-

AuthorSearch Results

-

August 28, 2024 at 1:31 pm #7549

In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

The Tailor of Haddon

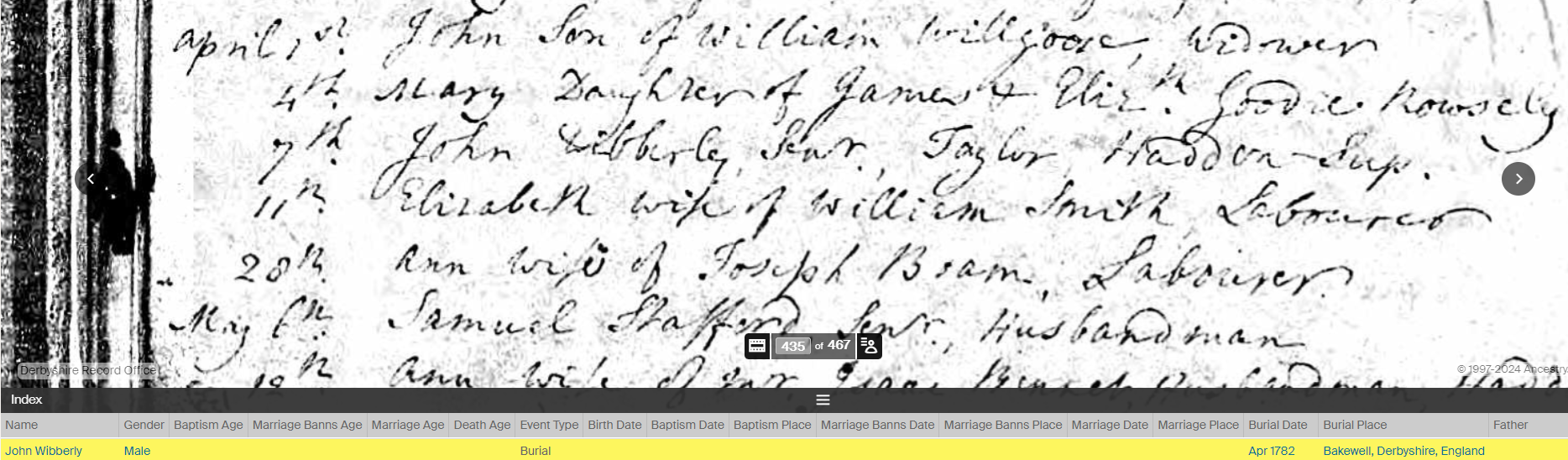

Wibberly and Newton of Over HaddonIt was noted in the Bakewell parish register in 1782 that John Wibberly 1705?-1782 (my 6x great grandfather) was “taylor of Haddon”.

James Marshall 1767-1848 (my 4x great grandfather), parish clerk of Elton, married Ann Newton 1770-1806 in Elton in 1792. In the Bakewell parish register, Ann was baptised on the 2rd of June 1770, her parents George and Dorothy Newton of Upper Haddon. The Bakewell registers at the time covered several smaller villages in the area, although what is currently known as Over Haddon was referred to as Upper Haddon in the earlier entries.

Newton:

George Newton 1728-1798 was the son of George Newton 1706- of Upper Haddon and Jane Sailes, who were married in 1727, both of Upper Haddon.

George Newton born in 1706 was the son of George Newton 1676- and Anne Carr, who were married in 1701, both of Upper Haddon.

George Newton born in 1676 was the son of John Newton 1647- and Alice who were married in 1673 in Bakewell. There is no last name for Alice on the marriage transcription.

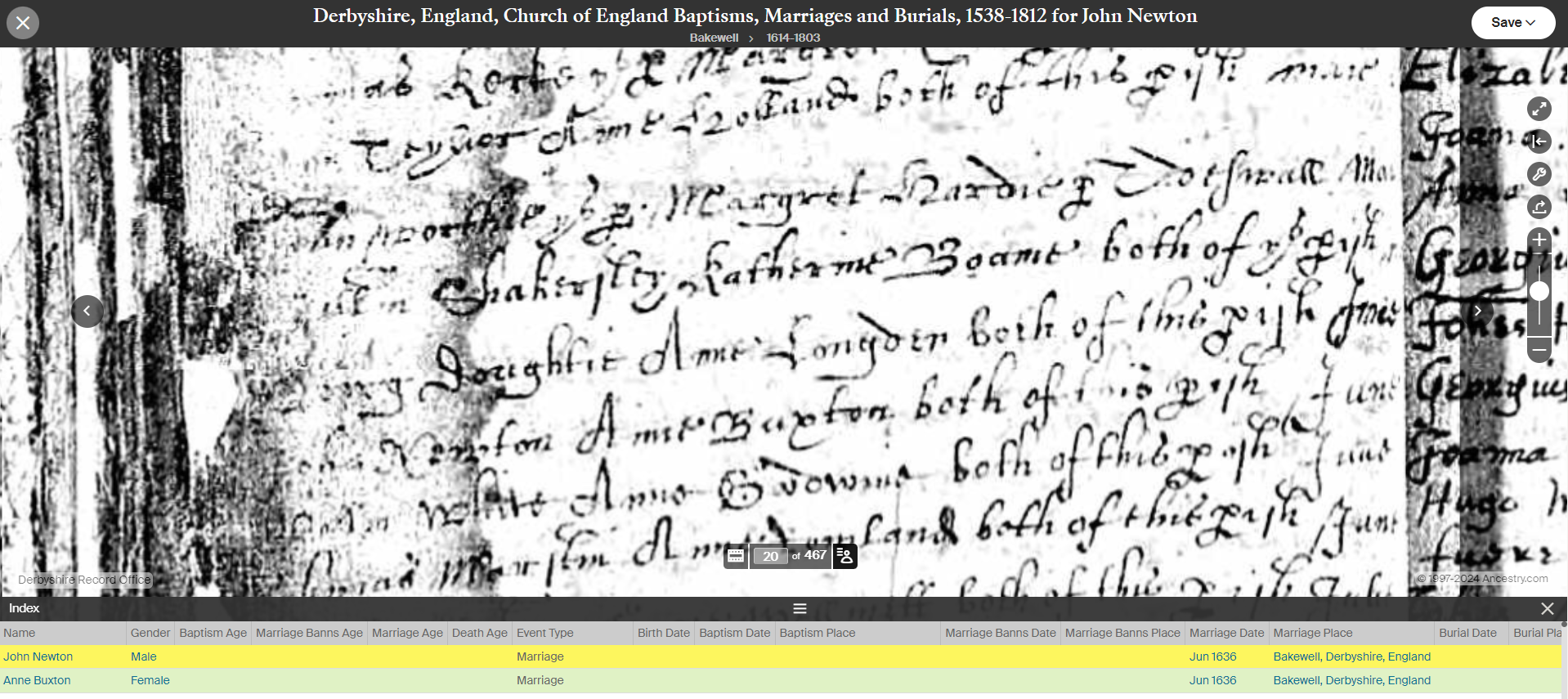

John Newton born in 1647 (my 9x great grandfather) was the son of John Newton and Anne Buxton (my 10x great grandparents), who were married in Bakewell in 1636.

1636 marriage of John Newton and Anne Buxton:

Wibberly

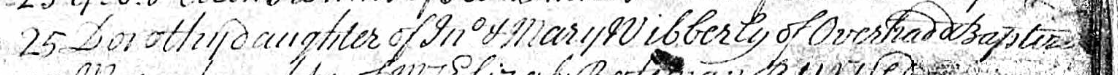

Dorothy Wibberly 1731-1827 married George Newton in 1755 in Bakewell. The entry in the parish registers says that they were both of Over Haddon. Dorothy was baptised in Bakewell on the 25th June 1731, her parents were John and Mary of Over Haddon.

John Wibberly and Mary his wife baptised nine children in Bakewell between 1730 and 1750, and on all of the entries in the parish registers it is stated that they were from Over Haddon. A parish register entry for John and Mary’s marriage has not yet been found, but a marriage in Beeley, a tiny nearby village, in 1728 to Mary Mellor looks likely.

John Wibberly died in Over Haddon in 1782. The entry in the Bakewell parish register notes that he was “taylor of Haddon”.

The tiny village of Over Haddon was historically associated with Haddon Hall.

A baptism for John Wibberly has not yet been found, however, there were Wibersley’s in the Bakewell registers from the early 1600s:

1619 Joyce Wibersley married Raphe Cowper.

1621 Jocosa Wibersley married Radulphus Cowper

1623 Agnes Wibersley married Richard Palfreyman

1635 Cisley Wibberlsy married ? Mr. Mason

1653 John Wibbersly married Grace DaykenHaddon Hall

Sir Richard Vernon (c. 1390 – 1451) of Haddon Hall.

Vernon’s property was widespread and varied. From his parents he inherited the manors of Marple and Wibersley, in Cheshire. Perhaps the Over Haddon Wibersley’s origins were from Sir Richard Vernon’s property in Cheshire. There is, however, a medieval wayside cross called Whibbersley Cross situated on Leash Fen in the East Moors of the Derbyshire Peak District. It may have served as a boundary cross marking the estate of Beauchief Abbey. Wayside crosses such as this mostly date from the 9th to 15th centuries.Found in both The History and Antiquities of Haddon Hall by S Raynor, 1836, and the 1663 household accounts published by Lysons, Haddon Hall had 140 domestic staff.

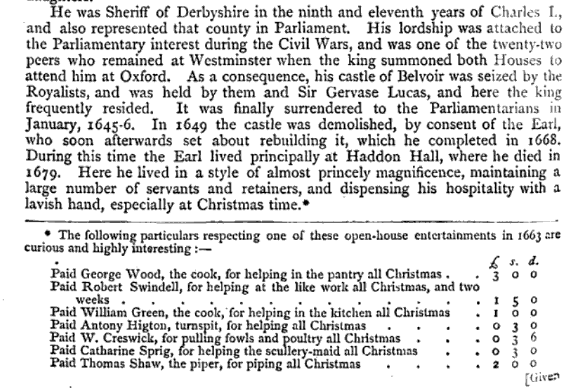

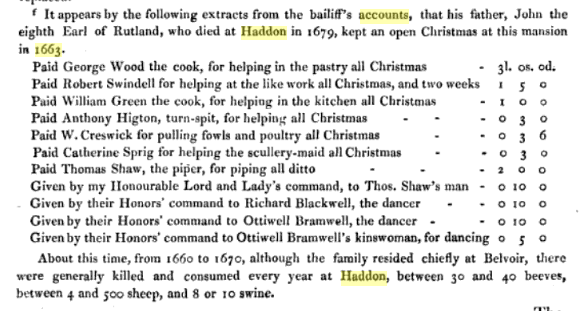

In the book Haddon Hall, an Illustrated Guide, 1871, an example from the 1663 Christmas accounts:

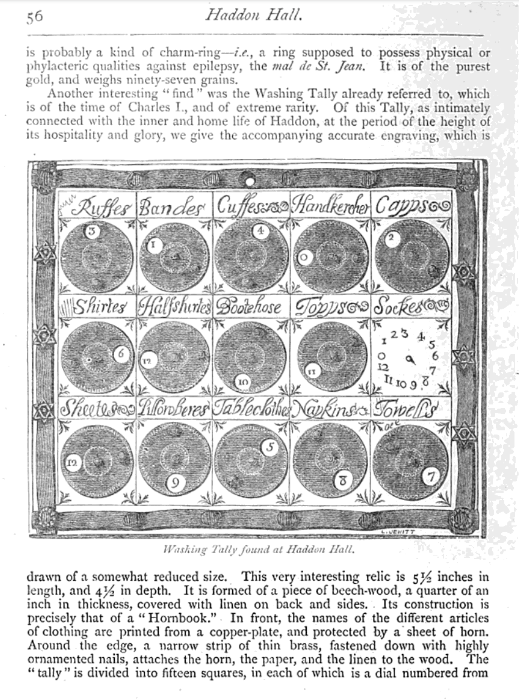

Also in this book, an early 1600s “washing tally” from Haddon Hall:

Over Haddon

Martha Taylor, “the fasting damsel”, was born in Over Haddon in 1649. She didn’t eat for almost two years before her death in 1684. One of the Quakers associated with the Marshall Quakers of Elton, John Gratton, visited the fasting damsel while he was living at Monyash, and occasionally “went two miles to see a woman at Over Haddon who pretended to live without meat.” from The Reliquary, 1861.

August 21, 2024 at 12:27 pm #7546In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

The Potters of Darley Bridge

Rebecca Knowles 1745-1823, my 5x great grandmother, married Charles Marshall 1742-1819, the churchwarden of Elton, in Darley, Derbyshire, in 1767. Rebecca was born in Darley in 1745, the youngest child of Roger Knowles 1695-1784, and Martha Potter 1702?-1772.

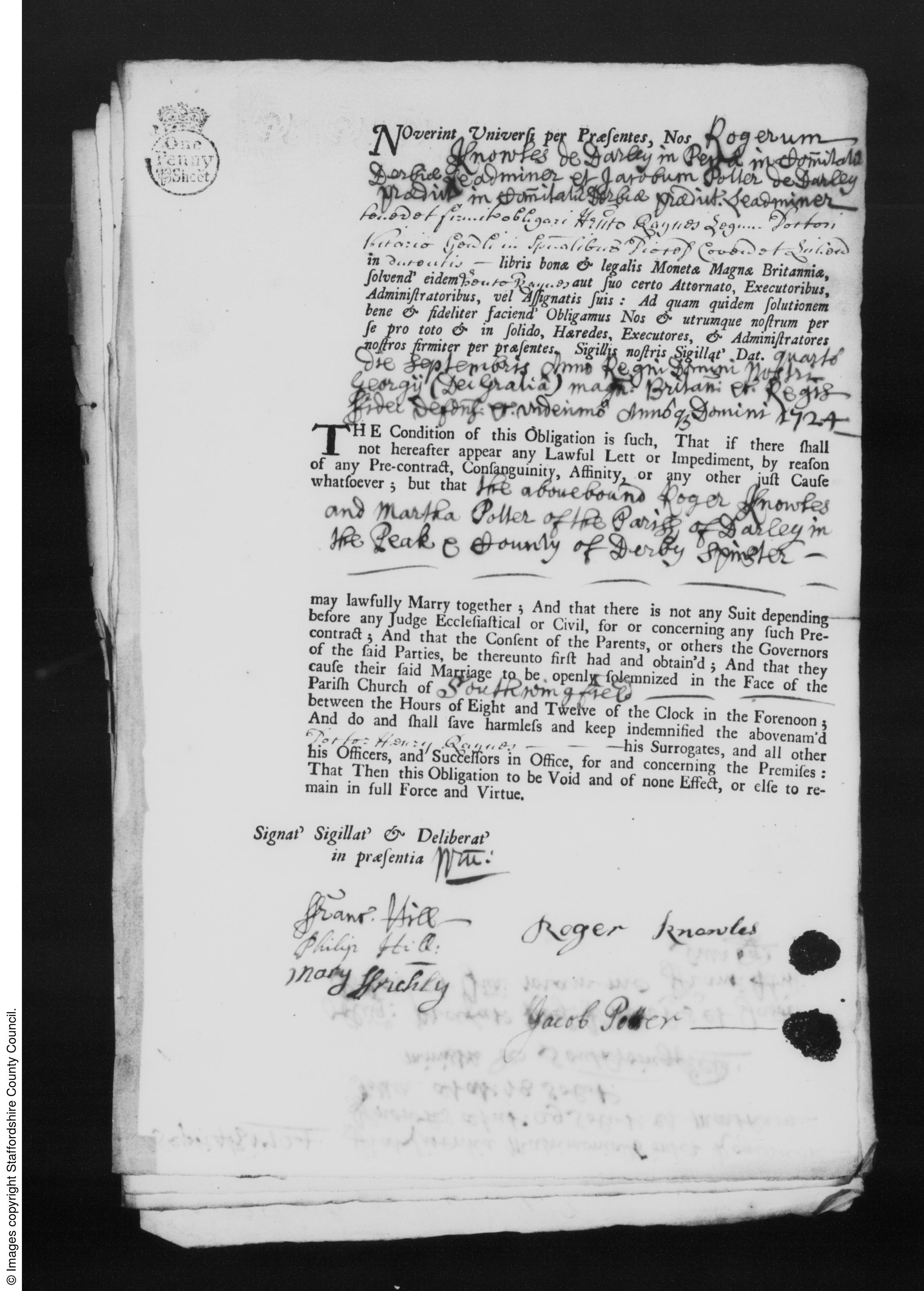

Although Roger and Martha were both from Darley, they were married in South Wingfield by licence in 1724. Roger’s occupation on the marriage licence was lead miner. (Lead miners in Derbyshire at that time usually mined their own land.) Jacob Potter signed the licence so I assumed that Jacob Potter was her father.

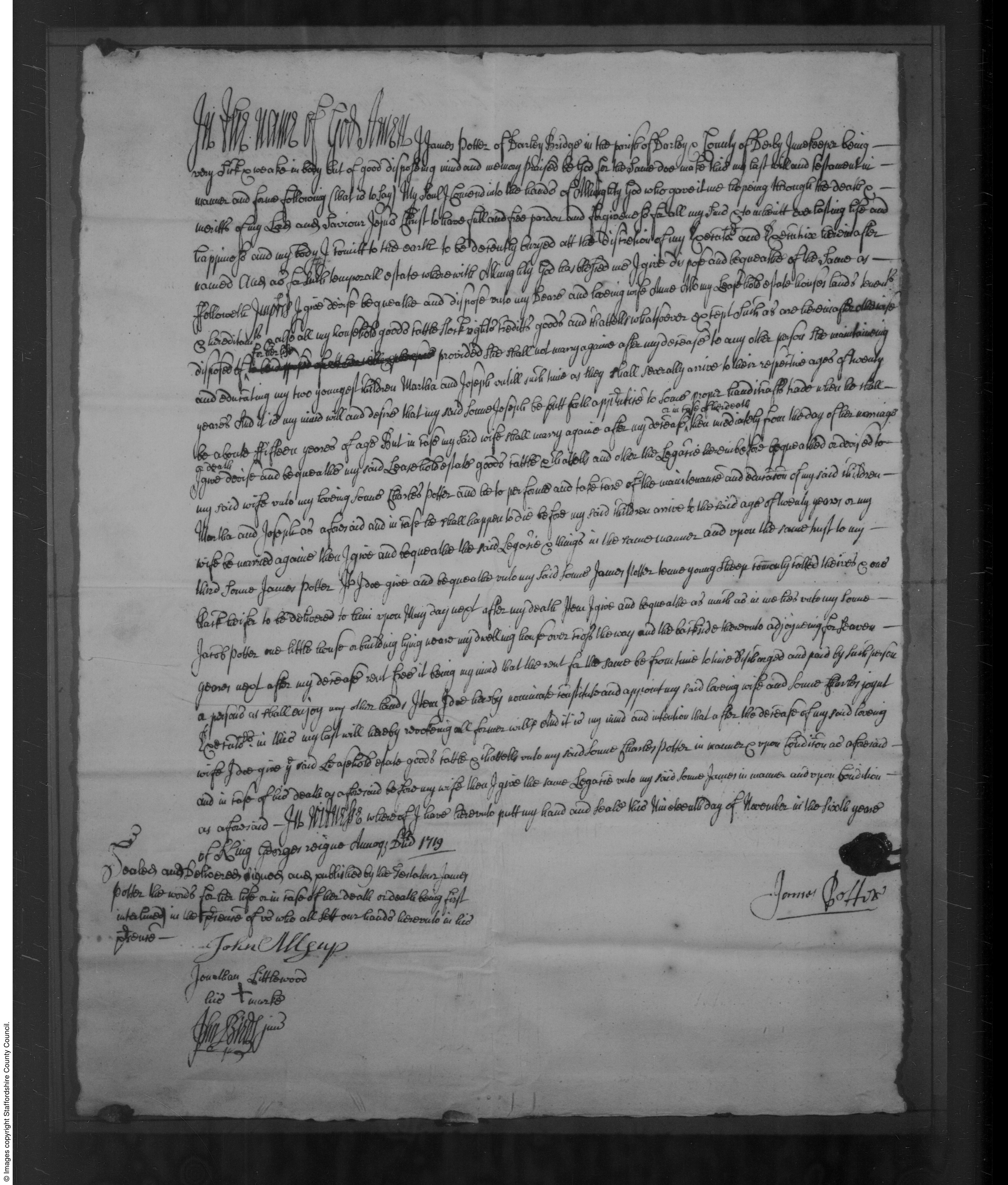

I then found the will of Jacobi Potter who died in 1719. However, he signed the will James Potter. Jacobi is latin for James. James Potter mentioned his daughter Martha in his will “when she comes of age”. Martha was the youngest child of James. James also mentioned in his will son James AND son Jacob, so there were both James’s and Jacob’s in the family, although at times in the documents James is written as Jacobi!

Jacob Potter who signed Martha’s marriage licence was her brother Jacob.

