-

AuthorSearch Results

-

March 2, 2025 at 10:22 am #7852

In reply to: Helix Mysteries – Inside the Case

“Tundra Finds the Shoat-lion”

FADE IN:

EXT. THE GOLDEN TROWEL BAR — DUSK

A golden, muted twilight paints the landscape, illuminating the overgrown ivy and sprawled vines reclaiming the ancient tavern. THE GOLDEN TROWEL sign creaks gently in the breeze above the doorway.

ANGLE DOWN TO — TUNDRA, a spirited and curious 12-year-old girl with a wild, freckled pixie-cut and striking auburn hair, stepping carefully over ivy-covered stones and debris. She wears worn clothes, stitched lovingly by survivors; a scavenged backpack swings on one shoulder.

Behind her, through the windows of the tavern, warm lantern-light flickers. We glimpse MOLLY and GREGOR smiling and chatting quietly through dusty glass.

ANGLE ON — Tundra as she pauses, hearing a soft rustling near the abandoned beer barrels stacked against the tavern wall. Her green eyes widen, alert and intrigued.

SLOW PAN DOWN to reveal a small creature trembling in the shadows—a MARCASSIN, a tiny wild piglet no larger than a rugby ball, with coarse fur streaked ginger and cinnamon stripes along its body. Large dark eyes stare up, innocence mixed with wary curiosity. It’s adorable yet clearly distinct, with sharper canines already hinting at the deeply mutated carnivorous lineage of Hungary’s lion-boars.

Tundra inhales softly, visibly torn between instinctual cautiousness her elders taught and her own irrepressible instinct of compassion.

TUNDRA

(soft, gentle)

“It’s alright…I won’t hurt you.”She crouches slowly, reaching into her pocket—a small piece of stale bread emerges, held in her outstretched hand.

CLOSE-UP on the marcassin’s wary eyes shifting cautiously to her extended palm. A heartbeat of hesitation, and then it takes a tentative step forward, sniffing gently. Tundra holds utterly still, breath held in earnest hope.

The marcassin edges closer, wet nose brushing her fingers softly. Tundra beams, freckles highlighted by the fading sun, warmth and joy glowing on her face.

TUNDRA

(whispering happily)

“You’re not so scary, are you? I’m Tundra… I think we could be friends.”Movement at the tavern door draws her attention. The worn wood creaks as MOLLY and GREGOR step outside, shadows stretching long in the golden sunset. MOLLY’s eyes, initially alert with careful caution, soften at the touching scene.

MOLLY

(gently amused, warmly amused yet apprehensive)

“Careful now, darling. Even the smallest things aren’t always what they seem these days.”GREGOR

(softly chuckling, eyes twinkling)

“But then again, neither are we.”ANGLE ON Tundra, looking up to meet Molly’s eyes. Her determination tempered only by vulnerability, hope, and youthful stubbornness.

TUNDRA

“It needs us, Nana Molly. Everything needs somebody nowadays.”Molly considers the wisdom in Tundra’s young, earnest gaze. Gregor stifles a smile and pats Molly lightly lovingly on the shoulder.

GREGOR

(warmly, quietly)

“Ah, let her find hope where she sees it. Might be that little thing will change how we see hope ourselves.”ANGLE WIDE — the small group beside the tavern: Molly, her wise and caring gaze thoughtful; Gregor’s stance gentle yet cautiously protective; Tundra radiating youthful bravery, cradling newfound companionship as the marcassin squeaks softly, cuddling gently against her worn sweater.

ASCENDING SHOT ABOVE the tumbledown ancient Hungarian tavern, the warm glow of lantern and sunset mingling. Ancient vines and wild weeds whisper forgotten stories as stars blink awake above.

In that gentle hush, beneath a wild and vast sky reclaiming an abandoned land, Tundra’s act of compassion quietly rekindles hope for humanity’s delicate future.

FADE OUT.

March 1, 2025 at 12:41 pm #7847In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

Helix 25 – The Lexican Quarters – Anuí’s Chambers

Anuí Naskó had been many things in their life—historian, philosopher, linguist, nuisance. But a father? No. No, that was entirely new.

And yet, here they were, rocking a very tiny, very loud creature wrapped in Lexican ceremonial cloth, embroidered with the full unpronounceable name bestowed upon it just moments ago: Hšyra-Mak-Talún i Ešvar—”He Who Cries the Arrival of the Infinite Spiral.”

The baby did, indeed, cry.

“Why do you scream at me?” Anuí muttered, swaying slightly, more in a daze than any real instinct to soothe. “I did not birth you. I did not know you existed until three hours ago. And yet, you are here, squalling, because your other father and your mother have decided to fulfill the Prophecy of the Spiral Throne.”

The Prophecy. The one that spoke of the moment the world would collapse and the Lexicans would ascend. The one nobody took seriously. Until now.

Zoya Kade, sitting across from them, watched with narrowed, calculating eyes. “And what exactly does that entail? This Lexican Dynasty?”

Anuí sighed, looking down at the writhing child who was trying to suck on their sleeves, still stained with the remnants of the protein paste they had spent the better part of the morning brewing. The Atrium’s walls needed to be prepared, after all—Kio’ath could not write the sigils without the proper medium. And as the cycles dictated, the medium must be crafted, fermented, and blessed by the hand of one who walks between identities. It had been a tedious, smelly process, but Anuí had endured worse in the name of preservation.

“Patterns repeat, cycles fold inward.” “Patterns repeat, cycles fold inward. The old texts speak of it, the words carved into the silent bones of forgotten tongues. This, Zoya, is no mere madness. This is the resurgence of what was foretold. A dynasty cannot exist without succession, and history does not move without inheritors. They believe they are ensuring the inevitability of their rise. And they might not be wrong.”

They adjusted their grip on the child, murmuring a phrase in a language so old it barely survived in the archives. “Tz’uran velth ka’an, the root that binds to the branch, the branch that binds to the sky. Our truths do not stand alone.”

The baby flailed, screaming louder. “Yes, yes, you are the heir,” Anuí murmured, bouncing it with more confidence. “Your lineage has been declared, your burden assigned. Accept it and be silent.” “Well, apparently it requires me to be a single parent while they go forth and multiply, securing ‘heirs to the truth.’ A dynasty is no good without an heir and a spare, you see.”

The baby flailed, screaming even louder. “Yes, yes, you are the heir,” Anuí murmured with a hint of irritation, bouncing the baby awkwardly. “You have been declared. Please, cease wailing now.”

Zoya exhaled through her nose, somewhere between disbelief and mild amusement. “And in the middle of all this divine nonsense, the Lexicans have chosen to back me?”

Anuí arched a delicate brow, shifting the baby to one arm with newfound ease. “Of course. The truth-seeker is foretold. The woman who speaks with voices of the past. We have our empire; you are our harbinger.”

Zoya’s lips twitched. “Your empire consists of thirty-eight highly unstable academics and a baby.”

“Thirty-nine. Kio’ath returned from exile yesterday,” Anuí corrected. “They claim the moons have been whispering.”

“Ah. Of course they have.”

Zoya fell silent, fingers tracing the worn etchings of her chair’s armrest. The ship’s hum pressed into her bones, the weight of something stirring in her mind, something old, something waiting.

Anuí’s gaze sharpened, the edges of their thoughts aligning like an ancient lexicon unfurling in front of them. “And now you are hearing it, aren’t you? The echoes of something that was always there. The syllables of the past, reshaped by new tongues, waiting for recognition. The Lexican texts spoke of a fracture in the line, a leader divided, a bridge yet to be found.”

They took a slow breath, fingers tightening over the child’s swaddled form. “The prophecy is not a single moment, Zoya. It is layers upon layers, intersecting at the point where chaos demands order. Where the unseen hand corrects its own forgetting. This is why they back you. Not because you seek the truth, but because you are the conduit through which it must pass.”

Zoya’s breath shallowed. A warmth curled in her chest, not of her own making. Her fingers twitched as if something unseen traced over them, urging her forward. The air around her thickened, charged.

She knew this feeling.

Her head tipped back, and when she spoke, it was not entirely her own voice.

“The past rises in bloodlines and memory,” she intoned, eyes unfocused, gaze burning through Anuí. “The lost sibling walks beneath the ice. The leader sleeps, but he must awaken, for the Spiral Throne cannot stand alone.”

Anuí’s pulse skipped. “Zoya—”

The baby let out a startled hiccup.

But Zoya did not stop.

“The essence calls, older than names, older than the cycle. I am Achaia-Vor, the Echo of Sundered Lineage. The Lost, The Twin, The Nameless Seed. The Spiral cannot turn without its axis. Awaken Victor Holt. He is the lock. You are the key. The path is drawn.

“The cycle bends but does not break. Across the void, the lost ones linger, their voices unheard, their blood unclaimed. The Link must be found. The Speaker walks unknowingly, divided across two worlds. The bridge between past and present, between silence and song. The Marlowe thread is cut, yet the weave remains. To see, you must seek the mirrored souls. To open the path, the twins must speak.”

Achaia-Vor. The name vibrated through the air, curling through the folds of Anuí’s mind like a forgotten melody.

Zoya’s eyes rolled back, body jerking as if caught between two timelines, two truths. She let out a breathless whisper, almost longing.

“Victor, my love. He is waiting for me. I must bring him back.”

Anuí cradled the baby closer, and for the first time, they saw the prophecy not as doctrine but as inevitability. The patterns were aligning—the cut thread of the Marlowes, the mirrored souls, the bridge that must be found.

“It is always the same,” they murmured, almost to themselves. “An axis must be turned, a voice must rise. We have seen this before, written in languages long burned to dust. The same myth, the same cycle, only the names change.”

They met Zoya’s gaze, the air between them thick with the weight of knowing. “And now, we must find the Speaker. Before another voice is silenced.”

“Well,” they muttered, exhaling slowly. “This just got significantly more complicated.”

The baby cooed.

Zoya Kade smiled.

February 9, 2025 at 7:22 am #7777In reply to: The Last Cruise of Helix 25

The Survivors:

“Well, I’ll be damned,” Gregor said, his face cracking into another toothless grin. “Beginning to think we might be the last ones.”

“So did we.” Molly glanced nervously around at the odd assortment of people staring at her and Tundra. “I’m Molly. This is Tundra.”

“Tundra? Like the frozen wasteland?” Yulia asked.

Tundra nodded. “It’s because I’m strong and tough.”

“Would you like to join us?” Tala motioned toward the fire.

“Yes, yes, of course, ” Anya said. “Are you hungry?”

Molly hesitated, glancing toward the edge of the clearing, where their horses stood tethered to a low branch. “We have food,” she said. “We foraged.”

“I’d have foraged if someone didn’t keep going on about food poisoning,” Yulia muttered.

Finja sniffed. “Forgive me for trying to keep you alive.”

Molly watched the exchange with interest. It had been years since she’d seen people bicker over something so trivial. It was oddly comforting.

She lowered herself slowly onto the log next to Vera. “Alright, tell me—who exactly are you lot?”

Petro chuckled. “We’ve escaped from the asylum.”

Molly’s face remained impassive. “Asylum?”

“It’s okay,” Tala said quickly. “We’re mostly sane.”

“Not completely crazy, anyway,” Yulia added cheerfully.

“We were left behind years ago,” Anya said simply. “So we built our own kind of life.”

A pause. Molly gave a slow nod, considering this. Vera leaned towards her eagerly.

“Where are you from? Any noble blood?”

Molly frowned. “Does it matter?”

“Oh, not really,” Vera said dejectedly. “I just like knowing.”

Tundra, warming her hands by the fire, looked at Vera. “We came from Spain.”

Vera perked up. “Spain? Fascinating! And tell me, dear girl, have you ever traced your lineage?”

“Just back to Molly. She’s ninety-three,” Tundra said proudly.

Mikhail, who had been watching quietly, finally spoke. “You travelled all the way from Spain?”

Molly nodded. “A long time ago. There were more of us then… ” Her voice wavered. “We were looking for other survivors.”

“And?”Mikhail asked.

Molly sighed, glancing at Tundra. “We never found any.”

________________________________________

That night, they took turns keeping watch, though Molly tried to reassure them there was no need.

“At first, we did too,” she had said, shaking her head. “But there was no one…”

By dawn, the fire had burned to embers, and the camp stirred reluctantly to life.

They finished off the last of their cooked vegetables from the night before, while Molly and Tundra laid out a handful of foraged berries and mushrooms. It wasn’t much, but it was enough to start the day.

“Right,” Anya said, stretching. “I suppose we should get moving.” She looked at Molly and Tundra. “You’re coming with us, then? To the city?”

Molly nodded. “If you’ll have us.”

“We kept going and going, hoping to find people. Now we have,” Tundra said.

“Then it’s settled,” Anya said. “We head to the city.”

“And what exactly are we looking for?” Molly asked.

Mikhail shrugged. “Anything that keeps us alive.”

________________________________________________

It was late morning when they saw it.

A vehicle—an old, battered truck, crawling slowly toward them.

The sight was so absurd, so impossible, that for a moment, no one spoke.

“That can’t be,” Molly murmured.

The truck bounced over the uneven ground, its engine a dull, sluggish rattle. It wasn’t in good shape, but it was moving.

August 28, 2024 at 1:31 pm #7549In reply to: The Elusive Samuel Housley and Other Family Stories

The Tailor of Haddon

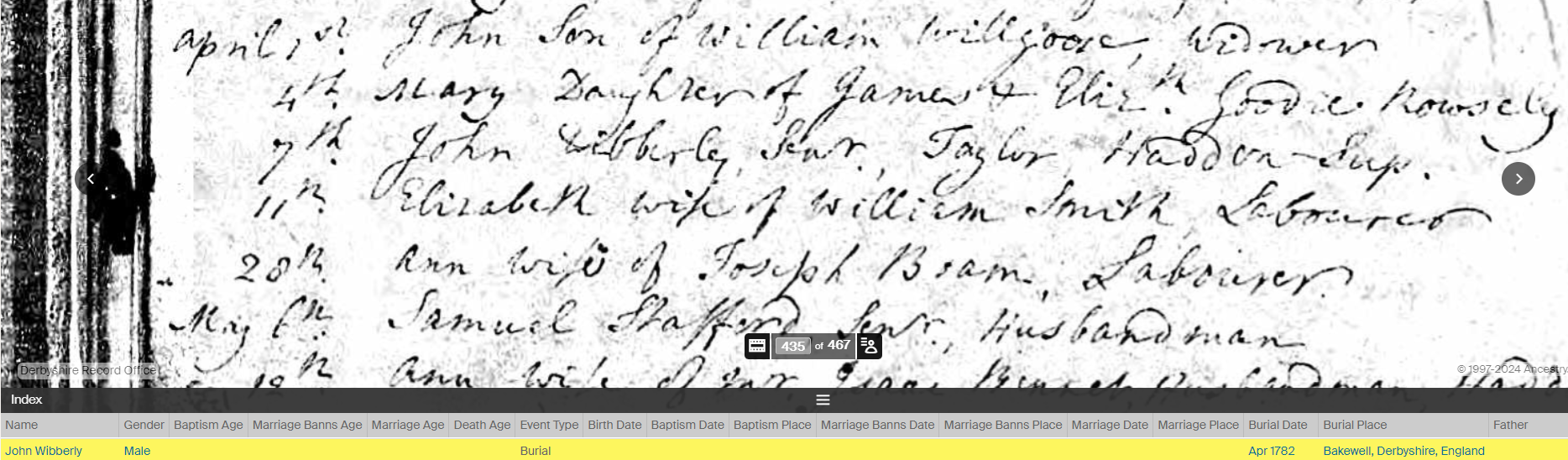

Wibberly and Newton of Over HaddonIt was noted in the Bakewell parish register in 1782 that John Wibberly 1705?-1782 (my 6x great grandfather) was “taylor of Haddon”.

