-

AuthorSearch Results

-

January 28, 2022 at 1:10 pm #6260

In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

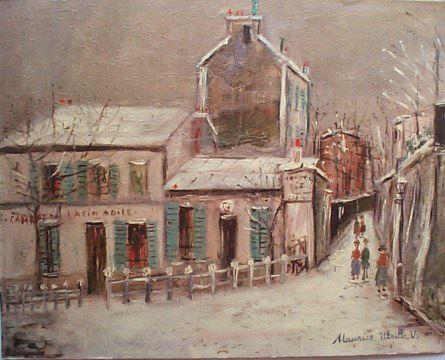

From Tanganyika with Love

With thanks to Mike Rushby.

- “The letters of Eleanor Dunbar Leslie to her parents and her sister in South Africa

concerning her life with George Gilman Rushby of Tanganyika, and the trials and

joys of bringing up a family in pioneering conditions.

These letters were transcribed from copies of letters typed by Eleanor Rushby from

the originals which were in the estate of Marjorie Leslie, Eleanor’s sister. Eleanor

kept no diary of her life in Tanganyika, so these letters were the living record of an

important part of her life.Prelude

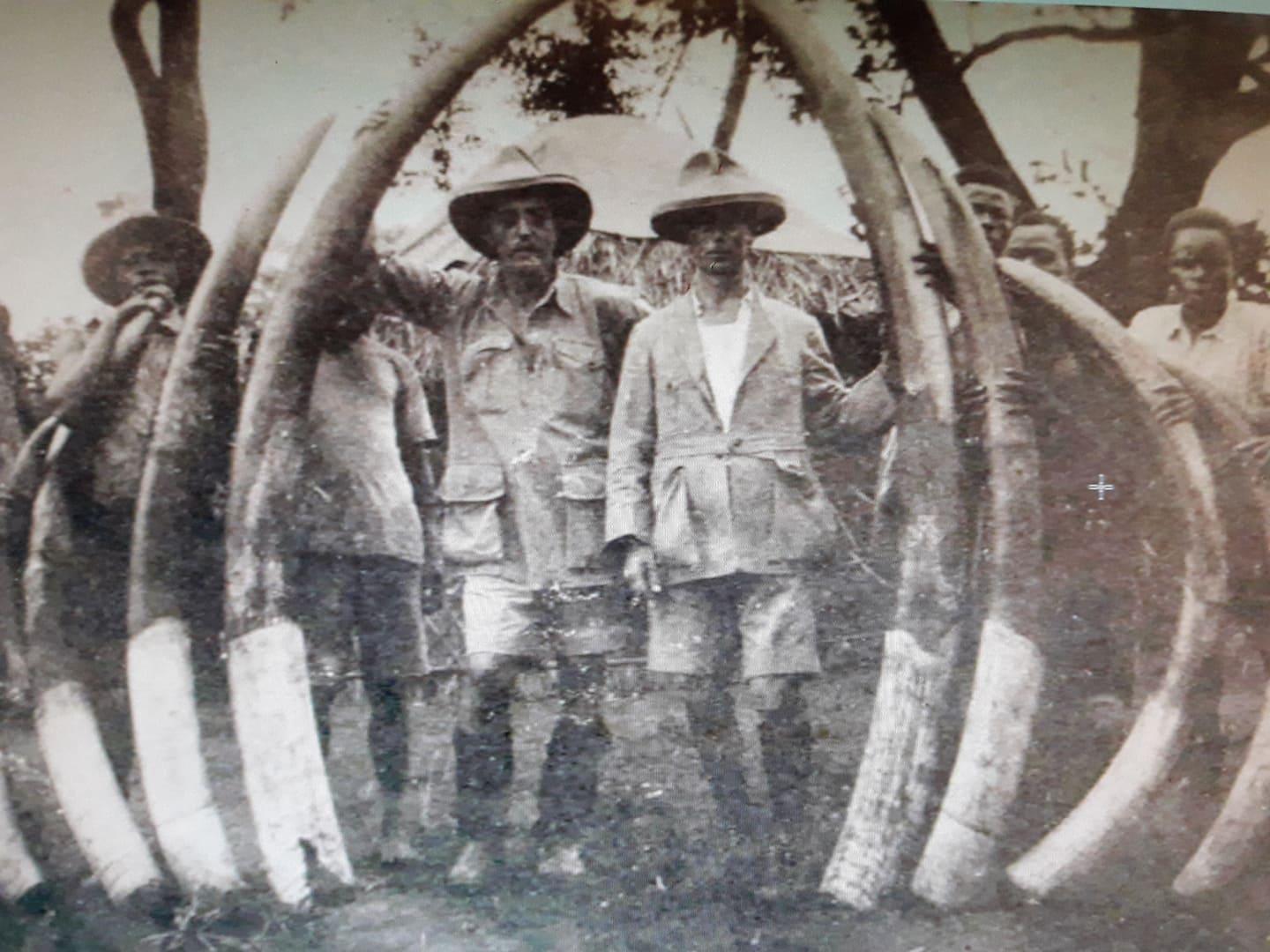

Having walked across Africa from the East coast to Ubangi Shauri Chad

in French Equatorial Africa, hunting elephant all the way, George Rushby

made his way down the Congo to Leopoldville. He then caught a ship to

Europe and had a holiday in Brussels and Paris before visiting his family

in England. He developed blackwater fever and was extremely ill for a

while. When he recovered he went to London to arrange his return to

Africa.Whilst staying at the Overseas Club he met Eileen Graham who had come

to England from Cape Town to study music. On hearing that George was

sailing for Cape Town she arranged to introduce him to her friend

Eleanor Dunbar Leslie. “You’ll need someone lively to show you around,”

she said. “She’s as smart as paint, a keen mountaineer, a very good school

teacher, and she’s attractive. You can’t miss her, because her father is a

well known Cape Town Magistrate. And,” she added “I’ve already written

and told her what ship you are arriving on.”Eleanor duly met the ship. She and George immediately fell in love.

Within thirty six hours he had proposed marriage and was accepted

despite the misgivings of her parents. As she was under contract to her

High School, she remained in South Africa for several months whilst

George headed for Tanganyika looking for a farm where he could build

their home.These details are a summary of chapter thirteen of the Biography of

George Gilman Rushby ‘The Hunter is Death “ by T.V.Bulpin.Dearest Marj,

Terrifically exciting news! I’ve just become engaged to an Englishman whom I

met last Monday. The result is a family upheaval which you will have no difficulty in

imagining!!The Aunts think it all highly romantic and cry in delight “Now isn’t that just like our

El!” Mummy says she doesn’t know what to think, that anyway I was always a harum

scarum and she rather expected something like this to happen. However I know that

she thinks George highly attractive. “Such a nice smile and gentle manner, and such

good hands“ she murmurs appreciatively. “But WHY AN ELEPHANT HUNTER?” she

ends in a wail, as though elephant hunting was an unmentionable profession.

Anyway I don’t think so. Anyone can marry a bank clerk or a lawyer or even a

millionaire – but whoever heard of anyone marrying anyone as exciting as an elephant

hunter? I’m thrilled to bits.Daddy also takes a dim view of George’s profession, and of George himself as

a husband for me. He says that I am so impulsive and have such wild enthusiasms that I

need someone conservative and steady to give me some serenity and some ballast.

Dad says George is a handsome fellow and a good enough chap he is sure, but

he is obviously a man of the world and hints darkly at a possible PAST. George says

he has nothing of the kind and anyway I’m the first girl he has asked to marry him. I don’t

care anyway, I’d gladly marry him tomorrow, but Dad has other ideas.He sat in his armchair to deliver his verdict, wearing the same look he must wear

on the bench. If we marry, and he doesn’t think it would be a good thing, George must

buy a comfortable house for me in Central Africa where I can stay safely when he goes

hunting. I interrupted to say “But I’m going too”, but dad snubbed me saying that in no

time at all I’ll have a family and one can’t go dragging babies around in the African Bush.”

