-

AuthorSearch Results

-

February 15, 2025 at 10:33 am #7794

In reply to: Helix Mysteries – Inside the Case

Some pictures selections

Evie and TP Investigating the Drying Machine Crime Scene

A cinematic sci-fi mini-scene aboard the vast and luxurious Helix 25. In the industrial depths of the ship, a futuristic drying machine hums ominously, crime scene tape lazily flickering in artificial gravity. Evie, a sharp-eyed investigator in a sleek yet practical uniform, stands with arms crossed, listening intently. Beside her, a translucent, retro-stylized holographic detective—Trevor Pee Marshall (TP)—adjusts his tiny mustache with a flourish, pointing dramatically at the drying machine with his cane. The air is thick with mystery, the ship’s high-tech environment reflecting off Evie’s determined face while TP’s flickering presence adds an almost comedic contrast. A perfect blend of noir and high-tech detective intrigue.

Riven Holt and Zoya Kade Confronting Each Other in a Dimly Lit Corridor

A dramatic, cinematic sci-fi scene aboard the vast and luxurious Helix 25. Riven Holt, a disciplined young officer with sharp features, stands in a high-tech corridor, his arms crossed, jaw tense—exuding authority and restraint. Opposite him, Zoya Kade, a sharp-eyed, wiry 83-year-old scientist-prophet, leans slightly forward, her mismatched layered robes adorned with tiny artifacts—beads, old circuits, and a fragment of a key. Her silver-white braid gleams under the soft emergency lighting, her piercing gaze challenging him. The corridor hums with unseen energy, a subtle red glow from a “restricted access” sign casting elongated shadows. Their confrontation is palpable—a struggle between order and untamed knowledge, hierarchy and rebellion. In the background, the walls of Helix 25 curve sleekly, high-tech yet strangely claustrophobic, reinforcing the ship’s ever-present watchfulness.

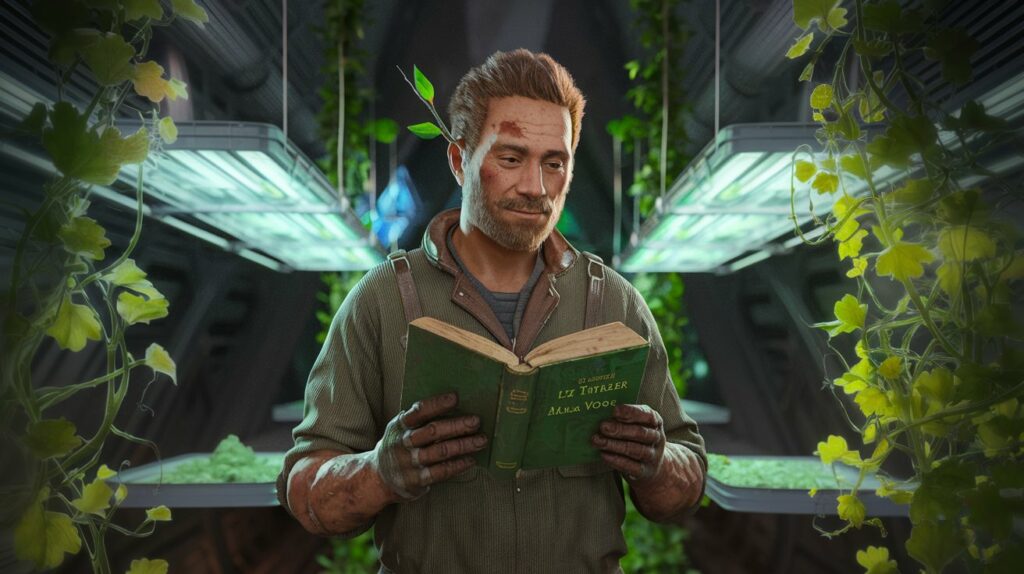

Romualdo, the Gardener, Among the Bioluminescent Plants

A richly detailed sci-fi portrait of Romualdo, the ship’s gardener, standing amidst the vibrant greenery of the Jardenery. He is a rugged yet gentle figure, dressed in a simple work jumpsuit with soil-streaked hands, a leaf-tipped stem tucked behind his ear like a cigarette. His eyes scan an old, well-worn book—one of Liz Tattler’s novels—that Dr. Amara Voss gave him for his collection. The glowing plants cast an ethereal blue-green light over him, creating an atmosphere both peaceful and mysterious. In the background, the towering vines and suspended hydroponic trays hint at the ship’s careful balance between survival and serenity.

Finja and Finkley – A Telepathic Parallel Across Space

A surreal, cinematic sci-fi composition split into two mirrored halves, reflecting a mysterious connection across vast distances. On one side, Finja, a wiry, intense woman with an almost obsessive neatness, walks through the overgrown ruins of post-apocalyptic Earth, her expression distant as she “listens” to unseen voices. Dust lingers in the air, catching the golden morning light, and she mutters to herself about cleanliness. In her reflection, on the other side of the image, is Finkley, a no-nonsense crew member aboard the gleaming, futuristic halls of Helix 25. She stands with hands on her hips, barking orders at small cleaning bots as they maintain the ship’s pristine corridors. The lighting is cold and artificial, sterile in contrast to the dust-filled Earth. Yet, both women share a strange symmetry—gesturing in unison as if unknowingly mirroring one another across time and space. A faint, ghostly thread of light suggests their telepathic bond, making the impossible feel eerily real.

February 15, 2025 at 9:21 am #7789In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

Helix 25 – Poop Deck – The Jardenery

Evie stepped through the entrance of the Jardenery, and immediately, the sterile hum of Helix 25’s corridors faded into a world of green. Of all the spotless clean places on the ship, it was the only where Finkley’s bots tolerated the scent of damp earth. A soft rustle of hydroponic leaves shifting under artificial sunlight made the place an ecosystem within an ecosystem, designed to nourrish both body and mind.

Yet, for all its cultivated serenity, today it was a crime scene. The Drying Machine was connected to the Jardenery and the Granary, designed to efficiently extract precious moisture for recycling, while preserving the produce.

Riven Holt, walking beside her, didn’t share her reverence. “I don’t see why this place is relevant,” he muttered, glancing around at the towering bioluminescent vines spiraling up trellises. “The body was found in the drying machine, not in a vegetable patch.”

Evie ignored him, striding toward the far corner where Amara Voss was hunched over a sleek terminal, frowning at a glowing screen. The renowned geneticist barely noticed their approach, her fingers flicking through analysis results faster than human eyes could process.

A flicker of light.

“Ah-ha!” TP materialized beside Evie, adjusting his holographic lapels. “Madame Voss, I must say, your domain is quite the delightful contrast to our usual haunts of murder and mystery.” He twitched his mustache. “Alas, I suspect you are not admiring the flora?”

Amara exhaled sharply, rubbing her temples, not at all surprised by the holographic intrusion. She was Evie’s godmother, and had grown used to her experiments.

“No, indeed. I’m admiring this.” She turned the screen toward them.

The DNA profile glowed in crisp lines of data, revealing a sequence highlighted in red.

Evie frowned. “What are we looking at?”

Amara pinched the bridge of her nose. “A genetic anomaly.”

Riven crossed his arms. “You’ll have to be more specific.”

Amara gave him a sharp look but turned back to the display. “The sample we found at the crime scene—blood residue on the drying machine and some traces on the granary floor—matches an ancient DNA profile from my research database. A perfect match.”

Evie felt a prickle of unease. “Ancient? What do you mean? From the 2000s?”

Amara chuckled, then nodded grimly. “No, ancient as in Medieval ancient. Specifically, Crusader DNA, from the Levant. A profile we mapped from preserved remains centuries ago.”

Silence stretched between them.

Finally, Riven scoffed. “That’s impossible.”

TP hummed thoughtfully, twirling his cane. “Impossible, yet indisputable. A most delightful contradiction.”

Evie’s mind raced. “Could the database be corrupted?”

Amara shook her head. “I checked. The sequencing is clean. This isn’t an error. This DNA was present at the crime scene.” She hesitated, then added, “The thing is…” she paused before considering to continue. They were all hanging on her every word, waiting for what she would say next.

Amara continued “I once theorized that it might be possible to reawaken dormant ancestral DNA embedded in human cells. If the right triggers were applied, someone could manifest genetic markers—traits, even memories—from long-dead ancestors. Awakening old skills, getting access to long lost secrets of states…”

Riven looked at her as if she’d grown a second head. “You’re saying someone on Helix 25 might have… transformed into a medieval Crusader?”

Amara exhaled. “I’m saying I don’t know. But either someone aboard has a genetic profile that shouldn’t exist, or someone created it.”