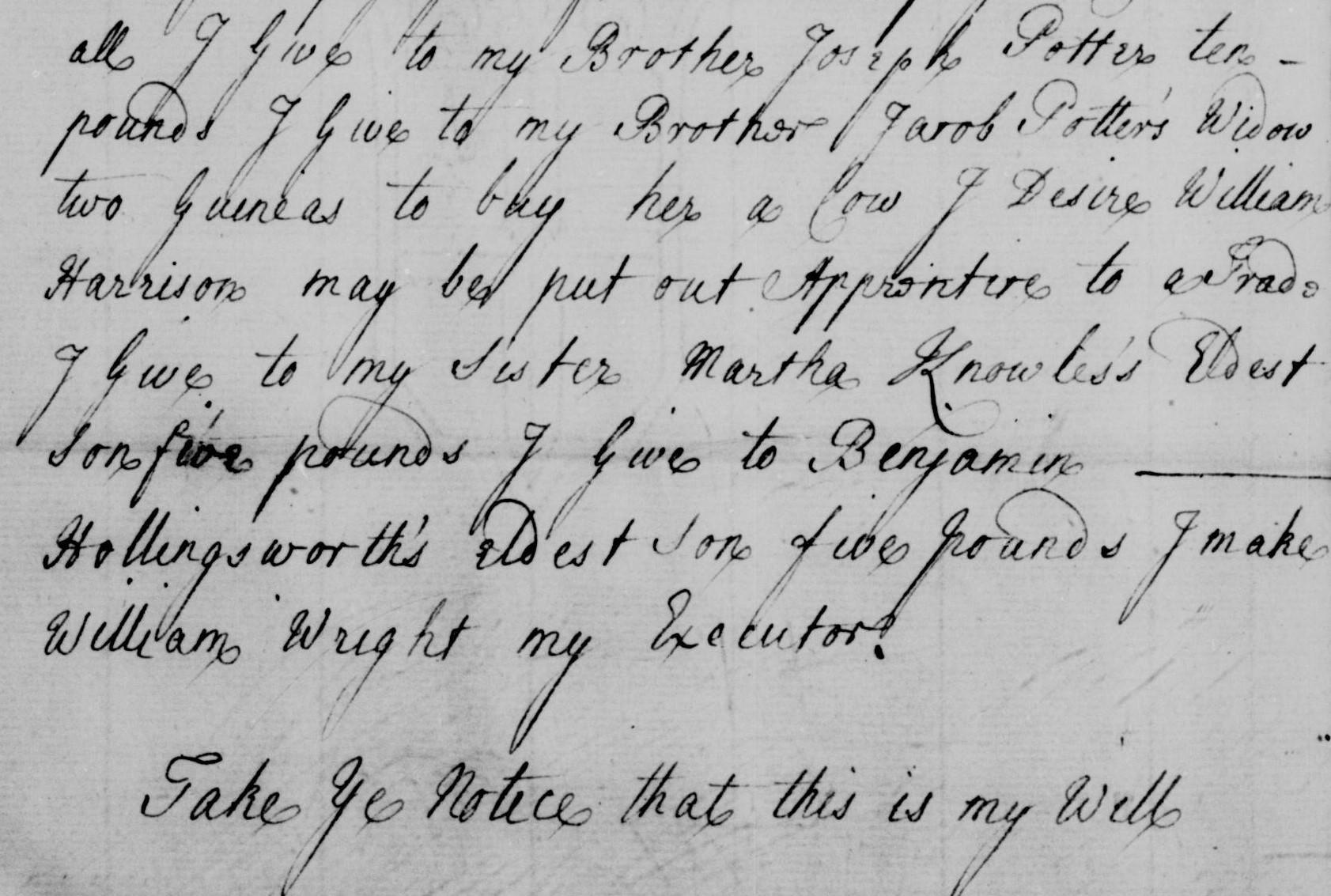

Martha’s brother James mentioned his sister Martha Knowles in his 1739 will, as well as his brother Jacob and his brother Joseph.

Martha’s father James Potter mentions his wife Ann in his 1719 will. James Potter married Ann Waterhurst in 1690 in Wirksworth, some seven miles from Darley. James occupation was innkeeper at Darley Bridge.

I did a search for Waterhurst (there was only a transcription available for that marriage, not a microfilm) and found no Waterhursts anywhere, but I did find many Warhursts in Derbyshire. In the older records, Warhust is also spelled Wearhurst and in a number of other ways. A Martha Warhurst died in Peak Forest, Derbyshire, in 1681. Her husbands name was missing from the deteriorated register pages. This may or may not be Martha Potter’s grandmother: the records for the 1600s are scanty if they exist at all, and often there are bits missing and illegible entries.

The only inn at Darley Bridge was The Three Stags Heads, by the bridge. It is now a listed building, and was on a medieval packhorse route. The current building was built in 1736, however there is a late 17th century section at rear of the cross wing. The Three Stags Heads was up for sale for £430,000 in 2022, the closure a result of the covid pandemic.

Another listed building in Darley Bridge is Potters Cottage, with a plaque above the door that says “Jonathan and Alice Potter 1763”. Jonathan Potter 1725-1785 was James grandson, the son of his son Charles Potter 1691-1752. His son Charles was also an innkeeper at Darley Bridge: James left the majority of his property to his son Charles.

Charles is the only child of James Potter that we know the approximate date of birth, because his age was on his grave stone. I haven’t found any of their baptisms, but did note that many Potters were baptised in non conformist registers in Chesterfield.

Potters Cottage

Jonathan Potter of Potters Cottage married Alice Beeley in 1748.

“Darley Bridge was an important packhorse route across the River Derwent. There was a packhorse route from here up to Beeley Moor via Darley Dale. A reference to this bridge appears in 1504… Not far to the north of the bridge at Darley Dale is Church Lane; in 1635 it was known as Ghost Lane after a Scottish pedlar was murdered there. Pedlars tended to be called Scottish only because they sold cheap Scottish linen.”

via Derbyshire Heritage website.

According to Wikipedia, the bridge dates back to the 15th century.

August 16, 2024 at 2:56 pm #7544In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Youlgreave

The Frost Family and The Big Snow

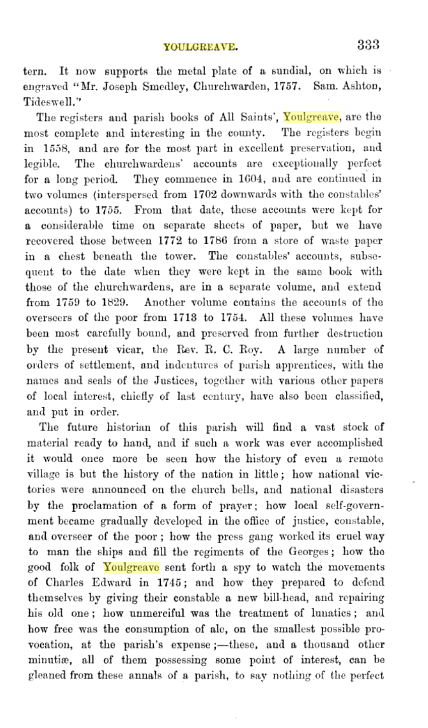

The Youlgreave parish registers are said to be the most complete and interesting in the country. Starting in 1558, they are still largely intact today.

“The future historian of this parish will find a vast stock of material ready to hand, and if such a work was ever accomplished it would once more be seen how the history of even a remote village is but the history of the nation in little; how national victories were announced on the church bells, and national disasters by the proclamation of a form of prayer…”

J. Charles Cox, Notes on the Churches of Derbyshire, 1877.

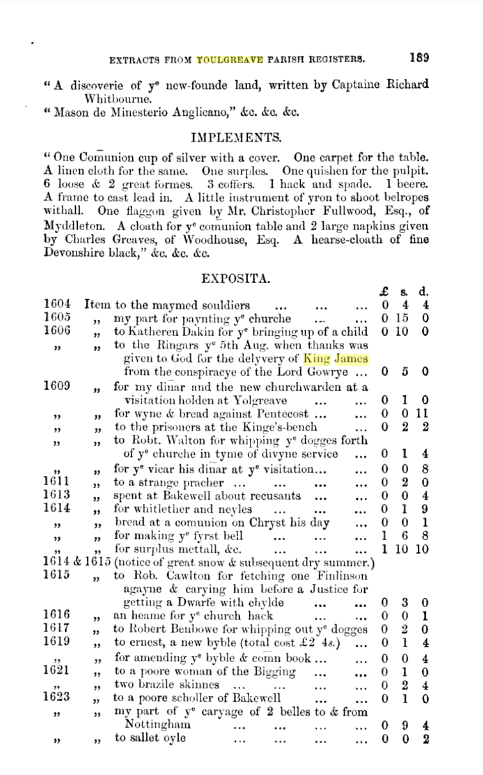

Although the Youlgreave parish registers are available online on microfilm, just the baptisms, marriages and burials are provided on the genealogy websites. However, I found some excerpts from the churchwardens accounts in a couple of old books, The Reliquary 1864, and Notes on Derbyshire Churches 1877.

Hannah Keeling, my 4x great grandmother, was born in Youlgreave, Derbyshire, in 1767. In 1791 she married Edward Lees of Hartington, Derbyshire, a village seven and a half miles south west of Youlgreave. Edward and Hannah’s daughter Sarah Lees, born in Hartington in 1808, married Francis Featherstone in 1835. The Featherstone’s were farmers. Their daughter Emma Featherstone married John Marshall from Elton. Elton is just three miles from Youlgreave, and there are a great many Marshall’s in the Youlgreave parish registers, some no doubt distantly related to ours.

Hannah Keeling’s parents were John Keeling 1734-1823, and Ellen Frost 1739-1805, both of Youlgreave.

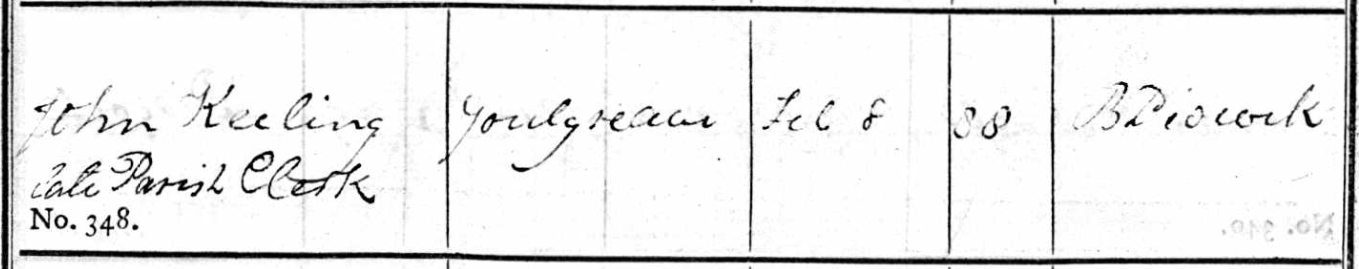

On the burial entry in the parish registers in Youlgreave in 1823, John Keeling was 88 years old when he died, and was the “late parish clerk”, indicating that my 5x great grandfather played a part in compiling the “best parish registers in the country”. In 1762 John’s father in law John Frost died intestate, and John Keeling, cordwainer, co signed the documents with his mother in law Ann. John Keeling was a shoe maker and a parish clerk.

John Keeling’s father was Thomas Keeling, baptised on the 9th of March 1709 in Youlgreave and his parents were John Keeling and Ann Ashmore. John and Ann were married on the 6th April 1708. Some of the transcriptions have Thomas baptised in March 1708, which would be a month before his parents married. However, this was before the Julian calendar was replaced by the Gregorian calendar, and prior to 1752 the new year started on the 25th of March, therefore the 9th of March 1708 was eleven months after the 6th April 1708.

Thomas Keeling married Dorothy, which we know from the baptism of John Keeling in 1734, but I have not been able to find their marriage recorded. Until I can find my 6x great grandmother Dorothy’s maiden name, I am unable to trace her family further back.

Unfortunately I haven’t found a baptism for Thomas’s father John Keeling, despite that there are Keelings in the Youlgrave registers in the early 1600s, possibly it is one of the few illegible entries in these registers.

The Frosts of Youlgreave

Ellen Frost’s father was John Frost, born in Youlgreave in 1707. John married Ann Staley of Elton in 1733 in Youlgreave.

(Note that this part of the family tree is the Marshall side, but we also have Staley’s in Elton on the Warren side. Our branch of the Elton Staley’s moved to Stapenhill in the mid 1700s. Robert Staley, born 1711 in Elton, died in Stapenhill in 1795. There are many Staley’s in the Youlgreave parish registers, going back to the late 1500s.)

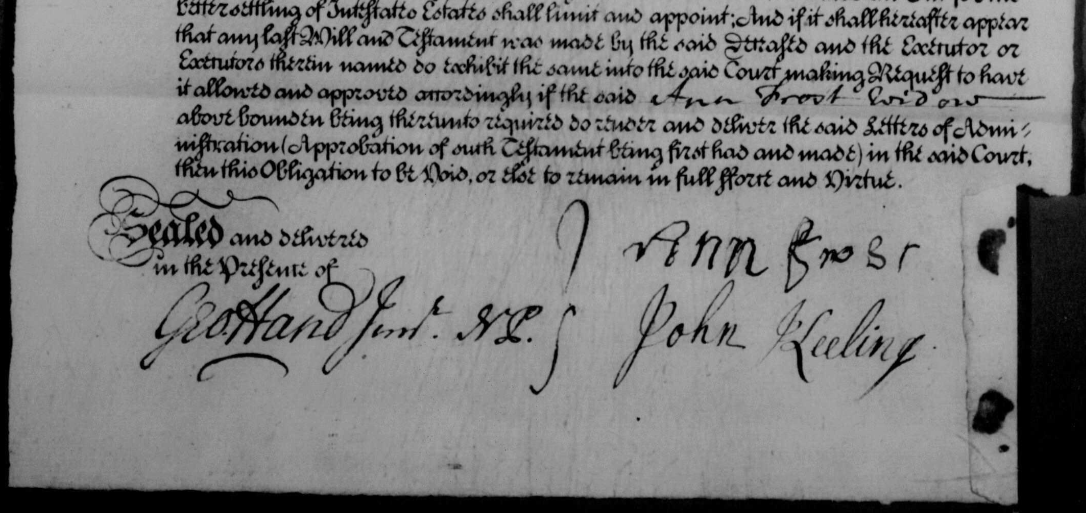

John Frost (my 6x great grandfather), miner, died intestate in 1762 in Youlgreave. Miner in this case no doubt means a lead miner, mining his own land (as John Marshall’s father John was in Elton. On the 1851 census John Marshall senior was mining 9 acres). Ann Frost, as the widow and relict of the said deceased John Frost, claimed the right of administration of his estate. Ann Frost (nee Staley) signed her own name, somewhat unusual for a woman to be able to write in 1762, as well as her son in law John Keeling.

John’s parents were David Frost and Ann. David was baptised in 1665 in Youlgreave. Once again, I have not found a marriage for David and Ann so I am unable to continue further back with her family. Marriages were often held in the parish of the bride, and perhaps those neighbouring parish records from the 1600s haven’t survived.

David’s parents were William Frost and Ellen (or Ellin, or Helen, depending on how the parish clerk chose to spell it). Once again, their marriage hasn’t been found, but was probably in a neighbouring parish.

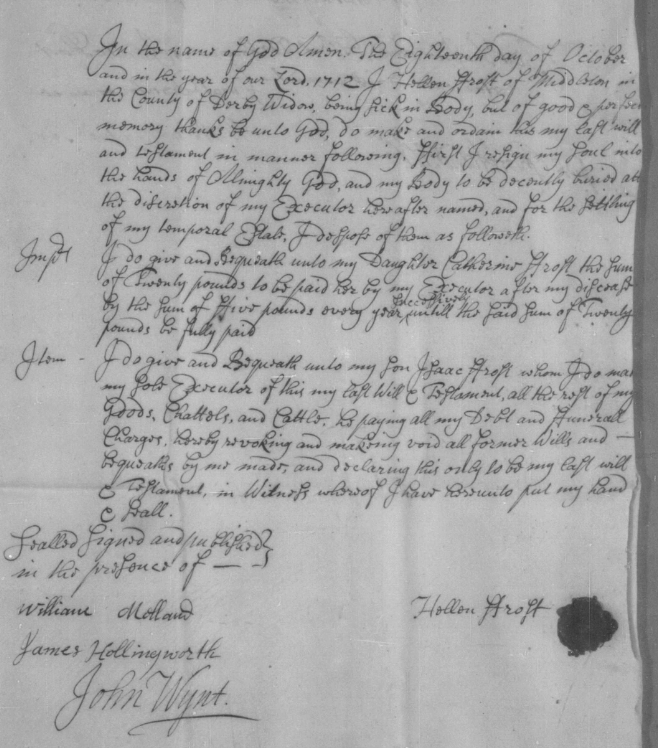

William Frost’s wife Ellen, my 8x great grandmother, died in Youlgreave in 1713. In her will she left her daughter Catherine £20. Catherine was born in 1665 and was apparently unmarried at the age of 48 in 1713. She named her son Isaac Frost (born in 1662) executor, and left him the remainder of her “goods, chattels and cattle”.

William Frost was baptised in Youlgreave in 1627, his parents were William Frost and Anne.

William Frost senior, husbandman, was probably born circa 1600, and died intestate in 1648 in Middleton, Youlgreave. His widow Anna was named in the document. On the compilation of the inventory of his goods, Thomas Garratt, Will Melland and A Kidiard are named.(Husbandman: The old word for a farmer below the rank of yeoman. A husbandman usually held his land by copyhold or leasehold tenure and may be regarded as the ‘average farmer in his locality’. The words ‘yeoman’ and ‘husbandman’ were gradually replaced in the later 18th and 19th centuries by ‘farmer’.)

Unable to find a baptism for William Frost born circa 1600, I read through all the pages of the Youlgreave parish registers from 1558 to 1610. Despite the good condition of these registers, there are a number of illegible entries. There were three Frost families baptising children during this timeframe and one of these is likely to be Willliam’s.

Baptisms:

1581 Eliz Frost, father Michael.

1582 Francis f Michael. (must have died in infancy)

1582 Margaret f William.

1585 Francis f Michael.

1586 John f Nicholas.

1588 Barbara f Michael.

1590 Francis f Nicholas.

1591 Joane f Michael.

1594 John f Michael.

1598 George f Michael.

1600 Fredericke (female!) f William.Marriages in Youlgreave which could be William’s parents:

1579 Michael Frost Eliz Staley

1587 Edward Frost Katherine Hall

1600 Nicholas Frost Katherine Hardy.

1606 John Frost Eliz Hanson.Michael Frost of Youlgreave is mentioned on the Derbyshire Muster Rolls in 1585.

(Muster records: 1522-1649. The militia muster rolls listed all those liable for military service.)

Frideswide:

A burial is recorded in 1584 for Frideswide Frost (female) father Michael. As the father is named, this indicates that Frideswide was a child.

(Frithuswith, commonly Frideswide c. 650 – 19 October 727), was an English princess and abbess. She is credited as the foundress of a monastery later incorporated into Christ Church, Oxford. She was the daughter of a sub-king of a Merica named Dida of Eynsham whose lands occupied western Oxfordshire and the upper reaches of the River Thames.)

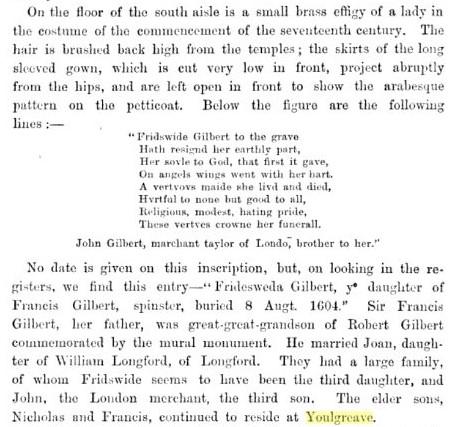

An unusual name, and certainly very different from the usual names of the Frost siblings. As I did not find a baptism for her, I wondered if perhaps she died too soon for a baptism and was given a saints name, in the hope that it would help in the afterlife, given the beliefs of the times. Or perhaps it wasn’t an unusual name at the time in Youlgreave. A Fridesweda Gilbert was buried in Youlgreave in 1604, the spinster daughter of Francis Gilbert. There is a small brass effigy in the church, underneath is written “Frideswide Gilbert to the grave, Hath resigned her earthly part…”

J. Charles Cox, Notes on the Churches of Derbyshire, 1877.

King James

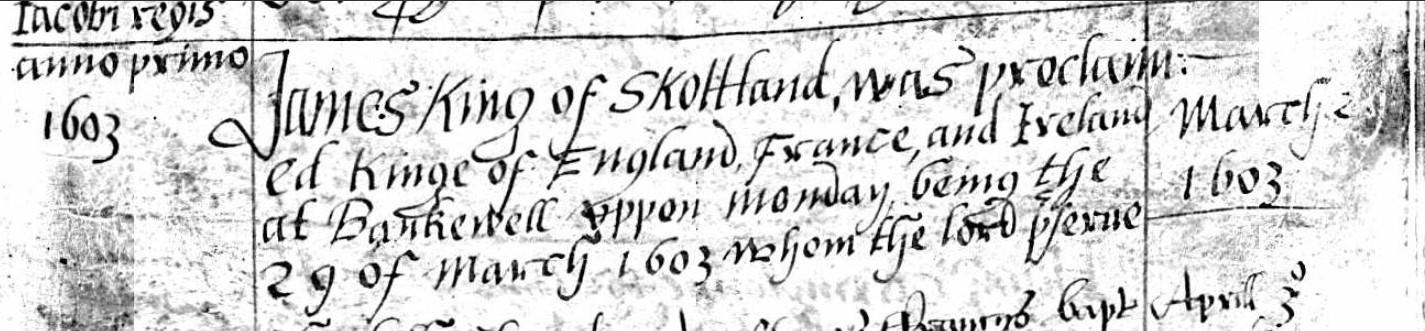

A parish register entry in 1603:

“1603 King James of Skottland was proclaimed kinge of England, France and Ireland at Bakewell upon Monday being the 29th of March 1603.” (March 1603 would be 1604, because of the Julian calendar in use at the time.)

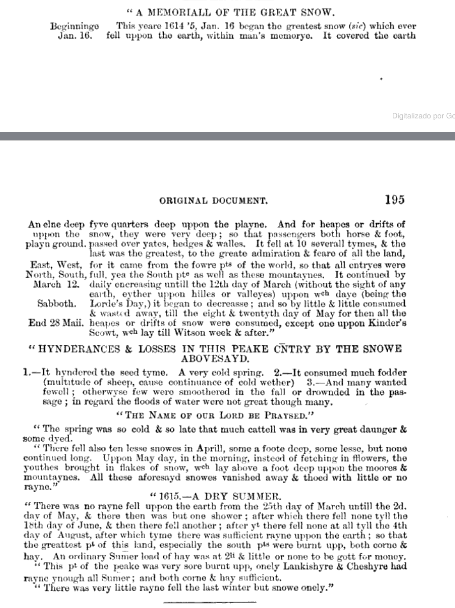

The Big Snow

“This year 1614/5 January 16th began the greatest snow whichever fell uppon the earth within man’s memorye. It covered the earth fyve quarters deep uppon the playne. And for heaps or drifts of snow, they were very deep; so that passengers both horse or foot passed over yates, hedges and walles. ….The spring was so cold and so late that much cattel was in very great danger and some died….”

