship and mastered his craft, not bound to serve a master, but originally hired by the day. The name derives from the French for day – jour.

Also on the 1851 census: their daughter Susan, born in Churchill Oxfordshire in 1844; son Frederick born in Bledington Gloucestershire in 1846; daughter Louisa born in Foxcote Oxfordshire in 1849; and 2 month old daughter Harriet born in Bledington in 1851.

On the 1861 census Thomas and Eliza were living in Evesham, Worcestershire, and daughter Susan was no longer living at home, but William, Fred, Louisa and Harriet were, as well as daughter Emily born in Churchill Oxfordshire in 1856. Thomas was a wheelwright.

On the 1871 census Thomas and Eliza were still living in Evesham, and Thomas was a wheelwright employing three apprentices. Son Fred, also a wheelwright, and his wife Ann Rebecca live with them.

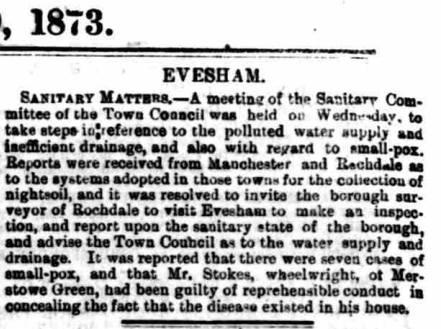

Mr Stokes, wheelwright, was found guilty of reprehensible conduct in concealing the fact that small-pox existed in his house, according to a mention in The Oxfordshire Weekly News on Wednesday 19 February 1873:

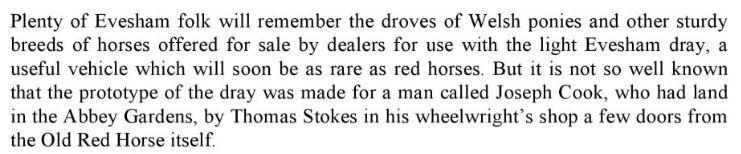

From Paul Weaver’s ancestry website:

“It was Thomas Stokes who built the first “Famous Vale of Evesham Light Gardening Dray for a Half-Legged Horse to Trot” (the quotation is from his account book), the forerunner of many that became so familiar a sight in the towns and villages from the 1860s onwards. He built many more for the use of the Vale gardeners.

Thomas also had long-standing business dealings with the people of the circus and fairgrounds, and had a contract to effect necessary repairs and renewals to their waggons whenever they visited the district. He built living waggons for many of the show people’s families as well as shooting galleries and other equipment peculiar to the trade of his wandering customers, and among the names figuring in his books are some still familiar today, such as Wilsons and Chipperfields.

He is also credited with inventing the wooden “Mushroom” which was used by housewives for many years to darn socks. He built and repaired all kinds of vehicles for the gentry as well as for the circus and fairground travellers.

Later he lived with his wife at Merstow Green, Evesham, in a house adjoining the Almonry.”

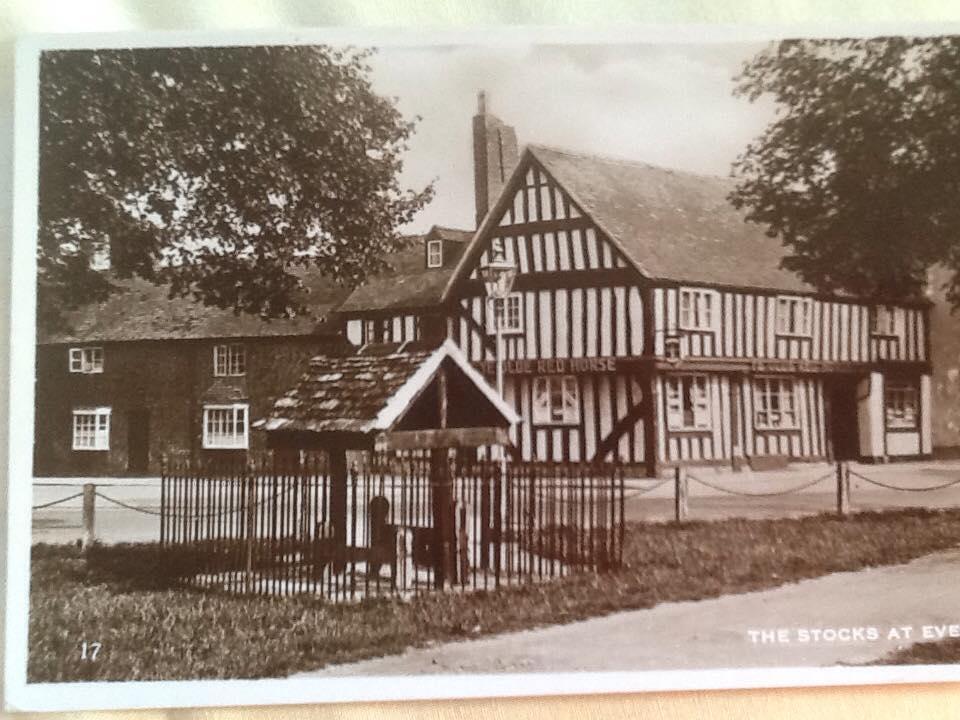

An excerpt from the book Evesham Inns and Signs by T.J.S. Baylis:

The Old Red Horse, Evesham:

Thomas died in 1885 aged 68 of paralysis, bronchitis and debility. His wife Eliza a year later in 1886.

Frederick Stokes

In Worcester in 1870 Fred married Ann Rebecca Day, who was born in Evesham in 1845.

Ann Rebecca Day:

In 1871 Fred was still living with his parents in Evesham, with his wife Ann Rebecca as well as their three month old daughter Annie Elizabeth. Fred and Ann (referred to as Rebecca) moved to La Quinta on Main Street, Broadway.

Rebecca Stokes in the doorway of La Quinta on Main Street Broadway, with her grandchildren Ralph and Dolly Edwards:

Fred was a wheelwright employing one man on the 1881 census. In 1891 they were still in Broadway, Fred’s occupation was wheelwright and coach painter, as well as his fifteen year old son Frederick.

In the Evesham Journal on Saturday 10 December 1892 it was reported that “Two cases of scarlet fever, the children of Mr. Stokes, wheelwright, Broadway, were certified by Mr. C. W. Morris to be isolated.”

Still in Broadway in 1901 and Fred’s son Albert was also a wheelwright. By 1911 Fred and Rebecca had only one son living at home in Broadway, Reginald, who was a coach painter. Fred was still a wheelwright aged 65.

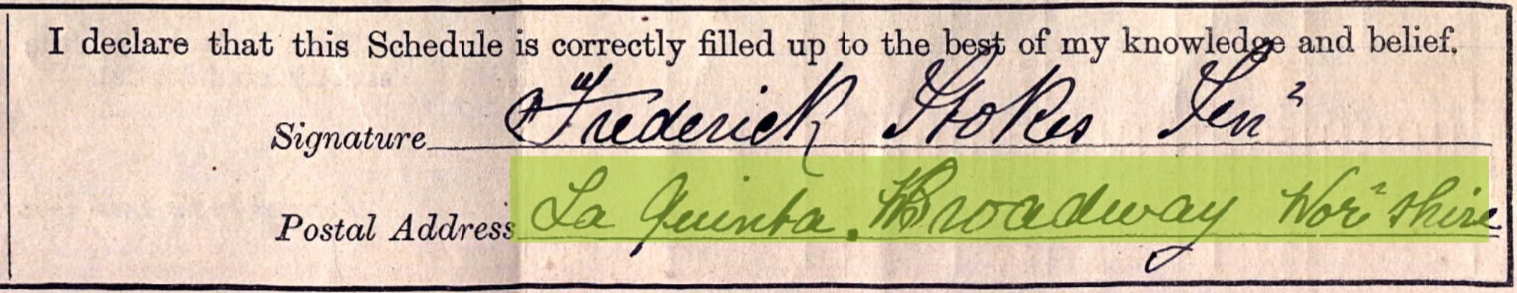

Fred’s signature on the 1911 census:

Rebecca died in 1912 and Fred in 1917.

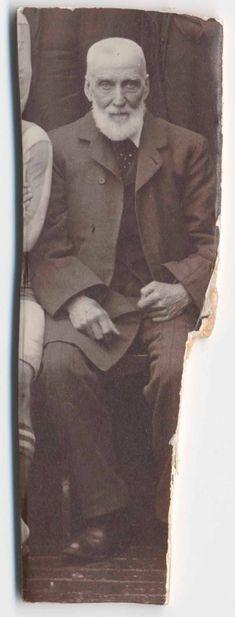

Fred Stokes:

In the book Evesham to Bredon From Old Photographs By Fred Archer:

October 22, 2022 at 1:18 pm #6338

October 22, 2022 at 1:18 pm #6338In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

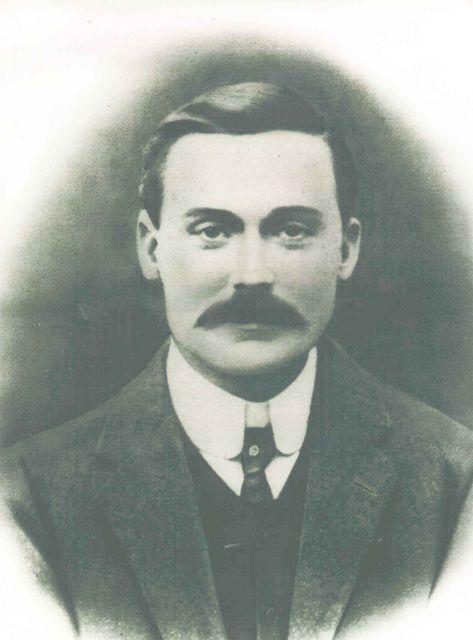

Albert Parker Edwards

1876-1930

Albert Parker Edwards, my great grandfather, was born in Aston, Warwickshire in 1876. On the 1881 census he was living with his parents Enoch and Amelia in Bournebrook, Northfield, Worcestershire. Enoch was a button tool maker at the time of the census.

