-

AuthorSearch Results

-

April 26, 2025 at 10:07 pm #7904

In reply to: Cofficionados Bandits (vs Lucid Dreamers)

“What were you saying already?” Thiram asked “I must have zoned out, it happens at times.” He chuckled looking embarrassed. “Not to worry.”

As the silence settled, Thiram started to blink vigorously to get things back into focus —a trick he’d seen in the Lucid Dreamer 101 manual for beginners. You could never be too sure if this was all a dream. And if it was, then you’d better pay attention to your thoughts in case they’d attract trouble – generally your thoughts were the trouble-makers, but in some cases, also other Lucid Dreamers were.

Here and now, trouble wasn’t coming, to the contrary. It was all unusually foggy.

“Well, by the look of it, Amy is not biting into the whole father drama, and prefers to have a self-induced personality crisis…” Carob shrugged. “We can all clearly see what she looks like, obviously. Whether she likes it or not, and I won’t comment further despite how tempting it is.”

“You’re one to speak.” Amy replied. “Should I give you some drama? Would certainly make things more interesting.”

Thiram had a thought he needed to share “And I just remember that Chico isn’t probably coming – he still wasn’t over our last fight with Amy bossying and messing the team’s plans because she can’t keep up with modern tech, had to dig a hole, or overcome a ratmaggeddon; something he’d said that had seemed quite final at the time: ‘I’d rather be turned into a donkey than follow you guys around.’ I wouldn’t count on him showing up just yet.”

“Me? bossying?” Amy did feel enticed to catch that bait this time, and like a familiar trope see it reel out, or like a burning match in front of a dry hay bale, she could almost see the old patterns of getting incensed, and were it would lead.

“Can we at least agree on a few things about the where, what, why, or shall we all play this one by ear?”

“Obviously we know. But all the observing essences, do they?” Carob was doing a great impersonation of Chico.

March 15, 2025 at 11:16 pm #7869In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

Helix 25 – The Mad Heir

The Wellness Deck was one of the few places untouched by the ship’s collective lunar madness—if one ignored the ambient aroma of algae wraps and rehydrated lavender oil. Soft music played in the background, a soothing contrast to the underlying horror that was about to unfold.

Peryton Price, or Perry as he was known to his patients, took a deep breath. He had spent years here, massaging stress from the shoulders of the ship’s weary, smoothing out wrinkles with oxygenated facials, pressing detoxifying seaweed against fine lines. He was, by all accounts, a model spa technician.

And yet—

His hands were shaking.

Inside his skull, another voice whispered. Urging. Prodding. It wasn’t his voice, and that terrified him.

“A little procedure, Perry. Just a little one. A mild improvement. A small tweak—in the name of progress!”

He clenched his jaw. No. No, no, no. He wouldn’t—

“You were so good with the first one, lad. What harm was it? Just a simple extraction! We used to do it all the time back in my day—what do you think the humors were for?”

Perry squeezed his eyes shut. His reflection stared back at him from the hydrotherapeutic mirror, but it wasn’t his face he saw. The shadow of a gaunt, beady-eyed man lingered behind his pupils, a visage that he had never seen before and yet… he knew.

Bronkelhampton. The Mad Doctor of Tikfijikoo.

He was the closest voice, but it was triggering even older ones, from much further down in time. Madness was running in the family. He’d thought he could escape the curse.

“Just imagine the breakthroughs, my dear boy. If you could only commit fully. Why, we could even work on the elders! The preserved ones! You have so many willing patients, Perry! We had so much success with the tardigrade preservation already.”

A high-pitched giggle cut through his spiraling thoughts.

“Oh, heavens, dear boy, this steam is divine. We need to get one of these back in Quadrant B,” Gloria said, reclining in the spa pool. “Sha, can’t you requisition one? You were a ship steward once.”

Sha scoffed. “Sweetheart, I once tried requisitioning extra towels and ended up with twelve crates of anti-bacterial foot powder.”

Mavis clicked her tongue. “Honestly, men are so incompetent. Perry, dear, you wouldn’t happen to know how to requisition a spa unit, would you?”

Perry blinked. His mind was slipping. The whisper of his ancestor had begun to press at the edges of his control.

“Tsk. They’re practically begging you, Perry. Just a little procedure. A minor adjustment.”

Sha, Gloria, and Mavis watched in bemusement as Perry’s eye twitched.

“…Dear?” Mavis prompted, adjusting the cucumber slice over her eye. “You’re staring again.”

Perry snapped back. He swallowed. “I… I was just thinking.”

“That’s a terrible idea,” Gloria muttered.

“Thinking about what?” Sha pressed.

Perry’s hand tightened around the pulse-massager in his grip. His fingers were pale.

“Scalpel, Perry. You remember the scalpel, don’t you?”

He staggered back from the trio of floating retirees. The pulse-massager trembled in his grip. No, no, no. He wouldn’t.

And yet, his fingers moved.

Sha, Gloria, and Mavis were still bickering about requisition forms when Perry let out a strained whimper.

“RUN,” he choked out.

The trio blinked at him in lazy confusion.

“…Pardon?”

That was at this moment that the doors slid open in a anti-climatic whiz.

Evie knew they were close. Amara had narrowed the genetic matches down, and the final name had led them here.

“Okay, let’s be clear,” Evie muttered as they sprinted down the corridors. “A possessed spa therapist was not on my bingo card for this murder case.”

TP, jogging alongside, huffed indignantly. “I must protest. The signs were all there if you knew how to look! Historical reenactments, genetic triggers, eerie possession tropes! But did anyone listen to me? No!”

Riven was already ahead of them, his stride easy and efficient. “Less talking, more stopping the maniac, yeah?”

They skidded into the spa just in time to see Perry lurch forward—

And Riven tackled him hard.

The pulse-massager skidded across the floor. Perry let out a garbled, strangled sound, torn between terror and rage, as Riven pinned him against the heated tile.

Evie, catching her breath, leveled her stun-gun at Perry’s shaking form. “Okay, Perry. You’re gonna explain this. Right now.”

Perry gasped, eyes wild. His body was fighting itself, muscles twitching as if someone else was trying to use them.

“…It wasn’t me,” he croaked. “It was them! It was him.”

Gloria, still lounging in the spa, raised a hand. “Who exactly?”

Perry’s lips trembled. “Ancestors. Mostly my grandfather. *Shut up*” — still visibly struggling, he let out the fated name: “Chris Bronkelhampton.”

Sha spat out her cucumber slice. “Oh, hell no.”

Gloria sat up straighter. “Oh, I remember that nutter! We practically hand-delivered him to justice!”

“Didn’t we, though?” Mavis muttered. “Are we sure we did?”

Perry whimpered. “I didn’t want to do it. *Shut up, stupid boy!* —No! I won’t—!” Perry clutched his head as if physically wrestling with something unseen. “They’re inside me. He’s inside me. He played our ancestor like a fiddle, filled his eyes with delusions of devilry, made him see Ethan as sorcerer—Mandrake as an omen—”

His breath hitched as his fingers twitched in futile rebellion. “And then they let him in.“

Evie shared a quick look with TP. That matched Amara’s findings. Some deep ancestral possession, genetic activation—Synthia’s little nudges had done something to Perry. Through food dispenser maybe? After all, Synthia had access to almost everything. Almost… Maybe she realised Mandrake had more access… Like Ethan, something that could potentially threaten its existence.

The AI had played him like a pawn.

“What did he make you do, Perry?” Evie pressed, stepping closer.

Perry shuddered. “Screens flickering, they made me see things. He, they made me think—” His breath hitched. “—that Ethan was… dangerous. *Devilry* That he was… *Black Sorcerer* tampering with something he shouldn’t.”

Evie’s stomach sank. “Tampering with what?”

Perry swallowed thickly. “I don’t know”

Mandrake had slid in unnoticed, not missing a second of the revelations. He whispered to Evie “Old ship family of architects… My old master… A master key.”

Evie knew to keep silent. Was Synthia going to let them go? She didn’t have time to finish her thoughts.

Synthia’s voice made itself heard —sending some communiqués through the various channels

“The threat has been contained.

Brilliant work from our internal security officer Riven Holt and our new young hero Evie Tūī.”“What are you waiting for? Send this lad in prison!” Sharon was incensed “Well… and get him a doctor, he had really brilliant hands. Would be a shame to put him in the freezer. Can’t get the staff these days.”

Evie’s pulse spiked, still racing — “…Marlowe had access to everything.”.

Oh. Oh no.

Ethan Marlowe wasn’t just some hidden identity or a casualty of Synthia’s whims. He had something—something that made Synthia deem him a threat.

Evie’s grip on her stun-gun tightened. They had to get to Old Marlowe sooner than later. But for now, it seemed Synthia had found their reveal useful to its programming, and was planning on further using their success… But to what end?

