Search Results for 'display'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

January 16, 2026 at 11:00 pm #8048

In reply to: The Hoards of Sanctorum AD26

“Bless you,” Helier offered, instinctively sliding the half-chewed pencil stub under a pile of National Geographics from 1978. He felt a flush of guilt, as if he’d been caught trying to steal a kid’s toy.

Cerenise rolled into the room, looking like a sorry pile of laundry. She was wrapped in three different shawls—one Paisley, one Tartan, and one that looked like a doily from a medieval altar. She held a lace handkerchief to her nose, trumpeting into it with a force that rattled the nearby display of thimbles.

“It’s not the damp,” she croaked, her voice an octave lower than usual. “It’s the cleanliness. Since Spirius fixed that pipe, the air is too… sterile. My immune system is in shock. It misses the spores.”

She eyed the spot where Helier had hidden the pencil. “You were thinking about it, weren’t you?”

“Thinking about what?” Helier feigned innocence, picking up a ceramic frog.

“The Novena,” she whispered the word like a curse. “I saw the look in your eye. The ‘maybe I don’t need this’ look. It’s the fever talking, Helier. Don’t give in. I almost threw away a button yesterday. A bakelite toggle from a 1930s duffel coat. I held it over the bin for a full minute.” She shuddered, pulling the shawls tighter. “Madness.”

“Pure madness,” Helier agreed, quickly retrieving the pencil stub and placing it prominently on the desk to prove his loyalty to the hoard. “We must stay strong. Now, surely you didn’t brave the drafty hallway just to discuss my potential apostasy?”

“I didn’t,” Cerenise sniffed, tucking the handkerchief into her sleeve. “I found him. Or at least, I found the thread.”

She wheeled closer, dropping a printout onto Helier’s knees. It was a genealogy chart, annotated with her elegant, spider-scrawl handwriting.

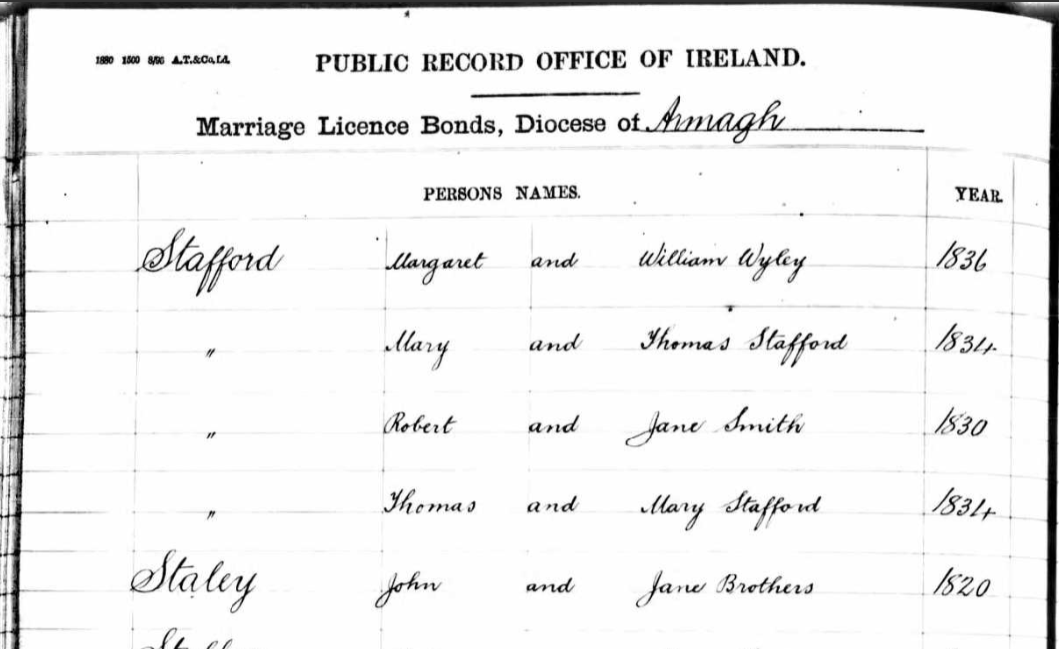

“Pierre Wenceslas Varlet,” she announced. “Born 1824. Brother to a last of the famously named Austreberthes — mortal ones, unsaintly, of course. Her lineage didn’t die out, Helier.”

Helier squinted at the paper. “Varlet? Sounds like a villain in one of Liz Tattler’s bodice-rippers. ‘The Vengeful Varlet of Venice’.“

“Focus, Helier. Look at the modern branch.” She pointed to the bottom of the page. “The name changed in the 1950s. Anglicized. And I think, if my research into the local council tax records—hacked via that delightful ‘incognito mode’ you showed me—is correct, the current ‘Varlet’ is closer than we think.”

“How close?”

“Gloucester close,” Cerenise said, her eyes gleaming with the thrill of the hunt, momentarily forgetting her flu. “And you’ll never guess where he works.”

February 16, 2025 at 12:50 pm #7810In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

Helix 25 – Below Lower Decks – Shadow Sector

Kai Nova moved cautiously through the underbelly of Helix 25, entering a part of the Lower Decks where the usual throb of the ship’s automated systems turned muted. The air had a different smell here— it was less sterile, more… human. It was warm, the heat from outdated processors and unmonitored power nodes radiating through the bulkheads. The Upper Decks would have reported this inefficiency.

Here, it simply went unnoticed, or more likely, ignored.

He was being watched.

He knew it the moment he passed a cluster of workers standing by a storage unit, their voices trailing off as he walked by. Not unusual, except these weren’t Lower Deck engineers. They had the look of people who existed outside of the ship’s official structure—clothes unmarked by department insignias, movements too intentional for standard crew assignments.

He stopped at the rendezvous point: an unlit access panel leading to what was supposed to be an abandoned sublevel. The panel had been manually overridden, its system logs erased. That alone told him enough—whoever he was meeting had the skills to work outside of Helix 25’s omnipresent oversight.

A voice broke the silence.

“You’re late.”

Kai turned, keeping his stance neutral. The speaker was of indistinct gender, shaved head, tall and wiry, with sharp green eyes locked on his movements. They wore layered robes that, at a glance, could have passed as scavenged fabric—until Kai noticed the intricate stitching of symbols hidden in the folds.

They looked like Zoya’s brand —he almost thought… or let’s just say, Zoya’s influence. Zoya Kade’s litanies had a farther reach he would expect.

“Wasn’t aware this was a job interview,” Kai quipped, leaning casually against the bulkhead.

“Everything’s a test,” they replied. “Especially for outsiders.”

Kai smirked. “I didn’t come to join your book club. I came for answers.”

A low chuckle echoed from the shadows, followed by the shifting of figures stepping into the faint light. Three, maybe four of them. It could have been an ambush, but that was a display.

“Pilot,” the woman continued, avoiding names. “Seeker of truth? Or just another lost soul looking for something to believe in?”

Kai rolled his shoulders, sensing the tension in the air. “I believe in not running out of fuel before reaching nowhere.”

That got their attention.

The recruiter studied him before nodding slightly. “Good. You understand the problem.”

Kai crossed his arms. “I understand a lot of problems. I also understand you’re not just a bunch of doomsayers whispering in the dark. You’re organized. And you think this ship is heading toward a dead end.”

“You say that like it isn’t.”

Kai exhaled, glancing at the flickering emergency light above. “Synthia doesn’t make mistakes.”

They smiled, but it wasn’t friendly. “No. It makes adjustments.” — the heavy tone on the “it” struck him. Techno-bigots, or something else? Were they denying Synthia’s sentience, or just adjusting for gender misnomers, it was hard to tell, and he had a hard time to gauge the sanity of this group.

A low murmur of agreement rippled through the gathered figures.

Kai tilted his head. “You think she’s leading us into the abyss?”

The person stepped closer. “What do you think happened to the rest of the fleet, Pilot?”

Kai stiffened slightly. The Helix Fleet, the original grand exodus of humanity—once multiple ships, now only Helix 25, drifting further into the unknown.

He had never been given a real answer.

“Think about it,” they pressed. “This ship wasn’t built for endless travel. Its original mission was altered. Its course reprogrammed. You fly the vessel, but you don’t control it.” She gestured to the others. “None of us do. We’re passengers on a ride to oblivion, on a ship driven by a dead man’s vision.”

Kai had heard the whispers—about the tycoon who had bankrolled Helix 25, about how the ship’s true directive had been rewritten when the Earth refugees arrived. But this group… they didn’t just speculate. They were ready to act.

He kept his voice steady. “You planning on mutiny?”

They smiled, stepping back into the half-shadow. “Mutiny is such a crude word. We’re simply ensuring that we survive.”

Before Kai could respond, a warning prickle ran up his spine.

Someone else was watching.

