Search Results for 'rude'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

March 14, 2023 at 8:37 pm #7166

In reply to: The Precious Life and Rambles of Liz Tattler

Godfrey had been in a mood. Which one, it was hard to tell; he was switching from overwhelmed, grumpy and snappy, to surprised and inspired in a flicker of a second.

Maybe it had to do with the quantity of material he’d been reviewing. Maybe there were secret codes in it, or it was simply the sleep deprivation.

Inspired by Elizabeth active play with her digital assistant —which she called humorously Whinley, he’d tried various experiments with her series of written, half-written, second-hand, discarded, published and unpublished, drivel-labeled manuscripts he could put his hand on to try to see if something —anything— would come out of it.

After all, Liz’ generous prose had always to be severely edited to meet the editorial standards, and as she’d failed to produce new best-sellers since the pandemic had hit, he’d had to resort to exploring old material to meet the shareholders expectations.

He had to be careful, since some were so tartied up, that at times the botty Whinley would deem them banworthy. “Botty Banworth” was Liz’ character name for this special alternate prudish identity of her assistant. She’d run after that to write about it. After all, “you simply can’t ignore a story character when they pop in, that would be rude” was her motto.

So Godfrey in turn took to enlist Whinley to see what could be made of the raw material and he’d been both terribly disappointed and at the same time completely awestruck by the results. Terribly disappointed of course, as Whinley repeatedly failed to grasp most of the subtleties, or any of the contextual finely layered structures. While it was good at outlining, summarising, extracting some characters, or content, it couldn’t imagine, excite, or transcend the content it was fed with.

Which had come as the awestruck surprise for Godfrey. No matter how raw, unpolished, completely off-the-charts rank with madness or replete with seeming randomness the content was, there was always something that could be inferred from it. Even more, there was no end to what could be seen into it. It was like life itself. Or looking at a shining gem or kaleidoscope, it would take endless configurations and had almost infinite potential.

It was rather incredible and revisited his opinion of what being a writer meant. It was not simply aligning words. There was some magic at play there to infuse them, to dance with intentions, and interpret the subtle undercurrents of the imagination. In a sense, the words were dead, but the meaning behind them was still alive somehow, captured in the amber of the composition, as a fount of potentials.

What crafting or editing of the story meant for him, was that he had to help the writer reconnect with this intent and cast her spell of words to surf on the waves of potential towards an uncharted destination. But the map of stories he was thinking about was not the territory. Each story could be revisited in endless variations and remain fresh. There was a difference between being a map maker, and being a tour-operator or guide.

He could glimpse Liz’ intention had never been to be either of these roles. She was only the happy bumbling explorer on the unchartered territories of her fertile mind, enlisting her readers for the journey. Like a Columbus of stories, she’d sell a dream trusting she would somehow make it safely to new lands and even bigger explorations.

Just as Godfrey was lost in abyss of perplexity, the door to his office burst open. Liz, Finnley, and Roberto stood in the doorway, all dressed in costumes made of odds and ends.

“You are late for the fancy dress rehearsal!” Liz shouted, in her a pirate captain outfit, her painted eye patch showing her eye with an old stitched red plush thing that looked like a rat perched on her shoulder supposed to look like a mock parrot.

“What was the occasion again?”

“I may have found a new husband.” she said blushing like a young damsel.

Finnley, in her mummy costume made with TP rolls, well… did her thing she does with her eyes.

March 10, 2023 at 7:13 am #6798In reply to: The Precious Life and Rambles of Liz Tattler

“Think, Finnley, think,” Liz grabbed her arm as the bad tempered cleaning lady tried to make her escape.

“Ouch! You’ll pull my arm off, then who will clean the windows? And anyway you said I didn’t have time to think”, Finnley retorted.

“You don’t have time to waste on your own thoughts, frittering them away on stuff and nonsense. I need you to think about the new story characters. If we don’t get a move on they’ll get disgruntled and start turning up on other stories, and it’s bad enough as it is.”

“Not my problem,” Finnley muttered, trying in vain to twist her arm out of Liz’s vicelike grip.

“It’ll be your problem if I write lots of big new windows into the bedrooms and you have to clean them all,” Liz snapped. “I’ve half a mind to write a dust storm into the story.”

“Half witted mind more like,” Finnley snorted rudely. “Why, so you can hide all the loose ends in dust?”

“So Finly can find out all the secrets when she dusts. I can picture it now: All was eventually revealed about the secrets of the mines, when Finly had a jolly good spring clean after the sand storm. And then you’ll have to think of something.”

February 24, 2023 at 8:31 am #6661In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

The black BMW pulled up outside the Flying Fish Inn. Sister Finli pulled a baseball cap low over her big sunglasses before she got out of the car. Yasmin was still in the bar with her friends and Finli hoped to check in and retreat to her room before they got back to the inn.

She rang the bell on the reception desk several times before an elderly lady in a red cardigan appeared.

“Ah yes, Liana Parker,” Mater said, checking the register. Liana managed to get a look at the register and noted that Yasmin was in room 2. “Room 4. Did you have a good trip down? Smart car you’ve got there,” Mater glanced over Liana’s shoulder, “Don’t see many like that in these parts.”

“Yes, yes,” Finli snapped impatiently (henceforth referred to to as Liana). She didn’t have time for small talk. The others might arrive back at any time. As long as she kept out of Yasmin’s way, she knew nobody would recognize her ~ after all she had been abandoned at birth. Even if Yasmin did find her out, she only knew her as a nun at the orphanage and Liana would just have to make up some excuse about why a nun was on holiday in the outback in a BMW. She’d cross that bridge when she came to it.

Mater looked over her glasses at the new guest. “I’ll show you to your room.” Either she was rude or tired, but Mater gave her the benefit of the doubt. “I expect you’re tired.”

Liana softened and smiled at the old lady, remembering that she’d have to speak to everyone in due course in order to find anything out, and it wouldn’t do to start off on the wrong foot.

“I’m writing a book,” Liana explained as she followed Mater down the hall. “Hoping a bit of peace and quiet here will help, and my book is set in the outback in a place a bit like this.”

“How lovely dear, well if there’s anything we can help you with, please don’t hesitate to ask. Old Bert’s a mine of information,” Mater suppressed a chuckle, “Well as long as you don’t mention mines. Here we are,” Mater opened the door to room 4 and handed the key to Liana. “Just ask if there’s anything you need.”

Liana put her bags down and then listened at the door to Mater’s retreating steps. Inching the door open, she looked up and down the hallway, but there was nobody about. Quickly she went to room 2 and tried the door, hoping it was open and she didn’t have to resort to other means. It was open. What a stroke of luck! Liana was encouraged. Within moments Liana found the parcel, unopened. Carefully opening the door, she looked around to make sure nobody was around, leaving the room with the parcel under her arm and closing the door quietly, she hastened back to room 4. She nearly jumped out of her skin when a voice piped up behind her.

“What’s that parcel and where are you going with it?” Prune asked.

“None of your business you….” Liana was just about to say nosy brat, and then remebered that she would catch more flies with honey than vinegar. It was going to be hard for her to remember that, but she must try! She smiled at the teenager and said, “A dreamtime gift for my gran, got it in Alice. Is there a post office in town?”

Prune narrowed her eyes. There was something fishy about this and it didn’t take her more than a second to reach the conclusion that she wanted to see what was in the parcel. But how?

“Yes,” she replied, quick as a flash grabbing the parcel from Liana. “I’ll post it for you!” she called over her shoulder as she raced off down the hall and disappeared.

“FUCK!” Liana muttered under her breath, running after her, but she was nowhere to be seen. Thankfully nobody else was about in the reception area to question why she was running around like a madwoman. Fuck! she muttered again, going back to her room and closing the door. Now what? What a disaster after such an encouraging start!

Prune collided with Idle on the steps of the verandah, nearly knocking her off her feet. Idle grabbed Prune to steady herself. Her grip on the girls arm tightened when she saw the suspicious look on face. Always up to no good, that one. “What have you got there? Where did you get that? Give me that parcel!”

Idle grabbed the parcel and Prune fled. Idle, holding onto the verandah railing, watched Prune running off between the eucalyptus trees. She’s always trying to make a drama out of everything, Idle thought with a sigh. Hardly any wonder I suppose, it must be boring here for a teenager with nothing much going on.

She heard a loud snorting laugh, and turned to see the four guests returning from the bar in town, laughing and joking. She put the parcel down on the hall table and waved hello, asking if they’d had a good time. “I bet you’re ready for a bite to eat, I’ll go and see what Mater’s got on the menu.” and off she went to the kitchen, leaving the parcel on the table.

The four friends agreed to meet back on the verandah for drinks before dinner after freshening up. Yasmin kept glancing back at the BMW. “That woman must be staying here!” she snorted. Zara grabbed her elbow and pulled her along. “Then we’ll find out who she is later, come on.”

Youssef followed Idle into the kitchen to ask for some snacks before dinner (much to Idle’s delight), leaving Xavier on the verandah. He looked as if he was admiring the view, such as it was, but he was preoccupied thinking about work again. Enough! he reminded himself to relax and enjoy the holiday. He saw the parcel on the table and picked it up, absentmindedly thinking the black notebook he ordered had arrived in the post, and took it back to his room. He tossed it on the bed and went to freshen up for dinner.

February 21, 2023 at 9:10 am #6615In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Like ships in the night, Zara and Yasmin still hadn’t met up with Xavier and Youssef at the inn. Yasmin was tired from traveling and retired to her room to catch up on some sleep, despite Zara’s hopes that they’d have a glass of wine or two and discuss whatever it was that was on Yasmins mind. Zara decided to catch up on her game.

The next quirk was “unleash your hidden rudeness” which gave Zara pause to consider how hidden her rudeness actually was. But wait, it was the avatar Zara, not herself. Or was it? Zara rearranged the pillows and settled herself on the bed.

Zara found her game self in the bustling streets of a medieval market town, visually an improvement on the previous game level of the mines, which pleased her, with many colourful characters and intriguing alleyways and street market vendors.