From the Youlgreave parish registers.

Our ancestor William Frost born circa 1600 would have been a teenager during the big snow.

October 18, 2023 at 3:20 pm #7281In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

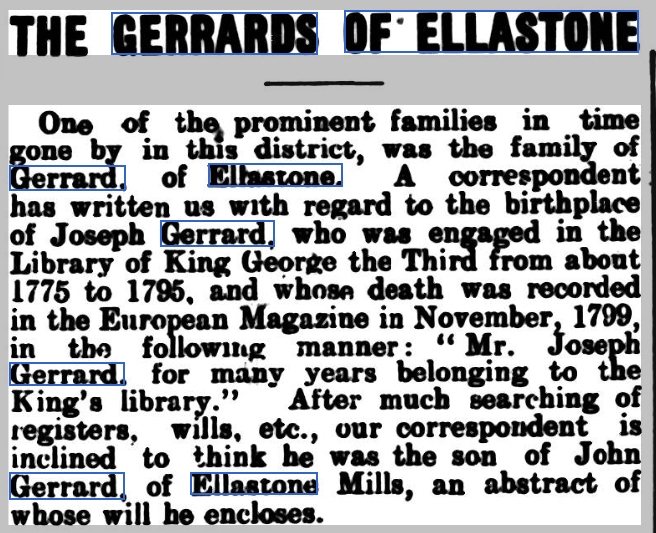

The 1935 Joseph Gerrard Challenge.

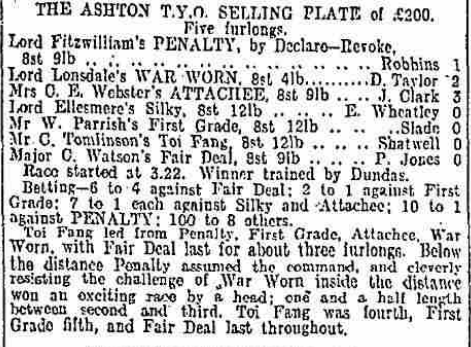

While researching the Gerrard family of Ellastone I chanced upon a 1935 newspaper article in the Ashbourne Register. There were two articles in 1935 in this paper about the Gerrards, the second a follow up to the first. An advertisement was also placed offering a £1 reward to anyone who could find Joseph Gerrard’s baptism record.

Ashbourne Telegraph – Friday 05 April 1935:

The author wanted to prove that the Joseph Gerrard “who was engaged in the library of King George the third from about 1775 to 1795, and whose death was recorded in the European Magazine in November 1799” was the son of John Gerrard of Ellastone Mills, Staffordshire. Included in the first article was a selected transcription of the 1796 will of John Gerrard. John’s son Joseph is mentioned in this will: John leaves him “£20 to buy a suit of mourning if he thinks proper.”

This Joseph Gerrard however, born in 1739, died in 1815 at Brailsford. Joseph’s brother John also died at Brailsford Mill, and both of their ages at death give a birth year of 1739. Maybe they were twins. William Gerrard and Joseph Gerrard of Brailsford Mill are mentioned in a 1811 newspaper article in the Derby Mercury.

I decided that there was nothing susbtantial about this claim, until I read the 1724 will of John Gerrard the elder, the father of John who died in 1796. In his will he leaves £100 to his son Joseph Gerrard, “secretary to the Bishop of Oxford”.

Perhaps there was something to this story after all. Joseph, baptised in 1701 in Ellastone, was the son of John Gerrard the elder.

I found Joseph Gerrard (and his son James Gerrard) mentioned in the Alumni Oxonienses: The Members of the University of Oxford, University of Oxford, Joseph Foster, 1888. “Joseph Gerard son of John of Elleston county Stafford, pleb, Oriel Coll, matric, 30th May 1718, age 18, BA. 9th March 1721-2; of Merton Coll MA 1728.”

In The Works of John Wesley 1735-1738, Joseph Gerrad is mentioned: “Joseph Gerard , matriculated at Oriel College 1718 , aged 18 , ordained 1727 to serve as curate of Cuddesdon , becoming rector of St. Martin’s , Oxford in 1729 , and vicar of Banbury in 1734.”

In The History of Banbury Alfred Beesley 1842 “a visitation of smallpox occured at Banbury (Oxfordshire) in 1731 and continued until 1733.” Joseph Gerrard was the vicar of Banbury in 1734.

According to the The History and Antiquities of the County of Buckingham George Lipscomb · 1847, Joseph Gerrard was made rector of Monks Risborough in 1738 “but he also continued to hold Stewkley until his death”.

The Speculum of Archbishop Thomas Secker by Secker, Thomas, 1693-1768, also mentions Joseph Gerrard under Monks Risborough and adds that he “resides constantly in the Parsonage ho. except when he goes for a few days to Steukley county Bucks (Buckinghamshire) of which he is vicar.” Joseph’s son James Gerrard 1741-1789 is also mentioned as being a rector at Monks Risborough in 1783.

Joseph Gerrard married Elizabeth Reynolds on 23 July 1739 in Monks Risborough, Buckinghamshire. They had five children between 1740 and 1750, including James baptised 1740 and Joseph baptised 1742.

Joseph died in 1785 in Monks Risborough.

So who was Joseph Gerrard of the Kings Library who died in 1799? It wasn’t Joseph’s son Joseph baptised in 1742 in Monks Risborough, because in his father’s 1785 will he mentions “my only son James”, indicating that Joseph died before that date.

September 18, 2023 at 8:29 am #7278In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

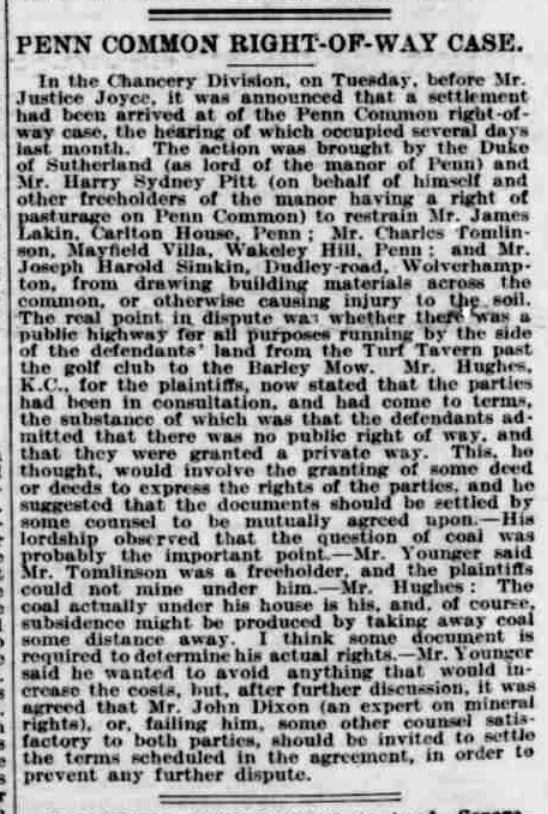

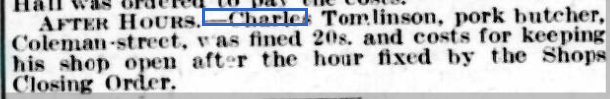

Tomlinson of Wergs and Hancox of Penn

John Tomlinson of Wergs (Tettenhall, Wolverhamton) 1766-1844, my 4X great grandfather, married Sarah Hancox 1772-1851. They were married on the 27th May 1793 by licence at St Peter in Wolverhampton.

Between 1794 and 1819 they had twelve children, although four of them died in childhood or infancy. Catherine was born in 1794, Thomas in 1795 who died 6 years later, William (my 3x great grandfather) in 1797, Jemima in 1800, John, Richard and Matilda between 1802 and 1806 who all died in childhood, Emma in 1809, Mary Ann in 1811, Sidney in 1814, and Elijah in 1817 who died two years later.On the 1841 census John and Sarah were living in Hockley in Birmingham, with three of their children, and surgeon Charles Reynolds. John’s occupation was “Ind” meaning living by independent means. He was living in Hockley when he died in 1844, and in his will he was “John Tomlinson, gentleman”.

Sarah Hancox was born in 1772 in Penn, Wolverhampton. Her father William Hancox was also born in Penn in 1737. Sarah’s mother Elizabeth Parkes married William’s brother Francis in 1767. Francis died in 1768, and in 1770 Elizabeth married William.

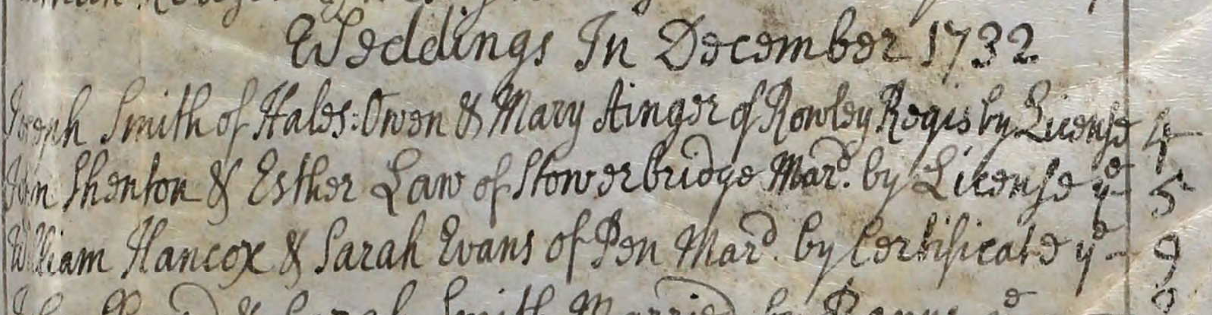

William’s father was William Hancox, yeoman, born in 1703 in Penn. He died intestate in 1772, his wife Sarah claiming her right to his estate. William Hancox and Sarah Evans, both of Penn, were married on the 9th December 1732 in Dudley, Worcestershire, by “certificate”. Marriages were usually either by banns or by licence. Apparently a marriage by certificate indicates that they were non conformists, or dissenters, and had the non conformist marriage “certified” in a Church of England church.

1732 marriage of William Hancox and Sarah Evans:

William and Sarah lost two daughters, Elizabeth, five years old, and Ann, three years old, within eight days of each other in February 1738.

William the elder’s father was John Hancox born in Penn in 1668. He married Elizabeth Wilkes from Sedgley in 1691 at Himley. John Hancox, “of Straw Hall” according to the Wolverhampton burial register, died in 1730. Straw Hall is in Penn. John’s parents were Walter Hancox and Mary Noake. Walter was born in Tettenhall in 1625, his father Richard Hancox. Mary Noake was born in Penn in 1634. Walter died in Penn in 1689.

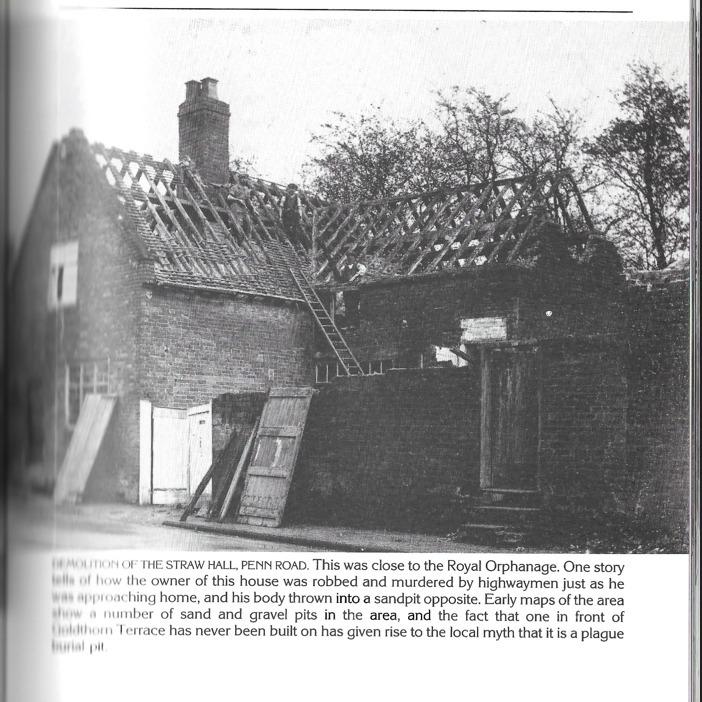

Straw Hall thanks to Bradney Mitchell:

“Here is a picture I have of Straw Hall, Penn Road.

The painting is by John Reid circa 1878.

Sketch commissioned by George Bradney Mitchell to record the town as it was before its redevelopment, in a book called Wolverhampton and its Environs. ©”

And a photo of the demolition of Straw Hall with an interesting story:

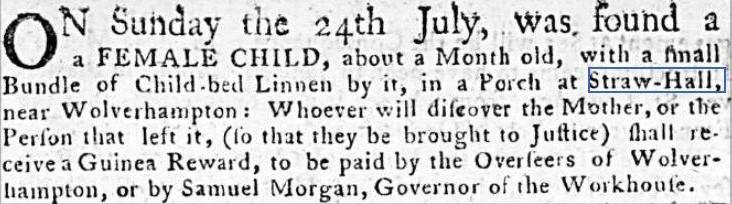

In 1757 a child was abandoned on the porch of Straw Hall. Aris’s Birmingham Gazette 1st August 1757:

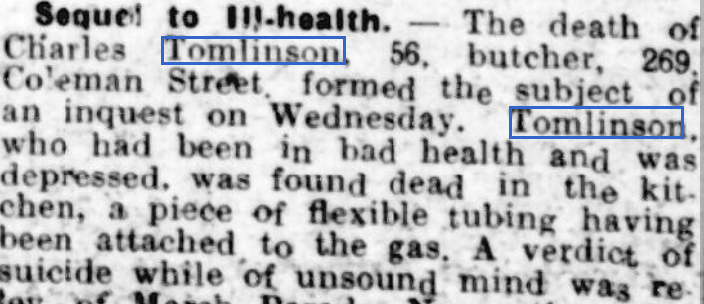

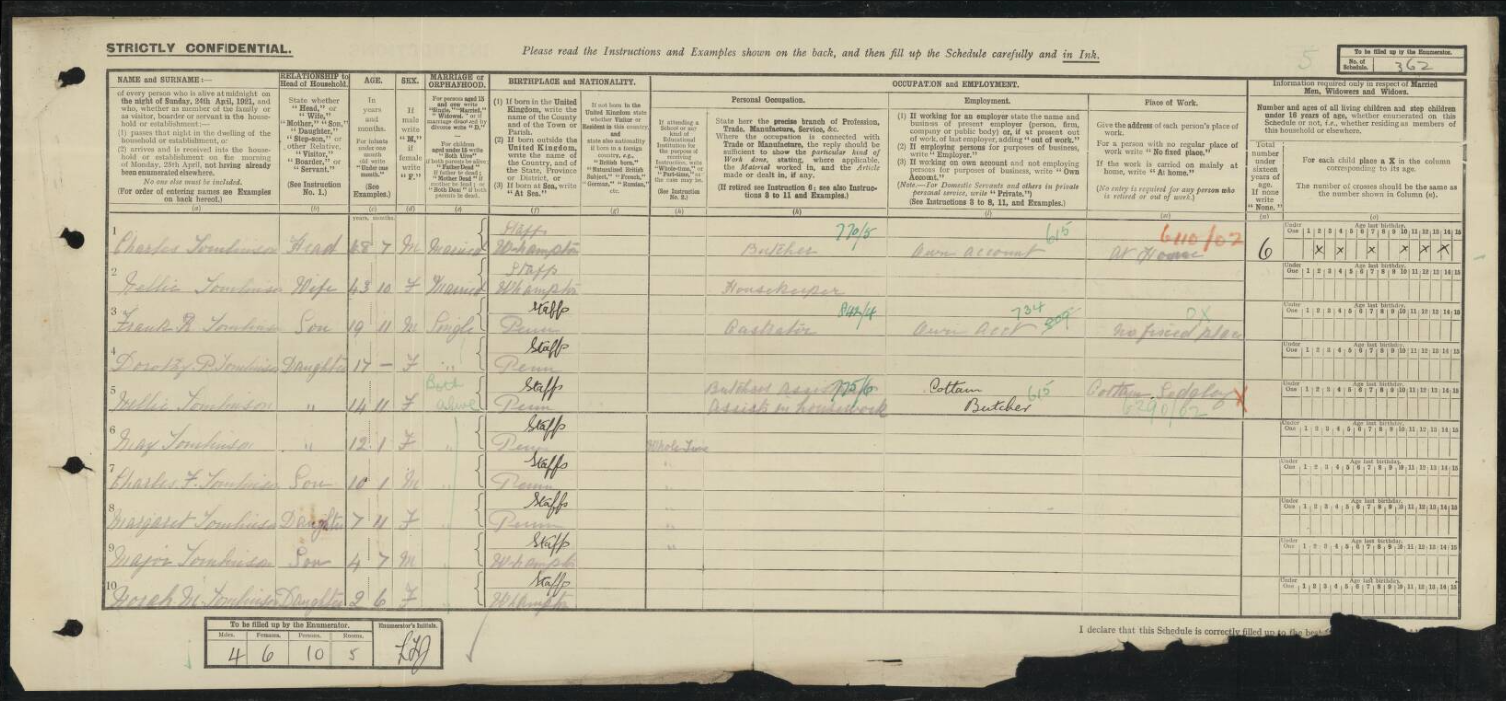

The Hancox family were living in Penn for at least 400 years. My great grandfather Charles Tomlinson built a house on Penn Common in the early 1900s, and other Tomlinson relatives have lived there. But none of the family knew of the Hancox connection to Penn. I don’t think that anyone imagined a Tomlinson ancestor would have been a gentleman, either.

Sarah Hancox’s brother William Hancox 1776-1848 had a busy year in 1804.

On 29 Aug 1804 he applied for a licence to marry Ann Grovenor of Claverley.

In August 1804 he had property up for auction in Penn. “part of Lightwoods, 3 plots, and the Coppice”