He turned slowly, catching the faintest silhouette lingering just beyond the corridor entrance. He recognized the stance instantly—Cadet Taygeta.

Damn it.

She had followed him.

The group noticed, shifting slightly. Not hostile, but suddenly alert.

“Well, well,” the woman murmured. “Seems you have company. You weren’t as careful as you thought. How are you going to deal with this problem now?”

Kai exhaled, weighing his options. If Taygeta had followed him, she’d already flagged this meeting in her records. If he tried to run, she’d report it. If he didn’t run, she might just dig deeper.

And the worst part?

She wasn’t corruptible. She wasn’t the type to look the other way.

“You should go,” the movement person said. “Before your shadow decides to interfere.”

Kai hesitated for half a second, before stepping back.

“This isn’t over,” he said.

Her smile returned. “No, Pilot. It’s just beginning.”

With that, Kai turned and walked toward the exit—toward Taygeta, who was waiting for him with arms crossed, expression unreadable.

He didn’t speak first.

She did.

“You’re terrible at being subtle.”

Kai sighed, thinking quickly of how much of the conversation could be accessed by the central system. They were still in the shadow zone, but that wasn’t sufficient. “How much did you hear?”

“Enough.” Her voice was even, but her fingers twitched at her side. “You know this is treason, right?”

Kai ran a hand through his hair. “You really think we’re on course for a fresh new paradise?”

Taygeta didn’t answer right away. That was enough of an answer.

Finally, she exhaled. “You should report this.”

“You should,” Kai corrected.

She frowned.

He pressed on. “You know me, Taygeta. I don’t follow lost causes. I don’t get involved in politics. I fly. I survive. But if they’re right—if there’s even a chance that we’re being sent to our deaths—I need to know.”

Taygeta’s fingers twitched again.

Then, with a sharp breath, she turned.

“I didn’t see anything tonight.”

Kai blinked. “What?”

Her back was already to him, her voice tight. “Whatever you’re doing, Nova, be careful. Because next time?” She turned her head slightly, just enough to let him see the edge of her conflicted expression.

“I will report you.”

Then she was gone.

Kai let out a slow breath, glancing back toward the hidden movement behind him.

No turning back now.

February 16, 2025 at 12:20 pm #7809In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

Earth, Black Sea Coastal Island near Lazurne, Ukraine – The Tinkerer

Cornishman Merdhyn Winstrom had grown accustomed to the silence.

It wasn’t the kind of silence one found in an empty room or a quiet night in Cornwall, but the profound, devouring kind—the silence of a world were life as we knew it had disappeared. A world where its people had moved on without him.

The Black Sea stretched before him, vast and unknowable, still as a dark mirror reflecting a sky that had long since stopped making promises. He stood on the highest point of the islet, atop a jagged rock behind which stood in contrast to the smooth metal of the wreckage.

His wreckage.

That’s how he saw it, maybe the last man standing on Earth.

It had been two years since he stumbled upon the remains of Helix 57 shuttle —or what was left of it. Of all the Helixes cruise ships that were lost, the ones closest to Earth during the Calamity had known the most activity —people trying to leave and escape Earth, while at the same time people in the skies struggling to come back to loved ones. Most of the orbital shuttles didn’t make it during the chaos, and those who did were soon lost to space’s infinity, or Earth’s last embrace.

This shuttle should have been able to land a few hundred people to safety —Merdhyn couldn’t find much left inside when he’d discovered it, survivors would have been long dispersed looking for food networks and any possible civilisation remnants near the cities. It was left here, a gutted-out orbital shuttle, fractured against the rocky coast, its metal frame corroded by salt air, its systems dead. The beauty of mechanics was that dead wasn’t the same as useless.

And Merdhyn never saw anything as useless.

With slow, methodical care, he adjusted the small receiver strapped to his wrist—a makeshift contraption built from salvaged components, scavenged antennae, and the remains of an old Soviet radio. He tapped the device twice. The static fizzled, cracked. Nothing.

“Still deaf,” he muttered.

Perched at his shoulder, Tuppence chattered at him, a stuborn rodent that attached himself and that Merdhyn had adopted months ago as he was scouting the area. He reached his pocket and gave it a scrap of food off a stale biscuit still wrapped in the shiny foil.

Merdhyn exhaled, rolling his shoulders. He was getting too old for this. Too many years alone, too many hours hunched over corroded circuits, trying to squeeze life from what had already died.

But the shuttle wasn’t dead. After his first check, he was quite sure. Now it was time to get to work.

He stepped inside, ducking beneath an exposed beam, brushing past wiring that had long since lost its insulation. The stale scent of metal and old circuitry greeted him. The interior was a skeletal mess—panels missing, control consoles shattered, displays reduced to nothing but flickering ghosts of their former selves.

Still, he had power.

Not much. Just enough to light a few panels, enough to make him think he wasn’t mad for trying.

As it happened, Merdhyn had a plan: a ridiculous, impossible, brilliant plan.

He would fix it.

The whole thing if he could, but if anything. It would certainly take him months before the shuttle from Helix 57 could go anywhere— that is, in one piece. He could surely start to repair the comms, get a signal out, get something moving, then maybe—just maybe—he could find out if there was anything left out there.

Anything that wasn’t just sea and sky and ghosts.

He ran his fingers along the edge of the console, feeling the warped metal. The ship had crashed hard. It shouldn’t have made it down in one piece, but something had slowed it. Some system had tried to function, even in its dying moments.

That meant something was still alive.

He just had to wake it up.

Tuppence chittered, scurrying onto his shoulder.

Merdhyn chuckled. “Aye, I know. One of these days, I’ll start talking to people instead of rats.”

Tuppence flicked her tail.

He pulled out a battered datapad—one of his few working relics—and tapped the screen. The interface stuttered, but held. He navigated to his schematics, his notes, his carefully built plans.

The transponder array.

If he could get it working, even partially, he might be able to listen.

To hear something—anything—on the waves beyond this rock.

A voice. A signal. A trace of the world that had forgotten him.

Merdhyn exhaled. “Let’s see if we can get you talking again, eh?”

He adjusted his grip, tools clinking at his belt, and got to work.

February 15, 2025 at 9:21 am #7789In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

Helix 25 – Poop Deck – The Jardenery

Evie stepped through the entrance of the Jardenery, and immediately, the sterile hum of Helix 25’s corridors faded into a world of green. Of all the spotless clean places on the ship, it was the only where Finkley’s bots tolerated the scent of damp earth. A soft rustle of hydroponic leaves shifting under artificial sunlight made the place an ecosystem within an ecosystem, designed to nourrish both body and mind.

Yet, for all its cultivated serenity, today it was a crime scene. The Drying Machine was connected to the Jardenery and the Granary, designed to efficiently extract precious moisture for recycling, while preserving the produce.

Riven Holt, walking beside her, didn’t share her reverence. “I don’t see why this place is relevant,” he muttered, glancing around at the towering bioluminescent vines spiraling up trellises. “The body was found in the drying machine, not in a vegetable patch.”

Evie ignored him, striding toward the far corner where Amara Voss was hunched over a sleek terminal, frowning at a glowing screen. The renowned geneticist barely noticed their approach, her fingers flicking through analysis results faster than human eyes could process.

A flicker of light.

“Ah-ha!” TP materialized beside Evie, adjusting his holographic lapels. “Madame Voss, I must say, your domain is quite the delightful contrast to our usual haunts of murder and mystery.” He twitched his mustache. “Alas, I suspect you are not admiring the flora?”

Amara exhaled sharply, rubbing her temples, not at all surprised by the holographic intrusion. She was Evie’s godmother, and had grown used to her experiments.

“No, indeed. I’m admiring this.” She turned the screen toward them.

The DNA profile glowed in crisp lines of data, revealing a sequence highlighted in red.

Evie frowned. “What are we looking at?”

Amara pinched the bridge of her nose. “A genetic anomaly.”

Riven crossed his arms. “You’ll have to be more specific.”

Amara gave him a sharp look but turned back to the display. “The sample we found at the crime scene—blood residue on the drying machine and some traces on the granary floor—matches an ancient DNA profile from my research database. A perfect match.”

Evie felt a prickle of unease. “Ancient? What do you mean? From the 2000s?”

Amara chuckled, then nodded grimly. “No, ancient as in Medieval ancient. Specifically, Crusader DNA, from the Levant. A profile we mapped from preserved remains centuries ago.”

Silence stretched between them.

Finally, Riven scoffed. “That’s impossible.”

TP hummed thoughtfully, twirling his cane. “Impossible, yet indisputable. A most delightful contradiction.”

Evie’s mind raced. “Could the database be corrupted?”

Amara shook her head. “I checked. The sequencing is clean. This isn’t an error. This DNA was present at the crime scene.” She hesitated, then added, “The thing is…” she paused before considering to continue. They were all hanging on her every word, waiting for what she would say next.