George takes his lectures with surprising calm. He says he can see Dad’s point of

view much better than I can. He told the parents today that he plans to buy a small

coffee farm in the Southern Highlands of Tanganyika and will build a cosy cottage which

will be a proper home for both of us, and that he will only hunt occasionally to keep the

pot boiling.Mummy, of course, just had to spill the beans. She said to George, “I suppose

you know that Eleanor knows very little about house keeping and can’t cook at all.” a fact

that I was keeping a dark secret. But George just said, “Oh she won’t have to work. The

boys do all that sort of thing. She can lie on a couch all day and read if she likes.” Well

you always did say that I was a “Lily of the field,” and what a good thing! If I were one of

those terribly capable women I’d probably die of frustration because it seems that

African house boys feel that they have lost face if their Memsahibs do anything but the

most gracious chores.George is absolutely marvellous. He is strong and gentle and awfully good

looking too. He is about 5 ft 10 ins tall and very broad. He wears his curly brown hair cut

very short and has a close clipped moustache. He has strongly marked eyebrows and

very striking blue eyes which sometimes turn grey or green. His teeth are strong and

even and he has a quiet voice.I expect all this sounds too good to be true, but come home quickly and see for

yourself. George is off to East Africa in three weeks time to buy our farm. I shall follow as

soon as he has bought it and we will be married in Dar es Salaam.Dad has taken George for a walk “to get to know him” and that’s why I have time

to write such a long screed. They should be back any minute now and I must fly and

apply a bit of glamour.Much love my dear,

your jubilant

EleanorS.S.Timavo. Durban. 28th.October. 1930.

Dearest Family,

Thank you for the lovely send off. I do wish you were all on board with me and

could come and dance with me at my wedding. We are having a very comfortable

voyage. There were only four of the passengers as far as Durban, all of them women,

but I believe we are taking on more here. I have a most comfortable deck cabin to

myself and the use of a sumptuous bathroom. No one is interested in deck games and I

am having a lazy time, just sunbathing and reading.I sit at the Captain’s table and the meals are delicious – beautifully served. The

butter for instance, is moulded into sprays of roses, most exquisitely done, and as for

the ice-cream, I’ve never tasted anything like them.The meals are continental type and we have hors d’oeuvre in a great variety

served on large round trays. The Italians souse theirs with oil, Ugh! We also of course

get lots of spaghetti which I have some difficulty in eating. However this presents no

problem to the Chief Engineer who sits opposite to me. He simply rolls it around his

fork and somehow the spaghetti flows effortlessly from fork to mouth exactly like an

ascending escalator. Wine is served at lunch and dinner – very mild and pleasant stuff.

Of the women passengers the one i liked best was a young German widow

from South west Africa who left the ship at East London to marry a man she had never

met. She told me he owned a drapers shop and she was very happy at the prospect

of starting a new life, as her previous marriage had ended tragically with the death of her

husband and only child in an accident.I was most interested to see the bridegroom and stood at the rail beside the gay

young widow when we docked at East London. I picked him out, without any difficulty,

from the small group on the quay. He was a tall thin man in a smart grey suit and with a

grey hat perched primly on his head. You can always tell from hats can’t you? I wasn’t

surprised to see, when this German raised his head, that he looked just like the Kaiser’s

“Little Willie”. Long thin nose and cold grey eyes and no smile of welcome on his tight

mouth for the cheery little body beside me. I quite expected him to jerk his thumb and

stalk off, expecting her to trot at his heel.However she went off blithely enough. Next day before the ship sailed, she

was back and I saw her talking to the Captain. She began to cry and soon after the

Captain patted her on the shoulder and escorted her to the gangway. Later the Captain

told me that the girl had come to ask him to allow her to work her passage back to

Germany where she had some relations. She had married the man the day before but

she disliked him because he had deceived her by pretending that he owned a shop

whereas he was only a window dresser. Bad show for both.The Captain and the Chief Engineer are the only officers who mix socially with

the passengers. The captain seems rather a melancholy type with, I should say, no

sense of humour. He speaks fair English with an American accent. He tells me that he

was on the San Francisco run during Prohibition years in America and saw many Film

Stars chiefly “under the influence” as they used to flock on board to drink. The Chief

Engineer is big and fat and cheerful. His English is anything but fluent but he makes up

for it in mime.I visited the relations and friends at Port Elizabeth and East London, and here at

Durban. I stayed with the Trotters and Swans and enjoyed myself very much at both

places. I have collected numerous wedding presents, china and cutlery, coffee

percolator and ornaments, and where I shall pack all these things I don’t know. Everyone has been terribly kind and I feel extremely well and happy.At the start of the voyage I had a bit of bad luck. You will remember that a

perfectly foul South Easter was blowing. Some men were busy working on a deck

engine and I stopped to watch and a tiny fragment of steel blew into my eye. There is

no doctor on board so the stewardess put some oil into the eye and bandaged it up.

The eye grew more and more painful and inflamed and when when we reached Port

Elizabeth the Captain asked the Port Doctor to look at it. The Doctor said it was a job for

an eye specialist and telephoned from the ship to make an appointment. Luckily for me,

Vincent Tofts turned up at the ship just then and took me off to the specialist and waited

whilst he extracted the fragment with a giant magnet. The specialist said that I was very

lucky as the thing just missed the pupil of my eye so my sight will not be affected. I was

temporarily blinded by the Belladona the eye-man put in my eye so he fitted me with a

pair of black goggles and Vincent escorted me back to the ship. Don’t worry the eye is

now as good as ever and George will not have to take a one-eyed bride for better or

worse.I have one worry and that is that the ship is going to be very much overdue by

the time we reach Dar es Salaam. She is taking on a big wool cargo and we were held

up for three days in East london and have been here in Durban for five days.

Today is the ninth Anniversary of the Fascist Movement and the ship was

dressed with bunting and flags. I must now go and dress for the gala dinner.Bless you all,

Eleanor.S.S.Timavo. 6th. November 1930

Dearest Family,

Nearly there now. We called in at Lourenco Marques, Beira, Mozambique and

Port Amelia. I was the only one of the original passengers left after Durban but there we

took on a Mrs Croxford and her mother and two men passengers. Mrs C must have

something, certainly not looks. She has a flat figure, heavily mascared eyes and crooked

mouth thickly coated with lipstick. But her rather sweet old mother-black-pearls-type tells

me they are worn out travelling around the world trying to shake off an admirer who

pursues Mrs C everywhere.The one male passenger is very quiet and pleasant. The old lady tells me that he

has recently lost his wife. The other passenger is a horribly bumptious type.

I had my hair beautifully shingled at Lourenco Marques, but what an experience it

was. Before we docked I asked the Captain whether he knew of a hairdresser, but he

said he did not and would have to ask the agent when he came aboard. The agent was

a very suave Asian. He said “Sure he did” and offered to take me in his car. I rather

doubtfully agreed — such a swarthy gentleman — and was driven, not to a hairdressing

establishment, but to his office. Then he spoke to someone on the telephone and in no

time at all a most dago-y type arrived carrying a little black bag. He was all patent

leather, hair, and flashing smile, and greeted me like an old and valued friend.

Before I had collected my scattered wits tthe Agent had flung open a door and

ushered me through, and I found myself seated before an ornate mirror in what was only

too obviously a bedroom. It was a bedroom with a difference though. The unmade bed

had no legs but hung from the ceiling on brass chains.The agent beamingly shut the door behind him and I was left with my imagination

and the afore mentioned oily hairdresser. He however was very business like. Before I

could say knife he had shingled my hair with a cut throat razor and then, before I could

protest, had smothered my neck in stinking pink powder applied with an enormous and

filthy swansdown powder puff. He held up a mirror for me to admire his handiwork but I

was aware only of the enormous bed reflected in it, and hurriedly murmuring “very nice,

very nice” I made my escape to the outer office where, to my relief, I found the Chief

Engineer who escorted me back to the ship.In the afternoon Mrs Coxford and the old lady and I hired a taxi and went to the

Polana Hotel for tea. Very swish but I like our Cape Peninsula beaches better.

At Lorenco Marques we took on more passengers. The Governor of

Portuguese Nyasaland and his wife and baby son. He was a large middle aged man,

very friendly and unassuming and spoke perfect English. His wife was German and

exquisite, as fragile looking and with the delicate colouring of a Dresden figurine. She

looked about 18 but she told me she was 28 and showed me photographs of two

other sons – hefty youngsters, whom she had left behind in Portugal and was missing

very much.It was frightfully hot at Beira and as I had no money left I did not go up to the

town, but Mrs Croxford and I spent a pleasant hour on the beach under the Casurina

trees.The Governor and his wife left the ship at Mozambique. He looked very

imposing in his starched uniform and she more Dresden Sheperdish than ever in a

flowered frock. There was a guard of honour and all the trimmings. They bade me a warm farewell and invited George and me to stay at any time.The German ship “Watussi” was anchored in the Bay and I decided to visit her

and try and have my hair washed and set. I had no sooner stepped on board when a

lady came up to me and said “Surely you are Beeba Leslie.” It was Mrs Egan and she

had Molly with her. Considering Mrs Egan had not seen me since I was five I think it was

jolly clever of her to recognise me. Molly is charming and was most friendly. She fixed

things with the hairdresser and sat with me until the job was done. Afterwards I had tea

with them.Port Amelia was our last stop. In fact the only person to go ashore was Mr

Taylor, the unpleasant man, and he returned at sunset very drunk indeed.