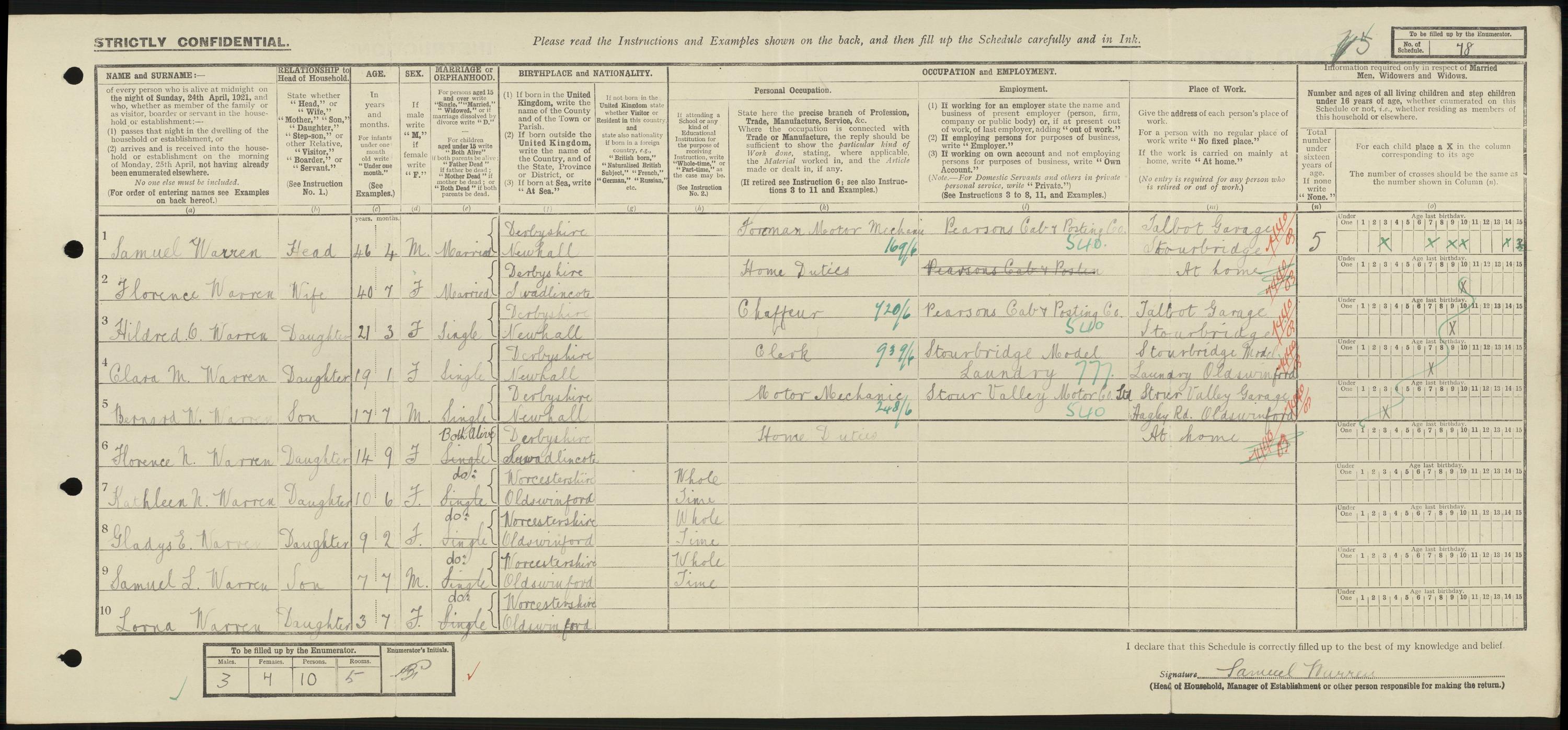

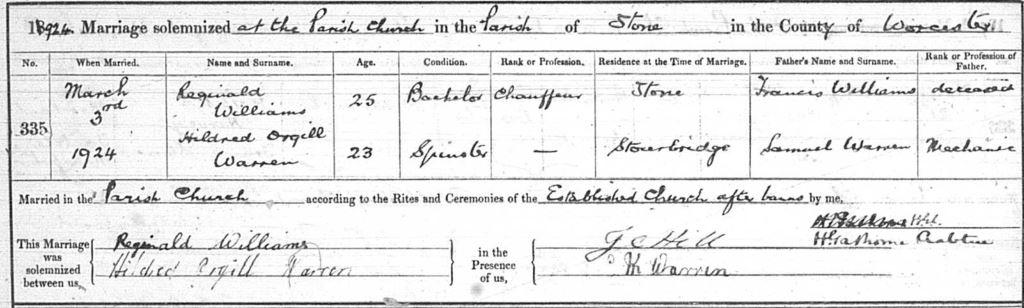

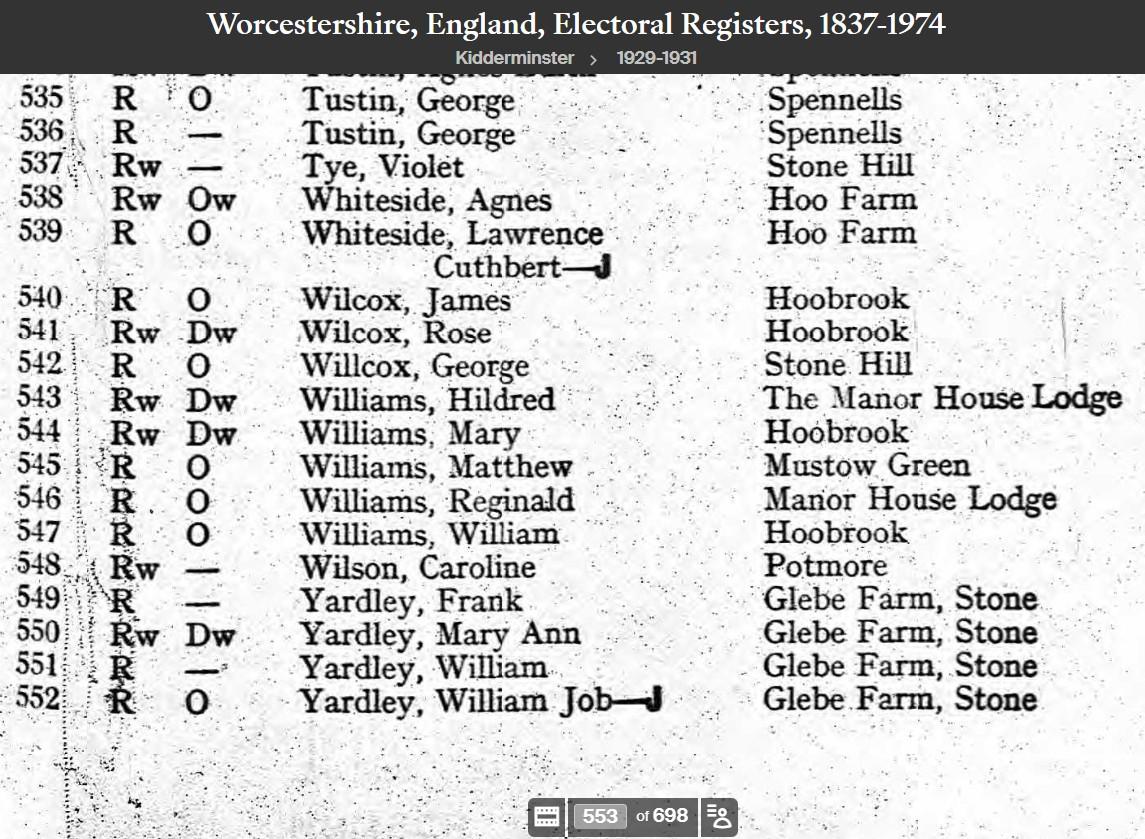

On 14 Sept 1804 their first son John was baptised in Penn. According to a later census John was born in Claverley. (before the parents got married)(Incidentally, John Hancox’s descendant married a Warren, who is a descendant of my 4x great grandfather Samuel Warren, on my mothers side, from Newhall, Derbyshire!)

On 30 Sept he married Ann in Penn.

In December he was a bankrupt pig and sheep dealer.

In July 1805 he’s in the papers under “certificates”: William Hancox the younger, sheep and pig dealer and chapman of Penn. (A certificate was issued after a bankruptcy if they fulfilled their obligations)

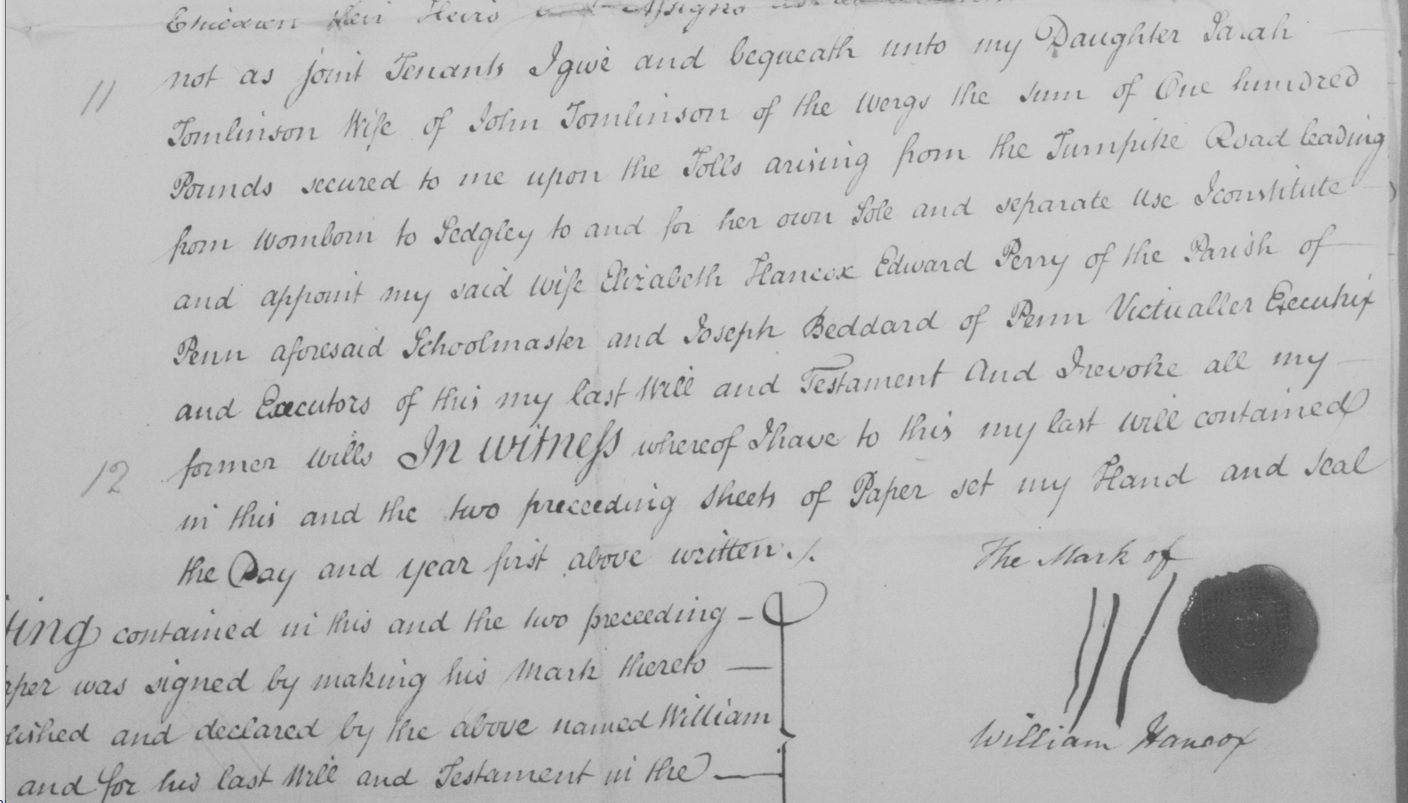

He was a pig dealer in Penn in 1841, a widower, living with unmarried daughter Elizabeth.Sarah’s father William Hancox died in 1816. In his will, he left his “daughter Sarah, wife of John Tomlinson of the Wergs the sum of £100 secured to me upon the tolls arising from the turnpike road leading from Wombourne to Sedgeley to and for her sole and separate use”.

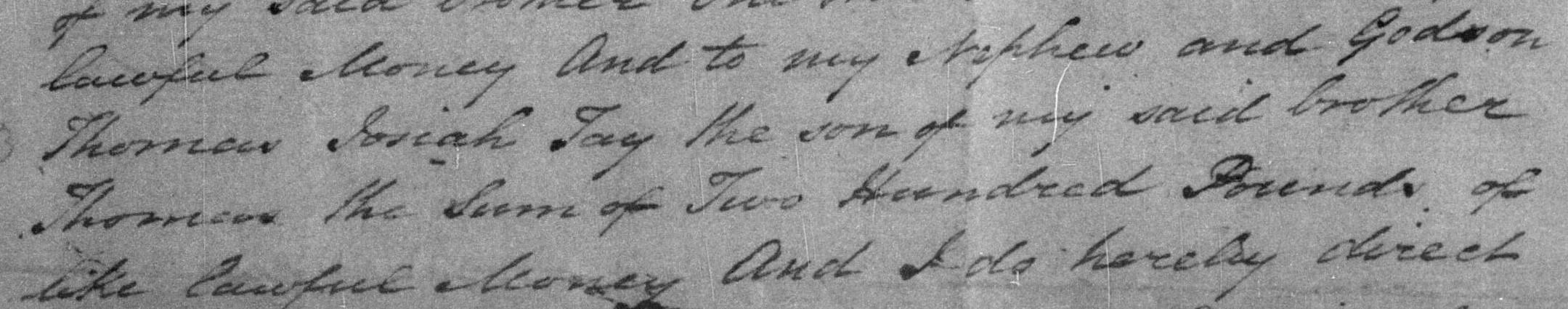

The trustees of toll road would decide not to collect tolls themselves but get someone else to do it by selling the collecting of tolls for a fixed price. This was called “farming the tolls”. The Act of Parliament which set up the trust would authorise the trustees to farm out the tolls. This example is different. The Trustees of turnpikes needed to raise money to carry out work on the highway. The usual way they did this was to mortgage the tolls – they borrowed money from someone and paid the borrower interest; as security they gave the borrower the right, if they were not paid, to take over the collection of tolls and keep the proceeds until they had been paid off. In this case William Hancox has lent £100 to the turnpike and is leaving it (the right to interest and/or have the whole sum repaid) to his daughter Sarah Tomlinson. (this information on tolls from the Wolverhampton family history group.)William Hancox, Penn Wood, maltster, left a considerable amount of property to his children in 1816. All household effects he left to his wife Elizabeth, and after her decease to his son Richard Hancox: four dwelling houses in John St, Wolverhampton, in the occupation of various Pratts, Wright and William Clarke. He left £200 to his daughter Frances Gordon wife of James Gordon, and £100 to his daughter Ann Pratt widow of John Pratt. To his son William Hancox, all his various properties in Penn wood. To Elizabeth Tay wife of Thomas Tay he left £200, and to Richard Hancox various other properties in Penn Wood, and to his daughter Lucy Tay wife of Josiah Tay more property in Lower Penn. All his shops in St John Wolverhamton to his son Edward Hancox, and more properties in Lower Penn to both Francis Hancox and Edward Hancox. To his daughter Ellen York £200, and property in Montgomery and Bilston to his son John Hancox. Sons Francis and Edward were underage at the time of the will. And to his daughter Sarah, his interest in the toll mentioned above.

Sarah Tomlinson, wife of John Tomlinson of the Wergs, in William Hancox will:

August 15, 2023 at 12:42 pm #7267

August 15, 2023 at 12:42 pm #7267In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Thomas Josiah Tay

22 Feb 1816 – 16 November 1878

“Make us glad according to the days wherein thou hast afflicted us, and the years wherein we have seen evil.”

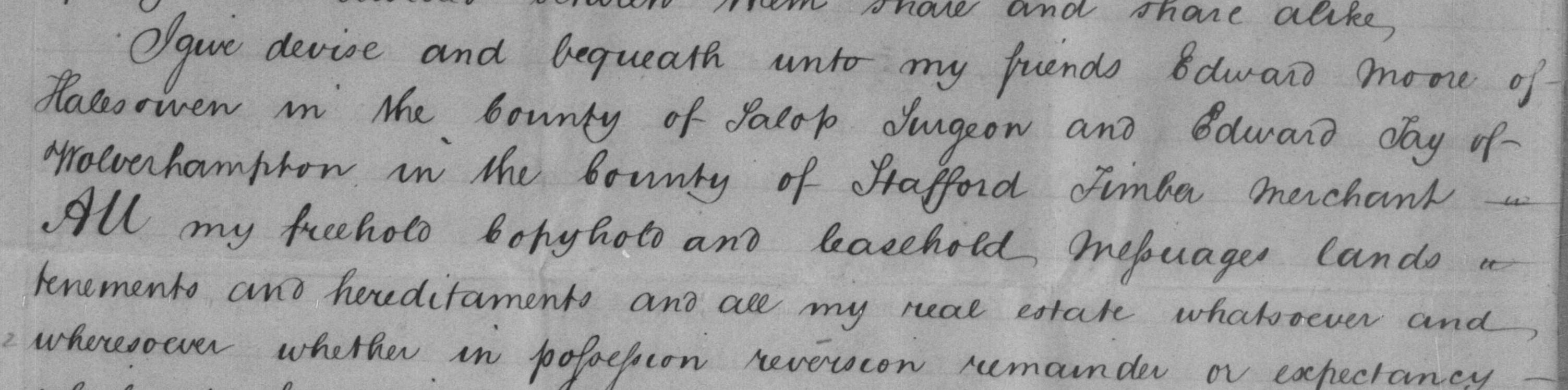

I first came across the name TAY in the 1844 will of John Tomlinson (1766-1844), gentleman of Wergs, Tettenhall. John’s friends, trustees and executors were Edward Moore, surgeon of Halesowen, and Edward Tay, timber merchant of Wolverhampton.

Edward Moore (born in 1805) was the son of John’s wife’s (Sarah Hancox born 1772) sister Lucy Hancox (born 1780) from her first marriage in 1801. In 1810 widowed Lucy married Josiah Tay (1775-1837).

Edward Tay was the son of Sarah Hancox sister Elizabeth (born 1778), who married Thomas Tay in 1800. Thomas Tay (1770-1841) and Josiah Tay were brothers.

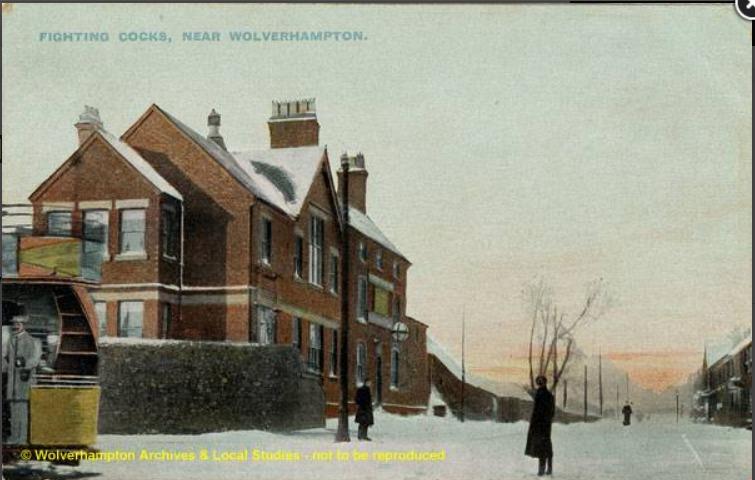

Edward Tay (1803-1862) was born in Sedgley and was buried in Penn. He was innkeeper of The Fighting Cocks, Dudley Road, Wolverhampton, as well as a builder and timber merchant, according to various censuses, trade directories, his marriage registration where his father Thomas Tay is also a timber merchant, as well as being named as a timber merchant in John Tomlinsons will.

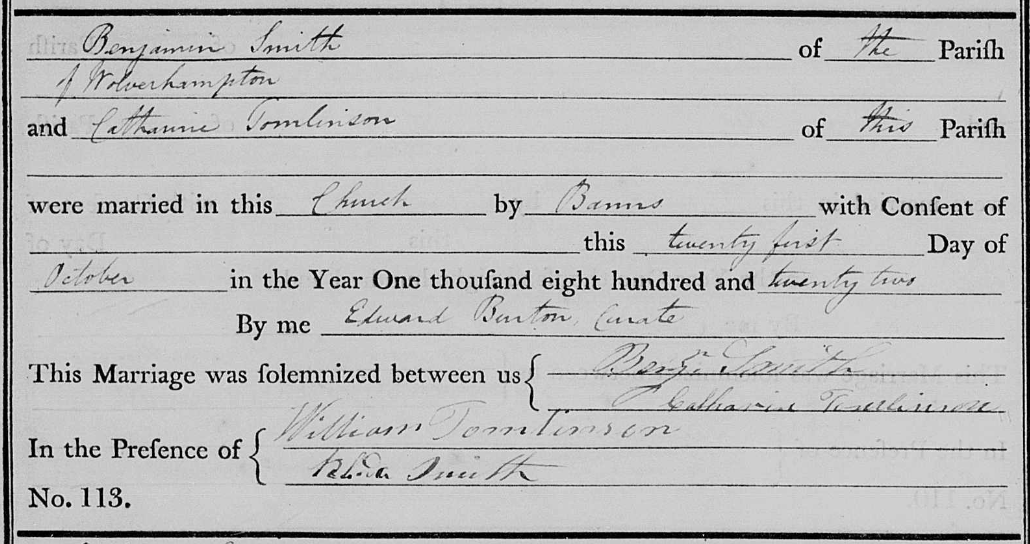

John Tomlinson’s daughter Catherine (born in 1794) married Benjamin Smith in Tettenhall in 1822. William Tomlinson (1797-1867), Catherine’s brother, and my 3x great grandfather, was one of the witnesses.

Their daughter Matilda Sarah Smith (1823-1910) married Thomas Josiah Tay in 1850 in Birmingham. Thomas Josiah Tay (1816-1878) was Edward Tay’s brother, the sons of Elizabeth Hancox and Thomas Tay.

Therefore, William Hancox 1737-1816 (the father of Sarah, Elizabeth and Lucy), was Matilda’s great grandfather and Thomas Josiah Tay’s grandfather.

Thomas Josiah Tay’s relationship to me is the husband of first cousin four times removed, as well as my first cousin, five times removed.

In 1837 Thomas Josiah Tay is mentioned in the will of his uncle Josiah Tay.

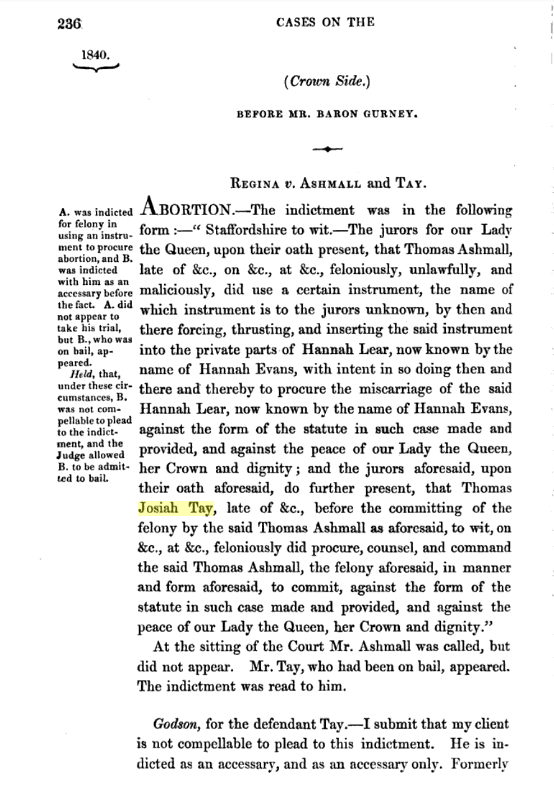

In 1841 Thomas Josiah Tay appears on the Stafford criminal registers for an “attempt to procure miscarriage”. He was found not guilty.

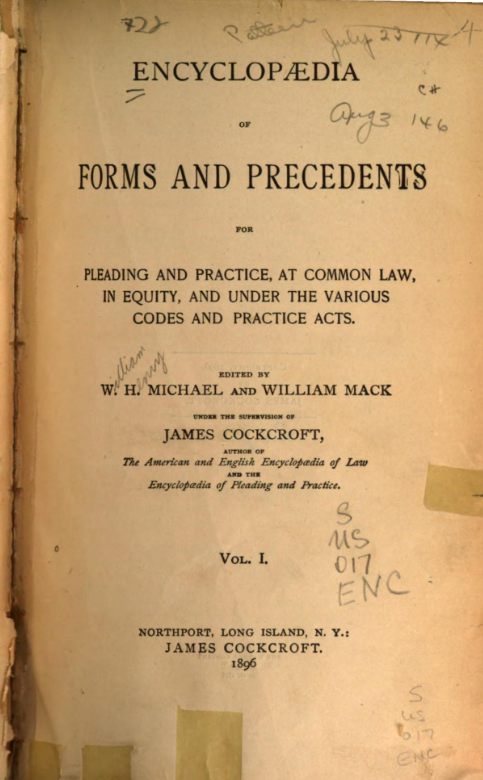

According to the Staffordshire Advertiser on 14th March 1840 the listing for the Assizes included: “Thomas Ashmall and Thomas Josiah Tay, for administering noxious ingredients to Hannah Evans, of Wolverhampton, with intent to procure abortion.”

The London Morning Herald on 19th March 1840 provides further information: “Mr Thomas Josiah Tay, a chemist and druggist, surrendered to take his trial on a charge of having administered drugs to Hannah Lear, now Hannah Evans, with intent to procure abortion.” She entered the service of Tay in 1837 and after four months “an intimacy was formed” and two months later she was “enciente”. Tay advised her to take some pills and a draught which he gave her and she became very ill. The prosecutrix admitted that she had made no mention of this until 1939. Verdict: not guilty.