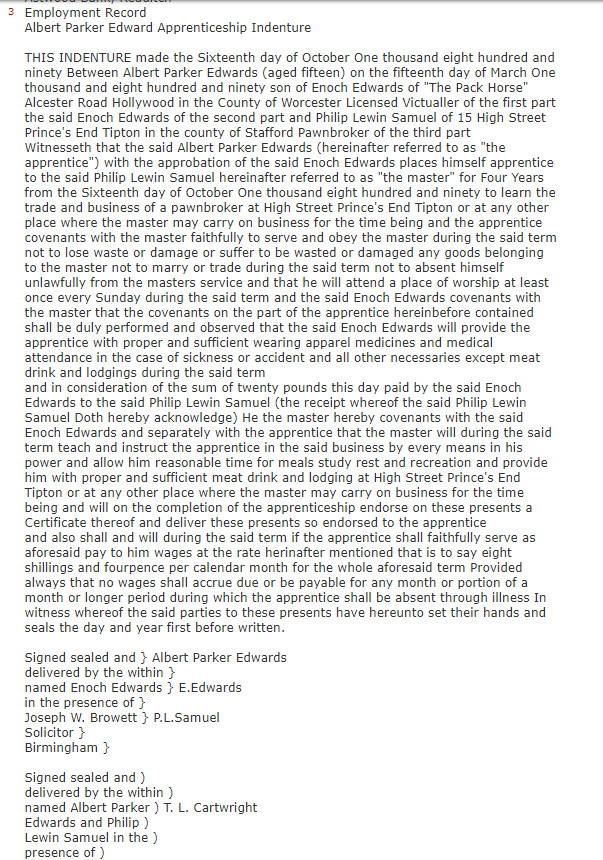

In 1890 Albert was indentured in an apprenticeship as a pawnbroker in Tipton, Staffordshire.

On the 1891 census Albert was a lodger in Tipton at the home of Phoebe Levy, pawnbroker, and Alberts occupation was an apprentice.

Albert married Annie Elizabeth Stokes in 1898 in Evesham, and their first son, my grandfather Albert Garnet Edwards (1898-1950), was born six months later in Crabbs Cross. On the 1901 census, Annie was in hospital as a patient and Albert was living at Crabbs Cross with a boarder, his brother Garnet Edwards. Their two year old son Albert Garnet was staying with his uncle Ralph, Albert Parkers brother, also in Crabbs Cross.

Albert and Annie kept the Cricketers Arms hotel on Beoley Road in Redditch until around 1920. They had a further four children while living there: Doris May Edwards (1902-1974), Ralph Clifford Edwards (1903-1988), Ena Flora Edwards (1908-1983) and Osmond Edwards (1910-2000).

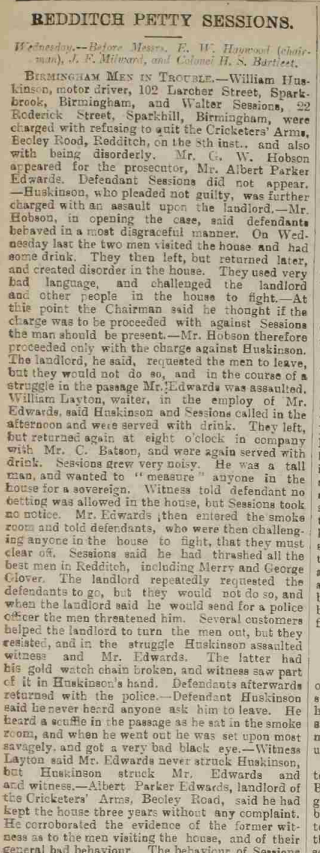

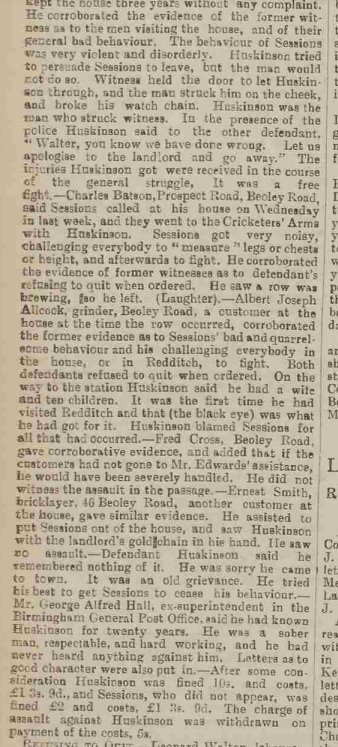

In 1906 Albert was assaulted during an incident in the Cricketers Arms.

Bromsgrove & Droitwich Messenger – Saturday 18 August 1906:

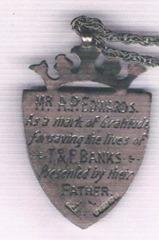

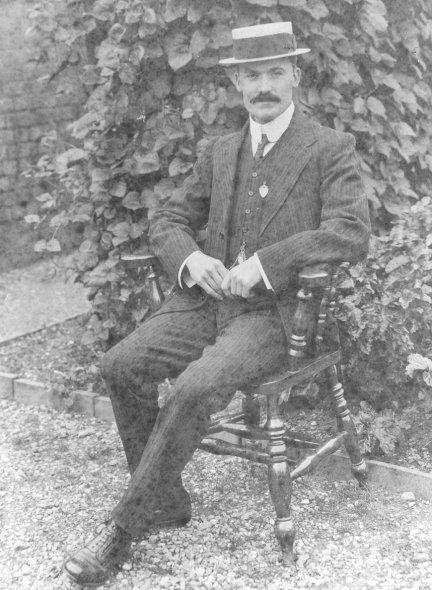

In 1910 a gold medal was given to Albert Parker Edwards by Mr. Banks, a policeman, in Redditch for saving the life of his two children from drowning in a brook on the Proctor farm which adjoined The Cricketers Arms. The story my father heard was that policeman Banks could not persuade the town of Redditch to come up with an award for Albert Parker Edwards so policeman Banks did it himself. William Banks, police constable, was living on Beoley Road on the 1911 census. His son Thomas was aged 5 and his daughter Frances was 8. It seems that when the father retired from the police he moved to Worcester. Thomas went into the hotel business and in 1939 was the manager of the Abbey hotel in Kenilworth. Frances married Edward Pardoe and was living along Redditch Road, Alvechurch in 1939.

My grandmother Peggy had the gold medal put on a gold chain for me in the 1970s. When I left England in the 1980s, I gave it back to her for safekeeping. When she died, the medal on the chain ended up in my fathers possession, who claims to have no knowledge that it was once given to me!

The medal:

Albert Parker Edwards wearing the medal:

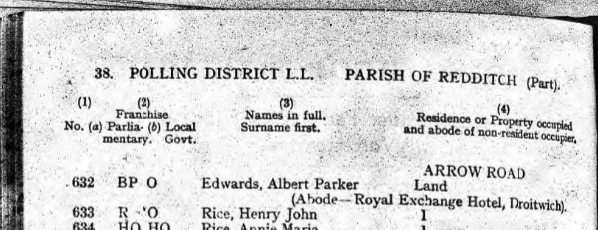

In 1921 Albert was at the The Royal Exchange hotel in Droitwich:

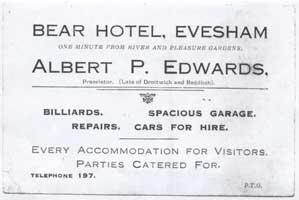

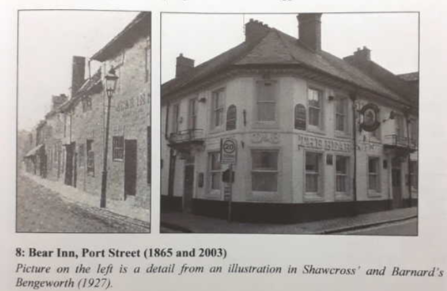

Between 1922 and 1927 Albert kept the Bear Hotel in Evesham:

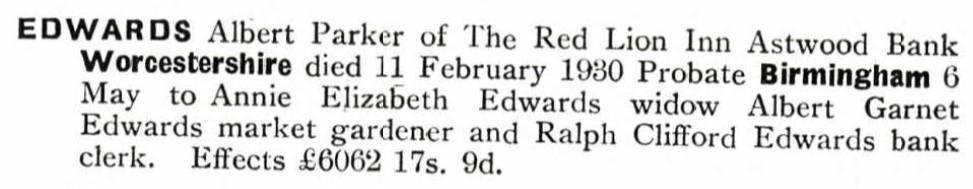

Then Albert and Annie moved to the Red Lion at Astwood Bank:

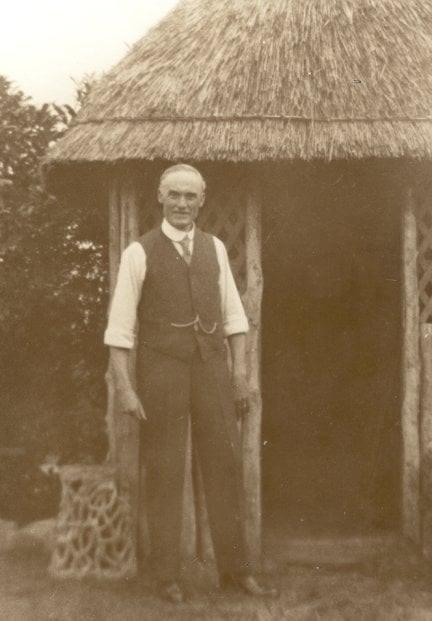

Albert in the garden behind the Red Lion:

They stayed at the Red Lion until Albert Parker Edwards died on the 11th of February, 1930 aged 53.