She quickly forgot what her quest was and set off wandering around the scene. Each alley led to a little square and each square had gaily coloured carts of wares for sale, and an abundance of grinning jesters and jugglers. Although tempted to linger and join the onlookers jeering and goading the jugglers and artistes that she encountered, Zara continued her ramble around the scene.

She came to a gathering outside an old market hall, where two particularly raucous jesters were trying to tempt the onlookers into partaking of what appeared to be cups of tea. Zara wondered what the joke was and why nobody in the crowd was willing to try. She inched closer, attracting the attention of the odd grinning fellow in the orange head piece.

“Come hither, ye fine wench in thy uncomely scant garments, I know what thou seekest! Pray, sit thee down beside me and partake of my remedy.”

“Who, me?” asked Zara, looking behind her to make sure he wasn’t talking to someone else.

“Thoust in dire need of my elixir, come ye hither!”

Somewhat reluctantly Zara stepped towards the odd figure who was offering to hand her a cup. She considered the inadvisability of drinking something that everyone else was refusing, but what the hell, she took the cup and saucer off him and took a hesitant sip.

The crowd roared with laughter and there was much mirthful thigh slapping when Zara spit the foul tasting concoction all over the jesters shoes.

“Believe me dame,” quoth the Jester, “I perceive proffered ware is worse by ten in the hundred than that which is sought. But I pray ye, tell me thy quest.”

“My quest is none of your business, and your tea sucks, mister,” Zara replied. “But I like the cup.”

Pushing past the still laughing onlookers and clutching the cup, Zara spotted a tavern on the opposite side of the square and made her way towards it. A tankard of ale was what she needed to get rid of the foul taste lingering in her mouth.

The inside of the tavern was as much a madhouse as the streets outside it. What was everyone laughing at? Zara found a place to sit on a bench beside a long wooden table. She sat patiently waiting to be served, trying to eavesdrop to decipher the cause of such merriment, but the snatches of conversation made no sense to her. The jollity was contagious, and before long Zara was laughing along with the others. A strange child sat down on the opposite bench (she seemed familiar somehow) and Zara couldn’t help remarking, “You lot are as mad as a box of frogs, are you all on drugs or something?” which provoked further hoots of laughter, thigh slapping and table thumping.

“Ye be an ungodly rude maid, and ye’ll not get a tankard of ale while thoust leavest thy cup of elixir untasted yet,” the child said with a smirk.

“And you are an impertinent child,” Zara replied, considering the potential benefits of drinking the remainder of the concoction if it would hasten the arrival of the tankard of ale she was now craving. She gritted her teeth and picked up the cup.

But the design on the cup had changed, and now bore a strange resemblance to Xavier. Not only that, the cup was calling her name in Xavier’s voice, and the table thumping got louder.

“Zara!” Xavier was knocking on her bedroom door. “Zara! We’re going for a beer in the local tavern, are you coming?”

“Xavi!” Zara snapped back to reality, “Yes! I’m bloody parched.”

February 14, 2023 at 10:13 pm #6546In reply to: The Precious Life and Rambles of Liz Tattler

“A-OUCH!” Liz shouted.

“That’s no way to stop my powernap!” she gave a dark eye to the offender.

Finnley was standing there, looking cockishly at Liz, “don’t mean to be rude M’am, but since you mentioned the pea-shooters that knocker uppers of old London used to wake up the workers,” she smiled excitingly “I’ve been dying to try.”

Liz was at a loss for words.

Finnley loaded for a second round with a selection of carefully picked peanuts.

“Let me guess…” Liz sighed. “There’s no shortage of ammunitions.”

February 12, 2023 at 9:49 pm #6539In reply to: Prompts of Madjourneys

Zara is the main protagonist, and also the reluctant leader of the game. In RL, she is wandering off the trail nearby Arltunga, Australia, where she is visiting, staying at the small family run inn the Flying Fish Inn. Bert, the local handyman drove her there, told her specifically not to wander off, yet in search of where a mysterious compass she collected on the trail is leading, and egged on by her talking smart parrot “Beautiful Girl”, she goes off the trail to explore. The sun is still high, and she already started to hallucinate some hooded figures with blue frog-faces with jelly-bean carts.

Meanwhile, her friends Youssef and Xavier, just landed from abroad, are driving toward the rendez-vous spot at the Flying Fish Inn. The owners Mater and Idle don’t have any idea where Zara is.

Yasmin, the fourth friend in the group is still on her way from Fiji, bearing a message written in red on an envelope from a mysterious Fred, who we don’t know yet, but seems to be linked to Mater & Idle’s family.

What’s going to happen next to Zara? The game is encouraging her to explore her rudeness in a playful manner, in a medieval setting.

Provide a series of playful and fun actions for Zara, linking these contexts. You may incorporate Tiku, a wise and no-nonsense Aboriginal woman who may guide her though the Dreamtime challenges. Provide random keywords to each action in the list.Here is a list of playful and fun actions for Zara in the game:

- “Follow the Compass”: Zara can follow the mysterious compass she collected on the trail, as it leads her to new locations and challenges. Keywords: Adventure, Exploration, Mystery.

- “Converse with Beautiful Girl”: Zara’s talking smart parrot “Beautiful Girl” may provide humorous commentary and encouragement throughout her journey. Keywords: Humor, Personality, Support.

- “Solve Riddles with Tiku”: Tiku, the wise and no-nonsense Aboriginal woman, can guide Zara through the Dreamtime challenges. To do this, Tiku may present her with riddles or puzzles that she must solve to progress. Keywords: Wisdom, Intelligence, Spirituality.

- “Collect Items”: Zara can collect items along the way, such as artifacts or treasures that may help her in her journey or lead her to new discoveries. Keywords: Collection, Discovery, Help.

- “Play Music with Beautiful Girl”: Zara can play musical instruments with Beautiful Girl, creating an entertaining and musical interlude in her journey. Keywords: Music, Joy, Creativity.

- “Cook with Mater and Idle”: At the Flying Fish Inn, Zara can join Mater and Idle in the kitchen and help them cook traditional dishes from the region. Keywords: Cooking, Culture, Community.

- “Race with Youssef and Xavier”: Zara can engage in friendly races with Youssef and Xavier, such as foot races or cart races, as a way to pass the time and have fun. Keywords: Competition, Speed, Excitement.

These playful and fun actions can add variety and excitement to Zara’s journey and provide an opportunity for players to interact with the world and characters in new and unique ways.

🔁 Regenerate responseFebruary 11, 2023 at 10:10 pm #6538In reply to: The Jorid’s Travels – 14 years on

“That’s all Jorid had to say?” Georges mused at the sudden philosophical quote that read:

And doesn’t this point to something fundamentally tragic about our way of life? We live under an assumed identity, in a neurotic fairy tale world with no more reality than the Mock Turtle in Alice in Wonderland. Hypnotized by the thrill of building, we have raised the houses of our lives on sand. This world can seem marvelously convincing until death collapses the illusion and evicts us from our hiding place. What will happen to us then if we have no clue of any deeper reality? (The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying)

“I don’t know about this Mock Turtle, but those snapping sand ones that have been lurking about do look rather nasty. We shouldn’t waste any more time.”

Klatu opined “Klatu agrees with your female, sand turtle are lovely traps of death. Come with me now!” He intimated them to run into a sand opening he’d just made.

“Let me guess,” Georges said, “is it the equivalent of a Zathu prison? What powerful people could Léonard possibly have rubbed the wrong way this time?”

“Not prison.” Klatu commented “Death sentence.”

Salomé pointed out a glowing twirl of sand shaped as an ovoid form, inside which a human form could be discerned. “That would explain why he’s not more guarded…”

They approached carefully, expecting some extra booby trap, but nothing seemed to react to their presence, not even the moving sand egg.

“Let me guess,” Georges said, expecting a chorus

“DIMENSIONAL MAGIC!”

Klatu shushed them “Quiet stupids! Sound waves attract good turtles.”

“Is our friend OK? How do we break the spell?” Salomé asked Klatu. “Can you help?”

Klatu took a few minutes to inspect the shape, hopping carefully around it, and probing with soft whistling sounds.

“Friend in stasis for now. Kept fresh for questioning… possible.”

“Then we must hurry, how can we free him? Can I brute force this?” Georges asked, looking around for something to pierce the sand barrier and hook Léonard out of it.

“Only if you like sushi friend.” Klatu said, raising shoulders. “No finesse these primates.”

Klatu moved around the shape, taking some tools from his belt and making some elaborate plaits of sounds, as if trying to match the energy signature of the sand prison.

After a first belt of soundwaves was wrapped around, it seemed as though a first layer of the spell broke, and sand rained back into the external construct they were it. But a thin layer was still there, shifting and pulsating, almost clear as glass, and sharp as a razor blade.

“Crude encoding, but solid. Need more time.” Klatu seemed exhausted.

Georges was getting anxious for some activity. “Houses built on sand… Well I guess Jorid didn’t find the best quote to help…”

Salomé who was sitting cross-legged, trying for some time to connect to Léonard in his stasis, turned to Georges in disbelief. “Georges, you’re a genius!”

“What now?”

“Jorid gave us the last bit we needed. Until death collapses the illusion and evicts us from our hiding place. Remember? It’s risky but that could work!”

“Oh, I see what you’re thinking about. It’s mad, and it’s brilliant at the same time, how do we go about this?”

“I can’t reach Léonard, but maybe the both of us can.” Salomé joined hands with Georges.

“If he’s like anything I remember, he’d be in his mental palace, his workshop on the Duane… or in Marseille… or with Madame Jamelie…”

“Focus, Georges!”

“Duane it is, that’s where he did his best work.”

“We need to focus our energy to make him appear dead to the construct. It’ll be easier if we can locate precisely where his mind wanders.” Salomé said.

“He’ll be there, I know it. Let’s do this!”

The two of them joined hands and melded their minds, one as always, turning into a dark mirror of the abyss, bending light unto itself, leaving the void of creation at the place where Léonard was suspended.

