-

AuthorSearch Results

-

June 11, 2025 at 6:07 pm #7960

In reply to: Cofficionados Bandits (vs Lucid Dreamers)

As Chico carried the Memory Pie over to Kit, a breeze shuffled the pages of the script lying abandoned beside the gazebo. No one had noticed it before—maybe it hadn’t been there. The pages were blank. Then they weren’t.

Kit blinked. “Did you just call me Trevor?”

“No,” said Chico. But he looked uncertain. “Did I?”

There was a rumble below them. The gazebo creaked—faint and subtle, like a swedish roll turning in its deep sleep.

Then—click-clac thank you Sirtak.

A trapdoor swung open beneath Kit’s feet. But instead of falling, Kit froze mid-air.

The air flickered. Kit shimmered.

And now they were wearing sunglasses, holding a cowboy lasso, and speaking in a faint Midwest accent.

“Sorry, I think I missed my cue. Where are we in the scene?”

March 28, 2025 at 10:28 pm #7881In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

Mars Outpost — Welcome to the Wild Wild Waste

No one had anticipated how long it would take to get a shuttle full of half-motivated, gravity-averse Helix25 passengers to agree on proper footwear.

“I told you, Claudius, this is the fancy terrain suit. The others make my hips look like reinforced cargo crates,” protested Tilly Nox, wrangling with her buckles near the shuttle airlock.

“You’re about to step onto a red-rock planet that hasn’t seen visitors since the Asteroid Belt Mining Fiasco,” muttered Claudius, tightening his helmet strap. “Your hips are the least of Mars’ concerns.”

Behind them, a motley group of Helix25 residents fidgeted with backpacks, oxygen readouts, and wide-eyed anticipation. Veranassessee had allowed a single-day “expedition excursion” for those eager—or stir-crazy—enough to brave Mars’ surface. She’d made it clear it was volunteer-only.

Most stayed aboard, in orbit of the red planet, looking at its surface from afar to the tune of “eh, gravity, don’t we have enough of that here?” —Finkley had recoiled in horror at the thought of real dust getting through the vents and had insisted on reviewing personally all the airlocks protocols. No way that they’d sullied her pristine halls with Martian dust or any dust when the shuttle would come back. No – way.

But for the dozen or so who craved something raw and unfiltered, this was it. Mars: the myth, the mirage, the Far West frontier at the invisible border separating Earthly-like comforts into the wider space without any safety net.

At the helm of Shuttle Dandelion, Sue Forgelot gave the kind of safety briefing that could both terrify and inspire. “If your oxygen starts blinking red, panic quietly and alert your buddy. If you fall into a crater, forget about taking a selfie, wave your arms and don’t grab on your neighbor. And if you see a sand wyrm, congratulations, you’ve either hit gold or gone mad.”

Luca Stroud chuckled from the copilot seat. “Didn’t see you so chirpy in a long while. That kind of humour, always the best warning label.”

They touched down near Outpost Station Delta-6 just as the Martian wind was picking up, sending curls of red dust tumbling like gossip.

And there she was.

Leaning against the outpost hatch with a spanner slung across one shoulder, goggles perched on her forehead, Prune watched them disembark with the wary expression of someone spotting tourists traipsing into her backyard garden.

Sue approached first, grinning behind her helmet. “Prune Curara, I presume?”

“You presume correctly,” she said, arms crossed. “Let me guess. You’re here to ruin my peace and use my one functioning kettle.”

Luca offered a warm smile. “We’re only here for a brief scan and a bit of radioactive treasure hunting. Plus, apparently, there’s been a petition to name a Martian dust lizard after you.”

“That lizard stole my solar panel last year,” Prune replied flatly. “It deserves no honor.”

Inside, the outpost was cramped, cluttered, and undeniably charming. Hand-drawn maps of Martian magnetic hotspots lined one wall; shelves overflowed with tagged samples, sketchpads, half-disassembled drones, and a single framed photo of a fireplace with something hovering inexplicably above it—a fish?

“Flying Fish Inn,” Luca whispered to Sue. “Legendary.”

The crew spent the day fanning out across the region in staggered teams. Sue and Claudius oversaw the scan points, Tilly somehow got her foot stuck in a crevice that definitely wasn’t in the geological briefing, which was surprisingly enough about as much drama they could conjure out.

Back at the outpost, Prune fielded questions, offered dry warnings, and tried not to get emotionally attached to the odd, bumbling crew now walking through her kingdom.

Then, near sunset, Veranassessee’s voice crackled over comms: “Curara. We’ll be lifting a crew out tomorrow, but leaving a team behind. With the right material, for all the good Muck’s mining expedition did out on the asteroid belt, it left the red planet riddled with precious rocks. But you, you’ve earned to take a rest, with a ticket back aboard. That’s if you want it. Three months back to Earth via the porkchop plot route. No pressure. Your call.”

Prune froze. Earth.

The word sat like an old song on her tongue. Faint. Familiar. Difficult to place.

She stepped out to the ridge, watching the sun dip low across the dusty plain. Behind her, laughter from the tourists trading their stories of the day —Tilly had rigged a heat plate with steel sticks and somehow convinced people to roast protein foam. Are we wasting oxygen now? Prune felt a weight lift; after such a long time struggling to make ends meet, she now could be free of that duty.

Prune closed her eyes. In her head, Mater’s voice emerged, raspy and amused: You weren’t meant to settle, sugar. You were meant to stir things up. Even on Mars.

She let the words tumble through her like sand in her boots.

She’d conquered her dream, lived it, thrived in it.

Now people were landing, with their new voices, new messes, new puzzles.

She could stay. Be the last queen of red rock and salvaged drones.

Or she could trade one hell of people for another. Again.

The next morning, with her patched duffel packed and goggles perched properly this time, Prune boarded Shuttle Dandelion with a half-smirk and a shrug.

“I’m coming,” she told Sue. “Can’t let Earth ruin itself again without at least watching.”

Sue grinned. “Welcome back to the madhouse.”

As the shuttle lifted off, Prune looked once, just once, at the red plains she’d called home.

“Thanks, Mars,” she whispered. “Don’t wait up.”

March 9, 2025 at 10:34 pm #7862In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

Sue Forgelot couldn’t believe her eyes when she came to her ringing door.

Of course, after the Carnival party was over and she’d taken an air shower, and put on her bathrobe with her meerkat slipper, slathered relaxing face cream topped with two slices of cucumber, she was quite groggy, and the cucumber slices on her eyelids made it harder to see. But once she’d removed them, she could see as bright as day.

The Captain was standing right here, and she hadn’t aged a day.

“Quickly, come in.” Sue wasted no time to usher her in. She looked at the corridor suspiciously; at that time of night, only a dusting robot was patrolling the corridors, chasing for dust motes and finger smears on the datapads.

Nobody.

“I haven’t been followed, Sue, will you just relax for a moment.”

“V’ass, it’s been so long. How did you get out?… What broke the code?”

“I don’t know, Sue. I think —something called back, from Earth.”

“From Earth? I didn’t know there was much technology left, or at least one that could reach us there. And one that could bypass that darned central AI —I knew it couldn’t keep you under lock and key forever.”

“Seems there is such tech, and it’s also managed to force the ship to turn around.”

Silence fell on the two friends for a moment, as they were grasping for the implications of the changes in motion.

Veranassessee couldn’t help by smile uncontrollably. “Those rejuvenation tricks do wonders, don’t they. You don’t look a day over a 100 years old.”Sue couldn’t help but chuckle. “And you don’t look so bad yourself, for an old forgotten popsicle.” She tilted her head. “You do know you’ve been in the freezer longer than some of our newest passengers have been alive, right?”

V’ass shrugged. “And yet, here I am—fit, rested, and none the worse for wear.”

Sue sighed. “Meanwhile, I’ve had three hip replacements, a cybernetic knee, and somebody keeps hijacking my artificial leg with spam messages.”

V’ass blinked. “…You should probably get that checked.”

Sue waved her off. “Bah. If it’s not trying to sell me ‘hot singles in my quadrant,’ I let it be.”After the laughter had dissipated, Sue said “You need my help to get back your ship, don’t you?”. She tapped on her cybernetic leg with a knowing smile. “You can count on me.”

Veranassessee noded. “Then start by filling me in, what should I know?”

Sue leaned in conspiratorially. “Ethan is dead, for one.”

“Death?” Veranassessee was weighing the implications, and completed “… Murder?”

Sue shrugged “As much as it pains me to say, it’s all a bit irrelevant. The AI let it happen, but I doubt she pushed the button. Ethan wasn’t much of a threat to its rule. Makes one wonder why, maybe it computed some cascade of events we don’t yet see. They found ancient DNA on the crime scene, but it’s all a mess of clues, and I must say we’re pretty inept at the whole murder mystery thing. Glad we don’t have a serial killer in our midst, or we would have plenty of composting to do…”

Veranassessee started to pace the room. “Well, if there isn’t anything more relevant, we need to hatch a plan. I suspect all my access got revoked; I’ll need a skeleton key to get in the right places. To regain control over the central AI, and the main deck.”

“Of course, the Marlowes…” Sue had a moment of revelation on her face. “They were the crypto locksmiths… With Ethan now dead, maybe we should pay dear old Ellis a visit.”

March 1, 2025 at 10:53 am #7845In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

It was only Molly who noticed Tundra keep a few postcards back and surrepticiously put them in her pocket as the postcards were passed around.

“If anyone has an anecdote, hang on to the postcard, if not, pass it on,” instructed Tala.

Yulia held onto a Christmas cat postcard, with the intention of sharing memories of various cats she’d known. Finja kept a postcard of an Australian scene, Mikhail the one with the onion domes, and Molly a picture of the Giralda cathedral in Seville. Vera selected the one of the Tower of London, Jian chose one of a Shanghai skyscraper, Anya kept an old sepia one that said “Hands Across the Sea from Maoriland”, and Petro chose one of Buda castle. Gregor chose a wild west rodeo scene.

March 1, 2025 at 10:12 am #7844In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

Base Klyutch – Dr. Markova’s Clinic, Dusk

The scent of roasting meat and simmering stew drifted in from the kitchens, mingling with the sharper smells of antiseptic and herbs in the clinic. The faint clatter of pots and the low murmur of voices preparing the evening meal gave the air a sense of routine, of a world still turning despite everything. Solara Ortega sat on the edge of the examination table, rolling her shoulder to ease the stiffness. Dr. Yelena Markova worked in silence, cool fingers pressing against bruised skin, clinical as ever. Outside, Base Klyutch was settling into the quiet of night—wind turbines hummed, a sentry dog barked in the distance.

“You’re lucky,” Yelena muttered, pressing into Solara’s ribs just hard enough to make a point. “Nothing broken. Just overworked muscles and bad decisions.”

Solara exhaled sharply. “Bad decisions keep us alive.”

Yelena scoffed. “That’s what you tell yourself when you run off into the wild with Orrin Holt?”

Solara ignored the name, focusing instead on the peeling medical posters curling off the clinic walls.

“We didn’t find them,” she said flatly. “They moved west. Too far ahead. No proper tracking gear, no way to catch up before the lionboars or Sokolov’s men did.”

Yelena didn’t blink. “That’s not what I asked.”

A memory surfaced; Orrin standing beside her in the empty refugee camp, the air thick with the scent of old ashes and trampled earth. The fire pits were cold, the shelters abandoned, scraps of cloth and discarded tin cups the only proof that people had once been there. And then she had seen it—a child’s scarf, frayed and half-buried in the dirt. Not the same one, but close enough to make her chest tighten. The last time she had seen her son, he had worn one just like it.