October 11, 2022 at 2:58 pm #6334

October 11, 2022 at 2:58 pm #6334In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The House on Penn Common

Toi Fang and the Duke of Sutherland

Tomlinsons

Grassholme

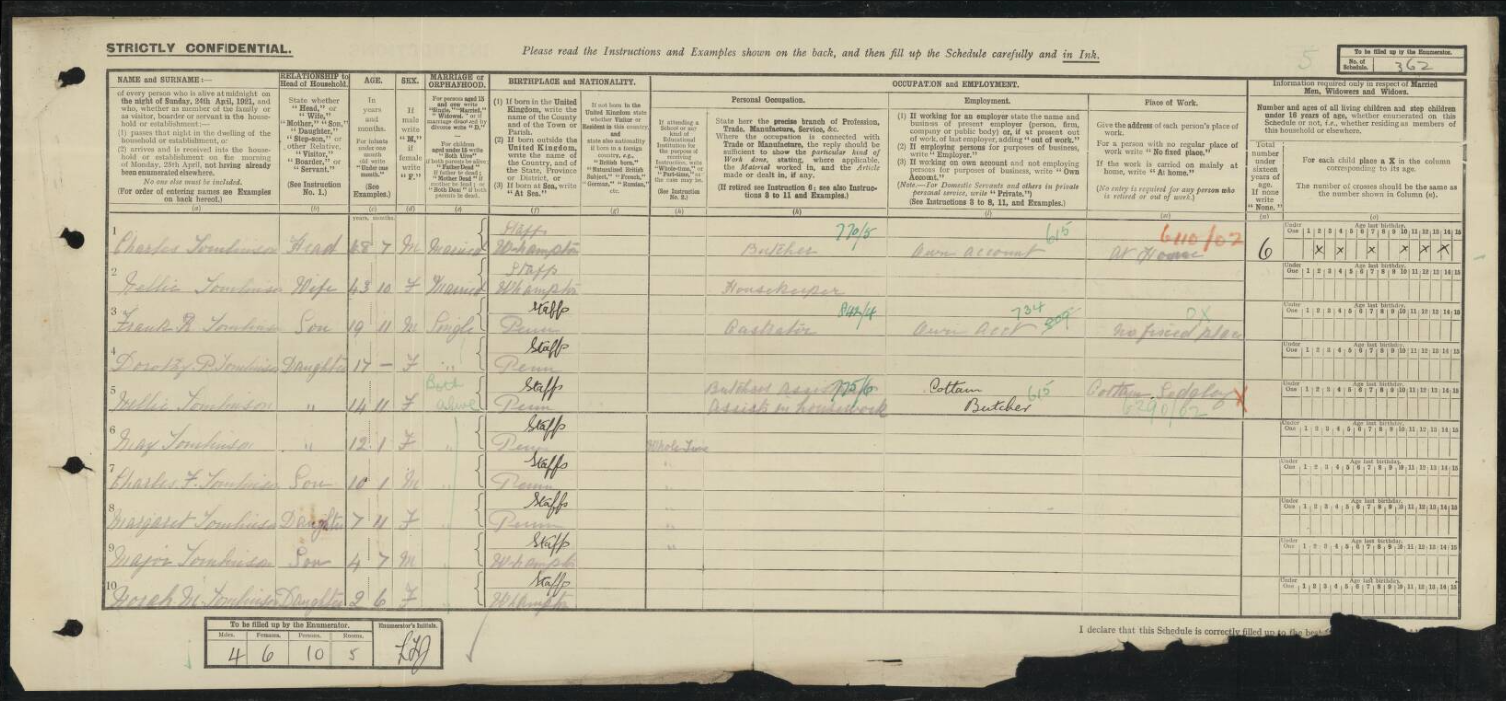

Charles Tomlinson (1873-1929) my great grandfather, was born in Wolverhampton in 1873. His father Charles Tomlinson (1847-1907) was a licensed victualler or publican, or alternatively a vet/castrator. He married Emma Grattidge (1853-1911) in 1872. On the 1881 census they were living at The Wheel in Wolverhampton.

Charles married Nellie Fisher (1877-1956) in Wolverhampton in 1896. In 1901 they were living next to the post office in Upper Penn, with children (Charles) Sidney Tomlinson (1896-1955), and Hilda Tomlinson (1898-1977) . Charles was a vet/castrator working on his own account.

In 1911 their address was 4, Wakely Hill, Penn, and living with them were their children Hilda, Frank Tomlinson (1901-1975), (Dorothy) Phyllis Tomlinson (1905-1982), Nellie Tomlinson (1906-1978) and May Tomlinson (1910-1983). Charles was a castrator working on his own account.

Charles and Nellie had a further four children: Charles Fisher Tomlinson (1911-1977), Margaret Tomlinson (1913-1989) (my grandmother Peggy), Major Tomlinson (1916-1984) and Norah Mary Tomlinson (1919-2010).

My father told me that my grandmother had fallen down the well at the house on Penn Common in 1915 when she was two years old, and sent me a photo of her standing next to the well when she revisted the house at a much later date.

Peggy next to the well on Penn Common:

My grandmother Peggy told me that her father had had a racehorse called Toi Fang. She remembered the racing colours were sky blue and orange, and had a set of racing silks made which she sent to my father.

Through a DNA match, I met Ian Tomlinson. Ian is the son of my fathers favourite cousin Roger, Frank’s son. Ian found some racing silks and sent a photo to my father (they are now in contact with each other as a result of my DNA match with Ian), wondering what they were.

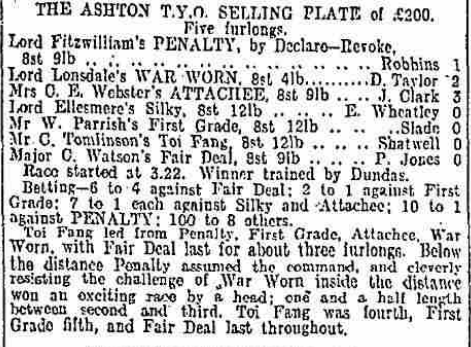

When Ian sent a photo of these racing silks, I had a look in the newspaper archives. In 1920 there are a number of mentions in the racing news of Mr C Tomlinson’s horse TOI FANG. I have not found any mention of Toi Fang in the newspapers in the following years.

The Scotsman – Monday 12 July 1920:

The other story that Ian Tomlinson recalled was about the house on Penn Common. Ian said he’d heard that the local titled person took Charles Tomlinson to court over building the house but that Tomlinson won the case because it was built on common land and was the first case of it’s kind.

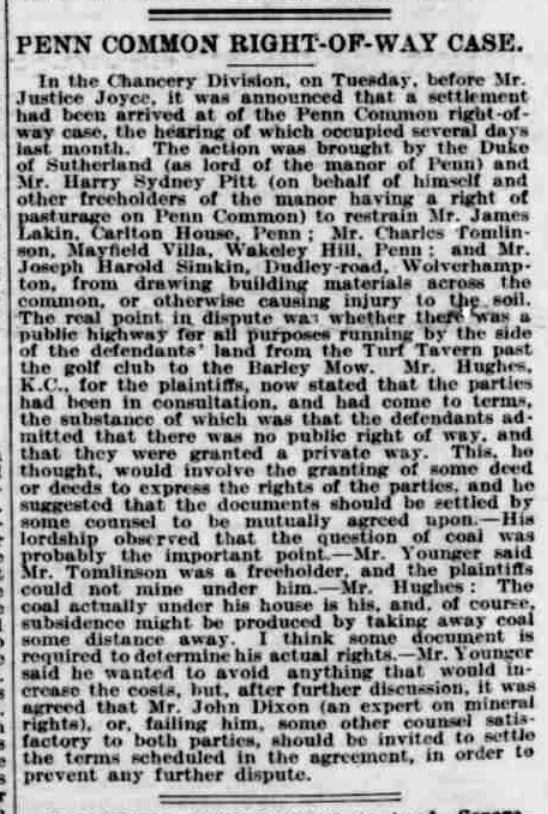

Penn Common Right of Way Case:

Staffordshire Advertiser March 9, 1912In the chancery division, on Tuesday, before Mr Justice Joyce, it was announced that a settlement had been arrived at of the Penn Common Right of Way case, the hearing of which occupied several days last month. The action was brought by the Duke of Sutherland (as Lord of the Manor of Penn) and Mr Harry Sydney Pitt (on behalf of himself and other freeholders of the manor having a right to pasturage on Penn Common) to restrain Mr James Lakin, Carlton House, Penn; Mr Charles Tomlinson, Mayfield Villa, Wakely Hill, Penn; and Mr Joseph Harold Simpkin, Dudley Road, Wolverhampton, from drawing building materials across the common, or otherwise causing injury to the soil.

The real point in dispute was whether there was a public highway for all purposes running by the side of the defendants land from the Turf Tavern past the golf club to the Barley Mow.

Mr Hughes, KC for the plaintiffs, now stated that the parties had been in consultation, and had come to terms, the substance of which was that the defendants admitted that there was no public right of way, and that they were granted a private way. This, he thought, would involve the granting of some deed or deeds to express the rights of the parties, and he suggested that the documents should be be settled by some counsel to be mutually agreed upon.His lordship observed that the question of coal was probably the important point. Mr Younger said Mr Tomlinson was a freeholder, and the plaintiffs could not mine under him. Mr Hughes: The coal actually under his house is his, and, of course, subsidence might be produced by taking away coal some distance away. I think some document is required to determine his actual rights.