We reached Port Amelia on the 3rd – my birthday. The boat had anchored by

the time I was dressed and when I went on deck I saw several row boats cluttered

around the gangway and in them were natives with cages of wild birds for sale. Such tiny

crowded cages. I was furious, you know me. I bought three cages, carried them out on

to the open deck and released the birds. I expected them to fly to the land but they flew

straight up into the rigging.The quiet male passenger wandered up and asked me what I was doing. I said

“I’m giving myself a birthday treat, I hate to see caged birds.” So next thing there he

was buying birds which he presented to me with “Happy Birthday.” I gladly set those

birds free too and they joined the others in the rigging.Then a grinning steward came up with three more cages. “For the lady with

compliments of the Captain.” They lost no time in joining their friends.

It had given me so much pleasure to free the birds that I was only a little

discouraged when the quiet man said thoughtfully “This should encourage those bird

catchers you know, they are sold out. When evening came and we were due to sail I

was sure those birds would fly home, but no, they are still there and they will probably

remain until we dock at Dar es Salaam.During the morning the Captain came up and asked me what my Christian name

is. He looked as grave as ever and I couldn’t think why it should interest him but said “the

name is Eleanor.” That night at dinner there was a large iced cake in the centre of the

table with “HELENA” in a delicate wreath of pink icing roses on the top. We had

champagne and everyone congratulated me and wished me good luck in my marriage.

A very nice gesture don’t you think. The unpleasant character had not put in an

appearance at dinner which made the party all the nicerI sat up rather late in the lounge reading a book and by the time I went to bed

there was not a soul around. I bathed and changed into my nighty,walked into my cabin,

shed my dressing gown, and pottered around. When I was ready for bed I put out my

hand to draw the curtains back and a hand grasped my wrist. It was that wretched

creature outside my window on the deck, still very drunk. Luckily I was wearing that

heavy lilac silk nighty. I was livid. “Let go at once”, I said, but he only grinned stupidly.

“I’m not hurting you” he said, “only looking”. “I’ll ring for the steward” said I, and by

stretching I managed to press the bell with my free hand. I rang and rang but no one

came and he just giggled. Then I said furiously, “Remember this name, George

Rushby, he is a fine boxer and he hates specimens like you. When he meets me at Dar

es Salaam I shall tell him about this and I bet you will be sorry.” However he still held on

so I turned and knocked hard on the adjoining wall which divided my cabin from Mrs

Croxfords. Soon Mrs Croxford and the old lady appeared in dressing gowns . This

seemed to amuse the drunk even more though he let go my wrist. So whilst the old

lady stayed with me, Mrs C fetched the quiet passenger who soon hustled him off. He has kept out of my way ever since. However I still mean to tell George because I feel

the fellow got off far too lightly. I reported the matter to the Captain but he just remarked

that he always knew the man was low class because he never wears a jacket to meals.

This is my last night on board and we again had free champagne and I was given

some tooled leather work by the Captain and a pair of good paste earrings by the old

lady. I have invited them and Mrs Croxford, the Chief Engineer, and the quiet

passenger to the wedding.This may be my last night as Eleanor Leslie and I have spent this long while

writing to you just as a little token of my affection and gratitude for all the years of your

love and care. I shall post this letter on the ship and must turn now and get some beauty

sleep. We have been told that we shall be in Dar es Salaam by 9 am. I am so excited

that I shall not sleep.Very much love, and just for fun I’ll sign my full name for the last time.

with my “bes respeks”,Eleanor Leslie.

Eleanor and George Rushby:

Splendid Hotel, Dar es Salaam 11th November 1930

Dearest Family,

I’m writing this in the bedroom whilst George is out buying a tin trunk in which to

pack all our wedding presents. I expect he will be gone a long time because he has

gone out with Hicky Wood and, though our wedding was four days ago, it’s still an

excuse for a party. People are all very cheery and friendly here.

I am wearing only pants and slip but am still hot. One swelters here in the

mornings, but a fresh sea breeze blows in the late afternoons and then Dar es Salaam is

heavenly.We arrived in Dar es Salaam harbour very early on Friday morning (7 th Nov).

The previous night the Captain had said we might not reach Dar. until 9 am, and certainly

no one would be allowed on board before 8 am. So I dawdled on the deck in my

dressing gown and watched the green coastline and the islands slipping by. I stood on

the deck outside my cabin and was not aware that I was looking out at the wrong side of

the landlocked harbour. Quite unknown to me George and some friends, the Hickson

Woods, were standing on the Gymkhana Beach on the opposite side of the channel

anxiously scanning the ship for a sign of me. George says he had a horrible idea I had

missed the ship. Blissfully unconscious of his anxiety I wandered into the bathroom

prepared for a good soak. The anchor went down when I was in the bath and suddenly

there was a sharp wrap on the door and I heard Mrs Croxford say “There’s a man in a

boat outside. He is looking out for someone and I’m sure it’s your George. I flung on

some clothes and rushed on deck with tousled hair and bare feet and it was George.

We had a marvellous reunion. George was wearing shorts and bush shirt and

looked just like the strong silent types one reads about in novels. I finished dressing then

George helped me bundle all the wedding presents I had collected en route into my

travelling rug and we went into the bar lounge to join the Hickson Woods. They are the

couple from whom George bought the land which is to be our coffee farm Hicky-Wood

was laughing when we joined them. he said he had called a chap to bring a couple of

beers thinking he was the steward but it turned out to be the Captain. He does wear

such a very plain uniform that I suppose it was easy to make the mistake, but Hicky

says he was not amused.Anyway as the H-W’s are to be our neighbours I’d better describe them. Kath

Wood is very attractive, dark Irish, with curly black hair and big brown eyes. She was

married before to Viv Lumb a great friend of George’s who died some years ago of

blackwater fever. They had one little girl, Maureen, and Kath and Hicky have a small son

of three called Michael. Hicky is slightly below average height and very neat and dapper

though well built. He is a great one for a party and good fun but George says he can be

bad tempered.Anyway we all filed off the ship and Hicky and Cath went on to the hotel whilst

George and I went through customs. Passing the customs was easy. Everyone

seemed to know George and that it was his wedding day and I just sailed through,

except for the little matter of the rug coming undone when George and I had to scramble

on the floor for candlesticks and fruit knives and a wooden nut bowl.

Outside the customs shed we were mobbed by a crowd of jabbering Africans

offering their services as porters, and soon my luggage was piled in one rickshaw whilst

George and I climbed into another and we were born smoothly away on rubber shod

wheels to the Splendid Hotel. The motion was pleasing enough but it seemed weird to

be pulled along by one human being whilst another pushed behind. We turned up a street called Acacia Avenue which, as its name implies, is lined

with flamboyant acacia trees now in the full glory of scarlet and gold. The rickshaw

stopped before the Splendid Hotel and I was taken upstairs into a pleasant room which

had its own private balcony overlooking the busy street.Here George broke the news that we were to be married in less than an hours

time. He would have to dash off and change and then go straight to the church. I would

be quite all right, Kath would be looking in and friends would fetch me.

I started to dress and soon there was a tap at the door and Mrs Hickson-Wood

came in with my bouquet. It was a lovely bunch of carnations and frangipani with lots of

asparagus fern and it went well with my primrose yellow frock. She admired my frock

and Leghorn hat and told me that her little girl Maureen was to be my flower girl. Then

she too left for the church.I was fully dressed when there was another knock on the door and I opened it to

be confronted by a Police Officer in a starched white uniform. I’m McCallum”, he said,

“I’ve come to drive you to the church.” Downstairs he introduced me to a big man in a

tussore silk suit. “This is Dr Shicore”, said McCallum, “He is going to give you away.”

