-

AuthorSearch Results

-

August 15, 2023 at 12:42 pm #7267

In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Thomas Josiah Tay

22 Feb 1816 – 16 November 1878

“Make us glad according to the days wherein thou hast afflicted us, and the years wherein we have seen evil.”

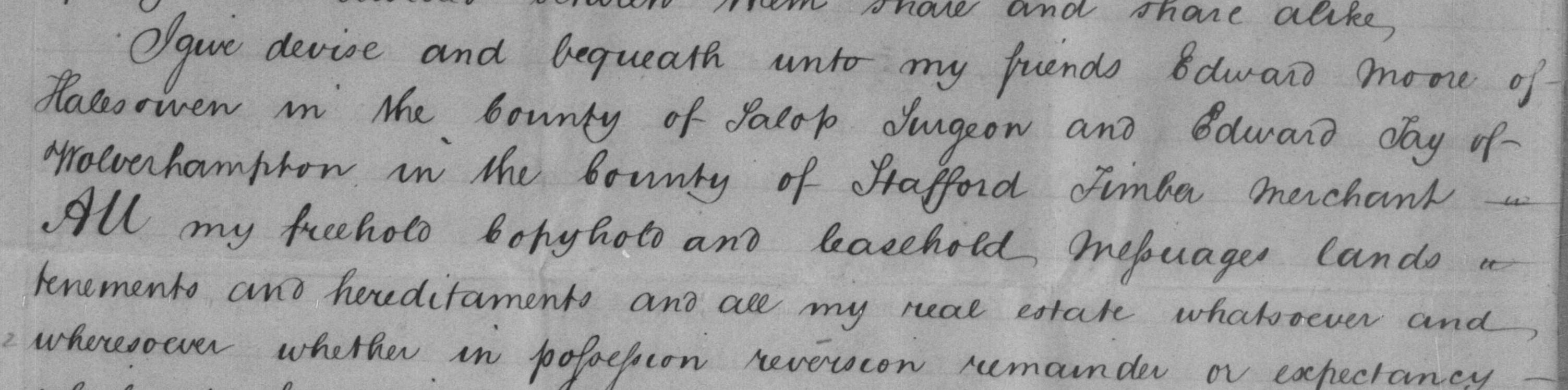

I first came across the name TAY in the 1844 will of John Tomlinson (1766-1844), gentleman of Wergs, Tettenhall. John’s friends, trustees and executors were Edward Moore, surgeon of Halesowen, and Edward Tay, timber merchant of Wolverhampton.

Edward Moore (born in 1805) was the son of John’s wife’s (Sarah Hancox born 1772) sister Lucy Hancox (born 1780) from her first marriage in 1801. In 1810 widowed Lucy married Josiah Tay (1775-1837).

Edward Tay was the son of Sarah Hancox sister Elizabeth (born 1778), who married Thomas Tay in 1800. Thomas Tay (1770-1841) and Josiah Tay were brothers.

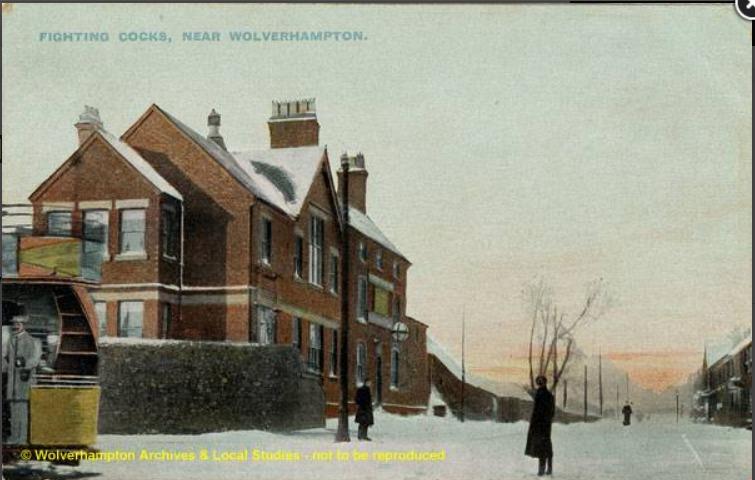

Edward Tay (1803-1862) was born in Sedgley and was buried in Penn. He was innkeeper of The Fighting Cocks, Dudley Road, Wolverhampton, as well as a builder and timber merchant, according to various censuses, trade directories, his marriage registration where his father Thomas Tay is also a timber merchant, as well as being named as a timber merchant in John Tomlinsons will.

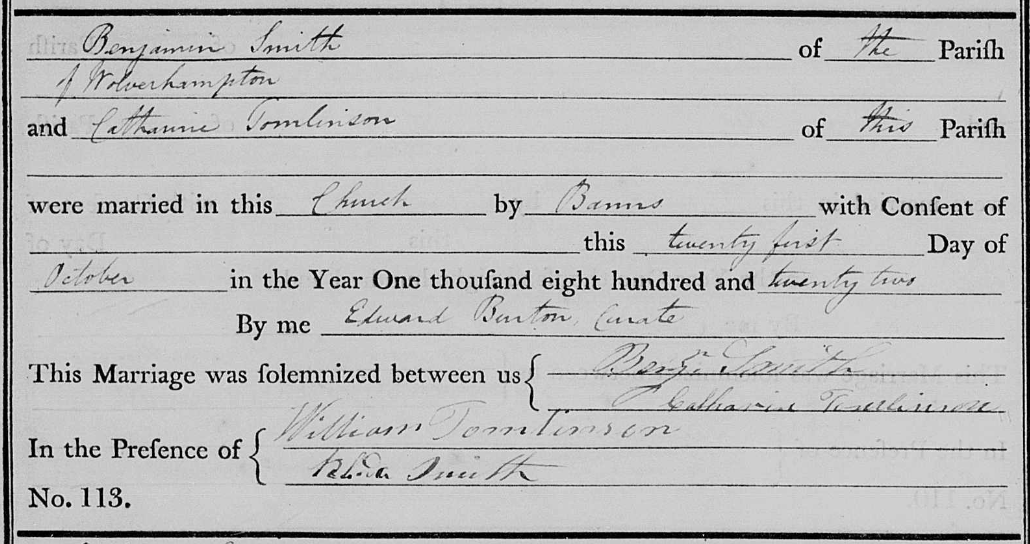

John Tomlinson’s daughter Catherine (born in 1794) married Benjamin Smith in Tettenhall in 1822. William Tomlinson (1797-1867), Catherine’s brother, and my 3x great grandfather, was one of the witnesses.

Their daughter Matilda Sarah Smith (1823-1910) married Thomas Josiah Tay in 1850 in Birmingham. Thomas Josiah Tay (1816-1878) was Edward Tay’s brother, the sons of Elizabeth Hancox and Thomas Tay.

Therefore, William Hancox 1737-1816 (the father of Sarah, Elizabeth and Lucy), was Matilda’s great grandfather and Thomas Josiah Tay’s grandfather.

Thomas Josiah Tay’s relationship to me is the husband of first cousin four times removed, as well as my first cousin, five times removed.

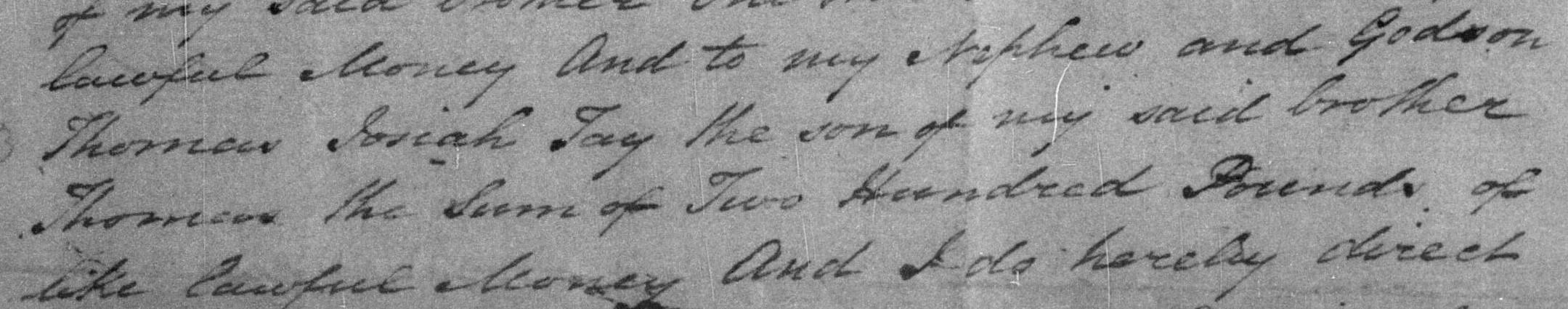

In 1837 Thomas Josiah Tay is mentioned in the will of his uncle Josiah Tay.

In 1841 Thomas Josiah Tay appears on the Stafford criminal registers for an “attempt to procure miscarriage”. He was found not guilty.

According to the Staffordshire Advertiser on 14th March 1840 the listing for the Assizes included: “Thomas Ashmall and Thomas Josiah Tay, for administering noxious ingredients to Hannah Evans, of Wolverhampton, with intent to procure abortion.”

The London Morning Herald on 19th March 1840 provides further information: “Mr Thomas Josiah Tay, a chemist and druggist, surrendered to take his trial on a charge of having administered drugs to Hannah Lear, now Hannah Evans, with intent to procure abortion.” She entered the service of Tay in 1837 and after four months “an intimacy was formed” and two months later she was “enciente”. Tay advised her to take some pills and a draught which he gave her and she became very ill. The prosecutrix admitted that she had made no mention of this until 1939. Verdict: not guilty.

