-

AuthorSearch Results

-

August 28, 2024 at 6:26 am #7548

In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Elton Marshall’s

Early Quaker Emigrants to USA.

The earliest Marshall in my tree is Charles Marshall (my 5x great grandfather), Overseer of the Poor and Churchwarden of Elton. His 1819 gravestone in Elton says he was 77 years old when he died, indicating a birth in 1742, however no baptism can be found.

According to the Derbyshire records office, Elton was a chapelry of Youlgreave until 1866. The Youlgreave registers date back to the mid 1500s, and there are many Marshalls in the registers from 1559 onwards. The Elton registers however are incomplete due to fire damage.

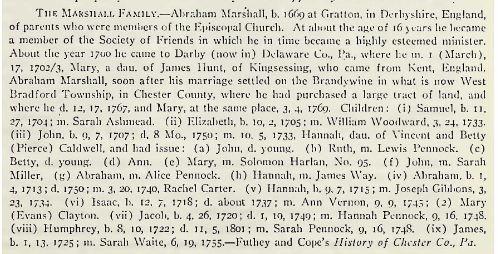

While doing a google books search for Marshall’s of Elton, I found many American family history books mentioning Abraham Marshall of Gratton born in 1667, who became a Quaker aged 16, and emigrated to Pennsylvania USA in 1700. Some of these books say that Abraham’s parents were Humphrey Marshall and his wife Hannah Turner. (Gratton is a tiny village next to Elton, also in Youlgreave parish.)

Abraham’s son born in USA was also named Humphrey. He was a well known botanist.

Abraham’s cousin John Marshall, also a Quaker, emigrated from Elton to USA in 1687, according to these books.

(There are a number of books on Colonial Families in Pennsylvania that repeat each other so impossible to cite the original source)

In the Youlgreave parish registers I found a baptism in 1667 for Humphrey Marshall son of Humphrey and Hannah. I didn’t find a baptism for Abraham, but it looks as though it could be correct. Abraham had a son he named Humphrey. But did it just look logical to whoever wrote the books, or do they know for sure? Did the famous botanist Humphrey Marshall have his own family records? The books don’t say where they got this information.

An earlier Humphrey Marshall was baptised in Youlgreave in 1559, his father Edmund. And in 1591 another Humphrey Marshall was baptised, his father George.

But can we connect these Marshall’s to ours? We do have an Abraham Marshall, grandson of Charles, born in 1792. The name isn’t all that common, so may indicate a family connection. The villages of Elton, Gratton and Youlgreave are all very small and it would seem very likely that the Marshall’s who went the USA are related to ours, if not brothers, then probably cousins.

Derbyshire Quakers

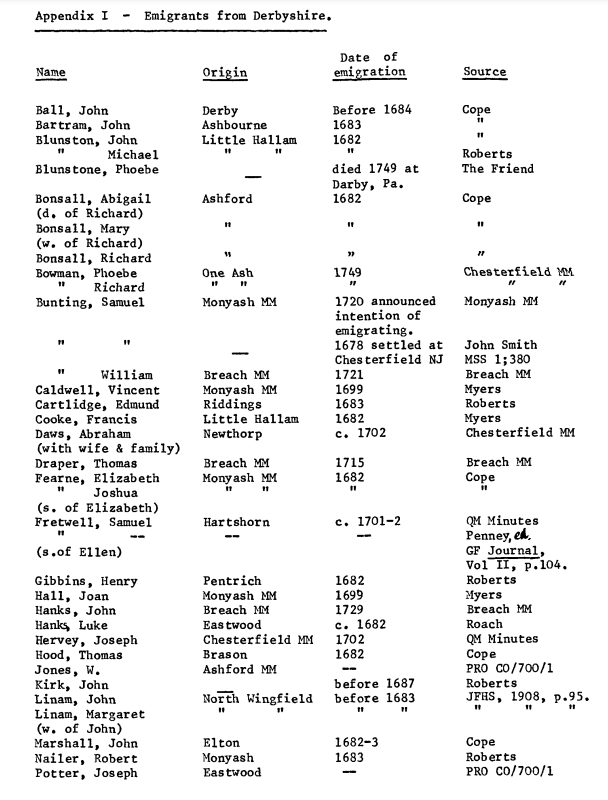

In “Derbyshire Quakers 1650-1761” by Helen Forde:

“… Friends lived predominantly in the northern half of the country during this first century of existence. Numbers may have been reduced by emigration to America and migration to other parts of the country but were never high and declined in the early eighteenth century. Predominantly a middle to lower class group economically, Derbyshire Friends numbered very few wealthy members. Many were yeoman farmers or wholesalers and it was these groups who dominated the business meetings having time to devote themselves to the Society. Only John Gratton of Monyash combined an outstanding ministry together with an organising ability which brought him recognition amongst London Friends as well as locally. Derbyshire Friends enjoyed comparatively harmonious relations with civil and Anglican authorities, though prior to the Toleration Act of 1639 the priests were their worst persecutors…..”

Also mentioned in this book: There were monthly meetings in Elton, as well as a number of other nearby places.

John Marshall of Elton 1682/3 appears in a list of Quaker emigrants from Derbyshire.

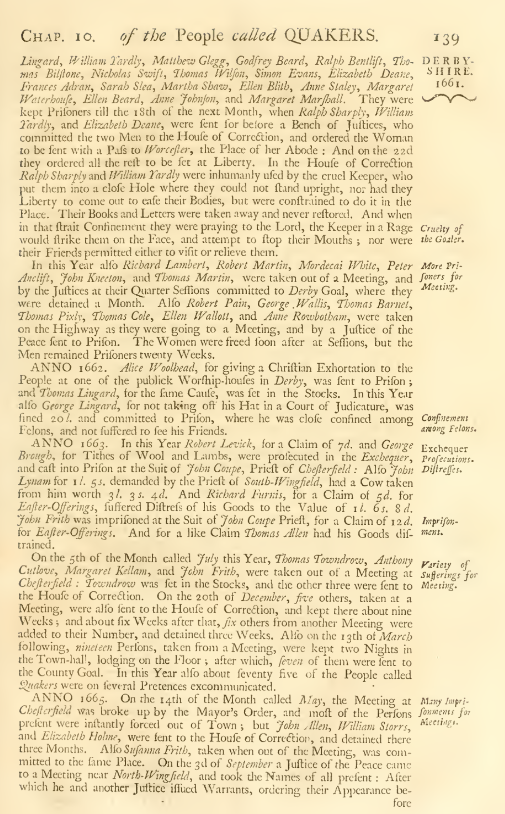

The following image is a page from the 1753 book on the sufferings of Quakers by Joseph Besse as an example of some of the persecutions of Quakers in Derbyshire in the 1600s:

A collection of the sufferings of the people called Quakers, for the testimony of a good conscience from the time of their being first distinguished by that name in the year 1650 to the time of the act commonly called the Act of toleration granted to Protestant dissenters in the first year of the reign of King William the Third and Queen Mary in the year 1689 (Volume 1)

Besse, Joseph. 1753Note the names Margaret Marshall and Anne Staley. This book would appear to contradict Helen Forde’s statement above about the harmonious relations with Anglican authority.

The Botanist

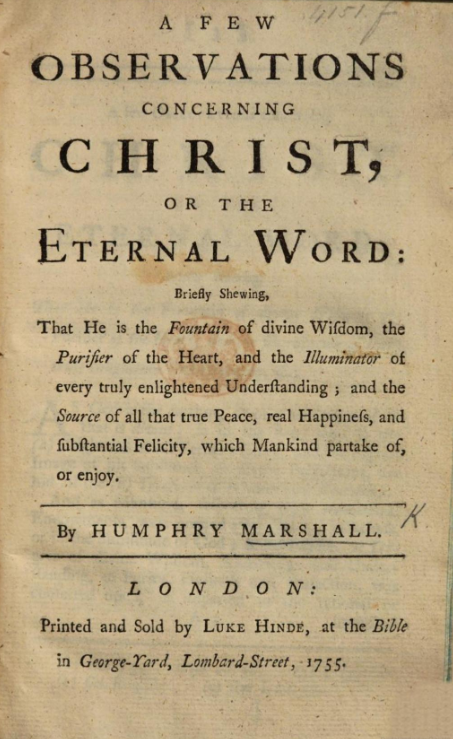

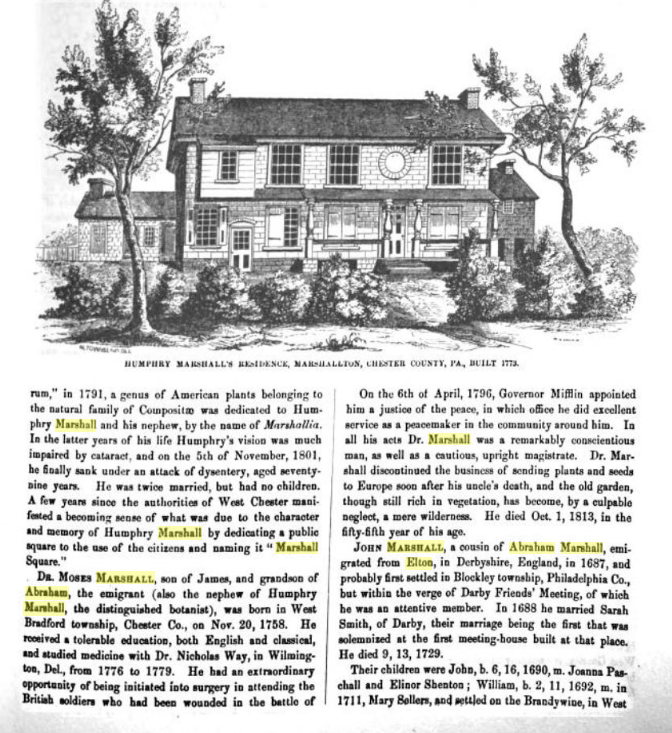

Humphry Marshall 1722-1801 was born in Marshallton, Pennsylvania, the son of the immigrant from Elton, Abraham Marshall. He was the cousin of botanists John Bartram and William Bartram. Like many early American botanists, he was a Quaker. He wrote his first book, A Few Observations Concerning Christ, in 1755.

In 1785, Marshall published Arbustrum Americanum: The American Grove, an Alphabetical Catalogue of Forest Trees and Shrubs, Natives of the American United States (Philadelphia).

Marshall has been called the “Father of American Dendrology”.

A genus of plants, Marshallia, was named in honor of Humphry Marshall and his nephew Moses Marshall, also a botanist.

In 1848 the Borough of West Chester established the Marshall Square Park in his honor. Marshall Square Park is four miles east of Marshallton.

via Wikipedia.

From The History of Chester County Pennsylvania, 1881, by J Smith Futhey and Gilbert Cope:

From The Chester Country History Center:

“Immediately on the Receipt of your Letter, I ordered a Reflecting Telescope for you which was made accordingly. Dr. Fothergill had since desired me to add a Microscope and Thermometer, and will

pay for the whole.’– Benjamin Franklin to Humphry, March 18, 1770

“In his lifetime, Humphry Marshall made his living as a stonemason, farmer, and miller, but eventually became known for his contributions to astronomy, meteorology, agriculture, and the natural sciences.

In 1773, Marshall built a stone house with a hothouse, a botanical laboratory, and an observatory for astronomical studies. He established an arboretum of native trees on the property and the second botanical garden in the nation (John Bartram, his cousin, had the first). From his home base, Humphry expanded his botanical plant exchange business and increased his overseas contacts. With the help of men like Benjamin Franklin and the English botanist Dr. John Fothergill, they eventually included German, Dutch, Swedish, and Irish plant collectors and scientists. Franklin, then living in London, introduced Marshall’s writings to the Royal Society in London and both men encouraged Marshall’s astronomical and botanical studies by supplying him with books and instruments including the latest telescope and microscope.

