-

AuthorSearch Results

-

May 10, 2025 at 9:02 am #7925

In reply to: Cofficionados – What’s Brewing

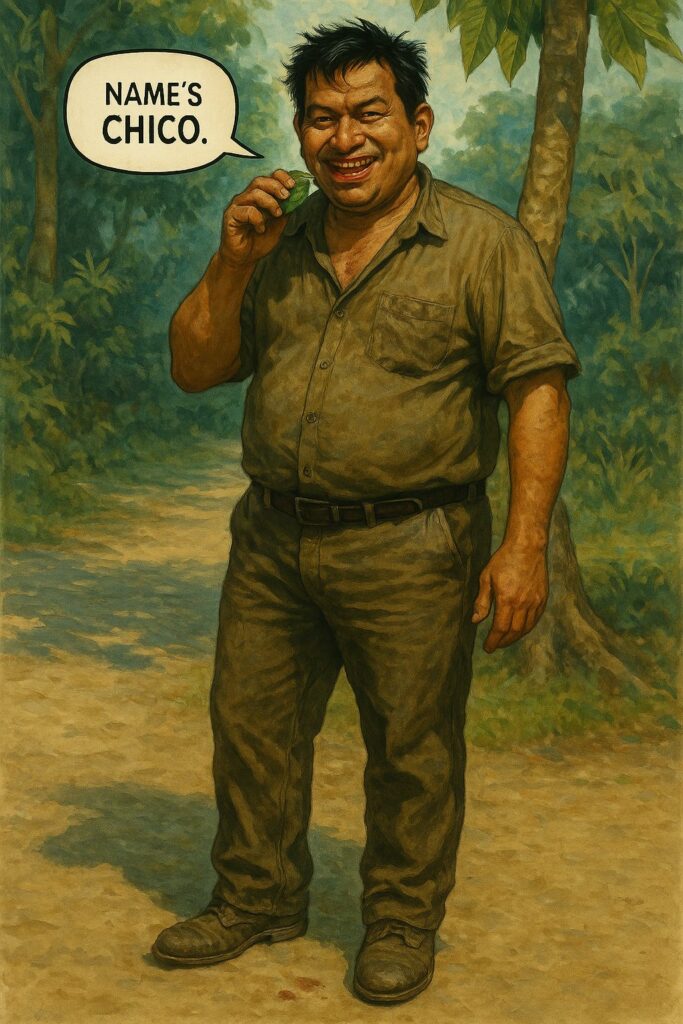

Chico Ray

Chico Ray

Directly Stated Visual and Behavioral Details:

-

Introduces himself casually: “Name’s Chico,” with no clear past, suggesting a self-aware or recently-written character.

-

Chews betel leaves, staining his teeth red, which gives him a slightly unsettling or feral appearance.

-

Spits on the floor, even in a freshly cleaned café—suggesting poor manners, or possibly defiance.

-

Appears from behind a trumpet tree, implying he lurks or emerges unpredictably.

-

Fabricates plausible-sounding geo-political nonsense (e.g., the coffee restrictions in Rwanda), then second-guesses whether it was fiction or memory.

Inferred Traits:

-

A sharp smile made more vivid by betel staining.

-

Likely wears earth-toned clothes, possibly tropical—evoking Southeast Asian or Central American flavors.

-

Comes off as a blend of rogue mystic and unreliable narrator, leaning toward surreal trickster.

-

Psychological ambiguity—he doubts his own origins, possibly a hallucination, dream being, or quantum hitchhiker.

What Remains Unclear:

-

Precise age or background.

-

His affiliations or loyalties—he doesn’t seem clearly aligned with the Bandits or Lucid Dreamers, but hovers provocatively at the edges.

March 2, 2025 at 10:22 am #7852In reply to: Helix Mysteries – Inside the Case

“Tundra Finds the Shoat-lion”

FADE IN:

EXT. THE GOLDEN TROWEL BAR — DUSK

A golden, muted twilight paints the landscape, illuminating the overgrown ivy and sprawled vines reclaiming the ancient tavern. THE GOLDEN TROWEL sign creaks gently in the breeze above the doorway.

ANGLE DOWN TO — TUNDRA, a spirited and curious 12-year-old girl with a wild, freckled pixie-cut and striking auburn hair, stepping carefully over ivy-covered stones and debris. She wears worn clothes, stitched lovingly by survivors; a scavenged backpack swings on one shoulder.

Behind her, through the windows of the tavern, warm lantern-light flickers. We glimpse MOLLY and GREGOR smiling and chatting quietly through dusty glass.

ANGLE ON — Tundra as she pauses, hearing a soft rustling near the abandoned beer barrels stacked against the tavern wall. Her green eyes widen, alert and intrigued.

SLOW PAN DOWN to reveal a small creature trembling in the shadows—a MARCASSIN, a tiny wild piglet no larger than a rugby ball, with coarse fur streaked ginger and cinnamon stripes along its body. Large dark eyes stare up, innocence mixed with wary curiosity. It’s adorable yet clearly distinct, with sharper canines already hinting at the deeply mutated carnivorous lineage of Hungary’s lion-boars.

Tundra inhales softly, visibly torn between instinctual cautiousness her elders taught and her own irrepressible instinct of compassion.

TUNDRA

(soft, gentle)

“It’s alright…I won’t hurt you.”She crouches slowly, reaching into her pocket—a small piece of stale bread emerges, held in her outstretched hand.

CLOSE-UP on the marcassin’s wary eyes shifting cautiously to her extended palm. A heartbeat of hesitation, and then it takes a tentative step forward, sniffing gently. Tundra holds utterly still, breath held in earnest hope.

The marcassin edges closer, wet nose brushing her fingers softly. Tundra beams, freckles highlighted by the fading sun, warmth and joy glowing on her face.

TUNDRA

(whispering happily)

“You’re not so scary, are you? I’m Tundra… I think we could be friends.”Movement at the tavern door draws her attention. The worn wood creaks as MOLLY and GREGOR step outside, shadows stretching long in the golden sunset. MOLLY’s eyes, initially alert with careful caution, soften at the touching scene.

MOLLY

(gently amused, warmly amused yet apprehensive)

“Careful now, darling. Even the smallest things aren’t always what they seem these days.”GREGOR

(softly chuckling, eyes twinkling)

“But then again, neither are we.”ANGLE ON Tundra, looking up to meet Molly’s eyes. Her determination tempered only by vulnerability, hope, and youthful stubbornness.

TUNDRA

“It needs us, Nana Molly. Everything needs somebody nowadays.”Molly considers the wisdom in Tundra’s young, earnest gaze. Gregor stifles a smile and pats Molly lightly lovingly on the shoulder.

GREGOR

(warmly, quietly)

“Ah, let her find hope where she sees it. Might be that little thing will change how we see hope ourselves.”ANGLE WIDE — the small group beside the tavern: Molly, her wise and caring gaze thoughtful; Gregor’s stance gentle yet cautiously protective; Tundra radiating youthful bravery, cradling newfound companionship as the marcassin squeaks softly, cuddling gently against her worn sweater.

ASCENDING SHOT ABOVE the tumbledown ancient Hungarian tavern, the warm glow of lantern and sunset mingling. Ancient vines and wild weeds whisper forgotten stories as stars blink awake above.

In that gentle hush, beneath a wild and vast sky reclaiming an abandoned land, Tundra’s act of compassion quietly rekindles hope for humanity’s delicate future.

FADE OUT.

February 16, 2025 at 12:50 pm #7810In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

Helix 25 – Below Lower Decks – Shadow Sector

Kai Nova moved cautiously through the underbelly of Helix 25, entering a part of the Lower Decks where the usual throb of the ship’s automated systems turned muted. The air had a different smell here— it was less sterile, more… human. It was warm, the heat from outdated processors and unmonitored power nodes radiating through the bulkheads. The Upper Decks would have reported this inefficiency.

