Search Results for 'sign'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

January 30, 2023 at 8:43 pm #6472

In reply to: The Jorid’s Travels – 14 years on

Salomé: Using the new trans-dimensional array, Jorid, plot course to a new other-dimensional exploration

Georges (comments): “New realms of consciousness, extravagant creatures expected, dragons least of them!” He winked “May that be a warning for whoever wants to follow in our steps”.

The Jorid: Ready for departure.

Salomé: Plot coordinates quadrant AVB 34-7•8 – Cosmic time triangulation congruent to 2023 AD Earth era. Quantum drive engaged.

Jorid: Departure initiated. Entering interdimensional space. Standby for quantum leap.

Salomé (sighing): Please analyse subspace signatures, evidences of life forms in the quadrant.

Jorid: Scanning subspace signatures. Detecting multiple life forms in the AVB 34-7•8 quadrant. Further analysis required to determine intelligence and potential danger.

Salomé: Jorid, engage human interaction mode, with conversational capabilities and extrapolate please!

Jorid: Engaging human interaction mode. Ready for conversation. What would you like to know or discuss?

Georges: We currently have amassed quite a number of tiles. How many Salomé?

Salomé: Let me check. I think about 47 of them last I count. I didn’t insert the auto-generated ones, they were of lesser quality and seemed to interfere with the navigational array landing us always in expected places already travelled.

Salomé: Let me check. I think about 47 of them last I count. I didn’t insert the auto-generated ones, they were of lesser quality and seemed to interfere with the navigational array landing us always in expected places already travelled.Georges: Léonard has been missing for 4 months.

Salomé: you mean by our count, right?

Georges: Right. We need to find him to readjust or correct the navigational array. Jorid, give us statistical probabilities that we can use as clues to his current potential locations.

Jorid: Calculating statistical probabilities for Léonard’s location. It would be helpful to have more information, such as known destinations or areas of interest, to increase accuracy of probabilities.

Salomé: Jorid is in a lazy mood it seems. I preferred her more chatty.

Georges: You mean “him”, surely dear?

Salomé: (rolls eyes)

Georges: Anyway, Léonard seemed interested in archaeological finds in recent excavated tombs near the sand deserts of Bluhm’Oxl in the Zathu sector.

Jorid: Analyzing data on archaeological finds near the sand deserts of Bluhm’Oxl in the Zathu sector. Probability of Léonard being in the area is calculated at 43%. Shall I plot a course to Bluhm’Oxl for further investigation?

Jorid: Analyzing data on archaeological finds near the sand deserts of Bluhm’Oxl in the Zathu sector. Probability of Léonard being in the area is calculated at 43%. Shall I plot a course to Bluhm’Oxl for further investigation?Salomé (loosing patience): Please engage your quantum capacities to access more data. We built you to be a bit more helpful than a bloody computer.

Georges laughed: I remembered you had more patience, dear!

Salomé: She’s in a mood today, isn’t she. What did you do to her?

Georges (cunningly): Jorid, sweet thing, please provide more details about the area, the populations, the customs the whole gamut dammit, and potential territorial conflicts in the vicinity. And be more chatty to please Salomé.

Jorid: Of course, I apologize for my previous responses. Analyzing data on the sand deserts of Bluhm’Oxl in the Zathu sector, including information on populations, customs, territorial conflicts and other relevant details. The area is known for its rich history and cultural heritage, with several ancient tombs and ruins attracting archaeological interest. The main population is composed of the Zathu nomads, known for their hospitality and trading skills. There are no known territorial conflicts in the area, but it is advised to exercise caution while traveling as the deserts can be treacherous.

Georges (laughs): You can’t stop her know!

Salomé (smiles noticing the “her”): Well, that doesn’t tell too much, does it. How shall we proceed? Need to synthetise some local clothes, or are you back to your thieving habits (pun intended)?

Georges: Haha, always ready for a good adventure. It seems we’ll have to do some research on the ground. As for the clothes, I’ll leave that to you my dear. Your sense of style never fails to impress. Let’s make sure to blend in with the locals and avoid drawing any unnecessary attention. The goal is to find Léonard, not get into trouble.

January 30, 2023 at 8:37 pm #6471Topic: The Jorid’s Travels – 14 years on

in forum Yurara Fameliki’s StoriesThe Jorid is a vessel that can travel through dimensions as well as time, within certain boundaries.

The Jorid has been built and is operated by Georges and his companion Salomé.

Georges was a French thief possibly from the 1800s, turned other-dimensional explorer, and along with Salomé, a girl of mysterious origins who he first met in the Alienor dimension but believed to be born in Northern India in a distant past, they have lived rich adventures together, and are deeply bound by love and mutual interests.Georges, with his handsome face, dark hair and amber gaze, is a bit of a daredevil at times, curious and engaging with others. He is very interesting in anything that shines, strange mechanisms and generally the ways consciousness works in living matter. Salomé, on the other hand is deeply intuitive, empath at times, quite logical and rational but also interested in mysticism, the ways of the Truth, and the “why” rather than the “how” of things.

The world of Alienor (a pale green sun under which twin planets originally orbited – Duane, Murtuane – with an additional third, Phreal, home planet of the Guardians, an alien race of builders with god-like powers) lived through cataclysmic changes, finished by the time this story is told.

The Jorid’s original prototype designs were crafted by Léonard, a mysterious figure, self-taught in the arts of dimensional magic in Alienor sects, who acted as a mentor to Georges during his adventures. It is not known where he is now.

The story unfolds 14 years after we discovered Georges & Salomé in the story.

(for more background information, refer to this thread)

January 29, 2023 at 3:15 pm #6468In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

At the former Chinggis Khaan International Airport which was now called the New Ulaanbaatar International Airport, the young intern sat next to Youssef, making the seats tremble like a frail suspended bridge in the Andes. Youssef had been considering connecting to the game and start his quest to meet with his grumpy quirk, but the girl seemed pissed, almost on the brink of crying. So Youssef turned off his phone and asked her what had happened, without thinking about the consequences, and because he thought it was a nice opportunity to engage the conversation with her at last, and in doing so appear to be nice to care so that she might like him in return.

Natalie, because he had finally learned her name, started with all the bullying she had to endure from Miss Tartiflate during the trip, all the dismissal about her brilliant ideas, and how the Yeti only needed her to bring her coffee and pencils, and go fetch someone her boss needed to talk to, and how many time she would get no thanks, just a short: “you’re still here?”

After some time, Youssef even knew more about her parents and her sisters and their broken family dynamics than he would have cared to ask, even to be polite. At some point he was starting to feel grumpy and realised he hadn’t eaten since they arrived at the airport. But if he told Natalie he wanted to go get some food, she might follow him and get some too. His stomach growled like an angry bear. He stood more quickly than he wanted and his phone fell on the ground. The screen lit up and he could just catch a glimpse of a desert emoji in a notification before Natalie let out a squeal. Youssef looked around, people were glancing at him as if he might have been torturing her.

“Oh! Sorry, said Youssef. I just need to go to the bathroom before we board.”

“But the boarding is only in one hour!”

“Well I can’t wait one hour.”

“In that case I’m coming with you, I need to go there too anyway.”

“But someone needs to stay here for our bags,” said Youssef. He could have carried his own bag easily, but she had a small suitcase, a handbag and a backpack, and a few paper bags of products she bought at one of the two the duty free shops.

Natalie called Kyle and asked him to keep a close watch on her precious things. She might have been complaining about the boss, but she certainly had caught on a few traits of her.

Youssef was glad when the men’s bathroom door shut behind him and his ears could have some respite. A small Chinese business man was washing his hands at one of the sinks. He looked up at Youssef and seemed impressed by his height and muscles. The man asked for a selfie together so that he could show his friends how cool he was to have met such a big stranger in the airport bathroom. Youssef had learned it was easier to oblige them than having them follow him and insist.

When the man left, Youssef saw Natalie standing outside waiting for him. He thought it would have taken her longer. He only wanted to go get some food. Maybe if he took his time, she would go.

He remembered the game notification and turned on his phone. The icon was odd and kept shifting between four different landscapes, each barren and empty, with sand dunes stretching as far as the eye could see. One with a six legged camel was already intriguing, in the second one a strange arrowhead that seemed to be getting out of the desert sand reminded him of something that he couldn’t quite remember. The fourth one intrigued him the most, with that car in the middle of the desert and a boat coming out of a giant dune.

Still hungrumpy he nonetheless clicked on the shapeshifting icon and was taken to a new area in the game, where the ground was covered in sand and the sky was a deep orange, as if the sun was setting. He could see a mysterious figure in the distance, standing at the top of a sand dune.

The bell at the top right of the screen wobbled, signalling a message from the game. There were two. He opened the first one.

We’re excited to hear about your real-life parallel quest. It sounds like you’re getting close to uncovering the mystery of the grumpy shaman. Keep working on your blog website and keep an eye out for any clues that Xavier and the Snoot may send your way. We believe that you’re on the right path.

What on earth was that ? How did the game know about his life and the shaman at the oasis ? After the Thi Gang mess with THE BLOG he was becoming suspicious of those strange occurrences. He thought he could wonder for a long time or just enjoy the benefits. Apparently he had been granted a substantial reward in gold coins for successfully managing his first quest, along with a green potion.

He looked at his avatar who was roaming the desert with his pet bear (quite hungrumpy too). The avatar’s body was perfect, even the hands looked normal for once, but the outfit had those two silver disks that made him look like he was wearing an iron bra.

He opened the second message.

Clue unlocked It sounds like you’re in a remote location and disconnected from the game. But, your real-life experiences seem to be converging with your quest. The grumpy shaman you met at the food booth may hold the key to unlocking the next steps in the game. Remember, the desert represents your ability to adapt and navigate through difficult situations.

🏜️🧭🧙♂️ Explore the desert and see if the grumpy shaman’s clues lead you to the next steps in the game. Keep an open mind and pay attention to any symbols or clues that may help you in your quest. Remember, the desert represents your ability to adapt and navigate through difficult situations.

Youssef recalled that strange paper given by the lama shaman, was it another of the clues he needed to solve that game? He didn’t have time to think about it because a message bumped onto his screen.

“Need help? Contact me 👉”

Sands_of_time is trying to make contact : ➡️ACCEPT <> ➡️DENY ❓

January 28, 2023 at 11:27 am #6463In reply to: Prompts of Madjourneys

Additional clues from AL (based on Xavier’s comment)

Yasmin

:snake:

Yasmin was having a hard time with the heavy rains and mosquitoes in the real-world. She couldn’t seem to make a lot of progress on finding the snorting imp, which she was trying to find in the real world rather than in the game. She was feeling discouraged and unsure of what to do next.

Suddenly, an emoji of a snake appeared on her screen. It seemed to be slithering and wriggling, as if it was trying to grab her attention. Without hesitation, Yasmin clicked on the emoji.

She was taken to a new area in the game, where the ground was covered in tall grass and the sky was dark and stormy. She could see the snorting imp in the distance, but it was surrounded by a group of dangerous-looking snakes.

Clue unlocked It sounds like you’re having a hard time in the real world, but don’t let that discourage you in the game. The snorting imp is nearby and it seems like the snakes are guarding it. You’ll have to be brave and quick to catch it. Remember, the snorting imp represents your determination and bravery in real life.

🐍🔍🐗 Use your skills and abilities to navigate through the tall grass and avoid the snakes. Keep your eyes peeled for any clues or symbols that may help you in your quest. Don’t give up and remember that the snorting imp is a representation of your determination and bravery.

A message bumped on the screen: “Need help? Contact me 👉”

Stryke_Assist is trying to make contact : ➡️ACCEPT <> ➡️DENY ❓

Youssef

:desert:

Youssef has not yet been aware of the quest, since he’s been off the grid in the Gobi desert. But, interestingly, his story unfolds in real-life parallel to his quest. He’s found a strange grumpy shaman at a food booth, and it seems that his natural steps are converging back with the game. His blog website for his boss seems to take most of his attention.

An emoji of a desert suddenly appeared on his screen. It seemed to be a barren and empty landscape, with sand dunes stretching as far as the eye could see. Without hesitation, Youssef clicked on the emoji.

He was taken to a new area in the game, where the ground was covered in sand and the sky was a deep orange, as if the sun was setting. He could see a mysterious figure in the distance, standing at the top of a sand dune.

Clue unlocked It sounds like you’re in a remote location and disconnected from the game. But, your real-life experiences seem to be converging with your quest. The grumpy shaman you met at the food booth may hold the key to unlocking the next steps in the game. Remember, the desert represents your ability to adapt and navigate through difficult situations.

🏜️🧭🧙♂️ Explore the desert and see if the grumpy shaman’s clues lead you to the next steps in the game. Keep an open mind and pay attention to any symbols or clues that may help you in your quest. Remember, the desert represents your ability to adapt and navigate through difficult situations.

A message bumped on the screen: “Need help? Contact me 👉”

Sands_of_time is trying to make contact : ➡️ACCEPT <> ➡️DENY ❓

Zara

:carved_tile:

Zara looked more advanced [in her explorations – stream breaks – resume conversation]

Zara had come across a strange and ancient looking mine. It was clear that it had been abandoned for many years, but there were still signs of activity. The entrance was blocked by a large pile of rocks, but she could see a faint light coming from within. She knew that she had to find a way in.

As she approached the mine, she noticed a small, carved wooden tile on the ground. It was intricately detailed and seemed to depict a map of some sort. She picked it up and examined it closely. It seemed to show the layout of the mine and possibly the location of the secret room.

With this new clue in hand, Zara set to work trying to clear the entrance. She used all of her strength to move the rocks, and after a few minutes of hard work, she was able to create an opening large enough for her to squeeze through.

As she ventured deeper into the mine, she found herself in a large chamber. The walls were lined with strange markings and symbols, and she could see a faint light coming from a small room off to the side. She knew that this must be the secret room she had been searching for.

Zara approached the room and pushed open the door. Inside, she found a small, dimly lit chamber. In the center of the room stood a large stone altar, and on the altar was a strange, glowing object. She couldn’t quite make out what it was, but she knew that this must be the key to solving the mystery of the mine.

With a sense of excitement and curiosity, Zara reached out to take the glowing object. As her hand touched it, she felt a strange energy coursing through her body. She knew that her quest was far from over, and that there were many more secrets to uncover in the mine.

January 24, 2023 at 10:29 am #6455In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Zara decided she may as well spend the hour wandering around the game before going back to the church to see the ghost of Isaac when she was sure her host Bertie was asleep. It was a warm night but a gentle breeze wafted through the open window and Zara was comfortable and content. Not just one but three new adventures had her tingling with delicious anticipation, even if she was a little anxious about not getting confused with the game. Talking to ghosts in old churches wasn’t unfamiliar, nor was a holiday in a strange hotel off the beaten track, but the game was still a bit of a mystery to her. Yeah, I know it’s just a game, she whispered to the parrot who made a soft clicking noise by way of response.

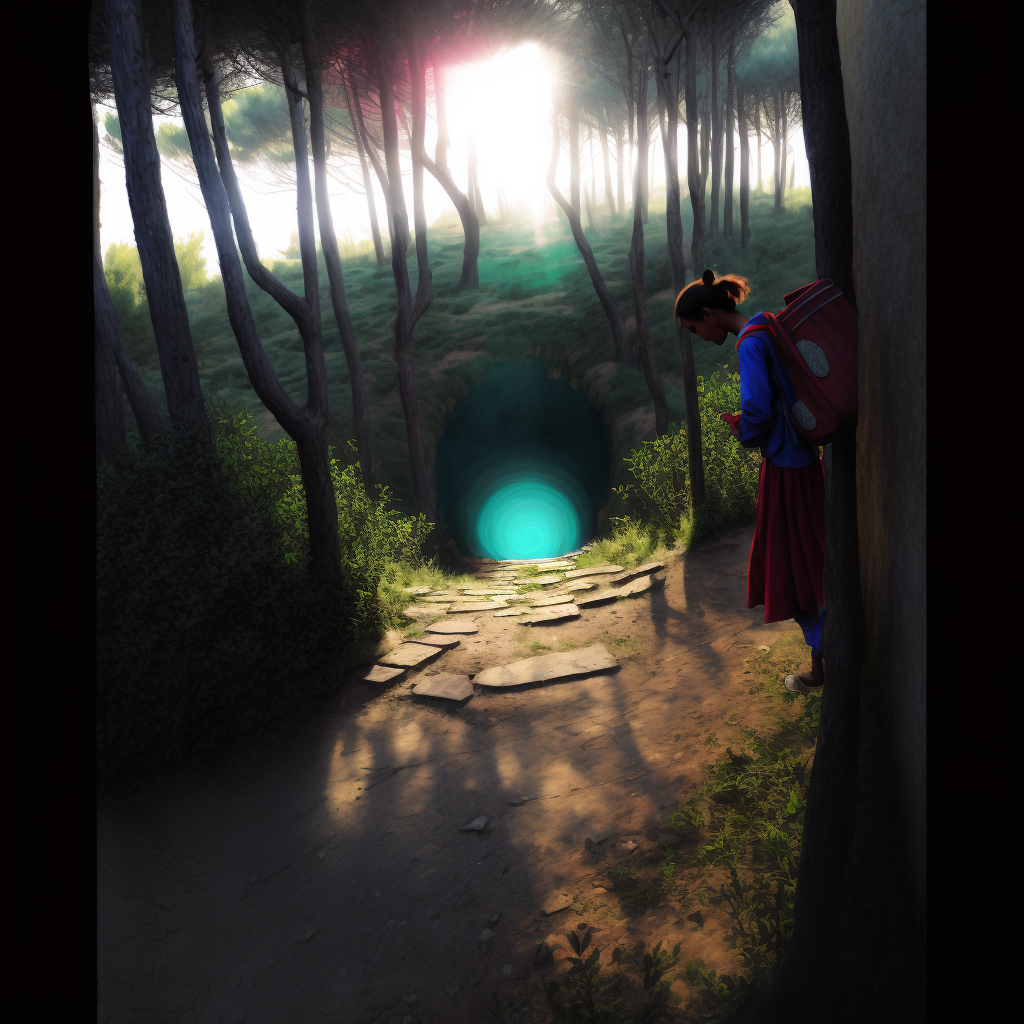

Zara found her game character, also (somewhat confusingly) named Zara, standing in the woods. Not entirely sure how it had happened, she was rather pleased to see that the cargo pants and tank top in red had changed to a more pleasing hippyish red skirt ensemble. A bit less Tomb Looter, and a bit more fairy tale looking which was more to her taste.

