Search Results for 'hear'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

January 10, 2023 at 10:31 pm #6364

In reply to: Train your subjective AI – text version

Please suggest a creative, a little ghostic but mostly uplifting plot outline for the continuation of the story of Twilight in her travels to join the freak circus and become famous for her craft on the west coast

— The Far-West saga — In 1850s, in a probable reality of South America, we get acquainted with Twilight (Twi) and her brothers Jo and Elroy. They have a precious blue bull in their possession, coveted by Ogrean, the kingpin of the town. Hopefully for them, Ogrean is arrested (temporarily) by Ted Marshall, the sheriff for his possible trafficking. Notably, Ogrean is possibly involved in some of the crystal skulls discoveries, during his travel to New Honduras. Twi who was dancing in the saloon of Madame Butterbutt, the town’s hallucinogenic toads-to-lick dispenser (insert some other romantic subplots involving the other dancer etc.) decides to go traveling in a freakus (freak show/circus). She is now close to the West Coast, where she hopes to succeed in her writing and other artistic skills.

As Twilight (Twi) travels with the freak circus, she faces many challenges and obstacles on her journey to the West Coast. Despite the difficulties, she remains determined to make a name for herself as a writer and artist.

As she travels through small towns and larger cities, she begins to realize that the world is much bigger than she ever imagined. She meets a diverse group of people, some of whom are kind and supportive, while others are cruel and dismissive of her dreams.

Despite the negative reactions she receives from some people, Twi persists and begins to gain a reputation as a talented writer and performer. As she gains more experience and confidence, she starts to incorporate her own unique style into her performances, which sets her apart from the other performers in the circus.

As she approaches the West Coast, she begins to feel a sense of excitement and anticipation. She has heard that the West Coast is a place of endless possibilities, where creative minds can thrive. She is determined to make her mark and become famous for her craft.

As she settles in the west, she finds herself surrounded by artists and writers like herself, who inspire her to push herself even further. She begins to gain a following and her writing is widely read. She discovers that her talent is not only limited to writing, but she also has a natural talent for other art forms as well.

Eventually, Twi’s reputation as a talented artist and writer precedes her and she becomes a sought-after performer in the West Coast, and her creative work is being showcased in galleries and theaters. As she continues to achieve success in her career, she begins to realize that the West Coast is not just a place of endless possibilities but also the place where she belongs, and the place where her dreams come true.

Throughout her journey, she also keeps in touch with her brothers, Jo and Elroy, who now run the farm and take care of the blue bull. They tell her that the bull, now named Blue-Dream, became a legend in the village and they get a good price for its breeding.

As the story continues, she finds herself also involved in some adventures and exciting subplots, like discovering a secret underground cave filled with precious crystals and some interesting characters, like the enigmatic sheriff Ted Marshall who always cross her path, and the mysterious Ogrean who seems to have a connection to her past and the bull.

The End.

January 10, 2023 at 10:15 pm #6363In reply to: Train your subjective AI – text version

try another short story, with a bit of drama with the following words:

road form charlton smooth everyone cottage hanging rush offer agree subject district included appear sha returning grattidge nottingham 848 tetbury chicken

It was a cold and gloomy day in the small village of Tetbury, nestled in the picturesque Cotswolds district. A young woman named Sha was returning home to her cottage after a long and tiring journey. She had been away visiting her family in Nottingham and was looking forward to relaxing in her cozy home.

As she walked down the dirt road that led to her cottage, she couldn’t help but notice that something was off. Her neighbor, Mr. Charlton, was outside hanging laundry and he didn’t acknowledge her as she walked by. Sha thought it was strange, as he was usually a friendly and sociable person.

When Sha arrived at her cottage, she was shocked to find that it had been broken into. The front door was ajar and the inside of her home had been ransacked. Sha immediately panicked and called the police, who arrived on the scene shortly thereafter.

The police officers, including Inspector Grattidge, took Sha’s statement and began to investigate the crime. They discovered that a group of burglars had been operating in the area, targeting homes and businesses in the district. The burglars had been known for their smooth operations and their ability to strike quickly, which led to their nickname “The Smooth Operators”.

As Sha waited for the police to finish their investigation, she couldn’t shake the feeling that something was not right. She had always thought of Tetbury as a safe and friendly place, and she couldn’t believe that something like this could happen in her community.

As the investigation went on, the police found out that the Smooth operators have been targeting houses with no security cameras, but Sha’s cottage was an exception, the police were able to find out that the group offered to pay a considerable sum of money to the people who reported the locations of the houses that had no cameras, and it was Mr. Charlton who was the informant and he even rushed to Sha’s cottage as soon as he knew the police was investigating the case, He was arrested for the crime and Sha was heartbroken to find out that her once friendly neighbor had betrayed her.

Feeling violated and betrayed, Sha decided that she could no longer stay in the village and she put her cottage up for sale. She packed up her belongings and moved away, leaving behind the memories of her peaceful home and the community she had once thought of as her own. The end.

November 4, 2022 at 2:19 pm #6342In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

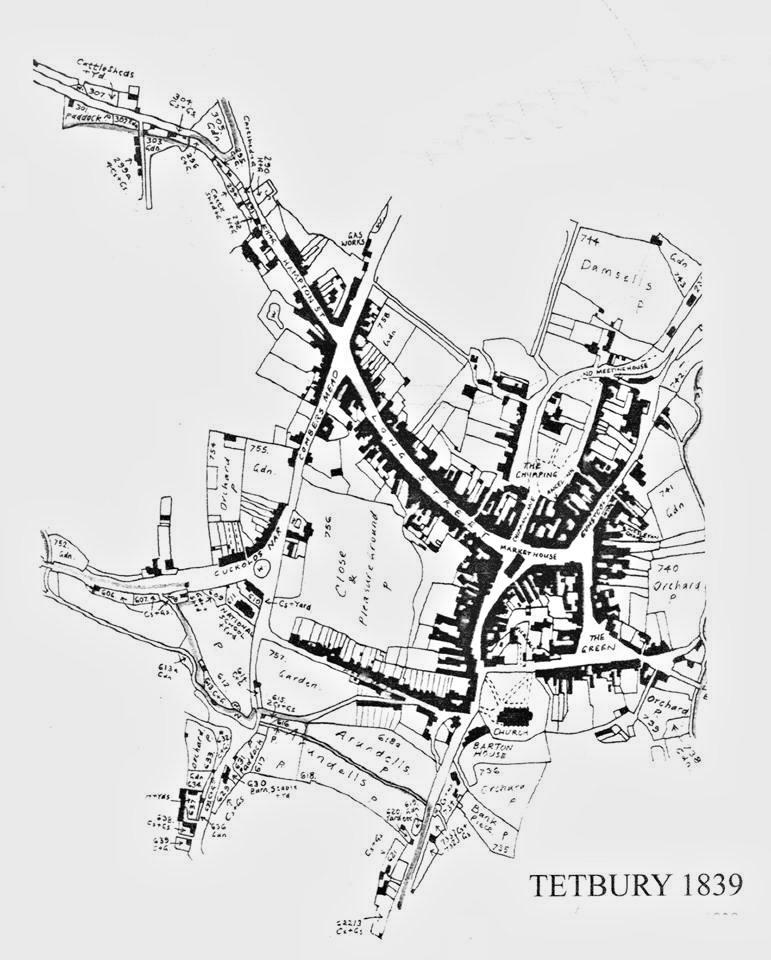

Brownings of Tetbury

Isaac Browning (1784-1848) married Mary Lock (1787-1870) in Tetbury in 1806. Both of them were born in Tetbury, Gloucestershire. Isaac was a stone mason. Between 1807 and 1832 they baptised fourteen children in Tetbury, and on 8 Nov 1829 Isaac and Mary baptised five daughters all on the same day.

I considered that they may have been quintuplets, with only the last born surviving, which would have answered my question about the name of the house La Quinta in Broadway, the home of Eliza Browning and Thomas Stokes son Fred. However, the other four daughters were found in various records and they were not all born the same year. (So I still don’t know why the house in Broadway had such an unusual name).

Their son George was born and baptised in 1827, but Louisa born 1821, Susan born 1822, Hesther born 1823 and Mary born 1826, were not baptised until 1829 along with Charlotte born in 1828. (These birth dates are guesswork based on the age on later censuses.) Perhaps George was baptised promptly because he was sickly and not expected to survive. Isaac and Mary had a son George born in 1814 who died in 1823. Presumably the five girls were healthy and could wait to be done as a job lot on the same day later.

Eliza Browning (1814-1886), my great great great grandmother, had a baby six years before she married Thomas Stokes. Her name was Ellen Harding Browning, which suggests that her fathers name was Harding. On the 1841 census seven year old Ellen was living with her grandfather Isaac Browning in Tetbury. Ellen Harding Browning married William Dee in Tetbury in 1857, and they moved to Western Australia.

Ellen Harding Browning Dee: (photo found on ancestry website)

OBITUARY. MRS. ELLEN DEE.

A very old and respected resident of Dongarra, in the person of Mrs. Ellen Dee, passed peacefully away on Sept. 27, at the advanced age of 74 years.The deceased had been ailing for some time, but was about and actively employed until Wednesday, Sept. 20, whenn she was heard groaning by some neighbours, who immediately entered her place and found her lying beside the fireplace. Tho deceased had been to bed over night, and had evidently been in the act of lighting thc fire, when she had a seizure. For some hours she was conscious, but had lost the power of speech, and later on became unconscious, in which state she remained until her death.

The deceased was born in Gloucestershire, England, in 1833, was married to William Dee in Tetbury Church 23 years later. Within a month she left England with her husband for Western Australian in the ship City oí Bristol. She resided in Fremantle for six months, then in Greenough for a short time, and afterwards (for 42 years) in Dongarra. She was, therefore, a colonist of about 51 years. She had a family of four girls and three boys, and five of her children survive her, also 35 grandchildren, and eight great grandchildren. She was very highly respected, and her sudden collapse came as a great shock to many.

Eliza married Thomas Stokes (1816-1885) in September 1840 in Hempstead, Gloucestershire. On the 1841 census, Eliza and her mother Mary Browning (nee Lock) were staying with Thomas Lock and family in Cirencester. Strangely, Thomas Stokes has not been found thus far on the 1841 census, and Thomas and Eliza’s first child William James Stokes birth was registered in Witham, in Essex, on the 6th of September 1841.

I don’t know why William James was born in Witham, or where Thomas was at the time of the census in 1841. One possibility is that as Thomas Stokes did a considerable amount of work with circus waggons, circus shooting galleries and so on as a journeyman carpenter initially and then later wheelwright, perhaps he was working with a traveling circus at the time.

But back to the Brownings ~ more on William James Stokes to follow.

One of Isaac and Mary’s fourteen children died in infancy: Ann was baptised and died in 1811. Two of their children died at nine years old: the first George, and Mary who died in 1835. Matilda was 21 years old when she died in 1844.

Jane Browning (1808-) married Thomas Buckingham in 1830 in Tetbury. In August 1838 Thomas was charged with feloniously stealing a black gelding.

Susan Browning (1822-1879) married William Cleaver in November 1844 in Tetbury. Oddly thereafter they use the name Bowman on the census. On the 1851 census Mary Browning (Susan’s mother), widow, has grandson George Bowman born in 1844 living with her. The confusion with the Bowman and Cleaver names was clarified upon finding the criminal registers:

30 January 1834. Offender: William Cleaver alias Bowman, Richard Bunting alias Barnfield and Jeremiah Cox, labourers of Tetbury. Crime: Stealing part of a dead fence from a rick barton in Tetbury, the property of Robert Tanner, farmer.

And again in 1836:

29 March 1836 Bowman, William alias Cleaver, of Tetbury, labourer age 18; 5’2.5” tall, brown hair, grey eyes, round visage with fresh complexion; several moles on left cheek, mole on right breast. Charged on the oath of Ann Washbourn & others that on the morning of the 31 March at Tetbury feloniously stolen a lead spout affixed to the dwelling of the said Ann Washbourn, her property. Found guilty 31 March 1836; Sentenced to 6 months.

On the 1851 census Susan Bowman was a servant living in at a large drapery shop in Cheltenham. She was listed as 29 years old, married and born in Tetbury, so although it was unusual for a married woman not to be living with her husband, (or her son for that matter, who was living with his grandmother Mary Browning), perhaps her husband William Bowman alias Cleaver was in trouble again. By 1861 they are both living together in Tetbury: William was a plasterer, and they had three year old Isaac and Thomas, one year old. In 1871 William was still a plasterer in Tetbury, living with wife Susan, and sons Isaac and Thomas. Interestingly, a William Cleaver is living next door but one!

Susan was 56 when she died in Tetbury in 1879.

Three of the Browning daughters went to London.

Louisa Browning (1821-1873) married Robert Claxton, coachman, in 1848 in Bryanston Square, Westminster, London. Ester Browning was a witness.

Ester Browning (1823-1893)(or Hester) married Charles Hudson Sealey, cabinet maker, in Bethnal Green, London, in 1854. Charles was born in Tetbury. Charlotte Browning was a witness.

Charlotte Browning (1828-1867?) was admitted to St Marylebone workhouse in London for “parturition”, or childbirth, in 1860. She was 33 years old. A birth was registered for a Charlotte Browning, no mothers maiden name listed, in 1860 in Marylebone. A death was registered in Camden, buried in Marylebone, for a Charlotte Browning in 1867 but no age was recorded. As the age and parents were usually recorded for a childs death, I assume this was Charlotte the mother.

I found Charlotte on the 1851 census by chance while researching her mother Mary Lock’s siblings. Hesther Lock married Lewin Chandler, and they were living in Stepney, London. Charlotte is listed as a neice. Although Browning is mistranscribed as Broomey, the original page says Browning. Another mistranscription on this record is Hesthers birthplace which is transcribed as Yorkshire. The original image shows Gloucestershire.

Isaac and Mary’s first son was John Browning (1807-1860). John married Hannah Coates in 1834. John’s brother Charles Browning (1819-1853) married Eliza Coates in 1842. Perhaps they were sisters. On the 1861 census Hannah Browning, John’s wife, was a visitor in the Harding household in a village called Coates near Tetbury. Thomas Harding born in 1801 was the head of the household. Perhaps he was the father of Ellen Harding Browning.

George Browning (1828-1870) married Louisa Gainey in Tetbury, and died in Tetbury at the age of 42. Their son Richard Lock Browning, a 32 year old mason, was sentenced to one month hard labour for game tresspass in Tetbury in 1884.

Isaac Browning (1832-1857) was the youngest son of Isaac and Mary. He was just 25 years old when he died in Tetbury.

October 22, 2022 at 1:18 pm #6338In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

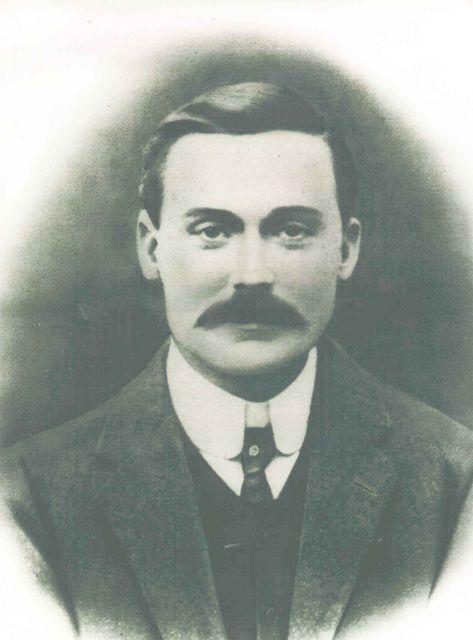

Albert Parker Edwards

1876-1930

Albert Parker Edwards, my great grandfather, was born in Aston, Warwickshire in 1876. On the 1881 census he was living with his parents Enoch and Amelia in Bournebrook, Northfield, Worcestershire. Enoch was a button tool maker at the time of the census.