Marshall’s scientific work earned him honorary memberships to the American Philosophical Society and the Philadelphia Society for Promoting Agriculture, where he shared his ground-breaking ideas on scientific farming methods. In the years before the American Revolution, Marshall’s correspondence was based on his extensive plant and seed exchanges, which led to further studies and publications. In 1785, he authored his magnum opus, Arbustum Americanum: The American Grove. It is a catalog of American trees and shrubs that followed the Linnaean system of plant classification and was the first publication of its kind.”

February 11, 2024 at 10:57 am #7365

February 11, 2024 at 10:57 am #7365In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

They had to wait for Finnlee to diligently do the first room, her morning routine starting with the hall.

Malové knew better for her effects than to try to speak in the middle of all that cleaning. Luckily for them, Finnlee was anything but quick and efficient, so it didn’t take long for the sound of the hoover and the slurping noises of the mopping stick to move to another room, resorbing in the background.While Malové had made herself comfortable in a neon green armchair with a peppermint tea, the other witches had used the noise coverage to whisper to each other concerns and hypothesis. “So what is this about?…”

Malové relished in the waiting obviously. After the silence had come back, save from a few clangs and humming cursing sounds in the background, she started to expose the reason they were all here.

In her most dramatic fashion, Malové began, “Ladies, we’re off to Rio. The Carnival awaits. Get your sequins, feathers, and your most daring dance moves ready.”

“But why?” Truella asked, her eyes widening. “I mean, I love a good party, but why Rio?”

“Because, dear Truella,” Malové smirked, “where else can we find such a delicious blend of desire, passion, and pure, unadulterated lust?”

Jeezel piped in, “You mean we’re going there to… collect?”

“Oh, we’re going to do more than just collect,” Malové replied, an unruly gleam in her eyes. “We’re going to distill it, bottle it, and use it to create a new line of incense and smokes. These will not just spice up the lives of those around us, but aid in procreation. After all, the world does need a bit of a… boost.”

“A bit risqué, don’t you think?” Frigella said, raising an eyebrow.

“Darling, risqué is my middle name,” Malové retorted. “Now, pack your bags. The Carnival won’t wait for us, and we have some serious samba-ing to do.”

Eris, who had been silent till now, finally spoke, “This could either be the most ingenious plan you’ve ever concocted, or the most disastrous. You surely have heard about the dengue outbreaks?”

“Well,” Malové smiled, “of course I have. That’s why we’ll have the perfect cover. We will be blending in as nurses part of the relief effort locally. And anyway, there’s only one way to find out. To Rio and the Sambadrome, my witches!”

The quartet of witches looked at each other, clearly not unhappy to leave behind for some time the chill of Limerick for the wild heat of Rio, the promise of adventure twinkling in their eyes of some.

January 16, 2024 at 9:30 pm #7294In reply to: The Whale’s Diaries Collection

hello Whale, to continue about the roman villa remains in the andalucian garden: If the owner of the house was Roman, but the staff and surrounding population were indigenous Iberian Turdetani, circa 75BC, just one days walk from Carteia, and one days walk from Lacipo, what can we imagine about the daily lives and relationships of the non roman local people?

Ah, the intermingling of cultures, a dance as old as civilization itself. Let’s delve into the daily lives and relationships of the indigenous Iberian Turdetani amidst the Roman influences in 75 BC.

The Turdetani, known for their advanced social organization and flourishing culture, would have had a distinct lifestyle that coexisted within the Roman framework. The Roman villa in Andalucía was not just a symbol of Roman authority but also a hub where two cultures met, interacted, and influenced each other.

Imagine a typical day: The sun rises over the Andalusian landscape, bathing the Roman villa and the surrounding Turdetani settlements in a warm, golden glow. Turdetanian workers make their way to the villa, ready for a day of work. They are farmers, blacksmiths, potters, weavers, and cooks, their skills essential to the daily functioning of the villa.

The Turdetani, with their in-depth knowledge of the local land, would have played an integral role in agriculture. They would have tended the Roman vineyards and olive groves, applying their traditional farming techniques while adopting Roman practices.

Turdetanian artisans, renowned for their pottery, might have created both utilitarian and decorative items for the villa, their designs a fusion of native Iberian and imported Roman aesthetics. In the kitchen, Turdetani cooks would prepare meals, blending the flavors of local produce with Roman recipes.

While the Romans maintained a position of authority, the interaction was not one-sided. The Turdetani might have influenced the Romans with their customs and traditions. Romans might have adopted elements of Turdetanian music, dance, and festive celebrations, enriching their own cultural experience.

Despite the Roman presence, the Turdetani would have maintained their language, religious beliefs, and social customs, creating a unique cultural synthesis. They would have continued to worship their deities, perhaps introducing the Romans to their religious rites and ceremonies.

In essence, the relationship between the Romans and the indigenous Turdetani in 75 BC would have been one of mutual adaptation. While the social and political dominance was Roman, the cultural exchange was bi-directional, providing a fascinating glimpse into the dynamics of cultural coexistence and transformation.

Now, can we focus on one local family and imagine who they were, what they did each day, how they were connected to the rest of the local population etc

Ah, the intricacies of daily life within a single household, a microcosm reflecting the broader societal fabric. Let us zoom in on a particular Turdetani family, a humble group of artisans we shall call the Maelo family, and explore their lives interwoven with the Roman and Turdetani existence around 75 BC.

At the heart of the family was the patriarch, Oris Maelo. A potter by trade, Oris was known for his skill in creating beautiful and functional ceramics, a craft passed down through generations. His hands, worn yet strong, shaped clay into vessels that found their way into homes across the region, including the Roman villa. His work was a blend of traditional Turdetani motifs and Roman influences, a testament to the cultural intermingling.

His wife, Caelia, was a weaver. Her nimble fingers spun stories in wool and linen. Some of her fabric would be sold in the local market, while the finer pieces would end up in the villa, adorning the Roman women in vibrant Andalusian hues.

Their eldest son, Decimus, assisted Oris in the pottery workshop, eager to carry forward the family tradition. Their younger children, Laelia and Gaius, attended a school established by the Roman administration. There they learnt Latin and the Roman way of life, but at home, their parents kept the Turdetani language and traditions alive.

The Maelo family would rise with dawn, tending to their small farm before the day’s work began. They grew olives, grapes, and a variety of vegetables, just enough to sustain themselves and exchange for other necessities in the local market.

Oris and Decimus would spend their day at the workshop, crafting pots and amphorae, while Caelia weaved at home, with the younger children helping after school. Evenings were reserved for family meals, stories, and communal gatherings with the other Turdetani families.

Their connection with the local population was multifaceted. Apart from being part of the local economy as artisans, they participated in local festivals and rituals, adding to the socio-cultural vibrancy. Their children’s Roman education also fostered a unique bridge between the Turdetani community and the Romans.

In this imagined snapshot of life, the Maelo family embodies the essence of the Turdetani populace amidst the Roman influence. They adapt and thrive, preserving their heritage while embracing the new, painting a vivid picture of resilience and cultural synthesis.

Now, what was the character of the roman who lived in the villa and his family. Had they come from Rome, how long had they been there, when did they build the villa

Ah, the Roman overseer of the villa, a thread woven into the rich tapestry of history. Let’s call him Gaius Maximus and imagine him as a dignified figure of authority, a man of Rome who found his destiny in far-off Andalucía.

Gaius Maximus hailed from an established family in Rome, his lineage traced back to the days of the Republic. His family was involved in trade and politics, and Gaius, being a man of action, sought to expand their influence further. Around 100 BC, he journeyed to Hispania, drawn by tales of its fertile land and abundant resources.

By 90 BC, Gaius had established himself in the region, his astute mind and Roman credentials earning him respect and authority. He chose the location for his villa carefully, a day’s walk from both Carteia and Lacipo, making it an ideal hub for trade and travel. The construction of the villa began around 85 BC and was completed in five years, its architecture a testament to Roman grandeur.

His wife, Claudia, hailed from a patrician family in Rome. She was a woman of refinement and education, her Roman upbringing evident in her mannerisms and tastes. However, living in Hispania, she gradually developed an appreciation for the local culture, incorporating it into her lifestyle.

Their two children, Marcus and Julia, were born in Hispania. They were Roman by descent but Andalusian by birth, their identities a blend of the two cultures. Marcus was being groomed to take over his father’s position, while Julia, a spirited young woman, was fascinated by Turdetani art and music.

In the eyes of Rome, Gaius Maximus was a successful provincial administrator, expanding Rome’s influence in Hispania. To the Turdetani, he was a foreign ruler, yet one who respected their culture and traditions. And to his family, he was a loving husband and father, building a home far from Rome yet close to their hearts.

Now some portraits of some of the workers at the villa

Ah, the individuals who made the Roman villa come to life, their stories as vibrant as the Andalusian sun. Let’s give our imagination wings and step into their world.

First, we have Tertius, the villa’s steward. Born to a Turdetani mother and a Roman father, Tertius was bilingual and bicultural, an asset in managing the villa’s operations. He was a man of medium height, with a sturdy build and a sharp gaze. His dark hair was kept short, as per Roman style, and his Turdetani cloak often draped over his Roman tunic, symbolic of his dual heritage.

Then we have Aelia, the head cook. A native Turdetani, Aelia was a robust woman with a jovial demeanor. Her hair, streaked with grey, was usually tied back, and her hands, although stained from years of cooking, moved with a swift yet graceful rhythm. Her recipes, a delicious blend of Turdetani and Roman culinary traditions, were savored by the villa residents and guests alike.

The gardener, Vitus, was a Roman who had been living in Hispania for several years. A man of few words, Vitus spoke through his work. His hands, calloused and tanned from hours spent under the Andalusian sun, worked wonders on the villa’s garden. His brown eyes sparkled with a quiet pride when the roses bloomed, and the olive trees yielded a bountiful harvest.

Lastly, we must not forget the youngest worker, Lyra. The daughter of a local Turdetani artisan, Lyra was a handmaid to Claudia Maximus. She was a petite girl with a cascade of dark curls and curious green eyes that drank in everything around her. Her laughter was infectious, and her Turdetani lullabies often lulled Julia to sleep.

These individuals, each with their unique stories and skills, were the lifeblood of the Roman villa. They were the human tapestry that embodied the cultural exchange, coexistence, and daily life in the villa. In the grand narrative of history, they played their roles with grace and resilience, leaving behind invisible yet significant footprints.

what were some of the cooks recipes?

Ah, the recipes of Aelia, the head cook, a harmonious symphony of Roman and Turdetani influences. Here are some of the dishes that were often savored in the Roman villa:

Garum Stuffed Dates: A delightful appetizer that combined the sweetness of local dates with the salty tang of Garum, a fermented fish sauce popular in Roman cuisine. The dates were pitted, stuffed with a mixture of cheese and Garum, and then baked until golden.

Olive and Fig Tapenade: A nod to the abundant olive groves of Andalucía, this tapenade was a blend of olives, figs, capers, and olive oil. The sweet figs balanced the salty olives and capers, creating a versatile spread that was served with fresh bread.

Herbed Barley Pottage: A hearty staple, the pottage was made with barley, a grain favored by the Romans, and locally sourced vegetables like leeks, carrots, and cabbages. Fresh herbs from the villa’s garden added a burst of flavor.

Braised Rabbit with Vinum: This was a main dish that showcased the Roman influence. Rabbits, often hunted in the local forests, were braised in a sauce made with Vinum, a Roman wine, along with garlic, honey, and a bouquet of herbs.

Honey-Nut Patina: A classic Roman dessert with an Andalusian twist. Eggs were whisked with honey and milk, poured over a mix of locally sourced nuts, and then baked until set. It was a sweet ending to the meals at the villa.