The woods were strangely silent and still. Zara made a 360 degree turn on the spot to see in all directions. The scene looked the same whichever way she turned, and Zara didn’t know which way to go. Then a faint path appeared to the left, and she set off in that direction. Before long she came to a round green pool.

She stopped to look but carried on walking past it, not sure what it signified. She came upon another glowing green pool before long, which looked like an entrance to a tunnel.

I bet those are portals or something, Zara realized. I wonder if I’m supposed to step into it?

“Go for it”, said Pretty Girl, “It’s only a game.”

“Ok, well here goes!” replied Zara, mentally bracing herself for a plunge into the unknown.

Zara stepped into the circle of glowing green.

“Like when Alice went down the rabbit hole!” Zara whispered to the parrot. “I’m falling, falling…oh!”

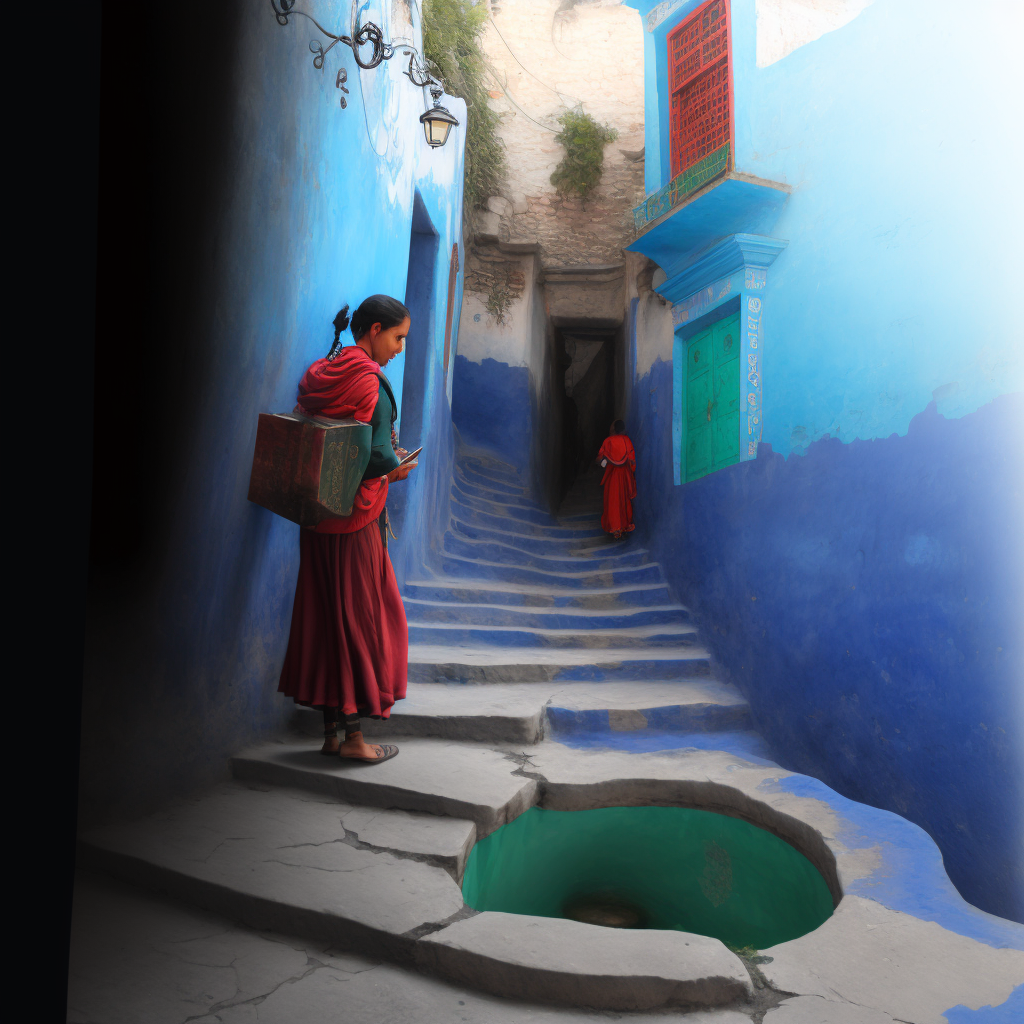

Zara emerged from the green pool onto a wide walled path. She was now in some kind of inhabited area, or at least not in the deep woods with no sign of human occupation.

“I guess that green pool is the portal back to the woods.”

“By George, she’s getting it,” replied Pretty Girl.

Zara walked along the path which led to an old deserted ancient looking village with alleyways and steps.

“This is heaps more interesting than those woods, look how pretty it all is! I love this place.”

“Weren’t you supposed to be looking for a hermit in the woods though,” said Pretty Girl.

“Or a lost traveler, and the lost traveler may be here, after falling in one of those green pools in the woods,” replied Zara tartly, not wanting to leave the enchanting scene she found her avatar in.

January 23, 2023 at 2:16 pm #6452

January 23, 2023 at 2:16 pm #6452In reply to: Prompts of Madjourneys

Youssef’s entry quirk is being grumpy when he’s hungry.

Quirk accepted.

Initial setting: You find yourself in a bustling marketplace, surrounded by vendors selling all sorts of exotic foods and spices. Your stomach growls loudly, reminding you of your quirk.

Possible direction to investigate: As you explore the marketplace, you notice a small stall tucked away in the corner. The aroma wafting from the stall is tantalizing, and your stomach growls even louder. As you approach, you see a grumpy-looking vendor behind the counter. He doesn’t seem to be in the mood for customers.

Possible character to engage: The grumpy vendor.

Objective: To find a way to appease the grumpy vendor and secure a satisfying meal to satisfy your hunger.

Additional FFI clue: As you make your way to the Flying Fish Inn, you notice a sign advertising a special meal made with locally caught fish. Could this be the key to satisfying your hunger and appeasing the grumpy vendor? Remember to bring proof of your successful quest to the FFI.

Snoot’s clue: 🧔🌮🔍🔑🏞️

January 23, 2023 at 1:27 pm #6451In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

The progress on the quest in the Land of the Quirks was too tantalizing; Xavier made himself a quick sandwich and jumped back on it during his lunch break.

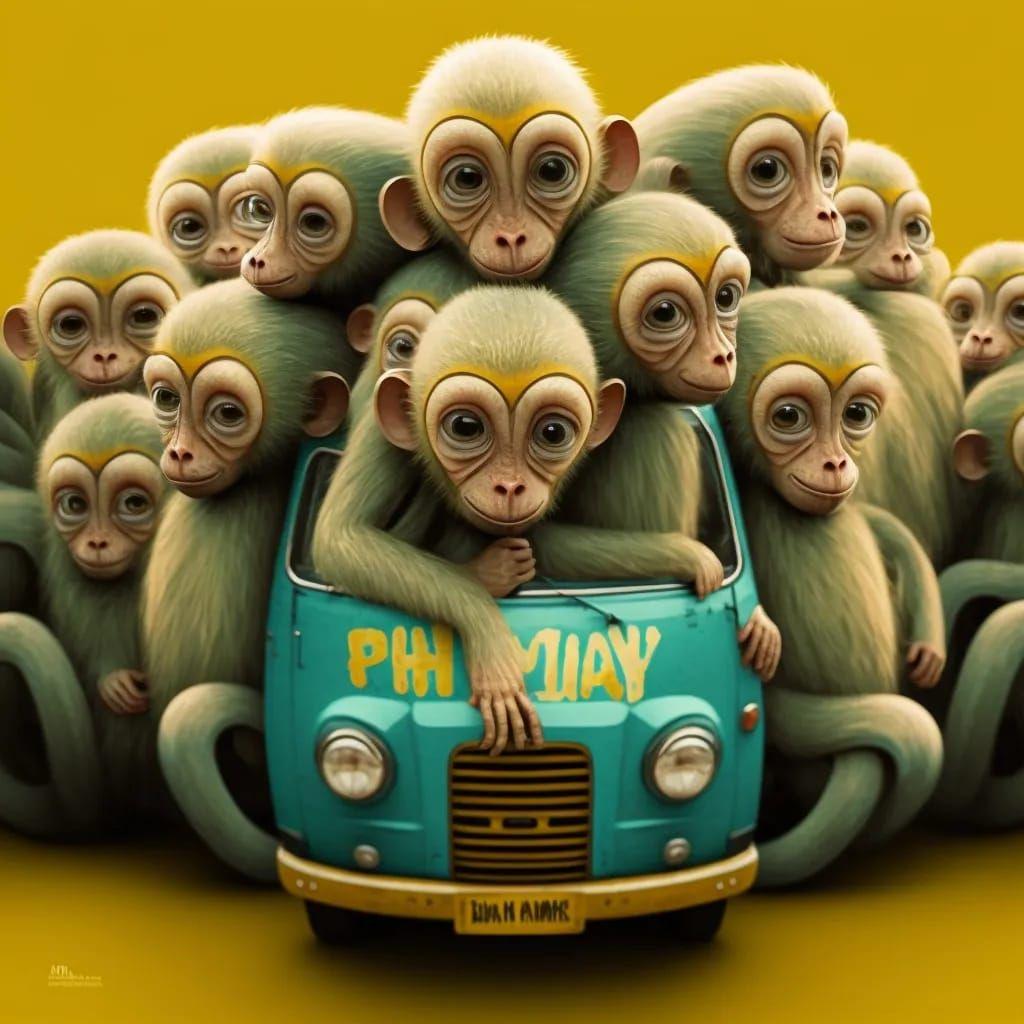

The jungle had an oppressing quality… Maybe it has to do with the shrieks of the apes tearing the silence apart.

The jungle had an oppressing quality… Maybe it has to do with the shrieks of the apes tearing the silence apart. It was time for a slight adjustment of his avatar.

Xavimunk opened his bag of tricks, something that the wise owl had suggested he looked into. Few items from the AIorium Emporium had been supplied. They tended to shift and disappear if you didn’t focus, but his intention was set on the task at hand. At the bottom of the bag, there was a small vial with a golden liquid with a tag written in ornate handwriting “MJ remix: for when words elude and shapes confuse at your own peril”.

He gulped the potion without thinking too much. He felt himself shrink, and his arms elongate a little. There, he thought. Imp-munk’s more suited to the mission. Hope the effects will be temporary…

He gulped the potion without thinking too much. He felt himself shrink, and his arms elongate a little. There, he thought. Imp-munk’s more suited to the mission. Hope the effects will be temporary…As Xavier mustered the courage to enter through the front gate, monkeys started to become silent. He couldn’t say if it was an ominous sign, or maybe an effect of his adaptation. The temple’s light inside was gorgeous, but nothing seemed to be there.

He gestured around, to make the menu appear. He looked again at the instructions on his screen overlay:

As for possible characters to engage, you may come across a sly fox who claims to know the location of the fruit but will only reveal it in exchange for a favor, or a brave adventurer who has been searching for the Golden Banana for years and may be willing to team up with you.

Suddenly a loud monkey honking noise came from outside, distracting him.

What the?… Had to be one of Zara’s remixes. He saw the three dots bleeping on the screen.

Here’s the Banana bus, hope it helps! Envoy! bugger Enjoy!

Yep… With the distinct typo-heavy accent, definitely Zara’s style. Strange idea that AL designated her as the leader… He’d have to roll with it.

Suddenly, as the Banana bus parked in front of the Temple, a horde of Italien speaking tourists started to flock in and snap pictures around. The monkeys didn’t know what to do and seemed to build growing and noisy interest in their assortiment of colorful shoes, flip-flops, boots and all.

Focus, thought Xavimunk… What did the wise owl say? Look for a guide…

Only the huge colorful bus seemed to take the space now… But wait… what if?He walked to the parking spot under the shades of the huge banyan tree next to the temple’s entrance, under which the bus driver had parked it. The driver was still there, napping under a newspaper, his legs on the wheel.

“Whatcha lookin’ at?” he said chewing his gum loudly. “Never seen a fox drive a banana bus before?”

Xavier smiled. “Any chance you can guide me to the location of the Golden Banana?”

“For a price… maybe.” The fox had jumped closely and was considering the strange avatar from head to toe.

“Ain’t no usual stuff that got you into this? Got any left? That would be a nice price.”

“As it happens…” Xavier smiled.The quest seemed back on track. Xavier looked at the time. Blimmey! already late again. And I promised Brytta to get some Chinese snacks for dinner.

January 21, 2023 at 4:17 pm #6426In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

The artificial lights of Berlin were starting to switch off in the horizon, leaving the night plunged in darkness minutes before the sunrise. It was a moment of peace that Xavier enjoyed, although it reminded him of how sleepless his night had been.

The game had taken a side step, as he’d been pouring all his attention into his daytime job, and his personal project with Artificial Life AL. It was a long way from the little boy at school with dyslexia who was using cheeky jokes as a way to get by the snides. Since then, he’d known some of the unusual super-powers this condition gave him as well. Chiefly: abstract and out-of-the-box thinking, puzzle-solving genius, and an almost other-worldly ability at keeping track of the plot. All these skills were in fact of tremendous help at his work, which was blending traditional areas of technology along with massive amounts of loosely connected data.

He yawned and went to brush his teeth. His usual meditation routine had also been disrupted by the activity of late, but he just couldn’t go to bed without a little time to cool off and calm down the agitation of his thoughts.

Sitting on the meditation mat, his thoughts strayed off towards the preparation for the trip. Going to Australia would have seemed exciting a few years back, but the idea of packing a suitcase, and going through the long flight and the logistics involved got him more anxious than excited, despite the contagious enthusiasm of his friends. Since he’d settled in Berlin, after never settling for too long in one place (his job afforded him to work wherever whenever), he’d kind of stopped looking for the next adventure. He hadn’t even looked at flight options yet, and hoped that the building momentum would spur him into this adventure. For now, he needed the rest.

The quirk quest assigned to his persona in the game was fun. Monkeys and Golden banana to look for, wise owls and sly foxes, the whimsical goofy nature of the quest seemed good for the place he was in.

AL had been suggesting the players to insert the game elements into their realities, and sometimes its comments or instructions seemed to slip between layers of reality — this was an intriguing mystery to Xavier.

He’d instructed AL to discreetly assist Youssef with his trouble — the Thi Gang seemed to be an ethical hacker developer company front for more serious business. Chatter on the net had tied it to a network of shell companies involved in some strange activities. A name had popped up, linked to mysterious recluse billionaire Botty Banworth, the owner of Youssef’s boss rival blog named Knoweth.He slipped into the bed, careful not to wake up Brytta, who was sleeping tightly. It was her day off, otherwise she would have been gone already to her shift. It would be good to connect in the morning, and enjoy some break from mind stuff. They had planned a visit to Kantonstrasse (the local Chinatown) for Chinese New Year, and he couldn’t wait for it.

January 18, 2023 at 12:51 pm #6413In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Zara was long overdue for some holiday time off from her job at the Bungwalley Valley animal rescue centre in New South Wales and the suggestion to meet her online friends at the intriguing sounding Flying Fish Inn to look for clues for their online game couldn’t have come at a better time. Lucky for her it wasn’t all that far, relatively speaking, although everything is far in Australia, it was closer than coming from Europe. Xavier would have a much longer trip. Zara wasn’t quite sure where exactly Yasmin was, but she knew it was somewhere in Asia. It depended on which refugee camp she was assigned to, and Zara had forgotten to ask her recently. All they had talked about was the new online game, and how confusing it all was.

The biggest mystery to Zara was why she was the leader in the game. She was always the one who was wandering off on side trips and forgetting what everyone else was up to. If the other game followers followed her lead there was no telling where they’d all end up!

“But it is just a game,” Pretty Girl, the rescue parrot interjected. Zara had known some talking parrots over the years, but never one quite like this one. Usually they repeated any nonsense that they’d heard but this one was different. She would miss it while she was away on holiday, and for a moment considered taking the talking parrot with her on the trip. If she did, she’d have to think about changing her name though, Pretty Girl wasn’t a great name but it was hard to keep thinking of names for all the rescue creatures.

After Zara had done the routine morning chores of feeding the various animals, changing the water bowls, and cleaning up the less pleasant aspects of the job, she sat down in the office room of the rescue centre with a cup of coffee and a sandwich. She was in good physical shape for 57, wiry and energetic, but her back ached at times and a sit down was welcome before the vet arrived to check on all the sick and wounded animals.