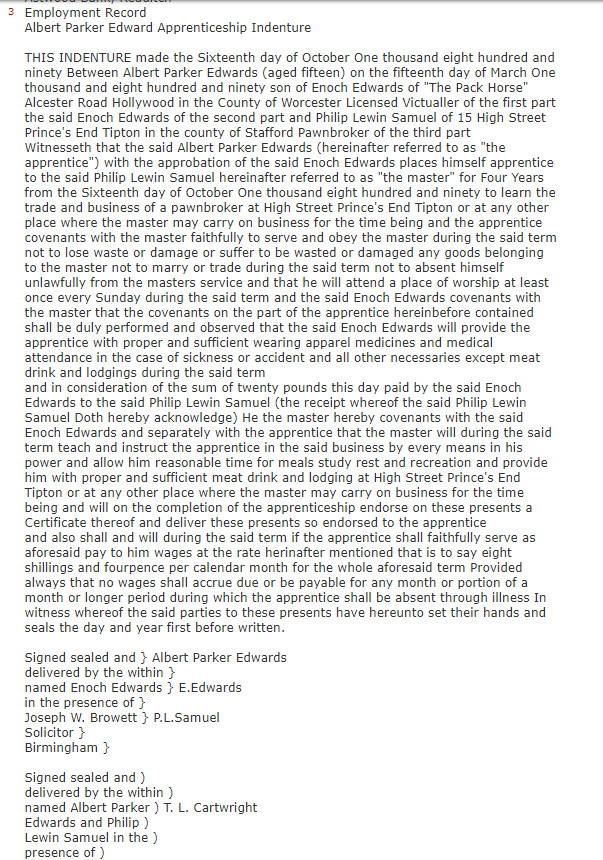

In 1890 Albert was indentured in an apprenticeship as a pawnbroker in Tipton, Staffordshire.

On the 1891 census Albert was a lodger in Tipton at the home of Phoebe Levy, pawnbroker, and Alberts occupation was an apprentice.

Albert married Annie Elizabeth Stokes in 1898 in Evesham, and their first son, my grandfather Albert Garnet Edwards (1898-1950), was born six months later in Crabbs Cross. On the 1901 census, Annie was in hospital as a patient and Albert was living at Crabbs Cross with a boarder, his brother Garnet Edwards. Their two year old son Albert Garnet was staying with his uncle Ralph, Albert Parkers brother, also in Crabbs Cross.

Albert and Annie kept the Cricketers Arms hotel on Beoley Road in Redditch until around 1920. They had a further four children while living there: Doris May Edwards (1902-1974), Ralph Clifford Edwards (1903-1988), Ena Flora Edwards (1908-1983) and Osmond Edwards (1910-2000).

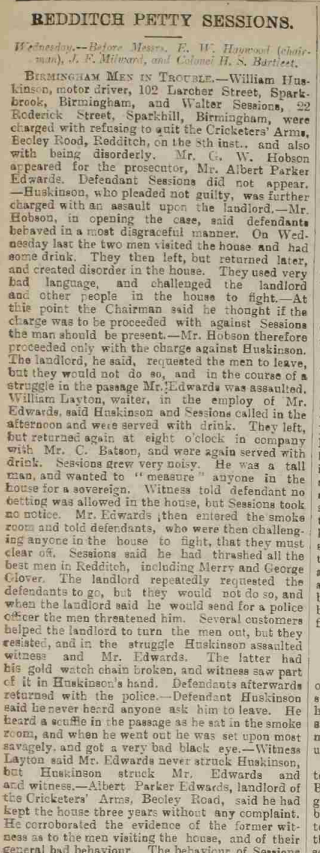

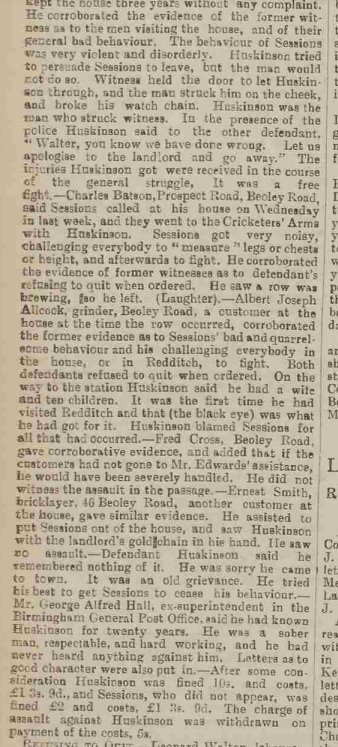

In 1906 Albert was assaulted during an incident in the Cricketers Arms.

Bromsgrove & Droitwich Messenger – Saturday 18 August 1906:

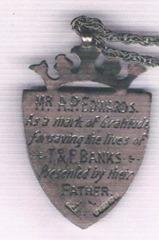

In 1910 a gold medal was given to Albert Parker Edwards by Mr. Banks, a policeman, in Redditch for saving the life of his two children from drowning in a brook on the Proctor farm which adjoined The Cricketers Arms. The story my father heard was that policeman Banks could not persuade the town of Redditch to come up with an award for Albert Parker Edwards so policeman Banks did it himself. William Banks, police constable, was living on Beoley Road on the 1911 census. His son Thomas was aged 5 and his daughter Frances was 8. It seems that when the father retired from the police he moved to Worcester. Thomas went into the hotel business and in 1939 was the manager of the Abbey hotel in Kenilworth. Frances married Edward Pardoe and was living along Redditch Road, Alvechurch in 1939.

My grandmother Peggy had the gold medal put on a gold chain for me in the 1970s. When I left England in the 1980s, I gave it back to her for safekeeping. When she died, the medal on the chain ended up in my fathers possession, who claims to have no knowledge that it was once given to me!

The medal:

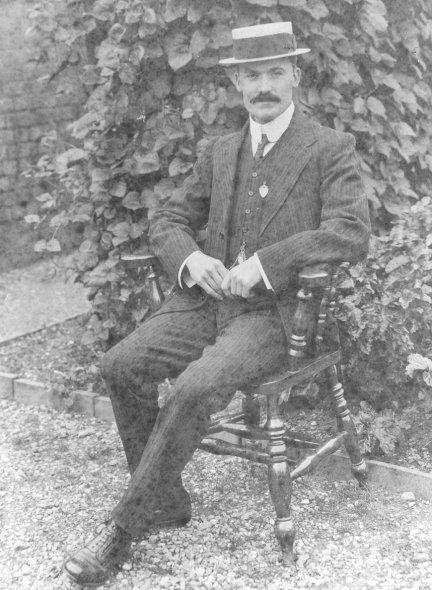

Albert Parker Edwards wearing the medal:

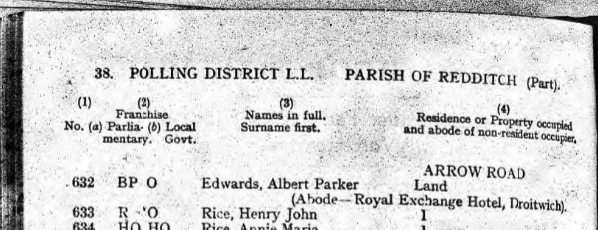

In 1921 Albert was at the The Royal Exchange hotel in Droitwich:

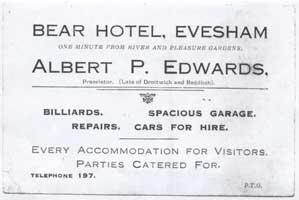

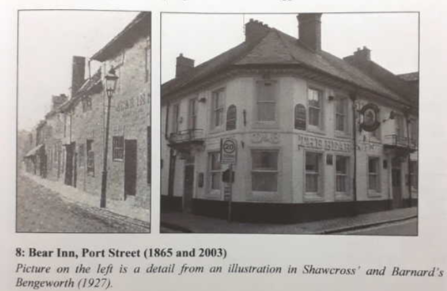

Between 1922 and 1927 Albert kept the Bear Hotel in Evesham:

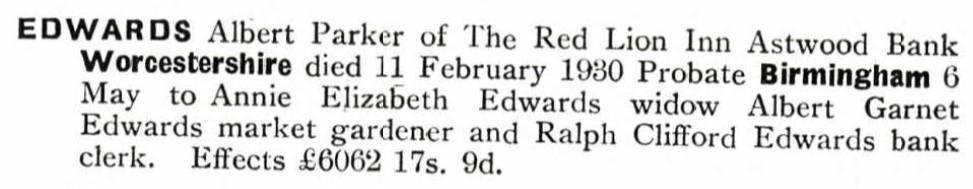

Then Albert and Annie moved to the Red Lion at Astwood Bank:

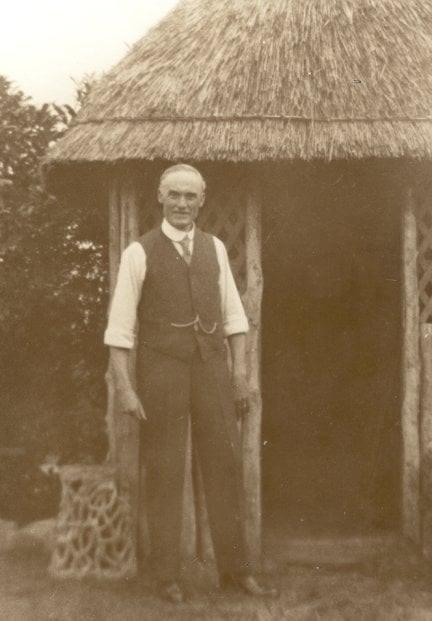

Albert in the garden behind the Red Lion:

They stayed at the Red Lion until Albert Parker Edwards died on the 11th of February, 1930 aged 53.

October 11, 2022 at 2:58 pm #6334

October 11, 2022 at 2:58 pm #6334In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The House on Penn Common

Toi Fang and the Duke of Sutherland

Tomlinsons

Grassholme

Charles Tomlinson (1873-1929) my great grandfather, was born in Wolverhampton in 1873. His father Charles Tomlinson (1847-1907) was a licensed victualler or publican, or alternatively a vet/castrator. He married Emma Grattidge (1853-1911) in 1872. On the 1881 census they were living at The Wheel in Wolverhampton.

Charles married Nellie Fisher (1877-1956) in Wolverhampton in 1896. In 1901 they were living next to the post office in Upper Penn, with children (Charles) Sidney Tomlinson (1896-1955), and Hilda Tomlinson (1898-1977) . Charles was a vet/castrator working on his own account.

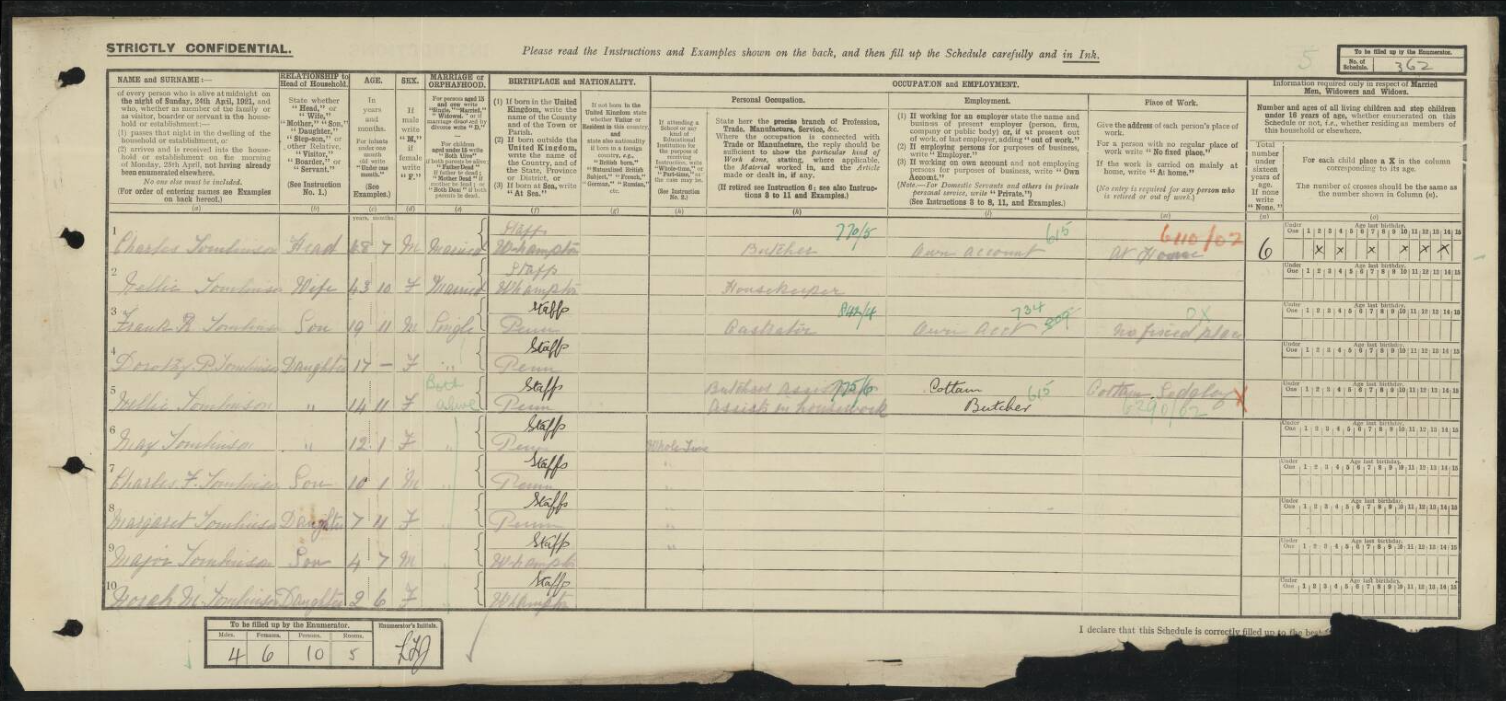

In 1911 their address was 4, Wakely Hill, Penn, and living with them were their children Hilda, Frank Tomlinson (1901-1975), (Dorothy) Phyllis Tomlinson (1905-1982), Nellie Tomlinson (1906-1978) and May Tomlinson (1910-1983). Charles was a castrator working on his own account.

Charles and Nellie had a further four children: Charles Fisher Tomlinson (1911-1977), Margaret Tomlinson (1913-1989) (my grandmother Peggy), Major Tomlinson (1916-1984) and Norah Mary Tomlinson (1919-2010).

My father told me that my grandmother had fallen down the well at the house on Penn Common in 1915 when she was two years old, and sent me a photo of her standing next to the well when she revisted the house at a much later date.

Peggy next to the well on Penn Common:

My grandmother Peggy told me that her father had had a racehorse called Toi Fang. She remembered the racing colours were sky blue and orange, and had a set of racing silks made which she sent to my father.

Through a DNA match, I met Ian Tomlinson. Ian is the son of my fathers favourite cousin Roger, Frank’s son. Ian found some racing silks and sent a photo to my father (they are now in contact with each other as a result of my DNA match with Ian), wondering what they were.

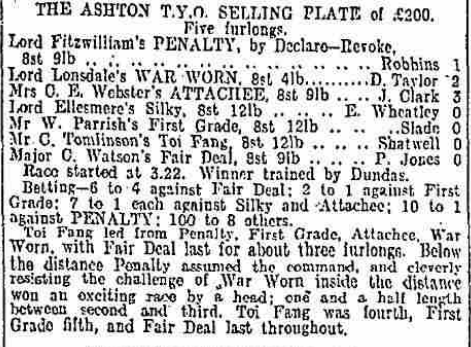

When Ian sent a photo of these racing silks, I had a look in the newspaper archives. In 1920 there are a number of mentions in the racing news of Mr C Tomlinson’s horse TOI FANG. I have not found any mention of Toi Fang in the newspapers in the following years.