TP’s mustache twitched. “Ah! A puzzle worthy of my finest deductive faculties. To find the source, we must trace back the lineage! And perhaps a… witness.”

Evie turned toward Amara. “Did Herbert ever come here?”

Before Amara could answer, a voice cut through the foliage.

“Herbert?”

They turned to find Romualdo, the Jardenery’s caretaker, standing near a towering fruit-bearing vine, his arms folded, a leaf-tipped stem tucked behind his ear like a cigarette. He was a broad-shouldered man with sun-weathered skin, dressed in a simple coverall, his presence almost too casual for someone surrounded by murder investigators.

Romualdo scratched his chin. “Yeah, he used to come around. Not for the plants, though. He wasn’t the gardening type.”

Evie stepped closer. “What did he want?”

Romualdo shrugged. “Questions, mostly. Liked to chat about history. Said he was looking for something old. Always wanted to know about heritage, bloodlines, forgotten things.” He shook his head. “Didn’t make much sense to me. But then again, I like practical things. Things that grow.”

Amara blushed, quickly catching herself. “Did he ever mention anything… specific? Like a name?”

Romualdo thought for a moment, then grinned. “Oh yeah. He asked about the Crusades.”

Evie stiffened. TP let out an appreciative hum.

“Fascinating,” TP mused. “Our dearly departed Herbert was not merely a victim, but perhaps a seeker of truths unknown. And, as any good mystery dictates, seekers who get too close often find themselves…” He tipped his hat. “Extinguished.”

Riven scowled. “That’s a bit dramatic.”

Romualdo snorted. “Sounds about right, though.” He picked up a tattered book from his workbench and waved it. “I lend out my books. Got myself the only complete collection of works of Liz Tattler in the whole ship. Doc Amara’s helping me with the reading. Before I could read, I only liked the covers, they were so romantic and intriguing, but now I can read most of them on my own.” Noticing he was making the Doctor uncomfortable, he switched back to the topic. “So yes, Herbert knew I was collector of books and he borrowed this one a few weeks ago. Kept coming back with more questions after reading it.”

Evie took the book and glanced at the cover. The Blood of the Past: Genetic Echoes Through History by Dr. Amara Voss.

She turned to Amara. “You wrote this?”

Amara stared at the book, her expression darkening. “A long time ago. Before I realized some theories should stay theories.”

Evie closed the book. “Looks like someone didn’t agree.”

Romualdo wiped his hands on his coveralls. “Well, I hope you figure it out soon. Hate to think the plants are breathing in murder residue.”

TP sighed dramatically. “Ah, the tragedy of contaminated air! Shall I alert the sanitation team?”

Riven rolled his eyes. “Let’s go.”

As they walked away, Evie’s grip tightened around the book. The deeper they dug, the stranger this murder became.

February 8, 2025 at 3:38 pm #7765In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

Zoya clicked her tongue, folding her arms as Evie and her flickering detective vanished into the dead man’s private world. She listened to the sounds of investigation. The sound of others touching what should have been hers first. She exhaled through her nose, slow and measured.

The body was elsewhere, dried and ruined. That didn’t matter. What mattered was here—hairs, nail clippings, that contained traces, strands, fragments of DNA waiting to be read like old parchments.

She stepped forward, the soft layers of her robes shifting.

“You can’t keep me out forever, young man.”

Riven didn’t move. Arms crossed, jaw locked, standing there like a sentry at some sacred threshold. Victor Holt’s grandson, through and through, she thought.

“I can keep you out long enough.”

Zoya clicked her tongue. Not quite amusement, not quite irritation.

“I should have suspected such obstinacy. You take after him, after all.”

Riven’s shoulders tensed.

Good. Let him feel it.

His voice was tight. “If you’re referring to my grandfather, you should choose your words carefully.”

Zoya smiled, slow and knowing. “I always choose my words carefully.”

Riven’s glare could have cut through metal.

Zoya tilted her head, studying him as she would an artifact pulled from the wreckage of an old world. So much of Victor Holt was in him—the posture, the unyielding spine, the desperate need to be right.

But Victor Holt had been wrong.

And that was why he was sleeping in a frozen cell of his own making.

She took another step forward, lowering her voice just enough that the curious would not hear what she said.

“He never understood the ship’s true mission. He clung to his authority, his rigid hierarchies, his outdated beliefs. He would have let us rot in luxury while the real work of survival slipped away. And when he refused to see reason—” she exhaled, her gaze never leaving his, “he stepped aside.”

Riven’s jaw locked. “He was forced aside.”

Zoya only smiled. “A matter of perspective.”

She let that hang. Let him sit with it.

She could see the war in his eyes—the desperate urge to refute her, to throw his grandfather’s legacy in her face, to remind her that Victor Holt was still here, still waiting in cryo, still a looming shadow over the ship. But Victor Holt’s silence was the greatest proof of his failure.

Riven clenched his jaw.

Anuí’s voice, smooth and patient, cut through the tension.

“She is not wrong.”

Zoya frowned. She had expected them to speak eventually. They always did.

They stood just a little apart, hand tucked in their robes, their expression unreadable.

“In its current state, the body is useless,” Anuí said lightly, as if stating something obvious, “but that does not mean it has left no trace.” Then they murmured “Nāvdaṭi hrás’ka… aṣṭīr pālachá.”

Zoya glanced at them, her eyes narrowing. In an old tongue forgotten by all, it meant The bones remember… the blood does not lie. She did not trust the Lexicans’ sudden interest in genetics.

They did not see history in bloodlines, did not place value in the remnants of DNA. They preferred their records rewritten, reclaimed, restructured to suit a new truth, not an old one.

Yet here they were, aligning themselves with her. And that was what gave her pause.

“Your people have never cared for the past as it was,” she murmured. “Only for what it could become.”

Anuí’s lips curved, withholding more than they gave. “Truth takes many forms.”

Zoya scoffed. They were here for their own reasons. That much was certain. She could use that

Riven’s fingers tightened at his sides. “I have my orders.”

Zoya lifted a brow. “And whose orders are those?”

The hesitation was slight. “It’s not up to me.”

Zoya stilled. The words were quiet, bitter, revealing.

Not up to him.

So, someone had ensured she wouldn’t step foot in that room. Not just delayed—denied.

She exhaled, long and slow. “I see.” She paused. “I will find out who gave that order.”

And when she did, they would regret it.

December 14, 2024 at 6:42 pm #7682In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

Matteo — Autumn 2023

The Jardin des Plantes park was quiet, the kind of quiet that settled after a brisk autumn rain. Matteo sat on a weathered wooden bench, watching a golden retriever chase the last of the fallen leaves tumbling across the gravel path. The damp air was carrying scents of the earth welcoming a retreat inside, and taking the time to be alone with his thoughts was something he’d missed.

His phone buzzed with a notification—a news update about the latest film adaptation from a Liz Tattler classic fiction. The name made him smile faintly. Juliette had loved Tattler’s novels, their whimsical characters, and the unflinching and unapologetic observations about life’s quiet mysteries and the unexpected rants about the virtues of cleaning and dustsceawung that propelled the word in the people’s top 100 favourite in the Oxford dictionary for several years consecutively.

“They’re so full of texture,” Juliette once said as she was sprawled on the bed of their tiny Parisian flat, a battered paperback in her hands. “Like you can feel the pages breathe.”

His image of her was still vivid, they’d stayed on good terms and he would still thumb up some of her posts from time to time —but it was only small moments rather than full scenes that used to come back, fragmented pieces of memories really —her dark hair falling messily over her face, her legs crossed in a casual way.

Paris had been a playground for them. For a while, they were caught in a whirlwind of late-night conversations in smoky cafés and lazy Sunday mornings wandering the Seine. They’d spent hours in bookstores, Juliette hunting for first editions and Matteo snapping pictures of the handwritten notes tucked between the pages of used novels.

A year ago, a different park in a different city—Hyde Park, London. She was there, twirling a scarf she’d picked up in Vienna the weekend before, the bright red of it like a ribbon of fire against the soft gray skies. They had been enamored with each other and with the spontaneity of hopping trains to new cities, their weekends folding into one another like pages of a travel journal. London one week, Paris the next, Berlin after that. Each city a postcard snapshot, vibrant and fleeting.

Juliette would tease him about his fascination with the little things—how he would linger too long over a cup of coffee at a café or stop to photograph a tree in the middle of nowhere. “You’re always looking for stories,” she’d said with a laugh, tucking a stray strand of hair behind her ear. “Even when you’re not sure what they mean.”

“Stories are everywhere,” he would reply, snapping a picture of her against the backdrop of the park, her scarf billowing in the wind. She had rolled her eyes but smiled, and in that moment, he had believed her smile was the most perfect thing he’d ever seen.