Here, it simply went unnoticed, or more likely, ignored.

He was being watched.

He knew it the moment he passed a cluster of workers standing by a storage unit, their voices trailing off as he walked by. Not unusual, except these weren’t Lower Deck engineers. They had the look of people who existed outside of the ship’s official structure—clothes unmarked by department insignias, movements too intentional for standard crew assignments.

He stopped at the rendezvous point: an unlit access panel leading to what was supposed to be an abandoned sublevel. The panel had been manually overridden, its system logs erased. That alone told him enough—whoever he was meeting had the skills to work outside of Helix 25’s omnipresent oversight.

A voice broke the silence.

“You’re late.”

Kai turned, keeping his stance neutral. The speaker was of indistinct gender, shaved head, tall and wiry, with sharp green eyes locked on his movements. They wore layered robes that, at a glance, could have passed as scavenged fabric—until Kai noticed the intricate stitching of symbols hidden in the folds.

They looked like Zoya’s brand —he almost thought… or let’s just say, Zoya’s influence. Zoya Kade’s litanies had a farther reach he would expect.

“Wasn’t aware this was a job interview,” Kai quipped, leaning casually against the bulkhead.

“Everything’s a test,” they replied. “Especially for outsiders.”

Kai smirked. “I didn’t come to join your book club. I came for answers.”

A low chuckle echoed from the shadows, followed by the shifting of figures stepping into the faint light. Three, maybe four of them. It could have been an ambush, but that was a display.

“Pilot,” the woman continued, avoiding names. “Seeker of truth? Or just another lost soul looking for something to believe in?”

Kai rolled his shoulders, sensing the tension in the air. “I believe in not running out of fuel before reaching nowhere.”

That got their attention.

The recruiter studied him before nodding slightly. “Good. You understand the problem.”

Kai crossed his arms. “I understand a lot of problems. I also understand you’re not just a bunch of doomsayers whispering in the dark. You’re organized. And you think this ship is heading toward a dead end.”

“You say that like it isn’t.”

Kai exhaled, glancing at the flickering emergency light above. “Synthia doesn’t make mistakes.”

They smiled, but it wasn’t friendly. “No. It makes adjustments.” — the heavy tone on the “it” struck him. Techno-bigots, or something else? Were they denying Synthia’s sentience, or just adjusting for gender misnomers, it was hard to tell, and he had a hard time to gauge the sanity of this group.

A low murmur of agreement rippled through the gathered figures.

Kai tilted his head. “You think she’s leading us into the abyss?”

The person stepped closer. “What do you think happened to the rest of the fleet, Pilot?”

Kai stiffened slightly. The Helix Fleet, the original grand exodus of humanity—once multiple ships, now only Helix 25, drifting further into the unknown.

He had never been given a real answer.

“Think about it,” they pressed. “This ship wasn’t built for endless travel. Its original mission was altered. Its course reprogrammed. You fly the vessel, but you don’t control it.” She gestured to the others. “None of us do. We’re passengers on a ride to oblivion, on a ship driven by a dead man’s vision.”

Kai had heard the whispers—about the tycoon who had bankrolled Helix 25, about how the ship’s true directive had been rewritten when the Earth refugees arrived. But this group… they didn’t just speculate. They were ready to act.

He kept his voice steady. “You planning on mutiny?”

They smiled, stepping back into the half-shadow. “Mutiny is such a crude word. We’re simply ensuring that we survive.”

Before Kai could respond, a warning prickle ran up his spine.

Someone else was watching.

He turned slowly, catching the faintest silhouette lingering just beyond the corridor entrance. He recognized the stance instantly—Cadet Taygeta.

Damn it.

She had followed him.

The group noticed, shifting slightly. Not hostile, but suddenly alert.

“Well, well,” the woman murmured. “Seems you have company. You weren’t as careful as you thought. How are you going to deal with this problem now?”

Kai exhaled, weighing his options. If Taygeta had followed him, she’d already flagged this meeting in her records. If he tried to run, she’d report it. If he didn’t run, she might just dig deeper.

And the worst part?

She wasn’t corruptible. She wasn’t the type to look the other way.

“You should go,” the movement person said. “Before your shadow decides to interfere.”

Kai hesitated for half a second, before stepping back.

“This isn’t over,” he said.

Her smile returned. “No, Pilot. It’s just beginning.”

With that, Kai turned and walked toward the exit—toward Taygeta, who was waiting for him with arms crossed, expression unreadable.

He didn’t speak first.

She did.

“You’re terrible at being subtle.”

Kai sighed, thinking quickly of how much of the conversation could be accessed by the central system. They were still in the shadow zone, but that wasn’t sufficient. “How much did you hear?”

“Enough.” Her voice was even, but her fingers twitched at her side. “You know this is treason, right?”

Kai ran a hand through his hair. “You really think we’re on course for a fresh new paradise?”

Taygeta didn’t answer right away. That was enough of an answer.

Finally, she exhaled. “You should report this.”

“You should,” Kai corrected.

She frowned.

He pressed on. “You know me, Taygeta. I don’t follow lost causes. I don’t get involved in politics. I fly. I survive. But if they’re right—if there’s even a chance that we’re being sent to our deaths—I need to know.”

Taygeta’s fingers twitched again.

Then, with a sharp breath, she turned.

“I didn’t see anything tonight.”

Kai blinked. “What?”

Her back was already to him, her voice tight. “Whatever you’re doing, Nova, be careful. Because next time?” She turned her head slightly, just enough to let him see the edge of her conflicted expression.

“I will report you.”

Then she was gone.

Kai let out a slow breath, glancing back toward the hidden movement behind him.

No turning back now.

February 3, 2025 at 7:54 am #7731In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

The colours were bright, garish really, an impossibly blue sea and sky and splashes of pillar box red on the square shaped cars and dated clothes, but it was his favourite postcard of them all. It wasn’t the most scenic, it wasn’t the most spectacular location, but it was an echo from those long ago days of summer, of seaside holidays, souvenirs and a dozen postcards to write at a beachside cafe. The days when the post was delivered by conscientious postmen such as he himself had been, and the postcards arrived at their destinations before the holidaymakers had returned to their suburban homes and city jobs. The scene in the postcard was bathed in glorious sunshine, but the message on the back told the usual tale of the weather and the rain and that it might brighten up tomorrow but they were having a lovely time and they’d be back on Sunday and would the recipients get them a loaf and a pint of milk.

Ellis Marlowe put the Margate postcard to the back of the pile in his hand and pondered the image on the next one. He sighed at the image of the Statue of Liberty, sickly green, sadly proclaiming the height of a lost empire, and quickly put it at the back of the pile. Nobody needed to dwell on that story.

His perusal of the next image, an alpine meadow with an attractively skirted peasant scampering in a field, was interrupted with a bang on his door as Finkley barged in without waiting for a response. “There’s been a murder on the ship! Murder! Poor sod’s been dessicated like a dried tomato…”

Ellis looked at her in astonishment. His hand shook slightly as he put his postcard collection back in the box, replaced the lid and returned it to his locker. “Murder?” he repeated. “Murder? On here? But we’re supposed to be safe here, we left all that behind.” Visibly shaken, Ellis repeated, almost shouting, “But we left all that behind!”

December 5, 2024 at 8:45 am #7646In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

Mon. November 25th, 10am.

The bell sat on the stool near Lucien’s workbench, its bronze surface polished to a faint glow. He had spent the last ten minutes running a soft cloth over its etched patterns, tracing the curves and grooves he’d never fully understood. It wasn’t the first time he had picked it up, and it wouldn’t be the last. Something about the bell kept him tethered to it, even after all these years. He could still remember the day he’d found it—a cold morning at a flea market in the north of Paris, the stalls cramped and overflowing with gaudy trinkets, antiques, and forgotten relics.