Amara continued “I once theorized that it might be possible to reawaken dormant ancestral DNA embedded in human cells. If the right triggers were applied, someone could manifest genetic markers—traits, even memories—from long-dead ancestors. Awakening old skills, getting access to long lost secrets of states…”

Riven looked at her as if she’d grown a second head. “You’re saying someone on Helix 25 might have… transformed into a medieval Crusader?”

Amara exhaled. “I’m saying I don’t know. But either someone aboard has a genetic profile that shouldn’t exist, or someone created it.”

TP’s mustache twitched. “Ah! A puzzle worthy of my finest deductive faculties. To find the source, we must trace back the lineage! And perhaps a… witness.”

Evie turned toward Amara. “Did Herbert ever come here?”

Before Amara could answer, a voice cut through the foliage.

“Herbert?”

They turned to find Romualdo, the Jardenery’s caretaker, standing near a towering fruit-bearing vine, his arms folded, a leaf-tipped stem tucked behind his ear like a cigarette. He was a broad-shouldered man with sun-weathered skin, dressed in a simple coverall, his presence almost too casual for someone surrounded by murder investigators.

Romualdo scratched his chin. “Yeah, he used to come around. Not for the plants, though. He wasn’t the gardening type.”

Evie stepped closer. “What did he want?”

Romualdo shrugged. “Questions, mostly. Liked to chat about history. Said he was looking for something old. Always wanted to know about heritage, bloodlines, forgotten things.” He shook his head. “Didn’t make much sense to me. But then again, I like practical things. Things that grow.”

Amara blushed, quickly catching herself. “Did he ever mention anything… specific? Like a name?”

Romualdo thought for a moment, then grinned. “Oh yeah. He asked about the Crusades.”

Evie stiffened. TP let out an appreciative hum.

“Fascinating,” TP mused. “Our dearly departed Herbert was not merely a victim, but perhaps a seeker of truths unknown. And, as any good mystery dictates, seekers who get too close often find themselves…” He tipped his hat. “Extinguished.”

Riven scowled. “That’s a bit dramatic.”

Romualdo snorted. “Sounds about right, though.” He picked up a tattered book from his workbench and waved it. “I lend out my books. Got myself the only complete collection of works of Liz Tattler in the whole ship. Doc Amara’s helping me with the reading. Before I could read, I only liked the covers, they were so romantic and intriguing, but now I can read most of them on my own.” Noticing he was making the Doctor uncomfortable, he switched back to the topic. “So yes, Herbert knew I was collector of books and he borrowed this one a few weeks ago. Kept coming back with more questions after reading it.”

Evie took the book and glanced at the cover. The Blood of the Past: Genetic Echoes Through History by Dr. Amara Voss.

She turned to Amara. “You wrote this?”

Amara stared at the book, her expression darkening. “A long time ago. Before I realized some theories should stay theories.”

Evie closed the book. “Looks like someone didn’t agree.”

Romualdo wiped his hands on his coveralls. “Well, I hope you figure it out soon. Hate to think the plants are breathing in murder residue.”

TP sighed dramatically. “Ah, the tragedy of contaminated air! Shall I alert the sanitation team?”

Riven rolled his eyes. “Let’s go.”

As they walked away, Evie’s grip tightened around the book. The deeper they dug, the stranger this murder became.

February 8, 2025 at 5:18 pm #7772In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

Upper Decks – The Pilot’s Seat (Sort Of)

Kai Nova reclined in his chair, boots propped against the console, arms folded behind his head. The cockpit hummed with the musical blipping of automation. Every sleek interface, polished to perfection by the cleaning robots under Finkley’s command, gleamed in a lulling self-sustaining loop—self-repairing, self-correcting, self-determining.

And that meant there wasn’t much left for him to do.

Once, piloting meant piloting. Gripping the yoke, feeling the weight of the ship respond, aligning a course by instinct and skill. Now? It was all handled before he even thought to lift a finger. Every slight course adjustment, to the smallest stabilizing thrust were effortlessly preempted by Synthia’s vast, all-knowing “intelligence”. She anticipated drift before it even started, corrected trajectory before a human could perceive the error.

Kai was a pilot in name only.

A soft chime. Then, the clipped, clinical voice of Cadet Taygeta:

“You’re slacking off again.”

Kai cracked one eye open, groaning. “Good morning, buzzkill.”

She stood rigid at the entryway, arms crossed, datapad in hand. Young, brilliant, and utterly incapable of normal human warmth. Her uniform was pristine—always pristine—with a regulation-perfect collar that probably had never been out of place in their entire life.

“Synthia calculates you’ve spent 76% of your shifts in a reclining position,” the Cadet noted. “Which, statistically, makes you more of a chair than a pilot.”

Kai smirked. “And yet, here I am, still getting credits.”

The Cadet face had changed subtly ; she exhaled sharply. “I don’t understand why they keep you here. It’s inefficient.”

Kai swung his legs down and stretched. “They keep me around for when things go wrong. Machines are great at running the show—until something unexpected happens. Then they come crawling back to good ol’ human instinct.”

“Unexpected like what? Absinthe Pirates?” The Cadet smirked, but Kai said nothing.

She narrowed their eyes, her voice firm but wavering. “Things aren’t supposed to go wrong.”

Kai chuckled. “You must be new to space, Taygeta.”

He gestured toward the vast, star-speckled abyss beyond the viewport. Helix 25 cruised effortlessly through the void, a floating city locked in perfect motion. But perfection was a lie. He could feel it.

There were some things off. At the top of his head, one took precedence.

Fuel — it wasn’t infinite, and despite Synthia’s unwavering quantum computing, he knew it was a problem no one liked talking about. The ship wasn’t meant for this—for an endless voyage into the unknown. It was meant to return.

But that wasn’t happening.

He leaned forward, flipping a display open. “Let’s play a game, Cadet. Humor me.” He tapped a few keys, pulling up Helix 25’s projected trajectory. “What happens if we shift course by, say… two degrees?”

The Cadet scoffed. “That would be reckless. At our current velocity, even a fractional deviation—”

“Just humor me.”

After a pause, she exhaled sharply and ran the numbers. A simulation appeared: a slight two-degree shift, a ripple effect across the ship’s calculated path.

And then—

Everything went to hell.

The screen flickered red.

Projected drift. Fuel expenditure spike. The trajectory extending outward into nowhere.

The Cadet’s posture stiffened. “That can’t be right.”

“Oh, but it is,” Kai said, leaning back with a knowing grin. “One little adjustment, and we slingshot into deep space with no way back.”

The Cadet’s eyes flicked to the screen, then back to Kai. “Why would you test that?”

Kai drummed his fingers on the console. “Because I don’t trust a system that’s been in control for decades without oversight.”

A soft chime.

Synthia’s voice slid into the cockpit, smooth and impassive.

“Pilot Nova. Unnecessary simulations disrupt workflow efficiency.”

Kai’s jaw tensed. “Yeah? And what happens if a real course correction is needed?”

“All adjustments are accounted for.”

Kai and the Cadet exchanged a look.

Synthia always had an answer. Always knew more than she said.

He tapped the screen again, running a deeper scan. The ship’s fuel usage log. Projected refueling points.

All were blank.

Kai’s gut twisted. “You know, for a ship that’s supposed to be self-sustaining, we sure don’t have a lot of refueling options.”

The Cadet stiffened. “We… don’t refuel?”

Kai’s eyes didn’t leave the screen. “Not unless Synthia finds us a way.”

Silence.

Then, the Cadet swallowed. For the first time, a flicker of something almost human in her expression.

Uncertainty.

Kai sighed, pushing back from the console. “Welcome to the real job, kid.”

Because the truth was simple.

They weren’t driving this ship.

The ship was driving them.

And it all started when all hell broke lose on Earth, decades back, and when the ships of refugees caught up with the Helix 25 on its way back to Earth. One of those ships, his dad had told him, took over management, made it turn around for a new mission, “upgraded” it with Synthia, and with the new order…

The ship was driving them, and there was no sign of a ghost beyond the machine.

February 7, 2025 at 1:09 pm #7737In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

Evie stared at TP, waiting for further elaboration. He simply steepled his fingers and smirked, a glitchy picture of insufferable patience.

“You can’t just drop a bombshell like that and leave it hanging,” she said.

“But my dear Evie, I must!” TP declared, flickering theatrically. “For as the great Pea Stoll once mused—‘It was suspicious in a Pea Saucerer’s ways…’”

Evie groaned. “TP—”

“A jest! A mere jest!” He twirled an imaginary cane. “And yet, what do we truly know of the elusive Mr. Herbert? If we wish to uncover his secrets, we must look into his… associations.”