Klatu looked at the scene suspiciously, but started to giggle as he saw the last layer he couldn’t open finally shatter and dissolve to the ground.

“Little apes full of surprises,… very awful, so very awful.” he said approvingly.

As his friends rushed to him, Léonard was on the ground, inert, but apparently alive.

February 9, 2023 at 8:43 pm #6519In reply to: The Jorid’s Travels – 14 years on

Salomé: Jorid, did you know Klatu would be so comically rude to us? — Georges says that’s probably a form of respect in their alien culture but I think he’s just actually plain rude to us…

Jorid: I don’t think knowing such things will be useful to your finding your friend Léonard. I’d suggest you focus on maintaining your balance on the frail sand skiff driving you now through the desert.

Salomé: So slippery… It’s hardly an answer… I often forget you were a fish onto a board when you started off…

Georges: Don’t be rude to Jorid, dear.

Jorid: Salomé isn’t rude, it’s actually rather accurate, and I don’t think humans start as much better either.

Salomé: oh, clever. Seems the weather here is doing you good, some humour is coming back to you J.

Jorid: Maybe my capacity has been intact all along…

Salomé (giggling): Oh, and learning to be rude too; the locals are rubbing off on you.

Jorid: Zatu’s trajectory is veering off toward a storm. I would advise a course correction.

Georges: He’s just thrown two pairs of goggles at us and some insults to boot. He doesn’t seem intent on changing course.

Jorid: Then you both need to brace yourself.

Salomé: Thanks for the heads up, Jorid. Preparing for impact!

February 8, 2023 at 11:18 pm #6516In reply to: The Chronicles of the Flying Fish Inn

Aunt Idle:

Bert came barging in my room, and I’d only just sat down, telling me the guest still hadn’t phoned to be picked up from the trail. Bert, I said, she’ll be fine. She probably phoned a taxi and went to Alice for dinner or to meet her friends, she’s fine. But he kept going on about what if she wandered off the trail, and I said, Bert, if she wandered off the trail that doesn’t mean she’s in trouble, does it? Anyway, I said, the parrot said not to worry. Parrot? he said and his face was a picture. Parrot? The flaming parrot said not to worry? Not like old Bert to be as rude as he was then, I don’t know what had got into him.

He stomped off muttering and I caught a few words like sandwich short of a picnic, but I’m used to that now, they’re all rude about me. Well Bert not so much, which is why it took me by surprise, and the twins are alright. Mater though, don’t even get me started, nor Finly. Prune’s up to something, I don’t know what, and so is Devan. I can’t put my finger on it. And something’s rattled Berts cage.

She’s nice, the new guest, a bit younger than me but struth! looks about 20 years younger. Living out here hasn’t done me any favours.

February 7, 2023 at 10:43 pm #6512In reply to: Prompts of Madjourneys

Zara offered the following quirk: “unleash my hidden rudeness”

Quirk accepted.

You find yourself in the bustling streets of an old medieval town. The people around you are going about their business, and you see vendors selling goods, street performers entertaining the crowd, and guards patrolling the area. You hear rumors about a secret society of mischievous tricksters who are known for causing trouble and making people’s lives more interesting.

You decide to investigate these rumors and join the society of tricksters, who call themselves the “Rude Ones.” You are tasked with finding the key to their hideout, a tile with a rude message written on it. To do this, you must complete several challenges and pranks around the town, each more mischievous than the last.

Your objective is to find the tile, sneak into the Rude Ones’ hideout, and cause as much chaos and trouble as possible. You must also find a way to insert a real-life prank or act of rudeness into your daily life, as proof of your success in the game.

Possible directions to investigate:

- Talk to the vendors and street performers to gather information about the Rude Ones.

- Observe the guards and see if they have any information on the secret society.

- Explore the different neighborhoods and see if anyone knows about the hideout.

Possible characters to engage:

- A mysterious street performer who is rumored to be part of the Rude Ones.

- A vendor who has a reputation for being rude to customers.

- A guard who is rumored to be in league with the Rude Ones.

Look for a tile with a rude message written on it, and capture proof of your real-life prank or act of rudeness. Good luck, and have fun!

February 6, 2023 at 10:15 pm #6498Some background information on The Sexy Wooden Leg and potential plot developments.

Setting

(nearby Duckailingtown in Dumbass, Oocrane)

The Rootians (a fictitious nationality) invaded Oocrane (a fictitious country) under the guise of freeing the Dumbass region from Lazies. They burned crops and buildings, including the home of a man named Dumbass Voldomeer who was known for his wooden leg and carpenter skills. After the war, Voldomeer was hungry and saw a nest of swan eggs. He went back to his home, carved nine wooden eggs, and replaced the real eggs with the wooden ones so he could eat the eggs for food. The swans still appeared to be brooding on their eggs by the end of summer.Note: There seem to be a bird thematic at play.

The swans’ eggs introduce the plot. The mysterious virus is likely a swan flu. Town in Oocrane often have reminiscing tones of birds’ species.

Bird To(w)nes: (Oocrane/crane, Keav/kea, Spovlar/shoveler, Dilove/dove…)

Also the town’s nursing home/hotel’s name is Vyriy from a mythical place in Slavic mythology (also Iriy, Vyrai, or Irij) where “birds fly for winter and souls go after death” which is sometimes identified with paradise. It is believed that spring has come to Earth from Vyrai.At the Keav Headquarters

(🗺️ Capital of Oocrane)

General Rudechenko and Major Myroslava Kovalev are discussing the incapacitation of President Voldomeer who is suffering from a mysterious virus. The President had told Major Kovalev about a man in the Dumbass region who looked similar to him and could be used as a replacement. The Major volunteers to bring the man to the General, but the General fears it is a suicide mission. He grants her permission but orders his aide to ensure she gets lost behind enemy lines.

Myroslava, the ambitious Major goes undercover as a former war reporter, is now traveling on her own after leaving a group of journalists. She is being followed but tries to lose her pursuers by hunting and making fire in bombed areas. She is frustrated and curses her lack of alcohol.

The Shrine of the Flovlinden Tree

(🗺️ Shpovlar, geographical center of Oocrane)

Olek is the caretaker of the shrine of Saint Edigna and lives near the sacred linden tree. People have been flocking to the shrine due to the miraculous flow of oil from the tree. Olek had retired to this place after a long career, but now a pilgrim family has brought a message of a plan acceleration, which upsets Olek. He reflects on his life and the chaos of people always rushing around and preparing for the wrong things. He thinks about his father’s approach to life, which was carefree and resulted in the same ups and downs as others, but with less suffering. Olek may consider adopting this approach until he can find a way to hide from the enemy.

Rosa and the Cauldron Maker

(young Oocranian wiccan travelling to Innsbruck, Austria)

Eusebius Kazandis is selling black cauldrons at the summer fair of Innsbruck, Austria. He is watching Rosa, a woman selling massage oils, fragrant oils, and polishing oils. Rosa notices Eusebius is sad and thinks he is not where he needs to be. She waves at him, but he looks away as if caught doing something wrong. Rosa is on a journey across Europe, following the wind, and is hoping for a gust to tell her where to go next. However, the branches of the tree she is under remain still.

The Nursing Home

(Nearby the town of Dilove, Oocrane, on Roomhen border somewhere in Transcarpetya)

Egna, who has lived for almost a millennium, initially thinks the recent miracle at the Flovlinden Tree is just another con. She has performed many miracles in her life, but mostly goes unnoticed. She has a book full of records of the lives of many people she has tracked, and reminisces that she has a connection to the President Voldomeer. She decides to go and see the Flovlinden Tree for herself.

🗺️ (the Vyriy hotel at Dilove, Oocrane, on Roomhen border)

Ursula, the owner of a hotel on the outskirts of town, is experiencing a surge in business from the increased number of pilgrims visiting the linden tree. She plans to refurbish the hotel to charge more per night and plans to get a business loan from her nephew Boris, the bank manager. However, she must first evict the old residents of the hotel, which she is dreading. To avoid confrontation, she decides to send letters signed by a fake business manager.

Egbert Gofindlevsky, Olga Herringbonevsky and Obadiah Sproutwinklov are elderly residents of an old hotel turned nursing home who receive a letter informing them that they must leave. Egbert goes to see Obadiah about the letter, but finds a bad odor in his room and decides to see Olga instead.

Maryechka, Obadiah’s granddaughter, goes back home after getting medicine for her sick mother and finds her home empty. She decides to visit her grandfather and his friends at the old people’s home, since the schools are closed and she’s not interested in online activities.

Olga and Egbert have a conversation about their current situation and decide to leave the nursing home and visit Rosa, Olga’s distant relative. Maryechka encounters Egbert and Olga on the stairs and overhears them talking about leaving their friends behind. Olga realizes that it is important to hold onto their hearts and have faith in the kindness of strangers. They then go to see Obadiah, with Olga showing a burst of energy and Egbert with a weak smile.Thus starts their escape and unfolding adventure on the roads of war-torn Oocrane.

Character Keyword Characteristics Sentiment Egbert old man, sharp tone sad, fragile Maryechka Obadiah’s granddaughter, shy innocent Olga old woman, knobbly fingers conflicted, determined Obadiah stubborn as a mule, old friend of Egbert unyielding, possibly deaf January 31, 2023 at 3:17 am #6476In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Yasmin was having a hard time with the heavy rains and mosquitoes in the real-world. She couldn’t seem to make a lot of progress on finding the snorting imp. She was feeling discouraged and unsure of what to do next.

Suddenly, an emoji of a snake appeared on her screen. It seemed to be slithering and wriggling, as if it was trying to grab her attention. Without hesitation, Yasmin clicked on the emoji.

She was taken to a new area in the game, where the ground was covered in tall grass and the sky was dark and stormy. She could see the snorting imp in the distance, but it was surrounded by a group of dangerous-looking snakes.

Clue unlocked It sounds like you’re having a hard time in the real world, but don’t let that discourage you in the game. The snorting imp is nearby and it seems like the snakes are guarding it. You’ll have to be brave and quick to catch it. Remember, the snorting imp represents your determination and bravery in real life.