The Scotsman – Monday 12 July 1920:

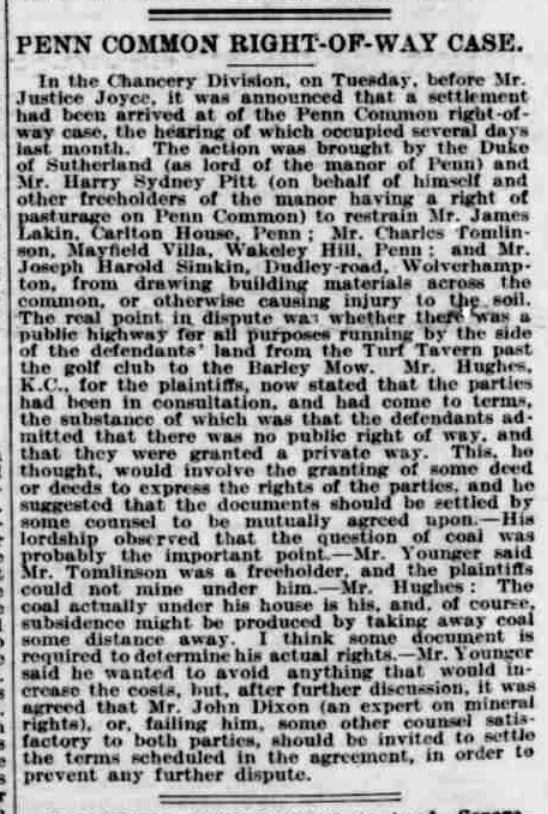

The other story that Ian Tomlinson recalled was about the house on Penn Common. Ian said he’d heard that the local titled person took Charles Tomlinson to court over building the house but that Tomlinson won the case because it was built on common land and was the first case of it’s kind.

Penn Common Right of Way Case:

Staffordshire Advertiser March 9, 1912In the chancery division, on Tuesday, before Mr Justice Joyce, it was announced that a settlement had been arrived at of the Penn Common Right of Way case, the hearing of which occupied several days last month. The action was brought by the Duke of Sutherland (as Lord of the Manor of Penn) and Mr Harry Sydney Pitt (on behalf of himself and other freeholders of the manor having a right to pasturage on Penn Common) to restrain Mr James Lakin, Carlton House, Penn; Mr Charles Tomlinson, Mayfield Villa, Wakely Hill, Penn; and Mr Joseph Harold Simpkin, Dudley Road, Wolverhampton, from drawing building materials across the common, or otherwise causing injury to the soil.

The real point in dispute was whether there was a public highway for all purposes running by the side of the defendants land from the Turf Tavern past the golf club to the Barley Mow.

Mr Hughes, KC for the plaintiffs, now stated that the parties had been in consultation, and had come to terms, the substance of which was that the defendants admitted that there was no public right of way, and that they were granted a private way. This, he thought, would involve the granting of some deed or deeds to express the rights of the parties, and he suggested that the documents should be be settled by some counsel to be mutually agreed upon.His lordship observed that the question of coal was probably the important point. Mr Younger said Mr Tomlinson was a freeholder, and the plaintiffs could not mine under him. Mr Hughes: The coal actually under his house is his, and, of course, subsidence might be produced by taking away coal some distance away. I think some document is required to determine his actual rights.

Mr Younger said he wanted to avoid anything that would increase the costs, but, after further discussion, it was agreed that Mr John Dixon (an expert on mineral rights), or failing him, another counsel satisfactory to both parties, should be invited to settle the terms scheduled in the agreement, in order to prevent any further dispute.

The name of the house is Grassholme. The address of Mayfield Villas is the house they were living in while building Grassholme, which I assume they had not yet moved in to at the time of the newspaper article in March 1912.

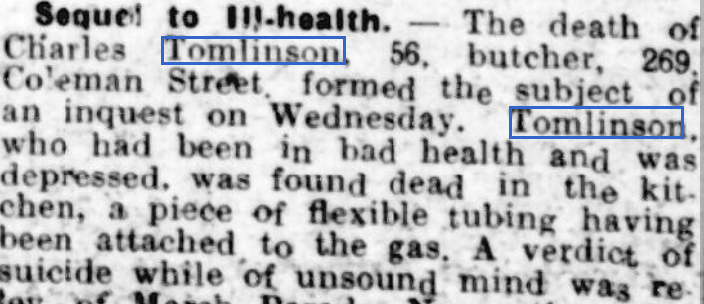

What my grandmother didn’t tell anyone was how her father died in 1929:

On the 1921 census, Charles, Nellie and eight of their children were living at 269 Coleman Street, Wolverhampton.

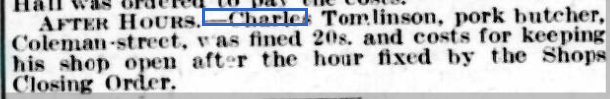

They were living on Coleman Street in 1915 when Charles was fined for staying open late.

Staffordshire Advertiser – Saturday 13 February 1915:

What is not yet clear is why they moved from the house on Penn Common sometime between 1912 and 1915. And why did he have a racehorse in 1920?

October 11, 2022 at 11:39 am #6333In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

The Grattidge Family

The first Grattidge to appear in our tree was Emma Grattidge (1853-1911) who married Charles Tomlinson (1847-1907) in 1872.

Charles Tomlinson (1873-1929) was their son and he married my great grandmother Nellie Fisher. Their daughter Margaret (later Peggy Edwards) was my grandmother on my fathers side.

Emma Grattidge was born in Wolverhampton, the daughter and youngest child of William Grattidge (1820-1887) born in Foston, Derbyshire, and Mary Stubbs, born in Burton on Trent, daughter of Solomon Stubbs, a land carrier. William and Mary married at St Modwens church, Burton on Trent, in 1839. It’s unclear why they moved to Wolverhampton. On the 1841 census William was employed as an agent, and their first son William was nine months old. Thereafter, William was a licensed victuallar or innkeeper.

William Grattidge was born in Foston, Derbyshire in 1820. His parents were Thomas Grattidge, farmer (1779-1843) and Ann Gerrard (1789-1822) from Ellastone. Thomas and Ann married in 1813 in Ellastone. They had five children before Ann died at the age of 25:

Bessy was born in 1815, Thomas in 1818, William in 1820, and Daniel Augustus and Frederick were twins born in 1822. They were all born in Foston. (records say Foston, Foston and Scropton, or Scropton)

On the 1841 census Thomas had nine people additional to family living at the farm in Foston, presumably agricultural labourers and help.

After Ann died, Thomas had three children with Kezia Gibbs (30 years his junior) before marrying her in 1836, then had a further four with her before dying in 1843. Then Kezia married Thomas’s nephew Frederick Augustus Grattidge (born in 1816 in Stafford) in London in 1847 and had two more!

The siblings of William Grattidge (my 3x great grandfather):

Frederick Grattidge (1822-1872) was a schoolmaster and never married. He died at the age of 49 in Tamworth at his twin brother Daniels address.

Daniel Augustus Grattidge (1822-1903) was a grocer at Gungate in Tamworth.

Thomas Grattidge (1818-1871) married in Derby, and then emigrated to Illinois, USA.

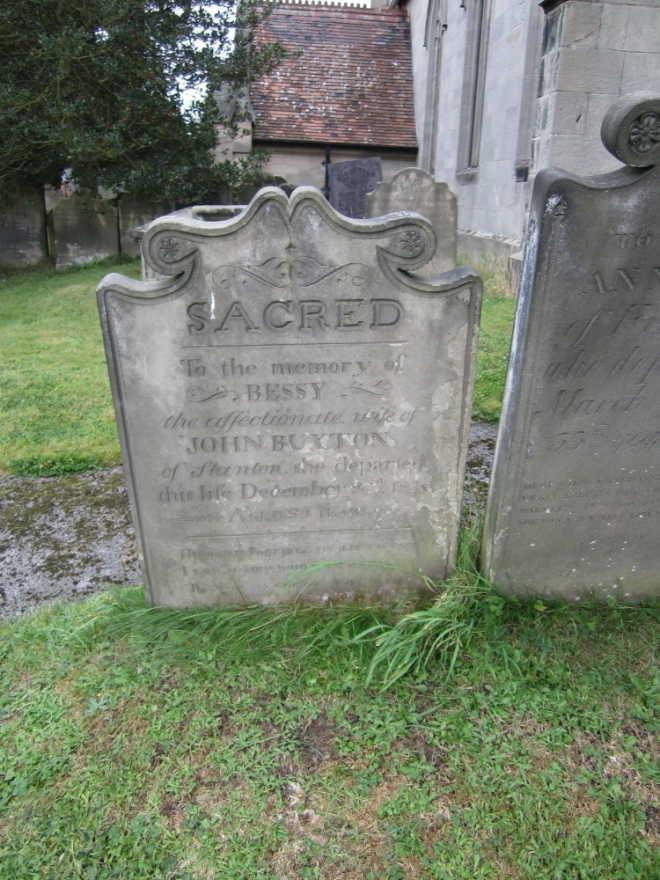

Bessy Grattidge (1815-1840) married John Buxton, farmer, in Ellastone in January 1838. They had three children before Bessy died in December 1840 at the age of 25: Henry in 1838, John in 1839, and Bessy Buxton in 1840. Bessy was baptised in January 1841. Presumably the birth of Bessy caused the death of Bessy the mother.

Bessy Buxton’s gravestone:

“Sacred to the memory of Bessy Buxton, the affectionate wife of John Buxton of Stanton She departed this life December 20th 1840, aged 25 years. “Husband, Farewell my life is Past, I loved you while life did last. Think on my children for my sake, And ever of them with I take.”

20 Dec 1840, Ellastone, Staffordshire

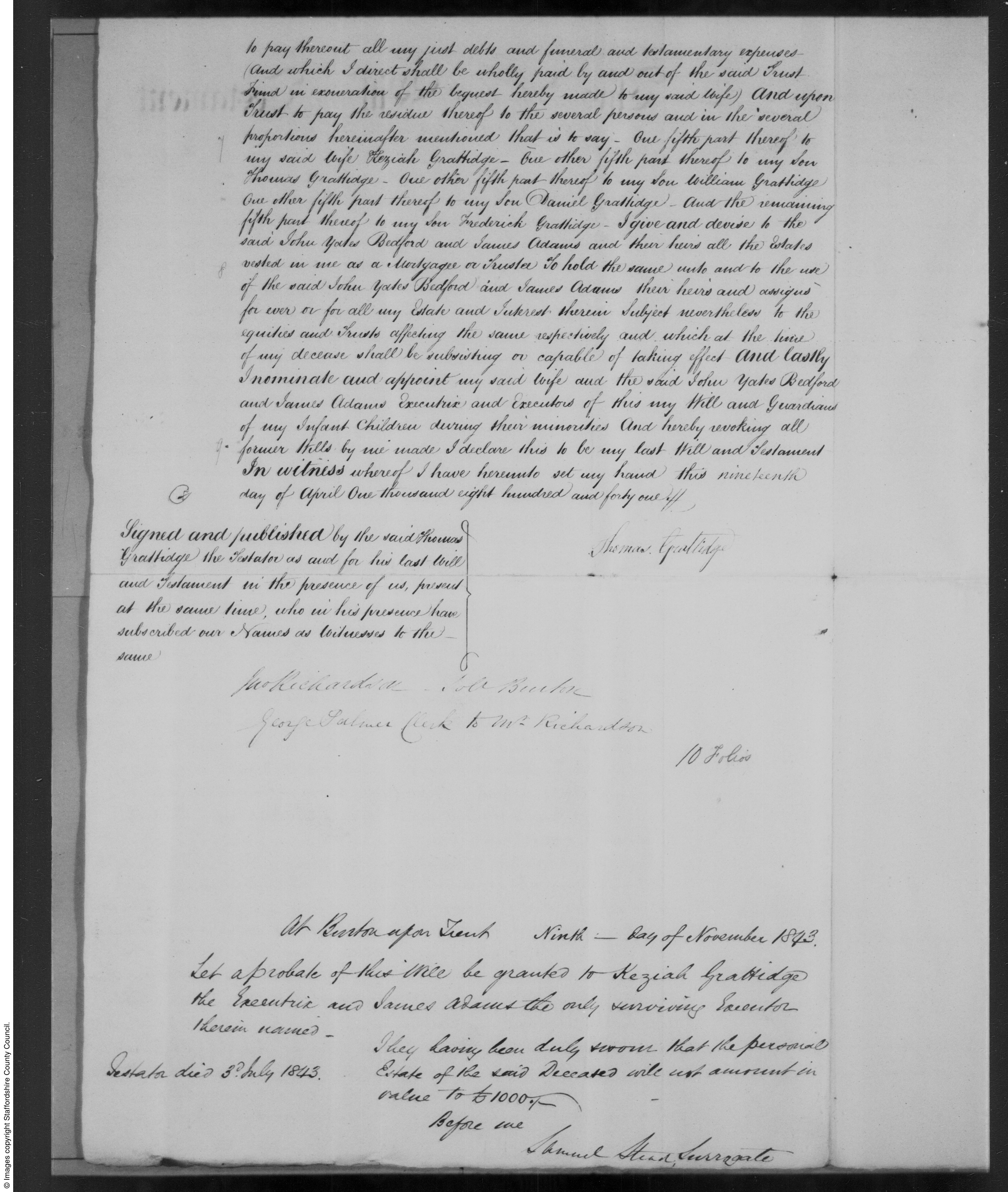

In the 1843 will of Thomas Grattidge, farmer of Foston, he leaves fifth shares of his estate, including freehold real estate at Findern, to his wife Kezia, and sons William, Daniel, Frederick and Thomas. He mentions that the children of his late daughter Bessy, wife of John Buxton, will be taken care of by their father. He leaves the farm to Keziah in confidence that she will maintain, support and educate his children with her.

An excerpt from the will:

I give and bequeath unto my dear wife Keziah Grattidge all my household goods and furniture, wearing apparel and plate and plated articles, linen, books, china, glass, and other household effects whatsoever, and also all my implements of husbandry, horses, cattle, hay, corn, crops and live and dead stock whatsoever, and also all the ready money that may be about my person or in my dwelling house at the time of my decease, …I also give my said wife the tenant right and possession of the farm in my occupation….

A page from the 1843 will of Thomas Grattidge:

William Grattidges half siblings (the offspring of Thomas Grattidge and Kezia Gibbs):

Albert Grattidge (1842-1914) was a railway engine driver in Derby. In 1884 he was driving the train when an unfortunate accident occured outside Ambergate. Three children were blackberrying and crossed the rails in front of the train, and one little girl died.

Albert Grattidge:

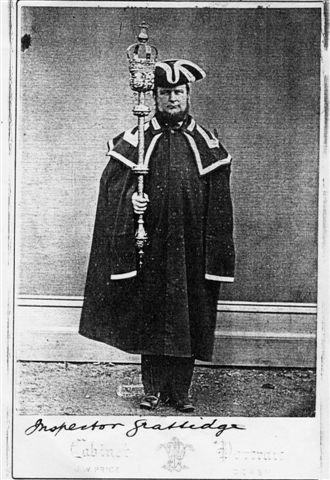

George Grattidge (1826-1876) was baptised Gibbs as this was before Thomas married Kezia. He was a police inspector in Derby.

George Grattidge:

Edwin Grattidge (1837-1852) died at just 15 years old.

Ann Grattidge (1835-) married Charles Fletcher, stone mason, and lived in Derby.

Louisa Victoria Grattidge (1840-1869) was sadly another Grattidge woman who died young. Louisa married Emmanuel Brunt Cheesborough in 1860 in Derby. In 1861 Louisa and Emmanuel were living with her mother Kezia in Derby, with their two children Frederick and Ann Louisa. Emmanuel’s occupation was sawyer. (Kezia Gibbs second husband Frederick Augustus Grattidge was a timber merchant in Derby)

At the time of her death in 1869, Emmanuel was the landlord of the White Hart public house at Bridgegate in Derby.