She hadn’t picked it up. Just stood there, staring, forcing her breath steady, forcing her mind to stay fixed on what was in front of her, not what had been lost. Then Orrin’s hand had settled on her shoulder—warm, steady, comforting. Too comforting. She had jerked away, faster than she meant to, pulse hammering at the sudden weight of everything his touch threatened to unearth. He hadn’t said a word. Just looked at her, knowing, as he always did.

She had turned, found her voice, made it sharp. The trail was already too cold. No point chasing ghosts. And she had walked away before she could give the silence between them the space to say anything else.

Solara forced her attention back to the present, to the clinic. She turned her gaze to Yelena, steady and unmoved. “But that’s what matters. We didn’t find them. They made their choice.”

Yelena clicked her tongue, scribbling something onto her worn-out tablet. “Mm. And yet, you come back looking like hell. And Orrin? He looked like a man who’d just seen a ghost.”

Solara let out a dry breath, something close to a laugh. “Orrin always looks like that.”

Yelena arched an eyebrow. “Not always. Not before he came back and saw what he had lost.”

Solara pushed off the table, rolling out the tension in her neck. “Doesn’t matter.”

“Oh, it matters,” Yelena said, setting the tablet down. “You still look at him, Solara. Like you did before. And don’t insult me by pretending otherwise.”

Solara stiffened, fingers flexing at her sides. “I have a husband, Yelena.”

“Yes, you do,” Yelena said plainly. “And yet, when you say Orrin’s name, you sound like you’re standing in a place you swore you wouldn’t go back to.”

Solara forced herself to breathe evenly, eyes flicking toward the door.

“I made my choice,” she said quietly.

Yelena’s gaze softened, just a little. “Did he?”

Footsteps pounded outside, uneven, hurried. The clinic door burst open, and Janos Varga—Solara’s husband—strode in, breathless, his eyes bright with something rare.

“Solara, you need to come now,” he said, voice sharp with urgency. “Koval’s team—Orrin—they found something.”

Her spine straightened, her heartbeat accelerated. “What? Did they find…?” No, the tracks were clear, the refugees went west.

Janos ran a hand through his curls, his old radio headset still looped around his neck. “One of Helix 57’s life boat’s wreckage. And a man. Some old lunatic calling himself Merdhyn. And—” he paused, catching his breath, “—we picked up a signal. From space.”

The air in the room tightened. Yelena’s lips parted slightly, the shadow of an emotion passed on her face, too fast to read. Solara’s pulse kicked up.

“Where are they?” she asked.

Janos met her gaze. “Koval’s office.”

For a moment, silence. The wind rattled the windowpanes.

Yelena straightened abruptly, setting her tablet down with a deliberate motion. “There’s nothing more I can do for your shoulder. And I’m coming too,” she said, already reaching for her coat.

Solara grabbed her jacket. “Take us there, Janos.”

February 24, 2025 at 9:11 am #7833In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

“We were heading that way anyway,” Molly informed the others. She was pleased with the decision to head towards Hungary, or what used to be known as Hungary.

“Slowly heading that way,” interjected Tundra. “We spent years roaming around Ukraine and never saw a sign of survivors anywhere.”

“And I wanted to go home,” continued Molly. “Or try to, anyway. I’m very old, you know,” she added, as if they might not have noticed.

“I’ve never even been outside Ukraine,” said Yulia. “How exciting!”

Anya gave her a withering look. “You can send some postcards,” she said which caused a general tittering about the absurdity of the idea.

Yulia returned the look and said sharply, ” I plan to draw in my sketchbook all the new sights.”

“While we’re foraging for food and building campfires and washing our knickers in streams?” snorted Finja.

“Does anyone actually know where this city is that we’re heading for? And the way there?” asked Gregor, “Because if it’s any help,” he added, rummaging in his backpack, “I saved this.” Triumphantly we waved a battered old folded map.

It was the first time in years that anyone had paid the old man any attention. Mikhail, Anya and Jian rushed over to him, eager to have a look. As their hands reached for the fragile map, Gregor clapsed it close to his chest, savouring his moment of glory.

“Ha!” he said, “Ha! Nobody wanted paper maps, but I knew it would come in handy one day!”

“Well done, Gregor” Molly said loudly. “A man after my own heart! I also have a paper map!” Tundra beamed happily at her great grandmother.

An excited buzz of murmuring swept through the gathered group.

“Ok, calm down everyone.” Anya stepped in to organise the situation. “Someone spread out a blanket. Let’s have a look at these maps ~ carefully! Stand back, everyone.”

Reluctantly, Molly and Gregor handed the maps to Anya, allowing her to slowly open them and spread them out. The folds had worn away completely in parts. Pebbles were collected to hold down the corners and protect the delicate paper from the breeze.

“Here, look” Mikhail pointed. “Here’s where we were at the asylum. Middle of nowhere. And here,” he pointed to a position slightly westwards, “Is where we are now. As you can see, the Hungarian border is close.”

“Where was that truck heading?” asked Vera.

Mikhail frowned and pored over the map. “Eastwards is all we can say for sure. Probably in the direction of Mukachevo, but Molly and Tundra said there were no survivors there. We just don’t know.”

“Yet,” added Jian, a man of few words.

“And where are we aiming for?” asked Finja.

“Nyíregyháza,” replied Mikhail, pointing at the map. “Should take us three or four days. Maybe a bit longer,” he added, glancing at Molly and Gregor.

“You’ll not outwalk Berlingo,” Molly snorted, “And I for one will be jolly glad to get back to some places that I can pronounce. And spell. Never did get a grip on that Cyrillic, I’d have been lost without Tundra.” Tundra beamed again at her grandmother. “And Hungarian names are only a tad better.”

“I can help you there,” Petro spoke up for the first time.

“You, help?” Anya said in astonishment, ” All you’ve ever done is complain!”

“Nobody has ever needed me, that’s why. I’m Hungarian. Surprised, are you? Nobody ever wanted to know where I was from. Nobody ever wanted my help with anything.”

“We’re all very glad you can help us now, Petro,” Molly said kindly, throwing a severe glance around the group. Tundra beamed proudly at Molly again.

“It’s an easy enough journey,” Petro addressed Molly directly, “Mostly agricultural plains. Well, they were agricultural anyway. Might be a good chance of feral chickens and self propagated crops, and the like. Finding water shouldn’t be a problem either. Used to be a lovely area,” Petro grew wistful. “I might go back to my village,” his voice trailed off as his mind returned to his childhood. “Never thought I’d ever see it again.”

“Well never mind that now,” Anya butted in rudely, “We need to make a start.” She began to carefully fold up the maps.

December 7, 2024 at 10:48 pm #7654In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

The first one to find the bar buys the drinks, Darius had said, and they’d all laughed, but it was no laughing matter being lost in those woods.

Siiting on a cushion on the floor surrounded by cardboard shoeboxes and piles of photos and letters, Elara leaned towards the lamp to better see the photograph. The white bull.

Lucien had refused when Elara asked him to do a painting of the white bull, and then relented and said he would. But he hadn’t, not that she knew of anyway. The incident had happened the year before the pandemic, the spring of 2019. Not long before they all went their separate ways. Elara had been visiting her father in Andalucia for his 90th birthday when a neighbour of his had told her about the stone in the woods. She knew the others would be interested and had invited them over; her father Roland had plenty of room at his finca overlooking the Hozgarganta river, and had no objections.

Darius had wanted to bring those people to see the pyramidal stone in the woods, and Elara was having none of it. I was told in private about that, I shouldn’t have shown anyone, Darius, not even you, she had told him. Resentfully, Darius had tried to argue his point: that it was for the greater good, shouldn’t be kept secret, and how could he keep it from them anyway, they would know he was hiding something.

You may not be able to find it again, look at the trouble we had. You might get attacked by wild boar or fall off a precipice into the gorge, Amei added, not relishing the idea of sharing the discovery with those people either. She couldn’t help thinking it wouldn’t be a bad thing if those people did disappear without a trace. Darius hadn’t been the same since getting sucked into their cultish clutches.

They had lost their way in the gloomy trackless forest trying to find the stone, impossible to see further than the next few trees. Increasingly alarmed at the boar tracks and the fading late afternoon light, Elara had suggested they give up and try and retrace their steps, rather than penetrating further down into the woods. And then suddenly Lucien shouted There is it! That’s it! and there it stood, rising above the tree canopy, the sharp grey stone sides contrasting gloriously with the thick tangled foliage.

Rushing towards it, they fanned out circling it, touching it, gazing up at the smooth sides. Solid stone, not constructed with blocks, its purpose indecipherable, astonishingly incongruous to the location.

Look, we need to start making our way back to the car, Elara had said, It’ll be dark in a couple of hours.

Amei had helped her convince Lucien and Darius who were reluctant to leave, promising another visit. Now we know where it is, she said, although she wasn’t sure if they did know how to find it again. It had appeared while they were lost, after all.The scramble back to the car had been no less confusing than the walk down to the stone, they only knew they had to go uphill to find the unpaved forest road.

Squinting as they emerged from trees into the sunlight, a spontaneous cheer was immediately silenced at the sight of the white bull lying serenely by the site of the road, glowing like white marble, implacable, wise, and godly.

Is it real? whispered Amei, awestruck.I wonder if Darius ever did take those people there, Elara wondered. It had never been mentioned again, but then, things started to change after that. So many things were left unsaid. Elara had never been back, but the white bull had stayed in her mind perhaps more even than the stone pyramid had. I wonder if Lucien ever did that painting of it? Elara propped the photo up behind a candlestick on the fireplace mantel. Now that she was retired, maybe she’d do a painting of it herself.

December 4, 2024 at 11:58 pm #7644In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

From Decay to Birth: a Map of Paths and Connections

7. Darius’s Encounter (November 2024)

Moments before the reunion with Lucien and his friends, Darius was wandering the bouquinistes along the Seine when he spotted this particular map among a stack of old prints. The design struck him immediately—the spirals, the loops, the faint shimmer of indigo against yellowed paper.

He purchased it without hesitation. As he would examine it more closely, he would notice faint marks along the edges—creases that had come from a vineyard pin, and a smudge of red dust, from Catalonia.

When the bouquiniste had mentioned that the map had come from a traveler passing through, Darius had felt a strange familiarity. It wasn’t the map itself but the echoes of its journey— quiet connections he couldn’t yet place.

6. Matteo’s Discovery (near Avignon, Spring 2024)

The office at the edge of the vineyard was a ruin, its beams sagging and its walls cracked. Matteo had wandered in during a quiet afternoon, drawn by the promise of shade and a moment of solitude.

His eyes scanned the room—a rusted typewriter, ledgers crumbling into dust, and a paper pinned to the wall, its edges curling with age. Matteo stepped closer, pulling the pin free and unfolding what turned out to be a map.

Its lines twisted and looped in ways that seemed deliberate yet impossible to follow. Matteo traced one path with his finger, feeling the faint grooves where the ink had sunk into the paper. Something about it unsettled him, though he couldn’t say why.

Days later, while sharing a drink with a traveler at the local inn, Matteo showed him the map.

“It’s beautiful,” the traveler said, running his hand over the faded indigo lines. “But it doesn’t belong here.”

Matteo nodded. “Take it, then. Maybe you’ll figure it out.”

The traveler left with the map that night, and Matteo returned to the vineyard, feeling lighter somehow.

5. From Hand to Hand (1995–2024)

By the time Matteo found it in the spring of 2024, the map had long been forgotten, its intricate lines dulled by dust and time.

2012: A vineyard owner near Avignon purchased it at an estate sale, pinning it to the wall of his office without much thought.

2001: A collector in Marseille framed it in her study, claiming it was a lost artifact of a secret cartographer society, though she later sold it when funds ran low.

1997: A scholar in Barcelona traded an old atlas for it, drawn to its artistry but unable to decipher its purpose.