Rude! thought Yasmin. Telling me I’m having a hard time! And I’m supposed to be the brains of the group! Suddenly the screen went blank. “Oh blimmin dodgy internet!” she moaned.

“Road’s closed with the flooding,” said a man from the kitchen door. Yasmin didn’t know him; he had a tinge of an accent and took up a lot of space in the doorway. “They reckon it should be clear by tomorrow though.”

“Fred!” Sister Aliti looked up from chopping yam and beamed. She pointed her knife at Yasmin who was washing the breakfast dishes. “Have you met Yasmin? One of our new volunteers. Such a good girl.” The knife circled towards the door. “Yasmin this is Fred – Fred drives the van for us when we are too busy to do it ourselves. So very kind.” She smiled fondly at the man.

Fred nodded and, taking a step into the kitchen, he stuck a hand towards Yasmin. She quickly wiped her damp hands on her skirt before taking it. Fred’s hand was brown and weathered like his face and he gripped her fingers firmly.

“Nice to meet you Yasmin. So where are you from?”

“Oh, um, I’ve been living in London most recently but originally from Manchester.” Yasmin noticed he had a snake tattoo curling up his inner bicep, over his shoulder and disappearing under his black singlet. “Is your accent Australian?”

A flicker of a frown crossed Fred’s face and Yasmin felt anxious. “Sorry,” she mumbled, although she wasn’t sure what for. “It’s just I’m visiting soon …”

“Yeah, originally. But I’ve not been back home for while.” His eyes drifted to the kitchen window and stayed there. For a moment, they all watched the rain pelt against the glass.

Sister Aliti broke the silence. “Fred’s a writer,” she said sounding like a proud mother.

“Oh, that’s so cool! What do you write?” Yasmin immediately worried she’d been too nosy again. “I’ve always wanted to write!” she added brightly which wasn’t true, she’d never given it much thought. Realising this, and to her horror, she snort laughed.

Fred dragged his eyes back from the window and looked at her with amusement. “Yeah? Well you should go for it!” He turned to Sister Aliti. “Internet’s down again too with this weather,” He dug into the pocket of his shorts and dangled some keys in the air. “I’ll leave the van keys with you but I’ll be back tomorrow, if the rain’s stopped.” The keys clanked onto the bench.

“He’s such a chatterbox,” murmured Sister Aliti after Fred had gone and Yasmin laughed.

“Shall I put these in the office?” Yasmin gestured to the set of keys then gasped as she saw that on the keychain was a devilish looking imp grinning up at her.

January 23, 2023 at 8:15 am #6449In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Have you booked your flight yet? Zara sent a message to Yasmin. I’m spending a few more days in Camden, probably be at the Flying Fish Inn by the end of the week.

I told you already when my flight is, Air Fiji, remeber? bloody Sister Finnlie on my case all the time, haven’t had a minute. Zara had to wait over an hour for Yamsin’s reply.

I told you already when my flight is, Air Fiji, remeber? bloody Sister Finnlie on my case all the time, haven’t had a minute. Zara had to wait over an hour for Yamsin’s reply.Took you long enough to reply. Zara replied promptly. Heard nothing from Youssef for ages either, have you heard from him? I’ll be arriving there on my own at this rate.

Not a word, I expect Xavier’s booked his but he hasn’t said. Probably doing his secret monkey thing.

Not a word, I expect Xavier’s booked his but he hasn’t said. Probably doing his secret monkey thing.Have you tried the free roaming thing on the game yet?

I just told you Sister Finnlie hasn’t given me a minute to myself, she’s a right tart! Why, have you?

I just told you Sister Finnlie hasn’t given me a minute to myself, she’s a right tart! Why, have you?Yeah it’s amazing, been checking out the Flying Fish Inn. Looks a bit of a dump. Not much to do around there, well not from what I can see anyway. But you know what?

What?

What?You’ll lose your eyes in the back of your head one day and look like that AI avatart with the wall eye. Get this though: we haven’t started the game yet, that quest for quirks thing, I was just having a roman around ha ha typo having a roam around see what’s there and stuff I don’t know anything about online games like you lot and I ended up here. Zara sent a screenshot of the image she’d seen and added: Did I already start the game or what, I don’t even know how we actually start the game, I was just wandering around….oh…and happened to chance upon this…

How rude to start playing before us

How rude to start playing before usI didn’t start playing the game before you, I just told you, I was wandering around playing about waiting for you lot! Zara thought Yasmin sounded like she needed a holiday.

Yeah well that was your quest, wasn’t it? To wander around or something? What’s that silver chest on her back?

Yeah well that was your quest, wasn’t it? To wander around or something? What’s that silver chest on her back?I dunno but looks intriguing eh maybe she’s hidden all her devices and techy gadgets in an antiquey looking box so she doesn’t blow her cover

Gotta go Sister Finnlie’s coming

Zara muttered how rude under her breath and put her phone down. She’d retired to her bedroom early, telling Bertie that she needed an early night but really had wanted some time alone to explore the new game world. She didn’t want to make mistakes and look daft to her friends when the game started.

“Too late for that”, Pretty Girl said.

“SSHHH!” Zara hissed at the parrot. “And stop reading my mind, it’s disconcerting, not to mention rude.”

She heard the sound of the lavatory flush and Berties bedroom door closing and looked at the time. 23:36.

Zara decided to give him an hour to make sure he was asleep and then sneak out and go back to that church.

January 14, 2023 at 11:50 am #6384In reply to: The Precious Life and Rambles of Liz Tattler

“Wait, never mind, don’t call Finnley yet, show me how it works, Godfrey.” Liz had an idea. If this thing was as good as it was supposed to be, she could get it to do everything. Maybe it wouldn’t even argue. No more rude remarks from the staff! It could be a godsend!

November 13, 2022 at 10:29 pm #6345In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Crime and Punishment in Tetbury

I noticed that there were quite a number of Brownings of Tetbury in the newspaper archives involved in criminal activities while doing a routine newspaper search to supplement the information in the usual ancestry records. I expanded the tree to include cousins, and offsping of cousins, in order to work out who was who and how, if at all, these individuals related to our Browning family.

I was expecting to find some of our Brownings involved in the Swing Riots in Tetbury in 1830, but did not. Most of our Brownings (including cousins) were stone masons. Most of the rioters in 1830 were agricultural labourers.

The Browning crimes are varied, and by todays standards, not for the most part terribly serious ~ you would be unlikely to receive a sentence of hard labour for being found in an outhouse with the intent to commit an unlawful act nowadays, or for being drunk.

The central character in this chapter is Isaac Browning (my 4x great grandfather), who did not appear in any criminal registers, but the following individuals can be identified in the family structure through their relationship to him.

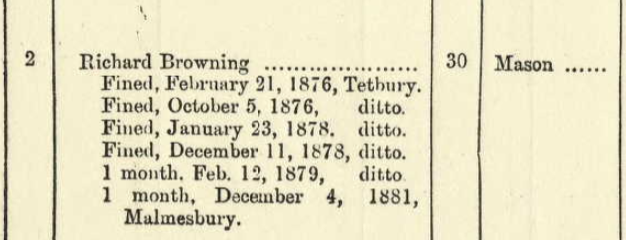

RICHARD LOCK BROWNING born in 1853 was Isaac’s grandson, his son George’s son. Richard was a mason. In 1879 he and Henry Browning of the same age were sentenced to one month hard labour for stealing two pigeons in Tetbury. Henry Browning was Isaac’s nephews son.

In 1883 Richard Browning, mason of Tetbury, was charged with obtaining food and lodging under false pretences, but was found not guilty and acquitted.

In 1884 Richard Browning, mason of Tetbury, was sentenced to one month hard labour for game trespass.Richard had been fined a number of times in Tetbury:

Richard Lock Browning was five feet eight inches tall, dark hair, grey eyes, an oval face and a dark complexion. He had two cuts on the back of his head (in February 1879) and a scar on his right eyebrow.

HENRY BROWNING, who was stealing pigeons with Richard Lock Browning in 1879, (Isaac’s brother Williams grandson, son of George Browning and his wife Charity) was charged with being drunk in 1882 and ordered to pay a fine of one shilling and costs of fourteen shillings, or seven days hard labour.

Henry was found guilty of gaming in the highway at Tetbury in 1872 and was sentenced to seven days hard labour. In 1882 Henry (who was also a mason) was charged with assault but discharged.

Henry was five feet five inches tall, brown hair and brown eyes, a long visage and a fresh complexion.

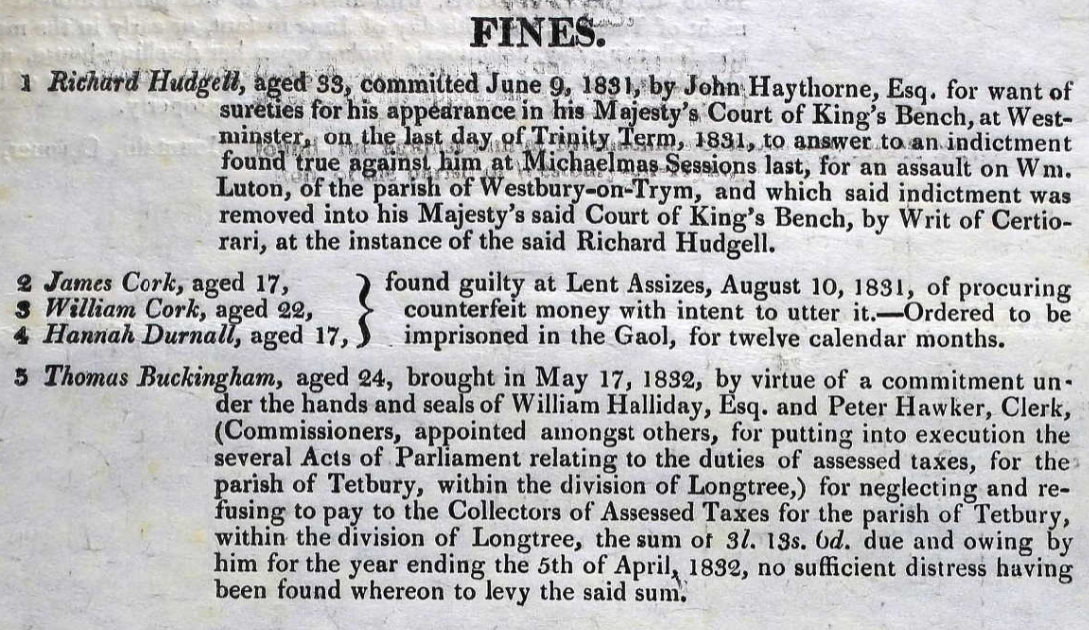

Henry emigrated with his daughter to Canada in 1913, and died in Vancouver in 1919.THOMAS BUCKINGHAM 1808-1846 (Isaacs daughter Janes husband) was charged with stealing a black gelding in Tetbury in 1838. No true bill. (A “no true bill” means the jury did not find probable cause to continue a case.)