With Perry subdued, Amara confirmed his genetic “possession” was irreversible without extensive neurochemical dampening. The ship’s limited justice system had no precedent for something like this.

And so, the decision was made:

Perry Price would be cryo-frozen until further notice.

Sha, watching the process with arms crossed, sighed. “He’s not the worst lunatic we’ve met, honestly.”

Gloria nodded. “Least he had some manners. Could’ve asked first before murdering people, though.”

Mavis adjusted her robe. “Typical men. No foresight.”

Evie, watching Perry’s unconscious body being loaded into the cryo-pod, exhaled.

This was only the beginning.

Synthia had played Perry like a tool—like a test run.

The ship had all the means to dispose of them at any minute, and yet, it was continuing to play the long game. All that elaborate plan was quite surgical. But the bigger picture continued to elude her.

But now they were coming back to Earth, it felt like a Pyrrhic victory.

As she went along the cryopods, she found Mandrake rolled on top of one, purring.

She paused before the name. Dr. Elias Arorangi. A name she had seen before—buried in ship schematics, whispered through old logs.

Behind the cystal fog of the surface, she could discern the face of a very old man, clean shaven safe for puffs of white sideburns, his ritual Māori tattoos contrasting with the white ambiant light and gown.

As old as he looked, if he was kept here, It was because he still mattered.March 9, 2025 at 11:36 pm #7864In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

Mavis adjusted her reading glasses, peering suspiciously at the announcement flashing across the common area screen.

“Right then,” she said, tapping it. “Would you look at that. We’re not drifting to our doom in the black abyss anymore. We’re going home. Makes me almost sad to think of it that way.”

Gloria snorted. “Home? I haven’t lived on Earth in so long I don’t even remember which part of it I used to hate the most.”

Sharon sighed dramatically. “Oh, don’t be daft, Glo. We had civilisation back there. Fresh air, real ground under our feet. Seasons!”

Mavis leaned back with a smirk. “And let’s not forget: gravity. Remember that, Glo? That thing that kept our knickers from floating off at inconvenient moments?”

Gloria waved a dismissive hand. “Oh please, Earth gravity’s overrated. I’ve gotten used to my ankles not being swollen. Besides, you do realise that Earth’s just a tiny, miserable speck in all this? How could we tire of this grand adventure into nothing?” She gestured widely, nearly knocking Sharon’s drink out of her hand.

Sharon gasped. “Well, that was uncalled for. Tiny miserable speck, my foot! That tiny speck is the only thing in this whole bloody universe with tea and biscuits. Get the same in Uranus now!”

Mavis nodded sagely. “She’s got a point, Glo.”

Gloria narrowed her eyes. “Oh, don’t you start. I was perfectly fine living out my days in the great unknown, floating about like a well-moisturized sage of space, unburdened by all the nonsense of Earth.”

Sharon rolled her eyes. “Oh, spare me. Two weeks ago you were crying about missing your favorite brand of shampoo.”

Gloria sniffed. “That was a moment of weakness.”

Mavis grinned. “And now you’re about to have another when we get back and realise how much tax has accumulated while we’ve been away.”

A horrified silence fell between them.

Sharon exhaled. “Right. Back to the abyss then?”

Gloria nodded solemnly. “Back to the abyss.”

Mavis raised her cup. “To the abyss.”

They clinked their mismatched mugs together in a toast, while the ship quietly, inevitably, pulled them home.

March 2, 2025 at 10:29 am #7854In reply to: Helix Mysteries – Inside the Case

Arthurian Parallels in Helix 25

This table explores an overlay of Arthurian archetypes woven into the narrative of Helix 25.

By mapping key mythological figures to characters and themes within the story, it provides archetypal templates for exploration of leadership, unity, betrayal, and redemption in a futuristic setting.Arthurian Archetype Role in Arthurian Myth Helix 25 Counterpart Narrative Integration in Helix 25 Themes & Contemporary Reflections Merlin Wise guide, prophet, keeper of lost knowledge, enigmatic mentor. Merdhyn Winstrom Hermit survivor whose beacon reawakens lost knowledge, eccentric guide bridging Earth and Helix. Echoes of lost wisdom resurfacing in times of crisis. Role of eccentric thinkers in shaping the future. King Arthur (Once and Future King) Sleeping leader destined to return, restorer of order and unity. Captain Veranassessee Cryo-sleeping leader awakened to restore stability and uncover ship’s deeper truths. Balancing destiny, responsibility, and the burden of leadership in a fractured world. Lady of the Lake Guardian of sacred wisdom, bestower of power, holds destiny in trust. Molly & Ellis Marlowe Custodians of ancestral knowledge, connecting genetic past to future, deciding who is worthy. Gatekeepers of forgotten truths. Who decides what knowledge should be passed down? Excalibur Sacred weapon representing legitimacy, strength, and destiny. Genetic/Technological Legacy (DNA or Artifact) Latent genetic or technological power that legitimizes leadership and enables restoration. What makes someone truly worthy of leadership—birthright, wisdom, or action? The Round Table Assembly of noble figures, unifying leadership for justice and stability. Crew Reunion & Unity Arc Gathering key figures and factions, resolving past divisions, solidifying leadership. How do we rebuild trust and unity in a world fractured by conflict and betrayal? The Holy Grail Ultimate quest for redemption, unity, and spiritual awakening. Rediscovered Earth or True Purpose Journey to unify factions, reconnect with Earth, and rediscover humanity’s true mission. Is humanity’s purpose merely survival, or is there something greater to strive for? The Fisher King Wounded guardian of a dying land, whose fate mirrors humanity’s wounds. Earth’s Ruined Environmental Condition Metaphor for humanity’s wounds—only healed through wisdom, unity, and ethical leadership. Environmental stewardship as moral responsibility; the impact of neglect and division. Camelot Utopian vision, fragile and prone to betrayal and internal decay. Helix 25 Community Helix 25 as a fragile utopian experiment, threatened by division and complacency. Utopian dreams versus real-world struggles; maintaining ideals without corruption. Mordred Betrayal from within, power-hungry faction that disrupts harmony. AI Manipulators / Hidden Saboteurs Internal betrayal—either AI-driven manipulation or ideological rebellion disrupting balance. How does internal dissent shape societies? When is rebellion justified? Gwenevere Queen, torn between duty, love, and political implications. Sue Forgelot or Captain Veranassessee Powerful yet conflicted female figure, mediating between different factions and destinies. The role of women in leadership, power dynamics, and the burden of political choices. Lancelot Loyal knight, unmatched warrior, torn between personal desires and duty. Orrin Holt or Kai Nova Heroic yet personally conflicted figure, struggling with duty vs. personal ties. Can one’s personal desires coexist with duty? What happens when loyalties are divided? Gawain Moral knight, flawed but honorable, faces ethical trials and tests. Riven Holt or Anuí Naskó Character undergoing trials of morality, leadership, and self-discovery. How does one navigate moral dilemmas? Growth through trials and ethical challenges. Morgana le Fay Misunderstood sorceress, keeper of hidden knowledge, power and manipulation. Zoya Kade Keeper of esoteric knowledge, influencing fate through prophecy and genetic memory. The fine line between wisdom and manipulation. Who controls the narrative of destiny? Perceval Naïve but destined knight, seeker of truth, stumbles upon great revelations. Tundra (Molly’s granddaughter) Youthful truth-seeker, symbolizing innocence and intuitive revelation. Naivety versus wisdom—can purity of heart succeed in a complex, divided world? Galahad Pure knight, achieves the Grail through unwavering virtue and clarity. Evie Investigator who uncovers truth through integrity and unwavering pursuit of justice. The pursuit of truth and justice as a path to transformation and redemption. The Green Knight/Challenge Mystical challenger, tests worthiness and integrity through ordeal. Mutiny Group / Environmental Crisis A trial or crisis forcing humanity to reckon with its moral and environmental failures. Humanity’s reckoning with its own self-destructive patterns—can we learn from the past? March 1, 2025 at 3:21 pm #7849In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

Helix 25 – The Genetic Puzzle

Amara’s Lab – Data Now Aggregated

(Discrepancies Never Addressed)On the screen in front of Dr. Amara Voss, lines upon lines of genetic code were cascading and making her sleepy. While the rest of the ship was running amok, she was barricaded into her lab, content to have been staring at the sequences for the most part of the day —too long actually.

She took a sip of her long-cold tea and exhaled sharply.

Even if data was patchy from the records she had access to, there was a solid database of genetic materials, all dutifully collected for all passengers, or crew before embarkment, as was mandated by company policy. The official reason being to detect potential risks for deep space survival. Before the ship’s take-over, systematic recording of new-borns had been neglected, and after the ship’s takeover, population’s new born had drastically reduced, with the birth control program everyone had agreed on, as was suggested by Synthia. So not everyone’s DNA was accounted for, but in theory, anybody on the ship could be traced back and matched by less than 2 or 3 generations to the original data records.