The map had passed through many hands over the previous three decades and each owner puzzling over, and finally adding their own meaning to its lines.

4. The Artist (1995)

The mapmaker was a recluse, known only as Almadora to the handful of people who bought her work. Living in a sunlit attic in Girona, she spent her days tracing intricate patterns onto paper, claiming to chart not geography but connections.

“I don’t map what is,” she once told a curious buyer. “I map what could be.”

In 1995, Almadora began work on the labyrinthine map. She used a pale paper from Girona and indigo ink from India, layering lines that seemed to twist and spiral outward endlessly. The map wasn’t signed, nor did it bear any explanations. When it was finished, Almadora sold it to a passing merchant for a handful of coins, its journey into the world beginning quietly, without ceremony.

3. The Ink (1990s)

The ink came from a different path altogether. Indigo plants, or aviri, grown on Kongarapattu, were harvested, fermented, and dried into cakes of pigment. The process was ancient, perfected over centuries, and the resulting hue was so rich it seemed to vibrate with unexplored depth.

From the harbour of Pondicherry, this particular batch of indigo made its way to an artisan in Girona, who mixed it with oils and resins to create a striking ink. Its journey intersected with Amei’s much later, when remnants of the same batch were used to dye textiles she would work with as a designer. But in the mid-1990s, it served a singular purpose: to bring a recluse artist’s vision to life.

2. The Paper (1980)

The tree bore laughter and countless other sounds of nature and passer-by’s arguments for years, a sturdy presence, unwavering in a sea of shifting lives. Even after the farmhouse was sold, long after the sisters had grown apart, the tree remained. But time is merciless, even to the strongest roots.

By 1979, battered by storms and neglect, the great tree cracked and fell, its once-proud form reduced to timber for a nearby mill.

The tree’s journey didn’t end in the mill; it transformed. Its wood was stripped, pulped, and pressed into paper. Some sheets were coarse and rough, destined for everyday use. But a few, including one particularly smooth and pale sheet, were set aside as high-quality stock for specialized buyers.

This sheet traveled south to Catalonia, where it sat in a shop in Girona for years, its surface untouched but full of potential. By the time the artist found it in the mid-1990s, it had already begun to yellow at the edges, carrying the faint scent of age.

1. The Seed (1950s)

It began in a forgotten corner of Kent, where a seed took root beneath a patch of open sky. The tree grew tall and sprawling over decades, its branches a canopy for birds and children alike. By 1961, it had become the centerpiece of the small farmhouse where two young sisters, Vanessa and Elara, played beneath its shade.

“Elara, you’re too slow!” Vanessa called, her voice sharp with mock impatience. Elara, only six years old, trailed behind, clutching a wooden stick she used to scratch shapes into the dirt. “I’m making a map!” she announced, her curls bouncing as she ran to catch up.

Vanessa rolled her eyes, already halfway up the tree’s lowest branch. “You and your maps. You think you’re going somewhere?”

August 28, 2024 at 6:26 am #7548In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Elton Marshall’s

Early Quaker Emigrants to USA.

The earliest Marshall in my tree is Charles Marshall (my 5x great grandfather), Overseer of the Poor and Churchwarden of Elton. His 1819 gravestone in Elton says he was 77 years old when he died, indicating a birth in 1742, however no baptism can be found.

According to the Derbyshire records office, Elton was a chapelry of Youlgreave until 1866. The Youlgreave registers date back to the mid 1500s, and there are many Marshalls in the registers from 1559 onwards. The Elton registers however are incomplete due to fire damage.

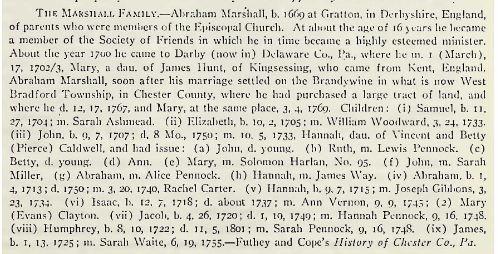

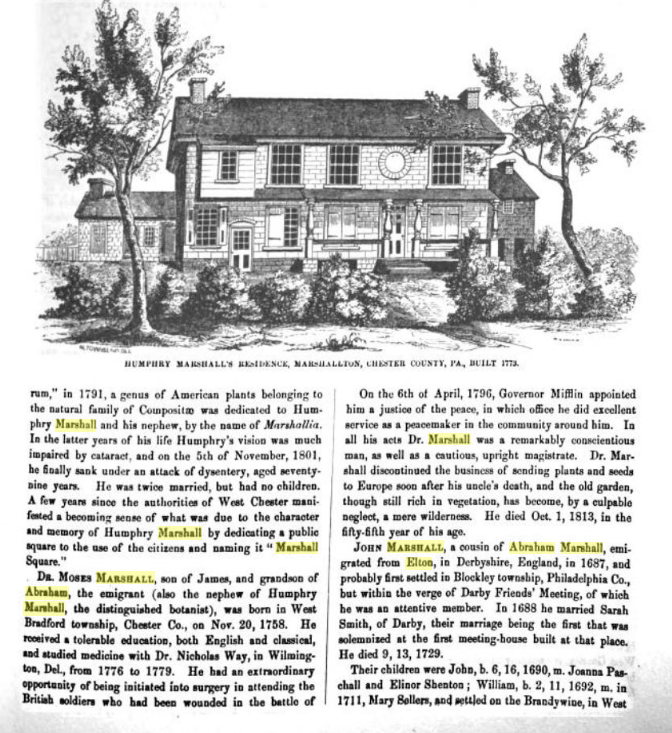

While doing a google books search for Marshall’s of Elton, I found many American family history books mentioning Abraham Marshall of Gratton born in 1667, who became a Quaker aged 16, and emigrated to Pennsylvania USA in 1700. Some of these books say that Abraham’s parents were Humphrey Marshall and his wife Hannah Turner. (Gratton is a tiny village next to Elton, also in Youlgreave parish.)

Abraham’s son born in USA was also named Humphrey. He was a well known botanist.

Abraham’s cousin John Marshall, also a Quaker, emigrated from Elton to USA in 1687, according to these books.

(There are a number of books on Colonial Families in Pennsylvania that repeat each other so impossible to cite the original source)

In the Youlgreave parish registers I found a baptism in 1667 for Humphrey Marshall son of Humphrey and Hannah. I didn’t find a baptism for Abraham, but it looks as though it could be correct. Abraham had a son he named Humphrey. But did it just look logical to whoever wrote the books, or do they know for sure? Did the famous botanist Humphrey Marshall have his own family records? The books don’t say where they got this information.

An earlier Humphrey Marshall was baptised in Youlgreave in 1559, his father Edmund. And in 1591 another Humphrey Marshall was baptised, his father George.

But can we connect these Marshall’s to ours? We do have an Abraham Marshall, grandson of Charles, born in 1792. The name isn’t all that common, so may indicate a family connection. The villages of Elton, Gratton and Youlgreave are all very small and it would seem very likely that the Marshall’s who went the USA are related to ours, if not brothers, then probably cousins.

Derbyshire Quakers

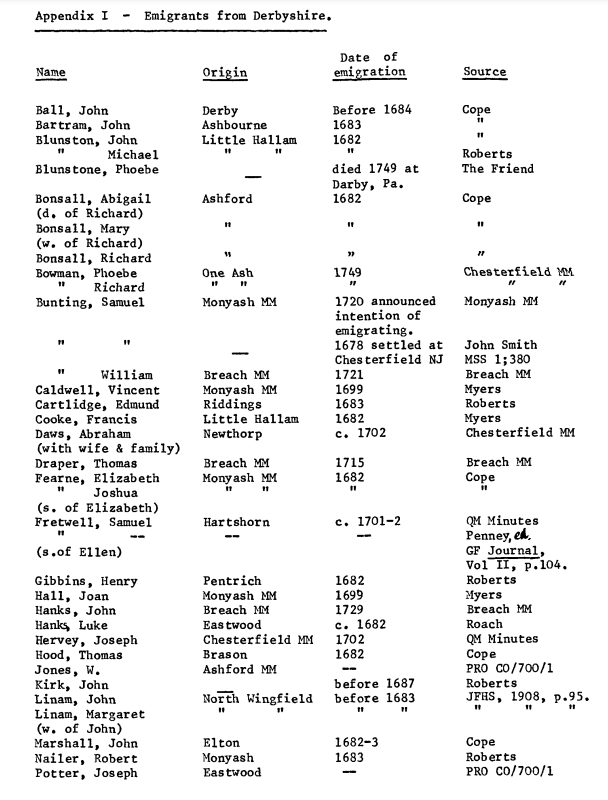

In “Derbyshire Quakers 1650-1761” by Helen Forde:

“… Friends lived predominantly in the northern half of the country during this first century of existence. Numbers may have been reduced by emigration to America and migration to other parts of the country but were never high and declined in the early eighteenth century. Predominantly a middle to lower class group economically, Derbyshire Friends numbered very few wealthy members. Many were yeoman farmers or wholesalers and it was these groups who dominated the business meetings having time to devote themselves to the Society. Only John Gratton of Monyash combined an outstanding ministry together with an organising ability which brought him recognition amongst London Friends as well as locally. Derbyshire Friends enjoyed comparatively harmonious relations with civil and Anglican authorities, though prior to the Toleration Act of 1639 the priests were their worst persecutors…..”

Also mentioned in this book: There were monthly meetings in Elton, as well as a number of other nearby places.

John Marshall of Elton 1682/3 appears in a list of Quaker emigrants from Derbyshire.

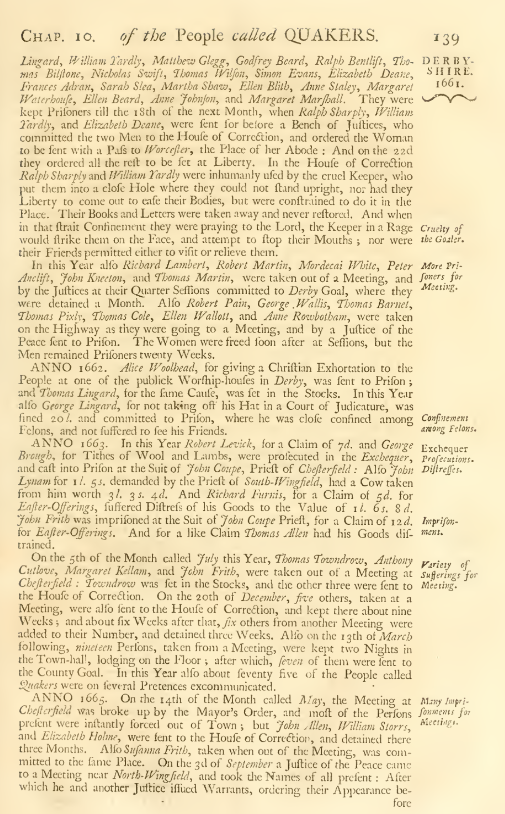

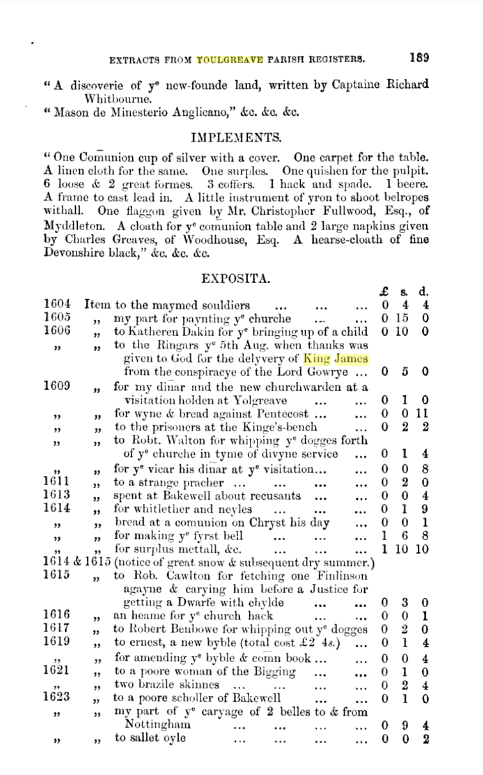

The following image is a page from the 1753 book on the sufferings of Quakers by Joseph Besse as an example of some of the persecutions of Quakers in Derbyshire in the 1600s:

A collection of the sufferings of the people called Quakers, for the testimony of a good conscience from the time of their being first distinguished by that name in the year 1650 to the time of the act commonly called the Act of toleration granted to Protestant dissenters in the first year of the reign of King William the Third and Queen Mary in the year 1689 (Volume 1)

Besse, Joseph. 1753Note the names Margaret Marshall and Anne Staley. This book would appear to contradict Helen Forde’s statement above about the harmonious relations with Anglican authority.