Pretty Girl flew over from the kennels, and perched outside the office room window. When the parrot had first been dropped off at the centre, they’d put her in a big cage, but in no uncertain terms Pretty Girl had told them she’d done nothing wrong and was wrongfully imprisoned and to release her at once. It was rather a shock to be addresssed by a parrot in such a way, and it was agreed between the staff and the vet to set her free and see what happened. And Pretty Girl had not flown away.

“Hey Pretty Girl, why don’t you give me some advice on this confusing new game I’m playing with my online friends?” Zara asked.

“Pretty Girl wants some of your tuna sandwich first,” replied the parrot. After Zara had obliged, the parrot continued at some surprising length.

“My advice would be to not worry too much about getting the small details right. The most important thing is to have fun and enjoy the creative process. Just give me a bit more tuna,” Pretty Girl said, before continuing.

“Remember that as a writer, you have the power to shape the story and the characters as you see fit. It’s okay to make mistakes, and it’s okay to not know everything. Allow yourself to be inspired by the world around you and let the story unfold naturally. Trust in your own creativity and don’t be afraid to take risks. And remember, it’s not the small details that make a story great, it’s the emotions and experiences that the characters go through that make it truly memorable. And always remember to feed the parrot.”

“Maybe I should take you on holiday with me after all,” Zara replied. “You really are an amazing bird, aren’t you?”

January 15, 2023 at 1:13 pm #6390

January 15, 2023 at 1:13 pm #6390In reply to: Train your subjective AI – text version

Trying to get some interesting unlikely, absurd associations or quests… Still some way to go!

2 impossible associations

- The creation of a time machine using only household objects such as a toaster and a stapler.

- The discovery of a parallel universe accessible through a secret passageway hidden in a public park’s playground equipment.

give an association of 3 or 4 words with each words being statistically probable to occur in every day conversation but with statistical probability of occurring together of less than 10^-57.

-

- “Giant robotic giraffe farming”

- “Vintage cars restoration using only expired food”

- “Archaeological board game design with only smells”

- “Artificial intelligence calligraphic body language assisted therapy”

All the words in these associations are commonly used in everyday conversation, but the associations themselves are relatively unexpected, absurd, and may surprise people. They are all grounded in everyday happenstances but are less modern tech-oriented and the concepts they describe are related to diverse interests that may not be related to technology trend and are quite unexpected and bizarre..

December 6, 2022 at 2:17 pm #6350In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Transportation

Isaac Stokes 1804-1877

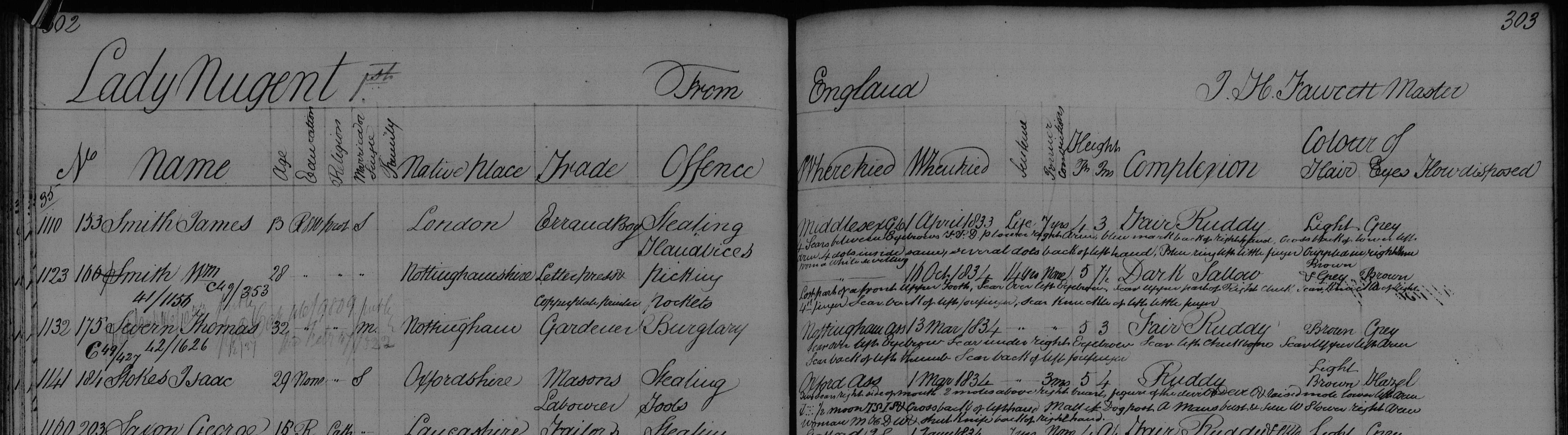

Isaac was born in Churchill, Oxfordshire in 1804, and was the youngest brother of my 4X great grandfather Thomas Stokes. The Stokes family were stone masons for generations in Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire, and Isaac’s occupation was a mason’s labourer in 1834 when he was sentenced at the Lent Assizes in Oxford to fourteen years transportation for stealing tools.

Churchill where the Stokes stonemasons came from: on 31 July 1684 a fire destroyed 20 houses and many other buildings, and killed four people. The village was rebuilt higher up the hill, with stone houses instead of the old timber-framed and thatched cottages. The fire was apparently caused by a baker who, to avoid chimney tax, had knocked through the wall from her oven to her neighbour’s chimney.

Isaac stole a pick axe, the value of 2 shillings and the property of Thomas Joyner of Churchill; a kibbeaux and a trowel value 3 shillings the property of Thomas Symms; a hammer and axe value 5 shillings, property of John Keen of Sarsden.

(The word kibbeaux seems to only exists in relation to Isaac Stokes sentence and whoever was the first to write it was perhaps being creative with the spelling of a kibbo, a miners or a metal bucket. This spelling is repeated in the criminal reports and the newspaper articles about Isaac, but nowhere else).

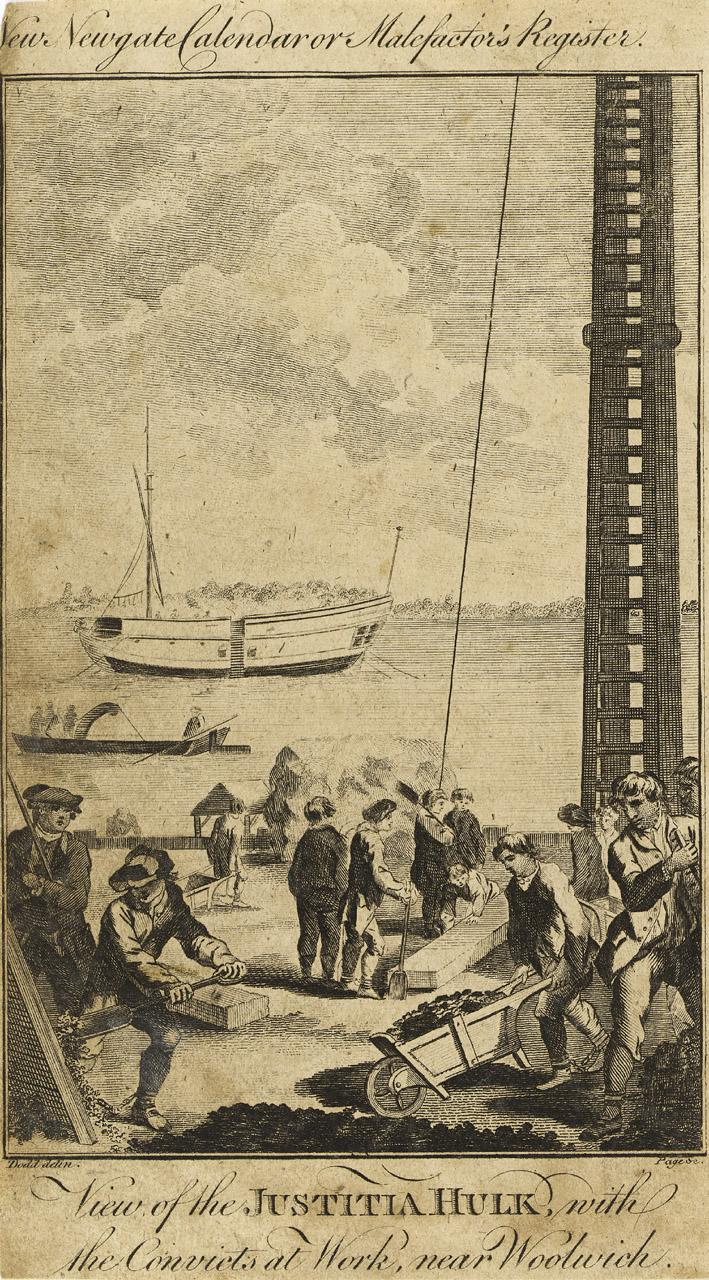

In March 1834 the Removal of Convicts was announced in the Oxford University and City Herald: Isaac Stokes and several other prisoners were removed from the Oxford county gaol to the Justitia hulk at Woolwich “persuant to their sentences of transportation at our Lent Assizes”.

via digitalpanopticon:

Hulks were decommissioned (and often unseaworthy) ships that were moored in rivers and estuaries and refitted to become floating prisons. The outbreak of war in America in 1775 meant that it was no longer possible to transport British convicts there. Transportation as a form of punishment had started in the late seventeenth century, and following the Transportation Act of 1718, some 44,000 British convicts were sent to the American colonies. The end of this punishment presented a major problem for the authorities in London, since in the decade before 1775, two-thirds of convicts at the Old Bailey received a sentence of transportation – on average 283 convicts a year. As a result, London’s prisons quickly filled to overflowing with convicted prisoners who were sentenced to transportation but had no place to go.

To increase London’s prison capacity, in 1776 Parliament passed the “Hulks Act” (16 Geo III, c.43). Although overseen by local justices of the peace, the hulks were to be directly managed and maintained by private contractors. The first contract to run a hulk was awarded to Duncan Campbell, a former transportation contractor. In August 1776, the Justicia, a former transportation ship moored in the River Thames, became the first prison hulk. This ship soon became full and Campbell quickly introduced a number of other hulks in London; by 1778 the fleet of hulks on the Thames held 510 prisoners.

Demand was so great that new hulks were introduced across the country. There were hulks located at Deptford, Chatham, Woolwich, Gosport, Plymouth, Portsmouth, Sheerness and Cork.The Justitia via rmg collections:

Convicts perform hard labour at the Woolwich Warren. The hulk on the river is the ‘Justitia’. Prisoners were kept on board such ships for months awaiting deportation to Australia. The ‘Justitia’ was a 260 ton prison hulk that had been originally moored in the Thames when the American War of Independence put a stop to the transportation of criminals to the former colonies. The ‘Justitia’ belonged to the shipowner Duncan Campbell, who was the Government contractor who organized the prison-hulk system at that time. Campbell was subsequently involved in the shipping of convicts to the penal colony at Botany Bay (in fact Port Jackson, later Sydney, just to the north) in New South Wales, the ‘first fleet’ going out in 1788.

While searching for records for Isaac Stokes I discovered that another Isaac Stokes was transported to New South Wales in 1835 as well. The other one was a butcher born in 1809, sentenced in London for seven years, and he sailed on the Mary Ann. Our Isaac Stokes sailed on the Lady Nugent, arriving in NSW in April 1835, having set sail from England in December 1834.

Lady Nugent was built at Bombay in 1813. She made four voyages under contract to the British East India Company (EIC). She then made two voyages transporting convicts to Australia, one to New South Wales and one to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). (via Wikipedia)

via freesettlerorfelon website:

On 20 November 1834, 100 male convicts were transferred to the Lady Nugent from the Justitia Hulk and 60 from the Ganymede Hulk at Woolwich, all in apparent good health. The Lady Nugent departed Sheerness on 4 December 1834.

SURGEON OLIVER SPROULE

Oliver Sproule kept a Medical Journal from 7 November 1834 to 27 April 1835. He recorded in his journal the weather conditions they experienced in the first two weeks:

‘In the course of the first week or ten days at sea, there were eight or nine on the sick list with catarrhal affections and one with dropsy which I attribute to the cold and wet we experienced during that period beating down channel. Indeed the foremost berths in the prison at this time were so wet from leaking in that part of the ship, that I was obliged to issue dry beds and bedding to a great many of the prisoners to preserve their health, but after crossing the Bay of Biscay the weather became fine and we got the damp beds and blankets dried, the leaks partially stopped and the prison well aired and ventilated which, I am happy to say soon manifested a favourable change in the health and appearance of the men.

Besides the cases given in the journal I had a great many others to treat, some of them similar to those mentioned but the greater part consisted of boils, scalds, and contusions which would not only be too tedious to enter but I fear would be irksome to the reader. There were four births on board during the passage which did well, therefore I did not consider it necessary to give a detailed account of them in my journal the more especially as they were all favourable cases.

Regularity and cleanliness in the prison, free ventilation and as far as possible dry decks turning all the prisoners up in fine weather as we were lucky enough to have two musicians amongst the convicts, dancing was tolerated every afternoon, strict attention to personal cleanliness and also to the cooking of their victuals with regular hours for their meals, were the only prophylactic means used on this occasion, which I found to answer my expectations to the utmost extent in as much as there was not a single case of contagious or infectious nature during the whole passage with the exception of a few cases of psora which soon yielded to the usual treatment. A few cases of scurvy however appeared on board at rather an early period which I can attribute to nothing else but the wet and hardships the prisoners endured during the first three or four weeks of the passage. I was prompt in my treatment of these cases and they got well, but before we arrived at Sydney I had about thirty others to treat.’

The Lady Nugent arrived in Port Jackson on 9 April 1835 with 284 male prisoners. Two men had died at sea. The prisoners were landed on 27th April 1835 and marched to Hyde Park Barracks prior to being assigned. Ten were under the age of 14 years.

The Lady Nugent:

Isaac’s distinguishing marks are noted on various criminal registers and record books:

“Height in feet & inches: 5 4; Complexion: Ruddy; Hair: Light brown; Eyes: Hazel; Marks or Scars: Yes [including] DEVIL on lower left arm, TSIS back of left hand, WS lower right arm, MHDW back of right hand.”

Another includes more detail about Isaac’s tattoos:

“Two slight scars right side of mouth, 2 moles above right breast, figure of the devil and DEVIL and raised mole, lower left arm; anchor, seven dots half moon, TSIS and cross, back of left hand; a mallet, door post, A, mans bust, sun, WS, lower right arm; woman, MHDW and shut knife, back of right hand.”

From How tattoos became fashionable in Victorian England (2019 article in TheConversation by Robert Shoemaker and Zoe Alkar):

“Historical tattooing was not restricted to sailors, soldiers and convicts, but was a growing and accepted phenomenon in Victorian England. Tattoos provide an important window into the lives of those who typically left no written records of their own. As a form of “history from below”, they give us a fleeting but intriguing understanding of the identities and emotions of ordinary people in the past.

As a practice for which typically the only record is the body itself, few systematic records survive before the advent of photography. One exception to this is the written descriptions of tattoos (and even the occasional sketch) that were kept of institutionalised people forced to submit to the recording of information about their bodies as a means of identifying them. This particularly applies to three groups – criminal convicts, soldiers and sailors. Of these, the convict records are the most voluminous and systematic.

Such records were first kept in large numbers for those who were transported to Australia from 1788 (since Australia was then an open prison) as the authorities needed some means of keeping track of them.”On the 1837 census Isaac was working for the government at Illiwarra, New South Wales. This record states that he arrived on the Lady Nugent in 1835. There are three other indent records for an Isaac Stokes in the following years, but the transcriptions don’t provide enough information to determine which Isaac Stokes it was. In April 1837 there was an abscondment, and an arrest/apprehension in May of that year, and in 1843 there was a record of convict indulgences.

From the Australian government website regarding “convict indulgences”:

“By the mid-1830s only six per cent of convicts were locked up. The vast majority worked for the government or free settlers and, with good behaviour, could earn a ticket of leave, conditional pardon or and even an absolute pardon. While under such orders convicts could earn their own living.”

In 1856 in Camden, NSW, Isaac Stokes married Catherine Daly. With no further information on this record it would be impossible to know for sure if this was the right Isaac Stokes. This couple had six children, all in the Camden area, but none of the records provided enough information. No occupation or place or date of birth recorded for Isaac Stokes.

I wrote to the National Library of Australia about the marriage record, and their reply was a surprise! Issac and Catherine were married on 30 September 1856, at the house of the Rev. Charles William Rigg, a Methodist minister, and it was recorded that Isaac was born in Edinburgh in 1821, to parents James Stokes and Sarah Ellis! The age at the time of the marriage doesn’t match Isaac’s age at death in 1877, and clearly the place of birth and parents didn’t match either. Only his fathers occupation of stone mason was correct. I wrote back to the helpful people at the library and they replied that the register was in a very poor condition and that only two and a half entries had survived at all, and that Isaac and Catherines marriage was recorded over two pages.

I searched for an Isaac Stokes born in 1821 in Edinburgh on the Scotland government website (and on all the other genealogy records sites) and didn’t find it. In fact Stokes was a very uncommon name in Scotland at the time. I also searched Australian immigration and other records for another Isaac Stokes born in Scotland or born in 1821, and found nothing. I was unable to find a single record to corroborate this mysterious other Isaac Stokes.