The break-up came unannounced, but not fully unexpected. There were signs here and there. Her love of the endless whirlwind of life, that was a match for his way of following life’s intents for him. When sometimes life went still during winter, he would also follow, but she wouldn’t. She had insatiable love for a life filled with animation, bursts of colours, sounds. It had been easy to be with her then, her curiosity pulling him along, their shared love of stories giving their time together a weight that felt timeless. It was when Drusilla’s condition worsened, that their rhythms became untangled, no longer synching at every heartbeat. And it was fine. Matteo had made his decision then to leave Paris and bring his mother to Avignon where she could receive the care she needed. Those past two weeks that brought the inevitable conclusion of their separation had left him surprisingly content. Happy for the past moments, and hopeful for the unwritten future.

He could see clearly that Juliette needed her freedom back; and she’d agreed. Regular train rides to Avignon, the weekends spent trying to make the sparse walls of his mother’s room feel like home as she started to forget her son’s girlfriend, and sometimes even her own son.

Last they were in this park together was one of their last shared moments of innocent happiness ; It was a beautiful sunny afternoon —or was it only coloured by memories? They had been sitting in the Jardin des Plantes, sharing a crêpe. Juliette had been scrolling through her phone, stopping at an announcement about an interview with Liz Tattler airing that evening. “You should watch it,” she’d said, her tone light but distant. “Her books are about people like us—drifting, figuring it out.”

He had smiled then, nodding, though he wasn’t sure if he’d meant it. A week later, she told him she was moving back to Lille, closer to her family until she figured out her next step. “It’s not you, Matteo,” she’d said, her eyes soft but resolute. “You need to be here, for her. I need… something else.”

Now, sitting in the park a few weeks later, Matteo pulled his phone from his pocket and opened his gallery. He scrolled through the pictures until he found one from their weekend in London—a black-and-white shot of Julia standing in front of a red telephone booth, her smile sharp and her eyes already focused on the next shooting star to catch.

Julia was right, he thought. People like them—they drifted, but they also found their way, sometimes in unexpected ways. He put on his earpods, listening to the beginning of Liz Tattler’s interview.

Her distinct raspy voice brimming with a cackling energy was already engrossing. Synchy as ever, she was saying:

“Every story begins with something lost, but it’s never about the loss. It’s about what you find because of it.”

December 8, 2024 at 6:06 am #7655In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

Amei switched on the TV for background noise as she tackled another pile of books. The usual mid-morning chatter filled the room—updates on the weather, a cooking segment, and finally, the news. She was only half-listening until the anchor’s voice caught her attention.

“In the race against climate change, scientists at Harvard are turning to an unexpected solution: chalk. The ambitious project involves launching a balloon into the stratosphere, carrying 600 kilograms of calcium carbonate, which would be sprayed 12 miles above the Earth’s surface. The idea? To reflect sunlight and slow global warming.”

Amei looked up. The screen showed an animated demonstration of the project—a balloon rising into the atmosphere, spraying fine particles into the air. The narration continued, but her focus drifted, caught on a single word: chalk.

Elara loved chalk. Amei smiled faintly, remembering how passionately she used to talk about it—the way she could turn something so mundane into a story of structure, history, and beauty. “It’s not just a rock,” Elara had said once, gesturing dramatically, “it’s a record of time.”

She wasn’t even sure where Elara was these days. The last time they’d spoken was during lockdown. Amei had called to check in, awkward but well-meaning, only to be met with curt responses and a tone that made it clear Elara wanted the conversation over.

She hadn’t tried again after that. It hurt more than she’d expected. Elara could be all or nothing when it came to friendships—brilliant and intense one moment, distant and impenetrable the next. Amei had always known that about her, but knowing didn’t make it any easier.

The news droned on in the background, but Amei reached for the remote and switched off the TV. Her mind was elsewhere, tangled in memories.

She’d first met Elara in a gallery on Southbank, a tiny exhibition tucked away in a brutalist building. It was near Amei’s shared flat, and with her flatmates out for the evening, she had gone alone, more out of boredom than genuine interest. The display wasn’t large—just a few photographs and abstract sculptures, their descriptions dense with scientific jargon.

Amei stood in front of a piece labelled The Geometry of Chaos—a spiraling wire structure that cast intricate, shifting shadows on the wall. She tilted her head, trying to look engaged, though her thoughts were already drifting towards home and her comfy bed.

“Magnificent, isn’t it?”

The voice startled her. She turned to see a dark-haired woman, arms crossed, studying the piece with an intensity that made Amei feel as though she must have missed something obvious. The woman wore a long, flowing skirt, layered necklaces, and a cardigan that looked hand-knitted. Her dark hair was piled into a messy bun, a few strands escaping to frame her face.

“It’s quite interesting,” Amei said. “But I’m not sure I get it.”

“It’s not about getting it. It’s about recognizing the pattern,” the woman replied, stepping closer. She pointed to the shadows on the wall. “See? The curve repeats itself. Infinite, but contained.”

“You sound like you know what you’re talking about.”

“I do,” she said. “Do you?”

Amei laughed, caught off guard. “Not very often. I think I’m more into… messy patterns.”

The woman’s sharp expression softened slightly. “Messy patterns are still patterns.” She smiled. “I’m Elara.”

“Amei,” she replied, returning the smile.

Elara’s gaze dropped, and she nodded toward Amei’s skirt. “I’ve been admiring your skirt. Gorgeous fabric. Where did you get it?”

“Oh, I made it, actually,” Amei felt proud.

Elara raised her eyebrows. “You made it? I’m impressed.”

And that was how it began. A chance meeting that turned into decades of close friendship. They’d left the gallery together, talking all the way to a nearby café.

December 7, 2024 at 11:52 am #7653In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

Matteo — Winter 2023: The Move

The rumble of the moving truck echoed faintly in the quiet residential street as Matteo leaned against the open door, arms crossed, waiting for the signal to load the boxes. He glanced at the crisp winter sky, a pale gray threatening snow, and then at the house behind him. Its windows were darkened by empty rooms, their once-lived-in warmth replaced by the starkness of transition. The ornate names artistically painted on the mailbox struck him somehow. Amei & Tabitha M.: his clients for the day.

The cold damp of London’s suburbia was making him long even more for the warmth of sunny days. With the past few moves he’s been managing for his company, the tipping had been generous; he could probably plan a spring break in South of France, or maybe make a more permanent move there.

The sound of the doorbell brought him back from his rêverie.

Inside the house, the faint sounds of boxes being taped and last-minute goodbyes carried through the hallways. Matteo had been part of these moves too many times to count now. People always left a little bit of themselves behind—forgotten trinkets, echoes of old conversations, or the faint imprint of a life lived. It was a rhythm he’d come to expect, and he knew his part in it: lift, carry, and disappear into the background.

Matteo straightened as the door opened and a girl that could have been in her early twenties, but looked like a teenager stepped out, bundled against the cold. She held a steaming mug in one hand and balanced a box awkwardly on her hip with the other.

“That’s the last of it,” she called over her shoulder. “Mum, are you sure you don’t want me to take the notebooks?”

“They’re fine in the car, Tabitha!” A voice—calm and steady, maybe tinged with weariness—floated from inside.

The girl named Tabitha turned to Matteo, offering the box. “This is fragile,” she said, a smile tugging at her lips. “Be nice to it.”

Matteo took the box carefully, glancing at the mug in her hand. “You’re not leaving that behind, are you?” he asked with a faint smile.

Tabitha laughed. “This? No way. That’s my lifeline. The mug stays.”

As Matteo carried the box to the truck, his eyes caught on something inside—a weathered postcard tucked haphazardly between the pages of a journal. The image on the front was striking: a swirling green fairy, dancing above a glass of absinthe. La Fée Verte was scrawled in looping letters across the top.

“Tabitha!” Her mother’s voice carried out to the driveway, and Matteo turned instinctively. She stepped out onto the porch, her scarf wrapped loosely around her neck, her breath visible in the chilly air. Matteo could see the resemblance—the same poise and humor in her gaze, though softened by something older, quieter.

“Put this somewhere, will you” she said, holding up another postcard, this one with a faded image of a winding mountain road.

Tabitha grinned, stepping forward to take it. “Thanks, Mum. That one’s special.” She tucked it into her coat pocket.

“Special how?” her mother asked lightly.

“It’s from Darius,” Tabitha said, her tone almost teasing. “… The one you never want to talk about.” she leaned teasingly. “One of his cryptic postcards —too bad I was too young to really remember him, he must have been fun to be around.”

Matteo’s ears perked at the name, though he kept his head down, settling the box in place. It wasn’t unusual to overhear snippets like this during a move, but something about the unusual name roused his curiosity.