Thomas did however neglect to pay his taxes in 1832:

LEWIN BUCKINGHAM (grandson of Isaac, his daughter Jane’s son) was found guilty in 1846 stealing two fowls in Tetbury when he was sixteen years old.

In 1846 he was sentence to one month hard labour (or pay ten shillings fine and ten shillings costs) for loitering with the intent to trespass in search of conies.

A year later in 1847, he and three other young men were sentenced to four months hard labour for larceny.

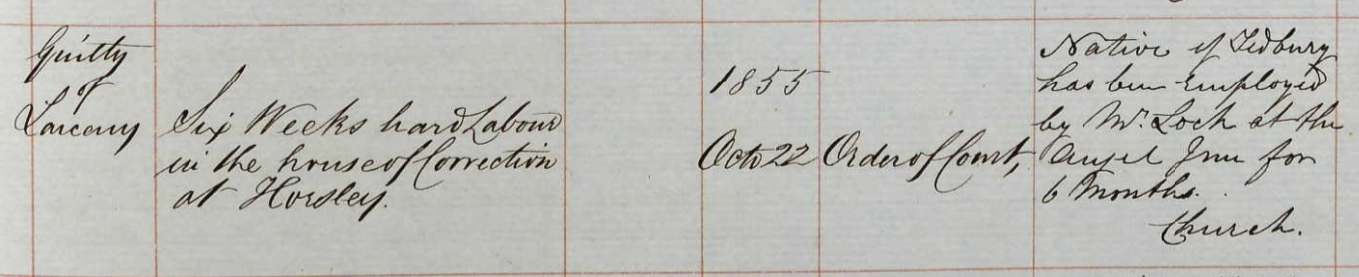

Lewin was five feet three inches tall, with brown hair and brown eyes, long visage, sallow complexion, and had a scar on his left arm.JOHN BUCKINGHAM born circa 1832, a Tetbury labourer (Isaac’s grandson, Lewin’s brother) was sentenced to six weeks hard labour for larceny in 1855 for stealing a duck in Cirencester. The notes on the register mention that he had been employed by Mr LOCK, Angel Inn. (John’s grandmother was Mary Lock so this is likely a relative).

The previous year in 1854 John was sentenced to one month or a one pound fine for assaulting and beating W. Wood.

John was five feet eight and three quarter inches tall, light brown hair and grey eyes, an oval visage and a fresh complexion. He had a scar on his left arm and inside his right knee.JOSEPH PERRET was born circa 1831 and he was a Tetbury labourer. (He was Isaac’s granddaughter Charlotte Buckingham’s husband)

In 1855 he assaulted William Wood and was sentenced to one month or a two pound ten shilling fine. Was it the same W Wood that his wifes cousin John assaulted the year before?

In 1869 Joseph was sentenced to one month hard labour for feloniously receiving a cupboard known to be stolen.JAMES BUCKINGAM born circa 1822 in Tetbury was a shoemaker. (Isaac’s nephew, his sister Hannah’s son)

In 1854 the Tetbury shoemaker was sentenced to four months hard labour for stealing 30 lbs of lead off someones house.

In 1856 the Tetbury shoemaker received two months hard labour or pay £2 fine and 12 s costs for being found in pursuit of game.

In 1868 he was sentenced to two months hard labour for stealing a gander. A unspecified previous conviction is noted.

1871 the Tetbury shoemaker was found in an outhouse for an unlawful purpose and received ten days hard labour. The register notes that his sister is Mrs Cook, the Green, Tetbury. (James sister Prudence married Thomas Cook)

James sister Charlotte married a shoemaker and moved to UTAH.

James was five feet eight inches tall, dark hair and blue eyes, a long visage and a florid complexion. He had a scar on his forehead and a mole on the right side of his neck and abdomen, and a scar on the right knee.July 13, 2022 at 3:09 am #6323In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

“Watch where you are going, Child!” Egbert’s tone was sharp.

“Excuse me,” said Maryechka, hunching her shoulders and making herself small as a mouse so she could squeeze past Egbert’s oversized suitcase.

“To be fair, Old Man,” said Olga, glad of the excuse to pause, “you are taking up all the available space on the stairs with those bags.” She peered at Maryechka. “You are Obadiah’s girl aren’t you?”

Maryechka nodded shyly. “He’s my grandpa.” She frowned at the suitcases. “Are you going on holiday?”

“Never you mind that,” said Egbert. “You run along and see your Grandpa.”

Maryechka ducked past the bag and ran up the steps.

“Oy,” said Olga. “What I wouldn’t give for the agility of youth again.” Gripping the wooden hand rail, she stretched out her ankle and grimaced.

“Obadiah is stubborn as a mule,” said Egbert. “I tried warning him! He said he’d die in his room if it came to it.”

“Pfft,” said Olga. “That one will land on his big stinking feet. And he can hear better than he lets on. Is it him spreading the tales about me?”

Egbert dropped his bags and sat heavily on the step. He put his head in his hands and groaned. “Is it right though, Olga? Is it right that we leave our friends to their fate?”

It occurred to Olga that Egbert may be hiding his head so as not to answer her question. However, realising his mental state was fragile, she thought it prudent to keep to the matter at hand. It will keep, she thought.

“Obadiah and myself, we grew up together,” continued Egbert with what sounded like a sob. “We worked together on the farm as young men.” He raised his head and glared at Olga. “How can you expect me to leave him without a word of farewell? Have you no heart?”

May 27, 2022 at 8:25 am #6300In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Looking for Carringtons

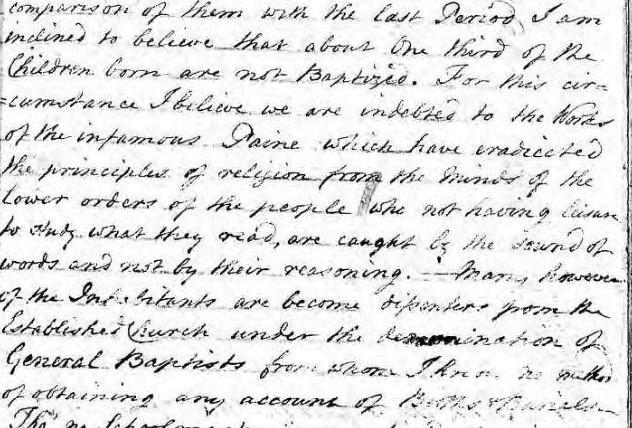

The Carringtons of Smalley, at least some of them, were Baptist ~ otherwise known as “non conformist”. Baptists don’t baptise at birth, believing it’s up to the person to choose when they are of an age to do so, although that appears to be fairly random in practice with small children being baptised. This makes it hard to find the birth dates registered as not every village had a Baptist church, and the baptisms would take place in another town. However some of the children were baptised in the village Anglican church as well, so they don’t seem to have been consistent. Perhaps at times a quick baptism locally for a sickly child was considered prudent, and preferable to no baptism at all. It’s impossible to know for sure and perhaps they were not strictly commited to a particular denomination.

Our Carrington’s start with Ellen Carrington who married William Housley in 1814. William Housley was previously married to Ellen’s older sister Mary Carrington. Ellen (born 1895 and baptised 1897) and her sister Nanny were baptised at nearby Ilkeston Baptist church but I haven’t found baptisms for Mary or siblings Richard and Francis. We know they were also children of William Carrington as he mentions them in his 1834 will. Son William was baptised at the local Smalley church in 1784, as was Thomas in 1896.

The absence of baptisms in Smalley with regard to Baptist influence was noted in the Smalley registers:

Smalley (chapelry of Morley) registers began in 1624, Morley registers began in 1540 with no obvious gaps in either. The gap with the missing registered baptisms would be 1786-1793. The Ilkeston Baptist register began in 1791. Information from the Smalley registers indicates that about a third of the children were not being baptised due to the Baptist influence.

William Housley son in law, daughter Mary Housley deceased, and daughter Eleanor (Ellen) Housley are all mentioned in William Housley’s 1834 will. On the marriage allegations and bonds for William Housley and Mary Carrington in 1806, her birth date is registered at 1787, her father William Carrington.