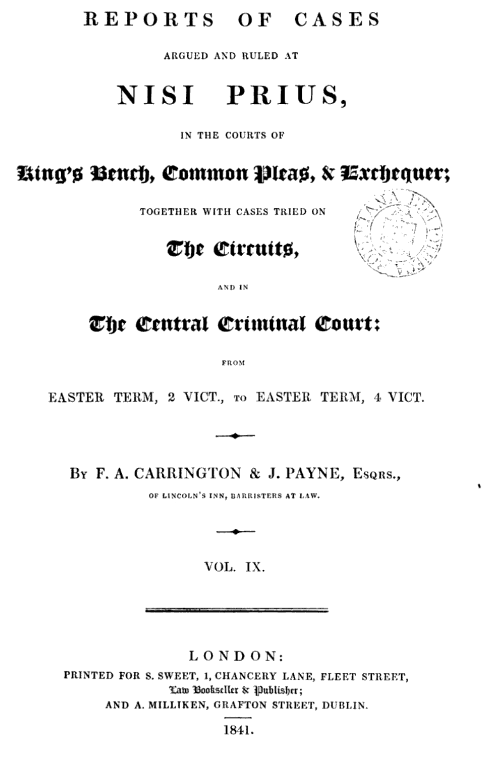

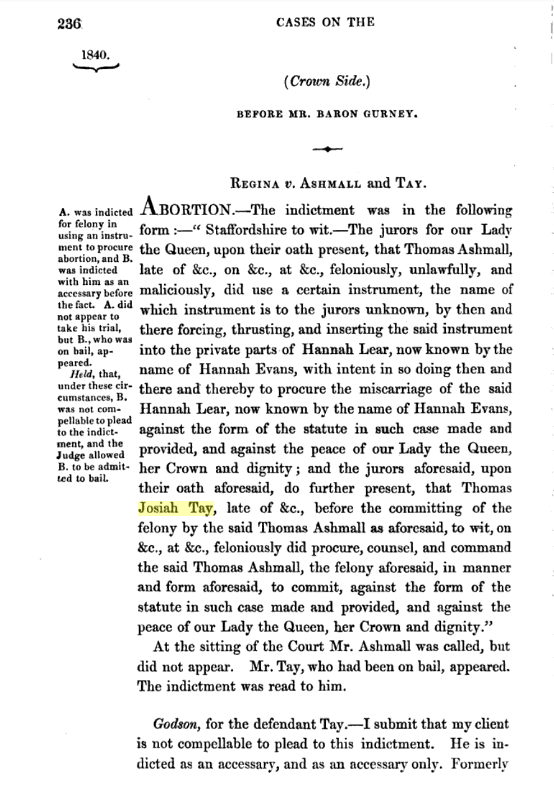

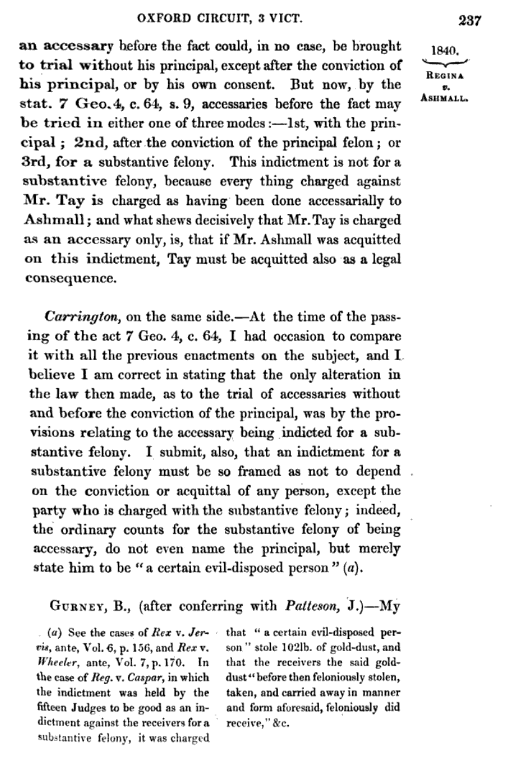

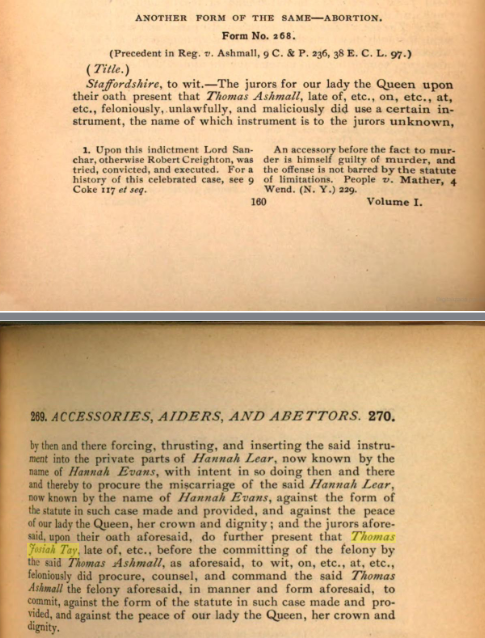

However, the case of Thomas Josiah Tay is also mentioned in a couple of law books, and the story varies slightly. In the 1841 Reports of Cases Argued and Rules at Nisi Prius, the Regina vs Ashmall and Tay case states that Thomas Ashmall feloniously, unlawfully, and maliciously, did use a certain instrument, and that Thomas Josiah Tay did procure the instrument, counsel and command Ashmall in the use of it. It concludes that Tay was not compellable to plead to the indictment, and that he did not.

The Regina vs Ashmall and Tay case is also mentioned in the Encyclopedia of Forms and Precedents, 1896.

In 1845 Thomas Josiah Tay married Isabella Southwick in Tettenhall. Two years later in 1847 Isabella died.

In 1850 Thomas Josiah married Matilda Sarah Smith. (granddaughter of John Tomlinson, as mentioned above)

On the 1851 census Thomas Josiah Tay was a farmer of 100 acres employing two labourers in Shelfield, Walsall, Staffordshire. Thomas Josiah and Matilda Sarah have a daughter Matilda under a year old, and they have a live in house servant.

In 1861 Thomas Josiah Tay, his wife and their four children Ann, James, Josiah and Alice, live in Chelmarsh, Shropshire. He was a farmer of 224 acres. Mercy Smith, Matilda’s sister, lives with them, a 28 year old dairy maid.

In 1863 Thomas Josiah Tay of Hampton Lode (Chelmarsh) Shropshire was bankrupt. Creditors include Frederick Weaver, druggist of Wolverhampton.

In 1869 Thomas Josiah Tay was again bankrupt. He was an innkeeper at The Fighting Cocks on Dudley Road, Wolverhampton, at the time, the same inn as his uncle Edward Tay, aforementioned timber merchant.

In 1871, Thomas Josiah Tay, his wife Matilda, and their three children Alice, Edward and Maryann, were living in Birmingham. Thomas Josiah was a commercial traveller.

He died on the 16th November 1878 at the age of 62 and was buried in Darlaston, Walsall. On his gravestone:

“Make us glad according to the days wherein thou hast afflicted us, and the years wherein we have seen evil.” Psalm XC 15 verse.

Edward Moore, surgeon, was also a MAGISTRATE in later years. On the 1871 census he states his occupation as “magistrate for counties Worcester and Stafford, and deputy lieutenant of Worcester, formerly surgeon”. He lived at Townsend House in Halesowen for many years. His wifes name was PATTERN Lucas. Her mothers name was Pattern Hewlitt from Birmingham, an unusal name that I have not heard before. On the 1871 census, Edward’s son was a 22 year old solicitor.

In 1861 an article appeared in the newspapers about the state of the morality of the women of Dudley. It was claimed that all the local magistrates agreed with the premise of the article, concerning unmarried women and their attitudes towards having illegitimate children. Letters appeared in subsequent newspapers signed by local magistrates, including Edward Moore, strongly disagreeing.

Staffordshire Advertiser 17 August 1861:

May 12, 2023 at 8:15 pm #7237

May 12, 2023 at 8:15 pm #7237In reply to: Washed off the sea ~ Creative larks

“Sod this for a lark,” he said, and then wondered what that actually meant. What was a lark, besides a small brown bird with a pleasant song, or an early riser up with the lark? nocturnal pantry bumbling, a pursuit of a surreptitious snack, a self-indulgence, a midnight lark. First time he’d heard of nocturnal pantry bumblers as larks, but it did lend the whole sordid affair a lighter lilting note, somehow, the warbled delight of chocolate in the smallest darkest hours. Lorries can be stolen for various purposes—sometimes just for a lark—and terrible things can happen. But wait, what? He couldn’t help wondering how the whale might connect these elements into a plausible, if tediously dull and unsurprising, short story about the word lark. Did I use too many commas, he wondered? And what about the apostrophe in the plural comma word? I bet AI doesn’t have any trouble with that. He asked who could think of caging larks that sang at heaven’s gates. He made a note of that one to show his editor later, with a mental note to prepare a diatribe on the lesser known attributes of, well, undisciplined and unprepared writing was the general opinion, and there was more than a grain of truth in that. Would AI write run on sentences and use too many whataretheycalled? Again, the newspapers tell these children about pills with fascinating properties, and taking a pill has become a lark. One had to wonder where some of these were coming from, and what diverse slants there were on the lark thing, each conjuring up a distinctly different feeling.

Suddenly he had an idea.

November 18, 2022 at 4:47 pm #6348In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Wong Sang

Wong Sang was born in China in 1884. In October 1916 he married Alice Stokes in Oxford.

Alice was the granddaughter of William Stokes of Churchill, Oxfordshire and William was the brother of Thomas Stokes the wheelwright (who was my 3X great grandfather). In other words Alice was my second cousin, three times removed, on my fathers paternal side.

Wong Sang was an interpreter, according to the baptism registers of his children and the Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital admission registers in 1930. The hospital register also notes that he was employed by the Blue Funnel Line, and that his address was 11, Limehouse Causeway, E 14. (London)

“The Blue Funnel Line offered regular First-Class Passenger and Cargo Services From the UK to South Africa, Malaya, China, Japan, Australia, Java, and America. Blue Funnel Line was Owned and Operated by Alfred Holt & Co., Liverpool.

The Blue Funnel Line, so-called because its ships have a blue funnel with a black top, is more appropriately known as the Ocean Steamship Company.”Wong Sang and Alice’s daughter, Frances Eileen Sang, was born on the 14th July, 1916 and baptised in 1920 at St Stephen in Poplar, Tower Hamlets, London. The birth date is noted in the 1920 baptism register and would predate their marriage by a few months, although on the death register in 1921 her age at death is four years old and her year of birth is recorded as 1917.

Charles Ronald Sang was baptised on the same day in May 1920, but his birth is recorded as April of that year. The family were living on Morant Street, Poplar.

James William Sang’s birth is recorded on the 1939 census and on the death register in 2000 as being the 8th March 1913. This definitely would predate the 1916 marriage in Oxford.

William Norman Sang was born on the 17th October 1922 in Poplar.

Alice and the three sons were living at 11, Limehouse Causeway on the 1939 census, the same address that Wong Sang was living at when he was admitted to Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital on the 15th January 1930. Wong Sang died in the hospital on the 8th March of that year at the age of 46.

Alice married John Patterson in 1933 in Stepney. John was living with Alice and her three sons on Limehouse Causeway on the 1939 census and his occupation was chef.

Via Old London Photographs:

“Limehouse Causeway is a street in east London that was the home to the original Chinatown of London. A combination of bomb damage during the Second World War and later redevelopment means that almost nothing is left of the original buildings of the street.”

Limehouse Causeway in 1925:

From The Story of Limehouse’s Lost Chinatown, poplarlondon website:

“Limehouse was London’s first Chinatown, home to a tightly-knit community who were demonised in popular culture and eventually erased from the cityscape.

As recounted in the BBC’s ‘Our Greatest Generation’ series, Connie was born to a Chinese father and an English mother in early 1920s Limehouse, where she used to play in the street with other British and British-Chinese children before running inside for teatime at one of their houses.

Limehouse was London’s first Chinatown between the 1880s and the 1960s, before the current Chinatown off Shaftesbury Avenue was established in the 1970s by an influx of immigrants from Hong Kong.

Connie’s memories of London’s first Chinatown as an “urban village” paint a very different picture to the seedy area portrayed in early twentieth century novels.

The pyramid in St Anne’s church marked the entrance to the opium den of Dr Fu Manchu, a criminal mastermind who threatened Western society by plotting world domination in a series of novels by Sax Rohmer.

Thomas Burke’s Limehouse Nights cemented stereotypes about prostitution, gambling and violence within the Chinese community, and whipped up anxiety about sexual relationships between Chinese men and white women.

Though neither novelist was familiar with the Chinese community, their depictions made Limehouse one of the most notorious areas of London.

Travel agent Thomas Cook even organised tours of the area for daring visitors, despite the rector of Limehouse warning that “those who look for the Limehouse of Mr Thomas Burke simply will not find it.”

All that remains is a handful of Chinese street names, such as Ming Street, Pekin Street, and Canton Street — but what was Limehouse’s chinatown really like, and why did it get swept away?

Chinese migration to Limehouse

Chinese sailors discharged from East India Company ships settled in the docklands from as early as the 1780s.