He’d spotted it on a cluttered table, nestled between a rusted lamp and a cracked porcelain dish. As he reached for it, she had appeared, her dark eyes sharp with curiosity and mischief. Éloïse. The bell had been their first conversation, its strange beauty sparking a connection that quickly spiraled into something far more dangerous. Her charm masking the shadows she moved in. Slowly she became the reason he distanced himself from Amei, Elara, and Darius. It hadn’t been intentional, at least not at first. But by the time he realized what was happening, it was already too late.

A sharp knock at the door yanked him from the memory. Lucien’s hand froze mid-polish, the cloth resting against the bell. The knock came again, louder this time, impatient. He knew who it would be, though the name on the patron’s lips changed depending on who was asking. Most called him “Monsieur Renard.” The Fox. A nickname as smooth and calculating as the man himself.

Lucien opened the door, and Monsieur Renard stepped in, his gray suit immaculate and his air of quiet authority as sharp as ever. His eyes swept the studio, frowning as they landed on the unfinished painting on the easel—a lavish banquet scene, rich with silver and velvet.

“Lucien,” Renard said smoothly, his voice cutting through the silence. “I trust you’ll be ready to deliver on this commission.”

Lucien stiffened. “I need more time.”

“Of course,” Renard replied with a small smile that didn’t reach his eyes. “We all need something we can’t have. You have until the end of the week. Don’t make her regret recommending you.”

As Renard spoke, his gaze fell on the bell perched on the stool. “What’s this?” he asked, stepping closer. He picked it up, his long and strong fingers brushing the polished surface. “Charming,” he murmured, turning it over. “A flea market find, I suppose?”

Lucien said nothing, his jaw tightening as Renard tipped the bell slightly, the etched patterns catching the faint light from the window. Without care, Renard dropped it back onto the stool, the force of the motion knocking it over. The bell struck the wood with a resonant tone that lingered in the air, low and haunting.

Renard didn’t even glance at it. “You’ve always had a weakness for the past,” he remarked lightly, turning his attention back to the painting. “I’ll leave you to it. Don’t disappoint.”

With that, he was gone, his polished shoes clicking against the floor as he disappeared down the hall.

Lucien stood in the silence, staring at the bell where it had fallen, its soft tone still reverberating in his mind. Slowly, he bent down and picked it up, cradling it in his hands. The polished bronze felt warm, almost alive, as if it were vibrating faintly beneath his fingertips. He wrapped it carefully in a piece of linen and placed it inside his suitcase, alongside his sketchbooks and a few hastily folded clothes. The suitcase had been half-packed for weeks, a quiet reflection of his own uncertainty—leaving or staying, running or standing still, he hadn’t known.

Crossing the room, he sat at his desk, staring at the blank paper in front of him. The pen felt heavy in his hand as he began to write: Sarah Bernhardt Cafe, November 30th , 4 PM. No excuses this time!

He paused, rereading the words, then wrote them again and again, folding each note with care. He didn’t know what he expected from his friends—Amei, Elara, Darius—but they were the only ones who might still know him, who might still see something in him worth saving. If there was a way out of the shadows Éloïse and Monsieur Renard had drawn him into, it lay with them.

As he sealed the last envelope, the low tone of the bell still hummed faintly in his memory, echoing like a call he couldn’t ignore.

December 4, 2024 at 8:16 am #7640In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

Sat. Nov. 30, 2024 – before the meeting

The afternoon light slanted through the tall studio windows, thin and watery, barely illuminating the scattered tools of Lucien’s trade. Brushes lay in disarray on the workbench, their bristles stiff with dried paint. The smell of turpentine hung heavy in the air, mingling with the faint dampness creeping in from the rain. He stood before the easel, staring at the unfinished painting, brush poised but unmoving.

The scene on the canvas was a lavish banquet, the kind of composition designed to impress: a gleaming silver tray, folds of deep red velvet, fruit piled high and glistening. Each detail was rendered with care, but the painting felt hollow, as if the soul of it had been left somewhere else. He hadn’t painted what he felt—only what was expected of him.

Lucien set the brush down and stepped back, wiping his hands on his scarf without thinking. It was streaked with paint from hours of work, colors smeared in careless frustration. He glanced toward the corner of the studio, where a suitcase leaned against the wall. It was packed with sketchbooks, a bundle wrapped in linen, and clothes hastily thrown in—things that spoke of neither arrival nor departure, but of uncertainty. He wasn’t sure if he was leaving something behind or preparing for an escape.

How had it come to this? The thought surfaced before he could stop it, heavy and unrelenting. He had asked himself the same question many times, but the answer always seemed too elusive—or too daunting—to pursue. To find it, he would have to follow the trails of bad choices and chance encounters, decisions made in desperation or carelessness. He wasn’t sure he had the courage to look that closely, to untangle the web that had slowly wrapped itself around his life.

He turned his attention back to the painting, its gaudy elegance mocking him. He wondered if the patron who had commissioned it would even notice the subtle imperfections he had left, the faint warping of reflections, the fruit teetering on the edge of overripeness. A quiet rebellion, almost invisible. It wasn’t much, but it was something.

His friends had once known him as someone who didn’t compromise. Elara would have scoffed at the idea of him bending to anyone’s expectations. Why paint at all if it isn’t your vision? she’d asked once, her voice sharp, her black coffee untouched beside her. Amei, on the other hand, might have smiled and said something cryptic about how all choices, even the wrong ones, led somewhere meaningful. And Darius—Lucien couldn’t imagine telling Darius. The thought of his disappointment was like a weight in his chest. It had been easier not to tell them at all, easier to let the years widen the distance between them. And yet, here he was, preparing to meet them again.

The clock on the far wall chimed softly, pulling him back to the present. It was getting late. Lucien walked to the suitcase and picked it up, its weight pulling slightly on his arm. Outside, the rain had started, tapping gently against the windowpanes. He slung the paint-streaked scarf around his neck and hesitated, glancing once more at the easel. The painting loomed there, unfinished, like so many things in his life. He thought about staying, about burying himself in the work until the world outside receded again. But he knew it wouldn’t help.

With a deep breath, Lucien stepped out into the rain, the suitcase rattling softly behind him. The café wasn’t far, but it felt like a journey he might not be ready to take.

December 2, 2024 at 8:35 pm #7634In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

Nov.30, 2024 2:33pm – Darius: The Map and the Moment

Darius strolled along the Seine, the late morning sky a patchwork of rainclouds and stubborn sunlight. The bouquinistes’ stalls were already open, their worn green boxes overflowing with vintage books, faded postcards, and yellowed maps with a faint smell of damp paper overpowered by the aroma of crêpes and nearby french fries stalls. He moved along the stalls with a casual air, his leather duffel slung over one shoulder, boots clicking against the cobblestones.

The duffel had seen more continents than most people, its scuffed surface hinting at his nomadic life. India, Brazil, Morocco, Nepal—it carried traces of them all. Inside were a few changes of clothes, a knife he’d once bought off a blacksmith in Rajasthan, and a rolled-up leather journal that served more as a collection of ideas than a record of events.

Darius wasn’t in Paris for nostalgia, though it tugged at him in moments like this. The city had always been Lucien’s thing —artistic, brooding, and layered with history. For Darius, Paris was just another waypoint. Another stop on a map that never quite seemed to end.

It was the map that stopped him, actually. A tattered, hand-drawn thing propped against a pile of secondhand books, its edges curling like a forgotten leaf. Darius leaned in, frowning at its odd geometry. It wasn’t a city plan or a geographical rendering; it was… something else.

“Ah, you’ve found my prize,” said the bouquiniste, a short older man with a grizzled beard and a cigarette dangling from his lips.

“This?” Darius held up the map, his dark fingers tracing the looping, interconnected lines. They reminded him of something—a mandala, maybe, or one of those intricate yantras he’d seen in a temple in Varanasi.

“It’s not a real place,” the bouquiniste continued, leaning closer as though revealing a secret. “More of a… philosophical map.”