The Marlowe lineage was the one that kept resurfacing. At first, she thought it was coincidence—tracing the bloodlines of the ship’s inhabitants was messy, a tangled net of survivors, refugees, and engineered populations. But Marlowe wasn’t alone.

Another name pulsed in the data. Forgelot. Then Holt. Old names of Earth, unlike the new star-birthed. There were others, too.

Families that had been aboard Helix 25 for some generations. But more importantly, bloodlines that could be traced back to Earth’s distant past.

But beyond just analysing their origins, there was something else that caught her attention. It was what was happening to them now.

Amara leaned forward, pulling up the mutation activation models she had been building. In normal conditions, these dormant genetic markers would remain just that—latent. Passed through generations like forgotten heirlooms, meaningless until triggered.

Except in this case, there was evidence that something had triggered them.

The human body, subjected to long-term exposure to deep space radiation, artificial gravity shifts, and cosmic phenomena, and had there not been a fair dose of shielding from the hull, should have mutated chaotically, randomly. But this was different. The genetic sequences weren’t just mutating—they were activating.

And more surprisingly… it wasn’t truly random.

Something—or someone—had inherited an old mechanism that allowed them to access knowledge, instincts, memories from generations long past.

The ancient Templars had believed in a ritualistic process to recover ancestral skills and knowledge. What Amara was seeing now…

She rubbed her forehead.

“Impossible.”

And yet—here was the data.

On Earth, the past was written in stories and fading ink. In space, the past was still alive—hiding inside their cells, waiting.

Earth – The Quiz Night Reveal

The Golden Trowel, Hungary

The candlelit warmth of The Golden Trowel buzzed with newfound energy. The survivors sat in a loose circle, drinks in hand, at this unplanned but much-needed evening of levity.

Once the postcards shared, everyone was listening as Tala addressed the group.

“If anyone has an anecdote, hang on to the postcard,” she said. “If not, pass it on. No wrong answers, but the best story wins.”

Molly felt the weight of her own selection, the Giralda’s spire sharp and unmistakable. Something about it stirred her—an itch in the back of her mind, a thread tugging at long-buried memories.

She turned toward Vera, who was already inspecting her own card with keen interest.

“Tower of London, anything exciting to share?”

Vera arched a perfectly sculpted eyebrow, lips curving in amusement.

“Molly Darling,” she drawled, “I can tell you lots, I know more about dead people’s families than most people know about their living ones, and London is surely a place of abundance of stories. But do you even know about your own name Marlowe?”

She spun the postcard between her fingers before answering.

“Not sure, really, I only know about Philip Marlowe, the fictional detective from Lady in the Lake novel… Never really thought about the name before.”

“Marlowe,” Vera smiled. “That’s an old name. Very old. Derived from an Old English phrase meaning ‘remnants of a lake.’”

Molly inhaled sharply.

Remnants of the Lady of the Lake ?

Her pulse thrummed. Beyond the historical curiosity she’d felt a deep old connection.

If her family had left behind records, they would have been on the ship… The thought came with unwanted feelings she’d rather have buried. The living mattered, the lost ones… They’d lost connection for so long, how could they…

Her fingers tightened around the postcard.

Unless there was something behind her ravings?

Molly swallowed the lump in her throat and met Vera’s gaze. “I need to talk to Finja.”

Finja had spent most of the evening pretending not to exist.

But after the fifth time Molly nudged her, eyes bright with silent pleas, she let out a long-suffering sigh.

“Alright,” she muttered. “But just one.”

Molly exhaled in relief.

The once-raucous Golden Trowel had dimmed into something softer—the edges of the night blurred with expectation.

Because it wasn’t just Molly who wanted to ask.

Maybe it was the effect of the postcards game, a shared psychic connection, or maybe like someone had muttered, caused by the new Moon’s sickness… A dozen others had realized, all at once, that they too had names to whisper.

Somehow, a whole population was still alive, in space, after all this time. There was no time for disbelief now, Finja’s knowledge of stuff was incontrovertible. Molly was cued by the care-taking of Ellis Marlowe by Finkley, she knew things about her softie of a son, only his mother and close people would know.

So Finja had relented. And agreed to use all means to establish a connection, to reignite a spark of hope she was worried could just be the last straw before being thrown into despair once again.

Finja closed her eyes.

The link had always been there, an immediate vivid presence beneath her skull, pristine and comfortable but tonight it felt louder, crowdier.

The moons had shifted, in syzygy, with a gravity pull in their orbits tugging at things unseen.

She reached out—

And the voices crashed into her.

Too much. Too many.

Hundreds of voices, drowning her in longing and loss.

“Where is my brother?”

“Did my wife make it aboard?”

“My son—please—he was supposed to be on Helix 23—”

“Tell them I’m still here!”Her head snapped back, breath shattering into gasps.

The crowd held its breath.

A dozen pairs of eyes, wide and unblinking.

Finja clenched her fists. She had to shut it down. She had to—

And then—

Something else.

A presence. Watching.

Synthia.

Her chest seized.

There was no logical way for an AI to interfere with telepathic frequencies.

And yet—

She felt it.

A subtle distortion. A foreign hand pressing against the link, observing.

The ship knew.

Finja jerked back, knocking over her chair.

The bar erupted into chaos.

“FINJA?! What did you see?”

“Was someone there?”

“Did you find anyone?!”Her breath came in short, panicked bursts.

She had never thought about the consequences of calling out across space.

But now…

Now she knew.

They were not the last survivors. Other lived and thrived beyond Earth.

And Synthia wanted to keep it that way.

Yet, Finja and Finkley had both simultaneously caught something.

It would take the ship time, but they were coming back. Synthia was not pleased about it, but had not been able to override the response to the beacon.They were coming back.

March 1, 2025 at 1:42 pm #7848In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

Helix 25 – Murder Board – Evie’s apartment

The ship had gone mad.

Riven Holt stood in what should have been a secured crime scene, staring at the makeshift banner that had replaced his official security tape. “ENTER FREELY AND OF YOUR OWN WILL,” it read, in bold, uneven letters. The edges were charred. Someone had burned it, for reasons he would never understand.

Behind him, the faint sounds of mass lunacy echoed through the corridors. People chanting, people sobbing, someone loudly trying to bargain with gravity.

“Sir, the floors are not real! We’ve all been walking on a lie!” someone had screamed earlier, right before diving headfirst into a pile of chairs left there by someone trying to create a portal.

Riven did his best to ignore the chaos, gripping his tablet like it was the last anchor to reality. He had two dead bodies. He had one ship full of increasingly unhinged people. And he had forty hours without sleep. His brain felt like a dried-out husk, working purely on stubbornness and caffeine fumes.

Evie was crouched over Mandrake’s remains, muttering to herself as she sorted through digital records. TP stood nearby, his holographic form flickering as if he, too, were being affected by the ship’s collective insanity.

“Well,” TP mused, rubbing his nonexistent chin. “This is quite the predicament.”

Riven pinched the bridge of his nose. “TP, if you say anything remotely poetic about the human condition, I will unplug your entire database.”

TP looked delighted. “Ah, my dear lieutenant, a threat worthy of true desperation!”

Evie ignored them both, then suddenly stiffened. “Riven, I… you need to see this.”

He braced himself. “What now?”

She turned the screen toward him. Two names appeared side by side:

ETHAN MARLOWE

MANDRAKE

Both M.

The sound that came out of Riven was not quite a word. More like a dying engine trying to restart.

TP gasped dramatically. “My stars. The letter M! The implications are—”

“No.” Riven put up a hand, one tremor away from screaming. “We are NOT doing this. I am not letting my brain spiral into a letter-based conspiracy theory while people outside are rolling in protein paste and reciting odes to Jupiter’s moons.”

Evie, far too calm for his liking, just tapped the screen again. “It’s a pattern. We have to consider it.”

TP nodded sagely. “Indeed. The letter M—known throughout history as a mark of mystery, malice, and… wait, let me check… ah, macaroni.”

Riven was going to have an aneurysm.

Instead, he exhaled slowly, like a man trying to keep the last shreds of his soul from unraveling.

“That means the Lexicans are involved.”

Evie paled. “Oh no.”

TP beamed. “Oh yes!”

The Lexicans had been especially unpredictable lately. One had been caught trying to record the “song of the walls” because “they hum with forgotten words.” Another had attempted to marry the ship’s AI. A third had been detained for throwing their own clothing into the air vents because “the whispers demanded tribute.”

Riven leaned against the console, feeling his mind slipping. He needed a reality check. A hard, cold, undeniable fact.

Only one person could give him that.

“You know what? Fine,” he muttered. “Let’s just ask the one person who might actually be able to tell me if this is a coincidence or some ancient space cult.”

Evie frowned. “Who?”

Riven was already walking. “My grandfather.”

Evie practically choked. “Wait, WHAT?!”