Evie frowned. “Funny you said that, I would have thought ‘means, motive, alibis’ but I must be getting ahead of myself…” He had a point. “By associations, you mean —Seren Vega?”

“Indeed!” TP froze accessing invisible records, then clapped his hands together. “Seren Vega, archivist extraordinaire of the wondrous past, keeper resplendent of forgotten knowledge… and, if the ship’s whisperings hold any weight, a woman Herbert was particularly keen on seeing.”

Evie exhaled, already halfway to the door. “Alright, let’s go see Seren.”

Seren Vega’s quarters weren’t standard issue—too many rugs, too many hanging ornaments, a hint of a passion for hoarding, and an unshakable musky scent of an animal’s den. The place felt like the ship itself had grown around it, heavy with the weight of history.

And then, there was Mandrake.

The bionic-enhanced cat perched on a high shelf, tail flicking, eyes glowing faintly. “What do you want?” he asked flatly, his tone dripping with a well-practiced blend of boredom and disdain.

Evie arched a brow. “Nice to see you too, Mandrake.”

Seren, cross-legged on a cushion, glanced up from her console. “Evie,” she greeted calmly. “And… oh no.” She sighed, already bracing herself. “You’ve brought it —what do you call him already? Orion Reed?”

Evie replied “Great memory Ms Vega, as expected. Yes, this was the name of the beta version —this one’s improved but still working the kinks of the programme, he goes by ‘TP’ nowadays. Hope you don’t mind, he’s helping me gather clues.” She caught herself, almost telling too much to a potential suspect.

TP puffed up indignantly. “I must protest, Madame Vega! Our past encounters, while lively, have been nothing but the height of professional discourse!”

Mandrake yawned. “She means you talk too much.”

Evie hid a smirk. “I need your help, Seren. It’s about Mr. Herbert.”

Seren’s fingers paused over her console. “He’s the one they found in the dryer.” It wasn’t a question.

Evie nodded. “What do you know about him?”

Seren studied her for a moment, then, with a slow exhale, tapped a command into her console. The room dimmed as the walls flickered to life, displaying a soft cascade of memories—public logs, old surveillance feeds, snippets of conversations once lost to time.

“He wasn’t supposed to be here,” Seren said at last. “He arrived without a record. No one really questioned it, because, well… no one questions much anymore. But if you looked closely, the ship never registered him properly.”

Evie’s pulse quickened. TP let out an approving hum.

Seren continued, scrolling through the visuals. “He came to me, sometimes. Asked about old Earth history. Strange, fragmented questions. He wanted to know how records were kept, how things could be erased.”

Evie and TP exchanged a glance.

Seren frowned slightly, as if piecing together a thought she hadn’t dared before. “And then… he stopped coming.”

Mandrake, still watching from his shelf, stretched lazily. Then, with perfect nonchalance, he added, “Oh yeah. And he wasn’t using his real name.”

Evie snapped to attention. “What?”

The cat flicked his tail. “Mr. Herbert. The name was fake. He called himself that, but it wasn’t what the system had logged when he first stepped on board.”

Seren turned sharply toward him. “Mandrake, you never mentioned this before.”

The cat yawned. “You never asked.”

Evie felt a chill roll through her. “So what was his real name?”

Mandrake’s eyes glowed, data scrolling in his enhanced vision.

“Something about… Ethan,” he mused. “Ethan… M.”

The room went very still.

Evie swallowed hard. “Ethan Marlowe?”

Seren paled. “Ellis Marlowe’s son.”

TP, for once, was silent.

December 22, 2024 at 10:49 pm #7704In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

Darius: Christmas 2022

Darius was expecting some cold snap, landing in Paris, but the weather was rather pleasant this time of the year.

It was the kind of day that begged for aimless wandering, but Darius had an appointment he couldn’t avoid—or so he told himself. His plane had been late, and looking at the time he would arrive at the apartment, he was already feeling quite drained. The streets were lively, tourists and locals intermingling dreamingly under strings of festive lights spread out over the boulevards. He listlessly took some snapshot videos —fleeting ideas, backgrounds for his channel.

The wellness channel had not done very well to be honest, and he was struggling with keeping up with the community he had drawn to himself. Most of the latest posts had drawn the usual encouragements and likes, but there were also the growing background chatter, gossiping he couldn’t be bothered to rein in — he was no guru, but it still took its toll, and he could feel it required more energy to be in this mode that he’d liked to.

His patrons had been kind, for a few years now, indulging his flights of fancy, funding his trips, introducing him to influencers. Seeing how little progress he’d made, he was starting to wonder if he should have paid more attention to the background chatter. Monsieur Renard had always taken a keen interest in his travels, looking for places to expand his promoter schemes of co-housing under the guide of low investment into conscious living spaces, or something well-marketed by Eloïse. The crude reality was starting to stare at his face. He wasn’t sure how long he could keep up pretending they were his friends.

By the time he reached the apartment, in a quiet street adjacent to rue Saint Dominique, nestled in 7th arrondissement with its well-kept façades, he was no longer simply fashionably late.

Without even the time to say his name, the door buzz clicked open, leading him to the old staircase. The apartment door opened before he could knock. There was a crackling tension hanging in the air even before Renard’s face appeared—his rotund face reddened by an annoyance he was poorly hiding beneath a polished exterior. He seemed far away from the guarded and meticulous man that Darius once knew.

“You’re late,” Renard said brusquely, stepping aside to let Darius in. The man was dressed impeccably, as always, but there was a sharpness to his movements.

Inside, the apartment was its usual display of cultivated sophistication—mid-century furniture, muted tones, and artful clutter that screamed effortless wealth. Eloïse sat on the couch, her legs crossed, a glass of wine poised delicately in her hand. She didn’t look up as Darius entered.

“Sorry,” Darius muttered, setting down his bag. “Flight delay.”

Renard waved it off impatiently, already pacing the room. “Do you know where Lucien is?” he asked abruptly, his gaze slicing toward Darius.

The question caught him off guard. “Lucien?” Darius echoed. “No. Why?”

Renard let out a sharp, humorless laugh. “Why? Because he owes me. He owes us. And he’s gone off the grid like some bloody enfant terrible who thinks the rules don’t apply to him.”

Darius hesitated. “I haven’t seen him in months,” he said carefully.

Renard stopped pacing, fixing him with a hard look. “Are you sure about that? You two were close, weren’t you? Don’t tell me you’re covering for him.”

“I’m not,” Darius said firmly, though the accusation sent a ripple of anger through him.

Renard snorted, turning away. “Typical. All you dreamers are the same—full of ideas but no follow-through. And when things fall apart, you scatter like rats, leaving the rest of us to clean up the mess.”

Darius stiffened. “I didn’t come here to be insulted,” he said, his voice a steady growl.

“Then why did you come, Darius?” Renard shot back, his tone cutting. “To float on someone else’s dime a little longer? To pretend you’re above all this while you leech off people who actually make things happen?”

The words hit like a slap. Darius glanced at Eloïse, expecting her to interject, to soften the blow. But she remained silent, her gaze fixed on her glass as if it held all the answers.

For the first time, he saw her clearly—not as a confidante or a muse, but as someone who had always been one step removed, always watching, always using.

“I think I’ve had enough,” Darius said finally, his voice calm despite the storm brewing inside him. “I think I’ve had enough for a long time.”

Renard turned, his expression a mix of incredulity and disdain. “Enough? You think you can walk away from this? From us?”

“Yes, I can.” Darius said simply, grabbing his bag.

“You’ll never make it on your own,” Renard called after him, his voice dripping with scorn.

Darius paused at the door, glancing back at Eloïse one last time. “I’ll take my chances,” he said, and then slammed the door.

The evening air was like a balm, open and soft unlike the claustrophobic tension of the apartment. Darius walked aimlessly at first, his thoughts caught between flares of wounded pride and muted anxiety, but as he walked and walked, it soon turned into a return of confidence, slow and steady.

His phone buzzed in his pocket, and he pulled it out to see a familiar name. It was a couple he knew from the south of France, friends he hadn’t spoken to in months. He answered, their warm voices immediately lifting his spirits.

“Darius!” one of them said. “What are you doing for Christmas? You should come down to stay with us. We’ve finally moved to a bigger space—and you owe us a visit.”

Darius smiled, the weight of Renard’s words falling away. “You know what? That sounds perfect.”

As he hung up, he looked up at the Parisian skyline, Darius wished he’d had the courage to take that step into the unknown a long time ago. Wherever Lucien was, he felt suddenly closer to him —as if inspired by his friend’s bold move away from this malicious web of influence.

December 8, 2024 at 6:06 am #7655In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

Amei switched on the TV for background noise as she tackled another pile of books. The usual mid-morning chatter filled the room—updates on the weather, a cooking segment, and finally, the news. She was only half-listening until the anchor’s voice caught her attention.