James Marshall 1767-1848 (my 4x great grandfather), parish clerk of Elton, married Ann Newton 1770-1806 in Elton in 1792. In the Bakewell parish register, Ann was baptised on the 2rd of June 1770, her parents George and Dorothy Newton of Upper Haddon. The Bakewell registers at the time covered several smaller villages in the area, although what is currently known as Over Haddon was referred to as Upper Haddon in the earlier entries.

Newton:

George Newton 1728-1798 was the son of George Newton 1706- of Upper Haddon and Jane Sailes, who were married in 1727, both of Upper Haddon.

George Newton born in 1706 was the son of George Newton 1676- and Anne Carr, who were married in 1701, both of Upper Haddon.

George Newton born in 1676 was the son of John Newton 1647- and Alice who were married in 1673 in Bakewell. There is no last name for Alice on the marriage transcription.

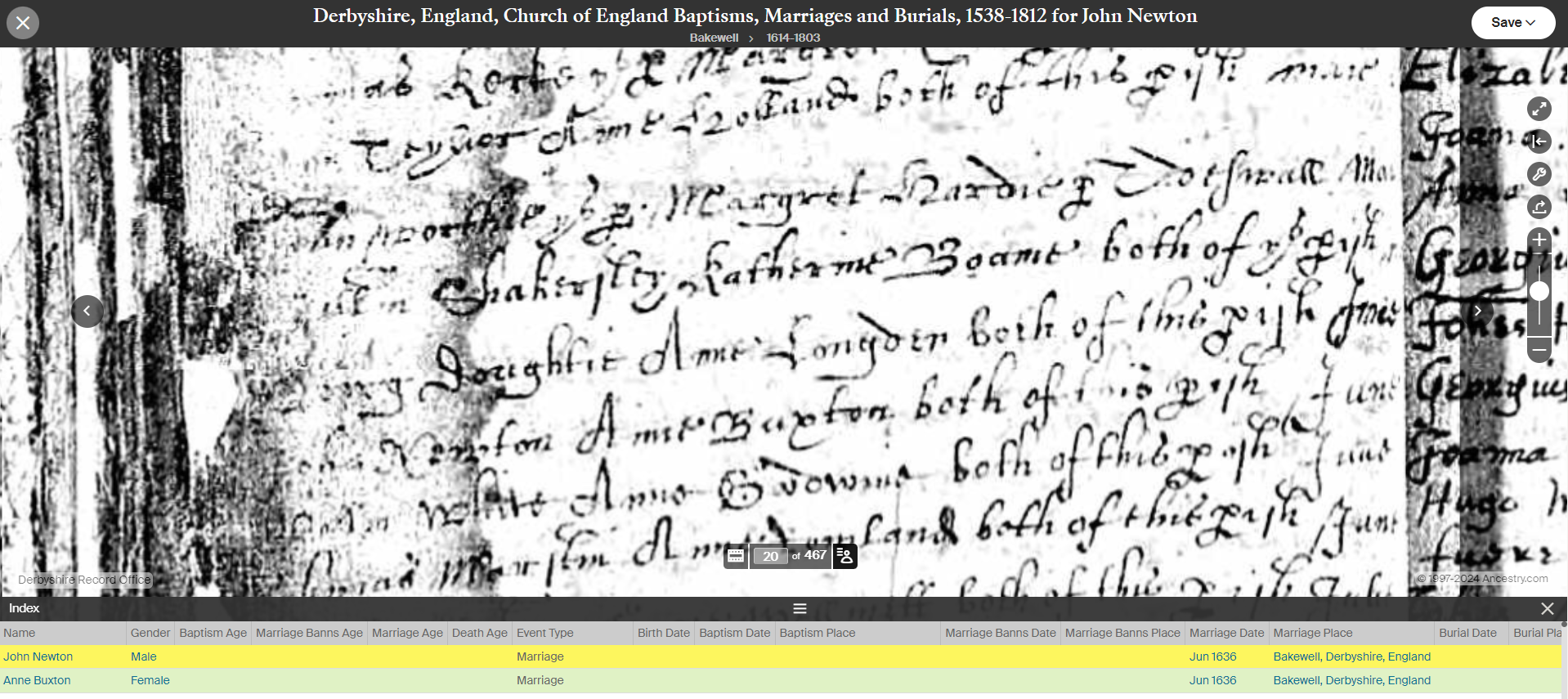

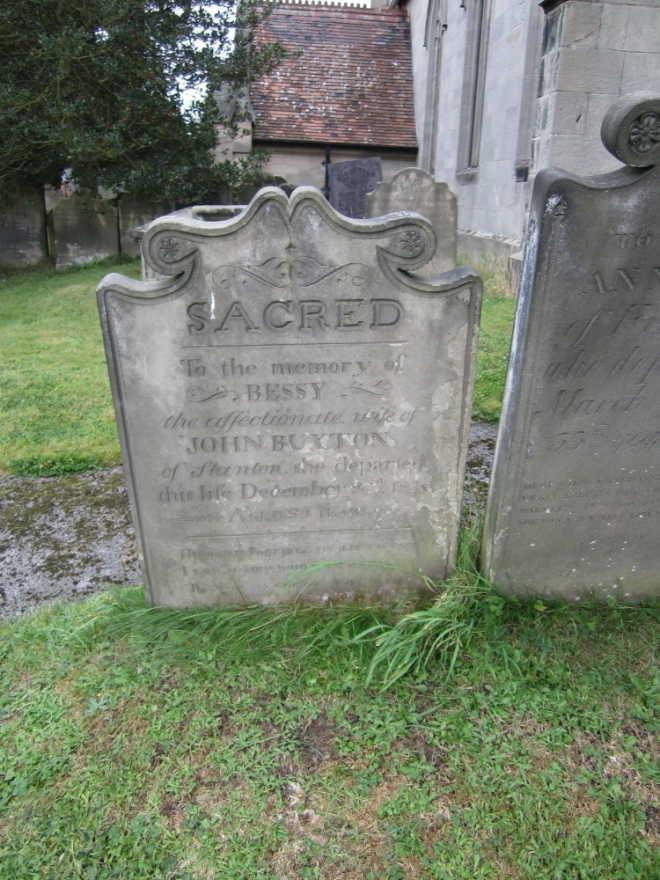

John Newton born in 1647 (my 9x great grandfather) was the son of John Newton and Anne Buxton (my 10x great grandparents), who were married in Bakewell in 1636.

1636 marriage of John Newton and Anne Buxton:

Wibberly

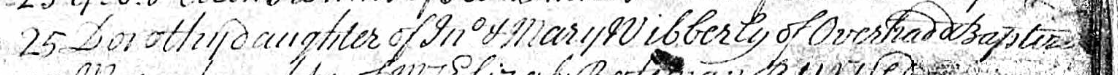

Dorothy Wibberly 1731-1827 married George Newton in 1755 in Bakewell. The entry in the parish registers says that they were both of Over Haddon. Dorothy was baptised in Bakewell on the 25th June 1731, her parents were John and Mary of Over Haddon.

John Wibberly and Mary his wife baptised nine children in Bakewell between 1730 and 1750, and on all of the entries in the parish registers it is stated that they were from Over Haddon. A parish register entry for John and Mary’s marriage has not yet been found, but a marriage in Beeley, a tiny nearby village, in 1728 to Mary Mellor looks likely.

John Wibberly died in Over Haddon in 1782. The entry in the Bakewell parish register notes that he was “taylor of Haddon”.

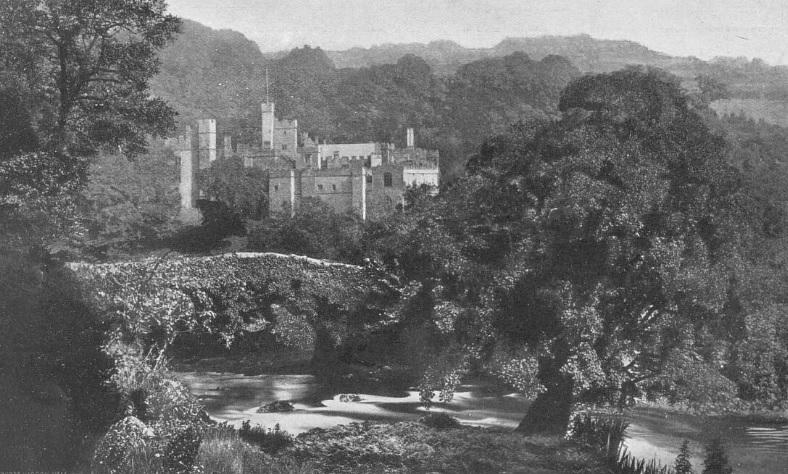

The tiny village of Over Haddon was historically associated with Haddon Hall.

A baptism for John Wibberly has not yet been found, however, there were Wibersley’s in the Bakewell registers from the early 1600s:

1619 Joyce Wibersley married Raphe Cowper.

1621 Jocosa Wibersley married Radulphus Cowper

1623 Agnes Wibersley married Richard Palfreyman

1635 Cisley Wibberlsy married ? Mr. Mason

1653 John Wibbersly married Grace DaykenHaddon Hall

Sir Richard Vernon (c. 1390 – 1451) of Haddon Hall.

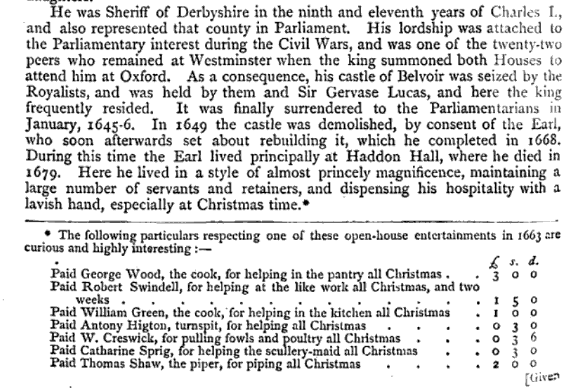

Vernon’s property was widespread and varied. From his parents he inherited the manors of Marple and Wibersley, in Cheshire. Perhaps the Over Haddon Wibersley’s origins were from Sir Richard Vernon’s property in Cheshire. There is, however, a medieval wayside cross called Whibbersley Cross situated on Leash Fen in the East Moors of the Derbyshire Peak District. It may have served as a boundary cross marking the estate of Beauchief Abbey. Wayside crosses such as this mostly date from the 9th to 15th centuries.Found in both The History and Antiquities of Haddon Hall by S Raynor, 1836, and the 1663 household accounts published by Lysons, Haddon Hall had 140 domestic staff.

In the book Haddon Hall, an Illustrated Guide, 1871, an example from the 1663 Christmas accounts:

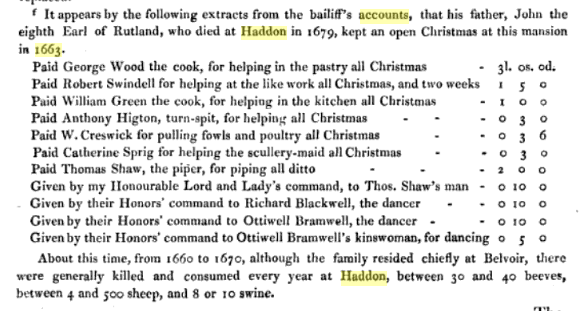

Also in this book, an early 1600s “washing tally” from Haddon Hall:

Over Haddon

Martha Taylor, “the fasting damsel”, was born in Over Haddon in 1649. She didn’t eat for almost two years before her death in 1684. One of the Quakers associated with the Marshall Quakers of Elton, John Gratton, visited the fasting damsel while he was living at Monyash, and occasionally “went two miles to see a woman at Over Haddon who pretended to live without meat.” from The Reliquary, 1861.

June 6, 2024 at 4:08 pm #7453In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

Wondering why she couldn’t focus, Jeezel frowned and checked the ingredients for the Concordia potion again. For a moment she thought she had already done it, but here it was again. And it had to be perfect.

Moon water imbued with lunar magic to set the stage of harmony. Rose petals for love and beauty. Lavender for its calming properties, essential to soothe and balance the collective energies. Honey for cooperation and its irresistible sweetness. Willow wand… Where was her willow wand? She would have to do it all over again if she didn’t find her willow wand.

A wet tongue on her hand was trying to catch her attention. The ingredients started to loose focus again.

“Stop Luminia. It has to be perfect,” said Jeezel, gently pushing the muzzle of her nine tailed fox away. “Help me find my willow wand instead, that would be helpful!”

“You’ve already done it a million times,” said Luminia with a sigh, “and each time you stop at the willow wand. You’re caught in a feverish loop. I need to pee.”

The ingredients and the smoking cauldron disappeared. Jeezel frowned as the techno beats of a pounding headache reminded her she was still alive.

“Just let me die and go out on your own, please…” Jeezel moaned.

“You know I don’t like to shape shift into a cat. Wandering lone dogs are too suspicious. And you need some fresh air. You’ve been simmering in your own juice the last couple of days.”

February 21, 2024 at 5:03 pm #7384In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

The lyrical tones of a familiar Irish accent halted Cedric’s reluctant attempts to make the long distance phone call. He glanced up at the burly man unsuccessfully attempting to order a Guinness and said to him kindly that they probably didn’t have any anyway, even if they could understand him.

“That’s a Limerick accent if ever I heard one, and it’s good, so it is, to hear it. Are you on holiday? Cedric’s the name.”

Rogers face brightened and his broad shoulders relaxed. “I’d give anything to be back in Limerick. Can you take me home with you?”

“Are you lost, son?” Cedric asked gently. “Not to worry my boy, I’m in a bit of a pickle meself to be honest, but we’ll sort something out, eh?”

“The monkeys ran away from me, so they did,” Roger said. “Frigella’s gonna have my guts for garters so she is, when she finds out I’ve mucked it all up again.”

Cedric’s eyes widened and his heart started racing. “And who might that be?” he said, doing his best to remain outwardly calm.

“But she sent me away and then there were all those monkeys and then I don’t know what happened.”

Clearly Roger was a bit ninepence in the shilling.