Darius raised an eyebrow. “A philosophical map?”

The man gestured toward the lines. “Each path represents a choice, a possibility. You could spend your life trying to follow it, or you could accept that you already have.”

Darius tilted his head, the edges of a smile forming. “That’s deep for ten euros.”

“It’s twenty,” the bouquiniste corrected, his grin flashing gold teeth.

Darius handed over the money without a second thought. The map was too strange to leave behind, and besides, it felt like something he was meant to find.

He rolled it up and tucked it into his duffel, turning back toward the city’s winding streets. The café wasn’t far now, but he still had time.

He stopped by a street vendor selling espresso shots and ordered one, the strong, bitter taste jolting his senses awake. As he leaned against a lamppost, he noticed his reflection in a shop window: a tall, broad-shouldered man, his dark skin glistening faintly in the misty air. His leather jacket was worn at the elbows, his boots dusted with dirt from some far-flung place.

He looked like a man who belonged everywhere and nowhere—a nomad who’d long since stopped wondering what home was supposed to feel like.

India had been the last big stop. It was messy, beautiful chaos. The temples had been impressive, sure, but it was the street food vendors, the crowded markets, the strolls on the beach with the peaceful cows sunbathing, and the quiet, forgotten alleys that stuck with him. He’d made some connections, met some people who’d lingered in his thoughts longer than they should have.

One of them had been a woman named Anila, who had handed him a fragment of something—an idea, a story, a warning. He couldn’t quite remember now. It felt like she’d been trying to tell him something important, but whatever it was had slipped through his fingers like water.

Darius shook his head, pushing the thought aside. The past was the past, and Paris was the present. He looked at the rolled-up map peeking out of his duffel and smirked. Maybe Lucien would know what to make of it. Or Elara, with her scientific mind and love of puzzles.

The group had always been a strange mix, like a band that shouldn’t work but somehow did. And now, after five years of silence, they were coming back together.

The idea made his stomach churn—not with nerves, exactly, but with a sense of inevitability. Things had been left unsaid back then, unfinished. And while Darius wasn’t usually one to linger on the past, something about this meeting felt… different.

The café was just around the corner now, its brass fixtures glinting through the drizzle. Darius slung his duffel higher on his shoulder and took one last sip of espresso before tossing the cup into a bin.

Whatever this reunion was about, he’d be ready for it.

But the map—it stayed on his mind, its looping lines and impossible paths pressing into his thoughts like a puzzle waiting to be solved.

December 1, 2024 at 10:36 pm #7630In reply to: Quintessence: Reversing the Fifth

Lucien pulled his suitcase through the rain-slick streets of Paris, the wheels rattling unevenly over the cobblestones. The rain fell in silver threads, blurring the city into streaks of light and shadow. His scarf, already streaked with paint, hung heavy and damp around his neck. Each step toward the café felt weighted, though he couldn’t tell if it was the suitcase behind him or the memories ahead.

The note he sent his friends had been simple. Sarah Bernhardt Café, November 30th , 4 PM. No excuses this time! Writing it had felt strange, as though summoning ghosts he wasn’t sure were ready to return. And now, with the café just blocks away, Lucien wasn’t sure if he wanted them to. Five years had passed since the four of them had last been together. He had told himself he needed this meeting—closure, perhaps—but a part of him still doubted.

He paused beneath a bookstore awning, the rain tracing fractured lines down the glass. His suitcase leaned against his leg, its weight pressing into him. Inside: a crumpled heap of clothes that smelled faintly of turpentine and the damp studio he had left behind, sketchbooks filled with forgotten drawings, and a small bundle wrapped in linen. Something he wasn’t ready to let go of—or couldn’t. He hadn’t decided yet if he was coming back or going away.

Lucien reached into his pocket and pulled out his last sketchbook. Flipping absently through its pages, he stopped at an old drawing of Darius, leaning over the edge of a rickety bridge, hand outstretched toward something unseen. He could still hear Darius’s voice: If you’re afraid of falling, you’ll never know what’s waiting. Lucien had scoffed then, but now the words lingered, uncomfortable in their truth.

The café came into view, its warm light pooling onto the wet street. Through the rain-speckled windows, he saw the familiar brass fixtures and etched glass, unchanged by time. He stepped inside, the warmth closing around him, and made his way to the corner table. Their table.

Setting the suitcase down, he folded into the chair and opened his sketchbook to a blank page. His pencil hovered. Outside, the rain fell softly, its rhythm steady against the glass. Inside, Lucien’s chest felt heavy. To make it go away, he started to scratch faint lines across the page.

November 20, 2024 at 9:21 pm #7609In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

“You! I never expected to see you here!” What was Thomas Cromwell doing in the colosseum in the year 1507? “Oh, of course, you were in Italy…what on earth are you wearing?” Truella asked, in some confusion. Never had she seen such an elaborate codpiece, and nobody else was wearing one.

He took his feathered cap off and ran a hand through his hair. “I’ve been to the very gates of purgatory trying to get back to Austin Friars, I unintentionally left Malove there.”

“In what year?” Truella was aghast. “How long has she been there? Who is she with? Is she safe?”

“There is no time to lose, how do I make this ~ this ~ thing go where and when I want?”

“Never mind that now, you had better come with us,” Trella was looking around to see where the others were. “We’ll all have to go. What’s the weather like? What are we going to do about clothes?”

“Clothes?” asked Jeezel, sneaking up behind them through some exotic foreign bushes, “Just you leave that to me! I’ve already found a marvellous museum costume shop. Did you get that codpiece there?” she said to Cromwell. ” I saw one in there similar to that, but with less padding.”

“Here you are,” announced Frella, suddenly appearing out of nowhere with her arms draped in costumes. “No time for shopping, so I did a quick spell.”

Why didn’t I think of just doing a spell? Truella wondered, not for the first time.

You never do was the unspoken reply that entered the scene with the appearance of Eris, armed with the approriate spells. “Right then. Here we go.”

November 5, 2024 at 1:14 pm #7583In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

Frella rolled her eyes. What were the odds of Truella turning up now!

“Well, don’t look so pleased to see me,” Truella said sarcastically. “I could have drowned you know, if Thomas hadn’t saved me. Are you going to introduce me to your friend?”

Frella looked helplessly at Oliver. “Perhaps you’d better go now, it’s all getting too complicated.”

“My good lady, would you curtail my pleasure at this unexpected meeting with a nephew I knew not existed?” Thomas interrupted, taking control of the situation, in as much as an out of control situation could be managed.

“My good man,” Frella replied tartly, “Would you curtail my pleasure with your nephew?”

“Now, now,” butted in Truella, trying to get a handle on the situation, “Surely nobody needs to have any pleasure curtailed. But Thomas has to get the boat back quickly, so I suggest someone explains to him who his nephew is. Then he can get back to the Thames. And I’ll walk back to your cottage, Frella, and borrow some dry clothes if you don’t mind, and then you can get on with….it, in peace.”

“Get on with what exactly!” Frella retorted, blushing furiously. “Oliver, why don’t you go back with your uncle, you know where the Thames is, don’t you? It just seems easier that way.”

Oliver laughed at the very idea of not knowing where the Thames was. “But my great great grand uncle Thomas died before I was born. I know of him, but he knows not of me. Well, he does now, admittedly.”

“So your name is Oliver,” mused Thomas, “Oliver Cromwell. And by the look of your doublet and hose, you’re a wealthy man. We have much to talk about. Pray step into the boat, my good sir, and we’ll find a way to get you back to your own time later. We must make haste for the sake of my boatman, Rafe.”

And with that they were off in a puff of river mist.

November 5, 2024 at 10:08 am #7582In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

The postcard was marked URGENT and the man in charge of postcards made haste to find Thomas Cromwell but he was nowhere to be found. The postcard was damp and the ink had run, but “send your boatman asap” was decipherable. The man in charge of postcards was not aware of any boatman by the name of Asap, but knowing Thomas it was possible he’d found another bright waif to train, probably one of the urchins hanging about the gates waiting for scraps from the kitchen.