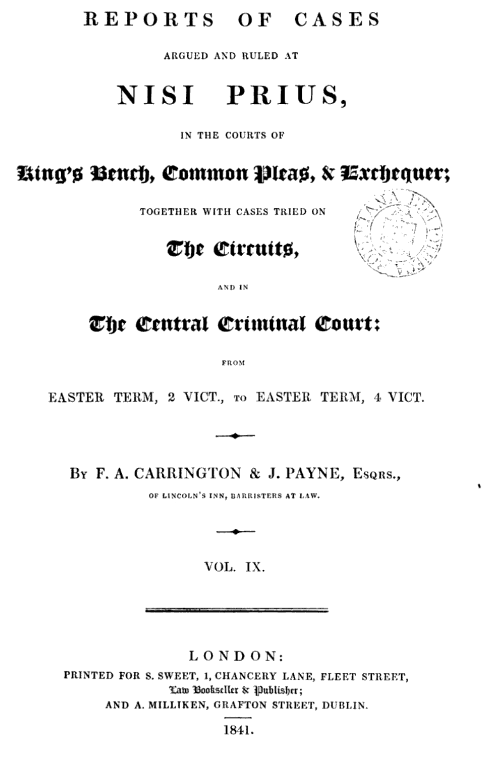

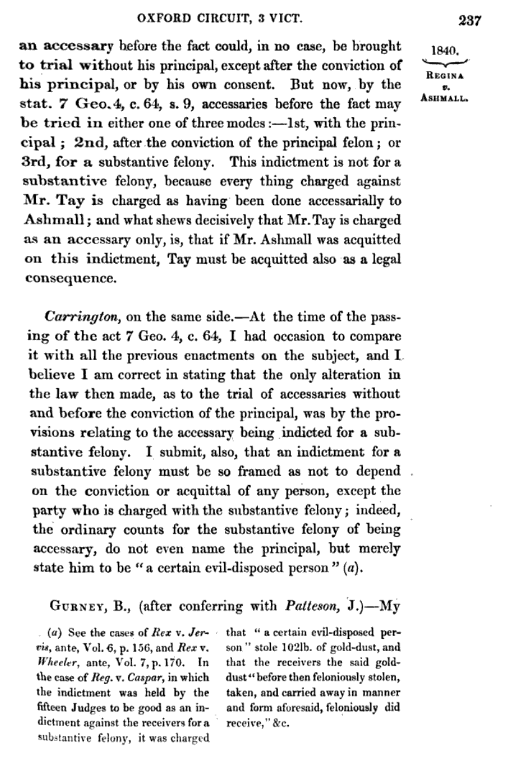

However, the case of Thomas Josiah Tay is also mentioned in a couple of law books, and the story varies slightly. In the 1841 Reports of Cases Argued and Rules at Nisi Prius, the Regina vs Ashmall and Tay case states that Thomas Ashmall feloniously, unlawfully, and maliciously, did use a certain instrument, and that Thomas Josiah Tay did procure the instrument, counsel and command Ashmall in the use of it. It concludes that Tay was not compellable to plead to the indictment, and that he did not.

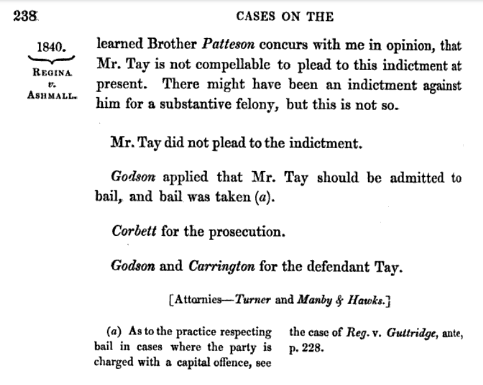

The Regina vs Ashmall and Tay case is also mentioned in the Encyclopedia of Forms and Precedents, 1896.

In 1845 Thomas Josiah Tay married Isabella Southwick in Tettenhall. Two years later in 1847 Isabella died.

In 1850 Thomas Josiah married Matilda Sarah Smith. (granddaughter of John Tomlinson, as mentioned above)

On the 1851 census Thomas Josiah Tay was a farmer of 100 acres employing two labourers in Shelfield, Walsall, Staffordshire. Thomas Josiah and Matilda Sarah have a daughter Matilda under a year old, and they have a live in house servant.

In 1861 Thomas Josiah Tay, his wife and their four children Ann, James, Josiah and Alice, live in Chelmarsh, Shropshire. He was a farmer of 224 acres. Mercy Smith, Matilda’s sister, lives with them, a 28 year old dairy maid.

In 1863 Thomas Josiah Tay of Hampton Lode (Chelmarsh) Shropshire was bankrupt. Creditors include Frederick Weaver, druggist of Wolverhampton.

In 1869 Thomas Josiah Tay was again bankrupt. He was an innkeeper at The Fighting Cocks on Dudley Road, Wolverhampton, at the time, the same inn as his uncle Edward Tay, aforementioned timber merchant.

In 1871, Thomas Josiah Tay, his wife Matilda, and their three children Alice, Edward and Maryann, were living in Birmingham. Thomas Josiah was a commercial traveller.

He died on the 16th November 1878 at the age of 62 and was buried in Darlaston, Walsall. On his gravestone:

“Make us glad according to the days wherein thou hast afflicted us, and the years wherein we have seen evil.” Psalm XC 15 verse.

Edward Moore, surgeon, was also a MAGISTRATE in later years. On the 1871 census he states his occupation as “magistrate for counties Worcester and Stafford, and deputy lieutenant of Worcester, formerly surgeon”. He lived at Townsend House in Halesowen for many years. His wifes name was PATTERN Lucas. Her mothers name was Pattern Hewlitt from Birmingham, an unusal name that I have not heard before. On the 1871 census, Edward’s son was a 22 year old solicitor.

In 1861 an article appeared in the newspapers about the state of the morality of the women of Dudley. It was claimed that all the local magistrates agreed with the premise of the article, concerning unmarried women and their attitudes towards having illegitimate children. Letters appeared in subsequent newspapers signed by local magistrates, including Edward Moore, strongly disagreeing.

Staffordshire Advertiser 17 August 1861:

July 4, 2023 at 7:52 pm #7261

July 4, 2023 at 7:52 pm #7261In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Long Lost Enoch Edwards

My father used to mention long lost Enoch Edwards. Nobody in the family knew where he went to and it was assumed that he went to USA, perhaps to Utah to join his sister Sophie who was a Mormon handcart pioneer, but no record of him was found in USA.

Andrew Enoch Edwards (my great great grandfather) was born in 1840, but was (almost) always known as Enoch. Although civil registration of births had started from 1 July 1837, neither Enoch nor his brother Stephen were registered. Enoch was baptised (as Andrew) on the same day as his brothers Reuben and Stephen in May 1843 at St Chad’s Catholic cathedral in Birmingham. It’s a mystery why these three brothers were baptised Catholic, as there are no other Catholic records for this family before or since. One possible theory is that there was a school attached to the church on Shadwell Street, and a Catholic baptism was required for the boys to go to the school. Enoch’s father John died of TB in 1844, and perhaps in 1843 he knew he was dying and wanted to ensure an education for his sons. The building of St Chads was completed in 1841, and it was close to where they lived.

Enoch appears (as Enoch rather than Andrew) on the 1841 census, six months old. The family were living at Unett Street in Birmingham: John and Sarah and children Mariah, Sophia, Matilda, a mysterious entry transcribed as Lene, a daughter, that I have been unable to find anywhere else, and Reuben and Stephen.

Enoch was just four years old when his father John, an engineer and millwright, died of consumption in 1844.

In 1851 Enoch’s widowed mother Sarah was a mangler living on Summer Street, Birmingham, Matilda a dressmaker, Reuben and Stephen were gun percussionists, and eleven year old Enoch was an errand boy.

On the 1861 census, Sarah was a confectionrer on Canal Street in Birmingham, Stephen was a blacksmith, and Enoch a button tool maker.

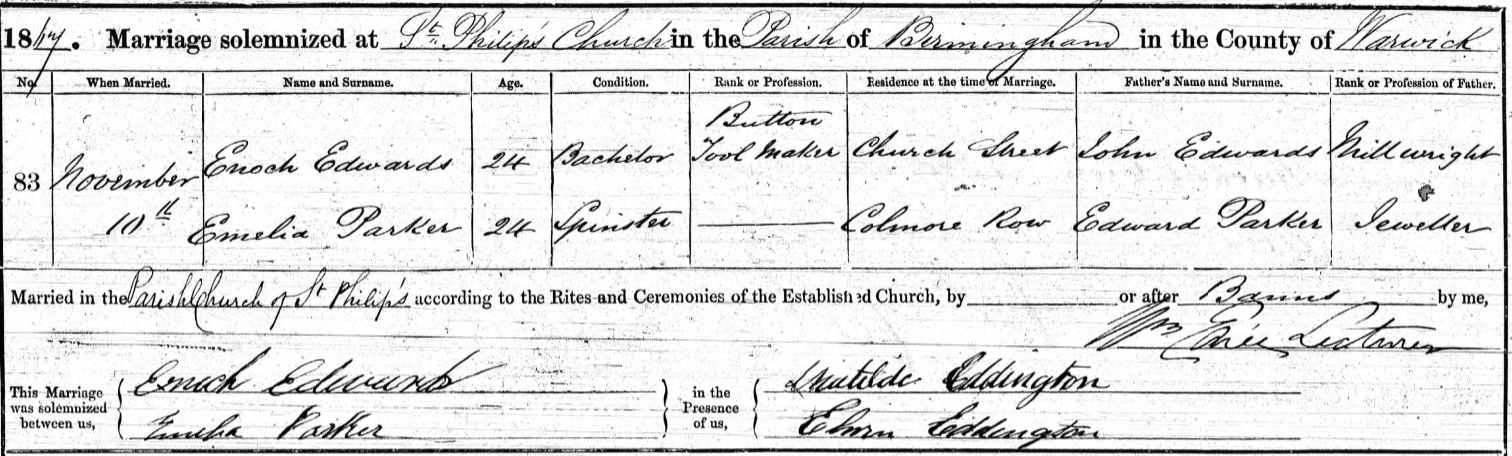

On the 10th November 1867 Enoch married Emelia Parker, daughter of jeweller and rope maker Edward Parker, at St Philip in Birmingham. Both Emelia and Enoch were able to sign their own names, and Matilda and Edwin Eddington were witnesses (Enoch’s sister and her husband). Enoch’s address was Church Street, and his occupation button tool maker.

Four years later in 1871, Enoch was a publican living on Clifton Road. Son Enoch Henry was two years old, and Ralph Ernest was three months. Eliza Barton lived with them as a general servant.

By 1881 Enoch was back working as a button tool maker in Bournebrook, Birmingham. Enoch and Emilia by then had three more children, Amelia, Albert Parker (my great grandfather) and Ada.

Garnet Frederick Edwards was born in 1882. This is the first instance of the name Garnet in the family, and subsequently Garnet has been the middle name for the eldest son (my brother, father and grandfather all have Garnet as a middle name).

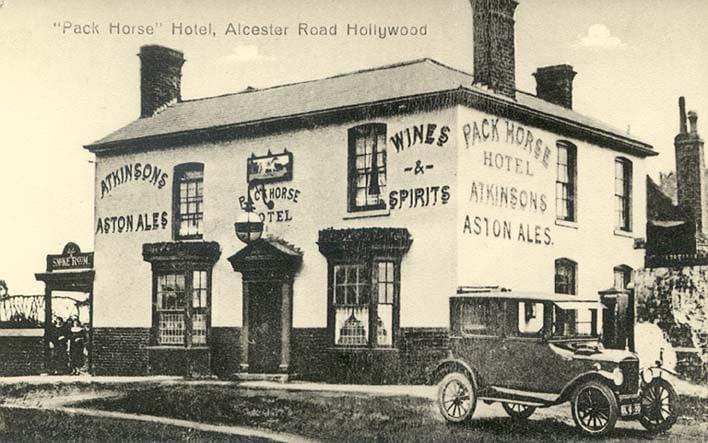

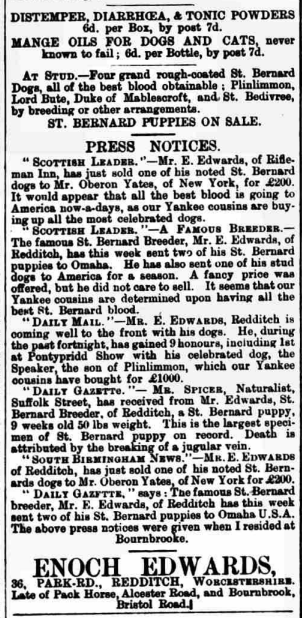

Enoch was the licensed victualler at the Pack Horse Hotel in 1991 at Kings Norton. By this time, only daughters Amelia and Ada and son Garnet are living at home.

Additional information from my fathers cousin, Paul Weaver:

“Enoch refused to allow his son Albert Parker to go to King Edwards School in Birmingham, where he had been awarded a place. Instead, in October 1890 he made Albert Parker Edwards take an apprenticeship with a pawnboker in Tipton.

Towards the end of the 19th century Enoch kept The Pack Horse in Alcester Road, Hollywood, where a twist was 1d an ounce, and beer was 2d a pint. The children had to get up early to get breakfast at 6 o’clock for the hay and straw men on their way to the Birmingham hay and straw market. Enoch is listed as a member of “The Kingswood & Pack Horse Association for the Prosecution of Offenders”, a kind of early Neighbourhood Watch, dated 25 October 1890.

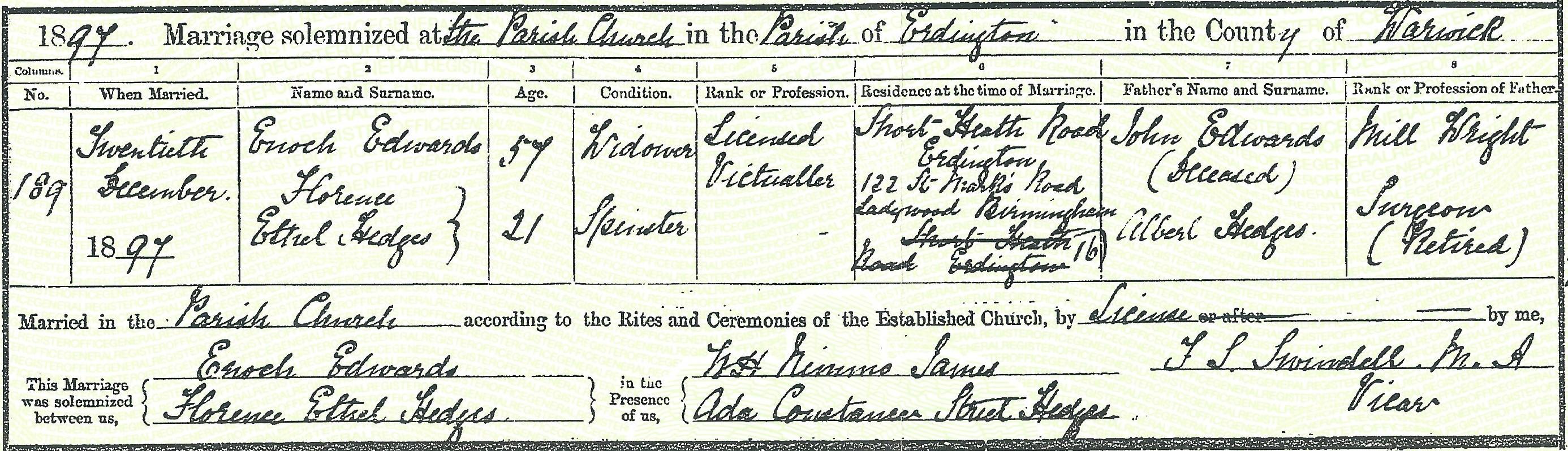

The Edwards family later moved to Redditch where they kept The Rifleman Inn at 35 Park Road. They must have left the Pack Horse by 1895 as another publican was in place by then.”Emelia his wife died in 1895 of consumption at the Rifleman Inn in Redditch, Worcestershire, and in 1897 Enoch married Florence Ethel Hedges in Aston. Enoch was 56 and Florence was just 21 years old.

The following year in 1898 their daughter Muriel Constance Freda Edwards was born in Deritend, Warwickshire.

In 1901 Enoch, (Andrew on the census), publican, Florence and Muriel were living in Dudley. It was hard to find where he went after this.From Paul Weaver:

“Family accounts have it that Enoch EDWARDS fell out with all his family, and at about the age of 60, he left all behind and emigrated to the U.S.A. Enoch was described as being an active man, and it is believed that he had another family when he settled in the U.S.A. Esmor STOKES has it that a postcard was received by the family from Enoch at Niagara Falls.

On 11 June 1902 Harry Wright (the local postmaster responsible in those days for licensing) brought an Enoch EDWARDS to the Bedfordshire Petty Sessions in Biggleswade regarding “Hole in the Wall”, believed to refer to the now defunct “Hole in the Wall” public house at 76 Shortmead Street, Biggleswade with Enoch being granted “temporary authority”. On 9 July 1902 the transfer was granted. A year later in the 1903 edition of Kelly’s Directory of Bedfordshire, Hunts and Northamptonshire there is an Enoch EDWARDS running the Wheatsheaf Public House, Church Street, St. Neots, Huntingdonshire which is 14 miles south of Biggleswade.”

It seems that Enoch and his new family moved away from the midlands in the early 1900s, but again the trail went cold.

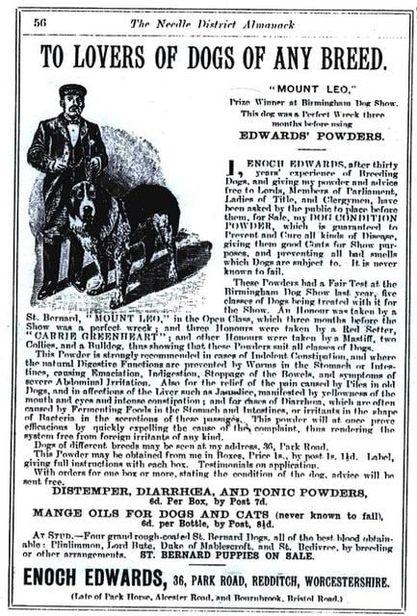

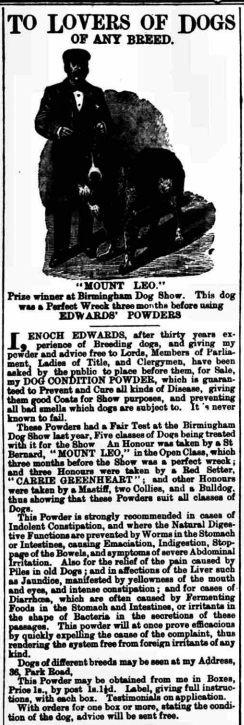

When I started doing the genealogy research, I joined a local facebook group for Redditch in Worcestershire. Enoch’s son Albert Parker Edwards (my great grandfather) spent most of his life there. I asked in the group about Enoch, and someone posted an illustrated advertisement for Enoch’s dog powders. Enoch was a well known breeder/keeper of St Bernards and is cited in a book naming individuals key to the recovery/establishment of ‘mastiff’ size dog breeds.

We had not known that Enoch was a breeder of champion St Bernard dogs!

Once I knew about the St Bernard dogs and the names Mount Leo and Plinlimmon via the newspaper adverts, I did an internet search on Enoch Edwards in conjunction with these dogs.

Enoch’s St Bernard dog “Mount Leo” was bred from the famous Plinlimmon, “the Emperor of Saint Bernards”. He was reported to have sent two puppies to Omaha and one of his stud dogs to America for a season, and in 1897 Enoch made the news for selling a St Bernard to someone in New York for £200. Plinlimmon, bred by Thomas Hall, was born in Liverpool, England on June 29, 1883. He won numerous dog shows throughout Europe in 1884, and in 1885, he was named Best Saint Bernard.

In the Birmingham Mail on 14th June 1890:

“Mr E Edwards, of Bournebrook, has been well to the fore with his dogs of late. He has gained nine honours during the past fortnight, including a first at the Pontypridd show with a St Bernard dog, The Speaker, a son of Plinlimmon.”

In the Alcester Chronicle on Saturday 05 June 1897:

It was discovered that Enoch, Florence and Muriel moved to Canada, not USA as the family had assumed. The 1911 census for Montreal St Jaqcues, Quebec, stated that Enoch, (Florence) Ethel, and (Muriel) Frida had emigrated in 1906. Enoch’s occupation was machinist in 1911. The census transcription is not very good. Edwards was transcribed as Edmand, but the dates of birth for all three are correct. Birthplace is correct ~ A for Anglitan (the census is in French) but race or tribe is also an A but the transcribers have put African black! Enoch by this time was 71 years old, his wife 33 and daughter 11.

Additional information from Paul Weaver:

“In 1906 he and his new family travelled to Canada with Enoch travelling first and Ethel and Frida joined him in Quebec on 25 June 1906 on board the ‘Canada’ from Liverpool.

Their immigration record suggests that they were planning to travel to Winnipeg, but five years later in 1911, Enoch, Florence Ethel and Frida were still living in St James, Montreal. Enoch was employed as a machinist by Canadian Government Railways working 50 hours. It is the 1911 census record that confirms his birth as November 1840. It also states that Enoch could neither read nor write but managed to earn $500 in 1910 for activity other than his main profession, although this may be referring to his innkeeping business interests.

By 1921 Florence and Muriel Frida are living in Langford, Neepawa, Manitoba with Peter FUCHS, an Ontarian farmer of German descent who Florence had married on 24 Jul 1913 implying that Enoch died sometime in 1911/12, although no record has been found.”The extra $500 in earnings was perhaps related to the St Bernard dogs. Enoch signed his name on the register on his marriage to Emelia, and I think it’s very unlikely that he could neither read nor write, as stated above.