Honestly, I felt exactly like Alice in Wonderland. Wouldn’t have been at all surprised if

the White Rabbit had popped up and said he was going to be my page.I walked out of the hotel and across the pavement in a dream and there, by the

curb, was a big dark blue police car decorated with white ribbons and with a tall African

Police Ascari holding the door open for me. I had hardly time to wonder what next when

the car drew up before a tall German looking church. It was in fact the Lutheran Church in

the days when Tanganyika was German East Africa.Mrs Hickson-Wood, very smart in mushroom coloured georgette and lace, and

her small daughter were waiting in the porch, so in we went. I was glad to notice my

friends from the boat sitting behind George’s friends who were all complete strangers to

me. The aisle seemed very long but at last I reached George waiting in the chancel with

Hicky-Wood, looking unfamiliar in a smart tussore suit. However this feeling of unreality

passed when he turned his head and smiled at me.In the vestry after the ceremony I was kissed affectionately by several complete

strangers and I felt happy and accepted by George’s friends. Outside the church,

standing apart from the rest of the guests, the Italian Captain and Chief Engineer were

waiting. They came up and kissed my hand, and murmured felicitations, but regretted

they could not spare the time to come to the reception. Really it was just as well

because they would not have fitted in at all well.Dr Shircore is the Director of Medical Services and he had very kindly lent his

large house for the reception. It was quite a party. The guests were mainly men with a

small sprinkling of wives. Champagne corks popped and there was an enormous cake

and soon voices were raised in song. The chief one was ‘Happy Days Are Here Again’

and I shall remember it for ever.The party was still in full swing when George and I left. The old lady from the ship

enjoyed it hugely. She came in an all black outfit with a corsage of artificial Lily-of-the-

Valley. Later I saw one of the men wearing the corsage in his buttonhole and the old

lady was wearing a carnation.When George and I got back to the hotel,I found that my luggage had been

moved to George’s room by his cook Lamek, who was squatting on his haunches and

clapped his hands in greeting. My dears, you should see Lamek – exactly like a

chimpanzee – receding forehead, wide flat nose, and long lip, and such splayed feet. It was quite a strain not to laugh, especially when he produced a gift for me. I have not yet

discovered where he acquired it. It was a faded mauve straw toque of the kind worn by

Queen Mary. I asked George to tell Lamek that I was touched by his generosity but felt

that I could not accept his gift. He did not mind at all especially as George gave him a

generous tip there and then.I changed into a cotton frock and shady straw hat and George changed into shorts

and bush shirt once more. We then sneaked into the dining room for lunch avoiding our

wedding guests who were carrying on the party in the lounge.After lunch we rejoined them and they all came down to the jetty to wave goodbye

as we set out by motor launch for Honeymoon Island. I enjoyed the launch trip very

much. The sea was calm and very blue and the palm fringed beaches of Dar es Salaam

are as romantic as any bride could wish. There are small coral islands dotted around the

Bay of which Honeymoon Island is the loveliest. I believe at one time it bore the less

romantic name of Quarantine Island. Near the Island, in the shallows, the sea is brilliant

green and I saw two pink jellyfish drifting by.There is no jetty on the island so the boat was stopped in shallow water and

George carried me ashore. I was enchanted with the Island and in no hurry to go to the

bungalow, so George and I took our bathing costumes from our suitcases and sent the

luggage up to the house together with a box of provisions.We bathed and lazed on the beach and suddenly it was sunset and it began to

get dark. We walked up the beach to the bungalow and began to unpack the stores,

tea, sugar, condensed milk, bread and butter, sardines and a large tin of ham. There

were also cups and saucers and plates and cutlery.We decided to have an early meal and George called out to the caretaker, “Boy

letta chai”. Thereupon the ‘boy’ materialised and jabbered to George in Ki-Swaheli. It

appeared he had no utensil in which to boil water. George, ever resourceful, removed

the ham from the tin and gave him that. We had our tea all right but next day the ham

was bad.Then came bed time. I took a hurricane lamp in one hand and my suitcase in the

other and wandered into the bedroom whilst George vanished into the bathroom. To

my astonishment I saw two perfectly bare iron bedsteads – no mattress or pillows. We

had brought sheets and mosquito nets but, believe me, they are a poor substitute for a

mattress.Anyway I arrayed myself in my pale yellow satin nightie and sat gingerly down

on the iron edge of the bed to await my groom who eventually appeared in a

handsome suit of silk pyjamas. His expression, as he took in the situation, was too much

for me and I burst out laughing and so did he.Somewhere in the small hours I woke up. The breeze had dropped and the

room was unbearably stuffy. I felt as dry as a bone. The lamp had been turned very

low and had gone out, but I remembered seeing a water tank in the yard and I decided

to go out in the dark and drink from the tap. In the dark I could not find my slippers so I

slipped my feet into George’s shoes, picked up his matches and groped my way out

of the room. I found the tank all right and with one hand on the tap and one cupped for

water I stooped to drink. Just then I heard a scratchy noise and sensed movements

around my feet. I struck a match and oh horrors! found that the damp spot on which I was

standing was alive with white crabs. In my hurry to escape I took a clumsy step, put

George’s big toe on the hem of my nightie and down I went on top of the crabs. I need

hardly say that George was awakened by an appalling shriek and came rushing to my

aid like a knight of old. Anyway, alarms and excursions not withstanding, we had a wonderful weekend on the island and I was sorry to return to the heat of Dar es Salaam, though the evenings

here are lovely and it is heavenly driving along the coast road by car or in a rickshaw.

I was surprised to find so many Indians here. Most of the shops, large and small,

seem to be owned by Indians and the place teems with them. The women wear

colourful saris and their hair in long black plaits reaching to their waists. Many wear baggy

trousers of silk or satin. They give a carnival air to the sea front towards sunset.

This long letter has been written in instalments throughout the day. My first break

was when I heard the sound of a band and rushed to the balcony in time to see The

Kings African Rifles band and Askaris march down the Avenue on their way to an

Armistice Memorial Service. They looked magnificent.I must end on a note of most primitive pride. George returned from his shopping

expedition and beamingly informed me that he had thrashed the man who annoyed me

on the ship. I felt extremely delighted and pressed for details. George told me that

when he went out shopping he noticed to his surprise that the ‘Timavo” was still in the

harbour. He went across to the Agents office and there saw a man who answered to the

description I had given. George said to him “Is your name Taylor?”, and when he said

“yes”, George said “Well my name is George Rushby”, whereupon he hit Taylor on the

jaw so that he sailed over the counter and down the other side. Very satisfactory, I feel.

With much love to all.Your cave woman

Eleanor.Mchewe Estate. P.O. Mbeya 22 November 1930

Dearest Family,

Well here we are at our Country Seat, Mchewe Estate. (pronounced

Mn,-che’-we) but I will start at the beginning of our journey and describe the farm later.

We left the hotel at Dar es Salaam for the station in a taxi crowded with baggage

and at the last moment Keith Wood ran out with the unwrapped bottom layer of our

wedding cake. It remained in its naked state from there to here travelling for two days in

the train on the luggage rack, four days in the car on my knee, reposing at night on the

roof of the car exposed to the winds of Heaven, and now rests beside me in the tent

looking like an old old tombstone. We have no tin large enough to hold it and one

simply can’t throw away ones wedding cake so, as George does not eat cake, I can see

myself eating wedding cake for tea for months to come, ants permitting.We travelled up by train from Dar to Dodoma, first through the lush vegetation of

the coastal belt to Morogoro, then through sisal plantations now very overgrown with

weeds owing to the slump in prices, and then on to the arid area around Dodoma. This

part of the country is very dry at this time of the year and not unlike parts of our Karoo.

The train journey was comfortable enough but slow as the engines here are fed with

wood and not coal as in South Africa.Dodoma is the nearest point on the railway to Mbeya so we left the train there to

continue our journey by road. We arrived at the one and only hotel in the early hours and

whilst someone went to rout out the night watchman the rest of us sat on the dismal

verandah amongst a litter of broken glass. Some bright spark remarked on the obvious –

that there had been a party the night before.When we were shown to a room I thought I rather preferred the verandah,

because the beds had not yet been made up and there was a bucket of vomit beside

the old fashioned washstand. However George soon got the boys to clean up the

room and I fell asleep to be awakened by George with an invitation to come and see

our car before breakfast.Yes, we have our own car. It is a Chev, with what is called a box body. That

means that sides, roof and doors are made by a local Indian carpenter. There is just the

one front seat with a kapok mattress on it. The tools are kept in a sort of cupboard fixed

to the side so there is a big space for carrying “safari kit” behind the cab seat.