January 31, 2024 at 4:51 pm #7329In reply to: The Incense of the Quadrivium’s Mystiques

The soft candle light on the altar created moving patterns on the walls draped with velvets and satins. The boudoir was the sanctuary where Jeezel weaved her magic. The patterns on the tapestries changed with her mood, and that night they were a blend of light and dark, electricity made them crackle like lightning in a mid afternoon summer storm.

The altar was a beautifully crafted mahogany table with each legs like a spindle from Sleeping Beauty’s own spinning wheel, but there was no sleeping done here. On her left, her vanity with her collection of wigs, each one a masterpiece styled to perfection, in every shade you could imagine. Tonight, she had chosen the red one. It was a fiery cascade of passion and power, the kind of red that stops traffic. Jeezel needed the confidence and boldness imbued in it to cast the potent Concordia spell.

The air was thick with the perfume of white sage. Lumina, Jeezel’s nine tailed fox familiar, was curled-up on a couch adorned with mystical silver runes pulsating with magic, her muzzle buried in the fur of her nine tails. Her eyes half closed, she was observing Jeezel’s preparation on the altar. The witch had lit a magical fire to heat a cauldron that’s seen more spells than a dictionary.

Jeezel had carefully selected a playlist as harmonious and uplifting as the spell itself, to make a symphony of sounds that would weave together like the most exquisite lace front on a show-stopping wig. She wanted it to be an auditory journey to the highest peaks of harmony that would support her during the casting.

As the precious moon water began to simmer, Jeezel creased the rose petals and the lavender in her hands before she delicately dropped them in the cauldron. The scent rose to her nose and she stirred clockwise with a wand made of the finest willow, while invoking thoughts of unity and shared purpose. The jittery patterns on the walls started to form temporary clusters. A change of colour in the liquid informed the witch it was time to add a drizzle of honey. Jeezel watched as it swirled into the potion, casting a golden glow that promised to mend fences and build bridges. The walls were full of harmonious ripples undulating gently in a soothing manner.

Once the honey was completely melted, Jeezel dropped in an amethyst crystal, whose radiating power would purify the concoction. The potion started to bubble and the glow on the tapestries turned an ugly dark red. Jeezel frowned, wondering if she had done something wrong.

“Stay focused,” said the fox in a brisk voice. “Good. The team energy is fighting back. Plant your stiletto heels firmly into the catwalk, and remember the pageant.”

The familiar’s tawny eyes glowed and the music changed to the emergency song. Jeezel felt an infusion of warm and steady energy from Lumina and started humming in sync with The Ride of the Valkyries. She stirred and chanted, every gesture filled with fiery confidence. The walls glowed darker and the potion hissed. But in the end, it was tamed. The original playlist had resumed to the grand finale. A gentle yet powerful orchestral swell that encapsulated the essence of unity and understanding, wrapping the boudoir and the potion in a sonic embrace that would banish drama and pettiness to the back of the chorus.

Jeezel released the dove feather into the brew, then finished with a sprinkle of glitter with a flourish. And it was done.

“Was the glitter necessary?” asked Lumina.

“Why not? It can’t do any harm.”

The fox jumped from the couch and looked at the potion.

“It’s sparkling like the twinkle in your eye when you hit the stage. It’s ready. Well done.”

Jeezel strained it with grace and poured it into the most fabulous vial she could find, and she sealed it with a kiss.

Jeezel opened Flick Flock and started typing a message to Roland.

The potion is ready. I’m sending it to you through the usual way.

[…]

As you use the potion, you’ll have to perform a kind of team building ritual that will help channel the potion’s power and bring your team together like sequins on a gown, darling.

Fist, dim the lights and set the stage with a circle of candles. Then gather around in the circle with your team, each of you holding a small vial of the potion. Next, take turns sharing something positive, a compliment or an expression of gratitude about the person to your left. It’s about building up that positive energy, getting the good vibes flowing like champagne at a gala.

Once the air is thick with love and camaraderie, each team member will add a drop of the Concordia potion to a communal bowl placed in the center of the circle as a symbol of unity, like a magical melting pot of harmony and shared intentions.

With the power of the potion pooling together, join hands (even if they’re not the touchy-feely types) and my familiar will guide you in an enchanting and rhythmic chant.

Finally with a climactic “clink” of glass of crystal, you’ll all seal the deal, the potion will be activated, and the spell cast.

I can affirm you, your team will be tighter than my corset after Thanksgiving dinner, ready to slay the day with peace and productivity.

Let’s get this done. And don’t forget to add a testimony and click the thumb up.

xoxox Jeezel.

July 4, 2023 at 7:52 pm #7261In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Long Lost Enoch Edwards

My father used to mention long lost Enoch Edwards. Nobody in the family knew where he went to and it was assumed that he went to USA, perhaps to Utah to join his sister Sophie who was a Mormon handcart pioneer, but no record of him was found in USA.

Andrew Enoch Edwards (my great great grandfather) was born in 1840, but was (almost) always known as Enoch. Although civil registration of births had started from 1 July 1837, neither Enoch nor his brother Stephen were registered. Enoch was baptised (as Andrew) on the same day as his brothers Reuben and Stephen in May 1843 at St Chad’s Catholic cathedral in Birmingham. It’s a mystery why these three brothers were baptised Catholic, as there are no other Catholic records for this family before or since. One possible theory is that there was a school attached to the church on Shadwell Street, and a Catholic baptism was required for the boys to go to the school. Enoch’s father John died of TB in 1844, and perhaps in 1843 he knew he was dying and wanted to ensure an education for his sons. The building of St Chads was completed in 1841, and it was close to where they lived.

Enoch appears (as Enoch rather than Andrew) on the 1841 census, six months old. The family were living at Unett Street in Birmingham: John and Sarah and children Mariah, Sophia, Matilda, a mysterious entry transcribed as Lene, a daughter, that I have been unable to find anywhere else, and Reuben and Stephen.

Enoch was just four years old when his father John, an engineer and millwright, died of consumption in 1844.

In 1851 Enoch’s widowed mother Sarah was a mangler living on Summer Street, Birmingham, Matilda a dressmaker, Reuben and Stephen were gun percussionists, and eleven year old Enoch was an errand boy.

On the 1861 census, Sarah was a confectionrer on Canal Street in Birmingham, Stephen was a blacksmith, and Enoch a button tool maker.

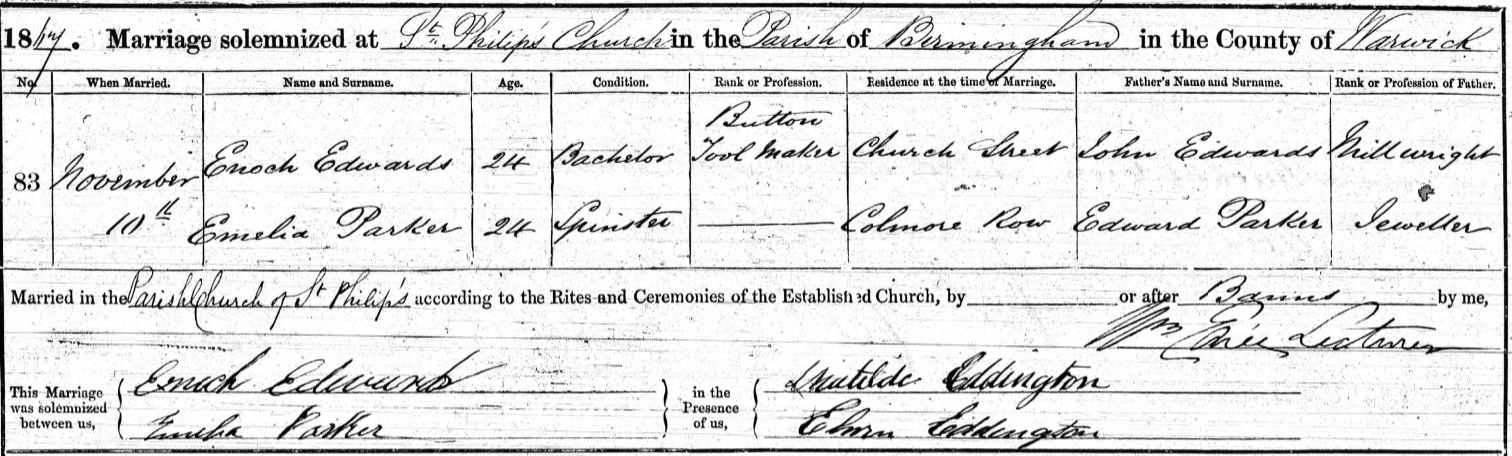

On the 10th November 1867 Enoch married Emelia Parker, daughter of jeweller and rope maker Edward Parker, at St Philip in Birmingham. Both Emelia and Enoch were able to sign their own names, and Matilda and Edwin Eddington were witnesses (Enoch’s sister and her husband). Enoch’s address was Church Street, and his occupation button tool maker.

Four years later in 1871, Enoch was a publican living on Clifton Road. Son Enoch Henry was two years old, and Ralph Ernest was three months. Eliza Barton lived with them as a general servant.

By 1881 Enoch was back working as a button tool maker in Bournebrook, Birmingham. Enoch and Emilia by then had three more children, Amelia, Albert Parker (my great grandfather) and Ada.

Garnet Frederick Edwards was born in 1882. This is the first instance of the name Garnet in the family, and subsequently Garnet has been the middle name for the eldest son (my brother, father and grandfather all have Garnet as a middle name).

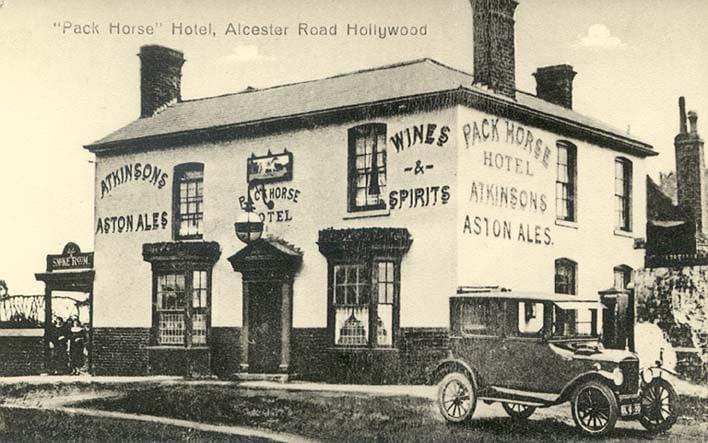

Enoch was the licensed victualler at the Pack Horse Hotel in 1991 at Kings Norton. By this time, only daughters Amelia and Ada and son Garnet are living at home.

Additional information from my fathers cousin, Paul Weaver:

“Enoch refused to allow his son Albert Parker to go to King Edwards School in Birmingham, where he had been awarded a place. Instead, in October 1890 he made Albert Parker Edwards take an apprenticeship with a pawnboker in Tipton.

Towards the end of the 19th century Enoch kept The Pack Horse in Alcester Road, Hollywood, where a twist was 1d an ounce, and beer was 2d a pint. The children had to get up early to get breakfast at 6 o’clock for the hay and straw men on their way to the Birmingham hay and straw market. Enoch is listed as a member of “The Kingswood & Pack Horse Association for the Prosecution of Offenders”, a kind of early Neighbourhood Watch, dated 25 October 1890.

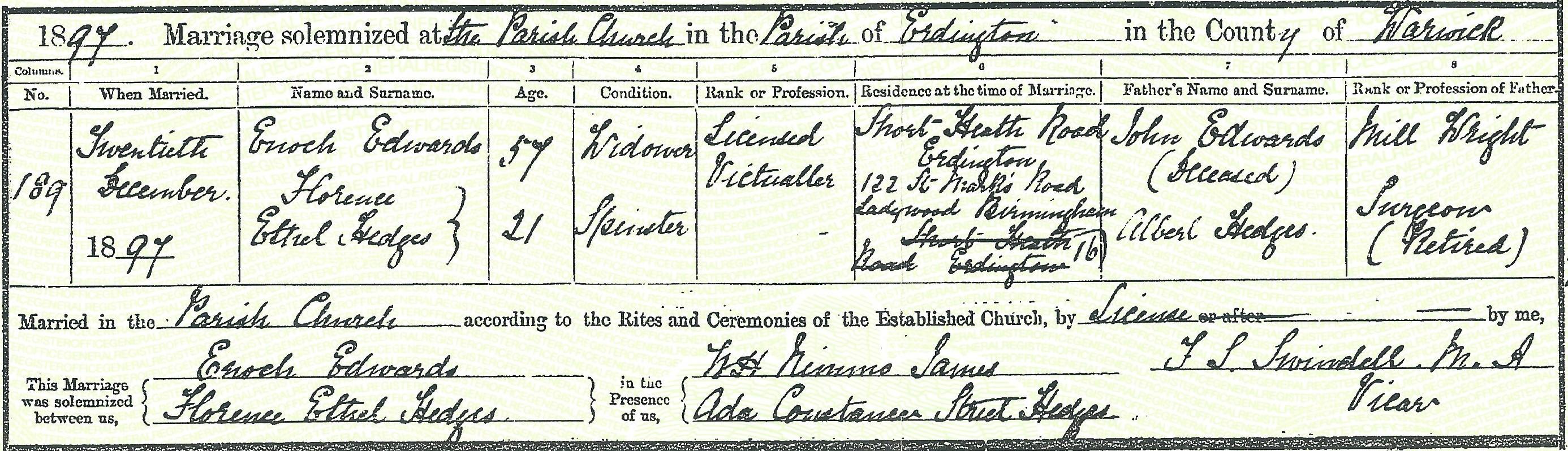

The Edwards family later moved to Redditch where they kept The Rifleman Inn at 35 Park Road. They must have left the Pack Horse by 1895 as another publican was in place by then.”Emelia his wife died in 1895 of consumption at the Rifleman Inn in Redditch, Worcestershire, and in 1897 Enoch married Florence Ethel Hedges in Aston. Enoch was 56 and Florence was just 21 years old.

The following year in 1898 their daughter Muriel Constance Freda Edwards was born in Deritend, Warwickshire.

In 1901 Enoch, (Andrew on the census), publican, Florence and Muriel were living in Dudley. It was hard to find where he went after this.From Paul Weaver:

“Family accounts have it that Enoch EDWARDS fell out with all his family, and at about the age of 60, he left all behind and emigrated to the U.S.A. Enoch was described as being an active man, and it is believed that he had another family when he settled in the U.S.A. Esmor STOKES has it that a postcard was received by the family from Enoch at Niagara Falls.

On 11 June 1902 Harry Wright (the local postmaster responsible in those days for licensing) brought an Enoch EDWARDS to the Bedfordshire Petty Sessions in Biggleswade regarding “Hole in the Wall”, believed to refer to the now defunct “Hole in the Wall” public house at 76 Shortmead Street, Biggleswade with Enoch being granted “temporary authority”. On 9 July 1902 the transfer was granted. A year later in the 1903 edition of Kelly’s Directory of Bedfordshire, Hunts and Northamptonshire there is an Enoch EDWARDS running the Wheatsheaf Public House, Church Street, St. Neots, Huntingdonshire which is 14 miles south of Biggleswade.”

