Search Results for 'sent'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

January 18, 2023 at 10:07 am #6412

In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Youssef was talking with Xavier in a personal chat. He had called his friend for help, because he felt out of his league with the Thi Gang thing. Notifications from the other chat room where Zara and Yasmine were in an eye roll asking questions about the game kept distracting him from his work. There were currently 820 messages of backlog. That was insane. How could he ever catch up with that. He wondered how Xavier could manage the personal chat room with him, trying to solve techy problems, answer Zaraloon and Yasminowl’s questions, and god knows what else from his work at his tech company!

“I got an anonymous tip, said Miss Tartiflate dashing into the yurt, almost tearing the curtains off the top of the entrance. Lama Yoneze is in the Gobi dessert! We have to move quick if we want to catch him.”

“You mean desert…”

“What ?”

“Doesn’t matter. But what about THE BLOG? I can’t fix anything if I don’t have an internet connection. I have to stay at the camp.”

“In your dreams! I’ve got us jeeps with satellite internet connection. It’s expensive, but I’m worth it. You’ll do it on our way to the deezert.”

Youssef rolled his eyes, a trick he learned from Yasmin during one or their online meetings.

“Are you sick?” asked Miss Tartiflate.

For all answers, Youssef snapped the laptop close and sent a message to Xavier.

“We found the Llama. Moving to the desert now. Jeep ride 🤮

Getting 😤 but feeling lucky I didn’t have time to eat any

Won’t barf up on the laptop. Not done with you yet!” January 17, 2023 at 8:17 am #6393

January 17, 2023 at 8:17 am #6393In reply to: Train your subjective AI – text version

Give me an unusual plot structure for a narrative

One unusual plot structure for a narrative could be a “reverse chronological” structure, where the story begins at the end and works backwards in time, revealing events and information in a non-linear way. Another could be a “choose your own adventure” style, where the reader is presented with a series of choices at different points in the story that determine the direction and outcome of the plot.

How would role playing qualify in terms of plot structure?

Role-playing games (RPGs) can be considered a unique form of plot structure because they are interactive and open-ended. In a traditional RPG, the players take on the roles of characters within a fictional setting and work together to create a shared narrative. The plot structure of an RPG is determined by the actions and decisions of the players, rather than a pre-written script. The game master (GM) creates an overarching plot and a set of rules for the players to follow, but the players’ choices and actions will determine the direction and outcome of the story. This makes the plot structure of an RPG fluid and ever-changing, unlike a traditional linear narrative.

What about “Cloud Atlas” in terms of plot structure?

“Cloud Atlas” is a novel written by David Mitchell that was later adapted into a film. It has a complex and non-linear plot structure, which employs multiple storylines that are set in different time periods and locations, and are connected by recurring themes and motifs. The novel is divided into six nested stories, each set in a different time period and location, that are told in a non-linear fashion. The story begins in the 19th century and then jumps back and forth between the 19th, 20th and 23rd century, and each story is interconnected and interrelated, with characters reappearing in different time periods, the events that happen in one story impacting the others. The novel is also notable for its use of different genres, such as science fiction, historical fiction, and thriller, and the way it explores the themes of destiny, reincarnation, and the power of human connection. The film adaptation also used this structure, with the different stories intertwined and characters reprising their roles in different settings and eras.

Take a story thread made of comments. In each comment is a text about characters in a particular plot, location, action etc. The comments are sequential, but they are not necessarily continuous. It is a mix between Cloud Atlas and RPG plot structures. How do you sort something that’s fundamentally non-linear to present it in an accessible way?

One way to sort and present a story thread made of comments that is fundamentally non-linear, yet accessible, is to group the comments based on their content. For example, you could group the comments by characters, and present them in chronological order of their appearance in the story. Another way could be grouping the comments by location, and present them in chronological order of when the action takes place in that particular location. You could also group comments by the type of action taking place, such as combat, conversation, or puzzle-solving, and present them in chronological order of when they occur in the story.

Another approach could be using visual aids, such as mind maps, timelines, or flowcharts, to help organize and present the information in a clear and easy-to-understand way. For example, you could use a mind map to show how different characters are connected, or a timeline to show the chronology of events. Additionally, you could use labels, such as “character introduction,” “location change,” or “plot twist,” to make it clear to the reader what type of information they can expect in each comment.

It’s also important to keep in mind the audience for which you are organizing the story. It should be easy for them to understand and follow the story, and if it’s a game, you should make sure it’s easy for the players to play and make decisions.

January 15, 2023 at 1:18 pm #6391In reply to: Train your subjective AI – text version

write the plot of an absurd non-linear novel, featuring 4 characters

The novel begins with the introduction of four characters: a retired archaeologist named Harold, a struggling musician named Samantha, a disillusioned corporate drone named Tim, and a reclusive inventor named Claire.

Harold, who is obsessed with ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, discovers a mysterious underground chamber beneath a pyramid in Egypt. Inside, he finds a strange device that he believes is a time machine. Harold decides to use the device to travel back in time to ancient Egypt in order to decipher the hieroglyphs.

Samantha, who is trying to make a name for herself as a musician, is struggling to come up with new material for her music. One day, she discovers that she can create beautiful music by communicating with plants telepathically. She becomes obsessed with this new form of music-making and decides to quit her day job and pursue it full-time.

Tim, who is stuck in a dead-end job, is feeling unfulfilled and uninspired. One day, he stumbles upon a robotic mime performance art show. The performance inspires him to quit his job and pursue his dream of becoming a mime artist.

Claire, who is a reclusive inventor, has been working on a project to create a type of artificial intelligence that can communicate with humans using calligraphic body language. She finally succeeds and creates an AI that she names “Calli”.

As the story progresses, the characters’ paths begin to intersect in unexpected ways. Harold gets stuck in ancient Egypt and has to rely on Samantha’s telepathic plant communication skills to find a way back to the present. Tim’s robotic mime art becomes a hit and he starts working with Claire to integrate Calli into his performances.

As the story reaches its climax, all four characters come together to use their unique skills and abilities to solve a problem that threatens the fate of the world.

Throughout the novel, the plot unfolds in a non-linear fashion, jumping back and forth in time and between the different character’s perspectives. The story is filled with absurdity and unexpected twists and turns, leaving the reader guessing until the very end.

What sort of problem that threatens the fate of the world will be resolved by their combined skills?

As the story progresses, the characters begin to uncover a sinister plot by a group of powerful individuals who are intent on using the time machine to alter the course of history for their own gain. They plan to use the time machine to go back in time and change key events that would give them immense wealth and power in the present. Harold and Samantha, with the help of Tim and Claire, must race against time to stop the villains from carrying out their plan.

Harold’s expertise in ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs plays a crucial role in deciphering the clues that lead to the location of the time machine. Samantha’s telepathic plant communication skills are used to locate the hidden underground chamber where the time machine is kept. Tim’s robotic mime art and Claire’s AI Calli are used to infiltrate the villains’ hideout and gather intelligence on their plans.

In the final act, the four characters come together to use their unique skills and abilities to stop the villains from altering history. Harold uses his knowledge of ancient Egypt to navigate the time machine and travel back in time to stop the villains from changing key events. Samantha uses her telepathic plant communication skills to communicate with the plants in the past and gather information on the villains’ whereabouts. Tim and Claire use their robotic mime and AI skills to create a diversion and distract the villains while Harold and Samantha complete their mission.

In the end, the four characters succeed in stopping the villains and saving the fate of the world. The novel ends with the four characters going their separate ways, but they all know that they will always have each other to rely on in the face of any challenge that comes their way.

January 13, 2023 at 9:00 pm #6381In reply to: Prompts of Madjourneys

Tell me more about the clues that Zara, Youssef, Xavier and Yasmin will find on their journeys to discover their inner quirky natures

As Zara, Youssef, Xavier and Yasmin journeyed through the Land of the Quirks to discover their inner quirky natures, they encountered various clues that helped them on their journey.

One of the clues they found was a mysterious map that led them to different locations, each one representing a different aspect of their personalities. The map also had various riddles and puzzles that they had to solve in order to progress to the next location.

Another clue they found was a series of journal entries written by a previous explorer who had also journeyed through the Land of the Quirks. The journal entries provided insight and wisdom on how to navigate the land and how to understand and accept one’s quirks.

They also encountered a group of strange and eccentric characters who each represented a different aspect of their personalities. These characters provided guidance and helped them understand different parts of themselves. They also helped them understand the importance of accepting and embracing their quirks.

They also found a series of symbols and artifacts that represented different parts of their personalities. These symbols and artifacts were like puzzle pieces that, when put together, helped them understand the bigger picture of their inner quirky natures.

As they continued their journey, they also learned that the key to discovering their inner quirky natures was not only about finding the physical “Key of Quirks”, but also about understanding and accepting themselves, their faults and their strengths, and learning to embrace their unique quirks.

Finding their inner quirks sounds quite definitive. how would you make the ending more open-ended, open to multiple series and iterations of the story without sounding repetitive

As Zara, Youssef, Xavier and Yasmin journeyed through the Land of the Quirks, they discovered their inner quirky natures, but the journey was far from over. They found that their inner quirks were constantly evolving and changing, and that the Land of the Quirks was a vast and mysterious place with many more secrets to uncover.

The group found that the “Key of Quirks” was not just a physical object but a symbol of self-discovery and self-acceptance. They learned that understanding and accepting oneself is a lifelong journey that never truly ends.

As they returned to their own world, they realized that they had gained a new perspective on life and that they would continue to carry the lessons they learned in the Land of the Quirks with them. They knew that they would always be on the lookout for new adventures and opportunities to continue exploring themselves and the world around them.

The group’s journey in the Land of the Quirks had come to an end but the story was not over. The characters would continue to grow, evolve and change as they experienced new adventures, challenges and self-discoveries. The ending was open-ended and leaves the possibility for multiple series and iterations of the story, each one exploring new aspects of the characters and the Land of the Quirks, without being repetitive.

Will they go a try to travel through another of the orbs?

It is possible that the group will want to explore other orbs and realms in the Land of the Quirks. The Land of the Quirks is described as a vast and mysterious place with many secrets to uncover, so the possibility of traveling through other orbs or realms is open. They may be tempted to see what other adventures and discoveries await them in these new places.

Alternatively, they might decide to take a break from their adventures, and reflect on what they’ve learned, applying it to their daily life, and maybe in the future, they will decide to come back to the Land of the Quirks and explore other orbs, or they may find other means of self-discovery and self-acceptance. In any case, the story leaves it open-ended and the characters have the freedom to choose what they want to do next.

How did they discover the orb in the first place?

It is not specified how the group discovered the orb in the first place. It could be that they stumbled upon it while on a hike or a camping trip, or it could be that they were on a mission to find it specifically. It could also be that the orb was something that had always been there but had gone unnoticed until one of the group members stumbled upon it.

Perhaps it was passed down from generation to generation as a legend, or maybe they found it while they were searching for something else. The story leaves it open-ended and it’s up to the reader’s imagination. The main focus of the story is on the journey and the lessons learned along the way, rather than the specifics of how the orb was discovered.

January 13, 2023 at 6:47 pm #6378Topic: Prompts of Madjourneys

A thread to share some of the prompts behind the AI-assisted journey into new adventures.

To start off…

Please write the exciting start of a novel.

Some elements you can integrate if you want:

– Four randomly chosen names full of panache that sound distinct from each other, slightly exotic and evocative

– the sentiment from this quotation: “Look around… Beauty is everywhere. You only have to look to see it.” – a group of four people ready for an adventure, standing in a cave with stalactites in front of a giant orb or bubble that seem to open to another brightly lit realm. Inside the bigger orb are some smaller orbs.

– the following term “mad journeys”Told it to continue and it brought dragons… Asked to tone down the fantasy stuff, here’s what came out:

They walked into a small village, where they were greeted by a group of people wearing clothes that looked like they were from the 1920s. The people told them that they were in the land of the “Quirks”, a place where everything and everyone was a little bit different, and that they had to find the “Key of Quirks” in order to leave the land.

The group set off on their journey to find the key, but little did they know that their adventure was about to become even more exciting and quirky than they could ever have imagined. They encountered a talking dog, a man who had a garden on top of his head, and a group of people who lived inside of giant mushrooms.

As they journeyed on, they faced challenges and made new friends, but most importantly they learn to embrace their own quirks and individuality. Eventually, they found the key and were able to leave the land of the Quirks, but they knew that they would always carry a piece of that land with them.

January 11, 2023 at 9:43 pm #6367In reply to: Train your subjective AI – text version

Something in the style of TPooh:

The family tree was a tangled web of branches and roots, stretching back centuries and even millennia. The branches were thick with the leaves of secrets, scandals, and mysteries that the family had accumulated over the years. They were a close-knit group, friends for all time, and they loved nothing more than exploring the twists and turns of their family history.

They met regularly in their dreams, in a place they called The City, where they could exchange stories and clues they had uncovered during their waking hours. They often found themselves in the midst of strange and puzzling occurrences, and they would spend hours discussing the possible meanings and connections of these events. They saw the world as a tapestry, with each thread and pattern contributing to the greater picture. They were the weavers of their own story, the authors of their own fate.