By the late nineteenth century, men from Shanghai had settled around Pennyfields Lane, while a Cantonese community lived on Limehouse Causeway.

Chinese sailors were often paid less and discriminated against by dock hirers, and so began to diversify their incomes by setting up hand laundry services and restaurants.

Old photographs show shopfronts emblazoned with Chinese characters with horse-drawn carts idling outside or Chinese men in suits and hats standing proudly in the doorways.

In oral histories collected by Yat Ming Loo, Connie’s husband Leslie doesn’t recall seeing any Chinese women as a child, since male Chinese sailors settled in London alone and married working-class English women.

In the 1920s, newspapers fear-mongered about interracial marriages, crime and gambling, and described chinatown as an East End “colony.”

Ironically, Chinese opium-smoking was also demonised in the press, despite Britain waging war against China in the mid-nineteenth century for suppressing the opium trade to alleviate addiction amongst its people.

The number of Chinese people who settled in Limehouse was also greatly exaggerated, and in reality only totalled around 300.

The real Chinatown

Although the press sought to characterise Limehouse as a monolithic Chinese community in the East End, Connie remembers seeing people of all nationalities in the shops and community spaces in Limehouse.

She doesn’t remember feeling discriminated against by other locals, though Connie does recall having her face measured and IQ tested by a member of the British Eugenics Society who was conducting research in the area.

Some of Connie’s happiest childhood memories were from her time at Chung-Hua Club, where she learned about Chinese culture and language.

Why did Chinatown disappear?

The caricature of Limehouse’s Chinatown as a den of vice hastened its erasure.

Police raids and deportations fuelled by the alarmist media coverage threatened the Chinese population of Limehouse, and slum clearance schemes to redevelop low-income areas dispersed Chinese residents in the 1930s.

The Defence of the Realm Act imposed at the beginning of the First World War criminalised opium use, gave the authorities increased powers to deport Chinese people and restricted their ability to work on British ships.

Dwindling maritime trade during World War II further stripped Chinese sailors of opportunities for employment, and any remnants of Chinatown were destroyed during the Blitz or erased by postwar development schemes.”

Wong Sang 1884-1930

The year 1918 was a troublesome one for Wong Sang, an interpreter and shipping agent for Blue Funnel Line. The Sang family were living at 156, Chrisp Street.

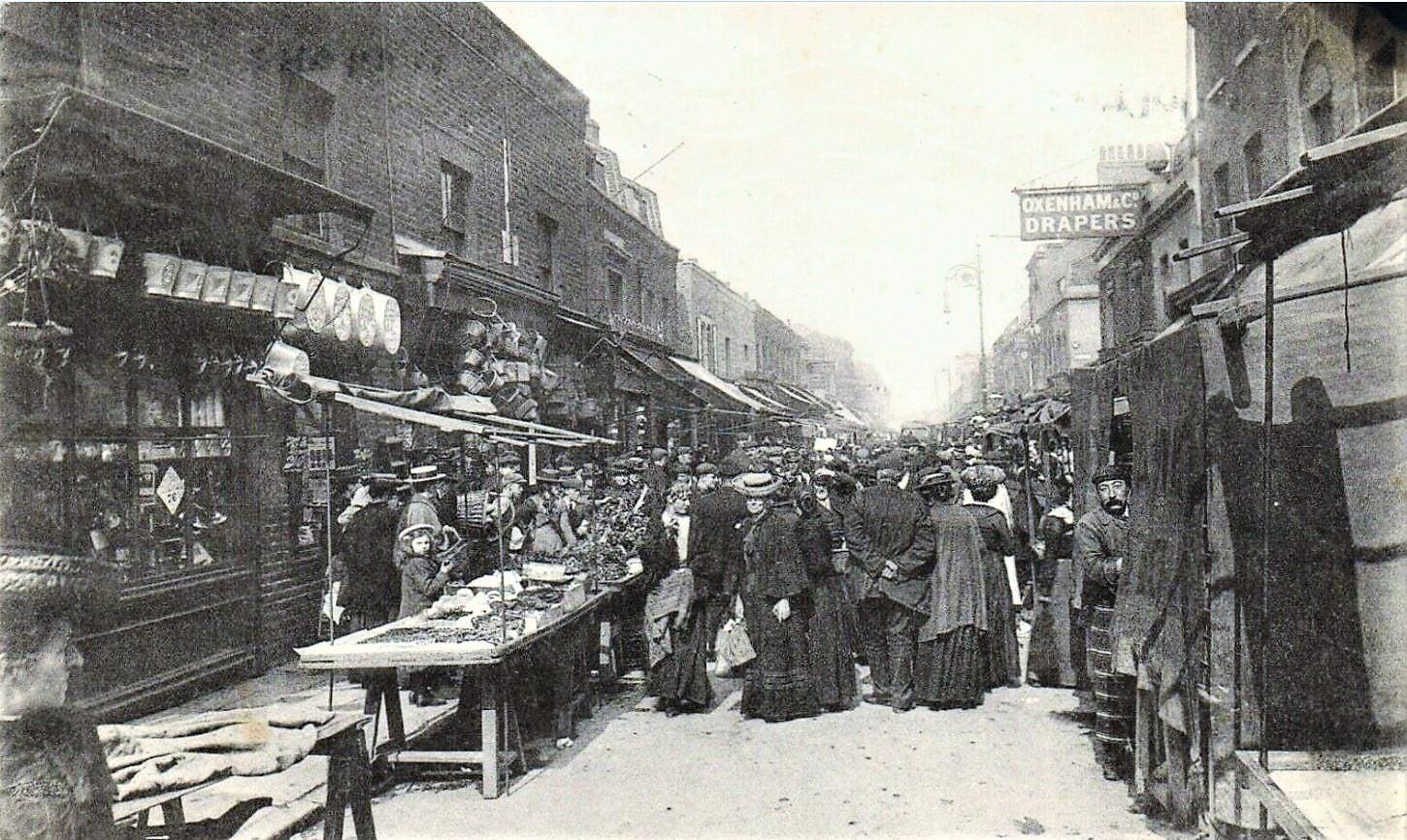

Chrisp Street, Poplar, in 1913 via Old London Photographs:

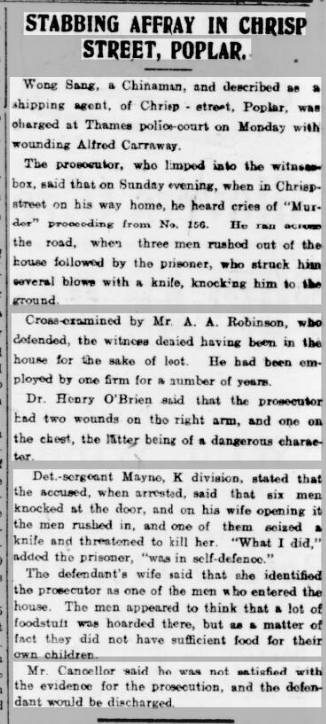

In February Wong Sang was discharged from a false accusation after defending his home from potential robbers.

East End News and London Shipping Chronicle – Friday 15 February 1918:

In August of that year he was involved in an incident that left him unconscious.

Faringdon Advertiser and Vale of the White Horse Gazette – Saturday 31 August 1918:

Wong Sang is mentioned in an 1922 article about “Oriental London”.

London and China Express – Thursday 09 February 1922:

A photograph of the Chee Kong Tong Chinese Freemason Society mentioned in the above article, via Old London Photographs:

Wong Sang was recommended by the London Metropolitan Police in 1928 to assist in a case in Wellingborough, Northampton.

Difficulty of Getting an Interpreter: Northampton Mercury – Friday 16 March 1928:

The difficulty was that “this man speaks the Cantonese language only…the Northeners and the Southerners in China have differing languages and the interpreter seemed to speak one that was in between these two.”

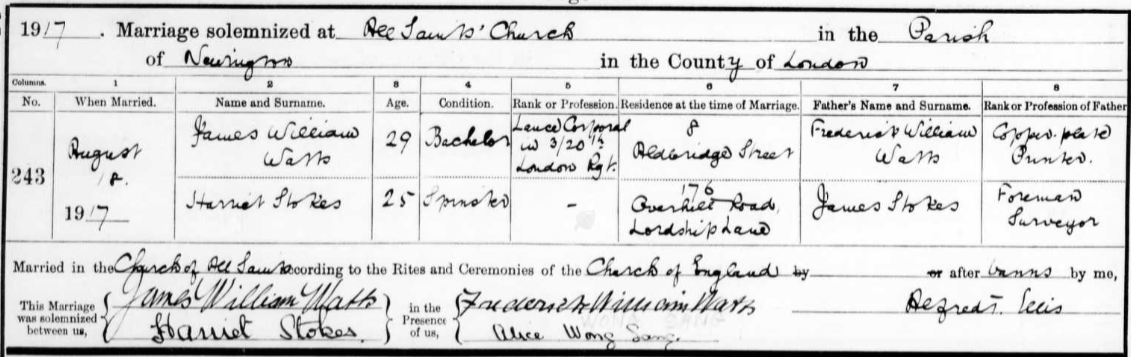

In 1917, Alice Wong Sang was a witness at her sister Harriet Stokes marriage to James William Watts in Southwark, London. Their father James Stokes occupation on the marriage register is foreman surveyor, but on the census he was a council roadman or labourer. (I initially rejected this as the correct marriage for Harriet because of the discrepancy with the occupations. Alice Wong Sang as a witness confirmed that it was indeed the correct one.)

James William Sang 1913-2000 was a clock fitter and watch assembler (on the 1939 census). He married Ivy Laura Fenton in 1963 in Sidcup, Kent. James died in Southwark in 2000.

Charles Ronald Sang 1920-1974 was a draughtsman (1939 census). He married Eileen Burgess in 1947 in Marylebone. Charles and Eileen had two sons: Keith born in 1951 and Roger born in 1952. He died in 1974 in Hertfordshire.

William Norman Sang 1922-2000 was a clerk and telephone operator (1939 census). William enlisted in the Royal Artillery in 1942. He married Lily Mullins in 1949 in Bethnal Green, and they had three daughters: Marion born in 1950, Christine in 1953, and Frances in 1959. He died in Redbridge in 2000.

I then found another two births registered in Poplar by Alice Sang, both daughters. Doris Winifred Sang was born in 1925, and Patricia Margaret Sang was born in 1933 ~ three years after Wong Sang’s death. Neither of the these daughters were on the 1939 census with Alice, John Patterson and the three sons. Margaret had presumably been evacuated because of the war to a family in Taunton, Somerset. Doris would have been fourteen and I have been unable to find her in 1939 (possibly because she died in 2017 and has not had the redaction removed yet on the 1939 census as only deceased people are viewable).

Doris Winifred Sang 1925-2017 was a nursing sister. She didn’t marry, and spent a year in USA between 1954 and 1955. She stayed in London, and died at the age of ninety two in 2017.

Patricia Margaret Sang 1933-1998 was also a nurse. She married Patrick L Nicely in Stepney in 1957. Patricia and Patrick had five children in London: Sharon born 1959, Donald in 1960, Malcolm was born and died in 1966, Alison was born in 1969 and David in 1971.

I was unable to find a birth registered for Alice’s first son, James William Sang (as he appeared on the 1939 census). I found Alice Stokes on the 1911 census as a 17 year old live in servant at a tobacconist on Pekin Street, Limehouse, living with Mr Sui Fong from Hong Kong and his wife Sarah Sui Fong from Berlin. I looked for a birth registered for James William Fong instead of Sang, and found it ~ mothers maiden name Stokes, and his date of birth matched the 1939 census: 8th March, 1913.