Mr Younger said he wanted to avoid anything that would increase the costs, but, after further discussion, it was agreed that Mr John Dixon (an expert on mineral rights), or failing him, another counsel satisfactory to both parties, should be invited to settle the terms scheduled in the agreement, in order to prevent any further dispute.

The name of the house is Grassholme. The address of Mayfield Villas is the house they were living in while building Grassholme, which I assume they had not yet moved in to at the time of the newspaper article in March 1912.

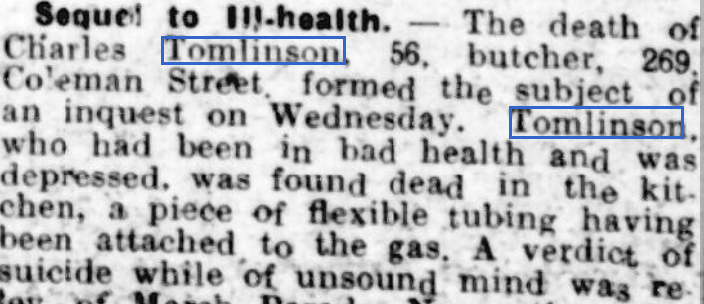

What my grandmother didn’t tell anyone was how her father died in 1929:

On the 1921 census, Charles, Nellie and eight of their children were living at 269 Coleman Street, Wolverhampton.

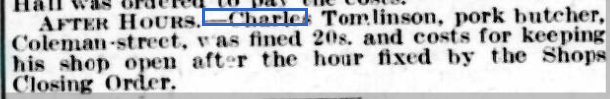

They were living on Coleman Street in 1915 when Charles was fined for staying open late.

Staffordshire Advertiser – Saturday 13 February 1915:

What is not yet clear is why they moved from the house on Penn Common sometime between 1912 and 1915. And why did he have a racehorse in 1920?

August 18, 2022 at 8:26 am #6324In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

STONE MANOR

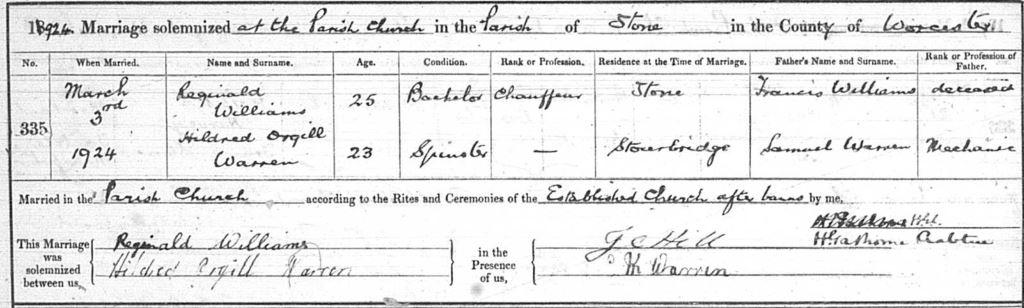

Hildred Orgill Warren born in 1900, my grandmothers sister, married Reginald Williams in Stone, Worcestershire in March 1924. Their daughter Joan was born there in October of that year.

Hildred was a chaffeur on the 1921 census, living at home in Stourbridge with her father (my great grandfather) Samuel Warren, mechanic. I recall my grandmother saying that Hildred was one of the first lady chauffeurs. On their wedding certificate, Reginald is also a chauffeur.

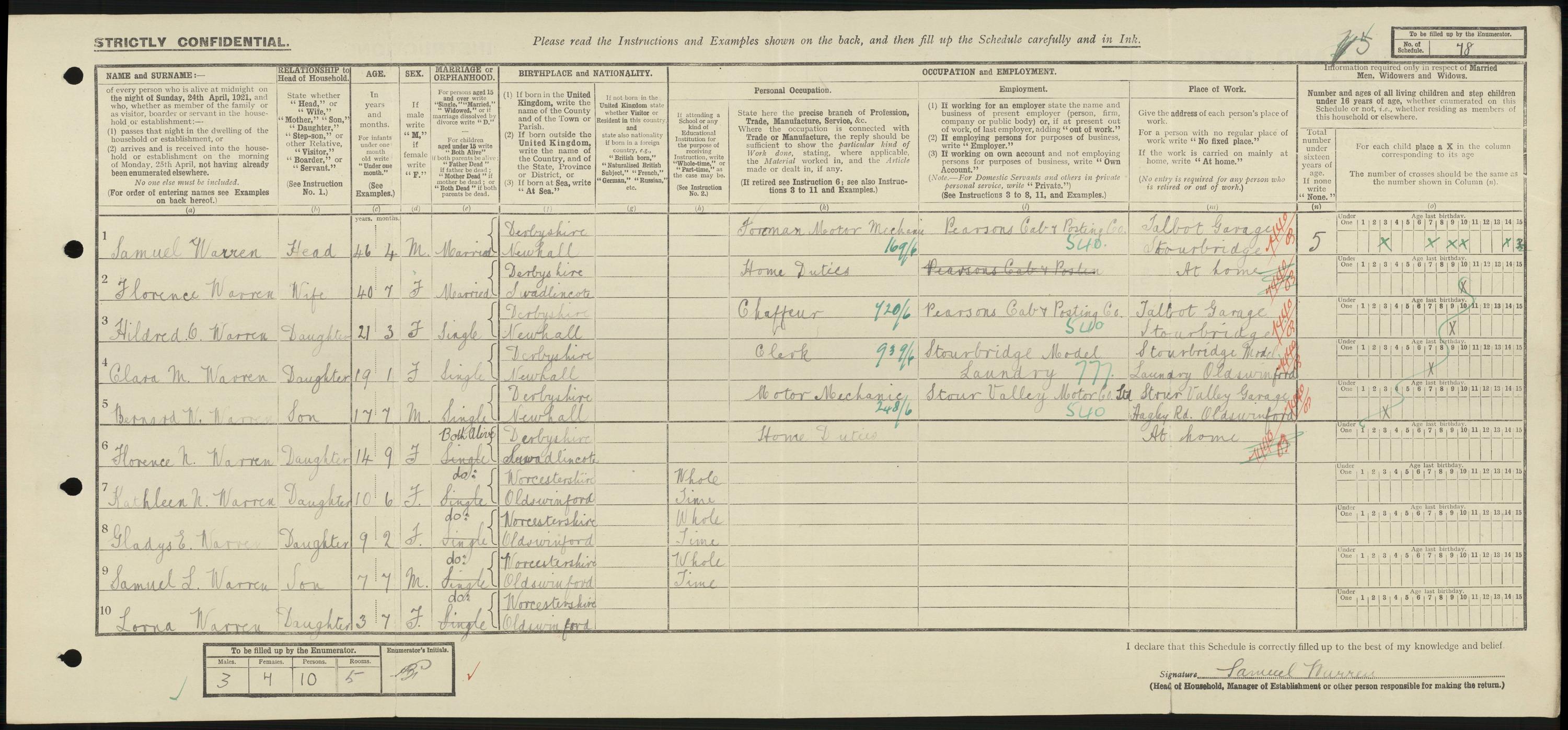

1921 census, Stourbridge:

Hildred and Reg worked at Stone Manor. There is a family story of Hildred being involved in a car accident involving a fatality and that she had to go to court.

Stone Manor is in a tiny village called Stone, near Kidderminster, Worcestershire. It used to be a private house, but has been a hotel and nightclub for some years. We knew in the family that Hildred and Reg worked at Stone Manor and that Joan was born there. Around 2007 Joan held a family party there.

Stone Manor, Stone, Worcestershire:

I asked on a Kidderminster Family Research group about Stone Manor in the 1920s:

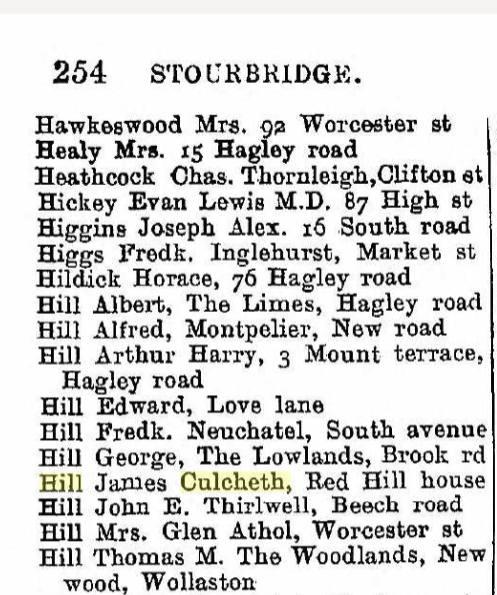

“the original Stone Manor burnt down and the current building dates from the early 1920’s and was built for James Culcheth Hill, completed in 1926”

But was there a fire at Stone Manor?