“Why you want to keep those?” Amei asked, tilting her head.

Tabitha shrugged. “They’re kind of… a map, I guess. Of people, not places.”

Amei paused, her expression softening. “He was always good at that,” she murmured, almost to herself.

The conversation lingered in Matteo’s mind as the day went on. By the time the truck was loaded, and he’d helped arrange the last of the boxes in Amei’s new, smaller apartment, the name and the postcard had taken root.

As Matteo stacked the final piece of furniture—a worn bookshelf—against the living room wall, he noticed Amei lingering near a window, her gaze distant.

“It’s different, isn’t it?” she said suddenly, not looking at him.

“Moving?” Matteo asked, unsure if the question was for him.

“Starting over,” she clarified, her voice quieter now. “Feels smaller, even when it’s supposed to be lighter.”

Matteo didn’t reply, sensing she wasn’t looking for an answer. He stepped back, nodding politely as she thanked him and disappeared into the kitchen.

The postcard stuck in his mind for days after. Matteo had heard of absinthe before, of course—its mystique, its history—but something about the way Tabitha had called the postcard a “map of people” resonated.

By the time spring arrived, Matteo was wandering through Avignon, chasing vague curiosities and half-formed questions. When he saw Lucien crouched over his chalk labyrinth, the memory of the postcard rose unbidden.

“Do you know where I can find absinthe?” he asked, the question more instinct than intent.

Lucien’s raised eyebrow and faint smile felt like another piece clicking into place. The connections were there—threads woven in patterns he couldn’t yet see. But for the first time in months, Matteo felt he was back on the right path.

December 5, 2024 at 11:01 pm #7647In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

Darius: A Map of People

June 2023 – Capesterre-Belle-Eau, Guadeloupe

The air in Capesterre-Belle-Eau was thick with humidity, the kind that clung to your skin and made every movement slow and deliberate. Darius leaned against the railing of the veranda, his gaze fixed on the horizon where the sky blends into the sea. The scent of wet earth and banana leaves filling the air. He was home.

It had been nearly a year since hurricane Fiona swept through Guadeloupe, its winds blowing a trail of destruction across homes, plantations, and lives. Capesterre-Belle-Eau had been among the hardest hit, its banana plantations reduced to ruin and its roads washed away in torrents of mud.

Darius hadn’t been here when it happened. He’d read about it from across the Atlantic, the news filtering through headlines and phone calls from his aunt, her voice brittle with worry.

“Darius, you should come back,” she’d said. “The land remembers everyone who’s left it.”

It was an unusual thing for her to say, but the words lingered. By the time he arrived in early 2023 to join the relief efforts, the worst of the crisis had passed, but the scars remained—on the land, on the people, and somewhere deep inside himself.

Home, and Not — Now, passing days having turned into quick six months, Darius was still here, though he couldn’t say why. He had thrown himself into the work, helped to rebuild homes, clear debris, and replant crops. But it wasn’t just the physical labor that kept him—it was the strange sensation of being rooted in a place he’d once fled.

Capesterre-Belle-Eau wasn’t just home; it was bones-deep memories of childhood. The long walks under the towering banana trees, the smell of frying codfish and steaming rice from his aunt’s kitchen, the rhythm of gwoka drums carrying through the evening air.

“Tu reviens pour rester cette fois ?” Come back to stay? a neighbor had asked the day he returned, her eyes sharp with curiosity.

He had laughed, brushing off the question. “On verra,” he’d replied. We’ll see.

But deep down, he knew the answer. He wasn’t back for good. He was here to make amends—not just to the land that had raised him but to himself.

A Map of Travels — On the veranda that afternoon, Darius opened his phone and scrolled through his photo gallery. Each image was pinned to a digital map, marking all the places he’d been since he got the phone. Of all places, it was Budapest which popped out, a poor snapshot of Buda Castle.

He found it a funny thought — just like where he was now, he hadn’t planned to stay so long there. He remembered the date: 2020, in the midst of the pandemic. He’d spent in Budapest most of it, sketching the empty streets.

Five years ago, their little group of four had all been reconnecting in Paris, full of plans that never came to fruition. By late 2019, the group had scattered, each of them drawn into their own orbits, until the first whispers of the pandemic began to ripple across the world.

Funding his travels had never been straightforward. He’d tried his hand at dozens of odd jobs over the years—bartending in Lisbon, teaching English in Marrakech, sketching portraits in tourist squares across Europe. He lived frugally, keeping his possessions light and his plans loose. Yet, his confidence had a way of opening doors; people trusted him without knowing why, offering him opportunities that always seemed to arrive at just the right time.

Even during the pandemic, when the world seemed to fold in on itself, he had found a way.

Darius had already arrived in Budapest by then, living cheaply in a rented studio above a bakery. The city had remained open longer than most in Europe or the world, its streets still alive with muted activity even as the rest of Europe closed down. He’d wandered freely for months, sketching graffiti-covered bridges, quiet cafes, and the crumbling facades of buildings that seemed to echo his own restlessness.

When the lockdowns finally came like everywhere else, it was just before winter, he’d stayed, uncertain of where else to go. His days became a rhythm of sketching, reading, and sending postcards. Amei was one of the few who replied—but never ostentatiously. It was enough to know she was still there, even if the distance between them felt greater than ever.

But the map didn’t tell the whole story. It didn’t show the faces, the laughter, the fleeting connections that had made those places matter.

Swatting at a buzzing mosquito, he reached for the small leather-bound folio on the table beside him. Inside was a collection of fragments: ticket stubs, pressed flowers, a frayed string bracelet gifted by a child in Guatemala, and a handful of postcards he’d sent to Amei but had never been sure she received.

One of them, yellowed at the edges, showed a labyrinth carved into stone. He turned it over, his own handwriting staring back at him.

“Amei,” it read. “I thought of you today. Of maps and paths and the people who make them worth walking. Wherever you are, I hope you’re well. —D.”

He hadn’t sent it. Amei’s responses had always been brief—a quick WhatsApp message, a thumbs-up on his photos, or a blue tick showing she’d read his posts. But they’d never quite managed to find their way back to the conversations they used to have.

The Market — The next morning, Darius wandered through the market in Trois-Rivières, a smaller town nestled between the sea and the mountains. The vendors called out their wares—bunches of golden bananas, pyramids of vibrant mangoes, bags of freshly ground cassava flour.

“Tiens, Darius!” called a woman selling baskets woven from dried palm fronds. “You’re not at work today?”

“Day off,” he said, smiling as he leaned against her stall. “Figured I’d treat myself.”

She handed him a small woven bracelet, her eyes twinkling. “A gift. For luck, wherever you go next.”

Darius accepted it with a quiet laugh. “Merci, tatie.”

As he turned to leave, he noticed a couple at the next stall—tourists, by the look of them, their backpacks and wide-eyed curiosity marking them as outsiders. They made him suddenly realise how much he missed the lifestyle.

The woman wore an orange scarf, its boldness standing out as if the color orange itself had disappeared from the spectrum, and only a single precious dash could be seen into all the tones of the market. Something else about them caught his attention. Maybe it was the way they moved together, or the way the man gestured as he spoke, as if every word carried weight.

“Nice scarf,” Darius said casually as he passed.

The woman smiled, adjusting the fabric. “Thanks. Picked it up in Rajasthan. It’s been with me everywhere since.”

Her partner added, “It’s funny, isn’t it? The things we carry. Sometimes it feels like they know more about where we’ve been than we do.”

Darius tilted his head, intrigued. “Do you ever think about maps? Not the ones that lead to places, but the ones that lead to people. Paths crossing because they’re meant to.”

The man grinned. “Maybe it’s not about the map itself,” he said. “Maybe it’s about being open to seeing the connections.”

A Letter to Amei — That evening, as the sun dipped below the horizon, Darius sat at the edge of the bay, his feet dangling above the water. The leather-bound folio sat open beside him, its contents spread out in the fading light.

He picked up the labyrinth postcard again, tracing its worn edges with his thumb.

“Amei,” he wrote on the back just under the previous message a second one —the words flowing easily this time. “Guadeloupe feels like a map of its own, its paths crossing mine in ways I can’t explain. It made me think of you. I hope you’re well. —D.”

He folded the card into an envelope and tucked it into his bag, resolving to send it the next day.

As he watched the waves lap against the rocks, he felt a sense of motion rolling like waves asking to be surfed. He didn’t know where the next path would lead next, but he felt it was time to move on again.

December 2, 2024 at 10:50 pm #7635In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

Sat. Nov. 30, 2024 5:55am — Matteo’s morning

Matteo’s mornings began the same way, no matter the city, no matter the season. A pot of strong coffee brewed slowly on the stove, filling his small apartment with its familiar, sense-sharpening scent. Outside, Paris was waking up, its streets already alive with the sound of delivery trucks and the murmurs of shopkeepers rolling open shutters.