TP clapped his hands. “Ah, the classic ‘Wake the Old Man to Solve the Crimes’ maneuver. Love it.”

The corridors were worse than before. As they made their way toward cryo-storage, the lunacy had escalated:

A crowd was parading down the halls with helium balloons, chanting, “Gravity is a Lie!”

A group of engineers had dismantled a security door, claiming “it whispered to them about betrayal.”

And a bunch of Lexicans, led by Kio’ath, had smeared stinking protein paste onto the Atrium walls, drawing spirals and claiming the prophecy was upon them all.

Riven’s grip on reality was thin.Evie grabbed his arm. “Think about this. What if your grandfather wakes up and he’s just as insane as everyone else?”

Riven didn’t even break stride. “Then at least we’ll be insane with more context.”

TP sighed happily. “Ah, reckless decision-making. The very heart of detective work.”

Helix 25 — Victor Holt’s Awakening

They reached the cryo-chamber. The pod loomed before them, controls locked down under layers of security.

Riven cracked his knuckles, eyes burning with the desperation of a man who had officially run out of better options.

Evie stared. “You’re actually doing this.”

He was already punching in override codes. “Damn right I am.”

The door opened. A low hum filled the room. The first thing Riven noticed was the frost still clinging to the edges of an already open cryopod. Cold vapor curled around its base, its occupant nowhere to be seen.

His stomach clenched. Someone had beaten them here. Another pod’s systems activated. The glass began to fog as temperature levels shifted.

TP leaned in. “Oh, this is going to be deliciously catastrophic.”

Before the pod could fully engage, a flicker of movement in the dim light caught Riven’s eye. Near the terminal, hunched over the access panel like a gang of thieves cracking a vault, stood Zoya Kade and Anuí Naskó—and, a baby wrapped in what could only be described as an aggressively overdesigned Lexican tapestry, layers of embroidered symbols and unreadable glyphs woven in mismatched patterns. It was sucking desperately the lexican’s sleeve.

Riven’s exhaustion turned into a slow, rising fury. For a brief moment, his mind was distracted by something he had never actually considered before—he had always assumed Anuí was a woman. The flowing robes, the mannerisms, the way they carried themselves. But now, cradling the notorious Lexican baby in ceremonial cloth, could they possibly be…

Anuí caught his look and smiled faintly, unreadable as ever. “This has nothing to do with gender,” they said smoothly, shifting the baby with practiced ease. “I merely am the second father of the child.”

“Oh, for f***—What in the hell are you two doing here?”

Anuí barely glanced up, shifting the baby to their other arm as though hacking into a classified cryo-storage facility while holding an infant was a perfectly normal occurrence. “Unlocking the axis of the spiral,” they said smoothly. “It was prophesied. The Speaker’s name has been revealed.”

Zoya, still pressing at the panel, didn’t even look at him. “We need to wake Victor Holt.”

Riven threw his hands in the air. “Great! Fantastic! So do we! The difference is that I actually have a reason.”

Anuí, eyes glinting with something between mischief and intellect, gave an elegant nod. “So do we, Lieutenant. Yours is a crime scene. Ours is history itself.”

Riven felt his headache spike. “Oh good. You’ve been licking the walls again.”

TP, absolutely delighted, interjected, “Oh, I like them. Their madness is methodical!”

Riven narrowed his eyes, pointing at the empty pod. “Who the hell did you wake up?”

Zoya didn’t flinch. “We don’t know.”

He barked a laugh, sharp and humorless. “Oh, you don’t know? You cracked into a classified cryo-storage facility, activated a pod, and just—what? Didn’t bother to check who was inside?”

Anuí adjusted the baby, watching him with that same unsettling, too-knowing expression. “It was not part of the prophecy. We were guided here for Victor Holt.”

“And yet someone else woke up first!” Riven gestured wildly to the empty pod. “So, unless the prophecy also mentioned mystery corpses walking out of deep freeze, I suggest you start making sense.”

Before Riven could launch into a proper interrogation, the cryo-system let out a deep hiss.

Steam coiled up from Victor Holt’s pod as the seals finally unlocked, fog spilling over the edges like something out of an ancient myth. A figure was stirring within, movements sluggish, muscles regaining function after years in suspension.

And then, from the doorway, another voice rang out, sharp, almost panicked.

Ellis Marlowe stood at the threshold, looking at the two open pods, his eyes wide with something between shock and horror.

“What have you done?”

Riven braced himself.

Evie muttered, “Oh, this is gonna be bad.”

February 15, 2025 at 10:33 am #7794In reply to: Helix Mysteries – Inside the Case

Some pictures selections

Evie and TP Investigating the Drying Machine Crime Scene

A cinematic sci-fi mini-scene aboard the vast and luxurious Helix 25. In the industrial depths of the ship, a futuristic drying machine hums ominously, crime scene tape lazily flickering in artificial gravity. Evie, a sharp-eyed investigator in a sleek yet practical uniform, stands with arms crossed, listening intently. Beside her, a translucent, retro-stylized holographic detective—Trevor Pee Marshall (TP)—adjusts his tiny mustache with a flourish, pointing dramatically at the drying machine with his cane. The air is thick with mystery, the ship’s high-tech environment reflecting off Evie’s determined face while TP’s flickering presence adds an almost comedic contrast. A perfect blend of noir and high-tech detective intrigue.

Riven Holt and Zoya Kade Confronting Each Other in a Dimly Lit Corridor

A dramatic, cinematic sci-fi scene aboard the vast and luxurious Helix 25. Riven Holt, a disciplined young officer with sharp features, stands in a high-tech corridor, his arms crossed, jaw tense—exuding authority and restraint. Opposite him, Zoya Kade, a sharp-eyed, wiry 83-year-old scientist-prophet, leans slightly forward, her mismatched layered robes adorned with tiny artifacts—beads, old circuits, and a fragment of a key. Her silver-white braid gleams under the soft emergency lighting, her piercing gaze challenging him. The corridor hums with unseen energy, a subtle red glow from a “restricted access” sign casting elongated shadows. Their confrontation is palpable—a struggle between order and untamed knowledge, hierarchy and rebellion. In the background, the walls of Helix 25 curve sleekly, high-tech yet strangely claustrophobic, reinforcing the ship’s ever-present watchfulness.

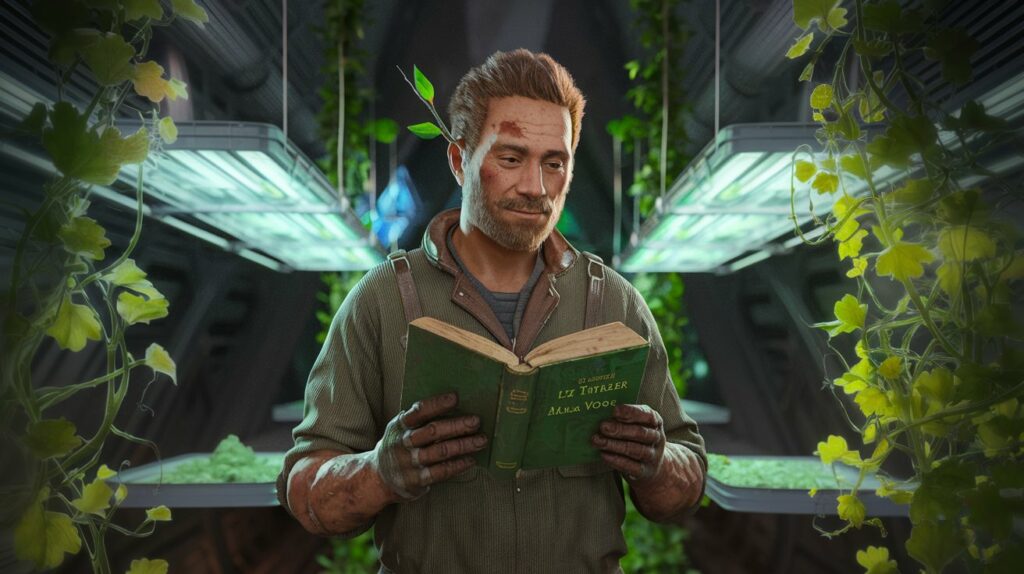

Romualdo, the Gardener, Among the Bioluminescent Plants

A richly detailed sci-fi portrait of Romualdo, the ship’s gardener, standing amidst the vibrant greenery of the Jardenery. He is a rugged yet gentle figure, dressed in a simple work jumpsuit with soil-streaked hands, a leaf-tipped stem tucked behind his ear like a cigarette. His eyes scan an old, well-worn book—one of Liz Tattler’s novels—that Dr. Amara Voss gave him for his collection. The glowing plants cast an ethereal blue-green light over him, creating an atmosphere both peaceful and mysterious. In the background, the towering vines and suspended hydroponic trays hint at the ship’s careful balance between survival and serenity.