“I’m not sure there was a fire at the Stone Manor… there seems to have been a fire at another big house a short distance away and it looks like stories have crossed over… as the dates are the same…”JC Hill was one of the witnesses at Hildred and Reginalds wedding in Stone in 1924. K Warren, Hildreds sister Kay, was the other:

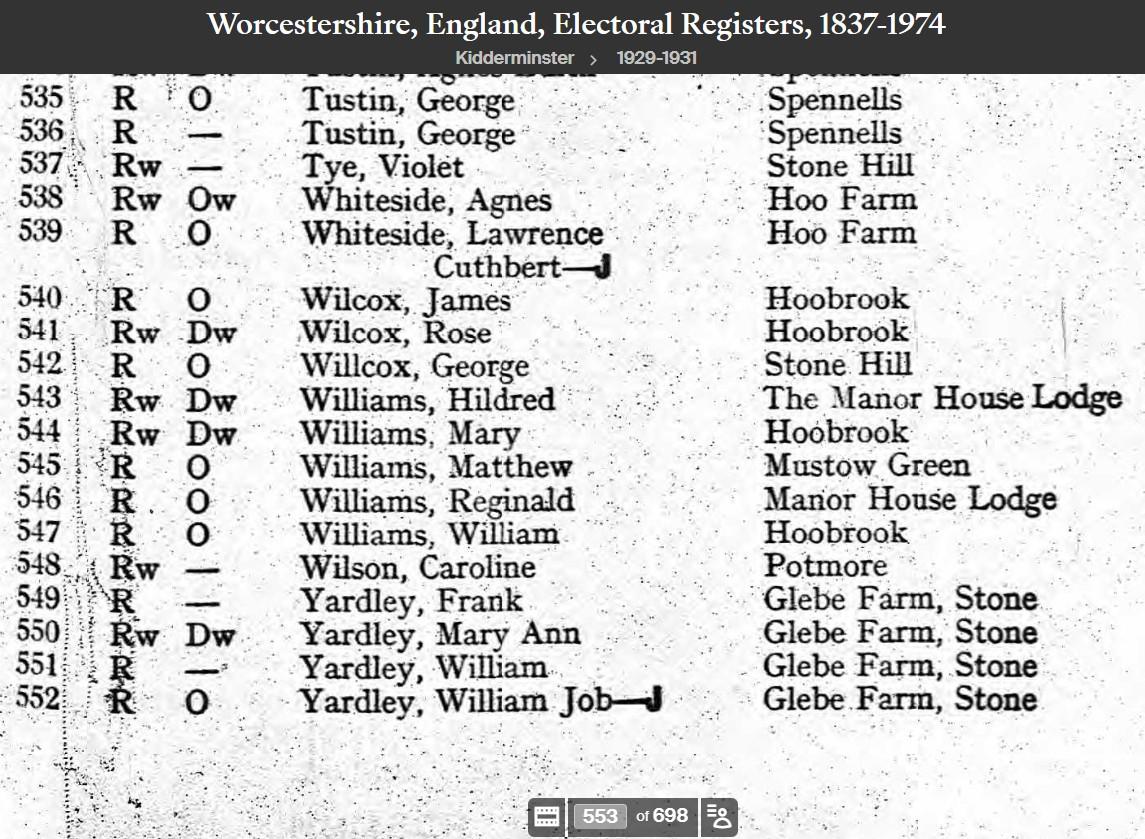

I searched the census and electoral rolls for James Culcheth Hill and found him at the Stone Manor on the 1929-1931 electoral rolls for Stone, and Hildred and Reginald living at The Manor House Lodge, Stone:

On the 1911 census James Culcheth Hill was a 12 year old student at Eastmans Royal Naval Academy, Northwood Park, Crawley, Winchester. He was born in Kidderminster in 1899. On the same census page, also a student at the school, is Reginald Culcheth Holcroft, born in 1900 in Stourbridge. The unusual middle name would seem to indicate that they might be related.

A member of the Kidderminster Family Research group kindly provided this article:

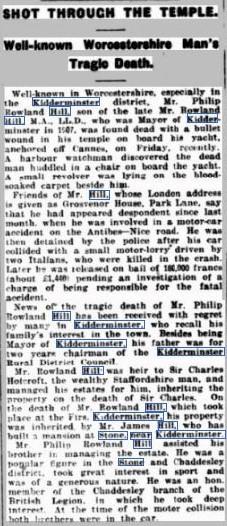

SHOT THROUGH THE TEMPLE

Well known Worcestershire man’s tragic death.

Dudley Chronicle 27 March 1930.

Well known in Worcestershire, especially the Kidderminster district, Mr Philip Rowland Hill MA LLD who was mayor of Kidderminster in 1907 was found dead with a bullet wound through his temple on board his yacht, anchored off Cannes, on Friday, recently. A harbour watchman discovered the dead man huddled in a chair on board the yacht. A small revolver was lying on the blood soaked carpet beside him.

Friends of Mr Hill, whose London address is given as Grosvenor House, Park Lane, say that he appeared despondent since last month when he was involved in a motor car accident on the Antibes ~ Nice road. He was then detained by the police after his car collided with a small motor lorry driven by two Italians, who were killed in the crash. Later he was released on bail of 180,000 francs (£1440) pending an investigation of a charge of being responsible for the fatal accident. …….

Mr Rowland Hill (Philips father) was heir to Sir Charles Holcroft, the wealthy Staffordshire man, and managed his estates for him, inheriting the property on the death of Sir Charles. On the death of Mr Rowland HIll, which took place at the Firs, Kidderminster, his property was inherited by Mr James (Culcheth) Hill who had built a mansion at Stone, near Kidderminster. Mr Philip Rowland Hill assisted his brother in managing the estate. …….

At the time of the collison both brothers were in the car.

This article doesn’t mention who was driving the car ~ could the family story of a car accident be this one? Hildred and Reg were working at Stone Manor, both were (or at least previously had been) chauffeurs, and Philip Hill was helping James Culcheth Hill manage the Stone Manor estate at the time.

This photograph was taken circa 1931 in Llanaeron, Wales. Hildred is in the middle on the back row:

Sally Gray sent the photo with this message:

“Joan gave me a short note: Photo was taken when they lived in Wales, at Llanaeron, before Janet was born, & Aunty Lorna (my mother) lived with them, to take Joan to school in Aberaeron, as they only spoke Welsh at the local school.”

Hildred and Reginalds daughter Janet was born in 1932 in Stratford. It would appear that Hildred and Reg moved to Wales just after the car accident, and shortly afterwards moved to Stratford.

In 1921 James Culcheth Hill was living at Red Hill House in Stourbridge. Although I have not been able to trace Reginald Williams yet, perhaps this Stourbridge connection with his employer explains how Hildred met Reginald.

Sir Reginald Culcheth Holcroft, the other pupil at the school in Winchester with James Culcheth Hill, was indeed related, as Sir Holcroft left his estate to James Culcheth Hill’s father. Sir Reginald was born in 1899 in Upper Swinford, Stourbridge. Hildred also lived in that part of Stourbridge in the early 1900s.

1921 Red Hill House:

The 2007 family reunion organized by Joan Williams at Stone Manor: Joan in black and white at the front.

Unrelated to the Warrens, my fathers friends (and customers at The Fox when my grandmother Peggy Edwards owned it) Geoff and Beryl Lamb later bought Stone Manor.

July 12, 2022 at 9:46 am #6320In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

When Maryechka arrived at the front gate of the Vyriy hotel with its gaudy plaster storks at the entrance, she sneaked into the side gate leading to the kitchens.

She had to be careful not to to be noticed by Larysa who often had her cigarette break hidden under the pine tree. Larysa didn’t like children, or at least, she disliked them slightly less than the elderly residents, whoever was the loudest and the uncleanliest was sure to suffer her disapproval.

Larysa was basically single-handedly managing the hotel, doing most of the chores to keep it afloat. The only thing she didn’t do was the catering, and packaged trays arrived every day for the residents. Maryechka’s grand-pa was no picky eater, and made a point of clearing his tray of food, but she suspected most of the other residents didn’t.

The only other employee she was told, was the gardener who would have been old enough to be a resident himself, and had died of a stroke before the summer. The small garden was clearly in need of tending after.Maryechka could see the coast was clear, and was making her ways to the stairs when she heard clanking in the stairs and voices arguing.

“Keep your voice down, you’re going to wake the dragon.”

“That’s your fault, you don’t pack light for your adventures. You really needed to take all these suitcases? How can we make a run for it with all that dead weight!”

July 6, 2022 at 11:41 am #6313In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

Egbert Gofindlevsky rapped on the door of room number 22. The letter flapped against his pin striped trouser leg as his hand shook uncontrollably, his habitual tremor exacerbated with the shock. Remembering that Obadiah Sproutwinklov was deaf, he banged loudly on the door with the flat of his hand. Eventually the door creaked open.

Egbert flapped the letter in from of Obadiah’s face. “Have you had one of these?” he asked.

“If you’d stop flapping it about I might be able to see what it is,” Obadiah replied. “Oh that! As a matter of fact I’ve had one just like it. The devils work, I tell you! A practical joke, and in very poor taste!”

Egbert was starting to wish he’d gone to see Olga Herringbonevsky first. “Can I come in?” he hissed, “So we can discuss it in private?”

Reluctantly Obadiah pulled the door open and ushered him inside the room. Egbert looked around for a place to sit, but upon noticing a distinct odour of urine decided to remain standing.

“Ursula is booting us out, where are we to go?”

“Eh?” replied Obadiah, cupping his ear. “Speak up, man!”

Egbert repeated his question.

“No need to shout!”

The two old men endeavoured to conduct a conversation on this unexepected turn of events, the upshot being that Obadiah had no intention of leaving his room at all henceforth, come what may, and would happily starve to death in his room rather than take to the streets.

Egbert considered this form of action unhelpful, as he himself had no wish to starve to death in his room, so he removed himself from room 22 with a disgruntled sigh and made his way to Olga’s room on the third floor.