He sipped his coffee by the window, gazing down at the cobblestones glistening from last night’s rain. The new brass sign above the Sarah Bernhardt Café caught the morning light, its sheen too pristine, too new. He’d started the server job there less than a week ago, stepping into a rhythm he already knew instinctively, though he wasn’t sure why.

Matteo had always been good at fitting in. Jobs like this were placeholders—ways to blend into the scenery while he waited for whatever it was that kept pulling him forward. The café had reopened just days ago after months of being closed for renovations, but to Matteo, it felt like it had always been waiting for him.

He set his coffee mug on the counter, reaching absently for the notebook he kept nearby. The act was automatic, as natural as breathing. Flipping open to a blank page, Matteo wrote down four names without hesitation:

Lucien. Elara. Darius. Amei.

He stared at the list, his pen hovering over the page. He didn’t know why he wrote it. The names had come unbidden, as though they were whispered into his ear from somewhere just beyond his reach. He ran his thumb along the edge of the page, feeling the faint indentation of his handwriting.

The strangest part wasn’t the names— it was the certainty that he’d see them that day.

Matteo glanced at the clock. He still had time before his shift. He grabbed his jacket, tucked the notebook into the inside pocket, and stepped out into the cool Parisian air.

Matteo’s feet carried him to a side street near the Seine, one he hadn’t consciously decided to visit. The narrow alley smelled of damp stone and dogs piss. Halfway down the alley, he stopped in front of a small shop he hadn’t noticed before. The sign above the door was worn, its painted letters faded: Les Reliques. The display in the window was an eclectic mix—a chessboard missing pieces, a cracked mirror, a wooden kaleidoscope—but Matteo’s attention was drawn to a brass bell sitting alone on a velvet cloth.

The door creaked as he stepped inside, the distinctive scent of freshly burnt papier d’Arménie and old dust enveloping him. A woman emerged from the back, wiry and pale, with sharp eyes that seemed to size Matteo up in an instant.

“You’ve never come inside,” she said, her voice soft but certain.

“I’ve never had a reason to,” Matteo replied, though even as he spoke, the door closed shut the outside sounds.

“Today, you might,” the woman said, stepping forward. “Looking for something specific?”

“Not exactly,” Matteo replied. His gaze shifted back to the bell, its smooth surface gleaming faintly in the dim light.

“Ah.” The shopkeeper followed his eyes and smiled faintly. “You’re drawn to it. Not uncommon.”

“What’s uncommon about a bell?”

The woman chuckled. “It’s not the bell itself. It’s what it represents. It calls attention to what already exists—patterns you might not notice otherwise.”

Matteo frowned, stepping closer. The bell was unremarkable, small enough to fit in the palm of his hand, with a simple handle and no visible markings.

“How much?”

“For you?” The shopkeeper tilted his head. “A trade.”

Matteo raised an eyebrow. “A trade for what?”

“Your time,” the woman said cryptically, before waving her hand. “But don’t worry. You’ve already paid it.”

It didn’t make sense, but then again, it didn’t need to. Matteo handed over a few coins anyway, and the woman wrapped the bell in a square of linen.

Back on the street, Matteo slipped the bell into his pocket, its weight unfamiliar but strangely comforting. The list in his notebook felt heavier now, as though connected to the bell in a way he couldn’t quite articulate.

Walking back toward the café, Matteo’s mind wandered. The names. The bell. The shopkeeper’s words about patterns. They felt like pieces of something larger, though the shape of it remained elusive.

The day had begun to align itself, its pieces sliding into place. Matteo stepped inside, the familiar hum of the café greeting him like an old friend. He stowed his coat, slipped the bell into his bag, and picked up a tray.

Later that day, he noticed a figure standing by the window, suitcase in hand. Lucien. Matteo didn’t know how he recognized him, but the instant he saw the man’s rain-damp curls and paint-streaked scarf, he knew.

By the time Lucien settled into his seat, Matteo was already moving toward him, notebook in hand, his practiced smile masking the faint hum of inevitability coursing through him.

He didn’t need to check the list. He knew the others would come. And when they did, he’d be ready. Or so he hoped.

December 2, 2024 at 8:35 pm #7634In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

Nov.30, 2024 2:33pm – Darius: The Map and the Moment

Darius strolled along the Seine, the late morning sky a patchwork of rainclouds and stubborn sunlight. The bouquinistes’ stalls were already open, their worn green boxes overflowing with vintage books, faded postcards, and yellowed maps with a faint smell of damp paper overpowered by the aroma of crêpes and nearby french fries stalls. He moved along the stalls with a casual air, his leather duffel slung over one shoulder, boots clicking against the cobblestones.

The duffel had seen more continents than most people, its scuffed surface hinting at his nomadic life. India, Brazil, Morocco, Nepal—it carried traces of them all. Inside were a few changes of clothes, a knife he’d once bought off a blacksmith in Rajasthan, and a rolled-up leather journal that served more as a collection of ideas than a record of events.

Darius wasn’t in Paris for nostalgia, though it tugged at him in moments like this. The city had always been Lucien’s thing —artistic, brooding, and layered with history. For Darius, Paris was just another waypoint. Another stop on a map that never quite seemed to end.

It was the map that stopped him, actually. A tattered, hand-drawn thing propped against a pile of secondhand books, its edges curling like a forgotten leaf. Darius leaned in, frowning at its odd geometry. It wasn’t a city plan or a geographical rendering; it was… something else.

“Ah, you’ve found my prize,” said the bouquiniste, a short older man with a grizzled beard and a cigarette dangling from his lips.

“This?” Darius held up the map, his dark fingers tracing the looping, interconnected lines. They reminded him of something—a mandala, maybe, or one of those intricate yantras he’d seen in a temple in Varanasi.

“It’s not a real place,” the bouquiniste continued, leaning closer as though revealing a secret. “More of a… philosophical map.”

Darius raised an eyebrow. “A philosophical map?”

The man gestured toward the lines. “Each path represents a choice, a possibility. You could spend your life trying to follow it, or you could accept that you already have.”

Darius tilted his head, the edges of a smile forming. “That’s deep for ten euros.”

“It’s twenty,” the bouquiniste corrected, his grin flashing gold teeth.

Darius handed over the money without a second thought. The map was too strange to leave behind, and besides, it felt like something he was meant to find.

He rolled it up and tucked it into his duffel, turning back toward the city’s winding streets. The café wasn’t far now, but he still had time.

He stopped by a street vendor selling espresso shots and ordered one, the strong, bitter taste jolting his senses awake. As he leaned against a lamppost, he noticed his reflection in a shop window: a tall, broad-shouldered man, his dark skin glistening faintly in the misty air. His leather jacket was worn at the elbows, his boots dusted with dirt from some far-flung place.

He looked like a man who belonged everywhere and nowhere—a nomad who’d long since stopped wondering what home was supposed to feel like.

India had been the last big stop. It was messy, beautiful chaos. The temples had been impressive, sure, but it was the street food vendors, the crowded markets, the strolls on the beach with the peaceful cows sunbathing, and the quiet, forgotten alleys that stuck with him. He’d made some connections, met some people who’d lingered in his thoughts longer than they should have.

One of them had been a woman named Anila, who had handed him a fragment of something—an idea, a story, a warning. He couldn’t quite remember now. It felt like she’d been trying to tell him something important, but whatever it was had slipped through his fingers like water.

Darius shook his head, pushing the thought aside. The past was the past, and Paris was the present. He looked at the rolled-up map peeking out of his duffel and smirked. Maybe Lucien would know what to make of it. Or Elara, with her scientific mind and love of puzzles.

The group had always been a strange mix, like a band that shouldn’t work but somehow did. And now, after five years of silence, they were coming back together.

The idea made his stomach churn—not with nerves, exactly, but with a sense of inevitability. Things had been left unsaid back then, unfinished. And while Darius wasn’t usually one to linger on the past, something about this meeting felt… different.

The café was just around the corner now, its brass fixtures glinting through the drizzle. Darius slung his duffel higher on his shoulder and took one last sip of espresso before tossing the cup into a bin.

Whatever this reunion was about, he’d be ready for it.

But the map—it stayed on his mind, its looping lines and impossible paths pressing into his thoughts like a puzzle waiting to be solved.

December 1, 2024 at 5:44 pm #7623In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

At the Café

The Sarah Bernardt Café shimmered under a pale grey November sky a busy last Saturday of the “Black Week”. Golden lights spilled onto cobblestones slick with rain, and the air buzzed with the din of a city alive in the moment. Inside, the crowd pressed together, laughing, arguing, living. And in a corner table by the fogged-up window, old friends were about to quietly converged, coming to a long overdue reunion.