On the 1921 census, Wong Sang is not listed as living with them but it is mentioned that Mr Wong Sang was the person returning the census. Also living with Alice and her sons James and Charles in 1921 are two visitors: (Florence) May Stokes, 17 years old, born in Woodstock, and Charles Stokes, aged 14, also born in Woodstock. May and Charles were Alice’s sister and brother.

I found Sharon Nicely on social media and she kindly shared photos of Wong Sang and Alice Stokes:

October 11, 2022 at 2:58 pm #6334

October 11, 2022 at 2:58 pm #6334In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The House on Penn Common

Toi Fang and the Duke of Sutherland

Tomlinsons

Grassholme

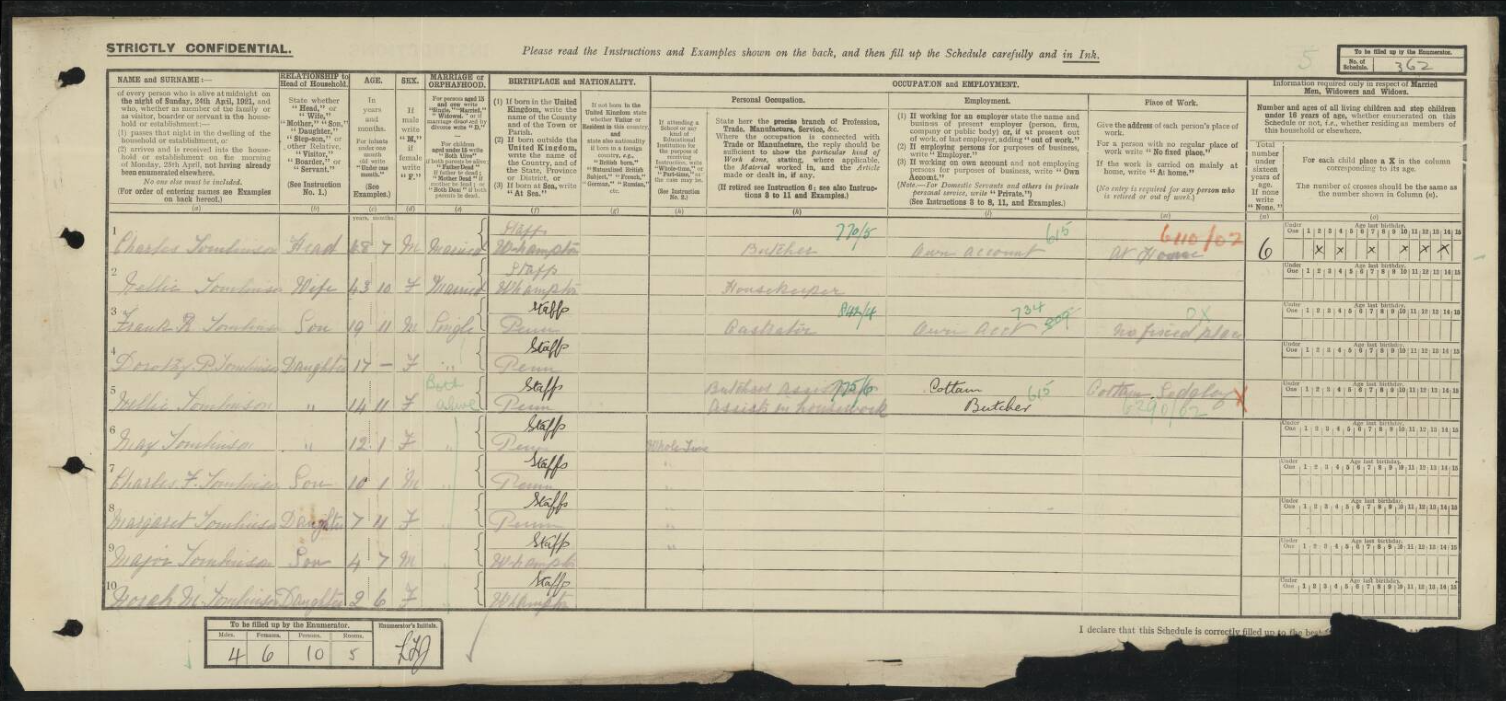

Charles Tomlinson (1873-1929) my great grandfather, was born in Wolverhampton in 1873. His father Charles Tomlinson (1847-1907) was a licensed victualler or publican, or alternatively a vet/castrator. He married Emma Grattidge (1853-1911) in 1872. On the 1881 census they were living at The Wheel in Wolverhampton.

Charles married Nellie Fisher (1877-1956) in Wolverhampton in 1896. In 1901 they were living next to the post office in Upper Penn, with children (Charles) Sidney Tomlinson (1896-1955), and Hilda Tomlinson (1898-1977) . Charles was a vet/castrator working on his own account.

In 1911 their address was 4, Wakely Hill, Penn, and living with them were their children Hilda, Frank Tomlinson (1901-1975), (Dorothy) Phyllis Tomlinson (1905-1982), Nellie Tomlinson (1906-1978) and May Tomlinson (1910-1983). Charles was a castrator working on his own account.

Charles and Nellie had a further four children: Charles Fisher Tomlinson (1911-1977), Margaret Tomlinson (1913-1989) (my grandmother Peggy), Major Tomlinson (1916-1984) and Norah Mary Tomlinson (1919-2010).

My father told me that my grandmother had fallen down the well at the house on Penn Common in 1915 when she was two years old, and sent me a photo of her standing next to the well when she revisted the house at a much later date.

Peggy next to the well on Penn Common:

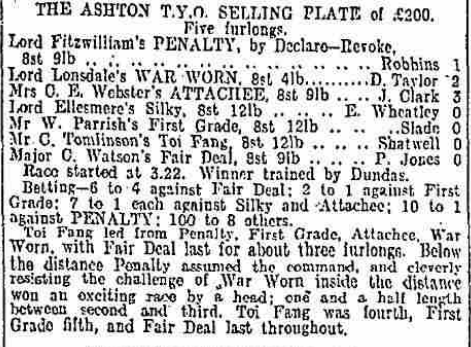

My grandmother Peggy told me that her father had had a racehorse called Toi Fang. She remembered the racing colours were sky blue and orange, and had a set of racing silks made which she sent to my father.

Through a DNA match, I met Ian Tomlinson. Ian is the son of my fathers favourite cousin Roger, Frank’s son. Ian found some racing silks and sent a photo to my father (they are now in contact with each other as a result of my DNA match with Ian), wondering what they were.

When Ian sent a photo of these racing silks, I had a look in the newspaper archives. In 1920 there are a number of mentions in the racing news of Mr C Tomlinson’s horse TOI FANG. I have not found any mention of Toi Fang in the newspapers in the following years.

The Scotsman – Monday 12 July 1920:

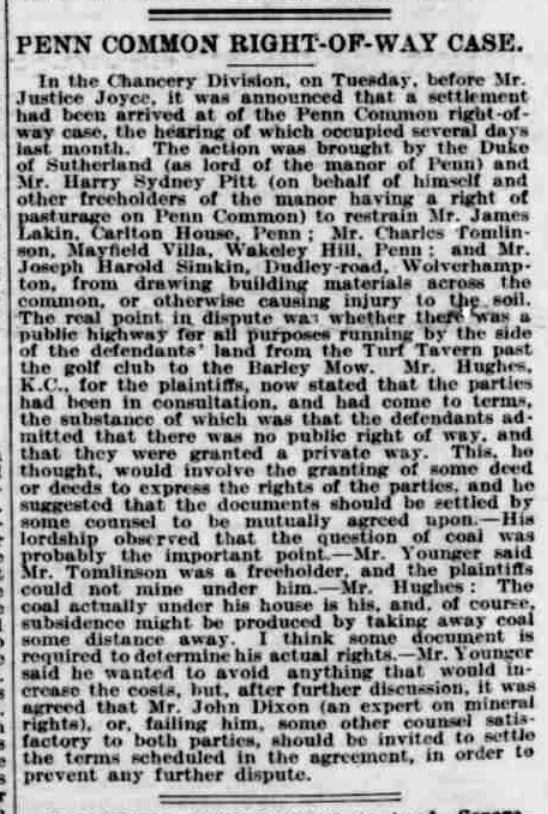

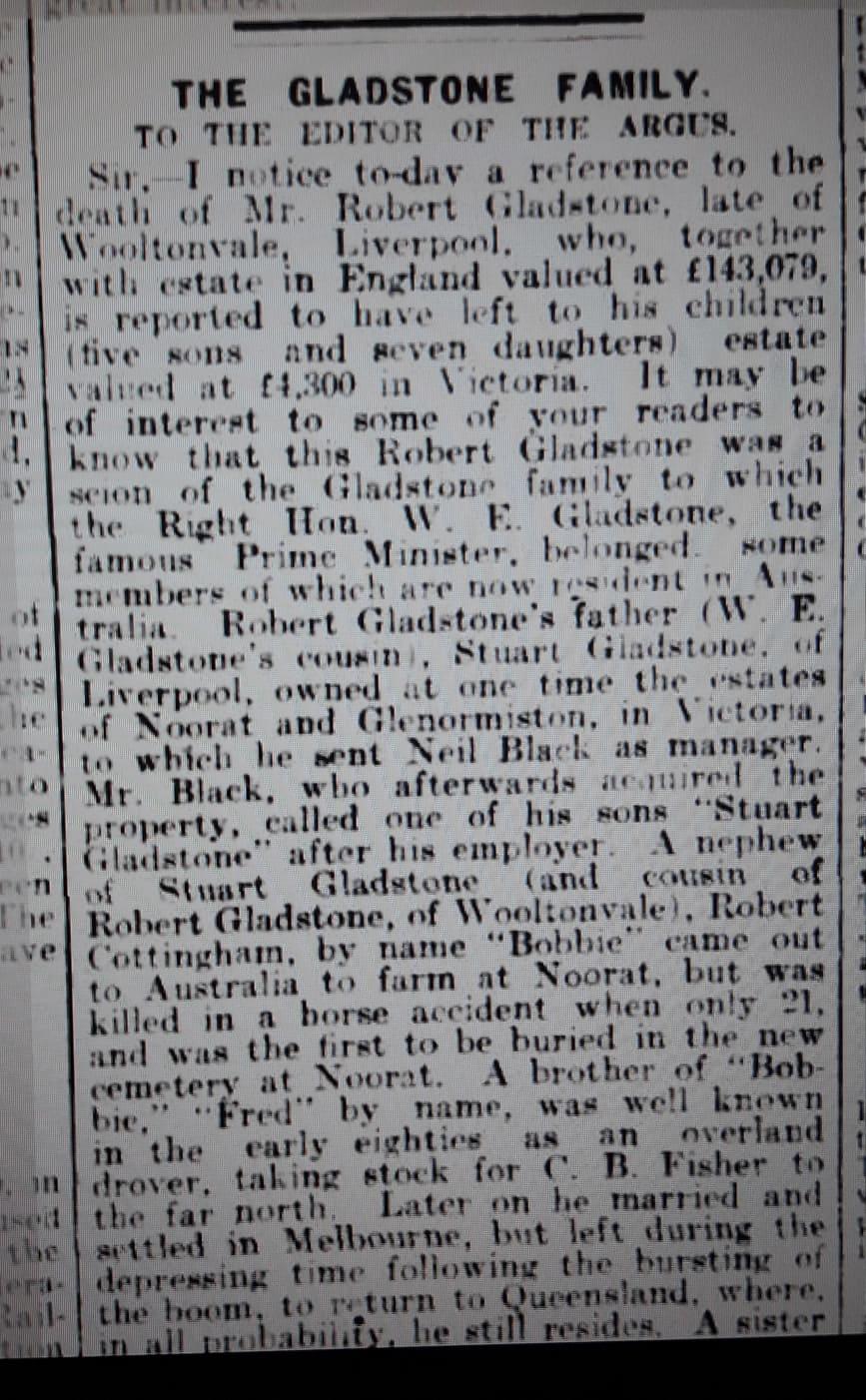

The other story that Ian Tomlinson recalled was about the house on Penn Common. Ian said he’d heard that the local titled person took Charles Tomlinson to court over building the house but that Tomlinson won the case because it was built on common land and was the first case of it’s kind.