But as the years went on, their dreams began to take on a darker and more ominous tone. They started having nightmares of monstrous beasts, and some of them even saw these beasts in the daylight, as if they were falling through the cracks in reality. They compared notes and found that they were often seeing the same beasts, and this led to heated debates about what these beasts represented and whether they were real or just figments of their imagination.

But no matter what they encountered, the family remained united in their quest to unravel the secrets of their past and to weave a tapestry that would be the envy of all. They were thick as thieves and they would never give up their pursuit of the truth, no matter how many rules they had to break along the way.

January 11, 2023 at 8:44 pm #6366In reply to: Train your subjective AI – text version

Asking the AI to expand on the glossary of the original Circle of Eights Story:

Locations

Malvina’s Cave: A dark and damp cave located in the heart of the Gripshawk mountains, known for its population of Glukenitch creatures.

Lan’ork: A vast and diverse continent known for its Eastern Lagunas, home to the Indogo flamingos. Dragon Head Peninsula: A rugged and mountainous region, home to the Langoat creatures and also known for its rich deposits of dragon ore.

Asgurdy: A sprawling desert region, known for its nomadic tribes who use Saurhse as mounts for transportation.

Golfindely: An idyllic coastal region known for its beautiful beaches and crystal clear waters, home to the Golfindel and Grake creatures.

Magical Schools

Dragonian Magic: A form of magic that is practiced by Dragonriders and Dragon tamers, which involves the manipulation of dragon energy and bonding with dragon companions.

Gripshawk Magic: A form of magic that is practiced by Gripshawks, which involves the manipulation of the natural elements and telepathic communication with other creatures.

Ugling Magic: A form of magic that is practiced by Uglings, which involves the use of charms, spells, and potions to manipulate the physical world.

Guilds

Dragon Riders Guild: A prestigious guild of dragon riders, responsible for maintaining peace and order in the world by using their dragon companions for protection and transportation.

Gripshawk Hunters Guild: A guild of skilled hunters who specialize in hunting and capturing exotic creatures for various purposes.

Ugling Alchemists Guild: A guild of alchemists and potion makers, who create various potions and elixirs for medicinal and magical purposes.

Organizations

The Order of the Buntifluën: A secret organization dedicated to the study and use of Buntifluën artefacts for the betterment of communication and understanding between sentient beings.

The Glubolín Network: A network of individuals who possess Glubolín devices, used for communication and sharing information across long distances.

The Sabulmantium Society: A society of scholars and adventurers who study the properties and uses of Sabulmantium devices for divination and navigation.

Here are a few new invented terms with their potential IPA pronunciations and definitions that would fit in this fantasy world:

Dragons:

Krynn [ ˈkrĭn ] : A subspecies of dragon known for its ability to control and manipulate time.

Creatures:

Kelpies [ ˈkĕl-pēz ] : Aquatic creatures resembling horses, known for their ability to shape-shift and lure unsuspecting victims into the water.

Magical Artefacts:

Dragonwhisper [ ˈdrā-gən-ˌhwis-pər ] : An ancient and powerful magical artifact, which allows the user to communicate and control dragons telepathically.

Necrotalisman [ ˈnĕk-rə-ˈtā-lĭz-mən ] : A magical artifact in the shape of a talisman that grants its wielder the ability to control and summon the dead.

Plants:

Blightthorn [ ˈblīt-ˌthôrn ] : A poisonous plant known for its dark purple flowers and thorny stem, its extract is used in dark magic

Faeleaf [ ˈfā-ˌlēf ] : A rare plant found in the deep forest known for its bright green leaves, its extract is used in healing potions

Locations:

The Shadowland [ ˈshā-dō-ˌland ] : A mysterious and dangerous land overrun by dark magic and controlled by Necromancers.

The Hidden Vale [ ˈhī-dən-ˈvāl ] : A secluded valley located deep in the mountains, home to the reclusive Faeleaf plants.

Organization:

The Necromancers’ Circle [ ˈnĕk-rə-ˈmän-sər-z-ˈsər-kəl ] : A secret organization of powerful necromancers who seek to expand their control over death and the dead.

Here are a few more invented terms with their potential IPA pronunciations and definitions that fit in this fantasy world, having less to do with necromancy, and more with various forms of consciousness or energy manipulation, magical or mythical creatures or species:

Creatures:

Eterneon [ ˈē-tər-ˈnē-ən ] : A species of winged creatures known for their ability to manipulate and harness the energy of the stars, they are highly sought after by astromancers and star-gazers.

Psicon [ ˈsī-ˌkän ] : A species of psychic creatures, known for their ability to read minds and influence emotions.

Magical Artefacts:

Energyshield [ ˈen-ər-jē-ˌshēld ] : A magical artifact that creates a protective barrier around the user, deflecting or absorbing any kind of energy-based attacks.

Empathstone [ ˈĕm-pāth-ˈstōn ] : A small, glowing stone which allows the user to sense and control the emotions of others.

Magical Schools:

Energyshaping [ ˈen-ər-jē-ˌshāp-ing ] : A school of magic that involves the manipulation and control of various forms of energy.

Empathymagic [ ˈĕm-pā-thē-ˈmaj-ik ] : A school of magic that involves the manipulation of emotions and the ability to sense the emotions of others.

Locations:

Eternity’s Edge [ ˈē-tər-nə-tēz-ˈēj] : A remote and mysterious cliff located high in the mountains, known for its strong emanations of star energy and rumored to be home to a hidden community of Eterneons.

Psicon’s Den [ ˈsī-kän-z-ˈdĕn] : A secret cave system located deep within the forest, it is said to be home to a colony of Psicon creatures.

Organizations:

The Energists Guild [ ˈen-ər-jist-z-ˈgild] : A powerful guild of magic users specializing in Energyshaping magic.

The Empath Council [ ˈĕm-pāth-ˈkoun-səl]: A secretive group of Empathymagic users, dedicated to the study and control of emotions.

January 10, 2023 at 11:00 pm #6365In reply to: Train your subjective AI – text version

Prune has got me into this AI stuff… It sounds like gibberish to me, but Idle sounded amazed at the stuff it spewed out.

With some info on our family story, Prune got it to try and predict the future…

Sounds like a big plate of bog, but we’ll see how it goes.

Sure, here are a few possible events that could occur between Mater’s 100th birthday and her death in the Flying Fish Inn story:

- Mater decides to throw herself a grand birthday party, inviting all of her friends and family from the small outback town. However, things take a turn for the strange when a group of extraterrestrial beings crash the party and reveal themselves to be long-time fans of Mater’s famous bush tucker cuisine.

- Mater begins to experience vivid dreams and hallucinations, in which she is visited by the ghost of her late husband. As the dreams become more frequent, the family begins to suspect that there may be something more to them than just Mater’s mind playing tricks on her.

- Mater’s granddaughter Prune becomes increasingly obsessed with her dream of traveling to Mars, and begins to notice strange occurrences happening around the inn that seem to be connected to her aspiration.

- A group of eccentric scientists arrive at the inn, conducting research on the local flora and fauna. They eventually discover a species of sentient plants living in the area, and Mater becomes convinced that the plants are communicating with her in her dreams.

- With her health declining, Mater begins to spend more and more time tending to her garden, where she is visited by an old kookaburra who seems to possess an otherworldly intelligence. The bird becomes Mater’s companion and confidant in the final days of her life.

- As the Great Fires ravage the Australian bush, Mater makes the difficult decision to shut down the inn and evacuate the guests. But as they flee, they realize that the fire is not just a natural disaster, but something far more sinister and mystical.

- In her final days, Mater begins to remember strange and vivid details of her life that she never could have known, as if she lived a previous life in another time and place. As she dies, she whispers something to Prune, which opens her eyes to a new reality that may have been hidden from her all along

- It turns out the family had a lot of secrets, and the only way to escape it, was to leave the inn, but it was not an escape for all. Through the series of events, secrets are revealed, and some truths cannot be undone.Note that these events are fictional and whimsical in nature, but as they keeps it grounded to a sense of doldrums in the Australian bush and occasionally guests help to unravel some of the overarching mysteries it could make a fitting storyline for the story.

December 6, 2022 at 2:17 pm #6350In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Transportation

Isaac Stokes 1804-1877

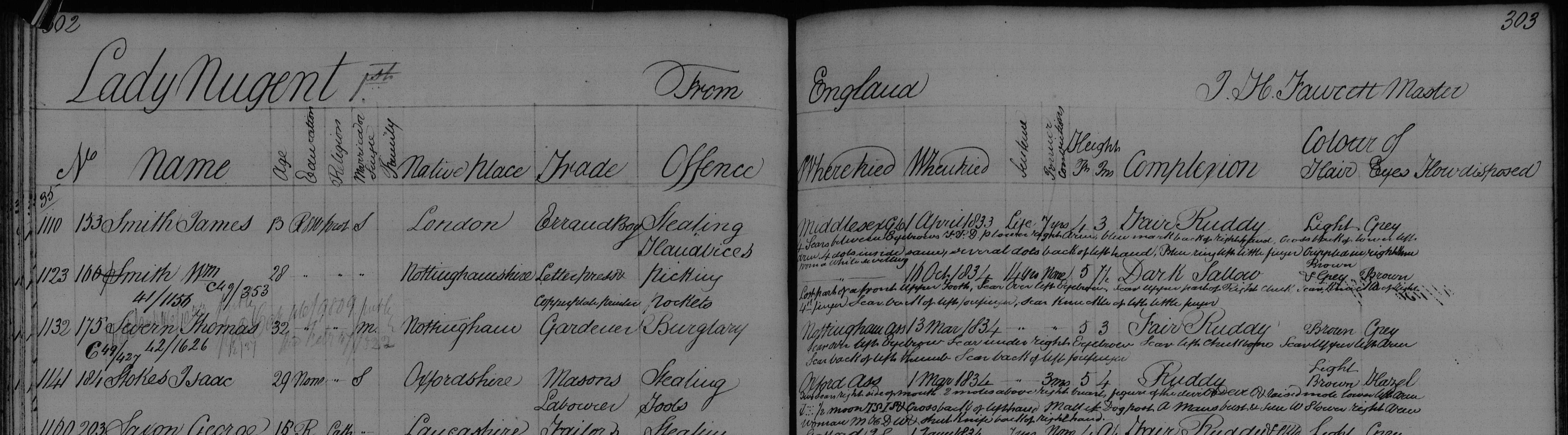

Isaac was born in Churchill, Oxfordshire in 1804, and was the youngest brother of my 4X great grandfather Thomas Stokes. The Stokes family were stone masons for generations in Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire, and Isaac’s occupation was a mason’s labourer in 1834 when he was sentenced at the Lent Assizes in Oxford to fourteen years transportation for stealing tools.

Churchill where the Stokes stonemasons came from: on 31 July 1684 a fire destroyed 20 houses and many other buildings, and killed four people. The village was rebuilt higher up the hill, with stone houses instead of the old timber-framed and thatched cottages. The fire was apparently caused by a baker who, to avoid chimney tax, had knocked through the wall from her oven to her neighbour’s chimney.

Isaac stole a pick axe, the value of 2 shillings and the property of Thomas Joyner of Churchill; a kibbeaux and a trowel value 3 shillings the property of Thomas Symms; a hammer and axe value 5 shillings, property of John Keen of Sarsden.

(The word kibbeaux seems to only exists in relation to Isaac Stokes sentence and whoever was the first to write it was perhaps being creative with the spelling of a kibbo, a miners or a metal bucket. This spelling is repeated in the criminal reports and the newspaper articles about Isaac, but nowhere else).