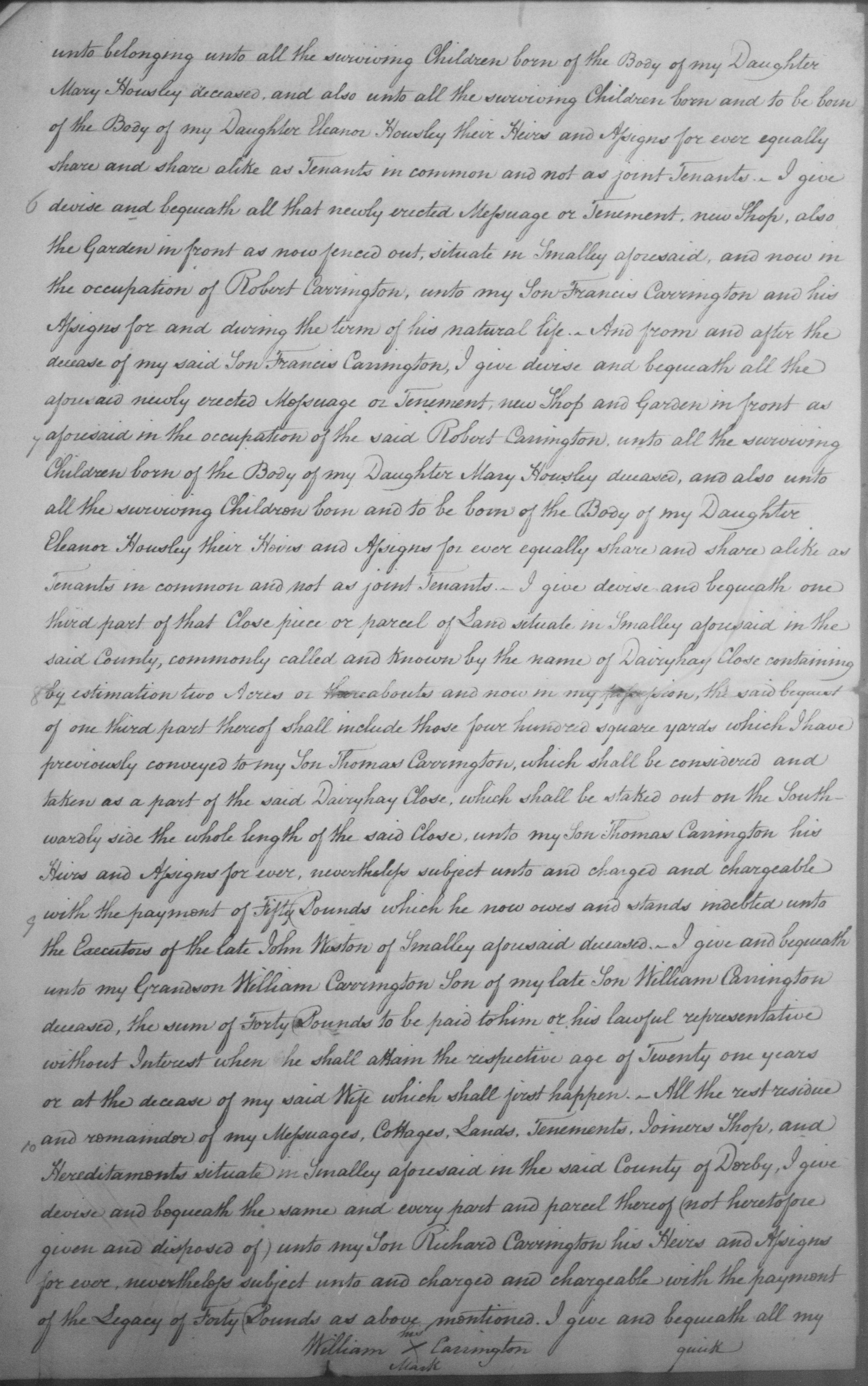

A Page from the will of William Carrington 1834:

William Carrington was baptised in nearby Horsley Woodhouse on 27 August 1758. His parents were William and Margaret Carrington “near the Hilltop”. He married Mary Malkin, also of Smalley, on the 27th August 1783.

When I started looking for Margaret Wright who married William Carrington the elder, I chanced upon the Smalley parish register micro fiche images wrongly labeled by the ancestry site as Longford. I subsequently found that the Derby Records office published a list of all the wrongly labeled Derbyshire towns that the ancestry site knew about for ten years at least but has not corrected!

Margaret Wright was baptised in Smalley (mislabeled as Longford although the register images clearly say Smalley!) on the 2nd March 1728. Her parents were John and Margaret Wright.

But I couldn’t find a birth or baptism anywhere for William Carrington. I found four sources for William and Margaret’s marriage and none of them suggested that William wasn’t local. On other public trees on ancestry sites, William’s father was Joshua Carrington from Chinley. Indeed, when doing a search for William Carrington born circa 1720 to 1725, this was the only one in Derbyshire. But why would a teenager move to the other side of the county? It wasn’t uncommon to be apprenticed in neighbouring villages or towns, but Chinley didn’t seem right to me. It seemed to me that it had been selected on the other trees because it was the only easily found result for the search, and not because it was the right one.

I spent days reading every page of the microfiche images of the parish registers locally looking for Carringtons, any Carringtons at all in the area prior to 1720. Had there been none at all, then the possibility of William being the first Carrington in the area having moved there from elsewhere would have been more reasonable.

But there were many Carringtons in Heanor, a mile or so from Smalley, in the 1600s and early 1700s, although they were often spelled Carenton, sometimes Carrianton in the parish registers. The earliest Carrington I found in the area was Alice Carrington baptised in Ilkeston in 1602. It seemed obvious that William’s parents were local and not from Chinley.

The Heanor parish registers of the time were not very clearly written. The handwriting was bad and the spelling variable, depending I suppose on what the name sounded like to the person writing in the registers at the time as the majority of the people were probably illiterate. The registers are also in a generally poor condition.

I found a burial of a child called William on the 16th January 1721, whose father was William Carenton of “Losko” (Loscoe is a nearby village also part of Heanor at that time). This looked promising! If a child died, a later born child would be given the same name. This was very common: in a couple of cases I’ve found three deceased infants with the same first name until a fourth one named the same survived. It seemed very likely that a subsequent son would be named William and he would be the William Carrington born circa 1720 to 1725 that we were looking for.

Heanor parish registers: William son of William Carenton of Losko buried January 19th 1721:

The Heanor parish registers between 1720 and 1729 are in many places illegible, however there are a couple of possibilities that could be the baptism of William in 1724 and 1725. A William son of William Carenton of Loscoe was buried in Jan 1721. In 1722 a Willian son of William Carenton (transcribed Tarenton) of Loscoe was buried. A subsequent son called William is likely. On 15 Oct 1724 a William son of William and Eliz (last name indecipherable) of Loscoe was baptised. A Mary, daughter of William Carrianton of Loscoe, was baptised in 1727.

I propose that William Carringtons was born in Loscoe and baptised in Heanor in 1724: if not 1724 then I would assume his baptism is one of the illegible or indecipherable entires within those few years. This falls short of absolute documented proof of course, but it makes sense to me.

In any case, if a William Carrington child died in Heanor in 1721 which we do have documented proof of, it further dismisses the case for William having arrived for no discernable reason from Chinley.

May 21, 2022 at 9:34 am #6299In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

Looking at the blemish feverish man on the camp bed, General Lyaksandro Rudechenko clenched his fists. The wooden leg, that had been the symbol of the Oocranian Resistance for the last year was now lying on the floor. President Voldomeer had contracted a virus that confounded their best doctors and the remaining chiefs of the Oocranian Resistance feared he would soon join the men fallen for their country.

— Nobody must know that the sexiest man of Oocrane is incapacitated. We need a replacement, said the General.

— President Voldomeer told me of a man, the very man who made that wooden leg, said Major Myroslava Kovalev, the candle light reflecting in her glass eye. He lives in the Dumbass region. He’s a secret twin or something, President Voldomeer was not so clear about that part, but at least they look alike. To make it more real, we can have his leg removed, she added pointing at the wooden leg.

She was proud of being one of the only women ranking that high in the military. His fellow people might not be Lazies, but they had some old idea about women, that were not the best choice for fighting. Myroslava had always wanted to prove them wrong, and this conflict had been her chance to rise almost to the top. She looked at the dying man who was once her ladder. He had been sexy, and certainly could do many things with his wooden leg. Now he was but the shadow of a man, pale and blurry as cataract. If she had loved him, she might have shed a tear.

Myroslava looked at General Rudechenko’s pockmarked face and shivered. She wouldn’t even share a cab with him. But he was the next in command, and before Voldomeer fell ill, she was on her way to take his place, even closer to the top.

— Let me bring him to you, she added.

— That’s a suicide mission, said the general. Permission granted.

— Thank you General ! said Myroslava doing the military salute before leaving the tent.

Despite his being from Dumbass and having made some mistakes in his life, Lyaksandro was not stupid. He knew quite well what that woman wanted. He called, Glib, his aide-de-camp.

— Make sure she gets lost behind the enemy lines.

March 17, 2022 at 10:37 am #6283In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Purdy Cousins

My great grandmother Mary Ann Gilman Purdy was one of five children. Her sister Ellen Purdy was a well traveled nurse, and her sister Kate Rushby was a publican whose son who went to Africa. But what of her eldest sister Elizabeth and her brother Richard?

Elizabeth Purdy 1869-1905 married Benjamin George Little in 1892 in Basford, Nottinghamshire. Their first child, Frieda Olive Little, was born in Eastwood in December 1896, and their second daughter Catherine Jane Little was born in Warrington, Cheshire, in 1898. A third daughter, Edna Francis Little was born in 1900, but died three months later.

When I noticed that this unidentified photograph in our family collection was taken by a photographer in Warrington, and as no other family has been found in Warrington, I concluded that these two little girls are Frieda and Catherine:

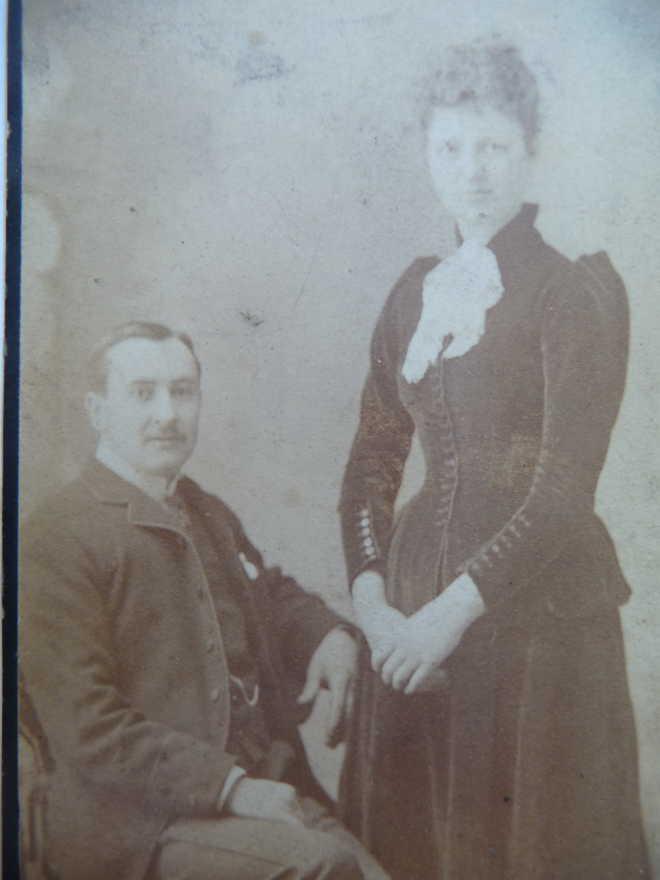

Benjamin Little, born in 1869, was the manager of a boot shop, according to the 1901 census, and a boot maker on the 1911 census. I found a photograph of Benjamin and Elizabeth Little on an ancestry website:

Frieda Olive Little 1896-1977 married Robert Warburton in 1924.