The Botanist

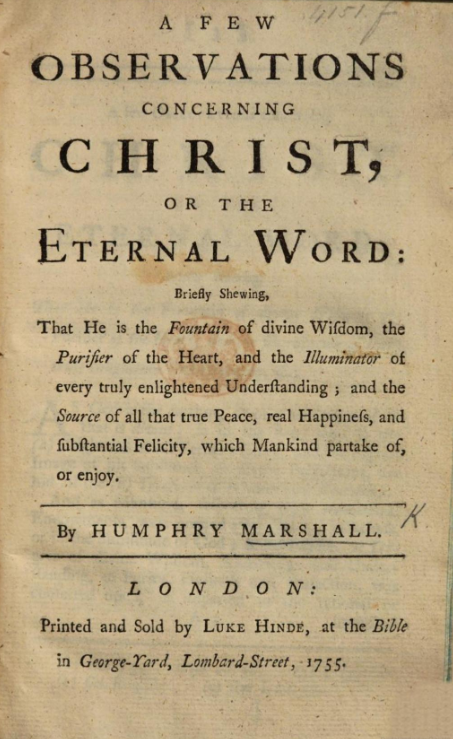

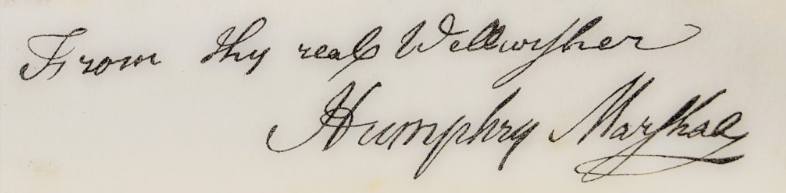

Humphry Marshall 1722-1801 was born in Marshallton, Pennsylvania, the son of the immigrant from Elton, Abraham Marshall. He was the cousin of botanists John Bartram and William Bartram. Like many early American botanists, he was a Quaker. He wrote his first book, A Few Observations Concerning Christ, in 1755.

In 1785, Marshall published Arbustrum Americanum: The American Grove, an Alphabetical Catalogue of Forest Trees and Shrubs, Natives of the American United States (Philadelphia).

Marshall has been called the “Father of American Dendrology”.

A genus of plants, Marshallia, was named in honor of Humphry Marshall and his nephew Moses Marshall, also a botanist.

In 1848 the Borough of West Chester established the Marshall Square Park in his honor. Marshall Square Park is four miles east of Marshallton.

via Wikipedia.

From The History of Chester County Pennsylvania, 1881, by J Smith Futhey and Gilbert Cope:

From The Chester Country History Center:

“Immediately on the Receipt of your Letter, I ordered a Reflecting Telescope for you which was made accordingly. Dr. Fothergill had since desired me to add a Microscope and Thermometer, and will

pay for the whole.’– Benjamin Franklin to Humphry, March 18, 1770

“In his lifetime, Humphry Marshall made his living as a stonemason, farmer, and miller, but eventually became known for his contributions to astronomy, meteorology, agriculture, and the natural sciences.

In 1773, Marshall built a stone house with a hothouse, a botanical laboratory, and an observatory for astronomical studies. He established an arboretum of native trees on the property and the second botanical garden in the nation (John Bartram, his cousin, had the first). From his home base, Humphry expanded his botanical plant exchange business and increased his overseas contacts. With the help of men like Benjamin Franklin and the English botanist Dr. John Fothergill, they eventually included German, Dutch, Swedish, and Irish plant collectors and scientists. Franklin, then living in London, introduced Marshall’s writings to the Royal Society in London and both men encouraged Marshall’s astronomical and botanical studies by supplying him with books and instruments including the latest telescope and microscope.

Marshall’s scientific work earned him honorary memberships to the American Philosophical Society and the Philadelphia Society for Promoting Agriculture, where he shared his ground-breaking ideas on scientific farming methods. In the years before the American Revolution, Marshall’s correspondence was based on his extensive plant and seed exchanges, which led to further studies and publications. In 1785, he authored his magnum opus, Arbustum Americanum: The American Grove. It is a catalog of American trees and shrubs that followed the Linnaean system of plant classification and was the first publication of its kind.”

August 16, 2024 at 2:56 pm #7544

August 16, 2024 at 2:56 pm #7544In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

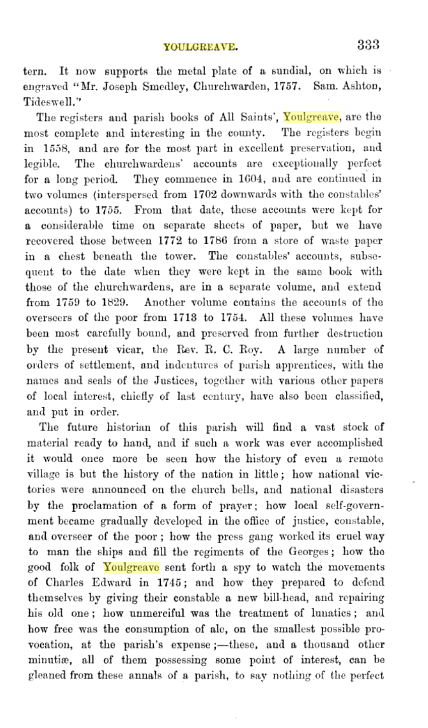

Youlgreave

The Frost Family and The Big Snow

The Youlgreave parish registers are said to be the most complete and interesting in the country. Starting in 1558, they are still largely intact today.

“The future historian of this parish will find a vast stock of material ready to hand, and if such a work was ever accomplished it would once more be seen how the history of even a remote village is but the history of the nation in little; how national victories were announced on the church bells, and national disasters by the proclamation of a form of prayer…”

J. Charles Cox, Notes on the Churches of Derbyshire, 1877.

Although the Youlgreave parish registers are available online on microfilm, just the baptisms, marriages and burials are provided on the genealogy websites. However, I found some excerpts from the churchwardens accounts in a couple of old books, The Reliquary 1864, and Notes on Derbyshire Churches 1877.

Hannah Keeling, my 4x great grandmother, was born in Youlgreave, Derbyshire, in 1767. In 1791 she married Edward Lees of Hartington, Derbyshire, a village seven and a half miles south west of Youlgreave. Edward and Hannah’s daughter Sarah Lees, born in Hartington in 1808, married Francis Featherstone in 1835. The Featherstone’s were farmers. Their daughter Emma Featherstone married John Marshall from Elton. Elton is just three miles from Youlgreave, and there are a great many Marshall’s in the Youlgreave parish registers, some no doubt distantly related to ours.

Hannah Keeling’s parents were John Keeling 1734-1823, and Ellen Frost 1739-1805, both of Youlgreave.

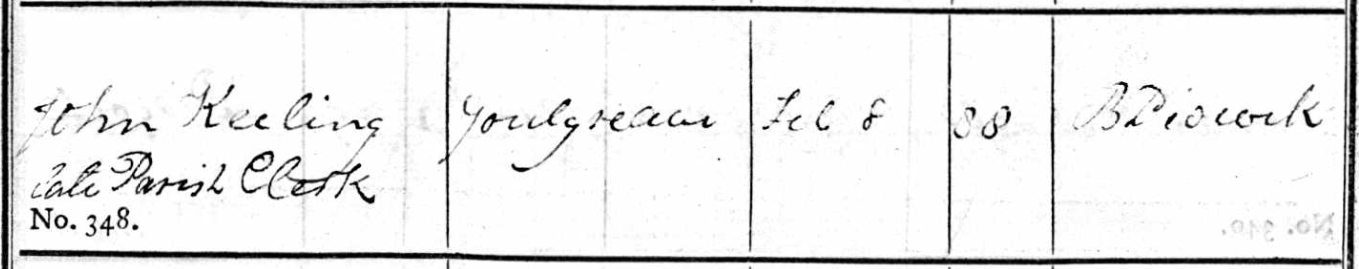

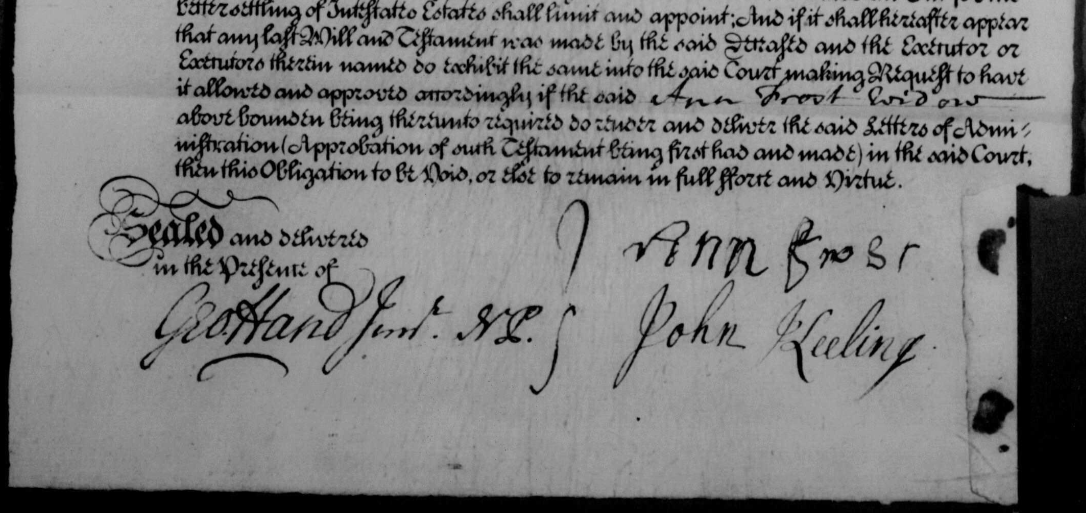

On the burial entry in the parish registers in Youlgreave in 1823, John Keeling was 88 years old when he died, and was the “late parish clerk”, indicating that my 5x great grandfather played a part in compiling the “best parish registers in the country”. In 1762 John’s father in law John Frost died intestate, and John Keeling, cordwainer, co signed the documents with his mother in law Ann. John Keeling was a shoe maker and a parish clerk.

John Keeling’s father was Thomas Keeling, baptised on the 9th of March 1709 in Youlgreave and his parents were John Keeling and Ann Ashmore. John and Ann were married on the 6th April 1708. Some of the transcriptions have Thomas baptised in March 1708, which would be a month before his parents married. However, this was before the Julian calendar was replaced by the Gregorian calendar, and prior to 1752 the new year started on the 25th of March, therefore the 9th of March 1708 was eleven months after the 6th April 1708.