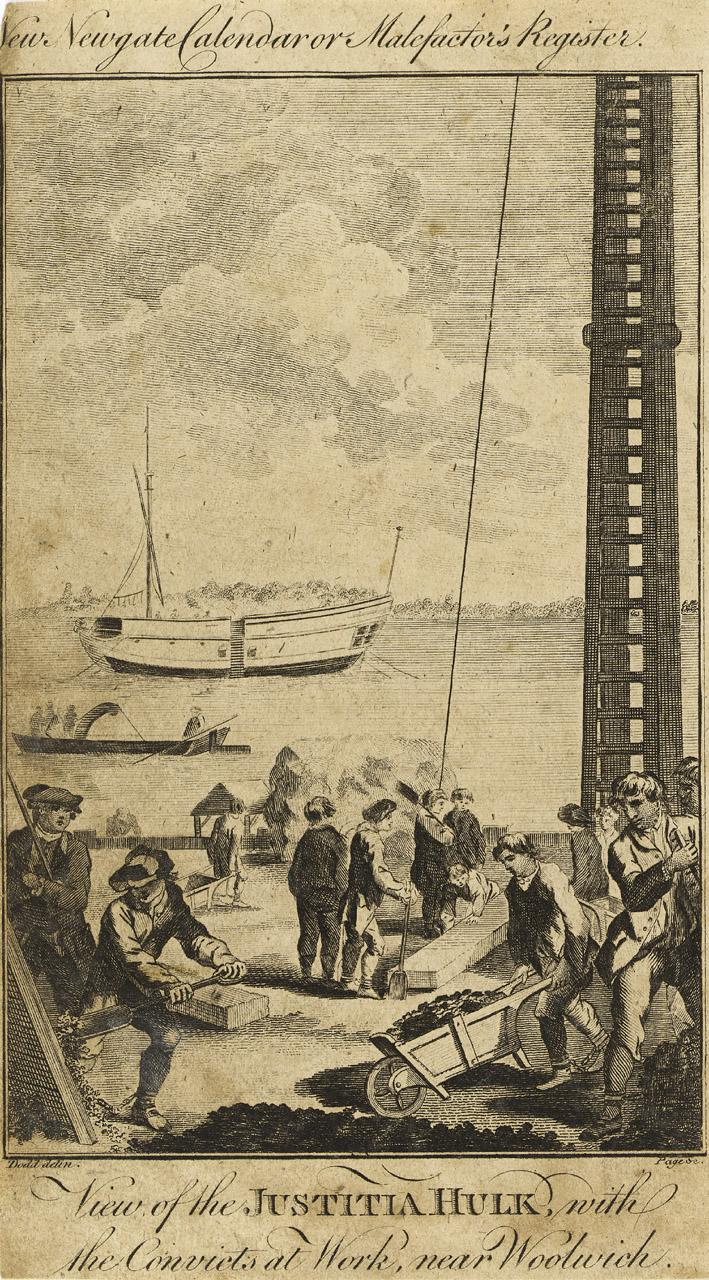

In March 1834 the Removal of Convicts was announced in the Oxford University and City Herald: Isaac Stokes and several other prisoners were removed from the Oxford county gaol to the Justitia hulk at Woolwich “persuant to their sentences of transportation at our Lent Assizes”.

via digitalpanopticon:

Hulks were decommissioned (and often unseaworthy) ships that were moored in rivers and estuaries and refitted to become floating prisons. The outbreak of war in America in 1775 meant that it was no longer possible to transport British convicts there. Transportation as a form of punishment had started in the late seventeenth century, and following the Transportation Act of 1718, some 44,000 British convicts were sent to the American colonies. The end of this punishment presented a major problem for the authorities in London, since in the decade before 1775, two-thirds of convicts at the Old Bailey received a sentence of transportation – on average 283 convicts a year. As a result, London’s prisons quickly filled to overflowing with convicted prisoners who were sentenced to transportation but had no place to go.

To increase London’s prison capacity, in 1776 Parliament passed the “Hulks Act” (16 Geo III, c.43). Although overseen by local justices of the peace, the hulks were to be directly managed and maintained by private contractors. The first contract to run a hulk was awarded to Duncan Campbell, a former transportation contractor. In August 1776, the Justicia, a former transportation ship moored in the River Thames, became the first prison hulk. This ship soon became full and Campbell quickly introduced a number of other hulks in London; by 1778 the fleet of hulks on the Thames held 510 prisoners.

Demand was so great that new hulks were introduced across the country. There were hulks located at Deptford, Chatham, Woolwich, Gosport, Plymouth, Portsmouth, Sheerness and Cork.The Justitia via rmg collections:

Convicts perform hard labour at the Woolwich Warren. The hulk on the river is the ‘Justitia’. Prisoners were kept on board such ships for months awaiting deportation to Australia. The ‘Justitia’ was a 260 ton prison hulk that had been originally moored in the Thames when the American War of Independence put a stop to the transportation of criminals to the former colonies. The ‘Justitia’ belonged to the shipowner Duncan Campbell, who was the Government contractor who organized the prison-hulk system at that time. Campbell was subsequently involved in the shipping of convicts to the penal colony at Botany Bay (in fact Port Jackson, later Sydney, just to the north) in New South Wales, the ‘first fleet’ going out in 1788.

While searching for records for Isaac Stokes I discovered that another Isaac Stokes was transported to New South Wales in 1835 as well. The other one was a butcher born in 1809, sentenced in London for seven years, and he sailed on the Mary Ann. Our Isaac Stokes sailed on the Lady Nugent, arriving in NSW in April 1835, having set sail from England in December 1834.

Lady Nugent was built at Bombay in 1813. She made four voyages under contract to the British East India Company (EIC). She then made two voyages transporting convicts to Australia, one to New South Wales and one to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). (via Wikipedia)

via freesettlerorfelon website:

On 20 November 1834, 100 male convicts were transferred to the Lady Nugent from the Justitia Hulk and 60 from the Ganymede Hulk at Woolwich, all in apparent good health. The Lady Nugent departed Sheerness on 4 December 1834.

SURGEON OLIVER SPROULE

Oliver Sproule kept a Medical Journal from 7 November 1834 to 27 April 1835. He recorded in his journal the weather conditions they experienced in the first two weeks:

‘In the course of the first week or ten days at sea, there were eight or nine on the sick list with catarrhal affections and one with dropsy which I attribute to the cold and wet we experienced during that period beating down channel. Indeed the foremost berths in the prison at this time were so wet from leaking in that part of the ship, that I was obliged to issue dry beds and bedding to a great many of the prisoners to preserve their health, but after crossing the Bay of Biscay the weather became fine and we got the damp beds and blankets dried, the leaks partially stopped and the prison well aired and ventilated which, I am happy to say soon manifested a favourable change in the health and appearance of the men.

Besides the cases given in the journal I had a great many others to treat, some of them similar to those mentioned but the greater part consisted of boils, scalds, and contusions which would not only be too tedious to enter but I fear would be irksome to the reader. There were four births on board during the passage which did well, therefore I did not consider it necessary to give a detailed account of them in my journal the more especially as they were all favourable cases.

Regularity and cleanliness in the prison, free ventilation and as far as possible dry decks turning all the prisoners up in fine weather as we were lucky enough to have two musicians amongst the convicts, dancing was tolerated every afternoon, strict attention to personal cleanliness and also to the cooking of their victuals with regular hours for their meals, were the only prophylactic means used on this occasion, which I found to answer my expectations to the utmost extent in as much as there was not a single case of contagious or infectious nature during the whole passage with the exception of a few cases of psora which soon yielded to the usual treatment. A few cases of scurvy however appeared on board at rather an early period which I can attribute to nothing else but the wet and hardships the prisoners endured during the first three or four weeks of the passage. I was prompt in my treatment of these cases and they got well, but before we arrived at Sydney I had about thirty others to treat.’

The Lady Nugent arrived in Port Jackson on 9 April 1835 with 284 male prisoners. Two men had died at sea. The prisoners were landed on 27th April 1835 and marched to Hyde Park Barracks prior to being assigned. Ten were under the age of 14 years.

The Lady Nugent:

Isaac’s distinguishing marks are noted on various criminal registers and record books:

“Height in feet & inches: 5 4; Complexion: Ruddy; Hair: Light brown; Eyes: Hazel; Marks or Scars: Yes [including] DEVIL on lower left arm, TSIS back of left hand, WS lower right arm, MHDW back of right hand.”

Another includes more detail about Isaac’s tattoos:

“Two slight scars right side of mouth, 2 moles above right breast, figure of the devil and DEVIL and raised mole, lower left arm; anchor, seven dots half moon, TSIS and cross, back of left hand; a mallet, door post, A, mans bust, sun, WS, lower right arm; woman, MHDW and shut knife, back of right hand.”

From How tattoos became fashionable in Victorian England (2019 article in TheConversation by Robert Shoemaker and Zoe Alkar):

“Historical tattooing was not restricted to sailors, soldiers and convicts, but was a growing and accepted phenomenon in Victorian England. Tattoos provide an important window into the lives of those who typically left no written records of their own. As a form of “history from below”, they give us a fleeting but intriguing understanding of the identities and emotions of ordinary people in the past.

As a practice for which typically the only record is the body itself, few systematic records survive before the advent of photography. One exception to this is the written descriptions of tattoos (and even the occasional sketch) that were kept of institutionalised people forced to submit to the recording of information about their bodies as a means of identifying them. This particularly applies to three groups – criminal convicts, soldiers and sailors. Of these, the convict records are the most voluminous and systematic.

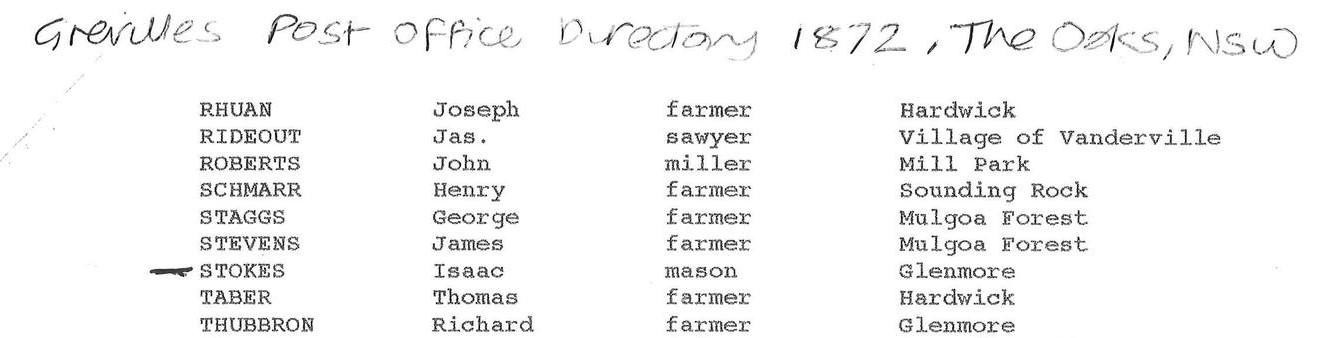

Such records were first kept in large numbers for those who were transported to Australia from 1788 (since Australia was then an open prison) as the authorities needed some means of keeping track of them.”On the 1837 census Isaac was working for the government at Illiwarra, New South Wales. This record states that he arrived on the Lady Nugent in 1835. There are three other indent records for an Isaac Stokes in the following years, but the transcriptions don’t provide enough information to determine which Isaac Stokes it was. In April 1837 there was an abscondment, and an arrest/apprehension in May of that year, and in 1843 there was a record of convict indulgences.

From the Australian government website regarding “convict indulgences”:

“By the mid-1830s only six per cent of convicts were locked up. The vast majority worked for the government or free settlers and, with good behaviour, could earn a ticket of leave, conditional pardon or and even an absolute pardon. While under such orders convicts could earn their own living.”

In 1856 in Camden, NSW, Isaac Stokes married Catherine Daly. With no further information on this record it would be impossible to know for sure if this was the right Isaac Stokes. This couple had six children, all in the Camden area, but none of the records provided enough information. No occupation or place or date of birth recorded for Isaac Stokes.

I wrote to the National Library of Australia about the marriage record, and their reply was a surprise! Issac and Catherine were married on 30 September 1856, at the house of the Rev. Charles William Rigg, a Methodist minister, and it was recorded that Isaac was born in Edinburgh in 1821, to parents James Stokes and Sarah Ellis! The age at the time of the marriage doesn’t match Isaac’s age at death in 1877, and clearly the place of birth and parents didn’t match either. Only his fathers occupation of stone mason was correct. I wrote back to the helpful people at the library and they replied that the register was in a very poor condition and that only two and a half entries had survived at all, and that Isaac and Catherines marriage was recorded over two pages.

I searched for an Isaac Stokes born in 1821 in Edinburgh on the Scotland government website (and on all the other genealogy records sites) and didn’t find it. In fact Stokes was a very uncommon name in Scotland at the time. I also searched Australian immigration and other records for another Isaac Stokes born in Scotland or born in 1821, and found nothing. I was unable to find a single record to corroborate this mysterious other Isaac Stokes.

As the age at death in 1877 was correct, I assume that either Isaac was lying, or that some mistake was made either on the register at the home of the Methodist minster, or a subsequent mistranscription or muddle on the remnants of the surviving register. Therefore I remain convinced that the Camden stonemason Isaac Stokes was indeed our Isaac from Oxfordshire.

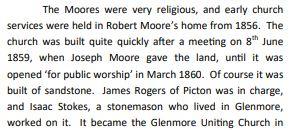

I found a history society newsletter article that mentioned Isaac Stokes, stone mason, had built the Glenmore church, near Camden, in 1859.

From the Wollondilly museum April 2020 newsletter:

From the Camden History website:

“The stone set over the porch of Glenmore Church gives the date of 1860. The church was begun in 1859 on land given by Joseph Moore. James Rogers of Picton was given the contract to build and local builder, Mr. Stokes, carried out the work. Elizabeth Moore, wife of Edward, laid the foundation stone. The first service was held on 19th March 1860. The cemetery alongside the church contains the headstones and memorials of the areas early pioneers.”

Isaac died on the 3rd September 1877. The inquest report puts his place of death as Bagdelly, near to Camden, and another death register has put Cambelltown, also very close to Camden. His age was recorded as 71 and the inquest report states his cause of death was “rupture of one of the large pulmonary vessels of the lung”. His wife Catherine died in childbirth in 1870 at the age of 43.

Isaac and Catherine’s children:

William Stokes 1857-1928

Catherine Stokes 1859-1846

Sarah Josephine Stokes 1861-1931

Ellen Stokes 1863-1932

Rosanna Stokes 1865-1919

Louisa Stokes 1868-1844.

It’s possible that Catherine Daly was a transported convict from Ireland.

Some time later I unexpectedly received a follow up email from The Oaks Heritage Centre in Australia.

“The Gaudry papers which we have in our archive record him (Isaac Stokes) as having built: the church, the school and the teachers residence. Isaac is recorded in the General return of convicts: 1837 and in Grevilles Post Office directory 1872 as a mason in Glenmore.”