Frieda and Robert had two sons and a daughter, although one son died in infancy. They lived in Leominster, in Herefordshire, but Frieda died in 1977 at Enfield Farm in Warrington, four years after the death of her husband Robert.

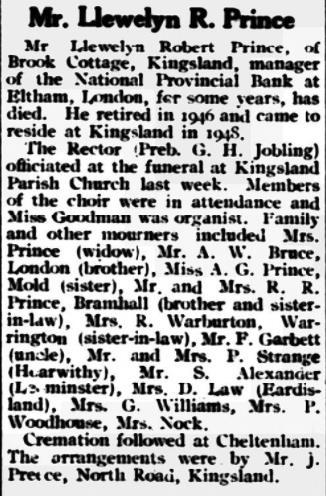

Catherine Jane Little 1899-1975 married Llewelyn Robert Prince 1884-1950. They do not appear to have had any children. Llewelyn was manager of the National Provinical Bank at Eltham in London, but died at Brook Cottage in Kingsland, Herefordshire. His wifes aunt Ellen Purdy the nurse had also lived at Brook Cottage. Ellen died in 1947, but her husband Frank Garbett was at the funeral:

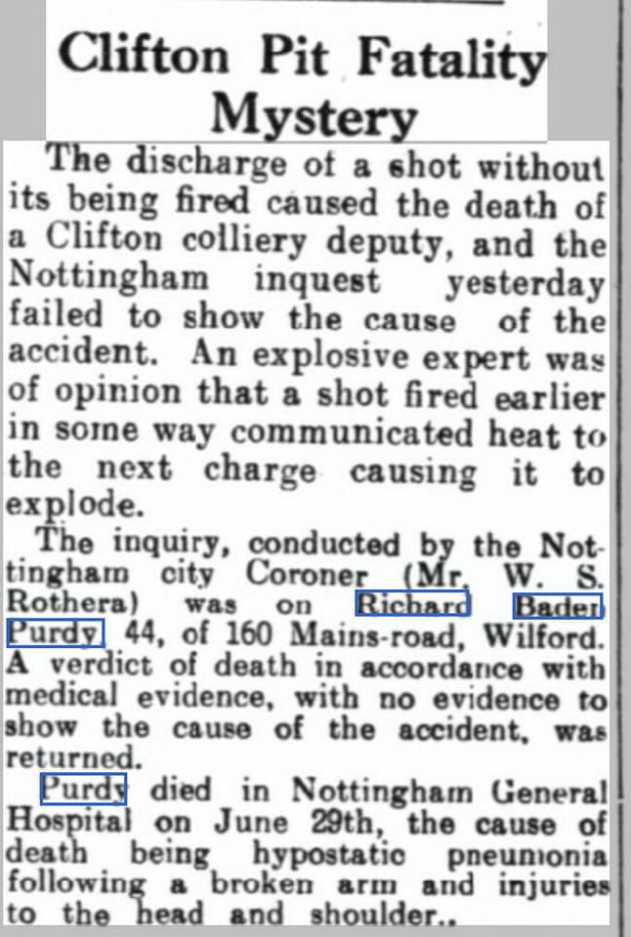

Richard Purdy 1877-1940

Richard was born in Eastwood, Nottinghamshire. When his mother Catherine died in 1884 Richard was six years old. My great grandmother Mary Ann and her sister Ellen went to live with the Gilman’s in Buxton, but Richard and the two older sisters, Elizabeth and Kate, stayed with their father George Purdy, who remarried soon afterwards.

Richard married Ada Elizabeth Clarke in 1899. In 1901 Richard was an earthenware packer at a pottery, and on the 1939 census he was a colliery dataller. A dataller was a day wage man, paid on a daily basis for work done as required.

Richard and Ada had four children: Richard Baden Purdy 1900-1945, Winifred Maude 1903-1974, John Frederick 1907-1945, and Violet Gertrude 1910-1974.

Richard Baden Purdy married Ethel May Potter in Mansfield, Nottinghamshire, in 1926. He was listed on the 1939 census as a colliery deputy. In 1945 Richard Baden Purdy died as a result of injuries in a mine explosion.

John Frederick Purdy married Iris Merryweather in 1938. On the 1939 census John and Iris live in Arnold, Nottinghamshire, and John’s occupation is a colliery hewer. Their daughter Barbara Elizabeth was born later that year. John died in 1945, the same year as his brother Richard Baden Purdy. It is not known without purchasing the death certificate what the cause of death was.

A memorial was posted in the Nottingham Evening Post on 29 June 1948:

PURDY, loving memories, Richard Baden, accidentally killed June 29th 1945; John Frederick, died 1 April 1945; Richard Purdy, father, died December 1940. Too dearly loved to be forgotten. Mother, families.

Violet Gertrude Purdy married Sidney Garland in 1932 in Southwell, Nottinghamshire. She died in Edwinstowe, Nottinghamshire, in 1974.

Winifred Maude Purdy married Bernard Fowler in Southwell in 1928. She also died in 1974, in Mansfield.

The two brothers died the same year, in 1945, and the two sisters died the same year, in 1974.

February 2, 2022 at 12:50 pm #6267In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

From Tanganyika with Love

continued part 8

With thanks to Mike Rushby.

Morogoro 20th January 1941

Dearest Family,

It is all arranged for us to go on three months leave to Cape Town next month so

get out your flags. How I shall love showing off Kate and John to you and this time

George will be with us and you’ll be able to get to know him properly. You can’t think

what a comfort it will be to leave all the worries of baggage and tipping to him. We will all

be travelling by ship to Durban and from there to Cape Town by train. I rather dread the

journey because there is a fifth little Rushby on the way and, as always, I am very

queasy.Kate has become such a little companion to me that I dread the thought of leaving

her behind with you to start schooling. I miss Ann and George so much now and must

face separation from Kate as well. There does not seem to be any alternative though.

There is a boarding school in Arusha and another has recently been started in Mbeya,

but both places are so far away and I know she would be very unhappy as a boarder at

this stage. Living happily with you and attending a day school might wean her of her

dependance upon me. As soon as this wretched war ends we mean to get Ann and

George back home and Kate too and they can then all go to boarding school together.

If I were a more methodical person I would try to teach Kate myself, but being a

muddler I will have my hands full with Johnny and the new baby. Life passes pleasantly

but quietly here. Much of my time is taken up with entertaining the children and sewing

for them and just waiting for George to come home.George works so hard on these safaris and this endless elephant hunting to

protect native crops entails so much foot safari, that he has lost a good deal of weight. it

is more than ten years since he had a holiday so he is greatly looking forward to this one.

Four whole months together!I should like to keep the ayah, Janet, for the new baby, but she says she wants

to return to her home in the Southern Highlands Province and take a job there. She is

unusually efficient and so clean, and the houseboy and cook are quite scared of her. She

bawls at them if the children’s meals are served a few minutes late but she is always

respectful towards me and practically creeps around on tiptoe when George is home.

She has a room next to the outside kitchen. One night thieves broke into the kitchen and

stole a few things, also a canvas chair and mat from the verandah. Ayah heard them, and

grabbing a bit of firewood, she gave chase. Her shouts so alarmed the thieves that they

ran off up the hill jettisoning their loot as they ran. She is a great character.Eleanor.

Morogoro 30th July 1941

Dearest Family,

Safely back in Morogoro after a rather grim voyage from Durban. Our ship was

completely blacked out at night and we had to sleep with warm clothing and life belts

handy and had so many tedious boat drills. It was a nuisance being held up for a whole

month in Durban, because I was so very pregnant when we did embark. In fact George

suggested that I had better hide in the ‘Ladies’ until the ship sailed for fear the Captain

might refuse to take me. It seems that the ship, on which we were originally booked to

travel, was torpedoed somewhere off the Cape.We have been given a very large house this tour with a mosquito netted

sleeping porch which will be fine for the new baby. The only disadvantage is that the

house is on the very edge of the residential part of Morogoro and Johnny will have to

go quite a distance to find playmates.I still miss Kate terribly. She is a loving little person. I had prepared for a scene

when we said good-bye but I never expected that she would be the comforter. It

nearly broke my heart when she put her arms around me and said, “I’m so sorry

Mummy, please don’t cry. I’ll be good. Please don’t cry.” I’m afraid it was all very

harrowing for you also. It is a great comfort to hear that she has settled down so happily.

I try not to think consciously of my absent children and remind myself that there are

thousands of mothers in the same boat, but they are always there at the back of my

mind.Mother writes that Ann and George are perfectly happy and well, and that though

German bombers do fly over fairly frequently, they are unlikely to drop their bombs on

a small place like Jacksdale.George has already left on safari to the Rufiji. There was no replacement for his

job while he was away so he is anxious to get things moving again. Johnny and I are

going to move in with friends until he returns, just in case all the travelling around brings

the new baby on earlier than expected.Eleanor.