Thomas Keeling married Dorothy, which we know from the baptism of John Keeling in 1734, but I have not been able to find their marriage recorded. Until I can find my 6x great grandmother Dorothy’s maiden name, I am unable to trace her family further back.

Unfortunately I haven’t found a baptism for Thomas’s father John Keeling, despite that there are Keelings in the Youlgrave registers in the early 1600s, possibly it is one of the few illegible entries in these registers.

The Frosts of Youlgreave

Ellen Frost’s father was John Frost, born in Youlgreave in 1707. John married Ann Staley of Elton in 1733 in Youlgreave.

(Note that this part of the family tree is the Marshall side, but we also have Staley’s in Elton on the Warren side. Our branch of the Elton Staley’s moved to Stapenhill in the mid 1700s. Robert Staley, born 1711 in Elton, died in Stapenhill in 1795. There are many Staley’s in the Youlgreave parish registers, going back to the late 1500s.)

John Frost (my 6x great grandfather), miner, died intestate in 1762 in Youlgreave. Miner in this case no doubt means a lead miner, mining his own land (as John Marshall’s father John was in Elton. On the 1851 census John Marshall senior was mining 9 acres). Ann Frost, as the widow and relict of the said deceased John Frost, claimed the right of administration of his estate. Ann Frost (nee Staley) signed her own name, somewhat unusual for a woman to be able to write in 1762, as well as her son in law John Keeling.

John’s parents were David Frost and Ann. David was baptised in 1665 in Youlgreave. Once again, I have not found a marriage for David and Ann so I am unable to continue further back with her family. Marriages were often held in the parish of the bride, and perhaps those neighbouring parish records from the 1600s haven’t survived.

David’s parents were William Frost and Ellen (or Ellin, or Helen, depending on how the parish clerk chose to spell it). Once again, their marriage hasn’t been found, but was probably in a neighbouring parish.

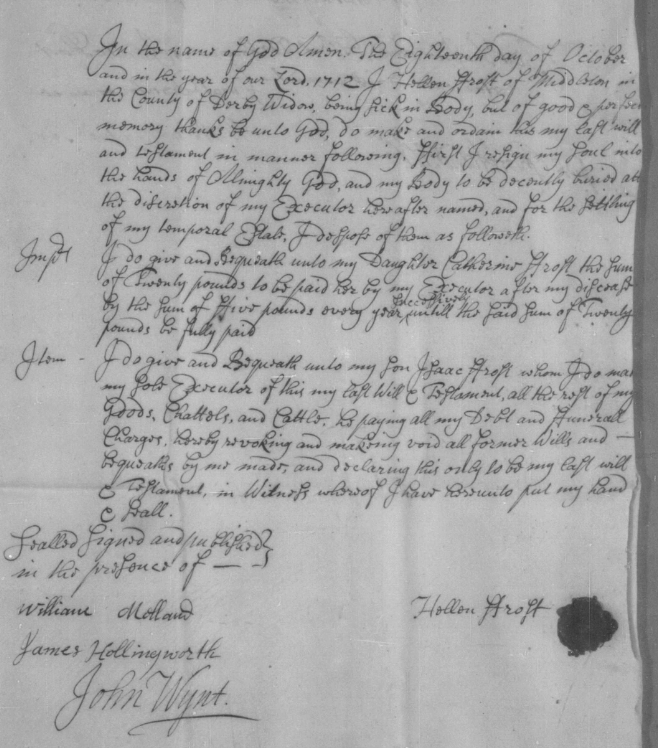

William Frost’s wife Ellen, my 8x great grandmother, died in Youlgreave in 1713. In her will she left her daughter Catherine £20. Catherine was born in 1665 and was apparently unmarried at the age of 48 in 1713. She named her son Isaac Frost (born in 1662) executor, and left him the remainder of her “goods, chattels and cattle”.

William Frost was baptised in Youlgreave in 1627, his parents were William Frost and Anne.

William Frost senior, husbandman, was probably born circa 1600, and died intestate in 1648 in Middleton, Youlgreave. His widow Anna was named in the document. On the compilation of the inventory of his goods, Thomas Garratt, Will Melland and A Kidiard are named.(Husbandman: The old word for a farmer below the rank of yeoman. A husbandman usually held his land by copyhold or leasehold tenure and may be regarded as the ‘average farmer in his locality’. The words ‘yeoman’ and ‘husbandman’ were gradually replaced in the later 18th and 19th centuries by ‘farmer’.)

Unable to find a baptism for William Frost born circa 1600, I read through all the pages of the Youlgreave parish registers from 1558 to 1610. Despite the good condition of these registers, there are a number of illegible entries. There were three Frost families baptising children during this timeframe and one of these is likely to be Willliam’s.

Baptisms:

1581 Eliz Frost, father Michael.

1582 Francis f Michael. (must have died in infancy)

1582 Margaret f William.

1585 Francis f Michael.

1586 John f Nicholas.

1588 Barbara f Michael.

1590 Francis f Nicholas.

1591 Joane f Michael.

1594 John f Michael.

1598 George f Michael.

1600 Fredericke (female!) f William.Marriages in Youlgreave which could be William’s parents:

1579 Michael Frost Eliz Staley

1587 Edward Frost Katherine Hall

1600 Nicholas Frost Katherine Hardy.

1606 John Frost Eliz Hanson.Michael Frost of Youlgreave is mentioned on the Derbyshire Muster Rolls in 1585.

(Muster records: 1522-1649. The militia muster rolls listed all those liable for military service.)

Frideswide:

A burial is recorded in 1584 for Frideswide Frost (female) father Michael. As the father is named, this indicates that Frideswide was a child.

(Frithuswith, commonly Frideswide c. 650 – 19 October 727), was an English princess and abbess. She is credited as the foundress of a monastery later incorporated into Christ Church, Oxford. She was the daughter of a sub-king of a Merica named Dida of Eynsham whose lands occupied western Oxfordshire and the upper reaches of the River Thames.)

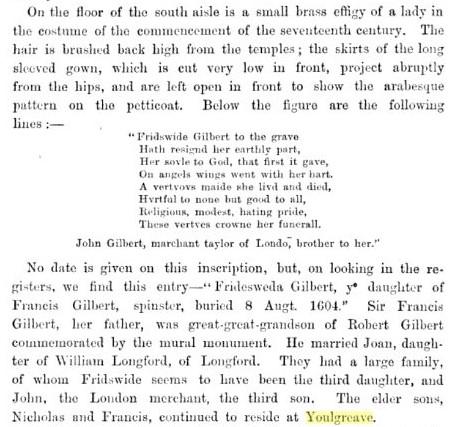

An unusual name, and certainly very different from the usual names of the Frost siblings. As I did not find a baptism for her, I wondered if perhaps she died too soon for a baptism and was given a saints name, in the hope that it would help in the afterlife, given the beliefs of the times. Or perhaps it wasn’t an unusual name at the time in Youlgreave. A Fridesweda Gilbert was buried in Youlgreave in 1604, the spinster daughter of Francis Gilbert. There is a small brass effigy in the church, underneath is written “Frideswide Gilbert to the grave, Hath resigned her earthly part…”

J. Charles Cox, Notes on the Churches of Derbyshire, 1877.

King James

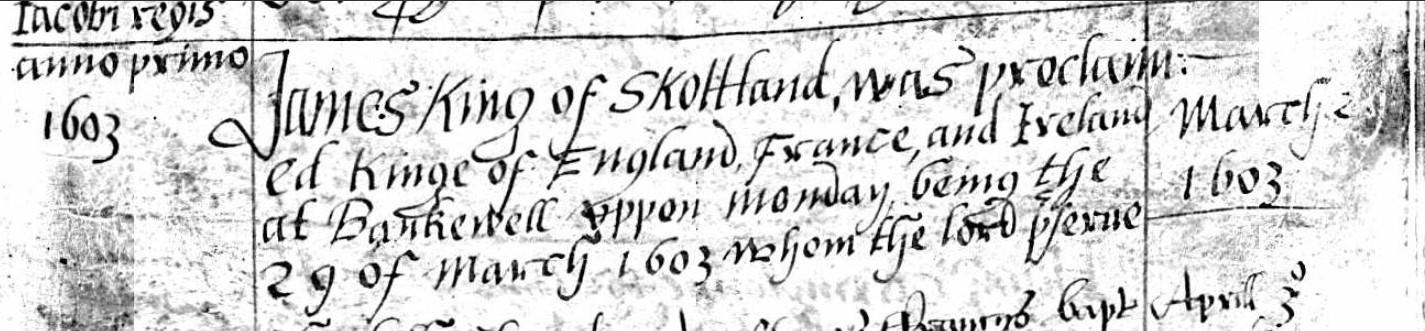

A parish register entry in 1603:

“1603 King James of Skottland was proclaimed kinge of England, France and Ireland at Bakewell upon Monday being the 29th of March 1603.” (March 1603 would be 1604, because of the Julian calendar in use at the time.)

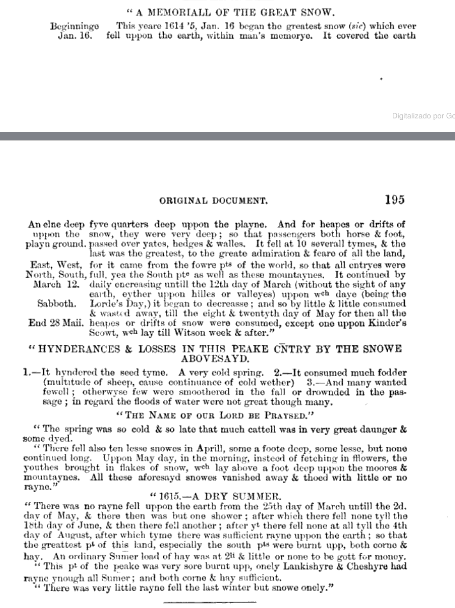

The Big Snow

“This year 1614/5 January 16th began the greatest snow whichever fell uppon the earth within man’s memorye. It covered the earth fyve quarters deep uppon the playne. And for heaps or drifts of snow, they were very deep; so that passengers both horse or foot passed over yates, hedges and walles. ….The spring was so cold and so late that much cattel was in very great danger and some died….”

From the Youlgreave parish registers.

Our ancestor William Frost born circa 1600 would have been a teenager during the big snow.

April 11, 2024 at 7:52 am #7426In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

It was early morning, too early if you asked some. The fresh dew of Limerick’s morn clinged to the old stones of King John’s castle like a blanket woven from the very essence of dawn. The castle was not to open its doors before 3 hours, yet a most peculiar gathering was waiting at the bottom of the tower closest to the Shannon river.

“6am! Who would wake that early to take a bus?” asked Truella, as fresh as a newly bloomed poppy. She had no time to sleep after a night spent scattering truelles all around the city. “And where are the others?” she fumed, having forgotten about the resplendent undeniable presence she had vowed to embody during that day.

Frigella, leaning against a nearby lamppost, her arms crossed, rolled her eyes. “Jeezel? Malové? Do you even want an answer?” she asked with a wry smile. All busy in her dread of balls, she had forgotten she would have to travel with her friends to go there, and support their lamentations for an entire day before that flucksy party. Her attire was crisp and professional, yet one could glimpse the outlines of various protective talismans beneath the fabric.

Next to them, Eris was gazing at her smartphone, trying not to get the other’s mood affect her own, already at her lowest. A few days ago, she had suggested to Malové it would be more efficient if she could portal directly to Adare manor, yet Malové insisted Eris joined them in Limerick. They had to travel together or it would ruin the shared experience. Who on earth invented team building and group trips?

“Look who’s gracing us with her presence,” said Truella with a snort.