November 13, 2022 at 10:29 pm #6345

November 13, 2022 at 10:29 pm #6345In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

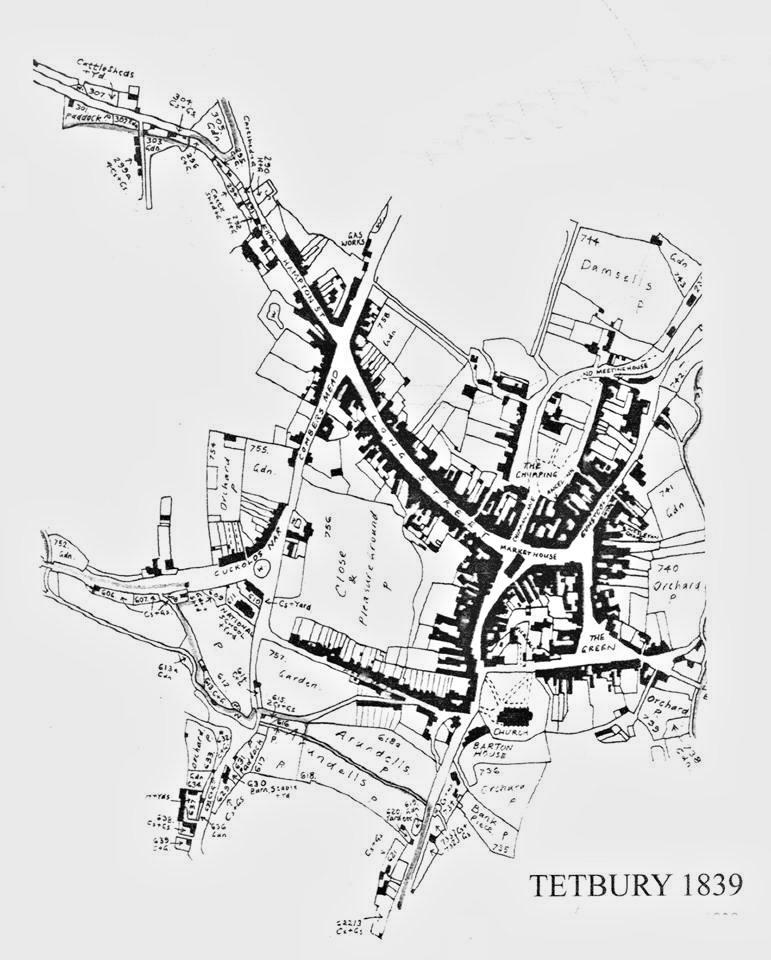

Crime and Punishment in Tetbury

I noticed that there were quite a number of Brownings of Tetbury in the newspaper archives involved in criminal activities while doing a routine newspaper search to supplement the information in the usual ancestry records. I expanded the tree to include cousins, and offsping of cousins, in order to work out who was who and how, if at all, these individuals related to our Browning family.

I was expecting to find some of our Brownings involved in the Swing Riots in Tetbury in 1830, but did not. Most of our Brownings (including cousins) were stone masons. Most of the rioters in 1830 were agricultural labourers.

The Browning crimes are varied, and by todays standards, not for the most part terribly serious ~ you would be unlikely to receive a sentence of hard labour for being found in an outhouse with the intent to commit an unlawful act nowadays, or for being drunk.

The central character in this chapter is Isaac Browning (my 4x great grandfather), who did not appear in any criminal registers, but the following individuals can be identified in the family structure through their relationship to him.

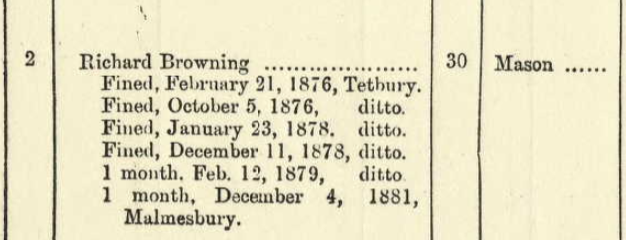

RICHARD LOCK BROWNING born in 1853 was Isaac’s grandson, his son George’s son. Richard was a mason. In 1879 he and Henry Browning of the same age were sentenced to one month hard labour for stealing two pigeons in Tetbury. Henry Browning was Isaac’s nephews son.

In 1883 Richard Browning, mason of Tetbury, was charged with obtaining food and lodging under false pretences, but was found not guilty and acquitted.

In 1884 Richard Browning, mason of Tetbury, was sentenced to one month hard labour for game trespass.Richard had been fined a number of times in Tetbury:

Richard Lock Browning was five feet eight inches tall, dark hair, grey eyes, an oval face and a dark complexion. He had two cuts on the back of his head (in February 1879) and a scar on his right eyebrow.

HENRY BROWNING, who was stealing pigeons with Richard Lock Browning in 1879, (Isaac’s brother Williams grandson, son of George Browning and his wife Charity) was charged with being drunk in 1882 and ordered to pay a fine of one shilling and costs of fourteen shillings, or seven days hard labour.

Henry was found guilty of gaming in the highway at Tetbury in 1872 and was sentenced to seven days hard labour. In 1882 Henry (who was also a mason) was charged with assault but discharged.

Henry was five feet five inches tall, brown hair and brown eyes, a long visage and a fresh complexion.

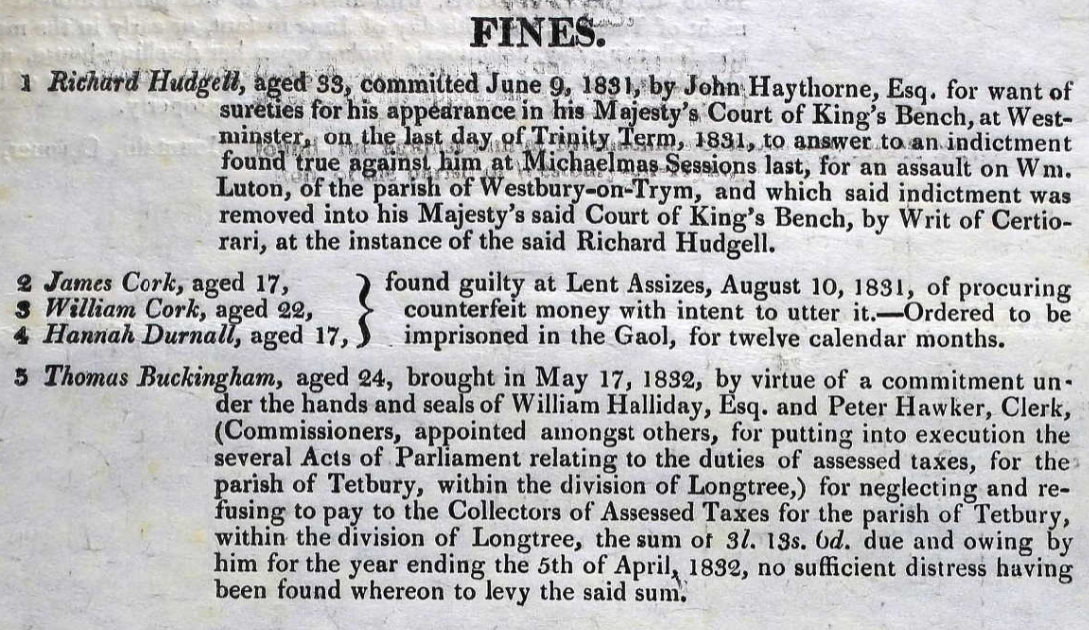

Henry emigrated with his daughter to Canada in 1913, and died in Vancouver in 1919.THOMAS BUCKINGHAM 1808-1846 (Isaacs daughter Janes husband) was charged with stealing a black gelding in Tetbury in 1838. No true bill. (A “no true bill” means the jury did not find probable cause to continue a case.)

Thomas did however neglect to pay his taxes in 1832:

LEWIN BUCKINGHAM (grandson of Isaac, his daughter Jane’s son) was found guilty in 1846 stealing two fowls in Tetbury when he was sixteen years old.

In 1846 he was sentence to one month hard labour (or pay ten shillings fine and ten shillings costs) for loitering with the intent to trespass in search of conies.

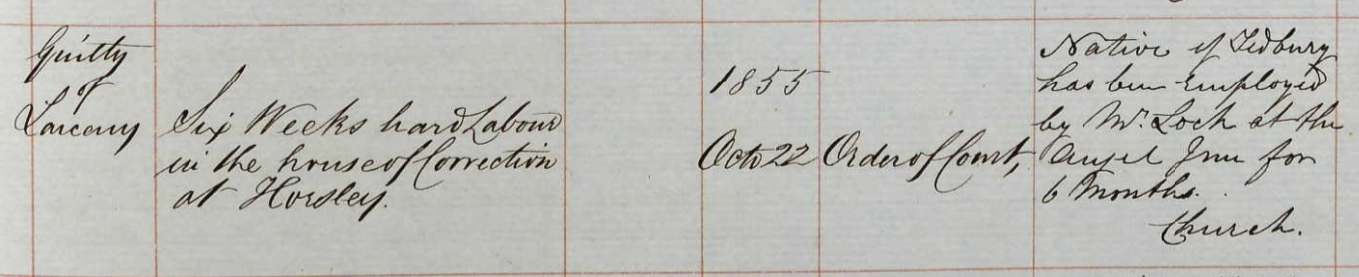

A year later in 1847, he and three other young men were sentenced to four months hard labour for larceny.

Lewin was five feet three inches tall, with brown hair and brown eyes, long visage, sallow complexion, and had a scar on his left arm.JOHN BUCKINGHAM born circa 1832, a Tetbury labourer (Isaac’s grandson, Lewin’s brother) was sentenced to six weeks hard labour for larceny in 1855 for stealing a duck in Cirencester. The notes on the register mention that he had been employed by Mr LOCK, Angel Inn. (John’s grandmother was Mary Lock so this is likely a relative).

The previous year in 1854 John was sentenced to one month or a one pound fine for assaulting and beating W. Wood.

John was five feet eight and three quarter inches tall, light brown hair and grey eyes, an oval visage and a fresh complexion. He had a scar on his left arm and inside his right knee.JOSEPH PERRET was born circa 1831 and he was a Tetbury labourer. (He was Isaac’s granddaughter Charlotte Buckingham’s husband)

In 1855 he assaulted William Wood and was sentenced to one month or a two pound ten shilling fine. Was it the same W Wood that his wifes cousin John assaulted the year before?

In 1869 Joseph was sentenced to one month hard labour for feloniously receiving a cupboard known to be stolen.JAMES BUCKINGAM born circa 1822 in Tetbury was a shoemaker. (Isaac’s nephew, his sister Hannah’s son)

In 1854 the Tetbury shoemaker was sentenced to four months hard labour for stealing 30 lbs of lead off someones house.

In 1856 the Tetbury shoemaker received two months hard labour or pay £2 fine and 12 s costs for being found in pursuit of game.

In 1868 he was sentenced to two months hard labour for stealing a gander. A unspecified previous conviction is noted.

1871 the Tetbury shoemaker was found in an outhouse for an unlawful purpose and received ten days hard labour. The register notes that his sister is Mrs Cook, the Green, Tetbury. (James sister Prudence married Thomas Cook)

James sister Charlotte married a shoemaker and moved to UTAH.

James was five feet eight inches tall, dark hair and blue eyes, a long visage and a florid complexion. He had a scar on his forehead and a mole on the right side of his neck and abdomen, and a scar on the right knee.November 10, 2022 at 12:08 pm #6344In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The Tetbury Riots

While researching the Tetbury riots (I had found some Browning names in the newspaper archives in association with the uprisings) I came across an article called “Elizabeth Parker, the Swing Riots, and the Tetbury parish clerk” by Jill Evans.

I noted the name of the parish clerk, Daniel Cole, because I know someone else of that name. The incident in the article was 1830.

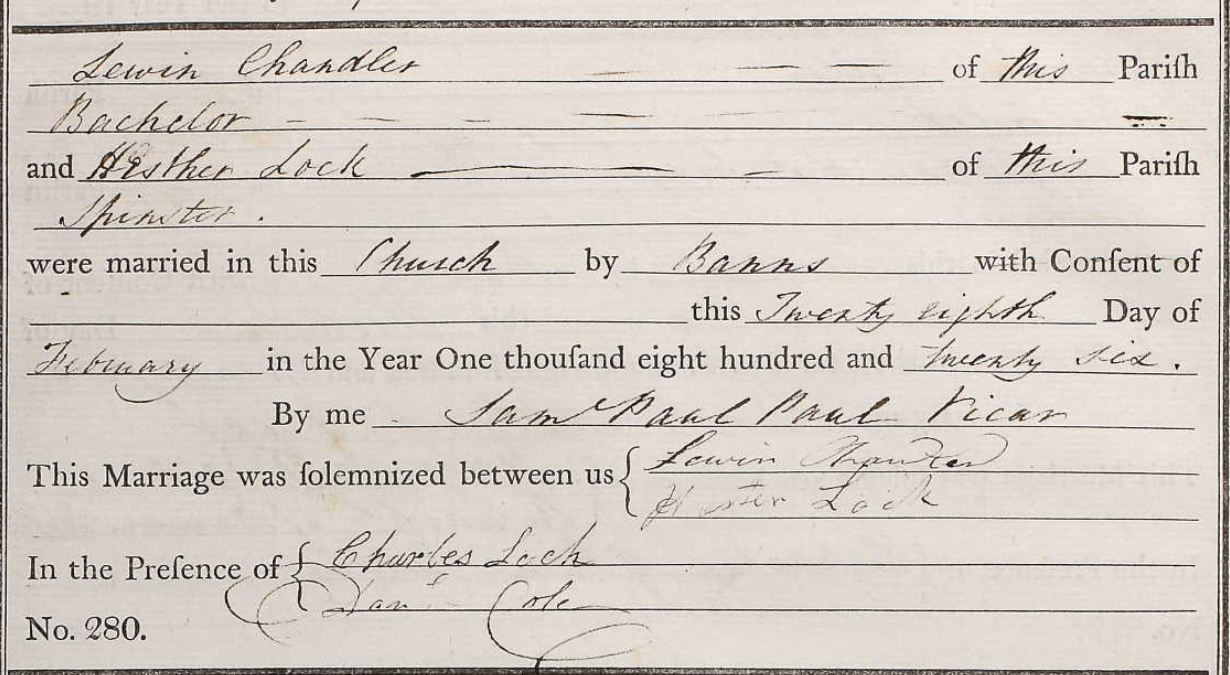

I found the 1826 marriage in the Tetbury parish registers (where Daniel was the parish clerk) of my 4x great grandmothers sister Hesther Lock. One of the witnesses was her brother Charles, and the other was Daniel Cole, the parish clerk.