It seems that Enoch and his new family moved away from the midlands in the early 1900s, but again the trail went cold.

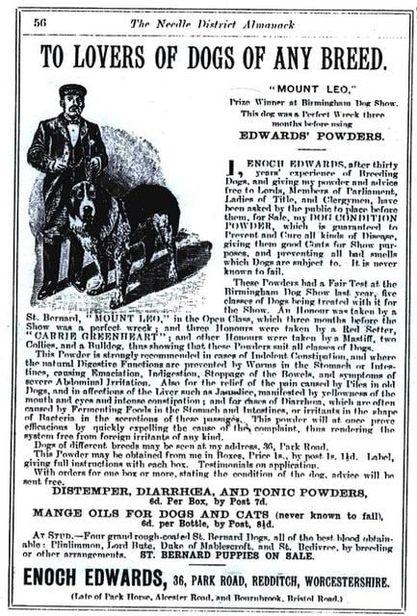

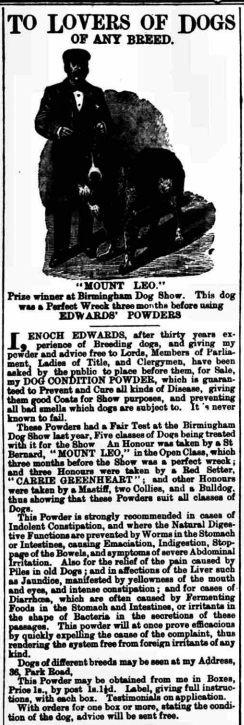

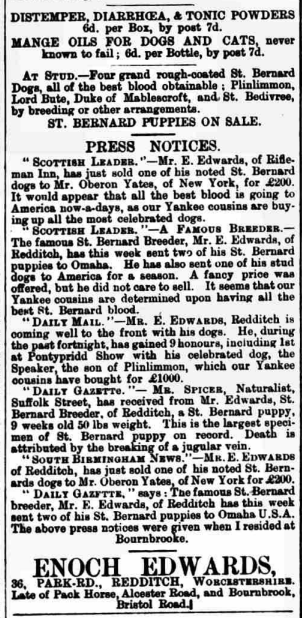

When I started doing the genealogy research, I joined a local facebook group for Redditch in Worcestershire. Enoch’s son Albert Parker Edwards (my great grandfather) spent most of his life there. I asked in the group about Enoch, and someone posted an illustrated advertisement for Enoch’s dog powders. Enoch was a well known breeder/keeper of St Bernards and is cited in a book naming individuals key to the recovery/establishment of ‘mastiff’ size dog breeds.

We had not known that Enoch was a breeder of champion St Bernard dogs!

Once I knew about the St Bernard dogs and the names Mount Leo and Plinlimmon via the newspaper adverts, I did an internet search on Enoch Edwards in conjunction with these dogs.

Enoch’s St Bernard dog “Mount Leo” was bred from the famous Plinlimmon, “the Emperor of Saint Bernards”. He was reported to have sent two puppies to Omaha and one of his stud dogs to America for a season, and in 1897 Enoch made the news for selling a St Bernard to someone in New York for £200. Plinlimmon, bred by Thomas Hall, was born in Liverpool, England on June 29, 1883. He won numerous dog shows throughout Europe in 1884, and in 1885, he was named Best Saint Bernard.

In the Birmingham Mail on 14th June 1890:

“Mr E Edwards, of Bournebrook, has been well to the fore with his dogs of late. He has gained nine honours during the past fortnight, including a first at the Pontypridd show with a St Bernard dog, The Speaker, a son of Plinlimmon.”

In the Alcester Chronicle on Saturday 05 June 1897:

It was discovered that Enoch, Florence and Muriel moved to Canada, not USA as the family had assumed. The 1911 census for Montreal St Jaqcues, Quebec, stated that Enoch, (Florence) Ethel, and (Muriel) Frida had emigrated in 1906. Enoch’s occupation was machinist in 1911. The census transcription is not very good. Edwards was transcribed as Edmand, but the dates of birth for all three are correct. Birthplace is correct ~ A for Anglitan (the census is in French) but race or tribe is also an A but the transcribers have put African black! Enoch by this time was 71 years old, his wife 33 and daughter 11.

Additional information from Paul Weaver:

“In 1906 he and his new family travelled to Canada with Enoch travelling first and Ethel and Frida joined him in Quebec on 25 June 1906 on board the ‘Canada’ from Liverpool.

Their immigration record suggests that they were planning to travel to Winnipeg, but five years later in 1911, Enoch, Florence Ethel and Frida were still living in St James, Montreal. Enoch was employed as a machinist by Canadian Government Railways working 50 hours. It is the 1911 census record that confirms his birth as November 1840. It also states that Enoch could neither read nor write but managed to earn $500 in 1910 for activity other than his main profession, although this may be referring to his innkeeping business interests.

By 1921 Florence and Muriel Frida are living in Langford, Neepawa, Manitoba with Peter FUCHS, an Ontarian farmer of German descent who Florence had married on 24 Jul 1913 implying that Enoch died sometime in 1911/12, although no record has been found.”The extra $500 in earnings was perhaps related to the St Bernard dogs. Enoch signed his name on the register on his marriage to Emelia, and I think it’s very unlikely that he could neither read nor write, as stated above.

However, it may not be Enoch’s wife Florence Ethel who married Peter Fuchs. A Florence Emma Edwards married Peter Fuchs, and on the 1921 census in Neepawa her daugther Muriel Elizabeth Edwards, born in 1902, lives with them. Quite a coincidence, two Florence and Muriel Edwards in Neepawa at the time. Muriel Elizabeth Edwards married and had two children but died at the age of 23 in 1925. Her mother Florence was living with the widowed husband and the two children on the 1931 census in Neepawa. As there was no other daughter on the 1911 census with Enoch, Florence and Muriel in Montreal, it must be a different Florence and daughter. We don’t know, though, why Muriel Constance Freda married in Neepawa.

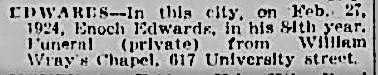

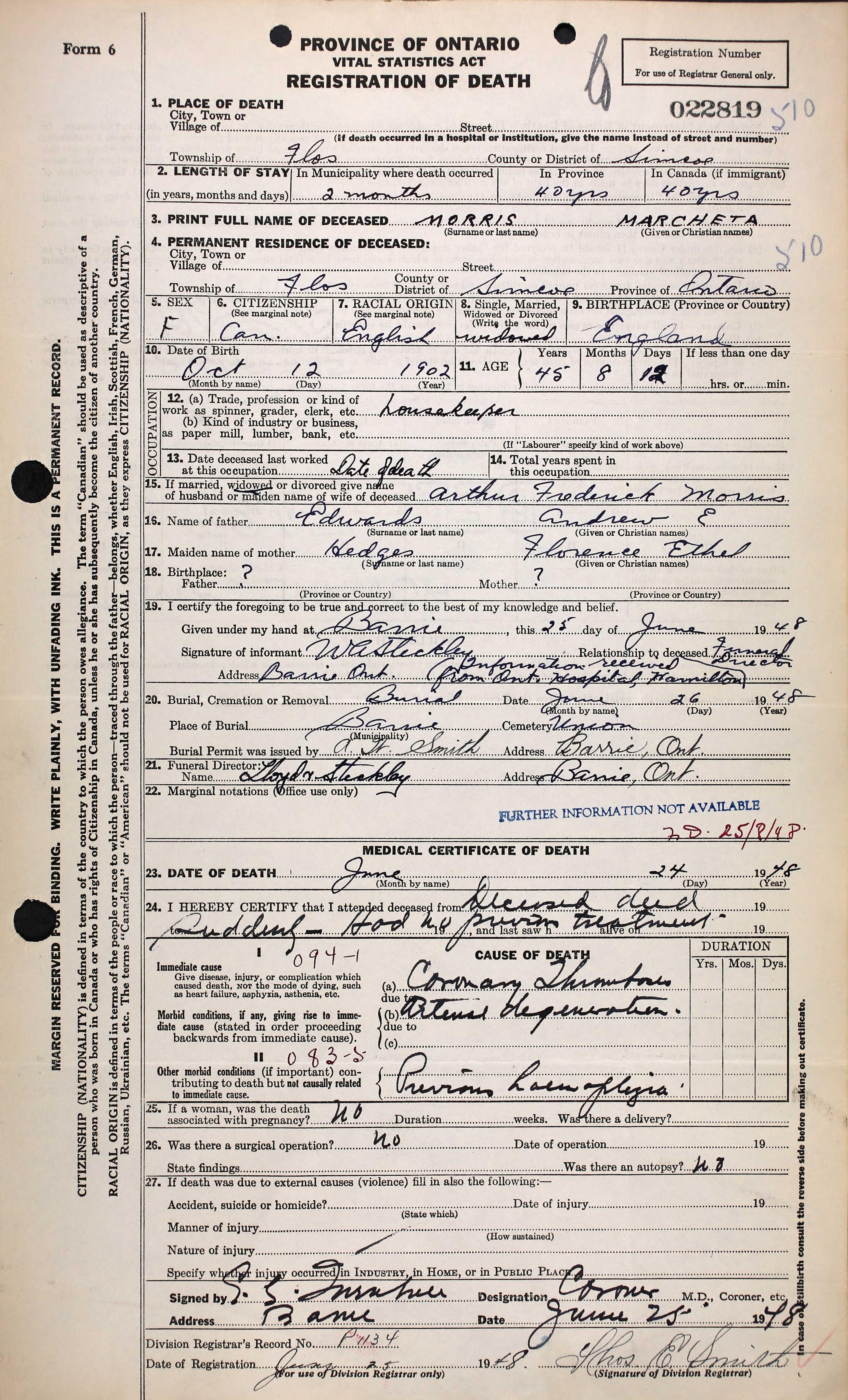

Indeed, Florence was not a widow in 1913. Enoch died in 1924 in Montreal, aged 84. Neither Enoch, Florence or their daughter has been found yet on the 1921 census. The search is not easy, as Enoch sometimes used the name Andrew, Florence used her middle name Ethel, and daughter Muriel used Freda, Valerie (the name she added when she married in Neepawa), and died as Marcheta. The only name she NEVER used was Constance!

A Canadian genealogist living in Montreal phoned the cemetery where Enoch was buried. She said “Enoch Edwards who died on Feb 27 1924 is not buried in the Mount Royal cemetery, he was only cremated there on March 4, 1924. There are no burial records but he died of an abcess and his body was sent to the cemetery for cremation from the Royal Victoria Hospital.”

1924 Obituary for Enoch Edwards:

Cimetière Mont-Royal Outremont, Montreal Region, Quebec, Canada

The Montreal Star 29 Feb 1924, Fri · Page 31

Muriel Constance Freda Valerie Edwards married Arthur Frederick Morris on 24 Oct 1925 in Neepawa, Manitoba. (She appears to have added the name Valerie when she married.)

Unexpectedly a death certificate appeared for Muriel via the hints on the ancestry website. Her name was “Marcheta Morris” on this document, however it also states that she was the widow of Arthur Frederick Morris and daughter of Andrew E Edwards and Florence Ethel Hedges. She died suddenly in June 1948 in Flos, Simcoe, Ontario of a coronary thrombosis, where she was living as a housekeeper.

June 13, 2023 at 10:31 am #7255

June 13, 2023 at 10:31 am #7255In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

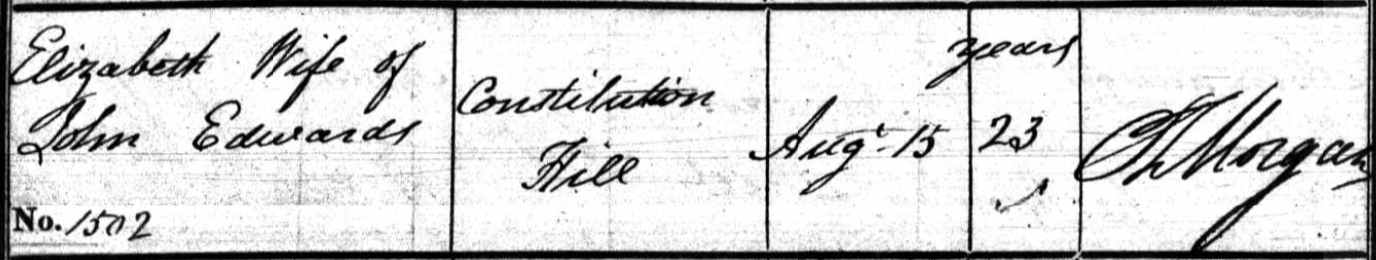

The First Wife of John Edwards

1794-1844

John was a widower when he married Sarah Reynolds from Kinlet. Both my fathers cousin and I had come to a dead end in the Edwards genealogy research as there were a number of possible births of a John Edwards in Birmingham at the time, and a number of possible first wives for a John Edwards at the time.

John Edwards was a millwright on the 1841 census, the only census he appeared on as he died in 1844, and 1841 was the first census. His birth is recorded as 1800, however on the 1841 census the ages were rounded up or down five years. He was an engineer on some of the marriage records of his children with Sarah, and on his death certificate, engineer and millwright, aged 49. The age of 49 at his death from tuberculosis in 1844 is likely to be more accurate than the census (Sarah his wife was present at his death), making a birth date of 1794 or 1795.

John married Sarah Reynolds in January 1827 in Birmingham, and I am descended from this marriage. Any children of John’s first marriage would no doubt have been living with John and Sarah, but had probably left home by the time of the 1841 census.

I found an Elizabeth Edwards, wife of John Edwards of Constitution Hill, died in August 1826 at the age of 23, as stated on the parish death register. It would be logical for a young widower with small children to marry again quickly. If this was John’s first wife, the marriage to Sarah six months later in January 1827 makes sense. Therefore, John’s first wife, I assumed, was Elizabeth, born in 1803.

Death of Elizabeth Edwards, 23 years old. St Mary, Birmingham, 15 Aug 1826:

There were two baptisms recorded for parents John and Elizabeth Edwards, Constitution Hill, and John’s occupation was an engineer on both baptisms.