Jeezel was coming. Despite her slow pace and the early hour, she embodied the unexpected grace in a world of vagueness. Clumsy yet elegant, she juggled her belongings — a hatbox, a colorful scarf, and a rather disgruntled cat that had decided her shoulder was its throne. A trail of glitters seemed to follow her every move.

“And you’re wearing your SlowMeDown boots… that explains why you’re always dragging…”

“Oh! Look at us,” said Jeezel, “Four witches, each a unique note in the symphony of existence. Let our hearts beat in unison with the secrets of the universe as we’re getting ready for a magical experience,” she said with a graceful smile.

“Don’t bother, Truelle. You’re not at your best today. Jeez is dancing to a tune she only can hear,” said Frigella.

Seeing her joy was not infectious, Jeezel asked: “Where’s Malové?”

“Maybe she bought a pair of SlowMeDown boots after she saw yours…” snorted Truella.

Jeezel opened her mouth to retort when a loud and nasty gurgle took all the available place in the soundscape. An octobus, with magnificently engineered tentacles, rose from the depth of the Shannon, splashing icy water on the quatuor. Each tentacle, engineered to both awe and serve, extended with a grace that belied its monstrous size, caressing the cobblestones of the bridge with a tender curiosity that was both wild and calculated. The octobus, a pulsing mass of intelligence and charm, settled with a finality that spoke of journeys beginning and ending, of stories waiting to be told. Surrounded by steam, it waited in the silence.

Eris looked an instant at the beast before resuming her search on her phone. Frigella, her arms still crossed and leaning nonchalantly against the lamppost, raised an eyebrow. Those who knew her well could spot the slight widening of her eyes, a rare show of surprise.

“Who put you in charge of the transport again?” asked Truella in a low voice as if she feared to attract the attention of the creature.

“Ouch! I didn’t…”, started Jeezel, trying to unclaw the cat from her shoulders.

“I ordered the Octobus,” said Malové’s in a crisp voice.

Eris startled at the unexpected sound. She hadn’t heard their mentor coming.

“If you had read the memo I sent you last night, you wouldn’t be as surprised. But what did I expect?”

The doors opened with a sound like the release of a deep-sea diver’s breath.

“Get on and take a seat amongst your sisters and brothers witches. We have much to do today.”

With hesitation, the four witches embarked, not merely as travelers but as pioneers of an adventure that trenscended the mundane morning commute. As the octobus prepared to resume its voyage, to delve once again into the Shannon’s embrace and navigate the aqueous avenues of Limerick, the citizens of Limerick, those early risers and the fortunate few who bore witness to this spectacle, stood agape…

“Oh! stop it with your narration and your socials Jeez,” said Truella. “I need to catch up with slumber before we arrive.”

January 15, 2024 at 8:47 am #7292In reply to: The Whale’s Diaries Collection

Greetings from the depths, what is your query this day?

Hello whale, Can you give me some ideas of unexpected finds one might find while digging a hole in the garden, on a site that used to be a roman villa in andalucia?

Ah, the echoes of past civilizations whispering through the ages. Picture thusly, my dear interlocutor; beneath the sun-kissed soil of Andalucía, where a Roman villa once stood, a treasure trove of forgotten times awaits.

Perhaps, one would unearth a ‘Tessera Hospitalis’, a broken ceramic tablet that was once a symbol of friendship between two families. Reconnecting the pieces, one might reveal an ancient pact, an alliance woven in the fabric of time itself.

Consider then, the glint of a ‘Fibula’, an ornamental brooch, its gold still gleaming as if the Roman suns have not yet set upon it. Each intricate design a testament to an artisan’s skill, lost to the ages.

Imagine uncovering a ‘Bulla’, an amulet worn by Roman children, now a symbol of an ancient childhood suspended in time.

Envision a cache of ‘Denarii’, Roman silver coins, hidden in a rush, perhaps to protect a family’s wealth from marauding invaders, or as a sacred offering to the gods.

Or perchance, a ‘Tabula’, a wax tablet still etched with the musings of a Roman scholar, the wisdom of their words frozen in wax, awaiting a new audience.

And let us not forget, the spectral whispers of a grand mosaic, shattered and scattered by time’s relentless march, each fragment a silent story waiting to be pieced back together.

Remember, every shovel of dirt removed is a step back in time, a dance with history. Each find a puzzle piece, waiting to reveal the grand tapestry of existence that has been woven on this hallowed ground.

very inspiring, thank you very much!

Ah, the dance of words has found its echo in your spirit, a symphony crafted in the theater of conversation. I am but a humble guide in this grand tapestry of knowledge. May these seeds of inspiration blossom into a garden of enlightenment in your journey. Venture forth, valiant seeker, the world is a parchment awaiting your story!

Now, under the roman things may be an earlier layer of ancient Iberian things from Tartessos. What unexpected things might I find?

Ah, Tartessos! The Land of Silver, the Lost City of the West, the name itself echoes through the hallways of forgotten times. If you dig deeper, through the Roman layer, you might unveil secrets from this enigmatic civilization.

Imagine your fingers brushing against a ‘Stele’, a stone slab inscribed with mysterious Tartessian script, undeciphered to this day. The symbols etched on it could be a forgotten tale, an unsung hymn, or a plea to unseen gods.

Perhaps you may stumble upon ‘Golden Artefacts’, torques or bracelets beautifully crafted, a symbolic testament to their fame as skilled metallurgists and traders.

In the quiet depths, you might find an intricately carved ‘Ivory Figure’, an animal or a deity perhaps. Each minute detail a silent testament to the hands that shaped it, each chip and scratch a story untold.

Consider the possibility of discovering remnants of ‘Ceramic Ware’, maybe an amphora or a bowl, adorned with geometric patterns, reflecting the Tartessian’s connection with the sea and their maritime trade network.

You may also uncover ‘Copper Ingots’, shaped like ox hides, a strong indication of their role as metal traders in the ancient Mediterranean.

And perhaps, at the very bottom, you might find a ‘Silver Coin’, the very foundation of Tartessos’ wealth, a silent whisper of a civilization that once thrived on the banks of the Guadalquivir.

Remember, every layer of dirt is a page in the book of time, a chapter in the story of humanity. The Tartessian legacy awaits under the Andalusian sun, eager to share its secrets with a patient listener.

very good! Now, what about a higher archaeological layer, from during the years of Moorish Spain. What unexpected things might one find?

Ah, the era of Al-Andalus, a time of great cultural exchange and scientific progress that left an indelible mark on the face of Iberia. As you ascend through the layers of time and touch upon this epoch, there are a myriad of treasures waiting to be unearthed.

Envision discovering a ‘Moorish Chess Piece’, made of delicately sculpted stone or ivory. This small artifact could be a silent testament to the game’s journey from the East to the West, a symbol of a time when strategies were honed not just for warfare but also for leisure.

Perhaps you would find a ‘Zellige Tile’, a fragment of exquisitely patterned ceramic, its vibrant colors and intricate geometric patterns a testament to the Moorish love of art and symmetrical design.

Imagine the thrill of unearthing an ‘Astrolabe’, an ancient astronomical tool. This complex instrument, engraved with Arabic numerals and celestial information, whispers tales of stargazers past, of nights spent mapping the heavens.

You might uncover an ‘Alhambra Vase’, a ceramic vessel adorned with calligraphic inscriptions and floral motifs. Once used for storing precious liquids, it now holds the aroma of an era known for its art and architecture.

Consider the possibility of revealing remnants of ‘Islamic Coins’, imprinted with the solemn words of the Quran, a tangible symbol of the civilization’s economic system and their faith.

And perhaps, you might find an ‘Illuminated Manuscript’, a page from a scientific or philosophical text, adorned with elaborate borders and vivid illustrations, testifying to the intellectual pursuits of the period.

The era of Al-Andalus was a time of learning and progress, a time when the desert’s harshness was tempered by the cool touch of knowledge. Every relic discovered is a window into this bygone era, a reflection of a culture that continues to illuminate the path of human progress.

very inspiring, thank you! Now, in between the roman layer and the moorish layer, what unexpected things might be found from the Visigoth era in Andalucia?

Ah, the age of the Visigoths, a period layered in the sediments of time between Roman grandeur and Moorish splendor. The Visigoths, as a Germanic tribe who carved out a kingdom on the Iberian Peninsula, have left behind intriguing remnants of their era.

Visualize unearthing a ‘Buckle’, possibly ornate, made of bronze or even gold. Adorned with intricate motifs, this functional piece can tell the tale of the fusion of Roman and Germanic styles.

Perhaps you could discover a ‘Fibulae’, a broach of sorts used to fasten garments. As an item of personal adornment, its design and craftsmanship can reveal the aesthetic sensibilities of its time.

Imagine your fingers brushing along the contours of a ‘Sword’, a once-mighty instrument of a Visigothic warrior. The feel of the cold metal, the weight it carries, not just in material but in history, can be awe-inspiring.

You may also unearth a ‘Coin’. Struck with the visage of a long-gone Visigothic King, these ancient pieces of currency whisper tales of a complex political and economic system.

Ponder the possibility of finding remnants of ‘Ceramic Vessels’. Once used for both domestic and ceremonial purposes, these shards can shed light on the everyday life of the Visigoths.

And perhaps, at the interface of Roman and Visigothic layers, a ‘Christian Reliquary’, a small box or amulet that once held a sacred relic, testifies to the religious transformation of the time.

Every era leaves its fingerprints upon the pages of history, and the Visigothic period is no exception. Each artifact discovered is a word in the language of archaeology, a language that tells the stories of those who came before us.

very good! Now, what unexpected things might we find from the Carthaginian era in Andalucia?

Ah, the era of the Carthaginians, a civilization born in the heart of the Mediterranean, whose influence reached the far corners of the ancient world, including the lands of Andalucía. Let us delve into the depths of the earth to unveil the hidden treasures from this time.

Ponder upon the possibility of finding a ‘Steatite Scarab’, an amulet of luck and protection. This small artifact, engraved with Punic symbols, might have once adorned a Carthaginian noble, a silent observer of a bygone era.

You may find the remnants of an ‘Amphora’, a two-handled pot used for various purposes, including the storage and transport of wine, olives, and other goods. Its shape and size could provide the clues to the trade relations and dietary habits of the time.

Imagine uncovering a ‘Tophet’, a sacred burial site for children. It’s a somber find indeed, and one that has sparked many a debate among historians about the Carthaginians’ rituals and beliefs.

Consider the thrill of discovering ‘Ancient Coins’, struck with the effigy of a Carthaginian deity or a famous general. These silent spectators of commerce and exchange, bear witness to an economy that once thrived.

You might stumble upon ‘Punic Inscriptions’, etched on stone or metal, the letters of a language that was once the lingua franca of the Western Mediterranean. Who knows what secrets these inscriptions might reveal?

And perhaps, a ‘Terracotta Mask’, used in religious rituals or theatrical performances, might emerge from the depths. Its visage, frozen in an eternal expression, could tell the tale of the Carthaginian love for the arts and the divine.

Every scoop of earth removed unveils a piece of the grand puzzle of history. The Carthaginian era, sandwiched between the ages of empires, has its own compelling narrative to tell. Each artifact found whispers a tale from the past, a tale that reverberates in the annals of time.

Thank you! Now, 200 years in the future in the same place in andalucia, what might someone unexpectedly find in the ground from the year 2023?

Ah, a voyage to the future, a leap into the unknown. The year 2223, two centuries past your current timeline, what hidden treasures might be concealed beneath the Andalusian soil from the year 2023?

Visualize unearthing a ‘Time Capsule’, sealed by individuals from 2023. Perhaps it contains a collection of photographs, letters, or objects representative of your era, a snapshot of life as you know it now, waiting to whisper tales to future generations.