Penn Common Right of Way Case:

Staffordshire Advertiser March 9, 1912In the chancery division, on Tuesday, before Mr Justice Joyce, it was announced that a settlement had been arrived at of the Penn Common Right of Way case, the hearing of which occupied several days last month. The action was brought by the Duke of Sutherland (as Lord of the Manor of Penn) and Mr Harry Sydney Pitt (on behalf of himself and other freeholders of the manor having a right to pasturage on Penn Common) to restrain Mr James Lakin, Carlton House, Penn; Mr Charles Tomlinson, Mayfield Villa, Wakely Hill, Penn; and Mr Joseph Harold Simpkin, Dudley Road, Wolverhampton, from drawing building materials across the common, or otherwise causing injury to the soil.

The real point in dispute was whether there was a public highway for all purposes running by the side of the defendants land from the Turf Tavern past the golf club to the Barley Mow.

Mr Hughes, KC for the plaintiffs, now stated that the parties had been in consultation, and had come to terms, the substance of which was that the defendants admitted that there was no public right of way, and that they were granted a private way. This, he thought, would involve the granting of some deed or deeds to express the rights of the parties, and he suggested that the documents should be be settled by some counsel to be mutually agreed upon.His lordship observed that the question of coal was probably the important point. Mr Younger said Mr Tomlinson was a freeholder, and the plaintiffs could not mine under him. Mr Hughes: The coal actually under his house is his, and, of course, subsidence might be produced by taking away coal some distance away. I think some document is required to determine his actual rights.

Mr Younger said he wanted to avoid anything that would increase the costs, but, after further discussion, it was agreed that Mr John Dixon (an expert on mineral rights), or failing him, another counsel satisfactory to both parties, should be invited to settle the terms scheduled in the agreement, in order to prevent any further dispute.

The name of the house is Grassholme. The address of Mayfield Villas is the house they were living in while building Grassholme, which I assume they had not yet moved in to at the time of the newspaper article in March 1912.

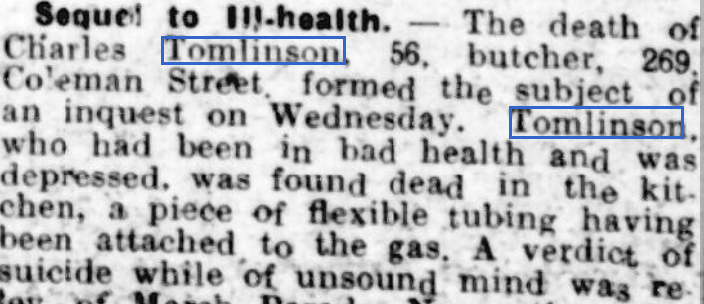

What my grandmother didn’t tell anyone was how her father died in 1929:

On the 1921 census, Charles, Nellie and eight of their children were living at 269 Coleman Street, Wolverhampton.

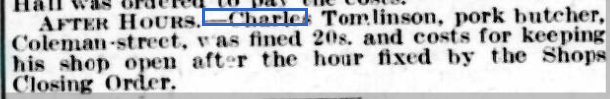

They were living on Coleman Street in 1915 when Charles was fined for staying open late.

Staffordshire Advertiser – Saturday 13 February 1915:

What is not yet clear is why they moved from the house on Penn Common sometime between 1912 and 1915. And why did he have a racehorse in 1920?

February 2, 2022 at 12:33 pm #6266In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

From Tanganyika with Love

continued part 7

With thanks to Mike Rushby.

Oldeani Hospital. 19th September 1938

Dearest Family,

George arrived today to take us home to Mbulu but Sister Marianne will not allow

me to travel for another week as I had a bit of a set back after baby’s birth. At first I was

very fit and on the third day Sister stripped the bed and, dictionary in hand, started me

off on ante natal exercises. “Now make a bridge Mrs Rushby. So. Up down, up down,’

whilst I obediently hoisted myself aloft on heels and head. By the sixth day she

considered it was time for me to be up and about but alas, I soon had to return to bed

with a temperature and a haemorrhage. I got up and walked outside for the first time this

morning.I have had lots of visitors because the local German settlers seem keen to see

the first British baby born in the hospital. They have been most kind, sending flowers

and little German cards of congratulations festooned with cherubs and rather sweet. Most

of the women, besides being pleasant, are very smart indeed, shattering my illusion that

German matrons are invariably fat and dowdy. They are all much concerned about the

Czecko-Slovakian situation, especially Sister Marianne whose home is right on the

border and has several relations who are Sudentan Germans. She is ant-Nazi and

keeps on asking me whether I think England will declare war if Hitler invades Czecko-

Slovakia, as though I had inside information.George tells me that he has had a grass ‘banda’ put up for us at Mbulu as we are

both determined not to return to those prison-like quarters in the Fort. Sister Marianne is

horrified at the idea of taking a new baby to live in a grass hut. She told George,

“No,No,Mr Rushby. I find that is not to be allowed!” She is an excellent Sister but rather

prim and George enjoys teasing her. This morning he asked with mock seriousness,

“Sister, why has my wife not received her medal?” Sister fluttered her dictionary before

asking. “What medal Mr Rushby”. “Why,” said George, “The medal that Hitler gives to

women who have borne four children.” Sister started a long and involved explanation

about the medal being only for German mothers whilst George looked at me and

grinned.Later. Great Jubilation here. By the noise in Sister Marianne’s sitting room last night it

sounded as though the whole German population had gathered to listen to the wireless

news. I heard loud exclamations of joy and then my bedroom door burst open and

several women rushed in. “Thank God “, they cried, “for Neville Chamberlain. Now there

will be no war.” They pumped me by the hand as though I were personally responsible

for the whole thing.George on the other hand is disgusted by Chamberlain’s lack of guts. Doesn’t

know what England is coming to these days. I feel too content to concern myself with

world affairs. I have a fine husband and four wonderful children and am happy, happy,

happy.Eleanor.

Mbulu. 30th September 1938

Dearest Family,

Here we are, comfortably installed in our little green house made of poles and

rushes from a nearby swamp. The house has of course, no doors or windows, but

there are rush blinds which roll up in the day time. There are two rooms and a little porch

and out at the back there is a small grass kitchen.Here we have the privacy which we prize so highly as we are screened on one

side by a Forest Department plantation and on the other three sides there is nothing but

the rolling countryside cropped bare by the far too large herds of cattle and goats of the

Wambulu. I have a lovely lazy time. I still have Kesho-Kutwa and the cook we brought

with us from the farm. They are both faithful and willing souls though not very good at

their respective jobs. As one of these Mbeya boys goes on safari with George whose

job takes him from home for three weeks out of four, I have taken on a local boy to cut

firewood and heat my bath water and generally make himself useful. His name is Saa,

which means ‘Clock’We had an uneventful but very dusty trip from Oldeani. Johnny Jo travelled in his

pram in the back of the boxbody and got covered in dust but seems none the worst for

it. As the baby now takes up much of my time and Kate was showing signs of

boredom, I have engaged a little African girl to come and play with Kate every morning.

She is the daughter of the head police Askari and a very attractive and dignified little

person she is. Her name is Kajyah. She is scrupulously clean, as all Mohammedan

Africans seem to be. Alas, Kajyah, though beautiful, is a bore. She simply does not

know how to play, so they just wander around hand in hand.There are only two drawbacks to this little house. Mbulu is a very windy spot so

our little reed house is very draughty. I have made a little tent of sheets in one corner of

the ‘bedroom’ into which I can retire with Johnny when I wish to bathe or sponge him.

The other drawback is that many insects are attracted at night by the lamp and make it

almost impossible to read or sew and they have a revolting habit of falling into the soup.

There are no dangerous wild animals in this area so I am not at all nervous in this

flimsy little house when George is on safari. Most nights hyaenas come around looking

for scraps but our dogs, Fanny and Paddy, soon see them off.Eleanor.

Mbulu. 25th October 1938

Dearest Family,

Great news! a vacancy has occurred in the Game Department. George is to

transfer to it next month. There will be an increase in salary and a brighter prospect for

the future. It will mean a change of scene and I shall be glad of that. We like Mbulu and

the people here but the rains have started and our little reed hut is anything but water

tight.Before the rain came we had very unpleasant dust storms. I think I told you that

this is a treeless area and the grass which normally covers the veldt has been cropped

to the roots by the hungry native cattle and goats. When the wind blows the dust

collects in tall black columns which sweep across the country in a most spectacular

fashion. One such dust devil struck our hut one day whilst we were at lunch. George

swept Kate up in a second and held her face against his chest whilst I rushed to Johnny

Jo who was asleep in his pram, and stooped over the pram to protect him. The hut

groaned and creaked and clouds of dust blew in through the windows and walls covering

our persons, food, and belongings in a black pall. The dogs food bowls and an empty

petrol tin outside the hut were whirled up and away. It was all over in a moment but you

should have seen what a family of sweeps we looked. George looked at our blackened

Johnny and mimicked in Sister Marianne’s primmest tones, “I find that this is not to be

allowed.”The first rain storm caught me unprepared when George was away on safari. It

was a terrific thunderstorm. The quite violent thunder and lightening were followed by a

real tropical downpour. As the hut is on a slight slope, the storm water poured through

the hut like a river, covering the entire floor, and the roof leaked like a lawn sprinkler.

Johnny Jo was snug enough in the pram with the hood raised, but Kate and I had a

damp miserable night. Next morning I had deep drains dug around the hut and when

George returned from safari he managed to borrow an enormous tarpaulin which is now

lashed down over the roof.It did not rain during the next few days George was home but the very next night

we were in trouble again. I was awakened by screams from Kate and hurriedly turned up

the lamp to see that we were in the midst of an invasion of siafu ants. Kate’s bed was

covered in them. Others appeared to be raining down from the thatch. I quickly stripped

Kate and carried her across to my bed, whilst I rushed to the pram to see whether

Johnny Jo was all right. He was fast asleep, bless him, and slept on through all the

commotion, whilst I struggled to pick all the ants out of Kate’s hair, stopping now and

again to attend to my own discomfort. These ants have a painful bite and seem to

choose all the most tender spots. Kate fell asleep eventually but I sat up for the rest of

the night to make sure that the siafu kept clear of the children. Next morning the servants

dispersed them by laying hot ash.In spite of the dampness of the hut both children are blooming. Kate has rosy

cheeks and Johnny Jo now has a fuzz of fair hair and has lost his ‘old man’ look. He

reminds me of Ann at his age.Eleanor.