Marriage of Lewin Chandler and Hesther Lock in 1826:

from the article:

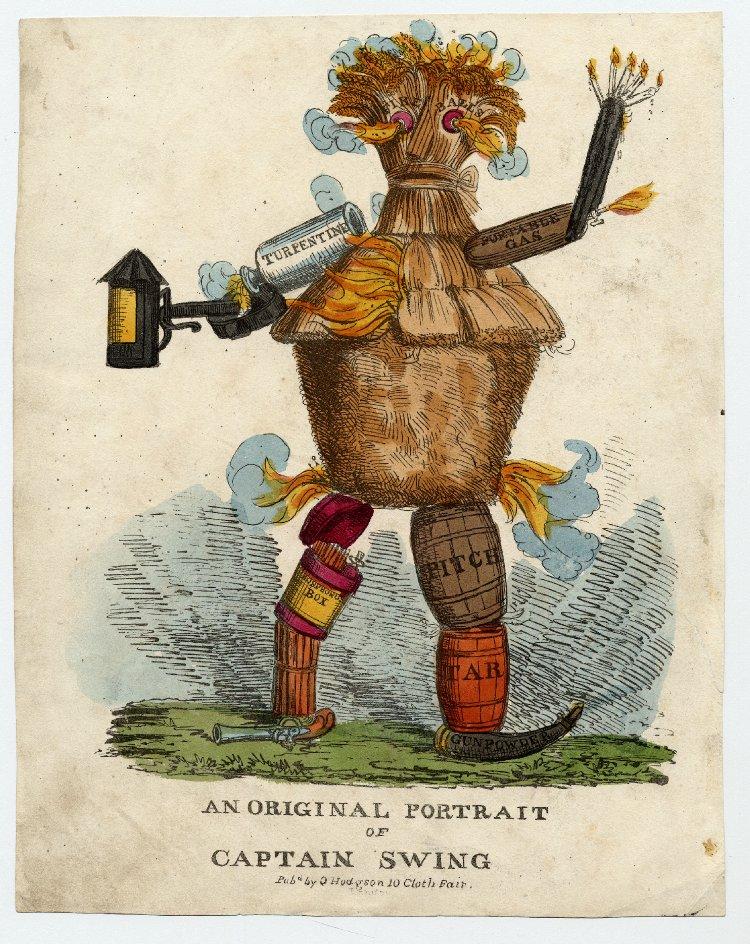

“The Swing Riots were disturbances which took place in 1830 and 1831, mostly in the southern counties of England. Agricultural labourers, who were already suffering due to low wages and a lack of work after several years of bad harvests, rose up when their employers introduced threshing machines into their workplaces. The riots got their name from the threatening letters which were sent to farmers and other employers, which were signed “Captain Swing.”

The riots spread into Gloucestershire in November 1830, with the Tetbury area seeing the worst of the disturbances. Amongst the many people arrested afterwards was one woman, Elizabeth Parker. She has sometimes been cited as one of only two females who were transported for taking part in the Swing Riots. In fact, she was sentenced to be transported for this crime, but never sailed, as she was pardoned a few months after being convicted. However, less than a year after being released from Gloucester Gaol, she was back, awaiting trial for another offence. The circumstances in both of the cases she was tried for reveal an intriguing relationship with one Daniel Cole, parish clerk and assistant poor law officer in Tetbury….

….Elizabeth Parker was committed to Gloucester Gaol on 4 December 1830. In the Gaol Registers, she was described as being 23 and a “labourer”. She was in fact a prostitute, and she was unusual for the time in that she could read and write. She was charged on the oaths of Daniel Cole and others with having been among a mob which destroyed a threshing machine belonging to Jacob Hayward, at his farm in Beverstone, on 26 November.

…..Elizabeth Parker was granted royal clemency in July 1831 and was released from prison. She returned to Tetbury and presumably continued in her usual occupation, but on 27 March 1832, she was committed to Gloucester Gaol again. This time, she was charged with stealing 2 five pound notes, 5 sovereigns and 5 half sovereigns, from the person of Daniel Cole.

Elizabeth was tried at the Lent Assizes which began on 28 March, 1832. The details of her trial were reported in the Morning Post. Daniel Cole was in the “Boat Inn” (meaning the Boot Inn, I think) in Tetbury, when Elizabeth Parker came in. Cole “accompanied her down the yard”, where he stayed with her for about half an hour. The next morning, he realised that all his money was gone. One of his five pound notes was identified by him in a shop, where Parker had bought some items.

Under cross-examination, Cole said he was the assistant overseer of the poor and collector of public taxes of the parish of Tetbury. He was married with one child. He went in to the inn at about 9 pm, and stayed about 2 hours, drinking in the parlour, with the landlord, Elizabeth Parker, and two others. He was not drunk, but he was “rather fresh.” He gave the prisoner no money. He saw Elizabeth Parker next morning at the Prince and Princess public house. He didn’t drink with her or give her any money. He did give her a shilling after she was committed. He never said that he would not have prosecuted her “if it was not for her own tongue”. (Presumably meaning he couldn’t trust her to keep her mouth shut.)”

Contemporary illustration of the Swing riots:

Captain Swing was the imaginary leader agricultural labourers who set fire to barns and haystacks in the southern and eastern counties of England from 1830. Although the riots were ruthlessly put down (19 hanged, 644 imprisoned and 481 transported), the rural agitation led the new Whig government to establish a Royal Commission on the Poor Laws and its report provided the basis for the 1834 New Poor Law enacted after the Great Reform Bills of 1833.

An original portrait of Captain Swing hand coloured lithograph circa 1830:

November 4, 2022 at 2:19 pm #6342

November 4, 2022 at 2:19 pm #6342In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Brownings of Tetbury

Isaac Browning (1784-1848) married Mary Lock (1787-1870) in Tetbury in 1806. Both of them were born in Tetbury, Gloucestershire. Isaac was a stone mason. Between 1807 and 1832 they baptised fourteen children in Tetbury, and on 8 Nov 1829 Isaac and Mary baptised five daughters all on the same day.

I considered that they may have been quintuplets, with only the last born surviving, which would have answered my question about the name of the house La Quinta in Broadway, the home of Eliza Browning and Thomas Stokes son Fred. However, the other four daughters were found in various records and they were not all born the same year. (So I still don’t know why the house in Broadway had such an unusual name).

Their son George was born and baptised in 1827, but Louisa born 1821, Susan born 1822, Hesther born 1823 and Mary born 1826, were not baptised until 1829 along with Charlotte born in 1828. (These birth dates are guesswork based on the age on later censuses.) Perhaps George was baptised promptly because he was sickly and not expected to survive. Isaac and Mary had a son George born in 1814 who died in 1823. Presumably the five girls were healthy and could wait to be done as a job lot on the same day later.

Eliza Browning (1814-1886), my great great great grandmother, had a baby six years before she married Thomas Stokes. Her name was Ellen Harding Browning, which suggests that her fathers name was Harding. On the 1841 census seven year old Ellen was living with her grandfather Isaac Browning in Tetbury. Ellen Harding Browning married William Dee in Tetbury in 1857, and they moved to Western Australia.

Ellen Harding Browning Dee: (photo found on ancestry website)

OBITUARY. MRS. ELLEN DEE.

A very old and respected resident of Dongarra, in the person of Mrs. Ellen Dee, passed peacefully away on Sept. 27, at the advanced age of 74 years.The deceased had been ailing for some time, but was about and actively employed until Wednesday, Sept. 20, whenn she was heard groaning by some neighbours, who immediately entered her place and found her lying beside the fireplace. Tho deceased had been to bed over night, and had evidently been in the act of lighting thc fire, when she had a seizure. For some hours she was conscious, but had lost the power of speech, and later on became unconscious, in which state she remained until her death.

The deceased was born in Gloucestershire, England, in 1833, was married to William Dee in Tetbury Church 23 years later. Within a month she left England with her husband for Western Australian in the ship City oí Bristol. She resided in Fremantle for six months, then in Greenough for a short time, and afterwards (for 42 years) in Dongarra. She was, therefore, a colonist of about 51 years. She had a family of four girls and three boys, and five of her children survive her, also 35 grandchildren, and eight great grandchildren. She was very highly respected, and her sudden collapse came as a great shock to many.

Eliza married Thomas Stokes (1816-1885) in September 1840 in Hempstead, Gloucestershire. On the 1841 census, Eliza and her mother Mary Browning (nee Lock) were staying with Thomas Lock and family in Cirencester. Strangely, Thomas Stokes has not been found thus far on the 1841 census, and Thomas and Eliza’s first child William James Stokes birth was registered in Witham, in Essex, on the 6th of September 1841.

I don’t know why William James was born in Witham, or where Thomas was at the time of the census in 1841. One possibility is that as Thomas Stokes did a considerable amount of work with circus waggons, circus shooting galleries and so on as a journeyman carpenter initially and then later wheelwright, perhaps he was working with a traveling circus at the time.

But back to the Brownings ~ more on William James Stokes to follow.

One of Isaac and Mary’s fourteen children died in infancy: Ann was baptised and died in 1811. Two of their children died at nine years old: the first George, and Mary who died in 1835. Matilda was 21 years old when she died in 1844.

Jane Browning (1808-) married Thomas Buckingham in 1830 in Tetbury. In August 1838 Thomas was charged with feloniously stealing a black gelding.

Susan Browning (1822-1879) married William Cleaver in November 1844 in Tetbury. Oddly thereafter they use the name Bowman on the census. On the 1851 census Mary Browning (Susan’s mother), widow, has grandson George Bowman born in 1844 living with her. The confusion with the Bowman and Cleaver names was clarified upon finding the criminal registers:

30 January 1834. Offender: William Cleaver alias Bowman, Richard Bunting alias Barnfield and Jeremiah Cox, labourers of Tetbury. Crime: Stealing part of a dead fence from a rick barton in Tetbury, the property of Robert Tanner, farmer.

And again in 1836:

29 March 1836 Bowman, William alias Cleaver, of Tetbury, labourer age 18; 5’2.5” tall, brown hair, grey eyes, round visage with fresh complexion; several moles on left cheek, mole on right breast. Charged on the oath of Ann Washbourn & others that on the morning of the 31 March at Tetbury feloniously stolen a lead spout affixed to the dwelling of the said Ann Washbourn, her property. Found guilty 31 March 1836; Sentenced to 6 months.

On the 1851 census Susan Bowman was a servant living in at a large drapery shop in Cheltenham. She was listed as 29 years old, married and born in Tetbury, so although it was unusual for a married woman not to be living with her husband, (or her son for that matter, who was living with his grandmother Mary Browning), perhaps her husband William Bowman alias Cleaver was in trouble again. By 1861 they are both living together in Tetbury: William was a plasterer, and they had three year old Isaac and Thomas, one year old. In 1871 William was still a plasterer in Tetbury, living with wife Susan, and sons Isaac and Thomas. Interestingly, a William Cleaver is living next door but one!

Susan was 56 when she died in Tetbury in 1879.

Three of the Browning daughters went to London.

Louisa Browning (1821-1873) married Robert Claxton, coachman, in 1848 in Bryanston Square, Westminster, London. Ester Browning was a witness.

Ester Browning (1823-1893)(or Hester) married Charles Hudson Sealey, cabinet maker, in Bethnal Green, London, in 1854. Charles was born in Tetbury. Charlotte Browning was a witness.

Charlotte Browning (1828-1867?) was admitted to St Marylebone workhouse in London for “parturition”, or childbirth, in 1860. She was 33 years old. A birth was registered for a Charlotte Browning, no mothers maiden name listed, in 1860 in Marylebone. A death was registered in Camden, buried in Marylebone, for a Charlotte Browning in 1867 but no age was recorded. As the age and parents were usually recorded for a childs death, I assume this was Charlotte the mother.