Lucien was the first to arrive, dragging a weathered suitcase behind him. Its wheels rattled unevenly on the cobblestones, a sound he hated. His dark curls, damp from the rain, clung to his forehead, and his scarf, streaked with old paint, hung loose around his neck. He folded himself into a corner chair, his suitcase tucked awkwardly beside him. When the server approached, Lucien waved him off with a distracted shake of his head and opened a battered sketchbook.

The next arrival was Elara. She entered briskly, shaking rain from her short gray-streaked hair, her eyes scanning the room as though searching for anomalies. A small roller bag trailed behind her, pristine and black, a sharp contrast to Lucien’s worn luggage. She stopped at the table and tilted her head.

“Still brooding?” she asked, pulling off her coat and folding it neatly over the back of a chair.

“Still talking?” Lucien didn’t look up, his pencil scratching faint lines across the page.

Elara smiled faintly. “Two minutes in, and you’re already immortalizing us? You know I hate being drawn.”

“You hate being caught off guard,” Lucien murmured. “But I never get your nose wrong.”

She laughed, the sound light but brief, and sank into her seat, placing her bag carefully beside her.

The door swung open again, and Darius entered, shaking the rain from his jacket. His presence seemed to fill the room immediately. He strode toward the table, a leather duffel slung over one shoulder and a well-worn travel pouch clutched in his hand. His boots clacked against the café’s tile floor, his movements easy, confident.

“Did you walk here?” Elara asked as he dropped his things with a thud and pulled out a chair.

“Ran into someone on the way,” he said, settling back. “Some guy selling maps. Got this one for ten euros—worth every cent.” He waved a yellowed scrap of paper that looked more fiction than cartography.

Lucien snorted. “Still paying for strangers’ stories, I see.”

“The good ones aren’t free.” Darius grinned and leaned back in his chair, propping one boot against the table leg.

The final arrival was Amei. Her entrance was quieter but no less noticeable. She unwound her scarf slowly, her layered clothing a mix of textures and colors that seemed to absorb the café’s golden light. A tote bag rested over her shoulder, bulging with what could have been books, or journals, or stories yet untold.

“You’re late,” Darius said, but his voice carried no accusation.

“Right on time,” Amei replied, lowering herself into the last chair. “You’re all just early.”

Her gaze swept across them, lingering on the bags piled at their feet. “I see I’m not the only one who came a long way.”

“Not all of us live in Paris,” Elara said, with a glance at Lucien.

“Only some of us make better life choices,” Lucien replied dryly.

The comment drew laughter—a tentative sound that loosened the air between them, thick as it was with five years of absence.

November 18, 2024 at 9:40 pm #7605

November 18, 2024 at 9:40 pm #7605In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

Although the small hotel was tucked in a relatively quiet corner, and despite the authentic but delightfully shabby interior of soothing dimensions ~ roomy and airy, but not vast and terrifyingly empty ~ the constant background hum of city life was making Truella yearn for the stillness of home. Not that home was silence, indeed not: the background tranquility was frequently punctuated with noises, many strident. A dog barks, a neighbour shouts, a car drives past from time to time. But the noises have an identifiable individuality and reason, unlike the continual maddening drone of the metropolis.

She was pleased to find her room had a little balcony. Even if the little wooden chair was rickety and uncomfortable, it was enough to perch on to enjoy a cigarette and breathe in the car fumes. Truella slept fitfully, waking to remember Tolkeinesque snapshots of dreams, drifting off again and returning to wakefullness with snatches of conversations in unknown tongues. Sitting on the balcony in the deep dark hours of the night, the street below, now quiet, shivered and changed, her head still swimming with dream images. She caught glimpses of people as they passed, vivid, clear and full of character. Many who passed were carrying bunches of grasses or herbs or wildflowers in their hands, the women with a basket over their arm and a shawl draped over their head or shoulders.

Hardly any men though, I wonder why?

When Truella mentioned it over breakfast the next moring, Eris said “You’ve been reading too much of that new gender and feminist anthropology stuff over on GreenGrotto.”

Laughing, Truella tipped another packet of sugar in her coffee. “I love the colour of the walls in here,” she said, gazing around the breakfast room. “A sort of bright but muted sun shining on a white wall. Nice old furniture, too.”

“Tell me about the old furniture, the mirror in my room is all speckled, makes me look like I have blemishes all over my face,” said Zeezel with a toss of her head. “Can I have your sugar, Frella, if you’re not having it,” adding I’m on holiday by way of excuse.

Absentmindely Frella passed over the paper packet. “I had strange dreams last night too…about that place we’re supposed to be going to a picnic to later.”

Catching everyones attention, she continued, “The abandoned colosseum with Giovanni, with all the vines and flowers. It was like a game board and the stone statues were the players and they moved around the board, Oh! and such a beautiful board it was with all the vines and flowers ….. ”

“Gosh” said Truella, leaning back and folding her hands. What an idea.

November 4, 2024 at 2:01 pm #7578In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

When Eris gave Jeezel carte blanche to decorate the meeting room, Frella and Truella looked at her as if she’d handed fireworks to a dragon. They protested immediately, arguing that giving Jeezel that much freedom was like inviting a storm draped in sequins and velvet. After all, Jeezel was a queen diva—a master of flair and excess, ready to transform any ordinary space into a grand stage for her dramatic vision. In their eyes, it would defeat the whole purpose! But Eris raised a firm hand, silencing her sister’s objections.

“Let’s be honest, Malové is no ordinary witch,” she began, addressing Truella, Frella, and even Jeezel, who was still stung by her sisters’ criticism of her decorating skills. “We don’t know how many centuries that witch has been roaming the world, gathering knowledge and sharpening her mind. But what we do know is that she’d detect any concealing spell in a heartbeat.”

“Yeah, you’re right,” Truella agreed. “I think that’s the smell…”

“You mean based on your last potion experiment?” snorted Frella.

“Girls, focus,” Eris said. “This meeting is long overdue, and we need to conceal the truth-revealing spell’s elements. Jeezel’s flair may be our best distraction. Malové has always dismissed her grandiosity as harmless extravagance, so for once, let’s use that to our advantage.”

While Eris spoke, Jeezel’s brow furrowed as she engaged in an animated dialogue with her inner diva, picturing every details. Frella rolled her eyes subtly, glancing off-camera as though for dramatic effect.

“Isn’t that a bit much for a meeting?” Truella groaned. “You already assigned us topics to prepare. Now we’re adding decorations?”

“You won’t have to lift a finger,” Jeezel declared. “I’ve got it all under control—and I already have everything we need. Here’s my vision: Halloween is coming, so the decor should be both elegant and enchanting. I’ll start by draping the room in velvet curtains in deep purples and midnight blacks—straight from my own bedroom.”

Truella’s jaw dropped, while Jeezel’s grin only widened.

“Oh! I love those,” Frella murmured approvingly.

“Next, delicate cobweb accents with a touch of silver thread to catch the light,” Jeezel continued. “Truella, we’ll need your excavation lamps with a few colored gels. They’ll cast a warm, inviting glow—a perfect mix of relaxation and intrigue, with shadows in just the right places. And for the season, a few glowing pumpkins tucked around the room will complete the scene.”

Jeezel’s inner diva briefly entertained the idea of mystical fog, but she discarded it—after all, this was a meeting, not a sabbat. Instead, she proposed a more subtle touch: “To conceal the spell’s elements, I’ll bring in a few charming critters. Faux ravens perched on shelves, bats hanging from the ceiling…a whimsical, creepy-cute vibe. We’ll adorn them with runes and sigils in an insconpicuous way and Frella can cast a gentle animation spell to make them shift ever so slightly. The movement will be just enough to escape Malové’s notice as she stays focused on the meeting. That way she’ll be oblivious to the spell being woven around her.”

“Are you starting to see where this is going?” Eris asked, looking at her sisters.

Frella nodded, and before Truella could chime in with any objections, Jeezel added, “And no Halloween gathering would be complete without wickedly delightful treats! Picture a grand table with themed snacks and drinks on polished silver trays and cauldrons. Caramel apples, spiced cider, chocolates shaped like magic potions—tempting enough to charm even a disciplined witch.”

“Now you’re talking my language,” Truella admitted, finally warming up to the idea.

“Perfect, then it’s settled,” Eris said, pleased. “You all have your tasks. They’ll help us reveal her hidden agenda and how the spell is influencing her. Truella, you’l handle Historical Artifacts and Lore. Frella, with your talent for connections, you’ll cover Coven Alliances and Mutual Interests. Jeezel, you’re in charge of Telluric and Cosmic Energies—it shouldn’t be hard with your endless videos on the subject. I’ll handle the rest: Magical Incense Innovations, Leadership Philosophy, and Coven Dynamics.”