As the age at death in 1877 was correct, I assume that either Isaac was lying, or that some mistake was made either on the register at the home of the Methodist minster, or a subsequent mistranscription or muddle on the remnants of the surviving register. Therefore I remain convinced that the Camden stonemason Isaac Stokes was indeed our Isaac from Oxfordshire.

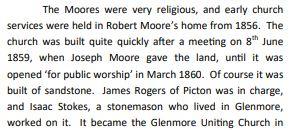

I found a history society newsletter article that mentioned Isaac Stokes, stone mason, had built the Glenmore church, near Camden, in 1859.

From the Wollondilly museum April 2020 newsletter:

From the Camden History website:

“The stone set over the porch of Glenmore Church gives the date of 1860. The church was begun in 1859 on land given by Joseph Moore. James Rogers of Picton was given the contract to build and local builder, Mr. Stokes, carried out the work. Elizabeth Moore, wife of Edward, laid the foundation stone. The first service was held on 19th March 1860. The cemetery alongside the church contains the headstones and memorials of the areas early pioneers.”

Isaac died on the 3rd September 1877. The inquest report puts his place of death as Bagdelly, near to Camden, and another death register has put Cambelltown, also very close to Camden. His age was recorded as 71 and the inquest report states his cause of death was “rupture of one of the large pulmonary vessels of the lung”. His wife Catherine died in childbirth in 1870 at the age of 43.

Isaac and Catherine’s children:

William Stokes 1857-1928

Catherine Stokes 1859-1846

Sarah Josephine Stokes 1861-1931

Ellen Stokes 1863-1932

Rosanna Stokes 1865-1919

Louisa Stokes 1868-1844.

It’s possible that Catherine Daly was a transported convict from Ireland.

Some time later I unexpectedly received a follow up email from The Oaks Heritage Centre in Australia.

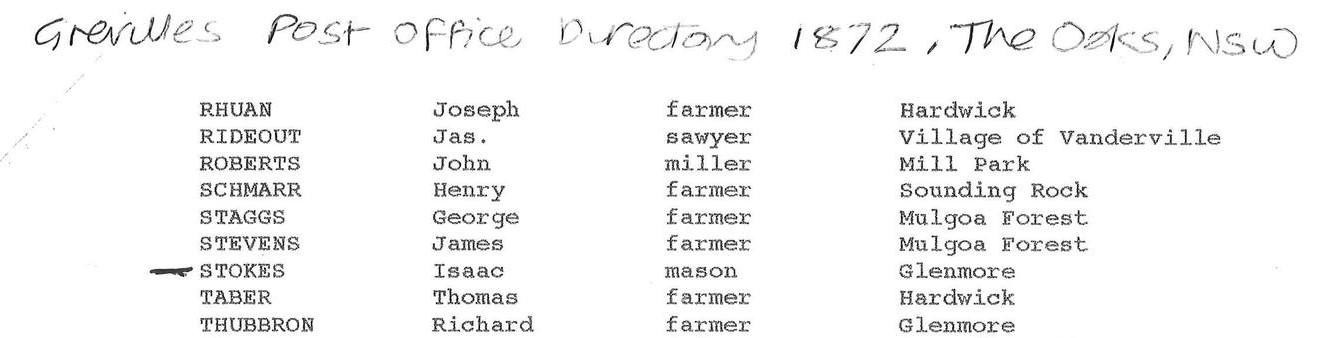

“The Gaudry papers which we have in our archive record him (Isaac Stokes) as having built: the church, the school and the teachers residence. Isaac is recorded in the General return of convicts: 1837 and in Grevilles Post Office directory 1872 as a mason in Glenmore.”

November 10, 2022 at 12:08 pm #6344

November 10, 2022 at 12:08 pm #6344In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The Tetbury Riots

While researching the Tetbury riots (I had found some Browning names in the newspaper archives in association with the uprisings) I came across an article called “Elizabeth Parker, the Swing Riots, and the Tetbury parish clerk” by Jill Evans.

I noted the name of the parish clerk, Daniel Cole, because I know someone else of that name. The incident in the article was 1830.

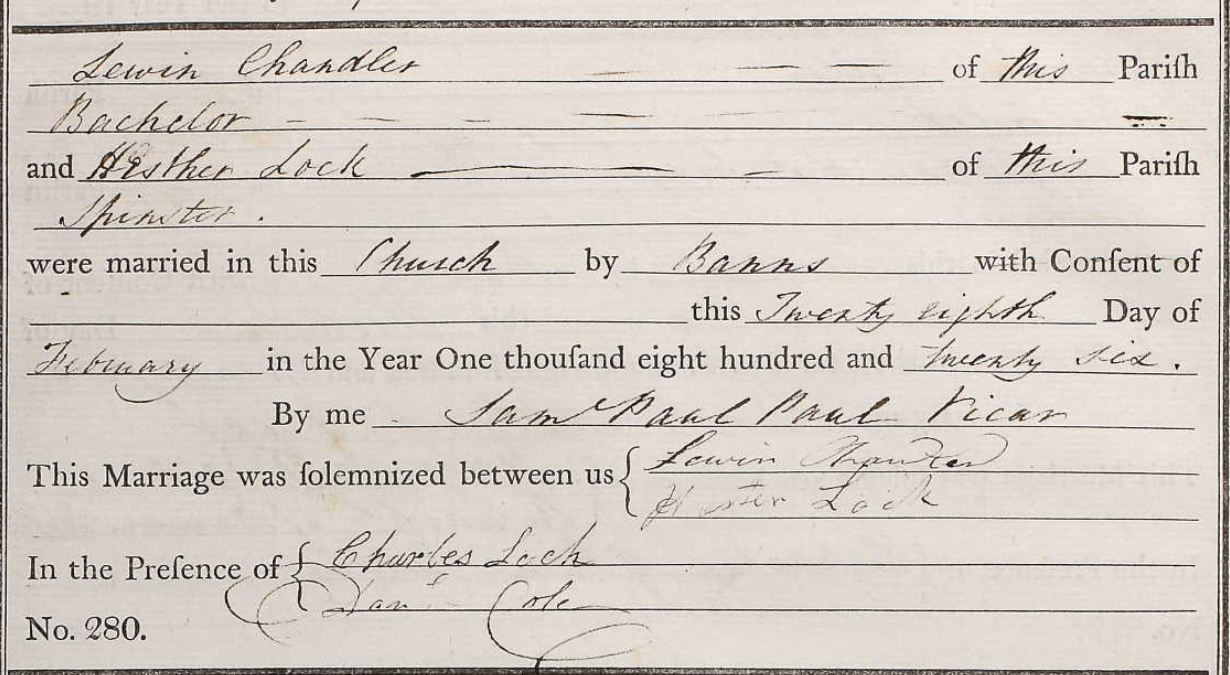

I found the 1826 marriage in the Tetbury parish registers (where Daniel was the parish clerk) of my 4x great grandmothers sister Hesther Lock. One of the witnesses was her brother Charles, and the other was Daniel Cole, the parish clerk.

Marriage of Lewin Chandler and Hesther Lock in 1826:

from the article:

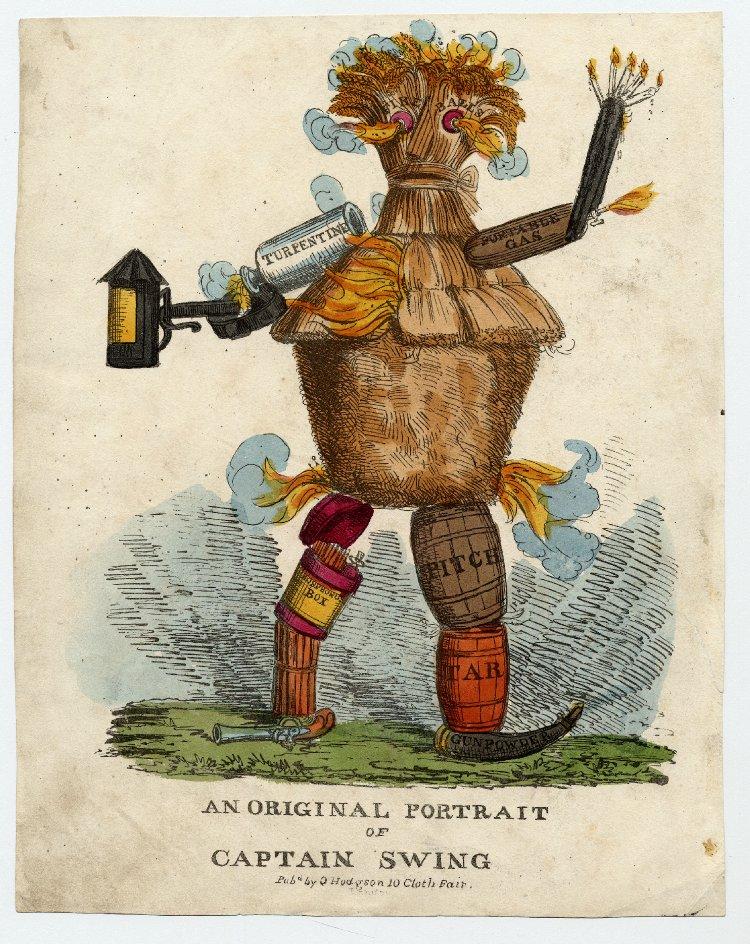

“The Swing Riots were disturbances which took place in 1830 and 1831, mostly in the southern counties of England. Agricultural labourers, who were already suffering due to low wages and a lack of work after several years of bad harvests, rose up when their employers introduced threshing machines into their workplaces. The riots got their name from the threatening letters which were sent to farmers and other employers, which were signed “Captain Swing.”

The riots spread into Gloucestershire in November 1830, with the Tetbury area seeing the worst of the disturbances. Amongst the many people arrested afterwards was one woman, Elizabeth Parker. She has sometimes been cited as one of only two females who were transported for taking part in the Swing Riots. In fact, she was sentenced to be transported for this crime, but never sailed, as she was pardoned a few months after being convicted. However, less than a year after being released from Gloucester Gaol, she was back, awaiting trial for another offence. The circumstances in both of the cases she was tried for reveal an intriguing relationship with one Daniel Cole, parish clerk and assistant poor law officer in Tetbury….

….Elizabeth Parker was committed to Gloucester Gaol on 4 December 1830. In the Gaol Registers, she was described as being 23 and a “labourer”. She was in fact a prostitute, and she was unusual for the time in that she could read and write. She was charged on the oaths of Daniel Cole and others with having been among a mob which destroyed a threshing machine belonging to Jacob Hayward, at his farm in Beverstone, on 26 November.

…..Elizabeth Parker was granted royal clemency in July 1831 and was released from prison. She returned to Tetbury and presumably continued in her usual occupation, but on 27 March 1832, she was committed to Gloucester Gaol again. This time, she was charged with stealing 2 five pound notes, 5 sovereigns and 5 half sovereigns, from the person of Daniel Cole.

Elizabeth was tried at the Lent Assizes which began on 28 March, 1832. The details of her trial were reported in the Morning Post. Daniel Cole was in the “Boat Inn” (meaning the Boot Inn, I think) in Tetbury, when Elizabeth Parker came in. Cole “accompanied her down the yard”, where he stayed with her for about half an hour. The next morning, he realised that all his money was gone. One of his five pound notes was identified by him in a shop, where Parker had bought some items.

Under cross-examination, Cole said he was the assistant overseer of the poor and collector of public taxes of the parish of Tetbury. He was married with one child. He went in to the inn at about 9 pm, and stayed about 2 hours, drinking in the parlour, with the landlord, Elizabeth Parker, and two others. He was not drunk, but he was “rather fresh.” He gave the prisoner no money. He saw Elizabeth Parker next morning at the Prince and Princess public house. He didn’t drink with her or give her any money. He did give her a shilling after she was committed. He never said that he would not have prosecuted her “if it was not for her own tongue”. (Presumably meaning he couldn’t trust her to keep her mouth shut.)”

Contemporary illustration of the Swing riots:

Captain Swing was the imaginary leader agricultural labourers who set fire to barns and haystacks in the southern and eastern counties of England from 1830. Although the riots were ruthlessly put down (19 hanged, 644 imprisoned and 481 transported), the rural agitation led the new Whig government to establish a Royal Commission on the Poor Laws and its report provided the basis for the 1834 New Poor Law enacted after the Great Reform Bills of 1833.

An original portrait of Captain Swing hand coloured lithograph circa 1830:

November 10, 2022 at 10:59 am #6343

November 10, 2022 at 10:59 am #6343In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

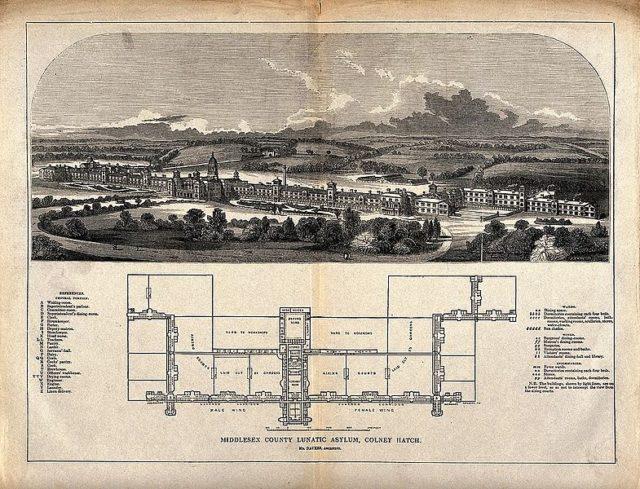

Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum

William James Stokes

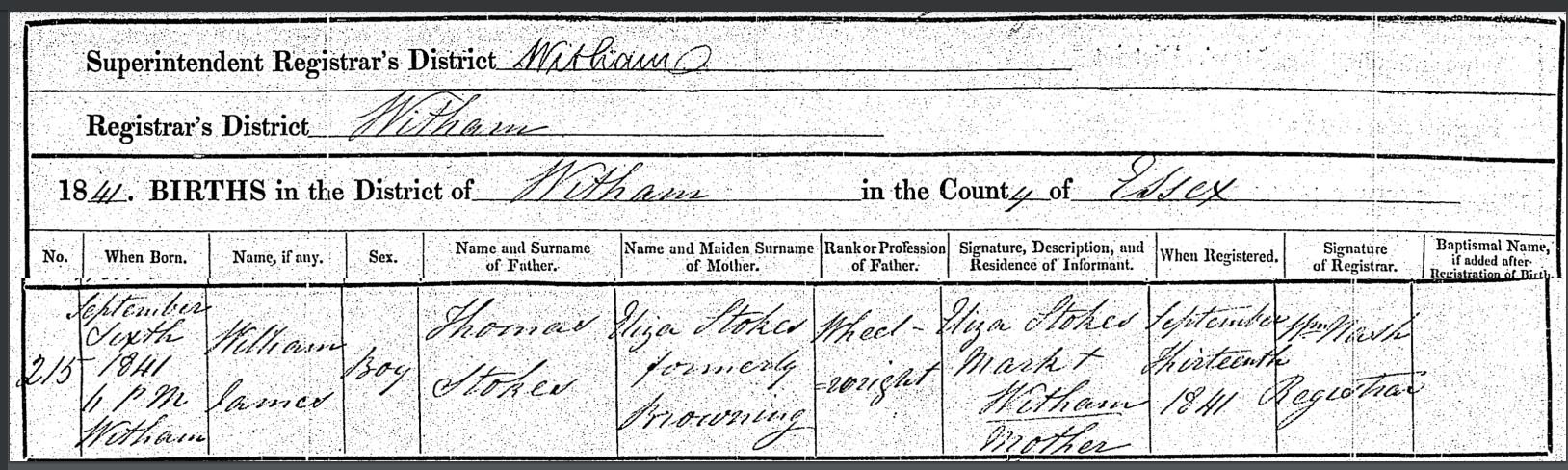

William James Stokes was the first son of Thomas Stokes and Eliza Browning. Oddly, his birth was registered in Witham in Essex, on the 6th September 1841.

Birth certificate of William James Stokes:

His father Thomas Stokes has not yet been found on the 1841 census, and his mother Eliza was staying with her uncle Thomas Lock in Cirencester in 1841. Eliza’s mother Mary Browning (nee Lock) was staying there too. Thomas and Eliza were married in September 1840 in Hempstead in Gloucestershire.

It’s a mystery why William was born in Essex but one possibility is that his father Thomas, who later worked with the Chipperfields making circus wagons, was staying with the Chipperfields who were wheelwrights in Witham in 1841. Or perhaps even away with a traveling circus at the time of the census, learning the circus waggon wheelwright trade. But this is a guess and it’s far from clear why Eliza would make the journey to Witham to have the baby when she was staying in Cirencester a few months prior.

In 1851 Thomas and Eliza, William and four younger siblings were living in Bledington in Oxfordshire.