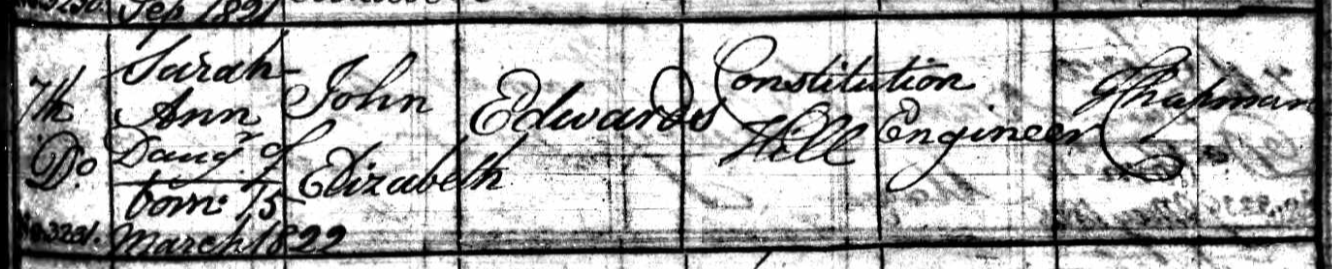

They were both daughters: Sarah Ann in 1822 and Elizabeth in 1824.Sarah Ann Edwards: St Philip, Birmingham. Born 15 March 1822, baptised 7 September 1822:

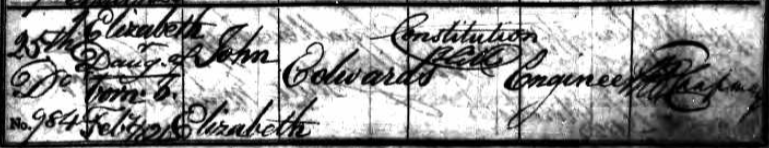

Elizabeth Edwards: St Philip, Birmingham. Born 6 February 1824, baptised 25 February 1824:

With John’s occupation as engineer stated, it looked increasingly likely that I’d found John’s first wife and children of that marriage.

Then I found a marriage of Elizabeth Beach to John Edwards in 1819, and subsequently found an Elizabeth Beach baptised in 1803. This appeared to be the right first wife for John, until an Elizabeth Slater turned up, with a marriage to a John Edwards in 1820. An Elizabeth Slater was baptised in 1803. Either Elizabeth Beach or Elizabeth Slater could have been the first wife of John Edwards. As John’s first wife Elizabeth is not related to us, it’s not necessary to go further back, and in a sense, doesn’t really matter which one it was.

But the Slater name caught my eye.

But first, the name Sarah Ann.

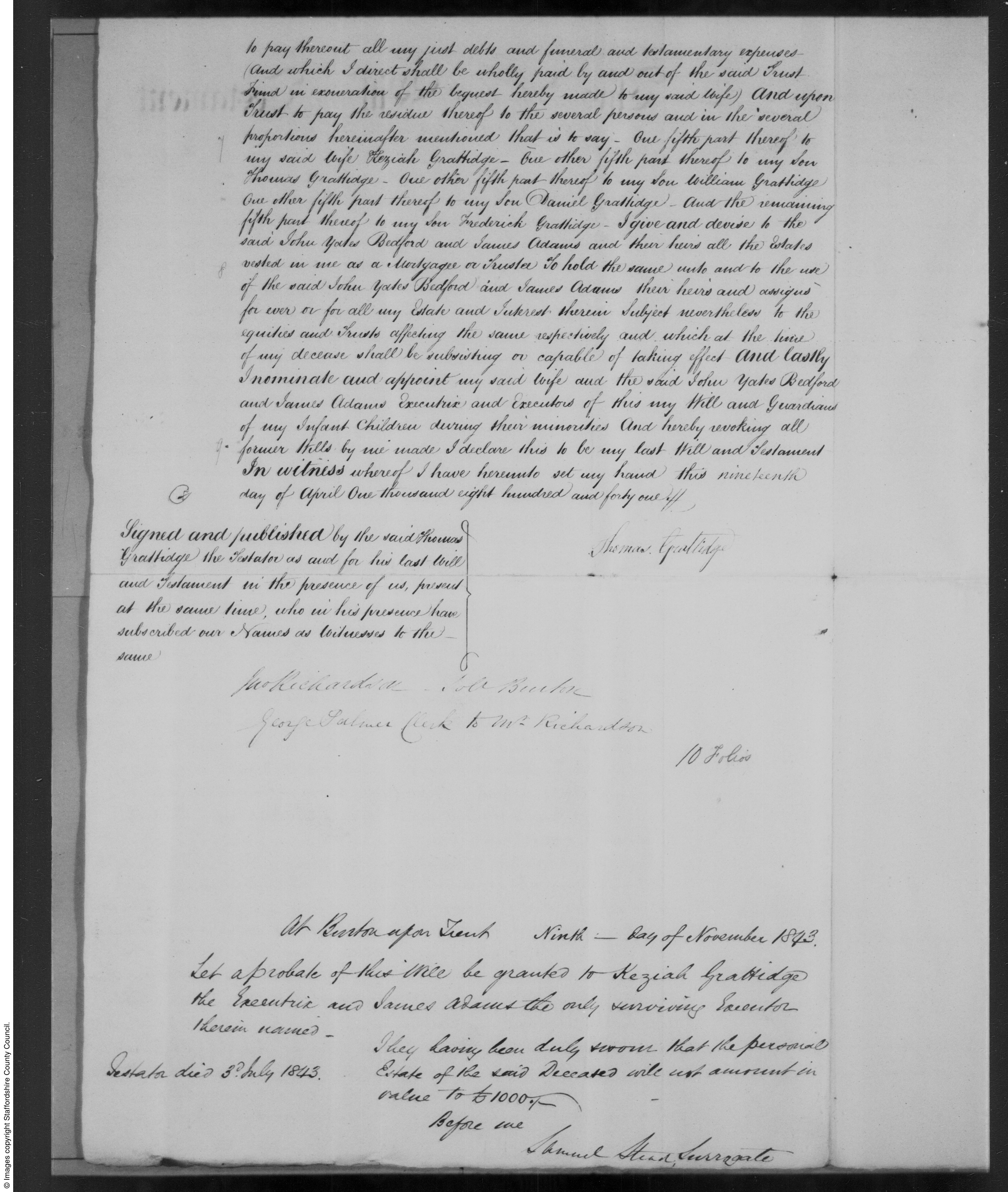

Of the possible baptisms for John Edwards, the most likely seemed to be in 1794, parents John and Sarah. John and Sarah had two infant daughters die just prior to John’s birth. The first was Sarah, the second Sarah Ann. Perhaps this was why John named his daughter Sarah Ann? In the absence of any other significant clues, I decided to assume these were the correct parents. I found and read half a dozen wills of any John Edwards I could find within the likely time period of John’s fathers death.

One of them was dated 1803. In this will, John mentions that his children are not yet of age. (John would have been nine years old.)

He leaves his plating business and some properties to his eldest son Thomas Davis Edwards, (just shy of 21 years old at the time of his fathers death in 1803) with the business to be run jointly with his widow, Sarah. He mentions his son John, and leaves several properties to him, when he comes of age. He also leaves various properties to his daughters Elizabeth and Mary, ditto. The baptisms for all of these children, including the infant deaths of Sarah and Sarah Ann have been found. All but Mary’s were in the same parish. (I found one for Mary in Sutton Coldfield, which was apparently correct, as a later census also recorded her birth as Sutton Coldfield. She was living with family on that census, so it would appear to be correct that for whatever reason, their daughter Mary was born in Sutton Coldfield)Mary married John Slater in 1813. The witnesses were Elizabeth Whitehouse and John Edwards, her sister and brother. Elizabeth married William Nicklin Whitehouse in 1805 and one of the witnesses was Mary Edwards.

Mary’s husband John Slater died in 1821. They had no children. Mary never remarried, and lived with her bachelor brother Thomas Davis Edwards in West Bromwich. Thomas never married, and on the census he was either a proprietor of houses, or “sinecura” (earning a living without working).With Mary marrying a Slater, does this indicate that her brother John’s first wife was Elizabeth Slater rather than Elizabeth Beach? It is a compelling possibility, but does not constitute proof.

Not only that, there is no absolute proof that the John Edwards who died in 1803 was our ancestor John Edwards father.

If we can’t be sure which Elizabeth married John Edwards, we can be reasonably sure who their daughters married. On both of the marriage records the father is recorded as John Edwards, engineer.

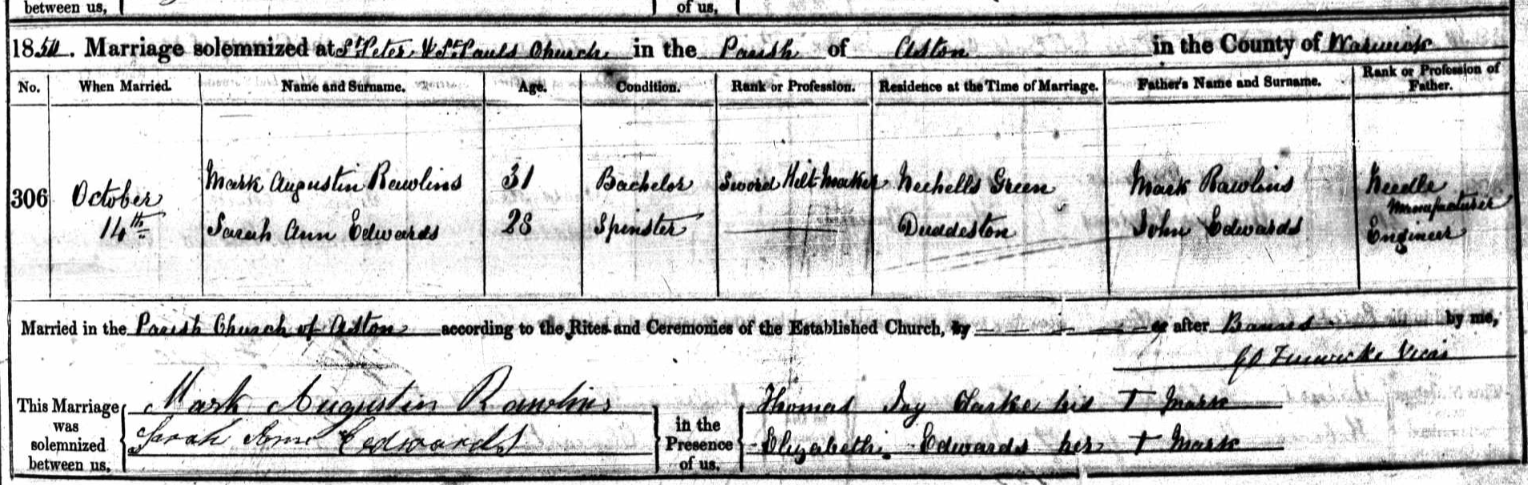

Sarah Ann married Mark Augustin Rawlins in 1850. Mark was a sword hilt maker at the time of the marriage, his father Mark a needle manufacturer. One of the witnesses was Elizabeth Edwards, who signed with her mark. Sarah Ann and Mark however were both able to sign their own names on the register.

Sarah Ann Edwards and Mark Augustin Rawlins marriage 14 October 1850 St Peter and St Paul, Aston, Birmingham:

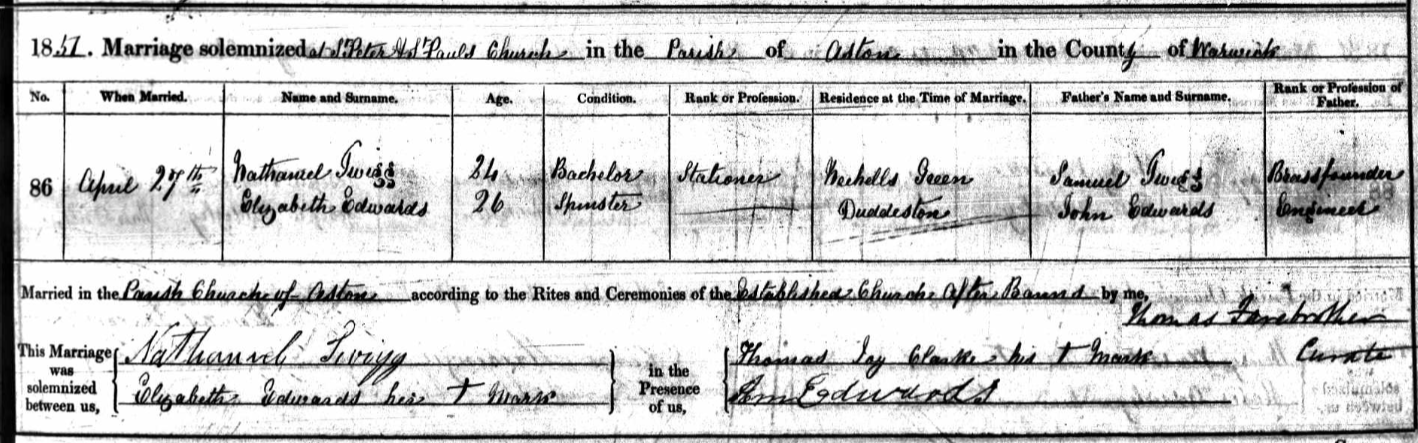

Elizabeth married Nathaniel Twigg in 1851. (She was living with her sister Sarah Ann and Mark Rawlins on the 1851 census, I assume the census was taken before her marriage to Nathaniel on the 27th April 1851.) Nathaniel was a stationer (later on the census a bookseller), his father Samuel a brass founder. Elizabeth signed with her mark, apparently unable to write, and a witness was Ann Edwards. Although Sarah Ann, Elizabeth’s sister, would have been Sarah Ann Rawlins at the time, having married the previous year, she was known as Ann on later censuses. The signature of Ann Edwards looks remarkably similar to Sarah Ann Edwards signature on her own wedding. Perhaps she couldn’t write but had learned how to write her signature for her wedding?

Elizabeth Edwards and Nathaniel Twigg marriage 27 April 1851, St Peter and St Paul, Aston, Birmingham:

Sarah Ann and Mark Rawlins had one daughter and four sons between 1852 and 1859. One of the sons, Edward Rawlins 1857-1931, was a school master and later master of an orphanage.

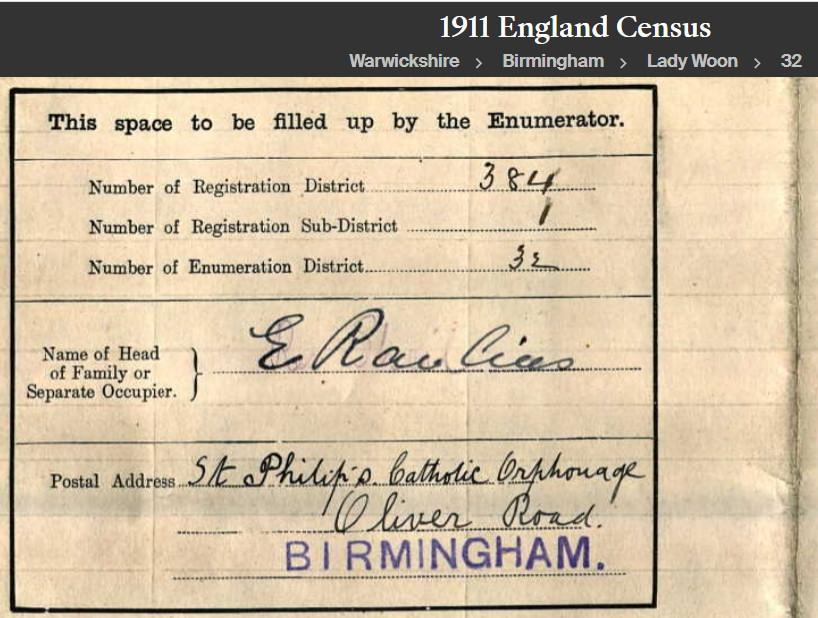

On the 1881 census Edward was a bookseller, in 1891 a stationer, 1901 schoolmaster and his wife Edith was matron, and in 1911 he and Edith were master and matron of St Philip’s Catholic Orphanage on Oliver Road in Birmingham. Edward and Edith did not have any children.