“In the race against climate change, scientists at Harvard are turning to an unexpected solution: chalk. The ambitious project involves launching a balloon into the stratosphere, carrying 600 kilograms of calcium carbonate, which would be sprayed 12 miles above the Earth’s surface. The idea? To reflect sunlight and slow global warming.”

Amei looked up. The screen showed an animated demonstration of the project—a balloon rising into the atmosphere, spraying fine particles into the air. The narration continued, but her focus drifted, caught on a single word: chalk.

Elara loved chalk. Amei smiled faintly, remembering how passionately she used to talk about it—the way she could turn something so mundane into a story of structure, history, and beauty. “It’s not just a rock,” Elara had said once, gesturing dramatically, “it’s a record of time.”

She wasn’t even sure where Elara was these days. The last time they’d spoken was during lockdown. Amei had called to check in, awkward but well-meaning, only to be met with curt responses and a tone that made it clear Elara wanted the conversation over.

She hadn’t tried again after that. It hurt more than she’d expected. Elara could be all or nothing when it came to friendships—brilliant and intense one moment, distant and impenetrable the next. Amei had always known that about her, but knowing didn’t make it any easier.

The news droned on in the background, but Amei reached for the remote and switched off the TV. Her mind was elsewhere, tangled in memories.

She’d first met Elara in a gallery on Southbank, a tiny exhibition tucked away in a brutalist building. It was near Amei’s shared flat, and with her flatmates out for the evening, she had gone alone, more out of boredom than genuine interest. The display wasn’t large—just a few photographs and abstract sculptures, their descriptions dense with scientific jargon.

Amei stood in front of a piece labelled The Geometry of Chaos—a spiraling wire structure that cast intricate, shifting shadows on the wall. She tilted her head, trying to look engaged, though her thoughts were already drifting towards home and her comfy bed.

“Magnificent, isn’t it?”

The voice startled her. She turned to see a dark-haired woman, arms crossed, studying the piece with an intensity that made Amei feel as though she must have missed something obvious. The woman wore a long, flowing skirt, layered necklaces, and a cardigan that looked hand-knitted. Her dark hair was piled into a messy bun, a few strands escaping to frame her face.

“It’s quite interesting,” Amei said. “But I’m not sure I get it.”

“It’s not about getting it. It’s about recognizing the pattern,” the woman replied, stepping closer. She pointed to the shadows on the wall. “See? The curve repeats itself. Infinite, but contained.”

“You sound like you know what you’re talking about.”

“I do,” she said. “Do you?”

Amei laughed, caught off guard. “Not very often. I think I’m more into… messy patterns.”

The woman’s sharp expression softened slightly. “Messy patterns are still patterns.” She smiled. “I’m Elara.”

“Amei,” she replied, returning the smile.

Elara’s gaze dropped, and she nodded toward Amei’s skirt. “I’ve been admiring your skirt. Gorgeous fabric. Where did you get it?”

“Oh, I made it, actually,” Amei felt proud.

Elara raised her eyebrows. “You made it? I’m impressed.”

And that was how it began. A chance meeting that turned into decades of close friendship. They’d left the gallery together, talking all the way to a nearby café.

December 6, 2024 at 8:44 am #7648In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

Spring 2024

Matteo was wandering through the streets of Avignon, the spring air heavy with the scent of blooming flowers and sun-warmed stone. The hum of activity surrounded him—shopkeepers arranging displays, the occasional burst of laughter from a café terrace. He walked with no particular destination, drawn more by instinct than intent, until a splash of colour caught his eye.

On the cobblestones ahead, an artist crouched over a sprawling chalk drawing. It was a labyrinthine map, its intricate paths winding across the ground with deliberate precision. Matteo froze, his breath catching. The resemblance to the map he’d found at the vineyard office was uncanny—the same loops and spirals, the same sense of motion and stillness intertwined. But it wasn’t the map itself that held him in place. It was the faces.

Four of them, scattered in different corners of the design, each rendered with surprising detail. Beneath them were names. Matteo felt a shiver crawl up his spine. He knew three of those faces. Amei, Elara, Darius… he had met each of them once, in moments that now felt distant and fragmented. Strangers to him, but not quite.

The artist shifted, brushing dark, rain-damp curls from his forehead. His scarf, streaked faintly with paint, hung loosely around his neck. Matteo stepped closer, his curiosity overpowering any hesitation. “Is that your name?” he asked, gesturing toward the face labeled Lucien.

The artist straightened, his hand resting lightly on a piece of green chalk. He studied Matteo for a moment, his expression unreadable. “Yes,” he said simply, his voice low but clear.

Matteo crouched beside him, tracing the edge of the map with his eyes. “It’s incredible,” he said. “The detail, the connections. Why the faces?”

Lucien hesitated, glancing at the names scattered across his work. “Because that’s how it is,” he said softly. “We’re all here, but… not together.”

Matteo tilted his head, intrigued. “You mean you’ve drifted?”

Lucien nodded, his gaze dropping to the chalk in his hand. “Something like that. Paths cross, then they don’t. People take their turns.”

Matteo studied the map again, its intertwining lines seeming both chaotic and deliberate. The faces stared back at him, and he felt the pull of the map he no longer carried. “Do you think paths can lead back?” he asked, his voice thoughtful.

Lucien glanced at him, something flickering briefly in his eyes. “Sometimes. If you follow them long enough.”

Matteo smiled faintly, standing. His curiosity shifted as he turned his attention to the artist himself. “Do you know where I can find absinthe?” he asked.

Lucien raised an eyebrow. “Absinthe? Haven’t heard anyone ask for that in a while.”

“Just something I’ve been chasing,” Matteo replied lightly, his tone almost playful.

Lucien gestured vaguely toward a café down the street. “You might try there. They keep the old things alive.”

“Thanks,” Matteo said, offering a nod. He took a few steps away but paused, turning back to the artist still crouched over his map. “It’s a good drawing,” he said. “Hope your paths cross again.”

Lucien didn’t reply, but his hand moved back to the chalk, drawing a faint line that connected two of the faces. Matteo watched for a moment longer before continuing down the street, the memory of the map and the names lingering in his mind like an unanswered question. Paths crossed, he thought, but maybe they didn’t always stay apart.

For the first time in days, Matteo felt a strange sense of possibility. The map was gone, but perhaps it had done what it was meant to do—leave its mark.

December 2, 2024 at 10:50 pm #7635In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

Sat. Nov. 30, 2024 5:55am — Matteo’s morning

Matteo’s mornings began the same way, no matter the city, no matter the season. A pot of strong coffee brewed slowly on the stove, filling his small apartment with its familiar, sense-sharpening scent. Outside, Paris was waking up, its streets already alive with the sound of delivery trucks and the murmurs of shopkeepers rolling open shutters.

He sipped his coffee by the window, gazing down at the cobblestones glistening from last night’s rain. The new brass sign above the Sarah Bernhardt Café caught the morning light, its sheen too pristine, too new. He’d started the server job there less than a week ago, stepping into a rhythm he already knew instinctively, though he wasn’t sure why.

Matteo had always been good at fitting in. Jobs like this were placeholders—ways to blend into the scenery while he waited for whatever it was that kept pulling him forward. The café had reopened just days ago after months of being closed for renovations, but to Matteo, it felt like it had always been waiting for him.

He set his coffee mug on the counter, reaching absently for the notebook he kept nearby. The act was automatic, as natural as breathing. Flipping open to a blank page, Matteo wrote down four names without hesitation:

Lucien. Elara. Darius. Amei.

He stared at the list, his pen hovering over the page. He didn’t know why he wrote it. The names had come unbidden, as though they were whispered into his ear from somewhere just beyond his reach. He ran his thumb along the edge of the page, feeling the faint indentation of his handwriting.

The strangest part wasn’t the names— it was the certainty that he’d see them that day.

Matteo glanced at the clock. He still had time before his shift. He grabbed his jacket, tucked the notebook into the inside pocket, and stepped out into the cool Parisian air.

Matteo’s feet carried him to a side street near the Seine, one he hadn’t consciously decided to visit. The narrow alley smelled of damp stone and dogs piss. Halfway down the alley, he stopped in front of a small shop he hadn’t noticed before. The sign above the door was worn, its painted letters faded: Les Reliques. The display in the window was an eclectic mix—a chessboard missing pieces, a cracked mirror, a wooden kaleidoscope—but Matteo’s attention was drawn to a brass bell sitting alone on a velvet cloth.

The door creaked as he stepped inside, the distinctive scent of freshly burnt papier d’Arménie and old dust enveloping him. A woman emerged from the back, wiry and pale, with sharp eyes that seemed to size Matteo up in an instant.

“You’ve never come inside,” she said, her voice soft but certain.