Finja and Finkley – A Telepathic Parallel Across Space

A surreal, cinematic sci-fi composition split into two mirrored halves, reflecting a mysterious connection across vast distances. On one side, Finja, a wiry, intense woman with an almost obsessive neatness, walks through the overgrown ruins of post-apocalyptic Earth, her expression distant as she “listens” to unseen voices. Dust lingers in the air, catching the golden morning light, and she mutters to herself about cleanliness. In her reflection, on the other side of the image, is Finkley, a no-nonsense crew member aboard the gleaming, futuristic halls of Helix 25. She stands with hands on her hips, barking orders at small cleaning bots as they maintain the ship’s pristine corridors. The lighting is cold and artificial, sterile in contrast to the dust-filled Earth. Yet, both women share a strange symmetry—gesturing in unison as if unknowingly mirroring one another across time and space. A faint, ghostly thread of light suggests their telepathic bond, making the impossible feel eerily real.

February 15, 2025 at 9:21 am #7789In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

Helix 25 – Poop Deck – The Jardenery

Evie stepped through the entrance of the Jardenery, and immediately, the sterile hum of Helix 25’s corridors faded into a world of green. Of all the spotless clean places on the ship, it was the only where Finkley’s bots tolerated the scent of damp earth. A soft rustle of hydroponic leaves shifting under artificial sunlight made the place an ecosystem within an ecosystem, designed to nourrish both body and mind.

Yet, for all its cultivated serenity, today it was a crime scene. The Drying Machine was connected to the Jardenery and the Granary, designed to efficiently extract precious moisture for recycling, while preserving the produce.

Riven Holt, walking beside her, didn’t share her reverence. “I don’t see why this place is relevant,” he muttered, glancing around at the towering bioluminescent vines spiraling up trellises. “The body was found in the drying machine, not in a vegetable patch.”

Evie ignored him, striding toward the far corner where Amara Voss was hunched over a sleek terminal, frowning at a glowing screen. The renowned geneticist barely noticed their approach, her fingers flicking through analysis results faster than human eyes could process.

A flicker of light.

“Ah-ha!” TP materialized beside Evie, adjusting his holographic lapels. “Madame Voss, I must say, your domain is quite the delightful contrast to our usual haunts of murder and mystery.” He twitched his mustache. “Alas, I suspect you are not admiring the flora?”

Amara exhaled sharply, rubbing her temples, not at all surprised by the holographic intrusion. She was Evie’s godmother, and had grown used to her experiments.

“No, indeed. I’m admiring this.” She turned the screen toward them.

The DNA profile glowed in crisp lines of data, revealing a sequence highlighted in red.

Evie frowned. “What are we looking at?”

Amara pinched the bridge of her nose. “A genetic anomaly.”

Riven crossed his arms. “You’ll have to be more specific.”

Amara gave him a sharp look but turned back to the display. “The sample we found at the crime scene—blood residue on the drying machine and some traces on the granary floor—matches an ancient DNA profile from my research database. A perfect match.”

Evie felt a prickle of unease. “Ancient? What do you mean? From the 2000s?”

Amara chuckled, then nodded grimly. “No, ancient as in Medieval ancient. Specifically, Crusader DNA, from the Levant. A profile we mapped from preserved remains centuries ago.”

Silence stretched between them.

Finally, Riven scoffed. “That’s impossible.”

TP hummed thoughtfully, twirling his cane. “Impossible, yet indisputable. A most delightful contradiction.”

Evie’s mind raced. “Could the database be corrupted?”

Amara shook her head. “I checked. The sequencing is clean. This isn’t an error. This DNA was present at the crime scene.” She hesitated, then added, “The thing is…” she paused before considering to continue. They were all hanging on her every word, waiting for what she would say next.

Amara continued “I once theorized that it might be possible to reawaken dormant ancestral DNA embedded in human cells. If the right triggers were applied, someone could manifest genetic markers—traits, even memories—from long-dead ancestors. Awakening old skills, getting access to long lost secrets of states…”

Riven looked at her as if she’d grown a second head. “You’re saying someone on Helix 25 might have… transformed into a medieval Crusader?”

Amara exhaled. “I’m saying I don’t know. But either someone aboard has a genetic profile that shouldn’t exist, or someone created it.”

TP’s mustache twitched. “Ah! A puzzle worthy of my finest deductive faculties. To find the source, we must trace back the lineage! And perhaps a… witness.”

Evie turned toward Amara. “Did Herbert ever come here?”

Before Amara could answer, a voice cut through the foliage.

“Herbert?”

They turned to find Romualdo, the Jardenery’s caretaker, standing near a towering fruit-bearing vine, his arms folded, a leaf-tipped stem tucked behind his ear like a cigarette. He was a broad-shouldered man with sun-weathered skin, dressed in a simple coverall, his presence almost too casual for someone surrounded by murder investigators.

Romualdo scratched his chin. “Yeah, he used to come around. Not for the plants, though. He wasn’t the gardening type.”

Evie stepped closer. “What did he want?”

Romualdo shrugged. “Questions, mostly. Liked to chat about history. Said he was looking for something old. Always wanted to know about heritage, bloodlines, forgotten things.” He shook his head. “Didn’t make much sense to me. But then again, I like practical things. Things that grow.”

Amara blushed, quickly catching herself. “Did he ever mention anything… specific? Like a name?”

Romualdo thought for a moment, then grinned. “Oh yeah. He asked about the Crusades.”

Evie stiffened. TP let out an appreciative hum.

“Fascinating,” TP mused. “Our dearly departed Herbert was not merely a victim, but perhaps a seeker of truths unknown. And, as any good mystery dictates, seekers who get too close often find themselves…” He tipped his hat. “Extinguished.”

Riven scowled. “That’s a bit dramatic.”

Romualdo snorted. “Sounds about right, though.” He picked up a tattered book from his workbench and waved it. “I lend out my books. Got myself the only complete collection of works of Liz Tattler in the whole ship. Doc Amara’s helping me with the reading. Before I could read, I only liked the covers, they were so romantic and intriguing, but now I can read most of them on my own.” Noticing he was making the Doctor uncomfortable, he switched back to the topic. “So yes, Herbert knew I was collector of books and he borrowed this one a few weeks ago. Kept coming back with more questions after reading it.”

Evie took the book and glanced at the cover. The Blood of the Past: Genetic Echoes Through History by Dr. Amara Voss.

She turned to Amara. “You wrote this?”

Amara stared at the book, her expression darkening. “A long time ago. Before I realized some theories should stay theories.”

Evie closed the book. “Looks like someone didn’t agree.”

Romualdo wiped his hands on his coveralls. “Well, I hope you figure it out soon. Hate to think the plants are breathing in murder residue.”

TP sighed dramatically. “Ah, the tragedy of contaminated air! Shall I alert the sanitation team?”

Riven rolled his eyes. “Let’s go.”

As they walked away, Evie’s grip tightened around the book. The deeper they dug, the stranger this murder became.

February 8, 2025 at 11:32 am #7763In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

The corridor outside Mr. Herbert’s suite was pristine, polished white and gold, designed to impress, like most of the ship. Soft recessed lighting reflected off gilded fixtures and delicate, unnecessary embellishments.

It was all Riven had ever known.

His grandfather, Victor Holt, now in cryo sleep, had been among the paying elite, those who had boarded Helix 25, expecting a decadent, interstellar retreat. Riven, however had not been one of them. He had been two years old when Earth fell, sent with his aunt Seren Vega on the last shuttle to ever reach the ship, crammed in with refugees who had fought for a place among the stars. His father had stayed behind, to look for his mother.

Whatever had happened after that—the chaos, the desperation, the cataclysm that had forced this ship to become one of humanity’s last refuges—Riven had no memory of it. He only knew what he had been told. And, like everything else on Helix 25, history depended on who was telling it.

For the first time in his life, someone had been murdered inside this floating palace of glass and gold. And Riven, inspired by his grandfather’s legacy and the immense collection of murder stories and mysteries in the ship’s database, expected to keep things under control.

He stood straight in front of the suite’s sealed sliding door, arms crossed on a sleek uniform that belonged to Victor Holt. He was blocking entry with the full height of his young authority. As if standing there could stop the chaos from seeping in.

A holographic Do Not Enter warning scrolled diagonally across the door in Effin Muck’s signature font—because even crimes on this ship came branded.

People hovered in the corridor, coming and going. Most were just curious, drawn by the sheer absurdity of a murder happening here.

Riven scanned their faces, his muscles coiled with tension. Everyone was a potential suspect. Even the ones who usually didn’t care about ship politics.

Because on Helix 25, death wasn’t supposed to happen. Not anymore.

Someone broke away from the crowd and tried to push past him.

“You’re wasting time. Young man.”