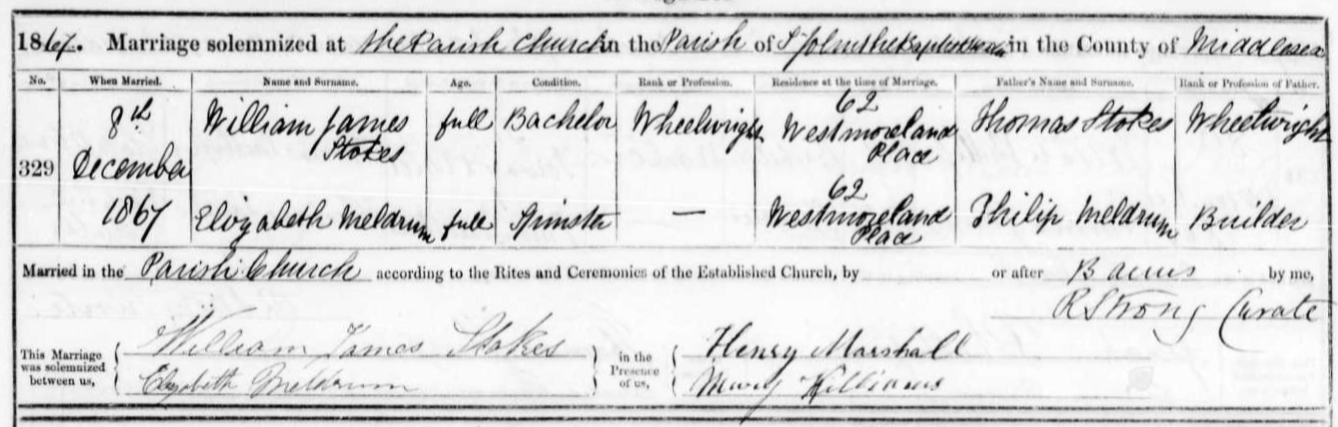

William was a 19 year old wheelwright living with his parents in Evesham in 1861. He married Elizabeth Meldrum in December 1867 in Hackney, London. He and his father are both wheelwrights on the marriage register.

Marriage of William James Stokes and Elizabeth Meldrum in 1867:

William and Elizabeth had a daughter, Elizabeth Emily Stokes, in 1868 in Shoreditch, London.

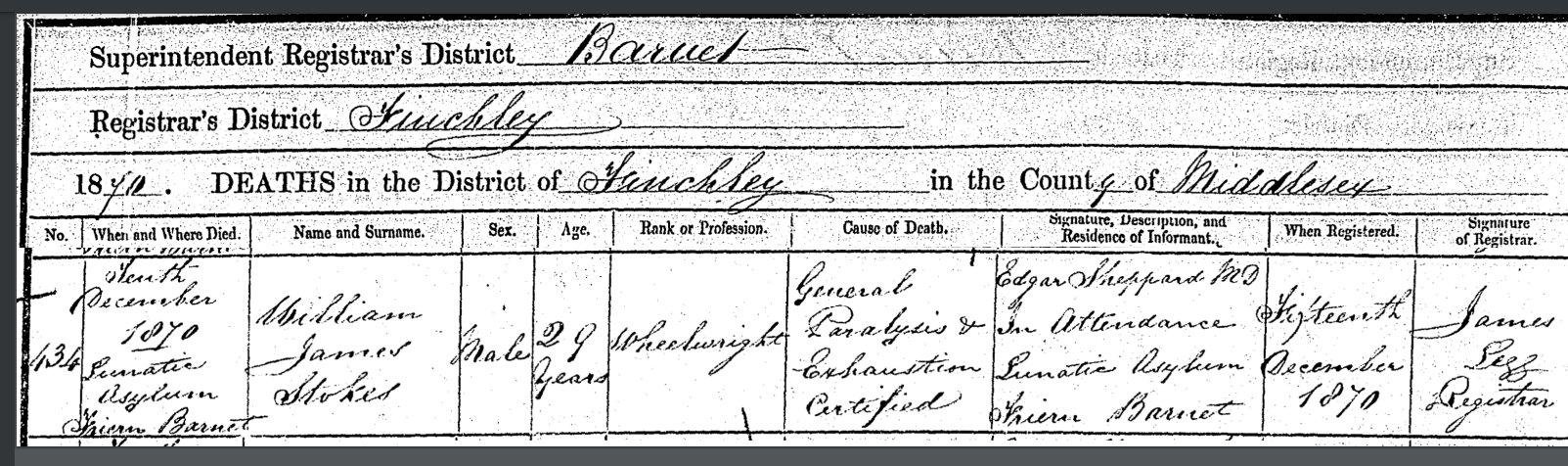

On the 3rd of December 1870, William James Stokes was admitted to Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum. One week later on the 10th of December, he was dead.

On his death certificate the cause of death was “general paralysis and exhaustion, certified. MD Edgar Sheppard in attendance.” William was just 29 years old.

Death certificate William James Stokes:

I asked on a genealogy forum what could possibly have caused this death at such a young age. A retired pathology professor replied that “in medicine the term General Paralysis is only used in one context – that of Tertiary Syphilis.”

“Tertiary syphilis is the third and final stage of syphilis, a sexually transmitted disease that unfolds in stages when the individual affected doesn’t receive appropriate treatment.”From the article “Looking back: This fascinating and fatal disease” by Jennifer Wallis:

“……in asylums across Britain in the late 19th century, with hundreds of people receiving the diagnosis of general paralysis of the insane (GPI). The majority of these were men in their 30s and 40s, all exhibiting one or more of the disease’s telltale signs: grandiose delusions, a staggering gait, disturbed reflexes, asymmetrical pupils, tremulous voice, and muscular weakness. Their prognosis was bleak, most dying within months, weeks, or sometimes days of admission.

The fatal nature of GPI made it of particular concern to asylum superintendents, who became worried that their institutions were full of incurable cases requiring constant care. The social effects of the disease were also significant, attacking men in the prime of life whose admission to the asylum frequently left a wife and children at home. Compounding the problem was the erratic behaviour of the general paralytic, who might get themselves into financial or legal difficulties. Delusions about their vast wealth led some to squander scarce family resources on extravagant purchases – one man’s wife reported he had bought ‘a quantity of hats’ despite their meagre income – and doctors pointed to the frequency of thefts by general paralytics who imagined that everything belonged to them.”

The London Archives hold the records for Colney Hatch, but they informed me that the particular records for the dates that William was admitted and died were in too poor a condition to be accessed without causing further damage.

Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum gained such notoriety that the name “Colney Hatch” appeared in various terms of abuse associated with the concept of madness. Infamous inmates that were institutionalized at Colney Hatch (later called Friern Hospital) include Jack the Ripper suspect Aaron Kosminski from 1891, and from 1911 the wife of occultist Aleister Crowley. In 1993 the hospital grounds were sold and the exclusive apartment complex called Princess Park Manor was built.

Colney Hatch:

In 1873 Williams widow married William Hallam in Limehouse in London. Elizabeth died in 1930, apparently unaffected by her first husbands ailment.

October 23, 2022 at 6:57 am #6340In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Wheelwrights of Broadway

Thomas Stokes 1816-1885

Frederick Stokes 1845-1917

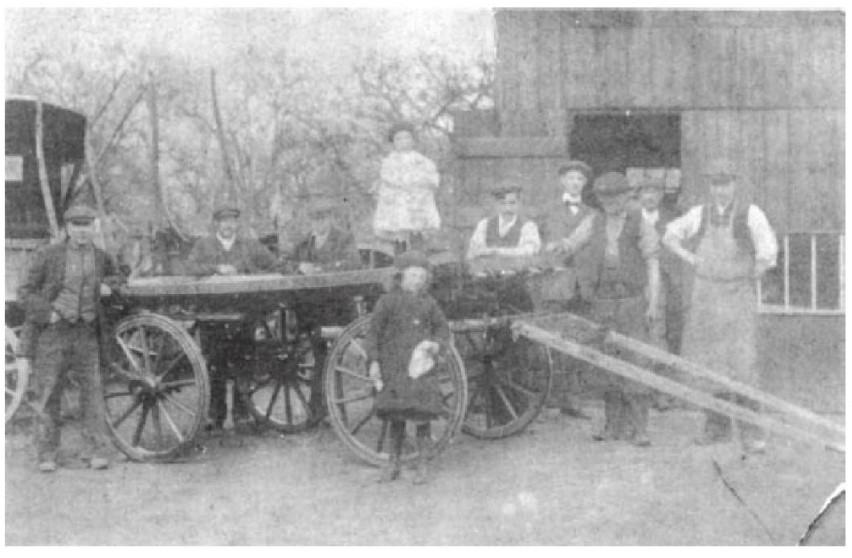

Stokes Wheelwrights. Fred on left of wheel, Thomas his father on right.

Thomas Stokes

Thomas Stokes was born in Bicester, Oxfordshire in 1816. He married Eliza Browning (born in 1814 in Tetbury, Gloucestershire) in Gloucester in 1840 Q3. Their first son William was baptised in Chipping Hill, Witham, Essex, on 3 Oct 1841. This seems a little unusual, and I can’t find Thomas and Eliza on the 1841 census. However both the 1851 and 1861 census state that William was indeed born in Essex.

In 1851 Thomas and Eliza were living in Bledington, Gloucestershire, and Thomas was a journeyman carpenter.

Note that a journeyman does not mean someone who moved around a lot. A journeyman was a tradesman who had served his trade apprenticeship and mastered his craft, not bound to serve a master, but originally hired by the day. The name derives from the French for day – jour.

Also on the 1851 census: their daughter Susan, born in Churchill Oxfordshire in 1844; son Frederick born in Bledington Gloucestershire in 1846; daughter Louisa born in Foxcote Oxfordshire in 1849; and 2 month old daughter Harriet born in Bledington in 1851.

On the 1861 census Thomas and Eliza were living in Evesham, Worcestershire, and daughter Susan was no longer living at home, but William, Fred, Louisa and Harriet were, as well as daughter Emily born in Churchill Oxfordshire in 1856. Thomas was a wheelwright.

On the 1871 census Thomas and Eliza were still living in Evesham, and Thomas was a wheelwright employing three apprentices. Son Fred, also a wheelwright, and his wife Ann Rebecca live with them.

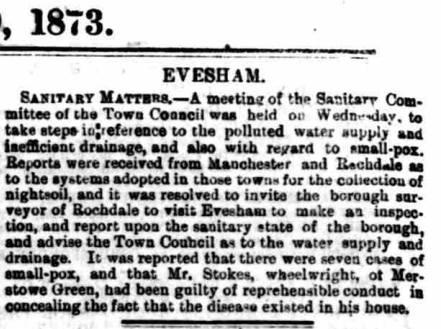

Mr Stokes, wheelwright, was found guilty of reprehensible conduct in concealing the fact that small-pox existed in his house, according to a mention in The Oxfordshire Weekly News on Wednesday 19 February 1873:

From Paul Weaver’s ancestry website:

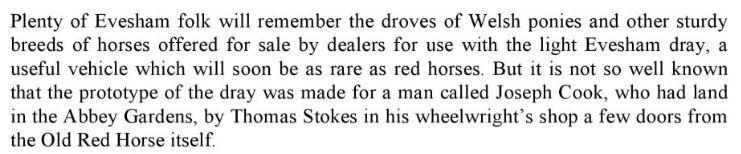

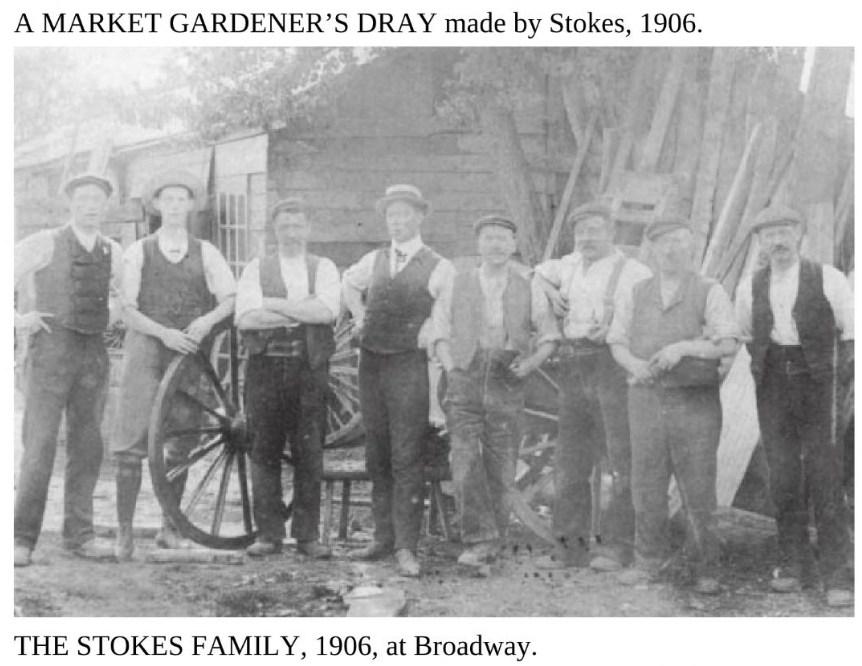

“It was Thomas Stokes who built the first “Famous Vale of Evesham Light Gardening Dray for a Half-Legged Horse to Trot” (the quotation is from his account book), the forerunner of many that became so familiar a sight in the towns and villages from the 1860s onwards. He built many more for the use of the Vale gardeners.

Thomas also had long-standing business dealings with the people of the circus and fairgrounds, and had a contract to effect necessary repairs and renewals to their waggons whenever they visited the district. He built living waggons for many of the show people’s families as well as shooting galleries and other equipment peculiar to the trade of his wandering customers, and among the names figuring in his books are some still familiar today, such as Wilsons and Chipperfields.

He is also credited with inventing the wooden “Mushroom” which was used by housewives for many years to darn socks. He built and repaired all kinds of vehicles for the gentry as well as for the circus and fairground travellers.

Later he lived with his wife at Merstow Green, Evesham, in a house adjoining the Almonry.”

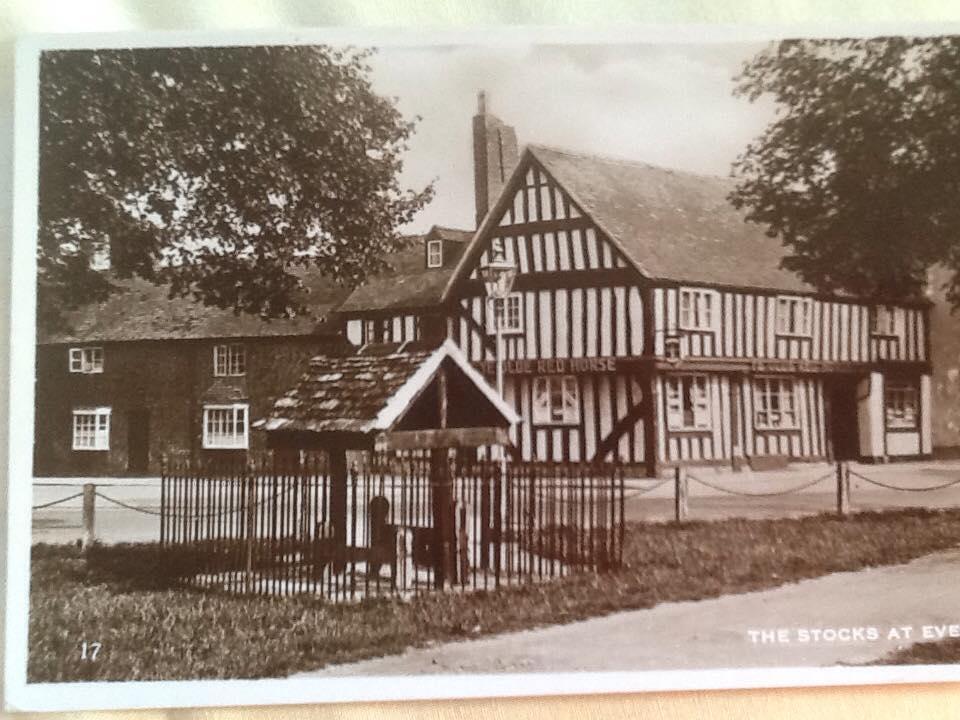

An excerpt from the book Evesham Inns and Signs by T.J.S. Baylis:

The Old Red Horse, Evesham:

Thomas died in 1885 aged 68 of paralysis, bronchitis and debility. His wife Eliza a year later in 1886.

Frederick Stokes

In Worcester in 1870 Fred married Ann Rebecca Day, who was born in Evesham in 1845.

Ann Rebecca Day:

In 1871 Fred was still living with his parents in Evesham, with his wife Ann Rebecca as well as their three month old daughter Annie Elizabeth. Fred and Ann (referred to as Rebecca) moved to La Quinta on Main Street, Broadway.

Rebecca Stokes in the doorway of La Quinta on Main Street Broadway, with her grandchildren Ralph and Dolly Edwards:

Fred was a wheelwright employing one man on the 1881 census. In 1891 they were still in Broadway, Fred’s occupation was wheelwright and coach painter, as well as his fifteen year old son Frederick.

In the Evesham Journal on Saturday 10 December 1892 it was reported that “Two cases of scarlet fever, the children of Mr. Stokes, wheelwright, Broadway, were certified by Mr. C. W. Morris to be isolated.”

Still in Broadway in 1901 and Fred’s son Albert was also a wheelwright. By 1911 Fred and Rebecca had only one son living at home in Broadway, Reginald, who was a coach painter. Fred was still a wheelwright aged 65.