July 6, 2022 at 11:02 am #6311In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

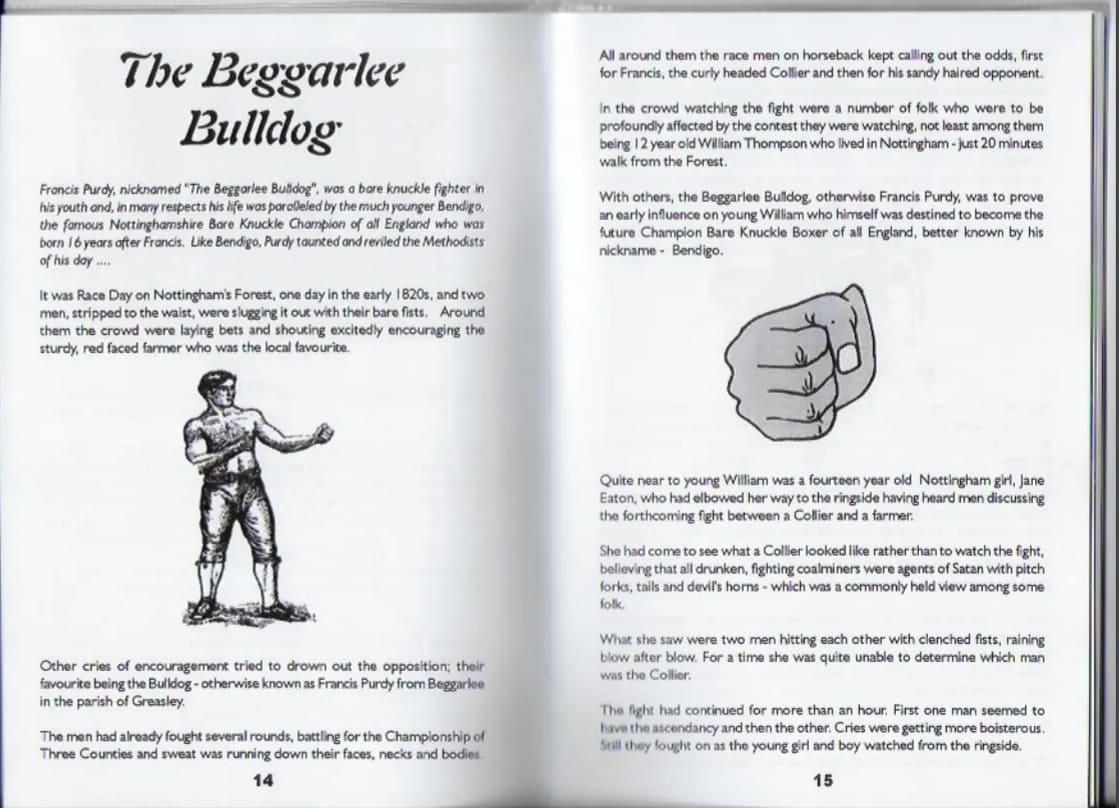

Most of the pilgims, if one could call them that, flocked to the linden tree in cars, although some came on motorbikes and bicycles. Olek was grateful that they hadn’t started arriving by the bus load, like Italian tourists. But his cousin Ursula was happy with this strange new turn of events.

Her shabby hotel on the outskirts of town had never been so busy and she was already planning to refurbish the premises and evict the decrepit and motley assortment of aged permanent residents who had just about kept her head above water, financially speaking, for the last twenty years. She could charge much more per night to these new tourists, who were smartly dressed and modern and didn’t argue about the price of a room. They did complain about the damp stained wallpaper though and the threadbare bedding. Ursula reckoned she could charge even more for the rooms if she redecorated, and had an idea to approach her nephew Boris the bank manager for a business loan.

But first she had to evict the old timers. It wasn’t her problem, she reminded herself, if they had nowhere else to go. After all, plenty of charitable aid money was flying around these days, they could easily just join up with some fleeing refugees. She’d even sent some of her old dresses to the collection agency. They may have been forty years old and smelled of moth balls, but they were well made and the refugees would surely be grateful.

Ursula wasn’t looking forward to telling them. No, not at all! She rather liked some of them and was dreading their reaction. You are a business woman, Ursula, she told herself, and you have to look after your own interests! But still she quailed at the thought of knocking on their doors, or announcing it in the communal dining room at supper. Then she had an idea. She’d type up some letters instead, and sign them as if they came from her new business manager. When the residents approached her about the letter she would smile sadly and shrug, saying it wasn’t her decision and that she was terribly sorry but her hands were tied.

July 1, 2022 at 9:51 am #6306In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Looking for Robert Staley

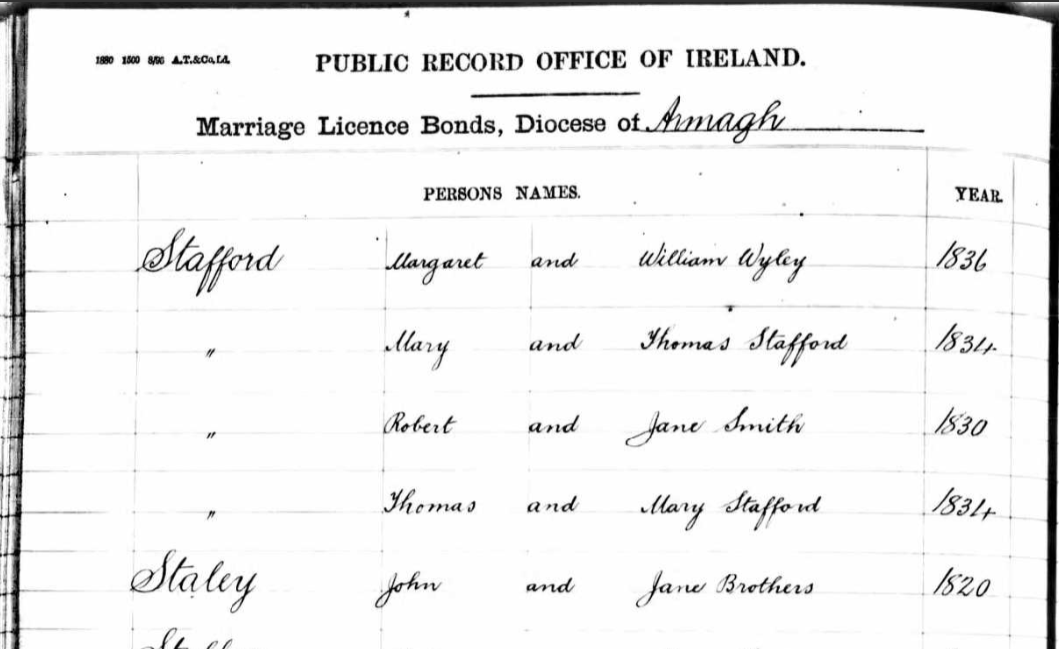

William Warren (1835-1880) of Newhall (Stapenhill) married Elizabeth Staley (1836-1907) in 1858. Elizabeth was born in Newhall, the daughter of John Staley (1795-1876) and Jane Brothers. John was born in Newhall, and Jane was born in Armagh, Ireland, and they were married in Armagh in 1820. Elizabeths older brothers were born in Ireland: William in 1826 and Thomas in Dublin in 1830. Francis was born in Liverpool in 1834, and then Elizabeth in Newhall in 1836; thereafter the children were born in Newhall.

Marriage of John Staley and Jane Brothers in 1820:

My grandmother related a story about an Elizabeth Staley who ran away from boarding school and eloped to Ireland, but later returned. The only Irish connection found so far is Jane Brothers, so perhaps she meant Elizabeth Staley’s mother. A boarding school seems unlikely, and it would seem that it was John Staley who went to Ireland.

The 1841 census states Jane’s age as 33, which would make her just 12 at the time of her marriage. The 1851 census states her age as 44, making her 13 at the time of her 1820 marriage, and the 1861 census estimates her birth year as a more likely 1804. Birth records in Ireland for her have not been found. It’s possible, perhaps, that she was in service in the Newhall area as a teenager (more likely than boarding school), and that John and Jane ran off to get married in Ireland, although I haven’t found any record of a child born to them early in their marriage. John was an agricultural labourer, and later a coal miner.

John Staley was the son of Joseph Staley (1756-1838) and Sarah Dumolo (1764-). Joseph and Sarah were married by licence in Newhall in 1782. Joseph was a carpenter on the marriage licence, but later a collier (although not necessarily a miner).

The Derbyshire Record Office holds records of an “Estimate of Joseph Staley of Newhall for the cost of continuing to work Pisternhill Colliery” dated 1820 and addresssed to Mr Bloud at Calke Abbey (presumably the owner of the mine)

Josephs parents were Robert Staley and Elizabeth. I couldn’t find a baptism or birth record for Robert Staley. Other trees on an ancestry site had his birth in Elton, but with no supporting documents. Robert, as stated in his 1795 will, was a Yeoman.

“Yeoman: A former class of small freeholders who farm their own land; a commoner of good standing.”

“Husbandman: The old word for a farmer below the rank of yeoman. A husbandman usually held his land by copyhold or leasehold tenure and may be regarded as the ‘average farmer in his locality’. The words ‘yeoman’ and ‘husbandman’ were gradually replaced in the later 18th and 19th centuries by ‘farmer’.”He left a number of properties in Newhall and Hartshorne (near Newhall) including dwellings, enclosures, orchards, various yards, barns and acreages. It seemed to me more likely that he had inherited them, rather than moving into the village and buying them.