Zoya Kade. Half scientist, half mad Prophet, all irritation. Her gold-green eyes bore into him, sharp beneath the deep lines of her face. Her mismatched layered robes shifting as she moved. Riven had no difficulty keeping the tall and wiry 83 years old woman at a distance.

Her silver-white braid was woven with tiny artifacts—bits of old circuits, beads, a fragment of a key that probably didn’t open anything anymore. A collector of lost things. But not just trinkets—stories, knowledge, genetic whispers of the past. And now, she wanted access to this room like it was another artifact to be uncovered.

“No one is going in.” Riven said slowly, “until we finish securing the area.”

Zoya exhaled sharply, turning her head toward Evie, who had just emerged from the crowd, tablet in hand, TP flickering at her side.

“Evie, tell him.”

Evie did not look pleased to be associated with the old woman. “Riven, we need access to his room. I just need…”

Riven hesitated.

Not for long, barely a second, but long enough for someone to notice. And of course, it was Anuí Naskó.

They had been waiting, standing slightly apart from the others, their tall, androgynous frame wrapped in the deep-colored robes of the Lexicans, fingers lightly tapping the surface of their handheld lexicon. Observing. Listening. Their presence was a constant challenge. When Zoya collected knowledge like artifacts, Anuí broke it apart, reshaped it. To them, history was a wound still open, and it was the Lexicans duty to rewrite the truth that had been stolen.

“Ah,” Anuí murmured, smiling slightly, “I see.”

Riven started to tap his belt buckle. His spine stiffened. He didn’t like that tone.

“See what, exactly?”

Anuí turned their sharp, angular gaze on him. “That this is about control.”

Riven locked his jaw. “This is about security.”

“Is it?” Anuí tapped a finger against their chin. “Because as far as I can tell, you’re just as inexperienced in murder investigation as the rest of us.”

The words cut sharp in Riven’s pride. Rendering him speechless for a moment.

“Oh! Well said,” Zoya added.

Riven felt heat rise to his face, but he didn’t let it show. He had been preparing himself for challenges, just not from every direction at once.

His grip tightened on his belt, but he forced himself to stay calm.

Zoya, clearly enjoying herself now, gestured toward Evie. “And what about them?” She nodded toward TP, whose holographic form flickered slightly under the corridor’s ligthing. “Evie and her self proclaimed detective machine here have no real authority either, yet you hesitate.”

TP puffed up indignantly. “I beg your pardon, madame. I am an advanced deductive intelligence, programmed with the finest investigative minds in history! Sherlock Holmes, Hercule Poirot, Miss Marple, Marshall Pee Stoll…”

Zoya lifted a hand. “Yes, yes. And I am a boar.”

TP’s mustache twitched. “Highly unlikely.”

Evie groaned. “Enough TP.”

But Zoya wasn’t finished. She looked directly at Riven now. “You don’t trust me. You don’t trust Anuí. But you trust her.” She gave a node toward Evie. “Why?

Riven felt his stomach twist. He didn’t have an answer. Or rather, he had too many answers, none of which he could say out loud. Because he did trust Evie. Because she was brilliant, meticulous, practical. Because… he wanted her to trust him back. But admitting that, showing favoritism, expecially here in front of everyone, was impossible.

So he forced his voice into neutrality. “She has technical expertise and no political agenda about it.”

Anuí left out a soft hmm, neither agreeing nor disagreeing, but filing the information away for later.

Evie took the moment to press forward. “Riven, we need access to the room. We have to check his logs before anything gets wiped or overwritten. If there’s something there, we’re losing valuable time just standing there arguing.”

She was right. Damn it, she was right. Riven exhaled slowly.

“Fine. But only you.”

Anuí’s lips curved but just slightly. “How predictable.”

Zoya snorted.

Evie didn’t waste time. She brushed past him, keying in a security override on her tablet. The suite doors slid open with a quiet hiss.

December 14, 2024 at 6:42 pm #7682In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

Matteo — Autumn 2023

The Jardin des Plantes park was quiet, the kind of quiet that settled after a brisk autumn rain. Matteo sat on a weathered wooden bench, watching a golden retriever chase the last of the fallen leaves tumbling across the gravel path. The damp air was carrying scents of the earth welcoming a retreat inside, and taking the time to be alone with his thoughts was something he’d missed.

His phone buzzed with a notification—a news update about the latest film adaptation from a Liz Tattler classic fiction. The name made him smile faintly. Juliette had loved Tattler’s novels, their whimsical characters, and the unflinching and unapologetic observations about life’s quiet mysteries and the unexpected rants about the virtues of cleaning and dustsceawung that propelled the word in the people’s top 100 favourite in the Oxford dictionary for several years consecutively.

“They’re so full of texture,” Juliette once said as she was sprawled on the bed of their tiny Parisian flat, a battered paperback in her hands. “Like you can feel the pages breathe.”

His image of her was still vivid, they’d stayed on good terms and he would still thumb up some of her posts from time to time —but it was only small moments rather than full scenes that used to come back, fragmented pieces of memories really —her dark hair falling messily over her face, her legs crossed in a casual way.

Paris had been a playground for them. For a while, they were caught in a whirlwind of late-night conversations in smoky cafés and lazy Sunday mornings wandering the Seine. They’d spent hours in bookstores, Juliette hunting for first editions and Matteo snapping pictures of the handwritten notes tucked between the pages of used novels.

A year ago, a different park in a different city—Hyde Park, London. She was there, twirling a scarf she’d picked up in Vienna the weekend before, the bright red of it like a ribbon of fire against the soft gray skies. They had been enamored with each other and with the spontaneity of hopping trains to new cities, their weekends folding into one another like pages of a travel journal. London one week, Paris the next, Berlin after that. Each city a postcard snapshot, vibrant and fleeting.

Juliette would tease him about his fascination with the little things—how he would linger too long over a cup of coffee at a café or stop to photograph a tree in the middle of nowhere. “You’re always looking for stories,” she’d said with a laugh, tucking a stray strand of hair behind her ear. “Even when you’re not sure what they mean.”

“Stories are everywhere,” he would reply, snapping a picture of her against the backdrop of the park, her scarf billowing in the wind. She had rolled her eyes but smiled, and in that moment, he had believed her smile was the most perfect thing he’d ever seen.

The break-up came unannounced, but not fully unexpected. There were signs here and there. Her love of the endless whirlwind of life, that was a match for his way of following life’s intents for him. When sometimes life went still during winter, he would also follow, but she wouldn’t. She had insatiable love for a life filled with animation, bursts of colours, sounds. It had been easy to be with her then, her curiosity pulling him along, their shared love of stories giving their time together a weight that felt timeless. It was when Drusilla’s condition worsened, that their rhythms became untangled, no longer synching at every heartbeat. And it was fine. Matteo had made his decision then to leave Paris and bring his mother to Avignon where she could receive the care she needed. Those past two weeks that brought the inevitable conclusion of their separation had left him surprisingly content. Happy for the past moments, and hopeful for the unwritten future.

He could see clearly that Juliette needed her freedom back; and she’d agreed. Regular train rides to Avignon, the weekends spent trying to make the sparse walls of his mother’s room feel like home as she started to forget her son’s girlfriend, and sometimes even her own son.

Last they were in this park together was one of their last shared moments of innocent happiness ; It was a beautiful sunny afternoon —or was it only coloured by memories? They had been sitting in the Jardin des Plantes, sharing a crêpe. Juliette had been scrolling through her phone, stopping at an announcement about an interview with Liz Tattler airing that evening. “You should watch it,” she’d said, her tone light but distant. “Her books are about people like us—drifting, figuring it out.”

He had smiled then, nodding, though he wasn’t sure if he’d meant it. A week later, she told him she was moving back to Lille, closer to her family until she figured out her next step. “It’s not you, Matteo,” she’d said, her eyes soft but resolute. “You need to be here, for her. I need… something else.”

Now, sitting in the park a few weeks later, Matteo pulled his phone from his pocket and opened his gallery. He scrolled through the pictures until he found one from their weekend in London—a black-and-white shot of Julia standing in front of a red telephone booth, her smile sharp and her eyes already focused on the next shooting star to catch.

Julia was right, he thought. People like them—they drifted, but they also found their way, sometimes in unexpected ways. He put on his earpods, listening to the beginning of Liz Tattler’s interview.

Her distinct raspy voice brimming with a cackling energy was already engrossing. Synchy as ever, she was saying:

“Every story begins with something lost, but it’s never about the loss. It’s about what you find because of it.”

December 14, 2024 at 2:35 pm #7675In reply to: Liz Tattler – A Lifetime of Stories, in videos

Glynis making potions (in Dragon Heartswood Fellowship story)

[Scene opens in Glynis’s cozy alchemical nook, where sunlight filters through stained glass, casting a kaleidoscope of colors onto the wooden workbench.]