However, it may not be Enoch’s wife Florence Ethel who married Peter Fuchs. A Florence Emma Edwards married Peter Fuchs, and on the 1921 census in Neepawa her daugther Muriel Elizabeth Edwards, born in 1902, lives with them. Quite a coincidence, two Florence and Muriel Edwards in Neepawa at the time. Muriel Elizabeth Edwards married and had two children but died at the age of 23 in 1925. Her mother Florence was living with the widowed husband and the two children on the 1931 census in Neepawa. As there was no other daughter on the 1911 census with Enoch, Florence and Muriel in Montreal, it must be a different Florence and daughter. We don’t know, though, why Muriel Constance Freda married in Neepawa.

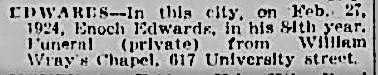

Indeed, Florence was not a widow in 1913. Enoch died in 1924 in Montreal, aged 84. Neither Enoch, Florence or their daughter has been found yet on the 1921 census. The search is not easy, as Enoch sometimes used the name Andrew, Florence used her middle name Ethel, and daughter Muriel used Freda, Valerie (the name she added when she married in Neepawa), and died as Marcheta. The only name she NEVER used was Constance!

A Canadian genealogist living in Montreal phoned the cemetery where Enoch was buried. She said “Enoch Edwards who died on Feb 27 1924 is not buried in the Mount Royal cemetery, he was only cremated there on March 4, 1924. There are no burial records but he died of an abcess and his body was sent to the cemetery for cremation from the Royal Victoria Hospital.”

1924 Obituary for Enoch Edwards:

Cimetière Mont-Royal Outremont, Montreal Region, Quebec, Canada

The Montreal Star 29 Feb 1924, Fri · Page 31

Muriel Constance Freda Valerie Edwards married Arthur Frederick Morris on 24 Oct 1925 in Neepawa, Manitoba. (She appears to have added the name Valerie when she married.)

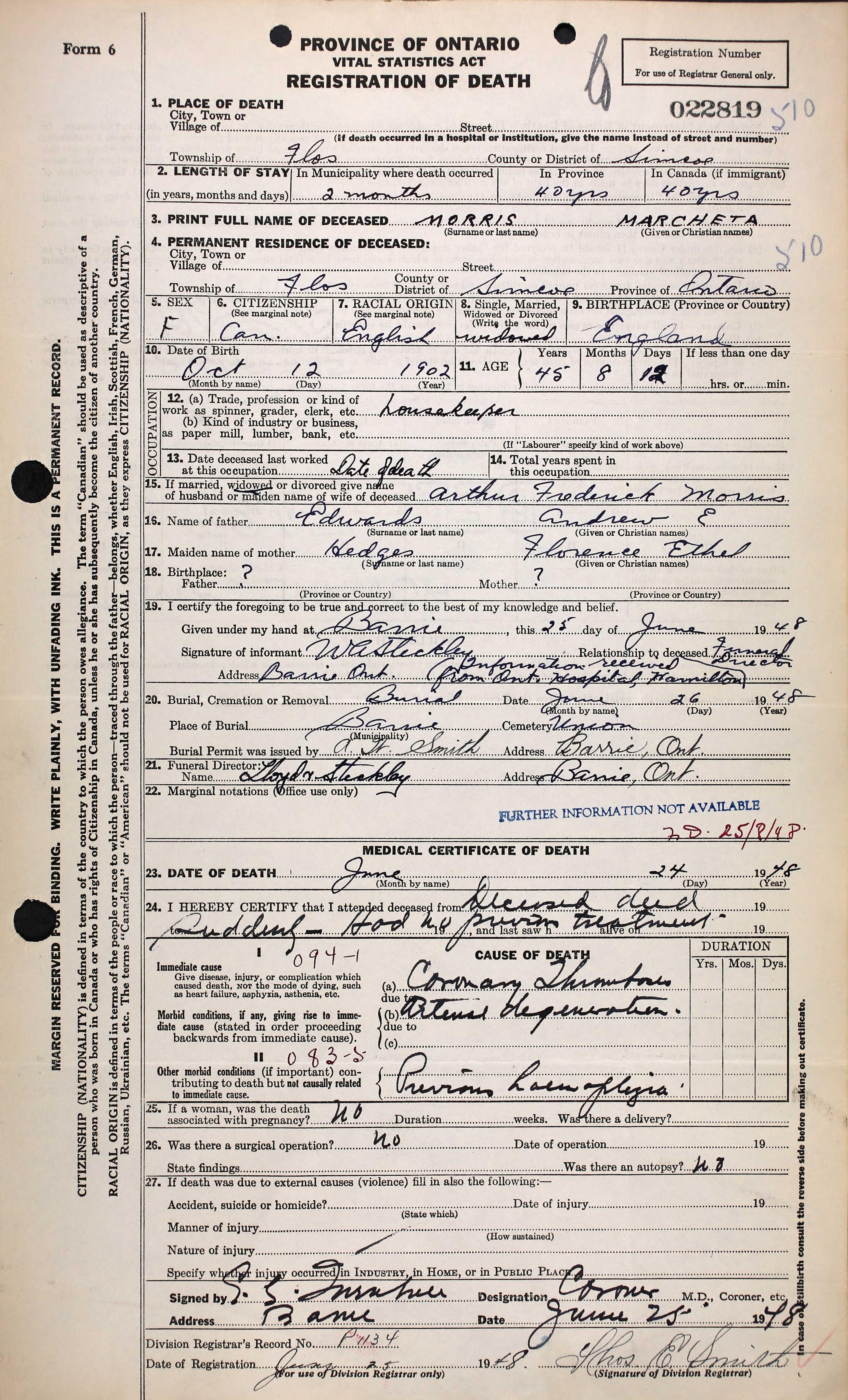

Unexpectedly a death certificate appeared for Muriel via the hints on the ancestry website. Her name was “Marcheta Morris” on this document, however it also states that she was the widow of Arthur Frederick Morris and daughter of Andrew E Edwards and Florence Ethel Hedges. She died suddenly in June 1948 in Flos, Simcoe, Ontario of a coronary thrombosis, where she was living as a housekeeper.

December 6, 2022 at 2:17 pm #6350

December 6, 2022 at 2:17 pm #6350In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Transportation

Isaac Stokes 1804-1877

Isaac was born in Churchill, Oxfordshire in 1804, and was the youngest brother of my 4X great grandfather Thomas Stokes. The Stokes family were stone masons for generations in Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire, and Isaac’s occupation was a mason’s labourer in 1834 when he was sentenced at the Lent Assizes in Oxford to fourteen years transportation for stealing tools.

Churchill where the Stokes stonemasons came from: on 31 July 1684 a fire destroyed 20 houses and many other buildings, and killed four people. The village was rebuilt higher up the hill, with stone houses instead of the old timber-framed and thatched cottages. The fire was apparently caused by a baker who, to avoid chimney tax, had knocked through the wall from her oven to her neighbour’s chimney.

Isaac stole a pick axe, the value of 2 shillings and the property of Thomas Joyner of Churchill; a kibbeaux and a trowel value 3 shillings the property of Thomas Symms; a hammer and axe value 5 shillings, property of John Keen of Sarsden.

(The word kibbeaux seems to only exists in relation to Isaac Stokes sentence and whoever was the first to write it was perhaps being creative with the spelling of a kibbo, a miners or a metal bucket. This spelling is repeated in the criminal reports and the newspaper articles about Isaac, but nowhere else).

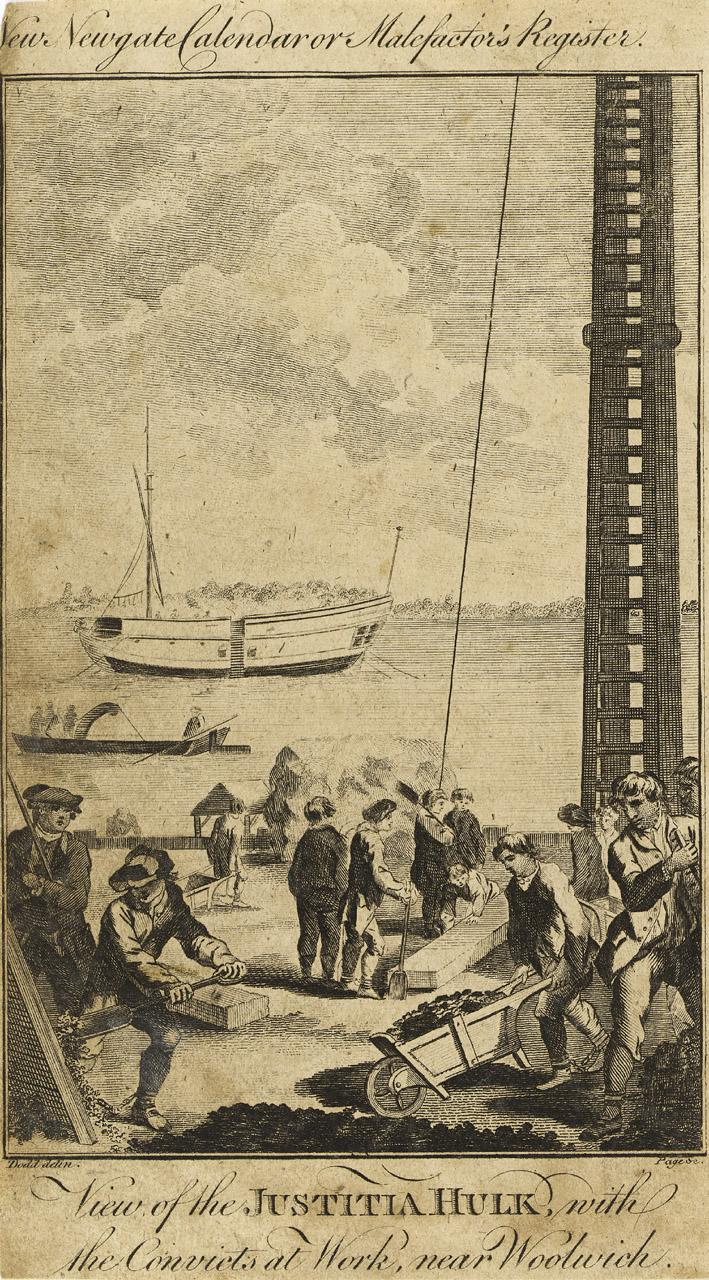

In March 1834 the Removal of Convicts was announced in the Oxford University and City Herald: Isaac Stokes and several other prisoners were removed from the Oxford county gaol to the Justitia hulk at Woolwich “persuant to their sentences of transportation at our Lent Assizes”.

via digitalpanopticon:

Hulks were decommissioned (and often unseaworthy) ships that were moored in rivers and estuaries and refitted to become floating prisons. The outbreak of war in America in 1775 meant that it was no longer possible to transport British convicts there. Transportation as a form of punishment had started in the late seventeenth century, and following the Transportation Act of 1718, some 44,000 British convicts were sent to the American colonies. The end of this punishment presented a major problem for the authorities in London, since in the decade before 1775, two-thirds of convicts at the Old Bailey received a sentence of transportation – on average 283 convicts a year. As a result, London’s prisons quickly filled to overflowing with convicted prisoners who were sentenced to transportation but had no place to go.

To increase London’s prison capacity, in 1776 Parliament passed the “Hulks Act” (16 Geo III, c.43). Although overseen by local justices of the peace, the hulks were to be directly managed and maintained by private contractors. The first contract to run a hulk was awarded to Duncan Campbell, a former transportation contractor. In August 1776, the Justicia, a former transportation ship moored in the River Thames, became the first prison hulk. This ship soon became full and Campbell quickly introduced a number of other hulks in London; by 1778 the fleet of hulks on the Thames held 510 prisoners.

Demand was so great that new hulks were introduced across the country. There were hulks located at Deptford, Chatham, Woolwich, Gosport, Plymouth, Portsmouth, Sheerness and Cork.The Justitia via rmg collections:

Convicts perform hard labour at the Woolwich Warren. The hulk on the river is the ‘Justitia’. Prisoners were kept on board such ships for months awaiting deportation to Australia. The ‘Justitia’ was a 260 ton prison hulk that had been originally moored in the Thames when the American War of Independence put a stop to the transportation of criminals to the former colonies. The ‘Justitia’ belonged to the shipowner Duncan Campbell, who was the Government contractor who organized the prison-hulk system at that time. Campbell was subsequently involved in the shipping of convicts to the penal colony at Botany Bay (in fact Port Jackson, later Sydney, just to the north) in New South Wales, the ‘first fleet’ going out in 1788.

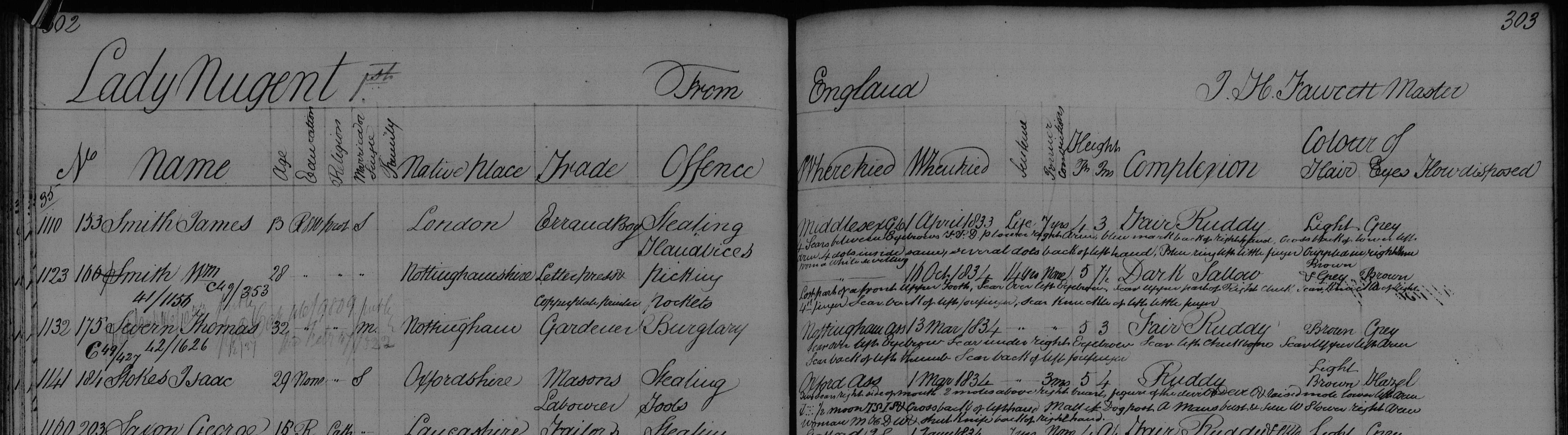

While searching for records for Isaac Stokes I discovered that another Isaac Stokes was transported to New South Wales in 1835 as well. The other one was a butcher born in 1809, sentenced in London for seven years, and he sailed on the Mary Ann. Our Isaac Stokes sailed on the Lady Nugent, arriving in NSW in April 1835, having set sail from England in December 1834.

Lady Nugent was built at Bombay in 1813. She made four voyages under contract to the British East India Company (EIC). She then made two voyages transporting convicts to Australia, one to New South Wales and one to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). (via Wikipedia)

via freesettlerorfelon website:

On 20 November 1834, 100 male convicts were transferred to the Lady Nugent from the Justitia Hulk and 60 from the Ganymede Hulk at Woolwich, all in apparent good health. The Lady Nugent departed Sheerness on 4 December 1834.

SURGEON OLIVER SPROULE

Oliver Sproule kept a Medical Journal from 7 November 1834 to 27 April 1835. He recorded in his journal the weather conditions they experienced in the first two weeks:

‘In the course of the first week or ten days at sea, there were eight or nine on the sick list with catarrhal affections and one with dropsy which I attribute to the cold and wet we experienced during that period beating down channel. Indeed the foremost berths in the prison at this time were so wet from leaking in that part of the ship, that I was obliged to issue dry beds and bedding to a great many of the prisoners to preserve their health, but after crossing the Bay of Biscay the weather became fine and we got the damp beds and blankets dried, the leaks partially stopped and the prison well aired and ventilated which, I am happy to say soon manifested a favourable change in the health and appearance of the men.

Besides the cases given in the journal I had a great many others to treat, some of them similar to those mentioned but the greater part consisted of boils, scalds, and contusions which would not only be too tedious to enter but I fear would be irksome to the reader. There were four births on board during the passage which did well, therefore I did not consider it necessary to give a detailed account of them in my journal the more especially as they were all favourable cases.

Regularity and cleanliness in the prison, free ventilation and as far as possible dry decks turning all the prisoners up in fine weather as we were lucky enough to have two musicians amongst the convicts, dancing was tolerated every afternoon, strict attention to personal cleanliness and also to the cooking of their victuals with regular hours for their meals, were the only prophylactic means used on this occasion, which I found to answer my expectations to the utmost extent in as much as there was not a single case of contagious or infectious nature during the whole passage with the exception of a few cases of psora which soon yielded to the usual treatment. A few cases of scurvy however appeared on board at rather an early period which I can attribute to nothing else but the wet and hardships the prisoners endured during the first three or four weeks of the passage. I was prompt in my treatment of these cases and they got well, but before we arrived at Sydney I had about thirty others to treat.’

The Lady Nugent arrived in Port Jackson on 9 April 1835 with 284 male prisoners. Two men had died at sea. The prisoners were landed on 27th April 1835 and marched to Hyde Park Barracks prior to being assigned. Ten were under the age of 14 years.

The Lady Nugent:

Isaac’s distinguishing marks are noted on various criminal registers and record books:

“Height in feet & inches: 5 4; Complexion: Ruddy; Hair: Light brown; Eyes: Hazel; Marks or Scars: Yes [including] DEVIL on lower left arm, TSIS back of left hand, WS lower right arm, MHDW back of right hand.”

Another includes more detail about Isaac’s tattoos:

“Two slight scars right side of mouth, 2 moles above right breast, figure of the devil and DEVIL and raised mole, lower left arm; anchor, seven dots half moon, TSIS and cross, back of left hand; a mallet, door post, A, mans bust, sun, WS, lower right arm; woman, MHDW and shut knife, back of right hand.”

From How tattoos became fashionable in Victorian England (2019 article in TheConversation by Robert Shoemaker and Zoe Alkar):

“Historical tattooing was not restricted to sailors, soldiers and convicts, but was a growing and accepted phenomenon in Victorian England. Tattoos provide an important window into the lives of those who typically left no written records of their own. As a form of “history from below”, they give us a fleeting but intriguing understanding of the identities and emotions of ordinary people in the past.

As a practice for which typically the only record is the body itself, few systematic records survive before the advent of photography. One exception to this is the written descriptions of tattoos (and even the occasional sketch) that were kept of institutionalised people forced to submit to the recording of information about their bodies as a means of identifying them. This particularly applies to three groups – criminal convicts, soldiers and sailors. Of these, the convict records are the most voluminous and systematic.

Such records were first kept in large numbers for those who were transported to Australia from 1788 (since Australia was then an open prison) as the authorities needed some means of keeping track of them.”On the 1837 census Isaac was working for the government at Illiwarra, New South Wales. This record states that he arrived on the Lady Nugent in 1835. There are three other indent records for an Isaac Stokes in the following years, but the transcriptions don’t provide enough information to determine which Isaac Stokes it was. In April 1837 there was an abscondment, and an arrest/apprehension in May of that year, and in 1843 there was a record of convict indulgences.

From the Australian government website regarding “convict indulgences”:

“By the mid-1830s only six per cent of convicts were locked up. The vast majority worked for the government or free settlers and, with good behaviour, could earn a ticket of leave, conditional pardon or and even an absolute pardon. While under such orders convicts could earn their own living.”

In 1856 in Camden, NSW, Isaac Stokes married Catherine Daly. With no further information on this record it would be impossible to know for sure if this was the right Isaac Stokes. This couple had six children, all in the Camden area, but none of the records provided enough information. No occupation or place or date of birth recorded for Isaac Stokes.

I wrote to the National Library of Australia about the marriage record, and their reply was a surprise! Issac and Catherine were married on 30 September 1856, at the house of the Rev. Charles William Rigg, a Methodist minister, and it was recorded that Isaac was born in Edinburgh in 1821, to parents James Stokes and Sarah Ellis! The age at the time of the marriage doesn’t match Isaac’s age at death in 1877, and clearly the place of birth and parents didn’t match either. Only his fathers occupation of stone mason was correct. I wrote back to the helpful people at the library and they replied that the register was in a very poor condition and that only two and a half entries had survived at all, and that Isaac and Catherines marriage was recorded over two pages.

I searched for an Isaac Stokes born in 1821 in Edinburgh on the Scotland government website (and on all the other genealogy records sites) and didn’t find it. In fact Stokes was a very uncommon name in Scotland at the time. I also searched Australian immigration and other records for another Isaac Stokes born in Scotland or born in 1821, and found nothing. I was unable to find a single record to corroborate this mysterious other Isaac Stokes.

As the age at death in 1877 was correct, I assume that either Isaac was lying, or that some mistake was made either on the register at the home of the Methodist minster, or a subsequent mistranscription or muddle on the remnants of the surviving register. Therefore I remain convinced that the Camden stonemason Isaac Stokes was indeed our Isaac from Oxfordshire.

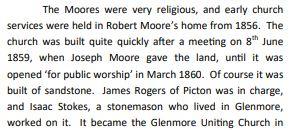

I found a history society newsletter article that mentioned Isaac Stokes, stone mason, had built the Glenmore church, near Camden, in 1859.

From the Wollondilly museum April 2020 newsletter:

From the Camden History website:

“The stone set over the porch of Glenmore Church gives the date of 1860. The church was begun in 1859 on land given by Joseph Moore. James Rogers of Picton was given the contract to build and local builder, Mr. Stokes, carried out the work. Elizabeth Moore, wife of Edward, laid the foundation stone. The first service was held on 19th March 1860. The cemetery alongside the church contains the headstones and memorials of the areas early pioneers.”

Isaac died on the 3rd September 1877. The inquest report puts his place of death as Bagdelly, near to Camden, and another death register has put Cambelltown, also very close to Camden. His age was recorded as 71 and the inquest report states his cause of death was “rupture of one of the large pulmonary vessels of the lung”. His wife Catherine died in childbirth in 1870 at the age of 43.