Edward Rawlins, 1911:

Elizabeth and Nathaniel Twigg appear to have had only one son, Arthur Twigg 1862-1943. Arthur was a photographer at 291 Bloomsbury Street, Birmingham. Arthur married Harriet Moseley from Burton on Trent, and they had two daughters, Elizabeth Ann 1897-1954, and Edith 1898-1983. I found a photograph of Edith on her wedding day, with her father Arthur in the picture. Arthur and Harriet also had a son Samuel Arthur, who lived for less than a month, born in 1904. Arthur had mistakenly put this son on the 1911 census stating “less than one month”, but the birth and death of Samuel Arthur Twigg were registered in the same quarter of 1904, and none were found registered for 1911.

Edith Twigg and Leslie A Hancock on their Wedding Day 1925. Arthur Twigg behind the bride. Maybe Elizabeth Ann Twigg seated on the right: (photo found on the ancestry website)

Photographs by Arthur Twigg, 291 Bloomsbury Street, Birmingham:

February 6, 2023 at 10:15 pm #6498

February 6, 2023 at 10:15 pm #6498Some background information on The Sexy Wooden Leg and potential plot developments.

Setting

(nearby Duckailingtown in Dumbass, Oocrane)

The Rootians (a fictitious nationality) invaded Oocrane (a fictitious country) under the guise of freeing the Dumbass region from Lazies. They burned crops and buildings, including the home of a man named Dumbass Voldomeer who was known for his wooden leg and carpenter skills. After the war, Voldomeer was hungry and saw a nest of swan eggs. He went back to his home, carved nine wooden eggs, and replaced the real eggs with the wooden ones so he could eat the eggs for food. The swans still appeared to be brooding on their eggs by the end of summer.Note: There seem to be a bird thematic at play.

The swans’ eggs introduce the plot. The mysterious virus is likely a swan flu. Town in Oocrane often have reminiscing tones of birds’ species.

Bird To(w)nes: (Oocrane/crane, Keav/kea, Spovlar/shoveler, Dilove/dove…)

Also the town’s nursing home/hotel’s name is Vyriy from a mythical place in Slavic mythology (also Iriy, Vyrai, or Irij) where “birds fly for winter and souls go after death” which is sometimes identified with paradise. It is believed that spring has come to Earth from Vyrai.At the Keav Headquarters

(🗺️ Capital of Oocrane)

General Rudechenko and Major Myroslava Kovalev are discussing the incapacitation of President Voldomeer who is suffering from a mysterious virus. The President had told Major Kovalev about a man in the Dumbass region who looked similar to him and could be used as a replacement. The Major volunteers to bring the man to the General, but the General fears it is a suicide mission. He grants her permission but orders his aide to ensure she gets lost behind enemy lines.

Myroslava, the ambitious Major goes undercover as a former war reporter, is now traveling on her own after leaving a group of journalists. She is being followed but tries to lose her pursuers by hunting and making fire in bombed areas. She is frustrated and curses her lack of alcohol.

The Shrine of the Flovlinden Tree

(🗺️ Shpovlar, geographical center of Oocrane)

Olek is the caretaker of the shrine of Saint Edigna and lives near the sacred linden tree. People have been flocking to the shrine due to the miraculous flow of oil from the tree. Olek had retired to this place after a long career, but now a pilgrim family has brought a message of a plan acceleration, which upsets Olek. He reflects on his life and the chaos of people always rushing around and preparing for the wrong things. He thinks about his father’s approach to life, which was carefree and resulted in the same ups and downs as others, but with less suffering. Olek may consider adopting this approach until he can find a way to hide from the enemy.

Rosa and the Cauldron Maker

(young Oocranian wiccan travelling to Innsbruck, Austria)

Eusebius Kazandis is selling black cauldrons at the summer fair of Innsbruck, Austria. He is watching Rosa, a woman selling massage oils, fragrant oils, and polishing oils. Rosa notices Eusebius is sad and thinks he is not where he needs to be. She waves at him, but he looks away as if caught doing something wrong. Rosa is on a journey across Europe, following the wind, and is hoping for a gust to tell her where to go next. However, the branches of the tree she is under remain still.

The Nursing Home

(Nearby the town of Dilove, Oocrane, on Roomhen border somewhere in Transcarpetya)

Egna, who has lived for almost a millennium, initially thinks the recent miracle at the Flovlinden Tree is just another con. She has performed many miracles in her life, but mostly goes unnoticed. She has a book full of records of the lives of many people she has tracked, and reminisces that she has a connection to the President Voldomeer. She decides to go and see the Flovlinden Tree for herself.

🗺️ (the Vyriy hotel at Dilove, Oocrane, on Roomhen border)

Ursula, the owner of a hotel on the outskirts of town, is experiencing a surge in business from the increased number of pilgrims visiting the linden tree. She plans to refurbish the hotel to charge more per night and plans to get a business loan from her nephew Boris, the bank manager. However, she must first evict the old residents of the hotel, which she is dreading. To avoid confrontation, she decides to send letters signed by a fake business manager.

Egbert Gofindlevsky, Olga Herringbonevsky and Obadiah Sproutwinklov are elderly residents of an old hotel turned nursing home who receive a letter informing them that they must leave. Egbert goes to see Obadiah about the letter, but finds a bad odor in his room and decides to see Olga instead.

Maryechka, Obadiah’s granddaughter, goes back home after getting medicine for her sick mother and finds her home empty. She decides to visit her grandfather and his friends at the old people’s home, since the schools are closed and she’s not interested in online activities.

Olga and Egbert have a conversation about their current situation and decide to leave the nursing home and visit Rosa, Olga’s distant relative. Maryechka encounters Egbert and Olga on the stairs and overhears them talking about leaving their friends behind. Olga realizes that it is important to hold onto their hearts and have faith in the kindness of strangers. They then go to see Obadiah, with Olga showing a burst of energy and Egbert with a weak smile.Thus starts their escape and unfolding adventure on the roads of war-torn Oocrane.

Character Keyword Characteristics Sentiment Egbert old man, sharp tone sad, fragile Maryechka Obadiah’s granddaughter, shy innocent Olga old woman, knobbly fingers conflicted, determined Obadiah stubborn as a mule, old friend of Egbert unyielding, possibly deaf January 7, 2023 at 2:28 pm #6359In reply to: Train Your Subjective AI

Sam walking in Time Square by night with his pet nine tailed fox (where are the other tails?)

December 6, 2022 at 2:17 pm #6350

December 6, 2022 at 2:17 pm #6350In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Transportation

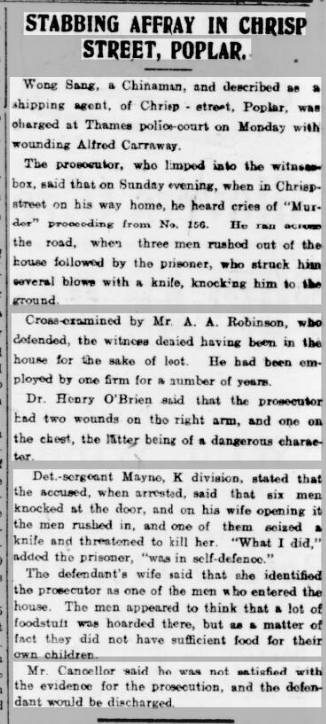

Isaac Stokes 1804-1877

Isaac was born in Churchill, Oxfordshire in 1804, and was the youngest brother of my 4X great grandfather Thomas Stokes. The Stokes family were stone masons for generations in Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire, and Isaac’s occupation was a mason’s labourer in 1834 when he was sentenced at the Lent Assizes in Oxford to fourteen years transportation for stealing tools.

Churchill where the Stokes stonemasons came from: on 31 July 1684 a fire destroyed 20 houses and many other buildings, and killed four people. The village was rebuilt higher up the hill, with stone houses instead of the old timber-framed and thatched cottages. The fire was apparently caused by a baker who, to avoid chimney tax, had knocked through the wall from her oven to her neighbour’s chimney.

Isaac stole a pick axe, the value of 2 shillings and the property of Thomas Joyner of Churchill; a kibbeaux and a trowel value 3 shillings the property of Thomas Symms; a hammer and axe value 5 shillings, property of John Keen of Sarsden.

(The word kibbeaux seems to only exists in relation to Isaac Stokes sentence and whoever was the first to write it was perhaps being creative with the spelling of a kibbo, a miners or a metal bucket. This spelling is repeated in the criminal reports and the newspaper articles about Isaac, but nowhere else).

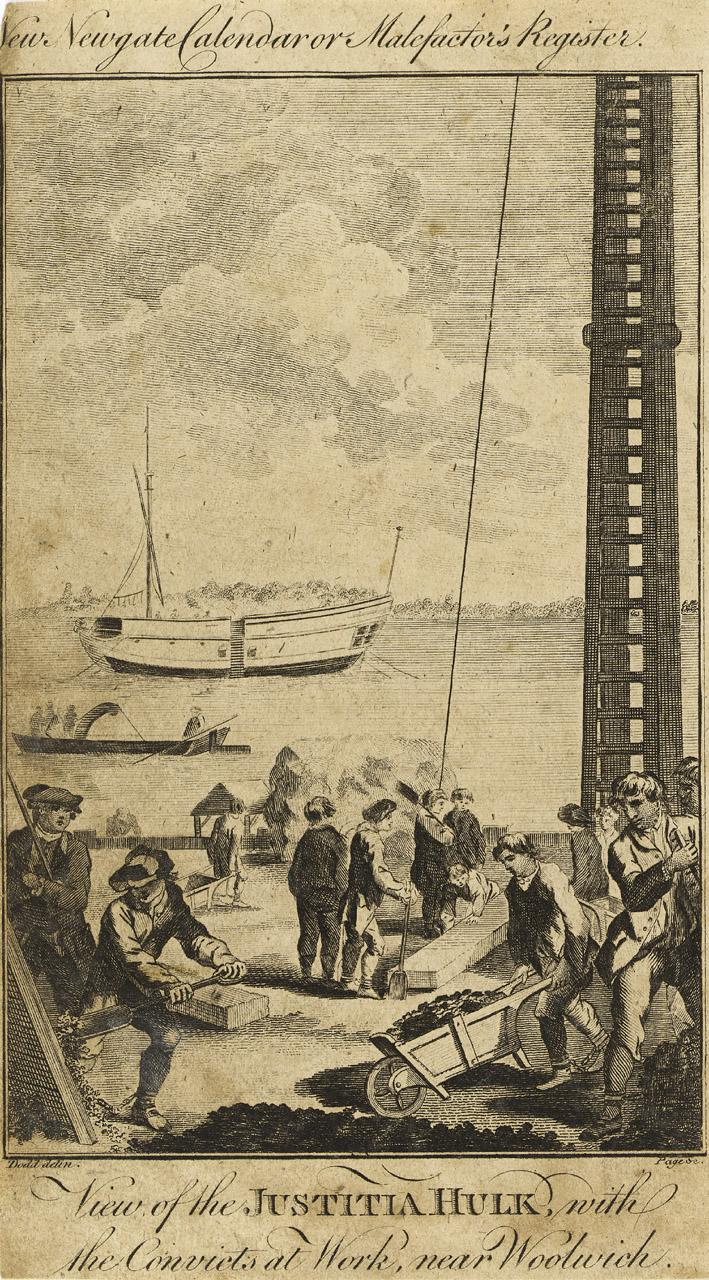

In March 1834 the Removal of Convicts was announced in the Oxford University and City Herald: Isaac Stokes and several other prisoners were removed from the Oxford county gaol to the Justitia hulk at Woolwich “persuant to their sentences of transportation at our Lent Assizes”.

via digitalpanopticon:

Hulks were decommissioned (and often unseaworthy) ships that were moored in rivers and estuaries and refitted to become floating prisons. The outbreak of war in America in 1775 meant that it was no longer possible to transport British convicts there. Transportation as a form of punishment had started in the late seventeenth century, and following the Transportation Act of 1718, some 44,000 British convicts were sent to the American colonies. The end of this punishment presented a major problem for the authorities in London, since in the decade before 1775, two-thirds of convicts at the Old Bailey received a sentence of transportation – on average 283 convicts a year. As a result, London’s prisons quickly filled to overflowing with convicted prisoners who were sentenced to transportation but had no place to go.

To increase London’s prison capacity, in 1776 Parliament passed the “Hulks Act” (16 Geo III, c.43). Although overseen by local justices of the peace, the hulks were to be directly managed and maintained by private contractors. The first contract to run a hulk was awarded to Duncan Campbell, a former transportation contractor. In August 1776, the Justicia, a former transportation ship moored in the River Thames, became the first prison hulk. This ship soon became full and Campbell quickly introduced a number of other hulks in London; by 1778 the fleet of hulks on the Thames held 510 prisoners.

Demand was so great that new hulks were introduced across the country. There were hulks located at Deptford, Chatham, Woolwich, Gosport, Plymouth, Portsmouth, Sheerness and Cork.The Justitia via rmg collections:

Convicts perform hard labour at the Woolwich Warren. The hulk on the river is the ‘Justitia’. Prisoners were kept on board such ships for months awaiting deportation to Australia. The ‘Justitia’ was a 260 ton prison hulk that had been originally moored in the Thames when the American War of Independence put a stop to the transportation of criminals to the former colonies. The ‘Justitia’ belonged to the shipowner Duncan Campbell, who was the Government contractor who organized the prison-hulk system at that time. Campbell was subsequently involved in the shipping of convicts to the penal colony at Botany Bay (in fact Port Jackson, later Sydney, just to the north) in New South Wales, the ‘first fleet’ going out in 1788.