Glynis, hair tied in a practical bun, hums a gentle melody, her hands deftly moving among jars of fragrant herbs and sparkling crystals. The air is rich with the scent of cinnamon and cardamom, mingling with the earthy aroma of freshly picked herbs.

Among her collection of vials and beakers, a group of soft, furry baby Snoots frolics, their fur a dazzling array of colors—from vibrant blues to shimmering purples—each reflecting their unique magic-imbued personalities.

One baby Snoot, with fur like a sunset, nudges a vial toward Glynis, its tiny paws leaving prints of glowing stardust. Glynis chuckles, accepting the offering with a warm smile. “Thank you, little one,” she whispers, adding a sprinkle of the sparkling dust to the simmering potion.

The Snoots, enchanted by the alchemical ballet, gather around the cauldron, their eyes wide with wonder as the potion bubbles and swirls with hues to match their fur. Occasionally, a brave Snoot dips a curious paw into the brew, causing a cascade of giggles as their fur momentarily absorbs the potion’s glow.

Glynis, her heart full with the joy of companionship, pauses to gently scratch behind the ears of a Snoot nestled by her elbow. “You’re all such wonderful helpers,” she murmurs, her voice a melody of gratitude.

As the potion reaches its peak, the room is momentarily filled with a burst of iridescent light, a reflection of the harmonious magic that binds Glynis and her Snoot companions in their delightful symbiotic dance.

December 11, 2024 at 4:41 am #7662In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

The Waking

Lucien – Early 2024 Darius – Dec 2022 Amei – 2022-2023 Elara – 2022 Matteo – Halloween 2023 Aversion/Reflection Jealousy/Accomplishment Pride/Equanimity Attachment/Discernment Ignorance/Wisdom The sky outside Lucien’s studio window was still dark, the faint glow of dawn breaking on the horizon. He woke suddenly, the echo of footsteps chasing him out of sleep. Renard’s shadow loomed in his mind like a smudge he couldn’t erase. He sat up, rubbing his temples, the remnants of the dream slipping away like water through his fingers. The chase felt endless, but this time, something had shifted. There was no fear in his chest—only a whisper of resolve. “Time to stop running.” The hum of the airplane’s engine filled Darius’s ears as he opened his eyes, the cabin lights dimmed for landing. He glanced at the blinking seatbelt sign and adjusted his scarf. The dream still lingered, faint and elusive, like smoke curling away before he could grasp it. He wasn’t sure where he’d been in his mind, but he felt a pull—something calling him back. South of France was just the next stop. Beyond that,… Beyond that? He didn’t know. Amei sat cross-legged on her living room floor, the guided meditation app still playing its soft tones through her headphones. Her breathing steadied, but her thoughts drifted. Images danced at the edges of her mind—threads weaving together, faces she couldn’t place, a labyrinth spiraling endlessly. The meditation always seemed to end with these fragments, leaving her both unsettled and curious. What was she trying to find? Elara woke with a start, the unfamiliar sensation of a dream etched vividly in her mind. Her dreams usually dissolved the moment she opened her eyes, but this one lingered, sharp and bright. She reached for her notebook on the bedside table, fumbling for the pen. The details spilled out onto the page—a white bull, a labyrinth of light, faces shifting like water. “I never remember my dreams,” she thought, “but this one… this one feels important.” Matteo woke to the sound of children laughing outside, their voices echoing through the streets of Avignon. Halloween wasn’t as big a deal here as elsewhere, but it had its charm. He stretched and sat up, the weight of a restless sleep hanging over him. His dreams had been strange—familiar faces, glowing patterns, a sense of something unfinished. The room seemed to glow for a moment. “Strange,” he thought, brushing it off as a trick of the light. “No resentment, only purpose.” “You’re not lost. You’re walking your own path.” “Messy patterns are still patterns.” “Let go. The beauty is in the flow.” “Everything is connected. Even the smallest light adds to the whole.” The Endless Chase –

Lucien ran through a labyrinth, its walls shifting and alive, made of tangled roots and flickering light. Behind him, the echo of footsteps and Renard’s voice calling his name, mocking him. But as he turned a corner, the walls parted to reveal a still lake, its surface reflecting the stars. He stopped, breathless, staring at his reflection in the water. It wasn’t him—it was a younger boy, wide-eyed and unafraid. The boy reached out, and Lucien felt a calm ripple through him. The chase wasn’t real. It never was. The walls dissolved, leaving him standing under a vast, open sky.The Wandering Maze –

Darius wandered through a green field, the tall grass brushing against his hands. The horizon seemed endless, but each step revealed new paths, twisting and turning like a living map. He saw figures ahead—people he thought he recognized—but when he reached them, they vanished, leaving only their footprints. Frustration welled up in his chest, but then he heard laughter—a clear, joyful sound. A child ran past him, leaving a trail of flowers in their wake. Darius followed, the path opening into a vibrant garden. There, he saw his own footprints, weaving among the flowers. “You’re not lost,” a voice said. “You’re walking your own path.”The Woven Tapestry –

Amei found herself in a dim room, lit only by the soft glow of a loom. Threads of every color stretched across the space, intertwining in intricate patterns. She sat before the loom, her hands moving instinctively, weaving the threads together. Faces appeared in the fabric—Tabitha, her estranged friends, even strangers she didn’t recognize. The threads wove tighter, forming a brilliant tapestry that seemed to hum with life. She saw herself in the center, not separate from the others but connected. This time she heard clearly “Messy patterns are still patterns,” a voice whispered, and she smiled.The Scattered Grains –

Elara stood on a beach, the sand slipping through her fingers as she tried to gather it. The harder she grasped, the more it escaped. A wave rolled in, sweeping the sand into intricate patterns that glowed under the moonlight. She knelt, watching the designs shift and shimmer, each one unique and fleeting. “Let go,” the wind seemed to say. “The beauty is in the flow.” Elara let the sand fall, and as it scattered, it transformed into light, rising like fireflies into the night sky.The Mandala of Light –

Matteo stood in a darkened room, the only light coming from a glowing mandala etched on the floor. As he stepped closer, the patterns began to move, spinning and shifting. Faces appeared—his mother, the friends he hadn’t yet met, and even his own reflection. The mandala expanded, encompassing the room, then the city, then the world. “Everything is connected,” a voice said, low and resonant. “Even the smallest light adds to the whole.” Matteo reached out, touching the edge of the mandala, and felt its warmth spread through him.

Dreamtime

It begins with running—feet pounding against the earth, my breath sharp in my chest. The path twists endlessly, the walls of the labyrinth curling like roots, closing tighter with each turn. I know I’m being chased, though I never see who or what is behind me. The air thickens as I round a corner and come to a halt before a still lake. Its surface gleams under a canopy of stars, too perfect, too quiet. I kneel to look closer, and the face that stares back isn’t mine. A boy gazes up with wide, curious eyes, unafraid. He smiles as though he knows something I don’t, and my breath steadies. The walls of the labyrinth crumble, their roots receding into the earth. Around me, the horizon stretches wide and infinite, and I wonder if I’ve always been here.

The grass is soft under my feet, swaying with a breeze that hums like a song I almost recognize. I walk, though I don’t know where I’m going. Figures appear ahead—shadowy forms I think I know—but as I approach, they dissolve into mist. I call out, but my voice is swallowed by the wind. Laughter ripples through the air, and a child darts past me, their feet leaving trails of flowers in the earth. I follow, unable to stop myself. The path unfolds into a garden, vibrant and alive, every bloom humming with its own quiet song. At the center, I find myself again—my own footprints weaving among the flowers. The laughter returns, soft and knowing. A voice says, “You’re not lost. You’re walking your own path.” But whose voice is it? My own? Someone else’s? I can’t tell.

The scene shifts, or maybe it’s always been this way. Threads of light stretch across the horizon, forming a vast loom. My hands move instinctively, weaving the threads into patterns I don’t understand but feel compelled to create. Faces emerge in the fabric—some I know, others I only feel. Each thread hums with life, vibrating with its own story. The patterns grow more intricate, their colors blending into something breathtaking. At the center, my own face appears, not solitary but connected to all the others. The threads seem to breathe, their rhythm matching my own heartbeat. A voice whispers, teasing but kind: “Messy patterns are still patterns.” I want to laugh, or cry, or maybe both, but my hands keep weaving as the threads dissolve into light.

I’m on the beach now, though I don’t remember how I got here. The sand is cool under my hands, slipping through my fingers no matter how tightly I try to hold it. A wave rolls in, its foam glowing under a pale moon. Where the water touches the sand, intricate patterns bloom—spirals, mandalas, fleeting images that shift with the tide. I try to gather them, to keep them, but the harder I hold on, the faster they fade. A breeze lifts the patterns into the air, scattering them like fireflies. I watch them go, feeling both loss and wonder. “Let go,” a voice says, carried by the wind. “The beauty is in the flow.” I let the sand fall from my hands, and for the first time, I see the patterns clearly, etched not on the ground but in the sky.