“Asap! Asap!” the postcard man called as he ran down to the river. “Boatman Asap!”

“There be no boatman by that name on the masters barge, lad. Are you speaking my language?” replied boatman Rafe.

“Have you seen the master?” the postcard man asked, “And be quick about you, whatever your name is.”

“Aye, I can tell you that. He’s asleep in the barge.”

“Asleep? Asleep? In the middle of the day? You fool, get out of my way!” the postcard man shoved Rafe out of the way roughly. “My Lord Cromwell! Asleep on the barge in the middle of the day! Call the physician, you dolt!”

“Calm yourself man, I am in no need of assistance,” Cromwell said, yawning and rubbing his eyes as he rose to see what all the shouting was about. Being in two places at once was becoming difficult to conceal. He would have to employ a man of concealment to cover for him while he was in Malove’s body.

I must have a word with Thurston about licorice spiders, Cromwell made a mental note to speak to his cook, while holding out his hand for the postcard. “Thank you, Babbidge”, he said to the man in charge of postcards, giving him a few coins. “You did well to find me. That will be all.”

“Rafe,” Cromwell said to the boatman after a slight pause, “Can you row to the future, do you think?”

“Whatever you say, master, just tell me where it is.”

“Therein lies the problem,” replied Thomas Cromwell, promptly falling asleep again.

While Malove was tucking into some sugared ghosts at the party, she felt an odd plucking sensation, as if one of her spells had been accessed.

A split second later, Cromwell woke up. There was no time to lose gathering ingredients for spells, or laborious complicated rituals. Cromwell made a mental note to streamline the future coven with more efficient simple magic.

“Take all your clothes off, Rafe.” Astonished, the boatman removed his hat and his cloak. Thomas Cromwell did likewise. “Now you put my clothes on, Rafe, and I’ll wear yours. Get out of the boat and go and find somewhere under a bush to hide until I come back. I’m taking your boat. Don’t, under any circumstances, allow yourself to be seen.”

Terrified, the boatman scuttled off to seek cover. He’d heard the rumours about Cromwell’s imminent arrest. He almost laughed maniacally when the thought crossed his mind that he wished he had a mirror to see himself in Lord Cromwell’s hat, but that thought quickly turned to horror when he imagined the hat ~ and the head ~ rolling under the scaffold. God save us all, he whispered, knowing that God wouldn’t.

In a split second, boatman Cromwell found himself rowing the barge through flooded orange groves. I must fill my pockets with oranges for Thurston to make spiced orange tarts, he thought, before I return.

“Ah, there you are, bedraggled wench, you did well to send for assistance. A biblical flood if ever I saw one. There’s just one small problem,” Cromwell said as he pulled Truella into the barge, ” I can save you from drowning, but we must return forthwith to the Thames. I can not put my boatman in danger for long.”

“The Thames in the 1500s?” Truella said stupidly, shivering in her wet clothes.

Cromwell looked at her tight blue breeches and thin unseemly vest. “Your clothes simply won’t do”.

“Some dry ones would be nice,” Truella admitted.

“It’s not that your clothes are too wet,” he replied, frowning. He could send Rafe for a kitchenmaids dress, but then what would the kitchenmaid wear? They had one dress only, not racks of garments like the people in the future. Not unless they were ladies.

Lord Thomas Cromwell cast another eye over Truella. She was a similar build to Anne of Chives.

“If you think I’m dressing up as one of Henry’s wives…”

Laughing, Cromwell admitted she had a point. “No, perhaps not a good idea, especially as he does not well like this one. No need for her to be the death of both of us.”

“Look, just drop me off in Limerick on the way home, it’s barely out of your way. It’s probably raining there too, but at least I won’t have to worry about clothes. I’d look awful in one of those linen caps anyway.”

Cromwell gave her an approving look and agreed to her idea. Within a split second they were in Ireland, but Cromwell was in for a surprise.

“Yoohoo, Frella!” Truella called, delighted to see her friend strolling along the river bank. “It’s me!”

Thomas Cromwell pulled the boat up to the river bank, tossing the rope to Frella’s friend to secure it. Frella’s friend grabbed the rope and froze in astonishment. “You! Fancy seeing YOU here! Uncle Thomas!”

October 30, 2024 at 3:58 pm #7576In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

After the postcard craze had passed, Frella returned to Herma’s cottage several times to study the camphor chest. Every day for a week, Herma let her into the living room, where she would sit quietly in front of the chest, sometimes for hours. The wood’s glossy surface would catch the light, warm and rich, like polished honey. Frella would trace the strange curves of the mysterious engravings with her fingers, feeling the subtle dips and rises beneath her touch. The patterns felt ancient, worn smooth in places, yet sharp along certain edges, as if holding onto secrets just out of reach.

Then, as she lifted the heavy lid, a soft creak would break the silence, the hinges groaning as if they hadn’t moved in ages. A burst of cool, earthy fragrance would immediately rise, filling the air with camphor’s sharp, clean scent, mingled with faint hints of aged cedar and spice.

It didn’t take long for Frella to notice that each time she opened the chest, she would find a new object among the old papers and postcards. It was never the same. Once, it was an old brass spyglass; another time, it might be an ornate compass with seven directions marked. Yet another day, she found a teddy bear. By some odd coincidence, each item always seemed to be something she needed in her life at that particular moment.

When Eris informed them that Malove was most likely under a powerful spell, Frella found the mirror. An inscription carved clumsily on its back read, “This Mystic Mirror belongs to Seraphina.” The mirror’s metal was cold, tarnished, and in need of a good polish. Jeezel would have surely raved about the intricate vines of silver and gold, twisting in delicate patterns that seemed to shift with the viewer’s perspective. But what captivated Frella most was the glass itself. It held a faint opalescent sheen, swirling with hints of colors, like a rainbow caught in crystal.

The first time Frella looked into it, she saw, behind her own reflection, an elderly woman with silver hair handing the mirror down to a little girl who looked just like Frella had as a child. The clothes were peculiar, and the room they stood in looked as if it belonged in a fantasy movie. Then the little girl began carefully carving something on the back of the mirror with what looked like a golden chisel. When she finally turned the mirror and looked into it, her reflection replaced Frella’s. She said something, but there was no sound. Frella had the distinct impression that the girl’s lips had formed the words, “We are the same. It’s yours now; you’ll need it soon.” Then she vanished, and Frella’s own reflection reappeared.

Still filled with awe at what just happened, Frella wondered if Seraphina was a long lost ancestor. “Was that chest also yours, Seraphina?” she asked in a whisper to the ghosts of the past.

July 25, 2024 at 7:58 am #7542In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

Shivering, Truella pulled the thin blanket over her head. Colder than a witches tit here, colder in summer than winter at home! It was no good, she may as well get up and go for a walk to try and warm up. Poking her head outside Truella gasped and coughed at the chill air. Shapes were becoming discernible in the dim pre dawn light, the other pods, the hedgerow, a couple of looming trees. Truella rummaged through her bag, hoping to find warm clothes yet knowing she hadn’t packed anything warm enough. Sighing, her teeth chattering, she pulled on everything she had in layers and pulled the blanket off the bed to use as a cape. With a towel over her head for extra warmth, she ventured out into the Irish morning.

The grass was sodden with dew and Truella’s feet were wet through and icy. Bracing her shoulders with determination, she forged ahead towards a gate leading into the next field. She struggled for a few minutes with the baler twine holding the gate closed, numb fingers refusing to cooperate. Cows watched her curiously, slowly munching. One lifted her tail and dropped a steaming splat on the grass, chewing continuously. I don’t think I could eat and do that at the same time.