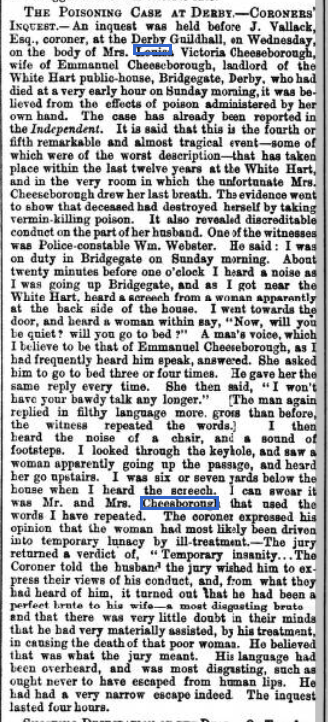

The Derby Mercury of 17th November 1869:

“On Wednesday morning Mr Coroner Vallack held an inquest in the Grand

Jury-room, Town-hall, on the body of Louisa Victoria Cheeseborough, aged

33, the wife of the landlord of the White Hart, Bridge-gate, who committed

suicide by poisoning at an early hour on Sunday morning. The following

evidence was taken:Mr Frederick Borough, surgeon, practising in Derby, deposed that he was

called in to see the deceased about four o’clock on Sunday morning last. He

accordingly examined the deceased and found the body quite warm, but dead.

He afterwards made enquiries of the husband, who said that he was afraid

that his wife had taken poison, also giving him at the same time the

remains of some blue material in a cup. The aunt of the deceased’s husband

told him that she had seen Mrs Cheeseborough put down a cup in the

club-room, as though she had just taken it from her mouth. The witness took

the liquid home with him, and informed them that an inquest would

necessarily have to be held on Monday. He had made a post mortem

examination of the body, and found that in the stomach there was a great

deal of congestion. There were remains of food in the stomach and, having

put the contents into a bottle, he took the stomach away. He also examined

the heart and found it very pale and flabby. All the other organs were

comparatively healthy; the liver was friable.Hannah Stone, aunt of the deceased’s husband, said she acted as a servant

in the house. On Saturday evening, while they were going to bed and whilst

witness was undressing, the deceased came into the room, went up to the

bedside, awoke her daughter, and whispered to her. but what she said the

witness did not know. The child jumped out of bed, but the deceased closed

the door and went away. The child followed her mother, and she also

followed them to the deceased’s bed-room, but the door being closed, they

then went to the club-room door and opening it they saw the deceased

standing with a candle in one hand. The daughter stayed with her in the

room whilst the witness went downstairs to fetch a candle for herself, and

as she was returning up again she saw the deceased put a teacup on the

table. The little girl began to scream, saying “Oh aunt, my mother is

going, but don’t let her go”. The deceased then walked into her bed-room,

and they went and stood at the door whilst the deceased undressed herself.

The daughter and the witness then returned to their bed-room. Presently

they went to see if the deceased was in bed, but she was sitting on the

floor her arms on the bedside. Her husband was sitting in a chair fast

asleep. The witness pulled her on the bed as well as she could.

Ann Louisa Cheesborough, a little girl, said that the deceased was her

mother. On Saturday evening last, about twenty minutes before eleven

o’clock, she went to bed, leaving her mother and aunt downstairs. Her aunt

came to bed as usual. By and bye, her mother came into her room – before

the aunt had retired to rest – and awoke her. She told the witness, in a

low voice, ‘that she should have all that she had got, adding that she

should also leave her her watch, as she was going to die’. She did not tell

her aunt what her mother had said, but followed her directly into the

club-room, where she saw her drink something from a cup, which she

afterwards placed on the table. Her mother then went into her own room and

shut the door. She screamed and called her father, who was downstairs. He

came up and went into her room. The witness then went to bed and fell

asleep. She did not hear any noise or quarrelling in the house after going

to bed.Police-constable Webster was on duty in Bridge-gate on Saturday evening

last, about twenty minutes to one o’clock. He knew the White Hart

public-house in Bridge-gate, and as he was approaching that place, he heard

a woman scream as though at the back side of the house. The witness went to

the door and heard the deceased keep saying ‘Will you be quiet and go to

bed’. The reply was most disgusting, and the language which the

police-constable said was uttered by the husband of the deceased, was

immoral in the extreme. He heard the poor woman keep pressing her husband

to go to bed quietly, and eventually he saw him through the keyhole of the

door pass and go upstairs. his wife having gone up a minute or so before.

Inspector Fearn deposed that on Sunday morning last, after he had heard of

the deceased’s death from supposed poisoning, he went to Cheeseborough’s

public house, and found in the club-room two nearly empty packets of

Battie’s Lincoln Vermin Killer – each labelled poison.Several of the Jury here intimated that they had seen some marks on the

deceased’s neck, as of blows, and expressing a desire that the surgeon

should return, and re-examine the body. This was accordingly done, after

which the following evidence was taken:Mr Borough said that he had examined the body of the deceased and observed

a mark on the left side of the neck, which he considered had come on since

death. He thought it was the commencement of decomposition.

This was the evidence, after which the jury returned a verdict “that the

deceased took poison whilst of unsound mind” and requested the Coroner to

censure the deceased’s husband.The Coroner told Cheeseborough that he was a disgusting brute and that the

jury only regretted that the law could not reach his brutal conduct.

However he had had a narrow escape. It was their belief that his poor

wife, who was driven to her own destruction by his brutal treatment, would

have been a living woman that day except for his cowardly conduct towards

her.The inquiry, which had lasted a considerable time, then closed.”

In this article it says:

“it was the “fourth or fifth remarkable and tragical event – some of which were of the worst description – that has taken place within the last twelve years at the White Hart and in the very room in which the unfortunate Louisa Cheesborough drew her last breath.”

Sheffield Independent – Friday 12 November 1869:

September 4, 2022 at 6:00 pm #6326

September 4, 2022 at 6:00 pm #6326In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

Stung by Egberts question, Olga reeled and almost lost her footing on the stairs. What had happened to her? That damned selfish individualism that was running rampant must have seeped into her room through the gaps in the windows or under the door. “No!” she shouted, her voice cracking.

“Say it isn’t true, Olga,” Egbert said, his voice breaking. “Not you as well.”

It took Olga a minute or two to still her racing heart. The near fall down the stairs had shaken her but with trembling hands she levered herself round to sit beside Egbert on the step.

Gripping his bony knee with her knobbly arthritic fingers, she took a deep breath.

“You are right to have said that, Egbert. If there is one thing we must hold onto, it’s our hearts. Nothing else matters, or at least nothing else matters as much as that. We are old and tired and we don’t like change. But if we escalate the importance of this frankly dreary and depressing home to the point where we lose our hearts…” she faltered and continued. “We will be homeless soon, very soon, and we know not what will happen to us. We must trust in the kindness of strangers, we must hope they have a heart.”

Egbert winced as Olga squeezed his knee. “And that is why”, Olga continued, slapping Egberts thigh with gusto, “We must have a heart…”

“If you’d just stop squeezing and hitting me, Olga…”

Olga loosened her grip on the old mans thigh bone and peered into his eyes. Quietly she thanked him. “You’ve cleared my mind and given me something to live for, and I thank you for that. But you do need to launder your clothes more often,” she added, pulling a face. She didn’t want the old coot to start blubbing, and he looked alarmingly close to tears.

“Come on, let’s go and see Obadiah. We’re all in this together. Homelessness and adventure can wait until tomorrow.” Olga heaved herself upright with a surprising burst of vitality. Noticing a weak smile trembling on Egberts lips, she said “That’s the spirit!”

July 13, 2022 at 3:09 am #6323In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

“Watch where you are going, Child!” Egbert’s tone was sharp.

“Excuse me,” said Maryechka, hunching her shoulders and making herself small as a mouse so she could squeeze past Egbert’s oversized suitcase.

“To be fair, Old Man,” said Olga, glad of the excuse to pause, “you are taking up all the available space on the stairs with those bags.” She peered at Maryechka. “You are Obadiah’s girl aren’t you?”

Maryechka nodded shyly. “He’s my grandpa.” She frowned at the suitcases. “Are you going on holiday?”

“Never you mind that,” said Egbert. “You run along and see your Grandpa.”

Maryechka ducked past the bag and ran up the steps.

“Oy,” said Olga. “What I wouldn’t give for the agility of youth again.” Gripping the wooden hand rail, she stretched out her ankle and grimaced.

“Obadiah is stubborn as a mule,” said Egbert. “I tried warning him! He said he’d die in his room if it came to it.”

“Pfft,” said Olga. “That one will land on his big stinking feet. And he can hear better than he lets on. Is it him spreading the tales about me?”

Egbert dropped his bags and sat heavily on the step. He put his head in his hands and groaned. “Is it right though, Olga? Is it right that we leave our friends to their fate?”

It occurred to Olga that Egbert may be hiding his head so as not to answer her question. However, realising his mental state was fragile, she thought it prudent to keep to the matter at hand. It will keep, she thought.

“Obadiah and myself, we grew up together,” continued Egbert with what sounded like a sob. “We worked together on the farm as young men.” He raised his head and glared at Olga. “How can you expect me to leave him without a word of farewell? Have you no heart?”

July 12, 2022 at 9:46 am #6320In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

When Maryechka arrived at the front gate of the Vyriy hotel with its gaudy plaster storks at the entrance, she sneaked into the side gate leading to the kitchens.

She had to be careful not to to be noticed by Larysa who often had her cigarette break hidden under the pine tree. Larysa didn’t like children, or at least, she disliked them slightly less than the elderly residents, whoever was the loudest and the uncleanliest was sure to suffer her disapproval.

Larysa was basically single-handedly managing the hotel, doing most of the chores to keep it afloat. The only thing she didn’t do was the catering, and packaged trays arrived every day for the residents. Maryechka’s grand-pa was no picky eater, and made a point of clearing his tray of food, but she suspected most of the other residents didn’t.

The only other employee she was told, was the gardener who would have been old enough to be a resident himself, and had died of a stroke before the summer. The small garden was clearly in need of tending after.Maryechka could see the coast was clear, and was making her ways to the stairs when she heard clanking in the stairs and voices arguing.

“Keep your voice down, you’re going to wake the dragon.”

“That’s your fault, you don’t pack light for your adventures. You really needed to take all these suitcases? How can we make a run for it with all that dead weight!”

July 12, 2022 at 8:30 am #6319In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

“Calm yourself, Egbert, and sit down. And be quiet! I can barely hear myself think with your frantic gibbering and flailing around,” Olga said, closing her eyes. “I need to think.”

Egbert clutched the eiderdown on either side of his bony trembling knees and clamped his remaining teeth together, drawing ragged whistling breaths in an attempt to calm himself. Olga was right, he needed to calm down. Besides the unfortunate effects of the letter on his habitual tremor, he felt sure his blood pressure had risen alarmingly. He dared not become so ill that he needed medical assistance, not with the state of the hospitals these days. He’d be lucky to survive the plague ridden wards.

What had become of him! He imagined his younger self looking on with horror, appalled at his feeble body and shattered mind. Imagine becoming so desperate that he wanted to fight to stay in this godforsaken dump, what had become of him! If only he knew of somewhere else to go, somewhere safe and pleasant, somewhere that smelled sweetly of meadows and honesuckle and freshly baked cherry pies, with the snorting of pigs in the yard…

But wait, that was Olga snoring. Useless old bag had fallen asleep! For the first time since Viktor had died he felt close to tears. What a sad sorry pathetic old man he’d become, desperately counting on a old woman to save him.

“Stop sniveling, Egbert, and go and pack a bag.” Olga had woken up from her momentary but illuminating lapse. “Don’t bring too much, we may have much walking to do. I hear the buses and trains are in a shambles and full of refugees. We don’t want to get herded up with them.”

Astonished, Egbert asked where they were going.

“To see Rosa. My cousins father in laws neice. Don’t look at me like that, immediate family are seldom the ones who help. The distant ones are another matter. And be honest Egbert,” Olga said with a piercing look, “Do we really want to stay here? You may think you do, but it’s the fear of change, that’s all. Change feels like too much bother, doesn’t it?”

Egbert nodded sadly, his eyes fixed on the stain on the grey carpet.

Olga leaned forward and took his hand gently. “Egbert, look at me.” He raised his head and looked into her eyes. He’d never seen a sparkle in her faded blue eyes before. “I still have another adventure in me. How about you?”

July 10, 2022 at 2:36 am #6317In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

The sharp rat-a-tat on the door startled Olga Herringbonevsky. The initial surprise quickly turned to annoyance. It was 11am and she wasn’t expecting a knock on the door at 11am. At 10am she expected a knock. It would be Larysa with the lukewarm cup of tea and a stale biscuit. Sometimes Olga complained about it and Larysa would say, Well you’re on the third floor so what do you expect? And she’d look cross and pour the tea so some of it slopped into the saucer. So the biscuits go stale on the way up do they? Olga would mutter. At 10:30am Larysa would return to collect the cup and saucer. I can’t do this much longer, she’d say. I’m not young any more and all these damn stairs. She’d been saying that for as long as Olga could remember.

For a moment, Olga contemplated ignoring the intrusion but the knocking started up again, this time accompanied by someone shouting her name.

With a very loud sigh, she put her book on the side table, face down so she would not lose her place for it was a most enjoyable whodunit, and hauled herself up from the chair. Her ankle was not good since she’d gone over on it the other day and Olga was in a very poor mood by the time she reached the door.

“Yes?” She glowered at Egbert.

“Have you seen this?” Egbert was waving a piece of paper at her.

“No,” Olga started to close the door.

“Olga stop!” Egbert’s face had reddened and Olga wondered if he might cry. Again, he waved the piece of paper in her face and then let his hand fall defeated to his side. “Olga, it’s bad news. You should have got a letter .”

Olga glanced at the pile of unopened letters on her dresser. It was never good news. She couldn’t be bothered with letters any more.

“Well, Egbert, I suppose you’d better come in”.

“That Ursula has a heart of steel,” said Olga when she’d heard the news.

“Pfft,” said Egbert. “She has no heart. This place has always been about money for her.”

“It’s bad times, Egbert. Bad times.”

Egbert nodded. “It is, Olga. But there must be something we can do.” He pursed his lips and Olga noticed that he would not meet her eyes.

“What? Spit it out, Old Man.”

He looked at her briefly before his eyes slid back to the dirty grey carpet. “I have heard stories, Olga. That you are … well connected. That you know people.”

Olga noticed that it had become difficult to breathe. Seeing Egbert looking at her with concern, she made an effort to steady herself. She took an extra big gasp of air and pointed to the book face-down on the side table. “That is a very good book I am reading. You may borrow it when I have finished.”

Egbert nodded. “Thank you.” he said and they both stared at the book.

“It was a long time ago, Egbert. And no business of anyone else.” Olga knew her voice was sharp but not sharp enough it seemed as Egbert was not done yet with all his prying words.

“Olga, you said it yourself. These are bad times. And desperate measures are needed or we will all perish.” Now he looked her in the eyes. “Old woman, swallow your pride. You must save yourself and all of us here.”

July 6, 2022 at 11:05 am #6312In reply to: The Sexy Wooden Leg

When she’d heard of the miracle happening at the Flovlinden Tree, Egna initially shrugged it off as another conman’s attempt at fooling the crowds.

“No, it’s real, my Auntie saw it.”

“Stop fretting” she’d told the little girl, as she was carefully removing the lice from her hair. “This is just someone’s idea of a smart joke. Don’t get fooled, you’re smarter than this.”