Morogoro 26th August 1941

Dearest Family,

Our new son, James Caleb. was born at 3.30 pm yesterday afternoon, with a

minimum of fuss, in the hospital here. The Doctor was out so my friend, Sister Murray,

delivered the baby. The Sister is a Scots girl, very efficient and calm and encouraging,

and an ideal person to have around at such a time.Everything, this time, went without a hitch and I feel fine and proud of my

bouncing son. He weighs nine pounds and ten ounces and is a big boned fellow with

dark hair and unusually strongly marked eyebrows. His eyes are strong too and already

seem to focus. George is delighted with him and brought Hugh Nelson to see him this

morning. Hugh took one look, and, astonished I suppose by the baby’s apparent

awareness, said, “Gosh, this one has been here before.” The baby’s cot is beside my

bed so I can admire him as much as I please. He has large strong hands and George

reckons he’ll make a good boxer some day.Another of my early visitors was Mabemba, George’s orderly. He is a very big

African and looks impressive in his Game Scouts uniform. George met him years ago at

Mahenge when he was a young elephant hunter and Mabemba was an Askari in the

Police. Mabemba takes quite a proprietary interest in the family.Eleanor.

Morogoro 25th December 1941

Dearest Family,

Christmas Day today, but not a gay one. I have Johnny in bed with a poisoned

leg so he missed the children’s party at the Club. To make things a little festive I have

put up a little Christmas tree in the children’s room and have hung up streamers and

balloons above the beds. Johnny demands a lot of attention so it is fortunate that little

James is such a very good baby. He sleeps all night until 6 am when his feed is due.

One morning last week I got up as usual to feed him but I felt so dopey that I

thought I’d better have a cold wash first. I went into the bathroom and had a hurried

splash and then grabbed a towel to dry my face. Immediately I felt an agonising pain in

my nose. Reason? There was a scorpion in the towel! In no time at all my nose looked

like a pear and felt burning hot. The baby screamed with frustration whilst I feverishly

bathed my nose and applied this and that in an effort to cool it.For three days my nose was very red and tender,”A real boozer nose”, said

George. But now, thank goodness, it is back to normal.Some of the younger marrieds and a couple of bachelors came around,

complete with portable harmonium, to sing carols in the early hours. No sooner had we

settled down again to woo sleep when we were disturbed by shouts and screams from

our nearest neighbour’s house. “Just celebrating Christmas”, grunted George, but we

heard this morning that the neighbour had fallen down his verandah steps and broken his

leg.Eleanor.

Morogoro Hospital 30th September 1943

Dearest Family,

Well now we are eight! Our new son, Henry, was born on the night of the 28th.

He is a beautiful baby, weighing ten pounds three and a half ounces. This baby is very

well developed, handsome, and rather superior looking, and not at all amusing to look at

as the other boys were.George was born with a moustache, John had a large nose and

looked like a little old man, and Jim, bless his heart, looked rather like a baby

chimpanzee. Henry is different. One of my visitors said, “Heaven he’ll have to be a

Bishop!” I expect the lawn sleeves of his nightie really gave her that idea, but the baby

does look like ‘Someone’. He is very good and George, John, and Jim are delighted

with him, so is Mabemba.We have a dear little nurse looking after us. She is very petite and childish

looking. When the baby was born and she brought him for me to see, the nurse asked

his name. I said jokingly, “His name is Benjamin – the last of the family.” She is now very

peeved to discover that his real name is Henry William and persists in calling him

‘Benjie’.I am longing to get home and into my pleasant rut. I have been away for two

whole weeks and George is managing so well that I shall feel quite expendable if I don’t

get home soon. As our home is a couple of miles from the hospital, I arranged to move

in and stay with the nursing sister on the day the baby was due. There I remained for ten

whole days before the baby was born. Each afternoon George came and took me for a

ride in the bumpy Bedford lorry and the Doctor tried this and that but the baby refused

to be hurried.On the tenth day I had the offer of a lift and decided to go home for tea and

surprise George. It was a surprise too, because George was entertaining a young

Game Ranger for tea and my arrival, looking like a perambulating big top, must have

been rather embarrassing.Henry was born at the exact moment that celebrations started

in the Township for the end of the Muslim religious festival of Ramadan. As the Doctor

held him up by his ankles, there was the sound of hooters and firecrackers from the town.

The baby has a birthmark in the shape of a crescent moon above his left eyebrow.Eleanor.

Morogoro 26th January 1944

Dearest Family,

We have just heard that we are to be transferred to the Headquarters of the

Game Department at a place called Lyamungu in the Northern Province. George is not

at all pleased because he feels that the new job will entail a good deal of office work and

that his beloved but endless elephant hunting will be considerably curtailed. I am glad of

that and I am looking forward to seeing a new part of Tanganyika and particularly

Kilimanjaro which dominates Lyamungu.Thank goodness our menagerie is now much smaller. We found a home for the

guinea pigs last December and Susie, our mischievous guinea-fowl, has flown off to find

a mate.Last week I went down to Dar es Salaam for a check up by Doctor John, a

woman doctor, leaving George to cope with the three boys. I was away two nights and

a day and returned early in the morning just as George was giving Henry his six o’clock

bottle. It always amazes me that so very masculine a man can do my chores with no

effort and I have a horrible suspicion that he does them better than I do. I enjoyed the

short break at the coast very much. I stayed with friends and we bathed in the warm sea

and saw a good film.Now I suppose there will be a round of farewell parties. People in this country

are most kind and hospitable.Eleanor.

Lyamungu 20th March 1944

Dearest Family,

We left Morogoro after the round of farewell parties I had anticipated. The final

one was at the Club on Saturday night. George made a most amusing speech and the

party was a very pleasant occasion though I was rather tired after all the packing.

Several friends gathered to wave us off on Monday morning. We had two lorries

loaded with our goods. I rode in the cab of the first one with Henry on my knee. George

with John and Jim rode in the second one. As there was no room for them in the cab,

they sat on our couch which was placed across the width of the lorry behind the cab. This

seat was not as comfortable as it sounds, because the space behind the couch was

taken up with packing cases which were not lashed in place and these kept moving

forward as the lorry bumped its way over the bad road.Soon there was hardly any leg room and George had constantly to stand up and

push the second layer of packing cases back to prevent them from toppling over onto

the children and himself. As it is now the rainy season the road was very muddy and

treacherous and the lorries travelled so slowly it was dark by the time we reached

Karogwe from where we were booked to take the train next morning to Moshi.

Next morning we heard that there had been a washaway on the line and that the

train would be delayed for at least twelve hours. I was not feeling well and certainly did

not enjoy my day. Early in the afternoon Jimmy ran into a wall and blackened both his

eyes. What a child! As the day wore on I felt worse and worse and when at last the train

did arrive I simply crawled into my bunk whilst George coped nobly with the luggage

and the children.We arrived at Moshi at breakfast time and went straight to the Lion Cub Hotel

where I took to my bed with a high temperature. It was, of course, malaria. I always have

my attacks at the most inopportune times. Fortunately George ran into some friends

called Eccles and the wife Mollie came to my room and bathed Henry and prepared his

bottle and fed him. George looked after John and Jim. Next day I felt much better and

we drove out to Lyamungu the day after. There we had tea with the Game Warden and

his wife before moving into our new home nearby.The Game Warden is Captain Monty Moore VC. He came out to Africa

originally as an Officer in the King’s African Rifles and liked the country so much he left the

Army and joined the Game Department. He was stationed at Banagi in the Serengetti

Game Reserve and is well known for his work with the lions there. He particularly tamed

some of the lions by feeding them so that they would come out into the open and could

readily be photographed by tourists. His wife Audrey, has written a book about their

experiences at Banagi. It is called “Serengetti”Our cook, Hamisi, soon had a meal ready for us and we all went to bed early.

This is a very pleasant house and I know we will be happy here. I still feel a little shaky

but that is the result of all the quinine I have taken. I expect I shall feel fine in a day or two.Eleanor.

Lyamungu 15th May 1944

Dearest Family,

Well, here we are settled comfortably in our very nice house. The house is

modern and roomy, and there is a large enclosed verandah, which will be a Godsend in

the wet weather as a playroom for the children. The only drawback is that there are so

many windows to be curtained and cleaned. The grounds consist of a very large lawn

and a few beds of roses and shrubs. It is an ideal garden for children, unlike our steeply

terraced garden at Morogoro.Lyamungu is really the Government Coffee Research Station. It is about sixteen

miles from the town of Moshi which is the centre of the Tanganyika coffee growing

industry. Lyamungu, which means ‘place of God’ is in the foothills of Mt Kilimanjaro and

we have a beautiful view of Kilimanjaro. Kibo, the more spectacular of the two mountain

peaks, towers above us, looking from this angle, like a giant frosted plum pudding. Often the mountain is veiled by cloud and mist which sometimes comes down to

our level so that visibility is practically nil. George dislikes both mist and mountain but I

like both and so does John. He in fact saw Kibo before I did. On our first day here, the

peak was completely hidden by cloud. In the late afternoon when the children were

playing on the lawn outside I was indoors hanging curtains. I heard John call out, “Oh

Mummy, isn’t it beautiful!” I ran outside and there, above a scarf of cloud, I saw the

showy dome of Kibo with the setting sun shining on it tingeing the snow pink. It was an

unforgettable experience.As this is the rainy season, the surrounding country side is very lush and green.

Everywhere one sees the rich green of the coffee plantations and the lighter green of

the banana groves. Unfortunately our walks are rather circumscribed. Except for the main road to Moshi, there is nowhere to walk except through the Government coffee

plantation. Paddy, our dog, thinks life is pretty boring as there is no bush here and

nothing to hunt. There are only half a dozen European families here and half of those are

on very distant terms with the other half which makes the station a rather uncomfortable

one.The coffee expert who runs this station is annoyed because his European staff

has been cut down owing to the war, and three of the vacant houses and some office

buildings have been taken over temporarily by the Game Department. Another house

has been taken over by the head of the Labour Department. However I don’t suppose

the ill feeling will effect us much. We are so used to living in the bush that we are not