Isaac and Catherine’s children:

William Stokes 1857-1928

Catherine Stokes 1859-1846

Sarah Josephine Stokes 1861-1931

Ellen Stokes 1863-1932

Rosanna Stokes 1865-1919

Louisa Stokes 1868-1844.

It’s possible that Catherine Daly was a transported convict from Ireland.

Some time later I unexpectedly received a follow up email from The Oaks Heritage Centre in Australia.

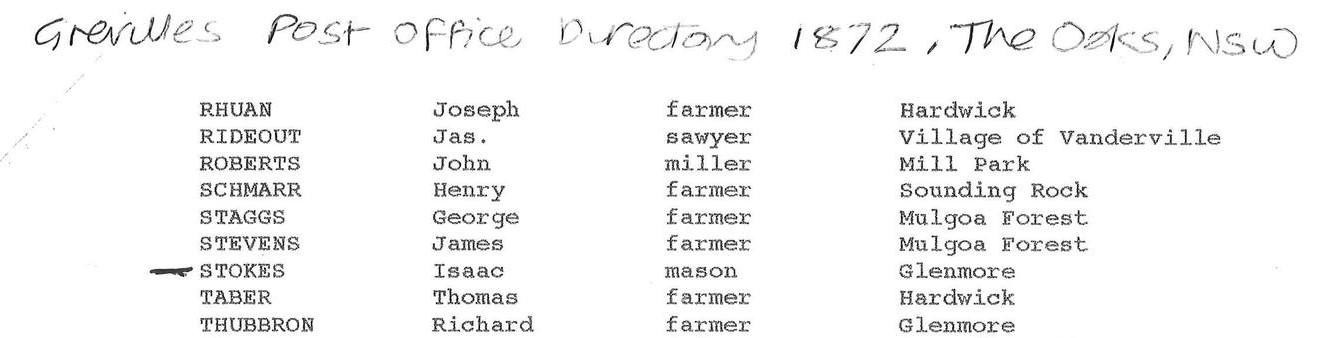

“The Gaudry papers which we have in our archive record him (Isaac Stokes) as having built: the church, the school and the teachers residence. Isaac is recorded in the General return of convicts: 1837 and in Grevilles Post Office directory 1872 as a mason in Glenmore.”

November 18, 2022 at 4:47 pm #6348

November 18, 2022 at 4:47 pm #6348In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Wong Sang

Wong Sang was born in China in 1884. In October 1916 he married Alice Stokes in Oxford.

Alice was the granddaughter of William Stokes of Churchill, Oxfordshire and William was the brother of Thomas Stokes the wheelwright (who was my 3X great grandfather). In other words Alice was my second cousin, three times removed, on my fathers paternal side.

Wong Sang was an interpreter, according to the baptism registers of his children and the Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital admission registers in 1930. The hospital register also notes that he was employed by the Blue Funnel Line, and that his address was 11, Limehouse Causeway, E 14. (London)

“The Blue Funnel Line offered regular First-Class Passenger and Cargo Services From the UK to South Africa, Malaya, China, Japan, Australia, Java, and America. Blue Funnel Line was Owned and Operated by Alfred Holt & Co., Liverpool.

The Blue Funnel Line, so-called because its ships have a blue funnel with a black top, is more appropriately known as the Ocean Steamship Company.”Wong Sang and Alice’s daughter, Frances Eileen Sang, was born on the 14th July, 1916 and baptised in 1920 at St Stephen in Poplar, Tower Hamlets, London. The birth date is noted in the 1920 baptism register and would predate their marriage by a few months, although on the death register in 1921 her age at death is four years old and her year of birth is recorded as 1917.

Charles Ronald Sang was baptised on the same day in May 1920, but his birth is recorded as April of that year. The family were living on Morant Street, Poplar.

James William Sang’s birth is recorded on the 1939 census and on the death register in 2000 as being the 8th March 1913. This definitely would predate the 1916 marriage in Oxford.

William Norman Sang was born on the 17th October 1922 in Poplar.

Alice and the three sons were living at 11, Limehouse Causeway on the 1939 census, the same address that Wong Sang was living at when he was admitted to Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital on the 15th January 1930. Wong Sang died in the hospital on the 8th March of that year at the age of 46.

Alice married John Patterson in 1933 in Stepney. John was living with Alice and her three sons on Limehouse Causeway on the 1939 census and his occupation was chef.

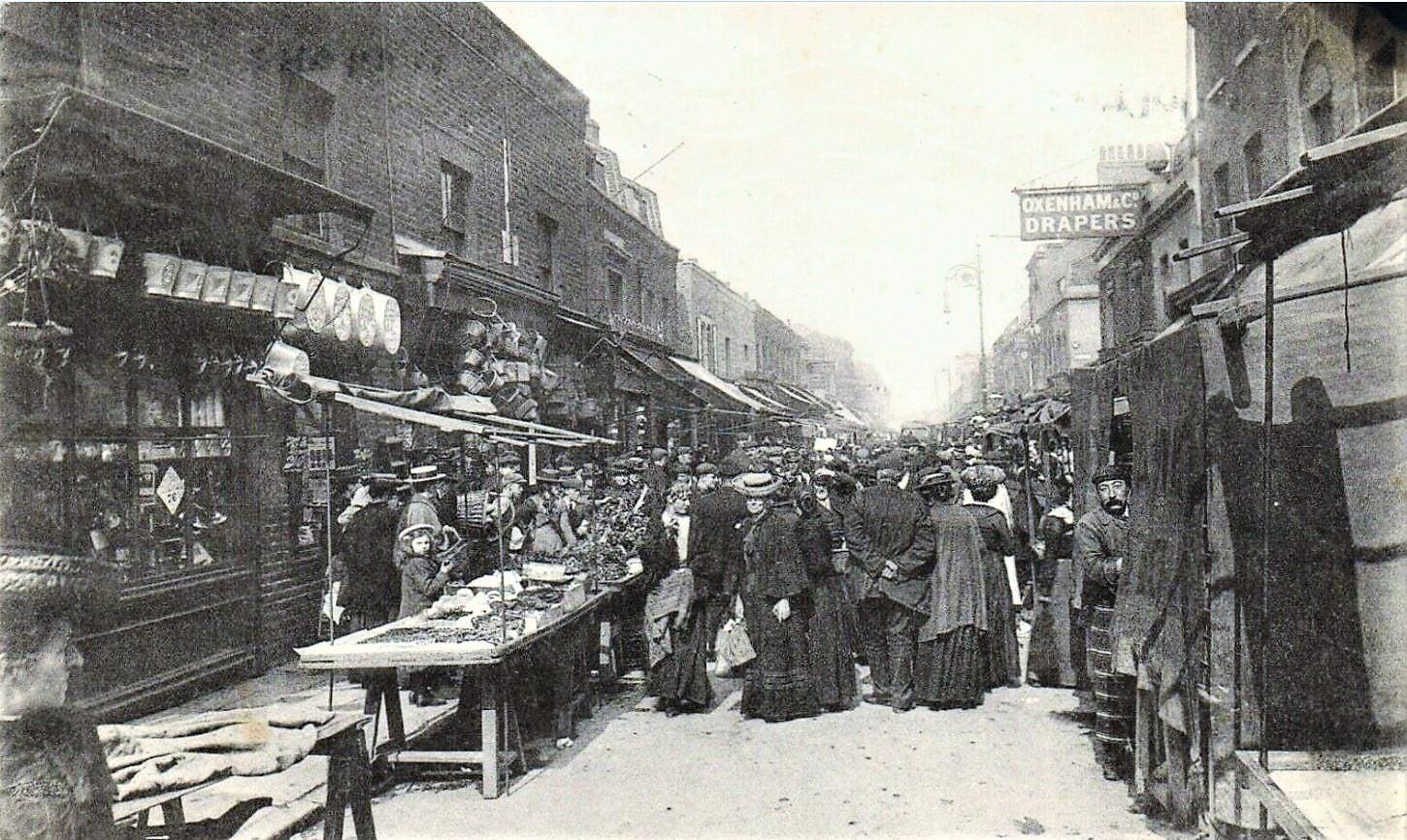

Via Old London Photographs:

“Limehouse Causeway is a street in east London that was the home to the original Chinatown of London. A combination of bomb damage during the Second World War and later redevelopment means that almost nothing is left of the original buildings of the street.”

Limehouse Causeway in 1925:

From The Story of Limehouse’s Lost Chinatown, poplarlondon website:

“Limehouse was London’s first Chinatown, home to a tightly-knit community who were demonised in popular culture and eventually erased from the cityscape.

As recounted in the BBC’s ‘Our Greatest Generation’ series, Connie was born to a Chinese father and an English mother in early 1920s Limehouse, where she used to play in the street with other British and British-Chinese children before running inside for teatime at one of their houses.

Limehouse was London’s first Chinatown between the 1880s and the 1960s, before the current Chinatown off Shaftesbury Avenue was established in the 1970s by an influx of immigrants from Hong Kong.

Connie’s memories of London’s first Chinatown as an “urban village” paint a very different picture to the seedy area portrayed in early twentieth century novels.

The pyramid in St Anne’s church marked the entrance to the opium den of Dr Fu Manchu, a criminal mastermind who threatened Western society by plotting world domination in a series of novels by Sax Rohmer.

Thomas Burke’s Limehouse Nights cemented stereotypes about prostitution, gambling and violence within the Chinese community, and whipped up anxiety about sexual relationships between Chinese men and white women.

Though neither novelist was familiar with the Chinese community, their depictions made Limehouse one of the most notorious areas of London.

Travel agent Thomas Cook even organised tours of the area for daring visitors, despite the rector of Limehouse warning that “those who look for the Limehouse of Mr Thomas Burke simply will not find it.”

All that remains is a handful of Chinese street names, such as Ming Street, Pekin Street, and Canton Street — but what was Limehouse’s chinatown really like, and why did it get swept away?

Chinese migration to Limehouse

Chinese sailors discharged from East India Company ships settled in the docklands from as early as the 1780s.

By the late nineteenth century, men from Shanghai had settled around Pennyfields Lane, while a Cantonese community lived on Limehouse Causeway.

Chinese sailors were often paid less and discriminated against by dock hirers, and so began to diversify their incomes by setting up hand laundry services and restaurants.

Old photographs show shopfronts emblazoned with Chinese characters with horse-drawn carts idling outside or Chinese men in suits and hats standing proudly in the doorways.

In oral histories collected by Yat Ming Loo, Connie’s husband Leslie doesn’t recall seeing any Chinese women as a child, since male Chinese sailors settled in London alone and married working-class English women.

In the 1920s, newspapers fear-mongered about interracial marriages, crime and gambling, and described chinatown as an East End “colony.”

Ironically, Chinese opium-smoking was also demonised in the press, despite Britain waging war against China in the mid-nineteenth century for suppressing the opium trade to alleviate addiction amongst its people.

The number of Chinese people who settled in Limehouse was also greatly exaggerated, and in reality only totalled around 300.

The real Chinatown

Although the press sought to characterise Limehouse as a monolithic Chinese community in the East End, Connie remembers seeing people of all nationalities in the shops and community spaces in Limehouse.

She doesn’t remember feeling discriminated against by other locals, though Connie does recall having her face measured and IQ tested by a member of the British Eugenics Society who was conducting research in the area.

Some of Connie’s happiest childhood memories were from her time at Chung-Hua Club, where she learned about Chinese culture and language.

Why did Chinatown disappear?

The caricature of Limehouse’s Chinatown as a den of vice hastened its erasure.

Police raids and deportations fuelled by the alarmist media coverage threatened the Chinese population of Limehouse, and slum clearance schemes to redevelop low-income areas dispersed Chinese residents in the 1930s.

The Defence of the Realm Act imposed at the beginning of the First World War criminalised opium use, gave the authorities increased powers to deport Chinese people and restricted their ability to work on British ships.

Dwindling maritime trade during World War II further stripped Chinese sailors of opportunities for employment, and any remnants of Chinatown were destroyed during the Blitz or erased by postwar development schemes.”

Wong Sang 1884-1930

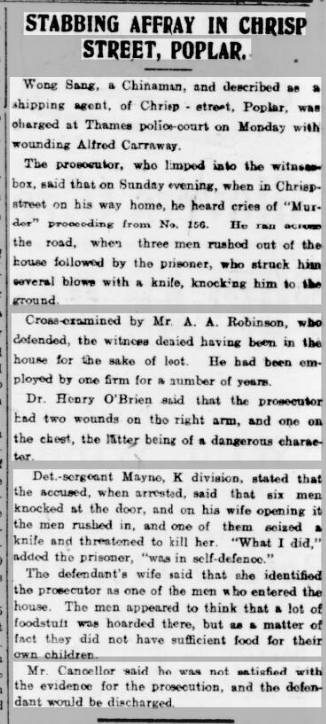

The year 1918 was a troublesome one for Wong Sang, an interpreter and shipping agent for Blue Funnel Line. The Sang family were living at 156, Chrisp Street.

Chrisp Street, Poplar, in 1913 via Old London Photographs:

In February Wong Sang was discharged from a false accusation after defending his home from potential robbers.

East End News and London Shipping Chronicle – Friday 15 February 1918:

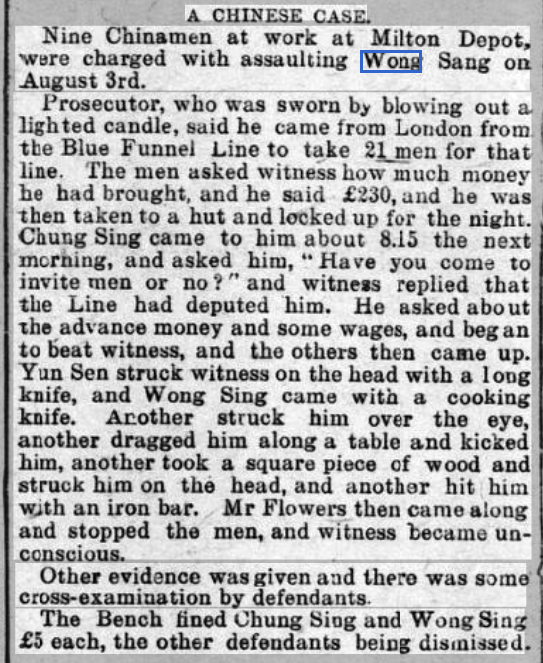

In August of that year he was involved in an incident that left him unconscious.

Faringdon Advertiser and Vale of the White Horse Gazette – Saturday 31 August 1918:

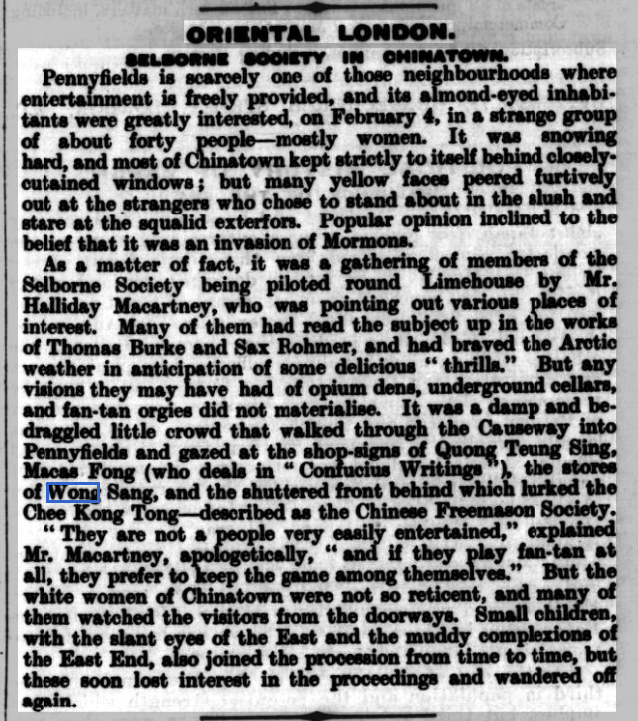

Wong Sang is mentioned in an 1922 article about “Oriental London”.

London and China Express – Thursday 09 February 1922:

A photograph of the Chee Kong Tong Chinese Freemason Society mentioned in the above article, via Old London Photographs:

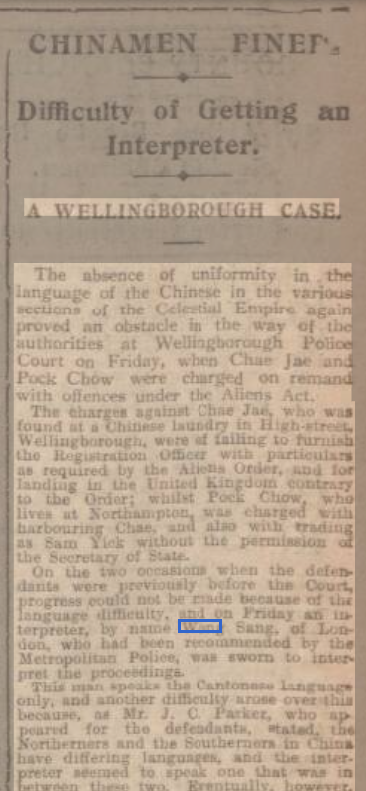

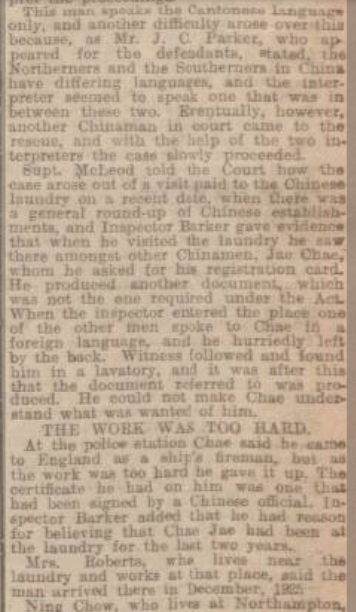

Wong Sang was recommended by the London Metropolitan Police in 1928 to assist in a case in Wellingborough, Northampton.

Difficulty of Getting an Interpreter: Northampton Mercury – Friday 16 March 1928:

The difficulty was that “this man speaks the Cantonese language only…the Northeners and the Southerners in China have differing languages and the interpreter seemed to speak one that was in between these two.”

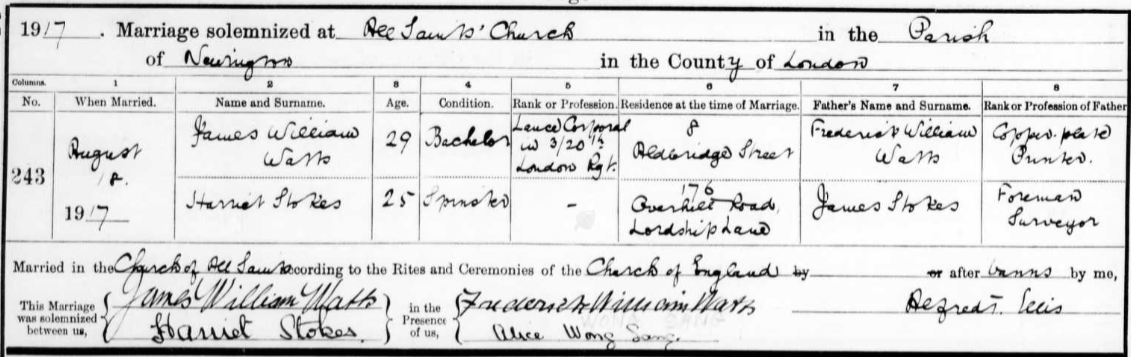

In 1917, Alice Wong Sang was a witness at her sister Harriet Stokes marriage to James William Watts in Southwark, London. Their father James Stokes occupation on the marriage register is foreman surveyor, but on the census he was a council roadman or labourer. (I initially rejected this as the correct marriage for Harriet because of the discrepancy with the occupations. Alice Wong Sang as a witness confirmed that it was indeed the correct one.)

James William Sang 1913-2000 was a clock fitter and watch assembler (on the 1939 census). He married Ivy Laura Fenton in 1963 in Sidcup, Kent. James died in Southwark in 2000.

Charles Ronald Sang 1920-1974 was a draughtsman (1939 census). He married Eileen Burgess in 1947 in Marylebone. Charles and Eileen had two sons: Keith born in 1951 and Roger born in 1952. He died in 1974 in Hertfordshire.

William Norman Sang 1922-2000 was a clerk and telephone operator (1939 census). William enlisted in the Royal Artillery in 1942. He married Lily Mullins in 1949 in Bethnal Green, and they had three daughters: Marion born in 1950, Christine in 1953, and Frances in 1959. He died in Redbridge in 2000.

I then found another two births registered in Poplar by Alice Sang, both daughters. Doris Winifred Sang was born in 1925, and Patricia Margaret Sang was born in 1933 ~ three years after Wong Sang’s death. Neither of the these daughters were on the 1939 census with Alice, John Patterson and the three sons. Margaret had presumably been evacuated because of the war to a family in Taunton, Somerset. Doris would have been fourteen and I have been unable to find her in 1939 (possibly because she died in 2017 and has not had the redaction removed yet on the 1939 census as only deceased people are viewable).

Doris Winifred Sang 1925-2017 was a nursing sister. She didn’t marry, and spent a year in USA between 1954 and 1955. She stayed in London, and died at the age of ninety two in 2017.

Patricia Margaret Sang 1933-1998 was also a nurse. She married Patrick L Nicely in Stepney in 1957. Patricia and Patrick had five children in London: Sharon born 1959, Donald in 1960, Malcolm was born and died in 1966, Alison was born in 1969 and David in 1971.

I was unable to find a birth registered for Alice’s first son, James William Sang (as he appeared on the 1939 census). I found Alice Stokes on the 1911 census as a 17 year old live in servant at a tobacconist on Pekin Street, Limehouse, living with Mr Sui Fong from Hong Kong and his wife Sarah Sui Fong from Berlin. I looked for a birth registered for James William Fong instead of Sang, and found it ~ mothers maiden name Stokes, and his date of birth matched the 1939 census: 8th March, 1913.