She sure wasn’t responsible for that one. If that were a true miracle, she would have known. The little calf next week being resuscitated after being dead a few minutes, well, that was her. Shame nobody was even there to notice. Most of the best miracles go about this way anyway.

So, after having lived close to a millennia in relatively rock solid health and with surprisingly unaging looks, Egna had thought she’d seen it all; at least last time the tree started to ooze sacred oil, it didn’t last for too long, people’s greed starting to sell it stopped it right in its tracks.

But maybe there was more to it this time. Egna’d often wondered why God had let her live that long. She was a useful instrument to Her for sure, but living in secrecy, claiming no ownership, most miracles were just facts of life. She somehow failed to see the point, even after 957 years of existence.

The little girl had left to go back to her nearby town. This side of the country was still quite safe from all the craziness. Egna knew well most of the branches of the ancestral trees leading to that particular little leaf. This one had probably no idea she shared a common ancestor with President Voldomeer, but Egna remembered the fellow. He was a clogmaker in the turn of the 18th century, as was his father before. That was until a rather unexpected turn of events precipitated him to a different path as his brother.

She had a book full of these records, as she’d tracked the lives of many, to keep them alive, and maybe remind people they all share so much in common. That is, if people were able to remember more than 2 generations before them.

“Well, that’s set.” she said to herself and to Her as She’s always listening “I’ll go and see for myself.”

her trusty old musty cloak at the door seemed to have been begging for the journey.June 6, 2022 at 9:17 am #6301In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

The Warrens of Stapenhill

There were so many Warren’s in Stapenhill that it was complicated to work out who was who. I had gone back as far as Samuel Warren marrying Catherine Holland, and this was as far back as my cousin Ian Warren had gone in his research some decades ago as well. The Holland family from Barton under Needwood are particularly interesting, and will be a separate chapter.

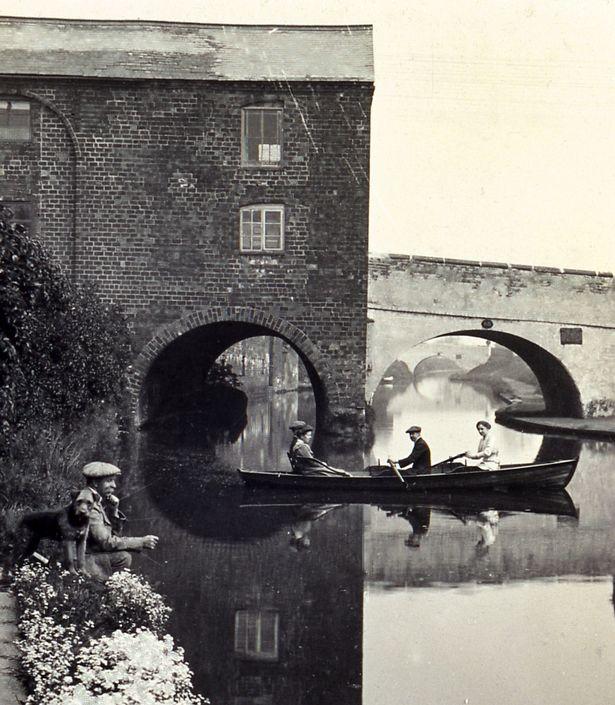

Stapenhill village by John Harden:

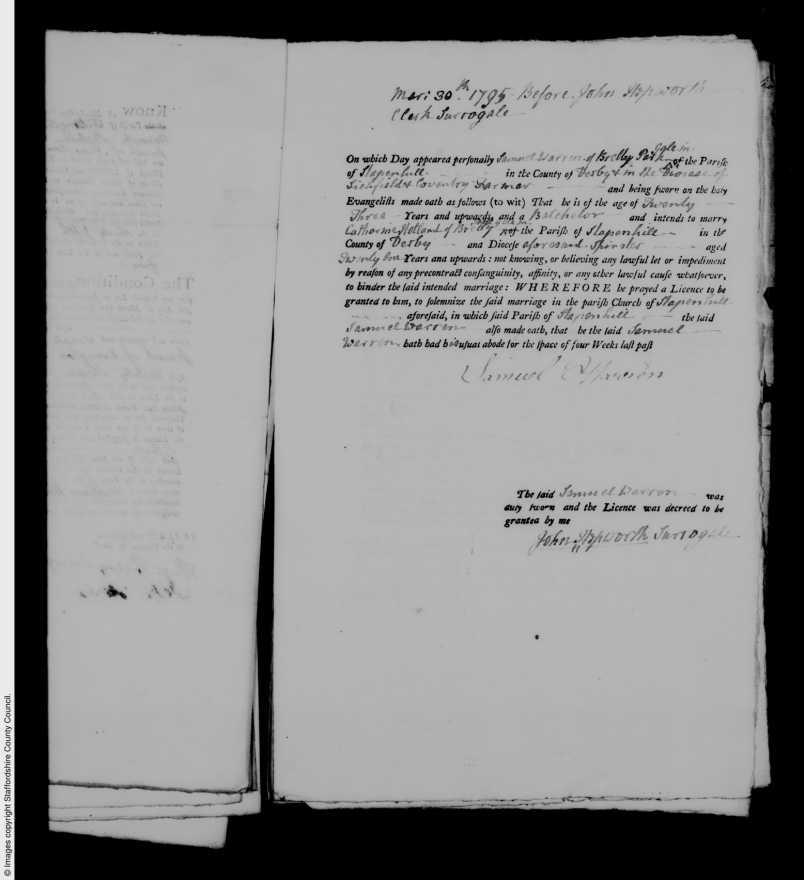

Resuming the research on the Warrens, Samuel Warren 1771-1837 married Catherine Holland 1775-1861 in 1795 and their son Samuel Warren 1800-1882 married Elizabeth Bridge, whose childless brother Benjamin Bridge left the Warren Brothers Boiler Works in Newhall to his nephews, the Warren brothers.

Samuel Warren and Catherine Holland marriage licence 1795:

Samuel (born 1771) was baptised at Stapenhill St Peter and his parents were William and Anne Warren. There were at least three William and Ann Warrens in town at the time. One of those William’s was born in 1744, which would seem to be the right age to be Samuel’s father, and one was born in 1710, which seemed a little too old. Another William, Guiliamos Warren (Latin was often used in early parish registers) was baptised in Stapenhill in 1729.

Stapenhill St Peter:

William Warren (born 1744) appeared to have been born several months before his parents wedding. William Warren and Ann Insley married 16 July 1744, but the baptism of William in 1744 was 24 February. This seemed unusual ~ children were often born less than nine months after a wedding, but not usually before the wedding! Then I remembered the change from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar in 1752. Prior to 1752, the first day of the year was Lady Day, March 25th, not January 1st. This meant that the birth in February 1744 was actually after the wedding in July 1744. Now it made sense. The first son was named William, and he was born seven months after the wedding.

William born in 1744 died intestate in 1822, and his wife Ann made a legal claim to his estate. However he didn’t marry Ann Holland (Ann was Catherines Hollands sister, who married Samuel Warren the year before) until 1796, so this William and Ann were not the parents of Samuel.

It seemed likely that William born in 1744 was Samuels brother. William Warren and Ann Insley had at least eight children between 1744 and 1771, and it seems that Samuel was their last child, born when William the elder was 61 and his wife Ann was 47.

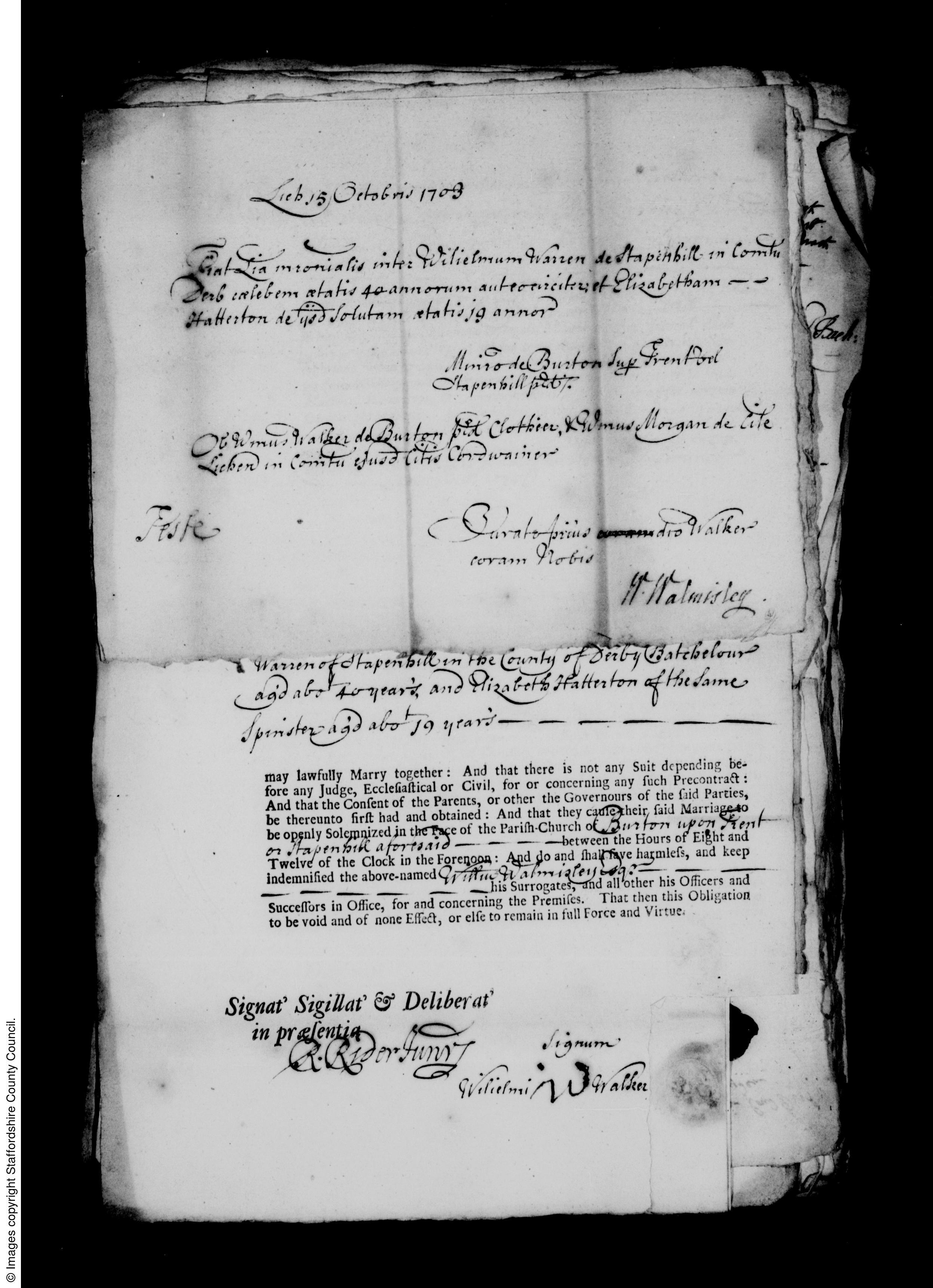

It seems it wasn’t unusual for the Warren men to marry rather late in life. William Warren’s (born 1710) parents were William Warren and Elizabeth Hatterton. On the marriage licence in 1702/1703 (it appears to say 1703 but is transcribed as 1702), William was a 40 year old bachelor from Stapenhill, which puts his date of birth at 1662. Elizabeth was considerably younger, aged 19.

William Warren and Elizabeth Hatterton marriage licence 1703:

These Warren’s were farmers, and they were literate and able to sign their own names on various documents. This is worth noting, as most made the mark of an X.

I found three Warren and Holland marriages. One was Samuel Warren and Catherine Holland in 1795, then William Warren and Ann Holland in 1796. William Warren and Ann Hollands daughter born in 1799 married John Holland in 1824.

Elizabeth Hatterton (wife of William Warren who was born circa 1662) was born in Burton upon Trent in 1685. Her parents were Edward Hatterton 1655-1722, and Sara.

A page from the 1722 will of Edward Hatterton:

The earliest Warren I found records for was William Warren who married Elizabeth Hatterton in 1703. The marriage licence states his age as 40 and that he was from Stapenhill, but none of the Stapenhill parish records online go back as far as 1662. On other public trees on ancestry websites, a birth record from Suffolk has been chosen, probably because it was the only record to be found online with the right name and date. Once again, I don’t think that is correct, and perhaps one day I’ll find some earlier Stapenhill records to prove that he was born in locally.

Subsequently, I found a list of the 1662 Hearth Tax for Stapenhill. On it were a number of Warrens, three William Warrens including one who was a constable. One of those William Warrens had a son he named William (as they did, hence the number of William Warrens in the tree) the same year as this hearth tax list.

But was it the William Warren with 2 chimneys, the one with one chimney who was too poor to pay it, or the one who was a constable?

from the list:

Will. Warryn 2

Richard Warryn 1

William Warren Constable

These names are not payable by Act:

Will. Warryn 1

Richard Warren John Watson

over seers of the poore and churchwardensThe Hearth Tax:

via wiki:

In England, hearth tax, also known as hearth money, chimney tax, or chimney money, was a tax imposed by Parliament in 1662, to support the Royal Household of King Charles II. Following the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, Parliament calculated that the Royal Household needed an annual income of £1,200,000. The hearth tax was a supplemental tax to make up the shortfall. It was considered easier to establish the number of hearths than the number of heads, hearths forming a more stationary subject for taxation than people. This form of taxation was new to England, but had precedents abroad. It generated considerable debate, but was supported by the economist Sir William Petty, and carried through the Commons by the influential West Country member Sir Courtenay Pole, 2nd Baronet (whose enemies nicknamed him “Sir Chimney Poll” as a result). The bill received Royal Assent on 19 May 1662, with the first payment due on 29 September 1662, Michaelmas.

One shilling was liable to be paid for every firehearth or stove, in all dwellings, houses, edifices or lodgings, and was payable at Michaelmas, 29 September and on Lady Day, 25 March. The tax thus amounted to two shillings per hearth or stove per year. The original bill contained a practical shortcoming in that it did not distinguish between owners and occupiers and was potentially a major burden on the poor as there were no exemptions. The bill was subsequently amended so that the tax was paid by the occupier. Further amendments introduced a range of exemptions that ensured that a substantial proportion of the poorer people did not have to pay the tax.Indeed it seems clear that William Warren the elder came from Stapenhill and not Suffolk, and one of the William Warrens paying hearth tax in 1662 was undoubtedly the father of William Warren who married Elizabeth Hatterton.

May 21, 2022 at 8:28 am #6298Topic: The Sexy Wooden Leg

in forum Yurara Fameliki’s StoriesThe Rootians invaded Oocrane when everybody was busy looking elsewhere. They entered through the Dumbass region under the pretense of freeing it from Lazies who had infiltrated administrations and media. They often cited a recent short movie from president Voldomeer Zumbaskee in which he appeared in purple leather panties adorned with diamonds, showing unashamedly his wooden leg. The same wooden leg that gave him the status of sexiest man of Oocrane and got him elected. In one of his famous discourses, he accused the Rootian president, Valdamir Potomsky of wanting to help himself to their crops of turnip and weed of which the world depended. And he told him if he expected Lazies he would be surprised by their resolution to defend their country.

By a simple game of chance that reality is so fond of, the man who made the president’s very wooden leg was also called Voldomeer Zumbasky. They might share a common ancestor, but many times in the past population records were destroyed and it was difficult to tell. That man lived in the small city of Duckailingtown in Dumbass, near the Rootian border. He was renowned to be a great carpenter and sculptor and before the war people would come from the neighbooring countries to buy his work.

During the invasion, crops and forests were burnt, buildings were destroyed and Dumbass Voldomeer lost one leg. There were no more trees or beams that hadn’t been turned to ashes, and he had only one block of wood left. Enough to make another wooden leg for himself. But he wondered: wasn’t there something more useful he could do with that block of wood ?