I found Charlotte on the 1851 census by chance while researching her mother Mary Lock’s siblings. Hesther Lock married Lewin Chandler, and they were living in Stepney, London. Charlotte is listed as a neice. Although Browning is mistranscribed as Broomey, the original page says Browning. Another mistranscription on this record is Hesthers birthplace which is transcribed as Yorkshire. The original image shows Gloucestershire.

Isaac and Mary’s first son was John Browning (1807-1860). John married Hannah Coates in 1834. John’s brother Charles Browning (1819-1853) married Eliza Coates in 1842. Perhaps they were sisters. On the 1861 census Hannah Browning, John’s wife, was a visitor in the Harding household in a village called Coates near Tetbury. Thomas Harding born in 1801 was the head of the household. Perhaps he was the father of Ellen Harding Browning.

George Browning (1828-1870) married Louisa Gainey in Tetbury, and died in Tetbury at the age of 42. Their son Richard Lock Browning, a 32 year old mason, was sentenced to one month hard labour for game tresspass in Tetbury in 1884.

Isaac Browning (1832-1857) was the youngest son of Isaac and Mary. He was just 25 years old when he died in Tetbury.

October 11, 2022 at 2:58 pm #6334In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The House on Penn Common

Toi Fang and the Duke of Sutherland

Tomlinsons

Grassholme

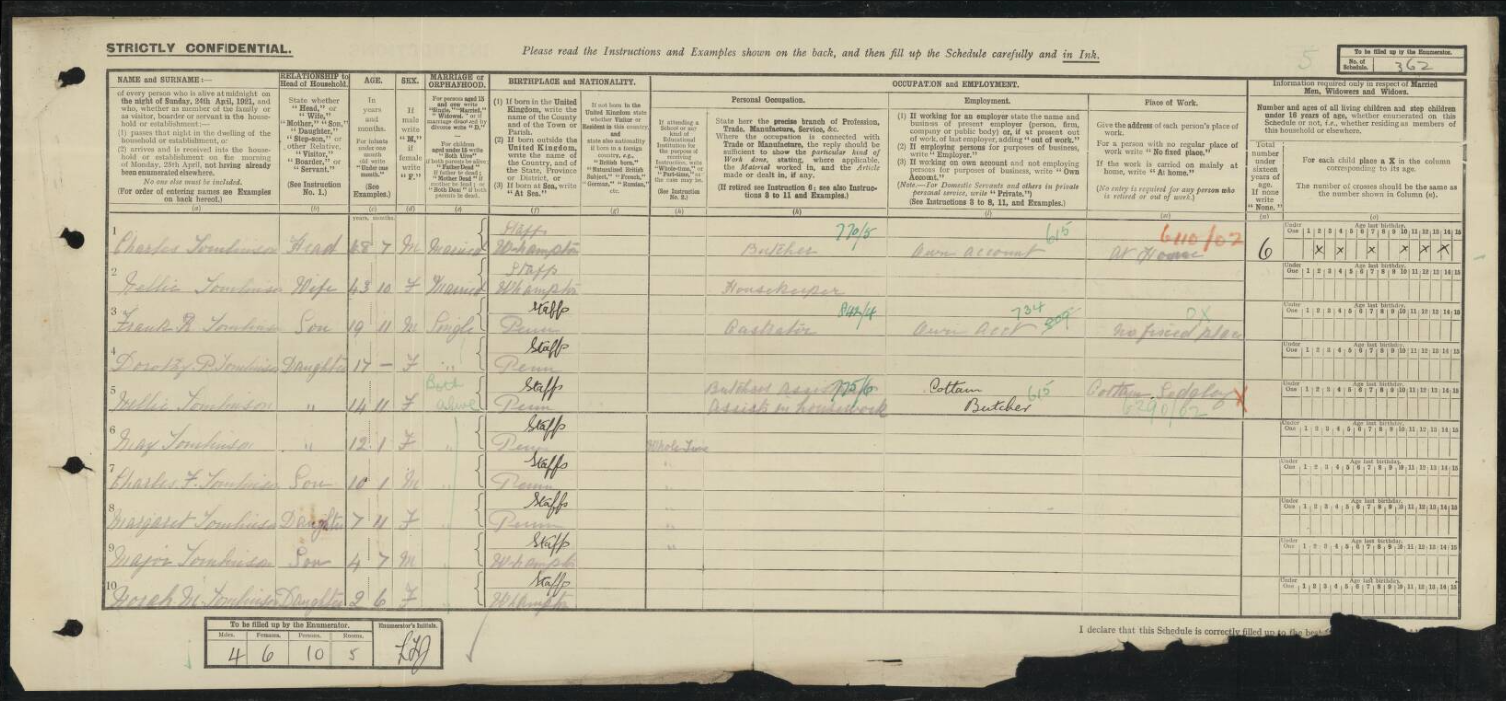

Charles Tomlinson (1873-1929) my great grandfather, was born in Wolverhampton in 1873. His father Charles Tomlinson (1847-1907) was a licensed victualler or publican, or alternatively a vet/castrator. He married Emma Grattidge (1853-1911) in 1872. On the 1881 census they were living at The Wheel in Wolverhampton.

Charles married Nellie Fisher (1877-1956) in Wolverhampton in 1896. In 1901 they were living next to the post office in Upper Penn, with children (Charles) Sidney Tomlinson (1896-1955), and Hilda Tomlinson (1898-1977) . Charles was a vet/castrator working on his own account.

In 1911 their address was 4, Wakely Hill, Penn, and living with them were their children Hilda, Frank Tomlinson (1901-1975), (Dorothy) Phyllis Tomlinson (1905-1982), Nellie Tomlinson (1906-1978) and May Tomlinson (1910-1983). Charles was a castrator working on his own account.

Charles and Nellie had a further four children: Charles Fisher Tomlinson (1911-1977), Margaret Tomlinson (1913-1989) (my grandmother Peggy), Major Tomlinson (1916-1984) and Norah Mary Tomlinson (1919-2010).

My father told me that my grandmother had fallen down the well at the house on Penn Common in 1915 when she was two years old, and sent me a photo of her standing next to the well when she revisted the house at a much later date.

Peggy next to the well on Penn Common:

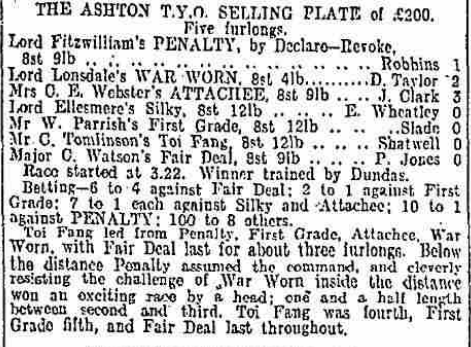

My grandmother Peggy told me that her father had had a racehorse called Toi Fang. She remembered the racing colours were sky blue and orange, and had a set of racing silks made which she sent to my father.

Through a DNA match, I met Ian Tomlinson. Ian is the son of my fathers favourite cousin Roger, Frank’s son. Ian found some racing silks and sent a photo to my father (they are now in contact with each other as a result of my DNA match with Ian), wondering what they were.

When Ian sent a photo of these racing silks, I had a look in the newspaper archives. In 1920 there are a number of mentions in the racing news of Mr C Tomlinson’s horse TOI FANG. I have not found any mention of Toi Fang in the newspapers in the following years.

The Scotsman – Monday 12 July 1920:

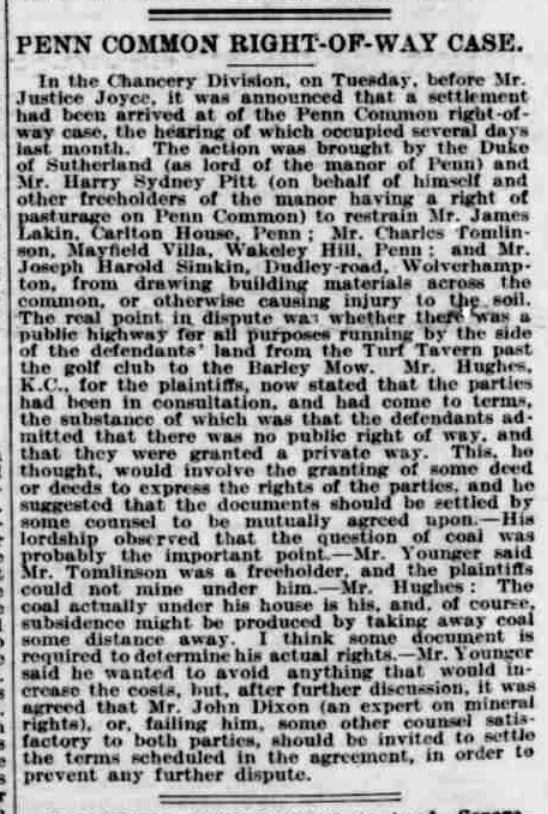

The other story that Ian Tomlinson recalled was about the house on Penn Common. Ian said he’d heard that the local titled person took Charles Tomlinson to court over building the house but that Tomlinson won the case because it was built on common land and was the first case of it’s kind.

Penn Common Right of Way Case:

Staffordshire Advertiser March 9, 1912In the chancery division, on Tuesday, before Mr Justice Joyce, it was announced that a settlement had been arrived at of the Penn Common Right of Way case, the hearing of which occupied several days last month. The action was brought by the Duke of Sutherland (as Lord of the Manor of Penn) and Mr Harry Sydney Pitt (on behalf of himself and other freeholders of the manor having a right to pasturage on Penn Common) to restrain Mr James Lakin, Carlton House, Penn; Mr Charles Tomlinson, Mayfield Villa, Wakely Hill, Penn; and Mr Joseph Harold Simpkin, Dudley Road, Wolverhampton, from drawing building materials across the common, or otherwise causing injury to the soil.

The real point in dispute was whether there was a public highway for all purposes running by the side of the defendants land from the Turf Tavern past the golf club to the Barley Mow.

Mr Hughes, KC for the plaintiffs, now stated that the parties had been in consultation, and had come to terms, the substance of which was that the defendants admitted that there was no public right of way, and that they were granted a private way. This, he thought, would involve the granting of some deed or deeds to express the rights of the parties, and he suggested that the documents should be be settled by some counsel to be mutually agreed upon.His lordship observed that the question of coal was probably the important point. Mr Younger said Mr Tomlinson was a freeholder, and the plaintiffs could not mine under him. Mr Hughes: The coal actually under his house is his, and, of course, subsidence might be produced by taking away coal some distance away. I think some document is required to determine his actual rights.

Mr Younger said he wanted to avoid anything that would increase the costs, but, after further discussion, it was agreed that Mr John Dixon (an expert on mineral rights), or failing him, another counsel satisfactory to both parties, should be invited to settle the terms scheduled in the agreement, in order to prevent any further dispute.

The name of the house is Grassholme. The address of Mayfield Villas is the house they were living in while building Grassholme, which I assume they had not yet moved in to at the time of the newspaper article in March 1912.

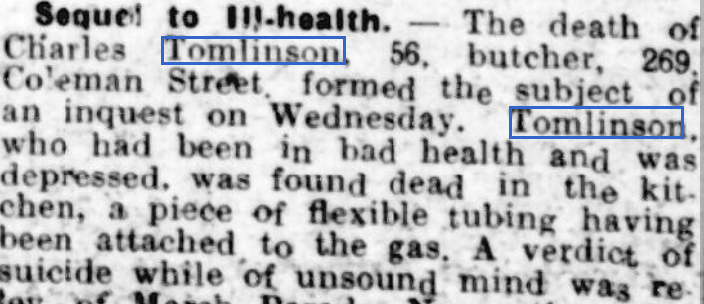

What my grandmother didn’t tell anyone was how her father died in 1929:

On the 1921 census, Charles, Nellie and eight of their children were living at 269 Coleman Street, Wolverhampton.

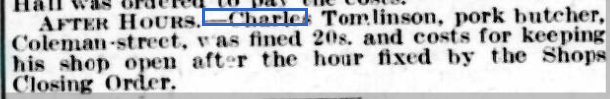

They were living on Coleman Street in 1915 when Charles was fined for staying open late.

Staffordshire Advertiser – Saturday 13 February 1915:

What is not yet clear is why they moved from the house on Penn Common sometime between 1912 and 1915. And why did he have a racehorse in 1920?

October 11, 2022 at 11:39 am #6333In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The Grattidge Family

The first Grattidge to appear in our tree was Emma Grattidge (1853-1911) who married Charles Tomlinson (1847-1907) in 1872.

Charles Tomlinson (1873-1929) was their son and he married my great grandmother Nellie Fisher. Their daughter Margaret (later Peggy Edwards) was my grandmother on my fathers side.

Emma Grattidge was born in Wolverhampton, the daughter and youngest child of William Grattidge (1820-1887) born in Foston, Derbyshire, and Mary Stubbs, born in Burton on Trent, daughter of Solomon Stubbs, a land carrier. William and Mary married at St Modwens church, Burton on Trent, in 1839. It’s unclear why they moved to Wolverhampton. On the 1841 census William was employed as an agent, and their first son William was nine months old. Thereafter, William was a licensed victuallar or innkeeper.