Heading off across the field which sloped gently upwards, Treulla picked up her pace, keeping her eyes down to avoid the cow pats. By the time she reached the oak tree along the top hedge, the sun started to make an appearance over the hill. Warmer from the exercise, she gazed over the countryside. How beautiful it was with the mist in the valleys, and everything so green.

If only it was warmer!

“Are you cold then, is that why you’re decked out like that? From a distance I thought I was seeing a ghost in a cloak and head shawl!” The woman smiled at Truella from the other side of the hedgerow. “Sorry, did I startle you? You’ll get your feet soaked walking in that wet grass, climb over that stile over there, the lane here’s better for a morning walk.”

It sounded like good advice and the woman seemed pleasant enough. “Are you here for the games too?” Truella asked, readjusting the blanket and towel after navigating the stile.

“Yes, I am. I’m retired, you see,” the woman said with a wide grin. “It’s a wonderful thing, not that you’d know, you’re much to young.”

“That must be nice,” Truella replied politely. “I sometimes wish I was retired.”

“Oh, my dear! It’s wonderful! I haven’t had a job for years, but it’s the strangest thing, now that I’ve officially retired, there’s a marvellous feeling of freedom. I don’t have to do anything. Well, I didn’t have to do anything before I retired but one always feels one should keep busy, do productive things, be seen to be doing some kind of work to justify ones existance. Have you seen the old priory?”

“No, only just got here yesterday.”

“You’ll love it, it’s up this path here, follow me. But now I’ve retired,” the woman continued, “I get up in the morning with a sense of liberation. I can do as little as I want ~ funny thing is that I’ve actually been doing more, but there’s no feeling of obligation, no things to cross off a list. All I’m expected to do as a retired person is tick along, trying not to be much of a bother for as long as I can.”

“I wish I was retired!” exclaimed Truella with feeling. “I wish I didn’t have to do the cow goddess stall, it’ll be such a bind having to stand there all evening.” She explained about the coven and the stalls, and the depressing productivity goals.

“But why not get someone else to do the stall for you?”

“It’s such short notice and I don’t know anyone here. It’s an idea though, maybe someone will turn up.”

July 18, 2024 at 2:29 pm #7535In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

It made sense to go to Ireland during the hot Andalucian summer, and it hadn’t taken much to convince Truella to take a break from her dig and her research. Thousands of years of history would still be there waiting for her when she got home, and it would be a pleasure to see some green lawns and fields. Maybe it would rain, indeed, it was likely that it would. And by the time the Roman Games were over, there would be less of the hot summer at home to endure. Still, it was a nuisance to have to get her winter clothes down out of the attic. She was sure to find it chilly, even cold.

Truella was not fond of water sports (or any sports, but particularly those involving water) and unfortunately the focus of the games seemed to be on swimming and boating. But one of the events has captured her interest. A miniaturisation spell was required, which contestants had to provide themselves, for the Puddles in Potholes races. The worst road in Limerick would be cordoned off and all the potholes filled with water (if they weren’t already full of rain water, which was likely). When Eris pointed out that a miniaturised person could drown in a puddle as easily as a full sized one could drown in a lake, Truella was ready with her answer. If she was drowning, she would immediately reverse the spell and resume her full size. Eris had raised an eyebrow, remarking that she had better make sure her spell was up to scratch, unlike her incense spells had been. Jeezel had wanted to know why she couldn’t just make an enlarging spell and just swim in the river, to which Truella has replied that she didn’t know how deep the river was and how much enlarging would be required. Snorting, Frella said she obviously didn’t know how deep the potholes in Limerick were.

Austreberthe had put their names down for the donkey chariot races, for which they had three days when they arrived to construct the cart and make the costumes. Luckily Frella had plenty of local contacts, and had willingly taken charge of assembling all the materials.

The Booths of the Gods would require some thought. Which Roman god would she choose to be? Which special godly power could she make a spell for? Truella sighed, and went to find her book of Roman gods and goddesses.

June 21, 2024 at 10:04 am #7516In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

“Wait! Look at that one up there!” Truella grabbed Rufus’s arm. “That cloth hanging right up there by the rafters, see it? Have you got a torch, it’s so dark up there.”

Obligingly, Rufus pulled a torch out of his leather coat pocket. “That looks like…”

“Brother Bartolo!” Truella finished for him in a whisper. “Why is there an ancient tapestry of him, with all those frog faced nuns?”

Rufus felt dizzy and clutched the bannisters to steady himself. It was all coming back to him in a rush: images and sounds crowded his mind, malodorous wafts assailed his nostrils.

“Why, whatever is the matter? You look like you’ve seen a ghost. Come, come and sit down in my room.”

“Don’t you remember?” Rufus asked, with a note of desperation in his voice. “You remember now, don’t you?”

“Come,” Truella insisted, tugging his arm. “Not here on the stairs.”

Rufus allowed Truella to lead him to her room, rubbing a hand over his eyes. He was so damn hot in this leather coat. The memories had first chilled him to the bone, and then a prickly sweat broke out.

Leading him into her room, Truella closed and locked the door behind them. “You look so hot,” she said softly and reached up to slide the heavy coat from his shoulders. They were close now, very close. “Take it off, darling, take it all off. We can talk later.”

Rufus didn’t wait to be asked twice. He slipped out of his clothes quickly as Truella’s dress fell to the floor. She bent down to remove her undergarments, and raised her head slowly. She gasped, not once but twice, the second time when her eyes were level with his manly chest. The Punic frog amulet! It was identical to the one she had found in her dig.

A terrible thought crossed her mind. Had he stolen it? Or were there two of them? Were they connected to the frog faced sisters? But she would think about all that later.

“Darling,” she breathed, “It’s been so long….”

June 7, 2024 at 9:03 pm #7459In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

There was an odd sight today.

Eris sat in the deserted courtyard area of the brand new Quadrivium office, Malové’s latest folly. She could savor the quiet that Fridays often brought, most of her colleagues from the coven preferring to work from home, leaving the usually bustling space tranquil and almost meditative. She took a bite of her sandwich, listening distractedly to the complaints of another witch sitting nearby, while her own mind still preoccupied with the myriad responsibilities and recent events that seemed to pile around like a stack of clothes due a trip to the laundry.

As she chewed thoughtfully, her eyes were drawn to an odd sight. A blackbird was performing a strange dance in front of the mirrored walls that lined one side of the patio. It hopped back and forth, its beak tapping on the surface, its feathers shimmering in the afternoon light, as if it were courting its own reflection or perhaps trying to feed it with a worm it had in its beak. Eris paused, intrigued by this peculiar behavior. What could it mean?

Her thoughts were interrupted by a series of sharp, melodic chirps. She looked around and spotted another bird perched nearby in the foliage of hanged planters lining the walls —a female blackbird, easily identifiable by her distinct brown coat. The female watched the male’s antics with a mix of curiosity and detachment, her chirps seeming to carry a message of their own.

Eris felt a shiver run down her spine, a familiar sensation that often preceded a moment of magical insight. The blackbird’s dance wasn’t just an oddity; it was a sign, a message from the universe, or perhaps from the magical currents that flowed unseen through the world.

She closed her eyes for a moment and took a deep breath, trying to connect with the energy around her. The image of the male blackbird, tirelessly courting its own reflection, seemed to mirror her own recent struggles. Had she been chasing an illusion, trying to nourish something that could not be sustained?

The female blackbird’s presence added another layer to the message. She was grounded, present, and observant—a contrast to the male’s futile efforts. Eris thought of her recent decisions, the dismissal of the cook, the strained relationships within the coven, and the cryptic postcards from Truella. Was the universe urging her to find balance, to ground herself and observe more keenly before taking action?