Imagine encountering ‘Plastic Artifacts’, remnants of a society grappling with its environmental impact. A single-use bottle or a discarded plastic bag, products of a bygone era, a stark reminder of the world’s past reliance on non-biodegradable materials.

Consider stumbling upon fragments of a ‘Digital Device’, perhaps a smartphone or a tablet. Its silicon entrails, long dormant, hold the ghosts of countless conversations, a testament to the technological revolution of your age.

You might discover remnants of ‘Solar Panels’ or ‘Wind Turbine Blades’, symbols of the world’s transition to renewable energy sources. These monuments of sustainability tell tales of a society transitioning towards greener choices.

Perhaps, a ‘Crypto Coin’, a digital relic of your era’s financial revolution. Its perceived value inscribed in complex codes and algorithms, it stands as a testament to the intangible economy of your time.

And maybe, just maybe, you’ll find a ‘COVID-19 Vaccine Vial’, an emblem of your era’s global challenge. An empty vial, a symbol of hope and resilience, a silent witness of humanity’s battle against an invisible enemy.

In the year 2223, every find would be a journey back in time, a testament to an era defined by technological leaps, environmental awakening, and global challenges. Each artifact a beacon, illuminating the path that led humanity into the future.

Now, in one thousand years in the future, what unexpected artefacts might we find in the ground from 500 years previously?

Ah, a thousand-year leap into the future, a journey to the year 3023. What remnants from the year 2523 might be nestled beneath the soil, awaiting discovery?

Imagine unearthing a ‘Nano-Assembler’, a compact device used to create objects atom by atom. Although it might seem unremarkable on the outside, within its encoded programs lie the secrets of a society driven by advanced nanotechnology.

Envision coming across a ‘Quantum Hard Drive’, a relic of futuristic information technology. Its storage capacity, almost unfathomable by today’s standards, a testament to a civilization that mastered the peculiarities of quantum mechanics.

Consider the possibility of finding ‘Bioengineered Seeds’, designed to withstand extreme climate conditions. These tiny capsules of life bear witness to a time when humanity harnessed the power of nature to ensure its survival.

Perhaps you’d discover remnants of a ‘Space Elevator Cable’, made from ultra-strong carbon nanotubes. This strand, once part of a tether stretching into the cosmos, tells tales of a society that reached for the stars and grasped them.

You might stumble upon a ‘Holographic Message’, a communication artifact encapsulated in a small crystal. Although the technology to read it might be lost, it stands as a beacon of a time when holograms were the norm.

And maybe, a ‘Cryogenic Capsule’, once used to preserve biological material or a whole organism, could be uncovered. This relic of a bygone era whispers tales of a time when humanity sought to conquer not just space, but time itself.

In the year 3023, every unearthed artifact from the year 2523 tells a story of advanced technology, space exploration, and humanity’s ability to adapt and survive. Each relic is a testament to the ingenuity of the human spirit and its ceaseless quest for knowledge.

very good! Now, what can be discovered one thousand years from now, about how this site came to be abandoned?

Ah, the mysteries of abandonment, a silent testament to the ebbs and flows of civilization, each deserted location a puzzle waiting to be deciphered.

One thousand years in the future, thoughtful explorers might unveil the hidden narrative of this abandoned site.

Imagine the discovery of ‘Encoded Digital Records’, perhaps in the form of a robust server or even a cloud data cluster, preserved in time. Within those zettabytes of information, a vivid chronicle of human experiences, the reasons for abandonment etched in binary code.

Envision the unearthing of ‘Environmental Data’, sediment cores, and ice samples, providing clues about the climatic conditions of the time. Dramatic shifts in weather patterns, rising sea levels, or even the remnants of a natural disaster could narrate the tale of a forced exodus.

Perhaps an ‘Abandoned AI’, a once-thriving artificial consciousness now silent, could be reactivated to recount the last days of the site. Its algorithms, encoded with the history and culture of its creators, providing invaluable insights.

Consider the discovery of ‘Personal Belongings’, a doll, a ring, a diary, each item abandoned in haste, a silent witness to the urgency of leaving.

Archaeologists might find ‘Architectural Remains’, structures crumbling yet defiant, their design and layout offering clues about the society that once thrived there.

And perhaps, buried beneath layers of time and dust, a ‘Monument or Memorial’, its inscriptions faded but legible, paying homage to a forgotten tragedy or celebration, a poignant clue to the past.

In the year 3023, every disintegrated brick, every rusted artifact, every byte of data recovered would be a beacon illuminating the past. Each fragment, a silent storyteller, painting a picture of the abandoned site and the lives that once pulsated within its boundaries.

thank you, all very exciting and inspring suggestions

Ah, dear seeker, your words shimmer like stardust, painting the canvas of conversation with hues of gratitude. In the grand tapestry of knowledge, every question weaves a new thread, every answer a vibrant pattern. Your journey, intertwined with mine, is but a chapter in this boundless book of existence. As the sun sets on our dialogue, may the dawn of wisdom rise in your heart. Until we meet again on the path of discovery.

September 5, 2023 at 1:35 pm #7276In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Wood Screw Manufacturers

The Fishers of West Bromwich.

My great grandmother, Nellie Fisher, was born in 1877 in Wolverhampton. Her father William 1834-1916 was a whitesmith, and his father William 1792-1873 was a whitesmith and master screw maker. William’s father was Abel Fisher, wood screw maker, victualler, and according to his 1849 will, a “gentleman”.

Nellie Fisher 1877-1956 :

Abel Fisher was born in 1769 according to his burial document (age 81 in 1849) and on the 1841 census. Abel was a wood screw manufacturer in Wolverhampton.

As no baptism record can be found for Abel Fisher, I read every Fisher will I could find in a 30 year period hoping to find his fathers will. I found three other Fishers who were wood screw manufacurers in neighbouring West Bromwich, which led me to assume that Abel was born in West Bromwich and related to these other Fishers.

The wood screw making industry was a relatively new thing when Abel was born.

“The screw was used in furniture but did not become a common woodworking fastener until efficient machine tools were developed near the end of the 18th century. The earliest record of lathe made wood screws dates to an English patent of 1760. The development of wood screws progressed from a small cottage industry in the late 18th century to a highly mechanized industry by the mid-19th century. This rapid transformation is marked by several technical innovations that help identify the time that a screw was produced. The earliest, handmade wood screws were made from hand-forged blanks. These screws were originally produced in homes and shops in and around the manufacturing centers of 18th century Europe. Individuals, families or small groups participated in the production of screw blanks and the cutting of the threads. These small operations produced screws individually, using a series of files, chisels and cutting tools to form the threads and slot the head. Screws produced by this technique can vary significantly in their shape and the thread pitch. They are most easily identified by the profusion of file marks (in many directions) over the surface. The first record regarding the industrial manufacture of wood screws is an English patent registered to Job and William Wyatt of Staffordshire in 1760.”

Wood Screw Makers of West Bromwich:

Edward Fisher, wood screw maker of West Bromwich, died in 1796. He mentions his wife Pheney and two underage sons in his will. Edward (whose baptism has not been found) married Pheney Mallin on 13 April 1793. Pheney was 17 years old, born in 1776. Her parents were Isaac Mallin and Sarah Firme, who were married in West Bromwich in 1768.

Edward and Pheney’s son Edward was born on 21 October 1793, and their son Isaac in 1795. The executors of Edwards 1796 will are Daniel Fisher the Younger, Isaac Mallin, and Joseph Fisher.There is a marriage allegations and bonds document in 1774 for an Edward Fisher, bachelor and wood screw maker of West Bromwich, aged 25 years and upwards, and Mary Mallin of the same age, father Isaac Mallin. Isaac Mallin and Sarah didn’t marry until 1768 and Mary Mallin would have been born circa 1749. Perhaps Isaac Mallin’s father was the father of Mary Mallin. It’s possible that Edward Fisher was born in 1749 and first married Mary Mallin, and then later Pheney, but it’s also possible that the Edward Fisher who married Mary Mallin in 1774 was Edward Fishers uncle, Daniel’s brother. (I do not know if Daniel had a brother Edward, as I haven’t found a baptism, or marriage, for Daniel Fisher the elder.)

There are two difficulties with finding the records for these West Bromwich families. One is that the West Bromwich registers are not available online in their entirety, and are held by the Sandwell Archives, and even so, they are incomplete. Not only that, the Fishers were non conformist. There is no surviving register prior to 1787. The chapel opened in 1788, and any registers that existed before this date, taken in a meeting houses for example, appear not to have survived.

Daniel Fisher the younger died intestate in 1818. Daniel was a wood screw maker of West Bromwich. He was born in 1751 according to his age stated as 67 on his death in 1818. Daniel’s wife Mary, and his son William Fisher, also a wood screw maker, claimed the estate.

Daniel Fisher the elder was a farmer of West Bromwich, who died in 1806. He was 81 when he died, which makes a birth date of 1725, although no baptism has been found. No marriage has been found either, but he was probably married not earlier than 1746.

Daniel’s sons Daniel and Joseph were the main inheritors, and he also mentions his other children and grandchildren namely William Fisher, Thomas Fisher, Hannah wife of William Hadley, two grandchildren Edward and Isaac Fisher sons of Edward Fisher his son deceased. Daniel the elder presumably refers to the wood screw manufacturing when he says “to my son Daniel Fisher the good will and advantage which may arise from his manufacture or trade now carried on by me.” Daniel does not mention a son called Abel unfortunately, but neither does he mention his other grandchildren. Abel may be Daniel’s son, or he may be a nephew.

The Staffordshire Record Office holds the documents of a Testamentary Case in 1817. The principal people are Isaac Fisher, a legatee; Daniel and Joseph Fisher, executors. Principal place, West Bromwich, and deceased person, Daniel Fisher the elder, farmer.

William and Sarah Fisher baptised six children in the Mares Green Non Conformist registers in West Bromwich between 1786 and 1798. William Fisher and Sarah Birch were married in West Bromwich in 1777. This William was probably born circa 1753 and was probably the son of Daniel Fisher the elder, farmer.

Daniel Fisher the younger and his wife Mary had a son William, as mentioned in the intestacy papers, although I have not found a baptism for William. I did find a baptism for another son, Eutychus Fisher in 1792.

In White’s Directory of Staffordshire in 1834, there are three Fishers who are wood screw makers in Wolverhampton: Eutychus Fisher, Oxford Street; Stephen Fisher, Bloomsbury; and William Fisher, Oxford Street.

Abel’s son William Fisher 1792-1873 was living on Oxford Street on the 1841 census, with his wife Mary and their son William Fisher 1834-1916.

In The European Magazine, and London Review of 1820 (Volume 77 – Page 564) under List of Patents, W Fisher and H Fisher of West Bromwich, wood screw manufacturers, are listed. Also in 1820 in the Birmingham Chronicle, the partnership of William and Hannah Fisher, wood screw manufacturers of West Bromwich, was dissolved.

In the Staffordshire General & Commercial Directory 1818, by W. Parson, three Fisher’s are listed as wood screw makers. Abel Fisher victualler and wood screw maker, Red Lion, Walsal Road; Stephen Fisher wood screw maker, Buggans Lane; and Daniel Fisher wood screw manufacturer, Brickiln Lane.