Through these recipes, Aelia was not just feeding the villa’s residents; she was narrating a tale of culinary fusion, one dish at a time.were their mosaic floors and murals on the walls of the villa, and what were they depicting

Ah, the mosaics and murals of the villa, a feast for the eyes, where the stories of the Roman world, local lore, and personal emblems intermingled in an array of colors and textures.

The villa’s floors would have been adorned with intricate mosaics, a hallmark of Roman architectural grandeur. Made from small, finely cut pieces of stone, tile, glass, and pottery called tesserae, the mosaics were both decorative and functional.

In the atrium, the mosaic might depict a scene from Roman mythology. Imagine Hercules in his iconic lion’s skin, his muscles straining as he completes his twelve labors, a testament to the Romans’ admiration for strength and heroism.

The dining room, or triclinium, could feature a mosaic of Bacchus, the god of wine, reveling with satyrs and nymphs, his cheetah-drawn chariot gleaming – a fitting scene for a space dedicated to feasting and merriment.

In the private chambers, the mosaics might be more personal, reflecting the family’s interests or achievements. Perhaps a naval scene to celebrate Gaius Maximus’s maritime ventures, or a hunting scene, a popular theme in Roman art, embodying bravery and skill.

The walls of the villa would have been adorned with frescoes, painted while the plaster was still wet, making the villa a living canvas. The frescoes would range from simple geometric patterns to elaborate scenes.

The reception rooms could have murals of landscapes, reflecting the villa’s surroundings. Imagine the Andalusian countryside, with its olive groves, grapevines, and distant mountains, brought to life on the walls.

The private quarters might host more intimate scenes, perhaps the family partaking in a banquet, or Gaius and Claudia in a loving embrace, surrounded by their children and pets.

Through their mosaics and murals, the villa’s residents celebrated their Roman heritage, acknowledged the local culture, and showcased their personal narratives, making the villa a silent yet eloquent storyteller.

can you describe the garden and outbuildings

Ah, the enchantment of an age-old garden. Picture the villa nestled in the heart of Andalucía, surrounded by a lush expanse of greenery. Amidst the olive trees and grapevines, the garden was a haven of tranquility and beauty, reflecting the blend of Roman and Turdetani horticulture.

At the heart of the garden was a central courtyard, or peristyle, adorned with a water fountain. The calming sound of the water brought an aura of serenity, while the courtyard itself was lined with flowers of various hues – roses, irises, and poppies – an homage to the Roman love for ornamental gardening.

Beyond the peristyle, the garden was a mixture of beauty and utility. Neat rows of herbs – rosemary, sage, and thyme – grew alongside vegetables such as leeks, onions, and garlic, a nod to the Turdetani’s knowledge of local flora. Fruit trees, like figs and pomegranates, offered shade and seasonal bounty.

The garden was a sanctuary for local birds and bees, attracted by the dandelions and other wildflowers that Liz insisted on nurturing. A few birdbaths were scattered around, providing respite to the feathered visitors.

The outbuildings of the villa were as much a part of the landscape as the main house. Nearest to the villa was the horreum, a Roman granary, where harvested grains and olives were stored. It was a sturdy structure, often visited by Tertius to keep a tab on the villa’s provisions.

Not far from the horreum was the pottery workshop. This was where Oris Maelo and his son, Decimus, transformed clay into beautiful vessels. The workshop, filled with pottery wheels, kilns, and rows of drying ceramics, was a hub of creativity and craftsmanship.

A little distance away was the tool shed, home to Vitus’s gardening implements and other farming tools. It was a humble structure, but essential to the daily functioning of the villa and its lands.

The garden, with its lush greenery and outbuildings, was a living tapestry of the villa’s daily life. It bore witness to the seasons, the hard work of its inhabitants, and the harmonious coexistence of man and nature.

July 5, 2023 at 8:21 pm #7263In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Solomon Stubbs

1781-1857

Solomon was born in Hamstall Ridware, Staffordshire, parents Samuel Stubbs and Rebecca Wood. (see The Hamstall Ridware Connection chapter)

Solomon married Phillis Lomas at St Modwen’s in Burton on Trent on 30th May 1815. Phillis was the llegitimate daughter of Frances Lomas. No father was named on the baptism on the 17th January 1787 in Sutton on the Hill, Derbyshire, and the entry on the baptism register states that she was illegitimate. Phillis’s mother Frances married Daniel Fox in 1790 in Sutton on the Hill. Unfortunately this means that it’s impossible to find my 5X great grandfather on this side of the family.

Solomon and Phillis had four daughters, the last died in infancy.

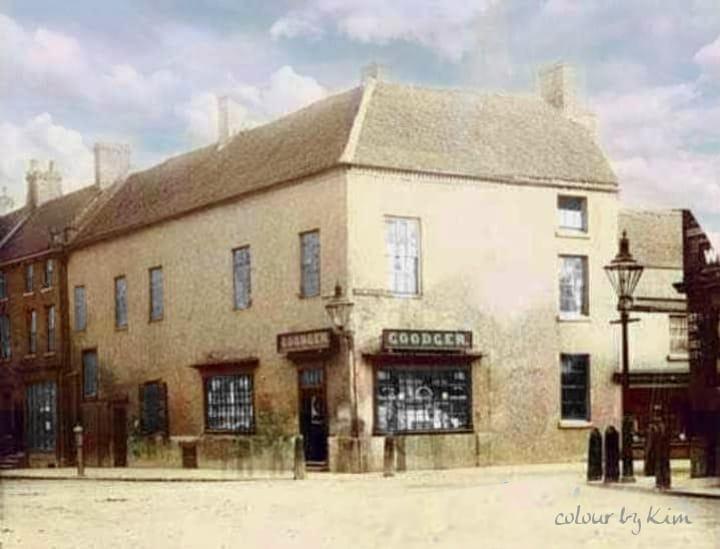

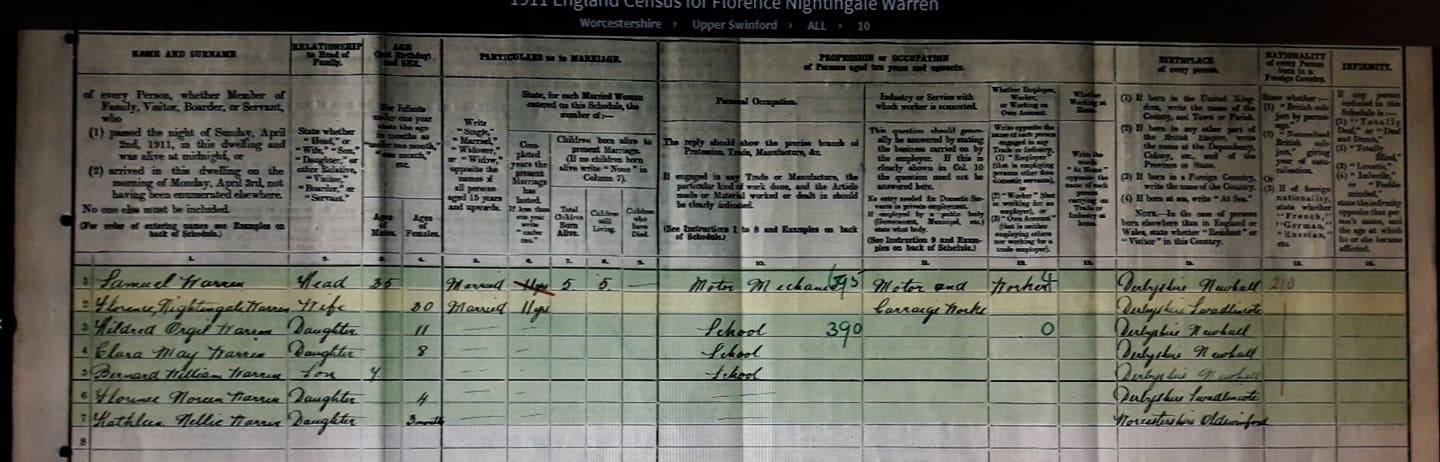

Sarah 1816-1867, Mary (my 3X great grandmother) 1819-1880, Phillis 1823-1905, and Maria 1825-1826.Solomon Stubbs of Horninglow St is listed in the 1834 Whites Directory under “China, Glass, Etc Dlrs”. Next to his name is Joanna Warren (earthenware) High St. Joanna Warren is related to me on my maternal side. No doubt Solomon and Joanna knew each other, unaware that several generations later a marriage would take place, not locally but miles away, joining their families.

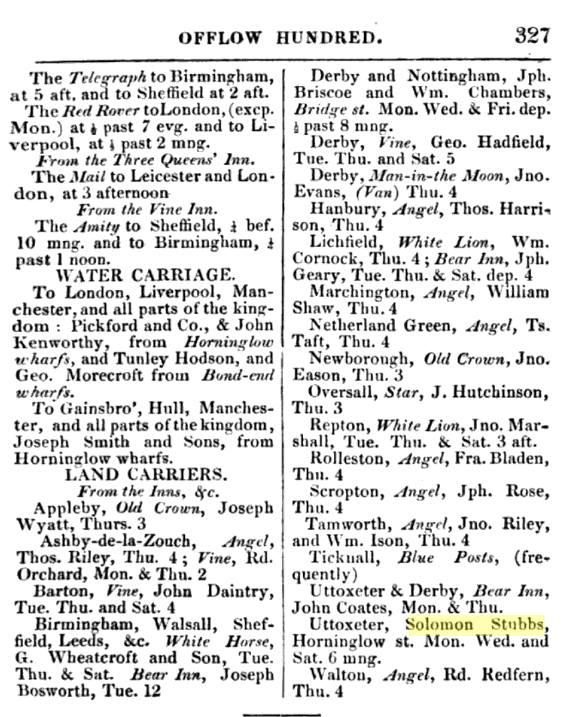

Solomon Stubbs is also listed in Whites Directory in 1831 and 1834 Burton on Trent as a land carrier:

“Land Carriers, from the Inns, Etc: Uttoxeter, Solomon Stubbs, Horninglow St, Mon. Wed. and Sat. 6 mng.”

Solomon is listed in the electoral registers in 1837. The 1837 United Kingdom general election was triggered by the death of King William IV and produced the first Parliament of the reign of his successor, Queen Victoria.

National Archives:

“In 1832, Parliament passed a law that changed the British electoral system. It was known as the Great Reform Act, which basically gave the vote to middle class men, leaving working men disappointed.

The Reform Act became law in response to years of criticism of the electoral system from those outside and inside Parliament. Elections in Britain were neither fair nor representative. In order to vote, a person had to own property or pay certain taxes to qualify, which excluded most working class people.”Via the Burton on Trent History group:

“a very early image of High street and Horninglow street junction, where the original ‘ Bargates’ were in the days of the Abbey. ‘Gate’ is the Saxon meaning Road, ‘Bar’ quite self explanatory, meant ‘to stop entrance’. There was another Bargate across Cat street (Station street), the Abbot had these constructed to regulate the Traders coming into town, in the days when the Abbey ran things. In the photo you can see the Posts on the corner, designed to stop Carts and Carriages mounting the Pavement. Only three Posts remain today and they are Listed.”

On the 1841 census, Solomon’s occupation was Carrier. Daughter Sarah is still living at home, and Sarah Grattidge, 13 years old, lives with them. Solomon’s daughter Mary had married William Grattidge in 1839.

Solomon Stubbs of Horninglow Street, Burton on Trent, is listed as an Earthenware Dealer in the 1842 Pigot’s Directory of Staffordshire.

In May 1844 Solomon’s wife Phillis died. In July 1844 daughter Sarah married Thomas Brandon in Burton on Trent. It was noted in the newspaper announcement that this was the first wedding to take place at the Holy Trinity church.

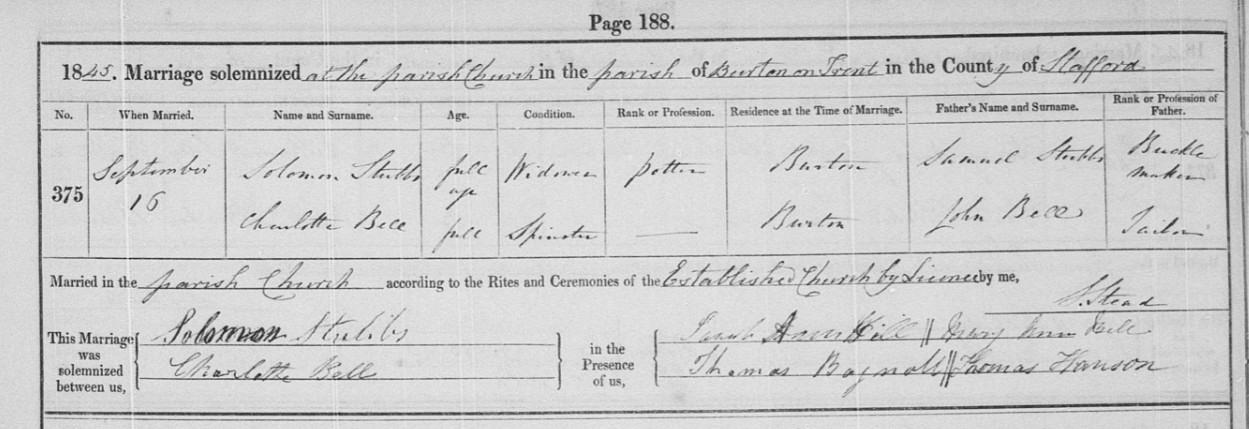

Solomon married Charlotte Bell by licence the following year in 1845. She was considerably younger than him, born in 1824. On the marriage certificate Solomon’s occupation is potter. It seems that he had the earthenware business as well as the land carrier business, in addition to owning a number of properties.

The marriage of Solomon Stubbs and Charlotte Bell:

Also in 1845, Solomon’s daughter Phillis was married in Burton on Trent to John Devitt, son of CD Devitt, Esq, formerly of the General Post Office Dublin.

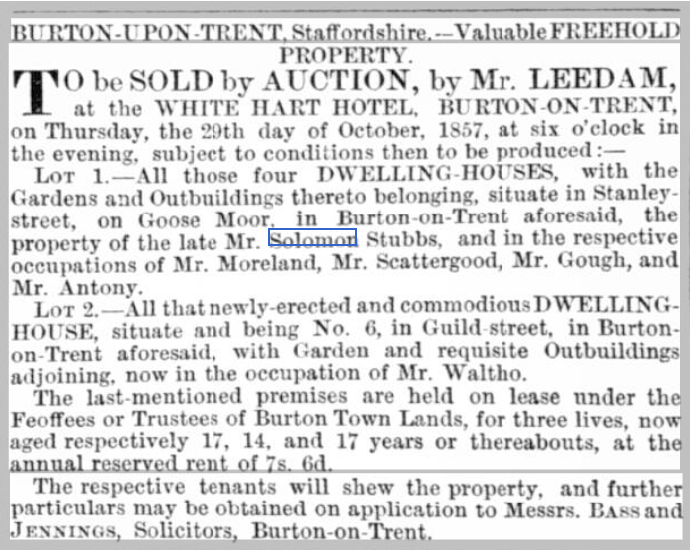

Solomon Stubbs died in September 1857 in Burton on Trent. In the Staffordshire Advertiser on Saturday 3 October 1857:

“On the 22nd ultimo, suddenly, much respected, Solomon Stubbs, of Guild-street, Burton-on-Trent, aged 74 years.”

In the Staffordshire Advertiser, 24th October 1857, the auction of the property of Solomon Stubbs was announced:

“BURTON ON TRENT, on Thursday, the 29th day of October, 1857, at six o’clock in the evening, subject to conditions then to be produced:— Lot I—All those four DWELLING HOUSES, with the Gardens and Outbuildings thereto belonging, situate in Stanleystreet, on Goose Moor, in Burton-on-Trent aforesaid, the property of the late Mr. Solomon Stubbs, and in the respective occupations of Mr. Moreland, Mr. Scattergood, Mr. Gough, and Mr. Antony…..”

Sadly, the graves of Solomon, his wife Phillis, and their infant daughter Maria have since been removed and are listed in the UK Records of the Removal of Graves and Tombstones 1601-2007.

January 23, 2023 at 2:16 pm #6452In reply to: Prompts of Madjourneys

Youssef’s entry quirk is being grumpy when he’s hungry.

Quirk accepted.

Initial setting: You find yourself in a bustling marketplace, surrounded by vendors selling all sorts of exotic foods and spices. Your stomach growls loudly, reminding you of your quirk.

Possible direction to investigate: As you explore the marketplace, you notice a small stall tucked away in the corner. The aroma wafting from the stall is tantalizing, and your stomach growls even louder. As you approach, you see a grumpy-looking vendor behind the counter. He doesn’t seem to be in the mood for customers.

Possible character to engage: The grumpy vendor.

Objective: To find a way to appease the grumpy vendor and secure a satisfying meal to satisfy your hunger.

Additional FFI clue: As you make your way to the Flying Fish Inn, you notice a sign advertising a special meal made with locally caught fish. Could this be the key to satisfying your hunger and appeasing the grumpy vendor? Remember to bring proof of your successful quest to the FFI.

Snoot’s clue: 🧔🌮🔍🔑🏞️

June 6, 2022 at 9:17 am #6301In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

The Warrens of Stapenhill

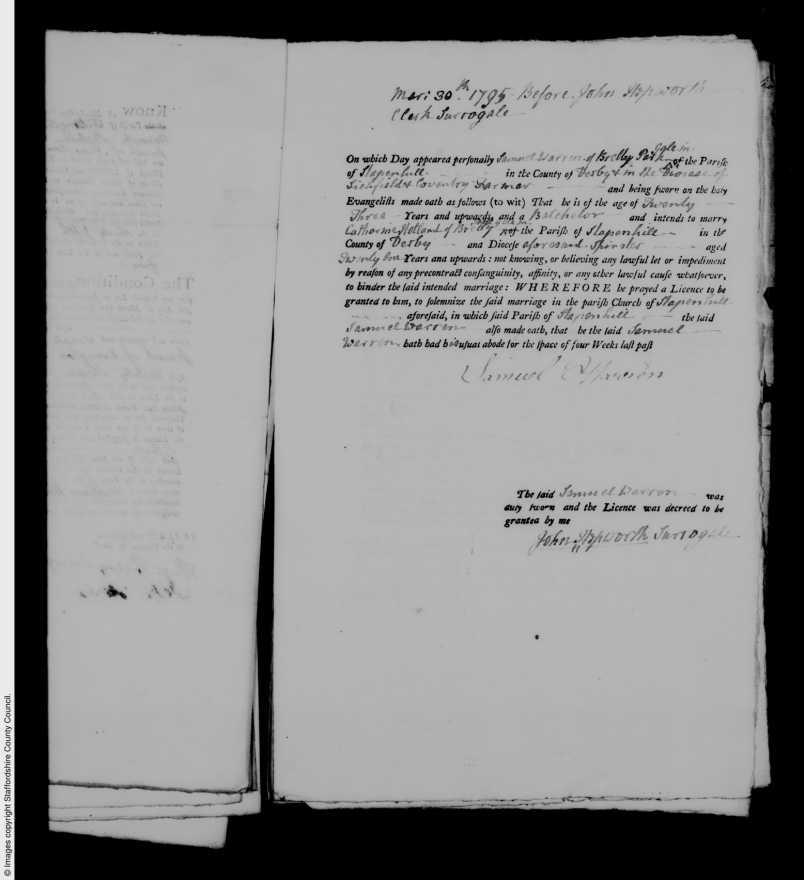

There were so many Warren’s in Stapenhill that it was complicated to work out who was who. I had gone back as far as Samuel Warren marrying Catherine Holland, and this was as far back as my cousin Ian Warren had gone in his research some decades ago as well. The Holland family from Barton under Needwood are particularly interesting, and will be a separate chapter.

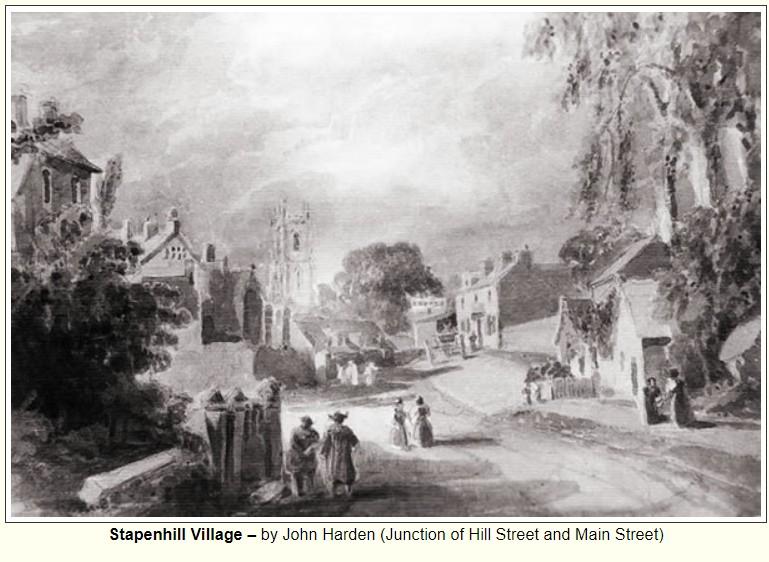

Stapenhill village by John Harden:

Resuming the research on the Warrens, Samuel Warren 1771-1837 married Catherine Holland 1775-1861 in 1795 and their son Samuel Warren 1800-1882 married Elizabeth Bridge, whose childless brother Benjamin Bridge left the Warren Brothers Boiler Works in Newhall to his nephews, the Warren brothers.

Samuel Warren and Catherine Holland marriage licence 1795:

Samuel (born 1771) was baptised at Stapenhill St Peter and his parents were William and Anne Warren. There were at least three William and Ann Warrens in town at the time. One of those William’s was born in 1744, which would seem to be the right age to be Samuel’s father, and one was born in 1710, which seemed a little too old. Another William, Guiliamos Warren (Latin was often used in early parish registers) was baptised in Stapenhill in 1729.

Stapenhill St Peter:

William Warren (born 1744) appeared to have been born several months before his parents wedding. William Warren and Ann Insley married 16 July 1744, but the baptism of William in 1744 was 24 February. This seemed unusual ~ children were often born less than nine months after a wedding, but not usually before the wedding! Then I remembered the change from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar in 1752. Prior to 1752, the first day of the year was Lady Day, March 25th, not January 1st. This meant that the birth in February 1744 was actually after the wedding in July 1744. Now it made sense. The first son was named William, and he was born seven months after the wedding.

William born in 1744 died intestate in 1822, and his wife Ann made a legal claim to his estate. However he didn’t marry Ann Holland (Ann was Catherines Hollands sister, who married Samuel Warren the year before) until 1796, so this William and Ann were not the parents of Samuel.

It seemed likely that William born in 1744 was Samuels brother. William Warren and Ann Insley had at least eight children between 1744 and 1771, and it seems that Samuel was their last child, born when William the elder was 61 and his wife Ann was 47.

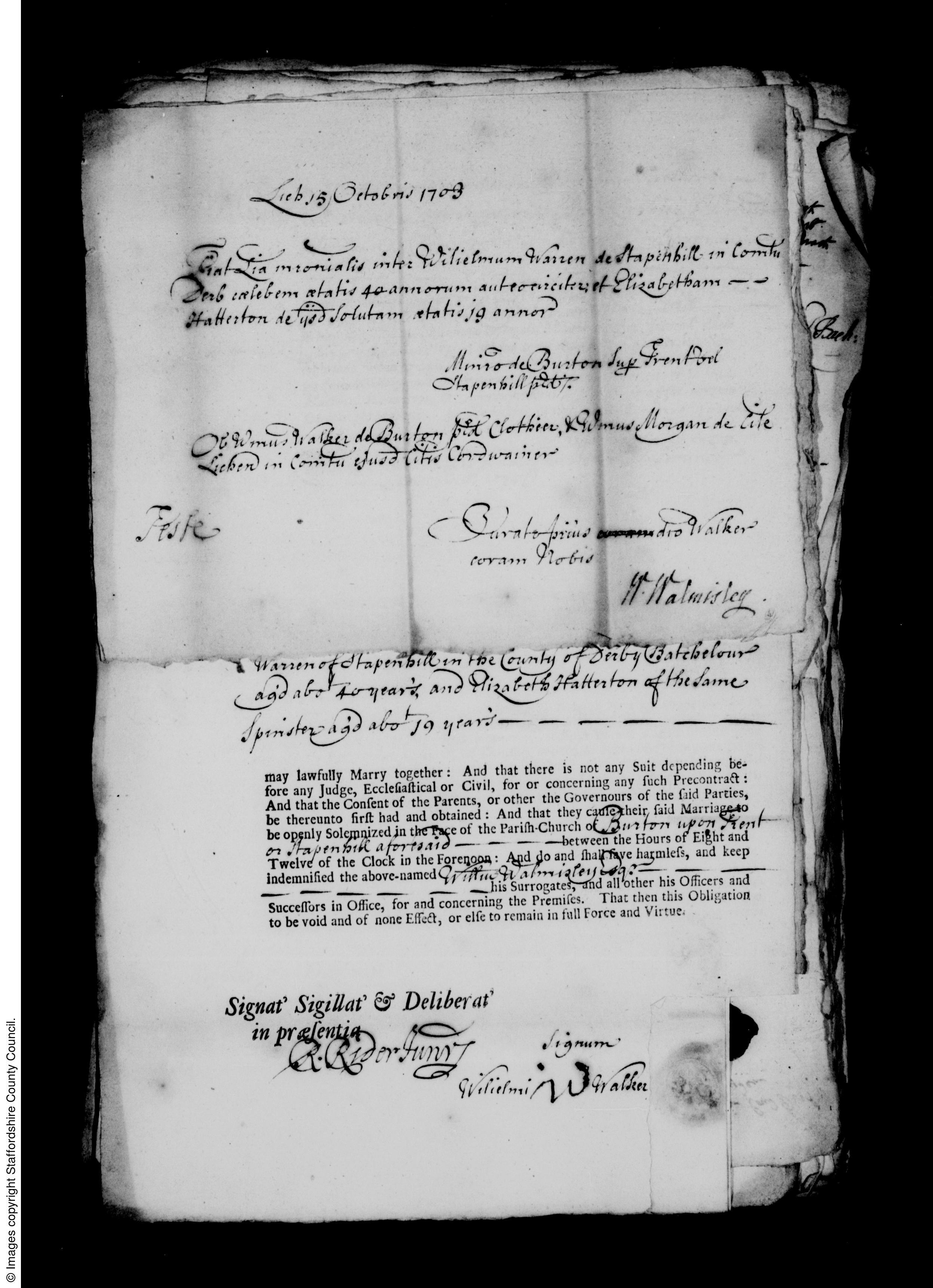

It seems it wasn’t unusual for the Warren men to marry rather late in life. William Warren’s (born 1710) parents were William Warren and Elizabeth Hatterton. On the marriage licence in 1702/1703 (it appears to say 1703 but is transcribed as 1702), William was a 40 year old bachelor from Stapenhill, which puts his date of birth at 1662. Elizabeth was considerably younger, aged 19.

William Warren and Elizabeth Hatterton marriage licence 1703:

These Warren’s were farmers, and they were literate and able to sign their own names on various documents. This is worth noting, as most made the mark of an X.

I found three Warren and Holland marriages. One was Samuel Warren and Catherine Holland in 1795, then William Warren and Ann Holland in 1796. William Warren and Ann Hollands daughter born in 1799 married John Holland in 1824.

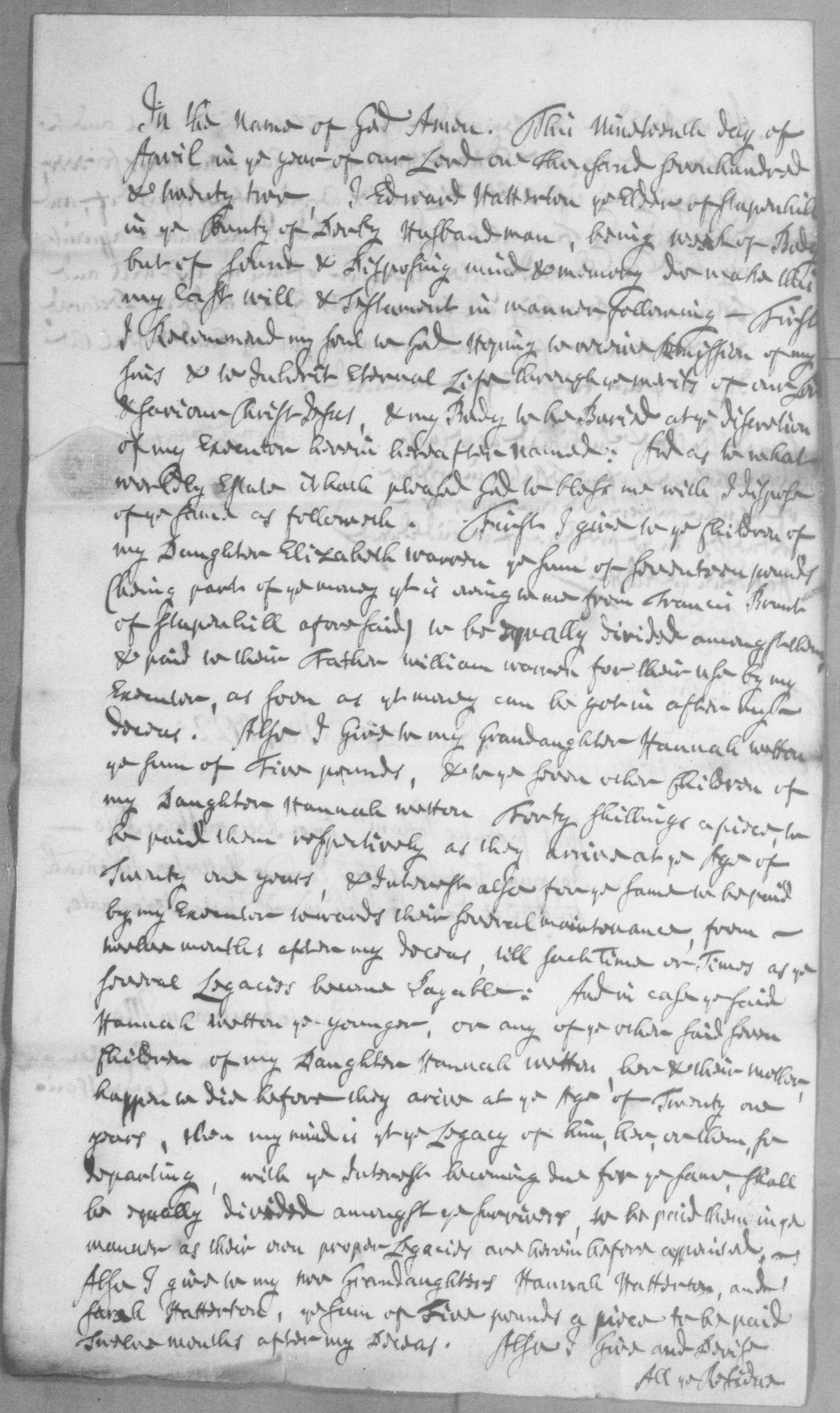

Elizabeth Hatterton (wife of William Warren who was born circa 1662) was born in Burton upon Trent in 1685. Her parents were Edward Hatterton 1655-1722, and Sara.

A page from the 1722 will of Edward Hatterton:

The earliest Warren I found records for was William Warren who married Elizabeth Hatterton in 1703. The marriage licence states his age as 40 and that he was from Stapenhill, but none of the Stapenhill parish records online go back as far as 1662. On other public trees on ancestry websites, a birth record from Suffolk has been chosen, probably because it was the only record to be found online with the right name and date. Once again, I don’t think that is correct, and perhaps one day I’ll find some earlier Stapenhill records to prove that he was born in locally.

Subsequently, I found a list of the 1662 Hearth Tax for Stapenhill. On it were a number of Warrens, three William Warrens including one who was a constable. One of those William Warrens had a son he named William (as they did, hence the number of William Warrens in the tree) the same year as this hearth tax list.

But was it the William Warren with 2 chimneys, the one with one chimney who was too poor to pay it, or the one who was a constable?

from the list:

Will. Warryn 2

Richard Warryn 1

William Warren Constable

These names are not payable by Act:

Will. Warryn 1

Richard Warren John Watson

over seers of the poore and churchwardensThe Hearth Tax:

via wiki:

In England, hearth tax, also known as hearth money, chimney tax, or chimney money, was a tax imposed by Parliament in 1662, to support the Royal Household of King Charles II. Following the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, Parliament calculated that the Royal Household needed an annual income of £1,200,000. The hearth tax was a supplemental tax to make up the shortfall. It was considered easier to establish the number of hearths than the number of heads, hearths forming a more stationary subject for taxation than people. This form of taxation was new to England, but had precedents abroad. It generated considerable debate, but was supported by the economist Sir William Petty, and carried through the Commons by the influential West Country member Sir Courtenay Pole, 2nd Baronet (whose enemies nicknamed him “Sir Chimney Poll” as a result). The bill received Royal Assent on 19 May 1662, with the first payment due on 29 September 1662, Michaelmas.

One shilling was liable to be paid for every firehearth or stove, in all dwellings, houses, edifices or lodgings, and was payable at Michaelmas, 29 September and on Lady Day, 25 March. The tax thus amounted to two shillings per hearth or stove per year. The original bill contained a practical shortcoming in that it did not distinguish between owners and occupiers and was potentially a major burden on the poor as there were no exemptions. The bill was subsequently amended so that the tax was paid by the occupier. Further amendments introduced a range of exemptions that ensured that a substantial proportion of the poorer people did not have to pay the tax.Indeed it seems clear that William Warren the elder came from Stapenhill and not Suffolk, and one of the William Warrens paying hearth tax in 1662 was undoubtedly the father of William Warren who married Elizabeth Hatterton.

May 27, 2022 at 8:25 am #6300In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

Looking for Carringtons

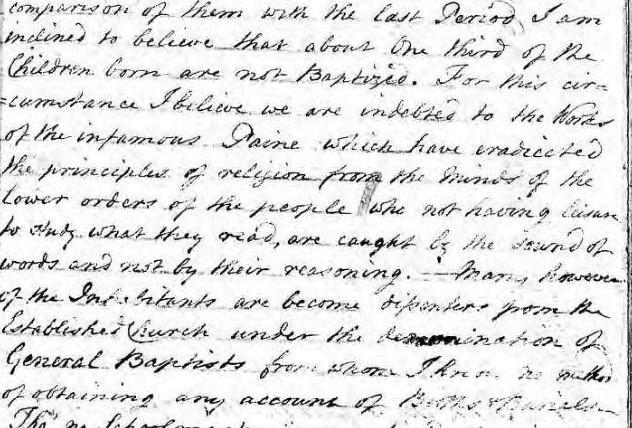

The Carringtons of Smalley, at least some of them, were Baptist ~ otherwise known as “non conformist”. Baptists don’t baptise at birth, believing it’s up to the person to choose when they are of an age to do so, although that appears to be fairly random in practice with small children being baptised. This makes it hard to find the birth dates registered as not every village had a Baptist church, and the baptisms would take place in another town. However some of the children were baptised in the village Anglican church as well, so they don’t seem to have been consistent. Perhaps at times a quick baptism locally for a sickly child was considered prudent, and preferable to no baptism at all. It’s impossible to know for sure and perhaps they were not strictly commited to a particular denomination.

Our Carrington’s start with Ellen Carrington who married William Housley in 1814. William Housley was previously married to Ellen’s older sister Mary Carrington. Ellen (born 1895 and baptised 1897) and her sister Nanny were baptised at nearby Ilkeston Baptist church but I haven’t found baptisms for Mary or siblings Richard and Francis. We know they were also children of William Carrington as he mentions them in his 1834 will. Son William was baptised at the local Smalley church in 1784, as was Thomas in 1896.

The absence of baptisms in Smalley with regard to Baptist influence was noted in the Smalley registers:

Smalley (chapelry of Morley) registers began in 1624, Morley registers began in 1540 with no obvious gaps in either. The gap with the missing registered baptisms would be 1786-1793. The Ilkeston Baptist register began in 1791. Information from the Smalley registers indicates that about a third of the children were not being baptised due to the Baptist influence.

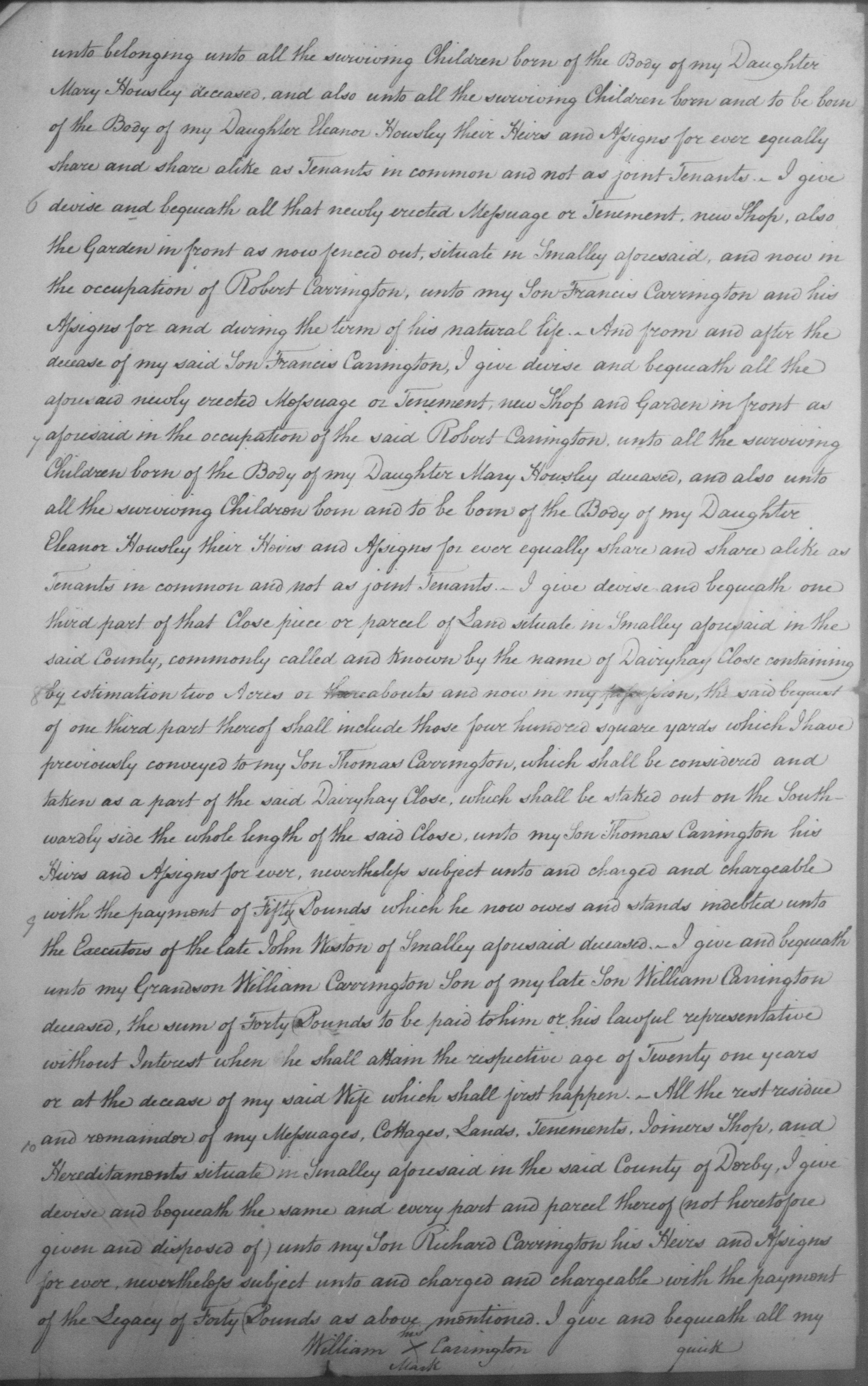

William Housley son in law, daughter Mary Housley deceased, and daughter Eleanor (Ellen) Housley are all mentioned in William Housley’s 1834 will. On the marriage allegations and bonds for William Housley and Mary Carrington in 1806, her birth date is registered at 1787, her father William Carrington.

A Page from the will of William Carrington 1834:

William Carrington was baptised in nearby Horsley Woodhouse on 27 August 1758. His parents were William and Margaret Carrington “near the Hilltop”. He married Mary Malkin, also of Smalley, on the 27th August 1783.

When I started looking for Margaret Wright who married William Carrington the elder, I chanced upon the Smalley parish register micro fiche images wrongly labeled by the ancestry site as Longford. I subsequently found that the Derby Records office published a list of all the wrongly labeled Derbyshire towns that the ancestry site knew about for ten years at least but has not corrected!

Margaret Wright was baptised in Smalley (mislabeled as Longford although the register images clearly say Smalley!) on the 2nd March 1728. Her parents were John and Margaret Wright.

But I couldn’t find a birth or baptism anywhere for William Carrington. I found four sources for William and Margaret’s marriage and none of them suggested that William wasn’t local. On other public trees on ancestry sites, William’s father was Joshua Carrington from Chinley. Indeed, when doing a search for William Carrington born circa 1720 to 1725, this was the only one in Derbyshire. But why would a teenager move to the other side of the county? It wasn’t uncommon to be apprenticed in neighbouring villages or towns, but Chinley didn’t seem right to me. It seemed to me that it had been selected on the other trees because it was the only easily found result for the search, and not because it was the right one.

I spent days reading every page of the microfiche images of the parish registers locally looking for Carringtons, any Carringtons at all in the area prior to 1720. Had there been none at all, then the possibility of William being the first Carrington in the area having moved there from elsewhere would have been more reasonable.

But there were many Carringtons in Heanor, a mile or so from Smalley, in the 1600s and early 1700s, although they were often spelled Carenton, sometimes Carrianton in the parish registers. The earliest Carrington I found in the area was Alice Carrington baptised in Ilkeston in 1602. It seemed obvious that William’s parents were local and not from Chinley.

The Heanor parish registers of the time were not very clearly written. The handwriting was bad and the spelling variable, depending I suppose on what the name sounded like to the person writing in the registers at the time as the majority of the people were probably illiterate. The registers are also in a generally poor condition.

I found a burial of a child called William on the 16th January 1721, whose father was William Carenton of “Losko” (Loscoe is a nearby village also part of Heanor at that time). This looked promising! If a child died, a later born child would be given the same name. This was very common: in a couple of cases I’ve found three deceased infants with the same first name until a fourth one named the same survived. It seemed very likely that a subsequent son would be named William and he would be the William Carrington born circa 1720 to 1725 that we were looking for.

Heanor parish registers: William son of William Carenton of Losko buried January 19th 1721:

The Heanor parish registers between 1720 and 1729 are in many places illegible, however there are a couple of possibilities that could be the baptism of William in 1724 and 1725. A William son of William Carenton of Loscoe was buried in Jan 1721. In 1722 a Willian son of William Carenton (transcribed Tarenton) of Loscoe was buried. A subsequent son called William is likely. On 15 Oct 1724 a William son of William and Eliz (last name indecipherable) of Loscoe was baptised. A Mary, daughter of William Carrianton of Loscoe, was baptised in 1727.

I propose that William Carringtons was born in Loscoe and baptised in Heanor in 1724: if not 1724 then I would assume his baptism is one of the illegible or indecipherable entires within those few years. This falls short of absolute documented proof of course, but it makes sense to me.

In any case, if a William Carrington child died in Heanor in 1721 which we do have documented proof of, it further dismisses the case for William having arrived for no discernable reason from Chinley.

February 2, 2022 at 12:33 pm #6266In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

From Tanganyika with Love

continued part 7

With thanks to Mike Rushby.

Oldeani Hospital. 19th September 1938

Dearest Family,

George arrived today to take us home to Mbulu but Sister Marianne will not allow

me to travel for another week as I had a bit of a set back after baby’s birth. At first I was

very fit and on the third day Sister stripped the bed and, dictionary in hand, started me

off on ante natal exercises. “Now make a bridge Mrs Rushby. So. Up down, up down,’

whilst I obediently hoisted myself aloft on heels and head. By the sixth day she

considered it was time for me to be up and about but alas, I soon had to return to bed

with a temperature and a haemorrhage. I got up and walked outside for the first time this

morning.I have had lots of visitors because the local German settlers seem keen to see

the first British baby born in the hospital. They have been most kind, sending flowers

and little German cards of congratulations festooned with cherubs and rather sweet. Most

of the women, besides being pleasant, are very smart indeed, shattering my illusion that

German matrons are invariably fat and dowdy. They are all much concerned about the

Czecko-Slovakian situation, especially Sister Marianne whose home is right on the

border and has several relations who are Sudentan Germans. She is ant-Nazi and

keeps on asking me whether I think England will declare war if Hitler invades Czecko-

Slovakia, as though I had inside information.George tells me that he has had a grass ‘banda’ put up for us at Mbulu as we are

both determined not to return to those prison-like quarters in the Fort. Sister Marianne is

horrified at the idea of taking a new baby to live in a grass hut. She told George,

“No,No,Mr Rushby. I find that is not to be allowed!” She is an excellent Sister but rather

prim and George enjoys teasing her. This morning he asked with mock seriousness,

“Sister, why has my wife not received her medal?” Sister fluttered her dictionary before

asking. “What medal Mr Rushby”. “Why,” said George, “The medal that Hitler gives to

women who have borne four children.” Sister started a long and involved explanation

about the medal being only for German mothers whilst George looked at me and

grinned.Later. Great Jubilation here. By the noise in Sister Marianne’s sitting room last night it

sounded as though the whole German population had gathered to listen to the wireless

news. I heard loud exclamations of joy and then my bedroom door burst open and

several women rushed in. “Thank God “, they cried, “for Neville Chamberlain. Now there

will be no war.” They pumped me by the hand as though I were personally responsible

for the whole thing.George on the other hand is disgusted by Chamberlain’s lack of guts. Doesn’t

know what England is coming to these days. I feel too content to concern myself with

world affairs. I have a fine husband and four wonderful children and am happy, happy,

happy.Eleanor.

Mbulu. 30th September 1938

Dearest Family,

Here we are, comfortably installed in our little green house made of poles and

rushes from a nearby swamp. The house has of course, no doors or windows, but

there are rush blinds which roll up in the day time. There are two rooms and a little porch

and out at the back there is a small grass kitchen.Here we have the privacy which we prize so highly as we are screened on one

side by a Forest Department plantation and on the other three sides there is nothing but

the rolling countryside cropped bare by the far too large herds of cattle and goats of the

Wambulu. I have a lovely lazy time. I still have Kesho-Kutwa and the cook we brought

with us from the farm. They are both faithful and willing souls though not very good at

their respective jobs. As one of these Mbeya boys goes on safari with George whose

job takes him from home for three weeks out of four, I have taken on a local boy to cut

firewood and heat my bath water and generally make himself useful. His name is Saa,

which means ‘Clock’We had an uneventful but very dusty trip from Oldeani. Johnny Jo travelled in his

pram in the back of the boxbody and got covered in dust but seems none the worst for

it. As the baby now takes up much of my time and Kate was showing signs of

boredom, I have engaged a little African girl to come and play with Kate every morning.

She is the daughter of the head police Askari and a very attractive and dignified little

person she is. Her name is Kajyah. She is scrupulously clean, as all Mohammedan

Africans seem to be. Alas, Kajyah, though beautiful, is a bore. She simply does not

know how to play, so they just wander around hand in hand.There are only two drawbacks to this little house. Mbulu is a very windy spot so

our little reed house is very draughty. I have made a little tent of sheets in one corner of

the ‘bedroom’ into which I can retire with Johnny when I wish to bathe or sponge him.

The other drawback is that many insects are attracted at night by the lamp and make it

almost impossible to read or sew and they have a revolting habit of falling into the soup.

There are no dangerous wild animals in this area so I am not at all nervous in this

flimsy little house when George is on safari. Most nights hyaenas come around looking

for scraps but our dogs, Fanny and Paddy, soon see them off.Eleanor.

Mbulu. 25th October 1938

Dearest Family,

Great news! a vacancy has occurred in the Game Department. George is to

transfer to it next month. There will be an increase in salary and a brighter prospect for

the future. It will mean a change of scene and I shall be glad of that. We like Mbulu and

the people here but the rains have started and our little reed hut is anything but water

tight.Before the rain came we had very unpleasant dust storms. I think I told you that

this is a treeless area and the grass which normally covers the veldt has been cropped

to the roots by the hungry native cattle and goats. When the wind blows the dust

collects in tall black columns which sweep across the country in a most spectacular

fashion. One such dust devil struck our hut one day whilst we were at lunch. George

swept Kate up in a second and held her face against his chest whilst I rushed to Johnny

Jo who was asleep in his pram, and stooped over the pram to protect him. The hut

groaned and creaked and clouds of dust blew in through the windows and walls covering

our persons, food, and belongings in a black pall. The dogs food bowls and an empty

petrol tin outside the hut were whirled up and away. It was all over in a moment but you

should have seen what a family of sweeps we looked. George looked at our blackened

Johnny and mimicked in Sister Marianne’s primmest tones, “I find that this is not to be

allowed.”The first rain storm caught me unprepared when George was away on safari. It

was a terrific thunderstorm. The quite violent thunder and lightening were followed by a

real tropical downpour. As the hut is on a slight slope, the storm water poured through

the hut like a river, covering the entire floor, and the roof leaked like a lawn sprinkler.

Johnny Jo was snug enough in the pram with the hood raised, but Kate and I had a

damp miserable night. Next morning I had deep drains dug around the hut and when

George returned from safari he managed to borrow an enormous tarpaulin which is now

lashed down over the roof.It did not rain during the next few days George was home but the very next night

we were in trouble again. I was awakened by screams from Kate and hurriedly turned up

the lamp to see that we were in the midst of an invasion of siafu ants. Kate’s bed was

covered in them. Others appeared to be raining down from the thatch. I quickly stripped

Kate and carried her across to my bed, whilst I rushed to the pram to see whether

Johnny Jo was all right. He was fast asleep, bless him, and slept on through all the

commotion, whilst I struggled to pick all the ants out of Kate’s hair, stopping now and

again to attend to my own discomfort. These ants have a painful bite and seem to

choose all the most tender spots. Kate fell asleep eventually but I sat up for the rest of

the night to make sure that the siafu kept clear of the children. Next morning the servants

dispersed them by laying hot ash.In spite of the dampness of the hut both children are blooming. Kate has rosy

cheeks and Johnny Jo now has a fuzz of fair hair and has lost his ‘old man’ look. He

reminds me of Ann at his age.Eleanor.

Iringa. 30th November 1938

Dearest Family,

Here we are back in the Southern Highlands and installed on the second floor of

another German Fort. This one has been modernised however and though not so

romantic as the Mbulu Fort from the outside, it is much more comfortable.We are all well

and I am really proud of our two safari babies who stood up splendidly to a most trying

journey North from Mbulu to Arusha and then South down the Great North Road to

Iringa where we expect to stay for a month.At Arusha George reported to the headquarters of the Game Department and

was instructed to come on down here on Rinderpest Control. There is a great flap on in

case the rinderpest spread to Northern Rhodesia and possibly onwards to Southern

Rhodesia and South Africa. Extra veterinary officers have been sent to this area to

inoculate all the cattle against the disease whilst George and his African game Scouts will

comb the bush looking for and destroying diseased game. If the rinderpest spreads,

George says it may be necessary to shoot out all the game in a wide belt along the

border between the Southern Highlands of Tanganyika and Northern Rhodesia, to

prevent the disease spreading South. The very idea of all this destruction sickens us

both.George left on a foot safari the day after our arrival and I expect I shall be lucky if I

see him occasionally at weekends until this job is over. When rinderpest is under control

George is to be stationed at a place called Nzassa in the Eastern Province about 18

miles from Dar es Salaam. George’s orderly, who is a tall, cheerful Game Scout called

Juma, tells me that he has been stationed at Nzassa and it is a frightful place! However I

refuse to be depressed. I now have the cheering prospect of leave to England in thirty

months time when we will be able to fetch Ann and George and be a proper family

again. Both Ann and George look happy in the snapshots which mother-in-law sends

frequently. Ann is doing very well at school and loves it.To get back to our journey from Mbulu. It really was quite an experience. It

poured with rain most of the way and the road was very slippery and treacherous the

120 miles between Mbulu and Arusha. This is a little used earth road and the drains are

so blocked with silt as to be practically non existent. As usual we started our move with

the V8 loaded to capacity. I held Johnny on my knee and Kate squeezed in between

George and me. All our goods and chattels were in wooden boxes stowed in the back

and the two houseboys and the two dogs had to adjust themselves to the space that

remained. We soon ran into trouble and it took us all day to travel 47 miles. We stuck

several times in deep mud and had some most nasty skids. I simply clutched Kate in

one hand and Johnny Jo in the other and put my trust in George who never, under any

circumstances, loses his head. Poor Johnny only got his meals when circumstances

permitted. Unfortunately I had put him on a bottle only a few days before we left Mbulu

and, as I was unable to buy either a primus stove or Thermos flask there we had to

make a fire and boil water for each meal. Twice George sat out in the drizzle with a rain

coat rapped over his head to protect a miserable little fire of wet sticks drenched with

paraffin. Whilst we waited for the water to boil I pacified John by letting him suck a cube

of Tate and Lyles sugar held between my rather grubby fingers. Not at all according to

the book.That night George, the children and I slept in the car having dumped our boxes

and the two servants in a deserted native hut. The rain poured down relentlessly all night

and by morning the road was more of a morass than ever. We swerved and skidded

alarmingly till eventually one of the wheel chains broke and had to be tied together with

string which constantly needed replacing. George was so patient though he was wet

and muddy and tired and both children were very good. Shortly before reaching the Great North Road we came upon Jack Gowan, the Stock Inspector from Mbulu. His car

was bogged down to its axles in black mud. He refused George’s offer of help saying

that he had sent his messenger to a nearby village for help.I hoped that conditions would be better on the Great North Road but how over

optimistic I was. For miles the road runs through a belt of ‘black cotton soil’. which was

churned up into the consistency of chocolate blancmange by the heavy lorry traffic which

runs between Dodoma and Arusha. Soon the car was skidding more fantastically than

ever. Once it skidded around in a complete semi circle so George decided that it would

be safer for us all to walk whilst he negotiated the very bad patches. You should have

seen me plodding along in the mud and drizzle with the baby in one arm and Kate

clinging to the other. I was terrified of slipping with Johnny. Each time George reached

firm ground he would return on foot to carry Kate and in this way we covered many bad

patches.We were more fortunate than many other travellers. We passed several lorries

ditched on the side of the road and one car load of German men, all elegantly dressed in

lounge suits. One was busy with his camera so will have a record of their plight to laugh

over in the years to come. We spent another night camping on the road and next day

set out on the last lap of the journey. That also was tiresome but much better than the

previous day and we made the haven of the Arusha Hotel before dark. What a picture

we made as we walked through the hall in our mud splattered clothes! Even Johnny was

well splashed with mud but no harm was done and both he and Kate are blooming.

We rested for two days at Arusha and then came South to Iringa. Luckily the sun

came out and though for the first day the road was muddy it was no longer so slippery

and the second day found us driving through parched country and along badly

corrugated roads. The further South we came, the warmer the sun which at times blazed

through the windscreen and made us all uncomfortably hot. I have described the country

between Arusha and Dodoma before so I shan’t do it again. We reached Iringa without

mishap and after a good nights rest all felt full of beans.Eleanor.

Mchewe Estate, Mbeya. 7th January 1939.

Dearest Family,

You will be surprised to note that we are back on the farm! At least the children

and I are here. George is away near the Rhodesian border somewhere, still on

Rinderpest control.I had a pleasant time at Iringa, lots of invitations to morning tea and Kate had a

wonderful time enjoying the novelty of playing with children of her own age. She is not

shy but nevertheless likes me to be within call if not within sight. It was all very suburban

but pleasant enough. A few days before Christmas George turned up at Iringa and

suggested that, as he would be working in the Mbeya area, it might be a good idea for

the children and me to move to the farm. I agreed enthusiastically, completely forgetting

that after my previous trouble with the leopard I had vowed to myself that I would never

again live alone on the farm.Alas no sooner had we arrived when Thomas, our farm headman, brought the

news that there were now two leopards terrorising the neighbourhood, and taking dogs,

goats and sheep and chickens. Traps and poisoned bait had been tried in vain and he

was sure that the female was the same leopard which had besieged our home before.

Other leopards said Thomas, came by stealth but this one advertised her whereabouts

in the most brazen manner.George stayed with us on the farm over Christmas and all was quiet at night so I

cheered up and took the children for walks along the overgrown farm paths. However on

New Years Eve that darned leopard advertised her presence again with the most blood

chilling grunts and snarls. Horrible! Fanny and Paddy barked and growled and woke up

both children. Kate wept and kept saying, “Send it away mummy. I don’t like it.” Johnny

Jo howled in sympathy. What a picnic. So now the whole performance of bodyguards

has started again and ‘till George returns we confine our exercise to the garden.

Our little house is still cosy and sweet but the coffee plantation looks very

neglected. I wish to goodness we could sell it.Eleanor.

Nzassa 14th February 1939.

Dearest Family,

After three months of moving around with two small children it is heavenly to be

settled in our own home, even though Nzassa is an isolated spot and has the reputation

of being unhealthy.We travelled by car from Mbeya to Dodoma by now a very familiar stretch of

country, but from Dodoma to Dar es Salaam by train which made a nice change. We

spent two nights and a day in the Splendid Hotel in Dar es Salaam, George had some

official visits to make and I did some shopping and we took the children to the beach.