William Grattidge was born in Foston, Derbyshire in 1820. His parents were Thomas Grattidge, farmer (1779-1843) and Ann Gerrard (1789-1822) from Ellastone. Thomas and Ann married in 1813 in Ellastone. They had five children before Ann died at the age of 25:

Bessy was born in 1815, Thomas in 1818, William in 1820, and Daniel Augustus and Frederick were twins born in 1822. They were all born in Foston. (records say Foston, Foston and Scropton, or Scropton)

On the 1841 census Thomas had nine people additional to family living at the farm in Foston, presumably agricultural labourers and help.

After Ann died, Thomas had three children with Kezia Gibbs (30 years his junior) before marrying her in 1836, then had a further four with her before dying in 1843. Then Kezia married Thomas’s nephew Frederick Augustus Grattidge (born in 1816 in Stafford) in London in 1847 and had two more!

The siblings of William Grattidge (my 3x great grandfather):

Frederick Grattidge (1822-1872) was a schoolmaster and never married. He died at the age of 49 in Tamworth at his twin brother Daniels address.

Daniel Augustus Grattidge (1822-1903) was a grocer at Gungate in Tamworth.

Thomas Grattidge (1818-1871) married in Derby, and then emigrated to Illinois, USA.

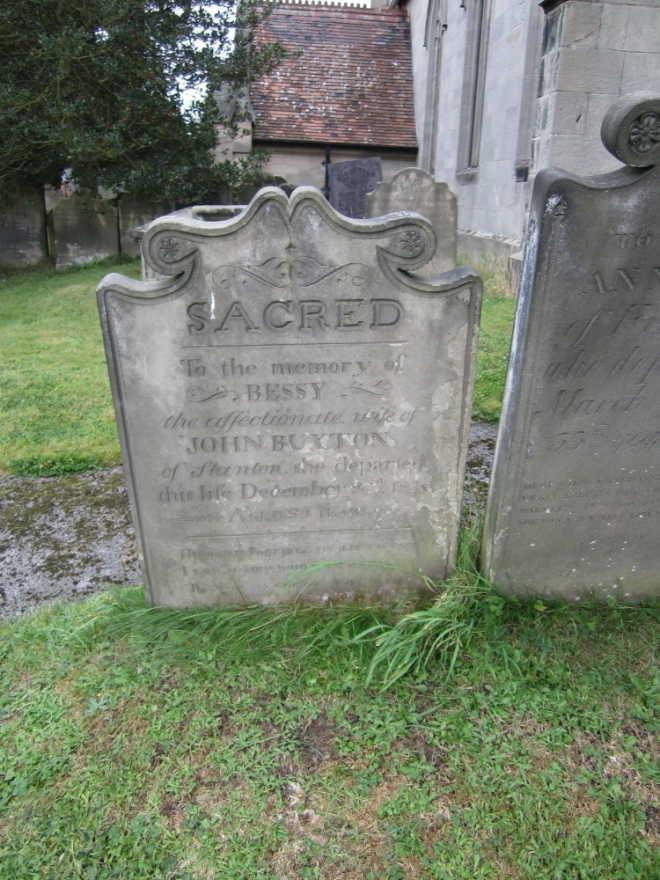

Bessy Grattidge (1815-1840) married John Buxton, farmer, in Ellastone in January 1838. They had three children before Bessy died in December 1840 at the age of 25: Henry in 1838, John in 1839, and Bessy Buxton in 1840. Bessy was baptised in January 1841. Presumably the birth of Bessy caused the death of Bessy the mother.

Bessy Buxton’s gravestone:

“Sacred to the memory of Bessy Buxton, the affectionate wife of John Buxton of Stanton She departed this life December 20th 1840, aged 25 years. “Husband, Farewell my life is Past, I loved you while life did last. Think on my children for my sake, And ever of them with I take.”

20 Dec 1840, Ellastone, Staffordshire

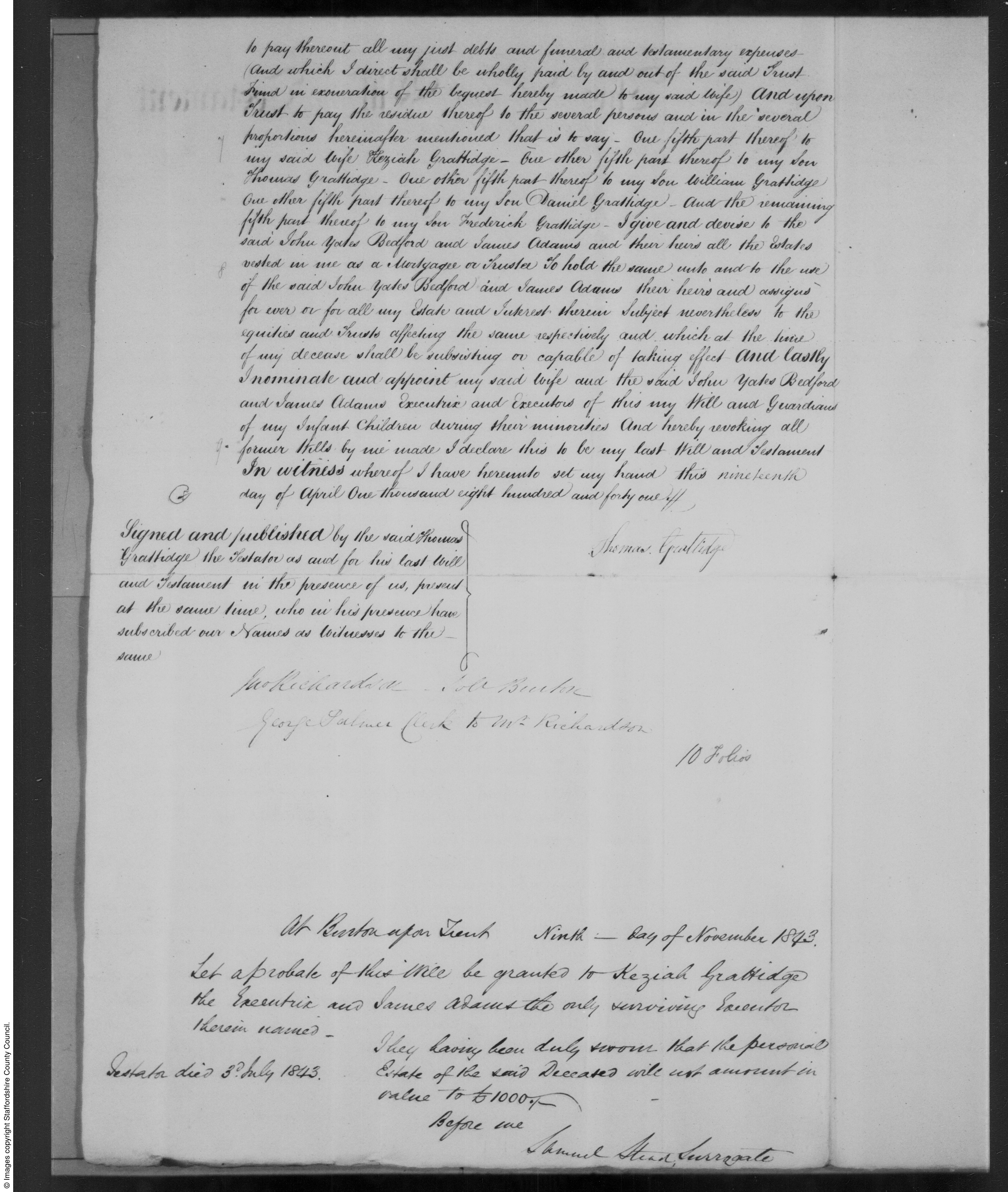

In the 1843 will of Thomas Grattidge, farmer of Foston, he leaves fifth shares of his estate, including freehold real estate at Findern, to his wife Kezia, and sons William, Daniel, Frederick and Thomas. He mentions that the children of his late daughter Bessy, wife of John Buxton, will be taken care of by their father. He leaves the farm to Keziah in confidence that she will maintain, support and educate his children with her.

An excerpt from the will:

I give and bequeath unto my dear wife Keziah Grattidge all my household goods and furniture, wearing apparel and plate and plated articles, linen, books, china, glass, and other household effects whatsoever, and also all my implements of husbandry, horses, cattle, hay, corn, crops and live and dead stock whatsoever, and also all the ready money that may be about my person or in my dwelling house at the time of my decease, …I also give my said wife the tenant right and possession of the farm in my occupation….

A page from the 1843 will of Thomas Grattidge:

William Grattidges half siblings (the offspring of Thomas Grattidge and Kezia Gibbs):

Albert Grattidge (1842-1914) was a railway engine driver in Derby. In 1884 he was driving the train when an unfortunate accident occured outside Ambergate. Three children were blackberrying and crossed the rails in front of the train, and one little girl died.

Albert Grattidge:

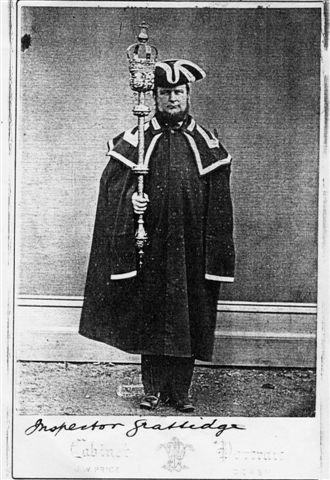

George Grattidge (1826-1876) was baptised Gibbs as this was before Thomas married Kezia. He was a police inspector in Derby.

George Grattidge:

Edwin Grattidge (1837-1852) died at just 15 years old.

Ann Grattidge (1835-) married Charles Fletcher, stone mason, and lived in Derby.

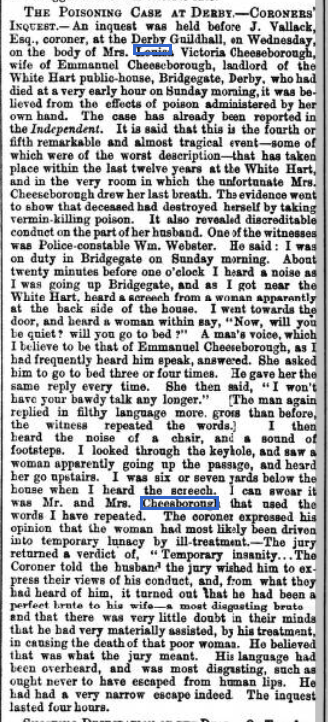

Louisa Victoria Grattidge (1840-1869) was sadly another Grattidge woman who died young. Louisa married Emmanuel Brunt Cheesborough in 1860 in Derby. In 1861 Louisa and Emmanuel were living with her mother Kezia in Derby, with their two children Frederick and Ann Louisa. Emmanuel’s occupation was sawyer. (Kezia Gibbs second husband Frederick Augustus Grattidge was a timber merchant in Derby)

At the time of her death in 1869, Emmanuel was the landlord of the White Hart public house at Bridgegate in Derby.

The Derby Mercury of 17th November 1869:

“On Wednesday morning Mr Coroner Vallack held an inquest in the Grand

Jury-room, Town-hall, on the body of Louisa Victoria Cheeseborough, aged

33, the wife of the landlord of the White Hart, Bridge-gate, who committed

suicide by poisoning at an early hour on Sunday morning. The following

evidence was taken:Mr Frederick Borough, surgeon, practising in Derby, deposed that he was

called in to see the deceased about four o’clock on Sunday morning last. He

accordingly examined the deceased and found the body quite warm, but dead.

He afterwards made enquiries of the husband, who said that he was afraid

that his wife had taken poison, also giving him at the same time the

remains of some blue material in a cup. The aunt of the deceased’s husband

told him that she had seen Mrs Cheeseborough put down a cup in the

club-room, as though she had just taken it from her mouth. The witness took

the liquid home with him, and informed them that an inquest would

necessarily have to be held on Monday. He had made a post mortem

examination of the body, and found that in the stomach there was a great

deal of congestion. There were remains of food in the stomach and, having

put the contents into a bottle, he took the stomach away. He also examined

the heart and found it very pale and flabby. All the other organs were

comparatively healthy; the liver was friable.Hannah Stone, aunt of the deceased’s husband, said she acted as a servant

in the house. On Saturday evening, while they were going to bed and whilst

witness was undressing, the deceased came into the room, went up to the

bedside, awoke her daughter, and whispered to her. but what she said the

witness did not know. The child jumped out of bed, but the deceased closed

the door and went away. The child followed her mother, and she also

followed them to the deceased’s bed-room, but the door being closed, they

then went to the club-room door and opening it they saw the deceased

standing with a candle in one hand. The daughter stayed with her in the

room whilst the witness went downstairs to fetch a candle for herself, and

as she was returning up again she saw the deceased put a teacup on the

table. The little girl began to scream, saying “Oh aunt, my mother is

going, but don’t let her go”. The deceased then walked into her bed-room,

and they went and stood at the door whilst the deceased undressed herself.

The daughter and the witness then returned to their bed-room. Presently

they went to see if the deceased was in bed, but she was sitting on the

floor her arms on the bedside. Her husband was sitting in a chair fast

asleep. The witness pulled her on the bed as well as she could.