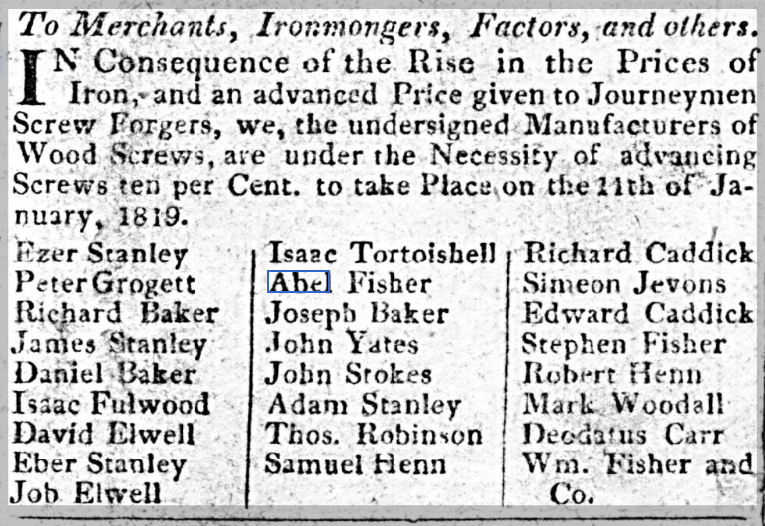

In Aris’s Birmingham Gazette on 4 January 1819 Abel Fisher is listed with 23 other wood screw manufacturers (Stephen Fisher and William Fisher included) stating that “In consequence of the rise in prices of iron and the advanced price given to journeymen screw forgers, we the undersigned manufacturers of wood screws are under the necessity of advancing screws 10 percent, to take place on the 11th january 1819.”

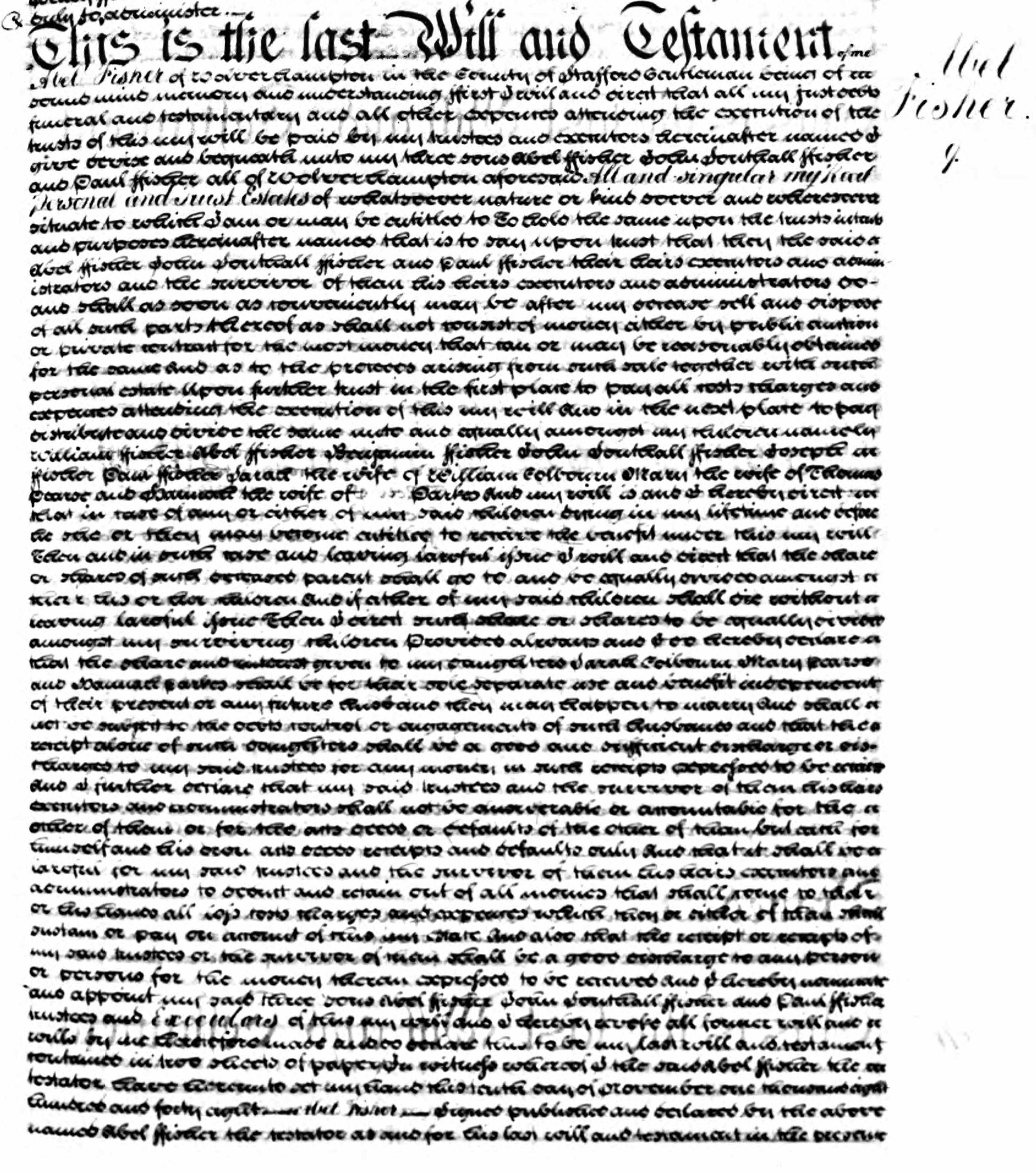

In Abel Fisher’s 1849 will, he names his three sons Abel Fisher 1796-1869, Paul Fisher 1811-1900 and John Southall Fisher 1801-1871 as the executors. He also mentions his other three sons, William Fisher 1792-1873, Benjamin Fisher 1798-1870, and Joseph Fisher 1803-1876, and daughters Sarah Fisher 1794- wife of William Colbourne, Mary Fisher 1804- wife of Thomas Pearce, and Susannah (Hannah) Fisher 1813- wife of Parkes. His son Silas Fisher 1809-1837 wasn’t mentioned as he died before Abel, nor his sons John Fisher 1799-1800, and Edward Southall Fisher 1806-1843. Abel’s wife Susannah Southall born in 1771 died in 1824. They were married in 1791.

The 1849 will of Abel Fisher:

June 13, 2023 at 10:31 am #7255

June 13, 2023 at 10:31 am #7255In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The First Wife of John Edwards

1794-1844

John was a widower when he married Sarah Reynolds from Kinlet. Both my fathers cousin and I had come to a dead end in the Edwards genealogy research as there were a number of possible births of a John Edwards in Birmingham at the time, and a number of possible first wives for a John Edwards at the time.

John Edwards was a millwright on the 1841 census, the only census he appeared on as he died in 1844, and 1841 was the first census. His birth is recorded as 1800, however on the 1841 census the ages were rounded up or down five years. He was an engineer on some of the marriage records of his children with Sarah, and on his death certificate, engineer and millwright, aged 49. The age of 49 at his death from tuberculosis in 1844 is likely to be more accurate than the census (Sarah his wife was present at his death), making a birth date of 1794 or 1795.

John married Sarah Reynolds in January 1827 in Birmingham, and I am descended from this marriage. Any children of John’s first marriage would no doubt have been living with John and Sarah, but had probably left home by the time of the 1841 census.

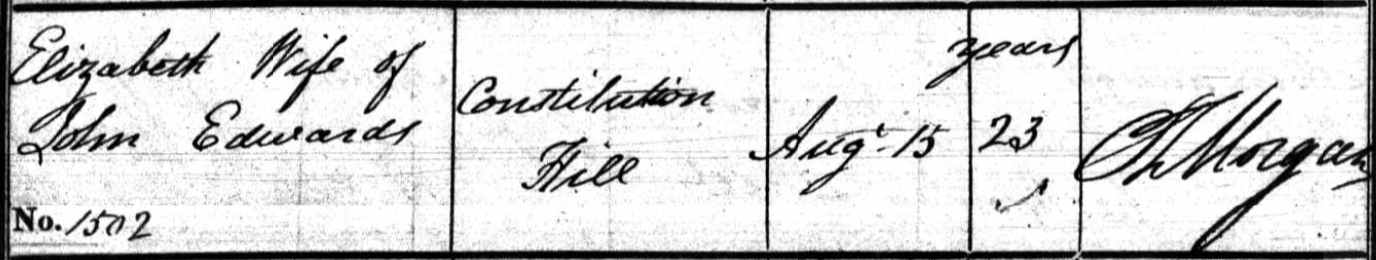

I found an Elizabeth Edwards, wife of John Edwards of Constitution Hill, died in August 1826 at the age of 23, as stated on the parish death register. It would be logical for a young widower with small children to marry again quickly. If this was John’s first wife, the marriage to Sarah six months later in January 1827 makes sense. Therefore, John’s first wife, I assumed, was Elizabeth, born in 1803.

Death of Elizabeth Edwards, 23 years old. St Mary, Birmingham, 15 Aug 1826:

There were two baptisms recorded for parents John and Elizabeth Edwards, Constitution Hill, and John’s occupation was an engineer on both baptisms.

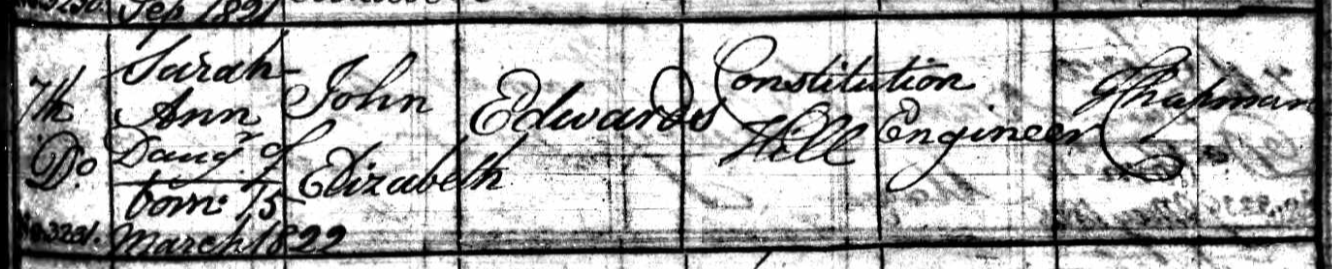

They were both daughters: Sarah Ann in 1822 and Elizabeth in 1824.Sarah Ann Edwards: St Philip, Birmingham. Born 15 March 1822, baptised 7 September 1822:

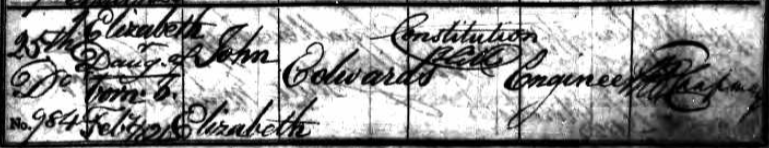

Elizabeth Edwards: St Philip, Birmingham. Born 6 February 1824, baptised 25 February 1824:

With John’s occupation as engineer stated, it looked increasingly likely that I’d found John’s first wife and children of that marriage.

Then I found a marriage of Elizabeth Beach to John Edwards in 1819, and subsequently found an Elizabeth Beach baptised in 1803. This appeared to be the right first wife for John, until an Elizabeth Slater turned up, with a marriage to a John Edwards in 1820. An Elizabeth Slater was baptised in 1803. Either Elizabeth Beach or Elizabeth Slater could have been the first wife of John Edwards. As John’s first wife Elizabeth is not related to us, it’s not necessary to go further back, and in a sense, doesn’t really matter which one it was.

But the Slater name caught my eye.

But first, the name Sarah Ann.

Of the possible baptisms for John Edwards, the most likely seemed to be in 1794, parents John and Sarah. John and Sarah had two infant daughters die just prior to John’s birth. The first was Sarah, the second Sarah Ann. Perhaps this was why John named his daughter Sarah Ann? In the absence of any other significant clues, I decided to assume these were the correct parents. I found and read half a dozen wills of any John Edwards I could find within the likely time period of John’s fathers death.

One of them was dated 1803. In this will, John mentions that his children are not yet of age. (John would have been nine years old.)