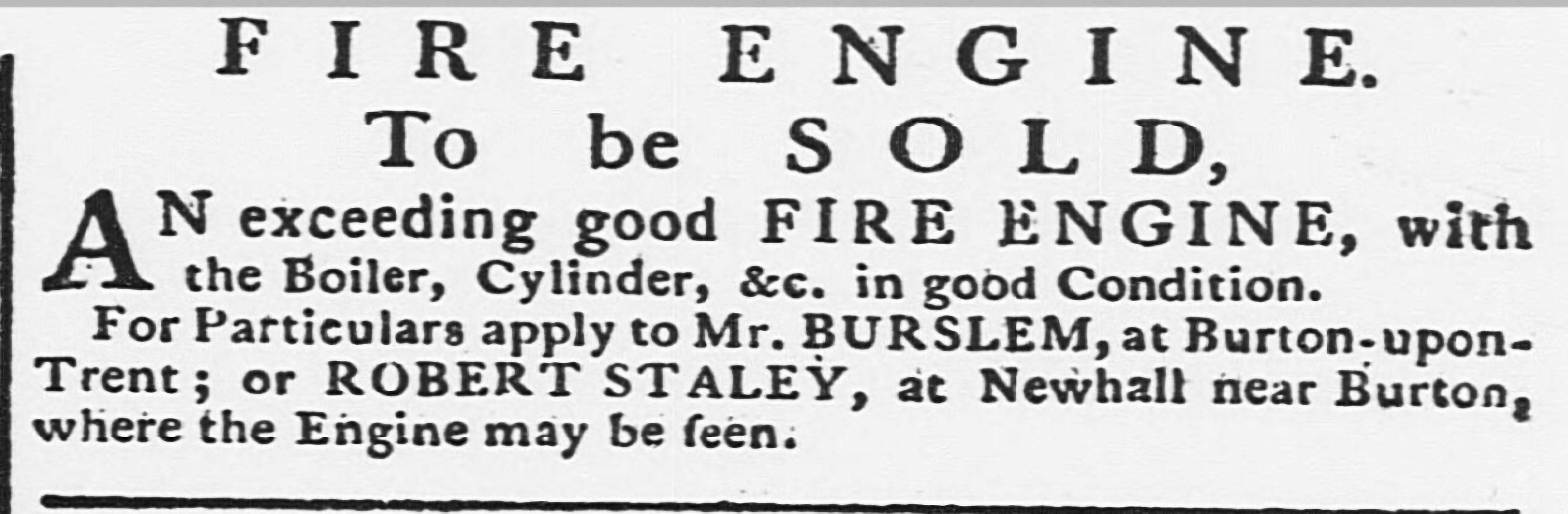

There is a mention of Robert Staley in a 1782 newpaper advertisement.

“Fire Engine To Be Sold. An exceedingly good fire engine, with the boiler, cylinder, etc in good condition. For particulars apply to Mr Burslem at Burton-upon-Trent, or Robert Staley at Newhall near Burton, where the engine may be seen.”

Was the fire engine perhaps connected with a foundry or a coal mine?

I noticed that Robert Staley was the witness at a 1755 marriage in Stapenhill between Barbara Burslem and Richard Daston the younger esquire. The other witness was signed Burslem Jnr.

Looking for Robert Staley

I assumed that once again, in the absence of the correct records, a similarly named and aged persons baptism had been added to the tree regardless of accuracy, so I looked through the Stapenhill/Newhall parish register images page by page. There were no Staleys in Newhall at all in the early 1700s, so it seemed that Robert did come from elsewhere and I expected to find the Staleys in a neighbouring parish. But I still didn’t find any Staleys.

I spoke to a couple of Staley descendants that I’d met during the family research. I met Carole via a DNA match some months previously and contacted her to ask about the Staleys in Elton. She also had Robert Staley born in Elton (indeed, there were many Staleys in Elton) but she didn’t have any documentation for his birth, and we decided to collaborate and try and find out more.

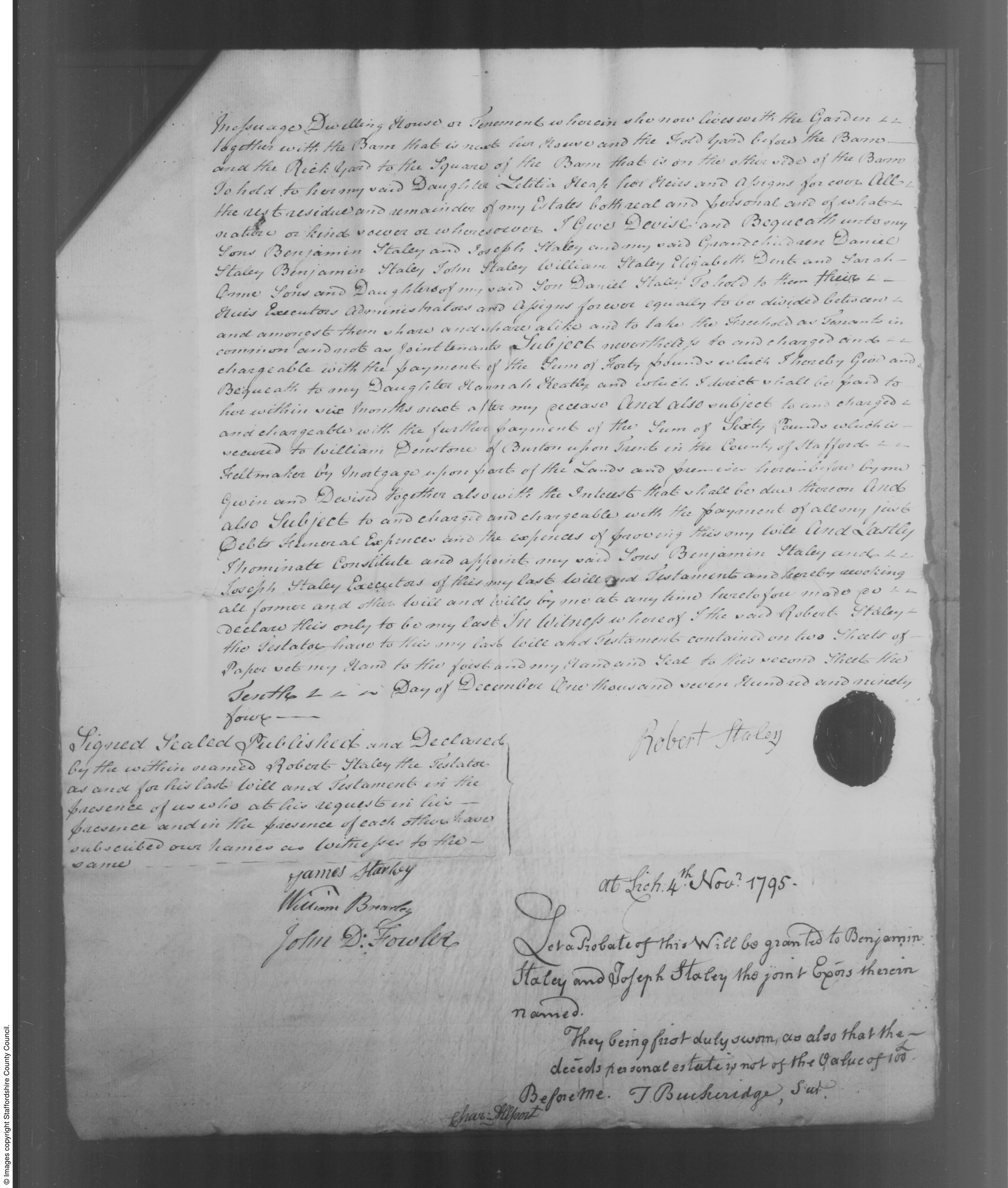

I couldn’t find the earlier Elton parish registers anywhere online, but eventually found the untranscribed microfiche images of the Bishops Transcripts for Elton.

via familysearch:

“In its most basic sense, a bishop’s transcript is a copy of a parish register. As bishop’s transcripts generally contain more or less the same information as parish registers, they are an invaluable resource when a parish register has been damaged, destroyed, or otherwise lost. Bishop’s transcripts are often of value even when parish registers exist, as priests often recorded either additional or different information in their transcripts than they did in the original registers.”Unfortunately there was a gap in the Bishops Transcripts between 1704 and 1711 ~ exactly where I needed to look. I subsequently found out that the Elton registers were incomplete as they had been damaged by fire.

I estimated Robert Staleys date of birth between 1710 and 1715. He died in 1795, and his son Daniel died in 1805: both of these wills were found online. Daniel married Mary Moon in Stapenhill in 1762, making a likely birth date for Daniel around 1740.

The marriage of Robert Staley (assuming this was Robert’s father) and Alice Maceland (or Marsland or Marsden, depending on how the parish clerk chose to spell it presumably) was in the Bishops Transcripts for Elton in 1704. They were married in Elton on 26th February. There followed the missing parish register pages and in all likelihood the records of the baptisms of their first children. No doubt Robert was one of them, probably the first male child.

(Incidentally, my grandfather’s Marshalls also came from Elton, a small Derbyshire village near Matlock. The Staley’s are on my grandmothers Warren side.)

The parish register pages resume in 1711. One of the first entries was the baptism of Robert Staley in 1711, parents Thomas and Ann. This was surely the one we were looking for, and Roberts parents weren’t Robert and Alice.