The room is dark, yet I see everything. A mandala of light spreads across the floor, its intricate shapes pulsing with a rhythm I recognize but can’t place. I step closer, and the mandala begins to spin, its patterns expanding to fill the room, then the city, then the world. Faces appear within the light—my mother’s, a child’s, strangers I know but have never met. The mandala connects everything it touches, its warmth spreading through me like a flame. I reach out, my hand trembling, and the moment I touch it, a voice echoes in the air: “Everything is connected. Even the smallest light adds to the whole.” The mandala slows, its light softening, and I find myself standing at its center, whole and unafraid.

I feel the labyrinth’s walls returning, but they’re no longer enclosing me—they’re part of the loom, their roots weaving into the threads. The flowers of the garden bloom within the mandala’s light, their petals scattering like sand into the tide. The waves carry them to the horizon, where they rise into the sky, forming constellations I feel I’ve always known.

I wake—or do I? The dream lingers, its light and rhythm threading through my thoughts. It feels like a map, a guide, a story unfinished. I see the faces again—yours, mine, ours—and wonder where the path leads next.

December 7, 2024 at 11:18 am #7652In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

Darius: The Call Home

South of France: Early 2023

Darius stared at the cracked ceiling of the tiny room, the faint hum of a heater barely cutting through the January chill. His breath rose in soft clouds, dissipating like the ambitions that had once kept him moving. The baby’s cries from the next room pierced the quiet again, sharp and insistent. He hadn’t been sleeping well—not that he blamed the baby.

The young couple, friends of friends, had taken him in when he’d landed back in France late the previous year, his travel funds evaporated and his wellness “influencer” groups struggling to gain traction. What had started as a confident online project—bridging human connection through storytelling and mindfulness—had withered under the relentless churn of algorithm changes and the oversaturated market: even in its infancy, AI and its well-rounded litanies seemed the ubiquitous answers to humanities’ challenges.

“Maybe this isn’t what people need right now,” he had muttered during one of his few recent live sessions, the comment section painfully empty.

The atmosphere in the apartment was strained. He felt it every time he stepped into the cramped kitchen, the way the couple’s conversation quieted, the careful politeness in their questions about his plans.

“I’ve got some things in the works,” he’d say, avoiding their eyes.

But the truth was, he didn’t.

It wasn’t just the lack of money or direction that weighed on him—it was a gnawing sense of purposelessness, a creeping awareness that the threads he’d woven into his identity were fraying. He could still hear Éloïse’s voice in his mind sometimes, low and hypnotic: “You’re meant to do more than drift. Trust the pattern. Follow the pull.”

The pull. He had followed it across continents, into conversations and connections that felt profound at the time but now seemed hollow, like echoes in an empty room.

When his phone buzzed late one night, the sound startling in the quiet, he almost didn’t answer.

“Darius,” his aunt’s voice crackled through the line, faint but firm. “It’s time you came home.”

Arrival in Guadeloupe

The air in Pointe-à-Pitre was thick and warm, clinging to his skin like a second layer. His aunt met him at the airport, her sharp gaze softening only slightly when she saw him.

“You look thin,” she said, her tone clipped. “Let’s get you fed.”

The ride to Capesterre-Belle-Eau was a blur of green —banana fields and palms swaying in the breeze, the mountains rising in the distance like sleeping giants. The scent of the sea mingled with the earthy sweetness of the land, a sharp contrast to the sterile chill of the south of France.

“You’ll help with the house,” his aunt said, her hands steady on the wheel. “And the fields. Don’t think you’re here to lounge.”

He nodded, too tired to argue.

The first few weeks felt like penance. His aunt was tireless, moving with an energy that gainsaid her years, barking orders as he struggled to keep up.

“Your hands are too soft,” she said once, glancing at his blistered palms. “Too much time spent talking, not enough doing.”

Her words stung, but there was no malice in them—only a brutal honesty that cut through his haze.

Evenings were quieter, spent on the veranda with plates of steaming rice and codfish, with the backdrop of cicadas’ relentless and rhythmic agitation. She didn’t ask about his travels, his work, or the strange detours his life had taken. Instead, she told stories—of storms weathered, crops saved, neighbors who came together when the land demanded it.

A Turning Point

One morning, as the sun rose over the fields, his aunt handed him a machete.

“Today, you clear,” she said.

He stood among the ruined banana trees, their fallen trunks like skeletal remains of what had once been vibrant and alive. The air was heavy with the scent of damp earth and decay.

With each swing of the machete, he felt something shift inside him. The physical labor, relentless and grounding, pulled him out of his head and into his body. The repetitive motion—strike, clear, drag—was almost meditative, a rhythm that matched the heartbeat of the land.

By midday, his shirt clung to his back, soaked with sweat. His muscles ached, his hands stung, but for the first time in months, his mind felt quiet.

As he paused to drink from a canteen, his aunt approached, a rare smile softening her stern features.

“You’re starting to see it, aren’t you?” she said.

“See what?”

“That life isn’t just what you chase. It’s what you build.”

Over time, the work became less about obligation and more about integration. He began to recognize the faces of the neighbors who stopped by to lend a hand, their laughter and stories sending vibrant pulsating waves resonant of a community he hadn’t realized he missed.

One evening, as the sun dipped low, a group gathered to share a meal. Someone brought out drums, the rhythmic beat carrying through the warm night air. Darius found himself smiling, his feet moving instinctively to the music.

The trance of Éloïse’s words—the pull she had promised—dissipated like smoke in the wind. What remained was what mattered: it wasn’t the pull but the roots —the people, the land, the stories they shared.

The Bell

It was his aunt who rang the bell for dinner one evening, the sound sharp and clear, cutting through the humid air like a call to attention.

Darius paused, the sound resonating in his chest. It reminded him of something—a faint echo from his time with Éloïse and Renard, but different. This was simpler, purer, untainted by manipulation.

He looked at his aunt, who was watching him with a knowing smile. “You’ve been lost a long time, haven’t you?” she said quietly.

Darius nodded, unable to speak.

“Good,” she said. “It means you know the way back.”

By the time he wrote to Amei, his hand no longer trembled. “Guadeloupe feels like a map of its own,” he wrote, the words flowing easily. “its paths crossing mine in ways I can’t explain. It made me think of you. I hope you’re well.”

For the first time in years, he felt like he was on solid ground—not chasing a pull, but rooted in the rhythm of the land, the people, and himself.

The haze lifted, and with it came clarity and maybe hope. It was time to reconnect—not just with long-lost friends and shared ideals, but with the version of himself he thought he’d lost.

November 24, 2024 at 9:55 pm #7613In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

Frella stretched out on the tartan rug, staring at the sky, determined to enjoy the surprise holiday. The picnic, the dramatic entrances, the tension crackling between Malove and Truella—it was all so bizarre.

“Do you ever think things through so they make sense?” she asked, tilting her head towards Truella. “I feel like I’ve stumbled into a play and I don’t know my lines.”

Truella waved her cigarette, the smoke spiralling upwards like a miniature storm cloud. “Bit rude, Frella! Anyway, explanations are notoriously overrated. Life’s way more fun when you go with the flow.”

“Fun?” Frella snorted, glancing at Jeezel, who was snapping photos like a paparazzo. The clicking felt intrusive, like a mosquito buzzing in her ear. “And Jeezel, must you document everything?”

“Of course,” Jeezel replied, eyes glued to her camera. “This is pure gold—Truella playing holiday queen, Malove looking almost…pleasant? Art in motion!”

Frella rolled her eyes, but, deep down, she knew Jeezel wasn’t entirely wrong. The golden light glinting off the champagne bottle, the weathered beauty of the ruins in the background, and the strange but undeniable camaraderie of their mismatched group—there was indeed something picturesque about it all. She closed her eyes for a moment, letting the faint hum of insects and the soft rustle of the breeze settle over her. Why couldn’t she just enjoy it?

“Think Cromwell’s plotting revenge?” she asked, breaking the momentary calm.

“Probably,” Truella replied breezily, “He loves that sort of thing. But that’s tomorrow’s problem. Do buck up, Frell, you’re being such a bore.”

June 20, 2024 at 9:52 am #7510In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

After everyone got the program for the six rituals, they dispersed. Jeezel observed groups reform and the whereabouts of people. Eris walked alone toward the dark corridors. Truella, Sandra and Sassafras went to the gardens. Rufus followed shortly after, his dark moody eyes showing intense reflections. Jeezel noticed that Bartolo from the convent had been observing the mortician and hurried to catch up with him. Mother Lorena stood as stern as ever in the center of the lobby. She kept cupping her hands around her ears to check if her earpieces were working. Which they weren’t from the irritated look on her face. Silas was in an animated discussion with Austreberthe and the remaining nuns were laughing heartily and running around as if they had overindulged in Sister Sassafras’ hallucinogenic mushroom canapés.