Ann Louisa Cheesborough, a little girl, said that the deceased was her

mother. On Saturday evening last, about twenty minutes before eleven

o’clock, she went to bed, leaving her mother and aunt downstairs. Her aunt

came to bed as usual. By and bye, her mother came into her room – before

the aunt had retired to rest – and awoke her. She told the witness, in a

low voice, ‘that she should have all that she had got, adding that she

should also leave her her watch, as she was going to die’. She did not tell

her aunt what her mother had said, but followed her directly into the

club-room, where she saw her drink something from a cup, which she

afterwards placed on the table. Her mother then went into her own room and

shut the door. She screamed and called her father, who was downstairs. He

came up and went into her room. The witness then went to bed and fell

asleep. She did not hear any noise or quarrelling in the house after going

to bed.Police-constable Webster was on duty in Bridge-gate on Saturday evening

last, about twenty minutes to one o’clock. He knew the White Hart

public-house in Bridge-gate, and as he was approaching that place, he heard

a woman scream as though at the back side of the house. The witness went to

the door and heard the deceased keep saying ‘Will you be quiet and go to

bed’. The reply was most disgusting, and the language which the

police-constable said was uttered by the husband of the deceased, was

immoral in the extreme. He heard the poor woman keep pressing her husband

to go to bed quietly, and eventually he saw him through the keyhole of the

door pass and go upstairs. his wife having gone up a minute or so before.

Inspector Fearn deposed that on Sunday morning last, after he had heard of

the deceased’s death from supposed poisoning, he went to Cheeseborough’s

public house, and found in the club-room two nearly empty packets of

Battie’s Lincoln Vermin Killer – each labelled poison.Several of the Jury here intimated that they had seen some marks on the

deceased’s neck, as of blows, and expressing a desire that the surgeon

should return, and re-examine the body. This was accordingly done, after

which the following evidence was taken:Mr Borough said that he had examined the body of the deceased and observed

a mark on the left side of the neck, which he considered had come on since

death. He thought it was the commencement of decomposition.

This was the evidence, after which the jury returned a verdict “that the

deceased took poison whilst of unsound mind” and requested the Coroner to

censure the deceased’s husband.The Coroner told Cheeseborough that he was a disgusting brute and that the

jury only regretted that the law could not reach his brutal conduct.

However he had had a narrow escape. It was their belief that his poor

wife, who was driven to her own destruction by his brutal treatment, would

have been a living woman that day except for his cowardly conduct towards

her.The inquiry, which had lasted a considerable time, then closed.”

In this article it says:

“it was the “fourth or fifth remarkable and tragical event – some of which were of the worst description – that has taken place within the last twelve years at the White Hart and in the very room in which the unfortunate Louisa Cheesborough drew her last breath.”

Sheffield Independent – Friday 12 November 1869:

August 18, 2022 at 8:26 am #6324

August 18, 2022 at 8:26 am #6324In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

STONE MANOR

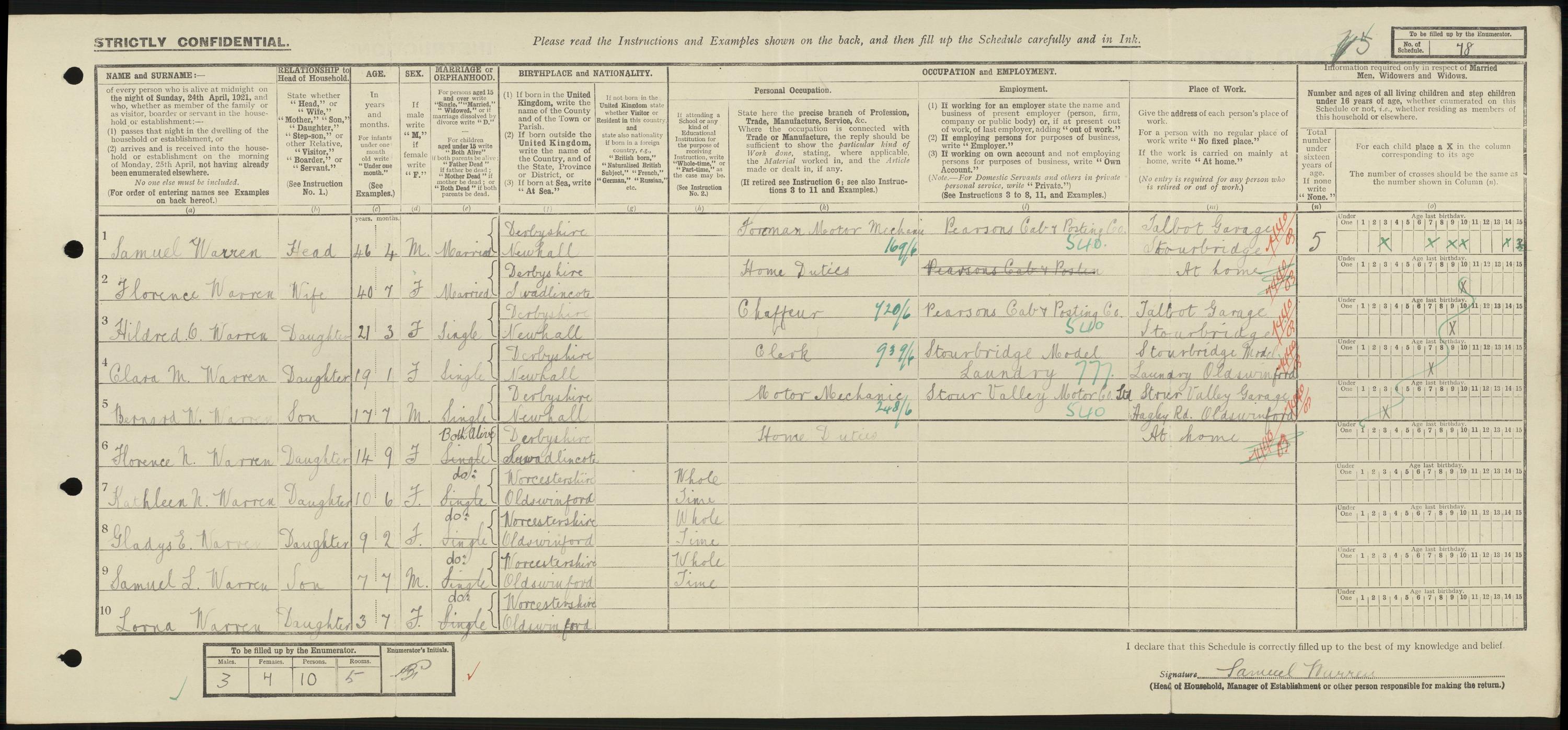

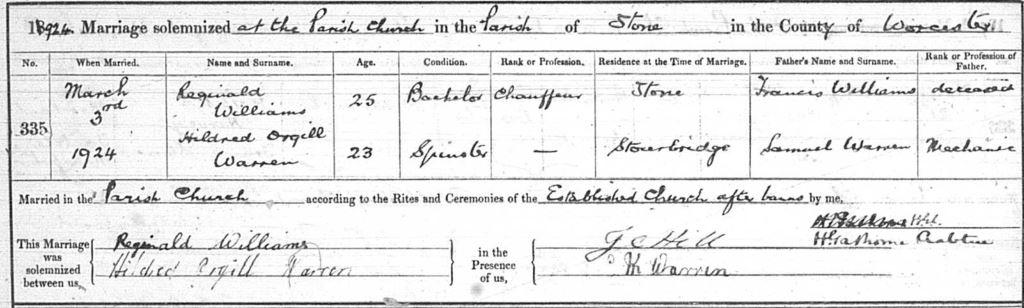

Hildred Orgill Warren born in 1900, my grandmothers sister, married Reginald Williams in Stone, Worcestershire in March 1924. Their daughter Joan was born there in October of that year.

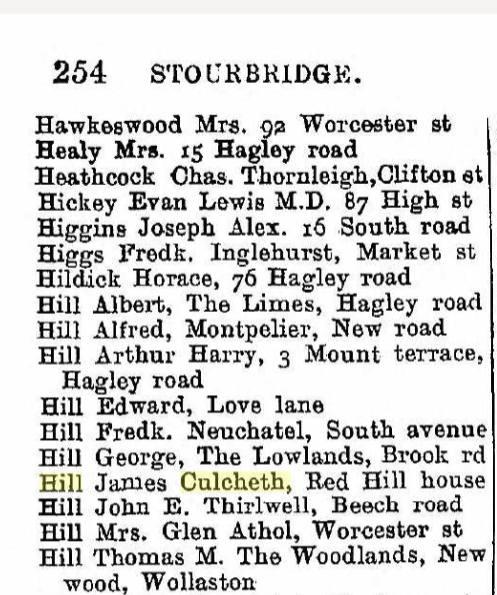

Hildred was a chaffeur on the 1921 census, living at home in Stourbridge with her father (my great grandfather) Samuel Warren, mechanic. I recall my grandmother saying that Hildred was one of the first lady chauffeurs. On their wedding certificate, Reginald is also a chauffeur.

1921 census, Stourbridge:

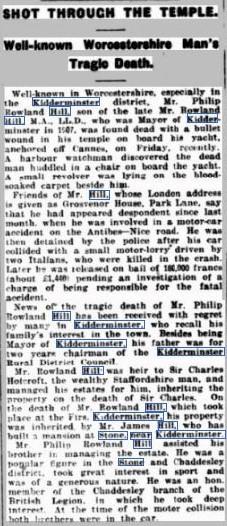

Hildred and Reg worked at Stone Manor. There is a family story of Hildred being involved in a car accident involving a fatality and that she had to go to court.

Stone Manor is in a tiny village called Stone, near Kidderminster, Worcestershire. It used to be a private house, but has been a hotel and nightclub for some years. We knew in the family that Hildred and Reg worked at Stone Manor and that Joan was born there. Around 2007 Joan held a family party there.

Stone Manor, Stone, Worcestershire:

I asked on a Kidderminster Family Research group about Stone Manor in the 1920s:

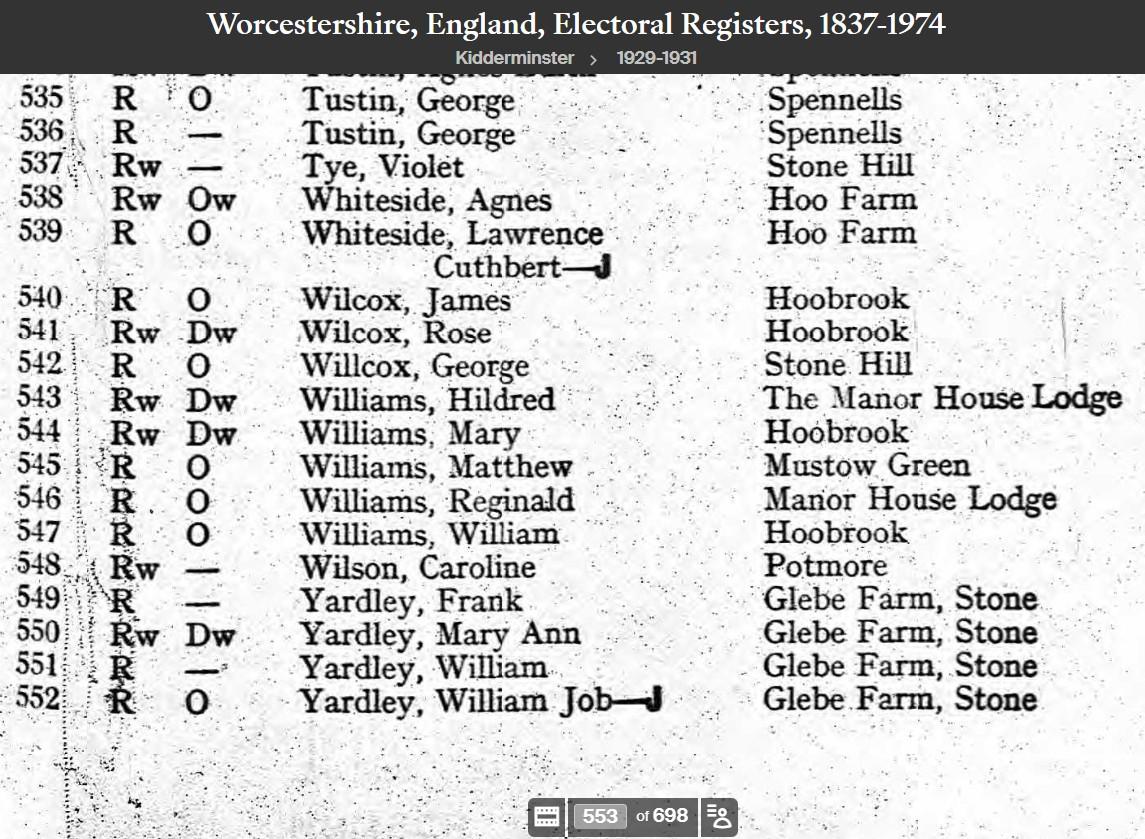

“the original Stone Manor burnt down and the current building dates from the early 1920’s and was built for James Culcheth Hill, completed in 1926”

But was there a fire at Stone Manor?

“I’m not sure there was a fire at the Stone Manor… there seems to have been a fire at another big house a short distance away and it looks like stories have crossed over… as the dates are the same…”JC Hill was one of the witnesses at Hildred and Reginalds wedding in Stone in 1924. K Warren, Hildreds sister Kay, was the other:

I searched the census and electoral rolls for James Culcheth Hill and found him at the Stone Manor on the 1929-1931 electoral rolls for Stone, and Hildred and Reginald living at The Manor House Lodge, Stone: