Search Results for 'lace'

-

AuthorSearch Results

-

February 7, 2026 at 11:31 pm #8056

In reply to: The Hoards of Sanctorum AD26

“Karstic Rock Cakes and a nice pot of Early Grey,” Mrs Fennel announced, having recovered her equilibrium and usefulness. “I’m sure everone could do with a nice cuppa after all the excitement,” she added, looking around for a surface upon which to play the tray.

“Put plenty of butter on mine, Mrs F,” said Cerenise, “You’re always too stingy with the butter.”

Had Mrs Fennel been easily able to bend down and place the laden tray on the floor in front of Cernise’s bath chair, she would have done, and with a degree of relish. It irked her to no mean degree that she was quite unable, due to an arthritic hip and the dastardly damp downpours and drenching deluges devastating her dersirable domain, to make such an otherwise ordinary human movement. Thus, she continued to survey the room for a potential surface, or a person attentive to her plight, being herself helplessly unable to proceed.

February 5, 2026 at 2:14 am #8054In reply to: The Hoards of Sanctorum AD26

Mrs. Fennel was beating the dust out of a rug with more violence than was strictly necessary. “Another bloody rug,” she moaned. “If I had a penny for every rug in this place, Boothroyd!”

She shook her head, then cursed, as a cascade of dust floated from her hair. “No idea which of them four picked this one up from god-knows-where, but they’re each as bad as the other.”

She paused to wipe her brow with a corner of her apron, wheezing slightly. “I’m telling you,” she whispered, peering at him conspiratorially, “it’s not just clutter anymore. It’s … REMAINS.”

Boothroyd looked up from a tray of seedlings, his brow furrowing. “Remains, Mrs. F?”

“Human remains!” she hissed, leaning in so close he could smell the peppermint gum on her breath. “A stinking, ancient bone in a plastic box, and Miss Cerenise acting like it’s a piece of the Crown Jewels. Then there’s Miss Yvoise, snapping photos on her fancy phone like she’s … I dunno … Sherlock Holmes or something. And the smell… dear lord, I couldn’t get out of there fast enough.”

Boothroyd grunted, his gaze drifting toward the cellar door. “They do seem particularly out of control lately. My boots are still damp from that ridiculous boat business. I’m not sure they know which century they’re living in.”

“Anyway bone or no,” Mrs. Fennel huffed, “if that gentleman from the Council shows up, that Varlet fellow they’re on about, we’ll all be out on the street, mark my words!”

February 5, 2026 at 1:31 am #8053In reply to: The Hoards of Sanctorum AD26

“Not so fast, Mrs. Fennel,” said Yvoise, blocking the woman’s path as she tried to make a hasty exit. “You don’t happen to have a clean tea towel on you, do you?”

Gratefully, Yvoise took the proffered tea towel Mrs. Fennel threw at her as she all but ran through the door. She wrapped it over her nose as she watched Cerenise poke delightedly at the yellow lace.

“Honestly, Cerenise, we need to make haste getting rid of it. That thing stinks.” Yvoise liked order; she had learned to arrange her own space around neat piles of files, records, and lists. To her, most of the house wasn’t just a mess — it was an abject failure of hoarding protocols. But she had also learned that in order to live in harmony with others, she had to hold her tongue. She sighed and opened the Relics and Records spreadsheet on her phone. Item 2753, she typed. One bone bobbin. She ventured as near as she could and, reaching out with her phone, snapped a photo of it. Admittedly it wasn’t much, but it did give her some feeling of control.

Helier hovered by the wall, leaning as far as possible away from the stench. “But whose bone is it?” he repeated.

“It’s not just about whose bone it is,” said Spirius, popping his head around the door. “It’s about why it’s here. Austreberthe was a great hoarder, a first-rate hoarder, but,” he paused dramatically, “she always had a reason. She wouldn’t just put it in a Tupperware container for fun.”

“True,” said Cerenise. “She really had a gift for squeezing the joy out of life.” She looked pointedly at Yvoise as she said this.

Fortunately, Yvoise was peering at her phone and didn’t notice. Enlarging the image, she looked puzzled. “There seem to be faint lines scratched into it,” she said. “Like a map.“

January 19, 2026 at 6:51 pm #8051In reply to: The Hoards of Sanctorum AD26

“Lace, did you say?” asked Cerenise with interest. “I must have a look at it. Stench, you say? How very odd. But I want to see it. Fetch me the container while I look for my mask and rubber gloves.”

“I’m not going near it again, I’ll get Boothroyd to bring it,” Spirius replied making a hasty exit.

“I’d have thought you’d have wanted to bottle the smell, Spirius.”

In due course the gardener appeared holding a container at arms length with a pained expression on his face. “Stinks worse than keeg, this does, and I’ve smelled some manure and compost in my time, but never anything as disgusting as this. Where am I to put it?”

Cerenise cleared a space on a table piled with old books and catalogues. “Gosh, that is a pong, isn’t it! Reminds me of something,” she said twitching her nose. “There is a delicate note of ~ what is it?”

“Dead rats?” suggested Boothroyd helpfully, adding “Will that be all?” as he backed towards the door.

As Cerenise lifted the lid, the gardener turned and fled.

“Why, it’s a Nottingham lace Lambrequin window drape if I’m not mistaken!” exclaimed Cerenise, gently lifting the delicate fabric and holding it up to the light. “Probably 1912 or thereabouts, and in perfect condition.”

“Perfectly rancid,” said Yvoise, her voice muffled by the thick towel she had wrapped around her mouth and nose.

“Come and look, it’s a delightful specimen. Not terribly rare, but it wonderful condition. Oh look! There’s another piece underneath. Aha! seventeenth century bone lace!”

Yvoise crept closer. “What’s that other thing? Is that where the smell’s coming from?”

“By Georges, I think you’re right. It’s a bone bobbin. Bone lace, they used to call it, until they started making bobbins out of wood.” Cerenise was pleased. She could get Mrs Fennel to wash the lace and then she could add it to her collection. “Spirius can bottle the bone bobbin and bury it in Bobbington Woods.”

Duly summoned from the kitchen, the faithful daily woman appeared, drying her hands on her apron.

“Pooo eee!” exclaimed Mrs Fennel, “That’ll need a good boil in bleach, will that!”

“Good lord woman, no! A gentle soak in some soap should do it. It won’t smell half so bad as soon as this bone bobbin is removed.”

“Did you say BONE bobbin?” asked Helier from a relatively safe distance just outside the door. “WHOSE bone?”

“By Georges!” Cerenise said again. “Whose bone indeed! Therein lies the clue to the mystery, you know.”

“Can’t you just put it in a parcel and mail it to someone horrible?” suggested Mrs Fennel.

“A capital idea, Mrs Fennel, a politician. So many horrible ones to choose from though,” Yvoise was already making a mental list.

“We can mail the smelly empty box to the prime minister, but we must keep the bone bobbin safe,” said Helier. “And we must find out whose bones it was made from. Cerenise is right. It’s the clue.”

“An empty smelly box, even better. More fitting, if I do say so myself, for the prime minister,” said Mrs Fennel with some relief. At least she wasn’t going to be required to wash the bone and the box as well as the smelly lace.

January 19, 2026 at 4:22 am #8050In reply to: The Hoards of Sanctorum AD26

The reek hit her with the force of a physical blow. Yvoise was sensitive to smell; for hundreds of years, Yvoise had cultivated the scent of library dust and dried wildflowers, a fragrance she believed to be the height of sophistication.

“Spirius,” she said at last. “The spiders are a symptom. This dreadful smell must surely be the manifestation of Austreberthe’s lingering ego. She always was a bit… pungent.”

Yvoise immediately felt guilty for speaking ill of the departed. “I’m so sorry,” she said, “that was not kind of me.” She was mostly annoyed at herself for not being able to comprehend Austreberthe’s choice to leave. She checked her smartwatch. Her ‘Conflict Resolution’ seminar was a lost cause; the group would have to resolve their own, dare she think it, rather petty tensions today. Of course, having the wisdom of hundreds of years’ experience does tend to give one a unique perspective.

“I think I overheard Cerenise say the Varlet descendant works in Gloucester?” Yvoise continued, her fingers tapping her phone. ”I’ve done a cross-reference on the municipal database and have found a Varlet who works for the Environmental Health Department.” She snorted. “Of course, the irony is, if that stench reaches the street… he won’t be coming for a family reunion; he’ll be coming with a condemnation order and a dumpster.”

The colour drained from Spirius’s face. Yvoise knew that the only thing a fellow hoarder feared more than fire was a man with a dumpster. “Don’t worry,” she said, kindly patting Spirius on the arm, “I was joking… I’m mostly, or nearly sure it won’t come to that.”

She pointed a manicured finger at the Topperware tower. “Be brave and open that top box. If there is a relic in there causing this stench, we need to neutralize it with vinegar immediately.”

Spirius reached out, his hand trembling as he gripped the lid of the highest container. As the lid clicked open, the frightful smell erupted into the room, a thick, dank smell of wet wool and lye soap. Spirius hastily set the container down and his hand flew to his nose.

“I believe it is her laundry,” he wheezed eventually. “I’m sure I saw a lace thingammy before I was overcome. Cerenise will surely want to know.”

“It’s a biohazard,” said Yvoise, as she quickly snapped some photos of it for her ‘Relics and Records’ files.

January 18, 2026 at 8:18 am #8049In reply to: The Hoards of Sanctorum AD26

Phurt was starting to think something fishy was a play, each time he thought his short spider life had ended he was pulled back from Spiderheaven by some unknown force. Not that he minded this time, there were plenty of places to hide and cast his strong silk cables. He had developed a sense of adventure and the sheer height of some of the mounds made him dizzy. It also made him want to be the first spider in the history of this thread to climb on top of that Mount Wobbly of the Topperware Chain.

Phurt had also noticed a strange and strong smell that seemed to come from the top of Mount Wobbly. Not that he minded the hygiene of the place; it was, to the contrary, a rather promising smell. It was the smell that said swarms of flies would gather there like an endless supply of blessed food.

Seeing that other spiders were gathering at the bottom of Mount Wobbly, he contorted his butt and secured his first cable.

Spirius had been investigating the origin of a strong smell that had started not long after Austreberthe puffed out of existence and became part of the dust she had spent her life chasing away. Which gave him one more proof that his theory of the holy body influence upon the physical world was true. He looked for a pen but they were behind two piles of unopened parcels he had started collecting when he had noticed that the postmen were leaving the boxes unattended and unprotected from the elements on the front porch of houses. His intentions were pure, as any saintly intentions are, but when he saw what good addition to the other boxes they made, he felt a pang of regret each time he thought of giving back those boxes to their rightful recipients.

Alas, most of them were dead by now, so he felt his duty was to keep those boxes intact to honour the memory of the dead.

Yvoise came in just as Spirius saw an odd and colourful australian jumping spider cast a delicate silk thread to one of the bottom row of his Tupperware collection.

“You should really do something about that smell,” she said. “I remember a time when decorum required holy people to exude only fragrance and essential oils.”

“Well, you know, it’s Austreberthe,” he said as wobbly as his heaps of plastic boxes. He had them all. You could even say he started the whole trend of pyramid schemes when his friend Pearl Topper saw him buy boxes from antiques shops. She invented the first plastic box as…

“Well, I asked you a question,” said Yvoise, interrupting his wandering thoughts.

“Have you noticed the spiders,” said Spirius.

“What spiders?”

“I think they’re trying to go up there,” Spirius said. “Look!”

He pointed a proud finger at the top of the highest Topperware tower in the Guyness book of records. A swarm of flies was circling around one of the boxes.

“And that means the smell comes from there.”

January 16, 2026 at 11:00 pm #8048In reply to: The Hoards of Sanctorum AD26

“Bless you,” Helier offered, instinctively sliding the half-chewed pencil stub under a pile of National Geographics from 1978. He felt a flush of guilt, as if he’d been caught trying to steal a kid’s toy.

Cerenise rolled into the room, looking like a sorry pile of laundry. She was wrapped in three different shawls—one Paisley, one Tartan, and one that looked like a doily from a medieval altar. She held a lace handkerchief to her nose, trumpeting into it with a force that rattled the nearby display of thimbles.

“It’s not the damp,” she croaked, her voice an octave lower than usual. “It’s the cleanliness. Since Spirius fixed that pipe, the air is too… sterile. My immune system is in shock. It misses the spores.”

She eyed the spot where Helier had hidden the pencil. “You were thinking about it, weren’t you?”

“Thinking about what?” Helier feigned innocence, picking up a ceramic frog.

“The Novena,” she whispered the word like a curse. “I saw the look in your eye. The ‘maybe I don’t need this’ look. It’s the fever talking, Helier. Don’t give in. I almost threw away a button yesterday. A bakelite toggle from a 1930s duffel coat. I held it over the bin for a full minute.” She shuddered, pulling the shawls tighter. “Madness.”

“Pure madness,” Helier agreed, quickly retrieving the pencil stub and placing it prominently on the desk to prove his loyalty to the hoard. “We must stay strong. Now, surely you didn’t brave the drafty hallway just to discuss my potential apostasy?”

“I didn’t,” Cerenise sniffed, tucking the handkerchief into her sleeve. “I found him. Or at least, I found the thread.”

She wheeled closer, dropping a printout onto Helier’s knees. It was a genealogy chart, annotated with her elegant, spider-scrawl handwriting.

“Pierre Wenceslas Varlet,” she announced. “Born 1824. Brother to a last of the famously named Austreberthes — mortal ones, unsaintly, of course. Her lineage didn’t die out, Helier.”

Helier squinted at the paper. “Varlet? Sounds like a villain in one of Liz Tattler’s bodice-rippers. ‘The Vengeful Varlet of Venice’.“

“Focus, Helier. Look at the modern branch.” She pointed to the bottom of the page. “The name changed in the 1950s. Anglicized. And I think, if my research into the local council tax records—hacked via that delightful ‘incognito mode’ you showed me—is correct, the current ‘Varlet’ is closer than we think.”

“How close?”

“Gloucester close,” Cerenise said, her eyes gleaming with the thrill of the hunt, momentarily forgetting her flu. “And you’ll never guess where he works.”

January 4, 2026 at 6:59 pm #8029In reply to: The Hoards of Sanctorum AD26

“While you’re off to another wild dragon chase, I’m calling the plumber,” Yvoise announced. She’d found one who accepted payment in Roman denarii. She began tapping furiously on her smartphone to recover the phone number, incensed at having been blocked again from Faceterest for sharing potentially unchecked facts (ignorants! she wanted to shout at the screen).

After a bit of struggle, the appointment was set. She adjusted her blazer; she had a ‘Health and Safety in the Workplace’ seminar to lead at Sanctus Training in twenty minutes, and she couldn’t smell like wet dog.

After a bit of struggle, the appointment was set. She adjusted her blazer; she had a ‘Health and Safety in the Workplace’ seminar to lead at Sanctus Training in twenty minutes, and she couldn’t smell like wet dog.“Make sure you bill it to the company account…!” Helier shouted over the noise Spirius was making huffing and struggling to load the antique musket.

“…under ‘Facility Maintenance’!”

“Obviously,” Yvoise scoffed. “We are a legitimate enterprise. Sanctus House has a reputation to uphold. Even if the landlord at Olympus Park keeps asking why our water consumption rivals a small water park.”

Spirius shuddered at the name. “Olympus Park. Pagan nonsense. I told you we should have bought the unit in St. Peter’s Industrial Estate.”

“The zoning laws were restrictive, Spirius,” Yvoise sighed. “Besides, ‘Sanctus Training Ltd’ looks excellent on a letterhead. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I have six junior executives coming in for a workshop on ‘Conflict Resolution.’ I plan to read them the entirety of the Treaty of Arras until they submit.”

“And dear old Boothroyd and I have a sewer dragon to exterminate in the name of all that’s Holy. Care to join, Helier?”

“Not really, had my share of those back in the day. I’ll help Yvoise with the plumbing. That’s more pressing. And might I remind you the dragon messing with the plumbing is only the first of the three tasks that Austreberthe placed in her will to be accomplished in the month following her demise…”

“Not now, Helier, I really need to get going!” Yvoise was feeling overwhelmed. “And where’s Cerenise? She could help with the second task. Finding the living descendants of the last named Austreberthe, was it? It’s all behind-desk type of stuff and doesn’t require her to get rid of anything…” she knew well Cerenise and her buttons.

“Yet.” Helier cut. “The third task may well be the toughest.”

“Don’t say it!” They all recoiled in horror.

“The No-ve-na of Cleans-ing” he said in a lugubrious voice.

“Damn it, Helier. You’re such a mood killer. Maybe better to look for a loophole for that one. We can’t just throw stuff away to make place for hers, as nice her tastes for floor tiling were.” Yvoise was in a rush to get to her appointment and couldn’t be bothered to enter a debate. She rushed to the front door.

“See you later… Helier-gator” snickered Laddie under her breath, as she was pretending to clean the unkempt cupboards.

January 2, 2026 at 6:03 pm #8022In reply to: The Hoards of Sanctorum AD26

“You know,” Helier broke the silence, his mouth half-full of the buffet’s assortments of nuts and crackers, “this was bound to happen… People tend to forget you after a while. I mean, how many new babies named after dear Austreberthe nowadays. None of course. I think our records mention 1907 was the last baby Austreberthe, and a decade ago the last mass in their memory… oh this is too heartbreaking…”

“Why so gloomy?” Cerenise was eyeing the speckled and stained silverware and the chipped Rouen faience in which the potato salad was served. “Your name is still moderately in fashion, you shouldn’t die of forgetfulness any time soon. Enjoy the food while it’s free.”

Yvoise couldn’t help but tut at her. She was half-distracted by the calligraphy on those placeholders which she found exquisite. People in this age… it was a rare find now, some pretty calligraphy. The only ‘calli-‘anything this age does well enough is callipygian, and even then, it’s mostly the Kashtardians… She said to the others “Don’t throw yours away, I must have the full set.”

Spirius was inspecting the candleholders. None had lids, a fact that frustrated him to no end. “I miss the good old time we could just slay dragons and get a good sainthood concession for a nice half-millenium.”

Yvoise tittered “simple people we were back then. Everything funny-looking was a dragon I seem to recall.”

Spirius, his plate full of charcuteries, helped himself of a few appetizing gherkins, holding one large up to contemplate. “Yeah, but those few we slew in that period were still some darn tough-skinned gators I would have you know. Those crazy Roman buggers and their games and old false gods —they couldn’t help but bring those strange beasts from Africa to Gaul, leaving us to clean up after them…”

“Indeed, much harder now. It’s like fifteen minutes of sainthood on Instatok and Faceterest and you’re already has-been.” Yvoise had started to pocket some of the paper menus. “Luckily, we still have those relics spread around to fan the flames of remembrance, don’t we.”

“I guess the young ones must look at us funny…” Cerenise chuckled amused at the thought, almost spilling her truffle brouillade.

“Oh well, apparently our youngest geeks aren’t above dealing in relics.” Helier said. “Speaking of Novena and the coming nine days,… you’ve surely noticed as I did what was mentioned in the will, have you not?”

December 31, 2025 at 7:34 pm #8018In reply to: The Hoards of Sanctorum AD26

It must be two hundred years at least since we’ve heard a will read at number 26, Cerenise thought to herself, still in a mild state of shock at the unexpected turn of events. She allowed her mind to wander, as she was wont to do.

Cerenise had spent the best part of a week choosing a suitable outfit to wear for the occasion and the dressing room adjoining her bedroom had become even more difficult to navigate. Making sure her bedroom door was securely locked before hopping out of her wicker bath chair (she didn’t want the others to see how nimble she still was), she spent hours inching her way through the small gaps between wardrobes and storage boxes and old wooden coffers, pulling out garment after garment and taking them to the Napoleon III cheval mirror to try on. She touched the rosewood lovingly each time and sighed. It was a beautiful mirror that had faithfully reflected her image for over 150 years.

Cerenise had spent the best part of a week choosing a suitable outfit to wear for the occasion and the dressing room adjoining her bedroom had become even more difficult to navigate. Making sure her bedroom door was securely locked before hopping out of her wicker bath chair (she didn’t want the others to see how nimble she still was), she spent hours inching her way through the small gaps between wardrobes and storage boxes and old wooden coffers, pulling out garment after garment and taking them to the Napoleon III cheval mirror to try on. She touched the rosewood lovingly each time and sighed. It was a beautiful mirror that had faithfully reflected her image for over 150 years.Holding a voluminous black taffetta mourning dress under her chin, Cerenise scrutinised her appearance. She looked well in black, she always felt, and it was such a good background for exotic shawls and scarves. Pulling the waist of the dress closer, it became apparent that a whalebone corset would be required if she was to wear the dress, a dreadful blight on the fun of wearing Victorian dresses. She lowered the dress and peered at her face. Not bad for, what was it now? One thousand 6 hundred and 43 years old? At around 45 years old, Cerenise decided that her face was perfect, not too young and not too old and old enough to command a modicum of respect. Thenceforth she stopped visibly aging, although she had allowed her fair hair to go silver white.

It was just after the siege of Gloucester in 1643, which often seemed like just yesterday, when Cerenise stopped walking in public. Unlike anyone else, she had relished the opportunity to stay in one place, and not be sent on errands miles away having to walk all the way in all weathers. Decades, or was it centuries, it was hard to keep track, of being a saint of travellers had worn thin by then, and she didn’t care if she never travelled again. She had done her share, although she still bestowed blessings when asked.

It was when she gave up walking in public that the hoarding started. Despite the dwellings having far fewer things in general in those days, there had always been pebbles and feathers, people’s teeth when they fell out, which they often did, and dried herbs and so forth. As the centuries rolled on, there were more and more things to hoard, reaching an awe inspiring crescendo in the last 30 years.

Cerenise, however, had wisely chosen to stop aging her teeth at the age of 21.

Physically, she was in surprisingly good shape for an apparent invalid but she spent hours every day behind locked doors, clambering and climbing among her many treasures, stored in many rooms of the labyrinthine old building. There was always just enough room for the bath chair to enter the door in each of her many rooms, and a good strong lock on the door. As soon as the door was locked, Cerenise parked the bath chair in front of the door and spent the day lifting boxes and climbing over bags and cupboards, a part of herself time travelling to wherever the treasures took her.

Eventually Cerenise settled on a long and shapeless but thickly woven, and thus warm, Neolithic style garment of unknown provenance but likely to be an Arts and Crafts replica. It was going to be cold in the library, and she could dress it up with a colourful shawl.

December 30, 2025 at 1:13 pm #8001In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

John Brooks

The Father of Catherine Housley’s Mother, Elizabeth Brooks.I had not managed to find out anything about the Brooks family in previous searches. We knew that Elizabeth Brooks father was J Brooks, cooper, from her marriage record. A cooper is a man who makes barrels.

Elizabeth was born in 1819 in Sutton Coldfield, parents John and Mary Brooks. Elizabeth had three brothers, all baptised in Sutton Coldfield: Thomas 1815-1821, John 1816-1821, and William Brooks, 1822-1875. William was known to Samuel Housley, the husband of Elizabeth, which we know from the Housley Letters, sent from the family in Smalley to George, Samuel’s brother, in USA, from the 1850s to 1870s. More to follow on William Brooks.

Elizabeth married Samuel Housley in Wolverhampton in 1844. Elizabeth and Samuel had three daughters in Smalley before Elizabeth’s death from TB in 1849, the youngest, just 6 weeks old at the time, was my great great grandmother Catherine Housley.

Elizabeth’s mother Mary died in 1823, and it not known if Elizabeth, then four, and William, a year old, stayed at home with their father or went to stay with relatives. There were no census records during those years.

John Brooks married Mary Wagstaff in 1814 in Birmingham. A witness at their marriage was Elizabeth Brooks, and this was probably John’s sister.

On the 1841 census (which was the first census in England) John Brooks, cooper, was living on Dudley Road, Wolverhampton, with wife Sarah. I was unable to find a marriage for them before a marriage in 1845 between John Brooks and Sarah Hughes, so presumably they lived together as man and wife before they married.

Then came the lucky find with John Brooks place of birth: Netherseal, Leicestershire. The place of birth on the 1841 census wasn’t specified, thereafter it was. On the 1851 census John Brooks, cooper, and Sarah his wife were living at Queens Cross, Dudley, with a three year old granddaughter E Brooks. John was born in 1791 in Netherseal.

It was commonplace for people to move to the industrial midlands around this time, from the surrounding countryside. However if they died before the 1851 census stating place of birth, it’s usually impossible to find out where they came from, particularly if they had a common name.

John Brooks doesn’t appear on any further census. I found seven deaths registered in Dudley for a John Brooks between 1851 and 1861, so presumably he is one of them.NETHERSEAL

On 27 June 1790 appears in the Netherseal parish register “John Brooks the son of John and Elizabeth Brooks Priestnal was baptised.” The name Priestnal does not appear in the transcription, nor the Bishops Transcripts, nor on any other sibling baptism. The Priestnal mystery will be solved in the next chapter.

John Brooks senior married Elizabeth Wilson by marriage licence on 20 November 1788 in Gresley, a neighbouring town in Derbyshire (incidentally near to Swadlincote and the ancestral lines of the Warren family, which also has branches in Netherseal. The Brooks family is the Marshall side). John Brooks was a farmer.

I haven’t found a baptism yet for John Brooks senior, but his death in Netherseal in 1846 provided the age at death, eighty years old, which puts his birth at 1766. The 1841 census has his birth as 1766 as well.

In 1841 John Brooks was 75, and “independent”, meaning that he was living on his own means. The name Brooks was transcribed as Broster, making this difficult to find, but it is clearly Brooks if you look at the original.

His wife Elizabeth, born in 1762, is also on the census, as well as the Jackson family: Joseph Jackon born 1804, Elizabeth Jackson his wife born 1799, and children Joseph, born 1833, William 1834, Thomas 1835, Stephen 1836, and Mary born 1838.

John and Elizabeths daughter Elizabeth Brooks, born in 1799, married Joseph Jackson, the son of an “opulent farmer” (newspaper archives) of Tatenhill, Staffordshire. They married on the 19th January 1832 in Burton on Trent. (Elizabeth Brooks was probably the witness on John Brooks junior’s marriage to Mary Wagstaff in Birmingham in 1814, although it could have been his mother, also Elizabeth Brooks.)

(Elizabeth Jackson nee Brooks was the aunt of Elizabeth in the portrait)

Joseph Jackson was declared bankrupt in 1833 (newspapers) and in 1834 a noticed in the newspapers “to the creditors of Joseph Jackson junior”, a victualler and farmer late of Netherseal, “following no business, who was lately dischared from his Majesty’s Gaol at Stafford” whose real estate was to be sold by auction. I haven’t yet found what he was in prison for.

In 1841 Joseph appeared again in the newspapers, in which he publicly stated that he had accused Thomas Webb, surgeon of Barton Under Needwood, of owing him money “just to annoy him” and “with a view to extort money from him”. and that he undertakes to pay Thomas Webb or his attorney, the costs within 14 days.

Joseph and Elizabeth had twins in 1841, born in Netherseal, John and Ruth. Elizabeth died in 1850.

Thereafter, Joseph was a labourer at the iron works in Wednesbury, and many generations of Jacksons continued working in the iron industry in Wednesbury ~ all orignially descended from farmers in Netherseal and Tatenhill.July 16, 2025 at 6:06 am #7969In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Gatacre Hall and The Old Book

In the early 1950s my uncle John and his friend, possibly John Clare, ventured into an abandoned old house while out walking in Shropshire. He (or his friend) saved an old book from the vandalised dereliction and took it home. Somehow my mother ended up with the book.

I remember that we had the book when we were living in USA, and that my mother said that John didn’t want the book in his house. He had said the abandoned hall had been spooky. The book was heavy and thick with a hard cover. I recall it was a “magazine” which seemed odd to me at the time; a compendium of information. I seem to recall the date 1553, but also recall that it was during the reign of Henry VIII. No doubt one of those recollections is wrong, probably the date. It was written in English, and had illustrations, presumably woodcuts.

I found out a few years ago that my mother had sold the book some years before. Had I known she was going to sell it, I’d have first asked her not to, and then at least made a note of the name of it, and taken photographs of it. It seems that she sold the book in Connecticut, USA, probably in the 1980’s.

My cousin and I were talking about the book and the story. We decided to try and find out which abandoned house it was although we didn’t have much to go on: it was in Shropshire, it was in a state of abandoned dereliction in the early 50s, and it contained antiquarian books.

I posted the story on a Shropshire History and Nostalgia facebook group, and almost immediately had a reply from someone whose husband remembered such a place with ancient books and manuscripts all over the floor, and the place was called Gatacre Hall in Claverley, near Bridgnorth. She also said that there was a story that the family had fled to Canada just after WWII, even leaving the dishes on the table.

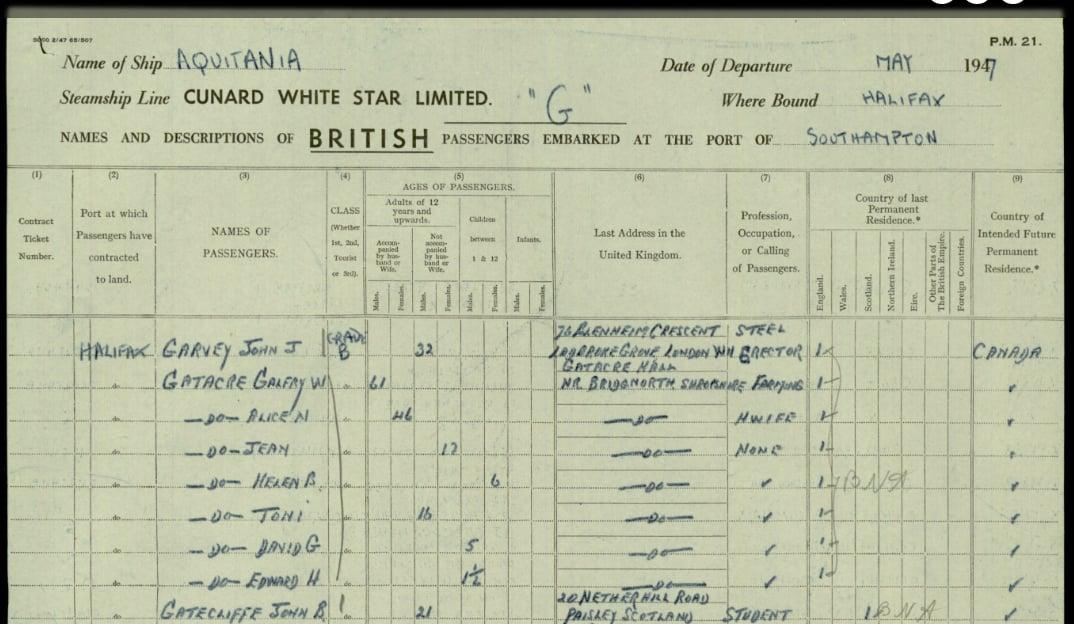

The Gatacre family sailing to Canada in 1947:

When my cousin heard the name Gatacre Hall she remembered that was the name of the place where her father had found the book.

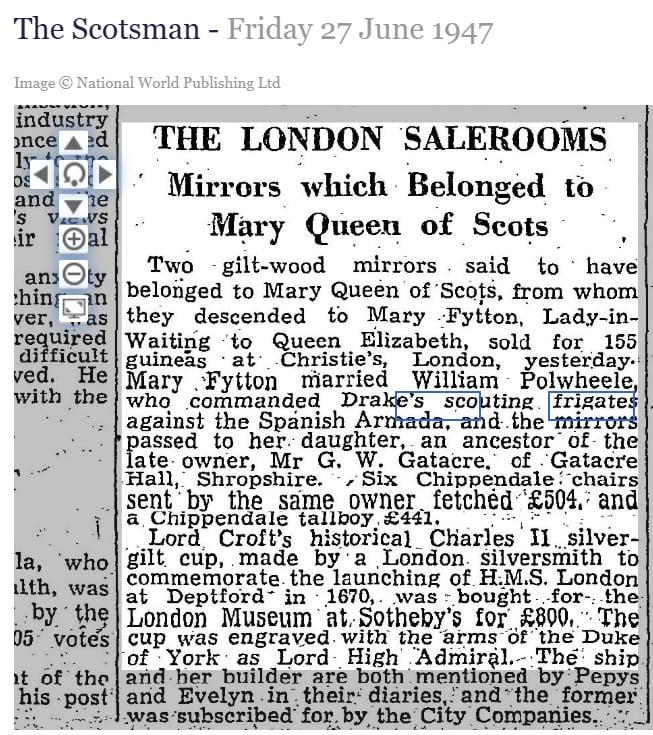

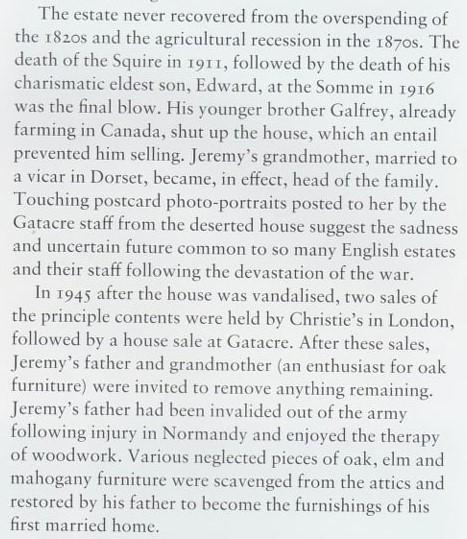

I looked into Gatacre Hall online, in the newspaper archives, the usual genealogy sites and google books searches and so on. The estate had been going downhill with debts for some years. The old squire died in 1911, and his eldest son died in 1916 at the Somme. Another son, Galfrey Gatacre, was already farming in BC, Canada. He was unable to sell Gatacre Hall because of an entail, so he closed the house up. Between 1945-1947 some important pieces of furniture were auctioned, and the rest appears to have been left in the empty house.

The family didn’t suddenly flee to Canada leaving the dishes on the table, although it was true that the family were living in Canada.

An interesting thing to note here is that not long after this book was found, my parents moved to BC Canada (where I was born), and a year later my uncle moved to Toronto (where he met his wife).

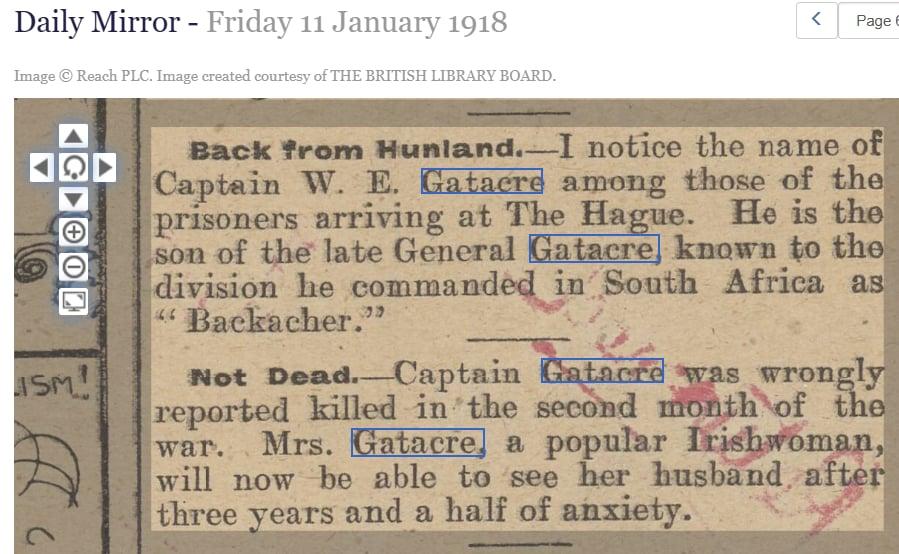

Captain Gatacre in 1918:

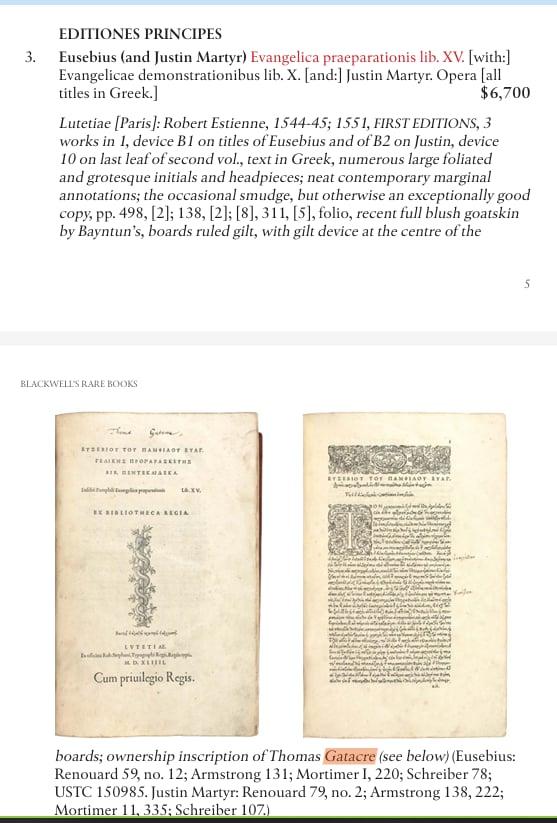

The Gatacre library was mentioned in the auction notes of a particular antiquarian book:

“Provenance: Contemporary ownership inscription and textual annotations of Thomas Gatacre (1533-1593). A younger son of William Gatacre of Gatacre Hall in Shropshire, he studied at the English college at the University of Leuven, where he rejected his Catholic roots and embraced evangelical Protestantism. He studied for eleven years at Oxford, and four years at Magdalene, Cambridge. In 1568 he was ordained deacon and priest by Bishop of London Edmund Grindal, and became domestic chaplain to Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester and was later collated to the rectory of St Edmund’s, Lombard Street. His scholarly annotations here reference other classical authors including Plato and Plutarch. His extensive library was mentioned in his will.”

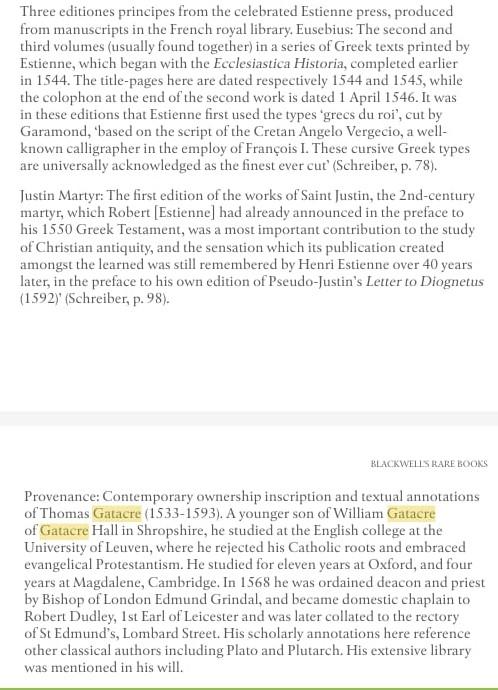

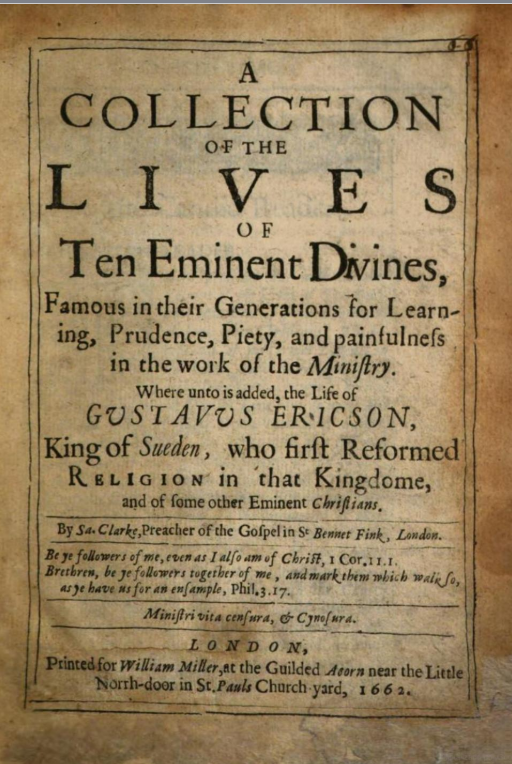

There are thirty four pages in this 1662 book about Thomas Gatacre d 1654:

June 14, 2025 at 8:13 pm #7963

June 14, 2025 at 8:13 pm #7963In reply to: Cofficionados Bandits (vs Lucid Dreamers)

“Well, I think that proves my point,” remarked Carob with a smirk.

“What do you mean”, Thiram said crossly, which sounded more like a resigned sigh than a question.

“Remember what I said? You can’t order a synchronicity, or expect one. They always just happen when you don’t expect it.”

“She’s right,” Any piped up. “We can’t just sit here waiting for a coincidence. We have to just carry on regardless until one appears.”

“Aunt Amy?” Kit asked, “How do we carry on regardless if we don’t know what our story is yet?”

“What I want to know is this,” Chico said with a twirl of his worry beads, “Who’s coming with me to fetch the gazebo back?” Chico squared his shoulders proudly, glad that his new colourful beads had replaced the urge to spit. He felt in control, a new man. A man to be respected. A leader.

With an elaborate triple reverse double flip of the worry beads, Chico turned and strode purposefully into the sunset, in the direction of the gazebo.

June 11, 2025 at 9:14 am #7958In reply to: Cofficionados Bandits (vs Lucid Dreamers)

Chico poured grenadine into an ornate art nouveau glass filled with ginger ale. He hesitated, eying the tin of chicory powder. After a moment of deliberation, he sprinkled a dash into the mix, then added the maraschino cherry.

“I’m not sure Ivar the Boneless, chief of the Draugaskald, will appreciate that twist on his Shirley Temple,” said Godrick. “He may be called Boneless, but he’s got an iron grip and a terrible temper when he’s parched.”

Chico almost dropped the glass. Muttering a quick prayer to the virgin cocktail goddess, he steadied his hand. Amy wouldn’t have appreciated him breaking her freshly conjured aunt Agatha Twothface’s crystal glasses service.

“I don’t know what you mean,” said Chico a tad too quickly. “Do I know you?”

“I’m usually the one making the drinks,” said Godrick. “I served you your first americano when you popped into existence. Chico, right?”

“Oh! Yes. Right. You’re the bartender,” Chico said. He fidgeted. Small talks had always made him feel like a badly tuned Quena flute.

“I am,” said Godrick with a wink. “And if you want a tip? Boneless may forgive you the chicory if you make his cocktail dirty.”

Chico pause, considered, then reached down, grabbed a pinch of dust from the gazebo floor, and sprinkled it on the Temple, like cocoa on a cappuccino foam. He’d worked at Stardust for years before appearing here, after all. When he looked up, Godrick was chuckling.

“Ok!” Godrick said. “Now, add some vodka. I think I’ll take it to Ivar myself.”

“Oh! Right.” Chico nodded, grabbed the vodka bottle and poured in a modest shot and placed it back on the table.

Godrick titled his head. “Looks like your poney wants a sip too.”

For a moment, Chico blinked in confusion at the black stuffed poney standing nearby. Then freshly baked memories flooded in.

Right, the poney’s name was Tyrone.

It had been a broken toy that someone had tossed in the street. Amy had insisted Chico take it home. “It needs saving,” she said. “And you need the company.”

At first, Chico didn’t know what to do with it. He ended up replacing some of the missing stuffing with dried chicory leaves.

The next morning, Tyrone was born and trotting around the apartment. All he ever wanted was strong alcohol.

Chico had a strange thought, scrolling across the teleprompter in his mind.

Is that how character building works?

June 10, 2025 at 7:39 pm #7956In reply to: Cofficionados Bandits (vs Lucid Dreamers)

“Solar kettle, my ass,” Chico muttered, failing to resist the urge to spit. After wiping his chin on his tattood forearm, he spoke up loudly, “That was no solar kettle in the gazebo. That was the Sabulmantium!”

An audible gasp echoed around the gathering, with some slight reeling and clutching here and there, dropping jaws, and in the case of young Kit, profoundly confused trembling.

Kit desperately wanted to ask someone what a Sabulmantium was, but chose to remain silent.

Amy was frowning, trying to remember. Sure, she knew about it, but what the hell did it DO?

A sly grin spread across Thiram’s face when he noticed Amy’s perplexed expression. It was a perfect example of a golden opportunity to replace a memory with a new one.

Reading Thiram’s mind, Carob said, “Never mind that now, there’s a typhoon coming and the gazebo has vanished over the top of those trees. I can’t for the life of me imagine how you can be thinking about tinkering with memories at a time like this! And where is the Sabulmantium now?”

“Please don’t distress yourself further, dear lady, ” Sir Humphrey gallantly came to Carob’s aid, much to her annoyance. “Fret not your pretty frizzy oh so tall head.”

Carob elbowed him in the eye goodnaturedly, causing him to stumble and fall. Carob was even more annoyed when the fall rendered Sir Humphrey unconscious, and she found herself trying to explain that she’d meant to elbow him in the ribs with a sporting chuckle and had not intentionally assaulted him.

Kit had been just about to ask Aunt Amy what a Sabulmantium was, but the moment was lost as Amy rushed to her fathers side.

After a few moments of varying degrees of anguish with all eyes on the prone figure of the Padre, Sir Humphrey sat up, asking where his Viking hat was.

And so it went on, at every mention of the Sabulmantium, an incident occured, occasioning a diversion on the memory lanes.

April 29, 2025 at 7:18 pm #7913In reply to: Cofficionados Bandits (vs Lucid Dreamers)

Amy wondered afterwards if she should have said “Why is it always my fault” and hoped nobody would think el gran apagón was her fault too. Another one of the issues with typecasting too soon.

The rumours and hoaxes were rife even before the electricity came back on. The crisis of the lack of coffee beans was coming to a head: morning riots were breaking out in the places most affected by the shortage. As soon as the blackouts started, improvised statistics and numbers were cobbled together into snappy psychological colour combination images and plastered everywhere suggesting that the lack of electricity was saving an incomprehensible number of cups of coffee per day, but without causing any coffee related social disorder events.

Amy had heard that el gran apagón was foretold to occur when the pope died, that it was extraterrestrials, that it was el naranjo and his sidekick effin muck, and all manner of things, but the concerns with the coffee shortage happening at the same time as the blackouts were manifold.

The population was looking for scapegoats. Oh dear god, what did I say that for.

April 27, 2025 at 1:39 pm #7909In reply to: Cofficionados Bandits (vs Lucid Dreamers)

A mad cackle started to shake the Universe again.

“Mmm…” Thiram interjected. “Not like you to be so hung up on details now? Although, I thought that was the whole point — coffee beans acclimation to whole unexpected new places, with the AI models predicting or hallucinating the shifts of weather patterns and all? Surely coffee beans no longer grow where they’re supposed to?”

They all looked at him with eyes like coffee cup’s saucers.

“And what’s that place you’re calling Florida by the way?” he felt pressed to add.

The cackling intensified, shaking their sense of geography to the core.

March 28, 2025 at 10:28 pm #7881In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

Mars Outpost — Welcome to the Wild Wild Waste

No one had anticipated how long it would take to get a shuttle full of half-motivated, gravity-averse Helix25 passengers to agree on proper footwear.

“I told you, Claudius, this is the fancy terrain suit. The others make my hips look like reinforced cargo crates,” protested Tilly Nox, wrangling with her buckles near the shuttle airlock.

“You’re about to step onto a red-rock planet that hasn’t seen visitors since the Asteroid Belt Mining Fiasco,” muttered Claudius, tightening his helmet strap. “Your hips are the least of Mars’ concerns.”

Behind them, a motley group of Helix25 residents fidgeted with backpacks, oxygen readouts, and wide-eyed anticipation. Veranassessee had allowed a single-day “expedition excursion” for those eager—or stir-crazy—enough to brave Mars’ surface. She’d made it clear it was volunteer-only.

Most stayed aboard, in orbit of the red planet, looking at its surface from afar to the tune of “eh, gravity, don’t we have enough of that here?” —Finkley had recoiled in horror at the thought of real dust getting through the vents and had insisted on reviewing personally all the airlocks protocols. No way that they’d sullied her pristine halls with Martian dust or any dust when the shuttle would come back. No – way.

But for the dozen or so who craved something raw and unfiltered, this was it. Mars: the myth, the mirage, the Far West frontier at the invisible border separating Earthly-like comforts into the wider space without any safety net.

At the helm of Shuttle Dandelion, Sue Forgelot gave the kind of safety briefing that could both terrify and inspire. “If your oxygen starts blinking red, panic quietly and alert your buddy. If you fall into a crater, forget about taking a selfie, wave your arms and don’t grab on your neighbor. And if you see a sand wyrm, congratulations, you’ve either hit gold or gone mad.”

Luca Stroud chuckled from the copilot seat. “Didn’t see you so chirpy in a long while. That kind of humour, always the best warning label.”

They touched down near Outpost Station Delta-6 just as the Martian wind was picking up, sending curls of red dust tumbling like gossip.

And there she was.

Leaning against the outpost hatch with a spanner slung across one shoulder, goggles perched on her forehead, Prune watched them disembark with the wary expression of someone spotting tourists traipsing into her backyard garden.

Sue approached first, grinning behind her helmet. “Prune Curara, I presume?”

“You presume correctly,” she said, arms crossed. “Let me guess. You’re here to ruin my peace and use my one functioning kettle.”

Luca offered a warm smile. “We’re only here for a brief scan and a bit of radioactive treasure hunting. Plus, apparently, there’s been a petition to name a Martian dust lizard after you.”

“That lizard stole my solar panel last year,” Prune replied flatly. “It deserves no honor.”

Inside, the outpost was cramped, cluttered, and undeniably charming. Hand-drawn maps of Martian magnetic hotspots lined one wall; shelves overflowed with tagged samples, sketchpads, half-disassembled drones, and a single framed photo of a fireplace with something hovering inexplicably above it—a fish?

“Flying Fish Inn,” Luca whispered to Sue. “Legendary.”

The crew spent the day fanning out across the region in staggered teams. Sue and Claudius oversaw the scan points, Tilly somehow got her foot stuck in a crevice that definitely wasn’t in the geological briefing, which was surprisingly enough about as much drama they could conjure out.

Back at the outpost, Prune fielded questions, offered dry warnings, and tried not to get emotionally attached to the odd, bumbling crew now walking through her kingdom.

Then, near sunset, Veranassessee’s voice crackled over comms: “Curara. We’ll be lifting a crew out tomorrow, but leaving a team behind. With the right material, for all the good Muck’s mining expedition did out on the asteroid belt, it left the red planet riddled with precious rocks. But you, you’ve earned to take a rest, with a ticket back aboard. That’s if you want it. Three months back to Earth via the porkchop plot route. No pressure. Your call.”

Prune froze. Earth.

The word sat like an old song on her tongue. Faint. Familiar. Difficult to place.

She stepped out to the ridge, watching the sun dip low across the dusty plain. Behind her, laughter from the tourists trading their stories of the day —Tilly had rigged a heat plate with steel sticks and somehow convinced people to roast protein foam. Are we wasting oxygen now? Prune felt a weight lift; after such a long time struggling to make ends meet, she now could be free of that duty.

Prune closed her eyes. In her head, Mater’s voice emerged, raspy and amused: You weren’t meant to settle, sugar. You were meant to stir things up. Even on Mars.

She let the words tumble through her like sand in her boots.

She’d conquered her dream, lived it, thrived in it.

Now people were landing, with their new voices, new messes, new puzzles.

She could stay. Be the last queen of red rock and salvaged drones.

Or she could trade one hell of people for another. Again.

The next morning, with her patched duffel packed and goggles perched properly this time, Prune boarded Shuttle Dandelion with a half-smirk and a shrug.

“I’m coming,” she told Sue. “Can’t let Earth ruin itself again without at least watching.”

Sue grinned. “Welcome back to the madhouse.”

As the shuttle lifted off, Prune looked once, just once, at the red plains she’d called home.

“Thanks, Mars,” she whispered. “Don’t wait up.”

March 23, 2025 at 7:37 am #7878In reply to: The Precious Life and Rambles of Liz Tattler

Liz threw another pen into the tin wastepaper basket with a clatter and called loudly for Finnley while giving her writing hand a shake to relieve the cramp.

Finnley appeared sporting her habitual scowl clearly visible above her paper mask. “I hope this is important because this red dust is going to take days to clean up as it is without you keep interrupting me.”

“Oh is that what you’ve been doing, I wondered where you were. Well, let’s thank our lucky stars THAT’S all over!”

“Might be over for you,” muttered Finnley, “But that hare brained scheme of Godfrey’s has caused a very great deal of work for me. He’s made more of a mess this time than even you could have, red dust everywhere and all these obsolete parts all over the place. Roberto’s on his sixth trip to the recycling depot, and he’s barely scratched the surface.”

“Good old Roberto, at least he doesn’t keep complaining. You should take a leaf out of his book, Finnley, you’d get more work done. And speaking of books, I need another packet of pens. I’m writing my books with a pen in future. On paper. Oh and get me another pack of paper.”

Mildly curious, despite her irritation, Finnely asked her why she was writing with a pen on paper. “Is it some sort of historical re enactment? Would you prefer parchment and a quill? Or perhaps a slab of clay and some etching tools? Shall we find you a nice cave,” Finnley was warming to the theme, “And some red ochre and charcoal?”

“It may come to that,” Liz replied grimly. “But some pens and paper will do for now. Godfrey can’t interfere in my stories if I write them on paper. Robots writing my stories, honestly, who would ever have believed such a thing was possible back when I started writing all my best sellers! How times have changed!”

“Yet some things never change, ” Finnley said darkly, running her duster across the parts of Liz’s desk that weren’t covered with stacks of blue scrawled papers.

“Thank you for asking,” Liz said sarcastically, as Finnley hadn’t asked, “It’s a story about six spinsters in the early 19th century.”

“Sounds gripping,” muttered Finnley.

“And a blind uncle who never married and lived to 102. He was so good at being blind that he knew all his sheep individually.”

“Perhaps that’s why he never needed to marry,” Finnley said with a lewd titter.

“The steamy scenes I had in mind won’t be in the sheep dip,” Liz replied, “Honestly, what a low degraded mind you must have.”

“Yeah, from proof reading your trashy novels,” Finnley replied as she flounced out in search of pens and paper.

March 22, 2025 at 11:16 am #7875In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

Mars Outpost — Fueling of Dreams (Prune)

I lean against the creaking bulkhead of this rust-stained fueling station, watching Mars breathe. Dust twirls across the ochre plains like it’s got somewhere important to be. The whole place rattles every time the wind picks up—like the metal shell itself is complaining. I find it oddly comforting. Reminds me of the Flying Fish Inn back home, where the fireplace wheezed like a drunk aunt and occasionally spit out sparks for drama.

Funny how that place, with all its chaos and secret stash hidey-holes, taught me more about surviving space than any training program ever could.

“Look at me now, Mater,” I catch myself thinking, tapping the edge of the viewport with a gloved knuckle. “Still scribbling starships in my head. Only now I’m living inside one.”

Behind me, the ancient transceiver gives its telltale blip… blip. I don’t need to check—I recognize the signal. Helix 25, closing in. The one ship people still whisper about like it’s a myth with plumbing. Part of me grins. Half nostalgia, half challenge.

Back in ’27, I shipped off to that mad boarding school with the oddball astronaut program. Professors called me a prodigy. I called it stubborn curiosity and a childhood steeped in ghost stories, half-baked prophecies, and improperly labeled pickle jars. The real trick wasn’t the calculus—it was surviving the Curara clan’s brand of creative chaos.

After graduation, I bought into a settlers’ programme. Big mistake. Turns out it was more con than colonization, sold with just enough truth to sting. Some people cracked. I just adjusted course. Spent some time bouncing between jobs, drifted home a couple times for stew and sideways advice, and kept my head sharp. Lesson logged: deceit’s just another puzzle with missing pieces.

A hiss behind the wall cuts into my thoughts—pipes complaining again. I spin, scan the console. Pressure’s holding. “Fine,” which out here means “still not exploding.” Good enough.

I remember the lottery ticket that got me here— 2049, commercial flights to Mars at last soared skyward— and Effin Muck’s big lottery. At last a seat to Mars, on section D. Just sheer luck that felt like a miracle at the time. But while I was floating spaceward, Earth went sideways: asteroid mining gone wrong, panic, nuclear strikes. I watched pieces of home disappear through a porthole while the Mars colonies went silent, one by one. All those big plans reduced to empty shells and flickering lights.

I was supposed to be evacuated, too. Instead, my lowly post at this fueling station—this rust bucket perched on a dusty plateau—kept me in place. Cosmic joke? Probably. But here I am. Still alive. Still tinkering with things that shouldn’t work. Still me.

I reprogrammed the oxygen scrubbers myself. Hacked them with a dusty old patch from Aunt Idle’s “Dream Time” stash. When the power systems started failing and had to cut all the AI support to save on power, I taught myself enough broken assembly code to trick ancient processors into behaving. Improvisation is my mother tongue.

“Mars is quieter than the Inn,” I say aloud, half to myself. “Only upside, really.”

Another ping from the transceiver—it’s getting closer. The Helix 25, humanity’s last-ditch bottle-in-space. They say it’s carrying what’s left of us. Part myth, part mobile city. If I didn’t have the logs, I’d half believe it was a fever dream.

But no dream prepares you for this kind of quiet.

I think about the Inn again. How everyone swore it had secret tunnels, cursed tiles, hallucinations in the pantry. Honestly, it probably did. But it also had love—scrambled, sarcastic love—and enough stories to keep you wondering if any of them were real. That’s where I learned to spot a lie, tell a better one, and stay grounded when the walls started talking.

I smack the comm panel until it stops crackling. That’s the secret to maintenance on Mars: decisive violence.

“All right, Helix,” I mutter. “Let’s see what you’ve got. I’ve got thruster fuel, half-functional docking protocols, and a mean kettle of tea if you’re lucky.”

I catch my reflection in the viewport glass—older, sure. Forty-two now. Taller. Calmer in the eyes. But the glint’s still there, the one that says I’ve seen worse, and I’m still standing. That kid at the Inn would’ve cheered.

Earth’s collapse wasn’t some natural catastrophe—it was textbook human arrogance. Effin Muck’s greedy asteroid mining scheme. World leaders playing hot potato with nuclear codes. It burned. Probably still does… But I can’t afford to stew in it. We’re not here to mourn; we’re here to rebuild. If someone’s going to help carry that torch, it might as well be someone who’s already walked through fire.

I fiddle with the dials on the fuel board. It hums like a tired dragon, but it’s awake. That’s all I need.

“Might be time to pass some of that brilliance along,” I mutter, mostly to the station walls. Somewhere, I bet my siblings are making fun of me. Probably watching soap dramas and eating improperly reheated stew. Bless them. They were my first reality check, and I still measure the world by how weird it is compared to them. Loved them for how hard they made me feel normal after all.

The wind howls across the shutters. I stand up straight, brush the dust off my sleeves. Helix 25 is almost here.

“Showtime,” I say, and grin. Not the nice kind. The kind that says I’ve got one wrench, three working systems, and no intention of rolling over.

The Flying Fish Inn shaped me with every loud, strange, inexplicable day. It gave me humor. It gave me bite. It gave me an unshakable sense of self when everything else fell apart.

So here I stand—keeper of the last Martian fueling post, scrappy guardian of whatever future shows up next.

I glance once more at the transceiver, then hit the big green button to unlock the landing bay.

“Welcome to Mars,” I say, deadpan. Then add, mostly to myself, “Let’s see if they’re ready for me.”

-

AuthorSearch Results