One morning of spring, one year after the war started. Food was scarce in Duckailingtown and Voldomeer’s belly growled as he walked past the nest of a couple of swans. He counted nine beautiful eggs that the parents were arranging with their beaks before lying on top to keep them warm. He found it so touching to see life in this place that he couldn’t bear the idea of simply stealing the eggs.

He went back home, a shelter made of bricks, his stomach aching from starvation. Looking at the block of wood on the floor, he got an idea. He spent the rest of the day and night to carve nine beautiful eggs so smooth that they appeared warm to the touch. He put so much care and love in his work that the swans would see no difference.

The next morning he went back to the nest with a leather bag, hopping heartily on his lone leg. The eggs were still there and by chance both the parents were missing. He didn’t care why. He took the eggs and replaced them with the wooden ones.

That day, he ate the best omelet with his friend Rooby, and as far as one could tell the swans were still brooding by the end of summer.

April 12, 2022 at 8:13 am #6290In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Leicestershire Blacksmiths

The Orgill’s of Measham led me further into Leicestershire as I traveled back in time.

I also realized I had uncovered a direct line of women and their mothers going back ten generations:

myself, Tracy Edwards 1957-

my mother Gillian Marshall 1933-

my grandmother Florence Warren 1906-1988

her mother and my great grandmother Florence Gretton 1881-1927

her mother Sarah Orgill 1840-1910

her mother Elizabeth Orgill 1803-1876

her mother Sarah Boss 1783-1847

her mother Elizabeth Page 1749-

her mother Mary Potter 1719-1780

and her mother and my 7x great grandmother Mary 1680-You could say it leads us to the very heart of England, as these Leicestershire villages are as far from the coast as it’s possible to be. There are countless other maternal lines to follow, of course, but only one of mothers of mothers, and ours takes us to Leicestershire.

The blacksmiths

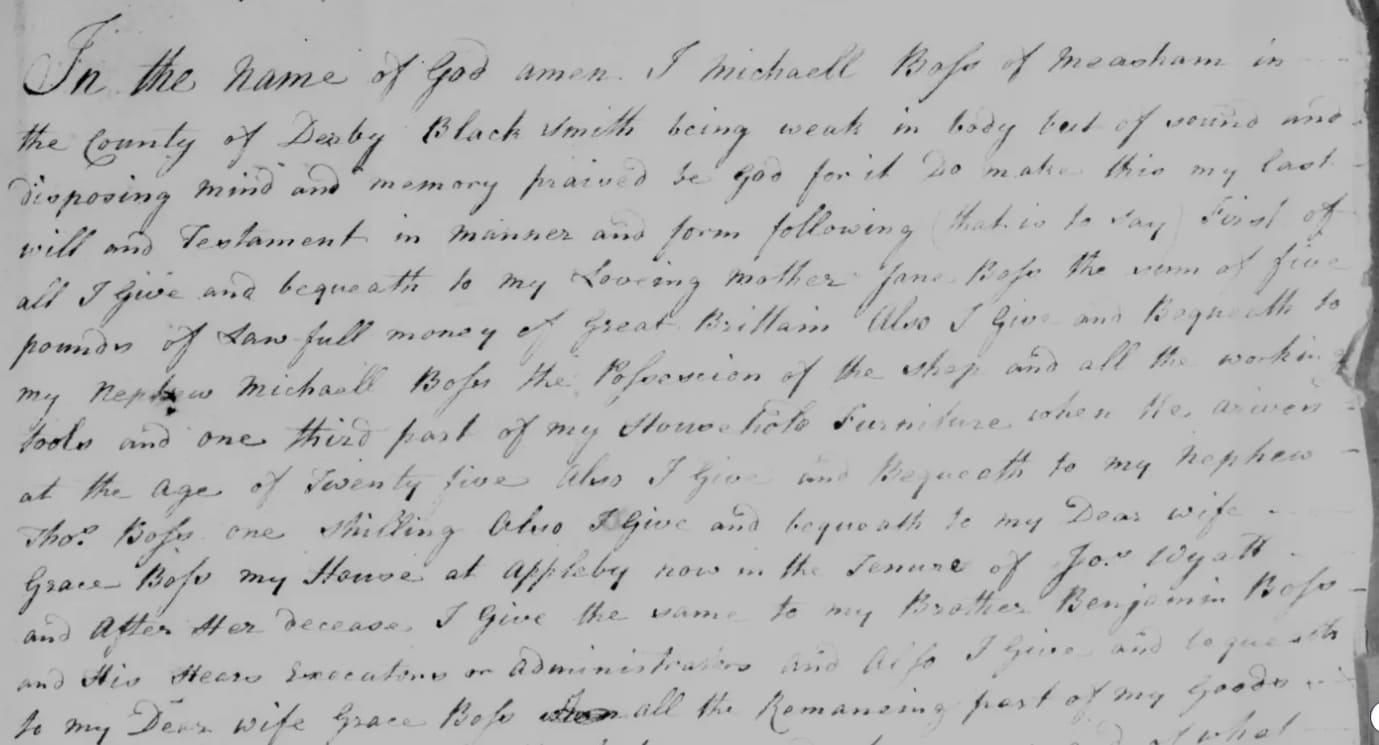

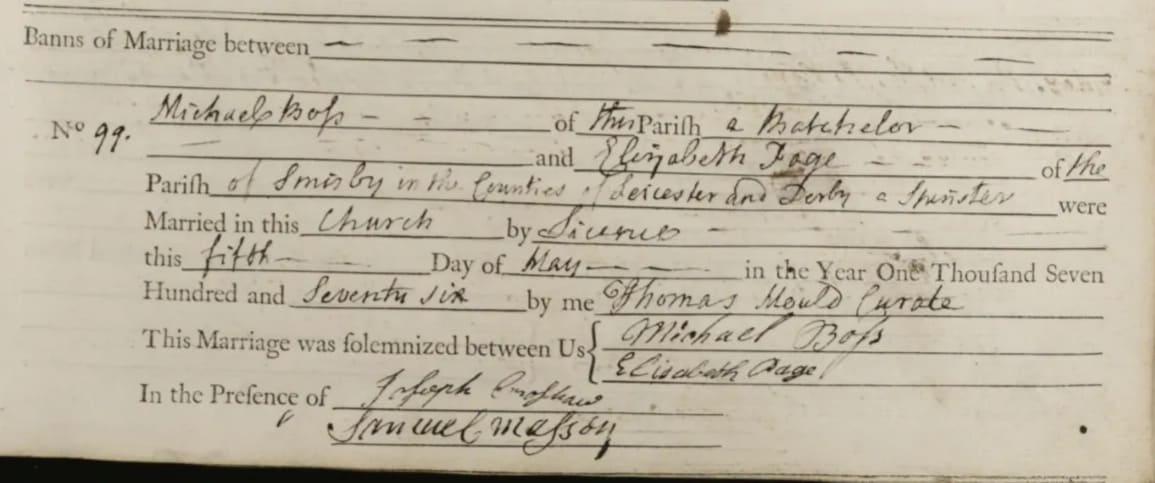

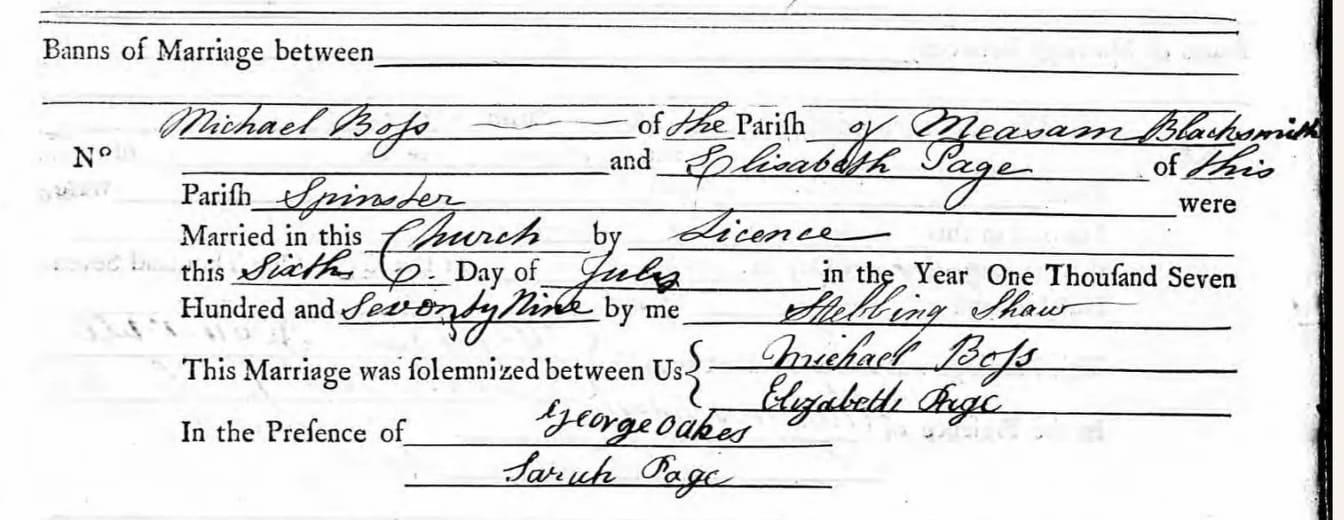

Sarah Boss was the daughter of Michael Boss 1755-1807, a blacksmith in Measham, and Elizabeth Page of nearby Hartshorn, just over the county border in Derbyshire.

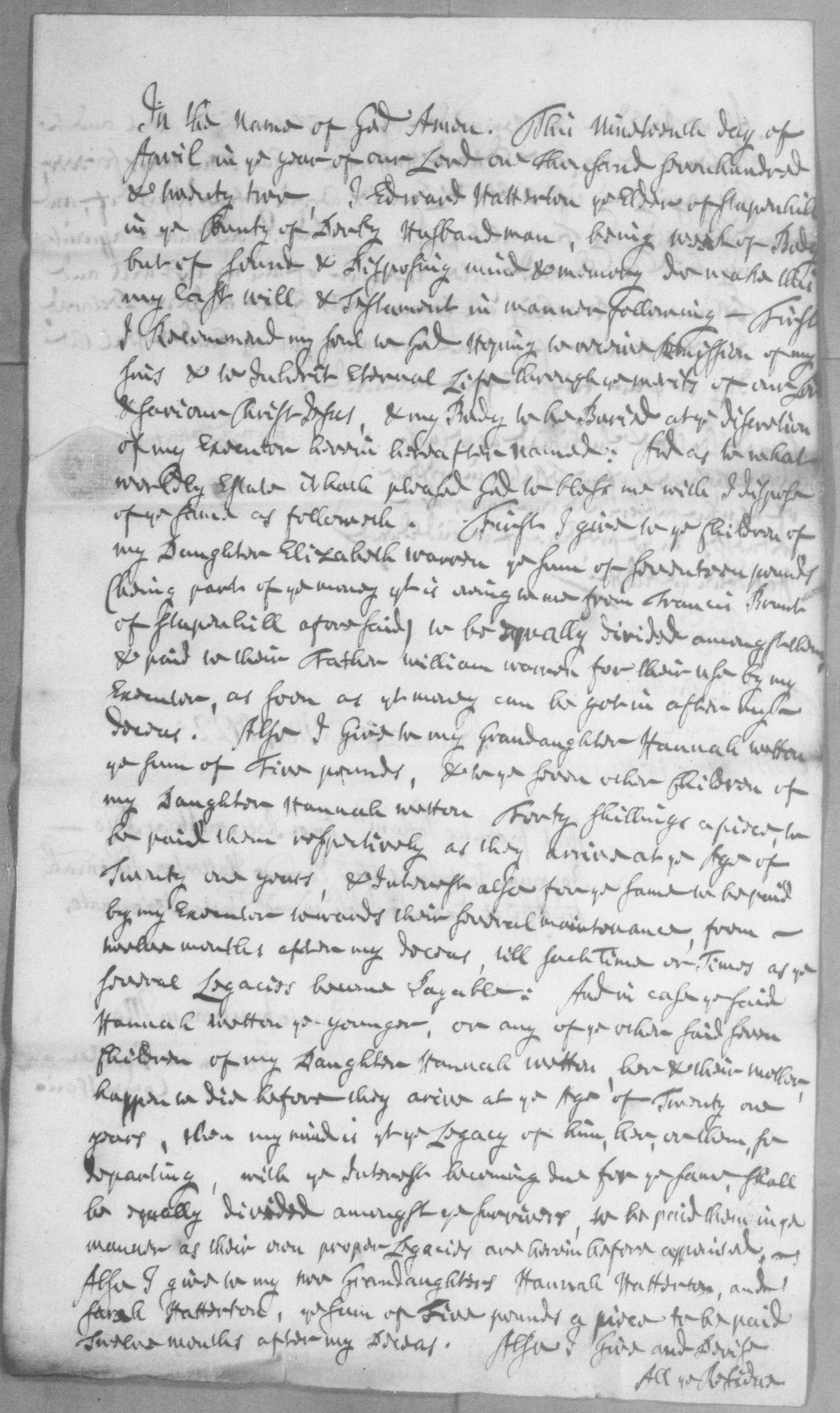

An earlier Michael Boss, a blacksmith of Measham, died in 1772, and in his will he left the possession of the blacksmiths shop and all the working tools and a third of the household furniture to Michael, who he named as his nephew. He left his house in Appleby Magna to his wife Grace, and five pounds to his mother Jane Boss. As none of Michael and Grace’s children are mentioned in the will, perhaps it can be assumed that they were childless.

The will of Michael Boss, 1772, Measham:

Michael Boss the uncle was born in Appleby Magna in 1724. His parents were Michael Boss of Nelson in the Thistles and Jane Peircivall of Appleby Magna, who were married in nearby Mancetter in 1720.

Information worth noting on the Appleby Magna website:

In 1752 the calendar in England was changed from the Julian Calendar to the Gregorian Calendar, as a result 11 days were famously “lost”. But for the recording of Church Registers another very significant change also took place, the start of the year was moved from March 25th to our more familiar January 1st.

Before 1752 the 1st day of each new year was March 25th, Lady Day (a significant date in the Christian calendar). The year number which we all now use for calculating ages didn’t change until March 25th. So, for example, the day after March 24th 1750 was March 25th 1751, and January 1743 followed December 1743.

This March to March recording can be seen very clearly in the Appleby Registers before 1752. Between 1752 and 1768 there appears slightly confused recording, so dates should be carefully checked. After 1768 the recording is more fully by the modern calendar year.Michael Boss the uncle married Grace Cuthbert. I haven’t yet found the birth or parents of Grace, but a blacksmith by the name of Edward Cuthbert is mentioned on an Appleby Magna history website:

An Eighteenth Century Blacksmith’s Shop in Little Appleby

by Alan RobertsCuthberts inventory

The inventory of Edward Cuthbert provides interesting information about the household possessions and living arrangements of an eighteenth century blacksmith. Edward Cuthbert (als. Cutboard) settled in Appleby after the Restoration to join the handful of blacksmiths already established in the parish, including the Wathews who were prominent horse traders. The blacksmiths may have all worked together in the same shop at one time. Edward and his wife Sarah recorded the baptisms of several of their children in the parish register. Somewhat sadly three of the boys named after their father all died either in infancy or as young children. Edward’s inventory which was drawn up in 1732, by which time he was probably a widower and his children had left home, suggests that they once occupied a comfortable two-storey house in Little Appleby with an attached workshop, well equipped with all the tools for repairing farm carts, ploughs and other implements, for shoeing horses and for general ironmongery.

Edward Cuthbert born circa 1660, married Joane Tuvenet in 1684 in Swepston cum Snarestone , and died in Appleby in 1732. Tuvenet is a French name and suggests a Huguenot connection, but this isn’t our family, and indeed this Edward Cuthbert is not likely to be Grace’s father anyway.