Lamek, who had travelled up on the same train, appeared after breakfast, and

helped George to pack all our luggage into the back of the car. Besides our suitcases

there was a huge bedroll, kitchen utensils and a box of provisions, tins of petrol and

water and all Lamek’s bits and pieces which included three chickens in a wicker cage and

an enormous bunch of bananas about 3 ft long.When all theses things were packed there remained only a small space between

goods and ceiling and into this Lamek squeezed. He lay on his back with his horny feet a

mere inch or so from the back of my head. In this way we travelled 400 miles over

bumpy earth roads and crude pole bridges, but whenever we stopped for a meal

Lamek wriggled out and, like Aladdin’s genie, produced good meals in no time at all.

In the afternoon we reached a large river called the Ruaha. Workmen were busy

building a large bridge across it but it is not yet ready so we crossed by a ford below

the bridge. George told me that the river was full of crocodiles but though I looked hard, I

did not see any. This is also elephant country but I did not see any of those either, only

piles of droppings on the road. I must tell you that the natives around these parts are called Wahehe and the river is Ruaha – enough to make a cat laugh. We saw some Wahehe out hunting with spears

and bows and arrows. They live in long low houses with the tiniest shuttered windows

and rounded roofs covered with earth.Near the river we also saw a few Masai herding cattle. They are rather terrifying to

look at – tall, angular, and very aloof. They wear nothing but a blanket knotted on one

shoulder, concealing nothing, and all carried one or two spears.

The road climbs steeply on the far side of the Ruaha and one has the most

tremendous views over the plains. We spent our first night up there in the high country.

Everything was taken out of the car, the bed roll opened up and George and I slept

comfortably in the back of the car whilst Lamek, rolled in a blanket, slept soundly by a

small fire nearby. Next morning we reached our first township, Iringa, and put up at the

Colonist Hotel. We had a comfortable room in the annex overlooking the golf course.

our room had its own little dressing room which was also the bathroom because, when

ordered to do so, the room boy carried in an oval galvanised bath and filled it with hot

water which he carried in a four gallon petrol tin.When we crossed to the main building for lunch, George was immediately hailed

by several men who wanted to meet the bride. I was paid some handsome

compliments but was not sure whether they were sincere or the result of a nice alcoholic

glow. Anyhow every one was very friendly.After lunch I went back to the bedroom leaving George chatting away. I waited and

waited – no George. I got awfully tired of waiting and thought I’d give him a fright so I

walked out onto the deserted golf course and hid behind some large boulders. Soon I

saw George returning to the room and the boy followed with a tea tray. Ah, now the hue

and cry will start, thought I, but no, no George appeared nor could I hear any despairing

cry. When sunset came I trailed crossly back to our hotel room where George lay

innocently asleep on his bed, hands folded on his chest like a crusader on his tomb. In a

moment he opened his eyes, smiled sleepily and said kindly, “Did you have a nice walk

my love?” So of course I couldn’t play the neglected wife as he obviously didn’t think

me one and we had a very pleasant dinner and party in the hotel that evening.

Next day we continued our journey but turned aside to visit the farm of a sprightly

old man named St.Leger Seaton whom George had known for many years, so it was

after dark before George decided that we had covered our quota of miles for the day.

Whilst he and Lamek unpacked I wandered off to a stream to cool my hot feet which had

baked all day on the floor boards of the car. In the rather dim moonlight I sat down on the

grassy bank and gratefully dabbled my feet in the cold water. A few minutes later I

started up with a shriek – I had the sensation of red hot pins being dug into all my most

sensitive parts. I started clawing my clothes off and, by the time George came to the

rescue with the lamp, I was practically in the nude. “Only Siafu ants,” said George calmly.

Take off all your clothes and get right in the water.” So I had a bathe whilst George

picked the ants off my clothes by the light of the lamp turned very low for modesty’s

sake. Siafu ants are beastly things. They are black ants with outsized heads and

pinchers. I shall be very, very careful where I sit in future.The next day was even hotter. There was no great variety in the scenery. Most

of the country was covered by a tree called Miombo, which is very ordinary when the

foliage is a mature deep green, but when in new leaf the trees look absolutely beautiful

as the leaves,surprisingly, are soft pastel shades of red and yellow.Once again we turned aside from the main road to visit one of George’s friends.

This man Major Hugh Jones MC, has a farm only a few miles from ours but just now he is supervising the making of an airstrip. Major Jones is quite a character. He is below

average height and skinny with an almost bald head and one nearly blind eye into which

he screws a monocle. He is a cultured person and will, I am sure, make an interesting

neighbour. George and Major Jones’ friends call him ‘Joni’ but he is generally known in

this country as ‘Ropesoles’ – as he is partial to that type of footwear.

We passed through Mbeya township after dark so I have no idea what the place

is like. The last 100 miles of our journey was very dusty and the last 15 miles extremely

bumpy. The road is used so little that in some places we had to plow our way through

long grass and I was delighted when at last George turned into a side road and said

“This is our place.” We drove along the bank of the Mchewe River, then up a hill and

stopped at a tent which was pitched beside the half built walls of our new home. We

were expected so there was hot water for baths and after a supper of tinned food and

good hot tea, I climbed thankfully into bed.Next morning I was awakened by the chattering of the African workmen and was

soon out to inspect the new surroundings. Our farm was once part of Hickson Wood’s

land and is separated from theirs by a river. Our houses cannot be more than a few

hundred yards apart as the crow flies but as both are built on the slopes of a long range

of high hills, and one can only cross the river at the foot of the slopes, it will be quite a

safari to go visiting on foot . Most of our land is covered with shoulder high grass but it

has been partly cleared of trees and scrub. Down by the river George has made a long

coffee nursery and a large vegetable garden but both coffee and vegetable seedlings

are too small to be of use.George has spared all the trees that will make good shade for the coffee later on.

There are several huge wild fig trees as big as oaks but with smooth silvery-green trunks

and branches and there are lots of acacia thorn trees with flat tops like Japanese sun

shades. I’ve seen lovely birds in the fig trees, Louries with bright plumage and crested

heads, and Blue Rollers, and in the grasslands there are widow birds with incredibly long

black tail feathers.There are monkeys too and horrible but fascinating tree lizards with blue bodies

and orange heads. There are so many, many things to tell you but they must wait for

another time as James, the house boy, has been to say “Bafu tiari” and if I don’t go at

once, the bath will be cold.I am very very happy and terribly interested in this new life so please don’t

worry about me.Much love to you all,

Eleanor.Mchewe Estate 29th. November 1930

Dearest Family,

I’ve lots of time to write letters just now because George is busy supervising the

building of the house from early morning to late afternoon – with a break for lunch of

course.On our second day here our tent was moved from the house site to a small

clearing further down the slope of our hill. Next to it the labourers built a ‘banda’ , which is

a three sided grass hut with thatched roof – much cooler than the tent in this weather.

There is also a little grass lav. so you see we have every convenience. I spend most of

my day in the banda reading or writing letters. Occasionally I wander up to the house site

and watch the building, but mostly I just sit.I did try exploring once. I wandered down a narrow path towards the river. I

thought I might paddle and explore the river a little but I came round a bend and there,

facing me, was a crocodile. At least for a moment I thought it was and my adrenaline

glands got very busy indeed. But it was only an enormous monitor lizard, four or five

feet long. It must have been as scared as I was because it turned and rushed off through

the grass. I turned and walked hastily back to the camp and as I passed the house site I

saw some boys killing a large puff adder. Now I do my walking in the evenings with

George. Nothing alarming ever seems to happen when he is around.It is interesting to watch the boys making bricks for the house. They make a pile

of mud which they trample with their feet until it is the right consistency. Then they fill

wooden moulds with the clayey mud, and press it down well and turn out beautiful shiny,

dark brown bricks which are laid out in rows and covered with grass to bake slowly in the

sun.Most of the materials for the building are right here at hand. The walls will be sun

dried bricks and there is a white clay which will make a good whitewash for the inside

walls. The chimney and walls will be of burnt brick and tiles and George is now busy

building a kiln for this purpose. Poles for the roof are being cut in the hills behind the

house and every day women come along with large bundles of thatching grass on their

heads. Our windows are modern steel casement ones and the doors have been made

at a mission in the district. George does some of the bricklaying himself. The other

bricklayer is an African from Northern Rhodesia called Pedro. It makes me perspire just

to look at Pedro who wears an overcoat all day in the very hot sun.