September 15, 2024 at 12:08 am #7554In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

Frella sat at her small kitchen table, sipping chamomile tea and tracing a finger over the worn edges of the mysterious postcard. Her phone buzzed—a message from Truella.

Frella! I found an old book under my table! Never seen it before! Called Me and Minn. Strange, right?

A crease appeared on Frella’s brow as she re-read the message. Didn’t Arona say she was looking for an old book?

Setting her cup down too quickly, Frella splashed tea onto the postcard. “Damn,” she muttered, watching the ink blur. With a flick of her fingers, a cloth floated over from the counter and gently dabbed at the spill. The stain faded as the cloth wiped it away.

Frella leaned back in her chair, staring at the postcard. Some magic was stirring—first the dream, now this.

Weirdo, Truella. I dreamed last night about a girl searching for an old book! Catch up with you and the others this morning and we can discuss!

Finishing her tea, Frella waved her hand, sending the cup and saucer floating to the sink. She stretched and stood. A meeting at the Quadrivium had been called for 10 AM, but first, there were errands. After a quick shower, she got dressed, donned her raincoat, and carefully tucked the postcard into her bag.

Stepping outside, she wheeled her bike onto the damp path. The crisp morning air, misted with drizzle, hinted at a secret just waiting to be uncovered.

March 19, 2023 at 5:49 pm #7173In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

The morning of the lager and cart race dawned bright and clear. The camping ground was full to overflowing with tents and camper vans, with several parked up outside the Flying Fish Inn. Zara overheard Finly complaining to Mater about all the extra work with all and sundry traipsing in and out using the toilets, and Bert muttering about where was all the extra water supposed to come from and what if the well ran dry, and was it all really worth it, and Zara saw him scowl when Idle told him to lighten up and enjoy it. “Hah! Enjoy it? Nothing good ever happens when a dust storm comes for the cart race,” he said pointedly to Idle, ” And damn near everyone asking about the old mines, I tell you, nothing good’s gonna come from a cart race in a dust storm, the mayor shoulda cancelled it.” Bert slammed the porch door as he stomped off outside, scowling at Zara on the way past.

Zara watched him go with a quizzical expression. What was going on here? Idle had told her about her affair with Howard some forty years ago, and how she’d had to disappear as soon as it became obvious that she was pregnant. Zara had sympathized and said what an ordeal it must have been, but Idle had laughed and said no not really, she’d had a lovely time in Fiji and had found a nice place to leave the baby. Then Howard had disappeared down the mines, and what was the story about Idle’s brother leaving mysteriously? Idle had been vague about that part, preferring to change the topic to Youssef. Was the Howard story why Bert was so reluctant for anyone to go down the mines? What on earth was going on?

And how had Yasmin’s parcel ended up in Xavier’s room? Xavi had soon noticed that he’d picked it up by mistake and returned it to Yasmin, but how had it ended up on the table on the verandah? It was perplexing, and made Yasmin disinclined to deliver it to Mater until she could fathom what had happened. She had tucked in under her mattress until she was sure what to do.

But that wasn’t the only thing that had piqued Zara’s curiosity. When Idle had said she’d had the baby in Fiji, and found a nice place to leave it, Zara couldn’t help but think of the orphanage where Yasmin was working. But no, surely that would be too much of a coincidence, and anyway, a 40 year old orphan wouldn’t still be there. But what about that woman in the BMW that Yasmin felt sure she recognized? No, surely it was all too pat. But then, what was that woman in the dark glasses doing in Betsy’s shop? Betsy was Howards wife. Idle had mentioned her when she told her story over the second bottle of wine.

Should she divulge Idle’s secrets to Yasmin and quiz her on the woman in dark glasses? Zara decided there would be no harm in it, after all, they would be leaving soon after the cart race, and what would it matter. She fetched two cups of coffee from the kitchen and took them to Yasmin’s room and knocked gently on the door.

“Are you awake?” she called softly.

“Yeah, come in Zara, I’ve been awake for ages,” Yasmin replied.

Zara put the coffee cups on the bedside table and sat on the side of Yasmins bed. “There’s something going on here, I have to tell you something. But first, have you worked out who that woman in the BMW is?”

Yasmin looked startled and said “How did you know? Yes I have. It’s Sister Finli from the orphanage, I’m sure of it. But why has she followed me here? And in disguise! It’s just creepy!”

“Aha!” Zara couldn’t suppress a rather triumphant smile. “I thought it was just a wacky idea, but listen to this, Idle told me something the other night when we sat up drinking wine.” As she told Idle’s story, Yasmin’s eyes widened and she put a hand over her open mouth.

“Could it be…?”

“Yes but why in disguise? What is she up to? What should we do, should we warn Idle?” Zara had warmed to Idle, and if there were any sides to be taken in the matter, she felt more for Idle than that unpleasant woman from the orphanage who was so disturbing to Yasmin.

“Oh I don’t know, maybe we should keep out of it!” Yasmin said. “That parcel though! What am I going to do about that parcel!”

Zara frowned. “Well, you have three options, Yas. Open it and read it… don’t look so horrified! Or deliver it as promised..”

“We’ll never know what it said though if we do that,” Yasmin was looking more relaxed now.

“Exactly, and I’m just too curious now.”

“And the third option?”

Ignoring the question, Zara asked where the parcel was. Yasmin grinned wickedly but a knock at the door interrupted her intention to retrieve the parcel from under the mattress. It was Youssef, who asked if he could come in.

“Shall we tell him?” Zara whispered, as Yasmin called out “Of course! Is Idle after you again? Quick, you can hide under my bed!”

“Not yet” Yasmin whispered back. “I need to think.”

February 15, 2023 at 10:54 am #6547In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

On her way back to her room Zara picked up a leaflet off the hall table about the upcoming lager and cart race. Before starting the game she had a look through it.

The leaflet also mentioned the competition held annually each January in Port Lincoln. The Tunarama Festival was a competition to determine just how far a person could chuck a frozen tuna. A full-fledged celebration was centered around the event, complete with a wide array of arts and cultural displays, other participation events, local market stalls, and some of the freshest seafood in the world.

There was unlikely to be any fresh seafood at the local lager and cart races, but judging from the photos of previous events, it looked colourful and well worth sticking around for, just for the photo opportunities.

Apparently the lager and cart races had started during the early days of the settler mining, and most of the carts used were relics from that era. Competitors dressed up in costumes and colourful wigs, many of which were found in the abandoned houses of the local area.

“The miners were a strange breed of men, but not all cut from the same cloth ~ they were daring outsiders, game for anything, adventurous rule breakers and outlaws with a penchant for extreme experience. Thus, outlandish and adventurous women ~ and men who were not interested in mining for gold in the usual sense ~ were magnetically drawn to the isolated outpost. After a long dark day of restriction and confinement in the mines, the evenings were a time of colour and wild abandon; bright, garish, bizarre Burlesque events were popular. Strange though it may seem, the town had one of the most extensive wig and corset emporiums in the country, although it was discretely tucked away in the barn behind a mundane haberdashery shop.”

The idea was to fill as many different receptacles with lager as possible, piling them onto the gaily decorated carts pulled by the costume clad participants. As the carts were raced along the track, onlookers ran alongside to catch any jars or bottles that fell off the carts before they hit the ground. Many crashed to the ground and were broken, but if anyone caught one, they were obliged to drink the contents there and then before running after the carts to catch another one.

Members of the public were encouraged to attend in fancy dress costumes and wigs. There were plenty of stationary food vendors carts at the lager and cart races as well, and stalls and tents set up to sell trinkets.

February 7, 2023 at 9:54 pm #6509In reply to: A Dog and a Dig – The trenches of the Time Capsule

Table of characters:

Characters Keyword Characteristics Sentiment Clara Woman in her late 40s, VanGogh’s owner Inquisitive, curious VanGogh Clara’s dog Curious Grandpa Bob Clara’s grandfather, widowed, early signs of dementia Skeptical, anxious Nora Clara’s friend, amateur archaeologist, nicknamed Alienor by Clara Adventure-seeking Jane Grandpa Bob’s wife, Clara’s mother, only Bob seem to see her, possibly a hallucination Teasing Julienne / Mr. Willets Neighbors of Clara & Bob – Bubbles (Time-dragglers squad, alternate timeline) Junior drag-queen, reporting to Linda Pol (office manager) adventurous, brave, concerned Will After Nora encountered a man with a white donkey, she awakes in a cottage. Will is introduced later, and drugs Nora unbeknownst to her. Later Bob & Clara come at his doorstep (they know him as the gargoyle statues selling man from the market), looking for her friend. Affable, mysterious, hiding secrets Some connecting threads:

- The discovery of a mysterious pear-shaped box with inscriptions by Clara and her grandfather.