Michael Boss and Elizabeth Page appear to have married twice: once in 1776, and once in 1779. Both of the documents exist and appear correct. Both marriages were by licence. They both mention Michael is a blacksmith.

Their first daughter, Elizabeth, was baptized in February 1777, just nine months after the first wedding. It’s not known when she was born, however, and it’s possible that the marriage was a hasty one. But why marry again three years later?

But Michael Boss and Elizabeth Page did not marry twice.

Elizabeth Page from Smisby was born in 1752 and married Michael Boss on the 5th of May 1776 in Measham. On the marriage licence allegations and bonds, Michael is a bachelor.

Baby Elizabeth was baptised in Measham on the 9th February 1777. Mother Elizabeth died on the 18th February 1777, also in Measham.

In 1779 Michael Boss married another Elizabeth Page! She was born in 1749 in Hartshorn, and Michael is a widower on the marriage licence allegations and bonds.

Hartshorn and Smisby are neighbouring villages, hence the confusion. But a closer look at the documents available revealed the clues. Both Elizabeth Pages were literate, and indeed their signatures on the marriage registers are different:

Marriage of Michael Boss and Elizabeth Page of Smisby in 1776:

Marriage of Michael Boss and Elizabeth Page of Harsthorn in 1779:

Not only did Michael Boss marry two women both called Elizabeth Page but he had an unusual start in life as well. His uncle Michael Boss left him the blacksmith business and a third of his furniture. This was all in the will. But which of Uncle Michaels brothers was nephew Michaels father?

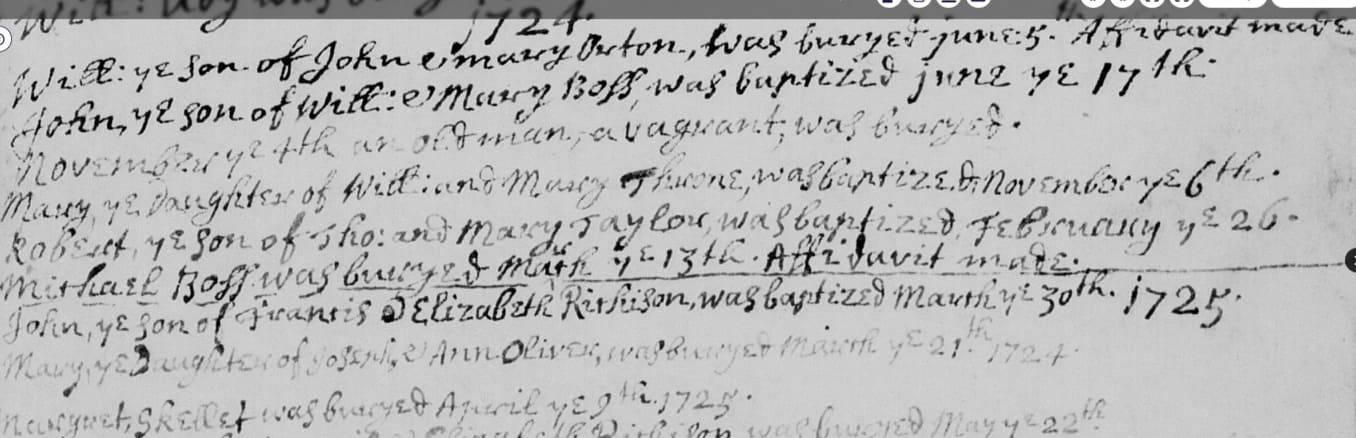

The only Michael Boss born at the right time was in 1750 in Edingale, Staffordshire, about eight miles from Appleby Magna. His parents were Thomas Boss and Ann Parker, married in Edingale in 1747. Thomas died in August 1750, and his son Michael was baptised in the December, posthumus son of Thomas and his widow Ann. Both entries are on the same page of the register.

Ann Boss, the young widow, married again. But perhaps Michael and his brother went to live with their childless uncle and aunt, Michael Boss and Grace Cuthbert.

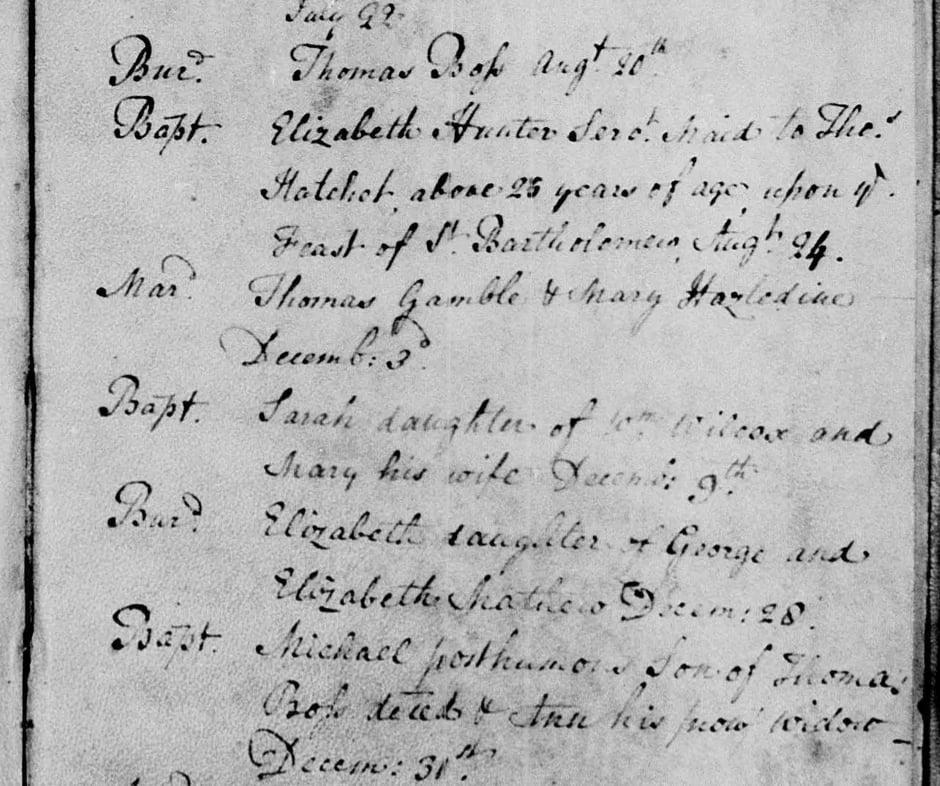

The great grandfather of Michael Boss (the Measham blacksmith born in 1850) was also Michael Boss, probably born in the 1660s. He died in Newton Regis in Warwickshire in 1724, four years after his son (also Michael Boss born 1693) married Jane Peircivall. The entry on the parish register states that Michael Boss was buried ye 13th Affadavit made.

I had not seen affadavit made on a parish register before, and this relates to the The Burying in Woollen Acts 1666–80. According to Wikipedia:

“Acts of the Parliament of England which required the dead, except plague victims and the destitute, to be buried in pure English woollen shrouds to the exclusion of any foreign textiles. It was a requirement that an affidavit be sworn in front of a Justice of the Peace (usually by a relative of the deceased), confirming burial in wool, with the punishment of a £5 fee for noncompliance. Burial entries in parish registers were marked with the word “affidavit” or its equivalent to confirm that affidavit had been sworn; it would be marked “naked” for those too poor to afford the woollen shroud. The legislation was in force until 1814, but was generally ignored after 1770.”

Michael Boss buried 1724 “Affadavit made”:

Elizabeth Page‘s father was William Page 1717-1783, a wheelwright in Hartshorn. (The father of the first wife Elizabeth was also William Page, but he was a husbandman in Smisby born in 1714. William Page, the father of the second wife, was born in Nailstone, Leicestershire, in 1717. His place of residence on his marriage to Mary Potter was spelled Nelson.)

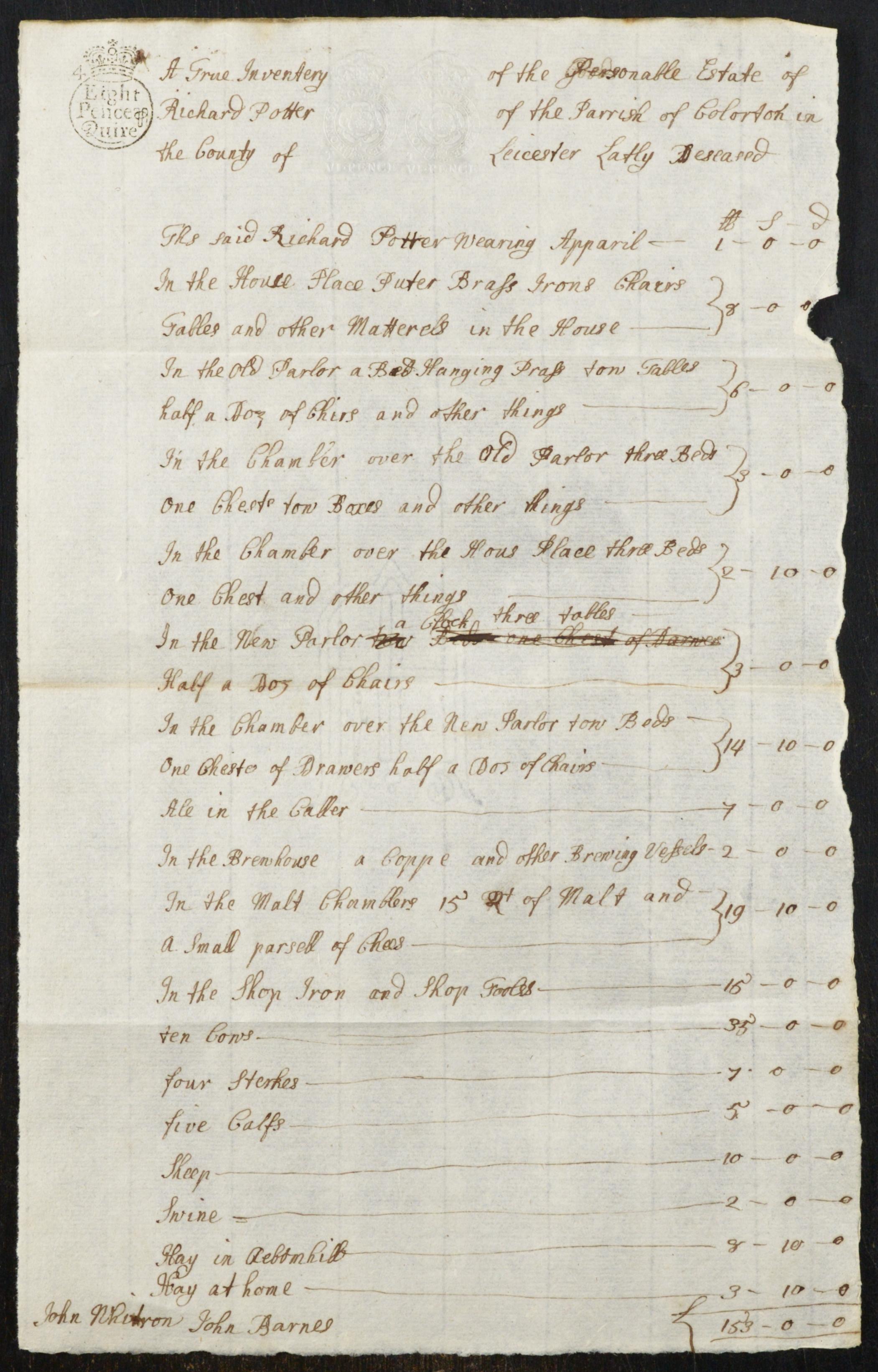

Her mother was Mary Potter 1719- of nearby Coleorton. Mary’s father, Richard Potter 1677-1731, was a blacksmith in Coleorton.