Lamek continues to please. He turns out excellent meals, chicken soup followed

by roast chicken, vegetables from the Hickson-Woods garden and a steamed pudding

or fruit to wind up the meal. I enjoy the chicken but George is fed up with it and longs for

good red meat. The chickens are only about as large as a partridge but then they cost

only sixpence each.I had my first visit to Mbeya two days ago. I put on my very best trousseau frock

for the occasion- that yellow striped silk one – and wore my wedding hat. George didn’t

comment, but I saw later that I was dreadfully overdressed.

Mbeya at the moment is a very small settlement consisting of a bundle of small

Indian shops – Dukas they call them, which stock European tinned foods and native soft

goods which seem to be mainly of Japanese origin. There is a one storied Government

office called the Boma and two attractive gabled houses of burnt brick which house the

District Officer and his Assistant. Both these houses have lovely gardens but i saw them

only from the outside as we did not call. After buying our stores George said “Lets go to the pub, I want you to meet Mrs Menzies.” Well the pub turned out to be just three or four grass rondavels on a bare

plot. The proprietor, Ken Menzies, came out to welcome us. I took to him at once

because he has the same bush sandy eyebrows as you have Dad. He told me that

unfortunately his wife is away at the coast, and then he ushered me through the door

saying “Here’s George with his bride.” then followed the Iringa welcome all over again,

only more so, because the room was full of diggers from the Lupa Goldfields about fifty

miles away.Champagne corks popped as I shook hands all around and George was

clapped on the back. I could see he was a favourite with everyone and I tried not to be

gauche and let him down. These men were all most kind and most appeared to be men

of more than average education. However several were unshaven and looked as

though they had slept in their clothes as I suppose they had. When they have a little luck

on the diggings they come in here to Menzies pub and spend the lot. George says

they bring their gold dust and small nuggets in tobacco tins or Kruschen salts jars and

hand them over to Ken Menzies saying “Tell me when I’ve spent the lot.” Ken then

weighs the gold and estimates its value and does exactly what the digger wants.

However the Diggers get good value for their money because besides the drink

they get companionship and good food and nursing if they need it. Mrs Menzies is a

trained nurse and most kind and capable from what I was told. There is no doctor or

hospital here so her experience as a nursing sister is invaluable.

We had lunch at the Hotel and afterwards I poured tea as I was the only female

present. Once the shyness had worn off I rather enjoyed myself.Now to end off I must tell you a funny story of how I found out that George likes

his women to be feminine. You will remember those dashing black silk pyjamas Aunt

Mary gave me, with flowered “happy coat” to match. Well last night I thought I’d give

George a treat and when the boy called me for my bath I left George in the ‘banda’

reading the London Times. After my bath I put on my Japanese pyjamas and coat,

peered into the shaving mirror which hangs from the tent pole and brushed my hair until it

shone. I must confess that with my fringe and shingled hair I thought I made quite a

glamourous Japanese girl. I walked coyly across to the ‘banda’. Alas no compliment.

George just glanced up from the Times and went on reading.

He was away rather a long time when it came to his turn to bath. I glanced up

when he came back and had a slight concussion. George, if you please, was arrayed in

my very best pale yellow satin nightie. The one with the lace and ribbon sash and little

bows on the shoulder. I knew exactly what he meant to convey. I was not to wear the

trousers in the family. I seethed inwardly, but pretending not to notice, I said calmly “shall

I call for food?” In this garb George sat down to dinner and it says a great deal for African

phlegm that the boy did not drop the dishes.We conversed politely about this and that, and then, as usual, George went off

to bed. I appeared to be engrossed in my book and did not stir. When I went to the

tent some time later George lay fast asleep still in my nightie, though all I could see of it

was the little ribbon bows looking farcically out of place on his broad shoulders.

This morning neither of us mentioned the incident, George was up and dressed

by the time I woke up but I have been smiling all day to think what a ridiculous picture

we made at dinner. So farewell to pyjamas and hey for ribbons and bows.Your loving

Eleanor.Mchewe Estate. Mbeya. 8th December 1930

Dearest Family,

A mere shadow of her former buxom self lifts a languid pen to write to you. I’m

convalescing after my first and I hope my last attack of malaria. It was a beastly

experience but all is now well and I am eating like a horse and will soon regain my

bounce.I took ill on the evening of the day I wrote my last letter to you. It started with a

splitting headache and fits of shivering. The symptoms were all too familiar to George

who got me into bed and filled me up with quinine. He then piled on all the available

blankets and packed me in hot water bottles. I thought I’d explode and said so and

George said just to lie still and I’d soon break into a good sweat. However nothing of the

kind happened and next day my temperature was 105 degrees. Instead of feeling

miserable as I had done at the onset, I now felt very merry and most chatty. George

now tells me I sang the most bawdy songs but I hardly think it likely. Do you?

You cannot imagine how tenderly George nursed me, not only that day but

throughout the whole eight days I was ill. As we do not employ any African house

women, and there are no white women in the neighbourhood at present to whom we

could appeal for help, George had to do everything for me. It was unbearably hot in the

tent so George decided to move me across to the Hickson-Woods vacant house. They

have not yet returned from the coast.George decided I was too weak to make the trip in the car so he sent a

messenger over to the Woods’ house for their Machila. A Machila is a canopied canvas

hammock slung from a bamboo pole and carried by four bearers. The Machila duly

arrived and I attempted to walk to it, clinging to George’s arm, but collapsed in a faint so

the trip was postponed to the next morning when I felt rather better. Being carried by

Machila is quite pleasant but I was in no shape to enjoy anything and got thankfully into

bed in the Hickson-Woods large, cool and rather dark bedroom. My condition did not

improve and George decided to send a runner for the Government Doctor at Tukuyu

about 60 miles away. Two days later Dr Theis arrived by car and gave me two

injections of quinine which reduced the fever. However I still felt very weak and had to

spend a further four days in bed.We have now decided to stay on here until the Hickson-Woods return by which

time our own house should be ready. George goes off each morning and does not

return until late afternoon. However don’t think “poor Eleanor” because I am very

comfortable here and there are lots of books to read and the days seem to pass very

quickly.The Hickson-Wood’s house was built by Major Jones and I believe the one on

his shamba is just like it. It is a square red brick building with a wide verandah all around

and, rather astonishingly, a conical thatched roof. There is a beautiful view from the front

of the house and a nice flower garden. The coffee shamba is lower down on the hill.

Mrs Wood’s first husband, George’s friend Vi Lumb, is buried in the flower

garden. He died of blackwater fever about five years ago. I’m told that before her

second marriage Kath lived here alone with her little daughter, Maureen, and ran the farm

entirely on her own. She must be quite a person. I bet she didn’t go and get malaria

within a few weeks of her marriage.The native tribe around here are called Wasafwa. They are pretty primitive but

seem amiable people. Most of the men, when they start work, wear nothing but some

kind of sheet of unbleached calico wrapped round their waists and hanging to mid calf. As soon as they have drawn their wages they go off to a duka and buy a pair of khaki

shorts for five or six shillings. Their women folk wear very short beaded skirts. I think the

base is goat skin but have never got close enough for a good look. They are very shy.

I hear from George that they have started on the roof of our house but I have not

seen it myself since the day I was carried here by Machila. My letters by the way go to

the Post Office by runner. George’s farm labourers take it in turn to act in this capacity.