Iringa. 30th November 1938

Dearest Family,

Here we are back in the Southern Highlands and installed on the second floor of

another German Fort. This one has been modernised however and though not so

romantic as the Mbulu Fort from the outside, it is much more comfortable.We are all well

and I am really proud of our two safari babies who stood up splendidly to a most trying

journey North from Mbulu to Arusha and then South down the Great North Road to

Iringa where we expect to stay for a month.At Arusha George reported to the headquarters of the Game Department and

was instructed to come on down here on Rinderpest Control. There is a great flap on in

case the rinderpest spread to Northern Rhodesia and possibly onwards to Southern

Rhodesia and South Africa. Extra veterinary officers have been sent to this area to

inoculate all the cattle against the disease whilst George and his African game Scouts will

comb the bush looking for and destroying diseased game. If the rinderpest spreads,

George says it may be necessary to shoot out all the game in a wide belt along the

border between the Southern Highlands of Tanganyika and Northern Rhodesia, to

prevent the disease spreading South. The very idea of all this destruction sickens us

both.George left on a foot safari the day after our arrival and I expect I shall be lucky if I

see him occasionally at weekends until this job is over. When rinderpest is under control

George is to be stationed at a place called Nzassa in the Eastern Province about 18

miles from Dar es Salaam. George’s orderly, who is a tall, cheerful Game Scout called

Juma, tells me that he has been stationed at Nzassa and it is a frightful place! However I

refuse to be depressed. I now have the cheering prospect of leave to England in thirty

months time when we will be able to fetch Ann and George and be a proper family

again. Both Ann and George look happy in the snapshots which mother-in-law sends

frequently. Ann is doing very well at school and loves it.To get back to our journey from Mbulu. It really was quite an experience. It

poured with rain most of the way and the road was very slippery and treacherous the

120 miles between Mbulu and Arusha. This is a little used earth road and the drains are

so blocked with silt as to be practically non existent. As usual we started our move with

the V8 loaded to capacity. I held Johnny on my knee and Kate squeezed in between

George and me. All our goods and chattels were in wooden boxes stowed in the back

and the two houseboys and the two dogs had to adjust themselves to the space that

remained. We soon ran into trouble and it took us all day to travel 47 miles. We stuck

several times in deep mud and had some most nasty skids. I simply clutched Kate in

one hand and Johnny Jo in the other and put my trust in George who never, under any

circumstances, loses his head. Poor Johnny only got his meals when circumstances

permitted. Unfortunately I had put him on a bottle only a few days before we left Mbulu

and, as I was unable to buy either a primus stove or Thermos flask there we had to

make a fire and boil water for each meal. Twice George sat out in the drizzle with a rain

coat rapped over his head to protect a miserable little fire of wet sticks drenched with

paraffin. Whilst we waited for the water to boil I pacified John by letting him suck a cube

of Tate and Lyles sugar held between my rather grubby fingers. Not at all according to

the book.That night George, the children and I slept in the car having dumped our boxes

and the two servants in a deserted native hut. The rain poured down relentlessly all night

and by morning the road was more of a morass than ever. We swerved and skidded

alarmingly till eventually one of the wheel chains broke and had to be tied together with

string which constantly needed replacing. George was so patient though he was wet

and muddy and tired and both children were very good. Shortly before reaching the Great North Road we came upon Jack Gowan, the Stock Inspector from Mbulu. His car

was bogged down to its axles in black mud. He refused George’s offer of help saying

that he had sent his messenger to a nearby village for help.I hoped that conditions would be better on the Great North Road but how over

optimistic I was. For miles the road runs through a belt of ‘black cotton soil’. which was

churned up into the consistency of chocolate blancmange by the heavy lorry traffic which

runs between Dodoma and Arusha. Soon the car was skidding more fantastically than

ever. Once it skidded around in a complete semi circle so George decided that it would

be safer for us all to walk whilst he negotiated the very bad patches. You should have

seen me plodding along in the mud and drizzle with the baby in one arm and Kate

clinging to the other. I was terrified of slipping with Johnny. Each time George reached

firm ground he would return on foot to carry Kate and in this way we covered many bad

patches.We were more fortunate than many other travellers. We passed several lorries

ditched on the side of the road and one car load of German men, all elegantly dressed in

lounge suits. One was busy with his camera so will have a record of their plight to laugh

over in the years to come. We spent another night camping on the road and next day

set out on the last lap of the journey. That also was tiresome but much better than the

previous day and we made the haven of the Arusha Hotel before dark. What a picture

we made as we walked through the hall in our mud splattered clothes! Even Johnny was

well splashed with mud but no harm was done and both he and Kate are blooming.

We rested for two days at Arusha and then came South to Iringa. Luckily the sun

came out and though for the first day the road was muddy it was no longer so slippery

and the second day found us driving through parched country and along badly

corrugated roads. The further South we came, the warmer the sun which at times blazed

through the windscreen and made us all uncomfortably hot. I have described the country

between Arusha and Dodoma before so I shan’t do it again. We reached Iringa without

mishap and after a good nights rest all felt full of beans.Eleanor.

Mchewe Estate, Mbeya. 7th January 1939.

Dearest Family,

You will be surprised to note that we are back on the farm! At least the children

and I are here. George is away near the Rhodesian border somewhere, still on

Rinderpest control.I had a pleasant time at Iringa, lots of invitations to morning tea and Kate had a

wonderful time enjoying the novelty of playing with children of her own age. She is not

shy but nevertheless likes me to be within call if not within sight. It was all very suburban

but pleasant enough. A few days before Christmas George turned up at Iringa and

suggested that, as he would be working in the Mbeya area, it might be a good idea for

the children and me to move to the farm. I agreed enthusiastically, completely forgetting

that after my previous trouble with the leopard I had vowed to myself that I would never

again live alone on the farm.Alas no sooner had we arrived when Thomas, our farm headman, brought the

news that there were now two leopards terrorising the neighbourhood, and taking dogs,

goats and sheep and chickens. Traps and poisoned bait had been tried in vain and he

was sure that the female was the same leopard which had besieged our home before.

Other leopards said Thomas, came by stealth but this one advertised her whereabouts

in the most brazen manner.George stayed with us on the farm over Christmas and all was quiet at night so I

cheered up and took the children for walks along the overgrown farm paths. However on

New Years Eve that darned leopard advertised her presence again with the most blood

chilling grunts and snarls. Horrible! Fanny and Paddy barked and growled and woke up

both children. Kate wept and kept saying, “Send it away mummy. I don’t like it.” Johnny

Jo howled in sympathy. What a picnic. So now the whole performance of bodyguards

has started again and ‘till George returns we confine our exercise to the garden.

Our little house is still cosy and sweet but the coffee plantation looks very

neglected. I wish to goodness we could sell it.Eleanor.

Nzassa 14th February 1939.

Dearest Family,

After three months of moving around with two small children it is heavenly to be

settled in our own home, even though Nzassa is an isolated spot and has the reputation

of being unhealthy.We travelled by car from Mbeya to Dodoma by now a very familiar stretch of

country, but from Dodoma to Dar es Salaam by train which made a nice change. We

spent two nights and a day in the Splendid Hotel in Dar es Salaam, George had some

official visits to make and I did some shopping and we took the children to the beach.

The bay is so sheltered that the sea is as calm as a pond and the water warm. It is

wonderful to see the sea once more and to hear tugs hooting and to watch the Arab

dhows putting out to sea with their oddly shaped sails billowing. I do love the bush, but

I love the sea best of all, as you know.We made an early start for Nzassa on the 3rd. For about four miles we bowled

along a good road. This brought us to a place called Temeke where George called on

the District Officer. His house appears to be the only European type house there. The

road between Temeke and the turn off to Nzassa is quite good, but the six mile stretch

from the turn off to Nzassa is a very neglected bush road. There is nothing to be seen

but the impenetrable bush on both sides with here and there a patch of swampy

ground where rice is planted in the wet season.After about six miles of bumpy road we reached Nzassa which is nothing more

than a sandy clearing in the bush. Our house however is a fine one. It was originally built

for the District Officer and there is a small court house which is now George’s office. The

District Officer died of blackwater fever so Nzassa was abandoned as an administrative

station being considered too unhealthy for Administrative Officers but suitable as

Headquarters for a Game Ranger. Later a bachelor Game Ranger was stationed here

but his health also broke down and he has been invalided to England. So now the

healthy Rushbys are here and we don’t mean to let the place get us down. So don’t

worry.The house consists of three very large and airy rooms with their doors opening

on to a wide front verandah which we shall use as a living room. There is also a wide

back verandah with a store room at one end and a bathroom at the other. Both

verandahs and the end windows of the house are screened my mosquito gauze wire

and further protected by a trellis work of heavy expanded metal. Hasmani, the Game

Scout, who has been acting as caretaker, tells me that the expanded metal is very

necessary because lions often come out of the bush at night and roam around the

house. Such a comforting thought!On our very first evening we discovered how necessary the mosquito gauze is.

After sunset the air outside is thick with mosquitos from the swamps. About an acre of

land has been cleared around the house. This is a sandy waste because there is no

water laid on here and absolutely nothing grows here except a rather revolting milky

desert bush called ‘Manyara’, and a few acacia trees. A little way from the house there is

a patch of citrus trees, grape fruit, I think, but whether they ever bear fruit I don’t know.

The clearing is bordered on three sides by dense dusty thorn bush which is

‘lousy with buffalo’ according to George. The open side is the road which leads down to

George’s office and the huts for the Game Scouts. Only Hasmani and George’s orderly

Juma and their wives and families live there, and the other huts provide shelter for the

Game Scouts from the bush who come to Nzassa to collect their pay and for a short

rest. I can see that my daily walk will always be the same, down the road to the huts and

back! However I don’t mind because it is far too hot to take much exercise.The climate here is really tropical and worse than on the coast because the thick

bush cuts us off from any sea breeze. George says it will be cooler when the rains start

but just now we literally drip all day. Kate wears nothing but a cotton sun suit, and Johnny

a napkin only, but still their little bodies are always moist. I have shorn off all Kate’s lovely

shoulder length curls and got George to cut my hair very short too.We simply must buy a refrigerator. The butter, and even the cheese we bought

in Dar. simply melted into pools of oil overnight, and all our meat went bad, so we are

living out of tins. However once we get organised I shall be quite happy here. I like this

spacious house and I have good servants. The cook, Hamisi Issa, is a Swahili from Lindi

whom we engaged in Dar es Salaam. He is a very dignified person, and like most

devout Mohammedan Cooks, keeps both his person and the kitchen spotless. I

engaged the house boy here. He is rather a timid little body but is very willing and quite

capable. He has an excessively plain but cheerful wife whom I have taken on as ayah. I

do not really need help with the children but feel I must have a woman around just in

case I go down with malaria when George is away on safari.Eleanor.

Nzassa 28th February 1939.

Dearest Family,

George’s birthday and we had a special tea party this afternoon which the

children much enjoyed. We have our frig now so I am able to make jellies and provide

them with really cool drinks.Our very first visitor left this morning after spending only one night here. He is Mr

Ionides, the Game Ranger from the Southern Province. He acted as stand in here for a

short while after George’s predecessor left for England on sick leave, and where he has

since died. Mr Ionides returned here to hand over the range and office formally to

George. He seems a strange man and is from all accounts a bit of a hermit. He was at

one time an Officer in the Regular Army but does not look like a soldier, he wears the

most extraordinary clothes but nevertheless contrives to look top-drawer. He was

educated at Rugby and Sandhurst and is, I should say, well read. Ionides told us that he

hated Nzassa, particularly the house which he thinks sinister and says he always slept

down in the office.The house, or at least one bedroom, seems to have the same effect on Kate.