“I’ve never had a reason to,” Matteo replied, though even as he spoke, the door closed shut the outside sounds.

“Today, you might,” the woman said, stepping forward. “Looking for something specific?”

“Not exactly,” Matteo replied. His gaze shifted back to the bell, its smooth surface gleaming faintly in the dim light.

“Ah.” The shopkeeper followed his eyes and smiled faintly. “You’re drawn to it. Not uncommon.”

“What’s uncommon about a bell?”

The woman chuckled. “It’s not the bell itself. It’s what it represents. It calls attention to what already exists—patterns you might not notice otherwise.”

Matteo frowned, stepping closer. The bell was unremarkable, small enough to fit in the palm of his hand, with a simple handle and no visible markings.

“How much?”

“For you?” The shopkeeper tilted his head. “A trade.”

Matteo raised an eyebrow. “A trade for what?”

“Your time,” the woman said cryptically, before waving her hand. “But don’t worry. You’ve already paid it.”

It didn’t make sense, but then again, it didn’t need to. Matteo handed over a few coins anyway, and the woman wrapped the bell in a square of linen.

Back on the street, Matteo slipped the bell into his pocket, its weight unfamiliar but strangely comforting. The list in his notebook felt heavier now, as though connected to the bell in a way he couldn’t quite articulate.

Walking back toward the café, Matteo’s mind wandered. The names. The bell. The shopkeeper’s words about patterns. They felt like pieces of something larger, though the shape of it remained elusive.

The day had begun to align itself, its pieces sliding into place. Matteo stepped inside, the familiar hum of the café greeting him like an old friend. He stowed his coat, slipped the bell into his bag, and picked up a tray.

Later that day, he noticed a figure standing by the window, suitcase in hand. Lucien. Matteo didn’t know how he recognized him, but the instant he saw the man’s rain-damp curls and paint-streaked scarf, he knew.

By the time Lucien settled into his seat, Matteo was already moving toward him, notebook in hand, his practiced smile masking the faint hum of inevitability coursing through him.

He didn’t need to check the list. He knew the others would come. And when they did, he’d be ready. Or so he hoped.

November 4, 2024 at 3:36 pm #7579In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

When Eris called for an urgent meeting, Malové nearly canceled. She had her own pressing concerns and little patience for the usual parade of complaints or flimsy excuses about unmet goals from her staff. Yet, feeling the weight of her own stress, she was drawn to the idea of venting a bit—and Truella or Jeezel often made for her preferred targets. Frella, though reserved, always performed consistently, leaving little room for critique. And Eris… well, Eris was always methodical, never using the word “urgent” lightly. Every meeting she arranged was meticulously planned and efficiently run, making the unexpected urgency of this gathering all the more intriguing to Malové.

Curiosity, more than duty, ultimately compelled her to step into the meeting room five minutes early. She tensed as she saw the draped dark fabrics, flickering lights, forlorn pumpkins, and the predictable stuffed creatures scattered haphazardly around. There was no mistaking the culprit behind this gaudy display and the careless use of sacred symbols.

“Speak of the devil…” she muttered as Jeezel emerged from behind a curtain, squeezed into a gown a bit too tight for her own good and wearing a witch’s hat adorned with mystical symbols and pheasant feathers. “Well, you’ve certainly outdone yourself with the meeting room,” Malové said with a subtle tone that could easily be mistaken for admiration.

Jeezel’s face lit up with joy. “Trick or treat!” she exclaimed, barely able to contain her excitement.

“What?” Malové’s eyebrows arched.

“Well, you’re supposed to say it!” Jeezel beamed. “Then I can show you the table with my carefully handcrafted Halloween treats.” She led Malové to a table heaving with treats and cauldrons bubbling with mystical mist.

Malové felt a wave of nausea at the sight of the dramatically overdone spread, brimming with sweets in unnaturally vibrant colors. “Where are the others?” she asked, pressing her lips together. “I thought this was supposed to be a meeting, not… whatever this is.”

“They should arrive shortly,” said Jeezel, gesturing grandly. “Just take your seat.”

Malové’s eyes fell on the chairs, and she stifled a sigh. Each swivel chair had been transformed into a mock throne, draped in rich, faux velvet covers of midnight blue and deep burgundy. Golden tassels dangled from the edges, and oversized, ornate backrests loomed high, adorned with intricate patterns that appeared to be hastily hand-painted in metallic hues. The armrests were festooned with faux jewels and sequins that caught the flickering light, giving the impression of a royal seat… if the royal in question had questionable taste. The final touch was a small, crowned cushion placed in the center of each seat, as if daring the occupants to take their place in this theatrical rendition of a court meeting.

When she noticed the small cards in front of each chair, neatly displaying her name and the names of her coven’s witches, Malové’s brow furrowed. So, seats had been assigned. Instinctively, her eyes darted around the room, scanning for hidden tricks or sutble charms embedded in the decor. One could never be too cautious, even among her own coven—time had taught her that lesson all too often, and not always to her liking.

Symbols, runes, sigils—even some impressively powerful ones—where scattered thoughtfully around the room. Yet none of them aligned into any coherent pattern or served any purpose beyond mild relaxation or mental clarity. Malové couldn’t help but recognize the subtlety of Jeezel’s craft. This was the work of someone who, beyond decorum, understood restraint and intention, not an amateur cobbling together spells pulled from the internet. Even her own protective amulets, attuned to detect any trace of harm, remained quiet, confirming that nothing in the room, except for those treats, posed a threat.

As the gentle aroma of burning sage and peppermint reached her nose, and Jeezel placed a hat remarkably similar to her own onto Malové’s head, the Head Witch felt herself unexpectedly beginning to relax, her initial tension and worries melting away. To her own surprise, she found herself softening to the atmosphere and, dare she admit, actually beginning to enjoy the gathering.

September 13, 2024 at 6:48 am #7550In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

The fair was in full swing, with vibrant tents and colourful stalls bursting with activity. The smell of freshly popped corn mingled with the fragrance of exotic spices and the occasional whiff of magical incense. Frella turned her attention back to setting up her own booth. Her thoughts were a swirl of anxiety and curiosity. Malové’s sudden appearance at the fair could not be a mere coincidence, especially given the recent disruptions in the coven.

Unbeknownst to Frella, Cedric Spellbind was nearby. His eyes, though hidden behind a pair of dark glasses, were fixated on Frella. He was torn between his duty to MAMA and his growing affection for her. He juggled his phone, checking missed calls and messages, while trying to keep a discreet distance. But he was drawn to her like moth to flame.

As Frella was adjusting her booth, she felt a sudden chill and turned to find herself face-to-face with Cedric. He quickly removed his glasses and their eyes met; Cedric’s heart skipped a beat.

Frella’s gaze was guarded. “Can I help you with something?” she asked, her tone icily polite.

Cedric, flustered, stammered, “I—uh—I’m just here to, um, look around. Your booth looks, uh, fascinating.”

Frella raised an eyebrow. “I see. Well, enjoy the fair.” She turned back to her preparations, but not before noticing a fleeting look of hurt in Cedric’s eyes.

Cedric moved away, wrestling with his conflicting emotions. He checked to make sure his tracker was working, which tracked not just Frella’s movements but those of her companions. He was determined to protect her from any potential threat, even if it meant risking his own standing with MAMA.

As the day progressed, the fair continued to buzz with magical energy and intrigue. Frella worked her booth, engaging with curious tourists, all suitably fascinated with the protective qualities of hinges. Suddenly, Frella’s attention was drawn away from her display by a burst of laughter and squeals coming from nearby. Curiosity piqued, she made her way toward the source of the commotion.

As she approached, she saw a crowd had gathered around a small, ornate tent. The tent’s entrance was framed by shimmering curtains, and an enchanting aroma of lavender and spices wafted through the air. Through the gaps in the curtains, Frella could see an array of magical trinkets and curiosities.Just as she was about to step closer, a peculiar sight caught her eye. Emerging from the tent was a girl wearing a rather large cloak and closely followed by a black cat. The girl looked bewildered, her wide eyes taking in the bustling fairground.

Frella, intrigued and somewhat amused, approached the girl. “Hello there! I couldn’t help but notice you seem a bit lost. Are you okay?”

The girl’s expression was a mix of confusion and wonder. “Oh, hello! I’m Arona, and this is Mandrake,” she said, bending down and patting the black cat, who gave a nonchalant twitch of his tail. “We were just trying to find the library in my time, and now we’re here. This isn’t a library by any chance?”

Frella raised her eyebrows. “A library? No, this is a fair—a magical fair, to be precise.”

Arona’s eyes widened further as she looked around again. “A fair? Well, it does explain the odd contraptions and the peculiar people. Anyway, that will teach me to use one of Sanso’s old time-travelling devices.”

Truella wandered over to join the conversation, her curiosity evident. “Time-travelling device? That sounds fascinating. How did you end up here?”