On the 1921 census, Wong Sang is not listed as living with them but it is mentioned that Mr Wong Sang was the person returning the census. Also living with Alice and her sons James and Charles in 1921 are two visitors: (Florence) May Stokes, 17 years old, born in Woodstock, and Charles Stokes, aged 14, also born in Woodstock. May and Charles were Alice’s sister and brother.

I found Sharon Nicely on social media and she kindly shared photos of Wong Sang and Alice Stokes:

November 14, 2022 at 12:09 pm #6346

November 14, 2022 at 12:09 pm #6346In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The Mormon Browning Who Went To Utah

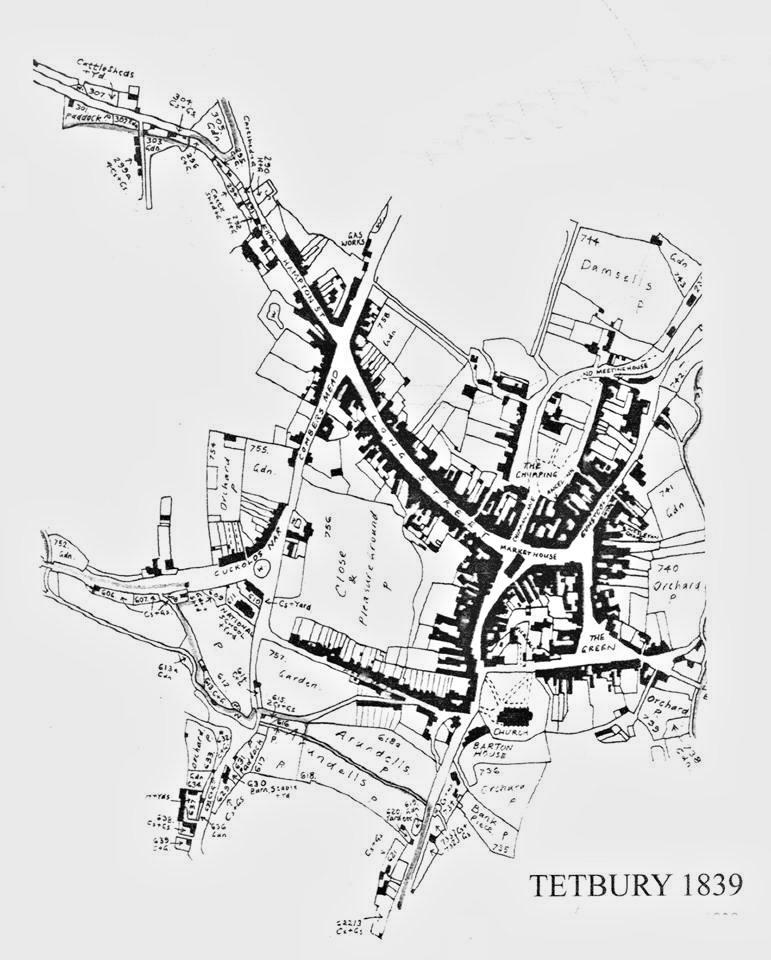

Isaac Browning’s (1784-1848) sister Hannah married Francis Buckingham. There were at least three Browning Buckingham marriages in Tetbury. Their daughter Charlotte married James Paskett, a shoemaker. Charlotte was born in 1818 and in 1871 she and her family emigrated to Utah, USA.

Charlotte’s relationship to me is first cousin five times removed.

James and Charlotte: (photos found online)

The house of James and Charlotte in Tetbury:

The home of James and Charlotte in Utah:

Obituary:

James Pope Paskett Dead.

Veteran of 87 Laid to rest. Special Correspondence Coalville, Summit Co., Oct 28—James Pope Paskett of Henefer died Oct. 24, 1903 of old age and general debility. Funeral services were held at Henefer today. Elders W.W. Cluff, Alma Elderge, Robert Jones, Oscar Wilkins and Bishop M.F. Harris were the speakers. There was a large attendance many coming from other wards in the stake. James Pope Paskett was born in Chippenham, Wiltshire, England, on March 12, 1817; married Chalotte Buckingham in the year 1839; eight children were born to them, three sons and five daughters, all of whom are living and residing in Utah, except one in Brisbane, Australia. Father Paskett joined the church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints in 1847, and emigrated to Utah in 1871, and has resided in Henefer ever since. He leaves his faithful and aged wife. He was respected and esteemed by all who knew him.

Charlotte died in Henefer, Utah, on 27th December 1910 at the age of 91.

James and Charlotte in later life:

November 13, 2022 at 10:29 pm #6345In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Crime and Punishment in Tetbury

I noticed that there were quite a number of Brownings of Tetbury in the newspaper archives involved in criminal activities while doing a routine newspaper search to supplement the information in the usual ancestry records. I expanded the tree to include cousins, and offsping of cousins, in order to work out who was who and how, if at all, these individuals related to our Browning family.

I was expecting to find some of our Brownings involved in the Swing Riots in Tetbury in 1830, but did not. Most of our Brownings (including cousins) were stone masons. Most of the rioters in 1830 were agricultural labourers.

The Browning crimes are varied, and by todays standards, not for the most part terribly serious ~ you would be unlikely to receive a sentence of hard labour for being found in an outhouse with the intent to commit an unlawful act nowadays, or for being drunk.

The central character in this chapter is Isaac Browning (my 4x great grandfather), who did not appear in any criminal registers, but the following individuals can be identified in the family structure through their relationship to him.

RICHARD LOCK BROWNING born in 1853 was Isaac’s grandson, his son George’s son. Richard was a mason. In 1879 he and Henry Browning of the same age were sentenced to one month hard labour for stealing two pigeons in Tetbury. Henry Browning was Isaac’s nephews son.

In 1883 Richard Browning, mason of Tetbury, was charged with obtaining food and lodging under false pretences, but was found not guilty and acquitted.

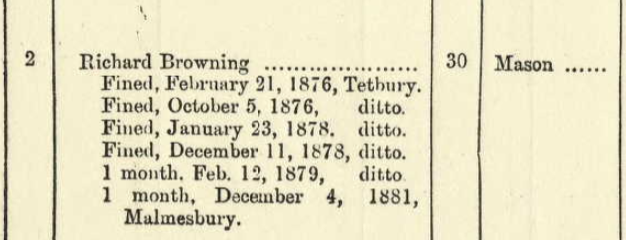

In 1884 Richard Browning, mason of Tetbury, was sentenced to one month hard labour for game trespass.Richard had been fined a number of times in Tetbury:

Richard Lock Browning was five feet eight inches tall, dark hair, grey eyes, an oval face and a dark complexion. He had two cuts on the back of his head (in February 1879) and a scar on his right eyebrow.

HENRY BROWNING, who was stealing pigeons with Richard Lock Browning in 1879, (Isaac’s brother Williams grandson, son of George Browning and his wife Charity) was charged with being drunk in 1882 and ordered to pay a fine of one shilling and costs of fourteen shillings, or seven days hard labour.

Henry was found guilty of gaming in the highway at Tetbury in 1872 and was sentenced to seven days hard labour. In 1882 Henry (who was also a mason) was charged with assault but discharged.

Henry was five feet five inches tall, brown hair and brown eyes, a long visage and a fresh complexion.

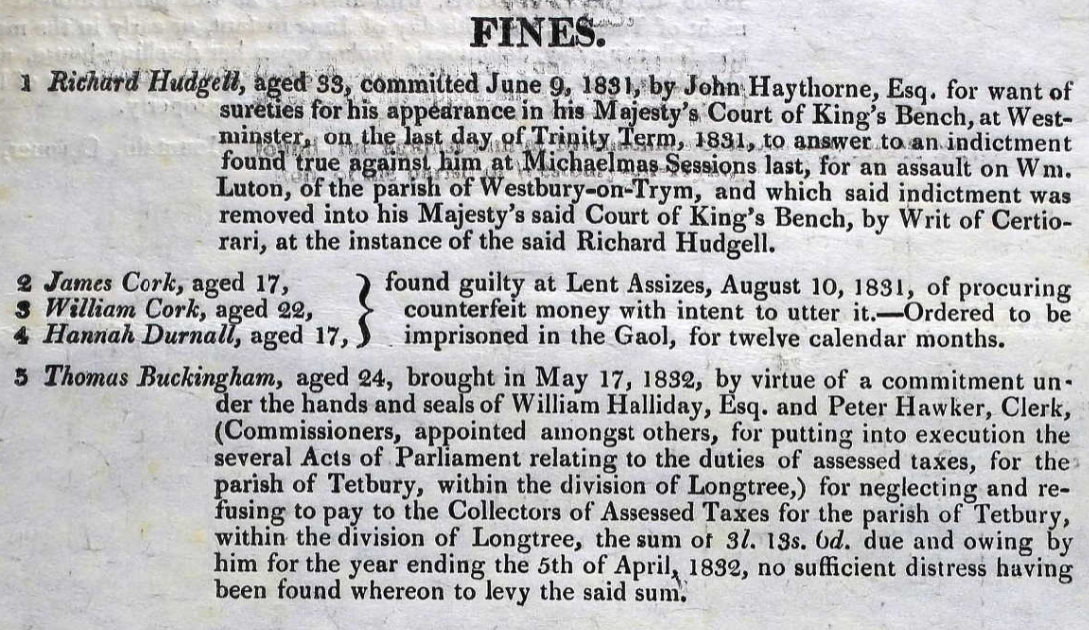

Henry emigrated with his daughter to Canada in 1913, and died in Vancouver in 1919.THOMAS BUCKINGHAM 1808-1846 (Isaacs daughter Janes husband) was charged with stealing a black gelding in Tetbury in 1838. No true bill. (A “no true bill” means the jury did not find probable cause to continue a case.)

Thomas did however neglect to pay his taxes in 1832:

LEWIN BUCKINGHAM (grandson of Isaac, his daughter Jane’s son) was found guilty in 1846 stealing two fowls in Tetbury when he was sixteen years old.

In 1846 he was sentence to one month hard labour (or pay ten shillings fine and ten shillings costs) for loitering with the intent to trespass in search of conies.

A year later in 1847, he and three other young men were sentenced to four months hard labour for larceny.

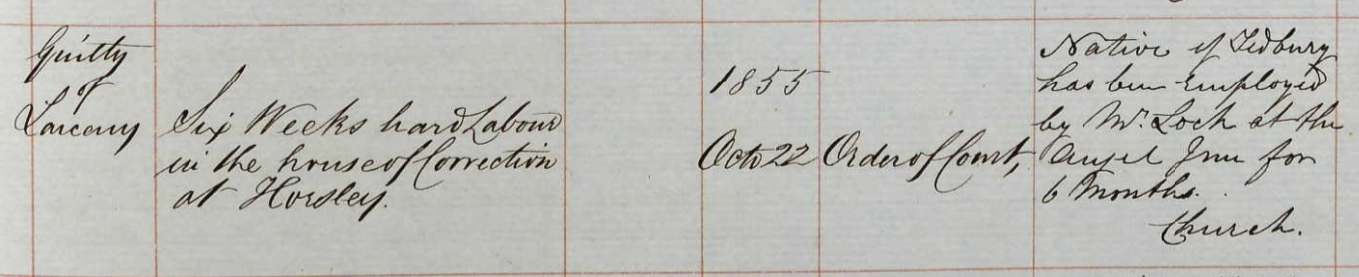

Lewin was five feet three inches tall, with brown hair and brown eyes, long visage, sallow complexion, and had a scar on his left arm.JOHN BUCKINGHAM born circa 1832, a Tetbury labourer (Isaac’s grandson, Lewin’s brother) was sentenced to six weeks hard labour for larceny in 1855 for stealing a duck in Cirencester. The notes on the register mention that he had been employed by Mr LOCK, Angel Inn. (John’s grandmother was Mary Lock so this is likely a relative).

The previous year in 1854 John was sentenced to one month or a one pound fine for assaulting and beating W. Wood.

John was five feet eight and three quarter inches tall, light brown hair and grey eyes, an oval visage and a fresh complexion. He had a scar on his left arm and inside his right knee.JOSEPH PERRET was born circa 1831 and he was a Tetbury labourer. (He was Isaac’s granddaughter Charlotte Buckingham’s husband)

In 1855 he assaulted William Wood and was sentenced to one month or a two pound ten shilling fine. Was it the same W Wood that his wifes cousin John assaulted the year before?

In 1869 Joseph was sentenced to one month hard labour for feloniously receiving a cupboard known to be stolen.JAMES BUCKINGAM born circa 1822 in Tetbury was a shoemaker. (Isaac’s nephew, his sister Hannah’s son)

In 1854 the Tetbury shoemaker was sentenced to four months hard labour for stealing 30 lbs of lead off someones house.

In 1856 the Tetbury shoemaker received two months hard labour or pay £2 fine and 12 s costs for being found in pursuit of game.

In 1868 he was sentenced to two months hard labour for stealing a gander. A unspecified previous conviction is noted.

1871 the Tetbury shoemaker was found in an outhouse for an unlawful purpose and received ten days hard labour. The register notes that his sister is Mrs Cook, the Green, Tetbury. (James sister Prudence married Thomas Cook)

James sister Charlotte married a shoemaker and moved to UTAH.

James was five feet eight inches tall, dark hair and blue eyes, a long visage and a florid complexion. He had a scar on his forehead and a mole on the right side of his neck and abdomen, and a scar on the right knee.November 10, 2022 at 10:59 am #6343In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

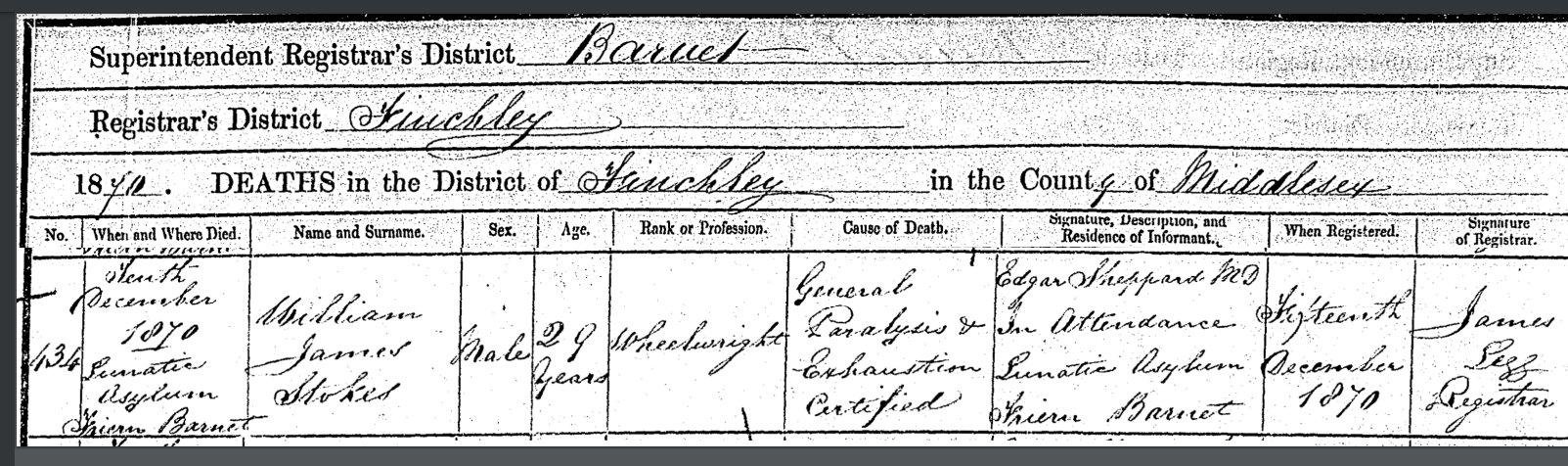

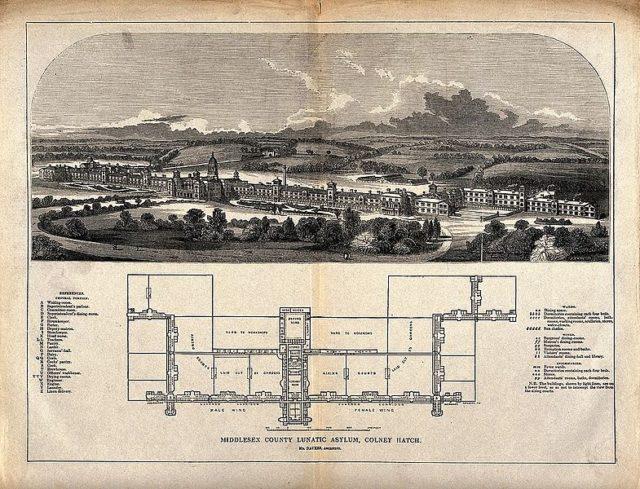

Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum

William James Stokes

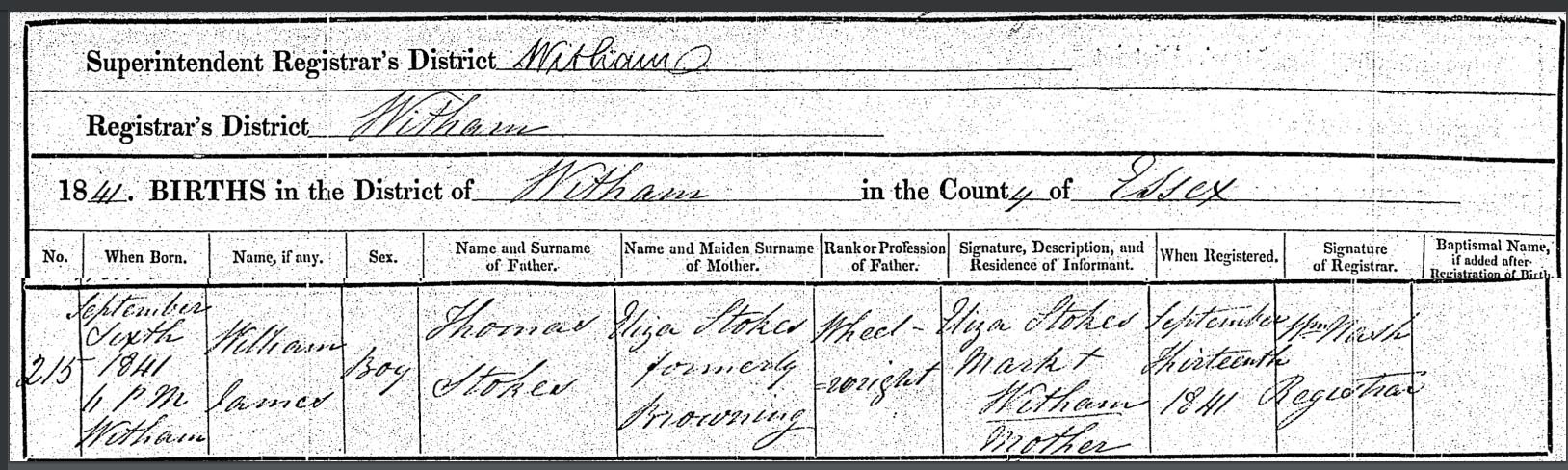

William James Stokes was the first son of Thomas Stokes and Eliza Browning. Oddly, his birth was registered in Witham in Essex, on the 6th September 1841.

Birth certificate of William James Stokes:

His father Thomas Stokes has not yet been found on the 1841 census, and his mother Eliza was staying with her uncle Thomas Lock in Cirencester in 1841. Eliza’s mother Mary Browning (nee Lock) was staying there too. Thomas and Eliza were married in September 1840 in Hempstead in Gloucestershire.

It’s a mystery why William was born in Essex but one possibility is that his father Thomas, who later worked with the Chipperfields making circus wagons, was staying with the Chipperfields who were wheelwrights in Witham in 1841. Or perhaps even away with a traveling circus at the time of the census, learning the circus waggon wheelwright trade. But this is a guess and it’s far from clear why Eliza would make the journey to Witham to have the baby when she was staying in Cirencester a few months prior.

In 1851 Thomas and Eliza, William and four younger siblings were living in Bledington in Oxfordshire.

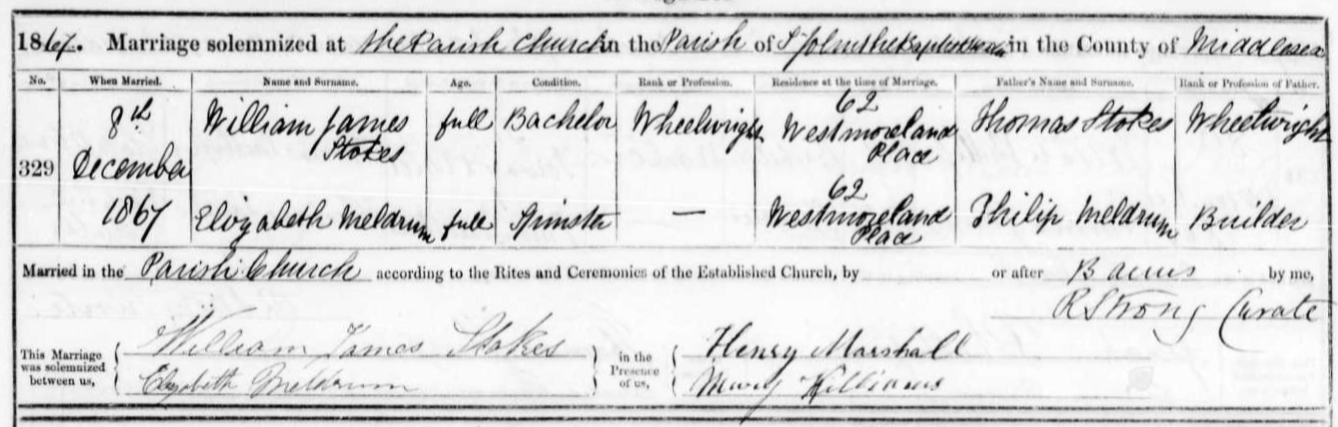

William was a 19 year old wheelwright living with his parents in Evesham in 1861. He married Elizabeth Meldrum in December 1867 in Hackney, London. He and his father are both wheelwrights on the marriage register.

Marriage of William James Stokes and Elizabeth Meldrum in 1867:

William and Elizabeth had a daughter, Elizabeth Emily Stokes, in 1868 in Shoreditch, London.