She has been very nervous at night ever since we arrived. At first the children occupied

the bedroom which is now George’s. One night, soon after our arrival, Kate woke up

screaming to say that ‘something’ had looked at her through the mosquito net. She was

in such a hysterical state that inspite of the heat and discomfort I was obliged to crawl into

her little bed with her and remained there for the rest of the night.Next night I left a night lamp burning but even so I had to sit by her bed until she

dropped off to sleep. Again I was awakened by ear-splitting screams and this time

found Kate standing rigid on her bed. I lifted her out and carried her to a chair meaning to

comfort her but she screeched louder than ever, “Look Mummy it’s under the bed. It’s

looking at us.” In vain I pointed out that there was nothing at all there. By this time

George had joined us and he carried Kate off to his bed in the other room whilst I got into

Kate’s bed thinking she might have been frightened by a rat which might also disturb

Johnny.Next morning our houseboy remarked that he had heard Kate screaming in the

night from his room behind the kitchen. I explained what had happened and he must

have told the old Scout Hasmani who waylaid me that afternoon and informed me quite

seriously that that particular room was haunted by a ‘sheitani’ (devil) who hates children.

He told me that whilst he was acting as caretaker before our arrival he one night had his

wife and small daughter in the room to keep him company. He said that his small

daughter woke up and screamed exactly as Kate had done! Silly coincidence I

suppose, but such strange things happen in Africa that I decided to move the children

into our room and George sleeps in solitary state in the haunted room! Kate now sleeps

peacefully once she goes to sleep but I have to stay with her until she does.I like this house and it does not seem at all sinister to me. As I mentioned before,

the rooms are high ceilinged and airy, and have cool cement floors. We have made one

end of the enclosed verandah into the living room and the other end is the playroom for

the children. The space in between is a sort of no-mans land taken over by the dogs as

their special territory.Eleanor.

Nzassa 25th March 1939.

Dearest Family,

George is on safari down in the Rufigi River area. He is away for about three

weeks in the month on this job. I do hate to see him go and just manage to tick over until

he comes back. But what fun and excitement when he does come home.

Usually he returns after dark by which time the children are in bed and I have

settled down on the verandah with a book. The first warning is usually given by the

dogs, Fanny and her son Paddy. They stir, sit up, look at each other and then go and sit

side by side by the door with their noses practically pressed to the mosquito gauze and

ears pricked. Soon I can hear the hum of the car, and so can Hasmani, the old Game

Scout who sleeps on the back verandah with rifle and ammunition by his side when

George is away. When he hears the car he turns up his lamp and hurries out to rouse

Juma, the houseboy. Juma pokes up the fire and prepares tea which George always

drinks whist a hot meal is being prepared. In the meantime I hurriedly comb my hair and

powder my nose so that when the car stops I am ready to rush out and welcome

George home. The boy and Hasmani and the garden boy appear to help with the

luggage and to greet George and the cook, who always accompanies George on

Safari. The home coming is always a lively time with much shouting of greetings.

‘Jambo’, and ‘Habari ya safari’, whilst the dogs, beside themselves with excitement,

rush around like lunatics.As though his return were not happiness enough, George usually collects the

mail on his way home so there is news of Ann and young George and letters from you

and bundles of newspapers and magazines. On the day following his return home,

George has to deal with official mail in the office but if the following day is a weekday we

all, the house servants as well as ourselves, pile into the boxbody and go to Dar es

Salaam. To us this means a mornings shopping followed by an afternoon on the beach.

It is a bit cooler now that the rains are on but still very humid. Kate keeps chubby

and rosy in spite of the climate but Johnny is too pale though sturdy enough. He is such

a good baby which is just as well because Kate is a very demanding little girl though

sunny tempered and sweet. I appreciate her company very much when George is

away because we are so far off the beaten track that no one ever calls.Eleanor.

Nzassa 28th April 1939.

Dearest Family,

You all seem to wonder how I can stand the loneliness and monotony of living at

Nzassa when George is on safari, but really and truly I do not mind. Hamisi the cook

always goes on safari with George and then the houseboy Juma takes over the cooking

and I do the lighter housework. the children are great company during the day, and when

they are settled for the night I sit on the verandah and read or write letters or I just dream.

The verandah is entirely enclosed with both wire mosquito gauze and a trellis

work of heavy expanded metal, so I am safe from all intruders be they human, animal, or

insect. Outside the air is alive with mosquitos and the cicadas keep up their monotonous

singing all night long. My only companions on the verandah are the pale ghecco lizards

on the wall and the two dogs. Fanny the white bull terrier, lies always near my feet

dozing happily, but her son Paddy, who is half Airedale has a less phlegmatic

disposition. He sits alert and on guard by the metal trellis work door. Often a lion grunts

from the surrounding bush and then his hackles rise and he stands up stiffly with his nose

pressed to the door. Old Hasmani from his bedroll on the back verandah, gives a little

cough just to show he is awake. Sometimes the lions are very close and then I hear the

click of a rifle bolt as Hasmani loads his rifle – but this is usually much later at night when

the lights are out. One morning I saw large pug marks between the wall of my bedroom

and the garage but I do not fear lions like I did that beastly leopard on the farm.

A great deal of witchcraft is still practiced in the bush villages in the

neighbourhood. I must tell you about old Hasmani’s baby in connection with this. Last

week Hasmani came to me in great distress to say that his baby was ‘Ngongwa sana ‘

(very ill) and he thought it would die. I hurried down to the Game Scouts quarters to see

whether I could do anything for the child and found the mother squatting in the sun

outside her hut with the baby on her lap. The mother was a young woman but not an

attractive one. She appeared sullen and indifferent compared with old Hasmani who

was very distressed. The child was very feverish and breathing with difficulty and

seemed to me to be suffering from bronchitis if not pneumonia. I rubbed his back and

chest with camphorated oil and dosed him with aspirin and liquid quinine. I repeated the

treatment every four hours, but next day there was no apparent improvement.

In the afternoon Hasmani begged me to give him that night off duty and asked for

a loan of ten shillings. He explained to me that it seemed to him that the white man’s

medicine had failed to cure his child and now he wished to take the child to the local witch

doctor. “For ten shillings” said Hasmani, “the Maganga will drive the devil out of my

child.” “How?” asked I. “With drums”, said Hasmani confidently. I did not know what to

do. I thought the child was too ill to be exposed to the night air, yet I knew that if I

refused his request and the child were to die, Hasmani and all the other locals would hold

me responsible. I very reluctantly granted his request. I was so troubled by the matter

that I sent for George’s office clerk. Daniel, and asked him to accompany Hasmani to the

ceremony and to report to me the next morning. It started to rain after dark and all night

long I lay awake in bed listening to the drums and the light rain. Next morning when I

went out to the kitchen to order breakfast I found a beaming Hasmani awaiting me.

“Memsahib”, he said. “My child is well, the fever is now quite gone, the Maganga drove

out the devil just as I told you.” Believe it or not, when I hurried to his quarters after

breakfast I found the mother suckling a perfectly healthy child! It may be my imagination

but I thought the mother looked pretty smug.The clerk Daniel told me that after Hasmani

had presented gifts of money and food to the ‘Maganga’, the naked baby was placed

on a goat skin near the drums. Most of the time he just lay there but sometimes the witch

doctor picked him up and danced with the child in his arms. Daniel seemed reluctant to

talk about it. Whatever mumbo jumbo was used all this happened a week ago and the

baby has never looked back.Eleanor.

Nzassa 3rd July 1939.

Dearest Family,

Did I tell you that one of George’s Game Scouts was murdered last month in the

Maneromango area towards the Rufigi border. He was on routine patrol, with a porter

carrying his bedding and food, when they suddenly came across a group of African

hunters who were busy cutting up a giraffe which they had just killed. These hunters were

all armed with muzzle loaders, spears and pangas, but as it is illegal to kill giraffe without

a permit, the Scout went up to the group to take their names. Some argument ensued

and the Scout was stabbed.The District Officer went to the area to investigate and decided to call in the Police

from Dar es Salaam. A party of police went out to search for the murderers but after

some days returned without making any arrests. George was on an elephant control

safari in the Bagamoyo District and on his return through Dar es Salaam he heard of the

murder. George was furious and distressed to hear the news and called in here for an

hour on his way to Maneromango to search for the murderers himself.After a great deal of strenuous investigation he arrested three poachers, put them

in jail for the night at Maneromango and then brought them to Dar es Salaam where they

are all now behind bars. George will now have to prosecute in the Magistrate’s Court

and try and ‘make a case’ so that the prisoners may be committed to the High Court to

be tried for murder. George is convinced of their guilt and justifiably proud to have

succeeded where the police failed.George had to borrow handcuffs for the prisoners from the Chief at

Maneromango and these he brought back to Nzassa after delivering the prisoners to

Dar es Salaam so that he may return them to the Chief when he revisits the area next

week.I had not seen handcuffs before and picked up a pair to examine them. I said to

George, engrossed in ‘The Times’, “I bet if you were arrested they’d never get

handcuffs on your wrist. Not these anyway, they look too small.” “Standard pattern,”

said George still concentrating on the newspaper, but extending an enormous relaxed

left wrist. So, my dears, I put a bracelet round his wrist and as there was a wide gap I

gave a hard squeeze with both hands. There was a sharp click as the handcuff engaged

in the first notch. George dropped the paper and said, “Now you’ve done it, my love,

one set of keys are in the Dar es Salaam Police Station, and the others with the Chief at

Maneromango.” You can imagine how utterly silly I felt but George was an angel about it

and said as he would have to go to Dar es Salaam we might as well all go.So we all piled into the car, George, the children and I in the front, and the cook

and houseboy, immaculate in snowy khanzus and embroidered white caps, a Game

Scout and the ayah in the back. George never once complain of the discomfort of the

handcuff but I was uncomfortably aware that it was much too tight because his arm

above the cuff looked red and swollen and the hand unnaturally pale. As the road is so

bad George had to use both hands on the wheel and all the time the dangling handcuff

clanked against the dashboard in an accusing way.We drove straight to the Police Station and I could hear the roars of laughter as

George explained his predicament. Later I had to put up with a good deal of chaffing

and congratulations upon putting the handcuffs on George.Eleanor.

Nzassa 5th August 1939

Dearest Family,

George made a point of being here for Kate’s fourth birthday last week. Just

because our children have no playmates George and I always do all we can to make

birthdays very special occasions. We went to Dar es Salaam the day before the

birthday and bought Kate a very sturdy tricycle with which she is absolutely delighted.

You will be glad to know that your parcels arrived just in time and Kate loved all your

gifts especially the little shop from Dad with all the miniature tins and packets of

groceries. The tea set was also a great success and is much in use.We had a lively party which ended with George and me singing ‘Happy

Birthday to you’, and ended with a wild game with balloons. Kate wore her frilly white net

party frock and looked so pretty that it seemed a shame that there was no one but us to

see her. Anyway it was a good party. I wish so much that you could see the children.

Kate keeps rosy and has not yet had malaria. Johnny Jo is sturdy but pale. He

runs a temperature now and again but I am not sure whether this is due to teething or

malaria. Both children of course take quinine every day as George and I do. George

quite frequently has malaria in spite of prophylactic quinine but this is not surprising as he

got the germ thoroughly established in his system in his early elephant hunting days. I

get it too occasionally but have not been really ill since that first time a month after my

arrival in the country.Johnny is such a good baby. His chief claim to beauty is his head of soft golden

curls but these are due to come off on his first birthday as George considers them too

girlish. George left on safari the day after the party and the very next morning our wood

boy had a most unfortunate accident. He was chopping a rather tough log when a chip

flew up and split his upper lip clean through from mouth to nostril exposing teeth and

gums. A truly horrible sight and very bloody. I cleaned up the wound as best I could

and sent him off to the hospital at Dar es Salaam on the office bicycle. He wobbled

away wretchedly down the road with a white cloth tied over his mouth to keep off the

dust. He returned next day with his lip stitched and very swollen and bearing a

resemblance to my lip that time I used the hair remover.Eleanor.