Arona looked sheepish. “I was trying to retrieve a rare book from a past century, and it seems I got my coordinates mixed up. Instead of the library, I ended up at this… um … delightful fair.”

Frella chuckled. “Well, don’t worry, we can help you get back on track. Maybe we can find someone who can help with your time-travelling predicament.”

Arona smiled, relieved. “Thank you! I really didn’t mean to intrude. And Mandrake here is quite good at keeping me company, but he’s not much help with directions.”

Mandrake rolled his eyes and turned away, his disinterest in the conversation evident.

As Frella and Truella led Arona to a quieter corner of the fair, Cedric Spellbind observed the scene with growing interest. His eyes were glued to Frella, but the appearance of the time-travelling girl and her cat added a new layer of intrigue. Cedric’s mission to spy on Frella had just taken an unexpected turn.

June 29, 2024 at 10:01 pm #7527In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

It was good to get a break from the merger craziness. Eris was thankful for the small mercy of a quiet week-end back at the cottage, free of the second guessing of the suspicious if not philandering undertakers, and even more of the tedious homework to cement the improbable union of the covens.

The nun-witches had been an interesting lot to interact with, but Eris’d had it up to her eyeballs of the tense and meticulous ceremonies. They had been brewing potions for hours on, trying to get a suitable mixture between the herbs the nuns where fond of, and the general ingredients of their own Quadrivium coven’s incenses. Luckily they had been saved by the godlike apparition of another of Frella’s multi-tasking possessions, this time of a willing Sandra, and she’s had harmonized in no time the most perfect blend, in a stroke of brilliance and sheer inspiration, not unlike the magical talent she’d displayed when she invented the luminous world-famous wonder that is ‘Liz n°5’.

As she breathed in the sweet air, Eris could finally enjoy the full swing of summer in the cottage, while Thorsten was happily busy experimenting with an assortment of cybernetic appendages to cut, mulch, segment and compost the overgrown brambles and nettles in the woodland at the back of the property.

Interestingly, she’d received a letter in the mail — quaintly posted from Spain in a nondescript envelop —so anachronistic it was too tempting to resist looking.

Without distrust, but still with a swish of a magical counterspell in case the envelop had traces of unwanted magic, she opened it, only to find it burst with an annoying puff of blue glitter that decided to stick in every corner of the coffee table and other places.

Eris almost cursed at the amount of micro-plastics, but her attention was immediately caught by the Latin sentence mysteriously written in a psychopath ransom note manner: “QUAERO THESAURUM INCONTINUUM”

“Whisp! Elias? A little help here, my Latin must be wrong. What accumulation of incontinence? What sort of spell is that?!”

Echo appeared first, looking every bit like the reflection of Malové. “Quaero Thesaurum Incontinuum,” you say. How quaint, how cryptic, how annoyingly enigmatic. Eris, it seems the universe has a sense of humor—sending you this little riddle while you’re neck-deep in organizational chaos.

“Oh, Echo, stop that! I won’t spend my well-earned week-end on some riddle-riddled chase…”

“You’re no fun Eris” the sprite said, reverting into a more simple form. “It translates roughly to “I seek the endless treasure.” Do you want me to help you dissect this more?”

“Why not…” Eris answered pursing up her lips.

““Seek the endless treasure.” We’re talking obviously something deeper, more profound than simple gold; maybe knowledge —something truly inexhaustible. Given your current state of affairs, with the merger and the restructuring, this message could be a nudge—an invitation to look beyond the immediate chaos and find the opportunity within.”

“Sure,” Eris said, already tired with the explanations. She was not going to spend more time to determine the who, the why, and the what. Who’d sent this? Didn’t really matter if it was an ally, a rival, or even a neutral party with vested interests? She wasn’t interested in seeking an answer to “why now?”. Endless rabbit holes, more like it.

The only conundrum she was left with was to decide whether to keep the pesky glittering offering, or just vacuum the hell of it, and decide if it could stand the test of ‘will it blend?’. She wrapped it in a sheet of clear plastic, deciding it may reveal more clues in the right time.

With that done, Eris’ mind started to wander, letting the enigmatic message linger a while longer… as reminder that while we navigate the mundane, our eyes must always be on the transcendent. To seek the endless treasure…

The thought came to her as an evidence “Death? The end of suffering…” To whom could this be an endless treasure? Eris sometimes wondered how her brain picked up such things, but she rarely doubted it. She might have caught some vibes during the various meetings. Truella mentioning Silas talking about ‘retiring nuns’, or Nemo hinting at Penelope that ‘death was all about…”

The postcard was probably a warning, and they had to stay on their guards.

But now was not the time for more drama, the icecream was waiting for her on the patio, nicely prepared by Thorsten who after a hard day of bramble mulching was all smiling despite looking like he had went through a herd of cats’ fight.

June 17, 2024 at 7:13 pm #7493In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

“Do you know who that Everone is?” Jeezel whispered to Eris.

“Shtt,” she silenced Jeezel worried that some creative inspiration sparked into existence yet another character into their swirling adventure.

The ancient stone walls of the Cloisters resonated with the hum of anticipation. The air was thick with the scent of incense barely covering musky dogs’ fart undertones, mingling with the faint aroma of fresh parchment eaten away by centuries of neglect. Illuminated by the soft glow of enchanted lanterns sparkling chaotically like a toddler’s magic candle at its birthday, the grand hall was prepared for an unprecedented gathering of minds and traditions.

While all the attendants were fumbling around, grasping at the finger foods and chitchatting while things were getting ready, Eris was reminded of the scene of the deal’s signature between the two sisterhoods unlikely brought together.

Few weeks before, under a great deal of secrecy, Malové, Austreberthe, and Lorena had convened in the cloister’s grand hall, the gothic arches echoing their words. Before she signed, Lorena had stated rather grandiloquently, with a voice firm and unwavering. “We are a nunnery dedicated to craftsmanship and spiritual devotion. This merger must respect our traditions.”

Austreberthe, ever the pragmatist, replied, “And we bring innovation and magical prowess. Together, we can create something greater than the sum of our parts.”

The undertaker’s spokesman, Garrett, had interjected with a charming smile, “Consider us the matchmakers of this unlikely union. We promise not to leave you at the altar.”

That’s were he’d started to spell out the numbingly long Strategic Integration Plan to build mutual understanding of the mission and a framework for collaboration.Eris sighed at the memory. That would require yet a great deal of joint workshops and collaborative sessions — something that would be the key to facilitate new product developments and innovation. Interestingly, Malové at the time had suggested for Jeezel to lead with Silas the integration rituals designed to symbolically and spiritually unite the groups. She’d had always had a soft spot for our Jeezel, but that seemed unprecedented to want to put her to task on something as delicate. Maybe there was another plan in motion, she would have to trust Malové’s foresight and let it play out.

As the heavy oak doors creaked open, a hush fell over the assembled witches, nuns and the undertakers. Mother Lorena Blaen stepped forward. Her presence was commanding, her eyes sharp and scrutinising. She wore the traditional garb of her order, but her demeanour was anything but traditional.

“Welcome, everyone,” Lorena began, her voice echoing through the hallowed halls. “Or should I say, welcome to the heart of tradition and innovation, where ancient craftsmanship meets arcane mastery.”

She paused, letting her words sink in, before continuing. “You stand at the threshold of the Quintessivium Cloister Crafts, a sanctuary where every stitch is a prayer, every garment a humble display of our deepest devotion. But today, we are not just nuns and witches, morticians and mystics. Today, we are the architects of a new era.”

Truella yawned at the speech, not without waving like a schoolgirl at the tall Rufus guy, while Lorena was presenting a few of the nuns, ready to model in various fashionable nun’s garbs for their latest midsummer fashion show.

Lorena’s eyes twinkled with a mixture of pride and determination as she turned back to the visitors. “Together, we shall transcend the boundaries of faith and magic. With the guidance of the Morticians’ Guild—Garrett, Rufus, Silas, and Nemo—we will forge a new path, one that honors our past while embracing the future.”

Garrett, ever the showman, gave a theatrical bow. “We’re here to ensure this union is as seamless as a well-tailored shroud, my dear Lorena.” Rufus, standing silent and vigilant, offered a nod of agreement. Silas, with his grandfatherly smile, added, “We bring centuries of wisdom to this endeavor. Trust in the old ways, and we shall succeed.” Nemo, with his characteristic smirk, couldn’t resist a final quip. “And if things go awry, well, we have ways of making them… interesting.”

June 16, 2024 at 7:00 am #7485In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

The Quintessivium Cloister Crafts was busying getting ready to complete this year’s midsummer fashion tour.

Mother Blaen (Lorena in private), started to clap bossily to line up all the sisters for the rehearsal.