- Clara sending photos of the artifact to Nora (Alienor), an amateur archaeologist.

- Nora’s journey from her place to reach the location where the box was discovered and her encounter with a man with a donkey (Will?).

- Grandpa Bob’s anxious behavior and the confusion over the torn piece of paper with a phone number.

- The parallel timeline of a potential breach in the timelines in Linda Pol’s office.

- The search for VanGogh and the discovery of a map tucked into his collar.

- The suggestion from Jane that Clara should be told something.

- Nora awakes at a cottage and spends time with Will who drugs her soup. Bob & Clara show up later, looking for her.

January 23, 2023 at 4:14 pm #6453In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Each group of people sharing the jeeps spent some time cleaning the jeeps from the sand, outside and inside. While cleaning the hood, Youssef noted that the storm had cleaned the eagles droppings. Soon, the young intern told them, avoiding their eyes, that the boss needed her to plan the shooting with the Lama. She said Kyle would take her place.

Each group of people sharing the jeeps spent some time cleaning the jeeps from the sand, outside and inside. While cleaning the hood, Youssef noted that the storm had cleaned the eagles droppings. Soon, the young intern told them, avoiding their eyes, that the boss needed her to plan the shooting with the Lama. She said Kyle would take her place.“Phew, the yak I shared the yurt with yesterday smelled better,” he said to the guys when he arrived.

Soon enough, Miss Tartiflate was going from jeep to jeep, her fiery hair half tied in a bun on top of her head, hurrying people to move faster as they needed to catch the shaman before he got away again. She carried her orange backpack at all time, as if she feared someone would steal its content. Rumour had it that it was THE NOTEBOOK where she wrote the blog entries in advance.

“No need to waste more time! We’ll have breakfast at the Oasis!” she shouted as she walked toward Youssef’s jeep. When she spotted him, she left her right index finger as if she just remembered something and turned the other way.

“Dunno what you did to her, but it seems Miss Yeti is avoiding you,” said Kyle with a wry smile.

Youssef grunted. Yeti was the nickname given to Miss Tartiflate by one of her former lover during a trip to Himalaya. First an affectionate nickname based on her first name, Henrietty, it soon started to spread among the production team when the love affair turned sour. It sticked and became widespread in the milieu. Everybody knew, but nobody ever dared say it to her face.

Youssef knew it wouldn’t last. He had heard that there was wifi at the oasis. He took a snack in his own backpack to quiet his stomach.

It took them two hours to arrive as sand dunes had moved on the trail during the storm. Kyle had talked most of the time, boring them to death with detailed accounts of his life back in Boston. He didn’t seem to notice that nobody cared about his love rejection stories or his tips to talk to women.

They parked outside the oasis among buses and vans. Kyle was following Youssef everywhere as if they were friends. Despite his unending flow of words, the guy managed to be funny.

Miss Tartiflate seemed unusually nervous, pulling on a strand of her orange hair and pushing back her glasses up her nose every two minutes. She was bossing everyone around to take the cameras and the lighting gear to the market where the shaman was apparently performing a rain dance. She didn’t want to miss it. When everybody was ready, she came right to Youssef. When she pushed back her glasses on her nose, he noticed her fingers were the colour of her hair. Her mouth was twitching nervously. She told him to find the wifi and restore THE BLOG or he could find another job.

“Phew! said Kyle. I don’t want to be near you when that happens.” He waved and left and joined the rest of the team.

Youssef smiled, happy to be alone at last, he took his backpack containing his laptop and his phone and followed everyone to the market in the luscious oasis.

At the center, near the lake, a crowd of tourists was gathered around a man wearing a colorful attire. Half his teeth and one eye were missing. The one that was left rolled furiously in his socket at the sound of a drum. He danced and jumped around like a monkey, and each of his movements were punctuated by the bells attached to the hem of his costume.

Youssef was glad he was not part of the shooting team, they looked miserable as they assembled the gears under a deluge of orders. As he walked toward the market, the scents of spicy food made his stomach growled. The vendors were looking at the crowd and exchanging comments and laughs. They were certainly waiting for the performance to end and the tourists to flood the place in search of trinkets and spices. Youssef spotted a food stall tucked away on the edge. It seemed too shabby to interest anyone, which was perfect for him.

The taciturn vendor, who looked caucasian, wore a yellow jacket and a bonnet oddly reminiscent of a llama’s scalp and ears. The dish he was preparing made Youssef drool.

“What’s that?” he asked.

“This is Lorgh Drülp

, said the vendor. Ancient recipe from the silk road. Very rare. Very tasty.”

He smiled when Youssef ordered a full plate with a side of tsampa. He told him to sit and wait on a stool beside an old and wobbly table.

January 23, 2023 at 2:16 pm #6452In reply to: Prompts of Madjourneys

Youssef’s entry quirk is being grumpy when he’s hungry.

Quirk accepted.

Initial setting: You find yourself in a bustling marketplace, surrounded by vendors selling all sorts of exotic foods and spices. Your stomach growls loudly, reminding you of your quirk.

Possible direction to investigate: As you explore the marketplace, you notice a small stall tucked away in the corner. The aroma wafting from the stall is tantalizing, and your stomach growls even louder. As you approach, you see a grumpy-looking vendor behind the counter. He doesn’t seem to be in the mood for customers.

Possible character to engage: The grumpy vendor.

Objective: To find a way to appease the grumpy vendor and secure a satisfying meal to satisfy your hunger.

Additional FFI clue: As you make your way to the Flying Fish Inn, you notice a sign advertising a special meal made with locally caught fish. Could this be the key to satisfying your hunger and appeasing the grumpy vendor? Remember to bring proof of your successful quest to the FFI.

Snoot’s clue: 🧔🌮🔍🔑🏞️

March 4, 2022 at 2:58 pm #6280In reply to: The Whale’s Diaries Collection

I started reading a book. In fact I started reading it three weeks ago, and have read the first page of the preface every night and fallen asleep. But my neck aches from doing too much gardening so I went back to bed to read this morning. I still fell asleep six times but at least I finished the preface. It’s the story of the family , initiated by the family collection of netsuke (whatever that is. Tiny Japanese carvings) But this is what stopped me reading and made me think (and then fall asleep each time I re read it)

“And I’m not entitled to nostalgia about all that lost wealth and glamour from a century ago. And I am not interested in thin. I want to know what the relationship has been between this wooden object that I am rolling between my fingers – hard and tricky and Japanese – and where it has been. I want to be able to reach to the handle of the door and turn it and feel it open. I want to walk into each room where this object has lived, to feel the volume of the space, to know what pictures were on the walls, how the light fell from the windows. And I want to know whose hands it has been in, and what they felt about it and thought about it – if they thought about it. I want to know what it has witnessed.” ― Edmund de Waal, The Hare With Amber Eyes: A Family’s Century of Art and Loss

And I felt almost bereft that none of the records tell me which way the light fell in through the windows.

I know who lived in the house in which years, but I don’t know who sat in the sun streaming through the window and which painting upon the wall they looked at and what the material was that covered the chair they sat on.

Were his clothes confortable (or hers, likely not), did he have an old favourite pair of trousers that his mother hated?

There is one house in particular that I keep coming back to. Like I got on the Housley train at Smalley and I can’t get off. Kidsley Grange Farm, they turned it into a nursing home and built extensions, and now it’s for sale for five hundred thousand pounds. But is the ghost still under the back stairs? Is there still a stain somewhere when a carafe of port was dropped?

Did Anns writing desk survive? Does someone have that, polished, with a vase of spring tulips on it? (on a mat of course so it doesn’t make a ring, despite that there are layers of beeswaxed rings already)

Does the desk remember the letters, the weight of a forearm or elbow, perhaps a smeared teardrop, or a comsumptive cough stain?

Is there perhaps a folded bit of paper or card that propped an uneven leg that fell through the floorboards that might tear into little squares if you found it and opened it, and would it be a rough draft of a letter never sent, or just a receipt for five head of cattle the summer before?

Did he hate the curtain material, or not even think of it? Did he love the house, or want to get away to see something new ~ or both?

Did he have a favourite cup, a favourite food, did he hate liver or cabbage?

Did he like his image when the photograph came from the studio or did he think it made his nose look big or his hair too thin, or did he wish he’d worn his other waistcoat?

Did he love his wife so much he couldn’t bear to see her dying, was it neglect or was it the unbearableness of it all that made him go away and drink?