The mail bag is given to them on Friday afternoon and by Saturday evening they are

back with our very welcome mail.Very much love,

Eleanor.Mbeya 23rd December 1930

Dearest Family,

George drove to Mbeya for stores last week and met Col. Sherwood-Kelly VC.

who has been sent by the Government to Mbeya as Game Ranger. His job will be to

protect native crops from raiding elephants and hippo etc., and to protect game from

poachers. He has had no training for this so he has asked George to go with him on his

first elephant safari to show him the ropes.George likes Col. Kelly and was quite willing to go on safari but not willing to

leave me alone on the farm as I am still rather shaky after malaria. So it was arranged that

I should go to Mbeya and stay with Mrs Harmer, the wife of the newly appointed Lands

and Mines Officer, whose husband was away on safari.So here I am in Mbeya staying in the Harmers temporary wattle and daub

house. Unfortunately I had a relapse of the malaria and stayed in bed for three days with

a temperature. Poor Mrs Harmer had her hands full because in the room next to mine

she was nursing a digger with blackwater fever. I could hear his delirious babble through

the thin wall – very distressing. He died poor fellow , and leaves a wife and seven

children.I feel better than I have done for weeks and this afternoon I walked down to the

store. There are great signs of activity and people say that Mbeya will grow rapidly now

owing to the boom on the gold fields and also to the fact that a large aerodrome is to be

built here. Mbeya is to be a night stop on the proposed air service between England

and South Africa. I seem to be the last of the pioneers. If all these schemes come about

Mbeya will become quite suburban.26th December 1930

George, Col. Kelly and Mr Harmer all returned to Mbeya on Christmas Eve and

it was decided that we should stay and have midday Christmas dinner with the

Harmers. Col. Kelly and the Assistant District Commissioner came too and it was quite a

festive occasion, We left Mbeya in the early afternoon and had our evening meal here at

Hickson-Wood’s farm. I wore my wedding dress.I went across to our house in the car this morning. George usually walks across to

save petrol which is very expensive here. He takes a short cut and wades through the

river. The distance by road is very much longer than the short cut. The men are now

thatching the roof of our cottage and it looks charming. It consists of a very large living

room-dinning room with a large inglenook fireplace at one end. The bedroom is a large

square room with a smaller verandah room adjoining it. There is a wide verandah in the

front, from which one has a glorious view over a wide valley to the Livingstone

Mountains on the horizon. Bathroom and storeroom are on the back verandah and the

kitchen is some distance behind the house to minimise the risk of fire.You can imagine how much I am looking forward to moving in. We have some

furniture which was made by an Indian carpenter at Iringa, refrectory dining table and

chairs, some small tables and two armchairs and two cupboards and a meatsafe. Other

things like bookshelves and extra cupboards we will have to make ourselves. George

has also bought a portable gramophone and records which will be a boon.

We also have an Irish wolfhound puppy, a skinny little chap with enormous feet

who keeps me company all day whilst George is across at our farm working on the

house.Lots and lots of love,

Eleanor.Mchewe Estate 8th Jan 1931

Dearest Family,

Alas, I have lost my little companion. The Doctor called in here on Boxing night

and ran over and killed Paddy, our pup. It was not his fault but I was very distressed

about it and George has promised to try and get another pup from the same litter.

The Hickson-Woods returned home on the 29th December so we decided to

move across to our nearly finished house on the 1st January. Hicky Wood decided that

we needed something special to mark the occasion so he went off and killed a sucking

pig behind the kitchen. The piglet’s screams were terrible and I felt that I would not be

able to touch any dinner. Lamek cooked and served sucking pig up in the traditional way

but it was high and quite literally, it stank. Our first meal in our own home was not a

success.However next day all was forgotten and I had something useful to do. George

hung doors and I held the tools and I also planted rose cuttings I had brought from

Mbeya and sowed several boxes with seeds.Dad asked me about the other farms in the area. I haven’t visited any but there

are five besides ours. One belongs to the Lutheran Mission at Utengule, a few miles

from here. The others all belong to British owners. Nearest to Mbeya, at the foot of a

very high peak which gives Mbeya its name, are two farms, one belonging to a South

African mining engineer named Griffiths, the other to I.G.Stewart who was an officer in the

Kings African Rifles. Stewart has a young woman called Queenie living with him. We are

some miles further along the range of hills and are some 23 miles from Mbeya by road.

The Mchewe River divides our land from the Hickson-Woods and beyond their farm is

Major Jones.All these people have been away from their farms for some time but have now

returned so we will have some neighbours in future. However although the houses are

not far apart as the crow flies, they are all built high in the foothills and it is impossible to

connect the houses because of the rivers and gorges in between. One has to drive right

down to the main road and then up again so I do not suppose we will go visiting very

often as the roads are very bumpy and eroded and petrol is so expensive that we all

save it for occasional trips to Mbeya.The rains are on and George has started to plant out some coffee seedlings. The

rains here are strange. One can hear the rain coming as it moves like a curtain along the

range of hills. It comes suddenly, pours for a little while and passes on and the sun

shines again.I do like it here and I wish you could see or dear little home.

Your loving,

Eleanor.Mchewe Estate. 1st April 1931

Dearest Family,

Everything is now running very smoothly in our home. Lamek continues to

produce palatable meals and makes wonderful bread which he bakes in a four gallon

petrol tin as we have no stove yet. He puts wood coals on the brick floor of the kitchen,

lays the tin lengh-wise on the coals and heaps more on top. The bread tins are then put

in the petrol tin, which has one end cut away, and the open end is covered by a flat

piece of tin held in place by a brick. Cakes are also backed in this make-shift oven and I

have never known Lamek to have a failure yet.Lamek has a helper, known as the ‘mpishi boy’ , who does most of the hard

work, cleans pots and pans and chops the firewood etc. Another of the mpishi boy’s

chores is to kill the two chickens we eat each day. The chickens run wild during the day

but are herded into a small chicken house at night. One of the kitchen boy’s first duties is

to let the chickens out first thing in the early morning. Some time after breakfast it dawns

on Lamek that he will need a chicken for lunch. he informs the kitchen boy who selects a

chicken and starts to chase it in which he is enthusiastically joined by our new Irish

wolfhound pup, Kelly. Together they race after the frantic fowl, over the flower beds and

around the house until finally the chicken collapses from sheer exhaustion. The kitchen

boy then hands it over to Lamek who murders it with the kitchen knife and then pops the

corpse into boiling water so the feathers can be stripped off with ease.I pointed out in vain, that it would be far simpler if the doomed chickens were kept

in the chicken house in the mornings when the others were let out and also that the correct

way to pluck chickens is when they are dry. Lamek just smiled kindly and said that that

may be so in Europe but that his way is the African way and none of his previous

Memsahibs has complained.My houseboy, named James, is clean and capable in the house and also a

good ‘dhobi’ or washboy. He takes the washing down to the river and probably

pounds it with stones, but I prefer not to look. The ironing is done with a charcoal iron

only we have no charcoal and he uses bits of wood from the kitchen fire but so far there

has not been a mishap.It gets dark here soon after sunset and then George lights the oil lamps and we

have tea and toast in front of the log fire which burns brightly in our inglenook. This is my

favourite hour of the day. Later George goes for his bath. I have mine in the mornings

and we have dinner at half past eight. Then we talk a bit and read a bit and sometimes

play the gramophone. I expect it all sounds pretty unexciting but it doesn’t seem so to

me.Very much love,

Eleanor.Mchewe Estate 20th April 1931

Dearest Family,

It is still raining here and the countryside looks very lush and green, very different

from the Mbeya district I first knew, when plains and hills were covered in long brown

grass – very course stuff that grows shoulder high.Most of the labourers are hill men and one can see little patches of cultivation in

the hills. Others live in small villages near by, each consisting of a cluster of thatched huts

and a few maize fields and perhaps a patch of bananas. We do not have labour lines on

the farm because our men all live within easy walking distance. Each worker has a labour

card with thirty little squares on it. One of these squares is crossed off for each days work

and when all thirty are marked in this way the labourer draws his pay and hies himself off

to the nearest small store and blows the lot. The card system is necessary because

these Africans are by no means slaves to work. They work only when they feel like it or

when someone in the family requires a new garment, or when they need a few shillings

to pay their annual tax. Their fields, chickens and goats provide them with the food they

need but they draw rations of maize meal beans and salt. Only our headman is on a

salary. His name is Thomas and he looks exactly like the statues of Julius Caesar, the

same bald head and muscular neck and sardonic expression. He comes from Northern

Rhodesia and is more intelligent than the locals.We still live mainly on chickens. We have a boy whose job it is to scour the

countryside for reasonable fat ones. His name is Lucas and he is quite a character. He

has such long horse teeth that he does not seem able to close his mouth and wears a

perpetual amiable smile. He brings his chickens in beehive shaped wicker baskets

which are suspended on a pole which Lucas carries on his shoulder.We buy our groceries in bulk from Mbeya, our vegetables come from our

garden by the river and our butter from Kath Wood. Our fresh milk we buy from the

natives. It is brought each morning by three little totos each carrying one bottle on his

shaven head. Did I tell you that the local Wasafwa file their teeth to points. These kids

grin at one with their little sharks teeth – quite an “all-ready-to-eat-you-with-my-dear” look.