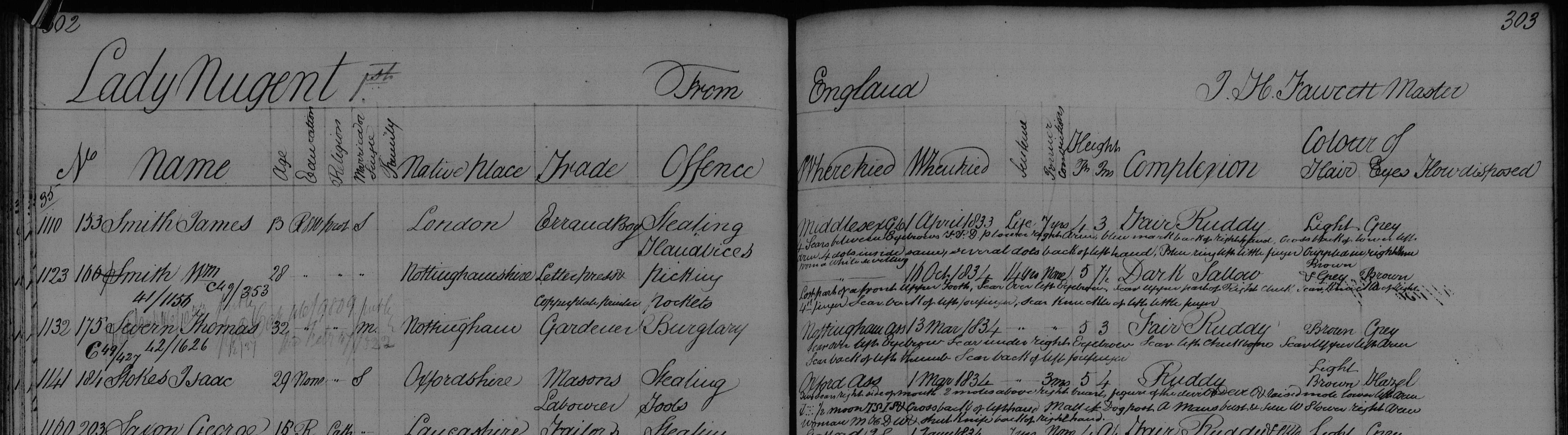

While searching for records for Isaac Stokes I discovered that another Isaac Stokes was transported to New South Wales in 1835 as well. The other one was a butcher born in 1809, sentenced in London for seven years, and he sailed on the Mary Ann. Our Isaac Stokes sailed on the Lady Nugent, arriving in NSW in April 1835, having set sail from England in December 1834.

Lady Nugent was built at Bombay in 1813. She made four voyages under contract to the British East India Company (EIC). She then made two voyages transporting convicts to Australia, one to New South Wales and one to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). (via Wikipedia)

via freesettlerorfelon website:

On 20 November 1834, 100 male convicts were transferred to the Lady Nugent from the Justitia Hulk and 60 from the Ganymede Hulk at Woolwich, all in apparent good health. The Lady Nugent departed Sheerness on 4 December 1834.

SURGEON OLIVER SPROULE

Oliver Sproule kept a Medical Journal from 7 November 1834 to 27 April 1835. He recorded in his journal the weather conditions they experienced in the first two weeks:

‘In the course of the first week or ten days at sea, there were eight or nine on the sick list with catarrhal affections and one with dropsy which I attribute to the cold and wet we experienced during that period beating down channel. Indeed the foremost berths in the prison at this time were so wet from leaking in that part of the ship, that I was obliged to issue dry beds and bedding to a great many of the prisoners to preserve their health, but after crossing the Bay of Biscay the weather became fine and we got the damp beds and blankets dried, the leaks partially stopped and the prison well aired and ventilated which, I am happy to say soon manifested a favourable change in the health and appearance of the men.

Besides the cases given in the journal I had a great many others to treat, some of them similar to those mentioned but the greater part consisted of boils, scalds, and contusions which would not only be too tedious to enter but I fear would be irksome to the reader. There were four births on board during the passage which did well, therefore I did not consider it necessary to give a detailed account of them in my journal the more especially as they were all favourable cases.

Regularity and cleanliness in the prison, free ventilation and as far as possible dry decks turning all the prisoners up in fine weather as we were lucky enough to have two musicians amongst the convicts, dancing was tolerated every afternoon, strict attention to personal cleanliness and also to the cooking of their victuals with regular hours for their meals, were the only prophylactic means used on this occasion, which I found to answer my expectations to the utmost extent in as much as there was not a single case of contagious or infectious nature during the whole passage with the exception of a few cases of psora which soon yielded to the usual treatment. A few cases of scurvy however appeared on board at rather an early period which I can attribute to nothing else but the wet and hardships the prisoners endured during the first three or four weeks of the passage. I was prompt in my treatment of these cases and they got well, but before we arrived at Sydney I had about thirty others to treat.’

The Lady Nugent arrived in Port Jackson on 9 April 1835 with 284 male prisoners. Two men had died at sea. The prisoners were landed on 27th April 1835 and marched to Hyde Park Barracks prior to being assigned. Ten were under the age of 14 years.

The Lady Nugent:

Isaac’s distinguishing marks are noted on various criminal registers and record books:

“Height in feet & inches: 5 4; Complexion: Ruddy; Hair: Light brown; Eyes: Hazel; Marks or Scars: Yes [including] DEVIL on lower left arm, TSIS back of left hand, WS lower right arm, MHDW back of right hand.”

Another includes more detail about Isaac’s tattoos:

“Two slight scars right side of mouth, 2 moles above right breast, figure of the devil and DEVIL and raised mole, lower left arm; anchor, seven dots half moon, TSIS and cross, back of left hand; a mallet, door post, A, mans bust, sun, WS, lower right arm; woman, MHDW and shut knife, back of right hand.”

From How tattoos became fashionable in Victorian England (2019 article in TheConversation by Robert Shoemaker and Zoe Alkar):

“Historical tattooing was not restricted to sailors, soldiers and convicts, but was a growing and accepted phenomenon in Victorian England. Tattoos provide an important window into the lives of those who typically left no written records of their own. As a form of “history from below”, they give us a fleeting but intriguing understanding of the identities and emotions of ordinary people in the past.

As a practice for which typically the only record is the body itself, few systematic records survive before the advent of photography. One exception to this is the written descriptions of tattoos (and even the occasional sketch) that were kept of institutionalised people forced to submit to the recording of information about their bodies as a means of identifying them. This particularly applies to three groups – criminal convicts, soldiers and sailors. Of these, the convict records are the most voluminous and systematic.

Such records were first kept in large numbers for those who were transported to Australia from 1788 (since Australia was then an open prison) as the authorities needed some means of keeping track of them.”On the 1837 census Isaac was working for the government at Illiwarra, New South Wales. This record states that he arrived on the Lady Nugent in 1835. There are three other indent records for an Isaac Stokes in the following years, but the transcriptions don’t provide enough information to determine which Isaac Stokes it was. In April 1837 there was an abscondment, and an arrest/apprehension in May of that year, and in 1843 there was a record of convict indulgences.

From the Australian government website regarding “convict indulgences”:

“By the mid-1830s only six per cent of convicts were locked up. The vast majority worked for the government or free settlers and, with good behaviour, could earn a ticket of leave, conditional pardon or and even an absolute pardon. While under such orders convicts could earn their own living.”

In 1856 in Camden, NSW, Isaac Stokes married Catherine Daly. With no further information on this record it would be impossible to know for sure if this was the right Isaac Stokes. This couple had six children, all in the Camden area, but none of the records provided enough information. No occupation or place or date of birth recorded for Isaac Stokes.

I wrote to the National Library of Australia about the marriage record, and their reply was a surprise! Issac and Catherine were married on 30 September 1856, at the house of the Rev. Charles William Rigg, a Methodist minister, and it was recorded that Isaac was born in Edinburgh in 1821, to parents James Stokes and Sarah Ellis! The age at the time of the marriage doesn’t match Isaac’s age at death in 1877, and clearly the place of birth and parents didn’t match either. Only his fathers occupation of stone mason was correct. I wrote back to the helpful people at the library and they replied that the register was in a very poor condition and that only two and a half entries had survived at all, and that Isaac and Catherines marriage was recorded over two pages.

I searched for an Isaac Stokes born in 1821 in Edinburgh on the Scotland government website (and on all the other genealogy records sites) and didn’t find it. In fact Stokes was a very uncommon name in Scotland at the time. I also searched Australian immigration and other records for another Isaac Stokes born in Scotland or born in 1821, and found nothing. I was unable to find a single record to corroborate this mysterious other Isaac Stokes.

As the age at death in 1877 was correct, I assume that either Isaac was lying, or that some mistake was made either on the register at the home of the Methodist minster, or a subsequent mistranscription or muddle on the remnants of the surviving register. Therefore I remain convinced that the Camden stonemason Isaac Stokes was indeed our Isaac from Oxfordshire.

I found a history society newsletter article that mentioned Isaac Stokes, stone mason, had built the Glenmore church, near Camden, in 1859.

From the Wollondilly museum April 2020 newsletter:

From the Camden History website:

“The stone set over the porch of Glenmore Church gives the date of 1860. The church was begun in 1859 on land given by Joseph Moore. James Rogers of Picton was given the contract to build and local builder, Mr. Stokes, carried out the work. Elizabeth Moore, wife of Edward, laid the foundation stone. The first service was held on 19th March 1860. The cemetery alongside the church contains the headstones and memorials of the areas early pioneers.”

Isaac died on the 3rd September 1877. The inquest report puts his place of death as Bagdelly, near to Camden, and another death register has put Cambelltown, also very close to Camden. His age was recorded as 71 and the inquest report states his cause of death was “rupture of one of the large pulmonary vessels of the lung”. His wife Catherine died in childbirth in 1870 at the age of 43.

Isaac and Catherine’s children:

William Stokes 1857-1928

Catherine Stokes 1859-1846

Sarah Josephine Stokes 1861-1931

Ellen Stokes 1863-1932

Rosanna Stokes 1865-1919

Louisa Stokes 1868-1844.

It’s possible that Catherine Daly was a transported convict from Ireland.

Some time later I unexpectedly received a follow up email from The Oaks Heritage Centre in Australia.

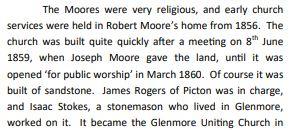

“The Gaudry papers which we have in our archive record him (Isaac Stokes) as having built: the church, the school and the teachers residence. Isaac is recorded in the General return of convicts: 1837 and in Grevilles Post Office directory 1872 as a mason in Glenmore.”

November 18, 2022 at 4:47 pm #6348

November 18, 2022 at 4:47 pm #6348In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

Wong Sang

Wong Sang was born in China in 1884. In October 1916 he married Alice Stokes in Oxford.

Alice was the granddaughter of William Stokes of Churchill, Oxfordshire and William was the brother of Thomas Stokes the wheelwright (who was my 3X great grandfather). In other words Alice was my second cousin, three times removed, on my fathers paternal side.

Wong Sang was an interpreter, according to the baptism registers of his children and the Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital admission registers in 1930. The hospital register also notes that he was employed by the Blue Funnel Line, and that his address was 11, Limehouse Causeway, E 14. (London)

“The Blue Funnel Line offered regular First-Class Passenger and Cargo Services From the UK to South Africa, Malaya, China, Japan, Australia, Java, and America. Blue Funnel Line was Owned and Operated by Alfred Holt & Co., Liverpool.

The Blue Funnel Line, so-called because its ships have a blue funnel with a black top, is more appropriately known as the Ocean Steamship Company.”Wong Sang and Alice’s daughter, Frances Eileen Sang, was born on the 14th July, 1916 and baptised in 1920 at St Stephen in Poplar, Tower Hamlets, London. The birth date is noted in the 1920 baptism register and would predate their marriage by a few months, although on the death register in 1921 her age at death is four years old and her year of birth is recorded as 1917.

Charles Ronald Sang was baptised on the same day in May 1920, but his birth is recorded as April of that year. The family were living on Morant Street, Poplar.

James William Sang’s birth is recorded on the 1939 census and on the death register in 2000 as being the 8th March 1913. This definitely would predate the 1916 marriage in Oxford.

William Norman Sang was born on the 17th October 1922 in Poplar.

Alice and the three sons were living at 11, Limehouse Causeway on the 1939 census, the same address that Wong Sang was living at when he was admitted to Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital on the 15th January 1930. Wong Sang died in the hospital on the 8th March of that year at the age of 46.

Alice married John Patterson in 1933 in Stepney. John was living with Alice and her three sons on Limehouse Causeway on the 1939 census and his occupation was chef.

Via Old London Photographs:

“Limehouse Causeway is a street in east London that was the home to the original Chinatown of London. A combination of bomb damage during the Second World War and later redevelopment means that almost nothing is left of the original buildings of the street.”

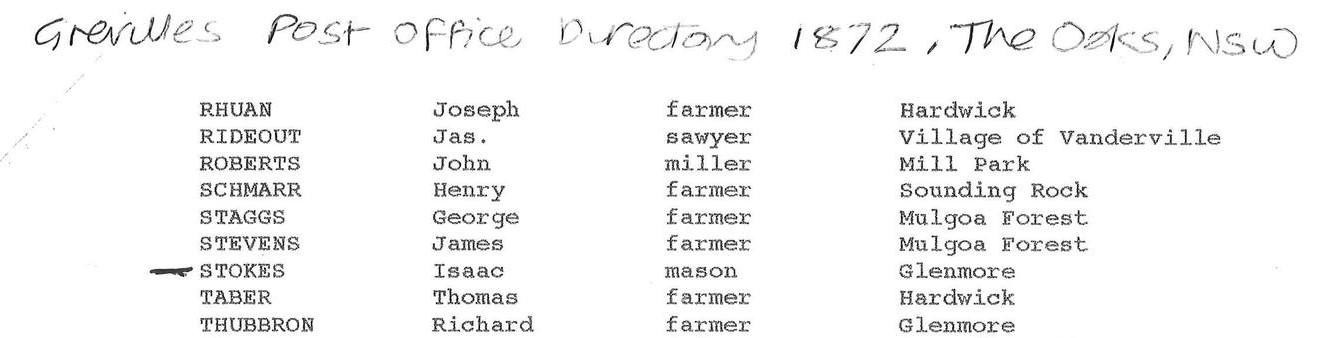

Limehouse Causeway in 1925:

From The Story of Limehouse’s Lost Chinatown, poplarlondon website:

“Limehouse was London’s first Chinatown, home to a tightly-knit community who were demonised in popular culture and eventually erased from the cityscape.

As recounted in the BBC’s ‘Our Greatest Generation’ series, Connie was born to a Chinese father and an English mother in early 1920s Limehouse, where she used to play in the street with other British and British-Chinese children before running inside for teatime at one of their houses.

Limehouse was London’s first Chinatown between the 1880s and the 1960s, before the current Chinatown off Shaftesbury Avenue was established in the 1970s by an influx of immigrants from Hong Kong.

Connie’s memories of London’s first Chinatown as an “urban village” paint a very different picture to the seedy area portrayed in early twentieth century novels.

The pyramid in St Anne’s church marked the entrance to the opium den of Dr Fu Manchu, a criminal mastermind who threatened Western society by plotting world domination in a series of novels by Sax Rohmer.

Thomas Burke’s Limehouse Nights cemented stereotypes about prostitution, gambling and violence within the Chinese community, and whipped up anxiety about sexual relationships between Chinese men and white women.

Though neither novelist was familiar with the Chinese community, their depictions made Limehouse one of the most notorious areas of London.