The bay is so sheltered that the sea is as calm as a pond and the water warm. It is

wonderful to see the sea once more and to hear tugs hooting and to watch the Arab

dhows putting out to sea with their oddly shaped sails billowing. I do love the bush, but

I love the sea best of all, as you know.We made an early start for Nzassa on the 3rd. For about four miles we bowled

along a good road. This brought us to a place called Temeke where George called on

the District Officer. His house appears to be the only European type house there. The

road between Temeke and the turn off to Nzassa is quite good, but the six mile stretch

from the turn off to Nzassa is a very neglected bush road. There is nothing to be seen

but the impenetrable bush on both sides with here and there a patch of swampy

ground where rice is planted in the wet season.After about six miles of bumpy road we reached Nzassa which is nothing more

than a sandy clearing in the bush. Our house however is a fine one. It was originally built

for the District Officer and there is a small court house which is now George’s office. The

District Officer died of blackwater fever so Nzassa was abandoned as an administrative

station being considered too unhealthy for Administrative Officers but suitable as

Headquarters for a Game Ranger. Later a bachelor Game Ranger was stationed here

but his health also broke down and he has been invalided to England. So now the

healthy Rushbys are here and we don’t mean to let the place get us down. So don’t

worry.The house consists of three very large and airy rooms with their doors opening

on to a wide front verandah which we shall use as a living room. There is also a wide

back verandah with a store room at one end and a bathroom at the other. Both

verandahs and the end windows of the house are screened my mosquito gauze wire

and further protected by a trellis work of heavy expanded metal. Hasmani, the Game

Scout, who has been acting as caretaker, tells me that the expanded metal is very

necessary because lions often come out of the bush at night and roam around the

house. Such a comforting thought!On our very first evening we discovered how necessary the mosquito gauze is.

After sunset the air outside is thick with mosquitos from the swamps. About an acre of

land has been cleared around the house. This is a sandy waste because there is no

water laid on here and absolutely nothing grows here except a rather revolting milky

desert bush called ‘Manyara’, and a few acacia trees. A little way from the house there is

a patch of citrus trees, grape fruit, I think, but whether they ever bear fruit I don’t know.

The clearing is bordered on three sides by dense dusty thorn bush which is

‘lousy with buffalo’ according to George. The open side is the road which leads down to

George’s office and the huts for the Game Scouts. Only Hasmani and George’s orderly

Juma and their wives and families live there, and the other huts provide shelter for the

Game Scouts from the bush who come to Nzassa to collect their pay and for a short

rest. I can see that my daily walk will always be the same, down the road to the huts and

back! However I don’t mind because it is far too hot to take much exercise.The climate here is really tropical and worse than on the coast because the thick

bush cuts us off from any sea breeze. George says it will be cooler when the rains start

but just now we literally drip all day. Kate wears nothing but a cotton sun suit, and Johnny

a napkin only, but still their little bodies are always moist. I have shorn off all Kate’s lovely

shoulder length curls and got George to cut my hair very short too.We simply must buy a refrigerator. The butter, and even the cheese we bought

in Dar. simply melted into pools of oil overnight, and all our meat went bad, so we are

living out of tins. However once we get organised I shall be quite happy here. I like this

spacious house and I have good servants. The cook, Hamisi Issa, is a Swahili from Lindi

whom we engaged in Dar es Salaam. He is a very dignified person, and like most

devout Mohammedan Cooks, keeps both his person and the kitchen spotless. I

engaged the house boy here. He is rather a timid little body but is very willing and quite

capable. He has an excessively plain but cheerful wife whom I have taken on as ayah. I

do not really need help with the children but feel I must have a woman around just in

case I go down with malaria when George is away on safari.Eleanor.

Nzassa 28th February 1939.

Dearest Family,

George’s birthday and we had a special tea party this afternoon which the

children much enjoyed. We have our frig now so I am able to make jellies and provide

them with really cool drinks.Our very first visitor left this morning after spending only one night here. He is Mr

Ionides, the Game Ranger from the Southern Province. He acted as stand in here for a

short while after George’s predecessor left for England on sick leave, and where he has

since died. Mr Ionides returned here to hand over the range and office formally to

George. He seems a strange man and is from all accounts a bit of a hermit. He was at

one time an Officer in the Regular Army but does not look like a soldier, he wears the

most extraordinary clothes but nevertheless contrives to look top-drawer. He was

educated at Rugby and Sandhurst and is, I should say, well read. Ionides told us that he

hated Nzassa, particularly the house which he thinks sinister and says he always slept

down in the office.The house, or at least one bedroom, seems to have the same effect on Kate.

She has been very nervous at night ever since we arrived. At first the children occupied

the bedroom which is now George’s. One night, soon after our arrival, Kate woke up

screaming to say that ‘something’ had looked at her through the mosquito net. She was

in such a hysterical state that inspite of the heat and discomfort I was obliged to crawl into

her little bed with her and remained there for the rest of the night.Next night I left a night lamp burning but even so I had to sit by her bed until she

dropped off to sleep. Again I was awakened by ear-splitting screams and this time

found Kate standing rigid on her bed. I lifted her out and carried her to a chair meaning to

comfort her but she screeched louder than ever, “Look Mummy it’s under the bed. It’s

looking at us.” In vain I pointed out that there was nothing at all there. By this time

George had joined us and he carried Kate off to his bed in the other room whilst I got into

Kate’s bed thinking she might have been frightened by a rat which might also disturb

Johnny.Next morning our houseboy remarked that he had heard Kate screaming in the

night from his room behind the kitchen. I explained what had happened and he must

have told the old Scout Hasmani who waylaid me that afternoon and informed me quite

seriously that that particular room was haunted by a ‘sheitani’ (devil) who hates children.

He told me that whilst he was acting as caretaker before our arrival he one night had his

wife and small daughter in the room to keep him company. He said that his small

daughter woke up and screamed exactly as Kate had done! Silly coincidence I

suppose, but such strange things happen in Africa that I decided to move the children

into our room and George sleeps in solitary state in the haunted room! Kate now sleeps

peacefully once she goes to sleep but I have to stay with her until she does.I like this house and it does not seem at all sinister to me. As I mentioned before,

the rooms are high ceilinged and airy, and have cool cement floors. We have made one

end of the enclosed verandah into the living room and the other end is the playroom for

the children. The space in between is a sort of no-mans land taken over by the dogs as

their special territory.Eleanor.

Nzassa 25th March 1939.

Dearest Family,

George is on safari down in the Rufigi River area. He is away for about three

weeks in the month on this job. I do hate to see him go and just manage to tick over until

he comes back. But what fun and excitement when he does come home.

Usually he returns after dark by which time the children are in bed and I have

settled down on the verandah with a book. The first warning is usually given by the

dogs, Fanny and her son Paddy. They stir, sit up, look at each other and then go and sit

side by side by the door with their noses practically pressed to the mosquito gauze and

ears pricked. Soon I can hear the hum of the car, and so can Hasmani, the old Game

Scout who sleeps on the back verandah with rifle and ammunition by his side when

George is away. When he hears the car he turns up his lamp and hurries out to rouse

Juma, the houseboy. Juma pokes up the fire and prepares tea which George always

drinks whist a hot meal is being prepared. In the meantime I hurriedly comb my hair and

powder my nose so that when the car stops I am ready to rush out and welcome

George home. The boy and Hasmani and the garden boy appear to help with the

luggage and to greet George and the cook, who always accompanies George on

Safari. The home coming is always a lively time with much shouting of greetings.

‘Jambo’, and ‘Habari ya safari’, whilst the dogs, beside themselves with excitement,

rush around like lunatics.As though his return were not happiness enough, George usually collects the

mail on his way home so there is news of Ann and young George and letters from you

and bundles of newspapers and magazines. On the day following his return home,

George has to deal with official mail in the office but if the following day is a weekday we

all, the house servants as well as ourselves, pile into the boxbody and go to Dar es

Salaam. To us this means a mornings shopping followed by an afternoon on the beach.

It is a bit cooler now that the rains are on but still very humid. Kate keeps chubby

and rosy in spite of the climate but Johnny is too pale though sturdy enough. He is such

a good baby which is just as well because Kate is a very demanding little girl though

sunny tempered and sweet. I appreciate her company very much when George is

away because we are so far off the beaten track that no one ever calls.Eleanor.

Nzassa 28th April 1939.

Dearest Family,

You all seem to wonder how I can stand the loneliness and monotony of living at

Nzassa when George is on safari, but really and truly I do not mind. Hamisi the cook

always goes on safari with George and then the houseboy Juma takes over the cooking

and I do the lighter housework. the children are great company during the day, and when

they are settled for the night I sit on the verandah and read or write letters or I just dream.

The verandah is entirely enclosed with both wire mosquito gauze and a trellis

work of heavy expanded metal, so I am safe from all intruders be they human, animal, or

insect. Outside the air is alive with mosquitos and the cicadas keep up their monotonous

singing all night long. My only companions on the verandah are the pale ghecco lizards

on the wall and the two dogs. Fanny the white bull terrier, lies always near my feet

dozing happily, but her son Paddy, who is half Airedale has a less phlegmatic

disposition. He sits alert and on guard by the metal trellis work door. Often a lion grunts

from the surrounding bush and then his hackles rise and he stands up stiffly with his nose

pressed to the door. Old Hasmani from his bedroll on the back verandah, gives a little

cough just to show he is awake. Sometimes the lions are very close and then I hear the

click of a rifle bolt as Hasmani loads his rifle – but this is usually much later at night when

the lights are out. One morning I saw large pug marks between the wall of my bedroom

and the garage but I do not fear lions like I did that beastly leopard on the farm.

A great deal of witchcraft is still practiced in the bush villages in the

neighbourhood. I must tell you about old Hasmani’s baby in connection with this. Last

week Hasmani came to me in great distress to say that his baby was ‘Ngongwa sana ‘

(very ill) and he thought it would die. I hurried down to the Game Scouts quarters to see

whether I could do anything for the child and found the mother squatting in the sun

outside her hut with the baby on her lap. The mother was a young woman but not an

attractive one. She appeared sullen and indifferent compared with old Hasmani who

was very distressed. The child was very feverish and breathing with difficulty and

seemed to me to be suffering from bronchitis if not pneumonia. I rubbed his back and

chest with camphorated oil and dosed him with aspirin and liquid quinine. I repeated the

treatment every four hours, but next day there was no apparent improvement.

In the afternoon Hasmani begged me to give him that night off duty and asked for

a loan of ten shillings. He explained to me that it seemed to him that the white man’s

medicine had failed to cure his child and now he wished to take the child to the local witch

doctor. “For ten shillings” said Hasmani, “the Maganga will drive the devil out of my

child.” “How?” asked I. “With drums”, said Hasmani confidently. I did not know what to

do. I thought the child was too ill to be exposed to the night air, yet I knew that if I

refused his request and the child were to die, Hasmani and all the other locals would hold

me responsible. I very reluctantly granted his request. I was so troubled by the matter

that I sent for George’s office clerk. Daniel, and asked him to accompany Hasmani to the

ceremony and to report to me the next morning. It started to rain after dark and all night

long I lay awake in bed listening to the drums and the light rain. Next morning when I

went out to the kitchen to order breakfast I found a beaming Hasmani awaiting me.

“Memsahib”, he said. “My child is well, the fever is now quite gone, the Maganga drove

out the devil just as I told you.” Believe it or not, when I hurried to his quarters after

breakfast I found the mother suckling a perfectly healthy child! It may be my imagination

but I thought the mother looked pretty smug.The clerk Daniel told me that after Hasmani

had presented gifts of money and food to the ‘Maganga’, the naked baby was placed

on a goat skin near the drums. Most of the time he just lay there but sometimes the witch

doctor picked him up and danced with the child in his arms. Daniel seemed reluctant to

talk about it. Whatever mumbo jumbo was used all this happened a week ago and the

baby has never looked back.Eleanor.

Nzassa 3rd July 1939.

Dearest Family,

Did I tell you that one of George’s Game Scouts was murdered last month in the

Maneromango area towards the Rufigi border. He was on routine patrol, with a porter

carrying his bedding and food, when they suddenly came across a group of African

hunters who were busy cutting up a giraffe which they had just killed. These hunters were

all armed with muzzle loaders, spears and pangas, but as it is illegal to kill giraffe without

a permit, the Scout went up to the group to take their names. Some argument ensued

and the Scout was stabbed.The District Officer went to the area to investigate and decided to call in the Police

from Dar es Salaam. A party of police went out to search for the murderers but after