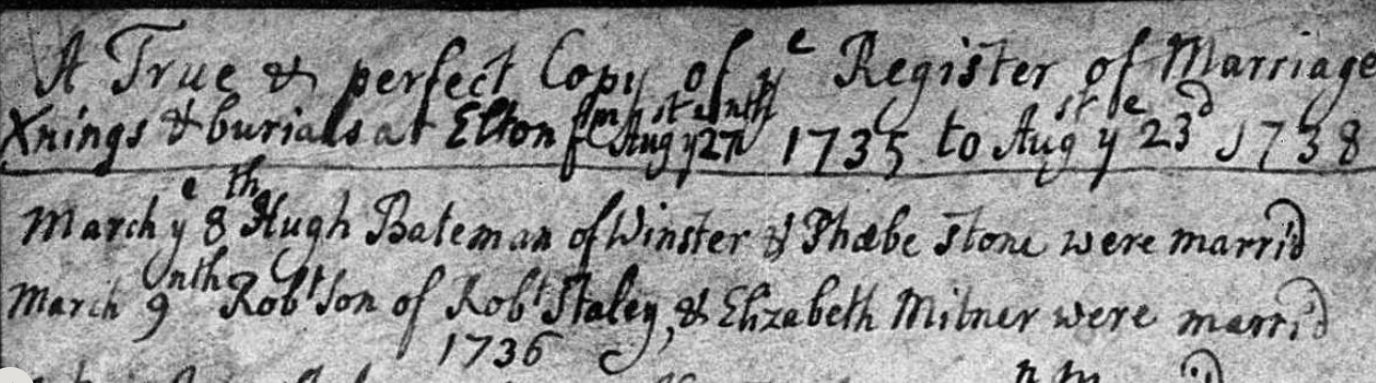

But then in 1735 a marriage was recorded between Robert son of Robert Staley (and this was unusual, the father of the groom isn’t usually recorded on the parish register) and Elizabeth Milner. They were married on the 9th March 1735. We know that the Robert we were looking for married an Elizabeth, as her name was on the Stapenhill baptisms of their later children, including Joseph Staleys. The 1735 marriage also fit with the assumed birth date of Daniel, circa 1740. A baptism was found for a Robert Staley in 1738 in the Elton registers, parents Robert and Elizabeth, as well as the baptism in 1736 for Mary, presumably their first child. Her burial is recorded the following year.

The marriage of Robert Staley and Elizabeth Milner in 1735:

There were several other Staley couples of a similar age in Elton, perhaps brothers and cousins. It seemed that Thomas and Ann’s son Robert was a different Robert, and that the one we were looking for was prior to that and on the missing pages.

Even so, this doesn’t prove that it was Elizabeth Staleys great grandfather who was born in Elton, but no other birth or baptism for Robert Staley has been found. It doesn’t explain why the Staleys moved to Stapenhill either, although the Enclosures Act and the Industrial Revolution could have been factors.

The 18th century saw the rise of the Industrial Revolution and many renowned Derbyshire Industrialists emerged. They created the turning point from what was until then a largely rural economy, to the development of townships based on factory production methods.

The Marsden Connection

There are some possible clues in the records of the Marsden family. Robert Staley married Alice Marsden (or Maceland or Marsland) in Elton in 1704. Robert Staley is mentioned in the 1730 will of John Marsden senior, of Baslow, Innkeeper (Peacock Inne & Whitlands Farm). He mentions his daughter Alice, wife of Robert Staley.

In a 1715 Marsden will there is an intriguing mention of an alias, which might explain the different spellings on various records for the name Marsden: “MARSDEN alias MASLAND, Christopher – of Baslow, husbandman, 28 Dec 1714. son Robert MARSDEN alias MASLAND….” etc.

Some potential reasons for a move from one parish to another are explained in this history of the Marsden family, and indeed this could relate to Robert Staley as he married into the Marsden family and his wife was a beneficiary of a Marsden will. The Chatsworth Estate, at various times, bought a number of farms in order to extend the park.

THE MARSDEN FAMILY

OXCLOSE AND PARKGATE

In the Parishes of

Baslow and Chatsworthby

David Dalrymple-Smith“John Marsden (b1653) another son of Edmund (b1611) faired well. By the time he died in

1730 he was publican of the Peacock, the Inn on Church Lane now called the Cavendish

Hotel, and the farmer at “Whitlands”, almost certainly Bubnell Cliff Farm.”“Coal mining was well known in the Chesterfield area. The coalfield extends as far as the

Gritstone edges, where thin seams outcrop especially in the Baslow area.”“…the occupants were evicted from the farmland below Dobb Edge and

the ground carefully cleared of all traces of occupation and farming. Shelter belts were

planted especially along the Heathy Lea Brook. An imposing new drive was laid to the

Chatsworth House with the Lodges and “The Golden Gates” at its northern end….”Although this particular event was later than any events relating to Robert Staley, it’s an indication of how farms and farmland disappeared, and a reason for families to move to another area:

“The Dukes of Devonshire (of Chatsworth) were major figures in the aristocracy and the government of the

time. Such a position demanded a display of wealth and ostentation. The 6th Duke of

Devonshire, the Bachelor Duke, was not content with the Chatsworth he inherited in 1811,

and immediately started improvements. After major changes around Edensor, he turned his

attention at the north end of the Park. In 1820 plans were made extend the Park up to the

Baslow parish boundary. As this would involve the destruction of most of the Farm at

Oxclose, the farmer at the Higher House Samuel Marsden (b1755) was given the tenancy of

Ewe Close a large farm near Bakewell.

Plans were revised in 1824 when the Dukes of Devonshire and Rutland “Exchanged Lands”,

reputedly during a game of dice. Over 3300 acres were involved in several local parishes, of

which 1000 acres were in Baslow. In the deal Devonshire acquired the southeast corner of

Baslow Parish.

Part of the deal was Gibbet Moor, which was developed for “Sport”. The shelf of land

between Parkgate and Robin Hood and a few extra fields was left untouched. The rest,

between Dobb Edge and Baslow, was agricultural land with farms, fields and houses. It was

this last part that gave the Duke the opportunity to improve the Park beyond his earlier

expectations.”The 1795 will of Robert Staley.

Inriguingly, Robert included the children of his son Daniel Staley in his will, but omitted to leave anything to Daniel. A perusal of Daniels 1808 will sheds some light on this: Daniel left his property to his six reputed children with Elizabeth Moon, and his reputed daughter Mary Brearly. Daniels wife was Mary Moon, Elizabeths husband William Moons daughter.

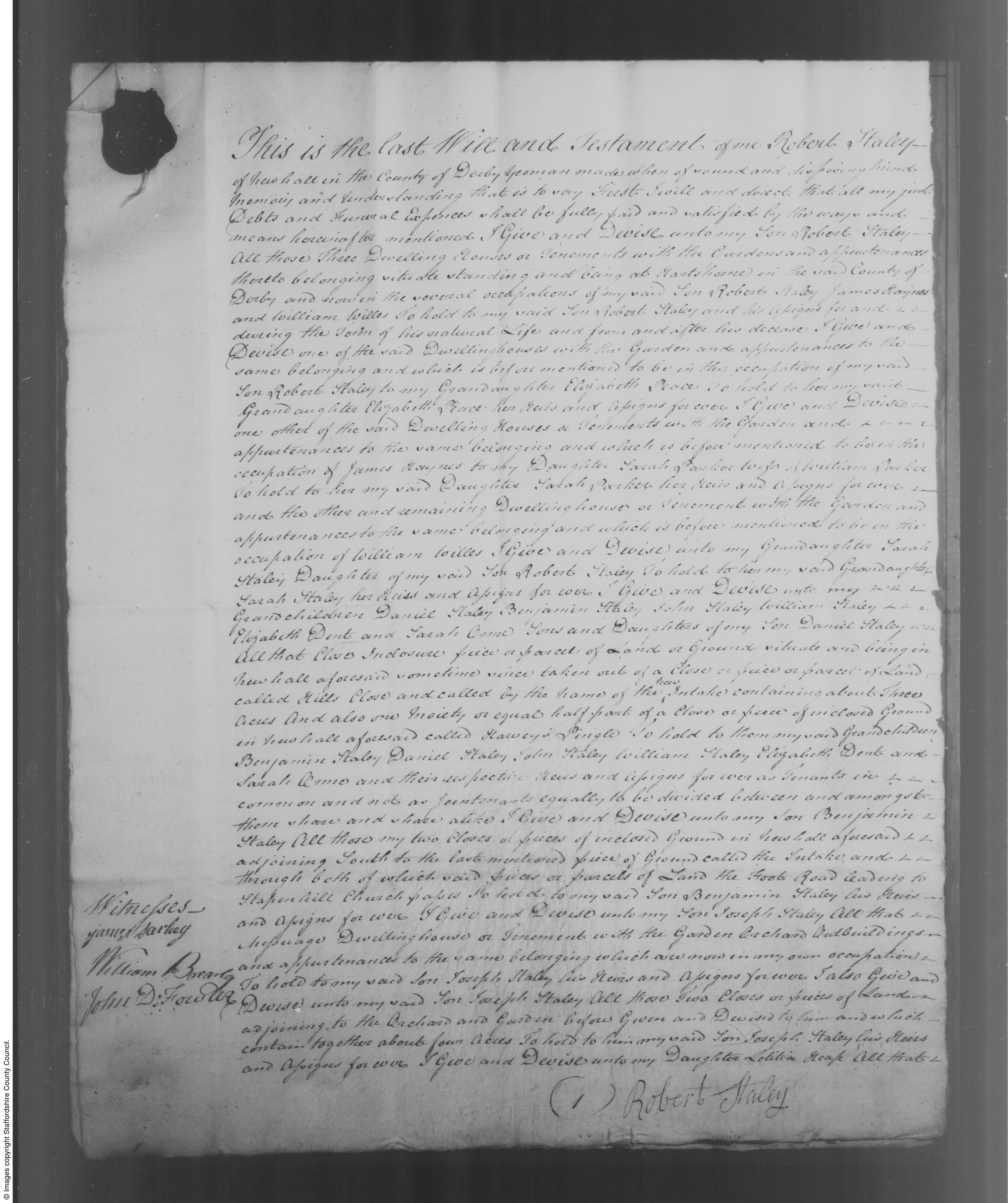

The will of Robert Staley, 1795:

The 1805 will of Daniel Staley, Robert’s son:

This is the last will and testament of me Daniel Staley of the Township of Newhall in the parish of Stapenhill in the County of Derby, Farmer. I will and order all of my just debts, funeral and testamentary expenses to be fully paid and satisfied by my executors hereinafter named by and out of my personal estate as soon as conveniently may be after my decease.