She could almost hear Elias whispers in her ears: Birds, in general, often represent thoughts or ideas flying about in our consciousness. The blackbird specifically, with its stark contrast and distinct presence, can represent deeper insights, truths, or messages that are coming to your awareness. The mirror, as a reflective surface, implies that these insights pertain directly to your perception of self or facets of your identity that may be emerging or needing attention. Putting this together, the imagery of the birds and their interactions could be nudging you to pay closer attention to your inner reflections. Are you nurturing the parts of yourself that truly need attention? Are there aspects of your identity or self-perception that require acknowledgment and care? The presence of the brown-coated female blackbird might also be a reminder to appreciate the varied and multifaceted nature of your experiences and the different roles you embody.

She opened her eyes, feeling a sense of clarity washing over her. The birds continued their vivid dialogue and unfathomable dances, unaware of the impact they had just made, although her insistent gaze had seemed to snap the blackbird out of its mesmerized pattern. He was now scurrying away looking over its shoulder, as if caught in an awkward moment.

Rising from her seat, Eris felt something. Not some sort of newfound sense of purpose, but a weight of a precious present, luminous and fragile, yet spacious and full with undecipherable meaning. She glanced one last time at the blackbirds, silently thanking them for their unspoken wisdom. As she walked back into the office, she knew that the path ahead would still be fraught with challenges, but she was ready to face them—grounded, observant, and attuned to the subtle messages that the world had to offer.

In the quiet of the Quadrivium office, on a deserted Friday afternoon, a blackbird’s dance had set the stage for the next chapter of her journey.

April 12, 2024 at 6:45 am #7428In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

An unexpected result (or was it an intentional one?) of the octobus ride was a profound appreciation for the arrival at the destination. Not one of the witches had been truly looking forward to the event, but when they entered the building they were deeply grateful for the smooth hard floors and walls and sharp minimalism, if that is what the sparse clean decor was called.

“This place is sorely in need of some steampunk hats,” remarked Truella. “And some Victorian clothes.”

“Beats the hell out of that gross octobus, though,” Jezeel said, who was swanning grandly around the large entrance foyer, her boots making a neat thud rather than a revolting sucking sound.

“I rather like it,” said Frella, “Steampunk hats wouldn’t fit in here at all. Are you sure that party is being held here?” For a moment, she felt a ray of hope. She was feeling that it might be possible to remain unnoticed and unbothered in the vast clean space if she sat somewhere looking serenely vacant and unapproachable.

Spotting the shiny black grand piano in the corner, Jezeel glided majestically over to it and hopped onto the back of it, striking a glamourous pose. Naturally everyone took flattering photos of her as was expected.

Eris had rushed off to find a lavatory, and eventually emerged holding a strange awkward bundle.

“What on earth is that and where did you find it?” Frella noticed the look of alarm on Eris’s face. Truella was still taking photos of Jez from various angles, much to Jezreel’s delight.

“What does it bloody look like!” Eris said in an exasperated tone, “It’s a baby, someone left it in the loo! Go and ask at the desk, find out who lost a baby. I think it’s nappy needs changing.”

Frella went off to ask, returning shortly with surprising news. “There is nobody checked in here with a baby, Eris. Nobody knows whose it is. Here, give it to me, the poor thing.”

Eris handed over the smelly bundle gratefully.

I can stay in my room with this baby, Frella thought, It will be the perfect excuse not to go to the party.

February 21, 2023 at 6:35 pm #6617In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Youssef had brought his black obsidian with him in the kitchen at breakfast. Idle—Youssef had realised that on top of being her way of life, it was also her name—was preparing a herbal brownie under the supervision of a colourful parrot perched on her shoulder.

“If you’re interested in rocks, you should go to Betsy’s. She’s got that ‘Gems & Minerals’ shop on Main street. She opened it with her hubby a few years back. Before he died.”

“Nutty Betsy, Pretty Girl likes her better,” said the parrot.

Idle looked at his backpack and his clothes.

“You seem the wandering type, lad. I was like you when I was younger, always gallivanting here, there, and everywhere with my brother. Now, I prefer wandering in my mind, if you know what I mean,” she said licking her finger full of chocolate. “Anyway, an advice. Don’t go down the mines alone. Betsy’s hubby’s still down there after one of the tunnels collapsed a few years back. She’s not been quite herself ever since.”

Main street was —well— the only street in town. They’ve been preparing for some kind of festival, putting banners on top of the shops and in between two trees near the gas station. Youssef stopped there to buy snacks that he stacked on top of the obsidian stone in his backpack. The young boy who worked there, Devan, seemed quite excited at the perspective of the Lager and Cart Race. It happened only every ten years and last time he was too young to participate.

The shop had not been difficult to find, at the other end of the street. A tiny sign covered in purple star sequins indicated “Betsy’s Gems & Minerals — We deliver worldwide”. He felt with his hand the black rock he had put in his backpack. If Idle had not mentioned the mines and the dead husband, Youssef might have reconsidered going in. But the coincidence with his dream and the game was too intriguing. He entered.

The shop was a mess. Crates full of stones, cardboard boxes and bubble wrappings. In the back, a plump woman, working on a giant starfish she held on her lap, was humming as she listened to loud rock music. Youssef recognised a song from the Last Shadow Puppets’ second album : The Element of Surprise. Apparently, the woman hadn’t heard him enter. She wore a dress and a hat sprinkled with golden stars, and her wrists were hidden under a ton of stone bracelets. The music track changed. The woman started shaking her head following the rhythm of the tune. She was gluing small red stones, she picked in a little box, on one of the starfish arms.

The shop was a mess. Crates full of stones, cardboard boxes and bubble wrappings. In the back, a plump woman, working on a giant starfish she held on her lap, was humming as she listened to loud rock music. Youssef recognised a song from the Last Shadow Puppets’ second album : The Element of Surprise. Apparently, the woman hadn’t heard him enter. She wore a dress and a hat sprinkled with golden stars, and her wrists were hidden under a ton of stone bracelets. The music track changed. The woman started shaking her head following the rhythm of the tune. She was gluing small red stones, she picked in a little box, on one of the starfish arms.“Bad Habits! Uhu. Bad Habits! Uhu.”

Youssef moved closer. His shadow covered the starfish. The woman raised her head and screamed, scattering the red stones in her workshop. The starfish fell from her lap onto the ground with a thud.

“Oh! My! Little devil. Look at what you made me do. I lost my marbles,” she said with a high pitched laugh. “Your mother never taught you? That’s bad habit to creep up on people like that. You scared the sheep out of me!”

“I’m so sorry,” said Youssef, getting on his knees to help her gather the stones.

When they were all back in their box, Youssef got back on his feet. The woman looked a him with a softened face.

“You such a cutie with your bear shirt. You make me think of my Howard. He was as tall as you are. I’m Betsy, obviously” she said with a giggle, extending her hand to him.

They shook hands, making the pearls of her bracelets clink together.

“I’m Youssef.”

Youssef didn’t need to insist too much. Betsy was a real juke box of gossips. He just had to ask one question from time to time, and she would get going again. He was starting to feel his quirk could be more than a curse after all.

“When the tunnel collapsed,” Betsy said, “I was ready to give up the stone shop. The pain was too much to bear, everything in the shop reminded me of Howard. And in a miners’ town, who would want to buy stones anyway. We’ve been in bad terms with Idle and her family for some time, but that tragic incident coincided with her brother Fred’s disappearance. They thought at first Fred had died in the mines with Howard, because they spent so much time discussing together in Room 8 at the Inn. I overheard them once, talking about something they found in the mines. But Howard never told me, he was so secretive about that. We even had a fight, you know. But Fred, the children found some message later that suggested he had just left the family. Imagine, the children! Idle was pissed with him of course. Abandoning her with that mother of theirs and that money pit of an Inn and the rest of the family. And I needed company. So we started to get together on a regular basis. She would bring her special cakes, and we would complain about our lives. At some point she got involved with that shamanic stuff she found online, and she helped me find my totem Bear. It was quite a revelation. Bear suggested I diversify and open an online shop and start making orgonites. I love those little gummy bears so much. So, I followed Bear’s advice and it has been working like a charm ever since. That’s why I trusted you straight away, lad. Not ’cause of your cute face. You got the Bear in your heart,” she said putting her finger at the center of his chest.