Splendid Hotel. Dar es Salaam 7th September 1939

Dearest Family,

So now another war has started and it has disrupted even our lives. We have left

Nzassa for good. George is now a Lieutenant in the King’s African Rifles and the children

and I are to go to a place called Morogoro to await further developments.

I was glad to read in today’s paper that South Africa has declared war on

Germany. I would have felt pretty small otherwise in this hotel which is crammed full of

men who have been called up for service in the Army. George seems exhilarated by

the prospect of active service. He is bursting out of his uniform ( at the shoulders only!)

and all too ready for the fray.The war came as a complete surprise to me stuck out in the bush as I was without

wireless or mail. George had been away for a fortnight so you can imagine how

surprised I was when a messenger arrived on a bicycle with a note from George. The

note informed me that war had been declared and that George, as a Reserve Officer in

the KAR had been called up. I was to start packing immediately and be ready by noon

next day when George would arrive with a lorry for our goods and chattels. I started to

pack immediately with the help of the houseboy and by the time George arrived with

the lorry only the frig remained to be packed and this was soon done.Throughout the morning Game Scouts had been arriving from outlying parts of

the District. I don’t think they had the least idea where they were supposed to go or

whom they were to fight but were ready to fight anybody, anywhere, with George.

They all looked very smart in well pressed uniforms hung about with water bottles and

ammunition pouches. The large buffalo badge on their round pill box hats absolutely

glittered with polish. All of course carried rifles and when George arrived they all lined up

and they looked most impressive. I took some snaps but unfortunately it was drizzling

and they may not come out well.We left Nzassa without a backward glance. We were pretty fed up with it by

then. The children and I are spending a few days here with George but our luggage, the

dogs, and the houseboys have already left by train for Morogoro where a small house

has been found for the children and me.George tells me that all the German males in this Territory were interned without a

hitch. The whole affair must have been very well organised. In every town and

settlement special constables were sworn in to do the job. It must have been a rather

unpleasant one but seems to have gone without incident. There is a big transit camp

here at Dar for the German men. Later they are to be sent out of the country, possibly to

Rhodesia.The Indian tailors in the town are all terribly busy making Army uniforms, shorts

and tunics in khaki drill. George swears that they have muddled their orders and he has

been given the wrong things. Certainly the tunic is far too tight. His hat, a khaki slouch hat

like you saw the Australians wearing in the last war, is also too small though it is the

largest they have in stock. We had a laugh over his other equipment which includes a

small canvas haversack and a whistle on a black cord. George says he feels like he is

back in his Boy Scouting boyhood.George has just come in to say the we will be leaving for Morogoro tomorrow

afternoon.Eleanor.

Morogoro 14th September 1939

Dearest Family,

Morogoro is a complete change from Nzassa. This is a large and sprawling

township. The native town and all the shops are down on the flat land by the railway but

all the European houses are away up the slope of the high Uluguru Mountains.

Morogoro was a flourishing town in the German days and all the streets are lined with

trees for coolness as is the case in other German towns. These trees are the flamboyant

acacia which has an umbrella top and throws a wide but light shade.Most of the houses have large gardens so they cover a considerable area and it

is quite a safari for me to visit friends on foot as our house is on the edge of this area and

the furthest away from the town. Here ones house is in accordance with ones seniority in

Government service. Ours is a simple affair, just three lofty square rooms opening on to

a wide enclosed verandah. Mosquitoes are bad here so all doors and windows are

screened and we will have to carry on with our daily doses of quinine.George came up to Morogoro with us on the train. This was fortunate because I

went down with a sharp attack of malaria at the hotel on the afternoon of our departure

from Dar es Salaam. George’s drastic cure of vast doses of quinine, a pillow over my

head, and the bed heaped with blankets soon brought down the temperature so I was

fit enough to board the train but felt pretty poorly on the trip. However next day I felt

much better which was a good thing as George had to return to Dar es Salaam after two

days. His train left late at night so I did not see him off but said good-bye at home

feeling dreadful but trying to keep the traditional stiff upper lip of the wife seeing her

husband off to the wars. He hopes to go off to Abyssinia but wrote from Dar es Salaam

to say that he is being sent down to Rhodesia by road via Mbeya to escort the first

detachment of Rhodesian white troops.First he will have to select suitable camping sites for night stops and arrange for

supplies of food. I am very pleased as it means he will be safe for a while anyway. We

are both worried about Ann and George in England and wonder if it would be safer to

have them sent out.Eleanor.

Morogoro 4th November 1939

Dearest Family,

My big news is that George has been released from the Army. He is very

indignant and disappointed because he hoped to go to Abyssinia but I am terribly,

terribly glad. The Chief Secretary wrote a very nice letter to George pointing out that he

would be doing a greater service to his country by his work of elephant control, giving

crop protection during the war years when foodstuffs are such a vital necessity, than by

doing a soldiers job. The Government plan to start a huge rice scheme in the Rufiji area,

and want George to control the elephant and hippo there. First of all though. he must go

to the Southern Highlands Province where there is another outbreak of Rinderpest, to

shoot out diseased game especially buffalo, which might spread the disease.So off we go again on our travels but this time we are leaving the two dogs

behind in the care of Daniel, the Game Clerk. Fanny is very pregnant and I hate leaving

her behind but the clerk has promised to look after her well. We are taking Hamisi, our

dignified Swahili cook and the houseboy Juma and his wife whom we brought with us

from Nzassa. The boy is not very good but his wife makes a cheerful and placid ayah

and adores Johnny.Eleanor.

Iringa 8th December 1939

Dearest Family,

The children and I are staying in a small German house leased from the

Custodian of Enemy Property. I can’t help feeling sorry for the owners who must be in

concentration camps somewhere.George is away in the bush dealing with the

Rinderpest emergency and the cook has gone with him. Now I have sent the houseboy

and the ayah away too. Two days ago my houseboy came and told me that he felt

very ill and asked me to write a ‘chit’ to the Indian Doctor. In the note I asked the Doctor

to let me know the nature of his complaint and to my horror I got a note from him to say

that the houseboy had a bad case of Venereal Disease. Was I horrified! I took it for

granted that his wife must be infected too and told them both that they would have to

return to their home in Nzassa. The boy shouted and the ayah wept but I paid them in

lieu of notice and gave them money for the journey home. So there I was left servant

less with firewood to chop, a smokey wood burning stove to control, and of course, the

two children.To add to my troubles Johnny had a temperature so I sent for the European

Doctor. He diagnosed malaria and was astonished at the size of Johnny’s spleen. He

said that he must have had suppressed malaria over a long period and the poor child

must now be fed maximum doses of quinine for a long time. The Doctor is a fatherly

soul, he has been recalled from retirement to do this job as so many of the young

doctors have been called up for service with the army.I told him about my houseboy’s complaint and the way I had sent him off

immediately, and he was very amused at my haste, saying that it is most unlikely that

they would have passed the disease onto their employers. Anyway I hated the idea. I

mean to engage a houseboy locally, but will do without an ayah until we return to

Morogoro in February.Something happened today to cheer me up. A telegram came from Daniel which

read, “FLANNEL HAS FIVE CUBS.”Eleanor.

Morogoro 10th March 1940

Dearest Family,

We are having very heavy rain and the countryside is a most beautiful green. In

spite of the weather George is away on safari though it must be very wet and

unpleasant. He does work so hard at his elephant hunting job and has got very thin. I

suppose this is partly due to those stomach pains he gets and the doctors don’t seem

to diagnose the trouble.Living in Morogoro is much like living in a country town in South Africa, particularly

as there are several South African women here. I go out quite often to morning teas. We

all take our war effort knitting, and natter, and are completely suburban.

I sometimes go and see an elderly couple who have been interred here. They

are cold shouldered by almost everyone else but I cannot help feeling sorry for them.

Usually I go by invitation because I know Mrs Ruppel prefers to be prepared and

always has sandwiches and cake. They both speak English but not fluently and

conversation is confined to talking about my children and theirs. Their two sons were

students in Germany when war broke out but are now of course in the German Army.

Such nice looking chaps from their photographs but I suppose thorough Nazis. As our

conversation is limited I usually ask to hear a gramophone record or two. They have a

large collection.Janet, the ayah whom I engaged at Mbeya, is proving a great treasure. She is a

trained hospital ayah and is most dependable and capable. She is, perhaps, a little strict

but the great thing is that I can trust her with the children out of my sight.

Last week I went out at night for the first time without George. The occasion was

a farewell sundowner given by the Commissioner of Prisoners and his wife. I was driven

home by the District Officer and he stopped his car by the back door in a large puddle.

Ayah came to the back door, storm lamp in hand, to greet me. My escort prepared to

drive off but the car stuck. I thought a push from me might help, so without informing the

driver, I pushed as hard as I could on the back of the car. Unfortunately the driver

decided on other tactics. He put the engine in reverse and I was knocked flat on my back

in the puddle. The car drove forward and away without the driver having the least idea of

what happened. The ayah was in quite a state, lifting me up and scolding me for my

stupidity as though I were Kate. I was a bit shaken but non the worse and will know

better next time.Eleanor.

Morogoro 14th July 1940

Dearest Family,

How good it was of Dad to send that cable to Mother offering to have Ann and

George to live with you if they are accepted for inclusion in the list of children to be

evacuated to South Africa. It would be wonderful to know that they are safely out of the

war zone and so much nearer to us but I do dread the thought of the long sea voyage

particularly since we heard the news of the sinking of that liner carrying child evacuees to

Canada. I worry about them so much particularly as George is so often away on safari.

He is so comforting and calm and I feel brave and confident when he is home.

We have had no news from England for five weeks but, when she last wrote,

mother said the children were very well and that she was sure they would be safe in the

country with her.Kate and John are growing fast. Kate is such a pretty little girl, rosy in spite of the

rather trying climate. I have allowed her hair to grow again and it hangs on her shoulders

in shiny waves. John is a more slightly built little boy than young George was, and quite

different in looks. He has Dad’s high forehead and cleft chin, widely spaced brown eyes

that are not so dark as mine and hair that is still fair and curly though ayah likes to smooth it

down with water every time she dresses him. He is a shy child, and although he plays

happily with Kate, he does not care to play with other children who go in the late

afternoons to a lawn by the old German ‘boma’.Kate has playmates of her own age but still rather clings to me. Whilst she loves

to have friends here to play with her, she will not go to play at their houses unless I go

too and stay. She always insists on accompanying me when I go out to morning tea

and always calls Janet “John’s ayah”. One morning I went to a knitting session at a

neighbours house. We are all knitting madly for the troops. As there were several other

women in the lounge and no other children, I installed Kate in the dining room with a

colouring book and crayons. My hostess’ black dog was chained to the dining room

table leg, but as he and Kate are on friendly terms I was not bothered by this.

Some time afterwards, during a lull in conversation, I heard a strange drumming

noise coming from the dining room. I went quickly to investigate and, to my horror, found

Kate lying on her back with the dog chain looped around her neck. The frightened dog