Travel agent Thomas Cook even organised tours of the area for daring visitors, despite the rector of Limehouse warning that “those who look for the Limehouse of Mr Thomas Burke simply will not find it.”

All that remains is a handful of Chinese street names, such as Ming Street, Pekin Street, and Canton Street — but what was Limehouse’s chinatown really like, and why did it get swept away?

Chinese migration to Limehouse

Chinese sailors discharged from East India Company ships settled in the docklands from as early as the 1780s.

By the late nineteenth century, men from Shanghai had settled around Pennyfields Lane, while a Cantonese community lived on Limehouse Causeway.

Chinese sailors were often paid less and discriminated against by dock hirers, and so began to diversify their incomes by setting up hand laundry services and restaurants.

Old photographs show shopfronts emblazoned with Chinese characters with horse-drawn carts idling outside or Chinese men in suits and hats standing proudly in the doorways.

In oral histories collected by Yat Ming Loo, Connie’s husband Leslie doesn’t recall seeing any Chinese women as a child, since male Chinese sailors settled in London alone and married working-class English women.

In the 1920s, newspapers fear-mongered about interracial marriages, crime and gambling, and described chinatown as an East End “colony.”

Ironically, Chinese opium-smoking was also demonised in the press, despite Britain waging war against China in the mid-nineteenth century for suppressing the opium trade to alleviate addiction amongst its people.

The number of Chinese people who settled in Limehouse was also greatly exaggerated, and in reality only totalled around 300.

The real Chinatown

Although the press sought to characterise Limehouse as a monolithic Chinese community in the East End, Connie remembers seeing people of all nationalities in the shops and community spaces in Limehouse.

She doesn’t remember feeling discriminated against by other locals, though Connie does recall having her face measured and IQ tested by a member of the British Eugenics Society who was conducting research in the area.

Some of Connie’s happiest childhood memories were from her time at Chung-Hua Club, where she learned about Chinese culture and language.

Why did Chinatown disappear?

The caricature of Limehouse’s Chinatown as a den of vice hastened its erasure.

Police raids and deportations fuelled by the alarmist media coverage threatened the Chinese population of Limehouse, and slum clearance schemes to redevelop low-income areas dispersed Chinese residents in the 1930s.

The Defence of the Realm Act imposed at the beginning of the First World War criminalised opium use, gave the authorities increased powers to deport Chinese people and restricted their ability to work on British ships.

Dwindling maritime trade during World War II further stripped Chinese sailors of opportunities for employment, and any remnants of Chinatown were destroyed during the Blitz or erased by postwar development schemes.”

Wong Sang 1884-1930

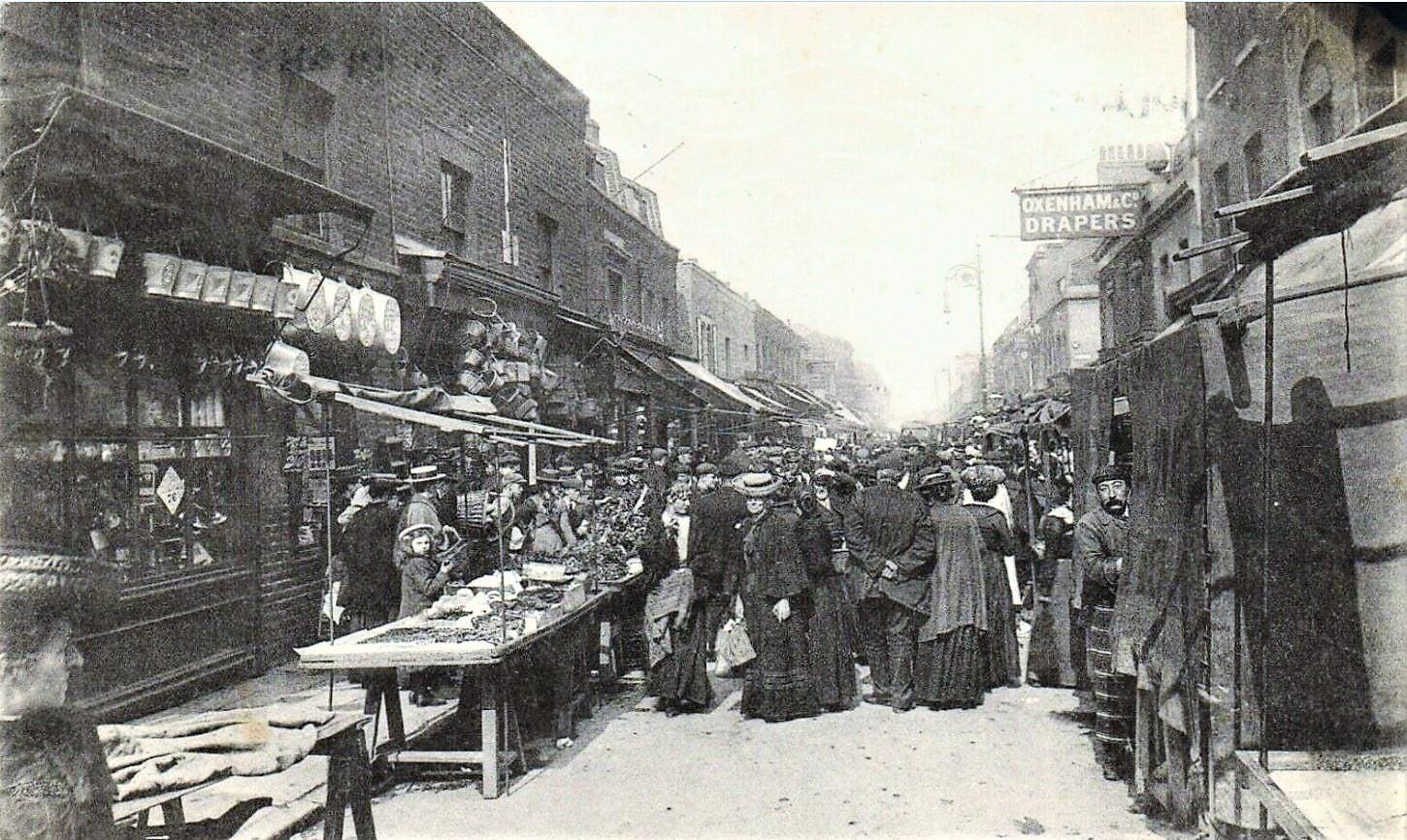

The year 1918 was a troublesome one for Wong Sang, an interpreter and shipping agent for Blue Funnel Line. The Sang family were living at 156, Chrisp Street.

Chrisp Street, Poplar, in 1913 via Old London Photographs:

In February Wong Sang was discharged from a false accusation after defending his home from potential robbers.

East End News and London Shipping Chronicle – Friday 15 February 1918:

In August of that year he was involved in an incident that left him unconscious.

Faringdon Advertiser and Vale of the White Horse Gazette – Saturday 31 August 1918:

Wong Sang is mentioned in an 1922 article about “Oriental London”.

London and China Express – Thursday 09 February 1922:

A photograph of the Chee Kong Tong Chinese Freemason Society mentioned in the above article, via Old London Photographs:

Wong Sang was recommended by the London Metropolitan Police in 1928 to assist in a case in Wellingborough, Northampton.

Difficulty of Getting an Interpreter: Northampton Mercury – Friday 16 March 1928:

The difficulty was that “this man speaks the Cantonese language only…the Northeners and the Southerners in China have differing languages and the interpreter seemed to speak one that was in between these two.”

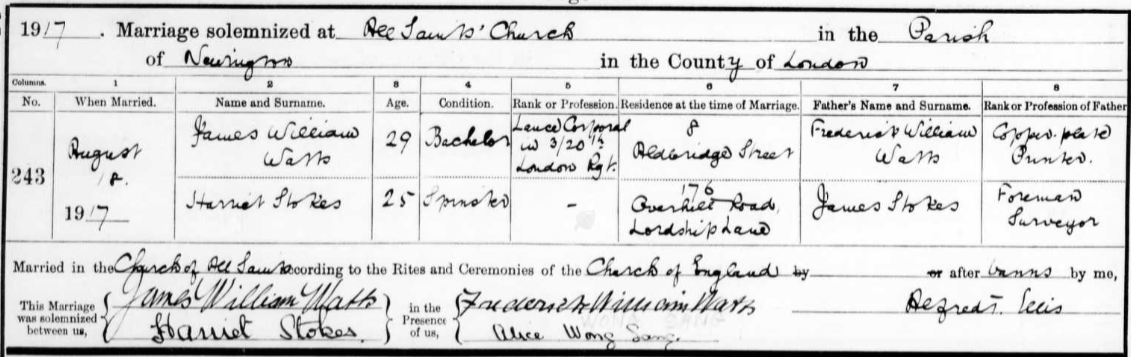

In 1917, Alice Wong Sang was a witness at her sister Harriet Stokes marriage to James William Watts in Southwark, London. Their father James Stokes occupation on the marriage register is foreman surveyor, but on the census he was a council roadman or labourer. (I initially rejected this as the correct marriage for Harriet because of the discrepancy with the occupations. Alice Wong Sang as a witness confirmed that it was indeed the correct one.)

James William Sang 1913-2000 was a clock fitter and watch assembler (on the 1939 census). He married Ivy Laura Fenton in 1963 in Sidcup, Kent. James died in Southwark in 2000.

Charles Ronald Sang 1920-1974 was a draughtsman (1939 census). He married Eileen Burgess in 1947 in Marylebone. Charles and Eileen had two sons: Keith born in 1951 and Roger born in 1952. He died in 1974 in Hertfordshire.

William Norman Sang 1922-2000 was a clerk and telephone operator (1939 census). William enlisted in the Royal Artillery in 1942. He married Lily Mullins in 1949 in Bethnal Green, and they had three daughters: Marion born in 1950, Christine in 1953, and Frances in 1959. He died in Redbridge in 2000.

I then found another two births registered in Poplar by Alice Sang, both daughters. Doris Winifred Sang was born in 1925, and Patricia Margaret Sang was born in 1933 ~ three years after Wong Sang’s death. Neither of the these daughters were on the 1939 census with Alice, John Patterson and the three sons. Margaret had presumably been evacuated because of the war to a family in Taunton, Somerset. Doris would have been fourteen and I have been unable to find her in 1939 (possibly because she died in 2017 and has not had the redaction removed yet on the 1939 census as only deceased people are viewable).

Doris Winifred Sang 1925-2017 was a nursing sister. She didn’t marry, and spent a year in USA between 1954 and 1955. She stayed in London, and died at the age of ninety two in 2017.

Patricia Margaret Sang 1933-1998 was also a nurse. She married Patrick L Nicely in Stepney in 1957. Patricia and Patrick had five children in London: Sharon born 1959, Donald in 1960, Malcolm was born and died in 1966, Alison was born in 1969 and David in 1971.

I was unable to find a birth registered for Alice’s first son, James William Sang (as he appeared on the 1939 census). I found Alice Stokes on the 1911 census as a 17 year old live in servant at a tobacconist on Pekin Street, Limehouse, living with Mr Sui Fong from Hong Kong and his wife Sarah Sui Fong from Berlin. I looked for a birth registered for James William Fong instead of Sang, and found it ~ mothers maiden name Stokes, and his date of birth matched the 1939 census: 8th March, 1913.

On the 1921 census, Wong Sang is not listed as living with them but it is mentioned that Mr Wong Sang was the person returning the census. Also living with Alice and her sons James and Charles in 1921 are two visitors: (Florence) May Stokes, 17 years old, born in Woodstock, and Charles Stokes, aged 14, also born in Woodstock. May and Charles were Alice’s sister and brother.

I found Sharon Nicely on social media and she kindly shared photos of Wong Sang and Alice Stokes:

November 4, 2022 at 2:19 pm #6342

November 4, 2022 at 2:19 pm #6342In reply to: Family Stories From The Other Side ~ Book Two

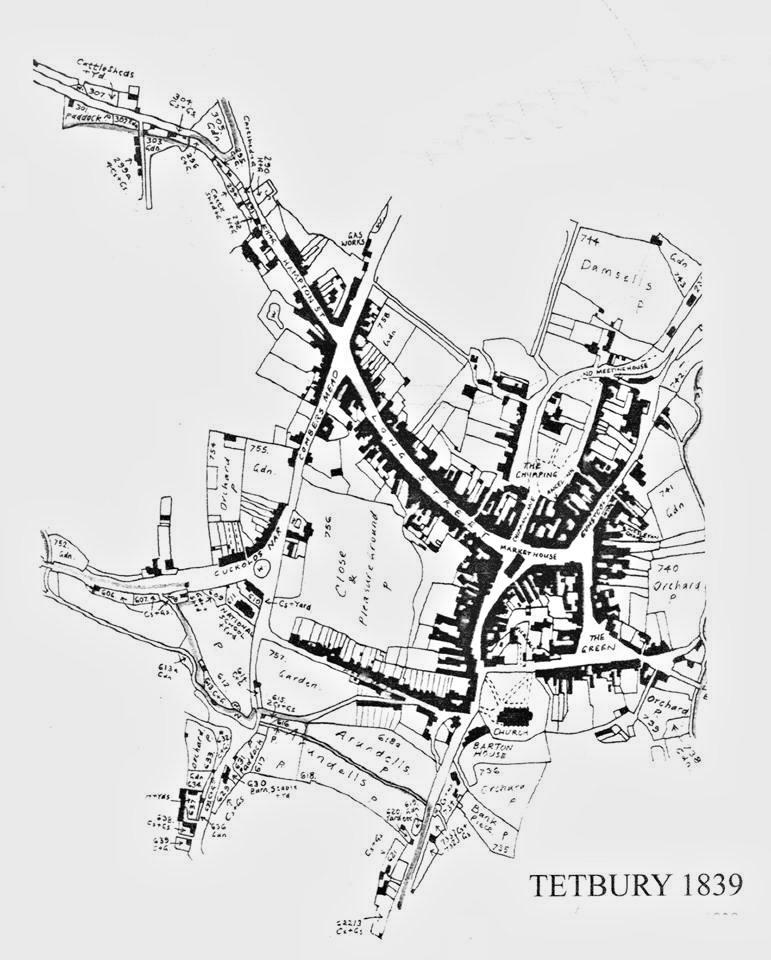

Brownings of Tetbury

Isaac Browning (1784-1848) married Mary Lock (1787-1870) in Tetbury in 1806. Both of them were born in Tetbury, Gloucestershire. Isaac was a stone mason. Between 1807 and 1832 they baptised fourteen children in Tetbury, and on 8 Nov 1829 Isaac and Mary baptised five daughters all on the same day.

I considered that they may have been quintuplets, with only the last born surviving, which would have answered my question about the name of the house La Quinta in Broadway, the home of Eliza Browning and Thomas Stokes son Fred. However, the other four daughters were found in various records and they were not all born the same year. (So I still don’t know why the house in Broadway had such an unusual name).