My inner Bear, of course, thought Youssef. That’s the magnet. His phone buzzed. He took it out and saw he had an alert from the game and a message from his friends.

You found the source of your quirk, the magnetic pull that attracts talkative people to you.

Now obtain the silver key in the shape of a tongue to fulfil your quest.Zara : Where are you!?

We’re at the bar, getting parched! They got Pale Ale!

We’re at the bar, getting parched! They got Pale Ale!“I have to go,” said Youssef.

“Wait,” said Betsy.

She foraged through her orgonite collection and handed Youssef one little gummy bear and an ornate metal badge.

“Bear wants me to give this to you. Howard made it. He said it was his forked tongue key.”

She looked at him, emotion in her eyes.

“I know you won’t listen if I tell you not to. So, be careful when you go into the mines.”

February 19, 2023 at 9:00 pm #6612

February 19, 2023 at 9:00 pm #6612In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

Two young women, identical to the purple lock of hair hiding their left eye, entered the room. They moved as one person to the table, balancing their arms and bouncing on the floor like little girls. Youssef couldn’t help a shiver as he remembered The Shining.

“We are the twins,” they said, looking at him from behind their purple lock of hair. “Don’t mind us.”

One spoke a few milliseconds after the other, giving their combined voice an otherworldly touch that wasn’t reassuring. One took the sheets of paper from under the obsidian stone and the other the notebooks. After an hesitation they left the stone on the table and went back to the door.

“Wait,” said Youssef as they were about to leave, “What was on that paper? It looked like a map.”

“We leave you the stone,” they said without looking at him. “You might need it.”

As they shut the door, Youssef jumped out of his bed and tried to catch up with them. People couldn’t just enter his room like that. But when he flung the door open, the corridor was empty. He had the impression echoes of a combined laugh remained in the air and, tired as he was, decided not to look for them. Better not break the veil between dream and reality.

Intrigued by what the girls said, he took the black stone from the table and the last snicker bar from his backpack. He noted he would have to go to the grocery store tomorrow to buy some. Once he was back on his bed, he engulfed the snack and, while chewing, turned the stone around, trying to figure out what the girls meant by “You might need it”. The stone was cold to the touch and his reflection kept changing but nothing particular happened. Disappointed, he put the stone on his pillow and resumed the game on his phone.

Youssef finds himself in a small ghost town in what looks like the middle of the Australian outback. He’s standing in the town square, surrounded by an old post office, a saloon, and a few other ramshackle buildings.

He had a hard time focusing on the game. He started to feel the fatigue from the day. He yawned and started to doze off.

Youssef is standing in the town square, surrounded by an old post office, a saloon, and a few other ramshackle buildings. Scraps of mist are floating towards him. A ghostly laugh resounds from behind. He turns swiftly only to see a flash of purple disappear in a dark alleyway. He starts to run to catch them but a man, thrown out of the saloon, stumbles in front of him and they roll together on the dust.

“It’s not that I don’t like you,” said the man, “but you’re heavy.”

Youssef rolls on the side, mumbling some excuses and looks at where the twins had disappeared but the alleyway was gone.

“I think you broke one of my rib with your stone,” says the man, feeling his chest.

He looks as old as the town itself and quite harmless in his clothes, too big for him.

“What stone?” asks Youssef.

The old man points at a fragment of black obsidian between them on the ground.

“Don’t show them,” he says, “or they’ll take it from you.”

“What did you do?”

“They don’t like it when you ask questions about the old mines.”

February 18, 2023 at 2:38 pm #6552In reply to: Orbs of Madjourneys

When Xavier woke up, the sun was already shining, its rays darting in pulsating waves throughout the land, blinding him. The room was already heating up, making the air difficult to breathe.

He’d heard the maid rummaging in the neighbouring rooms for some time now, which had roused him from sleep. He couldn’t recall seeing any “DO NOT DISTURB” sign on the doorknob, so staying in bed was only delaying the inevitable barging in of the lady who was now vacuuming vigorously in the corridor.

Feeling a bit dull from the restless sleep, he quickly rose from the bed and put on his clothes.

Once out of his room, he smiled at the cleaning lady (who seemed to be the same as the cooking lady), who harumphed back as a sort of greeting. Arriving in the kitchen, he wondered whether it was probably too late for breakfast —until he noticed the figure of the owner, who was quietly watching him through half-closed eyes in her rocking chair.

“Idle should have left some bread, butter and jam to eat if you’re hungry. It’s too late for bacon and sausages. You can help yourself with tea or coffee, there’s a fresh pot on the kitchen counter.”

“Thanks M’am.” He answered, startled by the unexpected appearance.

“No need. Finly didn’t wake you up, did she? She doesn’t like when people mess up her schedule.”

“Not at all, it was fine.” he lied politely, helping himself to some tea. He wasn’t sure buttered bread was enough reward to suffer a long, awkward conversation, given that the lady (Mater, she insisted he’s called him) wasn’t giving him any sign of wanting to leave.

“It shouldn’t be long until your friends come back from the airport. Your other friend, the big lad, he went for a walk around. Idle seems to have sold him a visit to our Gems & Rocks boutique down Main avenue.” She tittered. “Sounds grand when we say it —that’s just the only main road, but it helps with tourists bookings. And Betsy will probably tire him down quickly. She tends to get too excited when she gets clients down there; most of her business she does online now.”

Xavier was done with his tea, and looking for an exit strategy, but she finally seemed to pick up on the signals.

“… As I probably do; look at me wearing you down. Anyway, we have some preparing to do for the Carts & whatnot festival.”

When she was gone, Xavier’s attention was attracted by a small persistent ticking noise followed by some cracking.

It was on the front porch.

A young girl in her thirteens, hoodie on despite the heat, and prune coloured pants, was sitting on the bench reading.

She told him without raising her head from her book. “It’s Aunt Idle’s new pet bird. It’s quite a character.”

“What?”

“The noise, it’s from the bird. It’s been cracking nuts for the past twenty minutes. Hence the noise. And yes, it’s annoying as hell.”

She rose from the bench. “Your bear friend will be back quick I’m certain; it’s just a small boutique with some nice crystals, but mostly cheap orgonite new-agey stuff. Betsy only swears by that, protection for electromagnetic waves and stuff she says, but look around… we are probably got more at risk to be hit by Martian waves or solar coronal mass ejections that by the ones from the telecom tower nearby.”

Xavier didn’t know what to say, so he nodded and smiled. He felt a bit out of his element. When he looked around, the girl had already disappeared.

Now alone, he sat on the empty bench, stretched and yawned while trying to relax. It was so different from the anonymity in the city: less people here, but everything and everyone very tightly knit together, although they all seemed to irk and chafe at the thought.

The flapping of wings startled him.

“Hellooo.” The red parrot had landed on the backrest of the bench and dropped shells from a freshly cracked nut which rolled onto the ground.

Xavier didn’t think to respond; like with AL, sometimes he’d found using polite filler words was only projecting human traits to something unable to respond back, and would just muddle the prompt quality.

“So ruuuude.” The parrot nicked his earlobe gently.

“Ouch! Sorry! No need to become aggressive!”

“You arrrre one to talk. Rouge is on Yooour forehead.”

Xavier looked surprised at the bird in disbelief. Did the bird talk about the mirror test? “What sort of smart creature are you now?”

“Call meee Rose. Pretty Giiirl acceptable.”

Xavier smiled. The bird seemed quite fascinating all of a sudden.

It was strange, but the bird seemed left completely free to roam about; it gave him an idea.“Rose, Pretty Girl, do you know some nice places around you’d like to show me?”

“Of couuurse. Foôllow Pretty Girl.”

-

-

AuthorSearch Results