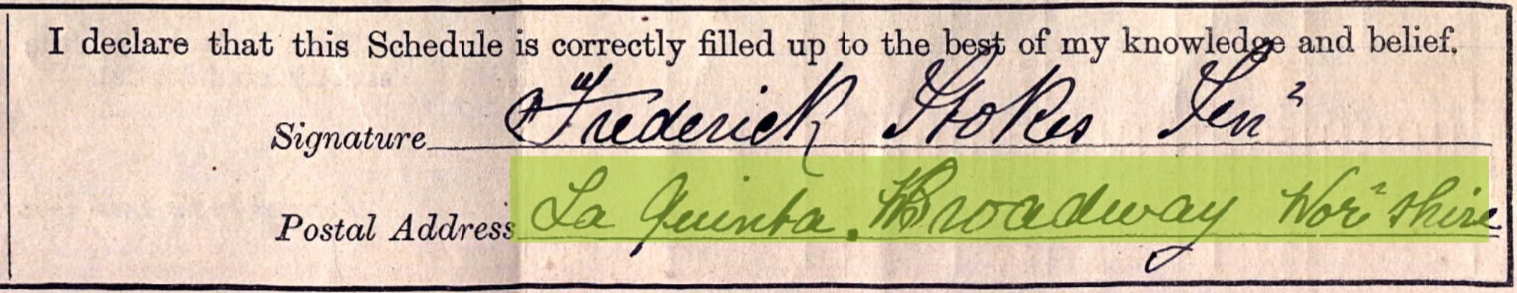

Fred’s signature on the 1911 census:

Rebecca died in 1912 and Fred in 1917.

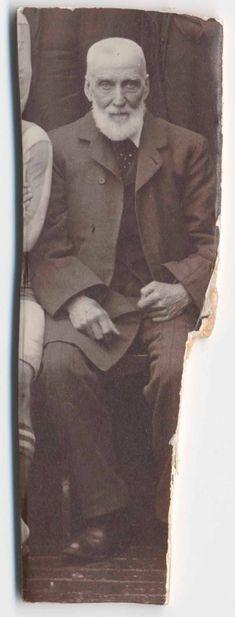

Fred Stokes:

In the book Evesham to Bredon From Old Photographs By Fred Archer:

October 19, 2022 at 6:46 am #6336

October 19, 2022 at 6:46 am #6336In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

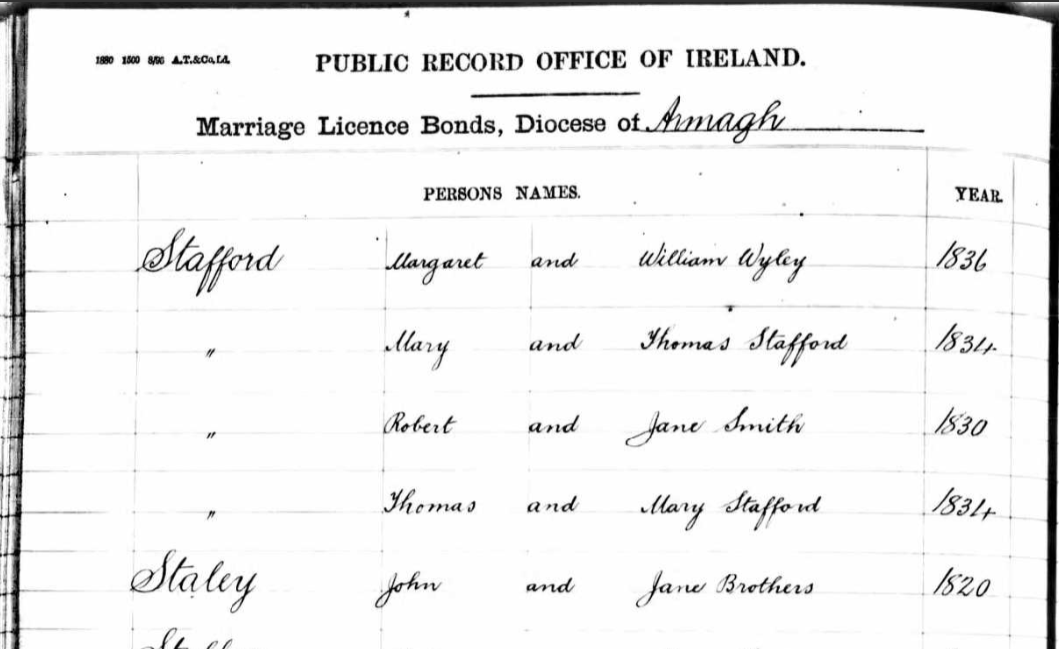

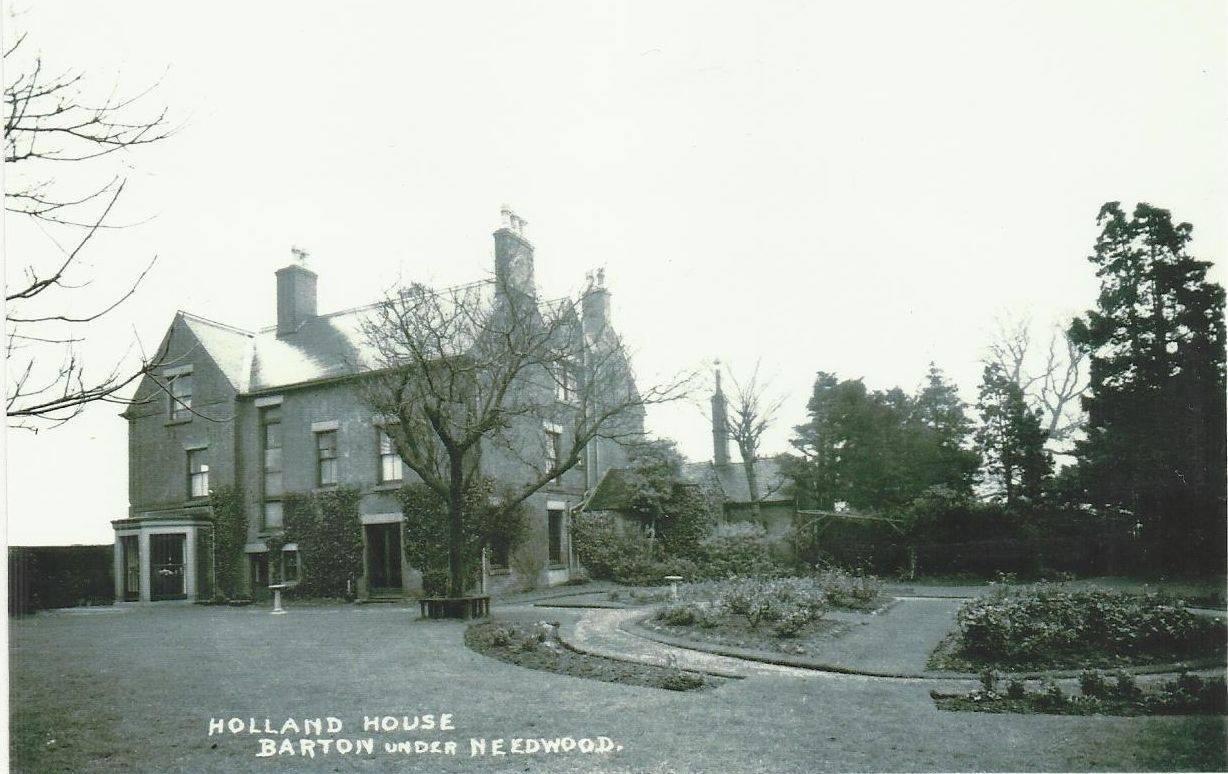

The Hamstall Ridware Connection

Stubbs and Woods

Hamstall Ridware

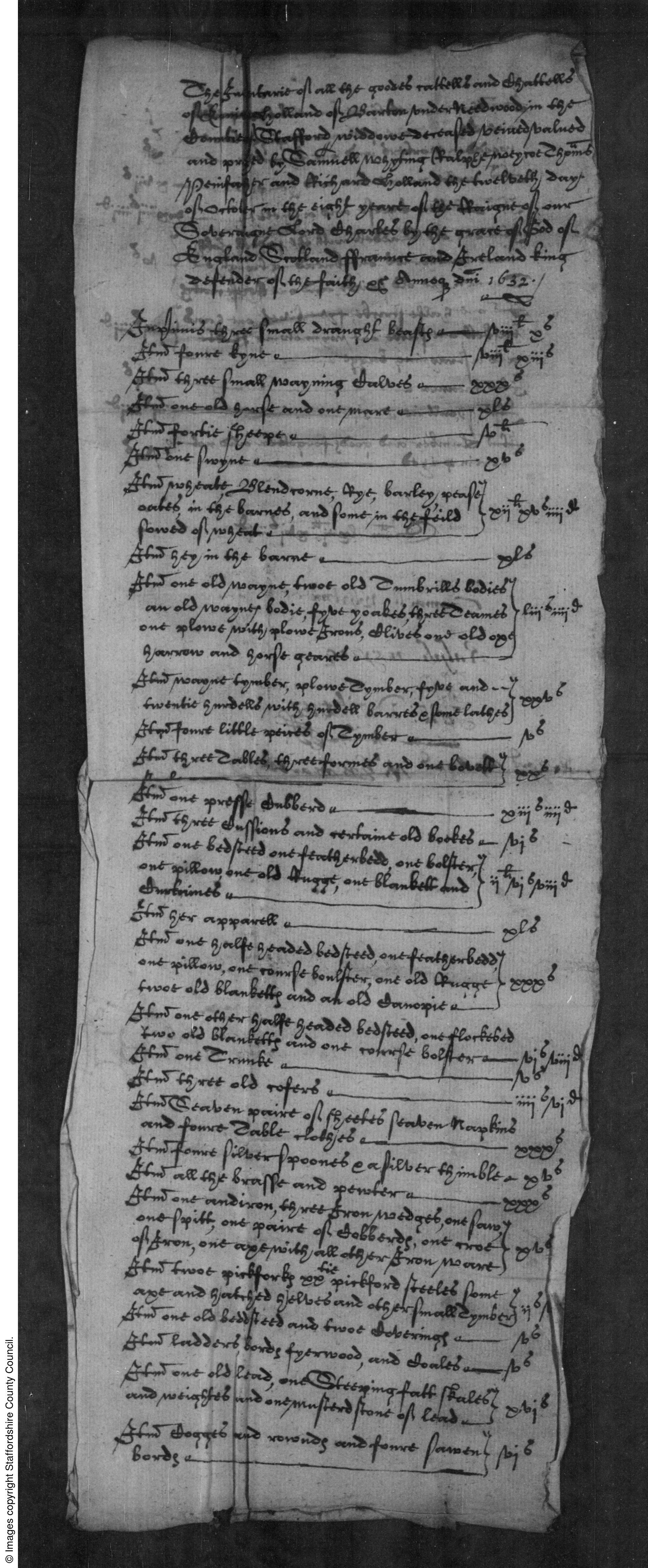

Hamstall RidwareCharles Tomlinson‘s (1847-1907) wife Emma Grattidge (1853-1911) was born in Wolverhampton, the daughter and youngest child of William Grattidge (1820-1887) born in Foston, Derbyshire, and Mary Stubbs (1819-1880), born in Burton on Trent, daughter of Solomon Stubbs.

Solomon Stubbs (1781-1857) was born in Hamstall Ridware in 1781, the son of Samuel and Rebecca. Samuel Stubbs (1743-) and Rebecca Wood (1754-) married in 1769 in Darlaston. Samuel and Rebecca had six other children, all born in Darlaston. Sadly four of them died in infancy. Son John was born in 1779 in Darlaston and died two years later in Hamstall Ridware in 1781, the same year that Solomon was born there.

But why did they move to Hamstall Ridware?

Samuel Stubbs was born in 1743 in Curdworth, Warwickshire (near to Birmingham). I had made a mistake on the tree (along with all of the public trees on the Ancestry website) and had Rebecca Wood born in Cheddleton, Staffordshire. Rebecca Wood from Cheddleton was also born in 1843, the right age for the marriage. The Rebecca Wood born in Darlaston in 1754 seemed too young, at just fifteen years old at the time of the marriage. I couldn’t find any explanation for why a woman from Cheddleton would marry in Darlaston and then move to Hamstall Ridware. People didn’t usually move around much other than intermarriage with neighbouring villages, especially women. I had a closer look at the Darlaston Rebecca, and did a search on her father William Wood. I found his 1784 will online in which he mentions his daughter Rebecca, wife of Samuel Stubbs. Clearly the right Rebecca Wood was the one born in Darlaston, which made much more sense.

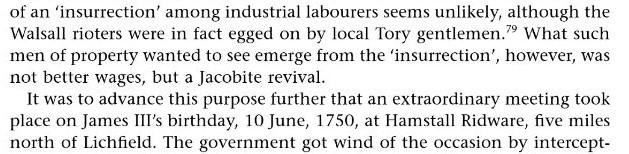

An excerpt from William Wood’s 1784 will mentioning daughter Rebecca married to Samuel Stubbs:

But why did they move to Hamstall Ridware circa 1780?

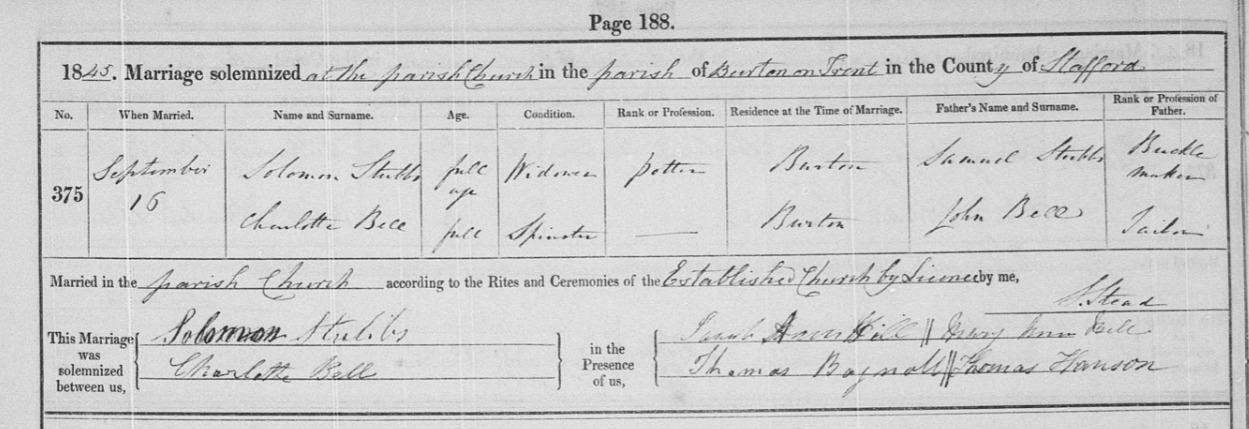

I had not intially noticed that Solomon Stubbs married again the year after his wife Phillis Lomas (1787-1844) died. Solomon married Charlotte Bell in 1845 in Burton on Trent and on the marriage register, Solomon’s father Samuel Stubbs occupation was mentioned: Samuel was a buckle maker.

Marriage of Solomon Stubbs and Charlotte Bell, father Samuel Stubbs buckle maker:

A rudimentary search on buckle making in the late 1700s provided a possible answer as to why Samuel and Rebecca left Darlaston in 1781. Shoe buckles had gone out of fashion, and by 1781 there were half as many buckle makers in Wolverhampton as there had been previously.

“Where there were 127 buckle makers at work in Wolverhampton, 68 in Bilston and 58 in Birmingham in 1770, their numbers had halved in 1781.”

via “historywebsite”(museum/metalware/steel)

Steel buckles had been the height of fashion, and the trade became enormous in Wolverhampton. Wolverhampton was a steel working town, renowned for its steel jewellery which was probably of many types. The trade directories show great numbers of “buckle makers”. Steel buckles were predominantly made in Wolverhampton: “from the late 1760s cut steel comes to the fore, from the thriving industry of the Wolverhampton area”. Bilston was also a great centre of buckle making, and other areas included Walsall. (It should be noted that Darlaston, Walsall, Bilston and Wolverhampton are all part of the same area)

In 1860, writing in defence of the Wolverhampton Art School, George Wallis talks about the cut steel industry in Wolverhampton. Referring to “the fine steel workers of the 17th and 18th centuries” he says: “Let them remember that 100 years ago [sc. c. 1760] a large trade existed with France and Spain in the fine steel goods of Birmingham and Wolverhampton, of which the latter were always allowed to be the best both in taste and workmanship. … A century ago French and Spanish merchants had their houses and agencies at Birmingham for the purchase of the steel goods of Wolverhampton…..The Great Revolution in France put an end to the demand for fine steel goods for a time and hostile tariffs finished what revolution began”.

The next search on buckle makers, Wolverhampton and Hamstall Ridware revealed an unexpected connecting link.

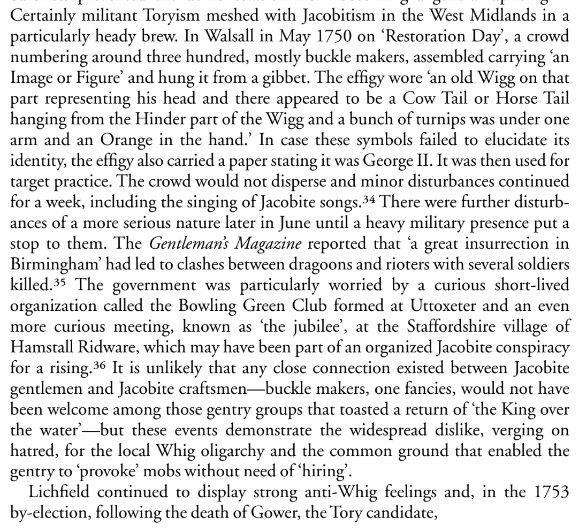

In Riotous Assemblies: Popular Protest in Hanoverian England by Adrian Randall:

In Walsall in 1750 on “Restoration Day” a crowd numbering 300 assembled, mostly buckle makers, singing Jacobite songs and other rebellious and riotous acts. The government was particularly worried about a curious meeting known as the “Jubilee” in Hamstall Ridware, which may have been part of a conspiracy for a Jacobite uprising.