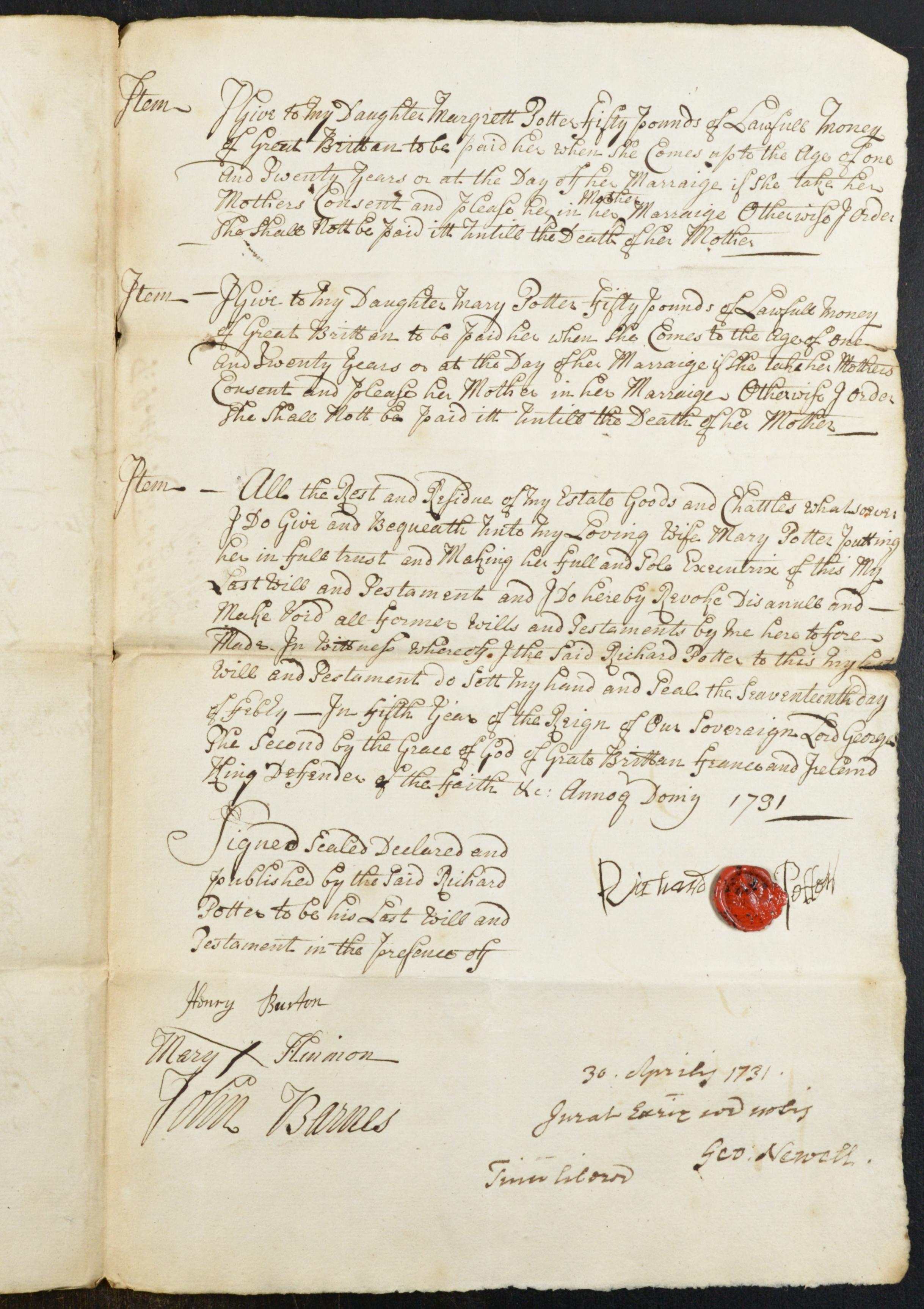

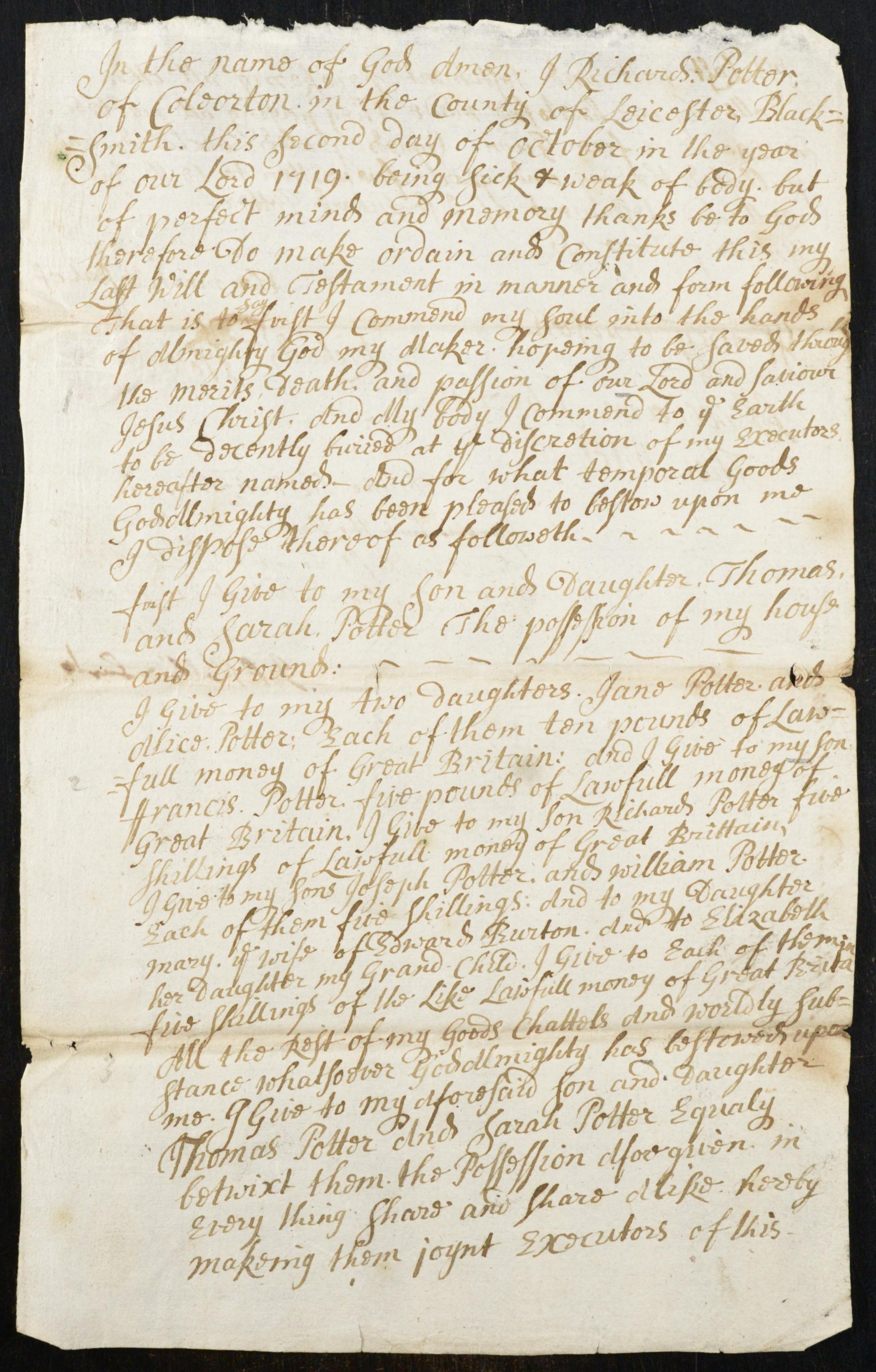

A page of the will of Richard Potter 1731:

Richard Potter states: “I will and order that my son Thomas Potter shall after my decease have one shilling paid to him and no more.” As he left £50 to each of his daughters, one can’t help but wonder what Thomas did to displease his father.

Richard stipulated that his son Thomas should have one shilling paid to him and not more, for several good considerations, and left “the house and ground lying in the parish of Whittwick in a place called the Long Lane to my wife Mary Potter to dispose of as she shall think proper.”

His son Richard inherited the blacksmith business: “I will and order that my son Richard Potter shall live and be with his mother and serve her duly and truly in the business of a blacksmith, and obey and serve her in all lawful commands six years after my decease, and then I give to him and his heirs…. my house and grounds Coulson House in the Liberty of Thringstone”

Richard wanted his son John to be a blacksmith too: “I will and order that my wife bring up my son John Potter at home with her and teach or cause him to be taught the trade of a blacksmith and that he shall serve her duly and truly seven years after my decease after the manner of an apprentice and at the death of his mother I give him that house and shop and building and the ground belonging to it which I now dwell in to him and his heirs forever.”

To his daughters Margrett and Mary Potter, upon their reaching the age of one and twenty, or the day after their marriage, he leaves £50 each. All the rest of his goods are left to his loving wife Mary.

An inventory of the belongings of Richard Potter, 1731:

Richard Potters father was also named Richard Potter 1649-1719, and he too was a blacksmith.

Richard Potter of Coleorton in the county of Leicester, blacksmith, stated in his will: “I give to my son and daughter Thomas and Sarah Potter the possession of my house and grounds.”

He leaves ten pounds each to his daughters Jane and Alice, to his son Francis he gives five pounds, and five shillings to his son Richard. Sons Joseph and William also receive five shillings each. To his daughter Mary, wife of Edward Burton, and her daughter Elizabeth, he gives five shillings each. The rest of his good, chattels and wordly substance he leaves equally between his son and daugter Thomas and Sarah. As there is no mention of his wife, it’s assumed that she predeceased him.

The will of Richard Potter, 1719:

Richard Potter’s (1649-1719) parents were William Potter and Alse Huldin, both born in the early 1600s. They were married in 1646 at Breedon on the Hill, Leicestershire. The name Huldin appears to originate in Finland.

William Potter was a blacksmith. In the 1659 parish registers of Breedon on the Hill, William Potter of Breedon blacksmith buryed the 14th July.

April 2, 2022 at 6:15 pm #6286In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Matthew Orgill and His Family

Matthew Orgill 1828-1907 was the Orgill brother who went to Australia, but returned to Measham. Matthew married Mary Orgill in Measham in October 1856, having returned from Victoria, Australia in May of that year.

Although Matthew was the first Orgill brother to go to Australia, he was the last one I found, and that was somewhat by accident, while perusing “Orgill” and “Measham” in a newspaper archives search. I chanced on Matthew’s obituary in the Nuneaton Observer, Friday 14 June 1907:

LATE MATTHEW ORGILL PEACEFUL END TO A BLAMELESS LIFE.

‘Sunset and Evening Star And one clear call for me.”

It is with very deep regret that we have to announce the death of Mr. Matthew Orgill, late of Measham, who passed peacefully away at his residence in Manor Court Road, Nuneaton, in the early hours of yesterday morning. Mr. Orgill, who was in his eightieth year, was a man with a striking history, and was a very fine specimen of our best English manhood. In early life be emigrated to South Africa—sailing in the “Hebrides” on 4th February. 1850—and was one of the first settlers at the Cape; afterwards he went on to Australia at the time of the Gold Rush, and ultimately came home to his native England and settled down in Measham, in Leicestershire, where he carried on a successful business for the long period of half-a-century.

He was full of reminiscences of life in the Colonies in the early days, and an hour or two in his company was an education itself. On the occasion of the recall of Sir Harry Smith from the Governorship of Natal (for refusing to be a party to the slaying of the wives and children in connection with the Kaffir War), Mr. Orgill was appointed to superintend the arrangements for the farewell demonstration. It was one of his boasts that he made the first missionary cart used in South Africa, which is in use to this day—a monument to the character of his work; while it is an interesting fact to note that among Mr. Orgill’s papers there is the original ground-plan of the city of Durban before a single house was built.

In Africa Mr. Orgill came in contact with the great missionary, David Livingstone, and between the two men there was a striking resemblance in character and a deep and lasting friendship. Mr. Orgill could give a most graphic description of the wreck of the “Birkenhead,” having been in the vicinity at the time when the ill-fated vessel went down. He played a most prominent part on the occasion of the famous wreck of the emigrant ship, “Minerva.” when, in conjunction with some half-a-dozen others, and at the eminent risk of their own lives, they rescued more than 100 of the unfortunate passengers. He was afterwards presented with an interesting relic as a memento of that thrilling experience, being a copper bolt from the vessel on which was inscribed the following words: “Relic of the ship Minerva, wrecked off Bluff Point, Port Natal. 8.A.. about 2 a.m.. Friday, July 5, 1850.”

Mr. Orgill was followed to the Colonies by no fewer than six of his brothers, all of whom did well, and one of whom married a niece (brother’s daughter) of the late Mr. William Ewart Gladstone.

On settling down in Measham his kindly and considerate disposition soon won for him a unique place in the hearts of all the people, by whom he was greatly beloved. He was a man of sterling worth and integrity. Upright and honourable in all his dealings, he led a Christian life that was a pattern to all with whom he came in contact, and of him it could truly he said that he wore the white flower of a blameless life.

He was a member of the Baptist Church, and although beyond much active service since settling down in Nuneaton less than two years ago he leaves behind him a record in Christian service attained by few. In politics he was a Radical of the old school. A great reader, he studied all the questions of the day, and could back up every belief he held by sound and fearless argument. The South African – war was a great grief to him. He knew the Boers from personal experience, and although he suffered at the time of the war for his outspoken condemnation, he had the satisfaction of living to see the people of England fully recognising their awful blunder. To give anything like an adequate idea of Mr. Orgill’s history would take up a great amount of space, and besides much of it has been written and commented on before; suffice it to say that it was strenuous, interesting, and eventful, and yet all through his hands remained unspotted and his heart was pure.

He is survived by three daughters, and was father-in-law to Mr. J. S. Massey. St Kilda. Manor Court Road, to whom deep and loving sympathy is extended in their sore bereavement by a wide circle of friends. The funeral is arranged to leave for Measham on Monday at twelve noon.

“To give anything like an adequate idea of Mr. Orgill’s history would take up a great amount of space, and besides much of it has been written and commented on before…”

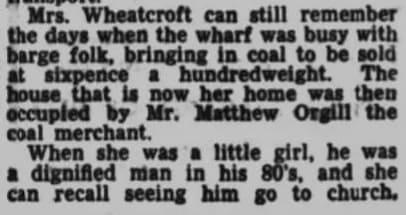

I had another look in the newspaper archives and found a number of articles mentioning him, including an intriguing excerpt in an article about local history published in the Burton Observer and Chronicle 8 August 1963:

on an upstairs window pane he scratched with his diamond ring “Matthew Orgill, 1st July, 1858”

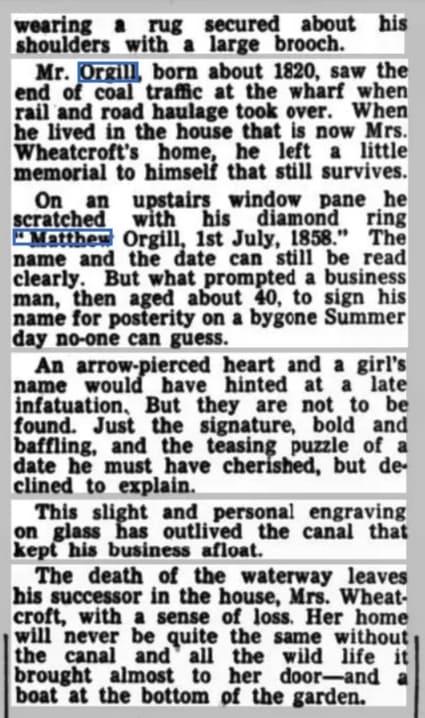

I asked on a Measham facebook group if anyone knew the location of the house mentioned in the article and someone kindly responded. This is the same building, seen from either side:

Coincidentally, I had already found this wonderful photograph of the same building, taken in 1910 ~ three years after Matthew’s death.

But what to make of the inscription in the window?

Matthew and Mary married in October 1856, and their first child (according to the records I’d found thus far) was a daughter Mary born in 1860. I had a look for a Matthew Orgill birth registered in 1858, the date Matthew had etched on the window, and found a death for a Matthew Orgill in 1859. Assuming I would find the birth of Matthew Orgill registered on the first of July 1958, to match the etching in the window, the corresponding birth was in July 1857!

Matthew and Mary had four children. Matthew, Mary, Clara and Hannah. Hannah Proudman Orgill married Joseph Stanton Massey. The Orgill name continues with their son Stanley Orgill Massey 1900-1979, who was a doctor and surgeon. Two of Stanley’s four sons were doctors, Paul Mackintosh Orgill Massey 1929-2009, and Michael Joseph Orgill Massey 1932-1989.

Mary Orgill 1827-1894, Matthews wife, was an Orgill too.

And this is where the Orgill branch of the tree gets complicated.

Mary’s father was Henry Orgill born in 1805 and her mother was Hannah Proudman born in 1805.

Henry Orgill’s father was Matthew Orgill born in 1769 and his mother was Frances Finch born in 1771.Mary’s husband Matthews parents are Matthew Orgill born in 1798 and Elizabeth Orgill born in 1803.

Another Orgill Orgill marriage!

Matthews parents, Matthew and Elizabeth, have the same grandparents as each other, Matthew Orgill born in 1736 and Ann Proudman born in 1735.

But Matthews grandparents are none other than Matthew Orgill born in 1769 and Frances Finch born in 1771 ~ the same grandparents as his wife Mary!

March 4, 2022 at 2:58 pm #6280In reply to: The Whale’s Diaries Collection

I started reading a book. In fact I started reading it three weeks ago, and have read the first page of the preface every night and fallen asleep. But my neck aches from doing too much gardening so I went back to bed to read this morning. I still fell asleep six times but at least I finished the preface. It’s the story of the family , initiated by the family collection of netsuke (whatever that is. Tiny Japanese carvings) But this is what stopped me reading and made me think (and then fall asleep each time I re read it)

“And I’m not entitled to nostalgia about all that lost wealth and glamour from a century ago. And I am not interested in thin. I want to know what the relationship has been between this wooden object that I am rolling between my fingers – hard and tricky and Japanese – and where it has been. I want to be able to reach to the handle of the door and turn it and feel it open. I want to walk into each room where this object has lived, to feel the volume of the space, to know what pictures were on the walls, how the light fell from the windows. And I want to know whose hands it has been in, and what they felt about it and thought about it – if they thought about it. I want to know what it has witnessed.” ― Edmund de Waal, The Hare With Amber Eyes: A Family’s Century of Art and Loss

And I felt almost bereft that none of the records tell me which way the light fell in through the windows.

I know who lived in the house in which years, but I don’t know who sat in the sun streaming through the window and which painting upon the wall they looked at and what the material was that covered the chair they sat on.

Were his clothes confortable (or hers, likely not), did he have an old favourite pair of trousers that his mother hated?

There is one house in particular that I keep coming back to. Like I got on the Housley train at Smalley and I can’t get off. Kidsley Grange Farm, they turned it into a nursing home and built extensions, and now it’s for sale for five hundred thousand pounds. But is the ghost still under the back stairs? Is there still a stain somewhere when a carafe of port was dropped?

Did Anns writing desk survive? Does someone have that, polished, with a vase of spring tulips on it? (on a mat of course so it doesn’t make a ring, despite that there are layers of beeswaxed rings already)

Does the desk remember the letters, the weight of a forearm or elbow, perhaps a smeared teardrop, or a comsumptive cough stain?

Is there perhaps a folded bit of paper or card that propped an uneven leg that fell through the floorboards that might tear into little squares if you found it and opened it, and would it be a rough draft of a letter never sent, or just a receipt for five head of cattle the summer before?