A few nights ago a message arrived from Kath Wood to say that Queenie

Stewart was very ill and would George drive her across to the Doctor at Tukuyu. I

wanted George to wait until morning because it was pouring with rain, and the mountain

road to Tukuyu is tricky even in dry weather, but he said it is dangerous to delay with any

kind of fever in Africa and he would have to start at once. So off he drove in the rain and I

did not see him again until the following night.George said that it had been a nightmare trip. Queenie had a high temperature

and it was lucky that Kath was able to go to attend to her. George needed all his

attention on the road which was officially closed to traffic, and very slippery, and in some

places badly eroded. In some places the decking of bridges had been removed and

George had to get out in the rain and replace it. As he had nothing with which to fasten

the decking to the runners it was a dangerous undertaking to cross the bridges especially

as the rivers are now in flood and flowing strongly. However they reached Tukuyu safely

and it was just as well they went because the Doctor diagnosed Queenies illness as

Spirillium Tick Fever which is a very nasty illness indeed.Eleanor.

Mchewe Estate. 20th May 1931

Dear Family,

I’m feeling fit and very happy though a bit lonely sometimes because George

spends much of his time away in the hills cutting a furrow miles long to bring water to the

house and to the upper part of the shamba so that he will be able to irrigate the coffee

during the dry season.It will be quite an engineering feat when it is done as George only has makeshift

surveying instruments. He has mounted an ordinary cheap spirit level on an old camera

tripod and has tacked two gramophone needles into the spirit level to give him a line.

The other day part of a bank gave way and practically buried two of George’s labourers

but they were quickly rescued and no harm was done. However he will not let them

work unless he is there to supervise.I keep busy so that the days pass quickly enough. I am delighted with the

material you sent me for curtains and loose covers and have hired a hand sewing

machine from Pedro-of-the-overcoat and am rattling away all day. The machine is an

ancient German one and when I say rattle, I mean rattle. It is a most cumbersome, heavy

affair of I should say, the same vintage as George Stevenson’s Rocket locomotive.

Anyway it sews and I am pleased with my efforts. We made a couch ourselves out of a

native bed, a mattress and some planks but all this is hidden under the chintz cover and

it looks quite the genuine bought article. I have some diversions too. Small black faced

monkeys sit in the trees outside our bedroom window and they are most entertaining to

watch. They are very mischievous though. When I went out into the garden this morning

before breakfast I found that the monkeys had pulled up all my carnations. There they

lay, roots in the air and whether they will take again I don’t know.I like the monkeys but hate the big mountain baboons that come and hang

around our chicken house. I am terrified that they will tear our pup into bits because he is

a plucky young thing and will rush out to bark at the baboons.George usually returns for the weekends but last time he did not because he had

a touch of malaria. He sent a boy down for the mail and some fresh bread. Old Lucas

arrived with chickens just as the messenger was setting off with mail and bread in a

haversack on his back. I thought it might be a good idea to send a chicken to George so

I selected a spry young rooster which I handed to the messenger. He, however,

complained that he needed both hands for climbing. I then had one of my bright ideas

and, putting a layer of newspaper over the bread, I tucked the rooster into the haversack

and buckled down the flap so only his head protruded.I thought no more about it until two days later when the messenger again

appeared for fresh bread. He brought a rather terse note from George saying that the

previous bread was uneatable as the rooster had eaten some of it and messed on the

rest. Ah me!The previous weekend the Hickson-Woods, Stewarts and ourselves, went

across to Tukuyu to attend a dance at the club there. the dance was very pleasant. All

the men wore dinner jackets and the ladies wore long frocks. As there were about

twenty men and only seven ladies we women danced every dance whilst the surplus

men got into a huddle around the bar. George and I spent the night with the Agricultural

Officer, Mr Eustace, and I met his fiancee, Lillian Austin from South Africa, to whom I took

a great liking. She is Governess to the children of Major Masters who has a farm in the

Tukuyu district.On the Sunday morning we had a look at the township. The Boma was an old German one and was once fortified as the Africans in this district are a very warlike tribe.

They are fine looking people. The men wear sort of togas and bands of cloth around

their heads and look like Roman Senators, but the women go naked except for a belt

from which two broad straps hang down, one in front and another behind. Not a graceful

garb I assure you.We also spent a pleasant hour in the Botanical Gardens, laid out during the last

war by the District Commissioner, Major Wells, with German prisoner of war labour.

There are beautiful lawns and beds of roses and other flowers and shady palm lined

walks and banana groves. The gardens are terraced with flights of brick steps connecting

the different levels and there is a large artificial pond with little islands in it. I believe Major

Wells designed the lake to resemble in miniature, the Lakes of Killarney.

I enjoyed the trip very much. We got home at 8 pm to find the front door locked

and the kitchen boy fast asleep on my newly covered couch! I hastily retreated to the

bedroom whilst George handled the situation.Eleanor.

January 20, 2022 at 9:16 am #6255In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

My Grandparents

George Samuel Marshall 1903-1995

Florence Noreen Warren (Nora) 1906-1988

I always called my grandfather Mop, apparently because I couldn’t say the name Grandpa, but whatever the reason, the name stuck. My younger brother also called him Mop, but our two cousins did not.

My earliest memories of my grandparents are the picnics. Grandma and Mop loved going out in the car for a picnic. Favourite spots were the Clee Hills in Shropshire, North Wales, especially Llanbedr, Malvern, and Derbyshire, and closer to home, the caves and silver birch woods at Kinver Edge, Arley by the river Severn, or Bridgnorth, where Grandma’s sister Hildreds family lived. Stourbridge was on the western edge of the Black Country in the Midlands, so one was quickly in the countryside heading west. They went north to Derbyshire less, simply because the first part of the trip entailed driving through Wolverhampton and other built up and not particularly pleasant urban areas. I’m sure they’d have gone there more often, as they were both born in Derbyshire, if not for that initial stage of the journey.

There was predominantly grey tartan car rug in the car for picnics, and a couple of folding chairs. There were always a couple of cushions on the back seat, and I fell asleep in the back more times than I can remember, despite intending to look at the scenery. On the way home Grandma would always sing, “Show me the way to go home, I’m tired and I want to go to bed, I had a little drink about an hour ago, And it’s gone right to my head.” I’ve looked online for that song, and have not found it anywhere!

Grandma didn’t just make sandwiches for picnics, there were extra containers of lettuce, tomatoes, pickles and so on. I used to love to wash up the picnic plates in the little brook on the Clee Hills, near Cleeton St Mary. The close cropped grass was ideal for picnics, and Mop and the sheep would Baaa at each other.

Mop would base the days outting on the weather forcast, but Grandma often used to say he always chose the opposite of what was suggested. She said if you want to go to Derbyshire, tell him you want to go to Wales. I recall him often saying, on a gloomy day, Look, there’s a bit of clear sky over there. Mop always did the driving as Grandma never learned to drive. Often she’d dust the dashboard with a tissue as we drove along.

My brother and I often spent the weekend at our grandparents house, so that our parents could go out on a Saturday night. They gave us 5 shillings pocket money, which I used to spend on two Ladybird books at 2 shillings and sixpence each. We had far too many sweets while watching telly in the evening ~ in the dark, as they always turned the lights off to watch television. The lemonade and pop was Corona, and came in returnable glass bottles. We had Woodpecker cider too, even though it had a bit of an alcohol content.

Mop smoked Kensitas and Grandma smoked Sovereign cigarettes, or No6, and the packets came with coupons. They often let me choose something for myself out of the catalogue when there were enough coupons saved up.

When I had my first garden, in a rented house a short walk from theirs, they took me to garden nurseries and taught me all about gardening. In their garden they had berberis across the front of the house under the window, and cotoneaster all along the side of the garage wall. The silver birth tree on the lawn had been purloined as a sapling from Kinver edge, when they first moved into the house. (they lived in that house on Park Road for more than 60 years). There were perennials and flowering shrubs along the sides of the back garden, and behind the silver birch, and behind that was the vegeatable garden. Right at the back was an Anderson shelter turned into a shed, the rhubarb, and the washing line, and the canes for the runner beans in front of those. There was a little rose covered arch on the path on the left, and privet hedges all around the perimeter.

My grandfather was a dental technician. He worked for various dentists on their premises over the years, but he always had a little workshop of his own at the back of his garage. His garage was full to the brim of anything that might potentially useful, but it was not chaotic. He knew exactly where to find anything, from the tiniest screw for spectacles to a useful bit of wire. He was “mechanicaly minded” and could always fix things like sewing machines and cars and so on.