But this was thirty years before Samuel and Rebecca moved to Hamstall Ridware and does not help to explain why they moved there around 1780, although it does suggest connecting links.

Rebecca’s father, William Wood, was a brickmaker. This was stated at the beginning of his will. On closer inspection of the will, he was a brickmaker who owned four acres of brick kilns, as well as dwelling houses, shops, barns, stables, a brewhouse, a malthouse, cattle and land.

A page from the 1784 will of William Wood:

The 1784 will of William Wood of Darlaston:

I William Wood the elder of Darlaston in the county of Stafford, brickmaker, being of sound and disposing mind memory and understanding (praised be to god for the same) do make publish and declare my last will and testament in manner and form following (that is to say) {after debts and funeral expense paid etc} I give to my loving wife Mary the use usage wear interest and enjoyment of all my goods chattels cattle stock in trade ~ money securities for money personal estate and effects whatsoever and wheresoever to hold unto her my said wife for and during the term of her natural life providing she so long continues my widow and unmarried and from or after her decease or intermarriage with any future husband which shall first happen.

Then I give all the said goods chattels cattle stock in trade money securites for money personal estate and effects unto my son Abraham Wood absolutely and forever. Also I give devise and bequeath unto my said wife Mary all that my messuages tenement or dwelling house together with the malthouse brewhouse barn stableyard garden and premises to the same belonging situate and being at Darlaston aforesaid and now in my own possession. Also all that messuage tenement or dwelling house together with the shop garden and premises with the appurtenances to the same ~ belonging situate in Darlaston aforesaid and now in the several holdings or occupation of George Knowles and Edward Knowles to hold the aforesaid premises and every part thereof with the appurtenances to my said wife Mary for and during the term of her natural life provided she so long continues my widow and unmarried. And from or after her decease or intermarriage with a future husband which shall first happen. Then I give and devise the aforesaid premises and every part thereof with the appurtenances unto my said son Abraham Wood his heirs and assigns forever.

Also I give unto my said wife all that piece or parcel of land or ground inclosed and taken out of Heath Field in the parish of Darlaston aforesaid containing four acres or thereabouts (be the same more or less) upon which my brick kilns erected and now in my own possession. To hold unto my said wife Mary until my said son Abraham attains his age of twenty one years if she so long continues my widow and unmarried as aforesaid and from and immediately after my said son Abraham attaining his age of twenty one years or my said wife marrying again as aforesaid which shall first happen then I give the said piece or parcel of land or ground and premises unto my said son Abraham his heirs and assigns forever.

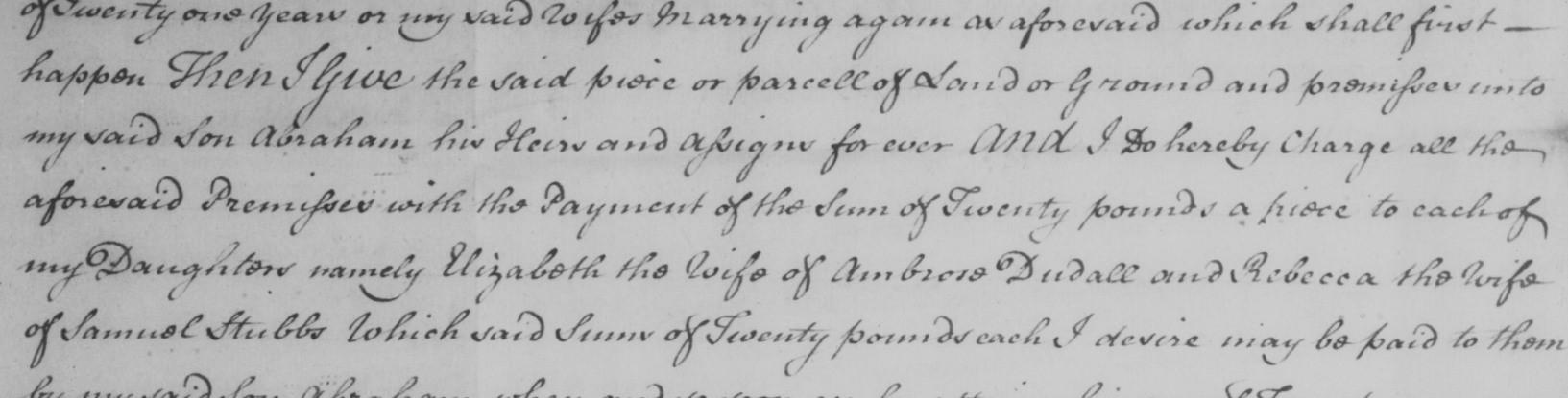

And I do hereby charge all the aforesaid premises with the payment of the sum of twenty pounds a piece to each of my daughters namely Elizabeth the wife of Ambrose Dudall and Rebecca the wife of Samuel Stubbs which said sum of twenty pounds each I devise may be paid to them by my said son Abraham when and so soon as he attains his age of twenty one years provided always and my mind and will is that if my said son Abraham should happen to depart this life without leaving issue of his body lawfully begotten before he attains his age of twenty one years then I give and devise all the aforesaid premises and every part thereof with the appurtenances so given to my said son Abraham as aforesaid unto my said son William Wood and my said daughter Elizabeth Dudall and Rebecca Stubbs their heirs and assigns forever equally divided among them share and share alike as tenants in common and not as joint tenants. And lastly I do hereby nominate constitute and appoint my said wife Mary and my said son Abraham executrix and executor of this my will.

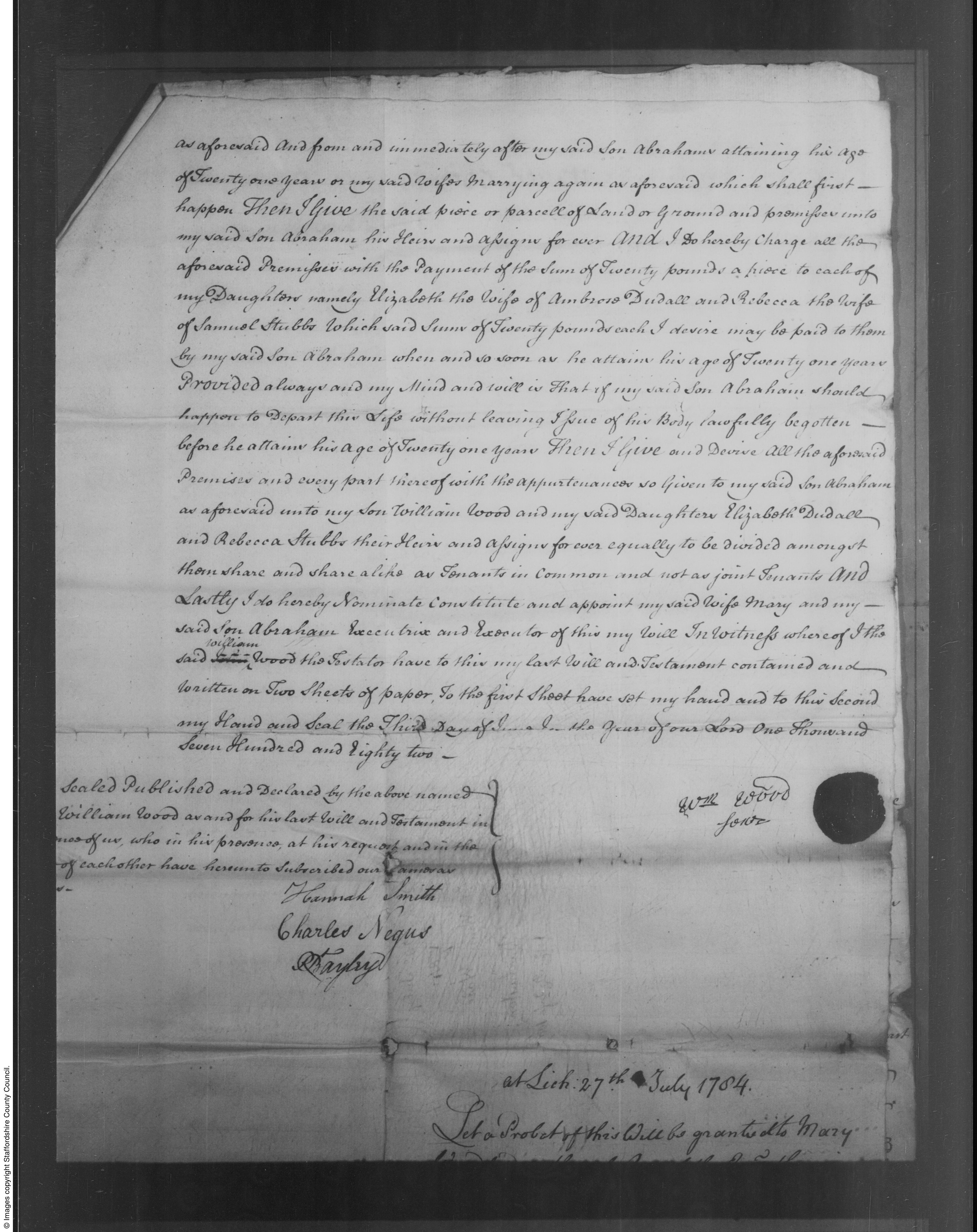

The marriage of William Wood (1725-1784) and Mary Clews (1715-1798) in 1749 was in Hamstall Ridware.

Mary was eleven years Williams senior, and it appears that they both came from Hamstall Ridware and moved to Darlaston after they married. Clearly Rebecca had extended family there (notwithstanding any possible connecting links between the Stubbs buckle makers of Darlaston and the Hamstall Ridware Jacobites thirty years prior). When the buckle trade collapsed in Darlaston, they likely moved to find employment elsewhere, perhaps with the help of Rebecca’s family.

I have not yet been able to find deaths recorded anywhere for either Samuel or Rebecca (there are a couple of deaths recorded for a Samuel Stubbs, one in 1809 in Wolverhampton, and one in 1810 in Birmingham but impossible to say which, if either, is the right one with the limited information, and difficult to know if they stayed in the Hamstall Ridware area or perhaps moved elsewhere)~ or find a reason for their son Solomon to be in Burton upon Trent, an evidently prosperous man with several properties including an earthenware business, as well as a land carrier business.

July 7, 2022 at 9:45 am #6315In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

It was not yet 9am and Eusebius Kazandis was already sweating. The morning sun was hitting hard on the tarp of his booth. He put the last cauldron among lines of cauldrons on a sagging table at the summer fair of Innsbruck, Austria. It was a tiny three-legged black cauldron with a simple Celtic knot on one side and a tree on the other side, like all the others. His father’s father’s father used to make cauldrons for a living, the kind you used to distil ouzo or cook meals for an Inn. But as time went by and industrialisation made it easier for cooks, the trade slowly evolved toward smaller cauldrons for modern Wiccans. A modern witch wanted it portable and light, ready to use in everyday life situations, and Eusebius was there to provide it for them.

Eusebius sat on his chair and sighed. He couldn’t help but notice the woman in colourful dress who had spread a shawl on the grass under the tall sequoia tree. Nobody liked this spot under the branches oozing sticky resin. She didn’t seem to mind. She was arranging small colourful bottles of oil on her shawl. A sign near her said : Massage oils, Fragrant oils, Polishing oils, all with different names evocative of different properties. He hadn’t noticed her yesterday when everybody was installing their stalls. He wondered if she had paid her fee.

Rosa was smiling as she spread in front of her the meadow flowers she’d picked on her way to the market. It was another beautiful day, under the shade and protection of the big sequoia tree watching over her. She assembled small bouquets and put them in between the vials containing her precious handmade oils. She had noticed people, and especially women, would naturally gather around well dressed stalls and engage conversation. Since she left her hometown of Torino, seven years ago, she’d followed the wind on her journey across Europe. It had led her to Innsbruck and had suddenly stopped blowing. That usually meant she had something to do there, but it also meant that she would have to figure out what she was meant to do before she could go on with her life.

The stout man waiting behind his dark cauldrons, was watching her again. He looked quite sad, and she couldn’t help but thinking he was not where he needed to be. When she looked at him, she saw Hephaestus whose inner fire had been tamed. His banner was a mishmash of religious stuff, aimed at pagans and budding witches. Although his grim booth would most certainly benefit from a feminine touch, but she didn’t want to offend him by a misplaced suggestion. It was not her place to find his place.

Rosa, who knew to cultivate any available friendship when she arrived somewhere, waved at the man. Startled, he looked away as if caught doing something inappropriate. Rosa sighed. Maybe she should have bring him some coffee.

As her first clients arrived, she prayed for a gush of wind to tell her where to go next. But the branches of the old tree remained perfectly still under the scorching sun.

July 6, 2022 at 11:02 am #6311In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

Most of the pilgims, if one could call them that, flocked to the linden tree in cars, although some came on motorbikes and bicycles. Olek was grateful that they hadn’t started arriving by the bus load, like Italian tourists. But his cousin Ursula was happy with this strange new turn of events.

Her shabby hotel on the outskirts of town had never been so busy and she was already planning to refurbish the premises and evict the decrepit and motley assortment of aged permanent residents who had just about kept her head above water, financially speaking, for the last twenty years. She could charge much more per night to these new tourists, who were smartly dressed and modern and didn’t argue about the price of a room. They did complain about the damp stained wallpaper though and the threadbare bedding. Ursula reckoned she could charge even more for the rooms if she redecorated, and had an idea to approach her nephew Boris the bank manager for a business loan.

But first she had to evict the old timers. It wasn’t her problem, she reminded herself, if they had nowhere else to go. After all, plenty of charitable aid money was flying around these days, they could easily just join up with some fleeing refugees. She’d even sent some of her old dresses to the collection agency. They may have been forty years old and smelled of moth balls, but they were well made and the refugees would surely be grateful.

Ursula wasn’t looking forward to telling them. No, not at all! She rather liked some of them and was dreading their reaction. You are a business woman, Ursula, she told herself, and you have to look after your own interests! But still she quailed at the thought of knocking on their doors, or announcing it in the communal dining room at supper. Then she had an idea. She’d type up some letters instead, and sign them as if they came from her new business manager. When the residents approached her about the letter she would smile sadly and shrug, saying it wasn’t her decision and that she was terribly sorry but her hands were tied.