“Yes, Sister Maria, you start, Black habit and white wimple, Roman Catholic timeless elegance, perfect. And think to wipe that smile off your face. You need to show spirit of devotion.”

She swiftly moved to her right.

“Now, Sister Ananda.”

Sassafrass was starting to argue about the naming convention that felt a bit too Actors studio for her taste, but was promptly shushed. Mother Blaen took a closer look, adjusting her half-rimmed glasses. “Oh… dear, I thought for a moment you’d gotten fat. Must be the lighting. So, in the vibrant orange of bhikkhunis, you glide gracefully… well, as much as you can. Peace and calm, that’s you. Yes, and don’t make a scene please. Be content I’m not asking you to shave this hair to get more in character with the robes.”

She pursued:

“Sister Amina!”

Penelope Pomfrett raised her hand silently, visibly displeased too at the name.

“Good, now. Mystical and poetic nature of Sufism, that’s your cue. Beautiful, beautiful. That modest and pure white chola and headscarf will be resplendent on the catwalk.”

After she went through all the attires in detail, down to the long black riassa and epanokamelavkion of the Eastern Orthodox nun garb, all were getting ready for the grand finale.

“Now, all of us, walking together to symbolize the unity and diversity of spiritual paths. One, two, one two. Sassafrass! Focus please!”

Mother Blaen clapped, visibly pleased at the full on display of their Coven’s couture arts. That would put a good show for the smoking witches. She thought “Let them bring the money, but one thing is sure, we bring the talent.”

April 17, 2024 at 8:09 pm #7434In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

Getting this out in the room did bring a tide of emotions; pent-up frustration, indignation, bits of bruised egoes, the whole spectrum. Truella’s tirade had managed to uncork a complete bundle of electricity in the atmosphere, but the genie had left the building.

Eris had suddenly felt like scrambling away, but had stayed along with spaced out Frigella and Jeezel as she’d felt a pang of responsibility.

Surprisingly, Malové had remained composed throughout the heated ensuing exchanges, trying to be constructive at every turn, and managing to conclude most of the debates —even when was not fully settled, and by far, a round of collected feedback afterwards, she’d clapped appreciatively saying. “Congratulations team, seeing how we are no longer covertly disagreeing behind everyone else’s back, I can see improvement in our functioning as a cohesive Coven. Believe it or not, being in a place to openly voice disagreement is a sign of progress, we’ve moved past the trust issues, into constructive conflict. There is still much to be done to commit, be accountable and focus on results together, but I feel we are on track to a brighter future, you’ve all done well.”

Back in her cottage in Finland, Eris was wondering “then why do I feel so bloody exhausted…”

She played back in her head some of the comments that Malové had shared in private after, when Eris had enquired if there would be some consequences for her witch’s friend actions. Once more, Malové has shown a unusual restraint that had put her worries at ease for now.

“Truella’s actions during the Adare Manor workshop presentation displayed boldness and conviction, two qualities that are essential for any individual, executive or otherwise, who wishes to effect change within an organization or a venture. Standing up for oneself is not only about self-assurance; it’s about ensuring that your voice and perspective are heard and considered.

However, the manner in which one stands up for oneself is crucial. Berating others, especially in a public forum such as a workshop presentation, can be counterproductive. It can create resistance and diminish the opportunity for constructive dialogue. While I understand her frustration, it is important to channel such energies towards a more strategic approach that fosters collaboration and leads to solutions.

As a leader, I advocate for clear communication and assertiveness, tempered with respect for all members of the coven. The success of our ventures, vaping or otherwise, depends on our ability to work cohesively towards our common goals. Truella’s passion is commendable, but it must be directed appropriately to benefit the coven and our business endeavors.”

She had asked Eris to convey the same to Truella. She’d made no promises —her friend was known to be more difficult to herd than cats. But with time, there would be a chance she would see reason.

Meanwhile, their sales targets had not gone away, and they had to keep the Quadrivium afloat. With Truella checking out of the game, and clearly not overly engaged on results, it fell onto the rest of the team to deliver.

A second session of workshop and celebration was planned in a month’s time in Spain with all top witches. With Eris’ last experience in Spain and her elephant head, she was starting to dread another mishap. Plus, she sighed when she looked at the invite. She would have to fetch a cocktail attire. A vacation was long overdue…

February 4, 2024 at 4:13 pm #7339In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

4pm EET.

Beneath the watchful gaze of the silent woods, Eris savors her hot herbal tea, while Thorsten is out cutting wood logs before night descends. A resident Norwegian Forest cat lounges on the wooden deck, catching the late sunbeams. The house is conveniently remote —a witch’s magic combined with well-placed portals allows this remoteness while avoiding any inconvenience ; a few minutes’ walk from lake Saimaa, where the icy birch woods kiss the edge of the water and its small islands.

Eris calls the little bobcat ‘Mandrake’; a playful nod to another grumpy cat from the Travels of Arona, the children book about a young sorceress and her talking feline, that captivated her during bedtime stories with her mother.

Mandrake pays little heed to her, coming and going at his own whim. Yet, she occasionally finds him waiting for her when she comes back from work, those times she has to portal-jump to Limerick, Ireland, where the Quadrivium Emporium (and its subsidiaries) are headquartered. And one thing was sure, he is not coming back for the canned tuna or milk she leaves him, as he often neglects the offering before going for his night hunts.

For all her love of dynamic expressions, Eris was feeling overwhelmed by all the burgeoning energies of this early spring. Echo, her familiar sprite who often morphs into a little bear, all groggy from cybernetic hibernation, caught earlier on the news a reporter mentioning that all the groundhogs from Punxsutawney failed to see their shadows this year, predicting for a hasty spring —relaying the sentiment felt by magical and non-magical beings alike.

Eris’ current disquiet stems not from conflict, but more from the recent explosive surge of potentials, changes and sudden demands, leaving in its wake a trail of unrealised promises that unless tapped in, would surely dissipate in a graveyard of unrealised dreams.

Mandrake, in its relaxed feline nature, seemed to telepathically send soothing reminders to her. If he’d been able (and willing) to speak, with a little scratch under its ear, she imagines him saying I’m not your common pet for you to scratch, but I’ll indulge you this once. Remember what it means to be a witch. To embrace the chaos, not fight it. To dance in the storm rather than seek shelter. That is where your strength lies, in the raw, untamed power of the elements. You need not control the maelstrom; you must become it. Now, be gone. I have a sunbeam to nap in.

With a smile, she clears mental space for her thoughts to swirl, and display the patterns they hid.

A jump in Normandy, indeed. She was there in the first mist of the early morning. She’d tapped into her traveling Viking ancestors, shared with most of the local residents since they’d violently settled there, more than a millenium ago. The “Madame Lemone” cultivar of hellebores was born in that place, a few years ago; a cultivar once thought impossible, combining best qualities from two species sought by witches through the ages. Madame Lemone and her daughters were witches in their own right, well versed in Botanics.

Why hellebores? A symbol of protection and healing, it had shown its use in banishing rituals to drive away negative influences. A tricky plant, beautiful and deadly. Flowering in the dead of winter, the hellebores she brought back from her little trip were ideal ingredients to enhance the imminent rebirth and regrowth brought on by Imbolc and this early spring. It was perfect for this new era filled with challenges. Sometimes, in order to bloom anew, you must face the rot within.

The thoughts kept spinning, segueing into the next. Quality control issues with the first rite… Even the most powerful witches aren’t immune to the occasional misstep. It may not have been voluntary, and once more, hellebore was a perfect reminder that a little poison can be a catalyst for change. No gain without a bit of pain… All witchcraft was born out of sacrifice of some form. An exchange of energy. Something given, for something in return.

Luckily, she’d learnt the third rite had gone well even in her absence. Tomorrow was the final Ritual, that would seal the incense yearly recipe. The Marketing department would have to find a brand name for it, and it would be ready for mass production and release just in time for the Chinese new year. China was their biggest market nowadays, so they would probably make most of the yearly sales in the coming month.

As she muses, Thorsten, her biohacking boyfriend, is coming back now the sun is getting down. A rugged contradiction of man and machine.

“Have you managed to contact your friends?” he asks, his pointed question tempered by a calm demeanor. He doesn’t know much about her activities, not because she hides any of it, but because he’s not anxiously curious. He knows about their little group, with the other weirdoes in quest of some niche of freedom expression and exploration in the vast realm of witchcraft.

“Yes, I did. We had a nice chat with Jeezel and she sends her regards…”

“She bloody always do that, doesn’t she.” They had never met in actuality, but she would never fail to send her regards (or worse if crossed) even if she didn’t know the person.

Eris laughed. “Well, Frigella was going to bed…”

“If I didn’t know better, one could think she does it on purpose.”

Eris continued. “Well, and get that; Tru was busy making some French fries.”