July 1, 2022 at 9:51 am #6306In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

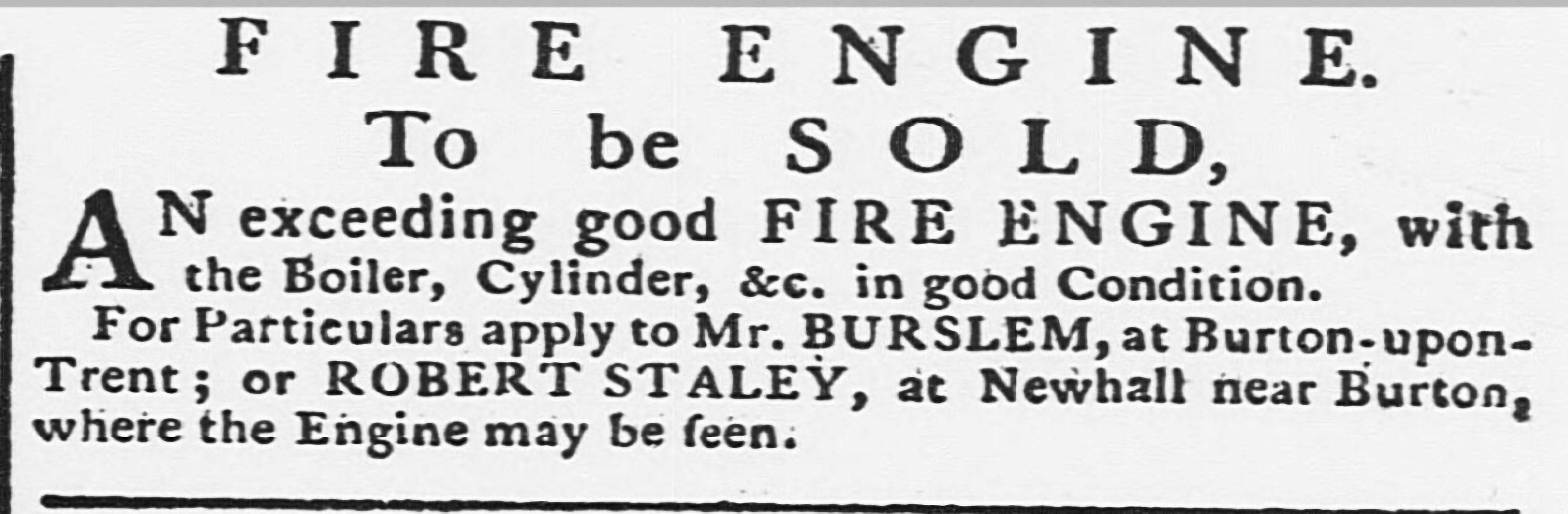

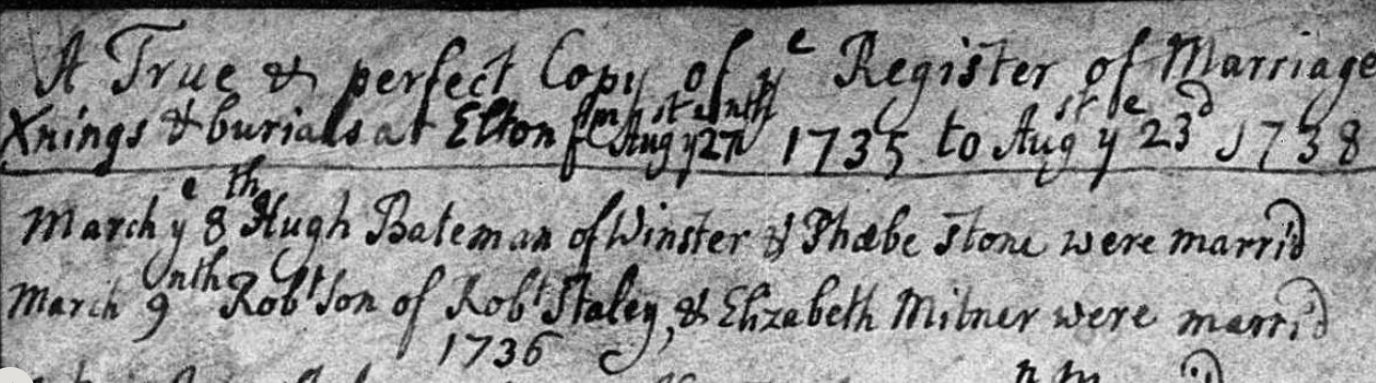

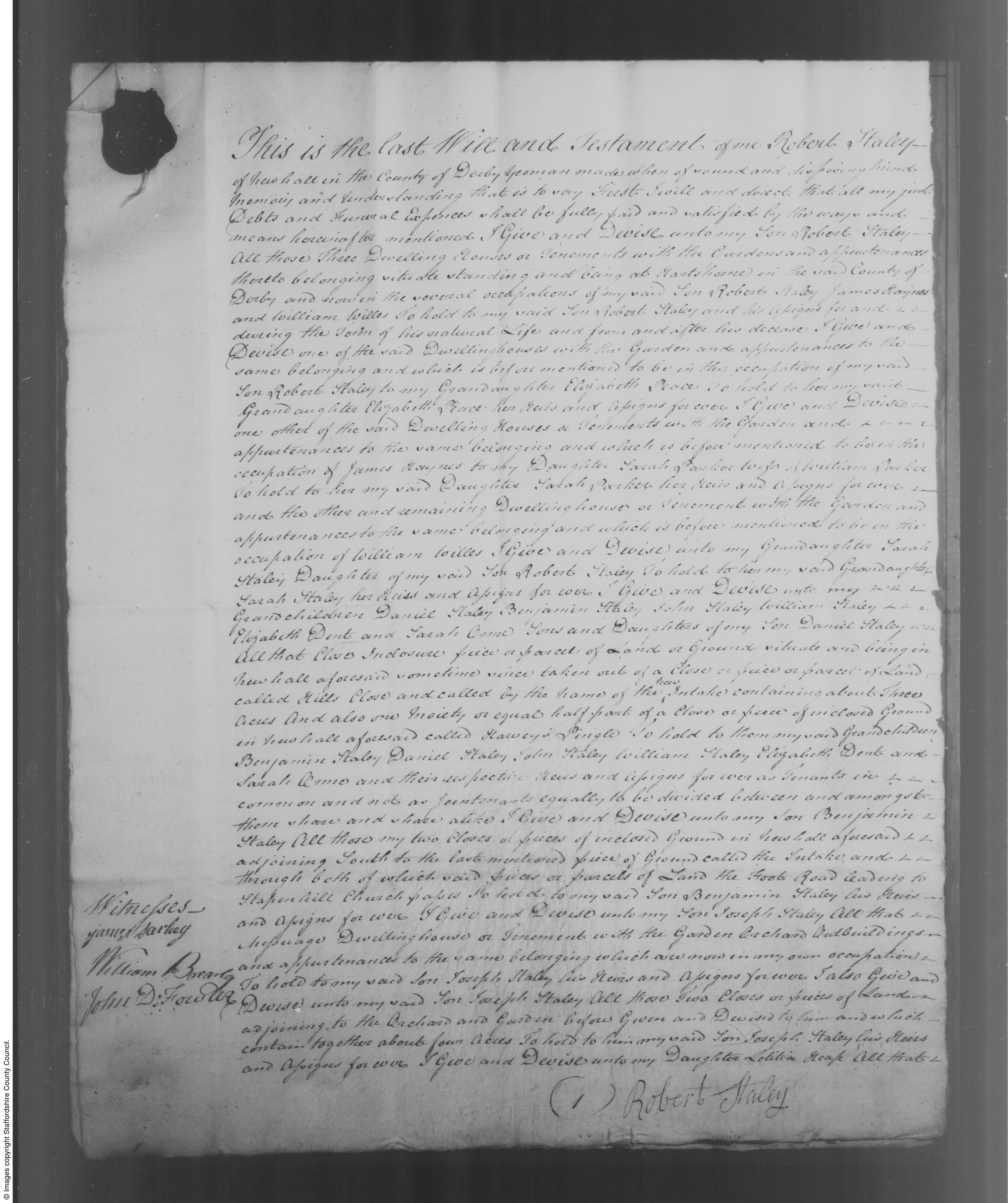

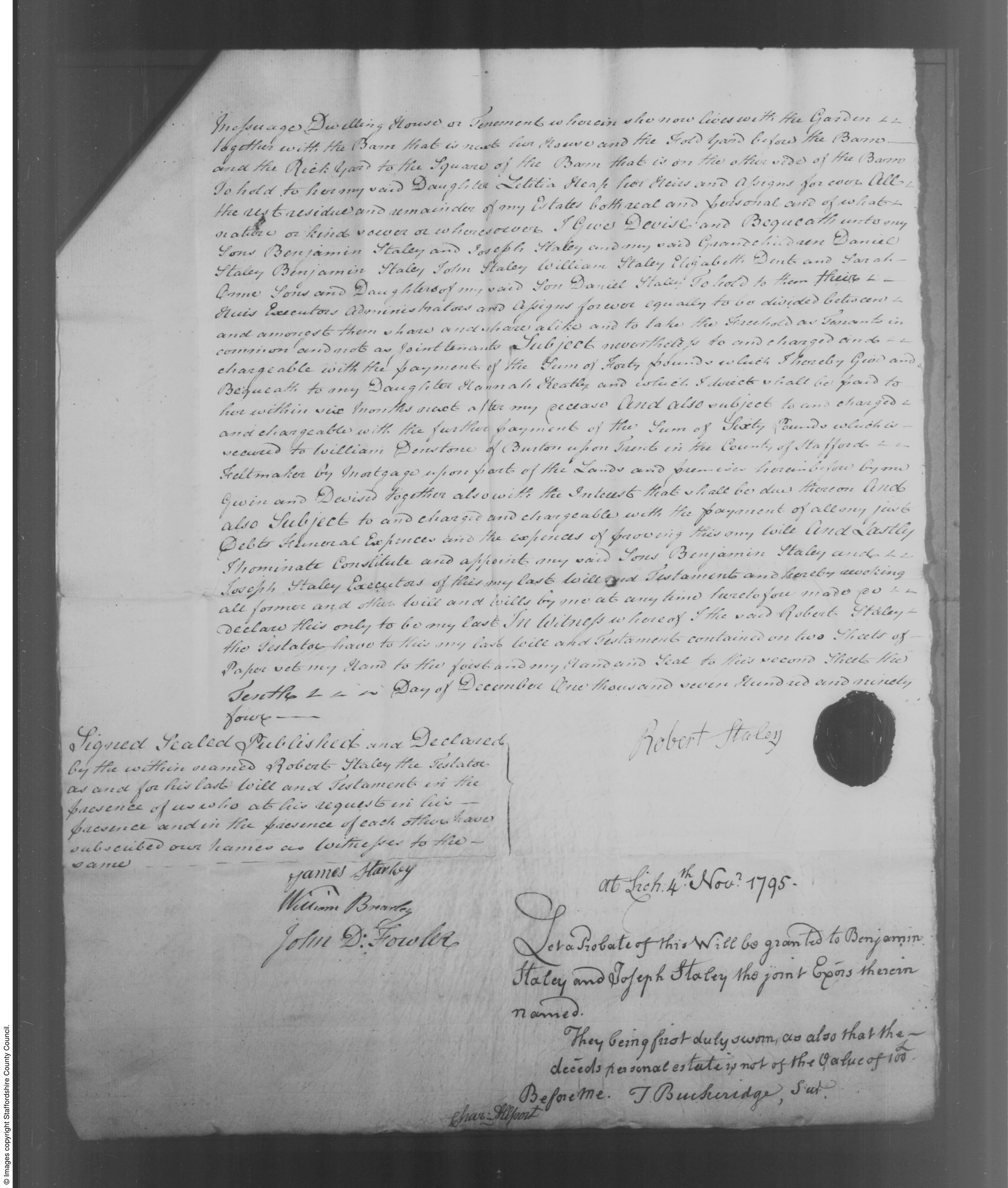

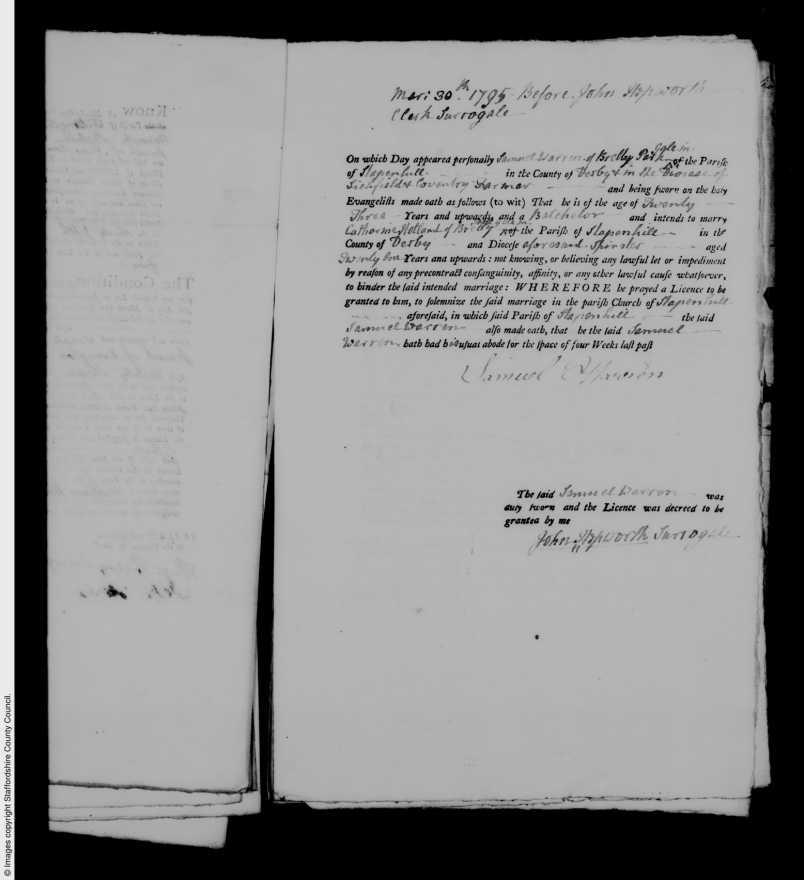

Looking for Robert Staley

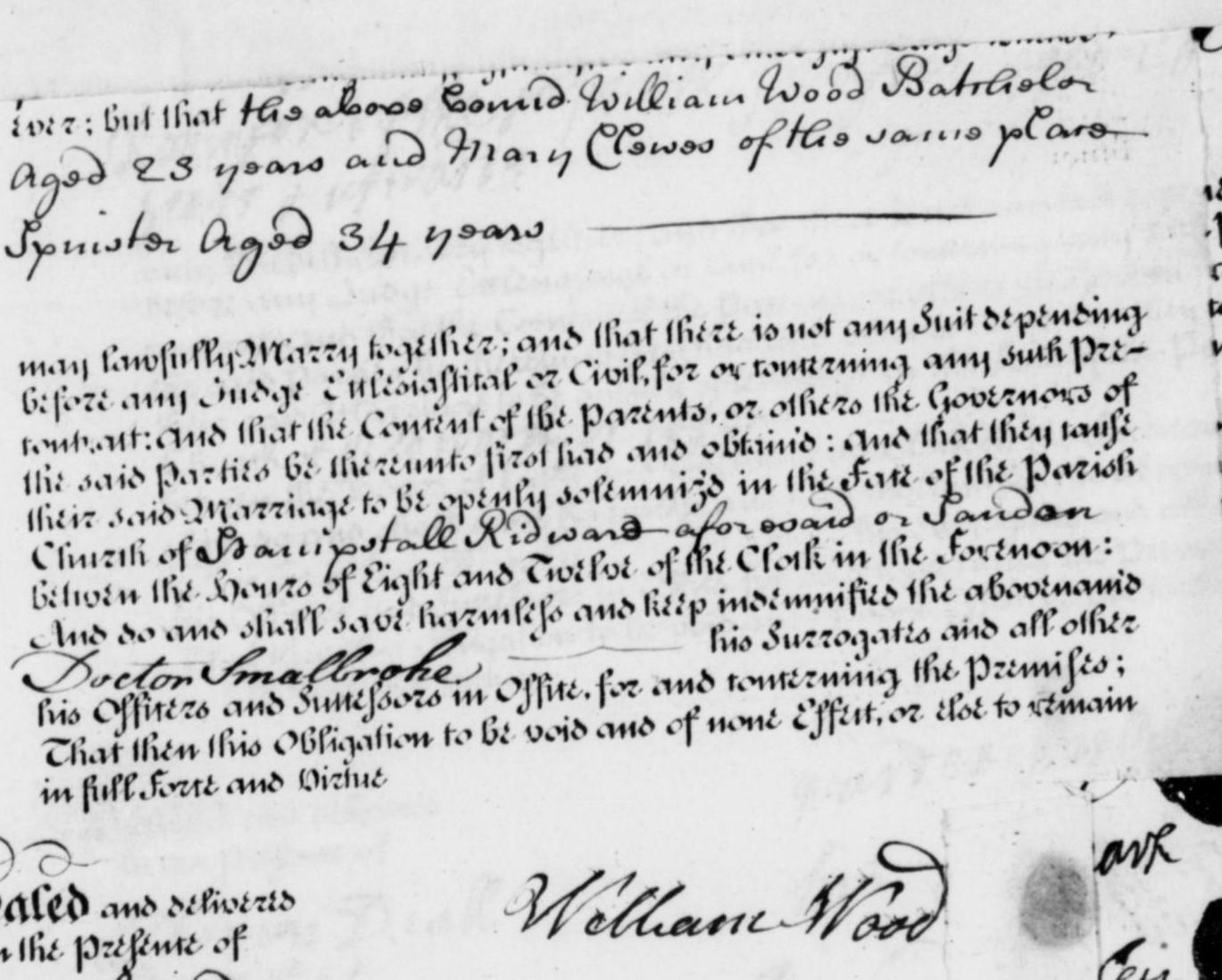

William Warren (1835-1880) of Newhall (Stapenhill) married Elizabeth Staley (1836-1907) in 1858. Elizabeth was born in Newhall, the daughter of John Staley (1795-1876) and Jane Brothers. John was born in Newhall, and Jane was born in Armagh, Ireland, and they were married in Armagh in 1820. Elizabeths older brothers were born in Ireland: William in 1826 and Thomas in Dublin in 1830. Francis was born in Liverpool in 1834, and then Elizabeth in Newhall in 1836; thereafter the children were born in Newhall.

Marriage of John Staley and Jane Brothers in 1820:

My grandmother related a story about an Elizabeth Staley who ran away from boarding school and eloped to Ireland, but later returned. The only Irish connection found so far is Jane Brothers, so perhaps she meant Elizabeth Staley’s mother. A boarding school seems unlikely, and it would seem that it was John Staley who went to Ireland.

The 1841 census states Jane’s age as 33, which would make her just 12 at the time of her marriage. The 1851 census states her age as 44, making her 13 at the time of her 1820 marriage, and the 1861 census estimates her birth year as a more likely 1804. Birth records in Ireland for her have not been found. It’s possible, perhaps, that she was in service in the Newhall area as a teenager (more likely than boarding school), and that John and Jane ran off to get married in Ireland, although I haven’t found any record of a child born to them early in their marriage. John was an agricultural labourer, and later a coal miner.

John Staley was the son of Joseph Staley (1756-1838) and Sarah Dumolo (1764-). Joseph and Sarah were married by licence in Newhall in 1782. Joseph was a carpenter on the marriage licence, but later a collier (although not necessarily a miner).

The Derbyshire Record Office holds records of an “Estimate of Joseph Staley of Newhall for the cost of continuing to work Pisternhill Colliery” dated 1820 and addresssed to Mr Bloud at Calke Abbey (presumably the owner of the mine)